User login

Do ACE inhibitors or ARBs help prevent kidney disease in patients with diabetes and normal BP?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2011 meta-analysis of 5 RCTs (total 2975 patients) that compared ACE inhibitor therapy with placebo in diabetic patients without hypertension and albuminuria found that ACE inhibitors reduced the risk of new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria by 18% (relative risk [RR]=0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73-0.92).1 Normal albuminuria was defined in all included studies as an albumin excretion rate of <30 mg/d on a timed specimen confirmed with 3 serial measurements.

The RCTs included patients treated with lisinopril, enalapril, and perindopril. All but one examined patients with type 1 diabetes (2781 patients). The study that evaluated type 2 diabetes (194 patients) assessed patients with hypertension who used other antihypertensives to achieve normal blood pressure targets before ACE inhibitor initiation, a potential limitation.

Compared with placebo or no treatment, ACE inhibitor therapy reduced the risk of death from any cause (6 studies; 11,350 patients; RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97).1 Patient populations across pooled RCTs were heterogeneous, including subjects with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, with or without hypertension, and with or without albuminuria.

ACE inhibitors increase risk of cough

Patients taking an ACE inhibitor have an increased risk of cough (6 studies; 11,791 patients; RR=1.84; 95% CI, 1.24-2.72).1 ACE inhibitor therapy doesn’t increase the risk of headache or hyperkalemia.

ARBs don’t help prevent diabetic kidney disease in normotensive patients

The 2011 meta-analysis also included 5 RCTs (4604 patients, approximately 3000 with type 2 diabetes and more than 1000 with type 1 diabetes) that compared ARBs with placebo in patients without hypertension.1 Unlike ACE inhibitor therapy, ARB treatment didn’t significantly affect new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria (RR=1.06; 95% CI, 0.67-1.69).

The trials evaluated losartan, candesartan, olmesartan, and valsartan. One study used other antihypertensives to achieve target blood pressure, and another included patients of any albuminuria status.

Compared with placebo or no treatment, ARBs didn’t reduce the risk of death (5 studies; 7653 patients; RR=1.12; 95% CI, 0.88-1.41).1 All 5 RCTs assessed normoalbuminuric patients. Three of the 5 studies examined normotensive patients; one evaluated only hypertensive patients, and another assessed mostly hypertensive patients.

ARBs usually don’t produce significant adverse effects

Within the meta-analysis, ARBs didn’t increase risk of cough, headache, or hyperkalemia.1

1. Lv J, Perkovic V, Foote CV, et al. Antihypertensive agents for preventing diabetic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(12):CD004136.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2011 meta-analysis of 5 RCTs (total 2975 patients) that compared ACE inhibitor therapy with placebo in diabetic patients without hypertension and albuminuria found that ACE inhibitors reduced the risk of new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria by 18% (relative risk [RR]=0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73-0.92).1 Normal albuminuria was defined in all included studies as an albumin excretion rate of <30 mg/d on a timed specimen confirmed with 3 serial measurements.

The RCTs included patients treated with lisinopril, enalapril, and perindopril. All but one examined patients with type 1 diabetes (2781 patients). The study that evaluated type 2 diabetes (194 patients) assessed patients with hypertension who used other antihypertensives to achieve normal blood pressure targets before ACE inhibitor initiation, a potential limitation.

Compared with placebo or no treatment, ACE inhibitor therapy reduced the risk of death from any cause (6 studies; 11,350 patients; RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97).1 Patient populations across pooled RCTs were heterogeneous, including subjects with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, with or without hypertension, and with or without albuminuria.

ACE inhibitors increase risk of cough

Patients taking an ACE inhibitor have an increased risk of cough (6 studies; 11,791 patients; RR=1.84; 95% CI, 1.24-2.72).1 ACE inhibitor therapy doesn’t increase the risk of headache or hyperkalemia.

ARBs don’t help prevent diabetic kidney disease in normotensive patients

The 2011 meta-analysis also included 5 RCTs (4604 patients, approximately 3000 with type 2 diabetes and more than 1000 with type 1 diabetes) that compared ARBs with placebo in patients without hypertension.1 Unlike ACE inhibitor therapy, ARB treatment didn’t significantly affect new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria (RR=1.06; 95% CI, 0.67-1.69).

The trials evaluated losartan, candesartan, olmesartan, and valsartan. One study used other antihypertensives to achieve target blood pressure, and another included patients of any albuminuria status.

Compared with placebo or no treatment, ARBs didn’t reduce the risk of death (5 studies; 7653 patients; RR=1.12; 95% CI, 0.88-1.41).1 All 5 RCTs assessed normoalbuminuric patients. Three of the 5 studies examined normotensive patients; one evaluated only hypertensive patients, and another assessed mostly hypertensive patients.

ARBs usually don’t produce significant adverse effects

Within the meta-analysis, ARBs didn’t increase risk of cough, headache, or hyperkalemia.1

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2011 meta-analysis of 5 RCTs (total 2975 patients) that compared ACE inhibitor therapy with placebo in diabetic patients without hypertension and albuminuria found that ACE inhibitors reduced the risk of new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria by 18% (relative risk [RR]=0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73-0.92).1 Normal albuminuria was defined in all included studies as an albumin excretion rate of <30 mg/d on a timed specimen confirmed with 3 serial measurements.

The RCTs included patients treated with lisinopril, enalapril, and perindopril. All but one examined patients with type 1 diabetes (2781 patients). The study that evaluated type 2 diabetes (194 patients) assessed patients with hypertension who used other antihypertensives to achieve normal blood pressure targets before ACE inhibitor initiation, a potential limitation.

Compared with placebo or no treatment, ACE inhibitor therapy reduced the risk of death from any cause (6 studies; 11,350 patients; RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97).1 Patient populations across pooled RCTs were heterogeneous, including subjects with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, with or without hypertension, and with or without albuminuria.

ACE inhibitors increase risk of cough

Patients taking an ACE inhibitor have an increased risk of cough (6 studies; 11,791 patients; RR=1.84; 95% CI, 1.24-2.72).1 ACE inhibitor therapy doesn’t increase the risk of headache or hyperkalemia.

ARBs don’t help prevent diabetic kidney disease in normotensive patients

The 2011 meta-analysis also included 5 RCTs (4604 patients, approximately 3000 with type 2 diabetes and more than 1000 with type 1 diabetes) that compared ARBs with placebo in patients without hypertension.1 Unlike ACE inhibitor therapy, ARB treatment didn’t significantly affect new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria (RR=1.06; 95% CI, 0.67-1.69).

The trials evaluated losartan, candesartan, olmesartan, and valsartan. One study used other antihypertensives to achieve target blood pressure, and another included patients of any albuminuria status.

Compared with placebo or no treatment, ARBs didn’t reduce the risk of death (5 studies; 7653 patients; RR=1.12; 95% CI, 0.88-1.41).1 All 5 RCTs assessed normoalbuminuric patients. Three of the 5 studies examined normotensive patients; one evaluated only hypertensive patients, and another assessed mostly hypertensive patients.

ARBs usually don’t produce significant adverse effects

Within the meta-analysis, ARBs didn’t increase risk of cough, headache, or hyperkalemia.1

1. Lv J, Perkovic V, Foote CV, et al. Antihypertensive agents for preventing diabetic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(12):CD004136.

1. Lv J, Perkovic V, Foote CV, et al. Antihypertensive agents for preventing diabetic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(12):CD004136.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes for angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, no for angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs).

In normotensive patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, ACE inhibitor therapy reduces the risk of developing diabetic kidney disease, defined as new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria, by 18% (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs], disease-oriented evidence).

ACE inhibitor treatment improves all-cause mortality by 16% in patients with diabetes, including patients with and without hypertension. Patients on ACE inhibitor therapy are at increased risk of cough (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs).

ARB therapy doesn’t lower the risk of developing kidney disease in normotensive patients with type 2 diabetes (SOR: C, meta-analysis of RCTs, disease-oriented evidence); nor does it reduce all-cause mortality in patients with or without hypertension (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs). ARBs aren’t associated with significant adverse events (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs).

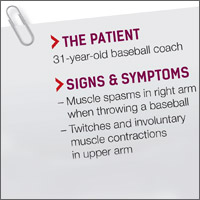

Single nontender ulcer on the glans

A 42-year-old gay man sought care for a nonhealing lesion on his penis that he’d had for 6 weeks. The patient acknowledged having unprotected sex with several partners in the month prior to the onset of the lesion. The lesion was asymptomatic and small, but rapidly developed into a superficial ulcer. The examination revealed a 1-cm ulcerated, erythematous plaque with raised and indurated edges on the glans (FIGURE). There was minimal drainage in the periurethral area. The patient didn’t have any other rashes or lesions on the skin or mucous membranes, or any regional lymphadenopathies.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Primary syphilis

The patient was given a diagnosis of primary syphilis based on his history and the clinical appearance of a syphilitic chancre. While chancres often occur on the shaft of the penis, they can also occur in the periurethral area, as was the case with this patient. The diagnosis of syphilis was confirmed with a positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay (TPPA).

Although the primary route of transmission is sexual contact, syphilis may also be transmitted from mother to fetus during pregnancy or birth, resulting in congenital syphilis. In addition, a considerable number of men who are diagnosed with syphilis are positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibodies.1 (Our patient was tested for HIV; the result was negative.)

The resurgence of syphilis. In 2000 and 2001, rates of syphilis cases reached a historic low (2.1 cases per 100,000).2 Since then, however, there has been a resurgence of syphilis—not just in men who have sex with men—but in all sexually active populations. In the United States during 2014 to 2015, the rate of primary and secondary syphilis increased to 7.5 cases per 100,000, which is the highest reported rate since 1994. From 2000 to 2015, this increase was primarily attributable to cases among men and, specifically, among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. But while the rate increased 18% among men during 2014 to 2015, it also increased by 27% among women.2

Social, epidemiologic, and individual risk factors can lead to higher levels of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in gay and bisexual men. In addition, lack of access to quality health care, homophobia, or stigma can all contribute to greater risk for this population.3 For these reasons, it is important for family physicians to immediately recognize this disease. (To learn more about the resurgence of syphilis, listen to the audiocast from Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA at http://bit.ly/2mRvYQe.)

The 4 stages of syphilis

The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary by the stage of disease.

