User login

Essure sales to halt in U.S. by end of 2018

The Essure permanent birth control device will no longer be sold or distributed after Dec. 31, 2018, in the United States.

Bayer, the manufacturer of Essure, notified the Food and Drug Administration of its decision to halt U.S. sales of the device, Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, announced July 20 in a press release. Dr. Gottlieb added that the agency would continue its commitment to postmarketing review of Essure. “We expect Bayer to meet its postmarket obligations concerning this device.”

Since its approval, Essure is estimated to have been used by more than 750,000 patients worldwide, the FDA release stated. The device has been associated with serious risks, including persistent pain, perforation of the uterus and fallopian tubes, and migration of the coils into the pelvis or abdomen.

“In April, when the FDA became aware that many patients were not being adequately counseled, we required a restriction, which limits the sale and distribution of the device to only health care providers and facilities that provide information to patients about the risks and benefits of this device and gives patients the opportunity to sign an acknowledgment that they fully understood these potential risks before having the device implanted. Since the FDA ordered Bayer to conduct the postmarket study and then to add a boxed warning and a Patient Decision Checklist to the labeling, there has been an approximate 70% decline in sales of Essure in the United States,” Dr. Gottlieb said in the FDA press release. The company stated its decision to halt sales and distribution of the device was because of commercial reasons.

“Numerous adverse events ... were reported to the FDA, including a significant collection of recent reports that have mentioned issues involving surgery to remove the device. We’re continuing our evaluation of these reports to better understand reasons for the device removal. The agency is committed to continuing to provide updates on our evaluation of this data as the information is collected and we develop new findings about the device.”

In September 2015, the FDA convened an expert panel to examine and follow up on complaints from Essure users that included abdominal pain, abnormal uterine bleeding, and device migration. In February 2016, the FDA ordered Bayer to conduct a postmarket (522) study to better evaluate the safety profile of the device when used in the real world. The following October, the agency issued the final guidance, “Labeling for Permanent Hysteroscopically Placed Tubal Implants Intended for Sterilization.” Soon thereafter, the FDA approved updated labeling for Essure that added a boxed warning and a Patient Decision Checklist.

In March 2018, the FDA reported a rise in new medical device reports submitted to the agency’s public database in 2017, with more than 90% of the reports involving potential device removal. The April restriction of sales and distribution was in response to concerns that not every patient was receiving adequate risk information.

“I want to stress that, even when Essure is no longer sold, the FDA will remain vigilant in protecting patients who’ve already had this device implanted. We’ll continue to monitor adverse events reported to our database, as well as other data sources. And we’ll communicate publicly on any new findings or concerns. The restriction on sale and distribution will remain in place. Regarding the postmarket 522 study, Bayer will continue to enroll new participants. Each study participant will be followed for a total of 3 years, and the company will continue to submit reports to the FDA on the study’s progress and results. Since Bayer will not be able to meet its expected enrollment numbers for this study that relied on enrolling patients who were newly implanted with Essure, we’ll be working with the company to best determine how to move forward to answer the critical questions we posed concerning certain patient complications that may be experienced by patients who have Essure,” Dr. Gottlieb stated.

He added that women who are using Essure successfully to prevent pregnancy should continue to do so, as “device removal has its own risks.”

The Essure permanent birth control device will no longer be sold or distributed after Dec. 31, 2018, in the United States.

Bayer, the manufacturer of Essure, notified the Food and Drug Administration of its decision to halt U.S. sales of the device, Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, announced July 20 in a press release. Dr. Gottlieb added that the agency would continue its commitment to postmarketing review of Essure. “We expect Bayer to meet its postmarket obligations concerning this device.”

Since its approval, Essure is estimated to have been used by more than 750,000 patients worldwide, the FDA release stated. The device has been associated with serious risks, including persistent pain, perforation of the uterus and fallopian tubes, and migration of the coils into the pelvis or abdomen.

“In April, when the FDA became aware that many patients were not being adequately counseled, we required a restriction, which limits the sale and distribution of the device to only health care providers and facilities that provide information to patients about the risks and benefits of this device and gives patients the opportunity to sign an acknowledgment that they fully understood these potential risks before having the device implanted. Since the FDA ordered Bayer to conduct the postmarket study and then to add a boxed warning and a Patient Decision Checklist to the labeling, there has been an approximate 70% decline in sales of Essure in the United States,” Dr. Gottlieb said in the FDA press release. The company stated its decision to halt sales and distribution of the device was because of commercial reasons.

“Numerous adverse events ... were reported to the FDA, including a significant collection of recent reports that have mentioned issues involving surgery to remove the device. We’re continuing our evaluation of these reports to better understand reasons for the device removal. The agency is committed to continuing to provide updates on our evaluation of this data as the information is collected and we develop new findings about the device.”

In September 2015, the FDA convened an expert panel to examine and follow up on complaints from Essure users that included abdominal pain, abnormal uterine bleeding, and device migration. In February 2016, the FDA ordered Bayer to conduct a postmarket (522) study to better evaluate the safety profile of the device when used in the real world. The following October, the agency issued the final guidance, “Labeling for Permanent Hysteroscopically Placed Tubal Implants Intended for Sterilization.” Soon thereafter, the FDA approved updated labeling for Essure that added a boxed warning and a Patient Decision Checklist.

In March 2018, the FDA reported a rise in new medical device reports submitted to the agency’s public database in 2017, with more than 90% of the reports involving potential device removal. The April restriction of sales and distribution was in response to concerns that not every patient was receiving adequate risk information.

“I want to stress that, even when Essure is no longer sold, the FDA will remain vigilant in protecting patients who’ve already had this device implanted. We’ll continue to monitor adverse events reported to our database, as well as other data sources. And we’ll communicate publicly on any new findings or concerns. The restriction on sale and distribution will remain in place. Regarding the postmarket 522 study, Bayer will continue to enroll new participants. Each study participant will be followed for a total of 3 years, and the company will continue to submit reports to the FDA on the study’s progress and results. Since Bayer will not be able to meet its expected enrollment numbers for this study that relied on enrolling patients who were newly implanted with Essure, we’ll be working with the company to best determine how to move forward to answer the critical questions we posed concerning certain patient complications that may be experienced by patients who have Essure,” Dr. Gottlieb stated.

He added that women who are using Essure successfully to prevent pregnancy should continue to do so, as “device removal has its own risks.”

The Essure permanent birth control device will no longer be sold or distributed after Dec. 31, 2018, in the United States.

Bayer, the manufacturer of Essure, notified the Food and Drug Administration of its decision to halt U.S. sales of the device, Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, announced July 20 in a press release. Dr. Gottlieb added that the agency would continue its commitment to postmarketing review of Essure. “We expect Bayer to meet its postmarket obligations concerning this device.”

Since its approval, Essure is estimated to have been used by more than 750,000 patients worldwide, the FDA release stated. The device has been associated with serious risks, including persistent pain, perforation of the uterus and fallopian tubes, and migration of the coils into the pelvis or abdomen.

“In April, when the FDA became aware that many patients were not being adequately counseled, we required a restriction, which limits the sale and distribution of the device to only health care providers and facilities that provide information to patients about the risks and benefits of this device and gives patients the opportunity to sign an acknowledgment that they fully understood these potential risks before having the device implanted. Since the FDA ordered Bayer to conduct the postmarket study and then to add a boxed warning and a Patient Decision Checklist to the labeling, there has been an approximate 70% decline in sales of Essure in the United States,” Dr. Gottlieb said in the FDA press release. The company stated its decision to halt sales and distribution of the device was because of commercial reasons.

“Numerous adverse events ... were reported to the FDA, including a significant collection of recent reports that have mentioned issues involving surgery to remove the device. We’re continuing our evaluation of these reports to better understand reasons for the device removal. The agency is committed to continuing to provide updates on our evaluation of this data as the information is collected and we develop new findings about the device.”

In September 2015, the FDA convened an expert panel to examine and follow up on complaints from Essure users that included abdominal pain, abnormal uterine bleeding, and device migration. In February 2016, the FDA ordered Bayer to conduct a postmarket (522) study to better evaluate the safety profile of the device when used in the real world. The following October, the agency issued the final guidance, “Labeling for Permanent Hysteroscopically Placed Tubal Implants Intended for Sterilization.” Soon thereafter, the FDA approved updated labeling for Essure that added a boxed warning and a Patient Decision Checklist.

In March 2018, the FDA reported a rise in new medical device reports submitted to the agency’s public database in 2017, with more than 90% of the reports involving potential device removal. The April restriction of sales and distribution was in response to concerns that not every patient was receiving adequate risk information.

“I want to stress that, even when Essure is no longer sold, the FDA will remain vigilant in protecting patients who’ve already had this device implanted. We’ll continue to monitor adverse events reported to our database, as well as other data sources. And we’ll communicate publicly on any new findings or concerns. The restriction on sale and distribution will remain in place. Regarding the postmarket 522 study, Bayer will continue to enroll new participants. Each study participant will be followed for a total of 3 years, and the company will continue to submit reports to the FDA on the study’s progress and results. Since Bayer will not be able to meet its expected enrollment numbers for this study that relied on enrolling patients who were newly implanted with Essure, we’ll be working with the company to best determine how to move forward to answer the critical questions we posed concerning certain patient complications that may be experienced by patients who have Essure,” Dr. Gottlieb stated.

He added that women who are using Essure successfully to prevent pregnancy should continue to do so, as “device removal has its own risks.”

Ibrutinib stacks up well on safety in pooled analysis

in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), according to findings from a pooled analysis.

Susan M. O’Brien, MD, of the University of California, Irvine, and her colleagues reported pooled data from four randomized, controlled trials that included a 756 patients treated with ibrutinib and 749 patients who received a comparator drug. Patients were treated for either CLL/SLL or MCL, and safety was assessed by comparing crude and exposure-adjusted incidence rates of reported adverse events (AEs).

