User login

Why is the mental health burden in EDs rising?

The mounting impact of mental illness on patients and the American health care system has been of growing concern, especially in recent years. As such, now more than ever, it is important to understand the mental health burden and investigate the factors contributing to the elevated use of emergency departments to treat patients with psychiatric illness.

In recent years, the overall prevalence of mental illness has not changed drastically. According to the 2014 National Survey of Drug Use and Health, 18.1% of adults indicated having “any mental illness,” a prevalence that had not changed much since 2008.1 It is possible, however, that despite the relative stability in the prevalence of mental illness, the acuity of mental illness may be on the rise. For instance, 4.1% of adults indicated having a “serious mental illness” (SMI) in 2014, a prevalence that was 0.4% higher than that of 2008 and 2009.1 Also, of note, the prevalence of SMI among the 18-to-25-year-old population in 2014 had increased in previous years.1 Meanwhile, 6.6% of adults indicated having experienced a major depressive episode at least once in the preceding 12 months. That prevalence has held relatively steady over recent years.1

Despite the rising need for mental health services, the number of inpatient psychiatric beds has declined. During the 32 years between 1970 and 2002, the United States experienced a staggering nearly 60% decline in the number of inpatient psychiatric beds.4 Moreover, the number of psychiatric beds within the national public sector fell from 50,509 in 2005 to 43,318 in 2010, which is about a 14% decline.5 This decrease translated to a decrease from 17.1 beds/100,000 people in 2005 to 14.1 beds/100,000 in 2010 – both of which fall drastically below the “minimum number of public psychiatric beds deemed necessary for adequate psychiatric services (50/100,000).”5 Similarly, psychiatric practice has been unable to keep up with the increasing population size – the population-adjusted median number of psychiatrists declined 10.2% between 2003 and 2013.6

While inpatient psychiatric beds and psychiatrist availability have declined, the frequency of ED use for mental health reasons has increased. Mental health or substance abuse diagnoses directly accounted for 4.3% of ED visits in 2007 and were associated with 12.5% of ED visits.7 Specifically, there was a 19.3% increase in the rate of nonmaternal treat-and-release ED visits for mental health reasons between 2008-2012.8 Moreover, in a study assessing frequent treat-and-release ED visits among Medicaid patients, investigators found that while most ED visits were for non–mental health purposes, the odds of frequent ED use were higher among patients with either a psychiatric disorder or substance use problem across all levels of overall health complexity.9

What factors have been driving adults to increasingly rely on ED visits for their mental health care? Given the immense complexity of the U.S. mental health delivery system, it is evident that there is no clear-cut explanation. However, several specific factors may have contributed and must be investigated to better our understanding of this public health conundrum. The opioid epidemic, transition out of the correctional system, and coverage changes under the Affordable Care Act are hypotheses that will be examined further in the context of this pressing issue.

References

1. “Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.”

2. “Increase in Suicide in the United States, 1999-2014.” NCHS Data Brief No. 241, April 2016.

3. Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

4. National Health Policy Forum Issue Brief (2007 Aug 1;[823]:1-21).

5. “No Room at the Inn: Trends and Consequences of Closing Public Psychiatric Hospitals, 2005-2010,” Arlington, Va.: Treatment Advocacy Center, July 19, 2012.

6. “Population of U.S. Practicing Psychiatrists Declined, 2003-13, Which May Help Explain Poor Access to Mental Health Care,” Health Aff (Millwood). 2016 Jul 1;35[7]:1271-7.

7. “Mental Health and Substance Abuse-Related Emergency Department Visits Among Adults, 2007: Statistical Brief #92,” in Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Statistical Briefs, (Rockville, Md.: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2010).

8. “Trends in Potentially Preventable Inpatient Hospital Admissions and Emergency Department Visits, 2015: Statistical Brief #195,” in Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Statistical Briefs, (Rockville, Md.: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality).

9. Nurs Res. 2015 Jan-Feb;64[1]3-12.

10. Ann Emerg Med. 2016 Apr;67[4]:525-30.

Ms. Kablanian is a 2nd-year medical student at the George Washington University, Washington, where she is enrolled in the Community and Urban Health Scholarly Concentration Program. Before attending medical school, she earned a master of public health degree in epidemiology from Columbia University, New York. She also holds a bachelor’s degree in biology and French from Scripps College, Claremont, Calif. Her interests include advocating for the urban underserved, contributing to medical curriculum development, and investigating population-level contributors to adverse health outcomes. Dr. Norris is assistant professor in the department of psychiatry & behavioral sciences, and assistant dean of student affairs at the George Washington University. He also is medical director of psychiatric & behavioral sciences at George Washington University Hospital. As part of his commitment to providing mental health care to patients with severe medical illness, Dr. Norris has been a leading voice within the psychiatric community on the value of palliative psychotherapy.

The mounting impact of mental illness on patients and the American health care system has been of growing concern, especially in recent years. As such, now more than ever, it is important to understand the mental health burden and investigate the factors contributing to the elevated use of emergency departments to treat patients with psychiatric illness.

In recent years, the overall prevalence of mental illness has not changed drastically. According to the 2014 National Survey of Drug Use and Health, 18.1% of adults indicated having “any mental illness,” a prevalence that had not changed much since 2008.1 It is possible, however, that despite the relative stability in the prevalence of mental illness, the acuity of mental illness may be on the rise. For instance, 4.1% of adults indicated having a “serious mental illness” (SMI) in 2014, a prevalence that was 0.4% higher than that of 2008 and 2009.1 Also, of note, the prevalence of SMI among the 18-to-25-year-old population in 2014 had increased in previous years.1 Meanwhile, 6.6% of adults indicated having experienced a major depressive episode at least once in the preceding 12 months. That prevalence has held relatively steady over recent years.1

Despite the rising need for mental health services, the number of inpatient psychiatric beds has declined. During the 32 years between 1970 and 2002, the United States experienced a staggering nearly 60% decline in the number of inpatient psychiatric beds.4 Moreover, the number of psychiatric beds within the national public sector fell from 50,509 in 2005 to 43,318 in 2010, which is about a 14% decline.5 This decrease translated to a decrease from 17.1 beds/100,000 people in 2005 to 14.1 beds/100,000 in 2010 – both of which fall drastically below the “minimum number of public psychiatric beds deemed necessary for adequate psychiatric services (50/100,000).”5 Similarly, psychiatric practice has been unable to keep up with the increasing population size – the population-adjusted median number of psychiatrists declined 10.2% between 2003 and 2013.6

While inpatient psychiatric beds and psychiatrist availability have declined, the frequency of ED use for mental health reasons has increased. Mental health or substance abuse diagnoses directly accounted for 4.3% of ED visits in 2007 and were associated with 12.5% of ED visits.7 Specifically, there was a 19.3% increase in the rate of nonmaternal treat-and-release ED visits for mental health reasons between 2008-2012.8 Moreover, in a study assessing frequent treat-and-release ED visits among Medicaid patients, investigators found that while most ED visits were for non–mental health purposes, the odds of frequent ED use were higher among patients with either a psychiatric disorder or substance use problem across all levels of overall health complexity.9

What factors have been driving adults to increasingly rely on ED visits for their mental health care? Given the immense complexity of the U.S. mental health delivery system, it is evident that there is no clear-cut explanation. However, several specific factors may have contributed and must be investigated to better our understanding of this public health conundrum. The opioid epidemic, transition out of the correctional system, and coverage changes under the Affordable Care Act are hypotheses that will be examined further in the context of this pressing issue.

References

1. “Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.”

2. “Increase in Suicide in the United States, 1999-2014.” NCHS Data Brief No. 241, April 2016.

3. Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

4. National Health Policy Forum Issue Brief (2007 Aug 1;[823]:1-21).

5. “No Room at the Inn: Trends and Consequences of Closing Public Psychiatric Hospitals, 2005-2010,” Arlington, Va.: Treatment Advocacy Center, July 19, 2012.

6. “Population of U.S. Practicing Psychiatrists Declined, 2003-13, Which May Help Explain Poor Access to Mental Health Care,” Health Aff (Millwood). 2016 Jul 1;35[7]:1271-7.

7. “Mental Health and Substance Abuse-Related Emergency Department Visits Among Adults, 2007: Statistical Brief #92,” in Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Statistical Briefs, (Rockville, Md.: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2010).

8. “Trends in Potentially Preventable Inpatient Hospital Admissions and Emergency Department Visits, 2015: Statistical Brief #195,” in Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Statistical Briefs, (Rockville, Md.: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality).

9. Nurs Res. 2015 Jan-Feb;64[1]3-12.

10. Ann Emerg Med. 2016 Apr;67[4]:525-30.

Ms. Kablanian is a 2nd-year medical student at the George Washington University, Washington, where she is enrolled in the Community and Urban Health Scholarly Concentration Program. Before attending medical school, she earned a master of public health degree in epidemiology from Columbia University, New York. She also holds a bachelor’s degree in biology and French from Scripps College, Claremont, Calif. Her interests include advocating for the urban underserved, contributing to medical curriculum development, and investigating population-level contributors to adverse health outcomes. Dr. Norris is assistant professor in the department of psychiatry & behavioral sciences, and assistant dean of student affairs at the George Washington University. He also is medical director of psychiatric & behavioral sciences at George Washington University Hospital. As part of his commitment to providing mental health care to patients with severe medical illness, Dr. Norris has been a leading voice within the psychiatric community on the value of palliative psychotherapy.

The mounting impact of mental illness on patients and the American health care system has been of growing concern, especially in recent years. As such, now more than ever, it is important to understand the mental health burden and investigate the factors contributing to the elevated use of emergency departments to treat patients with psychiatric illness.

In recent years, the overall prevalence of mental illness has not changed drastically. According to the 2014 National Survey of Drug Use and Health, 18.1% of adults indicated having “any mental illness,” a prevalence that had not changed much since 2008.1 It is possible, however, that despite the relative stability in the prevalence of mental illness, the acuity of mental illness may be on the rise. For instance, 4.1% of adults indicated having a “serious mental illness” (SMI) in 2014, a prevalence that was 0.4% higher than that of 2008 and 2009.1 Also, of note, the prevalence of SMI among the 18-to-25-year-old population in 2014 had increased in previous years.1 Meanwhile, 6.6% of adults indicated having experienced a major depressive episode at least once in the preceding 12 months. That prevalence has held relatively steady over recent years.1

Despite the rising need for mental health services, the number of inpatient psychiatric beds has declined. During the 32 years between 1970 and 2002, the United States experienced a staggering nearly 60% decline in the number of inpatient psychiatric beds.4 Moreover, the number of psychiatric beds within the national public sector fell from 50,509 in 2005 to 43,318 in 2010, which is about a 14% decline.5 This decrease translated to a decrease from 17.1 beds/100,000 people in 2005 to 14.1 beds/100,000 in 2010 – both of which fall drastically below the “minimum number of public psychiatric beds deemed necessary for adequate psychiatric services (50/100,000).”5 Similarly, psychiatric practice has been unable to keep up with the increasing population size – the population-adjusted median number of psychiatrists declined 10.2% between 2003 and 2013.6

While inpatient psychiatric beds and psychiatrist availability have declined, the frequency of ED use for mental health reasons has increased. Mental health or substance abuse diagnoses directly accounted for 4.3% of ED visits in 2007 and were associated with 12.5% of ED visits.7 Specifically, there was a 19.3% increase in the rate of nonmaternal treat-and-release ED visits for mental health reasons between 2008-2012.8 Moreover, in a study assessing frequent treat-and-release ED visits among Medicaid patients, investigators found that while most ED visits were for non–mental health purposes, the odds of frequent ED use were higher among patients with either a psychiatric disorder or substance use problem across all levels of overall health complexity.9

What factors have been driving adults to increasingly rely on ED visits for their mental health care? Given the immense complexity of the U.S. mental health delivery system, it is evident that there is no clear-cut explanation. However, several specific factors may have contributed and must be investigated to better our understanding of this public health conundrum. The opioid epidemic, transition out of the correctional system, and coverage changes under the Affordable Care Act are hypotheses that will be examined further in the context of this pressing issue.

References

1. “Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.”

2. “Increase in Suicide in the United States, 1999-2014.” NCHS Data Brief No. 241, April 2016.

3. Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

4. National Health Policy Forum Issue Brief (2007 Aug 1;[823]:1-21).

5. “No Room at the Inn: Trends and Consequences of Closing Public Psychiatric Hospitals, 2005-2010,” Arlington, Va.: Treatment Advocacy Center, July 19, 2012.

6. “Population of U.S. Practicing Psychiatrists Declined, 2003-13, Which May Help Explain Poor Access to Mental Health Care,” Health Aff (Millwood). 2016 Jul 1;35[7]:1271-7.

7. “Mental Health and Substance Abuse-Related Emergency Department Visits Among Adults, 2007: Statistical Brief #92,” in Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Statistical Briefs, (Rockville, Md.: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2010).

8. “Trends in Potentially Preventable Inpatient Hospital Admissions and Emergency Department Visits, 2015: Statistical Brief #195,” in Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Statistical Briefs, (Rockville, Md.: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality).

9. Nurs Res. 2015 Jan-Feb;64[1]3-12.

10. Ann Emerg Med. 2016 Apr;67[4]:525-30.

Ms. Kablanian is a 2nd-year medical student at the George Washington University, Washington, where she is enrolled in the Community and Urban Health Scholarly Concentration Program. Before attending medical school, she earned a master of public health degree in epidemiology from Columbia University, New York. She also holds a bachelor’s degree in biology and French from Scripps College, Claremont, Calif. Her interests include advocating for the urban underserved, contributing to medical curriculum development, and investigating population-level contributors to adverse health outcomes. Dr. Norris is assistant professor in the department of psychiatry & behavioral sciences, and assistant dean of student affairs at the George Washington University. He also is medical director of psychiatric & behavioral sciences at George Washington University Hospital. As part of his commitment to providing mental health care to patients with severe medical illness, Dr. Norris has been a leading voice within the psychiatric community on the value of palliative psychotherapy.

Flu susceptibility driven by birth year

Differences in susceptibility to an influenza A virus (IAV) strain may be traceable to the first lifetime influenza infection, according to a new statistical model, which could have implications for epidemiology and future flu vaccines.

In the Nov. 11 issue of Science, researchers described infection models of the H5N1 and H7N9 strains of influenza A. The former occurs more commonly in younger people, and the latter in older individuals, but the reasons for those associations have puzzled scientists.

The researchers, led by James Lloyd-Smith, PhD, of the department of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California, Los Angeles, looked at susceptibility to IAV strains by birth year, and found that this was the best predictor of vulnerability. For example, an analysis of H5N1 cases in Egypt, where had many H5N1 cases spread over the past decade, showed that individuals born in the same year had the same average risk of severe H5N1 infection, even after they had aged by 10 years. That suggests that it is the birth year, not advancing age, which influences susceptibility (Science. 2016 Nov 11;354[6313]:721-5. doi:10.1126/science.aag1322).

The researchers suggest that the immune system “imprints” on the hemagglutinin (HA) subtype during an individual’s first infection, which confers protection against severe disease caused by other, related viruses, though it may not reduce infection rates overall.

