User login

An alternative device for ESRD patients with central venous obstruction

CHICAGO – Catheter dependence is often the final option available for hemodialysis patients who have exhausted upper extremity access because of central venous obstruction. But an alternative device that combines a standard expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) arterial graft component with an entirely internalized central venous catheter component may provide an additional option that can help avoid catheters in selected patients, according to pooled results reported at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

Virginia L. Wong, MD, of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, reported on her group’s and others’ experience using the Hemodialysis Reliable Outflow (HeRO) graft (Merit Medical) to gain access to the superior vena cava (SVC), thus allowing for further upper extremity access options. The device has its limitations in patients with CVO, Dr. Wong noted, “but it can be an important tool for the dedicated access surgeon who is likely to be referred the most complicated patients who have run out of just about every other option.”

The Food and Drug Administration approved the HeRO graft for CVO in 2008, but a recent pooled analysis (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;50[1]:108-13), which showed a 1-year primary patency rate of 22% and a secondary patency rate of 60%, may provide clarity on how the device can be used to treat CVO in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients when the care team desires an alternative to femoral arteriovenous graft, Dr. Wong said. “The 1-year primary patency rate overall was not very good, but with aggressive thrombectomy programs the 1-year patency rate was decent,” she said.

The pooled analysis involved eight series from 2009 to 2015, but the largest series, which involved 164 patients, reported primary and secondary patency rates of 48.8% and 90.8%, respectively (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44[1]:93-9). “Patency for these alternative accesses may not be quite what we can achieve with standard upper-extremity access,” Dr. Wong said, “but these patients do not have the standard access as an option.”

Dr. Wong explained where the HeRO fits into the existing vascular practice. “The current data suggest that we should try to exhaust all traditional upper extremity access options before considering anything else, but the HeRO could be considered as an acceptable option for suitable patients,” she said. However, to achieve those outcomes, “you need to have an aggressive thrombectomy program.”

HeRO may be an option for salvage of an existing arm access, plagued by recalcitrant CVO, while still preserving the femoral sites and for future hemodialysis access and/or renal transplantation, Dr. Wong said.

The HeRO also has been used in alternative configurations, taking advantage of axillary or subclavian routes to the SVC when both internal jugular veins are occluded. Dr. Wong has used the femoral route to the inferior vena cava (IVC) for salvaging the femoral AV graft in which iliofemoral venous outflow has been compromised.

Anatomically, the patient must be able to accept a large-bore (19-Fr) access catheter into the central vein. Physiologically, the patient must be able to maintain patency of the long, low-resistance HeRO circuit, which can be up to 50 cm in length, she said. The protocol at Dr. Wong’s institution recommends an inflow arterial diameter of at least 3 mm, along with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 20% or greater and a minimum systolic blood pressure of 100 mm Hg for HeRO on the right side, and possibly higher when coming from the left.

Chronic hypotension is a frequent disqualifier, although some of these patients may benefit from midodrine hydrochloride, she said. In any event, a review of medications and consultation with nephrology and the dialysis unit are mandatory elements of patient screening. “I usually request hemodialysis run sheets from the last three sessions to see what systolic blood pressure excursion is like over the course of treatment,” she said.

The basic principles of hemo-access care are important when considering the HeRO for CVO patients, Dr. Wong said. These include site/side preservation, catheter avoidance and “not to burn any bridges” for future access. “Individualization of care and careful patient selection are probably the best bets if you’re just starting out,” she said. “Choose good patients before resorting to HeRO as the last option for a fairly marginal candidate.”

Dr. Wong had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

CHICAGO – Catheter dependence is often the final option available for hemodialysis patients who have exhausted upper extremity access because of central venous obstruction. But an alternative device that combines a standard expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) arterial graft component with an entirely internalized central venous catheter component may provide an additional option that can help avoid catheters in selected patients, according to pooled results reported at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

Virginia L. Wong, MD, of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, reported on her group’s and others’ experience using the Hemodialysis Reliable Outflow (HeRO) graft (Merit Medical) to gain access to the superior vena cava (SVC), thus allowing for further upper extremity access options. The device has its limitations in patients with CVO, Dr. Wong noted, “but it can be an important tool for the dedicated access surgeon who is likely to be referred the most complicated patients who have run out of just about every other option.”

The Food and Drug Administration approved the HeRO graft for CVO in 2008, but a recent pooled analysis (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;50[1]:108-13), which showed a 1-year primary patency rate of 22% and a secondary patency rate of 60%, may provide clarity on how the device can be used to treat CVO in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients when the care team desires an alternative to femoral arteriovenous graft, Dr. Wong said. “The 1-year primary patency rate overall was not very good, but with aggressive thrombectomy programs the 1-year patency rate was decent,” she said.

The pooled analysis involved eight series from 2009 to 2015, but the largest series, which involved 164 patients, reported primary and secondary patency rates of 48.8% and 90.8%, respectively (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44[1]:93-9). “Patency for these alternative accesses may not be quite what we can achieve with standard upper-extremity access,” Dr. Wong said, “but these patients do not have the standard access as an option.”

Dr. Wong explained where the HeRO fits into the existing vascular practice. “The current data suggest that we should try to exhaust all traditional upper extremity access options before considering anything else, but the HeRO could be considered as an acceptable option for suitable patients,” she said. However, to achieve those outcomes, “you need to have an aggressive thrombectomy program.”

HeRO may be an option for salvage of an existing arm access, plagued by recalcitrant CVO, while still preserving the femoral sites and for future hemodialysis access and/or renal transplantation, Dr. Wong said.

The HeRO also has been used in alternative configurations, taking advantage of axillary or subclavian routes to the SVC when both internal jugular veins are occluded. Dr. Wong has used the femoral route to the inferior vena cava (IVC) for salvaging the femoral AV graft in which iliofemoral venous outflow has been compromised.

Anatomically, the patient must be able to accept a large-bore (19-Fr) access catheter into the central vein. Physiologically, the patient must be able to maintain patency of the long, low-resistance HeRO circuit, which can be up to 50 cm in length, she said. The protocol at Dr. Wong’s institution recommends an inflow arterial diameter of at least 3 mm, along with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 20% or greater and a minimum systolic blood pressure of 100 mm Hg for HeRO on the right side, and possibly higher when coming from the left.

Chronic hypotension is a frequent disqualifier, although some of these patients may benefit from midodrine hydrochloride, she said. In any event, a review of medications and consultation with nephrology and the dialysis unit are mandatory elements of patient screening. “I usually request hemodialysis run sheets from the last three sessions to see what systolic blood pressure excursion is like over the course of treatment,” she said.

The basic principles of hemo-access care are important when considering the HeRO for CVO patients, Dr. Wong said. These include site/side preservation, catheter avoidance and “not to burn any bridges” for future access. “Individualization of care and careful patient selection are probably the best bets if you’re just starting out,” she said. “Choose good patients before resorting to HeRO as the last option for a fairly marginal candidate.”

Dr. Wong had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

CHICAGO – Catheter dependence is often the final option available for hemodialysis patients who have exhausted upper extremity access because of central venous obstruction. But an alternative device that combines a standard expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) arterial graft component with an entirely internalized central venous catheter component may provide an additional option that can help avoid catheters in selected patients, according to pooled results reported at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

Virginia L. Wong, MD, of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, reported on her group’s and others’ experience using the Hemodialysis Reliable Outflow (HeRO) graft (Merit Medical) to gain access to the superior vena cava (SVC), thus allowing for further upper extremity access options. The device has its limitations in patients with CVO, Dr. Wong noted, “but it can be an important tool for the dedicated access surgeon who is likely to be referred the most complicated patients who have run out of just about every other option.”

The Food and Drug Administration approved the HeRO graft for CVO in 2008, but a recent pooled analysis (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;50[1]:108-13), which showed a 1-year primary patency rate of 22% and a secondary patency rate of 60%, may provide clarity on how the device can be used to treat CVO in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients when the care team desires an alternative to femoral arteriovenous graft, Dr. Wong said. “The 1-year primary patency rate overall was not very good, but with aggressive thrombectomy programs the 1-year patency rate was decent,” she said.

The pooled analysis involved eight series from 2009 to 2015, but the largest series, which involved 164 patients, reported primary and secondary patency rates of 48.8% and 90.8%, respectively (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44[1]:93-9). “Patency for these alternative accesses may not be quite what we can achieve with standard upper-extremity access,” Dr. Wong said, “but these patients do not have the standard access as an option.”

