User login

Blast crisis, no crisis? Caring for the apathetic patient

The diagnosis was straightforward. My patient’s reaction was not.

One Saturday evening, I receive a call from the emergency room about a man with a very high white blood cell count. For the past 7 years, he had chronic myeloid leukemia – a cancer, but one of the few that can be well controlled for years. The discovery of the medications that can do it revolutionized care for the disease.

For the last 7 years, Mr. C didn’t take that medication regularly. He was young, with no other medical problems, and this was the only medication he was supposed to take. But his use was sporadic at best.

What was it, I wondered? Cost? Side effects? Not understanding the seriousness of having leukemia? No, the medication was fully covered by his insurance. No, he tolerated it well. Instead, his on-and-off medication schedule came across as a strange sense of apathy. He didn’t seem to recognize his agency in his own life.

Now, not only is his white count extremely high, but the majority are the cancerous cells. I look at his blood under the microscope – blasts everywhere. He has progressed from a chronic, indolent disease that can be kept at bay into the dreaded blast crisis, which is essentially an acute leukemia but even more challenging to treat.

It is very serious. I tell him this. “I am worried your leukemia has progressed into what we call a blast crisis,” I say. “Has anyone ever talked to you about this before?”

“Hmm, I think Dr. M may have said something,” he says. His medical chart over the last 7 years was populated with notes from his hematologist documenting their discussions of this possibility.

“This is serious,” I continue. “You will need to come into the hospital and we need to start medication to lower your white count. Otherwise you could have a stroke.”

“Okay.”

“As the white count comes down, your cells will break open and the chemicals in them can make you very sick. So we will have to check your blood often to watch for this.”

“Got it.”

“And we will change your chemotherapy pill.” I pause, letting it sink in, then repeat for emphasis: “This is very serious.”

“Sure thing, Doc.”

“I know I’ve said a lot. What are your thoughts?”

He looks at his wife, then back at me. He seems unfazed. Just as unfazed as when his hematologist warned this could happen. Just as unfazed as the day he learned his diagnosis.

He smiles and shrugs. “What will be, will be.”

As I listened to him, I honestly couldn’t tell if this was the best coping mechanism I had ever seen or the worst.

On one hand, his apathy had hurt him, clearly and indisputably. Refusing to acknowledge his agency in his medical outcomes allowed him to be cavalier about taking the cure. The cure was in a bottle on his kitchen shelf, an arm’s reach away, and he chose to reach elsewhere.

On the other hand, it was unusual to see someone so at peace with being so critically ill. His acceptance of his new reality was refreshing. There were no heartbreaking questions about whether this was his fault. There was no agonizing over what could have been. His apathy gave him closure and his loved ones comfort.

I’ve written before about how a cancer diagnosis involves holding two seemingly competing ideas in one’s mind at once. Last month, I wrote about how it is possible to be realistic about a grim prognosis while retaining hope that a treatment may work. I discussed that realism and hopefulness are compatible beliefs, and it’s okay – preferred, even – to hold them at once.

Mr. C’s strange sense of apathy made me think about another mental limbo, this one involving control. As doctors and patients, we like when we have agency over outcomes. Take these medications, and you will be okay. Undergo this procedure, and you will reduce your risk of recurrence. At the same time, poor outcomes still occur when everything is done “right.” When that happens, it can be psychologically beneficial to relinquish control. Doing so discards the unhelpful emotions of guilt and blame in favor of acceptance.

Mr. C’s apathy seemed to be present from day 1. But now, in a dire blast crisis, what was once a harmful attitude actually became a helpful one.

His “what will be, will be” attitude wasn’t inherently maladaptive; it was ill timed. Under the right circumstances, well-placed apathy can be leveraged as a positive coping mechanism.

But alas, if only there were a switch to turn on the right emotion at the right time. There’s no right or wrong or sensible reaction to cancer. There’s only a swirl of messy, overwhelming feelings. It’s trying to bring effective emotions to light at the right time while playing whack-a-mole with the others. It’s cognitive dissonance. It’s exhausting. Cancer doesn’t create personalities; it surfaces them.

It’s the last day of Mr. C’s hospitalization. His blast crisis is amazingly under good control.

“So,” I say. “Will you take your medications now?”

“Sure,” he says instinctively. I look at him. “I mean, honestly, Doc? I’m not sure.”

As we shake hands, I wonder if I’ll ever truly understand Mr. C’s motivations. But I can’t wonder too long. I can only control my part: I hand him his medications and wish him luck.

Minor details of this story were changed to protect privacy.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz.

The diagnosis was straightforward. My patient’s reaction was not.

One Saturday evening, I receive a call from the emergency room about a man with a very high white blood cell count. For the past 7 years, he had chronic myeloid leukemia – a cancer, but one of the few that can be well controlled for years. The discovery of the medications that can do it revolutionized care for the disease.

For the last 7 years, Mr. C didn’t take that medication regularly. He was young, with no other medical problems, and this was the only medication he was supposed to take. But his use was sporadic at best.

What was it, I wondered? Cost? Side effects? Not understanding the seriousness of having leukemia? No, the medication was fully covered by his insurance. No, he tolerated it well. Instead, his on-and-off medication schedule came across as a strange sense of apathy. He didn’t seem to recognize his agency in his own life.

Now, not only is his white count extremely high, but the majority are the cancerous cells. I look at his blood under the microscope – blasts everywhere. He has progressed from a chronic, indolent disease that can be kept at bay into the dreaded blast crisis, which is essentially an acute leukemia but even more challenging to treat.

It is very serious. I tell him this. “I am worried your leukemia has progressed into what we call a blast crisis,” I say. “Has anyone ever talked to you about this before?”

“Hmm, I think Dr. M may have said something,” he says. His medical chart over the last 7 years was populated with notes from his hematologist documenting their discussions of this possibility.

“This is serious,” I continue. “You will need to come into the hospital and we need to start medication to lower your white count. Otherwise you could have a stroke.”

“Okay.”

“As the white count comes down, your cells will break open and the chemicals in them can make you very sick. So we will have to check your blood often to watch for this.”

“Got it.”

“And we will change your chemotherapy pill.” I pause, letting it sink in, then repeat for emphasis: “This is very serious.”

“Sure thing, Doc.”

“I know I’ve said a lot. What are your thoughts?”

He looks at his wife, then back at me. He seems unfazed. Just as unfazed as when his hematologist warned this could happen. Just as unfazed as the day he learned his diagnosis.

He smiles and shrugs. “What will be, will be.”

As I listened to him, I honestly couldn’t tell if this was the best coping mechanism I had ever seen or the worst.

On one hand, his apathy had hurt him, clearly and indisputably. Refusing to acknowledge his agency in his medical outcomes allowed him to be cavalier about taking the cure. The cure was in a bottle on his kitchen shelf, an arm’s reach away, and he chose to reach elsewhere.

On the other hand, it was unusual to see someone so at peace with being so critically ill. His acceptance of his new reality was refreshing. There were no heartbreaking questions about whether this was his fault. There was no agonizing over what could have been. His apathy gave him closure and his loved ones comfort.

I’ve written before about how a cancer diagnosis involves holding two seemingly competing ideas in one’s mind at once. Last month, I wrote about how it is possible to be realistic about a grim prognosis while retaining hope that a treatment may work. I discussed that realism and hopefulness are compatible beliefs, and it’s okay – preferred, even – to hold them at once.

Mr. C’s strange sense of apathy made me think about another mental limbo, this one involving control. As doctors and patients, we like when we have agency over outcomes. Take these medications, and you will be okay. Undergo this procedure, and you will reduce your risk of recurrence. At the same time, poor outcomes still occur when everything is done “right.” When that happens, it can be psychologically beneficial to relinquish control. Doing so discards the unhelpful emotions of guilt and blame in favor of acceptance.

