User login

Human papillomavirus

To the Editor: I am an active primary care provider. After reading the update on human papillomavirus (HPV) in the March 2019 issue by Zhang and Batur,1 I was hoping for some clarification on a few points.

The statement is made that up to 70% of HPV-related cervical cancer cases can be prevented with vaccination. I have pulled the reference2 but cannot find supporting data for this claim. Is this proven or optimistic thinking based on the decreased incidence of abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) test results such as noted in the University of New Mexico HPV Pap registry database3? The authors do cite an additional reference4 documenting a decreased incidence of cervical cancer in the United States among 15- to 24-year-olds from 2003–2006 compared with 2011–2014. This study reported a 29% relative risk reduction in the group receiving the vaccine, with the absolute numbers 6 vs 8.4 cases per 1,000,000. Thus, can the authors provide further references to the statement that 70% of cervical cancers can be prevented by vaccination?

The authors also state that vaccine acceptance rates are highest when primary care providers announce that the vaccine is due rather than invite open-ended discussions. At first this shocked me, but then made me pause and wonder how often I do that—and when I do, why. I regularly do it with all the other vaccines recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. When the parent or patient asks for further information, I am armed to provide it. To date, I am struggling to provide data to educate the patient on the efficacy of the HPV vaccine, particularly the claim that it will prevent 70% of cervical cancers. Are there more data that I am missing?

Finally, let me state that I am a “vaccinator”—always have been, and always will be. I discuss the HPV vaccine with my patients and their parents and try to provide data to support my recommendation. However, I am concerned that this current practice regarding the HPV vaccine has been driven by scare tactics and has now turned to “just give it because I say so.” The University of New Mexico Center for HPV prevention reports up to a 50% reduction in cervical intraepithelial neoplasias (precancer lesions) in teens.3 This is exciting information and raises hope for the future successful battle against cervical cancer. I think it is also more accurate than stating to parents and patients that we have proof that we have prevented 70% of cervical cancers. When we explain it in this manner, the majority of parents and patients buy in and, I believe, enjoy and welcome this open-ended discussion.

- Zhang S, Batur P. Human papillomavirus in 2019: an update on cervical cancer prevention and screening guidelines. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(3):173–178. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.18018

- Thaxton L, Waxman AG. Cervical cancer prevention: immunization and screening 2015. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99(3): 469-477.

- Benard VB, Castle PE, Jenison SA, et al. Population-based incidence rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in the human papillomavirus vaccine era. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(6):833–837. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3609

- Guo F, Cofie LE, Berenson AB. Cervical cancer incidence in young US females after human papillomavirus vaccine introduction. Am J Prev Med 2018; 55(2):197–204. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.013

To the Editor: I am an active primary care provider. After reading the update on human papillomavirus (HPV) in the March 2019 issue by Zhang and Batur,1 I was hoping for some clarification on a few points.

The statement is made that up to 70% of HPV-related cervical cancer cases can be prevented with vaccination. I have pulled the reference2 but cannot find supporting data for this claim. Is this proven or optimistic thinking based on the decreased incidence of abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) test results such as noted in the University of New Mexico HPV Pap registry database3? The authors do cite an additional reference4 documenting a decreased incidence of cervical cancer in the United States among 15- to 24-year-olds from 2003–2006 compared with 2011–2014. This study reported a 29% relative risk reduction in the group receiving the vaccine, with the absolute numbers 6 vs 8.4 cases per 1,000,000. Thus, can the authors provide further references to the statement that 70% of cervical cancers can be prevented by vaccination?

The authors also state that vaccine acceptance rates are highest when primary care providers announce that the vaccine is due rather than invite open-ended discussions. At first this shocked me, but then made me pause and wonder how often I do that—and when I do, why. I regularly do it with all the other vaccines recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. When the parent or patient asks for further information, I am armed to provide it. To date, I am struggling to provide data to educate the patient on the efficacy of the HPV vaccine, particularly the claim that it will prevent 70% of cervical cancers. Are there more data that I am missing?

Finally, let me state that I am a “vaccinator”—always have been, and always will be. I discuss the HPV vaccine with my patients and their parents and try to provide data to support my recommendation. However, I am concerned that this current practice regarding the HPV vaccine has been driven by scare tactics and has now turned to “just give it because I say so.” The University of New Mexico Center for HPV prevention reports up to a 50% reduction in cervical intraepithelial neoplasias (precancer lesions) in teens.3 This is exciting information and raises hope for the future successful battle against cervical cancer. I think it is also more accurate than stating to parents and patients that we have proof that we have prevented 70% of cervical cancers. When we explain it in this manner, the majority of parents and patients buy in and, I believe, enjoy and welcome this open-ended discussion.

To the Editor: I am an active primary care provider. After reading the update on human papillomavirus (HPV) in the March 2019 issue by Zhang and Batur,1 I was hoping for some clarification on a few points.

The statement is made that up to 70% of HPV-related cervical cancer cases can be prevented with vaccination. I have pulled the reference2 but cannot find supporting data for this claim. Is this proven or optimistic thinking based on the decreased incidence of abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) test results such as noted in the University of New Mexico HPV Pap registry database3? The authors do cite an additional reference4 documenting a decreased incidence of cervical cancer in the United States among 15- to 24-year-olds from 2003–2006 compared with 2011–2014. This study reported a 29% relative risk reduction in the group receiving the vaccine, with the absolute numbers 6 vs 8.4 cases per 1,000,000. Thus, can the authors provide further references to the statement that 70% of cervical cancers can be prevented by vaccination?

The authors also state that vaccine acceptance rates are highest when primary care providers announce that the vaccine is due rather than invite open-ended discussions. At first this shocked me, but then made me pause and wonder how often I do that—and when I do, why. I regularly do it with all the other vaccines recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. When the parent or patient asks for further information, I am armed to provide it. To date, I am struggling to provide data to educate the patient on the efficacy of the HPV vaccine, particularly the claim that it will prevent 70% of cervical cancers. Are there more data that I am missing?

