User login

CLL: Genetic aberrations predict poor treatment response in elderly

In elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, complex karyotype abnormalities, certain KRAS and POT1 mutations, and newly discovered mutations in genes involved in the DNA damage response were found to predict a poor response to chlorambucil-based chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy and poor survival, according to a report in Blood.

These findings are from what the investigators described as the first comprehensive prospective analysis of chromosomal aberrations (including complex karyotype abnormalities), gene mutations, and clinical and biological features in elderly CLL patients who had multiple comorbidities. This patient population is generally considered ineligible for aggressive first-line agents such as fludarabine and cyclophosphamide, said Carmen Diana Herling, MD, of the Laboratory of Functional Genomics in Lymphoid Malignancies, University of Cologne (Germany), and her associates.

For their analysis, investigators studied 161 such patients enrolled in a clinical trial in which all were treated with chlorambucil alone, chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab, or chlorambucil plus rituximab. The median patient age was 75 years. Comprehensive genetic analyses were performed using peripheral blood drawn before the patients underwent treatment.

Karyotyping detected chromosomal aberrations in 68.68% of patients, while 31.2% carried translocations and 19.5% showed complex karyotypes. Gene sequencing detected 198 missense/nonsense mutations and other abnormalities in 76.4% of patients.

Dr. Herling and her associates found that complex karyotype abnormalities independently predicted poor response to chlorambucil and poor survival. “Thus, global karyotyping (i.e., by chromosome banding analysis) seems to substantially contribute to the identification of CLL patients with most adverse prognoses and should be considered a standard assessment in future CLL trials,” they said (Blood. 2016;128:395-404).

In addition, KRAS mutations correlated with a poor treatment response, particularly to rituximab. Targeting such patients for MEK, BRAF, or ERK inhibitors “might offer personalized treatment strategies to be investigated in such cases.”

Mutations in the POT1 gene also correlated with shorter survival after chlorambucil treatment. And finally, poor treatment response also correlated with previously unknown mutations in genes involved with the response to DNA damage. This “might contribute to the accumulation of genomic alterations and clonal evolution of CLL,” Dr. Herling and her associates said.

In elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, complex karyotype abnormalities, certain KRAS and POT1 mutations, and newly discovered mutations in genes involved in the DNA damage response were found to predict a poor response to chlorambucil-based chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy and poor survival, according to a report in Blood.

These findings are from what the investigators described as the first comprehensive prospective analysis of chromosomal aberrations (including complex karyotype abnormalities), gene mutations, and clinical and biological features in elderly CLL patients who had multiple comorbidities. This patient population is generally considered ineligible for aggressive first-line agents such as fludarabine and cyclophosphamide, said Carmen Diana Herling, MD, of the Laboratory of Functional Genomics in Lymphoid Malignancies, University of Cologne (Germany), and her associates.

For their analysis, investigators studied 161 such patients enrolled in a clinical trial in which all were treated with chlorambucil alone, chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab, or chlorambucil plus rituximab. The median patient age was 75 years. Comprehensive genetic analyses were performed using peripheral blood drawn before the patients underwent treatment.

Karyotyping detected chromosomal aberrations in 68.68% of patients, while 31.2% carried translocations and 19.5% showed complex karyotypes. Gene sequencing detected 198 missense/nonsense mutations and other abnormalities in 76.4% of patients.

Dr. Herling and her associates found that complex karyotype abnormalities independently predicted poor response to chlorambucil and poor survival. “Thus, global karyotyping (i.e., by chromosome banding analysis) seems to substantially contribute to the identification of CLL patients with most adverse prognoses and should be considered a standard assessment in future CLL trials,” they said (Blood. 2016;128:395-404).

In addition, KRAS mutations correlated with a poor treatment response, particularly to rituximab. Targeting such patients for MEK, BRAF, or ERK inhibitors “might offer personalized treatment strategies to be investigated in such cases.”

Mutations in the POT1 gene also correlated with shorter survival after chlorambucil treatment. And finally, poor treatment response also correlated with previously unknown mutations in genes involved with the response to DNA damage. This “might contribute to the accumulation of genomic alterations and clonal evolution of CLL,” Dr. Herling and her associates said.

In elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, complex karyotype abnormalities, certain KRAS and POT1 mutations, and newly discovered mutations in genes involved in the DNA damage response were found to predict a poor response to chlorambucil-based chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy and poor survival, according to a report in Blood.

These findings are from what the investigators described as the first comprehensive prospective analysis of chromosomal aberrations (including complex karyotype abnormalities), gene mutations, and clinical and biological features in elderly CLL patients who had multiple comorbidities. This patient population is generally considered ineligible for aggressive first-line agents such as fludarabine and cyclophosphamide, said Carmen Diana Herling, MD, of the Laboratory of Functional Genomics in Lymphoid Malignancies, University of Cologne (Germany), and her associates.

For their analysis, investigators studied 161 such patients enrolled in a clinical trial in which all were treated with chlorambucil alone, chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab, or chlorambucil plus rituximab. The median patient age was 75 years. Comprehensive genetic analyses were performed using peripheral blood drawn before the patients underwent treatment.

Karyotyping detected chromosomal aberrations in 68.68% of patients, while 31.2% carried translocations and 19.5% showed complex karyotypes. Gene sequencing detected 198 missense/nonsense mutations and other abnormalities in 76.4% of patients.

Dr. Herling and her associates found that complex karyotype abnormalities independently predicted poor response to chlorambucil and poor survival. “Thus, global karyotyping (i.e., by chromosome banding analysis) seems to substantially contribute to the identification of CLL patients with most adverse prognoses and should be considered a standard assessment in future CLL trials,” they said (Blood. 2016;128:395-404).

In addition, KRAS mutations correlated with a poor treatment response, particularly to rituximab. Targeting such patients for MEK, BRAF, or ERK inhibitors “might offer personalized treatment strategies to be investigated in such cases.”

Mutations in the POT1 gene also correlated with shorter survival after chlorambucil treatment. And finally, poor treatment response also correlated with previously unknown mutations in genes involved with the response to DNA damage. This “might contribute to the accumulation of genomic alterations and clonal evolution of CLL,” Dr. Herling and her associates said.

FROM BLOOD

Key clinical point: In elderly patients who have chronic lymphocytic leukemia and comorbidities, several genetic abnormalities predict a poor response to chlorambucil-based chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy.

Major finding: Complex karyotype abnormalities independently predicted poor response to chlorambucil and poor survival.

Data source: A series of karyotyping and other genetic studies involving 161 elderly patients with CLL and multiple comorbidities.

Disclosures: The participants in this study were drawn from a clinical trial funded by Hoffmann–La Roche; this analysis was supported by Volkswagenstiftung and grants from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Deutsche Jose Carreras Leukamie Foundation, Helmholtz-Gemeinschaft, Else Kroner–Fresenius Foundation, and Deutsche Krebshilfe. Dr. Herling reported having no relevant financial disclosures; her associates reported ties to Hoffmann–La Roche.

ATV injuries: where risk taking and medical helplessness collide

I. Hate. ATVs.

The modern world is full of potentially dangerous things that we regulate – sometimes by the knowledge of the person giving it (medication) or by age (tobacco, alcohol, cars). Or sometimes we simply ban something altogether (illicit drugs).

After years of neurology practice, I’ve learned to hate ATVs. Outside of firearms, I don’t think I’ve seen any gadget that has such a devastating effect on young lives.

My first medical encounter with one was 20-some years ago during my neurosurgery rotation. It was a man in his mid-20s. He was young, muscular, and clearly in excellent condition. And here he was, flaccid below the neck, and permanently on a ventilator.

I sat at the nurses station for a long time, looking at him and thinking about how a young life can go so horribly wrong so quickly. He hadn’t been drunk at the time. He’d simply had a wreck, the cause of which I never found out. After a few days, he was shipped off to a long-term ventilator facility, and I never saw him again.

Cars are dangerous, too, but are bigger and have gadgets to try to improve safety. ATVs are exposed, with only minimal, if any, protection for their riders. Their use is most typically by the young, meaning a disproportionate number of serious injuries will affect those at the beginning of adulthood.

Sadly, banning ATVs won’t stop injuries. There will always be people who do risky things in the name of being daring and having fun.

