User login

Tattoos: From Ancient Practice to Modern Treatment Dilemma

As dermatologists, we possess a vast knowledge of the epidermis. Some patients may choose to use the epidermis as a canvas for their art in the form of tattoos; however, tattoos can complicate dermatology visits in a myriad of ways. From patients seeking tattoo removal (a complicated task even with the most advanced laser treatments) to those whose native skin is obscured by a tattoo during melanoma screening, it is no wonder that many dermatologists become frustrated at the very mention of the word tattoo.

Tattoos have a long and complicated history entrenched in class divisions, gender identity, and culture. Although its origins are not well documented, many researchers believe that tattooing began in Egypt as early as 4000 BCE.1 From there, the practice spread east into South Asia and west to the British Isles and Scotland. The Iberians in the British Isles, the Picts in Scotland, the Gauls in Western Europe, and the Teutons in Germany all practiced tattooing, and the Romans were known to use tattooing to mark convicts and slaves.1 By 787 AD, tattooing was prevalent enough to warrant an official ban by Pope Hadrian I at the Second Ecumenical Council of Nicaea.2 The growing power of Christianity most likely contributed to the elimination of tattooing in the West, although many soldiers who fought in the Crusades received tattoos during their travels.3

Despite the long history of tattoos in both the East and West, Captain James Cook often is credited with discovering tattooing in the eighteenth century during his explorations in the Pacific.4 In Tahiti in 1769 and Hawaii in 1778, Cook encountered heavily tattooed populations who deposited dye into the skin by tapping sharpened instruments.3 These Polynesian tattoos, which were associated with healing and protective powers, often depicted genealogies and were composed of images of lines, stars, geometric designs, animals, and humans. Explorers in Polynesia who came after Cook noted that tattoo designs began to include rifles, cannons, and dates of chief’s deaths—an indication of the cultural exchange that occurred between Cook’s crew and the natives.3 The first tattooed peoples were displayed in the United States at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1876.2 Later, at the 1901 World’s Fair in Buffalo, New York, the first full “freak show” emerged, and tattooed “natives” were displayed.5 Since they were introduced in the West, tattoos have been associated with an element of the exotic in the United States.

Acknowledged by many to be the first professional tattooist in the United States, Martin Hildebrandt opened his shop in New York City, New York, in 1846.2 Initially, only sailors and soldiers were tattooed, which contributed to the concept of the so-called “tattooed serviceman.”5 However, after the Spanish-American War, tattoos became a fad among the high society in Europe. Tattooing at this time was still performed through the ancient Polynesian tapping method, making it both time-consuming and expensive. Tattoos generally were always placed in a private location, leading to popular speculation at the time about whom in the aristocracy possessed a tattoo, with some even speculating that Queen Victoria may have had a tattoo.1 However, this brief trend among the aristocracy came to an end when Samuel O’Reilly, an American tattoo artist, patented the first electric tattooing machine in 1891.6 His invention made tattooing faster, cheaper, and less painful, thereby making tattooing available to a much wider audience. In the United States, men in the military often were tattooed, especially during World Wars I and II, when patriotic themes and tattoos of important women in their lives (eg, the word Mom, the name of a sweetheart) became popular.

It is a popular belief that a tattoo renaissance occurred in the United States in the 1970s, sparked by an influx of Indonesian and Asian artistic styles. Today, tattoos are ubiquitous. A 2012 poll showed that 21% of adults in the United States have a tattoo.7 There are now 4 main types of tattoos: cosmetic (eg, permanent makeup), traumatic (eg, injury on asphalt), medical (eg, to mark radiation sites), and decorative—either amateur (often done by hand) or professional (done in tattoo parlors with electric tattooing needles).8

