User login

Auditory musical hallucinations: When a patient complains, ‘I hear a symphony!’

Nonpsychotic auditory musical hallucinations—hearing singing voices, musical tones, song lyrics, or instrumental music—occur in >20% of outpatients who have a diagnosis of an anxiety, affective, or schizophrenic disorder, with the highest prevalence (41%) in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).1 OCD comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders increases the frequency of auditory musical hallucinations. Auditory musical hallucinations mainly affect older (mean age, 61.5 years) females who have tinnitus and severe, high-frequency, sensorineural hearing loss.1 Auditory musical hallucinations occur in psychiatric diseases, ictal states of complex partial seizures, abnormalities of the auditory cortex, thalamic infarcts, subarachnoid hemorrhage, tumors of the brain stem, intoxication, and progressive deafness.1,2

What patients report hearing

Some patients identify 1 musical instrument that dominates others. The musical tones are reported to have a vibrating quality, similar to the sound produced by blowing air through a paper-covered comb. Some patients hear singing voices, predominantly deep in tone, although the words usually are not clear.

Patients with auditory musical hallucinations associated with deafness may not have dementia or psychosis. Both sensorineural and conductive involvement indicates a mixed type of deafness. Pure tone audiograms show a bilateral loss of >30 decibels, affecting the higher and lower ranges.2,3 Cerebral atrophy and microangiopathic changes are common co-occurring findings on MRI.

Treatment options

Reassure your patient that the experience is not necessarily associated with a psychotic disorder. Perform a complete history, physical, and neurologic examination. Rule out unilateral symptoms, tinnitus, and hearing loss. If she (he) is experiencing unilateral symptoms, pulsatile tinnitus, unilateral hearing loss, and a constant feeling of unsteadiness, further evaluation is necessary to exclude underlying pathology. Treating concurrent insomnia, depression, or anxiety might resolve the hallucinations.4

Nonpharmacotherapeutic treatments include hearing amplification, and masking tinnitus with a hearing aid emitting low-volume music or sounds of nature (ie, rainfall).4 Two cases have reported successful carbamazepine therapy; 2 other cases demonstrated success with clomipramine.5 Frequently, symptoms spontaneously remit.

Consider electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for patients with musical hallucinations that are refractory to medical treatment and cause distress; 3 patients with concurrent major depressive disorder showed improvement after ECT.6 Antipsychotics are not recommended as first-line treatment.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Hermesh H, Konas S, Shiloh R, et al. Musical hallucinations: prevalence in psychotic and nonpsychotic outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(2):191-197.

2. Schakenraad SM, Teunisse RJ, Olde Rikkert MG. Musical hallucinations in psychiatric patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(4):394-397.

3. Evers S, Ellger T. The clinical spectrum of musical hallucinations. J Neurol Sci. 2004;227(1):55-65.

4. Zegarra NM, Cuetter AC, Briones DF, et al. Nonpsychotic auditory musical hallucinations in elderly persons with progressive deafness. Clin Geriatr. 2007;15(11):33-37.

5. Mahendran R. The psychopathology of musical hallucinations. Singapore Med J. 2007;48(2):e68-e70.

6. Wengel SP, Burke WJ, Holemon D. Musical hallucinations. The sounds of silence? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37(2):163-166.

Nonpsychotic auditory musical hallucinations—hearing singing voices, musical tones, song lyrics, or instrumental music—occur in >20% of outpatients who have a diagnosis of an anxiety, affective, or schizophrenic disorder, with the highest prevalence (41%) in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).1 OCD comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders increases the frequency of auditory musical hallucinations. Auditory musical hallucinations mainly affect older (mean age, 61.5 years) females who have tinnitus and severe, high-frequency, sensorineural hearing loss.1 Auditory musical hallucinations occur in psychiatric diseases, ictal states of complex partial seizures, abnormalities of the auditory cortex, thalamic infarcts, subarachnoid hemorrhage, tumors of the brain stem, intoxication, and progressive deafness.1,2

What patients report hearing

Some patients identify 1 musical instrument that dominates others. The musical tones are reported to have a vibrating quality, similar to the sound produced by blowing air through a paper-covered comb. Some patients hear singing voices, predominantly deep in tone, although the words usually are not clear.

Patients with auditory musical hallucinations associated with deafness may not have dementia or psychosis. Both sensorineural and conductive involvement indicates a mixed type of deafness. Pure tone audiograms show a bilateral loss of >30 decibels, affecting the higher and lower ranges.2,3 Cerebral atrophy and microangiopathic changes are common co-occurring findings on MRI.

Treatment options

Reassure your patient that the experience is not necessarily associated with a psychotic disorder. Perform a complete history, physical, and neurologic examination. Rule out unilateral symptoms, tinnitus, and hearing loss. If she (he) is experiencing unilateral symptoms, pulsatile tinnitus, unilateral hearing loss, and a constant feeling of unsteadiness, further evaluation is necessary to exclude underlying pathology. Treating concurrent insomnia, depression, or anxiety might resolve the hallucinations.4

Nonpharmacotherapeutic treatments include hearing amplification, and masking tinnitus with a hearing aid emitting low-volume music or sounds of nature (ie, rainfall).4 Two cases have reported successful carbamazepine therapy; 2 other cases demonstrated success with clomipramine.5 Frequently, symptoms spontaneously remit.

Consider electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for patients with musical hallucinations that are refractory to medical treatment and cause distress; 3 patients with concurrent major depressive disorder showed improvement after ECT.6 Antipsychotics are not recommended as first-line treatment.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Nonpsychotic auditory musical hallucinations—hearing singing voices, musical tones, song lyrics, or instrumental music—occur in >20% of outpatients who have a diagnosis of an anxiety, affective, or schizophrenic disorder, with the highest prevalence (41%) in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).1 OCD comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders increases the frequency of auditory musical hallucinations. Auditory musical hallucinations mainly affect older (mean age, 61.5 years) females who have tinnitus and severe, high-frequency, sensorineural hearing loss.1 Auditory musical hallucinations occur in psychiatric diseases, ictal states of complex partial seizures, abnormalities of the auditory cortex, thalamic infarcts, subarachnoid hemorrhage, tumors of the brain stem, intoxication, and progressive deafness.1,2

What patients report hearing

Some patients identify 1 musical instrument that dominates others. The musical tones are reported to have a vibrating quality, similar to the sound produced by blowing air through a paper-covered comb. Some patients hear singing voices, predominantly deep in tone, although the words usually are not clear.

Patients with auditory musical hallucinations associated with deafness may not have dementia or psychosis. Both sensorineural and conductive involvement indicates a mixed type of deafness. Pure tone audiograms show a bilateral loss of >30 decibels, affecting the higher and lower ranges.2,3 Cerebral atrophy and microangiopathic changes are common co-occurring findings on MRI.

Treatment options

Reassure your patient that the experience is not necessarily associated with a psychotic disorder. Perform a complete history, physical, and neurologic examination. Rule out unilateral symptoms, tinnitus, and hearing loss. If she (he) is experiencing unilateral symptoms, pulsatile tinnitus, unilateral hearing loss, and a constant feeling of unsteadiness, further evaluation is necessary to exclude underlying pathology. Treating concurrent insomnia, depression, or anxiety might resolve the hallucinations.4

Nonpharmacotherapeutic treatments include hearing amplification, and masking tinnitus with a hearing aid emitting low-volume music or sounds of nature (ie, rainfall).4 Two cases have reported successful carbamazepine therapy; 2 other cases demonstrated success with clomipramine.5 Frequently, symptoms spontaneously remit.

Consider electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for patients with musical hallucinations that are refractory to medical treatment and cause distress; 3 patients with concurrent major depressive disorder showed improvement after ECT.6 Antipsychotics are not recommended as first-line treatment.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Hermesh H, Konas S, Shiloh R, et al. Musical hallucinations: prevalence in psychotic and nonpsychotic outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(2):191-197.

