User login

VIDEO: Innovation key to gastroenterology’s future

Many of the disorders that gastroenterologists treat do not have very effective treatments, so there is lots of room for innovation, Sidhartha R. Sinha, MD, told attendees at last year’s AGA Tech Summit.

Gastroenterologists should get involved in innovation early because there is much to learn, Dr. Sinha of Stanford (Calif.) University advised in this video interview from the meeting. It can be a tough business, but if one focuses on the clinical need and considers the number of patients who could benefit from such advances, then innovation can be a rewarding path to pursue, he noted.

Innovation in gastroenterology will be front and center again at the 2017 AGA Tech Summit, which is sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Many of the disorders that gastroenterologists treat do not have very effective treatments, so there is lots of room for innovation, Sidhartha R. Sinha, MD, told attendees at last year’s AGA Tech Summit.

Gastroenterologists should get involved in innovation early because there is much to learn, Dr. Sinha of Stanford (Calif.) University advised in this video interview from the meeting. It can be a tough business, but if one focuses on the clinical need and considers the number of patients who could benefit from such advances, then innovation can be a rewarding path to pursue, he noted.

Innovation in gastroenterology will be front and center again at the 2017 AGA Tech Summit, which is sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Many of the disorders that gastroenterologists treat do not have very effective treatments, so there is lots of room for innovation, Sidhartha R. Sinha, MD, told attendees at last year’s AGA Tech Summit.

Gastroenterologists should get involved in innovation early because there is much to learn, Dr. Sinha of Stanford (Calif.) University advised in this video interview from the meeting. It can be a tough business, but if one focuses on the clinical need and considers the number of patients who could benefit from such advances, then innovation can be a rewarding path to pursue, he noted.

Innovation in gastroenterology will be front and center again at the 2017 AGA Tech Summit, which is sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

FDA approves first home genetic health risk test

The Food and Drug Administration authorized 23andMe’s Personal Genome Service Genetic Health Risk (GHR) test, the first direct-to-consumer genetic screening test, according to a press release on Thursday, April 6.

FDA officials expect the product, which tests individuals for possible genetic predisposition for 10 diseases including Parkinson’s, late-onset Alzheimer’s, celiac disease, and hereditary hemochromatosis, to spur patients to consult with their physicians and make more informed lifestyle decisions.

“Consumers can now have direct access to certain genetic risk information,” said Jeffrey Shuren, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health in the release. “But it is important that people understand that genetic risk is just one piece of the bigger puzzle, it does not mean they will or won’t ultimately develop a disease.”

The FDA has exempted all further GHR tests developed by 23andMe from premarket review, noting future GHR tests developed by other makers, excluding those used for diagnostic purposes, may also achieve this exemption after submitting their first premarket review.

For the full details, see the original announcement.

[email protected]

On Twitter @EAZTweets

The Food and Drug Administration authorized 23andMe’s Personal Genome Service Genetic Health Risk (GHR) test, the first direct-to-consumer genetic screening test, according to a press release on Thursday, April 6.

FDA officials expect the product, which tests individuals for possible genetic predisposition for 10 diseases including Parkinson’s, late-onset Alzheimer’s, celiac disease, and hereditary hemochromatosis, to spur patients to consult with their physicians and make more informed lifestyle decisions.

“Consumers can now have direct access to certain genetic risk information,” said Jeffrey Shuren, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health in the release. “But it is important that people understand that genetic risk is just one piece of the bigger puzzle, it does not mean they will or won’t ultimately develop a disease.”

The FDA has exempted all further GHR tests developed by 23andMe from premarket review, noting future GHR tests developed by other makers, excluding those used for diagnostic purposes, may also achieve this exemption after submitting their first premarket review.

For the full details, see the original announcement.

[email protected]

On Twitter @EAZTweets

The Food and Drug Administration authorized 23andMe’s Personal Genome Service Genetic Health Risk (GHR) test, the first direct-to-consumer genetic screening test, according to a press release on Thursday, April 6.

FDA officials expect the product, which tests individuals for possible genetic predisposition for 10 diseases including Parkinson’s, late-onset Alzheimer’s, celiac disease, and hereditary hemochromatosis, to spur patients to consult with their physicians and make more informed lifestyle decisions.

“Consumers can now have direct access to certain genetic risk information,” said Jeffrey Shuren, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health in the release. “But it is important that people understand that genetic risk is just one piece of the bigger puzzle, it does not mean they will or won’t ultimately develop a disease.”

The FDA has exempted all further GHR tests developed by 23andMe from premarket review, noting future GHR tests developed by other makers, excluding those used for diagnostic purposes, may also achieve this exemption after submitting their first premarket review.

For the full details, see the original announcement.

[email protected]

On Twitter @EAZTweets

AATS Centennial Gala

This once-in-a-lifetime celebration of the 100th anniversary of AATS at the Centennial Gala will be held on Monday, May 1, at the famed Wang Theater at the Boch Center.

During this historic evening, the documentary film “In the Beginning” will be unveiled, which features an in-depth look at the formative years and challenges faced in cardiothoracic surgery and also includes interviews with Past Presidents and members of the Centennial Committee.

Buses depart from all meeting hotels (Sheraton, Marriott, and Westin) at 6:15 p.m.

This once-in-a-lifetime celebration of the 100th anniversary of AATS at the Centennial Gala will be held on Monday, May 1, at the famed Wang Theater at the Boch Center.

During this historic evening, the documentary film “In the Beginning” will be unveiled, which features an in-depth look at the formative years and challenges faced in cardiothoracic surgery and also includes interviews with Past Presidents and members of the Centennial Committee.

Buses depart from all meeting hotels (Sheraton, Marriott, and Westin) at 6:15 p.m.

This once-in-a-lifetime celebration of the 100th anniversary of AATS at the Centennial Gala will be held on Monday, May 1, at the famed Wang Theater at the Boch Center.

During this historic evening, the documentary film “In the Beginning” will be unveiled, which features an in-depth look at the formative years and challenges faced in cardiothoracic surgery and also includes interviews with Past Presidents and members of the Centennial Committee.

Buses depart from all meeting hotels (Sheraton, Marriott, and Westin) at 6:15 p.m.

A viral inducer of celiac disease?

A viral infection may be the culprit behind celiac disease, which is caused by an autoimmune response to dietary gluten. The findings are based on an engineered reovirus, which is normally benign. The researchers believe that a reovirus may disrupt intestinal immune homeostasis in susceptible individuals as a result of infection during childhood.

According to in vitro and mouse studies carried out by the researchers, one strain of reovirus suppresses peripheral regulatory T-cell conversion and promotes T helper 1 immune response at sites that normally induce tolerance to dietary antigens. The work appeared in the April issue of Science (2017;356:44-50).

The researchers decided to investigate reoviruses. They often infect humans, commonly in early childhood when gluten usually is first introduced. They also infect humans and mice similarly, allowing a more straightforward comparison between human and mouse studies than would be possible in other virus types.

The researchers created an engineered virus made from two reovirus strains, T1L and T3D, which naturally reassort in human hosts. T1L infects the intestine, while T3D does not. The new strain, T3D-RV, retains most of the characteristics of T3D but can also infect the intestine.

The researchers then conducted mouse studies and showed that both T1L and T3D-RV affect immune responses to dietary antigens at the inductive and effector sites of oral tolerance. However, the original T1L strain caused more changes in gene transcription, both in the number of genes and the intensity of transcription level. This suggested that T1L might uniquely alter immunogenic responses to dietary antigens.

A further test in mice showed that T1L also prompted a proinflammatory response in dendritic cells that take up ovalbumin, but T3D-RV did not. Furthermore, T1L interfered with induction of peripheral tolerance to oral ovalbumin, and T3D-RV did not.

With this data in hand, the researchers turned to human subjects. They compared 73 healthy controls to 160 patients with celiac disease who were on a gluten-free diet. Celiac disease patients had higher mean antireovirus antibody titers, though the result fell short of statistical significance (P = .06), and subjects with celiac disease were over-represented among subjects who had antireovirus titers above the median value.

