User login

Vismodegib-Induced Rash: A Case Report

An 88-year-old male with locally advanced basal-cell carcinoma (BCC) of the scalp who had received multiple resections, stem cell graft, and amniotic allograft continued to progress with severe ulcerations that extended into the dura. Patient was initiated on vismodegib 150 mg daily and subsequently developed a diffuse maculopapular rash within 14 days of treatment. The rash resolved with topical triamcinolone 0.1% and discontinuation of vismodegib. Loratadine 10 mg daily was concurrently administered for rash prophylaxis upon vismodegib re-initiation. Within 7 days of therapy, the rash returned, and subsequently vismodegib was discontinued and oral prednisone taper was initiated. Given limited effective treatment options, vismodegib was continued at a modified schedule of 150 mg daily for 2 weeks then 1 week off with prednisone 5 mg daily. To date, patient has completed 2 years of treatment with no return of rash or disease progression.

BCC occurs in 2 million patients annually in the US. Fortunately, most of these cases are responsive to local therapy with rare metastatic progression. The emergence of novel Hedgehog pathway inhibitors (vismodegib, sonidegib) provide effective options for advanced BCC. Although vismodegib has been reported to cause Grade 3-4 adverse events in 25% of patients, there are no reports of vismodegib-induced rash nor recommendations regarding management.

For many novel targeted therapies, the appropriate management of toxicities has not been well described. This case study presents a patient that continues to respond to therapy with a novel modified dosing scheme in addition to low-dose prednisone. We present this case report to offer a potential treatment option in patients who experience a vismodegib-induced rash.

An 88-year-old male with locally advanced basal-cell carcinoma (BCC) of the scalp who had received multiple resections, stem cell graft, and amniotic allograft continued to progress with severe ulcerations that extended into the dura. Patient was initiated on vismodegib 150 mg daily and subsequently developed a diffuse maculopapular rash within 14 days of treatment. The rash resolved with topical triamcinolone 0.1% and discontinuation of vismodegib. Loratadine 10 mg daily was concurrently administered for rash prophylaxis upon vismodegib re-initiation. Within 7 days of therapy, the rash returned, and subsequently vismodegib was discontinued and oral prednisone taper was initiated. Given limited effective treatment options, vismodegib was continued at a modified schedule of 150 mg daily for 2 weeks then 1 week off with prednisone 5 mg daily. To date, patient has completed 2 years of treatment with no return of rash or disease progression.

BCC occurs in 2 million patients annually in the US. Fortunately, most of these cases are responsive to local therapy with rare metastatic progression. The emergence of novel Hedgehog pathway inhibitors (vismodegib, sonidegib) provide effective options for advanced BCC. Although vismodegib has been reported to cause Grade 3-4 adverse events in 25% of patients, there are no reports of vismodegib-induced rash nor recommendations regarding management.

For many novel targeted therapies, the appropriate management of toxicities has not been well described. This case study presents a patient that continues to respond to therapy with a novel modified dosing scheme in addition to low-dose prednisone. We present this case report to offer a potential treatment option in patients who experience a vismodegib-induced rash.

An 88-year-old male with locally advanced basal-cell carcinoma (BCC) of the scalp who had received multiple resections, stem cell graft, and amniotic allograft continued to progress with severe ulcerations that extended into the dura. Patient was initiated on vismodegib 150 mg daily and subsequently developed a diffuse maculopapular rash within 14 days of treatment. The rash resolved with topical triamcinolone 0.1% and discontinuation of vismodegib. Loratadine 10 mg daily was concurrently administered for rash prophylaxis upon vismodegib re-initiation. Within 7 days of therapy, the rash returned, and subsequently vismodegib was discontinued and oral prednisone taper was initiated. Given limited effective treatment options, vismodegib was continued at a modified schedule of 150 mg daily for 2 weeks then 1 week off with prednisone 5 mg daily. To date, patient has completed 2 years of treatment with no return of rash or disease progression.

BCC occurs in 2 million patients annually in the US. Fortunately, most of these cases are responsive to local therapy with rare metastatic progression. The emergence of novel Hedgehog pathway inhibitors (vismodegib, sonidegib) provide effective options for advanced BCC. Although vismodegib has been reported to cause Grade 3-4 adverse events in 25% of patients, there are no reports of vismodegib-induced rash nor recommendations regarding management.

For many novel targeted therapies, the appropriate management of toxicities has not been well described. This case study presents a patient that continues to respond to therapy with a novel modified dosing scheme in addition to low-dose prednisone. We present this case report to offer a potential treatment option in patients who experience a vismodegib-induced rash.

Strollin’ the Colon: A Collaborated Effort to Provide Education and Screening Outreach for the Improvement of Awareness, Access, and Early Detection of Colorectal Cancer

Purpose: In 2015, the New Mexico VA Health Care System completion of colorectal cancer screening fell below the national VA average of 82%. The facility Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) mean aggregated data for Colorectal Cancer Screening was 74.14%. This presents an alarming truth: the failure to screen 25% of the Veteran population served.

The projects purpose stands to improve quality outcomes through the early detection and prevention of colorectal cancer by increasing provider and Veteran awareness.

Relevant Background/Problem: Colorectal cancer is the third leading cause of cancer deaths and remains preventable through appropriate and timely screening. In 2012, 134,784 people in the United States were diagnosed with colorectal cancer, of which 51,516 people died.

Barriers leading to low screening compliance include knowledge deficits, fear, access, and common myths and misconceptions. Providers and Veterans fail to understand the difference of recommended screening anddiagnostic guidelines; available prevention/ detection options/ personal risk factors; ultimately neglecting screening completion due to lack of symptoms.

Methods: We held an Outreach Colorectal Cancer Awareness Fair for the community. A 20-foot long inflatable colon, depicting various stages of abnormalities was brought in. Attendees completed screening questionnaires, focusing on risk factors/ history/ symptoms. These were reviewed on site with providers, and appropriate care was ordered: colonoscopy or FIT testing. Various educational booths served to provide education using evidence-based data. Follow-up letters and calls after the event served to increase Veteran compliance. The local news station showcased the VAMC in a positive light.

Results: We had 355 attendees. 104 Veterans completed screening. 71% of Veterans were identified as needing further diagnostic testing based on provider assessment. 6 Veterans were given FIT packets on that day; an additional 17 were later identified based on review of forms (total 22%). Initial return rate of FIT cards was 83%, exceeding facility norm, and 51 Veterans were scheduled for colonoscopy (49%).

Implications: The overall outcome from this event has been to greatly improve attitudes from the level of the patient and employee volunteers to the community and upper management: improving the overall awareness to screening and diagnostic modalities for colorectal cancer.

Purpose: In 2015, the New Mexico VA Health Care System completion of colorectal cancer screening fell below the national VA average of 82%. The facility Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) mean aggregated data for Colorectal Cancer Screening was 74.14%. This presents an alarming truth: the failure to screen 25% of the Veteran population served.

The projects purpose stands to improve quality outcomes through the early detection and prevention of colorectal cancer by increasing provider and Veteran awareness.

Relevant Background/Problem: Colorectal cancer is the third leading cause of cancer deaths and remains preventable through appropriate and timely screening. In 2012, 134,784 people in the United States were diagnosed with colorectal cancer, of which 51,516 people died.

Barriers leading to low screening compliance include knowledge deficits, fear, access, and common myths and misconceptions. Providers and Veterans fail to understand the difference of recommended screening anddiagnostic guidelines; available prevention/ detection options/ personal risk factors; ultimately neglecting screening completion due to lack of symptoms.