Finally, let me state that I am a “vaccinator”—always have been, and always will be. I discuss the HPV vaccine with my patients and their parents and try to provide data to support my recommendation. However, I am concerned that this current practice regarding the HPV vaccine has been driven by scare tactics and has now turned to “just give it because I say so.” The University of New Mexico Center for HPV prevention reports up to a 50% reduction in cervical intraepithelial neoplasias (precancer lesions) in teens.3 This is exciting information and raises hope for the future successful battle against cervical cancer. I think it is also more accurate than stating to parents and patients that we have proof that we have prevented 70% of cervical cancers. When we explain it in this manner, the majority of parents and patients buy in and, I believe, enjoy and welcome this open-ended discussion.

- Zhang S, Batur P. Human papillomavirus in 2019: an update on cervical cancer prevention and screening guidelines. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(3):173–178. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.18018

- Thaxton L, Waxman AG. Cervical cancer prevention: immunization and screening 2015. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99(3): 469-477.

- Benard VB, Castle PE, Jenison SA, et al. Population-based incidence rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in the human papillomavirus vaccine era. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(6):833–837. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3609

- Guo F, Cofie LE, Berenson AB. Cervical cancer incidence in young US females after human papillomavirus vaccine introduction. Am J Prev Med 2018; 55(2):197–204. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.013

- Zhang S, Batur P. Human papillomavirus in 2019: an update on cervical cancer prevention and screening guidelines. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(3):173–178. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.18018

- Thaxton L, Waxman AG. Cervical cancer prevention: immunization and screening 2015. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99(3): 469-477.

- Benard VB, Castle PE, Jenison SA, et al. Population-based incidence rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in the human papillomavirus vaccine era. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(6):833–837. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3609

- Guo F, Cofie LE, Berenson AB. Cervical cancer incidence in young US females after human papillomavirus vaccine introduction. Am J Prev Med 2018; 55(2):197–204. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.013

In reply: Human papillomavirus

In Reply: We would like to thank Dr. Lichtenberg for giving us the opportunity to clarify and expand on questions regarding HPV vaccine efficacy.

Our statement “HPV immunization can prevent up to 70% of cases of cervical cancer due to HPV as well as 90% of genital warts” was based on a statement by Thaxton and Waxman, ie, that immunization against HPV types 16 and 18 has the potential to prevent 70% of cancers of the cervix plus a large percentage of other lower anogenital tract cancers.1 This was meant to describe the prevention potential of the quadrivalent vaccine. The currently available Gardasil 9 targets the HPV types that account for 90% of cervical cancers,2 with projected effectiveness likely to vary based on geographic variation in HPV subtypes, ranging from 86.5% in Australia to 92% in North America.3 It is difficult to precisely calculate the effectiveness of HPV vaccination alone, given that cervical cancer prevention is twofold, with primary vaccination and secondary screening (with several notable updates to US national screening guidelines during the same time frame as vaccine development).4

It is true that the 29% decrease in US cervical cancer incidence rates during the years 2011–2014 compared with 2003–2006 is less than the predicted 70%.5 However, not all eligible US females are vaccinated; according to reports from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 49% of adolescents were appropriately immunized against HPV in 2017, an increase over the rate of only 35% in 2014.6 Low vaccination rates undoubtedly negatively impact any benefits from herd immunity, though the exact benefits of this population immunity are difficult to quantify.7

In Australia, a national school-based HPV vaccination program was initiated in 2007, making the vaccine available for free. Over 70% of girls ages 12 and 13 were vaccinated, and follow-up within the same decade showed a greater than 90% reduction in genital warts, as well as a reduction in high-grade cervical lesions.8 In addition, the incidence of genital warts in unvaccinated heterosexual males during the prevaccination vs the vaccination period decreased by up to 81% (a marker of herd immunity).9

In the US, the HPV subtypes found in the quadrivalent vaccine decreased by 71% in those ages 14 to 19, within 8 years of vaccine introduction.10 An analysis of US state cancer registries between 2009 and 2012 showed that in Michigan, the rates of high-grade, precancerous lesions declined by 37% each year for women ages 15 to 19, thought to be due to changes in screening and vaccination guidelines.11 Similarly, an analysis of 9 million privately insured US females showed that the presence of high-grade precancerous lesions significantly decreased between the years 2007 and 2014 in those ages 15 to 24 (vaccinated individuals), but not in those ages 25 to 39 (unvaccinated individuals).12 Most recently, a study of 10,206 women showed a 21.9% decrease in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse lesions due to HPV subtypes 16 or 18 in those who have received at least 1 dose of the vaccine; reduced rates in unvaccinated women were also seen, representing first evidence of herd immunity in the United States.13 In contrast, the rates of high-grade lesions due to nonvaccine HPV subtypes remained constant. Given that progression to cervical cancer can take 10 to 15 years or longer after HPV infection, true vaccine benefits will emerge once increased vaccination rates are achieved and after at least a decade of follow-up.

We applaud Dr. Lichtenberg’s efforts to clarify vaccine efficacy for appropriate counseling, as this is key to ensuring patient trust. Immunization fears have fueled the re-emergence of vaccine-preventable illnesses across the world. Given the wave of vaccine misinformation on the Internet, we all face patients and family members skeptical of vaccine efficacy and safety. Those requesting more information deserve an honest, informed discussion with their provider. Interestingly, however, among 955 unvaccinated women, the belief of not being at risk for HPV was the most common reason for not receiving the vaccine.14 Effective education can be achieved by focusing on the personal risks of HPV to the patient, as well as the overall favorable risk vs benefits of vaccination. Quoting an exact rate of cancer reduction is likely a less effective counseling strategy, and these efficacy estimates will change as vaccination rates and HPV prevalence within the population change over time.

