User login

Acquired Perforating Dermatosis in a Skin Graft

Case Report

A 57-year-old black woman with a history of dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease, diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, diastolic congestive heart failure, and chronic bronchitis was admitted to Howard University Hospital (Washington, DC) for acute chest pain and shortness of breath. During her hospital stay the dermatology team was consulted for evaluation of two 1.6-cm teardrop-shaped, yellow-white-chalky plaques noted in the center of an atrophic, hyperpigmented, shiny, contracted split-thickness skin graft (STSG) on the right posterior forearm (Figure 1). Twenty years prior, the patient received STSGs on the right and left forearm secondary to caustic burns. Two months before the current admission she noticed 2 adjacent teardrop-shaped white plaques within the center of the STSG on the right forearm. At a 3-month follow-up, she had developed more lesions within both graft sites of the bilateral forearm. There was no notable pruritus associated with the lesions.

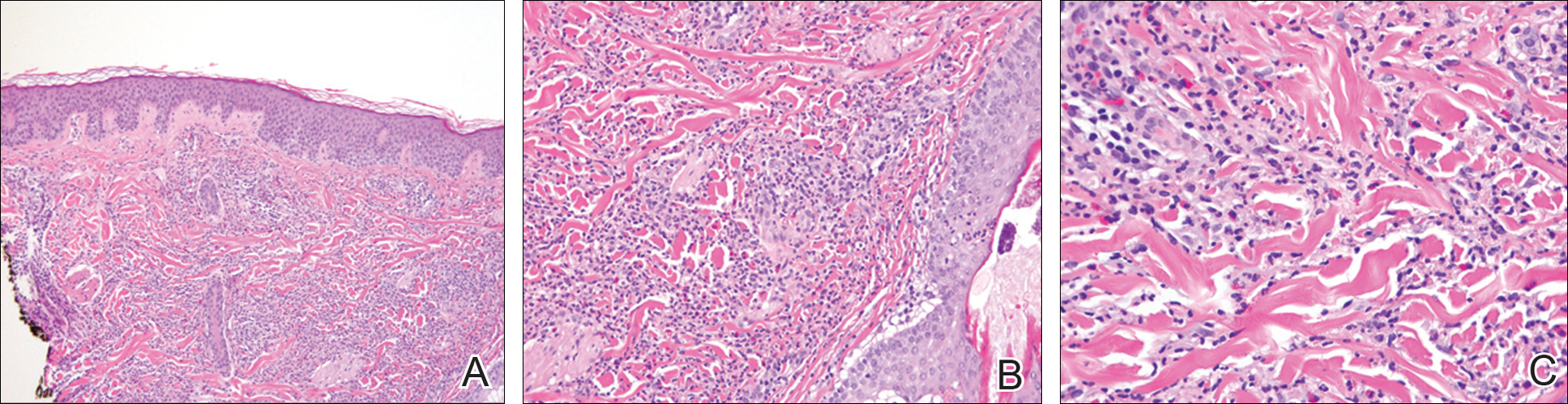

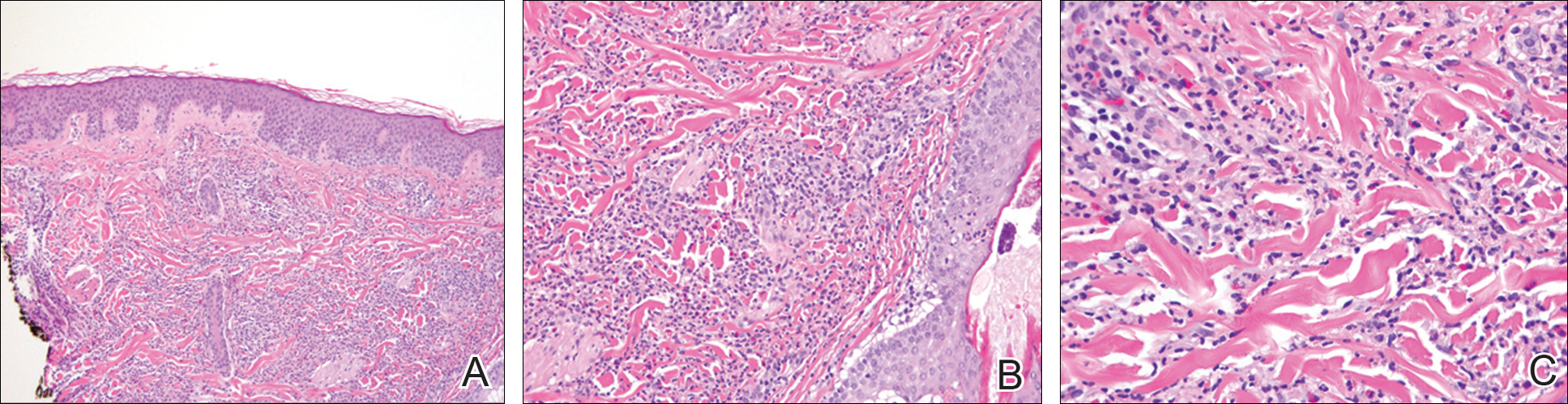

A 4-mm punch biopsy showed an orthokeratotic plug with basophilic inflammatory debris adjacent to acanthotic epidermis, necrotic basophilic debris at the superficial dermis with epidermal canals extending from the base of the lesion superiorly, and transepidermal elimination of elastic fibers (Figure 2A). A Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed the necrotic basophilic debris located in the superficial dermis admixed with a cluster of black wavy elastic fibers establishing the identity of the perforating substance (Figure 2B). Masson trichrome stain revealed loss of collagen structure within the aggregate of elastic fibers adjacent to the epidermis and no collagen within epidermal canals (Figure 2C). These histopathologic findings together with the clinical presentation were consistent with a diagnosis of acquired perforating dermatosis (APD).

Comment

Presentation

Acquired perforating dermatosis is a dermatologic condition characterized by multiple pruritic, dome-shaped papules and plaques with central keratotic plugs giving a craterlike appearance.1-4 A green-brown or black crust with an erythematous border typically surrounds the primary lesions.4 Acquired perforating dermatosis favors a distribution over the trunk, gluteal region, and the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities. Palmoplantar, intertriginous, and mucous membrane regions typically are spared.4 Occasionally, APD may present as generalized nodules and papules. Our case consisting of lesions that were localized to STSGs on the forearms supports the typical distribution; however, the presentation of APD occurring within a skin graft is unique.

From an epidemiologic standpoint, APD is more likely to affect men than women (1.5:1 ratio). Additionally, APD’s affected age range is 29 to 96 years (mean, 56.8 years),5 which is consistent with our patient’s age. Acquired perforating dermatosis has no racial predilection, though there is a predominance among black patients with concomitant chronic renal failure, as seen in our patient.3

Pathogenesis

The etiology of APD remains unknown.6 Some believe that the uremic or calcium deposits on the skin of patients with chronic kidney disease may trigger chronic pruritus, leading to epithelial hyperplasia and the development of perforating lesions.1,3 A prominent theory in the literature is that superficial trauma, such as scratching, induces necrosis of tissue, facilitating transepidermal elimination of connective tissue components.7 The Köbner phenomenon, which can easily be induced by scratching the skin, supports this idea.8 Fujimoto et al9 suggested that scratching exposes keratinocytes to advanced glycation end product–modified extracellular matrix proteins, particularly types I and III collagen. This exposure leads to the terminal differentiation of keratinocytes with the advanced glycation end receptor (CD36) followed by the upward movement of keratinocytes with glycated collagen. Others postulate fibronectin, involved in epidermal cell signaling, locomotion, and differentiation, is an antigenic trigger because patients with DM and uremia have increased levels of fibronectin in the serum and at sites of perforating skin lesions.10

Diseases Associated With APD

Acquired perforating dermatosis is an umbrella term for perforating disease found in adults. It is associated with systemic diseases, such as DM and pruritus of renal failure.11 Our patient had both dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease and DM. Acquired perforating dermatosis is observed in 4.5% to 11% of patients on hemodialysis12,13; however, APD may occur prior to or in the absence of dialysis.3 Other examples of systemic conditions associated with APD include obstructive uropathy, chronic nephritis, anuria, and hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Koebnerization also may trigger lesions to manifest in a linear pattern after localized trauma to the skin.7 Acquired perforating dermatosis is associated with other types of trauma, such as healing herpes zoster, or following exposure to drugs, such as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, bevacizumab, telaprevir, sorafenib, sirolimus, and indinavir.14-16 Rarely, there have been associations with a history of insect bites, scabies, lymphoma, and hepatobiliary disease.1-3

Histopathology

Acquired perforating dermatosis is classified as a perforating disease, along with reactive perforating collagenosis, elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS), perforating folliculitis, and perforating calcific elastosis. Perforating diseases are histologically characterized by the transepidermal penetration and elimination of altered connective tissue and inflammatory cells.5 Each disease differs based on their clinical and histological characteristics.

