User login

Is there a time limit for systemic menopausal hormone therapy?

The duration of hormone therapy needs to be an individualized decision, shared between the patient and her physician and assessed annually. Quality of life, vasomotor symptoms, current age, time since menopause, hysterectomy status, personal risks (of osteoporosis, breast cancer, heart disease, stroke, venous thromboembolism), and patient preferences need to be considered.

The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) and other organizations recommend that the lowest dose of hormone therapy be used for the shortest duration needed to manage menopausal symptoms.1–4 However, NAMS states that extending the duration of hormone therapy may be appropriate in women who have persistent symptoms or to prevent osteoporosis if the patient cannot tolerate alternative therapies.1

Forty-two percent of postmenopausal women continue to experience vasomotor symptoms at age 60 to 65.5 The median total duration of vasomotor symptoms is 7.4 years, and in black women and women with moderate or severe hot flashes the symptoms typically last 10 years.6 Vasomotor symptoms recur in 50% of women who discontinue hormone therapy, regardless of whether it is stopped abruptly or tapered.1

FACTORS TO CONSIDER WHEN PRESCRIBING HORMONE THERAPY

Bone health

A statement issued in 2013 by seven medical societies said that hormone therapy is effective and appropriate for preventing osteoporosis-related fracture in at-risk women under age 60 or within 10 years of menopause.7

The Women’s Health Initiative,8 a randomized placebo-controlled trial, showed a statistically significant lower risk of vertebral and nonvertebral fracture after 3 years of use of conjugated equine estrogen with medroxyprogesterone acetate than with placebo:

- Hazard ratio 0.76, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.69–0.83.

It also showed a mean increase of 3.7% (P < .001) in total hip bone mineral density. By the end of the trial intervention, women receiving either this combined therapy or conjugated equine estrogen alone saw a 33% overall reduction in hip fracture risk. The absolute risk reduction was 5 per 10,000 years of use.9

Karim et al,10 in a large observational study that followed initial hormone therapy users over 6.5 years, found that those who stopped it had a 55% greater risk of hip fracture and experienced significant bone loss as measured by bone mineral density compared with women who continued hormone therapy, and that the protective effects of hormone therapy disappeared as early as 2 years after stopping treatment.10

NAMS also recommends that women with premature menopause (before age 40) be offered and encouraged to use hormone therapy to preserve bone density and manage vasomotor symptoms until the age of natural menopause (age 51).1,11

Cardiovascular health

Large observational studies have found that hormone therapy is associated with a 30% to 50% lower cardiovascular risk.12 Randomized controlled trials of hormone therapy for 7 to 11 years suggest that coronary heart disease risk is modified by age and time since menopause.13,14

The Women’s Health Initiative and other randomized controlled trials suggest a lower risk of coronary heart disease in women who begin hormone therapy before age 60 and within 10 years of the onset of menopause, but an increased risk for women over age 60 and more than 10 years since menopause. However, several of these trends have not reached statistical significance (Table 1).13–15

The Women’s Health Initiative9 published its long-term follow-up results in 2013, with data on both the intervention phase (median of 7.2 years for estrogen-only therapy and 5.6 years for estrogen-progestin therapy) and the post-stopping phase (median 6.6 years for the estrogen-only group and 8.2 years for the estrogen-progestin group), with a total cumulative follow-up of 13 years. The overall 13-year cumulative absolute risk of coronary heart disease was 4 fewer events per 10,000 years of estrogen-only therapy and 3 additional events per 10,000 years of estrogen-progestin therapy. Neither result was statistically significant:

- Hazard ratio with estrogen-only use 0.94, 95% CI 0.82–1.09

- Hazard ratio with estrogen-progestin use 1.09, 95% CI 0.92–1.24.

The Danish Osteoporosis Study was the first randomized controlled trial of hormone therapy in women ages 45 through 58 who were recently menopausal (average within 7 months of menopause).15 Women assigned to hormone therapy in the form of oral estradiol with or without norethisterone (known as norethindrone in the United States) had a statistically significant lower risk of the primary composite end point of heart failure and myocardial infarction after 11 years of hormone therapy, and this finding persisted through 16 years of follow-up (Table 1).

Stroke

Overall stroke risk was significantly increased with hormone therapy in the Women’s Health Initiative trial (hazard ratio 1.32, 95% CI 1.12–1.56); however, the absolute increase in risk was small in both estrogen-alone and estrogen-progestin therapy users, 11 and 8 events, respectively, among 10,000 users. Younger women (ages 50–59) saw a nonsignificantly lower risk (2 fewer cases per 10,000 years of use).14 After 13 years of cumulative follow-up (combined intervention and follow-up phase), the risk of stroke persisted at 5 cases per 10,000 users for both arms, but only the estrogen-progestin results were statistically significant.9

The Danish Osteoporosis Study15 found no increased risk of stroke after 16 years of follow-up in recently menopausal women:

- Hazard ratio 0.89, 95% CI 0.48–1.65.

Venous thromboembolism

Data from both observational and randomized controlled trials demonstrate an increased risk of venous thromboembolism with oral hormone therapy, and the risk appears to be highest during the first few years of use.1 The pooled cohort from the Women’s Health Initiative had 18 additional cases of venous thromboembolism per 10,000 women in estrogen-progestin users compared with nonusers, and 7 additional cases in those using estrogen-only therapy.

Breast health

Observational studies and randomized controlled trials have provided data on longer use of hormone therapy and breast cancer risk, but the true magnitude of this risk is unclear.

The Danish Osteoporosis Study,15 in a younger cohort of women, showed no increased risk of breast cancer after 16 years of follow-up:

- Hazard ratio 0.90, 95% CI 0.52–1.57.

The Women’s Health Initiative9 showed a statistically nonsignificant lower risk of breast cancer in women of all ages exposed to conjugated equine estrogen alone for 7.1 years (6 fewer cases per 10,000 women-years of use), and after 6 years of follow-up this developed statistical significance:

- Hazard ratio 0.79, 95% CI 0.65–0.97.

In contrast, those using conjugated equine estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate had a statistically nonsignificant increase in the risk of new breast cancer after 3 to 5 years:

- 3-year relative risk 1.26, 95% CI 0.73–2.20

- 5-year relative risk 1.99, 95% CI 1.18–3.35

- Absolute risk 8 cases per 10,000 women-years of use.

The increased risk of breast cancer significantly declined within 3 years after stopping hormone therapy.

However, even after stopping hormone therapy, there remains a statistically small but significant increased risk of breast cancer, as demonstrated in the postintervention 13-year follow-up data on breast cancer risk and estrogen-progestin use from the Women’s Health Initiative9:

- Hazard ratio 1.28, 95% CI 1.11–1.48

- Absolute cumulative risk 9 cases per 10,000 women-years of use.

The Nurses’ Health Study, an observational study, prospectively followed 11,508 hysterectomized women on estrogen therapy and found that breast cancer risk increased with longer duration of use. An analysis by Chen et al16 found a trend toward increased breast cancer risk after 10 years of estrogen therapy, but this did not become statistically significant until 20 years of ongoing estrogen use. The risk of estrogen receptor-positive and progesterone receptor-positive breast cancer became statistically significant earlier, after 15 years. The relative risk associated with using estrogen for more than 15 years was 1.18, and the risk with using it for more than 20 years was 1.42.16

To put this in perspective, Chen et al17 found a similar breast cancer risk with alcohol consumption. The relative risk of invasive breast cancer was 1.15 in women who drank 3 to 6 servings of alcohol per week, 1 serving being equivalent to 4 oz of wine, which contains 11 g of alcohol.

Mortality

Studies have suggested that hormone therapy users have a lower mortality rate, even with long-term use.

A meta-analysis18 of 8 observational trials and 19 randomized controlled trials found that younger women (average age 54) on hormone therapy had a 28% lower total mortality rate compared with women not taking hormone therapy:

- Relative risk 0.72, 95% credible interval 0.62–0.82.

The Women’s Health Initiative19 suggested that the mortality rate was 30% lower in hormone therapy users younger than age 60 than in similar nonusers, though this difference did not reach statistical significance.

- Relative risk with estrogen-only therapy: 0.71, 95% CI 0.46–1.11

- Relative risk with combined estrogen-progestin therapy 0.69, 95% CI 0.44–1.07.

