User login

Blending classic clinical skills with new technology

Now that we can order MRI studies on a break from rounds walking to Starbucks, utilize portable ultrasounds to direct IV line placement, and use dual-energy CT to detect a gout attack that has not yet occurred, it seems like a romantic anachronism to extol the ongoing virtues of the seemingly lost art of the physical examination. Back “in the day,” the giants of medicine roamed the halls with their natural instruments of palpation and percussion and their skills in observation and auscultation. They were giants because they stood out then, just as skilled diagnosticians stand out today using an upgraded set of tools. Some physicians a few decades ago were able to recognize, describe, and diagnose late-stage endocarditis with a stethoscope, a magnifying glass, and an ophthalmoscope. The giants of today recognize the patient with endocarditis and document its presence using transesophageal echocardiography before the peripheral eponymous stigmata of Janeway and Osler appear or the blood cultures turn positive. The physical examination, history, diagnostic reasoning, and clinical technology are all essential for a blend that provides efficient and effective medical care. The blending is the challenge.

Clinicians are not created equal. We learn and prioritize our skills in different ways. But if we are not taught to value and trust the physical examination, if we don’t have the opportunity to see it influence patient management in positive ways, we may eschew it and instead indiscriminately use easily available laboratory and imaging tests—a more expensive and often misleading strategic approach. Today while in clinic, I saw a 54-year-old woman for evaluation of possible lupus who had arthritis of the hands and a high positive antinuclear antibody titer, but negative or normal results on other, previously ordered tests, including anti-DNA, rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide, hepatitis C studies, complement levels, and another half-dozen immune serologic tests. On examination, she had typical nodular osteoarthritis of the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints of her hand with squaring of her thumbs. The antinuclear antibody was most likely associated with her previously diagnosed autoimmune thyroid disease.

In an editorial in this issue of the Journal, Dr. Salvatore Mangione, the author of a book on physical diagnosis,1 cites a recent study indicating that the most common recognized diagnostic error related to the physical examination is that the appropriate examination isn’t done.2 I would add to that my concerns over the new common custom of cutting and pasting the findings from earlier physical examinations into later progress notes in the electronic record. So much for the value of being able to recognize “changing murmurs” when diagnosing infectious endocarditis.

The apparent efficiency (reflected in length of stay) and availability of technology, as well as a lack of physician skill and time, are often cited as reasons for the demise of the physical examination. Yet this does not need to be the case. If I had trained with portable ultrasonography readily available to confirm or refute my impressions, my skills at detecting low-grade synovitis would surely be better than they are. With a gold standard at hand, which may be technology or at times a skilled mentor, our examinations can be refined if we want them to be.

But the issue of limited physician time must be addressed. Efficiency is a critical concept in preserving how we practice and perform the physical examination. When we know what we are looking for, we are more likely to find it if it is present, or to have confidence that it is not present. I am far more likely to recognize a loud pulmonic second heart sound if I suspect that the dyspneic patient I am examining has pulmonary hypertension associated with her scleroderma than if I am doing a perfunctory cardiac auscultation in a patient admitted with cellulitis. Appropriate focus provides power to the directed physical examination. If I am looking for the cause of unexplained fevers, I will do a purposeful axillary and epitrochlear lymph node examination. I am not mindlessly probing the flesh.

Nishigori and colleagues have written of the “hypothesis-driven” physical examination.3 Busy clinicians, they say, don’t have time to perform a head-to-toe, by-the-book physical examination. Instead, we should, by a dynamic process, formulate a differential diagnosis from the history and other initial information, and then perform the directed physical examination in earnest, looking for evidence to support or refute our diagnostic hypothesis—and thus redirect it. Plus, in a nice break from electronic charting, we can actually explain our thought processes to the patient as we perform the examination.

This approach makes sense to me as both intellectually satisfying and clinically efficient. And then we can consider which lab tests and technologic gadgetry we should order, while walking to get the café latte we ordered with our cell phone app.

New technology can support and not necessarily replace old habits.

- Mangione S. Physical Diagnosis Secrets, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008.

- Verghese A, Charlton B, Kassirer JP, Ramsey M, Ioannidis JP. Inadequacies of physical examination as a cause of medical errors and adverse events: a collection of vignettes. Am J Med 2015; 128:1322–1324.

- Nishigori H, Masuda K, Kikukawa M, et al. A model teaching session for the hypothesis-driven physical examination. Medical Teacher 2011; 33:410–417.

Now that we can order MRI studies on a break from rounds walking to Starbucks, utilize portable ultrasounds to direct IV line placement, and use dual-energy CT to detect a gout attack that has not yet occurred, it seems like a romantic anachronism to extol the ongoing virtues of the seemingly lost art of the physical examination. Back “in the day,” the giants of medicine roamed the halls with their natural instruments of palpation and percussion and their skills in observation and auscultation. They were giants because they stood out then, just as skilled diagnosticians stand out today using an upgraded set of tools. Some physicians a few decades ago were able to recognize, describe, and diagnose late-stage endocarditis with a stethoscope, a magnifying glass, and an ophthalmoscope. The giants of today recognize the patient with endocarditis and document its presence using transesophageal echocardiography before the peripheral eponymous stigmata of Janeway and Osler appear or the blood cultures turn positive. The physical examination, history, diagnostic reasoning, and clinical technology are all essential for a blend that provides efficient and effective medical care. The blending is the challenge.

Clinicians are not created equal. We learn and prioritize our skills in different ways. But if we are not taught to value and trust the physical examination, if we don’t have the opportunity to see it influence patient management in positive ways, we may eschew it and instead indiscriminately use easily available laboratory and imaging tests—a more expensive and often misleading strategic approach. Today while in clinic, I saw a 54-year-old woman for evaluation of possible lupus who had arthritis of the hands and a high positive antinuclear antibody titer, but negative or normal results on other, previously ordered tests, including anti-DNA, rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide, hepatitis C studies, complement levels, and another half-dozen immune serologic tests. On examination, she had typical nodular osteoarthritis of the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints of her hand with squaring of her thumbs. The antinuclear antibody was most likely associated with her previously diagnosed autoimmune thyroid disease.

In an editorial in this issue of the Journal, Dr. Salvatore Mangione, the author of a book on physical diagnosis,1 cites a recent study indicating that the most common recognized diagnostic error related to the physical examination is that the appropriate examination isn’t done.2 I would add to that my concerns over the new common custom of cutting and pasting the findings from earlier physical examinations into later progress notes in the electronic record. So much for the value of being able to recognize “changing murmurs” when diagnosing infectious endocarditis.

The apparent efficiency (reflected in length of stay) and availability of technology, as well as a lack of physician skill and time, are often cited as reasons for the demise of the physical examination. Yet this does not need to be the case. If I had trained with portable ultrasonography readily available to confirm or refute my impressions, my skills at detecting low-grade synovitis would surely be better than they are. With a gold standard at hand, which may be technology or at times a skilled mentor, our examinations can be refined if we want them to be.

But the issue of limited physician time must be addressed. Efficiency is a critical concept in preserving how we practice and perform the physical examination. When we know what we are looking for, we are more likely to find it if it is present, or to have confidence that it is not present. I am far more likely to recognize a loud pulmonic second heart sound if I suspect that the dyspneic patient I am examining has pulmonary hypertension associated with her scleroderma than if I am doing a perfunctory cardiac auscultation in a patient admitted with cellulitis. Appropriate focus provides power to the directed physical examination. If I am looking for the cause of unexplained fevers, I will do a purposeful axillary and epitrochlear lymph node examination. I am not mindlessly probing the flesh.

