User login

MRD-negative status signals better outcomes in CAR T–treated ALL

CHICAGO – Minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative complete remission was strongly associated with improved survival outcomes in patients with B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) who received CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells, results of a retrospective study showed.

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) appeared to improve both disease-free and overall survival in those patients who had achieved MRD-negative complete remission, according to results of the study, which were presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“Based upon our interaction testing, the potential benefit [of transplant] appears to exist in both good-risk and bad-risk patients as identified through multivariate modeling,” said study investigator Kevin Anthony Hay, MD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle.

In a comment on the results, Sarah Cooley, MD, noted that the benefits of allogeneic transplant were apparent regardless of whether the patients met criteria for the good-risk subgroup, which was defined by levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and platelets along with exposure to fludarabine as part of the conditioning regimen.

“I think this suggests that the goal at this point is to get patients to an MRD-negative state and to potentially curative transplant,” said Dr. Cooley, director of investigator-initiated research at Masonic Medical Center at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

The retrospective analysis by Dr. Hay and his colleagues included 53 adults with relapsed or refractory ALL who had bone marrow or extramedullary disease at baseline and had received CD19 CAR T cells at or under the maximum tolerated dose at least 1 year prior to this analysis. Of that group, 45 (85%) achieved MRD-negative complete remission.

Those patients who did achieve MRD-negative complete remission had an improved median disease-free survival at 7.6 months versus 0.8 months (P less than .0001) and improved overall survival at 20.0 months versus 5.0 months (P = 0.014).

Most of the MRD-negative patients who relapsed did so within the first 6 months, an observation that led investigators to consider whether factors exist that could predict better outcomes.

In a multivariate analysis, they found three variables associated with disease free survival: higher LDH prior to lymphodepletion (hazard ratio, 1.39), along with higher platelet count prior to lymphodepletion and incorporation of fludarabine into the regimen, with hazard ratios of 0.65 and 0.34, respectively.

Using those three characteristics, investigators grouped patients as “good risk” if they had normal LDH, platelet count at or above 100 prior to lymphodepletion that included fludarabine. The 24-month disease-free survival for good-risk patients was 78%, and overall survival was 86%.

The role of allogeneic HSCT after ALL patients achieved MRD-negative complete remission with CAR T-cell therapy was one of the “major questions in the field,” Dr. Hay said.

In this analysis, Dr. Hay and colleagues found that patients who underwent transplant in MRD-negative complete remission had a 24-month disease free survival and overall survival of 61% and 72%, respectively, both of which were significantly higher than in patients with MRD-negative complete remission who had no transplant.

The disease-free survival benefit was not specific to the good-risk group, according to Dr. Hay, who said an interaction test demonstrated no significant interaction between risk group and allogeneic HSCT after CAR T-cell infusion (P = 0.53).

“This is a very important finding that should be further [studied] in an appropriately designed clinical trial,” Dr. Hay said during an oral presentation of the study results.

Dr. Hay and several coauthors reported financial disclosures related to Juno Therapeutics. Other disclosures reported by study coauthors included Cell Medica, Celgene, Eureka Therapeutics, Genentech/Roche, Gilead Sciences, Kite Pharma, Novartis, and others.

SOURCE: Hay KA. ASCO 2018, Abstract 7005.

CHICAGO – Minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative complete remission was strongly associated with improved survival outcomes in patients with B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) who received CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells, results of a retrospective study showed.

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) appeared to improve both disease-free and overall survival in those patients who had achieved MRD-negative complete remission, according to results of the study, which were presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“Based upon our interaction testing, the potential benefit [of transplant] appears to exist in both good-risk and bad-risk patients as identified through multivariate modeling,” said study investigator Kevin Anthony Hay, MD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle.

In a comment on the results, Sarah Cooley, MD, noted that the benefits of allogeneic transplant were apparent regardless of whether the patients met criteria for the good-risk subgroup, which was defined by levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and platelets along with exposure to fludarabine as part of the conditioning regimen.

“I think this suggests that the goal at this point is to get patients to an MRD-negative state and to potentially curative transplant,” said Dr. Cooley, director of investigator-initiated research at Masonic Medical Center at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

The retrospective analysis by Dr. Hay and his colleagues included 53 adults with relapsed or refractory ALL who had bone marrow or extramedullary disease at baseline and had received CD19 CAR T cells at or under the maximum tolerated dose at least 1 year prior to this analysis. Of that group, 45 (85%) achieved MRD-negative complete remission.

Those patients who did achieve MRD-negative complete remission had an improved median disease-free survival at 7.6 months versus 0.8 months (P less than .0001) and improved overall survival at 20.0 months versus 5.0 months (P = 0.014).

Most of the MRD-negative patients who relapsed did so within the first 6 months, an observation that led investigators to consider whether factors exist that could predict better outcomes.

In a multivariate analysis, they found three variables associated with disease free survival: higher LDH prior to lymphodepletion (hazard ratio, 1.39), along with higher platelet count prior to lymphodepletion and incorporation of fludarabine into the regimen, with hazard ratios of 0.65 and 0.34, respectively.

Using those three characteristics, investigators grouped patients as “good risk” if they had normal LDH, platelet count at or above 100 prior to lymphodepletion that included fludarabine. The 24-month disease-free survival for good-risk patients was 78%, and overall survival was 86%.

The role of allogeneic HSCT after ALL patients achieved MRD-negative complete remission with CAR T-cell therapy was one of the “major questions in the field,” Dr. Hay said.

In this analysis, Dr. Hay and colleagues found that patients who underwent transplant in MRD-negative complete remission had a 24-month disease free survival and overall survival of 61% and 72%, respectively, both of which were significantly higher than in patients with MRD-negative complete remission who had no transplant.

The disease-free survival benefit was not specific to the good-risk group, according to Dr. Hay, who said an interaction test demonstrated no significant interaction between risk group and allogeneic HSCT after CAR T-cell infusion (P = 0.53).

“This is a very important finding that should be further [studied] in an appropriately designed clinical trial,” Dr. Hay said during an oral presentation of the study results.

Dr. Hay and several coauthors reported financial disclosures related to Juno Therapeutics. Other disclosures reported by study coauthors included Cell Medica, Celgene, Eureka Therapeutics, Genentech/Roche, Gilead Sciences, Kite Pharma, Novartis, and others.

SOURCE: Hay KA. ASCO 2018, Abstract 7005.

CHICAGO – Minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative complete remission was strongly associated with improved survival outcomes in patients with B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) who received CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells, results of a retrospective study showed.

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) appeared to improve both disease-free and overall survival in those patients who had achieved MRD-negative complete remission, according to results of the study, which were presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“Based upon our interaction testing, the potential benefit [of transplant] appears to exist in both good-risk and bad-risk patients as identified through multivariate modeling,” said study investigator Kevin Anthony Hay, MD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle.

In a comment on the results, Sarah Cooley, MD, noted that the benefits of allogeneic transplant were apparent regardless of whether the patients met criteria for the good-risk subgroup, which was defined by levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and platelets along with exposure to fludarabine as part of the conditioning regimen.

“I think this suggests that the goal at this point is to get patients to an MRD-negative state and to potentially curative transplant,” said Dr. Cooley, director of investigator-initiated research at Masonic Medical Center at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

The retrospective analysis by Dr. Hay and his colleagues included 53 adults with relapsed or refractory ALL who had bone marrow or extramedullary disease at baseline and had received CD19 CAR T cells at or under the maximum tolerated dose at least 1 year prior to this analysis. Of that group, 45 (85%) achieved MRD-negative complete remission.

Those patients who did achieve MRD-negative complete remission had an improved median disease-free survival at 7.6 months versus 0.8 months (P less than .0001) and improved overall survival at 20.0 months versus 5.0 months (P = 0.014).

Most of the MRD-negative patients who relapsed did so within the first 6 months, an observation that led investigators to consider whether factors exist that could predict better outcomes.

In a multivariate analysis, they found three variables associated with disease free survival: higher LDH prior to lymphodepletion (hazard ratio, 1.39), along with higher platelet count prior to lymphodepletion and incorporation of fludarabine into the regimen, with hazard ratios of 0.65 and 0.34, respectively.

Using those three characteristics, investigators grouped patients as “good risk” if they had normal LDH, platelet count at or above 100 prior to lymphodepletion that included fludarabine. The 24-month disease-free survival for good-risk patients was 78%, and overall survival was 86%.

The role of allogeneic HSCT after ALL patients achieved MRD-negative complete remission with CAR T-cell therapy was one of the “major questions in the field,” Dr. Hay said.

In this analysis, Dr. Hay and colleagues found that patients who underwent transplant in MRD-negative complete remission had a 24-month disease free survival and overall survival of 61% and 72%, respectively, both of which were significantly higher than in patients with MRD-negative complete remission who had no transplant.

The disease-free survival benefit was not specific to the good-risk group, according to Dr. Hay, who said an interaction test demonstrated no significant interaction between risk group and allogeneic HSCT after CAR T-cell infusion (P = 0.53).

“This is a very important finding that should be further [studied] in an appropriately designed clinical trial,” Dr. Hay said during an oral presentation of the study results.

Dr. Hay and several coauthors reported financial disclosures related to Juno Therapeutics. Other disclosures reported by study coauthors included Cell Medica, Celgene, Eureka Therapeutics, Genentech/Roche, Gilead Sciences, Kite Pharma, Novartis, and others.

SOURCE: Hay KA. ASCO 2018, Abstract 7005.

REPORTING FROM ASCO 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients who achieved MRD-negative complete remission had an improved median disease-free survival at 7.6 months versus 0.8 months (P less than .0001)

Study details: A retrospective analysis including 53 patients with ALL who had bone marrow or extramedullary disease at baseline and had received CD19 CAR T cells at or under the maximum tolerated dose at least 1 year prior to this analysis.

