User login

Epinephrine for cardiac arrest: Better survival, more brain damage

Using epinephrine for cardiac arrest improves 30-day survival by less than 1%, and nearly doubles the risk of severe brain damage among survivors, according to PARAMEDIC2, a randomized, double-blind trial in more than 8,000 patients in Great Britain.

It’s clear what patients want. “Our own work with patients and the public before starting the trial identified survival without brain damage [as] more important to patients than survival alone. The findings of this trial will require careful consideration by the wider community and those responsible for clinical practice guidelines for cardiac arrest,” lead investigator Gavin D. Perkins, MD, professor of critical care medicine at the University of Warwick, Coventry, England, and lead author of the study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, wrote in a statement.

In PARAMEDIC2, after initial attempts with CPR and defibrillation failed, 4,012 patients were given epinephrine 1 mg by intravenous or intraosseous infusion every 3-5 minutes for a maximum of 10 doses, and 3,995 were given a saline placebo in the same fashion. The median time from emergency call to ambulance arrival was just over 6 minutes in both groups, with a further 14 minutes until drug administration.

The heart restarted in a higher proportion of epinephrine patients (36.3% vs. 11.7%), and 3.2% of epinephrine patients were alive at 30 days, versus 2.4% in the placebo arm, a 39% increase.

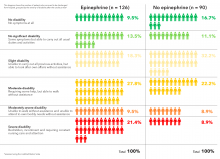

However, that slight benefit came at a significant cost. Of the 126 epinephrine patients who survived to hospital discharge, 39 (31%) had severe brain damage, compared with 16 (17.8%) among the 90 placebo survivors. Severe brain damage meant inability to walk and tend to bodily functions, or a persistent vegetative state (modified Rankin scale grade 4 or 5).

The trial addresses a long-standing question in resuscitation medicine, the role of epinephrine in cardiac arrest. It’s a devil’s bargain: Epinephrine increases blood flow to the heart, so helps with resuscitation, but it also reduces blood flow in the brain’s microvasculature, increasing the risk of brain damage.

“The benefit of epinephrine on survival demonstrated in this trial should be considered in comparison with other treatments in the chain of survival.” Early cardiac arrest recognition saves 1 in every 11 patients, bystander CPR saves 1 in every 15, and early defibrillation saves 1 in 5, the investigators noted.

The trial did not collect data on prearrest neurologic status, but the number of subjects with impaired function was probably very small and balanced between the groups, according to the report.

On average, patients were aged just under 70 years, 65% were men, and bystander CPR was performed in about 60% in both groups. They were enrolled by five ambulance services in England and Wales. Informed consent was obtained, when possible, after resuscitation.

The trial was funded by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research. The researchers had no relevant disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Perkins GD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1806842.

Epinephrine has been used in resuscitation efforts since the 1960s, yet no reliable evidence on the practice has been collected. Now, PARAMEDIC2 provides the most rigorous data on patient-centered outcomes with respect to epinephrine to date.

Epinephrine increased 30-day survival in patients with nonshockable rhythms by more than 100%, but the benefit was less clear in those with shockable rhythms. Shockable rhythms are more likely to occur in patients with cardiac or cardiovascular causes of arrest, which epinephrine may exacerbate. The results underscore the principle that drug administration should not compete with or delay defibrillation, and that epinephrine may have different effects in patients with different ECG rhythms.

The PARAMEDIC2 results leave us with several questions: Could other, additional treatments after a return of spontaneous circulation improve functional recovery, should drug use differ on the basis of cardiac rhythm, and would lower doses of epinephrine be superior to higher doses among patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest?

Clifton W. Callaway, MD, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh, and Michael W. Donnino, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1808255). They had no relevant disclosures.

Epinephrine has been used in resuscitation efforts since the 1960s, yet no reliable evidence on the practice has been collected. Now, PARAMEDIC2 provides the most rigorous data on patient-centered outcomes with respect to epinephrine to date.

Epinephrine increased 30-day survival in patients with nonshockable rhythms by more than 100%, but the benefit was less clear in those with shockable rhythms. Shockable rhythms are more likely to occur in patients with cardiac or cardiovascular causes of arrest, which epinephrine may exacerbate. The results underscore the principle that drug administration should not compete with or delay defibrillation, and that epinephrine may have different effects in patients with different ECG rhythms.

The PARAMEDIC2 results leave us with several questions: Could other, additional treatments after a return of spontaneous circulation improve functional recovery, should drug use differ on the basis of cardiac rhythm, and would lower doses of epinephrine be superior to higher doses among patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest?

Clifton W. Callaway, MD, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh, and Michael W. Donnino, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1808255). They had no relevant disclosures.

Epinephrine has been used in resuscitation efforts since the 1960s, yet no reliable evidence on the practice has been collected. Now, PARAMEDIC2 provides the most rigorous data on patient-centered outcomes with respect to epinephrine to date.

Epinephrine increased 30-day survival in patients with nonshockable rhythms by more than 100%, but the benefit was less clear in those with shockable rhythms. Shockable rhythms are more likely to occur in patients with cardiac or cardiovascular causes of arrest, which epinephrine may exacerbate. The results underscore the principle that drug administration should not compete with or delay defibrillation, and that epinephrine may have different effects in patients with different ECG rhythms.

The PARAMEDIC2 results leave us with several questions: Could other, additional treatments after a return of spontaneous circulation improve functional recovery, should drug use differ on the basis of cardiac rhythm, and would lower doses of epinephrine be superior to higher doses among patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest?

Clifton W. Callaway, MD, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh, and Michael W. Donnino, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1808255). They had no relevant disclosures.

Using epinephrine for cardiac arrest improves 30-day survival by less than 1%, and nearly doubles the risk of severe brain damage among survivors, according to PARAMEDIC2, a randomized, double-blind trial in more than 8,000 patients in Great Britain.

It’s clear what patients want. “Our own work with patients and the public before starting the trial identified survival without brain damage [as] more important to patients than survival alone. The findings of this trial will require careful consideration by the wider community and those responsible for clinical practice guidelines for cardiac arrest,” lead investigator Gavin D. Perkins, MD, professor of critical care medicine at the University of Warwick, Coventry, England, and lead author of the study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, wrote in a statement.

In PARAMEDIC2, after initial attempts with CPR and defibrillation failed, 4,012 patients were given epinephrine 1 mg by intravenous or intraosseous infusion every 3-5 minutes for a maximum of 10 doses, and 3,995 were given a saline placebo in the same fashion. The median time from emergency call to ambulance arrival was just over 6 minutes in both groups, with a further 14 minutes until drug administration.

The heart restarted in a higher proportion of epinephrine patients (36.3% vs. 11.7%), and 3.2% of epinephrine patients were alive at 30 days, versus 2.4% in the placebo arm, a 39% increase.

However, that slight benefit came at a significant cost. Of the 126 epinephrine patients who survived to hospital discharge, 39 (31%) had severe brain damage, compared with 16 (17.8%) among the 90 placebo survivors. Severe brain damage meant inability to walk and tend to bodily functions, or a persistent vegetative state (modified Rankin scale grade 4 or 5).

The trial addresses a long-standing question in resuscitation medicine, the role of epinephrine in cardiac arrest. It’s a devil’s bargain: Epinephrine increases blood flow to the heart, so helps with resuscitation, but it also reduces blood flow in the brain’s microvasculature, increasing the risk of brain damage.

“The benefit of epinephrine on survival demonstrated in this trial should be considered in comparison with other treatments in the chain of survival.” Early cardiac arrest recognition saves 1 in every 11 patients, bystander CPR saves 1 in every 15, and early defibrillation saves 1 in 5, the investigators noted.

The trial did not collect data on prearrest neurologic status, but the number of subjects with impaired function was probably very small and balanced between the groups, according to the report.

On average, patients were aged just under 70 years, 65% were men, and bystander CPR was performed in about 60% in both groups. They were enrolled by five ambulance services in England and Wales. Informed consent was obtained, when possible, after resuscitation.