Dr. Wong explained where the HeRO fits into the existing vascular practice. “The current data suggest that we should try to exhaust all traditional upper extremity access options before considering anything else, but the HeRO could be considered as an acceptable option for suitable patients,” she said. However, to achieve those outcomes, “you need to have an aggressive thrombectomy program.”

HeRO may be an option for salvage of an existing arm access, plagued by recalcitrant CVO, while still preserving the femoral sites and for future hemodialysis access and/or renal transplantation, Dr. Wong said.

The HeRO also has been used in alternative configurations, taking advantage of axillary or subclavian routes to the SVC when both internal jugular veins are occluded. Dr. Wong has used the femoral route to the inferior vena cava (IVC) for salvaging the femoral AV graft in which iliofemoral venous outflow has been compromised.

Anatomically, the patient must be able to accept a large-bore (19-Fr) access catheter into the central vein. Physiologically, the patient must be able to maintain patency of the long, low-resistance HeRO circuit, which can be up to 50 cm in length, she said. The protocol at Dr. Wong’s institution recommends an inflow arterial diameter of at least 3 mm, along with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 20% or greater and a minimum systolic blood pressure of 100 mm Hg for HeRO on the right side, and possibly higher when coming from the left.

Chronic hypotension is a frequent disqualifier, although some of these patients may benefit from midodrine hydrochloride, she said. In any event, a review of medications and consultation with nephrology and the dialysis unit are mandatory elements of patient screening. “I usually request hemodialysis run sheets from the last three sessions to see what systolic blood pressure excursion is like over the course of treatment,” she said.

The basic principles of hemo-access care are important when considering the HeRO for CVO patients, Dr. Wong said. These include site/side preservation, catheter avoidance and “not to burn any bridges” for future access. “Individualization of care and careful patient selection are probably the best bets if you’re just starting out,” she said. “Choose good patients before resorting to HeRO as the last option for a fairly marginal candidate.”

Dr. Wong had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Key clinical point: Combined graft-catheter device may preserve femoral access for hemodialysis for patients with central venous obstruction.

Major finding: One-year primary potency rate was 22% and secondary patency rate 60% for device recipients.

Data source: Literature review, including pooled results from eight studies involving 408 subjects.

Disclosures: Dr. Wong reported having no financial disclosures.

Rates of Deep Vein Thrombosis Occurring After Osteotomy About the Knee

Take-Home Points

- DVT and PE are uncommon complications following osteotomies about the knee.

- Use of oral contraceptives can increase the risk of a patient sustaining a postoperative DVT and PE following osteotomies about the knee.

- In the absence of significant risk factors, postoperative chemical DVT prophylaxis may be unnecessary in patients undergoing osteotomies about the knee.

High tibial osteotomy (HTO), distal femoral osteotomy (DFO), and tibial tubercle osteotomy (TTO) are viable treatment options for deformities about the knee and patella maltracking.1-4 Although TTO can be performed in many ways (eg, anteriorization, anteromedialization, medialization), the basic idea is to move the tibial tubercle to improve patellar tracking or to offload a patellar facet that has sustained trauma or degenerated.2 DFO is a surgical option for treating a valgus knee deformity (the lateral tibiofemoral compartment is offloaded) or for protecting a knee compartment after cartilage or meniscal restoration (medial closing wedge or lateral opening wedge).1 Similarly, HTO is an option for treating a varus knee deformity or isolated medial compartment arthritis; the diseased compartment is offloaded, and any malalignment is corrected. Akin to DFO, HTO is often performed to protect a knee compartment, typically the medial tibiofemoral compartment, after cartilage or meniscal restoration.2-4

Compared to most arthroscopic knee surgeries, these osteotomies are much more involved, have longer operative times, and restrict postoperative weight-bearing and range of motion.2-4 The rates of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) after these osteotomies are not well documented. In addition, there is no documentation of the risks in patients who smoke, are obese, or are using oral contraceptives (OCs) at time of surgery, despite the increased DVT and PE risks posed by smoking, obesity, and OC use in other surgical procedures.5-7 Although the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) issued clinical practice guidelines for DVT/PE prophylaxis after hip and knee arthroplasty, there is no standard prophylaxis guidelines for DVT/PE prevention after HTO, DFO, or TTO.8,9 Last, rates of DVT after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are well defined; they range from 2% to 12%.10,11 These rates may be surrogates for osteotomies about the knee, but this is only conjecture.

We conducted a study to determine the rates of symptomatic DVT and PE after HTO, DFO, or TTO in patients who did not receive postoperative DVT/PE prophylaxis. We also wanted to determine if age, body mass index (BMI), and smoking status have associations with the risk of developing either DVT or PE after HTO, DFO, or TTO. We hypothesized that the DVT and PE rates would both be <1%.

Methods

After this study was approved by our university’s Institutional Review Board, we searched the surgical database of Dr. Cole, a sports medicine fellowship–trained surgeon, to identify all patients who had HTO, DFO, or TTO performed between September 1, 2009 and September 30, 2014. Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes were used for the search. The code for HTO was 27457: osteotomy, proximal tibia, including fibular excision or osteotomy (includes correction of genu varus [bowleg] or genu valgus [knock-knee]); after epiphyseal closure). The code for DFO was 27450: osteotomy, femur, shaft or supracondylar; with fixation. Last, the code for TTO was 27418: anterior tibial tubercleplasty (eg, Maquet-type procedure). The 141 patients identified in the search were treated by Dr. Cole at a single institution and were included in the study. Study inclusion did not require a minimum follow-up. Follow-up duration was defined as the time between surgery and the final clinic note in the patient chart. No patient was excluded for lack of follow-up clinic visits, and none was lost to follow-up.

Age, BMI, smoking status, and OC use were recorded for all patients. For each procedure, the surgeon’s technique remained the same throughout the study period: HTO, medial opening-wedge osteotomy with plate-and-screw fixation; DFO, lateral opening-wedge osteotomy with plate-and-screw fixation; and TTO, mostly anteromedialization with screw fixation (though this was dictated by patellar contact pressures). A tourniquet was used in all cases. Each patient’s hospital electronic medical record and outpatient office notes were reviewed to determine if symptomatic DVT or PE developed after surgery. The diagnosis of symptomatic DVT was based on clinical symptoms and confirmatory ultrasound, and the PE diagnosis was based on computed tomography. Doppler ultrasound was performed only in symptomatic patients (ie, it was not routinely performed).

Per surgeon protocol, postoperative DVT prophylaxis was not administered. Patients were encouraged to begin dorsiflexion and plantar flexion of the ankle (ankle pumps) immediately and to mobilize as soon as comfortable. Each patient received a cold therapy machine with compression sleeve. Patients were allowed toe-touch weight-bearing for 6 weeks, and then progressed 25% per week for 4 weeks to full weight-bearing by 10 weeks. After surgery, each patient was placed in a brace, which was kept locked in extension for 10 days; when the brace was unlocked, the patient was allowed to range the knee.

Continuous variable data are reported as weighted means and weighted standard deviations. Categorical variable data are reported as frequencies and percentages.

Results

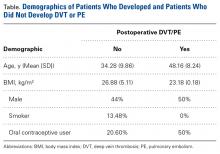

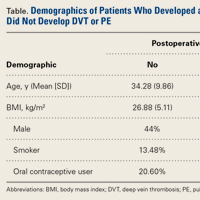

Our database search identified 141 patients (44% male, 56% female) who underwent HTO (47 patients, 33.3%), DFO (13 patients, 9.2%), or TTO (81 patients, 57.5%). Mean (SD) age was 34.28 (9.86) years, mean (SD) BMI was 26.88 (5.11) kg/m2, and mean (SD) follow-up was 17.1 (4.1) months. Of the female patients, 36.7% were using OCs at time of surgery. Of all patients, 13.48% were smokers.

Two patients (1.42%) had clinical symptoms consistent with DVT. In each case, the diagnosis was confirmed with Doppler ultrasound. The below-knee DVT was unilateral in 1 case and bilateral in the other.

The unilateral DVT occurred in a patient who underwent anteromedialization of the tibial tubercle and osteochondral allograft transfer to the lateral femoral condyle for patellar maltracking and a focal trochlear defect. The DVT was diagnosed 8 days after surgery and was treated with warfarin. Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) was used as a bridge until the warfarin level was therapeutic (4 days). This male patient had no significant medical history.

