User login

Be prepared to adjust dosing of psychotropics after bariatric surgery

Approximately 113,000 bariatric surgeries were performed in the United States in 2010; as many as 80% of persons seeking weight loss surgery have a history of a psychiatric disorder.1,2

Bariatric surgery can be “restrictive” (limiting food intake) or “malabsorptive” (limiting food absorption). Both types of procedures can cause significant changes in pharmacokinetics. Bariatric surgery patients who take a psychotropic are at risk of toxicity or relapse of their psychiatric illness because of inappropriate formulations— immediate-release vs sustained-release—or incomplete absorption of medications. You need to anticipate potential pharmacokinetic alterations after bariatric surgery and make appropriate changes to the patient’s medication regimen.

Pharmacokinetic concerns

Roux-en-Y surgery is a malabsorptive procedure that causes food to bypass the stomach, duodenum, and a variable length of jejunum. Secondary to bypass, iron deficiency anemia is a common nutritional complication.

Other changes that affect the pharmacokinetics of psychotropics after bariatric surgery include:

• an increase in percentage of lean body mass as weight loss occurs

• a decrease in glomerular filtration rate as kidney size decreases with postsurgical weight reduction

• reversal of obesity-associated fatty liver and cirrhotic changes.

With time, intestinal adaptation occurs to compensate for the reduced length of the intestinal tract; this adaptation produces mucosal hypertrophy and increases absorptive capacity.3

Medications to taper or avoid

The absorption and bioavailability of a medication depend on its dissolvability; the pH of the medium; surface area for absorption; and GI blood flow.4 Medications that have a long absorptive phase—namely, sustained-release, extended-release, long-acting, and enteric-coated formulations—show compromised dissolvability and absorption and reduced efficacy after bariatric surgery.

Avoid slow-release formulations, including ion-exchange resins with a semipermeable membrane and those with slowly dissolving characteristics; substitute an immediate-release formulation.

Medications that require acidic pH are incompletely absorbed because gastric exposure is reduced.

Lipophilic medications depend on bile availability; impaired enterohepatic circulation because of reduced intestinal absorptive surface causes loss of bile and, therefore, impaired absorption of lipophilic medications.

Medications that are poorly intrinsically absorbed and undergo enterohepatic circulation are likely to be underabsorbed after a malabsorptive bariatric procedure.

Lamotrigine, olanzapine, and quetiapine may show decreased efficacy because of possible reduced absorption.

The lithium level, which is influenced by volume of distribution, can become toxic postoperatively; consider measuring the serum lithium level.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Livingston EH. The incidence of bariatric surgery has plateaued in the U.S. Am J Surg. 2010;200(3):378-385.

2. Jones WR, Morgan JF. Obesity surgery. Psychiatric needs must be considered. BMJ. 2010;341:c5298. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5298.

3. Padwal R, Brocks D, Sharma AM. A systematic review of drug absorption following bariatric surgery and its theoretical implications. Obes Rev. 2010;11(1):41-50.

4. Lizer MH, Papageorgeon H, Glembot TM. Nutritional and pharmacologic challenges in the bariatric surgery patient. Obes Surg. 2010;20(12):1654-1659.

Approximately 113,000 bariatric surgeries were performed in the United States in 2010; as many as 80% of persons seeking weight loss surgery have a history of a psychiatric disorder.1,2

Bariatric surgery can be “restrictive” (limiting food intake) or “malabsorptive” (limiting food absorption). Both types of procedures can cause significant changes in pharmacokinetics. Bariatric surgery patients who take a psychotropic are at risk of toxicity or relapse of their psychiatric illness because of inappropriate formulations— immediate-release vs sustained-release—or incomplete absorption of medications. You need to anticipate potential pharmacokinetic alterations after bariatric surgery and make appropriate changes to the patient’s medication regimen.

Pharmacokinetic concerns

Roux-en-Y surgery is a malabsorptive procedure that causes food to bypass the stomach, duodenum, and a variable length of jejunum. Secondary to bypass, iron deficiency anemia is a common nutritional complication.

Other changes that affect the pharmacokinetics of psychotropics after bariatric surgery include:

• an increase in percentage of lean body mass as weight loss occurs

• a decrease in glomerular filtration rate as kidney size decreases with postsurgical weight reduction

• reversal of obesity-associated fatty liver and cirrhotic changes.

With time, intestinal adaptation occurs to compensate for the reduced length of the intestinal tract; this adaptation produces mucosal hypertrophy and increases absorptive capacity.3

Medications to taper or avoid

The absorption and bioavailability of a medication depend on its dissolvability; the pH of the medium; surface area for absorption; and GI blood flow.4 Medications that have a long absorptive phase—namely, sustained-release, extended-release, long-acting, and enteric-coated formulations—show compromised dissolvability and absorption and reduced efficacy after bariatric surgery.

Avoid slow-release formulations, including ion-exchange resins with a semipermeable membrane and those with slowly dissolving characteristics; substitute an immediate-release formulation.

Medications that require acidic pH are incompletely absorbed because gastric exposure is reduced.

Lipophilic medications depend on bile availability; impaired enterohepatic circulation because of reduced intestinal absorptive surface causes loss of bile and, therefore, impaired absorption of lipophilic medications.

Medications that are poorly intrinsically absorbed and undergo enterohepatic circulation are likely to be underabsorbed after a malabsorptive bariatric procedure.

Lamotrigine, olanzapine, and quetiapine may show decreased efficacy because of possible reduced absorption.

The lithium level, which is influenced by volume of distribution, can become toxic postoperatively; consider measuring the serum lithium level.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Approximately 113,000 bariatric surgeries were performed in the United States in 2010; as many as 80% of persons seeking weight loss surgery have a history of a psychiatric disorder.1,2

Bariatric surgery can be “restrictive” (limiting food intake) or “malabsorptive” (limiting food absorption). Both types of procedures can cause significant changes in pharmacokinetics. Bariatric surgery patients who take a psychotropic are at risk of toxicity or relapse of their psychiatric illness because of inappropriate formulations— immediate-release vs sustained-release—or incomplete absorption of medications. You need to anticipate potential pharmacokinetic alterations after bariatric surgery and make appropriate changes to the patient’s medication regimen.

Pharmacokinetic concerns

Roux-en-Y surgery is a malabsorptive procedure that causes food to bypass the stomach, duodenum, and a variable length of jejunum. Secondary to bypass, iron deficiency anemia is a common nutritional complication.

Other changes that affect the pharmacokinetics of psychotropics after bariatric surgery include:

• an increase in percentage of lean body mass as weight loss occurs

• a decrease in glomerular filtration rate as kidney size decreases with postsurgical weight reduction

• reversal of obesity-associated fatty liver and cirrhotic changes.

With time, intestinal adaptation occurs to compensate for the reduced length of the intestinal tract; this adaptation produces mucosal hypertrophy and increases absorptive capacity.3

Medications to taper or avoid

The absorption and bioavailability of a medication depend on its dissolvability; the pH of the medium; surface area for absorption; and GI blood flow.4 Medications that have a long absorptive phase—namely, sustained-release, extended-release, long-acting, and enteric-coated formulations—show compromised dissolvability and absorption and reduced efficacy after bariatric surgery.

Avoid slow-release formulations, including ion-exchange resins with a semipermeable membrane and those with slowly dissolving characteristics; substitute an immediate-release formulation.

Medications that require acidic pH are incompletely absorbed because gastric exposure is reduced.

Lipophilic medications depend on bile availability; impaired enterohepatic circulation because of reduced intestinal absorptive surface causes loss of bile and, therefore, impaired absorption of lipophilic medications.

Medications that are poorly intrinsically absorbed and undergo enterohepatic circulation are likely to be underabsorbed after a malabsorptive bariatric procedure.

Lamotrigine, olanzapine, and quetiapine may show decreased efficacy because of possible reduced absorption.

The lithium level, which is influenced by volume of distribution, can become toxic postoperatively; consider measuring the serum lithium level.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Livingston EH. The incidence of bariatric surgery has plateaued in the U.S. Am J Surg. 2010;200(3):378-385.

2. Jones WR, Morgan JF. Obesity surgery. Psychiatric needs must be considered. BMJ. 2010;341:c5298. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5298.

