User login

Very few infants born to HCV-infected mothers receive testing

Despite the increasing prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in pregnant women, infants exposed to the disease are screened at a very low rate, Catherine A. Chappell, MD, and her associates wrote in Pediatrics.

During 2006-2014, 87,924 women gave birth at the Magee-Womens Hospital at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, of whom 1,043 had HCV. Over this time, the HCV prevalence rate increased 60%, from 1,026 cases per 100,000 women to 1,637 cases per 100,000 women. Women with HCV were more likely to be white, have Medicaid, have opiate use disorder, have other substance use disorders, and be under the age of 30 years.

Infants born to HCV-infected women are significantly more likely to be preterm and of low birth weight.

An additional 32 infants who did not receive well child care did receive HCV testing. A total of nine infants, seven in the well child group and two in the non-well child group, tested positive for HCV.

“Of the infants tested with conclusive results, the HCV transmission rate was 8.4%, with 7.2% having chronic HCV infection,” which is in line with previous reports, according to the researchers.

“Because of the poor rates of pediatric HCV screening described, future researchers should focus on interventions to increase screening in infants who are at risk for perinatal HCV acquisition by including technology to improve the transfer of maternal HCV status to the pediatric record and increase pediatric provider awareness regarding HCV screening guidelines,” the investigators concluded.

SOURCE: Chappell CA et al. Pediatrics. 2018 May 2. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3273.

Despite the increasing prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in pregnant women, infants exposed to the disease are screened at a very low rate, Catherine A. Chappell, MD, and her associates wrote in Pediatrics.

During 2006-2014, 87,924 women gave birth at the Magee-Womens Hospital at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, of whom 1,043 had HCV. Over this time, the HCV prevalence rate increased 60%, from 1,026 cases per 100,000 women to 1,637 cases per 100,000 women. Women with HCV were more likely to be white, have Medicaid, have opiate use disorder, have other substance use disorders, and be under the age of 30 years.

Infants born to HCV-infected women are significantly more likely to be preterm and of low birth weight.

An additional 32 infants who did not receive well child care did receive HCV testing. A total of nine infants, seven in the well child group and two in the non-well child group, tested positive for HCV.

“Of the infants tested with conclusive results, the HCV transmission rate was 8.4%, with 7.2% having chronic HCV infection,” which is in line with previous reports, according to the researchers.

“Because of the poor rates of pediatric HCV screening described, future researchers should focus on interventions to increase screening in infants who are at risk for perinatal HCV acquisition by including technology to improve the transfer of maternal HCV status to the pediatric record and increase pediatric provider awareness regarding HCV screening guidelines,” the investigators concluded.

SOURCE: Chappell CA et al. Pediatrics. 2018 May 2. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3273.

Despite the increasing prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in pregnant women, infants exposed to the disease are screened at a very low rate, Catherine A. Chappell, MD, and her associates wrote in Pediatrics.

During 2006-2014, 87,924 women gave birth at the Magee-Womens Hospital at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, of whom 1,043 had HCV. Over this time, the HCV prevalence rate increased 60%, from 1,026 cases per 100,000 women to 1,637 cases per 100,000 women. Women with HCV were more likely to be white, have Medicaid, have opiate use disorder, have other substance use disorders, and be under the age of 30 years.

Infants born to HCV-infected women are significantly more likely to be preterm and of low birth weight.

An additional 32 infants who did not receive well child care did receive HCV testing. A total of nine infants, seven in the well child group and two in the non-well child group, tested positive for HCV.

“Of the infants tested with conclusive results, the HCV transmission rate was 8.4%, with 7.2% having chronic HCV infection,” which is in line with previous reports, according to the researchers.

“Because of the poor rates of pediatric HCV screening described, future researchers should focus on interventions to increase screening in infants who are at risk for perinatal HCV acquisition by including technology to improve the transfer of maternal HCV status to the pediatric record and increase pediatric provider awareness regarding HCV screening guidelines,” the investigators concluded.

SOURCE: Chappell CA et al. Pediatrics. 2018 May 2. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3273.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Slime is not sublime: It may cause hand dermatitis

A young, otherwise healthy 9-year-old girl was evaluated for pruritic hand dermatitis which lasted 5 months after exposure to homemade slime. Physical exam revealed erythematous, scaly plaques on the palmar surfaces of her hands; her fingernails had onychomadesis and longitudinal ridging. Despite frequent emolliation, her dermatitis persisted. She was then treated empirically for scabies and for culture-positive Staphylococcus aureus infection, which required a full round of cephalexin and mupirocin ointment. This also did not alleviate the dermatitis. A combination of homemade borax-containing slime avoidance, brief course of high-dose corticosteroids, and frequent bland emollients was prescribed because the dermatitis was assumed to be caused by an irritant.

After review of this case and evaluation of other children with hand dermatitis, Julia K. Gittler, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and her colleagues have made a case that “slime” and new-onset hand dermatitis may be linked.

SOURCE: Gittler JK et al. J Pediatr. 2018 May 3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.03.064 .

A young, otherwise healthy 9-year-old girl was evaluated for pruritic hand dermatitis which lasted 5 months after exposure to homemade slime. Physical exam revealed erythematous, scaly plaques on the palmar surfaces of her hands; her fingernails had onychomadesis and longitudinal ridging. Despite frequent emolliation, her dermatitis persisted. She was then treated empirically for scabies and for culture-positive Staphylococcus aureus infection, which required a full round of cephalexin and mupirocin ointment. This also did not alleviate the dermatitis. A combination of homemade borax-containing slime avoidance, brief course of high-dose corticosteroids, and frequent bland emollients was prescribed because the dermatitis was assumed to be caused by an irritant.

After review of this case and evaluation of other children with hand dermatitis, Julia K. Gittler, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and her colleagues have made a case that “slime” and new-onset hand dermatitis may be linked.

SOURCE: Gittler JK et al. J Pediatr. 2018 May 3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.03.064 .

A young, otherwise healthy 9-year-old girl was evaluated for pruritic hand dermatitis which lasted 5 months after exposure to homemade slime. Physical exam revealed erythematous, scaly plaques on the palmar surfaces of her hands; her fingernails had onychomadesis and longitudinal ridging. Despite frequent emolliation, her dermatitis persisted. She was then treated empirically for scabies and for culture-positive Staphylococcus aureus infection, which required a full round of cephalexin and mupirocin ointment. This also did not alleviate the dermatitis. A combination of homemade borax-containing slime avoidance, brief course of high-dose corticosteroids, and frequent bland emollients was prescribed because the dermatitis was assumed to be caused by an irritant.

After review of this case and evaluation of other children with hand dermatitis, Julia K. Gittler, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and her colleagues have made a case that “slime” and new-onset hand dermatitis may be linked.

SOURCE: Gittler JK et al. J Pediatr. 2018 May 3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.03.064 .

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

Do black women pay a price for hair care regimens?

A new analysis of 18 hair products used by black women finds that they contain 45 endocrine-disrupting or asthma-associated chemicals, a finding that could help explain why this population suffers from higher rates of chemical exposure and hormone-related health conditions.

“We found multiples of our targeted chemicals in all of our products,” said study lead author Jessica S. Helm, PhD, of the Silent Spring Institute, Newton, Mass., in an interview. “We’re concerned about the additive effect of multiple products being used together.”

According to the study, previous research has found that, compared with white women, U.S. black women have higher urinary levels of chemicals like phthalates and parabens. Black women also have higher rates of asthma and hormone-related health conditions like uterine fibroids and infertility, Dr. Helms said.

The researchers launched their study to better understand the possible role of hair care products in raising chemical levels in black women, Dr. Helm said.

The researchers tested 18 types of hair care products shown by a 2004-2005 survey to be popular among black women: hot oil treatments, anti-frizz products and polishes, leave-in conditioners, root stimulators, hair lotions, and relaxers. Researchers had purchased the products in 2008.