Mr. C’s apathy seemed to be present from day 1. But now, in a dire blast crisis, what was once a harmful attitude actually became a helpful one.

His “what will be, will be” attitude wasn’t inherently maladaptive; it was ill timed. Under the right circumstances, well-placed apathy can be leveraged as a positive coping mechanism.

But alas, if only there were a switch to turn on the right emotion at the right time. There’s no right or wrong or sensible reaction to cancer. There’s only a swirl of messy, overwhelming feelings. It’s trying to bring effective emotions to light at the right time while playing whack-a-mole with the others. It’s cognitive dissonance. It’s exhausting. Cancer doesn’t create personalities; it surfaces them.

It’s the last day of Mr. C’s hospitalization. His blast crisis is amazingly under good control.

“So,” I say. “Will you take your medications now?”

“Sure,” he says instinctively. I look at him. “I mean, honestly, Doc? I’m not sure.”

As we shake hands, I wonder if I’ll ever truly understand Mr. C’s motivations. But I can’t wonder too long. I can only control my part: I hand him his medications and wish him luck.

Minor details of this story were changed to protect privacy.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz.

The diagnosis was straightforward. My patient’s reaction was not.

One Saturday evening, I receive a call from the emergency room about a man with a very high white blood cell count. For the past 7 years, he had chronic myeloid leukemia – a cancer, but one of the few that can be well controlled for years. The discovery of the medications that can do it revolutionized care for the disease.

For the last 7 years, Mr. C didn’t take that medication regularly. He was young, with no other medical problems, and this was the only medication he was supposed to take. But his use was sporadic at best.

What was it, I wondered? Cost? Side effects? Not understanding the seriousness of having leukemia? No, the medication was fully covered by his insurance. No, he tolerated it well. Instead, his on-and-off medication schedule came across as a strange sense of apathy. He didn’t seem to recognize his agency in his own life.

Now, not only is his white count extremely high, but the majority are the cancerous cells. I look at his blood under the microscope – blasts everywhere. He has progressed from a chronic, indolent disease that can be kept at bay into the dreaded blast crisis, which is essentially an acute leukemia but even more challenging to treat.

It is very serious. I tell him this. “I am worried your leukemia has progressed into what we call a blast crisis,” I say. “Has anyone ever talked to you about this before?”

“Hmm, I think Dr. M may have said something,” he says. His medical chart over the last 7 years was populated with notes from his hematologist documenting their discussions of this possibility.

“This is serious,” I continue. “You will need to come into the hospital and we need to start medication to lower your white count. Otherwise you could have a stroke.”

“Okay.”

“As the white count comes down, your cells will break open and the chemicals in them can make you very sick. So we will have to check your blood often to watch for this.”

“Got it.”

“And we will change your chemotherapy pill.” I pause, letting it sink in, then repeat for emphasis: “This is very serious.”

“Sure thing, Doc.”

“I know I’ve said a lot. What are your thoughts?”

He looks at his wife, then back at me. He seems unfazed. Just as unfazed as when his hematologist warned this could happen. Just as unfazed as the day he learned his diagnosis.

He smiles and shrugs. “What will be, will be.”

As I listened to him, I honestly couldn’t tell if this was the best coping mechanism I had ever seen or the worst.

On one hand, his apathy had hurt him, clearly and indisputably. Refusing to acknowledge his agency in his medical outcomes allowed him to be cavalier about taking the cure. The cure was in a bottle on his kitchen shelf, an arm’s reach away, and he chose to reach elsewhere.

On the other hand, it was unusual to see someone so at peace with being so critically ill. His acceptance of his new reality was refreshing. There were no heartbreaking questions about whether this was his fault. There was no agonizing over what could have been. His apathy gave him closure and his loved ones comfort.

I’ve written before about how a cancer diagnosis involves holding two seemingly competing ideas in one’s mind at once. Last month, I wrote about how it is possible to be realistic about a grim prognosis while retaining hope that a treatment may work. I discussed that realism and hopefulness are compatible beliefs, and it’s okay – preferred, even – to hold them at once.

Mr. C’s strange sense of apathy made me think about another mental limbo, this one involving control. As doctors and patients, we like when we have agency over outcomes. Take these medications, and you will be okay. Undergo this procedure, and you will reduce your risk of recurrence. At the same time, poor outcomes still occur when everything is done “right.” When that happens, it can be psychologically beneficial to relinquish control. Doing so discards the unhelpful emotions of guilt and blame in favor of acceptance.

Mr. C’s apathy seemed to be present from day 1. But now, in a dire blast crisis, what was once a harmful attitude actually became a helpful one.

His “what will be, will be” attitude wasn’t inherently maladaptive; it was ill timed. Under the right circumstances, well-placed apathy can be leveraged as a positive coping mechanism.

But alas, if only there were a switch to turn on the right emotion at the right time. There’s no right or wrong or sensible reaction to cancer. There’s only a swirl of messy, overwhelming feelings. It’s trying to bring effective emotions to light at the right time while playing whack-a-mole with the others. It’s cognitive dissonance. It’s exhausting. Cancer doesn’t create personalities; it surfaces them.

It’s the last day of Mr. C’s hospitalization. His blast crisis is amazingly under good control.

“So,” I say. “Will you take your medications now?”

“Sure,” he says instinctively. I look at him. “I mean, honestly, Doc? I’m not sure.”

As we shake hands, I wonder if I’ll ever truly understand Mr. C’s motivations. But I can’t wonder too long. I can only control my part: I hand him his medications and wish him luck.

Minor details of this story were changed to protect privacy.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz.

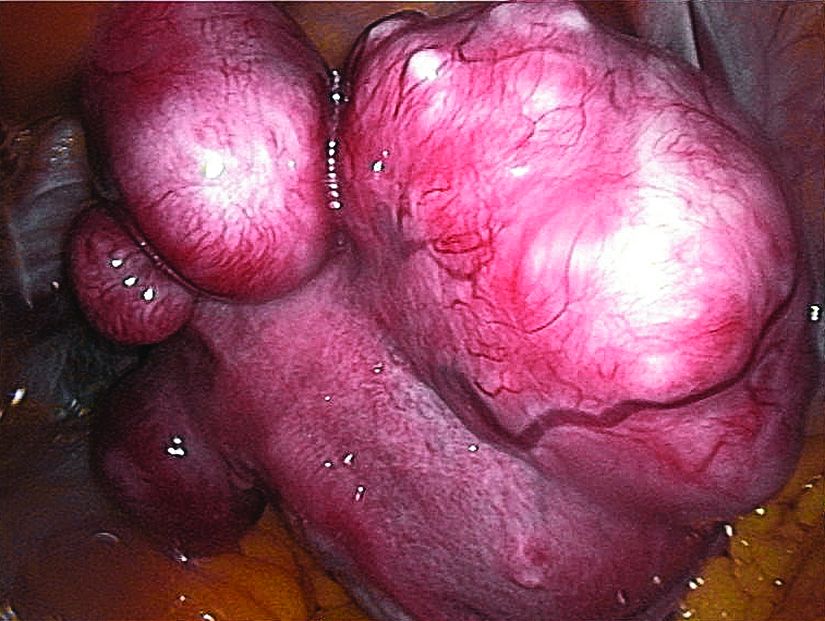

Ulipristal acetate tops placebo for uterine leiomyomas

according to a study of the intention-to-treat populations of the randomized, double-blind, phase III VENUS I and VENUS II trials.

In these pivotal studies, ulipristal (Ella) at either 5 mg or 10 mg significantly improved both rate of and time to amenorrhea, noted Andrea S. Lukes, MD, of Carolina Women’s Research and Wellness Center in Durham, N.C. To assess effects on quality of life, she and her associates analyzed baseline and 12-week responses to the widely validated Uterine Fibroid Symptom Health-Related Quality of Life (UFS-QOL) questionnaire, which examined factors such as symptom severity, energy and mood, physical and social activities, self-consciousness, and sexual functioning.