The comparator drugs included intravenous ofatumumab, oral chlorambucil, intravenous bendamustine plus rituximab, and intravenous temsirolimus.

While adverse event data have been published for each study analyzed, the researchers noted that the pooled analysis allows for an “in-depth assessment of the frequency and severity of both common AEs as well as additional AEs of clinical interest.”

Ibrutinib-treated patients had low rates of treatment discontinuation, compared with comparator-treatment patients (27% vs. 85%), the researchers reported in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia. Most discontinuations were caused by disease progression.

In terms of AEs, the types of events reported were similar among the drugs, with the three most common being infections, gastrointestinal disorders, and general disorders/administration-site conditions.

Diarrhea, muscle spasms, and arthralgia were reported more often among ibrutinib-treated patients. The prevalence of the most common all-grade AEs generally decreased over time with ibrutinib, peaking in the first 3 months of treatment. For serious AEs, only atrial fibrillation was higher with ibrutinib than comparator drugs when adjusted for exposure.

SOURCE: O’Brien SM et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 Jun 27. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2018.06.016.

in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), according to findings from a pooled analysis.

Susan M. O’Brien, MD, of the University of California, Irvine, and her colleagues reported pooled data from four randomized, controlled trials that included a 756 patients treated with ibrutinib and 749 patients who received a comparator drug. Patients were treated for either CLL/SLL or MCL, and safety was assessed by comparing crude and exposure-adjusted incidence rates of reported adverse events (AEs).

The comparator drugs included intravenous ofatumumab, oral chlorambucil, intravenous bendamustine plus rituximab, and intravenous temsirolimus.

While adverse event data have been published for each study analyzed, the researchers noted that the pooled analysis allows for an “in-depth assessment of the frequency and severity of both common AEs as well as additional AEs of clinical interest.”

Ibrutinib-treated patients had low rates of treatment discontinuation, compared with comparator-treatment patients (27% vs. 85%), the researchers reported in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia. Most discontinuations were caused by disease progression.

In terms of AEs, the types of events reported were similar among the drugs, with the three most common being infections, gastrointestinal disorders, and general disorders/administration-site conditions.

Diarrhea, muscle spasms, and arthralgia were reported more often among ibrutinib-treated patients. The prevalence of the most common all-grade AEs generally decreased over time with ibrutinib, peaking in the first 3 months of treatment. For serious AEs, only atrial fibrillation was higher with ibrutinib than comparator drugs when adjusted for exposure.

SOURCE: O’Brien SM et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 Jun 27. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2018.06.016.

in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), according to findings from a pooled analysis.

Susan M. O’Brien, MD, of the University of California, Irvine, and her colleagues reported pooled data from four randomized, controlled trials that included a 756 patients treated with ibrutinib and 749 patients who received a comparator drug. Patients were treated for either CLL/SLL or MCL, and safety was assessed by comparing crude and exposure-adjusted incidence rates of reported adverse events (AEs).

The comparator drugs included intravenous ofatumumab, oral chlorambucil, intravenous bendamustine plus rituximab, and intravenous temsirolimus.

While adverse event data have been published for each study analyzed, the researchers noted that the pooled analysis allows for an “in-depth assessment of the frequency and severity of both common AEs as well as additional AEs of clinical interest.”

Ibrutinib-treated patients had low rates of treatment discontinuation, compared with comparator-treatment patients (27% vs. 85%), the researchers reported in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia. Most discontinuations were caused by disease progression.

In terms of AEs, the types of events reported were similar among the drugs, with the three most common being infections, gastrointestinal disorders, and general disorders/administration-site conditions.

Diarrhea, muscle spasms, and arthralgia were reported more often among ibrutinib-treated patients. The prevalence of the most common all-grade AEs generally decreased over time with ibrutinib, peaking in the first 3 months of treatment. For serious AEs, only atrial fibrillation was higher with ibrutinib than comparator drugs when adjusted for exposure.

SOURCE: O’Brien SM et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 Jun 27. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2018.06.016.

FROM CLINICAL LYMPHOMA, MYELOMA & LEUKEMIA

The Aberrant Anterior Tibial Artery and its Surgical Risk

ABSTRACT

Vascular injury to the popliteal artery during knee surgery is uncommon, but it has significant consequences not only for the patient but also to the surgeon since it poses the threat of malpractice litigation. The vascular anatomy of the lower extremity is variable especially when it involves both the popliteal artery and its branches. An aberrant vascular course may increase the risk of iatrogenic vascular injury during surgery. Careful preoperative planning with advanced imaging can decrease the risk of a devastating vascular injury.

Continue to: Most non-traumatic injuries...

Most non-traumatic injuries to the popliteal artery are iatrogenic and may occur during total knee replacement,1-8 high tibial osteotomy,2,3,5-7 anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction,2,6 posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction,2,6,9,10 and arthroscopic meniscectomy.2,6,9 Despite the rare occurrence of complications involving the popliteal artery during such procedures, results of vessel injuries can be devastating and may also lead to malpractice litigation. Anatomic variations of the distal popliteal artery and its significance in surgery have been well documented in the literature.2-6,8,11 However, due to lack of awareness, this issue is often unintentionally disregarded. We present the case of an aberrant anterior tibial artery that was found during the review of a magnetic resonance imaging study. The patient was provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

