User login

Here’s what’s trending at SHM

HM17 On Demand now available

Couldn’t make it to Las Vegas for SHM’s annual meeting, Hospital Medicine 2017? HM17 On Demand gives you access to over 80 online audio and slide recordings from the hottest tracks, including clinical updates, rapid fire, pediatrics, comanagement, quality, and high-value care.

Additionally, you can earn up to 70 American Medical Association Physician Recognition Award Category 1 Credit(s) and up to 30 American Board of Internal Medicine Maintenance of Certification credits. HM17 attendees can also benefit by earning additional credits on the sessions you missed out on.

To easily access content through SHM’s Learning Portal, visit shmlearningportal.org/hm17-demand to learn more.

Chapter Excellence Awards

SHM is proud to recognize outstanding chapters for the fourth annual Chapter Excellence Awards. Each year, chapters strive to demonstrate growth, sustenance, and innovation within their chapter activities.

View more at www.hospitalmedicine.org/chapterexcellence. Please join SHM in congratulating the following chapters on their success!

Silver Chapters

Boston Association of Academic Hospital Medicine (BAAHM)

Charlotte Metro Area

Houston

Kentucky

Los Angeles

Minnesota

North Jersey

Pacific Northwest

Philadelphia Tri-State

Rocky Mountain

San Francisco Bay

South Central PA

Gold Chapters

New Mexico

Wiregrass

Platinum Chapters

IowaMaryland

Michigan

NYC/Westchester

St. Louis

Outstanding Chapter of the Year

Michigan

Rising Star Chapter

Wiregrass

Student Hospitalist Scholar grant winners

SHM’s Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant provides funds with which medical students can conduct mentored scholarly projects related to quality improvement and patient safety in the field of hospital medicine. The program offers a summer and a longitudinal option.

Congratulations to the 2017-2018 Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant recipients:Summer Program

Anton Garazha

Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science

“Effectiveness of Communication During ICU to Ward Transfer and Association with Medical ICU Readmission”

Cole Hirschfeld

Weill Cornell Medical College

“The Role of Diagnostic Bone Biopsies in the Management of Osteomyelitis”

Farah Hussain

University of Cincinnati College of Medicine

“Better Understanding Clinical Deterioration in a Children’s Hospital”

Longitudinal Program

Monisha Bhatia

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

“Using Electronic Medical Record Phenotypic Data to Predict Discharge Destination”

Victor Ekuta

University of California, San Diego School of Medicine

“Reducing CAUTI with Noninvasive UC Alternatives and Measure-vention”

Yun Li

Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth

“Developing and implementing clinical pathway(s) for hospitalized injection drug users due to injection-related infection sequelae”

Learn more about the Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant at hospitalmedicine.org/scholargrant.

SPARK ONE: A tool to teach residents

SPARK ONE is a comprehensive, online self-assessment tool created specifically for hospital medicine professionals. The activity contains 450+ vignette-style multiple-choice questions covering 100% of the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) exam blueprint. This online tool can be utilized as a training mechanism for resident education on hospital medicine.

As a benefit of SHM membership, residents will receive a free subscription. SPARK ONE provides in-depth review of the following content areas:

- Cardiology

- Pulmonary Disease and Critical Care Medicine

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Nephrology and Urology

- Endocrinology

- Hematology and Oncology

- Neurology

- Allergy, Immunology, Dermatology, Rheumatology and Transitions in Care

- Palliative Care, Medical Ethics and Decision-making

- Perioperative Medicine and Consultative Co-management

- Patient Safety

- Quality, Cost and Clinical Reasoning

“SPARK ONE provides a unique platform for academic institutions, engaging learners in directed learning sessions, reinforcing teaching points as we encounter specific conditions.” – Rachel E. Thompson, MD, MPH, SFHM

Visit hospitalmedicine.org/sparkone to learn more.

Sharpen your coding with the updated CODE-H

SHM’s Coding Optimally by Documenting Effectively for Hospitalists (CODE-H) has launched an updated program with all new content. It will now include eight recorded webinar sessions presented by expert faculty, downloadable resources, and an interactive discussion forum through the Hospital Medicine Exchange (HMX), enabling participants to ask questions and learn the most relevant best practices.

Following each webinar, learners will have the opportunity to complete an evaluation to redeem continuing medical education credits.

Webinars in the series include:

- E/M Basics Part I

- E/M Basics Part II

- Utilizing Other Providers in Your Practice

- EMR and Mitigating Risk

- Putting Time into Critical Care Documentation

- Time Based Services

- Navigating the Rules for Hospitalist Visits

- Challenges of Concurrent Care

To purchase CODE-H, visit hospitalmedicine.org/CODEH. If you have questions about the new program, please contact [email protected].

Set yourself apart as a Fellow in Hospital Medicine

The Fellow in Hospital Medicine (FHM) designation signals your commitment to the hospital medicine specialty and dedication to quality improvement and patient safety. This designation is available for hospital medicine practitioners, including practice administrators, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. If you meet the prerequisites and complete the requirements, which are rooted in the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine, you can apply for this prestigious designation and join more than 1,100 FHMs who are dedicated to the field of hospital medicine. Learn more and apply at hospitalmedicine.org/fellow.

New guide & modules on multimodal pain strategies for postoperative pain management

Pain management can pose multiple challenges in the acute care setting for hospitalists and front-line prescribers. While their first priority is to optimally manage pain in their patients, they also face the challenges of treating diverse patient populations, managing patient expectations, and considering how pain control and perceptions affect Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems scores. Furthermore, because of the ongoing opioid epidemic, prescribers must ensure that pain is managed responsibly and ethically.

To address these issues, SHM developed a guide to address how to work in an interdisciplinary team, identify impediments to implementation, and provide examples of appropriate pain management. In accompaniment with this Multimodal Pain Strategies Guide for Postoperative Pain Management, there are three modules presented by the authors which supplement the electronic guide.

To download the guide or view the modules, visit hospitalmedicine.org/pain.

Proven excellence through a unique education style: Academic Hospitalist Academy

Don’t miss the eighth annual Academic Hospitalist Academy (AHA), Sept. 25-28, 2017, at the Lakeway Resort and Spa in Austin, Texas. AHA attendees experience an energizing, interactive learning environment featuring didactics, small-group exercise and skill-building breakout sessions. Each full day of learning is facilitated by leading clinician-educators, hospitalist researchers, and clinical administrators in a 1 to 10 faculty to student ratio.

The Principal Goals of the Academy are to:

- Develop junior academic hospitalists as the premier teachers and educational leaders at their institutions

- Help academic hospitalists develop scholarly work and increase scholarly output

- Enhance awareness of the value of quality improvement and patient safety work

- Support academic promotion of all attendees

Don’t miss out on this unique, hands-on experience. Register before July 18, 2017, to receive the early-bird rates. Visit academichospitalist.org to learn more.

Choosing Wisely Case Study compendium now available

The Choosing Wisely Case Study Competition, hosted by SHM, sought submissions from hospitalists on innovative improvement initiatives implemented in their respective institutions. These initiatives reflect and promote movement toward reducing unnecessary medical tests and procedures and changing a culture that dictates, “More care is better care.”

Submissions were judged by the Choosing Wisely Subcommittee, a panel of SHM members, under adult and pediatric categories. One grand prize winner and three honorable mentions were selected from these categories. The compendium includes these case studies along with additional exemplary submissions.

View the Choosing Wisely Case Study Compendium at hospitalmedicine.org/choosingwisely.

Strengthen your interactions with the 5 Rs of Cultural Humility

Look inside this issue for your 5 Rs of Cultural Humility pocket card. It can be easily referenced on rounds and shared with colleagues. We hope to achieve heightened awareness of effective interactions. In addition to the definitions of each of the Rs, the card features questions to ask yourself before, during, and after every interaction to aid in attaining cultural humility.

For more information, visit hospitalmedicine.org/5Rs.

Brett Radler is communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

HM17 On Demand now available

Couldn’t make it to Las Vegas for SHM’s annual meeting, Hospital Medicine 2017? HM17 On Demand gives you access to over 80 online audio and slide recordings from the hottest tracks, including clinical updates, rapid fire, pediatrics, comanagement, quality, and high-value care.

