User login

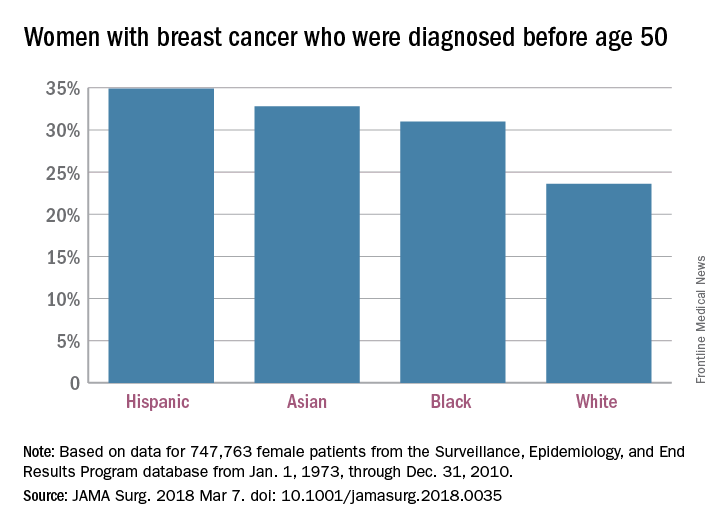

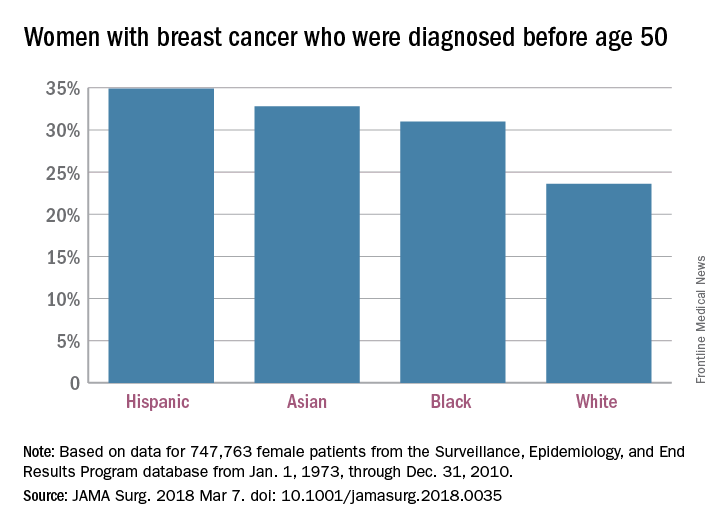

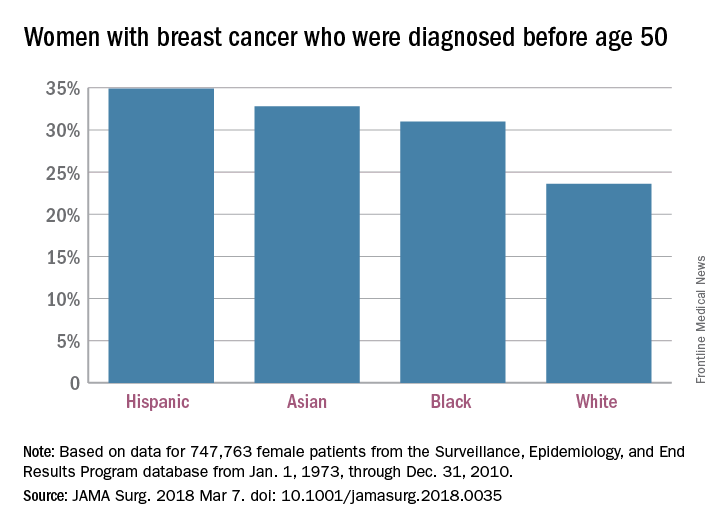

Age at time of breast cancer diagnosis differs by race/ethnicity

according to an analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program data for almost 750,000 women.

“Our finding challenges established norms with regard to screening practices and provides empirical evidence that race-based screening should be considered,” Sahael M. Stapleton, MD, and his associates at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, wrote in a research letter published online March 7 by JAMA Surgery.

The researchers charted age at diagnosis and race/ethnicity for the 747,763 women in the SEER database from Jan. 1, 1973, through Dec. 31, 2010; this revealed “two distinct distribution patterns of age at diagnosis for female breast cancers: White patients peak in their 60s, whereas nonwhite patients peak in their 40s,” the investigators wrote.

Their calculations show that “screening ages would need to decrease to 47 years for black, 46 years for Hispanic, and 47 years for Asian patients ... to achieve a similar capture rate for nonwhite patients as current guidelines do for white patients” at 50 years of age.

Dr. Stapleton reported receiving support from two Massachusetts General Hospital fellowships. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Stapleton SM et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Mar 7. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.003.

according to an analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program data for almost 750,000 women.

“Our finding challenges established norms with regard to screening practices and provides empirical evidence that race-based screening should be considered,” Sahael M. Stapleton, MD, and his associates at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, wrote in a research letter published online March 7 by JAMA Surgery.

The researchers charted age at diagnosis and race/ethnicity for the 747,763 women in the SEER database from Jan. 1, 1973, through Dec. 31, 2010; this revealed “two distinct distribution patterns of age at diagnosis for female breast cancers: White patients peak in their 60s, whereas nonwhite patients peak in their 40s,” the investigators wrote.

Their calculations show that “screening ages would need to decrease to 47 years for black, 46 years for Hispanic, and 47 years for Asian patients ... to achieve a similar capture rate for nonwhite patients as current guidelines do for white patients” at 50 years of age.

Dr. Stapleton reported receiving support from two Massachusetts General Hospital fellowships. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Stapleton SM et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Mar 7. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.003.

according to an analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program data for almost 750,000 women.

“Our finding challenges established norms with regard to screening practices and provides empirical evidence that race-based screening should be considered,” Sahael M. Stapleton, MD, and his associates at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, wrote in a research letter published online March 7 by JAMA Surgery.

The researchers charted age at diagnosis and race/ethnicity for the 747,763 women in the SEER database from Jan. 1, 1973, through Dec. 31, 2010; this revealed “two distinct distribution patterns of age at diagnosis for female breast cancers: White patients peak in their 60s, whereas nonwhite patients peak in their 40s,” the investigators wrote.

Their calculations show that “screening ages would need to decrease to 47 years for black, 46 years for Hispanic, and 47 years for Asian patients ... to achieve a similar capture rate for nonwhite patients as current guidelines do for white patients” at 50 years of age.

Dr. Stapleton reported receiving support from two Massachusetts General Hospital fellowships. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Stapleton SM et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Mar 7. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.003.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

ACC Late-Breaking Clinical Trial sessions preview for day 1

Practice-changing science will mark the five Late-Breaking Clinical Trial sessions at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology being held in Orlando, March 10-12, according to the meeting’s vice chair, Andrew Kates, MD.

Saturday’s session, held jointly with the Journal of the American College of Cardiology following the Opening Session, will be held from 9 a.m. to 10 a.m. in the Main Tent (Hall C).

ODYSSEY OUTCOMES

This will be the second cardiovascular outcomes trial of a proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor to report its primary outcomes. Last year’s blockbuster FOURIER trial results showed that the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab significantly reduced cardiovascular events in patients with stable atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease who were still at residual risk based on elevated LDL cholesterol levels.

ODYSSEY Outcomes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcomes After an Acute Coronary Syndrome During Treatment with Alirocumab trial looks at similar outcomes but in a post–acute coronary syndrome population.

“How it influences our practices and how it affects guidelines will depend on the data presented, and the strength of the data will really help us decide just where it fits in to clinical practice,” said Dr. Kates, a professor of medicine and the director of the cardiology fellowship program at Washington University in St. Louis.

VEST

The VEST Prevention of Early Sudden Death trial explores the hypothesis that wearable cardioverter defibrillators can impact mortality by reducing sudden death in the first 3 months after a heart attack in patients at high risk for life-threatening arrhythmias. This is a vulnerable period for these patients because they don’t yet meet guidelines for receiving implantable cardioverter defibrillators.

These eagerly awaited results, to be presented by Jeffrey E. Olgin, MD, will certainly influence clinical practice, Dr. Kates concluded.

Practice-changing science will mark the five Late-Breaking Clinical Trial sessions at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology being held in Orlando, March 10-12, according to the meeting’s vice chair, Andrew Kates, MD.

