User login

Obesity affects the ability to diagnose liver fibrosis

Body mass index accounts for a 43.7% discordance in fibrosis findings between magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) and transient elastography (TE), according to a study from the University of California, San Diego.

“This study demonstrates that BMI is a significant factor of discordancy between MRE and TE for the stage of significant fibrosis (2-4 vs. 0-1),” wrote Cyrielle Caussy, MD, and her colleagues (Clin Gastrolenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jan 15. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.10.037). “Furthermore, this study showed that the grade of obesity is also a significant predictor of discordancy between MRE and TE because the discordance rate between MRE and TE increases with the increase in BMI.”

Dr. Caussy of the University of California, San Diego, and her colleagues had noted that MRE and TE had discordant findings in obese patients. To ascertain under what conditions TE and MRE produce the same readings, Dr. Caussy and her associates conducted a cross-sectional study of two cohorts with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) who underwent contemporaneous MRE, TE, and liver biopsy. TE utilized both M and XL probes during imaging. The training cohort involved 119 adult patients undergoing NAFLD testing from October 2011 through January 2017. The validation cohort, consisting of 75 adults with NAFLD undergoing liver imaging from March 2010 through May 2013, was formed to validate the findings of the training cohort.

The study revealed that BMI was a significant predictor of the difference between MRE and TE results and made it difficult to assess the stage of liver fibrosis (2-4 vs. 0-1). After adjustment for age and sex, BMI accounted for a 5-unit increase of 1.694 (95% confidence interval, 1.145-2.507; P = .008). This was not a static relationship, and as BMI increased, so did the discordance between MRE and TE (P = .0309). Interestingly, the discordance rate was significantly higher in participants with BMIs greater than 35 kg/m2, compared with participants with BMIs below 35 (63.0% vs. 38.0%; P = .022), the investigators reported.

While the study revealed valuable information, it had both strengths and limitations. A strength of the study was the use of two cohorts, specifically the validation cohort. The use of the liver biopsy as a reference, which is the standard for assessing fibrosis, was also a strength of the study. A limitation was that the study was conducted at specialized, tertiary care centers using advanced imaging techniques that may not be available at other clinics. Additionally, the cohorts included a small number of patients with advanced fibrosis.

“The integration of the BMI in the screening strategy for the noninvasive detection of liver fibrosis in NAFLD should be considered, and this parameter would help to determine when MRE is not needed in future guidelines” wrote Dr. Caussy and her associates. “Further cost-effectiveness studies are necessary to evaluate the clinical utility of MRE, TE, and/or liver biopsy to develop optimal screening strategies for diagnosing NAFLD-associated fibrosis.”

Jun Chen, MD, Meng Yin, MD, and Richard L. Ehman, MD, all have intellectual property rights and financial interests in elastography technology. Dr. Ehman also serves as an noncompensated CEO of Resoundant. Claude B. Sirlin, MD, has served as a consultant to Bayer and GE Healthcare. All other authors did not disclose any conflicts.

The AGA Obesity Practice Guide provides a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at www.gastro.org/obesity.

SOURCE: Caussy C et al. Clin Gastrolenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jan 15. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.10.037.

Body mass index accounts for a 43.7% discordance in fibrosis findings between magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) and transient elastography (TE), according to a study from the University of California, San Diego.

“This study demonstrates that BMI is a significant factor of discordancy between MRE and TE for the stage of significant fibrosis (2-4 vs. 0-1),” wrote Cyrielle Caussy, MD, and her colleagues (Clin Gastrolenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jan 15. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.10.037). “Furthermore, this study showed that the grade of obesity is also a significant predictor of discordancy between MRE and TE because the discordance rate between MRE and TE increases with the increase in BMI.”

Dr. Caussy of the University of California, San Diego, and her colleagues had noted that MRE and TE had discordant findings in obese patients. To ascertain under what conditions TE and MRE produce the same readings, Dr. Caussy and her associates conducted a cross-sectional study of two cohorts with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) who underwent contemporaneous MRE, TE, and liver biopsy. TE utilized both M and XL probes during imaging. The training cohort involved 119 adult patients undergoing NAFLD testing from October 2011 through January 2017. The validation cohort, consisting of 75 adults with NAFLD undergoing liver imaging from March 2010 through May 2013, was formed to validate the findings of the training cohort.

The study revealed that BMI was a significant predictor of the difference between MRE and TE results and made it difficult to assess the stage of liver fibrosis (2-4 vs. 0-1). After adjustment for age and sex, BMI accounted for a 5-unit increase of 1.694 (95% confidence interval, 1.145-2.507; P = .008). This was not a static relationship, and as BMI increased, so did the discordance between MRE and TE (P = .0309). Interestingly, the discordance rate was significantly higher in participants with BMIs greater than 35 kg/m2, compared with participants with BMIs below 35 (63.0% vs. 38.0%; P = .022), the investigators reported.

While the study revealed valuable information, it had both strengths and limitations. A strength of the study was the use of two cohorts, specifically the validation cohort. The use of the liver biopsy as a reference, which is the standard for assessing fibrosis, was also a strength of the study. A limitation was that the study was conducted at specialized, tertiary care centers using advanced imaging techniques that may not be available at other clinics. Additionally, the cohorts included a small number of patients with advanced fibrosis.

“The integration of the BMI in the screening strategy for the noninvasive detection of liver fibrosis in NAFLD should be considered, and this parameter would help to determine when MRE is not needed in future guidelines” wrote Dr. Caussy and her associates. “Further cost-effectiveness studies are necessary to evaluate the clinical utility of MRE, TE, and/or liver biopsy to develop optimal screening strategies for diagnosing NAFLD-associated fibrosis.”

Jun Chen, MD, Meng Yin, MD, and Richard L. Ehman, MD, all have intellectual property rights and financial interests in elastography technology. Dr. Ehman also serves as an noncompensated CEO of Resoundant. Claude B. Sirlin, MD, has served as a consultant to Bayer and GE Healthcare. All other authors did not disclose any conflicts.

The AGA Obesity Practice Guide provides a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at www.gastro.org/obesity.

SOURCE: Caussy C et al. Clin Gastrolenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jan 15. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.10.037.

Body mass index accounts for a 43.7% discordance in fibrosis findings between magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) and transient elastography (TE), according to a study from the University of California, San Diego.

“This study demonstrates that BMI is a significant factor of discordancy between MRE and TE for the stage of significant fibrosis (2-4 vs. 0-1),” wrote Cyrielle Caussy, MD, and her colleagues (Clin Gastrolenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jan 15. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.10.037). “Furthermore, this study showed that the grade of obesity is also a significant predictor of discordancy between MRE and TE because the discordance rate between MRE and TE increases with the increase in BMI.”

Dr. Caussy of the University of California, San Diego, and her colleagues had noted that MRE and TE had discordant findings in obese patients. To ascertain under what conditions TE and MRE produce the same readings, Dr. Caussy and her associates conducted a cross-sectional study of two cohorts with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) who underwent contemporaneous MRE, TE, and liver biopsy. TE utilized both M and XL probes during imaging. The training cohort involved 119 adult patients undergoing NAFLD testing from October 2011 through January 2017. The validation cohort, consisting of 75 adults with NAFLD undergoing liver imaging from March 2010 through May 2013, was formed to validate the findings of the training cohort.

The study revealed that BMI was a significant predictor of the difference between MRE and TE results and made it difficult to assess the stage of liver fibrosis (2-4 vs. 0-1). After adjustment for age and sex, BMI accounted for a 5-unit increase of 1.694 (95% confidence interval, 1.145-2.507; P = .008). This was not a static relationship, and as BMI increased, so did the discordance between MRE and TE (P = .0309). Interestingly, the discordance rate was significantly higher in participants with BMIs greater than 35 kg/m2, compared with participants with BMIs below 35 (63.0% vs. 38.0%; P = .022), the investigators reported.

While the study revealed valuable information, it had both strengths and limitations. A strength of the study was the use of two cohorts, specifically the validation cohort. The use of the liver biopsy as a reference, which is the standard for assessing fibrosis, was also a strength of the study. A limitation was that the study was conducted at specialized, tertiary care centers using advanced imaging techniques that may not be available at other clinics. Additionally, the cohorts included a small number of patients with advanced fibrosis.