CASE

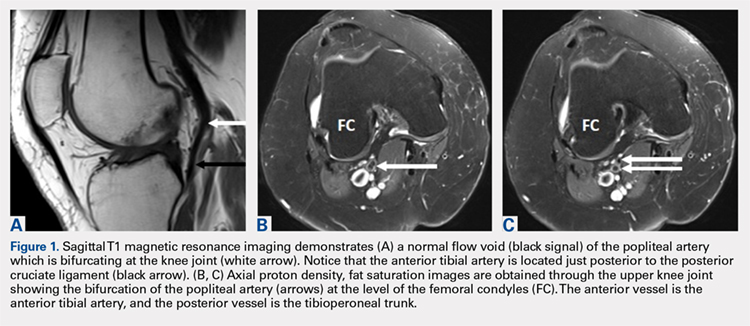

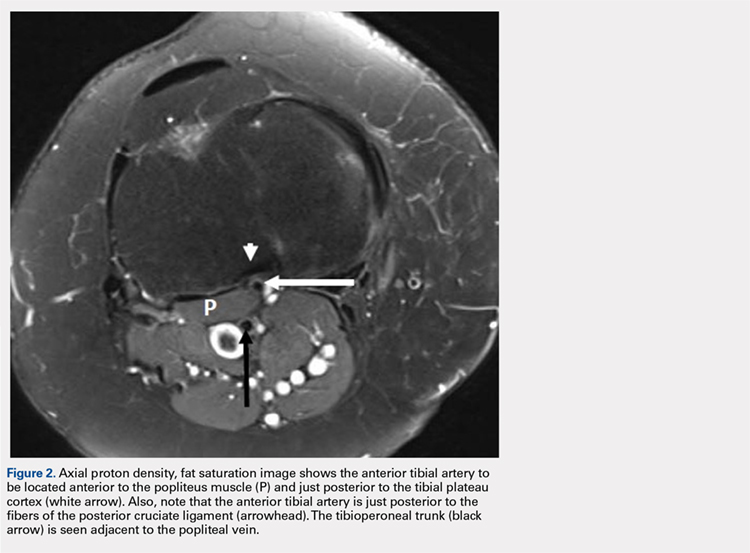

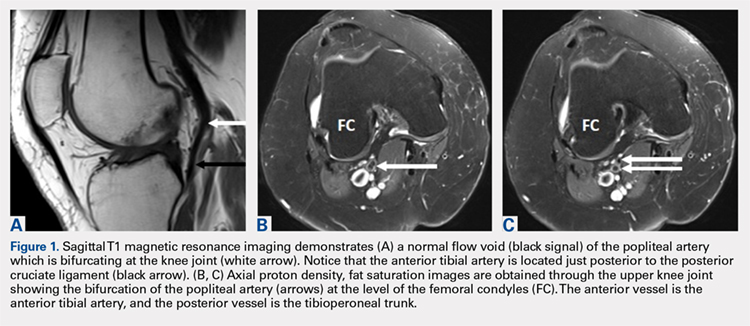

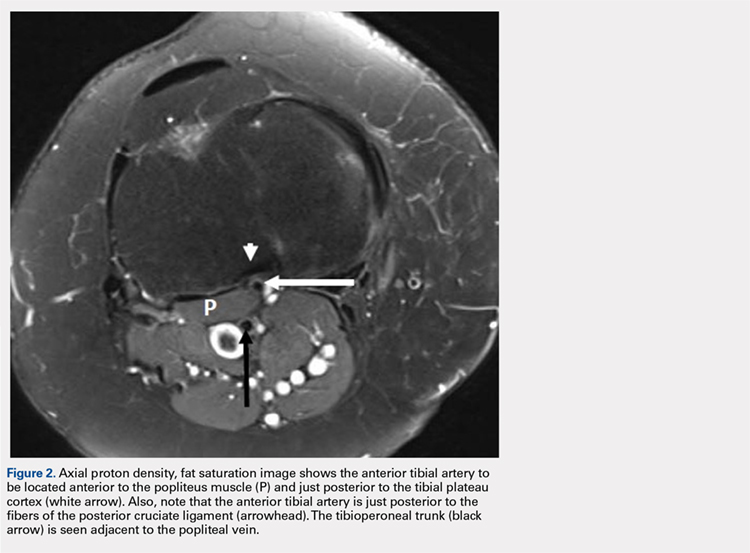

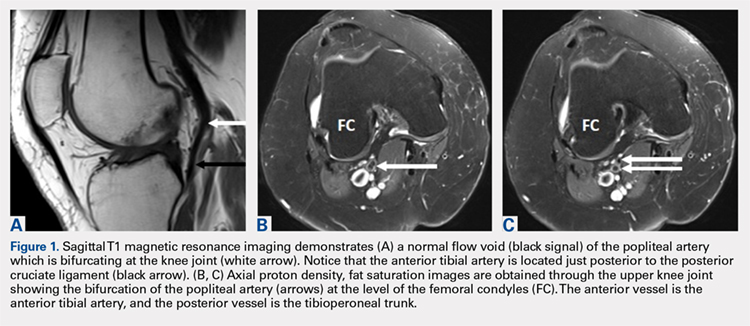

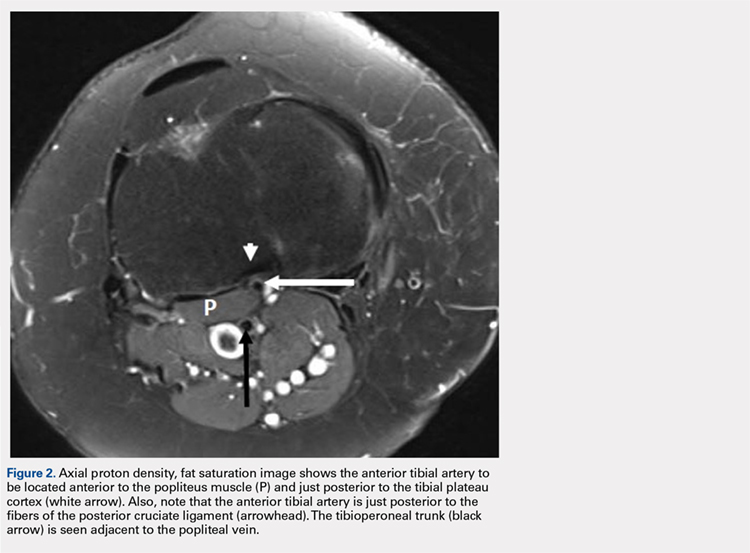

A 61-year-old woman presented with a history of right knee pain from osteoarthritis that had rapidly progressed over 1 week secondary to a fall. The patient had no history of previous knee surgery. After careful evaluation of her right knee pain, treatment options were discussed. The patient agreed to proceed with total knee arthroplasty (TKA). During preoperative planning, the patient’s previous magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was reviewed. The MRI study revealed an aberrant anterior tibial artery. The popliteal artery bifurcated at the level of the knee joint (Figures 1A-1C). After the bifurcation, the anterior tibial artery coursed anteriorly to the tibioperoneal trunk. The anterior tibial artery is seen just anterior to the popliteus muscle and just posterior to the tibial plateau cortex (Figure 2). Intraoperatively, an oscillating saw was utilized for the tibial cut. Care was taken not to penetrate the posterior cortex. An osteotome was used to elevate the tibial cut and hinge it open, and with a small mallet, finish the tibial cut. The patient had a successful TKA without complication.

DISCUSSION

Emerging from the adductor hiatus (Hunter’s canal), the normal course of the popliteal artery is a position slightly lateral in the intercondylar fossa. It courses obliquely and posteriorly to the popliteus then bifurcates into the anterior tibial artery and the tibioperoneal trunk at the inferior border of the popliteus. The tibioperoneal trunk bifurcates into both the posterior tibial artery and the peroneal artery at the proximal tibia well below the knee joint.

There are many reported cases of popliteal artery variations.2,3,6,7,9,11-13 Variations in the popliteal artery are consequences of persistent embryonic vessels from primitive segments of the artery or abnormal fusions among them.14 According to Kim and colleagues,11 variations can be classified by the modified Lippert’s system. This system has 3 categories with 3 subtypes (Table). Variations are not uncommon and occur in 7.4% to 12% of the population.2,4,5,7,13

Table. Modified Lippert’s System11

Category (Subtype) |

|

I | Normal level of popliteal arterial branching |

IA | Usual pattern |

IB | Trifurcation- No true tibioperoneal trunk |

IC | Anterior tibioperoneal trunk- Posterior tibial artery is first branch |

II | High division of popliteal artery |

IIA | Anterior tibial artery arises at or above the knee joint |

IIB | Posterior tibial artery arises at or above the knee joint |

IIC | Peroneal artery arises at or above the knee joint |

III | Hypoplastic or aplastic branching with altered distal supply |

IIIA | Hypoplastic-aplastic posterior tibial artery |

IIIB | Hypoplastic-aplastic anterior tibial artery |

IIIC | Hypoplastic-aplastic posterior and anterior tibial artery |

Of these variations, type IIA, a high bifurcation of the anterior tibial artery, arising at or above the knee joint from the popliteal artery is the most significant. Forty-two percent of these vessels course anterior to the popliteus and make direct contact with the cortex of the posterior tibia.4 It is also the most frequent variant type reported in 1.2% to 6% of the population.3,7,11-13

Continue to: Injury to the popliteal artery...

Injury to the popliteal artery during an orthopedic procedure is believed to be under reported6 but is considered a rare complication. The incidence of popliteal artery injury in TKA is thought to be 0.03% to 0.2%.1,2,5,7,8 Vessel injury in both high tibial osteotomy and arthroscopic surgeries (lateral meniscal repair) have also been reported.5,6,8,10 Despite the rare occurrence of this complication, it may have devastating outcomes. The injury can be repaired with vascular grafting depending on its severity; however, it could also lead to compartment syndrome, loss of function, chronic ulcers, and necrosis of the affected limb resulting in below the knee amputation. The current consensus is that the popliteal artery moves posteriorly away from the tibia when the knee is in 90° of flexion,5 which is the standard position for many orthopedic knee surgeries. This position limits the risk of injuring the vessel. However, Metzdorf and colleagues,4 Smith and colleagues,6 and Zaidi and colleagues8 suggested that the vessel not be displaced posteriorly with flexion. These studies reported that the behavior of the popliteal artery varied among individuals since in some cases it had moved closer to the tibia in flexion when compared with extension.

Regardless of the behavior of the artery, it is protected by the popliteus muscle in most orthopedic knee surgeries since the majority course posterior to the muscle. However, in cases of Lippert’s type IIA variation, it not only loses protection as it courses beneath the popliteus but also is extremely vulnerable from the close relationship to the posterior tibial cortex. Klecker and colleagues2 described the aberrant artery locations related to common orthopedic procedures, which demonstrated its close proximity to various surgical plane levels. The position of the aberrant artery is approximately 1 to 1.5 cm distal to the posterior tibial joint line, just posterior to the posterior capsule, and close to the posterior cruciate ligament insertion site where the transverse tibial cut is made during TKA. This location also corresponds to the position for an inlay block and the tibial tunnel for posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A transverse cut for a high tibial osteotomy is approximately 1.5 to 2.5 cm distal to the posterior tibial joint line; the aberrant artery appeared directly posterior to the tibial cortex. These relationships were equivalent findings in this case. Such relationships of the aberrant anterior tibial artery to both the posterior tibial cortex and the posterior capsule increase the risk of vessel (anterior tibial artery) injury intraoperatively. The risk further increases in a revision of total knee replacement. This is secondary to limited flexibility of the vessel from scar formation which requires a more distal incision.1,4

CONCLUSION

Vascular injuries in knee surgeries are rare and often overlooked. Despite their low occurrence rate, outcomes of these injuries have grave consequences not only regarding medical but also legal matters. Variations in the popliteal artery are not uncommon and could potentially contribute to risks of vessel injury. Of these variations, the high originating anterior tibial artery poses a special risk. However, due to the low occurrence rate of these injuries, screening the general population may not be cost-effective. Since many patients already have obtained necessary imaging (preferably MRI), a careful review of these images along with preoperative planning and special care during surgery is recommended to identify popliteal artery variants and avoid iatrogenic vascular injury.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.

- Abdel Karim MM, Anbar A, Keenan J. Position of the popliteal artery in revision total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(6):861-865. doi:10.1007/s00402-012-1479-6.

- Klecker RJ, Winalski CS, Aliabadi P, Minas T. The aberrant anterior tibial artery, magnetic resonance appearance, prevalence, and surgical implication. Am J Sports Medicine. 2008;36:720-727.

- Kropman RHJ, Kiela G, Moll FL, Vries JPM. Variations in anatomy of the popliteal artery and its side branches. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2011;45:536-540.

- Metzdorf A, Jakob RP, Petropoulos P, Middleton R. Arterial injury during revision total knee replacement. A case report. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1999;7:246-248.

- Shetty AA, Tindall AJ, Qureshi F, Divekar M, Fernando KWK. The Effect of knee flexion on the popliteal artery and its surgical significance. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:218-222.

- Smith PN, Gelinas J, Kennedy K, Thain L, Rorabeck CH, Bourne B. Popliteal vessels in knee surgery; a magnetic resonance imaging study. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1999;367:158-164

- Tindall AJ, Shetty AA, James KD, Middleton A, Fernando KWK. Prevalence and surgical significance of a high-origin anterior tibial artery. J Orthop Surg. 2006;14:13-16.

- Zaidi SHA, Cobb AG, Bentley G. Danger to the popliteal artery in high tibial osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:384-386.

- Keser S, Savranlar A, Bayar A, Ulukent SC, Ozer T, Tuncay I. Anatomic localization of the popliteal artery at the level of the knee joint: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:656-659.

- Makino A, Costa-Paz M, Aponte-Tinao L, Ayerza MA, Muscolo L. Popliteal artery laceration during arthroscopic posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(11):1396.

- Kim D, Orron DE, Skillman JJ. Surgical significance of popliteal arterial variants, a unified angiographic classification. Ann Surg. 1989;210:776-781.

- Day CP, Orme R. Popliteal artery branching patterns-an angiographic study. Clin Radiol. 2006;61:696-699.

