User login

When the diagnosis is hard to swallow, take these management steps

CASE REPORTMr. C, age 72, reports a lack of desire to swallow food. He denies feeling a lump in his throat. Over the past 6 months, he lost >30 lb.

The patient had a similar episode 2 years ago, which resolved without intervention. The death of his wife recently has led to isolation and lack of desire to swallow food.

Testing with standard food samples to elicit eating behaviors is normal. Electromyography and video fluoroscopy test results show no abnormalities.

What is phagophobia?The case of Mr. C brings to light the condition known as phagophobia—a sensation of not being able to swallow. Phagophobia mimics oral apraxia; pharyngoesophageal and neurologic functions as well as the ability to speak remain intact, however.1

It is estimated that about 6% of the adult general population reports dysphagia.2 About 47% of patients with dysphagic complaints do not show motor-manometric or radiological abnormalities of the upper digestive tract. A number of psychiatric conditions, including panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, anorexia nervosa, globus hystericus, hypersensitive gag reflex, and posttraumatic stress disorder can simulate this condition.3

When Barofsky and Fontaine4 compared phagophobia patients with other subjects—healthy controls, anorexia nervosa restrictors, dysphagic patients with esophageal obstruction, dysphagic patients with motility disturbance, and patients with non-motility non-obstructive dysphagia—they found that patients with psychogenic dysphagia did not appear to have an eating disorder. However, they did have a clinically significant level of psychological distress, particularly anxiety.

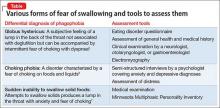

Diagnostic tools and management stepsThere are a number of approaches to assess your patient’s fear of swallowing (Table,5-7 page 68). Non-invasive assessment tools along with educational modalities usually are tried alone or together with psychopharmacological intervention. It is, however, imperative that you have an empathetic and understanding approach to such patients. When patients have confidence in the clinician they tend to respond more effectively with such approaches.

Investigations4 include questionnaires (swallow disorder history, Eating Disorder Inventory-2, and Symptom Checklist–90-R); weight assessment; testing with standardized food samples to elicit eating behaviors; self-reports; electromyography; and videofluoroscopy.

Education and reassurance includes individual demonstration of swallowing, combined with group therapy, exercises, and reassurance. Patients benefit from advice on how to maximize sensation within the oropharynx to increase taste, perception of temperature, and texture stimulation.8

Behavioral intervention involves practicing slow breathing and muscle relaxation techniques to gradually increase bite size and reduce the amount of time spent chewing each bite.

Introspection therapycomprises psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, and in vivo and introspective exposure; helps patients replace anxiety-producing thoughts with probability estimation and decatastrophizing. Introspective exposure targets the fear of choking by having the patient create sensations of throat tightening by holding a swallow in mid-action and by rapid swallowing. In vivo exposure targets the fear of swallowing by having the patient practice feeding foods (such as semi-solid easy-to-swallow choices), in and outside of the session.6

Aversion therapy requires that you pinch the patient’s hand while he (she) chews, and release the hand when he swallows.

Psychopharmacotherapeutic intervention. A number of medications can be used to help, such as imipramine up to 150 mg; desipramine, up to 150 mg; or lorazepam, 0.25 mg, twice daily, to address anxiety or panic symptoms.

Acknowledgment

Duy Li, BS, and Yu Hsuan Liao, BS, contributed to the development of the manuscript of this article.

1. Evans IM, Pia P. Phagophobia: behavioral treatment of a complex case involving fear of fear. Clinical Case Studies. 2011;10(1):37-52.

2. Kim CH, Hsu JJ, Williams DE, et al. A prospective psychological evaluation of patients with dysphagia of various etiologies. Dysphagia. 1996;11(1):34-40.

3. McNally RJ. Choking phobia: a review of the literature. Compr Psychiatry. 1994;35(1):83-89.

4. Barofsky I, Fontaine KR. Do psychogenic dysphagia patients have an eating disorder? Dysphagia. 1998;13(1):24-27.

5. Bishop LC, Riley WT. The psychiatric management of the globus syndrome. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1988;10(3):214-219.

6. Ball SG, Otto MW. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of choking phobia: 3 case studies Psychother Psychosom. 1994;62(3-4):207-211.

7. Epstein SJ, Deyoub P. Hypnotherapy for fear of choking: treatment implications of a case report. Int J Clin Hypn. 1981;29(2):117-127.

8. Scemes S, Wielenska RC, Savoia MG, et al. Choking phobia: full remission following behavior therapy. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2009;31(3):257-260.

CASE REPORTMr. C, age 72, reports a lack of desire to swallow food. He denies feeling a lump in his throat. Over the past 6 months, he lost >30 lb.

The patient had a similar episode 2 years ago, which resolved without intervention. The death of his wife recently has led to isolation and lack of desire to swallow food.

Testing with standard food samples to elicit eating behaviors is normal. Electromyography and video fluoroscopy test results show no abnormalities.

What is phagophobia?The case of Mr. C brings to light the condition known as phagophobia—a sensation of not being able to swallow. Phagophobia mimics oral apraxia; pharyngoesophageal and neurologic functions as well as the ability to speak remain intact, however.1

It is estimated that about 6% of the adult general population reports dysphagia.2 About 47% of patients with dysphagic complaints do not show motor-manometric or radiological abnormalities of the upper digestive tract. A number of psychiatric conditions, including panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, anorexia nervosa, globus hystericus, hypersensitive gag reflex, and posttraumatic stress disorder can simulate this condition.3

When Barofsky and Fontaine4 compared phagophobia patients with other subjects—healthy controls, anorexia nervosa restrictors, dysphagic patients with esophageal obstruction, dysphagic patients with motility disturbance, and patients with non-motility non-obstructive dysphagia—they found that patients with psychogenic dysphagia did not appear to have an eating disorder. However, they did have a clinically significant level of psychological distress, particularly anxiety.

Diagnostic tools and management stepsThere are a number of approaches to assess your patient’s fear of swallowing (Table,5-7 page 68). Non-invasive assessment tools along with educational modalities usually are tried alone or together with psychopharmacological intervention. It is, however, imperative that you have an empathetic and understanding approach to such patients. When patients have confidence in the clinician they tend to respond more effectively with such approaches.

Investigations4 include questionnaires (swallow disorder history, Eating Disorder Inventory-2, and Symptom Checklist–90-R); weight assessment; testing with standardized food samples to elicit eating behaviors; self-reports; electromyography; and videofluoroscopy.

Education and reassurance includes individual demonstration of swallowing, combined with group therapy, exercises, and reassurance. Patients benefit from advice on how to maximize sensation within the oropharynx to increase taste, perception of temperature, and texture stimulation.8

Behavioral intervention involves practicing slow breathing and muscle relaxation techniques to gradually increase bite size and reduce the amount of time spent chewing each bite.

Introspection therapycomprises psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, and in vivo and introspective exposure; helps patients replace anxiety-producing thoughts with probability estimation and decatastrophizing. Introspective exposure targets the fear of choking by having the patient create sensations of throat tightening by holding a swallow in mid-action and by rapid swallowing. In vivo exposure targets the fear of swallowing by having the patient practice feeding foods (such as semi-solid easy-to-swallow choices), in and outside of the session.6

Aversion therapy requires that you pinch the patient’s hand while he (she) chews, and release the hand when he swallows.

Psychopharmacotherapeutic intervention. A number of medications can be used to help, such as imipramine up to 150 mg; desipramine, up to 150 mg; or lorazepam, 0.25 mg, twice daily, to address anxiety or panic symptoms.

Acknowledgment

Duy Li, BS, and Yu Hsuan Liao, BS, contributed to the development of the manuscript of this article.

CASE REPORTMr. C, age 72, reports a lack of desire to swallow food. He denies feeling a lump in his throat. Over the past 6 months, he lost >30 lb.