The Danish Osteoporosis Study,15 at 16 years of follow-up, similarly demonstrated a 34% lower mortality rate in hormone therapy users, which was not statistically significant:

- Relative risk 0.66, 95% CI 0.41–1.08.

A Cochrane review20 in 2015 found that the subgroup of women who started hormone therapy before age 60 or within 10 years of menopause saw an overall benefit in terms of survival and lower risk of coronary heart disease: RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.52–0.95 (moderate-quality evidence).

TYPE OF FORMULATION

Compared with estrogen-progestin therapy, estrogen-only therapy has a more favorable risk profile in terms of coronary heart disease and breast cancer, although stroke risk remains elevated in users of conjugated equine estrogen with or without medroxyprogesterone acetate.

There is limited evidence directly comparing different formulations of hormone therapy, although they all effectively treat vasomotor symptoms.1

Oral vs transdermal formulations

Canonico et al,21 in a meta-analysis of observational studies, found that oral estrogen was associated with a higher risk of venous thromboembolism than transdermal estrogen:

- Relative risk with oral estrogen 2.5, 95% CI 1.9–3.4

- Relative risk with transdermal estrogen 1.2, 95% CI 0.9–1.7.

The Estrogen and Thromboembolism Risk (ESTHER) study22 was a multicenter case-control study of women ages 45 to 70 that assessed risk of venous thromboembolism in oral vs transdermal estrogen users. Compared with women not taking hormone therapy, current users of oral estrogen had a significantly higher risk of venous thromboembolism, while transdermal estrogen users did not:

- Odds ratio with oral estrogen 4.2, 95% CI 1.5–11.6

- Odds ratio with transdermal estrogen 0.9, 95% CI 0.4–2.1.

The Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS)23 did not support these findings. This 4-year randomized controlled trial, published in 2014, was designed to assess the risk of atherosclerosis progression with early menopause initiation of placebo vs low-dose oral hormone therapy (conjugated equine estrogen 0.45 mg daily with cyclical micronized progesterone) or transdermal hormone therapy (estradiol 50 µg/week with cyclical micronized progesterone).

In the 727 women in the study, there was one transient ischemic attack in the oral hormone therapy group, one unconfirmed stroke in the transdermal hormone therapy group, and one case of venous thromboembolism in each group, findings that were underpowered for statistical significance. Both oral and transdermal hormonal therapy had neutral effects on atherosclerosis progression, as assessed by arterial imaging. Transdermal hormone therapy was associated with improvements in markers of insulin resistance and was not associated with an increase in triglycerides, C-reactive protein, or sex hormone-binding globulin, as would be expected with transdermal circumvention of the first-pass hepatic effect.

BALANCING THE RISKS AND BENEFITS FOR THE PATIENT

The most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms in women at any age is hormone therapy, and the benefits are more likely to outweigh risks when initiated before age 60 or within 10 years of menopause.7 The Women’s Health Initiative randomized study was limited to 5.6 to 7.2 years of hormone therapy (13 years of cumulative follow-up), and the Danish Osteoporosis Study was limited to 11 years of use (16 years cumulative follow-up).

The coronary heart disease outcomes for longer durations of therapy remain uncertain. There is a small but statistically significant increased risk of stroke and venous thromboembolism with oral hormone therapy, and breast cancer risk is associated with long-term estrogen-progestin use.

Patients on hormone therapy should be evaluated annually regarding the need for ongoing therapy. Persistent moderate-severe vasomotor symptoms, quality of life benefits of hormone therapy, contraindications to its use (Table 2), and patient preference need to be assessed as well as baseline risks of cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, and fracture.

Risk calculators may facilitate the shared decision-making process. Examples are:

- The American College of Cardiology/American Heart association risk calculator for cardiovascular disease24 (www.cvriskcalculator.com)

- The World Health Organization Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX)25

(www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.jsp)

- The Gail model for breast cancer risk26 (www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool/).

- MenoPro, a menopause decision-support algorithm and companion mobile app developed by NAMS to help direct treatment decisions based on the 10-year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (www.menopause.org/for-professionals/-i-menopro-i-mobile-app).27

The discussion of the risks of hormone therapy with patients should incorporate the perspective of absolute risk. For example, a woman wishing to continue estrogen-progestin therapy should be told that the Women’s Health Initiative data suggest that, after 5 years of use, breast cancer risk may be increased by 8 additional cases per 10,000 users per year. According to the World Health Organization, this magnitude of risk is defined as rare (less than 1 event per 1,000 women).28

A strategy of prescribing the lowest dose to achieve the desired clinical benefits is prudent and recommended.1–3 Table 3 outlines the estrogen formulations now available in the United States, with their doses and formulations.

Unless contraindications develop (Table 2), patients may elect to continue hormone therapy if its benefits outweigh its risks. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 2014 practice recommendations for management of menopausal symptoms31 and the 2015 NAMS statement both recommend that hormone therapy not be discontinued based solely on a woman’s age.29

Hormone therapy is on the Beer’s list of potentially inappropriate medications for older adults,30 which remains a hurdle to its long-term use and seems to be at odds with these ACOG and NAMS statements.

Patients who choose to discontinue hormone therapy need to be monitored for persistent bothersome vasomotor symptoms, bone loss, osteoporosis, and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (previously referred to as vulvovaginal atrophy)31 and offered alternative therapies if needed.

- North American Menopause Society. The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of: The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2012; 19:257–271.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 141: Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol 2014; 123:202–216.

- Stuenkel CA, Davis SR, Gompel A, et al. Treatment of symptoms of the menopause: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100:3975–4011.

- de Villiers TJ, Pines A, Panay N, et al; International Menopause Society. Updated 2013 International Menopause Society recommendations on menopausal hormone therapy and preventive strategies for midlife health. Climacteric 2013; 16:316–337.

- Gartoulla P, Worsley R, Robin J, Davis S. Moderate to severe vasomotor and sexual symptoms remain problematic for women aged 60 to 65 years. Menopause 2015; 22:694–701.

- Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, et al. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms across the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:531–539.

- de Villiers TJ, Gass ML, Haines CJ, et al. Global consensus statement on menopausal hormone therapy. Climacteric 2013; 16:203–204.

- Cauley J, Robbins J, Chen Z, et al. Effects of estrogen plus progestin on risk of fracture and bone mineral density: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trial. JAMA 2003; 290:1729–1738.

- Manson J, Chlebowski R, Stefanick M, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA 2013; 310:1353–1368.

- Karim R, Dell RM, Greene DF, et al. Hip fracture in postmenopausal women after cessation of hormone therapy: results from a prospective study in a large health management organization. Menopause 2011; 18:1172–1177.

- Shifren J, Gass M, and the NAMS Recommendations for Clinical Care of Midlife Women Working Group. The North American Menopause Society recommendations for clinical care of midlife women. Menopause 2014; 21:1038–1062.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ. Hormone replacement therapy and the association with coronary heart disease and overall mortality: clinical application of the timing hypothesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2014; 142:68–75.

- Salpeter SR, Walsh JM, Greyber E, et al. Brief report: coronary heart disease events associated with hormone therapy in younger and older women. A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2006; 21:363–366.

- Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. JAMA 2007; 297:1465–1477.

- Schierbeck LL, Rejnmark L, Tofteng CL, et al. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on cardiovascular events in recently postmenopausal women: randomised trial. BMJ 2012; 345:e6409.

- Chen WY, Manson JE, Hankinson SE, et al. Unopposed estrogen therapy and the risk of breast cancer. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:1027–1032.

- Chen W, Rosner B, Hankinson SE, et al. Moderate alcohol consumption during adult life, drinking patterns, and breast cancer risk. JAMA 2011; 306:1884–1890.

- Salpeter SR, Cheng J, Thabane L, et al. Bayesian meta-analysis of hormone therapy and mortality in younger postmenopausal women. Am J Med 2009; 122:1016–1022.

- Hodis HN, Collins P, Mack WJ, Schierbeck LL. The timing hypothesis for coronary heart disease prevention with hormone therapy: past, present and future in perspective. Climacteric 2012; 15:217–228.

- Boardman HM, Hartley L, Eisinga A, et al. Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;3:CD002229.