“You can have two viruses of the same family infecting the intestine in the same way, inducing protective immunity, and being cleared, but only one sets the stage for disease. Finally, using these two viruses allows [us] to dissociate protective immunity from immunopathology. Only the virus that has the capacity to enter the site where dietary proteins are seen by the immune system can trigger disease,” said Bana Jabri, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at the University of Chicago.

Reovirus is unlikely to be the only, otherwise harmless, virus that could prompt wayward immune responses. The research points the way to the identification of viruses linked to celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases and could inform vaccine strategies to prevent such conditions.

The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the University of Chicago. No conflict of interest information was disclosed in the article.

A viral infection may be the culprit behind celiac disease, which is caused by an autoimmune response to dietary gluten. The findings are based on an engineered reovirus, which is normally benign. The researchers believe that a reovirus may disrupt intestinal immune homeostasis in susceptible individuals as a result of infection during childhood.

According to in vitro and mouse studies carried out by the researchers, one strain of reovirus suppresses peripheral regulatory T-cell conversion and promotes T helper 1 immune response at sites that normally induce tolerance to dietary antigens. The work appeared in the April issue of Science (2017;356:44-50).

The researchers decided to investigate reoviruses. They often infect humans, commonly in early childhood when gluten usually is first introduced. They also infect humans and mice similarly, allowing a more straightforward comparison between human and mouse studies than would be possible in other virus types.

The researchers created an engineered virus made from two reovirus strains, T1L and T3D, which naturally reassort in human hosts. T1L infects the intestine, while T3D does not. The new strain, T3D-RV, retains most of the characteristics of T3D but can also infect the intestine.

The researchers then conducted mouse studies and showed that both T1L and T3D-RV affect immune responses to dietary antigens at the inductive and effector sites of oral tolerance. However, the original T1L strain caused more changes in gene transcription, both in the number of genes and the intensity of transcription level. This suggested that T1L might uniquely alter immunogenic responses to dietary antigens.

A further test in mice showed that T1L also prompted a proinflammatory response in dendritic cells that take up ovalbumin, but T3D-RV did not. Furthermore, T1L interfered with induction of peripheral tolerance to oral ovalbumin, and T3D-RV did not.

With this data in hand, the researchers turned to human subjects. They compared 73 healthy controls to 160 patients with celiac disease who were on a gluten-free diet. Celiac disease patients had higher mean antireovirus antibody titers, though the result fell short of statistical significance (P = .06), and subjects with celiac disease were over-represented among subjects who had antireovirus titers above the median value.

“You can have two viruses of the same family infecting the intestine in the same way, inducing protective immunity, and being cleared, but only one sets the stage for disease. Finally, using these two viruses allows [us] to dissociate protective immunity from immunopathology. Only the virus that has the capacity to enter the site where dietary proteins are seen by the immune system can trigger disease,” said Bana Jabri, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at the University of Chicago.

Reovirus is unlikely to be the only, otherwise harmless, virus that could prompt wayward immune responses. The research points the way to the identification of viruses linked to celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases and could inform vaccine strategies to prevent such conditions.

The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the University of Chicago. No conflict of interest information was disclosed in the article.

A viral infection may be the culprit behind celiac disease, which is caused by an autoimmune response to dietary gluten. The findings are based on an engineered reovirus, which is normally benign. The researchers believe that a reovirus may disrupt intestinal immune homeostasis in susceptible individuals as a result of infection during childhood.

According to in vitro and mouse studies carried out by the researchers, one strain of reovirus suppresses peripheral regulatory T-cell conversion and promotes T helper 1 immune response at sites that normally induce tolerance to dietary antigens. The work appeared in the April issue of Science (2017;356:44-50).

The researchers decided to investigate reoviruses. They often infect humans, commonly in early childhood when gluten usually is first introduced. They also infect humans and mice similarly, allowing a more straightforward comparison between human and mouse studies than would be possible in other virus types.

The researchers created an engineered virus made from two reovirus strains, T1L and T3D, which naturally reassort in human hosts. T1L infects the intestine, while T3D does not. The new strain, T3D-RV, retains most of the characteristics of T3D but can also infect the intestine.

The researchers then conducted mouse studies and showed that both T1L and T3D-RV affect immune responses to dietary antigens at the inductive and effector sites of oral tolerance. However, the original T1L strain caused more changes in gene transcription, both in the number of genes and the intensity of transcription level. This suggested that T1L might uniquely alter immunogenic responses to dietary antigens.

A further test in mice showed that T1L also prompted a proinflammatory response in dendritic cells that take up ovalbumin, but T3D-RV did not. Furthermore, T1L interfered with induction of peripheral tolerance to oral ovalbumin, and T3D-RV did not.

With this data in hand, the researchers turned to human subjects. They compared 73 healthy controls to 160 patients with celiac disease who were on a gluten-free diet. Celiac disease patients had higher mean antireovirus antibody titers, though the result fell short of statistical significance (P = .06), and subjects with celiac disease were over-represented among subjects who had antireovirus titers above the median value.

“You can have two viruses of the same family infecting the intestine in the same way, inducing protective immunity, and being cleared, but only one sets the stage for disease. Finally, using these two viruses allows [us] to dissociate protective immunity from immunopathology. Only the virus that has the capacity to enter the site where dietary proteins are seen by the immune system can trigger disease,” said Bana Jabri, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at the University of Chicago.

Reovirus is unlikely to be the only, otherwise harmless, virus that could prompt wayward immune responses. The research points the way to the identification of viruses linked to celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases and could inform vaccine strategies to prevent such conditions.

The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the University of Chicago. No conflict of interest information was disclosed in the article.

FROM SCIENCE

Key clinical point: Celiac disease patients have high reovirus antibody titers.

Major finding: Researchers detail mechanistic pathway that could explain a viral link.

Data source: In vitro, human, and mouse observational studies.

Disclosures: The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the University of Chicago. No conflict of interest information was disclosed in the article.

Registration and Discount Package Information

Attendees may register for the Annual Meeting in three ways, although online registration is strongly encouraged.

1. Internet registration

Go to https://registration.experientevent.com/ShowAAT171/Attendee/Login.aspx

2. Register by phone

Call the AATS/Experient Customer Service Desk

(800) 424-5249 - Toll-free within the USA

(847) 996-5829 - International

3. Mail/fax registration

Send the meeting registration form, along with a check or credit card information, to:

AATS/Experient

5202 Presidents Court, Suite G100

Frederick, MD 21703

Fax: (301) 694-5124 (fax requires credit card information)

You cannot email a copy of your registration form.

Registration Cancellation Policy

Written requests for cancellations and refunds for registration must be received by April 26, 2017. Refunds will be subject to a $50 administrative fee and will be processed after the meeting. Refunds are not available after April 26, 2017. Requests can be sent to [email protected].

Information for International Travelers

Please be sure to check with your local embassy or consulate regarding the required travel documents for visiting Boston. Travel documents may take time to prepare in order to gain access to the United States. Refunds for registration fees will not be issued by the AATS if attendees are unable to travel into the United States due to inadequate travel documents.

For more information, please visit: http://travel.state.gov/content/visas/english/visit/visitor.html.

For information on what to expect if you are applying for a Visa to the United States and to review the Visa Application Guidelines, go to the U.S. Department of State’s website. Additionally, the International Visitors Office (IVO) of the National Academies has resources on all visa-related issues for the scientific community.

The AATS provides several documents that document your participation in the meeting. Official Letters of Invitation are available for meeting attendees. A personalized letter of invitation can be generated after you have been fully registered. Once your registration is fully paid and all verification documents have been received, a personalized letter of invitation can be generated for you. Please contact [email protected] with your request. Please note that you will receive an email confirmation, which you can also bring to your visa interview.

Please contact [email protected] with any further questions pertaining to invitation letters.

Attendees may register for the Annual Meeting in three ways, although online registration is strongly encouraged.