Primary syphilis is the stage of initial inoculation with T pallidum. It is during this stage that a firm, nonpruritic skin ulceration—a chancre—appears. Although the classic chancre is typically painless, it can be painful.

Secondary syphilis presents as a diffuse rash that frequently involves the palms and soles.

The third or latent stage of syphilis may last for 2 years with few, or no, symptoms. However, secondary and latent syphilis may entail a broad range of manifestations, which is why syphilis is known as the “great imitator.”

In the final stage—tertiary syphilis—gummas and neurologic or cardiac symptoms may be seen.

Differential includes fungal, bacterial infections

The differential diagnosis of syphilis includes other infections such as chancroid, condyloma acuminata, candidiasis, granuloma inguinale, and lymphogranuloma venereum.

Chancroid presents as multiple painful necrotizing genital ulcers that may be accompanied by inguinal lymphadenopathy. It is caused by the bacterium Haemophilus ducreyi.

Condyloma acuminata is characterized by skin-colored, nontender warts and is caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV).

Candidiasis is a fungal infection that is characterized by pruritus and whitish-colored patches on the penis.

Granuloma inguinale (Donovanosis) is a chronic bacterial infection caused by Klebsiella granulomatis. It initially appears as nodular lesions that evolve into ulcers, which progressively expand and are locally destructive.

Lymphogranuloma venereum is an STD that can be caused by 3 different types (serovars) of the bacteria Chlamydia trachomatis. It presents with self-limited genital papules and ulcers followed by painful inguinal and/or femoral lymphadenopathy.

Diagnosis can be confirmed with serologic tests

The diagnosis of syphilis can be made by direct identification of the bacterium or serologic tests. Direct tests include dark field microscopy of serous fluid from genital lesions. This provides an immediate diagnosis with a sensitivity rate of up to 97%.4 However, hospitals do not always have the equipment or experienced staff to perform this technique, which must be done within 10 minutes of acquiring a sample. A polymerase chain reaction test can also be used to detect T pallidum DNA from specimens of any lesion exudate, tissue, or body fluid, but these tests can be costly compared with other tests used to diagnose syphilis.5

Serologic tests are divided into 2 groups: treponemal (specific) and nontreponemal (nonspecific) tests. Treponemal tests, which include TPPA, T pallidum hemagglutination assays, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, will yield a positive result for current or previously treated syphilis because a positive result remains so for life. Nontreponemal tests, such as the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test and the venereal disease reference laboratory (VDRL) test, yield a titer that is a measure of disease activity (the titer drops with treatment and rises with reinfection). Because these are nonspecific tests, biological false positives may occur if the patient has other acute or chronic infections or autoimmune diseases.5

Treat with penicillin

The first-choice treatment for uncomplicated syphilis is a single dose of intramuscular (IM) penicillin G (2.4 million units). A single dose of oral azithromycin 2 g or doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 14 days can be used for patients who are allergic to penicillin.5-7 Ceftriaxone, either IM or intravenous 1 g/d for 10 to 14 days, is also effective.

Our patient declined parenteral treatment, so he was treated with oral azithromycin 2 g in a single dose. His RPR titer was taken again one week after completing the azithromycin, at which time there was a 4-fold drop (1:32 to 1:8), indicating a good response to therapy. At a follow-up appointment 6 months later, the infection hadn’t recurred. We also educated the patient on the nature of the infection, how he became infected, and safe-sex practices to prevent reinfection.

CORRESPONDENCE

Husein Husein-ElAhmed, MD, PhD, Department of Dermatology, Hospital de Baza, Avda Murcia s/n, CP: 18800, Granada, Spain; [email protected].

1. Hook EW 3rd. Syphilis. Lancet. 2016.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2015. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats15/std-surveillance-2015-print.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2017.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported cases of sexually transmitted diseases on the rise, some at alarming rate. November 17, 2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2015/std-surveillance-report-press-release.html. Accessed March 14, 2017.

4. Wheeler HL, Agarwal S, Goh BT. Dark ground microscopy and treponemal tests in the diagnosis of early syphilis. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:411-414.

5. WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Treponema pallidum (Syphilis). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/249572/1/9789241549806-eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed March 6, 2017.

6. Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

7. Janier M, Hegyi V, Dupin N, et al. 2014 European guideline on the management of syphilis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1581-1593.

A 42-year-old gay man sought care for a nonhealing lesion on his penis that he’d had for 6 weeks. The patient acknowledged having unprotected sex with several partners in the month prior to the onset of the lesion. The lesion was asymptomatic and small, but rapidly developed into a superficial ulcer. The examination revealed a 1-cm ulcerated, erythematous plaque with raised and indurated edges on the glans (FIGURE). There was minimal drainage in the periurethral area. The patient didn’t have any other rashes or lesions on the skin or mucous membranes, or any regional lymphadenopathies.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Primary syphilis

The patient was given a diagnosis of primary syphilis based on his history and the clinical appearance of a syphilitic chancre. While chancres often occur on the shaft of the penis, they can also occur in the periurethral area, as was the case with this patient. The diagnosis of syphilis was confirmed with a positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay (TPPA).

Although the primary route of transmission is sexual contact, syphilis may also be transmitted from mother to fetus during pregnancy or birth, resulting in congenital syphilis. In addition, a considerable number of men who are diagnosed with syphilis are positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibodies.1 (Our patient was tested for HIV; the result was negative.)

The resurgence of syphilis. In 2000 and 2001, rates of syphilis cases reached a historic low (2.1 cases per 100,000).2 Since then, however, there has been a resurgence of syphilis—not just in men who have sex with men—but in all sexually active populations. In the United States during 2014 to 2015, the rate of primary and secondary syphilis increased to 7.5 cases per 100,000, which is the highest reported rate since 1994. From 2000 to 2015, this increase was primarily attributable to cases among men and, specifically, among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. But while the rate increased 18% among men during 2014 to 2015, it also increased by 27% among women.2

Social, epidemiologic, and individual risk factors can lead to higher levels of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in gay and bisexual men. In addition, lack of access to quality health care, homophobia, or stigma can all contribute to greater risk for this population.3 For these reasons, it is important for family physicians to immediately recognize this disease. (To learn more about the resurgence of syphilis, listen to the audiocast from Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA at http://bit.ly/2mRvYQe.)

The 4 stages of syphilis

The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary by the stage of disease.

Primary syphilis is the stage of initial inoculation with T pallidum. It is during this stage that a firm, nonpruritic skin ulceration—a chancre—appears. Although the classic chancre is typically painless, it can be painful.

Secondary syphilis presents as a diffuse rash that frequently involves the palms and soles.

The third or latent stage of syphilis may last for 2 years with few, or no, symptoms. However, secondary and latent syphilis may entail a broad range of manifestations, which is why syphilis is known as the “great imitator.”

In the final stage—tertiary syphilis—gummas and neurologic or cardiac symptoms may be seen.

Differential includes fungal, bacterial infections

The differential diagnosis of syphilis includes other infections such as chancroid, condyloma acuminata, candidiasis, granuloma inguinale, and lymphogranuloma venereum.

Chancroid presents as multiple painful necrotizing genital ulcers that may be accompanied by inguinal lymphadenopathy. It is caused by the bacterium Haemophilus ducreyi.

Condyloma acuminata is characterized by skin-colored, nontender warts and is caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV).

Candidiasis is a fungal infection that is characterized by pruritus and whitish-colored patches on the penis.

Granuloma inguinale (Donovanosis) is a chronic bacterial infection caused by Klebsiella granulomatis. It initially appears as nodular lesions that evolve into ulcers, which progressively expand and are locally destructive.

Lymphogranuloma venereum is an STD that can be caused by 3 different types (serovars) of the bacteria Chlamydia trachomatis. It presents with self-limited genital papules and ulcers followed by painful inguinal and/or femoral lymphadenopathy.

Diagnosis can be confirmed with serologic tests

The diagnosis of syphilis can be made by direct identification of the bacterium or serologic tests. Direct tests include dark field microscopy of serous fluid from genital lesions. This provides an immediate diagnosis with a sensitivity rate of up to 97%.4 However, hospitals do not always have the equipment or experienced staff to perform this technique, which must be done within 10 minutes of acquiring a sample. A polymerase chain reaction test can also be used to detect T pallidum DNA from specimens of any lesion exudate, tissue, or body fluid, but these tests can be costly compared with other tests used to diagnose syphilis.5

Serologic tests are divided into 2 groups: treponemal (specific) and nontreponemal (nonspecific) tests. Treponemal tests, which include TPPA, T pallidum hemagglutination assays, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, will yield a positive result for current or previously treated syphilis because a positive result remains so for life. Nontreponemal tests, such as the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test and the venereal disease reference laboratory (VDRL) test, yield a titer that is a measure of disease activity (the titer drops with treatment and rises with reinfection). Because these are nonspecific tests, biological false positives may occur if the patient has other acute or chronic infections or autoimmune diseases.5

Treat with penicillin

The first-choice treatment for uncomplicated syphilis is a single dose of intramuscular (IM) penicillin G (2.4 million units). A single dose of oral azithromycin 2 g or doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 14 days can be used for patients who are allergic to penicillin.5-7 Ceftriaxone, either IM or intravenous 1 g/d for 10 to 14 days, is also effective.

Our patient declined parenteral treatment, so he was treated with oral azithromycin 2 g in a single dose. His RPR titer was taken again one week after completing the azithromycin, at which time there was a 4-fold drop (1:32 to 1:8), indicating a good response to therapy. At a follow-up appointment 6 months later, the infection hadn’t recurred. We also educated the patient on the nature of the infection, how he became infected, and safe-sex practices to prevent reinfection.

CORRESPONDENCE

Husein Husein-ElAhmed, MD, PhD, Department of Dermatology, Hospital de Baza, Avda Murcia s/n, CP: 18800, Granada, Spain; [email protected].

A 42-year-old gay man sought care for a nonhealing lesion on his penis that he’d had for 6 weeks. The patient acknowledged having unprotected sex with several partners in the month prior to the onset of the lesion. The lesion was asymptomatic and small, but rapidly developed into a superficial ulcer. The examination revealed a 1-cm ulcerated, erythematous plaque with raised and indurated edges on the glans (FIGURE). There was minimal drainage in the periurethral area. The patient didn’t have any other rashes or lesions on the skin or mucous membranes, or any regional lymphadenopathies.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Primary syphilis

The patient was given a diagnosis of primary syphilis based on his history and the clinical appearance of a syphilitic chancre. While chancres often occur on the shaft of the penis, they can also occur in the periurethral area, as was the case with this patient. The diagnosis of syphilis was confirmed with a positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay (TPPA).

