User login

Hydroxychloroquine throws off Quantiferon-TB Gold results, study finds

ORLANDO – according to investigators from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Among 46 patients with lupus, dermatomyositis, or blistering diseases who had been on hydroxychloroquine within a year of testing, QuantiFERON-TB Gold (QFT-G) – the go-to TB test in many places – yielded indeterminate results in 37%. Meanwhile, just 9.6% of tests were indeterminate among 73 patients with those diseases who had not been on hydroxychloroquine (P less than .001). The findings could not be explained by concomitant use of prednisone and other immunosuppressives; there were no statistically significant differences between the groups. “This was shocking to us. We need to come up with a better screening test in this patient population,” said lead investigator Rebecca Gaffney, a research fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, and a medical student at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ.*

It’s widely known that immunosuppressives interfere with QFT-G results, but antimalarials are considered immunomodulators, not immunosuppressives. The new study is probably the first to investigate the issue. The team is now pitting QFT-G against another TB blood test, the T-SPOT, in 100 patients to see if it’s a better option, in a trial that they expect to complete in 2018.

The investigators have a hunch that the T-SPOT might be better because, while QFT-G measures interferon-gamma concentrations in response to TB antigens, the T-SPOT “counts cells first to make sure you have a standard amount of cells, then looks at how many cells are releasing interferon-gamma,” Ms. Gaffney said, adding that “it seems like a more sensitive test,” especially for lymphocytopenic autoimmune patients. “We are really excited to see if there’s a better test for our patients, given all the clinical trials we do. We want to see what’s best, so there’s no barrier to receiving therapy.”

Subjects were around 50 years old on average, and the majority were women. Most were white, and about 20% were black.

There was no industry funding for the work, and Ms. Gaffney reported no disclosures.

*This article was updated on June 13. 2018.

ORLANDO – according to investigators from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Among 46 patients with lupus, dermatomyositis, or blistering diseases who had been on hydroxychloroquine within a year of testing, QuantiFERON-TB Gold (QFT-G) – the go-to TB test in many places – yielded indeterminate results in 37%. Meanwhile, just 9.6% of tests were indeterminate among 73 patients with those diseases who had not been on hydroxychloroquine (P less than .001). The findings could not be explained by concomitant use of prednisone and other immunosuppressives; there were no statistically significant differences between the groups. “This was shocking to us. We need to come up with a better screening test in this patient population,” said lead investigator Rebecca Gaffney, a research fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, and a medical student at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ.*

It’s widely known that immunosuppressives interfere with QFT-G results, but antimalarials are considered immunomodulators, not immunosuppressives. The new study is probably the first to investigate the issue. The team is now pitting QFT-G against another TB blood test, the T-SPOT, in 100 patients to see if it’s a better option, in a trial that they expect to complete in 2018.

The investigators have a hunch that the T-SPOT might be better because, while QFT-G measures interferon-gamma concentrations in response to TB antigens, the T-SPOT “counts cells first to make sure you have a standard amount of cells, then looks at how many cells are releasing interferon-gamma,” Ms. Gaffney said, adding that “it seems like a more sensitive test,” especially for lymphocytopenic autoimmune patients. “We are really excited to see if there’s a better test for our patients, given all the clinical trials we do. We want to see what’s best, so there’s no barrier to receiving therapy.”

Subjects were around 50 years old on average, and the majority were women. Most were white, and about 20% were black.

There was no industry funding for the work, and Ms. Gaffney reported no disclosures.

*This article was updated on June 13. 2018.

ORLANDO – according to investigators from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Among 46 patients with lupus, dermatomyositis, or blistering diseases who had been on hydroxychloroquine within a year of testing, QuantiFERON-TB Gold (QFT-G) – the go-to TB test in many places – yielded indeterminate results in 37%. Meanwhile, just 9.6% of tests were indeterminate among 73 patients with those diseases who had not been on hydroxychloroquine (P less than .001). The findings could not be explained by concomitant use of prednisone and other immunosuppressives; there were no statistically significant differences between the groups. “This was shocking to us. We need to come up with a better screening test in this patient population,” said lead investigator Rebecca Gaffney, a research fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, and a medical student at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ.*

It’s widely known that immunosuppressives interfere with QFT-G results, but antimalarials are considered immunomodulators, not immunosuppressives. The new study is probably the first to investigate the issue. The team is now pitting QFT-G against another TB blood test, the T-SPOT, in 100 patients to see if it’s a better option, in a trial that they expect to complete in 2018.

The investigators have a hunch that the T-SPOT might be better because, while QFT-G measures interferon-gamma concentrations in response to TB antigens, the T-SPOT “counts cells first to make sure you have a standard amount of cells, then looks at how many cells are releasing interferon-gamma,” Ms. Gaffney said, adding that “it seems like a more sensitive test,” especially for lymphocytopenic autoimmune patients. “We are really excited to see if there’s a better test for our patients, given all the clinical trials we do. We want to see what’s best, so there’s no barrier to receiving therapy.”

Subjects were around 50 years old on average, and the majority were women. Most were white, and about 20% were black.

There was no industry funding for the work, and Ms. Gaffney reported no disclosures.

*This article was updated on June 13. 2018.

REPORTING FROM ICCLE 2018

Electrocardiography: Flecainide Toxicity

Case

An 86-year-old woman, who recently had been seen in the same facility after a ground level fall, presented to the ED with to a 2- to 3-day history of vague abdominal pain, increasing weakness, nausea, and dry heaves.

Upon examination, the patient was unable to stand due to generalized weakness She arrived at the ED via emergency medical services. Her vital signs at presentation were significant for a systolic blood pressure (BP) of 90 mm Hg with a wide complex tachycardia concerning for ventricular tachycardia. The patient’s other vital signers were: heart rate, 136 beats/min; respiratory rate 20 breaths/min; and pulse oximetry was 94% on 4 liters/min of oxygen via nasal cannula.

The patient’s medical history was significant for atrial fibrillation and an indwelling pacemaker, for which she was chronically on flecai

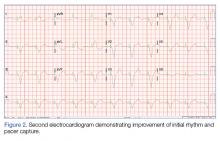

The initial electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed a wide complex rhythm with pacemaker spikes (Figure 1). Based on these findings, electrodes were placed on the patient in the event she required cardioversion. The patient was started on an amiodarone intravenous (IV) drip for presumptive ventricular tachycardia.

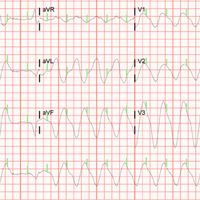

During the patient’s evaluation in the ED, she experienced transient drops in BP, which were responsive to an IV fluid bolus of normal saline, and the amiodarone drip was discontinued. The patient’s ECG findings were compared to previous ECG studies, as was her current medication list and prior health issues. After ruling-out other causes, flecainide toxicity was considered high in the differential, and she was given 1 ampule of bicarbonate IV, after which a second ECG showed heart rhythm converted from a wide-complex tachycardia to a paced rhythm, markedly improved from the initial ECG (Figure 2). Similarly, there was a marked improvement in BP.

An interrogation of the patient’s pacemaker revealed an atrial flutter with a rate below detection for mode switch, with one-to-one tracking/pacing. The pacemaker was reprogrammed to divide the DDIR mode with detection rate at 120 mm Hg with mode switch activated. This was felt to be consistent with flecainide toxicity precipitating the cardiac conduction issues.

Laboratory studies showed an elevated flecainide level at 1.39 mcg/mL (upper limits of normal of 1 mcg/mL). Other studies showed worsening congestive heart failure, with a brain natriuretic peptide of 8,057 pg/mL and mild dehydration, with serum creatinine increased from her baseline of 0.9 to 1.38 mg/dL.

The patient’s abdominal pain was further evaluated and she was found to have acute cholecystitis. She was admitted to the intensive care unit with cardiology and general surgery consulting.

Discussion

Flecainide acetate was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1984.1It is a Vaughan-Williams class IC antiarrhythmic with a sodium channel blocker action used to treat supra ventricular arrhythmias. The CAST trial in 1989 investigated the efficacy of this class of antiarrhythmics, which resulted in a revision of its role.2 Based on this study, flecainide is not recommended for patients with structural heart disease or coronary artery disease.2,3 However, it is recommended as a first-line therapy for pharmacologic cardioversion and maintenance of normal sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation and supraventricular tachycardia4,5 without the above caveats.