Methods: We held an Outreach Colorectal Cancer Awareness Fair for the community. A 20-foot long inflatable colon, depicting various stages of abnormalities was brought in. Attendees completed screening questionnaires, focusing on risk factors/ history/ symptoms. These were reviewed on site with providers, and appropriate care was ordered: colonoscopy or FIT testing. Various educational booths served to provide education using evidence-based data. Follow-up letters and calls after the event served to increase Veteran compliance. The local news station showcased the VAMC in a positive light.

Results: We had 355 attendees. 104 Veterans completed screening. 71% of Veterans were identified as needing further diagnostic testing based on provider assessment. 6 Veterans were given FIT packets on that day; an additional 17 were later identified based on review of forms (total 22%). Initial return rate of FIT cards was 83%, exceeding facility norm, and 51 Veterans were scheduled for colonoscopy (49%).

Implications: The overall outcome from this event has been to greatly improve attitudes from the level of the patient and employee volunteers to the community and upper management: improving the overall awareness to screening and diagnostic modalities for colorectal cancer.

Purpose: In 2015, the New Mexico VA Health Care System completion of colorectal cancer screening fell below the national VA average of 82%. The facility Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) mean aggregated data for Colorectal Cancer Screening was 74.14%. This presents an alarming truth: the failure to screen 25% of the Veteran population served.

The projects purpose stands to improve quality outcomes through the early detection and prevention of colorectal cancer by increasing provider and Veteran awareness.

Relevant Background/Problem: Colorectal cancer is the third leading cause of cancer deaths and remains preventable through appropriate and timely screening. In 2012, 134,784 people in the United States were diagnosed with colorectal cancer, of which 51,516 people died.

Barriers leading to low screening compliance include knowledge deficits, fear, access, and common myths and misconceptions. Providers and Veterans fail to understand the difference of recommended screening anddiagnostic guidelines; available prevention/ detection options/ personal risk factors; ultimately neglecting screening completion due to lack of symptoms.

Methods: We held an Outreach Colorectal Cancer Awareness Fair for the community. A 20-foot long inflatable colon, depicting various stages of abnormalities was brought in. Attendees completed screening questionnaires, focusing on risk factors/ history/ symptoms. These were reviewed on site with providers, and appropriate care was ordered: colonoscopy or FIT testing. Various educational booths served to provide education using evidence-based data. Follow-up letters and calls after the event served to increase Veteran compliance. The local news station showcased the VAMC in a positive light.

Results: We had 355 attendees. 104 Veterans completed screening. 71% of Veterans were identified as needing further diagnostic testing based on provider assessment. 6 Veterans were given FIT packets on that day; an additional 17 were later identified based on review of forms (total 22%). Initial return rate of FIT cards was 83%, exceeding facility norm, and 51 Veterans were scheduled for colonoscopy (49%).

Implications: The overall outcome from this event has been to greatly improve attitudes from the level of the patient and employee volunteers to the community and upper management: improving the overall awareness to screening and diagnostic modalities for colorectal cancer.

Improving Skin Irritation and Dermatitis Induced by Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters in Outpatient Chemotherapy Clinic Patients

Background: Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (PICC) is an intravenous line placed into the patient’s upper arm to safely administer chemotherapy. For years, many patients receiving chemotherapy through a PICC line in the Outpatient Chemotherapy Clinic developed skin irritation and dermatitis at the insertion site. Interventions included, but were not limited to, corticosteroid spray, anti-histamine, occlusive dressing change, and covering the PICC site with gauze. Sometimes, replacement was needed for severe irritation or infection. These complications can lead to chronic discomfort, hospitalization, and delayed treatment.

Purpose: The purpose of this project was to reduce the incidence of PICC line skin irritation and dermatitis in patients receiving outpatient chemotherapy.

Methods: Nursing procedure required the PICC line dressing to be changed weekly. The site was cleansed with chlorhexidine, dried, and a chlorhexidine-soaked sponge was applied at the catheter exit site. The catheter was then secured with a catheter stabilization device and covered with a transparent occlusive dressing. The revised method added Cavilon No-Sting Barrier Film. The film was applied except to the area around the catheter exit site after the chlorhexidine was dried to create a barrier between the skin and the occlusive dressing. Skin condition was measured using the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group Scoring Scale.

Results: Results were evaluated through retrospective chart review. During the 3-months pre-implementation, 33 PICC lines were placed, 5 were replaced, and 32% had documented skin irritation. During the 3-months post-implementation, 28 PICC lines were placed, 3 were replaced, and 4% had documented skin irritation.

Conclusion: The results demonstrate a significant reduction of skin irritation incidence and support the use of Cavilon No-Sting Barrier Film as part of the PICC line dressing change. Evaluation in different settings with different PICC line populations is needed to fully evaluate efficacy.

Background: Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (PICC) is an intravenous line placed into the patient’s upper arm to safely administer chemotherapy. For years, many patients receiving chemotherapy through a PICC line in the Outpatient Chemotherapy Clinic developed skin irritation and dermatitis at the insertion site. Interventions included, but were not limited to, corticosteroid spray, anti-histamine, occlusive dressing change, and covering the PICC site with gauze. Sometimes, replacement was needed for severe irritation or infection. These complications can lead to chronic discomfort, hospitalization, and delayed treatment.

Purpose: The purpose of this project was to reduce the incidence of PICC line skin irritation and dermatitis in patients receiving outpatient chemotherapy.

Methods: Nursing procedure required the PICC line dressing to be changed weekly. The site was cleansed with chlorhexidine, dried, and a chlorhexidine-soaked sponge was applied at the catheter exit site. The catheter was then secured with a catheter stabilization device and covered with a transparent occlusive dressing. The revised method added Cavilon No-Sting Barrier Film. The film was applied except to the area around the catheter exit site after the chlorhexidine was dried to create a barrier between the skin and the occlusive dressing. Skin condition was measured using the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group Scoring Scale.

Results: Results were evaluated through retrospective chart review. During the 3-months pre-implementation, 33 PICC lines were placed, 5 were replaced, and 32% had documented skin irritation. During the 3-months post-implementation, 28 PICC lines were placed, 3 were replaced, and 4% had documented skin irritation.

Conclusion: The results demonstrate a significant reduction of skin irritation incidence and support the use of Cavilon No-Sting Barrier Film as part of the PICC line dressing change. Evaluation in different settings with different PICC line populations is needed to fully evaluate efficacy.

Background: Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (PICC) is an intravenous line placed into the patient’s upper arm to safely administer chemotherapy. For years, many patients receiving chemotherapy through a PICC line in the Outpatient Chemotherapy Clinic developed skin irritation and dermatitis at the insertion site. Interventions included, but were not limited to, corticosteroid spray, anti-histamine, occlusive dressing change, and covering the PICC site with gauze. Sometimes, replacement was needed for severe irritation or infection. These complications can lead to chronic discomfort, hospitalization, and delayed treatment.

Purpose: The purpose of this project was to reduce the incidence of PICC line skin irritation and dermatitis in patients receiving outpatient chemotherapy.

Methods: Nursing procedure required the PICC line dressing to be changed weekly. The site was cleansed with chlorhexidine, dried, and a chlorhexidine-soaked sponge was applied at the catheter exit site. The catheter was then secured with a catheter stabilization device and covered with a transparent occlusive dressing. The revised method added Cavilon No-Sting Barrier Film. The film was applied except to the area around the catheter exit site after the chlorhexidine was dried to create a barrier between the skin and the occlusive dressing. Skin condition was measured using the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group Scoring Scale.

Results: Results were evaluated through retrospective chart review. During the 3-months pre-implementation, 33 PICC lines were placed, 5 were replaced, and 32% had documented skin irritation. During the 3-months post-implementation, 28 PICC lines were placed, 3 were replaced, and 4% had documented skin irritation.

Conclusion: The results demonstrate a significant reduction of skin irritation incidence and support the use of Cavilon No-Sting Barrier Film as part of the PICC line dressing change. Evaluation in different settings with different PICC line populations is needed to fully evaluate efficacy.

