User login

In pediatric ICU, being underweight can be deadly

SAN DIEGO – Underweight people don’t get much attention amid the obesity epidemic. But a new analysis of worldwide data finds that underweight pediatric ICU patients worldwide face a higher risk of death within 28 days than all their counterparts, even the overweight and obese.

While the report suggests that underweight patients weren’t sicker than the other children and young adults, they also faced a higher risk of fluid accumulation and all-stage acute kidney injury, compared with overweight children, study lead author Rajit K. Basu, MD, MS, of Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said in an interview. His team’s findings were released at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

“Obesity gets the lion’s share of the spotlight, but there is a large and likely growing population of children who, for reasons left to be fully parsed out, are underweight,” Dr. Basu said. “These patients have increased attributable risks for poor outcome.”

The new report is a follow-up analysis of a 2017 prospective study by the same team that tracked acute kidney injury and mortality in 4,683 pediatric ICU patients at 32 clinics in Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America. The patients, aged from 3 months to 25 years, were recruited over 3 months in 2014 (N Engl J Med 2017;376:11-20).

The researchers launched the study to better understand the risk facing underweight pediatric patients. “There is a paucity of data linking mortality to weight classification in children,” Dr. Basu said. “There are only a few reports, and there is a suggestion that the ‘obesity paradox’ – protection from morbidity and mortality because of excessive weight – exists.”

For the new analysis, researchers tracked 3,719 patients: 29% were underweight, 44% had normal weight, 11% were overweight, and 16% were obese.

The 28-day mortality rate was 4% overall and highest in the underweight patients at 6%, compared with normal (3%), overweight (2%), and obese patients (2%) (P less than .0001). Underweight patients had a higher adjusted risk of mortality, compared with normal-weight patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8).

Underweight patients also had “a higher risk of fluid accumulation and a higher incidence of all-stage acute kidney injury, compared to overweight children,” Dr. Basu said.

The study authors also examined mortality rates in the 14% of patients (n = 542) who had sepsis. Again, underweight patients had the highest risk of 28-day mortality (15%), compared with normal weight (7%), overweight (4%), and obese patients (5%) (P = 0.003).

Who are the underweight children? “Analysis of the comorbidities reveals that nearly one-third of these children had some neuromuscular and/or pulmonary comorbidities, implying that these children were most likely static cerebral palsy children or had neuromuscular developmental disorder,” Dr. Basu said. “The demographic data also interestingly pointed out that the underweight population was predominantly Eastern Asian in origin.”

But there wasn’t a sign of increased illness in the underweight patients. “We can say that these kids were no sicker compared to the overweight kids as assessed by objective severity-of-illness scoring tools used in the critically ill population,” he said.

Is there a link between fluid overload and higher mortality numbers in underweight children? “There is a preponderance of data now, particularly in children, associating excessive fluid accumulation and poor outcome,” Dr. Basu said, who pointed to a 2018 systematic review and analysis that linked fluid overload to a higher risk of in-hospital mortality (OR, 4.34; 95% CI, 3.01-6.26) (JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172[3]:257-68).

Fluid accumulation disrupts organs “via hydrostatic pressure overregulation, causing an imbalance in local mediators of hormonal homeostasis and through vascular congestion,” he said. However, best practices regarding fluid are not yet clear.

“Fluid accumulation does occur frequently,” he said, “and it is likely a very important and relevant part of practice for bedside providers to be mindful on a multiple-times-a-day basis of what is happening with net fluid balance and how that relates to end-organ function, particularly the lungs and the kidneys.”

The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding for the study. One of the authors received fellowship funding from Gambro/Baxter Healthcare.

SAN DIEGO – Underweight people don’t get much attention amid the obesity epidemic. But a new analysis of worldwide data finds that underweight pediatric ICU patients worldwide face a higher risk of death within 28 days than all their counterparts, even the overweight and obese.

While the report suggests that underweight patients weren’t sicker than the other children and young adults, they also faced a higher risk of fluid accumulation and all-stage acute kidney injury, compared with overweight children, study lead author Rajit K. Basu, MD, MS, of Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said in an interview. His team’s findings were released at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

“Obesity gets the lion’s share of the spotlight, but there is a large and likely growing population of children who, for reasons left to be fully parsed out, are underweight,” Dr. Basu said. “These patients have increased attributable risks for poor outcome.”

The new report is a follow-up analysis of a 2017 prospective study by the same team that tracked acute kidney injury and mortality in 4,683 pediatric ICU patients at 32 clinics in Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America. The patients, aged from 3 months to 25 years, were recruited over 3 months in 2014 (N Engl J Med 2017;376:11-20).

The researchers launched the study to better understand the risk facing underweight pediatric patients. “There is a paucity of data linking mortality to weight classification in children,” Dr. Basu said. “There are only a few reports, and there is a suggestion that the ‘obesity paradox’ – protection from morbidity and mortality because of excessive weight – exists.”

For the new analysis, researchers tracked 3,719 patients: 29% were underweight, 44% had normal weight, 11% were overweight, and 16% were obese.

The 28-day mortality rate was 4% overall and highest in the underweight patients at 6%, compared with normal (3%), overweight (2%), and obese patients (2%) (P less than .0001). Underweight patients had a higher adjusted risk of mortality, compared with normal-weight patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8).

Underweight patients also had “a higher risk of fluid accumulation and a higher incidence of all-stage acute kidney injury, compared to overweight children,” Dr. Basu said.

The study authors also examined mortality rates in the 14% of patients (n = 542) who had sepsis. Again, underweight patients had the highest risk of 28-day mortality (15%), compared with normal weight (7%), overweight (4%), and obese patients (5%) (P = 0.003).

Who are the underweight children? “Analysis of the comorbidities reveals that nearly one-third of these children had some neuromuscular and/or pulmonary comorbidities, implying that these children were most likely static cerebral palsy children or had neuromuscular developmental disorder,” Dr. Basu said. “The demographic data also interestingly pointed out that the underweight population was predominantly Eastern Asian in origin.”

But there wasn’t a sign of increased illness in the underweight patients. “We can say that these kids were no sicker compared to the overweight kids as assessed by objective severity-of-illness scoring tools used in the critically ill population,” he said.

Is there a link between fluid overload and higher mortality numbers in underweight children? “There is a preponderance of data now, particularly in children, associating excessive fluid accumulation and poor outcome,” Dr. Basu said, who pointed to a 2018 systematic review and analysis that linked fluid overload to a higher risk of in-hospital mortality (OR, 4.34; 95% CI, 3.01-6.26) (JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172[3]:257-68).

Fluid accumulation disrupts organs “via hydrostatic pressure overregulation, causing an imbalance in local mediators of hormonal homeostasis and through vascular congestion,” he said. However, best practices regarding fluid are not yet clear.

“Fluid accumulation does occur frequently,” he said, “and it is likely a very important and relevant part of practice for bedside providers to be mindful on a multiple-times-a-day basis of what is happening with net fluid balance and how that relates to end-organ function, particularly the lungs and the kidneys.”

The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding for the study. One of the authors received fellowship funding from Gambro/Baxter Healthcare.

SAN DIEGO – Underweight people don’t get much attention amid the obesity epidemic. But a new analysis of worldwide data finds that underweight pediatric ICU patients worldwide face a higher risk of death within 28 days than all their counterparts, even the overweight and obese.

While the report suggests that underweight patients weren’t sicker than the other children and young adults, they also faced a higher risk of fluid accumulation and all-stage acute kidney injury, compared with overweight children, study lead author Rajit K. Basu, MD, MS, of Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said in an interview. His team’s findings were released at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

“Obesity gets the lion’s share of the spotlight, but there is a large and likely growing population of children who, for reasons left to be fully parsed out, are underweight,” Dr. Basu said. “These patients have increased attributable risks for poor outcome.”

The new report is a follow-up analysis of a 2017 prospective study by the same team that tracked acute kidney injury and mortality in 4,683 pediatric ICU patients at 32 clinics in Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America. The patients, aged from 3 months to 25 years, were recruited over 3 months in 2014 (N Engl J Med 2017;376:11-20).

The researchers launched the study to better understand the risk facing underweight pediatric patients. “There is a paucity of data linking mortality to weight classification in children,” Dr. Basu said. “There are only a few reports, and there is a suggestion that the ‘obesity paradox’ – protection from morbidity and mortality because of excessive weight – exists.”

For the new analysis, researchers tracked 3,719 patients: 29% were underweight, 44% had normal weight, 11% were overweight, and 16% were obese.

The 28-day mortality rate was 4% overall and highest in the underweight patients at 6%, compared with normal (3%), overweight (2%), and obese patients (2%) (P less than .0001). Underweight patients had a higher adjusted risk of mortality, compared with normal-weight patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8).

Underweight patients also had “a higher risk of fluid accumulation and a higher incidence of all-stage acute kidney injury, compared to overweight children,” Dr. Basu said.

The study authors also examined mortality rates in the 14% of patients (n = 542) who had sepsis. Again, underweight patients had the highest risk of 28-day mortality (15%), compared with normal weight (7%), overweight (4%), and obese patients (5%) (P = 0.003).

Who are the underweight children? “Analysis of the comorbidities reveals that nearly one-third of these children had some neuromuscular and/or pulmonary comorbidities, implying that these children were most likely static cerebral palsy children or had neuromuscular developmental disorder,” Dr. Basu said. “The demographic data also interestingly pointed out that the underweight population was predominantly Eastern Asian in origin.”

But there wasn’t a sign of increased illness in the underweight patients. “We can say that these kids were no sicker compared to the overweight kids as assessed by objective severity-of-illness scoring tools used in the critically ill population,” he said.

Is there a link between fluid overload and higher mortality numbers in underweight children? “There is a preponderance of data now, particularly in children, associating excessive fluid accumulation and poor outcome,” Dr. Basu said, who pointed to a 2018 systematic review and analysis that linked fluid overload to a higher risk of in-hospital mortality (OR, 4.34; 95% CI, 3.01-6.26) (JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172[3]:257-68).

Fluid accumulation disrupts organs “via hydrostatic pressure overregulation, causing an imbalance in local mediators of hormonal homeostasis and through vascular congestion,” he said. However, best practices regarding fluid are not yet clear.