Class IC agents produce a selective block at the sodium (Na+) channels, resulting in the slowing of cardiac conduction.6,7 This high affinity for Na+ channels combined with slow unbinding kinetics during diastole explain the slowing of recovery time and prolongation of the refractory period.6,8,9 These electrophysiologic properties all can increase the PR, QRS, and QT interval duration. The QT interval is not significantly affected, as most of the QT prolongation is due to the QRS widening.6,10,11 Widening of the QRS by greater than 25% as compared to the baseline value is used as the threshold to decrease dosing or discontinue the use of flecainide.3The toxic effects of flecainide on cardiac conduction can produce prolonged QRS duration of up to 50%, and PR interval up to 30%, especially in rapid heart rates. Signs of intoxication are difficult to discern owing to its nonspecific presentation. A well-documented, but under-recognized, presentation of flecainide toxicity is the transformation of atrial fibrillation to atrial flutter.5,7,9,11-13 The reported rate of this pro arrhythmic effect can be as high as 3.5% to 5%.14,15Flecainide toxicity can occur secondary to chronic ingestion and may be precipitated in mild renal failure. The majority of flecainide is renally excreted and the half-life is 20 hours. Maximum therapeutic effect is seen between levels of 0.2 to 1 mcg/mL with levels greater than 0.7 to 1 mcg/mL associated with adverse effects.9 Systemic effects include dizziness and visual disturbances. A high degree of suspicion for flecainide toxicity is required when the patient’s initial presentation is nonspecific. In this circumstance, real-time bedside interrogation of the pacemaker is invaluable. Early diagnosis and treatment minimizes the risk for adverse sequelae, including death. Treatment includes increasing the excretion of flecainide, symptomatic support (including pacemaker placement, intravenous fat emulsion, or extracorporeal circulatory support) and administration of sodium bicarbonate, to transiently reverse the effect of the sodium channel blockade, in severe cases.15-17

1. Hudak JM, Banitt EH, Schmid JR. Discovery and development of flecainide. Am J Cardiol. 1984;53(5):17B-20B.

2. Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST) Investigators. Preliminary report: effect of encainide and flecainide on mortality in a randomized trial of arrhythmia suppression after myocardial infarction. The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST). N Engl J Med. 1989;321(6):406-412. doi:10.1056/NEJM198908103210629.

3. Andrikopoulos GK, Pastromas S, Tzeis S. Flecainide: Current status and perspectives in arrhythmia management. World J Cardiol. 2015;7(2):76-85. doi:10.4330/wjc.v7.i2.76.

4. Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(21):2719-2747. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs253.

5. Courand PY, Sibellas F, Ranc S, Mullier A, Kirkorian G, Bonnefoy E. Arrhythmogenic effect of flecainide toxicity. Cardiol J. 2013;20:203-205. doi:10.5603/CJ.2013.0035.

6. Holmes B, Heel RC. Flecainide. A preliminary review of its pharmacodynamic properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1985;29(1):1-33.

7. Taylor R, Gandhi MM, Lloyd G. Tachycardia due to atrial flutter with rapid 1:1 conduction following treatment of atrial fibrillation with flecainide. Br Med J. 2010;340:b4684.

8. Roden DM, Woosley RL. Drug therapy. Flecainide. N Engl J Med. 1986;315(1):36-41.

9. Levis JT. ECG diagnosis: flecainide toxicity. Perm J. 2012;16(4):53.

10. Hellestrand KJ, Bexton RS, Nathan AW, Spurrell RA, Camm AJ. Acute electrophysiological effects of flecainide acetate on cardiac conduction and refractoriness in man. Br Heart J. 1982;48(2):140-148.

11. Rognoni A, Bertolazzi M, Peron M, et al. Electrocardiographic changes in a rare case of flecainide poisoning: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:9137. doi:10.1186/1757-1626-2-9137.

12. Nabar A, Rodriguez LM, Timmermans C, Smeets JL, Wellens HJ. Radiofrequency ablation of “class IC atrial flutter” in patients with resistant atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83(5):785-787, A10.

13. Kola S, Mahata I, Kocheril AG. A case of flecainide toxicity. EP Lab Digest. 2015;15(5).

14. Falk RH. Proarrhythmia in patients treated for atrial fibrillation or flutter. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117(2):141-150.

15. Lloyd T, Zimmerman J, Griffin GD. Irreversible third-degree heart block and pacemaker implant in a case of flecainide toxicity. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(9):1418.e1-e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2013.04.025.

16. Corkeron MA, van Heerden PV, Newman SM, Dusci L. Extracorporeal circulatory support in near-fatal flecainide overdose. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1999;27(4):405-408.

17. Ellsworth H, Stellpflug SJ, Cole JB, Dolan JA, Harris CR. A life-threatening flecainide overdose treated with intravenous fat emulsion. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2013;36(3):e87-e89. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2012.03485.x.

Case

An 86-year-old woman, who recently had been seen in the same facility after a ground level fall, presented to the ED with to a 2- to 3-day history of vague abdominal pain, increasing weakness, nausea, and dry heaves.

Upon examination, the patient was unable to stand due to generalized weakness She arrived at the ED via emergency medical services. Her vital signs at presentation were significant for a systolic blood pressure (BP) of 90 mm Hg with a wide complex tachycardia concerning for ventricular tachycardia. The patient’s other vital signers were: heart rate, 136 beats/min; respiratory rate 20 breaths/min; and pulse oximetry was 94% on 4 liters/min of oxygen via nasal cannula.

The patient’s medical history was significant for atrial fibrillation and an indwelling pacemaker, for which she was chronically on flecai

The initial electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed a wide complex rhythm with pacemaker spikes (Figure 1). Based on these findings, electrodes were placed on the patient in the event she required cardioversion. The patient was started on an amiodarone intravenous (IV) drip for presumptive ventricular tachycardia.

During the patient’s evaluation in the ED, she experienced transient drops in BP, which were responsive to an IV fluid bolus of normal saline, and the amiodarone drip was discontinued. The patient’s ECG findings were compared to previous ECG studies, as was her current medication list and prior health issues. After ruling-out other causes, flecainide toxicity was considered high in the differential, and she was given 1 ampule of bicarbonate IV, after which a second ECG showed heart rhythm converted from a wide-complex tachycardia to a paced rhythm, markedly improved from the initial ECG (Figure 2). Similarly, there was a marked improvement in BP.

An interrogation of the patient’s pacemaker revealed an atrial flutter with a rate below detection for mode switch, with one-to-one tracking/pacing. The pacemaker was reprogrammed to divide the DDIR mode with detection rate at 120 mm Hg with mode switch activated. This was felt to be consistent with flecainide toxicity precipitating the cardiac conduction issues.

Laboratory studies showed an elevated flecainide level at 1.39 mcg/mL (upper limits of normal of 1 mcg/mL). Other studies showed worsening congestive heart failure, with a brain natriuretic peptide of 8,057 pg/mL and mild dehydration, with serum creatinine increased from her baseline of 0.9 to 1.38 mg/dL.

The patient’s abdominal pain was further evaluated and she was found to have acute cholecystitis. She was admitted to the intensive care unit with cardiology and general surgery consulting.

Discussion

Flecainide acetate was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1984.1It is a Vaughan-Williams class IC antiarrhythmic with a sodium channel blocker action used to treat supra ventricular arrhythmias. The CAST trial in 1989 investigated the efficacy of this class of antiarrhythmics, which resulted in a revision of its role.2 Based on this study, flecainide is not recommended for patients with structural heart disease or coronary artery disease.2,3 However, it is recommended as a first-line therapy for pharmacologic cardioversion and maintenance of normal sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation and supraventricular tachycardia4,5 without the above caveats.

