User login

Keeping up with New Payment Models

While in medical school, I learned about what was then called GRID (gay-related immune deficiency) and we now know as HIV/AIDS. I thought this condition would become so central to practice in nearly any specialty that I decided to try to keep up with all of the literature on it. It wasn’t yet in textbooks, so I thought it would be very important to keep up with all the new research studies and review articles about it.

I kept in my apartment a growing file of articles photocopied and torn out of journals. But I had badly misjudged the enormity of the task, and within a few years, there were far too many articles for me to read or keep up with in any fashion. Before long, HIV medicine became its own specialty, and while it has always been something I, like any hospitalist, need to know something about, I’ve left it to others to be the real HIV experts.

I was naive to have embarked on the quest. What seemed manageable at first became overwhelming very quickly. The same could be said for trying to keep up with new payment models.

New Professional Fee Reimbursement Models

For decades, most physicians could understand the general concept of how their professional activities generated revenue. But it’s gotten a lot more complicated lately.

The growing prevalence of capitation and other managed-care reimbursement models in the ’80s and ’90s might have been when reimbursement complexity began to increase significantly. But while nearly every doctor in the country heard about managed care, for many, it was something happening elsewhere that never made its way to them.

But for hospitalists, I think the arrival of the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS, originally Physician Quality Reporting Initiative, or PQRI) marks the swerve in reimbursement complexity. Some years ago I wrote in these pages about the importance of hospitalists understanding PQRS and described key features of the program.

Like HIV/AIDS medicine literature, the breadth and complexity of reimbursement programs from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (and other payors) seem to have grown logarithmically since PQRS. The still relatively new bundled payment and MACRA-related models are far more complicated than PQRS. And they change often. Calendar milestones come and go with changes in relevant metrics and performance thresholds, etc. Even the terminology changes frequently. Did you know, for example, that under MIPSi “Advancing Care Information” is essentially a new name for EHR Meaningful Use?

Bundled payments and MACRA are only a small portion of new models implemented over the last few years. There are many others, and dedicated effort is required just to keep track of whether each model influences only physicians (and other providers), only hospitals, or both.

Clinicians’ Responsibility for Keeping Up

My thinking about most hospitalists, or doctors in any specialty, keeping up with all of these models has evolved the same way it did with HIV/AIDS. I think it’s pretty clear that it’s folly to expect most clinicians to know more than the broad outlines of these programs.

Payment models are important. Someone needs to know them in detail, but clinicians should reserve brain cells for clinical knowledge base and focus only on the big picture of payment models. Think how well you’ve done learning and keeping up with CPT coding, observation versus inpatient status determinations, and clinical documentation. You probably still aren’t an expert at these things, so is it wise to set about becoming an expert in new payment models?

Instead, most hospitalists should rely on others to keep up with the precise details of these programs. Most commonly that will mean our employer will appoint or hire one or more people, or engage an outside party, to do this.

Don’t Feel Guilty

It’s common to leave a presentation or doctor’s lounge conversation on payment models feeling like you need to study up on the details of this or that payment model since good performance under that model will be important for your paycheck and to remain a viable “player.” And speakers sometimes intentionally or unintentionally enhance your anxiety about this. Maybe they love to show off what they know, and it’s easy for them to think only about their topic and not keep in mind all of the other stuff you need to know.

It’s terrific if someone in your practice is particularly interested in payment models and chooses to stay on top of them. Just make sure that doesn’t come at the expense of keeping up with changes in clinical practice. Most groups won’t have such a person and should rely on others, including SHM, without feeling the smallest bit of guilt.

SHM is advocating on behalf of hospitalists and working diligently to distill the impact MACRA and its various alternative payment frameworks will have on hospital medicine. With webinars, Q&As, and additional online and print resources, SHM will continue to provide digestible updates for hospitalists and their practices.

The End of Small-Group Physician Practice?

While the intent of these programs is to encourage and reward improvements in clinical practice, keeping up with and managing them is a tax that takes resources away from clinical practice. This is an especially difficult burden for small private practices and may prove to be a significant factor in nearly extinguishing them. There are relatively few small private hospitalist groups,ii but all of them should carefully consider how they will keep up with new reimbursement models.

While in medical school, I learned about what was then called GRID (gay-related immune deficiency) and we now know as HIV/AIDS. I thought this condition would become so central to practice in nearly any specialty that I decided to try to keep up with all of the literature on it. It wasn’t yet in textbooks, so I thought it would be very important to keep up with all the new research studies and review articles about it.

I kept in my apartment a growing file of articles photocopied and torn out of journals. But I had badly misjudged the enormity of the task, and within a few years, there were far too many articles for me to read or keep up with in any fashion. Before long, HIV medicine became its own specialty, and while it has always been something I, like any hospitalist, need to know something about, I’ve left it to others to be the real HIV experts.

I was naive to have embarked on the quest. What seemed manageable at first became overwhelming very quickly. The same could be said for trying to keep up with new payment models.

New Professional Fee Reimbursement Models

For decades, most physicians could understand the general concept of how their professional activities generated revenue. But it’s gotten a lot more complicated lately.

The growing prevalence of capitation and other managed-care reimbursement models in the ’80s and ’90s might have been when reimbursement complexity began to increase significantly. But while nearly every doctor in the country heard about managed care, for many, it was something happening elsewhere that never made its way to them.

But for hospitalists, I think the arrival of the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS, originally Physician Quality Reporting Initiative, or PQRI) marks the swerve in reimbursement complexity. Some years ago I wrote in these pages about the importance of hospitalists understanding PQRS and described key features of the program.

Like HIV/AIDS medicine literature, the breadth and complexity of reimbursement programs from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (and other payors) seem to have grown logarithmically since PQRS. The still relatively new bundled payment and MACRA-related models are far more complicated than PQRS. And they change often. Calendar milestones come and go with changes in relevant metrics and performance thresholds, etc. Even the terminology changes frequently. Did you know, for example, that under MIPSi “Advancing Care Information” is essentially a new name for EHR Meaningful Use?

Bundled payments and MACRA are only a small portion of new models implemented over the last few years. There are many others, and dedicated effort is required just to keep track of whether each model influences only physicians (and other providers), only hospitals, or both.

Clinicians’ Responsibility for Keeping Up

My thinking about most hospitalists, or doctors in any specialty, keeping up with all of these models has evolved the same way it did with HIV/AIDS. I think it’s pretty clear that it’s folly to expect most clinicians to know more than the broad outlines of these programs.

Payment models are important. Someone needs to know them in detail, but clinicians should reserve brain cells for clinical knowledge base and focus only on the big picture of payment models. Think how well you’ve done learning and keeping up with CPT coding, observation versus inpatient status determinations, and clinical documentation. You probably still aren’t an expert at these things, so is it wise to set about becoming an expert in new payment models?

Instead, most hospitalists should rely on others to keep up with the precise details of these programs. Most commonly that will mean our employer will appoint or hire one or more people, or engage an outside party, to do this.

Don’t Feel Guilty

It’s common to leave a presentation or doctor’s lounge conversation on payment models feeling like you need to study up on the details of this or that payment model since good performance under that model will be important for your paycheck and to remain a viable “player.” And speakers sometimes intentionally or unintentionally enhance your anxiety about this. Maybe they love to show off what they know, and it’s easy for them to think only about their topic and not keep in mind all of the other stuff you need to know.

It’s terrific if someone in your practice is particularly interested in payment models and chooses to stay on top of them. Just make sure that doesn’t come at the expense of keeping up with changes in clinical practice. Most groups won’t have such a person and should rely on others, including SHM, without feeling the smallest bit of guilt.

SHM is advocating on behalf of hospitalists and working diligently to distill the impact MACRA and its various alternative payment frameworks will have on hospital medicine. With webinars, Q&As, and additional online and print resources, SHM will continue to provide digestible updates for hospitalists and their practices.

The End of Small-Group Physician Practice?

