User login

Perceptions of hospital-dependent patients on their needs for hospitalization

In the United States, patients 65 years old or older accounted for more than one third of inpatient stays and 42% of inpatient care spending in 2012.1 Despite the identification of risk factors, the implementation of an array of interventions, and the institution of penalties on hospitals, a subset of older adults continues to spend significant time in the hospital.2,3

Hospital dependency is a concept that was only recently described. It identifies patients who improve while in the hospital but quickly deteriorate after leaving the hospital, resulting in recurring hospitalizations.4 Although little is known about hospital-dependent patients, studies have explored patients’ perspectives on readmissions.5,6 Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether there are individuals for whom frequent and prolonged hospitalizations are appropriate, and whether there are undisclosed factors that, if addressed, could decrease their hospital dependency. We conducted an exploratory study to ascertain hospital-dependent patients’ perspectives on their needs for hospitalizations.

METHODS

Study Design

This study was approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board. From March 2015 to September 2015, Dr. Liu conducted semistructured explorative interviews with patients on the medical units of an academic medical center. Dr. Liu was not directly involved in the care of these patients. An interview guide that includes open-ended questions was created to elicit patients’ perspectives on their need for hospitalizations, health status, and outside-hospital support. This guide was pilot-tested with 6 patients, whose transcripts were not included in the final analysis, to assess for ease of understanding. After the pilot interviews, the questions were revised, and the final guide consists of 12 questions (Supplemental Table).

Recruitment

We used predetermined criteria and a purposeful sampling strategy to select potential study participants. We identified participants by periodically (~once a week) reviewing the electronic medical records of all patients admitted to the medicine service during the study period. Eligible patients were 65 years old or older and had at least 3 hospitalizations over the preceding 6 months. Patients were excluded if they met our chronic critical illness criteria: mechanical ventilation for more than 21 days, history of tracheotomy for failed weaning from mechanical ventilation,7 presence of a conservator, or admission only for comfort measures. Participants were recruited until no new themes emerged.

Data Collection

Twenty-nine patients were eligible. We obtained permission from their inpatient providers to approach them about the study. Of the 29 patients, 26 agreed to be interviewed, and 3 declined. Of the 26 participants, 6 underwent pilot interviews, and 20 underwent formal interviews with use of the finalized interview guide. The interviews, conducted in the hospital while the participants were hospitalized, lasted 17 minutes on average. The interviews were transcribed and iteratively analyzed. The themes that emerged from the initial interviews were further explored and validated in subsequent interviews. Interviews were conducted until theoretical saturation was reached and no new themes were derived from them. Demographic information, including age, sex, ethnicity, and marital status, was also collected.

Analysis

Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed. Independently, two investigators used Atlas Ti software to analyze and code the interview transcriptions. An inductive approach was used to identify new codes from the data.8 The coders then met to discuss repeating ideas based on the codes. When a code was identified by one coder but not the other, or when there was disagreement about interpretation of a code, the coders returned to the relevant text to reach consensus and to determine whether to include or discard the code.9 We then organized and reorganized repeating ideas based on their conceptual similarities to determine the themes and subthemes.9

RESULTS

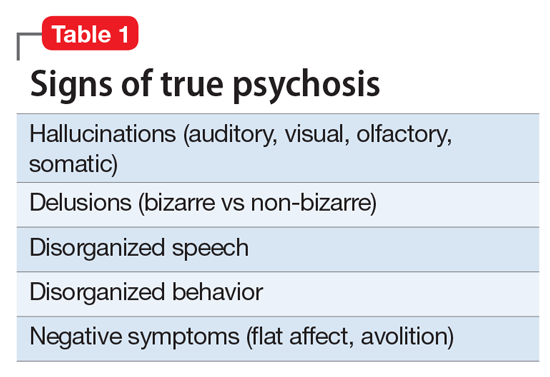

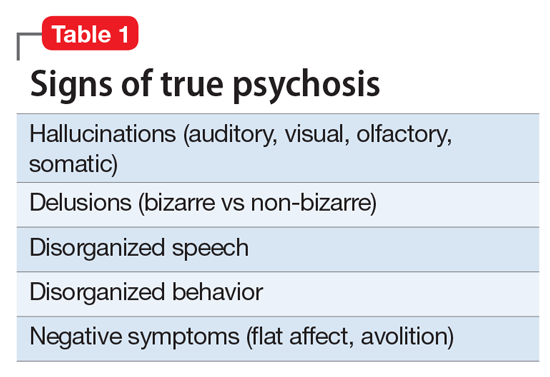

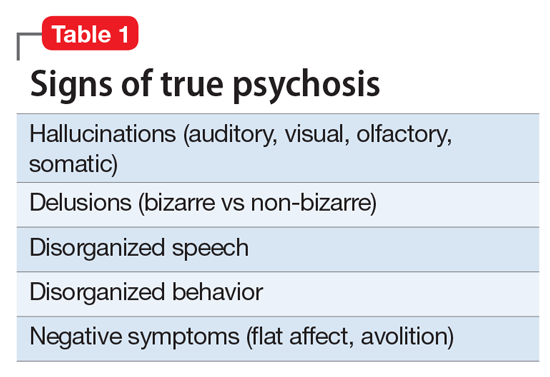

Twenty patients participated in the formal interviews. Participants’ baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1, and four dominant themes, and their subthemes and exemplary quotations, are listed in Table 2.

Perspectives on Hospital Care

Participants perceived their hospitalizations as inevitable and necessary for survival: “I think if I haven’t come to the hospital, I probably would have died.” Furthermore, participants thought only the hospital had the resources to help them (“The medications they were giving me … you can get that in the hospital but not outside the hospital”) and sustain them (“You are like an old car, and it breaks down little by little, so you have to go in periodically and get the problem fixed, so you will drive it around for a while”).

Feeling Safe in Hospital. Asked how being in the hospital makes them feel, participants attributed their feelings of safety to the constant observation, the availability of providers and nurses, and the idea that hospital care is helping. As one participant stated, “Makes me feel safer in case you go into something like cardiac arrest. You are right here where they can help you.”

Outside-Hospital Support. Despite multiple hospitalizations, most participants reported having social support (“I have the aide. I got the nurses come in. I have my daughter …”), physical support, and medical support (“I have all the doctors”) outside the hospital. A minority of participants questioned the usefulness of the services. One participant described declining the help of visiting nurses because she wanted to be independent and thought that, despite recurrent hospitalizations for physical symptoms, she still had the ability to manage her own medications.

Goals-of-Care Discussion. Some participants reported inadequate discussions about goals of care, health priorities, and health trajectories. In their reports, this inadequacy included not thinking about their goals, despite continued health decline. One participant stated, “Oh, God, I don’t know if I had any conversation like that. … I think until it is really brought to the front, you don’t make a decision really if you don’t have to.” Citing the value of a more established relationship and deeper trust, participants preferred having these serious and personal discussions with their ambulatory care clinicians: “Because I know my doctor much closer. I have been with him for a number of years. The doctors in the hospital seem to be nice and competent, but I don’t know them.”

DISCUSSION

Participants considered their hospitalizations a necessity and reported feeling safe in the hospital. Given that most already had support outside the hospital, increasing community services may be inadequate to alter participants’ perceived hospital care needs. On the other hand, a few participants reported declining services that might have prevented hospitalizations. Although there has been a study of treatment refusal among older adults with advanced illnesses,10 not much is known about refusal of services among this population. Investigators should examine the reasons for refusing services and the effect that refusal has on hospitalizations. Furthermore, although it would have been informative to ascertain clinician perspectives as well, we focused on patient perspectives because less is known on this topic.

