User login

EMA recommends orphan designation for pracinostat

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended that pracinostat receive orphan drug designation.

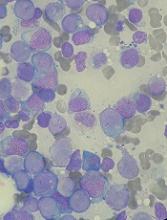

Pracinostat is an oral histone deacetylase inhibitor currently under investigation in a phase 3 study in combination with azacitidine for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in adult patients unfit to receive induction chemotherapy.

Orphan designation provides regulatory and financial incentives for companies to develop and market therapies that treat life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union, and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

Orphan designation provides incentives for companies seeking protocol assistance from the EMA during the product development phase and direct access to the centralized authorization procedure. The designation also provides a 10-year period of marketing exclusivity if a therapy receives regulatory approval.

The EMA’s Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products adopts an opinion on the granting of orphan drug designation, and that opinion is submitted to the European Commission for a final decision.

Phase 2 study

The EMA’s recommendation that pracinostat receive orphan drug designation is based on results of a phase 2 study, which were presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting.

The study included 50 patients who had a median age of 75 (range, 66-84). Sixty-six percent of patients had de novo AML, and 34% had secondary AML.

The patients received pracinostat at 60 mg orally on days 1, 3, and 5 of each week for 21 days of each 28-day cycle. They received azacitidine at 75 mg/m2 subcutaneously or intravenously on days 1-7 or days 1-5 and 8-9 (per site preference) of each 28-day cycle.

As of October 15, 2016, 90% of patients had discontinued treatment, 42% due to progressive disease, 28% due to adverse events (AEs), 14% due to patient decision, and 6% due to investigator decision.

Fifty-two percent of patients (n=26) achieved the primary endpoint of complete response (CR) plus CR with incomplete count recovery (CRi) plus morphologic leukemia-free state (MLFS).

Forty-two percent of patients had a CR, 4% had a CRi, and 6% achieved MLFS. The median duration of CR/CRi/MLFS was 13.2 months. The median duration of CR/CRi was 17.2 months.

The median overall survival was 19.1 months. The 1-year survival rate was 62%, and the 2-year survival rate was 41%.

The most common treatment-emergent AEs were nausea (78%), constipation (70%), fatigue (62%), decreased appetite (56%), diarrhea (50%), vomiting (40%), cough (36%), dyspnea (34%), hypokalemia (34%), peripheral edema (34%), pyrexia (34%), dizziness (32%), back pain (28%), insomnia (28%), febrile neutropenia (48%), thrombocytopenia (46%), anemia (38%), and neutropenia (38%).

Treatment-emergent AEs led to discontinuation in 14 patients. Three of these patients developed sepsis that proved fatal.

The other AEs leading to discontinuation included grade 3 acute axonal neuropathy, grade 3 parainfluenza, grade 3 prolonged QTc/atrial fibrillation, grade 1 acute kidney injury, grade 3 diverticulitis, grade 3 supraglottic ulcer, grade 2 upper respiratory infection, grade 3 fatigue (n=2), and grades 1 and 3 intermittent fatigue (n=2). ![]()

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended that pracinostat receive orphan drug designation.

Pracinostat is an oral histone deacetylase inhibitor currently under investigation in a phase 3 study in combination with azacitidine for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in adult patients unfit to receive induction chemotherapy.

Orphan designation provides regulatory and financial incentives for companies to develop and market therapies that treat life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union, and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

Orphan designation provides incentives for companies seeking protocol assistance from the EMA during the product development phase and direct access to the centralized authorization procedure. The designation also provides a 10-year period of marketing exclusivity if a therapy receives regulatory approval.

The EMA’s Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products adopts an opinion on the granting of orphan drug designation, and that opinion is submitted to the European Commission for a final decision.

Phase 2 study

The EMA’s recommendation that pracinostat receive orphan drug designation is based on results of a phase 2 study, which were presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting.

The study included 50 patients who had a median age of 75 (range, 66-84). Sixty-six percent of patients had de novo AML, and 34% had secondary AML.

The patients received pracinostat at 60 mg orally on days 1, 3, and 5 of each week for 21 days of each 28-day cycle. They received azacitidine at 75 mg/m2 subcutaneously or intravenously on days 1-7 or days 1-5 and 8-9 (per site preference) of each 28-day cycle.

As of October 15, 2016, 90% of patients had discontinued treatment, 42% due to progressive disease, 28% due to adverse events (AEs), 14% due to patient decision, and 6% due to investigator decision.

Fifty-two percent of patients (n=26) achieved the primary endpoint of complete response (CR) plus CR with incomplete count recovery (CRi) plus morphologic leukemia-free state (MLFS).

Forty-two percent of patients had a CR, 4% had a CRi, and 6% achieved MLFS. The median duration of CR/CRi/MLFS was 13.2 months. The median duration of CR/CRi was 17.2 months.

The median overall survival was 19.1 months. The 1-year survival rate was 62%, and the 2-year survival rate was 41%.

The most common treatment-emergent AEs were nausea (78%), constipation (70%), fatigue (62%), decreased appetite (56%), diarrhea (50%), vomiting (40%), cough (36%), dyspnea (34%), hypokalemia (34%), peripheral edema (34%), pyrexia (34%), dizziness (32%), back pain (28%), insomnia (28%), febrile neutropenia (48%), thrombocytopenia (46%), anemia (38%), and neutropenia (38%).

Treatment-emergent AEs led to discontinuation in 14 patients. Three of these patients developed sepsis that proved fatal.

The other AEs leading to discontinuation included grade 3 acute axonal neuropathy, grade 3 parainfluenza, grade 3 prolonged QTc/atrial fibrillation, grade 1 acute kidney injury, grade 3 diverticulitis, grade 3 supraglottic ulcer, grade 2 upper respiratory infection, grade 3 fatigue (n=2), and grades 1 and 3 intermittent fatigue (n=2). ![]()

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended that pracinostat receive orphan drug designation.

Pracinostat is an oral histone deacetylase inhibitor currently under investigation in a phase 3 study in combination with azacitidine for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in adult patients unfit to receive induction chemotherapy.

Orphan designation provides regulatory and financial incentives for companies to develop and market therapies that treat life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union, and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

Orphan designation provides incentives for companies seeking protocol assistance from the EMA during the product development phase and direct access to the centralized authorization procedure. The designation also provides a 10-year period of marketing exclusivity if a therapy receives regulatory approval.

The EMA’s Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products adopts an opinion on the granting of orphan drug designation, and that opinion is submitted to the European Commission for a final decision.

Phase 2 study

The EMA’s recommendation that pracinostat receive orphan drug designation is based on results of a phase 2 study, which were presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting.

The study included 50 patients who had a median age of 75 (range, 66-84). Sixty-six percent of patients had de novo AML, and 34% had secondary AML.

The patients received pracinostat at 60 mg orally on days 1, 3, and 5 of each week for 21 days of each 28-day cycle. They received azacitidine at 75 mg/m2 subcutaneously or intravenously on days 1-7 or days 1-5 and 8-9 (per site preference) of each 28-day cycle.

As of October 15, 2016, 90% of patients had discontinued treatment, 42% due to progressive disease, 28% due to adverse events (AEs), 14% due to patient decision, and 6% due to investigator decision.

Fifty-two percent of patients (n=26) achieved the primary endpoint of complete response (CR) plus CR with incomplete count recovery (CRi) plus morphologic leukemia-free state (MLFS).

Forty-two percent of patients had a CR, 4% had a CRi, and 6% achieved MLFS. The median duration of CR/CRi/MLFS was 13.2 months. The median duration of CR/CRi was 17.2 months.

The median overall survival was 19.1 months. The 1-year survival rate was 62%, and the 2-year survival rate was 41%.

The most common treatment-emergent AEs were nausea (78%), constipation (70%), fatigue (62%), decreased appetite (56%), diarrhea (50%), vomiting (40%), cough (36%), dyspnea (34%), hypokalemia (34%), peripheral edema (34%), pyrexia (34%), dizziness (32%), back pain (28%), insomnia (28%), febrile neutropenia (48%), thrombocytopenia (46%), anemia (38%), and neutropenia (38%).

Treatment-emergent AEs led to discontinuation in 14 patients. Three of these patients developed sepsis that proved fatal.

The other AEs leading to discontinuation included grade 3 acute axonal neuropathy, grade 3 parainfluenza, grade 3 prolonged QTc/atrial fibrillation, grade 1 acute kidney injury, grade 3 diverticulitis, grade 3 supraglottic ulcer, grade 2 upper respiratory infection, grade 3 fatigue (n=2), and grades 1 and 3 intermittent fatigue (n=2). ![]()

Dental Health: What It Means in Kidney Disease

Q) I teach nephrology at a local PA program, and they want us to integrate dental care into each module. What’s the connection between the two?

Dental health is frequently overlooked in the medical realm, as many clinicians feel that dental issues are out of our purview. Hematuria worries us, but bleeding gums and other signs of periodontal disease are often ignored. Surprisingly, many patients don’t seem to mind when their gums bleed every time they brush; they believe that this is normal, when really, it’s not.

Growing evidence supports associations between dental health and multiple medical issues—chronic kidney disease (CKD) among them. Periodontal disease is one of several inflammatory diseases caused by an interaction between gram-negative periodontal bacterial species and the immune system. It manifests with sore, red, bleeding gums and can lead to tooth loss if left untreated.

Chronic inflammation in the gums is a good indicator of inflammation elsewhere in the body. In and of itself, periodontitis can set off an inflammatory cascade in the body. Poor dentition can also lead to poor nutrition, which then causes a feedback loop, leading to even more inflammation.