While the intent of these programs is to encourage and reward improvements in clinical practice, keeping up with and managing them is a tax that takes resources away from clinical practice. This is an especially difficult burden for small private practices and may prove to be a significant factor in nearly extinguishing them. There are relatively few small private hospitalist groups,ii but all of them should carefully consider how they will keep up with new reimbursement models.

While in medical school, I learned about what was then called GRID (gay-related immune deficiency) and we now know as HIV/AIDS. I thought this condition would become so central to practice in nearly any specialty that I decided to try to keep up with all of the literature on it. It wasn’t yet in textbooks, so I thought it would be very important to keep up with all the new research studies and review articles about it.

I kept in my apartment a growing file of articles photocopied and torn out of journals. But I had badly misjudged the enormity of the task, and within a few years, there were far too many articles for me to read or keep up with in any fashion. Before long, HIV medicine became its own specialty, and while it has always been something I, like any hospitalist, need to know something about, I’ve left it to others to be the real HIV experts.

I was naive to have embarked on the quest. What seemed manageable at first became overwhelming very quickly. The same could be said for trying to keep up with new payment models.

New Professional Fee Reimbursement Models

For decades, most physicians could understand the general concept of how their professional activities generated revenue. But it’s gotten a lot more complicated lately.

The growing prevalence of capitation and other managed-care reimbursement models in the ’80s and ’90s might have been when reimbursement complexity began to increase significantly. But while nearly every doctor in the country heard about managed care, for many, it was something happening elsewhere that never made its way to them.

But for hospitalists, I think the arrival of the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS, originally Physician Quality Reporting Initiative, or PQRI) marks the swerve in reimbursement complexity. Some years ago I wrote in these pages about the importance of hospitalists understanding PQRS and described key features of the program.

Like HIV/AIDS medicine literature, the breadth and complexity of reimbursement programs from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (and other payors) seem to have grown logarithmically since PQRS. The still relatively new bundled payment and MACRA-related models are far more complicated than PQRS. And they change often. Calendar milestones come and go with changes in relevant metrics and performance thresholds, etc. Even the terminology changes frequently. Did you know, for example, that under MIPSi “Advancing Care Information” is essentially a new name for EHR Meaningful Use?

Bundled payments and MACRA are only a small portion of new models implemented over the last few years. There are many others, and dedicated effort is required just to keep track of whether each model influences only physicians (and other providers), only hospitals, or both.

Clinicians’ Responsibility for Keeping Up

My thinking about most hospitalists, or doctors in any specialty, keeping up with all of these models has evolved the same way it did with HIV/AIDS. I think it’s pretty clear that it’s folly to expect most clinicians to know more than the broad outlines of these programs.

Payment models are important. Someone needs to know them in detail, but clinicians should reserve brain cells for clinical knowledge base and focus only on the big picture of payment models. Think how well you’ve done learning and keeping up with CPT coding, observation versus inpatient status determinations, and clinical documentation. You probably still aren’t an expert at these things, so is it wise to set about becoming an expert in new payment models?

Instead, most hospitalists should rely on others to keep up with the precise details of these programs. Most commonly that will mean our employer will appoint or hire one or more people, or engage an outside party, to do this.

Don’t Feel Guilty

It’s common to leave a presentation or doctor’s lounge conversation on payment models feeling like you need to study up on the details of this or that payment model since good performance under that model will be important for your paycheck and to remain a viable “player.” And speakers sometimes intentionally or unintentionally enhance your anxiety about this. Maybe they love to show off what they know, and it’s easy for them to think only about their topic and not keep in mind all of the other stuff you need to know.

It’s terrific if someone in your practice is particularly interested in payment models and chooses to stay on top of them. Just make sure that doesn’t come at the expense of keeping up with changes in clinical practice. Most groups won’t have such a person and should rely on others, including SHM, without feeling the smallest bit of guilt.

SHM is advocating on behalf of hospitalists and working diligently to distill the impact MACRA and its various alternative payment frameworks will have on hospital medicine. With webinars, Q&As, and additional online and print resources, SHM will continue to provide digestible updates for hospitalists and their practices.

The End of Small-Group Physician Practice?

While the intent of these programs is to encourage and reward improvements in clinical practice, keeping up with and managing them is a tax that takes resources away from clinical practice. This is an especially difficult burden for small private practices and may prove to be a significant factor in nearly extinguishing them. There are relatively few small private hospitalist groups,ii but all of them should carefully consider how they will keep up with new reimbursement models.

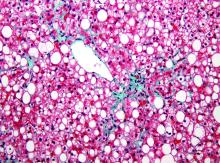

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease accelerates brain aging

TORONTO – Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease seems to accelerate physical brain aging by up to 7 years, according to a new subanalysis of the ongoing Framingham Heart Study.

However, while finding that the liver disorder directly endangers brains, the study also offers hope, Galit Weinstein, PhD, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016. “If indeed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a risk factor for brain aging and subsequent dementia, then it is a modifiable one,” said Dr. Weinstein of Boston University. “We have reason to hope that NAFLD remission could possibly improve cognitive outcomes” as patients age.

For this study, the researchers assessed the presence of NAFLD by abdominal CT scans and white-matter hyperintensities and brain volume (total, frontal, and hippocampal) by MRI. The resulting associations were then adjusted for age, sex, alcohol consumption, visceral adipose tissue, body mass index, menopausal status, systolic blood pressure, current smoking, diabetes, history of cardiovascular disease, physical activity, insulin resistance, and C-reactive protein.

There were no significant associations with white-matter hyperintensities or with hippocampal volume, but the researches did find a significant association with total brain volume: Even after adjustment for all of the covariates, patients with NAFLD had smaller-than-normal brains for their age. This can be seen as a pathologic acceleration of the brain aging process, Dr. Weinstein said.

The finding was most striking among the youngest subjects, she said, accounting for about a 7-year advance in brain aging for those younger than 60 years. Older patients with NAFLD showed about a 2-year advance in brain aging.

The effect is probably mediated by the liver’s complex interplay in metabolism and vascular functions, Dr. Weinstein said.

She had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

TORONTO – Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease seems to accelerate physical brain aging by up to 7 years, according to a new subanalysis of the ongoing Framingham Heart Study.

However, while finding that the liver disorder directly endangers brains, the study also offers hope, Galit Weinstein, PhD, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016. “If indeed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a risk factor for brain aging and subsequent dementia, then it is a modifiable one,” said Dr. Weinstein of Boston University. “We have reason to hope that NAFLD remission could possibly improve cognitive outcomes” as patients age.

For this study, the researchers assessed the presence of NAFLD by abdominal CT scans and white-matter hyperintensities and brain volume (total, frontal, and hippocampal) by MRI. The resulting associations were then adjusted for age, sex, alcohol consumption, visceral adipose tissue, body mass index, menopausal status, systolic blood pressure, current smoking, diabetes, history of cardiovascular disease, physical activity, insulin resistance, and C-reactive protein.

There were no significant associations with white-matter hyperintensities or with hippocampal volume, but the researches did find a significant association with total brain volume: Even after adjustment for all of the covariates, patients with NAFLD had smaller-than-normal brains for their age. This can be seen as a pathologic acceleration of the brain aging process, Dr. Weinstein said.

The finding was most striking among the youngest subjects, she said, accounting for about a 7-year advance in brain aging for those younger than 60 years. Older patients with NAFLD showed about a 2-year advance in brain aging.

The effect is probably mediated by the liver’s complex interplay in metabolism and vascular functions, Dr. Weinstein said.

She had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

TORONTO – Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease seems to accelerate physical brain aging by up to 7 years, according to a new subanalysis of the ongoing Framingham Heart Study.

However, while finding that the liver disorder directly endangers brains, the study also offers hope, Galit Weinstein, PhD, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016. “If indeed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a risk factor for brain aging and subsequent dementia, then it is a modifiable one,” said Dr. Weinstein of Boston University. “We have reason to hope that NAFLD remission could possibly improve cognitive outcomes” as patients age.