Additionally, you can earn up to 70 American Medical Association Physician Recognition Award Category 1 Credit(s) and up to 30 American Board of Internal Medicine Maintenance of Certification credits. HM17 attendees can also benefit by earning additional credits on the sessions you missed out on.

To easily access content through SHM’s Learning Portal, visit shmlearningportal.org/hm17-demand to learn more.

Chapter Excellence Awards

SHM is proud to recognize outstanding chapters for the fourth annual Chapter Excellence Awards. Each year, chapters strive to demonstrate growth, sustenance, and innovation within their chapter activities.

View more at www.hospitalmedicine.org/chapterexcellence. Please join SHM in congratulating the following chapters on their success!

Silver Chapters

Boston Association of Academic Hospital Medicine (BAAHM)

Charlotte Metro Area

Houston

Kentucky

Los Angeles

Minnesota

North Jersey

Pacific Northwest

Philadelphia Tri-State

Rocky Mountain

San Francisco Bay

South Central PA

Gold Chapters

New Mexico

Wiregrass

Platinum Chapters

IowaMaryland

Michigan

NYC/Westchester

St. Louis

Outstanding Chapter of the Year

Michigan

Rising Star Chapter

Wiregrass

Student Hospitalist Scholar grant winners

SHM’s Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant provides funds with which medical students can conduct mentored scholarly projects related to quality improvement and patient safety in the field of hospital medicine. The program offers a summer and a longitudinal option.

Congratulations to the 2017-2018 Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant recipients:Summer Program

Anton Garazha

Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science

“Effectiveness of Communication During ICU to Ward Transfer and Association with Medical ICU Readmission”

Cole Hirschfeld

Weill Cornell Medical College

“The Role of Diagnostic Bone Biopsies in the Management of Osteomyelitis”

Farah Hussain

University of Cincinnati College of Medicine

“Better Understanding Clinical Deterioration in a Children’s Hospital”

Longitudinal Program

Monisha Bhatia

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

“Using Electronic Medical Record Phenotypic Data to Predict Discharge Destination”

Victor Ekuta

University of California, San Diego School of Medicine

“Reducing CAUTI with Noninvasive UC Alternatives and Measure-vention”

Yun Li

Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth

“Developing and implementing clinical pathway(s) for hospitalized injection drug users due to injection-related infection sequelae”

Learn more about the Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant at hospitalmedicine.org/scholargrant.

SPARK ONE: A tool to teach residents

SPARK ONE is a comprehensive, online self-assessment tool created specifically for hospital medicine professionals. The activity contains 450+ vignette-style multiple-choice questions covering 100% of the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) exam blueprint. This online tool can be utilized as a training mechanism for resident education on hospital medicine.

As a benefit of SHM membership, residents will receive a free subscription. SPARK ONE provides in-depth review of the following content areas:

- Cardiology

- Pulmonary Disease and Critical Care Medicine

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Nephrology and Urology

- Endocrinology

- Hematology and Oncology

- Neurology

- Allergy, Immunology, Dermatology, Rheumatology and Transitions in Care

- Palliative Care, Medical Ethics and Decision-making

- Perioperative Medicine and Consultative Co-management

- Patient Safety

- Quality, Cost and Clinical Reasoning

“SPARK ONE provides a unique platform for academic institutions, engaging learners in directed learning sessions, reinforcing teaching points as we encounter specific conditions.” – Rachel E. Thompson, MD, MPH, SFHM

Visit hospitalmedicine.org/sparkone to learn more.

Sharpen your coding with the updated CODE-H

SHM’s Coding Optimally by Documenting Effectively for Hospitalists (CODE-H) has launched an updated program with all new content. It will now include eight recorded webinar sessions presented by expert faculty, downloadable resources, and an interactive discussion forum through the Hospital Medicine Exchange (HMX), enabling participants to ask questions and learn the most relevant best practices.

Following each webinar, learners will have the opportunity to complete an evaluation to redeem continuing medical education credits.

Webinars in the series include:

- E/M Basics Part I

- E/M Basics Part II

- Utilizing Other Providers in Your Practice

- EMR and Mitigating Risk

- Putting Time into Critical Care Documentation

- Time Based Services

- Navigating the Rules for Hospitalist Visits

- Challenges of Concurrent Care

To purchase CODE-H, visit hospitalmedicine.org/CODEH. If you have questions about the new program, please contact [email protected].

Set yourself apart as a Fellow in Hospital Medicine

The Fellow in Hospital Medicine (FHM) designation signals your commitment to the hospital medicine specialty and dedication to quality improvement and patient safety. This designation is available for hospital medicine practitioners, including practice administrators, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. If you meet the prerequisites and complete the requirements, which are rooted in the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine, you can apply for this prestigious designation and join more than 1,100 FHMs who are dedicated to the field of hospital medicine. Learn more and apply at hospitalmedicine.org/fellow.

New guide & modules on multimodal pain strategies for postoperative pain management

Pain management can pose multiple challenges in the acute care setting for hospitalists and front-line prescribers. While their first priority is to optimally manage pain in their patients, they also face the challenges of treating diverse patient populations, managing patient expectations, and considering how pain control and perceptions affect Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems scores. Furthermore, because of the ongoing opioid epidemic, prescribers must ensure that pain is managed responsibly and ethically.

To address these issues, SHM developed a guide to address how to work in an interdisciplinary team, identify impediments to implementation, and provide examples of appropriate pain management. In accompaniment with this Multimodal Pain Strategies Guide for Postoperative Pain Management, there are three modules presented by the authors which supplement the electronic guide.

To download the guide or view the modules, visit hospitalmedicine.org/pain.

Proven excellence through a unique education style: Academic Hospitalist Academy

Don’t miss the eighth annual Academic Hospitalist Academy (AHA), Sept. 25-28, 2017, at the Lakeway Resort and Spa in Austin, Texas. AHA attendees experience an energizing, interactive learning environment featuring didactics, small-group exercise and skill-building breakout sessions. Each full day of learning is facilitated by leading clinician-educators, hospitalist researchers, and clinical administrators in a 1 to 10 faculty to student ratio.

The Principal Goals of the Academy are to:

- Develop junior academic hospitalists as the premier teachers and educational leaders at their institutions

- Help academic hospitalists develop scholarly work and increase scholarly output

- Enhance awareness of the value of quality improvement and patient safety work

- Support academic promotion of all attendees

Don’t miss out on this unique, hands-on experience. Register before July 18, 2017, to receive the early-bird rates. Visit academichospitalist.org to learn more.

Choosing Wisely Case Study compendium now available

The Choosing Wisely Case Study Competition, hosted by SHM, sought submissions from hospitalists on innovative improvement initiatives implemented in their respective institutions. These initiatives reflect and promote movement toward reducing unnecessary medical tests and procedures and changing a culture that dictates, “More care is better care.”

Submissions were judged by the Choosing Wisely Subcommittee, a panel of SHM members, under adult and pediatric categories. One grand prize winner and three honorable mentions were selected from these categories. The compendium includes these case studies along with additional exemplary submissions.

View the Choosing Wisely Case Study Compendium at hospitalmedicine.org/choosingwisely.

Strengthen your interactions with the 5 Rs of Cultural Humility

Look inside this issue for your 5 Rs of Cultural Humility pocket card. It can be easily referenced on rounds and shared with colleagues. We hope to achieve heightened awareness of effective interactions. In addition to the definitions of each of the Rs, the card features questions to ask yourself before, during, and after every interaction to aid in attaining cultural humility.

For more information, visit hospitalmedicine.org/5Rs.

Brett Radler is communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

HM17 On Demand now available

Couldn’t make it to Las Vegas for SHM’s annual meeting, Hospital Medicine 2017? HM17 On Demand gives you access to over 80 online audio and slide recordings from the hottest tracks, including clinical updates, rapid fire, pediatrics, comanagement, quality, and high-value care.

Additionally, you can earn up to 70 American Medical Association Physician Recognition Award Category 1 Credit(s) and up to 30 American Board of Internal Medicine Maintenance of Certification credits. HM17 attendees can also benefit by earning additional credits on the sessions you missed out on.

To easily access content through SHM’s Learning Portal, visit shmlearningportal.org/hm17-demand to learn more.

Chapter Excellence Awards

SHM is proud to recognize outstanding chapters for the fourth annual Chapter Excellence Awards. Each year, chapters strive to demonstrate growth, sustenance, and innovation within their chapter activities.

