User login

Long-term durability low for nonmesh vaginal prolapse repair

SAN ANTONIO – At 5-year follow-up, outcomes were slightly better on most measures for transvaginal uterosacral ligament suspension versus transvaginal sacrospinous ligament fixation for apical prolapse, but the differences were not statistically significant, according to the first randomized trial to compare the two techniques.

Quality of life improvements were durable, but the overall 5-year success rate – defined as the absence of descent of the vaginal apex more than one-third into the vagina; anterior or posterior vaginal wall descent beyond the hymen; bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms; and further treatment for prolapse – was 39% in the 109 women randomized to bilateral uterosacral ligament suspension (ULS) and 30% in the 109 women randomized to unilateral sacrospinous ligament fixation (SSLF).

But there was a notable finding in the study. If women failed to meet all the requirements for success at any one visit, they were classified as surgical failures. However, many who missed the mark at one visit met all the requirements for success on other visits, including their last follow-up.

“We don’t think as surgeons that a bulge comes and goes on a yearly basis, but people actually moved in and out of success and failure over time, and that’s new,” Dr. Jelovsek said. “We just don’t understand the dynamic variables of anatomic prolapse, because no one’s looked at it. The assumption of ‘once a failure, always a failure’ may underestimate success rates.”

Nonetheless, using that approach in the study, the investigators found that the anatomic success was 54% in the ULS and 38% in the SSLF groups at 5 years, and 37% of women in the ULS group reported bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms, versus 42% of women with SSLF. A total of 12% of women with ULS and 8% of women with SSLF had undergone POP retreatment at 5 years, either by pessary or secondary surgery but, again, the differences were not statistically significant.

Of the 145 anatomic failures in the study, 41% were stage 3 or 4.

Quality of life improvements, assessed annually by phone, “were maintained over 5 years despite progressive increases in surgical failure rates over time,” with about a 70-point improvement in the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory and similar gains in other measures in both groups, Dr. Jelovsek reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

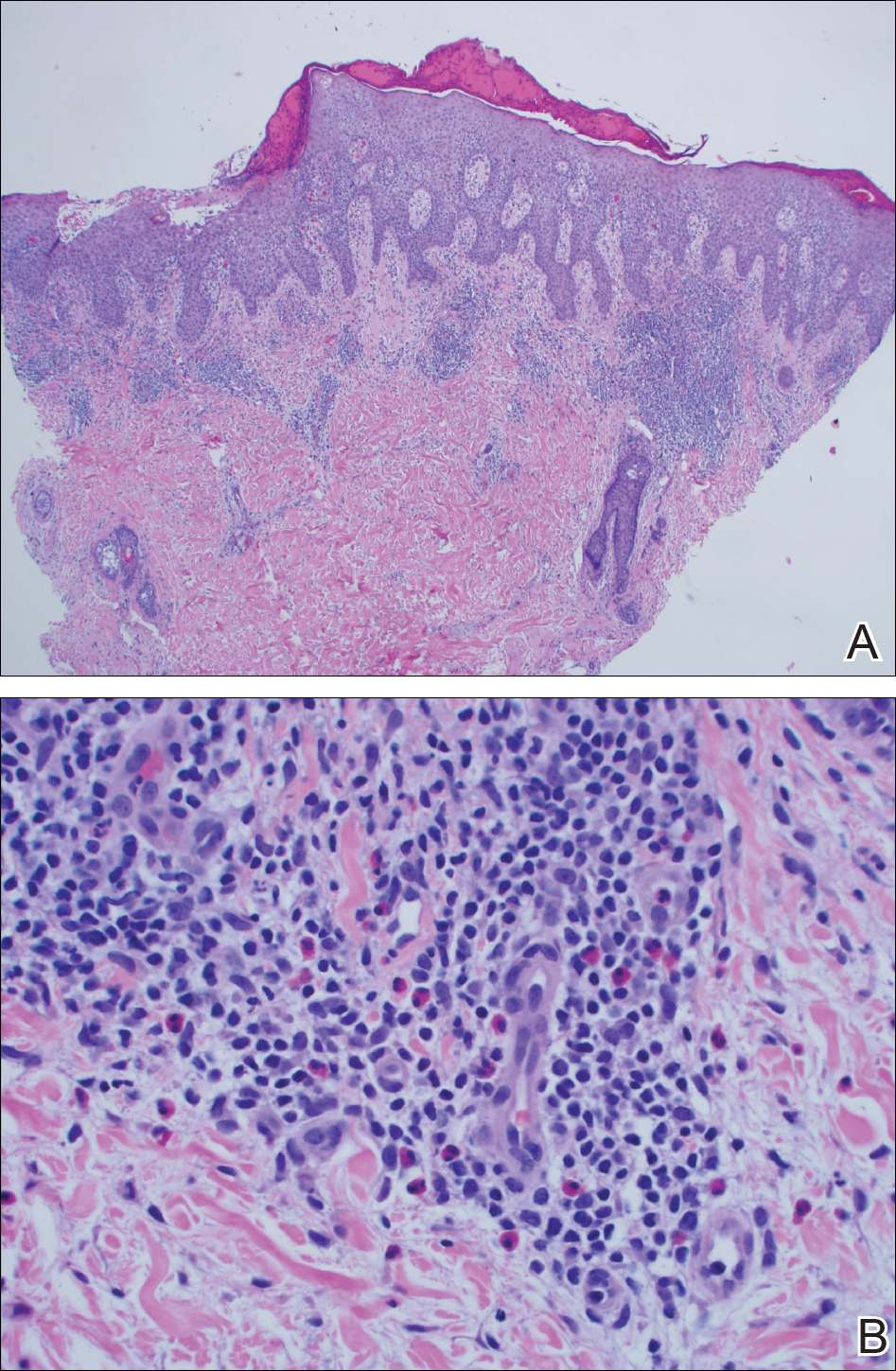

There were no between-group differences in suture exposure (about 25% in both groups) or sling erosion (about 3%) at 5 years.

There was a difference in granulation tissue: 28.9% with ULS and 18.8% with SSLF (odds ratio with ULS, 1.9; 95% confidence interval 1-3.7). The majority of adverse events occurred within 2 years of surgery.

Early pelvic floor muscle training made no difference in outcomes for the women randomized to it.

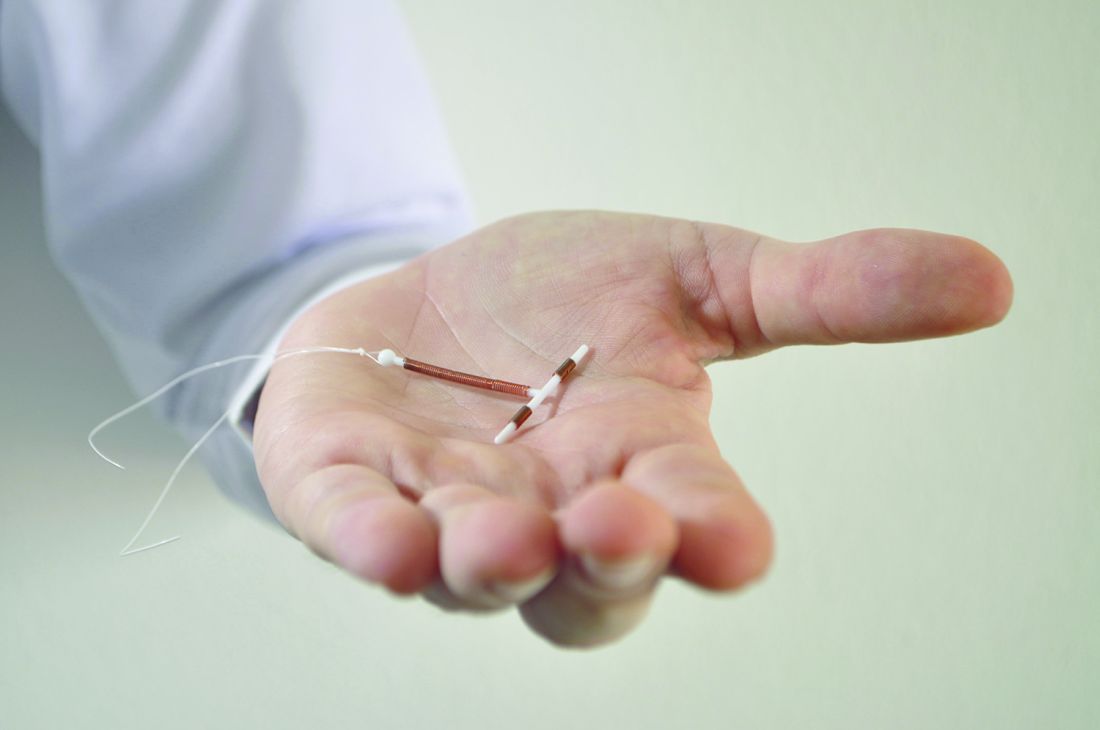

The women in the study had stage 2-4 prolapse at baseline. In addition to vaginal suspension surgery, they had vaginal hysterectomies if there was uterine prolapse, and all the women had concomitant retropubic midurethral sling surgery for stress incontinence.