Class IC agents produce a selective block at the sodium (Na+) channels, resulting in the slowing of cardiac conduction.6,7 This high affinity for Na+ channels combined with slow unbinding kinetics during diastole explain the slowing of recovery time and prolongation of the refractory period.6,8,9 These electrophysiologic properties all can increase the PR, QRS, and QT interval duration. The QT interval is not significantly affected, as most of the QT prolongation is due to the QRS widening.6,10,11 Widening of the QRS by greater than 25% as compared to the baseline value is used as the threshold to decrease dosing or discontinue the use of flecainide.3The toxic effects of flecainide on cardiac conduction can produce prolonged QRS duration of up to 50%, and PR interval up to 30%, especially in rapid heart rates. Signs of intoxication are difficult to discern owing to its nonspecific presentation. A well-documented, but under-recognized, presentation of flecainide toxicity is the transformation of atrial fibrillation to atrial flutter.5,7,9,11-13 The reported rate of this pro arrhythmic effect can be as high as 3.5% to 5%.14,15Flecainide toxicity can occur secondary to chronic ingestion and may be precipitated in mild renal failure. The majority of flecainide is renally excreted and the half-life is 20 hours. Maximum therapeutic effect is seen between levels of 0.2 to 1 mcg/mL with levels greater than 0.7 to 1 mcg/mL associated with adverse effects.9 Systemic effects include dizziness and visual disturbances. A high degree of suspicion for flecainide toxicity is required when the patient’s initial presentation is nonspecific. In this circumstance, real-time bedside interrogation of the pacemaker is invaluable. Early diagnosis and treatment minimizes the risk for adverse sequelae, including death. Treatment includes increasing the excretion of flecainide, symptomatic support (including pacemaker placement, intravenous fat emulsion, or extracorporeal circulatory support) and administration of sodium bicarbonate, to transiently reverse the effect of the sodium channel blockade, in severe cases.15-17

Case

An 86-year-old woman, who recently had been seen in the same facility after a ground level fall, presented to the ED with to a 2- to 3-day history of vague abdominal pain, increasing weakness, nausea, and dry heaves.

Upon examination, the patient was unable to stand due to generalized weakness She arrived at the ED via emergency medical services. Her vital signs at presentation were significant for a systolic blood pressure (BP) of 90 mm Hg with a wide complex tachycardia concerning for ventricular tachycardia. The patient’s other vital signers were: heart rate, 136 beats/min; respiratory rate 20 breaths/min; and pulse oximetry was 94% on 4 liters/min of oxygen via nasal cannula.

The patient’s medical history was significant for atrial fibrillation and an indwelling pacemaker, for which she was chronically on flecai

The initial electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed a wide complex rhythm with pacemaker spikes (Figure 1). Based on these findings, electrodes were placed on the patient in the event she required cardioversion. The patient was started on an amiodarone intravenous (IV) drip for presumptive ventricular tachycardia.

During the patient’s evaluation in the ED, she experienced transient drops in BP, which were responsive to an IV fluid bolus of normal saline, and the amiodarone drip was discontinued. The patient’s ECG findings were compared to previous ECG studies, as was her current medication list and prior health issues. After ruling-out other causes, flecainide toxicity was considered high in the differential, and she was given 1 ampule of bicarbonate IV, after which a second ECG showed heart rhythm converted from a wide-complex tachycardia to a paced rhythm, markedly improved from the initial ECG (Figure 2). Similarly, there was a marked improvement in BP.

An interrogation of the patient’s pacemaker revealed an atrial flutter with a rate below detection for mode switch, with one-to-one tracking/pacing. The pacemaker was reprogrammed to divide the DDIR mode with detection rate at 120 mm Hg with mode switch activated. This was felt to be consistent with flecainide toxicity precipitating the cardiac conduction issues.

Laboratory studies showed an elevated flecainide level at 1.39 mcg/mL (upper limits of normal of 1 mcg/mL). Other studies showed worsening congestive heart failure, with a brain natriuretic peptide of 8,057 pg/mL and mild dehydration, with serum creatinine increased from her baseline of 0.9 to 1.38 mg/dL.

The patient’s abdominal pain was further evaluated and she was found to have acute cholecystitis. She was admitted to the intensive care unit with cardiology and general surgery consulting.

Discussion

Flecainide acetate was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1984.1It is a Vaughan-Williams class IC antiarrhythmic with a sodium channel blocker action used to treat supra ventricular arrhythmias. The CAST trial in 1989 investigated the efficacy of this class of antiarrhythmics, which resulted in a revision of its role.2 Based on this study, flecainide is not recommended for patients with structural heart disease or coronary artery disease.2,3 However, it is recommended as a first-line therapy for pharmacologic cardioversion and maintenance of normal sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation and supraventricular tachycardia4,5 without the above caveats.

Class IC agents produce a selective block at the sodium (Na+) channels, resulting in the slowing of cardiac conduction.6,7 This high affinity for Na+ channels combined with slow unbinding kinetics during diastole explain the slowing of recovery time and prolongation of the refractory period.6,8,9 These electrophysiologic properties all can increase the PR, QRS, and QT interval duration. The QT interval is not significantly affected, as most of the QT prolongation is due to the QRS widening.6,10,11 Widening of the QRS by greater than 25% as compared to the baseline value is used as the threshold to decrease dosing or discontinue the use of flecainide.3The toxic effects of flecainide on cardiac conduction can produce prolonged QRS duration of up to 50%, and PR interval up to 30%, especially in rapid heart rates. Signs of intoxication are difficult to discern owing to its nonspecific presentation. A well-documented, but under-recognized, presentation of flecainide toxicity is the transformation of atrial fibrillation to atrial flutter.5,7,9,11-13 The reported rate of this pro arrhythmic effect can be as high as 3.5% to 5%.14,15Flecainide toxicity can occur secondary to chronic ingestion and may be precipitated in mild renal failure. The majority of flecainide is renally excreted and the half-life is 20 hours. Maximum therapeutic effect is seen between levels of 0.2 to 1 mcg/mL with levels greater than 0.7 to 1 mcg/mL associated with adverse effects.9 Systemic effects include dizziness and visual disturbances. A high degree of suspicion for flecainide toxicity is required when the patient’s initial presentation is nonspecific. In this circumstance, real-time bedside interrogation of the pacemaker is invaluable. Early diagnosis and treatment minimizes the risk for adverse sequelae, including death. Treatment includes increasing the excretion of flecainide, symptomatic support (including pacemaker placement, intravenous fat emulsion, or extracorporeal circulatory support) and administration of sodium bicarbonate, to transiently reverse the effect of the sodium channel blockade, in severe cases.15-17

1. Hudak JM, Banitt EH, Schmid JR. Discovery and development of flecainide. Am J Cardiol. 1984;53(5):17B-20B.

2. Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST) Investigators. Preliminary report: effect of encainide and flecainide on mortality in a randomized trial of arrhythmia suppression after myocardial infarction. The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST). N Engl J Med. 1989;321(6):406-412. doi:10.1056/NEJM198908103210629.

3. Andrikopoulos GK, Pastromas S, Tzeis S. Flecainide: Current status and perspectives in arrhythmia management. World J Cardiol. 2015;7(2):76-85. doi:10.4330/wjc.v7.i2.76.

4. Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(21):2719-2747. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs253.

5. Courand PY, Sibellas F, Ranc S, Mullier A, Kirkorian G, Bonnefoy E. Arrhythmogenic effect of flecainide toxicity. Cardiol J. 2013;20:203-205. doi:10.5603/CJ.2013.0035.

6. Holmes B, Heel RC. Flecainide. A preliminary review of its pharmacodynamic properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1985;29(1):1-33.

7. Taylor R, Gandhi MM, Lloyd G. Tachycardia due to atrial flutter with rapid 1:1 conduction following treatment of atrial fibrillation with flecainide. Br Med J. 2010;340:b4684.

8. Roden DM, Woosley RL. Drug therapy. Flecainide. N Engl J Med. 1986;315(1):36-41.

9. Levis JT. ECG diagnosis: flecainide toxicity. Perm J. 2012;16(4):53.

10. Hellestrand KJ, Bexton RS, Nathan AW, Spurrell RA, Camm AJ. Acute electrophysiological effects of flecainide acetate on cardiac conduction and refractoriness in man. Br Heart J. 1982;48(2):140-148.

11. Rognoni A, Bertolazzi M, Peron M, et al. Electrocardiographic changes in a rare case of flecainide poisoning: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:9137. doi:10.1186/1757-1626-2-9137.

12. Nabar A, Rodriguez LM, Timmermans C, Smeets JL, Wellens HJ. Radiofrequency ablation of “class IC atrial flutter” in patients with resistant atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83(5):785-787, A10.

13. Kola S, Mahata I, Kocheril AG. A case of flecainide toxicity. EP Lab Digest. 2015;15(5).

14. Falk RH. Proarrhythmia in patients treated for atrial fibrillation or flutter. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117(2):141-150.

15. Lloyd T, Zimmerman J, Griffin GD. Irreversible third-degree heart block and pacemaker implant in a case of flecainide toxicity. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(9):1418.e1-e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2013.04.025.

16. Corkeron MA, van Heerden PV, Newman SM, Dusci L. Extracorporeal circulatory support in near-fatal flecainide overdose. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1999;27(4):405-408.

17. Ellsworth H, Stellpflug SJ, Cole JB, Dolan JA, Harris CR. A life-threatening flecainide overdose treated with intravenous fat emulsion. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2013;36(3):e87-e89. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2012.03485.x.

