User login

Not recommending LAIV didn’t reduce flu vaccination in Oregon children

Oregon researchers studying the effect of not recommending intranasal live attenuated influenza vaccines (LAIV) in favor of injected influenza vaccines (IIV) for the 2016-2017 flu season found that the change in recommendation had a minimal impact on overall flu vaccination rates, but that patients who had been given injected flu vaccine previously were slightly more likely to return for it the following season.

Steve G. Robison, MPH, of the Immunization Program of the Oregon Health Authority in Salem, led the study to monitor the effects of the new recommendation in Oregon, where he and his coauthors noted that there is “a substantial vaccine-hesitant population” (Pediatrics. 2017 Oct 6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0516).

They considered data from the state’s immunization registry, simply counting seasonal immunization rates from 2012 to 2017. As a second assessment, they compared children who had previously received LAIV between Aug. 1 and Dec. 31, 2015, and children who received IIV during the same period, to see which cohort was more likely to return for flu vaccination the following season.

“Overall, 53.1% of children in the study with previous LAIV and 56.4% with a previous IIV returned for an IIV during the 2016-2017 season,” they reported. Those rates showed that the cohort with past injected vaccine was only 1.05 times more likely to return than the cohort with past nasal spray vaccine (95% confidence interval, 1.04-1.06). The investigators also concluded that overall rates have undergone “minimal changes” in the past 5 years, and the effect of the committee’s recommendation additionally was considered to be minimal.

Mr. Robison and his associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded in part by the CDC’s grants to Oregon statefor immunization surveillance.

Oregon researchers studying the effect of not recommending intranasal live attenuated influenza vaccines (LAIV) in favor of injected influenza vaccines (IIV) for the 2016-2017 flu season found that the change in recommendation had a minimal impact on overall flu vaccination rates, but that patients who had been given injected flu vaccine previously were slightly more likely to return for it the following season.

Steve G. Robison, MPH, of the Immunization Program of the Oregon Health Authority in Salem, led the study to monitor the effects of the new recommendation in Oregon, where he and his coauthors noted that there is “a substantial vaccine-hesitant population” (Pediatrics. 2017 Oct 6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0516).

They considered data from the state’s immunization registry, simply counting seasonal immunization rates from 2012 to 2017. As a second assessment, they compared children who had previously received LAIV between Aug. 1 and Dec. 31, 2015, and children who received IIV during the same period, to see which cohort was more likely to return for flu vaccination the following season.

“Overall, 53.1% of children in the study with previous LAIV and 56.4% with a previous IIV returned for an IIV during the 2016-2017 season,” they reported. Those rates showed that the cohort with past injected vaccine was only 1.05 times more likely to return than the cohort with past nasal spray vaccine (95% confidence interval, 1.04-1.06). The investigators also concluded that overall rates have undergone “minimal changes” in the past 5 years, and the effect of the committee’s recommendation additionally was considered to be minimal.

Mr. Robison and his associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded in part by the CDC’s grants to Oregon statefor immunization surveillance.

Oregon researchers studying the effect of not recommending intranasal live attenuated influenza vaccines (LAIV) in favor of injected influenza vaccines (IIV) for the 2016-2017 flu season found that the change in recommendation had a minimal impact on overall flu vaccination rates, but that patients who had been given injected flu vaccine previously were slightly more likely to return for it the following season.

Steve G. Robison, MPH, of the Immunization Program of the Oregon Health Authority in Salem, led the study to monitor the effects of the new recommendation in Oregon, where he and his coauthors noted that there is “a substantial vaccine-hesitant population” (Pediatrics. 2017 Oct 6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0516).

They considered data from the state’s immunization registry, simply counting seasonal immunization rates from 2012 to 2017. As a second assessment, they compared children who had previously received LAIV between Aug. 1 and Dec. 31, 2015, and children who received IIV during the same period, to see which cohort was more likely to return for flu vaccination the following season.

“Overall, 53.1% of children in the study with previous LAIV and 56.4% with a previous IIV returned for an IIV during the 2016-2017 season,” they reported. Those rates showed that the cohort with past injected vaccine was only 1.05 times more likely to return than the cohort with past nasal spray vaccine (95% confidence interval, 1.04-1.06). The investigators also concluded that overall rates have undergone “minimal changes” in the past 5 years, and the effect of the committee’s recommendation additionally was considered to be minimal.

Mr. Robison and his associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded in part by the CDC’s grants to Oregon statefor immunization surveillance.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: 53.1% of children in the study with previous LAIV and 56.4% with a previous IIV returned for an IIV during the 2016-2017 season.

Data source: Data from Oregon’s immunization registry.

Disclosures: Mr. Robison and his associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded in part by the CDC’s grants to Oregon state for immunization surveillance.

Expanding treatment options to deal with antibiotic resistance

SAN DIEGO – In an era of rising antibiotic resistance, new potential treatment options and policy changes took the stage at the start of an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Presenters covered emerging topics addressing infectious diseases, with a strong focus on HIV. A common emphasis, among all presentations, was the pressing need to update availability of newer and more effective drugs.

“There’s always something hot in ID, and often it’s transient. But what isn’t transient is the overwhelming problem of antibiotic resistance,” said Stan Deresinski, MD, infectious disease specialist from Stanford (Calif.) University. He added that: “A fear come true is the merger of antibiotic resistance and increased virulence.”

While long-term solutions are needed, a short-term answer is the increase in the kinds of antibiotics available, Dr. Deresinski said.

“As we look at this sort of event, we begin to look at ourselves in the near future as plague doctors,” warned Dr. Deresinski. “We need to deal with this, and the thing that can be done in the short term is the development of new antibiotics.”

The Food and Drug Administration has several avenues that could be used to provide for expedited antibiotics approval, such as fast tracking and priority approval of drugs. An additional program called Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN) that allows the FDA to designate an antibiotic as an anti-infectious disease product, making it eligible for fast tracking and priority approval, as well as the addition of 5 years of market exclusivity, may be used to incentivize the development of newer drugs.

In addition, Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) and the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group (ARLG) are two groups that will be essential for accelerating antibiotic development, Dr. Deresinski said.

CARB-X, which is a public-private partnership created by a White House executive order in 2014, focuses on preclinical discovery and development, and ARLG works under the mission statement, “prioritize, design, and execute clinical research that will reduce public health threat of antibacterial resistance.”

Among the hot topics in HIV, presenters described a series of studies conducted throughout the year assessing prexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and how interventions, such as the use of the drug tenofovir, can increase efficacy of oral prophylaxis in preventing HIV-1 transmission.

In a test of antiretroviral therapy, the use of long-acting intramuscular injectable therapy every 4 and 8 weeks had huge improvement in patient approval, 88% and 89% respectively, compared with the 43% approval rate that oral HIV-1 medications received, said Wendy Armstrong, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta.

“[This] therapy is really getting to the point that we dreamed of 25 years ago, when our goals were finding an effective agent: to have simple agents, less frequent dosing schemes, limited adverse effects, and limited drug-to-drug interaction,” said Dr. Armstrong.

Among other topics to be addressed at the conference, Dr. Deresinski noted that the recent drop in Zika infections, as well as an uptick seen in hepatitis A outbreaks among the homeless and drug-user populations, would be discussed later in the week.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

SAN DIEGO – In an era of rising antibiotic resistance, new potential treatment options and policy changes took the stage at the start of an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Presenters covered emerging topics addressing infectious diseases, with a strong focus on HIV. A common emphasis, among all presentations, was the pressing need to update availability of newer and more effective drugs.

“There’s always something hot in ID, and often it’s transient. But what isn’t transient is the overwhelming problem of antibiotic resistance,” said Stan Deresinski, MD, infectious disease specialist from Stanford (Calif.) University. He added that: “A fear come true is the merger of antibiotic resistance and increased virulence.”

While long-term solutions are needed, a short-term answer is the increase in the kinds of antibiotics available, Dr. Deresinski said.

