User login

Malpractice Counsel: A Pain in the…Scrotum

Case

A 52-year-old man presented to the ED for evaluation of right scrotal pain and swelling. The patient stated that the pain started several hours prior to presentation and had gradually worsened. He denied any trauma or inciting event to the affected area; he further denied abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, dysuria, polyuria, or fever. The patient’s remote medical history was significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), which he managed through dietary modification-only as he had refused pharmacological therapy. The patient admitted to smoking one half-pack of cigarettes per week, but denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

At presentation, the patient’s vital signs were all within normal range. The physical examination was remarkable only for right testicular tenderness and mild scrotal swelling, and there were no hernias or lymphadenopathy present.

The emergency physician (EP) ordered a urinalysis and color-flow Doppler ultrasound study of both testes, which the radiologist interpreted as an enlarged right epididymis with hyperemia; the left testicle was normal. The urinalysis was normal.

The patient was diagnosed with epididymitis and discharged home with a prescription for oral levofloxacin 500 mg daily for 10 days. He also was instructed to take ibuprofen for pain, apply ice to the affected area, keep the scrotal area elevated, and follow-up with a urologist in 1 week.

Approximately 8 hours after discharge, the patient returned to the same ED with complaints of increasing right testicular pain and swelling. The history and physical examination at this visit were essentially unchanged from his initial presentation. No laboratory evaluation, imaging studies, or other tests were ordered at the second visit.

The patient was discharged home with a prescription for a narcotic analgesic, which he was instructed to take in addition to the ibuprofen; he was also instructed to follow-up with a urologist within the next 2 to 3 days, instead of in 1 week.

The patient returned the following morning to the same ED with complaints of increased swelling and pain of the right testicle. In addition to the worsening testicular pain and swelling, he also had right inguinal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. Vital signs at this third presentation were: blood pressure (BP), 124/64 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 110 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and temperature, 99.8o F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

The patient was tachycardic on heart examination, but with regular rhythm and no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. The lung and abdominal examinations were normal. The genital examination revealed marked right scrotal swelling and tenderness, as well as tender right inguinal lymphadenopathy.

The EP ordered an intravenous (IV) bolus of 1 L normal saline and laboratory studies, which included lactic acid, blood cultures, urinalysis, and urine culture and sensitivity. The EP was concerned for a scrotal abscess and ordered a testicular Doppler color-flow ultrasound study. The laboratory studies revealed an elevated white blood count of 16.5 K/uL, elevated blood glucose of 364 mg/dL, and elevated lactate of 2.8 mg/dL. As demonstrated on the ultrasound study performed at the patient’s first presentation, the ultrasound again showed an enlarged right epididymis, but without orchitis or abscess. The scrotal wall had significant thickening, consistent with cellulitis. The EP ordered broad spectrum IV antibiotics and admitted the patient to the hospitalist with a consult request for urology services.

The patient continued to receive IV fluids and antibiotics throughout the evening. In the morning, he was seen by the same hospitalist/admitting physician from the previous evening. Upon physical examination, the hospitalist noted tenderness, swelling, and erythema in the patient’s perineal area. The patient’s BP had dropped to 100/60 mm Hg, and his HR had increased to 115 beats/min despite receiving nearly 2 L of normal saline IV throughout the previous evening and night.

The urologist examined the patient soon after the consult request and diagnosed him with Fournier’s gangrene. He started the patient on aggressive IV fluid resuscitation, after which the patient was immediately taken to the operating room for extensive surgical debridement and scrotectomy. The patient’s postoperative course was complicated by acute kidney injury, respiratory failure requiring ventilator support, and sepsis. After a lengthy hospital stay, the patient was discharged home, but required a scrotal skin graft, and experienced erectile dysfunction and depression.

The patient sued all of the EPs involved in his care, the hospital, the hospitalist/admitting physician, and the urologist for negligence. The plaintiff’s attorney argued that since the patient progressively deteriorated over the 24 to 36 hours during his three presentations to the ED, urology services should have been consulted earlier, and that the urologist should have seen the patient immediately at the time of hospital admission.

The attorneys for the defendants claimed the patient denied dysuria, penile lesions, or urethral discharge and that the history, physical examination, and testicular ultrasound were all consistent with the diagnosis of epididymitis. For this reason, they argued, there was no indication for an emergent consultation with urology services. The jury returned a defense verdict.

Discussion

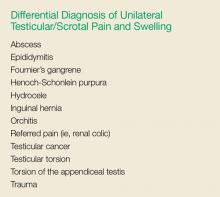

It is easy for a busy EP to have a differential diagnosis of only two disorders when evaluating a patient for unilateral testicular pain and swelling—in this case, testicular torsion and epididymitis. While these are the most common causes of testicular pain and swelling, this case emphasizes the need to also consider Fournier’s gangrene in the differential. A thorough history and physical examination, coupled with appropriate testing, will usually identify the correct diagnosis. While the differential diagnosis is broader than just these three disease processes (see the Box), we will review the evaluation and management of the three most serious: epididymitis, testicular torsion, and Fournier’s gangrene.

Noninfectious and Bacterial Epididymitis

Epididymitis is the most common cause of acute scrotal pain among US adults, accounting for approximately 600,000 cases each year.1 Infectious epididymitis is typically classified as acute (symptom duration of <6 weeks) or chronic (symptom duration of ≥6 weeks).2

Cases of noninfectious epididymitis are typically due to a chronic condition, such as autoimmune disease, cancer, or vasculitis. Although not as common, noninfectious epididymitis can also occur due to testicular trauma or amiodarone therapy.3,4

Patients with acute bacterial epididymitis typically present with scrotal pain and swelling ranging from mild to marked. These patients may also exhibit fever and chills, along with dysuria, frequency, and urgency, if associated with a urinary tract infection.2 The chronic presentation is more common though, and usually not associated with voiding issues.

Chronic epididymis is frequently seen in postpubertal boys and men following sexual activity, heavy physical exertion, and bicycle/motorcycle riding.2 On physical examination, palpation reveals induration and swelling of the involved epididymis with exquisite tenderness.2 Testicular swelling and pain, along with scrotal wall erythema, may be present in more advanced cases.2 The cremasteric reflex should be intact (ie, scratching the medial proximal thigh will cause ipsilateral testicle retraction). Similarly, the lie of both testicles while the patient is standing should be equal and symmetrical—ie, both testicles descended equally. However, in the presence of moderate-to-severe scrotal swelling, both of these physical findings may be impossible to confirm.

A urinalysis and urine culture should be ordered if there is any suspicion of epididymitis; pyuria will be present in approximately 50% of cases. However, since pyuria is neither sensitive nor specific for epididymitis, in most cases, a testicular ultrasound with Doppler flow is required to exclude testicular torsion. In cases of epididymitis, ultrasound usually demonstrates increased flow on the affected side, whereas in testicular torsion, there is decreased or absent blood flow.

The treatment for epididymitis involves antibiotics and symptomatic care. If epididymitis from chlamydia and/or gonorrhea is the suspected cause, or if the patient is younger than age 35 years, he should be given ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly plus oral doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 10 days. Patients who practice insertive anal sex should be treated with ceftriaxone, plus either oral ofloxacin 300 mg twice a day or oral levofloxacin 500 mg daily for 10 days.

In cases in which enteric organisms are suspected, the patient is older than age 35 years, or if patient status is posturinary tract instrumentation or vasectomy, he should be treated with either oral ofloxacin 300 mg twice a day or oral levofloxacin 500 mg daily for 10 days.2

For symptomatic relief, scrotal elevation, ice application, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are recommended.

Patients with epididymitis, regardless of etiology, should be instructed to follow-up with a urologist within 1 week. If the patient appears ill, septic, or in significant pain, admission to the hospital with IV antibiotics, IV fluids, and an urgent consult with urology services is required.

Testicular Torsion

Testicular torsion is a time-sensitive issue, requiring early diagnosis and rapid treatment to preserve the patient’s fertility. Most clinicians recommend detorsion within 6 hours of torsion onset because salvage rates are excellent when performed within this timeframe; after 12 hours, the testis will likely suffer irreversible damage due to ischemia.5,6

Testicular torsion can occur at any age, but is most commonly seen in a bimodal distribution—ie, neonates and postpubertal boys. The prevalence of testicular torsion in adult patients hospitalized with acute scrotal pain is approximately 25% to 50%.2

Patients with testicular torsion usually describe a sudden onset of severe, acute pain. The pain frequently occurs a few hours after vigorous physical activity or minor testicular trauma.2 Occasionally, the patient may complain of lower quadrant abdominal pain rather than testicular or scrotal pain. Nausea with vomiting can also be present.