1. Hudak JM, Banitt EH, Schmid JR. Discovery and development of flecainide. Am J Cardiol. 1984;53(5):17B-20B.

2. Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST) Investigators. Preliminary report: effect of encainide and flecainide on mortality in a randomized trial of arrhythmia suppression after myocardial infarction. The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST). N Engl J Med. 1989;321(6):406-412. doi:10.1056/NEJM198908103210629.

3. Andrikopoulos GK, Pastromas S, Tzeis S. Flecainide: Current status and perspectives in arrhythmia management. World J Cardiol. 2015;7(2):76-85. doi:10.4330/wjc.v7.i2.76.

4. Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(21):2719-2747. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs253.

5. Courand PY, Sibellas F, Ranc S, Mullier A, Kirkorian G, Bonnefoy E. Arrhythmogenic effect of flecainide toxicity. Cardiol J. 2013;20:203-205. doi:10.5603/CJ.2013.0035.

6. Holmes B, Heel RC. Flecainide. A preliminary review of its pharmacodynamic properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1985;29(1):1-33.

7. Taylor R, Gandhi MM, Lloyd G. Tachycardia due to atrial flutter with rapid 1:1 conduction following treatment of atrial fibrillation with flecainide. Br Med J. 2010;340:b4684.

8. Roden DM, Woosley RL. Drug therapy. Flecainide. N Engl J Med. 1986;315(1):36-41.

9. Levis JT. ECG diagnosis: flecainide toxicity. Perm J. 2012;16(4):53.

10. Hellestrand KJ, Bexton RS, Nathan AW, Spurrell RA, Camm AJ. Acute electrophysiological effects of flecainide acetate on cardiac conduction and refractoriness in man. Br Heart J. 1982;48(2):140-148.

11. Rognoni A, Bertolazzi M, Peron M, et al. Electrocardiographic changes in a rare case of flecainide poisoning: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:9137. doi:10.1186/1757-1626-2-9137.

12. Nabar A, Rodriguez LM, Timmermans C, Smeets JL, Wellens HJ. Radiofrequency ablation of “class IC atrial flutter” in patients with resistant atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83(5):785-787, A10.

13. Kola S, Mahata I, Kocheril AG. A case of flecainide toxicity. EP Lab Digest. 2015;15(5).

14. Falk RH. Proarrhythmia in patients treated for atrial fibrillation or flutter. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117(2):141-150.

15. Lloyd T, Zimmerman J, Griffin GD. Irreversible third-degree heart block and pacemaker implant in a case of flecainide toxicity. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(9):1418.e1-e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2013.04.025.

16. Corkeron MA, van Heerden PV, Newman SM, Dusci L. Extracorporeal circulatory support in near-fatal flecainide overdose. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1999;27(4):405-408.

17. Ellsworth H, Stellpflug SJ, Cole JB, Dolan JA, Harris CR. A life-threatening flecainide overdose treated with intravenous fat emulsion. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2013;36(3):e87-e89. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2012.03485.x.

Sarcoidosis Resulting in Exsanguinating Esophageal Variceal Hemorrhage

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disorder of unknown etiology and is characterized by the formation of granulomas throughout various organs in the body. The most common form is pulmonary sarcoidosis, which affects 90% of patients; the second most common form is oculocutaneous sarcoidosis;1 and the third most common form is hepatic sarcoidosis, which affects 63% to 90% of patients.2 Although the liver is frequently involved in all forms of sarcoidosis, only a fraction of patients present with clinically evident liver disease.1 Approximately 20% to 30% of patients have abnormalities on liver function tests, whereas only about 1% of patients show evidence of portal hypertension and cirrhosis.3 In fact, in the English literature, there were 35 reported cases of portal hypertension due to sarcoidosis between 1949 to 2001, of which 16 of the patients had no evidence of cirrhosis.4

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is usually made by a compilation of clinical signs and symptoms, imaging studies, and biopsies demonstrating noncaseating granulomas. This case report describes a patient who presented with portal hypertension and esophageal variceal bleeding secondary to sarcoidosis of the liver without cirrhotic changes.

Case

A 47-year-old woman presented to the ED via emergency medical services with a 1-hour history of hematemesis and melena. The patient stated that she felt fatigued, nauseated, and light-headed, but had no pain or focal weakness. Her medical history was significant for pulmonary and renal sarcoidosis. She underwent a liver biopsy 1 week prior to presentation, with a 6-day hospitalization period, due to new ascites found on examination.

The patient’s vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure (BP), 72/56 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 133 beats/min, respiratory rate, 24 breaths/min; and temperature, 97.0oF. Oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. Physical examination revealed an alert and oriented middle-aged woman in extremis who was vomiting dark-colored blood. The cardiac and pulmonary examination revealed no extraneous sounds; the abdominal examination showed ascites with a liver edge palpable 4 cm beneath the right costal margin. The patient had no scleral icterus, palmar erythema, spider angiomata, fetor hepaticus, caput medusa, cutaneous ecchymoses, or any other stigmata of cirrhosis.

Two large-bore peripheral intravenous (IV) catheters were placed and a massive blood transfusion protocol was initiated. Packed red blood cells (PRBCs) from the resuscitation-area refrigerator were infused immediately via a pressurized fluid warmer.

After consultation with gastroenterology and general surgery services, the patient was given 1 g ceftriaxone IV, 1 g tranexamic acid IV, 20 mcg desmopressin IV, 50 mcg octreotide IV, 40 mg pantoprazole IV, 8 mg ondansetron IV, 4 g calcium gluconate IV, and 100 mg hydrocortisone IV.

Throughout the patient’s first 10 minutes in the ED, she remained persistently hypotensive and continued to vomit. Since the patient’s sensorium was intact, the team quickly discussed goals of care with her. The patient’s wishes were for maximal life-sustaining therapy, including endotracheal intubation and chest compressions, if necessary.

After this discussion, the patient was given IV etomidate and rocuronium and was intubated using video-assisted laryngoscopy. Following intubation, she was sedated with an infusion of fentanyl and underwent orogastric tube placement to aspirate stomach contents. A total of 2.5 L of frank blood were drained from the patient’s stomach.

A size 9 French single lumen left-femoral central venous catheter also was placed, through which additional blood products were infused. The patient received a total of 28 U PRBCs, fresh frozen plasma, and platelets over a 3-hour period. During transfusion, the patient’s vital signs improved to a systolic BP ranging between 110 to 120 mm Hg and an HR ranging between 90 to 110 beats/min; she did not experience any further hypotensive episodes throughout her stay in the ED.

Laboratory studies were significant for metabolic acidosis, hyperkalemia, acute on chronic anemia, leukocytosis, and acute on chronic renal failure. Synthetic function of the liver and transaminases appeared normal (Table).

The patient’s hyperkalemia was treated with 1 g calcium chloride IV, 50 g dextrose IV, and 10 U regular insulin IV. A portable chest radiograph showed an appropriately positioned endotracheal tube, and an electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia without signs of hyperkalemia. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis from the patient’s recent hospitalization, 1 week prior to presentation, showed hepatomegaly, liver granulomas, ascites, and periportal lymphadenopathy (Figure 1).

A review of the patient’s recent liver biopsy and ascitic fluid analysis revealed noncaseating granulomas compressing the hepatic sinusoids, and a serum ascites albumin gradient greater than 1.1 g/dL, implying portal hypertension without cirrhosis. The surgical team attempted to place a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube, but the device could not be positioned properly due to the patient’s narrowed esophagus.

The ED nurses cleaned the patient, preserving her dignity; thereafter the patient’s adult children visited with her briefly before she was taken for an upper endoscopy, which was performed in the ED. The endoscopy revealed actively hemorrhaging esophageal varices at the gastroesophageal junction (Figure 2). The varices were treated with endoscopic ligation; the gastroenterologist placed a total of 11 bands, resulting in cessation of bleeding.

After the endoscopy, the patient was admitted to the medical intensive care unit (ICU). Approximately 1.5 hours after arriving at the ICU, she developed renewed hematemesis. Despite efforts to control bleeding and provide hemodynamic support, the patient died 1 hour later.

