User login

A New Technique for Obtaining Bone Graft in Cases of Distal Femur Nonunion: Passing a Reamer/Irrigator/Aspirator Retrograde Through the Nonunion Site

Bone grafting is the main method of treating nonunions.1 The multiple bone graft options available include autogenous bone grafts, allogenic bone grafts, and synthetic bone graft substitutes.2,3 Autogenous bone graft has long been considered the gold standard, as it reduces the risk of infection and eliminates the risk of immune rejection associated with allograft; in addition, autograft has the optimal combination of osteogenic, osteoinductive, and osteoconductive properties.2,4,5 Iliac crest bone graft (ICBG), though the most commonly used autogenous bone graft source, has been associated with infection, hematoma, poor cosmetic outcomes, hernia, neurovascular insults, and chronic persistent pain.6,7 Intramedullary bone graft harvest performed with the Reamer/Irrigator/Aspirator (RIA) system (DePuy Synthes) is a novel technique that allows for simultaneous débridement and collection of bone graft, protects against thermal necrosis and extravasation of marrow contents, and maintains biomechanical strength for weight-bearing.3,4,8,9 Furthermore, RIA aspirate is a rich source of autologous bone graft and provides equal or superior amounts of graft in comparison with ICBG.5-7,10-12

In some cases, RIA is associated with the complication of host bone fracture.4,6,7,11,12 In addition, introducing the reamer may contribute to pain at its entry site and may require violation of local soft-tissue attachments at the hip or knees.4,7,13 In this study, we assessed the possibility of using a new RIA technique to eliminate these adverse effects. We hypothesized that distal femoral nonunions could be successfully treated with the RIA passed retrograde through the nonunion site. This technique may obviate the need for a secondary surgical site (required in traditional intramedullary bone graft harvest), minimize the potential entry-site tissue (eg, hip abductor) damage encountered with the antegrade technique, and yield harvested bone graft in quantities similar to those obtained with the standard technique.

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval for this study, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of all patients with a distal femur nonunion treated with autogenous bone grafting between 2009 and 2013. Identified patients had undergone a novel intramedullary harvest technique that involved passing an RIA retrograde through the nonunion site. Data (patient demographics, volume of graft obtained, perioperative complications, postoperative clinical course) were extracted from the medical records. Before data collection, all patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of their case reports.

Technique

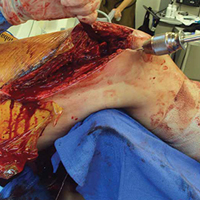

The patient was laid supine on a radiolucent table, and the affected extremity was prepared and draped free. A standard lateral incision previously used for the index procedure was employed. After implant removal, a rongeur, curette, and/or high-speed burr was used to débride the distal femur nonunion of all fibrous tissue. After mobilization and preparation of the distal femoral nonunion, varus angulation was accentuated with delivery of the proximal and distal segments of the nonunion into the wound (Figure A).

Six patients underwent 7 separate procedures for distal femoral nonunion. Of these patients, 5 underwent retrograde RIA through the nonunion site, as described above; the sixth underwent antegrade RIA in the traditional fashion and was therefore excluded. One of the 5 patients underwent another bone grafting procedure after the initial retrograde RIA treatment through the nonunion site. Several outcomes were measured: ability to obtain graft, volume of graft obtained, perioperative complications, and feasibility of the procedure.

Mean age of the 5 patients was 40.4 years (range, 22-66 years). Mean reamer size was 13.4 mm (mode, 14 mm), producing an average bone graft volume of 33 mL. There were no intraoperative or postoperative fractures. In 1 case, the reamer shaft broke during insertion and was retrieved with no retained hardware; passage was made with a new reamer shaft. No patient experienced additional pain or discomfort, as there was no separate entry site for the RIA.

Discussion

Bone grafting for nonunion is one of the most commonly performed procedures in orthopedic trauma surgery. Use of an intramedullary harvest system has become increasingly popular relative to alternative techniques. The RIA system is associated with less donor-site pain and provides relatively more bone graft volume in comparison with ICBG harvest.6,7,10,13 Conversely, intramedullary bone graft harvest may be associated with higher risk of host bone fractures, occurring either during surgery (technical error being the cause) or afterward (a result of patient noncompliance or overaggressive reaming).6,7,11,12 Multiple methods of reducing the risk of iatrogenic fracture caused by technical error of eccentric reaming have been described, including appropriate guide wire placement aided by frequent use of fluoroscopy in 2 planes.4 Despite these potential complications and improved donor-site pain complaints in comparison with ICBG harvest, traditional RIA harvest is still associated with pain at the entry site.4,7,13

In this study, we introduced a novel RIA technique for distal femur nonunion. This technique reduces the complications and adverse effects associated with RIA. It removes the added pain and discomfort associated with a separate entry site. As the reamer is introduced into the medullary canal through the femoral nonunion site, and proximal harvest is limited to the subtrochanteric region, the technique also avoids the complications associated with eccentric reaming of the distal and proximal femur, which may contribute to secondary fracture.6,7,11,12Although the proposed technique is practical, it may present some technical difficulties. First, failed fixation hardware must be removed, and by necessity some stripping of soft tissues is required. These actions are unavoidable, as hardware revision is inherent in the treatment of nonunion. During the procedure, the focus should be on minimizing the insult to bony healing. The nonunion also needs to be completely mobilized to allow adequate angulation, guide wire passage, and sequential reaming. The dual vascular insult of intramedullary reaming combined with the soft-tissue débridement and detachment required for hardware removal and mobilization can be concerning for devascularization of the fracture fragment. However, animal studies have suggested reaming does not affect metaphyseal blood flow; it affects only diaphyseal bone.6,14 The metaphyseal/diaphyseal location of these distal femur nonunions is thought to provide at least partial sparing from the endosteal injury that the RIA may cause. Another difficulty is that the angle of passage of the wire requires a relatively steeper curve to be able to pass beyond the medial distal femoral wall and proceed more proximally. Strong manipulation of the segment is required, which in 1 case caused the reamer shaft to break. This complication had minimal sequelae; the shaft was easily retrieved by withdrawing the ball-tipped guide wire. In addition, strong manipulation of the segment can lead to asymmetric medial reaming or fracture—an outcome easily avoided with a small bend in the distal tip of the guide wire and frequent use of fluoroscopy. In all cases in this series, we achieved proximal passage of the wire and the reamer.

Most RIA bone graft is harvested by reaming the medullary canal at the midshaft of the femur. Passing from the distal femoral nonunion precludes obtaining only a small source of potential distal femoral bone graft, though this metaphyseal bone typically is not used for fear of eccentric reaming and secondary fracture.6,7,11,12 The amount of bone graft obtained from selected patients who undergo retrograde RIA passage through the nonunion site should be similar to the amount obtained with the traditional antegrade method. Our newly proposed technique provided an average bone graft volume of 33 mL, which compares favorably with that reported in the literature for the traditional RIA technique.1,5,6,13,15,16

Conclusion

In distal femoral cases, retrograde passage of the RIA through the nonunion site is technically feasible and has reproducible yields of intramedullary bone graft. Adequate mobilization of the nonunion is a prerequisite for reamer harvest. However, this technique obviates the need for an additional entry point. Furthermore, the technique may limit the perioperative fracture risk previously seen with eccentric reaming of the distal and proximal femur using traditional intramedullary harvest.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E493-E496. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Conway JD. Autograft and nonunions: morbidity with intramedullary bone graft versus iliac crest bone graft. Orthop Clin North Am. 2010;41(1):75-84.

2. Schmidmaier G, Herrmann S, Green J, et al. Quantitative assessment of growth factors in reaming aspirate, iliac crest, and platelet preparation. Bone. 2006;39(5):1156-1163.

3. Miller MA, Ivkovic A, Porter R, et al. Autologous bone grafting on steroids: preliminary clinical results. A novel treatment for nonunions and segmental bone defects. Int Orthop. 2011;35(4):599-605.

4. Qvick LM, Ritter CA, Mutty CE, Rohrbacher BJ, Buyea CM, Anders MJ. Donor site morbidity with Reamer-Irrigator-Aspirator (RIA) use for autogenous bone graft harvesting in a single centre 204 case series. Injury. 2013;44(10):1263-1269.

5. Kanakaris NK, Morell D, Gudipati S, Britten S, Giannoudis PV. Reaming Irrigator Aspirator system: early experience of its multipurpose use. Injury. 2011;42(suppl 4):S28-S34.

