User login

Maximizing topical toenail fungus therapy

KAUAI, HAWAII – Two keys to effective topical treatment of onychomycosis are treat it early and address coexisting tinea pedis, according to Theodore Rosen, MD.

A third element in achieving treatment success is to use one of the newer topical agents: efinaconazole (Jublia) or tavaborole (Kerydin). The efficacy of efinaconazole approaches that of terbinafine, the most effective and widely prescribed oral agent, which has a 59% rate of almost complete cure, defined as less than 10% residual abnormal nail with no requirement for mycologic cure.

And while tavaborole isn’t quite as effective, it’s definitely better than previous topical agents, Dr. Rosen said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Both of these topicals are well tolerated and feature good nail permeation. They also allow for spread to the lateral nail folds and hyponychium. They even penetrate nail polish, although efinaconazole often causes the polish to lose its spiffy gloss, said Dr. Rosen, professor of dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

To underscore the importance of early treatment and addressing concomitant tinea pedis, he cited published secondary analyses of two identical double-blind, multicenter, 48-week clinical trials totaling 1,655 adults with onychomycosis who were randomized 3:1 to once-daily efinaconazole 10% topical solution or its vehicle.

Treat early

Phoebe Rich, MD, of the Oregon Dermatology and Research Center, Portland, broke down the outcomes according to disease duration, in a study of more than 1,500 patients with onychomycosis. She found that the complete cure rate at 52 weeks dropped off markedly in patients with a history of onychomycosis for 1 year or longer at baseline.

Complete cure – defined as no clinical involvement of the target toenail along with both a negative potassium hydroxide examination and a negative fungal culture at 52 weeks – was achieved in 43% of efinaconazole-treated patients with onychomycosis for less than 1 year. The rate then plunged to 17% in those with a disease duration of 1-5 years and 16% in patients with onychomycosis for more than 5 years. Nevertheless, the topical antifungal was significantly more effective than was the vehicle, across the board, with complete cure rates in the vehicle group of roughly 18%, 5%, and 2%, respectively, in patients with onychomycosis for less than 1 year, 1-5 years, and more than 5 years (J Drugs Dermatol. 2015 Jan;14[1]:58-62).

Tackle coexisting tinea pedis

Podiatrists analyzed the combined efinaconazole outcome data based on whether participants had no coexisting tinea pedis, baseline tinea pedis treated concomitantly with an investigator-approved topical antifungal, or tinea pedis left untreated. They concluded that treatment of coexisting tinea pedis decisively enhanced the efficacy of efinaconazole for onychomycosis.

A total of 21% of study participants had concomitant tinea pedis, and 61% of them were treated for it. At week 52, the onychomycosis complete cure rate was 29% in the efinaconazole group concurrently treated for tinea pedis, compared with just 16% if their tinea pedis was untreated (J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2015 Sep;105[5]:407-11).

“If you see tinea pedis, don’t blow it off. Treat it. Otherwise, you’re not getting rid of the fungal reservoir,” Dr. Rosen emphasized.

He noted that two topical agents approved for tinea pedis – naftifine 2% cream or gel and luliconazole 1% cream – are effective as once-daily therapy for 2 weeks, a considerably briefer regimen than with other approved topicals. And short-course therapy spells improved adherence, he added.

In the pivotal trials, naftifine had an effective treatment rate – a clinically useful endpoint defined as a small amount of residual scaling and/or redness but no itching – of 57%, while for luliconazole the rates were 33%-48%.

These two agents also are approved for treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris. Naftifine is approved as a once-daily treatment for 2 weeks, while luliconazole is, notably, a 7-day treatment. Luliconazole, in particular, is a relatively expensive drug, Dr. Rosen added, so insurers may require prior failure on clotrimazole.

When to treat onychomycosis topically

The pivotal trials of tavaborole and efinaconazole were conducted in patients with 20%-60% nail involvement. The infection didn’t extend to the matrix, and nail thickness and crumbly subungual debris were modest at baseline.

“There are always potential safety issues – drug interactions, GI disturbance, taste loss, headache, teratogenicity, cardiotoxicity, hepatotoxicity – anytime you put a pill in your mouth. So if you have a patient who’s dedicated enough to use a topical for 48 weeks and it’s a modestly affected nail, think about it,” Dr. Rosen advised.

He reported serving on scientific advisory boards for Aclaris, Anacor, Cipla, and Valeant.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

KAUAI, HAWAII – Two keys to effective topical treatment of onychomycosis are treat it early and address coexisting tinea pedis, according to Theodore Rosen, MD.

A third element in achieving treatment success is to use one of the newer topical agents: efinaconazole (Jublia) or tavaborole (Kerydin). The efficacy of efinaconazole approaches that of terbinafine, the most effective and widely prescribed oral agent, which has a 59% rate of almost complete cure, defined as less than 10% residual abnormal nail with no requirement for mycologic cure.

And while tavaborole isn’t quite as effective, it’s definitely better than previous topical agents, Dr. Rosen said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Both of these topicals are well tolerated and feature good nail permeation. They also allow for spread to the lateral nail folds and hyponychium. They even penetrate nail polish, although efinaconazole often causes the polish to lose its spiffy gloss, said Dr. Rosen, professor of dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

To underscore the importance of early treatment and addressing concomitant tinea pedis, he cited published secondary analyses of two identical double-blind, multicenter, 48-week clinical trials totaling 1,655 adults with onychomycosis who were randomized 3:1 to once-daily efinaconazole 10% topical solution or its vehicle.

Treat early

Phoebe Rich, MD, of the Oregon Dermatology and Research Center, Portland, broke down the outcomes according to disease duration, in a study of more than 1,500 patients with onychomycosis. She found that the complete cure rate at 52 weeks dropped off markedly in patients with a history of onychomycosis for 1 year or longer at baseline.

Complete cure – defined as no clinical involvement of the target toenail along with both a negative potassium hydroxide examination and a negative fungal culture at 52 weeks – was achieved in 43% of efinaconazole-treated patients with onychomycosis for less than 1 year. The rate then plunged to 17% in those with a disease duration of 1-5 years and 16% in patients with onychomycosis for more than 5 years. Nevertheless, the topical antifungal was significantly more effective than was the vehicle, across the board, with complete cure rates in the vehicle group of roughly 18%, 5%, and 2%, respectively, in patients with onychomycosis for less than 1 year, 1-5 years, and more than 5 years (J Drugs Dermatol. 2015 Jan;14[1]:58-62).

Tackle coexisting tinea pedis

Podiatrists analyzed the combined efinaconazole outcome data based on whether participants had no coexisting tinea pedis, baseline tinea pedis treated concomitantly with an investigator-approved topical antifungal, or tinea pedis left untreated. They concluded that treatment of coexisting tinea pedis decisively enhanced the efficacy of efinaconazole for onychomycosis.

A total of 21% of study participants had concomitant tinea pedis, and 61% of them were treated for it. At week 52, the onychomycosis complete cure rate was 29% in the efinaconazole group concurrently treated for tinea pedis, compared with just 16% if their tinea pedis was untreated (J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2015 Sep;105[5]:407-11).

“If you see tinea pedis, don’t blow it off. Treat it. Otherwise, you’re not getting rid of the fungal reservoir,” Dr. Rosen emphasized.

He noted that two topical agents approved for tinea pedis – naftifine 2% cream or gel and luliconazole 1% cream – are effective as once-daily therapy for 2 weeks, a considerably briefer regimen than with other approved topicals. And short-course therapy spells improved adherence, he added.

In the pivotal trials, naftifine had an effective treatment rate – a clinically useful endpoint defined as a small amount of residual scaling and/or redness but no itching – of 57%, while for luliconazole the rates were 33%-48%.

These two agents also are approved for treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris. Naftifine is approved as a once-daily treatment for 2 weeks, while luliconazole is, notably, a 7-day treatment. Luliconazole, in particular, is a relatively expensive drug, Dr. Rosen added, so insurers may require prior failure on clotrimazole.