What’s changed is that 100 years ago they’d likely have died of their injuries soon afterward. Today they’ll probably survive, debilitated long term because of medical advancements.

These are the situations where I feel helpless. There are all kinds of horrible diseases we handle that have no known cause or cure. That’s one kind of helpless. But the ones with easily avoidable risk factors (ATVs, illegal drugs, tobacco) that occur are just plain frustrating for us and tragic for the patients and families.

In the land of the free, freedom to endanger your own life and health are pretty deeply entrenched. The best we can do is present people with the facts and let them make informed decisions about risky behaviors (sadly, the young often believe they’re immortal). If we ban ATVs, we still won’t stop people from making bad decisions on motorcycles or in cars, or with firearms or illegal drugs.

Like so much in medicine, there are no easy answers, and there likely never will be.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I. Hate. ATVs.

The modern world is full of potentially dangerous things that we regulate – sometimes by the knowledge of the person giving it (medication) or by age (tobacco, alcohol, cars). Or sometimes we simply ban something altogether (illicit drugs).

After years of neurology practice, I’ve learned to hate ATVs. Outside of firearms, I don’t think I’ve seen any gadget that has such a devastating effect on young lives.

My first medical encounter with one was 20-some years ago during my neurosurgery rotation. It was a man in his mid-20s. He was young, muscular, and clearly in excellent condition. And here he was, flaccid below the neck, and permanently on a ventilator.

I sat at the nurses station for a long time, looking at him and thinking about how a young life can go so horribly wrong so quickly. He hadn’t been drunk at the time. He’d simply had a wreck, the cause of which I never found out. After a few days, he was shipped off to a long-term ventilator facility, and I never saw him again.

Cars are dangerous, too, but are bigger and have gadgets to try to improve safety. ATVs are exposed, with only minimal, if any, protection for their riders. Their use is most typically by the young, meaning a disproportionate number of serious injuries will affect those at the beginning of adulthood.

Sadly, banning ATVs won’t stop injuries. There will always be people who do risky things in the name of being daring and having fun.

What’s changed is that 100 years ago they’d likely have died of their injuries soon afterward. Today they’ll probably survive, debilitated long term because of medical advancements.

These are the situations where I feel helpless. There are all kinds of horrible diseases we handle that have no known cause or cure. That’s one kind of helpless. But the ones with easily avoidable risk factors (ATVs, illegal drugs, tobacco) that occur are just plain frustrating for us and tragic for the patients and families.

In the land of the free, freedom to endanger your own life and health are pretty deeply entrenched. The best we can do is present people with the facts and let them make informed decisions about risky behaviors (sadly, the young often believe they’re immortal). If we ban ATVs, we still won’t stop people from making bad decisions on motorcycles or in cars, or with firearms or illegal drugs.

Like so much in medicine, there are no easy answers, and there likely never will be.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I. Hate. ATVs.

The modern world is full of potentially dangerous things that we regulate – sometimes by the knowledge of the person giving it (medication) or by age (tobacco, alcohol, cars). Or sometimes we simply ban something altogether (illicit drugs).

After years of neurology practice, I’ve learned to hate ATVs. Outside of firearms, I don’t think I’ve seen any gadget that has such a devastating effect on young lives.

My first medical encounter with one was 20-some years ago during my neurosurgery rotation. It was a man in his mid-20s. He was young, muscular, and clearly in excellent condition. And here he was, flaccid below the neck, and permanently on a ventilator.

I sat at the nurses station for a long time, looking at him and thinking about how a young life can go so horribly wrong so quickly. He hadn’t been drunk at the time. He’d simply had a wreck, the cause of which I never found out. After a few days, he was shipped off to a long-term ventilator facility, and I never saw him again.

Cars are dangerous, too, but are bigger and have gadgets to try to improve safety. ATVs are exposed, with only minimal, if any, protection for their riders. Their use is most typically by the young, meaning a disproportionate number of serious injuries will affect those at the beginning of adulthood.

Sadly, banning ATVs won’t stop injuries. There will always be people who do risky things in the name of being daring and having fun.

What’s changed is that 100 years ago they’d likely have died of their injuries soon afterward. Today they’ll probably survive, debilitated long term because of medical advancements.

These are the situations where I feel helpless. There are all kinds of horrible diseases we handle that have no known cause or cure. That’s one kind of helpless. But the ones with easily avoidable risk factors (ATVs, illegal drugs, tobacco) that occur are just plain frustrating for us and tragic for the patients and families.

In the land of the free, freedom to endanger your own life and health are pretty deeply entrenched. The best we can do is present people with the facts and let them make informed decisions about risky behaviors (sadly, the young often believe they’re immortal). If we ban ATVs, we still won’t stop people from making bad decisions on motorcycles or in cars, or with firearms or illegal drugs.

Like so much in medicine, there are no easy answers, and there likely never will be.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Postop delirium linked to greater long-term cognitive decline

Patients with postoperative delirium have significantly worse preoperative short-term cognitive performance and significantly greater long-term cognitive decline, compared with patients without delirium, according to Sharon K. Inouye, MD, and her associates.

In a prospective cohort study of 560 patients aged 70 years and older, 134 patients were selected for the delirium group and 426 for the nondelirium group. The delirium group had a significantly greater decline (–1.03 points) at 1 month, compared with those without delirium (P = .003). After cognitive function had recovered at 2 months, there were no significant differences between groups (P = 0.99). After 2 months, both groups decline on average; however, the delirium group declined significantly more (–1.07) in adjusted mean scores at 36 months (P =.02).

From baseline to 36 months, there was a significant change for the delirium group (–1.30, P less than .01) and no significant change for the group without delirium (–0.23, P = .30). Researchers noted that the effect of delirium remains undiminished after consecutive rehospitalizations, intercurrent illnesses, and major postoperative complications were controlled for.

The patients underwent major noncardiac surgery, such as total hip or knee replacement, open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, colectomy, and lower-extremity arterial bypass.

“This study provides a novel presentation of the biphasic relationship of delirium and cognitive trajectory, both its well-recognized acute effects but also long-term effects,” the researchers wrote. “Our results suggest that after a period of initial recovery, patients with delirium experience a substantially accelerated trajectory of cognitive aging.”

Read the full study in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association (doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.005).

Patients with postoperative delirium have significantly worse preoperative short-term cognitive performance and significantly greater long-term cognitive decline, compared with patients without delirium, according to Sharon K. Inouye, MD, and her associates.

In a prospective cohort study of 560 patients aged 70 years and older, 134 patients were selected for the delirium group and 426 for the nondelirium group. The delirium group had a significantly greater decline (–1.03 points) at 1 month, compared with those without delirium (P = .003). After cognitive function had recovered at 2 months, there were no significant differences between groups (P = 0.99). After 2 months, both groups decline on average; however, the delirium group declined significantly more (–1.07) in adjusted mean scores at 36 months (P =.02).

From baseline to 36 months, there was a significant change for the delirium group (–1.30, P less than .01) and no significant change for the group without delirium (–0.23, P = .30). Researchers noted that the effect of delirium remains undiminished after consecutive rehospitalizations, intercurrent illnesses, and major postoperative complications were controlled for.

The patients underwent major noncardiac surgery, such as total hip or knee replacement, open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, colectomy, and lower-extremity arterial bypass.

“This study provides a novel presentation of the biphasic relationship of delirium and cognitive trajectory, both its well-recognized acute effects but also long-term effects,” the researchers wrote. “Our results suggest that after a period of initial recovery, patients with delirium experience a substantially accelerated trajectory of cognitive aging.”

Read the full study in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association (doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.005).

Patients with postoperative delirium have significantly worse preoperative short-term cognitive performance and significantly greater long-term cognitive decline, compared with patients without delirium, according to Sharon K. Inouye, MD, and her associates.

In a prospective cohort study of 560 patients aged 70 years and older, 134 patients were selected for the delirium group and 426 for the nondelirium group. The delirium group had a significantly greater decline (–1.03 points) at 1 month, compared with those without delirium (P = .003). After cognitive function had recovered at 2 months, there were no significant differences between groups (P = 0.99). After 2 months, both groups decline on average; however, the delirium group declined significantly more (–1.07) in adjusted mean scores at 36 months (P =.02).