The trial was funded by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research. The researchers had no relevant disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Perkins GD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1806842.

Using epinephrine for cardiac arrest improves 30-day survival by less than 1%, and nearly doubles the risk of severe brain damage among survivors, according to PARAMEDIC2, a randomized, double-blind trial in more than 8,000 patients in Great Britain.

It’s clear what patients want. “Our own work with patients and the public before starting the trial identified survival without brain damage [as] more important to patients than survival alone. The findings of this trial will require careful consideration by the wider community and those responsible for clinical practice guidelines for cardiac arrest,” lead investigator Gavin D. Perkins, MD, professor of critical care medicine at the University of Warwick, Coventry, England, and lead author of the study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, wrote in a statement.

In PARAMEDIC2, after initial attempts with CPR and defibrillation failed, 4,012 patients were given epinephrine 1 mg by intravenous or intraosseous infusion every 3-5 minutes for a maximum of 10 doses, and 3,995 were given a saline placebo in the same fashion. The median time from emergency call to ambulance arrival was just over 6 minutes in both groups, with a further 14 minutes until drug administration.

The heart restarted in a higher proportion of epinephrine patients (36.3% vs. 11.7%), and 3.2% of epinephrine patients were alive at 30 days, versus 2.4% in the placebo arm, a 39% increase.

However, that slight benefit came at a significant cost. Of the 126 epinephrine patients who survived to hospital discharge, 39 (31%) had severe brain damage, compared with 16 (17.8%) among the 90 placebo survivors. Severe brain damage meant inability to walk and tend to bodily functions, or a persistent vegetative state (modified Rankin scale grade 4 or 5).

The trial addresses a long-standing question in resuscitation medicine, the role of epinephrine in cardiac arrest. It’s a devil’s bargain: Epinephrine increases blood flow to the heart, so helps with resuscitation, but it also reduces blood flow in the brain’s microvasculature, increasing the risk of brain damage.

“The benefit of epinephrine on survival demonstrated in this trial should be considered in comparison with other treatments in the chain of survival.” Early cardiac arrest recognition saves 1 in every 11 patients, bystander CPR saves 1 in every 15, and early defibrillation saves 1 in 5, the investigators noted.

The trial did not collect data on prearrest neurologic status, but the number of subjects with impaired function was probably very small and balanced between the groups, according to the report.

On average, patients were aged just under 70 years, 65% were men, and bystander CPR was performed in about 60% in both groups. They were enrolled by five ambulance services in England and Wales. Informed consent was obtained, when possible, after resuscitation.

The trial was funded by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research. The researchers had no relevant disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Perkins GD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1806842.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of the 128 epinephrine patients who survived to hospital discharge, 39 (30.1%) had severe brain damage, compared with 16 (18.7%) among the 91 placebo survivors.

Study details: A randomized, double-blind trial of over 8,000 U.K. patients experiencing an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Disclosures: The trial was funded by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research. The researchers had no relevant disclosures to report.

Source: Perkins GD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1806842.

National Academies issues 5-step plan to address infections linked to opioid use disorder

Widespread opioid use disorder (OUD) has spawned new epidemics of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HIV infections as well as increased hospitalizations for bacteremia, endocarditis, skin and soft tissue infections, and osteomyelitis, according to a report arising from a National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) workshop titled Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic.

Optimal treatment of these infections is often impeded by untreated OUD, Sandra A. Springer, MD, and her colleagues wrote in an article published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine. Failing to address OUD can result in longer hospital stays; frequent readmissions because of a lack of adherence to antibiotic regimens; or reinfection, morbidity, and high costs. “Medical settings that manage such infections offer a potential means of engaging people in treatment of OUD; however, few providers and hospitals treating such infections have the needed resources and capabilities,” Dr. Springer, director, infectious disease outpatient clinic, Veterans Administration, Newington, and of Yale University, New Haven, both in Conn., and her colleagues wrote.

The authors outlined five action steps resulting from the NASEM workshop:

- Implement screening for OUD in all relevant health care settings.

- For patients with positive screening results, immediately prescribe effective medication for OUD and/or opioid withdrawal symptoms.

- Develop hospital-based protocols that facilitate OUD treatment initiation and linkage to community-based treatment upon discharge.

- Hospitals, medical schools, physician assistant schools, nursing schools, and residency programs should increase training to identify and treat OUD.

- Increase access to addiction care and funding to states to provide effective medications to treat OUD.

Opioid withdrawal and pain syndromes should be addressed with opioid agonist therapies to optimize infectious disease (ID) treatment and relieve pain, according to Dr. Springer and her colleagues. In addition, “Because ID specialists are likely to be consulted for anyone requiring long-term antibiotic therapy or patients with HIV and HCV infection, OUD screening should be a standard part of an ID consult assessment,” the authors wrote.

“All health care providers have a role in combating the OUD epidemic and its ID consequences. Those who treat infectious complications of OUD are well suited to screen for OUD and begin treatment with effective FDA-approved medications,” the authors concluded.

The workshop was held in March 2018 in Washington and videos and slide presentations from the meeting are available.

Dr. Springer and her colleagues reported grant funding from the National Institutes of Health, but no commercial conflicts.

SOURCE: Springer SA et al. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Jul 13. doi: 10.7326/M18-1203.

Widespread opioid use disorder (OUD) has spawned new epidemics of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HIV infections as well as increased hospitalizations for bacteremia, endocarditis, skin and soft tissue infections, and osteomyelitis, according to a report arising from a National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) workshop titled Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic.

Optimal treatment of these infections is often impeded by untreated OUD, Sandra A. Springer, MD, and her colleagues wrote in an article published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine. Failing to address OUD can result in longer hospital stays; frequent readmissions because of a lack of adherence to antibiotic regimens; or reinfection, morbidity, and high costs. “Medical settings that manage such infections offer a potential means of engaging people in treatment of OUD; however, few providers and hospitals treating such infections have the needed resources and capabilities,” Dr. Springer, director, infectious disease outpatient clinic, Veterans Administration, Newington, and of Yale University, New Haven, both in Conn., and her colleagues wrote.

The authors outlined five action steps resulting from the NASEM workshop:

- Implement screening for OUD in all relevant health care settings.

- For patients with positive screening results, immediately prescribe effective medication for OUD and/or opioid withdrawal symptoms.

- Develop hospital-based protocols that facilitate OUD treatment initiation and linkage to community-based treatment upon discharge.

- Hospitals, medical schools, physician assistant schools, nursing schools, and residency programs should increase training to identify and treat OUD.

- Increase access to addiction care and funding to states to provide effective medications to treat OUD.

Opioid withdrawal and pain syndromes should be addressed with opioid agonist therapies to optimize infectious disease (ID) treatment and relieve pain, according to Dr. Springer and her colleagues. In addition, “Because ID specialists are likely to be consulted for anyone requiring long-term antibiotic therapy or patients with HIV and HCV infection, OUD screening should be a standard part of an ID consult assessment,” the authors wrote.

“All health care providers have a role in combating the OUD epidemic and its ID consequences. Those who treat infectious complications of OUD are well suited to screen for OUD and begin treatment with effective FDA-approved medications,” the authors concluded.

The workshop was held in March 2018 in Washington and videos and slide presentations from the meeting are available.

Dr. Springer and her colleagues reported grant funding from the National Institutes of Health, but no commercial conflicts.

SOURCE: Springer SA et al. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Jul 13. doi: 10.7326/M18-1203.

Widespread opioid use disorder (OUD) has spawned new epidemics of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HIV infections as well as increased hospitalizations for bacteremia, endocarditis, skin and soft tissue infections, and osteomyelitis, according to a report arising from a National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) workshop titled Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic.

