User login

High levels of neuroinflammatory markers may drive increased Alzheimer’s prevalence among blacks

Potent proinflammatory markers appear to be significantly elevated in the brains of black patients with Alzheimer’s disease, compared to the brains of white patients, while cytokines with a potentially neuroprotective role are decreased, a Food and Drug Administration researcher reported Jan. 11 at an agency grand rounds presentation

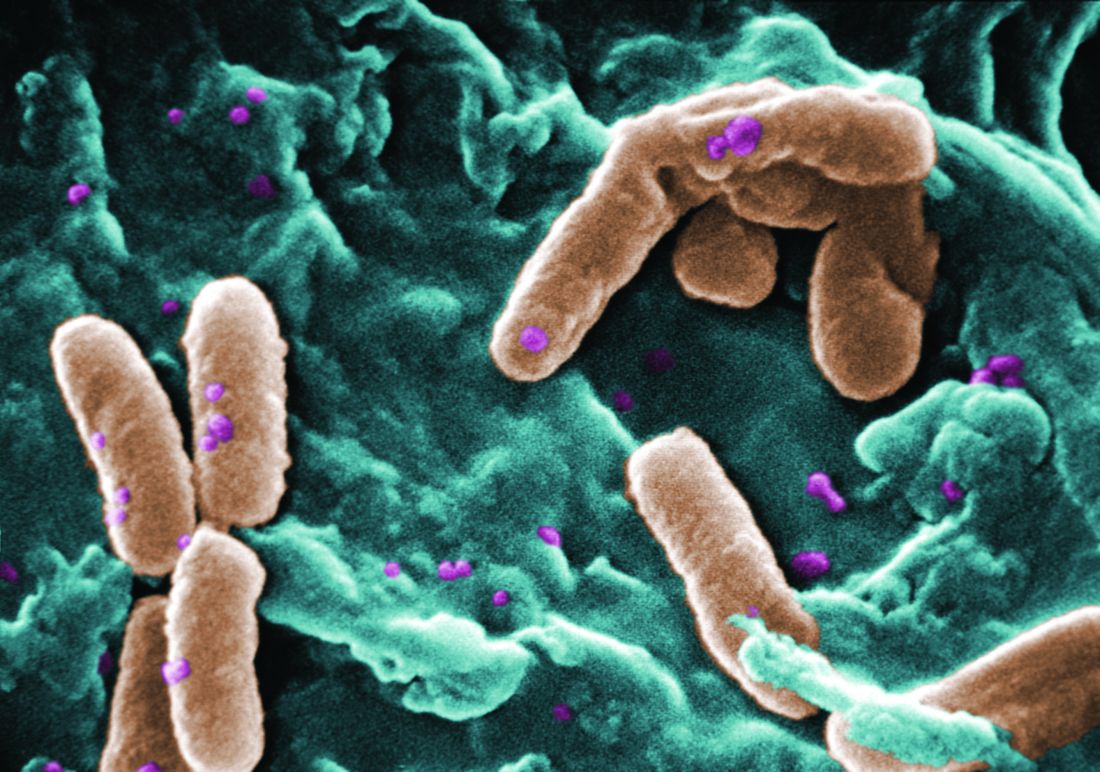

These differences may be driven by the NLRP3 gene, which, in the presence of neuronal insults like beta amyloid aggregates, can direct microglia to pump out a stew of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, Dr. Ferguson said.

“This proposed pathway may help explain why black patients are twice as likely as white ones to develop AD, said Dr. Ferguson, acting director of FDA Division of Neurotoxicology. “Once NLRP3 is activated, it leads to chronically increased levels of inflammatory cytokines. Once they are chronically increased, it could lead to increased synaptic dysfunction, cognitive impairment, and cell death.”

Dr. Ferguson and her colleague, Vijayalakshmi Varma, PhD, FDA research biologist, obtained brain tissue samples from 12 black patients with AD and 12 white ones. She did not have baseline severity staging for the cohort, but said that the patients were a mean of 81 years old, and had confirmed AD pathology at the time of death.

The researchers examined neurodegenerative proteins and cytokine levels in the BA21 area of the brain. Located in the temporal lobe, BA21 is important in language and auditory processing. It generally exhibits atrophy and the characteristic AD lesions of beta amyloid plaques and tau tangles early in the disease.

In a previously published report of this neuropathological cohort, the team examined a number of markers of neurodegeneration including S100B, the soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (sRAGE); glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF); and amyloid beta (AB) 40 and AB42 (J Alzheimers Dis. 2017:59; 57-66).

RAGE helps mediate the transport of AB through the cell membrane and the blood brain barrier. S100B is a protein that has been implicated in the formation of tau tangles; other studies suggest that it interacts with RAGE to promote tau phosphorylation.

Compared to levels in the brains of white patients, brains of black patients contained 17% more S100B and 121% more AB42. The AB42/40 ratio was increased by almost 500% over that seen in the white sample.

The new, unpublished data used this same neuropathological cohort, but examined 40 known neuroinflammatory markers. Compared to the white sample, the black sample showed:

IL-1B, thought to increase amyloid precursor protein and promote tau phosphorylation, increased by 109% MIG, an attractant for activated T-cells, increased by 37%

TRAIL, a ligand that induces apoptosis. increased by 50%

“S 100 B is an astrocytic calcium binding protein,” Dr. Ferguson said. “We know that there are increased brain and cerebrospinal levels of S100 be in mild-moderate Alzheimer’s. S100 B can trigger neuroinflammatory signaling pathways. S100 B is also a potential biomarker of blood-brain barrier permeability. We see increased serum levels in such things as unmedicated schizophrenia and depression as well as brain injury.”

However, Dr. Ferguson said, “There were a couple of cytokines significantly that were decreased in African-American sample, including IL-8. Decreased IL-8 brain levels have been described in those with Alzheimer’s and recent studies have indicated that IL-8 may have a protective role in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis.”

IL-3, which activates mature neutrophils and macrophages, was also significantly decreased.

The researchers also saw some gender differences. Women had about 20% less CCL25 and CCL26 than men, and 32% less CxCL1 (fracktalkine). CCL26 (Eotaxin-3) was decreased significantly (19%) in women. Fractalkine is essential for microglial cell migration. CCL25 and CCL26 are also mobilizers of immune cells.

Dr. Ferguson postulated that at least some of this neuroinflammatory profile could be related to the formation of inflammasomes – multi-protein oligomeric structures formed in microglia in the brain by the influence of the NLRP3 gene.

“There is a lot of evidence that inflammasomes are involved in AD pathogenesis,” she said. Messenger RNA for the NLRP3 inflammasome is up-regulated in blood from AD patients. Alzheimer’s transgenic mice without the gene show decreased hippocampal and cortical AB40 and 42, increased microglial phagocytosis, and better memory. There is also some evidence that the NLRP3 inflammasome releases minute protein particles called apoptosis-associated (ASC) specks. Some researchers think these particles help seed amyloid throughout the brain. Based on these findings, Dr. Ferguson postulated a potential pathway for the increased prevalence and severity of AD among blacks.

Proinflammatory cytokines are released in response to rising AB levels. These promote the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome within activated microglia. The inflammasome releases more chemokines and cytokines, leading to a chronic proinflammatory state that may actually promote amyloid seeding. This leads to synaptic dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, and neuronal death

Dr. Ferguson said work on the samples will continue.

“We also have CSF and hippocampal tissue and intend to look at similar endpoints in those,” she said. “If as a result of this, we can find gene variants associated with ethnicity and Alzheimer’s, we may be able to establish genetic profiles to identify those at high risk. If we can do that, we may be able to intervene early before the person starts showing cognitive deficits and slow the progression of the disease – even develop precision medications for disease intervention.”

This article was updated 1/11/18.

Potent proinflammatory markers appear to be significantly elevated in the brains of black patients with Alzheimer’s disease, compared to the brains of white patients, while cytokines with a potentially neuroprotective role are decreased, a Food and Drug Administration researcher reported Jan. 11 at an agency grand rounds presentation

These differences may be driven by the NLRP3 gene, which, in the presence of neuronal insults like beta amyloid aggregates, can direct microglia to pump out a stew of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, Dr. Ferguson said.

“This proposed pathway may help explain why black patients are twice as likely as white ones to develop AD, said Dr. Ferguson, acting director of FDA Division of Neurotoxicology. “Once NLRP3 is activated, it leads to chronically increased levels of inflammatory cytokines. Once they are chronically increased, it could lead to increased synaptic dysfunction, cognitive impairment, and cell death.”

Dr. Ferguson and her colleague, Vijayalakshmi Varma, PhD, FDA research biologist, obtained brain tissue samples from 12 black patients with AD and 12 white ones. She did not have baseline severity staging for the cohort, but said that the patients were a mean of 81 years old, and had confirmed AD pathology at the time of death.

The researchers examined neurodegenerative proteins and cytokine levels in the BA21 area of the brain. Located in the temporal lobe, BA21 is important in language and auditory processing. It generally exhibits atrophy and the characteristic AD lesions of beta amyloid plaques and tau tangles early in the disease.

