User login

Trachelectomy rate for early-stage cervical cancer rises to 17% in younger women

based on a recent analysis of the National Cancer Database.

Of 15,150 patients analyzed, the vast majority (97.1%) underwent hysterectomy, but trachelectomy performance increased from 1.5% (95% confidence interval, 0.8%-2.2%; P less than .001) in 2004 to 3.8% (95% CI, 2.7%-4.8%; P less than .001) by 2014. The increase was mostly seen among women younger than 30 years old. In that group, trachelectomy increased from 4.6% (95% CI, 1.0%-8.2%; P less than .001) in 2004 to 17% (95% CI, 10.2%-23.7%; P less than .001) in 2014. Rates among women aged 30-49 years were relatively stable over the same period.

“A possible explanation for this rise in trachelectomy is the trend in delayed childbearing in women in the United States,” wrote Rosa R. Cui, MD, a resident at Columbia University, New York, and her coauthors.

In the analysis, mortality risk and 5-year survival rates were similar between the two procedures. Overall cohort 5-year survival was nearly identical with hysterectomy and trachelectomy at 92.4% and 92.3%, respectively. For stages IA2, IB1, and IB not specified, tumor stage was not associated with differences in 5-year survival for the two procedures. As few patients with stage IB2 tumors received trachelectomy, that data was excluded from the analysis.

Though increasing tumor size made trachelectomy less likely, 30% of patients in the study who underwent trachelectomy had a tumor greater than 2 cm in diameter, and 4% had a tumor greater than 4 cm in diameter. The researchers noted studies published in the past few years suggest abdominal radical trachelectomy may be a safe option for larger tumors, compared with vaginal trachelectomy. In the current analysis, they did not find a statistically significant decrease in survival for trachelectomy patients with tumors greater than 2 cm in diameter, but the sample size was small.

“The trachelectomy procedure has evolved significantly since it was initially described and now encompasses several approaches,” and can be performed more or less conservatively depending on the diagnosis “without compromising outcomes,” wrote Dr. Cui and her coauthors.

The researchers noted that the National Cancer Database does not have data on fertility outcomes, a possible focus of future studies of trachelectomy.

Two coauthors disclosed grants and a fellowship from the National Cancer Institute, and others disclosed consulting for several pharmaceutical companies including Pfizer, Teva, and Eisai.

SOURCE: Cui RR et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jun;131(6):1085-94.

based on a recent analysis of the National Cancer Database.

Of 15,150 patients analyzed, the vast majority (97.1%) underwent hysterectomy, but trachelectomy performance increased from 1.5% (95% confidence interval, 0.8%-2.2%; P less than .001) in 2004 to 3.8% (95% CI, 2.7%-4.8%; P less than .001) by 2014. The increase was mostly seen among women younger than 30 years old. In that group, trachelectomy increased from 4.6% (95% CI, 1.0%-8.2%; P less than .001) in 2004 to 17% (95% CI, 10.2%-23.7%; P less than .001) in 2014. Rates among women aged 30-49 years were relatively stable over the same period.

“A possible explanation for this rise in trachelectomy is the trend in delayed childbearing in women in the United States,” wrote Rosa R. Cui, MD, a resident at Columbia University, New York, and her coauthors.

In the analysis, mortality risk and 5-year survival rates were similar between the two procedures. Overall cohort 5-year survival was nearly identical with hysterectomy and trachelectomy at 92.4% and 92.3%, respectively. For stages IA2, IB1, and IB not specified, tumor stage was not associated with differences in 5-year survival for the two procedures. As few patients with stage IB2 tumors received trachelectomy, that data was excluded from the analysis.

Though increasing tumor size made trachelectomy less likely, 30% of patients in the study who underwent trachelectomy had a tumor greater than 2 cm in diameter, and 4% had a tumor greater than 4 cm in diameter. The researchers noted studies published in the past few years suggest abdominal radical trachelectomy may be a safe option for larger tumors, compared with vaginal trachelectomy. In the current analysis, they did not find a statistically significant decrease in survival for trachelectomy patients with tumors greater than 2 cm in diameter, but the sample size was small.

“The trachelectomy procedure has evolved significantly since it was initially described and now encompasses several approaches,” and can be performed more or less conservatively depending on the diagnosis “without compromising outcomes,” wrote Dr. Cui and her coauthors.

The researchers noted that the National Cancer Database does not have data on fertility outcomes, a possible focus of future studies of trachelectomy.

Two coauthors disclosed grants and a fellowship from the National Cancer Institute, and others disclosed consulting for several pharmaceutical companies including Pfizer, Teva, and Eisai.

SOURCE: Cui RR et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jun;131(6):1085-94.

based on a recent analysis of the National Cancer Database.

Of 15,150 patients analyzed, the vast majority (97.1%) underwent hysterectomy, but trachelectomy performance increased from 1.5% (95% confidence interval, 0.8%-2.2%; P less than .001) in 2004 to 3.8% (95% CI, 2.7%-4.8%; P less than .001) by 2014. The increase was mostly seen among women younger than 30 years old. In that group, trachelectomy increased from 4.6% (95% CI, 1.0%-8.2%; P less than .001) in 2004 to 17% (95% CI, 10.2%-23.7%; P less than .001) in 2014. Rates among women aged 30-49 years were relatively stable over the same period.

“A possible explanation for this rise in trachelectomy is the trend in delayed childbearing in women in the United States,” wrote Rosa R. Cui, MD, a resident at Columbia University, New York, and her coauthors.

In the analysis, mortality risk and 5-year survival rates were similar between the two procedures. Overall cohort 5-year survival was nearly identical with hysterectomy and trachelectomy at 92.4% and 92.3%, respectively. For stages IA2, IB1, and IB not specified, tumor stage was not associated with differences in 5-year survival for the two procedures. As few patients with stage IB2 tumors received trachelectomy, that data was excluded from the analysis.

Though increasing tumor size made trachelectomy less likely, 30% of patients in the study who underwent trachelectomy had a tumor greater than 2 cm in diameter, and 4% had a tumor greater than 4 cm in diameter. The researchers noted studies published in the past few years suggest abdominal radical trachelectomy may be a safe option for larger tumors, compared with vaginal trachelectomy. In the current analysis, they did not find a statistically significant decrease in survival for trachelectomy patients with tumors greater than 2 cm in diameter, but the sample size was small.

“The trachelectomy procedure has evolved significantly since it was initially described and now encompasses several approaches,” and can be performed more or less conservatively depending on the diagnosis “without compromising outcomes,” wrote Dr. Cui and her coauthors.

The researchers noted that the National Cancer Database does not have data on fertility outcomes, a possible focus of future studies of trachelectomy.

Two coauthors disclosed grants and a fellowship from the National Cancer Institute, and others disclosed consulting for several pharmaceutical companies including Pfizer, Teva, and Eisai.

SOURCE: Cui RR et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jun;131(6):1085-94.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

What is causing my patients’ macrocytosis?

A 56-year-old man presents for his annual physical. He brings in blood work done for all employees in his workplace (he is an aerospace engineer), and wants to talk about the lab that has an asterisk by it. All his labs are normal, except that his mean corpuscular volume (MCV) is 101. His hematocrit (HCT) is 42. He has no symptoms and a normal physical exam.

What test or tests would most likely be abnormal?

A. Thyroid-stimulating hormone.

B. Vitamin B12/folate.

C. Testosterone.

D. Gamma-glutamyl-transferase (GGT).

The finding of macrocytosis is fairly common in primary care, estimated to be found in 3% of complete blood count results.1 Most students in medical school quickly learn that vitamin B12 and folate deficiency can cause macrocytic anemias. The standard workups for patients with macrocytosis began and ended with checking vitamin B12 and folate levels, which are usually normal in the vast majority of patients with macrocytosis.

For this patient, the correct answer would be an abnormal GGT, because chronic moderate to heavy alcohol use can raise GGT levels, as well as MCVs.