- Thaxton L, Waxman AG. Cervical cancer prevention: Immunization and screening 2015. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99(3):469–477. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.003

- McNamara M, Batur P, Walsh JM, Johnson KM. HPV update: vaccination, screening, and associated disease. J Gen Intern Med 2016; 31(11):1360–1366. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3725-z

- Zhai L, Tumban E. Gardasil-9: A global survey of projected efficacy. Antiviral Res 2016 Jun;130:101–109. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.03.016

- Zhang S, Batur P. Human papillomavirus in 2019: An update on cervical cancer prevention and screening guidelines. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(3):173–178. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.18018

- Guo F, Cofie LE, Berenson AB. Cervical cancer incidence in young U.S. females after human papillomavirus vaccine Introduction. Am J Prev Med 2018; 55(2):197–204. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.013

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus (HPV) coverage data. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/vacc-coverage/index.html. Accessed April 8, 2019.

- Nymark LS, Sharma T, Miller A, Enemark U, Griffiths UK. Inclusion of the value of herd immunity in economic evaluations of vaccines. A systematic review of methods used. Vaccine 2017; 35(49 Pt B):6828–6841. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.024

- Garland SM. The Australian experience with the human papillomavirus vaccine. Clin Ther 2014; 36(1):17–23. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.12.005

- Ali H, Donovan B, Wand H, et al. Genital warts in young Australians five years into national human papillomavirus vaccination programme: national surveillance data. BMJ 2013; 346:f2032. doi:10.1136/bmj.f2032

- Oliver SE, Unger ER, Lewis R, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus among females after vaccine introduction—National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 2003–2014. J Infect Dis 2017; 216(5):594–603. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix244

- Watson M, Soman A, Flagg EW, et al. Surveillance of high-grade cervical cancer precursors (CIN III/AIS) in four population-based cancer registries. Prev Med 2017; 103:60–65. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.07.027

- Flagg EW, Torrone EA, Weinstock H. Ecological association of human papillomavirus vaccination with cervical dysplasia prevalence in the United States, 2007–2014. Am J Public Health 2016; 106(12):2211–2218.

- McClung NM, Gargano JW, Bennett NM, et al; HPV-IMPACT Working Group. Trends in human papillomavirus vaccine types 16 and 18 in cervical precancers, 2008–2014. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019; 28(3):602–609. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0885

- Liddon NC, Hood JE, Leichliter JS. Intent to receive HPV vaccine and reasons for not vaccinating among unvaccinated adolescent and young women: findings from the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth. Vaccine 2012; 30(16):2676–2682. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.007

In Reply: We would like to thank Dr. Lichtenberg for giving us the opportunity to clarify and expand on questions regarding HPV vaccine efficacy.

Our statement “HPV immunization can prevent up to 70% of cases of cervical cancer due to HPV as well as 90% of genital warts” was based on a statement by Thaxton and Waxman, ie, that immunization against HPV types 16 and 18 has the potential to prevent 70% of cancers of the cervix plus a large percentage of other lower anogenital tract cancers.1 This was meant to describe the prevention potential of the quadrivalent vaccine. The currently available Gardasil 9 targets the HPV types that account for 90% of cervical cancers,2 with projected effectiveness likely to vary based on geographic variation in HPV subtypes, ranging from 86.5% in Australia to 92% in North America.3 It is difficult to precisely calculate the effectiveness of HPV vaccination alone, given that cervical cancer prevention is twofold, with primary vaccination and secondary screening (with several notable updates to US national screening guidelines during the same time frame as vaccine development).4

It is true that the 29% decrease in US cervical cancer incidence rates during the years 2011–2014 compared with 2003–2006 is less than the predicted 70%.5 However, not all eligible US females are vaccinated; according to reports from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 49% of adolescents were appropriately immunized against HPV in 2017, an increase over the rate of only 35% in 2014.6 Low vaccination rates undoubtedly negatively impact any benefits from herd immunity, though the exact benefits of this population immunity are difficult to quantify.7

In Australia, a national school-based HPV vaccination program was initiated in 2007, making the vaccine available for free. Over 70% of girls ages 12 and 13 were vaccinated, and follow-up within the same decade showed a greater than 90% reduction in genital warts, as well as a reduction in high-grade cervical lesions.8 In addition, the incidence of genital warts in unvaccinated heterosexual males during the prevaccination vs the vaccination period decreased by up to 81% (a marker of herd immunity).9

In the US, the HPV subtypes found in the quadrivalent vaccine decreased by 71% in those ages 14 to 19, within 8 years of vaccine introduction.10 An analysis of US state cancer registries between 2009 and 2012 showed that in Michigan, the rates of high-grade, precancerous lesions declined by 37% each year for women ages 15 to 19, thought to be due to changes in screening and vaccination guidelines.11 Similarly, an analysis of 9 million privately insured US females showed that the presence of high-grade precancerous lesions significantly decreased between the years 2007 and 2014 in those ages 15 to 24 (vaccinated individuals), but not in those ages 25 to 39 (unvaccinated individuals).12 Most recently, a study of 10,206 women showed a 21.9% decrease in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse lesions due to HPV subtypes 16 or 18 in those who have received at least 1 dose of the vaccine; reduced rates in unvaccinated women were also seen, representing first evidence of herd immunity in the United States.13 In contrast, the rates of high-grade lesions due to nonvaccine HPV subtypes remained constant. Given that progression to cervical cancer can take 10 to 15 years or longer after HPV infection, true vaccine benefits will emerge once increased vaccination rates are achieved and after at least a decade of follow-up.

We applaud Dr. Lichtenberg’s efforts to clarify vaccine efficacy for appropriate counseling, as this is key to ensuring patient trust. Immunization fears have fueled the re-emergence of vaccine-preventable illnesses across the world. Given the wave of vaccine misinformation on the Internet, we all face patients and family members skeptical of vaccine efficacy and safety. Those requesting more information deserve an honest, informed discussion with their provider. Interestingly, however, among 955 unvaccinated women, the belief of not being at risk for HPV was the most common reason for not receiving the vaccine.14 Effective education can be achieved by focusing on the personal risks of HPV to the patient, as well as the overall favorable risk vs benefits of vaccination. Quoting an exact rate of cancer reduction is likely a less effective counseling strategy, and these efficacy estimates will change as vaccination rates and HPV prevalence within the population change over time.

In Reply: We would like to thank Dr. Lichtenberg for giving us the opportunity to clarify and expand on questions regarding HPV vaccine efficacy.