From baseline to 36 months, there was a significant change for the delirium group (–1.30, P less than .01) and no significant change for the group without delirium (–0.23, P = .30). Researchers noted that the effect of delirium remains undiminished after consecutive rehospitalizations, intercurrent illnesses, and major postoperative complications were controlled for.

The patients underwent major noncardiac surgery, such as total hip or knee replacement, open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, colectomy, and lower-extremity arterial bypass.

“This study provides a novel presentation of the biphasic relationship of delirium and cognitive trajectory, both its well-recognized acute effects but also long-term effects,” the researchers wrote. “Our results suggest that after a period of initial recovery, patients with delirium experience a substantially accelerated trajectory of cognitive aging.”

Read the full study in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association (doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.005).

FROM ALZHEIMER’S & DEMENTIA

Surgeons raise red flag on proposed 2017 physician fee schedule

The physician fee schedule for 2017 proposed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has raised a red flag for the American College of Surgeons (ACS).

A proposal related to data collection on the transition of all 10- and 90- day global codes to 0-day codes in the proposed physician fee schedule 2017 is the area of greatest concern to the ACS. The provision would require all surgeons and other physicians who receive payment from these codes to devote many hours to collecting and reporting these data.

Two years ago, the CMS had pushed this exact transition through in regulation. However, Congress halted that transition in the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA), instead directing the CMS to study the effects of the transition by collecting data from a “representative sample” of physicians who receive payment from these codes.

For most surgical procedures, Medicare pays surgeons for either 10 or 90 days of care that include the procedure itself and postoperative care. Most global codes are 90-day codes. The CMS would have debundled the global payments 2 years ago had Congress not intervened.

However, in the proposed physician fee schedule update for 2017, the CMS would require all physicians to report data on these codes, something the ACS believes is overly burdensome.

“ACS believes that this proposal does not align with the MACRA requirement that CMS only collect data from a representative sample of physicians performing 10- or 90-day global codes,” ACS Regulatory Affairs Manager Vinita Ollapally told ACS Surgery News. “ACS is currently pursuing a legislative strategy that urges CMS to not finalize the proposal to collect data from all practitioners who perform 10- and 90-day global services, and instead revise the policy to collect data on 10- and 90-day global services from a ‘representative sample’ of practitioners.”

The college is developing a definition for what it believes that representative sample should include and expects to have that ready when the ACS files its comments on the physician fee schedule update proposal. Comments on the proposal are due Sept. 6.

The proposed update, published July 15 in the Federal Register, brings in several new policies aimed at improving physician payment for caring for patients with multiple chronic conditions; mental and behavioral health issues; and cognitive impairment or mobility-related issues.

Among the provisions in the 800+ page proposal are revised billing codes that would more accurately recognize the work of primary care and other cognitive specialties. The changes, according to the CMS, will help “better identify and value primary care, care management, and cognitive services.”

The agency is proposing several coding changes that “could improve health care delivery for all types of services holding the most promise for healthier people and smarter spending, and advance our health equity goals,” according to a CMS fact sheet.

The proposed fee schedule also would update how quality is measured and reported by accountable care organizations in the Medicare Shared Savings Program, align Accountable Care Organization reporting with the Physician Quality Reporting System, and change how beneficiaries are assigned to an ACO. Potentially misvalued services also would continue to be reviewed under the proposal.

The agency is also proposing a code to allow for the payment of advanced care planning services furnished via telehealth.

The physician fee schedule for 2017 proposed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has raised a red flag for the American College of Surgeons (ACS).

A proposal related to data collection on the transition of all 10- and 90- day global codes to 0-day codes in the proposed physician fee schedule 2017 is the area of greatest concern to the ACS. The provision would require all surgeons and other physicians who receive payment from these codes to devote many hours to collecting and reporting these data.

Two years ago, the CMS had pushed this exact transition through in regulation. However, Congress halted that transition in the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA), instead directing the CMS to study the effects of the transition by collecting data from a “representative sample” of physicians who receive payment from these codes.

For most surgical procedures, Medicare pays surgeons for either 10 or 90 days of care that include the procedure itself and postoperative care. Most global codes are 90-day codes. The CMS would have debundled the global payments 2 years ago had Congress not intervened.

However, in the proposed physician fee schedule update for 2017, the CMS would require all physicians to report data on these codes, something the ACS believes is overly burdensome.

“ACS believes that this proposal does not align with the MACRA requirement that CMS only collect data from a representative sample of physicians performing 10- or 90-day global codes,” ACS Regulatory Affairs Manager Vinita Ollapally told ACS Surgery News. “ACS is currently pursuing a legislative strategy that urges CMS to not finalize the proposal to collect data from all practitioners who perform 10- and 90-day global services, and instead revise the policy to collect data on 10- and 90-day global services from a ‘representative sample’ of practitioners.”

The college is developing a definition for what it believes that representative sample should include and expects to have that ready when the ACS files its comments on the physician fee schedule update proposal. Comments on the proposal are due Sept. 6.

The proposed update, published July 15 in the Federal Register, brings in several new policies aimed at improving physician payment for caring for patients with multiple chronic conditions; mental and behavioral health issues; and cognitive impairment or mobility-related issues.

Among the provisions in the 800+ page proposal are revised billing codes that would more accurately recognize the work of primary care and other cognitive specialties. The changes, according to the CMS, will help “better identify and value primary care, care management, and cognitive services.”

The agency is proposing several coding changes that “could improve health care delivery for all types of services holding the most promise for healthier people and smarter spending, and advance our health equity goals,” according to a CMS fact sheet.

The proposed fee schedule also would update how quality is measured and reported by accountable care organizations in the Medicare Shared Savings Program, align Accountable Care Organization reporting with the Physician Quality Reporting System, and change how beneficiaries are assigned to an ACO. Potentially misvalued services also would continue to be reviewed under the proposal.

The agency is also proposing a code to allow for the payment of advanced care planning services furnished via telehealth.

The physician fee schedule for 2017 proposed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has raised a red flag for the American College of Surgeons (ACS).

A proposal related to data collection on the transition of all 10- and 90- day global codes to 0-day codes in the proposed physician fee schedule 2017 is the area of greatest concern to the ACS. The provision would require all surgeons and other physicians who receive payment from these codes to devote many hours to collecting and reporting these data.

Two years ago, the CMS had pushed this exact transition through in regulation. However, Congress halted that transition in the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA), instead directing the CMS to study the effects of the transition by collecting data from a “representative sample” of physicians who receive payment from these codes.

For most surgical procedures, Medicare pays surgeons for either 10 or 90 days of care that include the procedure itself and postoperative care. Most global codes are 90-day codes. The CMS would have debundled the global payments 2 years ago had Congress not intervened.

However, in the proposed physician fee schedule update for 2017, the CMS would require all physicians to report data on these codes, something the ACS believes is overly burdensome.

“ACS believes that this proposal does not align with the MACRA requirement that CMS only collect data from a representative sample of physicians performing 10- or 90-day global codes,” ACS Regulatory Affairs Manager Vinita Ollapally told ACS Surgery News. “ACS is currently pursuing a legislative strategy that urges CMS to not finalize the proposal to collect data from all practitioners who perform 10- and 90-day global services, and instead revise the policy to collect data on 10- and 90-day global services from a ‘representative sample’ of practitioners.”

The college is developing a definition for what it believes that representative sample should include and expects to have that ready when the ACS files its comments on the physician fee schedule update proposal. Comments on the proposal are due Sept. 6.

The proposed update, published July 15 in the Federal Register, brings in several new policies aimed at improving physician payment for caring for patients with multiple chronic conditions; mental and behavioral health issues; and cognitive impairment or mobility-related issues.

Among the provisions in the 800+ page proposal are revised billing codes that would more accurately recognize the work of primary care and other cognitive specialties. The changes, according to the CMS, will help “better identify and value primary care, care management, and cognitive services.”

The agency is proposing several coding changes that “could improve health care delivery for all types of services holding the most promise for healthier people and smarter spending, and advance our health equity goals,” according to a CMS fact sheet.

The proposed fee schedule also would update how quality is measured and reported by accountable care organizations in the Medicare Shared Savings Program, align Accountable Care Organization reporting with the Physician Quality Reporting System, and change how beneficiaries are assigned to an ACO. Potentially misvalued services also would continue to be reviewed under the proposal.

The agency is also proposing a code to allow for the payment of advanced care planning services furnished via telehealth.