6. Dimitriou R, Mataliotakis GI, Angoules AG, Kanakaris NK, Giannoudis PV. Complications following autologous bone graft harvesting from the iliac crest and using the RIA: a systematic review. Injury. 2011;42(suppl 2):S3-S15.

7. Belthur MV, Conway JD, Jindal G, Ranade A, Herzenberg JE. Bone graft harvest using a new intramedullary system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(12):2973-2980.

8. Seagrave RA, Sojka J, Goodyear A, Munns SW. Utilizing Reamer Irrigator Aspirator (RIA) autograft for opening wedge high tibial osteotomy: a new surgical technique and report of three cases. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5(1):37-42.

9. Finnan RP, Prayson MJ, Goswami T, Miller D. Use of the Reamer-Irrigator-Aspirator for bone graft harvest: a mechanical comparison of three starting points in cadaveric femurs. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(1):36-41.

10. Masquelet AC, Benko PE, Mathevon H, Hannouche D, Obert L; French Society of Orthopaedics and Traumatic Surgery (SoFCOT). Harvest of cortico-cancellous intramedullary femoral bone graft using the Reamer-Irrigator-Aspirator (RIA). Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98(2):227-232.

11. Quintero AJ, Tarkin IS, Pape HC. Technical tricks when using the Reamer Irrigator Aspirator technique for autologous bone graft harvesting. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(1):42-45.

12. Cox G, Jones E, McGonagle D, Giannoudis PV. Reamer-Irrigator-Aspirator indications and clinical results: a systematic review. Int Orthop. 2011;35(7):951-956.

13. Dawson J, Kiner D, Gardner W 2nd, Swafford R, Nowotarski PJ. The Reamer-Irrigator-Aspirator as a device for harvesting bone graft compared with iliac crest bone graft: union rates and complications. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(10):584-590.

14. ElMaraghy AW, Humeniuk B, Anderson GI, Schemitsch EH, Richards RR. Femoral bone blood flow after reaming and intramedullary canal preparation: a canine study using laser Doppler flowmetry. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(2):220-226.

15. Finkemeier CG, Neiman R, Hallare D. RIA: one community’s experience. Orthop Clin North Am. 2010;41(1):99-103.

16. Myeroff C, Archdeacon M. Autogenous bone graft: donor sites and techniques. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(23):2227-2236.

Bone grafting is the main method of treating nonunions.1 The multiple bone graft options available include autogenous bone grafts, allogenic bone grafts, and synthetic bone graft substitutes.2,3 Autogenous bone graft has long been considered the gold standard, as it reduces the risk of infection and eliminates the risk of immune rejection associated with allograft; in addition, autograft has the optimal combination of osteogenic, osteoinductive, and osteoconductive properties.2,4,5 Iliac crest bone graft (ICBG), though the most commonly used autogenous bone graft source, has been associated with infection, hematoma, poor cosmetic outcomes, hernia, neurovascular insults, and chronic persistent pain.6,7 Intramedullary bone graft harvest performed with the Reamer/Irrigator/Aspirator (RIA) system (DePuy Synthes) is a novel technique that allows for simultaneous débridement and collection of bone graft, protects against thermal necrosis and extravasation of marrow contents, and maintains biomechanical strength for weight-bearing.3,4,8,9 Furthermore, RIA aspirate is a rich source of autologous bone graft and provides equal or superior amounts of graft in comparison with ICBG.5-7,10-12

In some cases, RIA is associated with the complication of host bone fracture.4,6,7,11,12 In addition, introducing the reamer may contribute to pain at its entry site and may require violation of local soft-tissue attachments at the hip or knees.4,7,13 In this study, we assessed the possibility of using a new RIA technique to eliminate these adverse effects. We hypothesized that distal femoral nonunions could be successfully treated with the RIA passed retrograde through the nonunion site. This technique may obviate the need for a secondary surgical site (required in traditional intramedullary bone graft harvest), minimize the potential entry-site tissue (eg, hip abductor) damage encountered with the antegrade technique, and yield harvested bone graft in quantities similar to those obtained with the standard technique.

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval for this study, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of all patients with a distal femur nonunion treated with autogenous bone grafting between 2009 and 2013. Identified patients had undergone a novel intramedullary harvest technique that involved passing an RIA retrograde through the nonunion site. Data (patient demographics, volume of graft obtained, perioperative complications, postoperative clinical course) were extracted from the medical records. Before data collection, all patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of their case reports.

Technique

The patient was laid supine on a radiolucent table, and the affected extremity was prepared and draped free. A standard lateral incision previously used for the index procedure was employed. After implant removal, a rongeur, curette, and/or high-speed burr was used to débride the distal femur nonunion of all fibrous tissue. After mobilization and preparation of the distal femoral nonunion, varus angulation was accentuated with delivery of the proximal and distal segments of the nonunion into the wound (Figure A).

Six patients underwent 7 separate procedures for distal femoral nonunion. Of these patients, 5 underwent retrograde RIA through the nonunion site, as described above; the sixth underwent antegrade RIA in the traditional fashion and was therefore excluded. One of the 5 patients underwent another bone grafting procedure after the initial retrograde RIA treatment through the nonunion site. Several outcomes were measured: ability to obtain graft, volume of graft obtained, perioperative complications, and feasibility of the procedure.

Mean age of the 5 patients was 40.4 years (range, 22-66 years). Mean reamer size was 13.4 mm (mode, 14 mm), producing an average bone graft volume of 33 mL. There were no intraoperative or postoperative fractures. In 1 case, the reamer shaft broke during insertion and was retrieved with no retained hardware; passage was made with a new reamer shaft. No patient experienced additional pain or discomfort, as there was no separate entry site for the RIA.

Discussion

Bone grafting for nonunion is one of the most commonly performed procedures in orthopedic trauma surgery. Use of an intramedullary harvest system has become increasingly popular relative to alternative techniques. The RIA system is associated with less donor-site pain and provides relatively more bone graft volume in comparison with ICBG harvest.6,7,10,13 Conversely, intramedullary bone graft harvest may be associated with higher risk of host bone fractures, occurring either during surgery (technical error being the cause) or afterward (a result of patient noncompliance or overaggressive reaming).6,7,11,12 Multiple methods of reducing the risk of iatrogenic fracture caused by technical error of eccentric reaming have been described, including appropriate guide wire placement aided by frequent use of fluoroscopy in 2 planes.4 Despite these potential complications and improved donor-site pain complaints in comparison with ICBG harvest, traditional RIA harvest is still associated with pain at the entry site.4,7,13

In this study, we introduced a novel RIA technique for distal femur nonunion. This technique reduces the complications and adverse effects associated with RIA. It removes the added pain and discomfort associated with a separate entry site. As the reamer is introduced into the medullary canal through the femoral nonunion site, and proximal harvest is limited to the subtrochanteric region, the technique also avoids the complications associated with eccentric reaming of the distal and proximal femur, which may contribute to secondary fracture.6,7,11,12Although the proposed technique is practical, it may present some technical difficulties. First, failed fixation hardware must be removed, and by necessity some stripping of soft tissues is required. These actions are unavoidable, as hardware revision is inherent in the treatment of nonunion. During the procedure, the focus should be on minimizing the insult to bony healing. The nonunion also needs to be completely mobilized to allow adequate angulation, guide wire passage, and sequential reaming. The dual vascular insult of intramedullary reaming combined with the soft-tissue débridement and detachment required for hardware removal and mobilization can be concerning for devascularization of the fracture fragment. However, animal studies have suggested reaming does not affect metaphyseal blood flow; it affects only diaphyseal bone.6,14 The metaphyseal/diaphyseal location of these distal femur nonunions is thought to provide at least partial sparing from the endosteal injury that the RIA may cause. Another difficulty is that the angle of passage of the wire requires a relatively steeper curve to be able to pass beyond the medial distal femoral wall and proceed more proximally. Strong manipulation of the segment is required, which in 1 case caused the reamer shaft to break. This complication had minimal sequelae; the shaft was easily retrieved by withdrawing the ball-tipped guide wire. In addition, strong manipulation of the segment can lead to asymmetric medial reaming or fracture—an outcome easily avoided with a small bend in the distal tip of the guide wire and frequent use of fluoroscopy. In all cases in this series, we achieved proximal passage of the wire and the reamer.