The bilateral DVT with PE occurred in a patient who underwent a medial opening-wedge HTO for a varus deformity with right medial compartment osteoarthritis and a meniscal tear. The DVT and PE were diagnosed 48 hours after surgery, when the patient complained of lightheadedness and lost consciousness. She had no medical problems but was using OCs at time of surgery. The patient died 3 days after surgery and subsequently was found to have a maternal-side family history of DVT (the patient and her family physician had been unaware of this history).

Discussion

As the rates of DVT and PE after osteotomies about the knee have not been well studied, we wanted to determine these rates after HTO, DFO, and TTO in patients who did not receive postoperative DVT prophylaxis. We hypothesized that DVT and PE rates would both be <1%, and this hypothesis was partly confirmed: The rate of PE after HTO, DFO, and TTO was <1%, and the rate of symptomatic DVT was >1%. Similarly, the patients who developed these complications were nonsmokers and had a BMI no higher than that of the patients who did not develop DVT or PE. In addition, only 1 patient developed DVT and PE, and she was using OCs and had a family history of DVT. Last, the patients who developed these complications were on average 14 years older than the patients who did not develop DVT or PE.

Although there is a plethora of reports on the incidence of DVT and PE after TKA, there is little on the incidence after osteotomies about the knee.8,12 The rate of DVT after TKA varies, but many studies place it between 2% and 12%, and routinely find a PE rate of <0.5%.10,11,13,14 Although the AAOS issued a clinical practice guideline for postoperative DVT prophylaxis after TKA, and evaluated the best available evidence, it could not reach consensus on a specific type of DVT prophylaxis, though the workgroup did recommend that patients be administered postoperative DVT prophylaxis of some kind.8,9 Similarly, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) issued clinical practice guidelines for preventing DVT and PE after elective TKA and total hip arthroplasty.15 According to the ACCP guidelines, patients should receive prophylaxis—LMWH, fondaparinux, apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, low-dose unfractionated heparin, adjusted-dose vitamin K antagonist, aspirin, or an intermittent pneumatic compression device—for a minimum of 14 days. Unfortunately, though there are similarities between TKAs and peri-knee osteotomies, these procedures are markedly different, and it is difficult to extrapolate and adapt recommendations and produce a consensus statement for knee arthroplasties. In addition, guidelines exist for hospitalized patients who are being treated for medical conditions or have undergone surgery, but all the patients in the present study had their osteotomies performed on an outpatient basis.

Martin and colleagues16 reviewed 323 cases of medial opening-wedge HTO and found a DVT rate of 1.4% in the absence of routine DVT prophylaxis, except in patients with a history of DVT. Their rate is almost identical to ours, but we also included other osteotomies in our study. Miller and colleagues17 reviewed 46 cases of medial opening-wedge HTO and found a 4.3% DVT rate, despite routine prophylaxis with once-daily 325-mg aspirin and ankle pumps. This finding contrasts with our 1.42% DVT rate in the absence of postoperative chemical DVT prophylaxis. Motycka and colleagues18 reviewed 65 HTO cases in which DVT prophylaxis (oral anticoagulant) was given for 6 weeks, and they found a DVT rate of 9.7%. Turner and colleagues19 performed venous ultrasound on 81 consecutive patients who underwent HTO and received DVT prophylaxis (twice-daily subcutaneous heparin), and they found a DVT rate of 41% and a PE rate of 1.2%, though only 8.6% of the DVT cases were symptomatic. Of note, whereas the lowest postoperative DVT rate was for patients who did not receive postoperative DVT prophylaxis, the rate of symptomatic DVT after these osteotomies ranged from 1.4% to 8.6% in patients who received prophylaxis.16,19 Given this evidence and our study results, it appears routine chemical DVT prophylaxis after osteotomies about the knee may not be necessary, though higher level evidence is needed in order to make definitive recommendations.

In the present study, the 2 patients who developed symptomatic DVT (1 subsequently developed PE) were nonsmokers in good health. The female patient (DVT plus PE) was using OCs at time of surgery. Studies have shown that patients who smoke and who use OCs are at increased risk for developing DVT or PE after surgery.5,6,12 Given that only 2 of our patients developed DVT/PE, and neither was a smoker, smoking was not associated with increased DVT or PE risk in this study population, in which 13.48% of patients were smokers at time of surgery. In addition, given that the 1 female patient who developed DVT/PE was using OCs and that 36.7% of all female patients in the study were using OCs, it is difficult to conclude whether OC use increased the female patient’s risk for DVT or PE. Furthermore, neither the literature nor the AAOS consensus statement supports discontinuing OCs for this surgical procedure.

Patients in this study did not receive chemical or mechanical DVT prophylaxis after surgery. Regarding various post-TKA DVT prophylaxis regimens, aspirin is as effective as LMWH in preventing DVT, and the risk for postoperative blood loss and wound complications is lower with aspirin than with rivaroxaban.20,21 Given that the present study’s postoperative rates of DVT (1.42%) and PE (0.71%) are equal to or less than rates already reported in the literature, routine DVT prophylaxis after osteotomies about the knee may be unnecessary in the absence of other significant risk factors.16,19 However, our study considered only symptomatic DVT and PE, so it is possible that the number of asymptomatic DVT cases is higher in this patient population. Definitively answering our study’s clinical question will require a multicenter registry study (prospective cohort study).

Study Limitations

The strengths of this study include the large number of patients treated by a single surgeon using the same postoperative protocol. Limitations of this study include the lack of a control group. Although we found a DVT rate of 1.42% and a PE rate of 0.71%, the literature on the accepted risks for DVT and PE after HTO, DFO, and TTO is unclear. With our results stratified by procedure, the DVT rate was 2% in the HTO group, 0% in the DFO group, and 1% in the TTO group. However, we were unable to reliably stratify these results by each specific procedure, as the number of patients in each group would be too low. This study involved reviewing charts; as patients were not contacted, it is possible a patient developed DVT or PE, was treated at an outside facility, and then never followed up with the treating surgeon. Patients were identified by CPT codes, so, if a patient underwent HTO, DFO, or TTO that was recorded under a different CPT code, it is possible the patient was missed by our search. All patients were seen after surgery, and we reviewed the outpatient office notes that were taken, so unless the DVT or PE occurred after a patient’s final postoperative visit, it would have been recorded. Similarly, the DVT and PE rates reported here cannot be extrapolated to overall risks for DVT and PE after osteotomies about the knee in all patients—only in patients who did not receive DVT prophylaxis after surgery.

Conclusion

The rates of DVT and PE after HTO, DFO, and TTO in patients who did not receive chemical prophylaxis are low: 1.42% and 0.71%, respectively. After these osteotomies, DVT/PE prophylaxis in the absence of known risk factors may not be warranted.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E23-E27. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Rossi R, Bonasia DE, Amendola A. The role of high tibial osteotomy in the varus knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(10):590-599.

2. Sherman SL, Erickson BJ, Cvetanovich GL, et al. Tibial tuberosity osteotomy: indications, techniques, and outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(8):2006-2017.

3. Wright JM, Crockett HC, Slawski DP, Madsen MW, Windsor RE. High tibial osteotomy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13(4):279-289.

4. Cameron JI, McCauley JC, Kermanshahi AY, Bugbee WD. Lateral opening-wedge distal femoral osteotomy: pain relief, functional improvement, and survivorship at 5 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(6):2009-2015.

5. Ng WM, Chan KY, Lim AB, Gan EC. The incidence of deep venous thrombosis following arthroscopic knee surgery. Med J Malaysia. 2005;60(suppl C):14-16.

6. Platzer P, Thalhammer G, Jaindl M, et al. Thromboembolic complications after spinal surgery in trauma patients. Acta Orthop. 2006;77(5):755-760.

7. Wallace G, Judge A, Prieto-Alhambra D, de Vries F, Arden NK, Cooper C. The effect of body mass index on the risk of post-operative complications during the 6 months following total hip replacement or total knee replacement surgery. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(7):918-927.

8. Lieberman JR, Pensak MJ. Prevention of venous thromboembolic disease after total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(19):1801-1811.

9. Mont MA, Jacobs JJ. AAOS clinical practice guideline: preventing venous thromboembolic disease in patients undergoing elective hip and knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(12):777-778.