- Kil SW, Jung GS. Anatomical variations of the popliteal artery and its tibial branches: Analysis in 1242 extremities. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;32:233-240.

- Senior HD. The development of the arteries of the human lower extremity. Am J Anat. 1919;25:55-94.

ABSTRACT

Vascular injury to the popliteal artery during knee surgery is uncommon, but it has significant consequences not only for the patient but also to the surgeon since it poses the threat of malpractice litigation. The vascular anatomy of the lower extremity is variable especially when it involves both the popliteal artery and its branches. An aberrant vascular course may increase the risk of iatrogenic vascular injury during surgery. Careful preoperative planning with advanced imaging can decrease the risk of a devastating vascular injury.

Continue to: Most non-traumatic injuries...

Most non-traumatic injuries to the popliteal artery are iatrogenic and may occur during total knee replacement,1-8 high tibial osteotomy,2,3,5-7 anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction,2,6 posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction,2,6,9,10 and arthroscopic meniscectomy.2,6,9 Despite the rare occurrence of complications involving the popliteal artery during such procedures, results of vessel injuries can be devastating and may also lead to malpractice litigation. Anatomic variations of the distal popliteal artery and its significance in surgery have been well documented in the literature.2-6,8,11 However, due to lack of awareness, this issue is often unintentionally disregarded. We present the case of an aberrant anterior tibial artery that was found during the review of a magnetic resonance imaging study. The patient was provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

CASE

A 61-year-old woman presented with a history of right knee pain from osteoarthritis that had rapidly progressed over 1 week secondary to a fall. The patient had no history of previous knee surgery. After careful evaluation of her right knee pain, treatment options were discussed. The patient agreed to proceed with total knee arthroplasty (TKA). During preoperative planning, the patient’s previous magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was reviewed. The MRI study revealed an aberrant anterior tibial artery. The popliteal artery bifurcated at the level of the knee joint (Figures 1A-1C). After the bifurcation, the anterior tibial artery coursed anteriorly to the tibioperoneal trunk. The anterior tibial artery is seen just anterior to the popliteus muscle and just posterior to the tibial plateau cortex (Figure 2). Intraoperatively, an oscillating saw was utilized for the tibial cut. Care was taken not to penetrate the posterior cortex. An osteotome was used to elevate the tibial cut and hinge it open, and with a small mallet, finish the tibial cut. The patient had a successful TKA without complication.

DISCUSSION

Emerging from the adductor hiatus (Hunter’s canal), the normal course of the popliteal artery is a position slightly lateral in the intercondylar fossa. It courses obliquely and posteriorly to the popliteus then bifurcates into the anterior tibial artery and the tibioperoneal trunk at the inferior border of the popliteus. The tibioperoneal trunk bifurcates into both the posterior tibial artery and the peroneal artery at the proximal tibia well below the knee joint.

There are many reported cases of popliteal artery variations.2,3,6,7,9,11-13 Variations in the popliteal artery are consequences of persistent embryonic vessels from primitive segments of the artery or abnormal fusions among them.14 According to Kim and colleagues,11 variations can be classified by the modified Lippert’s system. This system has 3 categories with 3 subtypes (Table). Variations are not uncommon and occur in 7.4% to 12% of the population.2,4,5,7,13

Table. Modified Lippert’s System11

Category (Subtype) |

|

I | Normal level of popliteal arterial branching |

IA | Usual pattern |

IB | Trifurcation- No true tibioperoneal trunk |

IC | Anterior tibioperoneal trunk- Posterior tibial artery is first branch |

II | High division of popliteal artery |

IIA | Anterior tibial artery arises at or above the knee joint |

IIB | Posterior tibial artery arises at or above the knee joint |

IIC | Peroneal artery arises at or above the knee joint |

III | Hypoplastic or aplastic branching with altered distal supply |

IIIA | Hypoplastic-aplastic posterior tibial artery |

IIIB | Hypoplastic-aplastic anterior tibial artery |

IIIC | Hypoplastic-aplastic posterior and anterior tibial artery |

Of these variations, type IIA, a high bifurcation of the anterior tibial artery, arising at or above the knee joint from the popliteal artery is the most significant. Forty-two percent of these vessels course anterior to the popliteus and make direct contact with the cortex of the posterior tibia.4 It is also the most frequent variant type reported in 1.2% to 6% of the population.3,7,11-13

Continue to: Injury to the popliteal artery...

Injury to the popliteal artery during an orthopedic procedure is believed to be under reported6 but is considered a rare complication. The incidence of popliteal artery injury in TKA is thought to be 0.03% to 0.2%.1,2,5,7,8 Vessel injury in both high tibial osteotomy and arthroscopic surgeries (lateral meniscal repair) have also been reported.5,6,8,10 Despite the rare occurrence of this complication, it may have devastating outcomes. The injury can be repaired with vascular grafting depending on its severity; however, it could also lead to compartment syndrome, loss of function, chronic ulcers, and necrosis of the affected limb resulting in below the knee amputation. The current consensus is that the popliteal artery moves posteriorly away from the tibia when the knee is in 90° of flexion,5 which is the standard position for many orthopedic knee surgeries. This position limits the risk of injuring the vessel. However, Metzdorf and colleagues,4 Smith and colleagues,6 and Zaidi and colleagues8 suggested that the vessel not be displaced posteriorly with flexion. These studies reported that the behavior of the popliteal artery varied among individuals since in some cases it had moved closer to the tibia in flexion when compared with extension.

Regardless of the behavior of the artery, it is protected by the popliteus muscle in most orthopedic knee surgeries since the majority course posterior to the muscle. However, in cases of Lippert’s type IIA variation, it not only loses protection as it courses beneath the popliteus but also is extremely vulnerable from the close relationship to the posterior tibial cortex. Klecker and colleagues2 described the aberrant artery locations related to common orthopedic procedures, which demonstrated its close proximity to various surgical plane levels. The position of the aberrant artery is approximately 1 to 1.5 cm distal to the posterior tibial joint line, just posterior to the posterior capsule, and close to the posterior cruciate ligament insertion site where the transverse tibial cut is made during TKA. This location also corresponds to the position for an inlay block and the tibial tunnel for posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A transverse cut for a high tibial osteotomy is approximately 1.5 to 2.5 cm distal to the posterior tibial joint line; the aberrant artery appeared directly posterior to the tibial cortex. These relationships were equivalent findings in this case. Such relationships of the aberrant anterior tibial artery to both the posterior tibial cortex and the posterior capsule increase the risk of vessel (anterior tibial artery) injury intraoperatively. The risk further increases in a revision of total knee replacement. This is secondary to limited flexibility of the vessel from scar formation which requires a more distal incision.1,4

CONCLUSION

Vascular injuries in knee surgeries are rare and often overlooked. Despite their low occurrence rate, outcomes of these injuries have grave consequences not only regarding medical but also legal matters. Variations in the popliteal artery are not uncommon and could potentially contribute to risks of vessel injury. Of these variations, the high originating anterior tibial artery poses a special risk. However, due to the low occurrence rate of these injuries, screening the general population may not be cost-effective. Since many patients already have obtained necessary imaging (preferably MRI), a careful review of these images along with preoperative planning and special care during surgery is recommended to identify popliteal artery variants and avoid iatrogenic vascular injury.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.

ABSTRACT

Vascular injury to the popliteal artery during knee surgery is uncommon, but it has significant consequences not only for the patient but also to the surgeon since it poses the threat of malpractice litigation. The vascular anatomy of the lower extremity is variable especially when it involves both the popliteal artery and its branches. An aberrant vascular course may increase the risk of iatrogenic vascular injury during surgery. Careful preoperative planning with advanced imaging can decrease the risk of a devastating vascular injury.

Continue to: Most non-traumatic injuries...

Most non-traumatic injuries to the popliteal artery are iatrogenic and may occur during total knee replacement,1-8 high tibial osteotomy,2,3,5-7 anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction,2,6 posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction,2,6,9,10 and arthroscopic meniscectomy.2,6,9 Despite the rare occurrence of complications involving the popliteal artery during such procedures, results of vessel injuries can be devastating and may also lead to malpractice litigation. Anatomic variations of the distal popliteal artery and its significance in surgery have been well documented in the literature.2-6,8,11 However, due to lack of awareness, this issue is often unintentionally disregarded. We present the case of an aberrant anterior tibial artery that was found during the review of a magnetic resonance imaging study. The patient was provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

CASE

A 61-year-old woman presented with a history of right knee pain from osteoarthritis that had rapidly progressed over 1 week secondary to a fall. The patient had no history of previous knee surgery. After careful evaluation of her right knee pain, treatment options were discussed. The patient agreed to proceed with total knee arthroplasty (TKA). During preoperative planning, the patient’s previous magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was reviewed. The MRI study revealed an aberrant anterior tibial artery. The popliteal artery bifurcated at the level of the knee joint (Figures 1A-1C). After the bifurcation, the anterior tibial artery coursed anteriorly to the tibioperoneal trunk. The anterior tibial artery is seen just anterior to the popliteus muscle and just posterior to the tibial plateau cortex (Figure 2). Intraoperatively, an oscillating saw was utilized for the tibial cut. Care was taken not to penetrate the posterior cortex. An osteotome was used to elevate the tibial cut and hinge it open, and with a small mallet, finish the tibial cut. The patient had a successful TKA without complication.

DISCUSSION

Emerging from the adductor hiatus (Hunter’s canal), the normal course of the popliteal artery is a position slightly lateral in the intercondylar fossa. It courses obliquely and posteriorly to the popliteus then bifurcates into the anterior tibial artery and the tibioperoneal trunk at the inferior border of the popliteus. The tibioperoneal trunk bifurcates into both the posterior tibial artery and the peroneal artery at the proximal tibia well below the knee joint.