In a previously published report of this neuropathological cohort, the team examined a number of markers of neurodegeneration including S100B, the soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (sRAGE); glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF); and amyloid beta (AB) 40 and AB42 (J Alzheimers Dis. 2017:59; 57-66).

RAGE helps mediate the transport of AB through the cell membrane and the blood brain barrier. S100B is a protein that has been implicated in the formation of tau tangles; other studies suggest that it interacts with RAGE to promote tau phosphorylation.

Compared to levels in the brains of white patients, brains of black patients contained 17% more S100B and 121% more AB42. The AB42/40 ratio was increased by almost 500% over that seen in the white sample.

The new, unpublished data used this same neuropathological cohort, but examined 40 known neuroinflammatory markers. Compared to the white sample, the black sample showed:

IL-1B, thought to increase amyloid precursor protein and promote tau phosphorylation, increased by 109% MIG, an attractant for activated T-cells, increased by 37%

TRAIL, a ligand that induces apoptosis. increased by 50%

“S 100 B is an astrocytic calcium binding protein,” Dr. Ferguson said. “We know that there are increased brain and cerebrospinal levels of S100 be in mild-moderate Alzheimer’s. S100 B can trigger neuroinflammatory signaling pathways. S100 B is also a potential biomarker of blood-brain barrier permeability. We see increased serum levels in such things as unmedicated schizophrenia and depression as well as brain injury.”

However, Dr. Ferguson said, “There were a couple of cytokines significantly that were decreased in African-American sample, including IL-8. Decreased IL-8 brain levels have been described in those with Alzheimer’s and recent studies have indicated that IL-8 may have a protective role in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis.”

IL-3, which activates mature neutrophils and macrophages, was also significantly decreased.

The researchers also saw some gender differences. Women had about 20% less CCL25 and CCL26 than men, and 32% less CxCL1 (fracktalkine). CCL26 (Eotaxin-3) was decreased significantly (19%) in women. Fractalkine is essential for microglial cell migration. CCL25 and CCL26 are also mobilizers of immune cells.

Dr. Ferguson postulated that at least some of this neuroinflammatory profile could be related to the formation of inflammasomes – multi-protein oligomeric structures formed in microglia in the brain by the influence of the NLRP3 gene.

“There is a lot of evidence that inflammasomes are involved in AD pathogenesis,” she said. Messenger RNA for the NLRP3 inflammasome is up-regulated in blood from AD patients. Alzheimer’s transgenic mice without the gene show decreased hippocampal and cortical AB40 and 42, increased microglial phagocytosis, and better memory. There is also some evidence that the NLRP3 inflammasome releases minute protein particles called apoptosis-associated (ASC) specks. Some researchers think these particles help seed amyloid throughout the brain. Based on these findings, Dr. Ferguson postulated a potential pathway for the increased prevalence and severity of AD among blacks.

Proinflammatory cytokines are released in response to rising AB levels. These promote the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome within activated microglia. The inflammasome releases more chemokines and cytokines, leading to a chronic proinflammatory state that may actually promote amyloid seeding. This leads to synaptic dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, and neuronal death

Dr. Ferguson said work on the samples will continue.

“We also have CSF and hippocampal tissue and intend to look at similar endpoints in those,” she said. “If as a result of this, we can find gene variants associated with ethnicity and Alzheimer’s, we may be able to establish genetic profiles to identify those at high risk. If we can do that, we may be able to intervene early before the person starts showing cognitive deficits and slow the progression of the disease – even develop precision medications for disease intervention.”

This article was updated 1/11/18.

Potent proinflammatory markers appear to be significantly elevated in the brains of black patients with Alzheimer’s disease, compared to the brains of white patients, while cytokines with a potentially neuroprotective role are decreased, a Food and Drug Administration researcher reported Jan. 11 at an agency grand rounds presentation

These differences may be driven by the NLRP3 gene, which, in the presence of neuronal insults like beta amyloid aggregates, can direct microglia to pump out a stew of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, Dr. Ferguson said.

“This proposed pathway may help explain why black patients are twice as likely as white ones to develop AD, said Dr. Ferguson, acting director of FDA Division of Neurotoxicology. “Once NLRP3 is activated, it leads to chronically increased levels of inflammatory cytokines. Once they are chronically increased, it could lead to increased synaptic dysfunction, cognitive impairment, and cell death.”

Dr. Ferguson and her colleague, Vijayalakshmi Varma, PhD, FDA research biologist, obtained brain tissue samples from 12 black patients with AD and 12 white ones. She did not have baseline severity staging for the cohort, but said that the patients were a mean of 81 years old, and had confirmed AD pathology at the time of death.

The researchers examined neurodegenerative proteins and cytokine levels in the BA21 area of the brain. Located in the temporal lobe, BA21 is important in language and auditory processing. It generally exhibits atrophy and the characteristic AD lesions of beta amyloid plaques and tau tangles early in the disease.

In a previously published report of this neuropathological cohort, the team examined a number of markers of neurodegeneration including S100B, the soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (sRAGE); glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF); and amyloid beta (AB) 40 and AB42 (J Alzheimers Dis. 2017:59; 57-66).

RAGE helps mediate the transport of AB through the cell membrane and the blood brain barrier. S100B is a protein that has been implicated in the formation of tau tangles; other studies suggest that it interacts with RAGE to promote tau phosphorylation.

Compared to levels in the brains of white patients, brains of black patients contained 17% more S100B and 121% more AB42. The AB42/40 ratio was increased by almost 500% over that seen in the white sample.

The new, unpublished data used this same neuropathological cohort, but examined 40 known neuroinflammatory markers. Compared to the white sample, the black sample showed:

IL-1B, thought to increase amyloid precursor protein and promote tau phosphorylation, increased by 109% MIG, an attractant for activated T-cells, increased by 37%

TRAIL, a ligand that induces apoptosis. increased by 50%

“S 100 B is an astrocytic calcium binding protein,” Dr. Ferguson said. “We know that there are increased brain and cerebrospinal levels of S100 be in mild-moderate Alzheimer’s. S100 B can trigger neuroinflammatory signaling pathways. S100 B is also a potential biomarker of blood-brain barrier permeability. We see increased serum levels in such things as unmedicated schizophrenia and depression as well as brain injury.”

However, Dr. Ferguson said, “There were a couple of cytokines significantly that were decreased in African-American sample, including IL-8. Decreased IL-8 brain levels have been described in those with Alzheimer’s and recent studies have indicated that IL-8 may have a protective role in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis.”

IL-3, which activates mature neutrophils and macrophages, was also significantly decreased.

The researchers also saw some gender differences. Women had about 20% less CCL25 and CCL26 than men, and 32% less CxCL1 (fracktalkine). CCL26 (Eotaxin-3) was decreased significantly (19%) in women. Fractalkine is essential for microglial cell migration. CCL25 and CCL26 are also mobilizers of immune cells.

Dr. Ferguson postulated that at least some of this neuroinflammatory profile could be related to the formation of inflammasomes – multi-protein oligomeric structures formed in microglia in the brain by the influence of the NLRP3 gene.

“There is a lot of evidence that inflammasomes are involved in AD pathogenesis,” she said. Messenger RNA for the NLRP3 inflammasome is up-regulated in blood from AD patients. Alzheimer’s transgenic mice without the gene show decreased hippocampal and cortical AB40 and 42, increased microglial phagocytosis, and better memory. There is also some evidence that the NLRP3 inflammasome releases minute protein particles called apoptosis-associated (ASC) specks. Some researchers think these particles help seed amyloid throughout the brain. Based on these findings, Dr. Ferguson postulated a potential pathway for the increased prevalence and severity of AD among blacks.

Proinflammatory cytokines are released in response to rising AB levels. These promote the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome within activated microglia. The inflammasome releases more chemokines and cytokines, leading to a chronic proinflammatory state that may actually promote amyloid seeding. This leads to synaptic dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, and neuronal death

Dr. Ferguson said work on the samples will continue.

“We also have CSF and hippocampal tissue and intend to look at similar endpoints in those,” she said. “If as a result of this, we can find gene variants associated with ethnicity and Alzheimer’s, we may be able to establish genetic profiles to identify those at high risk. If we can do that, we may be able to intervene early before the person starts showing cognitive deficits and slow the progression of the disease – even develop precision medications for disease intervention.”

This article was updated 1/11/18.

REPORTING FROM FDA GRAND ROUNDS

S-1 regimen noninferior to other frontline mCRC options

to other commonly used regimens, according to results of a randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial.

Median progression-free survival for patients receiving the S-1–containing regimen was 14.0 months, compared with 10.8 months for patients receiving either mFOLFOX6 or CapeOX plus bevacizumab (P less than .0001 for noninferiority; P less than .0815 for superiority), Yuji Yamada, MD, of National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo, and coauthors reported.