10. Kim YH, Kulkarni SS, Park JW, Kim JS. Prevalence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism treated with mechanical compression device after total knee arthroplasty in Asian patients. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9):1633-1637.

11. Kim YH, Yoo JH, Kim JS. Factors leading to decreased rates of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(7):974-980.

12. Raphael IJ, Tischler EH, Huang R, Rothman RH, Hozack WJ, Parvizi J. Aspirin: an alternative for pulmonary embolism prophylaxis after arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):482-488.

13. Won MH, Lee GW, Lee TJ, Moon KH. Prevalence and risk factors of thromboembolism after joint arthroplasty without chemical thromboprophylaxis in an Asian population. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(7):1106-1111.

14. Bozic KJ, Vail TP, Pekow PS, Maselli JH, Lindenauer PK, Auerbach AD. Does aspirin have a role in venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in total knee arthroplasty patients? J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(7):1053-1060.

15. Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e278S-e325S.

16. Martin R, Birmingham TB, Willits K, Litchfield R, Lebel ME, Giffin JR. Adverse event rates and classifications in medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1118-1126.

17. Miller BS, Downie B, McDonough EB, Wojtys EM. Complications after medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(6):639-646.

18. Motycka T, Eggerth G, Landsiedl F. The incidence of thrombosis in high tibial osteotomies with and without the use of a tourniquet. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2000;120(3-4):157-159.

19. Turner RS, Griffiths H, Heatley FW. The incidence of deep-vein thrombosis after upper tibial osteotomy. A venographic study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75(6):942-944.

20. Jiang Y, Du H, Liu J, Zhou Y. Aspirin combined with mechanical measures to prevent venous thromboembolism after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Chin Med J (Engl). 2014;127(12):2201-2205.

21. Zou Y, Tian S, Wang Y, Sun K. Administering aspirin, rivaroxaban and low-molecular-weight heparin to prevent deep venous thrombosis after total knee arthroplasty. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2014;25(7):660-664.

Take-Home Points

- DVT and PE are uncommon complications following osteotomies about the knee.

- Use of oral contraceptives can increase the risk of a patient sustaining a postoperative DVT and PE following osteotomies about the knee.

- In the absence of significant risk factors, postoperative chemical DVT prophylaxis may be unnecessary in patients undergoing osteotomies about the knee.

High tibial osteotomy (HTO), distal femoral osteotomy (DFO), and tibial tubercle osteotomy (TTO) are viable treatment options for deformities about the knee and patella maltracking.1-4 Although TTO can be performed in many ways (eg, anteriorization, anteromedialization, medialization), the basic idea is to move the tibial tubercle to improve patellar tracking or to offload a patellar facet that has sustained trauma or degenerated.2 DFO is a surgical option for treating a valgus knee deformity (the lateral tibiofemoral compartment is offloaded) or for protecting a knee compartment after cartilage or meniscal restoration (medial closing wedge or lateral opening wedge).1 Similarly, HTO is an option for treating a varus knee deformity or isolated medial compartment arthritis; the diseased compartment is offloaded, and any malalignment is corrected. Akin to DFO, HTO is often performed to protect a knee compartment, typically the medial tibiofemoral compartment, after cartilage or meniscal restoration.2-4

Compared to most arthroscopic knee surgeries, these osteotomies are much more involved, have longer operative times, and restrict postoperative weight-bearing and range of motion.2-4 The rates of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) after these osteotomies are not well documented. In addition, there is no documentation of the risks in patients who smoke, are obese, or are using oral contraceptives (OCs) at time of surgery, despite the increased DVT and PE risks posed by smoking, obesity, and OC use in other surgical procedures.5-7 Although the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) issued clinical practice guidelines for DVT/PE prophylaxis after hip and knee arthroplasty, there is no standard prophylaxis guidelines for DVT/PE prevention after HTO, DFO, or TTO.8,9 Last, rates of DVT after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are well defined; they range from 2% to 12%.10,11 These rates may be surrogates for osteotomies about the knee, but this is only conjecture.

We conducted a study to determine the rates of symptomatic DVT and PE after HTO, DFO, or TTO in patients who did not receive postoperative DVT/PE prophylaxis. We also wanted to determine if age, body mass index (BMI), and smoking status have associations with the risk of developing either DVT or PE after HTO, DFO, or TTO. We hypothesized that the DVT and PE rates would both be <1%.

Methods

After this study was approved by our university’s Institutional Review Board, we searched the surgical database of Dr. Cole, a sports medicine fellowship–trained surgeon, to identify all patients who had HTO, DFO, or TTO performed between September 1, 2009 and September 30, 2014. Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes were used for the search. The code for HTO was 27457: osteotomy, proximal tibia, including fibular excision or osteotomy (includes correction of genu varus [bowleg] or genu valgus [knock-knee]); after epiphyseal closure). The code for DFO was 27450: osteotomy, femur, shaft or supracondylar; with fixation. Last, the code for TTO was 27418: anterior tibial tubercleplasty (eg, Maquet-type procedure). The 141 patients identified in the search were treated by Dr. Cole at a single institution and were included in the study. Study inclusion did not require a minimum follow-up. Follow-up duration was defined as the time between surgery and the final clinic note in the patient chart. No patient was excluded for lack of follow-up clinic visits, and none was lost to follow-up.

Age, BMI, smoking status, and OC use were recorded for all patients. For each procedure, the surgeon’s technique remained the same throughout the study period: HTO, medial opening-wedge osteotomy with plate-and-screw fixation; DFO, lateral opening-wedge osteotomy with plate-and-screw fixation; and TTO, mostly anteromedialization with screw fixation (though this was dictated by patellar contact pressures). A tourniquet was used in all cases. Each patient’s hospital electronic medical record and outpatient office notes were reviewed to determine if symptomatic DVT or PE developed after surgery. The diagnosis of symptomatic DVT was based on clinical symptoms and confirmatory ultrasound, and the PE diagnosis was based on computed tomography. Doppler ultrasound was performed only in symptomatic patients (ie, it was not routinely performed).

Per surgeon protocol, postoperative DVT prophylaxis was not administered. Patients were encouraged to begin dorsiflexion and plantar flexion of the ankle (ankle pumps) immediately and to mobilize as soon as comfortable. Each patient received a cold therapy machine with compression sleeve. Patients were allowed toe-touch weight-bearing for 6 weeks, and then progressed 25% per week for 4 weeks to full weight-bearing by 10 weeks. After surgery, each patient was placed in a brace, which was kept locked in extension for 10 days; when the brace was unlocked, the patient was allowed to range the knee.

Continuous variable data are reported as weighted means and weighted standard deviations. Categorical variable data are reported as frequencies and percentages.

Results

Our database search identified 141 patients (44% male, 56% female) who underwent HTO (47 patients, 33.3%), DFO (13 patients, 9.2%), or TTO (81 patients, 57.5%). Mean (SD) age was 34.28 (9.86) years, mean (SD) BMI was 26.88 (5.11) kg/m2, and mean (SD) follow-up was 17.1 (4.1) months. Of the female patients, 36.7% were using OCs at time of surgery. Of all patients, 13.48% were smokers.

Two patients (1.42%) had clinical symptoms consistent with DVT. In each case, the diagnosis was confirmed with Doppler ultrasound. The below-knee DVT was unilateral in 1 case and bilateral in the other.

The unilateral DVT occurred in a patient who underwent anteromedialization of the tibial tubercle and osteochondral allograft transfer to the lateral femoral condyle for patellar maltracking and a focal trochlear defect. The DVT was diagnosed 8 days after surgery and was treated with warfarin. Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) was used as a bridge until the warfarin level was therapeutic (4 days). This male patient had no significant medical history.

The bilateral DVT with PE occurred in a patient who underwent a medial opening-wedge HTO for a varus deformity with right medial compartment osteoarthritis and a meniscal tear. The DVT and PE were diagnosed 48 hours after surgery, when the patient complained of lightheadedness and lost consciousness. She had no medical problems but was using OCs at time of surgery. The patient died 3 days after surgery and subsequently was found to have a maternal-side family history of DVT (the patient and her family physician had been unaware of this history).