The patient had a similar episode 2 years ago, which resolved without intervention. The death of his wife recently has led to isolation and lack of desire to swallow food.

Testing with standard food samples to elicit eating behaviors is normal. Electromyography and video fluoroscopy test results show no abnormalities.

What is phagophobia?The case of Mr. C brings to light the condition known as phagophobia—a sensation of not being able to swallow. Phagophobia mimics oral apraxia; pharyngoesophageal and neurologic functions as well as the ability to speak remain intact, however.1

It is estimated that about 6% of the adult general population reports dysphagia.2 About 47% of patients with dysphagic complaints do not show motor-manometric or radiological abnormalities of the upper digestive tract. A number of psychiatric conditions, including panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, anorexia nervosa, globus hystericus, hypersensitive gag reflex, and posttraumatic stress disorder can simulate this condition.3

When Barofsky and Fontaine4 compared phagophobia patients with other subjects—healthy controls, anorexia nervosa restrictors, dysphagic patients with esophageal obstruction, dysphagic patients with motility disturbance, and patients with non-motility non-obstructive dysphagia—they found that patients with psychogenic dysphagia did not appear to have an eating disorder. However, they did have a clinically significant level of psychological distress, particularly anxiety.

Diagnostic tools and management stepsThere are a number of approaches to assess your patient’s fear of swallowing (Table,5-7 page 68). Non-invasive assessment tools along with educational modalities usually are tried alone or together with psychopharmacological intervention. It is, however, imperative that you have an empathetic and understanding approach to such patients. When patients have confidence in the clinician they tend to respond more effectively with such approaches.

Investigations4 include questionnaires (swallow disorder history, Eating Disorder Inventory-2, and Symptom Checklist–90-R); weight assessment; testing with standardized food samples to elicit eating behaviors; self-reports; electromyography; and videofluoroscopy.

Education and reassurance includes individual demonstration of swallowing, combined with group therapy, exercises, and reassurance. Patients benefit from advice on how to maximize sensation within the oropharynx to increase taste, perception of temperature, and texture stimulation.8

Behavioral intervention involves practicing slow breathing and muscle relaxation techniques to gradually increase bite size and reduce the amount of time spent chewing each bite.

Introspection therapycomprises psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, and in vivo and introspective exposure; helps patients replace anxiety-producing thoughts with probability estimation and decatastrophizing. Introspective exposure targets the fear of choking by having the patient create sensations of throat tightening by holding a swallow in mid-action and by rapid swallowing. In vivo exposure targets the fear of swallowing by having the patient practice feeding foods (such as semi-solid easy-to-swallow choices), in and outside of the session.6

Aversion therapy requires that you pinch the patient’s hand while he (she) chews, and release the hand when he swallows.

Psychopharmacotherapeutic intervention. A number of medications can be used to help, such as imipramine up to 150 mg; desipramine, up to 150 mg; or lorazepam, 0.25 mg, twice daily, to address anxiety or panic symptoms.

Acknowledgment

Duy Li, BS, and Yu Hsuan Liao, BS, contributed to the development of the manuscript of this article.

1. Evans IM, Pia P. Phagophobia: behavioral treatment of a complex case involving fear of fear. Clinical Case Studies. 2011;10(1):37-52.

2. Kim CH, Hsu JJ, Williams DE, et al. A prospective psychological evaluation of patients with dysphagia of various etiologies. Dysphagia. 1996;11(1):34-40.

3. McNally RJ. Choking phobia: a review of the literature. Compr Psychiatry. 1994;35(1):83-89.

4. Barofsky I, Fontaine KR. Do psychogenic dysphagia patients have an eating disorder? Dysphagia. 1998;13(1):24-27.

5. Bishop LC, Riley WT. The psychiatric management of the globus syndrome. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1988;10(3):214-219.

6. Ball SG, Otto MW. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of choking phobia: 3 case studies Psychother Psychosom. 1994;62(3-4):207-211.

7. Epstein SJ, Deyoub P. Hypnotherapy for fear of choking: treatment implications of a case report. Int J Clin Hypn. 1981;29(2):117-127.

8. Scemes S, Wielenska RC, Savoia MG, et al. Choking phobia: full remission following behavior therapy. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2009;31(3):257-260.

1. Evans IM, Pia P. Phagophobia: behavioral treatment of a complex case involving fear of fear. Clinical Case Studies. 2011;10(1):37-52.

2. Kim CH, Hsu JJ, Williams DE, et al. A prospective psychological evaluation of patients with dysphagia of various etiologies. Dysphagia. 1996;11(1):34-40.

3. McNally RJ. Choking phobia: a review of the literature. Compr Psychiatry. 1994;35(1):83-89.

4. Barofsky I, Fontaine KR. Do psychogenic dysphagia patients have an eating disorder? Dysphagia. 1998;13(1):24-27.

5. Bishop LC, Riley WT. The psychiatric management of the globus syndrome. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1988;10(3):214-219.

6. Ball SG, Otto MW. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of choking phobia: 3 case studies Psychother Psychosom. 1994;62(3-4):207-211.

7. Epstein SJ, Deyoub P. Hypnotherapy for fear of choking: treatment implications of a case report. Int J Clin Hypn. 1981;29(2):117-127.

8. Scemes S, Wielenska RC, Savoia MG, et al. Choking phobia: full remission following behavior therapy. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2009;31(3):257-260.

How to assess and treat birth-related depression in new fathers

Only recently has paternal postpartum depression (PPD) received much attention. Research has shown that maternal PPD is associated with negative outcomes in the child’s cognitive development and social and marital problems for the parents. Likewise, depressed fathers are less likely to play outside with their child and more likely to put the child to bed awake.1

Recent studies reported that 10.4% of men experienced depression within 12 month of delivery.1 Edmondson et al2 estimate the prevalence of paternal PPD to be 8% between birth and 3 months, 26% from 3 to 6 months, and 9% from 6 to 12 months.

Risk factors

Risk factors for paternal PPD have not been studied extensively. Some studies have shown that immaturity, lack of social support, first or unplanned pregnancies, marital relationship problems, and unemployment were the most common risk factors for depression in men postnatally.3 A history of depression and other psychiatric disorders also increases risk.4 Psychosocial factors, such as quality of the spousal relationship, parenting distress, and perceived parenting efficacy, contribute to paternal depression.

Similarly, depressed postpartum fathers experience higher levels of parenting distress and a lower sense of parenting efficacy.5 Interestingly, negative life events were associated with increased risk for depression in mothers, but not fathers.3

Clinical presentation

Paternal PPD symptoms appear within 12 months after the birth of the child and last for at least 2 weeks. Signs and symptoms of depression in men might not resemble those seen in postpartum women. Men tend to show aggression, increased or easy irritability, and agitation, and might not seek help for emotional issues as readily as women do. Typical symptoms of depression often are present, such as sleep disturbance or changes in sleep patterns, difficulty concentrating, memory problems, and feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness, inadequacy, and excess guilt with suicidal ideation.6

Making the diagnosis

Maternal PPD commonly is evaluated using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale- Partner (EDPS-P) or Postpartum Depression Screening Scale. However, studies are lacking to determine which diagnostic modality is most accurate for diagnosing paternal PPD.

A paternal PPD screening tool could include the EDPS-P administered to mothers. Edmonson et al2 determined an EDPS-P score of >10 was the optimal cut-off point for screening for paternal depression, with a sensitivity of 89.5% and a specificity of 78.2%, compared with a structured clinical interview. Fisher et al4 determined that the EDPS-P report was a reliable method for detecting paternal PPD compared with validated depression scales completed by fathers. Madsen et al5 determined the Gotland Male Depression Scale, which detects typical male depressive symptoms, also was effective in recognizing paternal PPD at 6 weeks postpartum.7

Treatment of paternal PPD

Specific treatment for paternal PPD has not been studied extensively. Psychotherapy targeted at interpersonal family relationships and parenting is indicated for mild depression, whereas a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy is recommended for moderate or severe depression.

