User login

PORTEC-3: Possible benefit with combined CT/RT in high-risk endometrial cancer

CHICAGO – Adjuvant chemotherapy given during and after pelvic radiotherapy in women with high-risk endometrial cancer provided no significant 5-year failure-free or overall survival benefit, compared with pelvic radiotherapy alone, in the randomized PORTEC-3 intergroup trial. It did, however, show a trend toward improved 5-year failure-free survival (FFS).

Further, study participants with stage III endometrial cancer experienced a statistically significant 11% improvement in FFS – defined as relapse or endometrial cancer-related death – at 5 years, Stephanie M. de Boer, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The 5-year FFS rate in 330 women who received both chemotherapy and radiotherapy was 76%, vs. 69% in 330 women who received only radiotherapy (hazard ratio, 0.77). The respective 5-year overall survival rates were 82%, vs. 77% (HR, 0.79), said Dr. de Boer of Leiden University Medical Center, the Netherlands.

The differences did not reach statistical significance, but there was a “trend for better failure-free survival” beginning after 1 year and “a small suggestion for an overall survival benefit” after 3 years in patients treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, she said.

Among the 45% of study participants with stage III endometrial cancer, 5-year FFS and overall survival were significantly lower than in those with stage I-II disease (64% vs. 79% and 74% vs. 83%, respectively), but those with stage III disease experienced the greatest benefit with adjuvant chemotherapy.

“Five-year failure-free survival was 69% for those [with stage III disease] treated with radiotherapy and chemotherapy, vs. 58% for those treated with radiotherapy alone,” she said, noting that the hazard ratio was 0.66.

Five-year overall survival in the stage III patients was 79%, vs. 70% (HR, 0.69). Only the difference in FFS reached statistical significance, Dr. de Boer noted.

Study subjects were women with either Federation Internationale de Gynecologie et d’Obstetrique stage I grade 3 endometrial cancer with deep myometrial invasion and/or lymphovascular space invasion or with stage II or III disease or with serous/clear cell histology. They had a mean age of 62 years, good performance status, and no residual macroscopic tumor after surgery. They were randomly assigned to receive two cycles of cisplatin at 50 mg/m2 in week 1 and 4 of radiotherapy (48.6 Gy in 1.8 Gy fractions), followed by four cycles of carboplatin AUC5 and paclitaxel at 175 mg/m2 in 3-week intervals, or to receive radiotherapy alone.

Median follow-up was 60.2 months.

“The rationale of the PORTEC-3 trial was that 15% of endometrial cancer patients have high-risk disease features, and these patients are at increased risk of distant metastases and endometrial cancer–related death,” Dr. de Boer said.

Several trials have looked at intensified treatment in these patients and include some that have compared chemotherapy and radiation and that found no difference in progression-free survival or overall survival. A Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) phase II trial of concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy, however, showed promising results and a feasible toxicity profile, she said.

A phase III Nordic Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO)/European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) trial suggested that sequential chemotherapy and radiotherapy was associated with improved progression-free survival.

“But, various chemotherapy schedules and sequences have been used in these trials, and no extensive quality of life analysis was done,” she noted.

In PORTEC-3, radiotherapy and two cycles of concurrent cisplatin followed by four cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel showed some promise, and quality of life analyses showed no difference between groups at 1 and 2 years after randomization.

In fact, although the adverse events findings as reported in 2016 in Lancet Oncology showed that, during therapy and for the first 6 months after therapy, “significantly more and more severe toxicity” occurred in the chemotherapy and radiotherapy group, vs. the radiotherapy group alone, this effect was transient and not associated with long-term effects on quality of life.

“There was significant recovery without significant differences at 1 and 2 years after randomization,” Dr. de Boer said, adding that the toxicity translated to worse physical functioning and quality of life during and for 6 months after therapy but that no differences in quality of life, and only small differences in physical functioning, were seen at 1 and 2 years.

The residual effect on physical functioning may have been related to the tingling and numbness, which was the most important long-term side effect reported in the trial, she said, noting that 25% of patients in the chemotherapy and radiotherapy group reported tingling and numbness at 2 years, compared with 6% in the radiotherapy group.

Based on these findings, combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy cannot be recommended as standard for patients with stage I and II high-risk endometrial cancer, she said.

However, based on the 11% FFS benefit for stage III patients, “the combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy schedule is recommended to maximize failure-free survival,” she concluded, noting that interpretation of overall survival results may need longer follow-up.

Ritu Salani, MD, who was invited to discuss Dr. de Boer’s abstract, said the PORTEC-3 findings raise a number of questions for studies going forward, such as the role of therapy sequence.

“Radiation has always preceded chemotherapy, and I wonder if distant recurrences could actually be impacted if we do chemotherapy first, whether it’s a complete course or in a sandwich-approach style. I think these are questions that we need to continue to address,” said Dr. Salani of Ohio State University, Columbus.

Other questions posed by Dr. Salani focused on whether high risk early stage and advanced disease should be studied separately, whether maintenance therapy should be evaluated in this population, whether there was under-staging in PORTEC-3 as 42% of patients did not undergo lymphadenectomy, whether there is a role for sentinel node assessment, and whether residual disease status should be a surgical metric and if chemotherapy should be reserved for those with residual disease.

“I think we continue to have many treatment options, and I think our tumor board debates will continue. And I think PORTEC-3 will add to this discussion. But, at this point I think we’re left to individualize treatment and to continue to provide the best outcome for our patients while minimizing toxicity,” she concluded.

Dr. de Boer reported having no disclosures. Dr. Salani has received honoraria from Clovis Oncology and Lynparza and has served as a consultant or advisor for Genentech/Roche.

CHICAGO – Adjuvant chemotherapy given during and after pelvic radiotherapy in women with high-risk endometrial cancer provided no significant 5-year failure-free or overall survival benefit, compared with pelvic radiotherapy alone, in the randomized PORTEC-3 intergroup trial. It did, however, show a trend toward improved 5-year failure-free survival (FFS).

Further, study participants with stage III endometrial cancer experienced a statistically significant 11% improvement in FFS – defined as relapse or endometrial cancer-related death – at 5 years, Stephanie M. de Boer, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The 5-year FFS rate in 330 women who received both chemotherapy and radiotherapy was 76%, vs. 69% in 330 women who received only radiotherapy (hazard ratio, 0.77). The respective 5-year overall survival rates were 82%, vs. 77% (HR, 0.79), said Dr. de Boer of Leiden University Medical Center, the Netherlands.

The differences did not reach statistical significance, but there was a “trend for better failure-free survival” beginning after 1 year and “a small suggestion for an overall survival benefit” after 3 years in patients treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, she said.

Among the 45% of study participants with stage III endometrial cancer, 5-year FFS and overall survival were significantly lower than in those with stage I-II disease (64% vs. 79% and 74% vs. 83%, respectively), but those with stage III disease experienced the greatest benefit with adjuvant chemotherapy.

“Five-year failure-free survival was 69% for those [with stage III disease] treated with radiotherapy and chemotherapy, vs. 58% for those treated with radiotherapy alone,” she said, noting that the hazard ratio was 0.66.

Five-year overall survival in the stage III patients was 79%, vs. 70% (HR, 0.69). Only the difference in FFS reached statistical significance, Dr. de Boer noted.

Study subjects were women with either Federation Internationale de Gynecologie et d’Obstetrique stage I grade 3 endometrial cancer with deep myometrial invasion and/or lymphovascular space invasion or with stage II or III disease or with serous/clear cell histology. They had a mean age of 62 years, good performance status, and no residual macroscopic tumor after surgery. They were randomly assigned to receive two cycles of cisplatin at 50 mg/m2 in week 1 and 4 of radiotherapy (48.6 Gy in 1.8 Gy fractions), followed by four cycles of carboplatin AUC5 and paclitaxel at 175 mg/m2 in 3-week intervals, or to receive radiotherapy alone.

Median follow-up was 60.2 months.

“The rationale of the PORTEC-3 trial was that 15% of endometrial cancer patients have high-risk disease features, and these patients are at increased risk of distant metastases and endometrial cancer–related death,” Dr. de Boer said.