Histologic sections of APD show a plug of crusting or hyperkeratosis with variable parakeratosis, acanthosis, and occasional dyskeratotic keratinocytes. In the dermis, aggregates of neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells may be found.17 The histologic findings vary depending on the stage of evolution of the individual lesion. Early lesions show a concave depression with acanthosis, vacuolation of basal keratinocytes, and dermal inflammation.4 Additionally, transepidermal channels filled with keratin, pyknotic nuclear debris, inflammatory cells, elastin, or collagen can be noted.3 Over time, the elastic fibers, as detected by the Verhoeff-van Gieson stain, dissipate and the collagen acquires a basophilic staining. Adjacent to the channels, the basement membrane remains intact in early lesions but later shows discontinuities and electron-dense fibrinlike material.3 Occasionally, amorphous degenerated material within the perforations is the major histologic finding.11 Usually, the material cannot be clearly identified as collagen or elastin, but sometimes both are present.

In our case, we identified elastin as the perforating substance, which is less common than collagen, the typical perforating substance in APD. Elastin has occasionally been seen to serve as the only perforating substance from APD lesions among patients. Abe et al18 reported that the biopsy of a Japanese patient with keratotic follicular papules and serpiginous-arranged papules demonstrated elimination of atypical elastin fibers from the transepidermal channels. This patient was diagnosed with APD as well as EPS and perforating folliculitis based on the clinical presentation.18 Kim et al19 studied 30 Korean patients with APD. One had serpiginous hyperkeratotic plaques along the upper extremity and trunk that revealed transepidermal channels containing coarse elastic fibers and basophilic debris; however, due to the serpiginous morphology of lesions, both Abe et al18 and Kim et al19 favored a diagnosis of acquired EPS. Saray et al20 conducted a retrospective study of 22 Turkish patients with APD; 1 patient had a painful hyperkeratotic papule on the auricle that on histopathology showed degenerated elastin perforating through the keratotic plug, features similar to our case.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses include perforating diseases14,19 as well as other disorders that exhibit the Köbner phenomenon, such as psoriasis, lichen planus, and verruca vulgaris.21,22 Also, it is not uncommon for patients with APD to have coexisting folliculitis or prurigo nodularis.22

Treatment

Management is focused on treating the symptoms. For pruritus, sedating antihistamines and other antipruritic agents are efficacious.23 Topical, intra-lesional, or systemic corticosteroids and topical retinoids have shown variable resolution in APD lesions.24 Some case reports describe topical menthol, salicylic acid, sulfur, benzoyl peroxide, systemic antibiotics (eg, clindamycin, doxycycline), and allopurinol for elevated uric acid levels as effective treatment methods.6 Narrowband UVB phototherapy is beneficial for APD and renal disease.25,26 Renal transplantation has been curative for some patients with APD.27 Given that our patient’s lesions were asymptomatic, no treatment was offered at the time.

Conclusion

Our patient presented with APD localized exclusively to the site of a skin graft, and histologic examination identified elastin as the primary perforating substance. A medical history of DM and chronic kidney disease predisposes patients to APD. This case suggests that skin graft sites may be predisposed to the development of APD.

- Rodney IJ, Taylor CS, Cohen G. Derm Dx: what are these pruritic nodules? The Dermatologist. October 15, 2009. http://www.the-dermatologist.com/content/derm-dx-what-are-these-pruritic-nodules. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- Gagnon, AL, Desai T. Dermatological diseases in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Nephropathol. 2013;2:104-109.

- Kurban MS, Boueiz A, Kibbi AG. Cutaneous manifestations of chronic kidney disease. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:255-264.

- Wagner G, Sachse MM. Acquired reactive perforating dermatosis [published online May 29, 2013]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:723-729; 723-730.

- Karpouzis A, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: current status. J Dermatol. 2010;37:585-592.

- Healy R, Cerio R, Hollingsworth A, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis associated with pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:621-623.

- Cordova KB, Oberg TJ, Malik M, et al. Dermatologic conditions seen in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2009;22:45-55.

- Satchell AC, Crotty K, Lee S. Reactive perforating collagenosis: a condition that may be underdiagnosed. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:284-287.

- Fujimoto E, Kobayashi T, Fujimoto N, et al. AGE-modified collagens I and III induce keratinocyte terminal differentiation through AGE receptor CD36: epidermal-dermal interaction in acquired perforating dermatosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:405-414.

- Bilezikci B, Sechkin D, Demirhan B. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure: a possible role for fibronectin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:230-232.

- Rapini RP, Herbert AA, Drucker CR. Acquired perforating dermatosis. evidence for combined transepidermal elimination of both collagen and elastic fibers. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1074-1078.

- Hurwitz RM, Melton ME, Creech FT, et al. Perforating folliculitis in association with hemodialysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:101-108.

- Morton CA, Henderson IS, Jones MC, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a British dialysis population. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:671-677.

- Lübbe J, Sorg O, Malé PJ, et al. Sirolimus-induced inflammatory papules with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis [published online January 9, 2008]. Dermatology. 2008;216:239-242.

- Pernet C, Pageaux GP, Guillot B, et al. Telaprevir-induced acquired perforating dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1371-1372.

- Severino-Freire M, Sibaud V, Tournier E, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis associated with sorafenib therapy [published online September 11, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:328-330.

- Zelger B, Hintner H, Auböck J, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis. transepidermal elimination of DNA material and possible role of leukocytes in pathogenesis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:695-700.

- Abe R, Murase S, Nomura Y, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis appearing as elastosis perforans serpiginosa and perforating folliculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:653-654.

- Kim SW, Kim MS, Lee JH, et al. A clinicopathologic study of thirty cases of acquired perforating dermatosis in Korea. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:162-171.

- Saray Y, Seçkin D, Bilezikçi B. Acquired perforating dermatosis: clinicopathological features in twenty-two cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:679-688.

- Carter VH, Constantine VS. Kyrle’s disease. I. clinical findings in five cases and review of literature. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:624-632.

- Robinson-Bostom L, Digiovanna JJ. Cutaneous manifestations of end-stage renal disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:975-986.

- Hong SB, Park JH, Ihm CG, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:283-288.

- Morton CA, Henderson IS, Jones MC, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a British dialysis population. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:671-677.

- Ohe S, Danno K, Sasaki H, et al. Treatment of acquired perforating dermatosis with narrowband ultraviolet B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:892-894.

- Sezer E, Erkek E. Acquired perforating dermatosis successfully treated with photodynamic therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:50-52.

- Saldanha LF, Gonick HC, Rodriguez HJ, et al. Silicon-related syndrome in dialysis patients. Nephron. 1997;77:48-56.

Case Report

A 57-year-old black woman with a history of dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease, diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, diastolic congestive heart failure, and chronic bronchitis was admitted to Howard University Hospital (Washington, DC) for acute chest pain and shortness of breath. During her hospital stay the dermatology team was consulted for evaluation of two 1.6-cm teardrop-shaped, yellow-white-chalky plaques noted in the center of an atrophic, hyperpigmented, shiny, contracted split-thickness skin graft (STSG) on the right posterior forearm (Figure 1). Twenty years prior, the patient received STSGs on the right and left forearm secondary to caustic burns. Two months before the current admission she noticed 2 adjacent teardrop-shaped white plaques within the center of the STSG on the right forearm. At a 3-month follow-up, she had developed more lesions within both graft sites of the bilateral forearm. There was no notable pruritus associated with the lesions.

A 4-mm punch biopsy showed an orthokeratotic plug with basophilic inflammatory debris adjacent to acanthotic epidermis, necrotic basophilic debris at the superficial dermis with epidermal canals extending from the base of the lesion superiorly, and transepidermal elimination of elastic fibers (Figure 2A). A Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed the necrotic basophilic debris located in the superficial dermis admixed with a cluster of black wavy elastic fibers establishing the identity of the perforating substance (Figure 2B). Masson trichrome stain revealed loss of collagen structure within the aggregate of elastic fibers adjacent to the epidermis and no collagen within epidermal canals (Figure 2C). These histopathologic findings together with the clinical presentation were consistent with a diagnosis of acquired perforating dermatosis (APD).

Comment

Presentation

Acquired perforating dermatosis is a dermatologic condition characterized by multiple pruritic, dome-shaped papules and plaques with central keratotic plugs giving a craterlike appearance.1-4 A green-brown or black crust with an erythematous border typically surrounds the primary lesions.4 Acquired perforating dermatosis favors a distribution over the trunk, gluteal region, and the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities. Palmoplantar, intertriginous, and mucous membrane regions typically are spared.4 Occasionally, APD may present as generalized nodules and papules. Our case consisting of lesions that were localized to STSGs on the forearms supports the typical distribution; however, the presentation of APD occurring within a skin graft is unique.