Dr. David Savage and colleagues evaluated the etiology of macrocytosis in 300 consecutive hospitalized patients with macrocytosis.2 They found that the most common causes were medications, alcohol, liver disease, and reticulocytosis. The study was done in New York and was published in 2000, so zidovudine (AZT) was a common medication cause of the macrocytosis. This medication is much less commonly used today. Zidovudine causes macrocytosis in more than 80% of patients who take it. They also found in the study that very high MCVs (> 120) were most commonly associated with vitamin B12 deficiency.

Dr. Kaija Seppä and colleagues looked at all outpatients who had a blood count done over an 8-month period. A total of 9,527 blood counts were ordered, and 287 (3%) had macrocytosis.1 Further workup was done for 113 of the patients. The most common cause found for macrocytosis was alcohol abuse, in 74 (65%) of the patients (80% of the men and 36% of the women). No cause of the macrocytosis was found in 24 (21%) of the patients.

Dr. A. Wymer and colleagues looked at 2,800 adult outpatients who had complete blood counts. A total of 138 (3.7%) had macrocytosis, with 128 of these patients having charts that could be reviewed.3 A total of 73 patients had a workup for their macrocytosis. Alcohol was the diagnostic cause of the macrocytosis in 47 (64%). Only five of the patients had B12 deficiency (7%).

Dr. Seppä and colleagues also reported on hematologic morphologic features in nonanemic patients with macrocytosis due to alcohol abuse or vitamin B12 deficiency.4 They studied 136 patients with alcohol abuse and normal B12 levels, and 18 patients with pernicious anemia. The combination of a low red cell count or a high red cell distribution width with a normal platelet count was found in 94.4% of the vitamin-deficient patients but in only 14.6% of the abusers.

Pearl:

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. J Stud Alcohol. 1996 Jan;57(1):97-100.

2. Am J Med Sci. 2000 Jun;319(6):343-52.

3. J Gen Intern Med. 1990 May-Jun;5(3):192-7.

4. Alcohol. 1993 Sep-Oct;10(5):343-7.

5. South Med J. 2013 Feb;106(2):121-5.

A 56-year-old man presents for his annual physical. He brings in blood work done for all employees in his workplace (he is an aerospace engineer), and wants to talk about the lab that has an asterisk by it. All his labs are normal, except that his mean corpuscular volume (MCV) is 101. His hematocrit (HCT) is 42. He has no symptoms and a normal physical exam.

What test or tests would most likely be abnormal?

A. Thyroid-stimulating hormone.

B. Vitamin B12/folate.

C. Testosterone.

D. Gamma-glutamyl-transferase (GGT).

The finding of macrocytosis is fairly common in primary care, estimated to be found in 3% of complete blood count results.1 Most students in medical school quickly learn that vitamin B12 and folate deficiency can cause macrocytic anemias. The standard workups for patients with macrocytosis began and ended with checking vitamin B12 and folate levels, which are usually normal in the vast majority of patients with macrocytosis.

For this patient, the correct answer would be an abnormal GGT, because chronic moderate to heavy alcohol use can raise GGT levels, as well as MCVs.

Dr. David Savage and colleagues evaluated the etiology of macrocytosis in 300 consecutive hospitalized patients with macrocytosis.2 They found that the most common causes were medications, alcohol, liver disease, and reticulocytosis. The study was done in New York and was published in 2000, so zidovudine (AZT) was a common medication cause of the macrocytosis. This medication is much less commonly used today. Zidovudine causes macrocytosis in more than 80% of patients who take it. They also found in the study that very high MCVs (> 120) were most commonly associated with vitamin B12 deficiency.

Dr. Kaija Seppä and colleagues looked at all outpatients who had a blood count done over an 8-month period. A total of 9,527 blood counts were ordered, and 287 (3%) had macrocytosis.1 Further workup was done for 113 of the patients. The most common cause found for macrocytosis was alcohol abuse, in 74 (65%) of the patients (80% of the men and 36% of the women). No cause of the macrocytosis was found in 24 (21%) of the patients.

Dr. A. Wymer and colleagues looked at 2,800 adult outpatients who had complete blood counts. A total of 138 (3.7%) had macrocytosis, with 128 of these patients having charts that could be reviewed.3 A total of 73 patients had a workup for their macrocytosis. Alcohol was the diagnostic cause of the macrocytosis in 47 (64%). Only five of the patients had B12 deficiency (7%).

Dr. Seppä and colleagues also reported on hematologic morphologic features in nonanemic patients with macrocytosis due to alcohol abuse or vitamin B12 deficiency.4 They studied 136 patients with alcohol abuse and normal B12 levels, and 18 patients with pernicious anemia. The combination of a low red cell count or a high red cell distribution width with a normal platelet count was found in 94.4% of the vitamin-deficient patients but in only 14.6% of the abusers.

Pearl:

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. J Stud Alcohol. 1996 Jan;57(1):97-100.

2. Am J Med Sci. 2000 Jun;319(6):343-52.

3. J Gen Intern Med. 1990 May-Jun;5(3):192-7.

4. Alcohol. 1993 Sep-Oct;10(5):343-7.

5. South Med J. 2013 Feb;106(2):121-5.

A 56-year-old man presents for his annual physical. He brings in blood work done for all employees in his workplace (he is an aerospace engineer), and wants to talk about the lab that has an asterisk by it. All his labs are normal, except that his mean corpuscular volume (MCV) is 101. His hematocrit (HCT) is 42. He has no symptoms and a normal physical exam.

What test or tests would most likely be abnormal?

A. Thyroid-stimulating hormone.

B. Vitamin B12/folate.

C. Testosterone.

D. Gamma-glutamyl-transferase (GGT).

The finding of macrocytosis is fairly common in primary care, estimated to be found in 3% of complete blood count results.1 Most students in medical school quickly learn that vitamin B12 and folate deficiency can cause macrocytic anemias. The standard workups for patients with macrocytosis began and ended with checking vitamin B12 and folate levels, which are usually normal in the vast majority of patients with macrocytosis.

For this patient, the correct answer would be an abnormal GGT, because chronic moderate to heavy alcohol use can raise GGT levels, as well as MCVs.

Dr. David Savage and colleagues evaluated the etiology of macrocytosis in 300 consecutive hospitalized patients with macrocytosis.2 They found that the most common causes were medications, alcohol, liver disease, and reticulocytosis. The study was done in New York and was published in 2000, so zidovudine (AZT) was a common medication cause of the macrocytosis. This medication is much less commonly used today. Zidovudine causes macrocytosis in more than 80% of patients who take it. They also found in the study that very high MCVs (> 120) were most commonly associated with vitamin B12 deficiency.

Dr. Kaija Seppä and colleagues looked at all outpatients who had a blood count done over an 8-month period. A total of 9,527 blood counts were ordered, and 287 (3%) had macrocytosis.1 Further workup was done for 113 of the patients. The most common cause found for macrocytosis was alcohol abuse, in 74 (65%) of the patients (80% of the men and 36% of the women). No cause of the macrocytosis was found in 24 (21%) of the patients.

Dr. A. Wymer and colleagues looked at 2,800 adult outpatients who had complete blood counts. A total of 138 (3.7%) had macrocytosis, with 128 of these patients having charts that could be reviewed.3 A total of 73 patients had a workup for their macrocytosis. Alcohol was the diagnostic cause of the macrocytosis in 47 (64%). Only five of the patients had B12 deficiency (7%).

Dr. Seppä and colleagues also reported on hematologic morphologic features in nonanemic patients with macrocytosis due to alcohol abuse or vitamin B12 deficiency.4 They studied 136 patients with alcohol abuse and normal B12 levels, and 18 patients with pernicious anemia. The combination of a low red cell count or a high red cell distribution width with a normal platelet count was found in 94.4% of the vitamin-deficient patients but in only 14.6% of the abusers.

Pearl:

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. J Stud Alcohol. 1996 Jan;57(1):97-100.

2. Am J Med Sci. 2000 Jun;319(6):343-52.

3. J Gen Intern Med. 1990 May-Jun;5(3):192-7.

4. Alcohol. 1993 Sep-Oct;10(5):343-7.

5. South Med J. 2013 Feb;106(2):121-5.

Encouraging early results for CB-derived NK cells in MM

CHICAGO—Cord blood (CB) is a viable source of natural killer (NK) cells for adoptive cellular therapy for multiple myeloma (MM), according to a speaker at the 2018 ASCO Annual Meeting.