Although the primary route of transmission is sexual contact, syphilis may also be transmitted from mother to fetus during pregnancy or birth, resulting in congenital syphilis. In addition, a considerable number of men who are diagnosed with syphilis are positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibodies.1 (Our patient was tested for HIV; the result was negative.)

The resurgence of syphilis. In 2000 and 2001, rates of syphilis cases reached a historic low (2.1 cases per 100,000).2 Since then, however, there has been a resurgence of syphilis—not just in men who have sex with men—but in all sexually active populations. In the United States during 2014 to 2015, the rate of primary and secondary syphilis increased to 7.5 cases per 100,000, which is the highest reported rate since 1994. From 2000 to 2015, this increase was primarily attributable to cases among men and, specifically, among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. But while the rate increased 18% among men during 2014 to 2015, it also increased by 27% among women.2

Social, epidemiologic, and individual risk factors can lead to higher levels of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in gay and bisexual men. In addition, lack of access to quality health care, homophobia, or stigma can all contribute to greater risk for this population.3 For these reasons, it is important for family physicians to immediately recognize this disease. (To learn more about the resurgence of syphilis, listen to the audiocast from Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA at http://bit.ly/2mRvYQe.)

The 4 stages of syphilis

The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary by the stage of disease.

Primary syphilis is the stage of initial inoculation with T pallidum. It is during this stage that a firm, nonpruritic skin ulceration—a chancre—appears. Although the classic chancre is typically painless, it can be painful.

Secondary syphilis presents as a diffuse rash that frequently involves the palms and soles.

The third or latent stage of syphilis may last for 2 years with few, or no, symptoms. However, secondary and latent syphilis may entail a broad range of manifestations, which is why syphilis is known as the “great imitator.”

In the final stage—tertiary syphilis—gummas and neurologic or cardiac symptoms may be seen.

Differential includes fungal, bacterial infections

The differential diagnosis of syphilis includes other infections such as chancroid, condyloma acuminata, candidiasis, granuloma inguinale, and lymphogranuloma venereum.

Chancroid presents as multiple painful necrotizing genital ulcers that may be accompanied by inguinal lymphadenopathy. It is caused by the bacterium Haemophilus ducreyi.

Condyloma acuminata is characterized by skin-colored, nontender warts and is caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV).

Candidiasis is a fungal infection that is characterized by pruritus and whitish-colored patches on the penis.

Granuloma inguinale (Donovanosis) is a chronic bacterial infection caused by Klebsiella granulomatis. It initially appears as nodular lesions that evolve into ulcers, which progressively expand and are locally destructive.

Lymphogranuloma venereum is an STD that can be caused by 3 different types (serovars) of the bacteria Chlamydia trachomatis. It presents with self-limited genital papules and ulcers followed by painful inguinal and/or femoral lymphadenopathy.

Diagnosis can be confirmed with serologic tests

The diagnosis of syphilis can be made by direct identification of the bacterium or serologic tests. Direct tests include dark field microscopy of serous fluid from genital lesions. This provides an immediate diagnosis with a sensitivity rate of up to 97%.4 However, hospitals do not always have the equipment or experienced staff to perform this technique, which must be done within 10 minutes of acquiring a sample. A polymerase chain reaction test can also be used to detect T pallidum DNA from specimens of any lesion exudate, tissue, or body fluid, but these tests can be costly compared with other tests used to diagnose syphilis.5

Serologic tests are divided into 2 groups: treponemal (specific) and nontreponemal (nonspecific) tests. Treponemal tests, which include TPPA, T pallidum hemagglutination assays, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, will yield a positive result for current or previously treated syphilis because a positive result remains so for life. Nontreponemal tests, such as the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test and the venereal disease reference laboratory (VDRL) test, yield a titer that is a measure of disease activity (the titer drops with treatment and rises with reinfection). Because these are nonspecific tests, biological false positives may occur if the patient has other acute or chronic infections or autoimmune diseases.5

Treat with penicillin

The first-choice treatment for uncomplicated syphilis is a single dose of intramuscular (IM) penicillin G (2.4 million units). A single dose of oral azithromycin 2 g or doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 14 days can be used for patients who are allergic to penicillin.5-7 Ceftriaxone, either IM or intravenous 1 g/d for 10 to 14 days, is also effective.

Our patient declined parenteral treatment, so he was treated with oral azithromycin 2 g in a single dose. His RPR titer was taken again one week after completing the azithromycin, at which time there was a 4-fold drop (1:32 to 1:8), indicating a good response to therapy. At a follow-up appointment 6 months later, the infection hadn’t recurred. We also educated the patient on the nature of the infection, how he became infected, and safe-sex practices to prevent reinfection.

CORRESPONDENCE

Husein Husein-ElAhmed, MD, PhD, Department of Dermatology, Hospital de Baza, Avda Murcia s/n, CP: 18800, Granada, Spain; [email protected].

1. Hook EW 3rd. Syphilis. Lancet. 2016.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2015. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats15/std-surveillance-2015-print.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2017.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported cases of sexually transmitted diseases on the rise, some at alarming rate. November 17, 2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2015/std-surveillance-report-press-release.html. Accessed March 14, 2017.

4. Wheeler HL, Agarwal S, Goh BT. Dark ground microscopy and treponemal tests in the diagnosis of early syphilis. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:411-414.

5. WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Treponema pallidum (Syphilis). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/249572/1/9789241549806-eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed March 6, 2017.

6. Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

7. Janier M, Hegyi V, Dupin N, et al. 2014 European guideline on the management of syphilis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1581-1593.

1. Hook EW 3rd. Syphilis. Lancet. 2016.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2015. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats15/std-surveillance-2015-print.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2017.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported cases of sexually transmitted diseases on the rise, some at alarming rate. November 17, 2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2015/std-surveillance-report-press-release.html. Accessed March 14, 2017.

4. Wheeler HL, Agarwal S, Goh BT. Dark ground microscopy and treponemal tests in the diagnosis of early syphilis. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:411-414.

5. WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Treponema pallidum (Syphilis). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/249572/1/9789241549806-eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed March 6, 2017.

6. Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

7. Janier M, Hegyi V, Dupin N, et al. 2014 European guideline on the management of syphilis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1581-1593.

