User login

Review finds some therapies show promise in managing prurigo nodularis

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Recent success in the use of (PN) suggests that safer and more effective systemic therapies that provide relief and management of this debilitating chronic skin condition are possible, reported Azam A. Qureshi, BA, of the department of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, and his coauthors.

Their report was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

They conducted a systematic review of 35 clinical studies of different therapies for PN, published between Jan. 1, 1990, and March 22, 2018, using PubMed and Scopus databases. Their goal was twofold: to provide a summary of current evidence-based therapies and their corresponding level of evidence ratings, and to help researchers “identify gaps in PN treatment development and study.”

From 706 studies, the authors selected 35 clinical studies of treatment strategies for PN, for which the pathogenesis is virtually unknown, they noted. The studies included 15 prospective cohort studies, 11 retrospective reviews, 8 randomized controlled trials (with 10-127 patients), and 1 case series. Studies that failed to report treatment outcomes and those with fewer than five patients were excluded from the review.

Treatment modalities included topical agents, phototherapy and photochemotherapy, thalidomide, systemic immunomodulatory drugs, antiepileptics and antidepressants, and emerging treatment approaches. Many of the treatments evaluated in the review were found to offer limited promise for clinical application as a result of low efficacy or frequent side effects. The authors attributed the overall lack of success with treatments to the “heterogeneous nature of the etiology of chronic pruritus.”

Thalidomide was found to have limited use given its poor safety profile; lenalidomide achieved better outcomes, but treatment in one case was stopped because of possible drug-induced neuropathy or myopathy, they wrote. The systemic immunomodulatory agents methotrexate and cyclosporine exhibited successful treatment but also were found to have poor safety profiles. Greater promise was seen with antiepileptics and antidepressants, which were associated with fewer side effects. “Antidepressants, such as mirtazapine and amitriptyline, and antiepileptics, such as gabapentin and pregabalin, can offer significant relief to a good number of patients, though success is variable and as we found in our study, the evidence available is limited,” senior author Adam Friedman, MD, professor of dermatology at George Washington University, said in an interview.

Among the most positive outcomes achieved were those in which promising newer treatments, including targeting IL-31 signaling and opioid receptor modulation, were used. In particular, the authors cited nemolizumab, an IL-31 receptor A antagonist, which is currently in a phase 2 trial of PN. Beneficial effects of extended release nalbuphine, an opioid k-receptor agonist and mu-receptor antagonist, were found in an unpublished multicenter, double-blind randomized controlled trial, with no serious adverse effects attributed to treatment.

Among the emerging treatments are the neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists, which include serlopitant, which showed beneficial effects compared with placebo in an 8-week randomized controlled study, they wrote. The neurokinin-1 receptor “is a target of substance P, a mediator of itch and a probable pathogenic agent in PN,” they wrote. “Binding by these agents likely disrupts substance P signaling, thereby halting PN pathogenesis,” they added.

“Antidepressants such as mirtazapine and amitriptyline and antiepileptics such as gabapentin and pregabalin can offer significant relief to a good number of patients, though success is variable and as we found in our study, the evidence available is limited,” Dr. Friedman said in the interview.

Mr. Qureshi had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Friedman has received honoraria for participation in advisory boards for Menlo Therapeutics, and serves as an investigator for Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals. A third author received honoraria for participation in advisory boards for Menlo, and several other companies, and received grant/research support as an investigator from Menlo, Kiniksa, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Qureshi AA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.020.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Recent success in the use of (PN) suggests that safer and more effective systemic therapies that provide relief and management of this debilitating chronic skin condition are possible, reported Azam A. Qureshi, BA, of the department of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, and his coauthors.

Their report was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

They conducted a systematic review of 35 clinical studies of different therapies for PN, published between Jan. 1, 1990, and March 22, 2018, using PubMed and Scopus databases. Their goal was twofold: to provide a summary of current evidence-based therapies and their corresponding level of evidence ratings, and to help researchers “identify gaps in PN treatment development and study.”

From 706 studies, the authors selected 35 clinical studies of treatment strategies for PN, for which the pathogenesis is virtually unknown, they noted. The studies included 15 prospective cohort studies, 11 retrospective reviews, 8 randomized controlled trials (with 10-127 patients), and 1 case series. Studies that failed to report treatment outcomes and those with fewer than five patients were excluded from the review.

Treatment modalities included topical agents, phototherapy and photochemotherapy, thalidomide, systemic immunomodulatory drugs, antiepileptics and antidepressants, and emerging treatment approaches. Many of the treatments evaluated in the review were found to offer limited promise for clinical application as a result of low efficacy or frequent side effects. The authors attributed the overall lack of success with treatments to the “heterogeneous nature of the etiology of chronic pruritus.”

Thalidomide was found to have limited use given its poor safety profile; lenalidomide achieved better outcomes, but treatment in one case was stopped because of possible drug-induced neuropathy or myopathy, they wrote. The systemic immunomodulatory agents methotrexate and cyclosporine exhibited successful treatment but also were found to have poor safety profiles. Greater promise was seen with antiepileptics and antidepressants, which were associated with fewer side effects. “Antidepressants, such as mirtazapine and amitriptyline, and antiepileptics, such as gabapentin and pregabalin, can offer significant relief to a good number of patients, though success is variable and as we found in our study, the evidence available is limited,” senior author Adam Friedman, MD, professor of dermatology at George Washington University, said in an interview.

Among the most positive outcomes achieved were those in which promising newer treatments, including targeting IL-31 signaling and opioid receptor modulation, were used. In particular, the authors cited nemolizumab, an IL-31 receptor A antagonist, which is currently in a phase 2 trial of PN. Beneficial effects of extended release nalbuphine, an opioid k-receptor agonist and mu-receptor antagonist, were found in an unpublished multicenter, double-blind randomized controlled trial, with no serious adverse effects attributed to treatment.

Among the emerging treatments are the neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists, which include serlopitant, which showed beneficial effects compared with placebo in an 8-week randomized controlled study, they wrote. The neurokinin-1 receptor “is a target of substance P, a mediator of itch and a probable pathogenic agent in PN,” they wrote. “Binding by these agents likely disrupts substance P signaling, thereby halting PN pathogenesis,” they added.

“Antidepressants such as mirtazapine and amitriptyline and antiepileptics such as gabapentin and pregabalin can offer significant relief to a good number of patients, though success is variable and as we found in our study, the evidence available is limited,” Dr. Friedman said in the interview.

Mr. Qureshi had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Friedman has received honoraria for participation in advisory boards for Menlo Therapeutics, and serves as an investigator for Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals. A third author received honoraria for participation in advisory boards for Menlo, and several other companies, and received grant/research support as an investigator from Menlo, Kiniksa, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Qureshi AA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.020.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Recent success in the use of (PN) suggests that safer and more effective systemic therapies that provide relief and management of this debilitating chronic skin condition are possible, reported Azam A. Qureshi, BA, of the department of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, and his coauthors.

Their report was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

They conducted a systematic review of 35 clinical studies of different therapies for PN, published between Jan. 1, 1990, and March 22, 2018, using PubMed and Scopus databases. Their goal was twofold: to provide a summary of current evidence-based therapies and their corresponding level of evidence ratings, and to help researchers “identify gaps in PN treatment development and study.”

From 706 studies, the authors selected 35 clinical studies of treatment strategies for PN, for which the pathogenesis is virtually unknown, they noted. The studies included 15 prospective cohort studies, 11 retrospective reviews, 8 randomized controlled trials (with 10-127 patients), and 1 case series. Studies that failed to report treatment outcomes and those with fewer than five patients were excluded from the review.

Treatment modalities included topical agents, phototherapy and photochemotherapy, thalidomide, systemic immunomodulatory drugs, antiepileptics and antidepressants, and emerging treatment approaches. Many of the treatments evaluated in the review were found to offer limited promise for clinical application as a result of low efficacy or frequent side effects. The authors attributed the overall lack of success with treatments to the “heterogeneous nature of the etiology of chronic pruritus.”