Incidence of Venous Thromboembolism in Surgical Oncology Patients

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to assess the incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in high-risk surgical oncology patients at a Veterans Affairs institution.

Background: Oncology patients undergoing abdominal or pelvic surgeries are at high-risk of developing postoperativeVTE. Current guidelines published by the American Societyof Clinical Oncology (ASCO), National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), and American College of Chest Physicians(ACCP) recommend at least 4 weeks of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis postoperatively in high-risk oncology patients.

Methods: Electronic medical records were utilized to identify oncology patients aged 18 to 89 years undergoing general or urologic surgeries from June 1, 2013 to June 30, 2015. The primary objective was the incidence of VTE up to 30 days postoperatively in patients receiving optimal (OT) (4 weeks of anticoagulation if no contraindications) versus suboptimal (ST) thromboprophylaxis. Secondary objectives included incidence of early (days 0 to 7) and late (days 8 to 30) postoperative VTE, severity of VTE, and hematologic toxicities associated with VTE prophylaxis.

Data Analysis: Logistics regression with an alpha of 0.05 was utilized to analyze the primary outcome. Other outcomes were reported as descriptive statistics.

Results: A total of 167 patients were assessed (136 patients in the ST group and 31 patients in the OT group). There were 4 (2.9%) and 1 (3.2%) VTEs in the ST and OT groups, respectively (OR = 0.10; 95% CI, -2.13 to 2.32; P > 0.05). All VTEs occurred during the late postoperative period. In the ST group, 3 patients had an uncomplicated pulmonary embolism (PE) or deep venous thromboembolism, and 1 patient died due to thromboembolic complications. In the OT group, 1 patient had an uncomplicated PE. There were no significant differences in postoperative bleeding (11.4% versus 14.4%) or thrombocytopenia (45.7% versus 47.4%) in patients receiving pharmacologic versus non-pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis.

Implications: Provision of optimal thromboprophylaxis was low for high-risk surgical oncology patients; however, this was not associated with an increase in VTEs. Use of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis did not increase rates of bleeding or thrombocytopenia. Education is needed to increase compliance with guideline recommendations for postoperative thromboprophylaxis in high-risk surgical oncology patients at our institution.

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to assess the incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in high-risk surgical oncology patients at a Veterans Affairs institution.

Background: Oncology patients undergoing abdominal or pelvic surgeries are at high-risk of developing postoperativeVTE. Current guidelines published by the American Societyof Clinical Oncology (ASCO), National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), and American College of Chest Physicians(ACCP) recommend at least 4 weeks of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis postoperatively in high-risk oncology patients.

Methods: Electronic medical records were utilized to identify oncology patients aged 18 to 89 years undergoing general or urologic surgeries from June 1, 2013 to June 30, 2015. The primary objective was the incidence of VTE up to 30 days postoperatively in patients receiving optimal (OT) (4 weeks of anticoagulation if no contraindications) versus suboptimal (ST) thromboprophylaxis. Secondary objectives included incidence of early (days 0 to 7) and late (days 8 to 30) postoperative VTE, severity of VTE, and hematologic toxicities associated with VTE prophylaxis.

Data Analysis: Logistics regression with an alpha of 0.05 was utilized to analyze the primary outcome. Other outcomes were reported as descriptive statistics.

Results: A total of 167 patients were assessed (136 patients in the ST group and 31 patients in the OT group). There were 4 (2.9%) and 1 (3.2%) VTEs in the ST and OT groups, respectively (OR = 0.10; 95% CI, -2.13 to 2.32; P > 0.05). All VTEs occurred during the late postoperative period. In the ST group, 3 patients had an uncomplicated pulmonary embolism (PE) or deep venous thromboembolism, and 1 patient died due to thromboembolic complications. In the OT group, 1 patient had an uncomplicated PE. There were no significant differences in postoperative bleeding (11.4% versus 14.4%) or thrombocytopenia (45.7% versus 47.4%) in patients receiving pharmacologic versus non-pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis.

Implications: Provision of optimal thromboprophylaxis was low for high-risk surgical oncology patients; however, this was not associated with an increase in VTEs. Use of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis did not increase rates of bleeding or thrombocytopenia. Education is needed to increase compliance with guideline recommendations for postoperative thromboprophylaxis in high-risk surgical oncology patients at our institution.

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to assess the incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in high-risk surgical oncology patients at a Veterans Affairs institution.

Background: Oncology patients undergoing abdominal or pelvic surgeries are at high-risk of developing postoperativeVTE. Current guidelines published by the American Societyof Clinical Oncology (ASCO), National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), and American College of Chest Physicians(ACCP) recommend at least 4 weeks of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis postoperatively in high-risk oncology patients.

Methods: Electronic medical records were utilized to identify oncology patients aged 18 to 89 years undergoing general or urologic surgeries from June 1, 2013 to June 30, 2015. The primary objective was the incidence of VTE up to 30 days postoperatively in patients receiving optimal (OT) (4 weeks of anticoagulation if no contraindications) versus suboptimal (ST) thromboprophylaxis. Secondary objectives included incidence of early (days 0 to 7) and late (days 8 to 30) postoperative VTE, severity of VTE, and hematologic toxicities associated with VTE prophylaxis.

Data Analysis: Logistics regression with an alpha of 0.05 was utilized to analyze the primary outcome. Other outcomes were reported as descriptive statistics.

Results: A total of 167 patients were assessed (136 patients in the ST group and 31 patients in the OT group). There were 4 (2.9%) and 1 (3.2%) VTEs in the ST and OT groups, respectively (OR = 0.10; 95% CI, -2.13 to 2.32; P > 0.05). All VTEs occurred during the late postoperative period. In the ST group, 3 patients had an uncomplicated pulmonary embolism (PE) or deep venous thromboembolism, and 1 patient died due to thromboembolic complications. In the OT group, 1 patient had an uncomplicated PE. There were no significant differences in postoperative bleeding (11.4% versus 14.4%) or thrombocytopenia (45.7% versus 47.4%) in patients receiving pharmacologic versus non-pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis.

Implications: Provision of optimal thromboprophylaxis was low for high-risk surgical oncology patients; however, this was not associated with an increase in VTEs. Use of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis did not increase rates of bleeding or thrombocytopenia. Education is needed to increase compliance with guideline recommendations for postoperative thromboprophylaxis in high-risk surgical oncology patients at our institution.

PAP Test/HPV Co-test: Quality Improvement Initiative to Identify Approaches for Integrative Clinical Care Management

Purpose: Decrease turn-around time (TAT) and increase customer satisfaction.

Relevant Background: Cytologic screening (PAP test) lowered mortality of cervical carcinoma. As high-risk papilloma viruses (HPV) were associated with dysplasia and carcinoma, “co-testing” (HPV status and cytological screening on same specimen)was introduced. Women with negative Pap smear and positive high-risk HPV are at elevated risk.

Previous Status: Pap smears were signed-out; HPV Cotests were sent to reference laboratory; results were informed in supplementary report. This caused slow TAT for HPV Co-test (24% > 12 days) and distress when negative Pap smear was followed by a positive HPV Co-test.

Methods: A team of relevant individuals was convened to decrease TAT for HPV Co-test to 6 days, and to create an integrated Pap-smear/HPV Co-test report. The decision was made to bring HPV testing in-house, utilizing polymerase chain reaction-based assay. The technique was validated; precision, accuracy and lower levels of detection were determined. Standard Operating Procedures were written, and personnel competency was verified. Proficiency tests were performed. Staff met to coordinate logistics of sample transfer.

