User login

Id Reaction Associated With Red Tattoo Ink

To the Editor:

Although relatively uncommon, hypersensitivity reactions to tattoo pigment are on the rise due to the increasing popularity and prevalence of tattoos.1 Multiple adverse events have been described in association with tattoos, including inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic responses.2 An id reaction (also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization) develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. We describe a unique case of an id reaction and subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink.

A 40-year-old woman was referred to the New York University Skin and Cancer Unit (New York, New York) for evaluation of a pruritic eruption arising on and near sites of tattooed skin on the right foot and right upper arm of 8 months’ duration. The patient reported that she had obtained a polychromatic tattoo on the right dorsal foot 9 months prior to the current presentation. Approximately 1 month later, she developed pruritic papulonodular lesions localized to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo. Concomitantly, the patient developed a similar eruption confined to areas of red pigment in a polychromatic tattoo on the right upper arm that she had obtained 10 years prior. She was treated with intralesional triamcinolone to several of the lesions on the right dorsal foot with some benefit; however, a few days later she developed a generalized, erythematous, pruritic eruption on the back, abdomen, arms, and legs. Her medical history was remarkable only for mild iron-deficiency anemia. She had no known drug allergies or history of atopy and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the eruption.

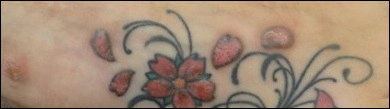

Skin examination revealed multiple, well-demarcated, eczematous papulonodules with surrounding erythema confined to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the right dorsal foot, with several similar lesions on the surrounding nontattooed skin (Figure 1). Linear, well-demarcated, eczematous, hyperpigmented plaques also were noted on the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the patient’s right upper arm (Figure 2). Eczematous plaques and scattered excoriations were noted on the back, abdomen, flanks, arms, and legs.

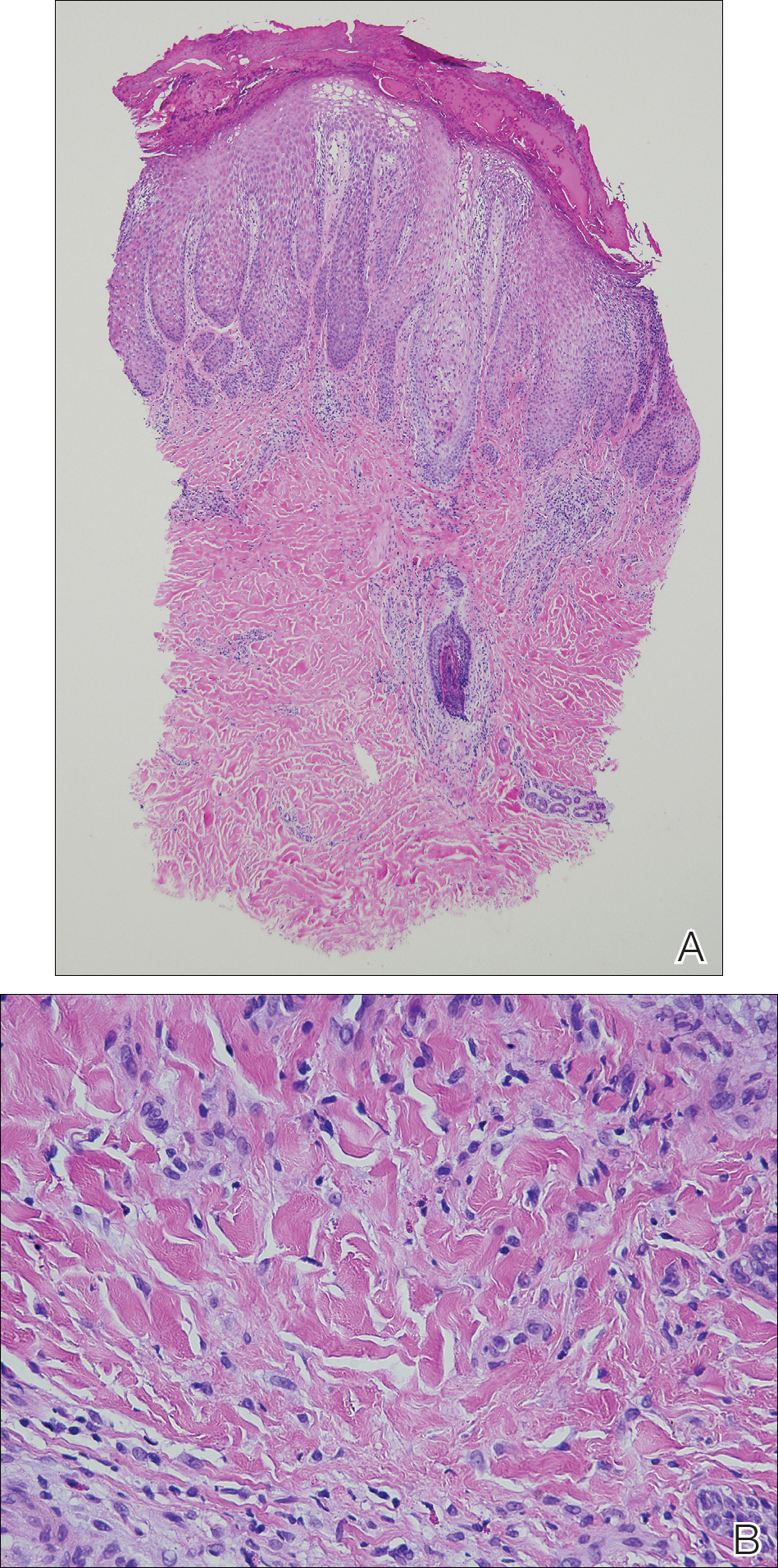

Patch testing with the North American Standard Series, metal series, and samples of the red pigments used in the tattoo on the foot were negative. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the dorsal right foot showed a psoriasiform spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining with diastase failed to reveal fungal hyphae. The histologic findings were consistent with allergic contact dermatitis. A punch biopsy of the eczematous reaction on nontattooed skin on the trunk demonstrated a perivascular dermatitis with eosinophils and subtle spongiosis consistent with an id reaction.

The patient was treated with fluocinonide ointment for several months with no effect. Subsequently, she received several short courses of oral prednisone, after which the affected areas of the tattoo on the arm and foot flattened and the id reaction resolved; however, after several months, the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the foot again became elevated and pruritic, and the patient developed widespread prurigo nodules on nontattooed skin on the trunk, arms, and legs. She was subsequently referred to a laser specialist for a trial of fractional laser treatment to cautiously remove the red tattoo pigment. After 2 treatments, the pruritus improved and the papular lesions appeared slightly flatter; however, the prurigo nodules remained. The tattoo on the patient’s foot was surgically removed; however, the prurigo nodules remained. Ultimately, the lesions cleared with a several-month course of mycophenolate mofetil.

Systemic allergic reactions to tattoo ink are rare but can cause considerable morbidity. An id reaction, also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization, is a reaction that develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. Although the pathogenesis of this reaction is not certain, it has been hypothesized that autoimmunity to skin antigens might play a role.3 Autologous epidermal cells are thought to become antigenic in the presence of acute inflammation at the primary cutaneous site. These antigenic autologous epidermal cells are postulated to enter the circulation and cause secondary eczematous lesions at distant sites. This proposed mechanism is supported by the development of positive skin reactions to autologous extracts of epidermal scaling in patients with active id reaction.3

Hematogenous dissemination of cytokines has been implicated in id reactions.4 Keratinocytes produce cytokines in response to conditions that are known to trigger id reactions.5 Epidermal cytokines released from the primary site of sensitization are thought to heighten sensitivity at distant skin areas.4 These cytokines regulate both cell-mediated and humoral cutaneous immune responses. Increased levels of activated HLA-DR isotype–positive T cells in patients with active autoeczemization favors a cellular-mediated immune mechanism. The presence of activated antigen-specific T cells also supports the role of allergic contact dermatitis in triggering id reactions.6

Allergic contact dermatitis is the most common hypersensitivity reaction to tattoo ink, with red pigments representing the most common cause of tattoo-related allergic contact dermatitis. Historically, cinnabar (mercuric sulfide) has been the most common red pigment to cause allergic contact dermatitis.7 More recently, mercury-free organic pigments (eg, azo dyes) have been used in polychromatic tattoos due to their ability to retain color over long periods of time8; however, these organic red tattoo pigments also have been implicated in allergic reactions.8-11 The composition of these new organic red tattoo pigments varies, but chemical analysis has revealed a mixture of aromatic azo compounds (eg, quinacridone),10 heavy metals (eg, aluminum, lead, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, iron, titanium),9,12 and intermediate reactive compounds (eg, naphthalene, 2-naphthol, chlorobenzene, benzene).8 Allergic contact dermatitis to red tattoo ink is well documented8,13; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms tattoo and dermatitis, tattoo and allergy, tattoo and autosensitization, tattoo and id reaction, and tattoo and autoeczematization yielded only 3 other reports of a concomitant id reaction.11,14,15

