User login

Neuroscience-based Nomenclature: Classifying psychotropics by mechanism of action rather than indication

An important new initiative to reclassify psychiatric medications is underway. Currently, psychotropic drugs are named primarily for their clinical use, usually as a member of 1 of 6 classes: antipsychotic, anti‑depressant, mood stabilizer, stimulant, anxiolytic, and hypnotic.1,2

This naming system creates confusion because so-called antidepressants commonly are used as anxiolytics, antipsychotics increasingly are used as antidepressants, and so on.1,2

Vocabulary based on clinical indications also leads to difficulty in classifying new agents, especially those with novel mechanisms of action or clinical uses. Therefore, there is a need to make the names of psychotropic drugs more rational and scientifically based, rather than indication-based. A task force of experts from major psychopharmacology societies around the world is developing an alternative naming system that is increasingly being accepted by the major experts and journals throughout the world, called Neuroscience-based Nomenclature (NbN).3-5

So, what is NbN?

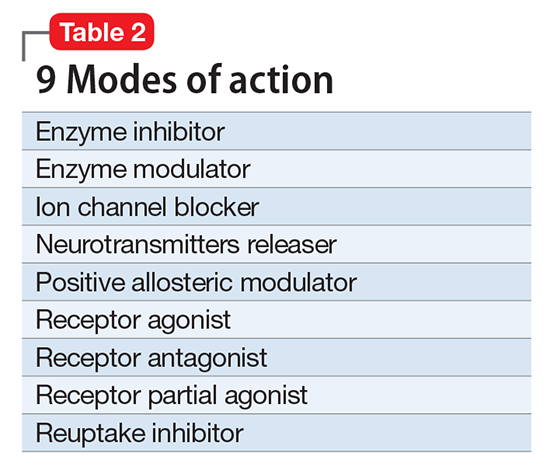

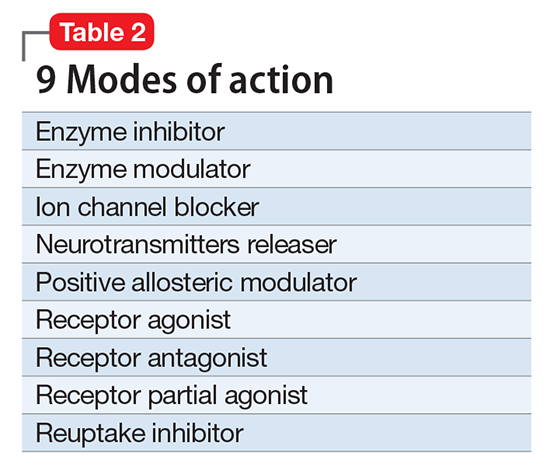

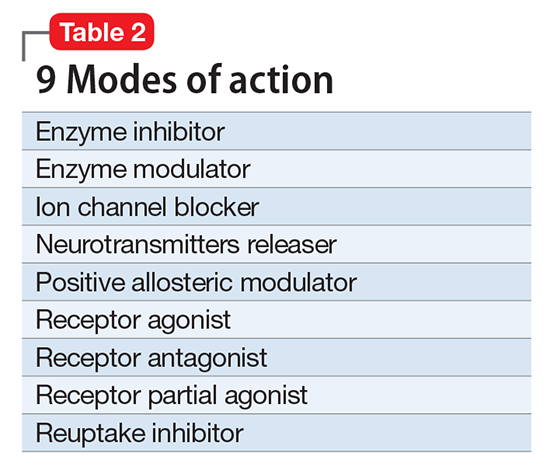

First and foremost, NbN renames the >100 known psychotropic drugs by 1 of the 11 principle pharmacological domains that include well-known terms such as serotonin dopamine, acetylcholine, and GABA (Table 1). Also included in NbN are 9 familiar modes of action, such as agonist, antagonist, reuptake inhibitor, and enzyme inhibitors (Table 2).3-5

NbN has 4 additional dimensions or layers3-5:

- The first layer enumerates the official indications as recognized by the regulatory agencies (ie, the FDA and other government organizations).

- The second layer states efficacy based on randomized controlled trials or substantial, evidence-based clinical data, as well as side effects (not the exhaustive list provided in manufacturers’ package inserts, but only the most common ones).

- The third layer is comprised of practical notes, highlighting potentially important drug interactions, metabolic issues, and specific warnings.

- The fourth section summarizes the neurobiological effects in laboratory animals and humans.

Specific dosages and titration regimens are not provided because they can vary among different countries, and NbN is intended for nomenclature and classification, not as a prescribing guide.

How does it work in practice?

Major journals in the field have begun adapting NbN for their published papers and

What is the current status?

Two international organizations endorse NbN, and the chief editors of nearly 3 dozen scientific journals, including

Clinicians should start adopting the NbN for the psychotropic drugs they prescribe every day. It is more scientific and consistent with the mechanism of action than with a specific disorder because many psychotropic medications have been found to be useful in >1 psychiatric disorder.

1. Nutt DJ. Beyond psychoanaleptics - can we improve antidepressant drug nomenclature? J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(4):343-345.

2. Stahl SM. Classifying psychotropic drugs by mode of action not by target disorders. CNS Spectr. 2013;18(3):113-117.

3. Zohar J, Stahl S, Moller HJ, et al. A review of the current nomenclature for psychotropic agents and an introduction to the Neuroscience-based Nomenclature. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015; 25(12):2318-2325.

4. Zohar J, Stahl S, Moller HJ, et al. Neuroscience based nomenclature. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2014:254.

5. Neuroscience-based nomenclature. http://nbnomenclature.org. Accessed April 12, 2017.

An important new initiative to reclassify psychiatric medications is underway. Currently, psychotropic drugs are named primarily for their clinical use, usually as a member of 1 of 6 classes: antipsychotic, anti‑depressant, mood stabilizer, stimulant, anxiolytic, and hypnotic.1,2

This naming system creates confusion because so-called antidepressants commonly are used as anxiolytics, antipsychotics increasingly are used as antidepressants, and so on.1,2

Vocabulary based on clinical indications also leads to difficulty in classifying new agents, especially those with novel mechanisms of action or clinical uses. Therefore, there is a need to make the names of psychotropic drugs more rational and scientifically based, rather than indication-based. A task force of experts from major psychopharmacology societies around the world is developing an alternative naming system that is increasingly being accepted by the major experts and journals throughout the world, called Neuroscience-based Nomenclature (NbN).3-5

So, what is NbN?

First and foremost, NbN renames the >100 known psychotropic drugs by 1 of the 11 principle pharmacological domains that include well-known terms such as serotonin dopamine, acetylcholine, and GABA (Table 1). Also included in NbN are 9 familiar modes of action, such as agonist, antagonist, reuptake inhibitor, and enzyme inhibitors (Table 2).3-5

NbN has 4 additional dimensions or layers3-5:

- The first layer enumerates the official indications as recognized by the regulatory agencies (ie, the FDA and other government organizations).

- The second layer states efficacy based on randomized controlled trials or substantial, evidence-based clinical data, as well as side effects (not the exhaustive list provided in manufacturers’ package inserts, but only the most common ones).

- The third layer is comprised of practical notes, highlighting potentially important drug interactions, metabolic issues, and specific warnings.

- The fourth section summarizes the neurobiological effects in laboratory animals and humans.

Specific dosages and titration regimens are not provided because they can vary among different countries, and NbN is intended for nomenclature and classification, not as a prescribing guide.

How does it work in practice?

Major journals in the field have begun adapting NbN for their published papers and

What is the current status?

Two international organizations endorse NbN, and the chief editors of nearly 3 dozen scientific journals, including

Clinicians should start adopting the NbN for the psychotropic drugs they prescribe every day. It is more scientific and consistent with the mechanism of action than with a specific disorder because many psychotropic medications have been found to be useful in >1 psychiatric disorder.

An important new initiative to reclassify psychiatric medications is underway. Currently, psychotropic drugs are named primarily for their clinical use, usually as a member of 1 of 6 classes: antipsychotic, anti‑depressant, mood stabilizer, stimulant, anxiolytic, and hypnotic.1,2

This naming system creates confusion because so-called antidepressants commonly are used as anxiolytics, antipsychotics increasingly are used as antidepressants, and so on.1,2

Vocabulary based on clinical indications also leads to difficulty in classifying new agents, especially those with novel mechanisms of action or clinical uses. Therefore, there is a need to make the names of psychotropic drugs more rational and scientifically based, rather than indication-based. A task force of experts from major psychopharmacology societies around the world is developing an alternative naming system that is increasingly being accepted by the major experts and journals throughout the world, called Neuroscience-based Nomenclature (NbN).3-5

So, what is NbN?

First and foremost, NbN renames the >100 known psychotropic drugs by 1 of the 11 principle pharmacological domains that include well-known terms such as serotonin dopamine, acetylcholine, and GABA (Table 1). Also included in NbN are 9 familiar modes of action, such as agonist, antagonist, reuptake inhibitor, and enzyme inhibitors (Table 2).3-5

NbN has 4 additional dimensions or layers3-5:

- The first layer enumerates the official indications as recognized by the regulatory agencies (ie, the FDA and other government organizations).

- The second layer states efficacy based on randomized controlled trials or substantial, evidence-based clinical data, as well as side effects (not the exhaustive list provided in manufacturers’ package inserts, but only the most common ones).

- The third layer is comprised of practical notes, highlighting potentially important drug interactions, metabolic issues, and specific warnings.

- The fourth section summarizes the neurobiological effects in laboratory animals and humans.

Specific dosages and titration regimens are not provided because they can vary among different countries, and NbN is intended for nomenclature and classification, not as a prescribing guide.

How does it work in practice?

Major journals in the field have begun adapting NbN for their published papers and

What is the current status?

Two international organizations endorse NbN, and the chief editors of nearly 3 dozen scientific journals, including

Clinicians should start adopting the NbN for the psychotropic drugs they prescribe every day. It is more scientific and consistent with the mechanism of action than with a specific disorder because many psychotropic medications have been found to be useful in >1 psychiatric disorder.

1. Nutt DJ. Beyond psychoanaleptics - can we improve antidepressant drug nomenclature? J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(4):343-345.

2. Stahl SM. Classifying psychotropic drugs by mode of action not by target disorders. CNS Spectr. 2013;18(3):113-117.

3. Zohar J, Stahl S, Moller HJ, et al. A review of the current nomenclature for psychotropic agents and an introduction to the Neuroscience-based Nomenclature. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015; 25(12):2318-2325.

4. Zohar J, Stahl S, Moller HJ, et al. Neuroscience based nomenclature. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2014:254.

5. Neuroscience-based nomenclature. http://nbnomenclature.org. Accessed April 12, 2017.

1. Nutt DJ. Beyond psychoanaleptics - can we improve antidepressant drug nomenclature? J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(4):343-345.

