User login

Ms. T, age 28, wishes to adopt a child. She has a history of bipolar disorder, but has been stable for several years. She asks her psychiatrist if her diagnosis will disqualify her as a potential parent. She also wants to know how the psychiatrist can help with the adoption process because he has been treating her long-term and is familiar with her psychiatric history.

Many adults with a history of psychiatric illness prefer to adopt rather than have biological children. Their preference may be fueled by concerns regarding psychiatric destabilization during pregnancy or fear of psychotropic-induced fetal teratogenicity. Child adoption laws vary from state to state. Although some licensed adoption agencies sympathize with potential adoptive parents with a history of mental illness, the law usually considers the following factors:

• the potential adopter’s emotional ties to the child

• their parenting skills

• emotional needs of the child

• the potential adopter’s desire to maintain continuity of the child’s care

• permanence of the family unit of the proposed home

• the physical, moral, and mental fitness of the potential parent.

The psychiatrist’s role

So long as the adoptee’s well-being is the reason for adoption, and the adoption is in the “best interest of the child,”1 a history of mental illness does not necessarily exclude an individual from adopting a child. The psychiatrist needs to consider the potential adopter’s motives, intellectual capacity, and judgment with regards to caregiving. The psychiatrist needs to assess the degree to which the patient’s mental disorder may or may not interfere with their parenting. The clinician also needs to consider potential changes that may occur in the adopter’s personal life, work hours, recreational and social activities, and sleep patterns.

It also is important to estimate the changes that an adoption may cause in the potential adopter’s living arrangements, daily schedule, and life events such as family vacations. Based on knowledge of the patient’s psychiatric history, a clinician may need to consider whether adoption-related stress could destabilize or exacerbate the potential parent’s psychiatric condition.2 Other psychosocial factors of importance are the reliability of the adopter’s support system, their history of previous child-rearing success, care-taking arrangements, etc.1

What to consider

The potential adoptee’s unique needs also should be considered. Is the child physically handicapped or mentally challenged, and is your patient capable of handling these issues? Would there be a good temperament fit between the potential adoptive parent and child?

Because child adoption laws vary from state to state, there are no established criteria for determining the eligibility of an individual with a history of mental illness. The success of a child adoption by an individual with a history of mental illness will depend on state laws and the policy of the adoption agency. Some U.S. states and territories (Alaska, Arizona, California, Kentucky, North Dakota, and Puerto Rico) regard parental mental illness as “aggravated circumstances.”1

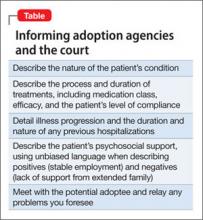

Although psychiatrists are not expected to be able to accurately predict the future, courts and adoption agencies may request a psychiatrist’s professional opinion on a specific adoption. See the Table for a list of suggested information to share when approached by an adoption agency or court.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Bacani-Oropilla T, Lippmann SB, Turns DM. Should the mentally ill adopt children? How physicians can influence the decision. Postgrad Med. 1988;84(6):201-205.

2. Linn L. Clinical manifestations of psychiatric disorder: the Homes-Rahe scale of stress of adjusting to change. In: Fredman A, Kaplan H, Sadock B, eds. Modern synopsis of comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, II. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1976:785.

Ms. T, age 28, wishes to adopt a child. She has a history of bipolar disorder, but has been stable for several years. She asks her psychiatrist if her diagnosis will disqualify her as a potential parent. She also wants to know how the psychiatrist can help with the adoption process because he has been treating her long-term and is familiar with her psychiatric history.

Many adults with a history of psychiatric illness prefer to adopt rather than have biological children. Their preference may be fueled by concerns regarding psychiatric destabilization during pregnancy or fear of psychotropic-induced fetal teratogenicity. Child adoption laws vary from state to state. Although some licensed adoption agencies sympathize with potential adoptive parents with a history of mental illness, the law usually considers the following factors:

• the potential adopter’s emotional ties to the child

• their parenting skills

• emotional needs of the child

• the potential adopter’s desire to maintain continuity of the child’s care

• permanence of the family unit of the proposed home

• the physical, moral, and mental fitness of the potential parent.

The psychiatrist’s role

So long as the adoptee’s well-being is the reason for adoption, and the adoption is in the “best interest of the child,”1 a history of mental illness does not necessarily exclude an individual from adopting a child. The psychiatrist needs to consider the potential adopter’s motives, intellectual capacity, and judgment with regards to caregiving. The psychiatrist needs to assess the degree to which the patient’s mental disorder may or may not interfere with their parenting. The clinician also needs to consider potential changes that may occur in the adopter’s personal life, work hours, recreational and social activities, and sleep patterns.