The researchers detected 45 of 66 target chemicals in the samples, including some that are banned in the European Union or regulated in California based on health concerns, according to Dr. Helms.

Most of the products contained parabens and phthalates (both 78%), UV filters (72%), and cyclosiloxanes (67%).

All products contained at least 1 of 19 targeted fragrances, while “hair lotions, root stimulators, and hair relaxers contained multiple fragrance chemicals per product, with an average of five to eight targeted fragrance chemicals detected per product versus an average of two in the anti-frizz products.”

How do the findings compare with previous research? “They’re roughly consistent with what’s been found before, but potentially on the higher end,” Dr. Helms said. “For some of these chemicals, there’s not a lot of data from the past.”

Most of the chemicals aren’t listed on product labels, Dr. Helm said. “It’s possible that some of the ingredients were unintentionally added as part of manufacturing or other processes.”

Dr. Helm urged physicians to consider the connections between hair care products and chemical exposure. “Maybe there’s an opportunity to use fewer products,” she said.

Dr. Helm acknowledged that it is difficult to find hair care products that don’t include fragrance. She recommends the use of products made from plants or organic ingredients, and she pointed to a Silver Spring Institute–affiliated app called DetoxMe that offers suggestions about reducing chemical exposure from consumer products.

The study was funded by the Rose Foundation, the Goldman Fund, and Hurricane Voices Breast Cancer Foundation. The authors report no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Helm JS et al. Environ Res. 2018 Apr 25. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.03.030.

A new analysis of 18 hair products used by black women finds that they contain 45 endocrine-disrupting or asthma-associated chemicals, a finding that could help explain why this population suffers from higher rates of chemical exposure and hormone-related health conditions.

“We found multiples of our targeted chemicals in all of our products,” said study lead author Jessica S. Helm, PhD, of the Silent Spring Institute, Newton, Mass., in an interview. “We’re concerned about the additive effect of multiple products being used together.”

According to the study, previous research has found that, compared with white women, U.S. black women have higher urinary levels of chemicals like phthalates and parabens. Black women also have higher rates of asthma and hormone-related health conditions like uterine fibroids and infertility, Dr. Helms said.

The researchers launched their study to better understand the possible role of hair care products in raising chemical levels in black women, Dr. Helm said.

The researchers tested 18 types of hair care products shown by a 2004-2005 survey to be popular among black women: hot oil treatments, anti-frizz products and polishes, leave-in conditioners, root stimulators, hair lotions, and relaxers. Researchers had purchased the products in 2008.

The researchers detected 45 of 66 target chemicals in the samples, including some that are banned in the European Union or regulated in California based on health concerns, according to Dr. Helms.

Most of the products contained parabens and phthalates (both 78%), UV filters (72%), and cyclosiloxanes (67%).

All products contained at least 1 of 19 targeted fragrances, while “hair lotions, root stimulators, and hair relaxers contained multiple fragrance chemicals per product, with an average of five to eight targeted fragrance chemicals detected per product versus an average of two in the anti-frizz products.”

How do the findings compare with previous research? “They’re roughly consistent with what’s been found before, but potentially on the higher end,” Dr. Helms said. “For some of these chemicals, there’s not a lot of data from the past.”

Most of the chemicals aren’t listed on product labels, Dr. Helm said. “It’s possible that some of the ingredients were unintentionally added as part of manufacturing or other processes.”

Dr. Helm urged physicians to consider the connections between hair care products and chemical exposure. “Maybe there’s an opportunity to use fewer products,” she said.

Dr. Helm acknowledged that it is difficult to find hair care products that don’t include fragrance. She recommends the use of products made from plants or organic ingredients, and she pointed to a Silver Spring Institute–affiliated app called DetoxMe that offers suggestions about reducing chemical exposure from consumer products.

The study was funded by the Rose Foundation, the Goldman Fund, and Hurricane Voices Breast Cancer Foundation. The authors report no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Helm JS et al. Environ Res. 2018 Apr 25. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.03.030.

A new analysis of 18 hair products used by black women finds that they contain 45 endocrine-disrupting or asthma-associated chemicals, a finding that could help explain why this population suffers from higher rates of chemical exposure and hormone-related health conditions.

“We found multiples of our targeted chemicals in all of our products,” said study lead author Jessica S. Helm, PhD, of the Silent Spring Institute, Newton, Mass., in an interview. “We’re concerned about the additive effect of multiple products being used together.”

According to the study, previous research has found that, compared with white women, U.S. black women have higher urinary levels of chemicals like phthalates and parabens. Black women also have higher rates of asthma and hormone-related health conditions like uterine fibroids and infertility, Dr. Helms said.

The researchers launched their study to better understand the possible role of hair care products in raising chemical levels in black women, Dr. Helm said.

The researchers tested 18 types of hair care products shown by a 2004-2005 survey to be popular among black women: hot oil treatments, anti-frizz products and polishes, leave-in conditioners, root stimulators, hair lotions, and relaxers. Researchers had purchased the products in 2008.

The researchers detected 45 of 66 target chemicals in the samples, including some that are banned in the European Union or regulated in California based on health concerns, according to Dr. Helms.

Most of the products contained parabens and phthalates (both 78%), UV filters (72%), and cyclosiloxanes (67%).

All products contained at least 1 of 19 targeted fragrances, while “hair lotions, root stimulators, and hair relaxers contained multiple fragrance chemicals per product, with an average of five to eight targeted fragrance chemicals detected per product versus an average of two in the anti-frizz products.”

How do the findings compare with previous research? “They’re roughly consistent with what’s been found before, but potentially on the higher end,” Dr. Helms said. “For some of these chemicals, there’s not a lot of data from the past.”

Most of the chemicals aren’t listed on product labels, Dr. Helm said. “It’s possible that some of the ingredients were unintentionally added as part of manufacturing or other processes.”

Dr. Helm urged physicians to consider the connections between hair care products and chemical exposure. “Maybe there’s an opportunity to use fewer products,” she said.

Dr. Helm acknowledged that it is difficult to find hair care products that don’t include fragrance. She recommends the use of products made from plants or organic ingredients, and she pointed to a Silver Spring Institute–affiliated app called DetoxMe that offers suggestions about reducing chemical exposure from consumer products.

The study was funded by the Rose Foundation, the Goldman Fund, and Hurricane Voices Breast Cancer Foundation. The authors report no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Helm JS et al. Environ Res. 2018 Apr 25. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.03.030.

Key clinical point: Endocrine-disrupting and asthma-associated chemicals are commonly found in hair care products used by black women.

Major finding: Of the 66 target chemicals, 45 were found in the 18 products tested.

Study details: Analysis of 18 hair care products purchased in 2008.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Goldman Fund, Hurricane Voices Breast Cancer Foundation, and the Rose Foundation. The authors report no relevant disclosures.

Source: Helm JS et al. Environ Res. 2018 Apr 25. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.03.030.

Most HIV patients need treatment for acute HCV

BOSTON – Fewer than 12% of HIV infected men will clear new hepatitis C infections on their own.

If they haven’t had a 2-log drop in their hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA loads after a month, they aren’t going to clear the infection, and need direct-acting antiretrovirals (DAAs), according to an observational European study of 465 HIV patients with newly acquired HCV infections, almost all of them men who have sex with men (MSM).

The findings spoke to a hot topic at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections (CROI): DAAs for acute HCV infection in patients with HIV. It’s a pressing problem; the incidence of sexually transmitted HCV among MSM with HIV is rising worldwide.

That’s a problem with HIV coinfection, and not just because far fewer patients will rid themselves of the virus. HCV is most likely to be spread by sexual contact in the acute phase; allowing patients destined to become chronic carriers to linger without treatment means that the infection will probably spread to new partners, according to researchers at CROI,

Proactive measures could help. Swiss investigators reported a 50% drop in new HCV infections when HIV-positive MSM were screened for the infection then treated immediately with DAAs. Some at the meeting argued that HCV screening – and treatment – should be automatic for patients taking pre-exposure HIV prophylaxis, as well as for newly diagnosed HIV.