For this study, the researchers assessed the presence of NAFLD by abdominal CT scans and white-matter hyperintensities and brain volume (total, frontal, and hippocampal) by MRI. The resulting associations were then adjusted for age, sex, alcohol consumption, visceral adipose tissue, body mass index, menopausal status, systolic blood pressure, current smoking, diabetes, history of cardiovascular disease, physical activity, insulin resistance, and C-reactive protein.

There were no significant associations with white-matter hyperintensities or with hippocampal volume, but the researches did find a significant association with total brain volume: Even after adjustment for all of the covariates, patients with NAFLD had smaller-than-normal brains for their age. This can be seen as a pathologic acceleration of the brain aging process, Dr. Weinstein said.

The finding was most striking among the youngest subjects, she said, accounting for about a 7-year advance in brain aging for those younger than 60 years. Older patients with NAFLD showed about a 2-year advance in brain aging.

The effect is probably mediated by the liver’s complex interplay in metabolism and vascular functions, Dr. Weinstein said.

She had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT AAIC 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: NAFLD was associated with a 7-year advance in brain aging in people younger than 60 years.

Data source: An analysis of 906 members of the Framingham Offspring Cohort.

Disclosures: Dr. Weinstein had no financial declarations.

VIDEO: Pivotal results nail osimertinib’s role in NSCLC

VIENNA – Osimertinib, a third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor that received U.S. marketing approval in November 2015 as second-line treatment for selected patients with non–small-cell lung cancer based on phase II trial data, now has the pivotal-trial results that completely justify that action.

During a median follow-up of just over 8 months, patients who had progressed on their first-line EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) and carried the T790M mutation and switched to osimertinib (Tagrisso) had “overwhelmingly” better response rates and progression-free survival, compared with patients put on standard-of-care chemotherapy in a multicenter randomized trial involving 419 patients, Vassiliki A. Papadimitrakopoulou, MD, reported at the World Conference on Lung Cancer.

The AZD9291 Versus Platinum-Based Doublet-Chemotherapy in Locally Advanced or Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (AURA3) trial enrolled 419 patients at 126 international sites during 2014 and 2015. The trial’s primary endpoint was investigator-assessed progression-free survival, which occurred after a median of 10.1 months with osimertinib and 4.4 months with standard chemotherapy, a statistically significant 70% relative risk reduction (P less than .001) in the hazard for death or progressive disease. The drug was as effective for patients with central nervous system metastases as it was for the other patients, which Dr. Papadimitrakopoulou attributed to osimertinib’s good penetration across the blood-brain barrier. The drug’s overall performance in AURA3 was completely consistent with the results of earlier studies that led to its U.S. approval.

Despite that approval, routine testing for T790M mutations and routine prescribing of osimertinib to positive patients “has not fully penetrated U.S. practice,” Dr. Papadimitrakopoulou said, but she hoped that these new confirmatory data will now firmly establish it as standard of care for the tested population.

Osimertinib is now under testing as first-line TKI treatment for EGFR-positive NSCLC regardless of the tumor’s T790M status. It’s going head to head with two first-generation EGFR TKIs, gefitinib and erlotinib, in the FLAURA trial, which should have reportable results in 2017. “We are very encouraged by the AURA3 data that osimertinib could beat the first-generation TKIs” for first-line treatment, she said.

AURA3 was sponsored by AstraZeneca, which markets osimertinib (Tagrisso). Dr. Papadimitrakopoulou is a consultant to, and has received research support from, AstraZeneca and several other companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Osimertinib overcomes the T790M mutation, which is the cause of about half of the non–small-cell lung cancers that are EGFR positive and develop resistance to a first- or-second generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor. The AURA3 results officially make osimertinib the standard of care for these patients.

Osimertinib’s performance in AURA3 was consistent with what it did in the earlier studies, producing an overall response rate of about 60%-70% and extending progression-free survival out to a median of 10-11 months.

Tetsuya Mitsudomi, MD, is professor of thoracic surgery at Kindai University in Osaka-Sayama, Japan. He has been a consultant to, and has received honoraria and research support from, AstraZeneca and several other companies. He was principal investigator for AURA2, one of the phase II studies of osimertinib. He made these comments as designated discussant for AURA3.

Osimertinib overcomes the T790M mutation, which is the cause of about half of the non–small-cell lung cancers that are EGFR positive and develop resistance to a first- or-second generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor. The AURA3 results officially make osimertinib the standard of care for these patients.

Osimertinib’s performance in AURA3 was consistent with what it did in the earlier studies, producing an overall response rate of about 60%-70% and extending progression-free survival out to a median of 10-11 months.

Tetsuya Mitsudomi, MD, is professor of thoracic surgery at Kindai University in Osaka-Sayama, Japan. He has been a consultant to, and has received honoraria and research support from, AstraZeneca and several other companies. He was principal investigator for AURA2, one of the phase II studies of osimertinib. He made these comments as designated discussant for AURA3.

Osimertinib overcomes the T790M mutation, which is the cause of about half of the non–small-cell lung cancers that are EGFR positive and develop resistance to a first- or-second generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor. The AURA3 results officially make osimertinib the standard of care for these patients.

Osimertinib’s performance in AURA3 was consistent with what it did in the earlier studies, producing an overall response rate of about 60%-70% and extending progression-free survival out to a median of 10-11 months.

Tetsuya Mitsudomi, MD, is professor of thoracic surgery at Kindai University in Osaka-Sayama, Japan. He has been a consultant to, and has received honoraria and research support from, AstraZeneca and several other companies. He was principal investigator for AURA2, one of the phase II studies of osimertinib. He made these comments as designated discussant for AURA3.

VIENNA – Osimertinib, a third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor that received U.S. marketing approval in November 2015 as second-line treatment for selected patients with non–small-cell lung cancer based on phase II trial data, now has the pivotal-trial results that completely justify that action.

During a median follow-up of just over 8 months, patients who had progressed on their first-line EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) and carried the T790M mutation and switched to osimertinib (Tagrisso) had “overwhelmingly” better response rates and progression-free survival, compared with patients put on standard-of-care chemotherapy in a multicenter randomized trial involving 419 patients, Vassiliki A. Papadimitrakopoulou, MD, reported at the World Conference on Lung Cancer.

The AZD9291 Versus Platinum-Based Doublet-Chemotherapy in Locally Advanced or Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (AURA3) trial enrolled 419 patients at 126 international sites during 2014 and 2015. The trial’s primary endpoint was investigator-assessed progression-free survival, which occurred after a median of 10.1 months with osimertinib and 4.4 months with standard chemotherapy, a statistically significant 70% relative risk reduction (P less than .001) in the hazard for death or progressive disease. The drug was as effective for patients with central nervous system metastases as it was for the other patients, which Dr. Papadimitrakopoulou attributed to osimertinib’s good penetration across the blood-brain barrier. The drug’s overall performance in AURA3 was completely consistent with the results of earlier studies that led to its U.S. approval.

Despite that approval, routine testing for T790M mutations and routine prescribing of osimertinib to positive patients “has not fully penetrated U.S. practice,” Dr. Papadimitrakopoulou said, but she hoped that these new confirmatory data will now firmly establish it as standard of care for the tested population.

Osimertinib is now under testing as first-line TKI treatment for EGFR-positive NSCLC regardless of the tumor’s T790M status. It’s going head to head with two first-generation EGFR TKIs, gefitinib and erlotinib, in the FLAURA trial, which should have reportable results in 2017. “We are very encouraged by the AURA3 data that osimertinib could beat the first-generation TKIs” for first-line treatment, she said.

AURA3 was sponsored by AstraZeneca, which markets osimertinib (Tagrisso). Dr. Papadimitrakopoulou is a consultant to, and has received research support from, AstraZeneca and several other companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

VIENNA – Osimertinib, a third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor that received U.S. marketing approval in November 2015 as second-line treatment for selected patients with non–small-cell lung cancer based on phase II trial data, now has the pivotal-trial results that completely justify that action.