Among 589 patients in the analysis, 169 received placebo, 215 received 5 mg ulipristal, and 205 received 10 mg ulipristal. At baseline, average total quality of life scores on UFS-QOL were 33 (standard deviation, 220), 32 (SD, 21), and 36 (SD, 23), respectively, the researchers wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

After 12 weeks of treatment, both doses of ulipristal were associated with significantly greater improvements on all UFS-QOL scales, compared with placebo (P less than .001). For example, on a scale of 0-100, symptom severity improved by a mean of 23 with ulipristal 5 mg and by a mean of 30 with ulipristal 10 mg (both P less than .001 versus placebo).

“Although a small proportion of patients experienced no change or some worsening in these outcomes, the majority of women reported clear improvements; for example, more than 70% of patients in the ulipristal treatment arms achieved a meaningful improvement of 30 or more points on the Revised Activities subscale,” the researchers wrote.

Additionally, significantly greater improvements in physical and social activities were seen for both ulipristal doses, compared with placebo, from baseline to the end of treatment.

The VENUS II trial included two 12-week treatment courses. In this trial, women who switched from ulipristal to placebo experienced some worsening in quality of life, while those who switched from placebo to ulipristal improved their UFS-QOL scores, the investigators said. Patients who stayed on ulipristal throughout continued to benefit from one treatment course to the next.

The researchers concluded that the findings, “taken together with the significant improvements in amenorrhea, suggest that ulipristal is a promising, noninvasive treatment option for women suffering from symptomatic uterine leiomyomas.”

Allergan provided funding. Dr. Lukes disclosed ties to Allergan, AbbVie, Myovant, Merck, and several other companies. Four of the coauthors are employees of Allergan, and the two remaining coauthors had links to a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Lukes AS et al. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133 (5):869-78.

In this study, 77%-87% of women who received ulipristal acetate reported more than a 20-point improvement in health-related quality of life, compared with only 36% of placebo recipients, Joanna L. Hatfield, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“However, women with leiomyomas report a 51-point mean improvement after hysterectomy,” she noted. “Clinicians need to keep this difference in mind when counseling women with leiomyomas.”

Ulipristal can cause fatigue and weight gain leading to treatment discontinuation, she noted. Very rare cases of liver failure also have been reported, and there is no evidence that liver enzyme screening identifies patients at risk.

Nonetheless, for the approximately half of women with symptomatic leiomyomas who desire uterine-sparing treatment, selective progesterone receptor modulators like ulipristal offer “a noninvasive way to manage bleeding and bulk symptoms,” Dr. Hatfield said.

She advocated for long-term safety studies and a large pregnancy registry, calling ulipristal “neither a panacea nor a Pandora’s box,” but a choice that “lies somewhere in the middle, just [like] nearly all options that present themselves in a woman’s life.”

Dr. Hatfield is director of the fibroid program at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. She did not report having conflicts of interest. She wrote an editorial accompanying the article by AS Lukes et al. (Obstet Gynecol. 2019 May;133[5]:867-8).

In this study, 77%-87% of women who received ulipristal acetate reported more than a 20-point improvement in health-related quality of life, compared with only 36% of placebo recipients, Joanna L. Hatfield, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“However, women with leiomyomas report a 51-point mean improvement after hysterectomy,” she noted. “Clinicians need to keep this difference in mind when counseling women with leiomyomas.”

Ulipristal can cause fatigue and weight gain leading to treatment discontinuation, she noted. Very rare cases of liver failure also have been reported, and there is no evidence that liver enzyme screening identifies patients at risk.

Nonetheless, for the approximately half of women with symptomatic leiomyomas who desire uterine-sparing treatment, selective progesterone receptor modulators like ulipristal offer “a noninvasive way to manage bleeding and bulk symptoms,” Dr. Hatfield said.

She advocated for long-term safety studies and a large pregnancy registry, calling ulipristal “neither a panacea nor a Pandora’s box,” but a choice that “lies somewhere in the middle, just [like] nearly all options that present themselves in a woman’s life.”

Dr. Hatfield is director of the fibroid program at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. She did not report having conflicts of interest. She wrote an editorial accompanying the article by AS Lukes et al. (Obstet Gynecol. 2019 May;133[5]:867-8).

In this study, 77%-87% of women who received ulipristal acetate reported more than a 20-point improvement in health-related quality of life, compared with only 36% of placebo recipients, Joanna L. Hatfield, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“However, women with leiomyomas report a 51-point mean improvement after hysterectomy,” she noted. “Clinicians need to keep this difference in mind when counseling women with leiomyomas.”

Ulipristal can cause fatigue and weight gain leading to treatment discontinuation, she noted. Very rare cases of liver failure also have been reported, and there is no evidence that liver enzyme screening identifies patients at risk.

Nonetheless, for the approximately half of women with symptomatic leiomyomas who desire uterine-sparing treatment, selective progesterone receptor modulators like ulipristal offer “a noninvasive way to manage bleeding and bulk symptoms,” Dr. Hatfield said.

She advocated for long-term safety studies and a large pregnancy registry, calling ulipristal “neither a panacea nor a Pandora’s box,” but a choice that “lies somewhere in the middle, just [like] nearly all options that present themselves in a woman’s life.”

Dr. Hatfield is director of the fibroid program at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. She did not report having conflicts of interest. She wrote an editorial accompanying the article by AS Lukes et al. (Obstet Gynecol. 2019 May;133[5]:867-8).

according to a study of the intention-to-treat populations of the randomized, double-blind, phase III VENUS I and VENUS II trials.

In these pivotal studies, ulipristal (Ella) at either 5 mg or 10 mg significantly improved both rate of and time to amenorrhea, noted Andrea S. Lukes, MD, of Carolina Women’s Research and Wellness Center in Durham, N.C. To assess effects on quality of life, she and her associates analyzed baseline and 12-week responses to the widely validated Uterine Fibroid Symptom Health-Related Quality of Life (UFS-QOL) questionnaire, which examined factors such as symptom severity, energy and mood, physical and social activities, self-consciousness, and sexual functioning.

Among 589 patients in the analysis, 169 received placebo, 215 received 5 mg ulipristal, and 205 received 10 mg ulipristal. At baseline, average total quality of life scores on UFS-QOL were 33 (standard deviation, 220), 32 (SD, 21), and 36 (SD, 23), respectively, the researchers wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

After 12 weeks of treatment, both doses of ulipristal were associated with significantly greater improvements on all UFS-QOL scales, compared with placebo (P less than .001). For example, on a scale of 0-100, symptom severity improved by a mean of 23 with ulipristal 5 mg and by a mean of 30 with ulipristal 10 mg (both P less than .001 versus placebo).

“Although a small proportion of patients experienced no change or some worsening in these outcomes, the majority of women reported clear improvements; for example, more than 70% of patients in the ulipristal treatment arms achieved a meaningful improvement of 30 or more points on the Revised Activities subscale,” the researchers wrote.

Additionally, significantly greater improvements in physical and social activities were seen for both ulipristal doses, compared with placebo, from baseline to the end of treatment.

The VENUS II trial included two 12-week treatment courses. In this trial, women who switched from ulipristal to placebo experienced some worsening in quality of life, while those who switched from placebo to ulipristal improved their UFS-QOL scores, the investigators said. Patients who stayed on ulipristal throughout continued to benefit from one treatment course to the next.

The researchers concluded that the findings, “taken together with the significant improvements in amenorrhea, suggest that ulipristal is a promising, noninvasive treatment option for women suffering from symptomatic uterine leiomyomas.”

Allergan provided funding. Dr. Lukes disclosed ties to Allergan, AbbVie, Myovant, Merck, and several other companies. Four of the coauthors are employees of Allergan, and the two remaining coauthors had links to a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Lukes AS et al. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133 (5):869-78.

according to a study of the intention-to-treat populations of the randomized, double-blind, phase III VENUS I and VENUS II trials.

