User login

How to identify DVT faster in pediatric osteomyelitis

MALMO, SWEDEN – Early identification of deep vein thrombosis in children with acute hematogenous osteomyelitis is critical given the need to plan anticoagulation management around the high likelihood that such patients will undergo multiple surgeries, Lawson A.B. Copley, MD, said at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

He and his coinvestigators have identified a handful of risk factors helpful in expediting recognition of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in children with suspected invasive infection of the musculoskeletal system.

“To improve the rate and timing of identification of DVT, we recommend performing early screening ultrasound on all children with these risk factors who are suspected of having acute hematogenous osteomyelitis,” declared Dr. Copley, professor of orthopaedic surgery and pediatrics at the University of Texas, Dallas.

Delayed diagnosis of DVT in the setting of acute hematogenous osteomyelitis (AHO) is common. Indeed, in a review of the experience at Children’s Medical Center Dallas during 2012-2014, the average time delay from ICU admission in patients suspected of having AHO to identification of DVT by ultrasound was 6.3 days.

“We’ve changed some things on the basis of that study in order to accelerate that timeline,” he explained.

Their major change was to identify actionable risk factors for DVT. This was accomplished by conducting a retrospective study of the EHR of nearly 902,000 Texas children during 2008-2016.

The study demonstrated that children with AHO complicated by DVT are, from the get-go, very different from AHO patients without DVT. They have higher illness severity of illness, are more likely to be admitted to the ICU, are prone to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection with prolonged bacteremia, and are much more likely to undergo multiple surgeries. Moreover, children with AHO and DVT differed substantially from other children with DVT: The dual diagnosis children lacked comorbid conditions, were prone to septic pulmonary emboli, didn’t develop postthrombotic syndrome marked by chronic venous stasis and ulcerations, and had invariably negative coagulopathy workups.

“There is no need, we feel, to perform a hypercoagulopathy workup in children with AHO complicated by DVT,” Dr. Copley said.

Drilling deeper into the data, he and his coinvestigators identified 224 new cases of DVT in the study population, for a prevalence of 2.5 per 10,000 children, along with 466 children with AHO. A total of 6% of children with AHO had DVT, and 12.1% of all children with DVT had AHO. The researchers then compared the demographics, laboratory parameters, and treatment in three cohorts: the 196 children with DVT without AHO, 28 with both AHO and DVT, and 438 with AHO without DVT.

Through this analysis, they came up with a list of risk factors warranting early screening ultrasound in children suspected of having AHO:

- An initial C-reactive protein level above 8 mg/dL, which was present in all 28 dual diagnosis children.

- ICU admission, which occurred in 19 of 28 (68%) children.

- A severity of illness score of at least 7 on a 10-point scale during the first several days in the hospital, present in 27 of the 28 children. The severity of illness scale was developed and validated by Dr. Copley and coworkers (J Pediatr Orthop. 2016 Oct 12. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000879).

- Bacteremia in the initial blood culture, present in 23 of 28 patients (82%).

- Just under 90% of the children with AHO and DVT had methicillin-resistant S. aureus, compared with 20% of those with AHO without DVT.

- Septic pulmonary emboli visualized on chest x-ray, a complication that occurred in 64% of the dual diagnosis group versus just 1% of patients with DVT without AHO.

- A band percentage of white blood cells greater than 1.5%, present in 86% of children with AHO and DVT.

More than 90% of children with AHO and DVT underwent surgery, with a mean of 2.7 surgeries per child, in contrast to the group with AHO without DVT, 55% of whom had surgery, with a mean of 0.7 surgeries per child.

Of note, there was no significant difference in the occurrence of pulmonary embolism between children with DVT without AHO versus those with DVT and AHO, with a rate of about 10% in both groups.

Dr. Copley reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

MALMO, SWEDEN – Early identification of deep vein thrombosis in children with acute hematogenous osteomyelitis is critical given the need to plan anticoagulation management around the high likelihood that such patients will undergo multiple surgeries, Lawson A.B. Copley, MD, said at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

He and his coinvestigators have identified a handful of risk factors helpful in expediting recognition of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in children with suspected invasive infection of the musculoskeletal system.

“To improve the rate and timing of identification of DVT, we recommend performing early screening ultrasound on all children with these risk factors who are suspected of having acute hematogenous osteomyelitis,” declared Dr. Copley, professor of orthopaedic surgery and pediatrics at the University of Texas, Dallas.

Delayed diagnosis of DVT in the setting of acute hematogenous osteomyelitis (AHO) is common. Indeed, in a review of the experience at Children’s Medical Center Dallas during 2012-2014, the average time delay from ICU admission in patients suspected of having AHO to identification of DVT by ultrasound was 6.3 days.

“We’ve changed some things on the basis of that study in order to accelerate that timeline,” he explained.

Their major change was to identify actionable risk factors for DVT. This was accomplished by conducting a retrospective study of the EHR of nearly 902,000 Texas children during 2008-2016.

The study demonstrated that children with AHO complicated by DVT are, from the get-go, very different from AHO patients without DVT. They have higher illness severity of illness, are more likely to be admitted to the ICU, are prone to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection with prolonged bacteremia, and are much more likely to undergo multiple surgeries. Moreover, children with AHO and DVT differed substantially from other children with DVT: The dual diagnosis children lacked comorbid conditions, were prone to septic pulmonary emboli, didn’t develop postthrombotic syndrome marked by chronic venous stasis and ulcerations, and had invariably negative coagulopathy workups.

“There is no need, we feel, to perform a hypercoagulopathy workup in children with AHO complicated by DVT,” Dr. Copley said.

Drilling deeper into the data, he and his coinvestigators identified 224 new cases of DVT in the study population, for a prevalence of 2.5 per 10,000 children, along with 466 children with AHO. A total of 6% of children with AHO had DVT, and 12.1% of all children with DVT had AHO. The researchers then compared the demographics, laboratory parameters, and treatment in three cohorts: the 196 children with DVT without AHO, 28 with both AHO and DVT, and 438 with AHO without DVT.

Through this analysis, they came up with a list of risk factors warranting early screening ultrasound in children suspected of having AHO:

- An initial C-reactive protein level above 8 mg/dL, which was present in all 28 dual diagnosis children.

- ICU admission, which occurred in 19 of 28 (68%) children.

- A severity of illness score of at least 7 on a 10-point scale during the first several days in the hospital, present in 27 of the 28 children. The severity of illness scale was developed and validated by Dr. Copley and coworkers (J Pediatr Orthop. 2016 Oct 12. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000879).

- Bacteremia in the initial blood culture, present in 23 of 28 patients (82%).

- Just under 90% of the children with AHO and DVT had methicillin-resistant S. aureus, compared with 20% of those with AHO without DVT.

- Septic pulmonary emboli visualized on chest x-ray, a complication that occurred in 64% of the dual diagnosis group versus just 1% of patients with DVT without AHO.

- A band percentage of white blood cells greater than 1.5%, present in 86% of children with AHO and DVT.

More than 90% of children with AHO and DVT underwent surgery, with a mean of 2.7 surgeries per child, in contrast to the group with AHO without DVT, 55% of whom had surgery, with a mean of 0.7 surgeries per child.

Of note, there was no significant difference in the occurrence of pulmonary embolism between children with DVT without AHO versus those with DVT and AHO, with a rate of about 10% in both groups.

Dr. Copley reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

MALMO, SWEDEN – Early identification of deep vein thrombosis in children with acute hematogenous osteomyelitis is critical given the need to plan anticoagulation management around the high likelihood that such patients will undergo multiple surgeries, Lawson A.B. Copley, MD, said at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

He and his coinvestigators have identified a handful of risk factors helpful in expediting recognition of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in children with suspected invasive infection of the musculoskeletal system.

“To improve the rate and timing of identification of DVT, we recommend performing early screening ultrasound on all children with these risk factors who are suspected of having acute hematogenous osteomyelitis,” declared Dr. Copley, professor of orthopaedic surgery and pediatrics at the University of Texas, Dallas.