At 2 years, composite success rates were about 60% in both groups (JAMA. 2014 Mar 12;311[10]:1023-34).

The study didn’t identify risk factors for failure, but they would be helpful to know, Dr. Jelovsek said. High-risk women might benefit from a more durable mesh repair. For now at least, “most women say the risk” of pain and other serious mesh complications “completely outweighs the bulge symptoms,” he said.

The trial, an extension of OPTIMAL (Operations and Pelvic Muscle Training in the Management of Apical Support Loss), was conducted at nine U.S. centers in the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Jelovsek reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – At 5-year follow-up, outcomes were slightly better on most measures for transvaginal uterosacral ligament suspension versus transvaginal sacrospinous ligament fixation for apical prolapse, but the differences were not statistically significant, according to the first randomized trial to compare the two techniques.

Quality of life improvements were durable, but the overall 5-year success rate – defined as the absence of descent of the vaginal apex more than one-third into the vagina; anterior or posterior vaginal wall descent beyond the hymen; bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms; and further treatment for prolapse – was 39% in the 109 women randomized to bilateral uterosacral ligament suspension (ULS) and 30% in the 109 women randomized to unilateral sacrospinous ligament fixation (SSLF).

But there was a notable finding in the study. If women failed to meet all the requirements for success at any one visit, they were classified as surgical failures. However, many who missed the mark at one visit met all the requirements for success on other visits, including their last follow-up.

“We don’t think as surgeons that a bulge comes and goes on a yearly basis, but people actually moved in and out of success and failure over time, and that’s new,” Dr. Jelovsek said. “We just don’t understand the dynamic variables of anatomic prolapse, because no one’s looked at it. The assumption of ‘once a failure, always a failure’ may underestimate success rates.”

Nonetheless, using that approach in the study, the investigators found that the anatomic success was 54% in the ULS and 38% in the SSLF groups at 5 years, and 37% of women in the ULS group reported bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms, versus 42% of women with SSLF. A total of 12% of women with ULS and 8% of women with SSLF had undergone POP retreatment at 5 years, either by pessary or secondary surgery but, again, the differences were not statistically significant.

Of the 145 anatomic failures in the study, 41% were stage 3 or 4.

Quality of life improvements, assessed annually by phone, “were maintained over 5 years despite progressive increases in surgical failure rates over time,” with about a 70-point improvement in the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory and similar gains in other measures in both groups, Dr. Jelovsek reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

There were no between-group differences in suture exposure (about 25% in both groups) or sling erosion (about 3%) at 5 years.

There was a difference in granulation tissue: 28.9% with ULS and 18.8% with SSLF (odds ratio with ULS, 1.9; 95% confidence interval 1-3.7). The majority of adverse events occurred within 2 years of surgery.

Early pelvic floor muscle training made no difference in outcomes for the women randomized to it.

The women in the study had stage 2-4 prolapse at baseline. In addition to vaginal suspension surgery, they had vaginal hysterectomies if there was uterine prolapse, and all the women had concomitant retropubic midurethral sling surgery for stress incontinence.

At 2 years, composite success rates were about 60% in both groups (JAMA. 2014 Mar 12;311[10]:1023-34).

The study didn’t identify risk factors for failure, but they would be helpful to know, Dr. Jelovsek said. High-risk women might benefit from a more durable mesh repair. For now at least, “most women say the risk” of pain and other serious mesh complications “completely outweighs the bulge symptoms,” he said.

The trial, an extension of OPTIMAL (Operations and Pelvic Muscle Training in the Management of Apical Support Loss), was conducted at nine U.S. centers in the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Jelovsek reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – At 5-year follow-up, outcomes were slightly better on most measures for transvaginal uterosacral ligament suspension versus transvaginal sacrospinous ligament fixation for apical prolapse, but the differences were not statistically significant, according to the first randomized trial to compare the two techniques.

Quality of life improvements were durable, but the overall 5-year success rate – defined as the absence of descent of the vaginal apex more than one-third into the vagina; anterior or posterior vaginal wall descent beyond the hymen; bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms; and further treatment for prolapse – was 39% in the 109 women randomized to bilateral uterosacral ligament suspension (ULS) and 30% in the 109 women randomized to unilateral sacrospinous ligament fixation (SSLF).

But there was a notable finding in the study. If women failed to meet all the requirements for success at any one visit, they were classified as surgical failures. However, many who missed the mark at one visit met all the requirements for success on other visits, including their last follow-up.

“We don’t think as surgeons that a bulge comes and goes on a yearly basis, but people actually moved in and out of success and failure over time, and that’s new,” Dr. Jelovsek said. “We just don’t understand the dynamic variables of anatomic prolapse, because no one’s looked at it. The assumption of ‘once a failure, always a failure’ may underestimate success rates.”

Nonetheless, using that approach in the study, the investigators found that the anatomic success was 54% in the ULS and 38% in the SSLF groups at 5 years, and 37% of women in the ULS group reported bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms, versus 42% of women with SSLF. A total of 12% of women with ULS and 8% of women with SSLF had undergone POP retreatment at 5 years, either by pessary or secondary surgery but, again, the differences were not statistically significant.

Of the 145 anatomic failures in the study, 41% were stage 3 or 4.

Quality of life improvements, assessed annually by phone, “were maintained over 5 years despite progressive increases in surgical failure rates over time,” with about a 70-point improvement in the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory and similar gains in other measures in both groups, Dr. Jelovsek reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

There were no between-group differences in suture exposure (about 25% in both groups) or sling erosion (about 3%) at 5 years.

There was a difference in granulation tissue: 28.9% with ULS and 18.8% with SSLF (odds ratio with ULS, 1.9; 95% confidence interval 1-3.7). The majority of adverse events occurred within 2 years of surgery.

Early pelvic floor muscle training made no difference in outcomes for the women randomized to it.

The women in the study had stage 2-4 prolapse at baseline. In addition to vaginal suspension surgery, they had vaginal hysterectomies if there was uterine prolapse, and all the women had concomitant retropubic midurethral sling surgery for stress incontinence.

At 2 years, composite success rates were about 60% in both groups (JAMA. 2014 Mar 12;311[10]:1023-34).

The study didn’t identify risk factors for failure, but they would be helpful to know, Dr. Jelovsek said. High-risk women might benefit from a more durable mesh repair. For now at least, “most women say the risk” of pain and other serious mesh complications “completely outweighs the bulge symptoms,” he said.

The trial, an extension of OPTIMAL (Operations and Pelvic Muscle Training in the Management of Apical Support Loss), was conducted at nine U.S. centers in the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Jelovsek reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The overall 5-year success rate was 39% in women randomized to bilateral uterosacral ligament suspension and 30% in women randomized to unilateral sacrospinous ligament fixation.

Data source: The first randomized trial to compare the two commonly used techniques was conducted among 218 women at nine U.S. centers in the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network.

Disclosures: The Pelvic Floor Disorders Network is funded by the National Institutes of Health. The lead investigator reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, and Evaluation

From the Department of Preventive Medicine and Environmental Health, University of Kentucky College of Public Health, Lexington, KY.

Abstract

- Objective: To review the classification, epidemiology, clinical presentation, and evaluation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: While smoking remains the most important risk factor for COPD in much of the developed world, other risk factors, including genetic factors and occupational or environmental exposures, remain important. COPD is the third leading cause of death in the United States. In 2011, 13.7 million adults aged ≥ 25 years were diagnosed with COPD in the United States, and as many as 12 million adults may have COPD that is undiagnosed. In 2010, COPD was responsible for an estimated 10.3 million physician office visits and 1.5 million emergency room visits and was estimated to be the second leading cause of disability-adjusted life years lost among the US population. COPD has primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention strategies. The treatment of COPD has improved in recent years, with new therapies improving patient quality of life.