Our statement “HPV immunization can prevent up to 70% of cases of cervical cancer due to HPV as well as 90% of genital warts” was based on a statement by Thaxton and Waxman, ie, that immunization against HPV types 16 and 18 has the potential to prevent 70% of cancers of the cervix plus a large percentage of other lower anogenital tract cancers.1 This was meant to describe the prevention potential of the quadrivalent vaccine. The currently available Gardasil 9 targets the HPV types that account for 90% of cervical cancers,2 with projected effectiveness likely to vary based on geographic variation in HPV subtypes, ranging from 86.5% in Australia to 92% in North America.3 It is difficult to precisely calculate the effectiveness of HPV vaccination alone, given that cervical cancer prevention is twofold, with primary vaccination and secondary screening (with several notable updates to US national screening guidelines during the same time frame as vaccine development).4

It is true that the 29% decrease in US cervical cancer incidence rates during the years 2011–2014 compared with 2003–2006 is less than the predicted 70%.5 However, not all eligible US females are vaccinated; according to reports from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 49% of adolescents were appropriately immunized against HPV in 2017, an increase over the rate of only 35% in 2014.6 Low vaccination rates undoubtedly negatively impact any benefits from herd immunity, though the exact benefits of this population immunity are difficult to quantify.7

In Australia, a national school-based HPV vaccination program was initiated in 2007, making the vaccine available for free. Over 70% of girls ages 12 and 13 were vaccinated, and follow-up within the same decade showed a greater than 90% reduction in genital warts, as well as a reduction in high-grade cervical lesions.8 In addition, the incidence of genital warts in unvaccinated heterosexual males during the prevaccination vs the vaccination period decreased by up to 81% (a marker of herd immunity).9

In the US, the HPV subtypes found in the quadrivalent vaccine decreased by 71% in those ages 14 to 19, within 8 years of vaccine introduction.10 An analysis of US state cancer registries between 2009 and 2012 showed that in Michigan, the rates of high-grade, precancerous lesions declined by 37% each year for women ages 15 to 19, thought to be due to changes in screening and vaccination guidelines.11 Similarly, an analysis of 9 million privately insured US females showed that the presence of high-grade precancerous lesions significantly decreased between the years 2007 and 2014 in those ages 15 to 24 (vaccinated individuals), but not in those ages 25 to 39 (unvaccinated individuals).12 Most recently, a study of 10,206 women showed a 21.9% decrease in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse lesions due to HPV subtypes 16 or 18 in those who have received at least 1 dose of the vaccine; reduced rates in unvaccinated women were also seen, representing first evidence of herd immunity in the United States.13 In contrast, the rates of high-grade lesions due to nonvaccine HPV subtypes remained constant. Given that progression to cervical cancer can take 10 to 15 years or longer after HPV infection, true vaccine benefits will emerge once increased vaccination rates are achieved and after at least a decade of follow-up.

We applaud Dr. Lichtenberg’s efforts to clarify vaccine efficacy for appropriate counseling, as this is key to ensuring patient trust. Immunization fears have fueled the re-emergence of vaccine-preventable illnesses across the world. Given the wave of vaccine misinformation on the Internet, we all face patients and family members skeptical of vaccine efficacy and safety. Those requesting more information deserve an honest, informed discussion with their provider. Interestingly, however, among 955 unvaccinated women, the belief of not being at risk for HPV was the most common reason for not receiving the vaccine.14 Effective education can be achieved by focusing on the personal risks of HPV to the patient, as well as the overall favorable risk vs benefits of vaccination. Quoting an exact rate of cancer reduction is likely a less effective counseling strategy, and these efficacy estimates will change as vaccination rates and HPV prevalence within the population change over time.

- Thaxton L, Waxman AG. Cervical cancer prevention: Immunization and screening 2015. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99(3):469–477. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.003

- McNamara M, Batur P, Walsh JM, Johnson KM. HPV update: vaccination, screening, and associated disease. J Gen Intern Med 2016; 31(11):1360–1366. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3725-z

- Zhai L, Tumban E. Gardasil-9: A global survey of projected efficacy. Antiviral Res 2016 Jun;130:101–109. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.03.016

- Zhang S, Batur P. Human papillomavirus in 2019: An update on cervical cancer prevention and screening guidelines. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(3):173–178. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.18018

- Guo F, Cofie LE, Berenson AB. Cervical cancer incidence in young U.S. females after human papillomavirus vaccine Introduction. Am J Prev Med 2018; 55(2):197–204. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.013

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus (HPV) coverage data. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/vacc-coverage/index.html. Accessed April 8, 2019.

- Nymark LS, Sharma T, Miller A, Enemark U, Griffiths UK. Inclusion of the value of herd immunity in economic evaluations of vaccines. A systematic review of methods used. Vaccine 2017; 35(49 Pt B):6828–6841. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.024

- Garland SM. The Australian experience with the human papillomavirus vaccine. Clin Ther 2014; 36(1):17–23. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.12.005

- Ali H, Donovan B, Wand H, et al. Genital warts in young Australians five years into national human papillomavirus vaccination programme: national surveillance data. BMJ 2013; 346:f2032. doi:10.1136/bmj.f2032

- Oliver SE, Unger ER, Lewis R, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus among females after vaccine introduction—National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 2003–2014. J Infect Dis 2017; 216(5):594–603. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix244

- Watson M, Soman A, Flagg EW, et al. Surveillance of high-grade cervical cancer precursors (CIN III/AIS) in four population-based cancer registries. Prev Med 2017; 103:60–65. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.07.027

- Flagg EW, Torrone EA, Weinstock H. Ecological association of human papillomavirus vaccination with cervical dysplasia prevalence in the United States, 2007–2014. Am J Public Health 2016; 106(12):2211–2218.