“Fluid accumulation does occur frequently,” he said, “and it is likely a very important and relevant part of practice for bedside providers to be mindful on a multiple-times-a-day basis of what is happening with net fluid balance and how that relates to end-organ function, particularly the lungs and the kidneys.”

The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding for the study. One of the authors received fellowship funding from Gambro/Baxter Healthcare.

REPORTING FROM KIDNEY WEEK 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Underweight patients had a higher adjusted risk of 28-day mortality than normal-weight patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8).

Study details: A follow-up analysis of 3,719 pediatric ICU patients, aged from 3 months to 25 years, recruited in a prospective study over 3 months in 2014 at 32 worldwide centers.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding for the study. One of the authors received fellowship funding from Gambro/Baxter Healthcare.

Autoimmune Progesterone Dermatitis

To the Editor:

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (APD) is a rare dermatologic condition that can be challenging to diagnose. The associated skin lesions are not only variable in physical presentation but also in the timing of the outbreak. The skin disorder stems from an internal reaction to elevated levels of progesterone during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis can be difficult to detect; although the typical menstrual cycle is 28 days, many women have longer or shorter hormonal phases, leading to cyclical irregularity that can cause the lesions to appear sporadic in nature when in fact they are not.1

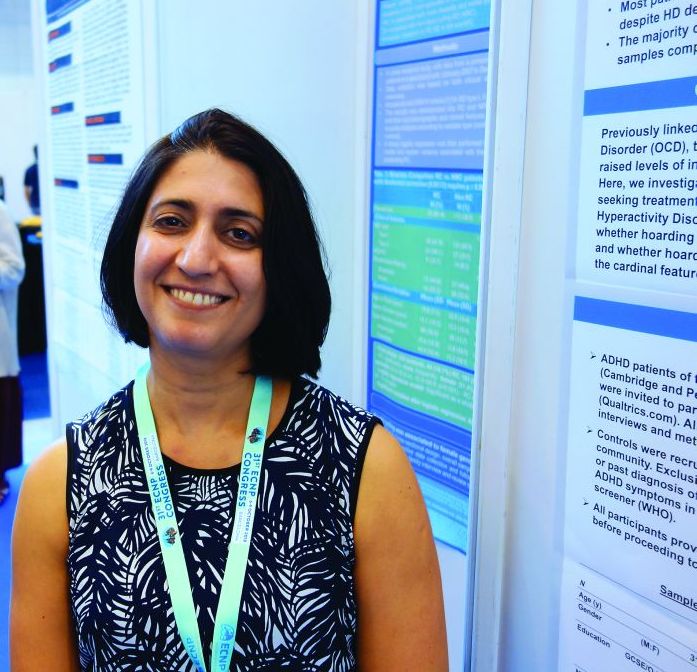

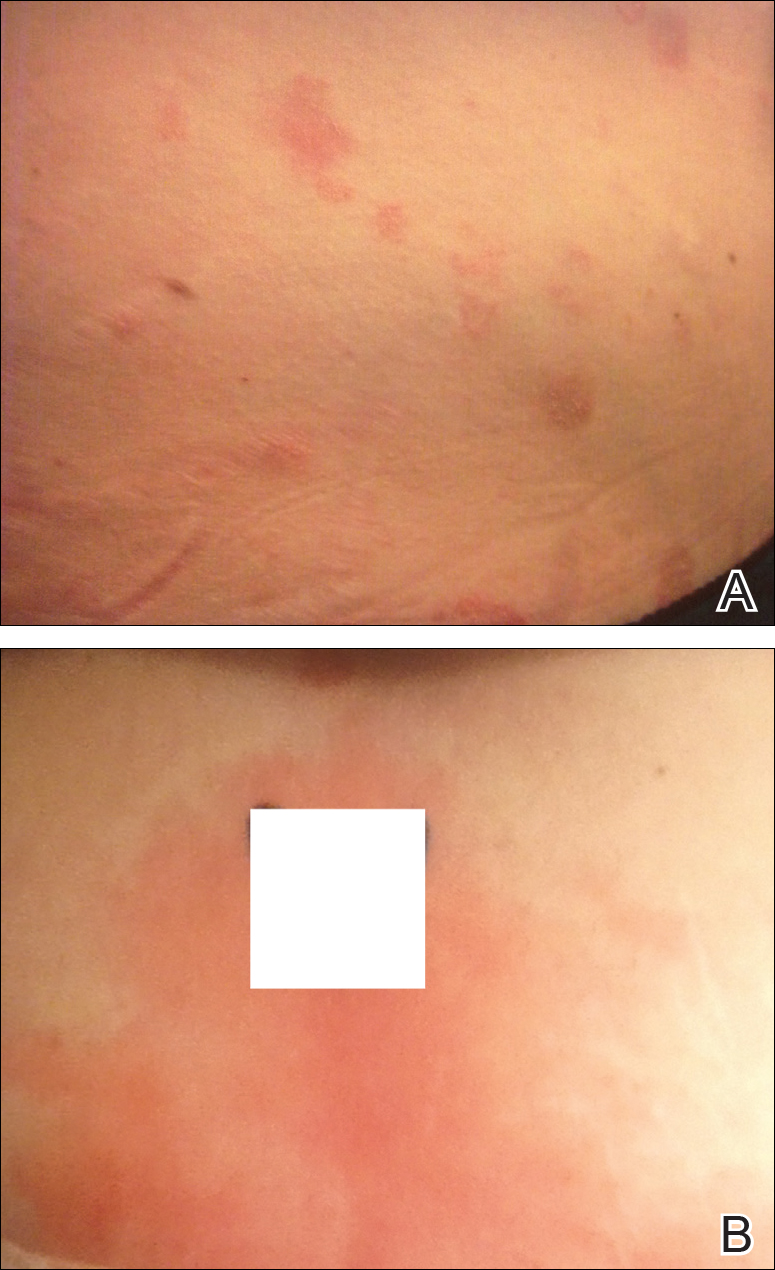

A 34-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis, psoriasis, and malignant melanoma presented to our dermatology clinic 2 days after a brief hospitalization during which she was diagnosed with a hypersensitivity reaction. Two days prior to her hospital admission, the patient developed a rash on the lower back with associated myalgia. The rash progressively worsened, spreading laterally to the flanks, which prompted her to seek medical attention. Blood work included a complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic panel, antinuclear antibody test, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, which all were within reference range. A 4-mm punch biopsy from the left lateral flank was performed and was consistent with a neutrophilic dermatosis. The patient’s symptoms diminished and she was discharged the next day with instructions to follow up with a dermatologist.

Physical examination at our clinic revealed multiple minimally indurated, erythematous plaques with superficial scaling along the left lower back and upper buttock (Figure 1). No other skin lesions were present, and palpation of the cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes was unremarkable. A repeat 6-mm punch biopsy was performed and she was sent for fasting blood work.

Histologic examination of the punch biopsy revealed a superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial dermatitis with scattered neutrophils and eosinophils. Findings were described as nonspecific, possibly representing a dermal hypersensitivity or urticarial reaction.

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase testing was within reference range, and therapy was initiated with oral dapsone 50 mg once daily as well as fexofenadine 180 mg once daily. The patient initially responded well to the oral therapy, but she experienced recurrence of the skin eruption at infrequent intervals over the next few months, requiring escalating doses of dapsone to control the symptoms. After further questioning at a subsequent visit a few months later, it was discovered that the eruption occurred near the onset of the patient’s irregular menstrual cycle.