- Canonico M, Plu-Bureau G, Lowe GD, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: systemic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2008; 336:1227–1231.

- Canonico M, Oger E, Plu-Bureau G, et al; Estrogen and Thromboembolism Risk (ESTHER) Study Group. Hormone therapy and venous thromboembolism among postmenopausal women: impact of the route of estrogen administration and progestogens: the ESTHER study. Circulation 2007; 115:840–845.

- Harman S, Black D, Naftolin F, et al. Arterial imaging outcomes and cardiovascular risk factors in recently menopausal women. Ann Intern Med 2014; 161:249–260.

- Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63:2935–2959.

- World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases. FRAX WHO fracture risk assessment tool. www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/. Accessed May 27, 2016.

- Gail M, Brinton L, Byar D, et al. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst 1989; 81:1879–1886.

- Manson J, Ames J, Shapiro M, et al. Algorithm and mobile app for menopausal symptom management and hormonal/non-hormonal therapy decision making: a clinical decision-support tool from the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2015; 22:247–253.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ. Postmenopausal hormone therapy in clinical perspective. Menopause 2007; 14:944–957.

- North American Menopause Society. The North American Menopause Society statement on continuing use of systemic hormone therapy after the age of 65. Menopause 2015; 22:693.

- American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63:2227–2246.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML; Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2014; 21:1063–1068.

The duration of hormone therapy needs to be an individualized decision, shared between the patient and her physician and assessed annually. Quality of life, vasomotor symptoms, current age, time since menopause, hysterectomy status, personal risks (of osteoporosis, breast cancer, heart disease, stroke, venous thromboembolism), and patient preferences need to be considered.

The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) and other organizations recommend that the lowest dose of hormone therapy be used for the shortest duration needed to manage menopausal symptoms.1–4 However, NAMS states that extending the duration of hormone therapy may be appropriate in women who have persistent symptoms or to prevent osteoporosis if the patient cannot tolerate alternative therapies.1

Forty-two percent of postmenopausal women continue to experience vasomotor symptoms at age 60 to 65.5 The median total duration of vasomotor symptoms is 7.4 years, and in black women and women with moderate or severe hot flashes the symptoms typically last 10 years.6 Vasomotor symptoms recur in 50% of women who discontinue hormone therapy, regardless of whether it is stopped abruptly or tapered.1

FACTORS TO CONSIDER WHEN PRESCRIBING HORMONE THERAPY

Bone health

A statement issued in 2013 by seven medical societies said that hormone therapy is effective and appropriate for preventing osteoporosis-related fracture in at-risk women under age 60 or within 10 years of menopause.7

The Women’s Health Initiative,8 a randomized placebo-controlled trial, showed a statistically significant lower risk of vertebral and nonvertebral fracture after 3 years of use of conjugated equine estrogen with medroxyprogesterone acetate than with placebo:

- Hazard ratio 0.76, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.69–0.83.

It also showed a mean increase of 3.7% (P < .001) in total hip bone mineral density. By the end of the trial intervention, women receiving either this combined therapy or conjugated equine estrogen alone saw a 33% overall reduction in hip fracture risk. The absolute risk reduction was 5 per 10,000 years of use.9

Karim et al,10 in a large observational study that followed initial hormone therapy users over 6.5 years, found that those who stopped it had a 55% greater risk of hip fracture and experienced significant bone loss as measured by bone mineral density compared with women who continued hormone therapy, and that the protective effects of hormone therapy disappeared as early as 2 years after stopping treatment.10

NAMS also recommends that women with premature menopause (before age 40) be offered and encouraged to use hormone therapy to preserve bone density and manage vasomotor symptoms until the age of natural menopause (age 51).1,11

Cardiovascular health

Large observational studies have found that hormone therapy is associated with a 30% to 50% lower cardiovascular risk.12 Randomized controlled trials of hormone therapy for 7 to 11 years suggest that coronary heart disease risk is modified by age and time since menopause.13,14

The Women’s Health Initiative and other randomized controlled trials suggest a lower risk of coronary heart disease in women who begin hormone therapy before age 60 and within 10 years of the onset of menopause, but an increased risk for women over age 60 and more than 10 years since menopause. However, several of these trends have not reached statistical significance (Table 1).13–15

The Women’s Health Initiative9 published its long-term follow-up results in 2013, with data on both the intervention phase (median of 7.2 years for estrogen-only therapy and 5.6 years for estrogen-progestin therapy) and the post-stopping phase (median 6.6 years for the estrogen-only group and 8.2 years for the estrogen-progestin group), with a total cumulative follow-up of 13 years. The overall 13-year cumulative absolute risk of coronary heart disease was 4 fewer events per 10,000 years of estrogen-only therapy and 3 additional events per 10,000 years of estrogen-progestin therapy. Neither result was statistically significant:

- Hazard ratio with estrogen-only use 0.94, 95% CI 0.82–1.09

- Hazard ratio with estrogen-progestin use 1.09, 95% CI 0.92–1.24.

The Danish Osteoporosis Study was the first randomized controlled trial of hormone therapy in women ages 45 through 58 who were recently menopausal (average within 7 months of menopause).15 Women assigned to hormone therapy in the form of oral estradiol with or without norethisterone (known as norethindrone in the United States) had a statistically significant lower risk of the primary composite end point of heart failure and myocardial infarction after 11 years of hormone therapy, and this finding persisted through 16 years of follow-up (Table 1).

Stroke

Overall stroke risk was significantly increased with hormone therapy in the Women’s Health Initiative trial (hazard ratio 1.32, 95% CI 1.12–1.56); however, the absolute increase in risk was small in both estrogen-alone and estrogen-progestin therapy users, 11 and 8 events, respectively, among 10,000 users. Younger women (ages 50–59) saw a nonsignificantly lower risk (2 fewer cases per 10,000 years of use).14 After 13 years of cumulative follow-up (combined intervention and follow-up phase), the risk of stroke persisted at 5 cases per 10,000 users for both arms, but only the estrogen-progestin results were statistically significant.9

The Danish Osteoporosis Study15 found no increased risk of stroke after 16 years of follow-up in recently menopausal women:

- Hazard ratio 0.89, 95% CI 0.48–1.65.

Venous thromboembolism

Data from both observational and randomized controlled trials demonstrate an increased risk of venous thromboembolism with oral hormone therapy, and the risk appears to be highest during the first few years of use.1 The pooled cohort from the Women’s Health Initiative had 18 additional cases of venous thromboembolism per 10,000 women in estrogen-progestin users compared with nonusers, and 7 additional cases in those using estrogen-only therapy.

Breast health

Observational studies and randomized controlled trials have provided data on longer use of hormone therapy and breast cancer risk, but the true magnitude of this risk is unclear.

The Danish Osteoporosis Study,15 in a younger cohort of women, showed no increased risk of breast cancer after 16 years of follow-up:

- Hazard ratio 0.90, 95% CI 0.52–1.57.

The Women’s Health Initiative9 showed a statistically nonsignificant lower risk of breast cancer in women of all ages exposed to conjugated equine estrogen alone for 7.1 years (6 fewer cases per 10,000 women-years of use), and after 6 years of follow-up this developed statistical significance:

- Hazard ratio 0.79, 95% CI 0.65–0.97.

In contrast, those using conjugated equine estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate had a statistically nonsignificant increase in the risk of new breast cancer after 3 to 5 years:

- 3-year relative risk 1.26, 95% CI 0.73–2.20

- 5-year relative risk 1.99, 95% CI 1.18–3.35

- Absolute risk 8 cases per 10,000 women-years of use.

The increased risk of breast cancer significantly declined within 3 years after stopping hormone therapy.

However, even after stopping hormone therapy, there remains a statistically small but significant increased risk of breast cancer, as demonstrated in the postintervention 13-year follow-up data on breast cancer risk and estrogen-progestin use from the Women’s Health Initiative9:

- Hazard ratio 1.28, 95% CI 1.11–1.48

- Absolute cumulative risk 9 cases per 10,000 women-years of use.