Some participants noted their lack of discussion with their clinicians about healthcare goals and probable health trajectories. Barriers to goals-of-care discussion among this highly vulnerable population have been researched from the perspectives of clinicians and other health professionals but not patients themselves.11,12 Of particular concern in our study is the participant-noted lack of discussion about health trajectories and health priorities, given the decline that occurs in this population and even in those with good care. This inadequacy in discussion suggests continued hospital care may not always be consistent with a patient’s goals. Patients’ desire to have this discussion with their clinicians, with whom they have a relationship, supports the need to involve ambulatory care clinicians, or ensure these patients are cared for by the same clinicians, across healthcare settings.13,14 Whoever provides the care, the clinician must align treatment with the patient’s goal, whether it is to continue hospital-level care or to transition to palliative care. Such an approach also reflects the core elements of person-centered care.15

Study Limitations

Participants were recruited from the medicine service at a single large academic center, limiting the study’s generalizability to patients admitted to surgical services or community hospitals. The patients in this small sample were English-speaking and predominantly Caucasian, so our findings may not represent the perspectives of non-English-speaking or minority patients. We did not perform statistical analysis to quantify intercoder reliability. Last, as this was a qualitative study, we cannot comment on the relative importance or prevalence of the reasons cited for frequent hospitalizations, and we cannot estimate the proportion of patients who had recurrent hospitalizations and were hospital-dependent.

Implication

Although quantitative research is needed to confirm our findings, the hospital-dependent patients in this study thought their survival required hospital-level care and resources. From their perspective, increasing posthospital and community support may be insufficient to prevent some hospitalizations. The lack of goals-of-care discussion supports attempts to increase efforts to facilitate discussion about health trajectories and health priorities between patients and their preferred clinicians.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Grace Jenq for providing feedback on the study design.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of Hospital Stays in the United States, 2012: Statistical Brief 180. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project; 2014. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK259100/. Published October 2014. Accessed February 17, 2016.

2. Auerbach AD, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Preventability and causes of readmissions in a national cohort of general medicine patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):484-493. PubMed

3. Donzé JD, Williams MV, Robinson EJ, et al. International validity of the HOSPITAL score to predict 30-day potentially avoidable hospital readmissions. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):496-502. PubMed

4. Reuben DB, Tinetti ME. The hospital-dependent patient. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):694-697. PubMed

5. Enguidanos S, Coulourides Kogan AM, Schreibeis-Baum H, Lendon J, Lorenz K. “Because I was sick”: seriously ill veterans’ perspectives on reason for 30-day readmissions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(3):537-542. PubMed

6. Kangovi S, Grande D, Meehan P, Mitra N, Shannon R, Long JA. Perceptions of readmitted patients on the transition from hospital to home. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(9):709-712. PubMed

7. Lamas D. Chronic critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(2):175-177. PubMed

8. Saldana J. Fundamentals of Qualitative Research. Cary, NC: Oxford University Press; 2011.

9. Auerbach CF, Silverstein LB. Qualitative Data: An Introduction to Coding and Analysis. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2003.

10. Rothman MD, Van Ness PH, O’Leary JR, Fried TR. Refusal of medical and surgical interventions by older persons with advanced chronic disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(7):982-987. PubMed

11. You JJ, Downar J, Fowler RA, et al; Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network. Barriers to goals of care discussions with seriously ill hospitalized patients and their families: a multicenter survey of clinicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):549-556. PubMed

12. Schoenborn NL, Bowman TL 2nd, Cayea D, Pollack CE, Feeser S, Boyd C. Primary care practitioners’ views on incorporating long-term prognosis in the care of older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):671-678. PubMed

13. Arora VM, Prochaska ML, Farnan JM, et al. Problems after discharge and understanding of communication with their primary care physicians among hospitalized seniors: a mixed methods study. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):385-391. PubMed

14. Jones CD, Vu MB, O’Donnell CM, et al. A failure to communicate: a qualitative exploration of care coordination between hospitalists and primary care providers around patient hospitalizations. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(4):417-424. PubMed

15. American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Person-Centered Care. Person-centered care: a definition and essential elements. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(1):15-18. PubMed

In the United States, patients 65 years old or older accounted for more than one third of inpatient stays and 42% of inpatient care spending in 2012.1 Despite the identification of risk factors, the implementation of an array of interventions, and the institution of penalties on hospitals, a subset of older adults continues to spend significant time in the hospital.2,3

Hospital dependency is a concept that was only recently described. It identifies patients who improve while in the hospital but quickly deteriorate after leaving the hospital, resulting in recurring hospitalizations.4 Although little is known about hospital-dependent patients, studies have explored patients’ perspectives on readmissions.5,6 Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether there are individuals for whom frequent and prolonged hospitalizations are appropriate, and whether there are undisclosed factors that, if addressed, could decrease their hospital dependency. We conducted an exploratory study to ascertain hospital-dependent patients’ perspectives on their needs for hospitalizations.

METHODS

Study Design

This study was approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board. From March 2015 to September 2015, Dr. Liu conducted semistructured explorative interviews with patients on the medical units of an academic medical center. Dr. Liu was not directly involved in the care of these patients. An interview guide that includes open-ended questions was created to elicit patients’ perspectives on their need for hospitalizations, health status, and outside-hospital support. This guide was pilot-tested with 6 patients, whose transcripts were not included in the final analysis, to assess for ease of understanding. After the pilot interviews, the questions were revised, and the final guide consists of 12 questions (Supplemental Table).

Recruitment

We used predetermined criteria and a purposeful sampling strategy to select potential study participants. We identified participants by periodically (~once a week) reviewing the electronic medical records of all patients admitted to the medicine service during the study period. Eligible patients were 65 years old or older and had at least 3 hospitalizations over the preceding 6 months. Patients were excluded if they met our chronic critical illness criteria: mechanical ventilation for more than 21 days, history of tracheotomy for failed weaning from mechanical ventilation,7 presence of a conservator, or admission only for comfort measures. Participants were recruited until no new themes emerged.

Data Collection

Twenty-nine patients were eligible. We obtained permission from their inpatient providers to approach them about the study. Of the 29 patients, 26 agreed to be interviewed, and 3 declined. Of the 26 participants, 6 underwent pilot interviews, and 20 underwent formal interviews with use of the finalized interview guide. The interviews, conducted in the hospital while the participants were hospitalized, lasted 17 minutes on average. The interviews were transcribed and iteratively analyzed. The themes that emerged from the initial interviews were further explored and validated in subsequent interviews. Interviews were conducted until theoretical saturation was reached and no new themes were derived from them. Demographic information, including age, sex, ethnicity, and marital status, was also collected.

Analysis

Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed. Independently, two investigators used Atlas Ti software to analyze and code the interview transcriptions. An inductive approach was used to identify new codes from the data.8 The coders then met to discuss repeating ideas based on the codes. When a code was identified by one coder but not the other, or when there was disagreement about interpretation of a code, the coders returned to the relevant text to reach consensus and to determine whether to include or discard the code.9 We then organized and reorganized repeating ideas based on their conceptual similarities to determine the themes and subthemes.9

RESULTS

Twenty patients participated in the formal interviews. Participants’ baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1, and four dominant themes, and their subthemes and exemplary quotations, are listed in Table 2.

Perspectives on Hospital Care

Participants perceived their hospitalizations as inevitable and necessary for survival: “I think if I haven’t come to the hospital, I probably would have died.” Furthermore, participants thought only the hospital had the resources to help them (“The medications they were giving me … you can get that in the hospital but not outside the hospital”) and sustain them (“You are like an old car, and it breaks down little by little, so you have to go in periodically and get the problem fixed, so you will drive it around for a while”).

Feeling Safe in Hospital. Asked how being in the hospital makes them feel, participants attributed their feelings of safety to the constant observation, the availability of providers and nurses, and the idea that hospital care is helping. As one participant stated, “Makes me feel safer in case you go into something like cardiac arrest. You are right here where they can help you.”

Outside-Hospital Support. Despite multiple hospitalizations, most participants reported having social support (“I have the aide. I got the nurses come in. I have my daughter …”), physical support, and medical support (“I have all the doctors”) outside the hospital. A minority of participants questioned the usefulness of the services. One participant described declining the help of visiting nurses because she wanted to be independent and thought that, despite recurrent hospitalizations for physical symptoms, she still had the ability to manage her own medications.