Optimal treatment of these infections is often impeded by untreated OUD, Sandra A. Springer, MD, and her colleagues wrote in an article published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine. Failing to address OUD can result in longer hospital stays; frequent readmissions because of a lack of adherence to antibiotic regimens; or reinfection, morbidity, and high costs. “Medical settings that manage such infections offer a potential means of engaging people in treatment of OUD; however, few providers and hospitals treating such infections have the needed resources and capabilities,” Dr. Springer, director, infectious disease outpatient clinic, Veterans Administration, Newington, and of Yale University, New Haven, both in Conn., and her colleagues wrote.

The authors outlined five action steps resulting from the NASEM workshop:

- Implement screening for OUD in all relevant health care settings.

- For patients with positive screening results, immediately prescribe effective medication for OUD and/or opioid withdrawal symptoms.

- Develop hospital-based protocols that facilitate OUD treatment initiation and linkage to community-based treatment upon discharge.

- Hospitals, medical schools, physician assistant schools, nursing schools, and residency programs should increase training to identify and treat OUD.

- Increase access to addiction care and funding to states to provide effective medications to treat OUD.

Opioid withdrawal and pain syndromes should be addressed with opioid agonist therapies to optimize infectious disease (ID) treatment and relieve pain, according to Dr. Springer and her colleagues. In addition, “Because ID specialists are likely to be consulted for anyone requiring long-term antibiotic therapy or patients with HIV and HCV infection, OUD screening should be a standard part of an ID consult assessment,” the authors wrote.

“All health care providers have a role in combating the OUD epidemic and its ID consequences. Those who treat infectious complications of OUD are well suited to screen for OUD and begin treatment with effective FDA-approved medications,” the authors concluded.

The workshop was held in March 2018 in Washington and videos and slide presentations from the meeting are available.

Dr. Springer and her colleagues reported grant funding from the National Institutes of Health, but no commercial conflicts.

SOURCE: Springer SA et al. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Jul 13. doi: 10.7326/M18-1203.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Development of a Pharmacist-Led Emergency Department Antimicrobial Surveillance Program

On September 18, 2014, President Barack Obama signed an executive order that made addressing antibiotic-resistant bacteria a national security policy.1 This legislation resulted in the creation of a large multidepartment task force to combat the global and domestic problem of antimicrobial resistance. The order required hospitals and other inpatient health care delivery facilities, including the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), to implement robust antimicrobial stewardship programs that adhere to best practices, such as those identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). More specifically, the VA was mandated to take steps to encourage other areas of health care, such as ambulatory surgery centers and outpatient clinics, to adopt antimicrobial stewardship programs.1 This order also reinforced the importance for VA facilities to continue to develop, improve, and sustain efforts in antimicrobial stewardship.

Prior to the order, in 2012 the Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center (RRVAMC) in Indianapolis, Indiana, implemented an inpatient antimicrobial stewardship program that included thrice-weekly meetings to review inpatient records and make stewardship recommendations with an infectious diseases physician champion and clinical pharmacists. These efforts led to the improved use of antimicrobial agents on the inpatient side of the medical center. During the first 4 years of implementation, the program helped to decrease the defined daily doses of broad-spectrum antibiotics per 1,000 patient days nearly 36%, from 532 in 2012 to 343 in 2015, as well as decrease the days of therapy of fluoroquinolones per 1,000 patient days 28.75%, from 80 in 2012 to 57 in 2015. Additionally, the program showed a significant decrease in the standardized antimicrobial administration ratio, a benchmark measure developed by the CDC to reflect a facility’s actual antimicrobial use to the expected use of a similar facility based on bed size, number of intensive care unit beds, location type, and medical school affiliation.2

While the RRVAMC antimicrobial stewardship team has been able to intervene on most of the inpatients admitted to the medical center, the outpatient arena has had few antimicrobial stewardship interventions. Recognizing a need to establish and expand pharmacy services and for improvement of outpatient antimicrobial stewardship, RRVAMC leadership decided to establish a pharmacist-led outpatient antimicrobial surveillance program, starting specifically within the emergency department (ED).

Clinical pharmacists in the ED setting are uniquely positioned to improve patient care and encourage the judicious use of antimicrobials for empiric treatment of urinary tract infections (UTIs). The CDC’s Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship recommends pharmacist availability in the ED setting, and previous literature has demonstrated pharmacist utility in ED postdischarge culture monitoring and surveillance.3-5

This article will highlight one such program review at the RRVAMC and demonstrate the need for pharmacist-led antimicrobial stewardship and monitoring in the ED. The purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that pharmacist intervention would be necessary to prospectively check for “bug-drug mismatch” and assure proper follow-up of urine cultures at this institution. The project was deemed to be quality improvement and thereby granted exemption by the RRVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Methods

This project took place at the RRVAMC, a 229-bed tertiary academic medical center that serves > 60,000 patients annually. The RRVAMC ED has 20 beds and received about 29,000 visits in 2014. Patients were eligible for initial evaluation if they had a urine culture collected in the ED within the 91-day period from September 1, 2015 to November 30, 2015. Patients were included for data analysis if it was documented that they were treated for actual or clinically suspected, based on signs and symptoms, uncomplicated UTI, complicated UTI, or UTI with pyelonephritis. Patients did not need to have a positive urine culture for inclusion, as infections could still be present despite negative culture results.6 Patients with positive cultures who were not clinically symptomatic of a UTI and were not treated as such by the ED provider (ie, asymptomatic bacteriuria) were excluded from the study.

Data collection took place via daily chart review of patient records in both the Computerized Patient Record System and Decentralized Hospital Computer Program medical applications as urine cultures were performed. Data were gathered and assessed by a postgraduate year-2 internal medicine pharmacy resident on rotation in the ED who reviewed cultures daily and made interventions based on the results as needed. The pharmacy resident was physically present within the ED during the first 30 days of the project. The pharmacy resident was not within the direct practice area during the final 61 days of the project but was in a different area of the hospital and available for consultation.

Primary data collected included urine culture results and susceptibilities, empiric antimicrobial choices, and admission status. Other data collected included duration of treatment and secondary antibiotics chosen, each of which specifically evaluated those patients who were not admitted to the hospital and were thus treated as outpatients. Additional data generated from this study were used to identify empiric antibiotics utilized for the treatment of UTIs and assess for appropriate selection and duration of therapy within this institution.

Results

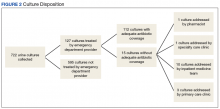

During the study period, 722 urine cultures were collected in the ED and were included for initial evaluation. Of these, 127 were treated by the ED provider pursuant to one of the indications specified and were included in the data analysis. Treatment with an antimicrobial agent provided adequate coverage for the identified pathogen in 112 patients, yielding a match rate of 88%. As all included cultures were collected in suspicion of an infection, those cultures yielding no growth were considered to have been adequately covered.