Thalidomide was found to have limited use given its poor safety profile; lenalidomide achieved better outcomes, but treatment in one case was stopped because of possible drug-induced neuropathy or myopathy, they wrote. The systemic immunomodulatory agents methotrexate and cyclosporine exhibited successful treatment but also were found to have poor safety profiles. Greater promise was seen with antiepileptics and antidepressants, which were associated with fewer side effects. “Antidepressants, such as mirtazapine and amitriptyline, and antiepileptics, such as gabapentin and pregabalin, can offer significant relief to a good number of patients, though success is variable and as we found in our study, the evidence available is limited,” senior author Adam Friedman, MD, professor of dermatology at George Washington University, said in an interview.

Among the most positive outcomes achieved were those in which promising newer treatments, including targeting IL-31 signaling and opioid receptor modulation, were used. In particular, the authors cited nemolizumab, an IL-31 receptor A antagonist, which is currently in a phase 2 trial of PN. Beneficial effects of extended release nalbuphine, an opioid k-receptor agonist and mu-receptor antagonist, were found in an unpublished multicenter, double-blind randomized controlled trial, with no serious adverse effects attributed to treatment.

Among the emerging treatments are the neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists, which include serlopitant, which showed beneficial effects compared with placebo in an 8-week randomized controlled study, they wrote. The neurokinin-1 receptor “is a target of substance P, a mediator of itch and a probable pathogenic agent in PN,” they wrote. “Binding by these agents likely disrupts substance P signaling, thereby halting PN pathogenesis,” they added.

“Antidepressants such as mirtazapine and amitriptyline and antiepileptics such as gabapentin and pregabalin can offer significant relief to a good number of patients, though success is variable and as we found in our study, the evidence available is limited,” Dr. Friedman said in the interview.

Mr. Qureshi had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Friedman has received honoraria for participation in advisory boards for Menlo Therapeutics, and serves as an investigator for Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals. A third author received honoraria for participation in advisory boards for Menlo, and several other companies, and received grant/research support as an investigator from Menlo, Kiniksa, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Qureshi AA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.020.

Key clinical point: Additional research is needed to develop more individualized treatment strategies, but data for some treatments are promising.

Major finding: Treatments identified as having beneficial effects in the review included nemolizumab, an IL-31 receptor A antagonist; nalbuphine, an opioid k-receptor agonist and mu-receptor antagonist, and serlopitant, a neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist.

Study details: A systematic review of 35 studies evaluating treatments for PN, published between Jan. 1, 1990, and March 22, 2018.

Disclosures: Mr. Qureshi had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Friedman has received honoraria for participation in advisory boards for Menlo Therapeutics, and serves as an investigator for Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals. A third author received honoraria for participation in advisory boards for Menlo, and several other companies, and received grant/research support as an investigator from Menlo, Kiniksa, and several other companies.

Source: Qureshi AA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.020.

Increased incidence of GI, colorectal cancers seen in young, obese patients

PHILADELPHIA – Researchers have identified a link between obesity and an increased incidence rate of gastrointestinal (GI) cancers in younger patients as well as an increased rate of colorectal, esophageal, and pancreatic cancer resections in obese patients of various ages, according to an award-winning presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

“These findings strengthen a contributing role of obesity in etiology as well as increasing incidence of these cancers, and call for more efforts targeting obesity,” Hisham Hussan, MD, assistant professor at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, stated in his presentation.

The abstract, presented by Dr. Hussan, received an American College of Gastroenterology Category Award in the subject of obesity. He noted in his presentation that the obesity rate in U.S. adults exceeded 37% in 2014. In addition, the temporal changes of obesity-related GI cancers with regard to age-specific groups are not known, he said.

“There’s sufficient evidence linking obesity to certain [GI cancers], such as esophagus, colon, pancreas, and gastric,” Dr. Hussan said. “However, the impact of rising obesity prevalence on the incidence of these obesity-related GI cancers is unknown.”

Dr. Hussan and his colleagues sought to investigate the incidence of obesity-related GI cancers by age group as well as whether there was an association between obesity-related GI cancers in both obese and nonobese patients.

“Our hypothesis is that the incidence of some obesity-related GI cancers is rising in some age groups, and we suspect that this corresponds with increasing rates of obese patients undergoing these cancerous resections,” he said in his presentation.

The researchers evaluated cancer incidence trends in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database between 2002 and 2013 as well as obesity trends from 91,116 obese patients (7.16%) and 1,181,127 nonobese patients (92.84%) in the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database who underwent cancer resection surgeries. Of these, 93.1% of patients underwent colorectal and 4.4% of patients underwent gastric cancer resections. Patients were considered obese if they had a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2. The researchers examined annual trends for incidence rates of obesity-related GI cancers by age group and obesity-related GI cancer resection by age and obesity, using a joinpoint regression analysis to determine the percentage change per year.

In patients aged between 20 and 49 years, the incidence of colorectal cancer increased by 1.5% compared with a decrease of 1.5% in patients aged between 50 and 64 years old, a 3.8% decrease in patients aged 65-74 years, and a 3.9% decrease in patients who were a minimum of 75 years old. Gastric cancer incidence also increased by 0.7% in patients aged between 20 and 49 years compared with a 0.5%, 1.1%, and 1.8% decrease among patients who were aged 50-64 years, 65-74 years, and at least 75 years, respectively. There was an increased cancer incidence among patients in the 20- to 49-year-old age group (0.8%), 50- to 64-year-old age group (1.0%), 65- to 74-year-old age group (0.7%), and the 75-and-older group (1.0%). Esophageal cancer was associated with a decreased incidence in the 20- to 49-year-old group (1.8%), 50- to 64-year-old group (1.1%), 65- to 74-year-old age group (1.2%), and the 75-and-older group (0.7%)

For obese patients who underwent colorectal cancer resection, there was a 13.1% increase in the 18- to 49-year-old group, a 10.3% increase in the 50- to 64-year-old group, an 11.3% increase in the 65- to 74-year-old group, and a 12.8% increase in the 75-year-or-older group, compared with an overall decreased incidence in the nonobese group. There was an increased rate of pancreatic cancer resections for obese patients in the 50-to 64-year-old group (26.9%) and 65- to 74-year-old group (27.6%), compared with nonobese patients. Patients in the 18- to 49-year-old group (11.2%), 50- to 64-year-old group (14.6%), and 65- to 74-year-old group (25.7%) also had a higher incidence of esophageal cancer resections.

The limitations of the study included defining BMI at the time of surgery, which does not account for weight loss due to cachexia, and relying on ICD-9 codes for obesity, which “may not be reliable in some cases.

“However, we [saw] an increase in obese patients who come for resection, so it could have probably been more pronounced if we had accounted for obesity at the earlier age before diagnosis,” he added.

Dr. Hussan reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hussan H. ACG 2018, Presentation 34.

PHILADELPHIA – Researchers have identified a link between obesity and an increased incidence rate of gastrointestinal (GI) cancers in younger patients as well as an increased rate of colorectal, esophageal, and pancreatic cancer resections in obese patients of various ages, according to an award-winning presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

“These findings strengthen a contributing role of obesity in etiology as well as increasing incidence of these cancers, and call for more efforts targeting obesity,” Hisham Hussan, MD, assistant professor at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, stated in his presentation.

The abstract, presented by Dr. Hussan, received an American College of Gastroenterology Category Award in the subject of obesity. He noted in his presentation that the obesity rate in U.S. adults exceeded 37% in 2014. In addition, the temporal changes of obesity-related GI cancers with regard to age-specific groups are not known, he said.

“There’s sufficient evidence linking obesity to certain [GI cancers], such as esophagus, colon, pancreas, and gastric,” Dr. Hussan said. “However, the impact of rising obesity prevalence on the incidence of these obesity-related GI cancers is unknown.”

Dr. Hussan and his colleagues sought to investigate the incidence of obesity-related GI cancers by age group as well as whether there was an association between obesity-related GI cancers in both obese and nonobese patients.