Goals-of-Care Discussion. Some participants reported inadequate discussions about goals of care, health priorities, and health trajectories. In their reports, this inadequacy included not thinking about their goals, despite continued health decline. One participant stated, “Oh, God, I don’t know if I had any conversation like that. … I think until it is really brought to the front, you don’t make a decision really if you don’t have to.” Citing the value of a more established relationship and deeper trust, participants preferred having these serious and personal discussions with their ambulatory care clinicians: “Because I know my doctor much closer. I have been with him for a number of years. The doctors in the hospital seem to be nice and competent, but I don’t know them.”

DISCUSSION

Participants considered their hospitalizations a necessity and reported feeling safe in the hospital. Given that most already had support outside the hospital, increasing community services may be inadequate to alter participants’ perceived hospital care needs. On the other hand, a few participants reported declining services that might have prevented hospitalizations. Although there has been a study of treatment refusal among older adults with advanced illnesses,10 not much is known about refusal of services among this population. Investigators should examine the reasons for refusing services and the effect that refusal has on hospitalizations. Furthermore, although it would have been informative to ascertain clinician perspectives as well, we focused on patient perspectives because less is known on this topic.

Some participants noted their lack of discussion with their clinicians about healthcare goals and probable health trajectories. Barriers to goals-of-care discussion among this highly vulnerable population have been researched from the perspectives of clinicians and other health professionals but not patients themselves.11,12 Of particular concern in our study is the participant-noted lack of discussion about health trajectories and health priorities, given the decline that occurs in this population and even in those with good care. This inadequacy in discussion suggests continued hospital care may not always be consistent with a patient’s goals. Patients’ desire to have this discussion with their clinicians, with whom they have a relationship, supports the need to involve ambulatory care clinicians, or ensure these patients are cared for by the same clinicians, across healthcare settings.13,14 Whoever provides the care, the clinician must align treatment with the patient’s goal, whether it is to continue hospital-level care or to transition to palliative care. Such an approach also reflects the core elements of person-centered care.15

Study Limitations

Participants were recruited from the medicine service at a single large academic center, limiting the study’s generalizability to patients admitted to surgical services or community hospitals. The patients in this small sample were English-speaking and predominantly Caucasian, so our findings may not represent the perspectives of non-English-speaking or minority patients. We did not perform statistical analysis to quantify intercoder reliability. Last, as this was a qualitative study, we cannot comment on the relative importance or prevalence of the reasons cited for frequent hospitalizations, and we cannot estimate the proportion of patients who had recurrent hospitalizations and were hospital-dependent.

Implication

Although quantitative research is needed to confirm our findings, the hospital-dependent patients in this study thought their survival required hospital-level care and resources. From their perspective, increasing posthospital and community support may be insufficient to prevent some hospitalizations. The lack of goals-of-care discussion supports attempts to increase efforts to facilitate discussion about health trajectories and health priorities between patients and their preferred clinicians.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Grace Jenq for providing feedback on the study design.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

In the United States, patients 65 years old or older accounted for more than one third of inpatient stays and 42% of inpatient care spending in 2012.1 Despite the identification of risk factors, the implementation of an array of interventions, and the institution of penalties on hospitals, a subset of older adults continues to spend significant time in the hospital.2,3

Hospital dependency is a concept that was only recently described. It identifies patients who improve while in the hospital but quickly deteriorate after leaving the hospital, resulting in recurring hospitalizations.4 Although little is known about hospital-dependent patients, studies have explored patients’ perspectives on readmissions.5,6 Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether there are individuals for whom frequent and prolonged hospitalizations are appropriate, and whether there are undisclosed factors that, if addressed, could decrease their hospital dependency. We conducted an exploratory study to ascertain hospital-dependent patients’ perspectives on their needs for hospitalizations.

METHODS

Study Design

This study was approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board. From March 2015 to September 2015, Dr. Liu conducted semistructured explorative interviews with patients on the medical units of an academic medical center. Dr. Liu was not directly involved in the care of these patients. An interview guide that includes open-ended questions was created to elicit patients’ perspectives on their need for hospitalizations, health status, and outside-hospital support. This guide was pilot-tested with 6 patients, whose transcripts were not included in the final analysis, to assess for ease of understanding. After the pilot interviews, the questions were revised, and the final guide consists of 12 questions (Supplemental Table).

Recruitment

We used predetermined criteria and a purposeful sampling strategy to select potential study participants. We identified participants by periodically (~once a week) reviewing the electronic medical records of all patients admitted to the medicine service during the study period. Eligible patients were 65 years old or older and had at least 3 hospitalizations over the preceding 6 months. Patients were excluded if they met our chronic critical illness criteria: mechanical ventilation for more than 21 days, history of tracheotomy for failed weaning from mechanical ventilation,7 presence of a conservator, or admission only for comfort measures. Participants were recruited until no new themes emerged.

Data Collection

Twenty-nine patients were eligible. We obtained permission from their inpatient providers to approach them about the study. Of the 29 patients, 26 agreed to be interviewed, and 3 declined. Of the 26 participants, 6 underwent pilot interviews, and 20 underwent formal interviews with use of the finalized interview guide. The interviews, conducted in the hospital while the participants were hospitalized, lasted 17 minutes on average. The interviews were transcribed and iteratively analyzed. The themes that emerged from the initial interviews were further explored and validated in subsequent interviews. Interviews were conducted until theoretical saturation was reached and no new themes were derived from them. Demographic information, including age, sex, ethnicity, and marital status, was also collected.

Analysis

Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed. Independently, two investigators used Atlas Ti software to analyze and code the interview transcriptions. An inductive approach was used to identify new codes from the data.8 The coders then met to discuss repeating ideas based on the codes. When a code was identified by one coder but not the other, or when there was disagreement about interpretation of a code, the coders returned to the relevant text to reach consensus and to determine whether to include or discard the code.9 We then organized and reorganized repeating ideas based on their conceptual similarities to determine the themes and subthemes.9

RESULTS

Twenty patients participated in the formal interviews. Participants’ baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1, and four dominant themes, and their subthemes and exemplary quotations, are listed in Table 2.

Perspectives on Hospital Care

Participants perceived their hospitalizations as inevitable and necessary for survival: “I think if I haven’t come to the hospital, I probably would have died.” Furthermore, participants thought only the hospital had the resources to help them (“The medications they were giving me … you can get that in the hospital but not outside the hospital”) and sustain them (“You are like an old car, and it breaks down little by little, so you have to go in periodically and get the problem fixed, so you will drive it around for a while”).

Feeling Safe in Hospital. Asked how being in the hospital makes them feel, participants attributed their feelings of safety to the constant observation, the availability of providers and nurses, and the idea that hospital care is helping. As one participant stated, “Makes me feel safer in case you go into something like cardiac arrest. You are right here where they can help you.”

Outside-Hospital Support. Despite multiple hospitalizations, most participants reported having social support (“I have the aide. I got the nurses come in. I have my daughter …”), physical support, and medical support (“I have all the doctors”) outside the hospital. A minority of participants questioned the usefulness of the services. One participant described declining the help of visiting nurses because she wanted to be independent and thought that, despite recurrent hospitalizations for physical symptoms, she still had the ability to manage her own medications.

Goals-of-Care Discussion. Some participants reported inadequate discussions about goals of care, health priorities, and health trajectories. In their reports, this inadequacy included not thinking about their goals, despite continued health decline. One participant stated, “Oh, God, I don’t know if I had any conversation like that. … I think until it is really brought to the front, you don’t make a decision really if you don’t have to.” Citing the value of a more established relationship and deeper trust, participants preferred having these serious and personal discussions with their ambulatory care clinicians: “Because I know my doctor much closer. I have been with him for a number of years. The doctors in the hospital seem to be nice and competent, but I don’t know them.”

