User login

IV fluid and narcotics for renal colic

A 40-year-old man presents with severe right flank pain for 1 hour. He has had this in the past when he passed a kidney stone. Urinalysis shows greater than 100 red blood cells per high power field (HPF). CT shows a 6-mm stone in the left ureter.

What do you recommend for therapy?

A. IV ketorolac and IV fluids.

B. IV morphine and IV fluids.

C. IV morphine.

D. IV ketorolac.

This is a common scenario, especially in emergency department settings and acute care clinics. Patients arrive in severe pain because of renal colic from kidney stones. Standard teaching that I received many years ago was that this patient should receive IV fluid to “help float the stone out” and narcotic pain medications to treat the severe pain the patient was in.

Is there good evidence that this is the best therapy?

There are scant data on the practice of IV fluid for treatment of renal stone passage. W. Patrick Springhart, MD, and his colleagues studied 43 patients who presented to the ED for treatment of renal colic.1 All patients had CT evaluation for stones and received intravenous analgesia. Twenty patients were randomized to receive 2 L of normal saline over 2 hours, and 23 patients received minimal IV saline (20 mL/hour). There were no differences between the two groups in pain scores, narcotic requirements, or stone passage rates.

In an older study, Tom-Harald Edna, PhD, and colleagues studied 60 patients with ureteral colic, randomizing them to receive either no fluid or 3 L of IV fluid over 6 hours.2 There was no significant difference in pain between treatment groups.

A Cochrane analysis in 2012 concluded that there was no reliable evidence to support the use of high-volume fluid therapy in the treatment of acute ureteral colic.3

Standard treatment of pain for renal colic has been to use narcotics. In a randomized, double-blind trial comparing ketorolac and meperidine, William Cordell, MD, and his colleagues found that pain relief was superior in ketorolac-treated patients. Seventy-five percent of ketorolac patients had a 50% reduction in pain scores versus only 23% of the patients who received meperidine (P less than .001).4

Anna Holdgate and Tamara Pollock reviewed 20 studies that evaluated NSAIDs and narcotics for acute renal colic. They concluded that patients treated with NSAIDs had greater pain relief with less vomiting than did patients treated with narcotics.5

In the past decade, tamsulosin has been frequently used in patients with renal stones to possibly help with pain and promote more rapid stone passage. A recent randomized, controlled trial with 512 patients, authored by Andrew Meltzer, MD, and his colleagues, showed no improvement in stone passage rate in patients taking tamsulosin, compared with the rate seen with placebo.6

Previously published meta-analyses of multiple studies have shown a benefit to the use of alpha-blockers. Thijs Campschroer and colleagues included 67 studies that altogether included 10,509 participants.7 They found that the use of alpha-blockers led to possibly shorter stone expulsion times (3.4 days), less NSAID use, and fewer hospitalizations, with the evidence graded as low to moderate quality. Stone size seems to matter because use of alpha-blockers does not seem to make a difference for stones larger than 5 mm.

I think IV ketorolac would be the best of the options presented here for this patient. If a patient can safely take NSAIDs, those are probably the best option. There does not appear to be any reason to bolus hydrate patients with acute renal colic.

Dr. Paauw is a professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. J Endourol. 2006 Oct;20(10):713-6.

2. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1983;17(2):175-8.

3. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Feb 15;(2):CD004926.

4. Ann Emerg Med. 1996 Aug;28(2):151-8.

5. BMJ. 2004 Jun 12;328(7453):1401.

6. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Aug 1;178(8):1051-7.

7. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Apr 5;4:CD008509.

A 40-year-old man presents with severe right flank pain for 1 hour. He has had this in the past when he passed a kidney stone. Urinalysis shows greater than 100 red blood cells per high power field (HPF). CT shows a 6-mm stone in the left ureter.

What do you recommend for therapy?

A. IV ketorolac and IV fluids.

B. IV morphine and IV fluids.

C. IV morphine.

D. IV ketorolac.

This is a common scenario, especially in emergency department settings and acute care clinics. Patients arrive in severe pain because of renal colic from kidney stones. Standard teaching that I received many years ago was that this patient should receive IV fluid to “help float the stone out” and narcotic pain medications to treat the severe pain the patient was in.

Is there good evidence that this is the best therapy?

There are scant data on the practice of IV fluid for treatment of renal stone passage. W. Patrick Springhart, MD, and his colleagues studied 43 patients who presented to the ED for treatment of renal colic.1 All patients had CT evaluation for stones and received intravenous analgesia. Twenty patients were randomized to receive 2 L of normal saline over 2 hours, and 23 patients received minimal IV saline (20 mL/hour). There were no differences between the two groups in pain scores, narcotic requirements, or stone passage rates.

In an older study, Tom-Harald Edna, PhD, and colleagues studied 60 patients with ureteral colic, randomizing them to receive either no fluid or 3 L of IV fluid over 6 hours.2 There was no significant difference in pain between treatment groups.

A Cochrane analysis in 2012 concluded that there was no reliable evidence to support the use of high-volume fluid therapy in the treatment of acute ureteral colic.3

Standard treatment of pain for renal colic has been to use narcotics. In a randomized, double-blind trial comparing ketorolac and meperidine, William Cordell, MD, and his colleagues found that pain relief was superior in ketorolac-treated patients. Seventy-five percent of ketorolac patients had a 50% reduction in pain scores versus only 23% of the patients who received meperidine (P less than .001).4

Anna Holdgate and Tamara Pollock reviewed 20 studies that evaluated NSAIDs and narcotics for acute renal colic. They concluded that patients treated with NSAIDs had greater pain relief with less vomiting than did patients treated with narcotics.5

In the past decade, tamsulosin has been frequently used in patients with renal stones to possibly help with pain and promote more rapid stone passage. A recent randomized, controlled trial with 512 patients, authored by Andrew Meltzer, MD, and his colleagues, showed no improvement in stone passage rate in patients taking tamsulosin, compared with the rate seen with placebo.6

Previously published meta-analyses of multiple studies have shown a benefit to the use of alpha-blockers. Thijs Campschroer and colleagues included 67 studies that altogether included 10,509 participants.7 They found that the use of alpha-blockers led to possibly shorter stone expulsion times (3.4 days), less NSAID use, and fewer hospitalizations, with the evidence graded as low to moderate quality. Stone size seems to matter because use of alpha-blockers does not seem to make a difference for stones larger than 5 mm.

I think IV ketorolac would be the best of the options presented here for this patient. If a patient can safely take NSAIDs, those are probably the best option. There does not appear to be any reason to bolus hydrate patients with acute renal colic.

Dr. Paauw is a professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. J Endourol. 2006 Oct;20(10):713-6.

2. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1983;17(2):175-8.

3. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Feb 15;(2):CD004926.

4. Ann Emerg Med. 1996 Aug;28(2):151-8.

5. BMJ. 2004 Jun 12;328(7453):1401.

6. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Aug 1;178(8):1051-7.

7. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Apr 5;4:CD008509.

A 40-year-old man presents with severe right flank pain for 1 hour. He has had this in the past when he passed a kidney stone. Urinalysis shows greater than 100 red blood cells per high power field (HPF). CT shows a 6-mm stone in the left ureter.

What do you recommend for therapy?

A. IV ketorolac and IV fluids.

B. IV morphine and IV fluids.

C. IV morphine.

D. IV ketorolac.

This is a common scenario, especially in emergency department settings and acute care clinics. Patients arrive in severe pain because of renal colic from kidney stones. Standard teaching that I received many years ago was that this patient should receive IV fluid to “help float the stone out” and narcotic pain medications to treat the severe pain the patient was in.

Is there good evidence that this is the best therapy?

There are scant data on the practice of IV fluid for treatment of renal stone passage. W. Patrick Springhart, MD, and his colleagues studied 43 patients who presented to the ED for treatment of renal colic.1 All patients had CT evaluation for stones and received intravenous analgesia. Twenty patients were randomized to receive 2 L of normal saline over 2 hours, and 23 patients received minimal IV saline (20 mL/hour). There were no differences between the two groups in pain scores, narcotic requirements, or stone passage rates.

In an older study, Tom-Harald Edna, PhD, and colleagues studied 60 patients with ureteral colic, randomizing them to receive either no fluid or 3 L of IV fluid over 6 hours.2 There was no significant difference in pain between treatment groups.