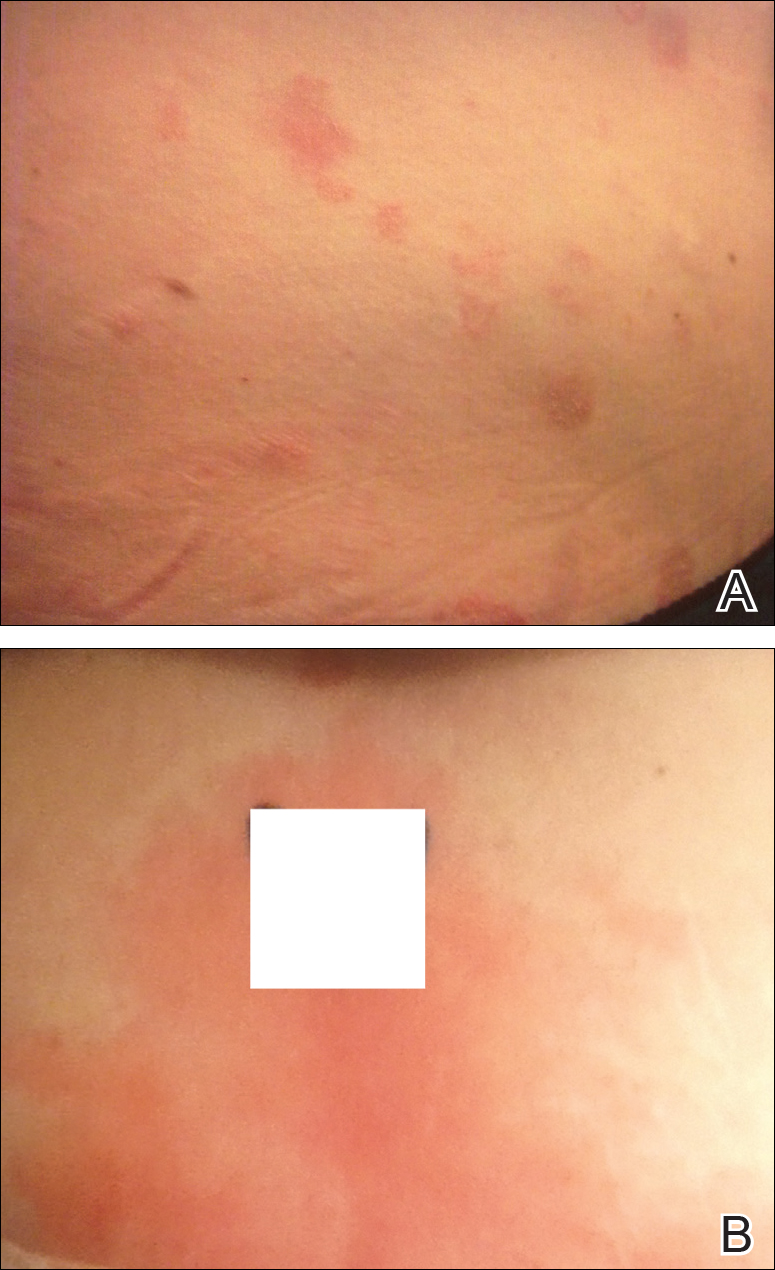

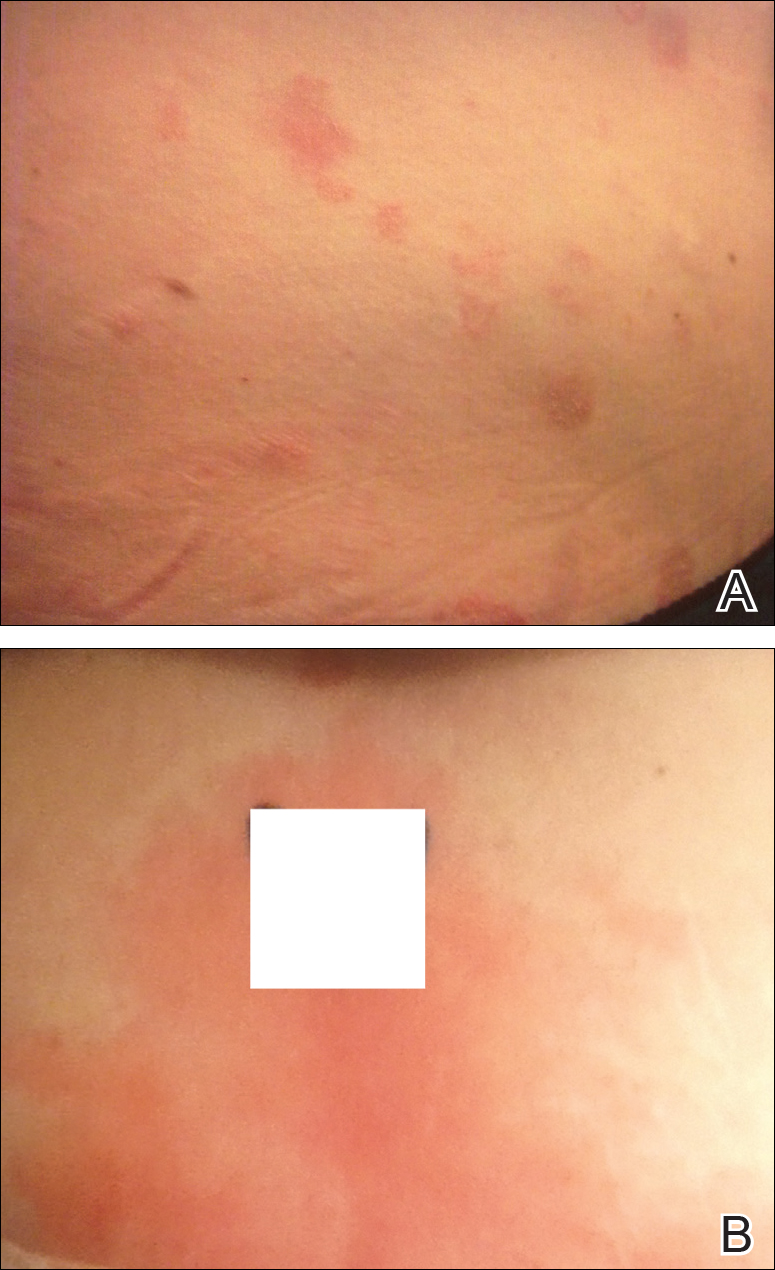

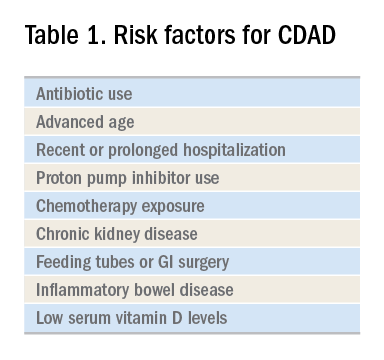

Approximately 1 year after her initial presentation, the patient returned for intradermal hormone injections to test for hormonally induced hypersensitivities. An injection of0.1 mL of a 50-mg/mL progesterone solution was administered in the right forearm as well as 0.1 mL of a 5-mg/mL estradiol solution and 0.1 mL of saline in the left forearm as a control. One hour after the injections, a strong positive reaction consisting of a 15-mm indurated plaque with surrounding wheal was noted at the site of the progesterone injection. The estradiol and saline control sites were clear of any dermal reaction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of APD was established, and the patient was referred to her gynecologist for treatment.

Due to the aggressive nature of her endometriosis, the gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist leuprolide acetate was the first-line treatment prescribed by her gynecologist; however, after 8 months of therapy with leuprolide acetate, she was still experiencing breakthrough myalgia with her menstrual cycle and opted for a hysterectomy with a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Within weeks of surgery, the myalgia ceased and the patient was completely asymptomatic.

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis was first described in 1921.2 In affected women, the body reacts to the progesterone hormone surge during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Symptoms begin approximately 3 to 4 days prior to menses and resolve 2 to 3 days after onset of flow. These progesterone hypersensitivity reactions can present within a spectrum of morphologies and severities. The lesions can appear eczematous, urticarial, as an angioedemalike reaction, as an erythema multiforme–like reaction with targetoid lesions, or in other nonspecific ways.1,3 Some patients experience a very mild, almost asymptomatic reaction, while others have a profound reaction progressing to anaphylaxis. Originally it was thought that exogenous exposure to progesterone led to a cross-reaction or hypersensitivity to the hormone; however, there have been cases reported in females as young as 12 years of age with no prior exposure.3,4 Reactions also can vary during pregnancy. There have been reports of spontaneous abortion in some affected females, but symptoms may dissipate in others, possibly due to a slow rise in progesterone causing a desensitization reaction.3,5

According to Bandino et al,6 there are 3 criteria for diagnosis of APD: (1) skin lesions related to the menstrual cycle, (2) positive response to intradermal testing with progesterone, and (3) symptomatic improvement after inhibiting progesterone secretions by suppressing ovulation.Areas checked with intradermal testing need to be evaluated 24 and 48 hours later for possible immediate or delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. Biopsy typically is not helpful in this diagnosis because results usually are nonspecific.

Treatment of APD is targeted toward suppressing the internal hormonal surge. By suppressing the progesterone hormone, the symptoms are alleviated. The discomfort from the skin reaction typically is unresponsive to steroids or antihistamines. Oral contraceptives are first line in most cases because they suppress ovulation. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues and tamoxifen also have been successful. For patients with severe disease that is recalcitrant to standard therapy or those who are postmenopausal, an oophorectemy is a curative option.2,4,5,7

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is a rare cyclical dermatologic condition in which the body responds to a surge of the patient’s own progesterone hormone. The disorder is difficult to diagnose because it can present with differing morphologies and biopsy is nonspecific. It also can be increasingly difficult to diagnose in women who do not have a typical 28-day menstrual cycle. In our patient, her irregular menstrual cycle may have caused a delay in diagnosis. Although the condition is rare, APD should be included in the differential diagnosis in females with a recurrent, cyclical, or recalcitrant cutaneous eruption.

- Wojnarowska F, Greaves MW, Peachey RD, et al. Progesterone-induced erythema multiforme. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:407-408.

- Lee MK, Lee WY, Yong SJ, et al. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis misdiagnosed as allergic contact dermatitis [published online February 9, 2011]. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:141-144.

- Baptist AP, Baldwin JL. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis in a patient with endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Mol Allergy. 2004;2:10.

- Baççıoğlu A, Kocak M, Bozdag O, et al. An unusual form of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (ADP): the role of diagnostic challenge test. World Allergy Organ J. 2007;10:S52.

- George R, Badawy SZ. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report [published online August 9, 2012]. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1155/2012/757854.

- Bandino JP, Thoppil J, Kennedy JS, et al. Iatrogenic autoimmune progesterone dermatitis causes by 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for preterm labor prevention. Cutis. 2011;88:241-243.

- Magen E, Feldman V. Autoimmune progesterone anaphylaxis in a 24-year-old woman. Isr Med Assoc J. 2012;14:518-519.

To the Editor:

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (APD) is a rare dermatologic condition that can be challenging to diagnose. The associated skin lesions are not only variable in physical presentation but also in the timing of the outbreak. The skin disorder stems from an internal reaction to elevated levels of progesterone during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis can be difficult to detect; although the typical menstrual cycle is 28 days, many women have longer or shorter hormonal phases, leading to cyclical irregularity that can cause the lesions to appear sporadic in nature when in fact they are not.1

A 34-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis, psoriasis, and malignant melanoma presented to our dermatology clinic 2 days after a brief hospitalization during which she was diagnosed with a hypersensitivity reaction. Two days prior to her hospital admission, the patient developed a rash on the lower back with associated myalgia. The rash progressively worsened, spreading laterally to the flanks, which prompted her to seek medical attention. Blood work included a complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic panel, antinuclear antibody test, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, which all were within reference range. A 4-mm punch biopsy from the left lateral flank was performed and was consistent with a neutrophilic dermatosis. The patient’s symptoms diminished and she was discharged the next day with instructions to follow up with a dermatologist.

Physical examination at our clinic revealed multiple minimally indurated, erythematous plaques with superficial scaling along the left lower back and upper buttock (Figure 1). No other skin lesions were present, and palpation of the cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes was unremarkable. A repeat 6-mm punch biopsy was performed and she was sent for fasting blood work.

Histologic examination of the punch biopsy revealed a superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial dermatitis with scattered neutrophils and eosinophils. Findings were described as nonspecific, possibly representing a dermal hypersensitivity or urticarial reaction.

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase testing was within reference range, and therapy was initiated with oral dapsone 50 mg once daily as well as fexofenadine 180 mg once daily. The patient initially responded well to the oral therapy, but she experienced recurrence of the skin eruption at infrequent intervals over the next few months, requiring escalating doses of dapsone to control the symptoms. After further questioning at a subsequent visit a few months later, it was discovered that the eruption occurred near the onset of the patient’s irregular menstrual cycle.