Several trials have looked at intensified treatment in these patients and include some that have compared chemotherapy and radiation and that found no difference in progression-free survival or overall survival. A Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) phase II trial of concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy, however, showed promising results and a feasible toxicity profile, she said.

A phase III Nordic Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO)/European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) trial suggested that sequential chemotherapy and radiotherapy was associated with improved progression-free survival.

“But, various chemotherapy schedules and sequences have been used in these trials, and no extensive quality of life analysis was done,” she noted.

In PORTEC-3, radiotherapy and two cycles of concurrent cisplatin followed by four cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel showed some promise, and quality of life analyses showed no difference between groups at 1 and 2 years after randomization.

In fact, although the adverse events findings as reported in 2016 in Lancet Oncology showed that, during therapy and for the first 6 months after therapy, “significantly more and more severe toxicity” occurred in the chemotherapy and radiotherapy group, vs. the radiotherapy group alone, this effect was transient and not associated with long-term effects on quality of life.

“There was significant recovery without significant differences at 1 and 2 years after randomization,” Dr. de Boer said, adding that the toxicity translated to worse physical functioning and quality of life during and for 6 months after therapy but that no differences in quality of life, and only small differences in physical functioning, were seen at 1 and 2 years.

The residual effect on physical functioning may have been related to the tingling and numbness, which was the most important long-term side effect reported in the trial, she said, noting that 25% of patients in the chemotherapy and radiotherapy group reported tingling and numbness at 2 years, compared with 6% in the radiotherapy group.

Based on these findings, combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy cannot be recommended as standard for patients with stage I and II high-risk endometrial cancer, she said.

However, based on the 11% FFS benefit for stage III patients, “the combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy schedule is recommended to maximize failure-free survival,” she concluded, noting that interpretation of overall survival results may need longer follow-up.

Ritu Salani, MD, who was invited to discuss Dr. de Boer’s abstract, said the PORTEC-3 findings raise a number of questions for studies going forward, such as the role of therapy sequence.

“Radiation has always preceded chemotherapy, and I wonder if distant recurrences could actually be impacted if we do chemotherapy first, whether it’s a complete course or in a sandwich-approach style. I think these are questions that we need to continue to address,” said Dr. Salani of Ohio State University, Columbus.

Other questions posed by Dr. Salani focused on whether high risk early stage and advanced disease should be studied separately, whether maintenance therapy should be evaluated in this population, whether there was under-staging in PORTEC-3 as 42% of patients did not undergo lymphadenectomy, whether there is a role for sentinel node assessment, and whether residual disease status should be a surgical metric and if chemotherapy should be reserved for those with residual disease.

“I think we continue to have many treatment options, and I think our tumor board debates will continue. And I think PORTEC-3 will add to this discussion. But, at this point I think we’re left to individualize treatment and to continue to provide the best outcome for our patients while minimizing toxicity,” she concluded.

Dr. de Boer reported having no disclosures. Dr. Salani has received honoraria from Clovis Oncology and Lynparza and has served as a consultant or advisor for Genentech/Roche.

CHICAGO – Adjuvant chemotherapy given during and after pelvic radiotherapy in women with high-risk endometrial cancer provided no significant 5-year failure-free or overall survival benefit, compared with pelvic radiotherapy alone, in the randomized PORTEC-3 intergroup trial. It did, however, show a trend toward improved 5-year failure-free survival (FFS).

Further, study participants with stage III endometrial cancer experienced a statistically significant 11% improvement in FFS – defined as relapse or endometrial cancer-related death – at 5 years, Stephanie M. de Boer, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The 5-year FFS rate in 330 women who received both chemotherapy and radiotherapy was 76%, vs. 69% in 330 women who received only radiotherapy (hazard ratio, 0.77). The respective 5-year overall survival rates were 82%, vs. 77% (HR, 0.79), said Dr. de Boer of Leiden University Medical Center, the Netherlands.

The differences did not reach statistical significance, but there was a “trend for better failure-free survival” beginning after 1 year and “a small suggestion for an overall survival benefit” after 3 years in patients treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, she said.

Among the 45% of study participants with stage III endometrial cancer, 5-year FFS and overall survival were significantly lower than in those with stage I-II disease (64% vs. 79% and 74% vs. 83%, respectively), but those with stage III disease experienced the greatest benefit with adjuvant chemotherapy.

“Five-year failure-free survival was 69% for those [with stage III disease] treated with radiotherapy and chemotherapy, vs. 58% for those treated with radiotherapy alone,” she said, noting that the hazard ratio was 0.66.

Five-year overall survival in the stage III patients was 79%, vs. 70% (HR, 0.69). Only the difference in FFS reached statistical significance, Dr. de Boer noted.

Study subjects were women with either Federation Internationale de Gynecologie et d’Obstetrique stage I grade 3 endometrial cancer with deep myometrial invasion and/or lymphovascular space invasion or with stage II or III disease or with serous/clear cell histology. They had a mean age of 62 years, good performance status, and no residual macroscopic tumor after surgery. They were randomly assigned to receive two cycles of cisplatin at 50 mg/m2 in week 1 and 4 of radiotherapy (48.6 Gy in 1.8 Gy fractions), followed by four cycles of carboplatin AUC5 and paclitaxel at 175 mg/m2 in 3-week intervals, or to receive radiotherapy alone.

Median follow-up was 60.2 months.

“The rationale of the PORTEC-3 trial was that 15% of endometrial cancer patients have high-risk disease features, and these patients are at increased risk of distant metastases and endometrial cancer–related death,” Dr. de Boer said.

Several trials have looked at intensified treatment in these patients and include some that have compared chemotherapy and radiation and that found no difference in progression-free survival or overall survival. A Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) phase II trial of concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy, however, showed promising results and a feasible toxicity profile, she said.

A phase III Nordic Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO)/European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) trial suggested that sequential chemotherapy and radiotherapy was associated with improved progression-free survival.

“But, various chemotherapy schedules and sequences have been used in these trials, and no extensive quality of life analysis was done,” she noted.

In PORTEC-3, radiotherapy and two cycles of concurrent cisplatin followed by four cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel showed some promise, and quality of life analyses showed no difference between groups at 1 and 2 years after randomization.

In fact, although the adverse events findings as reported in 2016 in Lancet Oncology showed that, during therapy and for the first 6 months after therapy, “significantly more and more severe toxicity” occurred in the chemotherapy and radiotherapy group, vs. the radiotherapy group alone, this effect was transient and not associated with long-term effects on quality of life.

“There was significant recovery without significant differences at 1 and 2 years after randomization,” Dr. de Boer said, adding that the toxicity translated to worse physical functioning and quality of life during and for 6 months after therapy but that no differences in quality of life, and only small differences in physical functioning, were seen at 1 and 2 years.

The residual effect on physical functioning may have been related to the tingling and numbness, which was the most important long-term side effect reported in the trial, she said, noting that 25% of patients in the chemotherapy and radiotherapy group reported tingling and numbness at 2 years, compared with 6% in the radiotherapy group.

Based on these findings, combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy cannot be recommended as standard for patients with stage I and II high-risk endometrial cancer, she said.

However, based on the 11% FFS benefit for stage III patients, “the combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy schedule is recommended to maximize failure-free survival,” she concluded, noting that interpretation of overall survival results may need longer follow-up.

Ritu Salani, MD, who was invited to discuss Dr. de Boer’s abstract, said the PORTEC-3 findings raise a number of questions for studies going forward, such as the role of therapy sequence.

“Radiation has always preceded chemotherapy, and I wonder if distant recurrences could actually be impacted if we do chemotherapy first, whether it’s a complete course or in a sandwich-approach style. I think these are questions that we need to continue to address,” said Dr. Salani of Ohio State University, Columbus.

Other questions posed by Dr. Salani focused on whether high risk early stage and advanced disease should be studied separately, whether maintenance therapy should be evaluated in this population, whether there was under-staging in PORTEC-3 as 42% of patients did not undergo lymphadenectomy, whether there is a role for sentinel node assessment, and whether residual disease status should be a surgical metric and if chemotherapy should be reserved for those with residual disease.