When to treat onychomycosis topically

The pivotal trials of tavaborole and efinaconazole were conducted in patients with 20%-60% nail involvement. The infection didn’t extend to the matrix, and nail thickness and crumbly subungual debris were modest at baseline.

“There are always potential safety issues – drug interactions, GI disturbance, taste loss, headache, teratogenicity, cardiotoxicity, hepatotoxicity – anytime you put a pill in your mouth. So if you have a patient who’s dedicated enough to use a topical for 48 weeks and it’s a modestly affected nail, think about it,” Dr. Rosen advised.

He reported serving on scientific advisory boards for Aclaris, Anacor, Cipla, and Valeant.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

KAUAI, HAWAII – Two keys to effective topical treatment of onychomycosis are treat it early and address coexisting tinea pedis, according to Theodore Rosen, MD.

A third element in achieving treatment success is to use one of the newer topical agents: efinaconazole (Jublia) or tavaborole (Kerydin). The efficacy of efinaconazole approaches that of terbinafine, the most effective and widely prescribed oral agent, which has a 59% rate of almost complete cure, defined as less than 10% residual abnormal nail with no requirement for mycologic cure.

And while tavaborole isn’t quite as effective, it’s definitely better than previous topical agents, Dr. Rosen said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Both of these topicals are well tolerated and feature good nail permeation. They also allow for spread to the lateral nail folds and hyponychium. They even penetrate nail polish, although efinaconazole often causes the polish to lose its spiffy gloss, said Dr. Rosen, professor of dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

To underscore the importance of early treatment and addressing concomitant tinea pedis, he cited published secondary analyses of two identical double-blind, multicenter, 48-week clinical trials totaling 1,655 adults with onychomycosis who were randomized 3:1 to once-daily efinaconazole 10% topical solution or its vehicle.

Treat early

Phoebe Rich, MD, of the Oregon Dermatology and Research Center, Portland, broke down the outcomes according to disease duration, in a study of more than 1,500 patients with onychomycosis. She found that the complete cure rate at 52 weeks dropped off markedly in patients with a history of onychomycosis for 1 year or longer at baseline.

Complete cure – defined as no clinical involvement of the target toenail along with both a negative potassium hydroxide examination and a negative fungal culture at 52 weeks – was achieved in 43% of efinaconazole-treated patients with onychomycosis for less than 1 year. The rate then plunged to 17% in those with a disease duration of 1-5 years and 16% in patients with onychomycosis for more than 5 years. Nevertheless, the topical antifungal was significantly more effective than was the vehicle, across the board, with complete cure rates in the vehicle group of roughly 18%, 5%, and 2%, respectively, in patients with onychomycosis for less than 1 year, 1-5 years, and more than 5 years (J Drugs Dermatol. 2015 Jan;14[1]:58-62).

Tackle coexisting tinea pedis

Podiatrists analyzed the combined efinaconazole outcome data based on whether participants had no coexisting tinea pedis, baseline tinea pedis treated concomitantly with an investigator-approved topical antifungal, or tinea pedis left untreated. They concluded that treatment of coexisting tinea pedis decisively enhanced the efficacy of efinaconazole for onychomycosis.

A total of 21% of study participants had concomitant tinea pedis, and 61% of them were treated for it. At week 52, the onychomycosis complete cure rate was 29% in the efinaconazole group concurrently treated for tinea pedis, compared with just 16% if their tinea pedis was untreated (J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2015 Sep;105[5]:407-11).

“If you see tinea pedis, don’t blow it off. Treat it. Otherwise, you’re not getting rid of the fungal reservoir,” Dr. Rosen emphasized.

He noted that two topical agents approved for tinea pedis – naftifine 2% cream or gel and luliconazole 1% cream – are effective as once-daily therapy for 2 weeks, a considerably briefer regimen than with other approved topicals. And short-course therapy spells improved adherence, he added.

In the pivotal trials, naftifine had an effective treatment rate – a clinically useful endpoint defined as a small amount of residual scaling and/or redness but no itching – of 57%, while for luliconazole the rates were 33%-48%.

These two agents also are approved for treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris. Naftifine is approved as a once-daily treatment for 2 weeks, while luliconazole is, notably, a 7-day treatment. Luliconazole, in particular, is a relatively expensive drug, Dr. Rosen added, so insurers may require prior failure on clotrimazole.

When to treat onychomycosis topically

The pivotal trials of tavaborole and efinaconazole were conducted in patients with 20%-60% nail involvement. The infection didn’t extend to the matrix, and nail thickness and crumbly subungual debris were modest at baseline.

“There are always potential safety issues – drug interactions, GI disturbance, taste loss, headache, teratogenicity, cardiotoxicity, hepatotoxicity – anytime you put a pill in your mouth. So if you have a patient who’s dedicated enough to use a topical for 48 weeks and it’s a modestly affected nail, think about it,” Dr. Rosen advised.

He reported serving on scientific advisory boards for Aclaris, Anacor, Cipla, and Valeant.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

CLL Index proves accurate in predicting survival, time to treat

An international prognostic index for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), known as CLL-IPI, was predictive of time from diagnosis to first treatment (TTFT) and 5-year median overall survival in patients across different risk categories treated with chemoimmunotherapy, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis published in Blood (2018 Jan 18;131[3]:365-8).

But limited data were available for patients treated with targeted therapies that are likely to have a profound effect on overall survival; thereby restricting the use of CLL-IPI in current clinical practice.

Novel therapies such as ibrutinib, idelalisib, and venetoclax have changed the treatment landscape for CLL, Stefano Molica, MD, of Azienda Ospedaliera Pugliese-Ciaccio, Catanzaro, Italy, and his colleagues wrote. “Because observation remains the standard of care for asymptomatic early-stage patients, the introduction of these agents does not impact the utility of the CLL-IPI for predicting time from diagnosis to first treatment, but it likely has a profound impact on the survival of patients of all risk categories once treatment is indicated.”

The CLL-IPI tool, first published in 2016 to predict clinical outcomes in CLL patients, combines five parameters: age, clinical stage, TP53 status [normal vs. del(17p) and/or TP53 mutation], immunoglobulin heavy chain–variable mutational status, and serum b2-microglobulin. The prognostic tool was validated across several studies conducted in different countries with diverse practice settings, including academic hospitals, national population-based cohorts, and clinical trials.

The researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to understand the utility of CLL-IPI tool in predicting OS and TTFT across each risk category of CLL patients.

They included nine studies with 7,843 patients to assess the impact of the CLL-IPI on overall survival. The patient distribution into the CLL-IPI risk categories was low risk (median 45.9%), intermediate risk (median 30%), high risk (median 16.5%), and very high risk (median 3.6%).

The researchers relied on 11 series comprising 7,383 patients to assess 5-year survival probability, which was 92% for low risk, 81% for intermediate risk, 60% for high risk, and 34% for very high risk. They used seven studies comprising 5,206 patients to assess TTFT and found that the probability of remaining treatment free at 5 years was 82% in the low-risk group, 45% in the intermediate-risk group, 30% in the high-risk group, and 16% in the very-high-risk group.

Although a significant step toward harmonizing international prognostication for CLL, additional studies validating the utility of the CLL-IPI for predicting OS in patients treated with targeted therapy are needed, they wrote.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

An international prognostic index for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), known as CLL-IPI, was predictive of time from diagnosis to first treatment (TTFT) and 5-year median overall survival in patients across different risk categories treated with chemoimmunotherapy, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis published in Blood (2018 Jan 18;131[3]:365-8).

But limited data were available for patients treated with targeted therapies that are likely to have a profound effect on overall survival; thereby restricting the use of CLL-IPI in current clinical practice.

Novel therapies such as ibrutinib, idelalisib, and venetoclax have changed the treatment landscape for CLL, Stefano Molica, MD, of Azienda Ospedaliera Pugliese-Ciaccio, Catanzaro, Italy, and his colleagues wrote. “Because observation remains the standard of care for asymptomatic early-stage patients, the introduction of these agents does not impact the utility of the CLL-IPI for predicting time from diagnosis to first treatment, but it likely has a profound impact on the survival of patients of all risk categories once treatment is indicated.”