- McClung NM, Gargano JW, Bennett NM, et al; HPV-IMPACT Working Group. Trends in human papillomavirus vaccine types 16 and 18 in cervical precancers, 2008–2014. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019; 28(3):602–609. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0885

- Liddon NC, Hood JE, Leichliter JS. Intent to receive HPV vaccine and reasons for not vaccinating among unvaccinated adolescent and young women: findings from the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth. Vaccine 2012; 30(16):2676–2682. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.007

- Thaxton L, Waxman AG. Cervical cancer prevention: Immunization and screening 2015. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99(3):469–477. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.003

- McNamara M, Batur P, Walsh JM, Johnson KM. HPV update: vaccination, screening, and associated disease. J Gen Intern Med 2016; 31(11):1360–1366. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3725-z

- Zhai L, Tumban E. Gardasil-9: A global survey of projected efficacy. Antiviral Res 2016 Jun;130:101–109. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.03.016

- Zhang S, Batur P. Human papillomavirus in 2019: An update on cervical cancer prevention and screening guidelines. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(3):173–178. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.18018

- Guo F, Cofie LE, Berenson AB. Cervical cancer incidence in young U.S. females after human papillomavirus vaccine Introduction. Am J Prev Med 2018; 55(2):197–204. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.013

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus (HPV) coverage data. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/vacc-coverage/index.html. Accessed April 8, 2019.

- Nymark LS, Sharma T, Miller A, Enemark U, Griffiths UK. Inclusion of the value of herd immunity in economic evaluations of vaccines. A systematic review of methods used. Vaccine 2017; 35(49 Pt B):6828–6841. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.024

- Garland SM. The Australian experience with the human papillomavirus vaccine. Clin Ther 2014; 36(1):17–23. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.12.005

- Ali H, Donovan B, Wand H, et al. Genital warts in young Australians five years into national human papillomavirus vaccination programme: national surveillance data. BMJ 2013; 346:f2032. doi:10.1136/bmj.f2032

- Oliver SE, Unger ER, Lewis R, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus among females after vaccine introduction—National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 2003–2014. J Infect Dis 2017; 216(5):594–603. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix244

- Watson M, Soman A, Flagg EW, et al. Surveillance of high-grade cervical cancer precursors (CIN III/AIS) in four population-based cancer registries. Prev Med 2017; 103:60–65. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.07.027

- Flagg EW, Torrone EA, Weinstock H. Ecological association of human papillomavirus vaccination with cervical dysplasia prevalence in the United States, 2007–2014. Am J Public Health 2016; 106(12):2211–2218.

- McClung NM, Gargano JW, Bennett NM, et al; HPV-IMPACT Working Group. Trends in human papillomavirus vaccine types 16 and 18 in cervical precancers, 2008–2014. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019; 28(3):602–609. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0885

- Liddon NC, Hood JE, Leichliter JS. Intent to receive HPV vaccine and reasons for not vaccinating among unvaccinated adolescent and young women: findings from the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth. Vaccine 2012; 30(16):2676–2682. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.007

Aleukemic leukemia cutis

To the Editor: I read with great interest the article “Aleukemic leukemia cutis” by Abraham et al,1 as we recently had a case of this at my institution. The case is unique and quite intriguing; however, I found the pathologic description confusing and imprecise.

The authors state, “The findings were consistent with leukemic T cells with monocytic differentiation.”1 This is based on their findings that the tumor cells expressed CD4, CD43, CD68, and lysozyme. However, the cells were negative for CD30, ALK-1, CD2, and CD3.

First, I must contest the authors’ claim that “the cells co-expressed T-cell markers (CD4 and CD43)”: CD4 and CD43 are not specific for T cells and are almost invariably seen on monocytes, especially in acute monoblastic/monocytic leukemia (AMoL; also known as M5 in the French-American-British classification system).2,3 Therefore, the immunophenotype is perfect for an AMoL, but since there was no significant blood or bone marrow involvement and it was limited to the skin, this would best fit with a myeloid sarcoma, which frequently has a monocytic immunoprofile.3,4

Additionally, this would not be a mixed-phenotype acute leukemia, T/myeloid, not otherwise specified, as that requires positivity for cytoplasmic CD3 or surface CD3, and that was conspicuously absent.5 Therefore, the appropriate workup and treatment should have essentially followed the course for acute myeloid leukemia,4 which is unclear from the present report as there is no mention of a molecular workup (eg, for FLT3 and NPM1 mutations). This would, in turn, have important treatment and prognostic implications.6

The reason for my comments is to bring to light the importance of exact pathologic diagnosis, especially when dealing with leukemia. We currently have a host of treatment options and prognostic tools for the various types of acute myeloid leukemia, but only when a clear and precise pathologic diagnosis is given.5

- Abraham TN, Morawiecki P, Flischel A, Agrawal B. Aleukemic leukemia cutis. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(2):85–86. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.18057

- Xu Y, McKenna RW, Wilson KS, Karandikar NJ, Schultz RA, Kroft SH. Immunophenotypic identification of acute myeloid leukemia with monocytic differentiation. Leukemia 2006; 20(7):1321–1324. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2404242

- Cronin DMP, George TI, Sundram UN. An updated approach to the diagnosis of myeloid leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol 2009; 132(1):101–110. doi:10.1309/AJCP6GR8BDEXPKHR

- Avni B, Koren-Michowitz M. Myeloid sarcoma: current approach and therapeutic options. Ther Adv Hematol 2011; 2(5):309–316. doi:10.1177/2040620711410774

- Weir EG, Ali Ansari-Lari M, Batista DAS, et al. Acute bilineal leukemia: a rare disease with poor outcome. Leukemia 2007; 21(11):2264–2270. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2404848

- De Kouchkovsky I, Abdul-Hay M. Acute myeloid leukemia: a comprehensive review and 2016 update. Blood Cancer J 2016; 6(7):e441. doi:10.1038/bcj.2016.50

To the Editor: I read with great interest the article “Aleukemic leukemia cutis” by Abraham et al,1 as we recently had a case of this at my institution. The case is unique and quite intriguing; however, I found the pathologic description confusing and imprecise.

The authors state, “The findings were consistent with leukemic T cells with monocytic differentiation.”1 This is based on their findings that the tumor cells expressed CD4, CD43, CD68, and lysozyme. However, the cells were negative for CD30, ALK-1, CD2, and CD3.