Disclosures: Researchers reported financial ties to Juno Therapeutics, Cell Medica, Celgene, Eureka Therapeutics, Genentech/Roche, Gilead Sciences, Kite Pharma, Novartis, and others.

Source: Hay KA. ASCO 2018, Abstract 7005.

Dr. William J. Gradishar shares breast cancer take-aways from ASCO 2018

CHICAGO – William J. Gradishar, MD, discussed the clinical impact of breast cancer research presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

In a video interview, Dr. Gradishar, the Betsy Bramsen Professor of Breast Oncology at Northwestern University, Chicago, said TAILORx was a “big win” in that it has no doubt diminished the number of women with early-stage breast cancer who will require chemotherapy. However, although the trial has provided some clarity, it also has left some questions open, particularly for patients under 50 years of age, he said.

Dr. Gradishar also discussed the results of combination trials of targeted therapy with either endocrine therapy or chemotherapy. In discussing SANDPIPER, which evaluated whether a phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor could enhance the effect of anti-hormonal therapy, he said that although it was a positive trial, “from a clinician’s standpoint, it’s probably not sufficient in my mind to get really excited about.”

CHICAGO – William J. Gradishar, MD, discussed the clinical impact of breast cancer research presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

In a video interview, Dr. Gradishar, the Betsy Bramsen Professor of Breast Oncology at Northwestern University, Chicago, said TAILORx was a “big win” in that it has no doubt diminished the number of women with early-stage breast cancer who will require chemotherapy. However, although the trial has provided some clarity, it also has left some questions open, particularly for patients under 50 years of age, he said.

Dr. Gradishar also discussed the results of combination trials of targeted therapy with either endocrine therapy or chemotherapy. In discussing SANDPIPER, which evaluated whether a phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor could enhance the effect of anti-hormonal therapy, he said that although it was a positive trial, “from a clinician’s standpoint, it’s probably not sufficient in my mind to get really excited about.”

CHICAGO – William J. Gradishar, MD, discussed the clinical impact of breast cancer research presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

In a video interview, Dr. Gradishar, the Betsy Bramsen Professor of Breast Oncology at Northwestern University, Chicago, said TAILORx was a “big win” in that it has no doubt diminished the number of women with early-stage breast cancer who will require chemotherapy. However, although the trial has provided some clarity, it also has left some questions open, particularly for patients under 50 years of age, he said.

Dr. Gradishar also discussed the results of combination trials of targeted therapy with either endocrine therapy or chemotherapy. In discussing SANDPIPER, which evaluated whether a phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor could enhance the effect of anti-hormonal therapy, he said that although it was a positive trial, “from a clinician’s standpoint, it’s probably not sufficient in my mind to get really excited about.”

REPORTING FROM ASCO 2018

Beltlike Lichen Planus Pigmentosus Complicated With Focal Amyloidosis

To the Editor:

A 68-year-old man presented with slightly itchy macules on the waist and abdomen of approximately 2 years’ duration. He reported that the initial lesions were dark red and subsequently coalesced to form a beltlike pigmentation on the abdomen. He denied any prior treatment, and the lesions did not spontaneously resolve. The patient was taking escitalopram oxalate, telmisartan, and aspirin for depression and cardiovascular disease that was diagnosed 3 years prior. He reported no exposure to UV radiation or a heat source. He denied use of any cosmetics on the body as well as a family history of similar symptoms.

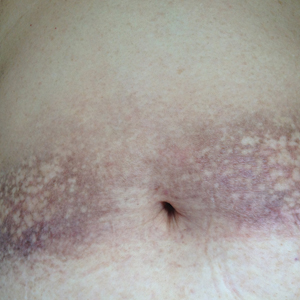

Physical examination showed reticulate brown-purple macules with slight scale on the surface that had become confluent, forming a beltlike pigmentation on the waist and abdomen (Figure 1). Wickham striae were not seen. The oral mucosa and nails were not affected. Microscopic examination for fungal infections was negative.