“I think we continue to have many treatment options, and I think our tumor board debates will continue. And I think PORTEC-3 will add to this discussion. But, at this point I think we’re left to individualize treatment and to continue to provide the best outcome for our patients while minimizing toxicity,” she concluded.

Dr. de Boer reported having no disclosures. Dr. Salani has received honoraria from Clovis Oncology and Lynparza and has served as a consultant or advisor for Genentech/Roche.

AT ASCO 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The 5-year FFS rate in 330 women who received both chemotherapy and radiotherapy was 76%, vs. 69% in 330 women who received only radiotherapy (HR, 0.77).

Data source: The randomized PORTEC-3 trial of 660 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. de Boer reported having no disclosures. Dr. Salani has received honoraria from Clovis Oncology and Lynparza and has served as a consultant or advisor for Genentech/Roche.

Hiring the right employees

Many of the personnel questions I receive concern the dreaded “marginal employee” – a person who has never done anything truly heinous to merit firing but also hasn’t done anything special to merit continued employment. I always advise getting rid of such people and then changing the hiring criteria that all too often result in poor hires.

Most bad hires come about because employers do not have a clear vision of the kind of employee they want. Many office manuals do not contain detailed job descriptions. If you don’t know exactly what you are looking for, your entire selection process will be inadequate from initial screening of applicants through assessments of their skills and personalities. Many physicians compound the problem with poor interview techniques and inadequate checking of references.

Once you have a clear job description in mind (and in print), take all the time you need to find the best possible match for it. This is not a place to cut corners. Screen your candidates carefully, and avoid lowering your expectations. This is the point at which it might be tempting to settle for a marginal candidate just to get the process over with.

It is also sometimes tempting to hire the candidate that you have the “best feeling” about, even though he or she is a poor match for the job, and then try to mold the job to that person. Every doctor knows that hunches are no substitute for hard data.

Be alert for red flags in resumes: significant time gaps between jobs, positions at companies that are no longer in business or are otherwise impossible to verify, job titles that don’t make sense given the applicant’s qualifications.

Background checks are a dicey subject, but publicly available information can be found, cheap or free, on multiple web sites created for that purpose. Be sure to tell applicants that you will be verifying facts in their resumes. It’s usually wise to get their written consent to do so.

Many employers skip the essential step of calling references, and many applicants know that. Some old bosses will be reluctant to tell you anything substantive, so I always ask, “Would you hire this person again?” You can interpret a lot from the answer – or lack of one.

Interviews often get short shrift as well. Many doctors tend to do all the talking. As I’ve observed numerous times, listening is not our strong suit, as a general rule. The purpose of an interview is to allow you to size up the prospective employee, not to deliver a lecture on the sterling attributes of your office. Important interview topics include educational background, skills, experience, and unrelated job history.

By law, you cannot ask an applicant’s age, date of birth, gender, creed, color, religion, or national origin. Other forbidden subjects include disabilities, marital status, military record, number of children (or who cares for them), addiction history, citizenship, criminal record, psychiatric history, absenteeism, or workman’s compensation.

However, there are acceptable alternatives to some of those questions. You can ask if applicants have ever gone by another name (for your background check), for example. You can ask if they are legally authorized to work in this country and whether they will be physically able to perform the duties specified in the job description. While past addictions are off limits, you do have a right to know about current addictions to illegal substances.

Once you have hired people whose skills and personalities best fit your needs, train them well. Then, give them the opportunity to succeed. “The best executive,” wrote Theodore Roosevelt, “is one who has sense enough to pick good people to do what he [or she] wants done and self-restraint enough to keep from meddling with them while they do it.” ”

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Many of the personnel questions I receive concern the dreaded “marginal employee” – a person who has never done anything truly heinous to merit firing but also hasn’t done anything special to merit continued employment. I always advise getting rid of such people and then changing the hiring criteria that all too often result in poor hires.

Most bad hires come about because employers do not have a clear vision of the kind of employee they want. Many office manuals do not contain detailed job descriptions. If you don’t know exactly what you are looking for, your entire selection process will be inadequate from initial screening of applicants through assessments of their skills and personalities. Many physicians compound the problem with poor interview techniques and inadequate checking of references.

Once you have a clear job description in mind (and in print), take all the time you need to find the best possible match for it. This is not a place to cut corners. Screen your candidates carefully, and avoid lowering your expectations. This is the point at which it might be tempting to settle for a marginal candidate just to get the process over with.

It is also sometimes tempting to hire the candidate that you have the “best feeling” about, even though he or she is a poor match for the job, and then try to mold the job to that person. Every doctor knows that hunches are no substitute for hard data.

Be alert for red flags in resumes: significant time gaps between jobs, positions at companies that are no longer in business or are otherwise impossible to verify, job titles that don’t make sense given the applicant’s qualifications.

Background checks are a dicey subject, but publicly available information can be found, cheap or free, on multiple web sites created for that purpose. Be sure to tell applicants that you will be verifying facts in their resumes. It’s usually wise to get their written consent to do so.

Many employers skip the essential step of calling references, and many applicants know that. Some old bosses will be reluctant to tell you anything substantive, so I always ask, “Would you hire this person again?” You can interpret a lot from the answer – or lack of one.

Interviews often get short shrift as well. Many doctors tend to do all the talking. As I’ve observed numerous times, listening is not our strong suit, as a general rule. The purpose of an interview is to allow you to size up the prospective employee, not to deliver a lecture on the sterling attributes of your office. Important interview topics include educational background, skills, experience, and unrelated job history.

By law, you cannot ask an applicant’s age, date of birth, gender, creed, color, religion, or national origin. Other forbidden subjects include disabilities, marital status, military record, number of children (or who cares for them), addiction history, citizenship, criminal record, psychiatric history, absenteeism, or workman’s compensation.

However, there are acceptable alternatives to some of those questions. You can ask if applicants have ever gone by another name (for your background check), for example. You can ask if they are legally authorized to work in this country and whether they will be physically able to perform the duties specified in the job description. While past addictions are off limits, you do have a right to know about current addictions to illegal substances.

Once you have hired people whose skills and personalities best fit your needs, train them well. Then, give them the opportunity to succeed. “The best executive,” wrote Theodore Roosevelt, “is one who has sense enough to pick good people to do what he [or she] wants done and self-restraint enough to keep from meddling with them while they do it.” ”

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Many of the personnel questions I receive concern the dreaded “marginal employee” – a person who has never done anything truly heinous to merit firing but also hasn’t done anything special to merit continued employment. I always advise getting rid of such people and then changing the hiring criteria that all too often result in poor hires.

Most bad hires come about because employers do not have a clear vision of the kind of employee they want. Many office manuals do not contain detailed job descriptions. If you don’t know exactly what you are looking for, your entire selection process will be inadequate from initial screening of applicants through assessments of their skills and personalities. Many physicians compound the problem with poor interview techniques and inadequate checking of references.

Once you have a clear job description in mind (and in print), take all the time you need to find the best possible match for it. This is not a place to cut corners. Screen your candidates carefully, and avoid lowering your expectations. This is the point at which it might be tempting to settle for a marginal candidate just to get the process over with.

It is also sometimes tempting to hire the candidate that you have the “best feeling” about, even though he or she is a poor match for the job, and then try to mold the job to that person. Every doctor knows that hunches are no substitute for hard data.

Be alert for red flags in resumes: significant time gaps between jobs, positions at companies that are no longer in business or are otherwise impossible to verify, job titles that don’t make sense given the applicant’s qualifications.

Background checks are a dicey subject, but publicly available information can be found, cheap or free, on multiple web sites created for that purpose. Be sure to tell applicants that you will be verifying facts in their resumes. It’s usually wise to get their written consent to do so.

Many employers skip the essential step of calling references, and many applicants know that. Some old bosses will be reluctant to tell you anything substantive, so I always ask, “Would you hire this person again?” You can interpret a lot from the answer – or lack of one.