First, I must contest the authors’ claim that “the cells co-expressed T-cell markers (CD4 and CD43)”: CD4 and CD43 are not specific for T cells and are almost invariably seen on monocytes, especially in acute monoblastic/monocytic leukemia (AMoL; also known as M5 in the French-American-British classification system).2,3 Therefore, the immunophenotype is perfect for an AMoL, but since there was no significant blood or bone marrow involvement and it was limited to the skin, this would best fit with a myeloid sarcoma, which frequently has a monocytic immunoprofile.3,4

Additionally, this would not be a mixed-phenotype acute leukemia, T/myeloid, not otherwise specified, as that requires positivity for cytoplasmic CD3 or surface CD3, and that was conspicuously absent.5 Therefore, the appropriate workup and treatment should have essentially followed the course for acute myeloid leukemia,4 which is unclear from the present report as there is no mention of a molecular workup (eg, for FLT3 and NPM1 mutations). This would, in turn, have important treatment and prognostic implications.6

The reason for my comments is to bring to light the importance of exact pathologic diagnosis, especially when dealing with leukemia. We currently have a host of treatment options and prognostic tools for the various types of acute myeloid leukemia, but only when a clear and precise pathologic diagnosis is given.5

To the Editor: I read with great interest the article “Aleukemic leukemia cutis” by Abraham et al,1 as we recently had a case of this at my institution. The case is unique and quite intriguing; however, I found the pathologic description confusing and imprecise.

The authors state, “The findings were consistent with leukemic T cells with monocytic differentiation.”1 This is based on their findings that the tumor cells expressed CD4, CD43, CD68, and lysozyme. However, the cells were negative for CD30, ALK-1, CD2, and CD3.

First, I must contest the authors’ claim that “the cells co-expressed T-cell markers (CD4 and CD43)”: CD4 and CD43 are not specific for T cells and are almost invariably seen on monocytes, especially in acute monoblastic/monocytic leukemia (AMoL; also known as M5 in the French-American-British classification system).2,3 Therefore, the immunophenotype is perfect for an AMoL, but since there was no significant blood or bone marrow involvement and it was limited to the skin, this would best fit with a myeloid sarcoma, which frequently has a monocytic immunoprofile.3,4

Additionally, this would not be a mixed-phenotype acute leukemia, T/myeloid, not otherwise specified, as that requires positivity for cytoplasmic CD3 or surface CD3, and that was conspicuously absent.5 Therefore, the appropriate workup and treatment should have essentially followed the course for acute myeloid leukemia,4 which is unclear from the present report as there is no mention of a molecular workup (eg, for FLT3 and NPM1 mutations). This would, in turn, have important treatment and prognostic implications.6

The reason for my comments is to bring to light the importance of exact pathologic diagnosis, especially when dealing with leukemia. We currently have a host of treatment options and prognostic tools for the various types of acute myeloid leukemia, but only when a clear and precise pathologic diagnosis is given.5

- Abraham TN, Morawiecki P, Flischel A, Agrawal B. Aleukemic leukemia cutis. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(2):85–86. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.18057

- Xu Y, McKenna RW, Wilson KS, Karandikar NJ, Schultz RA, Kroft SH. Immunophenotypic identification of acute myeloid leukemia with monocytic differentiation. Leukemia 2006; 20(7):1321–1324. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2404242

- Cronin DMP, George TI, Sundram UN. An updated approach to the diagnosis of myeloid leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol 2009; 132(1):101–110. doi:10.1309/AJCP6GR8BDEXPKHR

- Avni B, Koren-Michowitz M. Myeloid sarcoma: current approach and therapeutic options. Ther Adv Hematol 2011; 2(5):309–316. doi:10.1177/2040620711410774

- Weir EG, Ali Ansari-Lari M, Batista DAS, et al. Acute bilineal leukemia: a rare disease with poor outcome. Leukemia 2007; 21(11):2264–2270. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2404848

- De Kouchkovsky I, Abdul-Hay M. Acute myeloid leukemia: a comprehensive review and 2016 update. Blood Cancer J 2016; 6(7):e441. doi:10.1038/bcj.2016.50

- Abraham TN, Morawiecki P, Flischel A, Agrawal B. Aleukemic leukemia cutis. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(2):85–86. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.18057

- Xu Y, McKenna RW, Wilson KS, Karandikar NJ, Schultz RA, Kroft SH. Immunophenotypic identification of acute myeloid leukemia with monocytic differentiation. Leukemia 2006; 20(7):1321–1324. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2404242

- Cronin DMP, George TI, Sundram UN. An updated approach to the diagnosis of myeloid leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol 2009; 132(1):101–110. doi:10.1309/AJCP6GR8BDEXPKHR

- Avni B, Koren-Michowitz M. Myeloid sarcoma: current approach and therapeutic options. Ther Adv Hematol 2011; 2(5):309–316. doi:10.1177/2040620711410774

- Weir EG, Ali Ansari-Lari M, Batista DAS, et al. Acute bilineal leukemia: a rare disease with poor outcome. Leukemia 2007; 21(11):2264–2270. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2404848

- De Kouchkovsky I, Abdul-Hay M. Acute myeloid leukemia: a comprehensive review and 2016 update. Blood Cancer J 2016; 6(7):e441. doi:10.1038/bcj.2016.50

In reply: Aleukemic leukemia cutis

In Reply: We greatly appreciate our reader’s interest and response. He brings up a very good point. We have reviewed the reports and discussed it with our pathologists. On page 85, the sentence that begins, “The findings were consistent with leukemic T cells with monocytic differentiation” should actually read, “The findings were consistent with leukemic cells with monocytic differentiation.” The patient was appropriately treated for acute myeloid leukemia.

In Reply: We greatly appreciate our reader’s interest and response. He brings up a very good point. We have reviewed the reports and discussed it with our pathologists. On page 85, the sentence that begins, “The findings were consistent with leukemic T cells with monocytic differentiation” should actually read, “The findings were consistent with leukemic cells with monocytic differentiation.” The patient was appropriately treated for acute myeloid leukemia.