Patients with periodontal disease have higher levels of C-reactive protein and a higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate than those without the disease.1 And a recent study by Zhang et al showed that periodontal disease increased risk for all-cause mortality in patients with CKD.2

The high cost of CKD from both a financial and personal view makes any intervention worth exploring, as the risk factors are difficult to modify and the CKD population is growing worldwide. We, as medical providers, should reiterate what our dental colleagues have been saying for years: Encourage patients with CKD to practice good dental hygiene by brushing twice a day and flossing daily, in an attempt to improve their overall outcomes.

LCDR Julie Taylor, PA-C

United States Public Health Service, Boston

1. Zhang J, Jiang H, Sun M, Chen J. Association between periodontal disease and mortality in people with CKD: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):269.

2. Chen YT, Shin CJ, Ou SM, et al; Taiwan Geriatric Kidney Disease (TGKD) Research Group. Periodontal disease and risks of kidney function decline and mortality in older people: a community-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015; 66(2):223-230.

Q) I teach nephrology at a local PA program, and they want us to integrate dental care into each module. What’s the connection between the two?

Dental health is frequently overlooked in the medical realm, as many clinicians feel that dental issues are out of our purview. Hematuria worries us, but bleeding gums and other signs of periodontal disease are often ignored. Surprisingly, many patients don’t seem to mind when their gums bleed every time they brush; they believe that this is normal, when really, it’s not.

Growing evidence supports associations between dental health and multiple medical issues—chronic kidney disease (CKD) among them. Periodontal disease is one of several inflammatory diseases caused by an interaction between gram-negative periodontal bacterial species and the immune system. It manifests with sore, red, bleeding gums and can lead to tooth loss if left untreated.

Chronic inflammation in the gums is a good indicator of inflammation elsewhere in the body. In and of itself, periodontitis can set off an inflammatory cascade in the body. Poor dentition can also lead to poor nutrition, which then causes a feedback loop, leading to even more inflammation.

Patients with periodontal disease have higher levels of C-reactive protein and a higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate than those without the disease.1 And a recent study by Zhang et al showed that periodontal disease increased risk for all-cause mortality in patients with CKD.2

The high cost of CKD from both a financial and personal view makes any intervention worth exploring, as the risk factors are difficult to modify and the CKD population is growing worldwide. We, as medical providers, should reiterate what our dental colleagues have been saying for years: Encourage patients with CKD to practice good dental hygiene by brushing twice a day and flossing daily, in an attempt to improve their overall outcomes.

LCDR Julie Taylor, PA-C

United States Public Health Service, Boston

Q) I teach nephrology at a local PA program, and they want us to integrate dental care into each module. What’s the connection between the two?

Dental health is frequently overlooked in the medical realm, as many clinicians feel that dental issues are out of our purview. Hematuria worries us, but bleeding gums and other signs of periodontal disease are often ignored. Surprisingly, many patients don’t seem to mind when their gums bleed every time they brush; they believe that this is normal, when really, it’s not.

Growing evidence supports associations between dental health and multiple medical issues—chronic kidney disease (CKD) among them. Periodontal disease is one of several inflammatory diseases caused by an interaction between gram-negative periodontal bacterial species and the immune system. It manifests with sore, red, bleeding gums and can lead to tooth loss if left untreated.

Chronic inflammation in the gums is a good indicator of inflammation elsewhere in the body. In and of itself, periodontitis can set off an inflammatory cascade in the body. Poor dentition can also lead to poor nutrition, which then causes a feedback loop, leading to even more inflammation.

Patients with periodontal disease have higher levels of C-reactive protein and a higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate than those without the disease.1 And a recent study by Zhang et al showed that periodontal disease increased risk for all-cause mortality in patients with CKD.2

The high cost of CKD from both a financial and personal view makes any intervention worth exploring, as the risk factors are difficult to modify and the CKD population is growing worldwide. We, as medical providers, should reiterate what our dental colleagues have been saying for years: Encourage patients with CKD to practice good dental hygiene by brushing twice a day and flossing daily, in an attempt to improve their overall outcomes.

LCDR Julie Taylor, PA-C

United States Public Health Service, Boston

1. Zhang J, Jiang H, Sun M, Chen J. Association between periodontal disease and mortality in people with CKD: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):269.

2. Chen YT, Shin CJ, Ou SM, et al; Taiwan Geriatric Kidney Disease (TGKD) Research Group. Periodontal disease and risks of kidney function decline and mortality in older people: a community-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015; 66(2):223-230.

1. Zhang J, Jiang H, Sun M, Chen J. Association between periodontal disease and mortality in people with CKD: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):269.

2. Chen YT, Shin CJ, Ou SM, et al; Taiwan Geriatric Kidney Disease (TGKD) Research Group. Periodontal disease and risks of kidney function decline and mortality in older people: a community-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015; 66(2):223-230.

FDA: No more codeine or hydrocodone cold medicines for children

New safety labeling changes for prescription cough and cold medicines containing codeine or hydrocodone limit their use to adults 18 years or older.

The Food and Drug Administration took this action after “conducting an extensive review and convening a panel of outside experts,” which determined that the risks of these medicines outweigh their benefits in children younger than 18 years. The agency also is requiring companies to add a boxed warning to drug labels for prescription cough and cold medicines containing codeine or hydrocodone about the “risks of misuse, abuse, addiction, overdose, death, and slowed or difficult breathing,” according to an FDA safety announcement.

Common side effects of opioids include drowsiness, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, constipation, shortness of breath, and headache, according to the press release.

Reassure parents that cough because of a cold or upper respiratory infection is self-limited and generally does not need to be treated, the FDA advised. If children do need cough treatment, there are over-the-counter products such as dextromethorphan, as well as prescription benzonatate products, the FDA said. Encourage parents to check labels of nonprescription cough and cold products.

In a few states, some codeine cough medicines are available OTC. The FDA is considering regulatory action for these products, according to the safety announcement.

New safety labeling changes for prescription cough and cold medicines containing codeine or hydrocodone limit their use to adults 18 years or older.

The Food and Drug Administration took this action after “conducting an extensive review and convening a panel of outside experts,” which determined that the risks of these medicines outweigh their benefits in children younger than 18 years. The agency also is requiring companies to add a boxed warning to drug labels for prescription cough and cold medicines containing codeine or hydrocodone about the “risks of misuse, abuse, addiction, overdose, death, and slowed or difficult breathing,” according to an FDA safety announcement.

Common side effects of opioids include drowsiness, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, constipation, shortness of breath, and headache, according to the press release.

Reassure parents that cough because of a cold or upper respiratory infection is self-limited and generally does not need to be treated, the FDA advised. If children do need cough treatment, there are over-the-counter products such as dextromethorphan, as well as prescription benzonatate products, the FDA said. Encourage parents to check labels of nonprescription cough and cold products.

In a few states, some codeine cough medicines are available OTC. The FDA is considering regulatory action for these products, according to the safety announcement.

New safety labeling changes for prescription cough and cold medicines containing codeine or hydrocodone limit their use to adults 18 years or older.

The Food and Drug Administration took this action after “conducting an extensive review and convening a panel of outside experts,” which determined that the risks of these medicines outweigh their benefits in children younger than 18 years. The agency also is requiring companies to add a boxed warning to drug labels for prescription cough and cold medicines containing codeine or hydrocodone about the “risks of misuse, abuse, addiction, overdose, death, and slowed or difficult breathing,” according to an FDA safety announcement.

Common side effects of opioids include drowsiness, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, constipation, shortness of breath, and headache, according to the press release.

Reassure parents that cough because of a cold or upper respiratory infection is self-limited and generally does not need to be treated, the FDA advised. If children do need cough treatment, there are over-the-counter products such as dextromethorphan, as well as prescription benzonatate products, the FDA said. Encourage parents to check labels of nonprescription cough and cold products.

In a few states, some codeine cough medicines are available OTC. The FDA is considering regulatory action for these products, according to the safety announcement.

AUDIO: Immunotherapy’s role in NHL

ATLANTA – The use of immune checkpoint blockade is increasingly becoming standard therapy in Hodgkin lymphoma, but this approach has so far garnered mixed results in non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Stephen Ansell, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

In an interview, Dr. Ansell, professor of medicine and chair of the lymphoma group at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said responses have been variable with promising results from immune checkpoint inhibitors in primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, some NK/T-cell lymphomas, and primary CNS lymphoma. However, responses have been modest in low-grade lymphoma.

Dr. Ansell, who chaired a session at ASH 2017 on immunotherapy’s expanding role in non-Hodgkin lymphoma, said one of the major challenges of using immune checkpoint blockade in non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the complicated biology. For example, there are a lot of regulatory T cells that actually inhibit the immune response, and many of the T cells that are present within the tumor have an exhausted phenotype and are poorly functioning. Additionally, some of the cytokines that would seem to be stimulating the immune system can, over time, slowly produce T-cell exhaustion.

“Sort of like too much of a good thing ends up being a bad thing,” he said.

These are the issues that are fueling research today, Dr. Ansell said. Going forward he said he expects to see more combination approaches to therapy, such as using an agonistic positive signal plus the blocking of an inhibitory signal with chemotherapy.

Dr. Ansell reported that Mayo Clinic receives clinical trial support from Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Seattle Genetics, Trillium, and Affimed.

ATLANTA – The use of immune checkpoint blockade is increasingly becoming standard therapy in Hodgkin lymphoma, but this approach has so far garnered mixed results in non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Stephen Ansell, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

In an interview, Dr. Ansell, professor of medicine and chair of the lymphoma group at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said responses have been variable with promising results from immune checkpoint inhibitors in primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, some NK/T-cell lymphomas, and primary CNS lymphoma. However, responses have been modest in low-grade lymphoma.