Ex-vivo expanded cord blood NK cells were well tolerated without significant graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) or cytokine release syndrome (CRS) in a phase 2 study.

Nina Shah, MD, of the University of California San Francisco, reported these results as abstract 8006.*

The phase 2 study (NCT01729091) included 33 patients with symptomatic MM who were appropriate candidates for autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT).

For each patient, investigators chose cord blood units with at least a 4/6 match at HLA-A, -B and –DR.

Prior to the autologous graft, patients received lenalidomide and melphalan. Lenalidomide was given based on preclinical data suggesting synergy between that immunomodulatory agent and NK cells, Dr Shah said.

Patients were a median age of 59 (range, 25 – 72), 36% had a history of progressive disease or relapse, and 73% had adverse cytogenetics/FISH, were ISS III, or had a history of progressive disease or relapse.

Results

Dr Shah observed that in a generally high-risk population, responses to treatment with cord blood NK cells in the setting of ASCT were “encouraging,” with 79% of patients achieving very good partial response (VGPR) or better.

Twenty-one patients (64%) achieved a complete response (CR) or near CR. And 61% achieved minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity by day 100.

Patients had an estimated 3-year progression-free survival of 52%.

Three patients died, all from disease progression, and 13 patients have progressed.

The investigators observed no infusional toxicities, no GVHD, no CRS, and no neurotoxicity.

One patient experienced graft failure and was rescued with an autologous back-up graft.

"We are able to detect the donor-derived NK cells up to 13 days after infusion,” Dr Shah said, “but I think a more sensitive analysis with flow chimerism will not only allow us to detect more patients, but also better interrogate them to truly understand the in vivo phenotype and activation status of these cells."

Dr Shah indicated she and her colleagues became interested in studying cord blood for NK cell therapy because it is a known source of hematopoietic cells that is immediately available, does not require donor manipulation, and has more flexibility in genetic matching.

Previously, Dr Shah and colleagues conducted a phase 1 study, in which 12 patients received cord blood NK cells up to a dose of 1 x 108 NK cells/kg. “This was determined to be adequate and safe to move on to the phase 2,” she said.

Despite encouraging results, more research needs to be done, according to Dr Shah. “I don't think this is the end-all, be-all for NK cell therapy.”

Some future directions include combination with antibody therapy, improving NK persistence in vivo using cytokine manipulation, and possibly engineering chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified NK cells, Dr Shah observed.

It’s also possible that HLA match may not be needed: “If that is the case, we will truly have an off-the-shelf source of NK cells that we can apply more readily to various patients,” she said.

The study was supported by Celgene Corporation, Stading-Younger Cancer Research Foundation, and the MD Anderson High-Risk Multiple Myeloma Moonshot Project.

*Data in the presentation differ from the abstract.

CHICAGO—Cord blood (CB) is a viable source of natural killer (NK) cells for adoptive cellular therapy for multiple myeloma (MM), according to a speaker at the 2018 ASCO Annual Meeting.

Ex-vivo expanded cord blood NK cells were well tolerated without significant graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) or cytokine release syndrome (CRS) in a phase 2 study.

Nina Shah, MD, of the University of California San Francisco, reported these results as abstract 8006.*

The phase 2 study (NCT01729091) included 33 patients with symptomatic MM who were appropriate candidates for autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT).

For each patient, investigators chose cord blood units with at least a 4/6 match at HLA-A, -B and –DR.

Prior to the autologous graft, patients received lenalidomide and melphalan. Lenalidomide was given based on preclinical data suggesting synergy between that immunomodulatory agent and NK cells, Dr Shah said.

Patients were a median age of 59 (range, 25 – 72), 36% had a history of progressive disease or relapse, and 73% had adverse cytogenetics/FISH, were ISS III, or had a history of progressive disease or relapse.

Results

Dr Shah observed that in a generally high-risk population, responses to treatment with cord blood NK cells in the setting of ASCT were “encouraging,” with 79% of patients achieving very good partial response (VGPR) or better.

Twenty-one patients (64%) achieved a complete response (CR) or near CR. And 61% achieved minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity by day 100.

Patients had an estimated 3-year progression-free survival of 52%.

Three patients died, all from disease progression, and 13 patients have progressed.

The investigators observed no infusional toxicities, no GVHD, no CRS, and no neurotoxicity.

One patient experienced graft failure and was rescued with an autologous back-up graft.

"We are able to detect the donor-derived NK cells up to 13 days after infusion,” Dr Shah said, “but I think a more sensitive analysis with flow chimerism will not only allow us to detect more patients, but also better interrogate them to truly understand the in vivo phenotype and activation status of these cells."

Dr Shah indicated she and her colleagues became interested in studying cord blood for NK cell therapy because it is a known source of hematopoietic cells that is immediately available, does not require donor manipulation, and has more flexibility in genetic matching.

Previously, Dr Shah and colleagues conducted a phase 1 study, in which 12 patients received cord blood NK cells up to a dose of 1 x 108 NK cells/kg. “This was determined to be adequate and safe to move on to the phase 2,” she said.

Despite encouraging results, more research needs to be done, according to Dr Shah. “I don't think this is the end-all, be-all for NK cell therapy.”

Some future directions include combination with antibody therapy, improving NK persistence in vivo using cytokine manipulation, and possibly engineering chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified NK cells, Dr Shah observed.

It’s also possible that HLA match may not be needed: “If that is the case, we will truly have an off-the-shelf source of NK cells that we can apply more readily to various patients,” she said.

The study was supported by Celgene Corporation, Stading-Younger Cancer Research Foundation, and the MD Anderson High-Risk Multiple Myeloma Moonshot Project.

*Data in the presentation differ from the abstract.

CHICAGO—Cord blood (CB) is a viable source of natural killer (NK) cells for adoptive cellular therapy for multiple myeloma (MM), according to a speaker at the 2018 ASCO Annual Meeting.

Ex-vivo expanded cord blood NK cells were well tolerated without significant graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) or cytokine release syndrome (CRS) in a phase 2 study.

Nina Shah, MD, of the University of California San Francisco, reported these results as abstract 8006.*

The phase 2 study (NCT01729091) included 33 patients with symptomatic MM who were appropriate candidates for autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT).

For each patient, investigators chose cord blood units with at least a 4/6 match at HLA-A, -B and –DR.

Prior to the autologous graft, patients received lenalidomide and melphalan. Lenalidomide was given based on preclinical data suggesting synergy between that immunomodulatory agent and NK cells, Dr Shah said.

Patients were a median age of 59 (range, 25 – 72), 36% had a history of progressive disease or relapse, and 73% had adverse cytogenetics/FISH, were ISS III, or had a history of progressive disease or relapse.

Results

Dr Shah observed that in a generally high-risk population, responses to treatment with cord blood NK cells in the setting of ASCT were “encouraging,” with 79% of patients achieving very good partial response (VGPR) or better.

Twenty-one patients (64%) achieved a complete response (CR) or near CR. And 61% achieved minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity by day 100.

Patients had an estimated 3-year progression-free survival of 52%.

Three patients died, all from disease progression, and 13 patients have progressed.

The investigators observed no infusional toxicities, no GVHD, no CRS, and no neurotoxicity.

One patient experienced graft failure and was rescued with an autologous back-up graft.

"We are able to detect the donor-derived NK cells up to 13 days after infusion,” Dr Shah said, “but I think a more sensitive analysis with flow chimerism will not only allow us to detect more patients, but also better interrogate them to truly understand the in vivo phenotype and activation status of these cells."

Dr Shah indicated she and her colleagues became interested in studying cord blood for NK cell therapy because it is a known source of hematopoietic cells that is immediately available, does not require donor manipulation, and has more flexibility in genetic matching.

Previously, Dr Shah and colleagues conducted a phase 1 study, in which 12 patients received cord blood NK cells up to a dose of 1 x 108 NK cells/kg. “This was determined to be adequate and safe to move on to the phase 2,” she said.

Despite encouraging results, more research needs to be done, according to Dr Shah. “I don't think this is the end-all, be-all for NK cell therapy.”