CPAP May Be Vasculoprotective in Stroke and TIA

DENVER—Long-term continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for treatment of sleep apnea in patients with a recent mild stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) resulted in improved cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors, better neurologic function, and a reduction in the recurrent vascular event rate, compared with usual care, in the SLEEP TIGHT study.

“Up to 25% of patients will have a stroke, cardiovascular event, or death within 90 days after a minor stroke or TIA despite current preventive strategies. And, importantly, patients with a TIA or stroke have a high prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea—on the order of 60% to 80%,” explained H. Klar Yaggi, MD, MPH, at the 30th Anniversary Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

H. Klar Yaggi, MD, MPH

SLEEP TIGHT’s findings support the hypothesis that diagnosis and treatment of sleep apnea in patients with a recent minor stroke or TIA will address a major unmet need for better methods of reducing the high vascular risk present in this population, said Dr. Yaggi, Associate Professor of Medicine and Director of the Program in Sleep Medicine at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

A High-Risk Population

SLEEP TIGHT was a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored phase II, 12-month, multicenter, single-blind, randomized, proof-of-concept study. It included 252 patients, 80% of whom had a recent minor stroke, and the rest had a TIA. Patients had high levels of cardiovascular risk factors; two-thirds had hypertension, half were hyperlipidemic, 40% had diabetes, 15% had a prior myocardial infarction, 10% had atrial fibrillation, and the group’s mean BMI was 30. Polysomnography revealed that 76% of subjects had sleep apnea, as defined by an apnea–hypopnea index of at least five events per hour. In fact, they averaged about 23 events per hour, putting them in the moderate-severity range. As is common among patients with stroke or TIA and sleep apnea, they experienced less daytime sleepiness than is typical in a sleep clinic population, with a mean baseline Epworth Sleepiness Scale score of 7.

Participants were randomized to one of three groups: a usual care control group, a CPAP arm, or an enhanced CPAP arm. The enhanced intervention protocol was designed to boost CPAP adherence; it included targeted education, a customized cognitive intervention, and additional CPAP support beyond the standard CPAP protocols used in sleep medicine clinics. Patients with sleep apnea in the two intervention arms were then placed on CPAP.

At one year of follow-up, the stroke rate was 8.7 per 100 patient-years in the usual care group, compared with 5.5 per 100 person-years in the combined intervention arms. The composite cardiovascular event rate, composed of all-cause mortality, acute myocardial infarction, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or urgent coronary revascularization, was 13.1 per 100 person-years with usual care and 11.0 in the CPAP intervention arms. While these results are encouraging, SLEEP TIGHT wasn’t powered to show significant differences in these events.

Patient Adherence

Outcomes across the board didn’t differ significantly between the CPAP and enhanced CPAP groups. And since the mean number of hours of CPAP use per night was also similar in the two groups—3.9 hours with standard CPAP and 4.3 hours with enhanced CPAP—it’s likely that the phase III trial will rely upon the much simpler standard CPAP intervention, according to Dr. Yaggi.

He deemed CPAP adherence in this stroke or TIA population to be similar to the rates typically seen in routine sleep medicine practice. Roughly 40% of the patients with stroke or TIA were rated as having good adherence, 30% made some use of the therapy, and 30% had no or poor adherence.

Nonetheless, patients in the two intervention arms did significantly better than the usual care group, in terms of one-year changes in insulin resistance and glycosylated hemoglobin. They also had lower 24-hour mean systolic blood pressure and were more likely to convert to a favorable pattern of nocturnal blood pressure dipping. However, no differences between the intervention and usual care groups were seen in levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and interleukin-6, the two markers of systemic inflammation analyzed. Nor did the CPAP intervention provide any benefit in terms of heart rate variability and other measures of autonomic function.

Fifty-eight percent of patients in the intervention arms had a desirable NIH Stroke Scale score of 0 to 1, compared with 38% of the usual care group. In addition, daytime sleepiness, as reflected in Epworth Sleepiness Scale scores, was reduced at last follow-up to a significantly greater extent in the CPAP groups, Dr. Yaggi noted.

Greater CPAP use was associated with a favorable trend for improvement in the modified Rankin score: a 0.3-point reduction with no or poor CPAP use, a 0.4-point reduction with some use, and a 0.9-point reduction with good use.

The encouraging results will be helpful in designing a larger, event-driven, definitive phase III trial, Dr. Yaggi said.

—Bruce Jancin

Suggested Reading

Yaggi HK, Mittleman MA, Bravata DM, et al. Reducing cardiovascular risk through treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: 2 methodological approaches. Am Heart J. 2016;172:135-143.

DENVER—Long-term continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for treatment of sleep apnea in patients with a recent mild stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) resulted in improved cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors, better neurologic function, and a reduction in the recurrent vascular event rate, compared with usual care, in the SLEEP TIGHT study.

“Up to 25% of patients will have a stroke, cardiovascular event, or death within 90 days after a minor stroke or TIA despite current preventive strategies. And, importantly, patients with a TIA or stroke have a high prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea—on the order of 60% to 80%,” explained H. Klar Yaggi, MD, MPH, at the 30th Anniversary Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

H. Klar Yaggi, MD, MPH

SLEEP TIGHT’s findings support the hypothesis that diagnosis and treatment of sleep apnea in patients with a recent minor stroke or TIA will address a major unmet need for better methods of reducing the high vascular risk present in this population, said Dr. Yaggi, Associate Professor of Medicine and Director of the Program in Sleep Medicine at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

A High-Risk Population

SLEEP TIGHT was a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored phase II, 12-month, multicenter, single-blind, randomized, proof-of-concept study. It included 252 patients, 80% of whom had a recent minor stroke, and the rest had a TIA. Patients had high levels of cardiovascular risk factors; two-thirds had hypertension, half were hyperlipidemic, 40% had diabetes, 15% had a prior myocardial infarction, 10% had atrial fibrillation, and the group’s mean BMI was 30. Polysomnography revealed that 76% of subjects had sleep apnea, as defined by an apnea–hypopnea index of at least five events per hour. In fact, they averaged about 23 events per hour, putting them in the moderate-severity range. As is common among patients with stroke or TIA and sleep apnea, they experienced less daytime sleepiness than is typical in a sleep clinic population, with a mean baseline Epworth Sleepiness Scale score of 7.

Participants were randomized to one of three groups: a usual care control group, a CPAP arm, or an enhanced CPAP arm. The enhanced intervention protocol was designed to boost CPAP adherence; it included targeted education, a customized cognitive intervention, and additional CPAP support beyond the standard CPAP protocols used in sleep medicine clinics. Patients with sleep apnea in the two intervention arms were then placed on CPAP.

At one year of follow-up, the stroke rate was 8.7 per 100 patient-years in the usual care group, compared with 5.5 per 100 person-years in the combined intervention arms. The composite cardiovascular event rate, composed of all-cause mortality, acute myocardial infarction, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or urgent coronary revascularization, was 13.1 per 100 person-years with usual care and 11.0 in the CPAP intervention arms. While these results are encouraging, SLEEP TIGHT wasn’t powered to show significant differences in these events.

Patient Adherence

Outcomes across the board didn’t differ significantly between the CPAP and enhanced CPAP groups. And since the mean number of hours of CPAP use per night was also similar in the two groups—3.9 hours with standard CPAP and 4.3 hours with enhanced CPAP—it’s likely that the phase III trial will rely upon the much simpler standard CPAP intervention, according to Dr. Yaggi.

He deemed CPAP adherence in this stroke or TIA population to be similar to the rates typically seen in routine sleep medicine practice. Roughly 40% of the patients with stroke or TIA were rated as having good adherence, 30% made some use of the therapy, and 30% had no or poor adherence.

Nonetheless, patients in the two intervention arms did significantly better than the usual care group, in terms of one-year changes in insulin resistance and glycosylated hemoglobin. They also had lower 24-hour mean systolic blood pressure and were more likely to convert to a favorable pattern of nocturnal blood pressure dipping. However, no differences between the intervention and usual care groups were seen in levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and interleukin-6, the two markers of systemic inflammation analyzed. Nor did the CPAP intervention provide any benefit in terms of heart rate variability and other measures of autonomic function.