Dr. Ansell, who chaired a session at ASH 2017 on immunotherapy’s expanding role in non-Hodgkin lymphoma, said one of the major challenges of using immune checkpoint blockade in non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the complicated biology. For example, there are a lot of regulatory T cells that actually inhibit the immune response, and many of the T cells that are present within the tumor have an exhausted phenotype and are poorly functioning. Additionally, some of the cytokines that would seem to be stimulating the immune system can, over time, slowly produce T-cell exhaustion.

“Sort of like too much of a good thing ends up being a bad thing,” he said.

These are the issues that are fueling research today, Dr. Ansell said. Going forward he said he expects to see more combination approaches to therapy, such as using an agonistic positive signal plus the blocking of an inhibitory signal with chemotherapy.

Dr. Ansell reported that Mayo Clinic receives clinical trial support from Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Seattle Genetics, Trillium, and Affimed.

ATLANTA – The use of immune checkpoint blockade is increasingly becoming standard therapy in Hodgkin lymphoma, but this approach has so far garnered mixed results in non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Stephen Ansell, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

In an interview, Dr. Ansell, professor of medicine and chair of the lymphoma group at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said responses have been variable with promising results from immune checkpoint inhibitors in primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, some NK/T-cell lymphomas, and primary CNS lymphoma. However, responses have been modest in low-grade lymphoma.

Dr. Ansell, who chaired a session at ASH 2017 on immunotherapy’s expanding role in non-Hodgkin lymphoma, said one of the major challenges of using immune checkpoint blockade in non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the complicated biology. For example, there are a lot of regulatory T cells that actually inhibit the immune response, and many of the T cells that are present within the tumor have an exhausted phenotype and are poorly functioning. Additionally, some of the cytokines that would seem to be stimulating the immune system can, over time, slowly produce T-cell exhaustion.

“Sort of like too much of a good thing ends up being a bad thing,” he said.

These are the issues that are fueling research today, Dr. Ansell said. Going forward he said he expects to see more combination approaches to therapy, such as using an agonistic positive signal plus the blocking of an inhibitory signal with chemotherapy.

Dr. Ansell reported that Mayo Clinic receives clinical trial support from Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Seattle Genetics, Trillium, and Affimed.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ASH 2017

Novel herpes zoster vaccine is more cost effective than old vaccine

The novel herpes zoster subunit vaccine (HZ/su) is more effective and less expensive than the currently used live attenuated virus (ZVL), according to a study from the Center for Value-Based Research.

Phuc Le, PhD, of the Cleveland Clinic and her colleague Michael Rothberg, MD, conducted an economic analysis of vaccine strategies from the societal perspective. This included the direct medical costs and productivity losses associated with HZ disease and complications.

The one-, two-, and three-way sensitivity analyses examined how different variables affected the cost-effectiveness of different vaccine strategies. The one-way analysis examined the association of input variables and cost-effectiveness. This included HZ/su prices, waning rate and initial efficacy of a dose of HZ/su, and the adherence rate. This analysis revealed that, compared with no vaccination, HZ/su would provide cost savings up to a price of $160, or $80 per dose.

Regardless of circumstance, HZ/su was always more effective than ZVL according to the two-way sensitivity analysis. This analysis took into account the joint effect of price, adherence to two doses of HZ/su, efficacy, and the waning rate of one dose and two doses of HZ/su and ZVL. Compared with ZVL, HZ/su would be less costly up to a price of $350 per series.

Adherence rates to vaccination schedules were important in determining the efficacy and waning rate which ultimately effected cost-effectiveness. The three-way sensitivity analysis found that, if HZ/su adherence to the second dose was greater than 56.8%, results were insensitive to the variation of single-dose efficacy and waning rate of HZ/su. But if adherence rates fell below 40%, combinations of waning rate and lower efficacy made HZ/su cost ineffective. Most importantly, ZVL was never cost effective for 60-year-old patients.

Despite a projected price of $280 per series, HZ/su is still more effective and less expensive than ZVL for adults 60 years or older. According to Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg, the assumptions about the vaccine’s efficacy duration and price were reasonable. But, if the vaccine price were to rise in the future, or a single dose becomes much less effective than reported by GlaxoSmithKline, or if adherence to the second dose was remarkably low, the results of the study would be changed.

“An ACIP recommendation stating a preference for HZ/su over ZVL could lead to future price increases, which would render the vaccine no longer cost effective” wrote Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg. “Therefore, a recommendation linked to periodic reassessment of cost-effectiveness based on the vaccine price might help to mitigate the effect of the recommendation on vaccine affordability.”

Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg reported having no conflicts of interest.

The HZ/su vaccine is not yet approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, but in 2017, the FDA Advisory Committee unanimously voted in favor of its use in adults age 50 years and older.

SOURCE: Phuc L et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jan 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7431. Najafzadeh M. JAMA Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7442.

The herpes zoster (HZ) virus disproportionately affects elderly populations. As the U.S. population ages, tools and mechanisms to reduce the clinical and economic burden of HZ will be needed in the coming years.

The work of Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg presents the results of an economic evaluation on randomized clinical trials of a yet-to-be-approved novel HZ subunit vaccine (HZ/su) to determine the economic and clinical benefit of the new vaccine, compared with the currently used vaccine. Although HZ/su is intended to be a two-dose vaccine, the study focused on a one-time vaccine strategy because booster vaccines are unpopular and not recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

“If priced at $280 per two required doses, HZ/su appears to be a cost-saving option, compared with ZVL and a cost-effective option, compared with no-vaccine strategies,” wrote Dr. Najafzadeh. “However, the value of HZ/su vaccine would be even higher if it could be marketed at a price comparable to that of ZVL.” An added benefit of the HZ/su vaccine is that it can be used in immunocompromised patients.

Mehdi Najafzadeh, PhD , is an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. He also serves as an associate statistician/epidemiologist in the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The herpes zoster (HZ) virus disproportionately affects elderly populations. As the U.S. population ages, tools and mechanisms to reduce the clinical and economic burden of HZ will be needed in the coming years.

The work of Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg presents the results of an economic evaluation on randomized clinical trials of a yet-to-be-approved novel HZ subunit vaccine (HZ/su) to determine the economic and clinical benefit of the new vaccine, compared with the currently used vaccine. Although HZ/su is intended to be a two-dose vaccine, the study focused on a one-time vaccine strategy because booster vaccines are unpopular and not recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

“If priced at $280 per two required doses, HZ/su appears to be a cost-saving option, compared with ZVL and a cost-effective option, compared with no-vaccine strategies,” wrote Dr. Najafzadeh. “However, the value of HZ/su vaccine would be even higher if it could be marketed at a price comparable to that of ZVL.” An added benefit of the HZ/su vaccine is that it can be used in immunocompromised patients.

Mehdi Najafzadeh, PhD , is an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. He also serves as an associate statistician/epidemiologist in the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The herpes zoster (HZ) virus disproportionately affects elderly populations. As the U.S. population ages, tools and mechanisms to reduce the clinical and economic burden of HZ will be needed in the coming years.

The work of Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg presents the results of an economic evaluation on randomized clinical trials of a yet-to-be-approved novel HZ subunit vaccine (HZ/su) to determine the economic and clinical benefit of the new vaccine, compared with the currently used vaccine. Although HZ/su is intended to be a two-dose vaccine, the study focused on a one-time vaccine strategy because booster vaccines are unpopular and not recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

“If priced at $280 per two required doses, HZ/su appears to be a cost-saving option, compared with ZVL and a cost-effective option, compared with no-vaccine strategies,” wrote Dr. Najafzadeh. “However, the value of HZ/su vaccine would be even higher if it could be marketed at a price comparable to that of ZVL.” An added benefit of the HZ/su vaccine is that it can be used in immunocompromised patients.

Mehdi Najafzadeh, PhD , is an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. He also serves as an associate statistician/epidemiologist in the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The novel herpes zoster subunit vaccine (HZ/su) is more effective and less expensive than the currently used live attenuated virus (ZVL), according to a study from the Center for Value-Based Research.

Phuc Le, PhD, of the Cleveland Clinic and her colleague Michael Rothberg, MD, conducted an economic analysis of vaccine strategies from the societal perspective. This included the direct medical costs and productivity losses associated with HZ disease and complications.

The one-, two-, and three-way sensitivity analyses examined how different variables affected the cost-effectiveness of different vaccine strategies. The one-way analysis examined the association of input variables and cost-effectiveness. This included HZ/su prices, waning rate and initial efficacy of a dose of HZ/su, and the adherence rate. This analysis revealed that, compared with no vaccination, HZ/su would provide cost savings up to a price of $160, or $80 per dose.

Regardless of circumstance, HZ/su was always more effective than ZVL according to the two-way sensitivity analysis. This analysis took into account the joint effect of price, adherence to two doses of HZ/su, efficacy, and the waning rate of one dose and two doses of HZ/su and ZVL. Compared with ZVL, HZ/su would be less costly up to a price of $350 per series.

Adherence rates to vaccination schedules were important in determining the efficacy and waning rate which ultimately effected cost-effectiveness. The three-way sensitivity analysis found that, if HZ/su adherence to the second dose was greater than 56.8%, results were insensitive to the variation of single-dose efficacy and waning rate of HZ/su. But if adherence rates fell below 40%, combinations of waning rate and lower efficacy made HZ/su cost ineffective. Most importantly, ZVL was never cost effective for 60-year-old patients.

Despite a projected price of $280 per series, HZ/su is still more effective and less expensive than ZVL for adults 60 years or older. According to Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg, the assumptions about the vaccine’s efficacy duration and price were reasonable. But, if the vaccine price were to rise in the future, or a single dose becomes much less effective than reported by GlaxoSmithKline, or if adherence to the second dose was remarkably low, the results of the study would be changed.

“An ACIP recommendation stating a preference for HZ/su over ZVL could lead to future price increases, which would render the vaccine no longer cost effective” wrote Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg. “Therefore, a recommendation linked to periodic reassessment of cost-effectiveness based on the vaccine price might help to mitigate the effect of the recommendation on vaccine affordability.”

Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg reported having no conflicts of interest.

The HZ/su vaccine is not yet approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, but in 2017, the FDA Advisory Committee unanimously voted in favor of its use in adults age 50 years and older.

SOURCE: Phuc L et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jan 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7431. Najafzadeh M. JAMA Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7442.

The novel herpes zoster subunit vaccine (HZ/su) is more effective and less expensive than the currently used live attenuated virus (ZVL), according to a study from the Center for Value-Based Research.

Phuc Le, PhD, of the Cleveland Clinic and her colleague Michael Rothberg, MD, conducted an economic analysis of vaccine strategies from the societal perspective. This included the direct medical costs and productivity losses associated with HZ disease and complications.

The one-, two-, and three-way sensitivity analyses examined how different variables affected the cost-effectiveness of different vaccine strategies. The one-way analysis examined the association of input variables and cost-effectiveness. This included HZ/su prices, waning rate and initial efficacy of a dose of HZ/su, and the adherence rate. This analysis revealed that, compared with no vaccination, HZ/su would provide cost savings up to a price of $160, or $80 per dose.

Regardless of circumstance, HZ/su was always more effective than ZVL according to the two-way sensitivity analysis. This analysis took into account the joint effect of price, adherence to two doses of HZ/su, efficacy, and the waning rate of one dose and two doses of HZ/su and ZVL. Compared with ZVL, HZ/su would be less costly up to a price of $350 per series.

Adherence rates to vaccination schedules were important in determining the efficacy and waning rate which ultimately effected cost-effectiveness. The three-way sensitivity analysis found that, if HZ/su adherence to the second dose was greater than 56.8%, results were insensitive to the variation of single-dose efficacy and waning rate of HZ/su. But if adherence rates fell below 40%, combinations of waning rate and lower efficacy made HZ/su cost ineffective. Most importantly, ZVL was never cost effective for 60-year-old patients.

Despite a projected price of $280 per series, HZ/su is still more effective and less expensive than ZVL for adults 60 years or older. According to Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg, the assumptions about the vaccine’s efficacy duration and price were reasonable. But, if the vaccine price were to rise in the future, or a single dose becomes much less effective than reported by GlaxoSmithKline, or if adherence to the second dose was remarkably low, the results of the study would be changed.

“An ACIP recommendation stating a preference for HZ/su over ZVL could lead to future price increases, which would render the vaccine no longer cost effective” wrote Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg. “Therefore, a recommendation linked to periodic reassessment of cost-effectiveness based on the vaccine price might help to mitigate the effect of the recommendation on vaccine affordability.”

Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg reported having no conflicts of interest.

The HZ/su vaccine is not yet approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, but in 2017, the FDA Advisory Committee unanimously voted in favor of its use in adults age 50 years and older.

SOURCE: Phuc L et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jan 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7431. Najafzadeh M. JAMA Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7442.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Cost-effectiveness can be an important factor in considering patient treatment for herpes zoster.

Major finding:

Study details: The study was based on U.S. medical literature. Data were derived from adults 60 years or older in patient groups of 100-30,000 from July 1 to July 31, 2017.

Disclosures: None of the researchers had conflicts of interest to report.

Source: L. Phuc et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jan 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7431; Najafzadeh M. JAMA Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7442.

Phase 1 study: Human IL-10 plus checkpoint blockade looks promising in RCC, NSCLC

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Pegylated human interleukin-10 in combination with anti–PD-1 therapy is well tolerated and shows promise for the treatment of both renal cell carcinoma and non–small cell lung cancer, according to findings from a phase 1 study.

The IL-10 product, AM0010 (pegilodecakin), was shown to be well tolerated as monotherapy, and was evaluated in combination with anti–PD-1 therapy in the two expansion cohorts included in the current analysis, Martin Oft, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

Of 34 evaluable renal cell carcinoma (RCC) patients included in one expansion cohort, 15 (44%) had an objective response at a median follow-up of 27 months, and two of those had a complete response (CR), Dr. Oft of ARMO BioSciences, Redwood City, Calif. reported.

In contrast, only 4 of 16 evaluable patients who received AM0010 monotherapy (25%) had an objective response, he said.

In eight patients who received AM0010 + pembrolizumab (Keytruda), the objective response rate was 50%, and both patients who had a complete response were in that group. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 16.7 months. In 26 who received AM0010 + nivolumab (Opdivo), 11 had an objective response, but neither the complete response nor PFS rates had been reached in patients in that group, he noted.

The responses were durable.

“In fact, we had one patient who stopped treatment after a year in [complete remission] and is now 1 year in total remission without any further treatment,” he said.

Patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) also experienced some benefit from the combination therapy. Objective responses were observed in 11 of 27 evaluable NSCLC patients (41%) who were treated with AM0010 and an anti–PD-1(9 of 22 [41%] who received AM0010 and nivolumab, and 2 of 5 [40%] who received AM0010 and pembrolizumab).

Progression-free survival was not reached in this cohort.

An analysis by PD-L1 status showed that 33% of NSCLC patients with PD-L1 levels less than 1% achieved a response, 67% of those with PD-L1 levels of 1%-49% achieved a response, and 80% of those with PD-L1 levels of 50% or greater achieved a response, he said, adding that the responses were very durable in all three groups.

Of note, NSCLC patients with liver metastasis have been shown in prior trials to have a lower overall response rate to immune checkpoint inhibition, but in this trial, 7 of 9 patients with NSCLC metastasis to the liver had a partial response (PR), Dr. Oft said.

The RCC and NSCLC patients had a median of 1 and 2 prior therapies, respectively.

AM0010 was given subcutaneously at a dose of 10 or 20 mcg/kg daily, pembrolizumab was given intravenously at 2mg/kg every 3 weeks, and nivolumab was given intravenously at a dose of 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks.

Treatment-related adverse events included anemia, thrombocytopenia, and fatigue, and all were reversible and transient, Dr. Oft said, noting that grade 3 or 4 adverse events were mostly absent in patients receiving the lower dose; thus the recommended phase 2 dose is 10 mcg/kg.

“It’s important to note that three of those six patients [receiving the lower dose] in fact had a PR or CR so this lower dose did not come at the expense of efficacy,” he added.

The mechanistic rationale for combining AM0010 and anti-PD1 for the treatment of cancer patients lies in the fact that IL‐10 has anti‐inflammatory functions and stimulates the cytotoxicity and proliferation of antigen-activated CD8+ T cells. T cell receptor–mediated activation of CD8+ T cells elevates IL‐10 receptors and PD‐1, Dr. Oft explained.

The robust efficacy data and the observed CD8+ T cell activation seen in these expansion cohorts is promising and encourages the continued study of AM0010 in combination with PD-1 inhibition, he concluded, noting that larger studies are planned for the coming year.

Dr. Oft is a founder and employee of ARMO BioSciences, which sponsored this study.

SOURCE: Naing A et al. SITC Abstract 012.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Pegylated human interleukin-10 in combination with anti–PD-1 therapy is well tolerated and shows promise for the treatment of both renal cell carcinoma and non–small cell lung cancer, according to findings from a phase 1 study.

The IL-10 product, AM0010 (pegilodecakin), was shown to be well tolerated as monotherapy, and was evaluated in combination with anti–PD-1 therapy in the two expansion cohorts included in the current analysis, Martin Oft, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

Of 34 evaluable renal cell carcinoma (RCC) patients included in one expansion cohort, 15 (44%) had an objective response at a median follow-up of 27 months, and two of those had a complete response (CR), Dr. Oft of ARMO BioSciences, Redwood City, Calif. reported.

In contrast, only 4 of 16 evaluable patients who received AM0010 monotherapy (25%) had an objective response, he said.

In eight patients who received AM0010 + pembrolizumab (Keytruda), the objective response rate was 50%, and both patients who had a complete response were in that group. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 16.7 months. In 26 who received AM0010 + nivolumab (Opdivo), 11 had an objective response, but neither the complete response nor PFS rates had been reached in patients in that group, he noted.

The responses were durable.

“In fact, we had one patient who stopped treatment after a year in [complete remission] and is now 1 year in total remission without any further treatment,” he said.

Patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) also experienced some benefit from the combination therapy. Objective responses were observed in 11 of 27 evaluable NSCLC patients (41%) who were treated with AM0010 and an anti–PD-1(9 of 22 [41%] who received AM0010 and nivolumab, and 2 of 5 [40%] who received AM0010 and pembrolizumab).

Progression-free survival was not reached in this cohort.

An analysis by PD-L1 status showed that 33% of NSCLC patients with PD-L1 levels less than 1% achieved a response, 67% of those with PD-L1 levels of 1%-49% achieved a response, and 80% of those with PD-L1 levels of 50% or greater achieved a response, he said, adding that the responses were very durable in all three groups.

Of note, NSCLC patients with liver metastasis have been shown in prior trials to have a lower overall response rate to immune checkpoint inhibition, but in this trial, 7 of 9 patients with NSCLC metastasis to the liver had a partial response (PR), Dr. Oft said.

The RCC and NSCLC patients had a median of 1 and 2 prior therapies, respectively.

AM0010 was given subcutaneously at a dose of 10 or 20 mcg/kg daily, pembrolizumab was given intravenously at 2mg/kg every 3 weeks, and nivolumab was given intravenously at a dose of 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks.

Treatment-related adverse events included anemia, thrombocytopenia, and fatigue, and all were reversible and transient, Dr. Oft said, noting that grade 3 or 4 adverse events were mostly absent in patients receiving the lower dose; thus the recommended phase 2 dose is 10 mcg/kg.

“It’s important to note that three of those six patients [receiving the lower dose] in fact had a PR or CR so this lower dose did not come at the expense of efficacy,” he added.