- Conclusion: COPD remains a serious public health problem that is often underdiagnosed, particularly in its early stages.

Key words: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; epidemiology; mortality; smoking; evaluation.

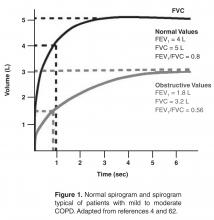

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by fixed airflow obstruction with breathing-related symptoms, such as chronic cough, exertional dyspnea, expectoration, and wheeze [1]. These symptoms may occur in conjunction with airway hyperresponsiveness and overlap with other chronic diseases such as asthma. Although COPD is a nonspecific term referring to a set of conditions that develop progressively as a result of a number of different disease processes, it most commonly refers to chronic bronchitis and emphysema. These conditions can be present with or without significant physical impairment. Despite being a very common disease and the third leading cause of death in the United States [2], COPD often is a silent and unrecognized disease, particularly in its early phases [3], and may go untreated.

In this article, we review the classification, epidemiology, clinical presentation, and assessment of patients with COPD.

Definition and Classification

Several different definitions have existed for COPD [4–8]. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), an international collaboration of leading experts in COPD launched in the late 90s with a goal to develop evidence-based recommendations for diagnosis and management of COPD [4], currently defines COPD as “a common, preventable and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that is due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases” [4].

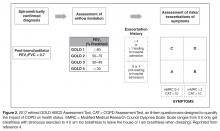

Severity of COPD has typically been determined using the degree of lung function impairment, although the wisdom of this approach has been questioned,

Previous definitions of COPD differentiated between chronic bronchitis, asthma, and emphysema, acknowledging that there is frequently overlap between these disease entities [12,13]. The GOLD definition of COPD does not differentiate between chronic bronchitis and emphysema but does note that although asthma and COPD can coexist [4], the largely reversible airflow limitation in asthma merits different therapeutic approaches than the largely irreversible airflow limitation of COPD. The overlap of asthma and COPD in a significant proportion of patients has been the focus of recent work [14].

Epidemiology

Prevalence of COPD

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) is an ongoing national random-digit-dialed telephone survey of landline and cellphone households designed to measure behavioral risk factors for the noninstitutionalized adult population of the US [15]. An affirmative response to the following question was defined as physician-diagnosed COPD: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema, or bronchitis?”[16]. Based on 2011 BRFSS survey, 13.7 million adults aged ≥ 25 years were estimated to have a self-reported physician diagnosis of COPD in the United States. The greatest age-adjusted prevalence was found to be clustered along the Ohio River Valley and the southern states [16].

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is an annually conducted, nationally representative survey of the civilian noninstitutionalized population aged 18 years and older. A positive response to one or both of the following questions was used to define COPD: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had emphysema?” and “During the past 12 months, have you been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had chronic bronchitis?” Age-adjusted COPD prevalence estimates showed significant interyear variation during 1999–2011 period, and were higher in women than in men with the highest prevalence noted in 2001 for both genders [16].

The NHIS estimates for COPD have 2 important limitations. First, these estimates depend on the proper recognition and diagnosis of COPD by both the study participants and their health care providers. This would tend to bias the estimates toward counting fewer cases than actually exist. A bias in the opposite direction, however, is that the term chronic bronchitis in this survey is not precisely defined and could be interpreted as recurrent episodes of acute bronchitis. The finding that “chronic bronchitis” has been reported in 3% to 4% of children supports the presence of this potential bias. The second limitation is that this survey is not able to validate, through physiologic evaluation, whether airway obstruction is present or absent.

These limitations were addressed, in part, by separate nationally representative US surveys that include an examination component, such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) [17]. An analysis of these data from 1988–1994 and 2007–2012 [18] demonstrated that over 70% of people with evidence of obstruction (based on an FEV1/FVC < 70%) did not have a diagnosis of lung disease (COPD or asthma). In addition, people with evidence of obstruction had a higher risk of mortality whether or not they had diagnosed lung disease [18].

Evaluation of “reversibility” of the airway obstruction requires the administration of bronchodilator, which is not a part of most population-based studies. A subset of participants in the NHANES 2007–2012 survey received a bronchodilator, with a decrease in the estimated prevalence of obstruction from 20.9% to 14.0% [19]. However, a closer look at similar data from a study where all people got a bronchodilator reveal that only a small proportion of people with “reversibility” actually had a significant response to the bronchodilator [20]. In a clinic-based study of subjects with COPD who were aged 69 years and older, 31% demonstrated reversibility, defined as a 15% improvement (from baseline) in FVC and FEV1 following administration of an inhaled bronchodilator [21]. In this study, subjects with more severe obstruction were more likely to have reversibility but would also be more likely to continue to have diminished lung function after maximum improvement was obtained, thus being classified as having “partial reversibility.”

The presence of significant reversibility or partial reversibility in patients with COPD [15] and nonreversible airflow obstruction in asthma patients [22] demonstrates that these diseases can coexist or, alternatively, that there is overlap and imprecision in the ways that these diseases are clinically diagnosed.

Morbidity and Mortality

COPD is a leading cause of disease morbidity and mortality in the United States. The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) conducts ongoing surveillance of several health indicators nationally. The NCHS collects physician office visit data using the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey [23], emergency department visit data and hospital outpatient data using the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey [24], hospitalization data using the National Hospital Discharge Survey [25], and death data using the mortality component of the National Vital Statistics System [26]. The following data include the number and rate of COPD events in adults in the United States (using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM], codes 490, 491, 492 and 496) in these data sets for the most recent years available.

In 2010, COPD was responsible for an estimated 10.3 million physician office visits, with a resulting age-adjusted rate of 494.8 per 10,000 US civilian population [16]. COPD was also responsible for an estimated 1.5 million emergency room visits, with a resulting age-adjusted rate of 72 visits per 10,000 population [16].

COPD is a leading cause of hospitalization in US adults, particularly in older populations. In 2010, almost 699,000 hospitalizations, were attributed to COPD. The age-adjusted rate of COPD hospitalizations (as the primary cause of hospitalization) was 32.2 per 10,000 population in 2010 [16].

Deaths due to or associated with COPD have not significantly changed since 1999. While the age-adjusted death rate among men declined during 1999–2010 (P = 0.001), the rate among women has not changed significantly (P = 0.127). In 2010, 63, 778 men and 69, 797 women aged ≥ 25 years died of COPD [26]. One of the limitations of using the mortality component of the National Vital Statistics System is that it is based on the underlying cause of death as reported on the death certificate; however, many decedents with COPD listed on the death certificate have their death attributed to another cause [27]. The significance of COPD as a contributor to death is undefined when it is present with diseases more likely to be attributed as the underlying cause of death, such as myocardial infarction or lung cancer [28].

COPD is a very costly disease, with estimated direct medical costs in 2004 of $20.9 billion. The estimated indirect costs related to morbidity (loss of work time and productivity) and premature mortality is an additional $16.3 billion, for a total of $37.2 billion [29]. Because COPD may be present but not listed as the underlying cause of death or the primary reason for hospitalization, these cited estimates may underestimate the true cost of COPD. For example, in another analysis of COPD costs in the US, the total for 2010 was estimated at $32.1 billion [30], but could be up to $100 billion [31] depending on the assumptions surrounding comorbid disease.

Another manifestation of the importance of COPD is its effect on the burden of disease in a population determined using disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs). DALYs for a disease or condition are calculated as the sum of the years of life lost due to premature mortality in the population and the years of life lost due to disability [32]. In 2010, COPD was estimated to be the second leading cause of DALYs lost among the North American population [33]. Worldwide, COPD is expected to move up from being the twelfth leading cause of DALYs lost in 1990 to the fifth leading cause in 2020 [34].

Gender Differences

Smoking-related diseases such as COPD and lung cancer are continuing to increase among women in the United States [35,36], while they have plateaued or are decreasing among men [27,37]. Some evidence has emerged that compared with men at a similar level of tobacco smoking, women may be more likely to develop COPD [38] or that the severity of COPD in women may be increased [39–41].