Approximately 1 year after her initial presentation, the patient returned for intradermal hormone injections to test for hormonally induced hypersensitivities. An injection of0.1 mL of a 50-mg/mL progesterone solution was administered in the right forearm as well as 0.1 mL of a 5-mg/mL estradiol solution and 0.1 mL of saline in the left forearm as a control. One hour after the injections, a strong positive reaction consisting of a 15-mm indurated plaque with surrounding wheal was noted at the site of the progesterone injection. The estradiol and saline control sites were clear of any dermal reaction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of APD was established, and the patient was referred to her gynecologist for treatment.

Due to the aggressive nature of her endometriosis, the gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist leuprolide acetate was the first-line treatment prescribed by her gynecologist; however, after 8 months of therapy with leuprolide acetate, she was still experiencing breakthrough myalgia with her menstrual cycle and opted for a hysterectomy with a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Within weeks of surgery, the myalgia ceased and the patient was completely asymptomatic.

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis was first described in 1921.2 In affected women, the body reacts to the progesterone hormone surge during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Symptoms begin approximately 3 to 4 days prior to menses and resolve 2 to 3 days after onset of flow. These progesterone hypersensitivity reactions can present within a spectrum of morphologies and severities. The lesions can appear eczematous, urticarial, as an angioedemalike reaction, as an erythema multiforme–like reaction with targetoid lesions, or in other nonspecific ways.1,3 Some patients experience a very mild, almost asymptomatic reaction, while others have a profound reaction progressing to anaphylaxis. Originally it was thought that exogenous exposure to progesterone led to a cross-reaction or hypersensitivity to the hormone; however, there have been cases reported in females as young as 12 years of age with no prior exposure.3,4 Reactions also can vary during pregnancy. There have been reports of spontaneous abortion in some affected females, but symptoms may dissipate in others, possibly due to a slow rise in progesterone causing a desensitization reaction.3,5

According to Bandino et al,6 there are 3 criteria for diagnosis of APD: (1) skin lesions related to the menstrual cycle, (2) positive response to intradermal testing with progesterone, and (3) symptomatic improvement after inhibiting progesterone secretions by suppressing ovulation.Areas checked with intradermal testing need to be evaluated 24 and 48 hours later for possible immediate or delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. Biopsy typically is not helpful in this diagnosis because results usually are nonspecific.

Treatment of APD is targeted toward suppressing the internal hormonal surge. By suppressing the progesterone hormone, the symptoms are alleviated. The discomfort from the skin reaction typically is unresponsive to steroids or antihistamines. Oral contraceptives are first line in most cases because they suppress ovulation. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues and tamoxifen also have been successful. For patients with severe disease that is recalcitrant to standard therapy or those who are postmenopausal, an oophorectemy is a curative option.2,4,5,7

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is a rare cyclical dermatologic condition in which the body responds to a surge of the patient’s own progesterone hormone. The disorder is difficult to diagnose because it can present with differing morphologies and biopsy is nonspecific. It also can be increasingly difficult to diagnose in women who do not have a typical 28-day menstrual cycle. In our patient, her irregular menstrual cycle may have caused a delay in diagnosis. Although the condition is rare, APD should be included in the differential diagnosis in females with a recurrent, cyclical, or recalcitrant cutaneous eruption.

To the Editor:

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (APD) is a rare dermatologic condition that can be challenging to diagnose. The associated skin lesions are not only variable in physical presentation but also in the timing of the outbreak. The skin disorder stems from an internal reaction to elevated levels of progesterone during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis can be difficult to detect; although the typical menstrual cycle is 28 days, many women have longer or shorter hormonal phases, leading to cyclical irregularity that can cause the lesions to appear sporadic in nature when in fact they are not.1

A 34-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis, psoriasis, and malignant melanoma presented to our dermatology clinic 2 days after a brief hospitalization during which she was diagnosed with a hypersensitivity reaction. Two days prior to her hospital admission, the patient developed a rash on the lower back with associated myalgia. The rash progressively worsened, spreading laterally to the flanks, which prompted her to seek medical attention. Blood work included a complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic panel, antinuclear antibody test, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, which all were within reference range. A 4-mm punch biopsy from the left lateral flank was performed and was consistent with a neutrophilic dermatosis. The patient’s symptoms diminished and she was discharged the next day with instructions to follow up with a dermatologist.

Physical examination at our clinic revealed multiple minimally indurated, erythematous plaques with superficial scaling along the left lower back and upper buttock (Figure 1). No other skin lesions were present, and palpation of the cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes was unremarkable. A repeat 6-mm punch biopsy was performed and she was sent for fasting blood work.

Histologic examination of the punch biopsy revealed a superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial dermatitis with scattered neutrophils and eosinophils. Findings were described as nonspecific, possibly representing a dermal hypersensitivity or urticarial reaction.

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase testing was within reference range, and therapy was initiated with oral dapsone 50 mg once daily as well as fexofenadine 180 mg once daily. The patient initially responded well to the oral therapy, but she experienced recurrence of the skin eruption at infrequent intervals over the next few months, requiring escalating doses of dapsone to control the symptoms. After further questioning at a subsequent visit a few months later, it was discovered that the eruption occurred near the onset of the patient’s irregular menstrual cycle.

Approximately 1 year after her initial presentation, the patient returned for intradermal hormone injections to test for hormonally induced hypersensitivities. An injection of0.1 mL of a 50-mg/mL progesterone solution was administered in the right forearm as well as 0.1 mL of a 5-mg/mL estradiol solution and 0.1 mL of saline in the left forearm as a control. One hour after the injections, a strong positive reaction consisting of a 15-mm indurated plaque with surrounding wheal was noted at the site of the progesterone injection. The estradiol and saline control sites were clear of any dermal reaction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of APD was established, and the patient was referred to her gynecologist for treatment.

Due to the aggressive nature of her endometriosis, the gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist leuprolide acetate was the first-line treatment prescribed by her gynecologist; however, after 8 months of therapy with leuprolide acetate, she was still experiencing breakthrough myalgia with her menstrual cycle and opted for a hysterectomy with a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Within weeks of surgery, the myalgia ceased and the patient was completely asymptomatic.

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis was first described in 1921.2 In affected women, the body reacts to the progesterone hormone surge during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Symptoms begin approximately 3 to 4 days prior to menses and resolve 2 to 3 days after onset of flow. These progesterone hypersensitivity reactions can present within a spectrum of morphologies and severities. The lesions can appear eczematous, urticarial, as an angioedemalike reaction, as an erythema multiforme–like reaction with targetoid lesions, or in other nonspecific ways.1,3 Some patients experience a very mild, almost asymptomatic reaction, while others have a profound reaction progressing to anaphylaxis. Originally it was thought that exogenous exposure to progesterone led to a cross-reaction or hypersensitivity to the hormone; however, there have been cases reported in females as young as 12 years of age with no prior exposure.3,4 Reactions also can vary during pregnancy. There have been reports of spontaneous abortion in some affected females, but symptoms may dissipate in others, possibly due to a slow rise in progesterone causing a desensitization reaction.3,5

According to Bandino et al,6 there are 3 criteria for diagnosis of APD: (1) skin lesions related to the menstrual cycle, (2) positive response to intradermal testing with progesterone, and (3) symptomatic improvement after inhibiting progesterone secretions by suppressing ovulation.Areas checked with intradermal testing need to be evaluated 24 and 48 hours later for possible immediate or delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. Biopsy typically is not helpful in this diagnosis because results usually are nonspecific.

Treatment of APD is targeted toward suppressing the internal hormonal surge. By suppressing the progesterone hormone, the symptoms are alleviated. The discomfort from the skin reaction typically is unresponsive to steroids or antihistamines. Oral contraceptives are first line in most cases because they suppress ovulation. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues and tamoxifen also have been successful. For patients with severe disease that is recalcitrant to standard therapy or those who are postmenopausal, an oophorectemy is a curative option.2,4,5,7

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is a rare cyclical dermatologic condition in which the body responds to a surge of the patient’s own progesterone hormone. The disorder is difficult to diagnose because it can present with differing morphologies and biopsy is nonspecific. It also can be increasingly difficult to diagnose in women who do not have a typical 28-day menstrual cycle. In our patient, her irregular menstrual cycle may have caused a delay in diagnosis. Although the condition is rare, APD should be included in the differential diagnosis in females with a recurrent, cyclical, or recalcitrant cutaneous eruption.

- Wojnarowska F, Greaves MW, Peachey RD, et al. Progesterone-induced erythema multiforme. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:407-408.

- Lee MK, Lee WY, Yong SJ, et al. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis misdiagnosed as allergic contact dermatitis [published online February 9, 2011]. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:141-144.

- Baptist AP, Baldwin JL. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis in a patient with endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Mol Allergy. 2004;2:10.

- Baççıoğlu A, Kocak M, Bozdag O, et al. An unusual form of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (ADP): the role of diagnostic challenge test. World Allergy Organ J. 2007;10:S52.

- George R, Badawy SZ. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report [published online August 9, 2012]. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1155/2012/757854.

- Bandino JP, Thoppil J, Kennedy JS, et al. Iatrogenic autoimmune progesterone dermatitis causes by 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for preterm labor prevention. Cutis. 2011;88:241-243.

- Magen E, Feldman V. Autoimmune progesterone anaphylaxis in a 24-year-old woman. Isr Med Assoc J. 2012;14:518-519.

- Wojnarowska F, Greaves MW, Peachey RD, et al. Progesterone-induced erythema multiforme. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:407-408.

- Lee MK, Lee WY, Yong SJ, et al. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis misdiagnosed as allergic contact dermatitis [published online February 9, 2011]. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:141-144.

- Baptist AP, Baldwin JL. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis in a patient with endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Mol Allergy. 2004;2:10.

- Baççıoğlu A, Kocak M, Bozdag O, et al. An unusual form of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (ADP): the role of diagnostic challenge test. World Allergy Organ J. 2007;10:S52.

- George R, Badawy SZ. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report [published online August 9, 2012]. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1155/2012/757854.

- Bandino JP, Thoppil J, Kennedy JS, et al. Iatrogenic autoimmune progesterone dermatitis causes by 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for preterm labor prevention. Cutis. 2011;88:241-243.