On physical examination, significant testicular swelling is usually present. Examining the patient in the standing position will often reveal an asymmetrical, high-riding testis with a transverse lie on the affected side. The cremasteric reflex is usually absent in patients with testicular torsion.

Because of the significant overlap in history and physical examination findings for epididymitis and testicular torsion, a testicular ultrasound with color Doppler should be ordered. Multiple studies have confirmed the high sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound in the diagnosis of testicular torsion.

The treatment for suspected or confirmed testicular torsion is immediate surgical exploration with intraoperative detorsion and fixation of the testes. The EP can attempt manual detorsion (ie, performed in a medial to lateral motion, similar to opening a book). However, this should not delay the EP from consulting with urology services.

Pediatric patients with testicular torsion usually have a more favorable outcome than do adults. In one retrospective study, patients younger than age 21 years had a 70% testicular salvage rate compared to only 41% of patients aged 21 years and older.7 Regardless of age, better outcomes are associated with shorter periods of torsion.

Fournier’s Gangrene

Fournier’s gangrene is a polymicrobial necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum and scrotum that typically develops initially as a benign infection or abscess but quickly spreads. Risk factors for Fournier’s gangrene include DM, alcohol abuse, and any immunocompromised state (eg, HIV, cancer).

If the patient presents early in onset, there may be only mild tenderness, erythema, or swelling of the affected area; however, this infection progresses rapidly. Later findings include marked tenderness, swelling, crepitus, blisters, and ecchymoses. Patients with Fournier’s gangrene also develop systemic signs of infection, including fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypotension. The key to diagnosis is careful examination of the perineal and scrotal area in any patient presenting with acute scrotal pain.

In the majority of cases, the diagnosis of Fournier’s gangrene is made clinically. Once the diagnosis is made, patients require immediate and aggressive IV fluid resuscitation, broad-spectrum IV antibiotics (typically vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam), and emergent evaluation by a urologist. It is essential that these patients undergo early and aggressive surgical exploration and debridement of necrotic tissue.2 Antibiotic therapy alone is associated with a 100% mortality rate, emphasizing the need for urgent surgery.2 Even with optimal medical and surgical management, the mortality rate remains significant.

Summary

This case emphasizes several important teaching points. The EP should be mindful of the patient who keeps returning to the ED with the same complaint—despite “appropriate” treatment—as the initial diagnosis may not be the correct one. Such returning patients require greater, not less, scrutiny. As with any patient, the EP should always take a complete history and perform a thorough physical examination at each presentation—as one would with a de novo patient. Finally, the EP should consider Fournier’s gangrene in addition to testicular torsion and epididymitis in the differential diagnosis for acute scrotal pain.

1. Trojian TH, Lishnak TS, Heiman D. Epididymitis and orchitis: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(7):583-587.

2. Eyre RC. Evaluation of acute scrotal pain in adults. UpToDate Web site. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-acute-scrotal-pain-in-adults. Updated July 31, 2017. Accessed September 7, 2017.

3. Shen Y, Liu H, Cheng J, Bu P. Amiodarone-induced epididymitis: a pathologically confirmed case report and review of the literature. Cardiology. 2014;128(4):349-351. doi:10.1159/000361038.

4. Tracy CR, Steers WD, Costabile R. Diagnosis and management of epididymitis. Urol Clin North Am. 2008;35(1):101-108. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2007.09.013.

5. Wampler SM, Llanes M. Common scrotal and testicular problems. Prim Care. 2010;37(3):613-626. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2010.04.009.

6. Dunne PJ, O’Loughlin BS. Testicular torsion: time is the enemy. Aust NZ J Surg. 2000;70(6):441-442.

7. Cummings JM, Boullier JA, Sekhon D, Bose K. Adult testicular torsion. J Urol. 2002;167(5):2109-2110.

Case

A 52-year-old man presented to the ED for evaluation of right scrotal pain and swelling. The patient stated that the pain started several hours prior to presentation and had gradually worsened. He denied any trauma or inciting event to the affected area; he further denied abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, dysuria, polyuria, or fever. The patient’s remote medical history was significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), which he managed through dietary modification-only as he had refused pharmacological therapy. The patient admitted to smoking one half-pack of cigarettes per week, but denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

At presentation, the patient’s vital signs were all within normal range. The physical examination was remarkable only for right testicular tenderness and mild scrotal swelling, and there were no hernias or lymphadenopathy present.

The emergency physician (EP) ordered a urinalysis and color-flow Doppler ultrasound study of both testes, which the radiologist interpreted as an enlarged right epididymis with hyperemia; the left testicle was normal. The urinalysis was normal.

The patient was diagnosed with epididymitis and discharged home with a prescription for oral levofloxacin 500 mg daily for 10 days. He also was instructed to take ibuprofen for pain, apply ice to the affected area, keep the scrotal area elevated, and follow-up with a urologist in 1 week.

Approximately 8 hours after discharge, the patient returned to the same ED with complaints of increasing right testicular pain and swelling. The history and physical examination at this visit were essentially unchanged from his initial presentation. No laboratory evaluation, imaging studies, or other tests were ordered at the second visit.

The patient was discharged home with a prescription for a narcotic analgesic, which he was instructed to take in addition to the ibuprofen; he was also instructed to follow-up with a urologist within the next 2 to 3 days, instead of in 1 week.

The patient returned the following morning to the same ED with complaints of increased swelling and pain of the right testicle. In addition to the worsening testicular pain and swelling, he also had right inguinal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. Vital signs at this third presentation were: blood pressure (BP), 124/64 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 110 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and temperature, 99.8o F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

The patient was tachycardic on heart examination, but with regular rhythm and no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. The lung and abdominal examinations were normal. The genital examination revealed marked right scrotal swelling and tenderness, as well as tender right inguinal lymphadenopathy.

The EP ordered an intravenous (IV) bolus of 1 L normal saline and laboratory studies, which included lactic acid, blood cultures, urinalysis, and urine culture and sensitivity. The EP was concerned for a scrotal abscess and ordered a testicular Doppler color-flow ultrasound study. The laboratory studies revealed an elevated white blood count of 16.5 K/uL, elevated blood glucose of 364 mg/dL, and elevated lactate of 2.8 mg/dL. As demonstrated on the ultrasound study performed at the patient’s first presentation, the ultrasound again showed an enlarged right epididymis, but without orchitis or abscess. The scrotal wall had significant thickening, consistent with cellulitis. The EP ordered broad spectrum IV antibiotics and admitted the patient to the hospitalist with a consult request for urology services.

The patient continued to receive IV fluids and antibiotics throughout the evening. In the morning, he was seen by the same hospitalist/admitting physician from the previous evening. Upon physical examination, the hospitalist noted tenderness, swelling, and erythema in the patient’s perineal area. The patient’s BP had dropped to 100/60 mm Hg, and his HR had increased to 115 beats/min despite receiving nearly 2 L of normal saline IV throughout the previous evening and night.

The urologist examined the patient soon after the consult request and diagnosed him with Fournier’s gangrene. He started the patient on aggressive IV fluid resuscitation, after which the patient was immediately taken to the operating room for extensive surgical debridement and scrotectomy. The patient’s postoperative course was complicated by acute kidney injury, respiratory failure requiring ventilator support, and sepsis. After a lengthy hospital stay, the patient was discharged home, but required a scrotal skin graft, and experienced erectile dysfunction and depression.

The patient sued all of the EPs involved in his care, the hospital, the hospitalist/admitting physician, and the urologist for negligence. The plaintiff’s attorney argued that since the patient progressively deteriorated over the 24 to 36 hours during his three presentations to the ED, urology services should have been consulted earlier, and that the urologist should have seen the patient immediately at the time of hospital admission.

The attorneys for the defendants claimed the patient denied dysuria, penile lesions, or urethral discharge and that the history, physical examination, and testicular ultrasound were all consistent with the diagnosis of epididymitis. For this reason, they argued, there was no indication for an emergent consultation with urology services. The jury returned a defense verdict.