Laser Tattoo Removal

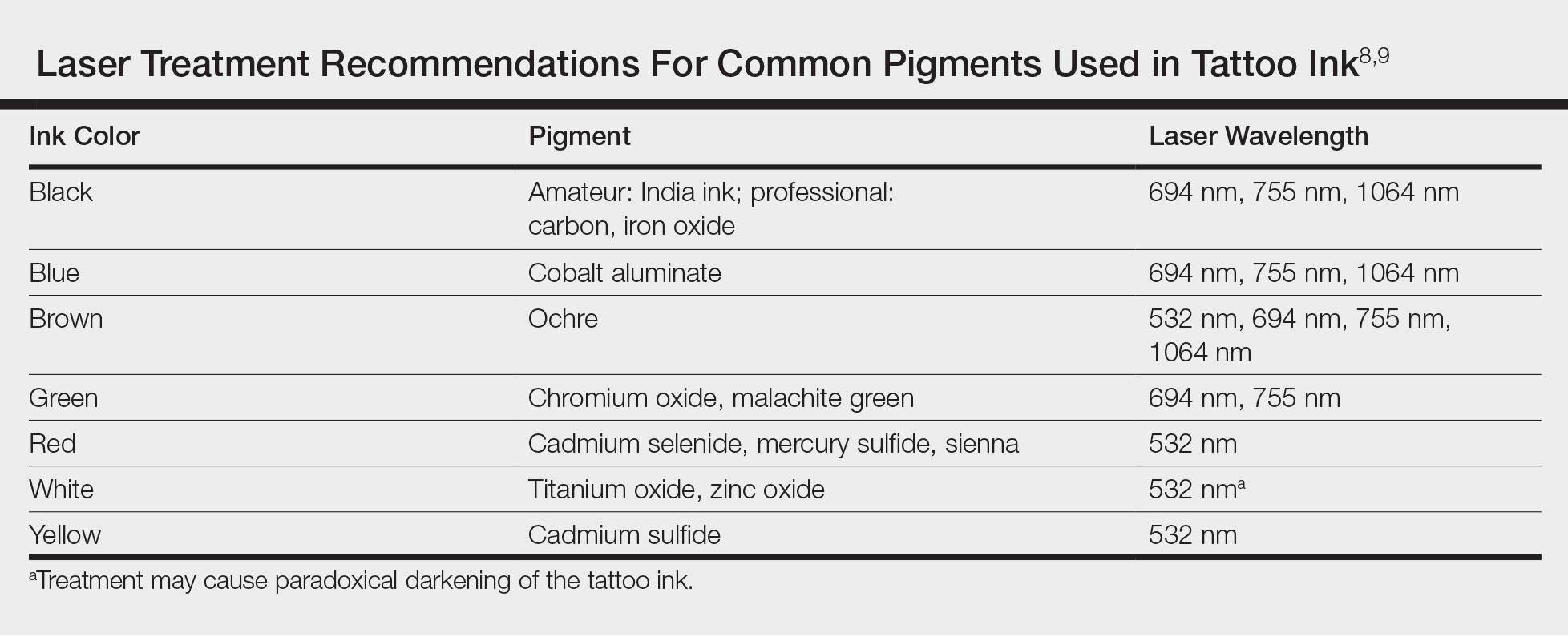

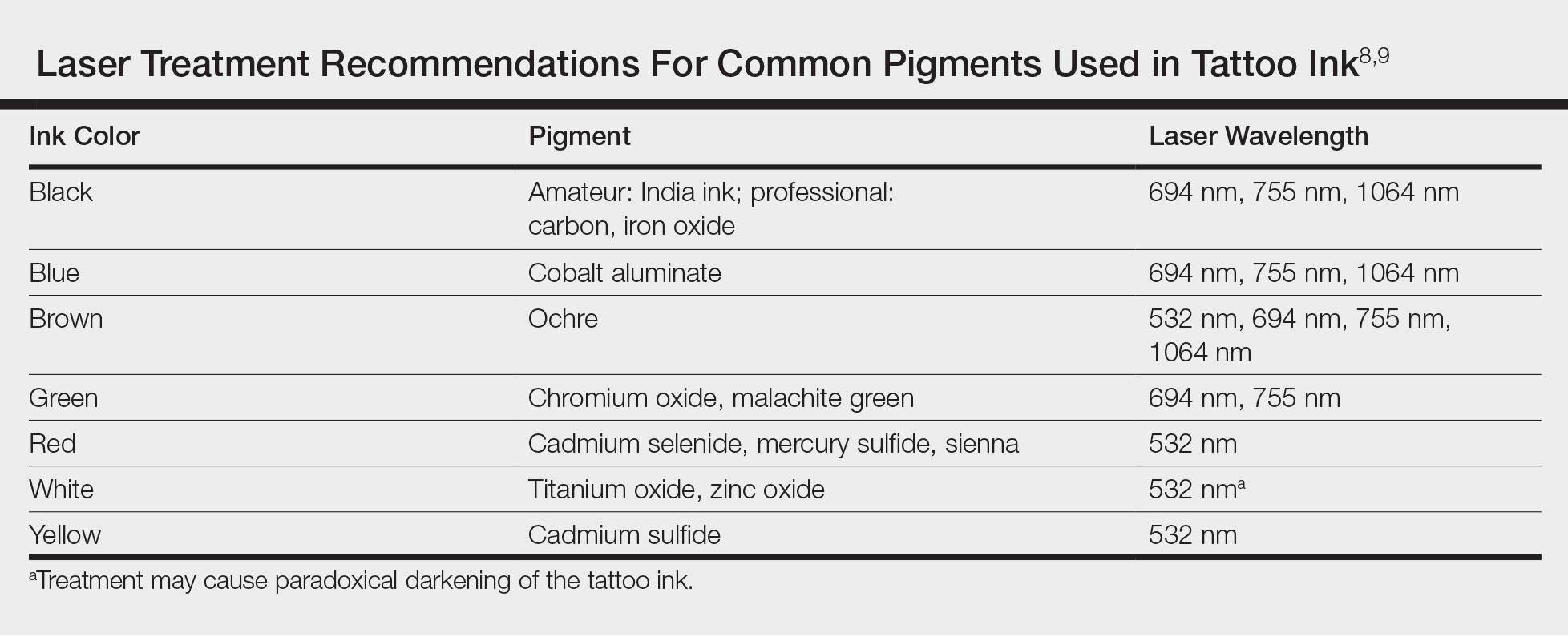

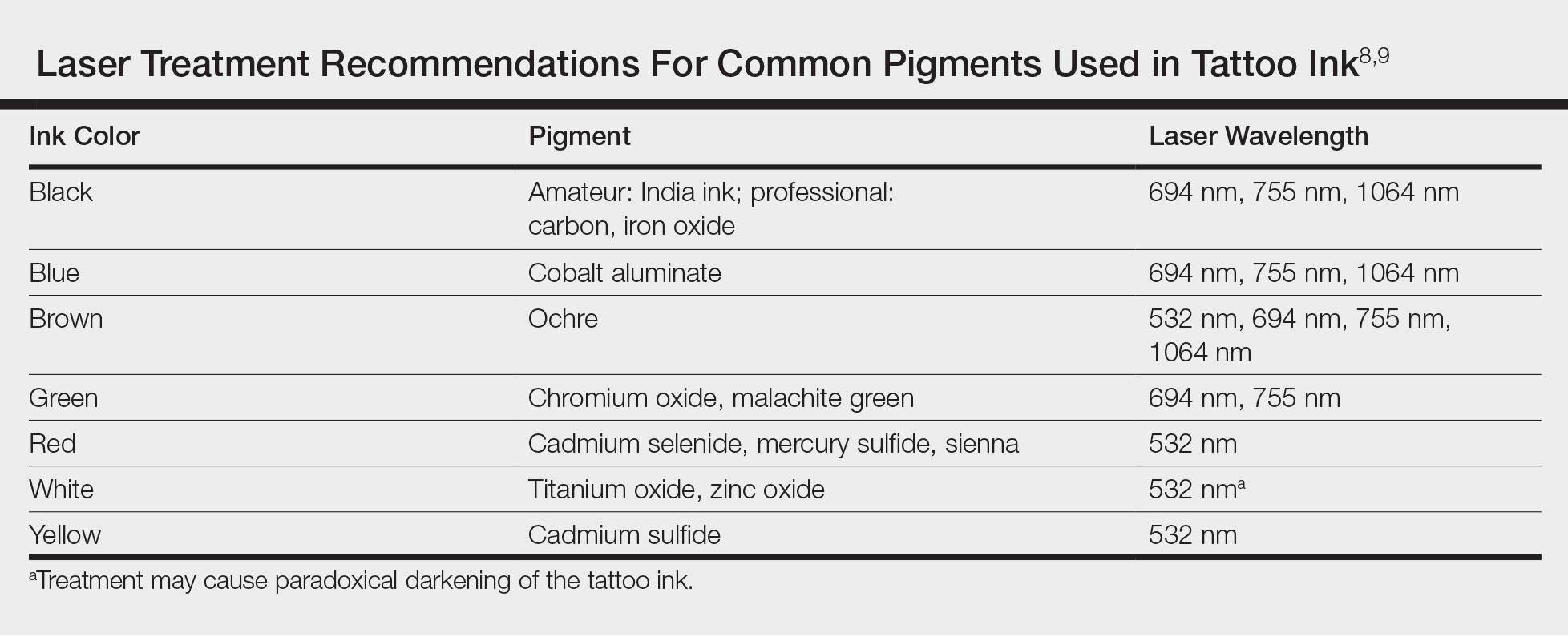

Today tattoos are easy and relatively cheap to get, and for most people they are not regarded as an important cultural milestone like they were in early Polynesian culture. As a result, dermatologists often may encounter patients seeking to have these permanent designs removed from their skin. Previously, tattoo removal was attempted using destructive processes such as scarification and cryotherapy and generally resulted in poor cosmetics outcomes. Today, lasers are at the forefront of tattoo removal. Traditional lasers use pulse durations in the nanosecond range, with newer generation lasers in the picosecond range delivering much shorter pulse durations, effectively delivering the same level of energy over less time. It is important to select the correct laser for optimal destruction of various tattoo ink colors (Table).8,9

Controversy persists as to whether tattoo pigment destruction by lasers is caused by thermal or acoustic damage.10 It may be a combination of both, with rapid heating of the particles leading to a local shockwave as the energy collapses.11 The goal of tattoo removal is to create smaller granules of pigment that can be taken up by the patient’s lymphatic system. The largest granule that can be taken up by the lymphatic system is 0.4 μm.10

In laser treatment of any skin condition, the laser energy is delivered in a pulse duration that should be less than the thermal relaxation time of the chromophores (water, melanin, hemoglobin, or tattoo pigment are the main targets within the skin).12 Most tattoo chromophores are 30 nm to 300 nm, with a thermal relaxation time of less than 10 nanoseconds.10,12 As the number of treatments progresses, laser settings should be adjusted for smaller ink particles. Patients should be warned about pain, side effects, and the need for multiple treatments. Common side effects of laser tattoo removal include purpura, pinpoint bleeding, erythema, edema, crusting, and blistering.8

After laser treatment, cytoplasmic water in the cell is converted into steam leading to cavitation of the lysosome, which presents as whitening of the skin. The whitening causes optical scatter, thereby preventing immediate retreatment of the area.11 The R20 laser tattoo removal method discussed by Kossida et al,13 advises practitioners to wait 20 minutes between treatments to allow the air bubbles from the conversion of water to steam to disappear. Kossida et al13 demonstrated more effective removal in tattoos that were treated with this method compared to standard treatment. The recognition that trapped air bubbles delay multiple treatment cycles has led to the experimental use of perfluorodecalin, a fluorocarbon liquid capable of dissolving the air bubbles, for immediate retreatment.14 By dissolving the trapped air and eliminating the white color, multiple treatments can be completed during 1 session.

Risks of Laser Tattoo Removal

It is important to emphasize that there are potential risks associated with laser treatment for tattoo removal, many of which we are only just beginning to understand. Common side effects of laser treatment for tattoo removal include blisters, pain, bleeding, hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation; however, there also are rare potential risks. Tattoo ink can paradoxically darken when it contains metals such as titanium or zinc, as often is found in tan or white inks.15 The laser energy causes a shift of the metal from an oxidized to a reduced state, leading to a darker rather than lighter tattoo upon application of the laser. There also have been documented cases of intraprocedural anaphylaxis, delayed urticaria, as well as generalized eczematous reactions.16-18 In these cases, the patients had never experienced any allergic symptoms prior to the laser tattoo removal procedure.

Additionally, patients with active allergy to the pigments used in tattoo ink provide a therapeutic dilemma, as laser treatment may potentially systematize the tattoo ink, leading to a more widespread allergic reaction. A case of a generalized eczematous reaction after carbon dioxide laser therapy in a patient with documented tattoo allergy has been reported.19 More research is needed to fully understand the nature of immediate as well as delayed hypersensitivity reactions associated with laser tattoo removal.

Final Thoughts

With thousands of years of established traditions, it is unlikely that tattooing will go away anytime soon. Fortunately, lasers are providing us with an effective and safe method of removal.

- Caplan J, ed. Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2000.

- DeMello M. Bodies of Inscription: Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2000.

- DeMello M. “Not just for bikers anymore”: popular representations of american tattooing. J Popular Culture. 1995;29:37-52.

- Anastasia DJM. Living marked: tattooed women and perceptions of beauty and femininity. In: Segal MT, ed. Interactions and Intersections of Gendered Bodies at Work, at Home, and at Play. Bingly, UK: Emerald; 2010.

- Mifflin M. Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo. New York: June Books; 1997.

- Atkinson M. Pretty in ink: conformity, resistance, and negotiation in women’s tattooing. Sex Roles. 2002;47:219-235.

- Braverman S. One in five US adults now has a tattoo. Harris Poll website. https://theharrispoll.com/new-york-n-y-february-23-2012-there-is-a-lot-of-culture-and-lore-associated-with-tattoos-from-ancient-art-to-modern-expressionism-and-there-are-many-reasons-people-choose-to-get-or-not-get-p/. Published February 23, 2012. Accessed May 25, 2018.

- Ho SG, Goh CL. Laser tattoo removal: a clinical update. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:9-15.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Sardana K, Ranjan R, Ghunawat S. Optimising laser tattoo removal. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:16-24.

- Shah SD, Aurangabadkar SJ. Newer trends in laser tattoo removal. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:25-29.