Most RIA bone graft is harvested by reaming the medullary canal at the midshaft of the femur. Passing from the distal femoral nonunion precludes obtaining only a small source of potential distal femoral bone graft, though this metaphyseal bone typically is not used for fear of eccentric reaming and secondary fracture.6,7,11,12 The amount of bone graft obtained from selected patients who undergo retrograde RIA passage through the nonunion site should be similar to the amount obtained with the traditional antegrade method. Our newly proposed technique provided an average bone graft volume of 33 mL, which compares favorably with that reported in the literature for the traditional RIA technique.1,5,6,13,15,16

Conclusion

In distal femoral cases, retrograde passage of the RIA through the nonunion site is technically feasible and has reproducible yields of intramedullary bone graft. Adequate mobilization of the nonunion is a prerequisite for reamer harvest. However, this technique obviates the need for an additional entry point. Furthermore, the technique may limit the perioperative fracture risk previously seen with eccentric reaming of the distal and proximal femur using traditional intramedullary harvest.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E493-E496. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

Bone grafting is the main method of treating nonunions.1 The multiple bone graft options available include autogenous bone grafts, allogenic bone grafts, and synthetic bone graft substitutes.2,3 Autogenous bone graft has long been considered the gold standard, as it reduces the risk of infection and eliminates the risk of immune rejection associated with allograft; in addition, autograft has the optimal combination of osteogenic, osteoinductive, and osteoconductive properties.2,4,5 Iliac crest bone graft (ICBG), though the most commonly used autogenous bone graft source, has been associated with infection, hematoma, poor cosmetic outcomes, hernia, neurovascular insults, and chronic persistent pain.6,7 Intramedullary bone graft harvest performed with the Reamer/Irrigator/Aspirator (RIA) system (DePuy Synthes) is a novel technique that allows for simultaneous débridement and collection of bone graft, protects against thermal necrosis and extravasation of marrow contents, and maintains biomechanical strength for weight-bearing.3,4,8,9 Furthermore, RIA aspirate is a rich source of autologous bone graft and provides equal or superior amounts of graft in comparison with ICBG.5-7,10-12

In some cases, RIA is associated with the complication of host bone fracture.4,6,7,11,12 In addition, introducing the reamer may contribute to pain at its entry site and may require violation of local soft-tissue attachments at the hip or knees.4,7,13 In this study, we assessed the possibility of using a new RIA technique to eliminate these adverse effects. We hypothesized that distal femoral nonunions could be successfully treated with the RIA passed retrograde through the nonunion site. This technique may obviate the need for a secondary surgical site (required in traditional intramedullary bone graft harvest), minimize the potential entry-site tissue (eg, hip abductor) damage encountered with the antegrade technique, and yield harvested bone graft in quantities similar to those obtained with the standard technique.

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval for this study, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of all patients with a distal femur nonunion treated with autogenous bone grafting between 2009 and 2013. Identified patients had undergone a novel intramedullary harvest technique that involved passing an RIA retrograde through the nonunion site. Data (patient demographics, volume of graft obtained, perioperative complications, postoperative clinical course) were extracted from the medical records. Before data collection, all patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of their case reports.

Technique

The patient was laid supine on a radiolucent table, and the affected extremity was prepared and draped free. A standard lateral incision previously used for the index procedure was employed. After implant removal, a rongeur, curette, and/or high-speed burr was used to débride the distal femur nonunion of all fibrous tissue. After mobilization and preparation of the distal femoral nonunion, varus angulation was accentuated with delivery of the proximal and distal segments of the nonunion into the wound (Figure A).

Six patients underwent 7 separate procedures for distal femoral nonunion. Of these patients, 5 underwent retrograde RIA through the nonunion site, as described above; the sixth underwent antegrade RIA in the traditional fashion and was therefore excluded. One of the 5 patients underwent another bone grafting procedure after the initial retrograde RIA treatment through the nonunion site. Several outcomes were measured: ability to obtain graft, volume of graft obtained, perioperative complications, and feasibility of the procedure.

Mean age of the 5 patients was 40.4 years (range, 22-66 years). Mean reamer size was 13.4 mm (mode, 14 mm), producing an average bone graft volume of 33 mL. There were no intraoperative or postoperative fractures. In 1 case, the reamer shaft broke during insertion and was retrieved with no retained hardware; passage was made with a new reamer shaft. No patient experienced additional pain or discomfort, as there was no separate entry site for the RIA.

Discussion

Bone grafting for nonunion is one of the most commonly performed procedures in orthopedic trauma surgery. Use of an intramedullary harvest system has become increasingly popular relative to alternative techniques. The RIA system is associated with less donor-site pain and provides relatively more bone graft volume in comparison with ICBG harvest.6,7,10,13 Conversely, intramedullary bone graft harvest may be associated with higher risk of host bone fractures, occurring either during surgery (technical error being the cause) or afterward (a result of patient noncompliance or overaggressive reaming).6,7,11,12 Multiple methods of reducing the risk of iatrogenic fracture caused by technical error of eccentric reaming have been described, including appropriate guide wire placement aided by frequent use of fluoroscopy in 2 planes.4 Despite these potential complications and improved donor-site pain complaints in comparison with ICBG harvest, traditional RIA harvest is still associated with pain at the entry site.4,7,13

In this study, we introduced a novel RIA technique for distal femur nonunion. This technique reduces the complications and adverse effects associated with RIA. It removes the added pain and discomfort associated with a separate entry site. As the reamer is introduced into the medullary canal through the femoral nonunion site, and proximal harvest is limited to the subtrochanteric region, the technique also avoids the complications associated with eccentric reaming of the distal and proximal femur, which may contribute to secondary fracture.6,7,11,12Although the proposed technique is practical, it may present some technical difficulties. First, failed fixation hardware must be removed, and by necessity some stripping of soft tissues is required. These actions are unavoidable, as hardware revision is inherent in the treatment of nonunion. During the procedure, the focus should be on minimizing the insult to bony healing. The nonunion also needs to be completely mobilized to allow adequate angulation, guide wire passage, and sequential reaming. The dual vascular insult of intramedullary reaming combined with the soft-tissue débridement and detachment required for hardware removal and mobilization can be concerning for devascularization of the fracture fragment. However, animal studies have suggested reaming does not affect metaphyseal blood flow; it affects only diaphyseal bone.6,14 The metaphyseal/diaphyseal location of these distal femur nonunions is thought to provide at least partial sparing from the endosteal injury that the RIA may cause. Another difficulty is that the angle of passage of the wire requires a relatively steeper curve to be able to pass beyond the medial distal femoral wall and proceed more proximally. Strong manipulation of the segment is required, which in 1 case caused the reamer shaft to break. This complication had minimal sequelae; the shaft was easily retrieved by withdrawing the ball-tipped guide wire. In addition, strong manipulation of the segment can lead to asymmetric medial reaming or fracture—an outcome easily avoided with a small bend in the distal tip of the guide wire and frequent use of fluoroscopy. In all cases in this series, we achieved proximal passage of the wire and the reamer.

Most RIA bone graft is harvested by reaming the medullary canal at the midshaft of the femur. Passing from the distal femoral nonunion precludes obtaining only a small source of potential distal femoral bone graft, though this metaphyseal bone typically is not used for fear of eccentric reaming and secondary fracture.6,7,11,12 The amount of bone graft obtained from selected patients who undergo retrograde RIA passage through the nonunion site should be similar to the amount obtained with the traditional antegrade method. Our newly proposed technique provided an average bone graft volume of 33 mL, which compares favorably with that reported in the literature for the traditional RIA technique.1,5,6,13,15,16

Conclusion

In distal femoral cases, retrograde passage of the RIA through the nonunion site is technically feasible and has reproducible yields of intramedullary bone graft. Adequate mobilization of the nonunion is a prerequisite for reamer harvest. However, this technique obviates the need for an additional entry point. Furthermore, the technique may limit the perioperative fracture risk previously seen with eccentric reaming of the distal and proximal femur using traditional intramedullary harvest.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E493-E496. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Conway JD. Autograft and nonunions: morbidity with intramedullary bone graft versus iliac crest bone graft. Orthop Clin North Am. 2010;41(1):75-84.

2. Schmidmaier G, Herrmann S, Green J, et al. Quantitative assessment of growth factors in reaming aspirate, iliac crest, and platelet preparation. Bone. 2006;39(5):1156-1163.

3. Miller MA, Ivkovic A, Porter R, et al. Autologous bone grafting on steroids: preliminary clinical results. A novel treatment for nonunions and segmental bone defects. Int Orthop. 2011;35(4):599-605.

4. Qvick LM, Ritter CA, Mutty CE, Rohrbacher BJ, Buyea CM, Anders MJ. Donor site morbidity with Reamer-Irrigator-Aspirator (RIA) use for autogenous bone graft harvesting in a single centre 204 case series. Injury. 2013;44(10):1263-1269.