Based on these results, “we consider S-1 and irinotecan plus bevacizumab to be an effective first-line therapy for mCRC and believe that it can be included as one of the recommended standard regimens,” Dr. Yamada and colleagues said (Ann Oncol. 2017 Dec 17. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx816).

S-1, a combination preparation that includes the 5-fluorouracil prodrug tegafur plus the modulators gimeracil and oteracil potassium, has been approved in Japan and is approved by the European Medicines Agency for gastric cancer, authors wrote.

Their phase 3 trial, known as TRICOLORE, included 487 patients randomly assigned to receive S-1 and irinotecan plus bevacizumab or a control group that received an oxaliplatin-based regimen (either mFOLFOX6 or CapeOX).

Oxaliplatin-based regimens are associated with milder alopecia and gastrointestinal toxicity, compared with irinotecan-based regimens but can result in prolonged peripheral neuropathy that can negatively impact quality of life and may lead to treatment discontinuation, Dr. Yamada and associates said.

Adverse events of grade 3 or higher occurred in 58.6% of the S-1/irinotecan/bevacizumab group and 64.9% of the control group. The most common grade 3 or greater adverse events were neutropenia and diarrhea in the S-1 group, and neutropenia and peripheral sensory neuropathy in the controls.

The median 14-month progression-free survival for S-1/irinotecan/bevacizumab establishes its noninferiority to the standard regimens, according to the authors: “Although superiority could not be proven, the median progression-free survival was 3.2 months longer in the experimental group than in the control group, and the quality of life results were favorable,” they wrote.

Quality of life was not statistically different between arms as measured by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal Trial Outcome Index, according to the report. However, scores on the FACT/Gynecologic Oncology Group-Neurotoxicity subscale showed a “significantly more favorable trend over time in the experimental group,” authors noted.

The study was supported in part by Taiho Pharmaceutical. Dr. Yamada reported receiving honoraria from Taiho, Chugai, and Yakult.

SOURCE: Yamada Y et al. Ann Oncol. 2017 Dec 17. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx816.

to other commonly used regimens, according to results of a randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial.

Median progression-free survival for patients receiving the S-1–containing regimen was 14.0 months, compared with 10.8 months for patients receiving either mFOLFOX6 or CapeOX plus bevacizumab (P less than .0001 for noninferiority; P less than .0815 for superiority), Yuji Yamada, MD, of National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo, and coauthors reported.

Based on these results, “we consider S-1 and irinotecan plus bevacizumab to be an effective first-line therapy for mCRC and believe that it can be included as one of the recommended standard regimens,” Dr. Yamada and colleagues said (Ann Oncol. 2017 Dec 17. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx816).

S-1, a combination preparation that includes the 5-fluorouracil prodrug tegafur plus the modulators gimeracil and oteracil potassium, has been approved in Japan and is approved by the European Medicines Agency for gastric cancer, authors wrote.

Their phase 3 trial, known as TRICOLORE, included 487 patients randomly assigned to receive S-1 and irinotecan plus bevacizumab or a control group that received an oxaliplatin-based regimen (either mFOLFOX6 or CapeOX).

Oxaliplatin-based regimens are associated with milder alopecia and gastrointestinal toxicity, compared with irinotecan-based regimens but can result in prolonged peripheral neuropathy that can negatively impact quality of life and may lead to treatment discontinuation, Dr. Yamada and associates said.

Adverse events of grade 3 or higher occurred in 58.6% of the S-1/irinotecan/bevacizumab group and 64.9% of the control group. The most common grade 3 or greater adverse events were neutropenia and diarrhea in the S-1 group, and neutropenia and peripheral sensory neuropathy in the controls.

The median 14-month progression-free survival for S-1/irinotecan/bevacizumab establishes its noninferiority to the standard regimens, according to the authors: “Although superiority could not be proven, the median progression-free survival was 3.2 months longer in the experimental group than in the control group, and the quality of life results were favorable,” they wrote.

Quality of life was not statistically different between arms as measured by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal Trial Outcome Index, according to the report. However, scores on the FACT/Gynecologic Oncology Group-Neurotoxicity subscale showed a “significantly more favorable trend over time in the experimental group,” authors noted.

The study was supported in part by Taiho Pharmaceutical. Dr. Yamada reported receiving honoraria from Taiho, Chugai, and Yakult.

SOURCE: Yamada Y et al. Ann Oncol. 2017 Dec 17. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx816.

to other commonly used regimens, according to results of a randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial.

Median progression-free survival for patients receiving the S-1–containing regimen was 14.0 months, compared with 10.8 months for patients receiving either mFOLFOX6 or CapeOX plus bevacizumab (P less than .0001 for noninferiority; P less than .0815 for superiority), Yuji Yamada, MD, of National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo, and coauthors reported.

Based on these results, “we consider S-1 and irinotecan plus bevacizumab to be an effective first-line therapy for mCRC and believe that it can be included as one of the recommended standard regimens,” Dr. Yamada and colleagues said (Ann Oncol. 2017 Dec 17. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx816).

S-1, a combination preparation that includes the 5-fluorouracil prodrug tegafur plus the modulators gimeracil and oteracil potassium, has been approved in Japan and is approved by the European Medicines Agency for gastric cancer, authors wrote.

Their phase 3 trial, known as TRICOLORE, included 487 patients randomly assigned to receive S-1 and irinotecan plus bevacizumab or a control group that received an oxaliplatin-based regimen (either mFOLFOX6 or CapeOX).

Oxaliplatin-based regimens are associated with milder alopecia and gastrointestinal toxicity, compared with irinotecan-based regimens but can result in prolonged peripheral neuropathy that can negatively impact quality of life and may lead to treatment discontinuation, Dr. Yamada and associates said.

Adverse events of grade 3 or higher occurred in 58.6% of the S-1/irinotecan/bevacizumab group and 64.9% of the control group. The most common grade 3 or greater adverse events were neutropenia and diarrhea in the S-1 group, and neutropenia and peripheral sensory neuropathy in the controls.

The median 14-month progression-free survival for S-1/irinotecan/bevacizumab establishes its noninferiority to the standard regimens, according to the authors: “Although superiority could not be proven, the median progression-free survival was 3.2 months longer in the experimental group than in the control group, and the quality of life results were favorable,” they wrote.

Quality of life was not statistically different between arms as measured by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal Trial Outcome Index, according to the report. However, scores on the FACT/Gynecologic Oncology Group-Neurotoxicity subscale showed a “significantly more favorable trend over time in the experimental group,” authors noted.

The study was supported in part by Taiho Pharmaceutical. Dr. Yamada reported receiving honoraria from Taiho, Chugai, and Yakult.

SOURCE: Yamada Y et al. Ann Oncol. 2017 Dec 17. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx816.

FROM Annals of Oncology

Key clinical point: The oral fluoropyrimidine S-1 combined with irinotecan and bevacizumab was noninferior to other commonly used first-line regimens in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC).

Major finding: Median progression-free-survival was 14.0 months for that regimen, compared with 10.8 months for patients receiving either mFOLFOX6 or CapeOX plus bevacizumab (P less than .0001 for noninferiority; P less than .0815 for superiority).

Data source: TRICOLORE, a randomized, open-label, phase 3, noninferiority trial including 487 mCRC patients enrolled at 53 institutions in Japan.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Tokyo Cooperative Oncology Group with funding from Taiho Pharmaceutica. Study authors reported disclosures related to Taiho, Chugai, Yakult, Ono, Eli Lilly, Eisai, Bayer, and others.

Source: Yamada Y et al. Ann Oncol. 2017 Dec 17. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx816.

Successive antiepileptic drug treatments offer diminished chances for seizure freedom

despite the wide availability of a variety of new antiepileptic drugs, according to Zhibin Chen, PhD, and his associates

The study included a total of 1,795 patients who were treated at the epilepsy unit of the Western Infirmary in Glasgow, Scotland, from July 1, 1982, to Oct. 31, 2012, and followed until Oct. 31, 2014, or until their deaths. They had a median follow-up of 11 years. Of this group, 1,144 patients were seizure free for a year or longer, including 816 who achieved seizure freedom after the first antiepileptic drug and 212 after receiving their second antiepileptic drug.

The odds ratio for each successive antiepileptic drug regimen’s failing if the first regimen failed was 1.73. The first antiepileptic drug regimen offered about a 50% probability of seizure freedom for 1 year or longer, but the probability of success was only 12% with the second regimen and 4% with the third. Attempts after the third regimen all had a probability of seizure freedom of around or below 1%. Patients who had a greater number of seizures prior to treatment, reported recreational drug use, or had first-degree relatives with a history of seizure were significantly less likely to achieve seizure freedom in a multivariate regression analysis.