Delayed diagnosis of DVT in the setting of acute hematogenous osteomyelitis (AHO) is common. Indeed, in a review of the experience at Children’s Medical Center Dallas during 2012-2014, the average time delay from ICU admission in patients suspected of having AHO to identification of DVT by ultrasound was 6.3 days.

“We’ve changed some things on the basis of that study in order to accelerate that timeline,” he explained.

Their major change was to identify actionable risk factors for DVT. This was accomplished by conducting a retrospective study of the EHR of nearly 902,000 Texas children during 2008-2016.

The study demonstrated that children with AHO complicated by DVT are, from the get-go, very different from AHO patients without DVT. They have higher illness severity of illness, are more likely to be admitted to the ICU, are prone to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection with prolonged bacteremia, and are much more likely to undergo multiple surgeries. Moreover, children with AHO and DVT differed substantially from other children with DVT: The dual diagnosis children lacked comorbid conditions, were prone to septic pulmonary emboli, didn’t develop postthrombotic syndrome marked by chronic venous stasis and ulcerations, and had invariably negative coagulopathy workups.

“There is no need, we feel, to perform a hypercoagulopathy workup in children with AHO complicated by DVT,” Dr. Copley said.

Drilling deeper into the data, he and his coinvestigators identified 224 new cases of DVT in the study population, for a prevalence of 2.5 per 10,000 children, along with 466 children with AHO. A total of 6% of children with AHO had DVT, and 12.1% of all children with DVT had AHO. The researchers then compared the demographics, laboratory parameters, and treatment in three cohorts: the 196 children with DVT without AHO, 28 with both AHO and DVT, and 438 with AHO without DVT.

Through this analysis, they came up with a list of risk factors warranting early screening ultrasound in children suspected of having AHO:

- An initial C-reactive protein level above 8 mg/dL, which was present in all 28 dual diagnosis children.

- ICU admission, which occurred in 19 of 28 (68%) children.

- A severity of illness score of at least 7 on a 10-point scale during the first several days in the hospital, present in 27 of the 28 children. The severity of illness scale was developed and validated by Dr. Copley and coworkers (J Pediatr Orthop. 2016 Oct 12. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000879).

- Bacteremia in the initial blood culture, present in 23 of 28 patients (82%).

- Just under 90% of the children with AHO and DVT had methicillin-resistant S. aureus, compared with 20% of those with AHO without DVT.

- Septic pulmonary emboli visualized on chest x-ray, a complication that occurred in 64% of the dual diagnosis group versus just 1% of patients with DVT without AHO.

- A band percentage of white blood cells greater than 1.5%, present in 86% of children with AHO and DVT.

More than 90% of children with AHO and DVT underwent surgery, with a mean of 2.7 surgeries per child, in contrast to the group with AHO without DVT, 55% of whom had surgery, with a mean of 0.7 surgeries per child.

Of note, there was no significant difference in the occurrence of pulmonary embolism between children with DVT without AHO versus those with DVT and AHO, with a rate of about 10% in both groups.

Dr. Copley reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2018

Key clinical point: Osteomyelitis patients with deep vein thrombosis are much sicker than those without DVT.

Major finding:

Study details: This was a retrospective study of the medical records of more than 900,000 Texas children.

Disclosures: Dr. Copley reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

Too much to disagree on to let politics enter an office visit

“I can’t believe you’re drinking that.”

The young woman across the desk from me seemed perplexed, and I didn’t know why.

I’m one of those people who always has something to drink in front of me while working. A bottle of Costco green tea, Diet Coke, coffee. I also have a SodaStream gadget at my office, and that bottle is what I had on my desk at the moment.

I naively said “Why? I doubt it’s any worse for me than any other soda.”

That sure set her off, and I got a lecture about SodaStream being an Israeli company and her opinions on the Middle East, Israel, Palestine, etc. I listened politely for a moment, then redirected her back to the reason for her visit.

Not being someone who follows the news in detail, I‘d been unaware there was any controversy behind the soda bottle on my desk that morning. To me, it was just my choice of beverage.

The trouble here is that it’s possible to politicize pretty much anything in a divided world. I try to stay, for better or worse, ignorant of such things. My soft drink choice reflects nothing more than what I felt like drinking when I went back to my office’s tiny break room between appointments.

If you dig far enough into any company’s – or person’s – background, you’ll find something you disagree with. Just like any drug I prescribe will have side effects.

It’s for this reason that I keep politics out of my office. Patients, such as this lady, may express theirs, but I’ll never express mine. Too many in this world see each other in an “us vs. them” frame, quick to declare someone with different views as the enemy, rather than another decent person with an honest difference of opinion.

And it’s irrelevant to what I’m trying to achieve at my office anyway – caring for patients.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

“I can’t believe you’re drinking that.”

The young woman across the desk from me seemed perplexed, and I didn’t know why.

I’m one of those people who always has something to drink in front of me while working. A bottle of Costco green tea, Diet Coke, coffee. I also have a SodaStream gadget at my office, and that bottle is what I had on my desk at the moment.

I naively said “Why? I doubt it’s any worse for me than any other soda.”

That sure set her off, and I got a lecture about SodaStream being an Israeli company and her opinions on the Middle East, Israel, Palestine, etc. I listened politely for a moment, then redirected her back to the reason for her visit.

Not being someone who follows the news in detail, I‘d been unaware there was any controversy behind the soda bottle on my desk that morning. To me, it was just my choice of beverage.

The trouble here is that it’s possible to politicize pretty much anything in a divided world. I try to stay, for better or worse, ignorant of such things. My soft drink choice reflects nothing more than what I felt like drinking when I went back to my office’s tiny break room between appointments.

If you dig far enough into any company’s – or person’s – background, you’ll find something you disagree with. Just like any drug I prescribe will have side effects.

It’s for this reason that I keep politics out of my office. Patients, such as this lady, may express theirs, but I’ll never express mine. Too many in this world see each other in an “us vs. them” frame, quick to declare someone with different views as the enemy, rather than another decent person with an honest difference of opinion.

And it’s irrelevant to what I’m trying to achieve at my office anyway – caring for patients.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

“I can’t believe you’re drinking that.”

The young woman across the desk from me seemed perplexed, and I didn’t know why.

I’m one of those people who always has something to drink in front of me while working. A bottle of Costco green tea, Diet Coke, coffee. I also have a SodaStream gadget at my office, and that bottle is what I had on my desk at the moment.

I naively said “Why? I doubt it’s any worse for me than any other soda.”

That sure set her off, and I got a lecture about SodaStream being an Israeli company and her opinions on the Middle East, Israel, Palestine, etc. I listened politely for a moment, then redirected her back to the reason for her visit.

Not being someone who follows the news in detail, I‘d been unaware there was any controversy behind the soda bottle on my desk that morning. To me, it was just my choice of beverage.

The trouble here is that it’s possible to politicize pretty much anything in a divided world. I try to stay, for better or worse, ignorant of such things. My soft drink choice reflects nothing more than what I felt like drinking when I went back to my office’s tiny break room between appointments.

If you dig far enough into any company’s – or person’s – background, you’ll find something you disagree with. Just like any drug I prescribe will have side effects.

It’s for this reason that I keep politics out of my office. Patients, such as this lady, may express theirs, but I’ll never express mine. Too many in this world see each other in an “us vs. them” frame, quick to declare someone with different views as the enemy, rather than another decent person with an honest difference of opinion.

And it’s irrelevant to what I’m trying to achieve at my office anyway – caring for patients.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Melanoma survival shorter in those given high dose glucocorticoids for ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis

than did patients taking low-dose steroids for the adverse event, according to a new retrospective analysis in Cancer.

“Treatment with high-dose glucocorticoids does not appear to confer any obvious advantage to patients with IH (ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis) and may negatively affect tumor response to CPI (checkpoint-inhibitor therapy),” wrote Alexander Faje, MD, a neuroendocrinologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “We recommend against the routine use of higher doses in these patients and that such treatment should be reserved for clinical indications like visual compromise or perhaps for intractable headache.”