- Magen E, Feldman V. Autoimmune progesterone anaphylaxis in a 24-year-old woman. Isr Med Assoc J. 2012;14:518-519.

Practice Points

- Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (APD) is a hypersensitivity reaction to the progesterone surge during a woman’s menstrual cycle.

- Patients with APD often are misdiagnosed for years due to the variability of each woman’s menstrual cycle, making the correlation difficult.

- It is important to keep APD in mind for any recalcitrant or recurrent rash in females. A thorough history is critical when formulating a diagnosis.

A new MI risk factor emerges, ASCVD guidelines challenged, and more

Today, an analysis that may challenge ASCVD guidelines, a new formula may predict adverse events from NSAIDs, a potentially important myocardial infarction risk factor is identified, and a diabetes drug gets a new cardiovascular indication.

Subscribe to Cardiocast wherever you get your podcasts.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Today, an analysis that may challenge ASCVD guidelines, a new formula may predict adverse events from NSAIDs, a potentially important myocardial infarction risk factor is identified, and a diabetes drug gets a new cardiovascular indication.

Subscribe to Cardiocast wherever you get your podcasts.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Today, an analysis that may challenge ASCVD guidelines, a new formula may predict adverse events from NSAIDs, a potentially important myocardial infarction risk factor is identified, and a diabetes drug gets a new cardiovascular indication.

Subscribe to Cardiocast wherever you get your podcasts.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Mohs Micrographic Surgery Overlying a Pacemaker

To the Editor:

Pacemakers and defibrillators are common in patients presenting for cutaneous surgery. The use and application of electrosurgery in this patient population has been reviewed extensively.1 The presence of a cardiac device immediately below a cutaneous surgical site presents as a potentially more complex surgical procedure. Damage to and/or manipulation of the cardiac device could activate the device and/or require subsequent repair of the unit. We present the case of a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) overlying a pacemaker along with a brief review of the literature.

An 89-year-old man presented to our Mohs surgical unit for treatment of a long-standing BCC on the left upper chest (Figure, A) via Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), which was utilized due to the infiltrative nature of the tumor and its close proximity to the cardiac device. He had a history of heart disease including paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, first-degree atrioventricular block, and sick sinus syndrome, and a pacemaker had been placed 5 years prior. The tumor was located on the skin directly above the pacemaker. The pacemaker and associated lead wires were easily palpable to touch. Prior to the procedure, treatment options were discussed with the patient’s cardiologist. Due to the size of the tumor (21×22 mm) and more importantly its location directly above the pacemaker, the BCC was treated with a single stage of MMS (Figure, B). In an effort to minimize potential exposure of the pacemaker, the surgical site was infiltrated with additional local anesthesia, which created a temporary edematous thickening to provide an increased barrier between the surgical site and pacemaker. Hemostasis was achieved with thermocautery, and a fusiform repair was completed without consequence (Figure, C). There were no postoperative changes or concerns, and preoperative and postoperative electrocardiograms reviewed by the patient’s cardiologist revealed no change.

Treatment of cutaneous lesions near pacemakers or defibrillators requires caution, both in avoidance of the device itself as well as electrocautery interference.1-4 There are multiple treatment options available, including MMS, excision, curettage and desiccation, topical therapies, and radiation therapy. The benefits of MMS for cutaneous tumors overlying cardiac devices include decreased risk of damaging the underlying pacemaker by minimizing surgical depth of the defect, minimizing the risk of recurrence and hence any additional procedures, and minimizing the risk of surgical complications via a smaller surgical defect.4 Monopolar electrosurgery is associated with the risk of interfering with pacemaker function; however, the use of bipolar electrocoagulation has been shown to be safer.1,3,4 Additionally, thermocautery carries the least risk because it involves heat only.2,5

Awareness of the cardiac device location, communication with the patient’s cardiologist, use of local anesthesia infiltrates to maximize distance between the surgical site and cardiac device, and appropriate hemostasis methods offer the most effective and safest means for surgical removal of tumors overlying cardiac devices.

- El-Gamal HM, Dufresne RG, Saddler K. Electrosurgery, pacemakers and ICDs: a survey of precautions and complications experienced by cutaneous surgeons. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:385-390.

- Chapas AM, Lee D, Rogers GS. Excision of malignant melanoma overlying a pacemaker. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:112-114.

- Matzke TJ, Christenson LJ, Christenson SD, et al. Pacemakers and implantable cardiac defibrillators in dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1155-1162.

- Herrmann JL, Mishra V, Greenway HT. Basal cell carcinoma overlying a cardiac pacemaker successfully treated using Mohs micrographic surgery. 2014;4:474-477.

- Lane JE, O’Brien EM, Kent DE. Optimization of thermocautery in excisional dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:669-675.

To the Editor:

Pacemakers and defibrillators are common in patients presenting for cutaneous surgery. The use and application of electrosurgery in this patient population has been reviewed extensively.1 The presence of a cardiac device immediately below a cutaneous surgical site presents as a potentially more complex surgical procedure. Damage to and/or manipulation of the cardiac device could activate the device and/or require subsequent repair of the unit. We present the case of a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) overlying a pacemaker along with a brief review of the literature.

An 89-year-old man presented to our Mohs surgical unit for treatment of a long-standing BCC on the left upper chest (Figure, A) via Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), which was utilized due to the infiltrative nature of the tumor and its close proximity to the cardiac device. He had a history of heart disease including paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, first-degree atrioventricular block, and sick sinus syndrome, and a pacemaker had been placed 5 years prior. The tumor was located on the skin directly above the pacemaker. The pacemaker and associated lead wires were easily palpable to touch. Prior to the procedure, treatment options were discussed with the patient’s cardiologist. Due to the size of the tumor (21×22 mm) and more importantly its location directly above the pacemaker, the BCC was treated with a single stage of MMS (Figure, B). In an effort to minimize potential exposure of the pacemaker, the surgical site was infiltrated with additional local anesthesia, which created a temporary edematous thickening to provide an increased barrier between the surgical site and pacemaker. Hemostasis was achieved with thermocautery, and a fusiform repair was completed without consequence (Figure, C). There were no postoperative changes or concerns, and preoperative and postoperative electrocardiograms reviewed by the patient’s cardiologist revealed no change.

Treatment of cutaneous lesions near pacemakers or defibrillators requires caution, both in avoidance of the device itself as well as electrocautery interference.1-4 There are multiple treatment options available, including MMS, excision, curettage and desiccation, topical therapies, and radiation therapy. The benefits of MMS for cutaneous tumors overlying cardiac devices include decreased risk of damaging the underlying pacemaker by minimizing surgical depth of the defect, minimizing the risk of recurrence and hence any additional procedures, and minimizing the risk of surgical complications via a smaller surgical defect.4 Monopolar electrosurgery is associated with the risk of interfering with pacemaker function; however, the use of bipolar electrocoagulation has been shown to be safer.1,3,4 Additionally, thermocautery carries the least risk because it involves heat only.2,5

Awareness of the cardiac device location, communication with the patient’s cardiologist, use of local anesthesia infiltrates to maximize distance between the surgical site and cardiac device, and appropriate hemostasis methods offer the most effective and safest means for surgical removal of tumors overlying cardiac devices.

To the Editor:

Pacemakers and defibrillators are common in patients presenting for cutaneous surgery. The use and application of electrosurgery in this patient population has been reviewed extensively.1 The presence of a cardiac device immediately below a cutaneous surgical site presents as a potentially more complex surgical procedure. Damage to and/or manipulation of the cardiac device could activate the device and/or require subsequent repair of the unit. We present the case of a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) overlying a pacemaker along with a brief review of the literature.

An 89-year-old man presented to our Mohs surgical unit for treatment of a long-standing BCC on the left upper chest (Figure, A) via Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), which was utilized due to the infiltrative nature of the tumor and its close proximity to the cardiac device. He had a history of heart disease including paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, first-degree atrioventricular block, and sick sinus syndrome, and a pacemaker had been placed 5 years prior. The tumor was located on the skin directly above the pacemaker. The pacemaker and associated lead wires were easily palpable to touch. Prior to the procedure, treatment options were discussed with the patient’s cardiologist. Due to the size of the tumor (21×22 mm) and more importantly its location directly above the pacemaker, the BCC was treated with a single stage of MMS (Figure, B). In an effort to minimize potential exposure of the pacemaker, the surgical site was infiltrated with additional local anesthesia, which created a temporary edematous thickening to provide an increased barrier between the surgical site and pacemaker. Hemostasis was achieved with thermocautery, and a fusiform repair was completed without consequence (Figure, C). There were no postoperative changes or concerns, and preoperative and postoperative electrocardiograms reviewed by the patient’s cardiologist revealed no change.

Treatment of cutaneous lesions near pacemakers or defibrillators requires caution, both in avoidance of the device itself as well as electrocautery interference.1-4 There are multiple treatment options available, including MMS, excision, curettage and desiccation, topical therapies, and radiation therapy. The benefits of MMS for cutaneous tumors overlying cardiac devices include decreased risk of damaging the underlying pacemaker by minimizing surgical depth of the defect, minimizing the risk of recurrence and hence any additional procedures, and minimizing the risk of surgical complications via a smaller surgical defect.4 Monopolar electrosurgery is associated with the risk of interfering with pacemaker function; however, the use of bipolar electrocoagulation has been shown to be safer.1,3,4 Additionally, thermocautery carries the least risk because it involves heat only.2,5

Awareness of the cardiac device location, communication with the patient’s cardiologist, use of local anesthesia infiltrates to maximize distance between the surgical site and cardiac device, and appropriate hemostasis methods offer the most effective and safest means for surgical removal of tumors overlying cardiac devices.

- El-Gamal HM, Dufresne RG, Saddler K. Electrosurgery, pacemakers and ICDs: a survey of precautions and complications experienced by cutaneous surgeons. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:385-390.

- Chapas AM, Lee D, Rogers GS. Excision of malignant melanoma overlying a pacemaker. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:112-114.

- Matzke TJ, Christenson LJ, Christenson SD, et al. Pacemakers and implantable cardiac defibrillators in dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1155-1162.

- Herrmann JL, Mishra V, Greenway HT. Basal cell carcinoma overlying a cardiac pacemaker successfully treated using Mohs micrographic surgery. 2014;4:474-477.