The mechanistic rationale for combining AM0010 and anti-PD1 for the treatment of cancer patients lies in the fact that IL‐10 has anti‐inflammatory functions and stimulates the cytotoxicity and proliferation of antigen-activated CD8+ T cells. T cell receptor–mediated activation of CD8+ T cells elevates IL‐10 receptors and PD‐1, Dr. Oft explained.

The robust efficacy data and the observed CD8+ T cell activation seen in these expansion cohorts is promising and encourages the continued study of AM0010 in combination with PD-1 inhibition, he concluded, noting that larger studies are planned for the coming year.

Dr. Oft is a founder and employee of ARMO BioSciences, which sponsored this study.

SOURCE: Naing A et al. SITC Abstract 012.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Pegylated human interleukin-10 in combination with anti–PD-1 therapy is well tolerated and shows promise for the treatment of both renal cell carcinoma and non–small cell lung cancer, according to findings from a phase 1 study.

The IL-10 product, AM0010 (pegilodecakin), was shown to be well tolerated as monotherapy, and was evaluated in combination with anti–PD-1 therapy in the two expansion cohorts included in the current analysis, Martin Oft, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

Of 34 evaluable renal cell carcinoma (RCC) patients included in one expansion cohort, 15 (44%) had an objective response at a median follow-up of 27 months, and two of those had a complete response (CR), Dr. Oft of ARMO BioSciences, Redwood City, Calif. reported.

In contrast, only 4 of 16 evaluable patients who received AM0010 monotherapy (25%) had an objective response, he said.

In eight patients who received AM0010 + pembrolizumab (Keytruda), the objective response rate was 50%, and both patients who had a complete response were in that group. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 16.7 months. In 26 who received AM0010 + nivolumab (Opdivo), 11 had an objective response, but neither the complete response nor PFS rates had been reached in patients in that group, he noted.

The responses were durable.

“In fact, we had one patient who stopped treatment after a year in [complete remission] and is now 1 year in total remission without any further treatment,” he said.

Patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) also experienced some benefit from the combination therapy. Objective responses were observed in 11 of 27 evaluable NSCLC patients (41%) who were treated with AM0010 and an anti–PD-1(9 of 22 [41%] who received AM0010 and nivolumab, and 2 of 5 [40%] who received AM0010 and pembrolizumab).

Progression-free survival was not reached in this cohort.

An analysis by PD-L1 status showed that 33% of NSCLC patients with PD-L1 levels less than 1% achieved a response, 67% of those with PD-L1 levels of 1%-49% achieved a response, and 80% of those with PD-L1 levels of 50% or greater achieved a response, he said, adding that the responses were very durable in all three groups.

Of note, NSCLC patients with liver metastasis have been shown in prior trials to have a lower overall response rate to immune checkpoint inhibition, but in this trial, 7 of 9 patients with NSCLC metastasis to the liver had a partial response (PR), Dr. Oft said.

The RCC and NSCLC patients had a median of 1 and 2 prior therapies, respectively.

AM0010 was given subcutaneously at a dose of 10 or 20 mcg/kg daily, pembrolizumab was given intravenously at 2mg/kg every 3 weeks, and nivolumab was given intravenously at a dose of 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks.

Treatment-related adverse events included anemia, thrombocytopenia, and fatigue, and all were reversible and transient, Dr. Oft said, noting that grade 3 or 4 adverse events were mostly absent in patients receiving the lower dose; thus the recommended phase 2 dose is 10 mcg/kg.

“It’s important to note that three of those six patients [receiving the lower dose] in fact had a PR or CR so this lower dose did not come at the expense of efficacy,” he added.

The mechanistic rationale for combining AM0010 and anti-PD1 for the treatment of cancer patients lies in the fact that IL‐10 has anti‐inflammatory functions and stimulates the cytotoxicity and proliferation of antigen-activated CD8+ T cells. T cell receptor–mediated activation of CD8+ T cells elevates IL‐10 receptors and PD‐1, Dr. Oft explained.

The robust efficacy data and the observed CD8+ T cell activation seen in these expansion cohorts is promising and encourages the continued study of AM0010 in combination with PD-1 inhibition, he concluded, noting that larger studies are planned for the coming year.

Dr. Oft is a founder and employee of ARMO BioSciences, which sponsored this study.

SOURCE: Naing A et al. SITC Abstract 012.

REPORTING FROM SITC 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: 15 of 34 RCC patients had an objective response and two of those had a complete response.

Study details: Expansion cohorts including 64 patients from a phase 1 study.

Disclosures: Dr. Oft is a founder and employee of ARMO BioSciences, which sponsored this study.

Source: A. Naing et al. SITC 2017 Abstract 012.

Office visits have a chronic problem

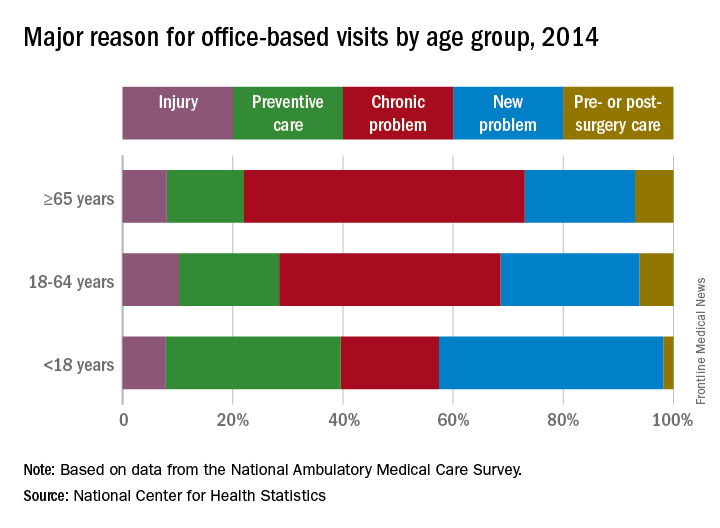

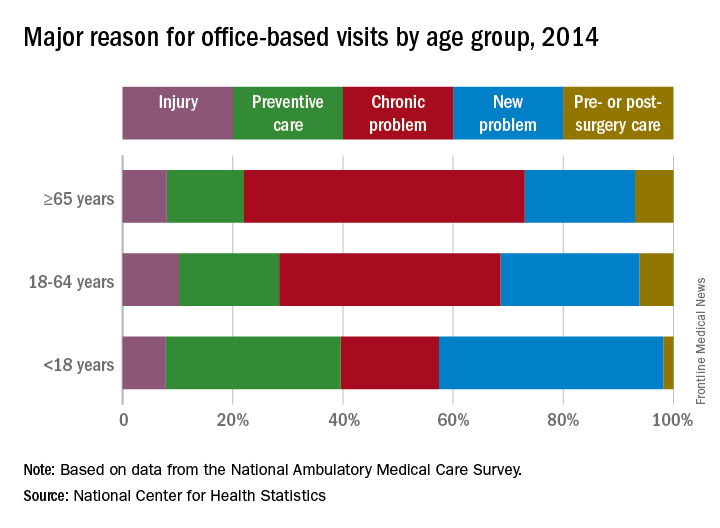

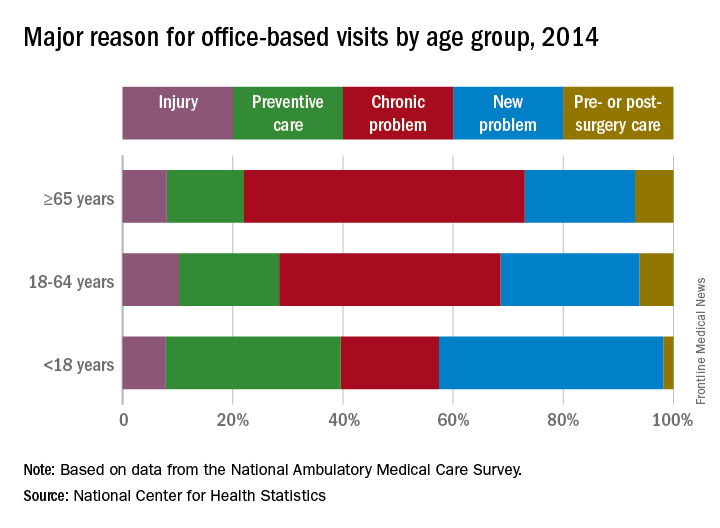

according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

That year, chronic problems were the major reason for 40% of all office-based physician visits, making them significantly more common than the other four broad categories of visit types: new problem (26%), preventive care (19%), injury (9%), and pre- or postsurgery care (6%), the NCHS said in a recent Data Brief.

Children were significantly more likely to have a new problem (41% of visits) or get preventive care (32%) than were the other age groups and were significantly less likely to have a chronic problem (18%) or to receive pre- or postsurgery care (2%), according to data from the 2014 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, which included 45,710 visit records from 9,989 physicians.

SOURCE: Ashman JJ et al. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;(292):1-8e.

according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

That year, chronic problems were the major reason for 40% of all office-based physician visits, making them significantly more common than the other four broad categories of visit types: new problem (26%), preventive care (19%), injury (9%), and pre- or postsurgery care (6%), the NCHS said in a recent Data Brief.

Children were significantly more likely to have a new problem (41% of visits) or get preventive care (32%) than were the other age groups and were significantly less likely to have a chronic problem (18%) or to receive pre- or postsurgery care (2%), according to data from the 2014 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, which included 45,710 visit records from 9,989 physicians.

SOURCE: Ashman JJ et al. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;(292):1-8e.

according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

That year, chronic problems were the major reason for 40% of all office-based physician visits, making them significantly more common than the other four broad categories of visit types: new problem (26%), preventive care (19%), injury (9%), and pre- or postsurgery care (6%), the NCHS said in a recent Data Brief.