Hypophysitis after treatment with a CTLA-4 inhibitor, such as ipilimumab, can approach 12%, though it is much less common with the checkpoint inhibitors that target PD-1 and PD-L1. Past studies examining the effects of glucocorticoids for immune-related adverse events have compared patients with severe events to those with minimal or no events. Since emergence of hypophysitis correlates with better overall survival, this is a flawed approach, the researchers said.

For their study, the researchers compared groups of patients with the same immune-related adverse events who received treatment with varying amounts of glucocorticoids.

They reviewed outcomes for 64 melanoma patients who had received ipilimumab monotherapy and were diagnosed with ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis treated in the Partners Healthcare system. Fourteen patients had received low-dose glucocorticoids, defined as a maximum average daily dose of 7.5 mg of prednisone or the equivalent. Fifty patients received high-dose glucocorticoids, defined as anything above that amount.

Overall survival and time to treatment failure were significantly higher in the low-dose group than the high-dose group (P = .002 for OS and P = .001 for TTF). Median overall survival was 23.3 months and time to treatment failure was 11.4 months in those given high-dose steroids. Median overall survival had not been reached in those given low-dose steroids.

While the findings are preliminary, the authors noted they may have implications for managing other immune-related adverse events. “Although the use of lower doses of immunosuppressive medications may be less of an option in many circumstances for other (immune-related adverse events), therapeutic parsimony would seem desirable with more tailored regimens as the biologic mechanisms underpinning these processes are further elucidated.”

SOURCE: Faje AT et al. Cancer. 2018 Jul 5.

The study results provide further evidence that hypophysitis appears to be an adverse effect of ipilimumab therapy that is linked with improved outcomes in melanoma. As hypophysitis tends to be self-limited, it can be treated safely with replacement therapy rather than high-dose steroid therapy, which was associated with reduced overall survival.

But the low number of patients on low-dose glucocorticoids – just 14 – is a limitation of the study and the group’s favorable outcomes could have been due to chance alone. Further, the 7.5-mg cut-off for high- vs. low-dose steroid therapy is somewhat arbitrary.

In support of the study’s overall conclusions, however, exploratory analyses have produced similar findings at somewhat higher cut-offs.

As the mechanism of hypophysitis is somewhat distinct compared with other immune-checkpoint toxicities, it might not be appropriate to generalize these findings to other toxic responses to these drugs.

The mechanisms of toxicities related to immune-checkpoint inhibitors are still not well defined. Unraveling those mechanisms may identify patients at high risk and hold the potential for aiding in the design of novel therapeutics that unleash antitumor immunity. Glucocorticoids are a fairly effective treatment for immune-related toxicities but remain a blunt, nonspecific way to suppress aberrant immunity. Designing inhibitors of culprit cellular populations or cytokines may combat toxicity without compromising the efficacy of immune therapy or promoting systemic immunosuppression.

Douglas B. Johnson, MD, is with Vanderbilt University Medical Center and Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center, Nashville, Tenn. He made his remarks in an editorial (Cancer 2018 Jul 5. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31627.

The study results provide further evidence that hypophysitis appears to be an adverse effect of ipilimumab therapy that is linked with improved outcomes in melanoma. As hypophysitis tends to be self-limited, it can be treated safely with replacement therapy rather than high-dose steroid therapy, which was associated with reduced overall survival.

But the low number of patients on low-dose glucocorticoids – just 14 – is a limitation of the study and the group’s favorable outcomes could have been due to chance alone. Further, the 7.5-mg cut-off for high- vs. low-dose steroid therapy is somewhat arbitrary.

In support of the study’s overall conclusions, however, exploratory analyses have produced similar findings at somewhat higher cut-offs.

As the mechanism of hypophysitis is somewhat distinct compared with other immune-checkpoint toxicities, it might not be appropriate to generalize these findings to other toxic responses to these drugs.

The mechanisms of toxicities related to immune-checkpoint inhibitors are still not well defined. Unraveling those mechanisms may identify patients at high risk and hold the potential for aiding in the design of novel therapeutics that unleash antitumor immunity. Glucocorticoids are a fairly effective treatment for immune-related toxicities but remain a blunt, nonspecific way to suppress aberrant immunity. Designing inhibitors of culprit cellular populations or cytokines may combat toxicity without compromising the efficacy of immune therapy or promoting systemic immunosuppression.

Douglas B. Johnson, MD, is with Vanderbilt University Medical Center and Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center, Nashville, Tenn. He made his remarks in an editorial (Cancer 2018 Jul 5. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31627.

The study results provide further evidence that hypophysitis appears to be an adverse effect of ipilimumab therapy that is linked with improved outcomes in melanoma. As hypophysitis tends to be self-limited, it can be treated safely with replacement therapy rather than high-dose steroid therapy, which was associated with reduced overall survival.

But the low number of patients on low-dose glucocorticoids – just 14 – is a limitation of the study and the group’s favorable outcomes could have been due to chance alone. Further, the 7.5-mg cut-off for high- vs. low-dose steroid therapy is somewhat arbitrary.

In support of the study’s overall conclusions, however, exploratory analyses have produced similar findings at somewhat higher cut-offs.

As the mechanism of hypophysitis is somewhat distinct compared with other immune-checkpoint toxicities, it might not be appropriate to generalize these findings to other toxic responses to these drugs.

The mechanisms of toxicities related to immune-checkpoint inhibitors are still not well defined. Unraveling those mechanisms may identify patients at high risk and hold the potential for aiding in the design of novel therapeutics that unleash antitumor immunity. Glucocorticoids are a fairly effective treatment for immune-related toxicities but remain a blunt, nonspecific way to suppress aberrant immunity. Designing inhibitors of culprit cellular populations or cytokines may combat toxicity without compromising the efficacy of immune therapy or promoting systemic immunosuppression.

Douglas B. Johnson, MD, is with Vanderbilt University Medical Center and Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center, Nashville, Tenn. He made his remarks in an editorial (Cancer 2018 Jul 5. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31627.

than did patients taking low-dose steroids for the adverse event, according to a new retrospective analysis in Cancer.

“Treatment with high-dose glucocorticoids does not appear to confer any obvious advantage to patients with IH (ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis) and may negatively affect tumor response to CPI (checkpoint-inhibitor therapy),” wrote Alexander Faje, MD, a neuroendocrinologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “We recommend against the routine use of higher doses in these patients and that such treatment should be reserved for clinical indications like visual compromise or perhaps for intractable headache.”

Hypophysitis after treatment with a CTLA-4 inhibitor, such as ipilimumab, can approach 12%, though it is much less common with the checkpoint inhibitors that target PD-1 and PD-L1. Past studies examining the effects of glucocorticoids for immune-related adverse events have compared patients with severe events to those with minimal or no events. Since emergence of hypophysitis correlates with better overall survival, this is a flawed approach, the researchers said.

For their study, the researchers compared groups of patients with the same immune-related adverse events who received treatment with varying amounts of glucocorticoids.

They reviewed outcomes for 64 melanoma patients who had received ipilimumab monotherapy and were diagnosed with ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis treated in the Partners Healthcare system. Fourteen patients had received low-dose glucocorticoids, defined as a maximum average daily dose of 7.5 mg of prednisone or the equivalent. Fifty patients received high-dose glucocorticoids, defined as anything above that amount.

Overall survival and time to treatment failure were significantly higher in the low-dose group than the high-dose group (P = .002 for OS and P = .001 for TTF). Median overall survival was 23.3 months and time to treatment failure was 11.4 months in those given high-dose steroids. Median overall survival had not been reached in those given low-dose steroids.

While the findings are preliminary, the authors noted they may have implications for managing other immune-related adverse events. “Although the use of lower doses of immunosuppressive medications may be less of an option in many circumstances for other (immune-related adverse events), therapeutic parsimony would seem desirable with more tailored regimens as the biologic mechanisms underpinning these processes are further elucidated.”