Data Analysis: In-house HPV testing twice weekly decreased TAT from 10.1 to 5.6 days. Integrated report: HPV test is performed when ordered by clinician or “reflex” if Pap smear is atypical; in both instances, final report is withheld until Co-test result is available. HPV is run inhouse in batches twice a week (5-hour test TAT). When HPV result is available, cytology technician enters Pap smear interpretation and HPV Co-test in a single, integrated report into VistA, it is released by the pathologist or cytotechnologist (day 3-5) and “view-alert” is issued for provider in CPRS. Integrated report consists of a section with cytology findings, and section with HPV status including subtype and risk information.

Results: Average TAT for release of integrated report decreased from 10.1 to 2.7 days. The laboratory achieved a 35% reduction in expenditure costs. Clinicians’ response was uniformly positive.

Implications: It is important to know how VA Medical Centers address PAP-HPV Co-test, and how the system can be modified; particularly, as our female Veteran population increases.

Purpose: Decrease turn-around time (TAT) and increase customer satisfaction.

Relevant Background: Cytologic screening (PAP test) lowered mortality of cervical carcinoma. As high-risk papilloma viruses (HPV) were associated with dysplasia and carcinoma, “co-testing” (HPV status and cytological screening on same specimen)was introduced. Women with negative Pap smear and positive high-risk HPV are at elevated risk.

Previous Status: Pap smears were signed-out; HPV Cotests were sent to reference laboratory; results were informed in supplementary report. This caused slow TAT for HPV Co-test (24% > 12 days) and distress when negative Pap smear was followed by a positive HPV Co-test.

Methods: A team of relevant individuals was convened to decrease TAT for HPV Co-test to 6 days, and to create an integrated Pap-smear/HPV Co-test report. The decision was made to bring HPV testing in-house, utilizing polymerase chain reaction-based assay. The technique was validated; precision, accuracy and lower levels of detection were determined. Standard Operating Procedures were written, and personnel competency was verified. Proficiency tests were performed. Staff met to coordinate logistics of sample transfer.

Data Analysis: In-house HPV testing twice weekly decreased TAT from 10.1 to 5.6 days. Integrated report: HPV test is performed when ordered by clinician or “reflex” if Pap smear is atypical; in both instances, final report is withheld until Co-test result is available. HPV is run inhouse in batches twice a week (5-hour test TAT). When HPV result is available, cytology technician enters Pap smear interpretation and HPV Co-test in a single, integrated report into VistA, it is released by the pathologist or cytotechnologist (day 3-5) and “view-alert” is issued for provider in CPRS. Integrated report consists of a section with cytology findings, and section with HPV status including subtype and risk information.

Results: Average TAT for release of integrated report decreased from 10.1 to 2.7 days. The laboratory achieved a 35% reduction in expenditure costs. Clinicians’ response was uniformly positive.

Implications: It is important to know how VA Medical Centers address PAP-HPV Co-test, and how the system can be modified; particularly, as our female Veteran population increases.

Purpose: Decrease turn-around time (TAT) and increase customer satisfaction.

Relevant Background: Cytologic screening (PAP test) lowered mortality of cervical carcinoma. As high-risk papilloma viruses (HPV) were associated with dysplasia and carcinoma, “co-testing” (HPV status and cytological screening on same specimen)was introduced. Women with negative Pap smear and positive high-risk HPV are at elevated risk.

Previous Status: Pap smears were signed-out; HPV Cotests were sent to reference laboratory; results were informed in supplementary report. This caused slow TAT for HPV Co-test (24% > 12 days) and distress when negative Pap smear was followed by a positive HPV Co-test.

Methods: A team of relevant individuals was convened to decrease TAT for HPV Co-test to 6 days, and to create an integrated Pap-smear/HPV Co-test report. The decision was made to bring HPV testing in-house, utilizing polymerase chain reaction-based assay. The technique was validated; precision, accuracy and lower levels of detection were determined. Standard Operating Procedures were written, and personnel competency was verified. Proficiency tests were performed. Staff met to coordinate logistics of sample transfer.

Data Analysis: In-house HPV testing twice weekly decreased TAT from 10.1 to 5.6 days. Integrated report: HPV test is performed when ordered by clinician or “reflex” if Pap smear is atypical; in both instances, final report is withheld until Co-test result is available. HPV is run inhouse in batches twice a week (5-hour test TAT). When HPV result is available, cytology technician enters Pap smear interpretation and HPV Co-test in a single, integrated report into VistA, it is released by the pathologist or cytotechnologist (day 3-5) and “view-alert” is issued for provider in CPRS. Integrated report consists of a section with cytology findings, and section with HPV status including subtype and risk information.

Results: Average TAT for release of integrated report decreased from 10.1 to 2.7 days. The laboratory achieved a 35% reduction in expenditure costs. Clinicians’ response was uniformly positive.

Implications: It is important to know how VA Medical Centers address PAP-HPV Co-test, and how the system can be modified; particularly, as our female Veteran population increases.

Gene therapy shows promise for severe hemophilia A

Image by Spencer Phillips

ORLANDO—An investigational gene therapy can safely reduce bleeding in patients with severe hemophilia A, a phase 1/2 study suggests.

The therapy is BMN 270, a recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector coding for human coagulation factor VIII (FVIII).

Six of the 7 patients treated with the highest dose of BMN 270 had FVIII levels above 50%, and the number of bleeding events fell substantially from baseline.

None of the patients developed inhibitors to FVIII, there were no serious adverse events, and none of the patients discontinued the therapy due to safety reasons.

John Pasi, PhD, of Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry in London, UK, presented the results of this study in a late-breaking oral presentation at the World Federation of Hemophilia 2016 World Congress.* The research was funded by BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc.

This phase 1/2 dose-escalation study was designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of BMN 270 in up to 12 patients with severe hemophilia A.

The primary endpoints are to assess the safety of a single dose of BMN 270 and the change from baseline of FVIII expression level at 16 weeks after infusion.

Secondary endpoints include assessing the impact of BMN 270 on the frequency of FVIII replacement therapy, the number of bleeding episodes requiring treatment, and any potential immune responses. Patients will be monitored for safety and durability of effect for 5 years.

Thus far, 9 patients with severe hemophilia A have received a single dose of BMN 270—1 at 6×1012 vg/kg, 1 at 2×1013 vg/kg, and 7 at 6 x 1013 vg/kg.

As of the July 6 data cutoff, post-treatment follow-up ranges from 12 weeks to 28 weeks.

Safety

The most common adverse events were arthralgia (9 events in 6 subjects), contusion (6 events in 3 subjects), back pain (4 events in 3 subjects), and ALT elevation (6 events in 6 subjects).

No clinically relevant sustained rises in ALT levels or other markers of liver toxicity have been observed.

The maximum ALT levels were between 23 U/L and 82 U/L (less than 2 times the upper limit of normal, which is 43 U/L for the central laboratory in this study) approximately 12 weeks after gene delivery and generally declined over the next few weeks. ALT rises have not been associated with any decrease in FVIII levels.

A steroid regimen administered to all high-dose patients has been well-tolerated. Patients are successfully tapering off of steroids. Two patients have been off steroid therapy for up to 2.5 weeks, with no adverse impact on FVIII expression or ALT levels.

Efficacy

The patient treated at the lowest dose (6×1012 vg/kg) had no change from baseline in FVIII levels. The patient treated at the mid-dose (2×1013 vg/kg) had a stable FVIII activity level greater than 2 IU/dL for more than 28 weeks.

All 7 patients treated at the highest dose (6×1013 vg/kg) had FVIII activity levels greater than 10 IU/dL after week 10.

As of each patient’s most recent reading, 6 of the 7 patients in the high-dose group had FVIII levels above 50%, as a percentage calculated based on the numbers of IU/dL. The seventh patient had levels above 10%.

Four patients who have been followed the longest had a mean FVIII level of 146% at their 20-week visit. Two patients with FVIII levels above 200% had no unexpected events or need for medical intervention.