In the Lung Health Study, which evaluated patients with mild COPD, more women than men demonstrated increased airway responsiveness, although this difference was thought to be related to airway caliber rather than gender [42]. Adult women are more likely to both develop and die of asthma than are men [43–45]. In NHANES III, whereas women reported more physician-diagnosed COPD and asthma than men, men and women had similar rates of decreased lung function, and a similar proportion of both men and women with low lung function had undiagnosed lung disease [3]. The current evidence is inadequate to determine whether women who smoke are more likely to develop COPD or have more severe COPD than men, although this question is being studied by various groups.

Risk Factors and Etiology

Smoking is the dominant risk factor for the development and progression of COPD; however, not all smokers develop COPD, and COPD does occur in persons who have never smoked [1], suggesting that other factors are important in the etiology of COPD. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency is an important cause of COPD in a very small percentage of cases [46]. Other undefined genetic factors certainly play an important role in COPD development [38]. The role of infections in both the development and progression of COPD is receiving increased attention, including the role of adenoviral infections in emphysema [47–49].

Occupational and environmental exposures to various pollutants (eg, particulate matter, agricultural dusts) are also important factors in the development of COPD [50,51]. Exposure to indoor air pollutants such as smoke from solid biomass fuels is a major risk factor for COPD especially among women and children in low- and middle-income countries [52,53]. Occupational exposure to fumes and dusts remains an important cause for COPD globally [53,54]. Exposure to outdoor air pollution is associated with a risk of development of COPD as well as exacerbation of the existing disease [53,55].

Clinical Presentation

COPD is heterogeneous in its presentation. Based on data from NHANES III, 44% of patients with severe airflow limitation (FEV1 < 50% of predicted) may not report symptoms [3]. Among patients with severe airflow limitation who do report symptoms, the symptoms reported most frequently include wheezing (64%) and shortness of breath (65%).

In recent years, COPD has been increasingly recognized as a systemic illness, with effects on nutritional status, muscle wasting, and depression [56–58]. A large proportion of patients probably have components of chronic bronchitis, asthma, and emphysema occurring together. Although some of this overlap may be related to misdiagnosis, some of it may be a measure of the presence of airflow limitation reversibility, as described above. Better defining individuals in these groups may ultimately help tailor better interventions.

Some of the barriers to COPD diagnosis and subsequent treatment often include insufficient knowledge and awareness about COPD especially among primary care physicians, misdiagnosis of COPD as other respiratory diseases such asthma, as well as patient-related barriers involving lack of awareness of early symptoms of COPD and considering them to be related to aging or smoking [59].

Evaluation

The evaluation of a patient with suspected COPD is oriented toward establishing the correct diagnosis and, once this has occurred, determining the extent of the impairment such that therapy can be appropriately targeted.

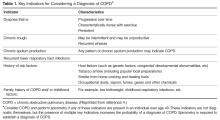

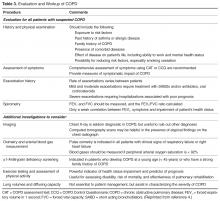

Components in the evaluation of COPD are listed in Table 3. Every patient with suspected COPD should undergo a thorough history and physical examination. The history should pay particular attention to the following: exposure to risk factors; past history of asthma or allergic disease; family history of COPD; presence of comorbid diseases; effect of disease on the patient’s life, including ability to work and mental health status; and possibilities for reducing risk factors, especially smoking cessation [4]. The physical examination is rarely diagnostic in COPD because most physical abnormalities do not occur until the advanced stages of the disease. Physical examination findings in

Pulmonary function testing is a critical part of the evaluation of suspected COPD. Whereas most patients with COPD can be managed by a primary care physician, patients with moderate or severe COPD should be evaluated by a specialist [4].

Once the diagnosis of moderate or severe COPD has been established, further testing, including chest radiograph, arterial blood gas determination, screening for α1-antitrypsin deficiency, 6-minute walk testing or exercise oxymetry may be indicated based on the patient’s history and/or clinical findings. Data from computed tomography scans are useful in some advanced cases.

Prognosis of COPD is often influenced by presence of various comorbidities including extrapulmonary, such as osteoporosis, metabolic syndrome, and depression that may be seen as parts of multimorbidity associated with aging [60,61]. Therefore, it is advised to look for comorbidities in COPD patients with any severity of airflow obstruction and treat them accordingly [4].

Therapy for COPD targets reducing risk factors, improving symptoms, and decreasing the risk of exacerbations [10]. Interventions include smoking cessation, vaccinations, decreasing exposures to occupational and environmental pollutants, pulmonary rehabilitation, bronchodilators, and corticosteroids. Select patients with advanced COPD may benefit from other interventions, such as surgical reduction of lung size, lung transplant, the phosphodiesterase inhibitor roflumilast and chronic treatment with antibiotics such as macrolides.

Conclusion

COPD is a common disease that is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, both in the United States and worldwide. Most cases of COPD are attributable to smoking. Although its incidence among men has plateaued, it continues to increase among women. COPD, particularly in its early stages, is under-diagnosed in the United States. An increased awareness among physicians of the prevalence of mild COPD and the importance of spirometry in diagnosing the disease is important in combating the disease.

Corresponding author: David M. Mannino, MD, Department of Preventive Medicine and Environmental Health, University of Kentucky College of Public Health, 111 Washington Avenue, Lexington, KY 40536, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: Dr. Mannino has received fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Sunovion, and Boehringer Ingelheim for advisory board services.

1. Rennard SI. COPD: overview of definitions, epidemiology, and factors influencing its development. Chest 1998;113(4 Suppl):235S–41S.

2. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2015: with special feature on racial and ethnic health disparities. Hyattsville, MD; 2016.

3. Mannino DM, Gagnon RC, Petty TL, Lydick E. Obstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:1683–9.

4. From the Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2017. Available at http://goldcopd.org.

5. Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Rodriguez-Roisin R. The 2011 revision of the global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD (GOLD) – why and what? Clin Respir J 2012;6:208–14.

6. Standards for the diagnosis and care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;152(5 Pt 2):S77–121.

7. Siafakas N, Vermeire P, Pride Na, et al. Optimal assessment and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Eur Respir J 1995;8:1398–420.

8. Celli BR, MacNee W, Agusti A, et al. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J 2004;23:932–46.

9. Swanney MP, Ruppel G, Enright PL, et al. Using the lower limit of normal for the FEV1/FVC ratio reduces the misclassification of airway obstruction. Thorax 2008;63:1046–51.

10. Bestall J, Paul E, Garrod R, et al. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1999;54:581–6.

11. Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agusti AG, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:347–65.

12. Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:1256–76.

13. Dirksen A, Christensen H, Evald T, et al. Bronchodilator and corticosteroid reversibility in ambulatory patients with airways obstruction. Danish Med Bull 1991;38:486–9.

14. Sin DD, Miravitlles M, Mannino DM, et al. What is asthma-COPD overlap syndrome? Towards a consensus definition from a round table discussion. Eur Respir J 2016;48:664–73.

15. Hansen EF, Phanareth K, Laursen LC, et al. Reversible and irreversible airflow obstruction as predictor of overall mortality in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159(4 Pt 1):1267–71.

16. Ford ES, Croft JB, Mannino DM, et al. COPD surveillance—United States, 1999-2011. Chest 2013;144:284–305.

17. Plan and operation of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-94. Series 1: programs and collection procedures. Vital and health statistics Ser 1, Programs and collection procedures. 1994:1–407.

18. Martinez CH, Mannino DM, Jaimes FA, et al. Undiagnosed Obstructive lung disease in the United States. Associated factors and long-term mortality. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015;12:1788–95.

19. Tilert T, Dillon C, Paulose-Ram R, et al. Estimating the U.S. prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007-2010. Respir Res 2013;14:103.

20. Prentice HA, Mannino DM, Caldwell GG, Bush HM. Significant bronchodilator responsiveness and “reversibility” in a population sample. COPD 2010;7:323–30.

21. Chang JT, Moran MB, Cugell DW, Webster JR. COPD in the elderly: a reversible cause of functional impairment. Chest 1995;108:736–40.

22. Ulrik C, Backer V. Nonreversible airflow obstruction in life-long nonsmokers with moderate to severe asthma. Eur Respir J 1999;14:892–6.