The CLL-IPI tool, first published in 2016 to predict clinical outcomes in CLL patients, combines five parameters: age, clinical stage, TP53 status [normal vs. del(17p) and/or TP53 mutation], immunoglobulin heavy chain–variable mutational status, and serum b2-microglobulin. The prognostic tool was validated across several studies conducted in different countries with diverse practice settings, including academic hospitals, national population-based cohorts, and clinical trials.

The researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to understand the utility of CLL-IPI tool in predicting OS and TTFT across each risk category of CLL patients.

They included nine studies with 7,843 patients to assess the impact of the CLL-IPI on overall survival. The patient distribution into the CLL-IPI risk categories was low risk (median 45.9%), intermediate risk (median 30%), high risk (median 16.5%), and very high risk (median 3.6%).

The researchers relied on 11 series comprising 7,383 patients to assess 5-year survival probability, which was 92% for low risk, 81% for intermediate risk, 60% for high risk, and 34% for very high risk. They used seven studies comprising 5,206 patients to assess TTFT and found that the probability of remaining treatment free at 5 years was 82% in the low-risk group, 45% in the intermediate-risk group, 30% in the high-risk group, and 16% in the very-high-risk group.

Although a significant step toward harmonizing international prognostication for CLL, additional studies validating the utility of the CLL-IPI for predicting OS in patients treated with targeted therapy are needed, they wrote.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

An international prognostic index for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), known as CLL-IPI, was predictive of time from diagnosis to first treatment (TTFT) and 5-year median overall survival in patients across different risk categories treated with chemoimmunotherapy, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis published in Blood (2018 Jan 18;131[3]:365-8).

But limited data were available for patients treated with targeted therapies that are likely to have a profound effect on overall survival; thereby restricting the use of CLL-IPI in current clinical practice.

Novel therapies such as ibrutinib, idelalisib, and venetoclax have changed the treatment landscape for CLL, Stefano Molica, MD, of Azienda Ospedaliera Pugliese-Ciaccio, Catanzaro, Italy, and his colleagues wrote. “Because observation remains the standard of care for asymptomatic early-stage patients, the introduction of these agents does not impact the utility of the CLL-IPI for predicting time from diagnosis to first treatment, but it likely has a profound impact on the survival of patients of all risk categories once treatment is indicated.”

The CLL-IPI tool, first published in 2016 to predict clinical outcomes in CLL patients, combines five parameters: age, clinical stage, TP53 status [normal vs. del(17p) and/or TP53 mutation], immunoglobulin heavy chain–variable mutational status, and serum b2-microglobulin. The prognostic tool was validated across several studies conducted in different countries with diverse practice settings, including academic hospitals, national population-based cohorts, and clinical trials.

The researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to understand the utility of CLL-IPI tool in predicting OS and TTFT across each risk category of CLL patients.

They included nine studies with 7,843 patients to assess the impact of the CLL-IPI on overall survival. The patient distribution into the CLL-IPI risk categories was low risk (median 45.9%), intermediate risk (median 30%), high risk (median 16.5%), and very high risk (median 3.6%).

The researchers relied on 11 series comprising 7,383 patients to assess 5-year survival probability, which was 92% for low risk, 81% for intermediate risk, 60% for high risk, and 34% for very high risk. They used seven studies comprising 5,206 patients to assess TTFT and found that the probability of remaining treatment free at 5 years was 82% in the low-risk group, 45% in the intermediate-risk group, 30% in the high-risk group, and 16% in the very-high-risk group.

Although a significant step toward harmonizing international prognostication for CLL, additional studies validating the utility of the CLL-IPI for predicting OS in patients treated with targeted therapy are needed, they wrote.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM BLOOD

Drugs identified after suicide deaths

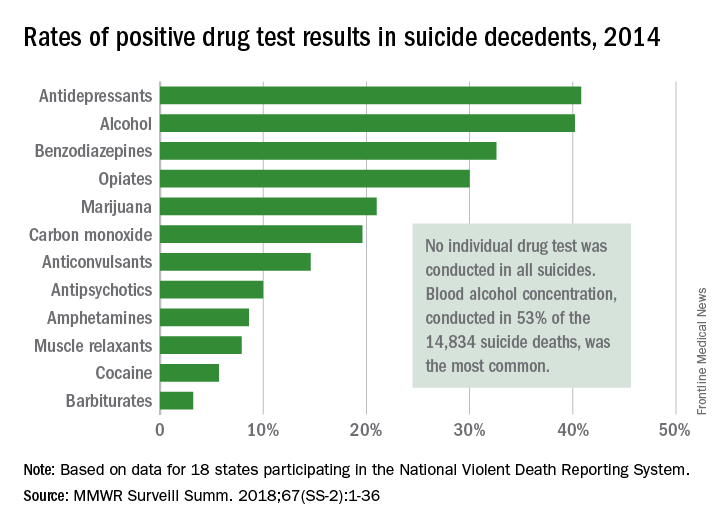

Antidepressants and alcohol were each identified in more than 40% of tests performed after suicide deaths in 2014, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Violent Death Reporting System.

Of the 14,834 suicide deaths reported that year in the system’s 18 participating states, tests for alcohol – conducted for 53% (7,883) of decedents – were the most commonly performed and were the second most likely to be positive among drugs with data available: The rate was 40.2%. Among the tests for blood alcohol concentration, a level of 0.08 g/dL or higher, which is over the legal limit in all states, was seen in almost 70% of positive results, Katherine A. Fowler, PhD, and her associates at the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control reported in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries.

The 18 states that collected statewide data for 2014 – Alaska, Colorado, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin – represent just over 33% of the U.S. population.

SOURCE: Fowler KA et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(SS-2):1-36. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6702a1.

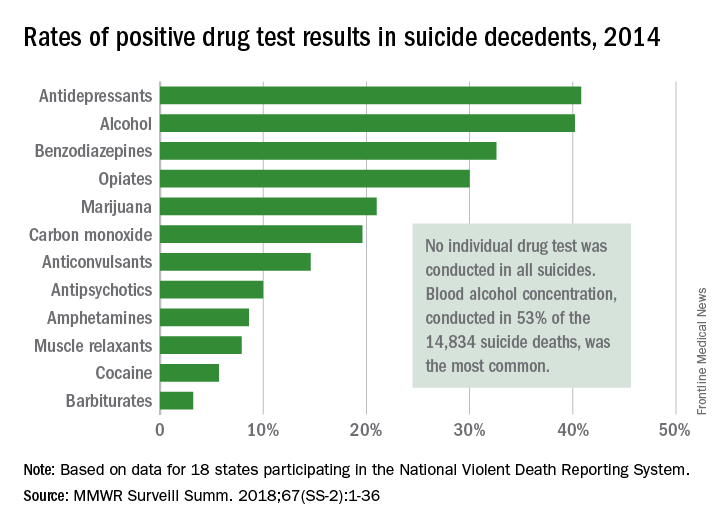

Antidepressants and alcohol were each identified in more than 40% of tests performed after suicide deaths in 2014, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Violent Death Reporting System.

Of the 14,834 suicide deaths reported that year in the system’s 18 participating states, tests for alcohol – conducted for 53% (7,883) of decedents – were the most commonly performed and were the second most likely to be positive among drugs with data available: The rate was 40.2%. Among the tests for blood alcohol concentration, a level of 0.08 g/dL or higher, which is over the legal limit in all states, was seen in almost 70% of positive results, Katherine A. Fowler, PhD, and her associates at the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control reported in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries.

The 18 states that collected statewide data for 2014 – Alaska, Colorado, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin – represent just over 33% of the U.S. population.

SOURCE: Fowler KA et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(SS-2):1-36. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6702a1.