“A paradigm shift in treatment and research strategies is needed to improve the long-term outcomes of newly diagnosed epilepsy. Patients with drug-resistant epilepsy should be considered early for nonpharmacological therapies, such as resective surgery and brain stimulation techniques,” the study investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Chen Z et al. JAMA Neurol. 2017 Dec 26. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.3949

despite the wide availability of a variety of new antiepileptic drugs, according to Zhibin Chen, PhD, and his associates

The study included a total of 1,795 patients who were treated at the epilepsy unit of the Western Infirmary in Glasgow, Scotland, from July 1, 1982, to Oct. 31, 2012, and followed until Oct. 31, 2014, or until their deaths. They had a median follow-up of 11 years. Of this group, 1,144 patients were seizure free for a year or longer, including 816 who achieved seizure freedom after the first antiepileptic drug and 212 after receiving their second antiepileptic drug.

The odds ratio for each successive antiepileptic drug regimen’s failing if the first regimen failed was 1.73. The first antiepileptic drug regimen offered about a 50% probability of seizure freedom for 1 year or longer, but the probability of success was only 12% with the second regimen and 4% with the third. Attempts after the third regimen all had a probability of seizure freedom of around or below 1%. Patients who had a greater number of seizures prior to treatment, reported recreational drug use, or had first-degree relatives with a history of seizure were significantly less likely to achieve seizure freedom in a multivariate regression analysis.

“A paradigm shift in treatment and research strategies is needed to improve the long-term outcomes of newly diagnosed epilepsy. Patients with drug-resistant epilepsy should be considered early for nonpharmacological therapies, such as resective surgery and brain stimulation techniques,” the study investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Chen Z et al. JAMA Neurol. 2017 Dec 26. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.3949

despite the wide availability of a variety of new antiepileptic drugs, according to Zhibin Chen, PhD, and his associates

The study included a total of 1,795 patients who were treated at the epilepsy unit of the Western Infirmary in Glasgow, Scotland, from July 1, 1982, to Oct. 31, 2012, and followed until Oct. 31, 2014, or until their deaths. They had a median follow-up of 11 years. Of this group, 1,144 patients were seizure free for a year or longer, including 816 who achieved seizure freedom after the first antiepileptic drug and 212 after receiving their second antiepileptic drug.

The odds ratio for each successive antiepileptic drug regimen’s failing if the first regimen failed was 1.73. The first antiepileptic drug regimen offered about a 50% probability of seizure freedom for 1 year or longer, but the probability of success was only 12% with the second regimen and 4% with the third. Attempts after the third regimen all had a probability of seizure freedom of around or below 1%. Patients who had a greater number of seizures prior to treatment, reported recreational drug use, or had first-degree relatives with a history of seizure were significantly less likely to achieve seizure freedom in a multivariate regression analysis.

“A paradigm shift in treatment and research strategies is needed to improve the long-term outcomes of newly diagnosed epilepsy. Patients with drug-resistant epilepsy should be considered early for nonpharmacological therapies, such as resective surgery and brain stimulation techniques,” the study investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Chen Z et al. JAMA Neurol. 2017 Dec 26. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.3949

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Sales of antiradiation drug skyrocket following Trump tweets

A Twitter battle over the size of each “nuclear button” possessed by President Donald Trump and North Korea’s Kim Jong-un has spiked sales of a drug that protects against radiation poisoning.

Troy Jones, who runs the website www.nukepills.com, said demand for potassium iodide soared last week, after President Trump tweeted that he had a “much bigger & more powerful” button than Kim – a statement that raised new fears about an escalating threat of nuclear war.

“North Korean Leader Kim Jong Un just stated that the ‘Nuclear Button is on his desk at all times.’ Will someone from his depleted and food starved regime please inform him that I too have a Nuclear Button, but it is a much bigger & more powerful one than his, and my Button works!”

– Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) Jan. 3, 2018

“On Jan. 2, I basically got in a month’s supply of potassium iodide and I sold out in 48 hours,” said Mr. Jones, who is a top U.S. distributor of the drug. His Mooresville, N.C., firm sells all three types of the product approved by the Food and Drug Administration. No prescription is required.

, he said.

Mr. Jones also sells to government agencies, hospitals and universities, which aren’t included in that count.

Alan Morris, president of the Williamsburg, Va.–based pharmaceutical firm Anbex, which also distributes KI, said he’s seen a bump in demand, too.

“We are a wonderful barometer of the level of anxiety in the country,” he said.

A spokeswoman for a third firm, Recipharm, which sells low-dose KI tablets, declined to comment on recent sales.

Mr. Jones said this is not the first time in recent months that jitters over growing nuclear tensions have boosted sales of KI, which comes in tablet and liquid form and should be taken within hours of exposure to radiation.

It’s the same substance often added to table salt to provide trace amounts of iodine that ensure proper thyroid function. Mr. Jones sells his tablets for about 65 cents each, though they’re cheaper in bulk. Mr. Morris said he sells the pills to the federal government for about 1 cent apiece.

Yet, neither the FDA nor the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that families stockpile potassium iodide as an antidote against nuclear emergency.

“KI cannot protect the body from radioactive elements other than radioactive iodine – if radioactive iodine is not present, taking KI is not protective and could cause harm,” the CDC’s website states.

The drug, which has a shelf life of up to 7 years, protects against absorption of radioactive iodine into the thyroid. But that means that it protects only the thyroid, not other organs or body systems, said Anupam Kotwal, MBBS, an endocrinologist speaking for the Endocrine Society.

“This is kind of mostly to protect children, people ages less than 18 and pregnant women,” Dr. Kotwal said.

States with nuclear reactors and populations within a 10-mile radius of the reactors stockpile potassium iodide to distribute in case of an emergency, according to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. An accident involving one of those reactors is far more likely than any nuclear threat from Kim Jong-un, Anbex’s Mr. Morris said.

Still, the escalating war of words between the United States and North Korea has unsettled many people, Mr. Jones said. Although some of his buyers may hold what could be regarded as fringe views, many others do not.

“It’s moms and dads,” he said. “They’re worried and they find that these products exist.”

Such concern was underscored last week, when the CDC announced a briefing on the “Public Health Response to a Nuclear Detonation.” One of the planned sessions is titled “Preparing for the Unthinkable.”

Hundreds of people shared the announcement on social media, with varying degrees of alarm that it could have been inspired by the presidential tweet.

A CDC spokeswoman, however, said the briefing had been “in the works” since last spring. The agency held a similar session on nuclear disaster preparedness in 2010.

“CDC has been active in this area for several years, including back in 2011, when the Fukushima nuclear power plant was damaged during a major earthquake,” the agency’s Kathy Harben said in an email.

Indeed, Jones saw big spikes in potassium iodide sales after the Fukushima Daichii disaster, after North Korea started launching missiles – and after President Trump was elected.

“I now follow his Twitter feed just to gauge the day’s sales and determine how much to stock and how many radiation emergency kits to prep for the coming week,” Mr. Jones said, adding later: “I don’t think he intended to have this kind of effect.”

KHN’s coverage of these topics is supported by Laura and John Arnold Foundation and Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

A Twitter battle over the size of each “nuclear button” possessed by President Donald Trump and North Korea’s Kim Jong-un has spiked sales of a drug that protects against radiation poisoning.

Troy Jones, who runs the website www.nukepills.com, said demand for potassium iodide soared last week, after President Trump tweeted that he had a “much bigger & more powerful” button than Kim – a statement that raised new fears about an escalating threat of nuclear war.

“North Korean Leader Kim Jong Un just stated that the ‘Nuclear Button is on his desk at all times.’ Will someone from his depleted and food starved regime please inform him that I too have a Nuclear Button, but it is a much bigger & more powerful one than his, and my Button works!”

– Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) Jan. 3, 2018

“On Jan. 2, I basically got in a month’s supply of potassium iodide and I sold out in 48 hours,” said Mr. Jones, who is a top U.S. distributor of the drug. His Mooresville, N.C., firm sells all three types of the product approved by the Food and Drug Administration. No prescription is required.

, he said.

Mr. Jones also sells to government agencies, hospitals and universities, which aren’t included in that count.

Alan Morris, president of the Williamsburg, Va.–based pharmaceutical firm Anbex, which also distributes KI, said he’s seen a bump in demand, too.

“We are a wonderful barometer of the level of anxiety in the country,” he said.

A spokeswoman for a third firm, Recipharm, which sells low-dose KI tablets, declined to comment on recent sales.

Mr. Jones said this is not the first time in recent months that jitters over growing nuclear tensions have boosted sales of KI, which comes in tablet and liquid form and should be taken within hours of exposure to radiation.

It’s the same substance often added to table salt to provide trace amounts of iodine that ensure proper thyroid function. Mr. Jones sells his tablets for about 65 cents each, though they’re cheaper in bulk. Mr. Morris said he sells the pills to the federal government for about 1 cent apiece.

Yet, neither the FDA nor the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that families stockpile potassium iodide as an antidote against nuclear emergency.

“KI cannot protect the body from radioactive elements other than radioactive iodine – if radioactive iodine is not present, taking KI is not protective and could cause harm,” the CDC’s website states.

The drug, which has a shelf life of up to 7 years, protects against absorption of radioactive iodine into the thyroid. But that means that it protects only the thyroid, not other organs or body systems, said Anupam Kotwal, MBBS, an endocrinologist speaking for the Endocrine Society.