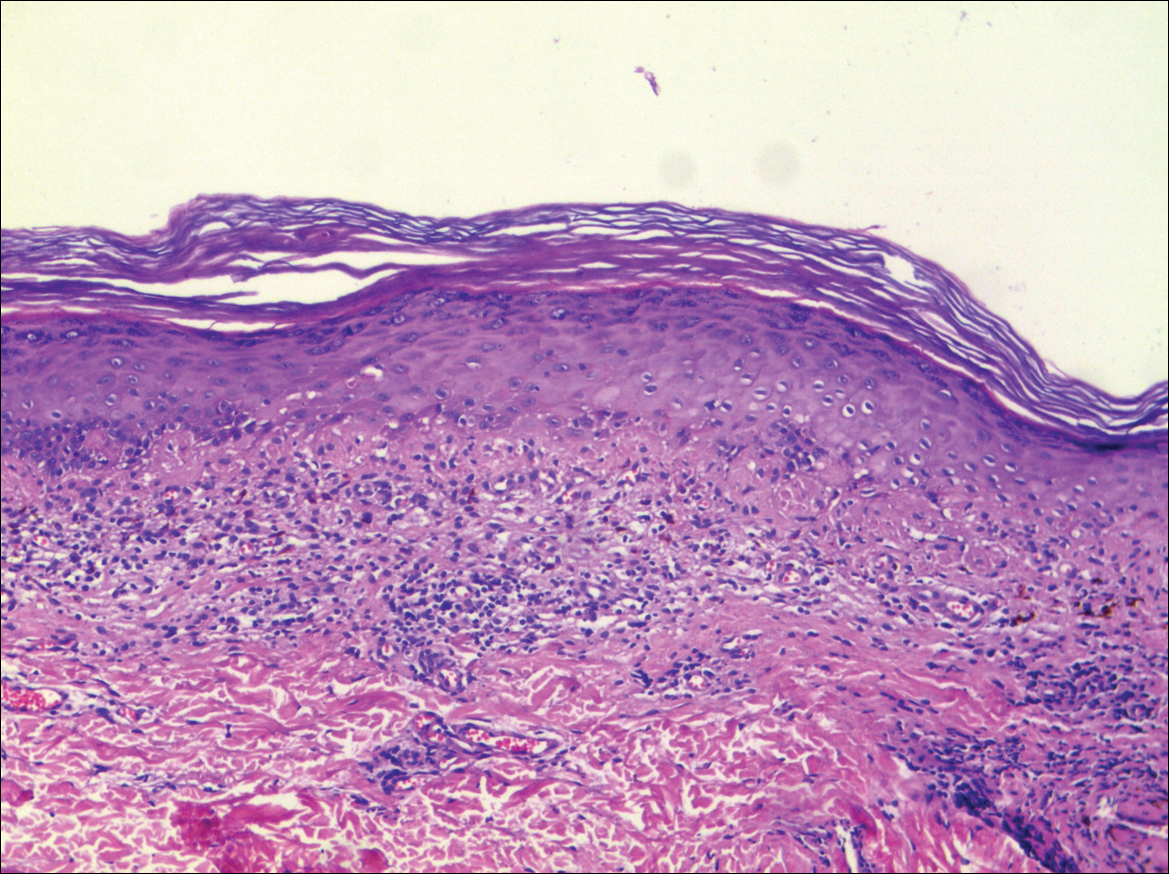

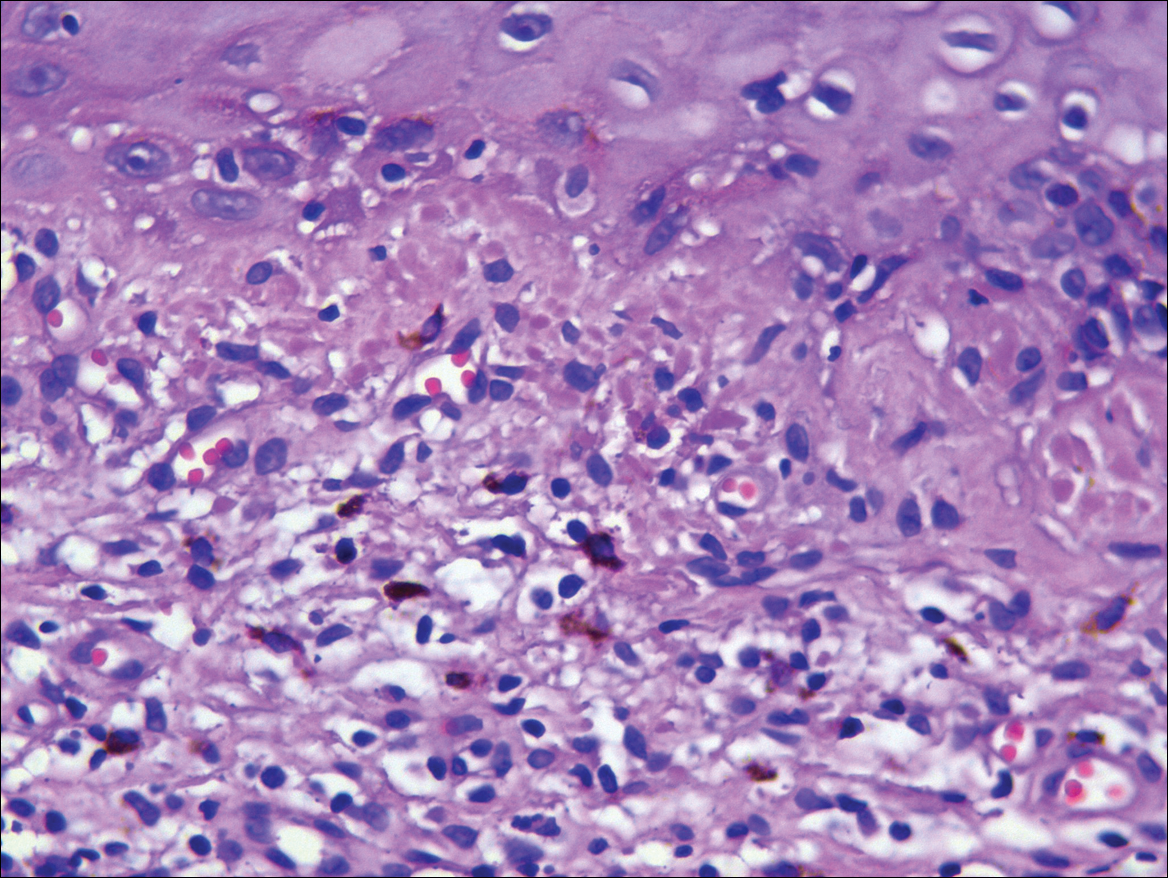

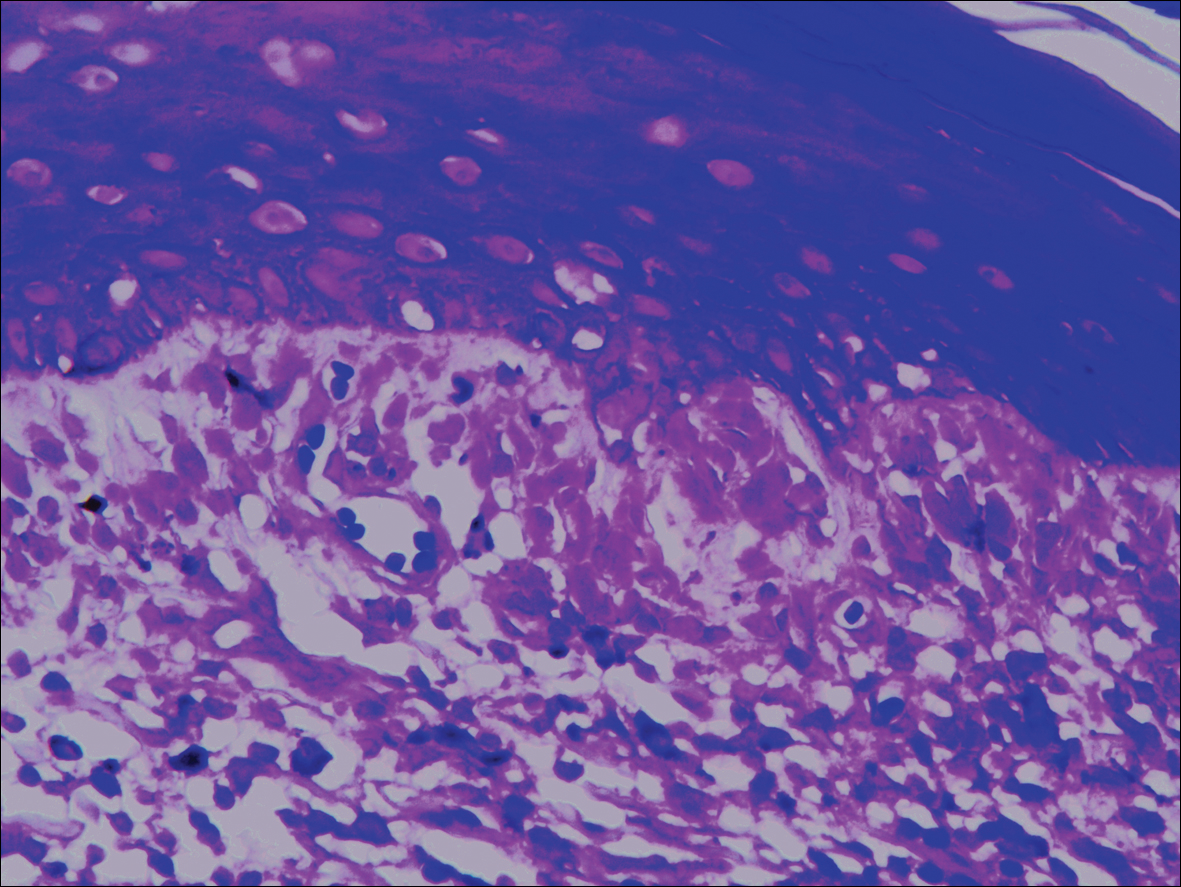

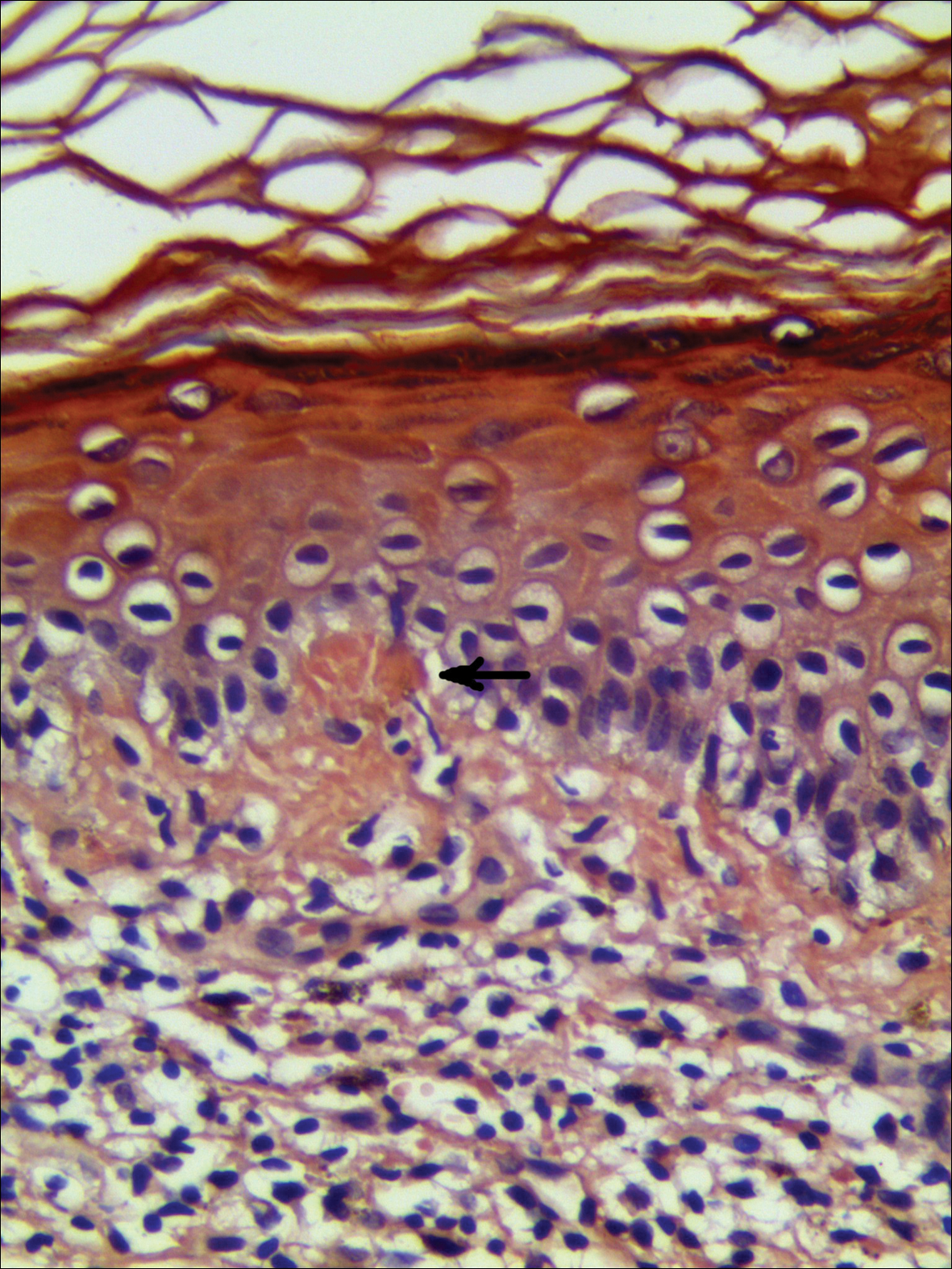

Systematic physical and laboratory examinations revealed no abnormalities. A skin biopsy from a macule on the abdomen showed hyperkeratosis, thinned out stratum spinosum with flattening of rete ridges, hypergranulosis with vacuolar alteration of the basal cell layer, and bandlike infiltration of lymphocytes and melanophages with incontinence of pigment (Figure 2). Focalized purplish homogeneous deposits were observed in the upper dermis (Figure 3), of which positive crystal violet staining indicated amyloidosis (Figure 4). Congo red stain revealed amyloid deposition (Figure 5). Thus, the diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) complicated with focal amyloidosis was made. The patient was treated with topical corticosteroids and tretinoin, and no notable therapeutic effects were observed at 3-month follow-up.

Lichen planus pigmentosus, a variant of lichen planus, is a condition of unknown etiology exhibiting dark brown macules and/or papules and a long clinical course. The face, neck, trunk, arms, and legs are the most common areas of presentation, whereas involvement of the scalp, nails, or oral mucosa is relatively rare.

The first clinicohistopathological study with a large sample size was documented by Bhutani et al1 in 1974 who termed the currently recognized entity lichen planus pigmentosus. Lichen planus pigmentosus is a frequently encountered hyperpigmentation disorder in Indians, whereas sporadic cases also are reported in other regions and ethnicities.2 In cases of LPP, the pigmentation is symmetrical, and its pattern most often is diffuse, then reticular, blotchy, and perifollicular.3 Two unique patterns of LPP have been documented, including linear/blaschkoid LPP and zosteriform LPP.4,5 Our patient showed a unique beltlike distribution pattern.