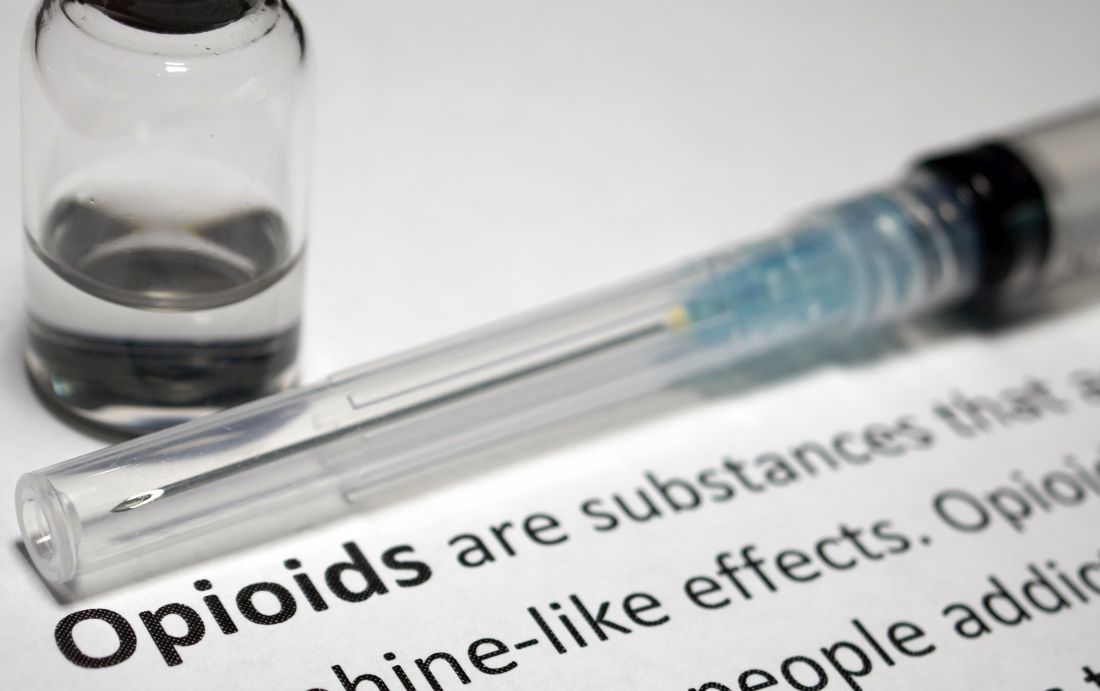

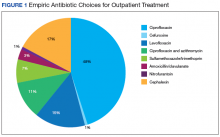

Nearly half (45%) of treatment plans included a fluoroquinolone. Of those treated on an outpatient basis, fluoroquinolones were even more frequently used, comprising 50 of 82 (61%) courses. Ciprofloxacin was the most frequently used treatment, used in 39 of the 82 outpatient regimens (48%). Cephalexin was the second most common and was used in 14 outpatient regimens (17%), followed by levofloxacin (15%) (Figure 1).

Mismatched cultures, or those where the prescribed antibiotic did not provide adequate coverage of the identified pathogens based on susceptibilities, occurred at a rate of 12%. Follow-up on these cultures was determined largely by the patient’s admission status. The majority of mismatched cultures were addressed by the inpatient team (10/15) upon admission.

Discussion

Empiric antibiotic selection for the treatment of UTIs continues to be the cornerstone of antibiotic management for the treatment of such a disease state.7 The noted drug-bug match rate of 88% in this study demonstrates effective initial empiric coverage and ensures a vast majority of veterans receive adequate coverage for identified pathogens. Additionally, this rate shows that the current system seems to be functioning appropriately and refutes the author’s preconceived ideas that the mismatch rate was higher at RRVAMC. However, these findings also demonstrate a predominant use of fluoroquinolones for empiric treatment in a majority of patients who could be better served with narrower spectrum agents. Only 2 of the outpatient regimens were for the treatment of pyelonephritis, the only indication in which a fluoroquinolone would be the standard of care per guideline recommendations.7

These findings were consistent with a similar study in which 83% of ED collected urine cultures ultimately grew bacteria susceptibleto empiric treatment.8 This number was similar to the current study despite the latter study consisting of predominantly female patients (93%) and excluding patients with a history of benign prostatic hypertrophy, catheter use, or history of genitourinary cancer, which are frequently found within the VA population. Thus, despite having a differing patient population at the current study’s facility with characteristics that would classify most to be treated as a complicated UTI, empiric coverage rates remained similar. The lower than anticipated intervention rate by the pharmacist on rotation in the ED can be directly attributed to this high empiric match rate, which could in turn be attributed to the extensive use of broad-spectrum antibiotics for treatment.

Empiric antimicrobial selection is based largely on local resistance patterns.7 Of particular importance is the resistance patterns of E coli, as it is the primary isolate responsible for UTIs worldwide. Thus, it is not unexpected that the most frequently isolated pathogen in the current study also was E coli. While clinical practice guidelines state that hospital-wide antibiograms often are skewed by cultures collected from inpatients or those with complicated infection, the current study found hospital-wide E coli resistance patterns, specifically those related to fluoroquinolone use, to be similar to those collected in the ED alone (78.5% hospital-wide susceptibility vs. 75% ED susceptibility). This was expected, as similar studies comparing E coli resistance patterns from ED-collected urine cultures to those institution-wide also have found similar rates of resistance.8,9 These findings are of particular importance as E coli resistance is noted to be increasing, varies with geographic area, and local resistance patterns are rarely known.7 Thus, these findings may aid ED providers in their empiric antimicrobial selections.

Ciprofloxacin was the most frequently used medication for the treatment of UTIs. While overall empiric selections were found to have favorable resistance patterns, it is difficult to interpret the appropriateness of ciprofloxacin’s use in the present study. First, there is a distinct lack of US-based clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of complicated UTIs. As the majority of this study population was male, it is difficult to directly extrapolate from the current Infectious Diseases Society of America treatment guidelines for uncomplicated cystitis and apply to the study population. Although recommended for the treatment of pyelonephritis, it is unclear whether ciprofloxacin should be utilized as a first-line empiric option for the treatment of UTIs in males.

Despite the lack of disease-specific recommendations for ciprofloxacin, recommendations exist regarding its use when local resistance patterns are known.7 It is currently recommended that these agents not be used when resistance rates of E coli exceed 20% for trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or 10% for fluoroquinolones. As this study demonstrated a nearly 25% resistance rate for E coli to fluoroquinolones in both the ED and institution-wide sample populations, it could potentially be ascertained that ciprofloxacin is an inappropriate choice for the empiric treatment of UTIs in this patient population. However, as noted, it is unknown whether this recommendation would still be applicable when applied to the treatment of complicated cystitis and greater male population, as overall rates of susceptible cultures to all organisms was similar to other published studies.8,9

While there is scant specific guidance related to the treatment of complicated UTIs, there is emerging guidance on the use of fluoroquinolones, both in general and specifically related to the treatment of UTIs. In July 2016, the FDA issued a drug safety communication regarding the use of and warnings for fluoroquinolones, which explicitly stated that “health care professionals should not prescribe systemic fluoroquinolones to patients who have other treatment options for acute bacterial sinusitis, acute bacterial exacerbation of chronic bronchitis, and uncomplicated UTIs because the risks outweigh the benefits in these patients.”10

This guidance has the potential to impact fluoroquinolone prescribing significantly at RRVAMC. Given the large number of fluoroquinolones prescribed for UTIs, the downstream effects that this shift in prescribing would have is unknown. As most nonfluoroquinolones used for UTI typically are narrower in antimicrobial spectrum (eg, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin, cephalexin, etc) the possibility exists that the match rate for empiric therapy may decrease. Thus, a larger need for closer follow-up to assure adequate coverage may arise, posing a more expanded role for an ED-based pharmacist than was demonstrated in the current study.

This new guidance also may place providers in an area of larger uncertainty with regards to treating both complicated and uncomplicated cystitis. Given the enhanced warnings on fluoroquinolone use, it is unknown whether prescribers would gravitate to utilizing similar options as their peers as alternatives to fluoroquinolones. Similarly, duration of therapy with nonfluoroquinolone agents is unclear as well; as the present study demonstrated a large range in treatment duration of outpatients (3-14 days). While the average observed duration of 8.3 days is intuitively fitting, as the majority of cases were in males, no published guideline exists that affirms the appropriateness of this finding. Such uncertainty and potential inconsistency between providers affords a large opportunity for developing a standardized treatment pathway for the treatment of UTIs to ensure both effective and guideline concordant treatment for patients, specifically with regards to antimicrobial selection and duration of treatment.

It is noteworthy to mention that all follow-ups on positive cultures inadequately covered by empiric therapy took place on the day organism identification and susceptibility data were released. This finding was somewhat surprising, as it was originally theorized that most ED-collected urine cultures were not monitored to completion by a pharmacist and that would be necessary in order to ensure proper follow-up of culture results. What is not clear is whether there is a robust process for the follow-up of urine cultures in the ED. Most of the bug-drug mismatches coincidentally were admitted to the inpatient teams where there were appropriate personnel to follow up and adjust the antibiotic selection. If there was a bug-drug mismatch, and the patient was not admitted, it is unclear whether there is a consistent process for follow-up.