The year 1968 may have marked an important inflection point. That year marked a shift in the identify of circulating viruses, from group 1 HA (which includes H5N1) to group 2 HA (which includes H7N9). Individuals born before 1968 were likely first infected with a group 1 virus, while those born later were most likely initially exposed to a group 2 virus. If the imprint theory is correct, younger people would have imprinted on group 2 viruses similar to H7N9, which would explain their greater vulnerability to group 1 viruses like H5N1.

“Imprinting was the dominant explanatory factor for observed incidence and mortality patterns for both H5N1 and H7N9. It was the only tested factor included in all plausible models for both viruses,” the researchers wrote.

According to the model, imprinting explains 75% of protection against severe infection and 80% of the protection against mortality for H5N1 and H7N9.

That information adds a previously unrecognized layer to influenza epidemiology, which should be accounted for in public health measures. “The methods shown here can provide rolling estimates of which age groups would be at highest risk for severe disease should particular novel HA subtypes emerge,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and the Department of Homeland Security. They reported having no financial disclosures.

A growing body of epidemiological evidence points to the prolonged effects of cross-immunity, including competition between strains during seasonal and pandemic outbreaks, reduced risk of pandemic infection in those with previous seasonal exposure, and – as reported by Gostic et al. – lifelong protection against viruses of different subtypes but in the same hemagglutinin (HA) homology group. Basic science efforts are now needed to fully validate the HA imprinting hypothesis. More broadly, further experimental and theoretical work should map the relationship between early childhood exposure to influenza and immune protection and the implications of lifelong immunity for vaccination strategies and pandemic risk.

Cécile Viboud, PhD, is the acting director of the division of international epidemiology and population studies at the Fogarty International Center at the National Institutes of Health. Suzanne L. Epstein, PhD, is the associate director for research at the office of tissues and advanced therapies at the Food and Drug Administration Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. They had no relevant financial disclosures and made these remarks in an editorial that accompanied the published study (Science. 2016 Nov 11;354[6313]:706-7. doi:10.1126/science.aak9816).

A growing body of epidemiological evidence points to the prolonged effects of cross-immunity, including competition between strains during seasonal and pandemic outbreaks, reduced risk of pandemic infection in those with previous seasonal exposure, and – as reported by Gostic et al. – lifelong protection against viruses of different subtypes but in the same hemagglutinin (HA) homology group. Basic science efforts are now needed to fully validate the HA imprinting hypothesis. More broadly, further experimental and theoretical work should map the relationship between early childhood exposure to influenza and immune protection and the implications of lifelong immunity for vaccination strategies and pandemic risk.

Cécile Viboud, PhD, is the acting director of the division of international epidemiology and population studies at the Fogarty International Center at the National Institutes of Health. Suzanne L. Epstein, PhD, is the associate director for research at the office of tissues and advanced therapies at the Food and Drug Administration Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. They had no relevant financial disclosures and made these remarks in an editorial that accompanied the published study (Science. 2016 Nov 11;354[6313]:706-7. doi:10.1126/science.aak9816).

A growing body of epidemiological evidence points to the prolonged effects of cross-immunity, including competition between strains during seasonal and pandemic outbreaks, reduced risk of pandemic infection in those with previous seasonal exposure, and – as reported by Gostic et al. – lifelong protection against viruses of different subtypes but in the same hemagglutinin (HA) homology group. Basic science efforts are now needed to fully validate the HA imprinting hypothesis. More broadly, further experimental and theoretical work should map the relationship between early childhood exposure to influenza and immune protection and the implications of lifelong immunity for vaccination strategies and pandemic risk.

Cécile Viboud, PhD, is the acting director of the division of international epidemiology and population studies at the Fogarty International Center at the National Institutes of Health. Suzanne L. Epstein, PhD, is the associate director for research at the office of tissues and advanced therapies at the Food and Drug Administration Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. They had no relevant financial disclosures and made these remarks in an editorial that accompanied the published study (Science. 2016 Nov 11;354[6313]:706-7. doi:10.1126/science.aak9816).

Differences in susceptibility to an influenza A virus (IAV) strain may be traceable to the first lifetime influenza infection, according to a new statistical model, which could have implications for epidemiology and future flu vaccines.

In the Nov. 11 issue of Science, researchers described infection models of the H5N1 and H7N9 strains of influenza A. The former occurs more commonly in younger people, and the latter in older individuals, but the reasons for those associations have puzzled scientists.

The researchers, led by James Lloyd-Smith, PhD, of the department of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California, Los Angeles, looked at susceptibility to IAV strains by birth year, and found that this was the best predictor of vulnerability. For example, an analysis of H5N1 cases in Egypt, where had many H5N1 cases spread over the past decade, showed that individuals born in the same year had the same average risk of severe H5N1 infection, even after they had aged by 10 years. That suggests that it is the birth year, not advancing age, which influences susceptibility (Science. 2016 Nov 11;354[6313]:721-5. doi:10.1126/science.aag1322).

The researchers suggest that the immune system “imprints” on the hemagglutinin (HA) subtype during an individual’s first infection, which confers protection against severe disease caused by other, related viruses, though it may not reduce infection rates overall.

The year 1968 may have marked an important inflection point. That year marked a shift in the identify of circulating viruses, from group 1 HA (which includes H5N1) to group 2 HA (which includes H7N9). Individuals born before 1968 were likely first infected with a group 1 virus, while those born later were most likely initially exposed to a group 2 virus. If the imprint theory is correct, younger people would have imprinted on group 2 viruses similar to H7N9, which would explain their greater vulnerability to group 1 viruses like H5N1.

“Imprinting was the dominant explanatory factor for observed incidence and mortality patterns for both H5N1 and H7N9. It was the only tested factor included in all plausible models for both viruses,” the researchers wrote.

According to the model, imprinting explains 75% of protection against severe infection and 80% of the protection against mortality for H5N1 and H7N9.

That information adds a previously unrecognized layer to influenza epidemiology, which should be accounted for in public health measures. “The methods shown here can provide rolling estimates of which age groups would be at highest risk for severe disease should particular novel HA subtypes emerge,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and the Department of Homeland Security. They reported having no financial disclosures.

Differences in susceptibility to an influenza A virus (IAV) strain may be traceable to the first lifetime influenza infection, according to a new statistical model, which could have implications for epidemiology and future flu vaccines.

In the Nov. 11 issue of Science, researchers described infection models of the H5N1 and H7N9 strains of influenza A. The former occurs more commonly in younger people, and the latter in older individuals, but the reasons for those associations have puzzled scientists.

The researchers, led by James Lloyd-Smith, PhD, of the department of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California, Los Angeles, looked at susceptibility to IAV strains by birth year, and found that this was the best predictor of vulnerability. For example, an analysis of H5N1 cases in Egypt, where had many H5N1 cases spread over the past decade, showed that individuals born in the same year had the same average risk of severe H5N1 infection, even after they had aged by 10 years. That suggests that it is the birth year, not advancing age, which influences susceptibility (Science. 2016 Nov 11;354[6313]:721-5. doi:10.1126/science.aag1322).

The researchers suggest that the immune system “imprints” on the hemagglutinin (HA) subtype during an individual’s first infection, which confers protection against severe disease caused by other, related viruses, though it may not reduce infection rates overall.

The year 1968 may have marked an important inflection point. That year marked a shift in the identify of circulating viruses, from group 1 HA (which includes H5N1) to group 2 HA (which includes H7N9). Individuals born before 1968 were likely first infected with a group 1 virus, while those born later were most likely initially exposed to a group 2 virus. If the imprint theory is correct, younger people would have imprinted on group 2 viruses similar to H7N9, which would explain their greater vulnerability to group 1 viruses like H5N1.