2. Stahl SM. Classifying psychotropic drugs by mode of action not by target disorders. CNS Spectr. 2013;18(3):113-117.

3. Zohar J, Stahl S, Moller HJ, et al. A review of the current nomenclature for psychotropic agents and an introduction to the Neuroscience-based Nomenclature. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015; 25(12):2318-2325.

4. Zohar J, Stahl S, Moller HJ, et al. Neuroscience based nomenclature. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2014:254.

5. Neuroscience-based nomenclature. http://nbnomenclature.org. Accessed April 12, 2017.

Suicide by cop: What motivates those who choose this method?

CASE Unresponsive and suicidal

Mr. Z, age 25, an unemployed immigrant from Eastern Europe, is found unresponsive at a subway station. Workup in the emergency room reveals a positive urine toxicology for benzodiazepines and a blood alcohol level of 101.6 mg/dL. When Mr. Z regains consciousness the next day, he says that he is suicidal. He recently broke up with his girlfriend and feels worthless, hopeless, and depressed. As a suicide attempt, he took quetiapine and diazepam chased with vodka.

Mr. Z reports a history of suicide attempts. He says he has been suffering from depression most of his life and has been diagnosed with bipolar I disorder and borderline personality disorder. His medication regimen consists of quetiapine, 200 mg/d, and duloxetine, 20 mg/d.

Before immigrating to the United States 5 years ago, he attempted to overdose on his mother’s prescribed diazepam and was in a coma for 2 days. Recently, he stole a bicycle with the intent of provoking the police to kill him. When caught, he deliberately disobeyed the officer’s order and advanced toward the officer in an aggressive manner. However, the officer stopped Mr. Z using a stun gun. Mr. Z reports that he still feels angry that his suicide attempt failed. He is an Orthodox Christian and says he is “very religious.”

[polldaddy:9731423]

The authors’ observations

The means of suicide differ among individuals. Some attempt suicide by themselves; others through the involuntary participation of others, such as the police. This is known as SBC. Other terms include “suicide by means of victim-precipitated homicide,”1 “hetero-suicide,”2 “suicide by proxy,”3 “copicide,”4 and “law enforcement-forced-assisted suicide.”5,6 SBC accounts for 10%7 to 36%6 of police shootings and can cause serious stress for the officers involved and creates a strain between the police and the community.8

SBC was first mentioned as “suicide by means of victim-precipitated homicide.” Wolfgang5 reported 588 cases of police officer-involved shooting in Philadelphia between January 1948 and December 31, 1952, and, concluded that 150 of these cases (26%) fit criteria for what the author termed “victim-precipitated homicide” because the victims involved were the direct precipitants of the situation leading to their death. Wolfgang stated:

Instead of a murderer performing the act of suicide by killing another person who represents the murder’s unconscious, and instead of a suicide representing the desire to kill turned on [the] self, the victim in these victim-precipitated homicide cases is considered to be a suicide prone [individual] who manifests his desire to destroy [him]self by engaging another person to perform the act.

The term “SBC” was coined in 1983 by Karl Harris, a Los Angeles County medical examiner.8 The social repercussions of this modality attracts media attention because of its negative social consequences.

Characteristics of SBC

SBC has characteristics similar to other means of suicide; it is more prevalent among men with psychiatric disorders, including major depression, bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, substance use disorders,9 poor stress response skills, recent stressors, and adverse life events,10 and history of suicide attempts.

Psychosocial characteristics include:

- mean age 31.8 years1

- male sex (98%)

- white (52%)

- approximately 40% involve some form of relationship conflict.6

In psychological autopsy studies, an estimated 70.5% of those involved in a SBC incident had ≥1 stressful life events,1 including terminal illness, loss of a job, a lawsuit, or domestic issues. However, the reason is unknown for the remaining 28% cases.2 Thirty-five percent of those involved in SBC incidents were married, 13.5% divorced, and 46.7% single.1 Seventy-seven percent had low socioeconomic status,11 with 49.3% unemployed at the time of the SBC incident.1

Pathological characteristics of SBC and other suicide means are similar. Among SBC cases, 39% had previously attempted suicide6; 56% have a psychiatric or chronic medical comorbidity. Alcohol and drug abuse were reported among 56% of individuals, and 66% had a criminal history.6 Additionally, comorbid psychiatric disorders, especially those of the impulsive and emotionally unstable types, such as borderline and antisocial personality disorder, have been found to play a major role in SBC incidents.12

Individual suicide vs SBC

Religious beliefs. The term “religiosity” is used to define an individual’s idiosyncratic religious belief or personal religious philosophy reconciling the concept of death by suicide and the afterlife. Although there are no studies that specifically reference the relationship between SBC and religiosity, religious belief and affiliation appear to be strong motivating factors. SBC victims might have an idiosyncratic view of religion related death by suicide. Whether suicide is performed while under delusional belief about God, the devil, or being possessed by demons,13 or to avoid the moral prohibition of most religious faiths in regard to suicide,6 the degree of religiosity in SBC is an important area for future research.

Mr. Z stated that his strong religious faith as an Orthodox Christian motivated the attempted SBC. He tried to provoke the officer to kill him, because as a devout Orthodox Christian, it is against his religious beliefs to kill himself. He reasoned that, because his beliefs preclude him from performing the suicidal act on his own,6,14 having an officer pull the trigger would relieve him from committing what he perceived as a sin.6

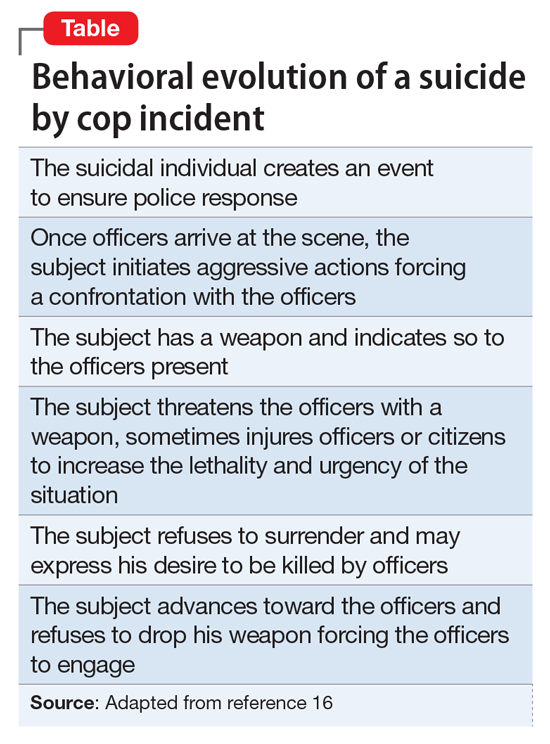

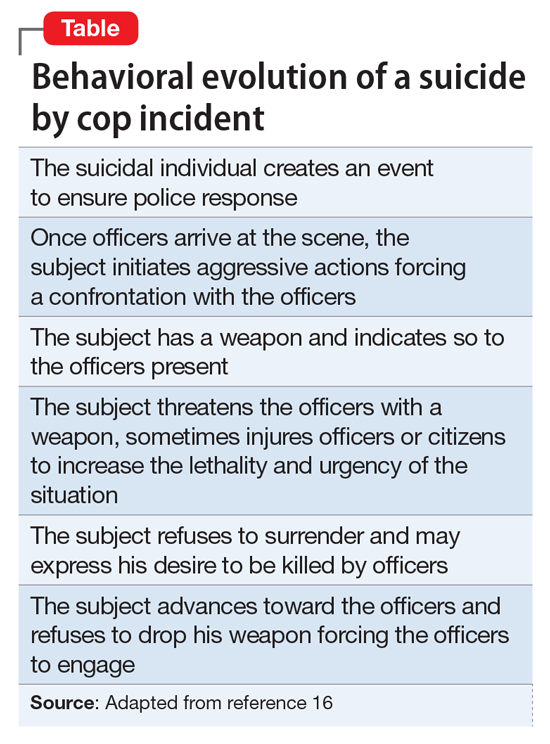

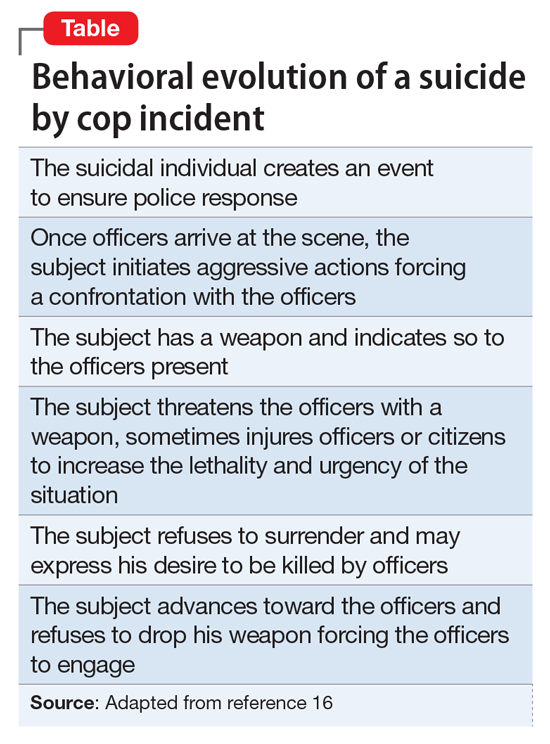

Lethal vs danger. Another difference is the level of urgency that individuals create around them when attempting SBC. Homant and Kennedy15 see this in terms of 2 ideas: lethal and danger. Lethal refers to the degree of harm posed toward the suicidal individual. Danger is the degree of harm posed by the suicidal individual toward others (ie, police officers, bystanders, hostages, family members, a spouse, etc.). SBC often is more dangerous and more lethal than other methods of suicide. SBC individuals might threaten the lives of others to provoke the police into using deadly force, such as aiming or brandishing a gun or weapon at police officers or bystanders, increasing the lethality and dangerousness of the situation. Individuals engaging in SBC might shoot or kill others to create a confrontation with the police in order to be killed in the process (Table16).

Instrumental vs expressive goals

Mohandie and Meloy6 identified 2 primary goals of those involved in SBC events: instrumental and expressive. Individuals in the instrumental category are:

- attempting to escape or avoid the consequences of criminal or shameful actions

- using the forced confrontation with police to reconcile a failed relationship

- hoping to avoid the exclusion clauses of life insurance policies

- rationalizing that while it may be morally wrong to commit suicide, being killed resolves the spiritual problem of suicide

- seeking what they believe to be a very effective and lethal means of accomplishing death.

An expressive goal is more personal and includes individuals who use the confrontation with the police to communicate:

- hopelessness, depression, and desperation

- a statement about their ultimate identification as victims

- their need to “save face” by dying or being forcibly overwhelmed rather than surrendering

- their intense power needs, rage, and revenge

- their need to draw attention to an important personal issue.