Targeting depression: Primary care tips and tools

THE CASE

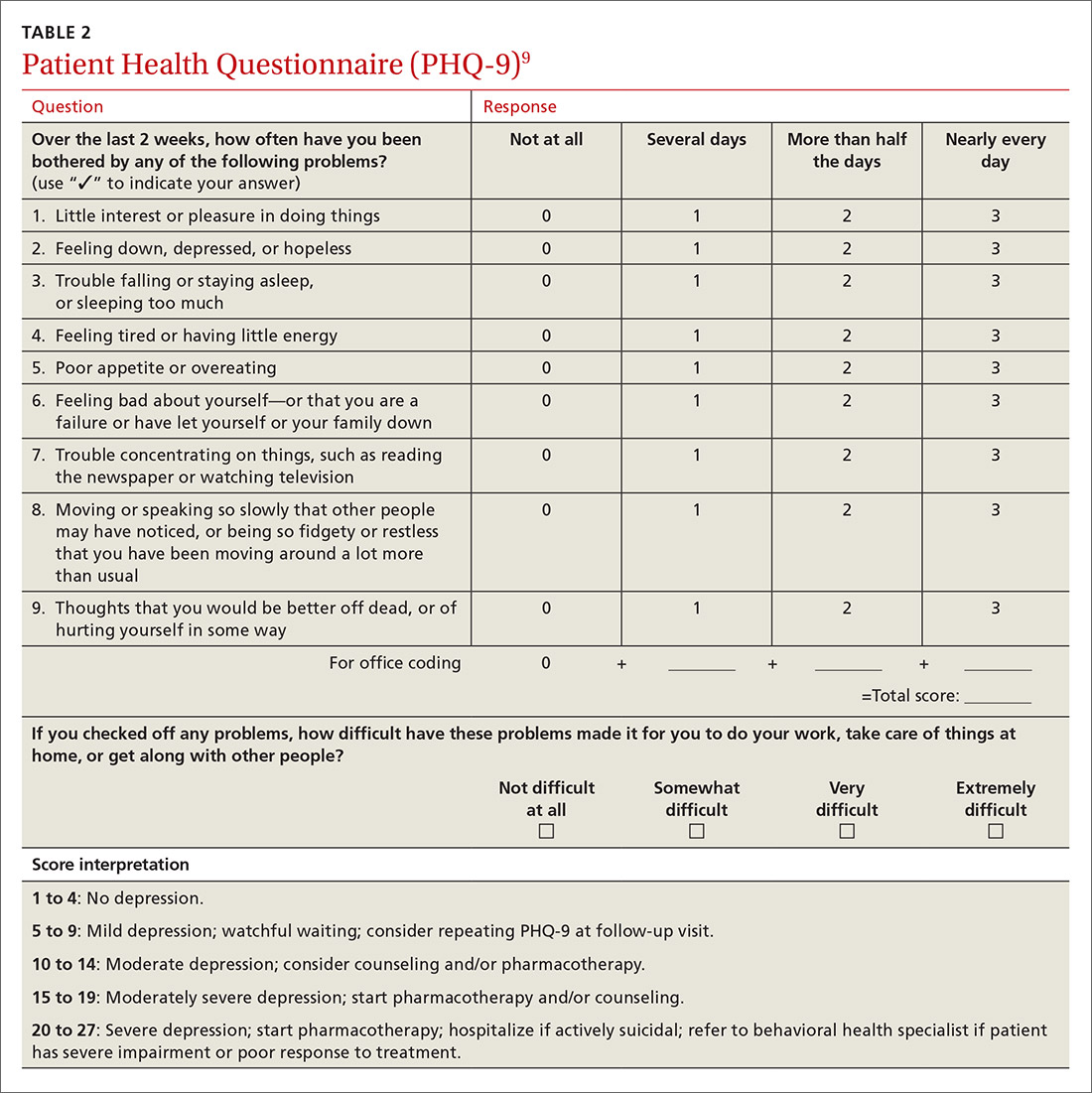

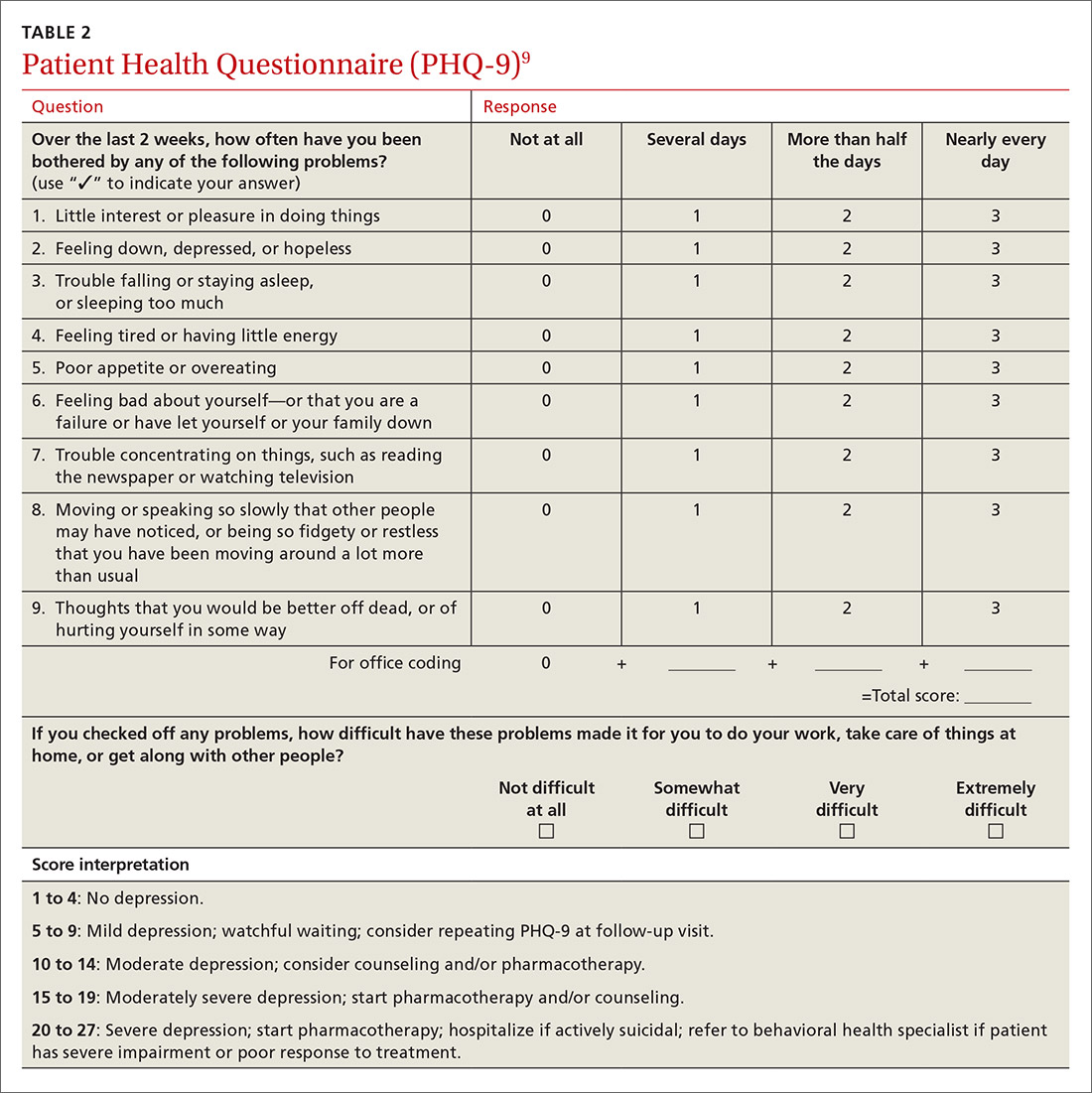

As you get ready to see your next patient, 52-year-old Jim M, you see in his chart that during an annual routine nurse screening (per office protocol), he scored positive for depressed mood/anhedonia on the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) and scored a 21 out of 27 on the full version (PHQ-9), suggesting that he has severe major depressive disorder and that antidepressants should be considered.

When you enter the exam room, you notice his sad expression, poor eye contact, and stooped posture. Mr. M says his wife “made him” come to see you. He reports low energy and not wanting to leave his house, which started about a year earlier after he lost his job. When you discuss his job loss and the impact it has had on him, he sheepishly admits to sometimes thinking that things would be better if he were dead. Upon further questioning, you learn that he does not have suicidal intentions or plans.

HOW WOULD YOU PROCEED WITH THIS PATIENT?

Depression is the most common mental health complaint in primary care settings; in 2015, an estimated 16.1 million (6.7%) adults in the United States ages 18 or older had at least one depressive episode in the past year.1 Depression results in significant health, work, and social life impairments,2 and comorbid anxiety is highly prevalent in patients with depression.

Primary care physicians see almost twice as many mental health patients as psychiatrists3 due to barriers in behavioral health treatment (such as wait times, cost, and stigma) and the fact that primary care physicians often provide first-line access to behavioral health resources. Depression is caused by biological, psychological, and social factors, and primary care physicians are ideally positioned to develop therapeutic, healing relationships with patients that coincide with the biopsychosocial model of the disease.4

This review will provide some useful tips and tools to ensure that these patients get the care they need.

Depression? Or are other factors at play?

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is defined as a clinically significant change in mood that lasts at least 2 weeks.5 The main symptoms of MDD include depressed mood and markedly diminished interest or pleasure; additional symptoms may include reduced self-esteem, weight/appetite changes, fatigue or reduced energy, guilt/worthlessness, decreased activity, poor concentration, and suicidal thinking.5 To meet the criteria for a diagnosis of MDD, patients must experience symptoms for most of the day, nearly every day. (Dysthymia or persistent depressive disorder is a type of depression that is milder and more chronic than MDD, but does not have as many symptoms as MDD.) The focus of this article will be on MDD.

Shared symptoms with other disorders

Depression often displays some of the same symptoms as bereavement disorder and adjustment disorder, as well as other conditions.

Grief over loss and depressive symptoms circumscribed to a stressor are considered bereavement disorder and adjustment disorder, respectively. These disorders are usually limited to weeks or months as the patient adapts to his/her particular situation.

Organic problems such as nutritional deficiencies and sleep apnea can cause, exacerbate, or mimic depression (TABLE 16). Pain and depression are often associated, in that chronic pain can precipitate or perpetuate depression.7

Bipolar disorder consists of both depressive and manic episodes; patients may be misdiagnosed and treated for depression alone.

Substance intoxication or withdrawal can precipitate or perpetuate depression. A period of abstinence of at least one month may be necessary to see if depressive symptoms persist or resolve.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder is defined as a period of depressed mood that is limited to the final week before the onset of menses and resolves in the week post-menses.

How to make the diagnosis

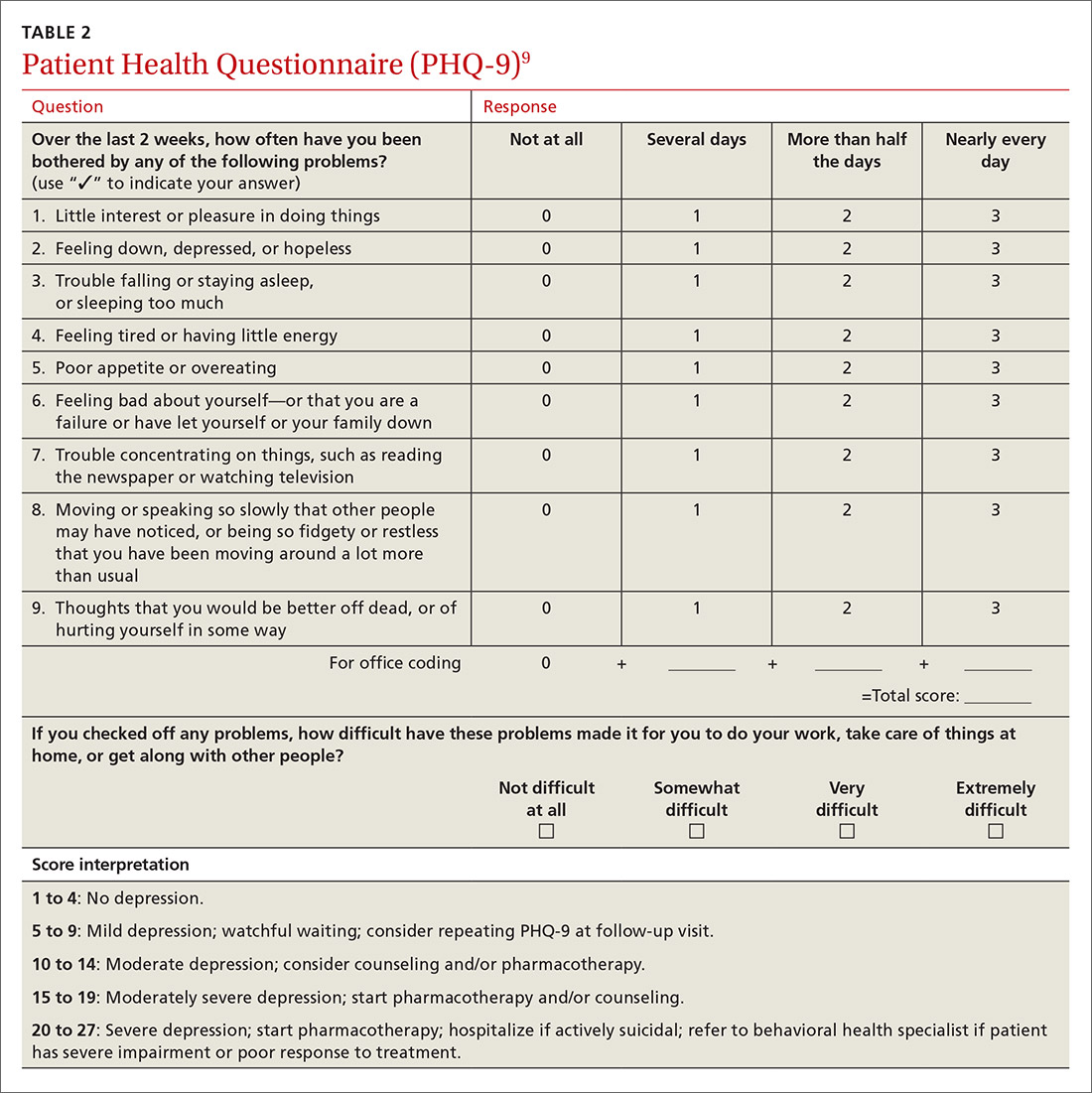

Inquiring about prolonged feelings of sadness and/or lack of enjoyment in activities is an effective way to begin the screening process for depression.8 Screening tools such as the PHQ-9 (TABLE 29), Beck Depression Inventory, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, and Geriatric Depression Scale are useful when combined with a clinical interview. Another useful tool is the Mood Disorder Questionnaire, which can help one determine if a patient is suffering from depression or bipolar disorder. It’s available at: http://www.dbsalliance.org/pdfs/MDQ.pdf. (Asking about a history of consecutive days of elevated, expansive, or irritable mood accompanied by increased activity or energy can also provide valuable insight.)