Several said that, on a population level, treatment in the acute phase would save money by preventing new infections. It’s also cheaper to treat in the acute phase because coinfected patients only need 8 weeks of DAA treatment rather than the usual 12-16 for chronic infection, according to another European study at the meeting.

“The idea of targeting acute HCV makes a lot of sense on all levels. If treatment” among patients with HIV “is two-thirds as long and more than two-thirds have persistent infection, there is no reason to hold” off just because of cost, said David Thomas, MD, director of the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, who moderated the study presentations.

Eight weeks is enough

The efficacy of an 8-week treatment course was established in a study of 63 MSM in the Netherlands and Belgium. They were 47 years old, on average, and all but three were HIV positive; two-thirds had HCV genotype 1, and the rest had genotype 4, some with extremely high viral loads.

Subjects received grazoprevir/elbasvir (Zepatier) once daily for 8 weeks, beginning at a mean of 4.5 months after their estimated infection date, and all within 6 months. Twelve weeks after the end of therapy, 59 (94%) were negative for HCV RNA on blood tests. Three of the patients who were still positive for HCV had new infections; the remaining patient had relapsed, and was the only true treatment failure.

The 2-log cutoff

“We are withholding effective treatment from people just because we’re concerned about the money,” said Christoph Boesecke, MD, of Bonn (Germany) University Hospital, who was the lead investigator in the study that found low spontaneous clearance rates with HIV coinfection.

Almost all the 465 subjects were on combination antiretroviral HIV therapy. Most had HCV genotype 1, but there were also type 3 and 4 cases. The investigators followed their subjects for at least a year after HCV infection. Just 55 (11.8%) cleared the infection on their own.

“Almost 90% of acutely infected patients face a chronic course. ... DAA drug labels, as well as clinical guidelines, need to be amended to allow usage of DAA during the acute phase of HCV infection in a high-risk population,” Dr. Boesecke and his team concluded.

Clearance was harbingered by a 2-log decline in HCV RNA by week 4. The 2-log drop cutoff is “the best predictor [we have] ... to identify patients” for early treatment. “There may be some patients you overtreat, but we have to keep in mind that we are not causing any harms with DAAs; maybe harms in terms of money, but not in terms of toxicity,” he said.

The message is beginning to get out. New European AIDS Clinical Society guidelines recommend DAA treatment for patients with HIV who don’t have a 2-log drop after a month.

‘Treatment as prevention’ works

The Swiss study added evidence to the frequent assertion at CROI that early treatment stops the spread of HCV.

The investigators screened 3,722 MSM from the Swiss HIV Cohort Study and found 178 (4.8%) men with replicating genotype 1 or 4 HCV infections. Of these cases, 31 were deemed incident and 147 chronic. Almost all the men agreed to treatment with standard-of-care DAAs, usually grazoprevir/elbasvir plus or minus ribavirin. Just about everyone had a sustained virologic response 12 weeks later.

The team rescreened the men after about a year, and found 28 infections; 16 were newly acquired, almost a 50% drop from baseline. The remaining 12 infections were chronic cases not treated earlier.

“Systemic screening followed by prompt DAA treatment can serve as a model to eliminate HCV in coinfected MSM,” said lead investigator Dominique Braun, MD, of the University of Zurich.

Dr. Boesecke is a consultant and/or speaker for AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck, and ViiV Healthcare. Dr. Thomas is a Merck consultant. Dr. Boerekamps and Dr. Braun’s studies were both funded by Merck, maker of elbasvir/grazoprevir.

SOURCE: Anne Boerekamps. 2018 CROI, Abstract 128. Christoph Boesecke. 2018 CROI, Abstract 129. Dominique Braun. 2018 CROI, Abstract 81LB.

BOSTON – Fewer than 12% of HIV infected men will clear new hepatitis C infections on their own.

If they haven’t had a 2-log drop in their hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA loads after a month, they aren’t going to clear the infection, and need direct-acting antiretrovirals (DAAs), according to an observational European study of 465 HIV patients with newly acquired HCV infections, almost all of them men who have sex with men (MSM).

The findings spoke to a hot topic at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections (CROI): DAAs for acute HCV infection in patients with HIV. It’s a pressing problem; the incidence of sexually transmitted HCV among MSM with HIV is rising worldwide.

That’s a problem with HIV coinfection, and not just because far fewer patients will rid themselves of the virus. HCV is most likely to be spread by sexual contact in the acute phase; allowing patients destined to become chronic carriers to linger without treatment means that the infection will probably spread to new partners, according to researchers at CROI,

Proactive measures could help. Swiss investigators reported a 50% drop in new HCV infections when HIV-positive MSM were screened for the infection then treated immediately with DAAs. Some at the meeting argued that HCV screening – and treatment – should be automatic for patients taking pre-exposure HIV prophylaxis, as well as for newly diagnosed HIV.

Several said that, on a population level, treatment in the acute phase would save money by preventing new infections. It’s also cheaper to treat in the acute phase because coinfected patients only need 8 weeks of DAA treatment rather than the usual 12-16 for chronic infection, according to another European study at the meeting.

“The idea of targeting acute HCV makes a lot of sense on all levels. If treatment” among patients with HIV “is two-thirds as long and more than two-thirds have persistent infection, there is no reason to hold” off just because of cost, said David Thomas, MD, director of the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, who moderated the study presentations.

Eight weeks is enough

The efficacy of an 8-week treatment course was established in a study of 63 MSM in the Netherlands and Belgium. They were 47 years old, on average, and all but three were HIV positive; two-thirds had HCV genotype 1, and the rest had genotype 4, some with extremely high viral loads.

Subjects received grazoprevir/elbasvir (Zepatier) once daily for 8 weeks, beginning at a mean of 4.5 months after their estimated infection date, and all within 6 months. Twelve weeks after the end of therapy, 59 (94%) were negative for HCV RNA on blood tests. Three of the patients who were still positive for HCV had new infections; the remaining patient had relapsed, and was the only true treatment failure.

The 2-log cutoff

“We are withholding effective treatment from people just because we’re concerned about the money,” said Christoph Boesecke, MD, of Bonn (Germany) University Hospital, who was the lead investigator in the study that found low spontaneous clearance rates with HIV coinfection.

Almost all the 465 subjects were on combination antiretroviral HIV therapy. Most had HCV genotype 1, but there were also type 3 and 4 cases. The investigators followed their subjects for at least a year after HCV infection. Just 55 (11.8%) cleared the infection on their own.

“Almost 90% of acutely infected patients face a chronic course. ... DAA drug labels, as well as clinical guidelines, need to be amended to allow usage of DAA during the acute phase of HCV infection in a high-risk population,” Dr. Boesecke and his team concluded.

Clearance was harbingered by a 2-log decline in HCV RNA by week 4. The 2-log drop cutoff is “the best predictor [we have] ... to identify patients” for early treatment. “There may be some patients you overtreat, but we have to keep in mind that we are not causing any harms with DAAs; maybe harms in terms of money, but not in terms of toxicity,” he said.

The message is beginning to get out. New European AIDS Clinical Society guidelines recommend DAA treatment for patients with HIV who don’t have a 2-log drop after a month.

‘Treatment as prevention’ works

The Swiss study added evidence to the frequent assertion at CROI that early treatment stops the spread of HCV.

The investigators screened 3,722 MSM from the Swiss HIV Cohort Study and found 178 (4.8%) men with replicating genotype 1 or 4 HCV infections. Of these cases, 31 were deemed incident and 147 chronic. Almost all the men agreed to treatment with standard-of-care DAAs, usually grazoprevir/elbasvir plus or minus ribavirin. Just about everyone had a sustained virologic response 12 weeks later.