2. Schakenraad SM, Teunisse RJ, Olde Rikkert MG. Musical hallucinations in psychiatric patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(4):394-397.

3. Evers S, Ellger T. The clinical spectrum of musical hallucinations. J Neurol Sci. 2004;227(1):55-65.

4. Zegarra NM, Cuetter AC, Briones DF, et al. Nonpsychotic auditory musical hallucinations in elderly persons with progressive deafness. Clin Geriatr. 2007;15(11):33-37.

5. Mahendran R. The psychopathology of musical hallucinations. Singapore Med J. 2007;48(2):e68-e70.

6. Wengel SP, Burke WJ, Holemon D. Musical hallucinations. The sounds of silence? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37(2):163-166.

1. Hermesh H, Konas S, Shiloh R, et al. Musical hallucinations: prevalence in psychotic and nonpsychotic outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(2):191-197.

2. Schakenraad SM, Teunisse RJ, Olde Rikkert MG. Musical hallucinations in psychiatric patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(4):394-397.

3. Evers S, Ellger T. The clinical spectrum of musical hallucinations. J Neurol Sci. 2004;227(1):55-65.

4. Zegarra NM, Cuetter AC, Briones DF, et al. Nonpsychotic auditory musical hallucinations in elderly persons with progressive deafness. Clin Geriatr. 2007;15(11):33-37.

5. Mahendran R. The psychopathology of musical hallucinations. Singapore Med J. 2007;48(2):e68-e70.

6. Wengel SP, Burke WJ, Holemon D. Musical hallucinations. The sounds of silence? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37(2):163-166.

Problematic pruritus: Seeking a cure for psychogenic itch

Psychogenic itch—an excessive impulse to scratch, gouge, or pick at skin in the absence of dermatologic cause—is common among psychiatric inpatients, but can be challenging to assess and manage in outpatients. Patients with psychogenic itch predominantly are female, with average age of onset between 30 and 45 years.1 Psychiatric disorders associated with psychogenic itch include depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, somatoform disorders, mania, psychosis, and substance abuse.2 Body dysmorphic disorder, trichotillomania, kleptomania, and borderline personality disorder may be comorbid in patients with psychogenic itch.3

Characteristics of psychogenic itch

Consider psychogenic itch in patients who have recurring physical symptoms and demand examination despite repeated negative results. Other indicators include psychological factors—loss of a loved one, unemployment, relocation, etc.—that may be associated with onset, severity, elicitation, or maintenance of the itching; impairments in the patient’s social or professional life; and marked preoccupation with itching or the state of her (his) skin. Characteristically, itching can be provoked by emotional triggers, most notably during stages of excitement, and also by mechanical or chemical stimuli.

Skin changes associated with psychogenic itch often are found on areas accessible to the patient’s hand: face, arms, legs, abdomen, thighs, upper back, and shoulders. These changes can be seen in varying stages, from discrete superficial excoriations, erosions, and ulcers to thick, darkened nodules and colorless atrophic scars. Patients often complain of burning. In some cases, a patient uses a tool or instrument to autoaggressively manipulate his (her) skin in response to tingling or stabbing sensations. Artificial lesions or eczemas brought on by self-

manipulation can occur. Stress, life changes, or inhibited rage may be evoking the burning sensation and subsequent complaints.

Interventions to consider

After you have ruled out other causes of pruritus and made a diagnosis of psychogenic itch, educate your patient about the multifactorial etiology. Explain possible associations between skin disorders and unconscious reaction patterns, and the role of emotional and cognitive stimuli.

Moisturizing the skin can help the dryness associated with repetitive scratching. Consider prescribing an antihistamine, moisturizer, topical steroid, antibiotic, or

occlusive dressing.

Some pharmacological properties of antidepressants that are not related to their antidepressant activity—eg, the histamine-1 blocking effect of tricyclic antidepressants—are beneficial for treating psychogenic itch.4 Sedating antihistamines (hydroxyzine) and antidepressants (doxepin) may help break cycles of itching and depression or itching and scratching.4 Tricyclic antidepressants also are recommended for treating burning, stabbing, or tingling sensations.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Yosipovitch G, Samuel LS. Neuropathic and psychogenic itch. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(1):32-41.

2. Krishnan A, Koo J. Psyche, opioids, and itch: therapeutic consequences. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18(4):314-322.

3. Arnold LM, Auchenbach MB, McElroy SL. Psychogenic excoriation. Clinical features, proposed diagnostic criteria, epidemiology and approaches to treatment. CNS Drugs. 2001;15(5):351-359.

4. Gupta MA, Guptat AK. The use of antidepressant drugs in dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(6):512-518.

Psychogenic itch—an excessive impulse to scratch, gouge, or pick at skin in the absence of dermatologic cause—is common among psychiatric inpatients, but can be challenging to assess and manage in outpatients. Patients with psychogenic itch predominantly are female, with average age of onset between 30 and 45 years.1 Psychiatric disorders associated with psychogenic itch include depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, somatoform disorders, mania, psychosis, and substance abuse.2 Body dysmorphic disorder, trichotillomania, kleptomania, and borderline personality disorder may be comorbid in patients with psychogenic itch.3

Characteristics of psychogenic itch

Consider psychogenic itch in patients who have recurring physical symptoms and demand examination despite repeated negative results. Other indicators include psychological factors—loss of a loved one, unemployment, relocation, etc.—that may be associated with onset, severity, elicitation, or maintenance of the itching; impairments in the patient’s social or professional life; and marked preoccupation with itching or the state of her (his) skin. Characteristically, itching can be provoked by emotional triggers, most notably during stages of excitement, and also by mechanical or chemical stimuli.

Skin changes associated with psychogenic itch often are found on areas accessible to the patient’s hand: face, arms, legs, abdomen, thighs, upper back, and shoulders. These changes can be seen in varying stages, from discrete superficial excoriations, erosions, and ulcers to thick, darkened nodules and colorless atrophic scars. Patients often complain of burning. In some cases, a patient uses a tool or instrument to autoaggressively manipulate his (her) skin in response to tingling or stabbing sensations. Artificial lesions or eczemas brought on by self-

manipulation can occur. Stress, life changes, or inhibited rage may be evoking the burning sensation and subsequent complaints.

Interventions to consider

After you have ruled out other causes of pruritus and made a diagnosis of psychogenic itch, educate your patient about the multifactorial etiology. Explain possible associations between skin disorders and unconscious reaction patterns, and the role of emotional and cognitive stimuli.

Moisturizing the skin can help the dryness associated with repetitive scratching. Consider prescribing an antihistamine, moisturizer, topical steroid, antibiotic, or

occlusive dressing.

Some pharmacological properties of antidepressants that are not related to their antidepressant activity—eg, the histamine-1 blocking effect of tricyclic antidepressants—are beneficial for treating psychogenic itch.4 Sedating antihistamines (hydroxyzine) and antidepressants (doxepin) may help break cycles of itching and depression or itching and scratching.4 Tricyclic antidepressants also are recommended for treating burning, stabbing, or tingling sensations.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Psychogenic itch—an excessive impulse to scratch, gouge, or pick at skin in the absence of dermatologic cause—is common among psychiatric inpatients, but can be challenging to assess and manage in outpatients. Patients with psychogenic itch predominantly are female, with average age of onset between 30 and 45 years.1 Psychiatric disorders associated with psychogenic itch include depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, somatoform disorders, mania, psychosis, and substance abuse.2 Body dysmorphic disorder, trichotillomania, kleptomania, and borderline personality disorder may be comorbid in patients with psychogenic itch.3

Characteristics of psychogenic itch

Consider psychogenic itch in patients who have recurring physical symptoms and demand examination despite repeated negative results. Other indicators include psychological factors—loss of a loved one, unemployment, relocation, etc.—that may be associated with onset, severity, elicitation, or maintenance of the itching; impairments in the patient’s social or professional life; and marked preoccupation with itching or the state of her (his) skin. Characteristically, itching can be provoked by emotional triggers, most notably during stages of excitement, and also by mechanical or chemical stimuli.