SOURCE: Faje AT et al. Cancer. 2018 Jul 5.

than did patients taking low-dose steroids for the adverse event, according to a new retrospective analysis in Cancer.

“Treatment with high-dose glucocorticoids does not appear to confer any obvious advantage to patients with IH (ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis) and may negatively affect tumor response to CPI (checkpoint-inhibitor therapy),” wrote Alexander Faje, MD, a neuroendocrinologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “We recommend against the routine use of higher doses in these patients and that such treatment should be reserved for clinical indications like visual compromise or perhaps for intractable headache.”

Hypophysitis after treatment with a CTLA-4 inhibitor, such as ipilimumab, can approach 12%, though it is much less common with the checkpoint inhibitors that target PD-1 and PD-L1. Past studies examining the effects of glucocorticoids for immune-related adverse events have compared patients with severe events to those with minimal or no events. Since emergence of hypophysitis correlates with better overall survival, this is a flawed approach, the researchers said.

For their study, the researchers compared groups of patients with the same immune-related adverse events who received treatment with varying amounts of glucocorticoids.

They reviewed outcomes for 64 melanoma patients who had received ipilimumab monotherapy and were diagnosed with ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis treated in the Partners Healthcare system. Fourteen patients had received low-dose glucocorticoids, defined as a maximum average daily dose of 7.5 mg of prednisone or the equivalent. Fifty patients received high-dose glucocorticoids, defined as anything above that amount.

Overall survival and time to treatment failure were significantly higher in the low-dose group than the high-dose group (P = .002 for OS and P = .001 for TTF). Median overall survival was 23.3 months and time to treatment failure was 11.4 months in those given high-dose steroids. Median overall survival had not been reached in those given low-dose steroids.

While the findings are preliminary, the authors noted they may have implications for managing other immune-related adverse events. “Although the use of lower doses of immunosuppressive medications may be less of an option in many circumstances for other (immune-related adverse events), therapeutic parsimony would seem desirable with more tailored regimens as the biologic mechanisms underpinning these processes are further elucidated.”

SOURCE: Faje AT et al. Cancer. 2018 Jul 5.

FROM CANCER

Key clinical point: Significantly lower overall survival and shorter time to treatment failure was seen in melanoma patients taking higher doses of glucocorticoids for ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis than in those taking lower doses.

Major finding: Median overall survival was 23.3 months and time to treatment failure was 11.4 months in those given high-dose steroids. Median overall survival had not been reached in those given low-dose steroids.

Study details: A retrospective review of 64 melanoma patients on single-agent ipilimumab therapy who were given glucocorticoids for ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis.

Disclosures: No funding source disclosed. The authors made no disclosures related to the submitted work.

Source: Faje AT et al. Cancer 2018 Jul 5.

Dr. Leslie Citrome: Addressing tardive dyskinesia

Sanjay Gupta, MD, of the University of Buffalo, spoke in an MDedge video earlier this year on the importance of using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale to screen for TD and treating the disorder with vesicular monoamine transporter-2 inhibitors.

In the episode, Dr. Citrome notes that despite recent advances in pharmacological options, clinicians can be challenged by TD.

Sanjay Gupta, MD, of the University of Buffalo, spoke in an MDedge video earlier this year on the importance of using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale to screen for TD and treating the disorder with vesicular monoamine transporter-2 inhibitors.

In the episode, Dr. Citrome notes that despite recent advances in pharmacological options, clinicians can be challenged by TD.

Sanjay Gupta, MD, of the University of Buffalo, spoke in an MDedge video earlier this year on the importance of using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale to screen for TD and treating the disorder with vesicular monoamine transporter-2 inhibitors.

In the episode, Dr. Citrome notes that despite recent advances in pharmacological options, clinicians can be challenged by TD.

Bug Bites More Than Just a Nuisance

As if it were not bad enough that illnesses from mosquito, tick, and flea bites tripled between 2004 and 2016, 9 new germs spread by mosquitoes and ticks were discovered or introduced into the US in the same 13 years.

According to the CDC’s first summary collectively examining data trends for all nationally notifiable diseases caused by the bite of an infected mosquito, tick, or flea, the most common tickborne diseases in 2016 were Lyme disease and ehrlichiosis/anaplasmosis. The most common mosquito-borne viruses were West Nile, dengue, and Zika.

The increase is due to many factors, the CDC says, but 1 issue is that mosquitoes and ticks are moving into new areas, putting more people at risk. The US is “not fully prepared” to meet the public health threat, the CDC warns: About 80% of vector control organizations lack critical prevention and control capacities. Reducing the spread of the diseases and responding effectively to outbreaks will require additional capacity at the state and local levels for tracking, diagnosing, and reporting cases.

As if it were not bad enough that illnesses from mosquito, tick, and flea bites tripled between 2004 and 2016, 9 new germs spread by mosquitoes and ticks were discovered or introduced into the US in the same 13 years.

According to the CDC’s first summary collectively examining data trends for all nationally notifiable diseases caused by the bite of an infected mosquito, tick, or flea, the most common tickborne diseases in 2016 were Lyme disease and ehrlichiosis/anaplasmosis. The most common mosquito-borne viruses were West Nile, dengue, and Zika.

The increase is due to many factors, the CDC says, but 1 issue is that mosquitoes and ticks are moving into new areas, putting more people at risk. The US is “not fully prepared” to meet the public health threat, the CDC warns: About 80% of vector control organizations lack critical prevention and control capacities. Reducing the spread of the diseases and responding effectively to outbreaks will require additional capacity at the state and local levels for tracking, diagnosing, and reporting cases.

As if it were not bad enough that illnesses from mosquito, tick, and flea bites tripled between 2004 and 2016, 9 new germs spread by mosquitoes and ticks were discovered or introduced into the US in the same 13 years.

According to the CDC’s first summary collectively examining data trends for all nationally notifiable diseases caused by the bite of an infected mosquito, tick, or flea, the most common tickborne diseases in 2016 were Lyme disease and ehrlichiosis/anaplasmosis. The most common mosquito-borne viruses were West Nile, dengue, and Zika.

The increase is due to many factors, the CDC says, but 1 issue is that mosquitoes and ticks are moving into new areas, putting more people at risk. The US is “not fully prepared” to meet the public health threat, the CDC warns: About 80% of vector control organizations lack critical prevention and control capacities. Reducing the spread of the diseases and responding effectively to outbreaks will require additional capacity at the state and local levels for tracking, diagnosing, and reporting cases.

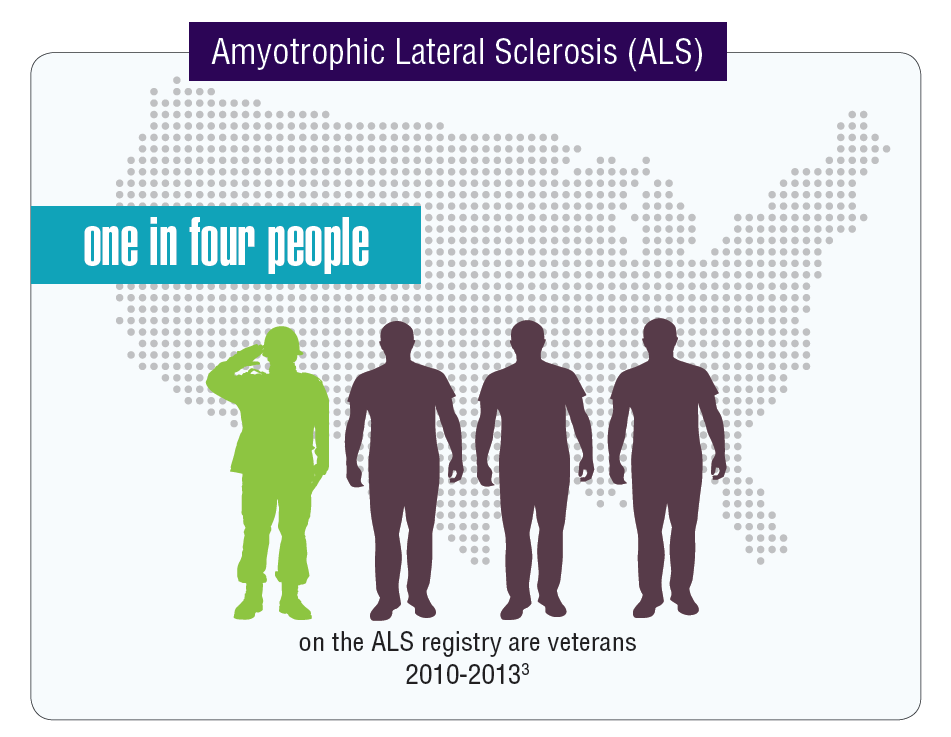

Federal Health Care Data Trends: Neurology

Data seem to indicate that service members and veterans may be at an increased risk of acquiring multiple neurologic diseases or injuries. The very nature of a career in the military often comes with a higher risk of sustaining a traumatic brain injury (TBI) either through combat or physical training, but other serious neurologic disorders seem to affect veterans disproportionally compared with those who did not serve in the Armed Forces.