Nishigori and colleagues have written of the “hypothesis-driven” physical examination.3 Busy clinicians, they say, don’t have time to perform a head-to-toe, by-the-book physical examination. Instead, we should, by a dynamic process, formulate a differential diagnosis from the history and other initial information, and then perform the directed physical examination in earnest, looking for evidence to support or refute our diagnostic hypothesis—and thus redirect it. Plus, in a nice break from electronic charting, we can actually explain our thought processes to the patient as we perform the examination.

This approach makes sense to me as both intellectually satisfying and clinically efficient. And then we can consider which lab tests and technologic gadgetry we should order, while walking to get the café latte we ordered with our cell phone app.

New technology can support and not necessarily replace old habits.

Now that we can order MRI studies on a break from rounds walking to Starbucks, utilize portable ultrasounds to direct IV line placement, and use dual-energy CT to detect a gout attack that has not yet occurred, it seems like a romantic anachronism to extol the ongoing virtues of the seemingly lost art of the physical examination. Back “in the day,” the giants of medicine roamed the halls with their natural instruments of palpation and percussion and their skills in observation and auscultation. They were giants because they stood out then, just as skilled diagnosticians stand out today using an upgraded set of tools. Some physicians a few decades ago were able to recognize, describe, and diagnose late-stage endocarditis with a stethoscope, a magnifying glass, and an ophthalmoscope. The giants of today recognize the patient with endocarditis and document its presence using transesophageal echocardiography before the peripheral eponymous stigmata of Janeway and Osler appear or the blood cultures turn positive. The physical examination, history, diagnostic reasoning, and clinical technology are all essential for a blend that provides efficient and effective medical care. The blending is the challenge.

Clinicians are not created equal. We learn and prioritize our skills in different ways. But if we are not taught to value and trust the physical examination, if we don’t have the opportunity to see it influence patient management in positive ways, we may eschew it and instead indiscriminately use easily available laboratory and imaging tests—a more expensive and often misleading strategic approach. Today while in clinic, I saw a 54-year-old woman for evaluation of possible lupus who had arthritis of the hands and a high positive antinuclear antibody titer, but negative or normal results on other, previously ordered tests, including anti-DNA, rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide, hepatitis C studies, complement levels, and another half-dozen immune serologic tests. On examination, she had typical nodular osteoarthritis of the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints of her hand with squaring of her thumbs. The antinuclear antibody was most likely associated with her previously diagnosed autoimmune thyroid disease.

In an editorial in this issue of the Journal, Dr. Salvatore Mangione, the author of a book on physical diagnosis,1 cites a recent study indicating that the most common recognized diagnostic error related to the physical examination is that the appropriate examination isn’t done.2 I would add to that my concerns over the new common custom of cutting and pasting the findings from earlier physical examinations into later progress notes in the electronic record. So much for the value of being able to recognize “changing murmurs” when diagnosing infectious endocarditis.

The apparent efficiency (reflected in length of stay) and availability of technology, as well as a lack of physician skill and time, are often cited as reasons for the demise of the physical examination. Yet this does not need to be the case. If I had trained with portable ultrasonography readily available to confirm or refute my impressions, my skills at detecting low-grade synovitis would surely be better than they are. With a gold standard at hand, which may be technology or at times a skilled mentor, our examinations can be refined if we want them to be.

But the issue of limited physician time must be addressed. Efficiency is a critical concept in preserving how we practice and perform the physical examination. When we know what we are looking for, we are more likely to find it if it is present, or to have confidence that it is not present. I am far more likely to recognize a loud pulmonic second heart sound if I suspect that the dyspneic patient I am examining has pulmonary hypertension associated with her scleroderma than if I am doing a perfunctory cardiac auscultation in a patient admitted with cellulitis. Appropriate focus provides power to the directed physical examination. If I am looking for the cause of unexplained fevers, I will do a purposeful axillary and epitrochlear lymph node examination. I am not mindlessly probing the flesh.

Nishigori and colleagues have written of the “hypothesis-driven” physical examination.3 Busy clinicians, they say, don’t have time to perform a head-to-toe, by-the-book physical examination. Instead, we should, by a dynamic process, formulate a differential diagnosis from the history and other initial information, and then perform the directed physical examination in earnest, looking for evidence to support or refute our diagnostic hypothesis—and thus redirect it. Plus, in a nice break from electronic charting, we can actually explain our thought processes to the patient as we perform the examination.

This approach makes sense to me as both intellectually satisfying and clinically efficient. And then we can consider which lab tests and technologic gadgetry we should order, while walking to get the café latte we ordered with our cell phone app.

New technology can support and not necessarily replace old habits.

- Mangione S. Physical Diagnosis Secrets, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008.

- Verghese A, Charlton B, Kassirer JP, Ramsey M, Ioannidis JP. Inadequacies of physical examination as a cause of medical errors and adverse events: a collection of vignettes. Am J Med 2015; 128:1322–1324.

- Nishigori H, Masuda K, Kikukawa M, et al. A model teaching session for the hypothesis-driven physical examination. Medical Teacher 2011; 33:410–417.

- Mangione S. Physical Diagnosis Secrets, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008.

- Verghese A, Charlton B, Kassirer JP, Ramsey M, Ioannidis JP. Inadequacies of physical examination as a cause of medical errors and adverse events: a collection of vignettes. Am J Med 2015; 128:1322–1324.

- Nishigori H, Masuda K, Kikukawa M, et al. A model teaching session for the hypothesis-driven physical examination. Medical Teacher 2011; 33:410–417.

Life after breast, prostate, and colon cancer: Primary care’s role

In 2015, about 1.6 million Americans received a diagnosis of cancer.1 In 2012, when 13.7 million people were living with cancer in the United States, the estimated 5-year survival rate of all cancers was 66.5%.1 Today, breast, prostate, and colon cancers have 5-year survival rates of 89.4%, 98.9%, and 64.9%, respectively.

With this rising trend in survival, primary care physicians have been steadily assuming the long-term care of these patients. The phrase “cancer survivorship” was coined by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network to describe the experience of living with, through, and beyond a cancer diagnosis.2

As cancer becomes a chronic medical condition, the primary care physician assumes a vital role in the treatment of the unique and evolving needs of this patient population.

This article discusses the specific needs of patients surviving breast, prostate, and colon cancer with special focus on surveillance guidelines for recurrence, development of concomitant malignancies, assessment of psychosocial and physical effects, and disease conditions related to the treatment of cancer itself.

FOLLOW-UP CARE AND SURVEILLANCE

Follow-up care in patients being treated for cancer is vital to survivorship. It includes promoting healthy living, managing treatment side effects, and monitoring for long-term side effects and possible recurrence.

Patients previously treated for malignancy are more susceptible to second primary cancers, for an array of reasons including the effects of prior treatment, shared environmental exposures such as smoking, and genetic susceptibility.2 Therefore, it is important for the primary care physician to recognize signs and symptoms and to screen cancer survivors appropriately. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has developed evidence-based recommendations for follow-up care,3 which we review here.

Breast cancer

For breast cancer patients, history and physical examinations are recommended every 3 to 6 months for the first 3 years, every 6 to 12 months in years 4 and 5, and annually thereafter.3

A repeat mammogram should be performed 1 year after the initial mammogram that led to the diagnosis. If the patient underwent radiation therapy, a repeat mammogram of the affected breast should be done 6 months after completion of radiation. Finally, a mammogram should be done every 6 to 12 months thereafter.3 It is also recommended that patients perform a monthly breast self-examination, but this does not replace the annual mammogram.3

Women who are treated with tamoxifen should have an annual gynecologic assessment if they have a uterus and should be encouraged to discuss any abnormal vaginal bleeding with their physician, given the increased risk of uterine cancer.2

ASCO does not recommend routine use of complete blood cell counts, complete metabolic panels, bone scans, chest radiography, computed tomography, ultrasonography, positron-emission tomography, or tumor markers in patients who are asymptomatic.3

Prostate cancer

ASCO’s recommendations for patients recovering from prostate cancer include regular histories and physical examinations and general health promotion. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing is recommended every 6 to 12 months for the first 5 years after treatment and annually thereafter. More frequent PSA testing may be required in men at higher risk of recurrence or in patients who may undergo additional treatment, including radiation and surgery.4 Higher risk of disease recurrence is thought to depend on disease-specific factors at the time of original diagnosis including pretreatment PSA, Gleason score, and tumor stage.4 This should be discussed between the oncologist and primary care physician.