Skin changes associated with psychogenic itch often are found on areas accessible to the patient’s hand: face, arms, legs, abdomen, thighs, upper back, and shoulders. These changes can be seen in varying stages, from discrete superficial excoriations, erosions, and ulcers to thick, darkened nodules and colorless atrophic scars. Patients often complain of burning. In some cases, a patient uses a tool or instrument to autoaggressively manipulate his (her) skin in response to tingling or stabbing sensations. Artificial lesions or eczemas brought on by self-

manipulation can occur. Stress, life changes, or inhibited rage may be evoking the burning sensation and subsequent complaints.

Interventions to consider

After you have ruled out other causes of pruritus and made a diagnosis of psychogenic itch, educate your patient about the multifactorial etiology. Explain possible associations between skin disorders and unconscious reaction patterns, and the role of emotional and cognitive stimuli.

Moisturizing the skin can help the dryness associated with repetitive scratching. Consider prescribing an antihistamine, moisturizer, topical steroid, antibiotic, or

occlusive dressing.

Some pharmacological properties of antidepressants that are not related to their antidepressant activity—eg, the histamine-1 blocking effect of tricyclic antidepressants—are beneficial for treating psychogenic itch.4 Sedating antihistamines (hydroxyzine) and antidepressants (doxepin) may help break cycles of itching and depression or itching and scratching.4 Tricyclic antidepressants also are recommended for treating burning, stabbing, or tingling sensations.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Yosipovitch G, Samuel LS. Neuropathic and psychogenic itch. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(1):32-41.

2. Krishnan A, Koo J. Psyche, opioids, and itch: therapeutic consequences. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18(4):314-322.

3. Arnold LM, Auchenbach MB, McElroy SL. Psychogenic excoriation. Clinical features, proposed diagnostic criteria, epidemiology and approaches to treatment. CNS Drugs. 2001;15(5):351-359.

4. Gupta MA, Guptat AK. The use of antidepressant drugs in dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(6):512-518.

1. Yosipovitch G, Samuel LS. Neuropathic and psychogenic itch. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(1):32-41.

2. Krishnan A, Koo J. Psyche, opioids, and itch: therapeutic consequences. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18(4):314-322.

3. Arnold LM, Auchenbach MB, McElroy SL. Psychogenic excoriation. Clinical features, proposed diagnostic criteria, epidemiology and approaches to treatment. CNS Drugs. 2001;15(5):351-359.

4. Gupta MA, Guptat AK. The use of antidepressant drugs in dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(6):512-518.

Adoption by mentally ill individuals: What to recommend

Ms. T, age 28, wishes to adopt a child. She has a history of bipolar disorder, but has been stable for several years. She asks her psychiatrist if her diagnosis will disqualify her as a potential parent. She also wants to know how the psychiatrist can help with the adoption process because he has been treating her long-term and is familiar with her psychiatric history.

Many adults with a history of psychiatric illness prefer to adopt rather than have biological children. Their preference may be fueled by concerns regarding psychiatric destabilization during pregnancy or fear of psychotropic-induced fetal teratogenicity. Child adoption laws vary from state to state. Although some licensed adoption agencies sympathize with potential adoptive parents with a history of mental illness, the law usually considers the following factors:

• the potential adopter’s emotional ties to the child

• their parenting skills

• emotional needs of the child

• the potential adopter’s desire to maintain continuity of the child’s care

• permanence of the family unit of the proposed home

• the physical, moral, and mental fitness of the potential parent.

The psychiatrist’s role

So long as the adoptee’s well-being is the reason for adoption, and the adoption is in the “best interest of the child,”1 a history of mental illness does not necessarily exclude an individual from adopting a child. The psychiatrist needs to consider the potential adopter’s motives, intellectual capacity, and judgment with regards to caregiving. The psychiatrist needs to assess the degree to which the patient’s mental disorder may or may not interfere with their parenting. The clinician also needs to consider potential changes that may occur in the adopter’s personal life, work hours, recreational and social activities, and sleep patterns.

It also is important to estimate the changes that an adoption may cause in the potential adopter’s living arrangements, daily schedule, and life events such as family vacations. Based on knowledge of the patient’s psychiatric history, a clinician may need to consider whether adoption-related stress could destabilize or exacerbate the potential parent’s psychiatric condition.2 Other psychosocial factors of importance are the reliability of the adopter’s support system, their history of previous child-rearing success, care-taking arrangements, etc.1

What to consider

The potential adoptee’s unique needs also should be considered. Is the child physically handicapped or mentally challenged, and is your patient capable of handling these issues? Would there be a good temperament fit between the potential adoptive parent and child?

Because child adoption laws vary from state to state, there are no established criteria for determining the eligibility of an individual with a history of mental illness. The success of a child adoption by an individual with a history of mental illness will depend on state laws and the policy of the adoption agency. Some U.S. states and territories (Alaska, Arizona, California, Kentucky, North Dakota, and Puerto Rico) regard parental mental illness as “aggravated circumstances.”1

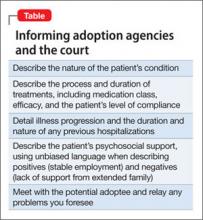

Although psychiatrists are not expected to be able to accurately predict the future, courts and adoption agencies may request a psychiatrist’s professional opinion on a specific adoption. See the Table for a list of suggested information to share when approached by an adoption agency or court.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Bacani-Oropilla T, Lippmann SB, Turns DM. Should the mentally ill adopt children? How physicians can influence the decision. Postgrad Med. 1988;84(6):201-205.

2. Linn L. Clinical manifestations of psychiatric disorder: the Homes-Rahe scale of stress of adjusting to change. In: Fredman A, Kaplan H, Sadock B, eds. Modern synopsis of comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, II. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1976:785.

Ms. T, age 28, wishes to adopt a child. She has a history of bipolar disorder, but has been stable for several years. She asks her psychiatrist if her diagnosis will disqualify her as a potential parent. She also wants to know how the psychiatrist can help with the adoption process because he has been treating her long-term and is familiar with her psychiatric history.

Many adults with a history of psychiatric illness prefer to adopt rather than have biological children. Their preference may be fueled by concerns regarding psychiatric destabilization during pregnancy or fear of psychotropic-induced fetal teratogenicity. Child adoption laws vary from state to state. Although some licensed adoption agencies sympathize with potential adoptive parents with a history of mental illness, the law usually considers the following factors:

• the potential adopter’s emotional ties to the child

• their parenting skills

• emotional needs of the child

• the potential adopter’s desire to maintain continuity of the child’s care

• permanence of the family unit of the proposed home

• the physical, moral, and mental fitness of the potential parent.

The psychiatrist’s role

So long as the adoptee’s well-being is the reason for adoption, and the adoption is in the “best interest of the child,”1 a history of mental illness does not necessarily exclude an individual from adopting a child. The psychiatrist needs to consider the potential adopter’s motives, intellectual capacity, and judgment with regards to caregiving. The psychiatrist needs to assess the degree to which the patient’s mental disorder may or may not interfere with their parenting. The clinician also needs to consider potential changes that may occur in the adopter’s personal life, work hours, recreational and social activities, and sleep patterns.