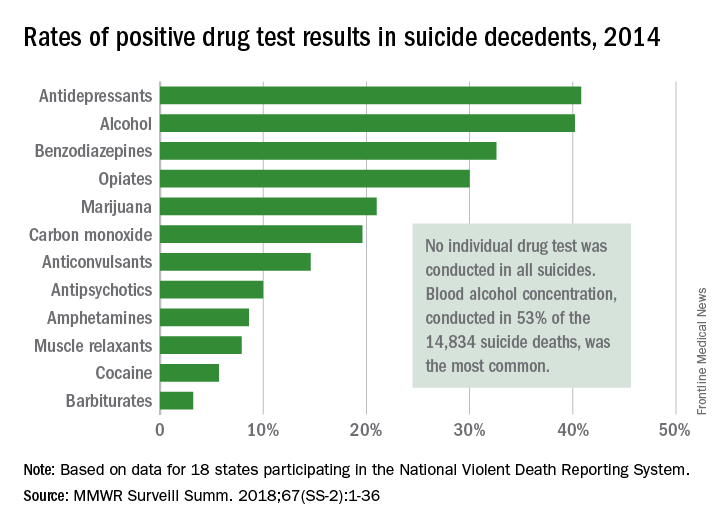

Antidepressants and alcohol were each identified in more than 40% of tests performed after suicide deaths in 2014, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Violent Death Reporting System.

Of the 14,834 suicide deaths reported that year in the system’s 18 participating states, tests for alcohol – conducted for 53% (7,883) of decedents – were the most commonly performed and were the second most likely to be positive among drugs with data available: The rate was 40.2%. Among the tests for blood alcohol concentration, a level of 0.08 g/dL or higher, which is over the legal limit in all states, was seen in almost 70% of positive results, Katherine A. Fowler, PhD, and her associates at the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control reported in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries.

The 18 states that collected statewide data for 2014 – Alaska, Colorado, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin – represent just over 33% of the U.S. population.

SOURCE: Fowler KA et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(SS-2):1-36. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6702a1.

FROM MMWR

Apalutamide wins big in SPARTAN prostate cancer trial

The androgen receptor antagonist apalutamide is highly effective for treating nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer that carries high risk for metastasis based on a rapidly rising prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, according to results of the randomized phase 3 SPARTAN trial.

“Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer is a uniformly fatal disease, with a median survival of around 2.5 years. The aim of this study was to see if the development of metastases in the transition from nonmetastatic to metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer could be slowed,” lead study author Eric J. Small, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, commented in a press briefing held in advance of the 2018 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium.

He and his coinvestigators randomized 1,207 men with high-risk nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer 2:1 to apalutamide (an investigational next-generation competitive inhibitor of the androgen receptor, also known as ARN-509) or placebo, with continuation of androgen-deprivation therapy in both groups. After development of metastases, patients were offered open-label abiraterone (Zytiga), the standard of care for this population, with prednisone.

Main results showed that, compared with placebo, apalutamide prolonged the time to metastasis (ascertained by central review of standard imaging) or death by more than 2 years, Dr. Small reported. The difference translated to a nearly three-fourths reduction in the risk of these events. In addition, the drug was well tolerated and had a rate of serious adverse events similar to that seen with placebo.

“This is a positive trial,” he summarized. “Overall, these data suggest that apalutamide should now be considered as a new standard of care for men with high-risk nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.”

The metastasis-free survival findings led to unblinding of the trial in July 2017, and all patients were offered open-label apalutamide. Full results of SPARTAN will be reported later this week at the symposium, which is sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, ASTRO, and the Society of Urologic Oncology.

Parsing the findings

“Until the results of studies presented at this meeting, there was really no obvious standard of care for these patients,” commented ASCO Expert and presscast moderator Sumanta K. Pal, MD. The gain in metastasis-free survival in SPARTAN was “very clinically meaningful.”

Results of the similar PROSPER trial, which compared enzalutamide (Xtandi) with placebo, will also be presented at the symposium, he noted. “We know from a press release issued in September of 2017 that this study also showed a significant delay in the time to onset of metastatic disease. It will be interesting to juxtapose these data once available. Enzalutamide is a drug familiar to the prostate cancer community given existing approvals in the setting of more advanced disease. The familiarity that oncologists already have with enzalutamide may help with clinical adoption.”

Ultimately, imaging advances that allow for earlier detection of metastases may shrink the population of men with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, according to Dr. Pal, who is also a medical oncologist and codirector of the Kidney Cancer Program at City of Hope, Duarte, Calif.

“The SPARTAN trial used a more conventional imaging approach, with CT scans and technetium bone scans,” he pointed out. “While it’s true that this is the current standard, imaging techniques such as fluciclovine PET, PSMA [prostate-specific membrane antigen] PET, may potentially improve our ability to detect disease spread earlier and thereby change our management strategy.”

Study details

The patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer enrolled in SPARTAN had a calculated PSA-doubling time of 10 months or less, a feature identifying those most at risk for developing metastases.

At a median follow-up of 20.3 months, median metastasis-free survival was 40.5 months with apalutamide versus 16.2 months with placebo (hazard ratio, 0.28; P less than .001), Dr. Small reported. An interim analysis of overall survival showed a trend favoring apalutamide (P = .07).

Fully 61% of patients in the apalutamide group were still on treatment at data cutoff, compared with 30% of placebo-treated patients.

Both groups had low rates of discontinuation attributable to adverse events (10.7% and 6.3%). Apalutamide-treated patients did not have any decrease from baseline in patient-reported health-related quality of life scores, which were similar to those of placebo-treated counterparts.

Dr. Small disclosed that he has a consulting or advisory role with Fortis, Gilead Sciences, and Valeant Pharmaceuticals International; has stock and other ownership interests with Fortis and Harpoon Therapeutics; and receives honoraria from Janssen-Cilag; in addition, his institution receives research funding from Janssen. The study was funded by Aragon Pharmaceuticals, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson.

The androgen receptor antagonist apalutamide is highly effective for treating nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer that carries high risk for metastasis based on a rapidly rising prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, according to results of the randomized phase 3 SPARTAN trial.

“Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer is a uniformly fatal disease, with a median survival of around 2.5 years. The aim of this study was to see if the development of metastases in the transition from nonmetastatic to metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer could be slowed,” lead study author Eric J. Small, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, commented in a press briefing held in advance of the 2018 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium.

He and his coinvestigators randomized 1,207 men with high-risk nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer 2:1 to apalutamide (an investigational next-generation competitive inhibitor of the androgen receptor, also known as ARN-509) or placebo, with continuation of androgen-deprivation therapy in both groups. After development of metastases, patients were offered open-label abiraterone (Zytiga), the standard of care for this population, with prednisone.

Main results showed that, compared with placebo, apalutamide prolonged the time to metastasis (ascertained by central review of standard imaging) or death by more than 2 years, Dr. Small reported. The difference translated to a nearly three-fourths reduction in the risk of these events. In addition, the drug was well tolerated and had a rate of serious adverse events similar to that seen with placebo.

“This is a positive trial,” he summarized. “Overall, these data suggest that apalutamide should now be considered as a new standard of care for men with high-risk nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.”

The metastasis-free survival findings led to unblinding of the trial in July 2017, and all patients were offered open-label apalutamide. Full results of SPARTAN will be reported later this week at the symposium, which is sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, ASTRO, and the Society of Urologic Oncology.

Parsing the findings

“Until the results of studies presented at this meeting, there was really no obvious standard of care for these patients,” commented ASCO Expert and presscast moderator Sumanta K. Pal, MD. The gain in metastasis-free survival in SPARTAN was “very clinically meaningful.”

Results of the similar PROSPER trial, which compared enzalutamide (Xtandi) with placebo, will also be presented at the symposium, he noted. “We know from a press release issued in September of 2017 that this study also showed a significant delay in the time to onset of metastatic disease. It will be interesting to juxtapose these data once available. Enzalutamide is a drug familiar to the prostate cancer community given existing approvals in the setting of more advanced disease. The familiarity that oncologists already have with enzalutamide may help with clinical adoption.”