In regard to digital rectal examinations, the oncologist and primary care physician should jointly determine the frequency of examination. The frequency of digital rectal examinations remains an area of controversy due to their low sensitivity for detecting recurrences. Digital rectal examinations may be omitted in patients with undetectable levels of PSA.4

In regard to second primary malignancies, prostate cancer survivors who have undergone pelvic radiation therapy have a slightly higher risk of bladder and colorectal cancer. The lifetime incidence of bladder cancer after pelvic radiation is 5% to 6%, compared with 2.4% in the general population.1,5 A prostate cancer survivor presenting with hematuria should be referred to a urologist for cystoscopy and evaluation of the upper urinary tract to rule out cancer.4

Similarly, patients presenting with rectal bleeding should be referred to a gastroenterologist and the treating radiation oncologist for complete evaluation. The risk of rectal cancer after pelvic radiation therapy increases to about the same level as in someone who has a first-degree relative with colorectal cancer.5 Therefore, it is recommended that patients undergo screening for colorectal cancer in conjunction with existing evidence-based guidelines. There is no evidence to suggest that increased intensity of screening improves overall or disease-specific survival.4

Colon cancer

In patients with resected colorectal cancer, continued surveillance is important to evaluate for recurrent cancer as well as for metachronous neoplasms. Consensus statements indicate that surveillance colonoscopy should be continued for those who have undergone surgical resection for stage I, II, or III colon or rectal cancers, and for those patients with stage IV who have undergone surgical resection with curative intent.6

Patients who undergo curative resection of rectal or colon cancer should have a colonoscopy 1 year after resection or 1 year after the colonoscopy was performed, to clear the colon of synchronous disease. Subsequently, if the colonoscopy done at 1 year is normal, the interval before the next colonoscopy is 3 years. If that colonoscopy is normal, the next colonoscopy is in 5 years. Time intervals may be shorter if there is evidence of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer or adenoma.

Patients who underwent low anterior resection of rectal cancer should undergo periodic examination of the rectum to evaluate for local recurrence. Although effectiveness is not proven, endoscopic ultrasonography or flexible sigmoidoscopy is suggested at 3- to 6-month intervals for the first 2 to 3 years after resection. This is independent of colonoscopy.6,7

Additionally, ASCO recommends a history and physical examination and carcinoembryonic antigen testing every 3 to 6 months for the first 5 years. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis should be done annually for the first 3 years after the end of treatment.7

HEALTH PROMOTION

Maintaining a healthy body weight and a nutritionally balanced diet should be encouraged in all cancer survivors. Poor diet, lack of exercise, excessive alcohol consumption, and smoking reduce quality of life and increase the risk of cancer.2

Diet

Numerous studies have looked at dietary modifications and risk reduction, and although there is no consensus on specific dietary guidelines, there is consensus that diet modification to maintain normal body weight will improve overall quality of life.8 Patients should be encouraged to consume a well-balanced diet consisting mostly of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and beans, and to limit consumption of animal protein.8

There is little evidence to support taking vitamins or other dietary supplements to prevent or control cancer or to prevent its recurrence. The primary care physician should assess supplement use on a regular basis during office visits.2

Exercise

Rest is an important component of the initial recovery process. Too much inactivity, however, leads to loss of physical conditioning and muscle strength. This in turn may negatively affect a patient’s ability to perform activities of daily living and may worsen fatigue associated with treatment.

Accordingly, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate activity and up to 75 minutes of more rigorous activity divided throughout the week.2,8 The regimen should include endurance and muscle strength training, which aid in balance, bone, health, and functional status. The intensity of exercise should be increased in a stepwise fashion, taking into account individual capabilities and limitations.2

Cancer survivors may need specific exercise recommendations and supervised programs to ensure safety and limit long-term side effects of their treatment. For example:

Patients with neuropathy should have their stability, balance, and gait assessed before starting a new program. These patients may benefit from an aerobic exercise program that includes riding a stationary bike rather than running.

Patients with poor bone health should have their fracture risk assessed.

Those with an ostomy bag should empty the bag before physical activity. They should avoid contact sports and activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure.

Patients suffering from lymphedema should wear compression garments when engaging in physical activity. They should undergo baseline and periodic reevaluation of the lymphedema and initiate strength training in the affected body part only if the lymphedema is stable (ie, no need for therapy for 3 months, no recent infections requiring antibiotics, and no change in circumference > 10%).2

Mental health

Health promotion should focus not only on the physical health of the patient, but also on his or her emotional and psychological well-being. As they make the transition from cancer patient to survivor, many individuals may develop or have worsening depression and anxiety due to fear of recurrence. These feelings of powerlessness can linger for years after the initial treatment.

Patients should be screened regularly for signs and symptoms of depression by asking about their family and social support. Referral to support groups, psychologists, and psychiatrists may be warranted.9

MITIGATING CANCER-RELATED FATIGUE

Cancer-related fatigue involves a patient’s subjective sense of physical, emotional, and cognitive exhaustion related to cancer or treatment that is disproportionate to that expected from recent daily activity.2 Fatigue is a common complaint among survivors and can occur months to years after treatment ends.10

Patients should be screened for fatigue at regular intervals. The primary care physician should focus the history to include information regarding the onset, pattern, duration, associated factors, assessment of other treatable comorbidities, medications, psychological well-being, nutritional status, and pain level of each patient who complains of fatigue.

Laboratory tests for treatable causes of fatigue include:

- A complete blood cell count to evaluate for anemia

- A comprehensive metabolic panel to evaluate electrolytes, renal function, and hepatic function

- The thyroid-stimulating hormone level to evaluate thyroid function, particularly in breast cancer patients who have received radiation therapy.2

If no organic cause is uncovered, the focus should shift to lifestyle interventions as the treatment of choice. The treatment of fatigue in this situation is increased physical activity with the goals discussed above. Psychological intervention may be required with cognitive behavioral therapy, psychological and supportive therapies, education on sleep hygiene, and possible sleep restriction.

If alternative causes of fatigue are ruled out and physical and psychological support fails to reduce symptoms, the practitioner can consider a psychostimulant such as methylphenidate, but this should be used cautiously.2

SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION

Intimate relationships and sexuality are an important part of life and are affected by a variety of factors including physical health, psychological well-being, body image perception, and overall status of relationships. As a side effect of chemotherapy, cancer survivors may complain of erectile dysfunction, penile shortening, dyspareunia, vaginal dryness, decreased libido, anorgasmy, and changes in body image. These issues are frequently unaddressed, whether due to the physician’s discomfort in discussing the topic or to the patient’s embarrassment and reluctance to discuss the matter.11

Breast cancer patients may experience sexual dysfunction both during and after treatment due to a combination of systemic effects of treatment, changes in physical appearance leading to impaired body image, strains on partner relationships, and psychological sequelae of diagnosis and treatment of cancer.12 Manipulation and radiation to the breast affect sexual functioning by altering body contour and image. Additionally, chemotherapy can lead to early menopause and hormonal alterations due to endocrine therapies, which can negatively affect sexual organs.11

Studies have shown that treatment with tamoxifen causes less sexual dysfunction than do aromatase inhibitors. In the Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination trial, therapy with anastrozole was associated with more vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and decreased libido compared with tamoxifen.12

Treatment requires a comprehensive history, a physical examination, and a discussion of relationship satisfaction with the patient.