Saturday’s session, held jointly with the Journal of the American College of Cardiology following the Opening Session, will be held from 9 a.m. to 10 a.m. in the Main Tent (Hall C).

ODYSSEY OUTCOMES

This will be the second cardiovascular outcomes trial of a proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor to report its primary outcomes. Last year’s blockbuster FOURIER trial results showed that the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab significantly reduced cardiovascular events in patients with stable atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease who were still at residual risk based on elevated LDL cholesterol levels.

ODYSSEY Outcomes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcomes After an Acute Coronary Syndrome During Treatment with Alirocumab trial looks at similar outcomes but in a post–acute coronary syndrome population.

“How it influences our practices and how it affects guidelines will depend on the data presented, and the strength of the data will really help us decide just where it fits in to clinical practice,” said Dr. Kates, a professor of medicine and the director of the cardiology fellowship program at Washington University in St. Louis.

VEST

The VEST Prevention of Early Sudden Death trial explores the hypothesis that wearable cardioverter defibrillators can impact mortality by reducing sudden death in the first 3 months after a heart attack in patients at high risk for life-threatening arrhythmias. This is a vulnerable period for these patients because they don’t yet meet guidelines for receiving implantable cardioverter defibrillators.

These eagerly awaited results, to be presented by Jeffrey E. Olgin, MD, will certainly influence clinical practice, Dr. Kates concluded.

Practice-changing science will mark the five Late-Breaking Clinical Trial sessions at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology being held in Orlando, March 10-12, according to the meeting’s vice chair, Andrew Kates, MD.

Saturday’s session, held jointly with the Journal of the American College of Cardiology following the Opening Session, will be held from 9 a.m. to 10 a.m. in the Main Tent (Hall C).

ODYSSEY OUTCOMES

This will be the second cardiovascular outcomes trial of a proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor to report its primary outcomes. Last year’s blockbuster FOURIER trial results showed that the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab significantly reduced cardiovascular events in patients with stable atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease who were still at residual risk based on elevated LDL cholesterol levels.

ODYSSEY Outcomes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcomes After an Acute Coronary Syndrome During Treatment with Alirocumab trial looks at similar outcomes but in a post–acute coronary syndrome population.

“How it influences our practices and how it affects guidelines will depend on the data presented, and the strength of the data will really help us decide just where it fits in to clinical practice,” said Dr. Kates, a professor of medicine and the director of the cardiology fellowship program at Washington University in St. Louis.

VEST

The VEST Prevention of Early Sudden Death trial explores the hypothesis that wearable cardioverter defibrillators can impact mortality by reducing sudden death in the first 3 months after a heart attack in patients at high risk for life-threatening arrhythmias. This is a vulnerable period for these patients because they don’t yet meet guidelines for receiving implantable cardioverter defibrillators.

These eagerly awaited results, to be presented by Jeffrey E. Olgin, MD, will certainly influence clinical practice, Dr. Kates concluded.

Payers part of the drug-pricing problem, says FDA commissioner

WASHINGTON –

“Payers are going to have to decide what they want,” Dr. Gottlieb said at the conference sponsored by America’s Health Insurance Plans. “Do they want the short-term profit boost that comes with these rebates or in the long-run assist in their function” to make things better for patients, for providers, and those who pay for care.

It is possible to spur competition while working within the confines of the rebate-based system, he said. “I don’t see these as binary choices. You can have your cake and eat it too. Or in this case your rebates.”

His comments received a quick rebuttal from AHIP.

“There is a lot of blame being pushed around,” Daniel Nam, AHIP executive director of federal programs, said in an interview. “Along with the blame are a lot of distractions, misdirections, and these easy one-off fixes or problems that pop their head up and come and go. ... We try to stay focused on what is the real problem and that is essentially the starting price.”

He noted that if a treatment has a high starting price, such at coming gene therapies that could cost $1 million per patient, “it creates a pressure on the industry and it threatens our health care system to be unsustainable in the long term. What we are worried about is that there is no check on [the pharmaceutical industry’s] ability to set high list prices and even subsequently increase them.”

Mr. Nam noted that there is a fine balance that needs to be achieved to allow manufacturers to profit while at the same time ensuring access to therapies at reasonable prices.

“We believe in the free market and competition, but we feel like there are levers that could bring down the list price very effectively,” such as meaningful competition. “The situation that we have now is really more about the list price being way too high and unchallenged at this moment.”

Mr. Nam also took issue with the characterization that insurers are gaming the rebate system for profit.

“With the rebates, plans and PBMs [pharmacy benefit managers] want the lowest net cost,” he said. “That is our end goal. When you have this accusation that plans manipulate the rebate structure in order to skim off a couple of dollars here and there ... they are giving plans a lot more credit than what they can actually do at the negotiation table.”

He said the rebate system “is not perfect by any means, but I think drawing a conclusion of an imperfect system that [creates] a perverse incentive for insurers is completely distracting from the real problem” of high list prices.

WASHINGTON –

“Payers are going to have to decide what they want,” Dr. Gottlieb said at the conference sponsored by America’s Health Insurance Plans. “Do they want the short-term profit boost that comes with these rebates or in the long-run assist in their function” to make things better for patients, for providers, and those who pay for care.

It is possible to spur competition while working within the confines of the rebate-based system, he said. “I don’t see these as binary choices. You can have your cake and eat it too. Or in this case your rebates.”

His comments received a quick rebuttal from AHIP.

“There is a lot of blame being pushed around,” Daniel Nam, AHIP executive director of federal programs, said in an interview. “Along with the blame are a lot of distractions, misdirections, and these easy one-off fixes or problems that pop their head up and come and go. ... We try to stay focused on what is the real problem and that is essentially the starting price.”

He noted that if a treatment has a high starting price, such at coming gene therapies that could cost $1 million per patient, “it creates a pressure on the industry and it threatens our health care system to be unsustainable in the long term. What we are worried about is that there is no check on [the pharmaceutical industry’s] ability to set high list prices and even subsequently increase them.”

Mr. Nam noted that there is a fine balance that needs to be achieved to allow manufacturers to profit while at the same time ensuring access to therapies at reasonable prices.

“We believe in the free market and competition, but we feel like there are levers that could bring down the list price very effectively,” such as meaningful competition. “The situation that we have now is really more about the list price being way too high and unchallenged at this moment.”

Mr. Nam also took issue with the characterization that insurers are gaming the rebate system for profit.

“With the rebates, plans and PBMs [pharmacy benefit managers] want the lowest net cost,” he said. “That is our end goal. When you have this accusation that plans manipulate the rebate structure in order to skim off a couple of dollars here and there ... they are giving plans a lot more credit than what they can actually do at the negotiation table.”

He said the rebate system “is not perfect by any means, but I think drawing a conclusion of an imperfect system that [creates] a perverse incentive for insurers is completely distracting from the real problem” of high list prices.

WASHINGTON –

“Payers are going to have to decide what they want,” Dr. Gottlieb said at the conference sponsored by America’s Health Insurance Plans. “Do they want the short-term profit boost that comes with these rebates or in the long-run assist in their function” to make things better for patients, for providers, and those who pay for care.

It is possible to spur competition while working within the confines of the rebate-based system, he said. “I don’t see these as binary choices. You can have your cake and eat it too. Or in this case your rebates.”

His comments received a quick rebuttal from AHIP.

“There is a lot of blame being pushed around,” Daniel Nam, AHIP executive director of federal programs, said in an interview. “Along with the blame are a lot of distractions, misdirections, and these easy one-off fixes or problems that pop their head up and come and go. ... We try to stay focused on what is the real problem and that is essentially the starting price.”

He noted that if a treatment has a high starting price, such at coming gene therapies that could cost $1 million per patient, “it creates a pressure on the industry and it threatens our health care system to be unsustainable in the long term. What we are worried about is that there is no check on [the pharmaceutical industry’s] ability to set high list prices and even subsequently increase them.”

Mr. Nam noted that there is a fine balance that needs to be achieved to allow manufacturers to profit while at the same time ensuring access to therapies at reasonable prices.

“We believe in the free market and competition, but we feel like there are levers that could bring down the list price very effectively,” such as meaningful competition. “The situation that we have now is really more about the list price being way too high and unchallenged at this moment.”

Mr. Nam also took issue with the characterization that insurers are gaming the rebate system for profit.