The diagnosis of id reaction associated with allergic contact dermatitis is made on the basis of clinical history, physical examination, and histopathology. Patch testing usually is not positive in cases of tattoo allergy; it is thought that the allergen is a tattoo ink byproduct possibly caused by photoinduced or metabolic change of the tattoo pigment and a haptenization process.1,8,16 Histologically, variable reaction patterns, including eczematous, lichenoid, granulomatous, and pseudolymphomatous reactions have been reported in association with delayed-type inflammatory reactions to tattoo pigments, but the lichenoid pattern is most commonly observed.8

Treatment options for allergic contact dermatitis to tattoo ink include topical, intralesional, and oral steroids; topical calcineurin inhibitors; and surgical excision of the tattoo. Q-switched lasers—ruby, Nd:YAG, and alexandrite—are the gold standard for removing tattoo pigments17; however, these lasers remove tattoo pigment by selective photothermolysis, resulting in extracellular extravasation of pigment, which can precipitate a heightened immune response that can lead to localized and generalized allergic reactions.18 Therefore, Q-switched lasers should be avoided in the setting of an allergic reaction to tattoo ink. Fractional ablative laser resurfacing may be a safer alternative for removal of tattoos in the setting of an allergic reaction.17 Further studies are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of this modality for allergic tattoo ink removal.17,18

Our case illustrates a rare cause of id reaction and the subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink. We present this case to raise awareness of the potential health and iatrogenic risks associated with tattoo placement. Further investigation of these color additives is warranted to better elucidate ink components responsible for these cutaneous allergic reactions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Vitaly Terushkin, MD (West Orange, New Jersey, and New York, New York), and Arielle Kauvar, MD (New York, New York), for their contributions to the patient’s clinical care.

- Vasold R, Engel E, Konig B, et al. Health risks of tattoo colors. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:9-13.

- Swigost AJ, Peltola J, Jacobson-Dunlop E, et al. Tattoo-related squamous proliferations: a specturm of reactive hyperplasia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:728-732.

- Cormia FE, Esplin BM. Autoeczematization; preliminary report. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;61:931-945.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Uchi H, Terao H, Koga T, et al. Cytokines and chemokines in the epidermis. J Dermatol Sci. 2000;24(suppl 1):S29-S38.

- Kasteler JS, Petersen MJ, Vance JE, et al. Circulating activated T lymphocytes in autoeczematization. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:795-798.

- Mortimer NJ, Chave TA, Johnston GA. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508-510.

- Garcovich S, Carbone T, Avitabile S, et al. Lichenoid red tattoo reaction: histological and immunological perspectives. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:93-96.

- Sowden JM, Byrne JP, Smith AG, et al. Red tattoo reactions: x-ray microanalysis and patch-test studies. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:576-580.

- Bendsoe N, Hansson C, Sterner O. Inflammatory reactions from organic pigments in red tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:70-73.

- Greve B, Chytry R, Raulin C. Contact dermatitis from red tattoo pigment (quinacridone) with secondary spread. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:265-266.

- Cristaudo A, Forte G, Bocca B, et al. Permanent tattoos: evidence of pseudolymphoma in three patients and metal composition of the dyes. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:776-780.

- Wenzel SM, Welzel J, Hafner C, et al. Permanent make-up colorants may cause severe skin reactions. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:223-227.

- Goldberg HM. Tattoo allergy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:1315-1316.

- Gamba CS, Smith FL, Wisell J, et al. Tattoo reactions in an HIV patient: autoeczematization and progressive allergic reaction to red ink after antiretroviral therapy initiation. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:395-398.

- Serup J, Hutton Carlsen K. Patch test study of 90 patients with tattoo reactions: negative outcome of allergy patch test to baseline batteries and culprit inks suggests allergen(s) are generated in the skin through haptenization. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:255-263.

- Ibrahimi OA, Syed Z, Sakamoto FH, et al. Treatment of tattoo allergy with ablative fractional resurfacing: a novel paradigm for tattoo removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1111-1114.

- Harper J, Losch AE, Otto SG, et al. New insight into the pathophysiology of tattoo reactions following laser tattoo removal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:313e-314e.

To the Editor:

Although relatively uncommon, hypersensitivity reactions to tattoo pigment are on the rise due to the increasing popularity and prevalence of tattoos.1 Multiple adverse events have been described in association with tattoos, including inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic responses.2 An id reaction (also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization) develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. We describe a unique case of an id reaction and subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink.

A 40-year-old woman was referred to the New York University Skin and Cancer Unit (New York, New York) for evaluation of a pruritic eruption arising on and near sites of tattooed skin on the right foot and right upper arm of 8 months’ duration. The patient reported that she had obtained a polychromatic tattoo on the right dorsal foot 9 months prior to the current presentation. Approximately 1 month later, she developed pruritic papulonodular lesions localized to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo. Concomitantly, the patient developed a similar eruption confined to areas of red pigment in a polychromatic tattoo on the right upper arm that she had obtained 10 years prior. She was treated with intralesional triamcinolone to several of the lesions on the right dorsal foot with some benefit; however, a few days later she developed a generalized, erythematous, pruritic eruption on the back, abdomen, arms, and legs. Her medical history was remarkable only for mild iron-deficiency anemia. She had no known drug allergies or history of atopy and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the eruption.

Skin examination revealed multiple, well-demarcated, eczematous papulonodules with surrounding erythema confined to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the right dorsal foot, with several similar lesions on the surrounding nontattooed skin (Figure 1). Linear, well-demarcated, eczematous, hyperpigmented plaques also were noted on the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the patient’s right upper arm (Figure 2). Eczematous plaques and scattered excoriations were noted on the back, abdomen, flanks, arms, and legs.

Patch testing with the North American Standard Series, metal series, and samples of the red pigments used in the tattoo on the foot were negative. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the dorsal right foot showed a psoriasiform spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining with diastase failed to reveal fungal hyphae. The histologic findings were consistent with allergic contact dermatitis. A punch biopsy of the eczematous reaction on nontattooed skin on the trunk demonstrated a perivascular dermatitis with eosinophils and subtle spongiosis consistent with an id reaction.

The patient was treated with fluocinonide ointment for several months with no effect. Subsequently, she received several short courses of oral prednisone, after which the affected areas of the tattoo on the arm and foot flattened and the id reaction resolved; however, after several months, the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the foot again became elevated and pruritic, and the patient developed widespread prurigo nodules on nontattooed skin on the trunk, arms, and legs. She was subsequently referred to a laser specialist for a trial of fractional laser treatment to cautiously remove the red tattoo pigment. After 2 treatments, the pruritus improved and the papular lesions appeared slightly flatter; however, the prurigo nodules remained. The tattoo on the patient’s foot was surgically removed; however, the prurigo nodules remained. Ultimately, the lesions cleared with a several-month course of mycophenolate mofetil.

Systemic allergic reactions to tattoo ink are rare but can cause considerable morbidity. An id reaction, also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization, is a reaction that develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. Although the pathogenesis of this reaction is not certain, it has been hypothesized that autoimmunity to skin antigens might play a role.3 Autologous epidermal cells are thought to become antigenic in the presence of acute inflammation at the primary cutaneous site. These antigenic autologous epidermal cells are postulated to enter the circulation and cause secondary eczematous lesions at distant sites. This proposed mechanism is supported by the development of positive skin reactions to autologous extracts of epidermal scaling in patients with active id reaction.3

Hematogenous dissemination of cytokines has been implicated in id reactions.4 Keratinocytes produce cytokines in response to conditions that are known to trigger id reactions.5 Epidermal cytokines released from the primary site of sensitization are thought to heighten sensitivity at distant skin areas.4 These cytokines regulate both cell-mediated and humoral cutaneous immune responses. Increased levels of activated HLA-DR isotype–positive T cells in patients with active autoeczemization favors a cellular-mediated immune mechanism. The presence of activated antigen-specific T cells also supports the role of allergic contact dermatitis in triggering id reactions.6

Allergic contact dermatitis is the most common hypersensitivity reaction to tattoo ink, with red pigments representing the most common cause of tattoo-related allergic contact dermatitis. Historically, cinnabar (mercuric sulfide) has been the most common red pigment to cause allergic contact dermatitis.7 More recently, mercury-free organic pigments (eg, azo dyes) have been used in polychromatic tattoos due to their ability to retain color over long periods of time8; however, these organic red tattoo pigments also have been implicated in allergic reactions.8-11 The composition of these new organic red tattoo pigments varies, but chemical analysis has revealed a mixture of aromatic azo compounds (eg, quinacridone),10 heavy metals (eg, aluminum, lead, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, iron, titanium),9,12 and intermediate reactive compounds (eg, naphthalene, 2-naphthol, chlorobenzene, benzene).8 Allergic contact dermatitis to red tattoo ink is well documented8,13; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms tattoo and dermatitis, tattoo and allergy, tattoo and autosensitization, tattoo and id reaction, and tattoo and autoeczematization yielded only 3 other reports of a concomitant id reaction.11,14,15

