User login

Contralateral nodal thyroid metastases show slow progression

BOSTON – More than a third of 63 patients with unilateral papillary thyroid carcinoma and ipsilateral lymph node metastases also had occult, contralateral, lateral-neck lymph nodes with metastases, but the low reported rate of contralateral neck recurrence has raised the question of whether routine resection of these contralateral lymph nodes benefits patients.

“Prophylactic contralateral lateral-neck dissection may not be relevant for patients with unilateral N1b tumors,” Dana Hartl, MD, PhD, said at the World Congress on Thyroid Cancer.

She envisioned a more targeted approach to using surgical resection of contralateral, lateral-neck lymph nodes. “We would still do this surgery for patients with lots of big, bulky nodules; it just takes an additional 10-20 minutes. It’s not that long or morbid. For patients with lots of [affected] nodes, you’ve got to clear it out. But for a patient with a small, level III node on one side I will no longer do [prophylactic, contralateral, lateral-neck lymph node removal].”

Dr. Hartl and her associates reviewed records for 63 patients with unilateral, unifocal papillary thyroid carcinoma who underwent prophylactic, contralateral, lymph node removal during 1997-2016. They ranged from 11-84 years old, and 60% had extrathyroidal extension of their primary tumor. The patients averaged having four lymph nodes with metastatic cells in the ipsilateral lateral neck, an average of five affected lymph nodes in the ipsilateral central neck, and an average of two affected lymph nodes in the contralateral central neck.

Among the 63 patients, 23 (37%) had metastases-containing lymph nodes at levels III and IV in the contralateral lateral neck, with a range of 1-17 metastases per node. All nodes were less than 1 cm in diameter. Extracapsular spread had occurred in 11 of the 23 cases.

The relatively frequent presence of metastases in the contralateral, lateral-neck lymph nodes contrasted with the reported low 5%-15% rate of recurrence in these lymph nodes in patients with N1b disease, Dr. Hartl said.

The analysis identified two factors that significantly linked with having contralateral, lateral-neck metastases: having a bilateral tumor with contralateral microcancer, or having at least four lymph nodes positive for metastases in the ipsilateral central compartment, she reported. When patients had fewer than five positive lymph nodes in the ipsilateral central neck, their risk for occult metastases in contralateral lymph nodes was 26%.

“It’s not very strong data; we were a little disappointed” with the results, Dr. Hartl said.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The finding reported by Dr. Hartl is consistent with recent experience with other tumor types, like prostate cancer, that often show low aggressiveness. The need to routinely resect what may be indolent microscopic metastases remains a big open question.

The dilemma for thyroid cancer was nicely summarized by Gilbert Welch, MD, and his associates who highlighted the risk of overdiagnosing thyroid cancer with aggressive screening. In South Korea, this resulted in a 15-fold increase in thyroid cancer diagnoses between 1993 and 2011, which led to substantial increases in the rates of thyroidectomy including patients with tumors too small to warrant surgery (N Engl J Med. 2014 Nov 6;371[19]:1765-7).

Pamela Hartzband, MD , is an endocrinologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. She had no disclosures. She made these comments in an interview.

The finding reported by Dr. Hartl is consistent with recent experience with other tumor types, like prostate cancer, that often show low aggressiveness. The need to routinely resect what may be indolent microscopic metastases remains a big open question.

The dilemma for thyroid cancer was nicely summarized by Gilbert Welch, MD, and his associates who highlighted the risk of overdiagnosing thyroid cancer with aggressive screening. In South Korea, this resulted in a 15-fold increase in thyroid cancer diagnoses between 1993 and 2011, which led to substantial increases in the rates of thyroidectomy including patients with tumors too small to warrant surgery (N Engl J Med. 2014 Nov 6;371[19]:1765-7).

Pamela Hartzband, MD , is an endocrinologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. She had no disclosures. She made these comments in an interview.

The finding reported by Dr. Hartl is consistent with recent experience with other tumor types, like prostate cancer, that often show low aggressiveness. The need to routinely resect what may be indolent microscopic metastases remains a big open question.

The dilemma for thyroid cancer was nicely summarized by Gilbert Welch, MD, and his associates who highlighted the risk of overdiagnosing thyroid cancer with aggressive screening. In South Korea, this resulted in a 15-fold increase in thyroid cancer diagnoses between 1993 and 2011, which led to substantial increases in the rates of thyroidectomy including patients with tumors too small to warrant surgery (N Engl J Med. 2014 Nov 6;371[19]:1765-7).

Pamela Hartzband, MD , is an endocrinologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. She had no disclosures. She made these comments in an interview.

BOSTON – More than a third of 63 patients with unilateral papillary thyroid carcinoma and ipsilateral lymph node metastases also had occult, contralateral, lateral-neck lymph nodes with metastases, but the low reported rate of contralateral neck recurrence has raised the question of whether routine resection of these contralateral lymph nodes benefits patients.

“Prophylactic contralateral lateral-neck dissection may not be relevant for patients with unilateral N1b tumors,” Dana Hartl, MD, PhD, said at the World Congress on Thyroid Cancer.

She envisioned a more targeted approach to using surgical resection of contralateral, lateral-neck lymph nodes. “We would still do this surgery for patients with lots of big, bulky nodules; it just takes an additional 10-20 minutes. It’s not that long or morbid. For patients with lots of [affected] nodes, you’ve got to clear it out. But for a patient with a small, level III node on one side I will no longer do [prophylactic, contralateral, lateral-neck lymph node removal].”

Dr. Hartl and her associates reviewed records for 63 patients with unilateral, unifocal papillary thyroid carcinoma who underwent prophylactic, contralateral, lymph node removal during 1997-2016. They ranged from 11-84 years old, and 60% had extrathyroidal extension of their primary tumor. The patients averaged having four lymph nodes with metastatic cells in the ipsilateral lateral neck, an average of five affected lymph nodes in the ipsilateral central neck, and an average of two affected lymph nodes in the contralateral central neck.

Among the 63 patients, 23 (37%) had metastases-containing lymph nodes at levels III and IV in the contralateral lateral neck, with a range of 1-17 metastases per node. All nodes were less than 1 cm in diameter. Extracapsular spread had occurred in 11 of the 23 cases.

The relatively frequent presence of metastases in the contralateral, lateral-neck lymph nodes contrasted with the reported low 5%-15% rate of recurrence in these lymph nodes in patients with N1b disease, Dr. Hartl said.

The analysis identified two factors that significantly linked with having contralateral, lateral-neck metastases: having a bilateral tumor with contralateral microcancer, or having at least four lymph nodes positive for metastases in the ipsilateral central compartment, she reported. When patients had fewer than five positive lymph nodes in the ipsilateral central neck, their risk for occult metastases in contralateral lymph nodes was 26%.

“It’s not very strong data; we were a little disappointed” with the results, Dr. Hartl said.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BOSTON – More than a third of 63 patients with unilateral papillary thyroid carcinoma and ipsilateral lymph node metastases also had occult, contralateral, lateral-neck lymph nodes with metastases, but the low reported rate of contralateral neck recurrence has raised the question of whether routine resection of these contralateral lymph nodes benefits patients.

“Prophylactic contralateral lateral-neck dissection may not be relevant for patients with unilateral N1b tumors,” Dana Hartl, MD, PhD, said at the World Congress on Thyroid Cancer.

She envisioned a more targeted approach to using surgical resection of contralateral, lateral-neck lymph nodes. “We would still do this surgery for patients with lots of big, bulky nodules; it just takes an additional 10-20 minutes. It’s not that long or morbid. For patients with lots of [affected] nodes, you’ve got to clear it out. But for a patient with a small, level III node on one side I will no longer do [prophylactic, contralateral, lateral-neck lymph node removal].”

Dr. Hartl and her associates reviewed records for 63 patients with unilateral, unifocal papillary thyroid carcinoma who underwent prophylactic, contralateral, lymph node removal during 1997-2016. They ranged from 11-84 years old, and 60% had extrathyroidal extension of their primary tumor. The patients averaged having four lymph nodes with metastatic cells in the ipsilateral lateral neck, an average of five affected lymph nodes in the ipsilateral central neck, and an average of two affected lymph nodes in the contralateral central neck.

Among the 63 patients, 23 (37%) had metastases-containing lymph nodes at levels III and IV in the contralateral lateral neck, with a range of 1-17 metastases per node. All nodes were less than 1 cm in diameter. Extracapsular spread had occurred in 11 of the 23 cases.

The relatively frequent presence of metastases in the contralateral, lateral-neck lymph nodes contrasted with the reported low 5%-15% rate of recurrence in these lymph nodes in patients with N1b disease, Dr. Hartl said.

The analysis identified two factors that significantly linked with having contralateral, lateral-neck metastases: having a bilateral tumor with contralateral microcancer, or having at least four lymph nodes positive for metastases in the ipsilateral central compartment, she reported. When patients had fewer than five positive lymph nodes in the ipsilateral central neck, their risk for occult metastases in contralateral lymph nodes was 26%.

“It’s not very strong data; we were a little disappointed” with the results, Dr. Hartl said.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT WCTC 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Thirty-seven percent of patients with unilateral N1b thyroid tumors also had metastases in their contralateral lateral-neck lymph nodes.

Data source: Review of 63 patients treated at a single French center during a 20-year period.

Disclosures: Dr. Hartl had no disclosures.

Multiple Primary Atypical Vascular Lesions Occurring in the Same Breast

Atypical vascular lesions (AVLs) of the breast are rare cutaneous vascular proliferations that present as erythematous, violaceous, or flesh-colored papules, patches, or plaques in women who have undergone radiation treatment for breast carcinoma.1,2 These lesions most commonly develop in the irradiated area within 3 to 6 years following radiation treatment.3

Various terms have been used to describe AVLs in the literature, including atypical hemangiomas, benign lymphangiomatous papules, benign lymphangioendotheliomas, lymphangioma circumscriptum, and acquired progressive lymphangiomas, suggesting benign behavior.4-10 However, their identity as benign lesions has been a source of controversy, with some investigators proposing that AVLs may be a precursor lesion to postirradiation angiosarcoma.2 Research has addressed if there are markers that can predict AVL types that are more likely to develop into angiosarcomas.1 Although most clinicians treat AVLs with complete excision, there currently are no specific guidelines to direct this practice.

We report the case of a patient with a history of 1 AVL that was excised who developed 3 additional AVLs in the same breast over the course of 15 months.

Case Report

A 55-year-old woman with a history of obesity, hypertension, and infiltrating ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast (grade 2, estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive) underwent a right breast lumpectomy and sentinel lymph node dissection. Three months later, she underwent re-excision for positive margins and started adjuvant hormonal therapy with tamoxifen. One month later, she began external beam radiation therapy and received a total dose of 6040 cGy over the course of 9 weeks (34 total treatments).

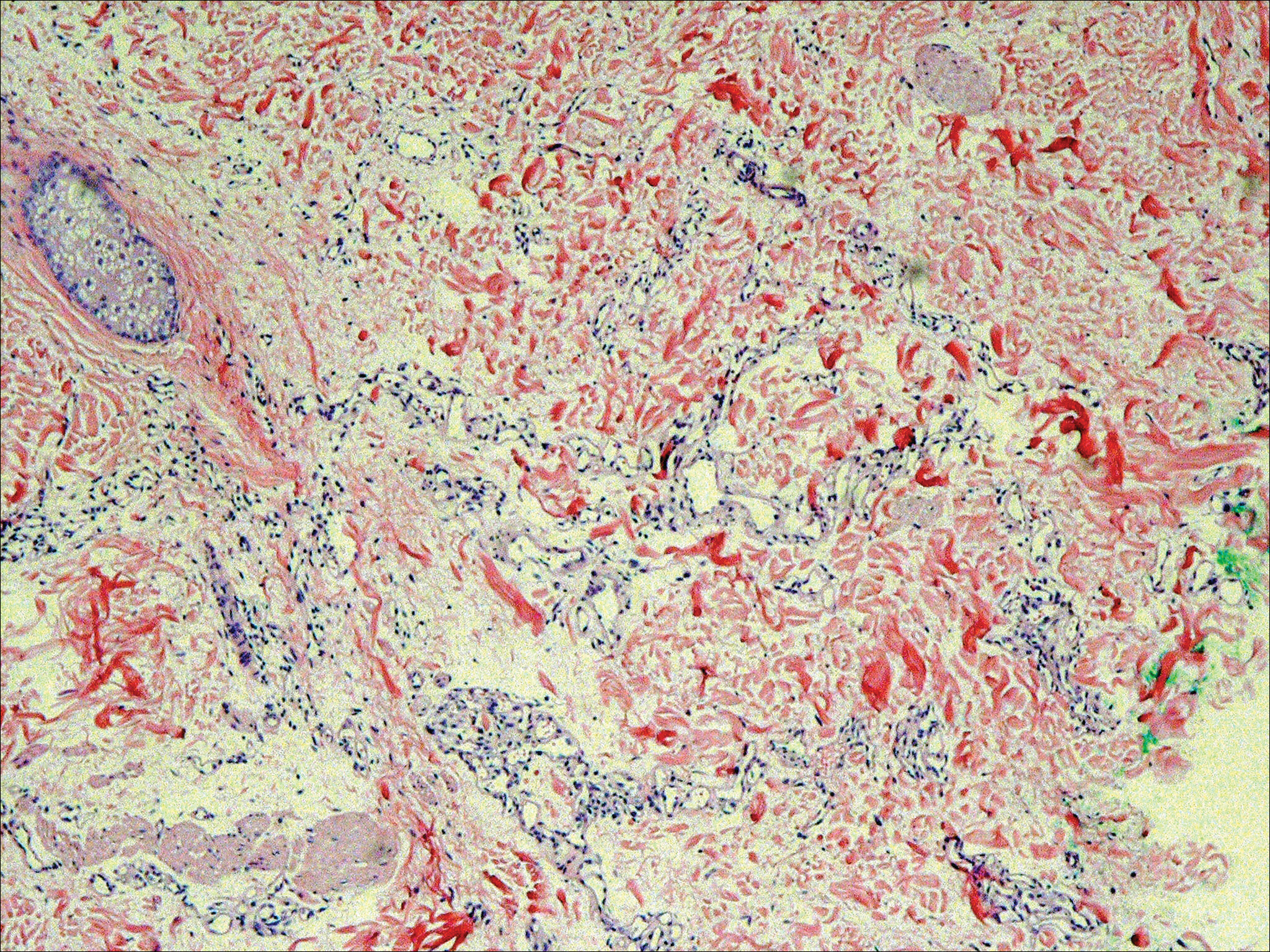

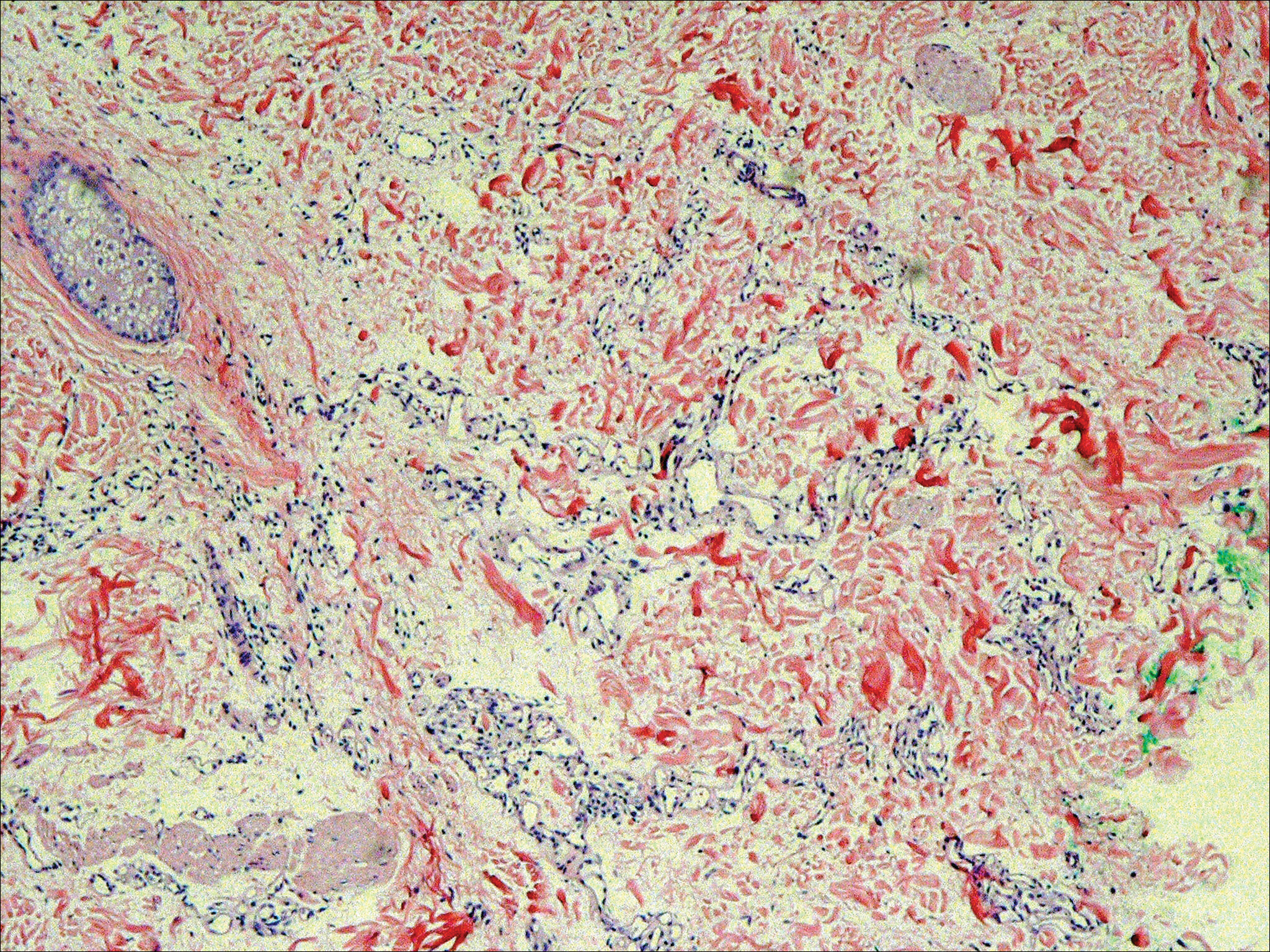

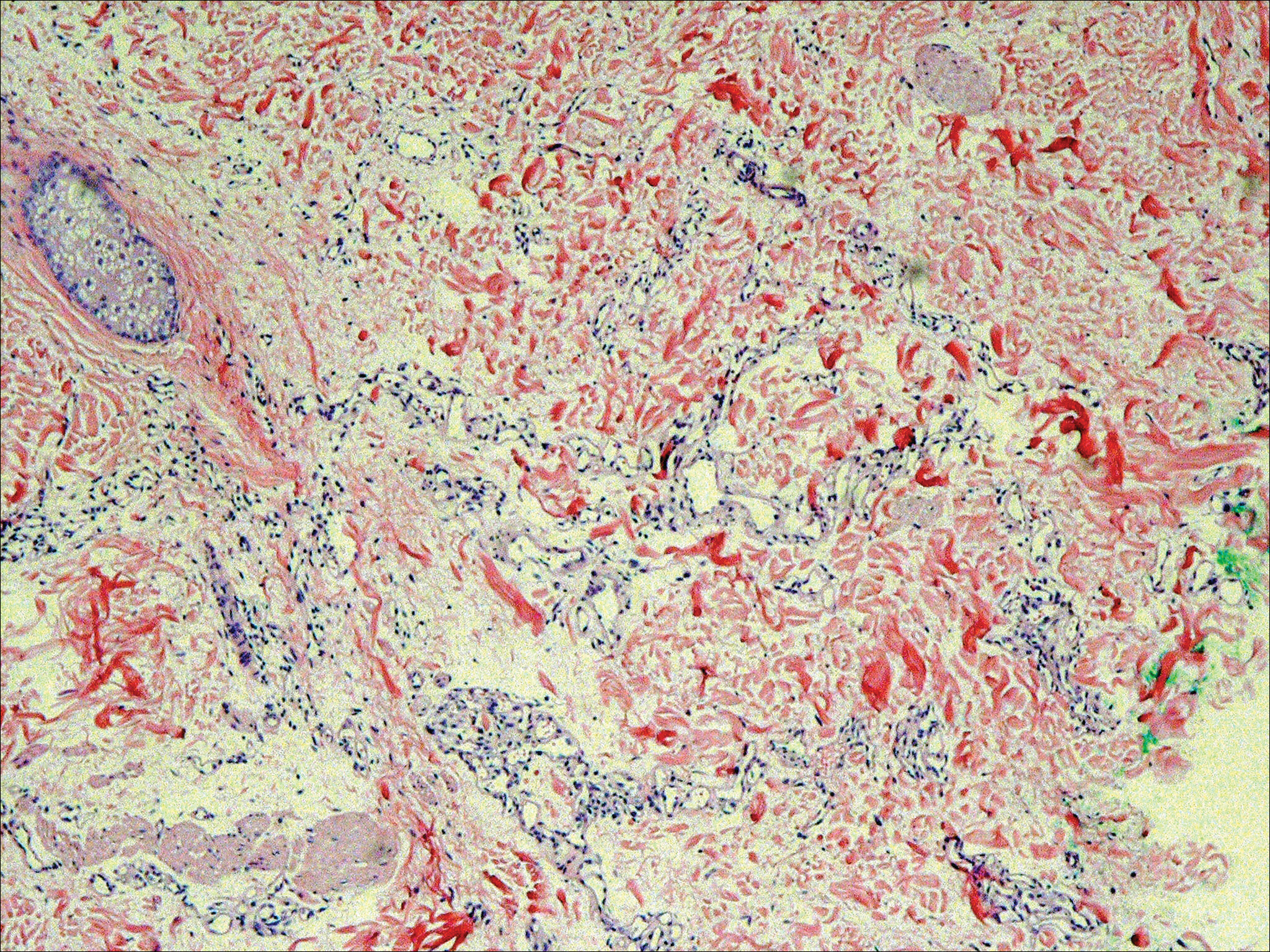

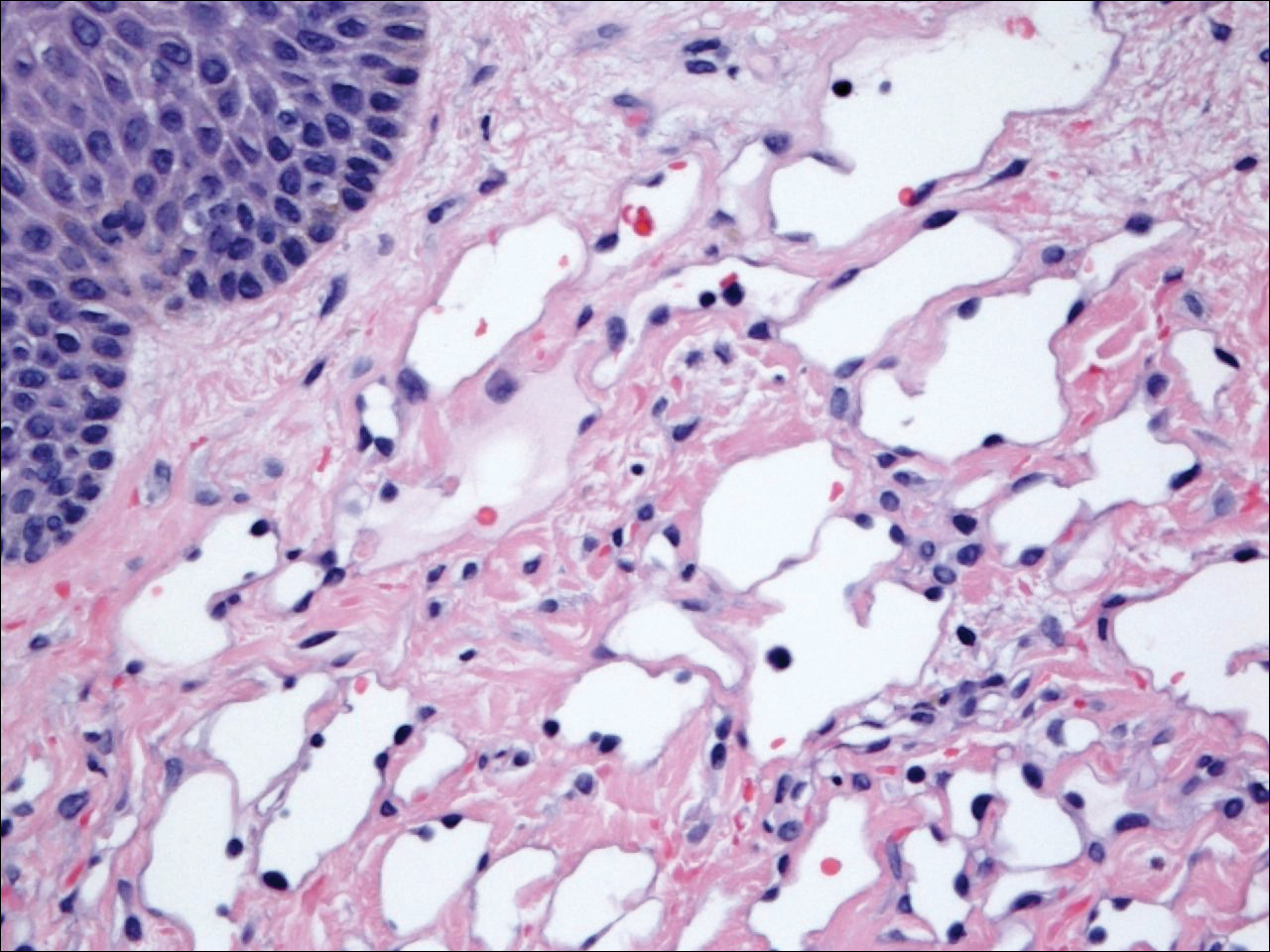

The patient presented to an outside dermatology clinic 2 years after completing external beam radiation therapy for evaluation of a new pink nodule on the right mid breast. The nodule was biopsied and discovered to be an AVL. Pathology showed an anastomosing proliferation of thin-walled vascular channels mainly located in the superficial dermis with notable endothelial nuclear atypia and hyperchromasia. There were several tiny foci with the beginnings of multilayering with prominent endothelial atypia (Figure 1). She underwent complete excision for this AVL with negative margins.

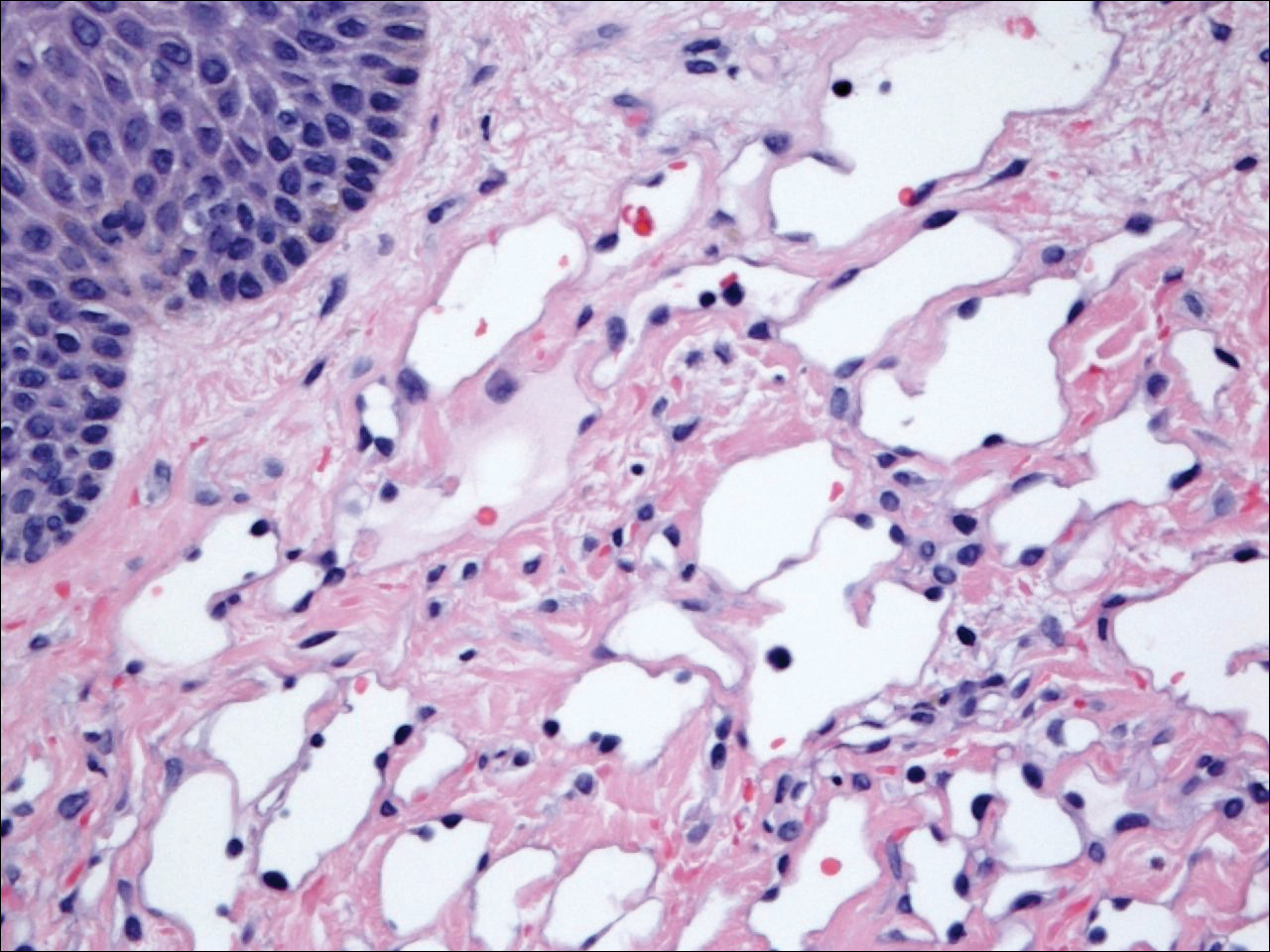

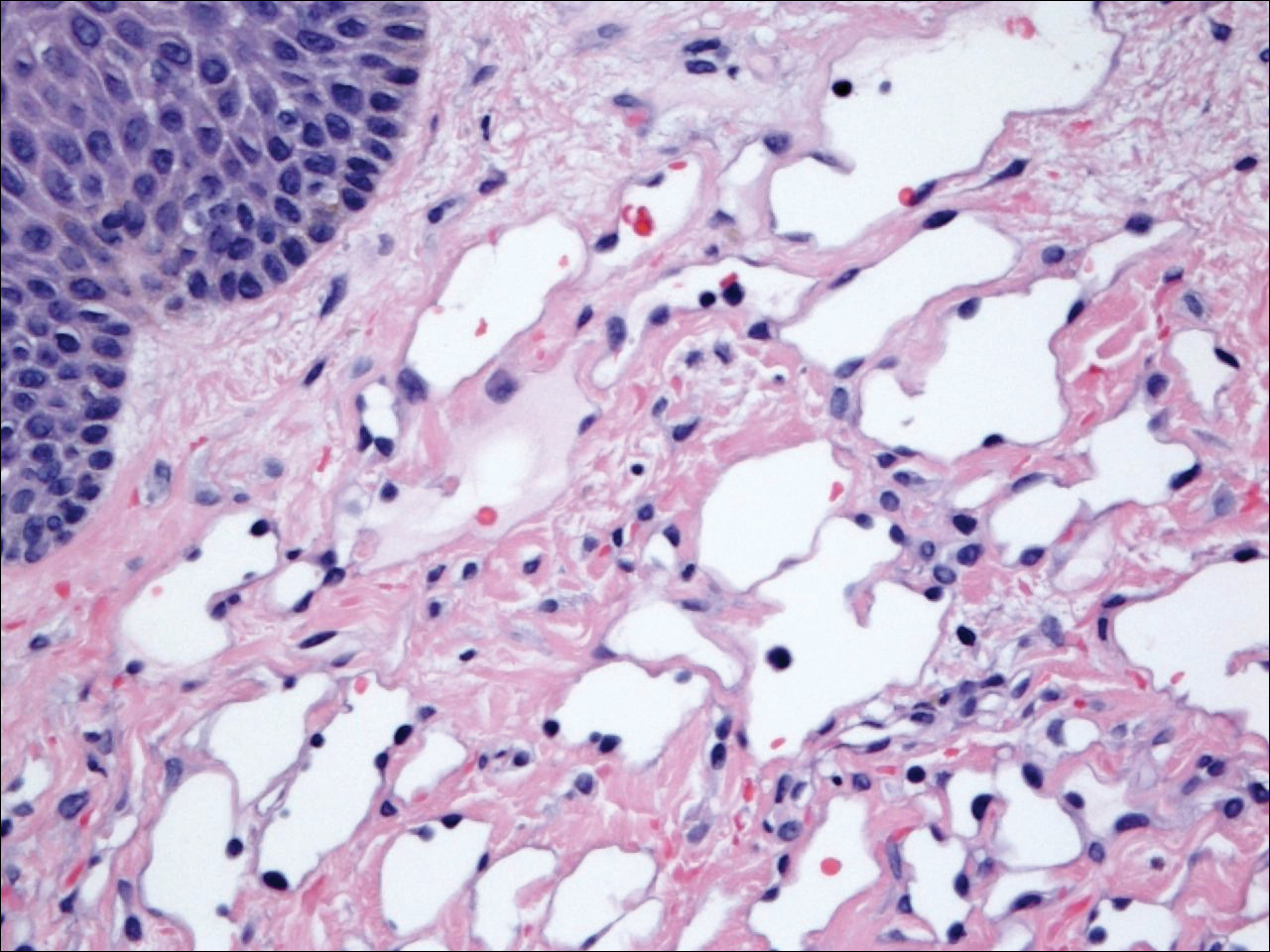

Six months after the initial AVL diagnosis, she presented to our dermatology clinic with another asymptomatic red bump on the right breast. On physical examination, a 4-mm firm, erythematous, well-circumscribed papule was noted on the medial aspect of the right breast along with a similar-appearing 4-mm papule on the right lateral aspect of the right breast (Figure 2). The patient was unsure of the duration of the second lesion but felt that it had been present at least as long as the other lesion. Both lesions clinically resembled typical capillary hemangiomas. A 6-mm punch biopsy of the right medial breast was performed and revealed enlarged vessels and capillaries in the upper dermis lined by endothelial cells with focal prominent nuclei without necrosis, overt atypia, mitosis, or tufting (Figure 3). Immunostaining was positive for CD34, factor VIII antigen, podoplanin (D2-40), and CD31, and negative for cytokeratin 7 and pankeratin. This staining was compatible with a lymphatic-type AVL.1 A diagnosis of AVL was made and complete excision with clear margins was performed. At the time of this excision, a biopsy of the right lateral breast was performed revealing thin-walled, dilated vascular channels in the superficial dermis with architecturally atypical angulated outlines, mild endothelial nuclear atypia, and hyperchromasia without endothelial multilayering. Clear margins were noted on the biopsy, but the patient subsequently declined re-excision of this third AVL.

During a subsequent follow-up visit 9 months later, the patient was noted to have a 2-mm red, vascular-appearing papule on the right upper medial breast (Figure 2). A 6-mm biopsy was performed and revealed thin-walled vascular channels in the superficial dermis with endothelial nuclear atypia consistent with an AVL.

Comment

Fineberg and Rosen8 were the first to describe AVLs in their 1994 study of 4 women with cutaneous vascular proliferations that developed after radiation and chemotherapy for breast cancer. They concluded that these AVLs were benign lesions distinct from angiosarcomas.8 However, further research has challenged the benign nature of AVLs. In 2005, Brenn and Fletcher2 studied 42 women diagnosed with either angiosarcoma or atypical radiation-associated cutaneous vascular lesions. They suggested that AVLs resided on the same spectrum as angiosarcomas and that AVLs may be precursor lesions to angiosarcomas.2 Furthermore, Hildebrandt et al11 in 2001 and Di Tommaso and Fabbri12 in 2003 published case reports of individual patients who developed an angiosarcoma from a preexisting AVL.

The controversy continued when Patton et al1 published a study in 2008 in which 32 cases of AVLs were reviewed. In this study, 2 histologic types of AVLs were described: vascular type and lymphatic type. Vascular-type AVLs are characterized by irregularly dispersed, pericyte-invested, capillary-sized vessels within the papillary or reticular dermis that often are associated with extravasated erythrocytes or hemosiderin. On the other hand, lymphatic-type AVLs display thin-walled, variably anastomosing, lymphatic vessels lined by attenuated or slightly protuberant endothelial cells. These subtypes have been suggested based on the antigens known to be present in certain tissues, specifically vascular and lymphatic tissue. Despite these seemingly distinct histologies, 6 lesions classified as vascular type displayed some histologic overlap with the lymphatic-type AVLs. The authors concluded that the vascular type showed greater potential to develop into an angiosarcoma based on the degree of endothelial atypia.1

In 2011, Santi et al13 found that both AVLs and angiosarcomas share inactivation mutations in the tumor suppressor gene TP53, providing further evidence to suggest that AVLs may be precursors to angiosarcomas.

Although the malignant potential of AVLs remains questionable, research has shown that they do have a propensity to recur.3 In 2007, Gengler et al3 determined that 20% of patients with AVLs experienced recurrence after a biopsy or excision with varying margins; however, the group stated that these new vascular lesions might not be recurrences but rather entirely new lesions in the same irradiated field (field-effect phenomenon). Several other studies demonstrated that more than 30% of patients with 1 AVL developed more lesions within the same irradiated area.3,14-16 Despite the high rate of recurrence documented in the literature, only 5 of more than 100 diagnosed AVLs have progressed to angiosarcoma.1,3

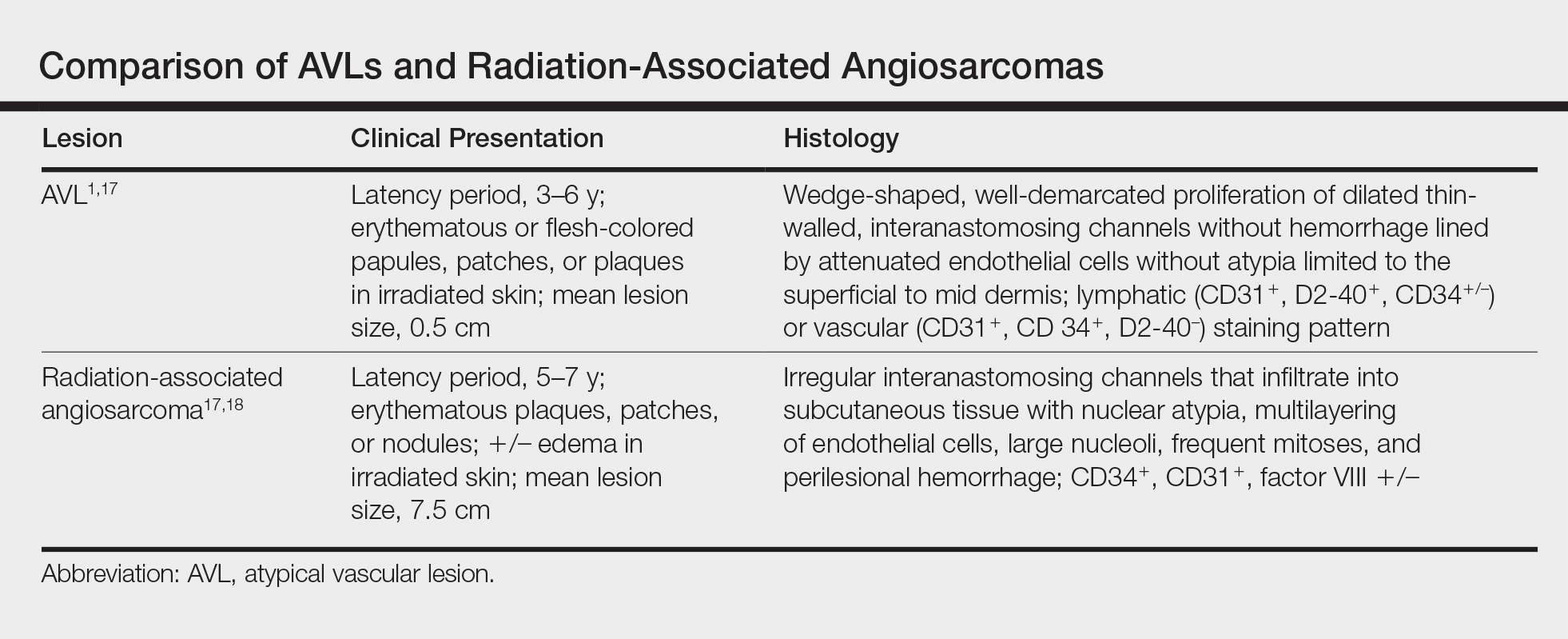

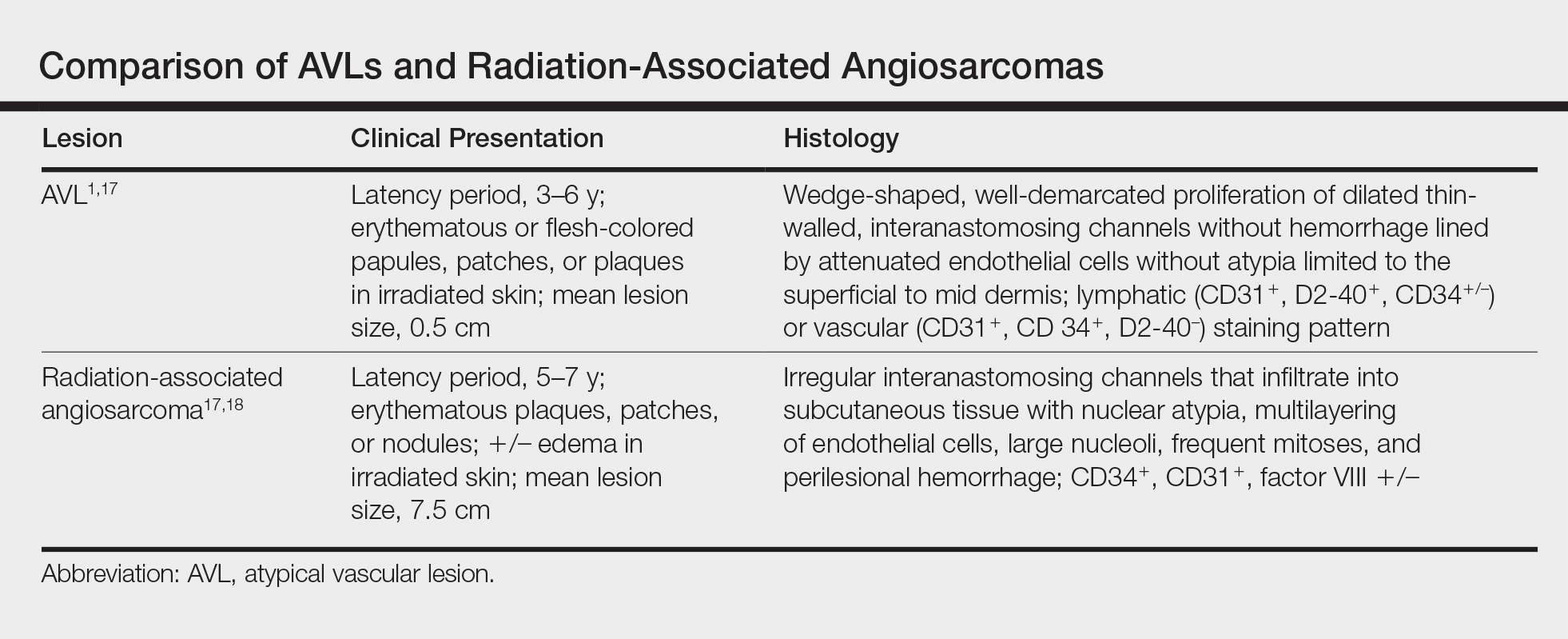

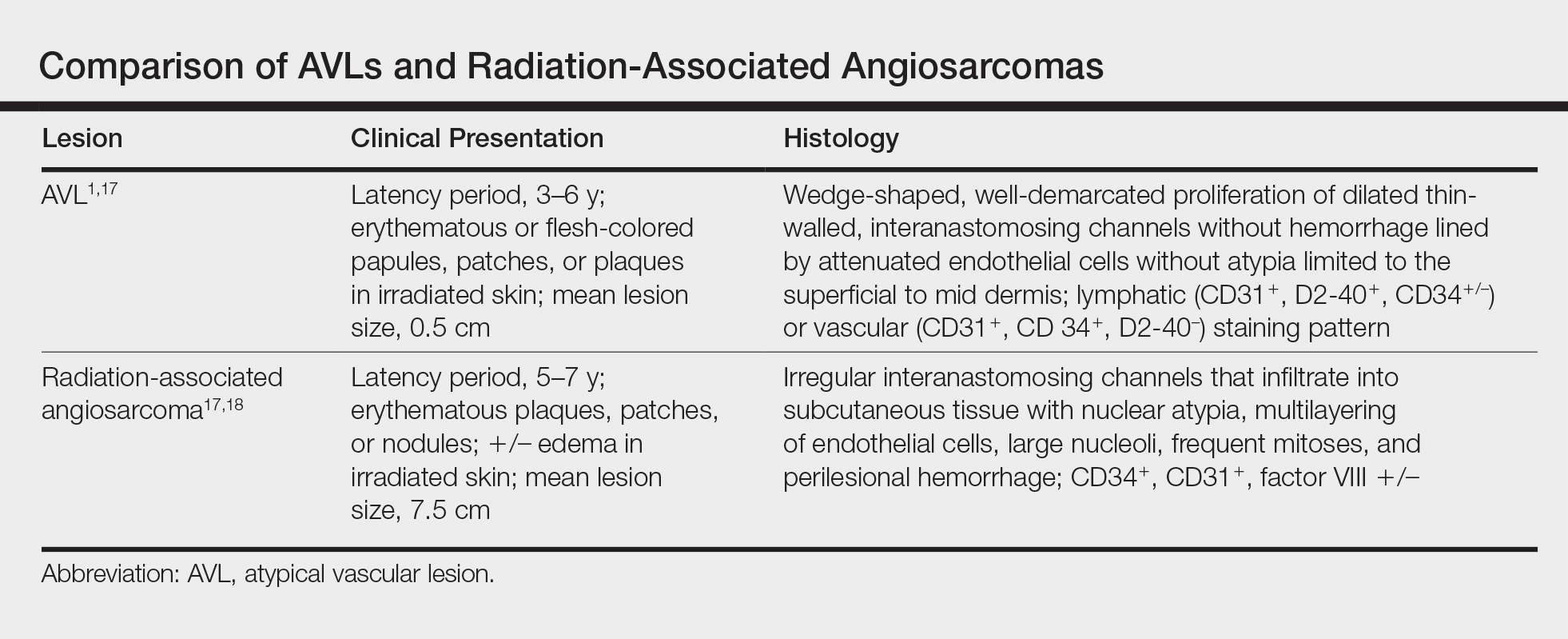

Many differences can be noted when comparing the histology of AVLs versus angiosarcomas, though some are subtle (Table). Angiosarcomas display poorly circumscribed vascular infiltration into the subcutaneous tissue, multilayering of endothelial cells, prominent nucleoli, hemorrhage, mitoses, and notable aytpia. Atypical vascular lesions lack these features and tend to be wedge shaped and display chronic inflammation.8,15,17-19 Atypical vascular lesions show superficial localized growth without destruction of adjacent adnexa, display dilated vascular spaces, and exhibit large endothelial cells.5,6,8,14,15,19,20 However, there is overlap between AVLs and angiosarcomas that can make diagnosis difficult.2,14,16,17,19 Areas within or just outside of an angiosarcoma, especially in well-differentiated angiosarcomas, can appear histologically identical to AVLs, and multiple biopsies may be required for diagnosis.17,19,21

Conclusion

More research is needed in the arenas of classification, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up recommendations for AVLs. In particular, more specific histologic markers may be needed to identify those AVLs that may progress to angiosarcomas. Although most AVLs are treated with excision, a consensus needs to be reached on adequate surgical margins. Lastly, due to the tendency of AVLs to recur coupled with their unknown malignant potential, recommendations are needed for consistent follow-up examinations.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:983-996.

- Gengler C, Coindre JM, Leroux A, et al. Vascular proliferations of the skin after radiation therapy for breast cancer: clinicopathologic analysis of a series in favor of a benign process; a study from the French sarcoma group. Cancer. 2007;109:1584-1598.

- Hoda SA, Cranor ML, Rosen PP. Hemangiomas of the breast with atypical histological features: further analysis of histological subtypes confirming their benign character. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:553-560.

- Wagamon K, Ranchoff RE, Rosenberg AS, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:912-913.

- Diaz-Cascajo C, Borghi S, Weyers W, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin following radiotherapy: a report of five new cases and review of the literature. Histopathology. 1999;35:319-327.

- Martín-González T, Sanz-Trelles A, Del Boz J, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules and plaques after radiotherapy [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:84-86.

- Fineberg S, Rosen PP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions of the skin and breast after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:757-763.

- Guillou L, Fletcher CD. Benign lymphangioendothelioma (acquired progressive lymphangioma): a lesion not to be confused with well-differentiated angiosarcoma and patch stage Kaposi’s sarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a series. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1047-1057.

- Rosso R, Gianelli U, Carnevali L. Acquired progressive lymphangioma of the skin following radiotherapy for breast carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:164-167.

- Hildebrandt G, Mittag M, Gutz U, et al. Cutaneous breast angiosarcoma after conservative treatment of breast cancer. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:580-583.

- Di Tommaso L, Fabbri A. Cutaneous angiosarcoma arising after radiotherapy treatment of a breast carcinoma: description of a case and review of the literature [in Italian]. Pathologica. 2003;95:196-202.

- Santi R, Cetica V, Franchi A, et al. Tumour suppressor gene TP53 mutations in atypical vascular lesions of breast skin following radiotherapy. Histopathology. 2011;58:455-466.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Mentzel T, et al. Benign vascular proliferations in irradiated skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:328-337.

- Brodie C, Provenzano E. Vascular proliferations of the breast. Histopathology. 2008;52:30-44.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Postradiation vascular proliferations: an increasing problem. Histopathology. 2006;48:106-114.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Kardum-Skelin I, Jelić-Puskarić B, Pazur M, et al. A case report of breast angiosarcoma. Coll Antropol. 2010;34:645-648.

- Mattoch IW, Robbins JB, Kempson RL, et al. Post-radiotherapy vascular proliferations in mammary skin: a clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:126-133.

- Bodet D, Rodríguez-Cano L, Bartralot R, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin associated with ovarian fibroma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2 suppl):S41-S44.

- Losch A, Chilek KD, Zirwas MJ. Post-radiation atypical vascular proliferation mimicking angiosarcoma eight months following breast-conserving therapy for breast carcinoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:47-48.

Atypical vascular lesions (AVLs) of the breast are rare cutaneous vascular proliferations that present as erythematous, violaceous, or flesh-colored papules, patches, or plaques in women who have undergone radiation treatment for breast carcinoma.1,2 These lesions most commonly develop in the irradiated area within 3 to 6 years following radiation treatment.3

Various terms have been used to describe AVLs in the literature, including atypical hemangiomas, benign lymphangiomatous papules, benign lymphangioendotheliomas, lymphangioma circumscriptum, and acquired progressive lymphangiomas, suggesting benign behavior.4-10 However, their identity as benign lesions has been a source of controversy, with some investigators proposing that AVLs may be a precursor lesion to postirradiation angiosarcoma.2 Research has addressed if there are markers that can predict AVL types that are more likely to develop into angiosarcomas.1 Although most clinicians treat AVLs with complete excision, there currently are no specific guidelines to direct this practice.

We report the case of a patient with a history of 1 AVL that was excised who developed 3 additional AVLs in the same breast over the course of 15 months.

Case Report

A 55-year-old woman with a history of obesity, hypertension, and infiltrating ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast (grade 2, estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive) underwent a right breast lumpectomy and sentinel lymph node dissection. Three months later, she underwent re-excision for positive margins and started adjuvant hormonal therapy with tamoxifen. One month later, she began external beam radiation therapy and received a total dose of 6040 cGy over the course of 9 weeks (34 total treatments).

The patient presented to an outside dermatology clinic 2 years after completing external beam radiation therapy for evaluation of a new pink nodule on the right mid breast. The nodule was biopsied and discovered to be an AVL. Pathology showed an anastomosing proliferation of thin-walled vascular channels mainly located in the superficial dermis with notable endothelial nuclear atypia and hyperchromasia. There were several tiny foci with the beginnings of multilayering with prominent endothelial atypia (Figure 1). She underwent complete excision for this AVL with negative margins.

Six months after the initial AVL diagnosis, she presented to our dermatology clinic with another asymptomatic red bump on the right breast. On physical examination, a 4-mm firm, erythematous, well-circumscribed papule was noted on the medial aspect of the right breast along with a similar-appearing 4-mm papule on the right lateral aspect of the right breast (Figure 2). The patient was unsure of the duration of the second lesion but felt that it had been present at least as long as the other lesion. Both lesions clinically resembled typical capillary hemangiomas. A 6-mm punch biopsy of the right medial breast was performed and revealed enlarged vessels and capillaries in the upper dermis lined by endothelial cells with focal prominent nuclei without necrosis, overt atypia, mitosis, or tufting (Figure 3). Immunostaining was positive for CD34, factor VIII antigen, podoplanin (D2-40), and CD31, and negative for cytokeratin 7 and pankeratin. This staining was compatible with a lymphatic-type AVL.1 A diagnosis of AVL was made and complete excision with clear margins was performed. At the time of this excision, a biopsy of the right lateral breast was performed revealing thin-walled, dilated vascular channels in the superficial dermis with architecturally atypical angulated outlines, mild endothelial nuclear atypia, and hyperchromasia without endothelial multilayering. Clear margins were noted on the biopsy, but the patient subsequently declined re-excision of this third AVL.

During a subsequent follow-up visit 9 months later, the patient was noted to have a 2-mm red, vascular-appearing papule on the right upper medial breast (Figure 2). A 6-mm biopsy was performed and revealed thin-walled vascular channels in the superficial dermis with endothelial nuclear atypia consistent with an AVL.

Comment

Fineberg and Rosen8 were the first to describe AVLs in their 1994 study of 4 women with cutaneous vascular proliferations that developed after radiation and chemotherapy for breast cancer. They concluded that these AVLs were benign lesions distinct from angiosarcomas.8 However, further research has challenged the benign nature of AVLs. In 2005, Brenn and Fletcher2 studied 42 women diagnosed with either angiosarcoma or atypical radiation-associated cutaneous vascular lesions. They suggested that AVLs resided on the same spectrum as angiosarcomas and that AVLs may be precursor lesions to angiosarcomas.2 Furthermore, Hildebrandt et al11 in 2001 and Di Tommaso and Fabbri12 in 2003 published case reports of individual patients who developed an angiosarcoma from a preexisting AVL.

The controversy continued when Patton et al1 published a study in 2008 in which 32 cases of AVLs were reviewed. In this study, 2 histologic types of AVLs were described: vascular type and lymphatic type. Vascular-type AVLs are characterized by irregularly dispersed, pericyte-invested, capillary-sized vessels within the papillary or reticular dermis that often are associated with extravasated erythrocytes or hemosiderin. On the other hand, lymphatic-type AVLs display thin-walled, variably anastomosing, lymphatic vessels lined by attenuated or slightly protuberant endothelial cells. These subtypes have been suggested based on the antigens known to be present in certain tissues, specifically vascular and lymphatic tissue. Despite these seemingly distinct histologies, 6 lesions classified as vascular type displayed some histologic overlap with the lymphatic-type AVLs. The authors concluded that the vascular type showed greater potential to develop into an angiosarcoma based on the degree of endothelial atypia.1

In 2011, Santi et al13 found that both AVLs and angiosarcomas share inactivation mutations in the tumor suppressor gene TP53, providing further evidence to suggest that AVLs may be precursors to angiosarcomas.

Although the malignant potential of AVLs remains questionable, research has shown that they do have a propensity to recur.3 In 2007, Gengler et al3 determined that 20% of patients with AVLs experienced recurrence after a biopsy or excision with varying margins; however, the group stated that these new vascular lesions might not be recurrences but rather entirely new lesions in the same irradiated field (field-effect phenomenon). Several other studies demonstrated that more than 30% of patients with 1 AVL developed more lesions within the same irradiated area.3,14-16 Despite the high rate of recurrence documented in the literature, only 5 of more than 100 diagnosed AVLs have progressed to angiosarcoma.1,3

Many differences can be noted when comparing the histology of AVLs versus angiosarcomas, though some are subtle (Table). Angiosarcomas display poorly circumscribed vascular infiltration into the subcutaneous tissue, multilayering of endothelial cells, prominent nucleoli, hemorrhage, mitoses, and notable aytpia. Atypical vascular lesions lack these features and tend to be wedge shaped and display chronic inflammation.8,15,17-19 Atypical vascular lesions show superficial localized growth without destruction of adjacent adnexa, display dilated vascular spaces, and exhibit large endothelial cells.5,6,8,14,15,19,20 However, there is overlap between AVLs and angiosarcomas that can make diagnosis difficult.2,14,16,17,19 Areas within or just outside of an angiosarcoma, especially in well-differentiated angiosarcomas, can appear histologically identical to AVLs, and multiple biopsies may be required for diagnosis.17,19,21

Conclusion

More research is needed in the arenas of classification, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up recommendations for AVLs. In particular, more specific histologic markers may be needed to identify those AVLs that may progress to angiosarcomas. Although most AVLs are treated with excision, a consensus needs to be reached on adequate surgical margins. Lastly, due to the tendency of AVLs to recur coupled with their unknown malignant potential, recommendations are needed for consistent follow-up examinations.

Atypical vascular lesions (AVLs) of the breast are rare cutaneous vascular proliferations that present as erythematous, violaceous, or flesh-colored papules, patches, or plaques in women who have undergone radiation treatment for breast carcinoma.1,2 These lesions most commonly develop in the irradiated area within 3 to 6 years following radiation treatment.3

Various terms have been used to describe AVLs in the literature, including atypical hemangiomas, benign lymphangiomatous papules, benign lymphangioendotheliomas, lymphangioma circumscriptum, and acquired progressive lymphangiomas, suggesting benign behavior.4-10 However, their identity as benign lesions has been a source of controversy, with some investigators proposing that AVLs may be a precursor lesion to postirradiation angiosarcoma.2 Research has addressed if there are markers that can predict AVL types that are more likely to develop into angiosarcomas.1 Although most clinicians treat AVLs with complete excision, there currently are no specific guidelines to direct this practice.

We report the case of a patient with a history of 1 AVL that was excised who developed 3 additional AVLs in the same breast over the course of 15 months.

Case Report

A 55-year-old woman with a history of obesity, hypertension, and infiltrating ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast (grade 2, estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive) underwent a right breast lumpectomy and sentinel lymph node dissection. Three months later, she underwent re-excision for positive margins and started adjuvant hormonal therapy with tamoxifen. One month later, she began external beam radiation therapy and received a total dose of 6040 cGy over the course of 9 weeks (34 total treatments).

The patient presented to an outside dermatology clinic 2 years after completing external beam radiation therapy for evaluation of a new pink nodule on the right mid breast. The nodule was biopsied and discovered to be an AVL. Pathology showed an anastomosing proliferation of thin-walled vascular channels mainly located in the superficial dermis with notable endothelial nuclear atypia and hyperchromasia. There were several tiny foci with the beginnings of multilayering with prominent endothelial atypia (Figure 1). She underwent complete excision for this AVL with negative margins.

Six months after the initial AVL diagnosis, she presented to our dermatology clinic with another asymptomatic red bump on the right breast. On physical examination, a 4-mm firm, erythematous, well-circumscribed papule was noted on the medial aspect of the right breast along with a similar-appearing 4-mm papule on the right lateral aspect of the right breast (Figure 2). The patient was unsure of the duration of the second lesion but felt that it had been present at least as long as the other lesion. Both lesions clinically resembled typical capillary hemangiomas. A 6-mm punch biopsy of the right medial breast was performed and revealed enlarged vessels and capillaries in the upper dermis lined by endothelial cells with focal prominent nuclei without necrosis, overt atypia, mitosis, or tufting (Figure 3). Immunostaining was positive for CD34, factor VIII antigen, podoplanin (D2-40), and CD31, and negative for cytokeratin 7 and pankeratin. This staining was compatible with a lymphatic-type AVL.1 A diagnosis of AVL was made and complete excision with clear margins was performed. At the time of this excision, a biopsy of the right lateral breast was performed revealing thin-walled, dilated vascular channels in the superficial dermis with architecturally atypical angulated outlines, mild endothelial nuclear atypia, and hyperchromasia without endothelial multilayering. Clear margins were noted on the biopsy, but the patient subsequently declined re-excision of this third AVL.

During a subsequent follow-up visit 9 months later, the patient was noted to have a 2-mm red, vascular-appearing papule on the right upper medial breast (Figure 2). A 6-mm biopsy was performed and revealed thin-walled vascular channels in the superficial dermis with endothelial nuclear atypia consistent with an AVL.

Comment

Fineberg and Rosen8 were the first to describe AVLs in their 1994 study of 4 women with cutaneous vascular proliferations that developed after radiation and chemotherapy for breast cancer. They concluded that these AVLs were benign lesions distinct from angiosarcomas.8 However, further research has challenged the benign nature of AVLs. In 2005, Brenn and Fletcher2 studied 42 women diagnosed with either angiosarcoma or atypical radiation-associated cutaneous vascular lesions. They suggested that AVLs resided on the same spectrum as angiosarcomas and that AVLs may be precursor lesions to angiosarcomas.2 Furthermore, Hildebrandt et al11 in 2001 and Di Tommaso and Fabbri12 in 2003 published case reports of individual patients who developed an angiosarcoma from a preexisting AVL.

The controversy continued when Patton et al1 published a study in 2008 in which 32 cases of AVLs were reviewed. In this study, 2 histologic types of AVLs were described: vascular type and lymphatic type. Vascular-type AVLs are characterized by irregularly dispersed, pericyte-invested, capillary-sized vessels within the papillary or reticular dermis that often are associated with extravasated erythrocytes or hemosiderin. On the other hand, lymphatic-type AVLs display thin-walled, variably anastomosing, lymphatic vessels lined by attenuated or slightly protuberant endothelial cells. These subtypes have been suggested based on the antigens known to be present in certain tissues, specifically vascular and lymphatic tissue. Despite these seemingly distinct histologies, 6 lesions classified as vascular type displayed some histologic overlap with the lymphatic-type AVLs. The authors concluded that the vascular type showed greater potential to develop into an angiosarcoma based on the degree of endothelial atypia.1

In 2011, Santi et al13 found that both AVLs and angiosarcomas share inactivation mutations in the tumor suppressor gene TP53, providing further evidence to suggest that AVLs may be precursors to angiosarcomas.

Although the malignant potential of AVLs remains questionable, research has shown that they do have a propensity to recur.3 In 2007, Gengler et al3 determined that 20% of patients with AVLs experienced recurrence after a biopsy or excision with varying margins; however, the group stated that these new vascular lesions might not be recurrences but rather entirely new lesions in the same irradiated field (field-effect phenomenon). Several other studies demonstrated that more than 30% of patients with 1 AVL developed more lesions within the same irradiated area.3,14-16 Despite the high rate of recurrence documented in the literature, only 5 of more than 100 diagnosed AVLs have progressed to angiosarcoma.1,3

Many differences can be noted when comparing the histology of AVLs versus angiosarcomas, though some are subtle (Table). Angiosarcomas display poorly circumscribed vascular infiltration into the subcutaneous tissue, multilayering of endothelial cells, prominent nucleoli, hemorrhage, mitoses, and notable aytpia. Atypical vascular lesions lack these features and tend to be wedge shaped and display chronic inflammation.8,15,17-19 Atypical vascular lesions show superficial localized growth without destruction of adjacent adnexa, display dilated vascular spaces, and exhibit large endothelial cells.5,6,8,14,15,19,20 However, there is overlap between AVLs and angiosarcomas that can make diagnosis difficult.2,14,16,17,19 Areas within or just outside of an angiosarcoma, especially in well-differentiated angiosarcomas, can appear histologically identical to AVLs, and multiple biopsies may be required for diagnosis.17,19,21

Conclusion

More research is needed in the arenas of classification, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up recommendations for AVLs. In particular, more specific histologic markers may be needed to identify those AVLs that may progress to angiosarcomas. Although most AVLs are treated with excision, a consensus needs to be reached on adequate surgical margins. Lastly, due to the tendency of AVLs to recur coupled with their unknown malignant potential, recommendations are needed for consistent follow-up examinations.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:983-996.

- Gengler C, Coindre JM, Leroux A, et al. Vascular proliferations of the skin after radiation therapy for breast cancer: clinicopathologic analysis of a series in favor of a benign process; a study from the French sarcoma group. Cancer. 2007;109:1584-1598.

- Hoda SA, Cranor ML, Rosen PP. Hemangiomas of the breast with atypical histological features: further analysis of histological subtypes confirming their benign character. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:553-560.

- Wagamon K, Ranchoff RE, Rosenberg AS, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:912-913.

- Diaz-Cascajo C, Borghi S, Weyers W, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin following radiotherapy: a report of five new cases and review of the literature. Histopathology. 1999;35:319-327.

- Martín-González T, Sanz-Trelles A, Del Boz J, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules and plaques after radiotherapy [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:84-86.

- Fineberg S, Rosen PP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions of the skin and breast after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:757-763.

- Guillou L, Fletcher CD. Benign lymphangioendothelioma (acquired progressive lymphangioma): a lesion not to be confused with well-differentiated angiosarcoma and patch stage Kaposi’s sarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a series. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1047-1057.

- Rosso R, Gianelli U, Carnevali L. Acquired progressive lymphangioma of the skin following radiotherapy for breast carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:164-167.

- Hildebrandt G, Mittag M, Gutz U, et al. Cutaneous breast angiosarcoma after conservative treatment of breast cancer. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:580-583.

- Di Tommaso L, Fabbri A. Cutaneous angiosarcoma arising after radiotherapy treatment of a breast carcinoma: description of a case and review of the literature [in Italian]. Pathologica. 2003;95:196-202.

- Santi R, Cetica V, Franchi A, et al. Tumour suppressor gene TP53 mutations in atypical vascular lesions of breast skin following radiotherapy. Histopathology. 2011;58:455-466.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Mentzel T, et al. Benign vascular proliferations in irradiated skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:328-337.

- Brodie C, Provenzano E. Vascular proliferations of the breast. Histopathology. 2008;52:30-44.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Postradiation vascular proliferations: an increasing problem. Histopathology. 2006;48:106-114.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Kardum-Skelin I, Jelić-Puskarić B, Pazur M, et al. A case report of breast angiosarcoma. Coll Antropol. 2010;34:645-648.

- Mattoch IW, Robbins JB, Kempson RL, et al. Post-radiotherapy vascular proliferations in mammary skin: a clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:126-133.

- Bodet D, Rodríguez-Cano L, Bartralot R, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin associated with ovarian fibroma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2 suppl):S41-S44.

- Losch A, Chilek KD, Zirwas MJ. Post-radiation atypical vascular proliferation mimicking angiosarcoma eight months following breast-conserving therapy for breast carcinoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:47-48.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:983-996.

- Gengler C, Coindre JM, Leroux A, et al. Vascular proliferations of the skin after radiation therapy for breast cancer: clinicopathologic analysis of a series in favor of a benign process; a study from the French sarcoma group. Cancer. 2007;109:1584-1598.

- Hoda SA, Cranor ML, Rosen PP. Hemangiomas of the breast with atypical histological features: further analysis of histological subtypes confirming their benign character. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:553-560.

- Wagamon K, Ranchoff RE, Rosenberg AS, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:912-913.

- Diaz-Cascajo C, Borghi S, Weyers W, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin following radiotherapy: a report of five new cases and review of the literature. Histopathology. 1999;35:319-327.

- Martín-González T, Sanz-Trelles A, Del Boz J, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules and plaques after radiotherapy [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:84-86.

- Fineberg S, Rosen PP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions of the skin and breast after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:757-763.

- Guillou L, Fletcher CD. Benign lymphangioendothelioma (acquired progressive lymphangioma): a lesion not to be confused with well-differentiated angiosarcoma and patch stage Kaposi’s sarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a series. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1047-1057.

- Rosso R, Gianelli U, Carnevali L. Acquired progressive lymphangioma of the skin following radiotherapy for breast carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:164-167.

- Hildebrandt G, Mittag M, Gutz U, et al. Cutaneous breast angiosarcoma after conservative treatment of breast cancer. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:580-583.

- Di Tommaso L, Fabbri A. Cutaneous angiosarcoma arising after radiotherapy treatment of a breast carcinoma: description of a case and review of the literature [in Italian]. Pathologica. 2003;95:196-202.

- Santi R, Cetica V, Franchi A, et al. Tumour suppressor gene TP53 mutations in atypical vascular lesions of breast skin following radiotherapy. Histopathology. 2011;58:455-466.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Mentzel T, et al. Benign vascular proliferations in irradiated skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:328-337.

- Brodie C, Provenzano E. Vascular proliferations of the breast. Histopathology. 2008;52:30-44.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Postradiation vascular proliferations: an increasing problem. Histopathology. 2006;48:106-114.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Kardum-Skelin I, Jelić-Puskarić B, Pazur M, et al. A case report of breast angiosarcoma. Coll Antropol. 2010;34:645-648.

- Mattoch IW, Robbins JB, Kempson RL, et al. Post-radiotherapy vascular proliferations in mammary skin: a clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:126-133.

- Bodet D, Rodríguez-Cano L, Bartralot R, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin associated with ovarian fibroma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2 suppl):S41-S44.

- Losch A, Chilek KD, Zirwas MJ. Post-radiation atypical vascular proliferation mimicking angiosarcoma eight months following breast-conserving therapy for breast carcinoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:47-48.

Practice Points

- Atypical vascular lesions (AVLs) of the breast can appear an average of 5 years following radiation therapy.

- Although the malignant potential of AVLs remains debatable, excision generally is recommended, as lesions tend to recur.

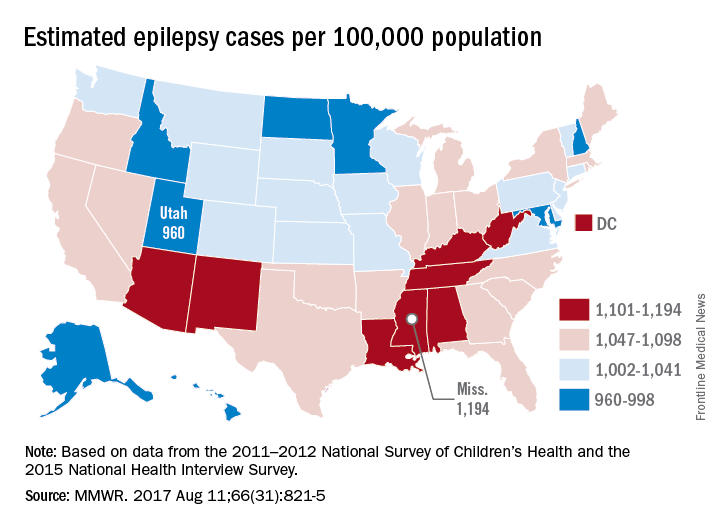

CDC: 3.4 million Americans have epilepsy

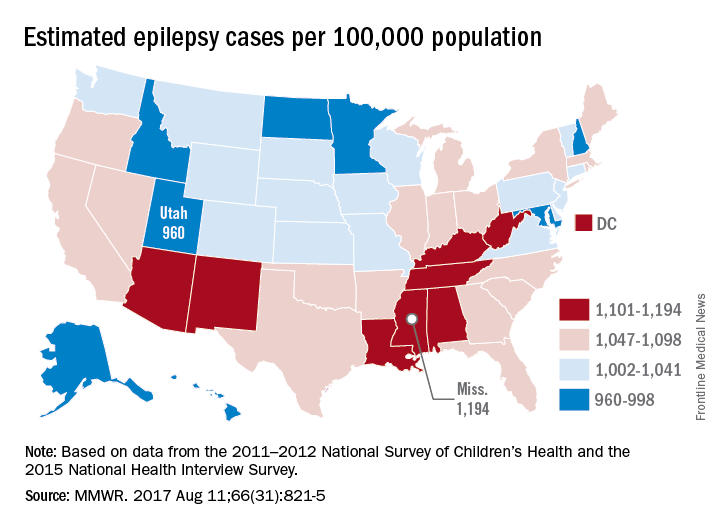

Epilepsy estimates available for the first time for every state show that the disorder is widespread, with at least 3.4 million people affected, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC data also show that the number of people with epilepsy is increasing, probably as a result of population growth. The number of affected adults went from 2.3 million in 2010 to 3 million in 2015, and the number of children with epilepsy rose from 450,000 in 2007 to 470,000 in 2015, CDC investigators reported (MMWR. 2017 Aug 11;66[31]:821-5).

“Millions of Americans are impacted by epilepsy, and unfortunately, this study shows cases are on the rise,” CDC Director Brenda Fitzgerald said in a separate statement. “Proper diagnosis is key to finding an effective treatment – and at CDC we are committed to researching, testing, and sharing strategies that will improve the lives of people with epilepsy.”

The CDC investigators based their estimates for children under age 18 years on data from the 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s Health; estimates for those age 18 and over are based on data from the 2015 National Health Interview Survey.

Epilepsy estimates available for the first time for every state show that the disorder is widespread, with at least 3.4 million people affected, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC data also show that the number of people with epilepsy is increasing, probably as a result of population growth. The number of affected adults went from 2.3 million in 2010 to 3 million in 2015, and the number of children with epilepsy rose from 450,000 in 2007 to 470,000 in 2015, CDC investigators reported (MMWR. 2017 Aug 11;66[31]:821-5).

“Millions of Americans are impacted by epilepsy, and unfortunately, this study shows cases are on the rise,” CDC Director Brenda Fitzgerald said in a separate statement. “Proper diagnosis is key to finding an effective treatment – and at CDC we are committed to researching, testing, and sharing strategies that will improve the lives of people with epilepsy.”

The CDC investigators based their estimates for children under age 18 years on data from the 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s Health; estimates for those age 18 and over are based on data from the 2015 National Health Interview Survey.

Epilepsy estimates available for the first time for every state show that the disorder is widespread, with at least 3.4 million people affected, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC data also show that the number of people with epilepsy is increasing, probably as a result of population growth. The number of affected adults went from 2.3 million in 2010 to 3 million in 2015, and the number of children with epilepsy rose from 450,000 in 2007 to 470,000 in 2015, CDC investigators reported (MMWR. 2017 Aug 11;66[31]:821-5).

“Millions of Americans are impacted by epilepsy, and unfortunately, this study shows cases are on the rise,” CDC Director Brenda Fitzgerald said in a separate statement. “Proper diagnosis is key to finding an effective treatment – and at CDC we are committed to researching, testing, and sharing strategies that will improve the lives of people with epilepsy.”

The CDC investigators based their estimates for children under age 18 years on data from the 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s Health; estimates for those age 18 and over are based on data from the 2015 National Health Interview Survey.

FROM MMWR

Revised thyroid Bethesda System resets malignant risks

BOSTON – Under the newly revised Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytology, slated for official release in October 2017, the six cytology-based diagnostic categories for thyroid lesions stay exactly the same as in the 10-year-old first edition, but some associated malignancy risks have changed.

Important changes include molecular testing to further assess malignancy risk in thyroid nodules and the introduction of lobectomy as a treatment option, “which really wasn’t an option 10 years ago,” in the first iteration of the Bethesda System (New York: Springer US, 2010), its coauthor Edmund S. Cibas, MD, said at the World Congress on Thyroid Cancer.

An Endocrine Pathology Society working group created the NIFTP designation in 2016 to describe an encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma that is characterized by lack of invasion, a follicular growth pattern, and nuclear features of papillary thyroid carcinoma with a very low risk of an adverse outcome (JAMA Oncology. 2016 Aug;2[8]:1023-9) (Cancer Cytopathol. 2016 Sep;124[9]:616-20).

NIFTP is not an overt malignancy. The revised Bethesda System “limits malignancy to cases with features of classic malignant papillary thyroid carcinoma,” explained Dr. Cibas, professor of pathology at Harvard Medical School and director of cytopathology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston.

Because the Bethesda System categories link to specific management recommendations, the new edition orients patients toward more conservative management decisions, specifically lobectomies instead of total thyroidectomies, he said in an interview.

The International Cytology Congress held a symposium during its meeting in Yokohama, Japan, in 2016, which resulted in the second edition of the Bethesda System (ACTA Cytol. 2016 Sep-Oct; 60[5]:399-405).

The changes in risk of malignancy occurred primarily in two categories, either “atypia of undetermined significance” (AUS) or “follicular lesions of undetermined significance” (FLUS). The risk of malignancy jumped from 5%-15% in the Bethesda System first edition up to 10%-30% in the revision. A smaller bump-up hit the category of “follicular neoplasm” or “suspicious for follicular neoplasm,” in which the risk of malignancy increased from 20%-30% in the first edition to 25%-40% in the revision. And, in the suspicion of malignancy category, the risk of malignancy actually lowered modestly, easing from 60%-75% in the first edition to 50%-75% in the revision.

Dr. Cibas highlighted the AUS/FLUS category with further notable features. The limit on laboratories reporting this category increased to 10% of total reports, up from 7% in the first edition. Management changed from the single options of a repeat fine-needle aspiration specimen to either that or molecular testing. Also, “the first edition was not clear that AUS and FLUS are synonyms. That will be a lot clearer” in the second edition, Dr. Cibas promised. The revision “will encourage labs that currently use [the terms] AUS and FLUS to mean two different things to make a choice between them.”

Another quirk of the AUS and FLUS category is that the risk of malignancy estimates are based on what Dr. Cibas called “flawed” data from only the selected subset of AUS or FLUS patients who have their nodule resected. “The reality is that most of the nodules are not resected” from patients with AUS or FLUS, so conclusions about the risk of malignancy come from a subset with considerable selection bias.

The definition of “follicular neoplasm” or “suspicious for follicular neoplasm” category also added “mild nuclear changes,” which can include increased nuclear size, contour irregularity, or chromatin clearing. The “suspicious for malignancy” category made a modest tweak to the risk of malignancy. Plus, “some of these patients will now undergo lobectomy rather than total thyroidectomy, which has been usual management.

The “suspicious for malignant” and “malignant” categories had little change aside from wider use of lobectomy, now feasible for any patient except those with metastatic disease, Dr. Cibas said.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BOSTON – Under the newly revised Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytology, slated for official release in October 2017, the six cytology-based diagnostic categories for thyroid lesions stay exactly the same as in the 10-year-old first edition, but some associated malignancy risks have changed.

Important changes include molecular testing to further assess malignancy risk in thyroid nodules and the introduction of lobectomy as a treatment option, “which really wasn’t an option 10 years ago,” in the first iteration of the Bethesda System (New York: Springer US, 2010), its coauthor Edmund S. Cibas, MD, said at the World Congress on Thyroid Cancer.

An Endocrine Pathology Society working group created the NIFTP designation in 2016 to describe an encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma that is characterized by lack of invasion, a follicular growth pattern, and nuclear features of papillary thyroid carcinoma with a very low risk of an adverse outcome (JAMA Oncology. 2016 Aug;2[8]:1023-9) (Cancer Cytopathol. 2016 Sep;124[9]:616-20).

NIFTP is not an overt malignancy. The revised Bethesda System “limits malignancy to cases with features of classic malignant papillary thyroid carcinoma,” explained Dr. Cibas, professor of pathology at Harvard Medical School and director of cytopathology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston.

Because the Bethesda System categories link to specific management recommendations, the new edition orients patients toward more conservative management decisions, specifically lobectomies instead of total thyroidectomies, he said in an interview.

The International Cytology Congress held a symposium during its meeting in Yokohama, Japan, in 2016, which resulted in the second edition of the Bethesda System (ACTA Cytol. 2016 Sep-Oct; 60[5]:399-405).

The changes in risk of malignancy occurred primarily in two categories, either “atypia of undetermined significance” (AUS) or “follicular lesions of undetermined significance” (FLUS). The risk of malignancy jumped from 5%-15% in the Bethesda System first edition up to 10%-30% in the revision. A smaller bump-up hit the category of “follicular neoplasm” or “suspicious for follicular neoplasm,” in which the risk of malignancy increased from 20%-30% in the first edition to 25%-40% in the revision. And, in the suspicion of malignancy category, the risk of malignancy actually lowered modestly, easing from 60%-75% in the first edition to 50%-75% in the revision.

Dr. Cibas highlighted the AUS/FLUS category with further notable features. The limit on laboratories reporting this category increased to 10% of total reports, up from 7% in the first edition. Management changed from the single options of a repeat fine-needle aspiration specimen to either that or molecular testing. Also, “the first edition was not clear that AUS and FLUS are synonyms. That will be a lot clearer” in the second edition, Dr. Cibas promised. The revision “will encourage labs that currently use [the terms] AUS and FLUS to mean two different things to make a choice between them.”

Another quirk of the AUS and FLUS category is that the risk of malignancy estimates are based on what Dr. Cibas called “flawed” data from only the selected subset of AUS or FLUS patients who have their nodule resected. “The reality is that most of the nodules are not resected” from patients with AUS or FLUS, so conclusions about the risk of malignancy come from a subset with considerable selection bias.

The definition of “follicular neoplasm” or “suspicious for follicular neoplasm” category also added “mild nuclear changes,” which can include increased nuclear size, contour irregularity, or chromatin clearing. The “suspicious for malignancy” category made a modest tweak to the risk of malignancy. Plus, “some of these patients will now undergo lobectomy rather than total thyroidectomy, which has been usual management.

The “suspicious for malignant” and “malignant” categories had little change aside from wider use of lobectomy, now feasible for any patient except those with metastatic disease, Dr. Cibas said.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BOSTON – Under the newly revised Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytology, slated for official release in October 2017, the six cytology-based diagnostic categories for thyroid lesions stay exactly the same as in the 10-year-old first edition, but some associated malignancy risks have changed.

Important changes include molecular testing to further assess malignancy risk in thyroid nodules and the introduction of lobectomy as a treatment option, “which really wasn’t an option 10 years ago,” in the first iteration of the Bethesda System (New York: Springer US, 2010), its coauthor Edmund S. Cibas, MD, said at the World Congress on Thyroid Cancer.

An Endocrine Pathology Society working group created the NIFTP designation in 2016 to describe an encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma that is characterized by lack of invasion, a follicular growth pattern, and nuclear features of papillary thyroid carcinoma with a very low risk of an adverse outcome (JAMA Oncology. 2016 Aug;2[8]:1023-9) (Cancer Cytopathol. 2016 Sep;124[9]:616-20).

NIFTP is not an overt malignancy. The revised Bethesda System “limits malignancy to cases with features of classic malignant papillary thyroid carcinoma,” explained Dr. Cibas, professor of pathology at Harvard Medical School and director of cytopathology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston.

Because the Bethesda System categories link to specific management recommendations, the new edition orients patients toward more conservative management decisions, specifically lobectomies instead of total thyroidectomies, he said in an interview.

The International Cytology Congress held a symposium during its meeting in Yokohama, Japan, in 2016, which resulted in the second edition of the Bethesda System (ACTA Cytol. 2016 Sep-Oct; 60[5]:399-405).

The changes in risk of malignancy occurred primarily in two categories, either “atypia of undetermined significance” (AUS) or “follicular lesions of undetermined significance” (FLUS). The risk of malignancy jumped from 5%-15% in the Bethesda System first edition up to 10%-30% in the revision. A smaller bump-up hit the category of “follicular neoplasm” or “suspicious for follicular neoplasm,” in which the risk of malignancy increased from 20%-30% in the first edition to 25%-40% in the revision. And, in the suspicion of malignancy category, the risk of malignancy actually lowered modestly, easing from 60%-75% in the first edition to 50%-75% in the revision.

Dr. Cibas highlighted the AUS/FLUS category with further notable features. The limit on laboratories reporting this category increased to 10% of total reports, up from 7% in the first edition. Management changed from the single options of a repeat fine-needle aspiration specimen to either that or molecular testing. Also, “the first edition was not clear that AUS and FLUS are synonyms. That will be a lot clearer” in the second edition, Dr. Cibas promised. The revision “will encourage labs that currently use [the terms] AUS and FLUS to mean two different things to make a choice between them.”

Another quirk of the AUS and FLUS category is that the risk of malignancy estimates are based on what Dr. Cibas called “flawed” data from only the selected subset of AUS or FLUS patients who have their nodule resected. “The reality is that most of the nodules are not resected” from patients with AUS or FLUS, so conclusions about the risk of malignancy come from a subset with considerable selection bias.

The definition of “follicular neoplasm” or “suspicious for follicular neoplasm” category also added “mild nuclear changes,” which can include increased nuclear size, contour irregularity, or chromatin clearing. The “suspicious for malignancy” category made a modest tweak to the risk of malignancy. Plus, “some of these patients will now undergo lobectomy rather than total thyroidectomy, which has been usual management.

The “suspicious for malignant” and “malignant” categories had little change aside from wider use of lobectomy, now feasible for any patient except those with metastatic disease, Dr. Cibas said.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCTC 2017

How to rule out secondary causes of osteoporosis

ESTES PARK, COLO. – Everyone diagnosed with osteoporosis deserves a laboratory assessment to rule out unsuspected secondary causes, according to Sterling West, MD. And he’s got a doozy of a workup he recommends to primary care physicians as “incredibly cost effective.”

“With this workup you’ll identify 98% of abnormalities at a mean cost of $366 per diagnosis. That’s incredibly cost effective. You’re going to get a lot of information with actually not very much outlay at all,” he said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

The tests he advocates that primary care physicians order in all their patients with osteoporosis include a complete blood count, a complete metabolic panel, a 24-hour urine calcium/sodium/creatinine, a serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level, and a serum phosphorus. In addition, men with osteoporosis should have their serum testosterone measured. A thyroid-stimulating hormone level should be obtained in patients who are taking thyroxine or if they look clinically hyperthyroid.

A measurement of parathyroid hormone is warranted as part of the screen in patients with an abnormal serum calcium. If the parathyroid hormone is normal, hyperparathyroidism can be ruled out.

Ordering a serum protein electrophoresis to check for multiple myeloma is appropriate in osteoporotic patients over age 50 years with an abnormal complete blood count.

This basic laboratory workup will identify patients with the relatively common secondary causes of low bone mineral density which account for 98% of all cases. These causes include vitamin D deficiency, malabsorption, hypogonadism, hypercalciuria, and myeloma.

“Leave the other 2% to me,” the rheumatologist suggested.

Special laboratory tests Dr. Sterling recommended that are best left to bone disease specialists include bone turnover markers, a serum tryptase/urine N-methylhistamine to screen for systemic mastocytosis, antitransglutaminase antibodies for celiac disease, a 24-hour urinary free cortisol and/or overnight dexamethasone suppression test to identify patients with Cushing syndrome, and bone biopsy.

Who should be referred to a bone specialist for a more extensive workup?

“If somebody is losing bone or fracturing and they’re on appropriate therapy and you believe they’re taking their medication, that’s for sure somebody that we should see. Also, a premenopausal woman with a high Z score who has had a fracture that’s atypical. And patients with stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease; those are some of the toughest cases and are best referred to a bone expert,” Dr. Sterling said.

On the other hand, if an osteoporotic patient simply can’t tolerate guideline-recommended initial therapy with an oral bisphosphonate such as alendronate (Fosamax) or risedronate (Actonel), there’s no need to bring in a specialist. Simply switch the patient to denosumab (Prolia), a monoclonal antibody against receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand, administered by subcutaneous injection once every 6 months. The cost is about $2,200 per year, but the drug is covered by Medicare Part B. Clinical trials have demonstrated that denosumab boosts bone mineral density by 6%-9%, with an absolute 5% reduction in fractures and a 40%-68% relative risk reduction, he noted.

Dr. West reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

ESTES PARK, COLO. – Everyone diagnosed with osteoporosis deserves a laboratory assessment to rule out unsuspected secondary causes, according to Sterling West, MD. And he’s got a doozy of a workup he recommends to primary care physicians as “incredibly cost effective.”

“With this workup you’ll identify 98% of abnormalities at a mean cost of $366 per diagnosis. That’s incredibly cost effective. You’re going to get a lot of information with actually not very much outlay at all,” he said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

The tests he advocates that primary care physicians order in all their patients with osteoporosis include a complete blood count, a complete metabolic panel, a 24-hour urine calcium/sodium/creatinine, a serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level, and a serum phosphorus. In addition, men with osteoporosis should have their serum testosterone measured. A thyroid-stimulating hormone level should be obtained in patients who are taking thyroxine or if they look clinically hyperthyroid.

A measurement of parathyroid hormone is warranted as part of the screen in patients with an abnormal serum calcium. If the parathyroid hormone is normal, hyperparathyroidism can be ruled out.

Ordering a serum protein electrophoresis to check for multiple myeloma is appropriate in osteoporotic patients over age 50 years with an abnormal complete blood count.

This basic laboratory workup will identify patients with the relatively common secondary causes of low bone mineral density which account for 98% of all cases. These causes include vitamin D deficiency, malabsorption, hypogonadism, hypercalciuria, and myeloma.

“Leave the other 2% to me,” the rheumatologist suggested.

Special laboratory tests Dr. Sterling recommended that are best left to bone disease specialists include bone turnover markers, a serum tryptase/urine N-methylhistamine to screen for systemic mastocytosis, antitransglutaminase antibodies for celiac disease, a 24-hour urinary free cortisol and/or overnight dexamethasone suppression test to identify patients with Cushing syndrome, and bone biopsy.

Who should be referred to a bone specialist for a more extensive workup?

“If somebody is losing bone or fracturing and they’re on appropriate therapy and you believe they’re taking their medication, that’s for sure somebody that we should see. Also, a premenopausal woman with a high Z score who has had a fracture that’s atypical. And patients with stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease; those are some of the toughest cases and are best referred to a bone expert,” Dr. Sterling said.

On the other hand, if an osteoporotic patient simply can’t tolerate guideline-recommended initial therapy with an oral bisphosphonate such as alendronate (Fosamax) or risedronate (Actonel), there’s no need to bring in a specialist. Simply switch the patient to denosumab (Prolia), a monoclonal antibody against receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand, administered by subcutaneous injection once every 6 months. The cost is about $2,200 per year, but the drug is covered by Medicare Part B. Clinical trials have demonstrated that denosumab boosts bone mineral density by 6%-9%, with an absolute 5% reduction in fractures and a 40%-68% relative risk reduction, he noted.

Dr. West reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

ESTES PARK, COLO. – Everyone diagnosed with osteoporosis deserves a laboratory assessment to rule out unsuspected secondary causes, according to Sterling West, MD. And he’s got a doozy of a workup he recommends to primary care physicians as “incredibly cost effective.”

“With this workup you’ll identify 98% of abnormalities at a mean cost of $366 per diagnosis. That’s incredibly cost effective. You’re going to get a lot of information with actually not very much outlay at all,” he said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

The tests he advocates that primary care physicians order in all their patients with osteoporosis include a complete blood count, a complete metabolic panel, a 24-hour urine calcium/sodium/creatinine, a serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level, and a serum phosphorus. In addition, men with osteoporosis should have their serum testosterone measured. A thyroid-stimulating hormone level should be obtained in patients who are taking thyroxine or if they look clinically hyperthyroid.

A measurement of parathyroid hormone is warranted as part of the screen in patients with an abnormal serum calcium. If the parathyroid hormone is normal, hyperparathyroidism can be ruled out.

Ordering a serum protein electrophoresis to check for multiple myeloma is appropriate in osteoporotic patients over age 50 years with an abnormal complete blood count.

This basic laboratory workup will identify patients with the relatively common secondary causes of low bone mineral density which account for 98% of all cases. These causes include vitamin D deficiency, malabsorption, hypogonadism, hypercalciuria, and myeloma.

“Leave the other 2% to me,” the rheumatologist suggested.

Special laboratory tests Dr. Sterling recommended that are best left to bone disease specialists include bone turnover markers, a serum tryptase/urine N-methylhistamine to screen for systemic mastocytosis, antitransglutaminase antibodies for celiac disease, a 24-hour urinary free cortisol and/or overnight dexamethasone suppression test to identify patients with Cushing syndrome, and bone biopsy.

Who should be referred to a bone specialist for a more extensive workup?

“If somebody is losing bone or fracturing and they’re on appropriate therapy and you believe they’re taking their medication, that’s for sure somebody that we should see. Also, a premenopausal woman with a high Z score who has had a fracture that’s atypical. And patients with stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease; those are some of the toughest cases and are best referred to a bone expert,” Dr. Sterling said.

On the other hand, if an osteoporotic patient simply can’t tolerate guideline-recommended initial therapy with an oral bisphosphonate such as alendronate (Fosamax) or risedronate (Actonel), there’s no need to bring in a specialist. Simply switch the patient to denosumab (Prolia), a monoclonal antibody against receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand, administered by subcutaneous injection once every 6 months. The cost is about $2,200 per year, but the drug is covered by Medicare Part B. Clinical trials have demonstrated that denosumab boosts bone mineral density by 6%-9%, with an absolute 5% reduction in fractures and a 40%-68% relative risk reduction, he noted.

Dr. West reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL INTERNAL MEDICINE PROGRAM

First trial of TAVR vs. SAVR in low-risk patients

PARIS – Five-year hemodynamic results of the first randomized trial of transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in low-surgical-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis showed continued superior valve performance in the TAVR group, Lars Sondergaard, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“The durability results are very encouraging. We can’t see that the TAVR patients are doing worse. So I think this is setting the scene to try to move forward in patients at low risk and also in younger patients,” declared Dr. Sondergaard, professor of cardiology at the University of Copenhagen.

He presented an update from the Nordic Aortic Valve Intervention (NOTION) trial, a prospective, multicenter, randomized, all-comers clinical trial in which 280 patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis at low surgical risk were assigned to surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) or to TAVR with the self-expanding CoreValve. Their mean age was 79 years, with an average Society of Thoracic Surgeons projected risk of mortality score of 3%. Eighty-two percent of participants had an STS score below 4%. Roughly 40% of TAVR patients got the first-generation CoreValve in the 26-mm size, 40% received the 29-mm version, and the rest got the 31-mm CoreValve.

Among patients in the lowest-surgical-risk and youngest subgroup – those aged 70-75 with a Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score below 4% – the composite primary endpoint rate at 4 years was 15.6% with TAVR compared with 27.2% with SAVR. However, only 62 NOTION participants fell into this category, so the between-group difference, while sizable, didn’t achieve statistical significance, according to Dr. Sondergaard.

There was a trade-off between the two valve replacement strategies with regard to procedural complications. The rate of new-onset atrial fibrillation was far higher in the SAVR group: 59.4% at 1 year and 60.2% at 4 years of follow-up, compared with 21.2% and 24.5% at 1 and 4 years, respectively, in the TAVR group.

On the other hand, 38% of the TAVR patients got a new pacemaker within the first year of follow-up, compared with only 2.4% in the SAVR group. At 4 years, 43.7% of the TAVR group had a pacemaker, versus 9% of the SAVR group.

Turning to the hemodynamic data, the cardiologist noted that the effective orifice area in the TAVR group went from 0.71 cm2 at baseline to 1.66 at 1 year and remained steady thereafter at 1.67 cm2 through 5 years. The TAVR group’s mean gradient improved from 45.4 mm Hg at baseline to 8.6 mm Hg at 1 year and 7.9 mm Hg at 5 years. These outcomes were significantly better than in the SAVR group, where the effective orifice area went from 0.74 cm2 at baseline to 1.32 at 1 year and 1.24 cm2 at 5 years, while the mean gradient fell from 44.9 mm Hg to 12.5 at 1 year and 13.6 mm Hg at 5 years.

Moderate hemodynamic structural valve deterioration was significantly more common in the SAVR group: 20.7% at 5 years, compared with 2.9% in the TAVR patients. The opposite was true with regard to moderate paravalvular leak, which occurred in 20.9% of the TAVI group but only 1.5% of SAVR patients.

Late complications were rare following either procedure. There were no cases of valve thrombosis through 5 years. The incidence of endocarditis at 5 years was 4.3% in the TAVR patients and similar at 5.9% in the SAVR group.

Discussant Samer Mansour, MD, of the University of Montreal, remarked that the rate of new pacemaker implantation following TAVR seemed extraordinarily high.

“This was early days,” Dr. Sondergaard explained. “We had a lower threshold for putting in a pacemaker and we put the valves in a little deeper.”

About half of new pacemaker recipients didn’t use the device after the first year, he added. Also, neither getting a new pacemaker nor moderate paravalvular leak was associated with increased mortality in the TAVR group.

Dr. Mansour observed that subtle but real differences in mortality probably wouldn’t show up in a 280-patient trial. Dr. Sondergaard concurred.

“We designed the NOTION trial in 2008-2009. Knowing what we know now, we should have had a larger study, but at that time TAVR volume wasn’t that big and it wasn’t realistic as a Nordic trial to include 1,000 patients. This was the best we could do,” he said.

Follow-up in the NOTION study will continue out to 10 years.

The study is funded by Medtronic. Dr. Sondergaard reported serving as a consultant to and receiving research grant support from the company.