Children were significantly more likely to have a new problem (41% of visits) or get preventive care (32%) than were the other age groups and were significantly less likely to have a chronic problem (18%) or to receive pre- or postsurgery care (2%), according to data from the 2014 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, which included 45,710 visit records from 9,989 physicians.

SOURCE: Ashman JJ et al. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;(292):1-8e.

Waiving Medicare coinsurance for positive colorectal screening likely beneficial

Currently, Medicare covers colorectal screening at no charge to the patient, but if a polyp is removed upon discovery during the procedure, the patient would then be subject to Medicare’s coinsurance payments for both the colonoscopy and the removal.

Researchers used the Microsimulation Screening Analysis–Colon model to estimate the cost-effectiveness of waiving coinsurance for every component of colorectal cancer screening. They estimated that, currently, using the colonoscopy regimen with coinsurance, 12.8 colorectal cancer deaths occurred per 1,000 people aged 65 years and 124.1 QALYs were gained per 1,000 people aged 65 years. The total number of procedures per 1,000 Medicare beneficiaries was 1,132, of which 410 (36%) were potentially subject to coinsurance requirements.

“We estimated that the total lifetime costs for [the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid], which included colorectal cancer screening, surveillance, and treatment with coinsurance, to be $2.675 million per 1,000 65-year-olds,” Ms. Peterse and her colleagues wrote.

Researchers noted that if the coinsurance was waived but there was no follow-on increase in the screening rate, the benefits of screening would not change but the total cost of screening and treatment would increase to $2.726 million per 1,000 people aged 65 years.

However, “an assumed 5-percentage-point increase in the rates of first colonoscopy screening and surveillance decreased the number of colorectal cancer deaths by 0.9 (6.4%), accompanied by an increase of $33,000 (1.2%) in total costs, with a cost per QALY gained (or cost-effectiveness ratio) of $4,086.”

They added that estimated screening benefits were similar when fecal testing was the primary screening method.

“In general, [fecal testing] screening was associated with lower number of procedures subject to coinsurance,” the researchers added. “If [fecal testing] screening becomes more popular in the United States, following trends observed in several settings, the costs of waiving coinsurance would be even lower.” The researchers also suggest that it could lead to reducing disparities of colorectal cancer in the United States as well.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Peterse EFP et al. Health Affairs. 2017 Dec;36(12):2151-9.

Currently, Medicare covers colorectal screening at no charge to the patient, but if a polyp is removed upon discovery during the procedure, the patient would then be subject to Medicare’s coinsurance payments for both the colonoscopy and the removal.

Researchers used the Microsimulation Screening Analysis–Colon model to estimate the cost-effectiveness of waiving coinsurance for every component of colorectal cancer screening. They estimated that, currently, using the colonoscopy regimen with coinsurance, 12.8 colorectal cancer deaths occurred per 1,000 people aged 65 years and 124.1 QALYs were gained per 1,000 people aged 65 years. The total number of procedures per 1,000 Medicare beneficiaries was 1,132, of which 410 (36%) were potentially subject to coinsurance requirements.

“We estimated that the total lifetime costs for [the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid], which included colorectal cancer screening, surveillance, and treatment with coinsurance, to be $2.675 million per 1,000 65-year-olds,” Ms. Peterse and her colleagues wrote.

Researchers noted that if the coinsurance was waived but there was no follow-on increase in the screening rate, the benefits of screening would not change but the total cost of screening and treatment would increase to $2.726 million per 1,000 people aged 65 years.

However, “an assumed 5-percentage-point increase in the rates of first colonoscopy screening and surveillance decreased the number of colorectal cancer deaths by 0.9 (6.4%), accompanied by an increase of $33,000 (1.2%) in total costs, with a cost per QALY gained (or cost-effectiveness ratio) of $4,086.”

They added that estimated screening benefits were similar when fecal testing was the primary screening method.

“In general, [fecal testing] screening was associated with lower number of procedures subject to coinsurance,” the researchers added. “If [fecal testing] screening becomes more popular in the United States, following trends observed in several settings, the costs of waiving coinsurance would be even lower.” The researchers also suggest that it could lead to reducing disparities of colorectal cancer in the United States as well.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Peterse EFP et al. Health Affairs. 2017 Dec;36(12):2151-9.

Currently, Medicare covers colorectal screening at no charge to the patient, but if a polyp is removed upon discovery during the procedure, the patient would then be subject to Medicare’s coinsurance payments for both the colonoscopy and the removal.

Researchers used the Microsimulation Screening Analysis–Colon model to estimate the cost-effectiveness of waiving coinsurance for every component of colorectal cancer screening. They estimated that, currently, using the colonoscopy regimen with coinsurance, 12.8 colorectal cancer deaths occurred per 1,000 people aged 65 years and 124.1 QALYs were gained per 1,000 people aged 65 years. The total number of procedures per 1,000 Medicare beneficiaries was 1,132, of which 410 (36%) were potentially subject to coinsurance requirements.

“We estimated that the total lifetime costs for [the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid], which included colorectal cancer screening, surveillance, and treatment with coinsurance, to be $2.675 million per 1,000 65-year-olds,” Ms. Peterse and her colleagues wrote.

Researchers noted that if the coinsurance was waived but there was no follow-on increase in the screening rate, the benefits of screening would not change but the total cost of screening and treatment would increase to $2.726 million per 1,000 people aged 65 years.

However, “an assumed 5-percentage-point increase in the rates of first colonoscopy screening and surveillance decreased the number of colorectal cancer deaths by 0.9 (6.4%), accompanied by an increase of $33,000 (1.2%) in total costs, with a cost per QALY gained (or cost-effectiveness ratio) of $4,086.”

They added that estimated screening benefits were similar when fecal testing was the primary screening method.

“In general, [fecal testing] screening was associated with lower number of procedures subject to coinsurance,” the researchers added. “If [fecal testing] screening becomes more popular in the United States, following trends observed in several settings, the costs of waiving coinsurance would be even lower.” The researchers also suggest that it could lead to reducing disparities of colorectal cancer in the United States as well.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Peterse EFP et al. Health Affairs. 2017 Dec;36(12):2151-9.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

Nonmalignant Cutaneous Findings Associated With Vemurafenib

To the Editor:

A 53-year-old woman was referred by her oncologist to our dermatology office with lesions on the face and body that presented 8 days after starting vemurafenib 960 mg twice daily for metastatic melanoma. The patient denied any symptoms from the lesions but was concerned they would spread to cover her entire face and body.

The patient's medical history included a diagnosis of metastatic melanoma 6 years prior to presentation. She stated that the primary cutaneous melanoma site was unknown. The patient had endured numerous surgeries to excise lymph node tumors, with some lesions up to 3 cm. The patient recently started vemurafenib, a treatment for BRAF V600E mutation-positive metastatic melanoma. The patient's personal history was notable for hepatitis A, B, and C, and her family history revealed her mother had metastatic lung cancer.