The team rescreened the men after about a year, and found 28 infections; 16 were newly acquired, almost a 50% drop from baseline. The remaining 12 infections were chronic cases not treated earlier.

“Systemic screening followed by prompt DAA treatment can serve as a model to eliminate HCV in coinfected MSM,” said lead investigator Dominique Braun, MD, of the University of Zurich.

Dr. Boesecke is a consultant and/or speaker for AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck, and ViiV Healthcare. Dr. Thomas is a Merck consultant. Dr. Boerekamps and Dr. Braun’s studies were both funded by Merck, maker of elbasvir/grazoprevir.

SOURCE: Anne Boerekamps. 2018 CROI, Abstract 128. Christoph Boesecke. 2018 CROI, Abstract 129. Dominique Braun. 2018 CROI, Abstract 81LB.

BOSTON – Fewer than 12% of HIV infected men will clear new hepatitis C infections on their own.

If they haven’t had a 2-log drop in their hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA loads after a month, they aren’t going to clear the infection, and need direct-acting antiretrovirals (DAAs), according to an observational European study of 465 HIV patients with newly acquired HCV infections, almost all of them men who have sex with men (MSM).

The findings spoke to a hot topic at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections (CROI): DAAs for acute HCV infection in patients with HIV. It’s a pressing problem; the incidence of sexually transmitted HCV among MSM with HIV is rising worldwide.

That’s a problem with HIV coinfection, and not just because far fewer patients will rid themselves of the virus. HCV is most likely to be spread by sexual contact in the acute phase; allowing patients destined to become chronic carriers to linger without treatment means that the infection will probably spread to new partners, according to researchers at CROI,

Proactive measures could help. Swiss investigators reported a 50% drop in new HCV infections when HIV-positive MSM were screened for the infection then treated immediately with DAAs. Some at the meeting argued that HCV screening – and treatment – should be automatic for patients taking pre-exposure HIV prophylaxis, as well as for newly diagnosed HIV.

Several said that, on a population level, treatment in the acute phase would save money by preventing new infections. It’s also cheaper to treat in the acute phase because coinfected patients only need 8 weeks of DAA treatment rather than the usual 12-16 for chronic infection, according to another European study at the meeting.

“The idea of targeting acute HCV makes a lot of sense on all levels. If treatment” among patients with HIV “is two-thirds as long and more than two-thirds have persistent infection, there is no reason to hold” off just because of cost, said David Thomas, MD, director of the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, who moderated the study presentations.

Eight weeks is enough

The efficacy of an 8-week treatment course was established in a study of 63 MSM in the Netherlands and Belgium. They were 47 years old, on average, and all but three were HIV positive; two-thirds had HCV genotype 1, and the rest had genotype 4, some with extremely high viral loads.

Subjects received grazoprevir/elbasvir (Zepatier) once daily for 8 weeks, beginning at a mean of 4.5 months after their estimated infection date, and all within 6 months. Twelve weeks after the end of therapy, 59 (94%) were negative for HCV RNA on blood tests. Three of the patients who were still positive for HCV had new infections; the remaining patient had relapsed, and was the only true treatment failure.

The 2-log cutoff

“We are withholding effective treatment from people just because we’re concerned about the money,” said Christoph Boesecke, MD, of Bonn (Germany) University Hospital, who was the lead investigator in the study that found low spontaneous clearance rates with HIV coinfection.

Almost all the 465 subjects were on combination antiretroviral HIV therapy. Most had HCV genotype 1, but there were also type 3 and 4 cases. The investigators followed their subjects for at least a year after HCV infection. Just 55 (11.8%) cleared the infection on their own.

“Almost 90% of acutely infected patients face a chronic course. ... DAA drug labels, as well as clinical guidelines, need to be amended to allow usage of DAA during the acute phase of HCV infection in a high-risk population,” Dr. Boesecke and his team concluded.

Clearance was harbingered by a 2-log decline in HCV RNA by week 4. The 2-log drop cutoff is “the best predictor [we have] ... to identify patients” for early treatment. “There may be some patients you overtreat, but we have to keep in mind that we are not causing any harms with DAAs; maybe harms in terms of money, but not in terms of toxicity,” he said.

The message is beginning to get out. New European AIDS Clinical Society guidelines recommend DAA treatment for patients with HIV who don’t have a 2-log drop after a month.

‘Treatment as prevention’ works

The Swiss study added evidence to the frequent assertion at CROI that early treatment stops the spread of HCV.

The investigators screened 3,722 MSM from the Swiss HIV Cohort Study and found 178 (4.8%) men with replicating genotype 1 or 4 HCV infections. Of these cases, 31 were deemed incident and 147 chronic. Almost all the men agreed to treatment with standard-of-care DAAs, usually grazoprevir/elbasvir plus or minus ribavirin. Just about everyone had a sustained virologic response 12 weeks later.

The team rescreened the men after about a year, and found 28 infections; 16 were newly acquired, almost a 50% drop from baseline. The remaining 12 infections were chronic cases not treated earlier.

“Systemic screening followed by prompt DAA treatment can serve as a model to eliminate HCV in coinfected MSM,” said lead investigator Dominique Braun, MD, of the University of Zurich.

Dr. Boesecke is a consultant and/or speaker for AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck, and ViiV Healthcare. Dr. Thomas is a Merck consultant. Dr. Boerekamps and Dr. Braun’s studies were both funded by Merck, maker of elbasvir/grazoprevir.

SOURCE: Anne Boerekamps. 2018 CROI, Abstract 128. Christoph Boesecke. 2018 CROI, Abstract 129. Dominique Braun. 2018 CROI, Abstract 81LB.

REPORTING FROM CROI

Family history of psoriasis and PsA predicts disease phenotype

BOSTON – Family history appeared to predict disease phenotypes for patients with psoriatic arthritis, according to the results of data presented at the 2018 Spondyloarthritis Treatment and Research Network annual meeting.

“Family history of psoriatic arthritis, compared with psoriasis, had increased risk for deformities and lower risk for plaque psoriasis,” Dilek Solmaz, MD, said.

Of the 1,393 patients analyzed, 444 had a family history of either psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. Of those, 335 had only psoriasis in their family, while 74 patients had a family history of psoriatic arthritis.

The researchers included onset age, sex, nail involvement, enthesitis, presence of deformities, and plaque type.

In a univariate analysis, psoriasis was a risk factors for younger onset, female sex, nail disease, enthesitis, plaque type psoriasis, and not achieving minimal disease activity. Family history of psoriatic arthritis appeared to be a significant risk factor for deformations (odds ratio, 2.557) and a lower risk for plaque psoriasis (OR, 0.417).

In a multivariate analysis for family history, patients who had a family history of psoriatic arthritis had an increased risk for deformities, compared with patients with family history of psoriasis (OR, 2.143). Those patients also appeared to have a decreased risk for experiencing plaque psoriasis, compared with patients with a history psoriasis (OR, 0.324). All ORs were within the 95% confidence intervals.

“The differences between family history of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and their relationship between pustular and plaque phenotypes could point to different genetic backgrounds, as well as pathogenic mechanisms,” Dr. Solmaz said.

BOSTON – Family history appeared to predict disease phenotypes for patients with psoriatic arthritis, according to the results of data presented at the 2018 Spondyloarthritis Treatment and Research Network annual meeting.

“Family history of psoriatic arthritis, compared with psoriasis, had increased risk for deformities and lower risk for plaque psoriasis,” Dilek Solmaz, MD, said.

Of the 1,393 patients analyzed, 444 had a family history of either psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. Of those, 335 had only psoriasis in their family, while 74 patients had a family history of psoriatic arthritis.

The researchers included onset age, sex, nail involvement, enthesitis, presence of deformities, and plaque type.

In a univariate analysis, psoriasis was a risk factors for younger onset, female sex, nail disease, enthesitis, plaque type psoriasis, and not achieving minimal disease activity. Family history of psoriatic arthritis appeared to be a significant risk factor for deformations (odds ratio, 2.557) and a lower risk for plaque psoriasis (OR, 0.417).