In these pivotal studies, ulipristal (Ella) at either 5 mg or 10 mg significantly improved both rate of and time to amenorrhea, noted Andrea S. Lukes, MD, of Carolina Women’s Research and Wellness Center in Durham, N.C. To assess effects on quality of life, she and her associates analyzed baseline and 12-week responses to the widely validated Uterine Fibroid Symptom Health-Related Quality of Life (UFS-QOL) questionnaire, which examined factors such as symptom severity, energy and mood, physical and social activities, self-consciousness, and sexual functioning.

Among 589 patients in the analysis, 169 received placebo, 215 received 5 mg ulipristal, and 205 received 10 mg ulipristal. At baseline, average total quality of life scores on UFS-QOL were 33 (standard deviation, 220), 32 (SD, 21), and 36 (SD, 23), respectively, the researchers wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

After 12 weeks of treatment, both doses of ulipristal were associated with significantly greater improvements on all UFS-QOL scales, compared with placebo (P less than .001). For example, on a scale of 0-100, symptom severity improved by a mean of 23 with ulipristal 5 mg and by a mean of 30 with ulipristal 10 mg (both P less than .001 versus placebo).

“Although a small proportion of patients experienced no change or some worsening in these outcomes, the majority of women reported clear improvements; for example, more than 70% of patients in the ulipristal treatment arms achieved a meaningful improvement of 30 or more points on the Revised Activities subscale,” the researchers wrote.

Additionally, significantly greater improvements in physical and social activities were seen for both ulipristal doses, compared with placebo, from baseline to the end of treatment.

The VENUS II trial included two 12-week treatment courses. In this trial, women who switched from ulipristal to placebo experienced some worsening in quality of life, while those who switched from placebo to ulipristal improved their UFS-QOL scores, the investigators said. Patients who stayed on ulipristal throughout continued to benefit from one treatment course to the next.

The researchers concluded that the findings, “taken together with the significant improvements in amenorrhea, suggest that ulipristal is a promising, noninvasive treatment option for women suffering from symptomatic uterine leiomyomas.”

Allergan provided funding. Dr. Lukes disclosed ties to Allergan, AbbVie, Myovant, Merck, and several other companies. Four of the coauthors are employees of Allergan, and the two remaining coauthors had links to a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Lukes AS et al. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133 (5):869-78.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: For women with symptomatic uterine leiomyomas, ulipristal at either 5 mg or 10 mg significantly improved both the rate of and time to amenorrhea, compared with placebo.

Major finding: Patients who received 5 or 10 mg ulipristal showed significant improvements in Uterine Fibroid Symptom Health-Related Quality of Life scales, compared with those who received placebo (P less than .001).

Study details: VENUS I and II, 12-week randomized controlled trials of ulipristal acetate or placebo in 589 women with symptomatic uterine leiomyomas and abnormal uterine bleeding.

Disclosures: Allergan provided funding. Dr. Lukes disclosed ties to Allergan, AbbVie, Myovant, Merck, and several other companies. Four of the coauthors are employees of Allergan, and the two remaining coauthors had links to a number of pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Lukes AS et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 May;133(5):869-78.

More data point to potency of genes in development of psychosis

Early findings suggest that positive environment is not protective

ORLANDO – A genetic profile that’s considered risky for psychosis matters more for patients who come from an environmental background that is considered good, while it doesn’t seem to make much of a difference among those whose environmental background is more adverse, according to research presented at the annual congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, are examining a wide variety of data – from socioeconomic factors to neuroimaging – to assess how these data all feed into the psychosis picture, asking whether some factors matter more than others and which factors can be used to predict the development of psychosis in the future.

“The goal of all of the research ... is to try and capture people earlier in the course of development where we can try and tweak the developmental trajectory,” said Raquel Gur, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry, neurology, and radiology at the university.

The findings come from the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort, a community sample of about 9,500 children and young adults aged 8-21 years, with an average age of 15 years, collected through pediatricians. About 1,600 had neuroimaging. Researchers followed 961 participants who had baseline measurements recorded and were seen at follow-up visits after 2 years and 4 years, or longer.

Participants had clinical testing done to determine traumatic stressful events and to look for symptoms seen as precursors to psychosis. They also had neurocognitive battery tests performed. Neuroimaging, genomics testing, and information from their electronic medical record were also examined.

One of the most salient findings so far in their ongoing analysis involved the relationship between polygenic risk score (PRS) and their environmental risk score (ERS), which factored in items such as household income from their geographic area, percentage of married adults in their area, crime rates in their area, and traumatic stressful events experienced personally. The ERS scores were grouped into “good” scores and “bad” scores.

Researchers saw a trend in which, among those with good ERS scores, the average PRS was higher for those with psychotic spectrum symptoms than for those with normal development, with very little overlapping of 95% confidence intervals. But among those with bad ERS scores, the average PRS was about the same for those with psychotic spectrum symptoms and those with normal development.

“If you have genetic vulnerability, a good environment is not going to protect you. You’re going to manifest it,” Dr. Gur said. “However, in a negative environment that has adversity that includes both a poor environment and traumatic events, the polygenic risk score matters less.”

They are continuing to explore and assess these findings.

The researchers also found differences in cognitive functioning among those with poor environmental scores, which dovetail with defects seen in schizophrenia, such as executive functioning.

“Neurocognitive functioning can be established with brief computerized testing,” Dr. Gur said, “and shows deficit in the psychosis spectrum group in domains that have been implicated in schizophrenia.”

Dr. Gur reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Early findings suggest that positive environment is not protective

Early findings suggest that positive environment is not protective

ORLANDO – A genetic profile that’s considered risky for psychosis matters more for patients who come from an environmental background that is considered good, while it doesn’t seem to make much of a difference among those whose environmental background is more adverse, according to research presented at the annual congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, are examining a wide variety of data – from socioeconomic factors to neuroimaging – to assess how these data all feed into the psychosis picture, asking whether some factors matter more than others and which factors can be used to predict the development of psychosis in the future.

“The goal of all of the research ... is to try and capture people earlier in the course of development where we can try and tweak the developmental trajectory,” said Raquel Gur, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry, neurology, and radiology at the university.

The findings come from the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort, a community sample of about 9,500 children and young adults aged 8-21 years, with an average age of 15 years, collected through pediatricians. About 1,600 had neuroimaging. Researchers followed 961 participants who had baseline measurements recorded and were seen at follow-up visits after 2 years and 4 years, or longer.

Participants had clinical testing done to determine traumatic stressful events and to look for symptoms seen as precursors to psychosis. They also had neurocognitive battery tests performed. Neuroimaging, genomics testing, and information from their electronic medical record were also examined.

One of the most salient findings so far in their ongoing analysis involved the relationship between polygenic risk score (PRS) and their environmental risk score (ERS), which factored in items such as household income from their geographic area, percentage of married adults in their area, crime rates in their area, and traumatic stressful events experienced personally. The ERS scores were grouped into “good” scores and “bad” scores.

Researchers saw a trend in which, among those with good ERS scores, the average PRS was higher for those with psychotic spectrum symptoms than for those with normal development, with very little overlapping of 95% confidence intervals. But among those with bad ERS scores, the average PRS was about the same for those with psychotic spectrum symptoms and those with normal development.

“If you have genetic vulnerability, a good environment is not going to protect you. You’re going to manifest it,” Dr. Gur said. “However, in a negative environment that has adversity that includes both a poor environment and traumatic events, the polygenic risk score matters less.”

They are continuing to explore and assess these findings.

The researchers also found differences in cognitive functioning among those with poor environmental scores, which dovetail with defects seen in schizophrenia, such as executive functioning.

“Neurocognitive functioning can be established with brief computerized testing,” Dr. Gur said, “and shows deficit in the psychosis spectrum group in domains that have been implicated in schizophrenia.”