The Nurses’ Health Study, an observational study, prospectively followed 11,508 hysterectomized women on estrogen therapy and found that breast cancer risk increased with longer duration of use. An analysis by Chen et al16 found a trend toward increased breast cancer risk after 10 years of estrogen therapy, but this did not become statistically significant until 20 years of ongoing estrogen use. The risk of estrogen receptor-positive and progesterone receptor-positive breast cancer became statistically significant earlier, after 15 years. The relative risk associated with using estrogen for more than 15 years was 1.18, and the risk with using it for more than 20 years was 1.42.16

To put this in perspective, Chen et al17 found a similar breast cancer risk with alcohol consumption. The relative risk of invasive breast cancer was 1.15 in women who drank 3 to 6 servings of alcohol per week, 1 serving being equivalent to 4 oz of wine, which contains 11 g of alcohol.

Mortality

Studies have suggested that hormone therapy users have a lower mortality rate, even with long-term use.

A meta-analysis18 of 8 observational trials and 19 randomized controlled trials found that younger women (average age 54) on hormone therapy had a 28% lower total mortality rate compared with women not taking hormone therapy:

- Relative risk 0.72, 95% credible interval 0.62–0.82.

The Women’s Health Initiative19 suggested that the mortality rate was 30% lower in hormone therapy users younger than age 60 than in similar nonusers, though this difference did not reach statistical significance.

- Relative risk with estrogen-only therapy: 0.71, 95% CI 0.46–1.11

- Relative risk with combined estrogen-progestin therapy 0.69, 95% CI 0.44–1.07.

The Danish Osteoporosis Study,15 at 16 years of follow-up, similarly demonstrated a 34% lower mortality rate in hormone therapy users, which was not statistically significant:

- Relative risk 0.66, 95% CI 0.41–1.08.

A Cochrane review20 in 2015 found that the subgroup of women who started hormone therapy before age 60 or within 10 years of menopause saw an overall benefit in terms of survival and lower risk of coronary heart disease: RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.52–0.95 (moderate-quality evidence).

TYPE OF FORMULATION

Compared with estrogen-progestin therapy, estrogen-only therapy has a more favorable risk profile in terms of coronary heart disease and breast cancer, although stroke risk remains elevated in users of conjugated equine estrogen with or without medroxyprogesterone acetate.

There is limited evidence directly comparing different formulations of hormone therapy, although they all effectively treat vasomotor symptoms.1

Oral vs transdermal formulations

Canonico et al,21 in a meta-analysis of observational studies, found that oral estrogen was associated with a higher risk of venous thromboembolism than transdermal estrogen:

- Relative risk with oral estrogen 2.5, 95% CI 1.9–3.4

- Relative risk with transdermal estrogen 1.2, 95% CI 0.9–1.7.

The Estrogen and Thromboembolism Risk (ESTHER) study22 was a multicenter case-control study of women ages 45 to 70 that assessed risk of venous thromboembolism in oral vs transdermal estrogen users. Compared with women not taking hormone therapy, current users of oral estrogen had a significantly higher risk of venous thromboembolism, while transdermal estrogen users did not:

- Odds ratio with oral estrogen 4.2, 95% CI 1.5–11.6

- Odds ratio with transdermal estrogen 0.9, 95% CI 0.4–2.1.

The Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS)23 did not support these findings. This 4-year randomized controlled trial, published in 2014, was designed to assess the risk of atherosclerosis progression with early menopause initiation of placebo vs low-dose oral hormone therapy (conjugated equine estrogen 0.45 mg daily with cyclical micronized progesterone) or transdermal hormone therapy (estradiol 50 µg/week with cyclical micronized progesterone).

In the 727 women in the study, there was one transient ischemic attack in the oral hormone therapy group, one unconfirmed stroke in the transdermal hormone therapy group, and one case of venous thromboembolism in each group, findings that were underpowered for statistical significance. Both oral and transdermal hormonal therapy had neutral effects on atherosclerosis progression, as assessed by arterial imaging. Transdermal hormone therapy was associated with improvements in markers of insulin resistance and was not associated with an increase in triglycerides, C-reactive protein, or sex hormone-binding globulin, as would be expected with transdermal circumvention of the first-pass hepatic effect.

BALANCING THE RISKS AND BENEFITS FOR THE PATIENT

The most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms in women at any age is hormone therapy, and the benefits are more likely to outweigh risks when initiated before age 60 or within 10 years of menopause.7 The Women’s Health Initiative randomized study was limited to 5.6 to 7.2 years of hormone therapy (13 years of cumulative follow-up), and the Danish Osteoporosis Study was limited to 11 years of use (16 years cumulative follow-up).

The coronary heart disease outcomes for longer durations of therapy remain uncertain. There is a small but statistically significant increased risk of stroke and venous thromboembolism with oral hormone therapy, and breast cancer risk is associated with long-term estrogen-progestin use.

Patients on hormone therapy should be evaluated annually regarding the need for ongoing therapy. Persistent moderate-severe vasomotor symptoms, quality of life benefits of hormone therapy, contraindications to its use (Table 2), and patient preference need to be assessed as well as baseline risks of cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, and fracture.

Risk calculators may facilitate the shared decision-making process. Examples are:

- The American College of Cardiology/American Heart association risk calculator for cardiovascular disease24 (www.cvriskcalculator.com)

- The World Health Organization Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX)25

(www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.jsp)

- The Gail model for breast cancer risk26 (www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool/).

- MenoPro, a menopause decision-support algorithm and companion mobile app developed by NAMS to help direct treatment decisions based on the 10-year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (www.menopause.org/for-professionals/-i-menopro-i-mobile-app).27

The discussion of the risks of hormone therapy with patients should incorporate the perspective of absolute risk. For example, a woman wishing to continue estrogen-progestin therapy should be told that the Women’s Health Initiative data suggest that, after 5 years of use, breast cancer risk may be increased by 8 additional cases per 10,000 users per year. According to the World Health Organization, this magnitude of risk is defined as rare (less than 1 event per 1,000 women).28

A strategy of prescribing the lowest dose to achieve the desired clinical benefits is prudent and recommended.1–3 Table 3 outlines the estrogen formulations now available in the United States, with their doses and formulations.

Unless contraindications develop (Table 2), patients may elect to continue hormone therapy if its benefits outweigh its risks. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 2014 practice recommendations for management of menopausal symptoms31 and the 2015 NAMS statement both recommend that hormone therapy not be discontinued based solely on a woman’s age.29

Hormone therapy is on the Beer’s list of potentially inappropriate medications for older adults,30 which remains a hurdle to its long-term use and seems to be at odds with these ACOG and NAMS statements.

Patients who choose to discontinue hormone therapy need to be monitored for persistent bothersome vasomotor symptoms, bone loss, osteoporosis, and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (previously referred to as vulvovaginal atrophy)31 and offered alternative therapies if needed.

The duration of hormone therapy needs to be an individualized decision, shared between the patient and her physician and assessed annually. Quality of life, vasomotor symptoms, current age, time since menopause, hysterectomy status, personal risks (of osteoporosis, breast cancer, heart disease, stroke, venous thromboembolism), and patient preferences need to be considered.

The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) and other organizations recommend that the lowest dose of hormone therapy be used for the shortest duration needed to manage menopausal symptoms.1–4 However, NAMS states that extending the duration of hormone therapy may be appropriate in women who have persistent symptoms or to prevent osteoporosis if the patient cannot tolerate alternative therapies.1

Forty-two percent of postmenopausal women continue to experience vasomotor symptoms at age 60 to 65.5 The median total duration of vasomotor symptoms is 7.4 years, and in black women and women with moderate or severe hot flashes the symptoms typically last 10 years.6 Vasomotor symptoms recur in 50% of women who discontinue hormone therapy, regardless of whether it is stopped abruptly or tapered.1

FACTORS TO CONSIDER WHEN PRESCRIBING HORMONE THERAPY

Bone health

A statement issued in 2013 by seven medical societies said that hormone therapy is effective and appropriate for preventing osteoporosis-related fracture in at-risk women under age 60 or within 10 years of menopause.7

The Women’s Health Initiative,8 a randomized placebo-controlled trial, showed a statistically significant lower risk of vertebral and nonvertebral fracture after 3 years of use of conjugated equine estrogen with medroxyprogesterone acetate than with placebo:

- Hazard ratio 0.76, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.69–0.83.