Some future directions include combination with antibody therapy, improving NK persistence in vivo using cytokine manipulation, and possibly engineering chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified NK cells, Dr Shah observed.

It’s also possible that HLA match may not be needed: “If that is the case, we will truly have an off-the-shelf source of NK cells that we can apply more readily to various patients,” she said.

The study was supported by Celgene Corporation, Stading-Younger Cancer Research Foundation, and the MD Anderson High-Risk Multiple Myeloma Moonshot Project.

*Data in the presentation differ from the abstract.

CAR T-cell technology making headway in MM

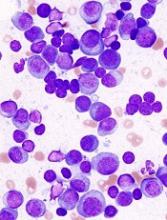

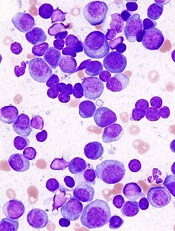

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell technology has been successfully used in the treatment of hematologic malignancies such as leukemias and lymphomas. Now, this technology has come to the forefront in multiple myeloma (MM).

Researchers at the National Cancer Institute, led by James N. Kochenderfer, MD, generated CAR T cells expressing the B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), which is uniquely found on MM cells.

In the first in humans study, 24 patients received CAR-BCMA T cells at doses ranging between 0.3 and 3 x 106 CAR+ T cells/kg. Sixteen patients were treated at the highest dose. These patients had a median of 9.5 lines of prior therapy and 63% were refractory to their last treatment.

Thirteen patients had responses that were either partial or better and the overall response rate was 81%. Median event-free survival was 31 weeks. At the time of the report, 6 patients still have ongoing responses.

Patient cases

The report highlights a case study of a patient who had a large abdominal mass that resolved on computed tomography imaging, with λ light chains decreasing dramatically and becoming undetectable after CAR T-cell infusion. Recovery of normal plasma cells was noticeable with λ chain increases, but the ratio of κ to λ ratio remained normal 6 months after CAR T-cell infusion.

Using immunohistochemistry staining of CS138 before and 2 months after CAR-BMCA infusion, the researchers found effective depletion in bone marrow plasma cells in patients who were evaluated.

In patients who responded to treatment, decline in serum BCMA was also observed. However, in a patient who later progressed, BCMA increases were seen, leading the researchers to suggest that BCMA may be a tumor marker for MM.

The researchers noted that peak levels of CAR T cells occurred between 7 and 14 days after infusion and highest levels were seen in patients who showed antimyeloma responses.

Toxicity

CAR T-cell technology is also associated with accompanying toxicities.

At the highest dose, cytokine release syndrome (CRS) was a substantial toxicity especially in 2 patients who had a significant MM burden: in one case 80% of bone marrow cells were MM plasma cells and in the other the MM burden was 90%.

Six of the 16 patients required vasopressor support for hypotension and 1 patient required mechanical ventilation. The researchers noted that CRS of grade 3/4 was seen in patients who had a higher MM plasma cell burden.

The researchers indicated there is room for improvement. “The importance of persistence of CAR T cells in treating MM requires additional study,” they stated.

The sometimes low or absence of BCMA expression on MM cells may prompt the search for other antigens. “Treatment outcomes varied substantially between patients, and much room for improvement remains in improving the durability of antimyeloma responses and in reducing toxicity,” they concluded.

The researchers reported their findings in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell technology has been successfully used in the treatment of hematologic malignancies such as leukemias and lymphomas. Now, this technology has come to the forefront in multiple myeloma (MM).

Researchers at the National Cancer Institute, led by James N. Kochenderfer, MD, generated CAR T cells expressing the B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), which is uniquely found on MM cells.

In the first in humans study, 24 patients received CAR-BCMA T cells at doses ranging between 0.3 and 3 x 106 CAR+ T cells/kg. Sixteen patients were treated at the highest dose. These patients had a median of 9.5 lines of prior therapy and 63% were refractory to their last treatment.

Thirteen patients had responses that were either partial or better and the overall response rate was 81%. Median event-free survival was 31 weeks. At the time of the report, 6 patients still have ongoing responses.

Patient cases

The report highlights a case study of a patient who had a large abdominal mass that resolved on computed tomography imaging, with λ light chains decreasing dramatically and becoming undetectable after CAR T-cell infusion. Recovery of normal plasma cells was noticeable with λ chain increases, but the ratio of κ to λ ratio remained normal 6 months after CAR T-cell infusion.

Using immunohistochemistry staining of CS138 before and 2 months after CAR-BMCA infusion, the researchers found effective depletion in bone marrow plasma cells in patients who were evaluated.

In patients who responded to treatment, decline in serum BCMA was also observed. However, in a patient who later progressed, BCMA increases were seen, leading the researchers to suggest that BCMA may be a tumor marker for MM.

The researchers noted that peak levels of CAR T cells occurred between 7 and 14 days after infusion and highest levels were seen in patients who showed antimyeloma responses.

Toxicity

CAR T-cell technology is also associated with accompanying toxicities.

At the highest dose, cytokine release syndrome (CRS) was a substantial toxicity especially in 2 patients who had a significant MM burden: in one case 80% of bone marrow cells were MM plasma cells and in the other the MM burden was 90%.

Six of the 16 patients required vasopressor support for hypotension and 1 patient required mechanical ventilation. The researchers noted that CRS of grade 3/4 was seen in patients who had a higher MM plasma cell burden.

The researchers indicated there is room for improvement. “The importance of persistence of CAR T cells in treating MM requires additional study,” they stated.

The sometimes low or absence of BCMA expression on MM cells may prompt the search for other antigens. “Treatment outcomes varied substantially between patients, and much room for improvement remains in improving the durability of antimyeloma responses and in reducing toxicity,” they concluded.

The researchers reported their findings in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell technology has been successfully used in the treatment of hematologic malignancies such as leukemias and lymphomas. Now, this technology has come to the forefront in multiple myeloma (MM).

Researchers at the National Cancer Institute, led by James N. Kochenderfer, MD, generated CAR T cells expressing the B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), which is uniquely found on MM cells.

In the first in humans study, 24 patients received CAR-BCMA T cells at doses ranging between 0.3 and 3 x 106 CAR+ T cells/kg. Sixteen patients were treated at the highest dose. These patients had a median of 9.5 lines of prior therapy and 63% were refractory to their last treatment.

Thirteen patients had responses that were either partial or better and the overall response rate was 81%. Median event-free survival was 31 weeks. At the time of the report, 6 patients still have ongoing responses.

Patient cases

The report highlights a case study of a patient who had a large abdominal mass that resolved on computed tomography imaging, with λ light chains decreasing dramatically and becoming undetectable after CAR T-cell infusion. Recovery of normal plasma cells was noticeable with λ chain increases, but the ratio of κ to λ ratio remained normal 6 months after CAR T-cell infusion.

Using immunohistochemistry staining of CS138 before and 2 months after CAR-BMCA infusion, the researchers found effective depletion in bone marrow plasma cells in patients who were evaluated.

In patients who responded to treatment, decline in serum BCMA was also observed. However, in a patient who later progressed, BCMA increases were seen, leading the researchers to suggest that BCMA may be a tumor marker for MM.

The researchers noted that peak levels of CAR T cells occurred between 7 and 14 days after infusion and highest levels were seen in patients who showed antimyeloma responses.

Toxicity

CAR T-cell technology is also associated with accompanying toxicities.

At the highest dose, cytokine release syndrome (CRS) was a substantial toxicity especially in 2 patients who had a significant MM burden: in one case 80% of bone marrow cells were MM plasma cells and in the other the MM burden was 90%.

Six of the 16 patients required vasopressor support for hypotension and 1 patient required mechanical ventilation. The researchers noted that CRS of grade 3/4 was seen in patients who had a higher MM plasma cell burden.

The researchers indicated there is room for improvement. “The importance of persistence of CAR T cells in treating MM requires additional study,” they stated.

The sometimes low or absence of BCMA expression on MM cells may prompt the search for other antigens. “Treatment outcomes varied substantially between patients, and much room for improvement remains in improving the durability of antimyeloma responses and in reducing toxicity,” they concluded.