Discussion

As the rates of DVT and PE after osteotomies about the knee have not been well studied, we wanted to determine these rates after HTO, DFO, and TTO in patients who did not receive postoperative DVT prophylaxis. We hypothesized that DVT and PE rates would both be <1%, and this hypothesis was partly confirmed: The rate of PE after HTO, DFO, and TTO was <1%, and the rate of symptomatic DVT was >1%. Similarly, the patients who developed these complications were nonsmokers and had a BMI no higher than that of the patients who did not develop DVT or PE. In addition, only 1 patient developed DVT and PE, and she was using OCs and had a family history of DVT. Last, the patients who developed these complications were on average 14 years older than the patients who did not develop DVT or PE.

Although there is a plethora of reports on the incidence of DVT and PE after TKA, there is little on the incidence after osteotomies about the knee.8,12 The rate of DVT after TKA varies, but many studies place it between 2% and 12%, and routinely find a PE rate of <0.5%.10,11,13,14 Although the AAOS issued a clinical practice guideline for postoperative DVT prophylaxis after TKA, and evaluated the best available evidence, it could not reach consensus on a specific type of DVT prophylaxis, though the workgroup did recommend that patients be administered postoperative DVT prophylaxis of some kind.8,9 Similarly, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) issued clinical practice guidelines for preventing DVT and PE after elective TKA and total hip arthroplasty.15 According to the ACCP guidelines, patients should receive prophylaxis—LMWH, fondaparinux, apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, low-dose unfractionated heparin, adjusted-dose vitamin K antagonist, aspirin, or an intermittent pneumatic compression device—for a minimum of 14 days. Unfortunately, though there are similarities between TKAs and peri-knee osteotomies, these procedures are markedly different, and it is difficult to extrapolate and adapt recommendations and produce a consensus statement for knee arthroplasties. In addition, guidelines exist for hospitalized patients who are being treated for medical conditions or have undergone surgery, but all the patients in the present study had their osteotomies performed on an outpatient basis.

Martin and colleagues16 reviewed 323 cases of medial opening-wedge HTO and found a DVT rate of 1.4% in the absence of routine DVT prophylaxis, except in patients with a history of DVT. Their rate is almost identical to ours, but we also included other osteotomies in our study. Miller and colleagues17 reviewed 46 cases of medial opening-wedge HTO and found a 4.3% DVT rate, despite routine prophylaxis with once-daily 325-mg aspirin and ankle pumps. This finding contrasts with our 1.42% DVT rate in the absence of postoperative chemical DVT prophylaxis. Motycka and colleagues18 reviewed 65 HTO cases in which DVT prophylaxis (oral anticoagulant) was given for 6 weeks, and they found a DVT rate of 9.7%. Turner and colleagues19 performed venous ultrasound on 81 consecutive patients who underwent HTO and received DVT prophylaxis (twice-daily subcutaneous heparin), and they found a DVT rate of 41% and a PE rate of 1.2%, though only 8.6% of the DVT cases were symptomatic. Of note, whereas the lowest postoperative DVT rate was for patients who did not receive postoperative DVT prophylaxis, the rate of symptomatic DVT after these osteotomies ranged from 1.4% to 8.6% in patients who received prophylaxis.16,19 Given this evidence and our study results, it appears routine chemical DVT prophylaxis after osteotomies about the knee may not be necessary, though higher level evidence is needed in order to make definitive recommendations.

In the present study, the 2 patients who developed symptomatic DVT (1 subsequently developed PE) were nonsmokers in good health. The female patient (DVT plus PE) was using OCs at time of surgery. Studies have shown that patients who smoke and who use OCs are at increased risk for developing DVT or PE after surgery.5,6,12 Given that only 2 of our patients developed DVT/PE, and neither was a smoker, smoking was not associated with increased DVT or PE risk in this study population, in which 13.48% of patients were smokers at time of surgery. In addition, given that the 1 female patient who developed DVT/PE was using OCs and that 36.7% of all female patients in the study were using OCs, it is difficult to conclude whether OC use increased the female patient’s risk for DVT or PE. Furthermore, neither the literature nor the AAOS consensus statement supports discontinuing OCs for this surgical procedure.

Patients in this study did not receive chemical or mechanical DVT prophylaxis after surgery. Regarding various post-TKA DVT prophylaxis regimens, aspirin is as effective as LMWH in preventing DVT, and the risk for postoperative blood loss and wound complications is lower with aspirin than with rivaroxaban.20,21 Given that the present study’s postoperative rates of DVT (1.42%) and PE (0.71%) are equal to or less than rates already reported in the literature, routine DVT prophylaxis after osteotomies about the knee may be unnecessary in the absence of other significant risk factors.16,19 However, our study considered only symptomatic DVT and PE, so it is possible that the number of asymptomatic DVT cases is higher in this patient population. Definitively answering our study’s clinical question will require a multicenter registry study (prospective cohort study).

Study Limitations

The strengths of this study include the large number of patients treated by a single surgeon using the same postoperative protocol. Limitations of this study include the lack of a control group. Although we found a DVT rate of 1.42% and a PE rate of 0.71%, the literature on the accepted risks for DVT and PE after HTO, DFO, and TTO is unclear. With our results stratified by procedure, the DVT rate was 2% in the HTO group, 0% in the DFO group, and 1% in the TTO group. However, we were unable to reliably stratify these results by each specific procedure, as the number of patients in each group would be too low. This study involved reviewing charts; as patients were not contacted, it is possible a patient developed DVT or PE, was treated at an outside facility, and then never followed up with the treating surgeon. Patients were identified by CPT codes, so, if a patient underwent HTO, DFO, or TTO that was recorded under a different CPT code, it is possible the patient was missed by our search. All patients were seen after surgery, and we reviewed the outpatient office notes that were taken, so unless the DVT or PE occurred after a patient’s final postoperative visit, it would have been recorded. Similarly, the DVT and PE rates reported here cannot be extrapolated to overall risks for DVT and PE after osteotomies about the knee in all patients—only in patients who did not receive DVT prophylaxis after surgery.

Conclusion

The rates of DVT and PE after HTO, DFO, and TTO in patients who did not receive chemical prophylaxis are low: 1.42% and 0.71%, respectively. After these osteotomies, DVT/PE prophylaxis in the absence of known risk factors may not be warranted.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E23-E27. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

Take-Home Points

- DVT and PE are uncommon complications following osteotomies about the knee.

- Use of oral contraceptives can increase the risk of a patient sustaining a postoperative DVT and PE following osteotomies about the knee.

- In the absence of significant risk factors, postoperative chemical DVT prophylaxis may be unnecessary in patients undergoing osteotomies about the knee.

High tibial osteotomy (HTO), distal femoral osteotomy (DFO), and tibial tubercle osteotomy (TTO) are viable treatment options for deformities about the knee and patella maltracking.1-4 Although TTO can be performed in many ways (eg, anteriorization, anteromedialization, medialization), the basic idea is to move the tibial tubercle to improve patellar tracking or to offload a patellar facet that has sustained trauma or degenerated.2 DFO is a surgical option for treating a valgus knee deformity (the lateral tibiofemoral compartment is offloaded) or for protecting a knee compartment after cartilage or meniscal restoration (medial closing wedge or lateral opening wedge).1 Similarly, HTO is an option for treating a varus knee deformity or isolated medial compartment arthritis; the diseased compartment is offloaded, and any malalignment is corrected. Akin to DFO, HTO is often performed to protect a knee compartment, typically the medial tibiofemoral compartment, after cartilage or meniscal restoration.2-4

Compared to most arthroscopic knee surgeries, these osteotomies are much more involved, have longer operative times, and restrict postoperative weight-bearing and range of motion.2-4 The rates of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) after these osteotomies are not well documented. In addition, there is no documentation of the risks in patients who smoke, are obese, or are using oral contraceptives (OCs) at time of surgery, despite the increased DVT and PE risks posed by smoking, obesity, and OC use in other surgical procedures.5-7 Although the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) issued clinical practice guidelines for DVT/PE prophylaxis after hip and knee arthroplasty, there is no standard prophylaxis guidelines for DVT/PE prevention after HTO, DFO, or TTO.8,9 Last, rates of DVT after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are well defined; they range from 2% to 12%.10,11 These rates may be surrogates for osteotomies about the knee, but this is only conjecture.

We conducted a study to determine the rates of symptomatic DVT and PE after HTO, DFO, or TTO in patients who did not receive postoperative DVT/PE prophylaxis. We also wanted to determine if age, body mass index (BMI), and smoking status have associations with the risk of developing either DVT or PE after HTO, DFO, or TTO. We hypothesized that the DVT and PE rates would both be <1%.