Dr. Gur reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – A genetic profile that’s considered risky for psychosis matters more for patients who come from an environmental background that is considered good, while it doesn’t seem to make much of a difference among those whose environmental background is more adverse, according to research presented at the annual congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, are examining a wide variety of data – from socioeconomic factors to neuroimaging – to assess how these data all feed into the psychosis picture, asking whether some factors matter more than others and which factors can be used to predict the development of psychosis in the future.

“The goal of all of the research ... is to try and capture people earlier in the course of development where we can try and tweak the developmental trajectory,” said Raquel Gur, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry, neurology, and radiology at the university.

The findings come from the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort, a community sample of about 9,500 children and young adults aged 8-21 years, with an average age of 15 years, collected through pediatricians. About 1,600 had neuroimaging. Researchers followed 961 participants who had baseline measurements recorded and were seen at follow-up visits after 2 years and 4 years, or longer.

Participants had clinical testing done to determine traumatic stressful events and to look for symptoms seen as precursors to psychosis. They also had neurocognitive battery tests performed. Neuroimaging, genomics testing, and information from their electronic medical record were also examined.

One of the most salient findings so far in their ongoing analysis involved the relationship between polygenic risk score (PRS) and their environmental risk score (ERS), which factored in items such as household income from their geographic area, percentage of married adults in their area, crime rates in their area, and traumatic stressful events experienced personally. The ERS scores were grouped into “good” scores and “bad” scores.

Researchers saw a trend in which, among those with good ERS scores, the average PRS was higher for those with psychotic spectrum symptoms than for those with normal development, with very little overlapping of 95% confidence intervals. But among those with bad ERS scores, the average PRS was about the same for those with psychotic spectrum symptoms and those with normal development.

“If you have genetic vulnerability, a good environment is not going to protect you. You’re going to manifest it,” Dr. Gur said. “However, in a negative environment that has adversity that includes both a poor environment and traumatic events, the polygenic risk score matters less.”

They are continuing to explore and assess these findings.

The researchers also found differences in cognitive functioning among those with poor environmental scores, which dovetail with defects seen in schizophrenia, such as executive functioning.

“Neurocognitive functioning can be established with brief computerized testing,” Dr. Gur said, “and shows deficit in the psychosis spectrum group in domains that have been implicated in schizophrenia.”

Dr. Gur reported no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM SIRS 2019

Version success more likely in lower BMI, multiparous breech pregnancies

according to results of a single-center retrospective study.

Writing in Obstetrics & Gynecology, Ofer Isakov, MD, PhD, and colleagues from the Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, reported the results of a study of 250 women with singleton pregnancies and breech presentation who underwent external cephalic version (ECV) to turn the baby at 36-41 weeks’ gestation.

The overall success rate of the procedure was 65%. However, women with no forebag – the pocket of amniotic fluid in front of the fetal presenting part – had a 3%-10% chance of successful version, while those with a forebag size greater than 1 cm had a 96%-97% probability of success.

Women with a BMI greater than 29 had a very low chance of success, which the authors suggested was likely attributable to a thicker abdominal wall that made manipulation more difficult. However, among women with a BMI of 29 or below, success was significantly associated with forebag size.

Among women with a forebag of 1 cm in size, multiparous women had a significantly higher chance of success than nulliparous women (81%-91% vs. 0%-24%, respectively).

Dr. Isakov and colleagues suggested that the impact of multiparity could relate to late engagement or the relative laxity of the abdomen in women who had experienced previous births.

The authors then developed a decision tree predictive model of success for ECV, which had a prediction accuracy of 92%.

“External version is a simple and effective procedure that can reduce the cesarean delivery rate, but counseling patients on the risks and success rates of version is challenging owing to the lack of validated models to predict success,” Dr. Isakov and colleagues wrote. “The ability to predict the outcome of an ECV attempt may improve the rates of patient consent and prevent the performance of many unpleasant procedures with low chance for success.”

They noted that their success rate was higher than that seen in other studies of ECV and suggested this may be because all the procedures were performed by a single experienced practitioner, and the mean BMI of the cohort was lower than that in earlier studies.

None of the authors declared any relevant financial disclosures, and there was no external funding.

SOURCE: Isakov O et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:869-78.

With cesarean delivery rates rising, there is a need for vigilance to prevent them from returning to the 2009 peak of 33% of deliveries, and ECV is one strategy to help reduce cesarean rates. While there are some risks associated with ECV, which could contribute to negative attitudes, the lack of acceptance of this procedure may be improved if clinicians can provide an individualized estimate for the chance of success. This study proposes creating a predictive model that discriminates between poor and good changes of ECV success.

The fact that this study is a single-center study with a single physician performing all the procedures does limit its generalizability. However the authors’ use of ultrasound measurements of the forebag is a novel contribution that provides an objective measure of this factor, as well as an objective estimate of the engagement of the breech, which has been lacking.

Dr. Gayle Olson Koutrouvelis is a professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston. These comments are adapted from an editorial accompanying the article by Isakov et al. (Obstet Gynecol. 2019; 133:855-6.). She declared no conflicts of interest.

With cesarean delivery rates rising, there is a need for vigilance to prevent them from returning to the 2009 peak of 33% of deliveries, and ECV is one strategy to help reduce cesarean rates. While there are some risks associated with ECV, which could contribute to negative attitudes, the lack of acceptance of this procedure may be improved if clinicians can provide an individualized estimate for the chance of success. This study proposes creating a predictive model that discriminates between poor and good changes of ECV success.

The fact that this study is a single-center study with a single physician performing all the procedures does limit its generalizability. However the authors’ use of ultrasound measurements of the forebag is a novel contribution that provides an objective measure of this factor, as well as an objective estimate of the engagement of the breech, which has been lacking.

Dr. Gayle Olson Koutrouvelis is a professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston. These comments are adapted from an editorial accompanying the article by Isakov et al. (Obstet Gynecol. 2019; 133:855-6.). She declared no conflicts of interest.

With cesarean delivery rates rising, there is a need for vigilance to prevent them from returning to the 2009 peak of 33% of deliveries, and ECV is one strategy to help reduce cesarean rates. While there are some risks associated with ECV, which could contribute to negative attitudes, the lack of acceptance of this procedure may be improved if clinicians can provide an individualized estimate for the chance of success. This study proposes creating a predictive model that discriminates between poor and good changes of ECV success.

The fact that this study is a single-center study with a single physician performing all the procedures does limit its generalizability. However the authors’ use of ultrasound measurements of the forebag is a novel contribution that provides an objective measure of this factor, as well as an objective estimate of the engagement of the breech, which has been lacking.

Dr. Gayle Olson Koutrouvelis is a professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston. These comments are adapted from an editorial accompanying the article by Isakov et al. (Obstet Gynecol. 2019; 133:855-6.). She declared no conflicts of interest.

according to results of a single-center retrospective study.

Writing in Obstetrics & Gynecology, Ofer Isakov, MD, PhD, and colleagues from the Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, reported the results of a study of 250 women with singleton pregnancies and breech presentation who underwent external cephalic version (ECV) to turn the baby at 36-41 weeks’ gestation.

The overall success rate of the procedure was 65%. However, women with no forebag – the pocket of amniotic fluid in front of the fetal presenting part – had a 3%-10% chance of successful version, while those with a forebag size greater than 1 cm had a 96%-97% probability of success.

Women with a BMI greater than 29 had a very low chance of success, which the authors suggested was likely attributable to a thicker abdominal wall that made manipulation more difficult. However, among women with a BMI of 29 or below, success was significantly associated with forebag size.

Among women with a forebag of 1 cm in size, multiparous women had a significantly higher chance of success than nulliparous women (81%-91% vs. 0%-24%, respectively).