View more at www.hospitalmedicine.org/chapterexcellence. Please join SHM in congratulating the following chapters on their success!

Silver Chapters

Boston Association of Academic Hospital Medicine (BAAHM)

Charlotte Metro Area

Houston

Kentucky

Los Angeles

Minnesota

North Jersey

Pacific Northwest

Philadelphia Tri-State

Rocky Mountain

San Francisco Bay

South Central PA

Gold Chapters

New Mexico

Wiregrass

Platinum Chapters

IowaMaryland

Michigan

NYC/Westchester

St. Louis

Outstanding Chapter of the Year

Michigan

Rising Star Chapter

Wiregrass

Student Hospitalist Scholar grant winners

SHM’s Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant provides funds with which medical students can conduct mentored scholarly projects related to quality improvement and patient safety in the field of hospital medicine. The program offers a summer and a longitudinal option.

Congratulations to the 2017-2018 Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant recipients:Summer Program

Anton Garazha

Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science

“Effectiveness of Communication During ICU to Ward Transfer and Association with Medical ICU Readmission”

Cole Hirschfeld

Weill Cornell Medical College

“The Role of Diagnostic Bone Biopsies in the Management of Osteomyelitis”

Farah Hussain

University of Cincinnati College of Medicine

“Better Understanding Clinical Deterioration in a Children’s Hospital”

Longitudinal Program

Monisha Bhatia

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

“Using Electronic Medical Record Phenotypic Data to Predict Discharge Destination”

Victor Ekuta

University of California, San Diego School of Medicine

“Reducing CAUTI with Noninvasive UC Alternatives and Measure-vention”

Yun Li

Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth

“Developing and implementing clinical pathway(s) for hospitalized injection drug users due to injection-related infection sequelae”

Learn more about the Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant at hospitalmedicine.org/scholargrant.

SPARK ONE: A tool to teach residents

SPARK ONE is a comprehensive, online self-assessment tool created specifically for hospital medicine professionals. The activity contains 450+ vignette-style multiple-choice questions covering 100% of the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) exam blueprint. This online tool can be utilized as a training mechanism for resident education on hospital medicine.

As a benefit of SHM membership, residents will receive a free subscription. SPARK ONE provides in-depth review of the following content areas:

- Cardiology

- Pulmonary Disease and Critical Care Medicine

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Nephrology and Urology

- Endocrinology

- Hematology and Oncology

- Neurology

- Allergy, Immunology, Dermatology, Rheumatology and Transitions in Care

- Palliative Care, Medical Ethics and Decision-making

- Perioperative Medicine and Consultative Co-management

- Patient Safety

- Quality, Cost and Clinical Reasoning

“SPARK ONE provides a unique platform for academic institutions, engaging learners in directed learning sessions, reinforcing teaching points as we encounter specific conditions.” – Rachel E. Thompson, MD, MPH, SFHM

Visit hospitalmedicine.org/sparkone to learn more.

Sharpen your coding with the updated CODE-H

SHM’s Coding Optimally by Documenting Effectively for Hospitalists (CODE-H) has launched an updated program with all new content. It will now include eight recorded webinar sessions presented by expert faculty, downloadable resources, and an interactive discussion forum through the Hospital Medicine Exchange (HMX), enabling participants to ask questions and learn the most relevant best practices.

Following each webinar, learners will have the opportunity to complete an evaluation to redeem continuing medical education credits.

Webinars in the series include:

- E/M Basics Part I

- E/M Basics Part II

- Utilizing Other Providers in Your Practice

- EMR and Mitigating Risk

- Putting Time into Critical Care Documentation

- Time Based Services

- Navigating the Rules for Hospitalist Visits

- Challenges of Concurrent Care

To purchase CODE-H, visit hospitalmedicine.org/CODEH. If you have questions about the new program, please contact [email protected].

Set yourself apart as a Fellow in Hospital Medicine

The Fellow in Hospital Medicine (FHM) designation signals your commitment to the hospital medicine specialty and dedication to quality improvement and patient safety. This designation is available for hospital medicine practitioners, including practice administrators, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. If you meet the prerequisites and complete the requirements, which are rooted in the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine, you can apply for this prestigious designation and join more than 1,100 FHMs who are dedicated to the field of hospital medicine. Learn more and apply at hospitalmedicine.org/fellow.

New guide & modules on multimodal pain strategies for postoperative pain management

Pain management can pose multiple challenges in the acute care setting for hospitalists and front-line prescribers. While their first priority is to optimally manage pain in their patients, they also face the challenges of treating diverse patient populations, managing patient expectations, and considering how pain control and perceptions affect Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems scores. Furthermore, because of the ongoing opioid epidemic, prescribers must ensure that pain is managed responsibly and ethically.

To address these issues, SHM developed a guide to address how to work in an interdisciplinary team, identify impediments to implementation, and provide examples of appropriate pain management. In accompaniment with this Multimodal Pain Strategies Guide for Postoperative Pain Management, there are three modules presented by the authors which supplement the electronic guide.

To download the guide or view the modules, visit hospitalmedicine.org/pain.

Proven excellence through a unique education style: Academic Hospitalist Academy

Don’t miss the eighth annual Academic Hospitalist Academy (AHA), Sept. 25-28, 2017, at the Lakeway Resort and Spa in Austin, Texas. AHA attendees experience an energizing, interactive learning environment featuring didactics, small-group exercise and skill-building breakout sessions. Each full day of learning is facilitated by leading clinician-educators, hospitalist researchers, and clinical administrators in a 1 to 10 faculty to student ratio.

The Principal Goals of the Academy are to:

- Develop junior academic hospitalists as the premier teachers and educational leaders at their institutions

- Help academic hospitalists develop scholarly work and increase scholarly output

- Enhance awareness of the value of quality improvement and patient safety work

- Support academic promotion of all attendees

Don’t miss out on this unique, hands-on experience. Register before July 18, 2017, to receive the early-bird rates. Visit academichospitalist.org to learn more.

Choosing Wisely Case Study compendium now available

The Choosing Wisely Case Study Competition, hosted by SHM, sought submissions from hospitalists on innovative improvement initiatives implemented in their respective institutions. These initiatives reflect and promote movement toward reducing unnecessary medical tests and procedures and changing a culture that dictates, “More care is better care.”

Submissions were judged by the Choosing Wisely Subcommittee, a panel of SHM members, under adult and pediatric categories. One grand prize winner and three honorable mentions were selected from these categories. The compendium includes these case studies along with additional exemplary submissions.

View the Choosing Wisely Case Study Compendium at hospitalmedicine.org/choosingwisely.

Strengthen your interactions with the 5 Rs of Cultural Humility

Look inside this issue for your 5 Rs of Cultural Humility pocket card. It can be easily referenced on rounds and shared with colleagues. We hope to achieve heightened awareness of effective interactions. In addition to the definitions of each of the Rs, the card features questions to ask yourself before, during, and after every interaction to aid in attaining cultural humility.

For more information, visit hospitalmedicine.org/5Rs.

Brett Radler is communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

A man with progressive dysphagia

A 71-year-old man was referred to the gastroenterology department for evaluation of 9 months of progressive swallowing difficulties associated with epigastric and chest discomfort.

He was a previous smoker (17 pack-years), with a history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, and cervical spinal stenosis requiring decompressive laminectomy with a postoperative course complicated by episodes of aspiration.

DYSPHAGIA: OROPHARYNGEAL OR ESOPHAGEAL

Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) can be caused by problems in the oropharynx or in the esophagus. Difficulty initiating a swallow can be thought of as oropharyngeal dysphagia, whereas the intermittent sensation of food stuck in the neck or chest is considered esophageal dysphagia.

Focused questioning can help differentiate oropharyngeal symptoms from esophageal symptoms. For example, difficulty clearing secretions or passing the food bolus beyond the mouth or frequent coughing spells while eating is consistent with oropharyngeal dysphagia and suggests a neurologic cause. Our patient, however, presented with a constellation of symptoms more suggestive of esophageal dysphagia.