There are many reported cases of popliteal artery variations.2,3,6,7,9,11-13 Variations in the popliteal artery are consequences of persistent embryonic vessels from primitive segments of the artery or abnormal fusions among them.14 According to Kim and colleagues,11 variations can be classified by the modified Lippert’s system. This system has 3 categories with 3 subtypes (Table). Variations are not uncommon and occur in 7.4% to 12% of the population.2,4,5,7,13

Table. Modified Lippert’s System11

Category (Subtype) |

|

I | Normal level of popliteal arterial branching |

IA | Usual pattern |

IB | Trifurcation- No true tibioperoneal trunk |

IC | Anterior tibioperoneal trunk- Posterior tibial artery is first branch |

II | High division of popliteal artery |

IIA | Anterior tibial artery arises at or above the knee joint |

IIB | Posterior tibial artery arises at or above the knee joint |

IIC | Peroneal artery arises at or above the knee joint |

III | Hypoplastic or aplastic branching with altered distal supply |

IIIA | Hypoplastic-aplastic posterior tibial artery |

IIIB | Hypoplastic-aplastic anterior tibial artery |

IIIC | Hypoplastic-aplastic posterior and anterior tibial artery |

Of these variations, type IIA, a high bifurcation of the anterior tibial artery, arising at or above the knee joint from the popliteal artery is the most significant. Forty-two percent of these vessels course anterior to the popliteus and make direct contact with the cortex of the posterior tibia.4 It is also the most frequent variant type reported in 1.2% to 6% of the population.3,7,11-13

Continue to: Injury to the popliteal artery...

Injury to the popliteal artery during an orthopedic procedure is believed to be under reported6 but is considered a rare complication. The incidence of popliteal artery injury in TKA is thought to be 0.03% to 0.2%.1,2,5,7,8 Vessel injury in both high tibial osteotomy and arthroscopic surgeries (lateral meniscal repair) have also been reported.5,6,8,10 Despite the rare occurrence of this complication, it may have devastating outcomes. The injury can be repaired with vascular grafting depending on its severity; however, it could also lead to compartment syndrome, loss of function, chronic ulcers, and necrosis of the affected limb resulting in below the knee amputation. The current consensus is that the popliteal artery moves posteriorly away from the tibia when the knee is in 90° of flexion,5 which is the standard position for many orthopedic knee surgeries. This position limits the risk of injuring the vessel. However, Metzdorf and colleagues,4 Smith and colleagues,6 and Zaidi and colleagues8 suggested that the vessel not be displaced posteriorly with flexion. These studies reported that the behavior of the popliteal artery varied among individuals since in some cases it had moved closer to the tibia in flexion when compared with extension.

Regardless of the behavior of the artery, it is protected by the popliteus muscle in most orthopedic knee surgeries since the majority course posterior to the muscle. However, in cases of Lippert’s type IIA variation, it not only loses protection as it courses beneath the popliteus but also is extremely vulnerable from the close relationship to the posterior tibial cortex. Klecker and colleagues2 described the aberrant artery locations related to common orthopedic procedures, which demonstrated its close proximity to various surgical plane levels. The position of the aberrant artery is approximately 1 to 1.5 cm distal to the posterior tibial joint line, just posterior to the posterior capsule, and close to the posterior cruciate ligament insertion site where the transverse tibial cut is made during TKA. This location also corresponds to the position for an inlay block and the tibial tunnel for posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A transverse cut for a high tibial osteotomy is approximately 1.5 to 2.5 cm distal to the posterior tibial joint line; the aberrant artery appeared directly posterior to the tibial cortex. These relationships were equivalent findings in this case. Such relationships of the aberrant anterior tibial artery to both the posterior tibial cortex and the posterior capsule increase the risk of vessel (anterior tibial artery) injury intraoperatively. The risk further increases in a revision of total knee replacement. This is secondary to limited flexibility of the vessel from scar formation which requires a more distal incision.1,4

CONCLUSION

Vascular injuries in knee surgeries are rare and often overlooked. Despite their low occurrence rate, outcomes of these injuries have grave consequences not only regarding medical but also legal matters. Variations in the popliteal artery are not uncommon and could potentially contribute to risks of vessel injury. Of these variations, the high originating anterior tibial artery poses a special risk. However, due to the low occurrence rate of these injuries, screening the general population may not be cost-effective. Since many patients already have obtained necessary imaging (preferably MRI), a careful review of these images along with preoperative planning and special care during surgery is recommended to identify popliteal artery variants and avoid iatrogenic vascular injury.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.

- Abdel Karim MM, Anbar A, Keenan J. Position of the popliteal artery in revision total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(6):861-865. doi:10.1007/s00402-012-1479-6.

- Klecker RJ, Winalski CS, Aliabadi P, Minas T. The aberrant anterior tibial artery, magnetic resonance appearance, prevalence, and surgical implication. Am J Sports Medicine. 2008;36:720-727.

- Kropman RHJ, Kiela G, Moll FL, Vries JPM. Variations in anatomy of the popliteal artery and its side branches. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2011;45:536-540.

- Metzdorf A, Jakob RP, Petropoulos P, Middleton R. Arterial injury during revision total knee replacement. A case report. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1999;7:246-248.

- Shetty AA, Tindall AJ, Qureshi F, Divekar M, Fernando KWK. The Effect of knee flexion on the popliteal artery and its surgical significance. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:218-222.

- Smith PN, Gelinas J, Kennedy K, Thain L, Rorabeck CH, Bourne B. Popliteal vessels in knee surgery; a magnetic resonance imaging study. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1999;367:158-164

- Tindall AJ, Shetty AA, James KD, Middleton A, Fernando KWK. Prevalence and surgical significance of a high-origin anterior tibial artery. J Orthop Surg. 2006;14:13-16.

- Zaidi SHA, Cobb AG, Bentley G. Danger to the popliteal artery in high tibial osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:384-386.

- Keser S, Savranlar A, Bayar A, Ulukent SC, Ozer T, Tuncay I. Anatomic localization of the popliteal artery at the level of the knee joint: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:656-659.

- Makino A, Costa-Paz M, Aponte-Tinao L, Ayerza MA, Muscolo L. Popliteal artery laceration during arthroscopic posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(11):1396.

- Kim D, Orron DE, Skillman JJ. Surgical significance of popliteal arterial variants, a unified angiographic classification. Ann Surg. 1989;210:776-781.

- Day CP, Orme R. Popliteal artery branching patterns-an angiographic study. Clin Radiol. 2006;61:696-699.

- Kil SW, Jung GS. Anatomical variations of the popliteal artery and its tibial branches: Analysis in 1242 extremities. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;32:233-240.

- Senior HD. The development of the arteries of the human lower extremity. Am J Anat. 1919;25:55-94.

- Abdel Karim MM, Anbar A, Keenan J. Position of the popliteal artery in revision total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(6):861-865. doi:10.1007/s00402-012-1479-6.

- Klecker RJ, Winalski CS, Aliabadi P, Minas T. The aberrant anterior tibial artery, magnetic resonance appearance, prevalence, and surgical implication. Am J Sports Medicine. 2008;36:720-727.

- Kropman RHJ, Kiela G, Moll FL, Vries JPM. Variations in anatomy of the popliteal artery and its side branches. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2011;45:536-540.

- Metzdorf A, Jakob RP, Petropoulos P, Middleton R. Arterial injury during revision total knee replacement. A case report. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1999;7:246-248.

- Shetty AA, Tindall AJ, Qureshi F, Divekar M, Fernando KWK. The Effect of knee flexion on the popliteal artery and its surgical significance. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:218-222.

- Smith PN, Gelinas J, Kennedy K, Thain L, Rorabeck CH, Bourne B. Popliteal vessels in knee surgery; a magnetic resonance imaging study. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1999;367:158-164

- Tindall AJ, Shetty AA, James KD, Middleton A, Fernando KWK. Prevalence and surgical significance of a high-origin anterior tibial artery. J Orthop Surg. 2006;14:13-16.

- Zaidi SHA, Cobb AG, Bentley G. Danger to the popliteal artery in high tibial osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:384-386.

- Keser S, Savranlar A, Bayar A, Ulukent SC, Ozer T, Tuncay I. Anatomic localization of the popliteal artery at the level of the knee joint: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:656-659.

- Makino A, Costa-Paz M, Aponte-Tinao L, Ayerza MA, Muscolo L. Popliteal artery laceration during arthroscopic posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(11):1396.

- Kim D, Orron DE, Skillman JJ. Surgical significance of popliteal arterial variants, a unified angiographic classification. Ann Surg. 1989;210:776-781.

- Day CP, Orme R. Popliteal artery branching patterns-an angiographic study. Clin Radiol. 2006;61:696-699.

- Kil SW, Jung GS. Anatomical variations of the popliteal artery and its tibial branches: Analysis in 1242 extremities. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;32:233-240.

- Senior HD. The development of the arteries of the human lower extremity. Am J Anat. 1919;25:55-94.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Surgeon must understand and be aware of aberrant vascular anatomy around the knee.

- Careful evaluation of advance imaging for aberrant vascular anatomy is required in surgeries around the knee.

- When aberrant vascular anatomy is recognized, appropriate preoperative planning is required.

PARP inhibitors didn’t impair QOL as ovarian cancer maintenance therapy

Women with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer who received maintenance therapy with a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor had no significant decreases in health-related quality of life, outcomes data from two randomized clinical trials show.

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) analyses from the SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov-21 trial comparing olaparib (Lynparza) with placebo and the ENGOT-OV16/NOVA trial comparing niraparib (Zejula) with placebo as maintenance therapy in women with ongoing responses to their last platinum-based chemotherapy showed that neither agent had major detrimental effects on patient-reported outcomes, further supporting the progression-free survival benefits previously seen with each agent in its respective trials.