For its part, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening adults for depression when adequate systems are in place (eg, referrals to settings that can provide necessary care) so as “to assure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up.”10-12

Assessing severity. Asking about functional impairments at work and at home and with academics and relationships will help determine severity, as will inquiring about a patient’s past or current suicidal thoughts. About two-thirds of all patients with depression contemplate suicide and 10% to 15% will attempt suicide.13

There is no evidence that inquiring about thoughts of death or suicide exacerbates suicidal risk.14,15 Confirming a diagnosis of MDD may require multiple visits, but should not delay treatment.

Making the most of the tools at your disposal

As a family physician (FP), you are especially well positioned to help patients suffering from MDD by offering education, counseling, and support; prescribing antidepressants; and coordinating care. Collaboration with behavioral health teams may be beneficial, especially in complex and treatment-resistant cases.

Counseling, alone or combined with pharmacotherapy, may improve patient outcomes.16,17 A first step may be recommending behavior modifications (such as adequate sleep, exercise, and a healthy diet). FPs can learn to utilize several counseling techniques, such as motivational interviewing, solution-focused therapy, and supportive therapy, for a variety of clinical situations in which behavioral change would be helpful.18 Establishing a therapeutic alliance through empathy and creating treatment expectations are key to helping patients overcome depression.19,20 Referral to a therapist can help identify and manage psychosocial factors that are often inherent in depression. Explaining to the patient that depression is best improved with a combination of medication and therapy is often helpful in motivating the patient to see a therapist.