Dr. Isakov and colleagues suggested that the impact of multiparity could relate to late engagement or the relative laxity of the abdomen in women who had experienced previous births.

The authors then developed a decision tree predictive model of success for ECV, which had a prediction accuracy of 92%.

“External version is a simple and effective procedure that can reduce the cesarean delivery rate, but counseling patients on the risks and success rates of version is challenging owing to the lack of validated models to predict success,” Dr. Isakov and colleagues wrote. “The ability to predict the outcome of an ECV attempt may improve the rates of patient consent and prevent the performance of many unpleasant procedures with low chance for success.”

They noted that their success rate was higher than that seen in other studies of ECV and suggested this may be because all the procedures were performed by a single experienced practitioner, and the mean BMI of the cohort was lower than that in earlier studies.

None of the authors declared any relevant financial disclosures, and there was no external funding.

SOURCE: Isakov O et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:869-78.

according to results of a single-center retrospective study.

Writing in Obstetrics & Gynecology, Ofer Isakov, MD, PhD, and colleagues from the Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, reported the results of a study of 250 women with singleton pregnancies and breech presentation who underwent external cephalic version (ECV) to turn the baby at 36-41 weeks’ gestation.

The overall success rate of the procedure was 65%. However, women with no forebag – the pocket of amniotic fluid in front of the fetal presenting part – had a 3%-10% chance of successful version, while those with a forebag size greater than 1 cm had a 96%-97% probability of success.

Women with a BMI greater than 29 had a very low chance of success, which the authors suggested was likely attributable to a thicker abdominal wall that made manipulation more difficult. However, among women with a BMI of 29 or below, success was significantly associated with forebag size.

Among women with a forebag of 1 cm in size, multiparous women had a significantly higher chance of success than nulliparous women (81%-91% vs. 0%-24%, respectively).

Dr. Isakov and colleagues suggested that the impact of multiparity could relate to late engagement or the relative laxity of the abdomen in women who had experienced previous births.

The authors then developed a decision tree predictive model of success for ECV, which had a prediction accuracy of 92%.

“External version is a simple and effective procedure that can reduce the cesarean delivery rate, but counseling patients on the risks and success rates of version is challenging owing to the lack of validated models to predict success,” Dr. Isakov and colleagues wrote. “The ability to predict the outcome of an ECV attempt may improve the rates of patient consent and prevent the performance of many unpleasant procedures with low chance for success.”

They noted that their success rate was higher than that seen in other studies of ECV and suggested this may be because all the procedures were performed by a single experienced practitioner, and the mean BMI of the cohort was lower than that in earlier studies.

None of the authors declared any relevant financial disclosures, and there was no external funding.

SOURCE: Isakov O et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:869-78.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Multiparity, larger forebag size, and lower BMI are predictors of external cephalic version success.

Major finding: Model of external cephalic version success shows prediction accuracy of 92%.

Study details: A single-center retrospective cohort study in 250 women with breech presentation.

Disclosures: None of the authors declared any relevant financial disclosures, and there was no external funding.

Source: Isakov O et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:869-78.

CAR T-cell therapy bb2121 performs well in phase 1 trial of refractory multiple myeloma

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy bb2121, which targets B-cell maturation agent (BCMA), appears safe and effective for treating patients with refractory multiple myeloma, according to results of a phase 1 trial.

The objective response rate of 85% among 33 heavily pretreated patients suggests “promising efficacy,” reported lead author Noopur Raje, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston and colleagues.

“Although comparisons among studies are complicated by differences in patient populations, CAR constructs, administered doses, and grading scales of toxic effects, the results observed with bb2121 indicate a favorable safety profile,” the investigators wrote in a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study initially involved 36 patients with refractory multiple myeloma who had received at least three lines of prior therapy, including an immunomodulatory agent and a proteasome inhibitor. Although leukapheresis and therapy manufacturing were successful in all patients, three patients were excluded from receiving the infusion because of disease progression.

The 33 remaining patients were lymphodepleted with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide. Bridging therapy was allowed during the manufacturing process but was stopped at least 2 weeks prior to infusion. In the dose-escalation phase of the study, b2121 was delivered as a single infusion at one of four dose levels: 50 × 106, 150 × 106, 450 × 106, or 800 × 106 CAR T cells. In the expansion phase, the treatment was given at either 150 x 106 or 450 x 106 CAR T cells. The primary endpoint was safety; the secondary endpoints were response rate and duration of response.

After a median follow-up of 11.3 months, most patients (85%) had responded to therapy, and almost half (45%) had achieved a complete response. Of the 15 complete responders, 6 relapsed. The median progression-free survival was 11.8 months; stated differently, two out of five patients (40%) had not experienced disease progression after 1 year. CAR T cells were detectable 1 month after infusion in 96% of patients; however, this value dropped to 86% at 3 months, 57% at 6 months, and 20% at 12 months. The investigators noted that CAR T-cell persistence was associated with treatment response.

All patients had adverse events. Most (85%) had grade 3 or higher hematologic toxicity, which the investigators considered to be the “expected toxic effects of lymphodepleting chemotherapy.” Although other adverse events occurred in the majority of patients, these were generally mild to moderate. Cytokine release syndrome occurred in 25 patients (76%), including two instances of grade 3 toxicity but none of grade 4 or higher. Fourteen patients (42%) developed neurologic toxicities: Most were grade 1 or 2, but one patient had a grade 4 toxicity that resolved after a month. Infections occurred at the same rate (42%), although, again, most were grade 1 or 2.

The study was funded by Bluebird Bio and Celgene. The investigators disclosed financial relationships with Bluebird and other drug companies.

SOURCE: Raje N et al. NEJM. 1 May 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817226.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy bb2121, which targets B-cell maturation agent (BCMA), appears safe and effective for treating patients with refractory multiple myeloma, according to results of a phase 1 trial.

The objective response rate of 85% among 33 heavily pretreated patients suggests “promising efficacy,” reported lead author Noopur Raje, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston and colleagues.

“Although comparisons among studies are complicated by differences in patient populations, CAR constructs, administered doses, and grading scales of toxic effects, the results observed with bb2121 indicate a favorable safety profile,” the investigators wrote in a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study initially involved 36 patients with refractory multiple myeloma who had received at least three lines of prior therapy, including an immunomodulatory agent and a proteasome inhibitor. Although leukapheresis and therapy manufacturing were successful in all patients, three patients were excluded from receiving the infusion because of disease progression.

The 33 remaining patients were lymphodepleted with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide. Bridging therapy was allowed during the manufacturing process but was stopped at least 2 weeks prior to infusion. In the dose-escalation phase of the study, b2121 was delivered as a single infusion at one of four dose levels: 50 × 106, 150 × 106, 450 × 106, or 800 × 106 CAR T cells. In the expansion phase, the treatment was given at either 150 x 106 or 450 x 106 CAR T cells. The primary endpoint was safety; the secondary endpoints were response rate and duration of response.

After a median follow-up of 11.3 months, most patients (85%) had responded to therapy, and almost half (45%) had achieved a complete response. Of the 15 complete responders, 6 relapsed. The median progression-free survival was 11.8 months; stated differently, two out of five patients (40%) had not experienced disease progression after 1 year. CAR T cells were detectable 1 month after infusion in 96% of patients; however, this value dropped to 86% at 3 months, 57% at 6 months, and 20% at 12 months. The investigators noted that CAR T-cell persistence was associated with treatment response.

All patients had adverse events. Most (85%) had grade 3 or higher hematologic toxicity, which the investigators considered to be the “expected toxic effects of lymphodepleting chemotherapy.” Although other adverse events occurred in the majority of patients, these were generally mild to moderate. Cytokine release syndrome occurred in 25 patients (76%), including two instances of grade 3 toxicity but none of grade 4 or higher. Fourteen patients (42%) developed neurologic toxicities: Most were grade 1 or 2, but one patient had a grade 4 toxicity that resolved after a month. Infections occurred at the same rate (42%), although, again, most were grade 1 or 2.

The study was funded by Bluebird Bio and Celgene. The investigators disclosed financial relationships with Bluebird and other drug companies.

SOURCE: Raje N et al. NEJM. 1 May 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817226.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy bb2121, which targets B-cell maturation agent (BCMA), appears safe and effective for treating patients with refractory multiple myeloma, according to results of a phase 1 trial.

The objective response rate of 85% among 33 heavily pretreated patients suggests “promising efficacy,” reported lead author Noopur Raje, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston and colleagues.

“Although comparisons among studies are complicated by differences in patient populations, CAR constructs, administered doses, and grading scales of toxic effects, the results observed with bb2121 indicate a favorable safety profile,” the investigators wrote in a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study initially involved 36 patients with refractory multiple myeloma who had received at least three lines of prior therapy, including an immunomodulatory agent and a proteasome inhibitor. Although leukapheresis and therapy manufacturing were successful in all patients, three patients were excluded from receiving the infusion because of disease progression.

The 33 remaining patients were lymphodepleted with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide. Bridging therapy was allowed during the manufacturing process but was stopped at least 2 weeks prior to infusion. In the dose-escalation phase of the study, b2121 was delivered as a single infusion at one of four dose levels: 50 × 106, 150 × 106, 450 × 106, or 800 × 106 CAR T cells. In the expansion phase, the treatment was given at either 150 x 106 or 450 x 106 CAR T cells. The primary endpoint was safety; the secondary endpoints were response rate and duration of response.

After a median follow-up of 11.3 months, most patients (85%) had responded to therapy, and almost half (45%) had achieved a complete response. Of the 15 complete responders, 6 relapsed. The median progression-free survival was 11.8 months; stated differently, two out of five patients (40%) had not experienced disease progression after 1 year. CAR T cells were detectable 1 month after infusion in 96% of patients; however, this value dropped to 86% at 3 months, 57% at 6 months, and 20% at 12 months. The investigators noted that CAR T-cell persistence was associated with treatment response.

All patients had adverse events. Most (85%) had grade 3 or higher hematologic toxicity, which the investigators considered to be the “expected toxic effects of lymphodepleting chemotherapy.” Although other adverse events occurred in the majority of patients, these were generally mild to moderate. Cytokine release syndrome occurred in 25 patients (76%), including two instances of grade 3 toxicity but none of grade 4 or higher. Fourteen patients (42%) developed neurologic toxicities: Most were grade 1 or 2, but one patient had a grade 4 toxicity that resolved after a month. Infections occurred at the same rate (42%), although, again, most were grade 1 or 2.

The study was funded by Bluebird Bio and Celgene. The investigators disclosed financial relationships with Bluebird and other drug companies.

SOURCE: Raje N et al. NEJM. 1 May 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817226.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Study compares tapering strategies in rheumatoid arthritis

Patients whose rheumatoid arthritis was in sustained remission had similar rates of flare for the first 9 months after they tapered off either their conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD), or their tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor, researchers reported.

After the first year, first author Elise van Mulligen of Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her associates found that flares rates were 10% lower among patients who first tapered conventional synthetic DMARDs, a difference that was not statistically significant. Because secondary endpoints also were similar between groups, patients should consider first tapering off their TNF inhibitor to save costs and reduce side effects, the researchers wrote in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

Over the past decade, better drugs, treat-to-target approaches, and earlier disease detection have vastly improved outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. As more patients achieve sustained remission, they are tapering off therapy in accordance with current guidelines. This multicenter, single-blinded, randomized trial (Tapering Strategies in Rheumatoid Arthritis [TARA]) is one of the first to compare tapering strategies, rather than looking at only whether tapering is feasible.

The study included 189 patients from the Netherlands whose rheumatoid arthritis was in sustained remission (Disease Activity Score [DAS] less than 2.4 and swollen joint count less than 1 for at least 3 months) on a conventional synthetic DMARD plus a TNF inhibitor. Patients were randomly assigned to either halve the conventional synthetic DMARD dose, or to double the TNF-inhibitor dosing interval. After 3 months, they cut the dose of their assigned taper medication to 25% of baseline. If they stayed in remission, they stopped the medication 3 months later. They avoided glucocorticoids throughout.

There were no serious adverse events related to tapering. Cumulative rates of flare at 1 year (DAS greater than 2.4 or swollen joint count greater than 1) were 33% for conventional synthetic DMARD taper (95% confidence interval, 24%-43%) and 43% (95% CI, 33%-53%) for TNF-inhibitor taper (P = .17). The two groups also had similar scores at 1 year on the DAS, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index, and European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions index.

The suggestion to first taper off TNF inhibitors reflects current European League Against Rheumatism guidelines, which advise first tapering glucocorticoids, then biologic DMARDS, and finally conventional synthetic DMARDs. “Our results and the fact that TNF blockers are more expensive than conventional synthetic DMARDs support the aforementioned tapering order,” the researchers concluded.

An unrestricted grant from ZonMW supported the work. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mulligen E et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Apr 6. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214970.

Patients whose rheumatoid arthritis was in sustained remission had similar rates of flare for the first 9 months after they tapered off either their conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD), or their tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor, researchers reported.

After the first year, first author Elise van Mulligen of Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her associates found that flares rates were 10% lower among patients who first tapered conventional synthetic DMARDs, a difference that was not statistically significant. Because secondary endpoints also were similar between groups, patients should consider first tapering off their TNF inhibitor to save costs and reduce side effects, the researchers wrote in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

Over the past decade, better drugs, treat-to-target approaches, and earlier disease detection have vastly improved outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. As more patients achieve sustained remission, they are tapering off therapy in accordance with current guidelines. This multicenter, single-blinded, randomized trial (Tapering Strategies in Rheumatoid Arthritis [TARA]) is one of the first to compare tapering strategies, rather than looking at only whether tapering is feasible.

The study included 189 patients from the Netherlands whose rheumatoid arthritis was in sustained remission (Disease Activity Score [DAS] less than 2.4 and swollen joint count less than 1 for at least 3 months) on a conventional synthetic DMARD plus a TNF inhibitor. Patients were randomly assigned to either halve the conventional synthetic DMARD dose, or to double the TNF-inhibitor dosing interval. After 3 months, they cut the dose of their assigned taper medication to 25% of baseline. If they stayed in remission, they stopped the medication 3 months later. They avoided glucocorticoids throughout.

There were no serious adverse events related to tapering. Cumulative rates of flare at 1 year (DAS greater than 2.4 or swollen joint count greater than 1) were 33% for conventional synthetic DMARD taper (95% confidence interval, 24%-43%) and 43% (95% CI, 33%-53%) for TNF-inhibitor taper (P = .17). The two groups also had similar scores at 1 year on the DAS, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index, and European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions index.

The suggestion to first taper off TNF inhibitors reflects current European League Against Rheumatism guidelines, which advise first tapering glucocorticoids, then biologic DMARDS, and finally conventional synthetic DMARDs. “Our results and the fact that TNF blockers are more expensive than conventional synthetic DMARDs support the aforementioned tapering order,” the researchers concluded.

An unrestricted grant from ZonMW supported the work. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mulligen E et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Apr 6. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214970.

Patients whose rheumatoid arthritis was in sustained remission had similar rates of flare for the first 9 months after they tapered off either their conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD), or their tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor, researchers reported.

After the first year, first author Elise van Mulligen of Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her associates found that flares rates were 10% lower among patients who first tapered conventional synthetic DMARDs, a difference that was not statistically significant. Because secondary endpoints also were similar between groups, patients should consider first tapering off their TNF inhibitor to save costs and reduce side effects, the researchers wrote in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

Over the past decade, better drugs, treat-to-target approaches, and earlier disease detection have vastly improved outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. As more patients achieve sustained remission, they are tapering off therapy in accordance with current guidelines. This multicenter, single-blinded, randomized trial (Tapering Strategies in Rheumatoid Arthritis [TARA]) is one of the first to compare tapering strategies, rather than looking at only whether tapering is feasible.