The researchers reported their findings in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

FDA approves first biosimilar pegfilgrastim

The US Food and Drug Association (FDA) has approved pegfilgrastim-jmdb (Fulphila™) as the first biosimilar to Neulasta®.

The agents reduce the risk of infection or the duration of febrile neutropenia in patients treated with immunosuppressive chemotherapy for non-myeloid hematologic malignancies.

The FDA approved Fulphila based on evidence that included extensive structural and functional characterization, animal study data, human pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data, clinical immunogenicity data, and other clinical safety and effectiveness data.

The evidence demonstrated that Fulphila is biosimilar to Amgen’s Neulasta. The FDA, in its announcement, noted that Fulphila has been approved as a biosimilar and not as an interchangeable product.

A biosimilar is a biological product approved based on data showing it is highly similar to a biological product already approved by the FDA, termed the reference product.

A biosimilar has no clinically meaningful differences from the reference product in terms of safety, purity, and effectiveness.

Common side effects of Fulphila include bone pain and pain in extremities.

The FDA cautions that patients with a history of serious allergic reaction to human granulocyte colony-stimulating factors, such as pegfilgrastim or filgrastim products, should not take Fulphila.

Serious side effects from Fulphila include:

- rupture of the spleen

- acute respiratory distress syndrome

- serious allergic reactions including anaphylaxis

- glomerulonephritis

- leukocytosis

- capillary leak syndrome

- potential for tumor growth

Fatal sickle cell crises have also occurred with Fulphila use.

Fulphila is not indicated for the mobilization of peripheral blood progenitor cells for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

The FDA is planning to release a comprehensive new plan to advance policy efforts that promote biosimilar product development, according to FDA Commissioner Scott Gotlieb, MD.

“We want to make sure that the pathway for developing biosimilar versions of approved biologics is efficient and effective, so that patients benefit from competition to existing biologics once lawful intellectual property has lapsed on these products,” he said in the announcement.

The FDA granted approval of Fulphila to Mylan GmbH. Mylan is co-developing Fulphila with Biocon.

Last fall, the agency had issued a complete response letter saying it could not approve the proposed biosimilar pending an update to the application.

The complete response letter did not raise any questions on the biosimilarity of Fulphila (investigational drug product MYL-1401H), pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic data, clinical data, or immunogenicity, however.

Mylan anticipates launching Fulphila in the coming weeks.

The US Food and Drug Association (FDA) has approved pegfilgrastim-jmdb (Fulphila™) as the first biosimilar to Neulasta®.

The agents reduce the risk of infection or the duration of febrile neutropenia in patients treated with immunosuppressive chemotherapy for non-myeloid hematologic malignancies.

The FDA approved Fulphila based on evidence that included extensive structural and functional characterization, animal study data, human pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data, clinical immunogenicity data, and other clinical safety and effectiveness data.

The evidence demonstrated that Fulphila is biosimilar to Amgen’s Neulasta. The FDA, in its announcement, noted that Fulphila has been approved as a biosimilar and not as an interchangeable product.

A biosimilar is a biological product approved based on data showing it is highly similar to a biological product already approved by the FDA, termed the reference product.

A biosimilar has no clinically meaningful differences from the reference product in terms of safety, purity, and effectiveness.

Common side effects of Fulphila include bone pain and pain in extremities.

The FDA cautions that patients with a history of serious allergic reaction to human granulocyte colony-stimulating factors, such as pegfilgrastim or filgrastim products, should not take Fulphila.

Serious side effects from Fulphila include:

- rupture of the spleen

- acute respiratory distress syndrome

- serious allergic reactions including anaphylaxis

- glomerulonephritis

- leukocytosis

- capillary leak syndrome

- potential for tumor growth

Fatal sickle cell crises have also occurred with Fulphila use.

Fulphila is not indicated for the mobilization of peripheral blood progenitor cells for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

The FDA is planning to release a comprehensive new plan to advance policy efforts that promote biosimilar product development, according to FDA Commissioner Scott Gotlieb, MD.

“We want to make sure that the pathway for developing biosimilar versions of approved biologics is efficient and effective, so that patients benefit from competition to existing biologics once lawful intellectual property has lapsed on these products,” he said in the announcement.

The FDA granted approval of Fulphila to Mylan GmbH. Mylan is co-developing Fulphila with Biocon.

Last fall, the agency had issued a complete response letter saying it could not approve the proposed biosimilar pending an update to the application.

The complete response letter did not raise any questions on the biosimilarity of Fulphila (investigational drug product MYL-1401H), pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic data, clinical data, or immunogenicity, however.

Mylan anticipates launching Fulphila in the coming weeks.

The US Food and Drug Association (FDA) has approved pegfilgrastim-jmdb (Fulphila™) as the first biosimilar to Neulasta®.

The agents reduce the risk of infection or the duration of febrile neutropenia in patients treated with immunosuppressive chemotherapy for non-myeloid hematologic malignancies.

The FDA approved Fulphila based on evidence that included extensive structural and functional characterization, animal study data, human pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data, clinical immunogenicity data, and other clinical safety and effectiveness data.

The evidence demonstrated that Fulphila is biosimilar to Amgen’s Neulasta. The FDA, in its announcement, noted that Fulphila has been approved as a biosimilar and not as an interchangeable product.

A biosimilar is a biological product approved based on data showing it is highly similar to a biological product already approved by the FDA, termed the reference product.

A biosimilar has no clinically meaningful differences from the reference product in terms of safety, purity, and effectiveness.

Common side effects of Fulphila include bone pain and pain in extremities.

The FDA cautions that patients with a history of serious allergic reaction to human granulocyte colony-stimulating factors, such as pegfilgrastim or filgrastim products, should not take Fulphila.

Serious side effects from Fulphila include:

- rupture of the spleen

- acute respiratory distress syndrome

- serious allergic reactions including anaphylaxis

- glomerulonephritis

- leukocytosis

- capillary leak syndrome

- potential for tumor growth

Fatal sickle cell crises have also occurred with Fulphila use.

Fulphila is not indicated for the mobilization of peripheral blood progenitor cells for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

The FDA is planning to release a comprehensive new plan to advance policy efforts that promote biosimilar product development, according to FDA Commissioner Scott Gotlieb, MD.

“We want to make sure that the pathway for developing biosimilar versions of approved biologics is efficient and effective, so that patients benefit from competition to existing biologics once lawful intellectual property has lapsed on these products,” he said in the announcement.

The FDA granted approval of Fulphila to Mylan GmbH. Mylan is co-developing Fulphila with Biocon.

Last fall, the agency had issued a complete response letter saying it could not approve the proposed biosimilar pending an update to the application.

The complete response letter did not raise any questions on the biosimilarity of Fulphila (investigational drug product MYL-1401H), pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic data, clinical data, or immunogenicity, however.

Mylan anticipates launching Fulphila in the coming weeks.

Pembrolizumab monotherapy shows activity in advanced recurrent ovarian cancer

CHICAGO – Pembrolizumab monotherapy is associated with antitumor activity in patients with advanced recurrent ovarian cancer, interim results from the phase 2 KEYNOTE-100 study suggest.

Notably, objective response rates among study subjects increased in tandem with increased programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, which helps define the population most likely to benefit from single agent pembrolizumab (Keytruda), Ursula A. Matulonis reported during an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Further, no new safety signals were identified, said Dr. Matulonis, medical director and program leader of the Medical Gynecologic Oncology Program at of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

All patients received intravenous pembrolizumab at 200 mg every 3 weeks for 2 years or until progression, death, unacceptable toxicity, or consent withdrawal, and tumor imaging was performed every 9 weeks for a year, then every 12 weeks thereafter until progressive disease, death, or study completion.

The overall response rate (ORR) among 285 patients in Cohort A, who had one to three prior chemotherapy lines for recurrent advanced ovarian cancer and a platinum-free or treatment-free interval of 3-12 months, was 7.4%, with mean duration of response of 8.2 months. The ORR among 91 patients in Cohort B, who had four to six prior chemotherapy lines and a platinum-free or treatment-free interval of at least 3 months, was 9.9%; the mean duration of response was not reached in Cohort B.