A Cochrane analysis in 2012 concluded that there was no reliable evidence to support the use of high-volume fluid therapy in the treatment of acute ureteral colic.3

Standard treatment of pain for renal colic has been to use narcotics. In a randomized, double-blind trial comparing ketorolac and meperidine, William Cordell, MD, and his colleagues found that pain relief was superior in ketorolac-treated patients. Seventy-five percent of ketorolac patients had a 50% reduction in pain scores versus only 23% of the patients who received meperidine (P less than .001).4

Anna Holdgate and Tamara Pollock reviewed 20 studies that evaluated NSAIDs and narcotics for acute renal colic. They concluded that patients treated with NSAIDs had greater pain relief with less vomiting than did patients treated with narcotics.5

In the past decade, tamsulosin has been frequently used in patients with renal stones to possibly help with pain and promote more rapid stone passage. A recent randomized, controlled trial with 512 patients, authored by Andrew Meltzer, MD, and his colleagues, showed no improvement in stone passage rate in patients taking tamsulosin, compared with the rate seen with placebo.6

Previously published meta-analyses of multiple studies have shown a benefit to the use of alpha-blockers. Thijs Campschroer and colleagues included 67 studies that altogether included 10,509 participants.7 They found that the use of alpha-blockers led to possibly shorter stone expulsion times (3.4 days), less NSAID use, and fewer hospitalizations, with the evidence graded as low to moderate quality. Stone size seems to matter because use of alpha-blockers does not seem to make a difference for stones larger than 5 mm.

I think IV ketorolac would be the best of the options presented here for this patient. If a patient can safely take NSAIDs, those are probably the best option. There does not appear to be any reason to bolus hydrate patients with acute renal colic.

Dr. Paauw is a professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. J Endourol. 2006 Oct;20(10):713-6.

2. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1983;17(2):175-8.

3. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Feb 15;(2):CD004926.

4. Ann Emerg Med. 1996 Aug;28(2):151-8.

5. BMJ. 2004 Jun 12;328(7453):1401.

6. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Aug 1;178(8):1051-7.

7. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Apr 5;4:CD008509.

Anti-RNPC3 antibody positive status linked to GI dysmotility in systemic sclerosis

in a two-center study, suggesting that anti-RNPC3 antibody status could serve as a biomarker for risk stratification of GI dysmotility in this patient population.

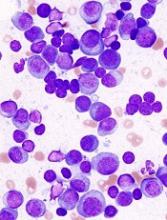

GI dysfunction is the most common internal complication of systemic sclerosis (SSc), affecting up to 90% of patients, and it presents with “striking” heterogeneity, first author Zsuzsanna H. McMahan, MD, of John Hopkins University, Baltimore, and her colleagues wrote in Arthritis Care & Research.

Recent published reports have suggested a link between anti-RNPC3 antibodies (for example, anti-U11/U12 ribonucleoprotein) and GI dysmotility, but have had limited generalizability and did not assess for any associations with distinct GI outcomes, the study authors noted.

In the current study, the investigators compared 37 SSc patients with severe GI dysfunction who required total parenteral nutrition and 38 SSc patients without symptoms of GI dysfunction (modified Medsger severity score of 0) in the Johns Hopkins Scleroderma Center database.

Patients were included in this “discovery cohort” if they had both clinical data and banked serum, and met 2013 ACR/EULAR criteria, 1980 ACR criteria, or at least three of five features of CREST (calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, telangiectasia) syndrome. The presence of severe GI dysmotility was determined by physician documentation in the clinical notes and/or the presence of esophageal dysmotility, gastroparesis, or small bowel dysmotility.

Anti-RNPC3 antibodies were more prevalent among patients on total parenteral nutrition (14% vs. 3%; P = .11), a finding that the authors said was consistent with the published literature.

Patients in the severe GI group also were significantly more likely to be male (38% vs. 16%; P = .031), to be black (43% vs. 13%; P less than or equal to .01), to have diffuse disease (65% vs. 34%; P less than or equal to .01), to have myopathy (24% vs. 5%; P = .05), and to have anti-U3RNP antibodies (12% vs. 0%; P = .05).

Severe GI patients were also significantly less likely to have anti-RNA pol 3 antibodies (3% vs. 25%; P = .01). Two patients in the severe GI group were double-positive for antibodies, having both anti-RNPC3 antibodies and antibodies to either Ro52 or PM-Scl.

“Since the number of anti-RNPC3 antibody positive patients in the John Hopkins discovery study was small, but anti-RNPC3 antibodies were over four times more frequent than expected in the severe GI group, we pursued additional analyses to understand this association using the current Pittsburgh Scleroderma cohort,” the research team explained.

This cohort included 39 anti-RNPC3 antibody positive cases and 117 matched anti-RNPC3 negative controls. Moderate to severe GI dysfunction (Medsger GI score of 2 or higher) was present in 36% of anti-RNPC3 positive patients vs. 15% of anti-RNPC3 negative patients (P less than or equal to. 01).

Anti-RNPC3-positive patients were more likely to be male (31% vs. 15%; P = .04), to be black (18% vs. 6%; P = .02), to have esophageal dysmotility (93% vs. 62%; P less than .01), and to have interstitial lung disease (ILD, 77% vs. 35%; P less than .01).

Even after adjustment for relevant covariates and potential confounders, moderate to severe GI disease was associated with anti-RNPC3 antibodies. For example, in an unadjusted model, moderate to severe GI disease was associated with a nearly fourfold higher likelihood of having anti-RNPC3 antibodies (odds ratio = 3.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.5-9.8). And in a model adjusted for age and race, moderate to severe GI disease was again associated with a 3.8 times increased odds of having anti-RNPC3 antibodies (95% CI, 1.4-10.0). But there was no significant association for age (OR = 1.0; 95% CI, 0.95-1.0) or black race (OR = 2.4; 95% CI, 0.7-8.5).

However, in a model adjusted for age, race, ILD, diffuse cutaneous disease, and myopathy, patients with moderate to severe GI disease continued to have a 3.8-fold increased odds of having anti-RNPC3 antibodies (95% CI, 1.0-14.3).

Older age at first visit, black race, diffuse cutaneous disease, and myopathy did not seem to play a role in the risk of having anti-RNPC3 antibodies.

They also observed an association with ILD, which they said trended toward significance (OR = 2.8; 95% CI, 1.0-8.2).

“The association between anti-RNPC3 antibodies and both pulmonary fibrosis and esophageal dysmotility in SSc is interesting. High rates of ILD are reported in association with anti-RNPC3 antibodies in SSc, with anti-RNPC3 antibody positive patients having an estimated 70% prevalence of ILD,” the study authors noted.

“In addition, recent studies suggest that microaspiration in SSc patients with uncontrolled reflux could contribute to the development of pulmonary fibrosis. Anti-RNPC3 antibodies may identify a specific subset of patients at higher risk for microaspiration that would benefit from more aggressive GERD management,” they wrote.

The Scleroderma Research Foundation funded the study. Additional support was provided by the Jerome L. Greene Scholar Award, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, the Johns Hopkins Clinician Scientist Career Development Award, and National Institutes of Health grants. No relevant conflicts of interest were declared by the authors.

SOURCE: McMahan Z et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Sep 22. doi: 10.1002/acr.23763

This study represents good work in confirming the association of anti-RNPC3 positivity with severe GI disease first noted by Johns Hopkins investigators in a single-center study (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Jun; 69[6]:1306-12). Now that Dr. McMahan and her associates have confirmed this association in the most severe of GI problems in SSc, it would be very useful to see if there is a lesser degree of GI involvement that also correlates (for example, using the validated UCLA Gastrointestinal Tract Questionnaire 2.0, which gives a continuous graded response).

Daniel E. Furst, MD, is professor of medicine (emeritus) at the University of California, Los Angeles, an adjunct professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, and research professor at the University of Florence (Italy). He is also in part-time practice in Los Angeles and Seattle.

This study represents good work in confirming the association of anti-RNPC3 positivity with severe GI disease first noted by Johns Hopkins investigators in a single-center study (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Jun; 69[6]:1306-12). Now that Dr. McMahan and her associates have confirmed this association in the most severe of GI problems in SSc, it would be very useful to see if there is a lesser degree of GI involvement that also correlates (for example, using the validated UCLA Gastrointestinal Tract Questionnaire 2.0, which gives a continuous graded response).

Daniel E. Furst, MD, is professor of medicine (emeritus) at the University of California, Los Angeles, an adjunct professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, and research professor at the University of Florence (Italy). He is also in part-time practice in Los Angeles and Seattle.

This study represents good work in confirming the association of anti-RNPC3 positivity with severe GI disease first noted by Johns Hopkins investigators in a single-center study (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Jun; 69[6]:1306-12). Now that Dr. McMahan and her associates have confirmed this association in the most severe of GI problems in SSc, it would be very useful to see if there is a lesser degree of GI involvement that also correlates (for example, using the validated UCLA Gastrointestinal Tract Questionnaire 2.0, which gives a continuous graded response).

Daniel E. Furst, MD, is professor of medicine (emeritus) at the University of California, Los Angeles, an adjunct professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, and research professor at the University of Florence (Italy). He is also in part-time practice in Los Angeles and Seattle.

in a two-center study, suggesting that anti-RNPC3 antibody status could serve as a biomarker for risk stratification of GI dysmotility in this patient population.

GI dysfunction is the most common internal complication of systemic sclerosis (SSc), affecting up to 90% of patients, and it presents with “striking” heterogeneity, first author Zsuzsanna H. McMahan, MD, of John Hopkins University, Baltimore, and her colleagues wrote in Arthritis Care & Research.