- Lane JE, O’Brien EM, Kent DE. Optimization of thermocautery in excisional dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:669-675.

- El-Gamal HM, Dufresne RG, Saddler K. Electrosurgery, pacemakers and ICDs: a survey of precautions and complications experienced by cutaneous surgeons. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:385-390.

- Chapas AM, Lee D, Rogers GS. Excision of malignant melanoma overlying a pacemaker. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:112-114.

- Matzke TJ, Christenson LJ, Christenson SD, et al. Pacemakers and implantable cardiac defibrillators in dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1155-1162.

- Herrmann JL, Mishra V, Greenway HT. Basal cell carcinoma overlying a cardiac pacemaker successfully treated using Mohs micrographic surgery. 2014;4:474-477.

- Lane JE, O’Brien EM, Kent DE. Optimization of thermocautery in excisional dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:669-675.

Practice Points

- Surgical treatment of a cutaneous lesion overlying a cardiac device requires caution, both in avoidance of the device itself as well as electrocautery interference.

- Local anesthesia infiltrates can be used to create a temporary edematous thickening to minimize potential exposure of the device during the procedure.

Adult ADHD? Screen for hoarding symptoms

BARCELONA – Clinically meaningful hoarding symptoms are present in roughly one in four adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, Sharon Morein-Zamir, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Her message to her fellow clinicians: “Nobody tends to ask about hoarding problems in adult ADHD clinics. Ask your ADHD patients carefully and routinely about hoarding symptoms. Screen them for it, ask their family members about it, and see whether it could be a problem contributing to daily impairment,” urged Dr. Morein-Zamir, a senior lecturer in clinical psychology at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge, England.

The clinician must broach the subject, because hoarding often is characterized by lack of insight.

“Patients don’t complain about it. You’ll have family members complain about it, neighbors complain about it, maybe social services, but the individuals themselves often don’t think they have a problem. And if they acknowledge it, they don’t seek treatment for it. So you really need to actively ask about the issue. They won’t raise it themselves,” she said.

Hoarding disorder and ADHD are considered two separate entities. But her study demonstrated that they share a common link: inattention symptoms.

the psychologist continued.

Indeed, one of the reasons why hoarding disorder is no longer grouped with obsessive-compulsive disorder in diagnostic schema is that inattention symptoms are not characteristic of OCD.

Dr. Morein-Zamir presented a cross-sectional study of 50 patients in an adult ADHD clinic and 46 age- and sex-matched controls. A total of 22 of the ADHD patients were on methylphenidate, 15 on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, 6 on amphetamine, and 7 were unmedicated.

Participants were assessed for hoarding using two validated measures well-suited for screening in daily practice: the Saving Inventory–Revised (SIR) and the Clutter Image Rating (CIR). Clinically meaningful hoarding symptoms – a designation requiring both a score of at least 42 on the SIR and 12 on the CIR – were present in 11 of 50 adult ADHD patients and none of the controls.

The group with clinically meaningful hoarding symptoms differed from the 39 ADHD patients without hoarding most noticeably in their more pronounced inattention symptoms as scored on the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a mean score of 32.8, compared with 28.8 in ADHD patients without clinically important hoarding. In contrast, the two groups scored similarly for hyperactivity/impulsivity on the patient-completed 18-item ASRS, as well as for depression and anxiety on the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS).

Within the ADHD group, only inattention as measured on the ASRS predicted hoarding severity on the SIR. In a multivariate regression analysis controlling for age, sex, hyperactivity/impulsivity on the ASRS, and DASS scores, inattention correlated strongly with all of the key hoarding dimensions: clutter, excessive acquisition, and difficulty discarding. Hyperactivity/impulsivity showed a modest correlation with clutter but not with the other hoarding dimensions.

Dr. Morein-Zamir observed that, while the last 3 or so years have seen booming interest in the development of manualized cognitive-behavioral therapy strategies for hoarding disorder, it’s not yet known whether those tools will be effective for treating high-level hoarding symptoms in patients with ADHD.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was funded by the British Academy.

BARCELONA – Clinically meaningful hoarding symptoms are present in roughly one in four adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, Sharon Morein-Zamir, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Her message to her fellow clinicians: “Nobody tends to ask about hoarding problems in adult ADHD clinics. Ask your ADHD patients carefully and routinely about hoarding symptoms. Screen them for it, ask their family members about it, and see whether it could be a problem contributing to daily impairment,” urged Dr. Morein-Zamir, a senior lecturer in clinical psychology at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge, England.

The clinician must broach the subject, because hoarding often is characterized by lack of insight.

“Patients don’t complain about it. You’ll have family members complain about it, neighbors complain about it, maybe social services, but the individuals themselves often don’t think they have a problem. And if they acknowledge it, they don’t seek treatment for it. So you really need to actively ask about the issue. They won’t raise it themselves,” she said.

Hoarding disorder and ADHD are considered two separate entities. But her study demonstrated that they share a common link: inattention symptoms.

the psychologist continued.

Indeed, one of the reasons why hoarding disorder is no longer grouped with obsessive-compulsive disorder in diagnostic schema is that inattention symptoms are not characteristic of OCD.

Dr. Morein-Zamir presented a cross-sectional study of 50 patients in an adult ADHD clinic and 46 age- and sex-matched controls. A total of 22 of the ADHD patients were on methylphenidate, 15 on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, 6 on amphetamine, and 7 were unmedicated.

Participants were assessed for hoarding using two validated measures well-suited for screening in daily practice: the Saving Inventory–Revised (SIR) and the Clutter Image Rating (CIR). Clinically meaningful hoarding symptoms – a designation requiring both a score of at least 42 on the SIR and 12 on the CIR – were present in 11 of 50 adult ADHD patients and none of the controls.

The group with clinically meaningful hoarding symptoms differed from the 39 ADHD patients without hoarding most noticeably in their more pronounced inattention symptoms as scored on the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a mean score of 32.8, compared with 28.8 in ADHD patients without clinically important hoarding. In contrast, the two groups scored similarly for hyperactivity/impulsivity on the patient-completed 18-item ASRS, as well as for depression and anxiety on the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS).

Within the ADHD group, only inattention as measured on the ASRS predicted hoarding severity on the SIR. In a multivariate regression analysis controlling for age, sex, hyperactivity/impulsivity on the ASRS, and DASS scores, inattention correlated strongly with all of the key hoarding dimensions: clutter, excessive acquisition, and difficulty discarding. Hyperactivity/impulsivity showed a modest correlation with clutter but not with the other hoarding dimensions.

Dr. Morein-Zamir observed that, while the last 3 or so years have seen booming interest in the development of manualized cognitive-behavioral therapy strategies for hoarding disorder, it’s not yet known whether those tools will be effective for treating high-level hoarding symptoms in patients with ADHD.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was funded by the British Academy.

BARCELONA – Clinically meaningful hoarding symptoms are present in roughly one in four adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, Sharon Morein-Zamir, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Her message to her fellow clinicians: “Nobody tends to ask about hoarding problems in adult ADHD clinics. Ask your ADHD patients carefully and routinely about hoarding symptoms. Screen them for it, ask their family members about it, and see whether it could be a problem contributing to daily impairment,” urged Dr. Morein-Zamir, a senior lecturer in clinical psychology at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge, England.

The clinician must broach the subject, because hoarding often is characterized by lack of insight.

“Patients don’t complain about it. You’ll have family members complain about it, neighbors complain about it, maybe social services, but the individuals themselves often don’t think they have a problem. And if they acknowledge it, they don’t seek treatment for it. So you really need to actively ask about the issue. They won’t raise it themselves,” she said.

Hoarding disorder and ADHD are considered two separate entities. But her study demonstrated that they share a common link: inattention symptoms.

the psychologist continued.

Indeed, one of the reasons why hoarding disorder is no longer grouped with obsessive-compulsive disorder in diagnostic schema is that inattention symptoms are not characteristic of OCD.

Dr. Morein-Zamir presented a cross-sectional study of 50 patients in an adult ADHD clinic and 46 age- and sex-matched controls. A total of 22 of the ADHD patients were on methylphenidate, 15 on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, 6 on amphetamine, and 7 were unmedicated.

Participants were assessed for hoarding using two validated measures well-suited for screening in daily practice: the Saving Inventory–Revised (SIR) and the Clutter Image Rating (CIR). Clinically meaningful hoarding symptoms – a designation requiring both a score of at least 42 on the SIR and 12 on the CIR – were present in 11 of 50 adult ADHD patients and none of the controls.

The group with clinically meaningful hoarding symptoms differed from the 39 ADHD patients without hoarding most noticeably in their more pronounced inattention symptoms as scored on the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a mean score of 32.8, compared with 28.8 in ADHD patients without clinically important hoarding. In contrast, the two groups scored similarly for hyperactivity/impulsivity on the patient-completed 18-item ASRS, as well as for depression and anxiety on the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS).

Within the ADHD group, only inattention as measured on the ASRS predicted hoarding severity on the SIR. In a multivariate regression analysis controlling for age, sex, hyperactivity/impulsivity on the ASRS, and DASS scores, inattention correlated strongly with all of the key hoarding dimensions: clutter, excessive acquisition, and difficulty discarding. Hyperactivity/impulsivity showed a modest correlation with clutter but not with the other hoarding dimensions.

Dr. Morein-Zamir observed that, while the last 3 or so years have seen booming interest in the development of manualized cognitive-behavioral therapy strategies for hoarding disorder, it’s not yet known whether those tools will be effective for treating high-level hoarding symptoms in patients with ADHD.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was funded by the British Academy.

REPORTING FROM THE ECNP CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Routinely screen adults with ADHD for hoarding disorder.

Major finding: Eleven of 50 (22%) unselected adults with ADHD displayed clinically meaningful hoarding symptoms.

Study details: This cross-sectional study included 50 adult ADHD patients and 46 matched controls who were assessed for hoarding symptoms and inattention.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was funded by the British Academy.

How do you evaluate and treat a patient with C. difficile–associated disease?

Metronidazole is no longer recommended

Case

A 45-year-old woman on omeprazole for gastroesophageal reflux disease and recent treatment with ciprofloxacin for a urinary tract infection (UTI), who also has had several days of frequent watery stools, is admitted. She does not appear ill, and her abdominal exam is benign. She has normal renal function and white blood cell count. How should she be evaluated and treated for Clostridium difficile–associated disease (CDAD)?