- Hsu VM, Aldahan AS, Mlacker S, et al. The picosecond laser for tattoo removal. Lasers Med Sci. 2016;31:1733-1737.

- Kossida T, Rigopoulos D, Katsambas A, et al. Optimal tattoo removal in a single laser session based on the method of repeated exposures.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:271-277.

- Biesman BS, O’Neil MP, Costner C. Rapid, high-fluence multipass Q-switched laser treatment of tattoos with a transparent perfluorodecalin-infused patch: a pilot study. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47:613-618.

- Bernstein EF. Laser tattoo removal. Semin Plast Surg. 2007;21:175-192.

- Wilken R, Ho D, Petukhova T, et al. Intraoperative localized urticarial reaction during Q-switched Nd:YAG laser tattoo removal. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:303-306.

- Hibler BP, Rossi AM. A case of delayed anaphylaxis after laser tattoo removal. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:80-81.

- Bernstein EF. A widespread allergic reaction to black tattoo ink caused by laser treatment. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47:180-182.

- Meesters AA, De Rie MA, Wolkerstorfer A. Generalized eczematous reaction after fractional carbon dioxide laser therapy for tattoo allergy. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:456-458.

As dermatologists, we possess a vast knowledge of the epidermis. Some patients may choose to use the epidermis as a canvas for their art in the form of tattoos; however, tattoos can complicate dermatology visits in a myriad of ways. From patients seeking tattoo removal (a complicated task even with the most advanced laser treatments) to those whose native skin is obscured by a tattoo during melanoma screening, it is no wonder that many dermatologists become frustrated at the very mention of the word tattoo.

Tattoos have a long and complicated history entrenched in class divisions, gender identity, and culture. Although its origins are not well documented, many researchers believe that tattooing began in Egypt as early as 4000 BCE.1 From there, the practice spread east into South Asia and west to the British Isles and Scotland. The Iberians in the British Isles, the Picts in Scotland, the Gauls in Western Europe, and the Teutons in Germany all practiced tattooing, and the Romans were known to use tattooing to mark convicts and slaves.1 By 787 AD, tattooing was prevalent enough to warrant an official ban by Pope Hadrian I at the Second Ecumenical Council of Nicaea.2 The growing power of Christianity most likely contributed to the elimination of tattooing in the West, although many soldiers who fought in the Crusades received tattoos during their travels.3

Despite the long history of tattoos in both the East and West, Captain James Cook often is credited with discovering tattooing in the eighteenth century during his explorations in the Pacific.4 In Tahiti in 1769 and Hawaii in 1778, Cook encountered heavily tattooed populations who deposited dye into the skin by tapping sharpened instruments.3 These Polynesian tattoos, which were associated with healing and protective powers, often depicted genealogies and were composed of images of lines, stars, geometric designs, animals, and humans. Explorers in Polynesia who came after Cook noted that tattoo designs began to include rifles, cannons, and dates of chief’s deaths—an indication of the cultural exchange that occurred between Cook’s crew and the natives.3 The first tattooed peoples were displayed in the United States at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1876.2 Later, at the 1901 World’s Fair in Buffalo, New York, the first full “freak show” emerged, and tattooed “natives” were displayed.5 Since they were introduced in the West, tattoos have been associated with an element of the exotic in the United States.

Acknowledged by many to be the first professional tattooist in the United States, Martin Hildebrandt opened his shop in New York City, New York, in 1846.2 Initially, only sailors and soldiers were tattooed, which contributed to the concept of the so-called “tattooed serviceman.”5 However, after the Spanish-American War, tattoos became a fad among the high society in Europe. Tattooing at this time was still performed through the ancient Polynesian tapping method, making it both time-consuming and expensive. Tattoos generally were always placed in a private location, leading to popular speculation at the time about whom in the aristocracy possessed a tattoo, with some even speculating that Queen Victoria may have had a tattoo.1 However, this brief trend among the aristocracy came to an end when Samuel O’Reilly, an American tattoo artist, patented the first electric tattooing machine in 1891.6 His invention made tattooing faster, cheaper, and less painful, thereby making tattooing available to a much wider audience. In the United States, men in the military often were tattooed, especially during World Wars I and II, when patriotic themes and tattoos of important women in their lives (eg, the word Mom, the name of a sweetheart) became popular.

It is a popular belief that a tattoo renaissance occurred in the United States in the 1970s, sparked by an influx of Indonesian and Asian artistic styles. Today, tattoos are ubiquitous. A 2012 poll showed that 21% of adults in the United States have a tattoo.7 There are now 4 main types of tattoos: cosmetic (eg, permanent makeup), traumatic (eg, injury on asphalt), medical (eg, to mark radiation sites), and decorative—either amateur (often done by hand) or professional (done in tattoo parlors with electric tattooing needles).8

Laser Tattoo Removal

Today tattoos are easy and relatively cheap to get, and for most people they are not regarded as an important cultural milestone like they were in early Polynesian culture. As a result, dermatologists often may encounter patients seeking to have these permanent designs removed from their skin. Previously, tattoo removal was attempted using destructive processes such as scarification and cryotherapy and generally resulted in poor cosmetics outcomes. Today, lasers are at the forefront of tattoo removal. Traditional lasers use pulse durations in the nanosecond range, with newer generation lasers in the picosecond range delivering much shorter pulse durations, effectively delivering the same level of energy over less time. It is important to select the correct laser for optimal destruction of various tattoo ink colors (Table).8,9

Controversy persists as to whether tattoo pigment destruction by lasers is caused by thermal or acoustic damage.10 It may be a combination of both, with rapid heating of the particles leading to a local shockwave as the energy collapses.11 The goal of tattoo removal is to create smaller granules of pigment that can be taken up by the patient’s lymphatic system. The largest granule that can be taken up by the lymphatic system is 0.4 μm.10

In laser treatment of any skin condition, the laser energy is delivered in a pulse duration that should be less than the thermal relaxation time of the chromophores (water, melanin, hemoglobin, or tattoo pigment are the main targets within the skin).12 Most tattoo chromophores are 30 nm to 300 nm, with a thermal relaxation time of less than 10 nanoseconds.10,12 As the number of treatments progresses, laser settings should be adjusted for smaller ink particles. Patients should be warned about pain, side effects, and the need for multiple treatments. Common side effects of laser tattoo removal include purpura, pinpoint bleeding, erythema, edema, crusting, and blistering.8

After laser treatment, cytoplasmic water in the cell is converted into steam leading to cavitation of the lysosome, which presents as whitening of the skin. The whitening causes optical scatter, thereby preventing immediate retreatment of the area.11 The R20 laser tattoo removal method discussed by Kossida et al,13 advises practitioners to wait 20 minutes between treatments to allow the air bubbles from the conversion of water to steam to disappear. Kossida et al13 demonstrated more effective removal in tattoos that were treated with this method compared to standard treatment. The recognition that trapped air bubbles delay multiple treatment cycles has led to the experimental use of perfluorodecalin, a fluorocarbon liquid capable of dissolving the air bubbles, for immediate retreatment.14 By dissolving the trapped air and eliminating the white color, multiple treatments can be completed during 1 session.

Risks of Laser Tattoo Removal

It is important to emphasize that there are potential risks associated with laser treatment for tattoo removal, many of which we are only just beginning to understand. Common side effects of laser treatment for tattoo removal include blisters, pain, bleeding, hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation; however, there also are rare potential risks. Tattoo ink can paradoxically darken when it contains metals such as titanium or zinc, as often is found in tan or white inks.15 The laser energy causes a shift of the metal from an oxidized to a reduced state, leading to a darker rather than lighter tattoo upon application of the laser. There also have been documented cases of intraprocedural anaphylaxis, delayed urticaria, as well as generalized eczematous reactions.16-18 In these cases, the patients had never experienced any allergic symptoms prior to the laser tattoo removal procedure.

Additionally, patients with active allergy to the pigments used in tattoo ink provide a therapeutic dilemma, as laser treatment may potentially systematize the tattoo ink, leading to a more widespread allergic reaction. A case of a generalized eczematous reaction after carbon dioxide laser therapy in a patient with documented tattoo allergy has been reported.19 More research is needed to fully understand the nature of immediate as well as delayed hypersensitivity reactions associated with laser tattoo removal.

Final Thoughts

With thousands of years of established traditions, it is unlikely that tattooing will go away anytime soon. Fortunately, lasers are providing us with an effective and safe method of removal.

As dermatologists, we possess a vast knowledge of the epidermis. Some patients may choose to use the epidermis as a canvas for their art in the form of tattoos; however, tattoos can complicate dermatology visits in a myriad of ways. From patients seeking tattoo removal (a complicated task even with the most advanced laser treatments) to those whose native skin is obscured by a tattoo during melanoma screening, it is no wonder that many dermatologists become frustrated at the very mention of the word tattoo.