“The integration of the BMI in the screening strategy for the noninvasive detection of liver fibrosis in NAFLD should be considered, and this parameter would help to determine when MRE is not needed in future guidelines” wrote Dr. Caussy and her associates. “Further cost-effectiveness studies are necessary to evaluate the clinical utility of MRE, TE, and/or liver biopsy to develop optimal screening strategies for diagnosing NAFLD-associated fibrosis.”

Jun Chen, MD, Meng Yin, MD, and Richard L. Ehman, MD, all have intellectual property rights and financial interests in elastography technology. Dr. Ehman also serves as an noncompensated CEO of Resoundant. Claude B. Sirlin, MD, has served as a consultant to Bayer and GE Healthcare. All other authors did not disclose any conflicts.

The AGA Obesity Practice Guide provides a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at www.gastro.org/obesity.

SOURCE: Caussy C et al. Clin Gastrolenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jan 15. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.10.037.

‘Cutting for Stone’ author closes out this year’s AAD plenary session

The plenary session at the 2018 American Academy of Dermatology annual meeting in San Diego includes the Clarence S. Livingood, MD Memorial Award and Lectureship, by Mary-Margaret Chren, MD, professor in residence, department of dermatology, University of California, San Francisco, on “The State of (Measuring) the Art of Dermatology.”

Dr. Chren will be followed by the AAD president’s address, given by outgoing president Henry W. Lim, MD, chairman of the department of dermatology and Clarence S. Livingood Chair in Dermatology at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Following Dr. Lim, Jan T. Vilcek, MD, PhD, will give the Eugene J. Van Scott Award for Innovative Therapy of the Skin and Phillip Frost Leadership Lecture on “How a TNF Inhibitor Advanced from Modest Beginnings to Unforeseen Therapeutic Successes.” Dr. Vilcek is research professor and professor emeritus of microbiology in the department of microbiology at New York University.

Suzanne M. Olbricht, MD, president-elect of the AAD and chief of dermatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, will follow.

Jennifer A. Doudna, PhD, professor of chemistry, and professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at the University of California, Berkeley, will give the Lila and Murray Gruber Memorial Cancer Research Award and Lectureship. Her talk is titled, “CRISPR Systems: Nature’s Toolkit for Genome Editing.”

Finally, this year’s guest speaker is Abraham Verghese, MD, whose talk is titled: “The Pathology Within: Burnout, Wellness, and the Search for Meaning in a Professional Life.”

Dr. Verghese, professor and Linda R. Meier and Joan F. Lane Provostial Professor, and vice chair for the Theory and Practice of Medicine, Stanford (Calif.) University, is the author of several books including “Cutting for Stone,” his first novel.

The plenary session is scheduled for Sunday, Feb. 18, from 8 a.m. to 11:30 a.m.

The plenary session at the 2018 American Academy of Dermatology annual meeting in San Diego includes the Clarence S. Livingood, MD Memorial Award and Lectureship, by Mary-Margaret Chren, MD, professor in residence, department of dermatology, University of California, San Francisco, on “The State of (Measuring) the Art of Dermatology.”

Dr. Chren will be followed by the AAD president’s address, given by outgoing president Henry W. Lim, MD, chairman of the department of dermatology and Clarence S. Livingood Chair in Dermatology at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Following Dr. Lim, Jan T. Vilcek, MD, PhD, will give the Eugene J. Van Scott Award for Innovative Therapy of the Skin and Phillip Frost Leadership Lecture on “How a TNF Inhibitor Advanced from Modest Beginnings to Unforeseen Therapeutic Successes.” Dr. Vilcek is research professor and professor emeritus of microbiology in the department of microbiology at New York University.

Suzanne M. Olbricht, MD, president-elect of the AAD and chief of dermatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, will follow.

Jennifer A. Doudna, PhD, professor of chemistry, and professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at the University of California, Berkeley, will give the Lila and Murray Gruber Memorial Cancer Research Award and Lectureship. Her talk is titled, “CRISPR Systems: Nature’s Toolkit for Genome Editing.”

Finally, this year’s guest speaker is Abraham Verghese, MD, whose talk is titled: “The Pathology Within: Burnout, Wellness, and the Search for Meaning in a Professional Life.”

Dr. Verghese, professor and Linda R. Meier and Joan F. Lane Provostial Professor, and vice chair for the Theory and Practice of Medicine, Stanford (Calif.) University, is the author of several books including “Cutting for Stone,” his first novel.

The plenary session is scheduled for Sunday, Feb. 18, from 8 a.m. to 11:30 a.m.

The plenary session at the 2018 American Academy of Dermatology annual meeting in San Diego includes the Clarence S. Livingood, MD Memorial Award and Lectureship, by Mary-Margaret Chren, MD, professor in residence, department of dermatology, University of California, San Francisco, on “The State of (Measuring) the Art of Dermatology.”

Dr. Chren will be followed by the AAD president’s address, given by outgoing president Henry W. Lim, MD, chairman of the department of dermatology and Clarence S. Livingood Chair in Dermatology at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Following Dr. Lim, Jan T. Vilcek, MD, PhD, will give the Eugene J. Van Scott Award for Innovative Therapy of the Skin and Phillip Frost Leadership Lecture on “How a TNF Inhibitor Advanced from Modest Beginnings to Unforeseen Therapeutic Successes.” Dr. Vilcek is research professor and professor emeritus of microbiology in the department of microbiology at New York University.

Suzanne M. Olbricht, MD, president-elect of the AAD and chief of dermatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, will follow.

Jennifer A. Doudna, PhD, professor of chemistry, and professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at the University of California, Berkeley, will give the Lila and Murray Gruber Memorial Cancer Research Award and Lectureship. Her talk is titled, “CRISPR Systems: Nature’s Toolkit for Genome Editing.”

Finally, this year’s guest speaker is Abraham Verghese, MD, whose talk is titled: “The Pathology Within: Burnout, Wellness, and the Search for Meaning in a Professional Life.”

Dr. Verghese, professor and Linda R. Meier and Joan F. Lane Provostial Professor, and vice chair for the Theory and Practice of Medicine, Stanford (Calif.) University, is the author of several books including “Cutting for Stone,” his first novel.

The plenary session is scheduled for Sunday, Feb. 18, from 8 a.m. to 11:30 a.m.

Intrapartum maternal oxygen may not be beneficial for resuscitating fetuses with category II heart tracings

DALLAS – Room air was not inferior to maternal oxygen supplementation for the management of category II fetal heart tracings in a clinical trial.

Umbilical cord blood lactate – a marker of fetal acidosis caused by oxygen deprivation – was virtually identical whether the women received oxygen or remained on room air, Nandini Raghuraman, MD, said at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Other blood gas measures were similar as well, and there were no differences in the number of cesarean sections or operative vaginal deliveries, said Dr. Raghuraman of Washington University, St. Louis.

“Our results suggest that room air is an acceptable alternative. However, we do need further studies, including a superiority trial.”

She noted that three randomized studies have compared oxygen to room air. “None demonstrated benefit to the fetus, and some demonstrated harm, including higher rates of delivery room resuscitation and higher neonatal acidemia. Importantly, all of these studies excluded patients with abnormal fetal heart tracings, which is the primary indication for maternal oxygen during labor and delivery.”

Her study comprised 114 women in active labor with a normal singleton fetus that developed category II heart tracings. Women received either oxygen at 10 L per minute by face mask, or stayed on room air with no face mask. The intervention continued to delivery.

The primary outcome was umbilical artery lactate. Secondary outcomes were umbilical artery blood gases, C-section for nonreassuring fetal heart status, and operative vaginal delivery.

The women were a mean age of 27.5 years; about three-quarters were black. Most (70%) had a labor induction, and 89% had received oxytocin. There were no between-group differences in the need for other fetal resuscitation strategies, including IV fluid bolus, total IV fluids, discontinuation or decrease in oxytocin, maternal repositioning, amnioinfusion, and time from randomization to delivery.

There was no difference in the primary outcome: Lactate levels were 3.4 mmol/L in the oxygen group and 3.5 mmol/L in the room air group.

Dr. Raghuraman also looked at lactate levels among those neonates who had recurrent decelerations and who did not. There was no significant difference in this comparison.

The secondary outcome of umbilical artery blood gases included measures of pH, base excess, partial CO2, and partial oxygen. There were no significant differences in any of these comparisons. Partial O2 was higher (though not significantly so) in the samples that had been exposed to oxygen, as would be expected, Dr. Raghuraman noted.