The study included 189 patients from the Netherlands whose rheumatoid arthritis was in sustained remission (Disease Activity Score [DAS] less than 2.4 and swollen joint count less than 1 for at least 3 months) on a conventional synthetic DMARD plus a TNF inhibitor. Patients were randomly assigned to either halve the conventional synthetic DMARD dose, or to double the TNF-inhibitor dosing interval. After 3 months, they cut the dose of their assigned taper medication to 25% of baseline. If they stayed in remission, they stopped the medication 3 months later. They avoided glucocorticoids throughout.

There were no serious adverse events related to tapering. Cumulative rates of flare at 1 year (DAS greater than 2.4 or swollen joint count greater than 1) were 33% for conventional synthetic DMARD taper (95% confidence interval, 24%-43%) and 43% (95% CI, 33%-53%) for TNF-inhibitor taper (P = .17). The two groups also had similar scores at 1 year on the DAS, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index, and European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions index.

The suggestion to first taper off TNF inhibitors reflects current European League Against Rheumatism guidelines, which advise first tapering glucocorticoids, then biologic DMARDS, and finally conventional synthetic DMARDs. “Our results and the fact that TNF blockers are more expensive than conventional synthetic DMARDs support the aforementioned tapering order,” the researchers concluded.

An unrestricted grant from ZonMW supported the work. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mulligen E et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Apr 6. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214970.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Interosseous tendon inflammation is common prior to RA

MAUI, HAWAII – Inflammation of the hand interosseous tendons found on MRI is a novel target in efforts to preempt the development and progression of rheumatoid arthritis, Paul Emery, MD, said at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

He and his coinvestigators have previously shown there is a high prevalence of interosseous tendon inflammation in the hands of patients with established RA, but now they’ve demonstrated that this phenomenon also occurs in anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP)–positive individuals at increased risk for RA, even before onset of clinical synovitis.

This finding is consistent with the notion that, even though RA is classically considered a disease of the synovial joints, the joint involvement is a relatively late phenomenon in the disease development process and extracapsular structures may be important early targets of RA-related inflammation. Indeed, the MRI finding of tenosynovitis of the wrist and finger flexor tendons is known to be the strongest predictor of progression to arthritis in patients with recent-onset arthralgia or other musculoskeletal symptoms but no clinical synovitis, according to Dr. Emery, professor of rheumatology and director of the University of Leeds (England) Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Center.

Because the interosseous muscles of the hands play a critical role in hand function – pianists and other musicians not infrequently present to rheumatologists with overuse injuries of the muscles and their tendons – Dr. Emery and his coworkers decided to take a comprehensive look at interosseous tendon inflammation across the full spectrum of RA and pre-RA. They conducted a retrospective study of clinical and hand MRI data on 93 CCP-positive patients who presented with new-onset musculoskeletal symptoms but no clinical synovitis; 47 patients with early RA, all of whom were disease-modifying antirheumatic drug–naive; 28 patients with late RA as defined by at least 1 year of symptoms, anti-CCP and/or rheumatoid factor positivity, a Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) of 3.2 or more, plus a history of exposure to one or more DMARDs at the time of their hand imaging; and 20 healthy controls.

The key finding is that the proportion of subjects with MRI evidence of interosseous tendon inflammation rose along the advancing RA continuum. It was present in 19% of the CCP-positive patients without clinical synovitis; 49% of the DMARD-naive early RA group; 57% of the late RA group; and in none of the healthy controls. Moreover, the number of inflamed interosseous tendons per patient also increased with RA progression.

A total of 12% of 507 nontender metacarpophalangeal joints showed MRI evidence of interosseous tendon inflammation, as did 28% of 141 tender ones (Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 23. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214331).

As part of the study, Dr. Emery and coinvestigators performed cadaveric dissections that demonstrated that the interosseous tendons don’t possess a tendon sheath and don’t directly communicate with the joint capsule.

A prospective study is warranted in order to confirm the observed association between interosseous tendon inflammation and clinical and subclinical synovitis and to establish the predictive value of hand MRI as a harbinger of RA, he noted.

Dr. Emery reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

MAUI, HAWAII – Inflammation of the hand interosseous tendons found on MRI is a novel target in efforts to preempt the development and progression of rheumatoid arthritis, Paul Emery, MD, said at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

He and his coinvestigators have previously shown there is a high prevalence of interosseous tendon inflammation in the hands of patients with established RA, but now they’ve demonstrated that this phenomenon also occurs in anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP)–positive individuals at increased risk for RA, even before onset of clinical synovitis.

This finding is consistent with the notion that, even though RA is classically considered a disease of the synovial joints, the joint involvement is a relatively late phenomenon in the disease development process and extracapsular structures may be important early targets of RA-related inflammation. Indeed, the MRI finding of tenosynovitis of the wrist and finger flexor tendons is known to be the strongest predictor of progression to arthritis in patients with recent-onset arthralgia or other musculoskeletal symptoms but no clinical synovitis, according to Dr. Emery, professor of rheumatology and director of the University of Leeds (England) Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Center.

Because the interosseous muscles of the hands play a critical role in hand function – pianists and other musicians not infrequently present to rheumatologists with overuse injuries of the muscles and their tendons – Dr. Emery and his coworkers decided to take a comprehensive look at interosseous tendon inflammation across the full spectrum of RA and pre-RA. They conducted a retrospective study of clinical and hand MRI data on 93 CCP-positive patients who presented with new-onset musculoskeletal symptoms but no clinical synovitis; 47 patients with early RA, all of whom were disease-modifying antirheumatic drug–naive; 28 patients with late RA as defined by at least 1 year of symptoms, anti-CCP and/or rheumatoid factor positivity, a Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) of 3.2 or more, plus a history of exposure to one or more DMARDs at the time of their hand imaging; and 20 healthy controls.

The key finding is that the proportion of subjects with MRI evidence of interosseous tendon inflammation rose along the advancing RA continuum. It was present in 19% of the CCP-positive patients without clinical synovitis; 49% of the DMARD-naive early RA group; 57% of the late RA group; and in none of the healthy controls. Moreover, the number of inflamed interosseous tendons per patient also increased with RA progression.

A total of 12% of 507 nontender metacarpophalangeal joints showed MRI evidence of interosseous tendon inflammation, as did 28% of 141 tender ones (Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 23. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214331).

As part of the study, Dr. Emery and coinvestigators performed cadaveric dissections that demonstrated that the interosseous tendons don’t possess a tendon sheath and don’t directly communicate with the joint capsule.

A prospective study is warranted in order to confirm the observed association between interosseous tendon inflammation and clinical and subclinical synovitis and to establish the predictive value of hand MRI as a harbinger of RA, he noted.

Dr. Emery reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

MAUI, HAWAII – Inflammation of the hand interosseous tendons found on MRI is a novel target in efforts to preempt the development and progression of rheumatoid arthritis, Paul Emery, MD, said at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

He and his coinvestigators have previously shown there is a high prevalence of interosseous tendon inflammation in the hands of patients with established RA, but now they’ve demonstrated that this phenomenon also occurs in anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP)–positive individuals at increased risk for RA, even before onset of clinical synovitis.

This finding is consistent with the notion that, even though RA is classically considered a disease of the synovial joints, the joint involvement is a relatively late phenomenon in the disease development process and extracapsular structures may be important early targets of RA-related inflammation. Indeed, the MRI finding of tenosynovitis of the wrist and finger flexor tendons is known to be the strongest predictor of progression to arthritis in patients with recent-onset arthralgia or other musculoskeletal symptoms but no clinical synovitis, according to Dr. Emery, professor of rheumatology and director of the University of Leeds (England) Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Center.