23. Hing E, Hall MJ, Ashman JJ, Xu J. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2007 outpatient department summary. Natl Health Stat Report 2010;28:1–32.

24. Niska R, Bhuiya F, Xu J. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2007 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Report 2010;26:1–31.

25. Kozak LJ, DeFrances CJ, Hall MJ. National hospital discharge survey: 2004 annual summary with detailed diagnosis and procedure data. Vital and health statistics Series 13, Data from the National Health Survey. 2006(162):1–209.

26. Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 2010. National vital statistics reports: from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2013;61:1–117.

27. Mannino DM, Brown C, Giovino GA. Obstructive lung disease deaths in the United States from 1979 through 1993. An analysis using multiple-cause mortality data. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;156(3 Pt 1):814–8.

28. Camilli AE, Robbins DR, Lebowitz MD. Death certificate reporting of confirmed airways obstructive disease. Am J Epidemiol 1991;133:795–800.

29. Miller JD, Foster T, Boulanger L, et al. Direct Costs of COPD in the U.S.: An Analysis of Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) Data. COPD 2005;2:311–8.

30. Ford ES, Murphy LB, Khavjou O, et al. Total and state-specific medical and absenteeism costs of COPD among adults aged >/= 18 years in the United States for 2010 and projections through 2020. Chest 2015;147:31–45.

31. Mannino DM. Counting costs in COPD: what do the numbers mean? Chest 2015;147:3–5.

32. Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2197–223.

33. Murray CJ, Abraham J, Ali MK, et al. The state of US health, 1990-2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA 2013;310:591–606.

34. Lopez AD, Murray CC. The global burden of disease 1990–2020. Nat Med 1998;4:1241–3.

35. Cohen SB-Z, Paré PD, Man SFP, Sin DD. The growing burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer in women. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:113–20.

36. Han MK, Postma D, Mannino DM, et al. Gender and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: why it matters. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1179–84.

37. Tanoue LT. Cigarette smoking and women’s respiratory health. Clin Chest Med 2000;21:47–65, viii.

38. Silverman EK, Weiss ST, Drazen JM, et al. Gender-related differences in severe, early-onset chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:2152–8.

39. Carter R, Nicotra B, Huber G. Differing effects of airway obstruction on physical work capacity and ventilation in men and women with COPD. Chest 1994;106:1730–9.

40. Foreman MG, Zhang L, Murphy J, et al. Early-onset chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with female sex, maternal factors, and African American race in the COPDGene Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;184:414–20.

41. Sørheim I-C, Johannessen A, Gulsvik A, et al. Gender differences in COPD: are women more susceptible to smoking effects than men? Thorax 2010;65:480–5.

42. Kanner RE, Connett JE, Altose MD, Buist AS, Lee WW, Tashkin DP, et al. Gender difference in airway hyperresponsiveness in smokers with mild COPD. The Lung Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;150:956–61.

43. De Marco R, Locatelli F, Sunyer J, Burney P. Differences in incidence of reported asthma related to age in men and women: a retrospective analysis of the data of the European Respiratory Health Survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:68–74.

44. Moorman JE, Moorman J, Mannino DM. Increasing US asthma mortality rates: who is really dying? J Asthma 2001;38:65–71.

45. Mannino DM, Homa DM, Pertowski CA, et al. Surveillance for asthma—United States, 1960–1995. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ 1998;47:1–27.

46. Snider GL. Molecular epidemiology: a key to better understanding of chronic obstructive lung disease. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 1995;50:3–6.

47. Hogg JC. Chronic bronchitis: the role of viruses. Semin Respir Infect 2000;15:32–40.

48. Kraft M, Cassell GH, Henson JE, et al. Detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in the airways of adults with chronic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158:998–1001.

49. Hegele RG, Hayashi S, Hogg JC, Paré PD. Mechanisms of airway narrowing and hyperresponsiveness in viral respiratory trad infections. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;151:1659–65.

50. Blanc PD, Iribarren C, Trupin L, et al. Occupational exposures and the risk of COPD: dusty trades revisited. Thorax 2009;64:6–12.

51. Becklake MR. Occupational exposures: evidence for a causal association with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respi Dis 1989;140(3 Pt 2):S85–S91.

52. Po JYT, FitzGerald JM, Carlsten C. Respiratory disease associated with solid biomass fuel exposure in rural women and children: systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2011;66:232–9.

53. Mannino DM, Buist AS. Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. Lancet 2007;370:765–73.

54. Trupin L, Earnest G, San Pedro M, et al. The occupational burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2003;22:462–9.

55. Andersen ZJ, Hvidberg M, Jensen SS, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:455–61.

56. Agusti À, Soriano JB. COPD as a systemic disease. COPD 2008;5:133–8.

57. Eisner MD, Blanc PD, Yelin EH, et al. COPD as a systemic disease: impact on physical functional limitations. Am J Med 2008;121:789–96.

58. Cekerevac I, Lazic Z, Petrovic M, Novkovic L. COPD and depression. Eur Respir J 2012;40(Suppl 56).

59. Fromer L. Diagnosing and treating COPD: understanding the challenges and finding solutions. Int J Gen Med 2011;4:729–39.

60. Cavaillès A, Brinchault-Rabin G, Dixmier A, et al. Comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir Rev 2013;22:454–75.

61. Barnes PJ. Gold 2017: A new report. Chest 2017;151:245–6.

62. Choo C. Combination therapy options in Stable COPD. US Pharm 2010;35:31–7.

From the Department of Preventive Medicine and Environmental Health, University of Kentucky College of Public Health, Lexington, KY.

Abstract

- Objective: To review the classification, epidemiology, clinical presentation, and evaluation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: While smoking remains the most important risk factor for COPD in much of the developed world, other risk factors, including genetic factors and occupational or environmental exposures, remain important. COPD is the third leading cause of death in the United States. In 2011, 13.7 million adults aged ≥ 25 years were diagnosed with COPD in the United States, and as many as 12 million adults may have COPD that is undiagnosed. In 2010, COPD was responsible for an estimated 10.3 million physician office visits and 1.5 million emergency room visits and was estimated to be the second leading cause of disability-adjusted life years lost among the US population. COPD has primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention strategies. The treatment of COPD has improved in recent years, with new therapies improving patient quality of life.

- Conclusion: COPD remains a serious public health problem that is often underdiagnosed, particularly in its early stages.

Key words: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; epidemiology; mortality; smoking; evaluation.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by fixed airflow obstruction with breathing-related symptoms, such as chronic cough, exertional dyspnea, expectoration, and wheeze [1]. These symptoms may occur in conjunction with airway hyperresponsiveness and overlap with other chronic diseases such as asthma. Although COPD is a nonspecific term referring to a set of conditions that develop progressively as a result of a number of different disease processes, it most commonly refers to chronic bronchitis and emphysema. These conditions can be present with or without significant physical impairment. Despite being a very common disease and the third leading cause of death in the United States [2], COPD often is a silent and unrecognized disease, particularly in its early phases [3], and may go untreated.

In this article, we review the classification, epidemiology, clinical presentation, and assessment of patients with COPD.

Definition and Classification

Several different definitions have existed for COPD [4–8]. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), an international collaboration of leading experts in COPD launched in the late 90s with a goal to develop evidence-based recommendations for diagnosis and management of COPD [4], currently defines COPD as “a common, preventable and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that is due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases” [4].

Severity of COPD has typically been determined using the degree of lung function impairment, although the wisdom of this approach has been questioned,

Previous definitions of COPD differentiated between chronic bronchitis, asthma, and emphysema, acknowledging that there is frequently overlap between these disease entities [12,13]. The GOLD definition of COPD does not differentiate between chronic bronchitis and emphysema but does note that although asthma and COPD can coexist [4], the largely reversible airflow limitation in asthma merits different therapeutic approaches than the largely irreversible airflow limitation of COPD. The overlap of asthma and COPD in a significant proportion of patients has been the focus of recent work [14].

Epidemiology

Prevalence of COPD

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) is an ongoing national random-digit-dialed telephone survey of landline and cellphone households designed to measure behavioral risk factors for the noninstitutionalized adult population of the US [15]. An affirmative response to the following question was defined as physician-diagnosed COPD: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema, or bronchitis?”[16]. Based on 2011 BRFSS survey, 13.7 million adults aged ≥ 25 years were estimated to have a self-reported physician diagnosis of COPD in the United States. The greatest age-adjusted prevalence was found to be clustered along the Ohio River Valley and the southern states [16].