Among all-comers, the ORR was 8.0%, including 7 complete responses and 23 partial responses. Mean duration of response was 8.2 months, and 65.5% of responses lasted at least 6 months. Further, responses were observed across all subgroups, Dr. Matulonis said, noting that responses were seen regardless of age, prior lines of treatment, progression-free/treatment-free interval duration, platinum sensitivity, and histology.

“The one factor that did predict response was a [combined positive score] of 10 or higher, where there were more responses,” she said.

The ORRs among those with PD-L1 expression as measured using the combined positive score (CPS), which is defined as the number of PD-L1–positive cells out of the total number of tumor cells x 100, was 5.0% in those with CPS less than 1, 10.2% in those with CPS of 1 or greater, and 17.1% in those with CPS of 10 or greater (vs. the 8.0% ORR in the study), she explained, noting that all complete responses occurred in those with CPS of 10 or higher.

Grade 3-4 treatment-related adverse events occurred in 19.7% of patients, and included fatigue in 2.7%, and anemia, colitis, increased amylase, increased blood alkaline phosphatase, ascites, and diarrhea in 0.8-1.3%. One treatment-related death occurred in a patient with Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and another occurred in a patient with hypoaldosteronism. Immune-mediated adverse events and infusion reactions were most commonly hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, and most cases were grade 1-2, she said.

KEYNOTE-100 is an ongoing study that followed KEYNOTE-028, which demonstrated the clinical activity of pembrolizumab in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. To date, KEYNOTE-100 has enrolled 376 patients with epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer and confirmed recurrence after frontline platinum-based therapy. All had a tumor sample available for biomarker analysis.

The patients had a mean age of 61 years, 64% and 35% had performance status scores of 0 and 1, respectively, and 75% had high-grade serous disease.

Median follow-up in Cohort A at the time of the current analysis was 16.7 months, and in Cohort B, the median follow-up was 17.3 months. Treatment was ongoing in 15 and 6 patients in the cohorts, respectively. Reasons for discontinuation included radiographic progression (204 and 62 patients), clinical progression (24 and 17 patients), adverse events (22 and 3 patients), and patient withdrawal (9 and 3 patients). Complete responses occurred in 1 and 0 patients in the groups, respectively.

Median progression-free survival in both cohorts was 2.1 months, and overall survival was not reached in Cohort A, while it was 17.6 months in the more heavily pretreated Cohort B.

“Recurrent ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death from gynecologic cancer. The majority of our patients relapse after first-line platinum and taxane-based chemotherapy, and the degree of platinum sensitivity will predict the tumor response rates with platinum, as well as survival time,” she said, noting that subsequent recurrences become increasingly platinum and treatment resistant.

Current treatment options in these patients include chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab; the ORRs with single-agent immune checkpoint blockade are about 10%, but in KEYNOTE-028, patients with PD-L1–positive advanced recurrent ovarian cancer had an ORR of 11.5% with pembrolizumab treatment, she said.

“With 16.9 months median follow-up, the results confirm that pembrolizumab monotherapy in recurrent ovarian cancer elicits modest antitumor efficacy,” Dr. Matulonis concluded, noting that further analysis for biomarkers predictive of pembrolizumab response are ongoing.

Invited discussant Janos Laszlo Tanyi, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the findings underscore the overall modest ORRs of 5.9%-15% seen with anti-PD-1 or PD-L1 monotherapy in patients with advanced recurrent ovarian cancer, but noted the importance of the finding that the subpopulation of patients with increased PD-L1 expression may experience greater benefit.

Dr. Matulonis reported consulting or advisory roles with 2X Oncology, Clovis Oncology, Fujifilm, Geneos Therapeutics, Lilly, Merck, and Myriad Genetics, and research funding from Merck and Novartis. Dr .Tanyi reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Matulonis UA et al. ASCO 2018, Abstract 5511.

CHICAGO – Pembrolizumab monotherapy is associated with antitumor activity in patients with advanced recurrent ovarian cancer, interim results from the phase 2 KEYNOTE-100 study suggest.

Notably, objective response rates among study subjects increased in tandem with increased programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, which helps define the population most likely to benefit from single agent pembrolizumab (Keytruda), Ursula A. Matulonis reported during an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Further, no new safety signals were identified, said Dr. Matulonis, medical director and program leader of the Medical Gynecologic Oncology Program at of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

All patients received intravenous pembrolizumab at 200 mg every 3 weeks for 2 years or until progression, death, unacceptable toxicity, or consent withdrawal, and tumor imaging was performed every 9 weeks for a year, then every 12 weeks thereafter until progressive disease, death, or study completion.

The overall response rate (ORR) among 285 patients in Cohort A, who had one to three prior chemotherapy lines for recurrent advanced ovarian cancer and a platinum-free or treatment-free interval of 3-12 months, was 7.4%, with mean duration of response of 8.2 months. The ORR among 91 patients in Cohort B, who had four to six prior chemotherapy lines and a platinum-free or treatment-free interval of at least 3 months, was 9.9%; the mean duration of response was not reached in Cohort B.

Among all-comers, the ORR was 8.0%, including 7 complete responses and 23 partial responses. Mean duration of response was 8.2 months, and 65.5% of responses lasted at least 6 months. Further, responses were observed across all subgroups, Dr. Matulonis said, noting that responses were seen regardless of age, prior lines of treatment, progression-free/treatment-free interval duration, platinum sensitivity, and histology.

“The one factor that did predict response was a [combined positive score] of 10 or higher, where there were more responses,” she said.

The ORRs among those with PD-L1 expression as measured using the combined positive score (CPS), which is defined as the number of PD-L1–positive cells out of the total number of tumor cells x 100, was 5.0% in those with CPS less than 1, 10.2% in those with CPS of 1 or greater, and 17.1% in those with CPS of 10 or greater (vs. the 8.0% ORR in the study), she explained, noting that all complete responses occurred in those with CPS of 10 or higher.

Grade 3-4 treatment-related adverse events occurred in 19.7% of patients, and included fatigue in 2.7%, and anemia, colitis, increased amylase, increased blood alkaline phosphatase, ascites, and diarrhea in 0.8-1.3%. One treatment-related death occurred in a patient with Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and another occurred in a patient with hypoaldosteronism. Immune-mediated adverse events and infusion reactions were most commonly hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, and most cases were grade 1-2, she said.

KEYNOTE-100 is an ongoing study that followed KEYNOTE-028, which demonstrated the clinical activity of pembrolizumab in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. To date, KEYNOTE-100 has enrolled 376 patients with epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer and confirmed recurrence after frontline platinum-based therapy. All had a tumor sample available for biomarker analysis.

The patients had a mean age of 61 years, 64% and 35% had performance status scores of 0 and 1, respectively, and 75% had high-grade serous disease.

Median follow-up in Cohort A at the time of the current analysis was 16.7 months, and in Cohort B, the median follow-up was 17.3 months. Treatment was ongoing in 15 and 6 patients in the cohorts, respectively. Reasons for discontinuation included radiographic progression (204 and 62 patients), clinical progression (24 and 17 patients), adverse events (22 and 3 patients), and patient withdrawal (9 and 3 patients). Complete responses occurred in 1 and 0 patients in the groups, respectively.

Median progression-free survival in both cohorts was 2.1 months, and overall survival was not reached in Cohort A, while it was 17.6 months in the more heavily pretreated Cohort B.

“Recurrent ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death from gynecologic cancer. The majority of our patients relapse after first-line platinum and taxane-based chemotherapy, and the degree of platinum sensitivity will predict the tumor response rates with platinum, as well as survival time,” she said, noting that subsequent recurrences become increasingly platinum and treatment resistant.

Current treatment options in these patients include chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab; the ORRs with single-agent immune checkpoint blockade are about 10%, but in KEYNOTE-028, patients with PD-L1–positive advanced recurrent ovarian cancer had an ORR of 11.5% with pembrolizumab treatment, she said.

“With 16.9 months median follow-up, the results confirm that pembrolizumab monotherapy in recurrent ovarian cancer elicits modest antitumor efficacy,” Dr. Matulonis concluded, noting that further analysis for biomarkers predictive of pembrolizumab response are ongoing.