“This is kind of mostly to protect children, people ages less than 18 and pregnant women,” Dr. Kotwal said.

States with nuclear reactors and populations within a 10-mile radius of the reactors stockpile potassium iodide to distribute in case of an emergency, according to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. An accident involving one of those reactors is far more likely than any nuclear threat from Kim Jong-un, Anbex’s Mr. Morris said.

Still, the escalating war of words between the United States and North Korea has unsettled many people, Mr. Jones said. Although some of his buyers may hold what could be regarded as fringe views, many others do not.

“It’s moms and dads,” he said. “They’re worried and they find that these products exist.”

Such concern was underscored last week, when the CDC announced a briefing on the “Public Health Response to a Nuclear Detonation.” One of the planned sessions is titled “Preparing for the Unthinkable.”

Hundreds of people shared the announcement on social media, with varying degrees of alarm that it could have been inspired by the presidential tweet.

A CDC spokeswoman, however, said the briefing had been “in the works” since last spring. The agency held a similar session on nuclear disaster preparedness in 2010.

“CDC has been active in this area for several years, including back in 2011, when the Fukushima nuclear power plant was damaged during a major earthquake,” the agency’s Kathy Harben said in an email.

Indeed, Jones saw big spikes in potassium iodide sales after the Fukushima Daichii disaster, after North Korea started launching missiles – and after President Trump was elected.

“I now follow his Twitter feed just to gauge the day’s sales and determine how much to stock and how many radiation emergency kits to prep for the coming week,” Mr. Jones said, adding later: “I don’t think he intended to have this kind of effect.”

KHN’s coverage of these topics is supported by Laura and John Arnold Foundation and Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

A Twitter battle over the size of each “nuclear button” possessed by President Donald Trump and North Korea’s Kim Jong-un has spiked sales of a drug that protects against radiation poisoning.

Troy Jones, who runs the website www.nukepills.com, said demand for potassium iodide soared last week, after President Trump tweeted that he had a “much bigger & more powerful” button than Kim – a statement that raised new fears about an escalating threat of nuclear war.

“North Korean Leader Kim Jong Un just stated that the ‘Nuclear Button is on his desk at all times.’ Will someone from his depleted and food starved regime please inform him that I too have a Nuclear Button, but it is a much bigger & more powerful one than his, and my Button works!”

– Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) Jan. 3, 2018

“On Jan. 2, I basically got in a month’s supply of potassium iodide and I sold out in 48 hours,” said Mr. Jones, who is a top U.S. distributor of the drug. His Mooresville, N.C., firm sells all three types of the product approved by the Food and Drug Administration. No prescription is required.

, he said.

Mr. Jones also sells to government agencies, hospitals and universities, which aren’t included in that count.

Alan Morris, president of the Williamsburg, Va.–based pharmaceutical firm Anbex, which also distributes KI, said he’s seen a bump in demand, too.

“We are a wonderful barometer of the level of anxiety in the country,” he said.

A spokeswoman for a third firm, Recipharm, which sells low-dose KI tablets, declined to comment on recent sales.

Mr. Jones said this is not the first time in recent months that jitters over growing nuclear tensions have boosted sales of KI, which comes in tablet and liquid form and should be taken within hours of exposure to radiation.

It’s the same substance often added to table salt to provide trace amounts of iodine that ensure proper thyroid function. Mr. Jones sells his tablets for about 65 cents each, though they’re cheaper in bulk. Mr. Morris said he sells the pills to the federal government for about 1 cent apiece.

Yet, neither the FDA nor the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that families stockpile potassium iodide as an antidote against nuclear emergency.

“KI cannot protect the body from radioactive elements other than radioactive iodine – if radioactive iodine is not present, taking KI is not protective and could cause harm,” the CDC’s website states.

The drug, which has a shelf life of up to 7 years, protects against absorption of radioactive iodine into the thyroid. But that means that it protects only the thyroid, not other organs or body systems, said Anupam Kotwal, MBBS, an endocrinologist speaking for the Endocrine Society.

“This is kind of mostly to protect children, people ages less than 18 and pregnant women,” Dr. Kotwal said.

States with nuclear reactors and populations within a 10-mile radius of the reactors stockpile potassium iodide to distribute in case of an emergency, according to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. An accident involving one of those reactors is far more likely than any nuclear threat from Kim Jong-un, Anbex’s Mr. Morris said.

Still, the escalating war of words between the United States and North Korea has unsettled many people, Mr. Jones said. Although some of his buyers may hold what could be regarded as fringe views, many others do not.

“It’s moms and dads,” he said. “They’re worried and they find that these products exist.”

Such concern was underscored last week, when the CDC announced a briefing on the “Public Health Response to a Nuclear Detonation.” One of the planned sessions is titled “Preparing for the Unthinkable.”

Hundreds of people shared the announcement on social media, with varying degrees of alarm that it could have been inspired by the presidential tweet.

A CDC spokeswoman, however, said the briefing had been “in the works” since last spring. The agency held a similar session on nuclear disaster preparedness in 2010.

“CDC has been active in this area for several years, including back in 2011, when the Fukushima nuclear power plant was damaged during a major earthquake,” the agency’s Kathy Harben said in an email.

Indeed, Jones saw big spikes in potassium iodide sales after the Fukushima Daichii disaster, after North Korea started launching missiles – and after President Trump was elected.

“I now follow his Twitter feed just to gauge the day’s sales and determine how much to stock and how many radiation emergency kits to prep for the coming week,” Mr. Jones said, adding later: “I don’t think he intended to have this kind of effect.”

KHN’s coverage of these topics is supported by Laura and John Arnold Foundation and Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Graft-versus-host Disease Presenting Along Blaschko Lines: Cutaneous Mosaicism

To the Editor:

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a common and serious complication seen most often with bone marrow transplantation and peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. With these therapies, functional lymphoid cells are transferred from an immunocompetent donor into a nongenetically identical recipient, or "host." Because of the allogeneic nature of these transplants, the transplanted lymphoid cells have a high potential to recognize and treat the host's cells as foreign, and the resultant clinical and pathologic picture is that of GVHD. The primary organ systems affected in this immune response are the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and hepatobiliary system.1,2 Cutaneous manifestations are by far the most common.3

Although notable gains have been made in elucidating the causes, risk factors, and mechanisms that result in the clinical picture of GVHD, gaps in our knowledge and understanding still exist. Our patient represents a unique case of unilateral GVHD occurring along Blaschko lines, which has important implications for both recognizing and understanding the pathogenesis of GVHD.

A 35-year-old woman was diagnosed with stage IV follicular lymphoma and received various chemotherapy regimens over the next 4 years. Unfortunately, her disease progressed despite treatment. At 39 years of age, she underwent a nonmyeloablative allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation from a single HLA-mismatched sibling. She was placed on prednisone and cyclosporine for immunosuppression. High-dose acyclovir prophylaxis also was initiated given her history of zoster affecting the right C3 dermatome. Successful engraftment was achieved, with molecular studies showing 100% of cells following transplantation were of donor origin. Restaging at 1 and 2 years following transplantation found her to be in complete remission.