When eliciting a history of esophageal symptoms, it is crucial to determine the progression of swallowing difficulty, as well as how it directly relates to eating solids or liquids, or both. Difficulty swallowing solid foods that has progressed over time to include liquids would raise concern for an obstruction such as a stricture, ring, or malignancy. On the other hand, abrupt onset of intermittent dysphagia to both solids and liquids would raise concern for a motility disorder of the esophagus. This patient presented with an abrupt onset of intermittent symptoms to both solids and liquids that was associated with substernal chest pain.

Once coronary disease was ruled out by cardiac biomarker testing, electrocardiography, and a pharmacologic stress test, our patient underwent upper endoscopy, which showed a normal esophageal mucosa without masses or obstruction and no evidence of peptic ulcer disease.

WHAT IS THE NEXT STEP?

When upper endoscopy is negative and cardiac causes and gastroesophageal reflux disease have been ruled out, an esophageal motility disorder should be considered.

1. After obstruction has been ruled out with upper endoscopy, which should be the next step in the investigation of esophageal dysphagia?

- A 24-hour pH recording

- Barium esophagography

- Modified barium swallow

- Computed tomography of the chest

Barium esophagography is the optimal fluoroscopic study to evaluate the esophageal phase of the swallow. This study requires the patient to swallow a thick barium solution and a 13-mm barium pill under video analysis. It is useful early in the investigation of esophageal dysphagia because it can potentially reveal areas of esophageal luminal narrowing not detected endoscopically, as well as detail the rate of esophageal emptying.1

The modified barium swallow, which is performed with the assistance of a speech pathologist, is similar but only shows the oropharynx as far as the cervical esophagus. Therefore, it would be the best fluoroscopic test to assess patients with possible aspiration or oropharyngeal dysphagia, whereas barium esophagography would be the test of choice in evaluating esophageal dysmotility or mechanical obstruction.

pH testing may be helpful in diagnosing gastroesophageal reflux disease but is less helpful in the evaluation of dysphagia.

Computed tomography of the chest may be useful to evaluate for extrinsic compression of the esophagus, but it is not the best next step in the evaluation of dysphagia.

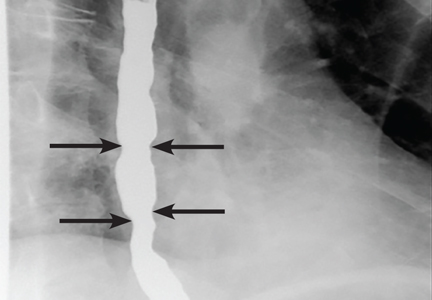

Our patient underwent barium esophagography, which revealed tertiary contractions in the mid and distal esophagus with slight narrowing of the lower cervical esophagus (Figure 1). (Primary contractions are elicited when initiating a swallow that propels the food bolus through the esophagus, while secondary contractions follow in response to esophageal distention to move all remaining esophageal contents from the thoracic esophagus. Tertiary contractions are abnormal, nonpropulsive, spontaneous contractions of the esophageal body that are initiated without swallowing.2)

EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS

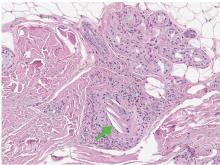

Histologic study of biopsies of the mid and distal esophagus from our patient’s upper endoscopy revealed 5 eosinophils per high-power field.

2. Does this patient meet the criteria for the diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis?

- Yes

- No

No. Having eosinophils in the esophagus is not enough to diagnose eosinophilic esophagitis, as eosinophils are also common in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Eosinophilic esophagitis is defined as a chronic immune-mediated esophageal disease with histologically eosinophil-predominant inflammation (with more than 15 eosinophils per high-power field). The diagnosis is additionally based on symptoms and endoscopic appearance.3 When investigating possible eosinophilic esophagitis, it is recommended that 2 to 4 samples be obtained from at least 2 different locations in the esophagus (eg, proximal and distal), because the inflammatory changes can be patchy.

WHAT DOES THE PATIENT HAVE?

3. What is the likely cause of this patient’s dysphagia?

- Eosinophilic esophagitis

- Achalasia

- Esophageal spasm

- Extrinsic compression

- Esophageal malignancy

Eosinophilic esophagitis causes characteristic symptoms that include difficulty swallowing, chest pain that does not respond to antisecretory therapy, and regurgitation of undigested food. As we discussed above, this patient has only 5 eosinophils per high-power field and does not meet the histologic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis.

Achalasia has a characteristic “bird’s beak” appearance on esophagography that results from distal tapering of the esophagus to the gastroesophageal junction,1 and this is not apparent on our patient’s study.

Review of this patient’s esophagogram also does not reveal any extrinsic compression, esophageal malignancy, or distal tapering suggesting achalasia. In light of the abrupt onset of symptoms related to both solids and liquids associated with atypical chest pain, the primary concern should be for esophageal spasm.

ONE MORE TEST

4. What study would you order next to better elucidate the cause of this patient’s esophageal disorder?

- High-resolution esophageal manometry

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with endoscopic ultrasonography

- 24-hour pH and impedance testing

- Wireless motility capsule

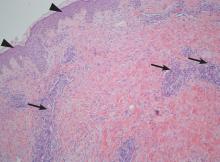

Esophageal manometry (Figure 2) is used to evaluate the function and coordination of the muscles of the esophagus, as in disorders of esophageal motility.

High-resolution manometry is the gold standard for evaluation of esophageal motility. It is appropriate in evaluating dysphagia or noncardiac chest pain without evidence of mechanical obstruction, ulceration, or inflammation.4,5

High-resolution manometry differs from conventional manometry in that the catheter has more sensors to measure intraluminal pressure (36 rather than the usual 7 to 12). The data are translated into pressure topography plots (Figure 3).6,7

Updated guidelines on how to interpret the findings of high-resolution manometry are known as the Chicago 3.0 criteria.4 According to this system, esophageal motility disorders are grouped on the basis of lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and then further subdivided based on the character of peristalsis.

EGD with endoscopic ultrasonography would not be appropriate at this time because there is little suspicion of an extraluminal mass that needs to be investigated.

A 24-hour pH and impedance study is helpful in determining the presence of esophageal acid exposure in patients presenting with gastroesophageal reflux disease. This patient does not have symptoms of heartburn or regurgitation; therefore, this investigation would not be of value.

A wireless motility capsule would help in investigating gastric and small-bowel motility and may be useful in the future for this patient, but at this point it would provide little additional utility.

ESOPHAGEAL SPASM

Our patient underwent high-resolution esophageal manometry. The results (Figure 4) revealed a normal resting pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter and complete relaxation in all swallows. The body of the esophagus demonstrated premature contractions in 90% of swallows. Overall, these findings were consistent with the diagnosis of distal esophageal spasm.

TREATMENTS FOR ESOPHAGEAL SPASM

In addition to incorporating data obtained from endoscopy, esophagography, and manometry, it is crucial to identify the patient’s predominant symptom when planning treatment. For example, is the prevailing symptom dysphagia or chest pain? Additional consideration must be given to medical, surgical, and psychiatric comorbidities.

5. Which of the following is appropriate medical therapy for esophageal spasm?

- Calcium channel blockers

- Nitrates

- Hydralazine

- Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitors

- All of the above

All of these have been used to treat distal esophageal spasm as well as other hypercontractile esophageal motility disorders.8–20

Calcium channel blockers have proven to be effective in randomized controlled trials. Diltiazem has been shown to be beneficial at doses ranging from 60 to 90 mg, as has nifedipine 10 to 20 mg 3 times daily. Although different drugs of this class tend to relax the lower esophageal sphincter to different degrees, when choosing among them in patients with hypercontractile disorders there is little concern for potentially precipitating reflux.8–13

Nitrates, hydralazine, and PDE5 inhibitors have been effective in uncontrolled studies but have not been studied in randomized trials.14–17

Other treatments. Patients may also benefit from neuromodulators such as trazodone and imipramine for chest pain and optimization of antisecretory therapy if they have concomitant gastroesophageal reflux disease.18–20

Patients who have documented esophageal hypercontractility along with reflux disease confirmed by an abnormal pH study show significant improvement in their chest pain symptoms with high doses of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). As our patient presented with chest pain and dysphagia, a dedicated pH study was not needed, and we could progress straight to manometry and a trial of a PPI.

Our patient was started on a PPI and nifedipine but developed a pruritic rash. As rash does not preclude using another medication in the same class, his treatment was changed to diltiazem 30 mg by mouth 3 times a day, and his dysphagia improved. However, he continued to experience intermittent chest pain with swallowing. After discussion of neuromodulator therapy, he declined additional pharmacologic therapy.

A NONPHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT?

6. Which of the following would you offer this patient as a nonpharmacologic alternative for his esophageal pain?

- St. John’s wort

- Ginkgo biloba

- Ginseng

- Peppermint extract

- Eucalyptus oil

In a small, open-label study in patients with esophageal spasm, the use of 5 drops of commercially available 11% peppermint extract in 10 mL of water significantly decreased simultaneous contractions and resolved chest pain.21 Esophageal manometry was performed 10 minutes after the peppermint solution was consumed, and the results showed improvement in esophageal spasm. While the authors of this study did not make any formal recommendations, the findings suggest that peppermint extract should be given 10 minutes before meals.

There is no evidence for or against the use of the other nonpharmacologic treatments mentioned here.

PAIN RELIEF

7. If a pharmacologic approach were chosen, which would be the best option for pain relief in this patient?

- Oxycodone 5 mg every 8 hours

- Acetaminophen 650 mg every 8 hours

- Ibuprofen 400 mg every evening at bedtime

- Trazodone 100 mg every evening at bedtime

- Imipramine 50 mg every evening at bedtime

- Aripiprazole 5 mg by mouth every day

Trazodone would be the most appropriate of these options. Doses of 100 mg to 150 mg every evening at bedtime have been shown to significantly improve global assessment scores of pain at 6 weeks.18

Imipramine 50 mg every evening at bedtime would be another option and also has been shown to reduce chest pain.19

Even though these were the doses that were investigated, in clinical practice it is common to start at lower doses (trazodone 50 mg or imipramine 10 mg) and to then titrate every 4 weeks based on the patient’s response.

Opiates (eg, oxycodone) should be avoided, as they can cause esophageal motility disorders such as spasm or achalasia.22

Acetaminophen and aripiprazole have not been studied exclusively for their effect on chest pain related to esophageal spasm.

RECURRENT SYMPTOMS

The patient’s dysphagia initially decreased while he was taking diltiazem 30 mg 3 times a day, but it recurred after 6 months. The dosage was increased to 60 mg 3 times a day over the course of the next year, with minimal response. (The maximum dose is 90 mg 4 times a day, but because of side effects of lightheadedness and dizziness, out patient could not tolerate more than 60 mg 3 times a day).

ENDOSCOPIC THERAPY

8. What endoscopic therapies are appropriate for patients with esophageal spasm that does not respond to medication?

- Bougie dilation

- Balloon dilation

- Onabotulinum toxin injection

- Expandable mesh stent placement

- Mucosal sclerotherapy

Onabotulinum toxin injections have been shown to improve dysphagia when given in a linear pattern.23

Endoscopic dilation has not been shown to be beneficial in this setting, as a study found no difference in efficacy between therapeutic (54-French) and sham (24-French) bougie dilation.24

Our patient received 100 units of onabotulinum toxin (10 units every centimeter in the distal 10 cm of the esophagus). Afterward, he experienced resolution of dysphagia, with only mild intermittent chest pain, which was controlled by taking peppermint extract as needed. The symptoms returned approximately 1 year later but responded to repeat endoscopy with onabotulinum toxin injections.23,25

Peroral endoscopic myotomy

Another relatively new endoscopic treatment for esophageal motility disorders is peroral endoscopic myotomy (Figure 5). During this procedure a tiny incision is made in the esophageal mucosa, permitting the endoscope to tunnel within the lining. The smooth muscle of the distal esophagus and lower esophageal sphincter is then cut, thereby freeing either the spastic muscle (in distal esophageal spasm) or the hyperactive lower esophageal sphincter (in achalasia).26,27

In an open trial, after undergoing peroral endoscopic myotomy for esophageal spasm and hypercontractile esophagus, 89% of patients had complete relief of dysphagia, and 92% had palliation of chest pain.28 Of note, the rate of relief of dysphagia was higher for patients with achalasia (98%) than for nonachalasia patients (71%).

- Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108:1238–1249;

- Hellemans J, Vantrappen G. Physiology. In: Vantrappen G, Hellemans J, eds. Diseases of the esophagus. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag Berlin, Heidelberg; 1974:40–102.

- Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Katzka DA; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108:679–692.

- Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al; International High Resolution Manometry Working Group. The Chicago classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015; 27:160–174.

- Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ; American Gastroenterological Association. AGA technical review on the clinical use of esophageal manometry. Gastroenterology 2005; 128:209–224.

- Ghosh SK, Pandolfino JE, Zhang Q, Jarosz A, Shah N, Kahrilas PJ. Quantifying esophageal peristalsis with high-resolution manometry: a study of 75 asymptomatic volunteers. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2006; 290:G988–G997.

- Kahrilas PJ, Sifrim D. High-resolution manometry and impedance-pH/manometry: valuable tools in clinical and investigational esophagology. Gastroenterology 2008; 135:756–769.

- Cattau EL Jr, Castell DO, Johnson DA, et al. Diltiazem therapy for symptoms associated with nutcracker esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 1991; 86:272–276.

- Richter JE, Dalton CB, Bradley LA, Castell DO. Oral nifedipine in the treatment of noncardiac chest pain in patients with the nutcracker esophagus. Gastroenterology 1987; 93:21–28.

- Drenth JP, Bos LP, Engels LG. Efficacy of diltiazem in the treatment of diffuse oesophageal spasm. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1990; 4:411–416.

- Thomas E, Witt P, Willis M, Morse J. Nifedipine therapy for diffuse esophageal spasm. South Med J 1986; 79:847–849.

- Davies HA, Lewis MJ, Rhodes J, Henderson AH. Trial of nifedipine for prevention of oesophageal spasm. Digestion 1987; 36:81–83.

- Richter JE, Dalton CB, Bradley LA, Castell DO. Oral nifedipine in the treatment of noncardiac chest pain in patients with the nutcracker esophagus. Gastroenterology 1987; 93:21–28.

- Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Gasbarrini G. Transdermal slow-release long-acting isosorbide dinitrate for ‘nutcracker’ oesophagus: an open study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000; 12:1061–1062.

- Mellow MH. Effect of isosorbide and hydralazine in painful primary esophageal motility disorders. Gastroenterology 1982; 83:364–370.

- Fox M, Sweis R, Wong T, Anggiansah A. Sildenafil relieves symptoms and normalizes motility in patients with oesophageal spasm: a report of two cases. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2007; 19:798–803.

- Orlando RC, Bozymski EM. Clinical and manometric effects of nitroglycerin in diffuse esophageal spasm. N Engl J Med 1973; 289:23–25.

- Clouse RE, Lustman PJ, Eckert TC, Ferney DM, Griffith LS. Low-dose trazodone for symptomatic patients with esophageal contraction abnormalities. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 1987; 92:1027–1036.

- Cannon RO 3rd, Quyyumi AA, Mincemoyer R, et al. Imipramine in patients with chest pain despite normal coronary angiograms. N Engl J Med 1994; 330:1411–1417.

- Achem SR, Kolts BE, Wears R, Burton L, Richter JE. Chest pain associated with nutcracker esophagus: a preliminary study of the role of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol 1993; 88:187–192.

- Pimentel M, Bonorris GG, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Peppermint oil improves the manometric findings in diffuse esophageal spasm. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 33:27–31.

- Kraichely RE, Arora AS, Murray JA. Opiate-induced oesophageal dysmotility. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010; 31:601–606.

- Storr M, Allescher HD, Rösch T, Born P, Weigert N, Classen M. Treatment of symptomatic diffuse esophageal spasm by endoscopic injections of botulinum toxin: a prospective study with long-term follow-up. Gastrointest Endosc 2001; 54:754–759.

- Winters C, Artnak EJ, Benjamin SB, Castell DO. Esophageal bougienage in symptomatic patients with the nutcracker esophagus. A primary esophageal motility disorder. JAMA 1984; 252:363–366.

- Vanuytsel T, Bisschops R, Farré R, et al. Botulinum toxin reduces dysphagia in patients with nonachalasia primary esophageal motility disorders. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 11:1115–1121.e2.

- Khashab MA, Messallam AA, Onimaru M, et al. International multicenter experience with peroral endoscopic myotomy for the treatment of spastic esophageal disorders refractory to medical therapy (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 81:1170–1177.