DISCUSSION

Participants considered their hospitalizations a necessity and reported feeling safe in the hospital. Given that most already had support outside the hospital, increasing community services may be inadequate to alter participants’ perceived hospital care needs. On the other hand, a few participants reported declining services that might have prevented hospitalizations. Although there has been a study of treatment refusal among older adults with advanced illnesses,10 not much is known about refusal of services among this population. Investigators should examine the reasons for refusing services and the effect that refusal has on hospitalizations. Furthermore, although it would have been informative to ascertain clinician perspectives as well, we focused on patient perspectives because less is known on this topic.

Some participants noted their lack of discussion with their clinicians about healthcare goals and probable health trajectories. Barriers to goals-of-care discussion among this highly vulnerable population have been researched from the perspectives of clinicians and other health professionals but not patients themselves.11,12 Of particular concern in our study is the participant-noted lack of discussion about health trajectories and health priorities, given the decline that occurs in this population and even in those with good care. This inadequacy in discussion suggests continued hospital care may not always be consistent with a patient’s goals. Patients’ desire to have this discussion with their clinicians, with whom they have a relationship, supports the need to involve ambulatory care clinicians, or ensure these patients are cared for by the same clinicians, across healthcare settings.13,14 Whoever provides the care, the clinician must align treatment with the patient’s goal, whether it is to continue hospital-level care or to transition to palliative care. Such an approach also reflects the core elements of person-centered care.15

Study Limitations

Participants were recruited from the medicine service at a single large academic center, limiting the study’s generalizability to patients admitted to surgical services or community hospitals. The patients in this small sample were English-speaking and predominantly Caucasian, so our findings may not represent the perspectives of non-English-speaking or minority patients. We did not perform statistical analysis to quantify intercoder reliability. Last, as this was a qualitative study, we cannot comment on the relative importance or prevalence of the reasons cited for frequent hospitalizations, and we cannot estimate the proportion of patients who had recurrent hospitalizations and were hospital-dependent.

Implication

Although quantitative research is needed to confirm our findings, the hospital-dependent patients in this study thought their survival required hospital-level care and resources. From their perspective, increasing posthospital and community support may be insufficient to prevent some hospitalizations. The lack of goals-of-care discussion supports attempts to increase efforts to facilitate discussion about health trajectories and health priorities between patients and their preferred clinicians.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Grace Jenq for providing feedback on the study design.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of Hospital Stays in the United States, 2012: Statistical Brief 180. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project; 2014. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK259100/. Published October 2014. Accessed February 17, 2016.

2. Auerbach AD, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Preventability and causes of readmissions in a national cohort of general medicine patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):484-493. PubMed

3. Donzé JD, Williams MV, Robinson EJ, et al. International validity of the HOSPITAL score to predict 30-day potentially avoidable hospital readmissions. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):496-502. PubMed

4. Reuben DB, Tinetti ME. The hospital-dependent patient. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):694-697. PubMed

5. Enguidanos S, Coulourides Kogan AM, Schreibeis-Baum H, Lendon J, Lorenz K. “Because I was sick”: seriously ill veterans’ perspectives on reason for 30-day readmissions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(3):537-542. PubMed

6. Kangovi S, Grande D, Meehan P, Mitra N, Shannon R, Long JA. Perceptions of readmitted patients on the transition from hospital to home. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(9):709-712. PubMed

7. Lamas D. Chronic critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(2):175-177. PubMed

8. Saldana J. Fundamentals of Qualitative Research. Cary, NC: Oxford University Press; 2011.

9. Auerbach CF, Silverstein LB. Qualitative Data: An Introduction to Coding and Analysis. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2003.

10. Rothman MD, Van Ness PH, O’Leary JR, Fried TR. Refusal of medical and surgical interventions by older persons with advanced chronic disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(7):982-987. PubMed

11. You JJ, Downar J, Fowler RA, et al; Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network. Barriers to goals of care discussions with seriously ill hospitalized patients and their families: a multicenter survey of clinicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):549-556. PubMed

12. Schoenborn NL, Bowman TL 2nd, Cayea D, Pollack CE, Feeser S, Boyd C. Primary care practitioners’ views on incorporating long-term prognosis in the care of older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):671-678. PubMed

13. Arora VM, Prochaska ML, Farnan JM, et al. Problems after discharge and understanding of communication with their primary care physicians among hospitalized seniors: a mixed methods study. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):385-391. PubMed

14. Jones CD, Vu MB, O’Donnell CM, et al. A failure to communicate: a qualitative exploration of care coordination between hospitalists and primary care providers around patient hospitalizations. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(4):417-424. PubMed

15. American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Person-Centered Care. Person-centered care: a definition and essential elements. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(1):15-18. PubMed

1. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of Hospital Stays in the United States, 2012: Statistical Brief 180. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project; 2014. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK259100/. Published October 2014. Accessed February 17, 2016.

2. Auerbach AD, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Preventability and causes of readmissions in a national cohort of general medicine patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):484-493. PubMed

3. Donzé JD, Williams MV, Robinson EJ, et al. International validity of the HOSPITAL score to predict 30-day potentially avoidable hospital readmissions. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):496-502. PubMed

4. Reuben DB, Tinetti ME. The hospital-dependent patient. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):694-697. PubMed

5. Enguidanos S, Coulourides Kogan AM, Schreibeis-Baum H, Lendon J, Lorenz K. “Because I was sick”: seriously ill veterans’ perspectives on reason for 30-day readmissions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(3):537-542. PubMed

6. Kangovi S, Grande D, Meehan P, Mitra N, Shannon R, Long JA. Perceptions of readmitted patients on the transition from hospital to home. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(9):709-712. PubMed

7. Lamas D. Chronic critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(2):175-177. PubMed

8. Saldana J. Fundamentals of Qualitative Research. Cary, NC: Oxford University Press; 2011.

9. Auerbach CF, Silverstein LB. Qualitative Data: An Introduction to Coding and Analysis. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2003.

10. Rothman MD, Van Ness PH, O’Leary JR, Fried TR. Refusal of medical and surgical interventions by older persons with advanced chronic disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(7):982-987. PubMed

11. You JJ, Downar J, Fowler RA, et al; Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network. Barriers to goals of care discussions with seriously ill hospitalized patients and their families: a multicenter survey of clinicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):549-556. PubMed

12. Schoenborn NL, Bowman TL 2nd, Cayea D, Pollack CE, Feeser S, Boyd C. Primary care practitioners’ views on incorporating long-term prognosis in the care of older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):671-678. PubMed

13. Arora VM, Prochaska ML, Farnan JM, et al. Problems after discharge and understanding of communication with their primary care physicians among hospitalized seniors: a mixed methods study. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):385-391. PubMed

14. Jones CD, Vu MB, O’Donnell CM, et al. A failure to communicate: a qualitative exploration of care coordination between hospitalists and primary care providers around patient hospitalizations. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(4):417-424. PubMed

15. American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Person-Centered Care. Person-centered care: a definition and essential elements. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(1):15-18. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Incidental pulmonary nodules reported on CT abdominal imaging: Frequency and factors affecting inclusion in the hospital discharge summary

Incidental findings create both medical and logistical challenges regarding communication.1,2 Pulmonary nodules are among the most frequent and medically relevant incidental findings, being noted in up to 8.4% of abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans.3 There are guidelines regarding proper follow-up and management of such incidental pulmonary nodules, but appropriate evidence-based surveillance imaging is often not performed, and many patients remain uninformed. Collins et al.4 reported that, before initiation of a standardized protocol, only 17.7% of incidental findings were communicated to patients admitted to the trauma service; after protocol initiation, the rate increased to 32.4%. The hospital discharge summary provides an opportunity to communicate incidental findings to patients and their medical care providers, but Kripalani et al.5 raised questions regarding the current completeness and accuracy of discharge summaries, reporting that 65% of discharge summaries omitted relevant diagnostic testing, and 30% omitted a follow-up plan.