Brief overview

C. difficile, a gram-positive anaerobic bacillus that exists in vegetative and spore forms, is a leading cause of hospital-associated diarrhea. C. difficile has a variety of presentations, ranging from asymptomatic colonization to CDAD, including severe diarrhea, ileus, and megacolon, and may be associated with a fatal outcome on rare occasions. The incidence of CDAD has been rising since the emergence of a hypervirulent strain (NAP1/BI/027) in the early 2000s and, not surprisingly, the number of deaths attributed to CDAD has also increased.1

CDAD requires acquisition of C. difficile as well as alteration in the colonic microbiota, often precipitated by antibiotics. The vegetative form of C. difficile can produce up to three toxins that are responsible for a cascade of reactions beginning with intestinal epithelial cell death followed by a significant inflammatory response and migration of neutrophils that eventually lead to the formation of the characteristic pseudomembranes.2

Until recently, the mainstay treatment for CDAD consisted of metronidazole and oral preparations of vancomycin. Recent results from randomized controlled trials and the increasing popularity of fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), however, have changed the therapeutic landscape of CDAD dramatically. Not surprisingly, the 2017 Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America joint guidelines for CDAD represent a significant change to the treatment of CDAD, compared with previous guidelines.3

Overview of data

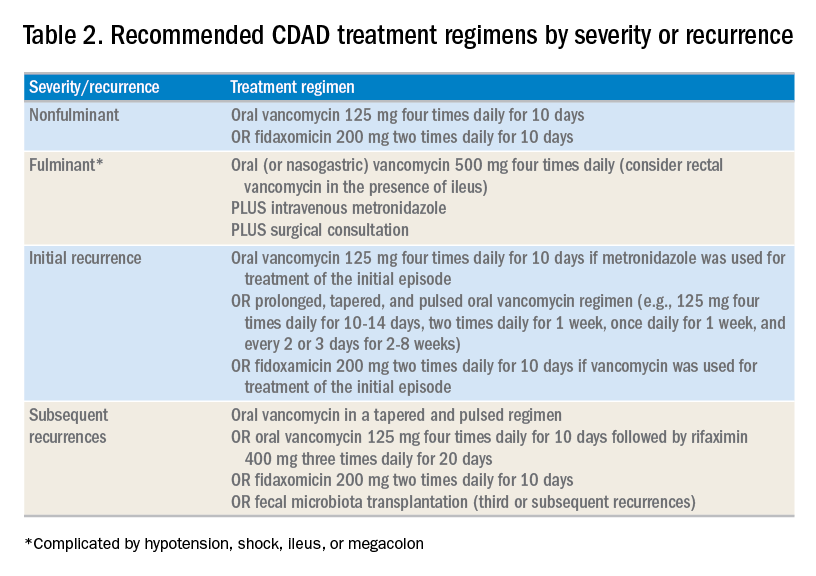

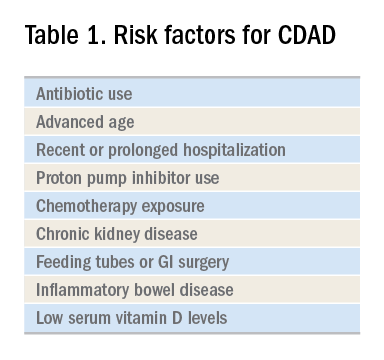

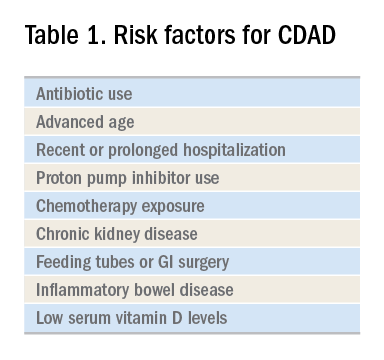

The hallmark of CDAD is a watery, nonbloody diarrhea. Given many other causes of diarrhea in hospitalized patients (e.g., direct effect of antibiotics, laxative use, tube feeding, etc.), hospitalists should focus on testing those patients who have three or more episodes of diarrhea in 24 hours and risk factors for CDAD (See Table 1).

Exposure to antibiotics remains the greatest risk factor. It’s important to note that, while most patients develop CDAD within the first month after receiving systemic antibiotics, many patients remain at risk for up to 3 months.4 Although exposure to antibiotics, particularly in health care settings, is a significant risk factor for CDAD, up to 30%-40% of community-associated cases may not have a substantial antibiotic or health care facility exposure.5

Hospitalists should also not overlook the association between proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use and the development of CDAD.3 Although the IDSA/SHEA guidelines do not recommend discontinuation of PPIs solely for treatment or prevention of CDAD, at the minimum, the indication for their continued use in patients with CDAD should be revisited.

Testing for CDAD ranges from immunoassays that detect an enzyme common to all strains of C. difficile, glutamate dehydrogenase antigen (GDH), or toxins to nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), such as polymerase chain reaction [PCR]).1,6 GDH tests have high sensitivity but poor specificity, while testing for the toxin has high specificity but lower sensitivity (40%-80%) for CDAD.1 Although NAATs are highly sensitive and specific, they often have a poor positive predictive value in low-risk populations (e.g., those who do not have true diarrhea or whose diarrhea resolves before test results return). In these patients, a positive NAAT test may reflect colonization with toxigenic C. difficile, not necessarily CDAD. Except in rare instances, laboratories should only accept unformed stools for testing. Since the choice of testing for C. difficile varies by institution, hospitalists should understand the algorithm used by their respective hospitals and familiarize themselves with the sensitivity and specificity of each test.

Once a patient is diagnosed with CDAD, the hospitalist should assess the severity of the disease. The IDSA/SHEA guidelines still use leukocytosis and creatinine to separate mild from severe cases; the presence of fever and hypoalbuminemia also points to a more complicated course.3

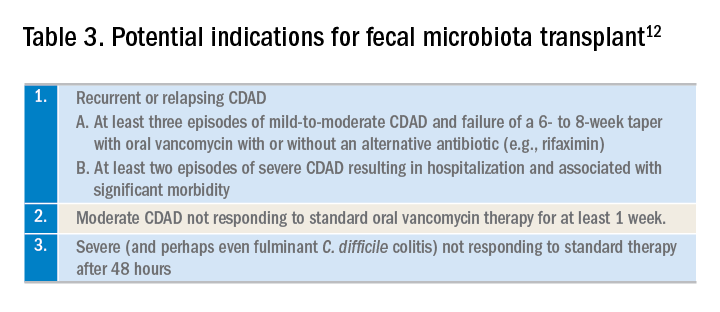

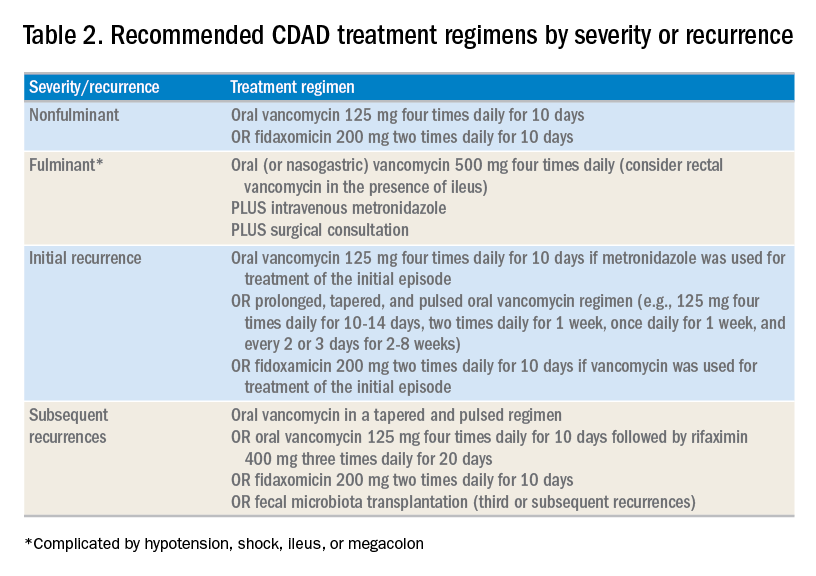

The treatment of CDAD involves a strategy of withdrawing the putative culprit antibiotic(s) whenever possible and initiating of antibiotics effective against C. difficile. Following the publication of two randomized controlled trials demonstrating the inferiority of metronidazole to vancomycin in clinical cure of CDAD,2,7 the IDSA/SHEA guidelines no longer recommend metronidazole for the treatment of CDAD. Instead, a 10-day course of oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin has been recommended.2 Although fidaxomicin is associated with lower rates of recurrence of CDAD, it is also substantially more expensive than oral vancomycin, with a 10-day course often costing over $3,000.8 When choosing oral vancomycin for completion of therapy following discharge, hospitalists should also consider whether the dispensing outpatient pharmacy can provide the less-expensive liquid preparation of vancomycin. In resource-poor settings, consideration can still be given to metronidazole, an inexpensive drug, compared with both oral vancomycin and fidaxomicin. “Test of cure” with follow-up stool testing is not recommended.