Click here to continue reading.

Data seem to indicate that service members and veterans may be at an increased risk of acquiring multiple neurologic diseases or injuries. The very nature of a career in the military often comes with a higher risk of sustaining a traumatic brain injury (TBI) either through combat or physical training, but other serious neurologic disorders seem to affect veterans disproportionally compared with those who did not serve in the Armed Forces.

Click here to continue reading.

Data seem to indicate that service members and veterans may be at an increased risk of acquiring multiple neurologic diseases or injuries. The very nature of a career in the military often comes with a higher risk of sustaining a traumatic brain injury (TBI) either through combat or physical training, but other serious neurologic disorders seem to affect veterans disproportionally compared with those who did not serve in the Armed Forces.

Click here to continue reading.

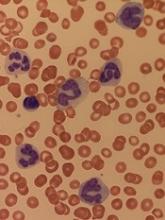

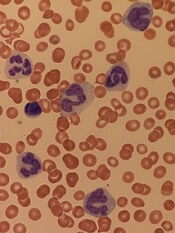

Study suggests dasatinib could treat AML, JMML

New research suggests dasatinib could treat certain patients with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The study showed that TNK2 inhibition has a negative effect on PTPN11-mutant leukemias.

PTPN11-mutant JMML and AML cells were sensitive to treatment with dasatinib, which inhibits TNK2.

Dasatinib also induced hematologic remission in a patient with PTPN11-mutant JMML.

Investigators reported these results in Science Signaling.

Past research showed that mutations in PTPN11 result in excessive cell proliferation and drive tumor growth in some cases of JMML and AML.

In the current study, investigators analyzed PTPN11-mutated leukemia cells and found that PTPN11 is activated by TNK2.

The investigators said TNK2 phosphorylates PTPN11, which then dephosphorylates TNK2 in a negative feedback loop. They also found that coexpression of TNK2 and mutant PTPN11 results in “robust” MAPK pathway activation.

Inhibiting TNK2 with dasatinib blocked MAPK signaling and colony formation in vitro.

Additional experiments showed that PTPN11-mutant AML samples were significantly more sensitive to dasatinib than wild-type AML samples.

Investigators also tested dasatinib in a sample from a JMML patient carrying a PTPN11 G60R mutation.

This patient’s cells were 10 times more sensitive to dasatinib than the average sample from a cohort of 151 patients who had AML, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, myeloproliferative neoplasms, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Because the JMML patient’s cells were so responsive to dasatinib, the investigators decided to administer the drug to the patient.

The patient achieved sustained hematologic remission with dasatinib, and this allowed him to receive a stem cell transplant using an unrelated cord blood donor. The patient had previously failed 2 transplants (with myeloablative conditioning) from a matched sibling donor.

The third transplant prolonged the patient’s life by a year, but he eventually died of relapsed disease.

The investigators said this case study and the in vitro results support further investigation into the efficacy of dasatinib and other TNK2 inhibitors in PTPN11-mutant leukemias.

New research suggests dasatinib could treat certain patients with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The study showed that TNK2 inhibition has a negative effect on PTPN11-mutant leukemias.

PTPN11-mutant JMML and AML cells were sensitive to treatment with dasatinib, which inhibits TNK2.

Dasatinib also induced hematologic remission in a patient with PTPN11-mutant JMML.

Investigators reported these results in Science Signaling.

Past research showed that mutations in PTPN11 result in excessive cell proliferation and drive tumor growth in some cases of JMML and AML.

In the current study, investigators analyzed PTPN11-mutated leukemia cells and found that PTPN11 is activated by TNK2.

The investigators said TNK2 phosphorylates PTPN11, which then dephosphorylates TNK2 in a negative feedback loop. They also found that coexpression of TNK2 and mutant PTPN11 results in “robust” MAPK pathway activation.

Inhibiting TNK2 with dasatinib blocked MAPK signaling and colony formation in vitro.

Additional experiments showed that PTPN11-mutant AML samples were significantly more sensitive to dasatinib than wild-type AML samples.

Investigators also tested dasatinib in a sample from a JMML patient carrying a PTPN11 G60R mutation.

This patient’s cells were 10 times more sensitive to dasatinib than the average sample from a cohort of 151 patients who had AML, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, myeloproliferative neoplasms, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Because the JMML patient’s cells were so responsive to dasatinib, the investigators decided to administer the drug to the patient.

The patient achieved sustained hematologic remission with dasatinib, and this allowed him to receive a stem cell transplant using an unrelated cord blood donor. The patient had previously failed 2 transplants (with myeloablative conditioning) from a matched sibling donor.

The third transplant prolonged the patient’s life by a year, but he eventually died of relapsed disease.

The investigators said this case study and the in vitro results support further investigation into the efficacy of dasatinib and other TNK2 inhibitors in PTPN11-mutant leukemias.

New research suggests dasatinib could treat certain patients with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The study showed that TNK2 inhibition has a negative effect on PTPN11-mutant leukemias.

PTPN11-mutant JMML and AML cells were sensitive to treatment with dasatinib, which inhibits TNK2.

Dasatinib also induced hematologic remission in a patient with PTPN11-mutant JMML.

Investigators reported these results in Science Signaling.

Past research showed that mutations in PTPN11 result in excessive cell proliferation and drive tumor growth in some cases of JMML and AML.

In the current study, investigators analyzed PTPN11-mutated leukemia cells and found that PTPN11 is activated by TNK2.

The investigators said TNK2 phosphorylates PTPN11, which then dephosphorylates TNK2 in a negative feedback loop. They also found that coexpression of TNK2 and mutant PTPN11 results in “robust” MAPK pathway activation.

Inhibiting TNK2 with dasatinib blocked MAPK signaling and colony formation in vitro.

Additional experiments showed that PTPN11-mutant AML samples were significantly more sensitive to dasatinib than wild-type AML samples.

Investigators also tested dasatinib in a sample from a JMML patient carrying a PTPN11 G60R mutation.

This patient’s cells were 10 times more sensitive to dasatinib than the average sample from a cohort of 151 patients who had AML, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, myeloproliferative neoplasms, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Because the JMML patient’s cells were so responsive to dasatinib, the investigators decided to administer the drug to the patient.

The patient achieved sustained hematologic remission with dasatinib, and this allowed him to receive a stem cell transplant using an unrelated cord blood donor. The patient had previously failed 2 transplants (with myeloablative conditioning) from a matched sibling donor.

The third transplant prolonged the patient’s life by a year, but he eventually died of relapsed disease.

The investigators said this case study and the in vitro results support further investigation into the efficacy of dasatinib and other TNK2 inhibitors in PTPN11-mutant leukemias.

FDA grants UCB product orphan designation

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to NiCord for hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

NiCord is created by expanding and enriching a unit of umbilical cord blood (UCB).

The product consists of a CD133-positive fraction—which is cultured for 21 days with nicotinamide, thrombopoietin, IL-6, FLT-3 ligand, and stem cell factor—and a CD133-negative fraction that is provided at the time of transplant.