Recent published reports have suggested a link between anti-RNPC3 antibodies (for example, anti-U11/U12 ribonucleoprotein) and GI dysmotility, but have had limited generalizability and did not assess for any associations with distinct GI outcomes, the study authors noted.

In the current study, the investigators compared 37 SSc patients with severe GI dysfunction who required total parenteral nutrition and 38 SSc patients without symptoms of GI dysfunction (modified Medsger severity score of 0) in the Johns Hopkins Scleroderma Center database.

Patients were included in this “discovery cohort” if they had both clinical data and banked serum, and met 2013 ACR/EULAR criteria, 1980 ACR criteria, or at least three of five features of CREST (calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, telangiectasia) syndrome. The presence of severe GI dysmotility was determined by physician documentation in the clinical notes and/or the presence of esophageal dysmotility, gastroparesis, or small bowel dysmotility.

Anti-RNPC3 antibodies were more prevalent among patients on total parenteral nutrition (14% vs. 3%; P = .11), a finding that the authors said was consistent with the published literature.

Patients in the severe GI group also were significantly more likely to be male (38% vs. 16%; P = .031), to be black (43% vs. 13%; P less than or equal to .01), to have diffuse disease (65% vs. 34%; P less than or equal to .01), to have myopathy (24% vs. 5%; P = .05), and to have anti-U3RNP antibodies (12% vs. 0%; P = .05).

Severe GI patients were also significantly less likely to have anti-RNA pol 3 antibodies (3% vs. 25%; P = .01). Two patients in the severe GI group were double-positive for antibodies, having both anti-RNPC3 antibodies and antibodies to either Ro52 or PM-Scl.

“Since the number of anti-RNPC3 antibody positive patients in the John Hopkins discovery study was small, but anti-RNPC3 antibodies were over four times more frequent than expected in the severe GI group, we pursued additional analyses to understand this association using the current Pittsburgh Scleroderma cohort,” the research team explained.

This cohort included 39 anti-RNPC3 antibody positive cases and 117 matched anti-RNPC3 negative controls. Moderate to severe GI dysfunction (Medsger GI score of 2 or higher) was present in 36% of anti-RNPC3 positive patients vs. 15% of anti-RNPC3 negative patients (P less than or equal to. 01).

Anti-RNPC3-positive patients were more likely to be male (31% vs. 15%; P = .04), to be black (18% vs. 6%; P = .02), to have esophageal dysmotility (93% vs. 62%; P less than .01), and to have interstitial lung disease (ILD, 77% vs. 35%; P less than .01).

Even after adjustment for relevant covariates and potential confounders, moderate to severe GI disease was associated with anti-RNPC3 antibodies. For example, in an unadjusted model, moderate to severe GI disease was associated with a nearly fourfold higher likelihood of having anti-RNPC3 antibodies (odds ratio = 3.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.5-9.8). And in a model adjusted for age and race, moderate to severe GI disease was again associated with a 3.8 times increased odds of having anti-RNPC3 antibodies (95% CI, 1.4-10.0). But there was no significant association for age (OR = 1.0; 95% CI, 0.95-1.0) or black race (OR = 2.4; 95% CI, 0.7-8.5).

However, in a model adjusted for age, race, ILD, diffuse cutaneous disease, and myopathy, patients with moderate to severe GI disease continued to have a 3.8-fold increased odds of having anti-RNPC3 antibodies (95% CI, 1.0-14.3).

Older age at first visit, black race, diffuse cutaneous disease, and myopathy did not seem to play a role in the risk of having anti-RNPC3 antibodies.

They also observed an association with ILD, which they said trended toward significance (OR = 2.8; 95% CI, 1.0-8.2).

“The association between anti-RNPC3 antibodies and both pulmonary fibrosis and esophageal dysmotility in SSc is interesting. High rates of ILD are reported in association with anti-RNPC3 antibodies in SSc, with anti-RNPC3 antibody positive patients having an estimated 70% prevalence of ILD,” the study authors noted.

“In addition, recent studies suggest that microaspiration in SSc patients with uncontrolled reflux could contribute to the development of pulmonary fibrosis. Anti-RNPC3 antibodies may identify a specific subset of patients at higher risk for microaspiration that would benefit from more aggressive GERD management,” they wrote.

The Scleroderma Research Foundation funded the study. Additional support was provided by the Jerome L. Greene Scholar Award, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, the Johns Hopkins Clinician Scientist Career Development Award, and National Institutes of Health grants. No relevant conflicts of interest were declared by the authors.

SOURCE: McMahan Z et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Sep 22. doi: 10.1002/acr.23763

in a two-center study, suggesting that anti-RNPC3 antibody status could serve as a biomarker for risk stratification of GI dysmotility in this patient population.

GI dysfunction is the most common internal complication of systemic sclerosis (SSc), affecting up to 90% of patients, and it presents with “striking” heterogeneity, first author Zsuzsanna H. McMahan, MD, of John Hopkins University, Baltimore, and her colleagues wrote in Arthritis Care & Research.

Recent published reports have suggested a link between anti-RNPC3 antibodies (for example, anti-U11/U12 ribonucleoprotein) and GI dysmotility, but have had limited generalizability and did not assess for any associations with distinct GI outcomes, the study authors noted.

In the current study, the investigators compared 37 SSc patients with severe GI dysfunction who required total parenteral nutrition and 38 SSc patients without symptoms of GI dysfunction (modified Medsger severity score of 0) in the Johns Hopkins Scleroderma Center database.

Patients were included in this “discovery cohort” if they had both clinical data and banked serum, and met 2013 ACR/EULAR criteria, 1980 ACR criteria, or at least three of five features of CREST (calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, telangiectasia) syndrome. The presence of severe GI dysmotility was determined by physician documentation in the clinical notes and/or the presence of esophageal dysmotility, gastroparesis, or small bowel dysmotility.

Anti-RNPC3 antibodies were more prevalent among patients on total parenteral nutrition (14% vs. 3%; P = .11), a finding that the authors said was consistent with the published literature.

Patients in the severe GI group also were significantly more likely to be male (38% vs. 16%; P = .031), to be black (43% vs. 13%; P less than or equal to .01), to have diffuse disease (65% vs. 34%; P less than or equal to .01), to have myopathy (24% vs. 5%; P = .05), and to have anti-U3RNP antibodies (12% vs. 0%; P = .05).

Severe GI patients were also significantly less likely to have anti-RNA pol 3 antibodies (3% vs. 25%; P = .01). Two patients in the severe GI group were double-positive for antibodies, having both anti-RNPC3 antibodies and antibodies to either Ro52 or PM-Scl.

“Since the number of anti-RNPC3 antibody positive patients in the John Hopkins discovery study was small, but anti-RNPC3 antibodies were over four times more frequent than expected in the severe GI group, we pursued additional analyses to understand this association using the current Pittsburgh Scleroderma cohort,” the research team explained.

This cohort included 39 anti-RNPC3 antibody positive cases and 117 matched anti-RNPC3 negative controls. Moderate to severe GI dysfunction (Medsger GI score of 2 or higher) was present in 36% of anti-RNPC3 positive patients vs. 15% of anti-RNPC3 negative patients (P less than or equal to. 01).

Anti-RNPC3-positive patients were more likely to be male (31% vs. 15%; P = .04), to be black (18% vs. 6%; P = .02), to have esophageal dysmotility (93% vs. 62%; P less than .01), and to have interstitial lung disease (ILD, 77% vs. 35%; P less than .01).

Even after adjustment for relevant covariates and potential confounders, moderate to severe GI disease was associated with anti-RNPC3 antibodies. For example, in an unadjusted model, moderate to severe GI disease was associated with a nearly fourfold higher likelihood of having anti-RNPC3 antibodies (odds ratio = 3.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.5-9.8). And in a model adjusted for age and race, moderate to severe GI disease was again associated with a 3.8 times increased odds of having anti-RNPC3 antibodies (95% CI, 1.4-10.0). But there was no significant association for age (OR = 1.0; 95% CI, 0.95-1.0) or black race (OR = 2.4; 95% CI, 0.7-8.5).

However, in a model adjusted for age, race, ILD, diffuse cutaneous disease, and myopathy, patients with moderate to severe GI disease continued to have a 3.8-fold increased odds of having anti-RNPC3 antibodies (95% CI, 1.0-14.3).

Older age at first visit, black race, diffuse cutaneous disease, and myopathy did not seem to play a role in the risk of having anti-RNPC3 antibodies.

They also observed an association with ILD, which they said trended toward significance (OR = 2.8; 95% CI, 1.0-8.2).

“The association between anti-RNPC3 antibodies and both pulmonary fibrosis and esophageal dysmotility in SSc is interesting. High rates of ILD are reported in association with anti-RNPC3 antibodies in SSc, with anti-RNPC3 antibody positive patients having an estimated 70% prevalence of ILD,” the study authors noted.