Discussion

Etiology

Esophageal variceal hemorrhage is caused by pressure elevation in the portal venous system, leading to engorged esophageal veins that can bleed spontaneously. Approximately 90% of portal hypertension is due to liver cirrhosis.5 The remaining 10% of cases are primarily vascular in etiology, with endothelial dysfunction and thrombosis leading to increased portal resistance. Noncirrhotic causes of portal hypertension include malignancy, congenital diseases, viral hepatitides, vascular thromboses or fistulae, constrictive pericarditis, fatty liver of pregnancy, drugs, radiation injury, and infiltrative diseases.5

Sarcoidosis may cause noncaseating granulomas to form in the liver, leading to portal hypertension and fatal exsanguination from esophageal variceal hemorrhage. Although the lesions of sarcoidosis classically form in the lungs, any organ system may be affected.6,7 Frank cirrhosis of the liver occurs in only 1% of sarcoidosis patients; however, radiographic involvement of the liver is seen in 5% to 15% of patients.8

There are several mechanisms which may be responsible for portal hypertension in patients with sarcoidosis, including granulomas causing mass effect on the hepatic sinusoids; arteriovenous shunts within the granuloma; granulomatous phlebitis within the sinusoids; or compressive periportal lymphadenopathy.9 Regardless of the mechanism, a review of the literature demonstrates an association between sarcoidosis and symptomatic portal hypertension.2,4,10,11Although our patient ultimately died, early initiation of massive blood transfusion protocol, airway protection, attention to electrolytes, and endoscopic control of the hemorrhage source provided the best chance for survival.

Medical Therapy

The first priority in managing and treating esophageal varices is to secure the patient’s airways to prevent aspiration. Two large bore IV lines should be placed to permit rapid infusion of crystalloid fluids or blood products. Initiating antibiotics, specifically IV ceftriaxone, to patients with variceal bleeding is a class I recommendation, as this is the only intervention shown to increase patient survival.12 Although proton pump inhibitors (PPI) and somatostatin analogues (typically octreotide) are frequently given, they are both class II recommendations because there is limited evidence supporting the benefit of their use.12 However, current guidelines recommend treating patients for variceal bleeding with an initial bolus of a PPI, followed by a continuous infusion of PPI for 72 hours. As previously noted, multiple studies, have failed to show any decrease in mortality associated with this treatment.12

Other agents that are used to treat variceal bleeding include octreotide and vasopressin. Octreotide, a somatostatin analog, is generally given as an initial IV bolus followed by continuous infusion, and has been shown to decrease transfusion requirements without mortality benefit.12 Vasopressin is generally given to critically ill patients, and is considered a third-line treatment for variceal bleeding.

Since our patient had a history of chronic kidney disease, desmopressin was empirically administered in the event platelet dysfunction was a contributing factor to bleeding.13 The absence of cirrhosis was significant because our patient was unlikely to have a bleeding diathesis caused by coagulation factor deficiency. Therefore, the goal transfusion ratio of blood products should be balanced, similar to that in traumatic exsanguination, rather than favoring an increased ratio of plasma to other blood products. Similarly, tranexamic acid was administered because insufficient tamponade rather than coagulopathy was the presumed cause of sustained hemorrhage.

An additional complicating factor in our patient’s care was the potential effect of the massive transfusion on electrolytes. Packed RBCs have a pH of approximately 6.8 and may carry up to 25 mmol/L of potassium, which may have exacerbated our patient’s underlying hyperkalemia.14 Rapid blood transfusion also places patients at risk for acute hypocalcemia secondary to citrate toxicity; this did not occur in our patient in part because the metabolic function of her liver was preserved and citrate could be broken down in the hepatocyte Krebs cycle.15 Calcium therapy doubled as treatment for the hyperkalemia and as prophylaxis against further hypocalcemia. No dysrhythmias were observed.

Surgical Intervention

Emergency physicians should consult with gastroenterology services so that an endoscopy can be performed as soon as possible to evaluate for and control bleeding. When an endoscopy cannot be performed rapidly, there are multiple balloon tamponade devices available that can be used to temporize the bleeding, such as the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube.12

Although balloon tamponade devices are typically reserved for the last line of therapy, endoscopy rather than transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) was the preferred method of hemorrhage source control in our patient for several reasons. First, although the working diagnosis of varices was based on the patient’s history, we wanted to evaluate for other causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding since our patient had no history of endoscopy. Therefore, endoscopy had both a therapeutic and diagnostic value. Secondly, though TIPS may decrease pressure within the bleeding varix, only endoscopy permits direct hemostasis. Also, endoscopy also was preferred over TIPS because our patient was too unstable to move to the interventional radiology suite.16

Conclusion

Although life-threatening esophageal variceal hemorrhage is a rare manifestation of an uncommon disease, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient who has sarcoidosis and presents with gastrointestinal bleeding. Additionally, when caring for a patient with massive hematemesis without evidence of liver cirrhosis, other etiologies of portal hypertension and esophageal varices, such as sarcoidosis, should be considered.

1. Rao DA, Dellaripa PF. Extrapulmonary manifestations of sarcoidosis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39(2):277-297. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2013.02.007.

2. Mistilis SP, Green JR, Schiff L. Hepatic sarcoidosis with portal hypertension. Am J Med. 1964;36(3):470-475. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(64)90175-5.

3. Tekeste H, Latour F, Levitt RE. Portal hypertension complicating sarcoid liver disease: case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1984;79(5):389-396.

4. Ivonye C, Elhammali B, Henriques-Forsythe M, Bennett-Gittens R, Oderinde A. Disseminated sarcoidosis resulting in portal hypertension and gastrointestinal bleeding: a rare presentation. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26(8):508-509. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22891173. Accessed May 16, 2018.

5. Tetangco EP, Silva RG, Lerma EV. Portal hypertension: etiology, evaluation, and management. Dis Mon. 2016;62(12):411-426. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2016.08.001.

6. Valeyre D, Prasse A, Nunes H, Uzunhan Y, Brillet PY, Müller-Quernheim J. Sarcoidosis. Lancet. 2014;383(9923):1155-1167. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60680-7.

7. Al-Kofahi K, Korsten P, Ascoli C, et al. Management of extrapulmonary sarcoidosis: challenges and solutions. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:1623-1634. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S74476.

8. Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2153-2165. doi:10.1056/NEJMra071714.

9. Ebert EC, Kierson M, Hagspiel KD. Gastrointestinal and hepatic manifestations of sarcoidosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(12):3184-3192. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02202.x.

10. Fraimow W, Myerson RM. Portal hypertension and bleeding esophageal varices secondary to sarcoidosis of the liver. Am J Med. 1957;23(6):995-998.

11. Saito H, Ohmori M, Iwamuro M, et al. Hepatic and gastric involvement in a case of systemic sarcoidosis presenting with rupture of esophageal varices. Intern Med. 2018;56(19):2583-2588. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.8768-16.

12. DeLaney M, Greene CJ. Emergency Department evaluation and management of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Emerg Med Pract. 2015;17(4):1-18; quiz 19.

13. Ozgönenel B, Rajpurkar M, Lusher JM. How do you treat bleeding disorders with desmopressin? Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(977):159-163. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2006.052118.

14. Sümpelmann R, Schürholz T, Thorns E, Hausdörfer J. Acid-base, electrolyte and metabolite concentrations in packed red blood cells for major transfusion in infants. Paediatr Anaesth. 2001;11(2):169-173. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9592.2001.00637.x.

15. Monchi M. Citrate pathophysiology and metabolism. Transfus Apher Sci. 2018;56(1):28-30. doi:10.1016/j.transci.2016.12.013.

16. Shah RP, Sze DY. Complications during transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;19(1):61-73. doi:10.1053/j.tvir.2016.01.007.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disorder of unknown etiology and is characterized by the formation of granulomas throughout various organs in the body. The most common form is pulmonary sarcoidosis, which affects 90% of patients; the second most common form is oculocutaneous sarcoidosis;1 and the third most common form is hepatic sarcoidosis, which affects 63% to 90% of patients.2 Although the liver is frequently involved in all forms of sarcoidosis, only a fraction of patients present with clinically evident liver disease.1 Approximately 20% to 30% of patients have abnormalities on liver function tests, whereas only about 1% of patients show evidence of portal hypertension and cirrhosis.3 In fact, in the English literature, there were 35 reported cases of portal hypertension due to sarcoidosis between 1949 to 2001, of which 16 of the patients had no evidence of cirrhosis.4

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is usually made by a compilation of clinical signs and symptoms, imaging studies, and biopsies demonstrating noncaseating granulomas. This case report describes a patient who presented with portal hypertension and esophageal variceal bleeding secondary to sarcoidosis of the liver without cirrhotic changes.