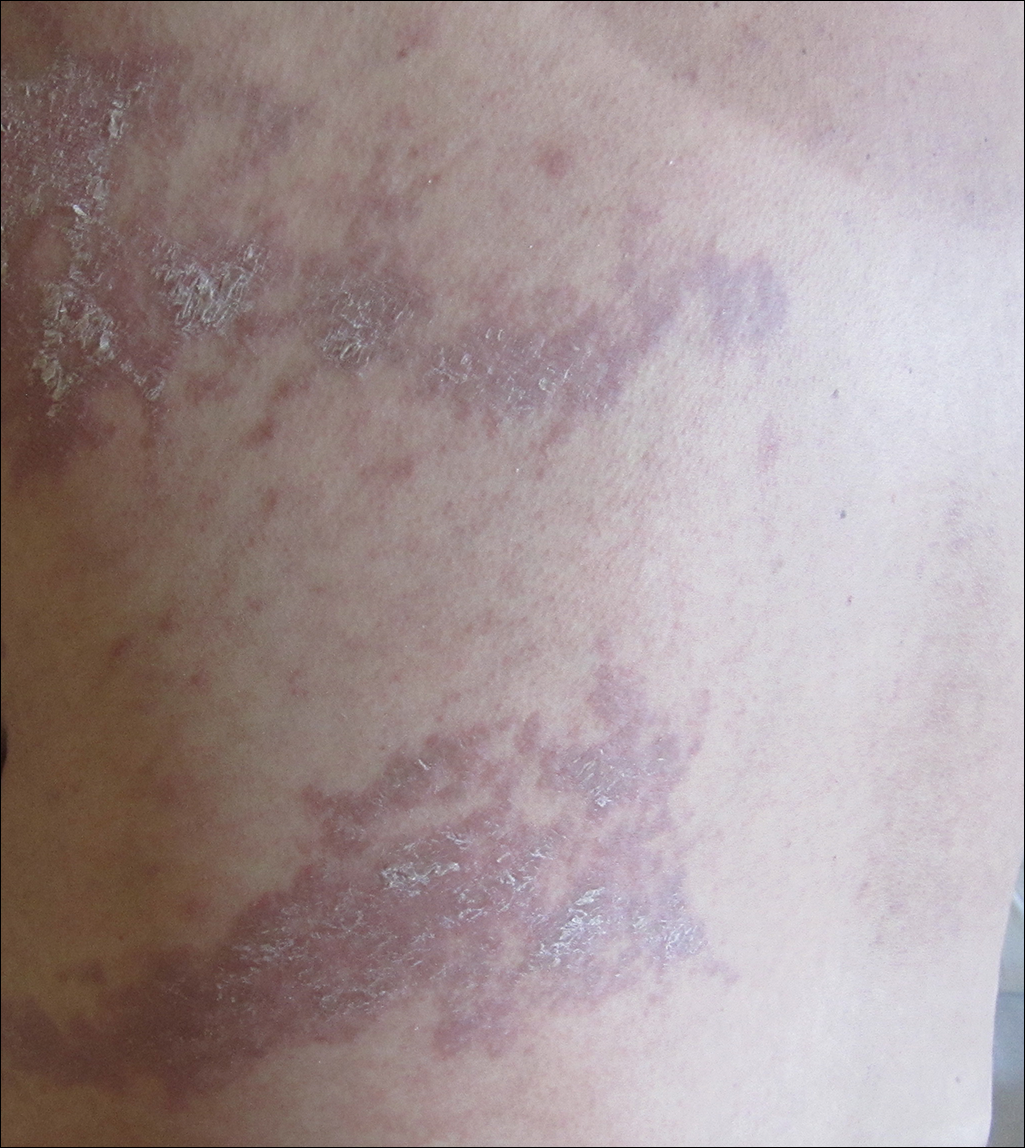

At 2 years following transplantation, she began a slow taper of immunosuppressive medications. She was successfully weaned off prednisone and continued to gradually reduce the cyclosporine dose. Toward the end of the cyclosporine taper 3 months later, she developed a pruritic eruption on the left proximal arm.

She was seen in a bone marrow transplant clinic 4 weeks after the rash developed. On examination, she had multiple, violaceous, lichenoid papules coalescing into linear bandlike plaques. One plaque extended along the left upper arm and 2 others encircled the left hemithorax, respecting the midline. She was treated empirically for zoster with valacyclovir 1 g 3 times daily based on the presumed dermatomal distribution of the eruption. Despite treatment, the rash progressed, and she developed fever. Eight days later, she was admitted with concern for disseminated zoster (Figure). Viral tissue cultures and polymerase chain reaction analysis of the lesions were negative for varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2. Biopsies of skin lesions on the arm and trunk were both consistent with GVHD.

Given the clinical history, characteristic lesion morphology, and distinct linear distribution along with histopathological confirmation, a diagnosis of GVHD along Blaschko lines was made. Recognizing the cause to be immunogenic rather than infectious, immunosuppressive medications were started. In addition to increasing the prednisone and cyclosporine back to therapeutic levels, she received weekly methylprednisolone. With treatment, she showed gradual but marked improvement.

Six cases of linear GVHD have occurred as an isotopic response along dermatomes previously affected by varicella-zoster virus.4-8 These cases give credence to the idea that a cutaneous viral infection may alter the skin through unknown mechanisms, predisposing it to become affected by GVHD. Notably, this phenomenon occurred despite absence of a persistent viral genome when assessed using polymerase chain reaction analysis.4

An additional 3 cases of GVHD occurring in a dermatomal distribution without any prior infections in those areas have been reported.9,10 Of note, 2 of 3 patients did have episodes of zoster occur at other sites following transplantation and did not develop GVHD symptoms in any of those locations.9 Interestingly, controversy exists as to whether the distribution of these lesions was dermatomal or followed Blaschko lines.11

Two cases of linear GVHD have been reported in which lesions were identified as occurring along Blaschko lines.12,13 The lines of Blaschko, first described in 1901, correspond to cellular migration patterns during embryological development.14 Postzygotic mutations causing epidermal cell mosaicism may result in skin disorders occurring in segmental areas defined by the Blaschko lines.15-17 Accordingly, the Blaschko-linear pattern in GVHD suggests cellular mosaicism as the etiology in this case. Although the host's immune system develops immunotolerance to both cellular lineages during maturation, transplanted lymphoid cells from a nongenetically identical sibling may identify just one of the cell lines as nonself, producing a selective pattern of GVHD18 confined to the distribution of the genetically disparate cell line, which occurs along the lines of Blaschko in the skin. Candidate genes for mutations that would produce a mosaic following transplant GVHD include any of the 25 to 30 known minor histocompatibility antigens (or any of the several hundred yet to be found).19 Although well established for monogenic dominant disorders, in 2007 it was recognized that a postzygotic mutation can cause many complex polygenetic disorders, including GVHD, to manifest in a limited segmental pattern. This understanding, along with retrospective case review, has brought into question previously reported "dermatomal" or "zosteriform" presentations of GVHD, asserting that the linear patterns were misidentified and thus inappropriately attributed to a postviral response.20 Recognition of the Blaschko-linear distribution holds significance in both identifying lesion etiology and understanding disease pathogenesis and treatment.

Our patient illustrates a case of a Blaschko-linear GVHD. The distinctive pattern of her physical findings strongly favored epidermal cell mosaicism as the etiology of her disease. More than just a phenotypically unique case, it provided further insight into the complex etiology underlying GVHD and iterated the basic concepts of Blaschko lines and genetic alterations in development.

- Thomas ED, Storb R, Clift RA, et al. Bone-marrow transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:895-902.

- Lee SJ, Vogelsang G, Flowers ME. Chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9:215-233.

- Johnson ML, Farmer ER. Graft versus host reactions in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:369-384.

- Baselga E, Drolet BA, Segura AD, et al. Dermatomal lichenoid chronic graft-vs-host disease following varicella-zoster infection despite absence of viral genome. J Cutan Pathol. 1996;23:576-581.

- Lacour JP, Sirvent N, Monpoux F, et al. Dermatomal chronic cutaneous graft versus host disease at the site of prior herpes zoster. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:587-589.

- Cordoba S, Fraga J, Bartolome B, et al. Giant cell lichenoid dermatitis within herpes zoster scars in a bone marrow recipient. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:255-257.

- Sanli H, Anadolu R, Arat M, et al. Dermatomal lichenoid graft-versus-host disease within herpes zoster scars. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:562-564.

- Martires KJ, Baird K, Citrin DE, et al. Localization of sclerotic-type chronic graft-versus-host disease to sites of skin injury: potential insight into the mechanism of isomorphic and isotopic responses. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1081-1086.

- Freemer CS, Farmer ER, Corio RL, et al. Lichenoid chronic graft-vs-host disease occurring in a dermatomal distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:70-72.

- Cohen PR, Hymes SR. Linear and dermatomal cutaneous graft-versus-host disease. South Med J. 1994;87:758-761.

- Reisfeld PL. Linear lichenoid graft-vs-host disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1207-1208.

- Beers B, Kalish RS, Kaye VN, et al. Unilateral linear lichenoid eruption after bone marrow transplantation: an unmasking of tolerance to an abnormal keratinocyte clone? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(5, pt 2):888-892.

- Wilson BB, Lockman DW. Linear lichenoid graft-vs-host disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1206-1207.

- Goldberg I, Sprecher E. Patterned disorders in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:498-503.

- Colman SD, Rasmussen SA, Ho VT, et al. Somatic mosaicism in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:484-490.

- Munro CS, Wilkie AO. Epidermal mosaicism producing localised acne: somatic mutation in FGFR2. Lancet. 1998;352:704-705.

- Sakuntabhai A, Dhitavat J, Burge S, et al. Mosaicism for ATP2A2 mutations causes segmental Darier's disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:1144-1147.

- Dickinson AM, Wang XN, Sviland L, et al. In situ dissection of the graft-versus-host activities of cytotoxic T cells specific for minor histocompatibility antigens. Nat Med. 2002;8:410-414.

- Hansen JA, Chien JW, Warren EH, et al. Defining genetic risk for graft- versus-host disease and mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Curr Opin Hematol. 2010;17:483-492.

- Happle R. Superimposed segmental manifestation of polygenic skin disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:690-699.

To the Editor:

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a common and serious complication seen most often with bone marrow transplantation and peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. With these therapies, functional lymphoid cells are transferred from an immunocompetent donor into a nongenetically identical recipient, or "host." Because of the allogeneic nature of these transplants, the transplanted lymphoid cells have a high potential to recognize and treat the host's cells as foreign, and the resultant clinical and pathologic picture is that of GVHD. The primary organ systems affected in this immune response are the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and hepatobiliary system.1,2 Cutaneous manifestations are by far the most common.3

Although notable gains have been made in elucidating the causes, risk factors, and mechanisms that result in the clinical picture of GVHD, gaps in our knowledge and understanding still exist. Our patient represents a unique case of unilateral GVHD occurring along Blaschko lines, which has important implications for both recognizing and understanding the pathogenesis of GVHD.