- Leconte M, Douard R, Gaudric M, Dumontier I, Chaussade S, Dousset B. Functional results after extended myotomy for diffuse oesophageal spasm. Br J Surg 2007; 94:1113–1118.

- Sharata AM, Dunst CM, Pescarus R, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for esophageal primary motility disorders: analysis of 100 consecutive patients. J Gastrointest Surg 2015; 19:161–170.

A 71-year-old man was referred to the gastroenterology department for evaluation of 9 months of progressive swallowing difficulties associated with epigastric and chest discomfort.

He was a previous smoker (17 pack-years), with a history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, and cervical spinal stenosis requiring decompressive laminectomy with a postoperative course complicated by episodes of aspiration.

DYSPHAGIA: OROPHARYNGEAL OR ESOPHAGEAL

Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) can be caused by problems in the oropharynx or in the esophagus. Difficulty initiating a swallow can be thought of as oropharyngeal dysphagia, whereas the intermittent sensation of food stuck in the neck or chest is considered esophageal dysphagia.

Focused questioning can help differentiate oropharyngeal symptoms from esophageal symptoms. For example, difficulty clearing secretions or passing the food bolus beyond the mouth or frequent coughing spells while eating is consistent with oropharyngeal dysphagia and suggests a neurologic cause. Our patient, however, presented with a constellation of symptoms more suggestive of esophageal dysphagia.

When eliciting a history of esophageal symptoms, it is crucial to determine the progression of swallowing difficulty, as well as how it directly relates to eating solids or liquids, or both. Difficulty swallowing solid foods that has progressed over time to include liquids would raise concern for an obstruction such as a stricture, ring, or malignancy. On the other hand, abrupt onset of intermittent dysphagia to both solids and liquids would raise concern for a motility disorder of the esophagus. This patient presented with an abrupt onset of intermittent symptoms to both solids and liquids that was associated with substernal chest pain.

Once coronary disease was ruled out by cardiac biomarker testing, electrocardiography, and a pharmacologic stress test, our patient underwent upper endoscopy, which showed a normal esophageal mucosa without masses or obstruction and no evidence of peptic ulcer disease.

WHAT IS THE NEXT STEP?

When upper endoscopy is negative and cardiac causes and gastroesophageal reflux disease have been ruled out, an esophageal motility disorder should be considered.

1. After obstruction has been ruled out with upper endoscopy, which should be the next step in the investigation of esophageal dysphagia?

- A 24-hour pH recording

- Barium esophagography

- Modified barium swallow

- Computed tomography of the chest

Barium esophagography is the optimal fluoroscopic study to evaluate the esophageal phase of the swallow. This study requires the patient to swallow a thick barium solution and a 13-mm barium pill under video analysis. It is useful early in the investigation of esophageal dysphagia because it can potentially reveal areas of esophageal luminal narrowing not detected endoscopically, as well as detail the rate of esophageal emptying.1

The modified barium swallow, which is performed with the assistance of a speech pathologist, is similar but only shows the oropharynx as far as the cervical esophagus. Therefore, it would be the best fluoroscopic test to assess patients with possible aspiration or oropharyngeal dysphagia, whereas barium esophagography would be the test of choice in evaluating esophageal dysmotility or mechanical obstruction.

pH testing may be helpful in diagnosing gastroesophageal reflux disease but is less helpful in the evaluation of dysphagia.

Computed tomography of the chest may be useful to evaluate for extrinsic compression of the esophagus, but it is not the best next step in the evaluation of dysphagia.

Our patient underwent barium esophagography, which revealed tertiary contractions in the mid and distal esophagus with slight narrowing of the lower cervical esophagus (Figure 1). (Primary contractions are elicited when initiating a swallow that propels the food bolus through the esophagus, while secondary contractions follow in response to esophageal distention to move all remaining esophageal contents from the thoracic esophagus. Tertiary contractions are abnormal, nonpropulsive, spontaneous contractions of the esophageal body that are initiated without swallowing.2)

EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS

Histologic study of biopsies of the mid and distal esophagus from our patient’s upper endoscopy revealed 5 eosinophils per high-power field.

2. Does this patient meet the criteria for the diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis?

- Yes

- No

No. Having eosinophils in the esophagus is not enough to diagnose eosinophilic esophagitis, as eosinophils are also common in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Eosinophilic esophagitis is defined as a chronic immune-mediated esophageal disease with histologically eosinophil-predominant inflammation (with more than 15 eosinophils per high-power field). The diagnosis is additionally based on symptoms and endoscopic appearance.3 When investigating possible eosinophilic esophagitis, it is recommended that 2 to 4 samples be obtained from at least 2 different locations in the esophagus (eg, proximal and distal), because the inflammatory changes can be patchy.

WHAT DOES THE PATIENT HAVE?

3. What is the likely cause of this patient’s dysphagia?

- Eosinophilic esophagitis

- Achalasia

- Esophageal spasm

- Extrinsic compression

- Esophageal malignancy

Eosinophilic esophagitis causes characteristic symptoms that include difficulty swallowing, chest pain that does not respond to antisecretory therapy, and regurgitation of undigested food. As we discussed above, this patient has only 5 eosinophils per high-power field and does not meet the histologic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis.

Achalasia has a characteristic “bird’s beak” appearance on esophagography that results from distal tapering of the esophagus to the gastroesophageal junction,1 and this is not apparent on our patient’s study.

Review of this patient’s esophagogram also does not reveal any extrinsic compression, esophageal malignancy, or distal tapering suggesting achalasia. In light of the abrupt onset of symptoms related to both solids and liquids associated with atypical chest pain, the primary concern should be for esophageal spasm.

ONE MORE TEST

4. What study would you order next to better elucidate the cause of this patient’s esophageal disorder?

- High-resolution esophageal manometry

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with endoscopic ultrasonography

- 24-hour pH and impedance testing

- Wireless motility capsule

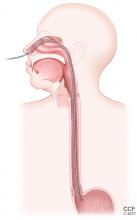

Esophageal manometry (Figure 2) is used to evaluate the function and coordination of the muscles of the esophagus, as in disorders of esophageal motility.

High-resolution manometry is the gold standard for evaluation of esophageal motility. It is appropriate in evaluating dysphagia or noncardiac chest pain without evidence of mechanical obstruction, ulceration, or inflammation.4,5

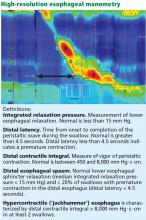

High-resolution manometry differs from conventional manometry in that the catheter has more sensors to measure intraluminal pressure (36 rather than the usual 7 to 12). The data are translated into pressure topography plots (Figure 3).6,7

Updated guidelines on how to interpret the findings of high-resolution manometry are known as the Chicago 3.0 criteria.4 According to this system, esophageal motility disorders are grouped on the basis of lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and then further subdivided based on the character of peristalsis.

EGD with endoscopic ultrasonography would not be appropriate at this time because there is little suspicion of an extraluminal mass that needs to be investigated.

A 24-hour pH and impedance study is helpful in determining the presence of esophageal acid exposure in patients presenting with gastroesophageal reflux disease. This patient does not have symptoms of heartburn or regurgitation; therefore, this investigation would not be of value.

A wireless motility capsule would help in investigating gastric and small-bowel motility and may be useful in the future for this patient, but at this point it would provide little additional utility.

ESOPHAGEAL SPASM

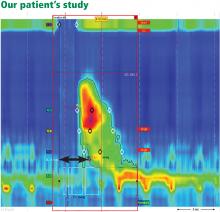

Our patient underwent high-resolution esophageal manometry. The results (Figure 4) revealed a normal resting pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter and complete relaxation in all swallows. The body of the esophagus demonstrated premature contractions in 90% of swallows. Overall, these findings were consistent with the diagnosis of distal esophageal spasm.

TREATMENTS FOR ESOPHAGEAL SPASM

In addition to incorporating data obtained from endoscopy, esophagography, and manometry, it is crucial to identify the patient’s predominant symptom when planning treatment. For example, is the prevailing symptom dysphagia or chest pain? Additional consideration must be given to medical, surgical, and psychiatric comorbidities.