“With the rebates, plans and PBMs [pharmacy benefit managers] want the lowest net cost,” he said. “That is our end goal. When you have this accusation that plans manipulate the rebate structure in order to skim off a couple of dollars here and there ... they are giving plans a lot more credit than what they can actually do at the negotiation table.”

He said the rebate system “is not perfect by any means, but I think drawing a conclusion of an imperfect system that [creates] a perverse incentive for insurers is completely distracting from the real problem” of high list prices.

REPORTING FROM AHIP 2018

Raltegravir not associated with IRIS in African trial

BOSTON – A randomized trial in sub-Saharan Africa found no evidence that first-line raltegravir (Isentress)triggers immune reconstitution syndrome in HIV patients.

It’s an important finding because raltegravir and other integrase inhibitors are replacing nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) as first-line treatments for HIV. There have been a few reports from observational studies that among severely immunocompromised, the rapid drop in viral load (VL) with the drugs might trigger immune reconstitution syndrome (IRIS), an exaggerated, dysfunctional, and sometimes fatal response to pathogens as the immune system begins to recover.

The 1,805 subjects in those four countries – a few children, but mostly adults – started the trial with median baseline CD4 counts of 37 cells/mcL and VLs of 249,770 copies/mL; 903 were randomized to standard treatment with two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors plus one NNRTI (Efavirenz), while 902 were randomized to the same regimen but with raltegravir during the first 12 weeks.

As expected, VLs came down very fast in the raltegravir group to a mean of only 80 copies/mL at 4 weeks, vs. a mean of 480 copies/mL in the standard treatment arm.

After a median of about a month, 225 fatal and 113 nonfatal IRIS events (adjudicated by a review committee blinded to randomization) occurred in 9.9% of patients in the raltegravir arm and 9.5% of patients on standard treatment, a nonsignificant difference (P = .79). IRIS was fatal in 4% of raltegravir patients and 3.4% of standard-care patients, also a nonsignificant difference (P = .54).

In both groups, TB-IRIS occurred in about 6%, cryptococcal-IRIS in about 2%, and IRIS of unknown etiology in about 2%. Also in both groups, IRIS risk was highest among older subjects as well as those who went into treatment with particularly low CD4 counts or tuberculosis (TB).

“Basically, the increase in IRIS was not there. We believe these results can be extrapolated across the class of integrase inhibitors. This provides great reassurance,” especially given the prospect of first-line integrase inhibitors in developing countries, where patients tend to present with more advanced disease, said lead investigator Diana Gibb, MD, an epidemiology professor and researcher at the University College London at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

The wrinkle in the findings was that “we didn’t see any benefit to adding raltegravir to the first 12 weeks of treatment. Everyone thought that by [driving] down the viral load faster, you might get less disease progression, and so fewer deaths. We didn’t see any difference at all. The mortality was identical at 24 weeks [around 10.5% in both arms] and at 48 weeks [around 12.5%]. The same if you looked at” severe AIDS complications, she said.

Fast, steep declines in VL “might not necessarily translate” to clinical benefit, Dr. Gibb said.

What did make a difference was IRIS prophylaxis.

The study included a second randomization at baseline, 906 subjects were randomized to enhanced prophylaxis with isoniazid, fluconazole, azithromycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and single-dose albendazole (Albenza); 899 others were randomized to standard prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole alone (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 20;377[3]:233-45).

Enhanced prophylaxis nearly halved the incidence of IRIS from 12% to 7.4%, and significantly reduced deaths at 48 weeks from 14.4% to 11% (P = .04).

“Patients with very low CD4 counts and high viral loads are the patients where this enhanced protocol package would be useful,” Dr. Gibb said.

The median age in the trial was 36 years; 4% of the subjects were 5-17 years old. Just over half the subjects were male.

The work was supported by the U.K. Department for International Development, the Wellcome Trust, and others. Dr. Gibb didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Gibb D et al. CROI, Abstract 23.

BOSTON – A randomized trial in sub-Saharan Africa found no evidence that first-line raltegravir (Isentress)triggers immune reconstitution syndrome in HIV patients.

It’s an important finding because raltegravir and other integrase inhibitors are replacing nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) as first-line treatments for HIV. There have been a few reports from observational studies that among severely immunocompromised, the rapid drop in viral load (VL) with the drugs might trigger immune reconstitution syndrome (IRIS), an exaggerated, dysfunctional, and sometimes fatal response to pathogens as the immune system begins to recover.

The 1,805 subjects in those four countries – a few children, but mostly adults – started the trial with median baseline CD4 counts of 37 cells/mcL and VLs of 249,770 copies/mL; 903 were randomized to standard treatment with two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors plus one NNRTI (Efavirenz), while 902 were randomized to the same regimen but with raltegravir during the first 12 weeks.

As expected, VLs came down very fast in the raltegravir group to a mean of only 80 copies/mL at 4 weeks, vs. a mean of 480 copies/mL in the standard treatment arm.

After a median of about a month, 225 fatal and 113 nonfatal IRIS events (adjudicated by a review committee blinded to randomization) occurred in 9.9% of patients in the raltegravir arm and 9.5% of patients on standard treatment, a nonsignificant difference (P = .79). IRIS was fatal in 4% of raltegravir patients and 3.4% of standard-care patients, also a nonsignificant difference (P = .54).

In both groups, TB-IRIS occurred in about 6%, cryptococcal-IRIS in about 2%, and IRIS of unknown etiology in about 2%. Also in both groups, IRIS risk was highest among older subjects as well as those who went into treatment with particularly low CD4 counts or tuberculosis (TB).

“Basically, the increase in IRIS was not there. We believe these results can be extrapolated across the class of integrase inhibitors. This provides great reassurance,” especially given the prospect of first-line integrase inhibitors in developing countries, where patients tend to present with more advanced disease, said lead investigator Diana Gibb, MD, an epidemiology professor and researcher at the University College London at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

The wrinkle in the findings was that “we didn’t see any benefit to adding raltegravir to the first 12 weeks of treatment. Everyone thought that by [driving] down the viral load faster, you might get less disease progression, and so fewer deaths. We didn’t see any difference at all. The mortality was identical at 24 weeks [around 10.5% in both arms] and at 48 weeks [around 12.5%]. The same if you looked at” severe AIDS complications, she said.

Fast, steep declines in VL “might not necessarily translate” to clinical benefit, Dr. Gibb said.

What did make a difference was IRIS prophylaxis.

The study included a second randomization at baseline, 906 subjects were randomized to enhanced prophylaxis with isoniazid, fluconazole, azithromycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and single-dose albendazole (Albenza); 899 others were randomized to standard prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole alone (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 20;377[3]:233-45).

Enhanced prophylaxis nearly halved the incidence of IRIS from 12% to 7.4%, and significantly reduced deaths at 48 weeks from 14.4% to 11% (P = .04).

“Patients with very low CD4 counts and high viral loads are the patients where this enhanced protocol package would be useful,” Dr. Gibb said.

The median age in the trial was 36 years; 4% of the subjects were 5-17 years old. Just over half the subjects were male.

The work was supported by the U.K. Department for International Development, the Wellcome Trust, and others. Dr. Gibb didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Gibb D et al. CROI, Abstract 23.

BOSTON – A randomized trial in sub-Saharan Africa found no evidence that first-line raltegravir (Isentress)triggers immune reconstitution syndrome in HIV patients.

It’s an important finding because raltegravir and other integrase inhibitors are replacing nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) as first-line treatments for HIV. There have been a few reports from observational studies that among severely immunocompromised, the rapid drop in viral load (VL) with the drugs might trigger immune reconstitution syndrome (IRIS), an exaggerated, dysfunctional, and sometimes fatal response to pathogens as the immune system begins to recover.

The 1,805 subjects in those four countries – a few children, but mostly adults – started the trial with median baseline CD4 counts of 37 cells/mcL and VLs of 249,770 copies/mL; 903 were randomized to standard treatment with two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors plus one NNRTI (Efavirenz), while 902 were randomized to the same regimen but with raltegravir during the first 12 weeks.

As expected, VLs came down very fast in the raltegravir group to a mean of only 80 copies/mL at 4 weeks, vs. a mean of 480 copies/mL in the standard treatment arm.

After a median of about a month, 225 fatal and 113 nonfatal IRIS events (adjudicated by a review committee blinded to randomization) occurred in 9.9% of patients in the raltegravir arm and 9.5% of patients on standard treatment, a nonsignificant difference (P = .79). IRIS was fatal in 4% of raltegravir patients and 3.4% of standard-care patients, also a nonsignificant difference (P = .54).