Invited discussant Janos Laszlo Tanyi, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the findings underscore the overall modest ORRs of 5.9%-15% seen with anti-PD-1 or PD-L1 monotherapy in patients with advanced recurrent ovarian cancer, but noted the importance of the finding that the subpopulation of patients with increased PD-L1 expression may experience greater benefit.

Dr. Matulonis reported consulting or advisory roles with 2X Oncology, Clovis Oncology, Fujifilm, Geneos Therapeutics, Lilly, Merck, and Myriad Genetics, and research funding from Merck and Novartis. Dr .Tanyi reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Matulonis UA et al. ASCO 2018, Abstract 5511.

CHICAGO – Pembrolizumab monotherapy is associated with antitumor activity in patients with advanced recurrent ovarian cancer, interim results from the phase 2 KEYNOTE-100 study suggest.

Notably, objective response rates among study subjects increased in tandem with increased programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, which helps define the population most likely to benefit from single agent pembrolizumab (Keytruda), Ursula A. Matulonis reported during an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Further, no new safety signals were identified, said Dr. Matulonis, medical director and program leader of the Medical Gynecologic Oncology Program at of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

All patients received intravenous pembrolizumab at 200 mg every 3 weeks for 2 years or until progression, death, unacceptable toxicity, or consent withdrawal, and tumor imaging was performed every 9 weeks for a year, then every 12 weeks thereafter until progressive disease, death, or study completion.

The overall response rate (ORR) among 285 patients in Cohort A, who had one to three prior chemotherapy lines for recurrent advanced ovarian cancer and a platinum-free or treatment-free interval of 3-12 months, was 7.4%, with mean duration of response of 8.2 months. The ORR among 91 patients in Cohort B, who had four to six prior chemotherapy lines and a platinum-free or treatment-free interval of at least 3 months, was 9.9%; the mean duration of response was not reached in Cohort B.

Among all-comers, the ORR was 8.0%, including 7 complete responses and 23 partial responses. Mean duration of response was 8.2 months, and 65.5% of responses lasted at least 6 months. Further, responses were observed across all subgroups, Dr. Matulonis said, noting that responses were seen regardless of age, prior lines of treatment, progression-free/treatment-free interval duration, platinum sensitivity, and histology.

“The one factor that did predict response was a [combined positive score] of 10 or higher, where there were more responses,” she said.

The ORRs among those with PD-L1 expression as measured using the combined positive score (CPS), which is defined as the number of PD-L1–positive cells out of the total number of tumor cells x 100, was 5.0% in those with CPS less than 1, 10.2% in those with CPS of 1 or greater, and 17.1% in those with CPS of 10 or greater (vs. the 8.0% ORR in the study), she explained, noting that all complete responses occurred in those with CPS of 10 or higher.

Grade 3-4 treatment-related adverse events occurred in 19.7% of patients, and included fatigue in 2.7%, and anemia, colitis, increased amylase, increased blood alkaline phosphatase, ascites, and diarrhea in 0.8-1.3%. One treatment-related death occurred in a patient with Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and another occurred in a patient with hypoaldosteronism. Immune-mediated adverse events and infusion reactions were most commonly hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, and most cases were grade 1-2, she said.

KEYNOTE-100 is an ongoing study that followed KEYNOTE-028, which demonstrated the clinical activity of pembrolizumab in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. To date, KEYNOTE-100 has enrolled 376 patients with epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer and confirmed recurrence after frontline platinum-based therapy. All had a tumor sample available for biomarker analysis.

The patients had a mean age of 61 years, 64% and 35% had performance status scores of 0 and 1, respectively, and 75% had high-grade serous disease.

Median follow-up in Cohort A at the time of the current analysis was 16.7 months, and in Cohort B, the median follow-up was 17.3 months. Treatment was ongoing in 15 and 6 patients in the cohorts, respectively. Reasons for discontinuation included radiographic progression (204 and 62 patients), clinical progression (24 and 17 patients), adverse events (22 and 3 patients), and patient withdrawal (9 and 3 patients). Complete responses occurred in 1 and 0 patients in the groups, respectively.

Median progression-free survival in both cohorts was 2.1 months, and overall survival was not reached in Cohort A, while it was 17.6 months in the more heavily pretreated Cohort B.

“Recurrent ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death from gynecologic cancer. The majority of our patients relapse after first-line platinum and taxane-based chemotherapy, and the degree of platinum sensitivity will predict the tumor response rates with platinum, as well as survival time,” she said, noting that subsequent recurrences become increasingly platinum and treatment resistant.

Current treatment options in these patients include chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab; the ORRs with single-agent immune checkpoint blockade are about 10%, but in KEYNOTE-028, patients with PD-L1–positive advanced recurrent ovarian cancer had an ORR of 11.5% with pembrolizumab treatment, she said.

“With 16.9 months median follow-up, the results confirm that pembrolizumab monotherapy in recurrent ovarian cancer elicits modest antitumor efficacy,” Dr. Matulonis concluded, noting that further analysis for biomarkers predictive of pembrolizumab response are ongoing.

Invited discussant Janos Laszlo Tanyi, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the findings underscore the overall modest ORRs of 5.9%-15% seen with anti-PD-1 or PD-L1 monotherapy in patients with advanced recurrent ovarian cancer, but noted the importance of the finding that the subpopulation of patients with increased PD-L1 expression may experience greater benefit.

Dr. Matulonis reported consulting or advisory roles with 2X Oncology, Clovis Oncology, Fujifilm, Geneos Therapeutics, Lilly, Merck, and Myriad Genetics, and research funding from Merck and Novartis. Dr .Tanyi reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Matulonis UA et al. ASCO 2018, Abstract 5511.

REPORTING FROM ASCO 2018

Key clinical point: Pembrolizumab monotherapy shows antitumor activity in advanced recurrent OC, particularly in those with higher PD-L1 expression.

Major finding: Overall response rates: 8.0% overall, 5.0% with CPS up to 1, 10.2% with CPS of 1+, and 17.1% with CPS of 10+.

Study details: Interim findings from the 376-patient phase 2 KEYNOTE-100 study.

Disclosures: Dr. Matulonis reported consulting or advisory roles with 2X Oncology, Clovis Oncology, Fujifilm, Geneos Therapeutics, Lilly, Merck, and Myriad Genetics, and research funding from Merck and Novartis. Dr. Tanyi reported having no disclosures.

Source: Matulonis UA et al. ASCO 2018, Abstract 5511.

Bladder injection may improve sexual function

An injection to the bladder may help improve sexual function along with relieving symptoms, according to a recent statistical analysis.

In a prospective observational study, 32 women with wet idiopathic overactive bladder received a 100 U/10 mL injection of onabotulinumtoxinA (onaBoNT-A) to their detrusor muscle while sedated.

The women in the study had overactive bladder syndrome with urgency urinary incontinence that was refractory to more conservative treatments. All were aged 18 years or older, sexually active, and in a relationship with the same partner for more than 3 months.

The researchers sought to distinguish the effect of the injection treatment on sexual function for women with an idiopathic, rather than neurogenic, version of the syndrome. Sexual function was assessed through a 19-item questionnaire, the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), before and after the treatment. To determine the efficacy of the treatment, participants kept a 3-day voiding diary, and completed two more forms: an overactive bladder screener questionnaire and the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Short Form.

Most of the participants (88.2%) saw an improvement in their overactive bladder symptoms. They also reported statistically meaningful improvement in sexual function on the FSFI, and specifically for arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and satisfaction, though not for desire and pain (average FSFI total score before and after treatment, 20.30 vs. 24.91; P = .0008).

“Although voiding diaries and questionnaires on urinary symptoms showed an improvement after onaBoNT-A injection, we documented a significant correlation only between the reduction of episodes of [urgency urinary incontinence] and improvement of FSFI total score. This finding shows that, in our population, the most relevant urinary symptom reducing the sexual function is urgency urinary incontinence,” Matteo Balzarro, MD, of Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata of Verona, Italy, and his coauthors wrote in the European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology.