We conducted a study to determine how often incidental pulmonary nodules found on abdominal CT are documented in the discharge summary, and to identify factors associated with pulmonary nodule inclusion.

METHODS

This was a retrospective cohort study of hospitalized patients ≥35 years of age who underwent in-patient abdominal CT between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2014. Patients were identified by cross-referencing hospital admissions with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes indicating abdominal CT (74176, 74177, 74178, 74160, 74150, 74170). Patients with chest CT (CPT codes 71260, 71250, 71270) during that hospitalization or within 30 days before admission were excluded to ensure that pulmonary nodules were incidental and asymptomatic. The index hospitalization was defined as the first hospitalization during which the patient was diagnosed with an incidental pulmonary nodule on abdominal CT, or the first hospitalization during the study period for patients without pulmonary nodules. All patient charts were manually reviewed, and baseline age, sex, and smoking status data collected.

Radiology reports were electronically screened for the words nodule and nodules and then confirmed through manual review of the full text reports. Nodules described as tiny (without other size description) were assumed to be <4 mm in size, per manual review of a small sample. Nodules were deemed as falling outside the Fleischner Society criteria guidelines (designed for indeterminate pulmonary nodules), and were therefore excluded, if any of seven criteria were met: The nodule was (1) cavitary, (2) associated with a known metastatic disease, (3) associated with a known granulomatous disease, (4) associated with a known inflammatory process, (5) reported likely to represent atelectasis, (6) reported likely to be a lymph node, or (7) previously biopsied.4

For each patient with pulmonary nodules, a personal history of cancer was obtained. Nodule size, characteristics, and stability compared with available prior imaging were recorded. Radiology reports were reviewed to determine if pulmonary nodules were mentioned in the summary headings of the reports or in the body of the reports and whether specific follow-up recommendations were provided. Hospital discharge summaries were reviewed for documentation of pulmonary nodule(s) and follow-up recommendations. Discharging service (medical/medical subspecialty, surgical/surgical subspecialty) was noted, along with the patients’ condition at discharge (alive, alive on hospice, deceased).

The frequency of incidental pulmonary nodules on abdominal CT during hospitalization and the frequency of nodules requiring follow-up were reported using a point estimate and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). The χ2 test was used to compare the frequency of pulmonary nodules across patient groups. In addition, for patients found to have incidental nodules requiring follow-up, the χ2 test was used to compare across groups the percentage of patients with discharge documentation of the incidental nodule. In all cases, 2-tailed Ps are reported, with P ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

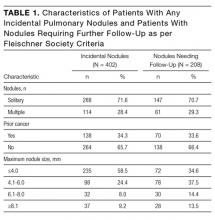

Between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2014, 7173 patients ≥35 years old underwent in-patient abdominal CT without concurrent chest CT. Of these patients, 62.2% were ≥60 years old, 50.6% were men, and 45.5% were current or former smokers. Incidental pulmonary nodules were noted in 402 patients (5.6%; 95% CI, 5.1%-6.2%), of whom 68.7% were ≥60 years old, 56.5% were men, and 46.3% were current or former smokers. Increasing age (P = 0.004) and male sex (P = 0.015) were associated with increased frequency of incidental pulmonary nodules, but smoking status (P = 0.586) was not. Of patients with incidental nodules, 71.6% had solitary nodules, and 58.5% had a maximum nodule size of ≤4 mm (Table 1). Based on smoking status, nodule size, and reported size stability, 208 patients (2.9%; 95% CI, 2.5%-3.3%) required follow-up surveillance as per 2005 Fleischner Society guidelines. Among solitary pulmonary nodules requiring further surveillance (n = 147), the mean risk of malignancy based on the Mayo Clinic solitary pulmonary nodule risk calculator was 7.9% (interquartile range, 3.0%-10.5%), with 28% having a malignancy risk of ≥10%.6

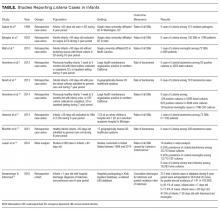

Of the 208 patients with nodules requiring further surveillance, only 48 (23%) received discharge summaries documenting the nodule; 34 of these summaries included a recommendation for nodule follow-up, with 19 of the recommendations including a time frame for repeat CT. Three factors were positively associated with documentation of the pulmonary nodule in the discharge summary: mention of the pulmonary nodule in the summary headings of the radiology report (P < 0.001), radiologist recommendation for further surveillance (P < 0.001), and medical discharging service (P = 0.016) (Table 2). The highest rate of pulmonary nodule inclusion in the discharge summary (42%) was noted among patients for whom the radiology report included specific recommendations.

DISCUSSION

The frequency of incidental pulmonary nodules reported on abdominal CT in our study (5.6%) is consistent with frequencies reported in similar studies. Wu et al.7 (reviewing 141,406 abdominal CT scans) and Alpert et al.8 (reviewing 12,287 abdominal CT scans) reported frequencies of 2.5% and 3%, respectively, while Rinaldi et al.3 (reviewing 243 abdominal CT scans) reported a higher frequency, 8.4%. Variation likely results from patient factors and the individual radiologist’s attention to incidental pulmonary findings. Rinaldi et al. suggested that up to 39% of abdominal CT scans include pulmonary nodules on independent review, raising the possibility of significant underreporting. In our study, we focused on pulmonary nodules included in the radiology report to tailor the relevance of our study to the hospital medicine community. We also included only those incidental nodules falling within the purview of the Fleischner Society criteria in order to analyze only findings with established follow-up guidelines.

The rate of pulmonary nodule documentation in our study was low overall (23%) but consistent with the literature. Collins et al.,4 for example, reported that only 17.7% of patients with trauma were notified of incidental CT findings by either the discharge summary or an appropriate specialist consultation. Various contributing factors can be hypothesized. First, incidental pulmonary nodules are discovered largely in the context of evaluation for other symptomatic conditions, which can overshadow their importance. Second, the lack of clear patient-friendly education materials regarding incidental pulmonary nodules can complicate discussions with patients. Third, many electronic health record (EHR) systems cannot automatically pull incidental findings into the discharge summary and instead rely on provider vigilance.

As our study does, the literature highlights the importance of the radiology report in communicating incidental findings. In a review of >1000 pulmonary angiographic CT studies, Blagev et al.9 reported an overall follow-up rate of 29% (28/96) among patients with incidental pulmonary nodules, but none of the 12 patients with pulmonary nodules mentioned in the body of the report (rather than in the summary headings) received adequate follow-up. Similarly, in Shuaib et al.,10 radiology reports that included follow-up recommendations were more likely to change patient treatment than reports without follow-up recommendations (70% vs 2%). However, our data also show that radiologist recommendations alone are insufficient to ensure adequate communication of incidental findings.

The literature regarding the most cost-effective means of addressing this quality gap is limited. Some institutions have integrated their EHR systems to allow radiologists to flag incidental findings for auto-population in a dedicated section of the discharge summary. Although these efforts can be helpful, documentation alone does not save lives without appropriate follow-up and intervention. Some institutions have hired dedicated nursing staff as incidental finding coordinators. For high-risk incidental findings, Sperry et al.11 reported that hiring an incidental findings coordinator helped their level I trauma center achieve nearly complete documentation, patient notification, and confirmation of posthospital follow-up appointments. Such solutions, however, are labor-intensive and still rely on appropriate primary care follow-up.

Strengths of our study include its relatively large size and particular focus on the issues and decisions facing hospital medicine providers. By focusing on incidental pulmonary nodules reported on abdominal CT, and excluding patients with concurrent chest CT, we avoided including patients with symptomatic or previously identified pulmonary findings. Study limitations include the cross-sectional, retrospective design, which did not include follow-up data regarding such outcomes as rates of appropriate follow-up surveillance and subsequent lung cancer diagnoses. Our single-center study findings may not apply to all hospital practice settings, though they are consistent with the literature with comparison data.