Depending on specific patient factors, pharmacotherapy options include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and atypical antipsychotics.8 SSRIs often are used because of their efficacy and relative lack of serious side effects, as demonstrated in numerous trials.2 Recovery is more likely with combination therapy than monotherapy.9 Fathers with psychosis or suicidal ideation should be referred for inpatient treatment.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Paulson JF, Dauber S, Leiferman JA. Individual and combined effects of postpartum depression in mothers and fathers on parenting behavior. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):659-668.

2. Edmondson OJ, Psychogiou L, Vlachos H, et al. Depression in fathers in the postnatal period: assessment of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale as a screening measure. J Affect Disord. 2010;125(1-3):365-368.

3. Schumacher M, Zubaran C, White G. Bringing birth-related paternal depression to the fore. Women Birth. 2008;21(2):65-70.

4. Fisher SD, Kopelman R, O’Hara MW. Partner report of paternal depression using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale-Partner. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(4):283-288.

5. Madsen SA, Juhl T. Paternal depression in the postnatal period assessed with traditional and male depression scales. Journal of Men’s Health and Gender. 2007;4(1):26-31.

6. Escribà-Agüir V, Artazcoz L. Gender differences in postpartum depression: a longitudinal cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(4):320-326.

7. Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L, et al. Psychotherapy versus the combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depression: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(3):279-288.

8. Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation anti-depressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9665):746-758.

9. Demontigny F, Girard ME, Lacharité C, et al. Psychosocial factors associated with paternal postnatal depression. J Affect Disord. 2013;15(150):44-49.

Only recently has paternal postpartum depression (PPD) received much attention. Research has shown that maternal PPD is associated with negative outcomes in the child’s cognitive development and social and marital problems for the parents. Likewise, depressed fathers are less likely to play outside with their child and more likely to put the child to bed awake.1

Recent studies reported that 10.4% of men experienced depression within 12 month of delivery.1 Edmondson et al2 estimate the prevalence of paternal PPD to be 8% between birth and 3 months, 26% from 3 to 6 months, and 9% from 6 to 12 months.

Risk factors

Risk factors for paternal PPD have not been studied extensively. Some studies have shown that immaturity, lack of social support, first or unplanned pregnancies, marital relationship problems, and unemployment were the most common risk factors for depression in men postnatally.3 A history of depression and other psychiatric disorders also increases risk.4 Psychosocial factors, such as quality of the spousal relationship, parenting distress, and perceived parenting efficacy, contribute to paternal depression.

Similarly, depressed postpartum fathers experience higher levels of parenting distress and a lower sense of parenting efficacy.5 Interestingly, negative life events were associated with increased risk for depression in mothers, but not fathers.3

Clinical presentation

Paternal PPD symptoms appear within 12 months after the birth of the child and last for at least 2 weeks. Signs and symptoms of depression in men might not resemble those seen in postpartum women. Men tend to show aggression, increased or easy irritability, and agitation, and might not seek help for emotional issues as readily as women do. Typical symptoms of depression often are present, such as sleep disturbance or changes in sleep patterns, difficulty concentrating, memory problems, and feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness, inadequacy, and excess guilt with suicidal ideation.6

Making the diagnosis

Maternal PPD commonly is evaluated using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale- Partner (EDPS-P) or Postpartum Depression Screening Scale. However, studies are lacking to determine which diagnostic modality is most accurate for diagnosing paternal PPD.

A paternal PPD screening tool could include the EDPS-P administered to mothers. Edmonson et al2 determined an EDPS-P score of >10 was the optimal cut-off point for screening for paternal depression, with a sensitivity of 89.5% and a specificity of 78.2%, compared with a structured clinical interview. Fisher et al4 determined that the EDPS-P report was a reliable method for detecting paternal PPD compared with validated depression scales completed by fathers. Madsen et al5 determined the Gotland Male Depression Scale, which detects typical male depressive symptoms, also was effective in recognizing paternal PPD at 6 weeks postpartum.7

Treatment of paternal PPD

Specific treatment for paternal PPD has not been studied extensively. Psychotherapy targeted at interpersonal family relationships and parenting is indicated for mild depression, whereas a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy is recommended for moderate or severe depression.

Depending on specific patient factors, pharmacotherapy options include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and atypical antipsychotics.8 SSRIs often are used because of their efficacy and relative lack of serious side effects, as demonstrated in numerous trials.2 Recovery is more likely with combination therapy than monotherapy.9 Fathers with psychosis or suicidal ideation should be referred for inpatient treatment.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Only recently has paternal postpartum depression (PPD) received much attention. Research has shown that maternal PPD is associated with negative outcomes in the child’s cognitive development and social and marital problems for the parents. Likewise, depressed fathers are less likely to play outside with their child and more likely to put the child to bed awake.1

Recent studies reported that 10.4% of men experienced depression within 12 month of delivery.1 Edmondson et al2 estimate the prevalence of paternal PPD to be 8% between birth and 3 months, 26% from 3 to 6 months, and 9% from 6 to 12 months.

Risk factors

Risk factors for paternal PPD have not been studied extensively. Some studies have shown that immaturity, lack of social support, first or unplanned pregnancies, marital relationship problems, and unemployment were the most common risk factors for depression in men postnatally.3 A history of depression and other psychiatric disorders also increases risk.4 Psychosocial factors, such as quality of the spousal relationship, parenting distress, and perceived parenting efficacy, contribute to paternal depression.

Similarly, depressed postpartum fathers experience higher levels of parenting distress and a lower sense of parenting efficacy.5 Interestingly, negative life events were associated with increased risk for depression in mothers, but not fathers.3

Clinical presentation

Paternal PPD symptoms appear within 12 months after the birth of the child and last for at least 2 weeks. Signs and symptoms of depression in men might not resemble those seen in postpartum women. Men tend to show aggression, increased or easy irritability, and agitation, and might not seek help for emotional issues as readily as women do. Typical symptoms of depression often are present, such as sleep disturbance or changes in sleep patterns, difficulty concentrating, memory problems, and feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness, inadequacy, and excess guilt with suicidal ideation.6

Making the diagnosis

Maternal PPD commonly is evaluated using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale- Partner (EDPS-P) or Postpartum Depression Screening Scale. However, studies are lacking to determine which diagnostic modality is most accurate for diagnosing paternal PPD.

A paternal PPD screening tool could include the EDPS-P administered to mothers. Edmonson et al2 determined an EDPS-P score of >10 was the optimal cut-off point for screening for paternal depression, with a sensitivity of 89.5% and a specificity of 78.2%, compared with a structured clinical interview. Fisher et al4 determined that the EDPS-P report was a reliable method for detecting paternal PPD compared with validated depression scales completed by fathers. Madsen et al5 determined the Gotland Male Depression Scale, which detects typical male depressive symptoms, also was effective in recognizing paternal PPD at 6 weeks postpartum.7

Treatment of paternal PPD

Specific treatment for paternal PPD has not been studied extensively. Psychotherapy targeted at interpersonal family relationships and parenting is indicated for mild depression, whereas a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy is recommended for moderate or severe depression.

Depending on specific patient factors, pharmacotherapy options include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and atypical antipsychotics.8 SSRIs often are used because of their efficacy and relative lack of serious side effects, as demonstrated in numerous trials.2 Recovery is more likely with combination therapy than monotherapy.9 Fathers with psychosis or suicidal ideation should be referred for inpatient treatment.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Paulson JF, Dauber S, Leiferman JA. Individual and combined effects of postpartum depression in mothers and fathers on parenting behavior. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):659-668.