Tattoos have a long and complicated history entrenched in class divisions, gender identity, and culture. Although its origins are not well documented, many researchers believe that tattooing began in Egypt as early as 4000 BCE.1 From there, the practice spread east into South Asia and west to the British Isles and Scotland. The Iberians in the British Isles, the Picts in Scotland, the Gauls in Western Europe, and the Teutons in Germany all practiced tattooing, and the Romans were known to use tattooing to mark convicts and slaves.1 By 787 AD, tattooing was prevalent enough to warrant an official ban by Pope Hadrian I at the Second Ecumenical Council of Nicaea.2 The growing power of Christianity most likely contributed to the elimination of tattooing in the West, although many soldiers who fought in the Crusades received tattoos during their travels.3

Despite the long history of tattoos in both the East and West, Captain James Cook often is credited with discovering tattooing in the eighteenth century during his explorations in the Pacific.4 In Tahiti in 1769 and Hawaii in 1778, Cook encountered heavily tattooed populations who deposited dye into the skin by tapping sharpened instruments.3 These Polynesian tattoos, which were associated with healing and protective powers, often depicted genealogies and were composed of images of lines, stars, geometric designs, animals, and humans. Explorers in Polynesia who came after Cook noted that tattoo designs began to include rifles, cannons, and dates of chief’s deaths—an indication of the cultural exchange that occurred between Cook’s crew and the natives.3 The first tattooed peoples were displayed in the United States at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1876.2 Later, at the 1901 World’s Fair in Buffalo, New York, the first full “freak show” emerged, and tattooed “natives” were displayed.5 Since they were introduced in the West, tattoos have been associated with an element of the exotic in the United States.

Acknowledged by many to be the first professional tattooist in the United States, Martin Hildebrandt opened his shop in New York City, New York, in 1846.2 Initially, only sailors and soldiers were tattooed, which contributed to the concept of the so-called “tattooed serviceman.”5 However, after the Spanish-American War, tattoos became a fad among the high society in Europe. Tattooing at this time was still performed through the ancient Polynesian tapping method, making it both time-consuming and expensive. Tattoos generally were always placed in a private location, leading to popular speculation at the time about whom in the aristocracy possessed a tattoo, with some even speculating that Queen Victoria may have had a tattoo.1 However, this brief trend among the aristocracy came to an end when Samuel O’Reilly, an American tattoo artist, patented the first electric tattooing machine in 1891.6 His invention made tattooing faster, cheaper, and less painful, thereby making tattooing available to a much wider audience. In the United States, men in the military often were tattooed, especially during World Wars I and II, when patriotic themes and tattoos of important women in their lives (eg, the word Mom, the name of a sweetheart) became popular.

It is a popular belief that a tattoo renaissance occurred in the United States in the 1970s, sparked by an influx of Indonesian and Asian artistic styles. Today, tattoos are ubiquitous. A 2012 poll showed that 21% of adults in the United States have a tattoo.7 There are now 4 main types of tattoos: cosmetic (eg, permanent makeup), traumatic (eg, injury on asphalt), medical (eg, to mark radiation sites), and decorative—either amateur (often done by hand) or professional (done in tattoo parlors with electric tattooing needles).8

Laser Tattoo Removal

Today tattoos are easy and relatively cheap to get, and for most people they are not regarded as an important cultural milestone like they were in early Polynesian culture. As a result, dermatologists often may encounter patients seeking to have these permanent designs removed from their skin. Previously, tattoo removal was attempted using destructive processes such as scarification and cryotherapy and generally resulted in poor cosmetics outcomes. Today, lasers are at the forefront of tattoo removal. Traditional lasers use pulse durations in the nanosecond range, with newer generation lasers in the picosecond range delivering much shorter pulse durations, effectively delivering the same level of energy over less time. It is important to select the correct laser for optimal destruction of various tattoo ink colors (Table).8,9

Controversy persists as to whether tattoo pigment destruction by lasers is caused by thermal or acoustic damage.10 It may be a combination of both, with rapid heating of the particles leading to a local shockwave as the energy collapses.11 The goal of tattoo removal is to create smaller granules of pigment that can be taken up by the patient’s lymphatic system. The largest granule that can be taken up by the lymphatic system is 0.4 μm.10

In laser treatment of any skin condition, the laser energy is delivered in a pulse duration that should be less than the thermal relaxation time of the chromophores (water, melanin, hemoglobin, or tattoo pigment are the main targets within the skin).12 Most tattoo chromophores are 30 nm to 300 nm, with a thermal relaxation time of less than 10 nanoseconds.10,12 As the number of treatments progresses, laser settings should be adjusted for smaller ink particles. Patients should be warned about pain, side effects, and the need for multiple treatments. Common side effects of laser tattoo removal include purpura, pinpoint bleeding, erythema, edema, crusting, and blistering.8

After laser treatment, cytoplasmic water in the cell is converted into steam leading to cavitation of the lysosome, which presents as whitening of the skin. The whitening causes optical scatter, thereby preventing immediate retreatment of the area.11 The R20 laser tattoo removal method discussed by Kossida et al,13 advises practitioners to wait 20 minutes between treatments to allow the air bubbles from the conversion of water to steam to disappear. Kossida et al13 demonstrated more effective removal in tattoos that were treated with this method compared to standard treatment. The recognition that trapped air bubbles delay multiple treatment cycles has led to the experimental use of perfluorodecalin, a fluorocarbon liquid capable of dissolving the air bubbles, for immediate retreatment.14 By dissolving the trapped air and eliminating the white color, multiple treatments can be completed during 1 session.

Risks of Laser Tattoo Removal

It is important to emphasize that there are potential risks associated with laser treatment for tattoo removal, many of which we are only just beginning to understand. Common side effects of laser treatment for tattoo removal include blisters, pain, bleeding, hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation; however, there also are rare potential risks. Tattoo ink can paradoxically darken when it contains metals such as titanium or zinc, as often is found in tan or white inks.15 The laser energy causes a shift of the metal from an oxidized to a reduced state, leading to a darker rather than lighter tattoo upon application of the laser. There also have been documented cases of intraprocedural anaphylaxis, delayed urticaria, as well as generalized eczematous reactions.16-18 In these cases, the patients had never experienced any allergic symptoms prior to the laser tattoo removal procedure.

Additionally, patients with active allergy to the pigments used in tattoo ink provide a therapeutic dilemma, as laser treatment may potentially systematize the tattoo ink, leading to a more widespread allergic reaction. A case of a generalized eczematous reaction after carbon dioxide laser therapy in a patient with documented tattoo allergy has been reported.19 More research is needed to fully understand the nature of immediate as well as delayed hypersensitivity reactions associated with laser tattoo removal.

Final Thoughts

With thousands of years of established traditions, it is unlikely that tattooing will go away anytime soon. Fortunately, lasers are providing us with an effective and safe method of removal.

- Caplan J, ed. Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2000.

- DeMello M. Bodies of Inscription: Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2000.

- DeMello M. “Not just for bikers anymore”: popular representations of american tattooing. J Popular Culture. 1995;29:37-52.

- Anastasia DJM. Living marked: tattooed women and perceptions of beauty and femininity. In: Segal MT, ed. Interactions and Intersections of Gendered Bodies at Work, at Home, and at Play. Bingly, UK: Emerald; 2010.

- Mifflin M. Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo. New York: June Books; 1997.

- Atkinson M. Pretty in ink: conformity, resistance, and negotiation in women’s tattooing. Sex Roles. 2002;47:219-235.

- Braverman S. One in five US adults now has a tattoo. Harris Poll website. https://theharrispoll.com/new-york-n-y-february-23-2012-there-is-a-lot-of-culture-and-lore-associated-with-tattoos-from-ancient-art-to-modern-expressionism-and-there-are-many-reasons-people-choose-to-get-or-not-get-p/. Published February 23, 2012. Accessed May 25, 2018.

- Ho SG, Goh CL. Laser tattoo removal: a clinical update. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:9-15.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Sardana K, Ranjan R, Ghunawat S. Optimising laser tattoo removal. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:16-24.

- Shah SD, Aurangabadkar SJ. Newer trends in laser tattoo removal. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:25-29.

- Hsu VM, Aldahan AS, Mlacker S, et al. The picosecond laser for tattoo removal. Lasers Med Sci. 2016;31:1733-1737.

- Kossida T, Rigopoulos D, Katsambas A, et al. Optimal tattoo removal in a single laser session based on the method of repeated exposures.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:271-277.

- Biesman BS, O’Neil MP, Costner C. Rapid, high-fluence multipass Q-switched laser treatment of tattoos with a transparent perfluorodecalin-infused patch: a pilot study. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47:613-618.

- Bernstein EF. Laser tattoo removal. Semin Plast Surg. 2007;21:175-192.

- Wilken R, Ho D, Petukhova T, et al. Intraoperative localized urticarial reaction during Q-switched Nd:YAG laser tattoo removal. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:303-306.

- Hibler BP, Rossi AM. A case of delayed anaphylaxis after laser tattoo removal. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:80-81.

- Bernstein EF. A widespread allergic reaction to black tattoo ink caused by laser treatment. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47:180-182.

- Meesters AA, De Rie MA, Wolkerstorfer A. Generalized eczematous reaction after fractional carbon dioxide laser therapy for tattoo allergy. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:456-458.

- Caplan J, ed. Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2000.