Interviews often get short shrift as well. Many doctors tend to do all the talking. As I’ve observed numerous times, listening is not our strong suit, as a general rule. The purpose of an interview is to allow you to size up the prospective employee, not to deliver a lecture on the sterling attributes of your office. Important interview topics include educational background, skills, experience, and unrelated job history.

By law, you cannot ask an applicant’s age, date of birth, gender, creed, color, religion, or national origin. Other forbidden subjects include disabilities, marital status, military record, number of children (or who cares for them), addiction history, citizenship, criminal record, psychiatric history, absenteeism, or workman’s compensation.

However, there are acceptable alternatives to some of those questions. You can ask if applicants have ever gone by another name (for your background check), for example. You can ask if they are legally authorized to work in this country and whether they will be physically able to perform the duties specified in the job description. While past addictions are off limits, you do have a right to know about current addictions to illegal substances.

Once you have hired people whose skills and personalities best fit your needs, train them well. Then, give them the opportunity to succeed. “The best executive,” wrote Theodore Roosevelt, “is one who has sense enough to pick good people to do what he [or she] wants done and self-restraint enough to keep from meddling with them while they do it.” ”

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Studies provide insight into link between cancer immunotherapy and autoimmune disease

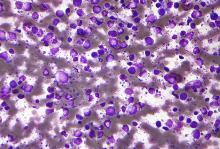

MADRID – Rheumatologists all over the world are beginning to find that the new class of anticancer immune checkpoint inhibitor therapies have the potential to elicit symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and other rheumatic diseases in patients with no previous history of them, and two reports from the European Congress of Rheumatology provide typical examples.

These immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) agents, which include ipilimumab (Yervoy), nivolumab (Opdivo), and pembrolizumab (Keytruda), target regulatory pathways in T cells to boost antitumor immune responses, leading to improved survival for many cancer patients, but the induction of rheumatic disease can sometimes lead to the suspension of the agents, according to investigators.

“This phenomenon was unknown to me and my group before [February 2016], when we started noting referrals of patients from oncology,” Dr. Calabrese said. “We were seeing symptoms of everything from Sjögren’s syndrome to inflammatory arthritis and myositis in patients being treated with these drugs for their cancer.” The same year, Dr. Calabrese and her team began coordinating an ongoing study to assess these patients.

Dr. Calabrese said that the cohort has shown so far that patients who develop autoimmune disease after immune checkpoint inhibitors “require much higher doses – of steroids in particular – to treat their symptoms,” and this can all too often result in being taken out of a clinical trial or having to stop cancer treatment.

Most of the patients in the cohort were treated with steroids only, while three patients received biologic agents, and four received methotrexate or antimalarials.

Dr. Calabrese said that the serology results were available for all the patients in the cohort and “were largely unremarkable.”

She noted that the rheumatic symptoms did not always resolve after pausing or stopping the cancer treatment. “We have some patients that have been off their checkpoint inhibitors for over a year and still have symptoms, so it’s looking like it might be a more long-term effect,” she said.

“In my unit, we also manage patients with myeloma, and I developed a weekly consultation with a cancer center,” Dr. Belkhir said. In 2015, she saw her first patient with RA and no previous history who had been treated with checkpoint inhibitors. That patient’s symptoms resolved after treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs alone.

Dr. Belkhir is sharing results from this and five other patients presenting with symptoms of RA after their cancer treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors, taken from a larger cohort of patients (n = 13) with a spectrum of rheumatic disease–like adverse effects. None of the six patients in this study had a previous clinical history of RA. They manifested their RA symptoms after a median of 1 month on cancer immunotherapy.

Some were able to continue their checkpoint inhibitors and be treated simultaneously for RA with steroids, antimalarials, methotrexate, and NSAIDs, Dr. Belkhir said. None received biologic agents, and each medication strategy, she said, was arrived at in consultation with the treating oncologist.

Dr. Belkhir’s team also looked closely at serology and found all six patients to be at least weakly, and mostly strongly, seropositive for RA. Three patients underwent testing for anticyclic citrullinated protein antibodies prior to starting cancer immunotherapy and two of these three were anti-CCP positive. Now, she said, the oncologists she’s working with are testing for anticyclic citrullinated peptides and rheumatoid factor prior to initiating cancer immunotherapy, so that this relationship is better understood.

“It is possible that antibodies were already present and that the anti-PD1 immunotherapy,” one type of immune checkpoint inhibitor, “acted as a trigger for the disease.” Animal studies have suggested a role for PD1 in the development of autoimmune disease, “but it’s not well investigated,” Dr. Belkhir said.

Dr. Belkhir and Dr. Calabrese both acknowledged that the understanding of checkpoint inhibitor–induced autoimmune disease is in its infancy. Clinical trials largely missed the phenomenon, the researchers said, because the trials were not designed to capture musculoskeletal adverse effects with the same granularity as other serious adverse events.

“This will be a long discussion in the months and the years ahead with oncologists,” Dr. Belkhir said.

Neither Dr. Calabrese nor Dr. Belkhir reported having any relevant conflicts of interest.

MADRID – Rheumatologists all over the world are beginning to find that the new class of anticancer immune checkpoint inhibitor therapies have the potential to elicit symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and other rheumatic diseases in patients with no previous history of them, and two reports from the European Congress of Rheumatology provide typical examples.

These immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) agents, which include ipilimumab (Yervoy), nivolumab (Opdivo), and pembrolizumab (Keytruda), target regulatory pathways in T cells to boost antitumor immune responses, leading to improved survival for many cancer patients, but the induction of rheumatic disease can sometimes lead to the suspension of the agents, according to investigators.

“This phenomenon was unknown to me and my group before [February 2016], when we started noting referrals of patients from oncology,” Dr. Calabrese said. “We were seeing symptoms of everything from Sjögren’s syndrome to inflammatory arthritis and myositis in patients being treated with these drugs for their cancer.” The same year, Dr. Calabrese and her team began coordinating an ongoing study to assess these patients.

Dr. Calabrese said that the cohort has shown so far that patients who develop autoimmune disease after immune checkpoint inhibitors “require much higher doses – of steroids in particular – to treat their symptoms,” and this can all too often result in being taken out of a clinical trial or having to stop cancer treatment.

Most of the patients in the cohort were treated with steroids only, while three patients received biologic agents, and four received methotrexate or antimalarials.

Dr. Calabrese said that the serology results were available for all the patients in the cohort and “were largely unremarkable.”

She noted that the rheumatic symptoms did not always resolve after pausing or stopping the cancer treatment. “We have some patients that have been off their checkpoint inhibitors for over a year and still have symptoms, so it’s looking like it might be a more long-term effect,” she said.

“In my unit, we also manage patients with myeloma, and I developed a weekly consultation with a cancer center,” Dr. Belkhir said. In 2015, she saw her first patient with RA and no previous history who had been treated with checkpoint inhibitors. That patient’s symptoms resolved after treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs alone.

Dr. Belkhir is sharing results from this and five other patients presenting with symptoms of RA after their cancer treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors, taken from a larger cohort of patients (n = 13) with a spectrum of rheumatic disease–like adverse effects. None of the six patients in this study had a previous clinical history of RA. They manifested their RA symptoms after a median of 1 month on cancer immunotherapy.

Some were able to continue their checkpoint inhibitors and be treated simultaneously for RA with steroids, antimalarials, methotrexate, and NSAIDs, Dr. Belkhir said. None received biologic agents, and each medication strategy, she said, was arrived at in consultation with the treating oncologist.

Dr. Belkhir’s team also looked closely at serology and found all six patients to be at least weakly, and mostly strongly, seropositive for RA. Three patients underwent testing for anticyclic citrullinated protein antibodies prior to starting cancer immunotherapy and two of these three were anti-CCP positive. Now, she said, the oncologists she’s working with are testing for anticyclic citrullinated peptides and rheumatoid factor prior to initiating cancer immunotherapy, so that this relationship is better understood.