For the 7 patients treated at the high dose, the median annualized bleeding rate measured from the day of gene transfer to the data cutoff fell from 20 to 5.

After week 7 post-infusion, there were no bleeds in 6 of the 7 patients. There were 10 bleeds from weeks 0 through 2 post-infusion, 7 bleeds from weeks 3 through 8, and 2 bleeds from weeks 9 through 28. From weeks 2 through 28, all but 1 bleed occurred in a single subject who is the lowest responder.

All of the patients in the high-dose cohort have switched to receiving FVIII therapy on-demand. Six of them were previously receiving FVIII therapy as prophylaxis.

“These data provide strong proof-of-concept evidence that restoration of clotting function may be achieved by gene therapy,” Dr Pasi said. “For the first time, patients have reason to hope to avoid bleeding and the opportunity to live a normal life.” ![]()

Image by Spencer Phillips

ORLANDO—An investigational gene therapy can safely reduce bleeding in patients with severe hemophilia A, a phase 1/2 study suggests.

The therapy is BMN 270, a recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector coding for human coagulation factor VIII (FVIII).

Six of the 7 patients treated with the highest dose of BMN 270 had FVIII levels above 50%, and the number of bleeding events fell substantially from baseline.

None of the patients developed inhibitors to FVIII, there were no serious adverse events, and none of the patients discontinued the therapy due to safety reasons.

John Pasi, PhD, of Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry in London, UK, presented the results of this study in a late-breaking oral presentation at the World Federation of Hemophilia 2016 World Congress.* The research was funded by BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc.

This phase 1/2 dose-escalation study was designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of BMN 270 in up to 12 patients with severe hemophilia A.

The primary endpoints are to assess the safety of a single dose of BMN 270 and the change from baseline of FVIII expression level at 16 weeks after infusion.

Secondary endpoints include assessing the impact of BMN 270 on the frequency of FVIII replacement therapy, the number of bleeding episodes requiring treatment, and any potential immune responses. Patients will be monitored for safety and durability of effect for 5 years.

Thus far, 9 patients with severe hemophilia A have received a single dose of BMN 270—1 at 6×1012 vg/kg, 1 at 2×1013 vg/kg, and 7 at 6 x 1013 vg/kg.

As of the July 6 data cutoff, post-treatment follow-up ranges from 12 weeks to 28 weeks.

Safety

The most common adverse events were arthralgia (9 events in 6 subjects), contusion (6 events in 3 subjects), back pain (4 events in 3 subjects), and ALT elevation (6 events in 6 subjects).

No clinically relevant sustained rises in ALT levels or other markers of liver toxicity have been observed.

The maximum ALT levels were between 23 U/L and 82 U/L (less than 2 times the upper limit of normal, which is 43 U/L for the central laboratory in this study) approximately 12 weeks after gene delivery and generally declined over the next few weeks. ALT rises have not been associated with any decrease in FVIII levels.

A steroid regimen administered to all high-dose patients has been well-tolerated. Patients are successfully tapering off of steroids. Two patients have been off steroid therapy for up to 2.5 weeks, with no adverse impact on FVIII expression or ALT levels.

Efficacy

The patient treated at the lowest dose (6×1012 vg/kg) had no change from baseline in FVIII levels. The patient treated at the mid-dose (2×1013 vg/kg) had a stable FVIII activity level greater than 2 IU/dL for more than 28 weeks.

All 7 patients treated at the highest dose (6×1013 vg/kg) had FVIII activity levels greater than 10 IU/dL after week 10.

As of each patient’s most recent reading, 6 of the 7 patients in the high-dose group had FVIII levels above 50%, as a percentage calculated based on the numbers of IU/dL. The seventh patient had levels above 10%.

Four patients who have been followed the longest had a mean FVIII level of 146% at their 20-week visit. Two patients with FVIII levels above 200% had no unexpected events or need for medical intervention.

For the 7 patients treated at the high dose, the median annualized bleeding rate measured from the day of gene transfer to the data cutoff fell from 20 to 5.

After week 7 post-infusion, there were no bleeds in 6 of the 7 patients. There were 10 bleeds from weeks 0 through 2 post-infusion, 7 bleeds from weeks 3 through 8, and 2 bleeds from weeks 9 through 28. From weeks 2 through 28, all but 1 bleed occurred in a single subject who is the lowest responder.

All of the patients in the high-dose cohort have switched to receiving FVIII therapy on-demand. Six of them were previously receiving FVIII therapy as prophylaxis.

“These data provide strong proof-of-concept evidence that restoration of clotting function may be achieved by gene therapy,” Dr Pasi said. “For the first time, patients have reason to hope to avoid bleeding and the opportunity to live a normal life.” ![]()

Image by Spencer Phillips

ORLANDO—An investigational gene therapy can safely reduce bleeding in patients with severe hemophilia A, a phase 1/2 study suggests.

The therapy is BMN 270, a recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector coding for human coagulation factor VIII (FVIII).

Six of the 7 patients treated with the highest dose of BMN 270 had FVIII levels above 50%, and the number of bleeding events fell substantially from baseline.

None of the patients developed inhibitors to FVIII, there were no serious adverse events, and none of the patients discontinued the therapy due to safety reasons.

John Pasi, PhD, of Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry in London, UK, presented the results of this study in a late-breaking oral presentation at the World Federation of Hemophilia 2016 World Congress.* The research was funded by BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc.

This phase 1/2 dose-escalation study was designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of BMN 270 in up to 12 patients with severe hemophilia A.

The primary endpoints are to assess the safety of a single dose of BMN 270 and the change from baseline of FVIII expression level at 16 weeks after infusion.

Secondary endpoints include assessing the impact of BMN 270 on the frequency of FVIII replacement therapy, the number of bleeding episodes requiring treatment, and any potential immune responses. Patients will be monitored for safety and durability of effect for 5 years.

Thus far, 9 patients with severe hemophilia A have received a single dose of BMN 270—1 at 6×1012 vg/kg, 1 at 2×1013 vg/kg, and 7 at 6 x 1013 vg/kg.

As of the July 6 data cutoff, post-treatment follow-up ranges from 12 weeks to 28 weeks.

Safety

The most common adverse events were arthralgia (9 events in 6 subjects), contusion (6 events in 3 subjects), back pain (4 events in 3 subjects), and ALT elevation (6 events in 6 subjects).

No clinically relevant sustained rises in ALT levels or other markers of liver toxicity have been observed.

The maximum ALT levels were between 23 U/L and 82 U/L (less than 2 times the upper limit of normal, which is 43 U/L for the central laboratory in this study) approximately 12 weeks after gene delivery and generally declined over the next few weeks. ALT rises have not been associated with any decrease in FVIII levels.

A steroid regimen administered to all high-dose patients has been well-tolerated. Patients are successfully tapering off of steroids. Two patients have been off steroid therapy for up to 2.5 weeks, with no adverse impact on FVIII expression or ALT levels.

Efficacy

The patient treated at the lowest dose (6×1012 vg/kg) had no change from baseline in FVIII levels. The patient treated at the mid-dose (2×1013 vg/kg) had a stable FVIII activity level greater than 2 IU/dL for more than 28 weeks.

All 7 patients treated at the highest dose (6×1013 vg/kg) had FVIII activity levels greater than 10 IU/dL after week 10.

As of each patient’s most recent reading, 6 of the 7 patients in the high-dose group had FVIII levels above 50%, as a percentage calculated based on the numbers of IU/dL. The seventh patient had levels above 10%.

Four patients who have been followed the longest had a mean FVIII level of 146% at their 20-week visit. Two patients with FVIII levels above 200% had no unexpected events or need for medical intervention.