Mr. Z chose what he believed to be an efficiently lethal way of dying in accord with his religious faith, knowing that a confrontation with the police could have a fatal ending. This case represents an instrumental motivation to die by SBC that was religiously motivated.

[polldaddy:9731428]

The authors’ observations

SBC presents a specific and serious challenge for law enforcement personnel, and should be approached in a manner different than other crisis situations. Because many individuals engaging in SBC have a history of mental illness, officers with training in handling individuals with psychiatric disorders—known as Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) in many areas—should be deployed as first responders. CITs have been shown to:

- reduce arrest rates of individuals with psychiatric disorders

- increase referral rates to appropriate treatment

- decrease police injuries when responding to calls

- decrease the need for escalation with specialized tactical response teams, such as Special Weapons And Tactics.17

Identification of SBC behavior is crucial during police response. Indicators of a SBC include:

- refusal to comply with police order

- refusal to surrender

- lack of interest in getting out of a barricade or hostage situation alive.18

In approaching a SBC incident, responding officers should be non-confrontational and try to talk to the suicidal individual.8 If force is needed to resolve the crisis, non-lethal measures should be used first.8 Law enforcement and mental health professionals should suspect a SBC situation in individuals who have had prior police contact and are exhibiting behaviors outlined in the Table.16

Once suicidality is identified, it should be treated promptly. Patients who are at imminent risk to themselves or others should be hospitalized to maintain their safety. Similar to other suicide modalities, the primary risk factor for SBC is untreated or inadequately treated psychiatric illness. Therefore, the crux of managing SBC involves identifying and treating the underlying mental disorder.

Pharmacological treatment should be guided by the patient’s symptoms and psychiatric diagnosis. For suicidal behavior associated with bipolar depression and other affective disorders, lithium has evidence of reducing suicidality. Studies have shown a 5.5-fold reduction in suicide risk and a >13-fold reduction in completed suicides with lithium treatment.19 In patients with schizophrenia, clozapine has been shown to reduce suicide risk and is the only FDA-approved agent for this indication.19 Although antidepressants can effectively treat depression, there are no studies that show that 1 antidepressant is more effective than others in reducing suicidality. This might be because of the long latency period between treatment initiation and symptom relief. Ketamine, an N-methyl-

OUTCOME Medication adjustment

After Mr. Z is medically stable, he is voluntarily transferred to the inpatient psychiatric unit where he is stabilized on quetiapine, 200 mg/d, and duloxetine, 60 mg/d, and attends daily group activity, milieu, and individual therapy. Because of Mr. Z’s chronic affective instability and suicidality, we consider lithium for its anti-suicide effects, but decide against it because of lithium’s high lethality in an overdose and Mr. Z’s history of poor compliance and alcohol use.

Because of Mr. Z’s socioeconomic challenges, it is necessary to contact his extended family and social support system to be part of treatment and safety planning. After a week on the psychiatric unit, his mood symptoms stabilize and he is discharged to his family and friends in the area, with a short supply of quetiapine and duloxetine, and free follow-up care within 3 days of discharge. His mood is euthymic; his affect is broad range; his thought process is coherent and logical; he denies suicidal ideation; and can verbalize a logical and concrete safety plan. His support system assures us that Mr. Z will follow up with his appointments.

His DSM-522 discharge diagnoses are borderline personality disorder, bipolar I disorder, and suicidal behavior disorder, current.

The authors’ observations

SBC increases friction and mistrust between the police and the public, traumatizes officers who are forced to use deadly measures, and results in the death of the suicidal individual. As mental health professionals, we need to be aware of this form of suicide in our screening assessment. Training police to differentiate violent offenders from psychiatric patients could reduce the number of SBCs.9 As shown by the CIT model, educating officers on behaviors indicating a mental illness could lead to more psychiatric admissions rather than incarceration17 or death. We advocate for continuous collaborative work and cross training between the police and mental health professionals and for more research on the link between religiosity and the motivation to die by SBC, because there appears to be a not-yet quantified but strong link between them.

1. Hutson HR, Anglin D, Yarbrough J, et al. Suicide by cop. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32(6):665-669.

2. Foote WE. Victim-precipitated homicide. In: Hall HV, ed. Lethal violence: a sourcebook on fatal domestic, acquaintance and stranger violence. London, United Kingdom: CRC Press; 1999:175-199.

3. Keram EA, Farrell BJ. Suicide by cop: issues in outcome and analysis. In: Sheehan DC, Warren JI, eds. Suicide and law enforcement. Quantico, VA: FBI Academy; 2001:587-597.

4. Violanti JM, Drylie JJ. Copicide: concepts, cases, and controversies of suicide by cop. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, LTD; 2008.

5. Wolfgang ME. Suicide by means of victim-precipitated homicide. J Clin Exp Psychopathol Q Rev Psychiatry Neurol. 1959;20:335-349.

6. Mohandie K, Meloy JR. Clinical and forensic indicators of “suicide by cop.” J Forensic Sci. 2000;45(2):384-389.

7. Wright RK, Davis JH. Studies in the epidemiology of murder a proposed classification system. J Forensic Sci. 1977;22(2):464-470.

8. Miller L. Suicide by cop: causes, reactions, and practical intervention strategies. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2006;8(3):165-174.

9. Dewey L, Allwood M, Fava J, et al. Suicide by cop: clinical risks and subtypes. Arch Suicide Res. 2013;17(4):448-461.

10. Foster T, Gillespie K, McClelland R, et al. Risk factors for suicide independent of DSM-III-R Axis I disorder. Case-control psychological autopsy study in Northern Ireland. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:175-179.

11. Lindsay M, Lester D. Criteria for suicide-by-cop incidents. Psychol Rep. 2008;102(2):603-605.

12. Cheng AT, Mann AH, Chan KA. Personality disorder and suicide. A case-control study. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:441-446.

13. Mohandie K, Meloy JR, Collins PI. Suicide by cop among officer‐involved shooting cases. J Forensic Sci. 2009;54(2):456-462.

14. Falk J, Riepert T, Rothschild MA. A case of suicide-by-cop. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2004;6(3):194-196.

15. Homant RJ, Kennedy DB. Suicide by police: a proposed typology of law enforcement officer-assisted suicide. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management. 2000;23(3):339-355.

16. Lester D. Suicide as a staged performance. Comprehensive Psychology. 2015:4(1):1-6.

17. SpringerBriefs in psychology. Best practices for those with psychiatric disorder in the criminal justice system. In: Walker LE, Pann JM, Shapiro DL, et al. Best practices in law enforcement crisis Interventions with those with psychiatric disorder. 2015;11-18.

18. Homant RJ, Kennedy DB, Hupp R. Real and perceived danger in police officer assisted suicide. J Crim Justice. 2000;28(1):43-52.

19. Ernst CL, Goldberg JF. Antisuicide properties of psychotropic drugs: a critical review. Harv Review Psychiatry. 2004;12(1):14-41.

20. Al Jurdi RK, Swann A, Mathew SJ. Psychopharmacological agents and suicide risk reduction: ketamine and other approaches. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(10):81.

21. Fink M, Kellner CH, McCall WV. The role of ECT in suicide prevention. Journal ECT. 2014;30(1):5-9.

22. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

CASE Unresponsive and suicidal

Mr. Z, age 25, an unemployed immigrant from Eastern Europe, is found unresponsive at a subway station. Workup in the emergency room reveals a positive urine toxicology for benzodiazepines and a blood alcohol level of 101.6 mg/dL. When Mr. Z regains consciousness the next day, he says that he is suicidal. He recently broke up with his girlfriend and feels worthless, hopeless, and depressed. As a suicide attempt, he took quetiapine and diazepam chased with vodka.

Mr. Z reports a history of suicide attempts. He says he has been suffering from depression most of his life and has been diagnosed with bipolar I disorder and borderline personality disorder. His medication regimen consists of quetiapine, 200 mg/d, and duloxetine, 20 mg/d.

Before immigrating to the United States 5 years ago, he attempted to overdose on his mother’s prescribed diazepam and was in a coma for 2 days. Recently, he stole a bicycle with the intent of provoking the police to kill him. When caught, he deliberately disobeyed the officer’s order and advanced toward the officer in an aggressive manner. However, the officer stopped Mr. Z using a stun gun. Mr. Z reports that he still feels angry that his suicide attempt failed. He is an Orthodox Christian and says he is “very religious.”

[polldaddy:9731423]

The authors’ observations

The means of suicide differ among individuals. Some attempt suicide by themselves; others through the involuntary participation of others, such as the police. This is known as SBC. Other terms include “suicide by means of victim-precipitated homicide,”1 “hetero-suicide,”2 “suicide by proxy,”3 “copicide,”4 and “law enforcement-forced-assisted suicide.”5,6 SBC accounts for 10%7 to 36%6 of police shootings and can cause serious stress for the officers involved and creates a strain between the police and the community.8

SBC was first mentioned as “suicide by means of victim-precipitated homicide.” Wolfgang5 reported 588 cases of police officer-involved shooting in Philadelphia between January 1948 and December 31, 1952, and, concluded that 150 of these cases (26%) fit criteria for what the author termed “victim-precipitated homicide” because the victims involved were the direct precipitants of the situation leading to their death. Wolfgang stated:

Instead of a murderer performing the act of suicide by killing another person who represents the murder’s unconscious, and instead of a suicide representing the desire to kill turned on [the] self, the victim in these victim-precipitated homicide cases is considered to be a suicide prone [individual] who manifests his desire to destroy [him]self by engaging another person to perform the act.

The term “SBC” was coined in 1983 by Karl Harris, a Los Angeles County medical examiner.8 The social repercussions of this modality attracts media attention because of its negative social consequences.

Characteristics of SBC

SBC has characteristics similar to other means of suicide; it is more prevalent among men with psychiatric disorders, including major depression, bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, substance use disorders,9 poor stress response skills, recent stressors, and adverse life events,10 and history of suicide attempts.