- DeMello M. Bodies of Inscription: Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2000.

- DeMello M. “Not just for bikers anymore”: popular representations of american tattooing. J Popular Culture. 1995;29:37-52.

- Anastasia DJM. Living marked: tattooed women and perceptions of beauty and femininity. In: Segal MT, ed. Interactions and Intersections of Gendered Bodies at Work, at Home, and at Play. Bingly, UK: Emerald; 2010.

- Mifflin M. Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo. New York: June Books; 1997.

- Atkinson M. Pretty in ink: conformity, resistance, and negotiation in women’s tattooing. Sex Roles. 2002;47:219-235.

- Braverman S. One in five US adults now has a tattoo. Harris Poll website. https://theharrispoll.com/new-york-n-y-february-23-2012-there-is-a-lot-of-culture-and-lore-associated-with-tattoos-from-ancient-art-to-modern-expressionism-and-there-are-many-reasons-people-choose-to-get-or-not-get-p/. Published February 23, 2012. Accessed May 25, 2018.

- Ho SG, Goh CL. Laser tattoo removal: a clinical update. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:9-15.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Sardana K, Ranjan R, Ghunawat S. Optimising laser tattoo removal. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:16-24.

- Shah SD, Aurangabadkar SJ. Newer trends in laser tattoo removal. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:25-29.

- Hsu VM, Aldahan AS, Mlacker S, et al. The picosecond laser for tattoo removal. Lasers Med Sci. 2016;31:1733-1737.

- Kossida T, Rigopoulos D, Katsambas A, et al. Optimal tattoo removal in a single laser session based on the method of repeated exposures.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:271-277.

- Biesman BS, O’Neil MP, Costner C. Rapid, high-fluence multipass Q-switched laser treatment of tattoos with a transparent perfluorodecalin-infused patch: a pilot study. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47:613-618.

- Bernstein EF. Laser tattoo removal. Semin Plast Surg. 2007;21:175-192.

- Wilken R, Ho D, Petukhova T, et al. Intraoperative localized urticarial reaction during Q-switched Nd:YAG laser tattoo removal. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:303-306.

- Hibler BP, Rossi AM. A case of delayed anaphylaxis after laser tattoo removal. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:80-81.

- Bernstein EF. A widespread allergic reaction to black tattoo ink caused by laser treatment. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47:180-182.

- Meesters AA, De Rie MA, Wolkerstorfer A. Generalized eczematous reaction after fractional carbon dioxide laser therapy for tattoo allergy. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:456-458.

Catching Up With Our Past CHEST Presidents

Where are they now? What have they been up to? CHEST’s Past Presidents each forged the way for the many successes of the American College of Chest Physicians, leading to enhanced patient care around the globe. Their outstanding leadership and vision are evidenced today in many of CHEST’s strategic initiatives.

D. Robert McCaffree, MD, MSHA, Master FCCP

CHEST President 1997 - 1998

I received the chain of office (yes, there is an actual chain) from Dr. Bart Chernow in New Orleans during CHEST 1997. I remember this time as being a time of beginnings, challenges, and changes. Bart had been the stimulus for the CHEST Foundation and the form and function of this foundation was being developed. The women’s caucus (probably not the official name) was becoming more organized and more of a force under the leadership of Dr. Diane Stover and Dr. Deborah Shure and others, and the Woman, Girls, Tobacco, and Lung Cancer educational program was being refined. It was this program that got my wife, Mary Anne, involved with the CHEST, and she became a Fellow (FCCP). The American College of Chest Physicians was in the midst of the national tobacco settlement efforts at this time. Our involvement began when Mike Moore, Attorney-General of Mississippi, filed the first suit against the tobacco industry in 1994. Under the stimulus of Dr. John Studdard, our current President, the college was the only medical organization to file an amicus curiae brief supporting this, thus thrusting us into the midst of the tobacco settlement debates and in a leadership position. During the time I was President-elect and President, I was fortunate to represent us both in the ENACT Coalition (composed of national health groups, such as the American Cancer Society), as well as on the Koop-Kessler Congressional Advisory Committee. I also testified before Congress on the tobacco issues and met at the White House with DHHS Secretary Donna Shalala. On a different front, our international activities were not as developed as now, but we did make two memorable trips to India. Many thanks to Dr. Kay Guntupalli for helping make those trips so memorable. After this absolutely wonderful year, I passed the chain to Dr. Allen Goldberg in Toronto.

Among other activities, I was Chief of Staff at the Oklahoma City VAMC for 18 years, retiring from that position in 2009. I was honored by having the MICU at the VA named after me. In the community, I helped start the Hospice of Oklahoma County and then the Hospice Foundation of Oklahoma, both of which I served as first chairman. I also helped start Palliative Care Week on the OUHSC campus. I am currently the vice-chair of the Health Alliance for the Uninsured in Oklahoma City, which helps support the many free clinics in our city. My wonderful wife, Mary Anne, is also involved in many community activities. On a personal level, we try to see our two children and two grandchildren as often as possible, which is not often enough. My free time activities include reading, playing the piano, fly fishing (not often enough), and exercise.

My time as President of the American College of Chest Physicians was one of the best and most important experiences of my life. My memories of working with Al Lever, David Eubanks, Marilyn Lederer, Lynne Marcus, Steve Welch, and all the other administrative and physician leaders during that time remain very dear to me. The influence of CHEST continues to this very day. I can never repay all that I have gained from this experience. I wish I had the space allowance to expand on my experiences. But while my word allowance is limited, my gratitude is unlimited.

Where are they now? What have they been up to? CHEST’s Past Presidents each forged the way for the many successes of the American College of Chest Physicians, leading to enhanced patient care around the globe. Their outstanding leadership and vision are evidenced today in many of CHEST’s strategic initiatives.

D. Robert McCaffree, MD, MSHA, Master FCCP

CHEST President 1997 - 1998

I received the chain of office (yes, there is an actual chain) from Dr. Bart Chernow in New Orleans during CHEST 1997. I remember this time as being a time of beginnings, challenges, and changes. Bart had been the stimulus for the CHEST Foundation and the form and function of this foundation was being developed. The women’s caucus (probably not the official name) was becoming more organized and more of a force under the leadership of Dr. Diane Stover and Dr. Deborah Shure and others, and the Woman, Girls, Tobacco, and Lung Cancer educational program was being refined. It was this program that got my wife, Mary Anne, involved with the CHEST, and she became a Fellow (FCCP). The American College of Chest Physicians was in the midst of the national tobacco settlement efforts at this time. Our involvement began when Mike Moore, Attorney-General of Mississippi, filed the first suit against the tobacco industry in 1994. Under the stimulus of Dr. John Studdard, our current President, the college was the only medical organization to file an amicus curiae brief supporting this, thus thrusting us into the midst of the tobacco settlement debates and in a leadership position. During the time I was President-elect and President, I was fortunate to represent us both in the ENACT Coalition (composed of national health groups, such as the American Cancer Society), as well as on the Koop-Kessler Congressional Advisory Committee. I also testified before Congress on the tobacco issues and met at the White House with DHHS Secretary Donna Shalala. On a different front, our international activities were not as developed as now, but we did make two memorable trips to India. Many thanks to Dr. Kay Guntupalli for helping make those trips so memorable. After this absolutely wonderful year, I passed the chain to Dr. Allen Goldberg in Toronto.

Among other activities, I was Chief of Staff at the Oklahoma City VAMC for 18 years, retiring from that position in 2009. I was honored by having the MICU at the VA named after me. In the community, I helped start the Hospice of Oklahoma County and then the Hospice Foundation of Oklahoma, both of which I served as first chairman. I also helped start Palliative Care Week on the OUHSC campus. I am currently the vice-chair of the Health Alliance for the Uninsured in Oklahoma City, which helps support the many free clinics in our city. My wonderful wife, Mary Anne, is also involved in many community activities. On a personal level, we try to see our two children and two grandchildren as often as possible, which is not often enough. My free time activities include reading, playing the piano, fly fishing (not often enough), and exercise.

My time as President of the American College of Chest Physicians was one of the best and most important experiences of my life. My memories of working with Al Lever, David Eubanks, Marilyn Lederer, Lynne Marcus, Steve Welch, and all the other administrative and physician leaders during that time remain very dear to me. The influence of CHEST continues to this very day. I can never repay all that I have gained from this experience. I wish I had the space allowance to expand on my experiences. But while my word allowance is limited, my gratitude is unlimited.

Where are they now? What have they been up to? CHEST’s Past Presidents each forged the way for the many successes of the American College of Chest Physicians, leading to enhanced patient care around the globe. Their outstanding leadership and vision are evidenced today in many of CHEST’s strategic initiatives.