Case

A 47-year-old woman presented to the ED via emergency medical services with a 1-hour history of hematemesis and melena. The patient stated that she felt fatigued, nauseated, and light-headed, but had no pain or focal weakness. Her medical history was significant for pulmonary and renal sarcoidosis. She underwent a liver biopsy 1 week prior to presentation, with a 6-day hospitalization period, due to new ascites found on examination.

The patient’s vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure (BP), 72/56 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 133 beats/min, respiratory rate, 24 breaths/min; and temperature, 97.0oF. Oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. Physical examination revealed an alert and oriented middle-aged woman in extremis who was vomiting dark-colored blood. The cardiac and pulmonary examination revealed no extraneous sounds; the abdominal examination showed ascites with a liver edge palpable 4 cm beneath the right costal margin. The patient had no scleral icterus, palmar erythema, spider angiomata, fetor hepaticus, caput medusa, cutaneous ecchymoses, or any other stigmata of cirrhosis.

Two large-bore peripheral intravenous (IV) catheters were placed and a massive blood transfusion protocol was initiated. Packed red blood cells (PRBCs) from the resuscitation-area refrigerator were infused immediately via a pressurized fluid warmer.

After consultation with gastroenterology and general surgery services, the patient was given 1 g ceftriaxone IV, 1 g tranexamic acid IV, 20 mcg desmopressin IV, 50 mcg octreotide IV, 40 mg pantoprazole IV, 8 mg ondansetron IV, 4 g calcium gluconate IV, and 100 mg hydrocortisone IV.

Throughout the patient’s first 10 minutes in the ED, she remained persistently hypotensive and continued to vomit. Since the patient’s sensorium was intact, the team quickly discussed goals of care with her. The patient’s wishes were for maximal life-sustaining therapy, including endotracheal intubation and chest compressions, if necessary.

After this discussion, the patient was given IV etomidate and rocuronium and was intubated using video-assisted laryngoscopy. Following intubation, she was sedated with an infusion of fentanyl and underwent orogastric tube placement to aspirate stomach contents. A total of 2.5 L of frank blood were drained from the patient’s stomach.

A size 9 French single lumen left-femoral central venous catheter also was placed, through which additional blood products were infused. The patient received a total of 28 U PRBCs, fresh frozen plasma, and platelets over a 3-hour period. During transfusion, the patient’s vital signs improved to a systolic BP ranging between 110 to 120 mm Hg and an HR ranging between 90 to 110 beats/min; she did not experience any further hypotensive episodes throughout her stay in the ED.

Laboratory studies were significant for metabolic acidosis, hyperkalemia, acute on chronic anemia, leukocytosis, and acute on chronic renal failure. Synthetic function of the liver and transaminases appeared normal (Table).

The patient’s hyperkalemia was treated with 1 g calcium chloride IV, 50 g dextrose IV, and 10 U regular insulin IV. A portable chest radiograph showed an appropriately positioned endotracheal tube, and an electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia without signs of hyperkalemia. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis from the patient’s recent hospitalization, 1 week prior to presentation, showed hepatomegaly, liver granulomas, ascites, and periportal lymphadenopathy (Figure 1).

A review of the patient’s recent liver biopsy and ascitic fluid analysis revealed noncaseating granulomas compressing the hepatic sinusoids, and a serum ascites albumin gradient greater than 1.1 g/dL, implying portal hypertension without cirrhosis. The surgical team attempted to place a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube, but the device could not be positioned properly due to the patient’s narrowed esophagus.

The ED nurses cleaned the patient, preserving her dignity; thereafter the patient’s adult children visited with her briefly before she was taken for an upper endoscopy, which was performed in the ED. The endoscopy revealed actively hemorrhaging esophageal varices at the gastroesophageal junction (Figure 2). The varices were treated with endoscopic ligation; the gastroenterologist placed a total of 11 bands, resulting in cessation of bleeding.

After the endoscopy, the patient was admitted to the medical intensive care unit (ICU). Approximately 1.5 hours after arriving at the ICU, she developed renewed hematemesis. Despite efforts to control bleeding and provide hemodynamic support, the patient died 1 hour later.

Discussion

Etiology

Esophageal variceal hemorrhage is caused by pressure elevation in the portal venous system, leading to engorged esophageal veins that can bleed spontaneously. Approximately 90% of portal hypertension is due to liver cirrhosis.5 The remaining 10% of cases are primarily vascular in etiology, with endothelial dysfunction and thrombosis leading to increased portal resistance. Noncirrhotic causes of portal hypertension include malignancy, congenital diseases, viral hepatitides, vascular thromboses or fistulae, constrictive pericarditis, fatty liver of pregnancy, drugs, radiation injury, and infiltrative diseases.5

Sarcoidosis may cause noncaseating granulomas to form in the liver, leading to portal hypertension and fatal exsanguination from esophageal variceal hemorrhage. Although the lesions of sarcoidosis classically form in the lungs, any organ system may be affected.6,7 Frank cirrhosis of the liver occurs in only 1% of sarcoidosis patients; however, radiographic involvement of the liver is seen in 5% to 15% of patients.8

There are several mechanisms which may be responsible for portal hypertension in patients with sarcoidosis, including granulomas causing mass effect on the hepatic sinusoids; arteriovenous shunts within the granuloma; granulomatous phlebitis within the sinusoids; or compressive periportal lymphadenopathy.9 Regardless of the mechanism, a review of the literature demonstrates an association between sarcoidosis and symptomatic portal hypertension.2,4,10,11Although our patient ultimately died, early initiation of massive blood transfusion protocol, airway protection, attention to electrolytes, and endoscopic control of the hemorrhage source provided the best chance for survival.

Medical Therapy

The first priority in managing and treating esophageal varices is to secure the patient’s airways to prevent aspiration. Two large bore IV lines should be placed to permit rapid infusion of crystalloid fluids or blood products. Initiating antibiotics, specifically IV ceftriaxone, to patients with variceal bleeding is a class I recommendation, as this is the only intervention shown to increase patient survival.12 Although proton pump inhibitors (PPI) and somatostatin analogues (typically octreotide) are frequently given, they are both class II recommendations because there is limited evidence supporting the benefit of their use.12 However, current guidelines recommend treating patients for variceal bleeding with an initial bolus of a PPI, followed by a continuous infusion of PPI for 72 hours. As previously noted, multiple studies, have failed to show any decrease in mortality associated with this treatment.12

Other agents that are used to treat variceal bleeding include octreotide and vasopressin. Octreotide, a somatostatin analog, is generally given as an initial IV bolus followed by continuous infusion, and has been shown to decrease transfusion requirements without mortality benefit.12 Vasopressin is generally given to critically ill patients, and is considered a third-line treatment for variceal bleeding.

Since our patient had a history of chronic kidney disease, desmopressin was empirically administered in the event platelet dysfunction was a contributing factor to bleeding.13 The absence of cirrhosis was significant because our patient was unlikely to have a bleeding diathesis caused by coagulation factor deficiency. Therefore, the goal transfusion ratio of blood products should be balanced, similar to that in traumatic exsanguination, rather than favoring an increased ratio of plasma to other blood products. Similarly, tranexamic acid was administered because insufficient tamponade rather than coagulopathy was the presumed cause of sustained hemorrhage.

An additional complicating factor in our patient’s care was the potential effect of the massive transfusion on electrolytes. Packed RBCs have a pH of approximately 6.8 and may carry up to 25 mmol/L of potassium, which may have exacerbated our patient’s underlying hyperkalemia.14 Rapid blood transfusion also places patients at risk for acute hypocalcemia secondary to citrate toxicity; this did not occur in our patient in part because the metabolic function of her liver was preserved and citrate could be broken down in the hepatocyte Krebs cycle.15 Calcium therapy doubled as treatment for the hyperkalemia and as prophylaxis against further hypocalcemia. No dysrhythmias were observed.