Vaginal dryness and dyspareunia can be treated with vaginal lubricants and moisturizers. Moisturizers are effective if used multiple times per week, whereas lubricants can be used on demand. Low-dose vaginal estrogen preparations can be used in select patients with severe vaginal dryness; the goal should be discussed. Hormone replacement therapy is contraindicated in breast cancer survivors due to the risk of recurrence.11

Prostate cancer survivors. Up to 70% of men felt their quality of life and sexual function were adversely affected after the diagnosis and treatment.13,14 Erectile dysfunction following radical prostatectomy and radiation therapy remains one of the leading causes of sexual dysfunction.14–15 Erectile dysfunction is multifactorial, with both psychogenic and organic causes. Comorbidities must be considered including hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking. Early penile rehabilitation is a proposed treatment strategy.14

First-line therapy for penile rehabilitation includes introduction of daily low-dose phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors as early as the time of catheter removal to within the first month after surgery. The need for daily dosing vs on-demand dosing has been controversial.15 Two large multicenter, double-blind studies had conflicting outcomes. The first reported that in men receiving nightly sildenafil (50 or 100 mg) after radical prostatectomy, 27% had increased return of spontaneous erectile function vs 4% with placebo16; the second study showed no difference between nightly and on-demand dosing.17 The consensus is that a phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor should be initiated early.

Second-line therapy includes intracavernosal injections and vacuum erection devices. Finally, a penile prosthesis implant can be offered to patients who have responded poorly to medical therapy.13

Colorectal cancer survivors suffer from sexually related problems similar to those stated above, including erectile dysfunction, ejaculation problems, dyspareunia, vaginal dryness, and decreased enjoyment.18 These patients should be provided treatments similar to those described above. In addition, they may suffer from body image issues, particularly those with a permanent ostomy.9

Sexual dysfunction is a multifaceted problem for patients. Encouraging couples to discuss sexual intimacy frequently helps to reveal and cope with the problems, whether physical or psychological. It is the primary care physician’s role to recognize any sexual concerns and refer to the appropriate specialist.

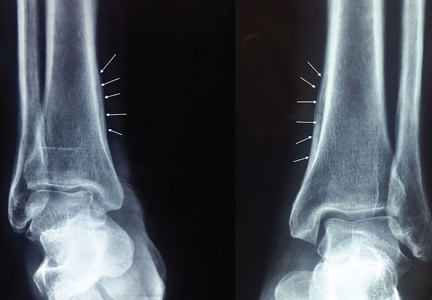

OSTEOPOROSIS

Osteoporosis is a metabolic bone disease characterized by low bone mineral density. As a result, bones become weak and fracture more easily from minor injuries.

Risk factors for osteoporosis include female sex, family history, advanced age, low body weight, low calcium and vitamin D levels, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, and low estrogen levels.19 Cancer treatment places patients at a greater risk for osteoporosis, particularly for those patients with chemotherapy-induced ovarian failure, those treated with aromatase inhibitors, men receiving androgen-deprivation therapy, and patients on glucocorticoid therapy. The morbidity and mortality associated with bone loss can be prevented with appropriate screening, lifestyle changes, and therapy.2

According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation Guideline for Preventing and Treating Osteoporosis, all men and postmenopausal women age 50 and older should be evaluated clinically for osteoporosis risk to determine the need for bone mineral density testing.2,19 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends bone mineral density testing in all women age 65 and older, and for women 60 to 64 who are at high risk for bone loss. ASCO agrees, and further suggests bone mineral density screening for women with breast cancer who have risk factors such as positive family history, body weight less than 70 kg, and prior nontraumatic fracture, as well as for postmenopausal women of any age receiving aromatase inhibitors and for premenopausal women with therapy-induced ovarian failure.11

Androgen deprivation therapy is a mainstay of treatment in recurrent and metastatic prostate cancer. The effect is severe hypogonadism with reductions in serum testosterone levels. Androgen deprivation therapy accelerates bone turnover, decreases bone mineral density, and contributes to fracture risk. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network additionally suggests measuring bone mineral density at baseline for all men receiving androgen deprivation therapy or other medications associated with bone loss, repeating it 1 year after androgen deprivation therapy and then every 2 years, or as clinically indicated.20

The gold standard for measuring bone mineral density is dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. The World Health Organization FRAX tool uses bone mineral density and several clinical factors to estimate the risk of fracture in the next 10 years, which can help guide therapy. Cancer patients with elevated fracture risk should be evaluated every 2 years. Counseling should be provided to address modifiable risk factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, and low calcium and vitamin D intake. Therapy should be strongly considered in patients with a bone mineral density below a T-score of –2.0. 2,19

Treatment begins with lifestyle modifications such as weight-bearing exercises to improve balance and muscle strength and to prevent falls, and adequate intake of calcium (≥ 1,200 mg daily) and vitamin D (800–1,000 IU daily) for adults age 50 and older. Treatment with bisphosphonates may be required.2,11,20

NEUROPATHY

Many chemotherapeutic agents can lead to neuropathy and can result in long-term disability in patients. Patients treated with taxane- and platinum-based chemotherapy are at particular risk.

Paclitaxel, used in the treatment of breast, ovarian, and lung cancer, can lead to distal neuropathy. This neuropathy commonly has a stocking-and-glove distribution and is primarily sensory; however, it may have motor and autonomic components. The neuropathy typically lessens when the medication is stopped, although in some patients it can persist and lead to long-term disability.

Treatment can include massage. Medications such as gabapentin and pregabalin can also be used, but randomized controlled trials do not support them, as they predominantly treat the tingling rather than the numbness.11

BLADDER AND BOWEL DYSFUNCTION

Urinary incontinence and dysfunction are frequent complications in prostate cancer survivors. Urinary function should be discussed regularly with patients, addressing quality of the urinary stream, difficulty emptying the bladder, timing, and incontinence.4 Urinary incontinence is frequently seen in postprostatectomy patients.

The cornerstone of treating urinary incontinence is determining the cause of the incontinence, whether it is stress or urge incontinence, or both.21 For those patients with urge incontinence alone, practitioners can address the problem with a combination of behavior modification, pelvic floor exercises, and anticholinergic medications such as oxybutynin. If the problem stems from difficulty initiating or a slow stream, physicians may consider alpha-blockers.4,21 If the incontinence is persistent, bothersome, and has components of stress incontinence, the patient should be referred to a urologist for urodynamic testing, cystoscopy, and surgical evaluation for possible placement of a male urethral sling or artificial urinary sphincter.21

Colorectal cancer survivors, particularly those who received radiation therapy, are at high risk of bowel dysfunction such as chronic diarrhea and stool incontinence. Patients should be educated about this possible side effect. Symptoms of bowel dysfunction can affect body image and interfere with social functioning and overall quality of life. Patients should be provided with coping tools such as antidiarrheal medication, stool bulking agents, changes in diet, and protective underwear.

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Evidence suggests that certain types of chemotherapy and radiation therapy increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. Prostate cancer survivors treated with androgen deprivation therapy, particularly those more than 75 years old, are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes.22

It is recommended that men be screened with fasting plasma glucose at baseline and yearly thereafter while receiving androgen deprivation therapy. Lipid panel testing should be done 1 year from initiation of androgen deprivation therapy and then, if results are normal, every 5 years or as clinically warranted. The focus should be on primary prevention with emphasis on smoking cessation, treating hypertension per guidelines, lifestyle modifications, and treatment with aspirin and statins when clinically appropriate.20

Radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and endocrine therapy have all been suggested to lead to cardiotoxicity in breast cancer patients. Anthracycline-based chemotherapies have a well-recognized association with cardiomyopathy. Factors associated with increased risk of anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy include older age, hypertension, pre-existing coronary artery disease, and previous mediastinal radiation.