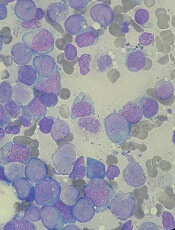

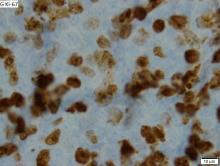

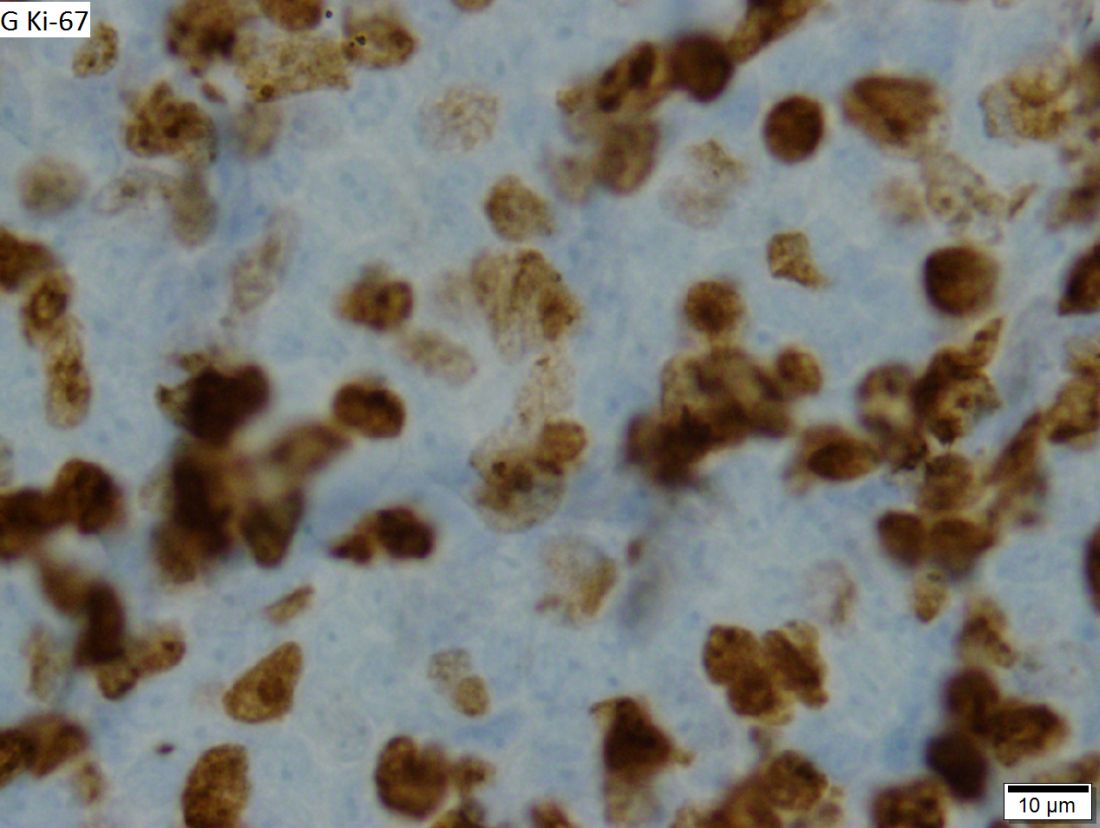

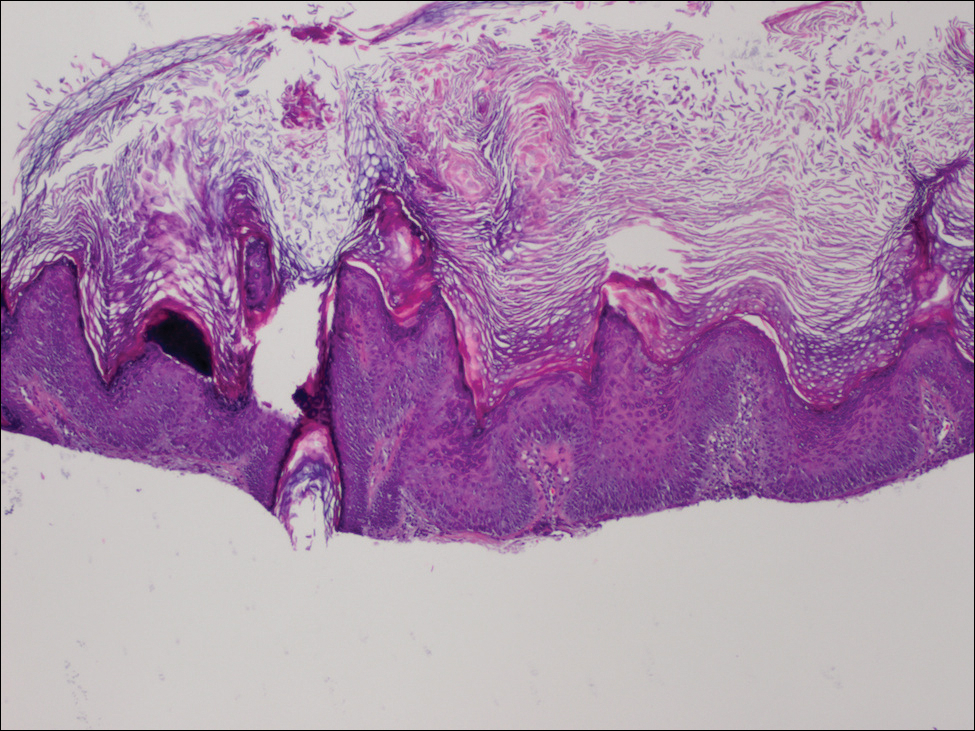

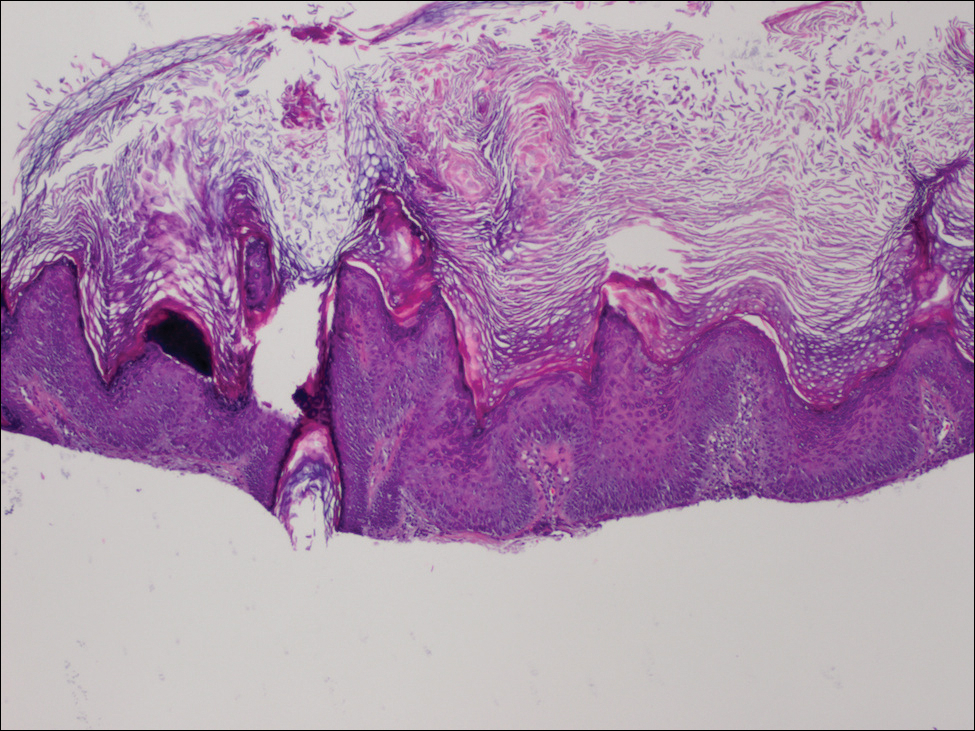

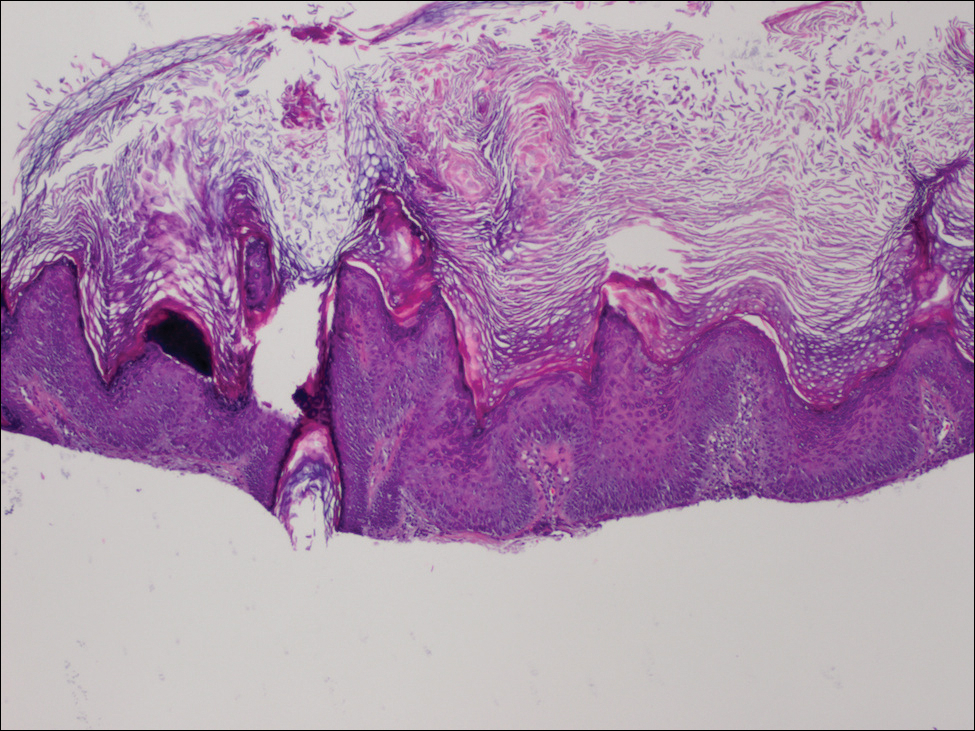

Physical examination revealed numerous 2- to 3-mm, round-oval, flesh-colored to light-brown papules on the cheeks, chest, abdomen (Figure 1), back, and both arms and legs. Some papules were inflamed and some had a stuck-on appearance. Lesions on the chest between the breasts and inframammary region were slightly inflamed. Two skin biopsies were performed. Biopsy of the lesion on the right lateral back revealed solar lentigo, early macular seborrheic keratosis, and a focus of inflamed mild solar keratosis. The dermis showed a mild superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammatory infiltrate composed mostly of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils. There were occasional melanophages present (Figure 2). Biopsy of the lesion between the breasts revealed inflamed verrucous seborrheic keratosis (Figure 3).

We treated the lesion on the right lateral back with cycles of cryotherapy and explained to the patient that the lesion between the breasts was benign. We also reiterated to the patient the importance of wearing sun-protective clothing and UVA/UVB sunblock with a sun protection factor of 30 or higher.

Our patient was diagnosed with pneumonia and subsequently had to discontinue vemurafenib. During the period of nontreatment, the keratotic lesions cleared with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and no epidermal changes, which showed a possible inference of a direct relationship between the vemurafenib and the appearance of the nonmalignant cutaneous lesions. Although this report only represents 1 patient, other patients possibly can benefit from a modified dose of vemurafenib, which either would resolve or lessen the quantity of these lesions.

Vemurafenib is the first US Food and Drug Administration-approved treatment for nonresectable metastatic melanoma with the BRAF V600E mutation as detected by a US Food and Drug Administration-approved test.1,2 Mutated BRAF is present in approximately 60% of cutaneous melanomas.3 Vemurafenib targets the oncogenic BRAF V600E making the protein inactive, thus inhibiting cell proliferation and leading to apoptosis and shrinkage of the metastatic tumors.3-5 Vemurafenib has a response rate of more than 50% and is associated with rapid improvement in quality of life.3

Cutaneous side effects include increased incidence of squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthomas, appearing approximately 7 to 8 weeks after starting vemurafenib.4 The incidence of these lesions increases in patients 65 years and older and in patients with prior skin cancer and chronic sun exposure. The paradoxical activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by mutant BRAF-selective inhibitors provides an explanation of the induction of squamous cell carcinomas.4 Prior to the initiation of vemurafenib, all patients should receive a total-body skin examination and every 2 months thereafter while on treatment. After discontinuation of the medicine, the patient should continue to receive total-body skin evaluations every 6 months indefinitely.