The pathogenesis of LPP still is unclear, and several inciting factors such as mustard oil, gold therapy,6 and hepatitis C virus infection have been cited.7 Mancuso and Berdondini8 reported a case of LPP flaring immediately after relapse of nephrotic syndrome. It also has been considered as a paraneoplastic phenomen.9 No exact cause was found in our patient after a series of relative examinations.

The histopathologic changes associated with LPP consist of atrophic epidermis; bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer in the epidermis; and prominent melanin incontinence in the upper dermis, which can be diverse depending on different sites of skin biopsy and the phase of LPP. Histopathologic findings in our patient were consistent with LPP. The differential diagnosis for the reticulate pattern of pigmentation seen in our patient included confluent and reticulated papillomatosis and poikilodermalike cutaneous amyloidosis, both easily excluded with histopathologic confirmation.

Local amyloidosis also was confirmed by crystal violet staining in our case and its etiology was uncertain. Generalized and local amyloidosis has been reported in association with lichen planus. The diagnosis of lichen planus was followed by the diagnosis of amyloidosis, and the typical skin lesions of these 2 conditions were able to be differentiated in these reported cases.10,11 However, beltlike pigmentation was the only manifestation for our patient and we could not separate the 2 conditions with the naked eye.

Chronic irritation to the skin resulting in excessive production of degenerate keratins and their subsequent conversion into amyloid deposits has been proposed to be an etiologic factor of amyloidosis.11 Because of the distribution pattern in our case, we believe focal amyloidosis could be attributed to chronic friction and scratching.

- Bhutani LK, Bedi TR, Pandhi RK, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus. Dermatologica. 1974;149:43-50.

- Kanwar AJ, Kaur S. Lichen planus pigmentosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(4, pt 1):815.

- Kanwar AJ, Dogra S, Handa S, et al. A study of 124 Indian patients with lichen planus pigmentosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:481-485.

- Akarsu S, Ilknur T, Özer E, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus distributed along the lines of Blaschko. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:253-254.

- Cho S, Whang KK. Lichen planus pigmentosus presenting in zosteriform pattern. J Dermatol. 1997;24:193-197.

- Ingber A, Weissmann-Katzenelson V, David M, et al. Lichen planus and lichen planus pigmentosus following gold therapy—case reports and review of the literature [in German]. Z Hautkr. 1986;61:315-319.

- Al-Mutairi N, El-Khalawany M. Clinicopathological characteristics of lichen planus pigmentosus and its response to tacrolimus ointment: an open label, non-randomized, prospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:535-540.

- Mancuso G, Berdondini RM. Coexistence of lichen planus pigmentosus and minimal change nephrotic syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:389-390.

- Sassolas B, Zagnoli A, Leroy JP, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus associated with acrokeratosis of Bazex. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:70-73.

- Maeda H, Ohta S, Saito Y, et al. Epidermal origin of the amyloid in localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:345-351.

- Hongcharu W, Baldassano M, Gonzalez E. Generalized lichen amyloidosis associated with chronic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:346-348.

To the Editor:

A 68-year-old man presented with slightly itchy macules on the waist and abdomen of approximately 2 years’ duration. He reported that the initial lesions were dark red and subsequently coalesced to form a beltlike pigmentation on the abdomen. He denied any prior treatment, and the lesions did not spontaneously resolve. The patient was taking escitalopram oxalate, telmisartan, and aspirin for depression and cardiovascular disease that was diagnosed 3 years prior. He reported no exposure to UV radiation or a heat source. He denied use of any cosmetics on the body as well as a family history of similar symptoms.

Physical examination showed reticulate brown-purple macules with slight scale on the surface that had become confluent, forming a beltlike pigmentation on the waist and abdomen (Figure 1). Wickham striae were not seen. The oral mucosa and nails were not affected. Microscopic examination for fungal infections was negative.

Systematic physical and laboratory examinations revealed no abnormalities. A skin biopsy from a macule on the abdomen showed hyperkeratosis, thinned out stratum spinosum with flattening of rete ridges, hypergranulosis with vacuolar alteration of the basal cell layer, and bandlike infiltration of lymphocytes and melanophages with incontinence of pigment (Figure 2). Focalized purplish homogeneous deposits were observed in the upper dermis (Figure 3), of which positive crystal violet staining indicated amyloidosis (Figure 4). Congo red stain revealed amyloid deposition (Figure 5). Thus, the diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) complicated with focal amyloidosis was made. The patient was treated with topical corticosteroids and tretinoin, and no notable therapeutic effects were observed at 3-month follow-up.

Lichen planus pigmentosus, a variant of lichen planus, is a condition of unknown etiology exhibiting dark brown macules and/or papules and a long clinical course. The face, neck, trunk, arms, and legs are the most common areas of presentation, whereas involvement of the scalp, nails, or oral mucosa is relatively rare.

The first clinicohistopathological study with a large sample size was documented by Bhutani et al1 in 1974 who termed the currently recognized entity lichen planus pigmentosus. Lichen planus pigmentosus is a frequently encountered hyperpigmentation disorder in Indians, whereas sporadic cases also are reported in other regions and ethnicities.2 In cases of LPP, the pigmentation is symmetrical, and its pattern most often is diffuse, then reticular, blotchy, and perifollicular.3 Two unique patterns of LPP have been documented, including linear/blaschkoid LPP and zosteriform LPP.4,5 Our patient showed a unique beltlike distribution pattern.

The pathogenesis of LPP still is unclear, and several inciting factors such as mustard oil, gold therapy,6 and hepatitis C virus infection have been cited.7 Mancuso and Berdondini8 reported a case of LPP flaring immediately after relapse of nephrotic syndrome. It also has been considered as a paraneoplastic phenomen.9 No exact cause was found in our patient after a series of relative examinations.

The histopathologic changes associated with LPP consist of atrophic epidermis; bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer in the epidermis; and prominent melanin incontinence in the upper dermis, which can be diverse depending on different sites of skin biopsy and the phase of LPP. Histopathologic findings in our patient were consistent with LPP. The differential diagnosis for the reticulate pattern of pigmentation seen in our patient included confluent and reticulated papillomatosis and poikilodermalike cutaneous amyloidosis, both easily excluded with histopathologic confirmation.

Local amyloidosis also was confirmed by crystal violet staining in our case and its etiology was uncertain. Generalized and local amyloidosis has been reported in association with lichen planus. The diagnosis of lichen planus was followed by the diagnosis of amyloidosis, and the typical skin lesions of these 2 conditions were able to be differentiated in these reported cases.10,11 However, beltlike pigmentation was the only manifestation for our patient and we could not separate the 2 conditions with the naked eye.

Chronic irritation to the skin resulting in excessive production of degenerate keratins and their subsequent conversion into amyloid deposits has been proposed to be an etiologic factor of amyloidosis.11 Because of the distribution pattern in our case, we believe focal amyloidosis could be attributed to chronic friction and scratching.

To the Editor:

A 68-year-old man presented with slightly itchy macules on the waist and abdomen of approximately 2 years’ duration. He reported that the initial lesions were dark red and subsequently coalesced to form a beltlike pigmentation on the abdomen. He denied any prior treatment, and the lesions did not spontaneously resolve. The patient was taking escitalopram oxalate, telmisartan, and aspirin for depression and cardiovascular disease that was diagnosed 3 years prior. He reported no exposure to UV radiation or a heat source. He denied use of any cosmetics on the body as well as a family history of similar symptoms.

Physical examination showed reticulate brown-purple macules with slight scale on the surface that had become confluent, forming a beltlike pigmentation on the waist and abdomen (Figure 1). Wickham striae were not seen. The oral mucosa and nails were not affected. Microscopic examination for fungal infections was negative.

Systematic physical and laboratory examinations revealed no abnormalities. A skin biopsy from a macule on the abdomen showed hyperkeratosis, thinned out stratum spinosum with flattening of rete ridges, hypergranulosis with vacuolar alteration of the basal cell layer, and bandlike infiltration of lymphocytes and melanophages with incontinence of pigment (Figure 2). Focalized purplish homogeneous deposits were observed in the upper dermis (Figure 3), of which positive crystal violet staining indicated amyloidosis (Figure 4). Congo red stain revealed amyloid deposition (Figure 5). Thus, the diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) complicated with focal amyloidosis was made. The patient was treated with topical corticosteroids and tretinoin, and no notable therapeutic effects were observed at 3-month follow-up.

Lichen planus pigmentosus, a variant of lichen planus, is a condition of unknown etiology exhibiting dark brown macules and/or papules and a long clinical course. The face, neck, trunk, arms, and legs are the most common areas of presentation, whereas involvement of the scalp, nails, or oral mucosa is relatively rare.

The first clinicohistopathological study with a large sample size was documented by Bhutani et al1 in 1974 who termed the currently recognized entity lichen planus pigmentosus. Lichen planus pigmentosus is a frequently encountered hyperpigmentation disorder in Indians, whereas sporadic cases also are reported in other regions and ethnicities.2 In cases of LPP, the pigmentation is symmetrical, and its pattern most often is diffuse, then reticular, blotchy, and perifollicular.3 Two unique patterns of LPP have been documented, including linear/blaschkoid LPP and zosteriform LPP.4,5 Our patient showed a unique beltlike distribution pattern.

The pathogenesis of LPP still is unclear, and several inciting factors such as mustard oil, gold therapy,6 and hepatitis C virus infection have been cited.7 Mancuso and Berdondini8 reported a case of LPP flaring immediately after relapse of nephrotic syndrome. It also has been considered as a paraneoplastic phenomen.9 No exact cause was found in our patient after a series of relative examinations.