There were fewer cesarean deliveries among the room air group (4% vs. 12.5%), although this was not statistically significant. Two neonates in the oxygen group were delivered by C-section for nonreassuring fetal heart tracings. There were more operative vaginal deliveries in the room air group (11.8% vs. 2%), but this difference was not statistically significant, with a wide confidence interval (0.71-45.2).

“These results alone are not enough to be practice changing,” Dr. Raghuraman said. “Before we can do that, we need to address efficacy, which this study has called into question. But we also need to explore the results of safety and harm, and until we do so our nurses will likely continue their usual practice of putting these patients on supplement oxygen.”

She had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Raghuraman N et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S7.

DALLAS – Room air was not inferior to maternal oxygen supplementation for the management of category II fetal heart tracings in a clinical trial.

Umbilical cord blood lactate – a marker of fetal acidosis caused by oxygen deprivation – was virtually identical whether the women received oxygen or remained on room air, Nandini Raghuraman, MD, said at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Other blood gas measures were similar as well, and there were no differences in the number of cesarean sections or operative vaginal deliveries, said Dr. Raghuraman of Washington University, St. Louis.

“Our results suggest that room air is an acceptable alternative. However, we do need further studies, including a superiority trial.”

She noted that three randomized studies have compared oxygen to room air. “None demonstrated benefit to the fetus, and some demonstrated harm, including higher rates of delivery room resuscitation and higher neonatal acidemia. Importantly, all of these studies excluded patients with abnormal fetal heart tracings, which is the primary indication for maternal oxygen during labor and delivery.”

Her study comprised 114 women in active labor with a normal singleton fetus that developed category II heart tracings. Women received either oxygen at 10 L per minute by face mask, or stayed on room air with no face mask. The intervention continued to delivery.

The primary outcome was umbilical artery lactate. Secondary outcomes were umbilical artery blood gases, C-section for nonreassuring fetal heart status, and operative vaginal delivery.

The women were a mean age of 27.5 years; about three-quarters were black. Most (70%) had a labor induction, and 89% had received oxytocin. There were no between-group differences in the need for other fetal resuscitation strategies, including IV fluid bolus, total IV fluids, discontinuation or decrease in oxytocin, maternal repositioning, amnioinfusion, and time from randomization to delivery.

There was no difference in the primary outcome: Lactate levels were 3.4 mmol/L in the oxygen group and 3.5 mmol/L in the room air group.

Dr. Raghuraman also looked at lactate levels among those neonates who had recurrent decelerations and who did not. There was no significant difference in this comparison.

The secondary outcome of umbilical artery blood gases included measures of pH, base excess, partial CO2, and partial oxygen. There were no significant differences in any of these comparisons. Partial O2 was higher (though not significantly so) in the samples that had been exposed to oxygen, as would be expected, Dr. Raghuraman noted.

There were fewer cesarean deliveries among the room air group (4% vs. 12.5%), although this was not statistically significant. Two neonates in the oxygen group were delivered by C-section for nonreassuring fetal heart tracings. There were more operative vaginal deliveries in the room air group (11.8% vs. 2%), but this difference was not statistically significant, with a wide confidence interval (0.71-45.2).

“These results alone are not enough to be practice changing,” Dr. Raghuraman said. “Before we can do that, we need to address efficacy, which this study has called into question. But we also need to explore the results of safety and harm, and until we do so our nurses will likely continue their usual practice of putting these patients on supplement oxygen.”

She had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Raghuraman N et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S7.

DALLAS – Room air was not inferior to maternal oxygen supplementation for the management of category II fetal heart tracings in a clinical trial.

Umbilical cord blood lactate – a marker of fetal acidosis caused by oxygen deprivation – was virtually identical whether the women received oxygen or remained on room air, Nandini Raghuraman, MD, said at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Other blood gas measures were similar as well, and there were no differences in the number of cesarean sections or operative vaginal deliveries, said Dr. Raghuraman of Washington University, St. Louis.

“Our results suggest that room air is an acceptable alternative. However, we do need further studies, including a superiority trial.”

She noted that three randomized studies have compared oxygen to room air. “None demonstrated benefit to the fetus, and some demonstrated harm, including higher rates of delivery room resuscitation and higher neonatal acidemia. Importantly, all of these studies excluded patients with abnormal fetal heart tracings, which is the primary indication for maternal oxygen during labor and delivery.”

Her study comprised 114 women in active labor with a normal singleton fetus that developed category II heart tracings. Women received either oxygen at 10 L per minute by face mask, or stayed on room air with no face mask. The intervention continued to delivery.

The primary outcome was umbilical artery lactate. Secondary outcomes were umbilical artery blood gases, C-section for nonreassuring fetal heart status, and operative vaginal delivery.

The women were a mean age of 27.5 years; about three-quarters were black. Most (70%) had a labor induction, and 89% had received oxytocin. There were no between-group differences in the need for other fetal resuscitation strategies, including IV fluid bolus, total IV fluids, discontinuation or decrease in oxytocin, maternal repositioning, amnioinfusion, and time from randomization to delivery.

There was no difference in the primary outcome: Lactate levels were 3.4 mmol/L in the oxygen group and 3.5 mmol/L in the room air group.

Dr. Raghuraman also looked at lactate levels among those neonates who had recurrent decelerations and who did not. There was no significant difference in this comparison.

The secondary outcome of umbilical artery blood gases included measures of pH, base excess, partial CO2, and partial oxygen. There were no significant differences in any of these comparisons. Partial O2 was higher (though not significantly so) in the samples that had been exposed to oxygen, as would be expected, Dr. Raghuraman noted.

There were fewer cesarean deliveries among the room air group (4% vs. 12.5%), although this was not statistically significant. Two neonates in the oxygen group were delivered by C-section for nonreassuring fetal heart tracings. There were more operative vaginal deliveries in the room air group (11.8% vs. 2%), but this difference was not statistically significant, with a wide confidence interval (0.71-45.2).

“These results alone are not enough to be practice changing,” Dr. Raghuraman said. “Before we can do that, we need to address efficacy, which this study has called into question. But we also need to explore the results of safety and harm, and until we do so our nurses will likely continue their usual practice of putting these patients on supplement oxygen.”

She had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Raghuraman N et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S7.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point: Room air was not inferior to maternal oxygen for the resuscitation of a fetus who developed category II heart rhythms.

Major finding: Umbilical artery lactate was 3.4 mmol/L in the oxygen group and 3.5 mmol/L in the room air group.

Study details: The trial randomized 114 women.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Washington University School of Medicine. Dr. Raghuraman had no financial disclosures.

Source: Raghuraman N et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S7.

Sharpening the saw

Few movies have universal appeal these days, but one that comes close is Bill Murray’s 1993 classic, “Groundhog Day,” in which Murray’s character is trapped in a time loop, living the same day over and over until he finally “gets it right.”

One reason that this film resonates with so many, I think, is that we are all, in essence, similarly trapped. Not in a same-day loop, of course; but each week seems eerily similar to the last, as does each month, each year – on and on, ad infinitum. That’s why it is so important, every so often, to step out of the “loop” and reassess the bigger picture.

I write this reminder every couple of years because it’s so easy to lose sight of the overall landscape among the pressures of our daily routines. Sooner or later, no matter how dedicated we are, the grind gets to all of us, leading to fatigue, irritability, and a progressive decline in motivation. And we are too busy to sit down and think about what we might do to break that vicious cycle. This is detrimental to our own well-being, as well as that of our patients.

There are many ways to maintain your intellectual and emotional health, but here’s how I do it: I take individual days off (average of 1 a month) to catch up on journals or taking a CME course; or to try something new – something I’ve been thinking about doing “someday, when there is time” – such as a guitar, bass, or sailing lesson, or a long weekend away with my wife. And we take longer vacations, without fail, each year.

I know how some of you feel about “wasting” a day – or, God forbid, a week. Patients might go elsewhere while you’re gone, and every day the office is idle you “lose money.” That whole paradigm is wrong. You bring in a given amount of revenue per year – more on some days, less on other days, none on weekends and vacations. It all averages out in the end.

Besides, this is much more important than money: This is breaking the routine, clearing the cobwebs, living your life. And trust me, your practice will still be there when you return.