The diagnosis of id reaction associated with allergic contact dermatitis is made on the basis of clinical history, physical examination, and histopathology. Patch testing usually is not positive in cases of tattoo allergy; it is thought that the allergen is a tattoo ink byproduct possibly caused by photoinduced or metabolic change of the tattoo pigment and a haptenization process.1,8,16 Histologically, variable reaction patterns, including eczematous, lichenoid, granulomatous, and pseudolymphomatous reactions have been reported in association with delayed-type inflammatory reactions to tattoo pigments, but the lichenoid pattern is most commonly observed.8

Treatment options for allergic contact dermatitis to tattoo ink include topical, intralesional, and oral steroids; topical calcineurin inhibitors; and surgical excision of the tattoo. Q-switched lasers—ruby, Nd:YAG, and alexandrite—are the gold standard for removing tattoo pigments17; however, these lasers remove tattoo pigment by selective photothermolysis, resulting in extracellular extravasation of pigment, which can precipitate a heightened immune response that can lead to localized and generalized allergic reactions.18 Therefore, Q-switched lasers should be avoided in the setting of an allergic reaction to tattoo ink. Fractional ablative laser resurfacing may be a safer alternative for removal of tattoos in the setting of an allergic reaction.17 Further studies are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of this modality for allergic tattoo ink removal.17,18

Our case illustrates a rare cause of id reaction and the subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink. We present this case to raise awareness of the potential health and iatrogenic risks associated with tattoo placement. Further investigation of these color additives is warranted to better elucidate ink components responsible for these cutaneous allergic reactions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Vitaly Terushkin, MD (West Orange, New Jersey, and New York, New York), and Arielle Kauvar, MD (New York, New York), for their contributions to the patient’s clinical care.

To the Editor:

Although relatively uncommon, hypersensitivity reactions to tattoo pigment are on the rise due to the increasing popularity and prevalence of tattoos.1 Multiple adverse events have been described in association with tattoos, including inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic responses.2 An id reaction (also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization) develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. We describe a unique case of an id reaction and subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink.

A 40-year-old woman was referred to the New York University Skin and Cancer Unit (New York, New York) for evaluation of a pruritic eruption arising on and near sites of tattooed skin on the right foot and right upper arm of 8 months’ duration. The patient reported that she had obtained a polychromatic tattoo on the right dorsal foot 9 months prior to the current presentation. Approximately 1 month later, she developed pruritic papulonodular lesions localized to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo. Concomitantly, the patient developed a similar eruption confined to areas of red pigment in a polychromatic tattoo on the right upper arm that she had obtained 10 years prior. She was treated with intralesional triamcinolone to several of the lesions on the right dorsal foot with some benefit; however, a few days later she developed a generalized, erythematous, pruritic eruption on the back, abdomen, arms, and legs. Her medical history was remarkable only for mild iron-deficiency anemia. She had no known drug allergies or history of atopy and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the eruption.

Skin examination revealed multiple, well-demarcated, eczematous papulonodules with surrounding erythema confined to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the right dorsal foot, with several similar lesions on the surrounding nontattooed skin (Figure 1). Linear, well-demarcated, eczematous, hyperpigmented plaques also were noted on the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the patient’s right upper arm (Figure 2). Eczematous plaques and scattered excoriations were noted on the back, abdomen, flanks, arms, and legs.

Patch testing with the North American Standard Series, metal series, and samples of the red pigments used in the tattoo on the foot were negative. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the dorsal right foot showed a psoriasiform spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining with diastase failed to reveal fungal hyphae. The histologic findings were consistent with allergic contact dermatitis. A punch biopsy of the eczematous reaction on nontattooed skin on the trunk demonstrated a perivascular dermatitis with eosinophils and subtle spongiosis consistent with an id reaction.

The patient was treated with fluocinonide ointment for several months with no effect. Subsequently, she received several short courses of oral prednisone, after which the affected areas of the tattoo on the arm and foot flattened and the id reaction resolved; however, after several months, the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the foot again became elevated and pruritic, and the patient developed widespread prurigo nodules on nontattooed skin on the trunk, arms, and legs. She was subsequently referred to a laser specialist for a trial of fractional laser treatment to cautiously remove the red tattoo pigment. After 2 treatments, the pruritus improved and the papular lesions appeared slightly flatter; however, the prurigo nodules remained. The tattoo on the patient’s foot was surgically removed; however, the prurigo nodules remained. Ultimately, the lesions cleared with a several-month course of mycophenolate mofetil.

Systemic allergic reactions to tattoo ink are rare but can cause considerable morbidity. An id reaction, also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization, is a reaction that develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. Although the pathogenesis of this reaction is not certain, it has been hypothesized that autoimmunity to skin antigens might play a role.3 Autologous epidermal cells are thought to become antigenic in the presence of acute inflammation at the primary cutaneous site. These antigenic autologous epidermal cells are postulated to enter the circulation and cause secondary eczematous lesions at distant sites. This proposed mechanism is supported by the development of positive skin reactions to autologous extracts of epidermal scaling in patients with active id reaction.3

Hematogenous dissemination of cytokines has been implicated in id reactions.4 Keratinocytes produce cytokines in response to conditions that are known to trigger id reactions.5 Epidermal cytokines released from the primary site of sensitization are thought to heighten sensitivity at distant skin areas.4 These cytokines regulate both cell-mediated and humoral cutaneous immune responses. Increased levels of activated HLA-DR isotype–positive T cells in patients with active autoeczemization favors a cellular-mediated immune mechanism. The presence of activated antigen-specific T cells also supports the role of allergic contact dermatitis in triggering id reactions.6

Allergic contact dermatitis is the most common hypersensitivity reaction to tattoo ink, with red pigments representing the most common cause of tattoo-related allergic contact dermatitis. Historically, cinnabar (mercuric sulfide) has been the most common red pigment to cause allergic contact dermatitis.7 More recently, mercury-free organic pigments (eg, azo dyes) have been used in polychromatic tattoos due to their ability to retain color over long periods of time8; however, these organic red tattoo pigments also have been implicated in allergic reactions.8-11 The composition of these new organic red tattoo pigments varies, but chemical analysis has revealed a mixture of aromatic azo compounds (eg, quinacridone),10 heavy metals (eg, aluminum, lead, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, iron, titanium),9,12 and intermediate reactive compounds (eg, naphthalene, 2-naphthol, chlorobenzene, benzene).8 Allergic contact dermatitis to red tattoo ink is well documented8,13; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms tattoo and dermatitis, tattoo and allergy, tattoo and autosensitization, tattoo and id reaction, and tattoo and autoeczematization yielded only 3 other reports of a concomitant id reaction.11,14,15

The diagnosis of id reaction associated with allergic contact dermatitis is made on the basis of clinical history, physical examination, and histopathology. Patch testing usually is not positive in cases of tattoo allergy; it is thought that the allergen is a tattoo ink byproduct possibly caused by photoinduced or metabolic change of the tattoo pigment and a haptenization process.1,8,16 Histologically, variable reaction patterns, including eczematous, lichenoid, granulomatous, and pseudolymphomatous reactions have been reported in association with delayed-type inflammatory reactions to tattoo pigments, but the lichenoid pattern is most commonly observed.8

Treatment options for allergic contact dermatitis to tattoo ink include topical, intralesional, and oral steroids; topical calcineurin inhibitors; and surgical excision of the tattoo. Q-switched lasers—ruby, Nd:YAG, and alexandrite—are the gold standard for removing tattoo pigments17; however, these lasers remove tattoo pigment by selective photothermolysis, resulting in extracellular extravasation of pigment, which can precipitate a heightened immune response that can lead to localized and generalized allergic reactions.18 Therefore, Q-switched lasers should be avoided in the setting of an allergic reaction to tattoo ink. Fractional ablative laser resurfacing may be a safer alternative for removal of tattoos in the setting of an allergic reaction.17 Further studies are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of this modality for allergic tattoo ink removal.17,18

Our case illustrates a rare cause of id reaction and the subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink. We present this case to raise awareness of the potential health and iatrogenic risks associated with tattoo placement. Further investigation of these color additives is warranted to better elucidate ink components responsible for these cutaneous allergic reactions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Vitaly Terushkin, MD (West Orange, New Jersey, and New York, New York), and Arielle Kauvar, MD (New York, New York), for their contributions to the patient’s clinical care.

- Vasold R, Engel E, Konig B, et al. Health risks of tattoo colors. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:9-13.

- Swigost AJ, Peltola J, Jacobson-Dunlop E, et al. Tattoo-related squamous proliferations: a specturm of reactive hyperplasia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:728-732.

- Cormia FE, Esplin BM. Autoeczematization; preliminary report. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;61:931-945.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Uchi H, Terao H, Koga T, et al. Cytokines and chemokines in the epidermis. J Dermatol Sci. 2000;24(suppl 1):S29-S38.

- Kasteler JS, Petersen MJ, Vance JE, et al. Circulating activated T lymphocytes in autoeczematization. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:795-798.

- Mortimer NJ, Chave TA, Johnston GA. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508-510.

- Garcovich S, Carbone T, Avitabile S, et al. Lichenoid red tattoo reaction: histological and immunological perspectives. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:93-96.