Surgical Intervention

Emergency physicians should consult with gastroenterology services so that an endoscopy can be performed as soon as possible to evaluate for and control bleeding. When an endoscopy cannot be performed rapidly, there are multiple balloon tamponade devices available that can be used to temporize the bleeding, such as the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube.12

Although balloon tamponade devices are typically reserved for the last line of therapy, endoscopy rather than transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) was the preferred method of hemorrhage source control in our patient for several reasons. First, although the working diagnosis of varices was based on the patient’s history, we wanted to evaluate for other causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding since our patient had no history of endoscopy. Therefore, endoscopy had both a therapeutic and diagnostic value. Secondly, though TIPS may decrease pressure within the bleeding varix, only endoscopy permits direct hemostasis. Also, endoscopy also was preferred over TIPS because our patient was too unstable to move to the interventional radiology suite.16

Conclusion

Although life-threatening esophageal variceal hemorrhage is a rare manifestation of an uncommon disease, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient who has sarcoidosis and presents with gastrointestinal bleeding. Additionally, when caring for a patient with massive hematemesis without evidence of liver cirrhosis, other etiologies of portal hypertension and esophageal varices, such as sarcoidosis, should be considered.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disorder of unknown etiology and is characterized by the formation of granulomas throughout various organs in the body. The most common form is pulmonary sarcoidosis, which affects 90% of patients; the second most common form is oculocutaneous sarcoidosis;1 and the third most common form is hepatic sarcoidosis, which affects 63% to 90% of patients.2 Although the liver is frequently involved in all forms of sarcoidosis, only a fraction of patients present with clinically evident liver disease.1 Approximately 20% to 30% of patients have abnormalities on liver function tests, whereas only about 1% of patients show evidence of portal hypertension and cirrhosis.3 In fact, in the English literature, there were 35 reported cases of portal hypertension due to sarcoidosis between 1949 to 2001, of which 16 of the patients had no evidence of cirrhosis.4

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is usually made by a compilation of clinical signs and symptoms, imaging studies, and biopsies demonstrating noncaseating granulomas. This case report describes a patient who presented with portal hypertension and esophageal variceal bleeding secondary to sarcoidosis of the liver without cirrhotic changes.

Case

A 47-year-old woman presented to the ED via emergency medical services with a 1-hour history of hematemesis and melena. The patient stated that she felt fatigued, nauseated, and light-headed, but had no pain or focal weakness. Her medical history was significant for pulmonary and renal sarcoidosis. She underwent a liver biopsy 1 week prior to presentation, with a 6-day hospitalization period, due to new ascites found on examination.

The patient’s vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure (BP), 72/56 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 133 beats/min, respiratory rate, 24 breaths/min; and temperature, 97.0oF. Oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. Physical examination revealed an alert and oriented middle-aged woman in extremis who was vomiting dark-colored blood. The cardiac and pulmonary examination revealed no extraneous sounds; the abdominal examination showed ascites with a liver edge palpable 4 cm beneath the right costal margin. The patient had no scleral icterus, palmar erythema, spider angiomata, fetor hepaticus, caput medusa, cutaneous ecchymoses, or any other stigmata of cirrhosis.

Two large-bore peripheral intravenous (IV) catheters were placed and a massive blood transfusion protocol was initiated. Packed red blood cells (PRBCs) from the resuscitation-area refrigerator were infused immediately via a pressurized fluid warmer.

After consultation with gastroenterology and general surgery services, the patient was given 1 g ceftriaxone IV, 1 g tranexamic acid IV, 20 mcg desmopressin IV, 50 mcg octreotide IV, 40 mg pantoprazole IV, 8 mg ondansetron IV, 4 g calcium gluconate IV, and 100 mg hydrocortisone IV.

Throughout the patient’s first 10 minutes in the ED, she remained persistently hypotensive and continued to vomit. Since the patient’s sensorium was intact, the team quickly discussed goals of care with her. The patient’s wishes were for maximal life-sustaining therapy, including endotracheal intubation and chest compressions, if necessary.

After this discussion, the patient was given IV etomidate and rocuronium and was intubated using video-assisted laryngoscopy. Following intubation, she was sedated with an infusion of fentanyl and underwent orogastric tube placement to aspirate stomach contents. A total of 2.5 L of frank blood were drained from the patient’s stomach.

A size 9 French single lumen left-femoral central venous catheter also was placed, through which additional blood products were infused. The patient received a total of 28 U PRBCs, fresh frozen plasma, and platelets over a 3-hour period. During transfusion, the patient’s vital signs improved to a systolic BP ranging between 110 to 120 mm Hg and an HR ranging between 90 to 110 beats/min; she did not experience any further hypotensive episodes throughout her stay in the ED.

Laboratory studies were significant for metabolic acidosis, hyperkalemia, acute on chronic anemia, leukocytosis, and acute on chronic renal failure. Synthetic function of the liver and transaminases appeared normal (Table).

The patient’s hyperkalemia was treated with 1 g calcium chloride IV, 50 g dextrose IV, and 10 U regular insulin IV. A portable chest radiograph showed an appropriately positioned endotracheal tube, and an electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia without signs of hyperkalemia. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis from the patient’s recent hospitalization, 1 week prior to presentation, showed hepatomegaly, liver granulomas, ascites, and periportal lymphadenopathy (Figure 1).

A review of the patient’s recent liver biopsy and ascitic fluid analysis revealed noncaseating granulomas compressing the hepatic sinusoids, and a serum ascites albumin gradient greater than 1.1 g/dL, implying portal hypertension without cirrhosis. The surgical team attempted to place a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube, but the device could not be positioned properly due to the patient’s narrowed esophagus.

The ED nurses cleaned the patient, preserving her dignity; thereafter the patient’s adult children visited with her briefly before she was taken for an upper endoscopy, which was performed in the ED. The endoscopy revealed actively hemorrhaging esophageal varices at the gastroesophageal junction (Figure 2). The varices were treated with endoscopic ligation; the gastroenterologist placed a total of 11 bands, resulting in cessation of bleeding.

After the endoscopy, the patient was admitted to the medical intensive care unit (ICU). Approximately 1.5 hours after arriving at the ICU, she developed renewed hematemesis. Despite efforts to control bleeding and provide hemodynamic support, the patient died 1 hour later.

Discussion

Etiology

Esophageal variceal hemorrhage is caused by pressure elevation in the portal venous system, leading to engorged esophageal veins that can bleed spontaneously. Approximately 90% of portal hypertension is due to liver cirrhosis.5 The remaining 10% of cases are primarily vascular in etiology, with endothelial dysfunction and thrombosis leading to increased portal resistance. Noncirrhotic causes of portal hypertension include malignancy, congenital diseases, viral hepatitides, vascular thromboses or fistulae, constrictive pericarditis, fatty liver of pregnancy, drugs, radiation injury, and infiltrative diseases.5

Sarcoidosis may cause noncaseating granulomas to form in the liver, leading to portal hypertension and fatal exsanguination from esophageal variceal hemorrhage. Although the lesions of sarcoidosis classically form in the lungs, any organ system may be affected.6,7 Frank cirrhosis of the liver occurs in only 1% of sarcoidosis patients; however, radiographic involvement of the liver is seen in 5% to 15% of patients.8

There are several mechanisms which may be responsible for portal hypertension in patients with sarcoidosis, including granulomas causing mass effect on the hepatic sinusoids; arteriovenous shunts within the granuloma; granulomatous phlebitis within the sinusoids; or compressive periportal lymphadenopathy.9 Regardless of the mechanism, a review of the literature demonstrates an association between sarcoidosis and symptomatic portal hypertension.2,4,10,11Although our patient ultimately died, early initiation of massive blood transfusion protocol, airway protection, attention to electrolytes, and endoscopic control of the hemorrhage source provided the best chance for survival.

Medical Therapy

The first priority in managing and treating esophageal varices is to secure the patient’s airways to prevent aspiration. Two large bore IV lines should be placed to permit rapid infusion of crystalloid fluids or blood products. Initiating antibiotics, specifically IV ceftriaxone, to patients with variceal bleeding is a class I recommendation, as this is the only intervention shown to increase patient survival.12 Although proton pump inhibitors (PPI) and somatostatin analogues (typically octreotide) are frequently given, they are both class II recommendations because there is limited evidence supporting the benefit of their use.12 However, current guidelines recommend treating patients for variceal bleeding with an initial bolus of a PPI, followed by a continuous infusion of PPI for 72 hours. As previously noted, multiple studies, have failed to show any decrease in mortality associated with this treatment.12

Other agents that are used to treat variceal bleeding include octreotide and vasopressin. Octreotide, a somatostatin analog, is generally given as an initial IV bolus followed by continuous infusion, and has been shown to decrease transfusion requirements without mortality benefit.12 Vasopressin is generally given to critically ill patients, and is considered a third-line treatment for variceal bleeding.

Since our patient had a history of chronic kidney disease, desmopressin was empirically administered in the event platelet dysfunction was a contributing factor to bleeding.13 The absence of cirrhosis was significant because our patient was unlikely to have a bleeding diathesis caused by coagulation factor deficiency. Therefore, the goal transfusion ratio of blood products should be balanced, similar to that in traumatic exsanguination, rather than favoring an increased ratio of plasma to other blood products. Similarly, tranexamic acid was administered because insufficient tamponade rather than coagulopathy was the presumed cause of sustained hemorrhage.