It also is important to estimate the changes that an adoption may cause in the potential adopter’s living arrangements, daily schedule, and life events such as family vacations. Based on knowledge of the patient’s psychiatric history, a clinician may need to consider whether adoption-related stress could destabilize or exacerbate the potential parent’s psychiatric condition.2 Other psychosocial factors of importance are the reliability of the adopter’s support system, their history of previous child-rearing success, care-taking arrangements, etc.1

What to consider

The potential adoptee’s unique needs also should be considered. Is the child physically handicapped or mentally challenged, and is your patient capable of handling these issues? Would there be a good temperament fit between the potential adoptive parent and child?

Because child adoption laws vary from state to state, there are no established criteria for determining the eligibility of an individual with a history of mental illness. The success of a child adoption by an individual with a history of mental illness will depend on state laws and the policy of the adoption agency. Some U.S. states and territories (Alaska, Arizona, California, Kentucky, North Dakota, and Puerto Rico) regard parental mental illness as “aggravated circumstances.”1

Although psychiatrists are not expected to be able to accurately predict the future, courts and adoption agencies may request a psychiatrist’s professional opinion on a specific adoption. See the Table for a list of suggested information to share when approached by an adoption agency or court.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Ms. T, age 28, wishes to adopt a child. She has a history of bipolar disorder, but has been stable for several years. She asks her psychiatrist if her diagnosis will disqualify her as a potential parent. She also wants to know how the psychiatrist can help with the adoption process because he has been treating her long-term and is familiar with her psychiatric history.

Many adults with a history of psychiatric illness prefer to adopt rather than have biological children. Their preference may be fueled by concerns regarding psychiatric destabilization during pregnancy or fear of psychotropic-induced fetal teratogenicity. Child adoption laws vary from state to state. Although some licensed adoption agencies sympathize with potential adoptive parents with a history of mental illness, the law usually considers the following factors:

• the potential adopter’s emotional ties to the child

• their parenting skills

• emotional needs of the child

• the potential adopter’s desire to maintain continuity of the child’s care

• permanence of the family unit of the proposed home

• the physical, moral, and mental fitness of the potential parent.

The psychiatrist’s role

So long as the adoptee’s well-being is the reason for adoption, and the adoption is in the “best interest of the child,”1 a history of mental illness does not necessarily exclude an individual from adopting a child. The psychiatrist needs to consider the potential adopter’s motives, intellectual capacity, and judgment with regards to caregiving. The psychiatrist needs to assess the degree to which the patient’s mental disorder may or may not interfere with their parenting. The clinician also needs to consider potential changes that may occur in the adopter’s personal life, work hours, recreational and social activities, and sleep patterns.

It also is important to estimate the changes that an adoption may cause in the potential adopter’s living arrangements, daily schedule, and life events such as family vacations. Based on knowledge of the patient’s psychiatric history, a clinician may need to consider whether adoption-related stress could destabilize or exacerbate the potential parent’s psychiatric condition.2 Other psychosocial factors of importance are the reliability of the adopter’s support system, their history of previous child-rearing success, care-taking arrangements, etc.1

What to consider

The potential adoptee’s unique needs also should be considered. Is the child physically handicapped or mentally challenged, and is your patient capable of handling these issues? Would there be a good temperament fit between the potential adoptive parent and child?

Because child adoption laws vary from state to state, there are no established criteria for determining the eligibility of an individual with a history of mental illness. The success of a child adoption by an individual with a history of mental illness will depend on state laws and the policy of the adoption agency. Some U.S. states and territories (Alaska, Arizona, California, Kentucky, North Dakota, and Puerto Rico) regard parental mental illness as “aggravated circumstances.”1

Although psychiatrists are not expected to be able to accurately predict the future, courts and adoption agencies may request a psychiatrist’s professional opinion on a specific adoption. See the Table for a list of suggested information to share when approached by an adoption agency or court.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Bacani-Oropilla T, Lippmann SB, Turns DM. Should the mentally ill adopt children? How physicians can influence the decision. Postgrad Med. 1988;84(6):201-205.

2. Linn L. Clinical manifestations of psychiatric disorder: the Homes-Rahe scale of stress of adjusting to change. In: Fredman A, Kaplan H, Sadock B, eds. Modern synopsis of comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, II. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1976:785.

1. Bacani-Oropilla T, Lippmann SB, Turns DM. Should the mentally ill adopt children? How physicians can influence the decision. Postgrad Med. 1988;84(6):201-205.

2. Linn L. Clinical manifestations of psychiatric disorder: the Homes-Rahe scale of stress of adjusting to change. In: Fredman A, Kaplan H, Sadock B, eds. Modern synopsis of comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, II. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1976:785.

8 tips for talking to parents and children about school shootings

In the aftermath of a school shooting, parents and teachers may seek a psychiatrist’s advice on how to best discuss these incidents with children. We offer guidelines on what to tell concerned parents, educators, and other adults who may interact with children affected by a school shooting.

6 tips for interacting with children

1. Talk about the event. Instruct adults to ask children to share their feelings about the incident and to show genuine interest in listening to the child’s thoughts and point of view. Adults shouldn’t pretend the event hasn’t occurred or isn’t serious. Children may be more worried if they think adults are too afraid to tell them what is happening. It is important to gently correct any misinformation older students may have received via social media.1

2. Reinforce that home is a safe haven. Overwhelming emotions and uncertainty can bring about a sense of insecurity in children. Children may come home seeking a safe environment. Advise parents to plan a night where family members participate in a favorite family activity.1 Tell parents to remind their children that trust-worthy adults—parents, emergency workers, police, firefighters, doctors, and the military—are helping provide safety, comfort, and support.2

3. Limit television time. If children are exposed to the news, parents should watch it with them briefly, but avoid letting children rewatch the same event repetitively. Constant exposure to the event may heighten a child’s anxiety and fears.

4. Maintain a normal routine. Tell parents they should maintain, as best they can, their normal routine for dinner, homework, chores, and bedtime, but to remain flexible.2 Children may have a hard time concentrating on schoolwork or falling asleep. Advise parents to spend extra time reading or playing quiet games with their children, particularly at bedtime. These activities are calming, foster a sense of closeness and security, and reinforce a feeling of normalcy.

5. Encourage emotions. Instruct parents to explain to their children that all feelings are okay and normal, and to let children talk about their feelings and help put them into perspective.1 Children may need help in expressing these feelings, so be patient. If an incident happened at the child’s school, teachers and administrators may conduct group sessions to help children express their concerns about being back in school.

6. Seek creativity or spirituality. Encourage parents and other adults to provide a creative outlet for children, such as making get well cards or sending letters to the survivors and their families. Writing thank you letters to doctors, nurses, fire-fighters, and police officers also may be comforting.1,2 Suggest that parents encourage their children to pray or think hopeful thoughts for the victims and their families.

2 tips for interacting with adults

7. Recommend they take care of themselves. Explain to adult caregivers that because children learn by observing, they shouldn’t ignore their own feelings of anxiety, grief, and anger. By expressing their emotions in a productive manner, adults will be better able to support their children. Encourage adults to talk to friends, family, religious leaders, or mental health counselors.

8. Advise adults to be alert for children who may need professional help. Tell them to be vigilant when monitoring a child’s emotional state. Children who may benefit from mental health counseling after a tragedy may exhibit warning signs, such as changes in behavior, appetite, and sleep patterns, which may indicate the child is experiencing grief, anxiety, or discomfort.

Remind adults to be aware of children who are at greater risk for mental health issues, including those who are already struggling with other recent traumatic experiences—past traumatic experiences, personal loss, depression, or other mental illness.1 Be particularly observant for children who may be at risk of suicide.1,2 Professional counseling may be needed for a child who is experiencing an emotional reaction that lasts >1 month and is impacting his or her daily functioning.1

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. American Psychological Association. Helping your children manage distress in the aftermath of a shooting. http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/aftermath.aspx. Updated April 2011. Accessed February 15, 2013.