Methods

After this study was approved by our university’s Institutional Review Board, we searched the surgical database of Dr. Cole, a sports medicine fellowship–trained surgeon, to identify all patients who had HTO, DFO, or TTO performed between September 1, 2009 and September 30, 2014. Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes were used for the search. The code for HTO was 27457: osteotomy, proximal tibia, including fibular excision or osteotomy (includes correction of genu varus [bowleg] or genu valgus [knock-knee]); after epiphyseal closure). The code for DFO was 27450: osteotomy, femur, shaft or supracondylar; with fixation. Last, the code for TTO was 27418: anterior tibial tubercleplasty (eg, Maquet-type procedure). The 141 patients identified in the search were treated by Dr. Cole at a single institution and were included in the study. Study inclusion did not require a minimum follow-up. Follow-up duration was defined as the time between surgery and the final clinic note in the patient chart. No patient was excluded for lack of follow-up clinic visits, and none was lost to follow-up.

Age, BMI, smoking status, and OC use were recorded for all patients. For each procedure, the surgeon’s technique remained the same throughout the study period: HTO, medial opening-wedge osteotomy with plate-and-screw fixation; DFO, lateral opening-wedge osteotomy with plate-and-screw fixation; and TTO, mostly anteromedialization with screw fixation (though this was dictated by patellar contact pressures). A tourniquet was used in all cases. Each patient’s hospital electronic medical record and outpatient office notes were reviewed to determine if symptomatic DVT or PE developed after surgery. The diagnosis of symptomatic DVT was based on clinical symptoms and confirmatory ultrasound, and the PE diagnosis was based on computed tomography. Doppler ultrasound was performed only in symptomatic patients (ie, it was not routinely performed).

Per surgeon protocol, postoperative DVT prophylaxis was not administered. Patients were encouraged to begin dorsiflexion and plantar flexion of the ankle (ankle pumps) immediately and to mobilize as soon as comfortable. Each patient received a cold therapy machine with compression sleeve. Patients were allowed toe-touch weight-bearing for 6 weeks, and then progressed 25% per week for 4 weeks to full weight-bearing by 10 weeks. After surgery, each patient was placed in a brace, which was kept locked in extension for 10 days; when the brace was unlocked, the patient was allowed to range the knee.

Continuous variable data are reported as weighted means and weighted standard deviations. Categorical variable data are reported as frequencies and percentages.

Results

Our database search identified 141 patients (44% male, 56% female) who underwent HTO (47 patients, 33.3%), DFO (13 patients, 9.2%), or TTO (81 patients, 57.5%). Mean (SD) age was 34.28 (9.86) years, mean (SD) BMI was 26.88 (5.11) kg/m2, and mean (SD) follow-up was 17.1 (4.1) months. Of the female patients, 36.7% were using OCs at time of surgery. Of all patients, 13.48% were smokers.

Two patients (1.42%) had clinical symptoms consistent with DVT. In each case, the diagnosis was confirmed with Doppler ultrasound. The below-knee DVT was unilateral in 1 case and bilateral in the other.

The unilateral DVT occurred in a patient who underwent anteromedialization of the tibial tubercle and osteochondral allograft transfer to the lateral femoral condyle for patellar maltracking and a focal trochlear defect. The DVT was diagnosed 8 days after surgery and was treated with warfarin. Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) was used as a bridge until the warfarin level was therapeutic (4 days). This male patient had no significant medical history.

The bilateral DVT with PE occurred in a patient who underwent a medial opening-wedge HTO for a varus deformity with right medial compartment osteoarthritis and a meniscal tear. The DVT and PE were diagnosed 48 hours after surgery, when the patient complained of lightheadedness and lost consciousness. She had no medical problems but was using OCs at time of surgery. The patient died 3 days after surgery and subsequently was found to have a maternal-side family history of DVT (the patient and her family physician had been unaware of this history).

Discussion

As the rates of DVT and PE after osteotomies about the knee have not been well studied, we wanted to determine these rates after HTO, DFO, and TTO in patients who did not receive postoperative DVT prophylaxis. We hypothesized that DVT and PE rates would both be <1%, and this hypothesis was partly confirmed: The rate of PE after HTO, DFO, and TTO was <1%, and the rate of symptomatic DVT was >1%. Similarly, the patients who developed these complications were nonsmokers and had a BMI no higher than that of the patients who did not develop DVT or PE. In addition, only 1 patient developed DVT and PE, and she was using OCs and had a family history of DVT. Last, the patients who developed these complications were on average 14 years older than the patients who did not develop DVT or PE.

Although there is a plethora of reports on the incidence of DVT and PE after TKA, there is little on the incidence after osteotomies about the knee.8,12 The rate of DVT after TKA varies, but many studies place it between 2% and 12%, and routinely find a PE rate of <0.5%.10,11,13,14 Although the AAOS issued a clinical practice guideline for postoperative DVT prophylaxis after TKA, and evaluated the best available evidence, it could not reach consensus on a specific type of DVT prophylaxis, though the workgroup did recommend that patients be administered postoperative DVT prophylaxis of some kind.8,9 Similarly, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) issued clinical practice guidelines for preventing DVT and PE after elective TKA and total hip arthroplasty.15 According to the ACCP guidelines, patients should receive prophylaxis—LMWH, fondaparinux, apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, low-dose unfractionated heparin, adjusted-dose vitamin K antagonist, aspirin, or an intermittent pneumatic compression device—for a minimum of 14 days. Unfortunately, though there are similarities between TKAs and peri-knee osteotomies, these procedures are markedly different, and it is difficult to extrapolate and adapt recommendations and produce a consensus statement for knee arthroplasties. In addition, guidelines exist for hospitalized patients who are being treated for medical conditions or have undergone surgery, but all the patients in the present study had their osteotomies performed on an outpatient basis.

Martin and colleagues16 reviewed 323 cases of medial opening-wedge HTO and found a DVT rate of 1.4% in the absence of routine DVT prophylaxis, except in patients with a history of DVT. Their rate is almost identical to ours, but we also included other osteotomies in our study. Miller and colleagues17 reviewed 46 cases of medial opening-wedge HTO and found a 4.3% DVT rate, despite routine prophylaxis with once-daily 325-mg aspirin and ankle pumps. This finding contrasts with our 1.42% DVT rate in the absence of postoperative chemical DVT prophylaxis. Motycka and colleagues18 reviewed 65 HTO cases in which DVT prophylaxis (oral anticoagulant) was given for 6 weeks, and they found a DVT rate of 9.7%. Turner and colleagues19 performed venous ultrasound on 81 consecutive patients who underwent HTO and received DVT prophylaxis (twice-daily subcutaneous heparin), and they found a DVT rate of 41% and a PE rate of 1.2%, though only 8.6% of the DVT cases were symptomatic. Of note, whereas the lowest postoperative DVT rate was for patients who did not receive postoperative DVT prophylaxis, the rate of symptomatic DVT after these osteotomies ranged from 1.4% to 8.6% in patients who received prophylaxis.16,19 Given this evidence and our study results, it appears routine chemical DVT prophylaxis after osteotomies about the knee may not be necessary, though higher level evidence is needed in order to make definitive recommendations.

In the present study, the 2 patients who developed symptomatic DVT (1 subsequently developed PE) were nonsmokers in good health. The female patient (DVT plus PE) was using OCs at time of surgery. Studies have shown that patients who smoke and who use OCs are at increased risk for developing DVT or PE after surgery.5,6,12 Given that only 2 of our patients developed DVT/PE, and neither was a smoker, smoking was not associated with increased DVT or PE risk in this study population, in which 13.48% of patients were smokers at time of surgery. In addition, given that the 1 female patient who developed DVT/PE was using OCs and that 36.7% of all female patients in the study were using OCs, it is difficult to conclude whether OC use increased the female patient’s risk for DVT or PE. Furthermore, neither the literature nor the AAOS consensus statement supports discontinuing OCs for this surgical procedure.

Patients in this study did not receive chemical or mechanical DVT prophylaxis after surgery. Regarding various post-TKA DVT prophylaxis regimens, aspirin is as effective as LMWH in preventing DVT, and the risk for postoperative blood loss and wound complications is lower with aspirin than with rivaroxaban.20,21 Given that the present study’s postoperative rates of DVT (1.42%) and PE (0.71%) are equal to or less than rates already reported in the literature, routine DVT prophylaxis after osteotomies about the knee may be unnecessary in the absence of other significant risk factors.16,19 However, our study considered only symptomatic DVT and PE, so it is possible that the number of asymptomatic DVT cases is higher in this patient population. Definitively answering our study’s clinical question will require a multicenter registry study (prospective cohort study).