The histopathologic changes associated with LPP consist of atrophic epidermis; bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer in the epidermis; and prominent melanin incontinence in the upper dermis, which can be diverse depending on different sites of skin biopsy and the phase of LPP. Histopathologic findings in our patient were consistent with LPP. The differential diagnosis for the reticulate pattern of pigmentation seen in our patient included confluent and reticulated papillomatosis and poikilodermalike cutaneous amyloidosis, both easily excluded with histopathologic confirmation.

Local amyloidosis also was confirmed by crystal violet staining in our case and its etiology was uncertain. Generalized and local amyloidosis has been reported in association with lichen planus. The diagnosis of lichen planus was followed by the diagnosis of amyloidosis, and the typical skin lesions of these 2 conditions were able to be differentiated in these reported cases.10,11 However, beltlike pigmentation was the only manifestation for our patient and we could not separate the 2 conditions with the naked eye.

Chronic irritation to the skin resulting in excessive production of degenerate keratins and their subsequent conversion into amyloid deposits has been proposed to be an etiologic factor of amyloidosis.11 Because of the distribution pattern in our case, we believe focal amyloidosis could be attributed to chronic friction and scratching.

- Bhutani LK, Bedi TR, Pandhi RK, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus. Dermatologica. 1974;149:43-50.

- Kanwar AJ, Kaur S. Lichen planus pigmentosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(4, pt 1):815.

- Kanwar AJ, Dogra S, Handa S, et al. A study of 124 Indian patients with lichen planus pigmentosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:481-485.

- Akarsu S, Ilknur T, Özer E, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus distributed along the lines of Blaschko. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:253-254.

- Cho S, Whang KK. Lichen planus pigmentosus presenting in zosteriform pattern. J Dermatol. 1997;24:193-197.

- Ingber A, Weissmann-Katzenelson V, David M, et al. Lichen planus and lichen planus pigmentosus following gold therapy—case reports and review of the literature [in German]. Z Hautkr. 1986;61:315-319.

- Al-Mutairi N, El-Khalawany M. Clinicopathological characteristics of lichen planus pigmentosus and its response to tacrolimus ointment: an open label, non-randomized, prospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:535-540.

- Mancuso G, Berdondini RM. Coexistence of lichen planus pigmentosus and minimal change nephrotic syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:389-390.

- Sassolas B, Zagnoli A, Leroy JP, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus associated with acrokeratosis of Bazex. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:70-73.

- Maeda H, Ohta S, Saito Y, et al. Epidermal origin of the amyloid in localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:345-351.

- Hongcharu W, Baldassano M, Gonzalez E. Generalized lichen amyloidosis associated with chronic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:346-348.

- Bhutani LK, Bedi TR, Pandhi RK, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus. Dermatologica. 1974;149:43-50.

- Kanwar AJ, Kaur S. Lichen planus pigmentosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(4, pt 1):815.

- Kanwar AJ, Dogra S, Handa S, et al. A study of 124 Indian patients with lichen planus pigmentosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:481-485.

- Akarsu S, Ilknur T, Özer E, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus distributed along the lines of Blaschko. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:253-254.

- Cho S, Whang KK. Lichen planus pigmentosus presenting in zosteriform pattern. J Dermatol. 1997;24:193-197.

- Ingber A, Weissmann-Katzenelson V, David M, et al. Lichen planus and lichen planus pigmentosus following gold therapy—case reports and review of the literature [in German]. Z Hautkr. 1986;61:315-319.

- Al-Mutairi N, El-Khalawany M. Clinicopathological characteristics of lichen planus pigmentosus and its response to tacrolimus ointment: an open label, non-randomized, prospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:535-540.

- Mancuso G, Berdondini RM. Coexistence of lichen planus pigmentosus and minimal change nephrotic syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:389-390.

- Sassolas B, Zagnoli A, Leroy JP, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus associated with acrokeratosis of Bazex. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:70-73.

- Maeda H, Ohta S, Saito Y, et al. Epidermal origin of the amyloid in localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:345-351.

- Hongcharu W, Baldassano M, Gonzalez E. Generalized lichen amyloidosis associated with chronic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:346-348.

Practice Points

- Lichen planus pigmentosus can present in a unique beltlike distribution pattern.

- Focal amyloidosis due to chronic friction and scratching cannot be excluded from the differential diagnosis.

Metastatic lung cancer: Pembrolizumab plus chemo prolongs survival

, according to results from the phase 3 KEYNOTE-189 trial.

The researchers found that while patients in all subgroups benefited from the addition of pembrolizumab to chemotherapy, patients with a tumor proportion score of at least 50% benefited the most.

In 2017, accelerated approval was granted for pembrolizumab in combination with carboplatin and pemetrexed as first-line therapy for patients with NSCLC lacking EGFR and ALK mutations. This approval was based on response rates and progression-free survival from the KEYNOTE-024 phase 2 trial.

KEYNOTE-189 solidifies these findings, according to investigators. “Together with the results from KEYNOTE-024, the data from KEYNOTE-189 suggest that introducing immunotherapy as a first-line therapy may have a favorable long-term effect on outcomes,” wrote lead author Leena Gandhi, MD, director of the Perlmutter Cancer Center at New York University, and her colleagues. The report was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The double-blind, phase 3 trial assessed 616 treatment-naive patients with metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC without ALK or EGFR mutations. Patients received a platinum-based drug and pemetrexed plus placebo or 200 mg of pembrolizumab every 3 weeks for four cycles. After this, patients received placebo or pembrolizumab with pemetrexed maintenance therapy for up to 35 cycles. Primary endpoints were overall and progression-free survival, determined by a blinded radiologist.

At 12 months, the estimated overall survival was 69.2% for patients treated with pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy, compared with 49.4% for patients treated with chemotherapy alone. For patients treated with the pembrolizumab combination, median progression-free survival was 8.8 months, compared with 4.9 months for those treated with just chemotherapy. Median follow-up time was 10.5 months.

“The survival benefit associated with the pembrolizumab combination was observed in all subgroups of PD-L1 tumor proportion scores,” the authors wrote, “including patients with a score of less than 1%, a population for which single-agent PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibition have a small chance of benefit.” As with previous studies, the subgroup of patients with a tumor proportion score greater than or equal to 50% received the greatest benefit when pembrolizumab was added.

The authors noted that further research is needed to determine whether patients with high PD-L1 expression (TMS ≥ 50%) would benefit more from pembrolizumab combination therapy compared with pembrolizumab monotherapy, which is currently indicated.

SOURCE: Gandhi et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801005.

The recent phase 3 KEYNOTE-189 trial by Gandhi and her colleagues solidifies a shift in first-line standard therapy for some lung cancer patients, according to Joan H. Schiller, MD.

“This trial illustrates that PD-1 pathway inhibitors can be successfully combined with chemotherapy,” Dr. Schiller wrote in an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the study, patients treated with carboplatin-pemetrexed-pembrolizumab therapy had longer overall and progression-free survival compared with patients treated with just chemotherapy.

“The magnitude of benefit is impressive,” Dr. Schiller wrote, “with a hazard ratio for death of 0.49 and 12-month overall survival of 69.2% in the pembrolizumab-combination group.”

However, “many unanswered questions remain,” Dr. Schiller said, particularly concerning the utility of the commonly used PD-L1 tumor proportion score, which “appears to be problematic, with some randomized trials showing benefit only with a score of 50% or more and others showing benefit at other cutoff points, including less than 1%.”

In the current study, all subgroups benefited from the addition of pembrolizumab, including patients with a score of less than 1%.

Despite the need for more research, Dr. Schiller said she believes that existing findings have revealed unprecedented benefits. “Is carboplatin-pemetrexed-pembrolizumab now the first-line standard therapy for patients with nonsquamous NSCLC lacking targetable mutations? In my opinion, the answer is yes.”

Dr. Schiller is with the Inova Schar Cancer Institute. These comments are adapted from an editorial (N Eng J Med. 2018 May 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1804364 ). The author reported financial support from Merck, Lily, AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, OncoGenex, Halozyme, Synta, Vertex, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Clovis, Xcovery, AbbVie, Astex, Janssen, and Free to Breathe.

The recent phase 3 KEYNOTE-189 trial by Gandhi and her colleagues solidifies a shift in first-line standard therapy for some lung cancer patients, according to Joan H. Schiller, MD.

“This trial illustrates that PD-1 pathway inhibitors can be successfully combined with chemotherapy,” Dr. Schiller wrote in an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the study, patients treated with carboplatin-pemetrexed-pembrolizumab therapy had longer overall and progression-free survival compared with patients treated with just chemotherapy.

“The magnitude of benefit is impressive,” Dr. Schiller wrote, “with a hazard ratio for death of 0.49 and 12-month overall survival of 69.2% in the pembrolizumab-combination group.”

However, “many unanswered questions remain,” Dr. Schiller said, particularly concerning the utility of the commonly used PD-L1 tumor proportion score, which “appears to be problematic, with some randomized trials showing benefit only with a score of 50% or more and others showing benefit at other cutoff points, including less than 1%.”

In the current study, all subgroups benefited from the addition of pembrolizumab, including patients with a score of less than 1%.

Despite the need for more research, Dr. Schiller said she believes that existing findings have revealed unprecedented benefits. “Is carboplatin-pemetrexed-pembrolizumab now the first-line standard therapy for patients with nonsquamous NSCLC lacking targetable mutations? In my opinion, the answer is yes.”