“Imprinting was the dominant explanatory factor for observed incidence and mortality patterns for both H5N1 and H7N9. It was the only tested factor included in all plausible models for both viruses,” the researchers wrote.

According to the model, imprinting explains 75% of protection against severe infection and 80% of the protection against mortality for H5N1 and H7N9.

That information adds a previously unrecognized layer to influenza epidemiology, which should be accounted for in public health measures. “The methods shown here can provide rolling estimates of which age groups would be at highest risk for severe disease should particular novel HA subtypes emerge,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and the Department of Homeland Security. They reported having no financial disclosures.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Early exposure to virus subtype explains 75% of protection against severe disease in later life.

Data source: Statistical model of retrospective data.

Disclosures: The researchers received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and the Department of Homeland Security. They reported having no financial disclosures.

Cooling, occlusion, and antihistamines are among the options that optimize ALA-PDT results

Treatment of a broad area, occluding extremities, and the use of antihistamines are among the measures that can help optimize the results of treating actinic keratoses (AKs) with topical photodynamic therapy (PDT) using aminolevulinic acid (ALA), according to Dr. Brian Berman.

For many patients with AKs, ALA-PDT can be an effective and well-tolerated option, Dr. Berman said in a presentation at the Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

ALA-PDT is a two-step process, Dr. Berman explained. The first step involves the application of ALA with presumed selective cellular uptake, followed by conversion to protoporphyrin IX (PpIX). Next, the light activation of PpIX causes cell death via high-energy oxygen molecules.

Dr. Berman’s recommendations for optimizing ALA-PDT to treat AKs include a shorter ALA incubation time; treatment of a broad area, not just the baseline visible AKs; occlusion of ALA for AKs on the arms and legs; increased skin temperature during ALA incubation; and moderate cooling during light exposure. To reduce pain, he recommended a very short ALA incubation time with a longer time of light exposure.

He referred to a 2004 study of 18 patients, which found that AK reductions were not significantly different at 1 month post treatment with ALA incubation times of 1, 2, or 3 hours (Arch Dermatol. 2004 Jan;140[1]:33-40). As for occlusion, a 2012 study found that AK clearance was significantly greater for extremities that were occluded during incubation in patients undergoing blue light ALA-PDT, compared with areas that were not occluded (J Drugs Dermatol. 2012 Dec;11[12]:1483-9).

Skin cooling can be useful in reducing patients’ pain, said Dr. Berman of the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery, University of Miami. Data from a retrospective study showed that cooling pain relief, with an air-cooling device during treatment, resulted in lower PpIX photobleaching in AK lesions, compared with no cooling (J Photochem Photobiol B. 2011 Apr 4;103[1]:1-7). But cooling was associated with decreased efficacy of the PDT treatment in terms of complete AK response (68% for the cooling device group vs. 82% for controls without cooling), he said.

Increasing skin temperature has been shown to reduce AK lesions significantly, compared with no heat, Dr. Berman pointed out. “PpIX synthesis is temperature dependent,” he said. The median difference in AK lesion counts was significantly greater on a heated extremity side than a control side in an unpublished study, he noted.

Finally, when it comes to facial AKs, less may be more in terms of treatment time. In a split face study, a “painless PDT” protocol of 15 minutes of ALA incubation with 1 hour of blue light yielded a 52% reduction in AKs at 8 weeks post treatment, vs. a 44% reduction with a standard treatment of 75 minutes of ALA incubation with 16 minutes, 45 seconds of blue light, Dr. Berman said.

Dr. Berman disclosed relationships with multiple companies including Ferndale, LEO, Halscion, Sensus, Exeltis, Dermira, Celumigen, Sun, DUSA, Biofrontera, and Berg. He holds stock in Halscion, Dermira, Celumigen, and Berg.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Treatment of a broad area, occluding extremities, and the use of antihistamines are among the measures that can help optimize the results of treating actinic keratoses (AKs) with topical photodynamic therapy (PDT) using aminolevulinic acid (ALA), according to Dr. Brian Berman.

For many patients with AKs, ALA-PDT can be an effective and well-tolerated option, Dr. Berman said in a presentation at the Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

ALA-PDT is a two-step process, Dr. Berman explained. The first step involves the application of ALA with presumed selective cellular uptake, followed by conversion to protoporphyrin IX (PpIX). Next, the light activation of PpIX causes cell death via high-energy oxygen molecules.

Dr. Berman’s recommendations for optimizing ALA-PDT to treat AKs include a shorter ALA incubation time; treatment of a broad area, not just the baseline visible AKs; occlusion of ALA for AKs on the arms and legs; increased skin temperature during ALA incubation; and moderate cooling during light exposure. To reduce pain, he recommended a very short ALA incubation time with a longer time of light exposure.

He referred to a 2004 study of 18 patients, which found that AK reductions were not significantly different at 1 month post treatment with ALA incubation times of 1, 2, or 3 hours (Arch Dermatol. 2004 Jan;140[1]:33-40). As for occlusion, a 2012 study found that AK clearance was significantly greater for extremities that were occluded during incubation in patients undergoing blue light ALA-PDT, compared with areas that were not occluded (J Drugs Dermatol. 2012 Dec;11[12]:1483-9).

Skin cooling can be useful in reducing patients’ pain, said Dr. Berman of the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery, University of Miami. Data from a retrospective study showed that cooling pain relief, with an air-cooling device during treatment, resulted in lower PpIX photobleaching in AK lesions, compared with no cooling (J Photochem Photobiol B. 2011 Apr 4;103[1]:1-7). But cooling was associated with decreased efficacy of the PDT treatment in terms of complete AK response (68% for the cooling device group vs. 82% for controls without cooling), he said.

Increasing skin temperature has been shown to reduce AK lesions significantly, compared with no heat, Dr. Berman pointed out. “PpIX synthesis is temperature dependent,” he said. The median difference in AK lesion counts was significantly greater on a heated extremity side than a control side in an unpublished study, he noted.

Finally, when it comes to facial AKs, less may be more in terms of treatment time. In a split face study, a “painless PDT” protocol of 15 minutes of ALA incubation with 1 hour of blue light yielded a 52% reduction in AKs at 8 weeks post treatment, vs. a 44% reduction with a standard treatment of 75 minutes of ALA incubation with 16 minutes, 45 seconds of blue light, Dr. Berman said.

Dr. Berman disclosed relationships with multiple companies including Ferndale, LEO, Halscion, Sensus, Exeltis, Dermira, Celumigen, Sun, DUSA, Biofrontera, and Berg. He holds stock in Halscion, Dermira, Celumigen, and Berg.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Treatment of a broad area, occluding extremities, and the use of antihistamines are among the measures that can help optimize the results of treating actinic keratoses (AKs) with topical photodynamic therapy (PDT) using aminolevulinic acid (ALA), according to Dr. Brian Berman.

For many patients with AKs, ALA-PDT can be an effective and well-tolerated option, Dr. Berman said in a presentation at the Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

ALA-PDT is a two-step process, Dr. Berman explained. The first step involves the application of ALA with presumed selective cellular uptake, followed by conversion to protoporphyrin IX (PpIX). Next, the light activation of PpIX causes cell death via high-energy oxygen molecules.

Dr. Berman’s recommendations for optimizing ALA-PDT to treat AKs include a shorter ALA incubation time; treatment of a broad area, not just the baseline visible AKs; occlusion of ALA for AKs on the arms and legs; increased skin temperature during ALA incubation; and moderate cooling during light exposure. To reduce pain, he recommended a very short ALA incubation time with a longer time of light exposure.