For patients who require systemic antibiotics that precipitated their CDAD, it is common practice to extend CDAD treatment by providing a “tail” coverage with an agent effective against CDAD for 7-10 days following the completion of the inciting antibiotic. A common clinical question relates to the management of patients with prior history of CDAD but in need of a new round of systemic antibiotic therapy. In these patients, concurrent prophylactic doses of oral vancomycin have been found to be effective in preventing recurrence.9 The IDSA/SHEA guidelines conclude that “it may be prudent to administer low doses of vancomycin or fidaxomicin (e.g., 125 mg or 200 mg, respectively, once daily) while systemic antibiotics are administered.”3

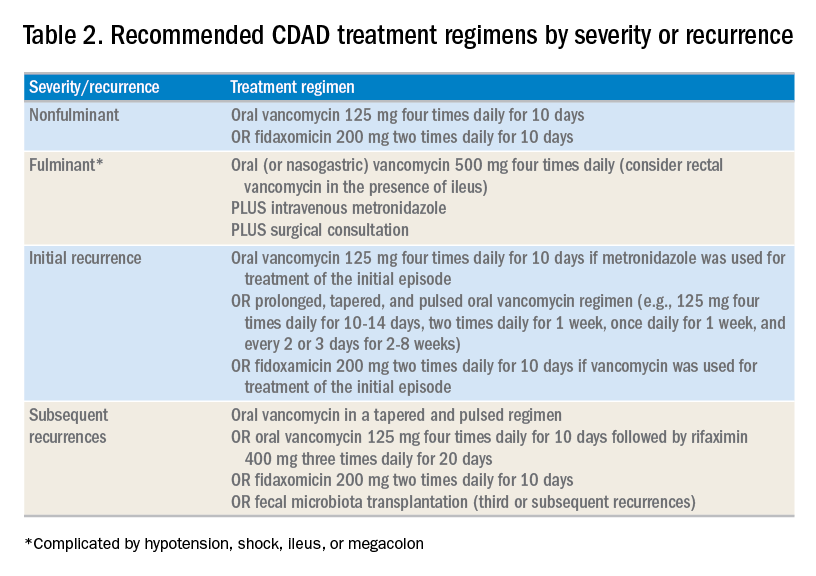

For patients whose presentation extends beyond diarrhea, the IDSA/SHEA guidelines have changed the nomenclature for CDAD from “severe, complicated” to “fulminant.” Although there are no strict definitions, the IDSA/SHEA guidelines suggest that fulminant CDAD is characterized by “hypotension or shock, ileus, or megacolon.” In these patients, surgical intervention can be life saving, though mortality rates may remain over 50%.10 Hospitalists whose patients with CDAD are experiencing an acute abdomen or concern for colonic perforation, megacolon, shock, or organ system failure should obtain prompt surgical consultation. Antibiotic treatment should consist of a combination of higher doses of oral vancomycin and intravenous metronidazole (See Table 2).

In addition to occasional treatment failures, a vexing characteristic of CDAD is its frequent recurrence rate, which may range from 15% to 30% or higher.11 The approach to recurrences is twofold: treatment of the C. difficile itself, and attempts to restore the colonic microbiome. The antibiotic treatment of the first recurrence of CDAD consists of either a 10-day course of fidaxomicin or a tapered, pulsed dose of vancomycin, which may be more effective than a repeat 10-day course of oral vancomycin.12 Although the treatment is unchanged for subsequent recurrences, the guidelines suggest consideration of rifaximin after a course of vancomycin (See Table 2).

Probiotics have been investigated as a means of restoring the colonic microbiome. Use of probiotics for both primary and secondary prevention of CDAD has resulted in conflicting data, with pooled analyses showing some benefit, while randomized controlled trials demonstrate less benefit.13 In addition, reports of bloodstream infections with Lactobacillus in frail patients and Saccharomyces in immunocompromised patients and those with central venous catheters raise doubts regarding their safety in certain patient populations.13 The IDSA/SHEA guidelines make no recommendations about the use of probiotics for the prevention of CDAD at this time.

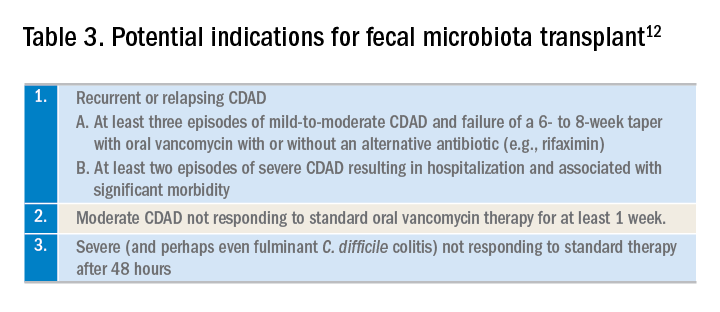

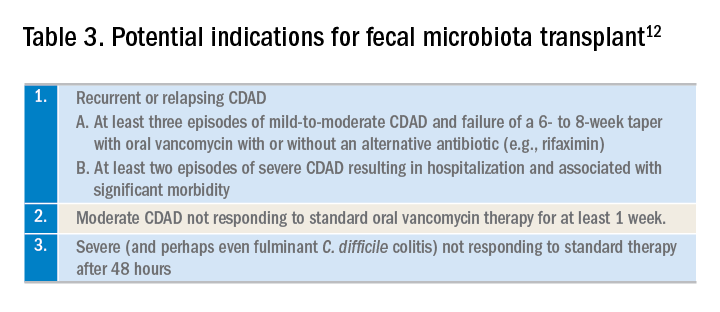

Fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), however, does appear to be effective, especially in comparison to antibiotics alone in patients with multiple recurrences of CDAD.13 The IDSA/SHEA guidelines recommend consideration for FMT after the second recurrence of CDAD. The Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Workgroup has also proposed a set of guidelines for consideration of FMT when available (See Table 3).

Application of data

The recent IDSA/SHEA guidelines have revised the treatment paradigm for CDAD. Most notably, metronidazole is no longer recommended for treatment of either initial or subsequent episodes of mild to severe CDAD, except when the cost of treatment may preclude the use of more effective therapies.

Initial episodes of mild to severe infection should be treated with either oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin. Recurrent episodes of CDAD should be treated with an agent different from that used for the initial episode, or with a pulsed, tapered regimen of oral vancomycin. FMT, where available, should be considered with multiple recurrences, or with moderate to severe infection not responding to standard therapy.

Fulminant CDAD, characterized by hypotension, shock, severe ileus, or megacolon, is a life-threatening medical emergency with a high mortality rate. Treatment should include high-dose oral vancomycin and intravenous metronidazole, with consideration of rectal vancomycin in patients with ileus. Immediate surgical consultation should be obtained to weigh the benefits of colectomy.

Back to our case

Our patient was treated with a 10-day course of vancomycin because this was uncomplicated CDAD and was her initial episode. Were she to develop a recurrence, she could be treated with a pulsed, tapered vancomycin regimen or fidaxomicin.

Bottom line

Vancomycin and fidaxomicin are recommended for the initial episode as well as recurrent CDAD. FMT should be considered for patients with multiple episodes of CDAD or treatment failures.

Dr. Roberts, Dr. Hillman, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

References

1. Louie TJ et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2011 Feb 3;364:422-31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910812.

2. Burnham CA et al. Diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection: an ongoing conundrum for clinicians and for clinical laboratories. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013 Jul;26:604-30. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00016-13.

3. McDonald LC et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Mar 19;66:987-94. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy149.

4. Hensgens MP et al. Time interval of increased risk for Clostridium difficile infection after exposure to antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012 Mar;67:742-8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr508. Epub 2011 Dec 6.

5. Chitnis AS et al. Epidemiology of community-associated Clostridium difficile infection, 2009 through 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Jul 22;173:1359-67. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.7056.

6. Solomon DA et al. ID learning unit: Understanding and interpreting testing for Clostridium difficile. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2014 Mar;1(1);ofu007. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofu007.

7. Johnson S et al. Vancomycin, metronidazole, or tolevamer for Clostridium difficile infection: results from two multinational, randomized, controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2014 Aug 1;59(3):345-54. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu313. Epub 2014 May 5.

8. https://m.goodrx.com/fidaxomicin, accessed June 24, 2018.

9. Van Hise NW et al. Efficacy of oral vancomycin in preventing recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in patients treated with systemic antimicrobial agents. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 1;63:651-3. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw401. Epub 2016 Jun 17.

10. Sailhamer EA et al. Fulminant Clostridium difficile colitis: Patterns of care and predictors of mortality. Arch Surg. 2009;144:433-9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.51.

11. Zar FA et al. A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:302-7. doi: 10.1086/519265. Epub 2007 Jun 19.

12. Bakken JS et al. Treating Clostridium difficile infection with fecal microbiota transplantation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:1044-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.08.014. Epub 2011 Aug 24.

13. Crow JR et al. Probiotics and fecal microbiota transplant for primary and secondary prevention of Clostridium difficile infection. Pharmacotherapy. 2015 Nov;35:1016-25. doi: 10.1002/phar.1644. Epub 2015 Nov 2.

Additional reading

1. McDonald LC et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Mar 19;66:987-94. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy149.

2. Burnham CA et al. Diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection: an ongoing conundrum for clinicians and for clinical laboratories. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013 Jul;26:604-30. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00016-13.

3. Crow JR, Davis SL, Chaykosky DM, Smith TT, Smith JM. Probiotics and fecal microbiota transplant for primary and secondary prevention of Clostridium difficile infection. Pharmacotherapy. 2015 Nov; 35:1016-25. doi: 10.1002/phar.1644. Epub 2015 Nov 2. Review.

Key points

1. Metronidazole is inferior to oral vancomycin and fidaxomicin for clinical cure of CDAD. The IDSA/SHEA guidelines now recommend a 10-day course of oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin for nonfulminant cases of CDAD.

2. For fulminant CDAD, the IDSA/SHEA guidelines suggest an increased dose of vancomycin and the addition of IV metronidazole. In such cases, surgical consultation should also be obtained.

3. After the second recurrence of Clostridium difficile infection, hospitalists should consider referral for FMT where available.

Quiz

The recent IDSA/SHEA guidelines no longer recommend metronidazole in the treatment of CDAD, except for which of the following scenarios (best answer)?

A. Treatment of a first episode of nonfulminant CDAD.

B. Treatment of recurrent CDAD following an initial course of oral vancomycin.

C. Treatment of fulminant infection with IV metronidazole in addition to oral or rectal vancomycin.

D. For prophylaxis following fecal microbiota transplant.

Answer: C. In fulminant infection, concurrent ileus may interfere with appropriate delivery of oral vancomycin to the colon. Adding intravenous metronidazole can allow this antibiotic to reach the bowel. Adding intravenous metronidazole to oral vancomycin is also recommended by IDSA/SHEA guidelines in cases of fulminant CDAD. Evidence from high-quality randomized controlled trials has shown that vancomycin is superior to oral metronidazole for treatment of initial and recurrent episodes of CDAD. There is no evidence to support the use of metronidazole for recurrent CDAD following an initial course of oral vancomycin or for prophylaxis following FMT.

Metronidazole is no longer recommended

Metronidazole is no longer recommended

Case