In both groups, TB-IRIS occurred in about 6%, cryptococcal-IRIS in about 2%, and IRIS of unknown etiology in about 2%. Also in both groups, IRIS risk was highest among older subjects as well as those who went into treatment with particularly low CD4 counts or tuberculosis (TB).

“Basically, the increase in IRIS was not there. We believe these results can be extrapolated across the class of integrase inhibitors. This provides great reassurance,” especially given the prospect of first-line integrase inhibitors in developing countries, where patients tend to present with more advanced disease, said lead investigator Diana Gibb, MD, an epidemiology professor and researcher at the University College London at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

The wrinkle in the findings was that “we didn’t see any benefit to adding raltegravir to the first 12 weeks of treatment. Everyone thought that by [driving] down the viral load faster, you might get less disease progression, and so fewer deaths. We didn’t see any difference at all. The mortality was identical at 24 weeks [around 10.5% in both arms] and at 48 weeks [around 12.5%]. The same if you looked at” severe AIDS complications, she said.

Fast, steep declines in VL “might not necessarily translate” to clinical benefit, Dr. Gibb said.

What did make a difference was IRIS prophylaxis.

The study included a second randomization at baseline, 906 subjects were randomized to enhanced prophylaxis with isoniazid, fluconazole, azithromycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and single-dose albendazole (Albenza); 899 others were randomized to standard prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole alone (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 20;377[3]:233-45).

Enhanced prophylaxis nearly halved the incidence of IRIS from 12% to 7.4%, and significantly reduced deaths at 48 weeks from 14.4% to 11% (P = .04).

“Patients with very low CD4 counts and high viral loads are the patients where this enhanced protocol package would be useful,” Dr. Gibb said.

The median age in the trial was 36 years; 4% of the subjects were 5-17 years old. Just over half the subjects were male.

The work was supported by the U.K. Department for International Development, the Wellcome Trust, and others. Dr. Gibb didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Gibb D et al. CROI, Abstract 23.

REPORTING FROM CROI

Key clinical point: Amid concern to the contrary, integrase inhibitors might not trigger IRIS in the severely immunocompromised.

Major finding: IRIS events – 225 fatal and 113 nonfatal – occurred in 9.9% of patients in the raltegravir arm and 9.5% of patients on standard treatment (P = .79).

Study details: Randomized trial with 1,805 subjects

Disclosures: The work was supported by the U.K. Department for International Development, the Wellcome Trust, and others. The lead investigator had no disclosures.

Source: Gibb D et al. CROI, Abstract 23.

High efficacy, no safety signals for herpes zoster vaccine post-HSCT

SALT LAKE CITY – A recently approved adjuvanted herpes zoster vaccine)(Shingrix) effectively and safely prevented herpes zoster in a population of patients with multiple myeloma and other hematologic malignancies who received autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

The use of recombinant varicella zoster virus glycoprotein E in combination with an adjuvant system gives immunosuppressed individuals who have received hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) a safe option for prevention of herpes zoster (HZ), said Javier de la Serna, MD, PhD, speaking at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

Presenting the findings at a late-breaking abstract session, Dr. de la Serna said that for the 1,721 participants in a placebo-controlled multicenter trial who received both doses of the vaccine, the incidence of HZ for vaccine recipients was 3.0%, compared with 9.4% of placebo recipients, for a vaccine efficacy of 68.2% (95% confidence interval, 55.6-77.5; P less than 0.0001). These results met the study’s primary objective.

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) prevention efficacy – a secondary endpoint – was 89.3% for those receiving the vaccine (HZ/su); the incidence of PHN was 0.5% in the HZ/su study arm, compared with 4.9% for those who received placebo (95% CI, 22.5-99.8). The study also tracked other HZ complications as a secondary endpoint, finding efficacy of 77.8% (95% CI, 19.1–95.0). “The vaccine was highly efficacious in preventing all the secondary outcomes,” said Dr. de la Serna of the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid.

The randomized, observer-blind phase 3 trial was conducted in 28 countries.Adults who received autologous HSCT were randomized 1:1 to receive HZ/su (n = 922) or placebo (n = 924) within 50-70 days of their transplant. Patients were excluded if they were expected to receive more than 6 months of anti–varicella zoster prophylaxis posttransplant, Dr. de la Serna said.

Participants received the first dose of HZ/su at the first study visit, and the second dose 30-60 days later. Patients were seen 1 month after the last vaccine dose, and then again at months 13 and 25, with telephone follow-up between the later visits. All participants were followed for at least 1 year, Dr. de la Serna said.

Episodes of HZ were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction assay, or, when samples were lacking or indeterminate, by agreement of at least three members of an ascertainment committee.

Of the two components of the HZ/su vaccine, glycoprotein E triggers both humoral immunity and activity of varicella zoster–specific CD4+ T cells; the adjuvant system – dubbed ASO1 – boosts immune response. The vaccine was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in October 2017 for use in adults aged 50 years and older.

In addition to the primary endpoint of vaccine efficacy in prevention of HZ cases during the study period, secondary objectives included monitoring vaccine reactogenicity and safety, and evaluating vaccine efficacy for the prevention of PHN and other complications of HZ.

Tertiary objectives included vaccine efficacy in preventing HZ during the first year posttransplant (vaccine efficacy 84.7%; 95% CI, 32.2-96.6), as well as efficacy in preventing hospitalizations related to HZ (vaccine efficacy 76.2%, 95% CI 61.1-86.0).

An exploratory analysis found vaccine efficacy of 71.8% for participants younger than 50 years (95% CI, 38.8 – 88.3). For patients aged 50 years and older, vaccine efficacy was 67.3% (95% CI, 52.6–77.9).

The safety of HZ/su was determined by analyzing data for all participants, but efficacy data included only those who received the second dose and did not develop HZ within a month of receiving the second vaccine dose.

In the efficacy group (n = 1,721), patients were mostly (n = 1,296) aged 50 years or older. Most patients (n = 937) received HSCT for multiple myeloma. Overall, participants were about 63% male, and 77% were of Caucasian/European ancestry.

Adverse events, solicited for the first 7 days after injections, were mostly mild and related to the local site pain and inflammation expected with an adjuvanted vaccine; HZ/su recipients also experienced more fatigue and muscle aches than did those receiving placebo. Median duration of symptoms was up to 3 days, with grade 3 events lasting up to 2 days.

Unsolicited and serious adverse events were similar between study arms, with a median safety follow-up period of 29 months. The investigators judged that no deaths were related to the vaccine, and there were no signals for increased rate of relapse or immune-mediated diseases.

The study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline; HZ/su(Shingrix) is marketed by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. de la Serna reported being on the advisory board or receiving honoraria from multiple pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: de la Serna J et al. 2018 BMT Tandem Meetings, Abstract LBA2.

SALT LAKE CITY – A recently approved adjuvanted herpes zoster vaccine)(Shingrix) effectively and safely prevented herpes zoster in a population of patients with multiple myeloma and other hematologic malignancies who received autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

The use of recombinant varicella zoster virus glycoprotein E in combination with an adjuvant system gives immunosuppressed individuals who have received hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) a safe option for prevention of herpes zoster (HZ), said Javier de la Serna, MD, PhD, speaking at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

Presenting the findings at a late-breaking abstract session, Dr. de la Serna said that for the 1,721 participants in a placebo-controlled multicenter trial who received both doses of the vaccine, the incidence of HZ for vaccine recipients was 3.0%, compared with 9.4% of placebo recipients, for a vaccine efficacy of 68.2% (95% confidence interval, 55.6-77.5; P less than 0.0001). These results met the study’s primary objective.

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) prevention efficacy – a secondary endpoint – was 89.3% for those receiving the vaccine (HZ/su); the incidence of PHN was 0.5% in the HZ/su study arm, compared with 4.9% for those who received placebo (95% CI, 22.5-99.8). The study also tracked other HZ complications as a secondary endpoint, finding efficacy of 77.8% (95% CI, 19.1–95.0). “The vaccine was highly efficacious in preventing all the secondary outcomes,” said Dr. de la Serna of the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid.

The randomized, observer-blind phase 3 trial was conducted in 28 countries.Adults who received autologous HSCT were randomized 1:1 to receive HZ/su (n = 922) or placebo (n = 924) within 50-70 days of their transplant. Patients were excluded if they were expected to receive more than 6 months of anti–varicella zoster prophylaxis posttransplant, Dr. de la Serna said.