- Sowden JM, Byrne JP, Smith AG, et al. Red tattoo reactions: x-ray microanalysis and patch-test studies. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:576-580.

- Bendsoe N, Hansson C, Sterner O. Inflammatory reactions from organic pigments in red tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:70-73.

- Greve B, Chytry R, Raulin C. Contact dermatitis from red tattoo pigment (quinacridone) with secondary spread. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:265-266.

- Cristaudo A, Forte G, Bocca B, et al. Permanent tattoos: evidence of pseudolymphoma in three patients and metal composition of the dyes. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:776-780.

- Wenzel SM, Welzel J, Hafner C, et al. Permanent make-up colorants may cause severe skin reactions. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:223-227.

- Goldberg HM. Tattoo allergy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:1315-1316.

- Gamba CS, Smith FL, Wisell J, et al. Tattoo reactions in an HIV patient: autoeczematization and progressive allergic reaction to red ink after antiretroviral therapy initiation. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:395-398.

- Serup J, Hutton Carlsen K. Patch test study of 90 patients with tattoo reactions: negative outcome of allergy patch test to baseline batteries and culprit inks suggests allergen(s) are generated in the skin through haptenization. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:255-263.

- Ibrahimi OA, Syed Z, Sakamoto FH, et al. Treatment of tattoo allergy with ablative fractional resurfacing: a novel paradigm for tattoo removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1111-1114.

- Harper J, Losch AE, Otto SG, et al. New insight into the pathophysiology of tattoo reactions following laser tattoo removal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:313e-314e.

- Vasold R, Engel E, Konig B, et al. Health risks of tattoo colors. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:9-13.

- Swigost AJ, Peltola J, Jacobson-Dunlop E, et al. Tattoo-related squamous proliferations: a specturm of reactive hyperplasia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:728-732.

- Cormia FE, Esplin BM. Autoeczematization; preliminary report. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;61:931-945.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Uchi H, Terao H, Koga T, et al. Cytokines and chemokines in the epidermis. J Dermatol Sci. 2000;24(suppl 1):S29-S38.

- Kasteler JS, Petersen MJ, Vance JE, et al. Circulating activated T lymphocytes in autoeczematization. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:795-798.

- Mortimer NJ, Chave TA, Johnston GA. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508-510.

- Garcovich S, Carbone T, Avitabile S, et al. Lichenoid red tattoo reaction: histological and immunological perspectives. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:93-96.

- Sowden JM, Byrne JP, Smith AG, et al. Red tattoo reactions: x-ray microanalysis and patch-test studies. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:576-580.

- Bendsoe N, Hansson C, Sterner O. Inflammatory reactions from organic pigments in red tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:70-73.

- Greve B, Chytry R, Raulin C. Contact dermatitis from red tattoo pigment (quinacridone) with secondary spread. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:265-266.

- Cristaudo A, Forte G, Bocca B, et al. Permanent tattoos: evidence of pseudolymphoma in three patients and metal composition of the dyes. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:776-780.

- Wenzel SM, Welzel J, Hafner C, et al. Permanent make-up colorants may cause severe skin reactions. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:223-227.

- Goldberg HM. Tattoo allergy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:1315-1316.

- Gamba CS, Smith FL, Wisell J, et al. Tattoo reactions in an HIV patient: autoeczematization and progressive allergic reaction to red ink after antiretroviral therapy initiation. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:395-398.

- Serup J, Hutton Carlsen K. Patch test study of 90 patients with tattoo reactions: negative outcome of allergy patch test to baseline batteries and culprit inks suggests allergen(s) are generated in the skin through haptenization. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:255-263.

- Ibrahimi OA, Syed Z, Sakamoto FH, et al. Treatment of tattoo allergy with ablative fractional resurfacing: a novel paradigm for tattoo removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1111-1114.

- Harper J, Losch AE, Otto SG, et al. New insight into the pathophysiology of tattoo reactions following laser tattoo removal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:313e-314e.

Practice Points

- Hypersensitivity reactions to tattoo pigment are on the rise due to the increasing popularity and prevalence of tattoos. Systemic allergic reactions to tattoo ink are rare but can cause considerable morbidity.

- Id reaction, also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization, is a reaction that develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization.

- Further investigation of color additives in tattoo pigments is warranted to better elucidate the components responsible for cutaneous allergic reactions associated with tattoo ink.

Primary Cutaneous Cryptococcosis in an Immunocompetent Iraq War Veteran

To the Editor:

Disseminated cryptococcosis is a well-known opportunistic infection in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, but it is not frequently seen as a primary infection of the skin in immunocompetent hosts. We report a case of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC) of the lower legs in an immunocompetent Iraq War veteran.

A 28-year-old female service member presented to the dermatology clinic with progressively enlarging plaquelike lesions on the shins of 6 months’ duration. The patient had resided and worked as a deployed soldier in the lower level of a bullet hole–laden, pigeon-infested observation tower in southern Iraq 9 months prior to the current presentation. During her 7-month deployment, she reported daily exposure to pigeon excreta on equipment and frequently sustained superficial abrasions and lacerations to the legs due to the cramped and hazardous working environment. The patient noticed intensely pruritic, bugbitelike papular lesions on the shins and calves 1 month after residing in the observation tower. She sought medical treatment and was given hydrocortisone cream 1% and calamine lotion for a presumed irritant dermatitis. Over the ensuing 3 months, the pruritus worsened, and the primary lesions coalesced into annular erythematous plaques (Figure).

After returning to the United States, the patient presented again for medical care and was given ketoconazole cream 1% for presumed tinea corporis, which resulted in no improvement. A dermatologic consultation and evaluation ensued with subsequent microbial workup showing no bacterial growth on wound culture and no fungal elements on a potassium hydroxide preparation. Hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining did not demonstrate any organisms. Tissue cultures for bacteria and acid-fast bacilli showed no growth. A fungal tissue culture ultimately confirmed the presence of Cryptococcus neoformans. A lumbar puncture showed no evidence of Cryptococcus on DNA probe testing. Serologic testing for HIV was negative, and brain magnetic resonance imaging showed no lesions. Sputum culture and staining showed no fungal elements, and a chest radiograph was normal. A diagnosis of PCC was made and therapy with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice daily was initiated, with the intention of completing a 6-month course. During the treatment, the pruritus resolved within 3 weeks and the lesions involuted over 3 months. From the time of onset of the lesions throughout treatment, the patient showed no pulmonary, neurologic, or other systemic symptoms. She currently is healthy with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis mainly affects individuals with underlying immunosuppression, most commonly due to advanced HIV, prolonged treatment with immunosuppressive medications, or organ transplantation.1 The most common route of inoculation is by inhalation of Cryptococcus spores with subsequent hematogenous dissemination.2 Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis with skin lesions and no concomitant systemic involvement has rarely been reported, and

Due to the worldwide deployment of US military service members, exotic cutaneous infectious diseases such as PCC may be encountered in dermatology practice. Prompt clinical and histologic diagnosis is imperative to assess for systemic disease and avoid cutaneous spread and morbidity in US service members and travelers returning home from the Middle East.

- Antony SA, Antony SJ. Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in nonimmunocompromised patients. Cutis. 1995;56:96-98.

- Mirza SA, Phelan M, Rimland D, et al. The changing epidemiology of cryptococcosis: an update from population-based active surveillance in 2 large metropolitan areas, 1992-2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:789-94.

- Kielstein P, Hotzel H, Schmalreck A, et al. Occurrence of Cryptococcus spp. in excreta of pigeons and pet birds. Mycoses. 2000;43:7-15.

- Leão CA, Ferreira-Paim K, Andrade-Silva L, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus gattii in an immunocompetent host [published online October 28, 2010]. Med Mycol. 2011;49:352-355.

- Zorman JV, Zupanc TL, Parac Z, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in a renal transplant recipient: case report. Mycoses. 2010;53:535-537.

To the Editor:

Disseminated cryptococcosis is a well-known opportunistic infection in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, but it is not frequently seen as a primary infection of the skin in immunocompetent hosts. We report a case of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC) of the lower legs in an immunocompetent Iraq War veteran.

A 28-year-old female service member presented to the dermatology clinic with progressively enlarging plaquelike lesions on the shins of 6 months’ duration. The patient had resided and worked as a deployed soldier in the lower level of a bullet hole–laden, pigeon-infested observation tower in southern Iraq 9 months prior to the current presentation. During her 7-month deployment, she reported daily exposure to pigeon excreta on equipment and frequently sustained superficial abrasions and lacerations to the legs due to the cramped and hazardous working environment. The patient noticed intensely pruritic, bugbitelike papular lesions on the shins and calves 1 month after residing in the observation tower. She sought medical treatment and was given hydrocortisone cream 1% and calamine lotion for a presumed irritant dermatitis. Over the ensuing 3 months, the pruritus worsened, and the primary lesions coalesced into annular erythematous plaques (Figure).