It also is important to estimate the changes that an adoption may cause in the potential adopter’s living arrangements, daily schedule, and life events such as family vacations. Based on knowledge of the patient’s psychiatric history, a clinician may need to consider whether adoption-related stress could destabilize or exacerbate the potential parent’s psychiatric condition.2 Other psychosocial factors of importance are the reliability of the adopter’s support system, their history of previous child-rearing success, care-taking arrangements, etc.1

What to consider

The potential adoptee’s unique needs also should be considered. Is the child physically handicapped or mentally challenged, and is your patient capable of handling these issues? Would there be a good temperament fit between the potential adoptive parent and child?

Because child adoption laws vary from state to state, there are no established criteria for determining the eligibility of an individual with a history of mental illness. The success of a child adoption by an individual with a history of mental illness will depend on state laws and the policy of the adoption agency. Some U.S. states and territories (Alaska, Arizona, California, Kentucky, North Dakota, and Puerto Rico) regard parental mental illness as “aggravated circumstances.”1

Although psychiatrists are not expected to be able to accurately predict the future, courts and adoption agencies may request a psychiatrist’s professional opinion on a specific adoption. See the Table for a list of suggested information to share when approached by an adoption agency or court.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Ms. T, age 28, wishes to adopt a child. She has a history of bipolar disorder, but has been stable for several years. She asks her psychiatrist if her diagnosis will disqualify her as a potential parent. She also wants to know how the psychiatrist can help with the adoption process because he has been treating her long-term and is familiar with her psychiatric history.

Many adults with a history of psychiatric illness prefer to adopt rather than have biological children. Their preference may be fueled by concerns regarding psychiatric destabilization during pregnancy or fear of psychotropic-induced fetal teratogenicity. Child adoption laws vary from state to state. Although some licensed adoption agencies sympathize with potential adoptive parents with a history of mental illness, the law usually considers the following factors:

• the potential adopter’s emotional ties to the child

• their parenting skills

• emotional needs of the child

• the potential adopter’s desire to maintain continuity of the child’s care

• permanence of the family unit of the proposed home

• the physical, moral, and mental fitness of the potential parent.

The psychiatrist’s role

So long as the adoptee’s well-being is the reason for adoption, and the adoption is in the “best interest of the child,”1 a history of mental illness does not necessarily exclude an individual from adopting a child. The psychiatrist needs to consider the potential adopter’s motives, intellectual capacity, and judgment with regards to caregiving. The psychiatrist needs to assess the degree to which the patient’s mental disorder may or may not interfere with their parenting. The clinician also needs to consider potential changes that may occur in the adopter’s personal life, work hours, recreational and social activities, and sleep patterns.

It also is important to estimate the changes that an adoption may cause in the potential adopter’s living arrangements, daily schedule, and life events such as family vacations. Based on knowledge of the patient’s psychiatric history, a clinician may need to consider whether adoption-related stress could destabilize or exacerbate the potential parent’s psychiatric condition.2 Other psychosocial factors of importance are the reliability of the adopter’s support system, their history of previous child-rearing success, care-taking arrangements, etc.1

What to consider

The potential adoptee’s unique needs also should be considered. Is the child physically handicapped or mentally challenged, and is your patient capable of handling these issues? Would there be a good temperament fit between the potential adoptive parent and child?

Because child adoption laws vary from state to state, there are no established criteria for determining the eligibility of an individual with a history of mental illness. The success of a child adoption by an individual with a history of mental illness will depend on state laws and the policy of the adoption agency. Some U.S. states and territories (Alaska, Arizona, California, Kentucky, North Dakota, and Puerto Rico) regard parental mental illness as “aggravated circumstances.”1

Although psychiatrists are not expected to be able to accurately predict the future, courts and adoption agencies may request a psychiatrist’s professional opinion on a specific adoption. See the Table for a list of suggested information to share when approached by an adoption agency or court.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Bacani-Oropilla T, Lippmann SB, Turns DM. Should the mentally ill adopt children? How physicians can influence the decision. Postgrad Med. 1988;84(6):201-205.

2. Linn L. Clinical manifestations of psychiatric disorder: the Homes-Rahe scale of stress of adjusting to change. In: Fredman A, Kaplan H, Sadock B, eds. Modern synopsis of comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, II. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1976:785.

1. Bacani-Oropilla T, Lippmann SB, Turns DM. Should the mentally ill adopt children? How physicians can influence the decision. Postgrad Med. 1988;84(6):201-205.

2. Linn L. Clinical manifestations of psychiatric disorder: the Homes-Rahe scale of stress of adjusting to change. In: Fredman A, Kaplan H, Sadock B, eds. Modern synopsis of comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, II. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1976:785.