“It is possible that antibodies were already present and that the anti-PD1 immunotherapy,” one type of immune checkpoint inhibitor, “acted as a trigger for the disease.” Animal studies have suggested a role for PD1 in the development of autoimmune disease, “but it’s not well investigated,” Dr. Belkhir said.

Dr. Belkhir and Dr. Calabrese both acknowledged that the understanding of checkpoint inhibitor–induced autoimmune disease is in its infancy. Clinical trials largely missed the phenomenon, the researchers said, because the trials were not designed to capture musculoskeletal adverse effects with the same granularity as other serious adverse events.

“This will be a long discussion in the months and the years ahead with oncologists,” Dr. Belkhir said.

Neither Dr. Calabrese nor Dr. Belkhir reported having any relevant conflicts of interest.

MADRID – Rheumatologists all over the world are beginning to find that the new class of anticancer immune checkpoint inhibitor therapies have the potential to elicit symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and other rheumatic diseases in patients with no previous history of them, and two reports from the European Congress of Rheumatology provide typical examples.

These immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) agents, which include ipilimumab (Yervoy), nivolumab (Opdivo), and pembrolizumab (Keytruda), target regulatory pathways in T cells to boost antitumor immune responses, leading to improved survival for many cancer patients, but the induction of rheumatic disease can sometimes lead to the suspension of the agents, according to investigators.

“This phenomenon was unknown to me and my group before [February 2016], when we started noting referrals of patients from oncology,” Dr. Calabrese said. “We were seeing symptoms of everything from Sjögren’s syndrome to inflammatory arthritis and myositis in patients being treated with these drugs for their cancer.” The same year, Dr. Calabrese and her team began coordinating an ongoing study to assess these patients.

Dr. Calabrese said that the cohort has shown so far that patients who develop autoimmune disease after immune checkpoint inhibitors “require much higher doses – of steroids in particular – to treat their symptoms,” and this can all too often result in being taken out of a clinical trial or having to stop cancer treatment.

Most of the patients in the cohort were treated with steroids only, while three patients received biologic agents, and four received methotrexate or antimalarials.

Dr. Calabrese said that the serology results were available for all the patients in the cohort and “were largely unremarkable.”

She noted that the rheumatic symptoms did not always resolve after pausing or stopping the cancer treatment. “We have some patients that have been off their checkpoint inhibitors for over a year and still have symptoms, so it’s looking like it might be a more long-term effect,” she said.

“In my unit, we also manage patients with myeloma, and I developed a weekly consultation with a cancer center,” Dr. Belkhir said. In 2015, she saw her first patient with RA and no previous history who had been treated with checkpoint inhibitors. That patient’s symptoms resolved after treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs alone.

Dr. Belkhir is sharing results from this and five other patients presenting with symptoms of RA after their cancer treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors, taken from a larger cohort of patients (n = 13) with a spectrum of rheumatic disease–like adverse effects. None of the six patients in this study had a previous clinical history of RA. They manifested their RA symptoms after a median of 1 month on cancer immunotherapy.

Some were able to continue their checkpoint inhibitors and be treated simultaneously for RA with steroids, antimalarials, methotrexate, and NSAIDs, Dr. Belkhir said. None received biologic agents, and each medication strategy, she said, was arrived at in consultation with the treating oncologist.

Dr. Belkhir’s team also looked closely at serology and found all six patients to be at least weakly, and mostly strongly, seropositive for RA. Three patients underwent testing for anticyclic citrullinated protein antibodies prior to starting cancer immunotherapy and two of these three were anti-CCP positive. Now, she said, the oncologists she’s working with are testing for anticyclic citrullinated peptides and rheumatoid factor prior to initiating cancer immunotherapy, so that this relationship is better understood.

“It is possible that antibodies were already present and that the anti-PD1 immunotherapy,” one type of immune checkpoint inhibitor, “acted as a trigger for the disease.” Animal studies have suggested a role for PD1 in the development of autoimmune disease, “but it’s not well investigated,” Dr. Belkhir said.

Dr. Belkhir and Dr. Calabrese both acknowledged that the understanding of checkpoint inhibitor–induced autoimmune disease is in its infancy. Clinical trials largely missed the phenomenon, the researchers said, because the trials were not designed to capture musculoskeletal adverse effects with the same granularity as other serious adverse events.

“This will be a long discussion in the months and the years ahead with oncologists,” Dr. Belkhir said.

Neither Dr. Calabrese nor Dr. Belkhir reported having any relevant conflicts of interest.

AT THE EULAR 2017 CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Rheumatic symptoms did not always resolve after pausing or stopping the cancer treatment, and some were able to continue their checkpoint inhibitors and be treated simultaneously for RA.

Data source: Two retrospective cohort reviews of patients on immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Disclosures: Neither Dr. Calabrese nor Dr. Belkhir reported having any relevant conflicts of interest.

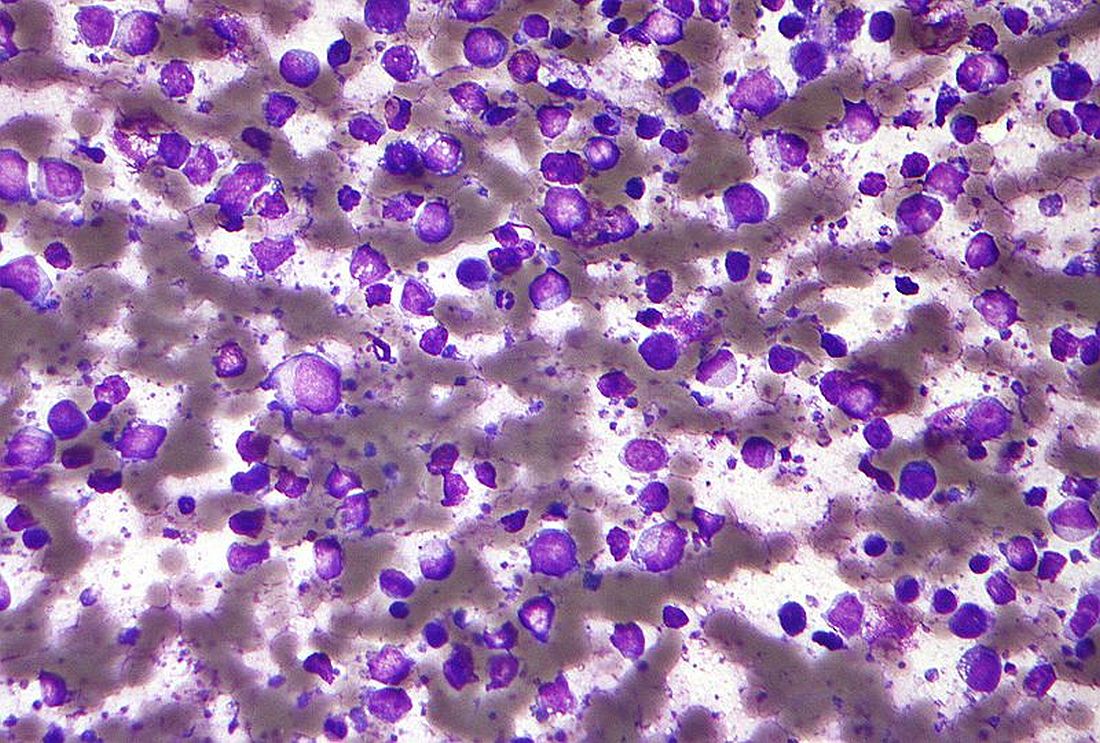

All isn’t well with HIV-exposed uninfected infants

MADRID – Children who were HIV-exposed antenatally but not infected are at double the risk of hospitalization for infectious diseases during their first year of life, compared with HIV-unexposed controls, according to what’s believed to be the first prospective study examining the issue in a Western industrialized country.

That’s one key take-away message from the study conducted in Brussels. Another key finding was that the sharply increased risk of hospitalization for infection during infancy was erased if HIV-infected mothers started antiretroviral therapy prior to, rather than during, pregnancy, Catherine Adler, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

She presented a prospective study of 125 HIV-positive and 119 HIV-negative pregnant Belgian women of comparable ethnic and sociodemographic backgrounds. All of the HIV-positive mothers were on antiretroviral therapy, which they started either prior to or during pregnancy.