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is an annually conducted, nationally representative survey of the civilian noninstitutionalized population aged 18 years and older. A positive response to one or both of the following questions was used to define COPD: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had emphysema?” and “During the past 12 months, have you been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had chronic bronchitis?” Age-adjusted COPD prevalence estimates showed significant interyear variation during 1999–2011 period, and were higher in women than in men with the highest prevalence noted in 2001 for both genders [16].

The NHIS estimates for COPD have 2 important limitations. First, these estimates depend on the proper recognition and diagnosis of COPD by both the study participants and their health care providers. This would tend to bias the estimates toward counting fewer cases than actually exist. A bias in the opposite direction, however, is that the term chronic bronchitis in this survey is not precisely defined and could be interpreted as recurrent episodes of acute bronchitis. The finding that “chronic bronchitis” has been reported in 3% to 4% of children supports the presence of this potential bias. The second limitation is that this survey is not able to validate, through physiologic evaluation, whether airway obstruction is present or absent.

These limitations were addressed, in part, by separate nationally representative US surveys that include an examination component, such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) [17]. An analysis of these data from 1988–1994 and 2007–2012 [18] demonstrated that over 70% of people with evidence of obstruction (based on an FEV1/FVC < 70%) did not have a diagnosis of lung disease (COPD or asthma). In addition, people with evidence of obstruction had a higher risk of mortality whether or not they had diagnosed lung disease [18].

Evaluation of “reversibility” of the airway obstruction requires the administration of bronchodilator, which is not a part of most population-based studies. A subset of participants in the NHANES 2007–2012 survey received a bronchodilator, with a decrease in the estimated prevalence of obstruction from 20.9% to 14.0% [19]. However, a closer look at similar data from a study where all people got a bronchodilator reveal that only a small proportion of people with “reversibility” actually had a significant response to the bronchodilator [20]. In a clinic-based study of subjects with COPD who were aged 69 years and older, 31% demonstrated reversibility, defined as a 15% improvement (from baseline) in FVC and FEV1 following administration of an inhaled bronchodilator [21]. In this study, subjects with more severe obstruction were more likely to have reversibility but would also be more likely to continue to have diminished lung function after maximum improvement was obtained, thus being classified as having “partial reversibility.”

The presence of significant reversibility or partial reversibility in patients with COPD [15] and nonreversible airflow obstruction in asthma patients [22] demonstrates that these diseases can coexist or, alternatively, that there is overlap and imprecision in the ways that these diseases are clinically diagnosed.

Morbidity and Mortality

COPD is a leading cause of disease morbidity and mortality in the United States. The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) conducts ongoing surveillance of several health indicators nationally. The NCHS collects physician office visit data using the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey [23], emergency department visit data and hospital outpatient data using the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey [24], hospitalization data using the National Hospital Discharge Survey [25], and death data using the mortality component of the National Vital Statistics System [26]. The following data include the number and rate of COPD events in adults in the United States (using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM], codes 490, 491, 492 and 496) in these data sets for the most recent years available.

In 2010, COPD was responsible for an estimated 10.3 million physician office visits, with a resulting age-adjusted rate of 494.8 per 10,000 US civilian population [16]. COPD was also responsible for an estimated 1.5 million emergency room visits, with a resulting age-adjusted rate of 72 visits per 10,000 population [16].

COPD is a leading cause of hospitalization in US adults, particularly in older populations. In 2010, almost 699,000 hospitalizations, were attributed to COPD. The age-adjusted rate of COPD hospitalizations (as the primary cause of hospitalization) was 32.2 per 10,000 population in 2010 [16].

Deaths due to or associated with COPD have not significantly changed since 1999. While the age-adjusted death rate among men declined during 1999–2010 (P = 0.001), the rate among women has not changed significantly (P = 0.127). In 2010, 63, 778 men and 69, 797 women aged ≥ 25 years died of COPD [26]. One of the limitations of using the mortality component of the National Vital Statistics System is that it is based on the underlying cause of death as reported on the death certificate; however, many decedents with COPD listed on the death certificate have their death attributed to another cause [27]. The significance of COPD as a contributor to death is undefined when it is present with diseases more likely to be attributed as the underlying cause of death, such as myocardial infarction or lung cancer [28].

COPD is a very costly disease, with estimated direct medical costs in 2004 of $20.9 billion. The estimated indirect costs related to morbidity (loss of work time and productivity) and premature mortality is an additional $16.3 billion, for a total of $37.2 billion [29]. Because COPD may be present but not listed as the underlying cause of death or the primary reason for hospitalization, these cited estimates may underestimate the true cost of COPD. For example, in another analysis of COPD costs in the US, the total for 2010 was estimated at $32.1 billion [30], but could be up to $100 billion [31] depending on the assumptions surrounding comorbid disease.

Another manifestation of the importance of COPD is its effect on the burden of disease in a population determined using disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs). DALYs for a disease or condition are calculated as the sum of the years of life lost due to premature mortality in the population and the years of life lost due to disability [32]. In 2010, COPD was estimated to be the second leading cause of DALYs lost among the North American population [33]. Worldwide, COPD is expected to move up from being the twelfth leading cause of DALYs lost in 1990 to the fifth leading cause in 2020 [34].

Gender Differences

Smoking-related diseases such as COPD and lung cancer are continuing to increase among women in the United States [35,36], while they have plateaued or are decreasing among men [27,37]. Some evidence has emerged that compared with men at a similar level of tobacco smoking, women may be more likely to develop COPD [38] or that the severity of COPD in women may be increased [39–41].

In the Lung Health Study, which evaluated patients with mild COPD, more women than men demonstrated increased airway responsiveness, although this difference was thought to be related to airway caliber rather than gender [42]. Adult women are more likely to both develop and die of asthma than are men [43–45]. In NHANES III, whereas women reported more physician-diagnosed COPD and asthma than men, men and women had similar rates of decreased lung function, and a similar proportion of both men and women with low lung function had undiagnosed lung disease [3]. The current evidence is inadequate to determine whether women who smoke are more likely to develop COPD or have more severe COPD than men, although this question is being studied by various groups.

Risk Factors and Etiology

Smoking is the dominant risk factor for the development and progression of COPD; however, not all smokers develop COPD, and COPD does occur in persons who have never smoked [1], suggesting that other factors are important in the etiology of COPD. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency is an important cause of COPD in a very small percentage of cases [46]. Other undefined genetic factors certainly play an important role in COPD development [38]. The role of infections in both the development and progression of COPD is receiving increased attention, including the role of adenoviral infections in emphysema [47–49].

Occupational and environmental exposures to various pollutants (eg, particulate matter, agricultural dusts) are also important factors in the development of COPD [50,51]. Exposure to indoor air pollutants such as smoke from solid biomass fuels is a major risk factor for COPD especially among women and children in low- and middle-income countries [52,53]. Occupational exposure to fumes and dusts remains an important cause for COPD globally [53,54]. Exposure to outdoor air pollution is associated with a risk of development of COPD as well as exacerbation of the existing disease [53,55].

Clinical Presentation

COPD is heterogeneous in its presentation. Based on data from NHANES III, 44% of patients with severe airflow limitation (FEV1 < 50% of predicted) may not report symptoms [3]. Among patients with severe airflow limitation who do report symptoms, the symptoms reported most frequently include wheezing (64%) and shortness of breath (65%).

In recent years, COPD has been increasingly recognized as a systemic illness, with effects on nutritional status, muscle wasting, and depression [56–58]. A large proportion of patients probably have components of chronic bronchitis, asthma, and emphysema occurring together. Although some of this overlap may be related to misdiagnosis, some of it may be a measure of the presence of airflow limitation reversibility, as described above. Better defining individuals in these groups may ultimately help tailor better interventions.

Some of the barriers to COPD diagnosis and subsequent treatment often include insufficient knowledge and awareness about COPD especially among primary care physicians, misdiagnosis of COPD as other respiratory diseases such asthma, as well as patient-related barriers involving lack of awareness of early symptoms of COPD and considering them to be related to aging or smoking [59].