More than once I’ve recounted the story of K. Alexander Müller, PhD, and J. Georg Bednorz, PhD, the Swiss Nobel laureates whose superconductivity research ground to a halt in 1986. The harder they pressed, the more elusive progress became. So Dr. Müller decided to take a break to read a new book on ceramics – a subject that had always interested him.

Nothing could have been less relevant to his work, of course; ceramics are among the poorest conductors known. But in that lower-pressure environment, Dr. Müller realized that a unique property of ceramics might apply to their project.

Back in the lab, the team created a ceramic compound that became the first successful “high-temperature” superconductor, which in turn triggered an explosion of research leading to breakthroughs in computing, electricity transmission, magnetically-elevated trains, and many applications yet to be realized.

Sharpening your saw may not change the world, but it will change you. Any nudge out of your comfort zone will give you fresh ideas and help you look at seemingly insoluble problems in completely new ways.

And to those who still can’t bear the thought of taking time off, remember the dying words that no one has spoken, ever: “I wish I had spent more time in my office!”

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Few movies have universal appeal these days, but one that comes close is Bill Murray’s 1993 classic, “Groundhog Day,” in which Murray’s character is trapped in a time loop, living the same day over and over until he finally “gets it right.”

One reason that this film resonates with so many, I think, is that we are all, in essence, similarly trapped. Not in a same-day loop, of course; but each week seems eerily similar to the last, as does each month, each year – on and on, ad infinitum. That’s why it is so important, every so often, to step out of the “loop” and reassess the bigger picture.

I write this reminder every couple of years because it’s so easy to lose sight of the overall landscape among the pressures of our daily routines. Sooner or later, no matter how dedicated we are, the grind gets to all of us, leading to fatigue, irritability, and a progressive decline in motivation. And we are too busy to sit down and think about what we might do to break that vicious cycle. This is detrimental to our own well-being, as well as that of our patients.

There are many ways to maintain your intellectual and emotional health, but here’s how I do it: I take individual days off (average of 1 a month) to catch up on journals or taking a CME course; or to try something new – something I’ve been thinking about doing “someday, when there is time” – such as a guitar, bass, or sailing lesson, or a long weekend away with my wife. And we take longer vacations, without fail, each year.

I know how some of you feel about “wasting” a day – or, God forbid, a week. Patients might go elsewhere while you’re gone, and every day the office is idle you “lose money.” That whole paradigm is wrong. You bring in a given amount of revenue per year – more on some days, less on other days, none on weekends and vacations. It all averages out in the end.

Besides, this is much more important than money: This is breaking the routine, clearing the cobwebs, living your life. And trust me, your practice will still be there when you return.

More than once I’ve recounted the story of K. Alexander Müller, PhD, and J. Georg Bednorz, PhD, the Swiss Nobel laureates whose superconductivity research ground to a halt in 1986. The harder they pressed, the more elusive progress became. So Dr. Müller decided to take a break to read a new book on ceramics – a subject that had always interested him.

Nothing could have been less relevant to his work, of course; ceramics are among the poorest conductors known. But in that lower-pressure environment, Dr. Müller realized that a unique property of ceramics might apply to their project.

Back in the lab, the team created a ceramic compound that became the first successful “high-temperature” superconductor, which in turn triggered an explosion of research leading to breakthroughs in computing, electricity transmission, magnetically-elevated trains, and many applications yet to be realized.

Sharpening your saw may not change the world, but it will change you. Any nudge out of your comfort zone will give you fresh ideas and help you look at seemingly insoluble problems in completely new ways.

And to those who still can’t bear the thought of taking time off, remember the dying words that no one has spoken, ever: “I wish I had spent more time in my office!”

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Few movies have universal appeal these days, but one that comes close is Bill Murray’s 1993 classic, “Groundhog Day,” in which Murray’s character is trapped in a time loop, living the same day over and over until he finally “gets it right.”

One reason that this film resonates with so many, I think, is that we are all, in essence, similarly trapped. Not in a same-day loop, of course; but each week seems eerily similar to the last, as does each month, each year – on and on, ad infinitum. That’s why it is so important, every so often, to step out of the “loop” and reassess the bigger picture.

I write this reminder every couple of years because it’s so easy to lose sight of the overall landscape among the pressures of our daily routines. Sooner or later, no matter how dedicated we are, the grind gets to all of us, leading to fatigue, irritability, and a progressive decline in motivation. And we are too busy to sit down and think about what we might do to break that vicious cycle. This is detrimental to our own well-being, as well as that of our patients.

There are many ways to maintain your intellectual and emotional health, but here’s how I do it: I take individual days off (average of 1 a month) to catch up on journals or taking a CME course; or to try something new – something I’ve been thinking about doing “someday, when there is time” – such as a guitar, bass, or sailing lesson, or a long weekend away with my wife. And we take longer vacations, without fail, each year.

I know how some of you feel about “wasting” a day – or, God forbid, a week. Patients might go elsewhere while you’re gone, and every day the office is idle you “lose money.” That whole paradigm is wrong. You bring in a given amount of revenue per year – more on some days, less on other days, none on weekends and vacations. It all averages out in the end.

Besides, this is much more important than money: This is breaking the routine, clearing the cobwebs, living your life. And trust me, your practice will still be there when you return.

More than once I’ve recounted the story of K. Alexander Müller, PhD, and J. Georg Bednorz, PhD, the Swiss Nobel laureates whose superconductivity research ground to a halt in 1986. The harder they pressed, the more elusive progress became. So Dr. Müller decided to take a break to read a new book on ceramics – a subject that had always interested him.

Nothing could have been less relevant to his work, of course; ceramics are among the poorest conductors known. But in that lower-pressure environment, Dr. Müller realized that a unique property of ceramics might apply to their project.

Back in the lab, the team created a ceramic compound that became the first successful “high-temperature” superconductor, which in turn triggered an explosion of research leading to breakthroughs in computing, electricity transmission, magnetically-elevated trains, and many applications yet to be realized.

Sharpening your saw may not change the world, but it will change you. Any nudge out of your comfort zone will give you fresh ideas and help you look at seemingly insoluble problems in completely new ways.

And to those who still can’t bear the thought of taking time off, remember the dying words that no one has spoken, ever: “I wish I had spent more time in my office!”

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Misleading Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Clinical Concern

Sjogren syndrome (SS) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disorder characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of lacrimal and salivary glands causing sicca syndrome.¹ The disease can extend beyond the exocrine glands, and systemic manifestations, including vasculitis, lung, renal or neurologic involvement, can occur.² Lung disease associated with SS is more commonly seen in women aged ≥ 60 years. The most common symptoms include dry cough, chest pain, and dyspnea on exertion. Sjogren syndrome also may produce several respiratory complications, including bronchial hyperresponsiveness, bronchiolitis, bronchiectasis, pulmonary infections, pulmonary amyloidosis, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, lymphomas, and interstitial lung diseases (ILD).² Although ILD typically occurs 5 to 10 years after the onset of SS, lung disease can precede SS.

Pulmonary involvement is associated with systemic manifestations, hypergammaglobulinemia, and anti-SSA and anti-SSB antibodies.² Laboratory tests that confirm a diagnosis of SS include antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-Ro/SSA, and anti-La/SSB antibodies.² Pulmonary function test (PFT) results appear to reflect impairment of either the lung (restrictive syndrome) or airways (obstructive syndrome).² Imaging abnormalities may include ground-glass attenuation, subpleural small nodules, nonseptal linear opacities, interlobular septal thickening, bronchiectasis, and cysts.³ Therefore, many ILD cases show similar imaging and pathologic findings; nevertheless, they have identifiable etiology that are not idiopathic.

Case Presentation

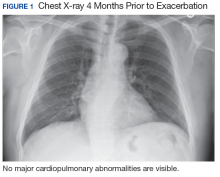

A 67-year-old man with a medical history of hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, and keratoconjunctivitis sicca (treated with eye drops) developed progressive shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, and weight loss (40 pounds) over the course of 6 months. A pulmonary function test showed a restrictive abnormality with decreased diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (eFigure available online at www.fedprac.com). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed the presence of significant thickening of the interlobular septi that was more pronounced in the subpleural regions of the lungs and lower lobes, which was consistent with usual interstitial pneumonia. A chest X-ray conducted 4 months prior showed no significant acute cardiopulmonary abnormalities (Figure 1). An open lung wedge biopsy revealed chronic organizing pneumonia with mild interstitial chronic inflammation, smooth muscle hypertrophy, and honeycomb changes consistent with usual interstitial pneumonia.