“In addition, recent studies suggest that microaspiration in SSc patients with uncontrolled reflux could contribute to the development of pulmonary fibrosis. Anti-RNPC3 antibodies may identify a specific subset of patients at higher risk for microaspiration that would benefit from more aggressive GERD management,” they wrote.

The Scleroderma Research Foundation funded the study. Additional support was provided by the Jerome L. Greene Scholar Award, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, the Johns Hopkins Clinician Scientist Career Development Award, and National Institutes of Health grants. No relevant conflicts of interest were declared by the authors.

SOURCE: McMahan Z et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Sep 22. doi: 10.1002/acr.23763

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Key clinical point: Antibody status may inform GI risk stratification in people with systemic sclerosis.

Major finding: Anti-RNPC3 antibody positive SSc patients are significantly more likely to have moderate to severe GI dysfunction. In a fully adjusted model, patients with moderate to severe GI disease had 3.8-fold higher odds of having anti-RNPC3 antibodies.

Study details: A comparison of anti-RNPC3 antibodies in a discovery cohort of SSc patients with severe GI dysfunction who were on total parenteral nutrition compared with asymptomatic patients from the Johns Hopkins Scleroderma Center. Followed by a case control study to confirm the findings using the Pittsburgh Scleroderma cohort.

Disclosures: The Scleroderma Research Foundation funded the study. Additional support was provided by the Jerome L. Greene Scholar Award, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, the Johns Hopkins Clinician Scientist Career Development Award, and National Institutes of Health grants. No relevant conflicts of interest were declared by the authors.

Source: McMahan Z et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Sep 22. doi: 10.1002/acr.23763.

Pulmonary NP ensures care continuity, reduces readmissions

SAN ANTONIO – Unplanned whose discharge process involved a pulmonary nurse practitioner to coordinate continuity of care, a study of more than 70 patients has found.

Despite an increase over time in the rate of discharges, readmissions fell, Sarah Barry, CRNP, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

“The technology-dependent pediatric population who is going home with tracheostomy and ventilator dependence is at risk for hospital readmission, and having an advanced practice provider in a continuity role promotes adherence to our standards of practice and improves transition to home,” Ms. Barry said in an interview.

She noted previous research showing that 40% of 109 home mechanical ventilation patients discharged between 2003 and 2009 had unplanned readmissions, 28% of which occurred within the first month after discharge.

Nearly two thirds (64%) of those readmissions were related to a pulmonary and/or tracheostomy problem. That study also found that changes in condition management 1 week before discharge, such as medications, ventilator settings, or feeding regimens, was associated with unplanned readmission.

That research “makes us ask ourselves if our readmissions are avoidable and what can we do to get these kids home safe and to keep them home,” Ms. Barry told attendees, adding that CHOP was unhappy with their readmission rates.

“Kids were often not making it to their first pulmonary appointment, and it was a burden for these families,” she said. “We questioned whether or not having a nurse practitioner in a role to promote adherence to our standards would have a positive impact on our unplanned route.”

They evaluated the effect of such an NP on unplanned readmissions among tracheostomy/ventilator-supported children. The NP’s role was to track patients, mostly from the progressive care unit, who required a tracheostomy and ventilator and were expected to be discharged home or to a long-term care facility. The NP provided continuity for medical management and coordinated care at discharge.

“We also do not make changes for 2 weeks before discharge so that we can focus on all the other coordination that goes into getting these kids home,” Ms. Barry said.

She reviewed the patients’ electronic charts to record time to scheduled follow-up visit, days until hospital readmission, admitting diagnosis at readmission, and length of stay after readmission. With consideration for the time needed for transition into this new process, the population studied was assessed within three cohorts.

The first cohort comprised the 22 children discharged between April 2016 and March 2017, the full year before a pulmonary NP began coordinating the discharge process. These patients averaged 1.8 discharges per month with an initial follow-up of 2-12 weeks.

Just over a quarter (27%) of the first cohort were readmitted before their scheduled follow-up, ranging from 2 to 25 days after discharge. Five percent were readmitted within a week of discharge, and 27% were readmitted within a month; their average length of stay was 13 days after readmission. Most (83%) of these discharges were respiratory related while the other 17% were gastrointestinal related.

The second cohort involved the 11 patients discharged between April 2017 and August 2017, the first 5 months after a pulmonary NP began overseeing the discharge readiness process.

“We chose 5 months because it took about 5months for me to develop my own protocols and standards of practice,” Ms. Barry explained.

An average 2.2 discharges occurred monthly with 2-8 weeks of initial postdischarge follow-up. Though nearly half these children (45%) were readmitted before their scheduled follow-up, their length of stay was shorter, an average of 11 days.

Readmission within a week after discharge occurred among 27% of the children, and 45% of them were readmitted within a month of discharge. Sixty percent of these patients were readmitted for respiratory issues, compared with 40% with GI issues.

The third cohort included all 38 patients discharged from September 2017 to August 2018, the year after a pulmonary NP had become fully established in the continuity role, with an average 3.2 discharges occurred per month. Readmission rates were considerably lower: Eighteen percent of patients were readmitted before their scheduled follow-up appointment, which ranged from 1 to 13 weeks after discharge.

Five percent were readmitted within a week of discharge, and 24% were readmitted within a month, ranging from 1 to 26 days post discharge. But length of stay was shorter still at an average of 9 days.

The reasons for readmission varied more in this cohort: While 56% were respiratory related, 22% were related to fever, and 11% were related to neurodevelopment concerns or social reasons, such as necessary involvement of social services.

Ms. Barry’s colleague, Howard B. Panitch, MD, also on the staff of CHOP, noted during the discussion that the NP’s role is invaluable in “keeping the inpatient teams honest.

“She reminds her colleagues in critical care that you can’t make that ventilator change when on your way out the door or very close to discharge.”

Ms. Barry had no disclosures. No external funding was noted.

SOURCE: Barry S et al. CHEST 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.743.

SAN ANTONIO – Unplanned whose discharge process involved a pulmonary nurse practitioner to coordinate continuity of care, a study of more than 70 patients has found.

Despite an increase over time in the rate of discharges, readmissions fell, Sarah Barry, CRNP, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

“The technology-dependent pediatric population who is going home with tracheostomy and ventilator dependence is at risk for hospital readmission, and having an advanced practice provider in a continuity role promotes adherence to our standards of practice and improves transition to home,” Ms. Barry said in an interview.

She noted previous research showing that 40% of 109 home mechanical ventilation patients discharged between 2003 and 2009 had unplanned readmissions, 28% of which occurred within the first month after discharge.

Nearly two thirds (64%) of those readmissions were related to a pulmonary and/or tracheostomy problem. That study also found that changes in condition management 1 week before discharge, such as medications, ventilator settings, or feeding regimens, was associated with unplanned readmission.

That research “makes us ask ourselves if our readmissions are avoidable and what can we do to get these kids home safe and to keep them home,” Ms. Barry told attendees, adding that CHOP was unhappy with their readmission rates.

“Kids were often not making it to their first pulmonary appointment, and it was a burden for these families,” she said. “We questioned whether or not having a nurse practitioner in a role to promote adherence to our standards would have a positive impact on our unplanned route.”

They evaluated the effect of such an NP on unplanned readmissions among tracheostomy/ventilator-supported children. The NP’s role was to track patients, mostly from the progressive care unit, who required a tracheostomy and ventilator and were expected to be discharged home or to a long-term care facility. The NP provided continuity for medical management and coordinated care at discharge.

“We also do not make changes for 2 weeks before discharge so that we can focus on all the other coordination that goes into getting these kids home,” Ms. Barry said.

She reviewed the patients’ electronic charts to record time to scheduled follow-up visit, days until hospital readmission, admitting diagnosis at readmission, and length of stay after readmission. With consideration for the time needed for transition into this new process, the population studied was assessed within three cohorts.

The first cohort comprised the 22 children discharged between April 2016 and March 2017, the full year before a pulmonary NP began coordinating the discharge process. These patients averaged 1.8 discharges per month with an initial follow-up of 2-12 weeks.

Just over a quarter (27%) of the first cohort were readmitted before their scheduled follow-up, ranging from 2 to 25 days after discharge. Five percent were readmitted within a week of discharge, and 27% were readmitted within a month; their average length of stay was 13 days after readmission. Most (83%) of these discharges were respiratory related while the other 17% were gastrointestinal related.

The second cohort involved the 11 patients discharged between April 2017 and August 2017, the first 5 months after a pulmonary NP began overseeing the discharge readiness process.

“We chose 5 months because it took about 5months for me to develop my own protocols and standards of practice,” Ms. Barry explained.

An average 2.2 discharges occurred monthly with 2-8 weeks of initial postdischarge follow-up. Though nearly half these children (45%) were readmitted before their scheduled follow-up, their length of stay was shorter, an average of 11 days.

Readmission within a week after discharge occurred among 27% of the children, and 45% of them were readmitted within a month of discharge. Sixty percent of these patients were readmitted for respiratory issues, compared with 40% with GI issues.