From an epidemiologic standpoint, APD is more likely to affect men than women (1.5:1 ratio). Additionally, APD’s affected age range is 29 to 96 years (mean, 56.8 years),5 which is consistent with our patient’s age. Acquired perforating dermatosis has no racial predilection, though there is a predominance among black patients with concomitant chronic renal failure, as seen in our patient.3

Pathogenesis

The etiology of APD remains unknown.6 Some believe that the uremic or calcium deposits on the skin of patients with chronic kidney disease may trigger chronic pruritus, leading to epithelial hyperplasia and the development of perforating lesions.1,3 A prominent theory in the literature is that superficial trauma, such as scratching, induces necrosis of tissue, facilitating transepidermal elimination of connective tissue components.7 The Köbner phenomenon, which can easily be induced by scratching the skin, supports this idea.8 Fujimoto et al9 suggested that scratching exposes keratinocytes to advanced glycation end product–modified extracellular matrix proteins, particularly types I and III collagen. This exposure leads to the terminal differentiation of keratinocytes with the advanced glycation end receptor (CD36) followed by the upward movement of keratinocytes with glycated collagen. Others postulate fibronectin, involved in epidermal cell signaling, locomotion, and differentiation, is an antigenic trigger because patients with DM and uremia have increased levels of fibronectin in the serum and at sites of perforating skin lesions.10

Diseases Associated With APD

Acquired perforating dermatosis is an umbrella term for perforating disease found in adults. It is associated with systemic diseases, such as DM and pruritus of renal failure.11 Our patient had both dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease and DM. Acquired perforating dermatosis is observed in 4.5% to 11% of patients on hemodialysis12,13; however, APD may occur prior to or in the absence of dialysis.3 Other examples of systemic conditions associated with APD include obstructive uropathy, chronic nephritis, anuria, and hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Koebnerization also may trigger lesions to manifest in a linear pattern after localized trauma to the skin.7 Acquired perforating dermatosis is associated with other types of trauma, such as healing herpes zoster, or following exposure to drugs, such as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, bevacizumab, telaprevir, sorafenib, sirolimus, and indinavir.14-16 Rarely, there have been associations with a history of insect bites, scabies, lymphoma, and hepatobiliary disease.1-3

Histopathology

Acquired perforating dermatosis is classified as a perforating disease, along with reactive perforating collagenosis, elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS), perforating folliculitis, and perforating calcific elastosis. Perforating diseases are histologically characterized by the transepidermal penetration and elimination of altered connective tissue and inflammatory cells.5 Each disease differs based on their clinical and histological characteristics.

Histologic sections of APD show a plug of crusting or hyperkeratosis with variable parakeratosis, acanthosis, and occasional dyskeratotic keratinocytes. In the dermis, aggregates of neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells may be found.17 The histologic findings vary depending on the stage of evolution of the individual lesion. Early lesions show a concave depression with acanthosis, vacuolation of basal keratinocytes, and dermal inflammation.4 Additionally, transepidermal channels filled with keratin, pyknotic nuclear debris, inflammatory cells, elastin, or collagen can be noted.3 Over time, the elastic fibers, as detected by the Verhoeff-van Gieson stain, dissipate and the collagen acquires a basophilic staining. Adjacent to the channels, the basement membrane remains intact in early lesions but later shows discontinuities and electron-dense fibrinlike material.3 Occasionally, amorphous degenerated material within the perforations is the major histologic finding.11 Usually, the material cannot be clearly identified as collagen or elastin, but sometimes both are present.

In our case, we identified elastin as the perforating substance, which is less common than collagen, the typical perforating substance in APD. Elastin has occasionally been seen to serve as the only perforating substance from APD lesions among patients. Abe et al18 reported that the biopsy of a Japanese patient with keratotic follicular papules and serpiginous-arranged papules demonstrated elimination of atypical elastin fibers from the transepidermal channels. This patient was diagnosed with APD as well as EPS and perforating folliculitis based on the clinical presentation.18 Kim et al19 studied 30 Korean patients with APD. One had serpiginous hyperkeratotic plaques along the upper extremity and trunk that revealed transepidermal channels containing coarse elastic fibers and basophilic debris; however, due to the serpiginous morphology of lesions, both Abe et al18 and Kim et al19 favored a diagnosis of acquired EPS. Saray et al20 conducted a retrospective study of 22 Turkish patients with APD; 1 patient had a painful hyperkeratotic papule on the auricle that on histopathology showed degenerated elastin perforating through the keratotic plug, features similar to our case.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses include perforating diseases14,19 as well as other disorders that exhibit the Köbner phenomenon, such as psoriasis, lichen planus, and verruca vulgaris.21,22 Also, it is not uncommon for patients with APD to have coexisting folliculitis or prurigo nodularis.22

Treatment

Management is focused on treating the symptoms. For pruritus, sedating antihistamines and other antipruritic agents are efficacious.23 Topical, intra-lesional, or systemic corticosteroids and topical retinoids have shown variable resolution in APD lesions.24 Some case reports describe topical menthol, salicylic acid, sulfur, benzoyl peroxide, systemic antibiotics (eg, clindamycin, doxycycline), and allopurinol for elevated uric acid levels as effective treatment methods.6 Narrowband UVB phototherapy is beneficial for APD and renal disease.25,26 Renal transplantation has been curative for some patients with APD.27 Given that our patient’s lesions were asymptomatic, no treatment was offered at the time.

Conclusion

Our patient presented with APD localized exclusively to the site of a skin graft, and histologic examination identified elastin as the primary perforating substance. A medical history of DM and chronic kidney disease predisposes patients to APD. This case suggests that skin graft sites may be predisposed to the development of APD.

Case Report

A 57-year-old black woman with a history of dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease, diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, diastolic congestive heart failure, and chronic bronchitis was admitted to Howard University Hospital (Washington, DC) for acute chest pain and shortness of breath. During her hospital stay the dermatology team was consulted for evaluation of two 1.6-cm teardrop-shaped, yellow-white-chalky plaques noted in the center of an atrophic, hyperpigmented, shiny, contracted split-thickness skin graft (STSG) on the right posterior forearm (Figure 1). Twenty years prior, the patient received STSGs on the right and left forearm secondary to caustic burns. Two months before the current admission she noticed 2 adjacent teardrop-shaped white plaques within the center of the STSG on the right forearm. At a 3-month follow-up, she had developed more lesions within both graft sites of the bilateral forearm. There was no notable pruritus associated with the lesions.

A 4-mm punch biopsy showed an orthokeratotic plug with basophilic inflammatory debris adjacent to acanthotic epidermis, necrotic basophilic debris at the superficial dermis with epidermal canals extending from the base of the lesion superiorly, and transepidermal elimination of elastic fibers (Figure 2A). A Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed the necrotic basophilic debris located in the superficial dermis admixed with a cluster of black wavy elastic fibers establishing the identity of the perforating substance (Figure 2B). Masson trichrome stain revealed loss of collagen structure within the aggregate of elastic fibers adjacent to the epidermis and no collagen within epidermal canals (Figure 2C). These histopathologic findings together with the clinical presentation were consistent with a diagnosis of acquired perforating dermatosis (APD).

Comment

Presentation

Acquired perforating dermatosis is a dermatologic condition characterized by multiple pruritic, dome-shaped papules and plaques with central keratotic plugs giving a craterlike appearance.1-4 A green-brown or black crust with an erythematous border typically surrounds the primary lesions.4 Acquired perforating dermatosis favors a distribution over the trunk, gluteal region, and the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities. Palmoplantar, intertriginous, and mucous membrane regions typically are spared.4 Occasionally, APD may present as generalized nodules and papules. Our case consisting of lesions that were localized to STSGs on the forearms supports the typical distribution; however, the presentation of APD occurring within a skin graft is unique.