In Reply: We greatly appreciate our reader’s interest and response. He brings up a very good point. We have reviewed the reports and discussed it with our pathologists. On page 85, the sentence that begins, “The findings were consistent with leukemic T cells with monocytic differentiation” should actually read, “The findings were consistent with leukemic cells with monocytic differentiation.” The patient was appropriately treated for acute myeloid leukemia.

Leadership and Professional Development: The Healing Power of Laughter

“The most radical act anyone can commit is to be happy.”

—Patch Adams

“The most radical act anyone can commit is to be happy.”

—Patch Adams

“The most radical act anyone can commit is to be happy.”

—Patch Adams

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Women Veterans Call Center Now Offers Text Feature

“What is my veteran status?” “Should I receive any benefits from VA, like the GI Bill?”

Now women veterans have another convenient way to get answers to questions like those. Texting 855.829.6636 (855.VA.WOMEN) connects women veterans to the Women Veterans Call Center, where they will find information about VA benefits, health care, and resources. The new texting feature aligns the service with those of other VA call centers, the VA says.

Women are among the fastest-growing veteran demographics , the VA says, accounting for > 30% of the increase in veterans who served between 2014 and 2018. The number of women using VA health care services has tripled since 2000 from about 160,000 to > 500,000. But the VA has found that women veterans underuse VA care, largely due to a lack of knowledge about benefits, services, and their eligibility for them. As the number of women veterans continues to grow, the VA says, it is expanding its outreach to ensure they receive enrollment and benefits information through user-friendly and responsive means. The VA says it works to meet the unique requirements of women, “offering privacy, dignity, and sensitivity to gender-specific needs.” In addition to linking callers to information, the call center staff make direct referrals to Women Veteran Program Managers at every VAMC.

Since 2013, the call center has received nearly 83,000 inbound calls and has initiated almost 1.3 million outbound calls, resulting in communication with > 650,000 veterans.

Staffed by trained, compassionate female VA employees (many are also veterans), the call center is available Monday through Friday 8 am to 10 pm ET and Saturdays from 8 am to 6:30 pm ET. Veterans can call for themselves or on behalf of another woman veteran. Calls are free and confidential, texts and chats are anonymous. Veterans can call as often as they like, the VA says—“until you have the answer to your questions.”

For more information about the Women Veterans Call Center, visit https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/programoverview/wvcc.asp.

“What is my veteran status?” “Should I receive any benefits from VA, like the GI Bill?”

Now women veterans have another convenient way to get answers to questions like those. Texting 855.829.6636 (855.VA.WOMEN) connects women veterans to the Women Veterans Call Center, where they will find information about VA benefits, health care, and resources. The new texting feature aligns the service with those of other VA call centers, the VA says.

Women are among the fastest-growing veteran demographics , the VA says, accounting for > 30% of the increase in veterans who served between 2014 and 2018. The number of women using VA health care services has tripled since 2000 from about 160,000 to > 500,000. But the VA has found that women veterans underuse VA care, largely due to a lack of knowledge about benefits, services, and their eligibility for them. As the number of women veterans continues to grow, the VA says, it is expanding its outreach to ensure they receive enrollment and benefits information through user-friendly and responsive means. The VA says it works to meet the unique requirements of women, “offering privacy, dignity, and sensitivity to gender-specific needs.” In addition to linking callers to information, the call center staff make direct referrals to Women Veteran Program Managers at every VAMC.

Since 2013, the call center has received nearly 83,000 inbound calls and has initiated almost 1.3 million outbound calls, resulting in communication with > 650,000 veterans.

Staffed by trained, compassionate female VA employees (many are also veterans), the call center is available Monday through Friday 8 am to 10 pm ET and Saturdays from 8 am to 6:30 pm ET. Veterans can call for themselves or on behalf of another woman veteran. Calls are free and confidential, texts and chats are anonymous. Veterans can call as often as they like, the VA says—“until you have the answer to your questions.”

For more information about the Women Veterans Call Center, visit https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/programoverview/wvcc.asp.

“What is my veteran status?” “Should I receive any benefits from VA, like the GI Bill?”

Now women veterans have another convenient way to get answers to questions like those. Texting 855.829.6636 (855.VA.WOMEN) connects women veterans to the Women Veterans Call Center, where they will find information about VA benefits, health care, and resources. The new texting feature aligns the service with those of other VA call centers, the VA says.

Women are among the fastest-growing veteran demographics , the VA says, accounting for > 30% of the increase in veterans who served between 2014 and 2018. The number of women using VA health care services has tripled since 2000 from about 160,000 to > 500,000. But the VA has found that women veterans underuse VA care, largely due to a lack of knowledge about benefits, services, and their eligibility for them. As the number of women veterans continues to grow, the VA says, it is expanding its outreach to ensure they receive enrollment and benefits information through user-friendly and responsive means. The VA says it works to meet the unique requirements of women, “offering privacy, dignity, and sensitivity to gender-specific needs.” In addition to linking callers to information, the call center staff make direct referrals to Women Veteran Program Managers at every VAMC.

Since 2013, the call center has received nearly 83,000 inbound calls and has initiated almost 1.3 million outbound calls, resulting in communication with > 650,000 veterans.

Staffed by trained, compassionate female VA employees (many are also veterans), the call center is available Monday through Friday 8 am to 10 pm ET and Saturdays from 8 am to 6:30 pm ET. Veterans can call for themselves or on behalf of another woman veteran. Calls are free and confidential, texts and chats are anonymous. Veterans can call as often as they like, the VA says—“until you have the answer to your questions.”

For more information about the Women Veterans Call Center, visit https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/programoverview/wvcc.asp.

Looking for the Link Between Smoking and STDs

Cigarette smoking has been linked to the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis (BV) and other genital infections including herpes simplex virus type 2, Chlamydia trachomatis, and oral and genital human papillomavirus (HPV). Nicotine’s major metabolite, cotinine, has been found to concentrate in cervical mucus.