Fifty-eight percent of patients in the intervention arms had a desirable NIH Stroke Scale score of 0 to 1, compared with 38% of the usual care group. In addition, daytime sleepiness, as reflected in Epworth Sleepiness Scale scores, was reduced at last follow-up to a significantly greater extent in the CPAP groups, Dr. Yaggi noted.

Greater CPAP use was associated with a favorable trend for improvement in the modified Rankin score: a 0.3-point reduction with no or poor CPAP use, a 0.4-point reduction with some use, and a 0.9-point reduction with good use.

The encouraging results will be helpful in designing a larger, event-driven, definitive phase III trial, Dr. Yaggi said.

—Bruce Jancin

DENVER—Long-term continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for treatment of sleep apnea in patients with a recent mild stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) resulted in improved cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors, better neurologic function, and a reduction in the recurrent vascular event rate, compared with usual care, in the SLEEP TIGHT study.

“Up to 25% of patients will have a stroke, cardiovascular event, or death within 90 days after a minor stroke or TIA despite current preventive strategies. And, importantly, patients with a TIA or stroke have a high prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea—on the order of 60% to 80%,” explained H. Klar Yaggi, MD, MPH, at the 30th Anniversary Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

H. Klar Yaggi, MD, MPH

SLEEP TIGHT’s findings support the hypothesis that diagnosis and treatment of sleep apnea in patients with a recent minor stroke or TIA will address a major unmet need for better methods of reducing the high vascular risk present in this population, said Dr. Yaggi, Associate Professor of Medicine and Director of the Program in Sleep Medicine at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

A High-Risk Population

SLEEP TIGHT was a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored phase II, 12-month, multicenter, single-blind, randomized, proof-of-concept study. It included 252 patients, 80% of whom had a recent minor stroke, and the rest had a TIA. Patients had high levels of cardiovascular risk factors; two-thirds had hypertension, half were hyperlipidemic, 40% had diabetes, 15% had a prior myocardial infarction, 10% had atrial fibrillation, and the group’s mean BMI was 30. Polysomnography revealed that 76% of subjects had sleep apnea, as defined by an apnea–hypopnea index of at least five events per hour. In fact, they averaged about 23 events per hour, putting them in the moderate-severity range. As is common among patients with stroke or TIA and sleep apnea, they experienced less daytime sleepiness than is typical in a sleep clinic population, with a mean baseline Epworth Sleepiness Scale score of 7.

Participants were randomized to one of three groups: a usual care control group, a CPAP arm, or an enhanced CPAP arm. The enhanced intervention protocol was designed to boost CPAP adherence; it included targeted education, a customized cognitive intervention, and additional CPAP support beyond the standard CPAP protocols used in sleep medicine clinics. Patients with sleep apnea in the two intervention arms were then placed on CPAP.

At one year of follow-up, the stroke rate was 8.7 per 100 patient-years in the usual care group, compared with 5.5 per 100 person-years in the combined intervention arms. The composite cardiovascular event rate, composed of all-cause mortality, acute myocardial infarction, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or urgent coronary revascularization, was 13.1 per 100 person-years with usual care and 11.0 in the CPAP intervention arms. While these results are encouraging, SLEEP TIGHT wasn’t powered to show significant differences in these events.

Patient Adherence

Outcomes across the board didn’t differ significantly between the CPAP and enhanced CPAP groups. And since the mean number of hours of CPAP use per night was also similar in the two groups—3.9 hours with standard CPAP and 4.3 hours with enhanced CPAP—it’s likely that the phase III trial will rely upon the much simpler standard CPAP intervention, according to Dr. Yaggi.

He deemed CPAP adherence in this stroke or TIA population to be similar to the rates typically seen in routine sleep medicine practice. Roughly 40% of the patients with stroke or TIA were rated as having good adherence, 30% made some use of the therapy, and 30% had no or poor adherence.

Nonetheless, patients in the two intervention arms did significantly better than the usual care group, in terms of one-year changes in insulin resistance and glycosylated hemoglobin. They also had lower 24-hour mean systolic blood pressure and were more likely to convert to a favorable pattern of nocturnal blood pressure dipping. However, no differences between the intervention and usual care groups were seen in levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and interleukin-6, the two markers of systemic inflammation analyzed. Nor did the CPAP intervention provide any benefit in terms of heart rate variability and other measures of autonomic function.

Fifty-eight percent of patients in the intervention arms had a desirable NIH Stroke Scale score of 0 to 1, compared with 38% of the usual care group. In addition, daytime sleepiness, as reflected in Epworth Sleepiness Scale scores, was reduced at last follow-up to a significantly greater extent in the CPAP groups, Dr. Yaggi noted.

Greater CPAP use was associated with a favorable trend for improvement in the modified Rankin score: a 0.3-point reduction with no or poor CPAP use, a 0.4-point reduction with some use, and a 0.9-point reduction with good use.

The encouraging results will be helpful in designing a larger, event-driven, definitive phase III trial, Dr. Yaggi said.

—Bruce Jancin

Suggested Reading

Yaggi HK, Mittleman MA, Bravata DM, et al. Reducing cardiovascular risk through treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: 2 methodological approaches. Am Heart J. 2016;172:135-143.

Suggested Reading

Yaggi HK, Mittleman MA, Bravata DM, et al. Reducing cardiovascular risk through treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: 2 methodological approaches. Am Heart J. 2016;172:135-143.

Skin rash in recent traveler? Think dengue fever

BOSTON – Maintain clinical suspicion for dengue fever among individuals with recent travel to endemic areas who present with a rash and other signs and symptoms of infection, an expert advised at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

Dengue fever accounts for nearly 10% of skin rashes among individuals returning from endemic areas, and related illness can range from mild to fatal, said Jose Dario Martinez, MD, chief of the Internal Medicine Clinic at University Hospital “J.E. Gonzalez,” UANL Monterrey, Mexico.

“This is the most prevalent arthropod-borne virus in the world at this time, and it is a resurgent disease in some countries, like Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia,” he noted.

Worldwide, more than 2.5 billion people are at risk of dengue infection, and between 50 million and 100 million cases occur each year, while about 250,000 to 500,000 cases of dengue hemorrhagic fever occur each year, and about 25,000 related deaths occur.

In 2005, there was a dengue outbreak in Texas, where 25 cases occurred; and in southern Florida, an outbreak of 90 cases was reported in 2009 and 2010. More recently, in 2015, there was an outbreak of 107 cases of locally-acquired dengue on the Big Island, Hawaii (MMWR). But in Mexico, 18,000 new cases occurred in 2015, Dr. Martinez said.

Of the RNA virus serotypes 1-4, type 1 (DENV1) is the most common, and DENV2 and 3 are the most severe, but up to 40% of cases are asymptomatic, he noted, adding that the virus has an incubation period of 2-8 days. When symptoms occur, they are representative of acute febrile illness, and may include headache, high fever, myalgia, arthralgia, retro-orbital pain, and fatigue. A faint, itchy, macular rash commonly occurs at 2-6 days into the illness. According to the World Health Organization, a probable dengue fever case includes acute febrile illness and at least two of either headache, retro-orbital pain, myalgia, arthralgia, rash, hemorrhagic manifestations, leukopenia, or supportive serology.

“Sometimes the nose bleeds, the gums bleed, and there is bruising in the patient,” Dr. Martinez said. “Most important are retro-orbital pain and hemorrhagic manifestations, but also supportive serology.”

About 1% of patients progress to dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome during the critical phase (days 4-7) of illness. This is most likely in those with serotypes 2 and 3, but can occur with all serotypes. Warning signs of such severe disease include abdominal pain or tenderness, persistent vomiting, pleural effusion or ascites, and of particular importance – mucosal bleeding, Dr. Martinez said.

By the WHO definition, a diagnosis of dengue hemorrhagic fever requires the presence of fever for at least 2-7 days, hemorrhagic tendencies, thrombocytopenia, and evidence and signs of plasma leakage; dengue shock syndrome requires these, as well as evidence of circulatory failure, such as rapid and weak pulse, narrow pulse pressure, hypotension, and shock.

It is important to maintain clinical suspicion for dengue fever, particularly in anyone who has traveled to an endemic area in the 2 weeks before presentation. Serologic tests are important to detect anti-dengue antibodies. IgG is important, because its presence could suggest recurrent infection and thus the potential for severe disease, Dr. Martinez said. Polymerase chain reaction can be used for detection in the first 4-5 days of infection, and the NS1 rapid test can be positive on the first day, he noted.