During a median follow-up of just over 8 months, patients who had progressed on their first-line EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) and carried the T790M mutation and switched to osimertinib (Tagrisso) had “overwhelmingly” better response rates and progression-free survival, compared with patients put on standard-of-care chemotherapy in a multicenter randomized trial involving 419 patients, Vassiliki A. Papadimitrakopoulou, MD, reported at the World Conference on Lung Cancer.

The AZD9291 Versus Platinum-Based Doublet-Chemotherapy in Locally Advanced or Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (AURA3) trial enrolled 419 patients at 126 international sites during 2014 and 2015. The trial’s primary endpoint was investigator-assessed progression-free survival, which occurred after a median of 10.1 months with osimertinib and 4.4 months with standard chemotherapy, a statistically significant 70% relative risk reduction (P less than .001) in the hazard for death or progressive disease. The drug was as effective for patients with central nervous system metastases as it was for the other patients, which Dr. Papadimitrakopoulou attributed to osimertinib’s good penetration across the blood-brain barrier. The drug’s overall performance in AURA3 was completely consistent with the results of earlier studies that led to its U.S. approval.

Despite that approval, routine testing for T790M mutations and routine prescribing of osimertinib to positive patients “has not fully penetrated U.S. practice,” Dr. Papadimitrakopoulou said, but she hoped that these new confirmatory data will now firmly establish it as standard of care for the tested population.

Osimertinib is now under testing as first-line TKI treatment for EGFR-positive NSCLC regardless of the tumor’s T790M status. It’s going head to head with two first-generation EGFR TKIs, gefitinib and erlotinib, in the FLAURA trial, which should have reportable results in 2017. “We are very encouraged by the AURA3 data that osimertinib could beat the first-generation TKIs” for first-line treatment, she said.

AURA3 was sponsored by AstraZeneca, which markets osimertinib (Tagrisso). Dr. Papadimitrakopoulou is a consultant to, and has received research support from, AstraZeneca and several other companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Progression-free survival averaged 10.1 months with osimertinib and 4.4 months in patients on standard chemotherapy.

Data source: AURA3, which randomized 419 patients at 126 international centers.

Disclosures: AURA3 was sponsored by AstraZeneca, which markets osimertinib (Tagrisso). Dr. Papadimitrakopoulou is a consultant to, and has received research support from, AstraZeneca and several other companies.

AGA Guideline: Preventing Crohn’s recurrence after resection

Patients whose Crohn’s disease fully remits after resection should not wait for endoscopic recurrence to start tumor-necrosis-factor inhibitors or thiopurines, according to a new guideline from the American Gastroenterological Association.

Patients who are low risk or worried about side effects, however, “may reasonably select endoscopy-guided pharmacological treatment,” the guidelines state (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.038).

Early pharmacologic prophylaxis usually begins within 8 weeks of surgery, they noted. Whether this approach bests endoscopy-guided treatment is unclear: In one small trial (Gastroenterology. 2013;145[4]:766-74.e1), early azathioprine therapy failed to best endoscopy-guided therapy for preventing clinical or endoscopic recurrence.

Early prophylaxis, however, is usually reasonable because most Crohn’s patients who undergo surgery have at least one risk factor for recurrence, Dr. Nguyen and his associates emphasize. They suggest reserving endoscopy-guided therapy for patients who have real concerns about side effects and are at low risk, such as nonsmokers who were diagnosed within 10 years and have less than 10-20 cm of fibrostenotic disease.

For prophylaxis, a moderate amount of evidence supports anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, thiopurines, or combined therapy over other agents, the guideline also states. In placebo-controlled clinical trials, anti-TNF therapy reduced the chances of clinical recurrence by 49% and endoscopic recurrence by 76%, while thiopurines cut these rates by 65% and 60%, respectively. Evidence favors anti-TNF agents over thiopurines for preventing recurrence, but it is of low quality, the guideline says. Furthermore, only indirect evidence supports combined therapy in patients at highest risk of recurrence.

Among the antibiotics, only nitroimidazoles such as metronidazole have been adequately studied, and they posted worse results than anti-TNF agents or thiopurines. Antibiotic therapy decreased the risk of endoscopic recurrence of Crohn’s disease by about 50%, but long-term use is associated with peripheral neuropathy and disease usually recurs within 2 years of stopping treatment. Accordingly, the guidelines suggest using a nitroimidazole for only 3-12 months, and only in lower-risk patients who are concerned about the adverse effects of anti-TNF agents and thiopurines.

The AGA made a conditional recommendation against the prophylactic use of budesonide, probiotics, and 5-aminosalicylates such as mesalamine. Only low-quality evidence supports their efficacy after resection, and by using these agents, clinicians may inadvertently boost the risk of recurrence by forgoing better therapies, the guideline states.

The initial endoscopy should be timed for 6-12 months after resection, regardless of whether patients are receiving pharmacologic prophylaxis, the guideline states. If there is endoscopic recurrence, then anti-TNF or thiopurine therapy should be started or optimized.

In the Postoperative Crohn’s Endoscopic Recurrence (POCER) trial, endoscopic monitoring and treatment escalation in the face of endoscopic recurrence cut the risk of subsequent clinical and endoscopic recurrence by about 18% and 27%, respectively, compared with continuing the original treatment regimen. Most patients received azathioprine or adalimumab with 3 months of metronidazole postoperatively, so “even [those] who were already on postoperative prophylaxis benefited from endoscopic monitoring with colonoscopy at 6-12 months,” the guideline notes. However, patients who elect early prophylaxis after resection can reasonably forego colonoscopy if endoscopic recurrence is unlikely to affect their treatment plan, the AGA states. The guideline strongly recommends ongoing surveillance endoscopies if patients decide against early postresection prophylaxis, but notes a lack of evidence on how far to space out these procedures.

None of the authors had relevant financial disclosures.

Patients whose Crohn’s disease fully remits after resection should not wait for endoscopic recurrence to start tumor-necrosis-factor inhibitors or thiopurines, according to a new guideline from the American Gastroenterological Association.

Patients who are low risk or worried about side effects, however, “may reasonably select endoscopy-guided pharmacological treatment,” the guidelines state (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.038).

Early pharmacologic prophylaxis usually begins within 8 weeks of surgery, they noted. Whether this approach bests endoscopy-guided treatment is unclear: In one small trial (Gastroenterology. 2013;145[4]:766-74.e1), early azathioprine therapy failed to best endoscopy-guided therapy for preventing clinical or endoscopic recurrence.

Early prophylaxis, however, is usually reasonable because most Crohn’s patients who undergo surgery have at least one risk factor for recurrence, Dr. Nguyen and his associates emphasize. They suggest reserving endoscopy-guided therapy for patients who have real concerns about side effects and are at low risk, such as nonsmokers who were diagnosed within 10 years and have less than 10-20 cm of fibrostenotic disease.

For prophylaxis, a moderate amount of evidence supports anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, thiopurines, or combined therapy over other agents, the guideline also states. In placebo-controlled clinical trials, anti-TNF therapy reduced the chances of clinical recurrence by 49% and endoscopic recurrence by 76%, while thiopurines cut these rates by 65% and 60%, respectively. Evidence favors anti-TNF agents over thiopurines for preventing recurrence, but it is of low quality, the guideline says. Furthermore, only indirect evidence supports combined therapy in patients at highest risk of recurrence.

Among the antibiotics, only nitroimidazoles such as metronidazole have been adequately studied, and they posted worse results than anti-TNF agents or thiopurines. Antibiotic therapy decreased the risk of endoscopic recurrence of Crohn’s disease by about 50%, but long-term use is associated with peripheral neuropathy and disease usually recurs within 2 years of stopping treatment. Accordingly, the guidelines suggest using a nitroimidazole for only 3-12 months, and only in lower-risk patients who are concerned about the adverse effects of anti-TNF agents and thiopurines.

The AGA made a conditional recommendation against the prophylactic use of budesonide, probiotics, and 5-aminosalicylates such as mesalamine. Only low-quality evidence supports their efficacy after resection, and by using these agents, clinicians may inadvertently boost the risk of recurrence by forgoing better therapies, the guideline states.