Ultimately, imaging advances that allow for earlier detection of metastases may shrink the population of men with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, according to Dr. Pal, who is also a medical oncologist and codirector of the Kidney Cancer Program at City of Hope, Duarte, Calif.

“The SPARTAN trial used a more conventional imaging approach, with CT scans and technetium bone scans,” he pointed out. “While it’s true that this is the current standard, imaging techniques such as fluciclovine PET, PSMA [prostate-specific membrane antigen] PET, may potentially improve our ability to detect disease spread earlier and thereby change our management strategy.”

Study details

The patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer enrolled in SPARTAN had a calculated PSA-doubling time of 10 months or less, a feature identifying those most at risk for developing metastases.

At a median follow-up of 20.3 months, median metastasis-free survival was 40.5 months with apalutamide versus 16.2 months with placebo (hazard ratio, 0.28; P less than .001), Dr. Small reported. An interim analysis of overall survival showed a trend favoring apalutamide (P = .07).

Fully 61% of patients in the apalutamide group were still on treatment at data cutoff, compared with 30% of placebo-treated patients.

Both groups had low rates of discontinuation attributable to adverse events (10.7% and 6.3%). Apalutamide-treated patients did not have any decrease from baseline in patient-reported health-related quality of life scores, which were similar to those of placebo-treated counterparts.

Dr. Small disclosed that he has a consulting or advisory role with Fortis, Gilead Sciences, and Valeant Pharmaceuticals International; has stock and other ownership interests with Fortis and Harpoon Therapeutics; and receives honoraria from Janssen-Cilag; in addition, his institution receives research funding from Janssen. The study was funded by Aragon Pharmaceuticals, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson.

The androgen receptor antagonist apalutamide is highly effective for treating nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer that carries high risk for metastasis based on a rapidly rising prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, according to results of the randomized phase 3 SPARTAN trial.

“Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer is a uniformly fatal disease, with a median survival of around 2.5 years. The aim of this study was to see if the development of metastases in the transition from nonmetastatic to metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer could be slowed,” lead study author Eric J. Small, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, commented in a press briefing held in advance of the 2018 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium.

He and his coinvestigators randomized 1,207 men with high-risk nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer 2:1 to apalutamide (an investigational next-generation competitive inhibitor of the androgen receptor, also known as ARN-509) or placebo, with continuation of androgen-deprivation therapy in both groups. After development of metastases, patients were offered open-label abiraterone (Zytiga), the standard of care for this population, with prednisone.

Main results showed that, compared with placebo, apalutamide prolonged the time to metastasis (ascertained by central review of standard imaging) or death by more than 2 years, Dr. Small reported. The difference translated to a nearly three-fourths reduction in the risk of these events. In addition, the drug was well tolerated and had a rate of serious adverse events similar to that seen with placebo.

“This is a positive trial,” he summarized. “Overall, these data suggest that apalutamide should now be considered as a new standard of care for men with high-risk nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.”

The metastasis-free survival findings led to unblinding of the trial in July 2017, and all patients were offered open-label apalutamide. Full results of SPARTAN will be reported later this week at the symposium, which is sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, ASTRO, and the Society of Urologic Oncology.

Parsing the findings

“Until the results of studies presented at this meeting, there was really no obvious standard of care for these patients,” commented ASCO Expert and presscast moderator Sumanta K. Pal, MD. The gain in metastasis-free survival in SPARTAN was “very clinically meaningful.”

Results of the similar PROSPER trial, which compared enzalutamide (Xtandi) with placebo, will also be presented at the symposium, he noted. “We know from a press release issued in September of 2017 that this study also showed a significant delay in the time to onset of metastatic disease. It will be interesting to juxtapose these data once available. Enzalutamide is a drug familiar to the prostate cancer community given existing approvals in the setting of more advanced disease. The familiarity that oncologists already have with enzalutamide may help with clinical adoption.”

Ultimately, imaging advances that allow for earlier detection of metastases may shrink the population of men with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, according to Dr. Pal, who is also a medical oncologist and codirector of the Kidney Cancer Program at City of Hope, Duarte, Calif.

“The SPARTAN trial used a more conventional imaging approach, with CT scans and technetium bone scans,” he pointed out. “While it’s true that this is the current standard, imaging techniques such as fluciclovine PET, PSMA [prostate-specific membrane antigen] PET, may potentially improve our ability to detect disease spread earlier and thereby change our management strategy.”

Study details

The patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer enrolled in SPARTAN had a calculated PSA-doubling time of 10 months or less, a feature identifying those most at risk for developing metastases.

At a median follow-up of 20.3 months, median metastasis-free survival was 40.5 months with apalutamide versus 16.2 months with placebo (hazard ratio, 0.28; P less than .001), Dr. Small reported. An interim analysis of overall survival showed a trend favoring apalutamide (P = .07).

Fully 61% of patients in the apalutamide group were still on treatment at data cutoff, compared with 30% of placebo-treated patients.

Both groups had low rates of discontinuation attributable to adverse events (10.7% and 6.3%). Apalutamide-treated patients did not have any decrease from baseline in patient-reported health-related quality of life scores, which were similar to those of placebo-treated counterparts.

Dr. Small disclosed that he has a consulting or advisory role with Fortis, Gilead Sciences, and Valeant Pharmaceuticals International; has stock and other ownership interests with Fortis and Harpoon Therapeutics; and receives honoraria from Janssen-Cilag; in addition, his institution receives research funding from Janssen. The study was funded by Aragon Pharmaceuticals, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson.

REPORTING FROM GUCS 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Median metastasis-free survival was 40.5 months with apalutamide versus 16.2 months with placebo (HR, 0.28; P less than .001).

Data source: A phase 3 randomized controlled trial among 1,207 men with high-risk nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (SPARTAN trial).

Disclosures: Dr. Small disclosed that he has a consulting or advisory role with Fortis, Gilead Sciences, and Valeant Pharmaceuticals International; has stock and other ownership interests with Fortis and Harpoon Therapeutics; and receives honoraria from Janssen-Cilag; in addition, his institution receives research funding from Janssen. The study was funded by Aragon Pharmaceuticals, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson.

Placental transfusion volume unaffected by oxytocin timing

DALLAS – Timing of maternal oxytocin administration did not affect total placental transfusion volume accomplished via delayed umbilical cord clamping, according to a recent randomized, controlled trial.

Of 144 infants born to women who consented to randomization, those whose mothers received intravenous oxytocin within 15 seconds of delivery (n = 70) gained a mean 86 g (standard deviation, 48; 95% confidence interval, 74-97) in the 3 minutes after delivery, before umbilical cord clamping. Infants whose mothers received oxytocin when the umbilical cord was clamped 3 minutes after delivery (n = 74) gained 87 g (SD, 50; 95% CI, 75-98; P for difference between groups = .92). The findings were presented during an abstract session at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

It had not previously been known whether immediate oxytocin administration enhanced or diminished placental transfusion volume, said Daniela Satragno, MD, the study’s first author.

The investigators had hypothesized that immediate oxytocin administration would increase the volume of placental transfusion, said Dr. Satragno, of Argentina’s Foundation for Maternal and Child Health. However, their study didn’t bear this out. “When umbilical cord clamping is delayed for 3 minutes, infants receive a clinically significant placental transfusion which is not modified by the administration of IV oxytocin immediately after birth,” wrote Dr. Satragno and her coauthors in the abstract accompanying the presentation.

The study in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology included healthy term infants born via vaginal delivery; Dr. Satragno said that consent was obtained from mothers in early labor, and that study recruiters did not approach women who were in more advanced stages of labor because of ethical concerns. Women with high-risk pregnancies and those with known fetal anomalies were excluded, as were any who required forceps deliveries, neonatal resuscitation, and those whose deliveries involved a short umbilical cord or a nuchal cord.