2. Edmondson OJ, Psychogiou L, Vlachos H, et al. Depression in fathers in the postnatal period: assessment of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale as a screening measure. J Affect Disord. 2010;125(1-3):365-368.

3. Schumacher M, Zubaran C, White G. Bringing birth-related paternal depression to the fore. Women Birth. 2008;21(2):65-70.

4. Fisher SD, Kopelman R, O’Hara MW. Partner report of paternal depression using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale-Partner. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(4):283-288.

5. Madsen SA, Juhl T. Paternal depression in the postnatal period assessed with traditional and male depression scales. Journal of Men’s Health and Gender. 2007;4(1):26-31.

6. Escribà-Agüir V, Artazcoz L. Gender differences in postpartum depression: a longitudinal cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(4):320-326.

7. Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L, et al. Psychotherapy versus the combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depression: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(3):279-288.

8. Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation anti-depressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9665):746-758.

9. Demontigny F, Girard ME, Lacharité C, et al. Psychosocial factors associated with paternal postnatal depression. J Affect Disord. 2013;15(150):44-49.

1. Paulson JF, Dauber S, Leiferman JA. Individual and combined effects of postpartum depression in mothers and fathers on parenting behavior. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):659-668.

2. Edmondson OJ, Psychogiou L, Vlachos H, et al. Depression in fathers in the postnatal period: assessment of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale as a screening measure. J Affect Disord. 2010;125(1-3):365-368.

3. Schumacher M, Zubaran C, White G. Bringing birth-related paternal depression to the fore. Women Birth. 2008;21(2):65-70.

4. Fisher SD, Kopelman R, O’Hara MW. Partner report of paternal depression using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale-Partner. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(4):283-288.

5. Madsen SA, Juhl T. Paternal depression in the postnatal period assessed with traditional and male depression scales. Journal of Men’s Health and Gender. 2007;4(1):26-31.

6. Escribà-Agüir V, Artazcoz L. Gender differences in postpartum depression: a longitudinal cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(4):320-326.

7. Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L, et al. Psychotherapy versus the combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depression: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(3):279-288.

8. Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation anti-depressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9665):746-758.

9. Demontigny F, Girard ME, Lacharité C, et al. Psychosocial factors associated with paternal postnatal depression. J Affect Disord. 2013;15(150):44-49.

6 Strategies to address risk factors for school violence

School shootings engender the deepest of public concern. They violate strongly held cross-culture beliefs about the sanctity of childhood and the obligation to protect children from harm.

Prevention and intervention approaches to school shootings have emerged (1) in the literature, from case studies, and (2) from discourse among experts.1 Approaches include:

• bolstering security at schools

• reducing the facilities’ vulnerability to intrusion

• increasing the capacity to respond at the moment of threat

• transforming the school climate

• increasing attachment and bonding.1,2

Psychiatrists often are consulted by school districts to provide expertise for the latter 2 approaches. Using the following strategies, you can help address risk factors for school violence.

Strengthen school attachment. Develop curricular and extracurricular programs for students that create, and contribute to, a sense of belonging. This, in turn, decreases alienation and reduces hostility. Unaddressed hostility can lead to depression, anger, and, subsequently, violence.

Reduce social aggression. Social aggression, such as teasing, taunting, humiliating, and bullying, is an important predictor of developmental outcomes in victims and perpetrators.3 Social aggression has been linked to peer victimization and low school attachment. Implement social skills programs, such as Making Choices, which have yielded positive effects on social aggression in elementary school students.4

Break codes of silence. This can involve encouraging schools to:

• develop an anonymous mechanism of voicing concerns

• take diligent action based on students’ concerns

• treat disclosures discreetly.

Establish resources for troubled and rejected students. Develop routine emergency modes of communication, such as a protocol for high-priority referral to mental health resources. These could reduce the likelihood of students acting out against the school.

Recommend that security be enhanced. Establishing the position of school resource officer might increase confidence and decrease feelings of vulnerability among teachers, students, and parents. This can increase the perception of school security, potentially helps school attachment, and promotes breaking down codes of silence.5

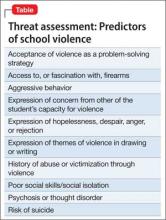

Increase communication within the school, and between the school and law enforcement agencies. Effective communication can help identify the location of an attacker and disrupt a developing event. Create an alert system to notify students, faculty, and parents with an automated text message or phone call during an emergency. Increased accessibility of the students by the school alert system might be a quicker way to reach the school community. Work with security agencies to develop a protocol for communicating and assessing threat potential. Also, develop guidelines to outline referral and assessing procedures for students whose writings may present indication for possible attack or whose class behavior may be alienating or intimidating to either faculty or other students. Behavior that can lead to school violence is outlined in the Table.

You also can educate school administrators about the following:

• School violence has been significantly associated with mental health problems, such as depression and inability to form age appropriate social connections,6 which in combination with extreme social rejection and specific personality-related issues (eg, antisocial personality disorder) can culminate in violent outbreaks.7 Work closely with school nurses and counselors to identify and treat vulnerable students.

• In most multiple-victim incidents, more than 1 person had information about the attack before it occurred that was not communicated to an authority figure. Educate school officials about being sensitive to warnings or threats about possible attack, and help develop ways get counseling for potential attackers.2

• Zero-tolerance policies are ineffective at preventing school shootings, mostly because of literal interpretation and inconsistent implementation of such policies.8 Help circumvent a more stringent zero-tolerance policy with adequate availability of mental health care for students who are identified as being at risk of perpetrating an attack.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Culley MR, Conkling M, Emshoff J, et al. Environmental and contextual influences on school violence and its prevention. J Prim Prev. 2006;27(3):217-227.

2. Wike TL, Fraser MW. School shooting: making sense of the senseless. Aggress Violent Behav. 2009;14(3):162-169.

3. Rudatsikira E, Singh P, Job J, et al. Variables associated with weapon-carrying among young adolescents in southern California. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(5):470-473.

4. Fraser MW, Galinsky MJ, Smokowski PR, et al. Social information-processing skills training to promote social competence and prevent aggressive behavior in the third grades. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(6):1045-1055.

5. Finn P. School resource officer programs. Finding the funding, reaping the benefits. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. 2006;75(8):1-13.

6. Ferguson C, Coulson M, Barnett J. Psychological profiles of school shooters: positive directions and one big wrong turn. J Police Crisis Negot. 2011;11:1-17.

7. Leary MR, Kowalski RM, Smith L, et al. Teasing, rejection and violence: case studies of the school shootings. Aggressive Behavior. 2003;29(3):202-214.

8. American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force. Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools?: an evidentiary review and recommendation. Am Psychol. 2008;63(9):852-862.

School shootings engender the deepest of public concern. They violate strongly held cross-culture beliefs about the sanctity of childhood and the obligation to protect children from harm.

Prevention and intervention approaches to school shootings have emerged (1) in the literature, from case studies, and (2) from discourse among experts.1 Approaches include:

• bolstering security at schools

• reducing the facilities’ vulnerability to intrusion

• increasing the capacity to respond at the moment of threat

• transforming the school climate

• increasing attachment and bonding.1,2

Psychiatrists often are consulted by school districts to provide expertise for the latter 2 approaches. Using the following strategies, you can help address risk factors for school violence.

Strengthen school attachment. Develop curricular and extracurricular programs for students that create, and contribute to, a sense of belonging. This, in turn, decreases alienation and reduces hostility. Unaddressed hostility can lead to depression, anger, and, subsequently, violence.

Reduce social aggression. Social aggression, such as teasing, taunting, humiliating, and bullying, is an important predictor of developmental outcomes in victims and perpetrators.3 Social aggression has been linked to peer victimization and low school attachment. Implement social skills programs, such as Making Choices, which have yielded positive effects on social aggression in elementary school students.4

Break codes of silence. This can involve encouraging schools to:

• develop an anonymous mechanism of voicing concerns

• take diligent action based on students’ concerns

• treat disclosures discreetly.