Study Limitations

The strengths of this study include the large number of patients treated by a single surgeon using the same postoperative protocol. Limitations of this study include the lack of a control group. Although we found a DVT rate of 1.42% and a PE rate of 0.71%, the literature on the accepted risks for DVT and PE after HTO, DFO, and TTO is unclear. With our results stratified by procedure, the DVT rate was 2% in the HTO group, 0% in the DFO group, and 1% in the TTO group. However, we were unable to reliably stratify these results by each specific procedure, as the number of patients in each group would be too low. This study involved reviewing charts; as patients were not contacted, it is possible a patient developed DVT or PE, was treated at an outside facility, and then never followed up with the treating surgeon. Patients were identified by CPT codes, so, if a patient underwent HTO, DFO, or TTO that was recorded under a different CPT code, it is possible the patient was missed by our search. All patients were seen after surgery, and we reviewed the outpatient office notes that were taken, so unless the DVT or PE occurred after a patient’s final postoperative visit, it would have been recorded. Similarly, the DVT and PE rates reported here cannot be extrapolated to overall risks for DVT and PE after osteotomies about the knee in all patients—only in patients who did not receive DVT prophylaxis after surgery.

Conclusion

The rates of DVT and PE after HTO, DFO, and TTO in patients who did not receive chemical prophylaxis are low: 1.42% and 0.71%, respectively. After these osteotomies, DVT/PE prophylaxis in the absence of known risk factors may not be warranted.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E23-E27. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Rossi R, Bonasia DE, Amendola A. The role of high tibial osteotomy in the varus knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(10):590-599.

2. Sherman SL, Erickson BJ, Cvetanovich GL, et al. Tibial tuberosity osteotomy: indications, techniques, and outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(8):2006-2017.

3. Wright JM, Crockett HC, Slawski DP, Madsen MW, Windsor RE. High tibial osteotomy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13(4):279-289.

4. Cameron JI, McCauley JC, Kermanshahi AY, Bugbee WD. Lateral opening-wedge distal femoral osteotomy: pain relief, functional improvement, and survivorship at 5 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(6):2009-2015.

5. Ng WM, Chan KY, Lim AB, Gan EC. The incidence of deep venous thrombosis following arthroscopic knee surgery. Med J Malaysia. 2005;60(suppl C):14-16.

6. Platzer P, Thalhammer G, Jaindl M, et al. Thromboembolic complications after spinal surgery in trauma patients. Acta Orthop. 2006;77(5):755-760.

7. Wallace G, Judge A, Prieto-Alhambra D, de Vries F, Arden NK, Cooper C. The effect of body mass index on the risk of post-operative complications during the 6 months following total hip replacement or total knee replacement surgery. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(7):918-927.

8. Lieberman JR, Pensak MJ. Prevention of venous thromboembolic disease after total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(19):1801-1811.

9. Mont MA, Jacobs JJ. AAOS clinical practice guideline: preventing venous thromboembolic disease in patients undergoing elective hip and knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(12):777-778.

10. Kim YH, Kulkarni SS, Park JW, Kim JS. Prevalence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism treated with mechanical compression device after total knee arthroplasty in Asian patients. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9):1633-1637.

11. Kim YH, Yoo JH, Kim JS. Factors leading to decreased rates of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(7):974-980.

12. Raphael IJ, Tischler EH, Huang R, Rothman RH, Hozack WJ, Parvizi J. Aspirin: an alternative for pulmonary embolism prophylaxis after arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):482-488.

13. Won MH, Lee GW, Lee TJ, Moon KH. Prevalence and risk factors of thromboembolism after joint arthroplasty without chemical thromboprophylaxis in an Asian population. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(7):1106-1111.

14. Bozic KJ, Vail TP, Pekow PS, Maselli JH, Lindenauer PK, Auerbach AD. Does aspirin have a role in venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in total knee arthroplasty patients? J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(7):1053-1060.

15. Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e278S-e325S.

16. Martin R, Birmingham TB, Willits K, Litchfield R, Lebel ME, Giffin JR. Adverse event rates and classifications in medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1118-1126.

17. Miller BS, Downie B, McDonough EB, Wojtys EM. Complications after medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(6):639-646.

18. Motycka T, Eggerth G, Landsiedl F. The incidence of thrombosis in high tibial osteotomies with and without the use of a tourniquet. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2000;120(3-4):157-159.

19. Turner RS, Griffiths H, Heatley FW. The incidence of deep-vein thrombosis after upper tibial osteotomy. A venographic study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75(6):942-944.

20. Jiang Y, Du H, Liu J, Zhou Y. Aspirin combined with mechanical measures to prevent venous thromboembolism after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Chin Med J (Engl). 2014;127(12):2201-2205.

21. Zou Y, Tian S, Wang Y, Sun K. Administering aspirin, rivaroxaban and low-molecular-weight heparin to prevent deep venous thrombosis after total knee arthroplasty. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2014;25(7):660-664.

1. Rossi R, Bonasia DE, Amendola A. The role of high tibial osteotomy in the varus knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(10):590-599.

2. Sherman SL, Erickson BJ, Cvetanovich GL, et al. Tibial tuberosity osteotomy: indications, techniques, and outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(8):2006-2017.

3. Wright JM, Crockett HC, Slawski DP, Madsen MW, Windsor RE. High tibial osteotomy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13(4):279-289.

4. Cameron JI, McCauley JC, Kermanshahi AY, Bugbee WD. Lateral opening-wedge distal femoral osteotomy: pain relief, functional improvement, and survivorship at 5 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(6):2009-2015.

5. Ng WM, Chan KY, Lim AB, Gan EC. The incidence of deep venous thrombosis following arthroscopic knee surgery. Med J Malaysia. 2005;60(suppl C):14-16.

6. Platzer P, Thalhammer G, Jaindl M, et al. Thromboembolic complications after spinal surgery in trauma patients. Acta Orthop. 2006;77(5):755-760.

7. Wallace G, Judge A, Prieto-Alhambra D, de Vries F, Arden NK, Cooper C. The effect of body mass index on the risk of post-operative complications during the 6 months following total hip replacement or total knee replacement surgery. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(7):918-927.

8. Lieberman JR, Pensak MJ. Prevention of venous thromboembolic disease after total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(19):1801-1811.

9. Mont MA, Jacobs JJ. AAOS clinical practice guideline: preventing venous thromboembolic disease in patients undergoing elective hip and knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(12):777-778.

10. Kim YH, Kulkarni SS, Park JW, Kim JS. Prevalence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism treated with mechanical compression device after total knee arthroplasty in Asian patients. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9):1633-1637.

11. Kim YH, Yoo JH, Kim JS. Factors leading to decreased rates of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(7):974-980.

12. Raphael IJ, Tischler EH, Huang R, Rothman RH, Hozack WJ, Parvizi J. Aspirin: an alternative for pulmonary embolism prophylaxis after arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):482-488.

13. Won MH, Lee GW, Lee TJ, Moon KH. Prevalence and risk factors of thromboembolism after joint arthroplasty without chemical thromboprophylaxis in an Asian population. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(7):1106-1111.

14. Bozic KJ, Vail TP, Pekow PS, Maselli JH, Lindenauer PK, Auerbach AD. Does aspirin have a role in venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in total knee arthroplasty patients? J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(7):1053-1060.

15. Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e278S-e325S.

16. Martin R, Birmingham TB, Willits K, Litchfield R, Lebel ME, Giffin JR. Adverse event rates and classifications in medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1118-1126.

17. Miller BS, Downie B, McDonough EB, Wojtys EM. Complications after medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(6):639-646.

18. Motycka T, Eggerth G, Landsiedl F. The incidence of thrombosis in high tibial osteotomies with and without the use of a tourniquet. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2000;120(3-4):157-159.

19. Turner RS, Griffiths H, Heatley FW. The incidence of deep-vein thrombosis after upper tibial osteotomy. A venographic study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75(6):942-944.

20. Jiang Y, Du H, Liu J, Zhou Y. Aspirin combined with mechanical measures to prevent venous thromboembolism after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Chin Med J (Engl). 2014;127(12):2201-2205.