The third cohort included all 38 patients discharged from September 2017 to August 2018, the year after a pulmonary NP had become fully established in the continuity role, with an average 3.2 discharges occurred per month. Readmission rates were considerably lower: Eighteen percent of patients were readmitted before their scheduled follow-up appointment, which ranged from 1 to 13 weeks after discharge.

Five percent were readmitted within a week of discharge, and 24% were readmitted within a month, ranging from 1 to 26 days post discharge. But length of stay was shorter still at an average of 9 days.

The reasons for readmission varied more in this cohort: While 56% were respiratory related, 22% were related to fever, and 11% were related to neurodevelopment concerns or social reasons, such as necessary involvement of social services.

Ms. Barry’s colleague, Howard B. Panitch, MD, also on the staff of CHOP, noted during the discussion that the NP’s role is invaluable in “keeping the inpatient teams honest.

“She reminds her colleagues in critical care that you can’t make that ventilator change when on your way out the door or very close to discharge.”

Ms. Barry had no disclosures. No external funding was noted.

SOURCE: Barry S et al. CHEST 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.743.

SAN ANTONIO – Unplanned whose discharge process involved a pulmonary nurse practitioner to coordinate continuity of care, a study of more than 70 patients has found.

Despite an increase over time in the rate of discharges, readmissions fell, Sarah Barry, CRNP, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

“The technology-dependent pediatric population who is going home with tracheostomy and ventilator dependence is at risk for hospital readmission, and having an advanced practice provider in a continuity role promotes adherence to our standards of practice and improves transition to home,” Ms. Barry said in an interview.

She noted previous research showing that 40% of 109 home mechanical ventilation patients discharged between 2003 and 2009 had unplanned readmissions, 28% of which occurred within the first month after discharge.

Nearly two thirds (64%) of those readmissions were related to a pulmonary and/or tracheostomy problem. That study also found that changes in condition management 1 week before discharge, such as medications, ventilator settings, or feeding regimens, was associated with unplanned readmission.

That research “makes us ask ourselves if our readmissions are avoidable and what can we do to get these kids home safe and to keep them home,” Ms. Barry told attendees, adding that CHOP was unhappy with their readmission rates.

“Kids were often not making it to their first pulmonary appointment, and it was a burden for these families,” she said. “We questioned whether or not having a nurse practitioner in a role to promote adherence to our standards would have a positive impact on our unplanned route.”

They evaluated the effect of such an NP on unplanned readmissions among tracheostomy/ventilator-supported children. The NP’s role was to track patients, mostly from the progressive care unit, who required a tracheostomy and ventilator and were expected to be discharged home or to a long-term care facility. The NP provided continuity for medical management and coordinated care at discharge.

“We also do not make changes for 2 weeks before discharge so that we can focus on all the other coordination that goes into getting these kids home,” Ms. Barry said.

She reviewed the patients’ electronic charts to record time to scheduled follow-up visit, days until hospital readmission, admitting diagnosis at readmission, and length of stay after readmission. With consideration for the time needed for transition into this new process, the population studied was assessed within three cohorts.

The first cohort comprised the 22 children discharged between April 2016 and March 2017, the full year before a pulmonary NP began coordinating the discharge process. These patients averaged 1.8 discharges per month with an initial follow-up of 2-12 weeks.

Just over a quarter (27%) of the first cohort were readmitted before their scheduled follow-up, ranging from 2 to 25 days after discharge. Five percent were readmitted within a week of discharge, and 27% were readmitted within a month; their average length of stay was 13 days after readmission. Most (83%) of these discharges were respiratory related while the other 17% were gastrointestinal related.

The second cohort involved the 11 patients discharged between April 2017 and August 2017, the first 5 months after a pulmonary NP began overseeing the discharge readiness process.

“We chose 5 months because it took about 5months for me to develop my own protocols and standards of practice,” Ms. Barry explained.

An average 2.2 discharges occurred monthly with 2-8 weeks of initial postdischarge follow-up. Though nearly half these children (45%) were readmitted before their scheduled follow-up, their length of stay was shorter, an average of 11 days.

Readmission within a week after discharge occurred among 27% of the children, and 45% of them were readmitted within a month of discharge. Sixty percent of these patients were readmitted for respiratory issues, compared with 40% with GI issues.

The third cohort included all 38 patients discharged from September 2017 to August 2018, the year after a pulmonary NP had become fully established in the continuity role, with an average 3.2 discharges occurred per month. Readmission rates were considerably lower: Eighteen percent of patients were readmitted before their scheduled follow-up appointment, which ranged from 1 to 13 weeks after discharge.

Five percent were readmitted within a week of discharge, and 24% were readmitted within a month, ranging from 1 to 26 days post discharge. But length of stay was shorter still at an average of 9 days.

The reasons for readmission varied more in this cohort: While 56% were respiratory related, 22% were related to fever, and 11% were related to neurodevelopment concerns or social reasons, such as necessary involvement of social services.

Ms. Barry’s colleague, Howard B. Panitch, MD, also on the staff of CHOP, noted during the discussion that the NP’s role is invaluable in “keeping the inpatient teams honest.

“She reminds her colleagues in critical care that you can’t make that ventilator change when on your way out the door or very close to discharge.”

Ms. Barry had no disclosures. No external funding was noted.

SOURCE: Barry S et al. CHEST 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.743.

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2018

Key clinical point: Use of pulmonary NP for continuity care decreases unplanned readmissions among pediatric tracheostomy/ventilator patients.

Major finding: Unplanned readmission rates declined from 27% to 18% before the patient’s first follow-up appointment.

Study details: A retrospective electronic chart review of 71 tracheostomy/ventilator-dependent children discharged between April 2016 and August 2018 at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Disclosures: Ms. Barry had no disclosures. No external funding was noted.

Source: Barry S et al. CHEST 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.743.

ADVENT-HF early results: High ASV compliance, no safety concerns

SAN ANTONIO – The in heart failure patients with sleep apnea, so far has better compliance than previous trials, with no safety concerns to date, according to investigator T. Douglas Bradley, MD.

On average, patients with obstructive sleep apnea were using the device 4.6 hours per night at 1 month and 4.1 hours at 12 months, while patients with central sleep apnea were using the device 5.2 hours per night both at 1 month and 12 months, Dr. Bradley said.

“This represents much better compliance than the other trials that have looked into this area, so we are quite happy about that,” Dr. Bradley said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

The study has been reviewed five times by the data safety monitoring board since the announcement of SERVE-HF trial results, with no safety concerns in either obstructive sleep apnea or central sleep apnea patients, Dr. Bradley noted in a podium presentation.

The compliance results have been submitted for publication, though efficacy results of the study will have to wait. The estimated study completion date is June 2020, according to the latest study information on ClinicalTrials.gov.

More than 600 patients have been enrolled in ADVENT-HF to date, and the investigators hope to enroll more than 800: “We should be there by the end of next year,” Dr. Bradley said.

He provided disclosures related to Philips Respironics (funding and devices) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

SAN ANTONIO – The in heart failure patients with sleep apnea, so far has better compliance than previous trials, with no safety concerns to date, according to investigator T. Douglas Bradley, MD.

On average, patients with obstructive sleep apnea were using the device 4.6 hours per night at 1 month and 4.1 hours at 12 months, while patients with central sleep apnea were using the device 5.2 hours per night both at 1 month and 12 months, Dr. Bradley said.

“This represents much better compliance than the other trials that have looked into this area, so we are quite happy about that,” Dr. Bradley said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

The study has been reviewed five times by the data safety monitoring board since the announcement of SERVE-HF trial results, with no safety concerns in either obstructive sleep apnea or central sleep apnea patients, Dr. Bradley noted in a podium presentation.

The compliance results have been submitted for publication, though efficacy results of the study will have to wait. The estimated study completion date is June 2020, according to the latest study information on ClinicalTrials.gov.

More than 600 patients have been enrolled in ADVENT-HF to date, and the investigators hope to enroll more than 800: “We should be there by the end of next year,” Dr. Bradley said.

He provided disclosures related to Philips Respironics (funding and devices) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

SAN ANTONIO – The in heart failure patients with sleep apnea, so far has better compliance than previous trials, with no safety concerns to date, according to investigator T. Douglas Bradley, MD.

On average, patients with obstructive sleep apnea were using the device 4.6 hours per night at 1 month and 4.1 hours at 12 months, while patients with central sleep apnea were using the device 5.2 hours per night both at 1 month and 12 months, Dr. Bradley said.

“This represents much better compliance than the other trials that have looked into this area, so we are quite happy about that,” Dr. Bradley said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

The study has been reviewed five times by the data safety monitoring board since the announcement of SERVE-HF trial results, with no safety concerns in either obstructive sleep apnea or central sleep apnea patients, Dr. Bradley noted in a podium presentation.

The compliance results have been submitted for publication, though efficacy results of the study will have to wait. The estimated study completion date is June 2020, according to the latest study information on ClinicalTrials.gov.