NiCord already has orphan drug designation from the FDA as a treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), Hodgkin lymphoma, and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The product also has breakthrough therapy designation from the FDA.

NiCord trials

Final results from a phase 1/2 study suggested that NiCord can be used as a stand-alone graft in patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies. The results were presented at the 2018 BMT Tandem Meetings in February.

The trial included 36 adolescents and adults with AML (n=17), ALL (n=9), MDS (n=7), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML, n=2), and Hodgkin lymphoma (n=1).

All patients received a single NiCord unit. Researchers compared engraftment results in the NiCord recipients to results in a cohort of 148 patients from the CIBMTR registry.

The registry patients underwent standard UCB transplants and had similar characteristics as the NiCord recipients. However, only 20% of the CIBMTR patients received a single UCB unit.

The median time to neutrophil engraftment was 11.5 days (range, 6-26) with NiCord and 21 days in the control cohort (P<0.001). The cumulative incidence of neutrophil engraftment was 94.4% and 89.7%, respectively.

The median time to platelet engraftment was 34 days (range, 25-96) with NiCord and 46 days in the controls (P<0.001). The cumulative incidence of platelet engraftment was 80.6% and 67.1%, respectively.

There was 1 case of primary graft failure among the NiCord recipients and 2 cases of secondary graft failure.

The estimated 2-year rate of non-relapse mortality in NiCord recipients was 23.8%, and the 2-year incidence of relapse was 33.2%.

The estimated disease-free survival was 49.1% at 1 year and 43.0% at 2 years. The overall survival was 51.2% at 1 year and 2 years.

At 100 days, the rate of grade 2-4 acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) was 44.0%, and the rate of grade 3-4 acute GVHD was 11.1%. The estimated 1-year rate of mild to severe chronic GVHD was 40.5%, and the 2-year rate of moderate to severe chronic GVHD was 9.8%.

These results prompted a phase 3 study of NiCord in patients with AML, ALL, CML, MDS, and lymphoma (NCT02730299). In this trial, researchers are comparing NiCord to standard single or double UCB transplant.

About orphan and breakthrough designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

Orphan designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new treatments for serious or life-threatening conditions.

Breakthrough designation entitles sponsors to more intensive FDA guidance on an efficient and accelerated development program, as well as eligibility for other actions to expedite FDA review, such as rolling submission and priority review.

To earn breakthrough designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to NiCord for hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

NiCord is created by expanding and enriching a unit of umbilical cord blood (UCB).

The product consists of a CD133-positive fraction—which is cultured for 21 days with nicotinamide, thrombopoietin, IL-6, FLT-3 ligand, and stem cell factor—and a CD133-negative fraction that is provided at the time of transplant.

NiCord already has orphan drug designation from the FDA as a treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), Hodgkin lymphoma, and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The product also has breakthrough therapy designation from the FDA.

NiCord trials

Final results from a phase 1/2 study suggested that NiCord can be used as a stand-alone graft in patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies. The results were presented at the 2018 BMT Tandem Meetings in February.

The trial included 36 adolescents and adults with AML (n=17), ALL (n=9), MDS (n=7), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML, n=2), and Hodgkin lymphoma (n=1).

All patients received a single NiCord unit. Researchers compared engraftment results in the NiCord recipients to results in a cohort of 148 patients from the CIBMTR registry.

The registry patients underwent standard UCB transplants and had similar characteristics as the NiCord recipients. However, only 20% of the CIBMTR patients received a single UCB unit.

The median time to neutrophil engraftment was 11.5 days (range, 6-26) with NiCord and 21 days in the control cohort (P<0.001). The cumulative incidence of neutrophil engraftment was 94.4% and 89.7%, respectively.

The median time to platelet engraftment was 34 days (range, 25-96) with NiCord and 46 days in the controls (P<0.001). The cumulative incidence of platelet engraftment was 80.6% and 67.1%, respectively.

There was 1 case of primary graft failure among the NiCord recipients and 2 cases of secondary graft failure.

The estimated 2-year rate of non-relapse mortality in NiCord recipients was 23.8%, and the 2-year incidence of relapse was 33.2%.

The estimated disease-free survival was 49.1% at 1 year and 43.0% at 2 years. The overall survival was 51.2% at 1 year and 2 years.

At 100 days, the rate of grade 2-4 acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) was 44.0%, and the rate of grade 3-4 acute GVHD was 11.1%. The estimated 1-year rate of mild to severe chronic GVHD was 40.5%, and the 2-year rate of moderate to severe chronic GVHD was 9.8%.

These results prompted a phase 3 study of NiCord in patients with AML, ALL, CML, MDS, and lymphoma (NCT02730299). In this trial, researchers are comparing NiCord to standard single or double UCB transplant.

About orphan and breakthrough designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

Orphan designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new treatments for serious or life-threatening conditions.

Breakthrough designation entitles sponsors to more intensive FDA guidance on an efficient and accelerated development program, as well as eligibility for other actions to expedite FDA review, such as rolling submission and priority review.

To earn breakthrough designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to NiCord for hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

NiCord is created by expanding and enriching a unit of umbilical cord blood (UCB).

The product consists of a CD133-positive fraction—which is cultured for 21 days with nicotinamide, thrombopoietin, IL-6, FLT-3 ligand, and stem cell factor—and a CD133-negative fraction that is provided at the time of transplant.

NiCord already has orphan drug designation from the FDA as a treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), Hodgkin lymphoma, and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The product also has breakthrough therapy designation from the FDA.

NiCord trials

Final results from a phase 1/2 study suggested that NiCord can be used as a stand-alone graft in patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies. The results were presented at the 2018 BMT Tandem Meetings in February.

The trial included 36 adolescents and adults with AML (n=17), ALL (n=9), MDS (n=7), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML, n=2), and Hodgkin lymphoma (n=1).

All patients received a single NiCord unit. Researchers compared engraftment results in the NiCord recipients to results in a cohort of 148 patients from the CIBMTR registry.

The registry patients underwent standard UCB transplants and had similar characteristics as the NiCord recipients. However, only 20% of the CIBMTR patients received a single UCB unit.

The median time to neutrophil engraftment was 11.5 days (range, 6-26) with NiCord and 21 days in the control cohort (P<0.001). The cumulative incidence of neutrophil engraftment was 94.4% and 89.7%, respectively.

The median time to platelet engraftment was 34 days (range, 25-96) with NiCord and 46 days in the controls (P<0.001). The cumulative incidence of platelet engraftment was 80.6% and 67.1%, respectively.

There was 1 case of primary graft failure among the NiCord recipients and 2 cases of secondary graft failure.

The estimated 2-year rate of non-relapse mortality in NiCord recipients was 23.8%, and the 2-year incidence of relapse was 33.2%.

The estimated disease-free survival was 49.1% at 1 year and 43.0% at 2 years. The overall survival was 51.2% at 1 year and 2 years.

At 100 days, the rate of grade 2-4 acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) was 44.0%, and the rate of grade 3-4 acute GVHD was 11.1%. The estimated 1-year rate of mild to severe chronic GVHD was 40.5%, and the 2-year rate of moderate to severe chronic GVHD was 9.8%.

These results prompted a phase 3 study of NiCord in patients with AML, ALL, CML, MDS, and lymphoma (NCT02730299). In this trial, researchers are comparing NiCord to standard single or double UCB transplant.

About orphan and breakthrough designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

Orphan designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new treatments for serious or life-threatening conditions.

Breakthrough designation entitles sponsors to more intensive FDA guidance on an efficient and accelerated development program, as well as eligibility for other actions to expedite FDA review, such as rolling submission and priority review.

To earn breakthrough designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need.

Product receives orphan designation for use in HSCT

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to dilanubicel (NLA101) for the reduction of morbidity and mortality associated with hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Dilanubicel is a universal-donor, ex-vivo-expanded hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell product.