It also showed a mean increase of 3.7% (P < .001) in total hip bone mineral density. By the end of the trial intervention, women receiving either this combined therapy or conjugated equine estrogen alone saw a 33% overall reduction in hip fracture risk. The absolute risk reduction was 5 per 10,000 years of use.9

Karim et al,10 in a large observational study that followed initial hormone therapy users over 6.5 years, found that those who stopped it had a 55% greater risk of hip fracture and experienced significant bone loss as measured by bone mineral density compared with women who continued hormone therapy, and that the protective effects of hormone therapy disappeared as early as 2 years after stopping treatment.10

NAMS also recommends that women with premature menopause (before age 40) be offered and encouraged to use hormone therapy to preserve bone density and manage vasomotor symptoms until the age of natural menopause (age 51).1,11

Cardiovascular health

Large observational studies have found that hormone therapy is associated with a 30% to 50% lower cardiovascular risk.12 Randomized controlled trials of hormone therapy for 7 to 11 years suggest that coronary heart disease risk is modified by age and time since menopause.13,14

The Women’s Health Initiative and other randomized controlled trials suggest a lower risk of coronary heart disease in women who begin hormone therapy before age 60 and within 10 years of the onset of menopause, but an increased risk for women over age 60 and more than 10 years since menopause. However, several of these trends have not reached statistical significance (Table 1).13–15

The Women’s Health Initiative9 published its long-term follow-up results in 2013, with data on both the intervention phase (median of 7.2 years for estrogen-only therapy and 5.6 years for estrogen-progestin therapy) and the post-stopping phase (median 6.6 years for the estrogen-only group and 8.2 years for the estrogen-progestin group), with a total cumulative follow-up of 13 years. The overall 13-year cumulative absolute risk of coronary heart disease was 4 fewer events per 10,000 years of estrogen-only therapy and 3 additional events per 10,000 years of estrogen-progestin therapy. Neither result was statistically significant:

- Hazard ratio with estrogen-only use 0.94, 95% CI 0.82–1.09

- Hazard ratio with estrogen-progestin use 1.09, 95% CI 0.92–1.24.

The Danish Osteoporosis Study was the first randomized controlled trial of hormone therapy in women ages 45 through 58 who were recently menopausal (average within 7 months of menopause).15 Women assigned to hormone therapy in the form of oral estradiol with or without norethisterone (known as norethindrone in the United States) had a statistically significant lower risk of the primary composite end point of heart failure and myocardial infarction after 11 years of hormone therapy, and this finding persisted through 16 years of follow-up (Table 1).

Stroke

Overall stroke risk was significantly increased with hormone therapy in the Women’s Health Initiative trial (hazard ratio 1.32, 95% CI 1.12–1.56); however, the absolute increase in risk was small in both estrogen-alone and estrogen-progestin therapy users, 11 and 8 events, respectively, among 10,000 users. Younger women (ages 50–59) saw a nonsignificantly lower risk (2 fewer cases per 10,000 years of use).14 After 13 years of cumulative follow-up (combined intervention and follow-up phase), the risk of stroke persisted at 5 cases per 10,000 users for both arms, but only the estrogen-progestin results were statistically significant.9

The Danish Osteoporosis Study15 found no increased risk of stroke after 16 years of follow-up in recently menopausal women:

- Hazard ratio 0.89, 95% CI 0.48–1.65.

Venous thromboembolism

Data from both observational and randomized controlled trials demonstrate an increased risk of venous thromboembolism with oral hormone therapy, and the risk appears to be highest during the first few years of use.1 The pooled cohort from the Women’s Health Initiative had 18 additional cases of venous thromboembolism per 10,000 women in estrogen-progestin users compared with nonusers, and 7 additional cases in those using estrogen-only therapy.

Breast health

Observational studies and randomized controlled trials have provided data on longer use of hormone therapy and breast cancer risk, but the true magnitude of this risk is unclear.

The Danish Osteoporosis Study,15 in a younger cohort of women, showed no increased risk of breast cancer after 16 years of follow-up:

- Hazard ratio 0.90, 95% CI 0.52–1.57.

The Women’s Health Initiative9 showed a statistically nonsignificant lower risk of breast cancer in women of all ages exposed to conjugated equine estrogen alone for 7.1 years (6 fewer cases per 10,000 women-years of use), and after 6 years of follow-up this developed statistical significance:

- Hazard ratio 0.79, 95% CI 0.65–0.97.

In contrast, those using conjugated equine estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate had a statistically nonsignificant increase in the risk of new breast cancer after 3 to 5 years:

- 3-year relative risk 1.26, 95% CI 0.73–2.20

- 5-year relative risk 1.99, 95% CI 1.18–3.35

- Absolute risk 8 cases per 10,000 women-years of use.

The increased risk of breast cancer significantly declined within 3 years after stopping hormone therapy.

However, even after stopping hormone therapy, there remains a statistically small but significant increased risk of breast cancer, as demonstrated in the postintervention 13-year follow-up data on breast cancer risk and estrogen-progestin use from the Women’s Health Initiative9:

- Hazard ratio 1.28, 95% CI 1.11–1.48

- Absolute cumulative risk 9 cases per 10,000 women-years of use.

The Nurses’ Health Study, an observational study, prospectively followed 11,508 hysterectomized women on estrogen therapy and found that breast cancer risk increased with longer duration of use. An analysis by Chen et al16 found a trend toward increased breast cancer risk after 10 years of estrogen therapy, but this did not become statistically significant until 20 years of ongoing estrogen use. The risk of estrogen receptor-positive and progesterone receptor-positive breast cancer became statistically significant earlier, after 15 years. The relative risk associated with using estrogen for more than 15 years was 1.18, and the risk with using it for more than 20 years was 1.42.16

To put this in perspective, Chen et al17 found a similar breast cancer risk with alcohol consumption. The relative risk of invasive breast cancer was 1.15 in women who drank 3 to 6 servings of alcohol per week, 1 serving being equivalent to 4 oz of wine, which contains 11 g of alcohol.

Mortality

Studies have suggested that hormone therapy users have a lower mortality rate, even with long-term use.

A meta-analysis18 of 8 observational trials and 19 randomized controlled trials found that younger women (average age 54) on hormone therapy had a 28% lower total mortality rate compared with women not taking hormone therapy:

- Relative risk 0.72, 95% credible interval 0.62–0.82.

The Women’s Health Initiative19 suggested that the mortality rate was 30% lower in hormone therapy users younger than age 60 than in similar nonusers, though this difference did not reach statistical significance.

- Relative risk with estrogen-only therapy: 0.71, 95% CI 0.46–1.11

- Relative risk with combined estrogen-progestin therapy 0.69, 95% CI 0.44–1.07.

The Danish Osteoporosis Study,15 at 16 years of follow-up, similarly demonstrated a 34% lower mortality rate in hormone therapy users, which was not statistically significant:

- Relative risk 0.66, 95% CI 0.41–1.08.

A Cochrane review20 in 2015 found that the subgroup of women who started hormone therapy before age 60 or within 10 years of menopause saw an overall benefit in terms of survival and lower risk of coronary heart disease: RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.52–0.95 (moderate-quality evidence).

TYPE OF FORMULATION

Compared with estrogen-progestin therapy, estrogen-only therapy has a more favorable risk profile in terms of coronary heart disease and breast cancer, although stroke risk remains elevated in users of conjugated equine estrogen with or without medroxyprogesterone acetate.

There is limited evidence directly comparing different formulations of hormone therapy, although they all effectively treat vasomotor symptoms.1

Oral vs transdermal formulations

Canonico et al,21 in a meta-analysis of observational studies, found that oral estrogen was associated with a higher risk of venous thromboembolism than transdermal estrogen:

- Relative risk with oral estrogen 2.5, 95% CI 1.9–3.4

- Relative risk with transdermal estrogen 1.2, 95% CI 0.9–1.7.

The Estrogen and Thromboembolism Risk (ESTHER) study22 was a multicenter case-control study of women ages 45 to 70 that assessed risk of venous thromboembolism in oral vs transdermal estrogen users. Compared with women not taking hormone therapy, current users of oral estrogen had a significantly higher risk of venous thromboembolism, while transdermal estrogen users did not:

- Odds ratio with oral estrogen 4.2, 95% CI 1.5–11.6

- Odds ratio with transdermal estrogen 0.9, 95% CI 0.4–2.1.

The Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS)23 did not support these findings. This 4-year randomized controlled trial, published in 2014, was designed to assess the risk of atherosclerosis progression with early menopause initiation of placebo vs low-dose oral hormone therapy (conjugated equine estrogen 0.45 mg daily with cyclical micronized progesterone) or transdermal hormone therapy (estradiol 50 µg/week with cyclical micronized progesterone).

In the 727 women in the study, there was one transient ischemic attack in the oral hormone therapy group, one unconfirmed stroke in the transdermal hormone therapy group, and one case of venous thromboembolism in each group, findings that were underpowered for statistical significance. Both oral and transdermal hormonal therapy had neutral effects on atherosclerosis progression, as assessed by arterial imaging. Transdermal hormone therapy was associated with improvements in markers of insulin resistance and was not associated with an increase in triglycerides, C-reactive protein, or sex hormone-binding globulin, as would be expected with transdermal circumvention of the first-pass hepatic effect.

BALANCING THE RISKS AND BENEFITS FOR THE PATIENT

The most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms in women at any age is hormone therapy, and the benefits are more likely to outweigh risks when initiated before age 60 or within 10 years of menopause.7 The Women’s Health Initiative randomized study was limited to 5.6 to 7.2 years of hormone therapy (13 years of cumulative follow-up), and the Danish Osteoporosis Study was limited to 11 years of use (16 years cumulative follow-up).

The coronary heart disease outcomes for longer durations of therapy remain uncertain. There is a small but statistically significant increased risk of stroke and venous thromboembolism with oral hormone therapy, and breast cancer risk is associated with long-term estrogen-progestin use.

Patients on hormone therapy should be evaluated annually regarding the need for ongoing therapy. Persistent moderate-severe vasomotor symptoms, quality of life benefits of hormone therapy, contraindications to its use (Table 2), and patient preference need to be assessed as well as baseline risks of cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, and fracture.

Risk calculators may facilitate the shared decision-making process. Examples are:

- The American College of Cardiology/American Heart association risk calculator for cardiovascular disease24 (www.cvriskcalculator.com)

- The World Health Organization Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX)25

(www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.jsp)

- The Gail model for breast cancer risk26 (www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool/).

- MenoPro, a menopause decision-support algorithm and companion mobile app developed by NAMS to help direct treatment decisions based on the 10-year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (www.menopause.org/for-professionals/-i-menopro-i-mobile-app).27

The discussion of the risks of hormone therapy with patients should incorporate the perspective of absolute risk. For example, a woman wishing to continue estrogen-progestin therapy should be told that the Women’s Health Initiative data suggest that, after 5 years of use, breast cancer risk may be increased by 8 additional cases per 10,000 users per year. According to the World Health Organization, this magnitude of risk is defined as rare (less than 1 event per 1,000 women).28

A strategy of prescribing the lowest dose to achieve the desired clinical benefits is prudent and recommended.1–3 Table 3 outlines the estrogen formulations now available in the United States, with their doses and formulations.

Unless contraindications develop (Table 2), patients may elect to continue hormone therapy if its benefits outweigh its risks. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 2014 practice recommendations for management of menopausal symptoms31 and the 2015 NAMS statement both recommend that hormone therapy not be discontinued based solely on a woman’s age.29

Hormone therapy is on the Beer’s list of potentially inappropriate medications for older adults,30 which remains a hurdle to its long-term use and seems to be at odds with these ACOG and NAMS statements.

Patients who choose to discontinue hormone therapy need to be monitored for persistent bothersome vasomotor symptoms, bone loss, osteoporosis, and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (previously referred to as vulvovaginal atrophy)31 and offered alternative therapies if needed.

- North American Menopause Society. The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of: The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2012; 19:257–271.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 141: Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol 2014; 123:202–216.

- Stuenkel CA, Davis SR, Gompel A, et al. Treatment of symptoms of the menopause: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100:3975–4011.

- de Villiers TJ, Pines A, Panay N, et al; International Menopause Society. Updated 2013 International Menopause Society recommendations on menopausal hormone therapy and preventive strategies for midlife health. Climacteric 2013; 16:316–337.

- Gartoulla P, Worsley R, Robin J, Davis S. Moderate to severe vasomotor and sexual symptoms remain problematic for women aged 60 to 65 years. Menopause 2015; 22:694–701.

- Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, et al. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms across the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:531–539.

- de Villiers TJ, Gass ML, Haines CJ, et al. Global consensus statement on menopausal hormone therapy. Climacteric 2013; 16:203–204.

- Cauley J, Robbins J, Chen Z, et al. Effects of estrogen plus progestin on risk of fracture and bone mineral density: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trial. JAMA 2003; 290:1729–1738.

- Manson J, Chlebowski R, Stefanick M, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA 2013; 310:1353–1368.

- Karim R, Dell RM, Greene DF, et al. Hip fracture in postmenopausal women after cessation of hormone therapy: results from a prospective study in a large health management organization. Menopause 2011; 18:1172–1177.

- Shifren J, Gass M, and the NAMS Recommendations for Clinical Care of Midlife Women Working Group. The North American Menopause Society recommendations for clinical care of midlife women. Menopause 2014; 21:1038–1062.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ. Hormone replacement therapy and the association with coronary heart disease and overall mortality: clinical application of the timing hypothesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2014; 142:68–75.

- Salpeter SR, Walsh JM, Greyber E, et al. Brief report: coronary heart disease events associated with hormone therapy in younger and older women. A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2006; 21:363–366.

- Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. JAMA 2007; 297:1465–1477.

- Schierbeck LL, Rejnmark L, Tofteng CL, et al. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on cardiovascular events in recently postmenopausal women: randomised trial. BMJ 2012; 345:e6409.

- Chen WY, Manson JE, Hankinson SE, et al. Unopposed estrogen therapy and the risk of breast cancer. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:1027–1032.

- Chen W, Rosner B, Hankinson SE, et al. Moderate alcohol consumption during adult life, drinking patterns, and breast cancer risk. JAMA 2011; 306:1884–1890.

- Salpeter SR, Cheng J, Thabane L, et al. Bayesian meta-analysis of hormone therapy and mortality in younger postmenopausal women. Am J Med 2009; 122:1016–1022.

- Hodis HN, Collins P, Mack WJ, Schierbeck LL. The timing hypothesis for coronary heart disease prevention with hormone therapy: past, present and future in perspective. Climacteric 2012; 15:217–228.

- Boardman HM, Hartley L, Eisinga A, et al. Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;3:CD002229.

- Canonico M, Plu-Bureau G, Lowe GD, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: systemic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2008; 336:1227–1231.

- Canonico M, Oger E, Plu-Bureau G, et al; Estrogen and Thromboembolism Risk (ESTHER) Study Group. Hormone therapy and venous thromboembolism among postmenopausal women: impact of the route of estrogen administration and progestogens: the ESTHER study. Circulation 2007; 115:840–845.

- Harman S, Black D, Naftolin F, et al. Arterial imaging outcomes and cardiovascular risk factors in recently menopausal women. Ann Intern Med 2014; 161:249–260.

- Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63:2935–2959.

- World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases. FRAX WHO fracture risk assessment tool. www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/. Accessed May 27, 2016.

- Gail M, Brinton L, Byar D, et al. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst 1989; 81:1879–1886.

- Manson J, Ames J, Shapiro M, et al. Algorithm and mobile app for menopausal symptom management and hormonal/non-hormonal therapy decision making: a clinical decision-support tool from the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2015; 22:247–253.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ. Postmenopausal hormone therapy in clinical perspective. Menopause 2007; 14:944–957.

- North American Menopause Society. The North American Menopause Society statement on continuing use of systemic hormone therapy after the age of 65. Menopause 2015; 22:693.

- American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63:2227–2246.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML; Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2014; 21:1063–1068.

- North American Menopause Society. The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of: The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2012; 19:257–271.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 141: Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol 2014; 123:202–216.

- Stuenkel CA, Davis SR, Gompel A, et al. Treatment of symptoms of the menopause: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100:3975–4011.