Given the limited number of mismatched cultures that required change in therapy, it is unknown if this role would expand if more narrow-spectrum agents were utilized, theoretically leading to a higher mismatch rate and necessitating closer follow-up. Furthermore, given the common practice of mailed prescriptions at the VA, it is all the more imperative that the cultures be acted upon on the day they were identified, as the mailing and processing time of prescriptions may limit the clinical utility in switching from a more broad-spectrum agent, to one more targeted for an identified organism. While a patient traveling back to the medical center for expedited prescription pickup at the pharmacy would alleviate this problem, many patients at the facility travel great distances or may not have readily available travel means to return to the medical center.

Future Directions

While minimal follow-up was required after a patient had left the ED, this study demonstrated a fundamental need for further refinements in antimicrobial stewardship activities within the ED. Duration of therapy, empiric selection, and proper dosing are key areas where the ED-based pharmacy resident was able to intervene during the time physically stationed in the ED. The data collected from this study demonstrated this and was ultimately combined with other ED-based interventions and utilized as supporting evidence in the pharmacy service business plan, outlining the necessity of a full-time pharmacy presence in the ED. The business plan submission, along with other ongoing RRVAMC initiatives, ultimately led to the approval for clinical pharmacy specialists to expand practice into the ED. These positions will continue to advance pharmacy practice within the ED, while affording opportunities for pharmacists to practice at the top of their licensure, provide individualized provider education, and deliver real-time antimicrobial stewardship interventions. Furthermore, as the majority of the study period was monitored outside of the ED, the project may provide a model for other VA institutions without full-time ED pharmacists to implement as a means to improve antimicrobial stewardship and further build an evidence base for expanding their pharmacy services to the ED.

Given the large number of fluoroquinolones utilized in the ED, this study has raised the question of what prescribing patterns look like with regards to outpatient UTI treatment within the realm of primary care at RRVAMC. Despite the great strides made with regards to antimicrobial stewardship at this facility on the inpatient side, no formal antimicrobial stewardship program exists for review in the outpatient setting, where literature suggests the majority of antibiotics are prescribed.3,11 While more robust protocols are in place for follow-up of culture data in the primary care realm at this facility, the prescribing patterns are relatively unknown.

A recent study completed at a similar VA facility found that 60% of antibiotics prescribed for cystitis, pharyngitis, or sinusitis on an outpatient basis were guideline-discordant, and CDC guidance has further recommended specific focus should be undertaken with regards to outpatient stewardship practices in the treatment of genitourinary infections.3,12 These findings highlight the need for outpatient antimicrobial stewardship and presents a compelling reason to further investigate outpatient prescribing within primary care at RRVAMC.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of the current study include the ability to monitor urine cultures in real time and to provide timely interventions in the event of a rare bug-drug mismatch. The evaluation of cultures in this study shows that the majority of cases had a drug selected with adequate coverage. The study did assure ED providers that, even though guidelines may suggest otherwise, urine cultures drawn in the ED at RRVAMC followed similar resistance patterns seen for the facility as a whole. Moreover, it is valuable as it captures data that are directly applicable to the VA patient population, in which there is little published data with regards to UTI treatment and no formal VA guidance.

A primary limitation of this study is the lack of differentiation between cultures collected from patients with or without indwelling catheters. However, only including patients who presented with signs and/or symptoms of a UTI limits the number of cultures that could potentially be deemed as colonization, thus minimizing the potential for nonpathogenic organisms to confound the results. This study also did not differentiate the setting from which the patient presented (eg, community, extended care facility, etc) that could have potentially provided guidance on resistance patterns for community-acquired UTIs and whether this may have differed from hospital-acquired or facility-acquired UTIs. Another limitation was the relatively short time frame for data collection. A data collection period greater than 91 days would allow for a larger sample size, thus making the data more robust and potentially allowing for the identification of other trends not seen in the current study. A longer data collection period also would have afforded the opportunity to track more robust clinical outcomes throughout the study, identifying whether treatment failure may have been linked to the use of certain classes or spectrums of activity of antibiotics.

Conclusion

Despite the E coli resistance rate to ciprofloxacin (> 20%), the empiric treatments chosen were > 85% effective, needing minimal follow-up once a patient left the ED. Nonetheless, a change in prescribing patterns based on recent national recommendations may provide expanded opportunities in antimicrobial stewardship for ED-based pharmacists. Further research is needed in antimicrobial stewardship within this facility’s outpatient primary care realm, potentially uncovering other opportunities for pharmacist intervention to assure guideline concordant care for the treatment of UTIs as well as other infections treated in primary care patients.

1. Obama B. Executive order–combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria. https://www.whitehouse.gov/the -press-office/2014/09/18/executive-order-combating-antibiotic-resistant-bacteria. Published September 18, 2014. Accessed June 7, 2018.

2. Livorsi DJ, O’Leary E, Pierce T, et al. A novel metric to monitor the influence of antimicrobial stewardship activities. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(6):721-723.

3. Sanchez GV, Fleming-Dutra KE, Roberts RM, Hick LA. Core elements of outpatient antibiotic stewardship. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(6):1-12.

4. Wymore ES, Casanova TJ, Broekenmeier RL, Martin JK Jr. Clinical pharmacist’s daily role in the emergency department of a community hospital. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2008;65(5):395-396, 398-399.

5. Frandzel S. ED pharmacists’ value on display at ASHP Midyear. http://www.pharmacypracticenews.com/ViewArticle.aspx?ses=ogst&d_id=53&a_id=22524. Published February 14, 2013. Accessed June 15, 2018.

6. Heytens S, DeSutter A, Coorevits L, et al. Women with symptoms of a urinary tract infection but a negative urine culture: PCR-based quantification of Escherichia coli suggests infection in most cases. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017;23(9)647-652.

7. Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(5):e103-e120.

8. Lingenfelter E, Drapkin Z, Fritz K, Youngquist S, Madsen T, Fix M. ED pharmacist monitoring of provider antibiotic selection aids appropriate treatment for outpatient urinary tract infection. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(8):1600-1603.

9. Zatorski C, Jordan JA, Cosgrove SE, Zocchi M, May L. Comparison of antibiotic susceptibility of Escherichia coli in urinary isolates from an emergency department with other institutional susceptibility data. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2015;72(24):2176-2180.

10. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: FDA updates warnings for oral and injectable fluoroquinolone antibiotics due to disabling side effects. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm511530.htm. Updated March 8, 2018. Accessed June 13, 2018.

11. Llor C, Bjerrum L. Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2014;5(6):229-241.

12. Meyer HE, Lund BC, Heintz BH, Alexander B, Egge JA, Livorsi DJ. Identifying opportunities to improve guideline-concordant antibiotic prescribing in veterans with acute respiratory infections or cystitis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(6):724-728.

On September 18, 2014, President Barack Obama signed an executive order that made addressing antibiotic-resistant bacteria a national security policy.1 This legislation resulted in the creation of a large multidepartment task force to combat the global and domestic problem of antimicrobial resistance. The order required hospitals and other inpatient health care delivery facilities, including the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), to implement robust antimicrobial stewardship programs that adhere to best practices, such as those identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). More specifically, the VA was mandated to take steps to encourage other areas of health care, such as ambulatory surgery centers and outpatient clinics, to adopt antimicrobial stewardship programs.1 This order also reinforced the importance for VA facilities to continue to develop, improve, and sustain efforts in antimicrobial stewardship.