The researchers noted that the small sample size resulted from multiple exclusion criteria applied to an already small population of 157 patients. They also remarked that a control group – which was absent from their study – would be difficult to have because of “ethical considerations.”

The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Balzarro M et al. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018 Jun;225:228-31.

An injection to the bladder may help improve sexual function along with relieving symptoms, according to a recent statistical analysis.

In a prospective observational study, 32 women with wet idiopathic overactive bladder received a 100 U/10 mL injection of onabotulinumtoxinA (onaBoNT-A) to their detrusor muscle while sedated.

The women in the study had overactive bladder syndrome with urgency urinary incontinence that was refractory to more conservative treatments. All were aged 18 years or older, sexually active, and in a relationship with the same partner for more than 3 months.

The researchers sought to distinguish the effect of the injection treatment on sexual function for women with an idiopathic, rather than neurogenic, version of the syndrome. Sexual function was assessed through a 19-item questionnaire, the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), before and after the treatment. To determine the efficacy of the treatment, participants kept a 3-day voiding diary, and completed two more forms: an overactive bladder screener questionnaire and the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Short Form.

Most of the participants (88.2%) saw an improvement in their overactive bladder symptoms. They also reported statistically meaningful improvement in sexual function on the FSFI, and specifically for arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and satisfaction, though not for desire and pain (average FSFI total score before and after treatment, 20.30 vs. 24.91; P = .0008).

“Although voiding diaries and questionnaires on urinary symptoms showed an improvement after onaBoNT-A injection, we documented a significant correlation only between the reduction of episodes of [urgency urinary incontinence] and improvement of FSFI total score. This finding shows that, in our population, the most relevant urinary symptom reducing the sexual function is urgency urinary incontinence,” Matteo Balzarro, MD, of Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata of Verona, Italy, and his coauthors wrote in the European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology.

The researchers noted that the small sample size resulted from multiple exclusion criteria applied to an already small population of 157 patients. They also remarked that a control group – which was absent from their study – would be difficult to have because of “ethical considerations.”

The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Balzarro M et al. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018 Jun;225:228-31.

An injection to the bladder may help improve sexual function along with relieving symptoms, according to a recent statistical analysis.

In a prospective observational study, 32 women with wet idiopathic overactive bladder received a 100 U/10 mL injection of onabotulinumtoxinA (onaBoNT-A) to their detrusor muscle while sedated.

The women in the study had overactive bladder syndrome with urgency urinary incontinence that was refractory to more conservative treatments. All were aged 18 years or older, sexually active, and in a relationship with the same partner for more than 3 months.

The researchers sought to distinguish the effect of the injection treatment on sexual function for women with an idiopathic, rather than neurogenic, version of the syndrome. Sexual function was assessed through a 19-item questionnaire, the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), before and after the treatment. To determine the efficacy of the treatment, participants kept a 3-day voiding diary, and completed two more forms: an overactive bladder screener questionnaire and the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Short Form.

Most of the participants (88.2%) saw an improvement in their overactive bladder symptoms. They also reported statistically meaningful improvement in sexual function on the FSFI, and specifically for arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and satisfaction, though not for desire and pain (average FSFI total score before and after treatment, 20.30 vs. 24.91; P = .0008).

“Although voiding diaries and questionnaires on urinary symptoms showed an improvement after onaBoNT-A injection, we documented a significant correlation only between the reduction of episodes of [urgency urinary incontinence] and improvement of FSFI total score. This finding shows that, in our population, the most relevant urinary symptom reducing the sexual function is urgency urinary incontinence,” Matteo Balzarro, MD, of Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata of Verona, Italy, and his coauthors wrote in the European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology.

The researchers noted that the small sample size resulted from multiple exclusion criteria applied to an already small population of 157 patients. They also remarked that a control group – which was absent from their study – would be difficult to have because of “ethical considerations.”

The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Balzarro M et al. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018 Jun;225:228-31.

FROM THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY AND REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Prostate cancer risk before age 55 higher for black men

according to a new study that drew subjects aged 40-54 years from three public and two private hospitals in the Chicago area.

Black race, rather than socioeconomic or clinical factors, appeared to be the strongest nonmodifiable predictor of prostate cancer risk in that age group, the researchers concluded, based on multivariate analyses that examined the association between prostate cancer risk and clinical setting, race, genetically determined West African ancestry, and clinical and socioeconomic risk factors.

The results suggest that screening practices should be altered, said study investigator Oluwarotimi S. Nettey, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago. “You might want to think about screening black men who are younger than 55.”

“In the prebiopsy space, most studies have looked at race, age, PSA [level], and prostate volume, and they’ve said that the reason we see that black men have disparate prostate cancer risk on diagnosis is probably because of access to care issues, so that’s been the confounder. We tried to control for this by looking at socioeconomic status through income, marriage, and education, as well as hospital setting,” said Dr. Nettey, who presented the study at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Urological Association.

Previous studies have examined populations and then conducted a secondary analysis on outcomes in black men. The current study has greater power and is more convincing because outcomes in black men was the primary outcome of the study, according to Robert L. Waterhouse Jr., MD, who is the public policy liaison for the R. Frank Jones Urological Society of the National Medical Association. Dr. Waterhouse, a urologist in Charlotte, N.C., attended the poster session and was not involved in the research.

“This study helps to provide some evidence that black heritage is indeed a significant risk factor in men who develop prostate cancer at an earlier age, and efforts at identifying prostate cancer at an earlier age [should consider] black race as a high-risk group,” said Dr. Waterhouse.

For patients of all ages, biopsies were positive in 63.1% of black men, compared with 41.5% of nonblack men (P less than .001). Cancers were also more advanced in black men: 47.5% were Gleason 3+4 in black men, compared with 40% in nonblack men (P less than .001), and 14.4% were Gleason 4+4 in black men, compared with 9.6% in nonblack men (P = .02).

After researchers controlled for other risk factors, black race was associated with heightened risk of prostate cancer diagnosis (OR, 5.66; P = .02), as was family history (OR, 4.98; P = .01).

There was no association between West African ancestry and prostate cancer risk either as a continuous variable or in quartiles.

Limitations of the study include the fact that race was self-reported and that this was a referred population.

The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Nettey reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Nettey OS et al. AUA Annual Meeting. Abstract MP 21-17.

according to a new study that drew subjects aged 40-54 years from three public and two private hospitals in the Chicago area.

Black race, rather than socioeconomic or clinical factors, appeared to be the strongest nonmodifiable predictor of prostate cancer risk in that age group, the researchers concluded, based on multivariate analyses that examined the association between prostate cancer risk and clinical setting, race, genetically determined West African ancestry, and clinical and socioeconomic risk factors.

The results suggest that screening practices should be altered, said study investigator Oluwarotimi S. Nettey, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago. “You might want to think about screening black men who are younger than 55.”

“In the prebiopsy space, most studies have looked at race, age, PSA [level], and prostate volume, and they’ve said that the reason we see that black men have disparate prostate cancer risk on diagnosis is probably because of access to care issues, so that’s been the confounder. We tried to control for this by looking at socioeconomic status through income, marriage, and education, as well as hospital setting,” said Dr. Nettey, who presented the study at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Urological Association.

Previous studies have examined populations and then conducted a secondary analysis on outcomes in black men. The current study has greater power and is more convincing because outcomes in black men was the primary outcome of the study, according to Robert L. Waterhouse Jr., MD, who is the public policy liaison for the R. Frank Jones Urological Society of the National Medical Association. Dr. Waterhouse, a urologist in Charlotte, N.C., attended the poster session and was not involved in the research.

“This study helps to provide some evidence that black heritage is indeed a significant risk factor in men who develop prostate cancer at an earlier age, and efforts at identifying prostate cancer at an earlier age [should consider] black race as a high-risk group,” said Dr. Waterhouse.

For patients of all ages, biopsies were positive in 63.1% of black men, compared with 41.5% of nonblack men (P less than .001). Cancers were also more advanced in black men: 47.5% were Gleason 3+4 in black men, compared with 40% in nonblack men (P less than .001), and 14.4% were Gleason 4+4 in black men, compared with 9.6% in nonblack men (P = .02).