3. Padwal R, Brocks D, Sharma AM. A systematic review of drug absorption following bariatric surgery and its theoretical implications. Obes Rev. 2010;11(1):41-50.

4. Lizer MH, Papageorgeon H, Glembot TM. Nutritional and pharmacologic challenges in the bariatric surgery patient. Obes Surg. 2010;20(12):1654-1659.

1. Livingston EH. The incidence of bariatric surgery has plateaued in the U.S. Am J Surg. 2010;200(3):378-385.

2. Jones WR, Morgan JF. Obesity surgery. Psychiatric needs must be considered. BMJ. 2010;341:c5298. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5298.

3. Padwal R, Brocks D, Sharma AM. A systematic review of drug absorption following bariatric surgery and its theoretical implications. Obes Rev. 2010;11(1):41-50.

4. Lizer MH, Papageorgeon H, Glembot TM. Nutritional and pharmacologic challenges in the bariatric surgery patient. Obes Surg. 2010;20(12):1654-1659.

Be aware: Sudden discontinuation of a psychotropic risks a lethal outcome

For mentally ill young men, especially, abruptly stopping a psychotropic medication can be lethal.1 Under such circumstances, excited delirium syndrome (EDS), also known as sudden in-custody death syndrome and Bell’s mania, can occur, warranting your careful observation.

Approximately 10% of EDS cases are fatal2; >95% of fatalities occur in men

(mean age, 36 years).3 Most cases involve stimulant abuse—usually cocaine, although cases associated with methamphetamine, phencyclidine, and LSD have been reported. Patients who present with EDS experience a characteristic loss of

the dopamine transporter in the striatum and excessive dopamine stimulation in

the striatum.

What should you watch for?

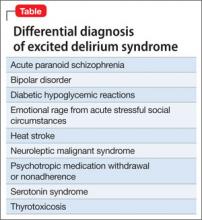

Other syndromes and disorders can mimic EDS (Table), but there are certain specific symptoms to look for. Patients who have EDS can present with delirium and an excited or agitated state. Other common symptoms include:

• altered sensorium

• aggressive, agitated behavior

• “superhuman” strength (including a tendency to break glass or unwillingness

to yield to overwhelming force)

• diaphoresis

• hyperthermia

• attraction to light.

Patients who have EDS often exhibit constant physical movement. They are likely to be naked or inadequately clothed; to sweat profusely; and to make unintelligible, animal-like noises. They are insensitive to extreme pain. In a small percentage of cases, EDS progresses to sudden cardiopulmonary arrestand death.3

Medication or restraints?

Many clinicians consider aggressive chemical sedation the first-line intervention for

EDS2,3; choice of medication varies from practice to practice. Restraints often are

necessary to ensure the safety of patient and staff, but use them only in conjunction with aggressive chemical sedation. Physical struggle is a greater contributor to catecholamine surge and metabolic acidosis than other types of exertion; methods of physical control should therefore minimize the time a patient spends struggling while safely achieving physical control.

What is the treatment for EDS?

Begin treatment while you are evaluating the patient for precipitating causes or additional pathology. There are cases of death from EDS even with minimal restraint (such as handcuffs),1,2 without the use of an electronic control device or so-called hog-tie restraint.

When providing pharmacotherapy for EDS, consider a benzodiazepine (midazolam, lorazepam, diazepam), an antipsychotic (haloperidol, droperidol, ziprasidone, olanzapine), or ketamine.4 Because these agents can have depressive respiratory and cardiovascular effects, continuously monitor heart and lungs.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Morrison A, Sadler D. Death of a psychiatric patient during physical restraint. Excited delirium—a case report. Med Sci Law. 2001;41(1):46-50.

2. Vilke GM, Debard ML, Chan TC, et al. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): defining based on a review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(5):897-905.

4. Vilke GM, Payne-James J, Karch SB. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): redefining an old diagnosis. J Forensic Leg Med. 2012;19(1):7-11.

4. Hick JL, Ho JD. Ketamine chemical restraint to facilitate rescue of a combative “jumper.” Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005; 9(1):85-89.

For mentally ill young men, especially, abruptly stopping a psychotropic medication can be lethal.1 Under such circumstances, excited delirium syndrome (EDS), also known as sudden in-custody death syndrome and Bell’s mania, can occur, warranting your careful observation.

Approximately 10% of EDS cases are fatal2; >95% of fatalities occur in men

(mean age, 36 years).3 Most cases involve stimulant abuse—usually cocaine, although cases associated with methamphetamine, phencyclidine, and LSD have been reported. Patients who present with EDS experience a characteristic loss of

the dopamine transporter in the striatum and excessive dopamine stimulation in

the striatum.

What should you watch for?

Other syndromes and disorders can mimic EDS (Table), but there are certain specific symptoms to look for. Patients who have EDS can present with delirium and an excited or agitated state. Other common symptoms include:

• altered sensorium

• aggressive, agitated behavior

• “superhuman” strength (including a tendency to break glass or unwillingness

to yield to overwhelming force)

• diaphoresis

• hyperthermia

• attraction to light.

Patients who have EDS often exhibit constant physical movement. They are likely to be naked or inadequately clothed; to sweat profusely; and to make unintelligible, animal-like noises. They are insensitive to extreme pain. In a small percentage of cases, EDS progresses to sudden cardiopulmonary arrestand death.3

Medication or restraints?

Many clinicians consider aggressive chemical sedation the first-line intervention for

EDS2,3; choice of medication varies from practice to practice. Restraints often are

necessary to ensure the safety of patient and staff, but use them only in conjunction with aggressive chemical sedation. Physical struggle is a greater contributor to catecholamine surge and metabolic acidosis than other types of exertion; methods of physical control should therefore minimize the time a patient spends struggling while safely achieving physical control.

What is the treatment for EDS?

Begin treatment while you are evaluating the patient for precipitating causes or additional pathology. There are cases of death from EDS even with minimal restraint (such as handcuffs),1,2 without the use of an electronic control device or so-called hog-tie restraint.

When providing pharmacotherapy for EDS, consider a benzodiazepine (midazolam, lorazepam, diazepam), an antipsychotic (haloperidol, droperidol, ziprasidone, olanzapine), or ketamine.4 Because these agents can have depressive respiratory and cardiovascular effects, continuously monitor heart and lungs.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

For mentally ill young men, especially, abruptly stopping a psychotropic medication can be lethal.1 Under such circumstances, excited delirium syndrome (EDS), also known as sudden in-custody death syndrome and Bell’s mania, can occur, warranting your careful observation.

Approximately 10% of EDS cases are fatal2; >95% of fatalities occur in men

(mean age, 36 years).3 Most cases involve stimulant abuse—usually cocaine, although cases associated with methamphetamine, phencyclidine, and LSD have been reported. Patients who present with EDS experience a characteristic loss of

the dopamine transporter in the striatum and excessive dopamine stimulation in

the striatum.

What should you watch for?

Other syndromes and disorders can mimic EDS (Table), but there are certain specific symptoms to look for. Patients who have EDS can present with delirium and an excited or agitated state. Other common symptoms include:

• altered sensorium

• aggressive, agitated behavior

• “superhuman” strength (including a tendency to break glass or unwillingness

to yield to overwhelming force)

• diaphoresis

• hyperthermia

• attraction to light.

Patients who have EDS often exhibit constant physical movement. They are likely to be naked or inadequately clothed; to sweat profusely; and to make unintelligible, animal-like noises. They are insensitive to extreme pain. In a small percentage of cases, EDS progresses to sudden cardiopulmonary arrestand death.3

Medication or restraints?

Many clinicians consider aggressive chemical sedation the first-line intervention for

EDS2,3; choice of medication varies from practice to practice. Restraints often are

necessary to ensure the safety of patient and staff, but use them only in conjunction with aggressive chemical sedation. Physical struggle is a greater contributor to catecholamine surge and metabolic acidosis than other types of exertion; methods of physical control should therefore minimize the time a patient spends struggling while safely achieving physical control.

What is the treatment for EDS?

Begin treatment while you are evaluating the patient for precipitating causes or additional pathology. There are cases of death from EDS even with minimal restraint (such as handcuffs),1,2 without the use of an electronic control device or so-called hog-tie restraint.