“These results show the significant benefit of maintenance olaparib to patients beyond the RECIST [Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors] definition of progression, the primary endpoint of SOLO2, and highlight the importance of including patient-centered outcomes in addition to HRQOL in trials of maintenance therapy, in line with the recommendations of the 5th Ovarian Cancer Consensus Conference,” wrote Michael Friedlander, MD, of the University of New South Wales Clinical School and Prince of Wales Hospital in Randwick, New South Wales, Australia, and his colleagues.

Similarly, Amit M. Oza, MD, of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, and his coinvestigators in the ENGOT-OV16/NOVA trial found that “niraparib has no significant negative effect on QOL in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. Combined with the evidence of increased progression-free survival with niraparib in the maintenance setting, these findings support the addition of niraparib as a component of standard of care.”

Both studies were published online in The Lancet Oncology: Friedlander M et al. Lancet Oncol 2018 Jul 16 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30343-7, and Oza AM et al. Lancet Oncol 2018 Jul 16 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30333-4.

SOLO2 QOL summary

In SOLO2, patients with a germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation and platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer that relapsed after at least two lines of chemotherapy were randomly assigned to receive either oral olaparib 300 mg twice daily (196 patients) or placebo (99 patients).

The prespecified primary HRQOL analysis looked at the change from baseline in the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Ovarian Cancer (FACT-O) Trial Outcome Index (TOI) score during the first 12 months of the study.

In addition, the investigators examined secondary planned QOL analyses, including duration of good quality of life, defined as time without significant symptoms of toxicity, or TWiST, and quality-adjusted progression-free survival (QAPFS).

The adjusted average mean change from baseline over the first 12 months in TOI was –2.90 with olaparib vs. –2.87 with placebo (nonsignificant).

In contrast, patients treated with olaparib had significantly better mean QAPFS (13.96 vs. 7.28 months) and TWiST (15.03 vs. 7.70 months) results.

“All these predefined endpoints support the benefit to patients of a prolongation of progression-free survival, which is the primary endpoint in maintenance trials in ovarian cancer, and should be routinely included in future trials,” wrote Dr. Friedlander and his associates.

ENGOT-OV16/NOVA QOL summary

Investigators for this trial enrolled patients into two independent cohorts based on germline BRCA mutations or lack thereof. In all, 138 patients were assigned to niraparib and 65 to placebo in the germline BRCA mutation cohort, and 234 to niraparib and 116 to placebo in the nonmutation cohort.

The current study assessed patient-reported outcomes in the intention-to-treat population using different validated instruments from those assessed in SOLO2: the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Ovarian Symptoms Index (FOSI) and European QOL five-dimension five-level questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L).

The outcomes were reported every 8 weeks for the first 14 treatment cycles and every 12 weeks thereafter.

The investigators looked at the effects of hematologic toxicities on QOL with disutility analyses (measuring the decrement on QOL of a particular symptom or complication) of the most common grade 3-4 adverse events (thrombocytopenia, anemia, and neutropenia) using a mixed model with covariates.

They found that overall QOL scores remained stable during treatment and the preprogression period among patients on niraparib in each cohort, and that there were no significant differences in preprogression EQ-5D-5L scores between niraparib- or placebo-treated patients in either cohort.

In addition, patient-reported lack of energy and pain, two of the most common baseline symptoms, either remained stable or improved during maintenance, although the proportion of patients reporting nausea increased at cycle 2. The incidence of nausea declined over subsequent cycles, and eventually approached baseline levels, the investigators said.

Hematologic toxicities were the most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events seen in patients treated with niraparib, including thrombocytopenia in 34%, anemia in 25%, and neutropenia in 20%. However, disutility analyses showed no significant effects of these toxicities on QOL measures.

“This analysis did not examine integrated measures of duration and QOL such as time without symptoms and toxicity or quality-adjusted progression-free survival. Although these analyses were beyond the scope of this report, these measures are potentially of interest and we plan to assess these as part of future research,” wrote Dr. Oza and his associates.

SOURCE: Friedlander M et al. Lancet Oncol 2018 Jul 16 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30343-7. Oza AM et al. Lancet Oncol 2018 Jul 16 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30333-4.

The QOL analyses of these two trials clearly show that neither olaparib nor niraparib has a detrimental effect on QOL in the maintenance setting of platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer. Future trials of the maintenance setting of recurrent ovarian cancer should include a predefined patient reported outcome (PRO) hypothesis and a statistical analysis plan including appropriate timing and duration of measurements. The completion of PRO instruments can be a burden to patients; thus, limiting PROs to those that inform a study-specific hypothesis can aid in achieving a high compliance rate. For example, the effect of gastrointestinal symptoms on QOL by EQ-5D-5L [European QOL five-dimension five-level questionnaire] is difficult to assess. As other drug classes are incorporated into treatment regimens for recurrent ovarian cancer, the use of the same PRO measures between trials, such as the Measure of Ovarian Symptoms and Treatment, might help in comparison of the therapeutic regimens.

Daisuke Aoki, MD, and Tatsuyuki Chiyoda, MD, are with the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Keio University, Tokyo. Dr. Aoki disclosed personal fees from AstraZeneca. Dr. Chiyoda reported no conflicts of interest. Their remarks are adapted and condensed from an editorial published online July 16, 2018, in The Lancet Oncology.

The QOL analyses of these two trials clearly show that neither olaparib nor niraparib has a detrimental effect on QOL in the maintenance setting of platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer. Future trials of the maintenance setting of recurrent ovarian cancer should include a predefined patient reported outcome (PRO) hypothesis and a statistical analysis plan including appropriate timing and duration of measurements. The completion of PRO instruments can be a burden to patients; thus, limiting PROs to those that inform a study-specific hypothesis can aid in achieving a high compliance rate. For example, the effect of gastrointestinal symptoms on QOL by EQ-5D-5L [European QOL five-dimension five-level questionnaire] is difficult to assess. As other drug classes are incorporated into treatment regimens for recurrent ovarian cancer, the use of the same PRO measures between trials, such as the Measure of Ovarian Symptoms and Treatment, might help in comparison of the therapeutic regimens.

Daisuke Aoki, MD, and Tatsuyuki Chiyoda, MD, are with the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Keio University, Tokyo. Dr. Aoki disclosed personal fees from AstraZeneca. Dr. Chiyoda reported no conflicts of interest. Their remarks are adapted and condensed from an editorial published online July 16, 2018, in The Lancet Oncology.

The QOL analyses of these two trials clearly show that neither olaparib nor niraparib has a detrimental effect on QOL in the maintenance setting of platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer. Future trials of the maintenance setting of recurrent ovarian cancer should include a predefined patient reported outcome (PRO) hypothesis and a statistical analysis plan including appropriate timing and duration of measurements. The completion of PRO instruments can be a burden to patients; thus, limiting PROs to those that inform a study-specific hypothesis can aid in achieving a high compliance rate. For example, the effect of gastrointestinal symptoms on QOL by EQ-5D-5L [European QOL five-dimension five-level questionnaire] is difficult to assess. As other drug classes are incorporated into treatment regimens for recurrent ovarian cancer, the use of the same PRO measures between trials, such as the Measure of Ovarian Symptoms and Treatment, might help in comparison of the therapeutic regimens.

Daisuke Aoki, MD, and Tatsuyuki Chiyoda, MD, are with the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Keio University, Tokyo. Dr. Aoki disclosed personal fees from AstraZeneca. Dr. Chiyoda reported no conflicts of interest. Their remarks are adapted and condensed from an editorial published online July 16, 2018, in The Lancet Oncology.

Women with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer who received maintenance therapy with a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor had no significant decreases in health-related quality of life, outcomes data from two randomized clinical trials show.

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) analyses from the SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov-21 trial comparing olaparib (Lynparza) with placebo and the ENGOT-OV16/NOVA trial comparing niraparib (Zejula) with placebo as maintenance therapy in women with ongoing responses to their last platinum-based chemotherapy showed that neither agent had major detrimental effects on patient-reported outcomes, further supporting the progression-free survival benefits previously seen with each agent in its respective trials.

“These results show the significant benefit of maintenance olaparib to patients beyond the RECIST [Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors] definition of progression, the primary endpoint of SOLO2, and highlight the importance of including patient-centered outcomes in addition to HRQOL in trials of maintenance therapy, in line with the recommendations of the 5th Ovarian Cancer Consensus Conference,” wrote Michael Friedlander, MD, of the University of New South Wales Clinical School and Prince of Wales Hospital in Randwick, New South Wales, Australia, and his colleagues.

Similarly, Amit M. Oza, MD, of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, and his coinvestigators in the ENGOT-OV16/NOVA trial found that “niraparib has no significant negative effect on QOL in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. Combined with the evidence of increased progression-free survival with niraparib in the maintenance setting, these findings support the addition of niraparib as a component of standard of care.”

Both studies were published online in The Lancet Oncology: Friedlander M et al. Lancet Oncol 2018 Jul 16 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30343-7, and Oza AM et al. Lancet Oncol 2018 Jul 16 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30333-4.

SOLO2 QOL summary

In SOLO2, patients with a germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation and platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer that relapsed after at least two lines of chemotherapy were randomly assigned to receive either oral olaparib 300 mg twice daily (196 patients) or placebo (99 patients).

The prespecified primary HRQOL analysis looked at the change from baseline in the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Ovarian Cancer (FACT-O) Trial Outcome Index (TOI) score during the first 12 months of the study.

In addition, the investigators examined secondary planned QOL analyses, including duration of good quality of life, defined as time without significant symptoms of toxicity, or TWiST, and quality-adjusted progression-free survival (QAPFS).

The adjusted average mean change from baseline over the first 12 months in TOI was –2.90 with olaparib vs. –2.87 with placebo (nonsignificant).