After returning to the United States, the patient presented again for medical care and was given ketoconazole cream 1% for presumed tinea corporis, which resulted in no improvement. A dermatologic consultation and evaluation ensued with subsequent microbial workup showing no bacterial growth on wound culture and no fungal elements on a potassium hydroxide preparation. Hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining did not demonstrate any organisms. Tissue cultures for bacteria and acid-fast bacilli showed no growth. A fungal tissue culture ultimately confirmed the presence of Cryptococcus neoformans. A lumbar puncture showed no evidence of Cryptococcus on DNA probe testing. Serologic testing for HIV was negative, and brain magnetic resonance imaging showed no lesions. Sputum culture and staining showed no fungal elements, and a chest radiograph was normal. A diagnosis of PCC was made and therapy with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice daily was initiated, with the intention of completing a 6-month course. During the treatment, the pruritus resolved within 3 weeks and the lesions involuted over 3 months. From the time of onset of the lesions throughout treatment, the patient showed no pulmonary, neurologic, or other systemic symptoms. She currently is healthy with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis mainly affects individuals with underlying immunosuppression, most commonly due to advanced HIV, prolonged treatment with immunosuppressive medications, or organ transplantation.1 The most common route of inoculation is by inhalation of Cryptococcus spores with subsequent hematogenous dissemination.2 Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis with skin lesions and no concomitant systemic involvement has rarely been reported, and

Due to the worldwide deployment of US military service members, exotic cutaneous infectious diseases such as PCC may be encountered in dermatology practice. Prompt clinical and histologic diagnosis is imperative to assess for systemic disease and avoid cutaneous spread and morbidity in US service members and travelers returning home from the Middle East.

To the Editor:

Disseminated cryptococcosis is a well-known opportunistic infection in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, but it is not frequently seen as a primary infection of the skin in immunocompetent hosts. We report a case of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC) of the lower legs in an immunocompetent Iraq War veteran.

A 28-year-old female service member presented to the dermatology clinic with progressively enlarging plaquelike lesions on the shins of 6 months’ duration. The patient had resided and worked as a deployed soldier in the lower level of a bullet hole–laden, pigeon-infested observation tower in southern Iraq 9 months prior to the current presentation. During her 7-month deployment, she reported daily exposure to pigeon excreta on equipment and frequently sustained superficial abrasions and lacerations to the legs due to the cramped and hazardous working environment. The patient noticed intensely pruritic, bugbitelike papular lesions on the shins and calves 1 month after residing in the observation tower. She sought medical treatment and was given hydrocortisone cream 1% and calamine lotion for a presumed irritant dermatitis. Over the ensuing 3 months, the pruritus worsened, and the primary lesions coalesced into annular erythematous plaques (Figure).

After returning to the United States, the patient presented again for medical care and was given ketoconazole cream 1% for presumed tinea corporis, which resulted in no improvement. A dermatologic consultation and evaluation ensued with subsequent microbial workup showing no bacterial growth on wound culture and no fungal elements on a potassium hydroxide preparation. Hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining did not demonstrate any organisms. Tissue cultures for bacteria and acid-fast bacilli showed no growth. A fungal tissue culture ultimately confirmed the presence of Cryptococcus neoformans. A lumbar puncture showed no evidence of Cryptococcus on DNA probe testing. Serologic testing for HIV was negative, and brain magnetic resonance imaging showed no lesions. Sputum culture and staining showed no fungal elements, and a chest radiograph was normal. A diagnosis of PCC was made and therapy with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice daily was initiated, with the intention of completing a 6-month course. During the treatment, the pruritus resolved within 3 weeks and the lesions involuted over 3 months. From the time of onset of the lesions throughout treatment, the patient showed no pulmonary, neurologic, or other systemic symptoms. She currently is healthy with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis mainly affects individuals with underlying immunosuppression, most commonly due to advanced HIV, prolonged treatment with immunosuppressive medications, or organ transplantation.1 The most common route of inoculation is by inhalation of Cryptococcus spores with subsequent hematogenous dissemination.2 Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis with skin lesions and no concomitant systemic involvement has rarely been reported, and

Due to the worldwide deployment of US military service members, exotic cutaneous infectious diseases such as PCC may be encountered in dermatology practice. Prompt clinical and histologic diagnosis is imperative to assess for systemic disease and avoid cutaneous spread and morbidity in US service members and travelers returning home from the Middle East.

- Antony SA, Antony SJ. Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in nonimmunocompromised patients. Cutis. 1995;56:96-98.

- Mirza SA, Phelan M, Rimland D, et al. The changing epidemiology of cryptococcosis: an update from population-based active surveillance in 2 large metropolitan areas, 1992-2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:789-94.

- Kielstein P, Hotzel H, Schmalreck A, et al. Occurrence of Cryptococcus spp. in excreta of pigeons and pet birds. Mycoses. 2000;43:7-15.

- Leão CA, Ferreira-Paim K, Andrade-Silva L, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus gattii in an immunocompetent host [published online October 28, 2010]. Med Mycol. 2011;49:352-355.

- Zorman JV, Zupanc TL, Parac Z, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in a renal transplant recipient: case report. Mycoses. 2010;53:535-537.

- Antony SA, Antony SJ. Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in nonimmunocompromised patients. Cutis. 1995;56:96-98.

- Mirza SA, Phelan M, Rimland D, et al. The changing epidemiology of cryptococcosis: an update from population-based active surveillance in 2 large metropolitan areas, 1992-2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:789-94.

- Kielstein P, Hotzel H, Schmalreck A, et al. Occurrence of Cryptococcus spp. in excreta of pigeons and pet birds. Mycoses. 2000;43:7-15.

- Leão CA, Ferreira-Paim K, Andrade-Silva L, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus gattii in an immunocompetent host [published online October 28, 2010]. Med Mycol. 2011;49:352-355.

- Zorman JV, Zupanc TL, Parac Z, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in a renal transplant recipient: case report. Mycoses. 2010;53:535-537.

Practice Points

- Disseminated cryptococcosis is not commonly seen as a primary cutaneous infection in immunocompetent hosts.

- When encountered, primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC) usually is associated with environments that predispose patients to skin wounds with simultaneous exposure to soil or vegetative debris contaminated with bird excreta.

- The variable presentation of PCC can cause clinical confusion and diagnostic delay; therefore, a high index of suspicion is required for timely diagnosis, particularly in US service members and travelers returning home from endemic areas.