In order to estimate the volume of placental transfusion, all infants were weighed on a 1-g precision scale placed at the level of the vagina both immediately after birth and after the umbilical cord was clamped at 3 minutes after delivery. All participating mothers received 10 IU of oxytocin, with the timing varying by intervention arm. A figure of 1.05 g/cc of blood was used to calculate transfusion volume, with change in infant weight used as a proxy for transfusion volume.

Hematocrit levels were also similar between the two groups: infants whose mothers received immediate oxytocin had a mean hematocrit of 57% (SD, 5), while those whose mothers had delayed oxytocin administration had a mean hematocrit of 56.8% (SD, 6).

Dr. Satragno and her collaborators also looked at a number of other secondary outcome measures, including incidence of jaundice and polycythemia in the infant, and maternal postpartum hemorrhage. There were no such adverse events that reached the level of clinical relevance among any of the mothers or infants in the study population, she said.

A larger study had been planned, said Dr. Satragno, but the data safety monitoring board recommended stopping the study for futility after the prespecified interim analysis of data from 144 patients – just 25% of the originally planned sample size.

In response to an audience question, Dr. Satragno acknowledged that blinding was not feasible with their study design, but that she did not think that this affected physician management in the first few minutes postpartum. She noted that delayed cord clamping has been an area of active research at her institution, and protocols are well established.

“Based on the available data, a recalculation of the sample size for a difference of 20% in the volume of placental transfusion would result in a trial of an unrealistically large magnitude,” said Dr. Satragno.

The study was funded by the Foundation for Maternal and Child Health. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Satragno D et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S26.

DALLAS – Timing of maternal oxytocin administration did not affect total placental transfusion volume accomplished via delayed umbilical cord clamping, according to a recent randomized, controlled trial.

Of 144 infants born to women who consented to randomization, those whose mothers received intravenous oxytocin within 15 seconds of delivery (n = 70) gained a mean 86 g (standard deviation, 48; 95% confidence interval, 74-97) in the 3 minutes after delivery, before umbilical cord clamping. Infants whose mothers received oxytocin when the umbilical cord was clamped 3 minutes after delivery (n = 74) gained 87 g (SD, 50; 95% CI, 75-98; P for difference between groups = .92). The findings were presented during an abstract session at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

It had not previously been known whether immediate oxytocin administration enhanced or diminished placental transfusion volume, said Daniela Satragno, MD, the study’s first author.

The investigators had hypothesized that immediate oxytocin administration would increase the volume of placental transfusion, said Dr. Satragno, of Argentina’s Foundation for Maternal and Child Health. However, their study didn’t bear this out. “When umbilical cord clamping is delayed for 3 minutes, infants receive a clinically significant placental transfusion which is not modified by the administration of IV oxytocin immediately after birth,” wrote Dr. Satragno and her coauthors in the abstract accompanying the presentation.

The study in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology included healthy term infants born via vaginal delivery; Dr. Satragno said that consent was obtained from mothers in early labor, and that study recruiters did not approach women who were in more advanced stages of labor because of ethical concerns. Women with high-risk pregnancies and those with known fetal anomalies were excluded, as were any who required forceps deliveries, neonatal resuscitation, and those whose deliveries involved a short umbilical cord or a nuchal cord.

In order to estimate the volume of placental transfusion, all infants were weighed on a 1-g precision scale placed at the level of the vagina both immediately after birth and after the umbilical cord was clamped at 3 minutes after delivery. All participating mothers received 10 IU of oxytocin, with the timing varying by intervention arm. A figure of 1.05 g/cc of blood was used to calculate transfusion volume, with change in infant weight used as a proxy for transfusion volume.

Hematocrit levels were also similar between the two groups: infants whose mothers received immediate oxytocin had a mean hematocrit of 57% (SD, 5), while those whose mothers had delayed oxytocin administration had a mean hematocrit of 56.8% (SD, 6).

Dr. Satragno and her collaborators also looked at a number of other secondary outcome measures, including incidence of jaundice and polycythemia in the infant, and maternal postpartum hemorrhage. There were no such adverse events that reached the level of clinical relevance among any of the mothers or infants in the study population, she said.

A larger study had been planned, said Dr. Satragno, but the data safety monitoring board recommended stopping the study for futility after the prespecified interim analysis of data from 144 patients – just 25% of the originally planned sample size.

In response to an audience question, Dr. Satragno acknowledged that blinding was not feasible with their study design, but that she did not think that this affected physician management in the first few minutes postpartum. She noted that delayed cord clamping has been an area of active research at her institution, and protocols are well established.

“Based on the available data, a recalculation of the sample size for a difference of 20% in the volume of placental transfusion would result in a trial of an unrealistically large magnitude,” said Dr. Satragno.

The study was funded by the Foundation for Maternal and Child Health. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Satragno D et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S26.

DALLAS – Timing of maternal oxytocin administration did not affect total placental transfusion volume accomplished via delayed umbilical cord clamping, according to a recent randomized, controlled trial.

Of 144 infants born to women who consented to randomization, those whose mothers received intravenous oxytocin within 15 seconds of delivery (n = 70) gained a mean 86 g (standard deviation, 48; 95% confidence interval, 74-97) in the 3 minutes after delivery, before umbilical cord clamping. Infants whose mothers received oxytocin when the umbilical cord was clamped 3 minutes after delivery (n = 74) gained 87 g (SD, 50; 95% CI, 75-98; P for difference between groups = .92). The findings were presented during an abstract session at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

It had not previously been known whether immediate oxytocin administration enhanced or diminished placental transfusion volume, said Daniela Satragno, MD, the study’s first author.

The investigators had hypothesized that immediate oxytocin administration would increase the volume of placental transfusion, said Dr. Satragno, of Argentina’s Foundation for Maternal and Child Health. However, their study didn’t bear this out. “When umbilical cord clamping is delayed for 3 minutes, infants receive a clinically significant placental transfusion which is not modified by the administration of IV oxytocin immediately after birth,” wrote Dr. Satragno and her coauthors in the abstract accompanying the presentation.

The study in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology included healthy term infants born via vaginal delivery; Dr. Satragno said that consent was obtained from mothers in early labor, and that study recruiters did not approach women who were in more advanced stages of labor because of ethical concerns. Women with high-risk pregnancies and those with known fetal anomalies were excluded, as were any who required forceps deliveries, neonatal resuscitation, and those whose deliveries involved a short umbilical cord or a nuchal cord.

In order to estimate the volume of placental transfusion, all infants were weighed on a 1-g precision scale placed at the level of the vagina both immediately after birth and after the umbilical cord was clamped at 3 minutes after delivery. All participating mothers received 10 IU of oxytocin, with the timing varying by intervention arm. A figure of 1.05 g/cc of blood was used to calculate transfusion volume, with change in infant weight used as a proxy for transfusion volume.

Hematocrit levels were also similar between the two groups: infants whose mothers received immediate oxytocin had a mean hematocrit of 57% (SD, 5), while those whose mothers had delayed oxytocin administration had a mean hematocrit of 56.8% (SD, 6).

Dr. Satragno and her collaborators also looked at a number of other secondary outcome measures, including incidence of jaundice and polycythemia in the infant, and maternal postpartum hemorrhage. There were no such adverse events that reached the level of clinical relevance among any of the mothers or infants in the study population, she said.

A larger study had been planned, said Dr. Satragno, but the data safety monitoring board recommended stopping the study for futility after the prespecified interim analysis of data from 144 patients – just 25% of the originally planned sample size.

In response to an audience question, Dr. Satragno acknowledged that blinding was not feasible with their study design, but that she did not think that this affected physician management in the first few minutes postpartum. She noted that delayed cord clamping has been an area of active research at her institution, and protocols are well established.

“Based on the available data, a recalculation of the sample size for a difference of 20% in the volume of placental transfusion would result in a trial of an unrealistically large magnitude,” said Dr. Satragno.

The study was funded by the Foundation for Maternal and Child Health. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Satragno D et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S26.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point: The timing of oxytocin administration didn’t affect placental transfusion volume with delayed cord clamping.