Dr. Schiller is with the Inova Schar Cancer Institute. These comments are adapted from an editorial (N Eng J Med. 2018 May 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1804364 ). The author reported financial support from Merck, Lily, AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, OncoGenex, Halozyme, Synta, Vertex, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Clovis, Xcovery, AbbVie, Astex, Janssen, and Free to Breathe.

The recent phase 3 KEYNOTE-189 trial by Gandhi and her colleagues solidifies a shift in first-line standard therapy for some lung cancer patients, according to Joan H. Schiller, MD.

“This trial illustrates that PD-1 pathway inhibitors can be successfully combined with chemotherapy,” Dr. Schiller wrote in an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the study, patients treated with carboplatin-pemetrexed-pembrolizumab therapy had longer overall and progression-free survival compared with patients treated with just chemotherapy.

“The magnitude of benefit is impressive,” Dr. Schiller wrote, “with a hazard ratio for death of 0.49 and 12-month overall survival of 69.2% in the pembrolizumab-combination group.”

However, “many unanswered questions remain,” Dr. Schiller said, particularly concerning the utility of the commonly used PD-L1 tumor proportion score, which “appears to be problematic, with some randomized trials showing benefit only with a score of 50% or more and others showing benefit at other cutoff points, including less than 1%.”

In the current study, all subgroups benefited from the addition of pembrolizumab, including patients with a score of less than 1%.

Despite the need for more research, Dr. Schiller said she believes that existing findings have revealed unprecedented benefits. “Is carboplatin-pemetrexed-pembrolizumab now the first-line standard therapy for patients with nonsquamous NSCLC lacking targetable mutations? In my opinion, the answer is yes.”

Dr. Schiller is with the Inova Schar Cancer Institute. These comments are adapted from an editorial (N Eng J Med. 2018 May 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1804364 ). The author reported financial support from Merck, Lily, AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, OncoGenex, Halozyme, Synta, Vertex, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Clovis, Xcovery, AbbVie, Astex, Janssen, and Free to Breathe.

, according to results from the phase 3 KEYNOTE-189 trial.

The researchers found that while patients in all subgroups benefited from the addition of pembrolizumab to chemotherapy, patients with a tumor proportion score of at least 50% benefited the most.

In 2017, accelerated approval was granted for pembrolizumab in combination with carboplatin and pemetrexed as first-line therapy for patients with NSCLC lacking EGFR and ALK mutations. This approval was based on response rates and progression-free survival from the KEYNOTE-024 phase 2 trial.

KEYNOTE-189 solidifies these findings, according to investigators. “Together with the results from KEYNOTE-024, the data from KEYNOTE-189 suggest that introducing immunotherapy as a first-line therapy may have a favorable long-term effect on outcomes,” wrote lead author Leena Gandhi, MD, director of the Perlmutter Cancer Center at New York University, and her colleagues. The report was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The double-blind, phase 3 trial assessed 616 treatment-naive patients with metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC without ALK or EGFR mutations. Patients received a platinum-based drug and pemetrexed plus placebo or 200 mg of pembrolizumab every 3 weeks for four cycles. After this, patients received placebo or pembrolizumab with pemetrexed maintenance therapy for up to 35 cycles. Primary endpoints were overall and progression-free survival, determined by a blinded radiologist.

At 12 months, the estimated overall survival was 69.2% for patients treated with pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy, compared with 49.4% for patients treated with chemotherapy alone. For patients treated with the pembrolizumab combination, median progression-free survival was 8.8 months, compared with 4.9 months for those treated with just chemotherapy. Median follow-up time was 10.5 months.

“The survival benefit associated with the pembrolizumab combination was observed in all subgroups of PD-L1 tumor proportion scores,” the authors wrote, “including patients with a score of less than 1%, a population for which single-agent PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibition have a small chance of benefit.” As with previous studies, the subgroup of patients with a tumor proportion score greater than or equal to 50% received the greatest benefit when pembrolizumab was added.

The authors noted that further research is needed to determine whether patients with high PD-L1 expression (TMS ≥ 50%) would benefit more from pembrolizumab combination therapy compared with pembrolizumab monotherapy, which is currently indicated.

SOURCE: Gandhi et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801005.

, according to results from the phase 3 KEYNOTE-189 trial.

The researchers found that while patients in all subgroups benefited from the addition of pembrolizumab to chemotherapy, patients with a tumor proportion score of at least 50% benefited the most.

In 2017, accelerated approval was granted for pembrolizumab in combination with carboplatin and pemetrexed as first-line therapy for patients with NSCLC lacking EGFR and ALK mutations. This approval was based on response rates and progression-free survival from the KEYNOTE-024 phase 2 trial.

KEYNOTE-189 solidifies these findings, according to investigators. “Together with the results from KEYNOTE-024, the data from KEYNOTE-189 suggest that introducing immunotherapy as a first-line therapy may have a favorable long-term effect on outcomes,” wrote lead author Leena Gandhi, MD, director of the Perlmutter Cancer Center at New York University, and her colleagues. The report was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The double-blind, phase 3 trial assessed 616 treatment-naive patients with metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC without ALK or EGFR mutations. Patients received a platinum-based drug and pemetrexed plus placebo or 200 mg of pembrolizumab every 3 weeks for four cycles. After this, patients received placebo or pembrolizumab with pemetrexed maintenance therapy for up to 35 cycles. Primary endpoints were overall and progression-free survival, determined by a blinded radiologist.

At 12 months, the estimated overall survival was 69.2% for patients treated with pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy, compared with 49.4% for patients treated with chemotherapy alone. For patients treated with the pembrolizumab combination, median progression-free survival was 8.8 months, compared with 4.9 months for those treated with just chemotherapy. Median follow-up time was 10.5 months.

“The survival benefit associated with the pembrolizumab combination was observed in all subgroups of PD-L1 tumor proportion scores,” the authors wrote, “including patients with a score of less than 1%, a population for which single-agent PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibition have a small chance of benefit.” As with previous studies, the subgroup of patients with a tumor proportion score greater than or equal to 50% received the greatest benefit when pembrolizumab was added.

The authors noted that further research is needed to determine whether patients with high PD-L1 expression (TMS ≥ 50%) would benefit more from pembrolizumab combination therapy compared with pembrolizumab monotherapy, which is currently indicated.

SOURCE: Gandhi et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801005.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: In patients with advanced NSCLC without targetable mutations, the addition of pembrolizumab to standard combination chemotherapy improves overall survival and progression-free survival.

Major finding: The estimated rate of overall survival at 12 months in patients treated with pembrolizumab-combination therapy was 69.2% (95% CI, 64.1-73.8) compared with 49.4% (95% CI, 42.1-56.2) in patients treated with placebo-combination therapy.

Study details: A double-blind, phase 3 trial of 616 patients with metastatic NSCLC lacking ALK or EGFR mutations (KEYNOTE-189).

Disclosures: Merck sponsored the study. Researchers reported financial support from Genentech/Roche, Pfizer, Ignyta, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, and other companies.

Source: Gandhi et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801005.

Compared With Interferon, Fingolimod Improves MRI Outcomes of Pediatric MS

NASHVILLE—In patients with pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis (MS), fingolimod significantly reduces MRI activity and slows brain volume loss for as long as two years, compared with interferon beta-1a, according to data described at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting.

Analyzing the PARADIGMS Data

PARADIGMS was a double-blind, double-dummy, active-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter study in which patients participated for as long as two years. The investigators randomized patients with pediatric-onset MS (ages 10 through 17) to oral fingolimod or interferon beta-1a. The dose of fingolimod was adjusted for body weight. MRI was performed at baseline and every six months thereafter until the end of the study core phase. A central reading center analyzed the MRI results. The key MRI outcomes were the number of new or newly enlarged T2 lesions and gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions, annual rate of brain volume change, number of new T1 hypointense lesions, change in total T2 hyperintense lesion volume, and number of combined unique active lesions.

The researchers randomized 107 participants to oral fingolimod and 108 to interferon beta-1a. At baseline, mean age was about 15. Most patients were female. Mean disease duration was one to two years. The average number of relapses in the year before screening was approximately 1.5. Participants had 2.6 to 3.1 gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions.

Data Support Fingolimod’s Efficacy in Pediatric MS

At the end of the study, fingolimod significantly reduced the annualized rate of new or newly enlarged T2 lesions by 52.6% and the number of gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions per scan by 66.0%, compared with interferon beta-1a. The odds ratio of freedom from new or newly enlarged T2 lesions was 4.51 in the fingolimod arm, compared with the interferon beta-1a arm. The odds ratio of freedom from gadolinium-enhancing lesions was 3.0 in the fingolimod arm, compared with the interferon beta-1a arm.

Compared with interferon beta-1a, treatment with fingolimod for as long as two years significantly reduced the annualized rate of brain volume change (least squares mean: −0.48 vs −0.80). Fingolimod reduced the annualized rate of new T1 hypointense lesions by 62.8% and the number of combined unique active lesions per scan by 60.7%, compared with interferon beta-1a. Fingolimod also reduced T2 hyperintense lesion volume, compared with interferon beta-1a (percentage change from baseline: 18.4% vs 32.4%).

“The rate of T2-related atrophy [in pediatric MS] is concerning, and I am particularly interested in looking at the extension study data as they come out, and we’ll see if there is a decrease during longer-term treatment,” said Dr. Chitnis.

“These results, overall, along with the efficacy demonstrated on the clinical relapse rate, support the overall benefit of fingolimod in pediatric patients with MS,” she concluded.

—Erik Greb

NASHVILLE—In patients with pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis (MS), fingolimod significantly reduces MRI activity and slows brain volume loss for as long as two years, compared with interferon beta-1a, according to data described at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting.