Prior to the order, in 2012 the Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center (RRVAMC) in Indianapolis, Indiana, implemented an inpatient antimicrobial stewardship program that included thrice-weekly meetings to review inpatient records and make stewardship recommendations with an infectious diseases physician champion and clinical pharmacists. These efforts led to the improved use of antimicrobial agents on the inpatient side of the medical center. During the first 4 years of implementation, the program helped to decrease the defined daily doses of broad-spectrum antibiotics per 1,000 patient days nearly 36%, from 532 in 2012 to 343 in 2015, as well as decrease the days of therapy of fluoroquinolones per 1,000 patient days 28.75%, from 80 in 2012 to 57 in 2015. Additionally, the program showed a significant decrease in the standardized antimicrobial administration ratio, a benchmark measure developed by the CDC to reflect a facility’s actual antimicrobial use to the expected use of a similar facility based on bed size, number of intensive care unit beds, location type, and medical school affiliation.2

While the RRVAMC antimicrobial stewardship team has been able to intervene on most of the inpatients admitted to the medical center, the outpatient arena has had few antimicrobial stewardship interventions. Recognizing a need to establish and expand pharmacy services and for improvement of outpatient antimicrobial stewardship, RRVAMC leadership decided to establish a pharmacist-led outpatient antimicrobial surveillance program, starting specifically within the emergency department (ED).

Clinical pharmacists in the ED setting are uniquely positioned to improve patient care and encourage the judicious use of antimicrobials for empiric treatment of urinary tract infections (UTIs). The CDC’s Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship recommends pharmacist availability in the ED setting, and previous literature has demonstrated pharmacist utility in ED postdischarge culture monitoring and surveillance.3-5

This article will highlight one such program review at the RRVAMC and demonstrate the need for pharmacist-led antimicrobial stewardship and monitoring in the ED. The purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that pharmacist intervention would be necessary to prospectively check for “bug-drug mismatch” and assure proper follow-up of urine cultures at this institution. The project was deemed to be quality improvement and thereby granted exemption by the RRVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Methods

This project took place at the RRVAMC, a 229-bed tertiary academic medical center that serves > 60,000 patients annually. The RRVAMC ED has 20 beds and received about 29,000 visits in 2014. Patients were eligible for initial evaluation if they had a urine culture collected in the ED within the 91-day period from September 1, 2015 to November 30, 2015. Patients were included for data analysis if it was documented that they were treated for actual or clinically suspected, based on signs and symptoms, uncomplicated UTI, complicated UTI, or UTI with pyelonephritis. Patients did not need to have a positive urine culture for inclusion, as infections could still be present despite negative culture results.6 Patients with positive cultures who were not clinically symptomatic of a UTI and were not treated as such by the ED provider (ie, asymptomatic bacteriuria) were excluded from the study.

Data collection took place via daily chart review of patient records in both the Computerized Patient Record System and Decentralized Hospital Computer Program medical applications as urine cultures were performed. Data were gathered and assessed by a postgraduate year-2 internal medicine pharmacy resident on rotation in the ED who reviewed cultures daily and made interventions based on the results as needed. The pharmacy resident was physically present within the ED during the first 30 days of the project. The pharmacy resident was not within the direct practice area during the final 61 days of the project but was in a different area of the hospital and available for consultation.

Primary data collected included urine culture results and susceptibilities, empiric antimicrobial choices, and admission status. Other data collected included duration of treatment and secondary antibiotics chosen, each of which specifically evaluated those patients who were not admitted to the hospital and were thus treated as outpatients. Additional data generated from this study were used to identify empiric antibiotics utilized for the treatment of UTIs and assess for appropriate selection and duration of therapy within this institution.

Results

During the study period, 722 urine cultures were collected in the ED and were included for initial evaluation. Of these, 127 were treated by the ED provider pursuant to one of the indications specified and were included in the data analysis. Treatment with an antimicrobial agent provided adequate coverage for the identified pathogen in 112 patients, yielding a match rate of 88%. As all included cultures were collected in suspicion of an infection, those cultures yielding no growth were considered to have been adequately covered.

Nearly half (45%) of treatment plans included a fluoroquinolone. Of those treated on an outpatient basis, fluoroquinolones were even more frequently used, comprising 50 of 82 (61%) courses. Ciprofloxacin was the most frequently used treatment, used in 39 of the 82 outpatient regimens (48%). Cephalexin was the second most common and was used in 14 outpatient regimens (17%), followed by levofloxacin (15%) (Figure 1).

Mismatched cultures, or those where the prescribed antibiotic did not provide adequate coverage of the identified pathogens based on susceptibilities, occurred at a rate of 12%. Follow-up on these cultures was determined largely by the patient’s admission status. The majority of mismatched cultures were addressed by the inpatient team (10/15) upon admission.

Discussion

Empiric antibiotic selection for the treatment of UTIs continues to be the cornerstone of antibiotic management for the treatment of such a disease state.7 The noted drug-bug match rate of 88% in this study demonstrates effective initial empiric coverage and ensures a vast majority of veterans receive adequate coverage for identified pathogens. Additionally, this rate shows that the current system seems to be functioning appropriately and refutes the author’s preconceived ideas that the mismatch rate was higher at RRVAMC. However, these findings also demonstrate a predominant use of fluoroquinolones for empiric treatment in a majority of patients who could be better served with narrower spectrum agents. Only 2 of the outpatient regimens were for the treatment of pyelonephritis, the only indication in which a fluoroquinolone would be the standard of care per guideline recommendations.7

These findings were consistent with a similar study in which 83% of ED collected urine cultures ultimately grew bacteria susceptibleto empiric treatment.8 This number was similar to the current study despite the latter study consisting of predominantly female patients (93%) and excluding patients with a history of benign prostatic hypertrophy, catheter use, or history of genitourinary cancer, which are frequently found within the VA population. Thus, despite having a differing patient population at the current study’s facility with characteristics that would classify most to be treated as a complicated UTI, empiric coverage rates remained similar. The lower than anticipated intervention rate by the pharmacist on rotation in the ED can be directly attributed to this high empiric match rate, which could in turn be attributed to the extensive use of broad-spectrum antibiotics for treatment.

Empiric antimicrobial selection is based largely on local resistance patterns.7 Of particular importance is the resistance patterns of E coli, as it is the primary isolate responsible for UTIs worldwide. Thus, it is not unexpected that the most frequently isolated pathogen in the current study also was E coli. While clinical practice guidelines state that hospital-wide antibiograms often are skewed by cultures collected from inpatients or those with complicated infection, the current study found hospital-wide E coli resistance patterns, specifically those related to fluoroquinolone use, to be similar to those collected in the ED alone (78.5% hospital-wide susceptibility vs. 75% ED susceptibility). This was expected, as similar studies comparing E coli resistance patterns from ED-collected urine cultures to those institution-wide also have found similar rates of resistance.8,9 These findings are of particular importance as E coli resistance is noted to be increasing, varies with geographic area, and local resistance patterns are rarely known.7 Thus, these findings may aid ED providers in their empiric antimicrobial selections.

Ciprofloxacin was the most frequently used medication for the treatment of UTIs. While overall empiric selections were found to have favorable resistance patterns, it is difficult to interpret the appropriateness of ciprofloxacin’s use in the present study. First, there is a distinct lack of US-based clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of complicated UTIs. As the majority of this study population was male, it is difficult to directly extrapolate from the current Infectious Diseases Society of America treatment guidelines for uncomplicated cystitis and apply to the study population. Although recommended for the treatment of pyelonephritis, it is unclear whether ciprofloxacin should be utilized as a first-line empiric option for the treatment of UTIs in males.