The differential diagnosis for dengue fever is broad, and can include chikungunya fever, malaria, leptospirosis, meningococcemia, drug eruption, and Zika fever.

Management of dengue fever includes bed rest, liquids, and mosquito net isolation to prevent re-infection, as more severe disease can occur after re-infection. Acetaminophen can be used for pain relief; aspirin should be avoided due to risk of bleeding, Dr. Martinez said.

Hospitalization and supportive care are required for those with dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome. Intensive care unit admission may be required.

Of note, a vaccine against dengue fever has shown promise in phase III trials. The vaccine has been approved in Mexico and Brazil, but not yet in the U.S.

Dr Martinez reported having no disclosures.

BOSTON – Maintain clinical suspicion for dengue fever among individuals with recent travel to endemic areas who present with a rash and other signs and symptoms of infection, an expert advised at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

Dengue fever accounts for nearly 10% of skin rashes among individuals returning from endemic areas, and related illness can range from mild to fatal, said Jose Dario Martinez, MD, chief of the Internal Medicine Clinic at University Hospital “J.E. Gonzalez,” UANL Monterrey, Mexico.

“This is the most prevalent arthropod-borne virus in the world at this time, and it is a resurgent disease in some countries, like Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia,” he noted.

Worldwide, more than 2.5 billion people are at risk of dengue infection, and between 50 million and 100 million cases occur each year, while about 250,000 to 500,000 cases of dengue hemorrhagic fever occur each year, and about 25,000 related deaths occur.

In 2005, there was a dengue outbreak in Texas, where 25 cases occurred; and in southern Florida, an outbreak of 90 cases was reported in 2009 and 2010. More recently, in 2015, there was an outbreak of 107 cases of locally-acquired dengue on the Big Island, Hawaii (MMWR). But in Mexico, 18,000 new cases occurred in 2015, Dr. Martinez said.

Of the RNA virus serotypes 1-4, type 1 (DENV1) is the most common, and DENV2 and 3 are the most severe, but up to 40% of cases are asymptomatic, he noted, adding that the virus has an incubation period of 2-8 days. When symptoms occur, they are representative of acute febrile illness, and may include headache, high fever, myalgia, arthralgia, retro-orbital pain, and fatigue. A faint, itchy, macular rash commonly occurs at 2-6 days into the illness. According to the World Health Organization, a probable dengue fever case includes acute febrile illness and at least two of either headache, retro-orbital pain, myalgia, arthralgia, rash, hemorrhagic manifestations, leukopenia, or supportive serology.

“Sometimes the nose bleeds, the gums bleed, and there is bruising in the patient,” Dr. Martinez said. “Most important are retro-orbital pain and hemorrhagic manifestations, but also supportive serology.”

About 1% of patients progress to dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome during the critical phase (days 4-7) of illness. This is most likely in those with serotypes 2 and 3, but can occur with all serotypes. Warning signs of such severe disease include abdominal pain or tenderness, persistent vomiting, pleural effusion or ascites, and of particular importance – mucosal bleeding, Dr. Martinez said.

By the WHO definition, a diagnosis of dengue hemorrhagic fever requires the presence of fever for at least 2-7 days, hemorrhagic tendencies, thrombocytopenia, and evidence and signs of plasma leakage; dengue shock syndrome requires these, as well as evidence of circulatory failure, such as rapid and weak pulse, narrow pulse pressure, hypotension, and shock.

It is important to maintain clinical suspicion for dengue fever, particularly in anyone who has traveled to an endemic area in the 2 weeks before presentation. Serologic tests are important to detect anti-dengue antibodies. IgG is important, because its presence could suggest recurrent infection and thus the potential for severe disease, Dr. Martinez said. Polymerase chain reaction can be used for detection in the first 4-5 days of infection, and the NS1 rapid test can be positive on the first day, he noted.

The differential diagnosis for dengue fever is broad, and can include chikungunya fever, malaria, leptospirosis, meningococcemia, drug eruption, and Zika fever.

Management of dengue fever includes bed rest, liquids, and mosquito net isolation to prevent re-infection, as more severe disease can occur after re-infection. Acetaminophen can be used for pain relief; aspirin should be avoided due to risk of bleeding, Dr. Martinez said.

Hospitalization and supportive care are required for those with dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome. Intensive care unit admission may be required.

Of note, a vaccine against dengue fever has shown promise in phase III trials. The vaccine has been approved in Mexico and Brazil, but not yet in the U.S.

Dr Martinez reported having no disclosures.

BOSTON – Maintain clinical suspicion for dengue fever among individuals with recent travel to endemic areas who present with a rash and other signs and symptoms of infection, an expert advised at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

Dengue fever accounts for nearly 10% of skin rashes among individuals returning from endemic areas, and related illness can range from mild to fatal, said Jose Dario Martinez, MD, chief of the Internal Medicine Clinic at University Hospital “J.E. Gonzalez,” UANL Monterrey, Mexico.

“This is the most prevalent arthropod-borne virus in the world at this time, and it is a resurgent disease in some countries, like Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia,” he noted.

Worldwide, more than 2.5 billion people are at risk of dengue infection, and between 50 million and 100 million cases occur each year, while about 250,000 to 500,000 cases of dengue hemorrhagic fever occur each year, and about 25,000 related deaths occur.

In 2005, there was a dengue outbreak in Texas, where 25 cases occurred; and in southern Florida, an outbreak of 90 cases was reported in 2009 and 2010. More recently, in 2015, there was an outbreak of 107 cases of locally-acquired dengue on the Big Island, Hawaii (MMWR). But in Mexico, 18,000 new cases occurred in 2015, Dr. Martinez said.

Of the RNA virus serotypes 1-4, type 1 (DENV1) is the most common, and DENV2 and 3 are the most severe, but up to 40% of cases are asymptomatic, he noted, adding that the virus has an incubation period of 2-8 days. When symptoms occur, they are representative of acute febrile illness, and may include headache, high fever, myalgia, arthralgia, retro-orbital pain, and fatigue. A faint, itchy, macular rash commonly occurs at 2-6 days into the illness. According to the World Health Organization, a probable dengue fever case includes acute febrile illness and at least two of either headache, retro-orbital pain, myalgia, arthralgia, rash, hemorrhagic manifestations, leukopenia, or supportive serology.

“Sometimes the nose bleeds, the gums bleed, and there is bruising in the patient,” Dr. Martinez said. “Most important are retro-orbital pain and hemorrhagic manifestations, but also supportive serology.”

About 1% of patients progress to dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome during the critical phase (days 4-7) of illness. This is most likely in those with serotypes 2 and 3, but can occur with all serotypes. Warning signs of such severe disease include abdominal pain or tenderness, persistent vomiting, pleural effusion or ascites, and of particular importance – mucosal bleeding, Dr. Martinez said.

By the WHO definition, a diagnosis of dengue hemorrhagic fever requires the presence of fever for at least 2-7 days, hemorrhagic tendencies, thrombocytopenia, and evidence and signs of plasma leakage; dengue shock syndrome requires these, as well as evidence of circulatory failure, such as rapid and weak pulse, narrow pulse pressure, hypotension, and shock.

It is important to maintain clinical suspicion for dengue fever, particularly in anyone who has traveled to an endemic area in the 2 weeks before presentation. Serologic tests are important to detect anti-dengue antibodies. IgG is important, because its presence could suggest recurrent infection and thus the potential for severe disease, Dr. Martinez said. Polymerase chain reaction can be used for detection in the first 4-5 days of infection, and the NS1 rapid test can be positive on the first day, he noted.

The differential diagnosis for dengue fever is broad, and can include chikungunya fever, malaria, leptospirosis, meningococcemia, drug eruption, and Zika fever.

Management of dengue fever includes bed rest, liquids, and mosquito net isolation to prevent re-infection, as more severe disease can occur after re-infection. Acetaminophen can be used for pain relief; aspirin should be avoided due to risk of bleeding, Dr. Martinez said.

Hospitalization and supportive care are required for those with dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome. Intensive care unit admission may be required.

Of note, a vaccine against dengue fever has shown promise in phase III trials. The vaccine has been approved in Mexico and Brazil, but not yet in the U.S.