1. Internet registration

Go to https://registration.experientevent.com/ShowAAT171/Attendee/Login.aspx

2. Register by phone

Call the AATS/Experient Customer Service Desk

(800) 424-5249 - Toll-free within the USA

(847) 996-5829 - International

3. Mail/fax registration

Send the meeting registration form, along with a check or credit card information, to:

AATS/Experient

5202 Presidents Court, Suite G100

Frederick, MD 21703

Fax: (301) 694-5124 (fax requires credit card information)

You cannot email a copy of your registration form.

Registration Cancellation Policy

Written requests for cancellations and refunds for registration must be received by April 26, 2017. Refunds will be subject to a $50 administrative fee and will be processed after the meeting. Refunds are not available after April 26, 2017. Requests can be sent to [email protected].

Information for International Travelers

Please be sure to check with your local embassy or consulate regarding the required travel documents for visiting Boston. Travel documents may take time to prepare in order to gain access to the United States. Refunds for registration fees will not be issued by the AATS if attendees are unable to travel into the United States due to inadequate travel documents.

For more information, please visit: http://travel.state.gov/content/visas/english/visit/visitor.html.

For information on what to expect if you are applying for a Visa to the United States and to review the Visa Application Guidelines, go to the U.S. Department of State’s website. Additionally, the International Visitors Office (IVO) of the National Academies has resources on all visa-related issues for the scientific community.

The AATS provides several documents that document your participation in the meeting. Official Letters of Invitation are available for meeting attendees. A personalized letter of invitation can be generated after you have been fully registered. Once your registration is fully paid and all verification documents have been received, a personalized letter of invitation can be generated for you. Please contact [email protected] with your request. Please note that you will receive an email confirmation, which you can also bring to your visa interview.

Please contact [email protected] with any further questions pertaining to invitation letters.

Attendees may register for the Annual Meeting in three ways, although online registration is strongly encouraged.

1. Internet registration

Go to https://registration.experientevent.com/ShowAAT171/Attendee/Login.aspx

2. Register by phone

Call the AATS/Experient Customer Service Desk

(800) 424-5249 - Toll-free within the USA

(847) 996-5829 - International

3. Mail/fax registration

Send the meeting registration form, along with a check or credit card information, to:

AATS/Experient

5202 Presidents Court, Suite G100

Frederick, MD 21703

Fax: (301) 694-5124 (fax requires credit card information)

You cannot email a copy of your registration form.

Registration Cancellation Policy

Written requests for cancellations and refunds for registration must be received by April 26, 2017. Refunds will be subject to a $50 administrative fee and will be processed after the meeting. Refunds are not available after April 26, 2017. Requests can be sent to [email protected].

Information for International Travelers

Please be sure to check with your local embassy or consulate regarding the required travel documents for visiting Boston. Travel documents may take time to prepare in order to gain access to the United States. Refunds for registration fees will not be issued by the AATS if attendees are unable to travel into the United States due to inadequate travel documents.

For more information, please visit: http://travel.state.gov/content/visas/english/visit/visitor.html.

For information on what to expect if you are applying for a Visa to the United States and to review the Visa Application Guidelines, go to the U.S. Department of State’s website. Additionally, the International Visitors Office (IVO) of the National Academies has resources on all visa-related issues for the scientific community.

The AATS provides several documents that document your participation in the meeting. Official Letters of Invitation are available for meeting attendees. A personalized letter of invitation can be generated after you have been fully registered. Once your registration is fully paid and all verification documents have been received, a personalized letter of invitation can be generated for you. Please contact [email protected] with your request. Please note that you will receive an email confirmation, which you can also bring to your visa interview.

Please contact [email protected] with any further questions pertaining to invitation letters.

Epilepsy or Seizure Disorder? The Effect of Cultural and Socioeconomic Factors on Self-Reported Prevalence

Barbara L. Kroner, PhD, MPH

Disclosure Information:

Dr. Kroner has no disclosures.

Dr. Kroner was lead author on the screening survey study discussed in this article (Kroner BL, et al. Epilepsy or seizure disorder? The effect of cultural and socioeconomic factors on self-reported prevalence. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;62:214-217).

Approximately three-quarters of 6420 adult residents of the District of Columbia (DC) screened for epilepsy said they were diagnosed with a seizure disorder rather than epilepsy when given both choices in our population-based survey. The term ‘seizure disorder’ was chosen consistently more often than ‘epilepsy’ in all demographic subgroups, including gender, age, income, education, race, and ethnicity—suggesting there may be a general lack of understanding among patients about what epilepsy means. An implication of these findings is that, although a wealth of information about epilepsy is publicly available for or disseminated by medical providers to people with epilepsy, they may not be getting the message.

Epilepsy can be a complex diagnosis, and people may not associate their seizure condition with the term epilepsy for a variety of reasons. Such reasons include stigma, symptomatic etiology, cultural background, and the terminology used by their medical providers. When there is a known cause for the seizures, such as injury, cancer, stroke, or underlying syndrome, the affected individuals may be more inclined to associate their diagnosis with descriptive phrases that include the term seizure disorder. Medical providers may also tend to use these phrases more often with certain demographic populations, such as the elderly and those with diverse cultural backgrounds.

We conducted the survey in DC, one of the nation’s most culturally, racially, and economically diverse populations, to estimate the prevalence and incidence of epilepsy in various demographic categories associated with the clinical term epilepsy or the more generic term seizure disorder. A single-page, bilingual epilepsy survey was mailed to a representative sample of 20,000 households; it included the standard epilepsy screening question, “Ever diagnosed with epilepsy or a seizure disorder?” Rather than the traditional Yes/No answer choices, we provided answer choices of No, Yes epilepsy, and Yes seizure disorder. A positive response to the screening question, “Currently taking any medicine to control seizures?” was categorized as having active epilepsy or seizure disorder. All response data then were weighted to the DC population size at the time the survey was conducted and to reflect the sampling design. Respondents indicating a diagnosis of epilepsy or seizure disorder were sent a follow-up survey about the etiology of the seizures. The follow-up surveys were reviewed by an epileptologist, who categorized the etiology for each respondent as symptomatic or not symptomatic.

A total of 6420 adults responded to the screening survey, for an overall adjusted response rate of 37%. Among the respondents, there were more females (60.5%) than males (39.5%) and slightly more blacks (45.2%) than whites (44.4%). Half of the adults were at least 50 years of age, and 40% had attended at least some graduate school. There were 107 respondents who reported they had received a diagnosis of epilepsy or a seizure disorder at some time in their life. Subsequent weighted estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for individual lifetime prevalence were 0.54% (95% CI, 0.34-0.74) for epilepsy and 1.30% (95% CI, 0.98-1.62) for seizure disorder, for an overall lifetime prevalence of 1.84% (95% CI, 1.47-2.21) for either condition. Adults with active epilepsy were also significantly more likely to identify their condition as seizure disorder than as epilepsy—0.70% (95% CI, 0.47-0.94) vs 0.21% (95% CI, 0.08-0.33).

For lifetime prevalence, seizure disorder was reported 2 to 3 times more often than epilepsy in almost all demographic subgroups except those 18 to 30 years of age, in whom the lifetime prevalence rates were equal for the 2 conditions. The prevalence of seizure disorder was significantly higher than epilepsy (non-overlapping 95% CI) among non-Hispanic blacks, females, those 50 years of age or older, those with only a high school education, those living in low-income neighborhoods, and those who had resided in DC for at least 5 years.

Similarly, the prevalence of active seizure disorder was higher than the prevalence of active epilepsy in all subgroups, including those 18 to 30 years of age. Active seizure disorder was significantly higher than active epilepsy among the same 6 demographic subgroups that were identified for lifetime prevalence: non-Hispanic blacks, females, those 50 years of age or older, those with only a high school education, those living in low-income neighborhoods, and those who had resided in DC for at least 5years. In 4 subgroups (young adults, Hispanic, race other than white or black, and those residing in DC for less than 5 years), all of the affected respondents identified their condition as seizure disorder, not as epilepsy.