Discussion

It is easy for a busy EP to have a differential diagnosis of only two disorders when evaluating a patient for unilateral testicular pain and swelling—in this case, testicular torsion and epididymitis. While these are the most common causes of testicular pain and swelling, this case emphasizes the need to also consider Fournier’s gangrene in the differential. A thorough history and physical examination, coupled with appropriate testing, will usually identify the correct diagnosis. While the differential diagnosis is broader than just these three disease processes (see the Box), we will review the evaluation and management of the three most serious: epididymitis, testicular torsion, and Fournier’s gangrene.

Noninfectious and Bacterial Epididymitis

Epididymitis is the most common cause of acute scrotal pain among US adults, accounting for approximately 600,000 cases each year.1 Infectious epididymitis is typically classified as acute (symptom duration of <6 weeks) or chronic (symptom duration of ≥6 weeks).2

Cases of noninfectious epididymitis are typically due to a chronic condition, such as autoimmune disease, cancer, or vasculitis. Although not as common, noninfectious epididymitis can also occur due to testicular trauma or amiodarone therapy.3,4

Patients with acute bacterial epididymitis typically present with scrotal pain and swelling ranging from mild to marked. These patients may also exhibit fever and chills, along with dysuria, frequency, and urgency, if associated with a urinary tract infection.2 The chronic presentation is more common though, and usually not associated with voiding issues.

Chronic epididymis is frequently seen in postpubertal boys and men following sexual activity, heavy physical exertion, and bicycle/motorcycle riding.2 On physical examination, palpation reveals induration and swelling of the involved epididymis with exquisite tenderness.2 Testicular swelling and pain, along with scrotal wall erythema, may be present in more advanced cases.2 The cremasteric reflex should be intact (ie, scratching the medial proximal thigh will cause ipsilateral testicle retraction). Similarly, the lie of both testicles while the patient is standing should be equal and symmetrical—ie, both testicles descended equally. However, in the presence of moderate-to-severe scrotal swelling, both of these physical findings may be impossible to confirm.

A urinalysis and urine culture should be ordered if there is any suspicion of epididymitis; pyuria will be present in approximately 50% of cases. However, since pyuria is neither sensitive nor specific for epididymitis, in most cases, a testicular ultrasound with Doppler flow is required to exclude testicular torsion. In cases of epididymitis, ultrasound usually demonstrates increased flow on the affected side, whereas in testicular torsion, there is decreased or absent blood flow.

The treatment for epididymitis involves antibiotics and symptomatic care. If epididymitis from chlamydia and/or gonorrhea is the suspected cause, or if the patient is younger than age 35 years, he should be given ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly plus oral doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 10 days. Patients who practice insertive anal sex should be treated with ceftriaxone, plus either oral ofloxacin 300 mg twice a day or oral levofloxacin 500 mg daily for 10 days.

In cases in which enteric organisms are suspected, the patient is older than age 35 years, or if patient status is posturinary tract instrumentation or vasectomy, he should be treated with either oral ofloxacin 300 mg twice a day or oral levofloxacin 500 mg daily for 10 days.2

For symptomatic relief, scrotal elevation, ice application, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are recommended.

Patients with epididymitis, regardless of etiology, should be instructed to follow-up with a urologist within 1 week. If the patient appears ill, septic, or in significant pain, admission to the hospital with IV antibiotics, IV fluids, and an urgent consult with urology services is required.

Testicular Torsion

Testicular torsion is a time-sensitive issue, requiring early diagnosis and rapid treatment to preserve the patient’s fertility. Most clinicians recommend detorsion within 6 hours of torsion onset because salvage rates are excellent when performed within this timeframe; after 12 hours, the testis will likely suffer irreversible damage due to ischemia.5,6

Testicular torsion can occur at any age, but is most commonly seen in a bimodal distribution—ie, neonates and postpubertal boys. The prevalence of testicular torsion in adult patients hospitalized with acute scrotal pain is approximately 25% to 50%.2

Patients with testicular torsion usually describe a sudden onset of severe, acute pain. The pain frequently occurs a few hours after vigorous physical activity or minor testicular trauma.2 Occasionally, the patient may complain of lower quadrant abdominal pain rather than testicular or scrotal pain. Nausea with vomiting can also be present.

On physical examination, significant testicular swelling is usually present. Examining the patient in the standing position will often reveal an asymmetrical, high-riding testis with a transverse lie on the affected side. The cremasteric reflex is usually absent in patients with testicular torsion.

Because of the significant overlap in history and physical examination findings for epididymitis and testicular torsion, a testicular ultrasound with color Doppler should be ordered. Multiple studies have confirmed the high sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound in the diagnosis of testicular torsion.

The treatment for suspected or confirmed testicular torsion is immediate surgical exploration with intraoperative detorsion and fixation of the testes. The EP can attempt manual detorsion (ie, performed in a medial to lateral motion, similar to opening a book). However, this should not delay the EP from consulting with urology services.

Pediatric patients with testicular torsion usually have a more favorable outcome than do adults. In one retrospective study, patients younger than age 21 years had a 70% testicular salvage rate compared to only 41% of patients aged 21 years and older.7 Regardless of age, better outcomes are associated with shorter periods of torsion.

Fournier’s Gangrene

Fournier’s gangrene is a polymicrobial necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum and scrotum that typically develops initially as a benign infection or abscess but quickly spreads. Risk factors for Fournier’s gangrene include DM, alcohol abuse, and any immunocompromised state (eg, HIV, cancer).

If the patient presents early in onset, there may be only mild tenderness, erythema, or swelling of the affected area; however, this infection progresses rapidly. Later findings include marked tenderness, swelling, crepitus, blisters, and ecchymoses. Patients with Fournier’s gangrene also develop systemic signs of infection, including fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypotension. The key to diagnosis is careful examination of the perineal and scrotal area in any patient presenting with acute scrotal pain.

In the majority of cases, the diagnosis of Fournier’s gangrene is made clinically. Once the diagnosis is made, patients require immediate and aggressive IV fluid resuscitation, broad-spectrum IV antibiotics (typically vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam), and emergent evaluation by a urologist. It is essential that these patients undergo early and aggressive surgical exploration and debridement of necrotic tissue.2 Antibiotic therapy alone is associated with a 100% mortality rate, emphasizing the need for urgent surgery.2 Even with optimal medical and surgical management, the mortality rate remains significant.

Summary

This case emphasizes several important teaching points. The EP should be mindful of the patient who keeps returning to the ED with the same complaint—despite “appropriate” treatment—as the initial diagnosis may not be the correct one. Such returning patients require greater, not less, scrutiny. As with any patient, the EP should always take a complete history and perform a thorough physical examination at each presentation—as one would with a de novo patient. Finally, the EP should consider Fournier’s gangrene in addition to testicular torsion and epididymitis in the differential diagnosis for acute scrotal pain.

Case

A 52-year-old man presented to the ED for evaluation of right scrotal pain and swelling. The patient stated that the pain started several hours prior to presentation and had gradually worsened. He denied any trauma or inciting event to the affected area; he further denied abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, dysuria, polyuria, or fever. The patient’s remote medical history was significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), which he managed through dietary modification-only as he had refused pharmacological therapy. The patient admitted to smoking one half-pack of cigarettes per week, but denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

At presentation, the patient’s vital signs were all within normal range. The physical examination was remarkable only for right testicular tenderness and mild scrotal swelling, and there were no hernias or lymphadenopathy present.

The emergency physician (EP) ordered a urinalysis and color-flow Doppler ultrasound study of both testes, which the radiologist interpreted as an enlarged right epididymis with hyperemia; the left testicle was normal. The urinalysis was normal.

The patient was diagnosed with epididymitis and discharged home with a prescription for oral levofloxacin 500 mg daily for 10 days. He also was instructed to take ibuprofen for pain, apply ice to the affected area, keep the scrotal area elevated, and follow-up with a urologist in 1 week.

Approximately 8 hours after discharge, the patient returned to the same ED with complaints of increasing right testicular pain and swelling. The history and physical examination at this visit were essentially unchanged from his initial presentation. No laboratory evaluation, imaging studies, or other tests were ordered at the second visit.

The patient was discharged home with a prescription for a narcotic analgesic, which he was instructed to take in addition to the ibuprofen; he was also instructed to follow-up with a urologist within the next 2 to 3 days, instead of in 1 week.