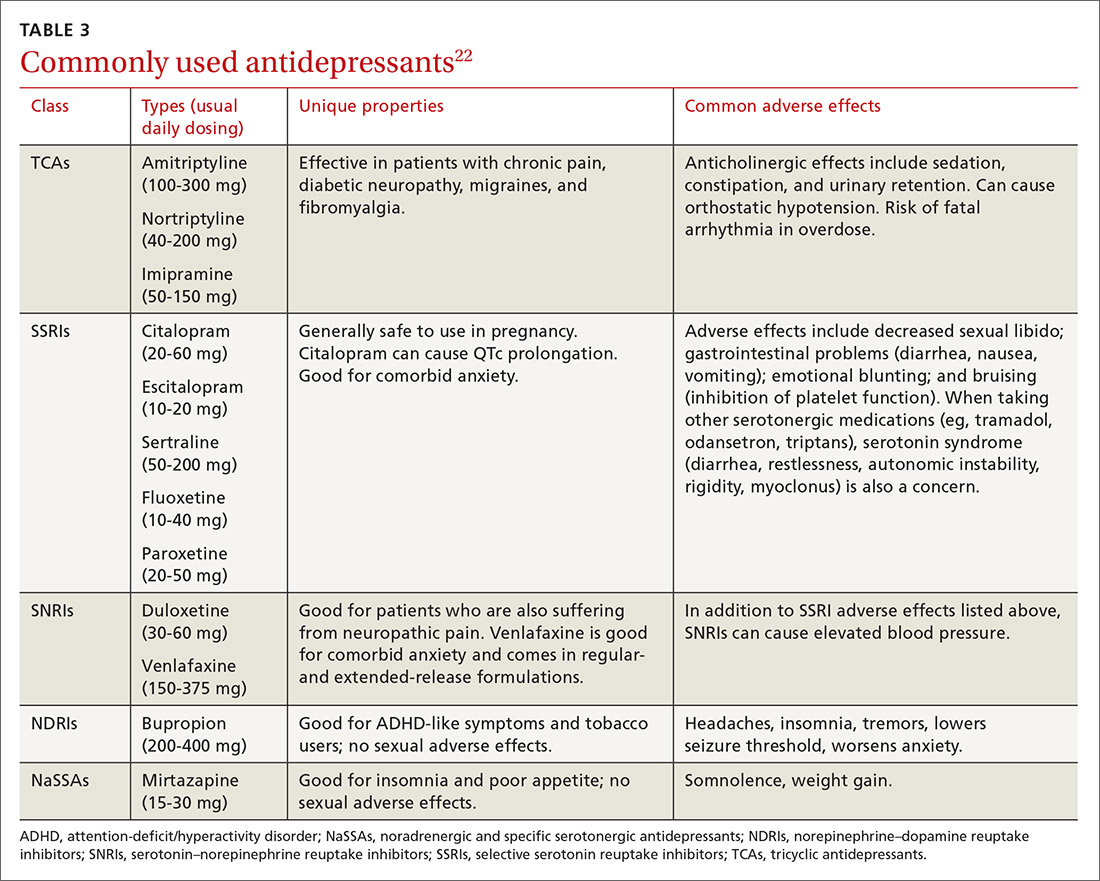

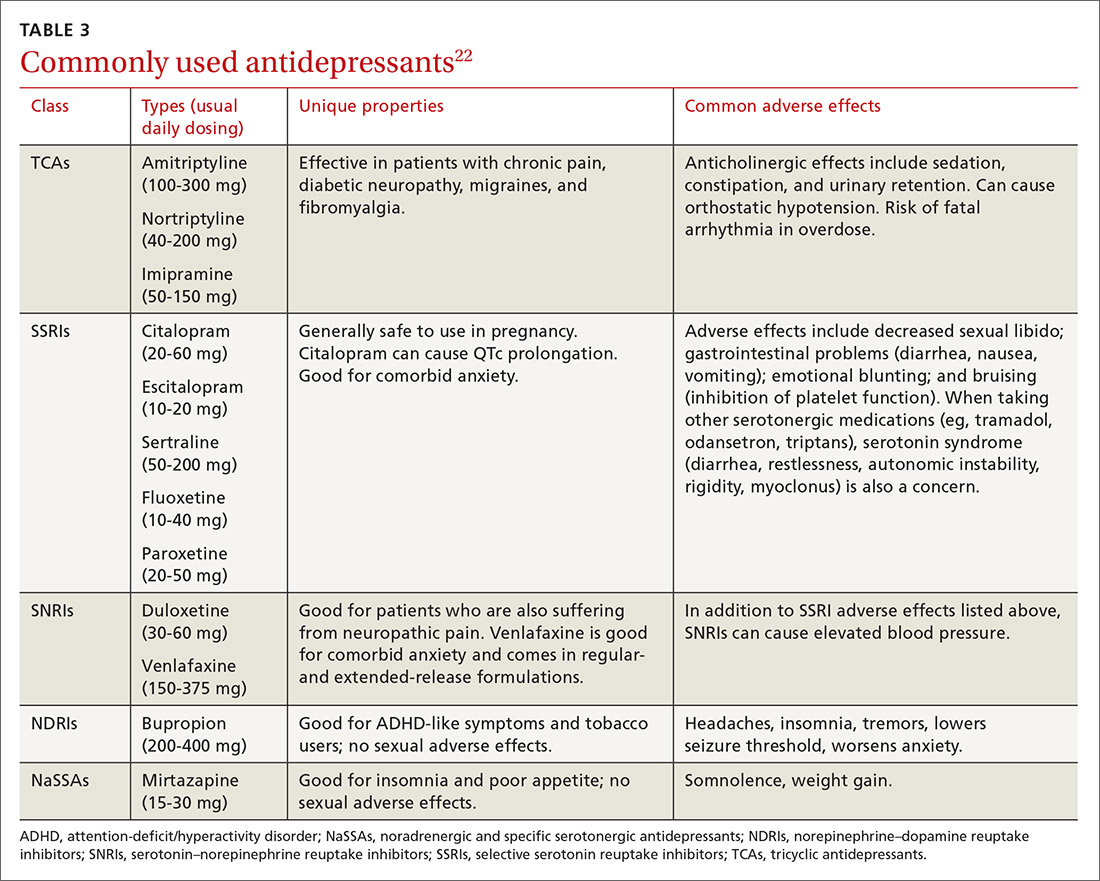

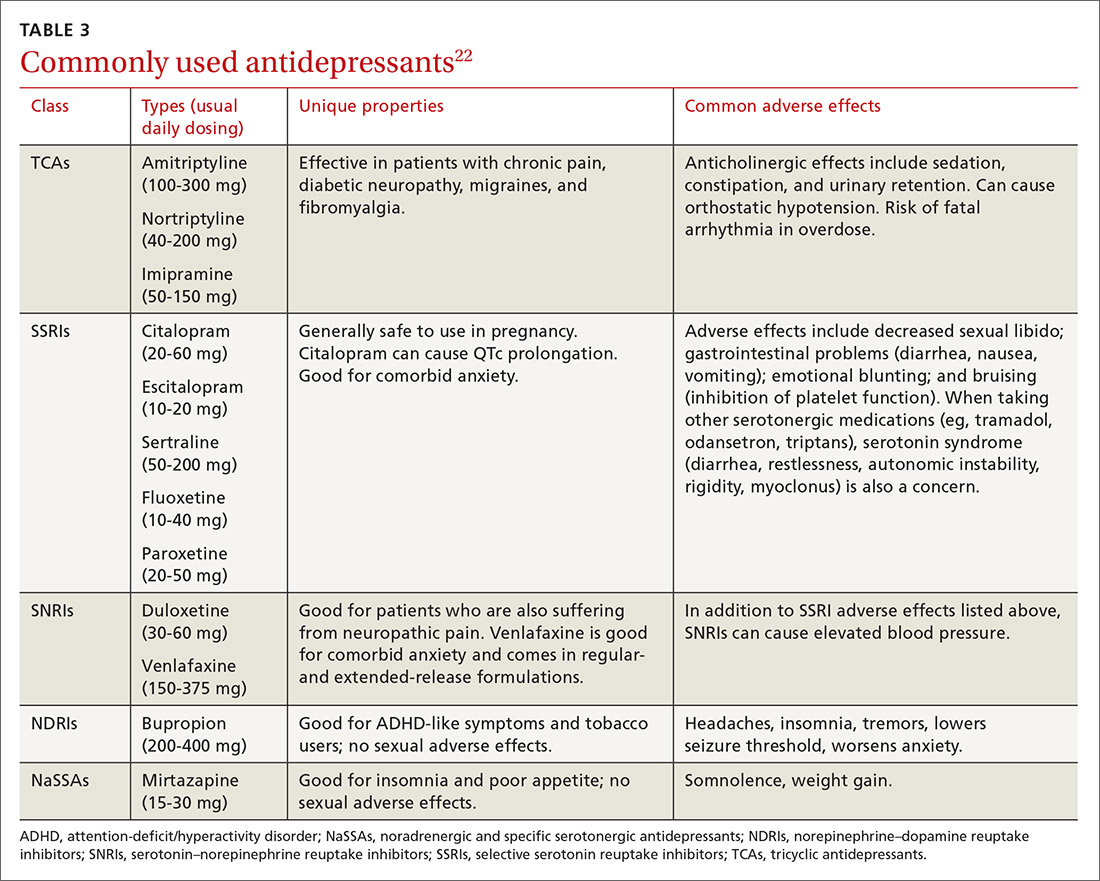

Selecting an antidepressant. There is insufficient evidence to show differences in remission rates or times to remission among antidepressants,21 so medication choice involves balancing factors such as cost, previous treatments, adverse effects, and comorbid conditions (TABLE 322). A recent systematic review and meta-analysis involving 66 studies and more than 15,000 patients found tricyclic/tetracyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to have the best evidence for treatment of depression in the primary care setting.23 Ask the patient about previous antidepressant prescriptions they were given, if any, and weigh the benefits and adverse effects with the patient.

Patients may notice a partial response as early as one to 2 weeks after starting treatment with antidepressants, but it’s important to tell them that a full response can take up to 4 to 6 weeks. The goal of treatment is remission of depressive symptoms, which is defined as scoring below the cutoff point on a validated depression scale, such as less than 5 on the PHQ-9.24 It’s advisable to increase the antidepressant dose if the patient has a partial response and switch to a new class if the patient has no response or severe adverse effects.

Antidepressants should be maintained for at least 6 months or the length of a previous episode, whichever is greater.24 Prophylactic treatment should be considered for patients who have had severe episodes in the past (eg, a history of suicidal ideations and/or past hospitalizations). If an antidepressant is discontinued, it should be tapered over one to 2 weeks to minimize the risk of discontinuation syndrome (flu-like symptoms, nausea, insomnia, and hyperarousal). There is a lack of consistent evidence for the use of St. John’s wort, and as such, it is not recommended.24

Adjunct medications can also be used when remission does not occur after 8 to 12 weeks of maximum antidepressant doses. Insomnia, which is a common complaint in patients with MDD, can be treated with trazodone (an off-label indication), diphenhydramine, or melatonin. (See “Insomnia: Getting to the cause, facilitating relief.”) Benzodiazepines and other hypnotics (eg, zolpidem) can be used initially until antidepressants have had time to become effective. Antipsychotics such as aripiprazole, risperidone, quetiapine, and ziprasidone can be used to treat psychotic symptoms of depression or boost antidepressant effectiveness.25 Lithium and thyroxine are effective for treatment-resistant depression.26 Nutraceuticals such as S-Adenosyl-L-methionine, methylfolate, omega-3, and vitamin D can reduce depressive symptoms when combined with an antidepressant.27

There is some evidence to support combining 2 antidepressants from different classes (eg, an SSRI plus a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor [SNRI] or norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor, or an SNRI plus a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant) when adjunct therapy has proven ineffective.28

Inpatient psychiatric admission is warranted in severe cases, such as when a patient has active suicidal intentions/plans or poor self-care.

Your critical role, even when depression is co-managed

Collaborative care for depression (patient contact with both primary and behavioral health care providers in the same clinic) significantly improves clinical outcomes at 6 months compared to primary care treatment alone.29 Patients who have failed 2 therapeutic trials (at least 6-8 weeks of separate antidepressant treatments without response) are considered treatment-resistant.30 Referral to a psychiatrist is appropriate in this setting to determine alternative treatment options.

› CASE

Based on further conversation with Mr. M, you learn that he actually began exhibiting symptoms of depression (anhedonia, poor concentration, insomnia) years before he lost his job, but that he had considered the symptoms “normal” for his age. He reports that he didn’t want to socialize with others anymore and harbors feelings of worthlessness. You tell him that you believe he is suffering from MDD and talk to him about some options for treatment. You decide together to begin a trial of escitalopram 10 mg/d, as it was covered by his insurance, has minimal adverse effects, and was a good match for his symptoms. You also educate and instruct Mr. M on self-management goals such as limiting alcohol intake, eating at least 2 meals a day, walking with his wife each evening, and following a regular sleep schedule. You discuss a safety plan with Mr. M, should his depressive symptoms worsen. Specifically, you tell him that if he begins to have suicidal intentions or plans, he should call 911 or go to the nearest emergency department.

Mr. M returns 4 weeks later and reports that his mood has slightly improved, as evidenced by a brighter affect and increased energy, so you increase the dose of escitalopram to 20 mg/d. At his third visit 4 weeks later, Mr. M discloses a remote history of trauma and current intermittent heavy drinking. After offering support and education and discussing his options, you refer Mr. M to a counselor in your clinic through a “warm handoff” (the counselor is brought briefly into the current session with the patient to meet and set up an appointment). During this time, he is given information about an outpatient substance abuse treatment group.

Mr. M’s PHQ-9 improves by 8 points by his fourth visit 4 weeks later. He reports that he is still taking the escitalopram and you recommend he continue to take it. Mr. M tells you he’s been seeing the counselor at your clinic every other week and that he has begun attending meetings with the substance abuse group. He also says that he and his wife go out for walks now and then. Mr. M says he feels as though he is a failure, prompting you to recommend that he explore the cognitive distortions (ie, inaccurate thoughts that reinforce negative feelings) with his therapist.

You schedule another appointment with Mr. M in 3 months to keep track of his progress. Fortunately, Mr. M’s therapist works in the same clinic as you, so you can contact her to discuss his progress with therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Raddock, MD, 2500 MetroHealth Drive, Cleveland, OH 44109; [email protected].

1. National Institute of Mental Health. Major depression among adults. National Institute of Mental Health Web site. Available at: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/major-depression-among-adults.shtml. 2014. Accessed June 22, 2016.

2. Cameron C, Habert J, Anand L, et al. Optimizing the management of depression: primary care experience. Psychiatry Res. 2014;220:S45-S57.

3. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:629-640.

4. Schotte CK, Van Den Bossche B, De Doncker D, et al. A biopsychosocial model as a guide for psychoeducation and treatment of depression. Depress Anxiety. 2006;23:312-324.

5. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013:160-161.

6. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003:830-834.

7. Fishbain DA, Cutler R, Rosomoff HL, et al. Chronic pain-associated depression: antecedent or consequence of chronic pain? A review. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:116-137.

8. Arroll B, Khin N, Kerse N. Screening for depression in primary care with two verbally asked questions: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2003;327:1144-1146.

9. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613.

10. US Preventive Services Task Force. Depression in adults: Screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/depression-in-adults-screening. Accessed March 13, 2017.

11. Thombs BD, Ziegelstein RC. Does depression screening improve depression outcomes in primary care? BMJ. 2014;348:g1253.

12. Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for depression in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315:380-387.

13. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003:543.

14. Gould MS, Marrocco FA, Kleinman M, et al. Evaluating iatrogenic risk of youth suicide screening programs: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:1635-1643.

15. Eynan R, Bergmans Y, Antony J, et al. The effects of suicide ideation assessments on urges to self-harm and suicide. Crisis. 2014;35:123-131.

16. Pampallona S, Bollini P, Tibaldi G, et al. Combined pharmacotherapy and psychological treatment for depression: a systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:714-719.

17. Ishak WW, Ha K, Kapitanski N, et al. The impact of psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and their combination on quality of life in depression. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2011;19:277-289.

18. Raddock M, Martukovich R, Berko E, et al. 7 tools to help patients adopt healthier behaviors. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:97-103.

19. Castonguay LG, Constantino MJ, Holtforth MG. The working alliance: Where are we and where should we go? Psychotherapy (Chic). 2006;43:271-279.

20. Greenberg RP, Constantino MJ, Bruce N. Are patient expectations still relevant for psychotherapy process and outcome? Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:657-678.

21. Warden D, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. The STAR*D Project results: a comprehensive review of findings. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9:449-459.

22. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003:558.

23. Linde K, Kriston L, Rücker G, et al. Efficacy and acceptability of pharmacological treatments for depressive disorders in primary care: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13:69-79.

24. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. 2010. Available at: http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Accessed December 23, 2016.

25. Zhou X, Keitner GI, Qin B, et al. Atypical antipsychotic treatment for treatment-resistant depression: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;18:pyv060.

26. Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, et al. A comparison of lithium and T(3) augmentation following two failed medication treatments for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1519-1530; quiz 1665.

27. Sarris J, Murphy J, Mischoulon D, et al. Adjunctive nutraceuticals for depression: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:575-587.

28. Dodd S, Horgan D, Malhi GS, et al. To combine or not to combine? A literature review of antidepressant combination therapy. J Affect Disord. 2005;89:1-11.

29. Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, et al. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2314-2321.

30. Papakostas GI, Fava M. Pharmacotherapy for Depression and Treatment-Resistant Depression. Hackensack, NJ: World Scientific. 2010:4.

THE CASE

As you get ready to see your next patient, 52-year-old Jim M, you see in his chart that during an annual routine nurse screening (per office protocol), he scored positive for depressed mood/anhedonia on the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) and scored a 21 out of 27 on the full version (PHQ-9), suggesting that he has severe major depressive disorder and that antidepressants should be considered.