From an epidemiologic standpoint, APD is more likely to affect men than women (1.5:1 ratio). Additionally, APD’s affected age range is 29 to 96 years (mean, 56.8 years),5 which is consistent with our patient’s age. Acquired perforating dermatosis has no racial predilection, though there is a predominance among black patients with concomitant chronic renal failure, as seen in our patient.3

Pathogenesis

The etiology of APD remains unknown.6 Some believe that the uremic or calcium deposits on the skin of patients with chronic kidney disease may trigger chronic pruritus, leading to epithelial hyperplasia and the development of perforating lesions.1,3 A prominent theory in the literature is that superficial trauma, such as scratching, induces necrosis of tissue, facilitating transepidermal elimination of connective tissue components.7 The Köbner phenomenon, which can easily be induced by scratching the skin, supports this idea.8 Fujimoto et al9 suggested that scratching exposes keratinocytes to advanced glycation end product–modified extracellular matrix proteins, particularly types I and III collagen. This exposure leads to the terminal differentiation of keratinocytes with the advanced glycation end receptor (CD36) followed by the upward movement of keratinocytes with glycated collagen. Others postulate fibronectin, involved in epidermal cell signaling, locomotion, and differentiation, is an antigenic trigger because patients with DM and uremia have increased levels of fibronectin in the serum and at sites of perforating skin lesions.10

Diseases Associated With APD

Acquired perforating dermatosis is an umbrella term for perforating disease found in adults. It is associated with systemic diseases, such as DM and pruritus of renal failure.11 Our patient had both dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease and DM. Acquired perforating dermatosis is observed in 4.5% to 11% of patients on hemodialysis12,13; however, APD may occur prior to or in the absence of dialysis.3 Other examples of systemic conditions associated with APD include obstructive uropathy, chronic nephritis, anuria, and hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Koebnerization also may trigger lesions to manifest in a linear pattern after localized trauma to the skin.7 Acquired perforating dermatosis is associated with other types of trauma, such as healing herpes zoster, or following exposure to drugs, such as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, bevacizumab, telaprevir, sorafenib, sirolimus, and indinavir.14-16 Rarely, there have been associations with a history of insect bites, scabies, lymphoma, and hepatobiliary disease.1-3

Histopathology

Acquired perforating dermatosis is classified as a perforating disease, along with reactive perforating collagenosis, elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS), perforating folliculitis, and perforating calcific elastosis. Perforating diseases are histologically characterized by the transepidermal penetration and elimination of altered connective tissue and inflammatory cells.5 Each disease differs based on their clinical and histological characteristics.

Histologic sections of APD show a plug of crusting or hyperkeratosis with variable parakeratosis, acanthosis, and occasional dyskeratotic keratinocytes. In the dermis, aggregates of neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells may be found.17 The histologic findings vary depending on the stage of evolution of the individual lesion. Early lesions show a concave depression with acanthosis, vacuolation of basal keratinocytes, and dermal inflammation.4 Additionally, transepidermal channels filled with keratin, pyknotic nuclear debris, inflammatory cells, elastin, or collagen can be noted.3 Over time, the elastic fibers, as detected by the Verhoeff-van Gieson stain, dissipate and the collagen acquires a basophilic staining. Adjacent to the channels, the basement membrane remains intact in early lesions but later shows discontinuities and electron-dense fibrinlike material.3 Occasionally, amorphous degenerated material within the perforations is the major histologic finding.11 Usually, the material cannot be clearly identified as collagen or elastin, but sometimes both are present.

In our case, we identified elastin as the perforating substance, which is less common than collagen, the typical perforating substance in APD. Elastin has occasionally been seen to serve as the only perforating substance from APD lesions among patients. Abe et al18 reported that the biopsy of a Japanese patient with keratotic follicular papules and serpiginous-arranged papules demonstrated elimination of atypical elastin fibers from the transepidermal channels. This patient was diagnosed with APD as well as EPS and perforating folliculitis based on the clinical presentation.18 Kim et al19 studied 30 Korean patients with APD. One had serpiginous hyperkeratotic plaques along the upper extremity and trunk that revealed transepidermal channels containing coarse elastic fibers and basophilic debris; however, due to the serpiginous morphology of lesions, both Abe et al18 and Kim et al19 favored a diagnosis of acquired EPS. Saray et al20 conducted a retrospective study of 22 Turkish patients with APD; 1 patient had a painful hyperkeratotic papule on the auricle that on histopathology showed degenerated elastin perforating through the keratotic plug, features similar to our case.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses include perforating diseases14,19 as well as other disorders that exhibit the Köbner phenomenon, such as psoriasis, lichen planus, and verruca vulgaris.21,22 Also, it is not uncommon for patients with APD to have coexisting folliculitis or prurigo nodularis.22

Treatment

Management is focused on treating the symptoms. For pruritus, sedating antihistamines and other antipruritic agents are efficacious.23 Topical, intra-lesional, or systemic corticosteroids and topical retinoids have shown variable resolution in APD lesions.24 Some case reports describe topical menthol, salicylic acid, sulfur, benzoyl peroxide, systemic antibiotics (eg, clindamycin, doxycycline), and allopurinol for elevated uric acid levels as effective treatment methods.6 Narrowband UVB phototherapy is beneficial for APD and renal disease.25,26 Renal transplantation has been curative for some patients with APD.27 Given that our patient’s lesions were asymptomatic, no treatment was offered at the time.

Conclusion

Our patient presented with APD localized exclusively to the site of a skin graft, and histologic examination identified elastin as the primary perforating substance. A medical history of DM and chronic kidney disease predisposes patients to APD. This case suggests that skin graft sites may be predisposed to the development of APD.

- Rodney IJ, Taylor CS, Cohen G. Derm Dx: what are these pruritic nodules? The Dermatologist. October 15, 2009. http://www.the-dermatologist.com/content/derm-dx-what-are-these-pruritic-nodules. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- Gagnon, AL, Desai T. Dermatological diseases in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Nephropathol. 2013;2:104-109.

- Kurban MS, Boueiz A, Kibbi AG. Cutaneous manifestations of chronic kidney disease. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:255-264.

- Wagner G, Sachse MM. Acquired reactive perforating dermatosis [published online May 29, 2013]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:723-729; 723-730.

- Karpouzis A, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: current status. J Dermatol. 2010;37:585-592.

- Healy R, Cerio R, Hollingsworth A, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis associated with pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:621-623.

- Cordova KB, Oberg TJ, Malik M, et al. Dermatologic conditions seen in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2009;22:45-55.

- Satchell AC, Crotty K, Lee S. Reactive perforating collagenosis: a condition that may be underdiagnosed. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:284-287.

- Fujimoto E, Kobayashi T, Fujimoto N, et al. AGE-modified collagens I and III induce keratinocyte terminal differentiation through AGE receptor CD36: epidermal-dermal interaction in acquired perforating dermatosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:405-414.

- Bilezikci B, Sechkin D, Demirhan B. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure: a possible role for fibronectin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:230-232.

- Rapini RP, Herbert AA, Drucker CR. Acquired perforating dermatosis. evidence for combined transepidermal elimination of both collagen and elastic fibers. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1074-1078.

- Hurwitz RM, Melton ME, Creech FT, et al. Perforating folliculitis in association with hemodialysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:101-108.

- Morton CA, Henderson IS, Jones MC, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a British dialysis population. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:671-677.

- Lübbe J, Sorg O, Malé PJ, et al. Sirolimus-induced inflammatory papules with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis [published online January 9, 2008]. Dermatology. 2008;216:239-242.

- Pernet C, Pageaux GP, Guillot B, et al. Telaprevir-induced acquired perforating dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1371-1372.

- Severino-Freire M, Sibaud V, Tournier E, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis associated with sorafenib therapy [published online September 11, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:328-330.

- Zelger B, Hintner H, Auböck J, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis. transepidermal elimination of DNA material and possible role of leukocytes in pathogenesis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:695-700.

- Abe R, Murase S, Nomura Y, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis appearing as elastosis perforans serpiginosa and perforating folliculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:653-654.

- Kim SW, Kim MS, Lee JH, et al. A clinicopathologic study of thirty cases of acquired perforating dermatosis in Korea. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:162-171.

- Saray Y, Seçkin D, Bilezikçi B. Acquired perforating dermatosis: clinicopathological features in twenty-two cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:679-688.

- Carter VH, Constantine VS. Kyrle’s disease. I. clinical findings in five cases and review of literature. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:624-632.

- Robinson-Bostom L, Digiovanna JJ. Cutaneous manifestations of end-stage renal disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:975-986.

- Hong SB, Park JH, Ihm CG, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:283-288.

- Morton CA, Henderson IS, Jones MC, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a British dialysis population. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:671-677.

- Ohe S, Danno K, Sasaki H, et al. Treatment of acquired perforating dermatosis with narrowband ultraviolet B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:892-894.

- Sezer E, Erkek E. Acquired perforating dermatosis successfully treated with photodynamic therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:50-52.

- Saldanha LF, Gonick HC, Rodriguez HJ, et al. Silicon-related syndrome in dialysis patients. Nephron. 1997;77:48-56.

- Rodney IJ, Taylor CS, Cohen G. Derm Dx: what are these pruritic nodules? The Dermatologist. October 15, 2009. http://www.the-dermatologist.com/content/derm-dx-what-are-these-pruritic-nodules. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- Gagnon, AL, Desai T. Dermatological diseases in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Nephropathol. 2013;2:104-109.

- Kurban MS, Boueiz A, Kibbi AG. Cutaneous manifestations of chronic kidney disease. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:255-264.