More than 600 patients have been enrolled in ADVENT-HF to date, and the investigators hope to enroll more than 800: “We should be there by the end of next year,” Dr. Bradley said.

He provided disclosures related to Philips Respironics (funding and devices) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2018

Bisphosphonate holiday may help to reduce atypical femur fracture risk

, according to a study of more than 150,000 Southern California health plan members presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research in Montreal.

A second study in the same group of women found that higher bone mineral density levels before bisphosphonate treatment may put women at greater risk for these fractures.

“Our findings suggest really strongly that among women who have achieved some level of bisphosphonate exposure a drug holiday is certainly a reasonable approach to trying to balance the risk of these atypical fractures versus the benefit of preventing more typical, or classic, hip fractures,” said presenter Annette L. Adams, PhD, MPH, a research scientist with Kaiser Permanente Southern California, who was an author on both studies.

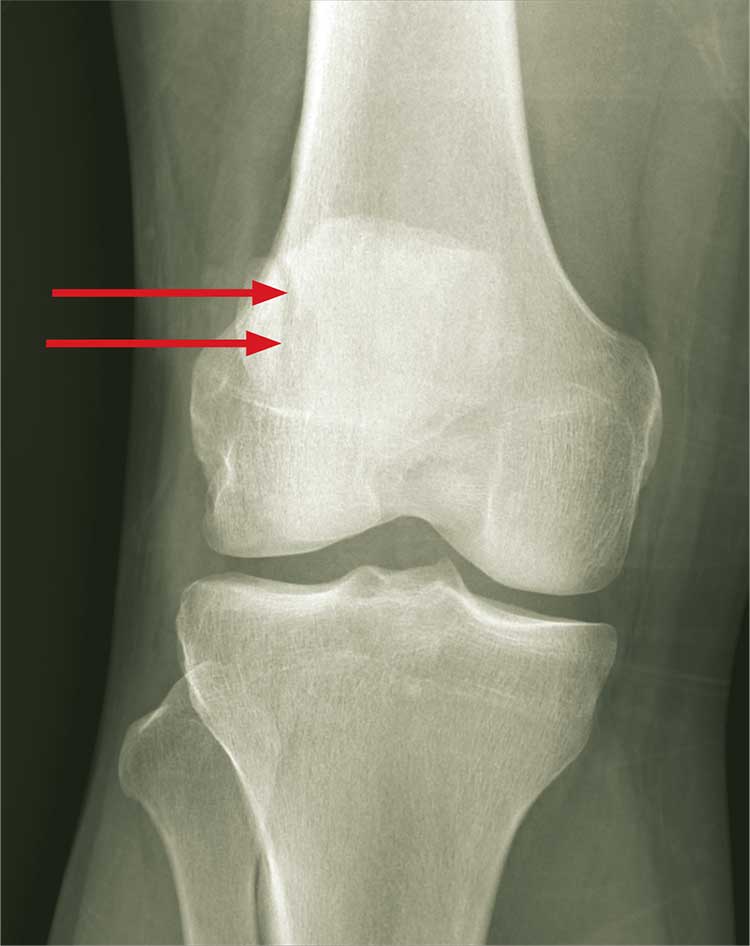

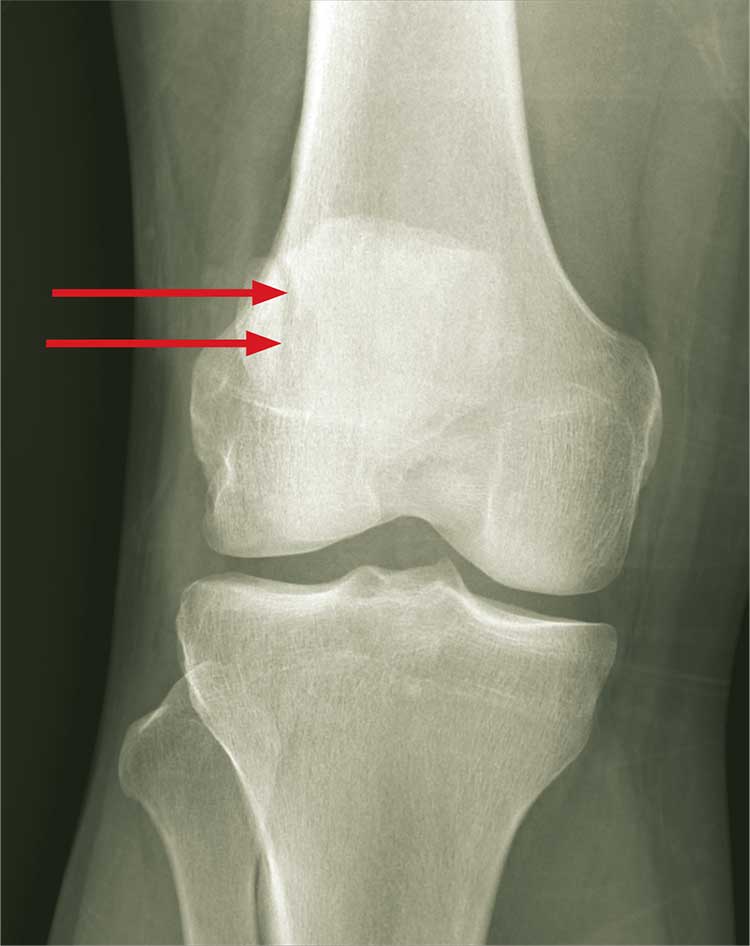

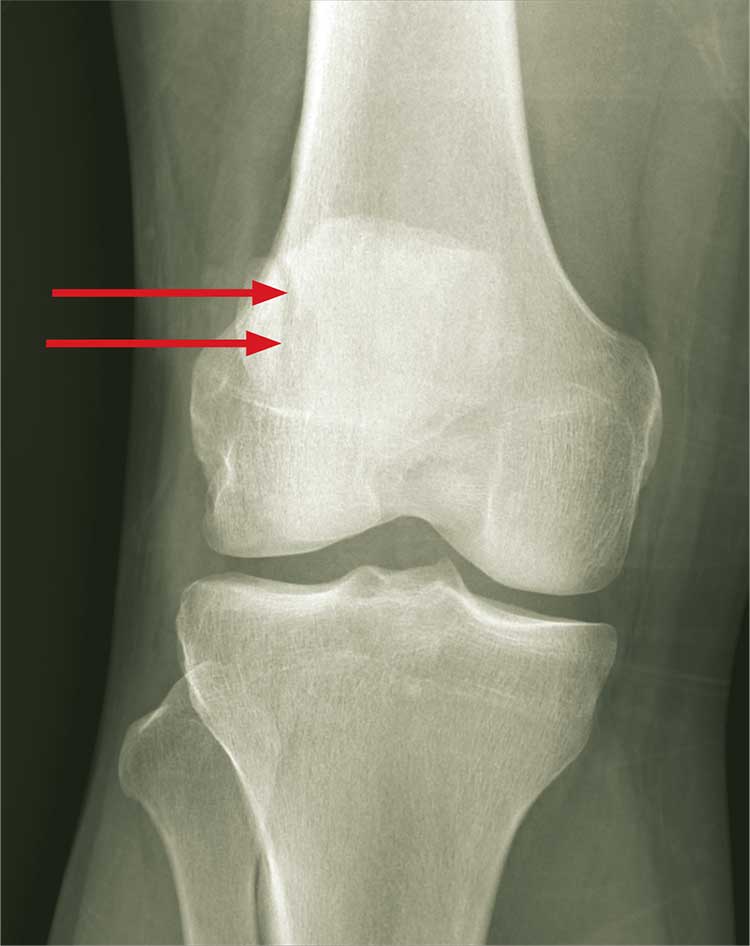

Atypical femur fractures (AFFs) occur below the trochanters in the femoral shaft area, around mid-thigh, Dr. Adams said. They appear different from other fractures, usually breaking in just two pieces transversely through the center of the bone, and occur with minimal to no trauma, she said.

“We’ve heard stories of women that are just sitting in a chair, and they stand up and their femur fractures,” Dr. Adams said. “Or they’re out in the garden on their knees, and they try to stand up and it fractures. These are not necessarily fall-related like many traditional hip fractures.”

The researchers observed a 44% reduction in women’s risk of AFFs in the first year of a so-called drug holiday, or discontinuation of bisphosphonates, after 3-5 years on treatment when compared with those who stayed on the medications (hazard ratio = 0.56; 95% confidence interval, 0.38-0.82). During the first to fourth years after discontinuation, AFF risk was decreased by 80% (HR = 0.20; 95% CI, 0.10-0.37), and after 4 years, AFF risk was reduced by 78% (HR = 0.22; 95% CI, 0.08-0.59) in comparison to bisphosphonate users.

Dr. Adams and her colleagues reviewed records from 152,934 women aged 50 or older who were members of Kaiser Permanente Southern California between Jan. 1, 2007, and Sept. 30, 2015. There were 185 AFFs overall (incidence rate 1.70 per 10,000 person-years).