For the 7 patients treated at the high dose, the median annualized bleeding rate measured from the day of gene transfer to the data cutoff fell from 20 to 5.

After week 7 post-infusion, there were no bleeds in 6 of the 7 patients. There were 10 bleeds from weeks 0 through 2 post-infusion, 7 bleeds from weeks 3 through 8, and 2 bleeds from weeks 9 through 28. From weeks 2 through 28, all but 1 bleed occurred in a single subject who is the lowest responder.

All of the patients in the high-dose cohort have switched to receiving FVIII therapy on-demand. Six of them were previously receiving FVIII therapy as prophylaxis.

“These data provide strong proof-of-concept evidence that restoration of clotting function may be achieved by gene therapy,” Dr Pasi said. “For the first time, patients have reason to hope to avoid bleeding and the opportunity to live a normal life.” ![]()

Molecule reverses effects of anticoagulants

A genetically engineered coagulation factor can reverse the effects of direct oral anticoagulants in vitro and in vivo, according to research published in Nature Medicine.

Researchers altered the shape of the coagulation factor, factor Xa (FXa), into a variant that appears to be more potent and longer-lasting than wild-type FXa.

The team found this variant, FXaI16L, could counteract the effects of rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran.

“This molecule holds the potential to fill an important unmet clinical need,” said study author Rodney A. Camire, PhD, of The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania.

“There are limited treatment options to stop uncontrolled bleeding in patients who are using the newer anticoagulant medications.”

Dr Camire and his colleagues first found that FXaI16L could reverse the effects of rivaroxaban and apixaban in vitro, increasing peak thrombin generation to near-normal levels.

The team then showed that FXaI16L restores hemostasis in mice treated with rivaroxaban and significantly decreases blood loss in injured mice treated with the drug.

FXaI16L also significantly decreased blood loss in injured mice treated with dabigatran.

FXaI16L was more than 50 times more potent in the hemostasis models tested than andexanet alfa, a FXa inhibitor antidote currently in clinical development.

The researchers said FXaI16L’s ability to reverse the effects of anticoagulants depends, at least partly, on the ability of the active site inhibitor to hinder antithrombin-dependent FXa inactivation, which allows uninhibited FXa to persist in plasma.

“Our next steps will be to test this approach in large animals to help determine whether this variant is effective and safe and may progress to clinical trials,” Dr Camire said. “If so, we may be able to develop an important treatment to rapidly control bleeding in both children and adults.” ![]()

A genetically engineered coagulation factor can reverse the effects of direct oral anticoagulants in vitro and in vivo, according to research published in Nature Medicine.

Researchers altered the shape of the coagulation factor, factor Xa (FXa), into a variant that appears to be more potent and longer-lasting than wild-type FXa.

The team found this variant, FXaI16L, could counteract the effects of rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran.

“This molecule holds the potential to fill an important unmet clinical need,” said study author Rodney A. Camire, PhD, of The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania.

“There are limited treatment options to stop uncontrolled bleeding in patients who are using the newer anticoagulant medications.”

Dr Camire and his colleagues first found that FXaI16L could reverse the effects of rivaroxaban and apixaban in vitro, increasing peak thrombin generation to near-normal levels.

The team then showed that FXaI16L restores hemostasis in mice treated with rivaroxaban and significantly decreases blood loss in injured mice treated with the drug.

FXaI16L also significantly decreased blood loss in injured mice treated with dabigatran.

FXaI16L was more than 50 times more potent in the hemostasis models tested than andexanet alfa, a FXa inhibitor antidote currently in clinical development.

The researchers said FXaI16L’s ability to reverse the effects of anticoagulants depends, at least partly, on the ability of the active site inhibitor to hinder antithrombin-dependent FXa inactivation, which allows uninhibited FXa to persist in plasma.

“Our next steps will be to test this approach in large animals to help determine whether this variant is effective and safe and may progress to clinical trials,” Dr Camire said. “If so, we may be able to develop an important treatment to rapidly control bleeding in both children and adults.” ![]()

A genetically engineered coagulation factor can reverse the effects of direct oral anticoagulants in vitro and in vivo, according to research published in Nature Medicine.

Researchers altered the shape of the coagulation factor, factor Xa (FXa), into a variant that appears to be more potent and longer-lasting than wild-type FXa.

The team found this variant, FXaI16L, could counteract the effects of rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran.

“This molecule holds the potential to fill an important unmet clinical need,” said study author Rodney A. Camire, PhD, of The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania.

“There are limited treatment options to stop uncontrolled bleeding in patients who are using the newer anticoagulant medications.”

Dr Camire and his colleagues first found that FXaI16L could reverse the effects of rivaroxaban and apixaban in vitro, increasing peak thrombin generation to near-normal levels.

The team then showed that FXaI16L restores hemostasis in mice treated with rivaroxaban and significantly decreases blood loss in injured mice treated with the drug.

FXaI16L also significantly decreased blood loss in injured mice treated with dabigatran.

FXaI16L was more than 50 times more potent in the hemostasis models tested than andexanet alfa, a FXa inhibitor antidote currently in clinical development.

The researchers said FXaI16L’s ability to reverse the effects of anticoagulants depends, at least partly, on the ability of the active site inhibitor to hinder antithrombin-dependent FXa inactivation, which allows uninhibited FXa to persist in plasma.

“Our next steps will be to test this approach in large animals to help determine whether this variant is effective and safe and may progress to clinical trials,” Dr Camire said. “If so, we may be able to develop an important treatment to rapidly control bleeding in both children and adults.” ![]()

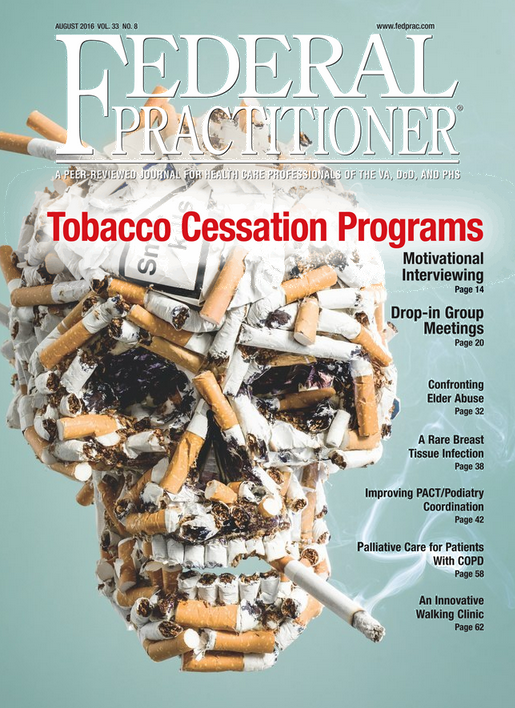

August 2016 Digital Edition

Click here to access the August 2016 Digital Edition.

Table of Contents

- One More Comment on Expanding the Scope of Practice for VA Advanced Practice Nurses

- A Motivational Interviewing Training Program for Tobacco Cessation Counseling in Primary Care

- Impact of a Drop-in Group Medical Appointment on Tobacco Quit Rates

- The Impact of Elder Abuse on a Growing Senior Veteran Population

- An Unusual Infection of Breast Tissue

- Characteristics of High-Functioning Collaborations Between Primary Care and Podiatry in VHA PACTs

- Integrating Palliative Care in COPD Treatment

- Development and Implementation of a Geriatric Walking Clinic

Click here to access the August 2016 Digital Edition.