“Our hypothesis is that the incidence of some obesity-related GI cancers is rising in some age groups, and we suspect that this corresponds with increasing rates of obese patients undergoing these cancerous resections,” he said in his presentation.

The researchers evaluated cancer incidence trends in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database between 2002 and 2013 as well as obesity trends from 91,116 obese patients (7.16%) and 1,181,127 nonobese patients (92.84%) in the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database who underwent cancer resection surgeries. Of these, 93.1% of patients underwent colorectal and 4.4% of patients underwent gastric cancer resections. Patients were considered obese if they had a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2. The researchers examined annual trends for incidence rates of obesity-related GI cancers by age group and obesity-related GI cancer resection by age and obesity, using a joinpoint regression analysis to determine the percentage change per year.

In patients aged between 20 and 49 years, the incidence of colorectal cancer increased by 1.5% compared with a decrease of 1.5% in patients aged between 50 and 64 years old, a 3.8% decrease in patients aged 65-74 years, and a 3.9% decrease in patients who were a minimum of 75 years old. Gastric cancer incidence also increased by 0.7% in patients aged between 20 and 49 years compared with a 0.5%, 1.1%, and 1.8% decrease among patients who were aged 50-64 years, 65-74 years, and at least 75 years, respectively. There was an increased cancer incidence among patients in the 20- to 49-year-old age group (0.8%), 50- to 64-year-old age group (1.0%), 65- to 74-year-old age group (0.7%), and the 75-and-older group (1.0%). Esophageal cancer was associated with a decreased incidence in the 20- to 49-year-old group (1.8%), 50- to 64-year-old group (1.1%), 65- to 74-year-old age group (1.2%), and the 75-and-older group (0.7%)

For obese patients who underwent colorectal cancer resection, there was a 13.1% increase in the 18- to 49-year-old group, a 10.3% increase in the 50- to 64-year-old group, an 11.3% increase in the 65- to 74-year-old group, and a 12.8% increase in the 75-year-or-older group, compared with an overall decreased incidence in the nonobese group. There was an increased rate of pancreatic cancer resections for obese patients in the 50-to 64-year-old group (26.9%) and 65- to 74-year-old group (27.6%), compared with nonobese patients. Patients in the 18- to 49-year-old group (11.2%), 50- to 64-year-old group (14.6%), and 65- to 74-year-old group (25.7%) also had a higher incidence of esophageal cancer resections.

The limitations of the study included defining BMI at the time of surgery, which does not account for weight loss due to cachexia, and relying on ICD-9 codes for obesity, which “may not be reliable in some cases.

“However, we [saw] an increase in obese patients who come for resection, so it could have probably been more pronounced if we had accounted for obesity at the earlier age before diagnosis,” he added.

Dr. Hussan reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hussan H. ACG 2018, Presentation 34.

PHILADELPHIA – Researchers have identified a link between obesity and an increased incidence rate of gastrointestinal (GI) cancers in younger patients as well as an increased rate of colorectal, esophageal, and pancreatic cancer resections in obese patients of various ages, according to an award-winning presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

“These findings strengthen a contributing role of obesity in etiology as well as increasing incidence of these cancers, and call for more efforts targeting obesity,” Hisham Hussan, MD, assistant professor at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, stated in his presentation.

The abstract, presented by Dr. Hussan, received an American College of Gastroenterology Category Award in the subject of obesity. He noted in his presentation that the obesity rate in U.S. adults exceeded 37% in 2014. In addition, the temporal changes of obesity-related GI cancers with regard to age-specific groups are not known, he said.

“There’s sufficient evidence linking obesity to certain [GI cancers], such as esophagus, colon, pancreas, and gastric,” Dr. Hussan said. “However, the impact of rising obesity prevalence on the incidence of these obesity-related GI cancers is unknown.”

Dr. Hussan and his colleagues sought to investigate the incidence of obesity-related GI cancers by age group as well as whether there was an association between obesity-related GI cancers in both obese and nonobese patients.

“Our hypothesis is that the incidence of some obesity-related GI cancers is rising in some age groups, and we suspect that this corresponds with increasing rates of obese patients undergoing these cancerous resections,” he said in his presentation.

The researchers evaluated cancer incidence trends in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database between 2002 and 2013 as well as obesity trends from 91,116 obese patients (7.16%) and 1,181,127 nonobese patients (92.84%) in the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database who underwent cancer resection surgeries. Of these, 93.1% of patients underwent colorectal and 4.4% of patients underwent gastric cancer resections. Patients were considered obese if they had a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2. The researchers examined annual trends for incidence rates of obesity-related GI cancers by age group and obesity-related GI cancer resection by age and obesity, using a joinpoint regression analysis to determine the percentage change per year.

In patients aged between 20 and 49 years, the incidence of colorectal cancer increased by 1.5% compared with a decrease of 1.5% in patients aged between 50 and 64 years old, a 3.8% decrease in patients aged 65-74 years, and a 3.9% decrease in patients who were a minimum of 75 years old. Gastric cancer incidence also increased by 0.7% in patients aged between 20 and 49 years compared with a 0.5%, 1.1%, and 1.8% decrease among patients who were aged 50-64 years, 65-74 years, and at least 75 years, respectively. There was an increased cancer incidence among patients in the 20- to 49-year-old age group (0.8%), 50- to 64-year-old age group (1.0%), 65- to 74-year-old age group (0.7%), and the 75-and-older group (1.0%). Esophageal cancer was associated with a decreased incidence in the 20- to 49-year-old group (1.8%), 50- to 64-year-old group (1.1%), 65- to 74-year-old age group (1.2%), and the 75-and-older group (0.7%)

For obese patients who underwent colorectal cancer resection, there was a 13.1% increase in the 18- to 49-year-old group, a 10.3% increase in the 50- to 64-year-old group, an 11.3% increase in the 65- to 74-year-old group, and a 12.8% increase in the 75-year-or-older group, compared with an overall decreased incidence in the nonobese group. There was an increased rate of pancreatic cancer resections for obese patients in the 50-to 64-year-old group (26.9%) and 65- to 74-year-old group (27.6%), compared with nonobese patients. Patients in the 18- to 49-year-old group (11.2%), 50- to 64-year-old group (14.6%), and 65- to 74-year-old group (25.7%) also had a higher incidence of esophageal cancer resections.

The limitations of the study included defining BMI at the time of surgery, which does not account for weight loss due to cachexia, and relying on ICD-9 codes for obesity, which “may not be reliable in some cases.

“However, we [saw] an increase in obese patients who come for resection, so it could have probably been more pronounced if we had accounted for obesity at the earlier age before diagnosis,” he added.

Dr. Hussan reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hussan H. ACG 2018, Presentation 34.

REPORTING FROM ACG 2018

Key clinical point: There is a higher incidence of colorectal and gastric cancer among obese patients under 50 years old.

Major finding: Obese patients of all age ranges had a higher rate of colorectal cancer resections, obese patients 75 and younger had a significantly higher incidence of esophageal cancer resections, and obese patients aged between 50 and 74 years had a higher rate of pancreatic resections, compared with nonobese patients.

Study details: A database analysis of cancer incidence trends in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database and patient cancer incidence and obesity trends in the National Inpatient Sample database between 2002 and 2013.

Disclosures: Dr. Hussan reports no conflicts of interest.

Source: Hussan H. ACG 2018, Presentation 34.

GARFIELD-AF registry: DOACs cut mortality 19%

MUNICH – Treatment of real-world patients newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation using a direct oral anticoagulant led to benefits that tracked the advantages previously seen in randomized, controlled trials of these drugs, based on findings from more than 26,000 patients enrolled in a global registry.

Atrial fibrillation patients enrolled in the GARFIELD-AF(Global Anticoagulant Registry in the Field) study who started treatment with a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) had a 19% relative risk reduction in all-cause mortality during 2 years of follow-up, compared with patients on an oral vitamin K antagonist (VKA) regimen (such as warfarin), a statistically significant difference after adjustment for 30 demographic, clinical, and registry variables, A. John Camm, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. The analysis also showed trends toward lower rates of stroke or systemic thrombosis as well as major bleeding events when patients received a DOAC, compared with those on VKA, but these differences were not statistically significant, reported Dr. Camm, a professor of clinical cardiology at St. George’s University of London.