Establish resources for troubled and rejected students. Develop routine emergency modes of communication, such as a protocol for high-priority referral to mental health resources. These could reduce the likelihood of students acting out against the school.

Recommend that security be enhanced. Establishing the position of school resource officer might increase confidence and decrease feelings of vulnerability among teachers, students, and parents. This can increase the perception of school security, potentially helps school attachment, and promotes breaking down codes of silence.5

Increase communication within the school, and between the school and law enforcement agencies. Effective communication can help identify the location of an attacker and disrupt a developing event. Create an alert system to notify students, faculty, and parents with an automated text message or phone call during an emergency. Increased accessibility of the students by the school alert system might be a quicker way to reach the school community. Work with security agencies to develop a protocol for communicating and assessing threat potential. Also, develop guidelines to outline referral and assessing procedures for students whose writings may present indication for possible attack or whose class behavior may be alienating or intimidating to either faculty or other students. Behavior that can lead to school violence is outlined in the Table.

You also can educate school administrators about the following:

• School violence has been significantly associated with mental health problems, such as depression and inability to form age appropriate social connections,6 which in combination with extreme social rejection and specific personality-related issues (eg, antisocial personality disorder) can culminate in violent outbreaks.7 Work closely with school nurses and counselors to identify and treat vulnerable students.

• In most multiple-victim incidents, more than 1 person had information about the attack before it occurred that was not communicated to an authority figure. Educate school officials about being sensitive to warnings or threats about possible attack, and help develop ways get counseling for potential attackers.2

• Zero-tolerance policies are ineffective at preventing school shootings, mostly because of literal interpretation and inconsistent implementation of such policies.8 Help circumvent a more stringent zero-tolerance policy with adequate availability of mental health care for students who are identified as being at risk of perpetrating an attack.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

School shootings engender the deepest of public concern. They violate strongly held cross-culture beliefs about the sanctity of childhood and the obligation to protect children from harm.

Prevention and intervention approaches to school shootings have emerged (1) in the literature, from case studies, and (2) from discourse among experts.1 Approaches include:

• bolstering security at schools

• reducing the facilities’ vulnerability to intrusion

• increasing the capacity to respond at the moment of threat

• transforming the school climate

• increasing attachment and bonding.1,2

Psychiatrists often are consulted by school districts to provide expertise for the latter 2 approaches. Using the following strategies, you can help address risk factors for school violence.

Strengthen school attachment. Develop curricular and extracurricular programs for students that create, and contribute to, a sense of belonging. This, in turn, decreases alienation and reduces hostility. Unaddressed hostility can lead to depression, anger, and, subsequently, violence.

Reduce social aggression. Social aggression, such as teasing, taunting, humiliating, and bullying, is an important predictor of developmental outcomes in victims and perpetrators.3 Social aggression has been linked to peer victimization and low school attachment. Implement social skills programs, such as Making Choices, which have yielded positive effects on social aggression in elementary school students.4

Break codes of silence. This can involve encouraging schools to:

• develop an anonymous mechanism of voicing concerns

• take diligent action based on students’ concerns

• treat disclosures discreetly.

Establish resources for troubled and rejected students. Develop routine emergency modes of communication, such as a protocol for high-priority referral to mental health resources. These could reduce the likelihood of students acting out against the school.

Recommend that security be enhanced. Establishing the position of school resource officer might increase confidence and decrease feelings of vulnerability among teachers, students, and parents. This can increase the perception of school security, potentially helps school attachment, and promotes breaking down codes of silence.5

Increase communication within the school, and between the school and law enforcement agencies. Effective communication can help identify the location of an attacker and disrupt a developing event. Create an alert system to notify students, faculty, and parents with an automated text message or phone call during an emergency. Increased accessibility of the students by the school alert system might be a quicker way to reach the school community. Work with security agencies to develop a protocol for communicating and assessing threat potential. Also, develop guidelines to outline referral and assessing procedures for students whose writings may present indication for possible attack or whose class behavior may be alienating or intimidating to either faculty or other students. Behavior that can lead to school violence is outlined in the Table.

You also can educate school administrators about the following:

• School violence has been significantly associated with mental health problems, such as depression and inability to form age appropriate social connections,6 which in combination with extreme social rejection and specific personality-related issues (eg, antisocial personality disorder) can culminate in violent outbreaks.7 Work closely with school nurses and counselors to identify and treat vulnerable students.

• In most multiple-victim incidents, more than 1 person had information about the attack before it occurred that was not communicated to an authority figure. Educate school officials about being sensitive to warnings or threats about possible attack, and help develop ways get counseling for potential attackers.2

• Zero-tolerance policies are ineffective at preventing school shootings, mostly because of literal interpretation and inconsistent implementation of such policies.8 Help circumvent a more stringent zero-tolerance policy with adequate availability of mental health care for students who are identified as being at risk of perpetrating an attack.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Culley MR, Conkling M, Emshoff J, et al. Environmental and contextual influences on school violence and its prevention. J Prim Prev. 2006;27(3):217-227.

2. Wike TL, Fraser MW. School shooting: making sense of the senseless. Aggress Violent Behav. 2009;14(3):162-169.

3. Rudatsikira E, Singh P, Job J, et al. Variables associated with weapon-carrying among young adolescents in southern California. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(5):470-473.

4. Fraser MW, Galinsky MJ, Smokowski PR, et al. Social information-processing skills training to promote social competence and prevent aggressive behavior in the third grades. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(6):1045-1055.

5. Finn P. School resource officer programs. Finding the funding, reaping the benefits. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. 2006;75(8):1-13.

6. Ferguson C, Coulson M, Barnett J. Psychological profiles of school shooters: positive directions and one big wrong turn. J Police Crisis Negot. 2011;11:1-17.

7. Leary MR, Kowalski RM, Smith L, et al. Teasing, rejection and violence: case studies of the school shootings. Aggressive Behavior. 2003;29(3):202-214.

8. American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force. Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools?: an evidentiary review and recommendation. Am Psychol. 2008;63(9):852-862.

1. Culley MR, Conkling M, Emshoff J, et al. Environmental and contextual influences on school violence and its prevention. J Prim Prev. 2006;27(3):217-227.

2. Wike TL, Fraser MW. School shooting: making sense of the senseless. Aggress Violent Behav. 2009;14(3):162-169.

3. Rudatsikira E, Singh P, Job J, et al. Variables associated with weapon-carrying among young adolescents in southern California. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(5):470-473.

4. Fraser MW, Galinsky MJ, Smokowski PR, et al. Social information-processing skills training to promote social competence and prevent aggressive behavior in the third grades. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(6):1045-1055.

5. Finn P. School resource officer programs. Finding the funding, reaping the benefits. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. 2006;75(8):1-13.

6. Ferguson C, Coulson M, Barnett J. Psychological profiles of school shooters: positive directions and one big wrong turn. J Police Crisis Negot. 2011;11:1-17.

7. Leary MR, Kowalski RM, Smith L, et al. Teasing, rejection and violence: case studies of the school shootings. Aggressive Behavior. 2003;29(3):202-214.

8. American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force. Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools?: an evidentiary review and recommendation. Am Psychol. 2008;63(9):852-862.

Assessing tremor to rule out psychogenic origin: It’s tricky

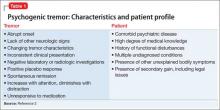

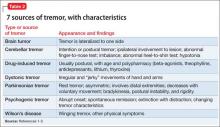

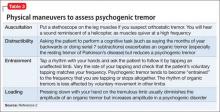

Tremors are a rhythmic and oscillatory movement of a body part with a relatively constant frequency.1 Several subtypes of tremors are classified on the basis of whether they occur during static or kinetic body positioning. Assessing tremors to rule out psychogenic origin is one of the trickiest tasks for a psychiatrist (Table 12). Non-organic movement disorders are not rare, and all common organic movement disorders can be mimicked by non-organic presentations.