He referred to a 2004 study of 18 patients, which found that AK reductions were not significantly different at 1 month post treatment with ALA incubation times of 1, 2, or 3 hours (Arch Dermatol. 2004 Jan;140[1]:33-40). As for occlusion, a 2012 study found that AK clearance was significantly greater for extremities that were occluded during incubation in patients undergoing blue light ALA-PDT, compared with areas that were not occluded (J Drugs Dermatol. 2012 Dec;11[12]:1483-9).

Skin cooling can be useful in reducing patients’ pain, said Dr. Berman of the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery, University of Miami. Data from a retrospective study showed that cooling pain relief, with an air-cooling device during treatment, resulted in lower PpIX photobleaching in AK lesions, compared with no cooling (J Photochem Photobiol B. 2011 Apr 4;103[1]:1-7). But cooling was associated with decreased efficacy of the PDT treatment in terms of complete AK response (68% for the cooling device group vs. 82% for controls without cooling), he said.

Increasing skin temperature has been shown to reduce AK lesions significantly, compared with no heat, Dr. Berman pointed out. “PpIX synthesis is temperature dependent,” he said. The median difference in AK lesion counts was significantly greater on a heated extremity side than a control side in an unpublished study, he noted.

Finally, when it comes to facial AKs, less may be more in terms of treatment time. In a split face study, a “painless PDT” protocol of 15 minutes of ALA incubation with 1 hour of blue light yielded a 52% reduction in AKs at 8 weeks post treatment, vs. a 44% reduction with a standard treatment of 75 minutes of ALA incubation with 16 minutes, 45 seconds of blue light, Dr. Berman said.

Dr. Berman disclosed relationships with multiple companies including Ferndale, LEO, Halscion, Sensus, Exeltis, Dermira, Celumigen, Sun, DUSA, Biofrontera, and Berg. He holds stock in Halscion, Dermira, Celumigen, and Berg.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

OA progresses equally with new focal partial- or full-thickness cartilage damage

A small, partial-thickness focal cartilage defect in the tibiofemoral joint compartment has the same impact on osteoarthritis disease progression – defined as new cartilage damage – as does a full-thickness lesion, according to an analysis of data from the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study.

Ali Guermazi, MD, PhD, of Boston University, and his associates used MRI to show that both full- and partial-thickness small focal defects (less than 1 cm) in the tibiofemoral compartment contributed significantly to the risk of incident cartilage damage 30 months later in other tibiofemoral compartment subregions (adjusted odds ratio, 1.62; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-2.47, for partial-thickness defects and aOR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.00-3.66, for full-thickness defects) when compared with subregions with no baseline cartilage damage, defined as a Kellgren-Lawrence grade of 0-1.

The results indicate that “partial-thickness and full-thickness defects are similarly relevant in regard to cartilage damage development in knee osteoarthritis,” the investigators wrote.

They studied 374 compartments (359 knees), of which 140 knees (39%) had radiographic osteoarthritis defined as a Kellgren-Lawrence grade of 2 or higher).

“It is potentially important to detect focal cartilage defects early as there are various options for repair of focal cartilage defects ... [and it could be possible to use MRI] to screen persons with early-stage osteoarthritis or those at high risk of osteoarthritis and initiate treatment for focal cartilage defects,” they wrote.

Read the full study in Arthritis & Rheumatology (2016 Oct 27. doi: 10.1002/art.39970).

A small, partial-thickness focal cartilage defect in the tibiofemoral joint compartment has the same impact on osteoarthritis disease progression – defined as new cartilage damage – as does a full-thickness lesion, according to an analysis of data from the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study.

Ali Guermazi, MD, PhD, of Boston University, and his associates used MRI to show that both full- and partial-thickness small focal defects (less than 1 cm) in the tibiofemoral compartment contributed significantly to the risk of incident cartilage damage 30 months later in other tibiofemoral compartment subregions (adjusted odds ratio, 1.62; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-2.47, for partial-thickness defects and aOR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.00-3.66, for full-thickness defects) when compared with subregions with no baseline cartilage damage, defined as a Kellgren-Lawrence grade of 0-1.

The results indicate that “partial-thickness and full-thickness defects are similarly relevant in regard to cartilage damage development in knee osteoarthritis,” the investigators wrote.

They studied 374 compartments (359 knees), of which 140 knees (39%) had radiographic osteoarthritis defined as a Kellgren-Lawrence grade of 2 or higher).

“It is potentially important to detect focal cartilage defects early as there are various options for repair of focal cartilage defects ... [and it could be possible to use MRI] to screen persons with early-stage osteoarthritis or those at high risk of osteoarthritis and initiate treatment for focal cartilage defects,” they wrote.

Read the full study in Arthritis & Rheumatology (2016 Oct 27. doi: 10.1002/art.39970).

A small, partial-thickness focal cartilage defect in the tibiofemoral joint compartment has the same impact on osteoarthritis disease progression – defined as new cartilage damage – as does a full-thickness lesion, according to an analysis of data from the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study.

Ali Guermazi, MD, PhD, of Boston University, and his associates used MRI to show that both full- and partial-thickness small focal defects (less than 1 cm) in the tibiofemoral compartment contributed significantly to the risk of incident cartilage damage 30 months later in other tibiofemoral compartment subregions (adjusted odds ratio, 1.62; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-2.47, for partial-thickness defects and aOR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.00-3.66, for full-thickness defects) when compared with subregions with no baseline cartilage damage, defined as a Kellgren-Lawrence grade of 0-1.

The results indicate that “partial-thickness and full-thickness defects are similarly relevant in regard to cartilage damage development in knee osteoarthritis,” the investigators wrote.

They studied 374 compartments (359 knees), of which 140 knees (39%) had radiographic osteoarthritis defined as a Kellgren-Lawrence grade of 2 or higher).

“It is potentially important to detect focal cartilage defects early as there are various options for repair of focal cartilage defects ... [and it could be possible to use MRI] to screen persons with early-stage osteoarthritis or those at high risk of osteoarthritis and initiate treatment for focal cartilage defects,” they wrote.

Read the full study in Arthritis & Rheumatology (2016 Oct 27. doi: 10.1002/art.39970).

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: 104 mutations found in single gene

according to a report published online in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

Identifying which specific mutations in the COL7A1 gene a given patient is carrying should allow clinicians to render a more accurate prognosis and may even dictate management strategies to counteract manifestations of the disease. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (EB) can have an extremely variable progression that depends, in part, on the underlying molecular defects in many different genes expressed in the dermal-epidermal junction, according to study investigators Hassan Vahidnezhad, MD, of the department of dermatology and cutaneous biology, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and his associates.

The study cohort included many consanguineous marriages, which are customary in Iran as in many parts of the Middle East, North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, many migrant communities from these regions now reside in Western countries and continue to practice these marriage customs, most commonly marriages between first cousins. “It is estimated that globally at least 20% of the human population live in communities with a preference for consanguineous marriage,” the researchers wrote (J Investig Dermatol. 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.10.023).

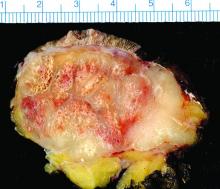

Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa is characterized by blistering of the sublamina densa that leads to erosions; chronic ulcers; and extensive scarring, especially at sites of trauma on the hands and feet. Blistering can also develop in corneal and gastrointestinal epithelium, which adversely affects vision and feeding, and patients often develop aggressive squamous cell carcinoma with its attendant premature mortality.

Dystrophic EB has long been associated with mutations in COL7A1 as well as other genes. COL7A1 encodes type VII collagen, “a major protein component of the anchoring fibrils, which play a critical role in securing the attachment of the dermal-epidermal basement membrane to the underlying dermis.” Many patients with dystrophic EB show marked reductions in, or a total absence of, anchoring fibrils.