5. Which of the following is appropriate medical therapy for esophageal spasm?

- Calcium channel blockers

- Nitrates

- Hydralazine

- Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitors

- All of the above

All of these have been used to treat distal esophageal spasm as well as other hypercontractile esophageal motility disorders.8–20

Calcium channel blockers have proven to be effective in randomized controlled trials. Diltiazem has been shown to be beneficial at doses ranging from 60 to 90 mg, as has nifedipine 10 to 20 mg 3 times daily. Although different drugs of this class tend to relax the lower esophageal sphincter to different degrees, when choosing among them in patients with hypercontractile disorders there is little concern for potentially precipitating reflux.8–13

Nitrates, hydralazine, and PDE5 inhibitors have been effective in uncontrolled studies but have not been studied in randomized trials.14–17

Other treatments. Patients may also benefit from neuromodulators such as trazodone and imipramine for chest pain and optimization of antisecretory therapy if they have concomitant gastroesophageal reflux disease.18–20

Patients who have documented esophageal hypercontractility along with reflux disease confirmed by an abnormal pH study show significant improvement in their chest pain symptoms with high doses of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). As our patient presented with chest pain and dysphagia, a dedicated pH study was not needed, and we could progress straight to manometry and a trial of a PPI.

Our patient was started on a PPI and nifedipine but developed a pruritic rash. As rash does not preclude using another medication in the same class, his treatment was changed to diltiazem 30 mg by mouth 3 times a day, and his dysphagia improved. However, he continued to experience intermittent chest pain with swallowing. After discussion of neuromodulator therapy, he declined additional pharmacologic therapy.

A NONPHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT?

6. Which of the following would you offer this patient as a nonpharmacologic alternative for his esophageal pain?

- St. John’s wort

- Ginkgo biloba

- Ginseng

- Peppermint extract

- Eucalyptus oil

In a small, open-label study in patients with esophageal spasm, the use of 5 drops of commercially available 11% peppermint extract in 10 mL of water significantly decreased simultaneous contractions and resolved chest pain.21 Esophageal manometry was performed 10 minutes after the peppermint solution was consumed, and the results showed improvement in esophageal spasm. While the authors of this study did not make any formal recommendations, the findings suggest that peppermint extract should be given 10 minutes before meals.

There is no evidence for or against the use of the other nonpharmacologic treatments mentioned here.

PAIN RELIEF

7. If a pharmacologic approach were chosen, which would be the best option for pain relief in this patient?

- Oxycodone 5 mg every 8 hours

- Acetaminophen 650 mg every 8 hours

- Ibuprofen 400 mg every evening at bedtime

- Trazodone 100 mg every evening at bedtime

- Imipramine 50 mg every evening at bedtime

- Aripiprazole 5 mg by mouth every day

Trazodone would be the most appropriate of these options. Doses of 100 mg to 150 mg every evening at bedtime have been shown to significantly improve global assessment scores of pain at 6 weeks.18

Imipramine 50 mg every evening at bedtime would be another option and also has been shown to reduce chest pain.19

Even though these were the doses that were investigated, in clinical practice it is common to start at lower doses (trazodone 50 mg or imipramine 10 mg) and to then titrate every 4 weeks based on the patient’s response.

Opiates (eg, oxycodone) should be avoided, as they can cause esophageal motility disorders such as spasm or achalasia.22

Acetaminophen and aripiprazole have not been studied exclusively for their effect on chest pain related to esophageal spasm.

RECURRENT SYMPTOMS

The patient’s dysphagia initially decreased while he was taking diltiazem 30 mg 3 times a day, but it recurred after 6 months. The dosage was increased to 60 mg 3 times a day over the course of the next year, with minimal response. (The maximum dose is 90 mg 4 times a day, but because of side effects of lightheadedness and dizziness, out patient could not tolerate more than 60 mg 3 times a day).

ENDOSCOPIC THERAPY

8. What endoscopic therapies are appropriate for patients with esophageal spasm that does not respond to medication?

- Bougie dilation

- Balloon dilation

- Onabotulinum toxin injection

- Expandable mesh stent placement

- Mucosal sclerotherapy

Onabotulinum toxin injections have been shown to improve dysphagia when given in a linear pattern.23

Endoscopic dilation has not been shown to be beneficial in this setting, as a study found no difference in efficacy between therapeutic (54-French) and sham (24-French) bougie dilation.24

Our patient received 100 units of onabotulinum toxin (10 units every centimeter in the distal 10 cm of the esophagus). Afterward, he experienced resolution of dysphagia, with only mild intermittent chest pain, which was controlled by taking peppermint extract as needed. The symptoms returned approximately 1 year later but responded to repeat endoscopy with onabotulinum toxin injections.23,25

Peroral endoscopic myotomy

Another relatively new endoscopic treatment for esophageal motility disorders is peroral endoscopic myotomy (Figure 5). During this procedure a tiny incision is made in the esophageal mucosa, permitting the endoscope to tunnel within the lining. The smooth muscle of the distal esophagus and lower esophageal sphincter is then cut, thereby freeing either the spastic muscle (in distal esophageal spasm) or the hyperactive lower esophageal sphincter (in achalasia).26,27

In an open trial, after undergoing peroral endoscopic myotomy for esophageal spasm and hypercontractile esophagus, 89% of patients had complete relief of dysphagia, and 92% had palliation of chest pain.28 Of note, the rate of relief of dysphagia was higher for patients with achalasia (98%) than for nonachalasia patients (71%).

A 71-year-old man was referred to the gastroenterology department for evaluation of 9 months of progressive swallowing difficulties associated with epigastric and chest discomfort.

He was a previous smoker (17 pack-years), with a history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, and cervical spinal stenosis requiring decompressive laminectomy with a postoperative course complicated by episodes of aspiration.

DYSPHAGIA: OROPHARYNGEAL OR ESOPHAGEAL

Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) can be caused by problems in the oropharynx or in the esophagus. Difficulty initiating a swallow can be thought of as oropharyngeal dysphagia, whereas the intermittent sensation of food stuck in the neck or chest is considered esophageal dysphagia.

Focused questioning can help differentiate oropharyngeal symptoms from esophageal symptoms. For example, difficulty clearing secretions or passing the food bolus beyond the mouth or frequent coughing spells while eating is consistent with oropharyngeal dysphagia and suggests a neurologic cause. Our patient, however, presented with a constellation of symptoms more suggestive of esophageal dysphagia.

When eliciting a history of esophageal symptoms, it is crucial to determine the progression of swallowing difficulty, as well as how it directly relates to eating solids or liquids, or both. Difficulty swallowing solid foods that has progressed over time to include liquids would raise concern for an obstruction such as a stricture, ring, or malignancy. On the other hand, abrupt onset of intermittent dysphagia to both solids and liquids would raise concern for a motility disorder of the esophagus. This patient presented with an abrupt onset of intermittent symptoms to both solids and liquids that was associated with substernal chest pain.

Once coronary disease was ruled out by cardiac biomarker testing, electrocardiography, and a pharmacologic stress test, our patient underwent upper endoscopy, which showed a normal esophageal mucosa without masses or obstruction and no evidence of peptic ulcer disease.

WHAT IS THE NEXT STEP?

When upper endoscopy is negative and cardiac causes and gastroesophageal reflux disease have been ruled out, an esophageal motility disorder should be considered.

1. After obstruction has been ruled out with upper endoscopy, which should be the next step in the investigation of esophageal dysphagia?

- A 24-hour pH recording

- Barium esophagography

- Modified barium swallow

- Computed tomography of the chest

Barium esophagography is the optimal fluoroscopic study to evaluate the esophageal phase of the swallow. This study requires the patient to swallow a thick barium solution and a 13-mm barium pill under video analysis. It is useful early in the investigation of esophageal dysphagia because it can potentially reveal areas of esophageal luminal narrowing not detected endoscopically, as well as detail the rate of esophageal emptying.1

The modified barium swallow, which is performed with the assistance of a speech pathologist, is similar but only shows the oropharynx as far as the cervical esophagus. Therefore, it would be the best fluoroscopic test to assess patients with possible aspiration or oropharyngeal dysphagia, whereas barium esophagography would be the test of choice in evaluating esophageal dysmotility or mechanical obstruction.

pH testing may be helpful in diagnosing gastroesophageal reflux disease but is less helpful in the evaluation of dysphagia.