Despite the lack of disease-specific recommendations for ciprofloxacin, recommendations exist regarding its use when local resistance patterns are known.7 It is currently recommended that these agents not be used when resistance rates of E coli exceed 20% for trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or 10% for fluoroquinolones. As this study demonstrated a nearly 25% resistance rate for E coli to fluoroquinolones in both the ED and institution-wide sample populations, it could potentially be ascertained that ciprofloxacin is an inappropriate choice for the empiric treatment of UTIs in this patient population. However, as noted, it is unknown whether this recommendation would still be applicable when applied to the treatment of complicated cystitis and greater male population, as overall rates of susceptible cultures to all organisms was similar to other published studies.8,9

While there is scant specific guidance related to the treatment of complicated UTIs, there is emerging guidance on the use of fluoroquinolones, both in general and specifically related to the treatment of UTIs. In July 2016, the FDA issued a drug safety communication regarding the use of and warnings for fluoroquinolones, which explicitly stated that “health care professionals should not prescribe systemic fluoroquinolones to patients who have other treatment options for acute bacterial sinusitis, acute bacterial exacerbation of chronic bronchitis, and uncomplicated UTIs because the risks outweigh the benefits in these patients.”10

This guidance has the potential to impact fluoroquinolone prescribing significantly at RRVAMC. Given the large number of fluoroquinolones prescribed for UTIs, the downstream effects that this shift in prescribing would have is unknown. As most nonfluoroquinolones used for UTI typically are narrower in antimicrobial spectrum (eg, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin, cephalexin, etc) the possibility exists that the match rate for empiric therapy may decrease. Thus, a larger need for closer follow-up to assure adequate coverage may arise, posing a more expanded role for an ED-based pharmacist than was demonstrated in the current study.

This new guidance also may place providers in an area of larger uncertainty with regards to treating both complicated and uncomplicated cystitis. Given the enhanced warnings on fluoroquinolone use, it is unknown whether prescribers would gravitate to utilizing similar options as their peers as alternatives to fluoroquinolones. Similarly, duration of therapy with nonfluoroquinolone agents is unclear as well; as the present study demonstrated a large range in treatment duration of outpatients (3-14 days). While the average observed duration of 8.3 days is intuitively fitting, as the majority of cases were in males, no published guideline exists that affirms the appropriateness of this finding. Such uncertainty and potential inconsistency between providers affords a large opportunity for developing a standardized treatment pathway for the treatment of UTIs to ensure both effective and guideline concordant treatment for patients, specifically with regards to antimicrobial selection and duration of treatment.

It is noteworthy to mention that all follow-ups on positive cultures inadequately covered by empiric therapy took place on the day organism identification and susceptibility data were released. This finding was somewhat surprising, as it was originally theorized that most ED-collected urine cultures were not monitored to completion by a pharmacist and that would be necessary in order to ensure proper follow-up of culture results. What is not clear is whether there is a robust process for the follow-up of urine cultures in the ED. Most of the bug-drug mismatches coincidentally were admitted to the inpatient teams where there were appropriate personnel to follow up and adjust the antibiotic selection. If there was a bug-drug mismatch, and the patient was not admitted, it is unclear whether there is a consistent process for follow-up.

Given the limited number of mismatched cultures that required change in therapy, it is unknown if this role would expand if more narrow-spectrum agents were utilized, theoretically leading to a higher mismatch rate and necessitating closer follow-up. Furthermore, given the common practice of mailed prescriptions at the VA, it is all the more imperative that the cultures be acted upon on the day they were identified, as the mailing and processing time of prescriptions may limit the clinical utility in switching from a more broad-spectrum agent, to one more targeted for an identified organism. While a patient traveling back to the medical center for expedited prescription pickup at the pharmacy would alleviate this problem, many patients at the facility travel great distances or may not have readily available travel means to return to the medical center.

Future Directions

While minimal follow-up was required after a patient had left the ED, this study demonstrated a fundamental need for further refinements in antimicrobial stewardship activities within the ED. Duration of therapy, empiric selection, and proper dosing are key areas where the ED-based pharmacy resident was able to intervene during the time physically stationed in the ED. The data collected from this study demonstrated this and was ultimately combined with other ED-based interventions and utilized as supporting evidence in the pharmacy service business plan, outlining the necessity of a full-time pharmacy presence in the ED. The business plan submission, along with other ongoing RRVAMC initiatives, ultimately led to the approval for clinical pharmacy specialists to expand practice into the ED. These positions will continue to advance pharmacy practice within the ED, while affording opportunities for pharmacists to practice at the top of their licensure, provide individualized provider education, and deliver real-time antimicrobial stewardship interventions. Furthermore, as the majority of the study period was monitored outside of the ED, the project may provide a model for other VA institutions without full-time ED pharmacists to implement as a means to improve antimicrobial stewardship and further build an evidence base for expanding their pharmacy services to the ED.

Given the large number of fluoroquinolones utilized in the ED, this study has raised the question of what prescribing patterns look like with regards to outpatient UTI treatment within the realm of primary care at RRVAMC. Despite the great strides made with regards to antimicrobial stewardship at this facility on the inpatient side, no formal antimicrobial stewardship program exists for review in the outpatient setting, where literature suggests the majority of antibiotics are prescribed.3,11 While more robust protocols are in place for follow-up of culture data in the primary care realm at this facility, the prescribing patterns are relatively unknown.

A recent study completed at a similar VA facility found that 60% of antibiotics prescribed for cystitis, pharyngitis, or sinusitis on an outpatient basis were guideline-discordant, and CDC guidance has further recommended specific focus should be undertaken with regards to outpatient stewardship practices in the treatment of genitourinary infections.3,12 These findings highlight the need for outpatient antimicrobial stewardship and presents a compelling reason to further investigate outpatient prescribing within primary care at RRVAMC.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of the current study include the ability to monitor urine cultures in real time and to provide timely interventions in the event of a rare bug-drug mismatch. The evaluation of cultures in this study shows that the majority of cases had a drug selected with adequate coverage. The study did assure ED providers that, even though guidelines may suggest otherwise, urine cultures drawn in the ED at RRVAMC followed similar resistance patterns seen for the facility as a whole. Moreover, it is valuable as it captures data that are directly applicable to the VA patient population, in which there is little published data with regards to UTI treatment and no formal VA guidance.

A primary limitation of this study is the lack of differentiation between cultures collected from patients with or without indwelling catheters. However, only including patients who presented with signs and/or symptoms of a UTI limits the number of cultures that could potentially be deemed as colonization, thus minimizing the potential for nonpathogenic organisms to confound the results. This study also did not differentiate the setting from which the patient presented (eg, community, extended care facility, etc) that could have potentially provided guidance on resistance patterns for community-acquired UTIs and whether this may have differed from hospital-acquired or facility-acquired UTIs. Another limitation was the relatively short time frame for data collection. A data collection period greater than 91 days would allow for a larger sample size, thus making the data more robust and potentially allowing for the identification of other trends not seen in the current study. A longer data collection period also would have afforded the opportunity to track more robust clinical outcomes throughout the study, identifying whether treatment failure may have been linked to the use of certain classes or spectrums of activity of antibiotics.

Conclusion

Despite the E coli resistance rate to ciprofloxacin (> 20%), the empiric treatments chosen were > 85% effective, needing minimal follow-up once a patient left the ED. Nonetheless, a change in prescribing patterns based on recent national recommendations may provide expanded opportunities in antimicrobial stewardship for ED-based pharmacists. Further research is needed in antimicrobial stewardship within this facility’s outpatient primary care realm, potentially uncovering other opportunities for pharmacist intervention to assure guideline concordant care for the treatment of UTIs as well as other infections treated in primary care patients.

On September 18, 2014, President Barack Obama signed an executive order that made addressing antibiotic-resistant bacteria a national security policy.1 This legislation resulted in the creation of a large multidepartment task force to combat the global and domestic problem of antimicrobial resistance. The order required hospitals and other inpatient health care delivery facilities, including the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), to implement robust antimicrobial stewardship programs that adhere to best practices, such as those identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). More specifically, the VA was mandated to take steps to encourage other areas of health care, such as ambulatory surgery centers and outpatient clinics, to adopt antimicrobial stewardship programs.1 This order also reinforced the importance for VA facilities to continue to develop, improve, and sustain efforts in antimicrobial stewardship.