Our study results highlight the need for a multidisciplinary systems-based approach to incidental pulmonary nodule documentation, communication, and follow-up surveillance.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Armao D, Smith JK. Overuse of computed tomography and the onslaught of incidental findings. N C Med J. 2014;75(2):127. PubMed

2. Gould MK, Tang T, Liu IL, et al. Recent trends in the identification of incidental pulmonary nodules. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(10):1208-1214. PubMed

3. Rinaldi MF, Bartalena T, Giannelli G, et al. Incidental lung nodules on CT examinations of the abdomen: prevalence and reporting rates in the PACS era. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74(3):e84-e88. PubMed

4. Collins CE, Cherng N, McDade T, et al. Improving patient notification of solid abdominal viscera incidental findings with a standardized protocol. J Trauma Manag Outcomes. 2015;9(1):1. PubMed

5. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841. PubMed

6. Swensen SJ, Silverstein MD, Ilstrup DM, Schleck CD, Edell ES. The probability of malignancy in solitary pulmonary nodules. Application to small radiologically indeterminate nodules. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(8):849-855. PubMed

7. Wu CC, Cronin CG, Chu JT, et al. Incidental pulmonary nodules detected on abdominal computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2012;36(6):641-645. PubMed

8. Alpert JB, Fantauzzi JP, Melamud K, Greenwood H, Naidich DP, Ko JP. Clinical significance of lung nodules reported on abdominal CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(4):793-799. PubMed

9. Blagev DP, Lloyd JF, Conner K, et al. Follow-up of incidental pulmonary nodules and the radiology report. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014;11(4):378-383. PubMed

10. Shuaib W, Johnson JO, Salastekar N, Maddu KK, Khosa F. Incidental findings detected on abdomino-pelvic multidetector computed tomography performed in the acute setting [published correction appears in Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(7):811. Waqas, Shuaib (corrected to Shuaib, Waqas)]. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(1):36-39. PubMed

11. Sperry JL, Massaro MS, Collage RD, et al. Incidental radiographic findings after injury: dedicated attention results in improved capture, documentation, and management. Surgery. 2010;148(4):618-624. PubMed

Incidental findings create both medical and logistical challenges regarding communication.1,2 Pulmonary nodules are among the most frequent and medically relevant incidental findings, being noted in up to 8.4% of abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans.3 There are guidelines regarding proper follow-up and management of such incidental pulmonary nodules, but appropriate evidence-based surveillance imaging is often not performed, and many patients remain uninformed. Collins et al.4 reported that, before initiation of a standardized protocol, only 17.7% of incidental findings were communicated to patients admitted to the trauma service; after protocol initiation, the rate increased to 32.4%. The hospital discharge summary provides an opportunity to communicate incidental findings to patients and their medical care providers, but Kripalani et al.5 raised questions regarding the current completeness and accuracy of discharge summaries, reporting that 65% of discharge summaries omitted relevant diagnostic testing, and 30% omitted a follow-up plan.

We conducted a study to determine how often incidental pulmonary nodules found on abdominal CT are documented in the discharge summary, and to identify factors associated with pulmonary nodule inclusion.

METHODS

This was a retrospective cohort study of hospitalized patients ≥35 years of age who underwent in-patient abdominal CT between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2014. Patients were identified by cross-referencing hospital admissions with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes indicating abdominal CT (74176, 74177, 74178, 74160, 74150, 74170). Patients with chest CT (CPT codes 71260, 71250, 71270) during that hospitalization or within 30 days before admission were excluded to ensure that pulmonary nodules were incidental and asymptomatic. The index hospitalization was defined as the first hospitalization during which the patient was diagnosed with an incidental pulmonary nodule on abdominal CT, or the first hospitalization during the study period for patients without pulmonary nodules. All patient charts were manually reviewed, and baseline age, sex, and smoking status data collected.

Radiology reports were electronically screened for the words nodule and nodules and then confirmed through manual review of the full text reports. Nodules described as tiny (without other size description) were assumed to be <4 mm in size, per manual review of a small sample. Nodules were deemed as falling outside the Fleischner Society criteria guidelines (designed for indeterminate pulmonary nodules), and were therefore excluded, if any of seven criteria were met: The nodule was (1) cavitary, (2) associated with a known metastatic disease, (3) associated with a known granulomatous disease, (4) associated with a known inflammatory process, (5) reported likely to represent atelectasis, (6) reported likely to be a lymph node, or (7) previously biopsied.4

For each patient with pulmonary nodules, a personal history of cancer was obtained. Nodule size, characteristics, and stability compared with available prior imaging were recorded. Radiology reports were reviewed to determine if pulmonary nodules were mentioned in the summary headings of the reports or in the body of the reports and whether specific follow-up recommendations were provided. Hospital discharge summaries were reviewed for documentation of pulmonary nodule(s) and follow-up recommendations. Discharging service (medical/medical subspecialty, surgical/surgical subspecialty) was noted, along with the patients’ condition at discharge (alive, alive on hospice, deceased).

The frequency of incidental pulmonary nodules on abdominal CT during hospitalization and the frequency of nodules requiring follow-up were reported using a point estimate and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). The χ2 test was used to compare the frequency of pulmonary nodules across patient groups. In addition, for patients found to have incidental nodules requiring follow-up, the χ2 test was used to compare across groups the percentage of patients with discharge documentation of the incidental nodule. In all cases, 2-tailed Ps are reported, with P ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2014, 7173 patients ≥35 years old underwent in-patient abdominal CT without concurrent chest CT. Of these patients, 62.2% were ≥60 years old, 50.6% were men, and 45.5% were current or former smokers. Incidental pulmonary nodules were noted in 402 patients (5.6%; 95% CI, 5.1%-6.2%), of whom 68.7% were ≥60 years old, 56.5% were men, and 46.3% were current or former smokers. Increasing age (P = 0.004) and male sex (P = 0.015) were associated with increased frequency of incidental pulmonary nodules, but smoking status (P = 0.586) was not. Of patients with incidental nodules, 71.6% had solitary nodules, and 58.5% had a maximum nodule size of ≤4 mm (Table 1). Based on smoking status, nodule size, and reported size stability, 208 patients (2.9%; 95% CI, 2.5%-3.3%) required follow-up surveillance as per 2005 Fleischner Society guidelines. Among solitary pulmonary nodules requiring further surveillance (n = 147), the mean risk of malignancy based on the Mayo Clinic solitary pulmonary nodule risk calculator was 7.9% (interquartile range, 3.0%-10.5%), with 28% having a malignancy risk of ≥10%.6

Of the 208 patients with nodules requiring further surveillance, only 48 (23%) received discharge summaries documenting the nodule; 34 of these summaries included a recommendation for nodule follow-up, with 19 of the recommendations including a time frame for repeat CT. Three factors were positively associated with documentation of the pulmonary nodule in the discharge summary: mention of the pulmonary nodule in the summary headings of the radiology report (P < 0.001), radiologist recommendation for further surveillance (P < 0.001), and medical discharging service (P = 0.016) (Table 2). The highest rate of pulmonary nodule inclusion in the discharge summary (42%) was noted among patients for whom the radiology report included specific recommendations.

DISCUSSION

The frequency of incidental pulmonary nodules reported on abdominal CT in our study (5.6%) is consistent with frequencies reported in similar studies. Wu et al.7 (reviewing 141,406 abdominal CT scans) and Alpert et al.8 (reviewing 12,287 abdominal CT scans) reported frequencies of 2.5% and 3%, respectively, while Rinaldi et al.3 (reviewing 243 abdominal CT scans) reported a higher frequency, 8.4%. Variation likely results from patient factors and the individual radiologist’s attention to incidental pulmonary findings. Rinaldi et al. suggested that up to 39% of abdominal CT scans include pulmonary nodules on independent review, raising the possibility of significant underreporting. In our study, we focused on pulmonary nodules included in the radiology report to tailor the relevance of our study to the hospital medicine community. We also included only those incidental nodules falling within the purview of the Fleischner Society criteria in order to analyze only findings with established follow-up guidelines.