D. Robert McCaffree, MD, MSHA, Master FCCP

CHEST President 1997 - 1998

I received the chain of office (yes, there is an actual chain) from Dr. Bart Chernow in New Orleans during CHEST 1997. I remember this time as being a time of beginnings, challenges, and changes. Bart had been the stimulus for the CHEST Foundation and the form and function of this foundation was being developed. The women’s caucus (probably not the official name) was becoming more organized and more of a force under the leadership of Dr. Diane Stover and Dr. Deborah Shure and others, and the Woman, Girls, Tobacco, and Lung Cancer educational program was being refined. It was this program that got my wife, Mary Anne, involved with the CHEST, and she became a Fellow (FCCP). The American College of Chest Physicians was in the midst of the national tobacco settlement efforts at this time. Our involvement began when Mike Moore, Attorney-General of Mississippi, filed the first suit against the tobacco industry in 1994. Under the stimulus of Dr. John Studdard, our current President, the college was the only medical organization to file an amicus curiae brief supporting this, thus thrusting us into the midst of the tobacco settlement debates and in a leadership position. During the time I was President-elect and President, I was fortunate to represent us both in the ENACT Coalition (composed of national health groups, such as the American Cancer Society), as well as on the Koop-Kessler Congressional Advisory Committee. I also testified before Congress on the tobacco issues and met at the White House with DHHS Secretary Donna Shalala. On a different front, our international activities were not as developed as now, but we did make two memorable trips to India. Many thanks to Dr. Kay Guntupalli for helping make those trips so memorable. After this absolutely wonderful year, I passed the chain to Dr. Allen Goldberg in Toronto.

Among other activities, I was Chief of Staff at the Oklahoma City VAMC for 18 years, retiring from that position in 2009. I was honored by having the MICU at the VA named after me. In the community, I helped start the Hospice of Oklahoma County and then the Hospice Foundation of Oklahoma, both of which I served as first chairman. I also helped start Palliative Care Week on the OUHSC campus. I am currently the vice-chair of the Health Alliance for the Uninsured in Oklahoma City, which helps support the many free clinics in our city. My wonderful wife, Mary Anne, is also involved in many community activities. On a personal level, we try to see our two children and two grandchildren as often as possible, which is not often enough. My free time activities include reading, playing the piano, fly fishing (not often enough), and exercise.

My time as President of the American College of Chest Physicians was one of the best and most important experiences of my life. My memories of working with Al Lever, David Eubanks, Marilyn Lederer, Lynne Marcus, Steve Welch, and all the other administrative and physician leaders during that time remain very dear to me. The influence of CHEST continues to this very day. I can never repay all that I have gained from this experience. I wish I had the space allowance to expand on my experiences. But while my word allowance is limited, my gratitude is unlimited.

Is Posthospital Syndrome a Result of Hospitalization-Induced Allostatic Overload?

After discharge from the hospital, patients have a significantly elevated risk for adverse events, including emergency department use, hospital readmission, and death. More than 1 in 3 patients discharged from the hospital require acute care in the month after hospital discharge, and more than 1 in 6 require readmission, with readmission diagnoses frequently differing from those of the preceding hospitalization.1-4 This heightened susceptibility to adverse events persists beyond 30 days but levels off by 7 weeks after discharge, suggesting that the period of increased risk is transient and dynamic.5

The term posthospital syndrome (PHS) describes this period of vulnerability to major adverse events following hospitalization.6 In addition to increased risk for readmission and mortality, patients in this period often show evidence of generalized dysfunction with new cognitive impairment, mobility disability, or functional decline.7-12 To date, the etiology of this vulnerability is neither well understood nor effectively addressed by transitional care interventions.13

One hypothesis to explain PHS is that stressors associated with the experience of hospitalization contribute to transient multisystem dysfunction that induces susceptibility to a broad range of medical maladies. These stressors include frequent sleep disruption, noxious sounds, painful stimuli, mobility restrictions, and poor nutrition.12 The stress hypothesis as a cause of PHS is therefore based, in large part, on evidence about allostasis and the deleterious effects of allostatic overload.

Allostasis defines a system functioning within normal stress-response parameters to promote adaptation and survival.14 In allostasis, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) exist in homeostatic balance and respond to environmental stimuli within a range of healthy physiologic parameters. The hallmark of a system in allostasis is the ability to rapidly activate, then successfully deactivate, a stress response once the stressor (ie, threat) has resolved.14,15 To promote survival and potentiate “fight or flight” mechanisms, an appropriate stress response necessarily impacts multiple physiologic systems that result in hemodynamic augmentation and gluconeogenesis to support the anticipated action of large muscle groups, heightened vigilance and memory capabilities to improve rapid decision-making, and enhancement of innate and adaptive immune capabilities to prepare for wound repair and infection defense.14-16 The stress response is subsequently terminated by negative feedback mechanisms of glucocorticoids as well as a shift of the ANS from sympathetic to parasympathetic tone.17,18

Extended or repetitive stress exposure, however, leads to dysregulation of allostatic mechanisms responsible for stress adaptation and hinders an efficient and effective stress response. After extended stress exposure, baseline (ie, resting) HPA activity resets, causing a disruption of normal diurnal cortisol rhythm and an increase in total cortisol concentration. Moreover, in response to stress, HPA and ANS system excitation becomes impaired, and negative feedback properties are undermined.14,15 This maladaptive state, known as allostatic overload, disrupts the finely tuned mechanisms that are the foundation of mind-body balance and yields pathophysiologic consequences to multiple organ systems. Downstream ramifications of allostatic overload include cognitive deterioration, cardiovascular and immune system dysfunction, and functional decline.14,15,19

Although a stress response is an expected and necessary aspect of acute illness that promotes survival, the central thesis of this work is that additional environmental and social stressors inherent in hospitalization may unnecessarily compound stress and increase the risk of HPA axis dysfunction, allostatic overload, and subsequent multisystem dysfunction, predisposing individuals to adverse outcomes after hospital discharge. Based on data from both human subjects and animal models, we present a possible pathophysiologic mechanism for the postdischarge vulnerability of PHS, encourage critical contemplation of traditional hospitalization, and suggest interventions that might improve outcomes.

POSTHOSPITAL SYNDROME

Posthospital syndrome (PHS) describes a transient period of vulnerability after hospitalization during which patients are at elevated risk for adverse events from a broad range of conditions. In support of this characterization, epidemiologic data have demonstrated high rates of adverse outcomes following hospitalization. For example, data have shown that more than 1 in 6 older adults is readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of discharge.20 Death is also common in this first month, during which rates of postdischarge mortality may exceed initial inpatient mortality.21,22 Elevated vulnerability after hospitalization is not restricted to older adults, as readmission risk among younger patients 18 to 64 years of age may be even higher for selected conditions, such as heart failure.3,23

Vulnerability after hospitalization is broad. In patients over age 65 initially admitted for heart failure or acute myocardial infarction, only 35% and 10% of readmissions are for recurrent heart failure or reinfarction, respectively.1 Nearly half of readmissions are for noncardiovascular causes.1 Similarly, following hospitalization for pneumonia, more than 60 percent of readmissions are for nonpulmonary etiologies. Moreover, the risk for all these causes of readmission is much higher than baseline risk, indicating an extended period of lack of resilience to many types of illness.24 These patterns of broad susceptibility also extend to younger adults hospitalized with common medical conditions.3

Accumulating evidence suggests that hospitalized patients face functional decline, debility, and risk for adverse events despite resolution of the presenting illness, implying perhaps that the hospital environment itself is hazardous to patients’ health. In 1993, Creditor hypothesized that the “hazards of hospitalization,” including enforced bed-rest, sensory deprivation, social isolation, and malnutrition lead to a “cascade of dependency” in which a collection of small insults to multiple organ systems precipitates loss of function and debility despite cure or resolution of presenting illness.12 Covinsky (2011) later defined hospitalization-associated disability as an iatrogenic hospital-related “disorder” characterized by new impairments in abilities to perform basic activities of daily living such as bathing, feeding, toileting, dressing, transferring, and walking at the time of hospital discharge.11 Others have described a postintensive-care syndrome (PICS),25 characterized by cognitive, psychiatric, and physical impairments acquired during hospitalization for critical illness that persist postdischarge and increase the long-term risk for adverse outcomes, including elevated mortality rates,26,27 readmission rates,28 and physical disabilities.29 Similar to the “hazards of hospitalization,” PICS is thought to be related to common experiences of ICU stays, including mobility restriction, sensory deprivation, sleep disruption, sedation, malnutrition, and polypharmacy.30-33

Taken together, these data suggest that adverse health consequences attributable to hospitalization extend across the spectrum of age, presenting disease severity, and hospital treatment location. As detailed below, the PHS hypothesis is rooted in a mechanistic understanding of the role of exogenous stressors in producing physiologic dysregulation and subsequent adverse health effects across multiple organ systems.

Nature of Stress in the Hospital

Compounding the stress of acute illness, hospitalized patients are routinely and repetitively exposed to a wide variety of environmental stressors that may have downstream adverse consequences (Table 1). In the absence of overt clinical manifestations of harm, the possible subclinical physiologic dysfunction generated by the following stress exposures may increase patients’ susceptibility to the manifestations of PHS.

Sleep Disruption

Sleep disruptions trigger potent stress responses,34,35 yet they are common occurrences during hospitalization. In surveys, about half of patients report poor sleep quality during hospitalization that persists for many months after discharge.36 In a simulated hospital setting, test subjects exposed to typical hospital sounds (paging system, machine alarms, etc.) experienced significant sleep-wake cycle abnormalities.37 Although no work has yet focused specifically on the physiologic consequences of sleep disruption and stress in hospitalized patients, in healthy humans, mild sleep disruption has clear effects on allostasis by disrupting HPA activity, raising cortisol levels, diminishing parasympathetic tone, and impairing cognitive performance.18,34,35,38,39

Malnourishment

Malnourishment in hospitalized patients is common, with one-fifth of hospitalized patients receiving nothing per mouth or clear liquid diets for more than 3 continuous days,40 and one-fifth of hospitalized elderly patients receiving less than half of their calculated nutrition requirements.41 Although the relationship between food restriction, cortisol levels, and postdischarge outcomes has not been fully explored, in healthy humans, meal anticipation, meal withdrawal (withholding an expected meal), and self-reported dietary restraint are known to generate stress responses.42,43 Furthermore, malnourishment during hospitalization is associated with increased 90-day and 1-year mortality after discharge,44 adding malnourishment to the list of plausible components of hospital-related stress.

Mobility Restriction

Physical activity counterbalances stress responses and minimizes downstream consequences of allostatic load,15 yet mobility limitations via physical and chemical restraints are common in hospitalized patients, particularly among the elderly.45-47 Many patients are tethered to devices that make ambulation hazardous, such as urinary catheters and infusion pumps. Even without physical or chemical restraints or a limited mobility order, patients may be hesitant to leave the room so as not to miss transport to a diagnostic study or an unscheduled physician’s visit. Indeed, mobility limitations of hospitalized patients increase the risk for adverse events after discharge, while interventions designed to encourage mobility are associated with improved postdischarge outcomes.47,48

Other Stressors

Other hospital-related aversive stimuli are less commonly quantified, but clearly exist. According to surveys of hospitalized patients, sources of emotional stress include social isolation; loss of autonomy and privacy; fear of serious illness; lack of control over activities of daily living; lack of clear communication between treatment team and patients; and death of a patient roommate.49,50 Furthermore, consider the physical discomfort and emotional distress of patients with urinary incontinence awaiting assistance for a diaper or bedding change or the pain of repetitive blood draws or other invasive testing. Although individualized, the subjective discomfort and emotional distress associated with these experiences undoubtedly contribute to the stress of hospitalization.

IMPACT OF ALLOSTATIC OVERLOAD ON PHYSIOLOGIC FUNCTION

Animal Models of Stress

Laboratory techniques reminiscent of the numerous environmental stressors associated with hospitalization have been used to reliably trigger allostatic overload in healthy young animals.51 These techniques include sequential exposure to aversive stimuli, including food and water deprivation, continuous overnight illumination, paired housing with known and unknown cagemates, mobility restriction, soiled cage conditions, and continuous noise. All of these techniques have been shown to cause HPA axis and ANS dysfunction, allostatic overload, and subsequent stress-mediated consequences to multiple organ systems.19,52-54 Given the remarkable similarity of these protocols to common experiences during hospitalization, animal models of stress may be useful in understanding the spectrum of maladaptive consequences experienced by patients within the hospital (Figure 1).

These animal models of stress have resulted in a number of instructive findings. For example, in rodents, extended stress exposure induces structural and functional remodeling of neuronal networks that precipitate learning and memory, working memory, and attention impairments.55-57 These exposures also result in cardiovascular abnormalities, including dyslipidemia, progressive atherosclerosis,58,59 and enhanced inflammatory cytokine expression,60 all of which increase both atherosclerotic burden and susceptibility to plaque rupture, leading to elevated risk for major cardiovascular adverse events. Moreover, these extended stress exposures in animals increase susceptibility to both bacterial and viral infections and increase their severity.16,61 This outcome appears to be driven by a stress-induced elevation of glucocorticoid levels, decreased leukocyte proliferation, altered leukocyte trafficking, and a transition to a proinflammatory cytokine environment.16, 61 Allostatic overload has also been shown to contribute to metabolic dysregulation involving insulin resistance, persistence of hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, catabolism of lean muscle, and visceral adipose tissue deposition.62-64 In addition to cardiovascular, immune, and metabolic consequences of allostatic overload, the spectrum of physiologic dysfunction in animal models is broad and includes mood disorder symptoms,65 intestinal barrier abnormalities,66 airway reactivity exacerbation,67 and enhanced tumor growth.68

Although the majority of this research highlights the multisystem effects of variable stress exposure in healthy animals, preliminary evidence suggests that aged or diseased animals subjected to additional stressors display a heightened inflammatory cytokine response that contributes to exaggerated sickness behavior and greater and prolonged cognitive deficits.69 Future studies exploring the consequences of extended stress exposure in animals with existing disease or debility may therefore more closely simulate the experience of hospitalized patients and perhaps further our understanding of PHS.

Hospitalized Patients

While no intervention studies have examined the effects of potential hospital stressors on the development of allostatic overload, there is evidence from small studies that dysregulated stress responses during hospitalization are associated with adverse events. For example, high serum cortisol, catecholamine, and proinflammatory cytokine levels during hospitalization have individually been associated with the development of cognitive dysfunction,70-72 increased risk of cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction and stroke in the year following discharge,73-76 and the development of wound infections after discharge.77 Moreover, elevated plasma glucose during admission for myocardial infarction in patients with or without diabetes has been associated with greater in-hospital and 1-year mortality,78 with a similar relationship seen between elevated plasma glucose and survival after admission for stroke79 and pneumonia.80 Furthermore, in addition to atherothrombosis, stress may contribute to the risk for venous thromboembolism,81 resulting in readmissions for deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism posthospitalization. Although potentially surrogate markers of illness acuity, a handful of studies have shown that these stress biomarkers are actually only weakly correlated with,82 or independent of,72,76 disease severity. As discussed in detail below, future studies utilizing a summative measure of multisystem physiologic dysfunction as opposed to individual biomarkers may more accurately reflect the cumulative stress effects of hospitalization and subsequent risk for adverse events.

Additional Considerations

Elderly patients, in particular, may have heightened susceptibility to the consequences of allostatic overload due to common geriatric issues such as multimorbidity and frailty. Patients with chronic diseases display both baseline HPA axis abnormalities as well as dysregulated stress responses and may therefore be more vulnerable to hospitalization-related stress. For example, when subjected to psychosocial stress, patients with chronic conditions such as diabetes, heart failure, or atherosclerosis demonstrate elevated cortisol levels, increased circulating markers of inflammation, as well as prolonged hemodynamic recovery after stress resolution compared with normal controls.83-85 Additionally, frailty may affect an individual’s susceptibility to exogenous stress. Indeed, frailty identified on hospital admission increases the risk for adverse outcomes during hospitalization and postdischarge.86 Although the specific etiology of this relationship is unclear, persons with frailty are known to have elevated levels of cortisol and other inflammatory markers,87,88 which may contribute to adverse outcomes in the face of additional stressors.

IMPLICATIONS AND NEXT STEPS

A large body of evidence stretching from bench to bedside suggests that environmental stressors associated with hospitalization are toxic. Understanding PHS within the context of hospital-induced allostatic overload presents a unifying theory for the interrelated multisystem dysfunction and increased susceptibility to adverse events that patients experience after discharge (Figure 2). Furthermore, it defines a potential pathophysiological mechanism for the cognitive impairment, elevated cardiovascular risk, immune system dysfunction, metabolic derangements, and functional decline associated with PHS. Additionally, this theory highlights environmental interventions to limit PHS development and suggests mechanisms to promote stress resilience. Although it is difficult to disentangle the consequences of the endogenous stress triggered by an acute illness from the exogenous stressors related to hospitalization, it is likely that the 2 simultaneous exposures compound risk for stress system dysregulation and allostatic overload. Moreover, hospitalized patients with preexisting HPA axis dysfunction at baseline from chronic disease or advancing age may be even more susceptible to these adverse outcomes. If this hypothesis is true, a reduction in PHS would require mitigation of the modifiable environmental stressors encountered by patients during hospitalization. Directed efforts to diminish ambient noise, limit nighttime disruptions, thoughtfully plan procedures, consider ongoing nutritional status, and promote opportunities for patients to exert some control over their environment may diminish the burden of extrinsic stressors encountered by all patients in the hospital and improve outcomes after discharge.

Hospitals are increasingly recognizing the importance of improving patients’ experience of hospitalization by reducing exposure to potential toxicities. For example, many hospitals are now attempting to reduce sleep disturbances and sleep latency through reduced nighttime noise and light levels, fewer nighttime interruptions for vital signs checks and medication administration, and commonsensical interventions like massages, herbal teas, and warm milk prior to bedtime.89 Likewise, intensive care units are targeting environmental and physical stressors with a multifaceted approach to decrease sedative use, promote healthy sleep cycles, and encourage exercise and ambulation even in those patients who are mechanically ventilated.30 Another promising development has been the increase of Hospital at Home programs. In these programs, patients who meet the criteria for inpatient admission are instead comprehensively managed at home for their acute illness through a multidisciplinary effort between physicians, nurses, social workers, physical therapists, and others. Patients hospitalized at home report higher levels of satisfaction and have modest functional gains, improved health-related quality of life, and decreased risk of mortality at 6 months compared with hospitalized patients.90,91 With some admitting diagnoses (eg, heart failure), hospitalization at home may be associated with decreased readmission risk.92 Although not yet investigated on a physiologic level, perhaps the benefits of hospital at home are partially due to the dramatic difference in exposure to environmental stressors.