Major finding: Placental transfusion volume was 86 g with immediate and 87 g with delayed oxytocin administration (P = .92), with infant weight used as proxy.

Study details: Randomized controlled trial of 144 healthy term infants delivered vaginally after uncomplicated pregnancy.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Foundation for Maternal and Child Health, where Dr. Satragno is employed.

Source: Satragno D et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S26.

Indiana gets Medicaid waiver that could slice enrollment

Indiana is the second state to win federal approval to add a work requirement for adult Medicaid recipients who gained coverage under the Affordable Care Act, but a less debated “lockout” provision in its new plan could lead to tens of thousands of enrollees losing coverage.

The federal approval was announced Feb. 2 by Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar in Indianapolis.

Medicaid participants who fail to submit their paperwork in a timely manner showing that they still qualify for the program will be blocked from enrollment for 3 months, according to the updated rules.

Since November 2015, more than 91,000 enrollees in Indiana were kicked off Medicaid for failing to complete the eligibility redetermination process, according to state records. The process requires applicants to show proof of income and family size, among other things, to see if they still qualify for the coverage. Until now, these enrollees could simply reapply anytime. Although many of those people likely were no longer eligible, state officials estimate about half of those who failed to comply with its reenrollment rules were still qualified.

Indiana’s Medicaid expansion began in February 2015, providing coverage to 240,000 people who were previously uninsured, helping drop the state’s uninsured rate from 14% in 2013 to 8% last year. The HHS approval extends the program, which was expiring this month, through 2020.

The new lockout builds on one already in place for Indiana residents who failed to pay monthly premiums and had annual incomes above the federal poverty level, or about $12,200 for an individual. They are barred for 6 months from coverage. During the first 2 years of the experiment, about 10,000 Indiana Medicaid enrollees were subject to the lockout for failing to pay the premium for 2 months in a row, according to state data.

In addition, more than 25,000 enrollees were dropped from the program after they failed to make the payments, although half of them found another source of coverage, usually through their jobs.

Another 46,000 were blocked from coverage because they failed to make the initial payment.

“The ‘lockout” is one of the worst policies to hit Medicaid in a long time,” said Joan Alker, executive director of the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, in Washington. “Forcing people to remain uninsured for months because they missed a paperwork deadline or missed a premium payment is too high a price to pay. From a health policy perspective, it makes no sense because during that period, chronic health conditions such as hypertension or diabetes are just likely to worsen.”

Indiana’s Medicaid expansion is being closely watched in part because it was spearheaded by then-governor Mike Pence, who is now vice president, and his top health consultant, Seema Verma, who now heads the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The expansion, known as Healthy Indiana, enabled nondisabled adults access to Medicaid. It has elicited criticism from patient advocates for complex and onerous rules that require these poor adults to make payments ranging from $1 to $27 per month into health savings accounts or risk losing their vision and dental benefits or even all their coverage, depending on their income level.

Indiana Medicaid officials said they added the newest lockout provision in an effort to prompt enrollees to get their paperwork submitted in time. The state initially requested a 6-month lockout.

“Enforcement may encourage better compliance,” the state officials wrote in their waiver application to CMS in July.

The new rule will lead to a 1% cut in Medicaid enrollment in the first year, state officials said. It will also lead to a $15 million reduction in Medicaid costs in 2018 and about $32 million in savings in 2019, the state estimated.

The number of Medicaid enrollees losing coverage for failing to comply with redetermining their eligibility has varied dramatically each quarter from a peak of 19,197 from February 2016 to April 2017 to 1,165 from November 2015 to January 2016, state reports show. In the latest state report, 12,470 enrollees lost coverage from August to October 2017.

The Kentucky Medicaid waiver approved by the Trump administration in January included a similar lockout provision for both failing to pay the monthly premiums or providing paperwork on time. Penalties there are 6 months for both measures. But the provision was overshadowed because of the attention to the first federal approval for a Medicaid work requirement.

Like Kentucky, Indiana’s Medicaid waiver’s work requirements, which mandate adult enrollees to work an average of 20 hours a month, go into effect in 2019. But Indiana’s waiver is more lenient. It exempts people aged 60 years and older and its work-hour requirements are gradually phased in over 18 months. For example, enrollees need to work only 5 hours per week until their 10th month on the program.

Most Medicaid adult enrollees do work, go to school, or are too sick to work, studies show.

Indiana also has a long list of exemptions and alternatives to employment. This includes attending school or job training, volunteering or caring for a dependent child or disabled parent. Nurses, doctors and physician assistants can give enrollees an exemption due to illness or injury.

Three patient advocacy groups have filed suit in federal court seeking to block the work requirements.

Robin Rudowitz, associate director for the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, said it’s difficult to gauge whether work requirements or renewal lockouts will have more of an impact on coverage. She noted both provisions apply to most demonstration beneficiaries. (KHN is an editorially independent program of the foundation).

“Any documentation requirement could lead to increased complexity in terms of states administering the requirements and individuals complying,” she said, adding that it could result “in potentially eligible people falling off of coverage.”

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Indiana is the second state to win federal approval to add a work requirement for adult Medicaid recipients who gained coverage under the Affordable Care Act, but a less debated “lockout” provision in its new plan could lead to tens of thousands of enrollees losing coverage.

The federal approval was announced Feb. 2 by Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar in Indianapolis.

Medicaid participants who fail to submit their paperwork in a timely manner showing that they still qualify for the program will be blocked from enrollment for 3 months, according to the updated rules.

Since November 2015, more than 91,000 enrollees in Indiana were kicked off Medicaid for failing to complete the eligibility redetermination process, according to state records. The process requires applicants to show proof of income and family size, among other things, to see if they still qualify for the coverage. Until now, these enrollees could simply reapply anytime. Although many of those people likely were no longer eligible, state officials estimate about half of those who failed to comply with its reenrollment rules were still qualified.

Indiana’s Medicaid expansion began in February 2015, providing coverage to 240,000 people who were previously uninsured, helping drop the state’s uninsured rate from 14% in 2013 to 8% last year. The HHS approval extends the program, which was expiring this month, through 2020.

The new lockout builds on one already in place for Indiana residents who failed to pay monthly premiums and had annual incomes above the federal poverty level, or about $12,200 for an individual. They are barred for 6 months from coverage. During the first 2 years of the experiment, about 10,000 Indiana Medicaid enrollees were subject to the lockout for failing to pay the premium for 2 months in a row, according to state data.

In addition, more than 25,000 enrollees were dropped from the program after they failed to make the payments, although half of them found another source of coverage, usually through their jobs.

Another 46,000 were blocked from coverage because they failed to make the initial payment.

“The ‘lockout” is one of the worst policies to hit Medicaid in a long time,” said Joan Alker, executive director of the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, in Washington. “Forcing people to remain uninsured for months because they missed a paperwork deadline or missed a premium payment is too high a price to pay. From a health policy perspective, it makes no sense because during that period, chronic health conditions such as hypertension or diabetes are just likely to worsen.”

Indiana’s Medicaid expansion is being closely watched in part because it was spearheaded by then-governor Mike Pence, who is now vice president, and his top health consultant, Seema Verma, who now heads the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The expansion, known as Healthy Indiana, enabled nondisabled adults access to Medicaid. It has elicited criticism from patient advocates for complex and onerous rules that require these poor adults to make payments ranging from $1 to $27 per month into health savings accounts or risk losing their vision and dental benefits or even all their coverage, depending on their income level.

Indiana Medicaid officials said they added the newest lockout provision in an effort to prompt enrollees to get their paperwork submitted in time. The state initially requested a 6-month lockout.

“Enforcement may encourage better compliance,” the state officials wrote in their waiver application to CMS in July.

The new rule will lead to a 1% cut in Medicaid enrollment in the first year, state officials said. It will also lead to a $15 million reduction in Medicaid costs in 2018 and about $32 million in savings in 2019, the state estimated.