The investigators explored COL7A1 mutations in a multiethnic database comprising 238 patients in 152 extended families from different parts of the country. (The approximately 80 million people in Iran include several ethnic groups with distinct ancestries, languages, cultures, and geographic areas of residence.) A total of 139 of these families were consanguineous.

A total of 104 distinct COL7A1 mutations were detected in 149 of the 152 families, for a detection rate of 98%. Many mutations had been reported previously, but 56 had never been reported before. Approximately 90% of the families in the study cohort showed homozygous recessive mutations, which appears to reflect the consanguinity of this population, Dr. Vahidnezhad and his associates said.

They concluded that “the overwhelming majority” of patients with dystrophic EB carry COL7A1 genes harboring mutations.

This study was supported by DEBRA International and the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Thomas Jefferson University. Dr. Vahidnezhad and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

according to a report published online in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

Identifying which specific mutations in the COL7A1 gene a given patient is carrying should allow clinicians to render a more accurate prognosis and may even dictate management strategies to counteract manifestations of the disease. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (EB) can have an extremely variable progression that depends, in part, on the underlying molecular defects in many different genes expressed in the dermal-epidermal junction, according to study investigators Hassan Vahidnezhad, MD, of the department of dermatology and cutaneous biology, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and his associates.

The study cohort included many consanguineous marriages, which are customary in Iran as in many parts of the Middle East, North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, many migrant communities from these regions now reside in Western countries and continue to practice these marriage customs, most commonly marriages between first cousins. “It is estimated that globally at least 20% of the human population live in communities with a preference for consanguineous marriage,” the researchers wrote (J Investig Dermatol. 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.10.023).

Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa is characterized by blistering of the sublamina densa that leads to erosions; chronic ulcers; and extensive scarring, especially at sites of trauma on the hands and feet. Blistering can also develop in corneal and gastrointestinal epithelium, which adversely affects vision and feeding, and patients often develop aggressive squamous cell carcinoma with its attendant premature mortality.

Dystrophic EB has long been associated with mutations in COL7A1 as well as other genes. COL7A1 encodes type VII collagen, “a major protein component of the anchoring fibrils, which play a critical role in securing the attachment of the dermal-epidermal basement membrane to the underlying dermis.” Many patients with dystrophic EB show marked reductions in, or a total absence of, anchoring fibrils.

The investigators explored COL7A1 mutations in a multiethnic database comprising 238 patients in 152 extended families from different parts of the country. (The approximately 80 million people in Iran include several ethnic groups with distinct ancestries, languages, cultures, and geographic areas of residence.) A total of 139 of these families were consanguineous.

A total of 104 distinct COL7A1 mutations were detected in 149 of the 152 families, for a detection rate of 98%. Many mutations had been reported previously, but 56 had never been reported before. Approximately 90% of the families in the study cohort showed homozygous recessive mutations, which appears to reflect the consanguinity of this population, Dr. Vahidnezhad and his associates said.

They concluded that “the overwhelming majority” of patients with dystrophic EB carry COL7A1 genes harboring mutations.

This study was supported by DEBRA International and the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Thomas Jefferson University. Dr. Vahidnezhad and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

according to a report published online in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

Identifying which specific mutations in the COL7A1 gene a given patient is carrying should allow clinicians to render a more accurate prognosis and may even dictate management strategies to counteract manifestations of the disease. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (EB) can have an extremely variable progression that depends, in part, on the underlying molecular defects in many different genes expressed in the dermal-epidermal junction, according to study investigators Hassan Vahidnezhad, MD, of the department of dermatology and cutaneous biology, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and his associates.

The study cohort included many consanguineous marriages, which are customary in Iran as in many parts of the Middle East, North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, many migrant communities from these regions now reside in Western countries and continue to practice these marriage customs, most commonly marriages between first cousins. “It is estimated that globally at least 20% of the human population live in communities with a preference for consanguineous marriage,” the researchers wrote (J Investig Dermatol. 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.10.023).

Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa is characterized by blistering of the sublamina densa that leads to erosions; chronic ulcers; and extensive scarring, especially at sites of trauma on the hands and feet. Blistering can also develop in corneal and gastrointestinal epithelium, which adversely affects vision and feeding, and patients often develop aggressive squamous cell carcinoma with its attendant premature mortality.

Dystrophic EB has long been associated with mutations in COL7A1 as well as other genes. COL7A1 encodes type VII collagen, “a major protein component of the anchoring fibrils, which play a critical role in securing the attachment of the dermal-epidermal basement membrane to the underlying dermis.” Many patients with dystrophic EB show marked reductions in, or a total absence of, anchoring fibrils.

The investigators explored COL7A1 mutations in a multiethnic database comprising 238 patients in 152 extended families from different parts of the country. (The approximately 80 million people in Iran include several ethnic groups with distinct ancestries, languages, cultures, and geographic areas of residence.) A total of 139 of these families were consanguineous.

A total of 104 distinct COL7A1 mutations were detected in 149 of the 152 families, for a detection rate of 98%. Many mutations had been reported previously, but 56 had never been reported before. Approximately 90% of the families in the study cohort showed homozygous recessive mutations, which appears to reflect the consanguinity of this population, Dr. Vahidnezhad and his associates said.

They concluded that “the overwhelming majority” of patients with dystrophic EB carry COL7A1 genes harboring mutations.

This study was supported by DEBRA International and the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Thomas Jefferson University. Dr. Vahidnezhad and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF INVESTIGATIVE DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: 104 distinct mutations in a single gene, COL7A1, were discovered in a multiethnic cohort of 152 Iranian families with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa.

Major finding: 104 distinct COL7A1 mutations were detected in 149 of the 152 families in the database, for a detection rate of 98%.

Data source: Analyses of mutations in the COL741 gene in 152 extended Iranian families with a high frequency of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa.

Disclosures: This study was supported by DEBRA International and the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Thomas Jefferson University. Dr. Vahidnezhad and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The voice of the patient in a doctor-centric world

The American health care system has been plagued by poor medical outcomes and an inefficient cost structure for many years.1,2 The primary loser in this game is the patient, the player who bears the brunt of health care expenses, either directly or through taxes, and whose voice has been largely ignored until recently. As with many other service industries, health care delivery represents a highly complex process that is difficult to define or measure. Innovative procedures and state-of-the-art medical therapies have provided effective options that extend or improve life, but at increasing cost.

Further complicating the existing cost-vs.-benefit debate is a relatively new polemic regarding the degree to which patient satisfaction should be a measure of health care quality. How satisfied will a patient be with his or her health care experience? This depends, in large part, on the medical outcome.3

Many public and private organizations use patient satisfaction surveys to measure the performance of health care delivery systems. In many cases, patient satisfaction data are being used to determine insurance payouts, physician compensation, and institutional rankings.5 It may seem logical to adopt pay-for-performance strategies based on patient satisfaction surveys, but there is a fundamental flaw: Survey data are not always accurate.

It is not entirely clear what constitutes a positive or negative health care experience. Much of this depends on the expectations of the consumer.6 Those with low expectations may be delighted with mediocre performance. Those with inflated expectations may be disappointed even when provided excellent customer service.

Surveys are not durable. That is, when performed under distinct environmental conditions or at different times, surveys may not produce the same results when repeated by the same respondent.7 Surveys are easily manipulated by simple changes in wording or punctuation. Some specific encounters may be rated as “unsatisfactory” because of external factors, circumstances beyond the control of the health care provider.