The two groups of women gave birth to 132 HEU and 123 HIV-unexposed babies, all born after 35 weeks’ gestation. The babies didn’t differ in terms of gender, prematurity rate, mode of delivery, or the use of antibiotics at delivery. However, 17% of the HEU babies had a birth weight below 2,500 g, compared with just 3% of the HIV-unexposed controls. Also, as a matter of policy, none of the HEU babies were breastfed, while 95% of the controls were, Dr. Adler explained.

The primary outcome in the study was the rate of hospitalization for infection during the first 12 months of life. The rate was 21% in the HEU babies, significantly greater than the 11% rate in HIV-unexposed babies. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for preterm birth, low birth weight, literacy, and maternal age, HEU status was associated with twofold increased risk of hospitalization for infection in infancy.

“The increased susceptibility of HEU infants to infectious disease is not restricted to children born in developing countries,” she declared.

The disparity in hospitalization rates was driven by hospitalization for viral infections, which occurred at a rate of 20% in the HEU group, versus 9% in controls. Particularly notable were the 10 hospitalizations for respiratory syncytial virus infection in the HEU patients, compared with just 1 in the controls.

Dr. Adler and her coinvestigators will continue following the children out to about 3 years of age. After age 12 months, the two groups no longer differed significantly in their risk of hospitalization for infection.

“The first year is a vulnerable period. Our data highlight the importance of a close follow-up of these infants,” she said.

The biggest risk factor for hospitalization for infectious illness in the HEU group was initiation of antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy. The hospitalization rate in HEU infants whose mothers began therapy prior to pregnancy was the same as in HIV-unexposed infants. The inference is that it’s not in utero exposure to antiretroviral drugs that is responsible for the increased risk of hospitalization during infancy.

“This observation supports the notion that it’s the activity of the maternal HIV infection – the exposure to a strongly proinflammatory state in the mother – that contributes to the risk of severe infection in HEU infants, probably by causing changes in innate immunity cells,” according to Dr. Adler.

Even though the increased risk of hospitalization for infectious illnesses in HEU children falls off after age 12 months, she continued, her group is following them out to about age 3 years because “we have the impression that they are at risk for neurodevelopmental problems, including language delay.”

Other researchers in the audience confirmed this risk, reporting that, as they follow HEU children through adolescence, they see an increased rate of attention deficits and associated comorbidities.

Dr. Adler called the administration of antiretroviral therapy to pregnant HIV-infected women in order to prevent maternal-to-child transmission of the disease “one of the major successes of the 21st century.”

“The number of new HIV infections among children has collapsed, leading to an increasing number of HIV-exposed but uninfected children. One million of them are born each year,” she said.

Dr. Adler reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

*The article was updated 6/15/17.

MADRID – Children who were HIV-exposed antenatally but not infected are at double the risk of hospitalization for infectious diseases during their first year of life, compared with HIV-unexposed controls, according to what’s believed to be the first prospective study examining the issue in a Western industrialized country.

That’s one key take-away message from the study conducted in Brussels. Another key finding was that the sharply increased risk of hospitalization for infection during infancy was erased if HIV-infected mothers started antiretroviral therapy prior to, rather than during, pregnancy, Catherine Adler, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

She presented a prospective study of 125 HIV-positive and 119 HIV-negative pregnant Belgian women of comparable ethnic and sociodemographic backgrounds. All of the HIV-positive mothers were on antiretroviral therapy, which they started either prior to or during pregnancy.

The two groups of women gave birth to 132 HEU and 123 HIV-unexposed babies, all born after 35 weeks’ gestation. The babies didn’t differ in terms of gender, prematurity rate, mode of delivery, or the use of antibiotics at delivery. However, 17% of the HEU babies had a birth weight below 2,500 g, compared with just 3% of the HIV-unexposed controls. Also, as a matter of policy, none of the HEU babies were breastfed, while 95% of the controls were, Dr. Adler explained.

The primary outcome in the study was the rate of hospitalization for infection during the first 12 months of life. The rate was 21% in the HEU babies, significantly greater than the 11% rate in HIV-unexposed babies. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for preterm birth, low birth weight, literacy, and maternal age, HEU status was associated with twofold increased risk of hospitalization for infection in infancy.

“The increased susceptibility of HEU infants to infectious disease is not restricted to children born in developing countries,” she declared.

The disparity in hospitalization rates was driven by hospitalization for viral infections, which occurred at a rate of 20% in the HEU group, versus 9% in controls. Particularly notable were the 10 hospitalizations for respiratory syncytial virus infection in the HEU patients, compared with just 1 in the controls.

Dr. Adler and her coinvestigators will continue following the children out to about 3 years of age. After age 12 months, the two groups no longer differed significantly in their risk of hospitalization for infection.

“The first year is a vulnerable period. Our data highlight the importance of a close follow-up of these infants,” she said.

The biggest risk factor for hospitalization for infectious illness in the HEU group was initiation of antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy. The hospitalization rate in HEU infants whose mothers began therapy prior to pregnancy was the same as in HIV-unexposed infants. The inference is that it’s not in utero exposure to antiretroviral drugs that is responsible for the increased risk of hospitalization during infancy.

“This observation supports the notion that it’s the activity of the maternal HIV infection – the exposure to a strongly proinflammatory state in the mother – that contributes to the risk of severe infection in HEU infants, probably by causing changes in innate immunity cells,” according to Dr. Adler.

Even though the increased risk of hospitalization for infectious illnesses in HEU children falls off after age 12 months, she continued, her group is following them out to about age 3 years because “we have the impression that they are at risk for neurodevelopmental problems, including language delay.”

Other researchers in the audience confirmed this risk, reporting that, as they follow HEU children through adolescence, they see an increased rate of attention deficits and associated comorbidities.

Dr. Adler called the administration of antiretroviral therapy to pregnant HIV-infected women in order to prevent maternal-to-child transmission of the disease “one of the major successes of the 21st century.”

“The number of new HIV infections among children has collapsed, leading to an increasing number of HIV-exposed but uninfected children. One million of them are born each year,” she said.

Dr. Adler reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

*The article was updated 6/15/17.

MADRID – Children who were HIV-exposed antenatally but not infected are at double the risk of hospitalization for infectious diseases during their first year of life, compared with HIV-unexposed controls, according to what’s believed to be the first prospective study examining the issue in a Western industrialized country.

That’s one key take-away message from the study conducted in Brussels. Another key finding was that the sharply increased risk of hospitalization for infection during infancy was erased if HIV-infected mothers started antiretroviral therapy prior to, rather than during, pregnancy, Catherine Adler, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

She presented a prospective study of 125 HIV-positive and 119 HIV-negative pregnant Belgian women of comparable ethnic and sociodemographic backgrounds. All of the HIV-positive mothers were on antiretroviral therapy, which they started either prior to or during pregnancy.

The two groups of women gave birth to 132 HEU and 123 HIV-unexposed babies, all born after 35 weeks’ gestation. The babies didn’t differ in terms of gender, prematurity rate, mode of delivery, or the use of antibiotics at delivery. However, 17% of the HEU babies had a birth weight below 2,500 g, compared with just 3% of the HIV-unexposed controls. Also, as a matter of policy, none of the HEU babies were breastfed, while 95% of the controls were, Dr. Adler explained.

The primary outcome in the study was the rate of hospitalization for infection during the first 12 months of life. The rate was 21% in the HEU babies, significantly greater than the 11% rate in HIV-unexposed babies. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for preterm birth, low birth weight, literacy, and maternal age, HEU status was associated with twofold increased risk of hospitalization for infection in infancy.

“The increased susceptibility of HEU infants to infectious disease is not restricted to children born in developing countries,” she declared.

The disparity in hospitalization rates was driven by hospitalization for viral infections, which occurred at a rate of 20% in the HEU group, versus 9% in controls. Particularly notable were the 10 hospitalizations for respiratory syncytial virus infection in the HEU patients, compared with just 1 in the controls.