It is intended to induce short-term hematopoiesis, which lasts until a patient’s immune system recovers.

However, dilanubicel may also produce long-term immunologic benefits and could potentially improve survival in HSCT recipients, according to Nohla Therapeutics, the company developing the product.

Dilanubicel is manufactured ahead of time, cryopreserved, and intended for immediate off-the-shelf use.

Phase 2 trials

The orphan drug designation for dilanubicel was supported by data from a phase 2, single-center study. Results from this study were presented in a poster at the 23rd Congress of European Hematology Association (EHA) in June.

The trial included 15 patients with hematologic malignancies who underwent a cord blood transplant. Conditioning consisted of fludarabine (75 mg/m2), cyclophosphamide (120 mg/kg), and total body irradiation (13.2 Gy).

Patients received unmanipulated cord blood unit(s), followed 4 hours later by dilanubicel infusion. Prophylaxis for graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) was cyclosporine/mycophenolate mofetil.

The researchers compared outcomes in the 15 dilanubicel recipients to outcomes in a concurrent control cohort of 50 patients treated with the same HSCT protocol, minus dilanubicel. There were no significant differences between the 2 cohorts with regard to baseline characteristics.

The time to neutrophil and platelet recovery were both significantly better in dilanubicel recipients than controls.

At day 100, the cumulative incidence of neutrophil recovery was 100% in dilanubicel recipients and 94% in controls (P=0.005). The median time to neutrophil recovery was 19 days (range, 9-31) and 25 days (range, 14-45), respectively.

The cumulative incidence of platelet recovery was 93% in dilanubicel recipients and 74% in controls (P=0.02). The median time to platelet recovery was 35 days (range, 21-86) and 48 days (range, 24-158), respectively.

At 100 days, there were no cases of grade 3-4 acute GVHD in dilanubicel recipients, but the incidence of grade 3-4 acute GVHD was 29% in the control group.

At 5 years, 27% of dilanubicel recipients had experienced chronic GVHD, compared to 38% of the control group.

There were no cases of transplant related mortality (TRM) in dilanubicel recipients, but the rate of TRM was 16% in the control group.

Two dilanubicel recipients (13%) relapsed post-transplant and subsequently died.

The 5-year disease-free survival rate was 87% in dilanubicel recipients and 66% in the control group. Overall survival rates were the same.

“Dilanubicel has shown encouraging initial activity as a novel cell therapy in patients with hematologic malignancies receiving a cord blood transplant,” said President and CEO of Nohla Therapeutics Katie Fanning.

“We believe the addition of dilanubicel has the potential to make a meaningful difference for these patients, and we look forward to having the top-line results from the fully enrolled, randomized, phase 2b trial later this year.”

The phase 2b trial (NCT01690520) has enrolled 160 patients with hematologic malignancies. The goal of the trial is to determine whether adding dilanubicel to standard donor cord blood transplant decreases the time to hematopoietic recovery, thereby reducing associated morbidities and mortality.

Another phase 2 trial, called LAUNCH (NCT03301597), is currently enrolling patients who have acute myeloid leukemia and chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression. The goals of this trial are to evaluate dilanubicel’s ability to reduce the rate of grade 3 or higher infections associated with chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and to identify the lowest effective cell dose of dilanubicel.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to dilanubicel (NLA101) for the reduction of morbidity and mortality associated with hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Dilanubicel is a universal-donor, ex-vivo-expanded hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell product.

It is intended to induce short-term hematopoiesis, which lasts until a patient’s immune system recovers.

However, dilanubicel may also produce long-term immunologic benefits and could potentially improve survival in HSCT recipients, according to Nohla Therapeutics, the company developing the product.

Dilanubicel is manufactured ahead of time, cryopreserved, and intended for immediate off-the-shelf use.

Phase 2 trials

The orphan drug designation for dilanubicel was supported by data from a phase 2, single-center study. Results from this study were presented in a poster at the 23rd Congress of European Hematology Association (EHA) in June.

The trial included 15 patients with hematologic malignancies who underwent a cord blood transplant. Conditioning consisted of fludarabine (75 mg/m2), cyclophosphamide (120 mg/kg), and total body irradiation (13.2 Gy).

Patients received unmanipulated cord blood unit(s), followed 4 hours later by dilanubicel infusion. Prophylaxis for graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) was cyclosporine/mycophenolate mofetil.

The researchers compared outcomes in the 15 dilanubicel recipients to outcomes in a concurrent control cohort of 50 patients treated with the same HSCT protocol, minus dilanubicel. There were no significant differences between the 2 cohorts with regard to baseline characteristics.

The time to neutrophil and platelet recovery were both significantly better in dilanubicel recipients than controls.

At day 100, the cumulative incidence of neutrophil recovery was 100% in dilanubicel recipients and 94% in controls (P=0.005). The median time to neutrophil recovery was 19 days (range, 9-31) and 25 days (range, 14-45), respectively.

The cumulative incidence of platelet recovery was 93% in dilanubicel recipients and 74% in controls (P=0.02). The median time to platelet recovery was 35 days (range, 21-86) and 48 days (range, 24-158), respectively.

At 100 days, there were no cases of grade 3-4 acute GVHD in dilanubicel recipients, but the incidence of grade 3-4 acute GVHD was 29% in the control group.

At 5 years, 27% of dilanubicel recipients had experienced chronic GVHD, compared to 38% of the control group.

There were no cases of transplant related mortality (TRM) in dilanubicel recipients, but the rate of TRM was 16% in the control group.

Two dilanubicel recipients (13%) relapsed post-transplant and subsequently died.

The 5-year disease-free survival rate was 87% in dilanubicel recipients and 66% in the control group. Overall survival rates were the same.

“Dilanubicel has shown encouraging initial activity as a novel cell therapy in patients with hematologic malignancies receiving a cord blood transplant,” said President and CEO of Nohla Therapeutics Katie Fanning.

“We believe the addition of dilanubicel has the potential to make a meaningful difference for these patients, and we look forward to having the top-line results from the fully enrolled, randomized, phase 2b trial later this year.”

The phase 2b trial (NCT01690520) has enrolled 160 patients with hematologic malignancies. The goal of the trial is to determine whether adding dilanubicel to standard donor cord blood transplant decreases the time to hematopoietic recovery, thereby reducing associated morbidities and mortality.

Another phase 2 trial, called LAUNCH (NCT03301597), is currently enrolling patients who have acute myeloid leukemia and chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression. The goals of this trial are to evaluate dilanubicel’s ability to reduce the rate of grade 3 or higher infections associated with chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and to identify the lowest effective cell dose of dilanubicel.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to dilanubicel (NLA101) for the reduction of morbidity and mortality associated with hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Dilanubicel is a universal-donor, ex-vivo-expanded hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell product.

It is intended to induce short-term hematopoiesis, which lasts until a patient’s immune system recovers.

However, dilanubicel may also produce long-term immunologic benefits and could potentially improve survival in HSCT recipients, according to Nohla Therapeutics, the company developing the product.

Dilanubicel is manufactured ahead of time, cryopreserved, and intended for immediate off-the-shelf use.

Phase 2 trials

The orphan drug designation for dilanubicel was supported by data from a phase 2, single-center study. Results from this study were presented in a poster at the 23rd Congress of European Hematology Association (EHA) in June.

The trial included 15 patients with hematologic malignancies who underwent a cord blood transplant. Conditioning consisted of fludarabine (75 mg/m2), cyclophosphamide (120 mg/kg), and total body irradiation (13.2 Gy).

Patients received unmanipulated cord blood unit(s), followed 4 hours later by dilanubicel infusion. Prophylaxis for graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) was cyclosporine/mycophenolate mofetil.

The researchers compared outcomes in the 15 dilanubicel recipients to outcomes in a concurrent control cohort of 50 patients treated with the same HSCT protocol, minus dilanubicel. There were no significant differences between the 2 cohorts with regard to baseline characteristics.

The time to neutrophil and platelet recovery were both significantly better in dilanubicel recipients than controls.