Many health care providers feel that surveys are poor indicators of individual performance. Some critics highlight a paucity of data. A limited number of returned surveys, relative to the total number of encounters, may yield results that are not statistically significant. Increasing the amount of data decreases the risk that a sample set taken from the studied population is the result of sampling error alone. Nonetheless, sampling error is never completely eliminated, and it is not entirely clear to what degree statistical significance should be used to substantiate satisfaction, a subjective measure.

Surveys often provide data in a very small range, making ranking of facilities or providers difficult. For example, national polling services utilize surveys with thousands of respondents and the margin of error often exceeds plus or minus 3%. Data sets with a smaller number of responses have margins of error that are even greater. Even plus or minus 3% is a sizable deviation when considering that health care survey results often are compared and ranked based on a distribution of scores in a narrow response range. In the author’s experience, a 6% difference in survey scores can represent the difference between a ranking of “excellent” and “poor.”

Many patients are disenfranchised by survey methodology. In the most extreme example, deceased or severely disabled patients are unable to provide feedback. Patients transferred to other facilities and those who are lost to follow-up will be missed also. Many patient surveys may not be successfully retrieved from the homeless, the illiterate, minors, or those without phone or e-mail access. Because surveys are voluntarily submitted, the results may skew opinion toward a select group of outspoken customers who may not be representative of the general population.

The use of patient satisfaction surveys, especially when they are linked to employee compensation, may create a system of survey-based value. This is similar to the problem of defensive medicine, where providers perform medicine in a way that reduces legal risk. Aware that patients will be asked to fill out satisfaction surveys, associates may perform in a way that increases patient satisfaction scores at the expense of patient outcomes or the bottom line. Some institutions may inappropriately “cherry-pick” the easy-to-treat patient and transfer medically complex cases elsewhere.

It is not clear how to best measure the quality of a health care experience. With the broad range of patient encounter types and the inherent complexity of collaboration among providers, it is difficult to determine to what degree satisfaction can be attributed to individual providers or specific environmental factors. Patients do not typically interact with a specific provider, but are treated by a service delivery system, which often encompasses multiple players and multiple physical locations. Moreover, it is not always clear when the patient encounter begins and ends.

Despite the criticism of patient satisfaction survey methodology, the patient must ultimately define the value of the health care service offering. This “voice of the customer” approach is a diversion from the antiquated practitioner-centric model. Traditionally, patient appointment times and locations are decided by the availability and convenience of the provider. Many consumers have compensated for this inefficiency by accessing local emergency departments for nonurgent ambulatory care. Nonetheless,EDs often suffer from long waits and higher costs. Facilities designed for urgent, but nonemergent, care have attempted to address convenience issues but these facilities sacrifice continuity and specialization of care. In a truly patient-centric health care model, patients would be provided the care that they need, when and where they need it.

The patient satisfaction survey remains a primary tool for linking patient-centered value to health care reform. Ranking the results among market competitors can provide an incentive for improvement. Health care professionals are competitive by nature and the extrinsic motivation of quality rankings can be beneficial if well controlled. Employers should use caution when using survey data for performance measurement because survey data are subject to a variety of sources of bias or error. Patient survey data should be used to drive improvement, not to punish. Further research on patient survey methodology is needed to elucidate improved methods of bringing the voice of the patient to the forefront of health care reform.

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2003 Aug 21;349(8):768-75.

2. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare hospital quality chartbook: Performance report on outcome measures. September 2014.

3. N Engl J Med. 2008 Oct 30;359(18):1921-31.

4. “Better Customer Insight – in Real Time,” by Emma K. Macdonald, Hugh N. Wilson, and Umut Konuş (Harvard Business Review, September 2012).

5. “The Dangers of Linking Pay to Customer Feedback,” by Rob Markey, (Harvard Business Review, Sept. 8, 2011).

6. “Health Care’s Service Fanatics,” by James I. Merlino and Ananth Raman, (Harvard Business Review, May 2013).

7. Trochim, WMK. Research Methods Knowledge Base.

Dr. Davis is a pediatric gastroenterologists at University of Florida Health, Gainesville. He has no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

The American health care system has been plagued by poor medical outcomes and an inefficient cost structure for many years.1,2 The primary loser in this game is the patient, the player who bears the brunt of health care expenses, either directly or through taxes, and whose voice has been largely ignored until recently. As with many other service industries, health care delivery represents a highly complex process that is difficult to define or measure. Innovative procedures and state-of-the-art medical therapies have provided effective options that extend or improve life, but at increasing cost.

Further complicating the existing cost-vs.-benefit debate is a relatively new polemic regarding the degree to which patient satisfaction should be a measure of health care quality. How satisfied will a patient be with his or her health care experience? This depends, in large part, on the medical outcome.3

Many public and private organizations use patient satisfaction surveys to measure the performance of health care delivery systems. In many cases, patient satisfaction data are being used to determine insurance payouts, physician compensation, and institutional rankings.5 It may seem logical to adopt pay-for-performance strategies based on patient satisfaction surveys, but there is a fundamental flaw: Survey data are not always accurate.

It is not entirely clear what constitutes a positive or negative health care experience. Much of this depends on the expectations of the consumer.6 Those with low expectations may be delighted with mediocre performance. Those with inflated expectations may be disappointed even when provided excellent customer service.

Surveys are not durable. That is, when performed under distinct environmental conditions or at different times, surveys may not produce the same results when repeated by the same respondent.7 Surveys are easily manipulated by simple changes in wording or punctuation. Some specific encounters may be rated as “unsatisfactory” because of external factors, circumstances beyond the control of the health care provider.

Many health care providers feel that surveys are poor indicators of individual performance. Some critics highlight a paucity of data. A limited number of returned surveys, relative to the total number of encounters, may yield results that are not statistically significant. Increasing the amount of data decreases the risk that a sample set taken from the studied population is the result of sampling error alone. Nonetheless, sampling error is never completely eliminated, and it is not entirely clear to what degree statistical significance should be used to substantiate satisfaction, a subjective measure.

Surveys often provide data in a very small range, making ranking of facilities or providers difficult. For example, national polling services utilize surveys with thousands of respondents and the margin of error often exceeds plus or minus 3%. Data sets with a smaller number of responses have margins of error that are even greater. Even plus or minus 3% is a sizable deviation when considering that health care survey results often are compared and ranked based on a distribution of scores in a narrow response range. In the author’s experience, a 6% difference in survey scores can represent the difference between a ranking of “excellent” and “poor.”

Many patients are disenfranchised by survey methodology. In the most extreme example, deceased or severely disabled patients are unable to provide feedback. Patients transferred to other facilities and those who are lost to follow-up will be missed also. Many patient surveys may not be successfully retrieved from the homeless, the illiterate, minors, or those without phone or e-mail access. Because surveys are voluntarily submitted, the results may skew opinion toward a select group of outspoken customers who may not be representative of the general population.

The use of patient satisfaction surveys, especially when they are linked to employee compensation, may create a system of survey-based value. This is similar to the problem of defensive medicine, where providers perform medicine in a way that reduces legal risk. Aware that patients will be asked to fill out satisfaction surveys, associates may perform in a way that increases patient satisfaction scores at the expense of patient outcomes or the bottom line. Some institutions may inappropriately “cherry-pick” the easy-to-treat patient and transfer medically complex cases elsewhere.

It is not clear how to best measure the quality of a health care experience. With the broad range of patient encounter types and the inherent complexity of collaboration among providers, it is difficult to determine to what degree satisfaction can be attributed to individual providers or specific environmental factors. Patients do not typically interact with a specific provider, but are treated by a service delivery system, which often encompasses multiple players and multiple physical locations. Moreover, it is not always clear when the patient encounter begins and ends.