Participants received the first dose of HZ/su at the first study visit, and the second dose 30-60 days later. Patients were seen 1 month after the last vaccine dose, and then again at months 13 and 25, with telephone follow-up between the later visits. All participants were followed for at least 1 year, Dr. de la Serna said.

Episodes of HZ were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction assay, or, when samples were lacking or indeterminate, by agreement of at least three members of an ascertainment committee.

Of the two components of the HZ/su vaccine, glycoprotein E triggers both humoral immunity and activity of varicella zoster–specific CD4+ T cells; the adjuvant system – dubbed ASO1 – boosts immune response. The vaccine was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in October 2017 for use in adults aged 50 years and older.

In addition to the primary endpoint of vaccine efficacy in prevention of HZ cases during the study period, secondary objectives included monitoring vaccine reactogenicity and safety, and evaluating vaccine efficacy for the prevention of PHN and other complications of HZ.

Tertiary objectives included vaccine efficacy in preventing HZ during the first year posttransplant (vaccine efficacy 84.7%; 95% CI, 32.2-96.6), as well as efficacy in preventing hospitalizations related to HZ (vaccine efficacy 76.2%, 95% CI 61.1-86.0).

An exploratory analysis found vaccine efficacy of 71.8% for participants younger than 50 years (95% CI, 38.8 – 88.3). For patients aged 50 years and older, vaccine efficacy was 67.3% (95% CI, 52.6–77.9).

The safety of HZ/su was determined by analyzing data for all participants, but efficacy data included only those who received the second dose and did not develop HZ within a month of receiving the second vaccine dose.

In the efficacy group (n = 1,721), patients were mostly (n = 1,296) aged 50 years or older. Most patients (n = 937) received HSCT for multiple myeloma. Overall, participants were about 63% male, and 77% were of Caucasian/European ancestry.

Adverse events, solicited for the first 7 days after injections, were mostly mild and related to the local site pain and inflammation expected with an adjuvanted vaccine; HZ/su recipients also experienced more fatigue and muscle aches than did those receiving placebo. Median duration of symptoms was up to 3 days, with grade 3 events lasting up to 2 days.

Unsolicited and serious adverse events were similar between study arms, with a median safety follow-up period of 29 months. The investigators judged that no deaths were related to the vaccine, and there were no signals for increased rate of relapse or immune-mediated diseases.

The study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline; HZ/su(Shingrix) is marketed by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. de la Serna reported being on the advisory board or receiving honoraria from multiple pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: de la Serna J et al. 2018 BMT Tandem Meetings, Abstract LBA2.

SALT LAKE CITY – A recently approved adjuvanted herpes zoster vaccine)(Shingrix) effectively and safely prevented herpes zoster in a population of patients with multiple myeloma and other hematologic malignancies who received autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

The use of recombinant varicella zoster virus glycoprotein E in combination with an adjuvant system gives immunosuppressed individuals who have received hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) a safe option for prevention of herpes zoster (HZ), said Javier de la Serna, MD, PhD, speaking at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

Presenting the findings at a late-breaking abstract session, Dr. de la Serna said that for the 1,721 participants in a placebo-controlled multicenter trial who received both doses of the vaccine, the incidence of HZ for vaccine recipients was 3.0%, compared with 9.4% of placebo recipients, for a vaccine efficacy of 68.2% (95% confidence interval, 55.6-77.5; P less than 0.0001). These results met the study’s primary objective.

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) prevention efficacy – a secondary endpoint – was 89.3% for those receiving the vaccine (HZ/su); the incidence of PHN was 0.5% in the HZ/su study arm, compared with 4.9% for those who received placebo (95% CI, 22.5-99.8). The study also tracked other HZ complications as a secondary endpoint, finding efficacy of 77.8% (95% CI, 19.1–95.0). “The vaccine was highly efficacious in preventing all the secondary outcomes,” said Dr. de la Serna of the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid.

The randomized, observer-blind phase 3 trial was conducted in 28 countries.Adults who received autologous HSCT were randomized 1:1 to receive HZ/su (n = 922) or placebo (n = 924) within 50-70 days of their transplant. Patients were excluded if they were expected to receive more than 6 months of anti–varicella zoster prophylaxis posttransplant, Dr. de la Serna said.

Participants received the first dose of HZ/su at the first study visit, and the second dose 30-60 days later. Patients were seen 1 month after the last vaccine dose, and then again at months 13 and 25, with telephone follow-up between the later visits. All participants were followed for at least 1 year, Dr. de la Serna said.

Episodes of HZ were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction assay, or, when samples were lacking or indeterminate, by agreement of at least three members of an ascertainment committee.

Of the two components of the HZ/su vaccine, glycoprotein E triggers both humoral immunity and activity of varicella zoster–specific CD4+ T cells; the adjuvant system – dubbed ASO1 – boosts immune response. The vaccine was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in October 2017 for use in adults aged 50 years and older.

In addition to the primary endpoint of vaccine efficacy in prevention of HZ cases during the study period, secondary objectives included monitoring vaccine reactogenicity and safety, and evaluating vaccine efficacy for the prevention of PHN and other complications of HZ.

Tertiary objectives included vaccine efficacy in preventing HZ during the first year posttransplant (vaccine efficacy 84.7%; 95% CI, 32.2-96.6), as well as efficacy in preventing hospitalizations related to HZ (vaccine efficacy 76.2%, 95% CI 61.1-86.0).

An exploratory analysis found vaccine efficacy of 71.8% for participants younger than 50 years (95% CI, 38.8 – 88.3). For patients aged 50 years and older, vaccine efficacy was 67.3% (95% CI, 52.6–77.9).

The safety of HZ/su was determined by analyzing data for all participants, but efficacy data included only those who received the second dose and did not develop HZ within a month of receiving the second vaccine dose.

In the efficacy group (n = 1,721), patients were mostly (n = 1,296) aged 50 years or older. Most patients (n = 937) received HSCT for multiple myeloma. Overall, participants were about 63% male, and 77% were of Caucasian/European ancestry.

Adverse events, solicited for the first 7 days after injections, were mostly mild and related to the local site pain and inflammation expected with an adjuvanted vaccine; HZ/su recipients also experienced more fatigue and muscle aches than did those receiving placebo. Median duration of symptoms was up to 3 days, with grade 3 events lasting up to 2 days.

Unsolicited and serious adverse events were similar between study arms, with a median safety follow-up period of 29 months. The investigators judged that no deaths were related to the vaccine, and there were no signals for increased rate of relapse or immune-mediated diseases.

The study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline; HZ/su(Shingrix) is marketed by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. de la Serna reported being on the advisory board or receiving honoraria from multiple pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: de la Serna J et al. 2018 BMT Tandem Meetings, Abstract LBA2.

REPORTING FROM THE 2018 BMT TANDEM MEETINGS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Efficacy was 68.17% for preventing herpes zoster among HSCT recipients.

Study details: A randomized, observer blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study of 1,846 post-HSCT recipients.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. de la Serna reported relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

Source: de la Serna J et al. 2018 BMT Tandem Meetings, Abstract LBA2.

OSA Endotypes and Phenotypes: Toward Personalized OSA Care

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) contributes a major health burden to society due to its high prevalence and substantial neurocognitive and cardiovascular consequences. Estimates suggest that at least 10% of adults in North America are afflicted with OSA, making it probably the most common respiratory disease in the developed world (Peppard et al. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177[9]:1006). Nasal CPAP is a highly efficacious therapy that has been shown to improve neurocognitive and cardiovascular outcomes. However, CPAP is not always well tolerated. Alternative therapies, such as oral appliances and upper airway surgery, have highly variable efficacy, and evidence of important clinical benefits are uncertain. Therefore, efforts are ongoing to determine optimal alternative strategies for therapy.

In order to treat any condition optimally, one needs to be able to predict who is at highest risk of developing the condition, then to assess the consequences if left untreated, and finally to be able to predict response to various treatment options. Currently, the OSA field is still in its early stages of our understanding. Clinically, we are often faced with patients who have varying presentations and manifestations, but, for reasons that are unclear. For instance, two individuals with the same body mass index may have very different clinical manifestations, one with severe OSA and one without any OSA. Similarly, two individuals with an apnea hypopnea index of 40 events per hour (ie, severe OSA) may have very different symptoms attributable to OSA, eg, one could be asymptomatic and the other could be debilitated from sleepiness. We and others have been making efforts to determine why these phenomenon occur. At present, the techniques to define mechanisms underlying OSA are labor-intensive, requiring one or two overnight experiments to gather meaningful data. Although we are gathering new insights based on these techniques, efforts are ongoing to simplify these approaches and to make assessment of pathophysiologic characteristics more accessible to the clinician (Orr et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017 Nov 30. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201707-1357LE. [Epub ahead of print]).