2. National Association of School Psychologists resources. A national tragedy: helping children cope. http://www.nasponline.org/resources/crisis_safety/terror_general.aspx. Published September 2001. Accessed February 15, 2013.

In the aftermath of a school shooting, parents and teachers may seek a psychiatrist’s advice on how to best discuss these incidents with children. We offer guidelines on what to tell concerned parents, educators, and other adults who may interact with children affected by a school shooting.

6 tips for interacting with children

1. Talk about the event. Instruct adults to ask children to share their feelings about the incident and to show genuine interest in listening to the child’s thoughts and point of view. Adults shouldn’t pretend the event hasn’t occurred or isn’t serious. Children may be more worried if they think adults are too afraid to tell them what is happening. It is important to gently correct any misinformation older students may have received via social media.1

2. Reinforce that home is a safe haven. Overwhelming emotions and uncertainty can bring about a sense of insecurity in children. Children may come home seeking a safe environment. Advise parents to plan a night where family members participate in a favorite family activity.1 Tell parents to remind their children that trust-worthy adults—parents, emergency workers, police, firefighters, doctors, and the military—are helping provide safety, comfort, and support.2

3. Limit television time. If children are exposed to the news, parents should watch it with them briefly, but avoid letting children rewatch the same event repetitively. Constant exposure to the event may heighten a child’s anxiety and fears.

4. Maintain a normal routine. Tell parents they should maintain, as best they can, their normal routine for dinner, homework, chores, and bedtime, but to remain flexible.2 Children may have a hard time concentrating on schoolwork or falling asleep. Advise parents to spend extra time reading or playing quiet games with their children, particularly at bedtime. These activities are calming, foster a sense of closeness and security, and reinforce a feeling of normalcy.

5. Encourage emotions. Instruct parents to explain to their children that all feelings are okay and normal, and to let children talk about their feelings and help put them into perspective.1 Children may need help in expressing these feelings, so be patient. If an incident happened at the child’s school, teachers and administrators may conduct group sessions to help children express their concerns about being back in school.

6. Seek creativity or spirituality. Encourage parents and other adults to provide a creative outlet for children, such as making get well cards or sending letters to the survivors and their families. Writing thank you letters to doctors, nurses, fire-fighters, and police officers also may be comforting.1,2 Suggest that parents encourage their children to pray or think hopeful thoughts for the victims and their families.

2 tips for interacting with adults

7. Recommend they take care of themselves. Explain to adult caregivers that because children learn by observing, they shouldn’t ignore their own feelings of anxiety, grief, and anger. By expressing their emotions in a productive manner, adults will be better able to support their children. Encourage adults to talk to friends, family, religious leaders, or mental health counselors.

8. Advise adults to be alert for children who may need professional help. Tell them to be vigilant when monitoring a child’s emotional state. Children who may benefit from mental health counseling after a tragedy may exhibit warning signs, such as changes in behavior, appetite, and sleep patterns, which may indicate the child is experiencing grief, anxiety, or discomfort.

Remind adults to be aware of children who are at greater risk for mental health issues, including those who are already struggling with other recent traumatic experiences—past traumatic experiences, personal loss, depression, or other mental illness.1 Be particularly observant for children who may be at risk of suicide.1,2 Professional counseling may be needed for a child who is experiencing an emotional reaction that lasts >1 month and is impacting his or her daily functioning.1

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

In the aftermath of a school shooting, parents and teachers may seek a psychiatrist’s advice on how to best discuss these incidents with children. We offer guidelines on what to tell concerned parents, educators, and other adults who may interact with children affected by a school shooting.

6 tips for interacting with children

1. Talk about the event. Instruct adults to ask children to share their feelings about the incident and to show genuine interest in listening to the child’s thoughts and point of view. Adults shouldn’t pretend the event hasn’t occurred or isn’t serious. Children may be more worried if they think adults are too afraid to tell them what is happening. It is important to gently correct any misinformation older students may have received via social media.1

2. Reinforce that home is a safe haven. Overwhelming emotions and uncertainty can bring about a sense of insecurity in children. Children may come home seeking a safe environment. Advise parents to plan a night where family members participate in a favorite family activity.1 Tell parents to remind their children that trust-worthy adults—parents, emergency workers, police, firefighters, doctors, and the military—are helping provide safety, comfort, and support.2

3. Limit television time. If children are exposed to the news, parents should watch it with them briefly, but avoid letting children rewatch the same event repetitively. Constant exposure to the event may heighten a child’s anxiety and fears.

4. Maintain a normal routine. Tell parents they should maintain, as best they can, their normal routine for dinner, homework, chores, and bedtime, but to remain flexible.2 Children may have a hard time concentrating on schoolwork or falling asleep. Advise parents to spend extra time reading or playing quiet games with their children, particularly at bedtime. These activities are calming, foster a sense of closeness and security, and reinforce a feeling of normalcy.

5. Encourage emotions. Instruct parents to explain to their children that all feelings are okay and normal, and to let children talk about their feelings and help put them into perspective.1 Children may need help in expressing these feelings, so be patient. If an incident happened at the child’s school, teachers and administrators may conduct group sessions to help children express their concerns about being back in school.

6. Seek creativity or spirituality. Encourage parents and other adults to provide a creative outlet for children, such as making get well cards or sending letters to the survivors and their families. Writing thank you letters to doctors, nurses, fire-fighters, and police officers also may be comforting.1,2 Suggest that parents encourage their children to pray or think hopeful thoughts for the victims and their families.

2 tips for interacting with adults

7. Recommend they take care of themselves. Explain to adult caregivers that because children learn by observing, they shouldn’t ignore their own feelings of anxiety, grief, and anger. By expressing their emotions in a productive manner, adults will be better able to support their children. Encourage adults to talk to friends, family, religious leaders, or mental health counselors.

8. Advise adults to be alert for children who may need professional help. Tell them to be vigilant when monitoring a child’s emotional state. Children who may benefit from mental health counseling after a tragedy may exhibit warning signs, such as changes in behavior, appetite, and sleep patterns, which may indicate the child is experiencing grief, anxiety, or discomfort.

Remind adults to be aware of children who are at greater risk for mental health issues, including those who are already struggling with other recent traumatic experiences—past traumatic experiences, personal loss, depression, or other mental illness.1 Be particularly observant for children who may be at risk of suicide.1,2 Professional counseling may be needed for a child who is experiencing an emotional reaction that lasts >1 month and is impacting his or her daily functioning.1

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. American Psychological Association. Helping your children manage distress in the aftermath of a shooting. http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/aftermath.aspx. Updated April 2011. Accessed February 15, 2013.

2. National Association of School Psychologists resources. A national tragedy: helping children cope. http://www.nasponline.org/resources/crisis_safety/terror_general.aspx. Published September 2001. Accessed February 15, 2013.

1. American Psychological Association. Helping your children manage distress in the aftermath of a shooting. http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/aftermath.aspx. Updated April 2011. Accessed February 15, 2013.

2. National Association of School Psychologists resources. A national tragedy: helping children cope. http://www.nasponline.org/resources/crisis_safety/terror_general.aspx. Published September 2001. Accessed February 15, 2013.

Stiff person syndrome: What psychiatrists need to know

Stiff person syndrome (SPS) is a rare autoimmune condition characterized by stiffness and rigidity in the lower limb muscles. Because SPS often is misdiagnosed as a psychiatric illness and psychiatric comorbidities are common in patients with this disorder,1 awareness and recognition of this unique condition is essential.

An insidious presentation

Patients with SPS present with:2

- axial muscle stiffness slowly progressing to proximal muscles

- unremarkable motor, sensory, and cranial nerve examinations with normal intellectual functioning

- normal muscle strength, although electromyography shows continuous motor activity

- spasms evoked by sudden movements, jarring noise, and emotional distress

- slow and cautious gait to avoid triggering spasms and falls.