5. Kanakaris NK, Morell D, Gudipati S, Britten S, Giannoudis PV. Reaming Irrigator Aspirator system: early experience of its multipurpose use. Injury. 2011;42(suppl 4):S28-S34.

6. Dimitriou R, Mataliotakis GI, Angoules AG, Kanakaris NK, Giannoudis PV. Complications following autologous bone graft harvesting from the iliac crest and using the RIA: a systematic review. Injury. 2011;42(suppl 2):S3-S15.

7. Belthur MV, Conway JD, Jindal G, Ranade A, Herzenberg JE. Bone graft harvest using a new intramedullary system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(12):2973-2980.

8. Seagrave RA, Sojka J, Goodyear A, Munns SW. Utilizing Reamer Irrigator Aspirator (RIA) autograft for opening wedge high tibial osteotomy: a new surgical technique and report of three cases. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5(1):37-42.

9. Finnan RP, Prayson MJ, Goswami T, Miller D. Use of the Reamer-Irrigator-Aspirator for bone graft harvest: a mechanical comparison of three starting points in cadaveric femurs. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(1):36-41.

10. Masquelet AC, Benko PE, Mathevon H, Hannouche D, Obert L; French Society of Orthopaedics and Traumatic Surgery (SoFCOT). Harvest of cortico-cancellous intramedullary femoral bone graft using the Reamer-Irrigator-Aspirator (RIA). Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98(2):227-232.

11. Quintero AJ, Tarkin IS, Pape HC. Technical tricks when using the Reamer Irrigator Aspirator technique for autologous bone graft harvesting. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(1):42-45.

12. Cox G, Jones E, McGonagle D, Giannoudis PV. Reamer-Irrigator-Aspirator indications and clinical results: a systematic review. Int Orthop. 2011;35(7):951-956.

13. Dawson J, Kiner D, Gardner W 2nd, Swafford R, Nowotarski PJ. The Reamer-Irrigator-Aspirator as a device for harvesting bone graft compared with iliac crest bone graft: union rates and complications. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(10):584-590.

14. ElMaraghy AW, Humeniuk B, Anderson GI, Schemitsch EH, Richards RR. Femoral bone blood flow after reaming and intramedullary canal preparation: a canine study using laser Doppler flowmetry. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(2):220-226.

15. Finkemeier CG, Neiman R, Hallare D. RIA: one community’s experience. Orthop Clin North Am. 2010;41(1):99-103.

16. Myeroff C, Archdeacon M. Autogenous bone graft: donor sites and techniques. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(23):2227-2236.

1. Conway JD. Autograft and nonunions: morbidity with intramedullary bone graft versus iliac crest bone graft. Orthop Clin North Am. 2010;41(1):75-84.

2. Schmidmaier G, Herrmann S, Green J, et al. Quantitative assessment of growth factors in reaming aspirate, iliac crest, and platelet preparation. Bone. 2006;39(5):1156-1163.

3. Miller MA, Ivkovic A, Porter R, et al. Autologous bone grafting on steroids: preliminary clinical results. A novel treatment for nonunions and segmental bone defects. Int Orthop. 2011;35(4):599-605.

4. Qvick LM, Ritter CA, Mutty CE, Rohrbacher BJ, Buyea CM, Anders MJ. Donor site morbidity with Reamer-Irrigator-Aspirator (RIA) use for autogenous bone graft harvesting in a single centre 204 case series. Injury. 2013;44(10):1263-1269.

5. Kanakaris NK, Morell D, Gudipati S, Britten S, Giannoudis PV. Reaming Irrigator Aspirator system: early experience of its multipurpose use. Injury. 2011;42(suppl 4):S28-S34.

6. Dimitriou R, Mataliotakis GI, Angoules AG, Kanakaris NK, Giannoudis PV. Complications following autologous bone graft harvesting from the iliac crest and using the RIA: a systematic review. Injury. 2011;42(suppl 2):S3-S15.

7. Belthur MV, Conway JD, Jindal G, Ranade A, Herzenberg JE. Bone graft harvest using a new intramedullary system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(12):2973-2980.

8. Seagrave RA, Sojka J, Goodyear A, Munns SW. Utilizing Reamer Irrigator Aspirator (RIA) autograft for opening wedge high tibial osteotomy: a new surgical technique and report of three cases. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5(1):37-42.

9. Finnan RP, Prayson MJ, Goswami T, Miller D. Use of the Reamer-Irrigator-Aspirator for bone graft harvest: a mechanical comparison of three starting points in cadaveric femurs. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(1):36-41.

10. Masquelet AC, Benko PE, Mathevon H, Hannouche D, Obert L; French Society of Orthopaedics and Traumatic Surgery (SoFCOT). Harvest of cortico-cancellous intramedullary femoral bone graft using the Reamer-Irrigator-Aspirator (RIA). Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98(2):227-232.

11. Quintero AJ, Tarkin IS, Pape HC. Technical tricks when using the Reamer Irrigator Aspirator technique for autologous bone graft harvesting. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(1):42-45.

12. Cox G, Jones E, McGonagle D, Giannoudis PV. Reamer-Irrigator-Aspirator indications and clinical results: a systematic review. Int Orthop. 2011;35(7):951-956.

13. Dawson J, Kiner D, Gardner W 2nd, Swafford R, Nowotarski PJ. The Reamer-Irrigator-Aspirator as a device for harvesting bone graft compared with iliac crest bone graft: union rates and complications. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(10):584-590.

14. ElMaraghy AW, Humeniuk B, Anderson GI, Schemitsch EH, Richards RR. Femoral bone blood flow after reaming and intramedullary canal preparation: a canine study using laser Doppler flowmetry. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(2):220-226.

15. Finkemeier CG, Neiman R, Hallare D. RIA: one community’s experience. Orthop Clin North Am. 2010;41(1):99-103.

16. Myeroff C, Archdeacon M. Autogenous bone graft: donor sites and techniques. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(23):2227-2236.

VIDEO: Obinutuzumab bests rituximab for PFS in follicular lymphoma

SAN DIEGO – For patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma, adding the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab to a standard-combination chemotherapy regimen resulted in significant improvements in survival, compared with chemotherapy alone. Obinutuzumab (Gazyva), a second-generation anti-CD20 antibody touted as the heir apparent to rituximab, is being explored in various combinations for the treatment of indolent lymphomas, including follicular lymphoma and marginal zone lymphoma.

In this video interview from the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Robert Marcus, FRCP, of King’s College Hospital, London, discussed results of the phase III GALLIUM study, in which patients with untreated follicular lymphoma were randomly assigned to one of three chemotherapy regimens with either obinutuzumab or rituximab. The primary endpoint of investigator-assessed 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) at a median follow-up of 34.5 months was 80% for patients with follicular lymphoma treated with obinutuzumab and one of three standard chemotherapy regimens, compared with 73.3% for patients treated with rituximab and chemotherapy. This difference translated into a hazard ratio (HR) favoring obinutuzumab of 0.68 (P = .0012).

Respective 3-year overall survival rates at 3 years were similar, however, at 94% and 92.1% (HR, 0.75; P = .21).

The GALLIUM trial is sponsored by F. Hoffmann-La Roche. Dr. Marcus disclosed consulting with and receiving honoraria from the company, and relationships with other companies.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN DIEGO – For patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma, adding the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab to a standard-combination chemotherapy regimen resulted in significant improvements in survival, compared with chemotherapy alone. Obinutuzumab (Gazyva), a second-generation anti-CD20 antibody touted as the heir apparent to rituximab, is being explored in various combinations for the treatment of indolent lymphomas, including follicular lymphoma and marginal zone lymphoma.

In this video interview from the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Robert Marcus, FRCP, of King’s College Hospital, London, discussed results of the phase III GALLIUM study, in which patients with untreated follicular lymphoma were randomly assigned to one of three chemotherapy regimens with either obinutuzumab or rituximab. The primary endpoint of investigator-assessed 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) at a median follow-up of 34.5 months was 80% for patients with follicular lymphoma treated with obinutuzumab and one of three standard chemotherapy regimens, compared with 73.3% for patients treated with rituximab and chemotherapy. This difference translated into a hazard ratio (HR) favoring obinutuzumab of 0.68 (P = .0012).

Respective 3-year overall survival rates at 3 years were similar, however, at 94% and 92.1% (HR, 0.75; P = .21).