Patients should be aware of the potential for mild to severe photosensitivity reactions. They should be advised to limit their sun exposure time and to wear sun-protective clothing when outdoors. The use of broad-spectrum UVA/UVB sunscreen and lip protectant with a sun protection factor of 30 or higher also should be stressed.6,7 Patients should be aware that UVA rays penetrate glass; therefore, UV-protective clothing should be worn throughout the day and during all seasons.7

In clinical trials of vemurafenib, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis was reported in 2 patients.8,9 Clinical trials also reported patients developing new primary malignant melanoma lesions.10 These findings further emphasize the need for patients to undergo total-body skin examinations during and after treatment.

Other possible dermatologic reactions include a generalized rash, erythema, alopecia, and pruritus.2,3 The development of benign growths associated with patients on vemurafenib include follicular plugging seen in keratosis pilaris, palmar and plantar hyperkeratosis, seborrheic dermatitis-like rashes, verrucous keratosis, and acantholytic dyskeratosis.8,11,12

We report a case of nonmalignant growths occurring 8 days after starting vemurafenib. This case illustrates potential cutaneous adverse reactions that were benign yet still of great concern to our patient. Many of these nonmalignant cutaneous findings are associated with abnormal follicular keratinization thought to be secondary to abnormal signaling of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway that occurs with the use of BRAF inhibitors.8 Although in this case malignant lesions were not discovered, the need for total-body skin examinations exists during all stages of treatment. Supportive care and reassurance should be given to patients along with local treatments including topical therapies (steroids, retinoids), cryotherapy, and biopsies or excisions when necessary.13,14

- Holstein S, Hohl R. Therapeutic additions and possible deletions in oncology in 2011. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;91:15-17.

- Zambon A, Niculescu-Dovaz I, Niculescu-Dovaz D, et al. Small molecule inhibitors of BRAF in clinical trials. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:789-792.

- Luke JJ, Hodi FS. Vemurafenib and BRAF inhibition: a new class of treatment for metastatic melanoma [published online November 14, 2011]. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:9-14.

- Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363:809-819.

- Tsai J, Lee JT, Wang W, et al. Discovery of a selective inhibitor of oncogenic B-Raf kinase with potent antimelanoma activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3041-3046.

- Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507-2516.

- Dummer R, Rinderknecht J, Goldinger SM. Ultraviolet A and photosensitivity during vemuranefib therapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:480-481.

- Bovd KP, Vincent B, Andrea A, et al. Nonmalignant cutaneous findings associated with vemurafenib use in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1375-1379.

- Wang CM, Fleming KF Hsu S. A case of vemurafenib-induced keratosis pilaris-like eruption. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:7.

- Zimmer L, Hillen U, Livingstone E, et al. Atypical melanocytic proliferations and new primary melanomas in patients with advanced melanoma undergoing selective BRAF inhibition. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2375-2383.

- Huang V, Hepper D, Anadkat M, et al. Cutaneous toxic effects associated with vemurafenib and inhibition of the BRAF pathway. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:628-633.

- Gupta M, Huang V, Linette G, et al. Unusual complication of vemurafenib treatment of metastatic melanoma: exacerbation of acantholytic dyskeratosis complicated by Kaposi varicelliform eruption. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:966-968;

- Sinha R, Edmonds K, Newton-Bishop JA, et al. Cutaneous adverse events associated with vemurafenib in patients with metastatic melanoma: practical advice on diagnosis, preventions and management of the main treatment related skin toxicities. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:987-994.

- Boussemart L, Routier E, Mateus C, et al. Prospective study of cutaneous side effects associated with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: a study of 42 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1691-1697.

To the Editor:

A 53-year-old woman was referred by her oncologist to our dermatology office with lesions on the face and body that presented 8 days after starting vemurafenib 960 mg twice daily for metastatic melanoma. The patient denied any symptoms from the lesions but was concerned they would spread to cover her entire face and body.

The patient's medical history included a diagnosis of metastatic melanoma 6 years prior to presentation. She stated that the primary cutaneous melanoma site was unknown. The patient had endured numerous surgeries to excise lymph node tumors, with some lesions up to 3 cm. The patient recently started vemurafenib, a treatment for BRAF V600E mutation-positive metastatic melanoma. The patient's personal history was notable for hepatitis A, B, and C, and her family history revealed her mother had metastatic lung cancer.

Physical examination revealed numerous 2- to 3-mm, round-oval, flesh-colored to light-brown papules on the cheeks, chest, abdomen (Figure 1), back, and both arms and legs. Some papules were inflamed and some had a stuck-on appearance. Lesions on the chest between the breasts and inframammary region were slightly inflamed. Two skin biopsies were performed. Biopsy of the lesion on the right lateral back revealed solar lentigo, early macular seborrheic keratosis, and a focus of inflamed mild solar keratosis. The dermis showed a mild superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammatory infiltrate composed mostly of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils. There were occasional melanophages present (Figure 2). Biopsy of the lesion between the breasts revealed inflamed verrucous seborrheic keratosis (Figure 3).

We treated the lesion on the right lateral back with cycles of cryotherapy and explained to the patient that the lesion between the breasts was benign. We also reiterated to the patient the importance of wearing sun-protective clothing and UVA/UVB sunblock with a sun protection factor of 30 or higher.

Our patient was diagnosed with pneumonia and subsequently had to discontinue vemurafenib. During the period of nontreatment, the keratotic lesions cleared with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and no epidermal changes, which showed a possible inference of a direct relationship between the vemurafenib and the appearance of the nonmalignant cutaneous lesions. Although this report only represents 1 patient, other patients possibly can benefit from a modified dose of vemurafenib, which either would resolve or lessen the quantity of these lesions.

Vemurafenib is the first US Food and Drug Administration-approved treatment for nonresectable metastatic melanoma with the BRAF V600E mutation as detected by a US Food and Drug Administration-approved test.1,2 Mutated BRAF is present in approximately 60% of cutaneous melanomas.3 Vemurafenib targets the oncogenic BRAF V600E making the protein inactive, thus inhibiting cell proliferation and leading to apoptosis and shrinkage of the metastatic tumors.3-5 Vemurafenib has a response rate of more than 50% and is associated with rapid improvement in quality of life.3

Cutaneous side effects include increased incidence of squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthomas, appearing approximately 7 to 8 weeks after starting vemurafenib.4 The incidence of these lesions increases in patients 65 years and older and in patients with prior skin cancer and chronic sun exposure. The paradoxical activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by mutant BRAF-selective inhibitors provides an explanation of the induction of squamous cell carcinomas.4 Prior to the initiation of vemurafenib, all patients should receive a total-body skin examination and every 2 months thereafter while on treatment. After discontinuation of the medicine, the patient should continue to receive total-body skin evaluations every 6 months indefinitely.

Patients should be aware of the potential for mild to severe photosensitivity reactions. They should be advised to limit their sun exposure time and to wear sun-protective clothing when outdoors. The use of broad-spectrum UVA/UVB sunscreen and lip protectant with a sun protection factor of 30 or higher also should be stressed.6,7 Patients should be aware that UVA rays penetrate glass; therefore, UV-protective clothing should be worn throughout the day and during all seasons.7

In clinical trials of vemurafenib, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis was reported in 2 patients.8,9 Clinical trials also reported patients developing new primary malignant melanoma lesions.10 These findings further emphasize the need for patients to undergo total-body skin examinations during and after treatment.

Other possible dermatologic reactions include a generalized rash, erythema, alopecia, and pruritus.2,3 The development of benign growths associated with patients on vemurafenib include follicular plugging seen in keratosis pilaris, palmar and plantar hyperkeratosis, seborrheic dermatitis-like rashes, verrucous keratosis, and acantholytic dyskeratosis.8,11,12

We report a case of nonmalignant growths occurring 8 days after starting vemurafenib. This case illustrates potential cutaneous adverse reactions that were benign yet still of great concern to our patient. Many of these nonmalignant cutaneous findings are associated with abnormal follicular keratinization thought to be secondary to abnormal signaling of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway that occurs with the use of BRAF inhibitors.8 Although in this case malignant lesions were not discovered, the need for total-body skin examinations exists during all stages of treatment. Supportive care and reassurance should be given to patients along with local treatments including topical therapies (steroids, retinoids), cryotherapy, and biopsies or excisions when necessary.13,14

To the Editor:

A 53-year-old woman was referred by her oncologist to our dermatology office with lesions on the face and body that presented 8 days after starting vemurafenib 960 mg twice daily for metastatic melanoma. The patient denied any symptoms from the lesions but was concerned they would spread to cover her entire face and body.

The patient's medical history included a diagnosis of metastatic melanoma 6 years prior to presentation. She stated that the primary cutaneous melanoma site was unknown. The patient had endured numerous surgeries to excise lymph node tumors, with some lesions up to 3 cm. The patient recently started vemurafenib, a treatment for BRAF V600E mutation-positive metastatic melanoma. The patient's personal history was notable for hepatitis A, B, and C, and her family history revealed her mother had metastatic lung cancer.

Physical examination revealed numerous 2- to 3-mm, round-oval, flesh-colored to light-brown papules on the cheeks, chest, abdomen (Figure 1), back, and both arms and legs. Some papules were inflamed and some had a stuck-on appearance. Lesions on the chest between the breasts and inframammary region were slightly inflamed. Two skin biopsies were performed. Biopsy of the lesion on the right lateral back revealed solar lentigo, early macular seborrheic keratosis, and a focus of inflamed mild solar keratosis. The dermis showed a mild superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammatory infiltrate composed mostly of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils. There were occasional melanophages present (Figure 2). Biopsy of the lesion between the breasts revealed inflamed verrucous seborrheic keratosis (Figure 3).