At day 100, the cumulative incidence of neutrophil recovery was 100% in dilanubicel recipients and 94% in controls (P=0.005). The median time to neutrophil recovery was 19 days (range, 9-31) and 25 days (range, 14-45), respectively.

The cumulative incidence of platelet recovery was 93% in dilanubicel recipients and 74% in controls (P=0.02). The median time to platelet recovery was 35 days (range, 21-86) and 48 days (range, 24-158), respectively.

At 100 days, there were no cases of grade 3-4 acute GVHD in dilanubicel recipients, but the incidence of grade 3-4 acute GVHD was 29% in the control group.

At 5 years, 27% of dilanubicel recipients had experienced chronic GVHD, compared to 38% of the control group.

There were no cases of transplant related mortality (TRM) in dilanubicel recipients, but the rate of TRM was 16% in the control group.

Two dilanubicel recipients (13%) relapsed post-transplant and subsequently died.

The 5-year disease-free survival rate was 87% in dilanubicel recipients and 66% in the control group. Overall survival rates were the same.

“Dilanubicel has shown encouraging initial activity as a novel cell therapy in patients with hematologic malignancies receiving a cord blood transplant,” said President and CEO of Nohla Therapeutics Katie Fanning.

“We believe the addition of dilanubicel has the potential to make a meaningful difference for these patients, and we look forward to having the top-line results from the fully enrolled, randomized, phase 2b trial later this year.”

The phase 2b trial (NCT01690520) has enrolled 160 patients with hematologic malignancies. The goal of the trial is to determine whether adding dilanubicel to standard donor cord blood transplant decreases the time to hematopoietic recovery, thereby reducing associated morbidities and mortality.

Another phase 2 trial, called LAUNCH (NCT03301597), is currently enrolling patients who have acute myeloid leukemia and chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression. The goals of this trial are to evaluate dilanubicel’s ability to reduce the rate of grade 3 or higher infections associated with chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and to identify the lowest effective cell dose of dilanubicel.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

Prolonged opioid use among U.S. IBD patients doubled during 2002-2016

WASHINGTON – based on statistics gathered in a database that included medical records from more than 40 million American patients.

Prolonged opioid treatment, defined as filling at least two prescriptions for an opioid at least 90 days apart in a calendar year, rose among patients diagnosed with either Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis from a low of 14% in 2002 to 26% in 2016, reaching a peak during the period of 29% in 2014, Marc Landsman, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.®

The sharpest rise during the 15-year period examined was an increase in this level of opioid use from 15% in 2004 to 21% in 2005. Prolonged opioid use remained at or above 26% of all U.S. patients identified with IBD in the database during each year from 2011 to 2016, said Dr. Landsman, a gastroenterologist at the MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland. He suggested that a multidisciplinary approach to pain relief including alternative approaches to pain management, “will be vital” for pain management in IBD patients.

“Pain is a very important symptom of IBD. Opioids have been easy to prescribe, but they may not be the correct drug to prescribe,” commented Gil Y. Melmed, MD, director of clinical inflammatory bowel disease at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. He agreed with Dr. Landsman that a more multidisciplinary approach to pain management, including behavioral interventions, might reduce reliance on opioids in these patients. In addition, good control of an IBD patient’s inflammatory disease with, for example, a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor often produces substantial pain reduction, although some patients may also need surgery to relieve obstructive pain, Dr. Melmed said in an interview.The analysis run by Dr. Landsman and his associates used data in the Explorys database that included 276,340 unique patients with a diagnosis in their insurance record of IBD who also underwent either flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy during the year when they first received the diagnosis.

The study also analyzed the type of medical insurance used by patients who received prolonged opioid treatment. During 2002, 43% of patients who received an opioid for a prolonged period had Medicare coverage, 35% had private insurance, and 20% had Medicaid coverage. The prevalence of Medicare and private insurance coverage among opioid recipients steadily shifted during the next 14 years, so that in 2016 private insurance was the most prevalent coverage among the IBD patients on prolonged opioid use, at 46%, with 33% on Medicare coverage and 15% covered by Medicaid. The changes in the prevalence of Medicare and private insurance coverage from 2002 to 2016 were statistically significant, Dr. Landsman said.

Dr. Landsman and Dr. Melmed had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Landsman M et al. DDW 2018. Presentation 14.

WASHINGTON – based on statistics gathered in a database that included medical records from more than 40 million American patients.

Prolonged opioid treatment, defined as filling at least two prescriptions for an opioid at least 90 days apart in a calendar year, rose among patients diagnosed with either Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis from a low of 14% in 2002 to 26% in 2016, reaching a peak during the period of 29% in 2014, Marc Landsman, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.®

The sharpest rise during the 15-year period examined was an increase in this level of opioid use from 15% in 2004 to 21% in 2005. Prolonged opioid use remained at or above 26% of all U.S. patients identified with IBD in the database during each year from 2011 to 2016, said Dr. Landsman, a gastroenterologist at the MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland. He suggested that a multidisciplinary approach to pain relief including alternative approaches to pain management, “will be vital” for pain management in IBD patients.

“Pain is a very important symptom of IBD. Opioids have been easy to prescribe, but they may not be the correct drug to prescribe,” commented Gil Y. Melmed, MD, director of clinical inflammatory bowel disease at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. He agreed with Dr. Landsman that a more multidisciplinary approach to pain management, including behavioral interventions, might reduce reliance on opioids in these patients. In addition, good control of an IBD patient’s inflammatory disease with, for example, a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor often produces substantial pain reduction, although some patients may also need surgery to relieve obstructive pain, Dr. Melmed said in an interview.The analysis run by Dr. Landsman and his associates used data in the Explorys database that included 276,340 unique patients with a diagnosis in their insurance record of IBD who also underwent either flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy during the year when they first received the diagnosis.

The study also analyzed the type of medical insurance used by patients who received prolonged opioid treatment. During 2002, 43% of patients who received an opioid for a prolonged period had Medicare coverage, 35% had private insurance, and 20% had Medicaid coverage. The prevalence of Medicare and private insurance coverage among opioid recipients steadily shifted during the next 14 years, so that in 2016 private insurance was the most prevalent coverage among the IBD patients on prolonged opioid use, at 46%, with 33% on Medicare coverage and 15% covered by Medicaid. The changes in the prevalence of Medicare and private insurance coverage from 2002 to 2016 were statistically significant, Dr. Landsman said.

Dr. Landsman and Dr. Melmed had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Landsman M et al. DDW 2018. Presentation 14.

WASHINGTON – based on statistics gathered in a database that included medical records from more than 40 million American patients.

Prolonged opioid treatment, defined as filling at least two prescriptions for an opioid at least 90 days apart in a calendar year, rose among patients diagnosed with either Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis from a low of 14% in 2002 to 26% in 2016, reaching a peak during the period of 29% in 2014, Marc Landsman, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.®

The sharpest rise during the 15-year period examined was an increase in this level of opioid use from 15% in 2004 to 21% in 2005. Prolonged opioid use remained at or above 26% of all U.S. patients identified with IBD in the database during each year from 2011 to 2016, said Dr. Landsman, a gastroenterologist at the MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland. He suggested that a multidisciplinary approach to pain relief including alternative approaches to pain management, “will be vital” for pain management in IBD patients.

“Pain is a very important symptom of IBD. Opioids have been easy to prescribe, but they may not be the correct drug to prescribe,” commented Gil Y. Melmed, MD, director of clinical inflammatory bowel disease at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. He agreed with Dr. Landsman that a more multidisciplinary approach to pain management, including behavioral interventions, might reduce reliance on opioids in these patients. In addition, good control of an IBD patient’s inflammatory disease with, for example, a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor often produces substantial pain reduction, although some patients may also need surgery to relieve obstructive pain, Dr. Melmed said in an interview.The analysis run by Dr. Landsman and his associates used data in the Explorys database that included 276,340 unique patients with a diagnosis in their insurance record of IBD who also underwent either flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy during the year when they first received the diagnosis.