Table of Contents

- One More Comment on Expanding the Scope of Practice for VA Advanced Practice Nurses

- A Motivational Interviewing Training Program for Tobacco Cessation Counseling in Primary Care

- Impact of a Drop-in Group Medical Appointment on Tobacco Quit Rates

- The Impact of Elder Abuse on a Growing Senior Veteran Population

- An Unusual Infection of Breast Tissue

- Characteristics of High-Functioning Collaborations Between Primary Care and Podiatry in VHA PACTs

- Integrating Palliative Care in COPD Treatment

- Development and Implementation of a Geriatric Walking Clinic

Click here to access the August 2016 Digital Edition.

Table of Contents

- One More Comment on Expanding the Scope of Practice for VA Advanced Practice Nurses

- A Motivational Interviewing Training Program for Tobacco Cessation Counseling in Primary Care

- Impact of a Drop-in Group Medical Appointment on Tobacco Quit Rates

- The Impact of Elder Abuse on a Growing Senior Veteran Population

- An Unusual Infection of Breast Tissue

- Characteristics of High-Functioning Collaborations Between Primary Care and Podiatry in VHA PACTs

- Integrating Palliative Care in COPD Treatment

- Development and Implementation of a Geriatric Walking Clinic

PULMONARY PRACTICE PEARLS FOR PRIMARY CARE PHYSICIANS: Burden of COPD Exacerbations: Focus on Optimal Management and Prevention

Study Highlights Cardiovascular Benefits, Lower GI Risks of Low-dose Aspirin

Resuming low-dose aspirin after an initial lower gastrointestinal bleed significantly increased the chances of recurrence but protected against serious cardiovascular events, based on a single-center retrospective study published in the August issue of Gastroenterology.

In contrast, “we did not find concomitant use of anticoagulants, antiplatelets, and steroids as a predictor of recurrent lower GI bleeding,” said Dr. Francis Chan of the Prince of Wales Hospital in Hong Kong and his associates. “This may be due to the low percentage of concomitant drug use in both groups. Multicenter studies with a large number of patients will be required to identify additional risk factors for recurrent lower GI bleeding with aspirin use.”

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Low-dose aspirin has long been known to help prevent coronary artery and cerebrovascular disease, and more recently has been found to potentially reduce the risk of several types of cancer, the researchers noted. Aspirin is well known to increase the risk of upper GI bleeding, but some studies have also linked it to lower GI bleeding. However, “patients with underlying cardiovascular diseases often require lifelong aspirin,” they added. The risks and benefits of stopping or remaining on aspirin after an initial lower GI bleed are unclear (Gastroenterology 2016 Apr 26. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.04.013).

Accordingly, the researchers retrospectively studied 295 patients who had an initial aspirin-associated lower GI bleed, defined as 325 mg aspirin a day within a week of bleeding onset. All patients had melena or hematochezia documented by an attending physician and had no endoscopic evidence of upper GI bleeding.

For patients who continued using aspirin at least half the time, the 5-year cumulative incidence of recurrent lower GI bleeding was 19% (95% confidence interval [CI], 13%-25%) – more than double the rate among patients who used aspirin 20% or less of the time (5-year cumulative incidence, 7%; 95% CI, 3%-13%; P = .01). However, the 5-year cumulative incidence of serious cardiovascular events among nonusers was 37% (95% CI, 27%-46%), while the rate among aspirin users was 23% (95% CI, 17%-30%; P = .02). Mortality from noncardiovascular causes was also higher among nonusers (27%) than users (8%; P less than .001), probably because nonusers of aspirin tended to be older than users, but perhaps also because aspirin had a “nonvascular protective effect,” the researchers said.

A multivariate analysis confirmed these findings, linking lower GI bleeding to aspirin but not to use of steroids, anticoagulants, or antiplatelet drugs, or to age, sex, alcohol consumption, smoking, comorbidities, or cardiovascular risks. Indeed, continued aspirin use nearly tripled the chances of a recurrent lower GI bleed (hazard ratio, 2.76; 95% CI, 1.3-6.0; P = .01), but cut the risk of serious cardiovascular events by about 40% (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.4-0.9; P = .02).

Deciding whether to resume aspirin after a severe lower GI bleed “presents a management dilemma for physicians, patients, and their families, particularly in the absence of risk-mitigating therapies and a lack of data on the risks and benefits of resuming aspirin,” the investigators emphasized. Their findings highlight the importance of weighing the cardiovascular benefits of aspirin against GI toxicity, they said. “Since there is substantial risk of recurrent bleeding, physicians should critically evaluate individual patients’ cardiovascular risk before resuming aspirin therapy. Our findings also suggest a need for a composite endpoint to evaluate clinically significant events throughout the GI tract in patients receiving antiplatelet drugs.”

The Chinese University of Hong Kong funded the study. Dr. Chan reported financial ties to Pfizer, Eisai, Takeda, Otsuka, and Astrazeneca.

Going back to low-dose aspirin after an index lower-gastrointestinal (LGI) bleed significantly increased recurrences of LGI bleeding while reducing rates of serious cardiovascular (CV) events and deaths, in a single-center, retrospective study of 295 patients from Hong Kong. Specifically, the 5-year cumulative risks of recurrent LGI bleeding were 19% in aspirin users vs. 7% for nonusers (P = .01), severe CV events (myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular accident) were 25% in aspirin users vs. 37% in nonusers (P = .02), and all-cause mortality rates for aspirin users vs. nonusers were 8.2% vs. 26.7% (P = .001).

This study complements what this research group previously published about resuming aspirin early in high-risk patients after severe ulcer hemorrhage to reduce the risk of fatal CV events (Ann Intern Med. 2010;151:1-9). Recurrent ulcer bleeding was more common in those who resumed aspirin, but fewer died of CV causes within 30 days. Until the investigators’ current publication, no reports on LGI hemorrhage were available to help clinicians weigh the risks and benefits of resuming aspirin. Despite some limitations of the current study, the message is clear about the benefits of aspirin even in the face of recurrent, nonfatal bleeding.

It seems wise to restart low-dose aspirin in patients who have a documented risk for CV events. Meanwhile, gastroenterologists can take care of the rebleeding and further study this problem.

Dennis Jensen, MD, is a digestive diseases specialist in the departments of medicine and gastroenterology at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles.

Going back to low-dose aspirin after an index lower-gastrointestinal (LGI) bleed significantly increased recurrences of LGI bleeding while reducing rates of serious cardiovascular (CV) events and deaths, in a single-center, retrospective study of 295 patients from Hong Kong. Specifically, the 5-year cumulative risks of recurrent LGI bleeding were 19% in aspirin users vs. 7% for nonusers (P = .01), severe CV events (myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular accident) were 25% in aspirin users vs. 37% in nonusers (P = .02), and all-cause mortality rates for aspirin users vs. nonusers were 8.2% vs. 26.7% (P = .001).

This study complements what this research group previously published about resuming aspirin early in high-risk patients after severe ulcer hemorrhage to reduce the risk of fatal CV events (Ann Intern Med. 2010;151:1-9). Recurrent ulcer bleeding was more common in those who resumed aspirin, but fewer died of CV causes within 30 days. Until the investigators’ current publication, no reports on LGI hemorrhage were available to help clinicians weigh the risks and benefits of resuming aspirin. Despite some limitations of the current study, the message is clear about the benefits of aspirin even in the face of recurrent, nonfatal bleeding.

It seems wise to restart low-dose aspirin in patients who have a documented risk for CV events. Meanwhile, gastroenterologists can take care of the rebleeding and further study this problem.

Dennis Jensen, MD, is a digestive diseases specialist in the departments of medicine and gastroenterology at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles.

Going back to low-dose aspirin after an index lower-gastrointestinal (LGI) bleed significantly increased recurrences of LGI bleeding while reducing rates of serious cardiovascular (CV) events and deaths, in a single-center, retrospective study of 295 patients from Hong Kong. Specifically, the 5-year cumulative risks of recurrent LGI bleeding were 19% in aspirin users vs. 7% for nonusers (P = .01), severe CV events (myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular accident) were 25% in aspirin users vs. 37% in nonusers (P = .02), and all-cause mortality rates for aspirin users vs. nonusers were 8.2% vs. 26.7% (P = .001).