- Wagner G, Sachse MM. Acquired reactive perforating dermatosis [published online May 29, 2013]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:723-729; 723-730.

- Karpouzis A, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: current status. J Dermatol. 2010;37:585-592.

- Healy R, Cerio R, Hollingsworth A, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis associated with pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:621-623.

- Cordova KB, Oberg TJ, Malik M, et al. Dermatologic conditions seen in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2009;22:45-55.

- Satchell AC, Crotty K, Lee S. Reactive perforating collagenosis: a condition that may be underdiagnosed. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:284-287.

- Fujimoto E, Kobayashi T, Fujimoto N, et al. AGE-modified collagens I and III induce keratinocyte terminal differentiation through AGE receptor CD36: epidermal-dermal interaction in acquired perforating dermatosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:405-414.

- Bilezikci B, Sechkin D, Demirhan B. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure: a possible role for fibronectin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:230-232.

- Rapini RP, Herbert AA, Drucker CR. Acquired perforating dermatosis. evidence for combined transepidermal elimination of both collagen and elastic fibers. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1074-1078.

- Hurwitz RM, Melton ME, Creech FT, et al. Perforating folliculitis in association with hemodialysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:101-108.

- Morton CA, Henderson IS, Jones MC, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a British dialysis population. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:671-677.

- Lübbe J, Sorg O, Malé PJ, et al. Sirolimus-induced inflammatory papules with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis [published online January 9, 2008]. Dermatology. 2008;216:239-242.

- Pernet C, Pageaux GP, Guillot B, et al. Telaprevir-induced acquired perforating dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1371-1372.

- Severino-Freire M, Sibaud V, Tournier E, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis associated with sorafenib therapy [published online September 11, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:328-330.

- Zelger B, Hintner H, Auböck J, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis. transepidermal elimination of DNA material and possible role of leukocytes in pathogenesis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:695-700.

- Abe R, Murase S, Nomura Y, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis appearing as elastosis perforans serpiginosa and perforating folliculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:653-654.

- Kim SW, Kim MS, Lee JH, et al. A clinicopathologic study of thirty cases of acquired perforating dermatosis in Korea. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:162-171.

- Saray Y, Seçkin D, Bilezikçi B. Acquired perforating dermatosis: clinicopathological features in twenty-two cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:679-688.

- Carter VH, Constantine VS. Kyrle’s disease. I. clinical findings in five cases and review of literature. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:624-632.

- Robinson-Bostom L, Digiovanna JJ. Cutaneous manifestations of end-stage renal disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:975-986.

- Hong SB, Park JH, Ihm CG, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:283-288.

- Morton CA, Henderson IS, Jones MC, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a British dialysis population. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:671-677.

- Ohe S, Danno K, Sasaki H, et al. Treatment of acquired perforating dermatosis with narrowband ultraviolet B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:892-894.

- Sezer E, Erkek E. Acquired perforating dermatosis successfully treated with photodynamic therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:50-52.

- Saldanha LF, Gonick HC, Rodriguez HJ, et al. Silicon-related syndrome in dialysis patients. Nephron. 1997;77:48-56.

Practice Points

- Acquired perforating dermatosis (APD) presents as pruritic crateriform papules and plaques with central keratotic plugs.

- A medical history of diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease predisposes patients to APD. This case suggests that skin graft sites may be predisposed to the development of APD.

Sweet Syndrome Induced by Oral Acetaminophen-Codeine Following Repair of a Facial Fracture

In 1964, Sweet1 described 8 women with acute onset of fever and erythematous plaques associated with a nonspecific infection of the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract. The lesions were histologically characterized by a neutrophilic infiltrate, and the author named the constellation of findings acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis.1 In 1968, Whittle et al2 reported on similar cases and coined the term Sweet syndrome (SS).

Although the etiology and pathogenesis of SS remain unknown, several theories have been proposed. Because SS often is preceded by a respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infection, it has been postulated that it may represent a hypersensitivity reaction or may be related to local or systemic dysregulation of cytokine secretion.3,4 In addition to respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infections, SS has been reported in association with malignancies, autoimmune diseases, drugs, vaccines, pregnancy, inflammatory bowel disease, and chemotherapy. It also may be idiopathic.5

The eruption of SS manifests as erythematous, indurated, and sharply demarcated plaques or nodules that typically favor the head, neck, and arms, with a particularly strong predilection for the dorsal aspects of the hands.6 Plaques and nodules are histologically characterized by a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate, papillary dermal edema, neutrophilic spongiosis, subcorneal pustules, and leukocytoclasia. Vasculitic features are not seen.7 The eruption typically resolves spontaneously in 5 to 12 weeks but recurs in approximately 30% of cases.8 Relatively common extracutaneous findings include ocular involvement, arthralgia, myalgia, and arthritis.4,9 Both cutaneous and extracutaneous findings typically are responsive to prednisone at a dosage of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily for 4 to 6 weeks. Prolonged low-dose prednisone for 2 to 3 additional months may be necessary to suppress recurrence.8 Potassium iodide at 900 mg daily may be used as an alternative regimen.3,8

Sweet syndrome is divided into 5 subcategories based on the underlying etiology: (1) classic or idiopathic, (2) paraneoplastic, (3) inflammatory and/or autoimmune disease related, (4) pregnancy related, and (5) drug induced.3 Although drug-induced SS comprises the minority of total cases (<5%), its reported incidence has been rising in recent years and has been associated with an escalating number of medications.10 We report a rare case of SS induced by administration of oral acetaminophen-codeine.

Case Report

A 32-year-old man with a history of diabetes mellitus underwent postoperative repair of a facial fracture. The patient was administered an oral acetaminophen-codeine suspension for postoperative pain control. One week later, he developed a painful eruption on the forehead and presented to the emergency department. He was prescribed acetaminophen-codeine 300/30-mg tablets every 6 hours in addition to hydrocortisone cream 1% applied every 6 hours. After this reintroduction of oral acetaminophen-codeine, he experienced intermittent fevers and an exacerbation of the initial cutaneous eruption. The patient presented for a second time 2 days after being seen in the emergency department and a dermatology consultation was obtained.

At the time of consultation, the patient was noted to have injected conjunctiva and erythematous, well-demarcated, and indurated plaques on the forehead with associated pain and burning (Figures 1A and 1B). Additional erythematous annular plaques were found on the palms, arms, and right knee. Laboratory workup revealed only mild anemia on complete blood cell count with a white blood cell count of 10.1×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L), hemoglobin of 12.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.4 g/dL), and hematocrit of 37.3% (reference range, 41%–50%). The platelet count was 284×103/µL (reference range, 150–350×103/µL). Basic metabolic panel was notable for an elevated glucose level of 418 mg/dL (reference range, 70–110 mg/dL). The most recent hemoglobin A1C (several months prior) was notable at 14.7% of total hemoglobin (reference range, 4%–7% of total hemoglobin). A 4-mm punch biopsy of the right side of the forehead demonstrated minimal to mild papillary dermal edema and a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate spanning the upper, middle, and lower dermis with evidence of mild leukocytoclasia and no evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure 2). These histologic features together with the clinical presentation were consistent with a diagnosis of SS.

After an initial dose of intravenous methylprednisolone sodium succinate 125 mg in the emergency department, the patient was admitted for additional intravenous steroid administration in the context of uncontrolled hyperglycemia and history of poor glucose control. Upon admission, acetaminophen-codeine was discontinued and the patient was transitioned to intravenous methylprednisolone sodium succinate 60 mg every 8 hours. The patient also was given intravenous diphenhydramine 25 mg every 6 hours and desonide ointment 0.05% was applied to facial lesions. The inpatient medication regimen resulted in notable improvement of

Comment

Although SS itself is relatively rare, there has been an increasing incidence of the drug-induced subtype, most often in association with use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte monocyte-stimulating factor. There also have been reported associations with a growing number of medications that include antibiotics, antiepileptic drugs, furosemide, hydralazine, and all-trans retinoic acid.11-19 Moghim

Several therapies for advanced melanoma also have been reviewed in the literature, including ipilimumab and vemurafenib,27-30 as have several medications for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome including azacitidine.31,32 A seve

Additional medications more recently involved in the pathogenesis of drug-induced SS include the chemotherapeutic agents topetecan, mitoxantrone, gemcitabine, and vorinostat.34-37 The antimalarial medication chloroquine also has been implicated, as have selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, hypomethylating agents, the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab, IL-2 therapies, aripiprazole, and several other medications.38-49

Despite drug-induced SS being reported in association with an increasing number of medications, there had been a lack of appropriate diagnostic criteria. To tha

Conclusion

The number of cases of drug-induced SS in the literature continues to climb; however, the association with acetaminophen-codeine is unique. The importance of this case lies in educating both physicians and pharmacists alike regarding a newly recognized adverse effect of acetaminophen-codeine. Because acetaminophen-codeine often is used for its analgesic properties, and the predominant symptom of the cutaneous eruption of SS is pain, the therapeutic value of acetaminophen-codeine is substantially diminished in acetaminophen-codeine–induced SS. Accordingly, in these cases, the medication may be discontinued or substituted upon recognition of this adverse reaction to reduce patient morbidity.

- Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Whittle CH, Back GA, Champion RH. Recurrent neutrophilic dermatosis of the face—a variant of Sweet’s syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1968;80:806-810.

- Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-536.

- Honigsmann H, Cohen PR, Wolff K. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome). Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1979;91:842-847.

- Limdiwala PG, Parikh SJ, Shah JS. Sweet’s Syndrome. Indian J Dent Res. 2014;25:401-405.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- Ratzinger G, Burgdorf W, Zelger BG, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: a histopathologic study of 31 cases with review of literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:125-133.

- Moschella SL, Davis MDP. Neutrophilic dermatoses. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012:423-428.

- Fett DL, Gibson LE, Su WP. Sweet’s syndrome: signs and symptoms and associated disorders. Mayo Clinic Proc. 1995;70:234-240.

- Carvalho R, Fernandes C, Afonso A, et al. Drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome by alclofenac. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2011;30:315-316.

- Moghimi J, Pahlevan D, Azizzadeh M, et al. Isotretinoin-associated Sweet’s syndrome: a case report. Daru. 2014;22:69.

- Cholongitas E, Pipili C, Dasenaki M, et al. Piperacillin/tazobactam-induced Sweet syndrome in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and autoimmune cholangitis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:203-204.

- Kandula S, Burke WS, Goldfarb JN. Clindamycin-induced Sweet syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:898-900.

- Jamet A, Lagarce L, Le Clec’h C, et al. Doxycycline-induced Sweet’s syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:595-596.

- Cartee TV, Chen SC. Sweet syndrome associated with hydralazine-induced lupus erythematosus. Cutis. 2012;89:121-124.

- Baybay H, Elhatimi A, Idrissi R, et al. Sweet’s syndrome following oral ciprofloxacin therapy. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2011;138:606-607.

- Khaled A, Kharfi M, Fazaa B, et al. A first case of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole induced Sweet’s syndrome in a child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:744-746.

- Calixto R, Menezes Y, Ostronoff M, et al. Favorable outcome of severe, extensive, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-induced, corticosteroid-resistant Sweet’s syndrome treated with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:E1-E2.

- Margaretten ME, Ruben BS, Fye K. Systemic sulfa-induced Sweet’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1044-1046.

- Tanguy-Schmidt A, Avenel-Audran M, Croué A, et al. Bortezomib-induced acute neutrophilic dermatosis. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136:443-446.

- Choonhakarn C, Chaowattanapanit S. Azathioprine-induced Sweet’s syndrome and published work review. J Dermatol. 2013;40:267-271.

- Cyrus N, Stavert R, Mason AR, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis after azathioprine exposure. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:592-597.

- Hurtado-Garcia R, Escribano-Stablé JC, Pascual JC, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis caused by azathioprine hypersensitivity. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1522-1525.

- Valentine MC, Walsh JS. Neutrophilic dermatosis caused by azathioprine. Skinmed. 2011;9:386-388.

- Kim JS, Roh HS, Lee JW, et al. Distinct variant of Sweet’s syndrome: bortezomib-induced histiocytoid Sweet’s syndrome in a patient with multiple myeloma. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1491-1493.

- Ozlem C, Deram B, Mustafa S, et al. Propylthiouracil-induced anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and agranulocytosis together with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor induced Sweet’s syndrome in a patient with Graves’ disease. Intern Med. 2011;50:1973-1976.

- Kyllo RL, Parker MK, Rosman I, et al. Ipilimumab-associated Sweet syndrome in a patient with high-risk melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:E85-E86.

- Pintova S, Sidhu H, Friedlander PA, et al. Sweet’s syndrome in a patient with metastatic melanoma after ipilimumab therapy. Melanoma Res. 2013;23:498-501.

- Yorio JT, Mays SR, Ciurea AM, et al. Case of vemurafenib-induced Sweet’s syndrome. J Dermatol. 2014;41:817-820.

- Pattanaprichakul P, Tetzlaff MT, Lapolla WJ, et al. Sweet syndrome following vemurafenib therapy for recurrent cholangiocarcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:326-328.

- Trickett HB, Cumpston A, Craig M. Azacitidine-associated Sweet’s syndrome. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69:869-871.

- Tintle S, Patel V, Ruskin A, et al. Azacitidine: a new medication associated with Sweet syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:E77-E79.

- Thieu KP, Rosenbach M, Xu X, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis complicating lenalidomide therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:709-710.

- Dickson EL, Bakhru A, Chan MP. Topotecan-induced Sweet’s syndrome: a case report. Gynecol Oncol Case Rep. 2013;4:50-52.

- Kümpfel T, Gerdes LA, Flaig M, et al. Drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome after mitoxantrone therapy in a patient with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2011;17:495-497.

- Martorell-Calatayud A, Requena C, Sanmartin O, et al. Gemcitabine-associated sweet syndrome-like eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1236-1238.

- Pang A, Tan KB, Aw D, et al. A case of Sweet’s syndrome due to 5-azacytidine and vorinostat in a patient with NK/T cell lymphoma. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:64-66.

- El Moutaoui L, Zouhair K, Benchikhi H. Sweet syndrome induced by chloroquine. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136:56-57.

- Rosmaninho A, Lobo I, Selores M. Sweet’s syndrome associated with the intake of a selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2011;30:298-301.

- Alencar C, Abramowtiz M, Parekh S, et al. Atypical presentations of Sweet’s syndrome in patients with MDS/AML receiving combinations of hypomethylating agents with histone deacetylase inhibitors. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:688-689.

- Keidel S, McColl A, Edmonds S. Sweet’s syndrome after adalimumab therapy for refractory relapsing polychondritis. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011.

- Rondina A, Watson AC. Bullous Sweet’s syndrome and pseudolymphoma precipitated by IL-2 therapy. Cutis. 2010;85:206-213.

- Gheorghe L, Cotruta B, Trifu V, et al. Drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome secondary to hepatitis C antiviral therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:957-959.

- Zobniw CM, Saad SA, Kostoff D, et al. Bortezomib-induced Sweet’s syndrome confirmed by rechallenge. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:E18-E21.

- Kolb-Mäurer A, Kneitz H, Goebeler M. Sweet-like syndrome induced by bortezomib. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:1200-1202.

- Thuillier D, Lenglet A, Chaby G, et al. Bortezomib-induced eruption: Sweet syndrome? two case reports [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136:427-430.

- Kim MJ, Jang KT, Choe YH. Azathioprine hypersensitivity presenting as sweet syndrome in a child with ulcerative colitis. Indian Pediatr. 2011;48:969-971.

- Truchuelo M, Bagazgoitia L, Alcántara J, et al. Sweet-like lesions induced by bortezomib: a review of the literature and a report of 2 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:829-831.

- Hoelt P, Fattouh K, Villani AP. Dermpath & clinic: drug-induced Sweet syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26:641-642.

- Walker DC, Cohen PR. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-associated acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: case report and review of drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:918-923.

- Thompson DF, Montarella KE. Drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:802-811.

In 1964, Sweet1 described 8 women with acute onset of fever and erythematous plaques associated with a nonspecific infection of the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract. The lesions were histologically characterized by a neutrophilic infiltrate, and the author named the constellation of findings acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis.1 In 1968, Whittle et al2 reported on similar cases and coined the term Sweet syndrome (SS).

Although the etiology and pathogenesis of SS remain unknown, several theories have been proposed. Because SS often is preceded by a respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infection, it has been postulated that it may represent a hypersensitivity reaction or may be related to local or systemic dysregulation of cytokine secretion.3,4 In addition to respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infections, SS has been reported in association with malignancies, autoimmune diseases, drugs, vaccines, pregnancy, inflammatory bowel disease, and chemotherapy. It also may be idiopathic.5

The eruption of SS manifests as erythematous, indurated, and sharply demarcated plaques or nodules that typically favor the head, neck, and arms, with a particularly strong predilection for the dorsal aspects of the hands.6 Plaques and nodules are histologically characterized by a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate, papillary dermal edema, neutrophilic spongiosis, subcorneal pustules, and leukocytoclasia. Vasculitic features are not seen.7 The eruption typically resolves spontaneously in 5 to 12 weeks but recurs in approximately 30% of cases.8 Relatively common extracutaneous findings include ocular involvement, arthralgia, myalgia, and arthritis.4,9 Both cutaneous and extracutaneous findings typically are responsive to prednisone at a dosage of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily for 4 to 6 weeks. Prolonged low-dose prednisone for 2 to 3 additional months may be necessary to suppress recurrence.8 Potassium iodide at 900 mg daily may be used as an alternative regimen.3,8

Sweet syndrome is divided into 5 subcategories based on the underlying etiology: (1) classic or idiopathic, (2) paraneoplastic, (3) inflammatory and/or autoimmune disease related, (4) pregnancy related, and (5) drug induced.3 Although drug-induced SS comprises the minority of total cases (<5%), its reported incidence has been rising in recent years and has been associated with an escalating number of medications.10 We report a rare case of SS induced by administration of oral acetaminophen-codeine.