Symptoms start slowly and insidiously. Axial muscle stiffness can result in spinal deformity. Involvement is asymmetrical, with a predilection for proximal lower limb and lumbar paraspinal muscles. Affected muscles reveal tight, hard, board-like rigidity. In later stages of SPS, mild atrophy and muscle weakness are likely.

Frequent misdiagnosis

Because facial muscle spasticity is prominent, SPS patients may be misdiagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, primary lateral sclerosis, or multiple sclerosis. Spasms affecting respiratory and thoracic paraspinal muscles (status spasticus) may be misdiagnosed as an anxiety-related condition. These spasms can be life-threatening and require IV diazepam and supportive measures.

More than 60% of SPS patients have a comorbid psychiatric disorder.3 Anxiety disorders—generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, and panic disorder—major depression, and alcohol abuse are the most frequent psychiatric comorbidities seen in SPS patients.3

SPS patients who panic when in public may be misdiagnosed with agoraphobia.3 Emotional stimuli may cause muscle spasms leading to falls. Treating muscle spasticity with γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonists and narcotics can lead to drug abuse and dependence. Muscle spasticity can fluctuate from hour to hour, abate with sleep, and get worse with emotional distress. These findings are why approximately 70% of SPS patients are initially misdiagnosed; conversion disorder is a frequent misdiagnosis.4 Mood disorder in SPS patients may be resistant to antidepressants until these patients are treated with immunotherapy.4

Treating SPS patients

Although early intervention can reduce long-term disability, approximately 50% of SPS patients eventually have to use a wheelchair as a result of pain and immobility.5

Antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase, which is the rate-limiting enzyme for GABA synthesis, are present in 85% of SPS patients.5 Therefore, treatment usually includes GABA-enhancing drugs, including sedative anxiolytics (clonazepam and diazepam), antiepileptics (gabapentin, levetiracetam, tiagabine, and vigabatrin), antispasticity drugs (baclofen, dantrolene, and tizanidine), and immunotherapy (corticosteroids, IV immunoglobulins, and rituximab).5 Antidepressants, biofeedback, and relaxation training also can offer relief. Psychotherapy and substance dependency interventions may be needed.

To achieve optimum outcomes in SPS patients, a close collaborative relationship among all treating clinicians—including primary care physicians, neurologists, anesthesiologists, and psychiatrists—is necessary.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Tinsley JA, Barth EM, Black JL, et al. Psychiatric consultations in stiff-man syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(10):444-449.

2. Egwuonwu S, Chedebeau F. Stiff-person syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(12):1261-1263.

3. Black JL, Barth EM, Williams DE, et al. Stiff-man syndrome. Results of interviews and psychologic testing. Psychosomatics. 1998;39(1):38-44.

4. Culav-Sumić J, Bosnjak I, Pastar Z, et al. Anxious depression and the stiff-person plus syndrome. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2008;21(4):242-245.

5. Hadavi S, Noyce AJ, Leslie RD, et al. Stiff person syndrome. Pract Neurol. 2011;11(5):272-282.

Stiff person syndrome (SPS) is a rare autoimmune condition characterized by stiffness and rigidity in the lower limb muscles. Because SPS often is misdiagnosed as a psychiatric illness and psychiatric comorbidities are common in patients with this disorder,1 awareness and recognition of this unique condition is essential.

An insidious presentation

Patients with SPS present with:2

- axial muscle stiffness slowly progressing to proximal muscles

- unremarkable motor, sensory, and cranial nerve examinations with normal intellectual functioning

- normal muscle strength, although electromyography shows continuous motor activity

- spasms evoked by sudden movements, jarring noise, and emotional distress

- slow and cautious gait to avoid triggering spasms and falls.

Symptoms start slowly and insidiously. Axial muscle stiffness can result in spinal deformity. Involvement is asymmetrical, with a predilection for proximal lower limb and lumbar paraspinal muscles. Affected muscles reveal tight, hard, board-like rigidity. In later stages of SPS, mild atrophy and muscle weakness are likely.

Frequent misdiagnosis

Because facial muscle spasticity is prominent, SPS patients may be misdiagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, primary lateral sclerosis, or multiple sclerosis. Spasms affecting respiratory and thoracic paraspinal muscles (status spasticus) may be misdiagnosed as an anxiety-related condition. These spasms can be life-threatening and require IV diazepam and supportive measures.

More than 60% of SPS patients have a comorbid psychiatric disorder.3 Anxiety disorders—generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, and panic disorder—major depression, and alcohol abuse are the most frequent psychiatric comorbidities seen in SPS patients.3

SPS patients who panic when in public may be misdiagnosed with agoraphobia.3 Emotional stimuli may cause muscle spasms leading to falls. Treating muscle spasticity with γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonists and narcotics can lead to drug abuse and dependence. Muscle spasticity can fluctuate from hour to hour, abate with sleep, and get worse with emotional distress. These findings are why approximately 70% of SPS patients are initially misdiagnosed; conversion disorder is a frequent misdiagnosis.4 Mood disorder in SPS patients may be resistant to antidepressants until these patients are treated with immunotherapy.4

Treating SPS patients

Although early intervention can reduce long-term disability, approximately 50% of SPS patients eventually have to use a wheelchair as a result of pain and immobility.5

Antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase, which is the rate-limiting enzyme for GABA synthesis, are present in 85% of SPS patients.5 Therefore, treatment usually includes GABA-enhancing drugs, including sedative anxiolytics (clonazepam and diazepam), antiepileptics (gabapentin, levetiracetam, tiagabine, and vigabatrin), antispasticity drugs (baclofen, dantrolene, and tizanidine), and immunotherapy (corticosteroids, IV immunoglobulins, and rituximab).5 Antidepressants, biofeedback, and relaxation training also can offer relief. Psychotherapy and substance dependency interventions may be needed.

To achieve optimum outcomes in SPS patients, a close collaborative relationship among all treating clinicians—including primary care physicians, neurologists, anesthesiologists, and psychiatrists—is necessary.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Stiff person syndrome (SPS) is a rare autoimmune condition characterized by stiffness and rigidity in the lower limb muscles. Because SPS often is misdiagnosed as a psychiatric illness and psychiatric comorbidities are common in patients with this disorder,1 awareness and recognition of this unique condition is essential.

An insidious presentation

Patients with SPS present with:2

- axial muscle stiffness slowly progressing to proximal muscles

- unremarkable motor, sensory, and cranial nerve examinations with normal intellectual functioning

- normal muscle strength, although electromyography shows continuous motor activity

- spasms evoked by sudden movements, jarring noise, and emotional distress

- slow and cautious gait to avoid triggering spasms and falls.

Symptoms start slowly and insidiously. Axial muscle stiffness can result in spinal deformity. Involvement is asymmetrical, with a predilection for proximal lower limb and lumbar paraspinal muscles. Affected muscles reveal tight, hard, board-like rigidity. In later stages of SPS, mild atrophy and muscle weakness are likely.

Frequent misdiagnosis

Because facial muscle spasticity is prominent, SPS patients may be misdiagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, primary lateral sclerosis, or multiple sclerosis. Spasms affecting respiratory and thoracic paraspinal muscles (status spasticus) may be misdiagnosed as an anxiety-related condition. These spasms can be life-threatening and require IV diazepam and supportive measures.