The rate of pulmonary nodule documentation in our study was low overall (23%) but consistent with the literature. Collins et al.,4 for example, reported that only 17.7% of patients with trauma were notified of incidental CT findings by either the discharge summary or an appropriate specialist consultation. Various contributing factors can be hypothesized. First, incidental pulmonary nodules are discovered largely in the context of evaluation for other symptomatic conditions, which can overshadow their importance. Second, the lack of clear patient-friendly education materials regarding incidental pulmonary nodules can complicate discussions with patients. Third, many electronic health record (EHR) systems cannot automatically pull incidental findings into the discharge summary and instead rely on provider vigilance.

As our study does, the literature highlights the importance of the radiology report in communicating incidental findings. In a review of >1000 pulmonary angiographic CT studies, Blagev et al.9 reported an overall follow-up rate of 29% (28/96) among patients with incidental pulmonary nodules, but none of the 12 patients with pulmonary nodules mentioned in the body of the report (rather than in the summary headings) received adequate follow-up. Similarly, in Shuaib et al.,10 radiology reports that included follow-up recommendations were more likely to change patient treatment than reports without follow-up recommendations (70% vs 2%). However, our data also show that radiologist recommendations alone are insufficient to ensure adequate communication of incidental findings.

The literature regarding the most cost-effective means of addressing this quality gap is limited. Some institutions have integrated their EHR systems to allow radiologists to flag incidental findings for auto-population in a dedicated section of the discharge summary. Although these efforts can be helpful, documentation alone does not save lives without appropriate follow-up and intervention. Some institutions have hired dedicated nursing staff as incidental finding coordinators. For high-risk incidental findings, Sperry et al.11 reported that hiring an incidental findings coordinator helped their level I trauma center achieve nearly complete documentation, patient notification, and confirmation of posthospital follow-up appointments. Such solutions, however, are labor-intensive and still rely on appropriate primary care follow-up.

Strengths of our study include its relatively large size and particular focus on the issues and decisions facing hospital medicine providers. By focusing on incidental pulmonary nodules reported on abdominal CT, and excluding patients with concurrent chest CT, we avoided including patients with symptomatic or previously identified pulmonary findings. Study limitations include the cross-sectional, retrospective design, which did not include follow-up data regarding such outcomes as rates of appropriate follow-up surveillance and subsequent lung cancer diagnoses. Our single-center study findings may not apply to all hospital practice settings, though they are consistent with the literature with comparison data.

Our study results highlight the need for a multidisciplinary systems-based approach to incidental pulmonary nodule documentation, communication, and follow-up surveillance.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Incidental findings create both medical and logistical challenges regarding communication.1,2 Pulmonary nodules are among the most frequent and medically relevant incidental findings, being noted in up to 8.4% of abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans.3 There are guidelines regarding proper follow-up and management of such incidental pulmonary nodules, but appropriate evidence-based surveillance imaging is often not performed, and many patients remain uninformed. Collins et al.4 reported that, before initiation of a standardized protocol, only 17.7% of incidental findings were communicated to patients admitted to the trauma service; after protocol initiation, the rate increased to 32.4%. The hospital discharge summary provides an opportunity to communicate incidental findings to patients and their medical care providers, but Kripalani et al.5 raised questions regarding the current completeness and accuracy of discharge summaries, reporting that 65% of discharge summaries omitted relevant diagnostic testing, and 30% omitted a follow-up plan.

We conducted a study to determine how often incidental pulmonary nodules found on abdominal CT are documented in the discharge summary, and to identify factors associated with pulmonary nodule inclusion.

METHODS

This was a retrospective cohort study of hospitalized patients ≥35 years of age who underwent in-patient abdominal CT between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2014. Patients were identified by cross-referencing hospital admissions with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes indicating abdominal CT (74176, 74177, 74178, 74160, 74150, 74170). Patients with chest CT (CPT codes 71260, 71250, 71270) during that hospitalization or within 30 days before admission were excluded to ensure that pulmonary nodules were incidental and asymptomatic. The index hospitalization was defined as the first hospitalization during which the patient was diagnosed with an incidental pulmonary nodule on abdominal CT, or the first hospitalization during the study period for patients without pulmonary nodules. All patient charts were manually reviewed, and baseline age, sex, and smoking status data collected.

Radiology reports were electronically screened for the words nodule and nodules and then confirmed through manual review of the full text reports. Nodules described as tiny (without other size description) were assumed to be <4 mm in size, per manual review of a small sample. Nodules were deemed as falling outside the Fleischner Society criteria guidelines (designed for indeterminate pulmonary nodules), and were therefore excluded, if any of seven criteria were met: The nodule was (1) cavitary, (2) associated with a known metastatic disease, (3) associated with a known granulomatous disease, (4) associated with a known inflammatory process, (5) reported likely to represent atelectasis, (6) reported likely to be a lymph node, or (7) previously biopsied.4

For each patient with pulmonary nodules, a personal history of cancer was obtained. Nodule size, characteristics, and stability compared with available prior imaging were recorded. Radiology reports were reviewed to determine if pulmonary nodules were mentioned in the summary headings of the reports or in the body of the reports and whether specific follow-up recommendations were provided. Hospital discharge summaries were reviewed for documentation of pulmonary nodule(s) and follow-up recommendations. Discharging service (medical/medical subspecialty, surgical/surgical subspecialty) was noted, along with the patients’ condition at discharge (alive, alive on hospice, deceased).

The frequency of incidental pulmonary nodules on abdominal CT during hospitalization and the frequency of nodules requiring follow-up were reported using a point estimate and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). The χ2 test was used to compare the frequency of pulmonary nodules across patient groups. In addition, for patients found to have incidental nodules requiring follow-up, the χ2 test was used to compare across groups the percentage of patients with discharge documentation of the incidental nodule. In all cases, 2-tailed Ps are reported, with P ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2014, 7173 patients ≥35 years old underwent in-patient abdominal CT without concurrent chest CT. Of these patients, 62.2% were ≥60 years old, 50.6% were men, and 45.5% were current or former smokers. Incidental pulmonary nodules were noted in 402 patients (5.6%; 95% CI, 5.1%-6.2%), of whom 68.7% were ≥60 years old, 56.5% were men, and 46.3% were current or former smokers. Increasing age (P = 0.004) and male sex (P = 0.015) were associated with increased frequency of incidental pulmonary nodules, but smoking status (P = 0.586) was not. Of patients with incidental nodules, 71.6% had solitary nodules, and 58.5% had a maximum nodule size of ≤4 mm (Table 1). Based on smoking status, nodule size, and reported size stability, 208 patients (2.9%; 95% CI, 2.5%-3.3%) required follow-up surveillance as per 2005 Fleischner Society guidelines. Among solitary pulmonary nodules requiring further surveillance (n = 147), the mean risk of malignancy based on the Mayo Clinic solitary pulmonary nodule risk calculator was 7.9% (interquartile range, 3.0%-10.5%), with 28% having a malignancy risk of ≥10%.6

Of the 208 patients with nodules requiring further surveillance, only 48 (23%) received discharge summaries documenting the nodule; 34 of these summaries included a recommendation for nodule follow-up, with 19 of the recommendations including a time frame for repeat CT. Three factors were positively associated with documentation of the pulmonary nodule in the discharge summary: mention of the pulmonary nodule in the summary headings of the radiology report (P < 0.001), radiologist recommendation for further surveillance (P < 0.001), and medical discharging service (P = 0.016) (Table 2). The highest rate of pulmonary nodule inclusion in the discharge summary (42%) was noted among patients for whom the radiology report included specific recommendations.