Dr Martinez reported having no disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AAD SUMMER ACADEMY 2016

Transfers to tertiary acute care surgery service point to shortage of rural general surgeons

Nearly half of all transfer patients admitted to a tertiary facility’s acute care surgery service over a 12-month period underwent only basic surgical procedures or required no intervention after the transfer, according to a retrospective chart review.

The 161 patients transferred through the acute care surgery system during the 2014 study period were in need of the services for which they were transferred; thus, the findings highlight a “concerning lack of general surgery resources” in the community, Brittany Misercola, MD, and her colleagues at Maine Medical Center, Portland, reported in the Journal of Surgical Research.

Acute care surgery (ACS) is a relatively new paradigm – borne in part out of a heavy call burden for trauma and general surgeons – for managing patients in need of non–trauma-related emergency surgery, the investigators explained.

“At the same time as the ACS paradigm has developed, rural areas are suffering worsening shortages of physicians, especially specialists like surgeons. Another change has been regionalization of sick, complex, and resource-intensive patients to larger hospitals with more specialized care.

However, no one has yet examined the effect of an ACS service in a predominantly rural area, given these changes in health care,” they wrote (J Surg Res. 2016. [doi:10.106/j.jss.2016.06.090]).

Patients included all adults aged 18 and older admitted between Jan. 1 and Dec. 31, 2014, excluding elective surgical and trauma patients. Transfer patients were admitted from 29 different institutions. The hospital is the largest in Maine, with a wide and rural catchment area. Transfer patients came from every county in the state, with a few from outside the state; 18% were transferred from a Maine Critical Access Hospital.

Compared with 611 local patients admitted through the emergency department or from local long-term care facilities, the transfer patients were older (61.2 years vs. 54.7 years), had more comorbidities (Charlson Comorbidity Index, or CCI, of 4 vs. 3.1), and required more resources (length of stay, 8.2 vs. 3.4 days; intensive care unit admission, 24% vs. 6%), the investigators reported.

Stratification by CCI showed that the difference in length of stay between transfer and local patients was largest in those with a low CCI (0-3), compared with those with a higher CCI.

The admission diagnosis was similar in the transferred and local patients, with pancreaticobiliary and small bowel complaints being the most common (29% and 30%, and 25% and 23%, respectively, for the two diagnoses). The most common interventions were laparoscopic cholecystectomy in both groups (29% and 25%, respectively). Subspecialty interventions were also similar in the groups, and were performed in 10% and 8%, respectively.

However, the transfer patients were more likely than the local patients to not require any intervention, including subspecialty care (32% vs. 23%), they said, noting that the most common reason for admission without operative intervention was “small bowel obstruction, followed by diverticulitis without drainable abscess and mesenteric ischemia.”

The transfer patients also were more likely to have Medicare (55% vs. 24%) and less likely to be privately insured (26% vs. 45%).

The discharge destination differed significantly between the groups, with local patients being more likely to be discharged directly to home (76% vs. 46%), and transfer patients more often discharged home with services (46% vs. 12%) or to acute rehabilitation or skilled nursing facilities (12% vs. 9%). In-hospital mortality and discharge to hospice care also were more likely among transfer patients (6% vs. 2%).

“If changes are not made to support rural hospitals in caring for these patients, tertiary centers in larger cities will see increasing volume of basic surgical emergencies. As such, investing in community hospitals is important to improve patient outcomes not only locally but also after transfer to tertiary referral centers,” they wrote, adding that additional research on the populations most affected is needed.

The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Nearly half of all transfer patients admitted to a tertiary facility’s acute care surgery service over a 12-month period underwent only basic surgical procedures or required no intervention after the transfer, according to a retrospective chart review.

The 161 patients transferred through the acute care surgery system during the 2014 study period were in need of the services for which they were transferred; thus, the findings highlight a “concerning lack of general surgery resources” in the community, Brittany Misercola, MD, and her colleagues at Maine Medical Center, Portland, reported in the Journal of Surgical Research.

Acute care surgery (ACS) is a relatively new paradigm – borne in part out of a heavy call burden for trauma and general surgeons – for managing patients in need of non–trauma-related emergency surgery, the investigators explained.

“At the same time as the ACS paradigm has developed, rural areas are suffering worsening shortages of physicians, especially specialists like surgeons. Another change has been regionalization of sick, complex, and resource-intensive patients to larger hospitals with more specialized care.

However, no one has yet examined the effect of an ACS service in a predominantly rural area, given these changes in health care,” they wrote (J Surg Res. 2016. [doi:10.106/j.jss.2016.06.090]).

Patients included all adults aged 18 and older admitted between Jan. 1 and Dec. 31, 2014, excluding elective surgical and trauma patients. Transfer patients were admitted from 29 different institutions. The hospital is the largest in Maine, with a wide and rural catchment area. Transfer patients came from every county in the state, with a few from outside the state; 18% were transferred from a Maine Critical Access Hospital.

Compared with 611 local patients admitted through the emergency department or from local long-term care facilities, the transfer patients were older (61.2 years vs. 54.7 years), had more comorbidities (Charlson Comorbidity Index, or CCI, of 4 vs. 3.1), and required more resources (length of stay, 8.2 vs. 3.4 days; intensive care unit admission, 24% vs. 6%), the investigators reported.

Stratification by CCI showed that the difference in length of stay between transfer and local patients was largest in those with a low CCI (0-3), compared with those with a higher CCI.

The admission diagnosis was similar in the transferred and local patients, with pancreaticobiliary and small bowel complaints being the most common (29% and 30%, and 25% and 23%, respectively, for the two diagnoses). The most common interventions were laparoscopic cholecystectomy in both groups (29% and 25%, respectively). Subspecialty interventions were also similar in the groups, and were performed in 10% and 8%, respectively.

However, the transfer patients were more likely than the local patients to not require any intervention, including subspecialty care (32% vs. 23%), they said, noting that the most common reason for admission without operative intervention was “small bowel obstruction, followed by diverticulitis without drainable abscess and mesenteric ischemia.”

The transfer patients also were more likely to have Medicare (55% vs. 24%) and less likely to be privately insured (26% vs. 45%).

The discharge destination differed significantly between the groups, with local patients being more likely to be discharged directly to home (76% vs. 46%), and transfer patients more often discharged home with services (46% vs. 12%) or to acute rehabilitation or skilled nursing facilities (12% vs. 9%). In-hospital mortality and discharge to hospice care also were more likely among transfer patients (6% vs. 2%).

“If changes are not made to support rural hospitals in caring for these patients, tertiary centers in larger cities will see increasing volume of basic surgical emergencies. As such, investing in community hospitals is important to improve patient outcomes not only locally but also after transfer to tertiary referral centers,” they wrote, adding that additional research on the populations most affected is needed.

The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Nearly half of all transfer patients admitted to a tertiary facility’s acute care surgery service over a 12-month period underwent only basic surgical procedures or required no intervention after the transfer, according to a retrospective chart review.

The 161 patients transferred through the acute care surgery system during the 2014 study period were in need of the services for which they were transferred; thus, the findings highlight a “concerning lack of general surgery resources” in the community, Brittany Misercola, MD, and her colleagues at Maine Medical Center, Portland, reported in the Journal of Surgical Research.

Acute care surgery (ACS) is a relatively new paradigm – borne in part out of a heavy call burden for trauma and general surgeons – for managing patients in need of non–trauma-related emergency surgery, the investigators explained.

“At the same time as the ACS paradigm has developed, rural areas are suffering worsening shortages of physicians, especially specialists like surgeons. Another change has been regionalization of sick, complex, and resource-intensive patients to larger hospitals with more specialized care.

However, no one has yet examined the effect of an ACS service in a predominantly rural area, given these changes in health care,” they wrote (J Surg Res. 2016. [doi:10.106/j.jss.2016.06.090]).

Patients included all adults aged 18 and older admitted between Jan. 1 and Dec. 31, 2014, excluding elective surgical and trauma patients. Transfer patients were admitted from 29 different institutions. The hospital is the largest in Maine, with a wide and rural catchment area. Transfer patients came from every county in the state, with a few from outside the state; 18% were transferred from a Maine Critical Access Hospital.