When you enter the exam room, you notice his sad expression, poor eye contact, and stooped posture. Mr. M says his wife “made him” come to see you. He reports low energy and not wanting to leave his house, which started about a year earlier after he lost his job. When you discuss his job loss and the impact it has had on him, he sheepishly admits to sometimes thinking that things would be better if he were dead. Upon further questioning, you learn that he does not have suicidal intentions or plans.

HOW WOULD YOU PROCEED WITH THIS PATIENT?

Depression is the most common mental health complaint in primary care settings; in 2015, an estimated 16.1 million (6.7%) adults in the United States ages 18 or older had at least one depressive episode in the past year.1 Depression results in significant health, work, and social life impairments,2 and comorbid anxiety is highly prevalent in patients with depression.

Primary care physicians see almost twice as many mental health patients as psychiatrists3 due to barriers in behavioral health treatment (such as wait times, cost, and stigma) and the fact that primary care physicians often provide first-line access to behavioral health resources. Depression is caused by biological, psychological, and social factors, and primary care physicians are ideally positioned to develop therapeutic, healing relationships with patients that coincide with the biopsychosocial model of the disease.4

This review will provide some useful tips and tools to ensure that these patients get the care they need.

Depression? Or are other factors at play?

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is defined as a clinically significant change in mood that lasts at least 2 weeks.5 The main symptoms of MDD include depressed mood and markedly diminished interest or pleasure; additional symptoms may include reduced self-esteem, weight/appetite changes, fatigue or reduced energy, guilt/worthlessness, decreased activity, poor concentration, and suicidal thinking.5 To meet the criteria for a diagnosis of MDD, patients must experience symptoms for most of the day, nearly every day. (Dysthymia or persistent depressive disorder is a type of depression that is milder and more chronic than MDD, but does not have as many symptoms as MDD.) The focus of this article will be on MDD.

Shared symptoms with other disorders

Depression often displays some of the same symptoms as bereavement disorder and adjustment disorder, as well as other conditions.

Grief over loss and depressive symptoms circumscribed to a stressor are considered bereavement disorder and adjustment disorder, respectively. These disorders are usually limited to weeks or months as the patient adapts to his/her particular situation.

Organic problems such as nutritional deficiencies and sleep apnea can cause, exacerbate, or mimic depression (TABLE 16). Pain and depression are often associated, in that chronic pain can precipitate or perpetuate depression.7

Bipolar disorder consists of both depressive and manic episodes; patients may be misdiagnosed and treated for depression alone.

Substance intoxication or withdrawal can precipitate or perpetuate depression. A period of abstinence of at least one month may be necessary to see if depressive symptoms persist or resolve.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder is defined as a period of depressed mood that is limited to the final week before the onset of menses and resolves in the week post-menses.

How to make the diagnosis

Inquiring about prolonged feelings of sadness and/or lack of enjoyment in activities is an effective way to begin the screening process for depression.8 Screening tools such as the PHQ-9 (TABLE 29), Beck Depression Inventory, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, and Geriatric Depression Scale are useful when combined with a clinical interview. Another useful tool is the Mood Disorder Questionnaire, which can help one determine if a patient is suffering from depression or bipolar disorder. It’s available at: http://www.dbsalliance.org/pdfs/MDQ.pdf. (Asking about a history of consecutive days of elevated, expansive, or irritable mood accompanied by increased activity or energy can also provide valuable insight.)

For its part, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening adults for depression when adequate systems are in place (eg, referrals to settings that can provide necessary care) so as “to assure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up.”10-12

Assessing severity. Asking about functional impairments at work and at home and with academics and relationships will help determine severity, as will inquiring about a patient’s past or current suicidal thoughts. About two-thirds of all patients with depression contemplate suicide and 10% to 15% will attempt suicide.13

There is no evidence that inquiring about thoughts of death or suicide exacerbates suicidal risk.14,15 Confirming a diagnosis of MDD may require multiple visits, but should not delay treatment.

Making the most of the tools at your disposal

As a family physician (FP), you are especially well positioned to help patients suffering from MDD by offering education, counseling, and support; prescribing antidepressants; and coordinating care. Collaboration with behavioral health teams may be beneficial, especially in complex and treatment-resistant cases.

Counseling, alone or combined with pharmacotherapy, may improve patient outcomes.16,17 A first step may be recommending behavior modifications (such as adequate sleep, exercise, and a healthy diet). FPs can learn to utilize several counseling techniques, such as motivational interviewing, solution-focused therapy, and supportive therapy, for a variety of clinical situations in which behavioral change would be helpful.18 Establishing a therapeutic alliance through empathy and creating treatment expectations are key to helping patients overcome depression.19,20 Referral to a therapist can help identify and manage psychosocial factors that are often inherent in depression. Explaining to the patient that depression is best improved with a combination of medication and therapy is often helpful in motivating the patient to see a therapist.

Selecting an antidepressant. There is insufficient evidence to show differences in remission rates or times to remission among antidepressants,21 so medication choice involves balancing factors such as cost, previous treatments, adverse effects, and comorbid conditions (TABLE 322). A recent systematic review and meta-analysis involving 66 studies and more than 15,000 patients found tricyclic/tetracyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to have the best evidence for treatment of depression in the primary care setting.23 Ask the patient about previous antidepressant prescriptions they were given, if any, and weigh the benefits and adverse effects with the patient.

Patients may notice a partial response as early as one to 2 weeks after starting treatment with antidepressants, but it’s important to tell them that a full response can take up to 4 to 6 weeks. The goal of treatment is remission of depressive symptoms, which is defined as scoring below the cutoff point on a validated depression scale, such as less than 5 on the PHQ-9.24 It’s advisable to increase the antidepressant dose if the patient has a partial response and switch to a new class if the patient has no response or severe adverse effects.

Antidepressants should be maintained for at least 6 months or the length of a previous episode, whichever is greater.24 Prophylactic treatment should be considered for patients who have had severe episodes in the past (eg, a history of suicidal ideations and/or past hospitalizations). If an antidepressant is discontinued, it should be tapered over one to 2 weeks to minimize the risk of discontinuation syndrome (flu-like symptoms, nausea, insomnia, and hyperarousal). There is a lack of consistent evidence for the use of St. John’s wort, and as such, it is not recommended.24

Adjunct medications can also be used when remission does not occur after 8 to 12 weeks of maximum antidepressant doses. Insomnia, which is a common complaint in patients with MDD, can be treated with trazodone (an off-label indication), diphenhydramine, or melatonin. (See “Insomnia: Getting to the cause, facilitating relief.”) Benzodiazepines and other hypnotics (eg, zolpidem) can be used initially until antidepressants have had time to become effective. Antipsychotics such as aripiprazole, risperidone, quetiapine, and ziprasidone can be used to treat psychotic symptoms of depression or boost antidepressant effectiveness.25 Lithium and thyroxine are effective for treatment-resistant depression.26 Nutraceuticals such as S-Adenosyl-L-methionine, methylfolate, omega-3, and vitamin D can reduce depressive symptoms when combined with an antidepressant.27

There is some evidence to support combining 2 antidepressants from different classes (eg, an SSRI plus a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor [SNRI] or norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor, or an SNRI plus a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant) when adjunct therapy has proven ineffective.28

Inpatient psychiatric admission is warranted in severe cases, such as when a patient has active suicidal intentions/plans or poor self-care.

Your critical role, even when depression is co-managed

Collaborative care for depression (patient contact with both primary and behavioral health care providers in the same clinic) significantly improves clinical outcomes at 6 months compared to primary care treatment alone.29 Patients who have failed 2 therapeutic trials (at least 6-8 weeks of separate antidepressant treatments without response) are considered treatment-resistant.30 Referral to a psychiatrist is appropriate in this setting to determine alternative treatment options.

› CASE

Based on further conversation with Mr. M, you learn that he actually began exhibiting symptoms of depression (anhedonia, poor concentration, insomnia) years before he lost his job, but that he had considered the symptoms “normal” for his age. He reports that he didn’t want to socialize with others anymore and harbors feelings of worthlessness. You tell him that you believe he is suffering from MDD and talk to him about some options for treatment. You decide together to begin a trial of escitalopram 10 mg/d, as it was covered by his insurance, has minimal adverse effects, and was a good match for his symptoms. You also educate and instruct Mr. M on self-management goals such as limiting alcohol intake, eating at least 2 meals a day, walking with his wife each evening, and following a regular sleep schedule. You discuss a safety plan with Mr. M, should his depressive symptoms worsen. Specifically, you tell him that if he begins to have suicidal intentions or plans, he should call 911 or go to the nearest emergency department.

Mr. M returns 4 weeks later and reports that his mood has slightly improved, as evidenced by a brighter affect and increased energy, so you increase the dose of escitalopram to 20 mg/d. At his third visit 4 weeks later, Mr. M discloses a remote history of trauma and current intermittent heavy drinking. After offering support and education and discussing his options, you refer Mr. M to a counselor in your clinic through a “warm handoff” (the counselor is brought briefly into the current session with the patient to meet and set up an appointment). During this time, he is given information about an outpatient substance abuse treatment group.

Mr. M’s PHQ-9 improves by 8 points by his fourth visit 4 weeks later. He reports that he is still taking the escitalopram and you recommend he continue to take it. Mr. M tells you he’s been seeing the counselor at your clinic every other week and that he has begun attending meetings with the substance abuse group. He also says that he and his wife go out for walks now and then. Mr. M says he feels as though he is a failure, prompting you to recommend that he explore the cognitive distortions (ie, inaccurate thoughts that reinforce negative feelings) with his therapist.

You schedule another appointment with Mr. M in 3 months to keep track of his progress. Fortunately, Mr. M’s therapist works in the same clinic as you, so you can contact her to discuss his progress with therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Raddock, MD, 2500 MetroHealth Drive, Cleveland, OH 44109; [email protected].

THE CASE

As you get ready to see your next patient, 52-year-old Jim M, you see in his chart that during an annual routine nurse screening (per office protocol), he scored positive for depressed mood/anhedonia on the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) and scored a 21 out of 27 on the full version (PHQ-9), suggesting that he has severe major depressive disorder and that antidepressants should be considered.