21. Zou Y, Tian S, Wang Y, Sun K. Administering aspirin, rivaroxaban and low-molecular-weight heparin to prevent deep venous thrombosis after total knee arthroplasty. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2014;25(7):660-664.

Now is time to embrace emerging PAD interventions

CHICAGO – Bioresorbable scaffolds, new drugs, adjuvant interventions, and stem and progenitor cell therapy will change how vascular surgeons treat peripheral artery disease in the next 5 years, so they must embrace these emerging treatments or run the risk of being displaced by other specialists, according to a presentation at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

“Vascular surgeons must position their practices to be the nexus for the evaluation and treatment of the patient and proactively engage in the critical trials of these new technologies,” said Patrick J. Geraghty, MD, of Washington University, St. Louis. “If our specialty fails to adapt to new treatment options, we risk getting sidelined as critical limb ischemia (CLI) treatment moves into a multimodality model.”

Dr. Geraghty focused on several future directions for PAD treatment: improved drug-eluting stents (DES) for superficial femoral artery disease; drug-coated balloons and modified DES for infrapopliteal disease; biologic modifiers for claudication and CLI; and bioresorbable, drug-eluting scaffolds for infrainguinal interventions.

“You’re not simply a plumber anymore; you’re a biological response modifier,” Dr. Geraghty said, explaining that biologic response modification technologies are the logical successor where standard surgical and endovascular techniques have either fallen short (as in early patency loss due to restenosis) or failed to offer effective alternatives (as in no-option advanced CLI patients). “And that takes many of us out of our comfort zone,” he said.

Dr. Geraghty noted the VIBRANT trial (J Vasc Surg. 2013;58[2]:386-95) and similar studies of non–drug eluting constructs identified early restenosis as the primary culprit in endovascular patency loss. “If you could reduce those early patency losses, you’d have an admirable primary patency rate for these complex lesions,” he said. “We’re able to reconstruct a vessel lumen. The question is, how to best maintain it?”

To answer that, Dr. Geraghty noted that the SIROCCO II trial (J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16[3]:331-8) failed to show an advantage for a sirolimus-eluting stent over bare nitinol stent for superficial femoral artery (SFA) disease, but the subsequent Zilver PTX trial showed the benefits of paclitaxel-eluting stents over 5 years (Circulation. 2016;133[15]:1472-83).

He noted that drug-coated balloons (DCBs) trials have yielded mixed results in infrapopliteal intervention. Most notably, the multicenter In.Pact DEEP trial (Circulation. 2015;131[5]:495-502) failed to show treatment efficacy, Dr. Geraghty said. “The In.Pact DEEP results sharply contrasted with the positive data from trials of similar DCBs in the SFA” (N Engl J Med. 2015;373[2]:145-53).

With regard to DES for infrapopliteal disease, Dr. Geraghty noted the promise of positive results of the ACHILLES (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60[22]:2290-5) and DESTINY (J Vasc Surg. 2012;55[2]:390-9) trials, along with the modest structural changes needed to convert from coronary to proximal tibial applications.

Bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) for CLI have also made recent advances. “It has been a slow road, but I’m happy that industry has pursued this aggressively,” Dr. Geraghty said. He pointed out that the ESPRIT I trial of bioresorbable everolimus-eluting vascular scaffolds in PAD involving the external iliac artery and SFA reported restenosis rates of 12.1% and 16.1% at 1 and 2 years, respectively (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9[11]:1178-87). A trial of the Absorb BVS (Abbott) for short infrapopliteal lesions showed primary patency rates of 96% and 85% at 1 and 2 years, he said (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9[7]:715-24).

“Vascular surgeons should be tracking BVS technology closely,” Dr. Geraghty said. “It achieves multiple desirable goals: immediate scaffolding for luminal restoration; mitigation of the restenotic stimulus via stent resorption; drug delivery for inhibition of restenosis; and the prospect of simpler re-interventions.”

Stem/progenitor cell therapies may also provide new solutions for no-option vasculature. One trial that showed “promising trends,” Dr. Geraghty said, is the RESTORE-CLI study of bone marrow aspiration (Mol Ther. 2012;20[6]:1280-6). “This trial reported a trend toward improved time to failure and reduced amputation-free survival, but did not meet its primary endpoint,” he said. “Likewise, the recently presented Biomet MOBILE data failed to meet its primary endpoint, but showed favorable trends in some treatment subgroups” (J Vasc Surg. 2011;54[6]:1650-8).

Dr. Geraghty noted that trial design in this field may need to change directions. “Look at the Delphi consensus matrices for the WIfI (Wound, Ischemia, foot Infection) Threatened limb Classification System (J Vasc Surg. 2014;59[1]:220-34). These show that complex wounds bear a significant risk of amputation, perhaps unmitigated by successful revascularization.” In addition, he called amputation-free survival “a rather blunt instrument” for evaluating how therapies impact limb outcomes and said it can confound the analysis of their effectiveness.

“Instead of confining the progenitor-cell therapies to no-option CLI trials, I’m eager to also see them investigated for treatment of claudication,” Dr. Geraghty said. “Can cell-based therapies possibly displace endovascular interventions as the first-line, least-harmful option for claudication?”

Dr. Geraghty also touched on intra/extravascular adjuvant therapies: antithrombin nanoparticles; inhibitory nanoparticles and polymeric wraps; and adventitial drug delivery techniques, among others.

“It’s critically important for vascular surgeons to position themselves for continued success in CLI treatment,” he said. “That involves aggressive practice branding, active trial participation, critical analysis of new technologies, and adoption of new, even disruptive, treatment modalities that show patient benefit.”

Dr. Geraghty disclosed stock ownership in Pulse Therapeutics; consultant fees from Bard Peripheral Vascular, Boston Scientific, Intact Vascular, Bard/Lutonix and Spectranetics; and serving as principal investigator for trials by Cook Medical, Bard/Lutonix, and Intact Vascular, with fees going to Washington University Medical School.

CHICAGO – Bioresorbable scaffolds, new drugs, adjuvant interventions, and stem and progenitor cell therapy will change how vascular surgeons treat peripheral artery disease in the next 5 years, so they must embrace these emerging treatments or run the risk of being displaced by other specialists, according to a presentation at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

“Vascular surgeons must position their practices to be the nexus for the evaluation and treatment of the patient and proactively engage in the critical trials of these new technologies,” said Patrick J. Geraghty, MD, of Washington University, St. Louis. “If our specialty fails to adapt to new treatment options, we risk getting sidelined as critical limb ischemia (CLI) treatment moves into a multimodality model.”

Dr. Geraghty focused on several future directions for PAD treatment: improved drug-eluting stents (DES) for superficial femoral artery disease; drug-coated balloons and modified DES for infrapopliteal disease; biologic modifiers for claudication and CLI; and bioresorbable, drug-eluting scaffolds for infrainguinal interventions.

“You’re not simply a plumber anymore; you’re a biological response modifier,” Dr. Geraghty said, explaining that biologic response modification technologies are the logical successor where standard surgical and endovascular techniques have either fallen short (as in early patency loss due to restenosis) or failed to offer effective alternatives (as in no-option advanced CLI patients). “And that takes many of us out of our comfort zone,” he said.

Dr. Geraghty noted the VIBRANT trial (J Vasc Surg. 2013;58[2]:386-95) and similar studies of non–drug eluting constructs identified early restenosis as the primary culprit in endovascular patency loss. “If you could reduce those early patency losses, you’d have an admirable primary patency rate for these complex lesions,” he said. “We’re able to reconstruct a vessel lumen. The question is, how to best maintain it?”

To answer that, Dr. Geraghty noted that the SIROCCO II trial (J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16[3]:331-8) failed to show an advantage for a sirolimus-eluting stent over bare nitinol stent for superficial femoral artery (SFA) disease, but the subsequent Zilver PTX trial showed the benefits of paclitaxel-eluting stents over 5 years (Circulation. 2016;133[15]:1472-83).

He noted that drug-coated balloons (DCBs) trials have yielded mixed results in infrapopliteal intervention. Most notably, the multicenter In.Pact DEEP trial (Circulation. 2015;131[5]:495-502) failed to show treatment efficacy, Dr. Geraghty said. “The In.Pact DEEP results sharply contrasted with the positive data from trials of similar DCBs in the SFA” (N Engl J Med. 2015;373[2]:145-53).