In a multivariate analysis for family history, patients who had a family history of psoriatic arthritis had an increased risk for deformities, compared with patients with family history of psoriasis (OR, 2.143). Those patients also appeared to have a decreased risk for experiencing plaque psoriasis, compared with patients with a history psoriasis (OR, 0.324). All ORs were within the 95% confidence intervals.

“The differences between family history of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and their relationship between pustular and plaque phenotypes could point to different genetic backgrounds, as well as pathogenic mechanisms,” Dr. Solmaz said.

BOSTON – Family history appeared to predict disease phenotypes for patients with psoriatic arthritis, according to the results of data presented at the 2018 Spondyloarthritis Treatment and Research Network annual meeting.

“Family history of psoriatic arthritis, compared with psoriasis, had increased risk for deformities and lower risk for plaque psoriasis,” Dilek Solmaz, MD, said.

Of the 1,393 patients analyzed, 444 had a family history of either psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. Of those, 335 had only psoriasis in their family, while 74 patients had a family history of psoriatic arthritis.

The researchers included onset age, sex, nail involvement, enthesitis, presence of deformities, and plaque type.

In a univariate analysis, psoriasis was a risk factors for younger onset, female sex, nail disease, enthesitis, plaque type psoriasis, and not achieving minimal disease activity. Family history of psoriatic arthritis appeared to be a significant risk factor for deformations (odds ratio, 2.557) and a lower risk for plaque psoriasis (OR, 0.417).

In a multivariate analysis for family history, patients who had a family history of psoriatic arthritis had an increased risk for deformities, compared with patients with family history of psoriasis (OR, 2.143). Those patients also appeared to have a decreased risk for experiencing plaque psoriasis, compared with patients with a history psoriasis (OR, 0.324). All ORs were within the 95% confidence intervals.

“The differences between family history of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and their relationship between pustular and plaque phenotypes could point to different genetic backgrounds, as well as pathogenic mechanisms,” Dr. Solmaz said.

REPORTING FROM SPARTAN 2018

Key clinical point: Family history of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis appear linked with disease phenotypes.

Major finding: Family history of PsA, compared with that of psoriasis, had increased risk for deformities and lower risk for plaque psoriasis.

Study details: Retrospective data from the poster session of SPARTAN 18

Disclosures: The study was funded in part by the UCB Axial Fellowship Grant.

Poor parent-infant relationship may affect a child’s motor skill development

TORONTO – In what is believed to be a landmark finding, researchers have shown than modifiable risk factors, such as parent-infant relationships, may play a role in preventing children from developing high motor problems during early life.

“Our findings suggest that early health and clinical problems, such as neonatal complications and abnormal neonatal neurological status, are useful indicators to help identify children at risk of poor motor development,” lead study author Nicole Baumann said in an interview in advance of the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. “Additionally, as a possible implication, children may benefit in motor development from early interventions that incorporate and focus on improving parent-infant relationships.”

For the current study, she and her associates investigated motor development using data from two different cohorts: the Bavarian Longitudinal Study in Germany (BLS) and the Arvo Ylppö Longitudinal Study in Finland (AYLS). A total of 4,741 and 1,423 children, respectively, underwent assessment from birth to age 56 months. Motor functioning was evaluated via standard physical and neurological assessments at birth and at 5, 20, and 56 months. Perinatal, neonatal, and early environmental information was collected at birth and at 5 months via medical records and reports from parents and research nurses.

The researchers identified two distinct trajectories of motor development problems from birth to 56 months: low (94.3% of BLS and 97.3% of AYLS) and high (5.7% of BLS and 2.7% of AYLS) motor problems.

In the BLS cohort, high motor problem trajectory was predicted by poor parent-infant relationship, such as the mother feeling insecure when taking care of the infant at home (OR 1.52); abnormal neonatal neurological status (odds ratio, 1.16); neonatal complications (OR, 1.12); and duration of initial hospitalization (OR, 1.02).

In the AYLS cohort, high motor problem trajectory was also predicted by abnormal neonatal neurological status (OR, 1.69) and duration of hospitalization (OR, 1.02). Although neonatal complications (OR, 1.08) and poor parent-infant relationship (OR, 1.09) did not significantly predict high motor problem trajectory in the AYLS cohort, trends identified were comparable with those obtained from the BLS cohort.

“Most surprising was that one of the four risk factors that remained as independent predictors of high motor problem trajectory was poor parent-infant relationship,” Ms. Baumann said. “As far as we are aware, parent-infant relationship has not been previously reported as a predictor of poor motor development.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that nearly 33% of children could not be assessed throughout the study period because of dropout. “Families with children who had poor health and were socially disadvantaged were less likely to continue participation, and may even suggest that our findings have an even larger effect than reported,” Ms. Baumann said. “This is a problem that affects many longitudinal studies, and it may affect group comparisons. However, simulations have shown that even when dropout is selective or correlated with the outcome that predictions only marginally change (Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195[3]:249-56).”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

TORONTO – In what is believed to be a landmark finding, researchers have shown than modifiable risk factors, such as parent-infant relationships, may play a role in preventing children from developing high motor problems during early life.

“Our findings suggest that early health and clinical problems, such as neonatal complications and abnormal neonatal neurological status, are useful indicators to help identify children at risk of poor motor development,” lead study author Nicole Baumann said in an interview in advance of the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. “Additionally, as a possible implication, children may benefit in motor development from early interventions that incorporate and focus on improving parent-infant relationships.”

For the current study, she and her associates investigated motor development using data from two different cohorts: the Bavarian Longitudinal Study in Germany (BLS) and the Arvo Ylppö Longitudinal Study in Finland (AYLS). A total of 4,741 and 1,423 children, respectively, underwent assessment from birth to age 56 months. Motor functioning was evaluated via standard physical and neurological assessments at birth and at 5, 20, and 56 months. Perinatal, neonatal, and early environmental information was collected at birth and at 5 months via medical records and reports from parents and research nurses.

The researchers identified two distinct trajectories of motor development problems from birth to 56 months: low (94.3% of BLS and 97.3% of AYLS) and high (5.7% of BLS and 2.7% of AYLS) motor problems.

In the BLS cohort, high motor problem trajectory was predicted by poor parent-infant relationship, such as the mother feeling insecure when taking care of the infant at home (OR 1.52); abnormal neonatal neurological status (odds ratio, 1.16); neonatal complications (OR, 1.12); and duration of initial hospitalization (OR, 1.02).

In the AYLS cohort, high motor problem trajectory was also predicted by abnormal neonatal neurological status (OR, 1.69) and duration of hospitalization (OR, 1.02). Although neonatal complications (OR, 1.08) and poor parent-infant relationship (OR, 1.09) did not significantly predict high motor problem trajectory in the AYLS cohort, trends identified were comparable with those obtained from the BLS cohort.

“Most surprising was that one of the four risk factors that remained as independent predictors of high motor problem trajectory was poor parent-infant relationship,” Ms. Baumann said. “As far as we are aware, parent-infant relationship has not been previously reported as a predictor of poor motor development.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that nearly 33% of children could not be assessed throughout the study period because of dropout. “Families with children who had poor health and were socially disadvantaged were less likely to continue participation, and may even suggest that our findings have an even larger effect than reported,” Ms. Baumann said. “This is a problem that affects many longitudinal studies, and it may affect group comparisons. However, simulations have shown that even when dropout is selective or correlated with the outcome that predictions only marginally change (Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195[3]:249-56).”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

TORONTO – In what is believed to be a landmark finding, researchers have shown than modifiable risk factors, such as parent-infant relationships, may play a role in preventing children from developing high motor problems during early life.