A 35-year-old woman was diagnosed with stage IV follicular lymphoma and received various chemotherapy regimens over the next 4 years. Unfortunately, her disease progressed despite treatment. At 39 years of age, she underwent a nonmyeloablative allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation from a single HLA-mismatched sibling. She was placed on prednisone and cyclosporine for immunosuppression. High-dose acyclovir prophylaxis also was initiated given her history of zoster affecting the right C3 dermatome. Successful engraftment was achieved, with molecular studies showing 100% of cells following transplantation were of donor origin. Restaging at 1 and 2 years following transplantation found her to be in complete remission.

At 2 years following transplantation, she began a slow taper of immunosuppressive medications. She was successfully weaned off prednisone and continued to gradually reduce the cyclosporine dose. Toward the end of the cyclosporine taper 3 months later, she developed a pruritic eruption on the left proximal arm.

She was seen in a bone marrow transplant clinic 4 weeks after the rash developed. On examination, she had multiple, violaceous, lichenoid papules coalescing into linear bandlike plaques. One plaque extended along the left upper arm and 2 others encircled the left hemithorax, respecting the midline. She was treated empirically for zoster with valacyclovir 1 g 3 times daily based on the presumed dermatomal distribution of the eruption. Despite treatment, the rash progressed, and she developed fever. Eight days later, she was admitted with concern for disseminated zoster (Figure). Viral tissue cultures and polymerase chain reaction analysis of the lesions were negative for varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2. Biopsies of skin lesions on the arm and trunk were both consistent with GVHD.

Given the clinical history, characteristic lesion morphology, and distinct linear distribution along with histopathological confirmation, a diagnosis of GVHD along Blaschko lines was made. Recognizing the cause to be immunogenic rather than infectious, immunosuppressive medications were started. In addition to increasing the prednisone and cyclosporine back to therapeutic levels, she received weekly methylprednisolone. With treatment, she showed gradual but marked improvement.

Six cases of linear GVHD have occurred as an isotopic response along dermatomes previously affected by varicella-zoster virus.4-8 These cases give credence to the idea that a cutaneous viral infection may alter the skin through unknown mechanisms, predisposing it to become affected by GVHD. Notably, this phenomenon occurred despite absence of a persistent viral genome when assessed using polymerase chain reaction analysis.4

An additional 3 cases of GVHD occurring in a dermatomal distribution without any prior infections in those areas have been reported.9,10 Of note, 2 of 3 patients did have episodes of zoster occur at other sites following transplantation and did not develop GVHD symptoms in any of those locations.9 Interestingly, controversy exists as to whether the distribution of these lesions was dermatomal or followed Blaschko lines.11

Two cases of linear GVHD have been reported in which lesions were identified as occurring along Blaschko lines.12,13 The lines of Blaschko, first described in 1901, correspond to cellular migration patterns during embryological development.14 Postzygotic mutations causing epidermal cell mosaicism may result in skin disorders occurring in segmental areas defined by the Blaschko lines.15-17 Accordingly, the Blaschko-linear pattern in GVHD suggests cellular mosaicism as the etiology in this case. Although the host's immune system develops immunotolerance to both cellular lineages during maturation, transplanted lymphoid cells from a nongenetically identical sibling may identify just one of the cell lines as nonself, producing a selective pattern of GVHD18 confined to the distribution of the genetically disparate cell line, which occurs along the lines of Blaschko in the skin. Candidate genes for mutations that would produce a mosaic following transplant GVHD include any of the 25 to 30 known minor histocompatibility antigens (or any of the several hundred yet to be found).19 Although well established for monogenic dominant disorders, in 2007 it was recognized that a postzygotic mutation can cause many complex polygenetic disorders, including GVHD, to manifest in a limited segmental pattern. This understanding, along with retrospective case review, has brought into question previously reported "dermatomal" or "zosteriform" presentations of GVHD, asserting that the linear patterns were misidentified and thus inappropriately attributed to a postviral response.20 Recognition of the Blaschko-linear distribution holds significance in both identifying lesion etiology and understanding disease pathogenesis and treatment.

Our patient illustrates a case of a Blaschko-linear GVHD. The distinctive pattern of her physical findings strongly favored epidermal cell mosaicism as the etiology of her disease. More than just a phenotypically unique case, it provided further insight into the complex etiology underlying GVHD and iterated the basic concepts of Blaschko lines and genetic alterations in development.

To the Editor:

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a common and serious complication seen most often with bone marrow transplantation and peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. With these therapies, functional lymphoid cells are transferred from an immunocompetent donor into a nongenetically identical recipient, or "host." Because of the allogeneic nature of these transplants, the transplanted lymphoid cells have a high potential to recognize and treat the host's cells as foreign, and the resultant clinical and pathologic picture is that of GVHD. The primary organ systems affected in this immune response are the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and hepatobiliary system.1,2 Cutaneous manifestations are by far the most common.3

Although notable gains have been made in elucidating the causes, risk factors, and mechanisms that result in the clinical picture of GVHD, gaps in our knowledge and understanding still exist. Our patient represents a unique case of unilateral GVHD occurring along Blaschko lines, which has important implications for both recognizing and understanding the pathogenesis of GVHD.

A 35-year-old woman was diagnosed with stage IV follicular lymphoma and received various chemotherapy regimens over the next 4 years. Unfortunately, her disease progressed despite treatment. At 39 years of age, she underwent a nonmyeloablative allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation from a single HLA-mismatched sibling. She was placed on prednisone and cyclosporine for immunosuppression. High-dose acyclovir prophylaxis also was initiated given her history of zoster affecting the right C3 dermatome. Successful engraftment was achieved, with molecular studies showing 100% of cells following transplantation were of donor origin. Restaging at 1 and 2 years following transplantation found her to be in complete remission.

At 2 years following transplantation, she began a slow taper of immunosuppressive medications. She was successfully weaned off prednisone and continued to gradually reduce the cyclosporine dose. Toward the end of the cyclosporine taper 3 months later, she developed a pruritic eruption on the left proximal arm.

She was seen in a bone marrow transplant clinic 4 weeks after the rash developed. On examination, she had multiple, violaceous, lichenoid papules coalescing into linear bandlike plaques. One plaque extended along the left upper arm and 2 others encircled the left hemithorax, respecting the midline. She was treated empirically for zoster with valacyclovir 1 g 3 times daily based on the presumed dermatomal distribution of the eruption. Despite treatment, the rash progressed, and she developed fever. Eight days later, she was admitted with concern for disseminated zoster (Figure). Viral tissue cultures and polymerase chain reaction analysis of the lesions were negative for varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2. Biopsies of skin lesions on the arm and trunk were both consistent with GVHD.

Given the clinical history, characteristic lesion morphology, and distinct linear distribution along with histopathological confirmation, a diagnosis of GVHD along Blaschko lines was made. Recognizing the cause to be immunogenic rather than infectious, immunosuppressive medications were started. In addition to increasing the prednisone and cyclosporine back to therapeutic levels, she received weekly methylprednisolone. With treatment, she showed gradual but marked improvement.

Six cases of linear GVHD have occurred as an isotopic response along dermatomes previously affected by varicella-zoster virus.4-8 These cases give credence to the idea that a cutaneous viral infection may alter the skin through unknown mechanisms, predisposing it to become affected by GVHD. Notably, this phenomenon occurred despite absence of a persistent viral genome when assessed using polymerase chain reaction analysis.4

An additional 3 cases of GVHD occurring in a dermatomal distribution without any prior infections in those areas have been reported.9,10 Of note, 2 of 3 patients did have episodes of zoster occur at other sites following transplantation and did not develop GVHD symptoms in any of those locations.9 Interestingly, controversy exists as to whether the distribution of these lesions was dermatomal or followed Blaschko lines.11

Two cases of linear GVHD have been reported in which lesions were identified as occurring along Blaschko lines.12,13 The lines of Blaschko, first described in 1901, correspond to cellular migration patterns during embryological development.14 Postzygotic mutations causing epidermal cell mosaicism may result in skin disorders occurring in segmental areas defined by the Blaschko lines.15-17 Accordingly, the Blaschko-linear pattern in GVHD suggests cellular mosaicism as the etiology in this case. Although the host's immune system develops immunotolerance to both cellular lineages during maturation, transplanted lymphoid cells from a nongenetically identical sibling may identify just one of the cell lines as nonself, producing a selective pattern of GVHD18 confined to the distribution of the genetically disparate cell line, which occurs along the lines of Blaschko in the skin. Candidate genes for mutations that would produce a mosaic following transplant GVHD include any of the 25 to 30 known minor histocompatibility antigens (or any of the several hundred yet to be found).19 Although well established for monogenic dominant disorders, in 2007 it was recognized that a postzygotic mutation can cause many complex polygenetic disorders, including GVHD, to manifest in a limited segmental pattern. This understanding, along with retrospective case review, has brought into question previously reported "dermatomal" or "zosteriform" presentations of GVHD, asserting that the linear patterns were misidentified and thus inappropriately attributed to a postviral response.20 Recognition of the Blaschko-linear distribution holds significance in both identifying lesion etiology and understanding disease pathogenesis and treatment.