Erythematous Pruritic Plaque on the Cheek

The Diagnosis: Tinea Faciei

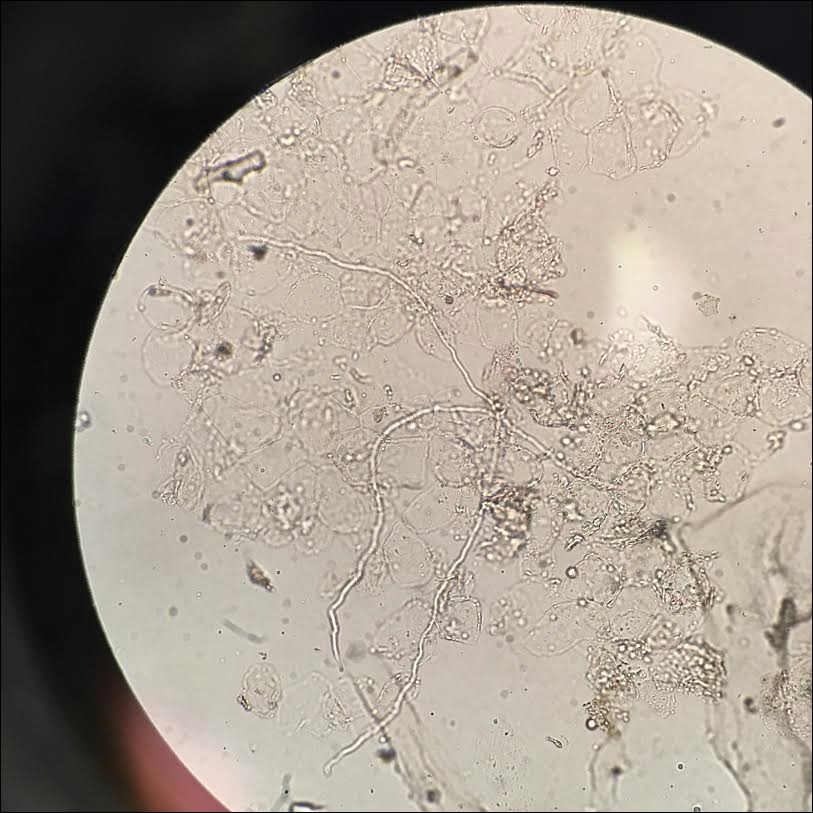

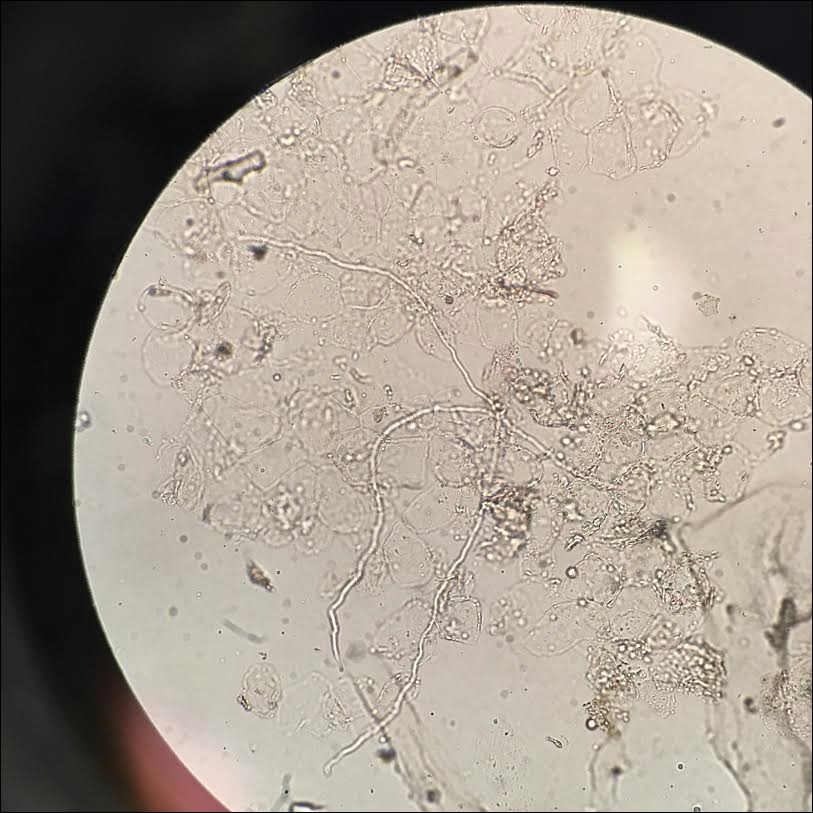

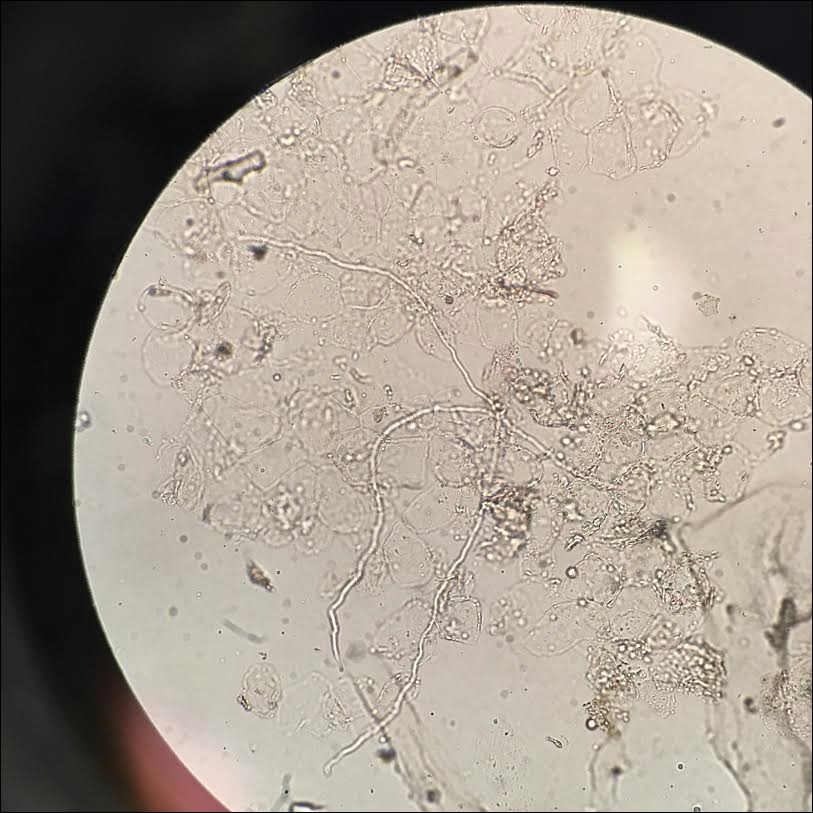

Given the morphology of the plaque, a potassium hydroxide preparation was performed and was positive for hyphal elements consistent with dermatophyte infection (Figure).

Tinea faciei is a fungal infection of the face caused by a dermatophyte that invades the stratum corneum.1 It is transmitted through direct contact with an infected individual or fomite.2 Infections typically are characterized by annular or serpiginous erythematous plaques with a scaly appearance and advancing edge. There may be associated vesicles, papules, or pustules with crusting around the advancing border.3 Tinea faciei can occur concomitantly with other dermatophytic infections and frequently presents atypically due to different characteristics of facial anatomy when compared to other tinea infections. As a result, it often is misdiagnosed.1

Tinea faciei represents roughly 19% of all superficial fungal infections and occurs more commonly in temperate humid regions.4 It can occur at any age but has bimodal peaks in incidence during childhood and early adulthood.5 The most common causative dermatophytes are Trichophyton tonsurans, Microsporum canis, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Trichophyton rubrum.1 Transmission is mainly through direct contact with infected individuals, animals, or soil, which likely occurred during the close quarters and exercises our patient experienced during basic training in the military.

Tinea faciei often is misdiagnosed and treated with topical corticosteroids. The steroids can give a false impression that the rash is resolving by initially decreasing the inflammatory component and reducing scale, which is referred to as tinea incognito. Once the steroid is stopped, however, the fungal infection often returns worse than the original presentation. The differential diagnosis includes subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, periorificial dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, rosacea, erythema annulare centrifugum, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, and contact dermatitis.1,3,6

Diagnosis of tinea faciei is best made with skin scraping of the active border of the lesion. The scraping is treated with potassium hydroxide 10%. Visualizing branching or curving hyphae confirms the diagnosis. Fungal speciation often is not performed due to the long time needed to culture. Wood lamp may fluoresce blue-green if tinea faciei is caused by Microsporum species; however, diagnosis in this manner is limited because other common species do not fluoresce.7

Options for treatment of tinea faciei include topical antifungals for 2 to 6 weeks for localized disease or oral antifungals for more extensive or unresponsive infections for 1 to 8 weeks depending on the agent that is used. If fungal folliculitis is present, oral medication should be given.1 Our patient was treated with oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks with follow-up after that time to ensure resolution.

- Lin RL, Szepietowski JC, Schwartz RA. Tinea faciei, an often deceptive facial eruption. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:437-440.

- Raimer SS, Beightler EL, Hebert AA, et al. Tinea faciei in infants caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:452-454.

- Shapiro L, Cohen HJ. Tinea faciei simulating other dermatoses. JAMA. 1971;215:2106-2107.

- Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51(suppl 4):2-15.

- Jorquera E, Moreno JC, Camacho F. Tinea faciei: epidemiology. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1991;119:101-104.

- Hsu S, Le EH, Khoshevis MR. Differential diagnosis of annular lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:289-296.

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

The Diagnosis: Tinea Faciei

Given the morphology of the plaque, a potassium hydroxide preparation was performed and was positive for hyphal elements consistent with dermatophyte infection (Figure).

Tinea faciei is a fungal infection of the face caused by a dermatophyte that invades the stratum corneum.1 It is transmitted through direct contact with an infected individual or fomite.2 Infections typically are characterized by annular or serpiginous erythematous plaques with a scaly appearance and advancing edge. There may be associated vesicles, papules, or pustules with crusting around the advancing border.3 Tinea faciei can occur concomitantly with other dermatophytic infections and frequently presents atypically due to different characteristics of facial anatomy when compared to other tinea infections. As a result, it often is misdiagnosed.1

Tinea faciei represents roughly 19% of all superficial fungal infections and occurs more commonly in temperate humid regions.4 It can occur at any age but has bimodal peaks in incidence during childhood and early adulthood.5 The most common causative dermatophytes are Trichophyton tonsurans, Microsporum canis, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Trichophyton rubrum.1 Transmission is mainly through direct contact with infected individuals, animals, or soil, which likely occurred during the close quarters and exercises our patient experienced during basic training in the military.

Tinea faciei often is misdiagnosed and treated with topical corticosteroids. The steroids can give a false impression that the rash is resolving by initially decreasing the inflammatory component and reducing scale, which is referred to as tinea incognito. Once the steroid is stopped, however, the fungal infection often returns worse than the original presentation. The differential diagnosis includes subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, periorificial dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, rosacea, erythema annulare centrifugum, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, and contact dermatitis.1,3,6

Diagnosis of tinea faciei is best made with skin scraping of the active border of the lesion. The scraping is treated with potassium hydroxide 10%. Visualizing branching or curving hyphae confirms the diagnosis. Fungal speciation often is not performed due to the long time needed to culture. Wood lamp may fluoresce blue-green if tinea faciei is caused by Microsporum species; however, diagnosis in this manner is limited because other common species do not fluoresce.7

Options for treatment of tinea faciei include topical antifungals for 2 to 6 weeks for localized disease or oral antifungals for more extensive or unresponsive infections for 1 to 8 weeks depending on the agent that is used. If fungal folliculitis is present, oral medication should be given.1 Our patient was treated with oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks with follow-up after that time to ensure resolution.