When providing pharmacotherapy for EDS, consider a benzodiazepine (midazolam, lorazepam, diazepam), an antipsychotic (haloperidol, droperidol, ziprasidone, olanzapine), or ketamine.4 Because these agents can have depressive respiratory and cardiovascular effects, continuously monitor heart and lungs.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Morrison A, Sadler D. Death of a psychiatric patient during physical restraint. Excited delirium—a case report. Med Sci Law. 2001;41(1):46-50.

2. Vilke GM, Debard ML, Chan TC, et al. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): defining based on a review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(5):897-905.

4. Vilke GM, Payne-James J, Karch SB. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): redefining an old diagnosis. J Forensic Leg Med. 2012;19(1):7-11.

4. Hick JL, Ho JD. Ketamine chemical restraint to facilitate rescue of a combative “jumper.” Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005; 9(1):85-89.

1. Morrison A, Sadler D. Death of a psychiatric patient during physical restraint. Excited delirium—a case report. Med Sci Law. 2001;41(1):46-50.

2. Vilke GM, Debard ML, Chan TC, et al. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): defining based on a review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(5):897-905.

4. Vilke GM, Payne-James J, Karch SB. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): redefining an old diagnosis. J Forensic Leg Med. 2012;19(1):7-11.

4. Hick JL, Ho JD. Ketamine chemical restraint to facilitate rescue of a combative “jumper.” Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005; 9(1):85-89.

Key steps to take when a patient commits suicide

The suicide of a patient is a relatively frequent occurrence in psychiatry. As many as 68% of consultant psychiatrists acknowledge the loss of a patient to suicide.1 Conservative estimates are that as many as 54% of psychiatry resident trainees experience patient suicide.2

Up to 57% of psychiatrists who have experienced a patient’s suicide have developed symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder.3 There are steps you can take personally, with your staff, and with the patient’s family to mitigate social,

ethical, and legal consequences of a patient committing suicide, and to improve risk management.

Steps to take for yourself

1. In an inpatient psychiatric facility, be aware of standard operating procedures after a suicide; inform only an immediate supervisor if you learn of a suicide. In a group practice, inform the owner of the practice and receive advice on how to proceed. Do not contact the coroner’s office, the police, the deceased’s family, or legal counsel until advised to do so by a direct supervisor.

2. Be prepared to work with the coroner’s or medical examiner’s office. Write a detailed note summarizing the patient’s clinical history before the suicide; describe the clinical team’s work with the patient, the treatment plan, and an estimate of suicide risk.

3. Contact a trusted colleague or mentor; seeking formal and informal support from colleagues has shown to be helpful in coping with patient suicide.4 Group

support helps diminish feelings of pain and loneliness and helps one regain a sense of empowerment and willingness to treat other suicidal patients.

4. If possible, attend the patient’s funeral. This gesture often is welcomed by the family and facilitates the grieving process. Attending the funeral is not an admission of responsibility for the suicide.

5. Participate in the audit process (ie, what went wrong?, Could something have been done differently?).

Steps to take with the patient’s family

1. Once standard operating procedure allows, and, preferably within 24 hours of the suicide, contact the patient’s family to express your grief; give the family an opportunity to ask questions. Early communication and support reduces anger displaced on the psychiatrist. Initial contact can be used to provide support and as an opportunity to share and communicate.

2. When speaking with the family, discuss treatment efforts and emphasize that all realistic efforts were made to help the patient. Let family members vent their anger and hostility; the grieving process is hard, complex, and painful when a loved one has committed suicide.

3. Support the family’s decisions about mourning rituals specific to their culture and needs; involving the clergy early on can be helpful. Discussing the autopsy report with the family can be another way to show support.

4. Continue to offer support through stressful times, such as anniversaries and birthdays.

Steps to take with staff

1. Make staff aware of the death as a group; encourage them to attend funeral services.

2. Avoid placing blame; encourage group support and venting of emotions.

3. Be available to the staff so that they can share feelings of hurt and disappointment with you.

4. Maintain the schedule on unit, restoring a sense of stability and normalcy.

5. A so-called psychological autopsy exercise is recommended, in which you can emphasize the learning experience and focus on improvements4 that can help formulate policy reforms for providing better care.

Steps to improve risk management

1. If you work in a hospital, immediately contact the risk management team.

2. Seek legal counsel as soon as possible and involve counsel at all stages.

3. Notify your malpractice insurance carrier.

4. Complete the patient’s medical record and describe the facts as they occurred. Date the records accurately with clarification on notes entered after the suicide. Avoid drawing conclusions. Do not apologize for, or justify, your treatment decisions.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Alexander DA, Klein S, Gray NM, et al. Suicide by patients: questionnaire study of its effect on consultant psychiatrists. BMJ. 2000;320(7249):1571-1574.

2. Courtenay KP, Stephens JP. The experience of patient suicide among trainees in psychiatry. The Psychiatrist. 2001;25:51-52.

3. Chemtob CM, Hamada RS, Bauer G, et al. Patients’ suicides: frequency and impact on psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145(2):224-228.

4. Kaye NS, Soreff SM. The psychiatrist’s role, responses, and responsibilities when a patient commits suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):739-743.

The suicide of a patient is a relatively frequent occurrence in psychiatry. As many as 68% of consultant psychiatrists acknowledge the loss of a patient to suicide.1 Conservative estimates are that as many as 54% of psychiatry resident trainees experience patient suicide.2

Up to 57% of psychiatrists who have experienced a patient’s suicide have developed symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder.3 There are steps you can take personally, with your staff, and with the patient’s family to mitigate social,

ethical, and legal consequences of a patient committing suicide, and to improve risk management.

Steps to take for yourself

1. In an inpatient psychiatric facility, be aware of standard operating procedures after a suicide; inform only an immediate supervisor if you learn of a suicide. In a group practice, inform the owner of the practice and receive advice on how to proceed. Do not contact the coroner’s office, the police, the deceased’s family, or legal counsel until advised to do so by a direct supervisor.

2. Be prepared to work with the coroner’s or medical examiner’s office. Write a detailed note summarizing the patient’s clinical history before the suicide; describe the clinical team’s work with the patient, the treatment plan, and an estimate of suicide risk.

3. Contact a trusted colleague or mentor; seeking formal and informal support from colleagues has shown to be helpful in coping with patient suicide.4 Group

support helps diminish feelings of pain and loneliness and helps one regain a sense of empowerment and willingness to treat other suicidal patients.

4. If possible, attend the patient’s funeral. This gesture often is welcomed by the family and facilitates the grieving process. Attending the funeral is not an admission of responsibility for the suicide.

5. Participate in the audit process (ie, what went wrong?, Could something have been done differently?).

Steps to take with the patient’s family

1. Once standard operating procedure allows, and, preferably within 24 hours of the suicide, contact the patient’s family to express your grief; give the family an opportunity to ask questions. Early communication and support reduces anger displaced on the psychiatrist. Initial contact can be used to provide support and as an opportunity to share and communicate.

2. When speaking with the family, discuss treatment efforts and emphasize that all realistic efforts were made to help the patient. Let family members vent their anger and hostility; the grieving process is hard, complex, and painful when a loved one has committed suicide.

3. Support the family’s decisions about mourning rituals specific to their culture and needs; involving the clergy early on can be helpful. Discussing the autopsy report with the family can be another way to show support.

4. Continue to offer support through stressful times, such as anniversaries and birthdays.

Steps to take with staff

1. Make staff aware of the death as a group; encourage them to attend funeral services.

2. Avoid placing blame; encourage group support and venting of emotions.

3. Be available to the staff so that they can share feelings of hurt and disappointment with you.

4. Maintain the schedule on unit, restoring a sense of stability and normalcy.

5. A so-called psychological autopsy exercise is recommended, in which you can emphasize the learning experience and focus on improvements4 that can help formulate policy reforms for providing better care.