The patient returned the following morning to the same ED with complaints of increased swelling and pain of the right testicle. In addition to the worsening testicular pain and swelling, he also had right inguinal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. Vital signs at this third presentation were: blood pressure (BP), 124/64 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 110 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and temperature, 99.8o F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

The patient was tachycardic on heart examination, but with regular rhythm and no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. The lung and abdominal examinations were normal. The genital examination revealed marked right scrotal swelling and tenderness, as well as tender right inguinal lymphadenopathy.

The EP ordered an intravenous (IV) bolus of 1 L normal saline and laboratory studies, which included lactic acid, blood cultures, urinalysis, and urine culture and sensitivity. The EP was concerned for a scrotal abscess and ordered a testicular Doppler color-flow ultrasound study. The laboratory studies revealed an elevated white blood count of 16.5 K/uL, elevated blood glucose of 364 mg/dL, and elevated lactate of 2.8 mg/dL. As demonstrated on the ultrasound study performed at the patient’s first presentation, the ultrasound again showed an enlarged right epididymis, but without orchitis or abscess. The scrotal wall had significant thickening, consistent with cellulitis. The EP ordered broad spectrum IV antibiotics and admitted the patient to the hospitalist with a consult request for urology services.

The patient continued to receive IV fluids and antibiotics throughout the evening. In the morning, he was seen by the same hospitalist/admitting physician from the previous evening. Upon physical examination, the hospitalist noted tenderness, swelling, and erythema in the patient’s perineal area. The patient’s BP had dropped to 100/60 mm Hg, and his HR had increased to 115 beats/min despite receiving nearly 2 L of normal saline IV throughout the previous evening and night.

The urologist examined the patient soon after the consult request and diagnosed him with Fournier’s gangrene. He started the patient on aggressive IV fluid resuscitation, after which the patient was immediately taken to the operating room for extensive surgical debridement and scrotectomy. The patient’s postoperative course was complicated by acute kidney injury, respiratory failure requiring ventilator support, and sepsis. After a lengthy hospital stay, the patient was discharged home, but required a scrotal skin graft, and experienced erectile dysfunction and depression.

The patient sued all of the EPs involved in his care, the hospital, the hospitalist/admitting physician, and the urologist for negligence. The plaintiff’s attorney argued that since the patient progressively deteriorated over the 24 to 36 hours during his three presentations to the ED, urology services should have been consulted earlier, and that the urologist should have seen the patient immediately at the time of hospital admission.

The attorneys for the defendants claimed the patient denied dysuria, penile lesions, or urethral discharge and that the history, physical examination, and testicular ultrasound were all consistent with the diagnosis of epididymitis. For this reason, they argued, there was no indication for an emergent consultation with urology services. The jury returned a defense verdict.

Discussion

It is easy for a busy EP to have a differential diagnosis of only two disorders when evaluating a patient for unilateral testicular pain and swelling—in this case, testicular torsion and epididymitis. While these are the most common causes of testicular pain and swelling, this case emphasizes the need to also consider Fournier’s gangrene in the differential. A thorough history and physical examination, coupled with appropriate testing, will usually identify the correct diagnosis. While the differential diagnosis is broader than just these three disease processes (see the Box), we will review the evaluation and management of the three most serious: epididymitis, testicular torsion, and Fournier’s gangrene.

Noninfectious and Bacterial Epididymitis

Epididymitis is the most common cause of acute scrotal pain among US adults, accounting for approximately 600,000 cases each year.1 Infectious epididymitis is typically classified as acute (symptom duration of <6 weeks) or chronic (symptom duration of ≥6 weeks).2

Cases of noninfectious epididymitis are typically due to a chronic condition, such as autoimmune disease, cancer, or vasculitis. Although not as common, noninfectious epididymitis can also occur due to testicular trauma or amiodarone therapy.3,4

Patients with acute bacterial epididymitis typically present with scrotal pain and swelling ranging from mild to marked. These patients may also exhibit fever and chills, along with dysuria, frequency, and urgency, if associated with a urinary tract infection.2 The chronic presentation is more common though, and usually not associated with voiding issues.

Chronic epididymis is frequently seen in postpubertal boys and men following sexual activity, heavy physical exertion, and bicycle/motorcycle riding.2 On physical examination, palpation reveals induration and swelling of the involved epididymis with exquisite tenderness.2 Testicular swelling and pain, along with scrotal wall erythema, may be present in more advanced cases.2 The cremasteric reflex should be intact (ie, scratching the medial proximal thigh will cause ipsilateral testicle retraction). Similarly, the lie of both testicles while the patient is standing should be equal and symmetrical—ie, both testicles descended equally. However, in the presence of moderate-to-severe scrotal swelling, both of these physical findings may be impossible to confirm.

A urinalysis and urine culture should be ordered if there is any suspicion of epididymitis; pyuria will be present in approximately 50% of cases. However, since pyuria is neither sensitive nor specific for epididymitis, in most cases, a testicular ultrasound with Doppler flow is required to exclude testicular torsion. In cases of epididymitis, ultrasound usually demonstrates increased flow on the affected side, whereas in testicular torsion, there is decreased or absent blood flow.

The treatment for epididymitis involves antibiotics and symptomatic care. If epididymitis from chlamydia and/or gonorrhea is the suspected cause, or if the patient is younger than age 35 years, he should be given ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly plus oral doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 10 days. Patients who practice insertive anal sex should be treated with ceftriaxone, plus either oral ofloxacin 300 mg twice a day or oral levofloxacin 500 mg daily for 10 days.

In cases in which enteric organisms are suspected, the patient is older than age 35 years, or if patient status is posturinary tract instrumentation or vasectomy, he should be treated with either oral ofloxacin 300 mg twice a day or oral levofloxacin 500 mg daily for 10 days.2

For symptomatic relief, scrotal elevation, ice application, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are recommended.

Patients with epididymitis, regardless of etiology, should be instructed to follow-up with a urologist within 1 week. If the patient appears ill, septic, or in significant pain, admission to the hospital with IV antibiotics, IV fluids, and an urgent consult with urology services is required.

Testicular Torsion

Testicular torsion is a time-sensitive issue, requiring early diagnosis and rapid treatment to preserve the patient’s fertility. Most clinicians recommend detorsion within 6 hours of torsion onset because salvage rates are excellent when performed within this timeframe; after 12 hours, the testis will likely suffer irreversible damage due to ischemia.5,6

Testicular torsion can occur at any age, but is most commonly seen in a bimodal distribution—ie, neonates and postpubertal boys. The prevalence of testicular torsion in adult patients hospitalized with acute scrotal pain is approximately 25% to 50%.2

Patients with testicular torsion usually describe a sudden onset of severe, acute pain. The pain frequently occurs a few hours after vigorous physical activity or minor testicular trauma.2 Occasionally, the patient may complain of lower quadrant abdominal pain rather than testicular or scrotal pain. Nausea with vomiting can also be present.

On physical examination, significant testicular swelling is usually present. Examining the patient in the standing position will often reveal an asymmetrical, high-riding testis with a transverse lie on the affected side. The cremasteric reflex is usually absent in patients with testicular torsion.

Because of the significant overlap in history and physical examination findings for epididymitis and testicular torsion, a testicular ultrasound with color Doppler should be ordered. Multiple studies have confirmed the high sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound in the diagnosis of testicular torsion.

The treatment for suspected or confirmed testicular torsion is immediate surgical exploration with intraoperative detorsion and fixation of the testes. The EP can attempt manual detorsion (ie, performed in a medial to lateral motion, similar to opening a book). However, this should not delay the EP from consulting with urology services.

Pediatric patients with testicular torsion usually have a more favorable outcome than do adults. In one retrospective study, patients younger than age 21 years had a 70% testicular salvage rate compared to only 41% of patients aged 21 years and older.7 Regardless of age, better outcomes are associated with shorter periods of torsion.

Fournier’s Gangrene

Fournier’s gangrene is a polymicrobial necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum and scrotum that typically develops initially as a benign infection or abscess but quickly spreads. Risk factors for Fournier’s gangrene include DM, alcohol abuse, and any immunocompromised state (eg, HIV, cancer).

If the patient presents early in onset, there may be only mild tenderness, erythema, or swelling of the affected area; however, this infection progresses rapidly. Later findings include marked tenderness, swelling, crepitus, blisters, and ecchymoses. Patients with Fournier’s gangrene also develop systemic signs of infection, including fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypotension. The key to diagnosis is careful examination of the perineal and scrotal area in any patient presenting with acute scrotal pain.