DISCUSSION

The frequency of incidental pulmonary nodules reported on abdominal CT in our study (5.6%) is consistent with frequencies reported in similar studies. Wu et al.7 (reviewing 141,406 abdominal CT scans) and Alpert et al.8 (reviewing 12,287 abdominal CT scans) reported frequencies of 2.5% and 3%, respectively, while Rinaldi et al.3 (reviewing 243 abdominal CT scans) reported a higher frequency, 8.4%. Variation likely results from patient factors and the individual radiologist’s attention to incidental pulmonary findings. Rinaldi et al. suggested that up to 39% of abdominal CT scans include pulmonary nodules on independent review, raising the possibility of significant underreporting. In our study, we focused on pulmonary nodules included in the radiology report to tailor the relevance of our study to the hospital medicine community. We also included only those incidental nodules falling within the purview of the Fleischner Society criteria in order to analyze only findings with established follow-up guidelines.

The rate of pulmonary nodule documentation in our study was low overall (23%) but consistent with the literature. Collins et al.,4 for example, reported that only 17.7% of patients with trauma were notified of incidental CT findings by either the discharge summary or an appropriate specialist consultation. Various contributing factors can be hypothesized. First, incidental pulmonary nodules are discovered largely in the context of evaluation for other symptomatic conditions, which can overshadow their importance. Second, the lack of clear patient-friendly education materials regarding incidental pulmonary nodules can complicate discussions with patients. Third, many electronic health record (EHR) systems cannot automatically pull incidental findings into the discharge summary and instead rely on provider vigilance.

As our study does, the literature highlights the importance of the radiology report in communicating incidental findings. In a review of >1000 pulmonary angiographic CT studies, Blagev et al.9 reported an overall follow-up rate of 29% (28/96) among patients with incidental pulmonary nodules, but none of the 12 patients with pulmonary nodules mentioned in the body of the report (rather than in the summary headings) received adequate follow-up. Similarly, in Shuaib et al.,10 radiology reports that included follow-up recommendations were more likely to change patient treatment than reports without follow-up recommendations (70% vs 2%). However, our data also show that radiologist recommendations alone are insufficient to ensure adequate communication of incidental findings.

The literature regarding the most cost-effective means of addressing this quality gap is limited. Some institutions have integrated their EHR systems to allow radiologists to flag incidental findings for auto-population in a dedicated section of the discharge summary. Although these efforts can be helpful, documentation alone does not save lives without appropriate follow-up and intervention. Some institutions have hired dedicated nursing staff as incidental finding coordinators. For high-risk incidental findings, Sperry et al.11 reported that hiring an incidental findings coordinator helped their level I trauma center achieve nearly complete documentation, patient notification, and confirmation of posthospital follow-up appointments. Such solutions, however, are labor-intensive and still rely on appropriate primary care follow-up.

Strengths of our study include its relatively large size and particular focus on the issues and decisions facing hospital medicine providers. By focusing on incidental pulmonary nodules reported on abdominal CT, and excluding patients with concurrent chest CT, we avoided including patients with symptomatic or previously identified pulmonary findings. Study limitations include the cross-sectional, retrospective design, which did not include follow-up data regarding such outcomes as rates of appropriate follow-up surveillance and subsequent lung cancer diagnoses. Our single-center study findings may not apply to all hospital practice settings, though they are consistent with the literature with comparison data.

Our study results highlight the need for a multidisciplinary systems-based approach to incidental pulmonary nodule documentation, communication, and follow-up surveillance.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Armao D, Smith JK. Overuse of computed tomography and the onslaught of incidental findings. N C Med J. 2014;75(2):127. PubMed

2. Gould MK, Tang T, Liu IL, et al. Recent trends in the identification of incidental pulmonary nodules. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(10):1208-1214. PubMed

3. Rinaldi MF, Bartalena T, Giannelli G, et al. Incidental lung nodules on CT examinations of the abdomen: prevalence and reporting rates in the PACS era. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74(3):e84-e88. PubMed

4. Collins CE, Cherng N, McDade T, et al. Improving patient notification of solid abdominal viscera incidental findings with a standardized protocol. J Trauma Manag Outcomes. 2015;9(1):1. PubMed

5. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841. PubMed

6. Swensen SJ, Silverstein MD, Ilstrup DM, Schleck CD, Edell ES. The probability of malignancy in solitary pulmonary nodules. Application to small radiologically indeterminate nodules. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(8):849-855. PubMed

7. Wu CC, Cronin CG, Chu JT, et al. Incidental pulmonary nodules detected on abdominal computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2012;36(6):641-645. PubMed

8. Alpert JB, Fantauzzi JP, Melamud K, Greenwood H, Naidich DP, Ko JP. Clinical significance of lung nodules reported on abdominal CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(4):793-799. PubMed

9. Blagev DP, Lloyd JF, Conner K, et al. Follow-up of incidental pulmonary nodules and the radiology report. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014;11(4):378-383. PubMed

10. Shuaib W, Johnson JO, Salastekar N, Maddu KK, Khosa F. Incidental findings detected on abdomino-pelvic multidetector computed tomography performed in the acute setting [published correction appears in Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(7):811. Waqas, Shuaib (corrected to Shuaib, Waqas)]. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(1):36-39. PubMed

11. Sperry JL, Massaro MS, Collage RD, et al. Incidental radiographic findings after injury: dedicated attention results in improved capture, documentation, and management. Surgery. 2010;148(4):618-624. PubMed

1. Armao D, Smith JK. Overuse of computed tomography and the onslaught of incidental findings. N C Med J. 2014;75(2):127. PubMed

2. Gould MK, Tang T, Liu IL, et al. Recent trends in the identification of incidental pulmonary nodules. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(10):1208-1214. PubMed

3. Rinaldi MF, Bartalena T, Giannelli G, et al. Incidental lung nodules on CT examinations of the abdomen: prevalence and reporting rates in the PACS era. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74(3):e84-e88. PubMed

4. Collins CE, Cherng N, McDade T, et al. Improving patient notification of solid abdominal viscera incidental findings with a standardized protocol. J Trauma Manag Outcomes. 2015;9(1):1. PubMed

5. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841. PubMed

6. Swensen SJ, Silverstein MD, Ilstrup DM, Schleck CD, Edell ES. The probability of malignancy in solitary pulmonary nodules. Application to small radiologically indeterminate nodules. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(8):849-855. PubMed

7. Wu CC, Cronin CG, Chu JT, et al. Incidental pulmonary nodules detected on abdominal computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2012;36(6):641-645. PubMed

8. Alpert JB, Fantauzzi JP, Melamud K, Greenwood H, Naidich DP, Ko JP. Clinical significance of lung nodules reported on abdominal CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(4):793-799. PubMed

9. Blagev DP, Lloyd JF, Conner K, et al. Follow-up of incidental pulmonary nodules and the radiology report. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014;11(4):378-383. PubMed

10. Shuaib W, Johnson JO, Salastekar N, Maddu KK, Khosa F. Incidental findings detected on abdomino-pelvic multidetector computed tomography performed in the acute setting [published correction appears in Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(7):811. Waqas, Shuaib (corrected to Shuaib, Waqas)]. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(1):36-39. PubMed

11. Sperry JL, Massaro MS, Collage RD, et al. Incidental radiographic findings after injury: dedicated attention results in improved capture, documentation, and management. Surgery. 2010;148(4):618-624. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Empiric <i>Listeria monocytogenes</i> antibiotic coverage for febrile infants (age, 0-90 days)

The “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

Evaluation and treatment of the febrile infant 0 to 90 days of age are common clinical issues in pediatrics, family medicine, emergency medicine, and pediatric hospital medicine. Traditional teaching has been that Listeria monocytogenes is 1 of the 3 most common pathogens causing neonatal sepsis. Many practitioners routinely use antibiotic regimens, including ampicillin, to specifically target Listeria. However, a large body of evidence, including a meta-analysis and several multicenter studies, has shown that listeriosis is extremely rare in the United States. The practice of empiric ampicillin thus exposes the patient to harms and costs with little if any potential benefit, while increasing pressure on the bacterial flora in the community to generate antibiotic resistance. Empiric ampicillin for all infants admitted for sepsis evaluation is a tradition-based practice no longer founded on the best available evidence.

CASE REPORT