The initial endoscopy should be timed for 6-12 months after resection, regardless of whether patients are receiving pharmacologic prophylaxis, the guideline states. If there is endoscopic recurrence, then anti-TNF or thiopurine therapy should be started or optimized.

In the Postoperative Crohn’s Endoscopic Recurrence (POCER) trial, endoscopic monitoring and treatment escalation in the face of endoscopic recurrence cut the risk of subsequent clinical and endoscopic recurrence by about 18% and 27%, respectively, compared with continuing the original treatment regimen. Most patients received azathioprine or adalimumab with 3 months of metronidazole postoperatively, so “even [those] who were already on postoperative prophylaxis benefited from endoscopic monitoring with colonoscopy at 6-12 months,” the guideline notes. However, patients who elect early prophylaxis after resection can reasonably forego colonoscopy if endoscopic recurrence is unlikely to affect their treatment plan, the AGA states. The guideline strongly recommends ongoing surveillance endoscopies if patients decide against early postresection prophylaxis, but notes a lack of evidence on how far to space out these procedures.

None of the authors had relevant financial disclosures.

Patients whose Crohn’s disease fully remits after resection should not wait for endoscopic recurrence to start tumor-necrosis-factor inhibitors or thiopurines, according to a new guideline from the American Gastroenterological Association.

Patients who are low risk or worried about side effects, however, “may reasonably select endoscopy-guided pharmacological treatment,” the guidelines state (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.038).

Early pharmacologic prophylaxis usually begins within 8 weeks of surgery, they noted. Whether this approach bests endoscopy-guided treatment is unclear: In one small trial (Gastroenterology. 2013;145[4]:766-74.e1), early azathioprine therapy failed to best endoscopy-guided therapy for preventing clinical or endoscopic recurrence.

Early prophylaxis, however, is usually reasonable because most Crohn’s patients who undergo surgery have at least one risk factor for recurrence, Dr. Nguyen and his associates emphasize. They suggest reserving endoscopy-guided therapy for patients who have real concerns about side effects and are at low risk, such as nonsmokers who were diagnosed within 10 years and have less than 10-20 cm of fibrostenotic disease.

For prophylaxis, a moderate amount of evidence supports anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, thiopurines, or combined therapy over other agents, the guideline also states. In placebo-controlled clinical trials, anti-TNF therapy reduced the chances of clinical recurrence by 49% and endoscopic recurrence by 76%, while thiopurines cut these rates by 65% and 60%, respectively. Evidence favors anti-TNF agents over thiopurines for preventing recurrence, but it is of low quality, the guideline says. Furthermore, only indirect evidence supports combined therapy in patients at highest risk of recurrence.

Among the antibiotics, only nitroimidazoles such as metronidazole have been adequately studied, and they posted worse results than anti-TNF agents or thiopurines. Antibiotic therapy decreased the risk of endoscopic recurrence of Crohn’s disease by about 50%, but long-term use is associated with peripheral neuropathy and disease usually recurs within 2 years of stopping treatment. Accordingly, the guidelines suggest using a nitroimidazole for only 3-12 months, and only in lower-risk patients who are concerned about the adverse effects of anti-TNF agents and thiopurines.

The AGA made a conditional recommendation against the prophylactic use of budesonide, probiotics, and 5-aminosalicylates such as mesalamine. Only low-quality evidence supports their efficacy after resection, and by using these agents, clinicians may inadvertently boost the risk of recurrence by forgoing better therapies, the guideline states.

The initial endoscopy should be timed for 6-12 months after resection, regardless of whether patients are receiving pharmacologic prophylaxis, the guideline states. If there is endoscopic recurrence, then anti-TNF or thiopurine therapy should be started or optimized.

In the Postoperative Crohn’s Endoscopic Recurrence (POCER) trial, endoscopic monitoring and treatment escalation in the face of endoscopic recurrence cut the risk of subsequent clinical and endoscopic recurrence by about 18% and 27%, respectively, compared with continuing the original treatment regimen. Most patients received azathioprine or adalimumab with 3 months of metronidazole postoperatively, so “even [those] who were already on postoperative prophylaxis benefited from endoscopic monitoring with colonoscopy at 6-12 months,” the guideline notes. However, patients who elect early prophylaxis after resection can reasonably forego colonoscopy if endoscopic recurrence is unlikely to affect their treatment plan, the AGA states. The guideline strongly recommends ongoing surveillance endoscopies if patients decide against early postresection prophylaxis, but notes a lack of evidence on how far to space out these procedures.

None of the authors had relevant financial disclosures.

Gene transfer for hemophilia B shows progress

SAN DIEGO—Researchers say they have optimized the SPK-9001 adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector

so that a “simple infusion” has significantly reduced bleeding events and the need for regular factor IX (FIX) infusions in 9 hemophilia B patients.

Eight of the patients were able to stop receiving FIX infusions and achieved an annualized bleeding rate (ABR) of 0. One patient had an ABR of 2 and required on-demand FIX therapy.

Lindsey George, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, presented these data, updating the interim results from the phase 1/2 trial of SPK-9001, during the plenary session of the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 3*).

The trial is sponsored by Spark Therapeutics in collaboration with Pfizer.

Dr George explained that the bulk of hemophilia gene transfer efforts have coalesced around the use of in vitro, liver-directed, recombinant AAV vectors.

Earlier data showed sustained FIX activity at approximately 5% with AAV-serotype 8 (AAV8) vectors at 2 x 1012 vg/kg. However, levels of FIX:C at 12% are necessary to avoid bleeding into the joints, and higher doses elicit a capsid immune response.

Therefore, the team hypothesized that a highly efficient vector capsid and expression cassette, administered at low doses, would increase FIX expression to therapeutic levels and minimize the risk of a capsid immune response.

They developed an AAV capsid (Spark100) with a liver promoter and an expression cassette consisting of a codon-optimized, single-strand transgene encoding FIX-Padua.

In a prior AAV liver-directed gene transfer clinical trial, no patient developed inhibitors.

So the team conducted a phase 1/2 trial in males age 18 and older who had FIX:C levels of 2% or less.

The patients had to have less than 1:5 neutralizing antibodies to Spark100, more than 50 factor exposure days, no prior history of FIX inhibitors, no active hepatitis B or C virus, and liver fibrosis of stage 2 or less. They had to have a negative HIV viral load with CD4 levels of 200/mm3 or more.

At baseline, patients had to be on prophylaxis or be receiving on-demand therapy and have 4 or more bleeding events the year prior to infusion or a history of hemophilic arthropathy.

Results

The researchers enrolled 9 participants, ages 18 to 52. Six patients were on prophylaxis, and 3 had on-demand therapy at baseline.

They received a 1-hour, outpatient, intravenous infusion of SPK-9001 at 5 x 1011 vg/kg and were followed up for 52 weeks, with a long-term follow-up of 14 years.

Five patients had a history of HCV, and 1 had a history of HIV and was maintained on antiretroviral therapy.

One patient had neutralizing antibody titers to Spark100 capsid at a 1:1 ratio.

Prior to receiving SPK-9001, the patients required an annual number of infusions ranging from 0 to 159. Three patients had ABRs of 0, but the remaining patients had ABRs of 1, 2, 4, 10, 12, and 49.

After receiving SPK-9001, 8 of the patients were able to stop receiving FIX infusions and

achieved an ABR of 0. One patient had an ABR of 2 and required on-demand FIX therapy.

Dr George described one patient, a 23-year-old male who had severe hemophilia B and was maintained on weekly rFIX-Fc prophylaxis. He had no history of HCV or HIV.

Prior to receiving SPK-9001, he had 98 infusions and 4 breakthrough bleeds. After SPK-9001, he had a FIX activity level of 33% of normal at 52 weeks, no bleeding episodes, and required no rescue factor.

He had no vector-related adverse events, required no immunosuppression, and was safely off prophylaxis.

“Clinically, what this has meant for this man is he is now off his prophylaxis, he has no longer had breakthrough bleeding events, and he has not required factor for any reason,” Dr George said.