The Diagnosis: Tinea Faciei

Given the morphology of the plaque, a potassium hydroxide preparation was performed and was positive for hyphal elements consistent with dermatophyte infection (Figure).

Tinea faciei is a fungal infection of the face caused by a dermatophyte that invades the stratum corneum.1 It is transmitted through direct contact with an infected individual or fomite.2 Infections typically are characterized by annular or serpiginous erythematous plaques with a scaly appearance and advancing edge. There may be associated vesicles, papules, or pustules with crusting around the advancing border.3 Tinea faciei can occur concomitantly with other dermatophytic infections and frequently presents atypically due to different characteristics of facial anatomy when compared to other tinea infections. As a result, it often is misdiagnosed.1

Tinea faciei represents roughly 19% of all superficial fungal infections and occurs more commonly in temperate humid regions.4 It can occur at any age but has bimodal peaks in incidence during childhood and early adulthood.5 The most common causative dermatophytes are Trichophyton tonsurans, Microsporum canis, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Trichophyton rubrum.1 Transmission is mainly through direct contact with infected individuals, animals, or soil, which likely occurred during the close quarters and exercises our patient experienced during basic training in the military.

Tinea faciei often is misdiagnosed and treated with topical corticosteroids. The steroids can give a false impression that the rash is resolving by initially decreasing the inflammatory component and reducing scale, which is referred to as tinea incognito. Once the steroid is stopped, however, the fungal infection often returns worse than the original presentation. The differential diagnosis includes subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, periorificial dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, rosacea, erythema annulare centrifugum, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, and contact dermatitis.1,3,6

Diagnosis of tinea faciei is best made with skin scraping of the active border of the lesion. The scraping is treated with potassium hydroxide 10%. Visualizing branching or curving hyphae confirms the diagnosis. Fungal speciation often is not performed due to the long time needed to culture. Wood lamp may fluoresce blue-green if tinea faciei is caused by Microsporum species; however, diagnosis in this manner is limited because other common species do not fluoresce.7

Options for treatment of tinea faciei include topical antifungals for 2 to 6 weeks for localized disease or oral antifungals for more extensive or unresponsive infections for 1 to 8 weeks depending on the agent that is used. If fungal folliculitis is present, oral medication should be given.1 Our patient was treated with oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks with follow-up after that time to ensure resolution.

- Lin RL, Szepietowski JC, Schwartz RA. Tinea faciei, an often deceptive facial eruption. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:437-440.

- Raimer SS, Beightler EL, Hebert AA, et al. Tinea faciei in infants caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:452-454.

- Shapiro L, Cohen HJ. Tinea faciei simulating other dermatoses. JAMA. 1971;215:2106-2107.

- Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51(suppl 4):2-15.

- Jorquera E, Moreno JC, Camacho F. Tinea faciei: epidemiology. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1991;119:101-104.

- Hsu S, Le EH, Khoshevis MR. Differential diagnosis of annular lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:289-296.

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

- Lin RL, Szepietowski JC, Schwartz RA. Tinea faciei, an often deceptive facial eruption. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:437-440.

- Raimer SS, Beightler EL, Hebert AA, et al. Tinea faciei in infants caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:452-454.

- Shapiro L, Cohen HJ. Tinea faciei simulating other dermatoses. JAMA. 1971;215:2106-2107.

- Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51(suppl 4):2-15.

- Jorquera E, Moreno JC, Camacho F. Tinea faciei: epidemiology. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1991;119:101-104.

- Hsu S, Le EH, Khoshevis MR. Differential diagnosis of annular lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:289-296.

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

A 19-year-old man with a medical history of keloids presented with a slowly enlarging, red, itchy plaque on the left cheek of 1 year's duration that first began to develop during basic training in the military. The patient denied other pain, pruritus, or separate dermatitis. He initially was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1%, which he used for 8 days prior to referral to the dermatology department. The patient denied other acute concerns. On physical examination, multiple erythematous papules coalescing into a large, 10-cm, papulosquamous, arciform plaque were noted on the left preauricular cheek.

ICYMI: Durvalumab boosts overall survival in stage III NSCLC

Patients with unresectable stage III non–small cell lung cancer who received durvalumab had their overall and progression-free survival boosted by about 12 months, compared with patients who received a placebo, according to results of the multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 PACIFIC trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018 Sep 25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809697).

We covered this story at the World Conference on Lung Cancer before it was published in the journal. Find our coverage at the link below.

Patients with unresectable stage III non–small cell lung cancer who received durvalumab had their overall and progression-free survival boosted by about 12 months, compared with patients who received a placebo, according to results of the multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 PACIFIC trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018 Sep 25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809697).

We covered this story at the World Conference on Lung Cancer before it was published in the journal. Find our coverage at the link below.

Patients with unresectable stage III non–small cell lung cancer who received durvalumab had their overall and progression-free survival boosted by about 12 months, compared with patients who received a placebo, according to results of the multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 PACIFIC trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018 Sep 25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809697).

We covered this story at the World Conference on Lung Cancer before it was published in the journal. Find our coverage at the link below.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Self-report of prenatal marijuana use not very reliable

Even in the setting of legalized marijuana use, estimated prevalence of marijuana use during pregnancy was lower by self-report than it was by umbilical cord testing.

Torri D. Metz, MD, of the University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City, and her colleagues surveyed women at two urban hospitals in Colorado, which has legalized both medical and recreational use of marijuana. They found that, while 6% of the 116 women in the study reported using marijuana in the past 30 days, umbilical cord testing showed as many as 22% had detectable levels of 11-nor-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol-9-carboxylic, and 10% had levels above quantification.

The majority of studies of maternal marijuana use during pregnancy rely on self-report, so this could affect attempts to assess the effects of such prenatal use, they said.

Adverse outcomes associated with marijuana use during pregnancy include fetal growth restriction, small for gestational age, preterm birth, and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes, studies have shown.

Read more in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Even in the setting of legalized marijuana use, estimated prevalence of marijuana use during pregnancy was lower by self-report than it was by umbilical cord testing.

Torri D. Metz, MD, of the University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City, and her colleagues surveyed women at two urban hospitals in Colorado, which has legalized both medical and recreational use of marijuana. They found that, while 6% of the 116 women in the study reported using marijuana in the past 30 days, umbilical cord testing showed as many as 22% had detectable levels of 11-nor-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol-9-carboxylic, and 10% had levels above quantification.

The majority of studies of maternal marijuana use during pregnancy rely on self-report, so this could affect attempts to assess the effects of such prenatal use, they said.

Adverse outcomes associated with marijuana use during pregnancy include fetal growth restriction, small for gestational age, preterm birth, and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes, studies have shown.

Read more in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Even in the setting of legalized marijuana use, estimated prevalence of marijuana use during pregnancy was lower by self-report than it was by umbilical cord testing.

Torri D. Metz, MD, of the University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City, and her colleagues surveyed women at two urban hospitals in Colorado, which has legalized both medical and recreational use of marijuana. They found that, while 6% of the 116 women in the study reported using marijuana in the past 30 days, umbilical cord testing showed as many as 22% had detectable levels of 11-nor-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol-9-carboxylic, and 10% had levels above quantification.

The majority of studies of maternal marijuana use during pregnancy rely on self-report, so this could affect attempts to assess the effects of such prenatal use, they said.

Adverse outcomes associated with marijuana use during pregnancy include fetal growth restriction, small for gestational age, preterm birth, and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes, studies have shown.

Read more in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Study elicits patients’ most disturbing epilepsy symptoms

NEW ORLEANS – according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. The most prominent symptoms and effects on daily life may differ in the early, middle, and late stages of the disease, the results suggest.

Lead study author Jacqueline A. French, MD, professor of neurology at New York University, and her colleagues interviewed 62 patients with focal-onset epilepsy to examine patients’ experiences living with epilepsy. The investigators focused on salient symptoms and functional impacts – those that were reported by at least 50% of patients and were associated with a high degree of disturbance (patients rated them 5 or greater on a scale from 0 [no disturbance] to 10 [high disturbance]).

Of 51 symptoms that patients described during the interviews, the following 8 met the salience criteria for the total cohort: twitching or tremors, confusion, difficulty in talking, loss of awareness of others’ presence, stiffening, impaired consciousness or loss of consciousness, difficulty in remembering, and dizziness or lightheadedness. Patients reported salient functional impacts on driving and transportation, work and school, and leisure and social activities. Some symptoms met salience criteria among patients in certain stages of the disease (for example, tongue biting in patients with early-stage epilepsy and anxiety, fear, or panic in late-stage epilepsy) but not among patients in the other cohorts.

“These findings underscore the need to consider all these experiences when developing patient-reported outcome measures for use in clinical trials,” said Dr. French and her colleagues. “It may be useful to tailor measures of patient experiences to the patient’s stage of disease.”