Steps to improve risk management

1. If you work in a hospital, immediately contact the risk management team.

2. Seek legal counsel as soon as possible and involve counsel at all stages.

3. Notify your malpractice insurance carrier.

4. Complete the patient’s medical record and describe the facts as they occurred. Date the records accurately with clarification on notes entered after the suicide. Avoid drawing conclusions. Do not apologize for, or justify, your treatment decisions.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

The suicide of a patient is a relatively frequent occurrence in psychiatry. As many as 68% of consultant psychiatrists acknowledge the loss of a patient to suicide.1 Conservative estimates are that as many as 54% of psychiatry resident trainees experience patient suicide.2

Up to 57% of psychiatrists who have experienced a patient’s suicide have developed symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder.3 There are steps you can take personally, with your staff, and with the patient’s family to mitigate social,

ethical, and legal consequences of a patient committing suicide, and to improve risk management.

Steps to take for yourself

1. In an inpatient psychiatric facility, be aware of standard operating procedures after a suicide; inform only an immediate supervisor if you learn of a suicide. In a group practice, inform the owner of the practice and receive advice on how to proceed. Do not contact the coroner’s office, the police, the deceased’s family, or legal counsel until advised to do so by a direct supervisor.

2. Be prepared to work with the coroner’s or medical examiner’s office. Write a detailed note summarizing the patient’s clinical history before the suicide; describe the clinical team’s work with the patient, the treatment plan, and an estimate of suicide risk.

3. Contact a trusted colleague or mentor; seeking formal and informal support from colleagues has shown to be helpful in coping with patient suicide.4 Group

support helps diminish feelings of pain and loneliness and helps one regain a sense of empowerment and willingness to treat other suicidal patients.

4. If possible, attend the patient’s funeral. This gesture often is welcomed by the family and facilitates the grieving process. Attending the funeral is not an admission of responsibility for the suicide.

5. Participate in the audit process (ie, what went wrong?, Could something have been done differently?).

Steps to take with the patient’s family

1. Once standard operating procedure allows, and, preferably within 24 hours of the suicide, contact the patient’s family to express your grief; give the family an opportunity to ask questions. Early communication and support reduces anger displaced on the psychiatrist. Initial contact can be used to provide support and as an opportunity to share and communicate.

2. When speaking with the family, discuss treatment efforts and emphasize that all realistic efforts were made to help the patient. Let family members vent their anger and hostility; the grieving process is hard, complex, and painful when a loved one has committed suicide.

3. Support the family’s decisions about mourning rituals specific to their culture and needs; involving the clergy early on can be helpful. Discussing the autopsy report with the family can be another way to show support.

4. Continue to offer support through stressful times, such as anniversaries and birthdays.

Steps to take with staff

1. Make staff aware of the death as a group; encourage them to attend funeral services.

2. Avoid placing blame; encourage group support and venting of emotions.

3. Be available to the staff so that they can share feelings of hurt and disappointment with you.

4. Maintain the schedule on unit, restoring a sense of stability and normalcy.

5. A so-called psychological autopsy exercise is recommended, in which you can emphasize the learning experience and focus on improvements4 that can help formulate policy reforms for providing better care.

Steps to improve risk management

1. If you work in a hospital, immediately contact the risk management team.

2. Seek legal counsel as soon as possible and involve counsel at all stages.

3. Notify your malpractice insurance carrier.

4. Complete the patient’s medical record and describe the facts as they occurred. Date the records accurately with clarification on notes entered after the suicide. Avoid drawing conclusions. Do not apologize for, or justify, your treatment decisions.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Alexander DA, Klein S, Gray NM, et al. Suicide by patients: questionnaire study of its effect on consultant psychiatrists. BMJ. 2000;320(7249):1571-1574.

2. Courtenay KP, Stephens JP. The experience of patient suicide among trainees in psychiatry. The Psychiatrist. 2001;25:51-52.

3. Chemtob CM, Hamada RS, Bauer G, et al. Patients’ suicides: frequency and impact on psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145(2):224-228.

4. Kaye NS, Soreff SM. The psychiatrist’s role, responses, and responsibilities when a patient commits suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):739-743.

1. Alexander DA, Klein S, Gray NM, et al. Suicide by patients: questionnaire study of its effect on consultant psychiatrists. BMJ. 2000;320(7249):1571-1574.

2. Courtenay KP, Stephens JP. The experience of patient suicide among trainees in psychiatry. The Psychiatrist. 2001;25:51-52.

3. Chemtob CM, Hamada RS, Bauer G, et al. Patients’ suicides: frequency and impact on psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145(2):224-228.

4. Kaye NS, Soreff SM. The psychiatrist’s role, responses, and responsibilities when a patient commits suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):739-743.

Adoption by mentally ill individuals: What to recommend

Ms. T, age 28, wishes to adopt a child. She has a history of bipolar disorder, but has been stable for several years. She asks her psychiatrist if her diagnosis will disqualify her as a potential parent. She also wants to know how the psychiatrist can help with the adoption process because he has been treating her long-term and is familiar with her psychiatric history.

Many adults with a history of psychiatric illness prefer to adopt rather than have biological children. Their preference may be fueled by concerns regarding psychiatric destabilization during pregnancy or fear of psychotropic-induced fetal teratogenicity. Child adoption laws vary from state to state. Although some licensed adoption agencies sympathize with potential adoptive parents with a history of mental illness, the law usually considers the following factors:

• the potential adopter’s emotional ties to the child

• their parenting skills

• emotional needs of the child

• the potential adopter’s desire to maintain continuity of the child’s care

• permanence of the family unit of the proposed home

• the physical, moral, and mental fitness of the potential parent.

The psychiatrist’s role

So long as the adoptee’s well-being is the reason for adoption, and the adoption is in the “best interest of the child,”1 a history of mental illness does not necessarily exclude an individual from adopting a child. The psychiatrist needs to consider the potential adopter’s motives, intellectual capacity, and judgment with regards to caregiving. The psychiatrist needs to assess the degree to which the patient’s mental disorder may or may not interfere with their parenting. The clinician also needs to consider potential changes that may occur in the adopter’s personal life, work hours, recreational and social activities, and sleep patterns.

It also is important to estimate the changes that an adoption may cause in the potential adopter’s living arrangements, daily schedule, and life events such as family vacations. Based on knowledge of the patient’s psychiatric history, a clinician may need to consider whether adoption-related stress could destabilize or exacerbate the potential parent’s psychiatric condition.2 Other psychosocial factors of importance are the reliability of the adopter’s support system, their history of previous child-rearing success, care-taking arrangements, etc.1

What to consider

The potential adoptee’s unique needs also should be considered. Is the child physically handicapped or mentally challenged, and is your patient capable of handling these issues? Would there be a good temperament fit between the potential adoptive parent and child?

Because child adoption laws vary from state to state, there are no established criteria for determining the eligibility of an individual with a history of mental illness. The success of a child adoption by an individual with a history of mental illness will depend on state laws and the policy of the adoption agency. Some U.S. states and territories (Alaska, Arizona, California, Kentucky, North Dakota, and Puerto Rico) regard parental mental illness as “aggravated circumstances.”1

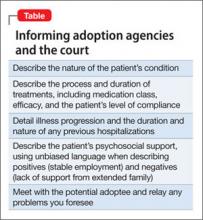

Although psychiatrists are not expected to be able to accurately predict the future, courts and adoption agencies may request a psychiatrist’s professional opinion on a specific adoption. See the Table for a list of suggested information to share when approached by an adoption agency or court.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Bacani-Oropilla T, Lippmann SB, Turns DM. Should the mentally ill adopt children? How physicians can influence the decision. Postgrad Med. 1988;84(6):201-205.

2. Linn L. Clinical manifestations of psychiatric disorder: the Homes-Rahe scale of stress of adjusting to change. In: Fredman A, Kaplan H, Sadock B, eds. Modern synopsis of comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, II. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1976:785.

Ms. T, age 28, wishes to adopt a child. She has a history of bipolar disorder, but has been stable for several years. She asks her psychiatrist if her diagnosis will disqualify her as a potential parent. She also wants to know how the psychiatrist can help with the adoption process because he has been treating her long-term and is familiar with her psychiatric history.

Many adults with a history of psychiatric illness prefer to adopt rather than have biological children. Their preference may be fueled by concerns regarding psychiatric destabilization during pregnancy or fear of psychotropic-induced fetal teratogenicity. Child adoption laws vary from state to state. Although some licensed adoption agencies sympathize with potential adoptive parents with a history of mental illness, the law usually considers the following factors:

• the potential adopter’s emotional ties to the child

• their parenting skills

• emotional needs of the child

• the potential adopter’s desire to maintain continuity of the child’s care

• permanence of the family unit of the proposed home

• the physical, moral, and mental fitness of the potential parent.