The analyses run by Dr. Camm and his associates also confirmed the superiority of oral anticoagulation. There was an adjusted 17% relative risk reduction in all-cause mortality during 2-year follow-up in patients on any form of oral anticoagulation, compared with patients who did not receive anticoagulation, a statistically significant difference. The comparison of patients on any oral anticoagulant with those not on treatment also showed a significant lowering of stroke or systemic embolism, as well as a 36% relative increase in the risk for a major bleeding episode that was close to statistical significance.

These findings in a registry of patients undergoing routine care “suggest that the effectiveness of oral anticoagulants in randomized clinical trials can be translated to the broad cross section of patients treated in everyday practice,” Dr. Camm said. However, he highlighted two important qualifications to the findings.

First, the analysis focused on the type of anticoagulation patients received at the time they entered the GARFIELD-AF registry and did not account for possible changes in treatment after that. Second, the analysis did not adjust for additional potential confounding variables, which Dr. Camm was certain existed and affected the findings.

“I’m concerned that a confounder we have not been able to account for is the quality of medical care that patients received,” he noted. “The substantial reduction in mortality [using a DOAC, compared with a VKA] is not simply due to reductions in stroke or major bleeding. We must look at other explanations, such as differences in quality of care and access to care.”

The analyses have also not yet looked at outcomes based on the specific DOAC a patient received – apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, or rivaroxaban – something that Dr. Camm said is in the works.

GARFIELD-AF enrolled nearly 35,000 patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation and at least one stroke risk factor in 35 countries from April 2013 to September 2016. The analysis winnowed this down to 26,742 patients who also had a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2 (which identifies patients with a high thrombotic risk) and had complete enrollment and follow-up data.

GARFIELD-AF was funded in part by Bayer. Dr. Camm reported being an adviser to Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, and Pfizer/Bristol-Myers Squibb.

MUNICH – Treatment of real-world patients newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation using a direct oral anticoagulant led to benefits that tracked the advantages previously seen in randomized, controlled trials of these drugs, based on findings from more than 26,000 patients enrolled in a global registry.

Atrial fibrillation patients enrolled in the GARFIELD-AF(Global Anticoagulant Registry in the Field) study who started treatment with a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) had a 19% relative risk reduction in all-cause mortality during 2 years of follow-up, compared with patients on an oral vitamin K antagonist (VKA) regimen (such as warfarin), a statistically significant difference after adjustment for 30 demographic, clinical, and registry variables, A. John Camm, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. The analysis also showed trends toward lower rates of stroke or systemic thrombosis as well as major bleeding events when patients received a DOAC, compared with those on VKA, but these differences were not statistically significant, reported Dr. Camm, a professor of clinical cardiology at St. George’s University of London.

The analyses run by Dr. Camm and his associates also confirmed the superiority of oral anticoagulation. There was an adjusted 17% relative risk reduction in all-cause mortality during 2-year follow-up in patients on any form of oral anticoagulation, compared with patients who did not receive anticoagulation, a statistically significant difference. The comparison of patients on any oral anticoagulant with those not on treatment also showed a significant lowering of stroke or systemic embolism, as well as a 36% relative increase in the risk for a major bleeding episode that was close to statistical significance.

These findings in a registry of patients undergoing routine care “suggest that the effectiveness of oral anticoagulants in randomized clinical trials can be translated to the broad cross section of patients treated in everyday practice,” Dr. Camm said. However, he highlighted two important qualifications to the findings.

First, the analysis focused on the type of anticoagulation patients received at the time they entered the GARFIELD-AF registry and did not account for possible changes in treatment after that. Second, the analysis did not adjust for additional potential confounding variables, which Dr. Camm was certain existed and affected the findings.

“I’m concerned that a confounder we have not been able to account for is the quality of medical care that patients received,” he noted. “The substantial reduction in mortality [using a DOAC, compared with a VKA] is not simply due to reductions in stroke or major bleeding. We must look at other explanations, such as differences in quality of care and access to care.”

The analyses have also not yet looked at outcomes based on the specific DOAC a patient received – apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, or rivaroxaban – something that Dr. Camm said is in the works.

GARFIELD-AF enrolled nearly 35,000 patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation and at least one stroke risk factor in 35 countries from April 2013 to September 2016. The analysis winnowed this down to 26,742 patients who also had a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2 (which identifies patients with a high thrombotic risk) and had complete enrollment and follow-up data.

GARFIELD-AF was funded in part by Bayer. Dr. Camm reported being an adviser to Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, and Pfizer/Bristol-Myers Squibb.

MUNICH – Treatment of real-world patients newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation using a direct oral anticoagulant led to benefits that tracked the advantages previously seen in randomized, controlled trials of these drugs, based on findings from more than 26,000 patients enrolled in a global registry.

Atrial fibrillation patients enrolled in the GARFIELD-AF(Global Anticoagulant Registry in the Field) study who started treatment with a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) had a 19% relative risk reduction in all-cause mortality during 2 years of follow-up, compared with patients on an oral vitamin K antagonist (VKA) regimen (such as warfarin), a statistically significant difference after adjustment for 30 demographic, clinical, and registry variables, A. John Camm, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. The analysis also showed trends toward lower rates of stroke or systemic thrombosis as well as major bleeding events when patients received a DOAC, compared with those on VKA, but these differences were not statistically significant, reported Dr. Camm, a professor of clinical cardiology at St. George’s University of London.

The analyses run by Dr. Camm and his associates also confirmed the superiority of oral anticoagulation. There was an adjusted 17% relative risk reduction in all-cause mortality during 2-year follow-up in patients on any form of oral anticoagulation, compared with patients who did not receive anticoagulation, a statistically significant difference. The comparison of patients on any oral anticoagulant with those not on treatment also showed a significant lowering of stroke or systemic embolism, as well as a 36% relative increase in the risk for a major bleeding episode that was close to statistical significance.

These findings in a registry of patients undergoing routine care “suggest that the effectiveness of oral anticoagulants in randomized clinical trials can be translated to the broad cross section of patients treated in everyday practice,” Dr. Camm said. However, he highlighted two important qualifications to the findings.

First, the analysis focused on the type of anticoagulation patients received at the time they entered the GARFIELD-AF registry and did not account for possible changes in treatment after that. Second, the analysis did not adjust for additional potential confounding variables, which Dr. Camm was certain existed and affected the findings.

“I’m concerned that a confounder we have not been able to account for is the quality of medical care that patients received,” he noted. “The substantial reduction in mortality [using a DOAC, compared with a VKA] is not simply due to reductions in stroke or major bleeding. We must look at other explanations, such as differences in quality of care and access to care.”

The analyses have also not yet looked at outcomes based on the specific DOAC a patient received – apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, or rivaroxaban – something that Dr. Camm said is in the works.

GARFIELD-AF enrolled nearly 35,000 patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation and at least one stroke risk factor in 35 countries from April 2013 to September 2016. The analysis winnowed this down to 26,742 patients who also had a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2 (which identifies patients with a high thrombotic risk) and had complete enrollment and follow-up data.

GARFIELD-AF was funded in part by Bayer. Dr. Camm reported being an adviser to Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, and Pfizer/Bristol-Myers Squibb.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Direct oral anticoagulant–treated patients had a 19% relative reduction in all-cause death, compared with patients on a vitamin K antagonist.

Study details: The GARFIELD-AF registry, which included 26,742 patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation.

Disclosures: GARFIELD-AF was funded in part by Bayer. Dr. Camm has been an adviser to Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, and Pfizer/Bristol-Myers Squibb.