In the majority of cases, the diagnosis of Fournier’s gangrene is made clinically. Once the diagnosis is made, patients require immediate and aggressive IV fluid resuscitation, broad-spectrum IV antibiotics (typically vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam), and emergent evaluation by a urologist. It is essential that these patients undergo early and aggressive surgical exploration and debridement of necrotic tissue.2 Antibiotic therapy alone is associated with a 100% mortality rate, emphasizing the need for urgent surgery.2 Even with optimal medical and surgical management, the mortality rate remains significant.

Summary

This case emphasizes several important teaching points. The EP should be mindful of the patient who keeps returning to the ED with the same complaint—despite “appropriate” treatment—as the initial diagnosis may not be the correct one. Such returning patients require greater, not less, scrutiny. As with any patient, the EP should always take a complete history and perform a thorough physical examination at each presentation—as one would with a de novo patient. Finally, the EP should consider Fournier’s gangrene in addition to testicular torsion and epididymitis in the differential diagnosis for acute scrotal pain.

1. Trojian TH, Lishnak TS, Heiman D. Epididymitis and orchitis: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(7):583-587.

2. Eyre RC. Evaluation of acute scrotal pain in adults. UpToDate Web site. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-acute-scrotal-pain-in-adults. Updated July 31, 2017. Accessed September 7, 2017.

3. Shen Y, Liu H, Cheng J, Bu P. Amiodarone-induced epididymitis: a pathologically confirmed case report and review of the literature. Cardiology. 2014;128(4):349-351. doi:10.1159/000361038.

4. Tracy CR, Steers WD, Costabile R. Diagnosis and management of epididymitis. Urol Clin North Am. 2008;35(1):101-108. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2007.09.013.

5. Wampler SM, Llanes M. Common scrotal and testicular problems. Prim Care. 2010;37(3):613-626. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2010.04.009.

6. Dunne PJ, O’Loughlin BS. Testicular torsion: time is the enemy. Aust NZ J Surg. 2000;70(6):441-442.

7. Cummings JM, Boullier JA, Sekhon D, Bose K. Adult testicular torsion. J Urol. 2002;167(5):2109-2110.

1. Trojian TH, Lishnak TS, Heiman D. Epididymitis and orchitis: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(7):583-587.

2. Eyre RC. Evaluation of acute scrotal pain in adults. UpToDate Web site. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-acute-scrotal-pain-in-adults. Updated July 31, 2017. Accessed September 7, 2017.

3. Shen Y, Liu H, Cheng J, Bu P. Amiodarone-induced epididymitis: a pathologically confirmed case report and review of the literature. Cardiology. 2014;128(4):349-351. doi:10.1159/000361038.

4. Tracy CR, Steers WD, Costabile R. Diagnosis and management of epididymitis. Urol Clin North Am. 2008;35(1):101-108. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2007.09.013.

5. Wampler SM, Llanes M. Common scrotal and testicular problems. Prim Care. 2010;37(3):613-626. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2010.04.009.

6. Dunne PJ, O’Loughlin BS. Testicular torsion: time is the enemy. Aust NZ J Surg. 2000;70(6):441-442.

7. Cummings JM, Boullier JA, Sekhon D, Bose K. Adult testicular torsion. J Urol. 2002;167(5):2109-2110.

Case Studies in Toxicology: Always Cook Your Boba

Case

A 45-year-old Chinese man with no known medical history presented to the ED with right-sided facial spasm and cheek swelling, which began immediately after he bit into a piece of taro root, approximately 2 hours prior to presentation. The patient stated that the root was an ingredient in a soup that a relative had made. According to the patient, after biting into the root, he immediately experienced a burning pain on the right side of his mouth. He further noted that he swallowed less than two bites of the root and stopped eating because the act of chewing was too painful.

Initial vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure, 140/100 mm Hg; heart rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 beats/min; and temperature, 97.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. The patient’s physical examination was remarkable for pain upon opening the mouth, as well as right-sided cheek and lip swelling and tenderness. The tongue and oropharynx were not erythematous or swollen. The patient was only able to speak in short sentences, secondary to oropharyngeal pain, but he was in no respiratory distress. No urticaria, pruritus, wheezing, or stridor was present.

During the patient’s workup, his 40-year-old wife also presented to the same ED for evaluation of burning pain and spasm on the left side of her mouth, which she stated also developed immediately after she bit into a piece of taro root contained in the same soup as that ingested by the patient.

The wife’s vital signs were unremarkable, and she was in no respiratory distress. Her physical examination was remarkable only for left-sided cheek and lip swelling and tenderness, associated with an erythematous oropharynx and pain with speaking.

What is taro? What are the manifestations of taro toxicity?

Taro commonly refers to plants from the Araceae family, usually Colocasia esculenta.1 Taro is ubiquitous in Southern Asia and Southeast India. It is a widely naturalized and perennial tropical plant primarily grown as a root vegetable, and is a common flavor in boba (bubble) tea. All members of Araceae contain calcium oxalate crystals in the form of raphides, sharp needle-shaped crystals packaged in idioblasts and contained within the waxy leaf.2 Pressure on the idioblasts, such as from mastication, triggers the release of the raphides. The needles pierce the surface of any tissue with which they come into contact, creating a gateway for proteolytic enzymes to enter the consumer.3 The leaves and root of Araceae must be cooked before eating to inactivate the raphides.

Oral exposure to uncooked taro leaves or taro root can result in mouth irritation and swelling that can progress to angioedema and airway obstruction. Although the traditional method of removing taro raphides is to soak the root in cold water overnight,4,5 this does not fully remove all of the raphides. Instead, taro root should be thoroughly cooked in boiling water to draw-out oxalates from the root into the cooking water, which must then be discarded. Consuming taro with warm milk also reduces the effect of the oxalates by about 80%.6

Many other plants of the Araceae family, such as Dieffenbachia (dumbcane), share similar toxicity and are commonly kept in the home and office.

Patients with oral exposure to taro may experience a delayed (also termed biphasic) anaphylactic reaction, ie, the development of anaphylactic symptoms more than 4 hours after the inciting event. Delayed anaphylaxis is distinct from delayed hypersensitivity, though both may be immunoglobulin E-mediated. Delayed hypersensitivity presents later (2-14 days) and with less immediately life-threatening effects, most commonly dermatitis (eg, poison ivy dermatitis).

While both of the patients in this case presented with mild symptoms, life-threatening angioedema of the oropharynx, anaphylaxis, and hypocalcemia have been reported7,8 and should be considered in any symptomatic patient with exposure to taro.

What is the differential diagnosis of plant-related mouth pain?

The oral mucosa is composed of superficial layers of mucin and epithelial cells that lie over the dermis and connective tissue. Local immune cells, including mast cells and Langerhans cells, reside in the deeper layers. The differential diagnosis of plant-based mouth pain can be divided into mechanical, chemical, and thermal causes.

Mechanical Causes. Causes of mechanical plant-based oral pain include structural damage when foreign matter, such as barbs, sharp leaves, or hard seeds, pierce the layers of the oral mucosa.

Chemical Causes. Chemical-related causes of oral pain include caustic ingestion, for example from detergents or cleaning agents that contaminate the broth. Araceae, such as taro or arum, have sharp calcium oxalate crystals tipped with phospholipases and proteases that cause mechanical pain on piercing mucous membranes, and chemical pain by enzymatically degrading epithelium and mucosa. Both chemical and mechanical irritation can lead to an inflammatory response. Raw taro can cause irritant contact stomatitis as the raphides pierce the oral mucosa. It can also cause allergic stomatitis if antigens related to the phospholipases or proteases are presented to Langerhans cells.9

Thermal Causes. The hot temperature of the ingested broth could cause thermal injury, but the injury is likely to be more diffuse.

How common is taro exposure, and how is it treated?

From 1995 to 1999, 15 cases of taro poisoning were reported to the Drug and Toxicology Information service in Zimbabwe.10 From 2005 to 2009, 21 out of 31 cases reported to the Hong Kong Poison Control Center involving gastrointestinal irritation involved the consumption of Colocasia fallax, a form of taro more common in Tibet, the Himalayas, and northern Indochina.7 Of the 31 cases, six patients were treated with diphenhydramine, epinephrine, and dexamethasone for angioedema.