Psychosocial characteristics include:

- mean age 31.8 years1

- male sex (98%)

- white (52%)

- approximately 40% involve some form of relationship conflict.6

In psychological autopsy studies, an estimated 70.5% of those involved in a SBC incident had ≥1 stressful life events,1 including terminal illness, loss of a job, a lawsuit, or domestic issues. However, the reason is unknown for the remaining 28% cases.2 Thirty-five percent of those involved in SBC incidents were married, 13.5% divorced, and 46.7% single.1 Seventy-seven percent had low socioeconomic status,11 with 49.3% unemployed at the time of the SBC incident.1

Pathological characteristics of SBC and other suicide means are similar. Among SBC cases, 39% had previously attempted suicide6; 56% have a psychiatric or chronic medical comorbidity. Alcohol and drug abuse were reported among 56% of individuals, and 66% had a criminal history.6 Additionally, comorbid psychiatric disorders, especially those of the impulsive and emotionally unstable types, such as borderline and antisocial personality disorder, have been found to play a major role in SBC incidents.12

Individual suicide vs SBC

Religious beliefs. The term “religiosity” is used to define an individual’s idiosyncratic religious belief or personal religious philosophy reconciling the concept of death by suicide and the afterlife. Although there are no studies that specifically reference the relationship between SBC and religiosity, religious belief and affiliation appear to be strong motivating factors. SBC victims might have an idiosyncratic view of religion related death by suicide. Whether suicide is performed while under delusional belief about God, the devil, or being possessed by demons,13 or to avoid the moral prohibition of most religious faiths in regard to suicide,6 the degree of religiosity in SBC is an important area for future research.

Mr. Z stated that his strong religious faith as an Orthodox Christian motivated the attempted SBC. He tried to provoke the officer to kill him, because as a devout Orthodox Christian, it is against his religious beliefs to kill himself. He reasoned that, because his beliefs preclude him from performing the suicidal act on his own,6,14 having an officer pull the trigger would relieve him from committing what he perceived as a sin.6

Lethal vs danger. Another difference is the level of urgency that individuals create around them when attempting SBC. Homant and Kennedy15 see this in terms of 2 ideas: lethal and danger. Lethal refers to the degree of harm posed toward the suicidal individual. Danger is the degree of harm posed by the suicidal individual toward others (ie, police officers, bystanders, hostages, family members, a spouse, etc.). SBC often is more dangerous and more lethal than other methods of suicide. SBC individuals might threaten the lives of others to provoke the police into using deadly force, such as aiming or brandishing a gun or weapon at police officers or bystanders, increasing the lethality and dangerousness of the situation. Individuals engaging in SBC might shoot or kill others to create a confrontation with the police in order to be killed in the process (Table16).

Instrumental vs expressive goals

Mohandie and Meloy6 identified 2 primary goals of those involved in SBC events: instrumental and expressive. Individuals in the instrumental category are:

- attempting to escape or avoid the consequences of criminal or shameful actions

- using the forced confrontation with police to reconcile a failed relationship

- hoping to avoid the exclusion clauses of life insurance policies

- rationalizing that while it may be morally wrong to commit suicide, being killed resolves the spiritual problem of suicide

- seeking what they believe to be a very effective and lethal means of accomplishing death.

An expressive goal is more personal and includes individuals who use the confrontation with the police to communicate:

- hopelessness, depression, and desperation

- a statement about their ultimate identification as victims

- their need to “save face” by dying or being forcibly overwhelmed rather than surrendering

- their intense power needs, rage, and revenge

- their need to draw attention to an important personal issue.

Mr. Z chose what he believed to be an efficiently lethal way of dying in accord with his religious faith, knowing that a confrontation with the police could have a fatal ending. This case represents an instrumental motivation to die by SBC that was religiously motivated.

[polldaddy:9731428]

The authors’ observations

SBC presents a specific and serious challenge for law enforcement personnel, and should be approached in a manner different than other crisis situations. Because many individuals engaging in SBC have a history of mental illness, officers with training in handling individuals with psychiatric disorders—known as Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) in many areas—should be deployed as first responders. CITs have been shown to:

- reduce arrest rates of individuals with psychiatric disorders

- increase referral rates to appropriate treatment

- decrease police injuries when responding to calls

- decrease the need for escalation with specialized tactical response teams, such as Special Weapons And Tactics.17

Identification of SBC behavior is crucial during police response. Indicators of a SBC include:

- refusal to comply with police order

- refusal to surrender

- lack of interest in getting out of a barricade or hostage situation alive.18

In approaching a SBC incident, responding officers should be non-confrontational and try to talk to the suicidal individual.8 If force is needed to resolve the crisis, non-lethal measures should be used first.8 Law enforcement and mental health professionals should suspect a SBC situation in individuals who have had prior police contact and are exhibiting behaviors outlined in the Table.16

Once suicidality is identified, it should be treated promptly. Patients who are at imminent risk to themselves or others should be hospitalized to maintain their safety. Similar to other suicide modalities, the primary risk factor for SBC is untreated or inadequately treated psychiatric illness. Therefore, the crux of managing SBC involves identifying and treating the underlying mental disorder.

Pharmacological treatment should be guided by the patient’s symptoms and psychiatric diagnosis. For suicidal behavior associated with bipolar depression and other affective disorders, lithium has evidence of reducing suicidality. Studies have shown a 5.5-fold reduction in suicide risk and a >13-fold reduction in completed suicides with lithium treatment.19 In patients with schizophrenia, clozapine has been shown to reduce suicide risk and is the only FDA-approved agent for this indication.19 Although antidepressants can effectively treat depression, there are no studies that show that 1 antidepressant is more effective than others in reducing suicidality. This might be because of the long latency period between treatment initiation and symptom relief. Ketamine, an N-methyl-

OUTCOME Medication adjustment

After Mr. Z is medically stable, he is voluntarily transferred to the inpatient psychiatric unit where he is stabilized on quetiapine, 200 mg/d, and duloxetine, 60 mg/d, and attends daily group activity, milieu, and individual therapy. Because of Mr. Z’s chronic affective instability and suicidality, we consider lithium for its anti-suicide effects, but decide against it because of lithium’s high lethality in an overdose and Mr. Z’s history of poor compliance and alcohol use.

Because of Mr. Z’s socioeconomic challenges, it is necessary to contact his extended family and social support system to be part of treatment and safety planning. After a week on the psychiatric unit, his mood symptoms stabilize and he is discharged to his family and friends in the area, with a short supply of quetiapine and duloxetine, and free follow-up care within 3 days of discharge. His mood is euthymic; his affect is broad range; his thought process is coherent and logical; he denies suicidal ideation; and can verbalize a logical and concrete safety plan. His support system assures us that Mr. Z will follow up with his appointments.

His DSM-522 discharge diagnoses are borderline personality disorder, bipolar I disorder, and suicidal behavior disorder, current.

The authors’ observations

SBC increases friction and mistrust between the police and the public, traumatizes officers who are forced to use deadly measures, and results in the death of the suicidal individual. As mental health professionals, we need to be aware of this form of suicide in our screening assessment. Training police to differentiate violent offenders from psychiatric patients could reduce the number of SBCs.9 As shown by the CIT model, educating officers on behaviors indicating a mental illness could lead to more psychiatric admissions rather than incarceration17 or death. We advocate for continuous collaborative work and cross training between the police and mental health professionals and for more research on the link between religiosity and the motivation to die by SBC, because there appears to be a not-yet quantified but strong link between them.

CASE Unresponsive and suicidal

Mr. Z, age 25, an unemployed immigrant from Eastern Europe, is found unresponsive at a subway station. Workup in the emergency room reveals a positive urine toxicology for benzodiazepines and a blood alcohol level of 101.6 mg/dL. When Mr. Z regains consciousness the next day, he says that he is suicidal. He recently broke up with his girlfriend and feels worthless, hopeless, and depressed. As a suicide attempt, he took quetiapine and diazepam chased with vodka.

Mr. Z reports a history of suicide attempts. He says he has been suffering from depression most of his life and has been diagnosed with bipolar I disorder and borderline personality disorder. His medication regimen consists of quetiapine, 200 mg/d, and duloxetine, 20 mg/d.

Before immigrating to the United States 5 years ago, he attempted to overdose on his mother’s prescribed diazepam and was in a coma for 2 days. Recently, he stole a bicycle with the intent of provoking the police to kill him. When caught, he deliberately disobeyed the officer’s order and advanced toward the officer in an aggressive manner. However, the officer stopped Mr. Z using a stun gun. Mr. Z reports that he still feels angry that his suicide attempt failed. He is an Orthodox Christian and says he is “very religious.”

[polldaddy:9731423]

The authors’ observations

The means of suicide differ among individuals. Some attempt suicide by themselves; others through the involuntary participation of others, such as the police. This is known as SBC. Other terms include “suicide by means of victim-precipitated homicide,”1 “hetero-suicide,”2 “suicide by proxy,”3 “copicide,”4 and “law enforcement-forced-assisted suicide.”5,6 SBC accounts for 10%7 to 36%6 of police shootings and can cause serious stress for the officers involved and creates a strain between the police and the community.8

SBC was first mentioned as “suicide by means of victim-precipitated homicide.” Wolfgang5 reported 588 cases of police officer-involved shooting in Philadelphia between January 1948 and December 31, 1952, and, concluded that 150 of these cases (26%) fit criteria for what the author termed “victim-precipitated homicide” because the victims involved were the direct precipitants of the situation leading to their death. Wolfgang stated:

Instead of a murderer performing the act of suicide by killing another person who represents the murder’s unconscious, and instead of a suicide representing the desire to kill turned on [the] self, the victim in these victim-precipitated homicide cases is considered to be a suicide prone [individual] who manifests his desire to destroy [him]self by engaging another person to perform the act.

The term “SBC” was coined in 1983 by Karl Harris, a Los Angeles County medical examiner.8 The social repercussions of this modality attracts media attention because of its negative social consequences.

Characteristics of SBC

SBC has characteristics similar to other means of suicide; it is more prevalent among men with psychiatric disorders, including major depression, bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, substance use disorders,9 poor stress response skills, recent stressors, and adverse life events,10 and history of suicide attempts.

Psychosocial characteristics include:

- mean age 31.8 years1

- male sex (98%)

- white (52%)

- approximately 40% involve some form of relationship conflict.6

In psychological autopsy studies, an estimated 70.5% of those involved in a SBC incident had ≥1 stressful life events,1 including terminal illness, loss of a job, a lawsuit, or domestic issues. However, the reason is unknown for the remaining 28% cases.2 Thirty-five percent of those involved in SBC incidents were married, 13.5% divorced, and 46.7% single.1 Seventy-seven percent had low socioeconomic status,11 with 49.3% unemployed at the time of the SBC incident.1

Pathological characteristics of SBC and other suicide means are similar. Among SBC cases, 39% had previously attempted suicide6; 56% have a psychiatric or chronic medical comorbidity. Alcohol and drug abuse were reported among 56% of individuals, and 66% had a criminal history.6 Additionally, comorbid psychiatric disorders, especially those of the impulsive and emotionally unstable types, such as borderline and antisocial personality disorder, have been found to play a major role in SBC incidents.12

Individual suicide vs SBC

Religious beliefs. The term “religiosity” is used to define an individual’s idiosyncratic religious belief or personal religious philosophy reconciling the concept of death by suicide and the afterlife. Although there are no studies that specifically reference the relationship between SBC and religiosity, religious belief and affiliation appear to be strong motivating factors. SBC victims might have an idiosyncratic view of religion related death by suicide. Whether suicide is performed while under delusional belief about God, the devil, or being possessed by demons,13 or to avoid the moral prohibition of most religious faiths in regard to suicide,6 the degree of religiosity in SBC is an important area for future research.