Prior to the order, in 2012 the Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center (RRVAMC) in Indianapolis, Indiana, implemented an inpatient antimicrobial stewardship program that included thrice-weekly meetings to review inpatient records and make stewardship recommendations with an infectious diseases physician champion and clinical pharmacists. These efforts led to the improved use of antimicrobial agents on the inpatient side of the medical center. During the first 4 years of implementation, the program helped to decrease the defined daily doses of broad-spectrum antibiotics per 1,000 patient days nearly 36%, from 532 in 2012 to 343 in 2015, as well as decrease the days of therapy of fluoroquinolones per 1,000 patient days 28.75%, from 80 in 2012 to 57 in 2015. Additionally, the program showed a significant decrease in the standardized antimicrobial administration ratio, a benchmark measure developed by the CDC to reflect a facility’s actual antimicrobial use to the expected use of a similar facility based on bed size, number of intensive care unit beds, location type, and medical school affiliation.2

While the RRVAMC antimicrobial stewardship team has been able to intervene on most of the inpatients admitted to the medical center, the outpatient arena has had few antimicrobial stewardship interventions. Recognizing a need to establish and expand pharmacy services and for improvement of outpatient antimicrobial stewardship, RRVAMC leadership decided to establish a pharmacist-led outpatient antimicrobial surveillance program, starting specifically within the emergency department (ED).

Clinical pharmacists in the ED setting are uniquely positioned to improve patient care and encourage the judicious use of antimicrobials for empiric treatment of urinary tract infections (UTIs). The CDC’s Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship recommends pharmacist availability in the ED setting, and previous literature has demonstrated pharmacist utility in ED postdischarge culture monitoring and surveillance.3-5

This article will highlight one such program review at the RRVAMC and demonstrate the need for pharmacist-led antimicrobial stewardship and monitoring in the ED. The purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that pharmacist intervention would be necessary to prospectively check for “bug-drug mismatch” and assure proper follow-up of urine cultures at this institution. The project was deemed to be quality improvement and thereby granted exemption by the RRVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Methods

This project took place at the RRVAMC, a 229-bed tertiary academic medical center that serves > 60,000 patients annually. The RRVAMC ED has 20 beds and received about 29,000 visits in 2014. Patients were eligible for initial evaluation if they had a urine culture collected in the ED within the 91-day period from September 1, 2015 to November 30, 2015. Patients were included for data analysis if it was documented that they were treated for actual or clinically suspected, based on signs and symptoms, uncomplicated UTI, complicated UTI, or UTI with pyelonephritis. Patients did not need to have a positive urine culture for inclusion, as infections could still be present despite negative culture results.6 Patients with positive cultures who were not clinically symptomatic of a UTI and were not treated as such by the ED provider (ie, asymptomatic bacteriuria) were excluded from the study.

Data collection took place via daily chart review of patient records in both the Computerized Patient Record System and Decentralized Hospital Computer Program medical applications as urine cultures were performed. Data were gathered and assessed by a postgraduate year-2 internal medicine pharmacy resident on rotation in the ED who reviewed cultures daily and made interventions based on the results as needed. The pharmacy resident was physically present within the ED during the first 30 days of the project. The pharmacy resident was not within the direct practice area during the final 61 days of the project but was in a different area of the hospital and available for consultation.

Primary data collected included urine culture results and susceptibilities, empiric antimicrobial choices, and admission status. Other data collected included duration of treatment and secondary antibiotics chosen, each of which specifically evaluated those patients who were not admitted to the hospital and were thus treated as outpatients. Additional data generated from this study were used to identify empiric antibiotics utilized for the treatment of UTIs and assess for appropriate selection and duration of therapy within this institution.

Results

During the study period, 722 urine cultures were collected in the ED and were included for initial evaluation. Of these, 127 were treated by the ED provider pursuant to one of the indications specified and were included in the data analysis. Treatment with an antimicrobial agent provided adequate coverage for the identified pathogen in 112 patients, yielding a match rate of 88%. As all included cultures were collected in suspicion of an infection, those cultures yielding no growth were considered to have been adequately covered.

Nearly half (45%) of treatment plans included a fluoroquinolone. Of those treated on an outpatient basis, fluoroquinolones were even more frequently used, comprising 50 of 82 (61%) courses. Ciprofloxacin was the most frequently used treatment, used in 39 of the 82 outpatient regimens (48%). Cephalexin was the second most common and was used in 14 outpatient regimens (17%), followed by levofloxacin (15%) (Figure 1).

Mismatched cultures, or those where the prescribed antibiotic did not provide adequate coverage of the identified pathogens based on susceptibilities, occurred at a rate of 12%. Follow-up on these cultures was determined largely by the patient’s admission status. The majority of mismatched cultures were addressed by the inpatient team (10/15) upon admission.

Discussion

Empiric antibiotic selection for the treatment of UTIs continues to be the cornerstone of antibiotic management for the treatment of such a disease state.7 The noted drug-bug match rate of 88% in this study demonstrates effective initial empiric coverage and ensures a vast majority of veterans receive adequate coverage for identified pathogens. Additionally, this rate shows that the current system seems to be functioning appropriately and refutes the author’s preconceived ideas that the mismatch rate was higher at RRVAMC. However, these findings also demonstrate a predominant use of fluoroquinolones for empiric treatment in a majority of patients who could be better served with narrower spectrum agents. Only 2 of the outpatient regimens were for the treatment of pyelonephritis, the only indication in which a fluoroquinolone would be the standard of care per guideline recommendations.7

These findings were consistent with a similar study in which 83% of ED collected urine cultures ultimately grew bacteria susceptibleto empiric treatment.8 This number was similar to the current study despite the latter study consisting of predominantly female patients (93%) and excluding patients with a history of benign prostatic hypertrophy, catheter use, or history of genitourinary cancer, which are frequently found within the VA population. Thus, despite having a differing patient population at the current study’s facility with characteristics that would classify most to be treated as a complicated UTI, empiric coverage rates remained similar. The lower than anticipated intervention rate by the pharmacist on rotation in the ED can be directly attributed to this high empiric match rate, which could in turn be attributed to the extensive use of broad-spectrum antibiotics for treatment.

Empiric antimicrobial selection is based largely on local resistance patterns.7 Of particular importance is the resistance patterns of E coli, as it is the primary isolate responsible for UTIs worldwide. Thus, it is not unexpected that the most frequently isolated pathogen in the current study also was E coli. While clinical practice guidelines state that hospital-wide antibiograms often are skewed by cultures collected from inpatients or those with complicated infection, the current study found hospital-wide E coli resistance patterns, specifically those related to fluoroquinolone use, to be similar to those collected in the ED alone (78.5% hospital-wide susceptibility vs. 75% ED susceptibility). This was expected, as similar studies comparing E coli resistance patterns from ED-collected urine cultures to those institution-wide also have found similar rates of resistance.8,9 These findings are of particular importance as E coli resistance is noted to be increasing, varies with geographic area, and local resistance patterns are rarely known.7 Thus, these findings may aid ED providers in their empiric antimicrobial selections.

Ciprofloxacin was the most frequently used medication for the treatment of UTIs. While overall empiric selections were found to have favorable resistance patterns, it is difficult to interpret the appropriateness of ciprofloxacin’s use in the present study. First, there is a distinct lack of US-based clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of complicated UTIs. As the majority of this study population was male, it is difficult to directly extrapolate from the current Infectious Diseases Society of America treatment guidelines for uncomplicated cystitis and apply to the study population. Although recommended for the treatment of pyelonephritis, it is unclear whether ciprofloxacin should be utilized as a first-line empiric option for the treatment of UTIs in males.

Despite the lack of disease-specific recommendations for ciprofloxacin, recommendations exist regarding its use when local resistance patterns are known.7 It is currently recommended that these agents not be used when resistance rates of E coli exceed 20% for trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or 10% for fluoroquinolones. As this study demonstrated a nearly 25% resistance rate for E coli to fluoroquinolones in both the ED and institution-wide sample populations, it could potentially be ascertained that ciprofloxacin is an inappropriate choice for the empiric treatment of UTIs in this patient population. However, as noted, it is unknown whether this recommendation would still be applicable when applied to the treatment of complicated cystitis and greater male population, as overall rates of susceptible cultures to all organisms was similar to other published studies.8,9