This study complements what this research group previously published about resuming aspirin early in high-risk patients after severe ulcer hemorrhage to reduce the risk of fatal CV events (Ann Intern Med. 2010;151:1-9). Recurrent ulcer bleeding was more common in those who resumed aspirin, but fewer died of CV causes within 30 days. Until the investigators’ current publication, no reports on LGI hemorrhage were available to help clinicians weigh the risks and benefits of resuming aspirin. Despite some limitations of the current study, the message is clear about the benefits of aspirin even in the face of recurrent, nonfatal bleeding.

It seems wise to restart low-dose aspirin in patients who have a documented risk for CV events. Meanwhile, gastroenterologists can take care of the rebleeding and further study this problem.

Dennis Jensen, MD, is a digestive diseases specialist in the departments of medicine and gastroenterology at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles.

Resuming low-dose aspirin after an initial lower gastrointestinal bleed significantly increased the chances of recurrence but protected against serious cardiovascular events, based on a single-center retrospective study published in the August issue of Gastroenterology.

In contrast, “we did not find concomitant use of anticoagulants, antiplatelets, and steroids as a predictor of recurrent lower GI bleeding,” said Dr. Francis Chan of the Prince of Wales Hospital in Hong Kong and his associates. “This may be due to the low percentage of concomitant drug use in both groups. Multicenter studies with a large number of patients will be required to identify additional risk factors for recurrent lower GI bleeding with aspirin use.”

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Low-dose aspirin has long been known to help prevent coronary artery and cerebrovascular disease, and more recently has been found to potentially reduce the risk of several types of cancer, the researchers noted. Aspirin is well known to increase the risk of upper GI bleeding, but some studies have also linked it to lower GI bleeding. However, “patients with underlying cardiovascular diseases often require lifelong aspirin,” they added. The risks and benefits of stopping or remaining on aspirin after an initial lower GI bleed are unclear (Gastroenterology 2016 Apr 26. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.04.013).

Accordingly, the researchers retrospectively studied 295 patients who had an initial aspirin-associated lower GI bleed, defined as 325 mg aspirin a day within a week of bleeding onset. All patients had melena or hematochezia documented by an attending physician and had no endoscopic evidence of upper GI bleeding.

For patients who continued using aspirin at least half the time, the 5-year cumulative incidence of recurrent lower GI bleeding was 19% (95% confidence interval [CI], 13%-25%) – more than double the rate among patients who used aspirin 20% or less of the time (5-year cumulative incidence, 7%; 95% CI, 3%-13%; P = .01). However, the 5-year cumulative incidence of serious cardiovascular events among nonusers was 37% (95% CI, 27%-46%), while the rate among aspirin users was 23% (95% CI, 17%-30%; P = .02). Mortality from noncardiovascular causes was also higher among nonusers (27%) than users (8%; P less than .001), probably because nonusers of aspirin tended to be older than users, but perhaps also because aspirin had a “nonvascular protective effect,” the researchers said.

A multivariate analysis confirmed these findings, linking lower GI bleeding to aspirin but not to use of steroids, anticoagulants, or antiplatelet drugs, or to age, sex, alcohol consumption, smoking, comorbidities, or cardiovascular risks. Indeed, continued aspirin use nearly tripled the chances of a recurrent lower GI bleed (hazard ratio, 2.76; 95% CI, 1.3-6.0; P = .01), but cut the risk of serious cardiovascular events by about 40% (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.4-0.9; P = .02).

Deciding whether to resume aspirin after a severe lower GI bleed “presents a management dilemma for physicians, patients, and their families, particularly in the absence of risk-mitigating therapies and a lack of data on the risks and benefits of resuming aspirin,” the investigators emphasized. Their findings highlight the importance of weighing the cardiovascular benefits of aspirin against GI toxicity, they said. “Since there is substantial risk of recurrent bleeding, physicians should critically evaluate individual patients’ cardiovascular risk before resuming aspirin therapy. Our findings also suggest a need for a composite endpoint to evaluate clinically significant events throughout the GI tract in patients receiving antiplatelet drugs.”

The Chinese University of Hong Kong funded the study. Dr. Chan reported financial ties to Pfizer, Eisai, Takeda, Otsuka, and Astrazeneca.

Resuming low-dose aspirin after an initial lower gastrointestinal bleed significantly increased the chances of recurrence but protected against serious cardiovascular events, based on a single-center retrospective study published in the August issue of Gastroenterology.

In contrast, “we did not find concomitant use of anticoagulants, antiplatelets, and steroids as a predictor of recurrent lower GI bleeding,” said Dr. Francis Chan of the Prince of Wales Hospital in Hong Kong and his associates. “This may be due to the low percentage of concomitant drug use in both groups. Multicenter studies with a large number of patients will be required to identify additional risk factors for recurrent lower GI bleeding with aspirin use.”

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Low-dose aspirin has long been known to help prevent coronary artery and cerebrovascular disease, and more recently has been found to potentially reduce the risk of several types of cancer, the researchers noted. Aspirin is well known to increase the risk of upper GI bleeding, but some studies have also linked it to lower GI bleeding. However, “patients with underlying cardiovascular diseases often require lifelong aspirin,” they added. The risks and benefits of stopping or remaining on aspirin after an initial lower GI bleed are unclear (Gastroenterology 2016 Apr 26. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.04.013).

Accordingly, the researchers retrospectively studied 295 patients who had an initial aspirin-associated lower GI bleed, defined as 325 mg aspirin a day within a week of bleeding onset. All patients had melena or hematochezia documented by an attending physician and had no endoscopic evidence of upper GI bleeding.

For patients who continued using aspirin at least half the time, the 5-year cumulative incidence of recurrent lower GI bleeding was 19% (95% confidence interval [CI], 13%-25%) – more than double the rate among patients who used aspirin 20% or less of the time (5-year cumulative incidence, 7%; 95% CI, 3%-13%; P = .01). However, the 5-year cumulative incidence of serious cardiovascular events among nonusers was 37% (95% CI, 27%-46%), while the rate among aspirin users was 23% (95% CI, 17%-30%; P = .02). Mortality from noncardiovascular causes was also higher among nonusers (27%) than users (8%; P less than .001), probably because nonusers of aspirin tended to be older than users, but perhaps also because aspirin had a “nonvascular protective effect,” the researchers said.

A multivariate analysis confirmed these findings, linking lower GI bleeding to aspirin but not to use of steroids, anticoagulants, or antiplatelet drugs, or to age, sex, alcohol consumption, smoking, comorbidities, or cardiovascular risks. Indeed, continued aspirin use nearly tripled the chances of a recurrent lower GI bleed (hazard ratio, 2.76; 95% CI, 1.3-6.0; P = .01), but cut the risk of serious cardiovascular events by about 40% (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.4-0.9; P = .02).

Deciding whether to resume aspirin after a severe lower GI bleed “presents a management dilemma for physicians, patients, and their families, particularly in the absence of risk-mitigating therapies and a lack of data on the risks and benefits of resuming aspirin,” the investigators emphasized. Their findings highlight the importance of weighing the cardiovascular benefits of aspirin against GI toxicity, they said. “Since there is substantial risk of recurrent bleeding, physicians should critically evaluate individual patients’ cardiovascular risk before resuming aspirin therapy. Our findings also suggest a need for a composite endpoint to evaluate clinically significant events throughout the GI tract in patients receiving antiplatelet drugs.”

The Chinese University of Hong Kong funded the study. Dr. Chan reported financial ties to Pfizer, Eisai, Takeda, Otsuka, and Astrazeneca.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY