User login

USPSTF recommendations: A 2017 roundup

Since the last Practice Alert update on the United States Preventive Services Task Force in May of 2016,1 the Task Force has released 19 recommendations on 13 topics that include: the use of aspirin and statins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD); support for breastfeeding; use of folic acid during pregnancy; and screening for syphilis, latent tuberculosis (TB), herpes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), colorectal cancer (CRC), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), celiac disease, and skin cancer. The Task Force also released a draft recommendation regarding prostate cancer screening in asymptomatic men (see “A change for prostate cancer screening?”) and addressed screening pelvic examinations in asymptomatic women, the subject of this month’s audiocast. (To listen, go to: http://bit.ly/2nIVoD5.)

Recommendations to implement

Recommendations from the past year that family physicians should put into practice are detailed below and in TABLE 1.2-8

CRC: Screen all individuals ages 50 to 75, but 76 to 85 selectively. The Task Force reaffirmed its 2008 finding that screening for CRC in adults ages 50 to 75 years is substantially beneficial.2 In contrast to the previous recommendation, however, the new one does not state which screening tests are preferred. The tests considered were 3 stool tests (fecal immunochemical test [FIT], FIT-tumor DNA testing [FIT-DNA], and guaiac-based fecal occult blood test [gFOBT]), as well as 3 direct visualization tests (colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and CT colonoscopy). The Task Force assessed various testing frequencies of each test and some test combinations. While the Task Force does not recommend any one screening strategy, there are still significant unknowns about FIT-DNA and CT colonoscopy. The American Academy of Family Physicians does not recommend using these 2 tests for screening purposes at this time.9

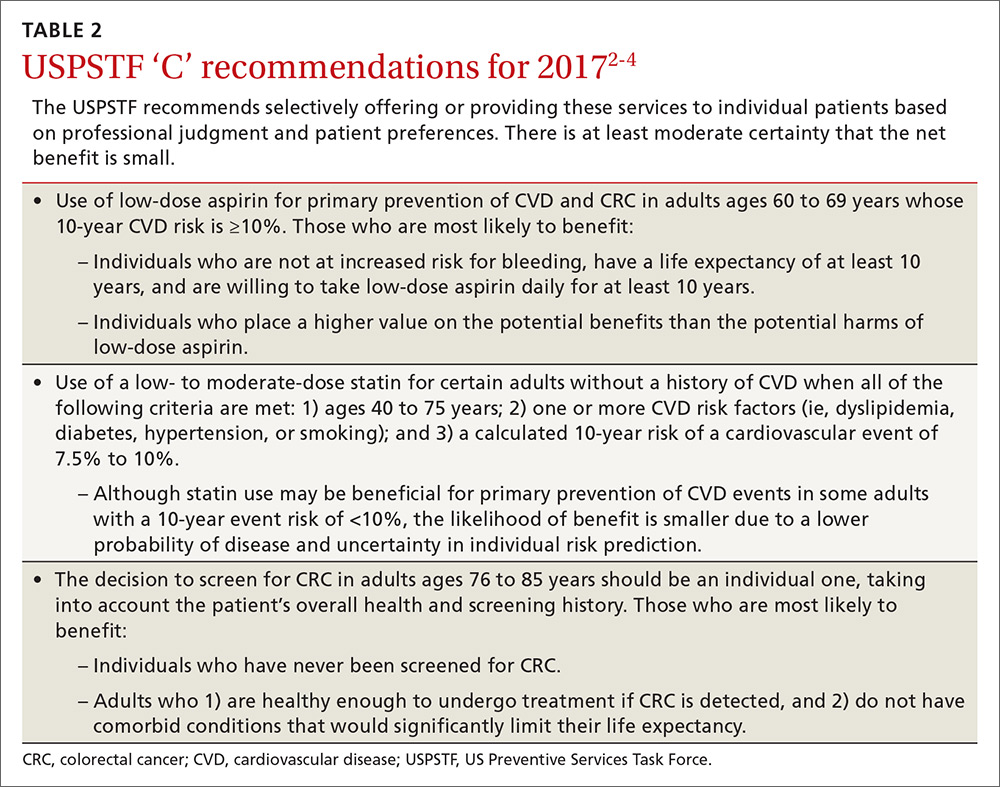

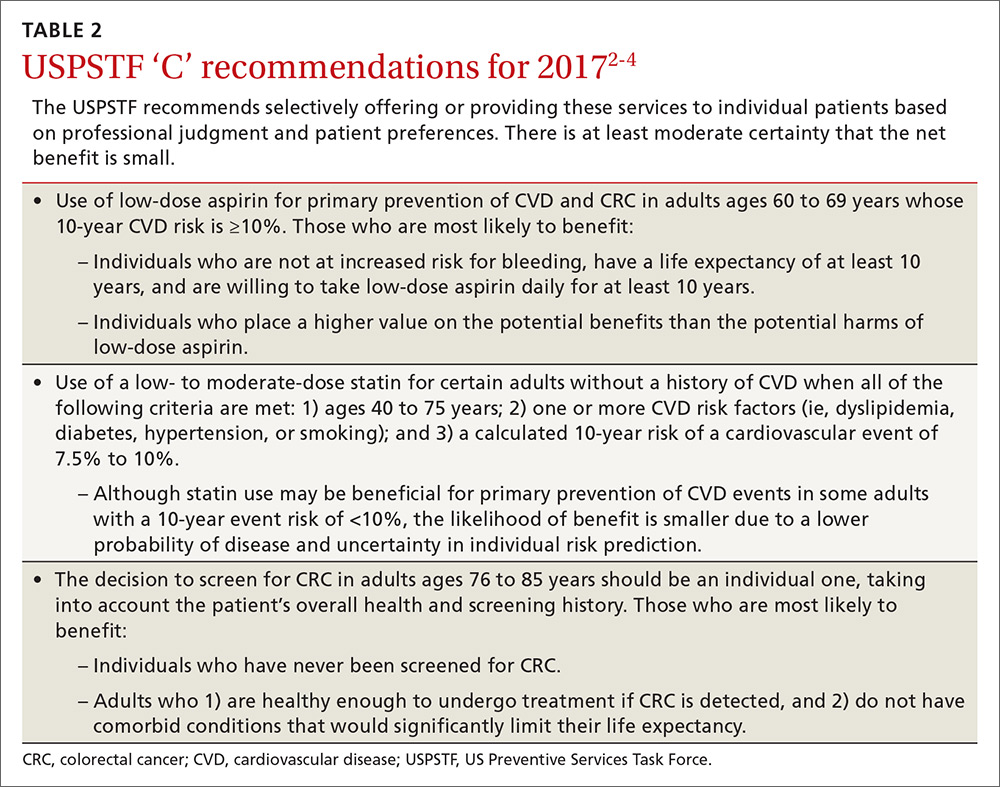

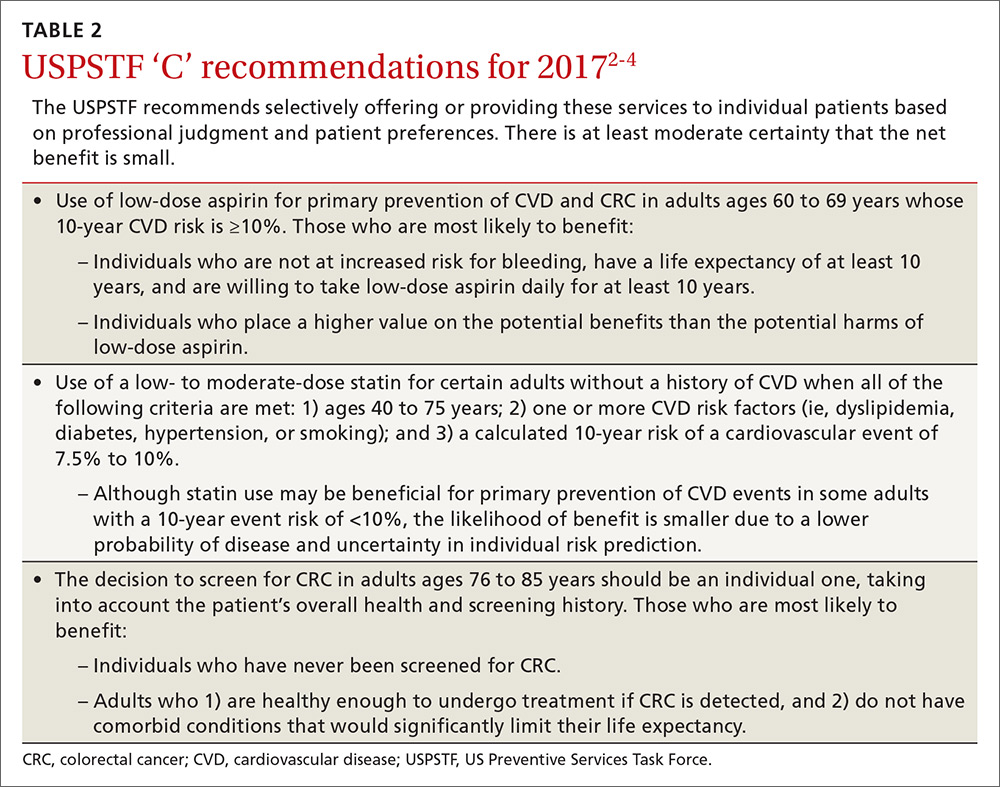

CRC screening for adults ages 76 to 85 was given a “C” recommendation, which means the value of the service to the population overall is small, but that certain individuals may benefit from it. The Task Force advises selectively offering a “C” service to individuals based on professional judgment and patient preferences. Regarding CRC screening in individuals 76 years or older, the ones most likely to benefit are those who have never been screened and those without significant comorbidities that could limit life expectancy. All “C” recommendations from the past year are listed in TABLE 2.2-4

CVD prevention: When aspirin or a statin is indicated. The Task Force released 2 recommendations for the prevention of CVD this past year. One pertained to the use of low-dose aspirin3 (which also helps to prevent CRC), and the other addressed the use of low- to moderate-dose statins.4 Each recommendation is fairly complicated and nuanced in terms of age and risk for CVD. A decision to use low-dose aspirin must also consider the risk of bleeding.

To calculate a patient’s risk for CVD, the Task Force recommends using the risk calculator developed by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (http://www.cvriskcalculator.com/).

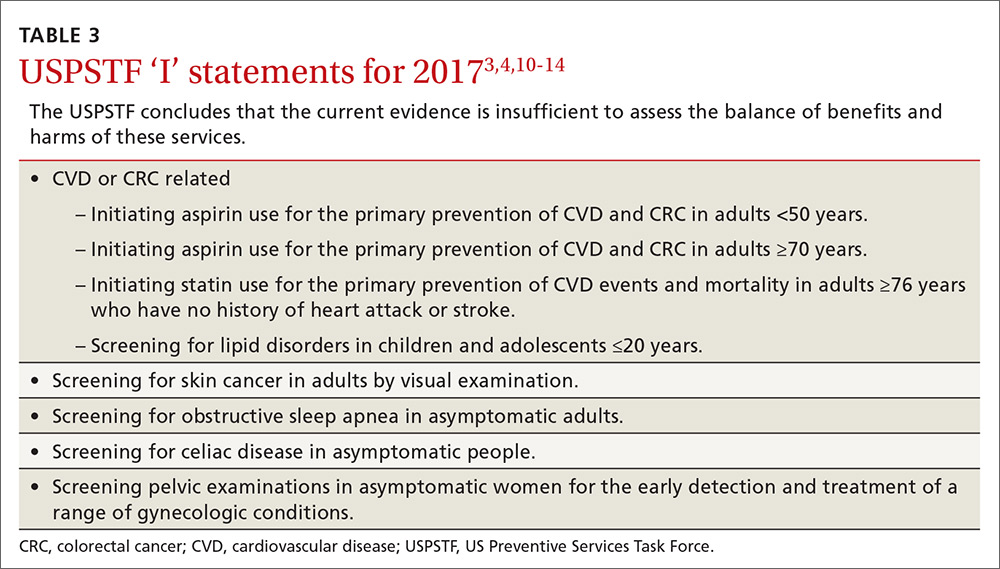

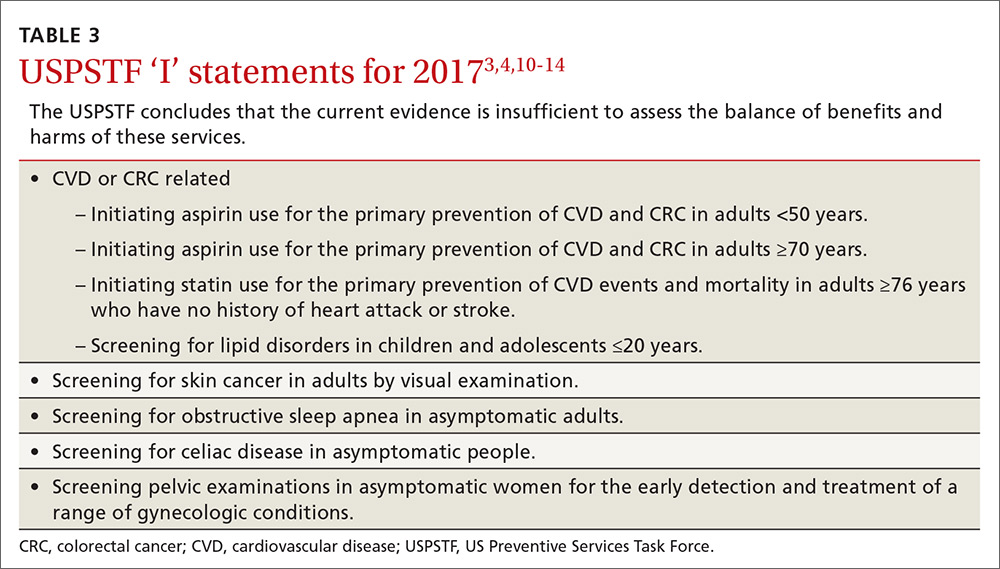

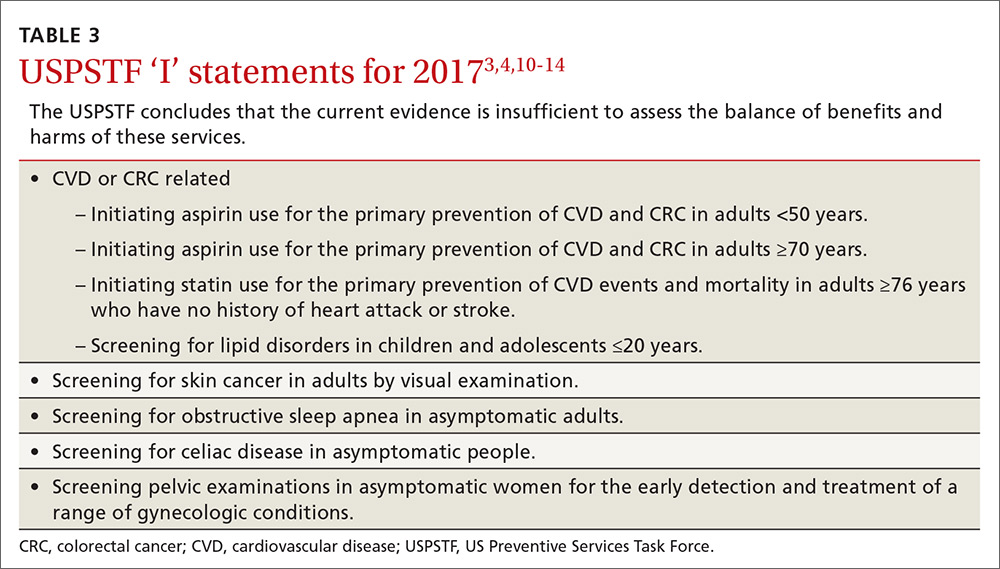

Adults for whom low-dose aspirin and low- to moderate-dose statins are recommended are described in TABLE 1.2-8 Patients for whom individual decision making is advised, rather than a generalized recommendation, are reviewed in TABLE 2.2-4 There is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation for the use of aspirin before age 50 or at age 70 and older,3 and for the use of statins in adults age 76 and older who do not have a history of CVD4 (TABLE 33,4,10-14). The use of low-dose aspirin and low-to-moderate dose statins have been the subject of JFP audiocasts in May 2016 and January 2017. (See http://bit.ly/2oiun8d and http://bit.ly/2oqkohR.)

2 pregnancy-related recommendations. To prevent neural tube defects in newborns, the Task Force now recommends daily folic acid, 0.4 to 0.8 mg (400 to 800 mcg), for all women who are planning on or are capable of becoming pregnant.5 This is an update of a 2009 recommendation that was worded slightly differently, recommending the supplement for all women of childbearing age.

A new recommendation on breastfeeding recognizes its benefits for both mother and baby and finds that interventions to encourage breastfeeding increase the prevalence of this practice and its duration.6 Interventions—provided to individuals or groups by professionals or peers or through formal education—include promoting the benefits of breastfeeding, giving practical advice and direct support on how to breastfeed, and offering psychological support.

Latent TB: Advantages of newer testing method. The recommendation on screening for latent tuberculosis (TB) is an update from the one made in 1996.7 At that time, screening for latent infection was performed using a tuberculin skin test (TST). Now a TST or interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) can be used. Testing with IGRA may be the best option for those who have received a bacille Calmette–Guérin vaccination (because it can cause a false-positive TST) or for those who are not likely to return to have their TST read.

Those at high risk for latent TB include people who were born or have resided in countries with a high TB prevalence, those who have lived in a correctional institution or homeless shelter, and anyone in a high-risk group based on local epidemiology of the disease. (Read more on TB in this month’s Case Report.) Others at high risk are those who are immune suppressed because of infection or medications, and those who work in health care or correctional facilities. Screening of these groups is usually conducted as part of occupational health or is considered part of routine health care.

Syphilis: Screen high-risk individuals in 2 steps. The recommendation on syphilis screening basically reaffirms the one from 2004.8 Those at high risk for syphilis include men who have sex with men (who now account for 90% of new cases), those who are HIV positive, and those who engage in commercial sex work. Other racial and demographic groups can be at high risk depending on the local epidemiology of the disease. In a separate recommendation, the Task Force advises screening all pregnant women for syphilis.

Screening for syphilis infection involves 2 steps: first, a nontreponemal test (Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL] or rapid plasma reagin [RPR] test); second, a confirmatory treponemal antibody detection test (fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption [FTA-ABS] or Treponema pallidum particle agglutination [TPPA] test). Treatment for syphilis remains benzathine penicillin with the number of injections depending on the stage of infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is the best source for current recommendations for treatment of all sexually transmitted infections.15

Screening tests to avoid

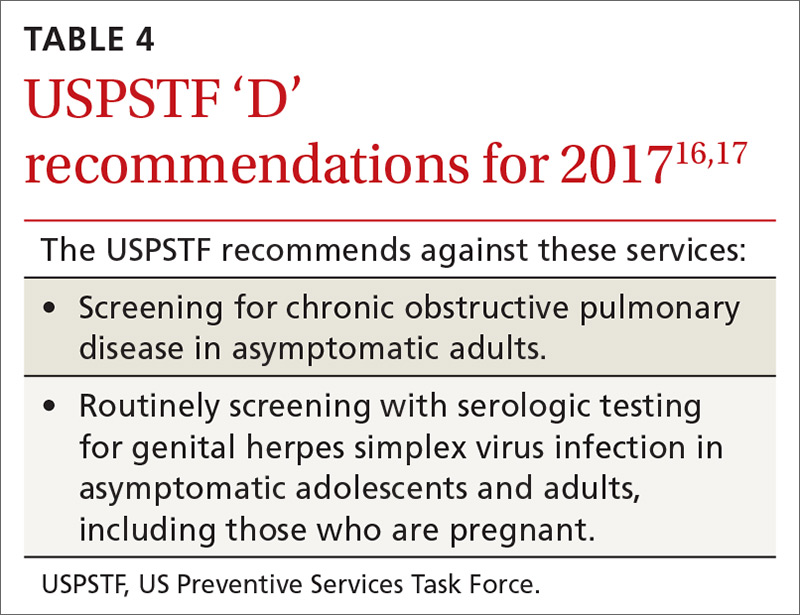

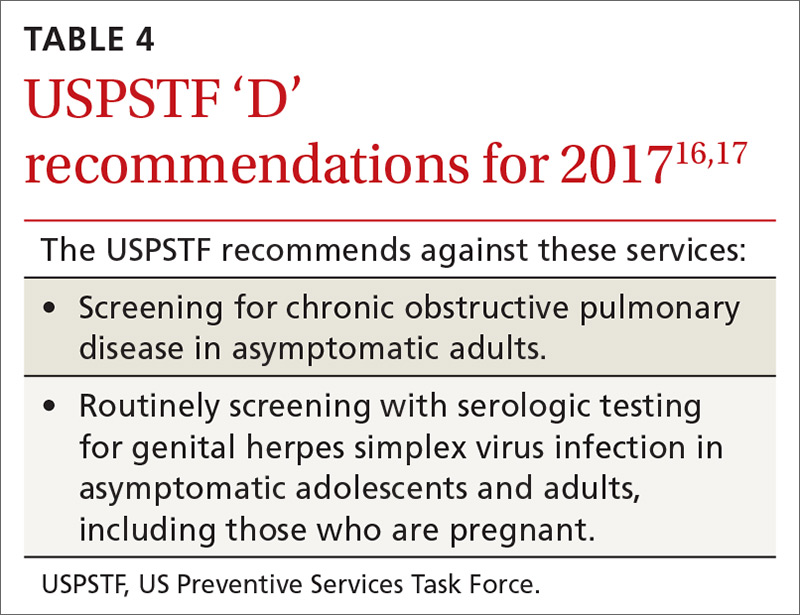

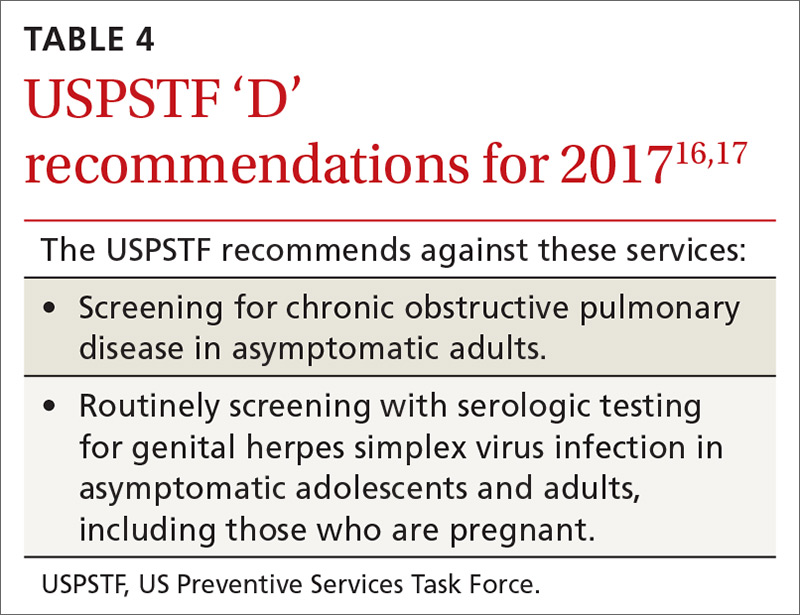

TABLE 416,17 lists screening tests the Task Force recommends against. While chronic obstructive pulmonary disease afflicts 14% of US adults ages 40 to 79 years and is the third leading cause of death in the country, the Task Force found that early detection in asymptomatic adults does not affect the course of the illness and is of no benefit.16

Genital herpes, also prevalent, infects an estimated one out of 6 individuals, ages 14 to 49. It causes little mortality, except in neonates, but those infected can have recurrent flares and suffer psychological harms from stigmatization. Most genital herpes is caused by herpes simplex virus-2, and there is a serological test to detect it. However, the Task Force recommends against using the test to screen asymptomatic adults and adolescents, including those who are pregnant. This recommendation is based on the test’s high false-positive rate, which can cause emotional harm, and on the lack of evidence that detection through screening improves outcomes.17

The evidence is lacking for these practices

The Task Force is one of only a few organizations that will not make a recommendation if evidence is lacking on benefits and harms. In addition to the ‘I’ statements regarding CVD and CRC mentioned earlier, the Task Force found insufficient evidence to recommend screening for lipid disorders in individuals ages 20 years or younger,10 performing a visual skin exam as a screening tool for skin cancer,11 screening for celiac disease,12 performing a periodic pelvic examination in asymptomatic women,13 and screening for obstructive sleep apnea using screening questionnaires14 (TABLE 33,4,10-14).

SIDEBAR

A change for prostate cancer screening?The USPSTF recently issued new draft recommendations regarding prostate cancer screening in asymptomatic men (available at: https://screeningforprostatecancer.org/).

The draft now divides men into 2 age groups, stating that the decision to screen for prostate cancer using a prostate specific antigen (PSA) test should be individualized for men ages 55 to 69 years (a C recommendation, meaning that there is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small), and that men ages 70 and older (lowered from age 75 in the previous 2012 recommendation1) should not be screened (a D recommendation, meaning that there is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits).

The USPSTF believes that clinicians should explain to men ages 55 to 69 years that screening offers a small potential benefit of reducing the chance of dying from prostate cancer, but also comes with potential harms, including false-positive results requiring additional testing/procedures, overdiagnosis and overtreatment, and treatment complications such as incontinence and impotence. In this way, each man has the chance to incorporate his values and preferences into the decision.

For men ages 70 and older, the potential benefits simply do not outweigh the potential harms, according to the USPSTF.

1. USPSTF. Final recommendation statement. Prostate cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prostate-cancer-screening#Pod1. Accessed April 11, 2017.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Eight USPSTF recommendations FPs need to know about. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:338-341.

2. USPSTF. Colorectal cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/colorectal-cancer-screening2. Accessed March 22, 2017.

3. USPSTF. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: preventive medications. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/aspirin-to-prevent-cardiovascular-disease-and-cancer. Accessed March 22, 2017.

4. USPSTF. Statin use for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/statin-use-in-adults-preventive-medication1. Accessed March 22, 2017.

5. USPSTF. Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/folic-acid-for-the-prevention-of-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication. Accessed March 22, 2017.

6. USPSTF. Breastfeeding: primary care interventions. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/breastfeeding-primary-care-interventions. Accessed March 22, 2017.

7. USPSTF. Latent tuberculosis infection: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/latent-tuberculosis-infection-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

8. USPSTF. Syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/syphilis-infection-in-nonpregnant-adults-and-adolescents. Accessed March 22, 2017.

9. AAFP. Colorectal cancer screening, adults. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/colorectal-cancer.html. Accessed March 22, 2017.

10. USPSTF. Lipid disorders in children and adolescents: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/lipid-disorders-in-children-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2017.

11. USPSTF. Skin cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/skin-cancer-screening2. Accessed March 22, 2017.

12. USPSTF. Celiac disease: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/celiac-disease-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

13. USPSTF. Gynecological conditions: periodic screening with the pelvic examination. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/gynecological-conditions-screening-with-the-pelvic-examination. Accessed March 22, 2017.

14. USPSTF. Obstructive sleep apnea in adults: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/obstructive-sleep-apnea-in-adults-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

15. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed March 22, 2017.

16. USPSTF. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

17. USPSTF. Genital herpes infection: serologic screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/genital-herpes-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2017.

Since the last Practice Alert update on the United States Preventive Services Task Force in May of 2016,1 the Task Force has released 19 recommendations on 13 topics that include: the use of aspirin and statins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD); support for breastfeeding; use of folic acid during pregnancy; and screening for syphilis, latent tuberculosis (TB), herpes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), colorectal cancer (CRC), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), celiac disease, and skin cancer. The Task Force also released a draft recommendation regarding prostate cancer screening in asymptomatic men (see “A change for prostate cancer screening?”) and addressed screening pelvic examinations in asymptomatic women, the subject of this month’s audiocast. (To listen, go to: http://bit.ly/2nIVoD5.)

Recommendations to implement

Recommendations from the past year that family physicians should put into practice are detailed below and in TABLE 1.2-8

CRC: Screen all individuals ages 50 to 75, but 76 to 85 selectively. The Task Force reaffirmed its 2008 finding that screening for CRC in adults ages 50 to 75 years is substantially beneficial.2 In contrast to the previous recommendation, however, the new one does not state which screening tests are preferred. The tests considered were 3 stool tests (fecal immunochemical test [FIT], FIT-tumor DNA testing [FIT-DNA], and guaiac-based fecal occult blood test [gFOBT]), as well as 3 direct visualization tests (colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and CT colonoscopy). The Task Force assessed various testing frequencies of each test and some test combinations. While the Task Force does not recommend any one screening strategy, there are still significant unknowns about FIT-DNA and CT colonoscopy. The American Academy of Family Physicians does not recommend using these 2 tests for screening purposes at this time.9

CRC screening for adults ages 76 to 85 was given a “C” recommendation, which means the value of the service to the population overall is small, but that certain individuals may benefit from it. The Task Force advises selectively offering a “C” service to individuals based on professional judgment and patient preferences. Regarding CRC screening in individuals 76 years or older, the ones most likely to benefit are those who have never been screened and those without significant comorbidities that could limit life expectancy. All “C” recommendations from the past year are listed in TABLE 2.2-4

CVD prevention: When aspirin or a statin is indicated. The Task Force released 2 recommendations for the prevention of CVD this past year. One pertained to the use of low-dose aspirin3 (which also helps to prevent CRC), and the other addressed the use of low- to moderate-dose statins.4 Each recommendation is fairly complicated and nuanced in terms of age and risk for CVD. A decision to use low-dose aspirin must also consider the risk of bleeding.

To calculate a patient’s risk for CVD, the Task Force recommends using the risk calculator developed by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (http://www.cvriskcalculator.com/).

Adults for whom low-dose aspirin and low- to moderate-dose statins are recommended are described in TABLE 1.2-8 Patients for whom individual decision making is advised, rather than a generalized recommendation, are reviewed in TABLE 2.2-4 There is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation for the use of aspirin before age 50 or at age 70 and older,3 and for the use of statins in adults age 76 and older who do not have a history of CVD4 (TABLE 33,4,10-14). The use of low-dose aspirin and low-to-moderate dose statins have been the subject of JFP audiocasts in May 2016 and January 2017. (See http://bit.ly/2oiun8d and http://bit.ly/2oqkohR.)

2 pregnancy-related recommendations. To prevent neural tube defects in newborns, the Task Force now recommends daily folic acid, 0.4 to 0.8 mg (400 to 800 mcg), for all women who are planning on or are capable of becoming pregnant.5 This is an update of a 2009 recommendation that was worded slightly differently, recommending the supplement for all women of childbearing age.

A new recommendation on breastfeeding recognizes its benefits for both mother and baby and finds that interventions to encourage breastfeeding increase the prevalence of this practice and its duration.6 Interventions—provided to individuals or groups by professionals or peers or through formal education—include promoting the benefits of breastfeeding, giving practical advice and direct support on how to breastfeed, and offering psychological support.

Latent TB: Advantages of newer testing method. The recommendation on screening for latent tuberculosis (TB) is an update from the one made in 1996.7 At that time, screening for latent infection was performed using a tuberculin skin test (TST). Now a TST or interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) can be used. Testing with IGRA may be the best option for those who have received a bacille Calmette–Guérin vaccination (because it can cause a false-positive TST) or for those who are not likely to return to have their TST read.

Those at high risk for latent TB include people who were born or have resided in countries with a high TB prevalence, those who have lived in a correctional institution or homeless shelter, and anyone in a high-risk group based on local epidemiology of the disease. (Read more on TB in this month’s Case Report.) Others at high risk are those who are immune suppressed because of infection or medications, and those who work in health care or correctional facilities. Screening of these groups is usually conducted as part of occupational health or is considered part of routine health care.

Syphilis: Screen high-risk individuals in 2 steps. The recommendation on syphilis screening basically reaffirms the one from 2004.8 Those at high risk for syphilis include men who have sex with men (who now account for 90% of new cases), those who are HIV positive, and those who engage in commercial sex work. Other racial and demographic groups can be at high risk depending on the local epidemiology of the disease. In a separate recommendation, the Task Force advises screening all pregnant women for syphilis.

Screening for syphilis infection involves 2 steps: first, a nontreponemal test (Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL] or rapid plasma reagin [RPR] test); second, a confirmatory treponemal antibody detection test (fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption [FTA-ABS] or Treponema pallidum particle agglutination [TPPA] test). Treatment for syphilis remains benzathine penicillin with the number of injections depending on the stage of infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is the best source for current recommendations for treatment of all sexually transmitted infections.15

Screening tests to avoid

TABLE 416,17 lists screening tests the Task Force recommends against. While chronic obstructive pulmonary disease afflicts 14% of US adults ages 40 to 79 years and is the third leading cause of death in the country, the Task Force found that early detection in asymptomatic adults does not affect the course of the illness and is of no benefit.16

Genital herpes, also prevalent, infects an estimated one out of 6 individuals, ages 14 to 49. It causes little mortality, except in neonates, but those infected can have recurrent flares and suffer psychological harms from stigmatization. Most genital herpes is caused by herpes simplex virus-2, and there is a serological test to detect it. However, the Task Force recommends against using the test to screen asymptomatic adults and adolescents, including those who are pregnant. This recommendation is based on the test’s high false-positive rate, which can cause emotional harm, and on the lack of evidence that detection through screening improves outcomes.17

The evidence is lacking for these practices

The Task Force is one of only a few organizations that will not make a recommendation if evidence is lacking on benefits and harms. In addition to the ‘I’ statements regarding CVD and CRC mentioned earlier, the Task Force found insufficient evidence to recommend screening for lipid disorders in individuals ages 20 years or younger,10 performing a visual skin exam as a screening tool for skin cancer,11 screening for celiac disease,12 performing a periodic pelvic examination in asymptomatic women,13 and screening for obstructive sleep apnea using screening questionnaires14 (TABLE 33,4,10-14).

SIDEBAR

A change for prostate cancer screening?The USPSTF recently issued new draft recommendations regarding prostate cancer screening in asymptomatic men (available at: https://screeningforprostatecancer.org/).

The draft now divides men into 2 age groups, stating that the decision to screen for prostate cancer using a prostate specific antigen (PSA) test should be individualized for men ages 55 to 69 years (a C recommendation, meaning that there is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small), and that men ages 70 and older (lowered from age 75 in the previous 2012 recommendation1) should not be screened (a D recommendation, meaning that there is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits).

The USPSTF believes that clinicians should explain to men ages 55 to 69 years that screening offers a small potential benefit of reducing the chance of dying from prostate cancer, but also comes with potential harms, including false-positive results requiring additional testing/procedures, overdiagnosis and overtreatment, and treatment complications such as incontinence and impotence. In this way, each man has the chance to incorporate his values and preferences into the decision.

For men ages 70 and older, the potential benefits simply do not outweigh the potential harms, according to the USPSTF.

1. USPSTF. Final recommendation statement. Prostate cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prostate-cancer-screening#Pod1. Accessed April 11, 2017.

Since the last Practice Alert update on the United States Preventive Services Task Force in May of 2016,1 the Task Force has released 19 recommendations on 13 topics that include: the use of aspirin and statins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD); support for breastfeeding; use of folic acid during pregnancy; and screening for syphilis, latent tuberculosis (TB), herpes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), colorectal cancer (CRC), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), celiac disease, and skin cancer. The Task Force also released a draft recommendation regarding prostate cancer screening in asymptomatic men (see “A change for prostate cancer screening?”) and addressed screening pelvic examinations in asymptomatic women, the subject of this month’s audiocast. (To listen, go to: http://bit.ly/2nIVoD5.)

Recommendations to implement

Recommendations from the past year that family physicians should put into practice are detailed below and in TABLE 1.2-8

CRC: Screen all individuals ages 50 to 75, but 76 to 85 selectively. The Task Force reaffirmed its 2008 finding that screening for CRC in adults ages 50 to 75 years is substantially beneficial.2 In contrast to the previous recommendation, however, the new one does not state which screening tests are preferred. The tests considered were 3 stool tests (fecal immunochemical test [FIT], FIT-tumor DNA testing [FIT-DNA], and guaiac-based fecal occult blood test [gFOBT]), as well as 3 direct visualization tests (colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and CT colonoscopy). The Task Force assessed various testing frequencies of each test and some test combinations. While the Task Force does not recommend any one screening strategy, there are still significant unknowns about FIT-DNA and CT colonoscopy. The American Academy of Family Physicians does not recommend using these 2 tests for screening purposes at this time.9

CRC screening for adults ages 76 to 85 was given a “C” recommendation, which means the value of the service to the population overall is small, but that certain individuals may benefit from it. The Task Force advises selectively offering a “C” service to individuals based on professional judgment and patient preferences. Regarding CRC screening in individuals 76 years or older, the ones most likely to benefit are those who have never been screened and those without significant comorbidities that could limit life expectancy. All “C” recommendations from the past year are listed in TABLE 2.2-4

CVD prevention: When aspirin or a statin is indicated. The Task Force released 2 recommendations for the prevention of CVD this past year. One pertained to the use of low-dose aspirin3 (which also helps to prevent CRC), and the other addressed the use of low- to moderate-dose statins.4 Each recommendation is fairly complicated and nuanced in terms of age and risk for CVD. A decision to use low-dose aspirin must also consider the risk of bleeding.

To calculate a patient’s risk for CVD, the Task Force recommends using the risk calculator developed by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (http://www.cvriskcalculator.com/).

Adults for whom low-dose aspirin and low- to moderate-dose statins are recommended are described in TABLE 1.2-8 Patients for whom individual decision making is advised, rather than a generalized recommendation, are reviewed in TABLE 2.2-4 There is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation for the use of aspirin before age 50 or at age 70 and older,3 and for the use of statins in adults age 76 and older who do not have a history of CVD4 (TABLE 33,4,10-14). The use of low-dose aspirin and low-to-moderate dose statins have been the subject of JFP audiocasts in May 2016 and January 2017. (See http://bit.ly/2oiun8d and http://bit.ly/2oqkohR.)

2 pregnancy-related recommendations. To prevent neural tube defects in newborns, the Task Force now recommends daily folic acid, 0.4 to 0.8 mg (400 to 800 mcg), for all women who are planning on or are capable of becoming pregnant.5 This is an update of a 2009 recommendation that was worded slightly differently, recommending the supplement for all women of childbearing age.

A new recommendation on breastfeeding recognizes its benefits for both mother and baby and finds that interventions to encourage breastfeeding increase the prevalence of this practice and its duration.6 Interventions—provided to individuals or groups by professionals or peers or through formal education—include promoting the benefits of breastfeeding, giving practical advice and direct support on how to breastfeed, and offering psychological support.

Latent TB: Advantages of newer testing method. The recommendation on screening for latent tuberculosis (TB) is an update from the one made in 1996.7 At that time, screening for latent infection was performed using a tuberculin skin test (TST). Now a TST or interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) can be used. Testing with IGRA may be the best option for those who have received a bacille Calmette–Guérin vaccination (because it can cause a false-positive TST) or for those who are not likely to return to have their TST read.

Those at high risk for latent TB include people who were born or have resided in countries with a high TB prevalence, those who have lived in a correctional institution or homeless shelter, and anyone in a high-risk group based on local epidemiology of the disease. (Read more on TB in this month’s Case Report.) Others at high risk are those who are immune suppressed because of infection or medications, and those who work in health care or correctional facilities. Screening of these groups is usually conducted as part of occupational health or is considered part of routine health care.

Syphilis: Screen high-risk individuals in 2 steps. The recommendation on syphilis screening basically reaffirms the one from 2004.8 Those at high risk for syphilis include men who have sex with men (who now account for 90% of new cases), those who are HIV positive, and those who engage in commercial sex work. Other racial and demographic groups can be at high risk depending on the local epidemiology of the disease. In a separate recommendation, the Task Force advises screening all pregnant women for syphilis.

Screening for syphilis infection involves 2 steps: first, a nontreponemal test (Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL] or rapid plasma reagin [RPR] test); second, a confirmatory treponemal antibody detection test (fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption [FTA-ABS] or Treponema pallidum particle agglutination [TPPA] test). Treatment for syphilis remains benzathine penicillin with the number of injections depending on the stage of infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is the best source for current recommendations for treatment of all sexually transmitted infections.15

Screening tests to avoid

TABLE 416,17 lists screening tests the Task Force recommends against. While chronic obstructive pulmonary disease afflicts 14% of US adults ages 40 to 79 years and is the third leading cause of death in the country, the Task Force found that early detection in asymptomatic adults does not affect the course of the illness and is of no benefit.16

Genital herpes, also prevalent, infects an estimated one out of 6 individuals, ages 14 to 49. It causes little mortality, except in neonates, but those infected can have recurrent flares and suffer psychological harms from stigmatization. Most genital herpes is caused by herpes simplex virus-2, and there is a serological test to detect it. However, the Task Force recommends against using the test to screen asymptomatic adults and adolescents, including those who are pregnant. This recommendation is based on the test’s high false-positive rate, which can cause emotional harm, and on the lack of evidence that detection through screening improves outcomes.17

The evidence is lacking for these practices

The Task Force is one of only a few organizations that will not make a recommendation if evidence is lacking on benefits and harms. In addition to the ‘I’ statements regarding CVD and CRC mentioned earlier, the Task Force found insufficient evidence to recommend screening for lipid disorders in individuals ages 20 years or younger,10 performing a visual skin exam as a screening tool for skin cancer,11 screening for celiac disease,12 performing a periodic pelvic examination in asymptomatic women,13 and screening for obstructive sleep apnea using screening questionnaires14 (TABLE 33,4,10-14).

SIDEBAR

A change for prostate cancer screening?The USPSTF recently issued new draft recommendations regarding prostate cancer screening in asymptomatic men (available at: https://screeningforprostatecancer.org/).

The draft now divides men into 2 age groups, stating that the decision to screen for prostate cancer using a prostate specific antigen (PSA) test should be individualized for men ages 55 to 69 years (a C recommendation, meaning that there is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small), and that men ages 70 and older (lowered from age 75 in the previous 2012 recommendation1) should not be screened (a D recommendation, meaning that there is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits).

The USPSTF believes that clinicians should explain to men ages 55 to 69 years that screening offers a small potential benefit of reducing the chance of dying from prostate cancer, but also comes with potential harms, including false-positive results requiring additional testing/procedures, overdiagnosis and overtreatment, and treatment complications such as incontinence and impotence. In this way, each man has the chance to incorporate his values and preferences into the decision.

For men ages 70 and older, the potential benefits simply do not outweigh the potential harms, according to the USPSTF.

1. USPSTF. Final recommendation statement. Prostate cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prostate-cancer-screening#Pod1. Accessed April 11, 2017.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Eight USPSTF recommendations FPs need to know about. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:338-341.

2. USPSTF. Colorectal cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/colorectal-cancer-screening2. Accessed March 22, 2017.

3. USPSTF. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: preventive medications. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/aspirin-to-prevent-cardiovascular-disease-and-cancer. Accessed March 22, 2017.

4. USPSTF. Statin use for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/statin-use-in-adults-preventive-medication1. Accessed March 22, 2017.

5. USPSTF. Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/folic-acid-for-the-prevention-of-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication. Accessed March 22, 2017.

6. USPSTF. Breastfeeding: primary care interventions. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/breastfeeding-primary-care-interventions. Accessed March 22, 2017.

7. USPSTF. Latent tuberculosis infection: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/latent-tuberculosis-infection-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

8. USPSTF. Syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/syphilis-infection-in-nonpregnant-adults-and-adolescents. Accessed March 22, 2017.

9. AAFP. Colorectal cancer screening, adults. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/colorectal-cancer.html. Accessed March 22, 2017.

10. USPSTF. Lipid disorders in children and adolescents: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/lipid-disorders-in-children-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2017.

11. USPSTF. Skin cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/skin-cancer-screening2. Accessed March 22, 2017.

12. USPSTF. Celiac disease: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/celiac-disease-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

13. USPSTF. Gynecological conditions: periodic screening with the pelvic examination. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/gynecological-conditions-screening-with-the-pelvic-examination. Accessed March 22, 2017.

14. USPSTF. Obstructive sleep apnea in adults: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/obstructive-sleep-apnea-in-adults-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

15. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed March 22, 2017.

16. USPSTF. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

17. USPSTF. Genital herpes infection: serologic screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/genital-herpes-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2017.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Eight USPSTF recommendations FPs need to know about. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:338-341.

2. USPSTF. Colorectal cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/colorectal-cancer-screening2. Accessed March 22, 2017.

3. USPSTF. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: preventive medications. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/aspirin-to-prevent-cardiovascular-disease-and-cancer. Accessed March 22, 2017.

4. USPSTF. Statin use for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/statin-use-in-adults-preventive-medication1. Accessed March 22, 2017.

5. USPSTF. Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/folic-acid-for-the-prevention-of-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication. Accessed March 22, 2017.

6. USPSTF. Breastfeeding: primary care interventions. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/breastfeeding-primary-care-interventions. Accessed March 22, 2017.

7. USPSTF. Latent tuberculosis infection: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/latent-tuberculosis-infection-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

8. USPSTF. Syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/syphilis-infection-in-nonpregnant-adults-and-adolescents. Accessed March 22, 2017.

9. AAFP. Colorectal cancer screening, adults. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/colorectal-cancer.html. Accessed March 22, 2017.

10. USPSTF. Lipid disorders in children and adolescents: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/lipid-disorders-in-children-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2017.

11. USPSTF. Skin cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/skin-cancer-screening2. Accessed March 22, 2017.

12. USPSTF. Celiac disease: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/celiac-disease-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

13. USPSTF. Gynecological conditions: periodic screening with the pelvic examination. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/gynecological-conditions-screening-with-the-pelvic-examination. Accessed March 22, 2017.

14. USPSTF. Obstructive sleep apnea in adults: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/obstructive-sleep-apnea-in-adults-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

15. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed March 22, 2017.

16. USPSTF. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

17. USPSTF. Genital herpes infection: serologic screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/genital-herpes-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2017.

Management of bow legs in children: A primary care protocol

ABSTRACT

Objective To reduce unnecessary orthopedic referrals by developing a protocol for managing physiologic bow legs in the primary care environment through the use of a noninvasive technique that simultaneously tracks normal varus progression and screens for potential pathologic bowing requiring an orthopedic referral.

Methods Retrospective study of 155 patients with physiologic genu varum and 10 with infantile Blount’s disease. We used fingerbreadth measurements to document progression or resolution of bow legs. Final diagnoses were made by one orthopedic surgeon using clinical and radiographic evidence. We divided genu varum patients into 3 groups: patients presenting with bow legs before 18 months of age (MOA), patients presenting between 18 and 23 MOA, and patients presenting at 24 MOA or older for analyses relevant to the development of the follow-up protocol.

Results Physiologic genu varum patients walked earlier than average infants (10 months vs 12-15 months; P<.001). Physiologic genu varum patients presenting before 18 MOA demonstrated initial signs of correction between 18 and 24 MOA and resolution by 30 MOA. Physiologic genu varum patients presenting between 18 and 23 MOA demonstrated initial signs of correction between 24 MOA and 30 MOA and resolution by 36 MOA.

Conclusion Primary care physicians can manage most children presenting with bow legs. Management focuses on following the progression or resolution of varus with regular follow-up. For patients presenting with bow legs, we recommend a follow-up protocol using mainly well-child checkups and a simple clinical assessment to monitor varus progression and screen for pathologic bowing.

Bow legs in young children can be a concern for parents.1,2 By far, the most common reason for bow legs is physiologic genu varum,3-5 a nonprogressive stage of normal development in young children that generally resolves spontaneously without treatment.1,6-11 Normally developing children undergo a varus phase between birth and 18 to 24 months of age (MOA), at which time there is usually a transition in alignment from varus to straight to valgus (knock knees), which will correct to straight or mild valgus throughout adolescence.1,6,7,9,10,12-17

The most common form of pathologic bow legs is Blount’s disease, also known as tibia vara, which must be differentiated from physiologic genu varum.8-10,15,18-24 The progressive varus deformity of Blount’s disease usually requires orthopedic intervention.1,10,23-26 Early diagnosis may spare patients complex interventions, improve prognosis, and limit complications that include gait abnormalities,4,8,10,27 knee joint instability,4,24,27 osteoarthritis,9,20,27 meniscal tears,27 and degenerative joint disease.19,20,27

Although variables such as walking age, race, weight, and gender have been suggested as risk factors for Blount’s disease, they have not been useful in differentiating between Blount’s pathology and physiologic genu varum.1,4,5,7,10,20,28 In the primary care setting, distinguishing physiologic from pathologic forms of bow legs is possible with a thorough history and physical exam and with radiographs, as warranted.1,2,15 More than 40% of genu varum/genu valgum cases referred for orthopedic consultation turn out to be the physiologic form,2 suggesting a need for guidelines in the primary care setting to help direct referral and follow-up. The purpose of this study was to provide recommendations to family physicians for evaluating and managing children with bow legs.

Materials and methods

This study, approved by the Internal Review Board of Akron Children’s Hospital, is a retrospective review of children seen by a single pediatric orthopedic surgeon (DSW) from 1970 to 2012. Four-hundred twenty-four children were received for evaluation of bow legs. Excluded from our final analysis were 220 subjects seen only once for this specific referral and 39 subjects diagnosed with a condition other than genu varum or Blount’s disease (ie, rickets, skeletal dysplasia, sequelae of trauma, or infection). Ten subjects with Blount’s disease and 155 subjects with physiologic genu varum were included in the final data analysis.

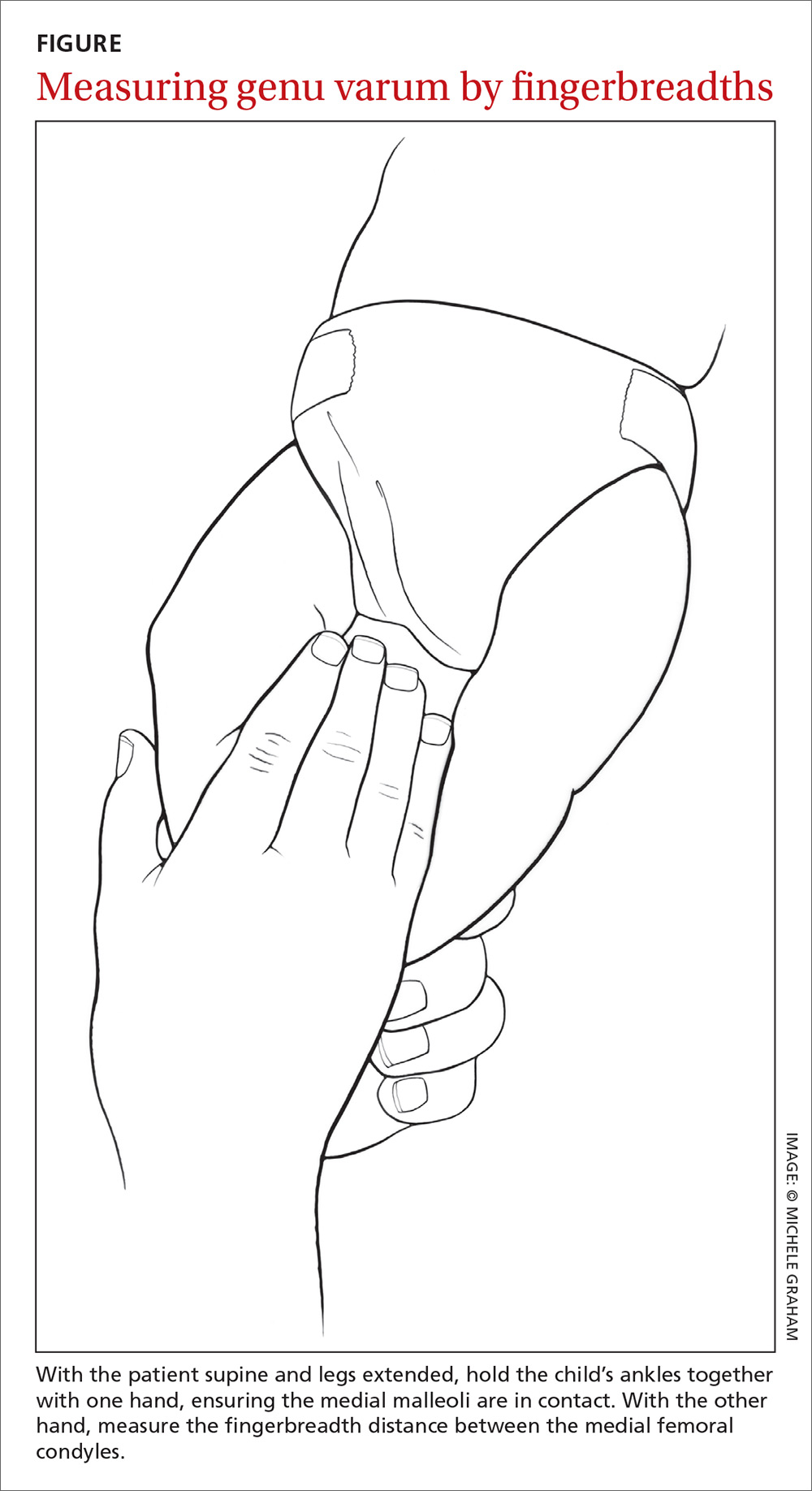

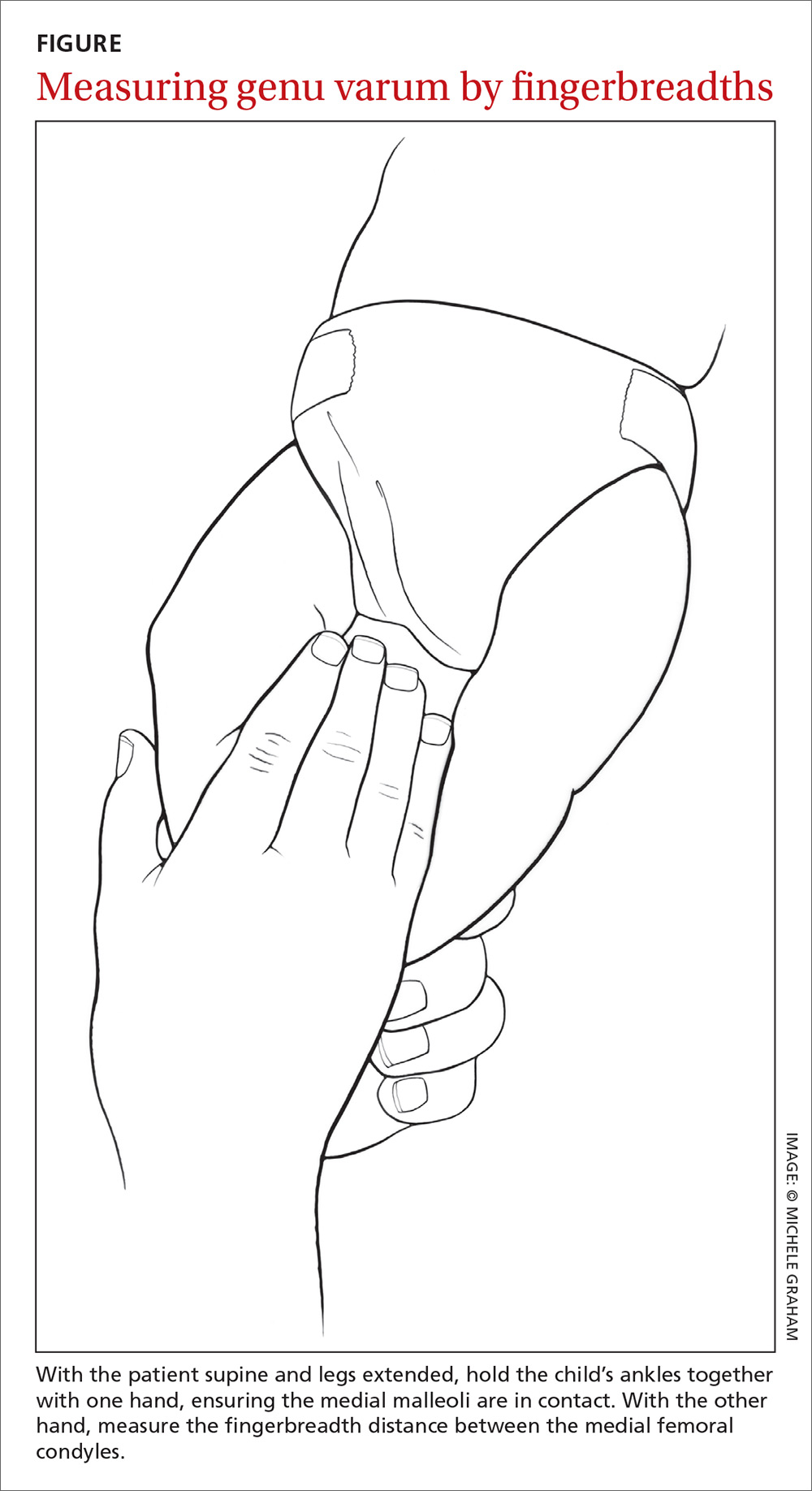

In addition to noting the age at which a patient walked independently, at each visit we documented age and the fingerbreadth (varus) distance between the medial femoral condyles with the child’s ankles held together. Parents reported age of independent walking for just 3 children with Blount’s disease and for 134 children with physiologic genu varum. Study variables for the genu varum data analysis were age of walking, age at presentation, age at varus correction, age at varus resolution, time between presentation and varus correction, and time between presentation and varus resolution. Varus correction is defined as any decrease in varus angulation since presentation. Varus resolution is defined as varus correction to less than or equal to half of the varus angulation at presentation. For inclusion in the age-at-resolution analysis, a child must have been evaluated at regular follow-up visits (all rechecks within 8 months).

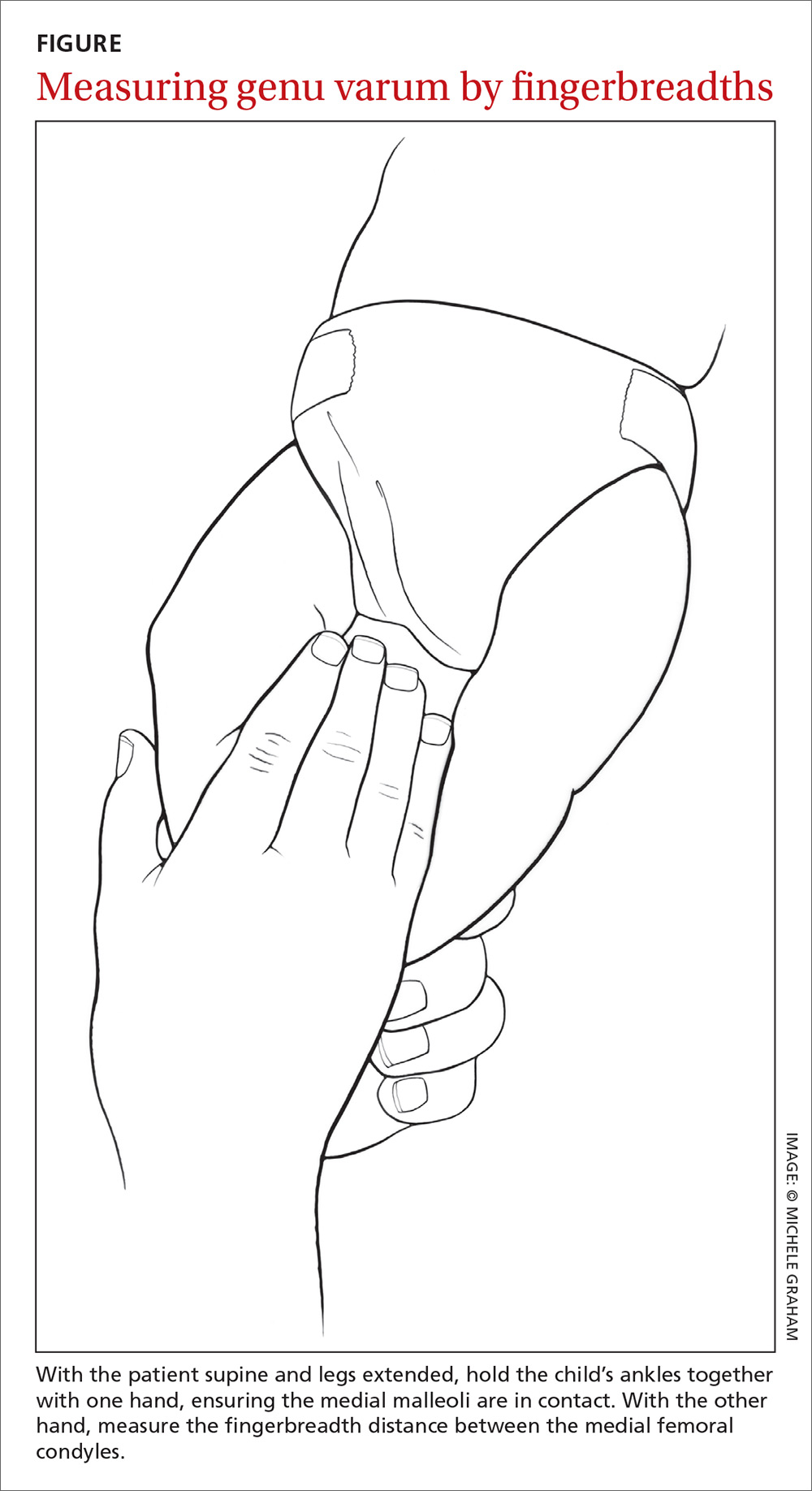

To measure varus distance, we used the fingerbreadth method described by Weiner in a study of 600 cases (FIGURE).6 This simple technique, which requires no special equipment, accurately detected differences in varus angulation and tracked the normal pattern of lower limb angular development. The patient should be supine on the examination table with legs extended. With one hand, the examiner holds the child’s ankles together, ensuring the medial malleoli are in contact. With the other hand, the examiner measures the fingerbreadth distance between the medial femoral condyles. Alternatively, a ruler may be used to measure the distance. This latter method may be especially useful in practices where the patient is likely to see more than one provider for well child care.

We divided the genu varum subject group into 3 subgroups by age at presentation: 103 subjects were younger than 18 months; 47 were 18 to 23 months; and 5 were 24 months or older. We used the data analysis toolkit in Microsoft Excel 2013 to perform a statistical analysis of study variables. We assumed the genu varum population is a normally distributed population. We used a 95% confidence level (α=0.05) for all calculations of confidence intervals (CIs), student t-tests, and tolerance intervals. Based on the data analysis results, we developed a series of follow-up and referral guidelines for practitioners.

Results

The mean walking age for those diagnosed with physiologic genu varum was 10 months (95% CI, 9.8-10.4), which is significantly younger than the 12 months of age (at the earliest) typical of toddlers in general (P<.001). There was no significant difference between the walking age of male and female children diagnosed with genu varum (P=.37).

Of the children presenting with the primary complaint of bow legs, 6% subsequently developed Blount’s disease. These patients presented at a mean age of 20.9 months and were diagnosed at a mean age of 23.9 months. Following the Blount’s disease diagnosis, we initiated therapy in all cases (3 surgical, 7 bracing).

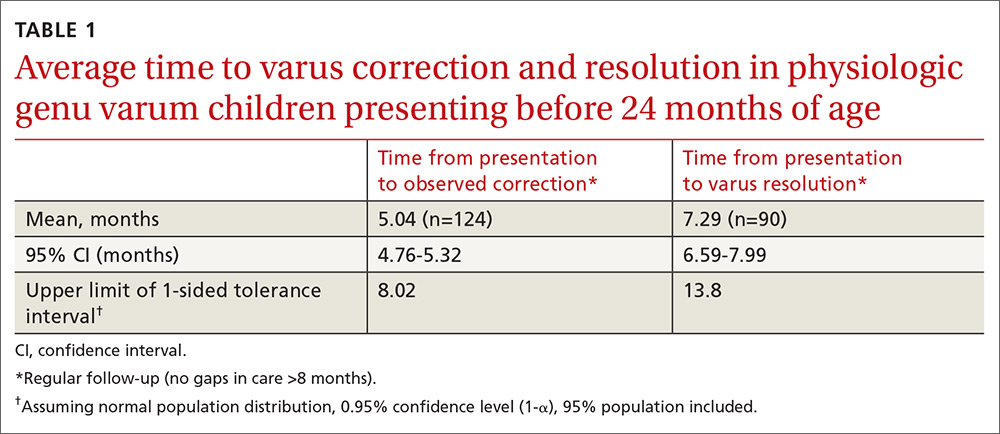

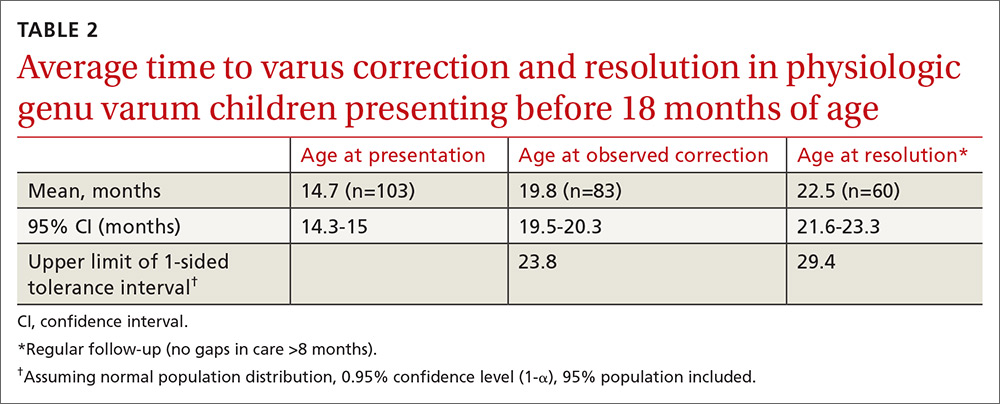

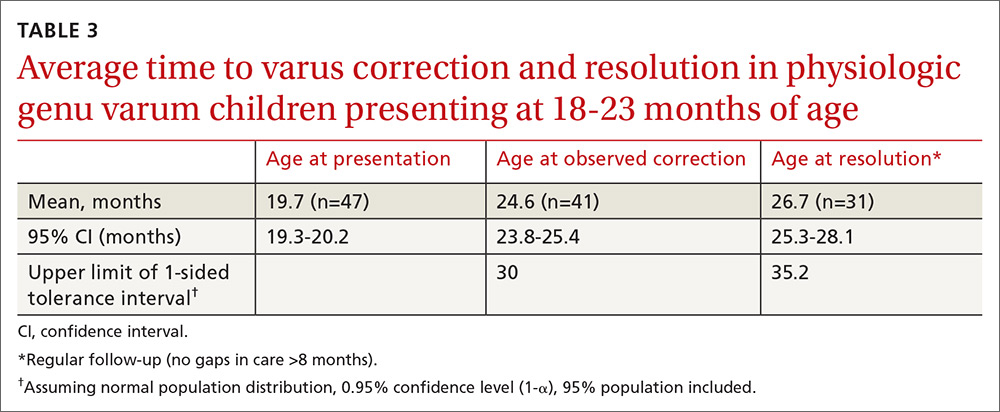

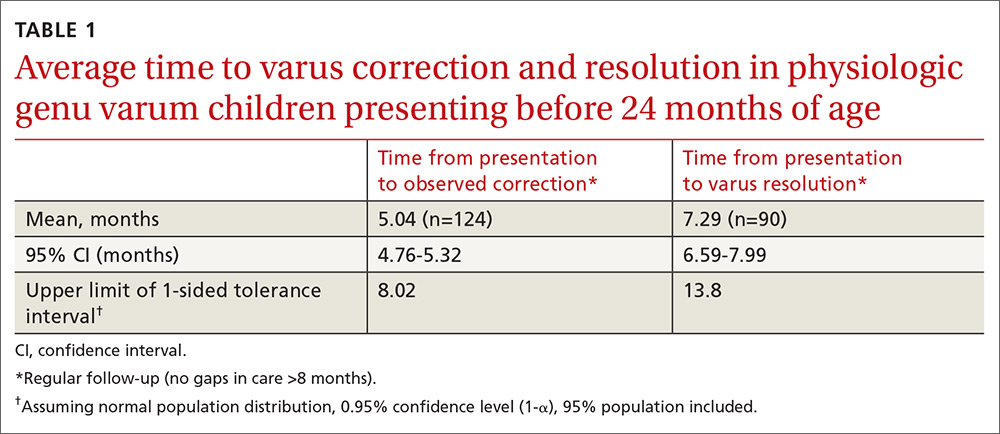

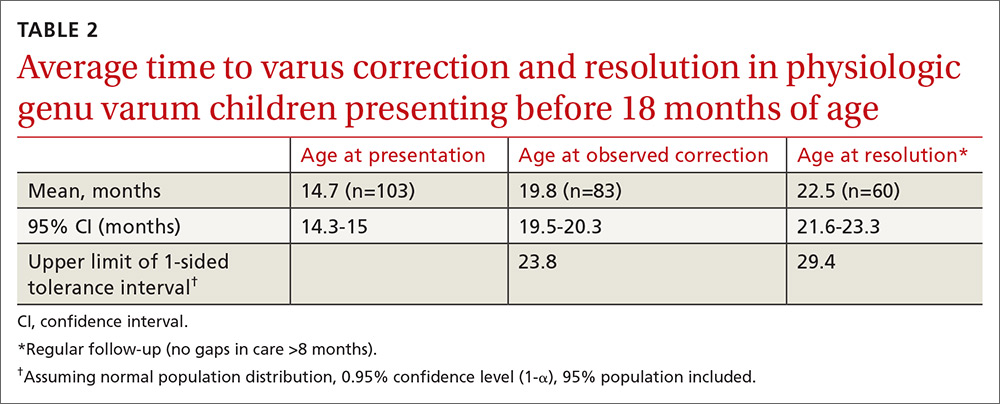

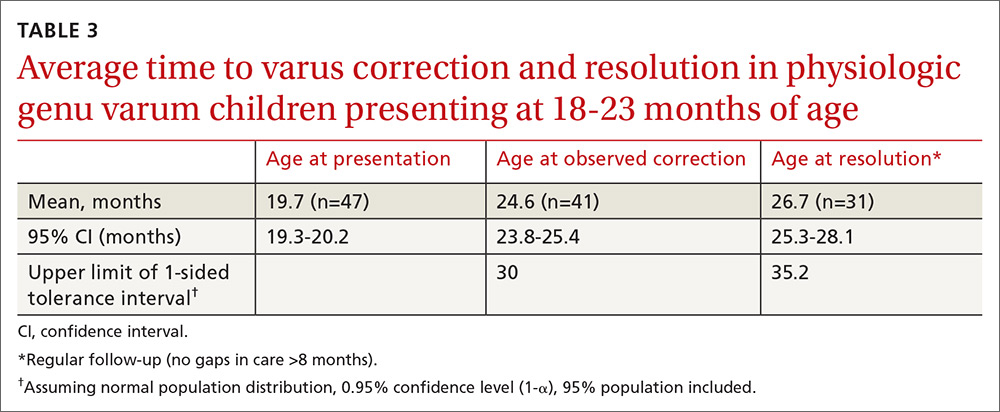

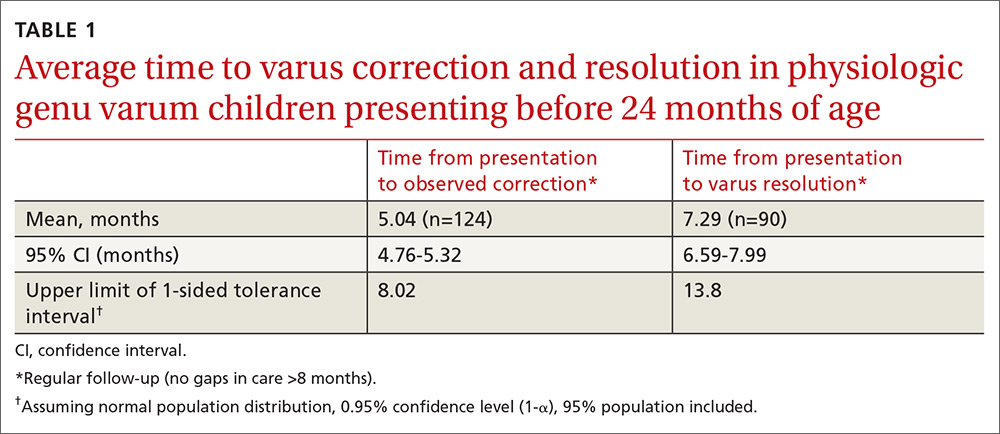

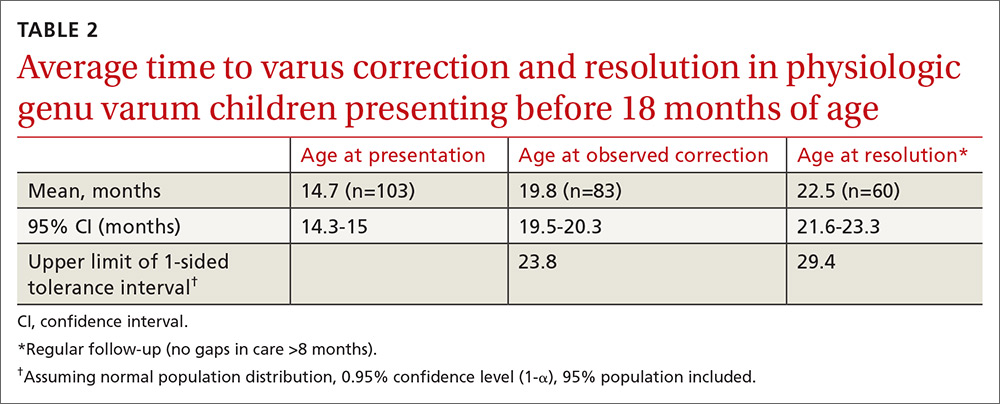

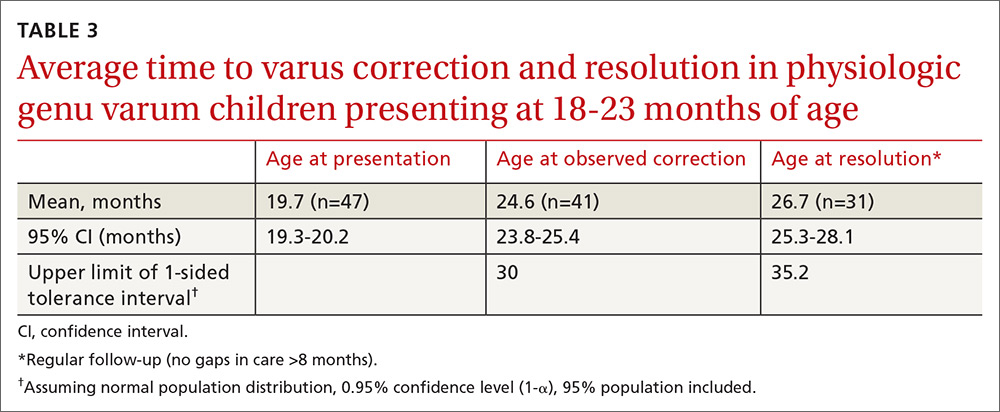

Physiologic genu varum patients presented at a mean age of 16.4 months, with only 3.23% presenting at older than 23 months. On average, physiologic genu varum patients presenting before 24 months of age showed measurable varus correction 5 months after presentation and achieved varus resolution 7.3 months after presentation (TABLE 1). Assuming the patient population is normally distributed, we can be 95% confident that 95% of physiologic genu varum patients presenting before 18 months of age will show measurable varus correction by 24 months and will resolve without intervention by 30 months (TABLE 2). Patients presenting between 18 and 23 months of age should show measurable varus correction by 30 months and resolution by 36 months (TABLE 3).

Discussion

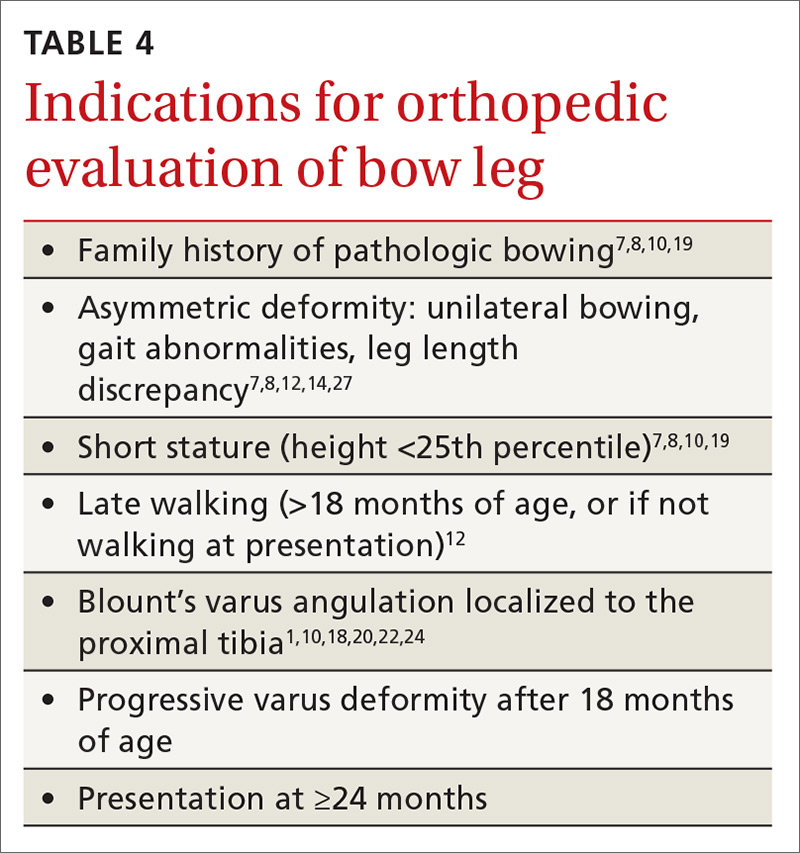

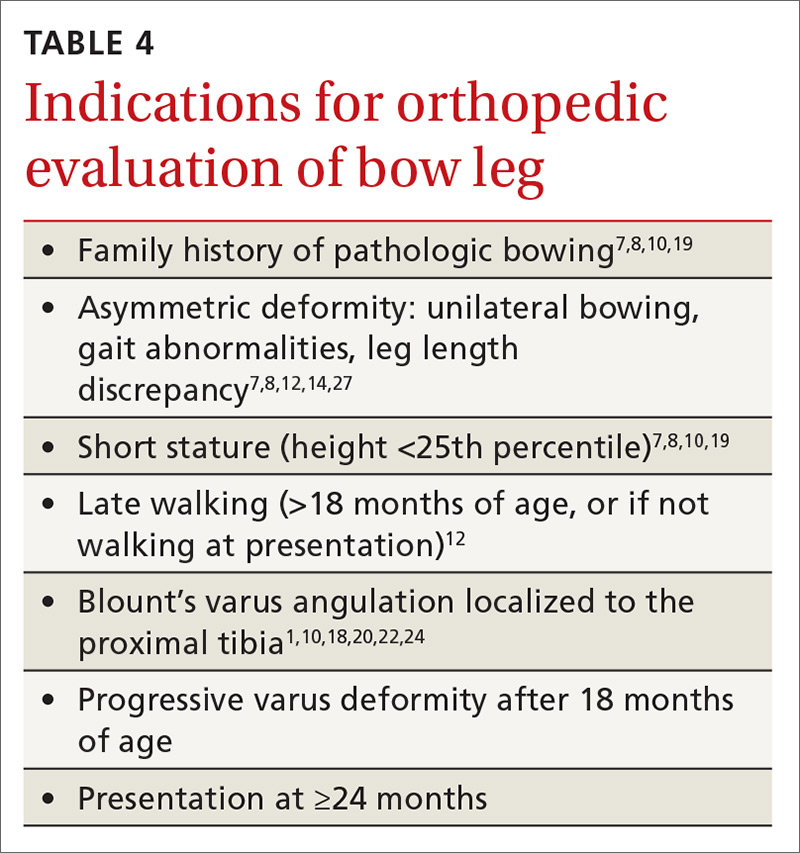

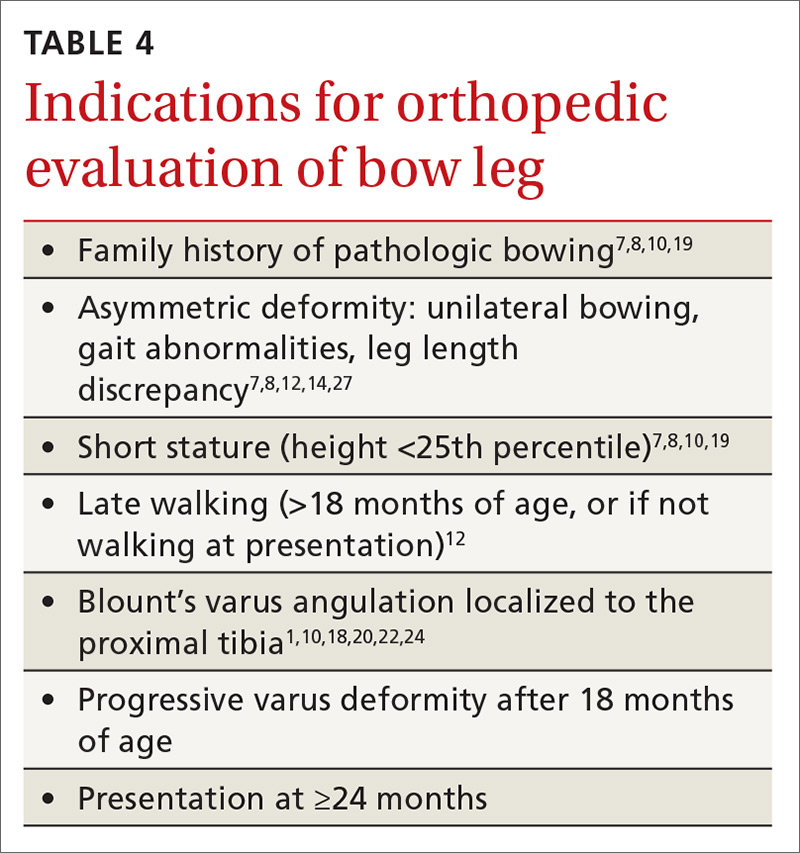

Primary care physicians have the ability to differentiate physiologic genu varum from pathologic forms of bow legs with a thorough history, physical exam, and radiographic examination, if necessary1,2,13 (TABLE 41,7,8,10,12,14,18-20,22,24,27). Several approaches to differentiating Blount’s disease and physiologic genu varum have been described in the literature.1,4,7,8,10,14,22,23

The average age at which children begin to walk independently is between 13 and 15 months.5,18,29-31 Recently, it has been suggested that the range be expanded to include 12 months of age.30 The association between early walking (at 10-11 months)12,20,22 and Blount’s disease is generally accepted in the orthopedic literature.1,4,7,10,19-22 However, some authors have suggested early walking also contributes to genu varum.1,5,8,10,18,28 The mean age of independent walking for children with physiologic genu varum suggested in the literature (10 months) was confirmed in our study and found to be significantly younger than the average for toddlers generally.1,22 Early walking is clearly associated with both physiologic genu varum and Blount’s disease, but no direct causation has been identified in either case. An alternative means of differentiating these entities is needed.

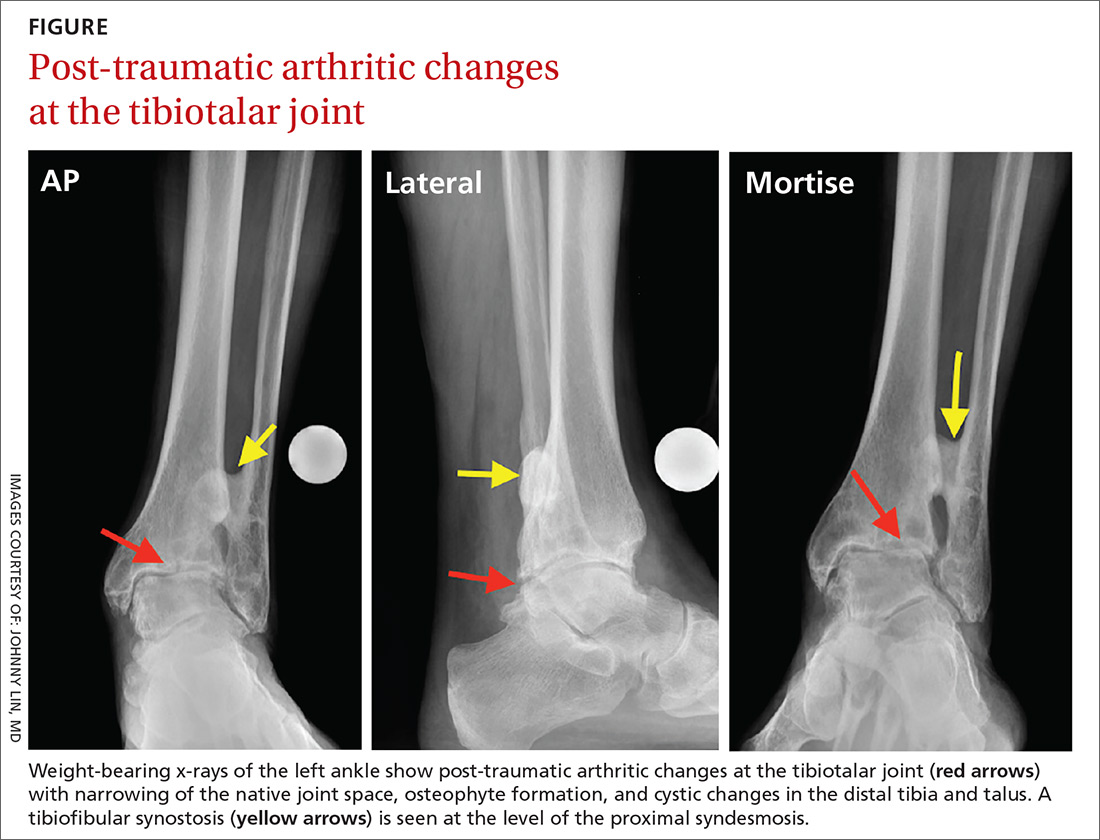

Radiographic examination of the knee is essential to the diagnosis of Blount’s disease as well as other, less common causes of pathologic bow legs (skeletal dysplasia, rickets, traumatic growth plate insults, infections, neoplasms).1,8,14,19 The common radiologic classification of staging for Blount’s disease is the Langenskiöld staging system, which involves identification of characteristic radiographic changes at the tibial physis.5,8,14,15,18,22,24

Sequential measurement of genu varum is most useful in differentiating between physiologic and pathologic processes. Physiologic genu varum, an exaggeration of the normal developmental pattern, characteristically resolves and evolves into physiologic genu valgum by 3 years of age.1,6-11 The pathophysiology of Blount’s disease is believed to be related to biomechanical overloading of the posteromedial proximal tibia during gait with the knee in a varus orientation. Excess loading on the proximal medial physis contributes to varus progression.4,10,14,20,25,27 Patients with Blount’s disease progress with varus and concomitant internal tibial torsion associated with growth plate irregularities and eventually exhibit premature closure.1,10,14,18,20,23,24,26 In the months prior to Blount’s disease diagnosis, increasing varus has been reported.4,7,10,19 Varus progression that differs from the expected pattern indicates possible pathologic bow legs and should prompt radiologic evaluation and, often, an orthopedic referral.3,4,7-9,12,13,21

In our study, only 3% of children with physiologic genu varum presented at 24 months of age or older, compared with 20% of Blount’s disease patients. We recommend considering orthopedic referral for any patient presenting with bow legs at 24 months of age or older. Additionally, consider orthopedic referral for any patient whose varus has not begun to correct within 8 months or has not resolved within 14 months of presentation, as more than 95% of patients with physiologic genu varum are expected to meet these milestones (TABLE 1). And do not hesitate to refer patients at any stage of follow-up if you suspect pathology or if parents are anxious.

If no sign of pathology is immediately identified, we recommend the following course of action:

- Record a reference fingerbreadth or ruler measurement at the initial presentation.

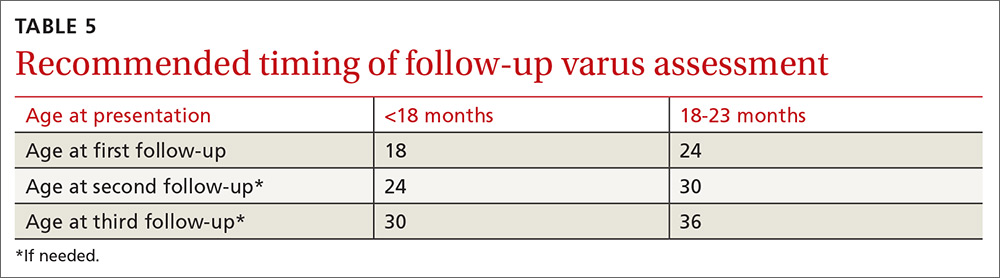

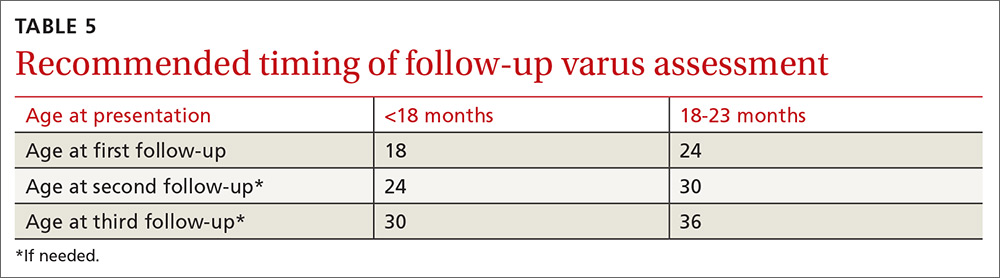

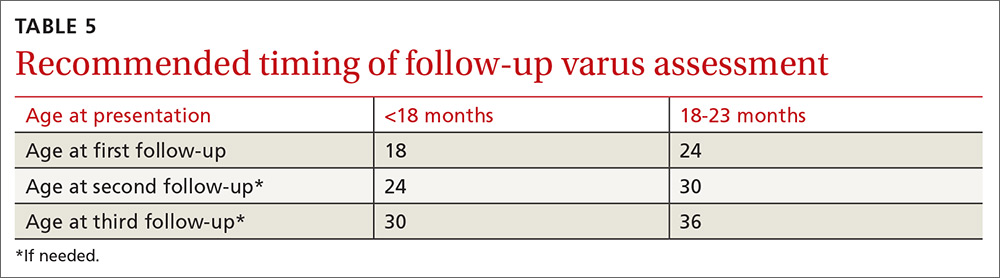

- Re-examine the knee varus at the next regular well-child visit (TABLE 5).

Re-examining the patient prior to the next well-child visit is unnecessary, as some degree of bowing is typical until age 18 to 24 months.1,6,7,9,12,13,17 Recommend orthopedic referral for any patient with varus that has progressed since initial presentation. Without signs of pathology, repeat varus assessment at the next well-child visit. This schedule minimizes the need for additional physician appointments by integrating follow-up into the typical well-child visits at 18, 24, 30, and 36 months of age.32 The 6-month follow-up interval was a feature of our study and is recommended in the related literature.12

- Consider orthopedic referral for patients whose varus has not corrected by the second follow-up appointment, as more than 95% of patients should have measurable varus correction at this visit. Most patients will have exhibited varus resolution by this time and will not require additional follow-up. For patients with observable correction who do not yet meet the criteria for resolution, we recommend a third, final follow-up appointment in another 6 months.

- Refer any patient whose varus has not resolved by the third follow-up appointment, as more than 95% of genu varum cases should have resolved by this time. This finding is echoed in the literature; any varus beyond 36 months of age is considered abnormal and suggestive of pathology.5,7,8,13,14 If evidence of Blount’s or skeletal dysplasia is identified, orthopedic management will likely consist of bracing (orthotics) or surgical management.

CORRESPONDENCE

Dennis S. Weiner, MD, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Akron Children’s Hospital, 300 Locust Street, Suite 250, Akron, OH, 44302; [email protected].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Meadow Newton, BS, assistant research coordinator, Akron Children’s Hospital, for her editing and technical assistance and Richard Steiner, PhD, The University of Akron, for his statistical review.

1. Weiner DS. Pediatric orthopedics for primary care physicians. 2nd ed. Jones K, ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2004.

2. Carli A, Saran N, Kruijt J, et al. Physiological referrals for paediatric musculoskeletal complaints: a costly problem that needs to be addressed. Paediatr Child Health. 2012;17:e93-e97.

3. Fabry G. Clinical practice. Static, axial, and rotational deformities of the lower extremities in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:529-534.

4. Davids JR, Blackhurst DW, Allen Jr BL. Clinical evaluation of bowed legs in children. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2000;9:278-284.

5. Bateson EM. The relationship between Blount’s disease and bow legs. Br J Radiol. 1968;41:107-114.

6. Weiner DS. The natural history of “bow legs” and “knock knees” in childhood. Orthopedics. 1981;4:156-160.

7. Greene WB. Genu varum and genu valgum in children: differential diagnosis and guidelines for evaluation. Compr Ther. 1996;22:22-29.

8. Do TT. Clinical and radiographic evaluation of bowlegs. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2001;13:42-46.

9. Bleck EE. Developmental orthopaedics. III: Toddlers. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1982;24:533-555.

10. Brooks WC, Gross RH. Genu Varum in Children: Diagnosis and Treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3:326-335.

11. Greenberg LA, Swartz AA. Genu varum and genu valgum. Another look. Am J Dis Child. 1971;121:219-221.

12. Scherl SA. Common lower extremity problems in children. Pediatr Rev. 2004;25:52-62.

13. Wall EJ. Practical primary pediatric orthopedics. Nurs Clin North Am. 2000;35:95-113.

14. Cheema JI, Grissom LE, Harcke HT. Radiographic characteristics of lower-extremity bowing in children. Radiographics. 2003;23:871-880.

15. McCarthy JJ, Betz RR, Kim A, et al. Early radiographic differentiation of infantile tibia vara from physiologic bowing using the femoral-tibial ratio. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:545-548.

16. Salenius P, Vankka E. The development of the tibiofemoral angle in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57:259-261.

17. Engel GM, Staheli LT. The natural history of torsion and other factors influencing gait in childhood. A study of the angle of gait, tibial torsion, knee angle, hip rotation, and development of the arch in normal children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1974;99:12-17.

18. Golding J, Bateson E, McNeil-Smith G. Infantile tibia vara. In: The Growth Plate and Its Disorders. Rang M, ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins; 1969:109-119.

19. Greene WB. Infantile tibia vara. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:130-143.

20. Golding J, McNeil-Smith JDG. Observations on the etiology of tibia vara. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1963;45-B:320-325.

21. Eggert P, Viemann M. Physiological bowlegs or infantile Blount’s disease. Some new aspects on an old problem. Pediatr Radiol. 1996;26:349-352.

22. Levine AM, Drennan JC. Physiological bowing and tibia vara. The metaphyseal-diaphyseal angle in the measurement of bowleg deformities. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:1158-1163.

23. Kessel L. Annotations on the etiology and treatment of tibia vara. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1970;52:93-99.

24. Blount WP. Tibia vara: osteochondrosis deformans tibiae. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1937;19:1-29.

25. Davids JR, Blackhurst DW, Allen BL Jr. Radiographic evaluation of bowed legs in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:257-263.

26. Cook SD, Lavernia CJ, Burke SW, et al. A biomechanical analysis of the etiology of tibia vara. J Pediatr Orthop. 1983;3:449-454.

27. Birch JG. Blount disease. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:408-418.

28. Bateson EM. Non-rachitic bow leg and knock-knee deformities in young Jamaican children. Br J Radiol. 1966;39:92-101.

29. Grantham-McGregor SM, Back EH. Gross motor development in Jamaican infants. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1971;13:79-87.

30. Størvold GV, Aarethun K, Bratberg GH. Age for onset of walking and prewalking strategies. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89:655-659.

31. Garrett M, McElroy AM, Staines A. Locomotor milestones and babywalkers: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2002;324:1494.

32. Simon GR, Baker C, Barden GA 3rd, et al; Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, Curry ES, Dunca PM, Hagan JF Jr, et al; Bright Futures Periodicity Schedule Workgroup. 2014 recommendations for pediatric preventive health care. Pediatrics. 2014;133:568-570.

ABSTRACT

Objective To reduce unnecessary orthopedic referrals by developing a protocol for managing physiologic bow legs in the primary care environment through the use of a noninvasive technique that simultaneously tracks normal varus progression and screens for potential pathologic bowing requiring an orthopedic referral.

Methods Retrospective study of 155 patients with physiologic genu varum and 10 with infantile Blount’s disease. We used fingerbreadth measurements to document progression or resolution of bow legs. Final diagnoses were made by one orthopedic surgeon using clinical and radiographic evidence. We divided genu varum patients into 3 groups: patients presenting with bow legs before 18 months of age (MOA), patients presenting between 18 and 23 MOA, and patients presenting at 24 MOA or older for analyses relevant to the development of the follow-up protocol.

Results Physiologic genu varum patients walked earlier than average infants (10 months vs 12-15 months; P<.001). Physiologic genu varum patients presenting before 18 MOA demonstrated initial signs of correction between 18 and 24 MOA and resolution by 30 MOA. Physiologic genu varum patients presenting between 18 and 23 MOA demonstrated initial signs of correction between 24 MOA and 30 MOA and resolution by 36 MOA.