The GALLIUM trial is sponsored by F. Hoffmann-La Roche. Dr. Marcus disclosed consulting with and receiving honoraria from the company, and relationships with other companies.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN DIEGO – For patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma, adding the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab to a standard-combination chemotherapy regimen resulted in significant improvements in survival, compared with chemotherapy alone. Obinutuzumab (Gazyva), a second-generation anti-CD20 antibody touted as the heir apparent to rituximab, is being explored in various combinations for the treatment of indolent lymphomas, including follicular lymphoma and marginal zone lymphoma.

In this video interview from the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Robert Marcus, FRCP, of King’s College Hospital, London, discussed results of the phase III GALLIUM study, in which patients with untreated follicular lymphoma were randomly assigned to one of three chemotherapy regimens with either obinutuzumab or rituximab. The primary endpoint of investigator-assessed 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) at a median follow-up of 34.5 months was 80% for patients with follicular lymphoma treated with obinutuzumab and one of three standard chemotherapy regimens, compared with 73.3% for patients treated with rituximab and chemotherapy. This difference translated into a hazard ratio (HR) favoring obinutuzumab of 0.68 (P = .0012).

Respective 3-year overall survival rates at 3 years were similar, however, at 94% and 92.1% (HR, 0.75; P = .21).

The GALLIUM trial is sponsored by F. Hoffmann-La Roche. Dr. Marcus disclosed consulting with and receiving honoraria from the company, and relationships with other companies.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT ASH 2016

Obinutuzumab bests rituximab in FL study

ASH Annual Meeting

SAN DIEGO—Interim results of the phase 3 GALLIUM trial suggest an obinutuzumab-based treatment regimen provides a progression-free survival (PFS) benefit over a rituximab-based regimen for patients with previously untreated follicular lymphoma (FL).

According to investigators, patients who received obinutuzumab plus chemotherapy followed by obinutuzumab maintenance had a “clinically meaningful” improvement in PFS, when compared to patients who received rituximab plus chemotherapy followed by rituximab maintenance.

However, there was no significant difference between the treatment arms with regard to overall survival. And the incidence of non-fatal adverse events (AEs) was higher among the patients who received obinutuzumab.

Nevertheless, the data suggest that obinutuzumab-based therapy significantly improves outcomes and should be considered as a first-line treatment for FL, according to Robert Marcus, MBBS, of King’s College Hospital in London, UK.

Dr Marcus presented data from GALLIUM during the plenary session at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 6). GALLIUM is sponsored by Hoffmann-La Roche.

Patients and treatment

The study has enrolled 1401 patients with previously untreated, indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma, including 1202 with FL.

Half of the FL patients (n=601) were randomized to obinutuzumab plus chemotherapy followed by obinutuzumab alone for up to 2 years, and half were randomized to rituximab plus chemotherapy followed by rituximab alone for up to 2 years.

The different chemotherapies used were CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone), CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisolone), and bendamustine. The regimens were selected by each participating study site prior to beginning enrollment.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the treatment arms. The median age was about 60 (overall range, 23-88), roughly 40% of patients had high-risk disease, and the median time from diagnosis to randomization was about 1.5 months.

A total of 341 patients in the rituximab arm and 361 patients in the obinutuzumab arm completed maintenance therapy.

The median follow-up was 34.5 months. Maintenance is ongoing in 114 patients—54 on rituximab and 60 on obinutuzumab.

Efficacy

At the end of induction, the overall response rate was 86.9% in the rituximab arm and 88.5% in the obinutuzumab arm. The complete response rates were 23.8% and 19.5%, respectively. And the rates of stable disease were 1.3% and 0.5%, respectively.

The study’s primary endpoint is investigator-assessed PFS. The 3-year PFS rate is 73.3% in the rituximab arm and 80% in the obinutuzumab arm (hazard ratio [HR]=0.66, P=0.0012).

According to an independent review committee, the 3-year PFS is 77.9% in the rituximab arm and 81.9% in the obinutuzumab arm (HR=0.71, P=0.0138).

The 3-year overall survival is 92.1% in the rituximab arm and 94% in the obinutuzumab arm (HR=0.75, P=0.21).

Safety

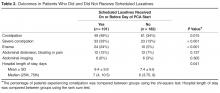

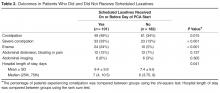

The overall incidence of AEs was 98.3% in the rituximab arm and 99.5% in the obinutuzumab arm. The incidence of serious AEs was 39.9% and 46.1%, respectively.

The incidence of AEs leading to treatment discontinuation was 14.2% and 16.3%, respectively. And the incidence of second neoplasms was 2.7% and 4.7%, respectively.

Grade 5 AEs occurred in 3.4% of patients in the rituximab arm and 4.0% of patients in the obinutuzumab arm. The investigators found that fatal AEs were more common in patients taking bendamustine, regardless of the treatment arm.

Grade 3 or higher AEs occurring in at least 5% of patients in either arm (rituximab and obinutuzumab, respectively) included neutropenia (67.8% and 74.6%), leukopenia (37.9% and 43.9%), febrile neutropenia (4.9% and 6.9%), infections and infestations (3.7% and 6.7%), and thrombocytopenia (2.7% and 6.1%). ![]()

ASH Annual Meeting

SAN DIEGO—Interim results of the phase 3 GALLIUM trial suggest an obinutuzumab-based treatment regimen provides a progression-free survival (PFS) benefit over a rituximab-based regimen for patients with previously untreated follicular lymphoma (FL).

According to investigators, patients who received obinutuzumab plus chemotherapy followed by obinutuzumab maintenance had a “clinically meaningful” improvement in PFS, when compared to patients who received rituximab plus chemotherapy followed by rituximab maintenance.

However, there was no significant difference between the treatment arms with regard to overall survival. And the incidence of non-fatal adverse events (AEs) was higher among the patients who received obinutuzumab.

Nevertheless, the data suggest that obinutuzumab-based therapy significantly improves outcomes and should be considered as a first-line treatment for FL, according to Robert Marcus, MBBS, of King’s College Hospital in London, UK.

Dr Marcus presented data from GALLIUM during the plenary session at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 6). GALLIUM is sponsored by Hoffmann-La Roche.

Patients and treatment

The study has enrolled 1401 patients with previously untreated, indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma, including 1202 with FL.

Half of the FL patients (n=601) were randomized to obinutuzumab plus chemotherapy followed by obinutuzumab alone for up to 2 years, and half were randomized to rituximab plus chemotherapy followed by rituximab alone for up to 2 years.

The different chemotherapies used were CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone), CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisolone), and bendamustine. The regimens were selected by each participating study site prior to beginning enrollment.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the treatment arms. The median age was about 60 (overall range, 23-88), roughly 40% of patients had high-risk disease, and the median time from diagnosis to randomization was about 1.5 months.

A total of 341 patients in the rituximab arm and 361 patients in the obinutuzumab arm completed maintenance therapy.

The median follow-up was 34.5 months. Maintenance is ongoing in 114 patients—54 on rituximab and 60 on obinutuzumab.

Efficacy

At the end of induction, the overall response rate was 86.9% in the rituximab arm and 88.5% in the obinutuzumab arm. The complete response rates were 23.8% and 19.5%, respectively. And the rates of stable disease were 1.3% and 0.5%, respectively.

The study’s primary endpoint is investigator-assessed PFS. The 3-year PFS rate is 73.3% in the rituximab arm and 80% in the obinutuzumab arm (hazard ratio [HR]=0.66, P=0.0012).

According to an independent review committee, the 3-year PFS is 77.9% in the rituximab arm and 81.9% in the obinutuzumab arm (HR=0.71, P=0.0138).

The 3-year overall survival is 92.1% in the rituximab arm and 94% in the obinutuzumab arm (HR=0.75, P=0.21).

Safety

The overall incidence of AEs was 98.3% in the rituximab arm and 99.5% in the obinutuzumab arm. The incidence of serious AEs was 39.9% and 46.1%, respectively.

The incidence of AEs leading to treatment discontinuation was 14.2% and 16.3%, respectively. And the incidence of second neoplasms was 2.7% and 4.7%, respectively.

Grade 5 AEs occurred in 3.4% of patients in the rituximab arm and 4.0% of patients in the obinutuzumab arm. The investigators found that fatal AEs were more common in patients taking bendamustine, regardless of the treatment arm.