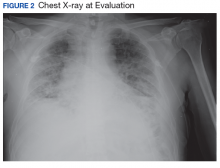

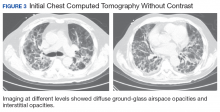

The patient had been diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) by a private physician and started pirfenidone and oxygen therapy. Three months later the patient presented to the VA Caribbean Healthcare System in San Juan Puerto Rico when he developed an exacerbation of IPF. The patient reported having fever, chills, dry cough, night sweats, and marked shortness of breath. He was found hypoxemic (partial pressure of O2 was 50 mm Hg) and required a venturi mask set to 50% fractioned of inspired O2 to maintain a peripheral oxygen saturation around 90%. A chest X-ray showed decreased lung volume with bilateral interstitial and alveolar disease (Figure 2). Leukocytosis was present at 17×10-3/µl. The chest CT scan showed interval worsening of diffuse ground-glass airspace opacities and worsening of interstitial opacities; there

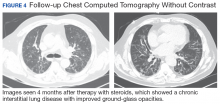

After careful clinical assessment (+ dry eyes) and radiographic pattern evaluation (diffuse bilateral interstitial and ground-glass opacities), the clinical diagnosis of IPF was queried after the patient’s rheumatologic workup came back positive for ANA and anti-Ro/SSA tests. Since the etiology of ILD was secondary to SS, pirfenidone was discontinued, and the patient was started on steroid therapy with subsequent marked clinical improvement. Parotid biopsy revealed the presence of inflammatory cells supporting the diagnosis of ILD associated to SS. The patient was discharged home on a tapering dose of steroids. Four months after therapy with steroids, a follow-up chest CT scan without contrast showed a chronic ILD with improved ground-glass opacities (Figure 4). The patient currently is in good health without oxygen supplementation.

Discussion

Diagnosis of SS is challenging, since it may mimic other conditions such as IPF. The most common type of SS-associated ILD is nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), although usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) can be visualized, as in this case study. Usual interstitial pneumonia

Diagnosing IPF cannot be solely based on a lung biopsy consistent with UIP. Appropriate diagnosis should consider the clinical presentation; PFT, laboratory findings (including rheumatologic workup), imaging (especially radiographic patterns), and biopsies. Moreover, the pathologic characteristic of IPF, which is UIP, can be found with other diseases, such as SS. Thus, it is important to make an accurate diagnosis to provide the appropriate treatment available. Patients with ILD associated with SS who have worsening symptoms, PFT, and radiographic abnormalities may be treated with oral prednisone (daily dose: 1 mg/kg).

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of making an adequate diagnosis of ILD considering that available treatments differ for all possible etiologies other than IPF. This is a true clinical concern taking into account that many patients might be receiving inappropriate therapy for IPF diagnosis, as illustrated in the case study.

1. Ito I, Nagai S, Kitaichi M, et al. Pulmonary manifestations of primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a clinical, radiologic, and pathologic study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(6):632-638.

2. Flament T, Bigot A, Chaigne B, Henique H, Diot E, Marchand-Adam S. Pulmonary manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome. Eur Respir Rev. 2016;25(140):110-123.

3. Koyama M, Johkoh T, Honda O, et al. Pulmonary involvement in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: spectrum of pulmonary abnormalities and computed tomography findings in 60 patients. J Thorac Imaging. 2001;16(4):290-296.

4. Wuyts WA, Cavazza A, Rossi G, Bonella F, Sverzellati N, Spagnolo P. Differential diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia: when is it truly idiopathic? Eur Respir Rev. 2014;23(133):308-319.

Sjogren syndrome (SS) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disorder characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of lacrimal and salivary glands causing sicca syndrome.¹ The disease can extend beyond the exocrine glands, and systemic manifestations, including vasculitis, lung, renal or neurologic involvement, can occur.² Lung disease associated with SS is more commonly seen in women aged ≥ 60 years. The most common symptoms include dry cough, chest pain, and dyspnea on exertion. Sjogren syndrome also may produce several respiratory complications, including bronchial hyperresponsiveness, bronchiolitis, bronchiectasis, pulmonary infections, pulmonary amyloidosis, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, lymphomas, and interstitial lung diseases (ILD).² Although ILD typically occurs 5 to 10 years after the onset of SS, lung disease can precede SS.

Pulmonary involvement is associated with systemic manifestations, hypergammaglobulinemia, and anti-SSA and anti-SSB antibodies.² Laboratory tests that confirm a diagnosis of SS include antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-Ro/SSA, and anti-La/SSB antibodies.² Pulmonary function test (PFT) results appear to reflect impairment of either the lung (restrictive syndrome) or airways (obstructive syndrome).² Imaging abnormalities may include ground-glass attenuation, subpleural small nodules, nonseptal linear opacities, interlobular septal thickening, bronchiectasis, and cysts.³ Therefore, many ILD cases show similar imaging and pathologic findings; nevertheless, they have identifiable etiology that are not idiopathic.

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old man with a medical history of hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, and keratoconjunctivitis sicca (treated with eye drops) developed progressive shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, and weight loss (40 pounds) over the course of 6 months. A pulmonary function test showed a restrictive abnormality with decreased diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (eFigure available online at www.fedprac.com). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed the presence of significant thickening of the interlobular septi that was more pronounced in the subpleural regions of the lungs and lower lobes, which was consistent with usual interstitial pneumonia. A chest X-ray conducted 4 months prior showed no significant acute cardiopulmonary abnormalities (Figure 1). An open lung wedge biopsy revealed chronic organizing pneumonia with mild interstitial chronic inflammation, smooth muscle hypertrophy, and honeycomb changes consistent with usual interstitial pneumonia.

The patient had been diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) by a private physician and started pirfenidone and oxygen therapy. Three months later the patient presented to the VA Caribbean Healthcare System in San Juan Puerto Rico when he developed an exacerbation of IPF. The patient reported having fever, chills, dry cough, night sweats, and marked shortness of breath. He was found hypoxemic (partial pressure of O2 was 50 mm Hg) and required a venturi mask set to 50% fractioned of inspired O2 to maintain a peripheral oxygen saturation around 90%. A chest X-ray showed decreased lung volume with bilateral interstitial and alveolar disease (Figure 2). Leukocytosis was present at 17×10-3/µl. The chest CT scan showed interval worsening of diffuse ground-glass airspace opacities and worsening of interstitial opacities; there

After careful clinical assessment (+ dry eyes) and radiographic pattern evaluation (diffuse bilateral interstitial and ground-glass opacities), the clinical diagnosis of IPF was queried after the patient’s rheumatologic workup came back positive for ANA and anti-Ro/SSA tests. Since the etiology of ILD was secondary to SS, pirfenidone was discontinued, and the patient was started on steroid therapy with subsequent marked clinical improvement. Parotid biopsy revealed the presence of inflammatory cells supporting the diagnosis of ILD associated to SS. The patient was discharged home on a tapering dose of steroids. Four months after therapy with steroids, a follow-up chest CT scan without contrast showed a chronic ILD with improved ground-glass opacities (Figure 4). The patient currently is in good health without oxygen supplementation.

Discussion

Diagnosis of SS is challenging, since it may mimic other conditions such as IPF. The most common type of SS-associated ILD is nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), although usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) can be visualized, as in this case study. Usual interstitial pneumonia

Diagnosing IPF cannot be solely based on a lung biopsy consistent with UIP. Appropriate diagnosis should consider the clinical presentation; PFT, laboratory findings (including rheumatologic workup), imaging (especially radiographic patterns), and biopsies. Moreover, the pathologic characteristic of IPF, which is UIP, can be found with other diseases, such as SS. Thus, it is important to make an accurate diagnosis to provide the appropriate treatment available. Patients with ILD associated with SS who have worsening symptoms, PFT, and radiographic abnormalities may be treated with oral prednisone (daily dose: 1 mg/kg).

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of making an adequate diagnosis of ILD considering that available treatments differ for all possible etiologies other than IPF. This is a true clinical concern taking into account that many patients might be receiving inappropriate therapy for IPF diagnosis, as illustrated in the case study.