Compared with 611 local patients admitted through the emergency department or from local long-term care facilities, the transfer patients were older (61.2 years vs. 54.7 years), had more comorbidities (Charlson Comorbidity Index, or CCI, of 4 vs. 3.1), and required more resources (length of stay, 8.2 vs. 3.4 days; intensive care unit admission, 24% vs. 6%), the investigators reported.

Stratification by CCI showed that the difference in length of stay between transfer and local patients was largest in those with a low CCI (0-3), compared with those with a higher CCI.

The admission diagnosis was similar in the transferred and local patients, with pancreaticobiliary and small bowel complaints being the most common (29% and 30%, and 25% and 23%, respectively, for the two diagnoses). The most common interventions were laparoscopic cholecystectomy in both groups (29% and 25%, respectively). Subspecialty interventions were also similar in the groups, and were performed in 10% and 8%, respectively.

However, the transfer patients were more likely than the local patients to not require any intervention, including subspecialty care (32% vs. 23%), they said, noting that the most common reason for admission without operative intervention was “small bowel obstruction, followed by diverticulitis without drainable abscess and mesenteric ischemia.”

The transfer patients also were more likely to have Medicare (55% vs. 24%) and less likely to be privately insured (26% vs. 45%).

The discharge destination differed significantly between the groups, with local patients being more likely to be discharged directly to home (76% vs. 46%), and transfer patients more often discharged home with services (46% vs. 12%) or to acute rehabilitation or skilled nursing facilities (12% vs. 9%). In-hospital mortality and discharge to hospice care also were more likely among transfer patients (6% vs. 2%).

“If changes are not made to support rural hospitals in caring for these patients, tertiary centers in larger cities will see increasing volume of basic surgical emergencies. As such, investing in community hospitals is important to improve patient outcomes not only locally but also after transfer to tertiary referral centers,” they wrote, adding that additional research on the populations most affected is needed.

The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF SURGICAL RESEARCH

Key clinical point: Transfer of patients to a tertiary facility and acute care surgery service who require basic surgical procedures or no intervention points to a shortage of general surgery capability in the rural areas.

Major finding: Transfer patients were more likely than local patients to not require any intervention, including subspecialty care (32% vs. 23%).

Data source: A retrospective review of 772 patient charts.

Disclosures: The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

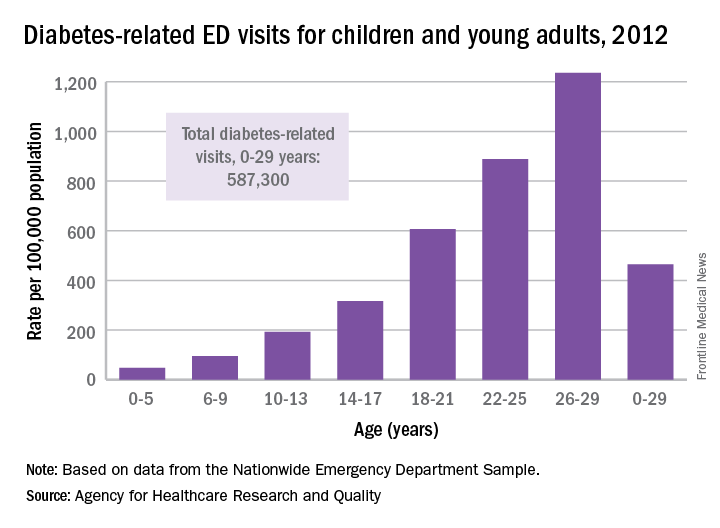

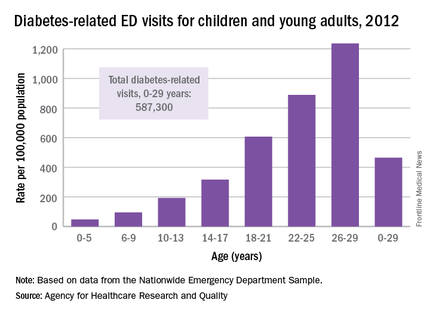

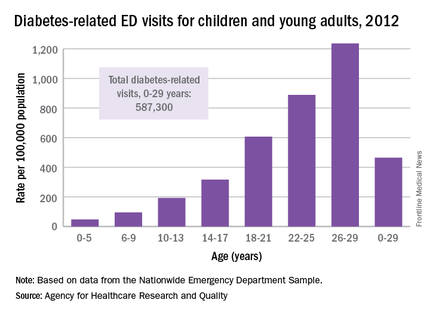

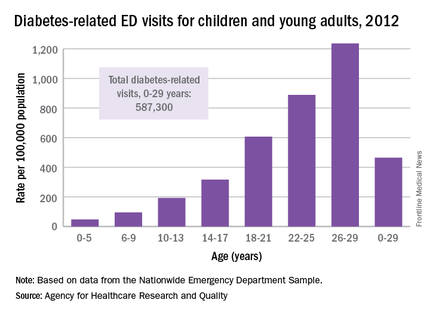

ED Visits Rise With Age in Children, Young Adults With Diabetes

The rate of diabetes-related emergency department visits was 464.5 per 100,000 U.S. population among Americans under age 30 in 2012, with young adults heading to the ED far more often than children, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Young adults aged 18-29 years made diabetes-related ED visits at a rate of 905 per 100,000 in 2012, compared with 149 per 100,000 for children 17 and under. Narrowing down the age groups shows even greater differences: The rate was 47 per 100,000 for children aged 5 years and under, 95 for children aged 6-9, 193 for 10- to 13-year-olds, 316.5 for those aged 14-17, 607 for 18- to 21-year-olds, 889 for 22- to 25-year-olds, and 1,236 for those aged 26-29 years, the AHRQ reported.

Patients aged 5 years and under were, however, the most likely to be admitted to the hospital in 2012: 29% of their diabetes-related ED visits resulted in admission, compared with 26% for those aged 26-29. Those aged 22-25 years were the least likely to be admitted, with 18% staying after their ED visit, and the overall admission rate for those aged 0-29 years was 23.5%, the report noted.

The ED visit rate for diabetes was higher for females than for males aged 0-29 years – 569 per 100,000 vs. 355 – but males were more likely to be admitted – 27% vs. 21% for females, according to data from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample.

The rate of diabetes-related emergency department visits was 464.5 per 100,000 U.S. population among Americans under age 30 in 2012, with young adults heading to the ED far more often than children, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Young adults aged 18-29 years made diabetes-related ED visits at a rate of 905 per 100,000 in 2012, compared with 149 per 100,000 for children 17 and under. Narrowing down the age groups shows even greater differences: The rate was 47 per 100,000 for children aged 5 years and under, 95 for children aged 6-9, 193 for 10- to 13-year-olds, 316.5 for those aged 14-17, 607 for 18- to 21-year-olds, 889 for 22- to 25-year-olds, and 1,236 for those aged 26-29 years, the AHRQ reported.

Patients aged 5 years and under were, however, the most likely to be admitted to the hospital in 2012: 29% of their diabetes-related ED visits resulted in admission, compared with 26% for those aged 26-29. Those aged 22-25 years were the least likely to be admitted, with 18% staying after their ED visit, and the overall admission rate for those aged 0-29 years was 23.5%, the report noted.

The ED visit rate for diabetes was higher for females than for males aged 0-29 years – 569 per 100,000 vs. 355 – but males were more likely to be admitted – 27% vs. 21% for females, according to data from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample.

The rate of diabetes-related emergency department visits was 464.5 per 100,000 U.S. population among Americans under age 30 in 2012, with young adults heading to the ED far more often than children, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Young adults aged 18-29 years made diabetes-related ED visits at a rate of 905 per 100,000 in 2012, compared with 149 per 100,000 for children 17 and under. Narrowing down the age groups shows even greater differences: The rate was 47 per 100,000 for children aged 5 years and under, 95 for children aged 6-9, 193 for 10- to 13-year-olds, 316.5 for those aged 14-17, 607 for 18- to 21-year-olds, 889 for 22- to 25-year-olds, and 1,236 for those aged 26-29 years, the AHRQ reported.

Patients aged 5 years and under were, however, the most likely to be admitted to the hospital in 2012: 29% of their diabetes-related ED visits resulted in admission, compared with 26% for those aged 26-29. Those aged 22-25 years were the least likely to be admitted, with 18% staying after their ED visit, and the overall admission rate for those aged 0-29 years was 23.5%, the report noted.