More than 60% of SPS patients have a comorbid psychiatric disorder.3 Anxiety disorders—generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, and panic disorder—major depression, and alcohol abuse are the most frequent psychiatric comorbidities seen in SPS patients.3

SPS patients who panic when in public may be misdiagnosed with agoraphobia.3 Emotional stimuli may cause muscle spasms leading to falls. Treating muscle spasticity with γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonists and narcotics can lead to drug abuse and dependence. Muscle spasticity can fluctuate from hour to hour, abate with sleep, and get worse with emotional distress. These findings are why approximately 70% of SPS patients are initially misdiagnosed; conversion disorder is a frequent misdiagnosis.4 Mood disorder in SPS patients may be resistant to antidepressants until these patients are treated with immunotherapy.4

Treating SPS patients

Although early intervention can reduce long-term disability, approximately 50% of SPS patients eventually have to use a wheelchair as a result of pain and immobility.5

Antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase, which is the rate-limiting enzyme for GABA synthesis, are present in 85% of SPS patients.5 Therefore, treatment usually includes GABA-enhancing drugs, including sedative anxiolytics (clonazepam and diazepam), antiepileptics (gabapentin, levetiracetam, tiagabine, and vigabatrin), antispasticity drugs (baclofen, dantrolene, and tizanidine), and immunotherapy (corticosteroids, IV immunoglobulins, and rituximab).5 Antidepressants, biofeedback, and relaxation training also can offer relief. Psychotherapy and substance dependency interventions may be needed.

To achieve optimum outcomes in SPS patients, a close collaborative relationship among all treating clinicians—including primary care physicians, neurologists, anesthesiologists, and psychiatrists—is necessary.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Tinsley JA, Barth EM, Black JL, et al. Psychiatric consultations in stiff-man syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(10):444-449.

2. Egwuonwu S, Chedebeau F. Stiff-person syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(12):1261-1263.

3. Black JL, Barth EM, Williams DE, et al. Stiff-man syndrome. Results of interviews and psychologic testing. Psychosomatics. 1998;39(1):38-44.

4. Culav-Sumić J, Bosnjak I, Pastar Z, et al. Anxious depression and the stiff-person plus syndrome. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2008;21(4):242-245.

5. Hadavi S, Noyce AJ, Leslie RD, et al. Stiff person syndrome. Pract Neurol. 2011;11(5):272-282.

1. Tinsley JA, Barth EM, Black JL, et al. Psychiatric consultations in stiff-man syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(10):444-449.

2. Egwuonwu S, Chedebeau F. Stiff-person syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(12):1261-1263.

3. Black JL, Barth EM, Williams DE, et al. Stiff-man syndrome. Results of interviews and psychologic testing. Psychosomatics. 1998;39(1):38-44.

4. Culav-Sumić J, Bosnjak I, Pastar Z, et al. Anxious depression and the stiff-person plus syndrome. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2008;21(4):242-245.

5. Hadavi S, Noyce AJ, Leslie RD, et al. Stiff person syndrome. Pract Neurol. 2011;11(5):272-282.

Teens, social media, and ‘sexting’: What to tell parents

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Children and adolescents who have unrestricted use of the internet and cell phones are at increased risk for being exposed to sexually explicit material. One study found almost 1 in 5 high school students have “sexted”—sending a text message with sexually explicit pictures—and almost twice as many reported that they had received a sexually explicit picture via cell phone.1 More than 25% of students acknowledged forwarding a sexually explicit picture to others; >33% did so despite knowing the legal consequences, including being arrested and facing pornography charges.1

Concerned parents may seek advice on how to prevent their child from receiving or sending sexually inappropriate material on the internet or on their cell phones. You can help parents keep their children safe by sharing the following tips from The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)2:

Keep up with technology. Advise parents to become familiar with popular social networking websites such as Facebook. Creating their own Facebook page and “friending” their child may help them facilitate a conversation about their individual online experiences.

Enable privacy features. Instruct parents to install parental controls on their child’s computer. Explain to parents that these monitoring systems can help them check their child’s e-mail, chat records, and instant messages. Many social networking sites have privacy features that can help block unwanted users from contacting a child.

Check up on your children. Parents should let children know they are aware of their online presence and will be keeping an eye on them. They should periodically check a child’s chat logs, messages, e-mails, and social networking profiles for inappropriate content, friends, messages, and images. Instruct parents to teach their children that nothing is private once it’s posted on the internet. Suggest keeping the child’s computer in a public location such as the family room or kitchen.

Limit time spent online. Explain to parents that they should limit their child’s internet and cell phone access.

Combating ‘sexting’

Suggest to parents that they explain to their child in an age-appropriate manner what sexting is before giving their child a cell phone. The AAP2 recommends that parents make sure their children understand the legal ramifications of sexting. A child who is caught sexting could be arrested, which may hurt his or her chances of being accepted into college or getting a job. A simple way to reduce a child’s opportunities for sexting is to restrict his or her access to a cell phone during social situations where peer pressure could influence behavior.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Strassberg DS, McKinnon RK, Sustaíta MA. Sexting by high school students: an exploratory and descriptive study [published online June 7, 2012]. Arch Sex Behav. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9969-8.

2. American Academy of Pediatrics. Talking to kids and teens about social media and sexting. http://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/news-features-and-safety-tips/pages/Talking-to-Kids-and-Teens-About-Social-Media-and-Sexting.aspx?. Published June 2009. Updated March 2, 2011. Accessed August 14, 2012.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Children and adolescents who have unrestricted use of the internet and cell phones are at increased risk for being exposed to sexually explicit material. One study found almost 1 in 5 high school students have “sexted”—sending a text message with sexually explicit pictures—and almost twice as many reported that they had received a sexually explicit picture via cell phone.1 More than 25% of students acknowledged forwarding a sexually explicit picture to others; >33% did so despite knowing the legal consequences, including being arrested and facing pornography charges.1

Concerned parents may seek advice on how to prevent their child from receiving or sending sexually inappropriate material on the internet or on their cell phones. You can help parents keep their children safe by sharing the following tips from The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)2:

Keep up with technology. Advise parents to become familiar with popular social networking websites such as Facebook. Creating their own Facebook page and “friending” their child may help them facilitate a conversation about their individual online experiences.

Enable privacy features. Instruct parents to install parental controls on their child’s computer. Explain to parents that these monitoring systems can help them check their child’s e-mail, chat records, and instant messages. Many social networking sites have privacy features that can help block unwanted users from contacting a child.

Check up on your children. Parents should let children know they are aware of their online presence and will be keeping an eye on them. They should periodically check a child’s chat logs, messages, e-mails, and social networking profiles for inappropriate content, friends, messages, and images. Instruct parents to teach their children that nothing is private once it’s posted on the internet. Suggest keeping the child’s computer in a public location such as the family room or kitchen.

Limit time spent online. Explain to parents that they should limit their child’s internet and cell phone access.

Combating ‘sexting’

Suggest to parents that they explain to their child in an age-appropriate manner what sexting is before giving their child a cell phone. The AAP2 recommends that parents make sure their children understand the legal ramifications of sexting. A child who is caught sexting could be arrested, which may hurt his or her chances of being accepted into college or getting a job. A simple way to reduce a child’s opportunities for sexting is to restrict his or her access to a cell phone during social situations where peer pressure could influence behavior.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Children and adolescents who have unrestricted use of the internet and cell phones are at increased risk for being exposed to sexually explicit material. One study found almost 1 in 5 high school students have “sexted”—sending a text message with sexually explicit pictures—and almost twice as many reported that they had received a sexually explicit picture via cell phone.1 More than 25% of students acknowledged forwarding a sexually explicit picture to others; >33% did so despite knowing the legal consequences, including being arrested and facing pornography charges.1

Concerned parents may seek advice on how to prevent their child from receiving or sending sexually inappropriate material on the internet or on their cell phones. You can help parents keep their children safe by sharing the following tips from The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)2:

Keep up with technology. Advise parents to become familiar with popular social networking websites such as Facebook. Creating their own Facebook page and “friending” their child may help them facilitate a conversation about their individual online experiences.