Additional surveys about epilepsy and seizure history were completed by 70 (65.4%) of the 107 respondents. Of these 70 respondents, 22 (31.4%) reported they were diagnosed with epilepsy and 48 (68.6%) reported they were diagnosed with seizure disorder. Symptomatic seizure etiology was noted by 35 (50%) of the respondents, and these were significantly more likely to identify their condition as seizure disorder than as epilepsy (29 [60.4%] vs 6 [27.3%]; P=.02). Specific causes of seizures in both groups included trauma only, stroke only, drugs or alcohol only, trauma plus stroke, alcohol or drug use, and chronic medical condition such as multiple sclerosis, hypertension, congenital arteriovenous malformation, migraines, and brain tumor. Of note, in the overall group of 19 respondents who had seizures due to trauma, 3 had gunshot wounds to the head, which might occur less frequently in the general adult epilepsy population than in DC. Because of the small numbers involved, we were not able to calculate prevalence rates for the symptomatic respondents stratified by demographic characteristics.

The consistently higher number of respondents who self-identified with seizure disorder rather than with epilepsy across all subgroups, including the highly educated, suggests that those who chose seizure disorder are unlikely to be false positive cases of epilepsy. In addition to respondents in the lower socioeconomic groups, females identified significantly more often with seizure disorder than with epilepsy, a finding that may be related to social factors such as stigma. Also, cultural factors and beliefs likely influenced the preference for reporting seizure disorder over epilepsy.

In summary, our findings suggest that both epilepsy and seizure disorder and perhaps other culturally sensitive terms need to be used with patients in clinical practice to ensure they understand their diagnosis and to maximize adherence to treatment and disease management. Patients should understand the synonymy of the 2 terms, particularly because of the overabundance of information available to the public and on the internet that is labeled as epilepsy-specific. In addition, epilepsy education and awareness campaigns ideally should include a more diverse definition of epilepsy in their messages to reach the broadest population of affected individuals, many of whom are in socioeconomic groups at high risk for epilepsy.

To read the full article about this study, please click here.

Barbara L. Kroner, PhD, MPH

Disclosure Information:

Dr. Kroner has no disclosures.

Dr. Kroner was lead author on the screening survey study discussed in this article (Kroner BL, et al. Epilepsy or seizure disorder? The effect of cultural and socioeconomic factors on self-reported prevalence. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;62:214-217).

Approximately three-quarters of 6420 adult residents of the District of Columbia (DC) screened for epilepsy said they were diagnosed with a seizure disorder rather than epilepsy when given both choices in our population-based survey. The term ‘seizure disorder’ was chosen consistently more often than ‘epilepsy’ in all demographic subgroups, including gender, age, income, education, race, and ethnicity—suggesting there may be a general lack of understanding among patients about what epilepsy means. An implication of these findings is that, although a wealth of information about epilepsy is publicly available for or disseminated by medical providers to people with epilepsy, they may not be getting the message.

Epilepsy can be a complex diagnosis, and people may not associate their seizure condition with the term epilepsy for a variety of reasons. Such reasons include stigma, symptomatic etiology, cultural background, and the terminology used by their medical providers. When there is a known cause for the seizures, such as injury, cancer, stroke, or underlying syndrome, the affected individuals may be more inclined to associate their diagnosis with descriptive phrases that include the term seizure disorder. Medical providers may also tend to use these phrases more often with certain demographic populations, such as the elderly and those with diverse cultural backgrounds.

We conducted the survey in DC, one of the nation’s most culturally, racially, and economically diverse populations, to estimate the prevalence and incidence of epilepsy in various demographic categories associated with the clinical term epilepsy or the more generic term seizure disorder. A single-page, bilingual epilepsy survey was mailed to a representative sample of 20,000 households; it included the standard epilepsy screening question, “Ever diagnosed with epilepsy or a seizure disorder?” Rather than the traditional Yes/No answer choices, we provided answer choices of No, Yes epilepsy, and Yes seizure disorder. A positive response to the screening question, “Currently taking any medicine to control seizures?” was categorized as having active epilepsy or seizure disorder. All response data then were weighted to the DC population size at the time the survey was conducted and to reflect the sampling design. Respondents indicating a diagnosis of epilepsy or seizure disorder were sent a follow-up survey about the etiology of the seizures. The follow-up surveys were reviewed by an epileptologist, who categorized the etiology for each respondent as symptomatic or not symptomatic.

A total of 6420 adults responded to the screening survey, for an overall adjusted response rate of 37%. Among the respondents, there were more females (60.5%) than males (39.5%) and slightly more blacks (45.2%) than whites (44.4%). Half of the adults were at least 50 years of age, and 40% had attended at least some graduate school. There were 107 respondents who reported they had received a diagnosis of epilepsy or a seizure disorder at some time in their life. Subsequent weighted estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for individual lifetime prevalence were 0.54% (95% CI, 0.34-0.74) for epilepsy and 1.30% (95% CI, 0.98-1.62) for seizure disorder, for an overall lifetime prevalence of 1.84% (95% CI, 1.47-2.21) for either condition. Adults with active epilepsy were also significantly more likely to identify their condition as seizure disorder than as epilepsy—0.70% (95% CI, 0.47-0.94) vs 0.21% (95% CI, 0.08-0.33).

For lifetime prevalence, seizure disorder was reported 2 to 3 times more often than epilepsy in almost all demographic subgroups except those 18 to 30 years of age, in whom the lifetime prevalence rates were equal for the 2 conditions. The prevalence of seizure disorder was significantly higher than epilepsy (non-overlapping 95% CI) among non-Hispanic blacks, females, those 50 years of age or older, those with only a high school education, those living in low-income neighborhoods, and those who had resided in DC for at least 5 years.

Similarly, the prevalence of active seizure disorder was higher than the prevalence of active epilepsy in all subgroups, including those 18 to 30 years of age. Active seizure disorder was significantly higher than active epilepsy among the same 6 demographic subgroups that were identified for lifetime prevalence: non-Hispanic blacks, females, those 50 years of age or older, those with only a high school education, those living in low-income neighborhoods, and those who had resided in DC for at least 5years. In 4 subgroups (young adults, Hispanic, race other than white or black, and those residing in DC for less than 5 years), all of the affected respondents identified their condition as seizure disorder, not as epilepsy.

Additional surveys about epilepsy and seizure history were completed by 70 (65.4%) of the 107 respondents. Of these 70 respondents, 22 (31.4%) reported they were diagnosed with epilepsy and 48 (68.6%) reported they were diagnosed with seizure disorder. Symptomatic seizure etiology was noted by 35 (50%) of the respondents, and these were significantly more likely to identify their condition as seizure disorder than as epilepsy (29 [60.4%] vs 6 [27.3%]; P=.02). Specific causes of seizures in both groups included trauma only, stroke only, drugs or alcohol only, trauma plus stroke, alcohol or drug use, and chronic medical condition such as multiple sclerosis, hypertension, congenital arteriovenous malformation, migraines, and brain tumor. Of note, in the overall group of 19 respondents who had seizures due to trauma, 3 had gunshot wounds to the head, which might occur less frequently in the general adult epilepsy population than in DC. Because of the small numbers involved, we were not able to calculate prevalence rates for the symptomatic respondents stratified by demographic characteristics.

The consistently higher number of respondents who self-identified with seizure disorder rather than with epilepsy across all subgroups, including the highly educated, suggests that those who chose seizure disorder are unlikely to be false positive cases of epilepsy. In addition to respondents in the lower socioeconomic groups, females identified significantly more often with seizure disorder than with epilepsy, a finding that may be related to social factors such as stigma. Also, cultural factors and beliefs likely influenced the preference for reporting seizure disorder over epilepsy.

In summary, our findings suggest that both epilepsy and seizure disorder and perhaps other culturally sensitive terms need to be used with patients in clinical practice to ensure they understand their diagnosis and to maximize adherence to treatment and disease management. Patients should understand the synonymy of the 2 terms, particularly because of the overabundance of information available to the public and on the internet that is labeled as epilepsy-specific. In addition, epilepsy education and awareness campaigns ideally should include a more diverse definition of epilepsy in their messages to reach the broadest population of affected individuals, many of whom are in socioeconomic groups at high risk for epilepsy.

To read the full article about this study, please click here.

Barbara L. Kroner, PhD, MPH

Disclosure Information:

Dr. Kroner has no disclosures.

Dr. Kroner was lead author on the screening survey study discussed in this article (Kroner BL, et al. Epilepsy or seizure disorder? The effect of cultural and socioeconomic factors on self-reported prevalence. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;62:214-217).

Approximately three-quarters of 6420 adult residents of the District of Columbia (DC) screened for epilepsy said they were diagnosed with a seizure disorder rather than epilepsy when given both choices in our population-based survey. The term ‘seizure disorder’ was chosen consistently more often than ‘epilepsy’ in all demographic subgroups, including gender, age, income, education, race, and ethnicity—suggesting there may be a general lack of understanding among patients about what epilepsy means. An implication of these findings is that, although a wealth of information about epilepsy is publicly available for or disseminated by medical providers to people with epilepsy, they may not be getting the message.

Epilepsy can be a complex diagnosis, and people may not associate their seizure condition with the term epilepsy for a variety of reasons. Such reasons include stigma, symptomatic etiology, cultural background, and the terminology used by their medical providers. When there is a known cause for the seizures, such as injury, cancer, stroke, or underlying syndrome, the affected individuals may be more inclined to associate their diagnosis with descriptive phrases that include the term seizure disorder. Medical providers may also tend to use these phrases more often with certain demographic populations, such as the elderly and those with diverse cultural backgrounds.

We conducted the survey in DC, one of the nation’s most culturally, racially, and economically diverse populations, to estimate the prevalence and incidence of epilepsy in various demographic categories associated with the clinical term epilepsy or the more generic term seizure disorder. A single-page, bilingual epilepsy survey was mailed to a representative sample of 20,000 households; it included the standard epilepsy screening question, “Ever diagnosed with epilepsy or a seizure disorder?” Rather than the traditional Yes/No answer choices, we provided answer choices of No, Yes epilepsy, and Yes seizure disorder. A positive response to the screening question, “Currently taking any medicine to control seizures?” was categorized as having active epilepsy or seizure disorder. All response data then were weighted to the DC population size at the time the survey was conducted and to reflect the sampling design. Respondents indicating a diagnosis of epilepsy or seizure disorder were sent a follow-up survey about the etiology of the seizures. The follow-up surveys were reviewed by an epileptologist, who categorized the etiology for each respondent as symptomatic or not symptomatic.

A total of 6420 adults responded to the screening survey, for an overall adjusted response rate of 37%. Among the respondents, there were more females (60.5%) than males (39.5%) and slightly more blacks (45.2%) than whites (44.4%). Half of the adults were at least 50 years of age, and 40% had attended at least some graduate school. There were 107 respondents who reported they had received a diagnosis of epilepsy or a seizure disorder at some time in their life. Subsequent weighted estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for individual lifetime prevalence were 0.54% (95% CI, 0.34-0.74) for epilepsy and 1.30% (95% CI, 0.98-1.62) for seizure disorder, for an overall lifetime prevalence of 1.84% (95% CI, 1.47-2.21) for either condition. Adults with active epilepsy were also significantly more likely to identify their condition as seizure disorder than as epilepsy—0.70% (95% CI, 0.47-0.94) vs 0.21% (95% CI, 0.08-0.33).

For lifetime prevalence, seizure disorder was reported 2 to 3 times more often than epilepsy in almost all demographic subgroups except those 18 to 30 years of age, in whom the lifetime prevalence rates were equal for the 2 conditions. The prevalence of seizure disorder was significantly higher than epilepsy (non-overlapping 95% CI) among non-Hispanic blacks, females, those 50 years of age or older, those with only a high school education, those living in low-income neighborhoods, and those who had resided in DC for at least 5 years.

Similarly, the prevalence of active seizure disorder was higher than the prevalence of active epilepsy in all subgroups, including those 18 to 30 years of age. Active seizure disorder was significantly higher than active epilepsy among the same 6 demographic subgroups that were identified for lifetime prevalence: non-Hispanic blacks, females, those 50 years of age or older, those with only a high school education, those living in low-income neighborhoods, and those who had resided in DC for at least 5years. In 4 subgroups (young adults, Hispanic, race other than white or black, and those residing in DC for less than 5 years), all of the affected respondents identified their condition as seizure disorder, not as epilepsy.

Additional surveys about epilepsy and seizure history were completed by 70 (65.4%) of the 107 respondents. Of these 70 respondents, 22 (31.4%) reported they were diagnosed with epilepsy and 48 (68.6%) reported they were diagnosed with seizure disorder. Symptomatic seizure etiology was noted by 35 (50%) of the respondents, and these were significantly more likely to identify their condition as seizure disorder than as epilepsy (29 [60.4%] vs 6 [27.3%]; P=.02). Specific causes of seizures in both groups included trauma only, stroke only, drugs or alcohol only, trauma plus stroke, alcohol or drug use, and chronic medical condition such as multiple sclerosis, hypertension, congenital arteriovenous malformation, migraines, and brain tumor. Of note, in the overall group of 19 respondents who had seizures due to trauma, 3 had gunshot wounds to the head, which might occur less frequently in the general adult epilepsy population than in DC. Because of the small numbers involved, we were not able to calculate prevalence rates for the symptomatic respondents stratified by demographic characteristics.

The consistently higher number of respondents who self-identified with seizure disorder rather than with epilepsy across all subgroups, including the highly educated, suggests that those who chose seizure disorder are unlikely to be false positive cases of epilepsy. In addition to respondents in the lower socioeconomic groups, females identified significantly more often with seizure disorder than with epilepsy, a finding that may be related to social factors such as stigma. Also, cultural factors and beliefs likely influenced the preference for reporting seizure disorder over epilepsy.

In summary, our findings suggest that both epilepsy and seizure disorder and perhaps other culturally sensitive terms need to be used with patients in clinical practice to ensure they understand their diagnosis and to maximize adherence to treatment and disease management. Patients should understand the synonymy of the 2 terms, particularly because of the overabundance of information available to the public and on the internet that is labeled as epilepsy-specific. In addition, epilepsy education and awareness campaigns ideally should include a more diverse definition of epilepsy in their messages to reach the broadest population of affected individuals, many of whom are in socioeconomic groups at high risk for epilepsy.

To read the full article about this study, please click here.

BRCA2 mutations linked to greater risk for pancreatic cancer

MIAMI BEACH – Although population-wide screening for pancreatic cancer is considered unfeasible and costly, new evidence suggests a benefit to screening a select population: people who test positive for BRCA2 genetic mutations.

Cross-sectional imaging of 117 people with BRCA2 mutations revealed pancreatic abnormalities in 10 patients, including a patient with pancreatic cancer whose only symptom was unexplained weight loss.

Pancreatic cancer is not as common as are some other malignancies, with an incidence estimated between 1% and 3%. However, it is a particularly deadly form of cancer, with only 7.7% of people living to 5 years after diagnosis, according to data from the National Cancer Institute.

A relatively low incidence is a good thing, but it also limits widespread screening. “There is a low predictive value of screening the population at large, and it is not considered cost effective,” said Eugene P. Ceppa, MD, a general surgeon at IU Health University Hospital, Indianapolis. However, patients at high risk for pancreatic adenocarcinoma might be worth targeting for screening, he added.

“This represents a 21% increase in the chance of pancreatic cancer in these patients,” Dr. Ceppa said.

Buoyed by these and other findings, Dr. Ceppa and his colleagues launched a study of their own. “Our hypothesis is that screening all BRCA2s would identify more patients with pancreatic cancer,” he said at the annual meeting of the Americas Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association.

Dr. Ceppa and coinvestigators reviewed electronic medical records at their institution from 2005 to 2015. They identified 204 BRCA mutation carriers, and after excluding 87 BRCA1 positive patients, further assessed the 117 with documented BRCA2 mutations. A total 47 people (40%) of this group had undergone cross-sectional imaging. The images were initially reviewed, and then re-reviewed for the study, by radiologists with specific expertise in pancreatology.

The cross-sectional imaging revealed pancreatic abnormalities in 10 people, including 1 patient with a pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma located in the head of the pancreas. Another nine patients had intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs). There were no significant demographic or clinical differences between the groups of patients with and without the imaging abnormalities, Dr. Ceppa said.

The investigators also compared the patients with BRCA2 mutations against a historical cohort representing the general population. They found 21% of patients with BRCA2 had a defined pancreatic abnormality, compared with 8% in the general population. The difference was statistically significant (P = .007).

Interestingly, the same comparison also revealed a rate of IPMN of 19%, versus 1%, respectively (P less than .001). “BRCA2 mutation carriers have significantly higher incidence of IPMN than the general population,” Dr. Ceppa said.

The study results support a high-risk screening protocol in asymptomatic BRCA patients regardless of family history, he said. In fact, a high-risk screening protocol implemented at his institution in 2013 led to a 14% detection rate of pancreatic cancer among BRCA2-positive patients, compared with a 3% rate in the general population.

“Your most significant finding might be the more IPMN patients – but how do we follow them, and will it be cost effective?” asked invited discussant Matthew J. Weiss, MD, of Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

One of the most notable impacts of instituting the high-risk screening protocol has been an increase in patient referrals from other specialists at Dr. Ceppa’s institution. “I’ve looked at every single breast surgeon in our department, and I know how each of them are referring,” he explained.

Following initial screening of BRCA2 mutation patients, Dr. Ceppa repeats screening at 6 months, 1 year, and then annually. “However, some insurers may balk at our recommendations for frequency of screening,” he noted.

Dr. Ceppa and Dr. Weiss had no relevant financial disclosures.

MIAMI BEACH – Although population-wide screening for pancreatic cancer is considered unfeasible and costly, new evidence suggests a benefit to screening a select population: people who test positive for BRCA2 genetic mutations.

Cross-sectional imaging of 117 people with BRCA2 mutations revealed pancreatic abnormalities in 10 patients, including a patient with pancreatic cancer whose only symptom was unexplained weight loss.

Pancreatic cancer is not as common as are some other malignancies, with an incidence estimated between 1% and 3%. However, it is a particularly deadly form of cancer, with only 7.7% of people living to 5 years after diagnosis, according to data from the National Cancer Institute.

A relatively low incidence is a good thing, but it also limits widespread screening. “There is a low predictive value of screening the population at large, and it is not considered cost effective,” said Eugene P. Ceppa, MD, a general surgeon at IU Health University Hospital, Indianapolis. However, patients at high risk for pancreatic adenocarcinoma might be worth targeting for screening, he added.

“This represents a 21% increase in the chance of pancreatic cancer in these patients,” Dr. Ceppa said.

Buoyed by these and other findings, Dr. Ceppa and his colleagues launched a study of their own. “Our hypothesis is that screening all BRCA2s would identify more patients with pancreatic cancer,” he said at the annual meeting of the Americas Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association.

Dr. Ceppa and coinvestigators reviewed electronic medical records at their institution from 2005 to 2015. They identified 204 BRCA mutation carriers, and after excluding 87 BRCA1 positive patients, further assessed the 117 with documented BRCA2 mutations. A total 47 people (40%) of this group had undergone cross-sectional imaging. The images were initially reviewed, and then re-reviewed for the study, by radiologists with specific expertise in pancreatology.

The cross-sectional imaging revealed pancreatic abnormalities in 10 people, including 1 patient with a pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma located in the head of the pancreas. Another nine patients had intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs). There were no significant demographic or clinical differences between the groups of patients with and without the imaging abnormalities, Dr. Ceppa said.

The investigators also compared the patients with BRCA2 mutations against a historical cohort representing the general population. They found 21% of patients with BRCA2 had a defined pancreatic abnormality, compared with 8% in the general population. The difference was statistically significant (P = .007).

Interestingly, the same comparison also revealed a rate of IPMN of 19%, versus 1%, respectively (P less than .001). “BRCA2 mutation carriers have significantly higher incidence of IPMN than the general population,” Dr. Ceppa said.

The study results support a high-risk screening protocol in asymptomatic BRCA patients regardless of family history, he said. In fact, a high-risk screening protocol implemented at his institution in 2013 led to a 14% detection rate of pancreatic cancer among BRCA2-positive patients, compared with a 3% rate in the general population.

“Your most significant finding might be the more IPMN patients – but how do we follow them, and will it be cost effective?” asked invited discussant Matthew J. Weiss, MD, of Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

One of the most notable impacts of instituting the high-risk screening protocol has been an increase in patient referrals from other specialists at Dr. Ceppa’s institution. “I’ve looked at every single breast surgeon in our department, and I know how each of them are referring,” he explained.

Following initial screening of BRCA2 mutation patients, Dr. Ceppa repeats screening at 6 months, 1 year, and then annually. “However, some insurers may balk at our recommendations for frequency of screening,” he noted.

Dr. Ceppa and Dr. Weiss had no relevant financial disclosures.

MIAMI BEACH – Although population-wide screening for pancreatic cancer is considered unfeasible and costly, new evidence suggests a benefit to screening a select population: people who test positive for BRCA2 genetic mutations.

Cross-sectional imaging of 117 people with BRCA2 mutations revealed pancreatic abnormalities in 10 patients, including a patient with pancreatic cancer whose only symptom was unexplained weight loss.

Pancreatic cancer is not as common as are some other malignancies, with an incidence estimated between 1% and 3%. However, it is a particularly deadly form of cancer, with only 7.7% of people living to 5 years after diagnosis, according to data from the National Cancer Institute.

A relatively low incidence is a good thing, but it also limits widespread screening. “There is a low predictive value of screening the population at large, and it is not considered cost effective,” said Eugene P. Ceppa, MD, a general surgeon at IU Health University Hospital, Indianapolis. However, patients at high risk for pancreatic adenocarcinoma might be worth targeting for screening, he added.

“This represents a 21% increase in the chance of pancreatic cancer in these patients,” Dr. Ceppa said.

Buoyed by these and other findings, Dr. Ceppa and his colleagues launched a study of their own. “Our hypothesis is that screening all BRCA2s would identify more patients with pancreatic cancer,” he said at the annual meeting of the Americas Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association.

Dr. Ceppa and coinvestigators reviewed electronic medical records at their institution from 2005 to 2015. They identified 204 BRCA mutation carriers, and after excluding 87 BRCA1 positive patients, further assessed the 117 with documented BRCA2 mutations. A total 47 people (40%) of this group had undergone cross-sectional imaging. The images were initially reviewed, and then re-reviewed for the study, by radiologists with specific expertise in pancreatology.

The cross-sectional imaging revealed pancreatic abnormalities in 10 people, including 1 patient with a pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma located in the head of the pancreas. Another nine patients had intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs). There were no significant demographic or clinical differences between the groups of patients with and without the imaging abnormalities, Dr. Ceppa said.

The investigators also compared the patients with BRCA2 mutations against a historical cohort representing the general population. They found 21% of patients with BRCA2 had a defined pancreatic abnormality, compared with 8% in the general population. The difference was statistically significant (P = .007).

Interestingly, the same comparison also revealed a rate of IPMN of 19%, versus 1%, respectively (P less than .001). “BRCA2 mutation carriers have significantly higher incidence of IPMN than the general population,” Dr. Ceppa said.

The study results support a high-risk screening protocol in asymptomatic BRCA patients regardless of family history, he said. In fact, a high-risk screening protocol implemented at his institution in 2013 led to a 14% detection rate of pancreatic cancer among BRCA2-positive patients, compared with a 3% rate in the general population.

“Your most significant finding might be the more IPMN patients – but how do we follow them, and will it be cost effective?” asked invited discussant Matthew J. Weiss, MD, of Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

One of the most notable impacts of instituting the high-risk screening protocol has been an increase in patient referrals from other specialists at Dr. Ceppa’s institution. “I’ve looked at every single breast surgeon in our department, and I know how each of them are referring,” he explained.

Following initial screening of BRCA2 mutation patients, Dr. Ceppa repeats screening at 6 months, 1 year, and then annually. “However, some insurers may balk at our recommendations for frequency of screening,” he noted.

Dr. Ceppa and Dr. Weiss had no relevant financial disclosures.

Key clinical point: Although general population screening for pancreatic cancer is considered costly, with a low predictive value, targeting screening to patients with BRCA2 mutations could detect more cases of this deadly disease.

Major finding: People with BRCA2 mutations had a significantly greater incidence of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, 19%, versus 1% in the general population (P less than .001).

Data source: Retrospective study of electronic medical records of 117 patients with BRCA2 mutations at a single academic institution.

Disclosures: Dr. Ceppa and Dr. Weiss had no relevant financial disclosures.

Wait times for cardiologist visits up 4.3 days since 2014

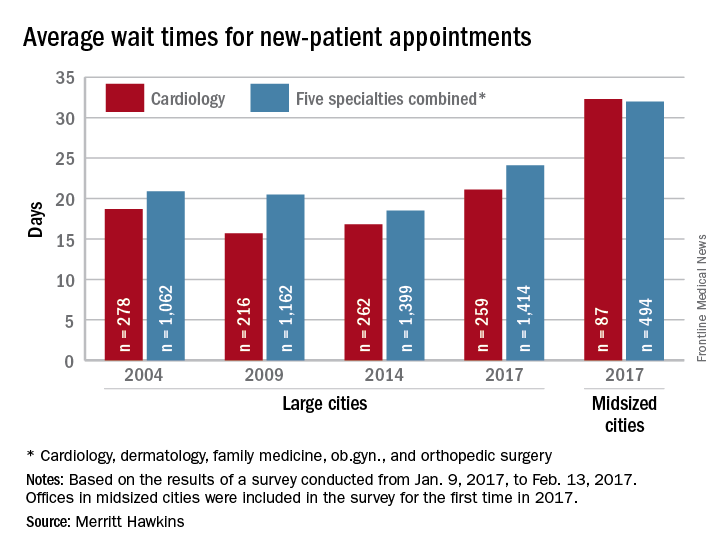

New patients are waiting 4.3 days longer for an appointment with a cardiologist in 2017 than they did in 2014, according to physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins.

The average wait time for a new patient to see a cardiologist for a checkup was 21.1 days in 2017, an almost 26% increase from the 16.8 days reported in 2014. Investigators called and made appointments with 259 randomly selected cardiologists in 15 large cities in January and February. It was the fourth such survey the company has conducted since 2004.

This year, the survey also included cardiologists in 15 midsized cities for the first time. The average wait time in these cities was even longer: 32.3 days for the 87 offices contacted. Odessa, Tex., had the longest average wait in a midsized city – 63 days – while Albany, N.Y., and Cedar Rapids, Iowa, had a shortest-for-the-group wait of 10 days, Merritt Hawkins reported. In the large cities, the longest average wait was 45 days (Boston) and the shortest wait was 12 days (Dallas and Houston).

The survey also included four other specialties – dermatology, family medicine, ob.gyn., and orthopedic surgery – and the average wait time for a new-patient appointment for all 1,414 physicians in all five specialties in the 15 large cities was 24.1 days, an increase of 30% from 2014. The average wait time for all specialties in the midsized cities was 32 days for the 494 offices surveyed, the company said.

“Physician appointment wait times are the longest they have been since we began conducting the survey,” Mark Smith, president of Merritt Hawkins, said in a written statement. “Growing physician appointment wait times are a significant indicator that the nation is experiencing a shortage of physicians.”

New patients are waiting 4.3 days longer for an appointment with a cardiologist in 2017 than they did in 2014, according to physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins.

The average wait time for a new patient to see a cardiologist for a checkup was 21.1 days in 2017, an almost 26% increase from the 16.8 days reported in 2014. Investigators called and made appointments with 259 randomly selected cardiologists in 15 large cities in January and February. It was the fourth such survey the company has conducted since 2004.

This year, the survey also included cardiologists in 15 midsized cities for the first time. The average wait time in these cities was even longer: 32.3 days for the 87 offices contacted. Odessa, Tex., had the longest average wait in a midsized city – 63 days – while Albany, N.Y., and Cedar Rapids, Iowa, had a shortest-for-the-group wait of 10 days, Merritt Hawkins reported. In the large cities, the longest average wait was 45 days (Boston) and the shortest wait was 12 days (Dallas and Houston).

The survey also included four other specialties – dermatology, family medicine, ob.gyn., and orthopedic surgery – and the average wait time for a new-patient appointment for all 1,414 physicians in all five specialties in the 15 large cities was 24.1 days, an increase of 30% from 2014. The average wait time for all specialties in the midsized cities was 32 days for the 494 offices surveyed, the company said.

“Physician appointment wait times are the longest they have been since we began conducting the survey,” Mark Smith, president of Merritt Hawkins, said in a written statement. “Growing physician appointment wait times are a significant indicator that the nation is experiencing a shortage of physicians.”

New patients are waiting 4.3 days longer for an appointment with a cardiologist in 2017 than they did in 2014, according to physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins.

The average wait time for a new patient to see a cardiologist for a checkup was 21.1 days in 2017, an almost 26% increase from the 16.8 days reported in 2014. Investigators called and made appointments with 259 randomly selected cardiologists in 15 large cities in January and February. It was the fourth such survey the company has conducted since 2004.

This year, the survey also included cardiologists in 15 midsized cities for the first time. The average wait time in these cities was even longer: 32.3 days for the 87 offices contacted. Odessa, Tex., had the longest average wait in a midsized city – 63 days – while Albany, N.Y., and Cedar Rapids, Iowa, had a shortest-for-the-group wait of 10 days, Merritt Hawkins reported. In the large cities, the longest average wait was 45 days (Boston) and the shortest wait was 12 days (Dallas and Houston).

The survey also included four other specialties – dermatology, family medicine, ob.gyn., and orthopedic surgery – and the average wait time for a new-patient appointment for all 1,414 physicians in all five specialties in the 15 large cities was 24.1 days, an increase of 30% from 2014. The average wait time for all specialties in the midsized cities was 32 days for the 494 offices surveyed, the company said.

“Physician appointment wait times are the longest they have been since we began conducting the survey,” Mark Smith, president of Merritt Hawkins, said in a written statement. “Growing physician appointment wait times are a significant indicator that the nation is experiencing a shortage of physicians.”

Visit some of Toronto’s best during CHEST 2017

Get ready to visit the metropolitan hub of Canada. Explore new grounds with the chest medicine community for current pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine topics presented by world-renowned faculty in a variety of innovative instruction formats.

You will have access to our cutting-edge education, Oct 28 - Nov 1, but don’t forget to take advantage of all that Toronto has to offer.

Food

Le Petit Dejeune offers an ever-changing menu that ranges from less expensive items, like soup, sandwiches, and salads, to some pricier stuffed crepes, quiche, and eggs florentine. While most Sundays, Saving Grace is packed, but there’s only a 15-minute wait, and the atmosphere is quite pleasant. Looking for the perfect cinnamon bun? Rosen’s Cinnamon Buns is the place to go. But you have to look closely for the bakery’s name, since the sign above the window still advertises the hair salon that used to reside in the same spot!

Nature parks

One of the city’s largest and oldest parks, High Park is Toronto’s version of New York City’s Central Park. There’s plenty to enjoy, such as Grenadier Pond, numerous ravine-based hiking trails, playgrounds, athletic areas, restaurants, a museum, and even a zoo!

If you want a different type of nature excursion, there is always beautiful Niagara Falls, Ontario, which is just a short drive from Toronto. Don’t miss seeing the Tesla monument in Queen Victoria Park, or go 10 minutes north of the Falls to the Botanical Gardens, home to the Butterfly Conservatory with over 2,000 butterflies.

Relaxation

After eventful days of absorbing all the new science CHEST 2017 has to offer, you may want to relax your mind and body. Elmwood spa, located in downtown Toronto, is where “four spacious floors of treatment and renewal options mean that Elmwood Spa can provide the convenience and flexibility to cater to demanding schedules,” according to Elmwood.

Learn more about Toronto opportunities at blogTO.com, and find out more about CHEST 2017 at chestmeeting.chestnet.org.

Get ready to visit the metropolitan hub of Canada. Explore new grounds with the chest medicine community for current pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine topics presented by world-renowned faculty in a variety of innovative instruction formats.

You will have access to our cutting-edge education, Oct 28 - Nov 1, but don’t forget to take advantage of all that Toronto has to offer.

Food

Le Petit Dejeune offers an ever-changing menu that ranges from less expensive items, like soup, sandwiches, and salads, to some pricier stuffed crepes, quiche, and eggs florentine. While most Sundays, Saving Grace is packed, but there’s only a 15-minute wait, and the atmosphere is quite pleasant. Looking for the perfect cinnamon bun? Rosen’s Cinnamon Buns is the place to go. But you have to look closely for the bakery’s name, since the sign above the window still advertises the hair salon that used to reside in the same spot!

Nature parks

One of the city’s largest and oldest parks, High Park is Toronto’s version of New York City’s Central Park. There’s plenty to enjoy, such as Grenadier Pond, numerous ravine-based hiking trails, playgrounds, athletic areas, restaurants, a museum, and even a zoo!

If you want a different type of nature excursion, there is always beautiful Niagara Falls, Ontario, which is just a short drive from Toronto. Don’t miss seeing the Tesla monument in Queen Victoria Park, or go 10 minutes north of the Falls to the Botanical Gardens, home to the Butterfly Conservatory with over 2,000 butterflies.

Relaxation

After eventful days of absorbing all the new science CHEST 2017 has to offer, you may want to relax your mind and body. Elmwood spa, located in downtown Toronto, is where “four spacious floors of treatment and renewal options mean that Elmwood Spa can provide the convenience and flexibility to cater to demanding schedules,” according to Elmwood.

Learn more about Toronto opportunities at blogTO.com, and find out more about CHEST 2017 at chestmeeting.chestnet.org.

Get ready to visit the metropolitan hub of Canada. Explore new grounds with the chest medicine community for current pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine topics presented by world-renowned faculty in a variety of innovative instruction formats.

You will have access to our cutting-edge education, Oct 28 - Nov 1, but don’t forget to take advantage of all that Toronto has to offer.

Food

Le Petit Dejeune offers an ever-changing menu that ranges from less expensive items, like soup, sandwiches, and salads, to some pricier stuffed crepes, quiche, and eggs florentine. While most Sundays, Saving Grace is packed, but there’s only a 15-minute wait, and the atmosphere is quite pleasant. Looking for the perfect cinnamon bun? Rosen’s Cinnamon Buns is the place to go. But you have to look closely for the bakery’s name, since the sign above the window still advertises the hair salon that used to reside in the same spot!

Nature parks

One of the city’s largest and oldest parks, High Park is Toronto’s version of New York City’s Central Park. There’s plenty to enjoy, such as Grenadier Pond, numerous ravine-based hiking trails, playgrounds, athletic areas, restaurants, a museum, and even a zoo!

If you want a different type of nature excursion, there is always beautiful Niagara Falls, Ontario, which is just a short drive from Toronto. Don’t miss seeing the Tesla monument in Queen Victoria Park, or go 10 minutes north of the Falls to the Botanical Gardens, home to the Butterfly Conservatory with over 2,000 butterflies.

Relaxation

After eventful days of absorbing all the new science CHEST 2017 has to offer, you may want to relax your mind and body. Elmwood spa, located in downtown Toronto, is where “four spacious floors of treatment and renewal options mean that Elmwood Spa can provide the convenience and flexibility to cater to demanding schedules,” according to Elmwood.

Learn more about Toronto opportunities at blogTO.com, and find out more about CHEST 2017 at chestmeeting.chestnet.org.

Is there clinical benefit to activity trackers?

SAN DIEGO – In the opinion of Ann R. Garment, MD, wearable activity trackers such as the Fitbit may have a role in improving the physical fitness of patients, but alone they do not promote moderate-to-vigorous physical activity or improve other health outcomes.

An estimated one in five Americans owns some type of wearable technology independent of their smartphones.

“However, these devices come with some challenges,” Dr. Garment, of New York University–Langone Medical Center’s division of general internal medicine, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. “First, you need to know how to use them. You have to power them up regularly. They can be expensive. And for those that interface with the Internet, there are privacy concerns.”

A 2014 PricewaterhouseCoopers survey of 1,000 U.S. consumers found that 56% believe that their life expectancy will grow an additional 10 years by wearing a device that tracks vital signs, 46% believe that it will help them lose weight, and 42% believe that it will help them dramatically improve their athletic ability.

General guidelines call for 30-60 minutes per day of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) at a pace of 100 steps per minute, in at least 10-minute bouts of activity. However, many studies set a goal of 10,000 steps per day, which does not necessarily need to be done as MVPA.

To assess the impact of wearable technology on helping patients to achieve weight loss, researchers studied 471 patients who were placed on a low-calorie diet, prescribed increases in physical activity, and had group counseling sessions (JAMA 2016 Sep 20;316[11]:1161-71).

At 6 months, the researchers randomized patients into either the standard intervention arm, which had access to materials on a website, telephone counseling sessions, and text message prompts; or to the enhanced intervention arm, which included all of those interventions plus the addition of a wearable device and accompanying web interface to monitor diet and physical activity.

In a separate, larger study, researchers randomly assigned 800 employees from 13 organizations in Singapore to one of four arms: control (no activity tracker or incentives), Fitbit Zip activity tracker without additional incentives, tracker plus charity incentives (money went to charity based on how much they exercised), or tracker plus cash incentives (money went to participants based on how much they exercised) (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016 Dec;4[12]:983-95).

The researchers tied incentives to weekly steps, and the primary outcome was minutes of MVPA per week, measured via a sealed accelerometer and assessed on an intention-to-treat basis at 6 months (end of intervention) and 12 months (after a 6-month postintervention follow-up period).

They found that the cash incentive was most effective at increasing MVPA at 6 months, but this effect was not sustained 6 months after the incentives were discontinued. At 12 months, the researchers “identified no evidence of improvements in health outcomes, either with or without incentives, calling into question the value of these devices for health promotion,” they wrote.

For her part, Dr. Garment concluded that activity trackers alone are not sufficient for increasing MVPA or improving health outcomes.

“Though it’s possible it would do better if it were coupled with other modalities or sustained incentives, we need more research before we can recommend it to our patients,” she said. “Perhaps one of the best things we can be doing for our health and recommending for our patients is to, in the words of food author Michael Pollan, ‘eat food, not too much, mostly plants.’ ”

Dr. Garment reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – In the opinion of Ann R. Garment, MD, wearable activity trackers such as the Fitbit may have a role in improving the physical fitness of patients, but alone they do not promote moderate-to-vigorous physical activity or improve other health outcomes.

An estimated one in five Americans owns some type of wearable technology independent of their smartphones.

“However, these devices come with some challenges,” Dr. Garment, of New York University–Langone Medical Center’s division of general internal medicine, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. “First, you need to know how to use them. You have to power them up regularly. They can be expensive. And for those that interface with the Internet, there are privacy concerns.”

A 2014 PricewaterhouseCoopers survey of 1,000 U.S. consumers found that 56% believe that their life expectancy will grow an additional 10 years by wearing a device that tracks vital signs, 46% believe that it will help them lose weight, and 42% believe that it will help them dramatically improve their athletic ability.

General guidelines call for 30-60 minutes per day of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) at a pace of 100 steps per minute, in at least 10-minute bouts of activity. However, many studies set a goal of 10,000 steps per day, which does not necessarily need to be done as MVPA.

To assess the impact of wearable technology on helping patients to achieve weight loss, researchers studied 471 patients who were placed on a low-calorie diet, prescribed increases in physical activity, and had group counseling sessions (JAMA 2016 Sep 20;316[11]:1161-71).