We ultimately believe that a thorough analysis of a sleep recording combined with demographic data and other readily available clinical data (perhaps plasma biomarkers) may yield sufficient information for us to know why OSA is occurring and what interventions might be helpful for an individual patient. Currently, our use of the polysomnogram to derive only an apnea hypopnea index does not take full advantage of the available data. An apnea hypopnea index can be readily obtained from home sleep testing and does not truly provide much insight into why a given individual has OSA, what symptoms are attributable to OSA, and what interventions might be considered for the afflicted individual. By analogy, if the only useful data derived from an ECG were a heart rate, the test would rapidly become obsolete. Along these lines, if the only role for the sleep clinician was to prescribe CPAP to everyone with an AHI greater than 5/h, there would be little need or interest in specialized training. In contrast, we suggest that rich insights regarding pathophysiology and mechanisms should be gathered and may influence clinical management of patients afflicted with OSA. Thus, we encourage more thorough analyses of available data to maximize information gleaned and, ultimately, to optimize clinical outcomes.

Recent studies suggest that sleep apnea occurs for varying reasons, a concept that is now thought to be clinically important (Jordan et al. Lancet. 2014;383[9918]:736). We draw a crucial distinction between endotypes (mechanisms underlying disease) and phenotypes (clinical expression of disease). Important endotypes include compromised upper airway anatomy, dysfunction in pharyngeal dilator muscles, unstable ventilatory control (high loop gain), and low arousal threshold (wake up easily), among others. Important phenotypes of sleep apnea are emerging and still evolving to include minimally symptomatic OSA, OSA with daytime sleepiness, and OSA with major cardiometabolic risk, among others. Several important concepts have emerged regarding different OSA endotypes and phenotypes:

1 The mechanism underlying OSA may predict potential response to therapeutic interventions. For instance, the endotype of OSA with unstable ventilatory control (high loop gain) may respond to agents such as oxygen and acetazolamide, which serve to stabilize control of breathing. In patients with anatomical compromise at the level of the velopharynx, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty may be an effective intervention. For patients with multiple pathophysiologic abnormalities, combination therapy may be required to alleviate OSA (Edwards et al. Sleep. 2016;9[11]:1973).

2 Given that OSA has many underlying etiologies, efforts are underway to determine whether individuals with different risk factors for OSA develop their disease based on varying mechanisms. As an example, people with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be at increased risk of OSA perhaps on the basis of a low threshold for arousal (Orr et al. JCSM. 2017, 13[1]: 57-63). Another example would be patients with neuromuscular disease who may be at risk of OSA primarily based on impaired pharyngeal dilator muscle function.

3 A new concept is emerging whereby endotypes of OSA may actually predict differing OSA phenotypes. In theory, loop gain-driven OSA may have different consequences from OSA driven by compromise of pharyngeal anatomy. To this point, data suggest that OSA in the elderly may not have as many consequences as OSA in younger people matched on severity of illness. OSA in the elderly has lower loop gain than OSA in younger people and is associated with less negative intrathoracic pressure at the time of arousal as compared with younger individuals with OSA (Kobayashi et al. Chest. 2010; 137[6]:1310). As such, the endotype of OSA in the elderly may explain why the clinical consequences are fewer than in the younger OSA counterparts.

4 The mechanism underlying OSA may be important in determining response to clinical interventions, such as nasal CPAP. Patients with a low arousal threshold may be prone to insomnia when placed on CPAP and could theoretically be poorly tolerant of therapy based on disrupted sleep architecture. Such patients may benefit from non-myorelaxant hypnotic therapy to consolidate sleep and improve CPAP adherence. In addition, patients with high loop gain (unstable ventilatory control) may be prone to develop central apneas when placed on CPAP therapy (Stanchina et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12[9]:1351). These patients may benefit from newer technologies, eg, auto or adaptive servo ventilation - ASV. High loop gain has also been shown to predict failure of upper airway surgery as a treatment for OSA by several groups (Li et al. JCSM. 2017;13[9]:1029). Such patients should, perhaps, undergo nonsurgical therapies for OSA.

We emphasize that some of the points being made are somewhat speculative and, thus, encourage further basic and clinical research to test our assumptions. Robust, multicenter clinical trials assessing hard outcomes will ultimately be required to change the current standard of care. Nonetheless, we believe that a more thorough understanding of OSA pathogenesis can help guide clinical care today and will be critical to the optimal treatment of afflicted individuals tomorrow.

Dr. Owens is Assistant Clinical Professor of Medicine; Dr. Deacon is a Post-Doctoral Research Scholar; and Dr. Malhotra is Kenneth M. Moser Professor of Medicine and Chief, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, University of California San Diego.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) contributes a major health burden to society due to its high prevalence and substantial neurocognitive and cardiovascular consequences. Estimates suggest that at least 10% of adults in North America are afflicted with OSA, making it probably the most common respiratory disease in the developed world (Peppard et al. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177[9]:1006). Nasal CPAP is a highly efficacious therapy that has been shown to improve neurocognitive and cardiovascular outcomes. However, CPAP is not always well tolerated. Alternative therapies, such as oral appliances and upper airway surgery, have highly variable efficacy, and evidence of important clinical benefits are uncertain. Therefore, efforts are ongoing to determine optimal alternative strategies for therapy.

In order to treat any condition optimally, one needs to be able to predict who is at highest risk of developing the condition, then to assess the consequences if left untreated, and finally to be able to predict response to various treatment options. Currently, the OSA field is still in its early stages of our understanding. Clinically, we are often faced with patients who have varying presentations and manifestations, but, for reasons that are unclear. For instance, two individuals with the same body mass index may have very different clinical manifestations, one with severe OSA and one without any OSA. Similarly, two individuals with an apnea hypopnea index of 40 events per hour (ie, severe OSA) may have very different symptoms attributable to OSA, eg, one could be asymptomatic and the other could be debilitated from sleepiness. We and others have been making efforts to determine why these phenomenon occur. At present, the techniques to define mechanisms underlying OSA are labor-intensive, requiring one or two overnight experiments to gather meaningful data. Although we are gathering new insights based on these techniques, efforts are ongoing to simplify these approaches and to make assessment of pathophysiologic characteristics more accessible to the clinician (Orr et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017 Nov 30. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201707-1357LE. [Epub ahead of print]).

We ultimately believe that a thorough analysis of a sleep recording combined with demographic data and other readily available clinical data (perhaps plasma biomarkers) may yield sufficient information for us to know why OSA is occurring and what interventions might be helpful for an individual patient. Currently, our use of the polysomnogram to derive only an apnea hypopnea index does not take full advantage of the available data. An apnea hypopnea index can be readily obtained from home sleep testing and does not truly provide much insight into why a given individual has OSA, what symptoms are attributable to OSA, and what interventions might be considered for the afflicted individual. By analogy, if the only useful data derived from an ECG were a heart rate, the test would rapidly become obsolete. Along these lines, if the only role for the sleep clinician was to prescribe CPAP to everyone with an AHI greater than 5/h, there would be little need or interest in specialized training. In contrast, we suggest that rich insights regarding pathophysiology and mechanisms should be gathered and may influence clinical management of patients afflicted with OSA. Thus, we encourage more thorough analyses of available data to maximize information gleaned and, ultimately, to optimize clinical outcomes.

Recent studies suggest that sleep apnea occurs for varying reasons, a concept that is now thought to be clinically important (Jordan et al. Lancet. 2014;383[9918]:736). We draw a crucial distinction between endotypes (mechanisms underlying disease) and phenotypes (clinical expression of disease). Important endotypes include compromised upper airway anatomy, dysfunction in pharyngeal dilator muscles, unstable ventilatory control (high loop gain), and low arousal threshold (wake up easily), among others. Important phenotypes of sleep apnea are emerging and still evolving to include minimally symptomatic OSA, OSA with daytime sleepiness, and OSA with major cardiometabolic risk, among others. Several important concepts have emerged regarding different OSA endotypes and phenotypes:

1 The mechanism underlying OSA may predict potential response to therapeutic interventions. For instance, the endotype of OSA with unstable ventilatory control (high loop gain) may respond to agents such as oxygen and acetazolamide, which serve to stabilize control of breathing. In patients with anatomical compromise at the level of the velopharynx, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty may be an effective intervention. For patients with multiple pathophysiologic abnormalities, combination therapy may be required to alleviate OSA (Edwards et al. Sleep. 2016;9[11]:1973).