“Our findings suggest that early health and clinical problems, such as neonatal complications and abnormal neonatal neurological status, are useful indicators to help identify children at risk of poor motor development,” lead study author Nicole Baumann said in an interview in advance of the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. “Additionally, as a possible implication, children may benefit in motor development from early interventions that incorporate and focus on improving parent-infant relationships.”

For the current study, she and her associates investigated motor development using data from two different cohorts: the Bavarian Longitudinal Study in Germany (BLS) and the Arvo Ylppö Longitudinal Study in Finland (AYLS). A total of 4,741 and 1,423 children, respectively, underwent assessment from birth to age 56 months. Motor functioning was evaluated via standard physical and neurological assessments at birth and at 5, 20, and 56 months. Perinatal, neonatal, and early environmental information was collected at birth and at 5 months via medical records and reports from parents and research nurses.

The researchers identified two distinct trajectories of motor development problems from birth to 56 months: low (94.3% of BLS and 97.3% of AYLS) and high (5.7% of BLS and 2.7% of AYLS) motor problems.

In the BLS cohort, high motor problem trajectory was predicted by poor parent-infant relationship, such as the mother feeling insecure when taking care of the infant at home (OR 1.52); abnormal neonatal neurological status (odds ratio, 1.16); neonatal complications (OR, 1.12); and duration of initial hospitalization (OR, 1.02).

In the AYLS cohort, high motor problem trajectory was also predicted by abnormal neonatal neurological status (OR, 1.69) and duration of hospitalization (OR, 1.02). Although neonatal complications (OR, 1.08) and poor parent-infant relationship (OR, 1.09) did not significantly predict high motor problem trajectory in the AYLS cohort, trends identified were comparable with those obtained from the BLS cohort.

“Most surprising was that one of the four risk factors that remained as independent predictors of high motor problem trajectory was poor parent-infant relationship,” Ms. Baumann said. “As far as we are aware, parent-infant relationship has not been previously reported as a predictor of poor motor development.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that nearly 33% of children could not be assessed throughout the study period because of dropout. “Families with children who had poor health and were socially disadvantaged were less likely to continue participation, and may even suggest that our findings have an even larger effect than reported,” Ms. Baumann said. “This is a problem that affects many longitudinal studies, and it may affect group comparisons. However, simulations have shown that even when dropout is selective or correlated with the outcome that predictions only marginally change (Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195[3]:249-56).”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

AT PAS 2018

Key clinical point: Four risk factors are independent predictors of high motor problem trajectory in young children.

Major finding: In the Bavarian Longitudinal Study cohort, high motor problem trajectory was predicted by abnormal neonatal neurological status (odds ratio, 1.16), duration of initial hospitalization (OR 1.02), neonatal complications (OR 1.12), and poor parent-infant relationship (OR 1.52).

Study details: A longitudinal analysis of 4,741 children from the Bavarian Longitudinal Study in Germany and 1,423 children from the Arvo Ylppö Longitudinal Study in Finland.

Disclosures: Ms. Baumann reported having no financial disclosures.

Objective compensation systems can eliminate gender pay gap

Innovative compensation systems aimed at achieving fairness, consistency, and transparency in

At the University of Alabama at Birmingham, research showed that a newly adopted compensation system – one not even designed to address gender disparities – boosted the salaries of female surgeons from 46% to 72% of the salaries of their male colleagues. A gender salary gap also narrowed at Oregon Health & Sciences University, Portland, after a new compensation policy was put into place.

The two studies were presented at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Recent studies have revealed significant gaps in the salaries of female physicians, compared with their male counterparts. The challenge in this kind of study is to fairly compare salaries by adjusting for hours worked, time taken for family obligations, negotiated starting salary, and other factors that play into salary level.

A 2016 analysis of 590 surgeons at 24 medical schools found that men made a mean of $323,000 a year, compared with $270,000 among women. The gap persisted after adjustment for factors like years of experience and publication history at $280,000 (women) and $312,000 (men). The pay gap among 744 surgical subspecialists was even wider at $343,000 (men) versus $267,000 (women). After adjustment, male surgical subspecialists made $329,000, while women made $285,000 (JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176[9]:1294-304).

In 2015, the administration at Oregon Health & Sciences University instituted a school-wide “Faculty First” compensation plan. It aligns faculty pay – based on specialty and academic rank – with 3-year rolling median salaries in the Western region as reported by the Association of American Medical Colleges.

A study of compensation at OHSU led by Heather E. Hoops, MD, examined the salaries earned by certain department of surgery faculty during 2009-2017 and promotion and retention rates during 1998-2007. The study excluded instructors, the chair of the department, and some other faculty members whose salaries were based on specific bonuses.

The researchers found that prior to the change in 2015, the 24 female faculty made significantly less than the 62 men (P = .004). After the “Faculty First” initiative was implemented in 2015, salaries for both genders grew significantly and gender salary gap was virtually closed after that time.

The researchers found no gender disparity in time to promotion among the faculty. No significant difference was found in the rate of departure between male and female faculty (P = .73), although women who were not promoted tended to leave more quickly than their male counterparts.

“Objective compensation plans may work by mitigating gender-based implicit bias in the salary negotiation process and differences in salary negotiation style between females and males,” Dr. Hoops and her coauthors wrote. “However, objective compensation plans do not supplant the need for other institutional interventions, such as implicit bias training and objective and transparent promotion criteria, to improve gender equality among surgeons.”

In the other study, University of Alabama at Birmingham researchers analyzed surgeon salaries earned during 2014-2017. In 2017, the university switched some surgeons to a new compensation system based on work revenue value units with incentives.

In an interview, study lead author Melanie Morris, MD, said the new pay system unexpectedly reduced the gender pay gap. “The rationale for this department compensation plan was to create a fair and transparent compensation system for all faculty,” she said. “In doing so, this plan unintentionally led to these described changes to equalize an unrecognized disparity. We are proud of the result and recognize there is still more work to do. Each institution should know their own data to see if a gender pay disparity exists and devise a plan to address it.”

OHSU Department of Surgery funded the Oregon study. The study authors report no disclosures. The University of Alabama at Birmingham study reports no funding. The study authors report no disclosures.

The complete manuscript of these studies and their presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 138th Annual Meeting, April 2018, in Phoenix, is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

SOURCE: Morris MS et al. ASA Annual Meeting 2018, Abstract 4. Hoops HE et al. ASA Annual Meeting 2018, Abstract 9.

Innovative compensation systems aimed at achieving fairness, consistency, and transparency in

At the University of Alabama at Birmingham, research showed that a newly adopted compensation system – one not even designed to address gender disparities – boosted the salaries of female surgeons from 46% to 72% of the salaries of their male colleagues. A gender salary gap also narrowed at Oregon Health & Sciences University, Portland, after a new compensation policy was put into place.

The two studies were presented at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Recent studies have revealed significant gaps in the salaries of female physicians, compared with their male counterparts. The challenge in this kind of study is to fairly compare salaries by adjusting for hours worked, time taken for family obligations, negotiated starting salary, and other factors that play into salary level.

A 2016 analysis of 590 surgeons at 24 medical schools found that men made a mean of $323,000 a year, compared with $270,000 among women. The gap persisted after adjustment for factors like years of experience and publication history at $280,000 (women) and $312,000 (men). The pay gap among 744 surgical subspecialists was even wider at $343,000 (men) versus $267,000 (women). After adjustment, male surgical subspecialists made $329,000, while women made $285,000 (JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176[9]:1294-304).

In 2015, the administration at Oregon Health & Sciences University instituted a school-wide “Faculty First” compensation plan. It aligns faculty pay – based on specialty and academic rank – with 3-year rolling median salaries in the Western region as reported by the Association of American Medical Colleges.

A study of compensation at OHSU led by Heather E. Hoops, MD, examined the salaries earned by certain department of surgery faculty during 2009-2017 and promotion and retention rates during 1998-2007. The study excluded instructors, the chair of the department, and some other faculty members whose salaries were based on specific bonuses.