Dr. Adler and her coinvestigators will continue following the children out to about 3 years of age. After age 12 months, the two groups no longer differed significantly in their risk of hospitalization for infection.

“The first year is a vulnerable period. Our data highlight the importance of a close follow-up of these infants,” she said.

The biggest risk factor for hospitalization for infectious illness in the HEU group was initiation of antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy. The hospitalization rate in HEU infants whose mothers began therapy prior to pregnancy was the same as in HIV-unexposed infants. The inference is that it’s not in utero exposure to antiretroviral drugs that is responsible for the increased risk of hospitalization during infancy.

“This observation supports the notion that it’s the activity of the maternal HIV infection – the exposure to a strongly proinflammatory state in the mother – that contributes to the risk of severe infection in HEU infants, probably by causing changes in innate immunity cells,” according to Dr. Adler.

Even though the increased risk of hospitalization for infectious illnesses in HEU children falls off after age 12 months, she continued, her group is following them out to about age 3 years because “we have the impression that they are at risk for neurodevelopmental problems, including language delay.”

Other researchers in the audience confirmed this risk, reporting that, as they follow HEU children through adolescence, they see an increased rate of attention deficits and associated comorbidities.

Dr. Adler called the administration of antiretroviral therapy to pregnant HIV-infected women in order to prevent maternal-to-child transmission of the disease “one of the major successes of the 21st century.”

“The number of new HIV infections among children has collapsed, leading to an increasing number of HIV-exposed but uninfected children. One million of them are born each year,” she said.

Dr. Adler reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

*The article was updated 6/15/17.

AT ESPID 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The rate of hospitalization for a serious infectious illness during the first 12 months of life was 21% in HIV-exposed uninfected children, significantly greater than the 11% rate in HIV-unexposed babies.

Data source: This prospective observational study included 125 HIV-positive and 119 HIV-negative pregnant Belgian women of comparable ethnic and sociodemographic backgrounds and their offspring, followed to date through the infants’ first birthday.

Disclosures: Dr. Adler reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Prophylaxis prevents PCP in rheumatic disease patients

MADRID – The benefits of primary prophylaxis for pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) outweighed the risks of treatment in patients taking prolonged, high-dose corticosteroids for various rheumatic diseases in a study presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

In a single-center, retrospective cohort study of 1,522 corticosteroid treatment episodes in 1,092 patients with a variety of rheumatic conditions given over a 12-year follow-up period, the estimated incidence of PCP was 2.37 per 100 person-years.

Significantly fewer cases of PCP occurred at 1 year, however, in the 262 patients who were cotreated with the antibiotic combination of trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), than in the 1,260 patients who received no such antibiotic prophylaxis in addition to their steroid therapy.

The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for no PCP at 1 year of follow-up in the prophylaxis group, versus the no prophylaxis group, was 0.096 (P = .022).

The TMP-SMX combination also significantly reduced the mortality associated with PCP, with an adjusted HR of 0.09, versus no prophylaxis (P = .023).

“Pneumocystis pneumonia is a major opportunistic infection in immunocompromised patients associated with high morbidity and mortality,” explained the presenting study investigator Jun Won Park, MD, of Seoul National University Hospital in the Republic of Korea.

Dr. Park added that corticosteroid therapy was an important risk factor for PCP but that the risk-benefit ratio had not been evaluated sufficiently in patients with rheumatic diseases and that there was “different opinion among rheumatologists regarding [the value of] PCP prophylaxis.”

The current study aimed to see if primary antibiotic prophylaxis could prevent PCP in patients with rheumatic diseases, which included patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Behçet’s disease.

For inclusion, patients had to have been treated with prednisolone at a dose of 30 mg/day or more (or its equivalent) for at least 4 weeks and observed for 1 year. Patients with a prior history of PCP or conditions associated with this opportunistic infection, such as HIV, cancer, or solid organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, were excluded.

Dr. Park reported that PCP prophylaxis was given at the discretion of the treating physician, and the mean duration of TMP-SMX was 230 days.

In the prophylaxis group, 34 adverse drug reactions occurred. Two of these reactions were serious – one case of pancytopenia and one case of Steven’s Johnson syndrome – but both resolved after the antibiotic treatment was discontinued.

A sensitivity analysis was performed, giving consistent results, and a risk-benefit analysis showed that the number needed to treat to prevent one case of PCP was 52, considering all rheumatic disease studied, while the number needed to cause one serious adverse drug reaction was 131.

Taken together, these results suggest a role for TMP-SMX as primary prophylaxis for PCP in patients with rheumatic diseases who need prolonged treatment with high-dose corticosteroids, Dr. Park said.

Dr. Park reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

MADRID – The benefits of primary prophylaxis for pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) outweighed the risks of treatment in patients taking prolonged, high-dose corticosteroids for various rheumatic diseases in a study presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

In a single-center, retrospective cohort study of 1,522 corticosteroid treatment episodes in 1,092 patients with a variety of rheumatic conditions given over a 12-year follow-up period, the estimated incidence of PCP was 2.37 per 100 person-years.

Significantly fewer cases of PCP occurred at 1 year, however, in the 262 patients who were cotreated with the antibiotic combination of trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), than in the 1,260 patients who received no such antibiotic prophylaxis in addition to their steroid therapy.

The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for no PCP at 1 year of follow-up in the prophylaxis group, versus the no prophylaxis group, was 0.096 (P = .022).

The TMP-SMX combination also significantly reduced the mortality associated with PCP, with an adjusted HR of 0.09, versus no prophylaxis (P = .023).

“Pneumocystis pneumonia is a major opportunistic infection in immunocompromised patients associated with high morbidity and mortality,” explained the presenting study investigator Jun Won Park, MD, of Seoul National University Hospital in the Republic of Korea.

Dr. Park added that corticosteroid therapy was an important risk factor for PCP but that the risk-benefit ratio had not been evaluated sufficiently in patients with rheumatic diseases and that there was “different opinion among rheumatologists regarding [the value of] PCP prophylaxis.”

The current study aimed to see if primary antibiotic prophylaxis could prevent PCP in patients with rheumatic diseases, which included patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Behçet’s disease.

For inclusion, patients had to have been treated with prednisolone at a dose of 30 mg/day or more (or its equivalent) for at least 4 weeks and observed for 1 year. Patients with a prior history of PCP or conditions associated with this opportunistic infection, such as HIV, cancer, or solid organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, were excluded.

Dr. Park reported that PCP prophylaxis was given at the discretion of the treating physician, and the mean duration of TMP-SMX was 230 days.

In the prophylaxis group, 34 adverse drug reactions occurred. Two of these reactions were serious – one case of pancytopenia and one case of Steven’s Johnson syndrome – but both resolved after the antibiotic treatment was discontinued.

A sensitivity analysis was performed, giving consistent results, and a risk-benefit analysis showed that the number needed to treat to prevent one case of PCP was 52, considering all rheumatic disease studied, while the number needed to cause one serious adverse drug reaction was 131.

Taken together, these results suggest a role for TMP-SMX as primary prophylaxis for PCP in patients with rheumatic diseases who need prolonged treatment with high-dose corticosteroids, Dr. Park said.

Dr. Park reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

MADRID – The benefits of primary prophylaxis for pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) outweighed the risks of treatment in patients taking prolonged, high-dose corticosteroids for various rheumatic diseases in a study presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

In a single-center, retrospective cohort study of 1,522 corticosteroid treatment episodes in 1,092 patients with a variety of rheumatic conditions given over a 12-year follow-up period, the estimated incidence of PCP was 2.37 per 100 person-years.

Significantly fewer cases of PCP occurred at 1 year, however, in the 262 patients who were cotreated with the antibiotic combination of trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), than in the 1,260 patients who received no such antibiotic prophylaxis in addition to their steroid therapy.

The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for no PCP at 1 year of follow-up in the prophylaxis group, versus the no prophylaxis group, was 0.096 (P = .022).

The TMP-SMX combination also significantly reduced the mortality associated with PCP, with an adjusted HR of 0.09, versus no prophylaxis (P = .023).