- de Villiers TJ, Pines A, Panay N, et al; International Menopause Society. Updated 2013 International Menopause Society recommendations on menopausal hormone therapy and preventive strategies for midlife health. Climacteric 2013; 16:316–337.

- Gartoulla P, Worsley R, Robin J, Davis S. Moderate to severe vasomotor and sexual symptoms remain problematic for women aged 60 to 65 years. Menopause 2015; 22:694–701.

- Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, et al. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms across the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:531–539.

- de Villiers TJ, Gass ML, Haines CJ, et al. Global consensus statement on menopausal hormone therapy. Climacteric 2013; 16:203–204.

- Cauley J, Robbins J, Chen Z, et al. Effects of estrogen plus progestin on risk of fracture and bone mineral density: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trial. JAMA 2003; 290:1729–1738.

- Manson J, Chlebowski R, Stefanick M, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA 2013; 310:1353–1368.

- Karim R, Dell RM, Greene DF, et al. Hip fracture in postmenopausal women after cessation of hormone therapy: results from a prospective study in a large health management organization. Menopause 2011; 18:1172–1177.

- Shifren J, Gass M, and the NAMS Recommendations for Clinical Care of Midlife Women Working Group. The North American Menopause Society recommendations for clinical care of midlife women. Menopause 2014; 21:1038–1062.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ. Hormone replacement therapy and the association with coronary heart disease and overall mortality: clinical application of the timing hypothesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2014; 142:68–75.

- Salpeter SR, Walsh JM, Greyber E, et al. Brief report: coronary heart disease events associated with hormone therapy in younger and older women. A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2006; 21:363–366.

- Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. JAMA 2007; 297:1465–1477.

- Schierbeck LL, Rejnmark L, Tofteng CL, et al. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on cardiovascular events in recently postmenopausal women: randomised trial. BMJ 2012; 345:e6409.

- Chen WY, Manson JE, Hankinson SE, et al. Unopposed estrogen therapy and the risk of breast cancer. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:1027–1032.

- Chen W, Rosner B, Hankinson SE, et al. Moderate alcohol consumption during adult life, drinking patterns, and breast cancer risk. JAMA 2011; 306:1884–1890.

- Salpeter SR, Cheng J, Thabane L, et al. Bayesian meta-analysis of hormone therapy and mortality in younger postmenopausal women. Am J Med 2009; 122:1016–1022.

- Hodis HN, Collins P, Mack WJ, Schierbeck LL. The timing hypothesis for coronary heart disease prevention with hormone therapy: past, present and future in perspective. Climacteric 2012; 15:217–228.

- Boardman HM, Hartley L, Eisinga A, et al. Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;3:CD002229.

- Canonico M, Plu-Bureau G, Lowe GD, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: systemic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2008; 336:1227–1231.

- Canonico M, Oger E, Plu-Bureau G, et al; Estrogen and Thromboembolism Risk (ESTHER) Study Group. Hormone therapy and venous thromboembolism among postmenopausal women: impact of the route of estrogen administration and progestogens: the ESTHER study. Circulation 2007; 115:840–845.

- Harman S, Black D, Naftolin F, et al. Arterial imaging outcomes and cardiovascular risk factors in recently menopausal women. Ann Intern Med 2014; 161:249–260.

- Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63:2935–2959.

- World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases. FRAX WHO fracture risk assessment tool. www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/. Accessed May 27, 2016.

- Gail M, Brinton L, Byar D, et al. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst 1989; 81:1879–1886.

- Manson J, Ames J, Shapiro M, et al. Algorithm and mobile app for menopausal symptom management and hormonal/non-hormonal therapy decision making: a clinical decision-support tool from the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2015; 22:247–253.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ. Postmenopausal hormone therapy in clinical perspective. Menopause 2007; 14:944–957.

- North American Menopause Society. The North American Menopause Society statement on continuing use of systemic hormone therapy after the age of 65. Menopause 2015; 22:693.

- American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63:2227–2246.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML; Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2014; 21:1063–1068.

KEY POINTS

- Hormone therapy is the most effective treatment available for the vasomotor symptoms of menopause, and it also is effective and appropriate for preventing osteoporosis-related fracture in at-risk women under age 60 or within 10 years of menopause.

- Oral hormone therapy is associated with a small but statistically significant increase in the risk of stroke and venous thromboembolism and breast cancer risk with combination therapy only.

- Extended hormone therapy may be appropriate to treat vasomotor symptoms or prevent osteoporosis when alternative therapies are not an option.

- The decision whether to continue hormone therapy should be revisited every year. Discussions with patients should include the perspective of absolute risk.

Geographic tongue

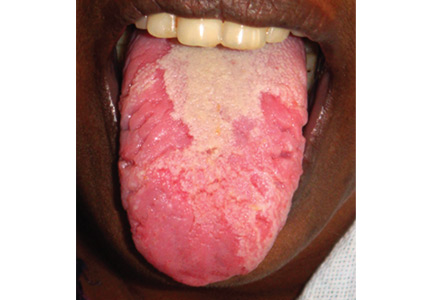

A previously healthy 35-year-old woman presented with reddish discoloration of her tongue for the past 7 days, accompanied by mild soreness over the area when eating spicy foods. The lesion had also changed shape repeatedly. She denied any other local or systemic symptoms.

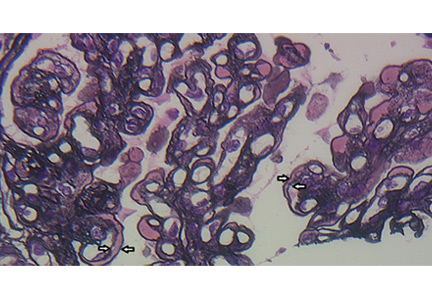

Lingual examination showed clearly delineated areas of shiny, erythematous mucosa on the dorsal and lateral aspects of the tongue, surrounded by white borders (Figure 1). Examination of the throat and oral cavity were unremarkable. All other systemic examinations were normal. Laboratory testing showed a normal hemogram, blood glucose, and metabolic profile.

These findings were suggestive of geographic tongue, a benign, self-limiting inflammation. The patient was reassured of the benign nature of the condition and was advised to avoid spicy food until resolution of the lesion. A follow-up examination 1 month later showed complete healing of the lesion.

A COMMON, BENIGN, SELF-LIMITING MUCOSAL CONDITION

Geographic tongue—also known as benign migratory glossitis and lingual erythema migrans—is commonly seen in daily practice, with a prevalence of 2% to 3% in the general population.1 In the United States, the condition is more prevalent in whites and blacks than in Hispanics, but has no association with age or sex.

This condition is characterized by circinate, maplike areas of erythema surrounded by well-demarcated scalloped white borders, typically on the dorsum and the lateral borders of the tongue.2 The appearance, which represents loss of filiform papillae (depapillation) from the lingual mucosa, can change in size, shape, or location in a matter of minutes or hours. The name “lingual erythema migrans” reflects the changing clinical picture.3 Rarely, the labial or palatal mucosa is affected.

POSTULATED TO BE AN INTRAORAL FORM OF PSORIASIS

The precise etiology remains obscure.2 Histopathologically, geographic tongue is characterized by hyperparakeratosis and acanthosis resembling psoriasis. Hence, it has been postulated that it represents a form of intraoral psoriasis.2,4 The condition is also associated with allergy, stress, diabetes mellitus, and anemia. Triggers include hot, spicy, and acidic foods and alcohol. Contrary to previous belief, geographic tongue has been found to have an inverse association with smoking.5 Although striking, the lesion rarely warrants further investigation.

REASSURANCE IS THE MAIN TREATMENT

Geographic tongue has a remitting and relapsing course with no complications or permanent sequelae.3 The differential diagnosis includes oral candidiasis, leukoplakia, vitamin deficiency glossitis, lichen planus, systemic lupus erythematosus, drug reaction, and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. The condition is differentiated from oral candidiasis by its presence in an otherwise healthy person and by the changing pattern of the lesions over time. Also, candidal pseudomembranes can be easily removed, leaving a painless red base. Evaluations to rule out anemia, nutritional deficiencies, and diabetes mellitus can be done if these conditions are suspected, as they are associated with geographic tongue.