2 Given that OSA has many underlying etiologies, efforts are underway to determine whether individuals with different risk factors for OSA develop their disease based on varying mechanisms. As an example, people with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be at increased risk of OSA perhaps on the basis of a low threshold for arousal (Orr et al. JCSM. 2017, 13[1]: 57-63). Another example would be patients with neuromuscular disease who may be at risk of OSA primarily based on impaired pharyngeal dilator muscle function.

3 A new concept is emerging whereby endotypes of OSA may actually predict differing OSA phenotypes. In theory, loop gain-driven OSA may have different consequences from OSA driven by compromise of pharyngeal anatomy. To this point, data suggest that OSA in the elderly may not have as many consequences as OSA in younger people matched on severity of illness. OSA in the elderly has lower loop gain than OSA in younger people and is associated with less negative intrathoracic pressure at the time of arousal as compared with younger individuals with OSA (Kobayashi et al. Chest. 2010; 137[6]:1310). As such, the endotype of OSA in the elderly may explain why the clinical consequences are fewer than in the younger OSA counterparts.

4 The mechanism underlying OSA may be important in determining response to clinical interventions, such as nasal CPAP. Patients with a low arousal threshold may be prone to insomnia when placed on CPAP and could theoretically be poorly tolerant of therapy based on disrupted sleep architecture. Such patients may benefit from non-myorelaxant hypnotic therapy to consolidate sleep and improve CPAP adherence. In addition, patients with high loop gain (unstable ventilatory control) may be prone to develop central apneas when placed on CPAP therapy (Stanchina et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12[9]:1351). These patients may benefit from newer technologies, eg, auto or adaptive servo ventilation - ASV. High loop gain has also been shown to predict failure of upper airway surgery as a treatment for OSA by several groups (Li et al. JCSM. 2017;13[9]:1029). Such patients should, perhaps, undergo nonsurgical therapies for OSA.

We emphasize that some of the points being made are somewhat speculative and, thus, encourage further basic and clinical research to test our assumptions. Robust, multicenter clinical trials assessing hard outcomes will ultimately be required to change the current standard of care. Nonetheless, we believe that a more thorough understanding of OSA pathogenesis can help guide clinical care today and will be critical to the optimal treatment of afflicted individuals tomorrow.

Dr. Owens is Assistant Clinical Professor of Medicine; Dr. Deacon is a Post-Doctoral Research Scholar; and Dr. Malhotra is Kenneth M. Moser Professor of Medicine and Chief, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, University of California San Diego.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) contributes a major health burden to society due to its high prevalence and substantial neurocognitive and cardiovascular consequences. Estimates suggest that at least 10% of adults in North America are afflicted with OSA, making it probably the most common respiratory disease in the developed world (Peppard et al. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177[9]:1006). Nasal CPAP is a highly efficacious therapy that has been shown to improve neurocognitive and cardiovascular outcomes. However, CPAP is not always well tolerated. Alternative therapies, such as oral appliances and upper airway surgery, have highly variable efficacy, and evidence of important clinical benefits are uncertain. Therefore, efforts are ongoing to determine optimal alternative strategies for therapy.

In order to treat any condition optimally, one needs to be able to predict who is at highest risk of developing the condition, then to assess the consequences if left untreated, and finally to be able to predict response to various treatment options. Currently, the OSA field is still in its early stages of our understanding. Clinically, we are often faced with patients who have varying presentations and manifestations, but, for reasons that are unclear. For instance, two individuals with the same body mass index may have very different clinical manifestations, one with severe OSA and one without any OSA. Similarly, two individuals with an apnea hypopnea index of 40 events per hour (ie, severe OSA) may have very different symptoms attributable to OSA, eg, one could be asymptomatic and the other could be debilitated from sleepiness. We and others have been making efforts to determine why these phenomenon occur. At present, the techniques to define mechanisms underlying OSA are labor-intensive, requiring one or two overnight experiments to gather meaningful data. Although we are gathering new insights based on these techniques, efforts are ongoing to simplify these approaches and to make assessment of pathophysiologic characteristics more accessible to the clinician (Orr et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017 Nov 30. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201707-1357LE. [Epub ahead of print]).

We ultimately believe that a thorough analysis of a sleep recording combined with demographic data and other readily available clinical data (perhaps plasma biomarkers) may yield sufficient information for us to know why OSA is occurring and what interventions might be helpful for an individual patient. Currently, our use of the polysomnogram to derive only an apnea hypopnea index does not take full advantage of the available data. An apnea hypopnea index can be readily obtained from home sleep testing and does not truly provide much insight into why a given individual has OSA, what symptoms are attributable to OSA, and what interventions might be considered for the afflicted individual. By analogy, if the only useful data derived from an ECG were a heart rate, the test would rapidly become obsolete. Along these lines, if the only role for the sleep clinician was to prescribe CPAP to everyone with an AHI greater than 5/h, there would be little need or interest in specialized training. In contrast, we suggest that rich insights regarding pathophysiology and mechanisms should be gathered and may influence clinical management of patients afflicted with OSA. Thus, we encourage more thorough analyses of available data to maximize information gleaned and, ultimately, to optimize clinical outcomes.

Recent studies suggest that sleep apnea occurs for varying reasons, a concept that is now thought to be clinically important (Jordan et al. Lancet. 2014;383[9918]:736). We draw a crucial distinction between endotypes (mechanisms underlying disease) and phenotypes (clinical expression of disease). Important endotypes include compromised upper airway anatomy, dysfunction in pharyngeal dilator muscles, unstable ventilatory control (high loop gain), and low arousal threshold (wake up easily), among others. Important phenotypes of sleep apnea are emerging and still evolving to include minimally symptomatic OSA, OSA with daytime sleepiness, and OSA with major cardiometabolic risk, among others. Several important concepts have emerged regarding different OSA endotypes and phenotypes:

1 The mechanism underlying OSA may predict potential response to therapeutic interventions. For instance, the endotype of OSA with unstable ventilatory control (high loop gain) may respond to agents such as oxygen and acetazolamide, which serve to stabilize control of breathing. In patients with anatomical compromise at the level of the velopharynx, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty may be an effective intervention. For patients with multiple pathophysiologic abnormalities, combination therapy may be required to alleviate OSA (Edwards et al. Sleep. 2016;9[11]:1973).

2 Given that OSA has many underlying etiologies, efforts are underway to determine whether individuals with different risk factors for OSA develop their disease based on varying mechanisms. As an example, people with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be at increased risk of OSA perhaps on the basis of a low threshold for arousal (Orr et al. JCSM. 2017, 13[1]: 57-63). Another example would be patients with neuromuscular disease who may be at risk of OSA primarily based on impaired pharyngeal dilator muscle function.

3 A new concept is emerging whereby endotypes of OSA may actually predict differing OSA phenotypes. In theory, loop gain-driven OSA may have different consequences from OSA driven by compromise of pharyngeal anatomy. To this point, data suggest that OSA in the elderly may not have as many consequences as OSA in younger people matched on severity of illness. OSA in the elderly has lower loop gain than OSA in younger people and is associated with less negative intrathoracic pressure at the time of arousal as compared with younger individuals with OSA (Kobayashi et al. Chest. 2010; 137[6]:1310). As such, the endotype of OSA in the elderly may explain why the clinical consequences are fewer than in the younger OSA counterparts.

4 The mechanism underlying OSA may be important in determining response to clinical interventions, such as nasal CPAP. Patients with a low arousal threshold may be prone to insomnia when placed on CPAP and could theoretically be poorly tolerant of therapy based on disrupted sleep architecture. Such patients may benefit from non-myorelaxant hypnotic therapy to consolidate sleep and improve CPAP adherence. In addition, patients with high loop gain (unstable ventilatory control) may be prone to develop central apneas when placed on CPAP therapy (Stanchina et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12[9]:1351). These patients may benefit from newer technologies, eg, auto or adaptive servo ventilation - ASV. High loop gain has also been shown to predict failure of upper airway surgery as a treatment for OSA by several groups (Li et al. JCSM. 2017;13[9]:1029). Such patients should, perhaps, undergo nonsurgical therapies for OSA.