The psychiatrist’s role

So long as the adoptee’s well-being is the reason for adoption, and the adoption is in the “best interest of the child,”1 a history of mental illness does not necessarily exclude an individual from adopting a child. The psychiatrist needs to consider the potential adopter’s motives, intellectual capacity, and judgment with regards to caregiving. The psychiatrist needs to assess the degree to which the patient’s mental disorder may or may not interfere with their parenting. The clinician also needs to consider potential changes that may occur in the adopter’s personal life, work hours, recreational and social activities, and sleep patterns.

It also is important to estimate the changes that an adoption may cause in the potential adopter’s living arrangements, daily schedule, and life events such as family vacations. Based on knowledge of the patient’s psychiatric history, a clinician may need to consider whether adoption-related stress could destabilize or exacerbate the potential parent’s psychiatric condition.2 Other psychosocial factors of importance are the reliability of the adopter’s support system, their history of previous child-rearing success, care-taking arrangements, etc.1

What to consider

The potential adoptee’s unique needs also should be considered. Is the child physically handicapped or mentally challenged, and is your patient capable of handling these issues? Would there be a good temperament fit between the potential adoptive parent and child?

Because child adoption laws vary from state to state, there are no established criteria for determining the eligibility of an individual with a history of mental illness. The success of a child adoption by an individual with a history of mental illness will depend on state laws and the policy of the adoption agency. Some U.S. states and territories (Alaska, Arizona, California, Kentucky, North Dakota, and Puerto Rico) regard parental mental illness as “aggravated circumstances.”1

Although psychiatrists are not expected to be able to accurately predict the future, courts and adoption agencies may request a psychiatrist’s professional opinion on a specific adoption. See the Table for a list of suggested information to share when approached by an adoption agency or court.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Ms. T, age 28, wishes to adopt a child. She has a history of bipolar disorder, but has been stable for several years. She asks her psychiatrist if her diagnosis will disqualify her as a potential parent. She also wants to know how the psychiatrist can help with the adoption process because he has been treating her long-term and is familiar with her psychiatric history.

Many adults with a history of psychiatric illness prefer to adopt rather than have biological children. Their preference may be fueled by concerns regarding psychiatric destabilization during pregnancy or fear of psychotropic-induced fetal teratogenicity. Child adoption laws vary from state to state. Although some licensed adoption agencies sympathize with potential adoptive parents with a history of mental illness, the law usually considers the following factors:

• the potential adopter’s emotional ties to the child

• their parenting skills

• emotional needs of the child

• the potential adopter’s desire to maintain continuity of the child’s care

• permanence of the family unit of the proposed home

• the physical, moral, and mental fitness of the potential parent.

The psychiatrist’s role

So long as the adoptee’s well-being is the reason for adoption, and the adoption is in the “best interest of the child,”1 a history of mental illness does not necessarily exclude an individual from adopting a child. The psychiatrist needs to consider the potential adopter’s motives, intellectual capacity, and judgment with regards to caregiving. The psychiatrist needs to assess the degree to which the patient’s mental disorder may or may not interfere with their parenting. The clinician also needs to consider potential changes that may occur in the adopter’s personal life, work hours, recreational and social activities, and sleep patterns.

It also is important to estimate the changes that an adoption may cause in the potential adopter’s living arrangements, daily schedule, and life events such as family vacations. Based on knowledge of the patient’s psychiatric history, a clinician may need to consider whether adoption-related stress could destabilize or exacerbate the potential parent’s psychiatric condition.2 Other psychosocial factors of importance are the reliability of the adopter’s support system, their history of previous child-rearing success, care-taking arrangements, etc.1

What to consider

The potential adoptee’s unique needs also should be considered. Is the child physically handicapped or mentally challenged, and is your patient capable of handling these issues? Would there be a good temperament fit between the potential adoptive parent and child?

Because child adoption laws vary from state to state, there are no established criteria for determining the eligibility of an individual with a history of mental illness. The success of a child adoption by an individual with a history of mental illness will depend on state laws and the policy of the adoption agency. Some U.S. states and territories (Alaska, Arizona, California, Kentucky, North Dakota, and Puerto Rico) regard parental mental illness as “aggravated circumstances.”1

Although psychiatrists are not expected to be able to accurately predict the future, courts and adoption agencies may request a psychiatrist’s professional opinion on a specific adoption. See the Table for a list of suggested information to share when approached by an adoption agency or court.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Bacani-Oropilla T, Lippmann SB, Turns DM. Should the mentally ill adopt children? How physicians can influence the decision. Postgrad Med. 1988;84(6):201-205.

2. Linn L. Clinical manifestations of psychiatric disorder: the Homes-Rahe scale of stress of adjusting to change. In: Fredman A, Kaplan H, Sadock B, eds. Modern synopsis of comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, II. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1976:785.

1. Bacani-Oropilla T, Lippmann SB, Turns DM. Should the mentally ill adopt children? How physicians can influence the decision. Postgrad Med. 1988;84(6):201-205.

2. Linn L. Clinical manifestations of psychiatric disorder: the Homes-Rahe scale of stress of adjusting to change. In: Fredman A, Kaplan H, Sadock B, eds. Modern synopsis of comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, II. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1976:785.

Pros and cons of pill splitting

Clinicians and patients look to pill splitting to reduce psychotropics’ costs and fine-tune pharmacotherapy, but pill splitting has not been rigorously studied for safety or efficacy. It is important to understand the risks and benefits of pill splitting before you recommend the practice to patients.

Pros of pill splitting

Lower costs for patients. Many psychotropics come in multiple strengths, and one larger pill often costs less than 2 smaller pills of equivalent dosage.1 Writing a prescription for a higher dose and instructing the patient to cut the pill in half can lower costs.

Fine-tune titration. Pill splitting allows you to prescribe a lower strength to gradually titrate dosages up or taper them down. This practice can prevent side effects and improve adherence because a lower dose may have a more favorable pharmacokinetic profile.

Improve tolerability. Patients might better tolerate half a pill taken twice daily rather than an entire pill once daily. A smaller dose may prevent a spike in serum level, which could aid tolerability.

- Will there be a cost saving for the patient?

- Can the patient understand and follow your recommendations?

- Can the patient tolerate minor dosage variability that can occur with pill splitting?

- Is the medication’s integrity maintained when the pill is split?

If the answer is yes to all 4 questions, then pill splitting is an option.

Cons of pill splitting

Unequal dosing. In most instances, pill splitting leads to slightly unequal dosing.2 This could be a problem if:

- the medication such as lithium has a narrow therapeutic index

- the patient’s condition is unstable

- the patient’s condition is stable but minor dose variations might cause problems, such as a patient who relapses with small dosing changes.

Table

Appropriate and inappropriate medications for pill splitting

| OK to split | Do not split |

| Adderall tablets | Adderall XR capsules* |

| Effexor tablets† | Effexor-XR capsule* |

| Paxil or paroxetine tablets | Paxil CR |

| Prozac 10 mg tablet or fluoxetine tablets | Prozac 20 mg capsule |

| Risperdal tablet | Risperdal M-TAB |

| Tegretol | Tegretol XR |

| Wellbutrin and bupropion tablets | Wellbutrin XL |

| Zyprexa tablets | Zyprexa Zydis |

| Abilify tablets | Concerta capsules |

| Celexa or citalopram tablets | Cymbalta capsules |

| Lamictal tablets† | Depakote ER |

| Lexapro tablets | Equetro* |

| Luvox tablets | Eskalith CR, Lithobid tablets |

| Remeron or mirtazapine tablets | Geodon capsules |

| Seroquel tablets | Ritalin LA* |

| Zoloft tablets | Strattera capsules |

| * Capsule can be opened and contents sprinkled on food | |

| † Tablets may have uneven shapes, making even cuts difficult | |

Scoring. Cutting unscored tablets can be difficult, especially if the pills are not round or oval. Because patients can get injured using a knife, recommend pill cutters, which are available at most pharmacies.