Conclusion Primary care physicians can manage most children presenting with bow legs. Management focuses on following the progression or resolution of varus with regular follow-up. For patients presenting with bow legs, we recommend a follow-up protocol using mainly well-child checkups and a simple clinical assessment to monitor varus progression and screen for pathologic bowing.

Bow legs in young children can be a concern for parents.1,2 By far, the most common reason for bow legs is physiologic genu varum,3-5 a nonprogressive stage of normal development in young children that generally resolves spontaneously without treatment.1,6-11 Normally developing children undergo a varus phase between birth and 18 to 24 months of age (MOA), at which time there is usually a transition in alignment from varus to straight to valgus (knock knees), which will correct to straight or mild valgus throughout adolescence.1,6,7,9,10,12-17

The most common form of pathologic bow legs is Blount’s disease, also known as tibia vara, which must be differentiated from physiologic genu varum.8-10,15,18-24 The progressive varus deformity of Blount’s disease usually requires orthopedic intervention.1,10,23-26 Early diagnosis may spare patients complex interventions, improve prognosis, and limit complications that include gait abnormalities,4,8,10,27 knee joint instability,4,24,27 osteoarthritis,9,20,27 meniscal tears,27 and degenerative joint disease.19,20,27

Although variables such as walking age, race, weight, and gender have been suggested as risk factors for Blount’s disease, they have not been useful in differentiating between Blount’s pathology and physiologic genu varum.1,4,5,7,10,20,28 In the primary care setting, distinguishing physiologic from pathologic forms of bow legs is possible with a thorough history and physical exam and with radiographs, as warranted.1,2,15 More than 40% of genu varum/genu valgum cases referred for orthopedic consultation turn out to be the physiologic form,2 suggesting a need for guidelines in the primary care setting to help direct referral and follow-up. The purpose of this study was to provide recommendations to family physicians for evaluating and managing children with bow legs.

Materials and methods

This study, approved by the Internal Review Board of Akron Children’s Hospital, is a retrospective review of children seen by a single pediatric orthopedic surgeon (DSW) from 1970 to 2012. Four-hundred twenty-four children were received for evaluation of bow legs. Excluded from our final analysis were 220 subjects seen only once for this specific referral and 39 subjects diagnosed with a condition other than genu varum or Blount’s disease (ie, rickets, skeletal dysplasia, sequelae of trauma, or infection). Ten subjects with Blount’s disease and 155 subjects with physiologic genu varum were included in the final data analysis.

In addition to noting the age at which a patient walked independently, at each visit we documented age and the fingerbreadth (varus) distance between the medial femoral condyles with the child’s ankles held together. Parents reported age of independent walking for just 3 children with Blount’s disease and for 134 children with physiologic genu varum. Study variables for the genu varum data analysis were age of walking, age at presentation, age at varus correction, age at varus resolution, time between presentation and varus correction, and time between presentation and varus resolution. Varus correction is defined as any decrease in varus angulation since presentation. Varus resolution is defined as varus correction to less than or equal to half of the varus angulation at presentation. For inclusion in the age-at-resolution analysis, a child must have been evaluated at regular follow-up visits (all rechecks within 8 months).

To measure varus distance, we used the fingerbreadth method described by Weiner in a study of 600 cases (FIGURE).6 This simple technique, which requires no special equipment, accurately detected differences in varus angulation and tracked the normal pattern of lower limb angular development. The patient should be supine on the examination table with legs extended. With one hand, the examiner holds the child’s ankles together, ensuring the medial malleoli are in contact. With the other hand, the examiner measures the fingerbreadth distance between the medial femoral condyles. Alternatively, a ruler may be used to measure the distance. This latter method may be especially useful in practices where the patient is likely to see more than one provider for well child care.

We divided the genu varum subject group into 3 subgroups by age at presentation: 103 subjects were younger than 18 months; 47 were 18 to 23 months; and 5 were 24 months or older. We used the data analysis toolkit in Microsoft Excel 2013 to perform a statistical analysis of study variables. We assumed the genu varum population is a normally distributed population. We used a 95% confidence level (α=0.05) for all calculations of confidence intervals (CIs), student t-tests, and tolerance intervals. Based on the data analysis results, we developed a series of follow-up and referral guidelines for practitioners.

Results

The mean walking age for those diagnosed with physiologic genu varum was 10 months (95% CI, 9.8-10.4), which is significantly younger than the 12 months of age (at the earliest) typical of toddlers in general (P<.001). There was no significant difference between the walking age of male and female children diagnosed with genu varum (P=.37).

Of the children presenting with the primary complaint of bow legs, 6% subsequently developed Blount’s disease. These patients presented at a mean age of 20.9 months and were diagnosed at a mean age of 23.9 months. Following the Blount’s disease diagnosis, we initiated therapy in all cases (3 surgical, 7 bracing).

Physiologic genu varum patients presented at a mean age of 16.4 months, with only 3.23% presenting at older than 23 months. On average, physiologic genu varum patients presenting before 24 months of age showed measurable varus correction 5 months after presentation and achieved varus resolution 7.3 months after presentation (TABLE 1). Assuming the patient population is normally distributed, we can be 95% confident that 95% of physiologic genu varum patients presenting before 18 months of age will show measurable varus correction by 24 months and will resolve without intervention by 30 months (TABLE 2). Patients presenting between 18 and 23 months of age should show measurable varus correction by 30 months and resolution by 36 months (TABLE 3).

Discussion

Primary care physicians have the ability to differentiate physiologic genu varum from pathologic forms of bow legs with a thorough history, physical exam, and radiographic examination, if necessary1,2,13 (TABLE 41,7,8,10,12,14,18-20,22,24,27). Several approaches to differentiating Blount’s disease and physiologic genu varum have been described in the literature.1,4,7,8,10,14,22,23

The average age at which children begin to walk independently is between 13 and 15 months.5,18,29-31 Recently, it has been suggested that the range be expanded to include 12 months of age.30 The association between early walking (at 10-11 months)12,20,22 and Blount’s disease is generally accepted in the orthopedic literature.1,4,7,10,19-22 However, some authors have suggested early walking also contributes to genu varum.1,5,8,10,18,28 The mean age of independent walking for children with physiologic genu varum suggested in the literature (10 months) was confirmed in our study and found to be significantly younger than the average for toddlers generally.1,22 Early walking is clearly associated with both physiologic genu varum and Blount’s disease, but no direct causation has been identified in either case. An alternative means of differentiating these entities is needed.

Radiographic examination of the knee is essential to the diagnosis of Blount’s disease as well as other, less common causes of pathologic bow legs (skeletal dysplasia, rickets, traumatic growth plate insults, infections, neoplasms).1,8,14,19 The common radiologic classification of staging for Blount’s disease is the Langenskiöld staging system, which involves identification of characteristic radiographic changes at the tibial physis.5,8,14,15,18,22,24

Sequential measurement of genu varum is most useful in differentiating between physiologic and pathologic processes. Physiologic genu varum, an exaggeration of the normal developmental pattern, characteristically resolves and evolves into physiologic genu valgum by 3 years of age.1,6-11 The pathophysiology of Blount’s disease is believed to be related to biomechanical overloading of the posteromedial proximal tibia during gait with the knee in a varus orientation. Excess loading on the proximal medial physis contributes to varus progression.4,10,14,20,25,27 Patients with Blount’s disease progress with varus and concomitant internal tibial torsion associated with growth plate irregularities and eventually exhibit premature closure.1,10,14,18,20,23,24,26 In the months prior to Blount’s disease diagnosis, increasing varus has been reported.4,7,10,19 Varus progression that differs from the expected pattern indicates possible pathologic bow legs and should prompt radiologic evaluation and, often, an orthopedic referral.3,4,7-9,12,13,21

In our study, only 3% of children with physiologic genu varum presented at 24 months of age or older, compared with 20% of Blount’s disease patients. We recommend considering orthopedic referral for any patient presenting with bow legs at 24 months of age or older. Additionally, consider orthopedic referral for any patient whose varus has not begun to correct within 8 months or has not resolved within 14 months of presentation, as more than 95% of patients with physiologic genu varum are expected to meet these milestones (TABLE 1). And do not hesitate to refer patients at any stage of follow-up if you suspect pathology or if parents are anxious.

If no sign of pathology is immediately identified, we recommend the following course of action:

- Record a reference fingerbreadth or ruler measurement at the initial presentation.

- Re-examine the knee varus at the next regular well-child visit (TABLE 5).

Re-examining the patient prior to the next well-child visit is unnecessary, as some degree of bowing is typical until age 18 to 24 months.1,6,7,9,12,13,17 Recommend orthopedic referral for any patient with varus that has progressed since initial presentation. Without signs of pathology, repeat varus assessment at the next well-child visit. This schedule minimizes the need for additional physician appointments by integrating follow-up into the typical well-child visits at 18, 24, 30, and 36 months of age.32 The 6-month follow-up interval was a feature of our study and is recommended in the related literature.12

- Consider orthopedic referral for patients whose varus has not corrected by the second follow-up appointment, as more than 95% of patients should have measurable varus correction at this visit. Most patients will have exhibited varus resolution by this time and will not require additional follow-up. For patients with observable correction who do not yet meet the criteria for resolution, we recommend a third, final follow-up appointment in another 6 months.

- Refer any patient whose varus has not resolved by the third follow-up appointment, as more than 95% of genu varum cases should have resolved by this time. This finding is echoed in the literature; any varus beyond 36 months of age is considered abnormal and suggestive of pathology.5,7,8,13,14 If evidence of Blount’s or skeletal dysplasia is identified, orthopedic management will likely consist of bracing (orthotics) or surgical management.

CORRESPONDENCE

Dennis S. Weiner, MD, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Akron Children’s Hospital, 300 Locust Street, Suite 250, Akron, OH, 44302; [email protected].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Meadow Newton, BS, assistant research coordinator, Akron Children’s Hospital, for her editing and technical assistance and Richard Steiner, PhD, The University of Akron, for his statistical review.

ABSTRACT

Objective To reduce unnecessary orthopedic referrals by developing a protocol for managing physiologic bow legs in the primary care environment through the use of a noninvasive technique that simultaneously tracks normal varus progression and screens for potential pathologic bowing requiring an orthopedic referral.

Methods Retrospective study of 155 patients with physiologic genu varum and 10 with infantile Blount’s disease. We used fingerbreadth measurements to document progression or resolution of bow legs. Final diagnoses were made by one orthopedic surgeon using clinical and radiographic evidence. We divided genu varum patients into 3 groups: patients presenting with bow legs before 18 months of age (MOA), patients presenting between 18 and 23 MOA, and patients presenting at 24 MOA or older for analyses relevant to the development of the follow-up protocol.

Results Physiologic genu varum patients walked earlier than average infants (10 months vs 12-15 months; P<.001). Physiologic genu varum patients presenting before 18 MOA demonstrated initial signs of correction between 18 and 24 MOA and resolution by 30 MOA. Physiologic genu varum patients presenting between 18 and 23 MOA demonstrated initial signs of correction between 24 MOA and 30 MOA and resolution by 36 MOA.

Conclusion Primary care physicians can manage most children presenting with bow legs. Management focuses on following the progression or resolution of varus with regular follow-up. For patients presenting with bow legs, we recommend a follow-up protocol using mainly well-child checkups and a simple clinical assessment to monitor varus progression and screen for pathologic bowing.

Bow legs in young children can be a concern for parents.1,2 By far, the most common reason for bow legs is physiologic genu varum,3-5 a nonprogressive stage of normal development in young children that generally resolves spontaneously without treatment.1,6-11 Normally developing children undergo a varus phase between birth and 18 to 24 months of age (MOA), at which time there is usually a transition in alignment from varus to straight to valgus (knock knees), which will correct to straight or mild valgus throughout adolescence.1,6,7,9,10,12-17

The most common form of pathologic bow legs is Blount’s disease, also known as tibia vara, which must be differentiated from physiologic genu varum.8-10,15,18-24 The progressive varus deformity of Blount’s disease usually requires orthopedic intervention.1,10,23-26 Early diagnosis may spare patients complex interventions, improve prognosis, and limit complications that include gait abnormalities,4,8,10,27 knee joint instability,4,24,27 osteoarthritis,9,20,27 meniscal tears,27 and degenerative joint disease.19,20,27

Although variables such as walking age, race, weight, and gender have been suggested as risk factors for Blount’s disease, they have not been useful in differentiating between Blount’s pathology and physiologic genu varum.1,4,5,7,10,20,28 In the primary care setting, distinguishing physiologic from pathologic forms of bow legs is possible with a thorough history and physical exam and with radiographs, as warranted.1,2,15 More than 40% of genu varum/genu valgum cases referred for orthopedic consultation turn out to be the physiologic form,2 suggesting a need for guidelines in the primary care setting to help direct referral and follow-up. The purpose of this study was to provide recommendations to family physicians for evaluating and managing children with bow legs.

Materials and methods

This study, approved by the Internal Review Board of Akron Children’s Hospital, is a retrospective review of children seen by a single pediatric orthopedic surgeon (DSW) from 1970 to 2012. Four-hundred twenty-four children were received for evaluation of bow legs. Excluded from our final analysis were 220 subjects seen only once for this specific referral and 39 subjects diagnosed with a condition other than genu varum or Blount’s disease (ie, rickets, skeletal dysplasia, sequelae of trauma, or infection). Ten subjects with Blount’s disease and 155 subjects with physiologic genu varum were included in the final data analysis.

In addition to noting the age at which a patient walked independently, at each visit we documented age and the fingerbreadth (varus) distance between the medial femoral condyles with the child’s ankles held together. Parents reported age of independent walking for just 3 children with Blount’s disease and for 134 children with physiologic genu varum. Study variables for the genu varum data analysis were age of walking, age at presentation, age at varus correction, age at varus resolution, time between presentation and varus correction, and time between presentation and varus resolution. Varus correction is defined as any decrease in varus angulation since presentation. Varus resolution is defined as varus correction to less than or equal to half of the varus angulation at presentation. For inclusion in the age-at-resolution analysis, a child must have been evaluated at regular follow-up visits (all rechecks within 8 months).