“Pneumocystis pneumonia is a major opportunistic infection in immunocompromised patients associated with high morbidity and mortality,” explained the presenting study investigator Jun Won Park, MD, of Seoul National University Hospital in the Republic of Korea.

Dr. Park added that corticosteroid therapy was an important risk factor for PCP but that the risk-benefit ratio had not been evaluated sufficiently in patients with rheumatic diseases and that there was “different opinion among rheumatologists regarding [the value of] PCP prophylaxis.”

The current study aimed to see if primary antibiotic prophylaxis could prevent PCP in patients with rheumatic diseases, which included patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Behçet’s disease.

For inclusion, patients had to have been treated with prednisolone at a dose of 30 mg/day or more (or its equivalent) for at least 4 weeks and observed for 1 year. Patients with a prior history of PCP or conditions associated with this opportunistic infection, such as HIV, cancer, or solid organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, were excluded.

Dr. Park reported that PCP prophylaxis was given at the discretion of the treating physician, and the mean duration of TMP-SMX was 230 days.

In the prophylaxis group, 34 adverse drug reactions occurred. Two of these reactions were serious – one case of pancytopenia and one case of Steven’s Johnson syndrome – but both resolved after the antibiotic treatment was discontinued.

A sensitivity analysis was performed, giving consistent results, and a risk-benefit analysis showed that the number needed to treat to prevent one case of PCP was 52, considering all rheumatic disease studied, while the number needed to cause one serious adverse drug reaction was 131.

Taken together, these results suggest a role for TMP-SMX as primary prophylaxis for PCP in patients with rheumatic diseases who need prolonged treatment with high-dose corticosteroids, Dr. Park said.

Dr. Park reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE EULAR 2017 CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for no PCP at 1 year of follow-up in the prophylaxis group, versus the no prophylaxis group, was 0.096 (P = .022).

Data source: A single-center, retrospective cohort study of 1,522 episodes of prolonged, high-dose steroid use in 1,092 patients with various rheumatic diseases.

Disclosures: Dr. Park reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Romosozumab cuts new vertebral fracture risk by 73%, but safety data are concerning

MADRID – Romosozumab, an investigational bone-building agent, reduced new vertebral fractures by 73% among postmenopausal women with osteoporosis.

Compared with placebo, the monoclonal antibody also reduced the risk of a clinical fracture by 36% after 12 months of treatment, Piet Geusens, MD, said at the European Congress of Rheumatology. The effect was maintained at 24 months, with a 50% reduction in fracture risk, said Dr. Geusens of Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

Romosozumab also significantly reduced clinical and nonvertebral fractures and increased bone mineral density at the total hip, femoral neck, and lumbar spine in the phase III FRAME study, cosponsored by Amgen and UCB Pharma.

But recently, the finding of increased cardiovascular events in another highly anticipated phase III study of romosozumab cast a cloud of doubt over its rising star. During an interview at EULAR, a UCB company spokesman said the company no longer anticipates a 2017 Food and Drug Administration approval.

FRAME randomized 7,180 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis to monthly injections of romosozumab 210 mg or placebo for 12 months; after that, patients who had been taking placebo switched to denosumab. Dr. Geusens presented only the first year’s placebo-controlled portion. The full FRAME study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine last September (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607948).

At baseline, the women had a mean bone mineral density T score of –2.7 at the lumbar spine, –2.4 at the total hip, and –2.7 at the femoral neck. Mean age was 71 years. About 20% of the women had a previous vertebral fracture, and 22% a previous nonvertebral fracture. The mean FRAX (fracture risk assessment tool) score was 13.4 in both groups.

After 12 months, a new vertebral fracture had occurred in 59 women taking placebo and 16 taking romosozumab (1.8% vs. 0.5%). This amounted to a 73% risk reduction, Dr. Geusens said. Although he did not present 24-month data, the published article cited the antibody’s sustained effect, with a 50% risk reduction evident after the 12-month comparison with denosumab.

The drug also exerted its benefit quickly, Dr. Geusens said. Most of the fractures in the active group occurred in the first 6 months of treatment, with only two additional fractures later.

Romosozumab also was associated with a 36% decrease in the risk of clinical fracture by 12 months (1.6% vs. 2.5% placebo). There was also a positive effect on nonvertebral fractures, which constituted more than 85% of the clinical fractures. Nonvertebral fractures occurred in 56 of those taking the antibody and 75 of those taking placebo (1.6% vs. 2.1%; hazard ratio [HR], .75).

By 12 months, bone mineral density had increased in the romosozumab group by 13% more than in the placebo group at the lumbar spine, by 7% more at the total hip, and by 6% more at the femoral neck.

Dr. Geusens did not address the adverse event profile during his talk. However, according to the published study, romosozumab was generally well tolerated. Serious hypersensitivity events occurred in seven romosozumab patients. Injection site reactions were mostly mild and occurred in 5% of the active group and 3% of the placebo group.

Two patients taking romosozumab experienced osteonecrosis of the jaw; both incidences occurred during the second 12 months and in conjunction with dental issues (tooth extraction and poorly fitted dentures). Anti-romosozumab antibodies developed in 18% and neutralizing antibodies in 0.7%.

Serious cardiovascular events occurred in about 1% of each treatment group, with 17 among those taking romosozumab and15 cardiovascular deaths among those taking placebo – not a significant difference.

UCB and Amgen were pleased with FRAME’s results and, last July, submitted a Biologics License Application to the FDA based on the positive data. A 2017 approval was anticipated, UCB spokesman Scott Fleming said in an interview. But in May, the primary safety analysis of another phase III study, ARCH, threw a monkey wrench in the works.

ARCH compared romosozumab to alendronate in 4,100 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. ARCH met its primary and secondary endpoints, reducing the incidence of new vertebral fractures by 50%, clinical fractures by 27%, and nonvertebral fractures by 19%. But significantly more women taking the antibody experienced an adjudicated serious cardiovascular event (2.5% vs. 1.9% on alendronate).

On May 21, the companies said these new data would delay romosozumab’s progress toward approval, despite the fact that the submission was based on FRAMES’s positive safety and efficacy data.

Mr. Fleming confirmed this in an interview.

“Amgen has agreed with the FDA that the ARCH data should be considered in the regulatory review prior to the initial marketing authorization, and as a result we do not expect approval of romosozumab in the U.S. to occur in 2017,” he said. “Patient safety is of utmost importance and whilst the cardiac imbalance observed in ARCH was not seen in FRAME, it is important and our responsibility to better understand this imbalance. Further analysis of the ARCH study data is ongoing and will be submitted to a future medical conference and for publication.”

Dr. Geusens refused to comment on the cardiovascular adverse events, saying he had not seen the ARCH data; nor did he explain the cardiovascular events that did occur in FRAME.

Romosozumab also is being reviewed in Canada and Japan; those processes are still underway. Mr. Fleming said the companies are preparing a European Medicines Agency application as well. “The preparation for the European regulatory submission will continue as planned – second half of 2017,” he said.

Dr. Geusens has received research support from Amgen and other pharmaceutical companies. He is a consultant for Amgen and a member of its speakers bureau.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

MADRID – Romosozumab, an investigational bone-building agent, reduced new vertebral fractures by 73% among postmenopausal women with osteoporosis.

Compared with placebo, the monoclonal antibody also reduced the risk of a clinical fracture by 36% after 12 months of treatment, Piet Geusens, MD, said at the European Congress of Rheumatology. The effect was maintained at 24 months, with a 50% reduction in fracture risk, said Dr. Geusens of Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

Romosozumab also significantly reduced clinical and nonvertebral fractures and increased bone mineral density at the total hip, femoral neck, and lumbar spine in the phase III FRAME study, cosponsored by Amgen and UCB Pharma.

But recently, the finding of increased cardiovascular events in another highly anticipated phase III study of romosozumab cast a cloud of doubt over its rising star. During an interview at EULAR, a UCB company spokesman said the company no longer anticipates a 2017 Food and Drug Administration approval.