Capsule splitting. Some psychotropics are sold only in capsules. Some capsules can be opened and sprinkled on food, but splitting the contents into approximately equal dosages can be difficult.

1. Cohen CI, Cohen SI. Potential cost savings from pill splitting of newer psychotropic medications. Psychiatr Serv 2000;51(4):527-9.

2. Teng J, Song CK, Williams RL, Polli J. Lack of medication dose uniformity in commonly split tablets. J Am Pharm Assoc 2002;42:195-9.

Dr. Rakesh Jain is director of psychopharmacology research, R/D Clinical Research, Inc., Lake Jackson, Texas.

Dr. Shailesh Jain is assistant professor, University of Texas Medical School at San Antonio.

Clinicians and patients look to pill splitting to reduce psychotropics’ costs and fine-tune pharmacotherapy, but pill splitting has not been rigorously studied for safety or efficacy. It is important to understand the risks and benefits of pill splitting before you recommend the practice to patients.

Pros of pill splitting

Lower costs for patients. Many psychotropics come in multiple strengths, and one larger pill often costs less than 2 smaller pills of equivalent dosage.1 Writing a prescription for a higher dose and instructing the patient to cut the pill in half can lower costs.

Fine-tune titration. Pill splitting allows you to prescribe a lower strength to gradually titrate dosages up or taper them down. This practice can prevent side effects and improve adherence because a lower dose may have a more favorable pharmacokinetic profile.

Improve tolerability. Patients might better tolerate half a pill taken twice daily rather than an entire pill once daily. A smaller dose may prevent a spike in serum level, which could aid tolerability.

- Will there be a cost saving for the patient?

- Can the patient understand and follow your recommendations?

- Can the patient tolerate minor dosage variability that can occur with pill splitting?

- Is the medication’s integrity maintained when the pill is split?

If the answer is yes to all 4 questions, then pill splitting is an option.

Cons of pill splitting

Unequal dosing. In most instances, pill splitting leads to slightly unequal dosing.2 This could be a problem if:

- the medication such as lithium has a narrow therapeutic index

- the patient’s condition is unstable

- the patient’s condition is stable but minor dose variations might cause problems, such as a patient who relapses with small dosing changes.

Table

Appropriate and inappropriate medications for pill splitting

| OK to split | Do not split |

| Adderall tablets | Adderall XR capsules* |

| Effexor tablets† | Effexor-XR capsule* |

| Paxil or paroxetine tablets | Paxil CR |

| Prozac 10 mg tablet or fluoxetine tablets | Prozac 20 mg capsule |

| Risperdal tablet | Risperdal M-TAB |

| Tegretol | Tegretol XR |

| Wellbutrin and bupropion tablets | Wellbutrin XL |

| Zyprexa tablets | Zyprexa Zydis |

| Abilify tablets | Concerta capsules |

| Celexa or citalopram tablets | Cymbalta capsules |

| Lamictal tablets† | Depakote ER |

| Lexapro tablets | Equetro* |

| Luvox tablets | Eskalith CR, Lithobid tablets |

| Remeron or mirtazapine tablets | Geodon capsules |

| Seroquel tablets | Ritalin LA* |

| Zoloft tablets | Strattera capsules |

| * Capsule can be opened and contents sprinkled on food | |

| † Tablets may have uneven shapes, making even cuts difficult | |

Scoring. Cutting unscored tablets can be difficult, especially if the pills are not round or oval. Because patients can get injured using a knife, recommend pill cutters, which are available at most pharmacies.

Capsule splitting. Some psychotropics are sold only in capsules. Some capsules can be opened and sprinkled on food, but splitting the contents into approximately equal dosages can be difficult.

Clinicians and patients look to pill splitting to reduce psychotropics’ costs and fine-tune pharmacotherapy, but pill splitting has not been rigorously studied for safety or efficacy. It is important to understand the risks and benefits of pill splitting before you recommend the practice to patients.

Pros of pill splitting

Lower costs for patients. Many psychotropics come in multiple strengths, and one larger pill often costs less than 2 smaller pills of equivalent dosage.1 Writing a prescription for a higher dose and instructing the patient to cut the pill in half can lower costs.

Fine-tune titration. Pill splitting allows you to prescribe a lower strength to gradually titrate dosages up or taper them down. This practice can prevent side effects and improve adherence because a lower dose may have a more favorable pharmacokinetic profile.

Improve tolerability. Patients might better tolerate half a pill taken twice daily rather than an entire pill once daily. A smaller dose may prevent a spike in serum level, which could aid tolerability.

- Will there be a cost saving for the patient?

- Can the patient understand and follow your recommendations?

- Can the patient tolerate minor dosage variability that can occur with pill splitting?

- Is the medication’s integrity maintained when the pill is split?

If the answer is yes to all 4 questions, then pill splitting is an option.

Cons of pill splitting

Unequal dosing. In most instances, pill splitting leads to slightly unequal dosing.2 This could be a problem if:

- the medication such as lithium has a narrow therapeutic index

- the patient’s condition is unstable

- the patient’s condition is stable but minor dose variations might cause problems, such as a patient who relapses with small dosing changes.

Table

Appropriate and inappropriate medications for pill splitting

| OK to split | Do not split |

| Adderall tablets | Adderall XR capsules* |

| Effexor tablets† | Effexor-XR capsule* |

| Paxil or paroxetine tablets | Paxil CR |

| Prozac 10 mg tablet or fluoxetine tablets | Prozac 20 mg capsule |

| Risperdal tablet | Risperdal M-TAB |

| Tegretol | Tegretol XR |

| Wellbutrin and bupropion tablets | Wellbutrin XL |

| Zyprexa tablets | Zyprexa Zydis |

| Abilify tablets | Concerta capsules |

| Celexa or citalopram tablets | Cymbalta capsules |

| Lamictal tablets† | Depakote ER |

| Lexapro tablets | Equetro* |

| Luvox tablets | Eskalith CR, Lithobid tablets |

| Remeron or mirtazapine tablets | Geodon capsules |

| Seroquel tablets | Ritalin LA* |

| Zoloft tablets | Strattera capsules |

| * Capsule can be opened and contents sprinkled on food | |

| † Tablets may have uneven shapes, making even cuts difficult | |

Scoring. Cutting unscored tablets can be difficult, especially if the pills are not round or oval. Because patients can get injured using a knife, recommend pill cutters, which are available at most pharmacies.

Capsule splitting. Some psychotropics are sold only in capsules. Some capsules can be opened and sprinkled on food, but splitting the contents into approximately equal dosages can be difficult.

1. Cohen CI, Cohen SI. Potential cost savings from pill splitting of newer psychotropic medications. Psychiatr Serv 2000;51(4):527-9.

2. Teng J, Song CK, Williams RL, Polli J. Lack of medication dose uniformity in commonly split tablets. J Am Pharm Assoc 2002;42:195-9.

Dr. Rakesh Jain is director of psychopharmacology research, R/D Clinical Research, Inc., Lake Jackson, Texas.

Dr. Shailesh Jain is assistant professor, University of Texas Medical School at San Antonio.

1. Cohen CI, Cohen SI. Potential cost savings from pill splitting of newer psychotropic medications. Psychiatr Serv 2000;51(4):527-9.

2. Teng J, Song CK, Williams RL, Polli J. Lack of medication dose uniformity in commonly split tablets. J Am Pharm Assoc 2002;42:195-9.

Dr. Rakesh Jain is director of psychopharmacology research, R/D Clinical Research, Inc., Lake Jackson, Texas.

Dr. Shailesh Jain is assistant professor, University of Texas Medical School at San Antonio.

Duloxetine: Dual-action antidepressant

Depression’s remission rates remain low,1 and its common somatic symptoms (aches and pains, headaches, backaches) often complicate diagnosis and treatment.2

Duloxetine, recently FDA-approved for treating major depression Table 1, has shown efficacy against depression’s emotional and somatic symptoms in clinical trials.

HOW IT WORKS

Duloxetine inhibits both serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake. Researchers suggest that antidepressants exhibiting this dual action may be more effective and act faster than single-action selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.3,4 Newer dual-action antidepressants also are more tolerable than dual-action tricyclic antidepressants.