Sjogren syndrome (SS) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disorder characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of lacrimal and salivary glands causing sicca syndrome.¹ The disease can extend beyond the exocrine glands, and systemic manifestations, including vasculitis, lung, renal or neurologic involvement, can occur.² Lung disease associated with SS is more commonly seen in women aged ≥ 60 years. The most common symptoms include dry cough, chest pain, and dyspnea on exertion. Sjogren syndrome also may produce several respiratory complications, including bronchial hyperresponsiveness, bronchiolitis, bronchiectasis, pulmonary infections, pulmonary amyloidosis, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, lymphomas, and interstitial lung diseases (ILD).² Although ILD typically occurs 5 to 10 years after the onset of SS, lung disease can precede SS.

Pulmonary involvement is associated with systemic manifestations, hypergammaglobulinemia, and anti-SSA and anti-SSB antibodies.² Laboratory tests that confirm a diagnosis of SS include antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-Ro/SSA, and anti-La/SSB antibodies.² Pulmonary function test (PFT) results appear to reflect impairment of either the lung (restrictive syndrome) or airways (obstructive syndrome).² Imaging abnormalities may include ground-glass attenuation, subpleural small nodules, nonseptal linear opacities, interlobular septal thickening, bronchiectasis, and cysts.³ Therefore, many ILD cases show similar imaging and pathologic findings; nevertheless, they have identifiable etiology that are not idiopathic.

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old man with a medical history of hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, and keratoconjunctivitis sicca (treated with eye drops) developed progressive shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, and weight loss (40 pounds) over the course of 6 months. A pulmonary function test showed a restrictive abnormality with decreased diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (eFigure available online at www.fedprac.com). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed the presence of significant thickening of the interlobular septi that was more pronounced in the subpleural regions of the lungs and lower lobes, which was consistent with usual interstitial pneumonia. A chest X-ray conducted 4 months prior showed no significant acute cardiopulmonary abnormalities (Figure 1). An open lung wedge biopsy revealed chronic organizing pneumonia with mild interstitial chronic inflammation, smooth muscle hypertrophy, and honeycomb changes consistent with usual interstitial pneumonia.

The patient had been diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) by a private physician and started pirfenidone and oxygen therapy. Three months later the patient presented to the VA Caribbean Healthcare System in San Juan Puerto Rico when he developed an exacerbation of IPF. The patient reported having fever, chills, dry cough, night sweats, and marked shortness of breath. He was found hypoxemic (partial pressure of O2 was 50 mm Hg) and required a venturi mask set to 50% fractioned of inspired O2 to maintain a peripheral oxygen saturation around 90%. A chest X-ray showed decreased lung volume with bilateral interstitial and alveolar disease (Figure 2). Leukocytosis was present at 17×10-3/µl. The chest CT scan showed interval worsening of diffuse ground-glass airspace opacities and worsening of interstitial opacities; there

After careful clinical assessment (+ dry eyes) and radiographic pattern evaluation (diffuse bilateral interstitial and ground-glass opacities), the clinical diagnosis of IPF was queried after the patient’s rheumatologic workup came back positive for ANA and anti-Ro/SSA tests. Since the etiology of ILD was secondary to SS, pirfenidone was discontinued, and the patient was started on steroid therapy with subsequent marked clinical improvement. Parotid biopsy revealed the presence of inflammatory cells supporting the diagnosis of ILD associated to SS. The patient was discharged home on a tapering dose of steroids. Four months after therapy with steroids, a follow-up chest CT scan without contrast showed a chronic ILD with improved ground-glass opacities (Figure 4). The patient currently is in good health without oxygen supplementation.

Discussion

Diagnosis of SS is challenging, since it may mimic other conditions such as IPF. The most common type of SS-associated ILD is nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), although usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) can be visualized, as in this case study. Usual interstitial pneumonia

Diagnosing IPF cannot be solely based on a lung biopsy consistent with UIP. Appropriate diagnosis should consider the clinical presentation; PFT, laboratory findings (including rheumatologic workup), imaging (especially radiographic patterns), and biopsies. Moreover, the pathologic characteristic of IPF, which is UIP, can be found with other diseases, such as SS. Thus, it is important to make an accurate diagnosis to provide the appropriate treatment available. Patients with ILD associated with SS who have worsening symptoms, PFT, and radiographic abnormalities may be treated with oral prednisone (daily dose: 1 mg/kg).

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of making an adequate diagnosis of ILD considering that available treatments differ for all possible etiologies other than IPF. This is a true clinical concern taking into account that many patients might be receiving inappropriate therapy for IPF diagnosis, as illustrated in the case study.

1. Ito I, Nagai S, Kitaichi M, et al. Pulmonary manifestations of primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a clinical, radiologic, and pathologic study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(6):632-638.

2. Flament T, Bigot A, Chaigne B, Henique H, Diot E, Marchand-Adam S. Pulmonary manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome. Eur Respir Rev. 2016;25(140):110-123.

3. Koyama M, Johkoh T, Honda O, et al. Pulmonary involvement in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: spectrum of pulmonary abnormalities and computed tomography findings in 60 patients. J Thorac Imaging. 2001;16(4):290-296.

4. Wuyts WA, Cavazza A, Rossi G, Bonella F, Sverzellati N, Spagnolo P. Differential diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia: when is it truly idiopathic? Eur Respir Rev. 2014;23(133):308-319.

1. Ito I, Nagai S, Kitaichi M, et al. Pulmonary manifestations of primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a clinical, radiologic, and pathologic study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(6):632-638.

2. Flament T, Bigot A, Chaigne B, Henique H, Diot E, Marchand-Adam S. Pulmonary manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome. Eur Respir Rev. 2016;25(140):110-123.

3. Koyama M, Johkoh T, Honda O, et al. Pulmonary involvement in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: spectrum of pulmonary abnormalities and computed tomography findings in 60 patients. J Thorac Imaging. 2001;16(4):290-296.

4. Wuyts WA, Cavazza A, Rossi G, Bonella F, Sverzellati N, Spagnolo P. Differential diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia: when is it truly idiopathic? Eur Respir Rev. 2014;23(133):308-319.

MDedge Daily News: A prodrome for multiple sclerosis?

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Is there a prodrome for multiple sclerosis? Betamethasone saves babies and dollars, patients want answers on religious hospitals’ care restrictions, and is faster always better in large-vessel stroke?

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Is there a prodrome for multiple sclerosis? Betamethasone saves babies and dollars, patients want answers on religious hospitals’ care restrictions, and is faster always better in large-vessel stroke?

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Is there a prodrome for multiple sclerosis? Betamethasone saves babies and dollars, patients want answers on religious hospitals’ care restrictions, and is faster always better in large-vessel stroke?

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Drug appears safe and active in PTCL, CTCL

LA JOLLA, CA—The dual PI3K δ/γ inhibitor tenalisib has demonstrated activity in a phase 1 trial of patients with relapsed/refractory T-cell lymphomas.

Tenalisib produced “encouraging” response rates of 44% in patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) and 50% in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), according to study investigator Bradley M. Haverkos, MD, of the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora.

Dr Haverkos also said tenalisib had an acceptable safety profile.

The most common treatment-related adverse event (AE) in both patient groups was transaminitis.

Dr Haverkos and his colleagues presented these results in a pair of posters and an oral presentation at the 10th Annual T-cell Lymphoma Forum.

The trial was sponsored by Rhizen Pharmaceuticals, the company developing tenalisib (formerly RP6530).

The researchers have enrolled 55 patients in this trial—28 with CTCL and 27 with PTCL.

The study has a standard 3+3 design, starting with a 200 mg daily fasting dose of tenalisib and escalating to an 800 mg daily fasting dose, followed by an 800 mg daily fed cohort.

There were 3 dose-limiting toxicities in the 800 mg fed cohort—transaminitis, rash, and neutropenia. Therefore, the 800 mg fasting dose was considered the maximum-tolerated dose.

Patients in the PTCL and CTCL expansion cohorts received the maximum-tolerated dose.

Patients were scheduled to receive 8 cycles (28 days each) of tenalisib, but treatment could be extended to 24 months.

The data cutoff was January 10, 2018.

Efficacy in PTCL

Most PTCL patients (n=24) had PTCL not otherwise specified (NOS), 2 had angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), and 1 had subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL).