Despite the criticism of patient satisfaction survey methodology, the patient must ultimately define the value of the health care service offering. This “voice of the customer” approach is a diversion from the antiquated practitioner-centric model. Traditionally, patient appointment times and locations are decided by the availability and convenience of the provider. Many consumers have compensated for this inefficiency by accessing local emergency departments for nonurgent ambulatory care. Nonetheless,EDs often suffer from long waits and higher costs. Facilities designed for urgent, but nonemergent, care have attempted to address convenience issues but these facilities sacrifice continuity and specialization of care. In a truly patient-centric health care model, patients would be provided the care that they need, when and where they need it.

The patient satisfaction survey remains a primary tool for linking patient-centered value to health care reform. Ranking the results among market competitors can provide an incentive for improvement. Health care professionals are competitive by nature and the extrinsic motivation of quality rankings can be beneficial if well controlled. Employers should use caution when using survey data for performance measurement because survey data are subject to a variety of sources of bias or error. Patient survey data should be used to drive improvement, not to punish. Further research on patient survey methodology is needed to elucidate improved methods of bringing the voice of the patient to the forefront of health care reform.

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2003 Aug 21;349(8):768-75.

2. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare hospital quality chartbook: Performance report on outcome measures. September 2014.

3. N Engl J Med. 2008 Oct 30;359(18):1921-31.

4. “Better Customer Insight – in Real Time,” by Emma K. Macdonald, Hugh N. Wilson, and Umut Konuş (Harvard Business Review, September 2012).

5. “The Dangers of Linking Pay to Customer Feedback,” by Rob Markey, (Harvard Business Review, Sept. 8, 2011).

6. “Health Care’s Service Fanatics,” by James I. Merlino and Ananth Raman, (Harvard Business Review, May 2013).

7. Trochim, WMK. Research Methods Knowledge Base.

Dr. Davis is a pediatric gastroenterologists at University of Florida Health, Gainesville. He has no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

The American health care system has been plagued by poor medical outcomes and an inefficient cost structure for many years.1,2 The primary loser in this game is the patient, the player who bears the brunt of health care expenses, either directly or through taxes, and whose voice has been largely ignored until recently. As with many other service industries, health care delivery represents a highly complex process that is difficult to define or measure. Innovative procedures and state-of-the-art medical therapies have provided effective options that extend or improve life, but at increasing cost.

Further complicating the existing cost-vs.-benefit debate is a relatively new polemic regarding the degree to which patient satisfaction should be a measure of health care quality. How satisfied will a patient be with his or her health care experience? This depends, in large part, on the medical outcome.3

Many public and private organizations use patient satisfaction surveys to measure the performance of health care delivery systems. In many cases, patient satisfaction data are being used to determine insurance payouts, physician compensation, and institutional rankings.5 It may seem logical to adopt pay-for-performance strategies based on patient satisfaction surveys, but there is a fundamental flaw: Survey data are not always accurate.

It is not entirely clear what constitutes a positive or negative health care experience. Much of this depends on the expectations of the consumer.6 Those with low expectations may be delighted with mediocre performance. Those with inflated expectations may be disappointed even when provided excellent customer service.

Surveys are not durable. That is, when performed under distinct environmental conditions or at different times, surveys may not produce the same results when repeated by the same respondent.7 Surveys are easily manipulated by simple changes in wording or punctuation. Some specific encounters may be rated as “unsatisfactory” because of external factors, circumstances beyond the control of the health care provider.

Many health care providers feel that surveys are poor indicators of individual performance. Some critics highlight a paucity of data. A limited number of returned surveys, relative to the total number of encounters, may yield results that are not statistically significant. Increasing the amount of data decreases the risk that a sample set taken from the studied population is the result of sampling error alone. Nonetheless, sampling error is never completely eliminated, and it is not entirely clear to what degree statistical significance should be used to substantiate satisfaction, a subjective measure.

Surveys often provide data in a very small range, making ranking of facilities or providers difficult. For example, national polling services utilize surveys with thousands of respondents and the margin of error often exceeds plus or minus 3%. Data sets with a smaller number of responses have margins of error that are even greater. Even plus or minus 3% is a sizable deviation when considering that health care survey results often are compared and ranked based on a distribution of scores in a narrow response range. In the author’s experience, a 6% difference in survey scores can represent the difference between a ranking of “excellent” and “poor.”

Many patients are disenfranchised by survey methodology. In the most extreme example, deceased or severely disabled patients are unable to provide feedback. Patients transferred to other facilities and those who are lost to follow-up will be missed also. Many patient surveys may not be successfully retrieved from the homeless, the illiterate, minors, or those without phone or e-mail access. Because surveys are voluntarily submitted, the results may skew opinion toward a select group of outspoken customers who may not be representative of the general population.

The use of patient satisfaction surveys, especially when they are linked to employee compensation, may create a system of survey-based value. This is similar to the problem of defensive medicine, where providers perform medicine in a way that reduces legal risk. Aware that patients will be asked to fill out satisfaction surveys, associates may perform in a way that increases patient satisfaction scores at the expense of patient outcomes or the bottom line. Some institutions may inappropriately “cherry-pick” the easy-to-treat patient and transfer medically complex cases elsewhere.

It is not clear how to best measure the quality of a health care experience. With the broad range of patient encounter types and the inherent complexity of collaboration among providers, it is difficult to determine to what degree satisfaction can be attributed to individual providers or specific environmental factors. Patients do not typically interact with a specific provider, but are treated by a service delivery system, which often encompasses multiple players and multiple physical locations. Moreover, it is not always clear when the patient encounter begins and ends.

Despite the criticism of patient satisfaction survey methodology, the patient must ultimately define the value of the health care service offering. This “voice of the customer” approach is a diversion from the antiquated practitioner-centric model. Traditionally, patient appointment times and locations are decided by the availability and convenience of the provider. Many consumers have compensated for this inefficiency by accessing local emergency departments for nonurgent ambulatory care. Nonetheless,EDs often suffer from long waits and higher costs. Facilities designed for urgent, but nonemergent, care have attempted to address convenience issues but these facilities sacrifice continuity and specialization of care. In a truly patient-centric health care model, patients would be provided the care that they need, when and where they need it.

The patient satisfaction survey remains a primary tool for linking patient-centered value to health care reform. Ranking the results among market competitors can provide an incentive for improvement. Health care professionals are competitive by nature and the extrinsic motivation of quality rankings can be beneficial if well controlled. Employers should use caution when using survey data for performance measurement because survey data are subject to a variety of sources of bias or error. Patient survey data should be used to drive improvement, not to punish. Further research on patient survey methodology is needed to elucidate improved methods of bringing the voice of the patient to the forefront of health care reform.

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2003 Aug 21;349(8):768-75.

2. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare hospital quality chartbook: Performance report on outcome measures. September 2014.

3. N Engl J Med. 2008 Oct 30;359(18):1921-31.

4. “Better Customer Insight – in Real Time,” by Emma K. Macdonald, Hugh N. Wilson, and Umut Konuş (Harvard Business Review, September 2012).

5. “The Dangers of Linking Pay to Customer Feedback,” by Rob Markey, (Harvard Business Review, Sept. 8, 2011).

6. “Health Care’s Service Fanatics,” by James I. Merlino and Ananth Raman, (Harvard Business Review, May 2013).

7. Trochim, WMK. Research Methods Knowledge Base.

Dr. Davis is a pediatric gastroenterologists at University of Florida Health, Gainesville. He has no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Study finds 19% of Merkel cell carcinomas are virus negative

Nineteen percent of Merkel cell carcinomas are not driven by the Merkel cell polyomavirus and are substantially more aggressive than those that are virus positive, according to a report published online in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.