The researchers found that prior to the change in 2015, the 24 female faculty made significantly less than the 62 men (P = .004). After the “Faculty First” initiative was implemented in 2015, salaries for both genders grew significantly and gender salary gap was virtually closed after that time.

The researchers found no gender disparity in time to promotion among the faculty. No significant difference was found in the rate of departure between male and female faculty (P = .73), although women who were not promoted tended to leave more quickly than their male counterparts.

“Objective compensation plans may work by mitigating gender-based implicit bias in the salary negotiation process and differences in salary negotiation style between females and males,” Dr. Hoops and her coauthors wrote. “However, objective compensation plans do not supplant the need for other institutional interventions, such as implicit bias training and objective and transparent promotion criteria, to improve gender equality among surgeons.”

In the other study, University of Alabama at Birmingham researchers analyzed surgeon salaries earned during 2014-2017. In 2017, the university switched some surgeons to a new compensation system based on work revenue value units with incentives.

In an interview, study lead author Melanie Morris, MD, said the new pay system unexpectedly reduced the gender pay gap. “The rationale for this department compensation plan was to create a fair and transparent compensation system for all faculty,” she said. “In doing so, this plan unintentionally led to these described changes to equalize an unrecognized disparity. We are proud of the result and recognize there is still more work to do. Each institution should know their own data to see if a gender pay disparity exists and devise a plan to address it.”

OHSU Department of Surgery funded the Oregon study. The study authors report no disclosures. The University of Alabama at Birmingham study reports no funding. The study authors report no disclosures.

The complete manuscript of these studies and their presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 138th Annual Meeting, April 2018, in Phoenix, is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

SOURCE: Morris MS et al. ASA Annual Meeting 2018, Abstract 4. Hoops HE et al. ASA Annual Meeting 2018, Abstract 9.

Innovative compensation systems aimed at achieving fairness, consistency, and transparency in

At the University of Alabama at Birmingham, research showed that a newly adopted compensation system – one not even designed to address gender disparities – boosted the salaries of female surgeons from 46% to 72% of the salaries of their male colleagues. A gender salary gap also narrowed at Oregon Health & Sciences University, Portland, after a new compensation policy was put into place.

The two studies were presented at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Recent studies have revealed significant gaps in the salaries of female physicians, compared with their male counterparts. The challenge in this kind of study is to fairly compare salaries by adjusting for hours worked, time taken for family obligations, negotiated starting salary, and other factors that play into salary level.

A 2016 analysis of 590 surgeons at 24 medical schools found that men made a mean of $323,000 a year, compared with $270,000 among women. The gap persisted after adjustment for factors like years of experience and publication history at $280,000 (women) and $312,000 (men). The pay gap among 744 surgical subspecialists was even wider at $343,000 (men) versus $267,000 (women). After adjustment, male surgical subspecialists made $329,000, while women made $285,000 (JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176[9]:1294-304).

In 2015, the administration at Oregon Health & Sciences University instituted a school-wide “Faculty First” compensation plan. It aligns faculty pay – based on specialty and academic rank – with 3-year rolling median salaries in the Western region as reported by the Association of American Medical Colleges.

A study of compensation at OHSU led by Heather E. Hoops, MD, examined the salaries earned by certain department of surgery faculty during 2009-2017 and promotion and retention rates during 1998-2007. The study excluded instructors, the chair of the department, and some other faculty members whose salaries were based on specific bonuses.

The researchers found that prior to the change in 2015, the 24 female faculty made significantly less than the 62 men (P = .004). After the “Faculty First” initiative was implemented in 2015, salaries for both genders grew significantly and gender salary gap was virtually closed after that time.

The researchers found no gender disparity in time to promotion among the faculty. No significant difference was found in the rate of departure between male and female faculty (P = .73), although women who were not promoted tended to leave more quickly than their male counterparts.

“Objective compensation plans may work by mitigating gender-based implicit bias in the salary negotiation process and differences in salary negotiation style between females and males,” Dr. Hoops and her coauthors wrote. “However, objective compensation plans do not supplant the need for other institutional interventions, such as implicit bias training and objective and transparent promotion criteria, to improve gender equality among surgeons.”

In the other study, University of Alabama at Birmingham researchers analyzed surgeon salaries earned during 2014-2017. In 2017, the university switched some surgeons to a new compensation system based on work revenue value units with incentives.

In an interview, study lead author Melanie Morris, MD, said the new pay system unexpectedly reduced the gender pay gap. “The rationale for this department compensation plan was to create a fair and transparent compensation system for all faculty,” she said. “In doing so, this plan unintentionally led to these described changes to equalize an unrecognized disparity. We are proud of the result and recognize there is still more work to do. Each institution should know their own data to see if a gender pay disparity exists and devise a plan to address it.”

OHSU Department of Surgery funded the Oregon study. The study authors report no disclosures. The University of Alabama at Birmingham study reports no funding. The study authors report no disclosures.

The complete manuscript of these studies and their presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 138th Annual Meeting, April 2018, in Phoenix, is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

SOURCE: Morris MS et al. ASA Annual Meeting 2018, Abstract 4. Hoops HE et al. ASA Annual Meeting 2018, Abstract 9.

Patient Knowledge of and Barriers to Breast, Colon, and Cervical Cancer Screenings: A Cross-Sectional Survey of TRICARE Beneficiaries (FULL)

The National Defense Appropriations Act for fiscal year 2009, Subtitle B, waived copayments for preventive cancer screening services for all TRICARE beneficiaries, excluding Medicare-eligible beneficiaries.1 These preventive services include screening for colorectal cancer (CRC), breast cancer, and cervical cancer based on current guidelines (eAppendix1).

Despite having unrestricted access to these cancer screenings, TRICARE Prime beneficiaries report overall screening completion rates that are below the national commercial benchmarks established by the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) for all 3 cancer types.2 Specifically, among TRICARE Prime beneficiaries enrolled in the western region of the U.S. in October 2013, the reported breast cancer screening rate was 61.6% (43,138/69,976) for women aged 42 to 69 years, which is well below the HEDIS 75th percentile of 76%. Similarly, the reported rate of cervical cancer screening among women aged 24 to 64 years was 68.3% (63,523/92,946), well below the HEDIS 75th percentile of 79%. Last, the reported rate of CRC screening among male and female TRICARE Prime members aged 51 to 75 years was 61.6% (52,860/85,827), also below the 2013 HEDIS 75th percentile of 63% based on internal review of TRICARE data used for HEDIS reporting.

Given the reported low screening rates, the Defense Health Agency (DHA) performed a cross-sectional survey to assess TRICARE Prime West region beneficiaries’ knowledge and understanding of preventive health screening, specifically for breast cancer, cervical cancer, and CRC, and to identify any potential barriers to access for these screenings.

Methods

A mostly closed-ended, 42-item telephone survey was designed and conducted (eAppendix2)

All women participating in the survey, regardless of age, were asked questions regarding cervical cancer screening. Women aged ≥ 42 years additionally were asked a second set of survey questions specific to breast cancer screening, and women aged between 51 and 64 years were asked a third set of questions related to CRC screening. The ages selected were 1 to 2 years after the recommended age for the respective screening to ensure adequate follow-up time for the member to obtain the screening. Men included in the survey were asked questions related only to CRC screening.

The target survey sample was 3,500 beneficiaries, separated into the following 4 strata: women aged 21 to 64 years of age enrolled in the direct care system (n = 1,250); women aged 21 to 64 years enrolled in the purchased (commercial) care network (n = 1,250); men aged 51 to 64 years enrolled in the direct care system (n = 500); and men aged 51 to 64 years enrolled in the purchased care network (n = 500). The random sample was drawn from an overall population of about 35,000 members. Sampling was performed without replacement until the target number of surveys was achieved. Survey completion was defined as the respondent having reached the end of the survey questionnaire but not necessarily having answered every question.