Diagnostic approach

Start by categorizing the tremor based on its activation condition (at rest, kinetic or intentional, postural or isometric), topographic distribution, and frequency. Observe the patient sitting in a chair with his hands on his lap for resting tremor. Postural or kinetic tremors can be assessed by stretching the arms and performing a finger-to-nose test. A resting tremor can indicate parkinsonism; intention tremor may indicate a cerebellar lesion. A psychogenic tremor can occur at rest or during postural or active movement, and often will occur in all 3 situations (Table 2).1-3

Some of the maneuvers listed in Table 3 are helpful to distinguish a psychogenic from an organic cause. The key is to look for variability in direction, amplitude, and frequency. Psychogenic tremor often increases when the limb is examined and reduces upon distraction, and also might be exacerbated with movement of other limbs. Patients with psychogenic tremor often have other “non-organic” neurologic signs, such as give-way weakness, deliberate slowness carrying out requested voluntary movement, and sensory signs that contradict neuroanatomical principles.

Investigation

Proceed as follows:

1. Perform laboratory testing: thyroid function panel and serum copper and ceruloplasmin levels.2

2. Perform surface electromyography to differentiate Parkinson’s disease and benign tremor disorders.2

3. Obtain a MRI to assess atypical tremor; findings might reveal Wilson’s disease (basal ganglia and brainstem involvement) or fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (pontocerebellar hypoplasia or cerebral white matter involvement).3

4. Consider dopaminergic functional imaging scanning. When positive, the scan can reveal symptoms of parkinsonism; negative findings can help consolidate a diagnosis of psychogenic tremor.3

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Bain P, Brin M, Deuschl G, et al. Criteria for the diagnosis of essential tremor. Neurology. 2000;54(11 suppl 4):S7.

2. Alty JE, Kempster PA. A practical guide to the differential diagnosis of tremor. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87(1031):623-629.

3. Crawford P, Zimmerman EE. Differentiation and diagnosis of tremor. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(6):697-702.

Tremors are a rhythmic and oscillatory movement of a body part with a relatively constant frequency.1 Several subtypes of tremors are classified on the basis of whether they occur during static or kinetic body positioning. Assessing tremors to rule out psychogenic origin is one of the trickiest tasks for a psychiatrist (Table 12). Non-organic movement disorders are not rare, and all common organic movement disorders can be mimicked by non-organic presentations.

Diagnostic approach

Start by categorizing the tremor based on its activation condition (at rest, kinetic or intentional, postural or isometric), topographic distribution, and frequency. Observe the patient sitting in a chair with his hands on his lap for resting tremor. Postural or kinetic tremors can be assessed by stretching the arms and performing a finger-to-nose test. A resting tremor can indicate parkinsonism; intention tremor may indicate a cerebellar lesion. A psychogenic tremor can occur at rest or during postural or active movement, and often will occur in all 3 situations (Table 2).1-3

Some of the maneuvers listed in Table 3 are helpful to distinguish a psychogenic from an organic cause. The key is to look for variability in direction, amplitude, and frequency. Psychogenic tremor often increases when the limb is examined and reduces upon distraction, and also might be exacerbated with movement of other limbs. Patients with psychogenic tremor often have other “non-organic” neurologic signs, such as give-way weakness, deliberate slowness carrying out requested voluntary movement, and sensory signs that contradict neuroanatomical principles.

Investigation

Proceed as follows:

1. Perform laboratory testing: thyroid function panel and serum copper and ceruloplasmin levels.2

2. Perform surface electromyography to differentiate Parkinson’s disease and benign tremor disorders.2

3. Obtain a MRI to assess atypical tremor; findings might reveal Wilson’s disease (basal ganglia and brainstem involvement) or fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (pontocerebellar hypoplasia or cerebral white matter involvement).3

4. Consider dopaminergic functional imaging scanning. When positive, the scan can reveal symptoms of parkinsonism; negative findings can help consolidate a diagnosis of psychogenic tremor.3

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Tremors are a rhythmic and oscillatory movement of a body part with a relatively constant frequency.1 Several subtypes of tremors are classified on the basis of whether they occur during static or kinetic body positioning. Assessing tremors to rule out psychogenic origin is one of the trickiest tasks for a psychiatrist (Table 12). Non-organic movement disorders are not rare, and all common organic movement disorders can be mimicked by non-organic presentations.

Diagnostic approach

Start by categorizing the tremor based on its activation condition (at rest, kinetic or intentional, postural or isometric), topographic distribution, and frequency. Observe the patient sitting in a chair with his hands on his lap for resting tremor. Postural or kinetic tremors can be assessed by stretching the arms and performing a finger-to-nose test. A resting tremor can indicate parkinsonism; intention tremor may indicate a cerebellar lesion. A psychogenic tremor can occur at rest or during postural or active movement, and often will occur in all 3 situations (Table 2).1-3

Some of the maneuvers listed in Table 3 are helpful to distinguish a psychogenic from an organic cause. The key is to look for variability in direction, amplitude, and frequency. Psychogenic tremor often increases when the limb is examined and reduces upon distraction, and also might be exacerbated with movement of other limbs. Patients with psychogenic tremor often have other “non-organic” neurologic signs, such as give-way weakness, deliberate slowness carrying out requested voluntary movement, and sensory signs that contradict neuroanatomical principles.

Investigation

Proceed as follows:

1. Perform laboratory testing: thyroid function panel and serum copper and ceruloplasmin levels.2

2. Perform surface electromyography to differentiate Parkinson’s disease and benign tremor disorders.2

3. Obtain a MRI to assess atypical tremor; findings might reveal Wilson’s disease (basal ganglia and brainstem involvement) or fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (pontocerebellar hypoplasia or cerebral white matter involvement).3

4. Consider dopaminergic functional imaging scanning. When positive, the scan can reveal symptoms of parkinsonism; negative findings can help consolidate a diagnosis of psychogenic tremor.3

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Bain P, Brin M, Deuschl G, et al. Criteria for the diagnosis of essential tremor. Neurology. 2000;54(11 suppl 4):S7.

2. Alty JE, Kempster PA. A practical guide to the differential diagnosis of tremor. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87(1031):623-629.

3. Crawford P, Zimmerman EE. Differentiation and diagnosis of tremor. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(6):697-702.

1. Bain P, Brin M, Deuschl G, et al. Criteria for the diagnosis of essential tremor. Neurology. 2000;54(11 suppl 4):S7.

2. Alty JE, Kempster PA. A practical guide to the differential diagnosis of tremor. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87(1031):623-629.

3. Crawford P, Zimmerman EE. Differentiation and diagnosis of tremor. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(6):697-702.

Be prepared to adjust dosing of psychotropics after bariatric surgery

Approximately 113,000 bariatric surgeries were performed in the United States in 2010; as many as 80% of persons seeking weight loss surgery have a history of a psychiatric disorder.1,2

Bariatric surgery can be “restrictive” (limiting food intake) or “malabsorptive” (limiting food absorption). Both types of procedures can cause significant changes in pharmacokinetics. Bariatric surgery patients who take a psychotropic are at risk of toxicity or relapse of their psychiatric illness because of inappropriate formulations— immediate-release vs sustained-release—or incomplete absorption of medications. You need to anticipate potential pharmacokinetic alterations after bariatric surgery and make appropriate changes to the patient’s medication regimen.

Pharmacokinetic concerns

Roux-en-Y surgery is a malabsorptive procedure that causes food to bypass the stomach, duodenum, and a variable length of jejunum. Secondary to bypass, iron deficiency anemia is a common nutritional complication.