Early detection of cardiomyopathy may lead to avoidance of irreversible cardiotoxicity, but there are currently no clear guidelines for cardiac screening in breast cancer survivors. If cardiomyopathy is detected, treatment should include beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors as well as modification of other cardiovascular risk factors.11

A SURVIVORSHIP CARE PLAN

There is life beyond the diagnosis of cancer. As patients are living longer, with an estimated 5-year survival rate of 66.5% of all cancers in the United States, there must be a transition of care from the oncologist to the primary care physician.1 While the oncologist will remain involved in the initial years of follow-up care, these visits will go from twice a year to once a year, and eventually the patient will make a full transition to care by the primary care physician. The timing of this changeover varies from physician to physician, but the primary care physician is ultimately responsible for the follow-up.

A tool to ease this transition is a survivorship care plan. The goal of a survivorship care plan is to individualize a follow-up plan while keeping in mind the necessary surveillance as outlined. These care plans are created with the patient and oncologist and then brought to the primary care physician. While there is an abundance of literature regarding the creation and initiation of survivorship care plans, the success of these plans is uncertain. Ultimately, the goal of a survivorship care plan is to create open dialogue among the oncologist, the primary care physician, and the patient. This unique patient population requires close follow-up by a multidisciplinary team with the primary care physician serving as the steward.

- National Cancer Institute (NIH). Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. SEER cancer stat fact sheets. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts. Accessed March 6, 2017.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines Survivorship: 2015. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/survivorship.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2017.

- Khatcheressian JL, Hurley P, Bantug E, et al. Breast cancer follow-up and management after primary treatment: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31:961–965.

- Resnick MJ, Lacchetti C, Bergman J, et al. Prostate cancer survivorship care guideline: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline endorsement. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33:1078–1085.

- Sountoulides P, Koletsas N, Kikidakis D, Paschalidis K, Sofikitis N. Secondary malignancies following radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Ther Adv Urol 2010; 2:119–125.

- Rex DK, Kahi CJ, Levin B, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after cancer resection: a consensus update by the American Cancer Society and US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 2006; 56:160–168.

- Meyerhardt JA, Mangu PB, Flynn PJ, et al; American Society of Clinical Oncology. Follow-up care, surveillance protocol, and secondary prevention measures for survivors of colorectal cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline endorsement. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31:4465–4470.

- Davies NJ, Batehup L, Thomas R. The role of diet and physical activity in breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer survivorship: a review of the literature. Br J Cancer 2011; 105(suppl 1):S52–S73.

- Miller K, editor. Excellent Care for Cancer Survivors: A Guide to Fully Meet Their Needs in Medical Offices and in the Community (Praeger Series on Contemporary Health & Living). 1st ed. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger; 2012.

- Stanton AL, Rowland JH, Ganz PA. Life after diagnosis and treatment of cancer in adulthood: contributions from psychosocial oncology research. Am Psychol 2015; 70:159–174.

- Stan D, Loprinzi CL, Ruddy KJ. Breast cancer survivorship issues. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2013; 27:805–827.

- Fallowfield L, Cella D, Cuzick J, Francis S, Locker G, Howell A. Quality of life of postmenopausal women in the Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination (ATAC) Adjuvant Breast Cancer Trial. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22:426–471.

- Chung E, Gillman M. Prostate cancer survivorship: a review of erectile dysfunction and penile rehabilitation after prostate cancer therapy. Med J Aust 2014; 200:582–585.

- Sherer BA, Levine LA. Current management of erectile dysfunction in prostate cancer survivors. Curr Opin Urol 2014; 24:401–416.

- Chung E, Brock G. Sexual rehabilitation and cancer survivorship: a state of art review of current literature and management strategies in male sexual dysfunction among prostate cancer survivors. J Sex Med 2013; 10(suppl 1):102–111.

- Padma-Nathan H, McCullough AR, Levine LA, et al; Study Group. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of postoperative nightly sildenafil citrate for the prevention of erectile dysfunction after bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Int J Impot Res 2008; 20:479–486.

- Montorsi F, Brock G, Lee J, et al. Effect of nightly versus on-demand vardenafil on recovery of erectile function in men following bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol 2008; 54:924–931.

- Den Oudsten BL, Traa MJ, Thong MS, et al. Higher prevalence of sexual dysfunction in colon and rectal cancer survivors compared with the normative population: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer 2012; 48:3161–3170.

- National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF). http://nof.org. Accessed March 3, 2017.

- Saylor PJ, Keating NL, Smith MR. Prostate cancer survivorship: prevention and treatment of the adverse effects of androgen deprivation therapy. J Gen Intern Med 2009; 24(suppl 2):S389–S394.

- Gupta S, Peterson AC. Stress urinary incontinence in the prostate cancer survivor. Curr Opin Urol 2014; 24:395–400.

- Morgans AK, Fan KH, Koyama T, et al. Influence of age on incident diabetes and cardiovascular disease in prostate cancer survivors receiving androgen deprivation therapy. J Urol 2015; 193:1226–1231.

In 2015, about 1.6 million Americans received a diagnosis of cancer.1 In 2012, when 13.7 million people were living with cancer in the United States, the estimated 5-year survival rate of all cancers was 66.5%.1 Today, breast, prostate, and colon cancers have 5-year survival rates of 89.4%, 98.9%, and 64.9%, respectively.

With this rising trend in survival, primary care physicians have been steadily assuming the long-term care of these patients. The phrase “cancer survivorship” was coined by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network to describe the experience of living with, through, and beyond a cancer diagnosis.2

As cancer becomes a chronic medical condition, the primary care physician assumes a vital role in the treatment of the unique and evolving needs of this patient population.

This article discusses the specific needs of patients surviving breast, prostate, and colon cancer with special focus on surveillance guidelines for recurrence, development of concomitant malignancies, assessment of psychosocial and physical effects, and disease conditions related to the treatment of cancer itself.

FOLLOW-UP CARE AND SURVEILLANCE

Follow-up care in patients being treated for cancer is vital to survivorship. It includes promoting healthy living, managing treatment side effects, and monitoring for long-term side effects and possible recurrence.

Patients previously treated for malignancy are more susceptible to second primary cancers, for an array of reasons including the effects of prior treatment, shared environmental exposures such as smoking, and genetic susceptibility.2 Therefore, it is important for the primary care physician to recognize signs and symptoms and to screen cancer survivors appropriately. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has developed evidence-based recommendations for follow-up care,3 which we review here.

Breast cancer

For breast cancer patients, history and physical examinations are recommended every 3 to 6 months for the first 3 years, every 6 to 12 months in years 4 and 5, and annually thereafter.3

A repeat mammogram should be performed 1 year after the initial mammogram that led to the diagnosis. If the patient underwent radiation therapy, a repeat mammogram of the affected breast should be done 6 months after completion of radiation. Finally, a mammogram should be done every 6 to 12 months thereafter.3 It is also recommended that patients perform a monthly breast self-examination, but this does not replace the annual mammogram.3

Women who are treated with tamoxifen should have an annual gynecologic assessment if they have a uterus and should be encouraged to discuss any abnormal vaginal bleeding with their physician, given the increased risk of uterine cancer.2

ASCO does not recommend routine use of complete blood cell counts, complete metabolic panels, bone scans, chest radiography, computed tomography, ultrasonography, positron-emission tomography, or tumor markers in patients who are asymptomatic.3

Prostate cancer

ASCO’s recommendations for patients recovering from prostate cancer include regular histories and physical examinations and general health promotion. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing is recommended every 6 to 12 months for the first 5 years after treatment and annually thereafter. More frequent PSA testing may be required in men at higher risk of recurrence or in patients who may undergo additional treatment, including radiation and surgery.4 Higher risk of disease recurrence is thought to depend on disease-specific factors at the time of original diagnosis including pretreatment PSA, Gleason score, and tumor stage.4 This should be discussed between the oncologist and primary care physician.