Evaluation

The evaluation of a patient with suspected COPD is oriented toward establishing the correct diagnosis and, once this has occurred, determining the extent of the impairment such that therapy can be appropriately targeted.

Components in the evaluation of COPD are listed in Table 3. Every patient with suspected COPD should undergo a thorough history and physical examination. The history should pay particular attention to the following: exposure to risk factors; past history of asthma or allergic disease; family history of COPD; presence of comorbid diseases; effect of disease on the patient’s life, including ability to work and mental health status; and possibilities for reducing risk factors, especially smoking cessation [4]. The physical examination is rarely diagnostic in COPD because most physical abnormalities do not occur until the advanced stages of the disease. Physical examination findings in

Pulmonary function testing is a critical part of the evaluation of suspected COPD. Whereas most patients with COPD can be managed by a primary care physician, patients with moderate or severe COPD should be evaluated by a specialist [4].

Once the diagnosis of moderate or severe COPD has been established, further testing, including chest radiograph, arterial blood gas determination, screening for α1-antitrypsin deficiency, 6-minute walk testing or exercise oxymetry may be indicated based on the patient’s history and/or clinical findings. Data from computed tomography scans are useful in some advanced cases.

Prognosis of COPD is often influenced by presence of various comorbidities including extrapulmonary, such as osteoporosis, metabolic syndrome, and depression that may be seen as parts of multimorbidity associated with aging [60,61]. Therefore, it is advised to look for comorbidities in COPD patients with any severity of airflow obstruction and treat them accordingly [4].

Therapy for COPD targets reducing risk factors, improving symptoms, and decreasing the risk of exacerbations [10]. Interventions include smoking cessation, vaccinations, decreasing exposures to occupational and environmental pollutants, pulmonary rehabilitation, bronchodilators, and corticosteroids. Select patients with advanced COPD may benefit from other interventions, such as surgical reduction of lung size, lung transplant, the phosphodiesterase inhibitor roflumilast and chronic treatment with antibiotics such as macrolides.

Conclusion

COPD is a common disease that is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, both in the United States and worldwide. Most cases of COPD are attributable to smoking. Although its incidence among men has plateaued, it continues to increase among women. COPD, particularly in its early stages, is under-diagnosed in the United States. An increased awareness among physicians of the prevalence of mild COPD and the importance of spirometry in diagnosing the disease is important in combating the disease.

Corresponding author: David M. Mannino, MD, Department of Preventive Medicine and Environmental Health, University of Kentucky College of Public Health, 111 Washington Avenue, Lexington, KY 40536, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: Dr. Mannino has received fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Sunovion, and Boehringer Ingelheim for advisory board services.

From the Department of Preventive Medicine and Environmental Health, University of Kentucky College of Public Health, Lexington, KY.

Abstract

- Objective: To review the classification, epidemiology, clinical presentation, and evaluation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: While smoking remains the most important risk factor for COPD in much of the developed world, other risk factors, including genetic factors and occupational or environmental exposures, remain important. COPD is the third leading cause of death in the United States. In 2011, 13.7 million adults aged ≥ 25 years were diagnosed with COPD in the United States, and as many as 12 million adults may have COPD that is undiagnosed. In 2010, COPD was responsible for an estimated 10.3 million physician office visits and 1.5 million emergency room visits and was estimated to be the second leading cause of disability-adjusted life years lost among the US population. COPD has primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention strategies. The treatment of COPD has improved in recent years, with new therapies improving patient quality of life.

- Conclusion: COPD remains a serious public health problem that is often underdiagnosed, particularly in its early stages.

Key words: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; epidemiology; mortality; smoking; evaluation.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by fixed airflow obstruction with breathing-related symptoms, such as chronic cough, exertional dyspnea, expectoration, and wheeze [1]. These symptoms may occur in conjunction with airway hyperresponsiveness and overlap with other chronic diseases such as asthma. Although COPD is a nonspecific term referring to a set of conditions that develop progressively as a result of a number of different disease processes, it most commonly refers to chronic bronchitis and emphysema. These conditions can be present with or without significant physical impairment. Despite being a very common disease and the third leading cause of death in the United States [2], COPD often is a silent and unrecognized disease, particularly in its early phases [3], and may go untreated.

In this article, we review the classification, epidemiology, clinical presentation, and assessment of patients with COPD.

Definition and Classification

Several different definitions have existed for COPD [4–8]. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), an international collaboration of leading experts in COPD launched in the late 90s with a goal to develop evidence-based recommendations for diagnosis and management of COPD [4], currently defines COPD as “a common, preventable and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that is due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases” [4].

Severity of COPD has typically been determined using the degree of lung function impairment, although the wisdom of this approach has been questioned,

Previous definitions of COPD differentiated between chronic bronchitis, asthma, and emphysema, acknowledging that there is frequently overlap between these disease entities [12,13]. The GOLD definition of COPD does not differentiate between chronic bronchitis and emphysema but does note that although asthma and COPD can coexist [4], the largely reversible airflow limitation in asthma merits different therapeutic approaches than the largely irreversible airflow limitation of COPD. The overlap of asthma and COPD in a significant proportion of patients has been the focus of recent work [14].

Epidemiology

Prevalence of COPD

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) is an ongoing national random-digit-dialed telephone survey of landline and cellphone households designed to measure behavioral risk factors for the noninstitutionalized adult population of the US [15]. An affirmative response to the following question was defined as physician-diagnosed COPD: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema, or bronchitis?”[16]. Based on 2011 BRFSS survey, 13.7 million adults aged ≥ 25 years were estimated to have a self-reported physician diagnosis of COPD in the United States. The greatest age-adjusted prevalence was found to be clustered along the Ohio River Valley and the southern states [16].

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is an annually conducted, nationally representative survey of the civilian noninstitutionalized population aged 18 years and older. A positive response to one or both of the following questions was used to define COPD: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had emphysema?” and “During the past 12 months, have you been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had chronic bronchitis?” Age-adjusted COPD prevalence estimates showed significant interyear variation during 1999–2011 period, and were higher in women than in men with the highest prevalence noted in 2001 for both genders [16].

The NHIS estimates for COPD have 2 important limitations. First, these estimates depend on the proper recognition and diagnosis of COPD by both the study participants and their health care providers. This would tend to bias the estimates toward counting fewer cases than actually exist. A bias in the opposite direction, however, is that the term chronic bronchitis in this survey is not precisely defined and could be interpreted as recurrent episodes of acute bronchitis. The finding that “chronic bronchitis” has been reported in 3% to 4% of children supports the presence of this potential bias. The second limitation is that this survey is not able to validate, through physiologic evaluation, whether airway obstruction is present or absent.

These limitations were addressed, in part, by separate nationally representative US surveys that include an examination component, such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) [17]. An analysis of these data from 1988–1994 and 2007–2012 [18] demonstrated that over 70% of people with evidence of obstruction (based on an FEV1/FVC < 70%) did not have a diagnosis of lung disease (COPD or asthma). In addition, people with evidence of obstruction had a higher risk of mortality whether or not they had diagnosed lung disease [18].

Evaluation of “reversibility” of the airway obstruction requires the administration of bronchodilator, which is not a part of most population-based studies. A subset of participants in the NHANES 2007–2012 survey received a bronchodilator, with a decrease in the estimated prevalence of obstruction from 20.9% to 14.0% [19]. However, a closer look at similar data from a study where all people got a bronchodilator reveal that only a small proportion of people with “reversibility” actually had a significant response to the bronchodilator [20]. In a clinic-based study of subjects with COPD who were aged 69 years and older, 31% demonstrated reversibility, defined as a 15% improvement (from baseline) in FVC and FEV1 following administration of an inhaled bronchodilator [21]. In this study, subjects with more severe obstruction were more likely to have reversibility but would also be more likely to continue to have diminished lung function after maximum improvement was obtained, thus being classified as having “partial reversibility.”

The presence of significant reversibility or partial reversibility in patients with COPD [15] and nonreversible airflow obstruction in asthma patients [22] demonstrates that these diseases can coexist or, alternatively, that there is overlap and imprecision in the ways that these diseases are clinically diagnosed.