In contrast, patients treated with olaparib had significantly better mean QAPFS (13.96 vs. 7.28 months) and TWiST (15.03 vs. 7.70 months) results.

“All these predefined endpoints support the benefit to patients of a prolongation of progression-free survival, which is the primary endpoint in maintenance trials in ovarian cancer, and should be routinely included in future trials,” wrote Dr. Friedlander and his associates.

ENGOT-OV16/NOVA QOL summary

Investigators for this trial enrolled patients into two independent cohorts based on germline BRCA mutations or lack thereof. In all, 138 patients were assigned to niraparib and 65 to placebo in the germline BRCA mutation cohort, and 234 to niraparib and 116 to placebo in the nonmutation cohort.

The current study assessed patient-reported outcomes in the intention-to-treat population using different validated instruments from those assessed in SOLO2: the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Ovarian Symptoms Index (FOSI) and European QOL five-dimension five-level questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L).

The outcomes were reported every 8 weeks for the first 14 treatment cycles and every 12 weeks thereafter.

The investigators looked at the effects of hematologic toxicities on QOL with disutility analyses (measuring the decrement on QOL of a particular symptom or complication) of the most common grade 3-4 adverse events (thrombocytopenia, anemia, and neutropenia) using a mixed model with covariates.

They found that overall QOL scores remained stable during treatment and the preprogression period among patients on niraparib in each cohort, and that there were no significant differences in preprogression EQ-5D-5L scores between niraparib- or placebo-treated patients in either cohort.

In addition, patient-reported lack of energy and pain, two of the most common baseline symptoms, either remained stable or improved during maintenance, although the proportion of patients reporting nausea increased at cycle 2. The incidence of nausea declined over subsequent cycles, and eventually approached baseline levels, the investigators said.

Hematologic toxicities were the most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events seen in patients treated with niraparib, including thrombocytopenia in 34%, anemia in 25%, and neutropenia in 20%. However, disutility analyses showed no significant effects of these toxicities on QOL measures.

“This analysis did not examine integrated measures of duration and QOL such as time without symptoms and toxicity or quality-adjusted progression-free survival. Although these analyses were beyond the scope of this report, these measures are potentially of interest and we plan to assess these as part of future research,” wrote Dr. Oza and his associates.

SOURCE: Friedlander M et al. Lancet Oncol 2018 Jul 16 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30343-7. Oza AM et al. Lancet Oncol 2018 Jul 16 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30333-4.

Women with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer who received maintenance therapy with a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor had no significant decreases in health-related quality of life, outcomes data from two randomized clinical trials show.

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) analyses from the SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov-21 trial comparing olaparib (Lynparza) with placebo and the ENGOT-OV16/NOVA trial comparing niraparib (Zejula) with placebo as maintenance therapy in women with ongoing responses to their last platinum-based chemotherapy showed that neither agent had major detrimental effects on patient-reported outcomes, further supporting the progression-free survival benefits previously seen with each agent in its respective trials.

“These results show the significant benefit of maintenance olaparib to patients beyond the RECIST [Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors] definition of progression, the primary endpoint of SOLO2, and highlight the importance of including patient-centered outcomes in addition to HRQOL in trials of maintenance therapy, in line with the recommendations of the 5th Ovarian Cancer Consensus Conference,” wrote Michael Friedlander, MD, of the University of New South Wales Clinical School and Prince of Wales Hospital in Randwick, New South Wales, Australia, and his colleagues.

Similarly, Amit M. Oza, MD, of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, and his coinvestigators in the ENGOT-OV16/NOVA trial found that “niraparib has no significant negative effect on QOL in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. Combined with the evidence of increased progression-free survival with niraparib in the maintenance setting, these findings support the addition of niraparib as a component of standard of care.”

Both studies were published online in The Lancet Oncology: Friedlander M et al. Lancet Oncol 2018 Jul 16 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30343-7, and Oza AM et al. Lancet Oncol 2018 Jul 16 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30333-4.

SOLO2 QOL summary

In SOLO2, patients with a germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation and platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer that relapsed after at least two lines of chemotherapy were randomly assigned to receive either oral olaparib 300 mg twice daily (196 patients) or placebo (99 patients).

The prespecified primary HRQOL analysis looked at the change from baseline in the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Ovarian Cancer (FACT-O) Trial Outcome Index (TOI) score during the first 12 months of the study.

In addition, the investigators examined secondary planned QOL analyses, including duration of good quality of life, defined as time without significant symptoms of toxicity, or TWiST, and quality-adjusted progression-free survival (QAPFS).

The adjusted average mean change from baseline over the first 12 months in TOI was –2.90 with olaparib vs. –2.87 with placebo (nonsignificant).

In contrast, patients treated with olaparib had significantly better mean QAPFS (13.96 vs. 7.28 months) and TWiST (15.03 vs. 7.70 months) results.

“All these predefined endpoints support the benefit to patients of a prolongation of progression-free survival, which is the primary endpoint in maintenance trials in ovarian cancer, and should be routinely included in future trials,” wrote Dr. Friedlander and his associates.

ENGOT-OV16/NOVA QOL summary

Investigators for this trial enrolled patients into two independent cohorts based on germline BRCA mutations or lack thereof. In all, 138 patients were assigned to niraparib and 65 to placebo in the germline BRCA mutation cohort, and 234 to niraparib and 116 to placebo in the nonmutation cohort.

The current study assessed patient-reported outcomes in the intention-to-treat population using different validated instruments from those assessed in SOLO2: the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Ovarian Symptoms Index (FOSI) and European QOL five-dimension five-level questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L).

The outcomes were reported every 8 weeks for the first 14 treatment cycles and every 12 weeks thereafter.

The investigators looked at the effects of hematologic toxicities on QOL with disutility analyses (measuring the decrement on QOL of a particular symptom or complication) of the most common grade 3-4 adverse events (thrombocytopenia, anemia, and neutropenia) using a mixed model with covariates.

They found that overall QOL scores remained stable during treatment and the preprogression period among patients on niraparib in each cohort, and that there were no significant differences in preprogression EQ-5D-5L scores between niraparib- or placebo-treated patients in either cohort.

In addition, patient-reported lack of energy and pain, two of the most common baseline symptoms, either remained stable or improved during maintenance, although the proportion of patients reporting nausea increased at cycle 2. The incidence of nausea declined over subsequent cycles, and eventually approached baseline levels, the investigators said.

Hematologic toxicities were the most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events seen in patients treated with niraparib, including thrombocytopenia in 34%, anemia in 25%, and neutropenia in 20%. However, disutility analyses showed no significant effects of these toxicities on QOL measures.

“This analysis did not examine integrated measures of duration and QOL such as time without symptoms and toxicity or quality-adjusted progression-free survival. Although these analyses were beyond the scope of this report, these measures are potentially of interest and we plan to assess these as part of future research,” wrote Dr. Oza and his associates.

SOURCE: Friedlander M et al. Lancet Oncol 2018 Jul 16 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30343-7. Oza AM et al. Lancet Oncol 2018 Jul 16 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30333-4.

FROM THE LANCET ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors do not adversely affect quality of life when used as maintenance therapy for platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer.

Major finding: Neither olaparib nor niraparib was associated with significant decrements in health related quality of life measures.

Study details: Quality-of-life analyses from two randomized phase 3 trials comparing a PARP inhibitor with placebo for maintenance in women with platinum-sensitive relapsed or recurrent ovarian cancer.

Disclosures: Solo 2/ENGOT Ov-21 was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Friedland reported personal fees from the company during the conduct of the study. Coauthors reported fees or other consideration from the company. ENGOT-OV16/NOVA was funded by Tesaro. Dr. Oza reported personal fees from Clovis Oncology, WebRx, and Intas Oncology. One coauthor was a Tesaro employee and stockholder at the time the study was completed, and others reported serving on advisory boards and/or receiving fees from Tesaro and other companies.

Source: Friedlander M et al. Lancet Oncol 2018 Jul 16 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30343-7. Oza AM et al. Lancet Oncol 2018 Jul 16 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30333-4.