Mr. Z stated that his strong religious faith as an Orthodox Christian motivated the attempted SBC. He tried to provoke the officer to kill him, because as a devout Orthodox Christian, it is against his religious beliefs to kill himself. He reasoned that, because his beliefs preclude him from performing the suicidal act on his own,6,14 having an officer pull the trigger would relieve him from committing what he perceived as a sin.6

Lethal vs danger. Another difference is the level of urgency that individuals create around them when attempting SBC. Homant and Kennedy15 see this in terms of 2 ideas: lethal and danger. Lethal refers to the degree of harm posed toward the suicidal individual. Danger is the degree of harm posed by the suicidal individual toward others (ie, police officers, bystanders, hostages, family members, a spouse, etc.). SBC often is more dangerous and more lethal than other methods of suicide. SBC individuals might threaten the lives of others to provoke the police into using deadly force, such as aiming or brandishing a gun or weapon at police officers or bystanders, increasing the lethality and dangerousness of the situation. Individuals engaging in SBC might shoot or kill others to create a confrontation with the police in order to be killed in the process (Table16).

Instrumental vs expressive goals

Mohandie and Meloy6 identified 2 primary goals of those involved in SBC events: instrumental and expressive. Individuals in the instrumental category are:

- attempting to escape or avoid the consequences of criminal or shameful actions

- using the forced confrontation with police to reconcile a failed relationship

- hoping to avoid the exclusion clauses of life insurance policies

- rationalizing that while it may be morally wrong to commit suicide, being killed resolves the spiritual problem of suicide

- seeking what they believe to be a very effective and lethal means of accomplishing death.

An expressive goal is more personal and includes individuals who use the confrontation with the police to communicate:

- hopelessness, depression, and desperation

- a statement about their ultimate identification as victims

- their need to “save face” by dying or being forcibly overwhelmed rather than surrendering

- their intense power needs, rage, and revenge

- their need to draw attention to an important personal issue.

Mr. Z chose what he believed to be an efficiently lethal way of dying in accord with his religious faith, knowing that a confrontation with the police could have a fatal ending. This case represents an instrumental motivation to die by SBC that was religiously motivated.

[polldaddy:9731428]

The authors’ observations

SBC presents a specific and serious challenge for law enforcement personnel, and should be approached in a manner different than other crisis situations. Because many individuals engaging in SBC have a history of mental illness, officers with training in handling individuals with psychiatric disorders—known as Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) in many areas—should be deployed as first responders. CITs have been shown to:

- reduce arrest rates of individuals with psychiatric disorders

- increase referral rates to appropriate treatment

- decrease police injuries when responding to calls

- decrease the need for escalation with specialized tactical response teams, such as Special Weapons And Tactics.17

Identification of SBC behavior is crucial during police response. Indicators of a SBC include:

- refusal to comply with police order

- refusal to surrender

- lack of interest in getting out of a barricade or hostage situation alive.18

In approaching a SBC incident, responding officers should be non-confrontational and try to talk to the suicidal individual.8 If force is needed to resolve the crisis, non-lethal measures should be used first.8 Law enforcement and mental health professionals should suspect a SBC situation in individuals who have had prior police contact and are exhibiting behaviors outlined in the Table.16

Once suicidality is identified, it should be treated promptly. Patients who are at imminent risk to themselves or others should be hospitalized to maintain their safety. Similar to other suicide modalities, the primary risk factor for SBC is untreated or inadequately treated psychiatric illness. Therefore, the crux of managing SBC involves identifying and treating the underlying mental disorder.

Pharmacological treatment should be guided by the patient’s symptoms and psychiatric diagnosis. For suicidal behavior associated with bipolar depression and other affective disorders, lithium has evidence of reducing suicidality. Studies have shown a 5.5-fold reduction in suicide risk and a >13-fold reduction in completed suicides with lithium treatment.19 In patients with schizophrenia, clozapine has been shown to reduce suicide risk and is the only FDA-approved agent for this indication.19 Although antidepressants can effectively treat depression, there are no studies that show that 1 antidepressant is more effective than others in reducing suicidality. This might be because of the long latency period between treatment initiation and symptom relief. Ketamine, an N-methyl-

OUTCOME Medication adjustment

After Mr. Z is medically stable, he is voluntarily transferred to the inpatient psychiatric unit where he is stabilized on quetiapine, 200 mg/d, and duloxetine, 60 mg/d, and attends daily group activity, milieu, and individual therapy. Because of Mr. Z’s chronic affective instability and suicidality, we consider lithium for its anti-suicide effects, but decide against it because of lithium’s high lethality in an overdose and Mr. Z’s history of poor compliance and alcohol use.

Because of Mr. Z’s socioeconomic challenges, it is necessary to contact his extended family and social support system to be part of treatment and safety planning. After a week on the psychiatric unit, his mood symptoms stabilize and he is discharged to his family and friends in the area, with a short supply of quetiapine and duloxetine, and free follow-up care within 3 days of discharge. His mood is euthymic; his affect is broad range; his thought process is coherent and logical; he denies suicidal ideation; and can verbalize a logical and concrete safety plan. His support system assures us that Mr. Z will follow up with his appointments.

His DSM-522 discharge diagnoses are borderline personality disorder, bipolar I disorder, and suicidal behavior disorder, current.

The authors’ observations

SBC increases friction and mistrust between the police and the public, traumatizes officers who are forced to use deadly measures, and results in the death of the suicidal individual. As mental health professionals, we need to be aware of this form of suicide in our screening assessment. Training police to differentiate violent offenders from psychiatric patients could reduce the number of SBCs.9 As shown by the CIT model, educating officers on behaviors indicating a mental illness could lead to more psychiatric admissions rather than incarceration17 or death. We advocate for continuous collaborative work and cross training between the police and mental health professionals and for more research on the link between religiosity and the motivation to die by SBC, because there appears to be a not-yet quantified but strong link between them.

1. Hutson HR, Anglin D, Yarbrough J, et al. Suicide by cop. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32(6):665-669.

2. Foote WE. Victim-precipitated homicide. In: Hall HV, ed. Lethal violence: a sourcebook on fatal domestic, acquaintance and stranger violence. London, United Kingdom: CRC Press; 1999:175-199.

3. Keram EA, Farrell BJ. Suicide by cop: issues in outcome and analysis. In: Sheehan DC, Warren JI, eds. Suicide and law enforcement. Quantico, VA: FBI Academy; 2001:587-597.

4. Violanti JM, Drylie JJ. Copicide: concepts, cases, and controversies of suicide by cop. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, LTD; 2008.

5. Wolfgang ME. Suicide by means of victim-precipitated homicide. J Clin Exp Psychopathol Q Rev Psychiatry Neurol. 1959;20:335-349.

6. Mohandie K, Meloy JR. Clinical and forensic indicators of “suicide by cop.” J Forensic Sci. 2000;45(2):384-389.

7. Wright RK, Davis JH. Studies in the epidemiology of murder a proposed classification system. J Forensic Sci. 1977;22(2):464-470.

8. Miller L. Suicide by cop: causes, reactions, and practical intervention strategies. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2006;8(3):165-174.

9. Dewey L, Allwood M, Fava J, et al. Suicide by cop: clinical risks and subtypes. Arch Suicide Res. 2013;17(4):448-461.

10. Foster T, Gillespie K, McClelland R, et al. Risk factors for suicide independent of DSM-III-R Axis I disorder. Case-control psychological autopsy study in Northern Ireland. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:175-179.

11. Lindsay M, Lester D. Criteria for suicide-by-cop incidents. Psychol Rep. 2008;102(2):603-605.

12. Cheng AT, Mann AH, Chan KA. Personality disorder and suicide. A case-control study. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:441-446.

13. Mohandie K, Meloy JR, Collins PI. Suicide by cop among officer‐involved shooting cases. J Forensic Sci. 2009;54(2):456-462.

14. Falk J, Riepert T, Rothschild MA. A case of suicide-by-cop. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2004;6(3):194-196.

15. Homant RJ, Kennedy DB. Suicide by police: a proposed typology of law enforcement officer-assisted suicide. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management. 2000;23(3):339-355.

16. Lester D. Suicide as a staged performance. Comprehensive Psychology. 2015:4(1):1-6.

17. SpringerBriefs in psychology. Best practices for those with psychiatric disorder in the criminal justice system. In: Walker LE, Pann JM, Shapiro DL, et al. Best practices in law enforcement crisis Interventions with those with psychiatric disorder. 2015;11-18.

18. Homant RJ, Kennedy DB, Hupp R. Real and perceived danger in police officer assisted suicide. J Crim Justice. 2000;28(1):43-52.

19. Ernst CL, Goldberg JF. Antisuicide properties of psychotropic drugs: a critical review. Harv Review Psychiatry. 2004;12(1):14-41.

20. Al Jurdi RK, Swann A, Mathew SJ. Psychopharmacological agents and suicide risk reduction: ketamine and other approaches. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(10):81.

21. Fink M, Kellner CH, McCall WV. The role of ECT in suicide prevention. Journal ECT. 2014;30(1):5-9.

22. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

1. Hutson HR, Anglin D, Yarbrough J, et al. Suicide by cop. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32(6):665-669.

2. Foote WE. Victim-precipitated homicide. In: Hall HV, ed. Lethal violence: a sourcebook on fatal domestic, acquaintance and stranger violence. London, United Kingdom: CRC Press; 1999:175-199.

3. Keram EA, Farrell BJ. Suicide by cop: issues in outcome and analysis. In: Sheehan DC, Warren JI, eds. Suicide and law enforcement. Quantico, VA: FBI Academy; 2001:587-597.

4. Violanti JM, Drylie JJ. Copicide: concepts, cases, and controversies of suicide by cop. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, LTD; 2008.

5. Wolfgang ME. Suicide by means of victim-precipitated homicide. J Clin Exp Psychopathol Q Rev Psychiatry Neurol. 1959;20:335-349.

6. Mohandie K, Meloy JR. Clinical and forensic indicators of “suicide by cop.” J Forensic Sci. 2000;45(2):384-389.

7. Wright RK, Davis JH. Studies in the epidemiology of murder a proposed classification system. J Forensic Sci. 1977;22(2):464-470.

8. Miller L. Suicide by cop: causes, reactions, and practical intervention strategies. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2006;8(3):165-174.

9. Dewey L, Allwood M, Fava J, et al. Suicide by cop: clinical risks and subtypes. Arch Suicide Res. 2013;17(4):448-461.

10. Foster T, Gillespie K, McClelland R, et al. Risk factors for suicide independent of DSM-III-R Axis I disorder. Case-control psychological autopsy study in Northern Ireland. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:175-179.