The patients’ median age at baseline was 63 (range, 40-89), and 63% are male. Sixty-three percent of patients had relapsed disease at baseline, 37% were refractory, and 93% had stage 3 or 4 disease. Patients had received a median of 3 prior therapies (range, 1-7).

The median duration of treatment with tenalisib was 1.9 months.

Fourteen patients were evaluable for efficacy. Eleven patients had progressed prior to the first protocol-defined assessment, and 2 patients had not reached their first efficacy assessment at the data cutoff.

Seven of the 14 evaluable patients responded (50%). Three patients (21%) had a complete response (CR), 4 (29%) had a partial response (PR), 3 (21%) had stable disease, and 4 (29%) progressed.

“There were several patients with lengthy responses,” Dr Haverkos noted. “One patient had an ongoing response at 16 months, another at 11 months, and a number of patients had ongoing responses at 7 months.”

All 3 patients with a CR had PTCL NOS and received the 800 mg fasting dose of tenalisib.

Two patients with a PR had PTCL NOS, 1 had AITL, and 1 had SPTCL. The SPTCL patient received the 200 mg dose.

The AITL patient and 1 of the PTCL NOS patients received the 800 mg fasting dose. The other PTCL NOS patient received the 400 mg dose.

Efficacy in CTCL

Most CTCL patients (n=23) had mycosis fungoides, but 5 had Sézary syndrome. The patients’ median age at baseline was 68 (range, 39-84), and 57% are female.

Forty-three percent of patients had relapsed disease at baseline, 57% were refractory, and 46% had stage 3 or 4 disease. Patients had received a median of 6 prior therapies (range, 2-15).

The median duration of treatment with tenalisib was 3.4 months.

Eighteen patients were evaluable for efficacy. Eight patients had progressed prior to the first protocol-defined assessment, and 2 patients had not yet reached their first efficacy assessment.

Eight of the 18 evaluable patients responded (44%), all with PRs. Seven patients (39%) had stable disease, and 3 (17%) progressed.

Four patients were still in response beyond 8 months of follow-up, and 1 patient was still in PR beyond 11 months.

Five patients with a PR had received the 800 mg fasting dose of tenalisib. Two received the 800 mg fed dose, and 1 patient received the drug at 400 mg.

Overall safety

Treatment-related AEs included transaminitis (25%, 14/55), diarrhea (11%, n=6), fatigue (6%, n=11), headache (9%, n=5), rash (9%, n=5), nausea (5%, n=3), vomiting (5%, n=3), pyrexia (5%, n=3), and dizziness (5%, n=3). Dizziness was only observed in CTCL patients.

Treatment-related grade 3 or higher AEs included transaminitis (20%, n=11), rash (5%, n=3), neutropenia (2%, n=1), hypophosphatemia (2%, n=1), international normalized ratio increase (2%, n=1), sepsis (2%, n=1), pyrexia (2%, n=1), and diplopia secondary to neuropathy (2%, n=1).

Seventy-six percent (n=42) of patients discontinued treatment. Sixty-eight percent (n=29) stopped due to progression, 5% (n=2) stopped at investigators’ discretion, 9% (n=4) withdrew consent, 12% (n=5) had a treatment-related AE, and 5% (n=2) had an unrelated AE.

Seventeen PTCL patients stopped treatment due to progression, as did 12 CTCL patients. One patient in each group stopped treatment at investigators’ discretion, and all 4 patients who withdrew consent had CTCL.

Four CTCL patients stopped treatment due to a related AE—transaminitis, sepsis, diarrhea, and diplopia secondary to neuropathy. One PTCL patient stopped treatment due to a related AE, which was transaminitis.

“Tenalisib at the 800 mg fasting dose has demonstrated acceptable safety and tolerability,” Dr Haverkos concluded. “We’ve observed encouraging response rates thus far, which support further evaluation of tenalisib in these patients.” ![]()

LA JOLLA, CA—The dual PI3K δ/γ inhibitor tenalisib has demonstrated activity in a phase 1 trial of patients with relapsed/refractory T-cell lymphomas.

Tenalisib produced “encouraging” response rates of 44% in patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) and 50% in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), according to study investigator Bradley M. Haverkos, MD, of the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora.

Dr Haverkos also said tenalisib had an acceptable safety profile.

The most common treatment-related adverse event (AE) in both patient groups was transaminitis.

Dr Haverkos and his colleagues presented these results in a pair of posters and an oral presentation at the 10th Annual T-cell Lymphoma Forum.

The trial was sponsored by Rhizen Pharmaceuticals, the company developing tenalisib (formerly RP6530).

The researchers have enrolled 55 patients in this trial—28 with CTCL and 27 with PTCL.

The study has a standard 3+3 design, starting with a 200 mg daily fasting dose of tenalisib and escalating to an 800 mg daily fasting dose, followed by an 800 mg daily fed cohort.

There were 3 dose-limiting toxicities in the 800 mg fed cohort—transaminitis, rash, and neutropenia. Therefore, the 800 mg fasting dose was considered the maximum-tolerated dose.

Patients in the PTCL and CTCL expansion cohorts received the maximum-tolerated dose.

Patients were scheduled to receive 8 cycles (28 days each) of tenalisib, but treatment could be extended to 24 months.

The data cutoff was January 10, 2018.

Efficacy in PTCL

Most PTCL patients (n=24) had PTCL not otherwise specified (NOS), 2 had angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), and 1 had subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL).

The patients’ median age at baseline was 63 (range, 40-89), and 63% are male. Sixty-three percent of patients had relapsed disease at baseline, 37% were refractory, and 93% had stage 3 or 4 disease. Patients had received a median of 3 prior therapies (range, 1-7).

The median duration of treatment with tenalisib was 1.9 months.

Fourteen patients were evaluable for efficacy. Eleven patients had progressed prior to the first protocol-defined assessment, and 2 patients had not reached their first efficacy assessment at the data cutoff.

Seven of the 14 evaluable patients responded (50%). Three patients (21%) had a complete response (CR), 4 (29%) had a partial response (PR), 3 (21%) had stable disease, and 4 (29%) progressed.

“There were several patients with lengthy responses,” Dr Haverkos noted. “One patient had an ongoing response at 16 months, another at 11 months, and a number of patients had ongoing responses at 7 months.”

All 3 patients with a CR had PTCL NOS and received the 800 mg fasting dose of tenalisib.

Two patients with a PR had PTCL NOS, 1 had AITL, and 1 had SPTCL. The SPTCL patient received the 200 mg dose.

The AITL patient and 1 of the PTCL NOS patients received the 800 mg fasting dose. The other PTCL NOS patient received the 400 mg dose.

Efficacy in CTCL

Most CTCL patients (n=23) had mycosis fungoides, but 5 had Sézary syndrome. The patients’ median age at baseline was 68 (range, 39-84), and 57% are female.

Forty-three percent of patients had relapsed disease at baseline, 57% were refractory, and 46% had stage 3 or 4 disease. Patients had received a median of 6 prior therapies (range, 2-15).

The median duration of treatment with tenalisib was 3.4 months.

Eighteen patients were evaluable for efficacy. Eight patients had progressed prior to the first protocol-defined assessment, and 2 patients had not yet reached their first efficacy assessment.

Eight of the 18 evaluable patients responded (44%), all with PRs. Seven patients (39%) had stable disease, and 3 (17%) progressed.

Four patients were still in response beyond 8 months of follow-up, and 1 patient was still in PR beyond 11 months.

Five patients with a PR had received the 800 mg fasting dose of tenalisib. Two received the 800 mg fed dose, and 1 patient received the drug at 400 mg.

Overall safety

Treatment-related AEs included transaminitis (25%, 14/55), diarrhea (11%, n=6), fatigue (6%, n=11), headache (9%, n=5), rash (9%, n=5), nausea (5%, n=3), vomiting (5%, n=3), pyrexia (5%, n=3), and dizziness (5%, n=3). Dizziness was only observed in CTCL patients.

Treatment-related grade 3 or higher AEs included transaminitis (20%, n=11), rash (5%, n=3), neutropenia (2%, n=1), hypophosphatemia (2%, n=1), international normalized ratio increase (2%, n=1), sepsis (2%, n=1), pyrexia (2%, n=1), and diplopia secondary to neuropathy (2%, n=1).