“As we look at this sort of event, we begin to look at ourselves in the near future as plague doctors,” warned Dr. Deresinski. “We need to deal with this, and the thing that can be done in the short term is the development of new antibiotics.”

The Food and Drug Administration has several avenues that could be used to provide for expedited antibiotics approval, such as fast tracking and priority approval of drugs. An additional program called Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN) that allows the FDA to designate an antibiotic as an anti-infectious disease product, making it eligible for fast tracking and priority approval, as well as the addition of 5 years of market exclusivity, may be used to incentivize the development of newer drugs.

In addition, Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) and the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group (ARLG) are two groups that will be essential for accelerating antibiotic development, Dr. Deresinski said.

CARB-X, which is a public-private partnership created by a White House executive order in 2014, focuses on preclinical discovery and development, and ARLG works under the mission statement, “prioritize, design, and execute clinical research that will reduce public health threat of antibacterial resistance.”

Among the hot topics in HIV, presenters described a series of studies conducted throughout the year assessing prexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and how interventions, such as the use of the drug tenofovir, can increase efficacy of oral prophylaxis in preventing HIV-1 transmission.

In a test of antiretroviral therapy, the use of long-acting intramuscular injectable therapy every 4 and 8 weeks had huge improvement in patient approval, 88% and 89% respectively, compared with the 43% approval rate that oral HIV-1 medications received, said Wendy Armstrong, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta.

“[This] therapy is really getting to the point that we dreamed of 25 years ago, when our goals were finding an effective agent: to have simple agents, less frequent dosing schemes, limited adverse effects, and limited drug-to-drug interaction,” said Dr. Armstrong.

Among other topics to be addressed at the conference, Dr. Deresinski noted that the recent drop in Zika infections, as well as an uptick seen in hepatitis A outbreaks among the homeless and drug-user populations, would be discussed later in the week.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

SAN DIEGO – In an era of rising antibiotic resistance, new potential treatment options and policy changes took the stage at the start of an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Presenters covered emerging topics addressing infectious diseases, with a strong focus on HIV. A common emphasis, among all presentations, was the pressing need to update availability of newer and more effective drugs.

“There’s always something hot in ID, and often it’s transient. But what isn’t transient is the overwhelming problem of antibiotic resistance,” said Stan Deresinski, MD, infectious disease specialist from Stanford (Calif.) University. He added that: “A fear come true is the merger of antibiotic resistance and increased virulence.”

While long-term solutions are needed, a short-term answer is the increase in the kinds of antibiotics available, Dr. Deresinski said.

“As we look at this sort of event, we begin to look at ourselves in the near future as plague doctors,” warned Dr. Deresinski. “We need to deal with this, and the thing that can be done in the short term is the development of new antibiotics.”

The Food and Drug Administration has several avenues that could be used to provide for expedited antibiotics approval, such as fast tracking and priority approval of drugs. An additional program called Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN) that allows the FDA to designate an antibiotic as an anti-infectious disease product, making it eligible for fast tracking and priority approval, as well as the addition of 5 years of market exclusivity, may be used to incentivize the development of newer drugs.

In addition, Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) and the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group (ARLG) are two groups that will be essential for accelerating antibiotic development, Dr. Deresinski said.

CARB-X, which is a public-private partnership created by a White House executive order in 2014, focuses on preclinical discovery and development, and ARLG works under the mission statement, “prioritize, design, and execute clinical research that will reduce public health threat of antibacterial resistance.”

Among the hot topics in HIV, presenters described a series of studies conducted throughout the year assessing prexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and how interventions, such as the use of the drug tenofovir, can increase efficacy of oral prophylaxis in preventing HIV-1 transmission.

In a test of antiretroviral therapy, the use of long-acting intramuscular injectable therapy every 4 and 8 weeks had huge improvement in patient approval, 88% and 89% respectively, compared with the 43% approval rate that oral HIV-1 medications received, said Wendy Armstrong, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta.

“[This] therapy is really getting to the point that we dreamed of 25 years ago, when our goals were finding an effective agent: to have simple agents, less frequent dosing schemes, limited adverse effects, and limited drug-to-drug interaction,” said Dr. Armstrong.

Among other topics to be addressed at the conference, Dr. Deresinski noted that the recent drop in Zika infections, as well as an uptick seen in hepatitis A outbreaks among the homeless and drug-user populations, would be discussed later in the week.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

AT IDWEEK 2017

FDA approves third indication for onabotulinumtoxinA

The Food and Drug Administration has approved onabotulinumtoxinA, marketed as Botox Cosmetic by Allergan, for a third indication: the temporary improvement in the appearance of “moderate to severe forehead lines associated with frontalis muscle activity” in adults, according to the manufacturer.

The company announced the latest approval in a press release on October 3.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved onabotulinumtoxinA, marketed as Botox Cosmetic by Allergan, for a third indication: the temporary improvement in the appearance of “moderate to severe forehead lines associated with frontalis muscle activity” in adults, according to the manufacturer.

The company announced the latest approval in a press release on October 3.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved onabotulinumtoxinA, marketed as Botox Cosmetic by Allergan, for a third indication: the temporary improvement in the appearance of “moderate to severe forehead lines associated with frontalis muscle activity” in adults, according to the manufacturer.

The company announced the latest approval in a press release on October 3.

How to have a rational approach to the FUO work-up

CHICAGO – When a child’s worried parents bring him back to be rechecked on his 8th day of fever, what’s next? If the initial work-up is unrevealing, when is it time to consider hospitalization? And which children can safely be managed as outpatients?

These tough scenarios are part of why “most pediatricians really don’t enjoy fever of unknown origin (FUO),” said Brian Williams, MD, speaking at a pediatric infectious disease update at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “It can be really time consuming and frustrating to tease all of this out.”

Dr. Williams comes into the picture when, for the pediatrician, “something about that history, that physical exam, and that lab work has them concerned that the child needs to be hospitalized for closer monitoring and a more extensive work-up.”

“There’s lots of variability for inclusion criteria in the studies for pediatrics,” said Dr. Williams, but most characterize FUO as a fever of at least 100.4° F for 8 days or longer with no clear diagnosis.

he said. “I think it’s one of those diagnoses where a thorough history and exam can oftentimes give you some clues that can help lead to your diagnosis.”

“It’s a diagnosis that always gets my full attention because sometimes you can find some pretty significant infections – an osteomyelitis or a severe pelvic abscess,” he said. “And there’s always the concern of some of these more serious underlying diseases, like rheumatologic diseases; there’s plenty of case reports of [inflammatory bowel disease] presenting with FUO.” Of course, he said, even more dire diagnoses like Hodgkin’s lymphoma and leukemia have to remain in the differential as well.

Although the broad diagnostic differential includes noninfectious causes, they are rarer by far than infections. When the etiology of FUO has been studied in the United States, said Dr. Williams, “infections pretty consistently dominate as the most common cause of FUO … as general pediatricians, it’s our job to really do a good evaluation for infection before we start going after some of these less common diagnoses – the rheumatologic and cancer diagnoses.”

A systematic approach is important, he said. “A really good fever history can, a lot of times, provide important and valuable information.” Take the time to get granular detail: Find out how often the fever is being checked and by whom, what symptoms accompany the fever, and how the fever is being measured.

And don’t forget to ask if there are fever-free days, he said. In an otherwise well-appearing child, a few days’ respite from fever can increase the likelihood that you’re really seeing back-to-back viral illnesses rather than a protracted unexplained fever.

A thorough head-to-toe review of symptoms and history is critical, too. Dr. Williams related the story of a well-appearing 9-year-old boy who’d had many days of high fever with accompanying elevated inflammatory markers. His exam was unremarkable, and the only untoward symptom he could recall was a few days’ worth of left upper quadrant tenderness when running in gym class. The child, said Dr. Williams, turned out to have nephronia. “Sometimes, really subtle clues from the history can guide you.”

Ask about exposures, including travel, animals, foods, insects, and sick contacts. “Obviously, children can get into just about anything,” said Dr. Williams. A detailed family and social history also may turn up clues.

An infection-focused musculoskeletal exam, to include the spine, is a must, as is a top-to-bottom search for lymphadenopathy as part of a complete physical exam.

At this point in the pediatrics office, said Dr. Williams, you’ve come to a decision point: “Does this work-up need to be initiated in the inpatient setting, or is this something that can be started in the outpatient setting?”

“There’s a lot of data to support that, initially, a lot of these patients can be worked up in the outpatient setting with close follow-up,” he said. The outpatient FUO work-up begins with some basic screening labs. In addition to a complete blood count, chemistries, and a urinalysis, labs should include blood and urine cultures, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels.

“I’ll actually rely pretty heavily on my ESR and CRP,” said Dr. Williams. “If I have an otherwise well-appearing child with a normal CRP and an unremarkable exam, I think it’s a pretty tough argument to keep that child hospitalized and do a more invasive work-up.”

The advent of the viral polymerase chain reaction panel has helped streamline the FUO work-up as well. In the setting of a well-appearing child with an unremarkable initial work-up, “a positive adenovirus can provide a lot of reassurance to the families.”

Dr. Williams usually also gets a chest radiograph at this point, knowing that pneumonia is in the differential for FUO. He said he’s seen mediastinal masses, as well as picked up dense right upper lobe infiltrates that were missed on exam.

If the answer is still unclear at this point, exam and laboratory findings from the first-tier inquiry can help guide the next steps.

Some less common infectious etiologies can be considered now, said Dr. Williams. These can include Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and cat scratch fever; the latter, he’s found, is the third-most-common cause of FUO in some case series. For the real mystery cases, next-generation sequencing is an option: A blood sample is used to search for DNA fragments from a huge variety of microorganisms. “It’s a little overwhelming,” and very expensive, he said.

If an oncologic process is suspected, second-tier labs can include lactate dehydrogenase, uric acid, ferritin levels, and a peripheral smear. A rheumatologic work-up can be started, with antinuclear antibody and complement levels. At this point, though, a general pediatrician would be considering consults, he said.

Empiric antibiotics can be a tempting diagnostic strategy in some cases. “Is a trial of antibiotics warranted? Usually we advise against it,” but a case can be made for a time-limited trial in certain circumstances, said Dr. Williams.

Dr. Williams is a consultant for Zavante Therapeutics, which markets fosfomycin.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – When a child’s worried parents bring him back to be rechecked on his 8th day of fever, what’s next? If the initial work-up is unrevealing, when is it time to consider hospitalization? And which children can safely be managed as outpatients?

These tough scenarios are part of why “most pediatricians really don’t enjoy fever of unknown origin (FUO),” said Brian Williams, MD, speaking at a pediatric infectious disease update at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “It can be really time consuming and frustrating to tease all of this out.”

Dr. Williams comes into the picture when, for the pediatrician, “something about that history, that physical exam, and that lab work has them concerned that the child needs to be hospitalized for closer monitoring and a more extensive work-up.”

“There’s lots of variability for inclusion criteria in the studies for pediatrics,” said Dr. Williams, but most characterize FUO as a fever of at least 100.4° F for 8 days or longer with no clear diagnosis.

he said. “I think it’s one of those diagnoses where a thorough history and exam can oftentimes give you some clues that can help lead to your diagnosis.”

“It’s a diagnosis that always gets my full attention because sometimes you can find some pretty significant infections – an osteomyelitis or a severe pelvic abscess,” he said. “And there’s always the concern of some of these more serious underlying diseases, like rheumatologic diseases; there’s plenty of case reports of [inflammatory bowel disease] presenting with FUO.” Of course, he said, even more dire diagnoses like Hodgkin’s lymphoma and leukemia have to remain in the differential as well.

Although the broad diagnostic differential includes noninfectious causes, they are rarer by far than infections. When the etiology of FUO has been studied in the United States, said Dr. Williams, “infections pretty consistently dominate as the most common cause of FUO … as general pediatricians, it’s our job to really do a good evaluation for infection before we start going after some of these less common diagnoses – the rheumatologic and cancer diagnoses.”

A systematic approach is important, he said. “A really good fever history can, a lot of times, provide important and valuable information.” Take the time to get granular detail: Find out how often the fever is being checked and by whom, what symptoms accompany the fever, and how the fever is being measured.

And don’t forget to ask if there are fever-free days, he said. In an otherwise well-appearing child, a few days’ respite from fever can increase the likelihood that you’re really seeing back-to-back viral illnesses rather than a protracted unexplained fever.

A thorough head-to-toe review of symptoms and history is critical, too. Dr. Williams related the story of a well-appearing 9-year-old boy who’d had many days of high fever with accompanying elevated inflammatory markers. His exam was unremarkable, and the only untoward symptom he could recall was a few days’ worth of left upper quadrant tenderness when running in gym class. The child, said Dr. Williams, turned out to have nephronia. “Sometimes, really subtle clues from the history can guide you.”

Ask about exposures, including travel, animals, foods, insects, and sick contacts. “Obviously, children can get into just about anything,” said Dr. Williams. A detailed family and social history also may turn up clues.

An infection-focused musculoskeletal exam, to include the spine, is a must, as is a top-to-bottom search for lymphadenopathy as part of a complete physical exam.

At this point in the pediatrics office, said Dr. Williams, you’ve come to a decision point: “Does this work-up need to be initiated in the inpatient setting, or is this something that can be started in the outpatient setting?”

“There’s a lot of data to support that, initially, a lot of these patients can be worked up in the outpatient setting with close follow-up,” he said. The outpatient FUO work-up begins with some basic screening labs. In addition to a complete blood count, chemistries, and a urinalysis, labs should include blood and urine cultures, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels.

“I’ll actually rely pretty heavily on my ESR and CRP,” said Dr. Williams. “If I have an otherwise well-appearing child with a normal CRP and an unremarkable exam, I think it’s a pretty tough argument to keep that child hospitalized and do a more invasive work-up.”

The advent of the viral polymerase chain reaction panel has helped streamline the FUO work-up as well. In the setting of a well-appearing child with an unremarkable initial work-up, “a positive adenovirus can provide a lot of reassurance to the families.”

Dr. Williams usually also gets a chest radiograph at this point, knowing that pneumonia is in the differential for FUO. He said he’s seen mediastinal masses, as well as picked up dense right upper lobe infiltrates that were missed on exam.

If the answer is still unclear at this point, exam and laboratory findings from the first-tier inquiry can help guide the next steps.

Some less common infectious etiologies can be considered now, said Dr. Williams. These can include Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and cat scratch fever; the latter, he’s found, is the third-most-common cause of FUO in some case series. For the real mystery cases, next-generation sequencing is an option: A blood sample is used to search for DNA fragments from a huge variety of microorganisms. “It’s a little overwhelming,” and very expensive, he said.

If an oncologic process is suspected, second-tier labs can include lactate dehydrogenase, uric acid, ferritin levels, and a peripheral smear. A rheumatologic work-up can be started, with antinuclear antibody and complement levels. At this point, though, a general pediatrician would be considering consults, he said.

Empiric antibiotics can be a tempting diagnostic strategy in some cases. “Is a trial of antibiotics warranted? Usually we advise against it,” but a case can be made for a time-limited trial in certain circumstances, said Dr. Williams.

Dr. Williams is a consultant for Zavante Therapeutics, which markets fosfomycin.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – When a child’s worried parents bring him back to be rechecked on his 8th day of fever, what’s next? If the initial work-up is unrevealing, when is it time to consider hospitalization? And which children can safely be managed as outpatients?

These tough scenarios are part of why “most pediatricians really don’t enjoy fever of unknown origin (FUO),” said Brian Williams, MD, speaking at a pediatric infectious disease update at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “It can be really time consuming and frustrating to tease all of this out.”

Dr. Williams comes into the picture when, for the pediatrician, “something about that history, that physical exam, and that lab work has them concerned that the child needs to be hospitalized for closer monitoring and a more extensive work-up.”

“There’s lots of variability for inclusion criteria in the studies for pediatrics,” said Dr. Williams, but most characterize FUO as a fever of at least 100.4° F for 8 days or longer with no clear diagnosis.

he said. “I think it’s one of those diagnoses where a thorough history and exam can oftentimes give you some clues that can help lead to your diagnosis.”

“It’s a diagnosis that always gets my full attention because sometimes you can find some pretty significant infections – an osteomyelitis or a severe pelvic abscess,” he said. “And there’s always the concern of some of these more serious underlying diseases, like rheumatologic diseases; there’s plenty of case reports of [inflammatory bowel disease] presenting with FUO.” Of course, he said, even more dire diagnoses like Hodgkin’s lymphoma and leukemia have to remain in the differential as well.

Although the broad diagnostic differential includes noninfectious causes, they are rarer by far than infections. When the etiology of FUO has been studied in the United States, said Dr. Williams, “infections pretty consistently dominate as the most common cause of FUO … as general pediatricians, it’s our job to really do a good evaluation for infection before we start going after some of these less common diagnoses – the rheumatologic and cancer diagnoses.”

A systematic approach is important, he said. “A really good fever history can, a lot of times, provide important and valuable information.” Take the time to get granular detail: Find out how often the fever is being checked and by whom, what symptoms accompany the fever, and how the fever is being measured.

And don’t forget to ask if there are fever-free days, he said. In an otherwise well-appearing child, a few days’ respite from fever can increase the likelihood that you’re really seeing back-to-back viral illnesses rather than a protracted unexplained fever.

A thorough head-to-toe review of symptoms and history is critical, too. Dr. Williams related the story of a well-appearing 9-year-old boy who’d had many days of high fever with accompanying elevated inflammatory markers. His exam was unremarkable, and the only untoward symptom he could recall was a few days’ worth of left upper quadrant tenderness when running in gym class. The child, said Dr. Williams, turned out to have nephronia. “Sometimes, really subtle clues from the history can guide you.”

Ask about exposures, including travel, animals, foods, insects, and sick contacts. “Obviously, children can get into just about anything,” said Dr. Williams. A detailed family and social history also may turn up clues.

An infection-focused musculoskeletal exam, to include the spine, is a must, as is a top-to-bottom search for lymphadenopathy as part of a complete physical exam.

At this point in the pediatrics office, said Dr. Williams, you’ve come to a decision point: “Does this work-up need to be initiated in the inpatient setting, or is this something that can be started in the outpatient setting?”

“There’s a lot of data to support that, initially, a lot of these patients can be worked up in the outpatient setting with close follow-up,” he said. The outpatient FUO work-up begins with some basic screening labs. In addition to a complete blood count, chemistries, and a urinalysis, labs should include blood and urine cultures, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels.

“I’ll actually rely pretty heavily on my ESR and CRP,” said Dr. Williams. “If I have an otherwise well-appearing child with a normal CRP and an unremarkable exam, I think it’s a pretty tough argument to keep that child hospitalized and do a more invasive work-up.”

The advent of the viral polymerase chain reaction panel has helped streamline the FUO work-up as well. In the setting of a well-appearing child with an unremarkable initial work-up, “a positive adenovirus can provide a lot of reassurance to the families.”

Dr. Williams usually also gets a chest radiograph at this point, knowing that pneumonia is in the differential for FUO. He said he’s seen mediastinal masses, as well as picked up dense right upper lobe infiltrates that were missed on exam.

If the answer is still unclear at this point, exam and laboratory findings from the first-tier inquiry can help guide the next steps.

Some less common infectious etiologies can be considered now, said Dr. Williams. These can include Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and cat scratch fever; the latter, he’s found, is the third-most-common cause of FUO in some case series. For the real mystery cases, next-generation sequencing is an option: A blood sample is used to search for DNA fragments from a huge variety of microorganisms. “It’s a little overwhelming,” and very expensive, he said.

If an oncologic process is suspected, second-tier labs can include lactate dehydrogenase, uric acid, ferritin levels, and a peripheral smear. A rheumatologic work-up can be started, with antinuclear antibody and complement levels. At this point, though, a general pediatrician would be considering consults, he said.

Empiric antibiotics can be a tempting diagnostic strategy in some cases. “Is a trial of antibiotics warranted? Usually we advise against it,” but a case can be made for a time-limited trial in certain circumstances, said Dr. Williams.

Dr. Williams is a consultant for Zavante Therapeutics, which markets fosfomycin.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 2017

LDL levels below 10 mg/dL shown safe, effective

BARCELONA – The maxim that lower is better for LDL cholesterol continues to hold true, even at jaw-droppingly low levels of less than 10 mg/dL in a new analysis of data from the FOURIER trial.

The Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research with PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects with Elevated Risk (FOURIER) trial was the pivotal efficacy and safety study for the proprotein convertase subtilisin–kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor evolocumab (Repatha) and enrolled patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and LDL cholesterol levels of at least 70 mg/dL (N Engl J Med. 2017 May 4;376[18]:1713-22).

After a median follow-up of 26 months, the incidence of the study’s primary endpoint (cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization) dropped by a statistically significant 15% in patients with an achieved LDL cholesterol of 20-49 mg/dL, compared with patients whose 4-week LDL cholesterol was at or above 100 mg/dL (primarily patients randomized to the study’s control arm), by 24% in all patients with LDL cholesterol less than 20 mg/dL, and by 31% in the 2% of patients whose LDL cholesterol levels fell below 10 mg/dL.

These strikingly improved event rates at the lowest levels of LDL cholesterol occurred with no signal of excess adverse events, Robert P. Giugliano, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

In contrast, the 13% of patents whose achieved LDL cholesterol was 50-69 mg/dL had an event rate just 6% below the referent group of 100 mg/dL or more, a nonsignificant difference. Existing cholesterol management guidelines that set LDL cholesterol targets for secondary prevention have used a level below 70 mg/dL as the target, such as the European Society of Cardiology’s 2016 guidelines (Eur Heart J. 2016 Oct 14;37[39]:2999-3058).

“The data suggest that we should target considerably lower LDL cholesterol than is currently recommended for our patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease,” said Dr. Giugliano, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Lowest is best with LDL. You don’t need a lot of LDL in the serum for normal human function,” he noted during the discussion of his report.

While FOURIER’s event curve continued to drop as LDL cholesterol fell below 10 mg/dL, the study’s wide-ranging safety assessment showed no signal of harm at the lowest levels. This “gives us some reassurance it’s safe,” he said in an interview. “We saw benefit that continued down to the lowest LDL levels, so it’s hard to pick a LDL target. I no longer feel comfortable treating my patients to just less than 70 mg/dL. I’m not sure what is the optimal LDL target, but I think it needs to be lower than that.”

To achieve such ultralow LDL levels, most patients need treatment with a PCSK9 inhibitor plus at least one and perhaps two additional cholesterol-lowering drugs, a statin and ezetimibe, he noted.

The FOURIER analyses Dr. Giugliano reported included data on the incidence during the study of 10 specific types of adverse events: noncardiovascular death, serious adverse events, adverse events leading to study discontinuation, and new onset of diabetes, cancer, cataract, neurocognitive deficit, significant liver enzyme increase, significant creatine kinase increase, and hemorrhagic stroke. The incidence of each of these was similar among the patients in five study subgroups based on achieved levels of LDL cholesterol: less than 20 mg/dL, 20-49 mg/dL, 50-69 mg/dL, 70-99 mg/dL, and 100 mg/dL or higher. In addition, the rates of both serious adverse events and adverse events leading to study discontinuation was roughly the same in the subgroup of patients with an achieved LDL cholesterol of less than 10 mg/dL as in those with an achieved LDL of at least 100 mg/dL.

Concurrently with Dr. Giugliano’s report, the results also appeared in an online article (Lancet. 2017 Aug 28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[17]32290-0).

FOURIER was funded by Amgen, the company that markets evolocumab (Repatha). Dr. Giugliano has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Amgen, and he has also been a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Pfizer.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BARCELONA – The maxim that lower is better for LDL cholesterol continues to hold true, even at jaw-droppingly low levels of less than 10 mg/dL in a new analysis of data from the FOURIER trial.

The Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research with PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects with Elevated Risk (FOURIER) trial was the pivotal efficacy and safety study for the proprotein convertase subtilisin–kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor evolocumab (Repatha) and enrolled patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and LDL cholesterol levels of at least 70 mg/dL (N Engl J Med. 2017 May 4;376[18]:1713-22).

After a median follow-up of 26 months, the incidence of the study’s primary endpoint (cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization) dropped by a statistically significant 15% in patients with an achieved LDL cholesterol of 20-49 mg/dL, compared with patients whose 4-week LDL cholesterol was at or above 100 mg/dL (primarily patients randomized to the study’s control arm), by 24% in all patients with LDL cholesterol less than 20 mg/dL, and by 31% in the 2% of patients whose LDL cholesterol levels fell below 10 mg/dL.

These strikingly improved event rates at the lowest levels of LDL cholesterol occurred with no signal of excess adverse events, Robert P. Giugliano, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

In contrast, the 13% of patents whose achieved LDL cholesterol was 50-69 mg/dL had an event rate just 6% below the referent group of 100 mg/dL or more, a nonsignificant difference. Existing cholesterol management guidelines that set LDL cholesterol targets for secondary prevention have used a level below 70 mg/dL as the target, such as the European Society of Cardiology’s 2016 guidelines (Eur Heart J. 2016 Oct 14;37[39]:2999-3058).

“The data suggest that we should target considerably lower LDL cholesterol than is currently recommended for our patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease,” said Dr. Giugliano, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Lowest is best with LDL. You don’t need a lot of LDL in the serum for normal human function,” he noted during the discussion of his report.

While FOURIER’s event curve continued to drop as LDL cholesterol fell below 10 mg/dL, the study’s wide-ranging safety assessment showed no signal of harm at the lowest levels. This “gives us some reassurance it’s safe,” he said in an interview. “We saw benefit that continued down to the lowest LDL levels, so it’s hard to pick a LDL target. I no longer feel comfortable treating my patients to just less than 70 mg/dL. I’m not sure what is the optimal LDL target, but I think it needs to be lower than that.”

To achieve such ultralow LDL levels, most patients need treatment with a PCSK9 inhibitor plus at least one and perhaps two additional cholesterol-lowering drugs, a statin and ezetimibe, he noted.

The FOURIER analyses Dr. Giugliano reported included data on the incidence during the study of 10 specific types of adverse events: noncardiovascular death, serious adverse events, adverse events leading to study discontinuation, and new onset of diabetes, cancer, cataract, neurocognitive deficit, significant liver enzyme increase, significant creatine kinase increase, and hemorrhagic stroke. The incidence of each of these was similar among the patients in five study subgroups based on achieved levels of LDL cholesterol: less than 20 mg/dL, 20-49 mg/dL, 50-69 mg/dL, 70-99 mg/dL, and 100 mg/dL or higher. In addition, the rates of both serious adverse events and adverse events leading to study discontinuation was roughly the same in the subgroup of patients with an achieved LDL cholesterol of less than 10 mg/dL as in those with an achieved LDL of at least 100 mg/dL.

Concurrently with Dr. Giugliano’s report, the results also appeared in an online article (Lancet. 2017 Aug 28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[17]32290-0).

FOURIER was funded by Amgen, the company that markets evolocumab (Repatha). Dr. Giugliano has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Amgen, and he has also been a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Pfizer.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BARCELONA – The maxim that lower is better for LDL cholesterol continues to hold true, even at jaw-droppingly low levels of less than 10 mg/dL in a new analysis of data from the FOURIER trial.

The Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research with PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects with Elevated Risk (FOURIER) trial was the pivotal efficacy and safety study for the proprotein convertase subtilisin–kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor evolocumab (Repatha) and enrolled patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and LDL cholesterol levels of at least 70 mg/dL (N Engl J Med. 2017 May 4;376[18]:1713-22).

After a median follow-up of 26 months, the incidence of the study’s primary endpoint (cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization) dropped by a statistically significant 15% in patients with an achieved LDL cholesterol of 20-49 mg/dL, compared with patients whose 4-week LDL cholesterol was at or above 100 mg/dL (primarily patients randomized to the study’s control arm), by 24% in all patients with LDL cholesterol less than 20 mg/dL, and by 31% in the 2% of patients whose LDL cholesterol levels fell below 10 mg/dL.

These strikingly improved event rates at the lowest levels of LDL cholesterol occurred with no signal of excess adverse events, Robert P. Giugliano, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

In contrast, the 13% of patents whose achieved LDL cholesterol was 50-69 mg/dL had an event rate just 6% below the referent group of 100 mg/dL or more, a nonsignificant difference. Existing cholesterol management guidelines that set LDL cholesterol targets for secondary prevention have used a level below 70 mg/dL as the target, such as the European Society of Cardiology’s 2016 guidelines (Eur Heart J. 2016 Oct 14;37[39]:2999-3058).

“The data suggest that we should target considerably lower LDL cholesterol than is currently recommended for our patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease,” said Dr. Giugliano, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Lowest is best with LDL. You don’t need a lot of LDL in the serum for normal human function,” he noted during the discussion of his report.

While FOURIER’s event curve continued to drop as LDL cholesterol fell below 10 mg/dL, the study’s wide-ranging safety assessment showed no signal of harm at the lowest levels. This “gives us some reassurance it’s safe,” he said in an interview. “We saw benefit that continued down to the lowest LDL levels, so it’s hard to pick a LDL target. I no longer feel comfortable treating my patients to just less than 70 mg/dL. I’m not sure what is the optimal LDL target, but I think it needs to be lower than that.”

To achieve such ultralow LDL levels, most patients need treatment with a PCSK9 inhibitor plus at least one and perhaps two additional cholesterol-lowering drugs, a statin and ezetimibe, he noted.

The FOURIER analyses Dr. Giugliano reported included data on the incidence during the study of 10 specific types of adverse events: noncardiovascular death, serious adverse events, adverse events leading to study discontinuation, and new onset of diabetes, cancer, cataract, neurocognitive deficit, significant liver enzyme increase, significant creatine kinase increase, and hemorrhagic stroke. The incidence of each of these was similar among the patients in five study subgroups based on achieved levels of LDL cholesterol: less than 20 mg/dL, 20-49 mg/dL, 50-69 mg/dL, 70-99 mg/dL, and 100 mg/dL or higher. In addition, the rates of both serious adverse events and adverse events leading to study discontinuation was roughly the same in the subgroup of patients with an achieved LDL cholesterol of less than 10 mg/dL as in those with an achieved LDL of at least 100 mg/dL.

Concurrently with Dr. Giugliano’s report, the results also appeared in an online article (Lancet. 2017 Aug 28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[17]32290-0).

FOURIER was funded by Amgen, the company that markets evolocumab (Repatha). Dr. Giugliano has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Amgen, and he has also been a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Pfizer.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients with an achieved LDL of less than 10 mg/dL had an event rate 31% below patients with an LDL at or above 100 mg/dL.

Data source: FOURIER, an international multicenter trial with 27,564 patients.

Disclosures: FOURIER was funded by Amgen, the company that markets evolocumab (Repatha). Dr. Giugliano has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Amgen, and he has also been a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Pfizer.

Clinicians persist in prescribing antibiotics for acne

Prescribing systemic antibiotics for acne remains a common clinical practice, despite recommendations to reduce antibiotic use, according to an extensive database review. The results were published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Despite ... recent recommendations regarding the importance of antibiotic stewardship and appropriate use of antibiotics in patients with acne, it is unclear whether there have been any significant changes in practice patterns,” wrote John S. Barbieri, MD, and his coauthors in the departments of dermatology, and biostatistics and epidemiology, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77[3]:456-63).

To assess prescribing practices, the researchers reviewed data from the OptumInsight Clinformatics Data Mart, which included medical and pharmacy claims for approximately 12-14 million annual covered lives. The study population included 572,630 individuals with at least two acne claims who were aged 12-40 years at the start of treatment.

The number of courses of spironolactone prescribed for acne per 100 female patients treated by dermatologists increased by 291% during the study period, from 2.08 to 8.13. Among nondermatologists, the number of spironolactone courses prescribed per 100 female patients increased from 1.43 to 4.09 over the same period, a 186% increase.

Overall, the number of oral antibiotic courses increased from 26.24 to 27.08 per 100 patients among dermatologists, and from 19.99 to 22.48 per 100 patients among nondermatologists. The median length of treatment on oral antibiotics was 126 days for patients being treated by dermatologists and 129 days among patients treated by nondermatologists.

The use of spironolactone “remains relatively uncommon” compared with oral antibiotics, the researchers pointed out, noting that the 2013 data show that for every course of spironolactone, there were 2.8 courses of oral antibiotics prescribed by dermatologists and 4.6 courses prescribed by nondermatologists.

Other prescribing trends during the time period among dermatologists included a drop in the number of combined oral contraceptive courses per 100 female patients, from 34.31 to 30.74 (and an increase from 31.70 to 32.13 among nondermatologists); and a drop in the number of isotretinoin courses prescribed per 100 patients, from 5.43 to 5.35 (and a drop from 2.24 to1.45 among nondermatologists).

“Given the importance of judicious use of oral antibiotics to prevent potential complications, increasing the use of concomitant topical retinoids and additional work to identify those patients who would benefit most from alternative agents such as spironolactone, combined oral contraceptive pills, or isotretinoin represent potential opportunities to improve the care of patients with acne,” they concluded.

The findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective nature of the study and lack of data on combination therapy, severity of illness, and treatment outcomes, they said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. There was no funding source.

Prescribing systemic antibiotics for acne remains a common clinical practice, despite recommendations to reduce antibiotic use, according to an extensive database review. The results were published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Despite ... recent recommendations regarding the importance of antibiotic stewardship and appropriate use of antibiotics in patients with acne, it is unclear whether there have been any significant changes in practice patterns,” wrote John S. Barbieri, MD, and his coauthors in the departments of dermatology, and biostatistics and epidemiology, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77[3]:456-63).

To assess prescribing practices, the researchers reviewed data from the OptumInsight Clinformatics Data Mart, which included medical and pharmacy claims for approximately 12-14 million annual covered lives. The study population included 572,630 individuals with at least two acne claims who were aged 12-40 years at the start of treatment.

The number of courses of spironolactone prescribed for acne per 100 female patients treated by dermatologists increased by 291% during the study period, from 2.08 to 8.13. Among nondermatologists, the number of spironolactone courses prescribed per 100 female patients increased from 1.43 to 4.09 over the same period, a 186% increase.

Overall, the number of oral antibiotic courses increased from 26.24 to 27.08 per 100 patients among dermatologists, and from 19.99 to 22.48 per 100 patients among nondermatologists. The median length of treatment on oral antibiotics was 126 days for patients being treated by dermatologists and 129 days among patients treated by nondermatologists.

The use of spironolactone “remains relatively uncommon” compared with oral antibiotics, the researchers pointed out, noting that the 2013 data show that for every course of spironolactone, there were 2.8 courses of oral antibiotics prescribed by dermatologists and 4.6 courses prescribed by nondermatologists.

Other prescribing trends during the time period among dermatologists included a drop in the number of combined oral contraceptive courses per 100 female patients, from 34.31 to 30.74 (and an increase from 31.70 to 32.13 among nondermatologists); and a drop in the number of isotretinoin courses prescribed per 100 patients, from 5.43 to 5.35 (and a drop from 2.24 to1.45 among nondermatologists).

“Given the importance of judicious use of oral antibiotics to prevent potential complications, increasing the use of concomitant topical retinoids and additional work to identify those patients who would benefit most from alternative agents such as spironolactone, combined oral contraceptive pills, or isotretinoin represent potential opportunities to improve the care of patients with acne,” they concluded.

The findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective nature of the study and lack of data on combination therapy, severity of illness, and treatment outcomes, they said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. There was no funding source.

Prescribing systemic antibiotics for acne remains a common clinical practice, despite recommendations to reduce antibiotic use, according to an extensive database review. The results were published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Despite ... recent recommendations regarding the importance of antibiotic stewardship and appropriate use of antibiotics in patients with acne, it is unclear whether there have been any significant changes in practice patterns,” wrote John S. Barbieri, MD, and his coauthors in the departments of dermatology, and biostatistics and epidemiology, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77[3]:456-63).

To assess prescribing practices, the researchers reviewed data from the OptumInsight Clinformatics Data Mart, which included medical and pharmacy claims for approximately 12-14 million annual covered lives. The study population included 572,630 individuals with at least two acne claims who were aged 12-40 years at the start of treatment.

The number of courses of spironolactone prescribed for acne per 100 female patients treated by dermatologists increased by 291% during the study period, from 2.08 to 8.13. Among nondermatologists, the number of spironolactone courses prescribed per 100 female patients increased from 1.43 to 4.09 over the same period, a 186% increase.

Overall, the number of oral antibiotic courses increased from 26.24 to 27.08 per 100 patients among dermatologists, and from 19.99 to 22.48 per 100 patients among nondermatologists. The median length of treatment on oral antibiotics was 126 days for patients being treated by dermatologists and 129 days among patients treated by nondermatologists.

The use of spironolactone “remains relatively uncommon” compared with oral antibiotics, the researchers pointed out, noting that the 2013 data show that for every course of spironolactone, there were 2.8 courses of oral antibiotics prescribed by dermatologists and 4.6 courses prescribed by nondermatologists.

Other prescribing trends during the time period among dermatologists included a drop in the number of combined oral contraceptive courses per 100 female patients, from 34.31 to 30.74 (and an increase from 31.70 to 32.13 among nondermatologists); and a drop in the number of isotretinoin courses prescribed per 100 patients, from 5.43 to 5.35 (and a drop from 2.24 to1.45 among nondermatologists).

“Given the importance of judicious use of oral antibiotics to prevent potential complications, increasing the use of concomitant topical retinoids and additional work to identify those patients who would benefit most from alternative agents such as spironolactone, combined oral contraceptive pills, or isotretinoin represent potential opportunities to improve the care of patients with acne,” they concluded.

The findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective nature of the study and lack of data on combination therapy, severity of illness, and treatment outcomes, they said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. There was no funding source.

FROM JAAD

Key clinical point: Spironolactone use for acne is gaining in popularity, although antibiotic use persists.

Major finding: Spironolactone prescriptions for female acne increased by 291% between 2004 and 2013.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of a prescription information database from 2004-2013 for 572,630 patients with acne.

Disclosures: The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. There was no funding source.

Death by meeting

I like to project an image of a renegade who at times ventures outside the norms of the profession, but when there are rules, I try to follow them. However, I will confess that for the last 10 or 12 years that I was in practice, I flagrantly disobeyed our hospital’s requirement for attendance at staff meetings. In fact, I didn’t attend a single one for more than a decade.

I can’t say that I have never attended what I would consider a good meeting. But

Often, the first problem is that the stated or implied goal of the meeting was poorly conceived. That is, if the person who called for the meeting had even considered setting a goal. If the purpose of the meeting was to convey information, there are so many more efficient ways to achieve that goal without pulling people away from their primary missions. In the case of a physician, this would translate to seeing patients.

In this electronic age, emails, videos, social media sites, hard-copy handouts, and memos reach the target audience more efficiently and with more clarity than a sit-down meeting does. If the purpose of the meeting also was to elicit feedback about the new information, that same suite of communication vehicles can be structured to function as effective sounding boards.

If the purpose of the meeting is to foster camaraderie and team spirit, then it clearly should be labeled as a team building exercise. However, the organizers should have done enough research into the proposed activity to be reasonably confident that it will achieve the goal of improved team spirit.

If the goal of the meeting is create something – for example – an office policy about stimulant medication, then that goal must be narrowly focused by an agenda published well ahead of the meeting. In this case, the agenda could include the questions: How often should the patient be seen? If the patient is not going to be seen, what questions should he or she be asked? Who will ask them? And where in the chart should this information be filed?

No meeting should last longer than an hour and a half, but an hour is optimal. If the goal has not been achieved, then a second meeting with a more realistic agenda should be scheduled. Attendees who have been assigned tasks for completion before the next meeting should be contacted several days before the rescheduled meeting. There are few things more frustrating than to sit down at a meeting and discover that homework critical to completing the goals has not been done.

Finally, I must caution to avoid meetings organized or chaired by people who have nothing better to do than go to meetings. Some of those folks may even enjoy the social atmosphere of a meeting, and many are likely being paid to attend. Meanwhile, they are squandering your productive face-to-face patient care time.

I like to project an image of a renegade who at times ventures outside the norms of the profession, but when there are rules, I try to follow them. However, I will confess that for the last 10 or 12 years that I was in practice, I flagrantly disobeyed our hospital’s requirement for attendance at staff meetings. In fact, I didn’t attend a single one for more than a decade.

I can’t say that I have never attended what I would consider a good meeting. But

Often, the first problem is that the stated or implied goal of the meeting was poorly conceived. That is, if the person who called for the meeting had even considered setting a goal. If the purpose of the meeting was to convey information, there are so many more efficient ways to achieve that goal without pulling people away from their primary missions. In the case of a physician, this would translate to seeing patients.

In this electronic age, emails, videos, social media sites, hard-copy handouts, and memos reach the target audience more efficiently and with more clarity than a sit-down meeting does. If the purpose of the meeting also was to elicit feedback about the new information, that same suite of communication vehicles can be structured to function as effective sounding boards.

If the purpose of the meeting is to foster camaraderie and team spirit, then it clearly should be labeled as a team building exercise. However, the organizers should have done enough research into the proposed activity to be reasonably confident that it will achieve the goal of improved team spirit.

If the goal of the meeting is create something – for example – an office policy about stimulant medication, then that goal must be narrowly focused by an agenda published well ahead of the meeting. In this case, the agenda could include the questions: How often should the patient be seen? If the patient is not going to be seen, what questions should he or she be asked? Who will ask them? And where in the chart should this information be filed?

No meeting should last longer than an hour and a half, but an hour is optimal. If the goal has not been achieved, then a second meeting with a more realistic agenda should be scheduled. Attendees who have been assigned tasks for completion before the next meeting should be contacted several days before the rescheduled meeting. There are few things more frustrating than to sit down at a meeting and discover that homework critical to completing the goals has not been done.

Finally, I must caution to avoid meetings organized or chaired by people who have nothing better to do than go to meetings. Some of those folks may even enjoy the social atmosphere of a meeting, and many are likely being paid to attend. Meanwhile, they are squandering your productive face-to-face patient care time.

I like to project an image of a renegade who at times ventures outside the norms of the profession, but when there are rules, I try to follow them. However, I will confess that for the last 10 or 12 years that I was in practice, I flagrantly disobeyed our hospital’s requirement for attendance at staff meetings. In fact, I didn’t attend a single one for more than a decade.

I can’t say that I have never attended what I would consider a good meeting. But

Often, the first problem is that the stated or implied goal of the meeting was poorly conceived. That is, if the person who called for the meeting had even considered setting a goal. If the purpose of the meeting was to convey information, there are so many more efficient ways to achieve that goal without pulling people away from their primary missions. In the case of a physician, this would translate to seeing patients.

In this electronic age, emails, videos, social media sites, hard-copy handouts, and memos reach the target audience more efficiently and with more clarity than a sit-down meeting does. If the purpose of the meeting also was to elicit feedback about the new information, that same suite of communication vehicles can be structured to function as effective sounding boards.

If the purpose of the meeting is to foster camaraderie and team spirit, then it clearly should be labeled as a team building exercise. However, the organizers should have done enough research into the proposed activity to be reasonably confident that it will achieve the goal of improved team spirit.

If the goal of the meeting is create something – for example – an office policy about stimulant medication, then that goal must be narrowly focused by an agenda published well ahead of the meeting. In this case, the agenda could include the questions: How often should the patient be seen? If the patient is not going to be seen, what questions should he or she be asked? Who will ask them? And where in the chart should this information be filed?

No meeting should last longer than an hour and a half, but an hour is optimal. If the goal has not been achieved, then a second meeting with a more realistic agenda should be scheduled. Attendees who have been assigned tasks for completion before the next meeting should be contacted several days before the rescheduled meeting. There are few things more frustrating than to sit down at a meeting and discover that homework critical to completing the goals has not been done.

Finally, I must caution to avoid meetings organized or chaired by people who have nothing better to do than go to meetings. Some of those folks may even enjoy the social atmosphere of a meeting, and many are likely being paid to attend. Meanwhile, they are squandering your productive face-to-face patient care time.

Anidulafungin effectively treated invasive pediatric candidiasis in open-label trial

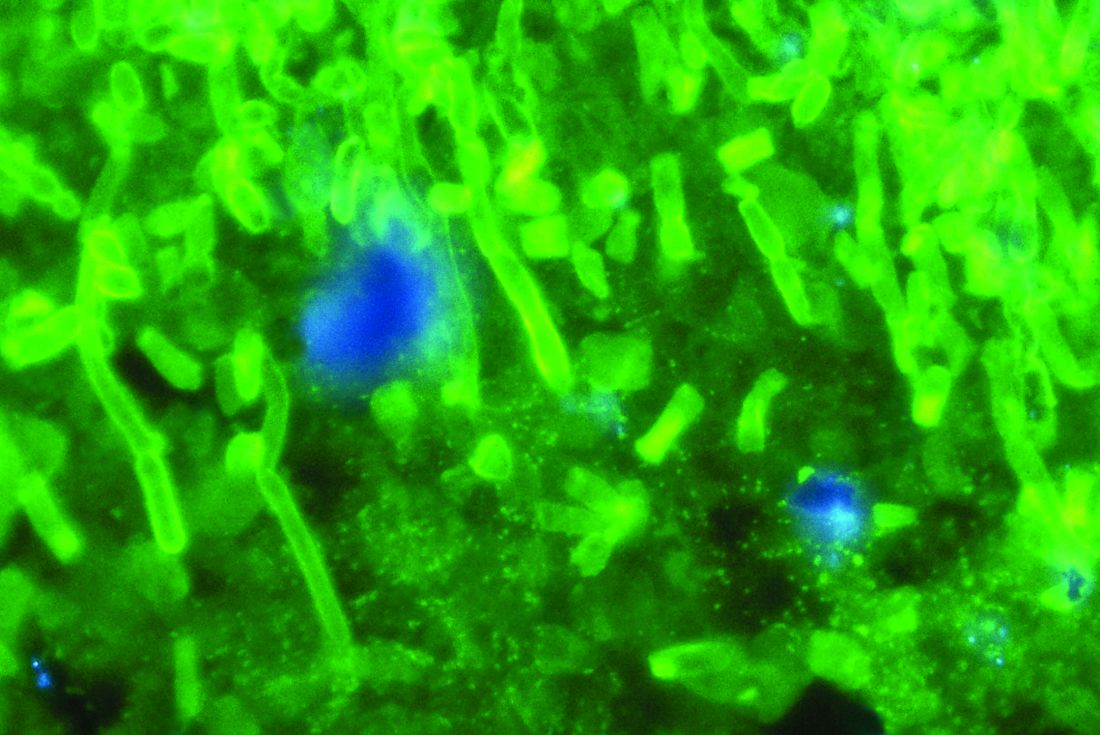

SAN DIEGO – The intravenous echinocandin anidulafungin effectively treated invasive candidiasis in a single-arm, multicenter, open-label trial of 47 children aged 2-17 years.

The overall global response rate of 72% resembled that from the prior adult registry study (76%), Emmanuel Roilides, MD, PhD, and his associates reported in a poster presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

At 6-week follow-up, two patients (4%) had relapsed, both with Candida parapsilosis, which was more resistant to treatment with anidulafungin (Eraxis) than other Candida species, the researchers reported. Treating the children with 3.0 mg/kg anidulafungin on day 1, followed by 1.5 mg/kg every 24 hours, yielded similar pharmacokinetics as the 200/100 mg regimen used in adults. The most common treatment-emergent adverse effects included diarrhea (23%), vomiting (23%), and fever (19%), which also reflected findings in adults, the investigators said. Five patients (10%) developed at least one severe treatment-emergent adverse event, including neutropenia, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, increased hepatic transaminases, hyponatremia, and myalgia. The study (NCT00761267) is ongoing and continues to recruit patients in 11 states in the United States and nine other countries, with final top-line results expected in 2019.

Although rates of invasive candidiasis appear to be decreasing in children overall, the population at risk is expanding, experts have noted. Relevant guidelines from the Infectious Disease Society of America and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases list amphotericin B, echinocandins, and azoles as treatment options, but these recommendations are extrapolated mainly from adult studies, noted Dr. Roilides, who is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Aristotle University School of Health Sciences and Hippokration General Hospital in Thessaloniki, Greece.

To better characterize the safety and efficacy of anidulafungin in children, the researchers enrolled patients up to 17 years of age who had signs and symptoms of invasive candidiasis and Candida cultured from a normally sterile site. Patients received intravenous anidulafungin (3 mg/kg on day 1, followed by 1.5 mg/kg every 24 hours) for at least 10 days, after which they could switch to oral fluconazole. Treatment continued for at least 14 days after blood cultures were negative and signs and symptoms resolved.

At interim data cutoff in October 2016, patients were exposed to anidulafungin for a median of 11.5 days (range, 1-28 days). Among 47 patients who received at least one dose of anidulafungin, about two-thirds were male, about 70% were white, and the average age was 8 years (standard deviation, 4.7 years). Rates of global success – a combination of clinical and microbiological response – were 82% in patients up to 5 years old and 67% in older children. Children whose baseline neutrophil count was at least 500 per mm3 had a 78% global response rate versus 50% among those with more severe neutropenia. C. parapsilosis had higher minimum inhibitory concentrations than other Candida species, and in vitro susceptibility rates of 85% for C. parapsilosis versus 100% for other species.

All patients experienced at least one treatment-emergent adverse effect. In addition to diarrhea, vomiting, and pyrexia, adverse events affecting more than 10% of patients included epistaxis (17%), headache (15%), and abdominal pain (13%). Half of patients switched to oral fluconazole. Four patients stopped treatment because of vomiting, generalized pruritus, or increased transaminases. A total of 15% of patients died, although no deaths were considered treatment related. The patient who stopped treatment because of pruritus later died of septic shock secondary to invasive candidiasis, despite having started treatment with fluconazole and micafungin, the investigators reported at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Nearly all patients had bloodstream infections, and catheters also cultured positive in more than two-thirds of cases, the researchers said. Many patients had multiple risk factors for infection such as central venous catheters, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, total parenteral nutrition, and chemotherapy. Cultures were most often positive for Candida albicans (38%), followed by C. parapsilosis (26%) and C. tropicalis (13%).

Pfizer makes anidulafungin and sponsored the study. Dr. Roilides disclosed research grants and advisory relationships with Pfizer, Astellas, Gilead, and Merck.

SAN DIEGO – The intravenous echinocandin anidulafungin effectively treated invasive candidiasis in a single-arm, multicenter, open-label trial of 47 children aged 2-17 years.

The overall global response rate of 72% resembled that from the prior adult registry study (76%), Emmanuel Roilides, MD, PhD, and his associates reported in a poster presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

At 6-week follow-up, two patients (4%) had relapsed, both with Candida parapsilosis, which was more resistant to treatment with anidulafungin (Eraxis) than other Candida species, the researchers reported. Treating the children with 3.0 mg/kg anidulafungin on day 1, followed by 1.5 mg/kg every 24 hours, yielded similar pharmacokinetics as the 200/100 mg regimen used in adults. The most common treatment-emergent adverse effects included diarrhea (23%), vomiting (23%), and fever (19%), which also reflected findings in adults, the investigators said. Five patients (10%) developed at least one severe treatment-emergent adverse event, including neutropenia, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, increased hepatic transaminases, hyponatremia, and myalgia. The study (NCT00761267) is ongoing and continues to recruit patients in 11 states in the United States and nine other countries, with final top-line results expected in 2019.

Although rates of invasive candidiasis appear to be decreasing in children overall, the population at risk is expanding, experts have noted. Relevant guidelines from the Infectious Disease Society of America and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases list amphotericin B, echinocandins, and azoles as treatment options, but these recommendations are extrapolated mainly from adult studies, noted Dr. Roilides, who is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Aristotle University School of Health Sciences and Hippokration General Hospital in Thessaloniki, Greece.

To better characterize the safety and efficacy of anidulafungin in children, the researchers enrolled patients up to 17 years of age who had signs and symptoms of invasive candidiasis and Candida cultured from a normally sterile site. Patients received intravenous anidulafungin (3 mg/kg on day 1, followed by 1.5 mg/kg every 24 hours) for at least 10 days, after which they could switch to oral fluconazole. Treatment continued for at least 14 days after blood cultures were negative and signs and symptoms resolved.

At interim data cutoff in October 2016, patients were exposed to anidulafungin for a median of 11.5 days (range, 1-28 days). Among 47 patients who received at least one dose of anidulafungin, about two-thirds were male, about 70% were white, and the average age was 8 years (standard deviation, 4.7 years). Rates of global success – a combination of clinical and microbiological response – were 82% in patients up to 5 years old and 67% in older children. Children whose baseline neutrophil count was at least 500 per mm3 had a 78% global response rate versus 50% among those with more severe neutropenia. C. parapsilosis had higher minimum inhibitory concentrations than other Candida species, and in vitro susceptibility rates of 85% for C. parapsilosis versus 100% for other species.

All patients experienced at least one treatment-emergent adverse effect. In addition to diarrhea, vomiting, and pyrexia, adverse events affecting more than 10% of patients included epistaxis (17%), headache (15%), and abdominal pain (13%). Half of patients switched to oral fluconazole. Four patients stopped treatment because of vomiting, generalized pruritus, or increased transaminases. A total of 15% of patients died, although no deaths were considered treatment related. The patient who stopped treatment because of pruritus later died of septic shock secondary to invasive candidiasis, despite having started treatment with fluconazole and micafungin, the investigators reported at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Nearly all patients had bloodstream infections, and catheters also cultured positive in more than two-thirds of cases, the researchers said. Many patients had multiple risk factors for infection such as central venous catheters, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, total parenteral nutrition, and chemotherapy. Cultures were most often positive for Candida albicans (38%), followed by C. parapsilosis (26%) and C. tropicalis (13%).

Pfizer makes anidulafungin and sponsored the study. Dr. Roilides disclosed research grants and advisory relationships with Pfizer, Astellas, Gilead, and Merck.

SAN DIEGO – The intravenous echinocandin anidulafungin effectively treated invasive candidiasis in a single-arm, multicenter, open-label trial of 47 children aged 2-17 years.

The overall global response rate of 72% resembled that from the prior adult registry study (76%), Emmanuel Roilides, MD, PhD, and his associates reported in a poster presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.