Case Report

A 32-year-old man with a history of diabetes mellitus underwent postoperative repair of a facial fracture. The patient was administered an oral acetaminophen-codeine suspension for postoperative pain control. One week later, he developed a painful eruption on the forehead and presented to the emergency department. He was prescribed acetaminophen-codeine 300/30-mg tablets every 6 hours in addition to hydrocortisone cream 1% applied every 6 hours. After this reintroduction of oral acetaminophen-codeine, he experienced intermittent fevers and an exacerbation of the initial cutaneous eruption. The patient presented for a second time 2 days after being seen in the emergency department and a dermatology consultation was obtained.

At the time of consultation, the patient was noted to have injected conjunctiva and erythematous, well-demarcated, and indurated plaques on the forehead with associated pain and burning (Figures 1A and 1B). Additional erythematous annular plaques were found on the palms, arms, and right knee. Laboratory workup revealed only mild anemia on complete blood cell count with a white blood cell count of 10.1×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L), hemoglobin of 12.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.4 g/dL), and hematocrit of 37.3% (reference range, 41%–50%). The platelet count was 284×103/µL (reference range, 150–350×103/µL). Basic metabolic panel was notable for an elevated glucose level of 418 mg/dL (reference range, 70–110 mg/dL). The most recent hemoglobin A1C (several months prior) was notable at 14.7% of total hemoglobin (reference range, 4%–7% of total hemoglobin). A 4-mm punch biopsy of the right side of the forehead demonstrated minimal to mild papillary dermal edema and a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate spanning the upper, middle, and lower dermis with evidence of mild leukocytoclasia and no evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure 2). These histologic features together with the clinical presentation were consistent with a diagnosis of SS.

After an initial dose of intravenous methylprednisolone sodium succinate 125 mg in the emergency department, the patient was admitted for additional intravenous steroid administration in the context of uncontrolled hyperglycemia and history of poor glucose control. Upon admission, acetaminophen-codeine was discontinued and the patient was transitioned to intravenous methylprednisolone sodium succinate 60 mg every 8 hours. The patient also was given intravenous diphenhydramine 25 mg every 6 hours and desonide ointment 0.05% was applied to facial lesions. The inpatient medication regimen resulted in notable improvement of

Comment

Although SS itself is relatively rare, there has been an increasing incidence of the drug-induced subtype, most often in association with use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte monocyte-stimulating factor. There also have been reported associations with a growing number of medications that include antibiotics, antiepileptic drugs, furosemide, hydralazine, and all-trans retinoic acid.11-19 Moghim

Several therapies for advanced melanoma also have been reviewed in the literature, including ipilimumab and vemurafenib,27-30 as have several medications for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome including azacitidine.31,32 A seve

Additional medications more recently involved in the pathogenesis of drug-induced SS include the chemotherapeutic agents topetecan, mitoxantrone, gemcitabine, and vorinostat.34-37 The antimalarial medication chloroquine also has been implicated, as have selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, hypomethylating agents, the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab, IL-2 therapies, aripiprazole, and several other medications.38-49

Despite drug-induced SS being reported in association with an increasing number of medications, there had been a lack of appropriate diagnostic criteria. To tha

Conclusion

The number of cases of drug-induced SS in the literature continues to climb; however, the association with acetaminophen-codeine is unique. The importance of this case lies in educating both physicians and pharmacists alike regarding a newly recognized adverse effect of acetaminophen-codeine. Because acetaminophen-codeine often is used for its analgesic properties, and the predominant symptom of the cutaneous eruption of SS is pain, the therapeutic value of acetaminophen-codeine is substantially diminished in acetaminophen-codeine–induced SS. Accordingly, in these cases, the medication may be discontinued or substituted upon recognition of this adverse reaction to reduce patient morbidity.

In 1964, Sweet1 described 8 women with acute onset of fever and erythematous plaques associated with a nonspecific infection of the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract. The lesions were histologically characterized by a neutrophilic infiltrate, and the author named the constellation of findings acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis.1 In 1968, Whittle et al2 reported on similar cases and coined the term Sweet syndrome (SS).

Although the etiology and pathogenesis of SS remain unknown, several theories have been proposed. Because SS often is preceded by a respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infection, it has been postulated that it may represent a hypersensitivity reaction or may be related to local or systemic dysregulation of cytokine secretion.3,4 In addition to respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infections, SS has been reported in association with malignancies, autoimmune diseases, drugs, vaccines, pregnancy, inflammatory bowel disease, and chemotherapy. It also may be idiopathic.5

The eruption of SS manifests as erythematous, indurated, and sharply demarcated plaques or nodules that typically favor the head, neck, and arms, with a particularly strong predilection for the dorsal aspects of the hands.6 Plaques and nodules are histologically characterized by a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate, papillary dermal edema, neutrophilic spongiosis, subcorneal pustules, and leukocytoclasia. Vasculitic features are not seen.7 The eruption typically resolves spontaneously in 5 to 12 weeks but recurs in approximately 30% of cases.8 Relatively common extracutaneous findings include ocular involvement, arthralgia, myalgia, and arthritis.4,9 Both cutaneous and extracutaneous findings typically are responsive to prednisone at a dosage of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily for 4 to 6 weeks. Prolonged low-dose prednisone for 2 to 3 additional months may be necessary to suppress recurrence.8 Potassium iodide at 900 mg daily may be used as an alternative regimen.3,8

Sweet syndrome is divided into 5 subcategories based on the underlying etiology: (1) classic or idiopathic, (2) paraneoplastic, (3) inflammatory and/or autoimmune disease related, (4) pregnancy related, and (5) drug induced.3 Although drug-induced SS comprises the minority of total cases (<5%), its reported incidence has been rising in recent years and has been associated with an escalating number of medications.10 We report a rare case of SS induced by administration of oral acetaminophen-codeine.

Case Report

A 32-year-old man with a history of diabetes mellitus underwent postoperative repair of a facial fracture. The patient was administered an oral acetaminophen-codeine suspension for postoperative pain control. One week later, he developed a painful eruption on the forehead and presented to the emergency department. He was prescribed acetaminophen-codeine 300/30-mg tablets every 6 hours in addition to hydrocortisone cream 1% applied every 6 hours. After this reintroduction of oral acetaminophen-codeine, he experienced intermittent fevers and an exacerbation of the initial cutaneous eruption. The patient presented for a second time 2 days after being seen in the emergency department and a dermatology consultation was obtained.

At the time of consultation, the patient was noted to have injected conjunctiva and erythematous, well-demarcated, and indurated plaques on the forehead with associated pain and burning (Figures 1A and 1B). Additional erythematous annular plaques were found on the palms, arms, and right knee. Laboratory workup revealed only mild anemia on complete blood cell count with a white blood cell count of 10.1×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L), hemoglobin of 12.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.4 g/dL), and hematocrit of 37.3% (reference range, 41%–50%). The platelet count was 284×103/µL (reference range, 150–350×103/µL). Basic metabolic panel was notable for an elevated glucose level of 418 mg/dL (reference range, 70–110 mg/dL). The most recent hemoglobin A1C (several months prior) was notable at 14.7% of total hemoglobin (reference range, 4%–7% of total hemoglobin). A 4-mm punch biopsy of the right side of the forehead demonstrated minimal to mild papillary dermal edema and a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate spanning the upper, middle, and lower dermis with evidence of mild leukocytoclasia and no evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure 2). These histologic features together with the clinical presentation were consistent with a diagnosis of SS.