Analyzing the PARADIGMS Data

PARADIGMS was a double-blind, double-dummy, active-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter study in which patients participated for as long as two years. The investigators randomized patients with pediatric-onset MS (ages 10 through 17) to oral fingolimod or interferon beta-1a. The dose of fingolimod was adjusted for body weight. MRI was performed at baseline and every six months thereafter until the end of the study core phase. A central reading center analyzed the MRI results. The key MRI outcomes were the number of new or newly enlarged T2 lesions and gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions, annual rate of brain volume change, number of new T1 hypointense lesions, change in total T2 hyperintense lesion volume, and number of combined unique active lesions.

The researchers randomized 107 participants to oral fingolimod and 108 to interferon beta-1a. At baseline, mean age was about 15. Most patients were female. Mean disease duration was one to two years. The average number of relapses in the year before screening was approximately 1.5. Participants had 2.6 to 3.1 gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions.

Data Support Fingolimod’s Efficacy in Pediatric MS

At the end of the study, fingolimod significantly reduced the annualized rate of new or newly enlarged T2 lesions by 52.6% and the number of gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions per scan by 66.0%, compared with interferon beta-1a. The odds ratio of freedom from new or newly enlarged T2 lesions was 4.51 in the fingolimod arm, compared with the interferon beta-1a arm. The odds ratio of freedom from gadolinium-enhancing lesions was 3.0 in the fingolimod arm, compared with the interferon beta-1a arm.

Compared with interferon beta-1a, treatment with fingolimod for as long as two years significantly reduced the annualized rate of brain volume change (least squares mean: −0.48 vs −0.80). Fingolimod reduced the annualized rate of new T1 hypointense lesions by 62.8% and the number of combined unique active lesions per scan by 60.7%, compared with interferon beta-1a. Fingolimod also reduced T2 hyperintense lesion volume, compared with interferon beta-1a (percentage change from baseline: 18.4% vs 32.4%).

“The rate of T2-related atrophy [in pediatric MS] is concerning, and I am particularly interested in looking at the extension study data as they come out, and we’ll see if there is a decrease during longer-term treatment,” said Dr. Chitnis.

“These results, overall, along with the efficacy demonstrated on the clinical relapse rate, support the overall benefit of fingolimod in pediatric patients with MS,” she concluded.

—Erik Greb

NASHVILLE—In patients with pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis (MS), fingolimod significantly reduces MRI activity and slows brain volume loss for as long as two years, compared with interferon beta-1a, according to data described at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting.

Analyzing the PARADIGMS Data

PARADIGMS was a double-blind, double-dummy, active-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter study in which patients participated for as long as two years. The investigators randomized patients with pediatric-onset MS (ages 10 through 17) to oral fingolimod or interferon beta-1a. The dose of fingolimod was adjusted for body weight. MRI was performed at baseline and every six months thereafter until the end of the study core phase. A central reading center analyzed the MRI results. The key MRI outcomes were the number of new or newly enlarged T2 lesions and gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions, annual rate of brain volume change, number of new T1 hypointense lesions, change in total T2 hyperintense lesion volume, and number of combined unique active lesions.

The researchers randomized 107 participants to oral fingolimod and 108 to interferon beta-1a. At baseline, mean age was about 15. Most patients were female. Mean disease duration was one to two years. The average number of relapses in the year before screening was approximately 1.5. Participants had 2.6 to 3.1 gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions.

Data Support Fingolimod’s Efficacy in Pediatric MS

At the end of the study, fingolimod significantly reduced the annualized rate of new or newly enlarged T2 lesions by 52.6% and the number of gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions per scan by 66.0%, compared with interferon beta-1a. The odds ratio of freedom from new or newly enlarged T2 lesions was 4.51 in the fingolimod arm, compared with the interferon beta-1a arm. The odds ratio of freedom from gadolinium-enhancing lesions was 3.0 in the fingolimod arm, compared with the interferon beta-1a arm.

Compared with interferon beta-1a, treatment with fingolimod for as long as two years significantly reduced the annualized rate of brain volume change (least squares mean: −0.48 vs −0.80). Fingolimod reduced the annualized rate of new T1 hypointense lesions by 62.8% and the number of combined unique active lesions per scan by 60.7%, compared with interferon beta-1a. Fingolimod also reduced T2 hyperintense lesion volume, compared with interferon beta-1a (percentage change from baseline: 18.4% vs 32.4%).

“The rate of T2-related atrophy [in pediatric MS] is concerning, and I am particularly interested in looking at the extension study data as they come out, and we’ll see if there is a decrease during longer-term treatment,” said Dr. Chitnis.

“These results, overall, along with the efficacy demonstrated on the clinical relapse rate, support the overall benefit of fingolimod in pediatric patients with MS,” she concluded.

—Erik Greb

Can Exercise Improve Vision in Children With MS?

A positive association was observed between moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in pediatric patients.

NASHVILLE—Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity is positively associated with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in children with multiple sclerosis (MS), according to research presented at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting. This finding may help to support an intervention targeting moderate-to-vigorous physical activity to improve anterior visual pathway integrity in children with MS.

More than one-third of pediatric patients with MS experience optic neuritis, and most experience visual pathway abnormalities, including reductions in the retinal nerve fiber layer and ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer. Previous studies in

To investigate the associations between mild-to-vigorous physical activity, the retinal nerve fiber layer, and the ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer in pediatric patients with MS, Alexander L. Pearson, a medical student at the University of Ottawa in Ontario, and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study.

The researchers recruited participants from the Pediatric MS and Demyelinating Disorders Center at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Eligible participants had a diagnosis of MS (according to the International Pediatric MS Study Group consensus definitions) and were younger than 18. Patients with neuroinflammatory abnormalities associated with underlying systemic or neurologic disorders, recurrent neuroinflammatory disorders other than MS, coexisting ocular pathologies, visual acuity ±6 diopters or worse, were excluded.

Participants received standardized visual evaluations, including ocular coherence tomography. Investigators performed evaluations more than 90 days after an optic neuritis episode using a spectral-domain ocular coherence tomography Cirrus scanner. Participants also completed the Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire (GLTEQ) more than 30 days after a relapse. This questionnaire was used to calculate the health contribution score.

Generalized linear models were used to assess the associations between moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, the retinal nerve fiber layer, and the ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer when controlling for sex, number of optic neuritis episodes, disease duration at time of ocular coherence tomography, and within-subject correlation between eyes. Bonferroni correction was used to adjust for multiple comparisons.

Thirty patients participated in this study; 23 were female. Ocular coherence tomography was performed at a mean age of 15.7 (range, 10.6–18.0) and a median of 1.9 years from disease onset. The median retinal nerve fiber layer was 90 μm, and the median ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer was 73.5 μm. The median amount of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity was 26.5 metabolic equivalents per week.

The research team found that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity was positively associated with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness. Although the retinal nerve fiber layer and ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer were moderately correlated, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity was not associated with the ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer, said the authors.

“Next steps include a trial using mild-to-vigorous physical activity to improve anterior visual pathway integrity in children with MS,” the researchers concluded.

A positive association was observed between moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in pediatric patients.

A positive association was observed between moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in pediatric patients.

NASHVILLE—Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity is positively associated with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in children with multiple sclerosis (MS), according to research presented at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting. This finding may help to support an intervention targeting moderate-to-vigorous physical activity to improve anterior visual pathway integrity in children with MS.

More than one-third of pediatric patients with MS experience optic neuritis, and most experience visual pathway abnormalities, including reductions in the retinal nerve fiber layer and ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer. Previous studies in

To investigate the associations between mild-to-vigorous physical activity, the retinal nerve fiber layer, and the ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer in pediatric patients with MS, Alexander L. Pearson, a medical student at the University of Ottawa in Ontario, and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study.

The researchers recruited participants from the Pediatric MS and Demyelinating Disorders Center at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Eligible participants had a diagnosis of MS (according to the International Pediatric MS Study Group consensus definitions) and were younger than 18. Patients with neuroinflammatory abnormalities associated with underlying systemic or neurologic disorders, recurrent neuroinflammatory disorders other than MS, coexisting ocular pathologies, visual acuity ±6 diopters or worse, were excluded.

Participants received standardized visual evaluations, including ocular coherence tomography. Investigators performed evaluations more than 90 days after an optic neuritis episode using a spectral-domain ocular coherence tomography Cirrus scanner. Participants also completed the Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire (GLTEQ) more than 30 days after a relapse. This questionnaire was used to calculate the health contribution score.

Generalized linear models were used to assess the associations between moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, the retinal nerve fiber layer, and the ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer when controlling for sex, number of optic neuritis episodes, disease duration at time of ocular coherence tomography, and within-subject correlation between eyes. Bonferroni correction was used to adjust for multiple comparisons.

Thirty patients participated in this study; 23 were female. Ocular coherence tomography was performed at a mean age of 15.7 (range, 10.6–18.0) and a median of 1.9 years from disease onset. The median retinal nerve fiber layer was 90 μm, and the median ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer was 73.5 μm. The median amount of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity was 26.5 metabolic equivalents per week.

The research team found that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity was positively associated with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness. Although the retinal nerve fiber layer and ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer were moderately correlated, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity was not associated with the ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer, said the authors.

“Next steps include a trial using mild-to-vigorous physical activity to improve anterior visual pathway integrity in children with MS,” the researchers concluded.

NASHVILLE—Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity is positively associated with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in children with multiple sclerosis (MS), according to research presented at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting. This finding may help to support an intervention targeting moderate-to-vigorous physical activity to improve anterior visual pathway integrity in children with MS.

More than one-third of pediatric patients with MS experience optic neuritis, and most experience visual pathway abnormalities, including reductions in the retinal nerve fiber layer and ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer. Previous studies in

To investigate the associations between mild-to-vigorous physical activity, the retinal nerve fiber layer, and the ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer in pediatric patients with MS, Alexander L. Pearson, a medical student at the University of Ottawa in Ontario, and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study.

The researchers recruited participants from the Pediatric MS and Demyelinating Disorders Center at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Eligible participants had a diagnosis of MS (according to the International Pediatric MS Study Group consensus definitions) and were younger than 18. Patients with neuroinflammatory abnormalities associated with underlying systemic or neurologic disorders, recurrent neuroinflammatory disorders other than MS, coexisting ocular pathologies, visual acuity ±6 diopters or worse, were excluded.

Participants received standardized visual evaluations, including ocular coherence tomography. Investigators performed evaluations more than 90 days after an optic neuritis episode using a spectral-domain ocular coherence tomography Cirrus scanner. Participants also completed the Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire (GLTEQ) more than 30 days after a relapse. This questionnaire was used to calculate the health contribution score.

Generalized linear models were used to assess the associations between moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, the retinal nerve fiber layer, and the ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer when controlling for sex, number of optic neuritis episodes, disease duration at time of ocular coherence tomography, and within-subject correlation between eyes. Bonferroni correction was used to adjust for multiple comparisons.

Thirty patients participated in this study; 23 were female. Ocular coherence tomography was performed at a mean age of 15.7 (range, 10.6–18.0) and a median of 1.9 years from disease onset. The median retinal nerve fiber layer was 90 μm, and the median ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer was 73.5 μm. The median amount of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity was 26.5 metabolic equivalents per week.

The research team found that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity was positively associated with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness. Although the retinal nerve fiber layer and ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer were moderately correlated, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity was not associated with the ganglion cell inner-plexiform layer, said the authors.

“Next steps include a trial using mild-to-vigorous physical activity to improve anterior visual pathway integrity in children with MS,” the researchers concluded.

More Frequent Dosing of Interferon Beta-1a May Benefit Patients With MS With Breakthrough Disease

NASHVILLE—Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) with breakthrough disease may benefit from intramuscular interferon beta 1-a treatment twice per week, according to research described at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting. “Advantages to using an intramuscular interferon beta 1-a preparation include no skin reactions and a lower incidence of interferon neutralizing antibodies,” said Robert W. Baumhefner, MD, a neurologist at the Veteran Affairs West Los Angeles Medical Center.

Previous clinical trials have suggested a dose-response effect for interferon beta in MS. The European Interferon Beta-1a Dose Comparison Study, however, found no change in efficacy with just doubling the standard dose of intramuscular interferon beta-1a once per week. This may not be the same as increasing the frequency of intramuscular interferon administration, said Baumhefner. In addition, none of the previous studies have information on patients with breakthrough disease on standard-dose intramuscular interferon beta-1a switched to twice-weekly dosing.

Dr. Baumhefner conducted a retrospective observational study of patients MS with breakthrough disease receiving intramuscular interferon beta 1-a once per week who were switched to intramuscular interferon beta 1-a twice per week.

A total of 107 patients with MS were started on intramuscular interferon beta 1-a from 1995 to 2015 at the MS clinic of the VA West Los Angeles Medical Center. Of these, 59 patients with breakthrough disease were switched to twice-weekly intramuscular interferon beta-1a. There was adequate follow-up for at least two years for 52 of these patients. In addition, participants were followed up an average of every four months.

At each visit, an interval history of any relapse; scores on the Incapacity Status Scale, Functional Systems Scale, and Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS); and a proprietary graded neurologic examination were obtained. Annual MRI of the brain using a contrast-enhanced MS protocol was obtained in most patients. Baumhefner defined breakthrough disease as continued clinical relapses, new T2 or enhanced lesions on MRI, or worsening of EDSS or neurologic examination.

Of the 52 patients with adequate follow-up, 26 had no further breakthrough disease for 14 months or longer (range, 14-192 months). Five patients did not tolerate the increase in frequency of administration. Interferon beta neutralizing antibody testing was performed on 25 patients while they were receiving twice-weekly dosing. One patient who failed twice-weekly interferon beta had consistently elevated titers on two determinations (4%). African American patients, those with a higher EDSS score when switching, and patients with a longer duration of stability on weekly dosed treatment may be less likely to respond, the researcher concluded.

NASHVILLE—Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) with breakthrough disease may benefit from intramuscular interferon beta 1-a treatment twice per week, according to research described at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting. “Advantages to using an intramuscular interferon beta 1-a preparation include no skin reactions and a lower incidence of interferon neutralizing antibodies,” said Robert W. Baumhefner, MD, a neurologist at the Veteran Affairs West Los Angeles Medical Center.

Previous clinical trials have suggested a dose-response effect for interferon beta in MS. The European Interferon Beta-1a Dose Comparison Study, however, found no change in efficacy with just doubling the standard dose of intramuscular interferon beta-1a once per week. This may not be the same as increasing the frequency of intramuscular interferon administration, said Baumhefner. In addition, none of the previous studies have information on patients with breakthrough disease on standard-dose intramuscular interferon beta-1a switched to twice-weekly dosing.

Dr. Baumhefner conducted a retrospective observational study of patients MS with breakthrough disease receiving intramuscular interferon beta 1-a once per week who were switched to intramuscular interferon beta 1-a twice per week.

A total of 107 patients with MS were started on intramuscular interferon beta 1-a from 1995 to 2015 at the MS clinic of the VA West Los Angeles Medical Center. Of these, 59 patients with breakthrough disease were switched to twice-weekly intramuscular interferon beta-1a. There was adequate follow-up for at least two years for 52 of these patients. In addition, participants were followed up an average of every four months.

At each visit, an interval history of any relapse; scores on the Incapacity Status Scale, Functional Systems Scale, and Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS); and a proprietary graded neurologic examination were obtained. Annual MRI of the brain using a contrast-enhanced MS protocol was obtained in most patients. Baumhefner defined breakthrough disease as continued clinical relapses, new T2 or enhanced lesions on MRI, or worsening of EDSS or neurologic examination.

Of the 52 patients with adequate follow-up, 26 had no further breakthrough disease for 14 months or longer (range, 14-192 months). Five patients did not tolerate the increase in frequency of administration. Interferon beta neutralizing antibody testing was performed on 25 patients while they were receiving twice-weekly dosing. One patient who failed twice-weekly interferon beta had consistently elevated titers on two determinations (4%). African American patients, those with a higher EDSS score when switching, and patients with a longer duration of stability on weekly dosed treatment may be less likely to respond, the researcher concluded.

NASHVILLE—Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) with breakthrough disease may benefit from intramuscular interferon beta 1-a treatment twice per week, according to research described at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting. “Advantages to using an intramuscular interferon beta 1-a preparation include no skin reactions and a lower incidence of interferon neutralizing antibodies,” said Robert W. Baumhefner, MD, a neurologist at the Veteran Affairs West Los Angeles Medical Center.

Previous clinical trials have suggested a dose-response effect for interferon beta in MS. The European Interferon Beta-1a Dose Comparison Study, however, found no change in efficacy with just doubling the standard dose of intramuscular interferon beta-1a once per week. This may not be the same as increasing the frequency of intramuscular interferon administration, said Baumhefner. In addition, none of the previous studies have information on patients with breakthrough disease on standard-dose intramuscular interferon beta-1a switched to twice-weekly dosing.

Dr. Baumhefner conducted a retrospective observational study of patients MS with breakthrough disease receiving intramuscular interferon beta 1-a once per week who were switched to intramuscular interferon beta 1-a twice per week.

A total of 107 patients with MS were started on intramuscular interferon beta 1-a from 1995 to 2015 at the MS clinic of the VA West Los Angeles Medical Center. Of these, 59 patients with breakthrough disease were switched to twice-weekly intramuscular interferon beta-1a. There was adequate follow-up for at least two years for 52 of these patients. In addition, participants were followed up an average of every four months.

At each visit, an interval history of any relapse; scores on the Incapacity Status Scale, Functional Systems Scale, and Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS); and a proprietary graded neurologic examination were obtained. Annual MRI of the brain using a contrast-enhanced MS protocol was obtained in most patients. Baumhefner defined breakthrough disease as continued clinical relapses, new T2 or enhanced lesions on MRI, or worsening of EDSS or neurologic examination.

Of the 52 patients with adequate follow-up, 26 had no further breakthrough disease for 14 months or longer (range, 14-192 months). Five patients did not tolerate the increase in frequency of administration. Interferon beta neutralizing antibody testing was performed on 25 patients while they were receiving twice-weekly dosing. One patient who failed twice-weekly interferon beta had consistently elevated titers on two determinations (4%). African American patients, those with a higher EDSS score when switching, and patients with a longer duration of stability on weekly dosed treatment may be less likely to respond, the researcher concluded.

Ocrelizumab’s Benefits on Confirmed Disability Improvement Persist in Open-Label Extension

This outcome remains more likely in patients who started on ocrelizumab than in those who switched to it from interferon beta.

NASHVILLE—The benefits of ocrelizumab on 24-week confirmed disability improvement, which were demonstrated in two-year, double-blind, controlled trials, were maintained for two years in an open-label extension study in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS), according to data described at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting.

The 96-week, double-blind, controlled periods of the OPERA I and II trials demonstrated the efficacy and safety of ocrelizumab in relapsing-remitting MS. Upon completion of the controlled treatment periods, all patients were eligible to enter an open-label extension phase during which they would receive ocrelizumab. Robert T. Naismith, MD, Associate Professor of Neurology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and colleagues reviewed data from this extension phase to assess the effect of switching to ocrelizumab or maintaining ocrelizumab therapy on the proportion of patients experiencing disability improvement.

Difference Between Groups Endured