An additional complicating factor in our patient’s care was the potential effect of the massive transfusion on electrolytes. Packed RBCs have a pH of approximately 6.8 and may carry up to 25 mmol/L of potassium, which may have exacerbated our patient’s underlying hyperkalemia.14 Rapid blood transfusion also places patients at risk for acute hypocalcemia secondary to citrate toxicity; this did not occur in our patient in part because the metabolic function of her liver was preserved and citrate could be broken down in the hepatocyte Krebs cycle.15 Calcium therapy doubled as treatment for the hyperkalemia and as prophylaxis against further hypocalcemia. No dysrhythmias were observed.

Surgical Intervention

Emergency physicians should consult with gastroenterology services so that an endoscopy can be performed as soon as possible to evaluate for and control bleeding. When an endoscopy cannot be performed rapidly, there are multiple balloon tamponade devices available that can be used to temporize the bleeding, such as the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube.12

Although balloon tamponade devices are typically reserved for the last line of therapy, endoscopy rather than transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) was the preferred method of hemorrhage source control in our patient for several reasons. First, although the working diagnosis of varices was based on the patient’s history, we wanted to evaluate for other causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding since our patient had no history of endoscopy. Therefore, endoscopy had both a therapeutic and diagnostic value. Secondly, though TIPS may decrease pressure within the bleeding varix, only endoscopy permits direct hemostasis. Also, endoscopy also was preferred over TIPS because our patient was too unstable to move to the interventional radiology suite.16

Conclusion

Although life-threatening esophageal variceal hemorrhage is a rare manifestation of an uncommon disease, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient who has sarcoidosis and presents with gastrointestinal bleeding. Additionally, when caring for a patient with massive hematemesis without evidence of liver cirrhosis, other etiologies of portal hypertension and esophageal varices, such as sarcoidosis, should be considered.

1. Rao DA, Dellaripa PF. Extrapulmonary manifestations of sarcoidosis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39(2):277-297. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2013.02.007.

2. Mistilis SP, Green JR, Schiff L. Hepatic sarcoidosis with portal hypertension. Am J Med. 1964;36(3):470-475. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(64)90175-5.

3. Tekeste H, Latour F, Levitt RE. Portal hypertension complicating sarcoid liver disease: case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1984;79(5):389-396.

4. Ivonye C, Elhammali B, Henriques-Forsythe M, Bennett-Gittens R, Oderinde A. Disseminated sarcoidosis resulting in portal hypertension and gastrointestinal bleeding: a rare presentation. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26(8):508-509. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22891173. Accessed May 16, 2018.

5. Tetangco EP, Silva RG, Lerma EV. Portal hypertension: etiology, evaluation, and management. Dis Mon. 2016;62(12):411-426. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2016.08.001.

6. Valeyre D, Prasse A, Nunes H, Uzunhan Y, Brillet PY, Müller-Quernheim J. Sarcoidosis. Lancet. 2014;383(9923):1155-1167. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60680-7.

7. Al-Kofahi K, Korsten P, Ascoli C, et al. Management of extrapulmonary sarcoidosis: challenges and solutions. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:1623-1634. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S74476.

8. Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2153-2165. doi:10.1056/NEJMra071714.

9. Ebert EC, Kierson M, Hagspiel KD. Gastrointestinal and hepatic manifestations of sarcoidosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(12):3184-3192. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02202.x.

10. Fraimow W, Myerson RM. Portal hypertension and bleeding esophageal varices secondary to sarcoidosis of the liver. Am J Med. 1957;23(6):995-998.

11. Saito H, Ohmori M, Iwamuro M, et al. Hepatic and gastric involvement in a case of systemic sarcoidosis presenting with rupture of esophageal varices. Intern Med. 2018;56(19):2583-2588. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.8768-16.

12. DeLaney M, Greene CJ. Emergency Department evaluation and management of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Emerg Med Pract. 2015;17(4):1-18; quiz 19.

13. Ozgönenel B, Rajpurkar M, Lusher JM. How do you treat bleeding disorders with desmopressin? Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(977):159-163. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2006.052118.

14. Sümpelmann R, Schürholz T, Thorns E, Hausdörfer J. Acid-base, electrolyte and metabolite concentrations in packed red blood cells for major transfusion in infants. Paediatr Anaesth. 2001;11(2):169-173. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9592.2001.00637.x.

15. Monchi M. Citrate pathophysiology and metabolism. Transfus Apher Sci. 2018;56(1):28-30. doi:10.1016/j.transci.2016.12.013.

16. Shah RP, Sze DY. Complications during transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;19(1):61-73. doi:10.1053/j.tvir.2016.01.007.

1. Rao DA, Dellaripa PF. Extrapulmonary manifestations of sarcoidosis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39(2):277-297. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2013.02.007.

2. Mistilis SP, Green JR, Schiff L. Hepatic sarcoidosis with portal hypertension. Am J Med. 1964;36(3):470-475. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(64)90175-5.

3. Tekeste H, Latour F, Levitt RE. Portal hypertension complicating sarcoid liver disease: case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1984;79(5):389-396.

4. Ivonye C, Elhammali B, Henriques-Forsythe M, Bennett-Gittens R, Oderinde A. Disseminated sarcoidosis resulting in portal hypertension and gastrointestinal bleeding: a rare presentation. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26(8):508-509. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22891173. Accessed May 16, 2018.

5. Tetangco EP, Silva RG, Lerma EV. Portal hypertension: etiology, evaluation, and management. Dis Mon. 2016;62(12):411-426. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2016.08.001.

6. Valeyre D, Prasse A, Nunes H, Uzunhan Y, Brillet PY, Müller-Quernheim J. Sarcoidosis. Lancet. 2014;383(9923):1155-1167. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60680-7.

7. Al-Kofahi K, Korsten P, Ascoli C, et al. Management of extrapulmonary sarcoidosis: challenges and solutions. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:1623-1634. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S74476.

8. Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2153-2165. doi:10.1056/NEJMra071714.

9. Ebert EC, Kierson M, Hagspiel KD. Gastrointestinal and hepatic manifestations of sarcoidosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(12):3184-3192. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02202.x.

10. Fraimow W, Myerson RM. Portal hypertension and bleeding esophageal varices secondary to sarcoidosis of the liver. Am J Med. 1957;23(6):995-998.

11. Saito H, Ohmori M, Iwamuro M, et al. Hepatic and gastric involvement in a case of systemic sarcoidosis presenting with rupture of esophageal varices. Intern Med. 2018;56(19):2583-2588. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.8768-16.

12. DeLaney M, Greene CJ. Emergency Department evaluation and management of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Emerg Med Pract. 2015;17(4):1-18; quiz 19.

13. Ozgönenel B, Rajpurkar M, Lusher JM. How do you treat bleeding disorders with desmopressin? Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(977):159-163. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2006.052118.

14. Sümpelmann R, Schürholz T, Thorns E, Hausdörfer J. Acid-base, electrolyte and metabolite concentrations in packed red blood cells for major transfusion in infants. Paediatr Anaesth. 2001;11(2):169-173. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9592.2001.00637.x.

15. Monchi M. Citrate pathophysiology and metabolism. Transfus Apher Sci. 2018;56(1):28-30. doi:10.1016/j.transci.2016.12.013.

16. Shah RP, Sze DY. Complications during transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;19(1):61-73. doi:10.1053/j.tvir.2016.01.007.

Trio of blood biomarkers elevated in children with LRTIs

TORONTO – While C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, and proadrenomedullin are associated with development of severe clinical outcomes in children with lower respiratory tract infections, proadrenomedullin is most strongly associated with disease severity, preliminary results from a prospective cohort study showed.

“Despite the fact that pneumonia guidelines call the site of care decision the most important decision in the management of pediatric pneumonia, no validated risk stratification tools exist for pediatric lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI),” lead study author Todd A. Florin, MD, said at the annual Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. “Biomarkers offer an objective means of classifying disease severity and clinical outcomes.”

PCT is a precursor of calcitonin secreted by the thyroid, lung, and intestine in response to bacterial infections. It also has been shown to be associated with adverse outcomes and mortality in adults, with results generally suggesting that it is a stronger predictor of severity than CRP. “There is limited data on the association of CRP or PCT with severe outcomes in children with LRTIs,” Dr. Florin noted. “One recent U.S. study of 532 children did demonstrate an association of elevated PCT with ICU admission, chest drainage, and hospital length of stay in children with [community-acquired pneumonia] CAP.”