A tool that quantifies hospital-associated stress may help health providers appreciate the experience of patients and better target interventions to aspects of their structure and process that contribute to allostatic overload. Importantly, allostatic overload cannot be identified by one biomarker of stress but instead requires evidence of dysregulation across inflammatory, neuroendocrine, hormonal, and cardiometabolic systems. Future studies to address the burden of stress faced by hospitalized patients should consider a summative measure of multisystem dysregulation as opposed to isolated assessments of individual biomarkers. Allostatic load has previously been operationalized as the summation of a variety of hemodynamic, hormonal, and metabolic factors, including blood pressure, lipid profile, glycosylated hemoglobin, cortisol, catecholamine levels, and inflammatory markers.93 To develop a hospital-associated allostatic load index, models should ideally be adjusted for acute illness severity, patient-reported stress, and capacity for stress resilience. This tool could then be used to quantify hospitalization-related allostatic load and identify those at greatest risk for adverse events after discharge, as well as measure the effectiveness of strategic environmental interventions (Table 2). A natural first experiment may be a comparison of the allostatic load of hospitalized patients versus those hospitalized at home.

The risk of adverse outcomes after discharge is likely a function of the vulnerability of the patient and the degree to which the patient’s healthcare team and social support network mitigates this vulnerability. That is, there is a risk that a person struggles in the postdischarge period and, in many circumstances, a strong healthcare team and social network can identify health problems early and prevent them from progressing to the point that they require hospitalization.13,94-96 There are also hospital occurrences, outside of allostatic load, that can lead to complications that lengthen the stay, weaken the patient, and directly contribute to subsequent vulnerability.94,97 Our contention is that the allostatic load of hospitalization, which may also vary by patient depending on the circumstances of hospitalization, is just one contributor, albeit potentially an important one, to vulnerability to medical problems after discharge.

In conclusion, a plausible etiology of PHS is the maladaptive mind-body consequences of common stressors during hospitalization that compound the stress of acute illness and produce allostatic overload. This stress-induced dysfunction potentially contributes to a spectrum of generalized disease susceptibility and risk of adverse outcomes after discharge. Focused efforts to diminish patient exposure to hospital-related stressors during and after hospitalization might diminish the presence or severity of PHS. Viewing PHS from this perspective enables the development of hypothesis-driven risk-prediction models, encourages critical contemplation of traditional hospitalization, and suggests that targeted environmental interventions may significantly reduce adverse outcomes.

1. Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355-363. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.216476.

2. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-1428. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa0803563.

3. Ranasinghe I, Wang Y, Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Bernheim SM, Krumholz HM. Readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia among young and middle-aged adults: a retrospective observational cohort study. PLoS Med. 2014;11(9):e1001737. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001737.

4. Vashi AA, Fox JP, Carr BG, et al. Use of hospital-based acute care among patients recently discharged from the hospital. JAMA. 2013;309(4):364-371. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.216219.

5. Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Kulkarni VT, et al. Trajectories of risk after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h411. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h411.

6. Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome--an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100-102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1212324.

7. Ferrante LE, Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, Leo-Summers LS, Gill TM. Functional trajectories among older persons before and after critical illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):523-529. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7889.

8. Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, Guo Z. Hospitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA. 2004;292(17):2115-2124. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.17.2115.

9. Inouye SK, Zhang Y, Han L, Leo-Summers L, Jones R, Marcantonio E. Recoverable cognitive dysfunction at hospital admission in older persons during acute illness. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(12):1276-1281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00613.x.

10. Lindquist LA, Go L, Fleisher J, Jain N, Baker D. Improvements in cognition following hospital discharge of community dwelling seniors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(7):765-770. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1681-1.

11. Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-associated disability: “She was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure.” JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782-1793. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1556.

12. Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(3):219-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-118-3-199302010-00011.

13. Dharmarajan K, Krumholz HM. Strategies to reduce 30-day readmissions in older patients hospitalized with heart failure and acute myocardial infarction. Curr Geriatr Rep. 2014;3(4):306-315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13670-014-0103-8.

14. McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(3):171-179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199801153380307.

15. McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Stress- and allostasis-induced brain plasticity. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:431-445. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-052209-100430.

16. Dhabhar FS. Enhancing versus suppressive effects of stress on immune function: implications for immunoprotection and immunopathology. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2009;16(5):300-317. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000216188.

17. Thayer JF, Sternberg E. Beyond heart rate variability: vagal regulation of allostatic systems. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1088:361-372. http://dx.doi.org/10.1196/annals.1366.014.

18. Jacobson L, Akana SF, Cascio CS, Shinsako J, Dallman MF. Circadian variations in plasma corticosterone permit normal termination of adrenocorticotropin responses to stress. Endocrinology. 1988;122(4):1343-1348. http://dx.doi.org/10.1210/endo-122-4-1343.

19. McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(3):873-904. http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00041.2006.

20. Medicare Hospital Quality Chartbook 2014: Performance Report on Outcome Measures. Prepared by Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation for Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/hospitalqualityinits/downloads/medicare-hospital-quality-chartbook-2014.pdf. Accessed February 26, 2018.

21. Bueno H, Ross JS, Wang Y, et al. Trends in length of stay and short-term outcomes among Medicare patients hospitalized for heart failure, 1993-2006. JAMA. 2010;303(21):2141-2147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.748.

22. Drye EE, Normand SL, Wang Y, et al. Comparison of hospital risk-standardized mortality rates calculated by using in-hospital and 30-day models: an observational study with implications for hospital profiling. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(1 Pt 1):19-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-156-1-201201030-00004.

23. Dharmarajan K, Hsieh A, Dreyer RP, Welsh J, Qin L, Krumholz HM. Relationship between age and trajectories of rehospitalization risk in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(2):421-426. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14583.

24. Krumholz HM, Hsieh A, Dreyer RP, Welsh J, Desai NR, Dharmarajan K. Trajectories of risk for specific readmission diagnoses after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0160492. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160492.

25. Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):502-509. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75.

26. Brinkman S, de Jonge E, Abu-Hanna A, Arbous MS, de Lange DW, de Keizer NF. Mortality after hospital discharge in ICU patients. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(5):1229-1236. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827ca4e1.

27. Steenbergen S, Rijkenberg S, Adonis T, Kroeze G, van Stijn I, Endeman H. Long-term treated intensive care patients outcomes: the one-year mortality rate, quality of life, health care use and long-term complications as reported by general practitioners. BMC Anesthesiol. 2015;15:142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12871-015-0121-x.

28. Hill AD, Fowler RA, Pinto R, Herridge MS, Cuthbertson BH, Scales DC. Long-term outcomes and healthcare utilization following critical illness--a population-based study. Crit Care. 2016;20:76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1248-y.

29. Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, et al. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(5):369-379. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70051-7.

30. Balas MC, Vasilevskis EE, Olsen KM, et al. Effectiveness and safety of the awakening and breathing coordination, delirium monitoring/management, and early exercise/mobility bundle. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(5):1024-1036. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000000129.

31. Kress JP, Hall JB. ICU-acquired weakness and recovery from critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(17):1626-1635. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1209390.

32. Mendez-Tellez PA, Needham DM. Early physical rehabilitation in the ICU and ventilator liberation. Respir Care. 2012;57(10):1663-1669. http://dx.doi.org/10.4187/respcare.01931.

33. Schweickert WD, Hall J. ICU-acquired weakness. Chest. 2007;131(5):1541-1549. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.06-2065.

34. Balbo M, Leproult R, Van Cauter E. Impact of sleep and its disturbances on hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis activity. Int J Endocrinol. 2010;2010:759234. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2010/759234.

35. Spiegel K, Leproult R, Van Cauter E. Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function. Lancet. 1999;354(9188):1435-1439. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01376-8.

36. Orwelius L, Nordlund A, Nordlund P, Edell-Gustafsson U, Sjoberg F. Prevalence of sleep disturbances and long-term reduced health-related quality of life after critical care: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Crit Care. 2008;12(4):R97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/cc6973.

37. Buxton OM, Ellenbogen JM, Wang W, et al. Sleep disruption due to hospital noises: a prospective evaluation. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(3):170-179. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-157-3-201208070-00472.

38. Sunbul M, Kanar BG, Durmus E, Kivrak T, Sari I. Acute sleep deprivation is associated with increased arterial stiffness in healthy young adults. Sleep Breath. 2014;18(1):215-220. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11325-013-0873-9.

39. Van Dongen HP, Maislin G, Mullington JM, Dinges DF. The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep. 2003;26(2):117-126. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/sleep/26.2.117.

40. Franklin GA, McClave SA, Hurt RT, et al. Physician-delivered malnutrition: why do patients receive nothing by mouth or a clear liquid diet in a university hospital setting? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35(3):337-342. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0148607110374060.