Capsid immune responses

Seven patients had less than 1:1 Spark100 neutralizing antibody at baseline and did not require steroids.

Their mean steady-state FIX activity was 31.9 + 7.4% at a follow-up of 12 to 52 weeks. Their liver function tests remained less than 1.5 times the upper limit of normal.

Two patients had capsid immune responses requiring steroid treatment.

One patient, a 45-year-old male, had a FIX:C of 1.9%, experienced 49 bleeding events prior to receiving SPK-9001, and was treated on-demand.

After SPK-9001, he had no vector-related adverse events, received a course of prednisone, and, at 20 weeks follow-up, had experienced no bleeding events and did not require factor use.

The second patient who had a capsid immune response was 36 years of age and on FIX prophylaxis. He had a history of HCV and no history of HIV.

After SPK-9001, he experienced no bleeding and required no factor use. He had grade 1 transaminase toxicity, which returned to within normal limits.

He is taking 40 mg prednisone daily and has stable FIX:C activity at 49 days after vector infusion.

Overall transgene-derived FIX activity

At a follow-up of 7 to 52 weeks, for a cumulative 238 weeks for all patients, their mean steady-state FIX activity was 28.3 + 10.0% of normal.

They had no vector or procedure-related unexpected adverse events, although 1 patient had transient grade 1 transaminase toxicity.

No patient developed FIX alloinhibitory antibodies.

One patient had FIX:C activity of 68% of normal at 7 weeks, and the first patient infused had 33% FIX:C activity at 52 weeks.

The transgene-derived FIX activity resulted in a significant reduction in bleeding events (P<0.05) and factor use (P<0.05). All patients stopped their prophylaxis.

The researchers recommend a larger cohort and continued observation to confirm these results.

Dr George noted that SPK-9001 has received breakthrough therapy designation from the US Food and Drug Administration. ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

SAN DIEGO—Researchers say they have optimized the SPK-9001 adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector

so that a “simple infusion” has significantly reduced bleeding events and the need for regular factor IX (FIX) infusions in 9 hemophilia B patients.

Eight of the patients were able to stop receiving FIX infusions and achieved an annualized bleeding rate (ABR) of 0. One patient had an ABR of 2 and required on-demand FIX therapy.

Lindsey George, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, presented these data, updating the interim results from the phase 1/2 trial of SPK-9001, during the plenary session of the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 3*).

The trial is sponsored by Spark Therapeutics in collaboration with Pfizer.

Dr George explained that the bulk of hemophilia gene transfer efforts have coalesced around the use of in vitro, liver-directed, recombinant AAV vectors.

Earlier data showed sustained FIX activity at approximately 5% with AAV-serotype 8 (AAV8) vectors at 2 x 1012 vg/kg. However, levels of FIX:C at 12% are necessary to avoid bleeding into the joints, and higher doses elicit a capsid immune response.

Therefore, the team hypothesized that a highly efficient vector capsid and expression cassette, administered at low doses, would increase FIX expression to therapeutic levels and minimize the risk of a capsid immune response.

They developed an AAV capsid (Spark100) with a liver promoter and an expression cassette consisting of a codon-optimized, single-strand transgene encoding FIX-Padua.

In a prior AAV liver-directed gene transfer clinical trial, no patient developed inhibitors.

So the team conducted a phase 1/2 trial in males age 18 and older who had FIX:C levels of 2% or less.

The patients had to have less than 1:5 neutralizing antibodies to Spark100, more than 50 factor exposure days, no prior history of FIX inhibitors, no active hepatitis B or C virus, and liver fibrosis of stage 2 or less. They had to have a negative HIV viral load with CD4 levels of 200/mm3 or more.

At baseline, patients had to be on prophylaxis or be receiving on-demand therapy and have 4 or more bleeding events the year prior to infusion or a history of hemophilic arthropathy.

Results

The researchers enrolled 9 participants, ages 18 to 52. Six patients were on prophylaxis, and 3 had on-demand therapy at baseline.

They received a 1-hour, outpatient, intravenous infusion of SPK-9001 at 5 x 1011 vg/kg and were followed up for 52 weeks, with a long-term follow-up of 14 years.

Five patients had a history of HCV, and 1 had a history of HIV and was maintained on antiretroviral therapy.

One patient had neutralizing antibody titers to Spark100 capsid at a 1:1 ratio.

Prior to receiving SPK-9001, the patients required an annual number of infusions ranging from 0 to 159. Three patients had ABRs of 0, but the remaining patients had ABRs of 1, 2, 4, 10, 12, and 49.

After receiving SPK-9001, 8 of the patients were able to stop receiving FIX infusions and

achieved an ABR of 0. One patient had an ABR of 2 and required on-demand FIX therapy.

Dr George described one patient, a 23-year-old male who had severe hemophilia B and was maintained on weekly rFIX-Fc prophylaxis. He had no history of HCV or HIV.

Prior to receiving SPK-9001, he had 98 infusions and 4 breakthrough bleeds. After SPK-9001, he had a FIX activity level of 33% of normal at 52 weeks, no bleeding episodes, and required no rescue factor.

He had no vector-related adverse events, required no immunosuppression, and was safely off prophylaxis.

“Clinically, what this has meant for this man is he is now off his prophylaxis, he has no longer had breakthrough bleeding events, and he has not required factor for any reason,” Dr George said.

Capsid immune responses

Seven patients had less than 1:1 Spark100 neutralizing antibody at baseline and did not require steroids.

Their mean steady-state FIX activity was 31.9 + 7.4% at a follow-up of 12 to 52 weeks. Their liver function tests remained less than 1.5 times the upper limit of normal.

Two patients had capsid immune responses requiring steroid treatment.

One patient, a 45-year-old male, had a FIX:C of 1.9%, experienced 49 bleeding events prior to receiving SPK-9001, and was treated on-demand.

After SPK-9001, he had no vector-related adverse events, received a course of prednisone, and, at 20 weeks follow-up, had experienced no bleeding events and did not require factor use.

The second patient who had a capsid immune response was 36 years of age and on FIX prophylaxis. He had a history of HCV and no history of HIV.

After SPK-9001, he experienced no bleeding and required no factor use. He had grade 1 transaminase toxicity, which returned to within normal limits.

He is taking 40 mg prednisone daily and has stable FIX:C activity at 49 days after vector infusion.

Overall transgene-derived FIX activity

At a follow-up of 7 to 52 weeks, for a cumulative 238 weeks for all patients, their mean steady-state FIX activity was 28.3 + 10.0% of normal.

They had no vector or procedure-related unexpected adverse events, although 1 patient had transient grade 1 transaminase toxicity.

No patient developed FIX alloinhibitory antibodies.

One patient had FIX:C activity of 68% of normal at 7 weeks, and the first patient infused had 33% FIX:C activity at 52 weeks.

The transgene-derived FIX activity resulted in a significant reduction in bleeding events (P<0.05) and factor use (P<0.05). All patients stopped their prophylaxis.

The researchers recommend a larger cohort and continued observation to confirm these results.

Dr George noted that SPK-9001 has received breakthrough therapy designation from the US Food and Drug Administration. ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

SAN DIEGO—Researchers say they have optimized the SPK-9001 adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector

so that a “simple infusion” has significantly reduced bleeding events and the need for regular factor IX (FIX) infusions in 9 hemophilia B patients.

Eight of the patients were able to stop receiving FIX infusions and achieved an annualized bleeding rate (ABR) of 0. One patient had an ABR of 2 and required on-demand FIX therapy.

Lindsey George, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, presented these data, updating the interim results from the phase 1/2 trial of SPK-9001, during the plenary session of the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 3*).

The trial is sponsored by Spark Therapeutics in collaboration with Pfizer.

Dr George explained that the bulk of hemophilia gene transfer efforts have coalesced around the use of in vitro, liver-directed, recombinant AAV vectors.