From 2011 to 2013, two cases of mouth irritation and swelling after eating raw taro leaves were reported to the British Columbia Poison Control Center.11 Those two patients were observed for 6 hours without specific treatment and discharged.

Case Conclusion

Due to concerns of the potential for anaphylaxis, both patients were treated intravenously with 50 mg diphenhydramine and 10 mg dexamethasone. The husband was also given 650 mg acetaminophen orally for pain relief; his wife declined pain medication. Laboratory evaluation, including a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function panel, and urinalysis were ordered for both patients; all results were within normal limits for both patients.

After an uneventful 6-hour observation period, both patients were discharged home with instructions to return to the ED if they develop any signs of allergic reaction and to call emergency medical services for any sign of anaphylaxis.

1. Rao RV, Matthews PJ, Eyzaguirre PB, Hunter D, eds. 2010. The Global Diversity of Taro: Ethnobotany and Conservation. Rome, Italy; Biouniversity International; 2010. http://www.bioversityinternational.org/fileadmin/user_upload/online_library/publications/pdfs/1402.pdf#page=11. Accessed September 15, 2017.

2. Franceschi VR, Nakata PA. Calcium oxalate in plants: formation and function. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2005;56:41-71. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144106.

3. Herbert DA. Stinging crystals in plants. Science. 1924;60(1548):204-205. doi:10.1126/science.60.1548.204-a.

4. Njintang YN, Mbofung CMF. Effect of precooking time and drying temperature on the physico-chemical characteristics and in-vitro carbohydrate digestibility of taro flour. LWT – Food Sci and Tech. 2006;39(6):684-691. doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2005.03.022.

5. Savage GP, Dubois M. The effect of soaking and cooking on the oxalate content of taro leaves. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2006;57(5-6):376-381. doi:10.1080/09637480600855239.

6. Oscarsson, KV. Savage GP. Composition and availability of soluble and insoluble oxalates in raw and cooked taro (Colocasia esculenta var. Schott) leaves. Food Chem 101. 2007;101(2):559-562. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.02.014.

7. Pang CT, Ng HW, Lau FL. Oral mucosal irritating plant ingestion in Hong Kong, epidemiology and its clinical presentation. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2010;17(5):477-481.

8. Yuen E. Upper airway obstruction as a presentation of Taro poisoning. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2001;8(3):163-165.

9. Davis CC, Squier CA, Lilly GE. Irritant contact stomatitis: a review of the condition. J Periodontol. 1998;69(6):620-631. doi:10.1902/jop.1998.69.6.620.

10 Tagwireyi D, Ball DE. The management of Elephant’s Ear poisoning. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2001;20(4):189-192. doi:10.1191/096032701678766822.

11. Omura JD, Blake C, McIntyre L, Li D, Kosatsky T. Two cases of poisoning by raw taro leaf and how a poison control centre, food safety inspectors, and a specialty supermarket chain found a solution.” Environ Health Rev. 2014;57(3):59-64. doi.org/10.5864/d2014-027.

Case

A 45-year-old Chinese man with no known medical history presented to the ED with right-sided facial spasm and cheek swelling, which began immediately after he bit into a piece of taro root, approximately 2 hours prior to presentation. The patient stated that the root was an ingredient in a soup that a relative had made. According to the patient, after biting into the root, he immediately experienced a burning pain on the right side of his mouth. He further noted that he swallowed less than two bites of the root and stopped eating because the act of chewing was too painful.

Initial vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure, 140/100 mm Hg; heart rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 beats/min; and temperature, 97.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. The patient’s physical examination was remarkable for pain upon opening the mouth, as well as right-sided cheek and lip swelling and tenderness. The tongue and oropharynx were not erythematous or swollen. The patient was only able to speak in short sentences, secondary to oropharyngeal pain, but he was in no respiratory distress. No urticaria, pruritus, wheezing, or stridor was present.

During the patient’s workup, his 40-year-old wife also presented to the same ED for evaluation of burning pain and spasm on the left side of her mouth, which she stated also developed immediately after she bit into a piece of taro root contained in the same soup as that ingested by the patient.

The wife’s vital signs were unremarkable, and she was in no respiratory distress. Her physical examination was remarkable only for left-sided cheek and lip swelling and tenderness, associated with an erythematous oropharynx and pain with speaking.

What is taro? What are the manifestations of taro toxicity?

Taro commonly refers to plants from the Araceae family, usually Colocasia esculenta.1 Taro is ubiquitous in Southern Asia and Southeast India. It is a widely naturalized and perennial tropical plant primarily grown as a root vegetable, and is a common flavor in boba (bubble) tea. All members of Araceae contain calcium oxalate crystals in the form of raphides, sharp needle-shaped crystals packaged in idioblasts and contained within the waxy leaf.2 Pressure on the idioblasts, such as from mastication, triggers the release of the raphides. The needles pierce the surface of any tissue with which they come into contact, creating a gateway for proteolytic enzymes to enter the consumer.3 The leaves and root of Araceae must be cooked before eating to inactivate the raphides.

Oral exposure to uncooked taro leaves or taro root can result in mouth irritation and swelling that can progress to angioedema and airway obstruction. Although the traditional method of removing taro raphides is to soak the root in cold water overnight,4,5 this does not fully remove all of the raphides. Instead, taro root should be thoroughly cooked in boiling water to draw-out oxalates from the root into the cooking water, which must then be discarded. Consuming taro with warm milk also reduces the effect of the oxalates by about 80%.6

Many other plants of the Araceae family, such as Dieffenbachia (dumbcane), share similar toxicity and are commonly kept in the home and office.

Patients with oral exposure to taro may experience a delayed (also termed biphasic) anaphylactic reaction, ie, the development of anaphylactic symptoms more than 4 hours after the inciting event. Delayed anaphylaxis is distinct from delayed hypersensitivity, though both may be immunoglobulin E-mediated. Delayed hypersensitivity presents later (2-14 days) and with less immediately life-threatening effects, most commonly dermatitis (eg, poison ivy dermatitis).

While both of the patients in this case presented with mild symptoms, life-threatening angioedema of the oropharynx, anaphylaxis, and hypocalcemia have been reported7,8 and should be considered in any symptomatic patient with exposure to taro.

What is the differential diagnosis of plant-related mouth pain?

The oral mucosa is composed of superficial layers of mucin and epithelial cells that lie over the dermis and connective tissue. Local immune cells, including mast cells and Langerhans cells, reside in the deeper layers. The differential diagnosis of plant-based mouth pain can be divided into mechanical, chemical, and thermal causes.

Mechanical Causes. Causes of mechanical plant-based oral pain include structural damage when foreign matter, such as barbs, sharp leaves, or hard seeds, pierce the layers of the oral mucosa.

Chemical Causes. Chemical-related causes of oral pain include caustic ingestion, for example from detergents or cleaning agents that contaminate the broth. Araceae, such as taro or arum, have sharp calcium oxalate crystals tipped with phospholipases and proteases that cause mechanical pain on piercing mucous membranes, and chemical pain by enzymatically degrading epithelium and mucosa. Both chemical and mechanical irritation can lead to an inflammatory response. Raw taro can cause irritant contact stomatitis as the raphides pierce the oral mucosa. It can also cause allergic stomatitis if antigens related to the phospholipases or proteases are presented to Langerhans cells.9

Thermal Causes. The hot temperature of the ingested broth could cause thermal injury, but the injury is likely to be more diffuse.

How common is taro exposure, and how is it treated?

From 1995 to 1999, 15 cases of taro poisoning were reported to the Drug and Toxicology Information service in Zimbabwe.10 From 2005 to 2009, 21 out of 31 cases reported to the Hong Kong Poison Control Center involving gastrointestinal irritation involved the consumption of Colocasia fallax, a form of taro more common in Tibet, the Himalayas, and northern Indochina.7 Of the 31 cases, six patients were treated with diphenhydramine, epinephrine, and dexamethasone for angioedema.

From 2011 to 2013, two cases of mouth irritation and swelling after eating raw taro leaves were reported to the British Columbia Poison Control Center.11 Those two patients were observed for 6 hours without specific treatment and discharged.