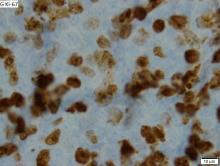

MCL treatment choices depend partly on age

CHICAGO – Treatment for mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) depends at least in part on patient age, with some important differences in those aged 65 years or younger versus those over age 65, according to Kristie A. Blum, MD.

“For the [younger] early-stage patients I’ll think about radiation and maybe observation, although I think [observation] is pretty uncommon,” Dr. Blum, acting hematology and medical oncology professor at Emory University in Atlanta, said at the American Society of Hematology Meeting on Hematologic Malignancies.

For advanced-stage patients, a number of options, including observation, can be considered, she said.

Observation

Observation is acceptable in highly selected advanced stage cases. In a 2009 study of 97 mantle cell patients, 31 were observed for more than 3 months before treatment was initiated (median time to treatment, 12 months), and at median follow-up of 55 months, overall survival (OS) was significantly better in the observation group (not reached vs. 64 months in treated patients), she said (J Clin Oncol. 2009 Mar 10;27[8]:1209-13).

Observed patients had better performance status and lower-risk standard International Prognostic Index scores, compared with treated patients, and the authors concluded that a “watch-and-wait” approach is acceptable in select patients.

“In addition, if you looked at their overall survival from the time of first treatment, there was no difference in the groups, suggesting you really weren’t hurting people by delaying their therapy,” Dr. Blum said.

In a more recent series of 440 favorable-risk MCL patients, 17% were observed for at least 3 months (median time to treatment, 35 months), 80% were observed for at least 12 months, and 13% were observed for 5 years.

Again, median OS was better for observed patients than for those treated initially, at 72 months vs. 52.5 months (Ann Oncol. 2017;28[10]:2489-95).

“So I do think there is a subset of patients that can safely be observed with mantle cell [lymphoma],” she said.

Transplant-based approaches

Transplant-based approaches in younger patients with advanced disease include the Nordic regimen plus autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), R-CHOP/R-DHAP plus ASCT, and R-bendamustine/R-cytarabine – all with post-ASCT maintenance rituximab, Dr. Blum said.

Cytarabine-containing induction was established as the pretransplant standard of care by the 474-patient MCL Younger trial, which demonstrated significantly prolonged time to treatment failure (9.1 vs. 3.9 years), with alternating pretransplant R-CHOP/R-DHAP versus R-CHOP for six cycles, though this was associated with increased toxicity. (Lancet. 2016 Aug 6;388[10044]:565-75).

For example, grade 3-4 thrombocytopenia occurred in 73% vs. 9% of patients, she noted.

The Nordic MCL2 trial showed that an intensive regimen involving alternating Maxi-CHOP and AraC followed by transplant results in median OS of about 12 years and PFS of about 8 years.

“I do want to highlight, though, that again, the high-risk patients don’t do very well,” she said, noting that median PFS even with this intensive approach was only 2.5 years in those at high risk based on MCL International Prognostic Index (MIPI) score, compared with 12.7 years for patients with a low-risk MIPI score.

Newer induction regimens also show some promise and appear feasible in younger patients based on early data, she said, noting that the SWOG S1106 trial comparing R-bendamustine and R-HyperCVAD showed a minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity rate of 78% in the R-bendamustine group. Another study evaluating R-bendamustine followed by AraC showed a 96% complete remission and PFS at 13 months of 96%, with MRD-negativity of 93% (Br J Haematol. 2016 Apr;173[1]:89-95).

Transplant also is an option in advanced stage patients aged 66-70 years who are fit and willing, Dr. Blum said.

“I spend a long time talking to these patients about whether they want a transplant or not,” she said.

For induction in those patients who choose transplant, Dr. Blum said she prefers bendamustine-based regimens, “because these have been published in patients up to the age of 70.”

Transplant timing is usually at the first complete remission.

Data show that 5-year OS after such early ASCT in patients with no more than two prior lines of chemotherapy is about 60%, compared with about 44% with late ASCT. For reduced intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplant in that study, the 5-year OS was 62% for early transplant and 31% for late transplant (J Clin Oncol. 2014 Feb 1;32[4]:273-81).

R-HyperCVAD

R-HyperCVAD is another option in younger patients, and is usually given for eight cycles, followed by transplant only in those who aren’t in complete remission, Dr. Blum said.

Median failure-free survival among patients aged 65 years and younger in one study of this regimen was 6.5 years and OS was 13.4 years. In those over age 65, median failure-free survival was about 3 years (Br J Haematol. 2016 Jan;172[1]:80-88).

The SWOG 0213 study looked at this in a multicenter fashion, she said, noting that 39% of patients – 48% of whom were aged 65 and older – could not complete all eight cycles.

“Again, there was a high rate of this sort of infectious toxicity,” she said.

Median PFS was about 5 years in this study as well, and OS was nearly 7 years. For those over age 65, median PFS was just 1.6 years.

“So I don’t typically recommend this for the 65- to 70-year-olds,” she said.

Older nontransplant candidates

When treating patients who are unfit for transplant, Dr. Blum pointed to the results of the StiL and BRIGHT studies, which both showed that R-bendamustine was noninferior to R-CHOP as first-line treatment.

In addition, recent data on combined bendamustine and cytarabine (R-BAC500) showed that in 57 patients with a median age of 71 years, 95% received at least four cycles, and 67% completed six cycles. CR was 91% , and 2-year OS and PFS were 86% and 81%, respectively.

However, grade 3-4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia occurred in 49% and 52% of patients, respectively (Lancet Haematol. 2017 Jan 1;4[1]:e15-e23).

The bortezomib-containing regimen VR-CAP has also been shown to be of benefit for older MCL patients not eligible for transplant, she said.

Median PFS with VR-CAP in a study of 487 newly diagnosed MCL patients was about 25 months vs. 14 months with R-CHOP (N Engl J Med. 2015 Mar 5;372:944-53).

“R-lenalidomide has activity in the front-line setting as well,” Dr. Blum said, citing a multicenter phase 2 study of 38 patients with a mean age of 65 years. The intention-to-treat analysis showed an overall response rate of 87%, CR rate of 61%, and 2-year PFS of 85% (N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1835-44).

Maintenance therapy

As for maintenance therapy in younger patients, a phase 3 study of 299 patients showed that rituximab maintenance was associated with significantly better 4-year PFS (83% vs. 64% with observation), and 4-year OS (89% vs. 80% with observation), she said (N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 28;377:1250-60).

“I do think that rituximab maintenance is the standard of care now, based on this study,” Dr. Blum said, adding that there is also a role for rituximab maintenance in older patients.

A European Mantle Cell Network study of patients aged 60 and older (median age of 70) showed an OS of 62% with R-CHOP vs. 47% with R-FC (rituximab, fludarabine, and cyclophosphamide), and – among those then randomized to maintenance rituximab or interferon alpha – 4-year PFS of 58% vs. 29%, respectively (N Engl J Med. 2012;367:520-31).

“Now I will tell you that most of these patients are getting bendamustine. We don’t really know the role for rituximab maintenance after bendamustine-based induction, but at this point I think it’s reasonable to consider adding it,” she said.

Dr. Blum is a consultant for Acerta, AstraZeneca, and Molecular Templates and has received research funding from Acerta, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Cephalon, Immunomedics, Janssen, Merck, Millennium, Molecular Templates, Novartis, Pharmacyclics, and Seattle Genetics.

CHICAGO – Treatment for mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) depends at least in part on patient age, with some important differences in those aged 65 years or younger versus those over age 65, according to Kristie A. Blum, MD.

“For the [younger] early-stage patients I’ll think about radiation and maybe observation, although I think [observation] is pretty uncommon,” Dr. Blum, acting hematology and medical oncology professor at Emory University in Atlanta, said at the American Society of Hematology Meeting on Hematologic Malignancies.

For advanced-stage patients, a number of options, including observation, can be considered, she said.

Observation

Observation is acceptable in highly selected advanced stage cases. In a 2009 study of 97 mantle cell patients, 31 were observed for more than 3 months before treatment was initiated (median time to treatment, 12 months), and at median follow-up of 55 months, overall survival (OS) was significantly better in the observation group (not reached vs. 64 months in treated patients), she said (J Clin Oncol. 2009 Mar 10;27[8]:1209-13).

Observed patients had better performance status and lower-risk standard International Prognostic Index scores, compared with treated patients, and the authors concluded that a “watch-and-wait” approach is acceptable in select patients.

“In addition, if you looked at their overall survival from the time of first treatment, there was no difference in the groups, suggesting you really weren’t hurting people by delaying their therapy,” Dr. Blum said.

In a more recent series of 440 favorable-risk MCL patients, 17% were observed for at least 3 months (median time to treatment, 35 months), 80% were observed for at least 12 months, and 13% were observed for 5 years.

Again, median OS was better for observed patients than for those treated initially, at 72 months vs. 52.5 months (Ann Oncol. 2017;28[10]:2489-95).

“So I do think there is a subset of patients that can safely be observed with mantle cell [lymphoma],” she said.

Transplant-based approaches

Transplant-based approaches in younger patients with advanced disease include the Nordic regimen plus autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), R-CHOP/R-DHAP plus ASCT, and R-bendamustine/R-cytarabine – all with post-ASCT maintenance rituximab, Dr. Blum said.

Cytarabine-containing induction was established as the pretransplant standard of care by the 474-patient MCL Younger trial, which demonstrated significantly prolonged time to treatment failure (9.1 vs. 3.9 years), with alternating pretransplant R-CHOP/R-DHAP versus R-CHOP for six cycles, though this was associated with increased toxicity. (Lancet. 2016 Aug 6;388[10044]:565-75).

For example, grade 3-4 thrombocytopenia occurred in 73% vs. 9% of patients, she noted.

The Nordic MCL2 trial showed that an intensive regimen involving alternating Maxi-CHOP and AraC followed by transplant results in median OS of about 12 years and PFS of about 8 years.

“I do want to highlight, though, that again, the high-risk patients don’t do very well,” she said, noting that median PFS even with this intensive approach was only 2.5 years in those at high risk based on MCL International Prognostic Index (MIPI) score, compared with 12.7 years for patients with a low-risk MIPI score.

Newer induction regimens also show some promise and appear feasible in younger patients based on early data, she said, noting that the SWOG S1106 trial comparing R-bendamustine and R-HyperCVAD showed a minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity rate of 78% in the R-bendamustine group. Another study evaluating R-bendamustine followed by AraC showed a 96% complete remission and PFS at 13 months of 96%, with MRD-negativity of 93% (Br J Haematol. 2016 Apr;173[1]:89-95).

Transplant also is an option in advanced stage patients aged 66-70 years who are fit and willing, Dr. Blum said.

“I spend a long time talking to these patients about whether they want a transplant or not,” she said.

For induction in those patients who choose transplant, Dr. Blum said she prefers bendamustine-based regimens, “because these have been published in patients up to the age of 70.”

Transplant timing is usually at the first complete remission.

Data show that 5-year OS after such early ASCT in patients with no more than two prior lines of chemotherapy is about 60%, compared with about 44% with late ASCT. For reduced intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplant in that study, the 5-year OS was 62% for early transplant and 31% for late transplant (J Clin Oncol. 2014 Feb 1;32[4]:273-81).

R-HyperCVAD

R-HyperCVAD is another option in younger patients, and is usually given for eight cycles, followed by transplant only in those who aren’t in complete remission, Dr. Blum said.

Median failure-free survival among patients aged 65 years and younger in one study of this regimen was 6.5 years and OS was 13.4 years. In those over age 65, median failure-free survival was about 3 years (Br J Haematol. 2016 Jan;172[1]:80-88).

The SWOG 0213 study looked at this in a multicenter fashion, she said, noting that 39% of patients – 48% of whom were aged 65 and older – could not complete all eight cycles.

“Again, there was a high rate of this sort of infectious toxicity,” she said.

Median PFS was about 5 years in this study as well, and OS was nearly 7 years. For those over age 65, median PFS was just 1.6 years.

“So I don’t typically recommend this for the 65- to 70-year-olds,” she said.

Older nontransplant candidates

When treating patients who are unfit for transplant, Dr. Blum pointed to the results of the StiL and BRIGHT studies, which both showed that R-bendamustine was noninferior to R-CHOP as first-line treatment.

In addition, recent data on combined bendamustine and cytarabine (R-BAC500) showed that in 57 patients with a median age of 71 years, 95% received at least four cycles, and 67% completed six cycles. CR was 91% , and 2-year OS and PFS were 86% and 81%, respectively.

However, grade 3-4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia occurred in 49% and 52% of patients, respectively (Lancet Haematol. 2017 Jan 1;4[1]:e15-e23).

The bortezomib-containing regimen VR-CAP has also been shown to be of benefit for older MCL patients not eligible for transplant, she said.

Median PFS with VR-CAP in a study of 487 newly diagnosed MCL patients was about 25 months vs. 14 months with R-CHOP (N Engl J Med. 2015 Mar 5;372:944-53).

“R-lenalidomide has activity in the front-line setting as well,” Dr. Blum said, citing a multicenter phase 2 study of 38 patients with a mean age of 65 years. The intention-to-treat analysis showed an overall response rate of 87%, CR rate of 61%, and 2-year PFS of 85% (N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1835-44).

Maintenance therapy

As for maintenance therapy in younger patients, a phase 3 study of 299 patients showed that rituximab maintenance was associated with significantly better 4-year PFS (83% vs. 64% with observation), and 4-year OS (89% vs. 80% with observation), she said (N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 28;377:1250-60).

“I do think that rituximab maintenance is the standard of care now, based on this study,” Dr. Blum said, adding that there is also a role for rituximab maintenance in older patients.

A European Mantle Cell Network study of patients aged 60 and older (median age of 70) showed an OS of 62% with R-CHOP vs. 47% with R-FC (rituximab, fludarabine, and cyclophosphamide), and – among those then randomized to maintenance rituximab or interferon alpha – 4-year PFS of 58% vs. 29%, respectively (N Engl J Med. 2012;367:520-31).

“Now I will tell you that most of these patients are getting bendamustine. We don’t really know the role for rituximab maintenance after bendamustine-based induction, but at this point I think it’s reasonable to consider adding it,” she said.

Dr. Blum is a consultant for Acerta, AstraZeneca, and Molecular Templates and has received research funding from Acerta, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Cephalon, Immunomedics, Janssen, Merck, Millennium, Molecular Templates, Novartis, Pharmacyclics, and Seattle Genetics.

CHICAGO – Treatment for mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) depends at least in part on patient age, with some important differences in those aged 65 years or younger versus those over age 65, according to Kristie A. Blum, MD.

“For the [younger] early-stage patients I’ll think about radiation and maybe observation, although I think [observation] is pretty uncommon,” Dr. Blum, acting hematology and medical oncology professor at Emory University in Atlanta, said at the American Society of Hematology Meeting on Hematologic Malignancies.

For advanced-stage patients, a number of options, including observation, can be considered, she said.

Observation

Observation is acceptable in highly selected advanced stage cases. In a 2009 study of 97 mantle cell patients, 31 were observed for more than 3 months before treatment was initiated (median time to treatment, 12 months), and at median follow-up of 55 months, overall survival (OS) was significantly better in the observation group (not reached vs. 64 months in treated patients), she said (J Clin Oncol. 2009 Mar 10;27[8]:1209-13).

Observed patients had better performance status and lower-risk standard International Prognostic Index scores, compared with treated patients, and the authors concluded that a “watch-and-wait” approach is acceptable in select patients.

“In addition, if you looked at their overall survival from the time of first treatment, there was no difference in the groups, suggesting you really weren’t hurting people by delaying their therapy,” Dr. Blum said.

In a more recent series of 440 favorable-risk MCL patients, 17% were observed for at least 3 months (median time to treatment, 35 months), 80% were observed for at least 12 months, and 13% were observed for 5 years.