11. Lindsay M, Lester D. Criteria for suicide-by-cop incidents. Psychol Rep. 2008;102(2):603-605.

12. Cheng AT, Mann AH, Chan KA. Personality disorder and suicide. A case-control study. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:441-446.

13. Mohandie K, Meloy JR, Collins PI. Suicide by cop among officer‐involved shooting cases. J Forensic Sci. 2009;54(2):456-462.

14. Falk J, Riepert T, Rothschild MA. A case of suicide-by-cop. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2004;6(3):194-196.

15. Homant RJ, Kennedy DB. Suicide by police: a proposed typology of law enforcement officer-assisted suicide. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management. 2000;23(3):339-355.

16. Lester D. Suicide as a staged performance. Comprehensive Psychology. 2015:4(1):1-6.

17. SpringerBriefs in psychology. Best practices for those with psychiatric disorder in the criminal justice system. In: Walker LE, Pann JM, Shapiro DL, et al. Best practices in law enforcement crisis Interventions with those with psychiatric disorder. 2015;11-18.

18. Homant RJ, Kennedy DB, Hupp R. Real and perceived danger in police officer assisted suicide. J Crim Justice. 2000;28(1):43-52.

19. Ernst CL, Goldberg JF. Antisuicide properties of psychotropic drugs: a critical review. Harv Review Psychiatry. 2004;12(1):14-41.

20. Al Jurdi RK, Swann A, Mathew SJ. Psychopharmacological agents and suicide risk reduction: ketamine and other approaches. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(10):81.

21. Fink M, Kellner CH, McCall WV. The role of ECT in suicide prevention. Journal ECT. 2014;30(1):5-9.

22. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Opioid abuse

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Reducing CV risk in diabetes: An ADA update

More than 29 million Americans have diabetes, and each year another 1.7 million are given the diagnosis.1 Prediabetes is even more common; over one-third of US adults ages 20 years and older, and more than half of those who are ages 65 and older, have attained this precursor status, representing another 86 million Americans.1

Because the evidence base for the management of diabetes is rapidly expanding, the American Diabetes Association’s (ADA) Professional Practice Committee updates its Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes annually to incorporate new evidence into its recommendations. The 2017 Standards of Care are available at: professional.diabetes.org/jfp.2

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality for people with diabetes, and is the largest contributor to the direct and indirect costs of the disease.2 As a result, all patients with diabetes should have cardiovascular (CV) risk factors, including dyslipidemia, hypertension, smoking, a family history of premature coronary disease, and the presence of albuminuria, assessed at least annually.2 Numerous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of controlling individual CV risk factors in preventing or slowing ASCVD in people with diabetes. Even larger benefits, including reduced ASCVD morbidity and mortality, can be achieved when multiple risk factors are addressed simultaneously.3

To hone your management of CV risks in patients with diabetes, we’ve put together this Q&A pointing out the elements of the ADA’s 2017 Standards of Care that are most relevant to the management of patients at risk for, or with established, ASCVD.

Screening

Since ASCVD so commonly co-occurs with diabetes, should I routinely screen asymptomatic patients with diabetes for heart disease?

No. The current evidence suggests that outcomes are NOT improved by screening people before they develop symptoms of ASCVD,4 and widespread ASCVD screening has not been shown to be cost-effective. Cardiac testing should be reserved for those with typical or atypical symptoms or those with an abnormal resting electrocardiogram (EKG).

Lifestyle modification

What are the benefits of lifestyle interventions?

The benefits include not only lost pounds, but improved mobility, physical and sexual functioning, and health-related quality of life. Recommend that all overweight patients with diabetes take advantage of intensive lifestyle interventions focusing on weight loss through decreased caloric intake and increased physical activity as per the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) trial.5 Although the intensive lifestyle intervention in the Look AHEAD trial did not decrease CV outcomes over 10 years of follow-up, it did improve control of CV risk factors and led to people in the intervention group taking fewer glucose-, blood pressure (BP)-, and lipid-lowering medications than those in the standard care group.

There is no one diet that is recommended for all people with diabetes. Weight reduction often requires intensive intervention. In order for weight loss diets to be sustainable, they must include patient preferences.

People with diabetes should be encouraged to receive individualized medical nutrition therapy (MNT), preferably from a registered dietitian who is well versed in nutritional management for diabetes. Such MNT is associated with a 0.5% to 2% decrease in A1c levels for people with type 2 diabetes.6-9 Specific healthy diets include the Mediterranean, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH), and plant-based diets.

A new lifestyle recommendation in this year’s ADA Standards is that periods of prolonged sitting should be interrupted every 30 minutes with a period of physical activity. This appears to have glycemic benefits.2

Hypertension/BP management

When should I initiate hypertension treatment in patients with diabetes?

Nonpharmacologic therapy is reasonable in people with diabetes and mildly elevated BP (>120/80 mm Hg). If systolic blood pressure (SBP) is confirmed to be >140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) is confirmed to be >90 mm Hg, the ADA recommends initiating pharmacologic therapy along with nonpharmacologic strategies. For patients with confirmed office-based BP >160/100 mm Hg, the ADA advises initiating lifestyle modifications as well as 2 pharmacologic medications (or a single pill combination of agents).2

What is the recommended BP target for patients with diabetes and hypertension?

These patients should be treated with a combination of measures, including lifestyle modification and pharmacologic therapy, to a target BP of <140/90 mm Hg. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown benefits with this target in terms of a reduction in the incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD) events, stroke, and diabetic kidney disease.10,11

A 2012 meta-analysis of randomized trials involving adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and comparing intensive BP targets (≤130 mm Hg SBP and ≤80 mm Hg DBP) with standard targets (≤140-160 mm Hg SBP and ≤85-100 mm Hg DBP) found no significant reduction in mortality or nonfatal MIs associated with more intense BP control. There was a statistically significant 35% relative risk (RR) reduction in stroke with intensive targets, but lower BP was also associated with an increased risk of hypotension and syncope.12

The 2010 Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial,13 which randomized 5518 patients with T2DM at high risk for ASCVD to either a target SBP of <120 mm Hg or 130 to 140 mm Hg, found that the patients with the lower SBP target did not benefit in the primary end point (a composite of nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, and CV death), but did benefit from nominally significant lower rates of total stroke and nonfatal stroke.

Based on these data, the ADA Standards of Care suggest that, “more intensive BP control may be reasonable in certain motivated, ACCORD-like patients (40-79 years of age with prior evidence of CVD or multiple CV risk factors) who have been educated about the added treatment burden, side effects, and costs of more intensive BP control and for patients who prefer to lower their risk of stroke beyond what can be achieved with usual care.”

Another major study, the 2015 Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) trial,14 demonstrated that treating patients with hypertension to a target SBP <120 mm Hg compared to the usual target of <140 mm Hg resulted in a 25% lower RR of the primary outcome (a composite of MI, other acute coronary syndromes, stroke, heart failure, or death from CV causes) and about a 25% reduction in all-cause mortality; however, people with diabetes were not included in the trial, so the applicability of the results to decisions about BP management in patients with diabetes is not known.

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of over 100,000 participants looked at SBP lowering in adults with T2DM and found that each 10-mm Hg reduction in SBP was associated with a significantly lower risk of morbidity, CV events, CHD, stroke, albuminuria, and retinopathy.10 When trials were stratified by mean baseline SBP (<140 mm Hg or ≥140 mm Hg), RRs for outcomes other than stroke, retinopathy, and renal failure were lower in studies with greater baseline SBP.

The latest ADA Standards of Care recommend that a lower BP target of 130/80 mm Hg may be appropriate for patients at high risk of CVD if this target can be achieved without undue treatment burden. A DBP of <80 mm Hg may also be appropriate in certain patients including those with a long life expectancy, CKD, elevated urinary albumin excretion, and those with evidence of CVD or associated risk factors.15 Of note, treating older adults with diabetes to an SBP target of <130 mm Hg has not been shown to improve cardiovascular outcomes,16 and treating to a diastolic target of <70 mm Hg has been associated with a greater risk of mortality.17

What are the current recommended treatment options?

Treatment for hypertension in adults with diabetes without albuminuria should include any of the classes of medications demonstrated to reduce CV events in patients with diabetes, such as:

- angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors,

- angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs),

- thiazide-like diuretics, and

- dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers.

These recommendations are based on evidence suggesting the lack of superiority of ACE inhibitors and ARBs over other classes of antihypertensive agents for the prevention of CV outcomes in all patients with diabetes.18 However, in people with diabetes at high risk for ASCVD and/or with albuminuria, ACE inhibitors and ARBs do reduce ASCVD outcomes and the progression of kidney disease.19-24 Thus, ACE inhibitors and ARBs continue to be recommended as first-line medications for the treatment of hypertension in patients with diabetes and urine albumin/creatinine ratios ≥30 mg/g, as these medications are associated with a reduction in the rate of kidney disease progression.

The use of both an ACE inhibitor and an ARB in combination is not recommended.25,26 For patients treated with ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or diuretics, serum creatinine/estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and serum potassium levels should be monitored.

What are the recommended lifestyle modifications for patients with diabetes and hypertension?

Regular exercise and healthy eating are recommended for all people with diabetes to optimize glycemic control and lose weight (if they are overweight or obese). For patients with hypertension, the DASH diet (available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/dash/) is effective at lowering BP. The DASH diet emphasizes reducing sodium intake, increasing potassium intake, limiting alcohol intake, and increasing physical activity. Specifically, sodium intake should be restricted to <2300 mg/d and patients should consume approximately 8 to 10 servings of fruits and vegetables per day and 2 to 3 servings of low-fat dairy per day. Alcohol should be limited to 2 drinks per day for men and one drink per day for women.

Most adults with diabetes should perform 150 minutes per week of moderate to vigorous exercise, spread over at least 3 days/week. In addition, it is recommended that resistance exercises be performed at least 2 to 3 days/week. Prolonged inactivity is detrimental to health and should be interrupted with activity every 30 minutes.27

Finally, as a part of lifestyle management for all patients with diabetes, smoking cessation is important, as is attention to stress, depression, and anxiety.

Is there an advantage to nighttime dosing of antihypertensive medications?

Yes. Growing evidence suggests that there is an ASCVD benefit to avoiding nocturnal BP dipping. A 2011 RCT of 448 participants with T2DM and hypertension showed a decrease in CV events and mortality during 5.4 years of follow-up if at least one antihypertensive medication was taken at bedtime.28 As a result of this and other evidence,29 consider administering one or more antihypertensive medications at bedtime, although this is not a formal recommendation in the ADA Standards of Care.

Are there any additional issues to be aware of when treating patients with diabetes and hypertension?