The cohort included women who used a bisphosphonate and had at least one available pretreatment bone mineral density (BMD) total hip scan. AFFs were identified and verified by physician review of x-ray images for fractures occurring during the study period with ICD-9 codes for subtrochanteric or femoral shaft fractures. Women were considered to have discontinued bisphosphonates if there was a gap of over 3 months between the last bisphosphonate use and cohort entry anniversaries. Researchers included information on potential confounders of the association between discontinuation time and AFF such as age, race/ethnicity, smoking status, fracture history, duration of bisphosphonate use, discontinuation of glucocorticoid use, and pretreatment total hip T-score.

A second study in the same cohort consistently showed that women with higher pretreatment BMD had a larger risk of AFFs.

Researchers assessed the relationship of bisphosphonate duration to AFF risk before and after treatment, including pretreatment BMD in multivariate Cox models. In a multivariate model without pretreatment BMD, those with longer bisphosphonate duration had higher AFF risk. Compared to those taking the drug for less than 1 year, the relative hazard (RH) for 1-4 years of bisphosphonate use was 3 (95% CI, 1.4-7.3), for 4-8 years of bisphosphonate use was 15 (95% CI, 7-33), and for over 8 years was 37 (95% CI, 16-83).

Pretreatment BMD, when added to the model, did not attenuate the relationship of bisphosphonate duration and AFF risk. However, it showed those with higher BMD had a 40% increase in AFF risk per standard deviation of BMD increase (HR = 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2-1.7).

In those with normal pretreatment BMD (T-score greater than –1), the RH for 4-8 years of bisphosphonate use (versus less than 1 year) was 35, compared with 15 in those with osteopenic BMD (T-score –1 to –2.5) and 6 in those with osteoporotic BMD (T-score less than –2.5).

If confirmed in other studies, the results suggest that pretreatment BMD could impact clinical decisions around patient selection for bisphosphonate initiation and drug holidays, Dr. Adams said.

She reported receiving grant and research support from Merck.

SOURCES: Adams A et al. ASBMR 2018 Abstract 1005, and Black D et al. ASBMR 2018 Abstract 1007

, according to a study of more than 150,000 Southern California health plan members presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research in Montreal.

A second study in the same group of women found that higher bone mineral density levels before bisphosphonate treatment may put women at greater risk for these fractures.

“Our findings suggest really strongly that among women who have achieved some level of bisphosphonate exposure a drug holiday is certainly a reasonable approach to trying to balance the risk of these atypical fractures versus the benefit of preventing more typical, or classic, hip fractures,” said presenter Annette L. Adams, PhD, MPH, a research scientist with Kaiser Permanente Southern California, who was an author on both studies.

Atypical femur fractures (AFFs) occur below the trochanters in the femoral shaft area, around mid-thigh, Dr. Adams said. They appear different from other fractures, usually breaking in just two pieces transversely through the center of the bone, and occur with minimal to no trauma, she said.

“We’ve heard stories of women that are just sitting in a chair, and they stand up and their femur fractures,” Dr. Adams said. “Or they’re out in the garden on their knees, and they try to stand up and it fractures. These are not necessarily fall-related like many traditional hip fractures.”

The researchers observed a 44% reduction in women’s risk of AFFs in the first year of a so-called drug holiday, or discontinuation of bisphosphonates, after 3-5 years on treatment when compared with those who stayed on the medications (hazard ratio = 0.56; 95% confidence interval, 0.38-0.82). During the first to fourth years after discontinuation, AFF risk was decreased by 80% (HR = 0.20; 95% CI, 0.10-0.37), and after 4 years, AFF risk was reduced by 78% (HR = 0.22; 95% CI, 0.08-0.59) in comparison to bisphosphonate users.

Dr. Adams and her colleagues reviewed records from 152,934 women aged 50 or older who were members of Kaiser Permanente Southern California between Jan. 1, 2007, and Sept. 30, 2015. There were 185 AFFs overall (incidence rate 1.70 per 10,000 person-years).

The cohort included women who used a bisphosphonate and had at least one available pretreatment bone mineral density (BMD) total hip scan. AFFs were identified and verified by physician review of x-ray images for fractures occurring during the study period with ICD-9 codes for subtrochanteric or femoral shaft fractures. Women were considered to have discontinued bisphosphonates if there was a gap of over 3 months between the last bisphosphonate use and cohort entry anniversaries. Researchers included information on potential confounders of the association between discontinuation time and AFF such as age, race/ethnicity, smoking status, fracture history, duration of bisphosphonate use, discontinuation of glucocorticoid use, and pretreatment total hip T-score.

A second study in the same cohort consistently showed that women with higher pretreatment BMD had a larger risk of AFFs.

Researchers assessed the relationship of bisphosphonate duration to AFF risk before and after treatment, including pretreatment BMD in multivariate Cox models. In a multivariate model without pretreatment BMD, those with longer bisphosphonate duration had higher AFF risk. Compared to those taking the drug for less than 1 year, the relative hazard (RH) for 1-4 years of bisphosphonate use was 3 (95% CI, 1.4-7.3), for 4-8 years of bisphosphonate use was 15 (95% CI, 7-33), and for over 8 years was 37 (95% CI, 16-83).

Pretreatment BMD, when added to the model, did not attenuate the relationship of bisphosphonate duration and AFF risk. However, it showed those with higher BMD had a 40% increase in AFF risk per standard deviation of BMD increase (HR = 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2-1.7).

In those with normal pretreatment BMD (T-score greater than –1), the RH for 4-8 years of bisphosphonate use (versus less than 1 year) was 35, compared with 15 in those with osteopenic BMD (T-score –1 to –2.5) and 6 in those with osteoporotic BMD (T-score less than –2.5).

If confirmed in other studies, the results suggest that pretreatment BMD could impact clinical decisions around patient selection for bisphosphonate initiation and drug holidays, Dr. Adams said.

She reported receiving grant and research support from Merck.

SOURCES: Adams A et al. ASBMR 2018 Abstract 1005, and Black D et al. ASBMR 2018 Abstract 1007

, according to a study of more than 150,000 Southern California health plan members presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research in Montreal.

A second study in the same group of women found that higher bone mineral density levels before bisphosphonate treatment may put women at greater risk for these fractures.

“Our findings suggest really strongly that among women who have achieved some level of bisphosphonate exposure a drug holiday is certainly a reasonable approach to trying to balance the risk of these atypical fractures versus the benefit of preventing more typical, or classic, hip fractures,” said presenter Annette L. Adams, PhD, MPH, a research scientist with Kaiser Permanente Southern California, who was an author on both studies.

Atypical femur fractures (AFFs) occur below the trochanters in the femoral shaft area, around mid-thigh, Dr. Adams said. They appear different from other fractures, usually breaking in just two pieces transversely through the center of the bone, and occur with minimal to no trauma, she said.

“We’ve heard stories of women that are just sitting in a chair, and they stand up and their femur fractures,” Dr. Adams said. “Or they’re out in the garden on their knees, and they try to stand up and it fractures. These are not necessarily fall-related like many traditional hip fractures.”

The researchers observed a 44% reduction in women’s risk of AFFs in the first year of a so-called drug holiday, or discontinuation of bisphosphonates, after 3-5 years on treatment when compared with those who stayed on the medications (hazard ratio = 0.56; 95% confidence interval, 0.38-0.82). During the first to fourth years after discontinuation, AFF risk was decreased by 80% (HR = 0.20; 95% CI, 0.10-0.37), and after 4 years, AFF risk was reduced by 78% (HR = 0.22; 95% CI, 0.08-0.59) in comparison to bisphosphonate users.

Dr. Adams and her colleagues reviewed records from 152,934 women aged 50 or older who were members of Kaiser Permanente Southern California between Jan. 1, 2007, and Sept. 30, 2015. There were 185 AFFs overall (incidence rate 1.70 per 10,000 person-years).

The cohort included women who used a bisphosphonate and had at least one available pretreatment bone mineral density (BMD) total hip scan. AFFs were identified and verified by physician review of x-ray images for fractures occurring during the study period with ICD-9 codes for subtrochanteric or femoral shaft fractures. Women were considered to have discontinued bisphosphonates if there was a gap of over 3 months between the last bisphosphonate use and cohort entry anniversaries. Researchers included information on potential confounders of the association between discontinuation time and AFF such as age, race/ethnicity, smoking status, fracture history, duration of bisphosphonate use, discontinuation of glucocorticoid use, and pretreatment total hip T-score.

A second study in the same cohort consistently showed that women with higher pretreatment BMD had a larger risk of AFFs.

Researchers assessed the relationship of bisphosphonate duration to AFF risk before and after treatment, including pretreatment BMD in multivariate Cox models. In a multivariate model without pretreatment BMD, those with longer bisphosphonate duration had higher AFF risk. Compared to those taking the drug for less than 1 year, the relative hazard (RH) for 1-4 years of bisphosphonate use was 3 (95% CI, 1.4-7.3), for 4-8 years of bisphosphonate use was 15 (95% CI, 7-33), and for over 8 years was 37 (95% CI, 16-83).