Other changes that affect the pharmacokinetics of psychotropics after bariatric surgery include:

• an increase in percentage of lean body mass as weight loss occurs

• a decrease in glomerular filtration rate as kidney size decreases with postsurgical weight reduction

• reversal of obesity-associated fatty liver and cirrhotic changes.

With time, intestinal adaptation occurs to compensate for the reduced length of the intestinal tract; this adaptation produces mucosal hypertrophy and increases absorptive capacity.3

Medications to taper or avoid

The absorption and bioavailability of a medication depend on its dissolvability; the pH of the medium; surface area for absorption; and GI blood flow.4 Medications that have a long absorptive phase—namely, sustained-release, extended-release, long-acting, and enteric-coated formulations—show compromised dissolvability and absorption and reduced efficacy after bariatric surgery.

Avoid slow-release formulations, including ion-exchange resins with a semipermeable membrane and those with slowly dissolving characteristics; substitute an immediate-release formulation.

Medications that require acidic pH are incompletely absorbed because gastric exposure is reduced.

Lipophilic medications depend on bile availability; impaired enterohepatic circulation because of reduced intestinal absorptive surface causes loss of bile and, therefore, impaired absorption of lipophilic medications.

Medications that are poorly intrinsically absorbed and undergo enterohepatic circulation are likely to be underabsorbed after a malabsorptive bariatric procedure.

Lamotrigine, olanzapine, and quetiapine may show decreased efficacy because of possible reduced absorption.

The lithium level, which is influenced by volume of distribution, can become toxic postoperatively; consider measuring the serum lithium level.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Livingston EH. The incidence of bariatric surgery has plateaued in the U.S. Am J Surg. 2010;200(3):378-385.

2. Jones WR, Morgan JF. Obesity surgery. Psychiatric needs must be considered. BMJ. 2010;341:c5298. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5298.

3. Padwal R, Brocks D, Sharma AM. A systematic review of drug absorption following bariatric surgery and its theoretical implications. Obes Rev. 2010;11(1):41-50.

4. Lizer MH, Papageorgeon H, Glembot TM. Nutritional and pharmacologic challenges in the bariatric surgery patient. Obes Surg. 2010;20(12):1654-1659.

Approximately 113,000 bariatric surgeries were performed in the United States in 2010; as many as 80% of persons seeking weight loss surgery have a history of a psychiatric disorder.1,2

Bariatric surgery can be “restrictive” (limiting food intake) or “malabsorptive” (limiting food absorption). Both types of procedures can cause significant changes in pharmacokinetics. Bariatric surgery patients who take a psychotropic are at risk of toxicity or relapse of their psychiatric illness because of inappropriate formulations— immediate-release vs sustained-release—or incomplete absorption of medications. You need to anticipate potential pharmacokinetic alterations after bariatric surgery and make appropriate changes to the patient’s medication regimen.

Pharmacokinetic concerns

Roux-en-Y surgery is a malabsorptive procedure that causes food to bypass the stomach, duodenum, and a variable length of jejunum. Secondary to bypass, iron deficiency anemia is a common nutritional complication.

Other changes that affect the pharmacokinetics of psychotropics after bariatric surgery include:

• an increase in percentage of lean body mass as weight loss occurs

• a decrease in glomerular filtration rate as kidney size decreases with postsurgical weight reduction

• reversal of obesity-associated fatty liver and cirrhotic changes.

With time, intestinal adaptation occurs to compensate for the reduced length of the intestinal tract; this adaptation produces mucosal hypertrophy and increases absorptive capacity.3

Medications to taper or avoid

The absorption and bioavailability of a medication depend on its dissolvability; the pH of the medium; surface area for absorption; and GI blood flow.4 Medications that have a long absorptive phase—namely, sustained-release, extended-release, long-acting, and enteric-coated formulations—show compromised dissolvability and absorption and reduced efficacy after bariatric surgery.

Avoid slow-release formulations, including ion-exchange resins with a semipermeable membrane and those with slowly dissolving characteristics; substitute an immediate-release formulation.

Medications that require acidic pH are incompletely absorbed because gastric exposure is reduced.

Lipophilic medications depend on bile availability; impaired enterohepatic circulation because of reduced intestinal absorptive surface causes loss of bile and, therefore, impaired absorption of lipophilic medications.

Medications that are poorly intrinsically absorbed and undergo enterohepatic circulation are likely to be underabsorbed after a malabsorptive bariatric procedure.

Lamotrigine, olanzapine, and quetiapine may show decreased efficacy because of possible reduced absorption.

The lithium level, which is influenced by volume of distribution, can become toxic postoperatively; consider measuring the serum lithium level.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Approximately 113,000 bariatric surgeries were performed in the United States in 2010; as many as 80% of persons seeking weight loss surgery have a history of a psychiatric disorder.1,2

Bariatric surgery can be “restrictive” (limiting food intake) or “malabsorptive” (limiting food absorption). Both types of procedures can cause significant changes in pharmacokinetics. Bariatric surgery patients who take a psychotropic are at risk of toxicity or relapse of their psychiatric illness because of inappropriate formulations— immediate-release vs sustained-release—or incomplete absorption of medications. You need to anticipate potential pharmacokinetic alterations after bariatric surgery and make appropriate changes to the patient’s medication regimen.

Pharmacokinetic concerns

Roux-en-Y surgery is a malabsorptive procedure that causes food to bypass the stomach, duodenum, and a variable length of jejunum. Secondary to bypass, iron deficiency anemia is a common nutritional complication.

Other changes that affect the pharmacokinetics of psychotropics after bariatric surgery include:

• an increase in percentage of lean body mass as weight loss occurs

• a decrease in glomerular filtration rate as kidney size decreases with postsurgical weight reduction

• reversal of obesity-associated fatty liver and cirrhotic changes.

With time, intestinal adaptation occurs to compensate for the reduced length of the intestinal tract; this adaptation produces mucosal hypertrophy and increases absorptive capacity.3

Medications to taper or avoid

The absorption and bioavailability of a medication depend on its dissolvability; the pH of the medium; surface area for absorption; and GI blood flow.4 Medications that have a long absorptive phase—namely, sustained-release, extended-release, long-acting, and enteric-coated formulations—show compromised dissolvability and absorption and reduced efficacy after bariatric surgery.

Avoid slow-release formulations, including ion-exchange resins with a semipermeable membrane and those with slowly dissolving characteristics; substitute an immediate-release formulation.

Medications that require acidic pH are incompletely absorbed because gastric exposure is reduced.

Lipophilic medications depend on bile availability; impaired enterohepatic circulation because of reduced intestinal absorptive surface causes loss of bile and, therefore, impaired absorption of lipophilic medications.

Medications that are poorly intrinsically absorbed and undergo enterohepatic circulation are likely to be underabsorbed after a malabsorptive bariatric procedure.

Lamotrigine, olanzapine, and quetiapine may show decreased efficacy because of possible reduced absorption.

The lithium level, which is influenced by volume of distribution, can become toxic postoperatively; consider measuring the serum lithium level.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Livingston EH. The incidence of bariatric surgery has plateaued in the U.S. Am J Surg. 2010;200(3):378-385.

2. Jones WR, Morgan JF. Obesity surgery. Psychiatric needs must be considered. BMJ. 2010;341:c5298. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5298.

3. Padwal R, Brocks D, Sharma AM. A systematic review of drug absorption following bariatric surgery and its theoretical implications. Obes Rev. 2010;11(1):41-50.

4. Lizer MH, Papageorgeon H, Glembot TM. Nutritional and pharmacologic challenges in the bariatric surgery patient. Obes Surg. 2010;20(12):1654-1659.

1. Livingston EH. The incidence of bariatric surgery has plateaued in the U.S. Am J Surg. 2010;200(3):378-385.

2. Jones WR, Morgan JF. Obesity surgery. Psychiatric needs must be considered. BMJ. 2010;341:c5298. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5298.