Reassurance is the main treatment. Topical corticosteroids and local anesthetics may provide symptomatic relief in mild forms of the disease. Topical tacrolimus and systemic cyclosporine have been reported as useful in severe cases.6

- Masferrer E, Jucgla A. Images in clinical medicine. Geographic tongue. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:e44.

- Assimakopoulos D, Patrikakos G, Fotika C, Elisaf M. Benign migratory glossitis or geographic tongue: an enigmatic oral lesion. Am J Med 2002; 113:751–755.

- Scully C, Hegarty A. The oral cavity and lips. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:69–100.

- Zargari O. The prevalence and significance of fissured tongue and geographical tongue in psoriatic patients. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006; 31:192–195.

- Shulman JD, Carpenter WM. Prevalence and risk factors associated with geographic tongue among US adults. Oral Dis 2006; 12:381–386.

- Ishibashi M, Tojo G, Watanabe M, Tamabuchi T, Masu T, Aiba S. Geographic tongue treated with topical tacrolimus. J Dermatol Case Rep 2010; 4:57–59.

A previously healthy 35-year-old woman presented with reddish discoloration of her tongue for the past 7 days, accompanied by mild soreness over the area when eating spicy foods. The lesion had also changed shape repeatedly. She denied any other local or systemic symptoms.

Lingual examination showed clearly delineated areas of shiny, erythematous mucosa on the dorsal and lateral aspects of the tongue, surrounded by white borders (Figure 1). Examination of the throat and oral cavity were unremarkable. All other systemic examinations were normal. Laboratory testing showed a normal hemogram, blood glucose, and metabolic profile.

These findings were suggestive of geographic tongue, a benign, self-limiting inflammation. The patient was reassured of the benign nature of the condition and was advised to avoid spicy food until resolution of the lesion. A follow-up examination 1 month later showed complete healing of the lesion.

A COMMON, BENIGN, SELF-LIMITING MUCOSAL CONDITION

Geographic tongue—also known as benign migratory glossitis and lingual erythema migrans—is commonly seen in daily practice, with a prevalence of 2% to 3% in the general population.1 In the United States, the condition is more prevalent in whites and blacks than in Hispanics, but has no association with age or sex.

This condition is characterized by circinate, maplike areas of erythema surrounded by well-demarcated scalloped white borders, typically on the dorsum and the lateral borders of the tongue.2 The appearance, which represents loss of filiform papillae (depapillation) from the lingual mucosa, can change in size, shape, or location in a matter of minutes or hours. The name “lingual erythema migrans” reflects the changing clinical picture.3 Rarely, the labial or palatal mucosa is affected.

POSTULATED TO BE AN INTRAORAL FORM OF PSORIASIS

The precise etiology remains obscure.2 Histopathologically, geographic tongue is characterized by hyperparakeratosis and acanthosis resembling psoriasis. Hence, it has been postulated that it represents a form of intraoral psoriasis.2,4 The condition is also associated with allergy, stress, diabetes mellitus, and anemia. Triggers include hot, spicy, and acidic foods and alcohol. Contrary to previous belief, geographic tongue has been found to have an inverse association with smoking.5 Although striking, the lesion rarely warrants further investigation.

REASSURANCE IS THE MAIN TREATMENT

Geographic tongue has a remitting and relapsing course with no complications or permanent sequelae.3 The differential diagnosis includes oral candidiasis, leukoplakia, vitamin deficiency glossitis, lichen planus, systemic lupus erythematosus, drug reaction, and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. The condition is differentiated from oral candidiasis by its presence in an otherwise healthy person and by the changing pattern of the lesions over time. Also, candidal pseudomembranes can be easily removed, leaving a painless red base. Evaluations to rule out anemia, nutritional deficiencies, and diabetes mellitus can be done if these conditions are suspected, as they are associated with geographic tongue.

Reassurance is the main treatment. Topical corticosteroids and local anesthetics may provide symptomatic relief in mild forms of the disease. Topical tacrolimus and systemic cyclosporine have been reported as useful in severe cases.6

A previously healthy 35-year-old woman presented with reddish discoloration of her tongue for the past 7 days, accompanied by mild soreness over the area when eating spicy foods. The lesion had also changed shape repeatedly. She denied any other local or systemic symptoms.

Lingual examination showed clearly delineated areas of shiny, erythematous mucosa on the dorsal and lateral aspects of the tongue, surrounded by white borders (Figure 1). Examination of the throat and oral cavity were unremarkable. All other systemic examinations were normal. Laboratory testing showed a normal hemogram, blood glucose, and metabolic profile.

These findings were suggestive of geographic tongue, a benign, self-limiting inflammation. The patient was reassured of the benign nature of the condition and was advised to avoid spicy food until resolution of the lesion. A follow-up examination 1 month later showed complete healing of the lesion.

A COMMON, BENIGN, SELF-LIMITING MUCOSAL CONDITION

Geographic tongue—also known as benign migratory glossitis and lingual erythema migrans—is commonly seen in daily practice, with a prevalence of 2% to 3% in the general population.1 In the United States, the condition is more prevalent in whites and blacks than in Hispanics, but has no association with age or sex.

This condition is characterized by circinate, maplike areas of erythema surrounded by well-demarcated scalloped white borders, typically on the dorsum and the lateral borders of the tongue.2 The appearance, which represents loss of filiform papillae (depapillation) from the lingual mucosa, can change in size, shape, or location in a matter of minutes or hours. The name “lingual erythema migrans” reflects the changing clinical picture.3 Rarely, the labial or palatal mucosa is affected.

POSTULATED TO BE AN INTRAORAL FORM OF PSORIASIS

The precise etiology remains obscure.2 Histopathologically, geographic tongue is characterized by hyperparakeratosis and acanthosis resembling psoriasis. Hence, it has been postulated that it represents a form of intraoral psoriasis.2,4 The condition is also associated with allergy, stress, diabetes mellitus, and anemia. Triggers include hot, spicy, and acidic foods and alcohol. Contrary to previous belief, geographic tongue has been found to have an inverse association with smoking.5 Although striking, the lesion rarely warrants further investigation.

REASSURANCE IS THE MAIN TREATMENT

Geographic tongue has a remitting and relapsing course with no complications or permanent sequelae.3 The differential diagnosis includes oral candidiasis, leukoplakia, vitamin deficiency glossitis, lichen planus, systemic lupus erythematosus, drug reaction, and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. The condition is differentiated from oral candidiasis by its presence in an otherwise healthy person and by the changing pattern of the lesions over time. Also, candidal pseudomembranes can be easily removed, leaving a painless red base. Evaluations to rule out anemia, nutritional deficiencies, and diabetes mellitus can be done if these conditions are suspected, as they are associated with geographic tongue.

Reassurance is the main treatment. Topical corticosteroids and local anesthetics may provide symptomatic relief in mild forms of the disease. Topical tacrolimus and systemic cyclosporine have been reported as useful in severe cases.6

- Masferrer E, Jucgla A. Images in clinical medicine. Geographic tongue. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:e44.

- Assimakopoulos D, Patrikakos G, Fotika C, Elisaf M. Benign migratory glossitis or geographic tongue: an enigmatic oral lesion. Am J Med 2002; 113:751–755.

- Scully C, Hegarty A. The oral cavity and lips. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:69–100.

- Zargari O. The prevalence and significance of fissured tongue and geographical tongue in psoriatic patients. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006; 31:192–195.

- Shulman JD, Carpenter WM. Prevalence and risk factors associated with geographic tongue among US adults. Oral Dis 2006; 12:381–386.

- Ishibashi M, Tojo G, Watanabe M, Tamabuchi T, Masu T, Aiba S. Geographic tongue treated with topical tacrolimus. J Dermatol Case Rep 2010; 4:57–59.

- Masferrer E, Jucgla A. Images in clinical medicine. Geographic tongue. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:e44.

- Assimakopoulos D, Patrikakos G, Fotika C, Elisaf M. Benign migratory glossitis or geographic tongue: an enigmatic oral lesion. Am J Med 2002; 113:751–755.

- Scully C, Hegarty A. The oral cavity and lips. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:69–100.

- Zargari O. The prevalence and significance of fissured tongue and geographical tongue in psoriatic patients. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006; 31:192–195.