When you enter the exam room, you notice his sad expression, poor eye contact, and stooped posture. Mr. M says his wife “made him” come to see you. He reports low energy and not wanting to leave his house, which started about a year earlier after he lost his job. When you discuss his job loss and the impact it has had on him, he sheepishly admits to sometimes thinking that things would be better if he were dead. Upon further questioning, you learn that he does not have suicidal intentions or plans.

HOW WOULD YOU PROCEED WITH THIS PATIENT?

Depression is the most common mental health complaint in primary care settings; in 2015, an estimated 16.1 million (6.7%) adults in the United States ages 18 or older had at least one depressive episode in the past year.1 Depression results in significant health, work, and social life impairments,2 and comorbid anxiety is highly prevalent in patients with depression.

Primary care physicians see almost twice as many mental health patients as psychiatrists3 due to barriers in behavioral health treatment (such as wait times, cost, and stigma) and the fact that primary care physicians often provide first-line access to behavioral health resources. Depression is caused by biological, psychological, and social factors, and primary care physicians are ideally positioned to develop therapeutic, healing relationships with patients that coincide with the biopsychosocial model of the disease.4

This review will provide some useful tips and tools to ensure that these patients get the care they need.

Depression? Or are other factors at play?

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is defined as a clinically significant change in mood that lasts at least 2 weeks.5 The main symptoms of MDD include depressed mood and markedly diminished interest or pleasure; additional symptoms may include reduced self-esteem, weight/appetite changes, fatigue or reduced energy, guilt/worthlessness, decreased activity, poor concentration, and suicidal thinking.5 To meet the criteria for a diagnosis of MDD, patients must experience symptoms for most of the day, nearly every day. (Dysthymia or persistent depressive disorder is a type of depression that is milder and more chronic than MDD, but does not have as many symptoms as MDD.) The focus of this article will be on MDD.

Shared symptoms with other disorders

Depression often displays some of the same symptoms as bereavement disorder and adjustment disorder, as well as other conditions.

Grief over loss and depressive symptoms circumscribed to a stressor are considered bereavement disorder and adjustment disorder, respectively. These disorders are usually limited to weeks or months as the patient adapts to his/her particular situation.

Organic problems such as nutritional deficiencies and sleep apnea can cause, exacerbate, or mimic depression (TABLE 16). Pain and depression are often associated, in that chronic pain can precipitate or perpetuate depression.7

Bipolar disorder consists of both depressive and manic episodes; patients may be misdiagnosed and treated for depression alone.

Substance intoxication or withdrawal can precipitate or perpetuate depression. A period of abstinence of at least one month may be necessary to see if depressive symptoms persist or resolve.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder is defined as a period of depressed mood that is limited to the final week before the onset of menses and resolves in the week post-menses.

How to make the diagnosis

Inquiring about prolonged feelings of sadness and/or lack of enjoyment in activities is an effective way to begin the screening process for depression.8 Screening tools such as the PHQ-9 (TABLE 29), Beck Depression Inventory, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, and Geriatric Depression Scale are useful when combined with a clinical interview. Another useful tool is the Mood Disorder Questionnaire, which can help one determine if a patient is suffering from depression or bipolar disorder. It’s available at: http://www.dbsalliance.org/pdfs/MDQ.pdf. (Asking about a history of consecutive days of elevated, expansive, or irritable mood accompanied by increased activity or energy can also provide valuable insight.)

For its part, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening adults for depression when adequate systems are in place (eg, referrals to settings that can provide necessary care) so as “to assure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up.”10-12

Assessing severity. Asking about functional impairments at work and at home and with academics and relationships will help determine severity, as will inquiring about a patient’s past or current suicidal thoughts. About two-thirds of all patients with depression contemplate suicide and 10% to 15% will attempt suicide.13

There is no evidence that inquiring about thoughts of death or suicide exacerbates suicidal risk.14,15 Confirming a diagnosis of MDD may require multiple visits, but should not delay treatment.

Making the most of the tools at your disposal

As a family physician (FP), you are especially well positioned to help patients suffering from MDD by offering education, counseling, and support; prescribing antidepressants; and coordinating care. Collaboration with behavioral health teams may be beneficial, especially in complex and treatment-resistant cases.

Counseling, alone or combined with pharmacotherapy, may improve patient outcomes.16,17 A first step may be recommending behavior modifications (such as adequate sleep, exercise, and a healthy diet). FPs can learn to utilize several counseling techniques, such as motivational interviewing, solution-focused therapy, and supportive therapy, for a variety of clinical situations in which behavioral change would be helpful.18 Establishing a therapeutic alliance through empathy and creating treatment expectations are key to helping patients overcome depression.19,20 Referral to a therapist can help identify and manage psychosocial factors that are often inherent in depression. Explaining to the patient that depression is best improved with a combination of medication and therapy is often helpful in motivating the patient to see a therapist.

Selecting an antidepressant. There is insufficient evidence to show differences in remission rates or times to remission among antidepressants,21 so medication choice involves balancing factors such as cost, previous treatments, adverse effects, and comorbid conditions (TABLE 322). A recent systematic review and meta-analysis involving 66 studies and more than 15,000 patients found tricyclic/tetracyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to have the best evidence for treatment of depression in the primary care setting.23 Ask the patient about previous antidepressant prescriptions they were given, if any, and weigh the benefits and adverse effects with the patient.

Patients may notice a partial response as early as one to 2 weeks after starting treatment with antidepressants, but it’s important to tell them that a full response can take up to 4 to 6 weeks. The goal of treatment is remission of depressive symptoms, which is defined as scoring below the cutoff point on a validated depression scale, such as less than 5 on the PHQ-9.24 It’s advisable to increase the antidepressant dose if the patient has a partial response and switch to a new class if the patient has no response or severe adverse effects.

Antidepressants should be maintained for at least 6 months or the length of a previous episode, whichever is greater.24 Prophylactic treatment should be considered for patients who have had severe episodes in the past (eg, a history of suicidal ideations and/or past hospitalizations). If an antidepressant is discontinued, it should be tapered over one to 2 weeks to minimize the risk of discontinuation syndrome (flu-like symptoms, nausea, insomnia, and hyperarousal). There is a lack of consistent evidence for the use of St. John’s wort, and as such, it is not recommended.24

Adjunct medications can also be used when remission does not occur after 8 to 12 weeks of maximum antidepressant doses. Insomnia, which is a common complaint in patients with MDD, can be treated with trazodone (an off-label indication), diphenhydramine, or melatonin. (See “Insomnia: Getting to the cause, facilitating relief.”) Benzodiazepines and other hypnotics (eg, zolpidem) can be used initially until antidepressants have had time to become effective. Antipsychotics such as aripiprazole, risperidone, quetiapine, and ziprasidone can be used to treat psychotic symptoms of depression or boost antidepressant effectiveness.25 Lithium and thyroxine are effective for treatment-resistant depression.26 Nutraceuticals such as S-Adenosyl-L-methionine, methylfolate, omega-3, and vitamin D can reduce depressive symptoms when combined with an antidepressant.27

There is some evidence to support combining 2 antidepressants from different classes (eg, an SSRI plus a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor [SNRI] or norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor, or an SNRI plus a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant) when adjunct therapy has proven ineffective.28

Inpatient psychiatric admission is warranted in severe cases, such as when a patient has active suicidal intentions/plans or poor self-care.

Your critical role, even when depression is co-managed

Collaborative care for depression (patient contact with both primary and behavioral health care providers in the same clinic) significantly improves clinical outcomes at 6 months compared to primary care treatment alone.29 Patients who have failed 2 therapeutic trials (at least 6-8 weeks of separate antidepressant treatments without response) are considered treatment-resistant.30 Referral to a psychiatrist is appropriate in this setting to determine alternative treatment options.

› CASE

Based on further conversation with Mr. M, you learn that he actually began exhibiting symptoms of depression (anhedonia, poor concentration, insomnia) years before he lost his job, but that he had considered the symptoms “normal” for his age. He reports that he didn’t want to socialize with others anymore and harbors feelings of worthlessness. You tell him that you believe he is suffering from MDD and talk to him about some options for treatment. You decide together to begin a trial of escitalopram 10 mg/d, as it was covered by his insurance, has minimal adverse effects, and was a good match for his symptoms. You also educate and instruct Mr. M on self-management goals such as limiting alcohol intake, eating at least 2 meals a day, walking with his wife each evening, and following a regular sleep schedule. You discuss a safety plan with Mr. M, should his depressive symptoms worsen. Specifically, you tell him that if he begins to have suicidal intentions or plans, he should call 911 or go to the nearest emergency department.

Mr. M returns 4 weeks later and reports that his mood has slightly improved, as evidenced by a brighter affect and increased energy, so you increase the dose of escitalopram to 20 mg/d. At his third visit 4 weeks later, Mr. M discloses a remote history of trauma and current intermittent heavy drinking. After offering support and education and discussing his options, you refer Mr. M to a counselor in your clinic through a “warm handoff” (the counselor is brought briefly into the current session with the patient to meet and set up an appointment). During this time, he is given information about an outpatient substance abuse treatment group.

Mr. M’s PHQ-9 improves by 8 points by his fourth visit 4 weeks later. He reports that he is still taking the escitalopram and you recommend he continue to take it. Mr. M tells you he’s been seeing the counselor at your clinic every other week and that he has begun attending meetings with the substance abuse group. He also says that he and his wife go out for walks now and then. Mr. M says he feels as though he is a failure, prompting you to recommend that he explore the cognitive distortions (ie, inaccurate thoughts that reinforce negative feelings) with his therapist.

You schedule another appointment with Mr. M in 3 months to keep track of his progress. Fortunately, Mr. M’s therapist works in the same clinic as you, so you can contact her to discuss his progress with therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Raddock, MD, 2500 MetroHealth Drive, Cleveland, OH 44109; [email protected].

1. National Institute of Mental Health. Major depression among adults. National Institute of Mental Health Web site. Available at: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/major-depression-among-adults.shtml. 2014. Accessed June 22, 2016.

2. Cameron C, Habert J, Anand L, et al. Optimizing the management of depression: primary care experience. Psychiatry Res. 2014;220:S45-S57.

3. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:629-640.

4. Schotte CK, Van Den Bossche B, De Doncker D, et al. A biopsychosocial model as a guide for psychoeducation and treatment of depression. Depress Anxiety. 2006;23:312-324.