Enable privacy features. Instruct parents to install parental controls on their child’s computer. Explain to parents that these monitoring systems can help them check their child’s e-mail, chat records, and instant messages. Many social networking sites have privacy features that can help block unwanted users from contacting a child.

Check up on your children. Parents should let children know they are aware of their online presence and will be keeping an eye on them. They should periodically check a child’s chat logs, messages, e-mails, and social networking profiles for inappropriate content, friends, messages, and images. Instruct parents to teach their children that nothing is private once it’s posted on the internet. Suggest keeping the child’s computer in a public location such as the family room or kitchen.

Limit time spent online. Explain to parents that they should limit their child’s internet and cell phone access.

Combating ‘sexting’

Suggest to parents that they explain to their child in an age-appropriate manner what sexting is before giving their child a cell phone. The AAP2 recommends that parents make sure their children understand the legal ramifications of sexting. A child who is caught sexting could be arrested, which may hurt his or her chances of being accepted into college or getting a job. A simple way to reduce a child’s opportunities for sexting is to restrict his or her access to a cell phone during social situations where peer pressure could influence behavior.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Strassberg DS, McKinnon RK, Sustaíta MA. Sexting by high school students: an exploratory and descriptive study [published online June 7, 2012]. Arch Sex Behav. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9969-8.

2. American Academy of Pediatrics. Talking to kids and teens about social media and sexting. http://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/news-features-and-safety-tips/pages/Talking-to-Kids-and-Teens-About-Social-Media-and-Sexting.aspx?. Published June 2009. Updated March 2, 2011. Accessed August 14, 2012.

1. Strassberg DS, McKinnon RK, Sustaíta MA. Sexting by high school students: an exploratory and descriptive study [published online June 7, 2012]. Arch Sex Behav. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9969-8.

2. American Academy of Pediatrics. Talking to kids and teens about social media and sexting. http://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/news-features-and-safety-tips/pages/Talking-to-Kids-and-Teens-About-Social-Media-and-Sexting.aspx?. Published June 2009. Updated March 2, 2011. Accessed August 14, 2012.

Sleep terrors in adults: How to help control this potentially dangerous condition

Sleep terrors (STs)—also known as night terrors—are characterized by sudden arousal accompanied by a piercing scream or cry in the first few hours after falling asleep. These parasomnias arise out of slow-wave sleep (stages 3 and 4 of nonrapid eye movement [non-REM] sleep) and affect approximately 5% of adults.1 The condition is twice as common in men than women, and usually affects children but may not develop until adulthood.1

During STs, a patient may act scared, afraid, agitated, anxious, or panicky without being fully aware of his or her surroundings. The episode may last 30 seconds to 5 minutes; most patients don’t remember the event the next morning. STs may leave individuals feeling exhausted and perplexed the next day. Verbalization during the episode is incoherent and a patient’s perception of the environment seems altered. Tachycardia, tachypnea, sweating, flushed skin, or mydriasis are prominent. When ST patients walk, they may do so violently and can cause harm to themselves or others.

The differential diagnosis of STs includes posttraumatic stress disorder; nocturnal seizures characterized by excessive motor activity and organic CNS lesions; REM sleep behavior disorder; sleep choking syndrome; and nocturnal panic attacks. Patients with STs report high rates of stressful events—eg, divorce or bereavement—in the previous year. They are more likely to have a history of mood and anxiety disorders and high levels of depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive and phobic traits. One study found patients with STs were 4.3 times more likely to have had a car accident in the past year.2

Evaluating and treating STs

Rule out comorbid conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea and periodic limb movement disorder. Encourage your patient to improve his or her sleep hygiene by maintaining a regular sleep/wake cycle, exercising, and limiting caffeine and alcohol and exposure to bright light before bedtime.

Self-help techniques. To avoid injury, encourage your patient to remove dangerous objects from their sleeping area. Suggest locking the doors to the room or home, and putting medications in a secure place. Patients also may consider keeping their mattress close to the floor to limit the risk of injury.

Pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Along with counseling and support, your patient may benefit from cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation therapy, or hypnosis.3 Anticipatory arousal therapy may help by interrupting the altered underlying electrophysiology of partial arousal.

If your patient is concerned about physical injury during STs, consider prescribing clonazepam, temazepam, or diazepam.4 Trazodone and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as paroxetine5 also have been used to treat STs.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Crisp AH. The sleepwalking/night terrors syndrome in adults. Postgrad Med J. 1996;72(852):599-604.

2. Oudiette D, Leu S, Pottier M, et al. Dreamlike mentations during sleepwalking and sleep terrors in adults. Sleep. 2009;32(12):1621-1627.

3. Lowe P, Humphreys C, Williams SJ. Night terrors: women’s experiences of (not) sleeping where there is domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2007;13(6):549-561.

4. Schenck CH, Mahowald MW. Long-term nightly benzodiazepine treatment of injurious parasomnias and other disorders of disrupted nocturnal sleep in 170 adults. Am J Med. 1996;100(3):333-337.

5. Lillywhite AR, Wilson SJ, Nutt DJ. Successful treatment of night terrors and somnambulism with paroxetine. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164(4):551-554.

Sleep terrors (STs)—also known as night terrors—are characterized by sudden arousal accompanied by a piercing scream or cry in the first few hours after falling asleep. These parasomnias arise out of slow-wave sleep (stages 3 and 4 of nonrapid eye movement [non-REM] sleep) and affect approximately 5% of adults.1 The condition is twice as common in men than women, and usually affects children but may not develop until adulthood.1

During STs, a patient may act scared, afraid, agitated, anxious, or panicky without being fully aware of his or her surroundings. The episode may last 30 seconds to 5 minutes; most patients don’t remember the event the next morning. STs may leave individuals feeling exhausted and perplexed the next day. Verbalization during the episode is incoherent and a patient’s perception of the environment seems altered. Tachycardia, tachypnea, sweating, flushed skin, or mydriasis are prominent. When ST patients walk, they may do so violently and can cause harm to themselves or others.

The differential diagnosis of STs includes posttraumatic stress disorder; nocturnal seizures characterized by excessive motor activity and organic CNS lesions; REM sleep behavior disorder; sleep choking syndrome; and nocturnal panic attacks. Patients with STs report high rates of stressful events—eg, divorce or bereavement—in the previous year. They are more likely to have a history of mood and anxiety disorders and high levels of depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive and phobic traits. One study found patients with STs were 4.3 times more likely to have had a car accident in the past year.2

Evaluating and treating STs

Rule out comorbid conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea and periodic limb movement disorder. Encourage your patient to improve his or her sleep hygiene by maintaining a regular sleep/wake cycle, exercising, and limiting caffeine and alcohol and exposure to bright light before bedtime.

Self-help techniques. To avoid injury, encourage your patient to remove dangerous objects from their sleeping area. Suggest locking the doors to the room or home, and putting medications in a secure place. Patients also may consider keeping their mattress close to the floor to limit the risk of injury.

Pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Along with counseling and support, your patient may benefit from cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation therapy, or hypnosis.3 Anticipatory arousal therapy may help by interrupting the altered underlying electrophysiology of partial arousal.

If your patient is concerned about physical injury during STs, consider prescribing clonazepam, temazepam, or diazepam.4 Trazodone and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as paroxetine5 also have been used to treat STs.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Sleep terrors (STs)—also known as night terrors—are characterized by sudden arousal accompanied by a piercing scream or cry in the first few hours after falling asleep. These parasomnias arise out of slow-wave sleep (stages 3 and 4 of nonrapid eye movement [non-REM] sleep) and affect approximately 5% of adults.1 The condition is twice as common in men than women, and usually affects children but may not develop until adulthood.1