The number of Medicaid enrollees losing coverage for failing to comply with redetermining their eligibility has varied dramatically each quarter from a peak of 19,197 from February 2016 to April 2017 to 1,165 from November 2015 to January 2016, state reports show. In the latest state report, 12,470 enrollees lost coverage from August to October 2017.

The Kentucky Medicaid waiver approved by the Trump administration in January included a similar lockout provision for both failing to pay the monthly premiums or providing paperwork on time. Penalties there are 6 months for both measures. But the provision was overshadowed because of the attention to the first federal approval for a Medicaid work requirement.

Like Kentucky, Indiana’s Medicaid waiver’s work requirements, which mandate adult enrollees to work an average of 20 hours a month, go into effect in 2019. But Indiana’s waiver is more lenient. It exempts people aged 60 years and older and its work-hour requirements are gradually phased in over 18 months. For example, enrollees need to work only 5 hours per week until their 10th month on the program.

Most Medicaid adult enrollees do work, go to school, or are too sick to work, studies show.

Indiana also has a long list of exemptions and alternatives to employment. This includes attending school or job training, volunteering or caring for a dependent child or disabled parent. Nurses, doctors and physician assistants can give enrollees an exemption due to illness or injury.

Three patient advocacy groups have filed suit in federal court seeking to block the work requirements.

Robin Rudowitz, associate director for the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, said it’s difficult to gauge whether work requirements or renewal lockouts will have more of an impact on coverage. She noted both provisions apply to most demonstration beneficiaries. (KHN is an editorially independent program of the foundation).

“Any documentation requirement could lead to increased complexity in terms of states administering the requirements and individuals complying,” she said, adding that it could result “in potentially eligible people falling off of coverage.”

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Indiana is the second state to win federal approval to add a work requirement for adult Medicaid recipients who gained coverage under the Affordable Care Act, but a less debated “lockout” provision in its new plan could lead to tens of thousands of enrollees losing coverage.

The federal approval was announced Feb. 2 by Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar in Indianapolis.

Medicaid participants who fail to submit their paperwork in a timely manner showing that they still qualify for the program will be blocked from enrollment for 3 months, according to the updated rules.

Since November 2015, more than 91,000 enrollees in Indiana were kicked off Medicaid for failing to complete the eligibility redetermination process, according to state records. The process requires applicants to show proof of income and family size, among other things, to see if they still qualify for the coverage. Until now, these enrollees could simply reapply anytime. Although many of those people likely were no longer eligible, state officials estimate about half of those who failed to comply with its reenrollment rules were still qualified.

Indiana’s Medicaid expansion began in February 2015, providing coverage to 240,000 people who were previously uninsured, helping drop the state’s uninsured rate from 14% in 2013 to 8% last year. The HHS approval extends the program, which was expiring this month, through 2020.

The new lockout builds on one already in place for Indiana residents who failed to pay monthly premiums and had annual incomes above the federal poverty level, or about $12,200 for an individual. They are barred for 6 months from coverage. During the first 2 years of the experiment, about 10,000 Indiana Medicaid enrollees were subject to the lockout for failing to pay the premium for 2 months in a row, according to state data.

In addition, more than 25,000 enrollees were dropped from the program after they failed to make the payments, although half of them found another source of coverage, usually through their jobs.

Another 46,000 were blocked from coverage because they failed to make the initial payment.

“The ‘lockout” is one of the worst policies to hit Medicaid in a long time,” said Joan Alker, executive director of the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, in Washington. “Forcing people to remain uninsured for months because they missed a paperwork deadline or missed a premium payment is too high a price to pay. From a health policy perspective, it makes no sense because during that period, chronic health conditions such as hypertension or diabetes are just likely to worsen.”

Indiana’s Medicaid expansion is being closely watched in part because it was spearheaded by then-governor Mike Pence, who is now vice president, and his top health consultant, Seema Verma, who now heads the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The expansion, known as Healthy Indiana, enabled nondisabled adults access to Medicaid. It has elicited criticism from patient advocates for complex and onerous rules that require these poor adults to make payments ranging from $1 to $27 per month into health savings accounts or risk losing their vision and dental benefits or even all their coverage, depending on their income level.

Indiana Medicaid officials said they added the newest lockout provision in an effort to prompt enrollees to get their paperwork submitted in time. The state initially requested a 6-month lockout.

“Enforcement may encourage better compliance,” the state officials wrote in their waiver application to CMS in July.

The new rule will lead to a 1% cut in Medicaid enrollment in the first year, state officials said. It will also lead to a $15 million reduction in Medicaid costs in 2018 and about $32 million in savings in 2019, the state estimated.

The number of Medicaid enrollees losing coverage for failing to comply with redetermining their eligibility has varied dramatically each quarter from a peak of 19,197 from February 2016 to April 2017 to 1,165 from November 2015 to January 2016, state reports show. In the latest state report, 12,470 enrollees lost coverage from August to October 2017.

The Kentucky Medicaid waiver approved by the Trump administration in January included a similar lockout provision for both failing to pay the monthly premiums or providing paperwork on time. Penalties there are 6 months for both measures. But the provision was overshadowed because of the attention to the first federal approval for a Medicaid work requirement.

Like Kentucky, Indiana’s Medicaid waiver’s work requirements, which mandate adult enrollees to work an average of 20 hours a month, go into effect in 2019. But Indiana’s waiver is more lenient. It exempts people aged 60 years and older and its work-hour requirements are gradually phased in over 18 months. For example, enrollees need to work only 5 hours per week until their 10th month on the program.

Most Medicaid adult enrollees do work, go to school, or are too sick to work, studies show.

Indiana also has a long list of exemptions and alternatives to employment. This includes attending school or job training, volunteering or caring for a dependent child or disabled parent. Nurses, doctors and physician assistants can give enrollees an exemption due to illness or injury.

Three patient advocacy groups have filed suit in federal court seeking to block the work requirements.

Robin Rudowitz, associate director for the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, said it’s difficult to gauge whether work requirements or renewal lockouts will have more of an impact on coverage. She noted both provisions apply to most demonstration beneficiaries. (KHN is an editorially independent program of the foundation).

“Any documentation requirement could lead to increased complexity in terms of states administering the requirements and individuals complying,” she said, adding that it could result “in potentially eligible people falling off of coverage.”

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

MAGNIMS and McDonald Criteria Have Similar Accuracy

The 2016 Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Multiple Sclerosis (MAGNIMS) criteria have accuracy similar to that of the 2010 McDonald criteria in predicting the development of clinically definite multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a retrospective study.

“Among the different modifications proposed, our results support removal of the distinction between symptomatic and asymptomatic lesions, which simplifies the clinical use of MRI criteria, and suggest that further consideration be given to increasing the number of lesions needed to define periventricular involvement from one to three, because this might slightly increase specificity,” said Massimo Filippi, MD, of the neuroimaging research unit in the division of neuroscience at San Raffaele Scientific Institute at Vita-Salute San Raffaele University in Milan, and colleagues. The report was published online ahead of print December 21, 2017, in Lancet Neurology. “Further effort is still needed to improve cortical lesion assessment, and more studies should be done to evaluate the effect of including optic nerve assessment as an additional dissemination in space [DIS] criterion.”

An Effort to Draft Revisions

In an effort to guide revisions of MS diagnostic criteria, Dr. Filippi and other members of the MAGNIMS network compared the performance of the 2010 McDonald and 2016 MAGNIMS criteria for MS in a cohort of 368 patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) who were screened between June 16, 1995, and January 27, 2017. They used a time-dependent receiver operating characteristic curve analysis to evaluate MRI criteria performance for DIS, dissemination in time (DIT), and DIS plus DIT. Changes to the DIS definition contained in the 2016 MAGNIMS criteria included removal of the distinction between symptomatic and asymptomatic lesions, increasing the number of lesions needed to define periventricular involvement to three, combining cortical and juxtacortical lesions, and inclusion of optic nerve evaluation. For DIT, removal of the distinction between symptomatic and asymptomatic lesions was suggested.