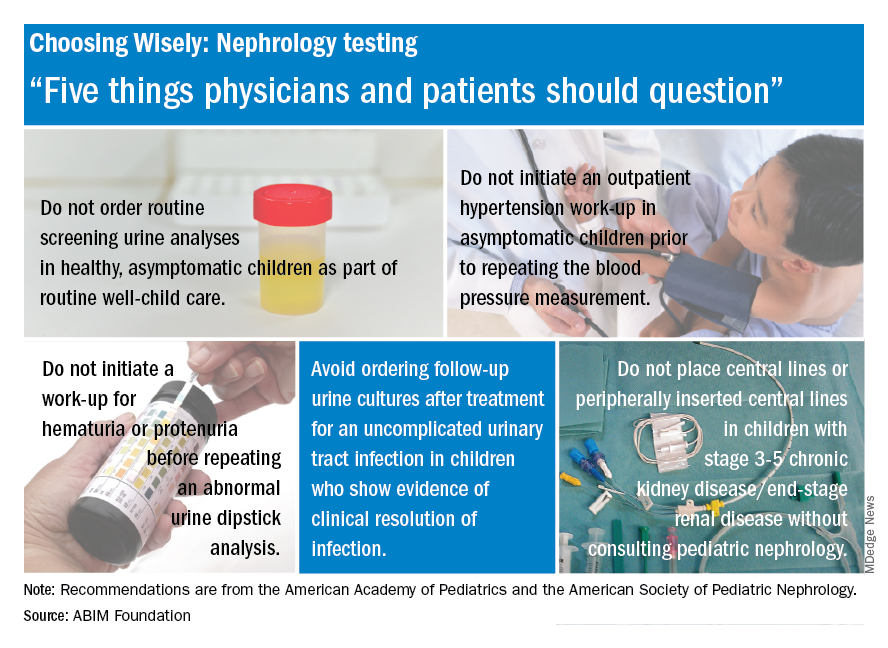

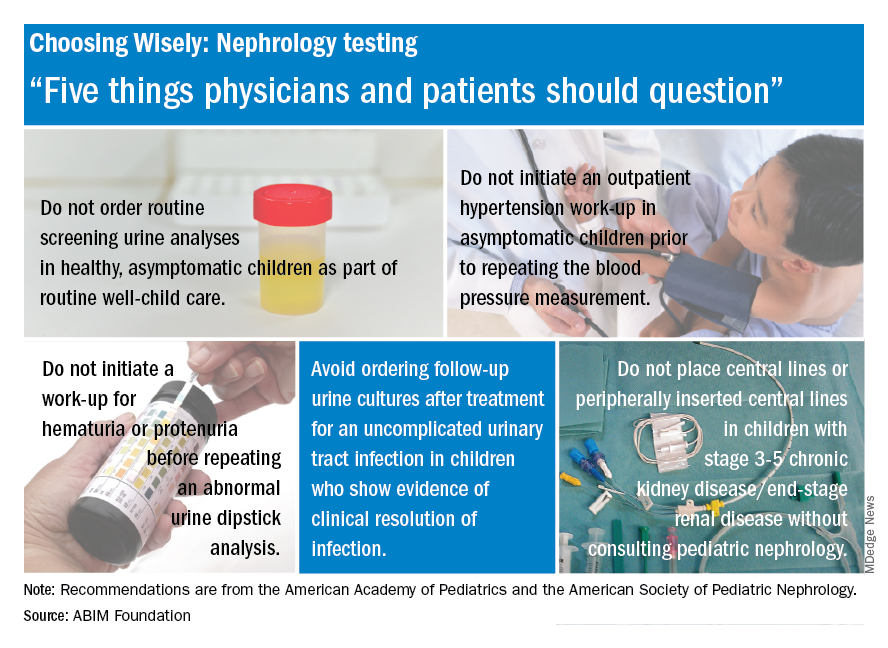

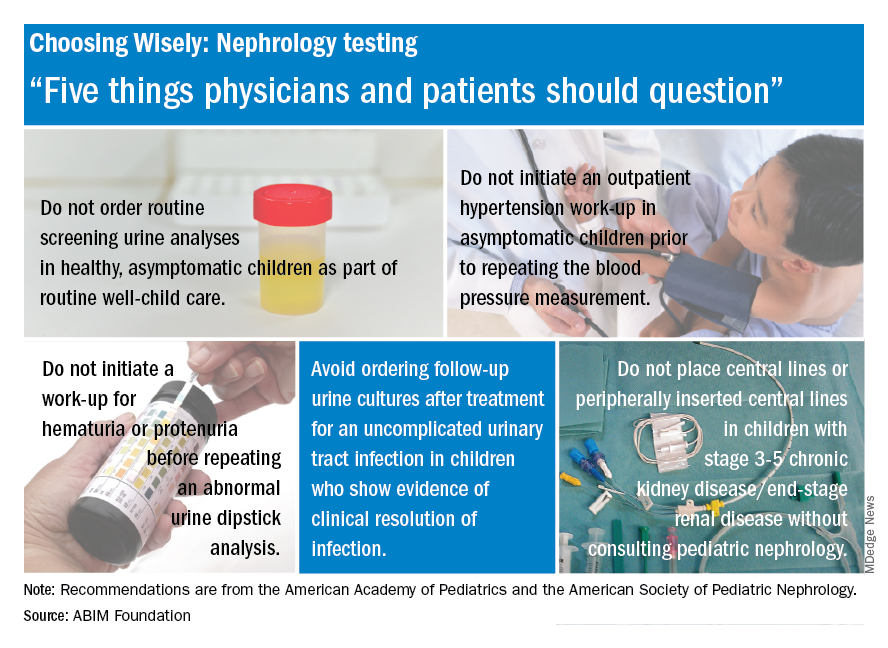

Recommendations aim to reduce pediatric nephrology testing

Evidence-based recommendations for appropriate nephrology testing in children are the latest installment of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation’s “Choosing Wisely” campaign.

The list includes recommendations on when not to order screening urine analyses and urine cultures, initiate hypertension workups, and place central lines. “Sometimes parents or physicians want to ensure all available testing is done, but unnecessary testing can create more fear, cost, and risk for children. Good communication and discussion of options can help reduce the likelihood of unnecessary testing,” said Doug Silverstein, MD, chairperson of the AAP section on nephrology.

Evidence-based recommendations for appropriate nephrology testing in children are the latest installment of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation’s “Choosing Wisely” campaign.

The list includes recommendations on when not to order screening urine analyses and urine cultures, initiate hypertension workups, and place central lines. “Sometimes parents or physicians want to ensure all available testing is done, but unnecessary testing can create more fear, cost, and risk for children. Good communication and discussion of options can help reduce the likelihood of unnecessary testing,” said Doug Silverstein, MD, chairperson of the AAP section on nephrology.

Evidence-based recommendations for appropriate nephrology testing in children are the latest installment of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation’s “Choosing Wisely” campaign.

The list includes recommendations on when not to order screening urine analyses and urine cultures, initiate hypertension workups, and place central lines. “Sometimes parents or physicians want to ensure all available testing is done, but unnecessary testing can create more fear, cost, and risk for children. Good communication and discussion of options can help reduce the likelihood of unnecessary testing,” said Doug Silverstein, MD, chairperson of the AAP section on nephrology.

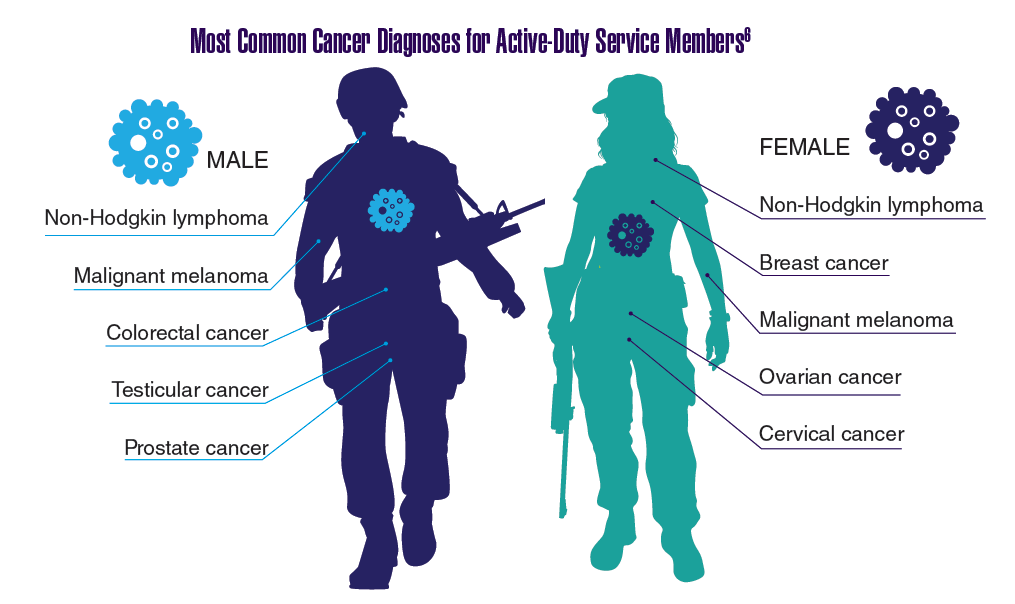

Federal Health Care Data Trends: Oncology

In 2012, a study conducted by Zullig and colleagues revealed that about 40,000 cancer cases are reported annually to the Veterans Affairs Central Cancer Registry.1 This represented about 3% of all cancer cases in the US. Within the VA patient population, the most commonly diagnosed cancers are prostate, lung and bronchial, colorectal, urinary and bladder cancers, and skin melanomas. This mirrors the commonly diagnosed cancers within the total US patient population.

Click here to continue reading.

In 2012, a study conducted by Zullig and colleagues revealed that about 40,000 cancer cases are reported annually to the Veterans Affairs Central Cancer Registry.1 This represented about 3% of all cancer cases in the US. Within the VA patient population, the most commonly diagnosed cancers are prostate, lung and bronchial, colorectal, urinary and bladder cancers, and skin melanomas. This mirrors the commonly diagnosed cancers within the total US patient population.

Click here to continue reading.

In 2012, a study conducted by Zullig and colleagues revealed that about 40,000 cancer cases are reported annually to the Veterans Affairs Central Cancer Registry.1 This represented about 3% of all cancer cases in the US. Within the VA patient population, the most commonly diagnosed cancers are prostate, lung and bronchial, colorectal, urinary and bladder cancers, and skin melanomas. This mirrors the commonly diagnosed cancers within the total US patient population.

Click here to continue reading.

How to “Nudge” Patients to Screen for HIV

What’s the best way to encourage patients to get screened for HIV? Money is a time-honored effective incentive, but researchers from University of California say the default option may be even better. They conducted, to their knowledge, the first head-to-head study of 2 types of behavioral economics interventions (cash incentives vs opt-out) in any health behavior context. The working hypothesis was based on “nudge theory,” a concept in behavioral science, political theory, and economics that says using positive reinforcement and indirect suggestions can influence behavior and decision making.

In the study, patients aged 13 to 64 years were told the emergency department was offering rapid screening HIV tests, with results available within 2 hours. Then each patient was given a test offer: opt-in (“You can let me, your nurse, or your doctor know if you’d like a test today”); active choice (“Would you like a test today?”); or opt-out (“You will be tested unless you decline.”) Patients assigned to a positive monetary incentive were told “To encourage testing today we are offering a $1 (or $5 or $10) cash incentive.”