Yes. Sometimes patients who have had diabetes for many years have significant orthostatic hypotension secondary to autonomic neuropathy. Postural changes in BP and pulse may require adjustment of BP targets. Home BP self-monitoring and 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring may indicate white-coat or masked hypertension.

Lipid management

What is the current evidence for lipid treatment in diabetes?

Lipid abnormalities are common in people with diabetes and contribute to the overall high risk of ASCVD in these patients. Subgroup analyses of patients in large trials with diabetes30 and trials involving patients with diabetes31 have shown significant improvements in primary and secondary prevention of ASCVD with statin use. A 2008 meta-analysis of 18,686 people with diabetes showed a 9% reduction in all-cause mortality and a 13% reduction in vascular mortality for each 39-mg/dL reduction in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol.32 Absolute reductions in mortality are greatest in those with highest risk, but the benefits of statin therapy are clear for low- and moderate-risk individuals with diabetes, too.33,34 As a result, statins are the medications of choice for lipid lowering and CV risk reduction and should be used in addition to lifestyle management.

Who should get a statin, and how do I choose the optimum dosage?

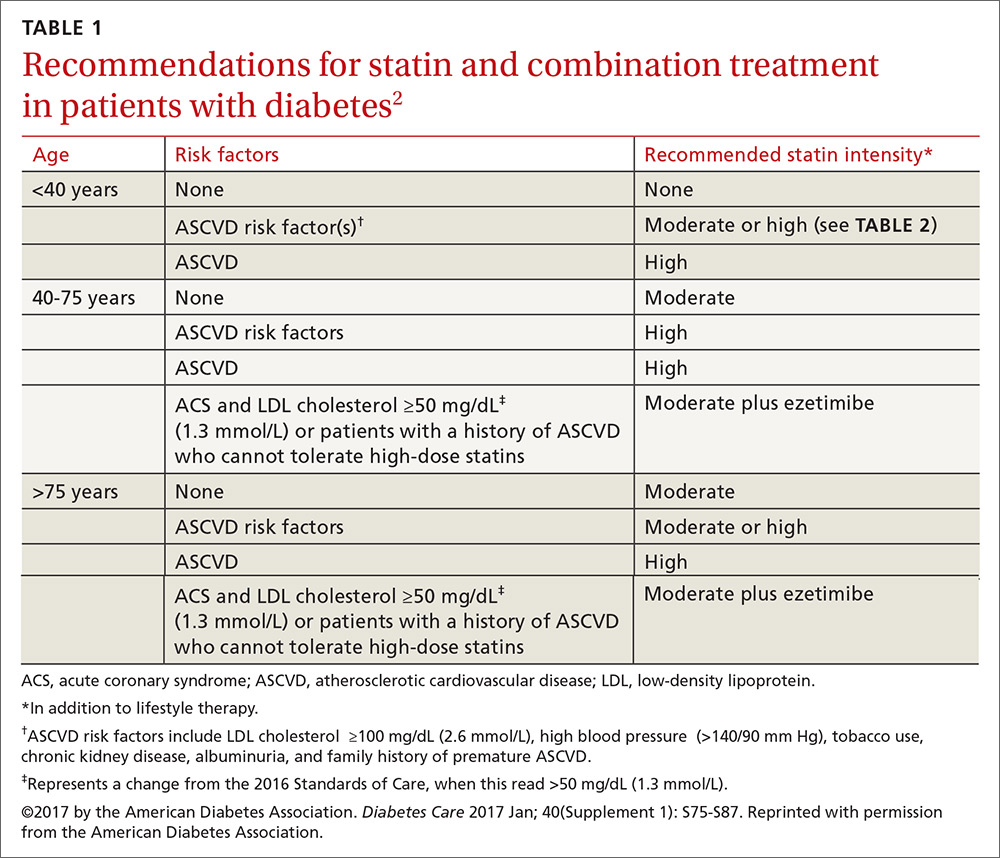

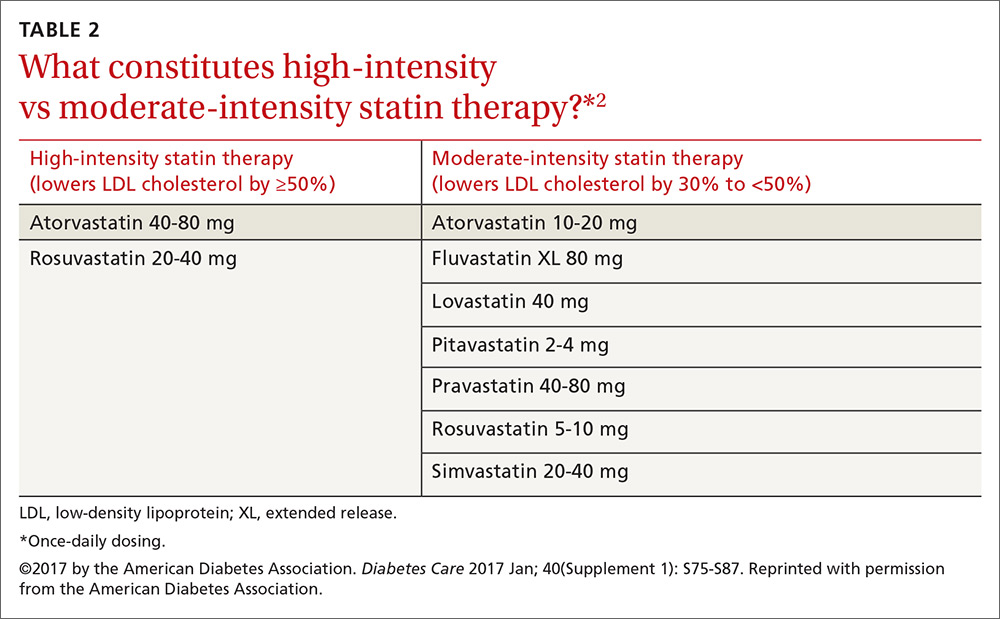

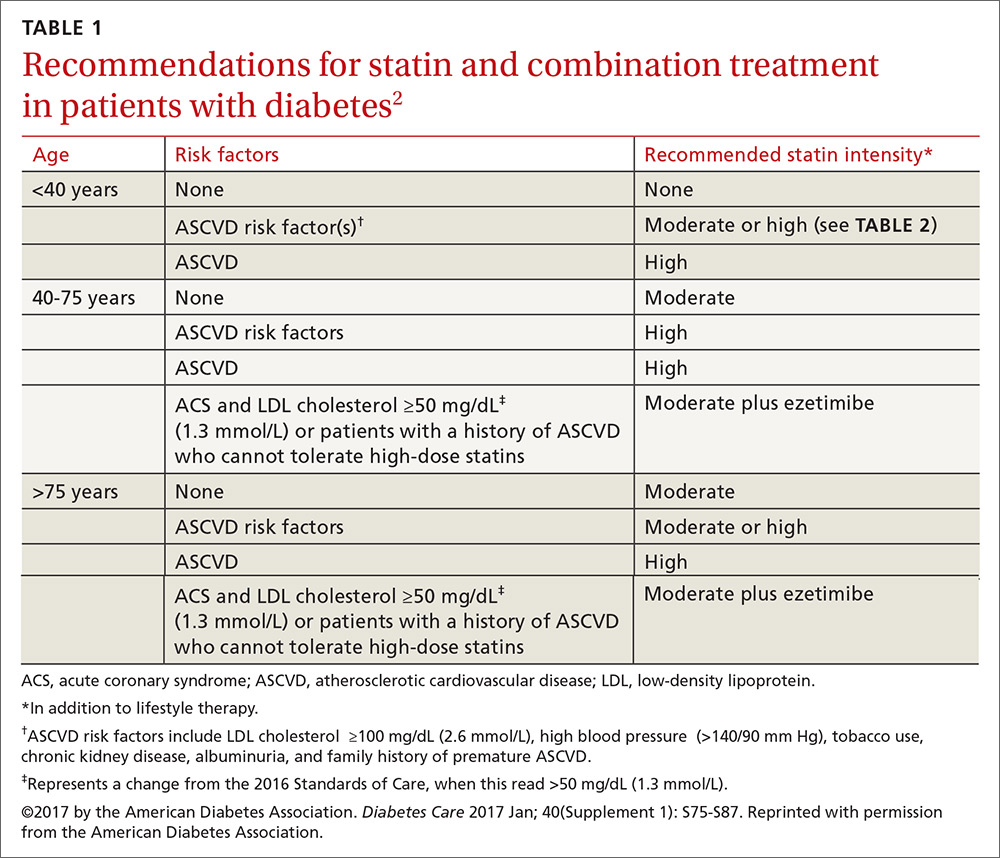

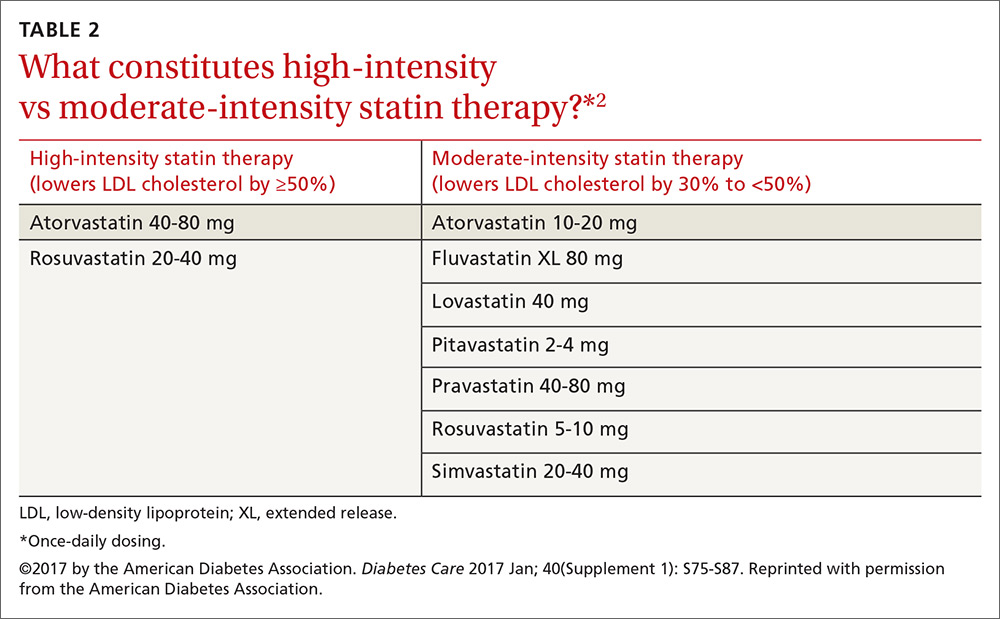

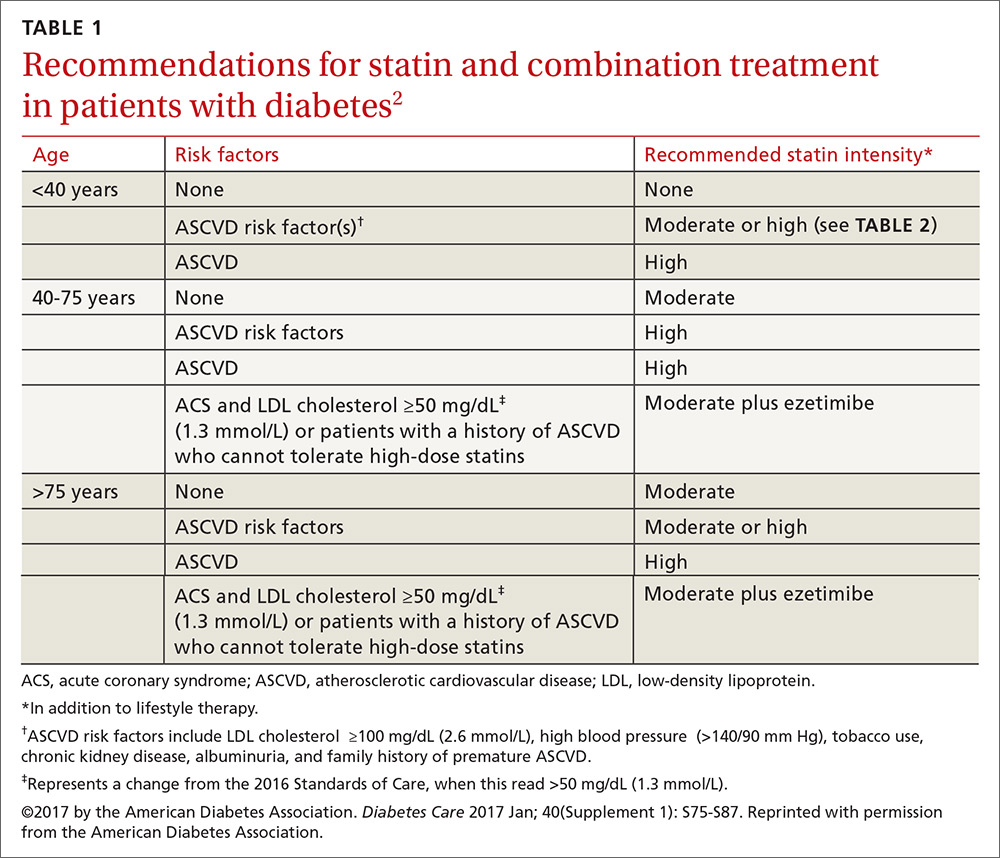

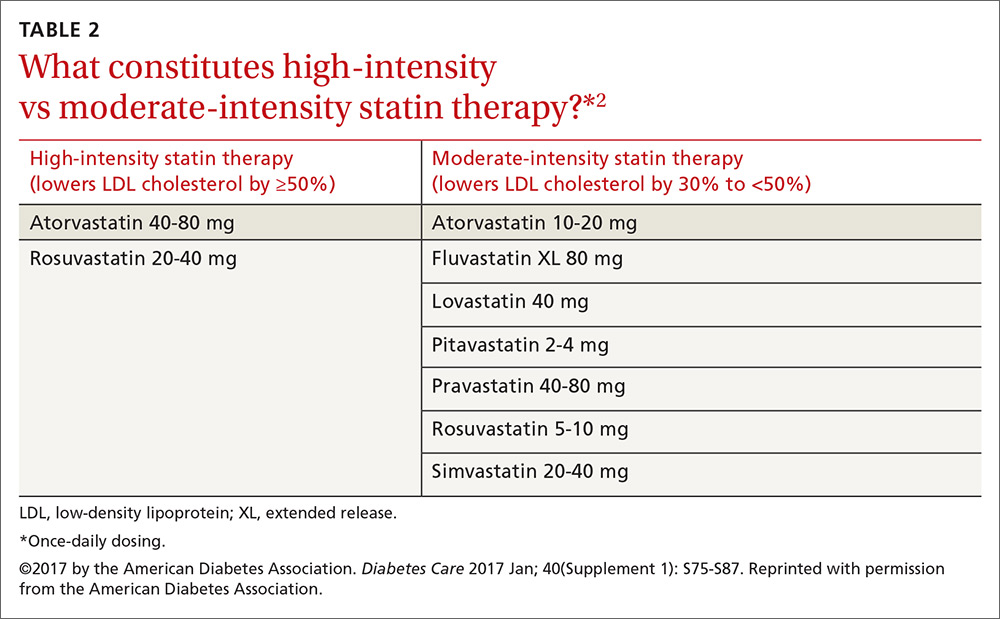

Patients ages 40 to 75 years with diabetes but without additional ASCVD risk factors should receive a moderate-intensity statin, according to the ADA (see TABLES 12 and 22). For those with additional CV risk factors, a high-intensity statin should be considered. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association ASCVD risk calculator (available at: http://www.cvriskcalculator.com/) may be useful for some patients, but generally, risk is already known to be high for most patients with diabetes. For patients of all ages with diabetes and established ASCVD, high-intensity statin therapy should be added to lifestyle modifications.35-37

For patients with diabetes who are <40 years with additional ASCVD risk factors, few clinical trial data exist; nevertheless, consider a moderate- or high-intensity statin and lifestyle therapy. Similarly, for patients >75 years who have diabetes and no additional ASCVD risk factors, consider a moderate-intensity statin and lifestyle modifications. For older adults with additional ASCVD risk factors, consider high-intensity statin therapy.35-37

Statins and cognition. It should be noted that published data have not demonstrated an adverse effect of statins on cognition.38 Statins, however, have been linked to an increased risk of developing diabetes,39,40 although the absolute increase in risk is small, and much smaller than the benefit derived from preventing the development of coronary disease.

Should total cholesterol and LDL levels be used as targets with statin treatment?

No. Statin doses have primarily been tested against placebo in clinical trials, rather than testing to specific target LDL levels, suggesting that the initiation and intensification of statin therapy be based on a patient’s risk profile.35 When maximally tolerated doses of statins do not lower LDL cholesterol by more than 30% from the patient’s baseline, there is currently no good evidence that combination therapy would be helpful, so regular monitoring of lipid levels has limited value. A lipid profile that includes levels of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides should be obtained at initial medical evaluation, at diagnosis of diabetes, and every 5 years thereafter or before the initiation of statin therapy. Ongoing testing may be appropriate in individual circumstances and to monitor for adherence to, or efficacy of, therapy.

What should I do for my patients who can’t tolerate statins?

Try a lower dose or a different statin before eliminating the class. Research has shown that even small doses (eg, rosuvastatin 5 mg) have some benefit.41

How do combination treatments figure into the current treatment of lipids in patients with diabetes?

It depends on the agent and the patient’s profile.