Table 1

Duloxetine: Fast facts

| Drug brand name: Cymbalta |

| Class Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor |

| FDA-approved indication: Treatment of major depressive episodes |

| Approval date: August 3 2004 |

| Manufacturer: Eli Lilly and Co. |

| Dosing form: 20 mg, 30 mg, 60 mg capsules |

| Recommended dosage: 40 to 60 mg/d |

| Maximum dosage(studied in major depression): 120 mg/d |

Researchers have seen synergism between serotonergic and noradrenergic pain modulation at the spinal cord,4,5 suggesting that dual-action antidepressants may ameliorate major depression’s somatic symptoms.

Table 2

Plasma levels of these agents may affect—or be affected by— duloxetine coadministration

| CYP 2D6 substrates |

| Amitriptyline |

| Beta blockers Propranolol, metoprolol, timolol |

| Desipramine |

| Fluoxetine |

| Fluvoxamine |

| Haloperidol |

| Nortriptyline |

| Risperidone |

| Thioridazine |

| Type 1C antiarrhythmics Propafenone, flecainide |

| Venlafaxine |

| CYP 2D6 inhibitors |

| Cimetidine |

| Fluoxetine |

| Haloperidol |

| Paroxetine |

| Quinidine |

| CYP 1A2 inhibitors |

| Cimetidine |

| Ciprofloxacin |

| Enoxacin |

| Source: Reference 7 |

PHARMACOKINETICS

Despite its 12-hour plasma half-life, duloxetine has shown efficacy in clinical trials when given once daily. Mean plasma clearance is approximately 101 L/hr, with a mean volume of distribution of about 1640 L, meaning that duloxetine is distributed throughout the body.

The agent is more than 90% protein bound; thus, giving duloxetine concomitantly with another highly protein-bound agent could increase the side-effect risk of either drug.

Food does not alter duloxetine’s absorption but delays maximum concentration by about 4 hours Duloxetine may be taken before or after meals, though taking it after meals could reduce the risk of nausea—a common early side effect.

Duloxetine is metabolized by the 2D6 and 1A2 isoenzymes of the cytochrome P-450 system. It inhibits the CYP 2D6 isoenzyme but to a lesser extent than fluoxetine does.6 Co-administering duloxetine with a CYP 2D6 substrate or inhibitor or a CYP 1A2 inhibitor Table 27 could elevate plasma levels of duloxetine or the other agent, possibly increasing adverse effects.

EFFICACY

In an 8-week, placebo-controlled trial, Goldstein et al8 compared fluoxetine, 20 mg/d, and duloxetine, 40 mg/d titrated to 120 mg/d over 3 weeks, in 173 patients with major depressive disorder. Participants’ scores at baseline were 15 on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D-17) and 4 on the Clinical Global Improvement-Severity scale. Estimated probability of remission was 56% with duloxetine, 30% with fluoxetine, and 32% with placebo, with remission defined as achieving a HAM-D-17 score 7.

In two prospective, double-blind, placebocontrolled trials of 512 patients with major depression,9,10 duloxetine, 60 mg/d, reduced body, back, and shoulder pain based on Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores; pre- and posttreatment VAS scores were not listed in the published studies. Estimated probability of remission in these two studies was 44% and 43% among patients taking duloxetine vs 16% and 28% in the placebo groups. Remission again was defined as HAM-D-17 score 7.

TOLERABILITY

In the two double-blind studies just mentioned,9,10 Detke et al reported adverse event-related drop out rates of 12.5% and 13.8% for duloxetine, 60 mg/d, vs 4.3% and 2.3% for placebo. Nausea, insomnia, headaches, somnolence, dry mouth, and sweating were most frequently reported.

Dizziness. Mild dizziness was reported in 11.3% of patients who abruptly stopped duloxetine after 9 weeks.9

Headaches. In one comparator trial,8 fewer headaches (20%) were reported among patients taking duloxetine, 40 to 120 mg/d, vs those taking fluoxetine, 20 mg/d (33.3%), or placebo (31.4%).

Hypertension. Detke et al10 found no statistical separation in systolic and diastolic blood pressures between the duloxetine (60 mg/d) and placebo groups. Likewise, Goldstein et al8 found a similar incidence of hypertension among patients taking duloxetine, 40 to 120 mg/d, or placebo. In clinical trials,11 duloxetine increased blood pressure by a mean of 2.0 mm Hg (systolic) and 0.5 mm Hg (diastolic).

As with several other noradrenergic medications, FDA recommends that clinicians check blood pressures before starting duloxetine therapy and periodically thereafter.

Duloxetine has not been studied in persons with poorly controlled hypertension.

Nausea. Mild to moderate nausea was the most common adverse event in one study;9 the effect dissipated after a median of 7 days. One patient reported severe nausea, and 1 patient out of 123 stopped the medication because of nausea.

Sexual dysfunction. Using the Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale (ASEX), Goldstein et al8 prospectively assessed sexual function in 70 men and women taking duloxetine or placebo. No statistical difference was seen between the two groups from baseline to endpoint.

In another study,12 duloxetine showed worsening only in ASEX item 4 (“How easily can you reach an orgasm?”), indicating some adverse sexual effects in men. No such differences were found in women. Duloxetine’s effect on sexual function needs to be studied further.

Duloxetine is an FDA Use-in-Pregnancy category C medication, meaning that risk to the fetus has not been ruled out. The agent is contraindicated in patients taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors and in those with narrow-angle glaucoma. FDA recommends not using duloxetine in patients with hepatic insufficiency, endstage renal disease, and substantial alcohol use.

DOSING STRATEGIES

Duloxetine, 40 to 120 mg/d, appears to be safe and effective for most adults.8-10 FDA recommends starting at 40 mg/d (20 mg bid) to 60 mg/d (once-daily or 30 mg bid) with no regard to meals. Dosages >60 mg/d have not shown additional benefit. Age and tolerability should drive initial dosing and titration. Side-effect incidence has not been directly compared at 60, 90, and 120 mg/d.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

In clinical trials, duloxetine has shown a high estimated probability of remission in major depression and has shown efficacy against depression’s physical and emotional symptoms. Based on efficacy and safety data, duloxetine appears to be a first-line treatment option for major depression.

Related resources

- Gray GE. Concise guide to evidence-based psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004.

- Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB (eds). Textbook of psychopharmacology (3rd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004.

Drug brand names

- Amitriptyline • Elavil

- Cimetidine • Tagamet

- Ciprofloxacin • Cipro

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Enoxacin • Penetrex

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Flecainide • Tambocor

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Metoprolol • Toprol

- Nortriptyline • Pamelor

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Propafenone • Rythmol

- Propranolol • Inderal

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Thioridazine • Mellaril

- Timolol • Blocadren, others

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

Dr. Rakesh Jain receives research grants from Eli Lilly and Co., Forest Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck and Co., Organon, Pfizer Inc., and Sepracor. He is a consultant to and speaker for Eli Lilly and Co., and is a speaker for GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer Inc., and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Shailesh Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of compefting products.

1. Thase ME, Entsuah AR, Rudolph RL. Remission rates during treatment with venlafaxine or serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:234-41.

2. Fava M. The role of the serotonergic and noradrenergic neurotransmitter systems in the treatment of psychological and physical symptoms of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(suppl 13):26-9.

3. Tran PV, Bymaster FP, McNamara RK, Potter WZ. Dual monoamine modulation for improved treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;23:78-86.

4. Ansari A. The efficacy of newer antidepressants in the treatment of chronic pain: a review of current literature. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2000;7:257-77.

5. Willis WD, Westlund KN. Neuroanatomy of the pain system and the pathways that modulate pain. J Clin Neurophysiol 1997;14:2-31.

6. Skinner MH, Kuan HY, Pan A, et al. Duloxetine is both an inhibitor and a substrate of cytochrome P4502D6 in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2003;73:170-7.

7. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock's pocket handbook of psychotropic drug treatment (3rd ed). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2001.

8. Goldstein DJ, Mallinckrodt C, Lu Y, Demitrack M. Duloxetine in the treatment of major depression disorder: a double-blind clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:225-31.

9. Detke MJ, Lu Y, Goldstein DJ, et al. Duloxetine 60 mg once-daily for major depressive disorder: a randomized double-blind placebocontrolled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:308-15.