Grade 3 or higher AEs occurring in at least 5% of patients in either arm (rituximab and obinutuzumab, respectively) included neutropenia (67.8% and 74.6%), leukopenia (37.9% and 43.9%), febrile neutropenia (4.9% and 6.9%), infections and infestations (3.7% and 6.7%), and thrombocytopenia (2.7% and 6.1%). ![]()

ASH Annual Meeting

SAN DIEGO—Interim results of the phase 3 GALLIUM trial suggest an obinutuzumab-based treatment regimen provides a progression-free survival (PFS) benefit over a rituximab-based regimen for patients with previously untreated follicular lymphoma (FL).

According to investigators, patients who received obinutuzumab plus chemotherapy followed by obinutuzumab maintenance had a “clinically meaningful” improvement in PFS, when compared to patients who received rituximab plus chemotherapy followed by rituximab maintenance.

However, there was no significant difference between the treatment arms with regard to overall survival. And the incidence of non-fatal adverse events (AEs) was higher among the patients who received obinutuzumab.

Nevertheless, the data suggest that obinutuzumab-based therapy significantly improves outcomes and should be considered as a first-line treatment for FL, according to Robert Marcus, MBBS, of King’s College Hospital in London, UK.

Dr Marcus presented data from GALLIUM during the plenary session at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 6). GALLIUM is sponsored by Hoffmann-La Roche.

Patients and treatment

The study has enrolled 1401 patients with previously untreated, indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma, including 1202 with FL.

Half of the FL patients (n=601) were randomized to obinutuzumab plus chemotherapy followed by obinutuzumab alone for up to 2 years, and half were randomized to rituximab plus chemotherapy followed by rituximab alone for up to 2 years.

The different chemotherapies used were CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone), CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisolone), and bendamustine. The regimens were selected by each participating study site prior to beginning enrollment.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the treatment arms. The median age was about 60 (overall range, 23-88), roughly 40% of patients had high-risk disease, and the median time from diagnosis to randomization was about 1.5 months.

A total of 341 patients in the rituximab arm and 361 patients in the obinutuzumab arm completed maintenance therapy.

The median follow-up was 34.5 months. Maintenance is ongoing in 114 patients—54 on rituximab and 60 on obinutuzumab.

Efficacy

At the end of induction, the overall response rate was 86.9% in the rituximab arm and 88.5% in the obinutuzumab arm. The complete response rates were 23.8% and 19.5%, respectively. And the rates of stable disease were 1.3% and 0.5%, respectively.

The study’s primary endpoint is investigator-assessed PFS. The 3-year PFS rate is 73.3% in the rituximab arm and 80% in the obinutuzumab arm (hazard ratio [HR]=0.66, P=0.0012).

According to an independent review committee, the 3-year PFS is 77.9% in the rituximab arm and 81.9% in the obinutuzumab arm (HR=0.71, P=0.0138).

The 3-year overall survival is 92.1% in the rituximab arm and 94% in the obinutuzumab arm (HR=0.75, P=0.21).

Safety

The overall incidence of AEs was 98.3% in the rituximab arm and 99.5% in the obinutuzumab arm. The incidence of serious AEs was 39.9% and 46.1%, respectively.

The incidence of AEs leading to treatment discontinuation was 14.2% and 16.3%, respectively. And the incidence of second neoplasms was 2.7% and 4.7%, respectively.

Grade 5 AEs occurred in 3.4% of patients in the rituximab arm and 4.0% of patients in the obinutuzumab arm. The investigators found that fatal AEs were more common in patients taking bendamustine, regardless of the treatment arm.

Grade 3 or higher AEs occurring in at least 5% of patients in either arm (rituximab and obinutuzumab, respectively) included neutropenia (67.8% and 74.6%), leukopenia (37.9% and 43.9%), febrile neutropenia (4.9% and 6.9%), infections and infestations (3.7% and 6.7%), and thrombocytopenia (2.7% and 6.1%). ![]()

Fanconi anemia linked to cancer gene

Researchers say they have discovered an important molecular link between Fanconi anemia (FA) and PTEN, a gene associated with uterine, prostate, and brain cancer.

They say this discovery enhances our understanding of the molecular basis of Fanconi anemia and could lead to improved treatment outcomes for both Fanconi anemia and cancer patients.

The researchers detailed their discovery in Scientific Reports.

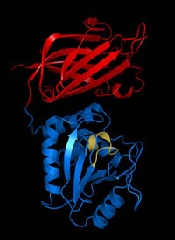

They explained that Fanconi anemia proteins function primarily in DNA interstrand crosslink (ICL) repair, and they wanted to determine the role of the PTEN phosphatase in this process.

“The PTEN gene codes for a phosphatase—an enzyme that removes phosphate groups from proteins,” said study author Niall Howlett, PhD, of the University of Rhode Island in Kingston, Rhode Island.

“Many Fanconi anemia proteins have phosphate groups attached to them when they become activated. However, how these phosphate groups are removed is poorly understood.”

With this in mind, the researchers performed an experiment to determine if Fanconi anemia and PTEN are biochemically linked.

The team knew that cells from Fanconi anemia patients are sensitive to ICL-inducing agents, so they set out to determine if PTEN-deficient cells are sensitive to these agents as well.

“By testing if cells with mutations in the PTEN gene were also sensitive to [ICL-inducing] agents, we discovered that Fanconi anemia patient cells and PTEN-deficient cells were practically indistinguishable in terms of sensitivity to these drugs,” Dr Howlett said.

“This strongly suggested that the Fanconi anemia proteins and PTEN might work together to repair the DNA damage caused by [ICL-inducing] agents.”

Using epistasis analysis, Dr Howlett and his colleagues found that Fanconi anemia proteins and PTEN do indeed function together in ICL repair.

“Before this work, Fanconi anemia and PTEN weren’t even on the same radar,” Dr Howlett said. “This is really important to understanding how this disease arises and what its molecular underpinnings are. The more we can find out about its molecular basis, the more likely we are to come up with strategies to treat the disease.”

Dr Howlett and his colleagues believe their research is equally important to cancer patients. Since this study showed that cells missing PTEN are highly sensitive to ICL-inducing agents, the team believes it should be possible to predict whether a particular cancer patient will respond to this class of drugs by conducting a simple DNA test.

“We can now predict that if a patient has cancer associated with mutations in PTEN, then it is likely that the cancer will be sensitive to [ICL-inducing] agents,” Dr Howlett said. “This could lead to improved outcomes for patients with certain types of PTEN mutations.” ![]()

Researchers say they have discovered an important molecular link between Fanconi anemia (FA) and PTEN, a gene associated with uterine, prostate, and brain cancer.

They say this discovery enhances our understanding of the molecular basis of Fanconi anemia and could lead to improved treatment outcomes for both Fanconi anemia and cancer patients.

The researchers detailed their discovery in Scientific Reports.

They explained that Fanconi anemia proteins function primarily in DNA interstrand crosslink (ICL) repair, and they wanted to determine the role of the PTEN phosphatase in this process.

“The PTEN gene codes for a phosphatase—an enzyme that removes phosphate groups from proteins,” said study author Niall Howlett, PhD, of the University of Rhode Island in Kingston, Rhode Island.

“Many Fanconi anemia proteins have phosphate groups attached to them when they become activated. However, how these phosphate groups are removed is poorly understood.”

With this in mind, the researchers performed an experiment to determine if Fanconi anemia and PTEN are biochemically linked.

The team knew that cells from Fanconi anemia patients are sensitive to ICL-inducing agents, so they set out to determine if PTEN-deficient cells are sensitive to these agents as well.

“By testing if cells with mutations in the PTEN gene were also sensitive to [ICL-inducing] agents, we discovered that Fanconi anemia patient cells and PTEN-deficient cells were practically indistinguishable in terms of sensitivity to these drugs,” Dr Howlett said.

“This strongly suggested that the Fanconi anemia proteins and PTEN might work together to repair the DNA damage caused by [ICL-inducing] agents.”

Using epistasis analysis, Dr Howlett and his colleagues found that Fanconi anemia proteins and PTEN do indeed function together in ICL repair.

“Before this work, Fanconi anemia and PTEN weren’t even on the same radar,” Dr Howlett said. “This is really important to understanding how this disease arises and what its molecular underpinnings are. The more we can find out about its molecular basis, the more likely we are to come up with strategies to treat the disease.”

Dr Howlett and his colleagues believe their research is equally important to cancer patients. Since this study showed that cells missing PTEN are highly sensitive to ICL-inducing agents, the team believes it should be possible to predict whether a particular cancer patient will respond to this class of drugs by conducting a simple DNA test.