Seventy-six percent (n=42) of patients discontinued treatment. Sixty-eight percent (n=29) stopped due to progression, 5% (n=2) stopped at investigators’ discretion, 9% (n=4) withdrew consent, 12% (n=5) had a treatment-related AE, and 5% (n=2) had an unrelated AE.

Seventeen PTCL patients stopped treatment due to progression, as did 12 CTCL patients. One patient in each group stopped treatment at investigators’ discretion, and all 4 patients who withdrew consent had CTCL.

Four CTCL patients stopped treatment due to a related AE—transaminitis, sepsis, diarrhea, and diplopia secondary to neuropathy. One PTCL patient stopped treatment due to a related AE, which was transaminitis.

“Tenalisib at the 800 mg fasting dose has demonstrated acceptable safety and tolerability,” Dr Haverkos concluded. “We’ve observed encouraging response rates thus far, which support further evaluation of tenalisib in these patients.” ![]()

LA JOLLA, CA—The dual PI3K δ/γ inhibitor tenalisib has demonstrated activity in a phase 1 trial of patients with relapsed/refractory T-cell lymphomas.

Tenalisib produced “encouraging” response rates of 44% in patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) and 50% in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), according to study investigator Bradley M. Haverkos, MD, of the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora.

Dr Haverkos also said tenalisib had an acceptable safety profile.

The most common treatment-related adverse event (AE) in both patient groups was transaminitis.

Dr Haverkos and his colleagues presented these results in a pair of posters and an oral presentation at the 10th Annual T-cell Lymphoma Forum.

The trial was sponsored by Rhizen Pharmaceuticals, the company developing tenalisib (formerly RP6530).

The researchers have enrolled 55 patients in this trial—28 with CTCL and 27 with PTCL.

The study has a standard 3+3 design, starting with a 200 mg daily fasting dose of tenalisib and escalating to an 800 mg daily fasting dose, followed by an 800 mg daily fed cohort.

There were 3 dose-limiting toxicities in the 800 mg fed cohort—transaminitis, rash, and neutropenia. Therefore, the 800 mg fasting dose was considered the maximum-tolerated dose.

Patients in the PTCL and CTCL expansion cohorts received the maximum-tolerated dose.

Patients were scheduled to receive 8 cycles (28 days each) of tenalisib, but treatment could be extended to 24 months.

The data cutoff was January 10, 2018.

Efficacy in PTCL

Most PTCL patients (n=24) had PTCL not otherwise specified (NOS), 2 had angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), and 1 had subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL).

The patients’ median age at baseline was 63 (range, 40-89), and 63% are male. Sixty-three percent of patients had relapsed disease at baseline, 37% were refractory, and 93% had stage 3 or 4 disease. Patients had received a median of 3 prior therapies (range, 1-7).

The median duration of treatment with tenalisib was 1.9 months.

Fourteen patients were evaluable for efficacy. Eleven patients had progressed prior to the first protocol-defined assessment, and 2 patients had not reached their first efficacy assessment at the data cutoff.

Seven of the 14 evaluable patients responded (50%). Three patients (21%) had a complete response (CR), 4 (29%) had a partial response (PR), 3 (21%) had stable disease, and 4 (29%) progressed.

“There were several patients with lengthy responses,” Dr Haverkos noted. “One patient had an ongoing response at 16 months, another at 11 months, and a number of patients had ongoing responses at 7 months.”

All 3 patients with a CR had PTCL NOS and received the 800 mg fasting dose of tenalisib.

Two patients with a PR had PTCL NOS, 1 had AITL, and 1 had SPTCL. The SPTCL patient received the 200 mg dose.

The AITL patient and 1 of the PTCL NOS patients received the 800 mg fasting dose. The other PTCL NOS patient received the 400 mg dose.

Efficacy in CTCL

Most CTCL patients (n=23) had mycosis fungoides, but 5 had Sézary syndrome. The patients’ median age at baseline was 68 (range, 39-84), and 57% are female.

Forty-three percent of patients had relapsed disease at baseline, 57% were refractory, and 46% had stage 3 or 4 disease. Patients had received a median of 6 prior therapies (range, 2-15).

The median duration of treatment with tenalisib was 3.4 months.

Eighteen patients were evaluable for efficacy. Eight patients had progressed prior to the first protocol-defined assessment, and 2 patients had not yet reached their first efficacy assessment.

Eight of the 18 evaluable patients responded (44%), all with PRs. Seven patients (39%) had stable disease, and 3 (17%) progressed.

Four patients were still in response beyond 8 months of follow-up, and 1 patient was still in PR beyond 11 months.

Five patients with a PR had received the 800 mg fasting dose of tenalisib. Two received the 800 mg fed dose, and 1 patient received the drug at 400 mg.

Overall safety

Treatment-related AEs included transaminitis (25%, 14/55), diarrhea (11%, n=6), fatigue (6%, n=11), headache (9%, n=5), rash (9%, n=5), nausea (5%, n=3), vomiting (5%, n=3), pyrexia (5%, n=3), and dizziness (5%, n=3). Dizziness was only observed in CTCL patients.

Treatment-related grade 3 or higher AEs included transaminitis (20%, n=11), rash (5%, n=3), neutropenia (2%, n=1), hypophosphatemia (2%, n=1), international normalized ratio increase (2%, n=1), sepsis (2%, n=1), pyrexia (2%, n=1), and diplopia secondary to neuropathy (2%, n=1).

Seventy-six percent (n=42) of patients discontinued treatment. Sixty-eight percent (n=29) stopped due to progression, 5% (n=2) stopped at investigators’ discretion, 9% (n=4) withdrew consent, 12% (n=5) had a treatment-related AE, and 5% (n=2) had an unrelated AE.

Seventeen PTCL patients stopped treatment due to progression, as did 12 CTCL patients. One patient in each group stopped treatment at investigators’ discretion, and all 4 patients who withdrew consent had CTCL.

Four CTCL patients stopped treatment due to a related AE—transaminitis, sepsis, diarrhea, and diplopia secondary to neuropathy. One PTCL patient stopped treatment due to a related AE, which was transaminitis.

“Tenalisib at the 800 mg fasting dose has demonstrated acceptable safety and tolerability,” Dr Haverkos concluded. “We’ve observed encouraging response rates thus far, which support further evaluation of tenalisib in these patients.” ![]()

Product increases FIX levels in hemophilia B

MADRID—The recombinant factor IX (FIX) product CB 2679d/ISU304 can increase FIX levels in patients with severe hemophilia B, according to a phase 1/2 trial.

Results showed a continuous linear increase in FIX activity levels following daily subcutaneous (SQ) dosing of CB 2679d for 6 days.

Adverse events were mild to moderate, and none of the patients have developed inhibitors to CB 2679d or FIX.

Howard Levy, MB ChB, PhD, chief medical officer of Catalyst Biosciences, Inc., presented these results at the 11th Annual Congress of The European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders (EAHAD).

The research was sponsored by Catalyst Biosciences, Inc.

This phase 1/2 trial was divided into 5 cohorts.

In cohort 1, researchers compared single doses of intravenous (IV) CB 2679d and IV BeneFIX (recombinant FIX). CB 2679d proved 22 times more potent than BeneFIX. The products’ half-lives were 27.0 hours and 21.0 hours, respectively.

In cohorts 2 and 3, researchers compared single, ascending doses of IV CB 2679d to SQ CB 2679d. The bioavailability of SQ CB 2679d was 18.5%, and the half-life was 98.7 hours.

Cohort 4 was dropped, as it was another comparison of IV and SQ CB 2679d, which was considered unnecessary.

Cohort 5 included 5 patients who received daily doses of SQ CB 2679d. For 6 days, patients received CB 2679d at a dose of 140 IU/kg SQ.

The patients’ FIX activity levels increased from a median of <1% at baseline to a median of 15.7% (interquartile range, 14.9% to 16.6%) after all 6 doses.

The increase in FIX activity levels after the daily dosing was linear, indicating that continued SQ dosing may increase FIX activity further.

The median half-life was 63.2 hours (interquartile range, 60.2 to 64 hours), with the result that activity levels were still at 4% to 6.4% five days after the last dose.

No inhibitors to CB 2679d or FIX were observed in any of the cohorts in this trial.

In cohort 5, adverse events included pain, erythema, redness, and bruising after injections. Bruising occurred only with initial injections, and the severity of pain, erythema, and redness decreased over time (from moderate to mild).