10. Detke MJ, Lu Y, Goldstein DJ, et al. Duloxetine 60 mg once daily dosing versus placebo in the treatment of major depression. J Psychiatr Res 2002;36:383-90.

11. Cymbalta prescribing information Eli Lilly and Co 2004.

12. Goldstein DJ, Lu Y, Detke MJ, et al. Duloxetine in the treatment of depression: a double-blind placebo-controlled comparison with paroxetine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004;24:389-99.

Depression’s remission rates remain low,1 and its common somatic symptoms (aches and pains, headaches, backaches) often complicate diagnosis and treatment.2

Duloxetine, recently FDA-approved for treating major depression Table 1, has shown efficacy against depression’s emotional and somatic symptoms in clinical trials.

HOW IT WORKS

Duloxetine inhibits both serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake. Researchers suggest that antidepressants exhibiting this dual action may be more effective and act faster than single-action selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.3,4 Newer dual-action antidepressants also are more tolerable than dual-action tricyclic antidepressants.

Table 1

Duloxetine: Fast facts

| Drug brand name: Cymbalta |

| Class Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor |

| FDA-approved indication: Treatment of major depressive episodes |

| Approval date: August 3 2004 |

| Manufacturer: Eli Lilly and Co. |

| Dosing form: 20 mg, 30 mg, 60 mg capsules |

| Recommended dosage: 40 to 60 mg/d |

| Maximum dosage(studied in major depression): 120 mg/d |

Researchers have seen synergism between serotonergic and noradrenergic pain modulation at the spinal cord,4,5 suggesting that dual-action antidepressants may ameliorate major depression’s somatic symptoms.

Table 2

Plasma levels of these agents may affect—or be affected by— duloxetine coadministration

| CYP 2D6 substrates |

| Amitriptyline |

| Beta blockers Propranolol, metoprolol, timolol |

| Desipramine |

| Fluoxetine |

| Fluvoxamine |

| Haloperidol |

| Nortriptyline |

| Risperidone |

| Thioridazine |

| Type 1C antiarrhythmics Propafenone, flecainide |

| Venlafaxine |

| CYP 2D6 inhibitors |

| Cimetidine |

| Fluoxetine |

| Haloperidol |

| Paroxetine |

| Quinidine |

| CYP 1A2 inhibitors |

| Cimetidine |

| Ciprofloxacin |

| Enoxacin |

| Source: Reference 7 |

PHARMACOKINETICS

Despite its 12-hour plasma half-life, duloxetine has shown efficacy in clinical trials when given once daily. Mean plasma clearance is approximately 101 L/hr, with a mean volume of distribution of about 1640 L, meaning that duloxetine is distributed throughout the body.

The agent is more than 90% protein bound; thus, giving duloxetine concomitantly with another highly protein-bound agent could increase the side-effect risk of either drug.

Food does not alter duloxetine’s absorption but delays maximum concentration by about 4 hours Duloxetine may be taken before or after meals, though taking it after meals could reduce the risk of nausea—a common early side effect.

Duloxetine is metabolized by the 2D6 and 1A2 isoenzymes of the cytochrome P-450 system. It inhibits the CYP 2D6 isoenzyme but to a lesser extent than fluoxetine does.6 Co-administering duloxetine with a CYP 2D6 substrate or inhibitor or a CYP 1A2 inhibitor Table 27 could elevate plasma levels of duloxetine or the other agent, possibly increasing adverse effects.

EFFICACY

In an 8-week, placebo-controlled trial, Goldstein et al8 compared fluoxetine, 20 mg/d, and duloxetine, 40 mg/d titrated to 120 mg/d over 3 weeks, in 173 patients with major depressive disorder. Participants’ scores at baseline were 15 on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D-17) and 4 on the Clinical Global Improvement-Severity scale. Estimated probability of remission was 56% with duloxetine, 30% with fluoxetine, and 32% with placebo, with remission defined as achieving a HAM-D-17 score 7.

In two prospective, double-blind, placebocontrolled trials of 512 patients with major depression,9,10 duloxetine, 60 mg/d, reduced body, back, and shoulder pain based on Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores; pre- and posttreatment VAS scores were not listed in the published studies. Estimated probability of remission in these two studies was 44% and 43% among patients taking duloxetine vs 16% and 28% in the placebo groups. Remission again was defined as HAM-D-17 score 7.

TOLERABILITY

In the two double-blind studies just mentioned,9,10 Detke et al reported adverse event-related drop out rates of 12.5% and 13.8% for duloxetine, 60 mg/d, vs 4.3% and 2.3% for placebo. Nausea, insomnia, headaches, somnolence, dry mouth, and sweating were most frequently reported.

Dizziness. Mild dizziness was reported in 11.3% of patients who abruptly stopped duloxetine after 9 weeks.9

Headaches. In one comparator trial,8 fewer headaches (20%) were reported among patients taking duloxetine, 40 to 120 mg/d, vs those taking fluoxetine, 20 mg/d (33.3%), or placebo (31.4%).

Hypertension. Detke et al10 found no statistical separation in systolic and diastolic blood pressures between the duloxetine (60 mg/d) and placebo groups. Likewise, Goldstein et al8 found a similar incidence of hypertension among patients taking duloxetine, 40 to 120 mg/d, or placebo. In clinical trials,11 duloxetine increased blood pressure by a mean of 2.0 mm Hg (systolic) and 0.5 mm Hg (diastolic).

As with several other noradrenergic medications, FDA recommends that clinicians check blood pressures before starting duloxetine therapy and periodically thereafter.

Duloxetine has not been studied in persons with poorly controlled hypertension.

Nausea. Mild to moderate nausea was the most common adverse event in one study;9 the effect dissipated after a median of 7 days. One patient reported severe nausea, and 1 patient out of 123 stopped the medication because of nausea.

Sexual dysfunction. Using the Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale (ASEX), Goldstein et al8 prospectively assessed sexual function in 70 men and women taking duloxetine or placebo. No statistical difference was seen between the two groups from baseline to endpoint.

In another study,12 duloxetine showed worsening only in ASEX item 4 (“How easily can you reach an orgasm?”), indicating some adverse sexual effects in men. No such differences were found in women. Duloxetine’s effect on sexual function needs to be studied further.

Duloxetine is an FDA Use-in-Pregnancy category C medication, meaning that risk to the fetus has not been ruled out. The agent is contraindicated in patients taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors and in those with narrow-angle glaucoma. FDA recommends not using duloxetine in patients with hepatic insufficiency, endstage renal disease, and substantial alcohol use.

DOSING STRATEGIES

Duloxetine, 40 to 120 mg/d, appears to be safe and effective for most adults.8-10 FDA recommends starting at 40 mg/d (20 mg bid) to 60 mg/d (once-daily or 30 mg bid) with no regard to meals. Dosages >60 mg/d have not shown additional benefit. Age and tolerability should drive initial dosing and titration. Side-effect incidence has not been directly compared at 60, 90, and 120 mg/d.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

In clinical trials, duloxetine has shown a high estimated probability of remission in major depression and has shown efficacy against depression’s physical and emotional symptoms. Based on efficacy and safety data, duloxetine appears to be a first-line treatment option for major depression.

Related resources

- Gray GE. Concise guide to evidence-based psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004.

- Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB (eds). Textbook of psychopharmacology (3rd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004.

Drug brand names

- Amitriptyline • Elavil

- Cimetidine • Tagamet

- Ciprofloxacin • Cipro

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Enoxacin • Penetrex

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Flecainide • Tambocor

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Metoprolol • Toprol

- Nortriptyline • Pamelor

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Propafenone • Rythmol

- Propranolol • Inderal

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Thioridazine • Mellaril

- Timolol • Blocadren, others

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

Dr. Rakesh Jain receives research grants from Eli Lilly and Co., Forest Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck and Co., Organon, Pfizer Inc., and Sepracor. He is a consultant to and speaker for Eli Lilly and Co., and is a speaker for GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer Inc., and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Shailesh Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of compefting products.

Depression’s remission rates remain low,1 and its common somatic symptoms (aches and pains, headaches, backaches) often complicate diagnosis and treatment.2