3. Padwal R, Brocks D, Sharma AM. A systematic review of drug absorption following bariatric surgery and its theoretical implications. Obes Rev. 2010;11(1):41-50.

4. Lizer MH, Papageorgeon H, Glembot TM. Nutritional and pharmacologic challenges in the bariatric surgery patient. Obes Surg. 2010;20(12):1654-1659.

A diverted or stolen prescription has been signed in your name. What do you do now?

For a busy clinician, learning that a prescription pad has been stolen, sub-mitted with a counterfeit signature, and used to acquire a controlled substance comes as a shock. It evokes a sense of betrayal and raises a number of medico-legal issues that can be avoided if you know how to protect yourself.

Prescription pad security

One of the simplest ways to reduce prescription pad theft is to lock the pads in a secure location when the office is closed.1 Establish and maintain an inventory of prescription pads; you should number and count pads weekly. For Schedule-II controlled substance prescription pads, document the control number on each new pad.1 The best way to ensure that all pads are accounted for is by using sequential numbering similar to bank check numbers.

Do not allow staff to sign your prescription pad. Limit access to prescription pads to authorized personnel; be sure that they keep the prescription pad in their pocket, not on their desk or a counter, and not in examining rooms, where they could be stolen. For electronic prescribing, always lock the drawer where the computer prescription paper sits.1

Some physicians might find it helpful to invest in tamper-resistant prescription pads. As of April 2008, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services mandates that for a prescription pad to be considered tamper-resistant it must include 1 or more industry-recognized features designed to prevent unauthorized copying, erasure, or modification of prescriptions.2

When you order prescription pads, do not print your Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) number on the pads. Also, check that your printer maintains strict process controls over prescription pad production, storage, and delivery.1

Other ways to prevent fraudulent prescriptions include using a gel pen to write prescriptions, because these pens contain pigments that are quickly absorbed, preventing ink from being washed away with chemical solvents.1 Never leave blank space on a written prescription and do not sign blank prescription pads beforehand.3 Write instructions clearly on each prescription, informing pharmacists of ways to verify the prescription’s authenticity.

Legal responsibilities

In case your prescription pads are stolen, even after taking precautionary measures, make the following actions to report and record fraudulent charges:

• If your prescription pads for Schedule-II medications—known as “triplicates”— are missing, give the control number of the first and last prescription in the pad to your state’s pharmacy organization. Some states have an electronic alert system to aid with filing a fraud claim (eg, the Texas Pharmacy Association has a section on its Web site for reporting prescription fraud and theft).

• Immediately inform the local police department and local DEA office of the theft.3 Keep a copy of all communications for future reference.

• If a pharmacy alerts you that a fraudulent prescription has been filled using one of your pads, request a copy of each filled prescription. Keep these records and file a copy with the police department and DEA.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Seven helpful tips to improve prescription security in your medical practice. Standard Register Healthcare. http:// www.standardregister. com/securescrip/guide-to-prescription-pad-security. asp. Accessed June 6, 2012.

2. Guide to tamper-resistant Rx pads. Standard Register Healthcare. http://www. securescrip.com/guide-to-tamper-resistant-rx-pads. asp. Accessed June 6, 2012.

3. U.S. Department of Justice. Drug Enforcement Administration. Office of Diversion Control. Practitioner’s manual. Section III – security requirements. http://www. deadiversion.usdoj.gov/pubs/ manuals/pract/section3. htm. Accessed June 6, 2012.

For a busy clinician, learning that a prescription pad has been stolen, sub-mitted with a counterfeit signature, and used to acquire a controlled substance comes as a shock. It evokes a sense of betrayal and raises a number of medico-legal issues that can be avoided if you know how to protect yourself.

Prescription pad security

One of the simplest ways to reduce prescription pad theft is to lock the pads in a secure location when the office is closed.1 Establish and maintain an inventory of prescription pads; you should number and count pads weekly. For Schedule-II controlled substance prescription pads, document the control number on each new pad.1 The best way to ensure that all pads are accounted for is by using sequential numbering similar to bank check numbers.

Do not allow staff to sign your prescription pad. Limit access to prescription pads to authorized personnel; be sure that they keep the prescription pad in their pocket, not on their desk or a counter, and not in examining rooms, where they could be stolen. For electronic prescribing, always lock the drawer where the computer prescription paper sits.1

Some physicians might find it helpful to invest in tamper-resistant prescription pads. As of April 2008, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services mandates that for a prescription pad to be considered tamper-resistant it must include 1 or more industry-recognized features designed to prevent unauthorized copying, erasure, or modification of prescriptions.2

When you order prescription pads, do not print your Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) number on the pads. Also, check that your printer maintains strict process controls over prescription pad production, storage, and delivery.1

Other ways to prevent fraudulent prescriptions include using a gel pen to write prescriptions, because these pens contain pigments that are quickly absorbed, preventing ink from being washed away with chemical solvents.1 Never leave blank space on a written prescription and do not sign blank prescription pads beforehand.3 Write instructions clearly on each prescription, informing pharmacists of ways to verify the prescription’s authenticity.

Legal responsibilities

In case your prescription pads are stolen, even after taking precautionary measures, make the following actions to report and record fraudulent charges:

• If your prescription pads for Schedule-II medications—known as “triplicates”— are missing, give the control number of the first and last prescription in the pad to your state’s pharmacy organization. Some states have an electronic alert system to aid with filing a fraud claim (eg, the Texas Pharmacy Association has a section on its Web site for reporting prescription fraud and theft).

• Immediately inform the local police department and local DEA office of the theft.3 Keep a copy of all communications for future reference.

• If a pharmacy alerts you that a fraudulent prescription has been filled using one of your pads, request a copy of each filled prescription. Keep these records and file a copy with the police department and DEA.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

For a busy clinician, learning that a prescription pad has been stolen, sub-mitted with a counterfeit signature, and used to acquire a controlled substance comes as a shock. It evokes a sense of betrayal and raises a number of medico-legal issues that can be avoided if you know how to protect yourself.

Prescription pad security

One of the simplest ways to reduce prescription pad theft is to lock the pads in a secure location when the office is closed.1 Establish and maintain an inventory of prescription pads; you should number and count pads weekly. For Schedule-II controlled substance prescription pads, document the control number on each new pad.1 The best way to ensure that all pads are accounted for is by using sequential numbering similar to bank check numbers.

Do not allow staff to sign your prescription pad. Limit access to prescription pads to authorized personnel; be sure that they keep the prescription pad in their pocket, not on their desk or a counter, and not in examining rooms, where they could be stolen. For electronic prescribing, always lock the drawer where the computer prescription paper sits.1

Some physicians might find it helpful to invest in tamper-resistant prescription pads. As of April 2008, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services mandates that for a prescription pad to be considered tamper-resistant it must include 1 or more industry-recognized features designed to prevent unauthorized copying, erasure, or modification of prescriptions.2

When you order prescription pads, do not print your Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) number on the pads. Also, check that your printer maintains strict process controls over prescription pad production, storage, and delivery.1

Other ways to prevent fraudulent prescriptions include using a gel pen to write prescriptions, because these pens contain pigments that are quickly absorbed, preventing ink from being washed away with chemical solvents.1 Never leave blank space on a written prescription and do not sign blank prescription pads beforehand.3 Write instructions clearly on each prescription, informing pharmacists of ways to verify the prescription’s authenticity.

Legal responsibilities

In case your prescription pads are stolen, even after taking precautionary measures, make the following actions to report and record fraudulent charges:

• If your prescription pads for Schedule-II medications—known as “triplicates”— are missing, give the control number of the first and last prescription in the pad to your state’s pharmacy organization. Some states have an electronic alert system to aid with filing a fraud claim (eg, the Texas Pharmacy Association has a section on its Web site for reporting prescription fraud and theft).