Computed tomography of the chest may be useful to evaluate for extrinsic compression of the esophagus, but it is not the best next step in the evaluation of dysphagia.

Our patient underwent barium esophagography, which revealed tertiary contractions in the mid and distal esophagus with slight narrowing of the lower cervical esophagus (Figure 1). (Primary contractions are elicited when initiating a swallow that propels the food bolus through the esophagus, while secondary contractions follow in response to esophageal distention to move all remaining esophageal contents from the thoracic esophagus. Tertiary contractions are abnormal, nonpropulsive, spontaneous contractions of the esophageal body that are initiated without swallowing.2)

EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS

Histologic study of biopsies of the mid and distal esophagus from our patient’s upper endoscopy revealed 5 eosinophils per high-power field.

2. Does this patient meet the criteria for the diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis?

- Yes

- No

No. Having eosinophils in the esophagus is not enough to diagnose eosinophilic esophagitis, as eosinophils are also common in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Eosinophilic esophagitis is defined as a chronic immune-mediated esophageal disease with histologically eosinophil-predominant inflammation (with more than 15 eosinophils per high-power field). The diagnosis is additionally based on symptoms and endoscopic appearance.3 When investigating possible eosinophilic esophagitis, it is recommended that 2 to 4 samples be obtained from at least 2 different locations in the esophagus (eg, proximal and distal), because the inflammatory changes can be patchy.

WHAT DOES THE PATIENT HAVE?

3. What is the likely cause of this patient’s dysphagia?

- Eosinophilic esophagitis

- Achalasia

- Esophageal spasm

- Extrinsic compression

- Esophageal malignancy

Eosinophilic esophagitis causes characteristic symptoms that include difficulty swallowing, chest pain that does not respond to antisecretory therapy, and regurgitation of undigested food. As we discussed above, this patient has only 5 eosinophils per high-power field and does not meet the histologic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis.

Achalasia has a characteristic “bird’s beak” appearance on esophagography that results from distal tapering of the esophagus to the gastroesophageal junction,1 and this is not apparent on our patient’s study.

Review of this patient’s esophagogram also does not reveal any extrinsic compression, esophageal malignancy, or distal tapering suggesting achalasia. In light of the abrupt onset of symptoms related to both solids and liquids associated with atypical chest pain, the primary concern should be for esophageal spasm.

ONE MORE TEST

4. What study would you order next to better elucidate the cause of this patient’s esophageal disorder?

- High-resolution esophageal manometry

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with endoscopic ultrasonography

- 24-hour pH and impedance testing

- Wireless motility capsule

Esophageal manometry (Figure 2) is used to evaluate the function and coordination of the muscles of the esophagus, as in disorders of esophageal motility.

High-resolution manometry is the gold standard for evaluation of esophageal motility. It is appropriate in evaluating dysphagia or noncardiac chest pain without evidence of mechanical obstruction, ulceration, or inflammation.4,5

High-resolution manometry differs from conventional manometry in that the catheter has more sensors to measure intraluminal pressure (36 rather than the usual 7 to 12). The data are translated into pressure topography plots (Figure 3).6,7

Updated guidelines on how to interpret the findings of high-resolution manometry are known as the Chicago 3.0 criteria.4 According to this system, esophageal motility disorders are grouped on the basis of lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and then further subdivided based on the character of peristalsis.

EGD with endoscopic ultrasonography would not be appropriate at this time because there is little suspicion of an extraluminal mass that needs to be investigated.

A 24-hour pH and impedance study is helpful in determining the presence of esophageal acid exposure in patients presenting with gastroesophageal reflux disease. This patient does not have symptoms of heartburn or regurgitation; therefore, this investigation would not be of value.

A wireless motility capsule would help in investigating gastric and small-bowel motility and may be useful in the future for this patient, but at this point it would provide little additional utility.

ESOPHAGEAL SPASM

Our patient underwent high-resolution esophageal manometry. The results (Figure 4) revealed a normal resting pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter and complete relaxation in all swallows. The body of the esophagus demonstrated premature contractions in 90% of swallows. Overall, these findings were consistent with the diagnosis of distal esophageal spasm.

TREATMENTS FOR ESOPHAGEAL SPASM

In addition to incorporating data obtained from endoscopy, esophagography, and manometry, it is crucial to identify the patient’s predominant symptom when planning treatment. For example, is the prevailing symptom dysphagia or chest pain? Additional consideration must be given to medical, surgical, and psychiatric comorbidities.

5. Which of the following is appropriate medical therapy for esophageal spasm?

- Calcium channel blockers

- Nitrates

- Hydralazine

- Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitors

- All of the above

All of these have been used to treat distal esophageal spasm as well as other hypercontractile esophageal motility disorders.8–20

Calcium channel blockers have proven to be effective in randomized controlled trials. Diltiazem has been shown to be beneficial at doses ranging from 60 to 90 mg, as has nifedipine 10 to 20 mg 3 times daily. Although different drugs of this class tend to relax the lower esophageal sphincter to different degrees, when choosing among them in patients with hypercontractile disorders there is little concern for potentially precipitating reflux.8–13

Nitrates, hydralazine, and PDE5 inhibitors have been effective in uncontrolled studies but have not been studied in randomized trials.14–17

Other treatments. Patients may also benefit from neuromodulators such as trazodone and imipramine for chest pain and optimization of antisecretory therapy if they have concomitant gastroesophageal reflux disease.18–20

Patients who have documented esophageal hypercontractility along with reflux disease confirmed by an abnormal pH study show significant improvement in their chest pain symptoms with high doses of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). As our patient presented with chest pain and dysphagia, a dedicated pH study was not needed, and we could progress straight to manometry and a trial of a PPI.

Our patient was started on a PPI and nifedipine but developed a pruritic rash. As rash does not preclude using another medication in the same class, his treatment was changed to diltiazem 30 mg by mouth 3 times a day, and his dysphagia improved. However, he continued to experience intermittent chest pain with swallowing. After discussion of neuromodulator therapy, he declined additional pharmacologic therapy.

A NONPHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT?

6. Which of the following would you offer this patient as a nonpharmacologic alternative for his esophageal pain?

- St. John’s wort

- Ginkgo biloba

- Ginseng

- Peppermint extract

- Eucalyptus oil

In a small, open-label study in patients with esophageal spasm, the use of 5 drops of commercially available 11% peppermint extract in 10 mL of water significantly decreased simultaneous contractions and resolved chest pain.21 Esophageal manometry was performed 10 minutes after the peppermint solution was consumed, and the results showed improvement in esophageal spasm. While the authors of this study did not make any formal recommendations, the findings suggest that peppermint extract should be given 10 minutes before meals.

There is no evidence for or against the use of the other nonpharmacologic treatments mentioned here.

PAIN RELIEF

7. If a pharmacologic approach were chosen, which would be the best option for pain relief in this patient?

- Oxycodone 5 mg every 8 hours

- Acetaminophen 650 mg every 8 hours

- Ibuprofen 400 mg every evening at bedtime

- Trazodone 100 mg every evening at bedtime

- Imipramine 50 mg every evening at bedtime

- Aripiprazole 5 mg by mouth every day

Trazodone would be the most appropriate of these options. Doses of 100 mg to 150 mg every evening at bedtime have been shown to significantly improve global assessment scores of pain at 6 weeks.18

Imipramine 50 mg every evening at bedtime would be another option and also has been shown to reduce chest pain.19

Even though these were the doses that were investigated, in clinical practice it is common to start at lower doses (trazodone 50 mg or imipramine 10 mg) and to then titrate every 4 weeks based on the patient’s response.

Opiates (eg, oxycodone) should be avoided, as they can cause esophageal motility disorders such as spasm or achalasia.22

Acetaminophen and aripiprazole have not been studied exclusively for their effect on chest pain related to esophageal spasm.

RECURRENT SYMPTOMS

The patient’s dysphagia initially decreased while he was taking diltiazem 30 mg 3 times a day, but it recurred after 6 months. The dosage was increased to 60 mg 3 times a day over the course of the next year, with minimal response. (The maximum dose is 90 mg 4 times a day, but because of side effects of lightheadedness and dizziness, out patient could not tolerate more than 60 mg 3 times a day).

ENDOSCOPIC THERAPY

8. What endoscopic therapies are appropriate for patients with esophageal spasm that does not respond to medication?