In regard to digital rectal examinations, the oncologist and primary care physician should jointly determine the frequency of examination. The frequency of digital rectal examinations remains an area of controversy due to their low sensitivity for detecting recurrences. Digital rectal examinations may be omitted in patients with undetectable levels of PSA.4

In regard to second primary malignancies, prostate cancer survivors who have undergone pelvic radiation therapy have a slightly higher risk of bladder and colorectal cancer. The lifetime incidence of bladder cancer after pelvic radiation is 5% to 6%, compared with 2.4% in the general population.1,5 A prostate cancer survivor presenting with hematuria should be referred to a urologist for cystoscopy and evaluation of the upper urinary tract to rule out cancer.4

Similarly, patients presenting with rectal bleeding should be referred to a gastroenterologist and the treating radiation oncologist for complete evaluation. The risk of rectal cancer after pelvic radiation therapy increases to about the same level as in someone who has a first-degree relative with colorectal cancer.5 Therefore, it is recommended that patients undergo screening for colorectal cancer in conjunction with existing evidence-based guidelines. There is no evidence to suggest that increased intensity of screening improves overall or disease-specific survival.4

Colon cancer

In patients with resected colorectal cancer, continued surveillance is important to evaluate for recurrent cancer as well as for metachronous neoplasms. Consensus statements indicate that surveillance colonoscopy should be continued for those who have undergone surgical resection for stage I, II, or III colon or rectal cancers, and for those patients with stage IV who have undergone surgical resection with curative intent.6

Patients who undergo curative resection of rectal or colon cancer should have a colonoscopy 1 year after resection or 1 year after the colonoscopy was performed, to clear the colon of synchronous disease. Subsequently, if the colonoscopy done at 1 year is normal, the interval before the next colonoscopy is 3 years. If that colonoscopy is normal, the next colonoscopy is in 5 years. Time intervals may be shorter if there is evidence of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer or adenoma.

Patients who underwent low anterior resection of rectal cancer should undergo periodic examination of the rectum to evaluate for local recurrence. Although effectiveness is not proven, endoscopic ultrasonography or flexible sigmoidoscopy is suggested at 3- to 6-month intervals for the first 2 to 3 years after resection. This is independent of colonoscopy.6,7

Additionally, ASCO recommends a history and physical examination and carcinoembryonic antigen testing every 3 to 6 months for the first 5 years. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis should be done annually for the first 3 years after the end of treatment.7

HEALTH PROMOTION

Maintaining a healthy body weight and a nutritionally balanced diet should be encouraged in all cancer survivors. Poor diet, lack of exercise, excessive alcohol consumption, and smoking reduce quality of life and increase the risk of cancer.2

Diet

Numerous studies have looked at dietary modifications and risk reduction, and although there is no consensus on specific dietary guidelines, there is consensus that diet modification to maintain normal body weight will improve overall quality of life.8 Patients should be encouraged to consume a well-balanced diet consisting mostly of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and beans, and to limit consumption of animal protein.8

There is little evidence to support taking vitamins or other dietary supplements to prevent or control cancer or to prevent its recurrence. The primary care physician should assess supplement use on a regular basis during office visits.2

Exercise

Rest is an important component of the initial recovery process. Too much inactivity, however, leads to loss of physical conditioning and muscle strength. This in turn may negatively affect a patient’s ability to perform activities of daily living and may worsen fatigue associated with treatment.

Accordingly, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate activity and up to 75 minutes of more rigorous activity divided throughout the week.2,8 The regimen should include endurance and muscle strength training, which aid in balance, bone, health, and functional status. The intensity of exercise should be increased in a stepwise fashion, taking into account individual capabilities and limitations.2

Cancer survivors may need specific exercise recommendations and supervised programs to ensure safety and limit long-term side effects of their treatment. For example:

Patients with neuropathy should have their stability, balance, and gait assessed before starting a new program. These patients may benefit from an aerobic exercise program that includes riding a stationary bike rather than running.

Patients with poor bone health should have their fracture risk assessed.

Those with an ostomy bag should empty the bag before physical activity. They should avoid contact sports and activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure.

Patients suffering from lymphedema should wear compression garments when engaging in physical activity. They should undergo baseline and periodic reevaluation of the lymphedema and initiate strength training in the affected body part only if the lymphedema is stable (ie, no need for therapy for 3 months, no recent infections requiring antibiotics, and no change in circumference > 10%).2

Mental health

Health promotion should focus not only on the physical health of the patient, but also on his or her emotional and psychological well-being. As they make the transition from cancer patient to survivor, many individuals may develop or have worsening depression and anxiety due to fear of recurrence. These feelings of powerlessness can linger for years after the initial treatment.

Patients should be screened regularly for signs and symptoms of depression by asking about their family and social support. Referral to support groups, psychologists, and psychiatrists may be warranted.9

MITIGATING CANCER-RELATED FATIGUE

Cancer-related fatigue involves a patient’s subjective sense of physical, emotional, and cognitive exhaustion related to cancer or treatment that is disproportionate to that expected from recent daily activity.2 Fatigue is a common complaint among survivors and can occur months to years after treatment ends.10

Patients should be screened for fatigue at regular intervals. The primary care physician should focus the history to include information regarding the onset, pattern, duration, associated factors, assessment of other treatable comorbidities, medications, psychological well-being, nutritional status, and pain level of each patient who complains of fatigue.

Laboratory tests for treatable causes of fatigue include:

- A complete blood cell count to evaluate for anemia

- A comprehensive metabolic panel to evaluate electrolytes, renal function, and hepatic function

- The thyroid-stimulating hormone level to evaluate thyroid function, particularly in breast cancer patients who have received radiation therapy.2

If no organic cause is uncovered, the focus should shift to lifestyle interventions as the treatment of choice. The treatment of fatigue in this situation is increased physical activity with the goals discussed above. Psychological intervention may be required with cognitive behavioral therapy, psychological and supportive therapies, education on sleep hygiene, and possible sleep restriction.

If alternative causes of fatigue are ruled out and physical and psychological support fails to reduce symptoms, the practitioner can consider a psychostimulant such as methylphenidate, but this should be used cautiously.2

SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION

Intimate relationships and sexuality are an important part of life and are affected by a variety of factors including physical health, psychological well-being, body image perception, and overall status of relationships. As a side effect of chemotherapy, cancer survivors may complain of erectile dysfunction, penile shortening, dyspareunia, vaginal dryness, decreased libido, anorgasmy, and changes in body image. These issues are frequently unaddressed, whether due to the physician’s discomfort in discussing the topic or to the patient’s embarrassment and reluctance to discuss the matter.11

Breast cancer patients may experience sexual dysfunction both during and after treatment due to a combination of systemic effects of treatment, changes in physical appearance leading to impaired body image, strains on partner relationships, and psychological sequelae of diagnosis and treatment of cancer.12 Manipulation and radiation to the breast affect sexual functioning by altering body contour and image. Additionally, chemotherapy can lead to early menopause and hormonal alterations due to endocrine therapies, which can negatively affect sexual organs.11

Studies have shown that treatment with tamoxifen causes less sexual dysfunction than do aromatase inhibitors. In the Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination trial, therapy with anastrozole was associated with more vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and decreased libido compared with tamoxifen.12

Treatment requires a comprehensive history, a physical examination, and a discussion of relationship satisfaction with the patient.