Again, median OS was better for observed patients than for those treated initially, at 72 months vs. 52.5 months (Ann Oncol. 2017;28[10]:2489-95).

“So I do think there is a subset of patients that can safely be observed with mantle cell [lymphoma],” she said.

Transplant-based approaches

Transplant-based approaches in younger patients with advanced disease include the Nordic regimen plus autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), R-CHOP/R-DHAP plus ASCT, and R-bendamustine/R-cytarabine – all with post-ASCT maintenance rituximab, Dr. Blum said.

Cytarabine-containing induction was established as the pretransplant standard of care by the 474-patient MCL Younger trial, which demonstrated significantly prolonged time to treatment failure (9.1 vs. 3.9 years), with alternating pretransplant R-CHOP/R-DHAP versus R-CHOP for six cycles, though this was associated with increased toxicity. (Lancet. 2016 Aug 6;388[10044]:565-75).

For example, grade 3-4 thrombocytopenia occurred in 73% vs. 9% of patients, she noted.

The Nordic MCL2 trial showed that an intensive regimen involving alternating Maxi-CHOP and AraC followed by transplant results in median OS of about 12 years and PFS of about 8 years.

“I do want to highlight, though, that again, the high-risk patients don’t do very well,” she said, noting that median PFS even with this intensive approach was only 2.5 years in those at high risk based on MCL International Prognostic Index (MIPI) score, compared with 12.7 years for patients with a low-risk MIPI score.

Newer induction regimens also show some promise and appear feasible in younger patients based on early data, she said, noting that the SWOG S1106 trial comparing R-bendamustine and R-HyperCVAD showed a minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity rate of 78% in the R-bendamustine group. Another study evaluating R-bendamustine followed by AraC showed a 96% complete remission and PFS at 13 months of 96%, with MRD-negativity of 93% (Br J Haematol. 2016 Apr;173[1]:89-95).

Transplant also is an option in advanced stage patients aged 66-70 years who are fit and willing, Dr. Blum said.

“I spend a long time talking to these patients about whether they want a transplant or not,” she said.

For induction in those patients who choose transplant, Dr. Blum said she prefers bendamustine-based regimens, “because these have been published in patients up to the age of 70.”

Transplant timing is usually at the first complete remission.

Data show that 5-year OS after such early ASCT in patients with no more than two prior lines of chemotherapy is about 60%, compared with about 44% with late ASCT. For reduced intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplant in that study, the 5-year OS was 62% for early transplant and 31% for late transplant (J Clin Oncol. 2014 Feb 1;32[4]:273-81).

R-HyperCVAD

R-HyperCVAD is another option in younger patients, and is usually given for eight cycles, followed by transplant only in those who aren’t in complete remission, Dr. Blum said.

Median failure-free survival among patients aged 65 years and younger in one study of this regimen was 6.5 years and OS was 13.4 years. In those over age 65, median failure-free survival was about 3 years (Br J Haematol. 2016 Jan;172[1]:80-88).

The SWOG 0213 study looked at this in a multicenter fashion, she said, noting that 39% of patients – 48% of whom were aged 65 and older – could not complete all eight cycles.

“Again, there was a high rate of this sort of infectious toxicity,” she said.

Median PFS was about 5 years in this study as well, and OS was nearly 7 years. For those over age 65, median PFS was just 1.6 years.

“So I don’t typically recommend this for the 65- to 70-year-olds,” she said.

Older nontransplant candidates

When treating patients who are unfit for transplant, Dr. Blum pointed to the results of the StiL and BRIGHT studies, which both showed that R-bendamustine was noninferior to R-CHOP as first-line treatment.

In addition, recent data on combined bendamustine and cytarabine (R-BAC500) showed that in 57 patients with a median age of 71 years, 95% received at least four cycles, and 67% completed six cycles. CR was 91% , and 2-year OS and PFS were 86% and 81%, respectively.

However, grade 3-4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia occurred in 49% and 52% of patients, respectively (Lancet Haematol. 2017 Jan 1;4[1]:e15-e23).

The bortezomib-containing regimen VR-CAP has also been shown to be of benefit for older MCL patients not eligible for transplant, she said.

Median PFS with VR-CAP in a study of 487 newly diagnosed MCL patients was about 25 months vs. 14 months with R-CHOP (N Engl J Med. 2015 Mar 5;372:944-53).

“R-lenalidomide has activity in the front-line setting as well,” Dr. Blum said, citing a multicenter phase 2 study of 38 patients with a mean age of 65 years. The intention-to-treat analysis showed an overall response rate of 87%, CR rate of 61%, and 2-year PFS of 85% (N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1835-44).

Maintenance therapy

As for maintenance therapy in younger patients, a phase 3 study of 299 patients showed that rituximab maintenance was associated with significantly better 4-year PFS (83% vs. 64% with observation), and 4-year OS (89% vs. 80% with observation), she said (N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 28;377:1250-60).

“I do think that rituximab maintenance is the standard of care now, based on this study,” Dr. Blum said, adding that there is also a role for rituximab maintenance in older patients.

A European Mantle Cell Network study of patients aged 60 and older (median age of 70) showed an OS of 62% with R-CHOP vs. 47% with R-FC (rituximab, fludarabine, and cyclophosphamide), and – among those then randomized to maintenance rituximab or interferon alpha – 4-year PFS of 58% vs. 29%, respectively (N Engl J Med. 2012;367:520-31).

“Now I will tell you that most of these patients are getting bendamustine. We don’t really know the role for rituximab maintenance after bendamustine-based induction, but at this point I think it’s reasonable to consider adding it,” she said.

Dr. Blum is a consultant for Acerta, AstraZeneca, and Molecular Templates and has received research funding from Acerta, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Cephalon, Immunomedics, Janssen, Merck, Millennium, Molecular Templates, Novartis, Pharmacyclics, and Seattle Genetics.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM MHM 2018

Brain mapping takes next step toward precision psychiatry

Brain mapping patterns varied with clinical mental health diagnoses in a study of 218 patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

“Psychiatry is now the last area of medicine in which diseases are diagnosed solely on the basis of symptoms, and biomarkers to assist treatment remain to be developed,” wrote Thomas Wolfers of Radboud University, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and his colleagues. They also said schizophrenia and bipolar disorder “are excellent examples of highly heterogeneous mental disorders.”

To explore brain structure homogeneity, the researchers used brain scans and mapping models to compare results in 218 adults aged 18-65 years with schizophrenia disorders (163 with schizophrenia and 190 with bipolar disorder) and 256 healthy controls. Demographics were similar between the groups.

The MRI data showed that the same abnormalities in more than 2% of patients with the same disorder occurred in very few loci. Schizophrenia patients showed significantly reduced gray matter in the frontal, cerebellar, and temporal regions; most bipolar patients showed changes in the cerebellar region.

The researchers identified extreme deviations across patients and controls in gray and white matter.

In gray matter, schizophrenia patients had a significantly higher percentage of extreme negative deviations across voxels (0.9% of voxels), compared with both bipolar patients and healthy controls (0.24% and 0.23%, respectively).

In white matter, a similar pattern emerged; schizophrenia patients had a significantly higher percentage of extreme negative deviations (0.62%), compared with healthy controls and bipolar patients (0.25% and 0.41%, respectively). In addition, extreme positive deviations were significantly higher among the controls (1.14% of voxels), compared with schizophrenia and bipolar patients (0.83% for both).

The findings support data from previous studies suggesting reduced cortical volume in schizophrenia patients, compared with healthy controls and bipolar disorder patients, the researchers noted.

“In this study, patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder differed extremely on an individual level; the lack of substantial overlap among patients in terms of extreme deviations from the normative model is evidence of the high degree of biological heterogeneity in both disorders,” wrote Mr. Wolfers and his colleagues.

The main limitations of the study were the inability to control for confounding variables and to make conclusions about causality, the researchers said. However, the absence of overlap in patients with the same disorder supports the use of brain mapping to study individual pathophysiologic signatures in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder patients, they concluded.