Case Conclusion

Due to concerns of the potential for anaphylaxis, both patients were treated intravenously with 50 mg diphenhydramine and 10 mg dexamethasone. The husband was also given 650 mg acetaminophen orally for pain relief; his wife declined pain medication. Laboratory evaluation, including a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function panel, and urinalysis were ordered for both patients; all results were within normal limits for both patients.

After an uneventful 6-hour observation period, both patients were discharged home with instructions to return to the ED if they develop any signs of allergic reaction and to call emergency medical services for any sign of anaphylaxis.

Case

A 45-year-old Chinese man with no known medical history presented to the ED with right-sided facial spasm and cheek swelling, which began immediately after he bit into a piece of taro root, approximately 2 hours prior to presentation. The patient stated that the root was an ingredient in a soup that a relative had made. According to the patient, after biting into the root, he immediately experienced a burning pain on the right side of his mouth. He further noted that he swallowed less than two bites of the root and stopped eating because the act of chewing was too painful.

Initial vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure, 140/100 mm Hg; heart rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 beats/min; and temperature, 97.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. The patient’s physical examination was remarkable for pain upon opening the mouth, as well as right-sided cheek and lip swelling and tenderness. The tongue and oropharynx were not erythematous or swollen. The patient was only able to speak in short sentences, secondary to oropharyngeal pain, but he was in no respiratory distress. No urticaria, pruritus, wheezing, or stridor was present.

During the patient’s workup, his 40-year-old wife also presented to the same ED for evaluation of burning pain and spasm on the left side of her mouth, which she stated also developed immediately after she bit into a piece of taro root contained in the same soup as that ingested by the patient.

The wife’s vital signs were unremarkable, and she was in no respiratory distress. Her physical examination was remarkable only for left-sided cheek and lip swelling and tenderness, associated with an erythematous oropharynx and pain with speaking.

What is taro? What are the manifestations of taro toxicity?

Taro commonly refers to plants from the Araceae family, usually Colocasia esculenta.1 Taro is ubiquitous in Southern Asia and Southeast India. It is a widely naturalized and perennial tropical plant primarily grown as a root vegetable, and is a common flavor in boba (bubble) tea. All members of Araceae contain calcium oxalate crystals in the form of raphides, sharp needle-shaped crystals packaged in idioblasts and contained within the waxy leaf.2 Pressure on the idioblasts, such as from mastication, triggers the release of the raphides. The needles pierce the surface of any tissue with which they come into contact, creating a gateway for proteolytic enzymes to enter the consumer.3 The leaves and root of Araceae must be cooked before eating to inactivate the raphides.

Oral exposure to uncooked taro leaves or taro root can result in mouth irritation and swelling that can progress to angioedema and airway obstruction. Although the traditional method of removing taro raphides is to soak the root in cold water overnight,4,5 this does not fully remove all of the raphides. Instead, taro root should be thoroughly cooked in boiling water to draw-out oxalates from the root into the cooking water, which must then be discarded. Consuming taro with warm milk also reduces the effect of the oxalates by about 80%.6

Many other plants of the Araceae family, such as Dieffenbachia (dumbcane), share similar toxicity and are commonly kept in the home and office.

Patients with oral exposure to taro may experience a delayed (also termed biphasic) anaphylactic reaction, ie, the development of anaphylactic symptoms more than 4 hours after the inciting event. Delayed anaphylaxis is distinct from delayed hypersensitivity, though both may be immunoglobulin E-mediated. Delayed hypersensitivity presents later (2-14 days) and with less immediately life-threatening effects, most commonly dermatitis (eg, poison ivy dermatitis).

While both of the patients in this case presented with mild symptoms, life-threatening angioedema of the oropharynx, anaphylaxis, and hypocalcemia have been reported7,8 and should be considered in any symptomatic patient with exposure to taro.

What is the differential diagnosis of plant-related mouth pain?

The oral mucosa is composed of superficial layers of mucin and epithelial cells that lie over the dermis and connective tissue. Local immune cells, including mast cells and Langerhans cells, reside in the deeper layers. The differential diagnosis of plant-based mouth pain can be divided into mechanical, chemical, and thermal causes.

Mechanical Causes. Causes of mechanical plant-based oral pain include structural damage when foreign matter, such as barbs, sharp leaves, or hard seeds, pierce the layers of the oral mucosa.

Chemical Causes. Chemical-related causes of oral pain include caustic ingestion, for example from detergents or cleaning agents that contaminate the broth. Araceae, such as taro or arum, have sharp calcium oxalate crystals tipped with phospholipases and proteases that cause mechanical pain on piercing mucous membranes, and chemical pain by enzymatically degrading epithelium and mucosa. Both chemical and mechanical irritation can lead to an inflammatory response. Raw taro can cause irritant contact stomatitis as the raphides pierce the oral mucosa. It can also cause allergic stomatitis if antigens related to the phospholipases or proteases are presented to Langerhans cells.9

Thermal Causes. The hot temperature of the ingested broth could cause thermal injury, but the injury is likely to be more diffuse.

How common is taro exposure, and how is it treated?

From 1995 to 1999, 15 cases of taro poisoning were reported to the Drug and Toxicology Information service in Zimbabwe.10 From 2005 to 2009, 21 out of 31 cases reported to the Hong Kong Poison Control Center involving gastrointestinal irritation involved the consumption of Colocasia fallax, a form of taro more common in Tibet, the Himalayas, and northern Indochina.7 Of the 31 cases, six patients were treated with diphenhydramine, epinephrine, and dexamethasone for angioedema.

From 2011 to 2013, two cases of mouth irritation and swelling after eating raw taro leaves were reported to the British Columbia Poison Control Center.11 Those two patients were observed for 6 hours without specific treatment and discharged.

Case Conclusion

Due to concerns of the potential for anaphylaxis, both patients were treated intravenously with 50 mg diphenhydramine and 10 mg dexamethasone. The husband was also given 650 mg acetaminophen orally for pain relief; his wife declined pain medication. Laboratory evaluation, including a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function panel, and urinalysis were ordered for both patients; all results were within normal limits for both patients.

After an uneventful 6-hour observation period, both patients were discharged home with instructions to return to the ED if they develop any signs of allergic reaction and to call emergency medical services for any sign of anaphylaxis.

1. Rao RV, Matthews PJ, Eyzaguirre PB, Hunter D, eds. 2010. The Global Diversity of Taro: Ethnobotany and Conservation. Rome, Italy; Biouniversity International; 2010. http://www.bioversityinternational.org/fileadmin/user_upload/online_library/publications/pdfs/1402.pdf#page=11. Accessed September 15, 2017.

2. Franceschi VR, Nakata PA. Calcium oxalate in plants: formation and function. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2005;56:41-71. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144106.

3. Herbert DA. Stinging crystals in plants. Science. 1924;60(1548):204-205. doi:10.1126/science.60.1548.204-a.

4. Njintang YN, Mbofung CMF. Effect of precooking time and drying temperature on the physico-chemical characteristics and in-vitro carbohydrate digestibility of taro flour. LWT – Food Sci and Tech. 2006;39(6):684-691. doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2005.03.022.

5. Savage GP, Dubois M. The effect of soaking and cooking on the oxalate content of taro leaves. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2006;57(5-6):376-381. doi:10.1080/09637480600855239.

6. Oscarsson, KV. Savage GP. Composition and availability of soluble and insoluble oxalates in raw and cooked taro (Colocasia esculenta var. Schott) leaves. Food Chem 101. 2007;101(2):559-562. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.02.014.

7. Pang CT, Ng HW, Lau FL. Oral mucosal irritating plant ingestion in Hong Kong, epidemiology and its clinical presentation. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2010;17(5):477-481.

8. Yuen E. Upper airway obstruction as a presentation of Taro poisoning. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2001;8(3):163-165.

9. Davis CC, Squier CA, Lilly GE. Irritant contact stomatitis: a review of the condition. J Periodontol. 1998;69(6):620-631. doi:10.1902/jop.1998.69.6.620.

10 Tagwireyi D, Ball DE. The management of Elephant’s Ear poisoning. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2001;20(4):189-192. doi:10.1191/096032701678766822.

11. Omura JD, Blake C, McIntyre L, Li D, Kosatsky T. Two cases of poisoning by raw taro leaf and how a poison control centre, food safety inspectors, and a specialty supermarket chain found a solution.” Environ Health Rev. 2014;57(3):59-64. doi.org/10.5864/d2014-027.