Vaginal dryness and dyspareunia can be treated with vaginal lubricants and moisturizers. Moisturizers are effective if used multiple times per week, whereas lubricants can be used on demand. Low-dose vaginal estrogen preparations can be used in select patients with severe vaginal dryness; the goal should be discussed. Hormone replacement therapy is contraindicated in breast cancer survivors due to the risk of recurrence.11

Prostate cancer survivors. Up to 70% of men felt their quality of life and sexual function were adversely affected after the diagnosis and treatment.13,14 Erectile dysfunction following radical prostatectomy and radiation therapy remains one of the leading causes of sexual dysfunction.14–15 Erectile dysfunction is multifactorial, with both psychogenic and organic causes. Comorbidities must be considered including hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking. Early penile rehabilitation is a proposed treatment strategy.14

First-line therapy for penile rehabilitation includes introduction of daily low-dose phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors as early as the time of catheter removal to within the first month after surgery. The need for daily dosing vs on-demand dosing has been controversial.15 Two large multicenter, double-blind studies had conflicting outcomes. The first reported that in men receiving nightly sildenafil (50 or 100 mg) after radical prostatectomy, 27% had increased return of spontaneous erectile function vs 4% with placebo16; the second study showed no difference between nightly and on-demand dosing.17 The consensus is that a phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor should be initiated early.

Second-line therapy includes intracavernosal injections and vacuum erection devices. Finally, a penile prosthesis implant can be offered to patients who have responded poorly to medical therapy.13

Colorectal cancer survivors suffer from sexually related problems similar to those stated above, including erectile dysfunction, ejaculation problems, dyspareunia, vaginal dryness, and decreased enjoyment.18 These patients should be provided treatments similar to those described above. In addition, they may suffer from body image issues, particularly those with a permanent ostomy.9

Sexual dysfunction is a multifaceted problem for patients. Encouraging couples to discuss sexual intimacy frequently helps to reveal and cope with the problems, whether physical or psychological. It is the primary care physician’s role to recognize any sexual concerns and refer to the appropriate specialist.

OSTEOPOROSIS

Osteoporosis is a metabolic bone disease characterized by low bone mineral density. As a result, bones become weak and fracture more easily from minor injuries.

Risk factors for osteoporosis include female sex, family history, advanced age, low body weight, low calcium and vitamin D levels, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, and low estrogen levels.19 Cancer treatment places patients at a greater risk for osteoporosis, particularly for those patients with chemotherapy-induced ovarian failure, those treated with aromatase inhibitors, men receiving androgen-deprivation therapy, and patients on glucocorticoid therapy. The morbidity and mortality associated with bone loss can be prevented with appropriate screening, lifestyle changes, and therapy.2

According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation Guideline for Preventing and Treating Osteoporosis, all men and postmenopausal women age 50 and older should be evaluated clinically for osteoporosis risk to determine the need for bone mineral density testing.2,19 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends bone mineral density testing in all women age 65 and older, and for women 60 to 64 who are at high risk for bone loss. ASCO agrees, and further suggests bone mineral density screening for women with breast cancer who have risk factors such as positive family history, body weight less than 70 kg, and prior nontraumatic fracture, as well as for postmenopausal women of any age receiving aromatase inhibitors and for premenopausal women with therapy-induced ovarian failure.11

Androgen deprivation therapy is a mainstay of treatment in recurrent and metastatic prostate cancer. The effect is severe hypogonadism with reductions in serum testosterone levels. Androgen deprivation therapy accelerates bone turnover, decreases bone mineral density, and contributes to fracture risk. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network additionally suggests measuring bone mineral density at baseline for all men receiving androgen deprivation therapy or other medications associated with bone loss, repeating it 1 year after androgen deprivation therapy and then every 2 years, or as clinically indicated.20

The gold standard for measuring bone mineral density is dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. The World Health Organization FRAX tool uses bone mineral density and several clinical factors to estimate the risk of fracture in the next 10 years, which can help guide therapy. Cancer patients with elevated fracture risk should be evaluated every 2 years. Counseling should be provided to address modifiable risk factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, and low calcium and vitamin D intake. Therapy should be strongly considered in patients with a bone mineral density below a T-score of –2.0. 2,19

Treatment begins with lifestyle modifications such as weight-bearing exercises to improve balance and muscle strength and to prevent falls, and adequate intake of calcium (≥ 1,200 mg daily) and vitamin D (800–1,000 IU daily) for adults age 50 and older. Treatment with bisphosphonates may be required.2,11,20

NEUROPATHY

Many chemotherapeutic agents can lead to neuropathy and can result in long-term disability in patients. Patients treated with taxane- and platinum-based chemotherapy are at particular risk.

Paclitaxel, used in the treatment of breast, ovarian, and lung cancer, can lead to distal neuropathy. This neuropathy commonly has a stocking-and-glove distribution and is primarily sensory; however, it may have motor and autonomic components. The neuropathy typically lessens when the medication is stopped, although in some patients it can persist and lead to long-term disability.

Treatment can include massage. Medications such as gabapentin and pregabalin can also be used, but randomized controlled trials do not support them, as they predominantly treat the tingling rather than the numbness.11

BLADDER AND BOWEL DYSFUNCTION

Urinary incontinence and dysfunction are frequent complications in prostate cancer survivors. Urinary function should be discussed regularly with patients, addressing quality of the urinary stream, difficulty emptying the bladder, timing, and incontinence.4 Urinary incontinence is frequently seen in postprostatectomy patients.

The cornerstone of treating urinary incontinence is determining the cause of the incontinence, whether it is stress or urge incontinence, or both.21 For those patients with urge incontinence alone, practitioners can address the problem with a combination of behavior modification, pelvic floor exercises, and anticholinergic medications such as oxybutynin. If the problem stems from difficulty initiating or a slow stream, physicians may consider alpha-blockers.4,21 If the incontinence is persistent, bothersome, and has components of stress incontinence, the patient should be referred to a urologist for urodynamic testing, cystoscopy, and surgical evaluation for possible placement of a male urethral sling or artificial urinary sphincter.21

Colorectal cancer survivors, particularly those who received radiation therapy, are at high risk of bowel dysfunction such as chronic diarrhea and stool incontinence. Patients should be educated about this possible side effect. Symptoms of bowel dysfunction can affect body image and interfere with social functioning and overall quality of life. Patients should be provided with coping tools such as antidiarrheal medication, stool bulking agents, changes in diet, and protective underwear.

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Evidence suggests that certain types of chemotherapy and radiation therapy increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. Prostate cancer survivors treated with androgen deprivation therapy, particularly those more than 75 years old, are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes.22

It is recommended that men be screened with fasting plasma glucose at baseline and yearly thereafter while receiving androgen deprivation therapy. Lipid panel testing should be done 1 year from initiation of androgen deprivation therapy and then, if results are normal, every 5 years or as clinically warranted. The focus should be on primary prevention with emphasis on smoking cessation, treating hypertension per guidelines, lifestyle modifications, and treatment with aspirin and statins when clinically appropriate.20

Radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and endocrine therapy have all been suggested to lead to cardiotoxicity in breast cancer patients. Anthracycline-based chemotherapies have a well-recognized association with cardiomyopathy. Factors associated with increased risk of anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy include older age, hypertension, pre-existing coronary artery disease, and previous mediastinal radiation.

Early detection of cardiomyopathy may lead to avoidance of irreversible cardiotoxicity, but there are currently no clear guidelines for cardiac screening in breast cancer survivors. If cardiomyopathy is detected, treatment should include beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors as well as modification of other cardiovascular risk factors.11

A SURVIVORSHIP CARE PLAN

There is life beyond the diagnosis of cancer. As patients are living longer, with an estimated 5-year survival rate of 66.5% of all cancers in the United States, there must be a transition of care from the oncologist to the primary care physician.1 While the oncologist will remain involved in the initial years of follow-up care, these visits will go from twice a year to once a year, and eventually the patient will make a full transition to care by the primary care physician. The timing of this changeover varies from physician to physician, but the primary care physician is ultimately responsible for the follow-up.