“We can now predict that if a patient has cancer associated with mutations in PTEN, then it is likely that the cancer will be sensitive to [ICL-inducing] agents,” Dr Howlett said. “This could lead to improved outcomes for patients with certain types of PTEN mutations.” ![]()

Researchers say they have discovered an important molecular link between Fanconi anemia (FA) and PTEN, a gene associated with uterine, prostate, and brain cancer.

They say this discovery enhances our understanding of the molecular basis of Fanconi anemia and could lead to improved treatment outcomes for both Fanconi anemia and cancer patients.

The researchers detailed their discovery in Scientific Reports.

They explained that Fanconi anemia proteins function primarily in DNA interstrand crosslink (ICL) repair, and they wanted to determine the role of the PTEN phosphatase in this process.

“The PTEN gene codes for a phosphatase—an enzyme that removes phosphate groups from proteins,” said study author Niall Howlett, PhD, of the University of Rhode Island in Kingston, Rhode Island.

“Many Fanconi anemia proteins have phosphate groups attached to them when they become activated. However, how these phosphate groups are removed is poorly understood.”

With this in mind, the researchers performed an experiment to determine if Fanconi anemia and PTEN are biochemically linked.

The team knew that cells from Fanconi anemia patients are sensitive to ICL-inducing agents, so they set out to determine if PTEN-deficient cells are sensitive to these agents as well.

“By testing if cells with mutations in the PTEN gene were also sensitive to [ICL-inducing] agents, we discovered that Fanconi anemia patient cells and PTEN-deficient cells were practically indistinguishable in terms of sensitivity to these drugs,” Dr Howlett said.

“This strongly suggested that the Fanconi anemia proteins and PTEN might work together to repair the DNA damage caused by [ICL-inducing] agents.”

Using epistasis analysis, Dr Howlett and his colleagues found that Fanconi anemia proteins and PTEN do indeed function together in ICL repair.

“Before this work, Fanconi anemia and PTEN weren’t even on the same radar,” Dr Howlett said. “This is really important to understanding how this disease arises and what its molecular underpinnings are. The more we can find out about its molecular basis, the more likely we are to come up with strategies to treat the disease.”

Dr Howlett and his colleagues believe their research is equally important to cancer patients. Since this study showed that cells missing PTEN are highly sensitive to ICL-inducing agents, the team believes it should be possible to predict whether a particular cancer patient will respond to this class of drugs by conducting a simple DNA test.

“We can now predict that if a patient has cancer associated with mutations in PTEN, then it is likely that the cancer will be sensitive to [ICL-inducing] agents,” Dr Howlett said. “This could lead to improved outcomes for patients with certain types of PTEN mutations.” ![]()

VA Highlights Cancer Treatment Innovation, Best Practices at Launch Pad Event

The connections forged by the Cancer Moonshot will outlive the Obama administration, Greg Simon, executive director of the Cancer Moonshot Task Force, told a group of VA, nonprofit, and health care industry experts at the Launch Pad: Pathways to Cancer Innovation summit last month in Washington, DC. The event, cosponsored by the VA and the Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF), was a forum for discussing possible new approaches to oncology care and touting progress that has already occurred at the VA.

Related: Innovation and Cancer Moonshot Highlight AVAHO Conference

At the event, the VA and PCF also signed an agreement for a $50 million Precision Oncology Program that will expand prostate cancer clinical research among veterans and develop new treatment options and cures for prostate cancer patients.

Speakers at the summit included VA Secretary Robert McDonald VA Undersecretary of Health David J. Shulkin, MD; and Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Policy and Services Jennifer S. Lee, MD. According to Dr. Shulkin, the Million Veteran Program (MVP) has already surpassed 520,000 enrollees and has contracted with the U.S. Department of Energy to use its supercomputers to speed analysis and computation. In 2016, the VA managed 181,000 prostate cancer cases, and 26,000 deaths are projected. According to Shulkin, the VA also has developed the Center for Compassionate Innovation to enhance the health of veterans and their well-being by offering emerging therapies that are safe and ethical, particularly after traditional treatments have been unsuccessful.

Related: Building Better Models for Innovation in Health Care

At the meeting, a number of health care providers also discussed ongoing oncology programs that the VA hopes to expand. Drew Moghanaki, MD, MPH, director of clinical radiation oncology research at Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC in Richmond, Virginia, discussed efforts to make radiation oncology more precise for patients with lung cancer. Bruce Montgomery, MD, of the VA Puget Sound in Seattle, Washington, presented on the germline DNA testing of veterans with advanced prostate cancer, and Durham VAMC’s Neil Spector, MD, provided an update on using the Precision Oncology Program for more targeted therapies. Jennifer MacDonald, MD, VA’s director of clinical innovations and education, discussed the pilot and growth of virtual tumor boards to speed diagnosis and treatment to rural veterans with suspected cancers. The virtual tumor board was a recent example of a program developed through the Diffusion of Best Practices initiative spearheaded by Shereef Elnahal, MD, across the VA.

“Fighting and treating cancer among our veterans is a team effort, which is why this Launch Pad event and this partnership are so important,” Secretary McDonald told the group. “To effectively serve our veterans and to keep VA on the cutting edge of medical research, we need government, corporate, and nonprofit organizations working together. We are truly grateful to the Prostate Cancer Foundation for this important show of support. Our work together will save veterans’ lives.”

The connections forged by the Cancer Moonshot will outlive the Obama administration, Greg Simon, executive director of the Cancer Moonshot Task Force, told a group of VA, nonprofit, and health care industry experts at the Launch Pad: Pathways to Cancer Innovation summit last month in Washington, DC. The event, cosponsored by the VA and the Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF), was a forum for discussing possible new approaches to oncology care and touting progress that has already occurred at the VA.

Related: Innovation and Cancer Moonshot Highlight AVAHO Conference

At the event, the VA and PCF also signed an agreement for a $50 million Precision Oncology Program that will expand prostate cancer clinical research among veterans and develop new treatment options and cures for prostate cancer patients.

Speakers at the summit included VA Secretary Robert McDonald VA Undersecretary of Health David J. Shulkin, MD; and Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Policy and Services Jennifer S. Lee, MD. According to Dr. Shulkin, the Million Veteran Program (MVP) has already surpassed 520,000 enrollees and has contracted with the U.S. Department of Energy to use its supercomputers to speed analysis and computation. In 2016, the VA managed 181,000 prostate cancer cases, and 26,000 deaths are projected. According to Shulkin, the VA also has developed the Center for Compassionate Innovation to enhance the health of veterans and their well-being by offering emerging therapies that are safe and ethical, particularly after traditional treatments have been unsuccessful.

Related: Building Better Models for Innovation in Health Care

At the meeting, a number of health care providers also discussed ongoing oncology programs that the VA hopes to expand. Drew Moghanaki, MD, MPH, director of clinical radiation oncology research at Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC in Richmond, Virginia, discussed efforts to make radiation oncology more precise for patients with lung cancer. Bruce Montgomery, MD, of the VA Puget Sound in Seattle, Washington, presented on the germline DNA testing of veterans with advanced prostate cancer, and Durham VAMC’s Neil Spector, MD, provided an update on using the Precision Oncology Program for more targeted therapies. Jennifer MacDonald, MD, VA’s director of clinical innovations and education, discussed the pilot and growth of virtual tumor boards to speed diagnosis and treatment to rural veterans with suspected cancers. The virtual tumor board was a recent example of a program developed through the Diffusion of Best Practices initiative spearheaded by Shereef Elnahal, MD, across the VA.

“Fighting and treating cancer among our veterans is a team effort, which is why this Launch Pad event and this partnership are so important,” Secretary McDonald told the group. “To effectively serve our veterans and to keep VA on the cutting edge of medical research, we need government, corporate, and nonprofit organizations working together. We are truly grateful to the Prostate Cancer Foundation for this important show of support. Our work together will save veterans’ lives.”

The connections forged by the Cancer Moonshot will outlive the Obama administration, Greg Simon, executive director of the Cancer Moonshot Task Force, told a group of VA, nonprofit, and health care industry experts at the Launch Pad: Pathways to Cancer Innovation summit last month in Washington, DC. The event, cosponsored by the VA and the Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF), was a forum for discussing possible new approaches to oncology care and touting progress that has already occurred at the VA.

Related: Innovation and Cancer Moonshot Highlight AVAHO Conference

At the event, the VA and PCF also signed an agreement for a $50 million Precision Oncology Program that will expand prostate cancer clinical research among veterans and develop new treatment options and cures for prostate cancer patients.