Earlier data showed sustained FIX activity at approximately 5% with AAV-serotype 8 (AAV8) vectors at 2 x 1012 vg/kg. However, levels of FIX:C at 12% are necessary to avoid bleeding into the joints, and higher doses elicit a capsid immune response.

Therefore, the team hypothesized that a highly efficient vector capsid and expression cassette, administered at low doses, would increase FIX expression to therapeutic levels and minimize the risk of a capsid immune response.

They developed an AAV capsid (Spark100) with a liver promoter and an expression cassette consisting of a codon-optimized, single-strand transgene encoding FIX-Padua.

In a prior AAV liver-directed gene transfer clinical trial, no patient developed inhibitors.

So the team conducted a phase 1/2 trial in males age 18 and older who had FIX:C levels of 2% or less.

The patients had to have less than 1:5 neutralizing antibodies to Spark100, more than 50 factor exposure days, no prior history of FIX inhibitors, no active hepatitis B or C virus, and liver fibrosis of stage 2 or less. They had to have a negative HIV viral load with CD4 levels of 200/mm3 or more.

At baseline, patients had to be on prophylaxis or be receiving on-demand therapy and have 4 or more bleeding events the year prior to infusion or a history of hemophilic arthropathy.

Results

The researchers enrolled 9 participants, ages 18 to 52. Six patients were on prophylaxis, and 3 had on-demand therapy at baseline.

They received a 1-hour, outpatient, intravenous infusion of SPK-9001 at 5 x 1011 vg/kg and were followed up for 52 weeks, with a long-term follow-up of 14 years.

Five patients had a history of HCV, and 1 had a history of HIV and was maintained on antiretroviral therapy.

One patient had neutralizing antibody titers to Spark100 capsid at a 1:1 ratio.

Prior to receiving SPK-9001, the patients required an annual number of infusions ranging from 0 to 159. Three patients had ABRs of 0, but the remaining patients had ABRs of 1, 2, 4, 10, 12, and 49.

After receiving SPK-9001, 8 of the patients were able to stop receiving FIX infusions and

achieved an ABR of 0. One patient had an ABR of 2 and required on-demand FIX therapy.

Dr George described one patient, a 23-year-old male who had severe hemophilia B and was maintained on weekly rFIX-Fc prophylaxis. He had no history of HCV or HIV.

Prior to receiving SPK-9001, he had 98 infusions and 4 breakthrough bleeds. After SPK-9001, he had a FIX activity level of 33% of normal at 52 weeks, no bleeding episodes, and required no rescue factor.

He had no vector-related adverse events, required no immunosuppression, and was safely off prophylaxis.

“Clinically, what this has meant for this man is he is now off his prophylaxis, he has no longer had breakthrough bleeding events, and he has not required factor for any reason,” Dr George said.

Capsid immune responses

Seven patients had less than 1:1 Spark100 neutralizing antibody at baseline and did not require steroids.

Their mean steady-state FIX activity was 31.9 + 7.4% at a follow-up of 12 to 52 weeks. Their liver function tests remained less than 1.5 times the upper limit of normal.

Two patients had capsid immune responses requiring steroid treatment.

One patient, a 45-year-old male, had a FIX:C of 1.9%, experienced 49 bleeding events prior to receiving SPK-9001, and was treated on-demand.

After SPK-9001, he had no vector-related adverse events, received a course of prednisone, and, at 20 weeks follow-up, had experienced no bleeding events and did not require factor use.

The second patient who had a capsid immune response was 36 years of age and on FIX prophylaxis. He had a history of HCV and no history of HIV.

After SPK-9001, he experienced no bleeding and required no factor use. He had grade 1 transaminase toxicity, which returned to within normal limits.

He is taking 40 mg prednisone daily and has stable FIX:C activity at 49 days after vector infusion.

Overall transgene-derived FIX activity

At a follow-up of 7 to 52 weeks, for a cumulative 238 weeks for all patients, their mean steady-state FIX activity was 28.3 + 10.0% of normal.

They had no vector or procedure-related unexpected adverse events, although 1 patient had transient grade 1 transaminase toxicity.

No patient developed FIX alloinhibitory antibodies.

One patient had FIX:C activity of 68% of normal at 7 weeks, and the first patient infused had 33% FIX:C activity at 52 weeks.

The transgene-derived FIX activity resulted in a significant reduction in bleeding events (P<0.05) and factor use (P<0.05). All patients stopped their prophylaxis.

The researchers recommend a larger cohort and continued observation to confirm these results.

Dr George noted that SPK-9001 has received breakthrough therapy designation from the US Food and Drug Administration. ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

MPNs limit daily activities and ability to work

2016 ASH Annual Meeting

SAN DIEGO—Many patients living with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) have a high burden of disease that affects their quality of life and limits their ability to work, according to research presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting.

Researchers conducted the first-ever international survey of MPN patients, including those with myelofibrosis (MF), polycythemia vera (PV), and essential thrombocythemia (ET).

Patients reported a high prevalence of symptoms, an increase in the number of symptoms from diagnosis, and reductions in emotional well-being, quality of life, and ability to work.

“The survey results help paint the full picture of the impact of these diseases,” said Claire Harrison, DM, of Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in London, UK.

“The dominating symptom is fatigue, which validates what we are seeing in the clinic. The novel findings regarding the impact on patient’s work life show the consequences of MPNs.”

Dr Harrison and her colleagues reported these findings at the meeting as (abstract 4267*).

The international MPN LANDMARK survey included 699 patients with MPNs (174 with MF, 223 with PV, and 302 with ET), and physicians who treated these conditions across Germany, Italy, UK, Japan, Canada, and Australia.

Patients completed an online questionnaire to measure MPN-related symptoms experienced over the past year and the impact of their condition on quality of life and ability to work.

Patients reported that their disease negatively impacted their ability to complete daily activities by 40%. Patients also noted 35% impairment in their capacity to work. Patients who missed work over the last 7 days due to illness reported missing an average of 3.1 hours due to their disease and/or symptom burden.

“For one quarter of PV patients, the disease stopped them from working, and another one quarter voluntarily reduced their work time,” Dr Harrison said. “This was surprising. Even though their disease was managed, it impacted their work life.”

She noted that many of her PV patients are young, working professionals.

Results also showed that about three-quarters of patients who experienced symptoms suffered a significant reduction in quality of life due to symptoms (83% of MF patients, 72% of PV patients, and 74% of ET patients).

These results are consistent with those from a previous US LANDMARK survey of MPN patients.

The most commonly reported symptom in the last 12 months was fatigue (54% of MF patients, 45% of PV patients, and 64% of ET patients). This was also the symptom patients stated they most wanted to resolve.

“Patients stated doctors often don’t ask enough about the details of symptoms,” Dr Harrison said.

In addition to physical symptoms, about one-third of patients felt anxious or worried about their disease (34% of MF patients, 29% of PV patients, and 26% of ET patients).

“We found a mismatch in aspirations of MPN patients and their physicians,” Dr Harrison said. “For example, physicians said it was important to teach PV patients to prevent blood clots. PV patients were more concerned with having a better quality of life and slowing disease progression.”

A comprehensive symptom assessment is important to help physicians understand other hardships of these diseases, she said, noting “in our service, we enlist nutritionists and psychologists and also use physiotherapists and occupational therapists.” ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

2016 ASH Annual Meeting

SAN DIEGO—Many patients living with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) have a high burden of disease that affects their quality of life and limits their ability to work, according to research presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting.

Researchers conducted the first-ever international survey of MPN patients, including those with myelofibrosis (MF), polycythemia vera (PV), and essential thrombocythemia (ET).

Patients reported a high prevalence of symptoms, an increase in the number of symptoms from diagnosis, and reductions in emotional well-being, quality of life, and ability to work.

“The survey results help paint the full picture of the impact of these diseases,” said Claire Harrison, DM, of Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in London, UK.

“The dominating symptom is fatigue, which validates what we are seeing in the clinic. The novel findings regarding the impact on patient’s work life show the consequences of MPNs.”

Dr Harrison and her colleagues reported these findings at the meeting as (abstract 4267*).