Data Elements

The preventive health survey collected information on beneficiaries’ knowledge of and satisfaction with their PCM, the primary location where they sought health care in the previous 12 months, preference for scheduling cancer screening tests, and general knowledge about the frequency and type of screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers. Responses were scored based on guidelines effective as of 2009. In addition, the survey collected information on the beneficiary’s overall health status, current age, highest level of education achieved, current employment status, place of residence (on or off a military installation), race, and whether the beneficiary carried other health insurance aside from TRICARE.

Survey Mode and Fielding

A sampling population of eligible beneficiaries was created from a database of all TRICARE Prime beneficiaries. An automated system was used to randomly draw potential participants from the sample. Survey interviewers were given the beneficiary’s name and telephone number but no other identifiable information. Phone numbers from the sample were dialed up to 6 times before the number was classified as a “no answer.” Interviewers read to each beneficiary a statement describing the survey and participation risk and benefits and explained that participation was voluntary and the participant could end the survey at any time without penalty or prejudice. The survey commenced only after verbal consent was obtained.

Sample Weighting and Statistical Analysis

Each survey record was weighted to control for potential bias associated with unequal rates of noncoverage and nonresponse in the sampled population. A design weight was calculated as the ratio of the frame size and the sample size in each stratum. For each stratum, an adjusted response rate (RR) was calculated as the number of completed surveys divided by the number of eligible respondents. Since all respondents were eligible, the RR was not adjusted. The ratio of the design weight to the adjusted RR was calculated and assigned to each survey.

Frequency distributions and descriptive statistics were calculated for all close-ended survey items. Open-ended survey items were summarized and assessed qualitatively. When appropriate, open-ended responses were categorized and included in descriptive analyses. No formal statistical testing was performed.

Results

A total of 6,563 beneficiaries were contacted, and 3,688 agreed to participate (56%), resulting in 3,500 TRICARE beneficiaries completing the survey (95% completion rate), of whom 71% (2,500) were female. The overall cooperation rates were similar across the 4 strata. Interviews ceased once 3,500 surveys were completed. The largest distribution of respondents was aged between 55 and 64 years (37%) (Table 1). Respondents aged 21 to 24 years comprised the smallest percentage of the sample (7%). Nearly a third of respondents were dependents of ADSMs (30%), another 30% were retirees, and most respondents self-identified as white (Table 1).

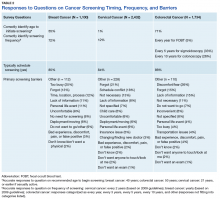

Barriers to Screening

A series of survey questions was asked about specific barriers to cancer screening, including the convenience of appointment times for the respondent’s last cancer screening. The majority (69%, 2,415 of 3,500) responded that the appointment times were convenient. Among those who stated that times were not convenient and those who had not scheduled an examination, 66% responded that they did not know or were not sure how to schedule a cancer screening test.

Screening Preferences

Less than half of survey respondents (48%) reported that they received screening guideline information from their physician or provider; 24% reported that they performed their own research. Only 9% reported that they learned about the guidelines through TRICARE materials, and 7% of respondents indicated that media, family, or friends were their source of screening information.

The survey respondents who indicated that they had not scheduled a screening examination were asked when (time of day) they preferred to have a screening. Less than half (47%) reported that varying available appointment times would not affect their ability to obtain screening. One-quarter preferred times for screening during working hours, 20% preferred times after working hours, 6% preferred times before working hours, and 2% responded that they were unsure or did not know. The majority (89%) reported that they would prefer to receive all available screenings on the same day if possible.

Breast Cancer Screening

Nearly all (98%) of the 1,100 women aged between 42 and 64 years reported having received a mammogram. These women were asked a specific subset of questions related to breast cancer screening. Respondents were asked to state the recommended age at which women should begin receiving mammogram screenings. More than half (55%) provided the correct response (40 years old, per the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force guidelines).3,4 About three-quarters of respondents (789) correctly responded annually to the question regarding how often women should receive mammograms.

The survey also sought to identify barriers that prevented women from obtaining necessary breast cancer screening. However, the majority surveyed (85%) noted that the question was not applicable because they typically scheduled screening appointments. Only a few (3%) reported factors such as either themselves or someone they know having had a negative experience, discomfort, pain, or concerns of a falsepositive result as reasons for not obtaining breast cancer screening. Of the 112 respondents to the open-ended question, 25% reported that their schedules prevented them from scheduling a mammogram in the past; 12% reported that an inconvenient clinic location, appointment time, or process prevented them from receiving a screening; and 13% reported forgetting to schedule the screening (Table 2).

Cervical Cancer Screening

Female respondents aged between 21 and 64 years (n = 2,432) were asked about the recommended age at which women should begin receiving cervical cancer screening. Only 1% of respondents provided the correct response (that screening begins at 21 years of age per the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Report guidelines), while 88% provided an incorrect response, and 11% were unsure or did not provide any response.5 Among all respondents, 98% reported having had a cervical cancer screening.

Respondents were asked how frequently women should have a Papanicolaou (Pap) test. Responses such as “2 to 3 years,” “2 years,” or “every other year” were labeled as correct, whereas responses such as “every 6 months” or “greater than 3 years” were labeled as incorrect. Just 12% of respondents provided a correct response, whereas 86% answered incorrectly, and 2% did not answer or did not know. Of those who answered incorrectly, the most common response was “annually” or “every year,” with no notable differences according to race, age, or beneficiary category.

To better understand barriers to screening, respondents were asked to identify reasons they might not have sought cervical cancer screening. The majority (84%) reported that they typically scheduled appointments and that the question was not applicable. However, among 228 respondents who provided an open-ended response and who had not previously undergone a hysterectomy, 8% stated that they had received no reminder or that they lacked sufficient information to schedule the appointment, 21% forgot to schedule, 18% reported a scheduling conflict or difficulty in receiving care, and 13% noted that they did not believe in annual screening (Table 2).

Colorectal Cancer Screening

Eighty-seven percent of eligible respondents (n = 1,734) reported having ever had a sigmoidoscopy and/or colonoscopy. Respondents were asked for their understanding of the recommended age for men and women to begin CRC screening.6 Nearly three-quarters of respondents provided a correct response (n = 1,225), compared with 23% of respondents (n = 407) who answered incorrectly and 6% (n = 102) who did not provide a response or stated they did not know. Correct responses were numerically higher among white respondents (73%) compared with black (62%) and other (62%) respondents as well as among persons aged < 60 years (73%) vs those aged > 60 years (67%).

Respondents aged between 51 and 64 years were asked how often the average person should receive colon cancer screenings. The most common response was that screening should occur every 5 years (33%) followed by every 10 years (26%). This aligns with the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force’s recommendations for flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years or colonoscopy every 10 years.

Eligible respondents were asked to identify reasons they did not seek CRC screening. Eighty-six percent of respondents indicated that they typically scheduled CRC screening and that the question was not applicable. Among respondents who provided an open-ended response, 26% cited feeling uncomfortable with the procedure, 15% cited forgetting to schedule a screening, 15% noted a lack of information on screening, and 11% reported no need for screening (Table 2). Among the 1,734 respondents, 80% reported that they would prefer a fecal occult blood test (FOBT) over either a colonoscopy or a sigmoidoscopy. Only 51% reported that their PCM had previously discussed the different types of CRC screenings at some point.

Discussion

The purpose of this large, representative survey was to obtain information on beneficiaries’ knowledge, perceived barriers, and beliefs regarding breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screenings to identify factors contributing to low completion rates. As far as is known, this is the first study to address these questions in a TRICARE population. Overall, the findings suggest that beneficiaries consider cancer screening important, largely relying on their PCM or their research to better understand how and when to obtain such screenings. The majority received 1 or more screenings prior to the survey, but there were some common knowledge gaps about how to schedule screening appointments, relevant TRICARE medical benefits, and the current recommendations regarding screening timing and frequency. A commonly reported issue across all surveyed groups was inconvenient screening times.