A tool to ease this transition is a survivorship care plan. The goal of a survivorship care plan is to individualize a follow-up plan while keeping in mind the necessary surveillance as outlined. These care plans are created with the patient and oncologist and then brought to the primary care physician. While there is an abundance of literature regarding the creation and initiation of survivorship care plans, the success of these plans is uncertain. Ultimately, the goal of a survivorship care plan is to create open dialogue among the oncologist, the primary care physician, and the patient. This unique patient population requires close follow-up by a multidisciplinary team with the primary care physician serving as the steward.

In 2015, about 1.6 million Americans received a diagnosis of cancer.1 In 2012, when 13.7 million people were living with cancer in the United States, the estimated 5-year survival rate of all cancers was 66.5%.1 Today, breast, prostate, and colon cancers have 5-year survival rates of 89.4%, 98.9%, and 64.9%, respectively.

With this rising trend in survival, primary care physicians have been steadily assuming the long-term care of these patients. The phrase “cancer survivorship” was coined by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network to describe the experience of living with, through, and beyond a cancer diagnosis.2

As cancer becomes a chronic medical condition, the primary care physician assumes a vital role in the treatment of the unique and evolving needs of this patient population.

This article discusses the specific needs of patients surviving breast, prostate, and colon cancer with special focus on surveillance guidelines for recurrence, development of concomitant malignancies, assessment of psychosocial and physical effects, and disease conditions related to the treatment of cancer itself.

FOLLOW-UP CARE AND SURVEILLANCE

Follow-up care in patients being treated for cancer is vital to survivorship. It includes promoting healthy living, managing treatment side effects, and monitoring for long-term side effects and possible recurrence.

Patients previously treated for malignancy are more susceptible to second primary cancers, for an array of reasons including the effects of prior treatment, shared environmental exposures such as smoking, and genetic susceptibility.2 Therefore, it is important for the primary care physician to recognize signs and symptoms and to screen cancer survivors appropriately. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has developed evidence-based recommendations for follow-up care,3 which we review here.

Breast cancer

For breast cancer patients, history and physical examinations are recommended every 3 to 6 months for the first 3 years, every 6 to 12 months in years 4 and 5, and annually thereafter.3

A repeat mammogram should be performed 1 year after the initial mammogram that led to the diagnosis. If the patient underwent radiation therapy, a repeat mammogram of the affected breast should be done 6 months after completion of radiation. Finally, a mammogram should be done every 6 to 12 months thereafter.3 It is also recommended that patients perform a monthly breast self-examination, but this does not replace the annual mammogram.3

Women who are treated with tamoxifen should have an annual gynecologic assessment if they have a uterus and should be encouraged to discuss any abnormal vaginal bleeding with their physician, given the increased risk of uterine cancer.2

ASCO does not recommend routine use of complete blood cell counts, complete metabolic panels, bone scans, chest radiography, computed tomography, ultrasonography, positron-emission tomography, or tumor markers in patients who are asymptomatic.3

Prostate cancer

ASCO’s recommendations for patients recovering from prostate cancer include regular histories and physical examinations and general health promotion. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing is recommended every 6 to 12 months for the first 5 years after treatment and annually thereafter. More frequent PSA testing may be required in men at higher risk of recurrence or in patients who may undergo additional treatment, including radiation and surgery.4 Higher risk of disease recurrence is thought to depend on disease-specific factors at the time of original diagnosis including pretreatment PSA, Gleason score, and tumor stage.4 This should be discussed between the oncologist and primary care physician.

In regard to digital rectal examinations, the oncologist and primary care physician should jointly determine the frequency of examination. The frequency of digital rectal examinations remains an area of controversy due to their low sensitivity for detecting recurrences. Digital rectal examinations may be omitted in patients with undetectable levels of PSA.4

In regard to second primary malignancies, prostate cancer survivors who have undergone pelvic radiation therapy have a slightly higher risk of bladder and colorectal cancer. The lifetime incidence of bladder cancer after pelvic radiation is 5% to 6%, compared with 2.4% in the general population.1,5 A prostate cancer survivor presenting with hematuria should be referred to a urologist for cystoscopy and evaluation of the upper urinary tract to rule out cancer.4

Similarly, patients presenting with rectal bleeding should be referred to a gastroenterologist and the treating radiation oncologist for complete evaluation. The risk of rectal cancer after pelvic radiation therapy increases to about the same level as in someone who has a first-degree relative with colorectal cancer.5 Therefore, it is recommended that patients undergo screening for colorectal cancer in conjunction with existing evidence-based guidelines. There is no evidence to suggest that increased intensity of screening improves overall or disease-specific survival.4

Colon cancer

In patients with resected colorectal cancer, continued surveillance is important to evaluate for recurrent cancer as well as for metachronous neoplasms. Consensus statements indicate that surveillance colonoscopy should be continued for those who have undergone surgical resection for stage I, II, or III colon or rectal cancers, and for those patients with stage IV who have undergone surgical resection with curative intent.6

Patients who undergo curative resection of rectal or colon cancer should have a colonoscopy 1 year after resection or 1 year after the colonoscopy was performed, to clear the colon of synchronous disease. Subsequently, if the colonoscopy done at 1 year is normal, the interval before the next colonoscopy is 3 years. If that colonoscopy is normal, the next colonoscopy is in 5 years. Time intervals may be shorter if there is evidence of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer or adenoma.

Patients who underwent low anterior resection of rectal cancer should undergo periodic examination of the rectum to evaluate for local recurrence. Although effectiveness is not proven, endoscopic ultrasonography or flexible sigmoidoscopy is suggested at 3- to 6-month intervals for the first 2 to 3 years after resection. This is independent of colonoscopy.6,7

Additionally, ASCO recommends a history and physical examination and carcinoembryonic antigen testing every 3 to 6 months for the first 5 years. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis should be done annually for the first 3 years after the end of treatment.7

HEALTH PROMOTION

Maintaining a healthy body weight and a nutritionally balanced diet should be encouraged in all cancer survivors. Poor diet, lack of exercise, excessive alcohol consumption, and smoking reduce quality of life and increase the risk of cancer.2

Diet

Numerous studies have looked at dietary modifications and risk reduction, and although there is no consensus on specific dietary guidelines, there is consensus that diet modification to maintain normal body weight will improve overall quality of life.8 Patients should be encouraged to consume a well-balanced diet consisting mostly of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and beans, and to limit consumption of animal protein.8

There is little evidence to support taking vitamins or other dietary supplements to prevent or control cancer or to prevent its recurrence. The primary care physician should assess supplement use on a regular basis during office visits.2

Exercise

Rest is an important component of the initial recovery process. Too much inactivity, however, leads to loss of physical conditioning and muscle strength. This in turn may negatively affect a patient’s ability to perform activities of daily living and may worsen fatigue associated with treatment.

Accordingly, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate activity and up to 75 minutes of more rigorous activity divided throughout the week.2,8 The regimen should include endurance and muscle strength training, which aid in balance, bone, health, and functional status. The intensity of exercise should be increased in a stepwise fashion, taking into account individual capabilities and limitations.2

Cancer survivors may need specific exercise recommendations and supervised programs to ensure safety and limit long-term side effects of their treatment. For example:

Patients with neuropathy should have their stability, balance, and gait assessed before starting a new program. These patients may benefit from an aerobic exercise program that includes riding a stationary bike rather than running.