We emphasize that some of the points being made are somewhat speculative and, thus, encourage further basic and clinical research to test our assumptions. Robust, multicenter clinical trials assessing hard outcomes will ultimately be required to change the current standard of care. Nonetheless, we believe that a more thorough understanding of OSA pathogenesis can help guide clinical care today and will be critical to the optimal treatment of afflicted individuals tomorrow.

Dr. Owens is Assistant Clinical Professor of Medicine; Dr. Deacon is a Post-Doctoral Research Scholar; and Dr. Malhotra is Kenneth M. Moser Professor of Medicine and Chief, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, University of California San Diego.

Dermatology residency match: Is the glut of applications for limited positions corrupting the process?

SAN DIEGO – Whether was the topic of discussion at a session on dermatoethics at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“I think it is unethical and we need to address it,” Jane M. Grant-Kels, MD, said during the session. “What we are doing through the process of physicians getting into dermatology residency programs is telling them to lie to us and to do well on a single examination,” the United States Medical Licensing Examination.

Lionel G. Bercovitch, MD, is among the dermatologists who acknowledge the unarguable fact that application rates are high but don’t see it as a crisis of credibility.

“I don’t believe that dermatology match is broken, unethical, or unfair. The match is not perfect, but it’s fair,” contended Dr. Bercovitch, professor of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I. “The problem [of an application glut] is real, but it’s not an ethical issue.”

Dr. Grant-Kels sees it in ethical terms because, in her view, “everyone is gaming the system. It makes applicants liars” when they profess interest in moving to a remote location or planning to practice a certain type of dermatology.

The “extremely competitive” process leads a majority of applicants to “shot gun” their filings to many programs such that dermatology residency programs are “deluged” with applications, Dr. Grant-Kels said. Data from the Association of American Medical Colleges for 2017 showed an average of just over 500 applications received by each U.S. dermatology residency program.

As a result, residency programs feel forced to apply blind filters that generally cull out more than a third of the applications received. Dr. Grant-Kels decried the need for programs to impose arbitrary barriers to entering dermatology based on a score from a single examination or other criteria like membership in Alpha Omega Alpha or current location.

“Blanket screening methods run the risk of excluding genuinely interested and qualified candidates who do not fall above a threshold. This violates the principal of nonmaleficence,” she said. “Screens are unfair.”

[polldaddy:{"method":"iframe","type":"survey","src":"//newspolls2017.polldaddy.com/s/dermatology-residency-match?iframe=1"}]

Dr. Grant-Kels proposed a pair of potential remedies: putting a cap on the number of applications someone can make and – a more realistic approach – mentors’ giving guidance to prospective applicants.

“It’s a problem that kids are applying to dermatology programs who have no business applying, who really don’t have a chance,” she said.

Dr. Bercovitch noted that most dermatology residency programs are too small and that, while the number of residency slots has been rising, it has not kept pace with increasing demand from physicians seeking residency slots. He saw no ethical reason for physicians to feel they should rein in the number of applications they file, and he said the only obligations for residency programs are to strictly adhere to the Match rules and both federal and state civil rights and labor laws and to be nondiscriminatory and avoid nepotism and conflicts of interest. Because programs cannot seriously consider nor interview several hundred applicants each year, some type of filtering is needed, and no filter is fair or perfect, he conceded.

“Filters are inherently unfair” to certain applicants, “but how else to effectively screen” hundreds of applications, Dr. Bercovitch asked.

“We need to talk about this. It’s not a good system. If we don’t talk about it, it will never change,” Dr. Grant-Kels said.

Dr. Grant-Kels and Dr. Bercovitch had no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Whether was the topic of discussion at a session on dermatoethics at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“I think it is unethical and we need to address it,” Jane M. Grant-Kels, MD, said during the session. “What we are doing through the process of physicians getting into dermatology residency programs is telling them to lie to us and to do well on a single examination,” the United States Medical Licensing Examination.

Lionel G. Bercovitch, MD, is among the dermatologists who acknowledge the unarguable fact that application rates are high but don’t see it as a crisis of credibility.

“I don’t believe that dermatology match is broken, unethical, or unfair. The match is not perfect, but it’s fair,” contended Dr. Bercovitch, professor of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I. “The problem [of an application glut] is real, but it’s not an ethical issue.”

Dr. Grant-Kels sees it in ethical terms because, in her view, “everyone is gaming the system. It makes applicants liars” when they profess interest in moving to a remote location or planning to practice a certain type of dermatology.

The “extremely competitive” process leads a majority of applicants to “shot gun” their filings to many programs such that dermatology residency programs are “deluged” with applications, Dr. Grant-Kels said. Data from the Association of American Medical Colleges for 2017 showed an average of just over 500 applications received by each U.S. dermatology residency program.

As a result, residency programs feel forced to apply blind filters that generally cull out more than a third of the applications received. Dr. Grant-Kels decried the need for programs to impose arbitrary barriers to entering dermatology based on a score from a single examination or other criteria like membership in Alpha Omega Alpha or current location.

“Blanket screening methods run the risk of excluding genuinely interested and qualified candidates who do not fall above a threshold. This violates the principal of nonmaleficence,” she said. “Screens are unfair.”

[polldaddy:{"method":"iframe","type":"survey","src":"//newspolls2017.polldaddy.com/s/dermatology-residency-match?iframe=1"}]

Dr. Grant-Kels proposed a pair of potential remedies: putting a cap on the number of applications someone can make and – a more realistic approach – mentors’ giving guidance to prospective applicants.

“It’s a problem that kids are applying to dermatology programs who have no business applying, who really don’t have a chance,” she said.

Dr. Bercovitch noted that most dermatology residency programs are too small and that, while the number of residency slots has been rising, it has not kept pace with increasing demand from physicians seeking residency slots. He saw no ethical reason for physicians to feel they should rein in the number of applications they file, and he said the only obligations for residency programs are to strictly adhere to the Match rules and both federal and state civil rights and labor laws and to be nondiscriminatory and avoid nepotism and conflicts of interest. Because programs cannot seriously consider nor interview several hundred applicants each year, some type of filtering is needed, and no filter is fair or perfect, he conceded.

“Filters are inherently unfair” to certain applicants, “but how else to effectively screen” hundreds of applications, Dr. Bercovitch asked.

“We need to talk about this. It’s not a good system. If we don’t talk about it, it will never change,” Dr. Grant-Kels said.

Dr. Grant-Kels and Dr. Bercovitch had no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Whether was the topic of discussion at a session on dermatoethics at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“I think it is unethical and we need to address it,” Jane M. Grant-Kels, MD, said during the session. “What we are doing through the process of physicians getting into dermatology residency programs is telling them to lie to us and to do well on a single examination,” the United States Medical Licensing Examination.

Lionel G. Bercovitch, MD, is among the dermatologists who acknowledge the unarguable fact that application rates are high but don’t see it as a crisis of credibility.

“I don’t believe that dermatology match is broken, unethical, or unfair. The match is not perfect, but it’s fair,” contended Dr. Bercovitch, professor of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I. “The problem [of an application glut] is real, but it’s not an ethical issue.”

Dr. Grant-Kels sees it in ethical terms because, in her view, “everyone is gaming the system. It makes applicants liars” when they profess interest in moving to a remote location or planning to practice a certain type of dermatology.

The “extremely competitive” process leads a majority of applicants to “shot gun” their filings to many programs such that dermatology residency programs are “deluged” with applications, Dr. Grant-Kels said. Data from the Association of American Medical Colleges for 2017 showed an average of just over 500 applications received by each U.S. dermatology residency program.

As a result, residency programs feel forced to apply blind filters that generally cull out more than a third of the applications received. Dr. Grant-Kels decried the need for programs to impose arbitrary barriers to entering dermatology based on a score from a single examination or other criteria like membership in Alpha Omega Alpha or current location.

“Blanket screening methods run the risk of excluding genuinely interested and qualified candidates who do not fall above a threshold. This violates the principal of nonmaleficence,” she said. “Screens are unfair.”

[polldaddy:{"method":"iframe","type":"survey","src":"//newspolls2017.polldaddy.com/s/dermatology-residency-match?iframe=1"}]

Dr. Grant-Kels proposed a pair of potential remedies: putting a cap on the number of applications someone can make and – a more realistic approach – mentors’ giving guidance to prospective applicants.