After an initial dose of intravenous methylprednisolone sodium succinate 125 mg in the emergency department, the patient was admitted for additional intravenous steroid administration in the context of uncontrolled hyperglycemia and history of poor glucose control. Upon admission, acetaminophen-codeine was discontinued and the patient was transitioned to intravenous methylprednisolone sodium succinate 60 mg every 8 hours. The patient also was given intravenous diphenhydramine 25 mg every 6 hours and desonide ointment 0.05% was applied to facial lesions. The inpatient medication regimen resulted in notable improvement of

Comment

Although SS itself is relatively rare, there has been an increasing incidence of the drug-induced subtype, most often in association with use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte monocyte-stimulating factor. There also have been reported associations with a growing number of medications that include antibiotics, antiepileptic drugs, furosemide, hydralazine, and all-trans retinoic acid.11-19 Moghim

Several therapies for advanced melanoma also have been reviewed in the literature, including ipilimumab and vemurafenib,27-30 as have several medications for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome including azacitidine.31,32 A seve

Additional medications more recently involved in the pathogenesis of drug-induced SS include the chemotherapeutic agents topetecan, mitoxantrone, gemcitabine, and vorinostat.34-37 The antimalarial medication chloroquine also has been implicated, as have selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, hypomethylating agents, the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab, IL-2 therapies, aripiprazole, and several other medications.38-49

Despite drug-induced SS being reported in association with an increasing number of medications, there had been a lack of appropriate diagnostic criteria. To tha

Conclusion

The number of cases of drug-induced SS in the literature continues to climb; however, the association with acetaminophen-codeine is unique. The importance of this case lies in educating both physicians and pharmacists alike regarding a newly recognized adverse effect of acetaminophen-codeine. Because acetaminophen-codeine often is used for its analgesic properties, and the predominant symptom of the cutaneous eruption of SS is pain, the therapeutic value of acetaminophen-codeine is substantially diminished in acetaminophen-codeine–induced SS. Accordingly, in these cases, the medication may be discontinued or substituted upon recognition of this adverse reaction to reduce patient morbidity.

- Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Whittle CH, Back GA, Champion RH. Recurrent neutrophilic dermatosis of the face—a variant of Sweet’s syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1968;80:806-810.

- Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-536.

- Honigsmann H, Cohen PR, Wolff K. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome). Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1979;91:842-847.

- Limdiwala PG, Parikh SJ, Shah JS. Sweet’s Syndrome. Indian J Dent Res. 2014;25:401-405.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- Ratzinger G, Burgdorf W, Zelger BG, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: a histopathologic study of 31 cases with review of literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:125-133.

- Moschella SL, Davis MDP. Neutrophilic dermatoses. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012:423-428.

- Fett DL, Gibson LE, Su WP. Sweet’s syndrome: signs and symptoms and associated disorders. Mayo Clinic Proc. 1995;70:234-240.

- Carvalho R, Fernandes C, Afonso A, et al. Drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome by alclofenac. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2011;30:315-316.

- Moghimi J, Pahlevan D, Azizzadeh M, et al. Isotretinoin-associated Sweet’s syndrome: a case report. Daru. 2014;22:69.

- Cholongitas E, Pipili C, Dasenaki M, et al. Piperacillin/tazobactam-induced Sweet syndrome in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and autoimmune cholangitis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:203-204.

- Kandula S, Burke WS, Goldfarb JN. Clindamycin-induced Sweet syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:898-900.

- Jamet A, Lagarce L, Le Clec’h C, et al. Doxycycline-induced Sweet’s syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:595-596.

- Cartee TV, Chen SC. Sweet syndrome associated with hydralazine-induced lupus erythematosus. Cutis. 2012;89:121-124.

- Baybay H, Elhatimi A, Idrissi R, et al. Sweet’s syndrome following oral ciprofloxacin therapy. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2011;138:606-607.

- Khaled A, Kharfi M, Fazaa B, et al. A first case of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole induced Sweet’s syndrome in a child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:744-746.

- Calixto R, Menezes Y, Ostronoff M, et al. Favorable outcome of severe, extensive, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-induced, corticosteroid-resistant Sweet’s syndrome treated with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:E1-E2.

- Margaretten ME, Ruben BS, Fye K. Systemic sulfa-induced Sweet’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1044-1046.

- Tanguy-Schmidt A, Avenel-Audran M, Croué A, et al. Bortezomib-induced acute neutrophilic dermatosis. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136:443-446.

- Choonhakarn C, Chaowattanapanit S. Azathioprine-induced Sweet’s syndrome and published work review. J Dermatol. 2013;40:267-271.

- Cyrus N, Stavert R, Mason AR, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis after azathioprine exposure. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:592-597.

- Hurtado-Garcia R, Escribano-Stablé JC, Pascual JC, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis caused by azathioprine hypersensitivity. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1522-1525.

- Valentine MC, Walsh JS. Neutrophilic dermatosis caused by azathioprine. Skinmed. 2011;9:386-388.

- Kim JS, Roh HS, Lee JW, et al. Distinct variant of Sweet’s syndrome: bortezomib-induced histiocytoid Sweet’s syndrome in a patient with multiple myeloma. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1491-1493.

- Ozlem C, Deram B, Mustafa S, et al. Propylthiouracil-induced anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and agranulocytosis together with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor induced Sweet’s syndrome in a patient with Graves’ disease. Intern Med. 2011;50:1973-1976.

- Kyllo RL, Parker MK, Rosman I, et al. Ipilimumab-associated Sweet syndrome in a patient with high-risk melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:E85-E86.

- Pintova S, Sidhu H, Friedlander PA, et al. Sweet’s syndrome in a patient with metastatic melanoma after ipilimumab therapy. Melanoma Res. 2013;23:498-501.

- Yorio JT, Mays SR, Ciurea AM, et al. Case of vemurafenib-induced Sweet’s syndrome. J Dermatol. 2014;41:817-820.

- Pattanaprichakul P, Tetzlaff MT, Lapolla WJ, et al. Sweet syndrome following vemurafenib therapy for recurrent cholangiocarcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:326-328.

- Trickett HB, Cumpston A, Craig M. Azacitidine-associated Sweet’s syndrome. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69:869-871.

- Tintle S, Patel V, Ruskin A, et al. Azacitidine: a new medication associated with Sweet syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:E77-E79.

- Thieu KP, Rosenbach M, Xu X, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis complicating lenalidomide therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:709-710.

- Dickson EL, Bakhru A, Chan MP. Topotecan-induced Sweet’s syndrome: a case report. Gynecol Oncol Case Rep. 2013;4:50-52.

- Kümpfel T, Gerdes LA, Flaig M, et al. Drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome after mitoxantrone therapy in a patient with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2011;17:495-497.

- Martorell-Calatayud A, Requena C, Sanmartin O, et al. Gemcitabine-associated sweet syndrome-like eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1236-1238.

- Pang A, Tan KB, Aw D, et al. A case of Sweet’s syndrome due to 5-azacytidine and vorinostat in a patient with NK/T cell lymphoma. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:64-66.

- El Moutaoui L, Zouhair K, Benchikhi H. Sweet syndrome induced by chloroquine. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136:56-57.

- Rosmaninho A, Lobo I, Selores M. Sweet’s syndrome associated with the intake of a selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2011;30:298-301.

- Alencar C, Abramowtiz M, Parekh S, et al. Atypical presentations of Sweet’s syndrome in patients with MDS/AML receiving combinations of hypomethylating agents with histone deacetylase inhibitors. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:688-689.

- Keidel S, McColl A, Edmonds S. Sweet’s syndrome after adalimumab therapy for refractory relapsing polychondritis. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011.

- Rondina A, Watson AC. Bullous Sweet’s syndrome and pseudolymphoma precipitated by IL-2 therapy. Cutis. 2010;85:206-213.

- Gheorghe L, Cotruta B, Trifu V, et al. Drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome secondary to hepatitis C antiviral therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:957-959.

- Zobniw CM, Saad SA, Kostoff D, et al. Bortezomib-induced Sweet’s syndrome confirmed by rechallenge. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:E18-E21.

- Kolb-Mäurer A, Kneitz H, Goebeler M. Sweet-like syndrome induced by bortezomib. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:1200-1202.

- Thuillier D, Lenglet A, Chaby G, et al. Bortezomib-induced eruption: Sweet syndrome? two case reports [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136:427-430.

- Kim MJ, Jang KT, Choe YH. Azathioprine hypersensitivity presenting as sweet syndrome in a child with ulcerative colitis. Indian Pediatr. 2011;48:969-971.

- Truchuelo M, Bagazgoitia L, Alcántara J, et al. Sweet-like lesions induced by bortezomib: a review of the literature and a report of 2 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:829-831.

- Hoelt P, Fattouh K, Villani AP. Dermpath & clinic: drug-induced Sweet syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26:641-642.

- Walker DC, Cohen PR. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-associated acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: case report and review of drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:918-923.

- Thompson DF, Montarella KE. Drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:802-811.

- Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Whittle CH, Back GA, Champion RH. Recurrent neutrophilic dermatosis of the face—a variant of Sweet’s syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1968;80:806-810.

- Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-536.