Our patient illustrates a case of a Blaschko-linear GVHD. The distinctive pattern of her physical findings strongly favored epidermal cell mosaicism as the etiology of her disease. More than just a phenotypically unique case, it provided further insight into the complex etiology underlying GVHD and iterated the basic concepts of Blaschko lines and genetic alterations in development.

- Thomas ED, Storb R, Clift RA, et al. Bone-marrow transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:895-902.

- Lee SJ, Vogelsang G, Flowers ME. Chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9:215-233.

- Johnson ML, Farmer ER. Graft versus host reactions in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:369-384.

- Baselga E, Drolet BA, Segura AD, et al. Dermatomal lichenoid chronic graft-vs-host disease following varicella-zoster infection despite absence of viral genome. J Cutan Pathol. 1996;23:576-581.

- Lacour JP, Sirvent N, Monpoux F, et al. Dermatomal chronic cutaneous graft versus host disease at the site of prior herpes zoster. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:587-589.

- Cordoba S, Fraga J, Bartolome B, et al. Giant cell lichenoid dermatitis within herpes zoster scars in a bone marrow recipient. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:255-257.

- Sanli H, Anadolu R, Arat M, et al. Dermatomal lichenoid graft-versus-host disease within herpes zoster scars. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:562-564.

- Martires KJ, Baird K, Citrin DE, et al. Localization of sclerotic-type chronic graft-versus-host disease to sites of skin injury: potential insight into the mechanism of isomorphic and isotopic responses. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1081-1086.

- Freemer CS, Farmer ER, Corio RL, et al. Lichenoid chronic graft-vs-host disease occurring in a dermatomal distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:70-72.

- Cohen PR, Hymes SR. Linear and dermatomal cutaneous graft-versus-host disease. South Med J. 1994;87:758-761.

- Reisfeld PL. Linear lichenoid graft-vs-host disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1207-1208.

- Beers B, Kalish RS, Kaye VN, et al. Unilateral linear lichenoid eruption after bone marrow transplantation: an unmasking of tolerance to an abnormal keratinocyte clone? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(5, pt 2):888-892.

- Wilson BB, Lockman DW. Linear lichenoid graft-vs-host disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1206-1207.

- Goldberg I, Sprecher E. Patterned disorders in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:498-503.

- Colman SD, Rasmussen SA, Ho VT, et al. Somatic mosaicism in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:484-490.

- Munro CS, Wilkie AO. Epidermal mosaicism producing localised acne: somatic mutation in FGFR2. Lancet. 1998;352:704-705.

- Sakuntabhai A, Dhitavat J, Burge S, et al. Mosaicism for ATP2A2 mutations causes segmental Darier's disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:1144-1147.

- Dickinson AM, Wang XN, Sviland L, et al. In situ dissection of the graft-versus-host activities of cytotoxic T cells specific for minor histocompatibility antigens. Nat Med. 2002;8:410-414.

- Hansen JA, Chien JW, Warren EH, et al. Defining genetic risk for graft- versus-host disease and mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Curr Opin Hematol. 2010;17:483-492.

- Happle R. Superimposed segmental manifestation of polygenic skin disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:690-699.

- Thomas ED, Storb R, Clift RA, et al. Bone-marrow transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:895-902.

- Lee SJ, Vogelsang G, Flowers ME. Chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9:215-233.

- Johnson ML, Farmer ER. Graft versus host reactions in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:369-384.

- Baselga E, Drolet BA, Segura AD, et al. Dermatomal lichenoid chronic graft-vs-host disease following varicella-zoster infection despite absence of viral genome. J Cutan Pathol. 1996;23:576-581.

- Lacour JP, Sirvent N, Monpoux F, et al. Dermatomal chronic cutaneous graft versus host disease at the site of prior herpes zoster. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:587-589.

- Cordoba S, Fraga J, Bartolome B, et al. Giant cell lichenoid dermatitis within herpes zoster scars in a bone marrow recipient. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:255-257.

- Sanli H, Anadolu R, Arat M, et al. Dermatomal lichenoid graft-versus-host disease within herpes zoster scars. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:562-564.

- Martires KJ, Baird K, Citrin DE, et al. Localization of sclerotic-type chronic graft-versus-host disease to sites of skin injury: potential insight into the mechanism of isomorphic and isotopic responses. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1081-1086.

- Freemer CS, Farmer ER, Corio RL, et al. Lichenoid chronic graft-vs-host disease occurring in a dermatomal distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:70-72.

- Cohen PR, Hymes SR. Linear and dermatomal cutaneous graft-versus-host disease. South Med J. 1994;87:758-761.

- Reisfeld PL. Linear lichenoid graft-vs-host disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1207-1208.

- Beers B, Kalish RS, Kaye VN, et al. Unilateral linear lichenoid eruption after bone marrow transplantation: an unmasking of tolerance to an abnormal keratinocyte clone? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(5, pt 2):888-892.

- Wilson BB, Lockman DW. Linear lichenoid graft-vs-host disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1206-1207.

- Goldberg I, Sprecher E. Patterned disorders in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:498-503.

- Colman SD, Rasmussen SA, Ho VT, et al. Somatic mosaicism in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:484-490.

- Munro CS, Wilkie AO. Epidermal mosaicism producing localised acne: somatic mutation in FGFR2. Lancet. 1998;352:704-705.

- Sakuntabhai A, Dhitavat J, Burge S, et al. Mosaicism for ATP2A2 mutations causes segmental Darier's disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:1144-1147.

- Dickinson AM, Wang XN, Sviland L, et al. In situ dissection of the graft-versus-host activities of cytotoxic T cells specific for minor histocompatibility antigens. Nat Med. 2002;8:410-414.

- Hansen JA, Chien JW, Warren EH, et al. Defining genetic risk for graft- versus-host disease and mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Curr Opin Hematol. 2010;17:483-492.

- Happle R. Superimposed segmental manifestation of polygenic skin disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:690-699.

Practice Points

- Recognizing the characteristic manners in which different linear dermatoses present can aid in correctly identifying disorders that most commonly present in either a dermatomal or Blaschko-linear-type distribution.

- A blaschkoid-type distribution is the result of cutaneous mosaicism that occurs during embryological development and therefore subsequently produces a unique phenotypical presentation for various genetically influenced skin disorders, including graft-versus-host disease.

Hormone therapy may reduce depressive symptoms in early menopause

Hormone therapy may reduce the likelihood of depressive symptoms during early menopause, according to data from a placebo-controlled study published online Jan. 10 in JAMA Psychiatry.

Researchers randomized 172 medically healthy women who were perimenopausal or early postmenopausal to either patches of 0.1 mg of 17 beta-estradiol or placebo patches for 12 months, as well as oral micronized progesterone or placebo every 2-3 months.

Women in the placebo arm were more than twice as likely to score at least 16 on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D) at least once during the study, compared with women in the hormone therapy arm (32.3% vs. 17.3%; odds ratio, 2.5; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-5.7; P = .03). They also scored at least 16 on the scale during more visits than did women in the intervention arm (P = .002).

Women who received placebo had a significantly higher mean CES-D score over the course of the 12-month study, compared with those in the intervention arm. At 6 months, mean unadjusted CES-D scores were 5.6 in the placebo group and 4.2 in the intervention group. At 12 months, the scores were 5.7 and 4 respectively.

“Importantly, these results were significant despite statistically adjusting for change in vasomotor symptom bother, suggesting that TE+IMP [transdermal estradiol + intermittent micronized progesterone] has direct prophylactic mood benefits that are independent from its beneficial effects on menopausal symptoms, as previously observed in women with major depressive disorder treated with TE+IMP,” wrote Jennifer L. Gordon, PhD, of the psychology department at the University of Regina, Saskatchewan, and her associates.

The effect of hormone therapy on depression scores changed significantly depending on the women’s stage of menopause. Women in the early menopause transition experienced significant mood benefits, but women in the late menopause transition and those who were postmenopausal did not.

Treatment effects also were influenced by stress, as women who reported experiencing more stressful life events in the 6 months before enrolling in the study showed greater mood benefits than did those with fewer stressful life events.

However, baseline estradiol levels, baseline vasomotor symptoms, history of depression, and history of abuse did not significantly change the effects of treatment.

, compared with the placebo group, and one woman in the treatment group experienced acute deep vein thrombosis that led her to stop treatment and receive medical care. Two cases of major depressive disorder were noted in the placebo group.

Dr. Gordon and her associates cited several limitations. For example, they said, the active and placebo patches used in the study were not identical. “However, our findings remain significant when adjusting for participants’ beliefs about their treatment condition,” they wrote.