Previous qualitative studies of epilepsy symptoms and burdens were based on small numbers of patients and interviews at a single center. For the present study, the researchers conducted qualitative, semistructured, in-person interviews with adults with focal epilepsy in different areas of the United States (such as California, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania). Patients were grouped by early, middle, or late disease stage. Patients in the early cohort (n = 19) had at least two seizures in the past year, a diagnosis of focal epilepsy in the past year, and had not yet received antiepileptic drug (AED) treatment or had received treatment with only one AED and had not failed treatment. Patients in the middle cohort (n = 17) had at least one seizure in the past year, a diagnosis of focal epilepsy within the past 5 years, and had failed one AED because of lack of efficacy or had received their first add-on AED. Patients in the late cohort (n = 26) had at least one seizure every 3 months during the past year, a diagnosis of focal epilepsy at age 12 years or older, and inadequate response to treatment of at least 3 months with two AEDs that were tolerated and appropriately chosen.

Patients’ mean age was 37 years (range, 19-60 years), 73% were female, 79% were white, 69% had a college degree as their highest level of education, and 65% were employed. Patients’ seizure types included simple partial without motor signs (52%), simple partial with motor signs (16%), complex partial (68%), or secondarily generalized (65%).

While driving or transportation was a salient impact for all three groups, memory loss was a salient impact in the early and middle cohorts only. Headaches and sadness or depression were salient impacts for the late cohort only.

This study was funded by Eisai and two of the authors are former or current employees of Eisai.

SOURCE: French JA et al. AES 2018, Abstract 1.196.

NEW ORLEANS – according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. The most prominent symptoms and effects on daily life may differ in the early, middle, and late stages of the disease, the results suggest.

Lead study author Jacqueline A. French, MD, professor of neurology at New York University, and her colleagues interviewed 62 patients with focal-onset epilepsy to examine patients’ experiences living with epilepsy. The investigators focused on salient symptoms and functional impacts – those that were reported by at least 50% of patients and were associated with a high degree of disturbance (patients rated them 5 or greater on a scale from 0 [no disturbance] to 10 [high disturbance]).

Of 51 symptoms that patients described during the interviews, the following 8 met the salience criteria for the total cohort: twitching or tremors, confusion, difficulty in talking, loss of awareness of others’ presence, stiffening, impaired consciousness or loss of consciousness, difficulty in remembering, and dizziness or lightheadedness. Patients reported salient functional impacts on driving and transportation, work and school, and leisure and social activities. Some symptoms met salience criteria among patients in certain stages of the disease (for example, tongue biting in patients with early-stage epilepsy and anxiety, fear, or panic in late-stage epilepsy) but not among patients in the other cohorts.

“These findings underscore the need to consider all these experiences when developing patient-reported outcome measures for use in clinical trials,” said Dr. French and her colleagues. “It may be useful to tailor measures of patient experiences to the patient’s stage of disease.”

Previous qualitative studies of epilepsy symptoms and burdens were based on small numbers of patients and interviews at a single center. For the present study, the researchers conducted qualitative, semistructured, in-person interviews with adults with focal epilepsy in different areas of the United States (such as California, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania). Patients were grouped by early, middle, or late disease stage. Patients in the early cohort (n = 19) had at least two seizures in the past year, a diagnosis of focal epilepsy in the past year, and had not yet received antiepileptic drug (AED) treatment or had received treatment with only one AED and had not failed treatment. Patients in the middle cohort (n = 17) had at least one seizure in the past year, a diagnosis of focal epilepsy within the past 5 years, and had failed one AED because of lack of efficacy or had received their first add-on AED. Patients in the late cohort (n = 26) had at least one seizure every 3 months during the past year, a diagnosis of focal epilepsy at age 12 years or older, and inadequate response to treatment of at least 3 months with two AEDs that were tolerated and appropriately chosen.

Patients’ mean age was 37 years (range, 19-60 years), 73% were female, 79% were white, 69% had a college degree as their highest level of education, and 65% were employed. Patients’ seizure types included simple partial without motor signs (52%), simple partial with motor signs (16%), complex partial (68%), or secondarily generalized (65%).

While driving or transportation was a salient impact for all three groups, memory loss was a salient impact in the early and middle cohorts only. Headaches and sadness or depression were salient impacts for the late cohort only.

This study was funded by Eisai and two of the authors are former or current employees of Eisai.

SOURCE: French JA et al. AES 2018, Abstract 1.196.

NEW ORLEANS – according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. The most prominent symptoms and effects on daily life may differ in the early, middle, and late stages of the disease, the results suggest.

Lead study author Jacqueline A. French, MD, professor of neurology at New York University, and her colleagues interviewed 62 patients with focal-onset epilepsy to examine patients’ experiences living with epilepsy. The investigators focused on salient symptoms and functional impacts – those that were reported by at least 50% of patients and were associated with a high degree of disturbance (patients rated them 5 or greater on a scale from 0 [no disturbance] to 10 [high disturbance]).

Of 51 symptoms that patients described during the interviews, the following 8 met the salience criteria for the total cohort: twitching or tremors, confusion, difficulty in talking, loss of awareness of others’ presence, stiffening, impaired consciousness or loss of consciousness, difficulty in remembering, and dizziness or lightheadedness. Patients reported salient functional impacts on driving and transportation, work and school, and leisure and social activities. Some symptoms met salience criteria among patients in certain stages of the disease (for example, tongue biting in patients with early-stage epilepsy and anxiety, fear, or panic in late-stage epilepsy) but not among patients in the other cohorts.

“These findings underscore the need to consider all these experiences when developing patient-reported outcome measures for use in clinical trials,” said Dr. French and her colleagues. “It may be useful to tailor measures of patient experiences to the patient’s stage of disease.”

Previous qualitative studies of epilepsy symptoms and burdens were based on small numbers of patients and interviews at a single center. For the present study, the researchers conducted qualitative, semistructured, in-person interviews with adults with focal epilepsy in different areas of the United States (such as California, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania). Patients were grouped by early, middle, or late disease stage. Patients in the early cohort (n = 19) had at least two seizures in the past year, a diagnosis of focal epilepsy in the past year, and had not yet received antiepileptic drug (AED) treatment or had received treatment with only one AED and had not failed treatment. Patients in the middle cohort (n = 17) had at least one seizure in the past year, a diagnosis of focal epilepsy within the past 5 years, and had failed one AED because of lack of efficacy or had received their first add-on AED. Patients in the late cohort (n = 26) had at least one seizure every 3 months during the past year, a diagnosis of focal epilepsy at age 12 years or older, and inadequate response to treatment of at least 3 months with two AEDs that were tolerated and appropriately chosen.

Patients’ mean age was 37 years (range, 19-60 years), 73% were female, 79% were white, 69% had a college degree as their highest level of education, and 65% were employed. Patients’ seizure types included simple partial without motor signs (52%), simple partial with motor signs (16%), complex partial (68%), or secondarily generalized (65%).

While driving or transportation was a salient impact for all three groups, memory loss was a salient impact in the early and middle cohorts only. Headaches and sadness or depression were salient impacts for the late cohort only.

This study was funded by Eisai and two of the authors are former or current employees of Eisai.

SOURCE: French JA et al. AES 2018, Abstract 1.196.

REPORTING FROM AES 2018

Key clinical point: The most prominent symptoms and functional impacts of epilepsy may differ in the early, middle, and late stages of the disease.

Major finding: More than 50% of patients reported functional impacts on driving and transportation, work and school, and leisure and social activities.

Study details: An analysis of data from semistructured interviews with 62 adults with focal epilepsy.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Eisai and two of the authors are former or current employees of Eisai.

Source: French JA et al. AES 2018, Abstract 1.196.

AHA: Statins associated with high degree of safety

The benefits of statins highly offset the associated risks in appropriate patients, according to a scientific statement issued by the American Heart Association.

“The review covers the general patient population, as well as demographic subgroups, including the elderly, children, pregnant women, East Asians, and patients with specific conditions.” wrote Connie B. Newman, MD, of New York University, together with her colleagues. The report is in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology.

After an extensive review of the literature pertaining to statin safety and tolerability, Dr. Newman and her colleagues reported the compiled findings from several randomized controlled trials, in addition to observational data, where required. They found that the risk of serious muscle complications, such as rhabdomyolysis, attributable to statin use was less than 0.1%. Furthermore, they noted that the risk of serious hepatotoxicity was even less likely, occurring in about 1 in 10,000 patients treated with therapy.

“There is no convincing evidence for a causal relationship between statins and cancer, cataracts, cognitive dysfunction, peripheral neuropathy, erectile dysfunction, or tendinitis,” the experts wrote. “In U.S. clinical practices, roughly 10% of patients stop taking a statin because of subjective complaints, most commonly muscle symptoms without raised creatine kinase,” they further reported.

Contrastingly, data from randomized trials have shown that the change in the incidence of muscle-related symptoms in patients treated with statins versus placebo is less than 1%. Moreover, the incidence is even lower, with an estimated rate of 0.1%, in those who stopped statin therapy because of these symptoms. Given these results, Dr. Newman and her colleagues said that muscle-related symptoms among statin-treated patients are not due to the pharmacological activity of the statin.

“Restarting statin therapy in these patients can be challenging, but it is important, especially in patients at high risk of cardiovascular events, for whom prevention of these events is a priority,” they added.