Speakers at the summit included VA Secretary Robert McDonald VA Undersecretary of Health David J. Shulkin, MD; and Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Policy and Services Jennifer S. Lee, MD. According to Dr. Shulkin, the Million Veteran Program (MVP) has already surpassed 520,000 enrollees and has contracted with the U.S. Department of Energy to use its supercomputers to speed analysis and computation. In 2016, the VA managed 181,000 prostate cancer cases, and 26,000 deaths are projected. According to Shulkin, the VA also has developed the Center for Compassionate Innovation to enhance the health of veterans and their well-being by offering emerging therapies that are safe and ethical, particularly after traditional treatments have been unsuccessful.

Related: Building Better Models for Innovation in Health Care

At the meeting, a number of health care providers also discussed ongoing oncology programs that the VA hopes to expand. Drew Moghanaki, MD, MPH, director of clinical radiation oncology research at Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC in Richmond, Virginia, discussed efforts to make radiation oncology more precise for patients with lung cancer. Bruce Montgomery, MD, of the VA Puget Sound in Seattle, Washington, presented on the germline DNA testing of veterans with advanced prostate cancer, and Durham VAMC’s Neil Spector, MD, provided an update on using the Precision Oncology Program for more targeted therapies. Jennifer MacDonald, MD, VA’s director of clinical innovations and education, discussed the pilot and growth of virtual tumor boards to speed diagnosis and treatment to rural veterans with suspected cancers. The virtual tumor board was a recent example of a program developed through the Diffusion of Best Practices initiative spearheaded by Shereef Elnahal, MD, across the VA.

“Fighting and treating cancer among our veterans is a team effort, which is why this Launch Pad event and this partnership are so important,” Secretary McDonald told the group. “To effectively serve our veterans and to keep VA on the cutting edge of medical research, we need government, corporate, and nonprofit organizations working together. We are truly grateful to the Prostate Cancer Foundation for this important show of support. Our work together will save veterans’ lives.”

Shulkin: VA "Not a Political Issue”

Federal Practitioner sat down for an exclusive interview with VA Under Secretary of Health David J. Shulkin, MD at the recent Launch Pad: Pathways to Cancer Innovation, November 29, 2016. As the clock winds down on the current administration, the interview covered a wide range of topic. The below video that discusses VA progress over the past 18 months since Shulkin was confirmed and the prospects for change in the new administration. Future videos will cover the Veterans Choice Program, employee morale and recruitment challenges, improving rural care, transparency, and the unique nature of VA’s mission and care.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Federal Practitioner sat down for an exclusive interview with VA Under Secretary of Health David J. Shulkin, MD at the recent Launch Pad: Pathways to Cancer Innovation, November 29, 2016. As the clock winds down on the current administration, the interview covered a wide range of topic. The below video that discusses VA progress over the past 18 months since Shulkin was confirmed and the prospects for change in the new administration. Future videos will cover the Veterans Choice Program, employee morale and recruitment challenges, improving rural care, transparency, and the unique nature of VA’s mission and care.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Federal Practitioner sat down for an exclusive interview with VA Under Secretary of Health David J. Shulkin, MD at the recent Launch Pad: Pathways to Cancer Innovation, November 29, 2016. As the clock winds down on the current administration, the interview covered a wide range of topic. The below video that discusses VA progress over the past 18 months since Shulkin was confirmed and the prospects for change in the new administration. Future videos will cover the Veterans Choice Program, employee morale and recruitment challenges, improving rural care, transparency, and the unique nature of VA’s mission and care.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Combo shows early promise in newly diagnosed AML

© Todd Buchanan 2016

SAN DIEGO—A targeted therapy combined with standard chemotherapy can produce rapid, deep remissions in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to research presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting.

In this phase 1b study, investigators tested vadastuximab talirine, an antibody drug conjugate targeting CD33, in combination with 7+3 chemotherapy—a continuous infusion of cytarabine for 7 days plus daunorubicin for 3 days.

The combination produced a high rate of response, which included minimal residual disease (MRD)-negative complete remissions (CRs).

The treatment also resulted in “acceptable” on-target myelosuppression and non-hematologic adverse events (AEs) similar to what would be expected with 7+3 alone, according to study investigator Harry Erba, MD, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Dr Erba presented these results in abstract 211.* The research was sponsored by Seattle Genetics, Inc.

The study included 42 newly diagnosed AML patients with a median age of 45.5. Half the patients had intermediate-risk karyotypes, 36% had adverse karyotypes, and 17% had secondary AML.

Patients received escalating doses of vadastuximab talirine (10+10 mcg/kg [n=4] and 20+10 mcg/kg [n=38]) in combination with 7+3 induction (cytarabine at 100 mg/m2 and daunorubicin at 60 mg/m2) on days 1 and 4 of a 28-day treatment cycle. Responses were assessed on days 15 and 28.

A second induction regimen and post-remission therapies were prescribed according to investigator choice and did not include vadastuximab talirine.

Results

The maximum tolerated dose of vadastuximab talirine was 20+10 mcg/kg.

Hematologic treatment-related AEs included febrile neutropenia (43%, grade 1-3), thrombocytopenia (38%, grade 3-4), anemia (24%, grade 3), and neutropenia (17%, grade 3-4).

Non-hematologic treatment-related AEs included nausea (17%), fatigue (14%), diarrhea (7%), and decreased appetite (7%). All of these AEs were grade 1-2.

None of the patients experienced infusion-related reactions, veno-occlusive disease, or significant liver damage.

A total of 76% of patients responded to treatment, with 60% percent achieving a CR and 17% achieving a CR with incomplete blood count recovery (CRi).

The 76% response rate is close to what would be expected for a well-chosen population fit for a clinical trial, Dr Erba said.

There was a hint of additional benefit as well, he added.

“The first hint was that 30 out of the 32 patients [who achieved a CR/CRi] required only 1 round of chemotherapy to achieve that remission,” Dr Erba said. “This also suggested that deeper remissions may be possible.”

MRD assessments using a sensitive flow cytometric assay revealed that 25 of the 32 patients (78%) who achieved a CR/CRi were MRD-negative.

Dr Erba said a randomized, phase 2 trial of vadastuximab talirine plus 7+3 versus 7+3 alone is planned for the first quarter of 2017. ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

© Todd Buchanan 2016

SAN DIEGO—A targeted therapy combined with standard chemotherapy can produce rapid, deep remissions in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to research presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting.

In this phase 1b study, investigators tested vadastuximab talirine, an antibody drug conjugate targeting CD33, in combination with 7+3 chemotherapy—a continuous infusion of cytarabine for 7 days plus daunorubicin for 3 days.

The combination produced a high rate of response, which included minimal residual disease (MRD)-negative complete remissions (CRs).

The treatment also resulted in “acceptable” on-target myelosuppression and non-hematologic adverse events (AEs) similar to what would be expected with 7+3 alone, according to study investigator Harry Erba, MD, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Dr Erba presented these results in abstract 211.* The research was sponsored by Seattle Genetics, Inc.

The study included 42 newly diagnosed AML patients with a median age of 45.5. Half the patients had intermediate-risk karyotypes, 36% had adverse karyotypes, and 17% had secondary AML.

Patients received escalating doses of vadastuximab talirine (10+10 mcg/kg [n=4] and 20+10 mcg/kg [n=38]) in combination with 7+3 induction (cytarabine at 100 mg/m2 and daunorubicin at 60 mg/m2) on days 1 and 4 of a 28-day treatment cycle. Responses were assessed on days 15 and 28.

A second induction regimen and post-remission therapies were prescribed according to investigator choice and did not include vadastuximab talirine.

Results

The maximum tolerated dose of vadastuximab talirine was 20+10 mcg/kg.

Hematologic treatment-related AEs included febrile neutropenia (43%, grade 1-3), thrombocytopenia (38%, grade 3-4), anemia (24%, grade 3), and neutropenia (17%, grade 3-4).

Non-hematologic treatment-related AEs included nausea (17%), fatigue (14%), diarrhea (7%), and decreased appetite (7%). All of these AEs were grade 1-2.

None of the patients experienced infusion-related reactions, veno-occlusive disease, or significant liver damage.

A total of 76% of patients responded to treatment, with 60% percent achieving a CR and 17% achieving a CR with incomplete blood count recovery (CRi).

The 76% response rate is close to what would be expected for a well-chosen population fit for a clinical trial, Dr Erba said.

There was a hint of additional benefit as well, he added.

“The first hint was that 30 out of the 32 patients [who achieved a CR/CRi] required only 1 round of chemotherapy to achieve that remission,” Dr Erba said. “This also suggested that deeper remissions may be possible.”