Fenofibrate. The ADA does not recommend automatically adding fenofibrate to statin therapy because the combination is associated with increased risks for abnormal transaminase levels, myositis, and rhabdomyolysis. In the ACCORD trial, the combination of fenofibrate and simvastatin did not reduce the rate of fatal CV events, nonfatal MIs, or nonfatal strokes compared with simvastatin alone.42

That said, a subgroup analysis suggested a benefit for men with both a triglyceride level ≥204 mg/dL (2.3 mmol/L) and an HDL cholesterol level ≤34 mg/dL (0.9 mmol/L).42 For this reason, the combination of a statin and fenofibrate may be considered for men who meet these laboratory parameters. In addition, consider medical therapy for triglyceride levels ≥500 mg/dL to reduce the risk of pancreatitis.

Ezetimibe. Recommendations regarding ezetimibe are based on the IMPROVE-IT (Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial), a 2015 RCT including over 18,000 patients that compared treatment with ezetimibe and simvastatin to simvastatin alone.43 Individuals in the trial were ≥50 years of age and had experienced an ACS within the preceding 10 days. In those with diabetes, the combination of moderate-intensity simvastatin (40 mg) and ezetimibe (10 mg) significantly reduced major adverse CV events with an absolute risk reduction of 5% (40% vs 45%) and an RR reduction of 14% over moderate-intensity simvastatin (40 mg) alone.

Based on these results, patients with diabetes and a recent ACS should be considered for combination therapy with ezetimibe and a moderate-intensity statin. The combination should also be considered in patients with diabetes and a history of ASCVD who cannot tolerate high-intensity statins.43

Niacin. The ADA currently does not recommend niacin in combination with a statin because of lack of efficacy on major ASCVD outcomes, possible increased risk of ischemic stroke, and adverse effects.44

What are the recommendations for the use of PCSK-9 inhibitors?

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK-9) inhibitors (ie, evolucumab and alirocumab) may be considered as adjunctive therapy to statins for patients with diabetes at high risk for ASCVD events who require additional lowering of LDL cholesterol. They may also be considered for those in whom high-intensity statin therapy is indicated, but not tolerated.

Antiplatelet agents

Who should take aspirin for primary prevention of CVD?

Both women and men ages ≥50 years who have diabetes and at least one additional CV risk factor (family history of premature ASCVD, hypertension, tobacco use, dyslipidemia, or albuminuria) should consider taking daily aspirin therapy (75-162 mg/d) if they do not have an excessive bleeding risk.45,46 The most common dose in the United States is 81 mg. This recommendation is supported by a 2010 consensus statement of the American Diabetes Association, American Heart Association, and the American College of Cardiology.47

Should patients with diabetes and heart disease receive antiplatelet therapy?

Yes. The evidence is clear that people with known diabetes and ASCVD benefit from aspirin therapy, according to the 2017 Standards of Care. Clopidogrel 75 mg/d is an appropriate alternative for patients who are allergic to aspirin. Dual antiplatelet therapy (a P2Y12 receptor antagonist and aspirin) should be used for as long as one year after an ACS and may have benefits beyond this period.48

Established heart disease

Are there specific recommendations for patients with diabetes and CHD?

According to the ADA Standards, there is good evidence that both aspirin and statin therapy are beneficial for patients with known ASCVD, and that high-intensity statin therapy should be used. In addition, consider ACE inhibitors to reduce the future risk of CV events. In patients with a prior MI, continue beta-blocker therapy for at least 2 years post event.49

Which medications should I avoid, or approach with caution, in patients with congestive heart failure (CHF)?

Thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, and metformin all require careful attention. This is especially important to know when you consider that almost half of all patients with T2DM will develop heart failure.50

Thiazolidinediones. The 2017 Standards of Care state that patients with diabetes and symptomatic congestive heart failure should not receive thiazolidinediones, as they can worsen heart failure status via fluid retention. As such, they are contraindicated in patients with class III and IV heart failure.51