Pretreatment BMD, when added to the model, did not attenuate the relationship of bisphosphonate duration and AFF risk. However, it showed those with higher BMD had a 40% increase in AFF risk per standard deviation of BMD increase (HR = 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2-1.7).

In those with normal pretreatment BMD (T-score greater than –1), the RH for 4-8 years of bisphosphonate use (versus less than 1 year) was 35, compared with 15 in those with osteopenic BMD (T-score –1 to –2.5) and 6 in those with osteoporotic BMD (T-score less than –2.5).

If confirmed in other studies, the results suggest that pretreatment BMD could impact clinical decisions around patient selection for bisphosphonate initiation and drug holidays, Dr. Adams said.

She reported receiving grant and research support from Merck.

SOURCES: Adams A et al. ASBMR 2018 Abstract 1005, and Black D et al. ASBMR 2018 Abstract 1007

REPORTING FROM ASBMR 2018

Endocrine Society updates guidelines for congenital adrenal hyperplasia

recently updated by the Endocrine Society.

The guidelines are an update to the 2010 Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline on congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) due to steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency. They were published in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Richard J. Auchus, MD, PhD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and coauthor of the 2018 guidelines, said many of the guidelines remain the same, such as use of neonatal screening. However, neonatal diagnosis methods should use gestational age and birth weight or liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry for secondary screening. The authors also noted that the addition of commercially available serum 21-deoxycortisol measurements, while untested, could potentially help identify CAH carriers.

Changes in genital reconstructive surgery were also addressed in the new guidelines, and a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found a “favorable benefit to risk ratio” for both early and late genital reconstructive surgery. Dr. Auchus said the timing of the surgery remains controversial and that there were “downsides of both approaches.”

“I wish there was a straightforward and perfect solution, but I don’t think there is,” he said in an interview.

Dexamethasone for the prenatal treatment of CAH, and prenatal therapy in general is still regarded as experimental and is not recommended, Dr. Auchus said. The authors encouraged pregnant women who are considering prenatal treatment of CAH to go through Institutional Review Board–approved centers that can obtain outcomes. Pregnant women should not receive a glucocorticoid that traverses the placenta, such as dexamethasone.

Classical CAH should be treated with hydrocortisone maintenance therapy, while nonclassic CAH patients should receive glucocorticoid treatment, such as in cases of early onset and rapid progression of pubarche or bone age in children and overt virilization in adolescents.

Dr. Auchus said the new guidelines have been reorganized so information is easier to find, with recommendations beginning at birth before transitioning into recommendations for childhood and adulthood.

“I think the pediatric endocrinologists are familiar with the management of this disease, but I think a lot of the internal medicine endocrinologists don’t get much training in fellowships, and I think it will be easy for them now to find the information,” Dr. Auchus said. “[I]n the previous set of guidelines, it would’ve been difficult for them to find the information that’s scattered throughout.”

However, Dr. Auchus noted, the guidelines were careful to avoid recommendations of specific levels for analyzing biomarkers for monitoring treatment and specific doses. “[W]e gave some general ideas about ranges: that they should be low, they should be normal, they should be not very high, but it’s okay if it’s a little bit high,” he added.

Also, the evidence for the recommendations is limited to best practice guidelines because of a lack of randomized controlled trials, he noted.

“We certainly do need additional long-term data on these patients,” Dr. Auchus said. “[I]t’s our hope that with some of the networks that have been developed for studying adrenal diseases that we can collect that information in a minimally intrusive way for the benefit of all the current and future patients.”

The guidelines were funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health. The authors report various personal and organizational financial interests in the form of paid consultancies, researcher support positions, advisory board memberships and investigator roles. See the full study for a complete list of disclosures.

SOURCE: Speiser PW et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Sep 27. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01865.

recently updated by the Endocrine Society.

The guidelines are an update to the 2010 Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline on congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) due to steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency. They were published in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Richard J. Auchus, MD, PhD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and coauthor of the 2018 guidelines, said many of the guidelines remain the same, such as use of neonatal screening. However, neonatal diagnosis methods should use gestational age and birth weight or liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry for secondary screening. The authors also noted that the addition of commercially available serum 21-deoxycortisol measurements, while untested, could potentially help identify CAH carriers.

Changes in genital reconstructive surgery were also addressed in the new guidelines, and a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found a “favorable benefit to risk ratio” for both early and late genital reconstructive surgery. Dr. Auchus said the timing of the surgery remains controversial and that there were “downsides of both approaches.”

“I wish there was a straightforward and perfect solution, but I don’t think there is,” he said in an interview.

Dexamethasone for the prenatal treatment of CAH, and prenatal therapy in general is still regarded as experimental and is not recommended, Dr. Auchus said. The authors encouraged pregnant women who are considering prenatal treatment of CAH to go through Institutional Review Board–approved centers that can obtain outcomes. Pregnant women should not receive a glucocorticoid that traverses the placenta, such as dexamethasone.

Classical CAH should be treated with hydrocortisone maintenance therapy, while nonclassic CAH patients should receive glucocorticoid treatment, such as in cases of early onset and rapid progression of pubarche or bone age in children and overt virilization in adolescents.

Dr. Auchus said the new guidelines have been reorganized so information is easier to find, with recommendations beginning at birth before transitioning into recommendations for childhood and adulthood.

“I think the pediatric endocrinologists are familiar with the management of this disease, but I think a lot of the internal medicine endocrinologists don’t get much training in fellowships, and I think it will be easy for them now to find the information,” Dr. Auchus said. “[I]n the previous set of guidelines, it would’ve been difficult for them to find the information that’s scattered throughout.”

However, Dr. Auchus noted, the guidelines were careful to avoid recommendations of specific levels for analyzing biomarkers for monitoring treatment and specific doses. “[W]e gave some general ideas about ranges: that they should be low, they should be normal, they should be not very high, but it’s okay if it’s a little bit high,” he added.

Also, the evidence for the recommendations is limited to best practice guidelines because of a lack of randomized controlled trials, he noted.

“We certainly do need additional long-term data on these patients,” Dr. Auchus said. “[I]t’s our hope that with some of the networks that have been developed for studying adrenal diseases that we can collect that information in a minimally intrusive way for the benefit of all the current and future patients.”

The guidelines were funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health. The authors report various personal and organizational financial interests in the form of paid consultancies, researcher support positions, advisory board memberships and investigator roles. See the full study for a complete list of disclosures.

SOURCE: Speiser PW et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Sep 27. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01865.

recently updated by the Endocrine Society.

The guidelines are an update to the 2010 Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline on congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) due to steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency. They were published in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Richard J. Auchus, MD, PhD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and coauthor of the 2018 guidelines, said many of the guidelines remain the same, such as use of neonatal screening. However, neonatal diagnosis methods should use gestational age and birth weight or liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry for secondary screening. The authors also noted that the addition of commercially available serum 21-deoxycortisol measurements, while untested, could potentially help identify CAH carriers.

Changes in genital reconstructive surgery were also addressed in the new guidelines, and a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found a “favorable benefit to risk ratio” for both early and late genital reconstructive surgery. Dr. Auchus said the timing of the surgery remains controversial and that there were “downsides of both approaches.”

“I wish there was a straightforward and perfect solution, but I don’t think there is,” he said in an interview.

Dexamethasone for the prenatal treatment of CAH, and prenatal therapy in general is still regarded as experimental and is not recommended, Dr. Auchus said. The authors encouraged pregnant women who are considering prenatal treatment of CAH to go through Institutional Review Board–approved centers that can obtain outcomes. Pregnant women should not receive a glucocorticoid that traverses the placenta, such as dexamethasone.

Classical CAH should be treated with hydrocortisone maintenance therapy, while nonclassic CAH patients should receive glucocorticoid treatment, such as in cases of early onset and rapid progression of pubarche or bone age in children and overt virilization in adolescents.

Dr. Auchus said the new guidelines have been reorganized so information is easier to find, with recommendations beginning at birth before transitioning into recommendations for childhood and adulthood.

“I think the pediatric endocrinologists are familiar with the management of this disease, but I think a lot of the internal medicine endocrinologists don’t get much training in fellowships, and I think it will be easy for them now to find the information,” Dr. Auchus said. “[I]n the previous set of guidelines, it would’ve been difficult for them to find the information that’s scattered throughout.”

However, Dr. Auchus noted, the guidelines were careful to avoid recommendations of specific levels for analyzing biomarkers for monitoring treatment and specific doses. “[W]e gave some general ideas about ranges: that they should be low, they should be normal, they should be not very high, but it’s okay if it’s a little bit high,” he added.

Also, the evidence for the recommendations is limited to best practice guidelines because of a lack of randomized controlled trials, he noted.