User login

Hypofractionated radiation has untapped potential as RCC mets therapy

Hypofractionated radiation therapy (RT) may be a more viable treatment option for oligometastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) than is generally recognized, a recent literature review has suggested.

Advances in stereotactic RT offer “new opportunities in RCC management” with limited toxicity, reported Francesca De Felice, PhD, of Sapienza University in Rome and her coauthor. The authors suggested that future studies investigate RT in combination with immunotherapy.

“Due to the assumption that RCC is a radioresistant tumor,” the authors wrote in Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, “RT has long been considered a futile approach to manage primary disease” and is predominantly used for treatment of distant metastases with palliative intent. “This review provides highlights in current RCC strategies to potentially suggest a more tailored treatment approach in clinical daily practice.”

The investigators concluded that hypofractionated RT (greater than 3 Gy/fraction) deserves more serious consideration. “It has enormous advantages,” the authors wrote, “assuring ablative doses to the target meanwhile preserving surrounding normal tissues. Using stereotactic technique, surprising high local control rates have been achieved in several tumors (such as lung, liver, and bone), in both primary and oligometastatic setting[s].”

In five studies, single-dose RT (ranging from 8 to 24 Gy) was used to treat patients with RCC and extracranial metastases. Of the patients in these studies, 89% of them achieved local control, median overall survival (OS) ranged from 11.7 months to 21 months, and severe RT-related toxicity occurred 0%-4% of the time.

“Although [there is a] high level of data heterogeneity,” the authors wrote, “this systematic review suggested that stereotactic RT is associated with excellent local control rates and low toxicity incidence. Thus, if feasible, stereotactic RT represents an effective and safe approach to treat RCC metastasis.”

The authors cautioned that “the optimal high dose required for local tumor control has not yet been defined.”

The authors suggested that, in the future, immunotherapy in combination with RT may “produce synergistic effects, resulting in better response rate and duration, given the known immune-modulated abscopal effect of RT.” First, questions about treatment sequencing, dosing, and patient selection would need to be answered. “Further research should be aimed at these clinical needs in order to achieve the maximum benefit to RCC patient[s].”

This study did not receive specific funding.

SOURCE: Felice F et al. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018 Aug 1. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.06.002

Hypofractionated radiation therapy (RT) may be a more viable treatment option for oligometastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) than is generally recognized, a recent literature review has suggested.

Advances in stereotactic RT offer “new opportunities in RCC management” with limited toxicity, reported Francesca De Felice, PhD, of Sapienza University in Rome and her coauthor. The authors suggested that future studies investigate RT in combination with immunotherapy.

“Due to the assumption that RCC is a radioresistant tumor,” the authors wrote in Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, “RT has long been considered a futile approach to manage primary disease” and is predominantly used for treatment of distant metastases with palliative intent. “This review provides highlights in current RCC strategies to potentially suggest a more tailored treatment approach in clinical daily practice.”

The investigators concluded that hypofractionated RT (greater than 3 Gy/fraction) deserves more serious consideration. “It has enormous advantages,” the authors wrote, “assuring ablative doses to the target meanwhile preserving surrounding normal tissues. Using stereotactic technique, surprising high local control rates have been achieved in several tumors (such as lung, liver, and bone), in both primary and oligometastatic setting[s].”

In five studies, single-dose RT (ranging from 8 to 24 Gy) was used to treat patients with RCC and extracranial metastases. Of the patients in these studies, 89% of them achieved local control, median overall survival (OS) ranged from 11.7 months to 21 months, and severe RT-related toxicity occurred 0%-4% of the time.

“Although [there is a] high level of data heterogeneity,” the authors wrote, “this systematic review suggested that stereotactic RT is associated with excellent local control rates and low toxicity incidence. Thus, if feasible, stereotactic RT represents an effective and safe approach to treat RCC metastasis.”

The authors cautioned that “the optimal high dose required for local tumor control has not yet been defined.”

The authors suggested that, in the future, immunotherapy in combination with RT may “produce synergistic effects, resulting in better response rate and duration, given the known immune-modulated abscopal effect of RT.” First, questions about treatment sequencing, dosing, and patient selection would need to be answered. “Further research should be aimed at these clinical needs in order to achieve the maximum benefit to RCC patient[s].”

This study did not receive specific funding.

SOURCE: Felice F et al. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018 Aug 1. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.06.002

Hypofractionated radiation therapy (RT) may be a more viable treatment option for oligometastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) than is generally recognized, a recent literature review has suggested.

Advances in stereotactic RT offer “new opportunities in RCC management” with limited toxicity, reported Francesca De Felice, PhD, of Sapienza University in Rome and her coauthor. The authors suggested that future studies investigate RT in combination with immunotherapy.

“Due to the assumption that RCC is a radioresistant tumor,” the authors wrote in Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, “RT has long been considered a futile approach to manage primary disease” and is predominantly used for treatment of distant metastases with palliative intent. “This review provides highlights in current RCC strategies to potentially suggest a more tailored treatment approach in clinical daily practice.”

The investigators concluded that hypofractionated RT (greater than 3 Gy/fraction) deserves more serious consideration. “It has enormous advantages,” the authors wrote, “assuring ablative doses to the target meanwhile preserving surrounding normal tissues. Using stereotactic technique, surprising high local control rates have been achieved in several tumors (such as lung, liver, and bone), in both primary and oligometastatic setting[s].”

In five studies, single-dose RT (ranging from 8 to 24 Gy) was used to treat patients with RCC and extracranial metastases. Of the patients in these studies, 89% of them achieved local control, median overall survival (OS) ranged from 11.7 months to 21 months, and severe RT-related toxicity occurred 0%-4% of the time.

“Although [there is a] high level of data heterogeneity,” the authors wrote, “this systematic review suggested that stereotactic RT is associated with excellent local control rates and low toxicity incidence. Thus, if feasible, stereotactic RT represents an effective and safe approach to treat RCC metastasis.”

The authors cautioned that “the optimal high dose required for local tumor control has not yet been defined.”

The authors suggested that, in the future, immunotherapy in combination with RT may “produce synergistic effects, resulting in better response rate and duration, given the known immune-modulated abscopal effect of RT.” First, questions about treatment sequencing, dosing, and patient selection would need to be answered. “Further research should be aimed at these clinical needs in order to achieve the maximum benefit to RCC patient[s].”

This study did not receive specific funding.

SOURCE: Felice F et al. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018 Aug 1. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.06.002

FROM CRITICAL REVIEWS IN ONCOLOGY/HEMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Hypofractionated radiation therapy (RT) is a safe and efficient treatment strategy in patients with oligometastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

Major finding: In five studies, single-dose RT was used to treat patients with RCC and extracranial metastases; 89% of patients achieved local control, median overall survival (OS) was as high as 21 months, and severe RT-related toxicity occurred 0%-4% of the time.

Study details: A literature review of radiation therapy for RCC.

Disclosures: None.

Source: Felice F et al. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018 Aug 1. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.06.002.

Blood disorders researcher is finalist for Trailblazer Prize

Daniel Bauer, MD, PhD, a pediatric hematologist and blood disorders researcher in Boston, is one of three finalists for the inaugural Trailblazer Prize for Clinician-Scientists, which is awarded by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Bauer, of Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center and Harvard Medical School, was selected based on his research using genome editing to tease out the causes of blood disorders, such as sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia.

All three finalists for the Trailblazer Prize are early career clinician-scientists whose work has the potential to or has led to innovations in patient care, according to the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health.

The other two finalists are Jaehyuk Choi, MD, PhD, of Northwestern University in Chicago and Michael Fox, MD, PhD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

Dr. Choi was selected for using genomics to identify mutations in skin cells that can lead to autoinflammatory diseases and cancer. Dr. Fox was selected for the development of innovative techniques to map human brain connectivity that can be used in novel treatments for Parkinson’s disease and depression.

The winner will be announced during a ceremony in Washington on Oct. 24, 2018, and will receive a $10,000 honorarium.

Daniel Bauer, MD, PhD, a pediatric hematologist and blood disorders researcher in Boston, is one of three finalists for the inaugural Trailblazer Prize for Clinician-Scientists, which is awarded by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Bauer, of Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center and Harvard Medical School, was selected based on his research using genome editing to tease out the causes of blood disorders, such as sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia.

All three finalists for the Trailblazer Prize are early career clinician-scientists whose work has the potential to or has led to innovations in patient care, according to the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health.

The other two finalists are Jaehyuk Choi, MD, PhD, of Northwestern University in Chicago and Michael Fox, MD, PhD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

Dr. Choi was selected for using genomics to identify mutations in skin cells that can lead to autoinflammatory diseases and cancer. Dr. Fox was selected for the development of innovative techniques to map human brain connectivity that can be used in novel treatments for Parkinson’s disease and depression.

The winner will be announced during a ceremony in Washington on Oct. 24, 2018, and will receive a $10,000 honorarium.

Daniel Bauer, MD, PhD, a pediatric hematologist and blood disorders researcher in Boston, is one of three finalists for the inaugural Trailblazer Prize for Clinician-Scientists, which is awarded by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Bauer, of Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center and Harvard Medical School, was selected based on his research using genome editing to tease out the causes of blood disorders, such as sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia.

All three finalists for the Trailblazer Prize are early career clinician-scientists whose work has the potential to or has led to innovations in patient care, according to the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health.

The other two finalists are Jaehyuk Choi, MD, PhD, of Northwestern University in Chicago and Michael Fox, MD, PhD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

Dr. Choi was selected for using genomics to identify mutations in skin cells that can lead to autoinflammatory diseases and cancer. Dr. Fox was selected for the development of innovative techniques to map human brain connectivity that can be used in novel treatments for Parkinson’s disease and depression.

The winner will be announced during a ceremony in Washington on Oct. 24, 2018, and will receive a $10,000 honorarium.

Increasing incidence of metastatic RCC raises concerns for SREs

The incidence of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) continues to rise, according to a recent study. In turn, skeletal-related events are also becoming more common.

Many patients with metastatic disease have skeletal involvement, so knowledge of skeletal-related events (SREs) is more important than ever, reported Masood Umer, MD, of Aga Khan University Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan, and his coauthors. SREs include nerve compression, hypercalcemia, impending fractures, and pathological fractures, any one of which may require medical or surgical intervention.

Beyond SREs, “bone metastases in RCC [have a] negative impact on progression-free survival and overall survival of patients treated with systemic therapies,” the authors wrote in Annals of Medicine and Surgery.

The authors conducted a literature review of skeletal metastasis in RCC, which included 947 patients, assessing incidence and discussing appropriate medical and surgical interventions.

A total of 26.7% of patients with RCC also had skeletal metastasis. The most common sites of metastasis were the proximal femur, pelvis, and spine. It was estimated that 85% of patients with metastatic RCC may experience SREs and related complications, with an average of more than two events per individual.

A multimodal approach is required, potentially involving surgical and medical interventions. For isolated bony metastases and fractures, surgery is often beneficial. Denosumab is the leading medical treatment; compared with zoledronic acid, denosumab prolongs time to first SRE by a median of approximately 8 months and reduces risk of first SRE by almost 20%. Risks of osteonecrosis are similar between agents.

The authors noted that research concerning the impact of targeted therapies on rates of bone metastasis and SREs is limited by patient exclusions in clinical trials. Granted, these agents have likely made for better outcomes.

“Advancement in targeted therapy in recent decades [has] made some improvement in treatment of SREs and has helped in improving patent’s quality of life, but still we are in need of further improvement in treatment modalities,” they concluded

This study did not receive specific funding.

SOURCE: Umer M et al. Ann Med Surg. 2018 Jan 21. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2018.01.002.

The incidence of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) continues to rise, according to a recent study. In turn, skeletal-related events are also becoming more common.

Many patients with metastatic disease have skeletal involvement, so knowledge of skeletal-related events (SREs) is more important than ever, reported Masood Umer, MD, of Aga Khan University Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan, and his coauthors. SREs include nerve compression, hypercalcemia, impending fractures, and pathological fractures, any one of which may require medical or surgical intervention.

Beyond SREs, “bone metastases in RCC [have a] negative impact on progression-free survival and overall survival of patients treated with systemic therapies,” the authors wrote in Annals of Medicine and Surgery.

The authors conducted a literature review of skeletal metastasis in RCC, which included 947 patients, assessing incidence and discussing appropriate medical and surgical interventions.

A total of 26.7% of patients with RCC also had skeletal metastasis. The most common sites of metastasis were the proximal femur, pelvis, and spine. It was estimated that 85% of patients with metastatic RCC may experience SREs and related complications, with an average of more than two events per individual.

A multimodal approach is required, potentially involving surgical and medical interventions. For isolated bony metastases and fractures, surgery is often beneficial. Denosumab is the leading medical treatment; compared with zoledronic acid, denosumab prolongs time to first SRE by a median of approximately 8 months and reduces risk of first SRE by almost 20%. Risks of osteonecrosis are similar between agents.

The authors noted that research concerning the impact of targeted therapies on rates of bone metastasis and SREs is limited by patient exclusions in clinical trials. Granted, these agents have likely made for better outcomes.

“Advancement in targeted therapy in recent decades [has] made some improvement in treatment of SREs and has helped in improving patent’s quality of life, but still we are in need of further improvement in treatment modalities,” they concluded

This study did not receive specific funding.

SOURCE: Umer M et al. Ann Med Surg. 2018 Jan 21. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2018.01.002.

The incidence of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) continues to rise, according to a recent study. In turn, skeletal-related events are also becoming more common.

Many patients with metastatic disease have skeletal involvement, so knowledge of skeletal-related events (SREs) is more important than ever, reported Masood Umer, MD, of Aga Khan University Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan, and his coauthors. SREs include nerve compression, hypercalcemia, impending fractures, and pathological fractures, any one of which may require medical or surgical intervention.

Beyond SREs, “bone metastases in RCC [have a] negative impact on progression-free survival and overall survival of patients treated with systemic therapies,” the authors wrote in Annals of Medicine and Surgery.

The authors conducted a literature review of skeletal metastasis in RCC, which included 947 patients, assessing incidence and discussing appropriate medical and surgical interventions.

A total of 26.7% of patients with RCC also had skeletal metastasis. The most common sites of metastasis were the proximal femur, pelvis, and spine. It was estimated that 85% of patients with metastatic RCC may experience SREs and related complications, with an average of more than two events per individual.

A multimodal approach is required, potentially involving surgical and medical interventions. For isolated bony metastases and fractures, surgery is often beneficial. Denosumab is the leading medical treatment; compared with zoledronic acid, denosumab prolongs time to first SRE by a median of approximately 8 months and reduces risk of first SRE by almost 20%. Risks of osteonecrosis are similar between agents.

The authors noted that research concerning the impact of targeted therapies on rates of bone metastasis and SREs is limited by patient exclusions in clinical trials. Granted, these agents have likely made for better outcomes.

“Advancement in targeted therapy in recent decades [has] made some improvement in treatment of SREs and has helped in improving patent’s quality of life, but still we are in need of further improvement in treatment modalities,” they concluded

This study did not receive specific funding.

SOURCE: Umer M et al. Ann Med Surg. 2018 Jan 21. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2018.01.002.

FROM ANNALS OF MEDICINE AND SURGERY

Key clinical point: As the incidence of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) continues to rise, knowledge of skeletal-related events and appropriate interventions is essential.

Major finding: About 85% of patients with metastatic RCC experience skeletal-related events and associated complications.

Study details: A literature review of skeletal metastasis in RCC.

Disclosures: The study did not receive specific funding.

Source: Umer M et al. Ann Med Surg. 2018 Jan 21. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2018.01.002.

Dr. Eric Howell joins SHM as chief operating officer

Veteran hospitalist will help define organizational goals

The Society of Hospital Medicine has announced the appointment of Eric Howell, MD, MHM, to the position of chief operating officer (COO).

“Having been involved with SHM in many capacities since first joining, I am honored to now transition to chief operating officer,” Dr. Howell said. “I always tell everyone that my goal is to make the world a better place, and I know that SHM’s staff will be able to do just that through the development and deployment of a variety of products, tools, and services to help hospitalists improve patient care.”

In his new role as COO at SHM, Dr. Howell will lead senior management’s strategic planning as well as define organizational goals to drive extensive, sustainable growth. In addition to serving as SHM’s COO, Dr. Howell will continue his role as director of the hospital medicine division of Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore and professor of medicine in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, also in Baltimore. Dr. Howell joined the Johns Hopkins Bayview hospitalist program in 2000, began the Howard County (Md.) General Hospital hospitalist program in 2010, and now oversees more than 200 physicians and clinical staff providing patient care in three hospitals.

“Eric has the perfect background to take SHM, its staff, and its membership to the next level,” said Laurence Wellikson, MD, MHM, chief executive officer of SHM. “His foundational leadership in the hospital medicine movement makes him the ideal person to lead SHM forward in its quest to provide hospitalists with the tools necessary to make a noteworthy difference in their institutions and in the lives of their patients.”

Dr. Howell is also a past president of SHM, the course director for the SHM Leadership Academies, and most recently, served as the senior physician advisor to SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement, which conducts quality improvement programs for hospitalist teams. He received his electrical engineering degree from the University of Maryland, which he said has served as an instrumental piece of his background for managing and implementing change in the hospital. His research has focused on the relationship between the emergency department and medicine floors, improving communication, throughput, and patient outcomes.

Veteran hospitalist will help define organizational goals

Veteran hospitalist will help define organizational goals

The Society of Hospital Medicine has announced the appointment of Eric Howell, MD, MHM, to the position of chief operating officer (COO).

“Having been involved with SHM in many capacities since first joining, I am honored to now transition to chief operating officer,” Dr. Howell said. “I always tell everyone that my goal is to make the world a better place, and I know that SHM’s staff will be able to do just that through the development and deployment of a variety of products, tools, and services to help hospitalists improve patient care.”

In his new role as COO at SHM, Dr. Howell will lead senior management’s strategic planning as well as define organizational goals to drive extensive, sustainable growth. In addition to serving as SHM’s COO, Dr. Howell will continue his role as director of the hospital medicine division of Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore and professor of medicine in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, also in Baltimore. Dr. Howell joined the Johns Hopkins Bayview hospitalist program in 2000, began the Howard County (Md.) General Hospital hospitalist program in 2010, and now oversees more than 200 physicians and clinical staff providing patient care in three hospitals.

“Eric has the perfect background to take SHM, its staff, and its membership to the next level,” said Laurence Wellikson, MD, MHM, chief executive officer of SHM. “His foundational leadership in the hospital medicine movement makes him the ideal person to lead SHM forward in its quest to provide hospitalists with the tools necessary to make a noteworthy difference in their institutions and in the lives of their patients.”

Dr. Howell is also a past president of SHM, the course director for the SHM Leadership Academies, and most recently, served as the senior physician advisor to SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement, which conducts quality improvement programs for hospitalist teams. He received his electrical engineering degree from the University of Maryland, which he said has served as an instrumental piece of his background for managing and implementing change in the hospital. His research has focused on the relationship between the emergency department and medicine floors, improving communication, throughput, and patient outcomes.

The Society of Hospital Medicine has announced the appointment of Eric Howell, MD, MHM, to the position of chief operating officer (COO).

“Having been involved with SHM in many capacities since first joining, I am honored to now transition to chief operating officer,” Dr. Howell said. “I always tell everyone that my goal is to make the world a better place, and I know that SHM’s staff will be able to do just that through the development and deployment of a variety of products, tools, and services to help hospitalists improve patient care.”

In his new role as COO at SHM, Dr. Howell will lead senior management’s strategic planning as well as define organizational goals to drive extensive, sustainable growth. In addition to serving as SHM’s COO, Dr. Howell will continue his role as director of the hospital medicine division of Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore and professor of medicine in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, also in Baltimore. Dr. Howell joined the Johns Hopkins Bayview hospitalist program in 2000, began the Howard County (Md.) General Hospital hospitalist program in 2010, and now oversees more than 200 physicians and clinical staff providing patient care in three hospitals.

“Eric has the perfect background to take SHM, its staff, and its membership to the next level,” said Laurence Wellikson, MD, MHM, chief executive officer of SHM. “His foundational leadership in the hospital medicine movement makes him the ideal person to lead SHM forward in its quest to provide hospitalists with the tools necessary to make a noteworthy difference in their institutions and in the lives of their patients.”

Dr. Howell is also a past president of SHM, the course director for the SHM Leadership Academies, and most recently, served as the senior physician advisor to SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement, which conducts quality improvement programs for hospitalist teams. He received his electrical engineering degree from the University of Maryland, which he said has served as an instrumental piece of his background for managing and implementing change in the hospital. His research has focused on the relationship between the emergency department and medicine floors, improving communication, throughput, and patient outcomes.

Little overlap between surgical M&M and AHRQ on adverse events

Limited overlap in adverse events identified by surgical morbidity and mortality (M&M) conferences and by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality patient safety indicators (PSIs) demonstrates that the two processes tend to capture different, but equally important, measures, according to study results published in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Just 18 of 149 (12.1%) PSI-defined events were identified by both processes in a retrospective, observational study of complications at the UC Davis Medical Center’s department of surgery. Most events (62.4%) were identified by only the M&M review, while 25.5% were identified by only the PSIs, reported Jamie E. Anderson, MD, MPH, of the department of surgery at UC Davis Medical Center in Sacramento and coauthors.

The study authors identified 6,563 surgical hospitalizations in the year 2016, of which 647 (9.9%) had at least one event that was either submitted for review for a departmental M&M conference, identified as a PSI event from administrative data, or both. Cases in patients aged less than 18 years were excluded.

Hospital administrative data were reported using ICD-10 CM/PCS codes. Investigators identified all PSI cases, which included pressure ulcer, retained surgical item, iatrogenic pneumothorax, central venous catheter–related blood stream infection, postoperative hip fracture, perioperative hematoma or hemorrhage requiring a procedure, postoperative acute kidney injury requiring dialysis, postoperative respiratory failure, perioperative pulmonary embolism or deep venous thrombosis, postoperative sepsis, postoperative wound dehiscence, and unrecognized abdominopelvic accidental puncture or laceration.

Complications submitted to the M&M conference were reviewed for PSI-defined events, and included events from general surgery, bariatric surgery, burn, cardiothoracic, colorectal, surgical oncology, plastic, vascular, transplant, and trauma. PSI-defined events were then reviewed to verify whether they counted as “true” PSI events and further classified as a documentation error, intentional exclusion, or inherent limitation of the PSI, the authors reported.

Of 6,563 surgical hospitalizations, 647 had at least one complication identified by M&M, PSI, or both. Of these, 116 had at least one PSI-defined event identified by either M&M or PSI. The remaining hospitalizations had unrelated complications and were excluded from analysis.

Of the 116 hospitalizations, there were 149 PSI-defined events, of which 18 (12.1%) were identified by both methods. Most events (62.4%) were identified by only the M&M review, and 25.5% were identified by only the PSIs. Perioperative hemorrhage/hematoma and postoperative sepsis were most likely to be identified by both.

Of the 93 PSI-defined events captured by only M&M, 11 (11.8%) met AHRQ criteria and were considered “true” events, or “false negatives.” All 38 events identified by PSI alone were correctly identified as true PSI events, Dr. Anderson and colleagues reported.

The findings indicate that the AHRQ PSI and surgical M&M conference “should be considered complementary approaches for identifying complications,” the authors wrote.

The PSI data captured central venous catheter–related blood stream infection and pressure ulcers, but the M&M conferences did not include these outcomes. The M&M reviewed more cases of postoperative sepsis, abdominopelvic accidental laceration, and the one case of retained surgical item.

“These two processes of identifying complications have different purposes, and each approach captured different events,” they added.

The M&M conference “balances clinician education and quality improvement with an underlying theme of accountability,” they said, with increased emphasis on examining adverse events in the context of systems-based practices. PSI, on the other hand, is intended as a “resource-nonintensive means” to help hospitals identify preventable events and facilitate quality improvement, they said.

“In an era in which there are numerous mechanisms to measure surgical quality, the traditional M&M conference is still relevant for identifying and discussing surgical complications,” the authors concluded. “We believe that our center’s existing M&M case-finding process is fundamentally sound, but it could be improved by including all PSI-flagged hospitalizations in our M&M process. This may result in review of some false-positive records, but it will enable our department to address certain potentially preventable complications that are currently overlooked.”

Two of the study coauthors received salary support from the AHRQ to support the agency’s Quality Indicator Program, one of whom serves on the agency’s Quality Indicators Expert Workgroup. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Anderson J et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 Jul 5. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.06.008.

Limited overlap in adverse events identified by surgical morbidity and mortality (M&M) conferences and by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality patient safety indicators (PSIs) demonstrates that the two processes tend to capture different, but equally important, measures, according to study results published in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Just 18 of 149 (12.1%) PSI-defined events were identified by both processes in a retrospective, observational study of complications at the UC Davis Medical Center’s department of surgery. Most events (62.4%) were identified by only the M&M review, while 25.5% were identified by only the PSIs, reported Jamie E. Anderson, MD, MPH, of the department of surgery at UC Davis Medical Center in Sacramento and coauthors.

The study authors identified 6,563 surgical hospitalizations in the year 2016, of which 647 (9.9%) had at least one event that was either submitted for review for a departmental M&M conference, identified as a PSI event from administrative data, or both. Cases in patients aged less than 18 years were excluded.

Hospital administrative data were reported using ICD-10 CM/PCS codes. Investigators identified all PSI cases, which included pressure ulcer, retained surgical item, iatrogenic pneumothorax, central venous catheter–related blood stream infection, postoperative hip fracture, perioperative hematoma or hemorrhage requiring a procedure, postoperative acute kidney injury requiring dialysis, postoperative respiratory failure, perioperative pulmonary embolism or deep venous thrombosis, postoperative sepsis, postoperative wound dehiscence, and unrecognized abdominopelvic accidental puncture or laceration.

Complications submitted to the M&M conference were reviewed for PSI-defined events, and included events from general surgery, bariatric surgery, burn, cardiothoracic, colorectal, surgical oncology, plastic, vascular, transplant, and trauma. PSI-defined events were then reviewed to verify whether they counted as “true” PSI events and further classified as a documentation error, intentional exclusion, or inherent limitation of the PSI, the authors reported.

Of 6,563 surgical hospitalizations, 647 had at least one complication identified by M&M, PSI, or both. Of these, 116 had at least one PSI-defined event identified by either M&M or PSI. The remaining hospitalizations had unrelated complications and were excluded from analysis.

Of the 116 hospitalizations, there were 149 PSI-defined events, of which 18 (12.1%) were identified by both methods. Most events (62.4%) were identified by only the M&M review, and 25.5% were identified by only the PSIs. Perioperative hemorrhage/hematoma and postoperative sepsis were most likely to be identified by both.

Of the 93 PSI-defined events captured by only M&M, 11 (11.8%) met AHRQ criteria and were considered “true” events, or “false negatives.” All 38 events identified by PSI alone were correctly identified as true PSI events, Dr. Anderson and colleagues reported.

The findings indicate that the AHRQ PSI and surgical M&M conference “should be considered complementary approaches for identifying complications,” the authors wrote.

The PSI data captured central venous catheter–related blood stream infection and pressure ulcers, but the M&M conferences did not include these outcomes. The M&M reviewed more cases of postoperative sepsis, abdominopelvic accidental laceration, and the one case of retained surgical item.

“These two processes of identifying complications have different purposes, and each approach captured different events,” they added.

The M&M conference “balances clinician education and quality improvement with an underlying theme of accountability,” they said, with increased emphasis on examining adverse events in the context of systems-based practices. PSI, on the other hand, is intended as a “resource-nonintensive means” to help hospitals identify preventable events and facilitate quality improvement, they said.

“In an era in which there are numerous mechanisms to measure surgical quality, the traditional M&M conference is still relevant for identifying and discussing surgical complications,” the authors concluded. “We believe that our center’s existing M&M case-finding process is fundamentally sound, but it could be improved by including all PSI-flagged hospitalizations in our M&M process. This may result in review of some false-positive records, but it will enable our department to address certain potentially preventable complications that are currently overlooked.”

Two of the study coauthors received salary support from the AHRQ to support the agency’s Quality Indicator Program, one of whom serves on the agency’s Quality Indicators Expert Workgroup. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Anderson J et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 Jul 5. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.06.008.

Limited overlap in adverse events identified by surgical morbidity and mortality (M&M) conferences and by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality patient safety indicators (PSIs) demonstrates that the two processes tend to capture different, but equally important, measures, according to study results published in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Just 18 of 149 (12.1%) PSI-defined events were identified by both processes in a retrospective, observational study of complications at the UC Davis Medical Center’s department of surgery. Most events (62.4%) were identified by only the M&M review, while 25.5% were identified by only the PSIs, reported Jamie E. Anderson, MD, MPH, of the department of surgery at UC Davis Medical Center in Sacramento and coauthors.

The study authors identified 6,563 surgical hospitalizations in the year 2016, of which 647 (9.9%) had at least one event that was either submitted for review for a departmental M&M conference, identified as a PSI event from administrative data, or both. Cases in patients aged less than 18 years were excluded.

Hospital administrative data were reported using ICD-10 CM/PCS codes. Investigators identified all PSI cases, which included pressure ulcer, retained surgical item, iatrogenic pneumothorax, central venous catheter–related blood stream infection, postoperative hip fracture, perioperative hematoma or hemorrhage requiring a procedure, postoperative acute kidney injury requiring dialysis, postoperative respiratory failure, perioperative pulmonary embolism or deep venous thrombosis, postoperative sepsis, postoperative wound dehiscence, and unrecognized abdominopelvic accidental puncture or laceration.

Complications submitted to the M&M conference were reviewed for PSI-defined events, and included events from general surgery, bariatric surgery, burn, cardiothoracic, colorectal, surgical oncology, plastic, vascular, transplant, and trauma. PSI-defined events were then reviewed to verify whether they counted as “true” PSI events and further classified as a documentation error, intentional exclusion, or inherent limitation of the PSI, the authors reported.

Of 6,563 surgical hospitalizations, 647 had at least one complication identified by M&M, PSI, or both. Of these, 116 had at least one PSI-defined event identified by either M&M or PSI. The remaining hospitalizations had unrelated complications and were excluded from analysis.

Of the 116 hospitalizations, there were 149 PSI-defined events, of which 18 (12.1%) were identified by both methods. Most events (62.4%) were identified by only the M&M review, and 25.5% were identified by only the PSIs. Perioperative hemorrhage/hematoma and postoperative sepsis were most likely to be identified by both.

Of the 93 PSI-defined events captured by only M&M, 11 (11.8%) met AHRQ criteria and were considered “true” events, or “false negatives.” All 38 events identified by PSI alone were correctly identified as true PSI events, Dr. Anderson and colleagues reported.

The findings indicate that the AHRQ PSI and surgical M&M conference “should be considered complementary approaches for identifying complications,” the authors wrote.

The PSI data captured central venous catheter–related blood stream infection and pressure ulcers, but the M&M conferences did not include these outcomes. The M&M reviewed more cases of postoperative sepsis, abdominopelvic accidental laceration, and the one case of retained surgical item.

“These two processes of identifying complications have different purposes, and each approach captured different events,” they added.

The M&M conference “balances clinician education and quality improvement with an underlying theme of accountability,” they said, with increased emphasis on examining adverse events in the context of systems-based practices. PSI, on the other hand, is intended as a “resource-nonintensive means” to help hospitals identify preventable events and facilitate quality improvement, they said.

“In an era in which there are numerous mechanisms to measure surgical quality, the traditional M&M conference is still relevant for identifying and discussing surgical complications,” the authors concluded. “We believe that our center’s existing M&M case-finding process is fundamentally sound, but it could be improved by including all PSI-flagged hospitalizations in our M&M process. This may result in review of some false-positive records, but it will enable our department to address certain potentially preventable complications that are currently overlooked.”

Two of the study coauthors received salary support from the AHRQ to support the agency’s Quality Indicator Program, one of whom serves on the agency’s Quality Indicators Expert Workgroup. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Anderson J et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 Jul 5. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.06.008.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS

Key clinical point: Surgical morbidity and mortality conferences and AHRQ patient safety indicators should be considered complementary measures of adverse events because of a limited overlap in identifying adverse events.

Major finding: Eighteen of 149 (12.1%) PSI-defined events were identified by both processes; most (62.4%) were identified by only M&M review, and 25.5% by only PSI.

Study details: A retrospective observational study of all complications in 2016 at the UC Davis Medical Center department of surgery.

Disclosures: Two of the study coauthors received salary support from the AHRQ to support the agency’s Quality Indicator Program, one of whom serves on the agency’s Quality Indicators Expert Workgroup. No other disclosures were reported.

Source: Anderson J et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 Jul 5. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.06.008.

Is the most effective emergency contraception easily obtained at US pharmacies?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

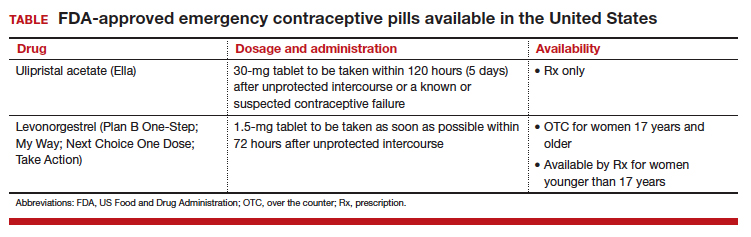

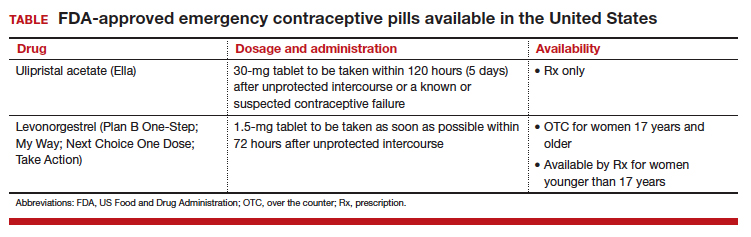

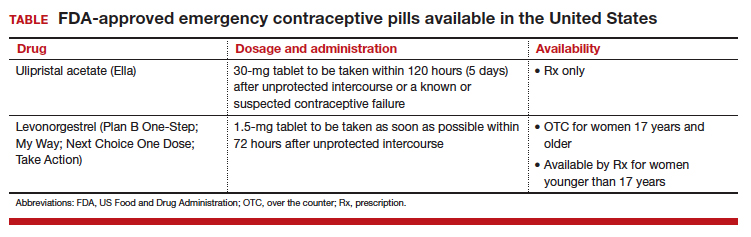

Although it is available only by prescription, ulipristal acetate provides emergency contraception that is more effective than the emergency contraception provided by levonorgestrel (LNG), which is available without a prescription (TABLE). In addition, ulipristal acetate appears more effective than LNG in obese and overweight women.1,2 Package labeling for ulipristal acetate indicates that a single 30-mg tablet should be taken orally within 5 days of unprotected sex.

According to a survey of pharmacy availability of ulipristal acetate in Hawaii, 2.6% of retail pharmacies had the drug immediately available, compared with 82.4% for LNG, and 22.8% reported the ability to order it.3 To assess pharmacy availability of ulipristal acetate on a nationwide scale, Shigesato and colleagues conducted a national “secret shopper” telephone survey in 10 cities (each with a population of at least 500,000) in all major regions of the United States.

Details of the study

Independent pharmacies (defined as having fewer than 5 locations within the city) and chain pharmacies were included in the survey. The survey callers, representing themselves as uninsured 18-year-old women attempting to fill a prescription for ulipristal acetate, followed a semistructured questionnaire and recorded the responses. They asked about the immediate availability of ulipristal acetate and LNG, the pharmacy’s ability to order ulipristal acetate if not immediately available, out-of-pocket costs, instructions for use, and the differences between ulipristal acetate and LNG. Questions were directed to whichever pharmacy staff member answered the phone; callers did not specifically ask to speak to a pharmacist.

Of the 344 pharmacies included in this analysis, 10% (33) indicated that they could fill a prescription for ulipristal acetate immediately. While availability did not vary by region, there was a difference in immediate availability by city.

Almost three-quarters of pharmacies without immediate drug availability indicated that they could order ulipristal acetate, with a median predicted time for availability of 24 hours. Of the chain pharmacies, 81% (167 of 205) reported the ability to order ulipristal acetate, compared with 55% (57 of 106) of independent pharmacies.

When asked if ulipristal acetate was different from LNG, more than one-third of pharmacy personnel contacted stated either that there was no difference between ulipristal acetate and LNG or that they were not sure of a difference.

Study strengths and weaknesses

The authors noted that the secret shopper methodology, along with having callers speak to the pharmacy staff person who answered the call (rather than asking for the pharmacist), provided data that closely approximates real-world patient experiences.

Since more pharmacies than anticipated met exclusion criteria for the study, the estimate of ulipristal acetate immediate availability was less precise than the power analysis predicted. Further, results from the 10 large, geographically diverse cities may not be representative of all similarly sized cities nationally or all areas of the United States.

As the authors point out, a low prevalence of pharmacies stock ulipristal acetate, and more than 25% are not able to order this emergency contraception. This underscores the fact that access to the most effective oral emergency contraception is limited for US women. I agree with the authors’ speculation that access to ulipristal acetate may be even lower in rural areas. In many European countries, ulipristal acetate is available without a prescription. Clinicians caring for women who may benefit from emergency contraception, particularly those using short-acting or less effective contraceptives, may wish to prescribe ulipristal acetate in advance of need.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kapp N, Abitbol JL, Mathé H, et al. Effect of body weight and BMI on the efficacy of levonorgestrel emergency contraception. Contraception. 2015;91(2):97–104.

- Glasier A, Cameron ST, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Contraception. 2011;84(4):363–367.

- Bullock H, Steele S, Kurata N, et al. Pharmacy access to ulipristal acetate in Hawaii: is a prescription enough? Contraception. 2016;93(5):452–454.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Although it is available only by prescription, ulipristal acetate provides emergency contraception that is more effective than the emergency contraception provided by levonorgestrel (LNG), which is available without a prescription (TABLE). In addition, ulipristal acetate appears more effective than LNG in obese and overweight women.1,2 Package labeling for ulipristal acetate indicates that a single 30-mg tablet should be taken orally within 5 days of unprotected sex.

According to a survey of pharmacy availability of ulipristal acetate in Hawaii, 2.6% of retail pharmacies had the drug immediately available, compared with 82.4% for LNG, and 22.8% reported the ability to order it.3 To assess pharmacy availability of ulipristal acetate on a nationwide scale, Shigesato and colleagues conducted a national “secret shopper” telephone survey in 10 cities (each with a population of at least 500,000) in all major regions of the United States.

Details of the study

Independent pharmacies (defined as having fewer than 5 locations within the city) and chain pharmacies were included in the survey. The survey callers, representing themselves as uninsured 18-year-old women attempting to fill a prescription for ulipristal acetate, followed a semistructured questionnaire and recorded the responses. They asked about the immediate availability of ulipristal acetate and LNG, the pharmacy’s ability to order ulipristal acetate if not immediately available, out-of-pocket costs, instructions for use, and the differences between ulipristal acetate and LNG. Questions were directed to whichever pharmacy staff member answered the phone; callers did not specifically ask to speak to a pharmacist.

Of the 344 pharmacies included in this analysis, 10% (33) indicated that they could fill a prescription for ulipristal acetate immediately. While availability did not vary by region, there was a difference in immediate availability by city.

Almost three-quarters of pharmacies without immediate drug availability indicated that they could order ulipristal acetate, with a median predicted time for availability of 24 hours. Of the chain pharmacies, 81% (167 of 205) reported the ability to order ulipristal acetate, compared with 55% (57 of 106) of independent pharmacies.

When asked if ulipristal acetate was different from LNG, more than one-third of pharmacy personnel contacted stated either that there was no difference between ulipristal acetate and LNG or that they were not sure of a difference.

Study strengths and weaknesses

The authors noted that the secret shopper methodology, along with having callers speak to the pharmacy staff person who answered the call (rather than asking for the pharmacist), provided data that closely approximates real-world patient experiences.

Since more pharmacies than anticipated met exclusion criteria for the study, the estimate of ulipristal acetate immediate availability was less precise than the power analysis predicted. Further, results from the 10 large, geographically diverse cities may not be representative of all similarly sized cities nationally or all areas of the United States.

As the authors point out, a low prevalence of pharmacies stock ulipristal acetate, and more than 25% are not able to order this emergency contraception. This underscores the fact that access to the most effective oral emergency contraception is limited for US women. I agree with the authors’ speculation that access to ulipristal acetate may be even lower in rural areas. In many European countries, ulipristal acetate is available without a prescription. Clinicians caring for women who may benefit from emergency contraception, particularly those using short-acting or less effective contraceptives, may wish to prescribe ulipristal acetate in advance of need.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Although it is available only by prescription, ulipristal acetate provides emergency contraception that is more effective than the emergency contraception provided by levonorgestrel (LNG), which is available without a prescription (TABLE). In addition, ulipristal acetate appears more effective than LNG in obese and overweight women.1,2 Package labeling for ulipristal acetate indicates that a single 30-mg tablet should be taken orally within 5 days of unprotected sex.

According to a survey of pharmacy availability of ulipristal acetate in Hawaii, 2.6% of retail pharmacies had the drug immediately available, compared with 82.4% for LNG, and 22.8% reported the ability to order it.3 To assess pharmacy availability of ulipristal acetate on a nationwide scale, Shigesato and colleagues conducted a national “secret shopper” telephone survey in 10 cities (each with a population of at least 500,000) in all major regions of the United States.

Details of the study

Independent pharmacies (defined as having fewer than 5 locations within the city) and chain pharmacies were included in the survey. The survey callers, representing themselves as uninsured 18-year-old women attempting to fill a prescription for ulipristal acetate, followed a semistructured questionnaire and recorded the responses. They asked about the immediate availability of ulipristal acetate and LNG, the pharmacy’s ability to order ulipristal acetate if not immediately available, out-of-pocket costs, instructions for use, and the differences between ulipristal acetate and LNG. Questions were directed to whichever pharmacy staff member answered the phone; callers did not specifically ask to speak to a pharmacist.

Of the 344 pharmacies included in this analysis, 10% (33) indicated that they could fill a prescription for ulipristal acetate immediately. While availability did not vary by region, there was a difference in immediate availability by city.

Almost three-quarters of pharmacies without immediate drug availability indicated that they could order ulipristal acetate, with a median predicted time for availability of 24 hours. Of the chain pharmacies, 81% (167 of 205) reported the ability to order ulipristal acetate, compared with 55% (57 of 106) of independent pharmacies.

When asked if ulipristal acetate was different from LNG, more than one-third of pharmacy personnel contacted stated either that there was no difference between ulipristal acetate and LNG or that they were not sure of a difference.

Study strengths and weaknesses

The authors noted that the secret shopper methodology, along with having callers speak to the pharmacy staff person who answered the call (rather than asking for the pharmacist), provided data that closely approximates real-world patient experiences.

Since more pharmacies than anticipated met exclusion criteria for the study, the estimate of ulipristal acetate immediate availability was less precise than the power analysis predicted. Further, results from the 10 large, geographically diverse cities may not be representative of all similarly sized cities nationally or all areas of the United States.

As the authors point out, a low prevalence of pharmacies stock ulipristal acetate, and more than 25% are not able to order this emergency contraception. This underscores the fact that access to the most effective oral emergency contraception is limited for US women. I agree with the authors’ speculation that access to ulipristal acetate may be even lower in rural areas. In many European countries, ulipristal acetate is available without a prescription. Clinicians caring for women who may benefit from emergency contraception, particularly those using short-acting or less effective contraceptives, may wish to prescribe ulipristal acetate in advance of need.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kapp N, Abitbol JL, Mathé H, et al. Effect of body weight and BMI on the efficacy of levonorgestrel emergency contraception. Contraception. 2015;91(2):97–104.

- Glasier A, Cameron ST, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Contraception. 2011;84(4):363–367.

- Bullock H, Steele S, Kurata N, et al. Pharmacy access to ulipristal acetate in Hawaii: is a prescription enough? Contraception. 2016;93(5):452–454.

- Kapp N, Abitbol JL, Mathé H, et al. Effect of body weight and BMI on the efficacy of levonorgestrel emergency contraception. Contraception. 2015;91(2):97–104.

- Glasier A, Cameron ST, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Contraception. 2011;84(4):363–367.

- Bullock H, Steele S, Kurata N, et al. Pharmacy access to ulipristal acetate in Hawaii: is a prescription enough? Contraception. 2016;93(5):452–454.

Breastfeeding lowered later stroke risk in WHI

Postmenopausal women who breastfed their children had a lower risk of stroke compared with women who had children but never breastfed, with non-Hispanic black women showing a significantly stronger association between breastfeeding and lower stroke risk, according to results from the prospective Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study.

“Some studies have reported that breastfeeding may reduce the rates of breast cancer, ovarian cancer and risk of developing type 2 diabetes in mothers. Recent findings point to the benefits of breastfeeding on heart disease and other specific cardiovascular risk factors,” Lisette T. Jacobson, PhD, of the department of preventive medicine and public health at the University of Kansas, Wichita, said in a statement.

Dr. Jacobson and her colleagues evaluated 80,191 women from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Observational Study who were aged 50-79 at baseline. The average age was 64 years, and 83% were white, 8% were non-Hispanic black, 4% were Hispanic, and 5% were another race or ethnicity. Of the women observed, 58% had breastfed and 3.4% had a stroke within an average of 13 years of follow-up. The investigators used three adjusted regression models to analyze stroke risk: Model 1 was minimally adjusted, model 2 was adjusted for nonmodifiable potential confounders, and model 3 was adjusted for modifiable lifestyle factors.

There was a 23% lower risk of stroke among all postmenopausal women who breastfed compared with those who never breastfed, with women who breastfed between 1 month and 6 months carrying a 19% lower risk of stroke. In the minimally adjusted model, non-Hispanic white women who breastfed carried a 21% lower risk, Hispanic women had an adjusted 32% lower risk, and women of other races and ethnicity had a 24% lower risk of stroke. However, women who were non-Hispanic black had a stronger association with breastfeeding and stroke reduction, with a 48% lower risk, and non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black women showed a stronger association between longer duration of breastfeeding and lower stroke risk when results were minimally adjusted, the investigators said. All differences were statistically significant.

The investigators noted the study’s observational nature and said they were not able to determine what caused breastfeeding’s association with lower stroke risk, with other factors potentially affecting results.

“Breastfeeding is only one of many factors that could potentially protect against stroke,” Dr. Jacobson said in the report, published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association. “Others include getting adequate exercise, choosing healthy foods, not smoking, and seeking treatment if needed to keep your blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar in the normal range.”

They also noted potential limitations in the study: the WHI cohort’s low number of strokes in follow-up, lack of classification of stroke, recall bias due to the women self-reporting strokes, average age at baseline, and lack of data on pregnancy.

“Our study did not address whether racial/ethnic differences in breastfeeding contribute to disparities in stroke risk,” Dr. Jacobson said. “Additional research should consider the degree to which breastfeeding might alter racial/ethnic differences in stroke risk.”

“This is an observational, prospective cohort study that was performed very carefully, but it is important to not conclude causality in that breastfeeding results in a reduction in late life stroke,” Larry B. Goldstein, MD, said in an email interview.

Dr. Goldstein, a neurologist who has published several guidelines on primary prevention and early management of stroke with the American Heart Association, noted that although the authors addressed many confounders, studies of this type are still open to residual confounding. He said one of the factors the authors could not measure was eclampsia and preeclampsia, which inhibits breastfeeding.

“The possibility of unmeasured confounding despite how well the study was done is still there. But having said that, the recommendations for breastfeeding are strong from the American Academy of Pediatrics and from the World Health Organization,” and other studies have found an association with a reduction in later life cardiovascular disease, said Dr. Goldstein, the Ruth L. Works professor and chairman in the department of neurology at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. “But just in terms of the benefits to the mother and to the child from breastfeeding, this is another potential plus [in that] even if it doesn’t pan out, it doesn’t really change the recommendation for breastfeeding.”

Dr. Goldstein noted that finding these results in a different prospective cohort would strengthen the recommendations, as would examining whether factors such as lifestyle affected stroke risk for women.

“Showing causality is always going to be difficult,” he stressed. “There is no particular causal mechanism that’s been espoused for how this might decrease stroke risk in later life.”

This study is funded by Frontiers: The Heartland Institute for Clinical and Translational Research and the Wichita Center for Graduate Medical Education–Kansas Bioscience Authority. The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institutes of Health, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Jacobson LT et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018 Aug 22. doi:10.1161/JAHA.118.008739.

This is an important study for pediatricians who counsel breastfeeding mothers and families on the benefits of breastfeeding for mothers and their families.

The current study is important because of its large scale and the fact that it shows an association between any breastfeeding longer than 1 month and protection against stroke, especially for the non-Hispanic black population. These women face higher risks of cardiovascular disease, including hypertension and heart disease, and also higher risks from obesity and hypertension. Longer duration of breastfeeding showed an association with decreased risk of stroke for both non-Hispanic white women and non-Hispanic black women in this study.

On the basis of this study, pediatricians can include potential protection against strokes, as part of the list of protective effects when counseling mothers, either prenatally or in the postpartum setting. Women of childbearing age are not at high risk for stroke, but breastfeeding is a healthy life choice that has significant benefits not just during the period of direct breastfeeding but for years afterward. This study also emphasizes that the benefits of breastfeeding are often dose related. In other words, the longer the mother breastfeeds, the greater the health benefits are for her and for her child.

It would be helpful to have further long-term prospective studies that collect information about breastfeeding at the time that the mother is breastfeeding and then throughout her lifespan. That way, the risk of stroke as well as other cardiovascular risks and cancer risks could be more precisely delineated without the potential for recall bias.

Joan Younger Meek, MD, is chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding and associate dean for graduate medical education at Florida State University, Orlando. These comments were excerpted from an email interview. She has no relevant conflicts of interest.

This is an important study for pediatricians who counsel breastfeeding mothers and families on the benefits of breastfeeding for mothers and their families.

The current study is important because of its large scale and the fact that it shows an association between any breastfeeding longer than 1 month and protection against stroke, especially for the non-Hispanic black population. These women face higher risks of cardiovascular disease, including hypertension and heart disease, and also higher risks from obesity and hypertension. Longer duration of breastfeeding showed an association with decreased risk of stroke for both non-Hispanic white women and non-Hispanic black women in this study.

On the basis of this study, pediatricians can include potential protection against strokes, as part of the list of protective effects when counseling mothers, either prenatally or in the postpartum setting. Women of childbearing age are not at high risk for stroke, but breastfeeding is a healthy life choice that has significant benefits not just during the period of direct breastfeeding but for years afterward. This study also emphasizes that the benefits of breastfeeding are often dose related. In other words, the longer the mother breastfeeds, the greater the health benefits are for her and for her child.

It would be helpful to have further long-term prospective studies that collect information about breastfeeding at the time that the mother is breastfeeding and then throughout her lifespan. That way, the risk of stroke as well as other cardiovascular risks and cancer risks could be more precisely delineated without the potential for recall bias.

Joan Younger Meek, MD, is chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding and associate dean for graduate medical education at Florida State University, Orlando. These comments were excerpted from an email interview. She has no relevant conflicts of interest.

This is an important study for pediatricians who counsel breastfeeding mothers and families on the benefits of breastfeeding for mothers and their families.

The current study is important because of its large scale and the fact that it shows an association between any breastfeeding longer than 1 month and protection against stroke, especially for the non-Hispanic black population. These women face higher risks of cardiovascular disease, including hypertension and heart disease, and also higher risks from obesity and hypertension. Longer duration of breastfeeding showed an association with decreased risk of stroke for both non-Hispanic white women and non-Hispanic black women in this study.

On the basis of this study, pediatricians can include potential protection against strokes, as part of the list of protective effects when counseling mothers, either prenatally or in the postpartum setting. Women of childbearing age are not at high risk for stroke, but breastfeeding is a healthy life choice that has significant benefits not just during the period of direct breastfeeding but for years afterward. This study also emphasizes that the benefits of breastfeeding are often dose related. In other words, the longer the mother breastfeeds, the greater the health benefits are for her and for her child.

It would be helpful to have further long-term prospective studies that collect information about breastfeeding at the time that the mother is breastfeeding and then throughout her lifespan. That way, the risk of stroke as well as other cardiovascular risks and cancer risks could be more precisely delineated without the potential for recall bias.

Joan Younger Meek, MD, is chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding and associate dean for graduate medical education at Florida State University, Orlando. These comments were excerpted from an email interview. She has no relevant conflicts of interest.

Postmenopausal women who breastfed their children had a lower risk of stroke compared with women who had children but never breastfed, with non-Hispanic black women showing a significantly stronger association between breastfeeding and lower stroke risk, according to results from the prospective Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study.

“Some studies have reported that breastfeeding may reduce the rates of breast cancer, ovarian cancer and risk of developing type 2 diabetes in mothers. Recent findings point to the benefits of breastfeeding on heart disease and other specific cardiovascular risk factors,” Lisette T. Jacobson, PhD, of the department of preventive medicine and public health at the University of Kansas, Wichita, said in a statement.

Dr. Jacobson and her colleagues evaluated 80,191 women from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Observational Study who were aged 50-79 at baseline. The average age was 64 years, and 83% were white, 8% were non-Hispanic black, 4% were Hispanic, and 5% were another race or ethnicity. Of the women observed, 58% had breastfed and 3.4% had a stroke within an average of 13 years of follow-up. The investigators used three adjusted regression models to analyze stroke risk: Model 1 was minimally adjusted, model 2 was adjusted for nonmodifiable potential confounders, and model 3 was adjusted for modifiable lifestyle factors.

There was a 23% lower risk of stroke among all postmenopausal women who breastfed compared with those who never breastfed, with women who breastfed between 1 month and 6 months carrying a 19% lower risk of stroke. In the minimally adjusted model, non-Hispanic white women who breastfed carried a 21% lower risk, Hispanic women had an adjusted 32% lower risk, and women of other races and ethnicity had a 24% lower risk of stroke. However, women who were non-Hispanic black had a stronger association with breastfeeding and stroke reduction, with a 48% lower risk, and non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black women showed a stronger association between longer duration of breastfeeding and lower stroke risk when results were minimally adjusted, the investigators said. All differences were statistically significant.

The investigators noted the study’s observational nature and said they were not able to determine what caused breastfeeding’s association with lower stroke risk, with other factors potentially affecting results.

“Breastfeeding is only one of many factors that could potentially protect against stroke,” Dr. Jacobson said in the report, published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association. “Others include getting adequate exercise, choosing healthy foods, not smoking, and seeking treatment if needed to keep your blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar in the normal range.”

They also noted potential limitations in the study: the WHI cohort’s low number of strokes in follow-up, lack of classification of stroke, recall bias due to the women self-reporting strokes, average age at baseline, and lack of data on pregnancy.

“Our study did not address whether racial/ethnic differences in breastfeeding contribute to disparities in stroke risk,” Dr. Jacobson said. “Additional research should consider the degree to which breastfeeding might alter racial/ethnic differences in stroke risk.”

“This is an observational, prospective cohort study that was performed very carefully, but it is important to not conclude causality in that breastfeeding results in a reduction in late life stroke,” Larry B. Goldstein, MD, said in an email interview.

Dr. Goldstein, a neurologist who has published several guidelines on primary prevention and early management of stroke with the American Heart Association, noted that although the authors addressed many confounders, studies of this type are still open to residual confounding. He said one of the factors the authors could not measure was eclampsia and preeclampsia, which inhibits breastfeeding.

“The possibility of unmeasured confounding despite how well the study was done is still there. But having said that, the recommendations for breastfeeding are strong from the American Academy of Pediatrics and from the World Health Organization,” and other studies have found an association with a reduction in later life cardiovascular disease, said Dr. Goldstein, the Ruth L. Works professor and chairman in the department of neurology at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. “But just in terms of the benefits to the mother and to the child from breastfeeding, this is another potential plus [in that] even if it doesn’t pan out, it doesn’t really change the recommendation for breastfeeding.”

Dr. Goldstein noted that finding these results in a different prospective cohort would strengthen the recommendations, as would examining whether factors such as lifestyle affected stroke risk for women.

“Showing causality is always going to be difficult,” he stressed. “There is no particular causal mechanism that’s been espoused for how this might decrease stroke risk in later life.”

This study is funded by Frontiers: The Heartland Institute for Clinical and Translational Research and the Wichita Center for Graduate Medical Education–Kansas Bioscience Authority. The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institutes of Health, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Jacobson LT et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018 Aug 22. doi:10.1161/JAHA.118.008739.

Postmenopausal women who breastfed their children had a lower risk of stroke compared with women who had children but never breastfed, with non-Hispanic black women showing a significantly stronger association between breastfeeding and lower stroke risk, according to results from the prospective Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study.

“Some studies have reported that breastfeeding may reduce the rates of breast cancer, ovarian cancer and risk of developing type 2 diabetes in mothers. Recent findings point to the benefits of breastfeeding on heart disease and other specific cardiovascular risk factors,” Lisette T. Jacobson, PhD, of the department of preventive medicine and public health at the University of Kansas, Wichita, said in a statement.

Dr. Jacobson and her colleagues evaluated 80,191 women from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Observational Study who were aged 50-79 at baseline. The average age was 64 years, and 83% were white, 8% were non-Hispanic black, 4% were Hispanic, and 5% were another race or ethnicity. Of the women observed, 58% had breastfed and 3.4% had a stroke within an average of 13 years of follow-up. The investigators used three adjusted regression models to analyze stroke risk: Model 1 was minimally adjusted, model 2 was adjusted for nonmodifiable potential confounders, and model 3 was adjusted for modifiable lifestyle factors.

There was a 23% lower risk of stroke among all postmenopausal women who breastfed compared with those who never breastfed, with women who breastfed between 1 month and 6 months carrying a 19% lower risk of stroke. In the minimally adjusted model, non-Hispanic white women who breastfed carried a 21% lower risk, Hispanic women had an adjusted 32% lower risk, and women of other races and ethnicity had a 24% lower risk of stroke. However, women who were non-Hispanic black had a stronger association with breastfeeding and stroke reduction, with a 48% lower risk, and non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black women showed a stronger association between longer duration of breastfeeding and lower stroke risk when results were minimally adjusted, the investigators said. All differences were statistically significant.

The investigators noted the study’s observational nature and said they were not able to determine what caused breastfeeding’s association with lower stroke risk, with other factors potentially affecting results.

“Breastfeeding is only one of many factors that could potentially protect against stroke,” Dr. Jacobson said in the report, published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association. “Others include getting adequate exercise, choosing healthy foods, not smoking, and seeking treatment if needed to keep your blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar in the normal range.”

They also noted potential limitations in the study: the WHI cohort’s low number of strokes in follow-up, lack of classification of stroke, recall bias due to the women self-reporting strokes, average age at baseline, and lack of data on pregnancy.

“Our study did not address whether racial/ethnic differences in breastfeeding contribute to disparities in stroke risk,” Dr. Jacobson said. “Additional research should consider the degree to which breastfeeding might alter racial/ethnic differences in stroke risk.”

“This is an observational, prospective cohort study that was performed very carefully, but it is important to not conclude causality in that breastfeeding results in a reduction in late life stroke,” Larry B. Goldstein, MD, said in an email interview.

Dr. Goldstein, a neurologist who has published several guidelines on primary prevention and early management of stroke with the American Heart Association, noted that although the authors addressed many confounders, studies of this type are still open to residual confounding. He said one of the factors the authors could not measure was eclampsia and preeclampsia, which inhibits breastfeeding.

“The possibility of unmeasured confounding despite how well the study was done is still there. But having said that, the recommendations for breastfeeding are strong from the American Academy of Pediatrics and from the World Health Organization,” and other studies have found an association with a reduction in later life cardiovascular disease, said Dr. Goldstein, the Ruth L. Works professor and chairman in the department of neurology at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. “But just in terms of the benefits to the mother and to the child from breastfeeding, this is another potential plus [in that] even if it doesn’t pan out, it doesn’t really change the recommendation for breastfeeding.”

Dr. Goldstein noted that finding these results in a different prospective cohort would strengthen the recommendations, as would examining whether factors such as lifestyle affected stroke risk for women.