Mr. Wolfers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was supported by grants from multiple organizations, including the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research and the Wellcome Trust U.K. Strategic Award.

SOURCE: Wolfers T et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2467.

A growing body of evidence suggests that “conventional psychiatric diagnoses of serious mental illness (SMI), when tested, do not show a common biology,” wrote Carol A. Tamminga, MD, and Elena I. Ivleva, MD, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. The editorialists noted the work of the Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes consortium to identify subtype disease clusters.

However, they wrote: “We question whether these biotype structures represent disease groups as opposed to mere brain biomarker clusters. Dr. Tamminga and Dr. Ivleva also expressed concern about whether biologically based subgroups would be clinically useful and questioned what evidence would be needed to accept such subtypes as disease subgroups.

Their ideas for further exploration included identifying a characteristic genetic fingerprint to help determine a common pathophysiology. In addition, “a disorder clustered by biological features might also show a distinctive pharmacological profile,” they wrote.

Next steps include making severe mental illness into a condition diagnosable based on biomarkers that also can serve as a foundation for treatment, which would be “a revolution in our ability to understand and treat complex brain disorders,” they noted (JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2451).

Dr. Tamminga and Dr. Ivleva are affiliated with the University of Texas, Dallas. Both of them serve as researchers with the Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes consortium and reported funding from the National Institute for Mental Health.

A growing body of evidence suggests that “conventional psychiatric diagnoses of serious mental illness (SMI), when tested, do not show a common biology,” wrote Carol A. Tamminga, MD, and Elena I. Ivleva, MD, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. The editorialists noted the work of the Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes consortium to identify subtype disease clusters.

However, they wrote: “We question whether these biotype structures represent disease groups as opposed to mere brain biomarker clusters. Dr. Tamminga and Dr. Ivleva also expressed concern about whether biologically based subgroups would be clinically useful and questioned what evidence would be needed to accept such subtypes as disease subgroups.

Their ideas for further exploration included identifying a characteristic genetic fingerprint to help determine a common pathophysiology. In addition, “a disorder clustered by biological features might also show a distinctive pharmacological profile,” they wrote.

Next steps include making severe mental illness into a condition diagnosable based on biomarkers that also can serve as a foundation for treatment, which would be “a revolution in our ability to understand and treat complex brain disorders,” they noted (JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2451).

Dr. Tamminga and Dr. Ivleva are affiliated with the University of Texas, Dallas. Both of them serve as researchers with the Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes consortium and reported funding from the National Institute for Mental Health.

A growing body of evidence suggests that “conventional psychiatric diagnoses of serious mental illness (SMI), when tested, do not show a common biology,” wrote Carol A. Tamminga, MD, and Elena I. Ivleva, MD, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. The editorialists noted the work of the Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes consortium to identify subtype disease clusters.

However, they wrote: “We question whether these biotype structures represent disease groups as opposed to mere brain biomarker clusters. Dr. Tamminga and Dr. Ivleva also expressed concern about whether biologically based subgroups would be clinically useful and questioned what evidence would be needed to accept such subtypes as disease subgroups.

Their ideas for further exploration included identifying a characteristic genetic fingerprint to help determine a common pathophysiology. In addition, “a disorder clustered by biological features might also show a distinctive pharmacological profile,” they wrote.

Next steps include making severe mental illness into a condition diagnosable based on biomarkers that also can serve as a foundation for treatment, which would be “a revolution in our ability to understand and treat complex brain disorders,” they noted (JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2451).

Dr. Tamminga and Dr. Ivleva are affiliated with the University of Texas, Dallas. Both of them serve as researchers with the Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes consortium and reported funding from the National Institute for Mental Health.

Brain mapping patterns varied with clinical mental health diagnoses in a study of 218 patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

“Psychiatry is now the last area of medicine in which diseases are diagnosed solely on the basis of symptoms, and biomarkers to assist treatment remain to be developed,” wrote Thomas Wolfers of Radboud University, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and his colleagues. They also said schizophrenia and bipolar disorder “are excellent examples of highly heterogeneous mental disorders.”

To explore brain structure homogeneity, the researchers used brain scans and mapping models to compare results in 218 adults aged 18-65 years with schizophrenia disorders (163 with schizophrenia and 190 with bipolar disorder) and 256 healthy controls. Demographics were similar between the groups.

The MRI data showed that the same abnormalities in more than 2% of patients with the same disorder occurred in very few loci. Schizophrenia patients showed significantly reduced gray matter in the frontal, cerebellar, and temporal regions; most bipolar patients showed changes in the cerebellar region.

The researchers identified extreme deviations across patients and controls in gray and white matter.

In gray matter, schizophrenia patients had a significantly higher percentage of extreme negative deviations across voxels (0.9% of voxels), compared with both bipolar patients and healthy controls (0.24% and 0.23%, respectively).

In white matter, a similar pattern emerged; schizophrenia patients had a significantly higher percentage of extreme negative deviations (0.62%), compared with healthy controls and bipolar patients (0.25% and 0.41%, respectively). In addition, extreme positive deviations were significantly higher among the controls (1.14% of voxels), compared with schizophrenia and bipolar patients (0.83% for both).

The findings support data from previous studies suggesting reduced cortical volume in schizophrenia patients, compared with healthy controls and bipolar disorder patients, the researchers noted.

“In this study, patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder differed extremely on an individual level; the lack of substantial overlap among patients in terms of extreme deviations from the normative model is evidence of the high degree of biological heterogeneity in both disorders,” wrote Mr. Wolfers and his colleagues.

The main limitations of the study were the inability to control for confounding variables and to make conclusions about causality, the researchers said. However, the absence of overlap in patients with the same disorder supports the use of brain mapping to study individual pathophysiologic signatures in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder patients, they concluded.

Mr. Wolfers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was supported by grants from multiple organizations, including the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research and the Wellcome Trust U.K. Strategic Award.

SOURCE: Wolfers T et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2467.

Brain mapping patterns varied with clinical mental health diagnoses in a study of 218 patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

“Psychiatry is now the last area of medicine in which diseases are diagnosed solely on the basis of symptoms, and biomarkers to assist treatment remain to be developed,” wrote Thomas Wolfers of Radboud University, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and his colleagues. They also said schizophrenia and bipolar disorder “are excellent examples of highly heterogeneous mental disorders.”

To explore brain structure homogeneity, the researchers used brain scans and mapping models to compare results in 218 adults aged 18-65 years with schizophrenia disorders (163 with schizophrenia and 190 with bipolar disorder) and 256 healthy controls. Demographics were similar between the groups.

The MRI data showed that the same abnormalities in more than 2% of patients with the same disorder occurred in very few loci. Schizophrenia patients showed significantly reduced gray matter in the frontal, cerebellar, and temporal regions; most bipolar patients showed changes in the cerebellar region.

The researchers identified extreme deviations across patients and controls in gray and white matter.

In gray matter, schizophrenia patients had a significantly higher percentage of extreme negative deviations across voxels (0.9% of voxels), compared with both bipolar patients and healthy controls (0.24% and 0.23%, respectively).

In white matter, a similar pattern emerged; schizophrenia patients had a significantly higher percentage of extreme negative deviations (0.62%), compared with healthy controls and bipolar patients (0.25% and 0.41%, respectively). In addition, extreme positive deviations were significantly higher among the controls (1.14% of voxels), compared with schizophrenia and bipolar patients (0.83% for both).

The findings support data from previous studies suggesting reduced cortical volume in schizophrenia patients, compared with healthy controls and bipolar disorder patients, the researchers noted.

“In this study, patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder differed extremely on an individual level; the lack of substantial overlap among patients in terms of extreme deviations from the normative model is evidence of the high degree of biological heterogeneity in both disorders,” wrote Mr. Wolfers and his colleagues.

The main limitations of the study were the inability to control for confounding variables and to make conclusions about causality, the researchers said. However, the absence of overlap in patients with the same disorder supports the use of brain mapping to study individual pathophysiologic signatures in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder patients, they concluded.