1. Rao RV, Matthews PJ, Eyzaguirre PB, Hunter D, eds. 2010. The Global Diversity of Taro: Ethnobotany and Conservation. Rome, Italy; Biouniversity International; 2010. http://www.bioversityinternational.org/fileadmin/user_upload/online_library/publications/pdfs/1402.pdf#page=11. Accessed September 15, 2017.

2. Franceschi VR, Nakata PA. Calcium oxalate in plants: formation and function. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2005;56:41-71. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144106.

3. Herbert DA. Stinging crystals in plants. Science. 1924;60(1548):204-205. doi:10.1126/science.60.1548.204-a.

4. Njintang YN, Mbofung CMF. Effect of precooking time and drying temperature on the physico-chemical characteristics and in-vitro carbohydrate digestibility of taro flour. LWT – Food Sci and Tech. 2006;39(6):684-691. doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2005.03.022.

5. Savage GP, Dubois M. The effect of soaking and cooking on the oxalate content of taro leaves. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2006;57(5-6):376-381. doi:10.1080/09637480600855239.

6. Oscarsson, KV. Savage GP. Composition and availability of soluble and insoluble oxalates in raw and cooked taro (Colocasia esculenta var. Schott) leaves. Food Chem 101. 2007;101(2):559-562. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.02.014.

7. Pang CT, Ng HW, Lau FL. Oral mucosal irritating plant ingestion in Hong Kong, epidemiology and its clinical presentation. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2010;17(5):477-481.

8. Yuen E. Upper airway obstruction as a presentation of Taro poisoning. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2001;8(3):163-165.

9. Davis CC, Squier CA, Lilly GE. Irritant contact stomatitis: a review of the condition. J Periodontol. 1998;69(6):620-631. doi:10.1902/jop.1998.69.6.620.

10 Tagwireyi D, Ball DE. The management of Elephant’s Ear poisoning. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2001;20(4):189-192. doi:10.1191/096032701678766822.

11. Omura JD, Blake C, McIntyre L, Li D, Kosatsky T. Two cases of poisoning by raw taro leaf and how a poison control centre, food safety inspectors, and a specialty supermarket chain found a solution.” Environ Health Rev. 2014;57(3):59-64. doi.org/10.5864/d2014-027.

Heart Failure in the Emergency Department

Patients with heart failure (HF) present daily to busy EDs. An estimated 6.5 million Americans are living with this diagnosis, and the number is predicted to grow to 8 million by 2023.1 Most HF patients (82.1%) who present to EDs are hospitalized, while a selected minority are either managed in the ED and discharged (11.6%) or managed in observation units (OU) (6.3%).2 The prognosis after HF is initially diagnosed is poor, with a 5-year mortality of 50%,3 and after a single HF hospitalization, 29% will die within 1 year.4

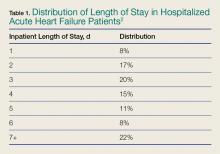

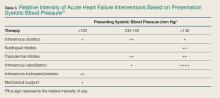

One-third of the total Medicare budget is spent on HF, despite the fact that HF represents only 10.5% of the Medicare population.2 Up to 80% of HF costs are for hospitalizations, which cost an average of $11,840 per inpatient admission.5,6 The high costs are due to an average length of stay (LOS) of 5.2 days7 (Table 1).

Adding to hospital costs is the degree of “reactivism,” with approximately 20% of patients discharged from the ED returning within 2 weeks, of whom nearly 50% will be hospitalized.11 Following HF hospitalization and discharge, the 30-day readmission rate is 26.2%,2 increasing to 36% by 90 days.12 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has incentivized hospitals and providers to reduce admissions, but penalize hospitals that do not. Overall, CMS will reduce payments by up to 3% to hospitals with excess readmissions for select conditions, including HF.13

Causes of Heart Failure

Heart failure represents a final common pathway, which in the United States is most often due to coronary artery disease (CAD). Many types of pathology ultimately result in left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, and much of its rising prevalence is a result of the success we now have in managing historically fatal cardiovascular (CV) conditions. These include hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), CAD, and valvular and other CV structural conditions.

Heart failure is caused by either a dilated ventricle with a reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and inability to eject volume, or a stiffened ventricle with a preserved EF (HFpEF) that is unable to receive increased venous return. Both conditions acutely decompensate pulmonary congestion. A preserved EF is defined as an EF at or greater than 50%, whereas a reduced EF is at or less than 40%, with the 41% to 49% range considered as borderline preserved EF.3

While there are important differences in the treatment of chronic and subacute HF, driven by the EF, the effect of EF on early decision-making and treatment in the ED is negligible: Although the probability of HFpEF increases with increasing initial ED systolic blood pressure (SBP), clinical presentation and treatment in the ED are initially identical—regardless of the EF.

Noninvasive continuous transcutaneous hemodynamic monitoring is available for ED use, and may provide further insight into the underlying pathophysiology. A study of 127 acute heart failure (AHF) ED patients identified three hemodynamic AHF phenotypes. These include normal cardiac index (CI) and systemic vascular resistance index (SVRI), low CI and SVRI, and low CI and elevated SVRI.14 While it is attractive to suggest therapeutic interventions based on these measurements, outcome data are lacking.

Presentation

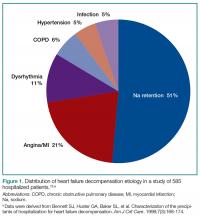

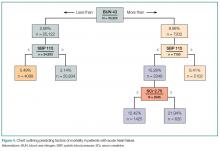

The most common ED presentation of patients suffering from AHF is dyspnea secondary to volume overload, or as the result of acute hypertension with relatively less volume overload. However, regardless of the cause of dyspnea, it is not only the most common resulting complaint, but one that requires immediate treatment. Ultimately, 59% of all HF admissions are attributed to volume overload and dyspnea (Figure 1).15

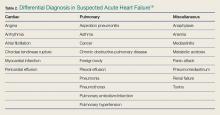

Heart failure can also present in a more protean manner, with cough, fatigue, and edema, as well as more subtle symptoms predominating and resulting in a complicated differential diagnosis (Table 2).16

Because HF is a disease that most significantly affects older patients who frequently have concomitant morbidities (eg, myocardial ischemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] exacerbation, uncontrolled DM), other less clinically obvious disease presentations may actually be the cause of the AHF exacerbation.

Diagnosis

A focused history and physical examination that is part of all ED evaluations should be expedited whenever there is evidence of hemodynamic instability or respiratory compromise. An early working diagnosis is essential to avoid a delay in appropriate treatment, which is associated with increased mortality.

When HF is likely, the potential etiology and precipitants for decompensation must be considered. This list is long, but medication noncompliance and dietary indiscretion are the most common causes.

Symptoms and Prior History of HF

The classic symptoms for AHF include dyspnea at rest or exertion, and orthopnea, both of which unfortunately have poor sensitivity and specificity for AHF. As an isolated symptom, dyspnea is of marginal diagnostic utility (sensitivity and specificity for an HF diagnosis is 56% and 53%, respectively), and orthopnea is only slightly better (sensitivity and specificity 77% and 50%, respectively). A prior HF diagnosis makes repeat presentations much more likely (sensitivity and specificity 60% and 90%, respectively).17

Physical Examination

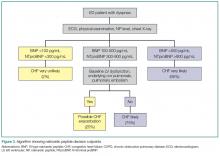

Simple observation and a directed examination can rapidly point to the diagnosis (Figure 2).

Electrocardiography

Because CAD is one of the most common underlying AHF etiologies, an electrocardiogram (ECG) should always be obtained early for a patient presenting with potential AHF. Although the ECG does not usually contribute to ED management, the identification of new ST-segment changes or a malignant arrhythmia will guide critical management decisions.

Imaging Studies

Chest X-ray Imaging. A chest X-ray (CXR) study must be considered early when a patient presents with signs and symptoms suggestive of AHF. Although the classic findings of HF (eg, Kerley B lines [short horizontal lines perpendicular to the pleural surface],18 interstitial congestion, pulmonary effusion) can lag behind the clinical presentation, and also be nondiagnostic in the setting of mild HF, the CXR is an effective aid in identifying other causes of dyspnea such as pneumonia. Ultimately, the utility of the CXR for diagnosis is similar to that of the history and physical examination in that it will be diagnostic when positive but cannot exclude AHF if normal.