Morbidity and Mortality

COPD is a leading cause of disease morbidity and mortality in the United States. The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) conducts ongoing surveillance of several health indicators nationally. The NCHS collects physician office visit data using the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey [23], emergency department visit data and hospital outpatient data using the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey [24], hospitalization data using the National Hospital Discharge Survey [25], and death data using the mortality component of the National Vital Statistics System [26]. The following data include the number and rate of COPD events in adults in the United States (using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM], codes 490, 491, 492 and 496) in these data sets for the most recent years available.

In 2010, COPD was responsible for an estimated 10.3 million physician office visits, with a resulting age-adjusted rate of 494.8 per 10,000 US civilian population [16]. COPD was also responsible for an estimated 1.5 million emergency room visits, with a resulting age-adjusted rate of 72 visits per 10,000 population [16].

COPD is a leading cause of hospitalization in US adults, particularly in older populations. In 2010, almost 699,000 hospitalizations, were attributed to COPD. The age-adjusted rate of COPD hospitalizations (as the primary cause of hospitalization) was 32.2 per 10,000 population in 2010 [16].

Deaths due to or associated with COPD have not significantly changed since 1999. While the age-adjusted death rate among men declined during 1999–2010 (P = 0.001), the rate among women has not changed significantly (P = 0.127). In 2010, 63, 778 men and 69, 797 women aged ≥ 25 years died of COPD [26]. One of the limitations of using the mortality component of the National Vital Statistics System is that it is based on the underlying cause of death as reported on the death certificate; however, many decedents with COPD listed on the death certificate have their death attributed to another cause [27]. The significance of COPD as a contributor to death is undefined when it is present with diseases more likely to be attributed as the underlying cause of death, such as myocardial infarction or lung cancer [28].

COPD is a very costly disease, with estimated direct medical costs in 2004 of $20.9 billion. The estimated indirect costs related to morbidity (loss of work time and productivity) and premature mortality is an additional $16.3 billion, for a total of $37.2 billion [29]. Because COPD may be present but not listed as the underlying cause of death or the primary reason for hospitalization, these cited estimates may underestimate the true cost of COPD. For example, in another analysis of COPD costs in the US, the total for 2010 was estimated at $32.1 billion [30], but could be up to $100 billion [31] depending on the assumptions surrounding comorbid disease.

Another manifestation of the importance of COPD is its effect on the burden of disease in a population determined using disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs). DALYs for a disease or condition are calculated as the sum of the years of life lost due to premature mortality in the population and the years of life lost due to disability [32]. In 2010, COPD was estimated to be the second leading cause of DALYs lost among the North American population [33]. Worldwide, COPD is expected to move up from being the twelfth leading cause of DALYs lost in 1990 to the fifth leading cause in 2020 [34].

Gender Differences

Smoking-related diseases such as COPD and lung cancer are continuing to increase among women in the United States [35,36], while they have plateaued or are decreasing among men [27,37]. Some evidence has emerged that compared with men at a similar level of tobacco smoking, women may be more likely to develop COPD [38] or that the severity of COPD in women may be increased [39–41].

In the Lung Health Study, which evaluated patients with mild COPD, more women than men demonstrated increased airway responsiveness, although this difference was thought to be related to airway caliber rather than gender [42]. Adult women are more likely to both develop and die of asthma than are men [43–45]. In NHANES III, whereas women reported more physician-diagnosed COPD and asthma than men, men and women had similar rates of decreased lung function, and a similar proportion of both men and women with low lung function had undiagnosed lung disease [3]. The current evidence is inadequate to determine whether women who smoke are more likely to develop COPD or have more severe COPD than men, although this question is being studied by various groups.

Risk Factors and Etiology

Smoking is the dominant risk factor for the development and progression of COPD; however, not all smokers develop COPD, and COPD does occur in persons who have never smoked [1], suggesting that other factors are important in the etiology of COPD. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency is an important cause of COPD in a very small percentage of cases [46]. Other undefined genetic factors certainly play an important role in COPD development [38]. The role of infections in both the development and progression of COPD is receiving increased attention, including the role of adenoviral infections in emphysema [47–49].

Occupational and environmental exposures to various pollutants (eg, particulate matter, agricultural dusts) are also important factors in the development of COPD [50,51]. Exposure to indoor air pollutants such as smoke from solid biomass fuels is a major risk factor for COPD especially among women and children in low- and middle-income countries [52,53]. Occupational exposure to fumes and dusts remains an important cause for COPD globally [53,54]. Exposure to outdoor air pollution is associated with a risk of development of COPD as well as exacerbation of the existing disease [53,55].

Clinical Presentation

COPD is heterogeneous in its presentation. Based on data from NHANES III, 44% of patients with severe airflow limitation (FEV1 < 50% of predicted) may not report symptoms [3]. Among patients with severe airflow limitation who do report symptoms, the symptoms reported most frequently include wheezing (64%) and shortness of breath (65%).

In recent years, COPD has been increasingly recognized as a systemic illness, with effects on nutritional status, muscle wasting, and depression [56–58]. A large proportion of patients probably have components of chronic bronchitis, asthma, and emphysema occurring together. Although some of this overlap may be related to misdiagnosis, some of it may be a measure of the presence of airflow limitation reversibility, as described above. Better defining individuals in these groups may ultimately help tailor better interventions.

Some of the barriers to COPD diagnosis and subsequent treatment often include insufficient knowledge and awareness about COPD especially among primary care physicians, misdiagnosis of COPD as other respiratory diseases such asthma, as well as patient-related barriers involving lack of awareness of early symptoms of COPD and considering them to be related to aging or smoking [59].

Evaluation

The evaluation of a patient with suspected COPD is oriented toward establishing the correct diagnosis and, once this has occurred, determining the extent of the impairment such that therapy can be appropriately targeted.

Components in the evaluation of COPD are listed in Table 3. Every patient with suspected COPD should undergo a thorough history and physical examination. The history should pay particular attention to the following: exposure to risk factors; past history of asthma or allergic disease; family history of COPD; presence of comorbid diseases; effect of disease on the patient’s life, including ability to work and mental health status; and possibilities for reducing risk factors, especially smoking cessation [4]. The physical examination is rarely diagnostic in COPD because most physical abnormalities do not occur until the advanced stages of the disease. Physical examination findings in

Pulmonary function testing is a critical part of the evaluation of suspected COPD. Whereas most patients with COPD can be managed by a primary care physician, patients with moderate or severe COPD should be evaluated by a specialist [4].

Once the diagnosis of moderate or severe COPD has been established, further testing, including chest radiograph, arterial blood gas determination, screening for α1-antitrypsin deficiency, 6-minute walk testing or exercise oxymetry may be indicated based on the patient’s history and/or clinical findings. Data from computed tomography scans are useful in some advanced cases.

Prognosis of COPD is often influenced by presence of various comorbidities including extrapulmonary, such as osteoporosis, metabolic syndrome, and depression that may be seen as parts of multimorbidity associated with aging [60,61]. Therefore, it is advised to look for comorbidities in COPD patients with any severity of airflow obstruction and treat them accordingly [4].

Therapy for COPD targets reducing risk factors, improving symptoms, and decreasing the risk of exacerbations [10]. Interventions include smoking cessation, vaccinations, decreasing exposures to occupational and environmental pollutants, pulmonary rehabilitation, bronchodilators, and corticosteroids. Select patients with advanced COPD may benefit from other interventions, such as surgical reduction of lung size, lung transplant, the phosphodiesterase inhibitor roflumilast and chronic treatment with antibiotics such as macrolides.

Conclusion

COPD is a common disease that is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, both in the United States and worldwide. Most cases of COPD are attributable to smoking. Although its incidence among men has plateaued, it continues to increase among women. COPD, particularly in its early stages, is under-diagnosed in the United States. An increased awareness among physicians of the prevalence of mild COPD and the importance of spirometry in diagnosing the disease is important in combating the disease.

Corresponding author: David M. Mannino, MD, Department of Preventive Medicine and Environmental Health, University of Kentucky College of Public Health, 111 Washington Avenue, Lexington, KY 40536, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: Dr. Mannino has received fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Sunovion, and Boehringer Ingelheim for advisory board services.

1. Rennard SI. COPD: overview of definitions, epidemiology, and factors influencing its development. Chest 1998;113(4 Suppl):235S–41S.

2. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2015: with special feature on racial and ethnic health disparities. Hyattsville, MD; 2016.

3. Mannino DM, Gagnon RC, Petty TL, Lydick E. Obstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:1683–9.