The international MPN LANDMARK survey included 699 patients with MPNs (174 with MF, 223 with PV, and 302 with ET), and physicians who treated these conditions across Germany, Italy, UK, Japan, Canada, and Australia.

Patients completed an online questionnaire to measure MPN-related symptoms experienced over the past year and the impact of their condition on quality of life and ability to work.

Patients reported that their disease negatively impacted their ability to complete daily activities by 40%. Patients also noted 35% impairment in their capacity to work. Patients who missed work over the last 7 days due to illness reported missing an average of 3.1 hours due to their disease and/or symptom burden.

“For one quarter of PV patients, the disease stopped them from working, and another one quarter voluntarily reduced their work time,” Dr Harrison said. “This was surprising. Even though their disease was managed, it impacted their work life.”

She noted that many of her PV patients are young, working professionals.

Results also showed that about three-quarters of patients who experienced symptoms suffered a significant reduction in quality of life due to symptoms (83% of MF patients, 72% of PV patients, and 74% of ET patients).

These results are consistent with those from a previous US LANDMARK survey of MPN patients.

The most commonly reported symptom in the last 12 months was fatigue (54% of MF patients, 45% of PV patients, and 64% of ET patients). This was also the symptom patients stated they most wanted to resolve.

“Patients stated doctors often don’t ask enough about the details of symptoms,” Dr Harrison said.

In addition to physical symptoms, about one-third of patients felt anxious or worried about their disease (34% of MF patients, 29% of PV patients, and 26% of ET patients).

“We found a mismatch in aspirations of MPN patients and their physicians,” Dr Harrison said. “For example, physicians said it was important to teach PV patients to prevent blood clots. PV patients were more concerned with having a better quality of life and slowing disease progression.”

A comprehensive symptom assessment is important to help physicians understand other hardships of these diseases, she said, noting “in our service, we enlist nutritionists and psychologists and also use physiotherapists and occupational therapists.” ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

2016 ASH Annual Meeting

SAN DIEGO—Many patients living with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) have a high burden of disease that affects their quality of life and limits their ability to work, according to research presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting.

Researchers conducted the first-ever international survey of MPN patients, including those with myelofibrosis (MF), polycythemia vera (PV), and essential thrombocythemia (ET).

Patients reported a high prevalence of symptoms, an increase in the number of symptoms from diagnosis, and reductions in emotional well-being, quality of life, and ability to work.

“The survey results help paint the full picture of the impact of these diseases,” said Claire Harrison, DM, of Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in London, UK.

“The dominating symptom is fatigue, which validates what we are seeing in the clinic. The novel findings regarding the impact on patient’s work life show the consequences of MPNs.”

Dr Harrison and her colleagues reported these findings at the meeting as (abstract 4267*).

The international MPN LANDMARK survey included 699 patients with MPNs (174 with MF, 223 with PV, and 302 with ET), and physicians who treated these conditions across Germany, Italy, UK, Japan, Canada, and Australia.

Patients completed an online questionnaire to measure MPN-related symptoms experienced over the past year and the impact of their condition on quality of life and ability to work.

Patients reported that their disease negatively impacted their ability to complete daily activities by 40%. Patients also noted 35% impairment in their capacity to work. Patients who missed work over the last 7 days due to illness reported missing an average of 3.1 hours due to their disease and/or symptom burden.

“For one quarter of PV patients, the disease stopped them from working, and another one quarter voluntarily reduced their work time,” Dr Harrison said. “This was surprising. Even though their disease was managed, it impacted their work life.”

She noted that many of her PV patients are young, working professionals.

Results also showed that about three-quarters of patients who experienced symptoms suffered a significant reduction in quality of life due to symptoms (83% of MF patients, 72% of PV patients, and 74% of ET patients).

These results are consistent with those from a previous US LANDMARK survey of MPN patients.

The most commonly reported symptom in the last 12 months was fatigue (54% of MF patients, 45% of PV patients, and 64% of ET patients). This was also the symptom patients stated they most wanted to resolve.

“Patients stated doctors often don’t ask enough about the details of symptoms,” Dr Harrison said.

In addition to physical symptoms, about one-third of patients felt anxious or worried about their disease (34% of MF patients, 29% of PV patients, and 26% of ET patients).

“We found a mismatch in aspirations of MPN patients and their physicians,” Dr Harrison said. “For example, physicians said it was important to teach PV patients to prevent blood clots. PV patients were more concerned with having a better quality of life and slowing disease progression.”

A comprehensive symptom assessment is important to help physicians understand other hardships of these diseases, she said, noting “in our service, we enlist nutritionists and psychologists and also use physiotherapists and occupational therapists.” ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

Half of CML patients can stop TKI therapy, study suggests

© Todd Buchanan 2016

SAN DIEGO—Updated results of the EURO-SKI trial support the idea that certain chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients can safely stop tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy.

About half of the patients studied, who had been in deep molecular remission for at least 1 year, had no evidence of relapse for at least 1 year after stopping TKI therapy.

Francis-Xavier Mahon, MD, PhD, of the Bergonie Cancer Center at the University of Bordeaux in France, presented this finding at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 787*).

Stopping treatment is an emerging goal of CML management. Several studies have demonstrated the feasibility of stopping treatment, and consistent results over time have validated the concept of treatment-free remission (TFR), Dr Mahon said.

“A sustained deep molecular response on long-term TKI therapy seems to be necessary prior to attempting TFR,” he noted. “However, the exact preconditions for stopping CML treatments are not yet defined.”

Dr Mahon and his colleagues studied 821 chronic phase CML patients treated with TKIs (imatinib, dasatinib, or nilotinib) for at least 3 years. The patients were in deep molecular remission (MR4) for at least a year.

Dr Mahon reported on an intention-to-stop-treatment analysis of 755 patients. Their median age at diagnosis was 52 years, median time from diagnosis to stopping TKI therapy was 7.7 years, median duration of TKI therapy was 7.4 years, and median duration of deep molecular remission before stopping TKI therapy was 4.7 years.

At a median follow-up of 14.9 months, about half of patients (378/755) were still alive and in major molecular response. Molecular recurrence-free survival was 61% at 6 months, 55% at 12 months, 52% at 18 months, 50% at 24 months, and 47% at 36 months.

Most loss of molecular response came within the first 6 months after stopping treatment. Most patients regained their previous remission level after resuming TKI therapy, and no study participants progressed to a dangerous state of advanced disease.

Dr Mahon noted that longer duration of imatinib therapy prior to stopping TKIs, optimally 5.8 years or longer, correlates to a higher probability of relapse-free survival. Gender, age, and other variables, such as Sokal scores, do not predict the probability of successful stopping.

“With inclusion and relapse criteria less strict than in many previous trials, and with decentralized but standardized PCR monitoring, stopping of TKI therapy in a large cohort of CML patients appears feasible and safe,” Dr Mahon said. “This trial demonstrates that half of patients are still off treatment without molecular recurrence after a median 15 months.”

Current guidelines recommend that most patients who achieve remission with TKI therapy continue taking the drugs indefinitely, yet it is unclear whether continued therapy is necessary for all patients.

The European Leukemia Net are expected to propose new guidelines in the next 6 months, which Dr Mahon hopes will define a consensus regarding durability of TKI therapy and provide recommendations on whether stopping TKIs can be moved into the clinic for appropriate patients. ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

© Todd Buchanan 2016

SAN DIEGO—Updated results of the EURO-SKI trial support the idea that certain chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients can safely stop tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy.

About half of the patients studied, who had been in deep molecular remission for at least 1 year, had no evidence of relapse for at least 1 year after stopping TKI therapy.

Francis-Xavier Mahon, MD, PhD, of the Bergonie Cancer Center at the University of Bordeaux in France, presented this finding at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 787*).

Stopping treatment is an emerging goal of CML management. Several studies have demonstrated the feasibility of stopping treatment, and consistent results over time have validated the concept of treatment-free remission (TFR), Dr Mahon said.