In 2014, researchers from Montana State University confirmed that the composition of the vaginal microbiota is “strongly associated with smoking.” They reported that women whose vaginal microbiota lacked significant numbers of Lactobacillus spp were 25-fold more likely to report current smoking than those with microbiota dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus (L crispatus). The researchers note that most Lactobacillus spp are thought to provide broad-spectrum protection to pathogenic infections by reducing vaginal pH.

But what is the mechanistic link between smoking and its effects on the vaginal microenvironment? The researchers conducted further study to assess the metabolome, a set of small molecule chemicals that includes host and microbial-produced and modified biomolecules as well as exogenous chemicals. The metabolome is an important characteristic of the vaginal microenvironment; the researchers say; differences in some metabolites are associated with functional variations of the vaginal microbiota.

The analysis revealed samples clustered into 3 community state types (CSTs): CST-I (L crispatus dominated), CST-III (L iners dominated) and CST-IV (low Lactobacillus). Overall, smoking did not affect the vaginal metabolome after controlling for CSTs, but the researchers identified “an extensive and diverse range” of vaginal metabolites for which profiles were affected by both the microbiology and smoking status. They found 607 compounds in 36 women, including 12 metabolites that differed significantly between smokers and nonsmokers. Bacterial composition was the most pronounced driver of the vaginal metabolome, they say, associated with changes in 57% of all metabolites. As expected, nicotine, cotinine, and hydroxycotinine were markedly elevated in smokers’ vaginas.

Another “key finding,” the researchers say, was a significant increase in the abundance of various biogenic amines among smokers, far more pronounced in women with a low level of Lactobacillus. Biogenic amines are essential, they note, to mammalian and bacterial physiology. (Several are implicated in the “fishy” odor of BV.)

Their study serves as a pilot study, the researchers say, for future examinations of the connections between smoking and poor gynecologic and reproductive health outcomes.

Cigarette smoking has been linked to the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis (BV) and other genital infections including herpes simplex virus type 2, Chlamydia trachomatis, and oral and genital human papillomavirus (HPV). Nicotine’s major metabolite, cotinine, has been found to concentrate in cervical mucus.

In 2014, researchers from Montana State University confirmed that the composition of the vaginal microbiota is “strongly associated with smoking.” They reported that women whose vaginal microbiota lacked significant numbers of Lactobacillus spp were 25-fold more likely to report current smoking than those with microbiota dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus (L crispatus). The researchers note that most Lactobacillus spp are thought to provide broad-spectrum protection to pathogenic infections by reducing vaginal pH.

But what is the mechanistic link between smoking and its effects on the vaginal microenvironment? The researchers conducted further study to assess the metabolome, a set of small molecule chemicals that includes host and microbial-produced and modified biomolecules as well as exogenous chemicals. The metabolome is an important characteristic of the vaginal microenvironment; the researchers say; differences in some metabolites are associated with functional variations of the vaginal microbiota.

The analysis revealed samples clustered into 3 community state types (CSTs): CST-I (L crispatus dominated), CST-III (L iners dominated) and CST-IV (low Lactobacillus). Overall, smoking did not affect the vaginal metabolome after controlling for CSTs, but the researchers identified “an extensive and diverse range” of vaginal metabolites for which profiles were affected by both the microbiology and smoking status. They found 607 compounds in 36 women, including 12 metabolites that differed significantly between smokers and nonsmokers. Bacterial composition was the most pronounced driver of the vaginal metabolome, they say, associated with changes in 57% of all metabolites. As expected, nicotine, cotinine, and hydroxycotinine were markedly elevated in smokers’ vaginas.

Another “key finding,” the researchers say, was a significant increase in the abundance of various biogenic amines among smokers, far more pronounced in women with a low level of Lactobacillus. Biogenic amines are essential, they note, to mammalian and bacterial physiology. (Several are implicated in the “fishy” odor of BV.)

Their study serves as a pilot study, the researchers say, for future examinations of the connections between smoking and poor gynecologic and reproductive health outcomes.

Cigarette smoking has been linked to the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis (BV) and other genital infections including herpes simplex virus type 2, Chlamydia trachomatis, and oral and genital human papillomavirus (HPV). Nicotine’s major metabolite, cotinine, has been found to concentrate in cervical mucus.

In 2014, researchers from Montana State University confirmed that the composition of the vaginal microbiota is “strongly associated with smoking.” They reported that women whose vaginal microbiota lacked significant numbers of Lactobacillus spp were 25-fold more likely to report current smoking than those with microbiota dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus (L crispatus). The researchers note that most Lactobacillus spp are thought to provide broad-spectrum protection to pathogenic infections by reducing vaginal pH.

But what is the mechanistic link between smoking and its effects on the vaginal microenvironment? The researchers conducted further study to assess the metabolome, a set of small molecule chemicals that includes host and microbial-produced and modified biomolecules as well as exogenous chemicals. The metabolome is an important characteristic of the vaginal microenvironment; the researchers say; differences in some metabolites are associated with functional variations of the vaginal microbiota.

The analysis revealed samples clustered into 3 community state types (CSTs): CST-I (L crispatus dominated), CST-III (L iners dominated) and CST-IV (low Lactobacillus). Overall, smoking did not affect the vaginal metabolome after controlling for CSTs, but the researchers identified “an extensive and diverse range” of vaginal metabolites for which profiles were affected by both the microbiology and smoking status. They found 607 compounds in 36 women, including 12 metabolites that differed significantly between smokers and nonsmokers. Bacterial composition was the most pronounced driver of the vaginal metabolome, they say, associated with changes in 57% of all metabolites. As expected, nicotine, cotinine, and hydroxycotinine were markedly elevated in smokers’ vaginas.

Another “key finding,” the researchers say, was a significant increase in the abundance of various biogenic amines among smokers, far more pronounced in women with a low level of Lactobacillus. Biogenic amines are essential, they note, to mammalian and bacterial physiology. (Several are implicated in the “fishy” odor of BV.)

Their study serves as a pilot study, the researchers say, for future examinations of the connections between smoking and poor gynecologic and reproductive health outcomes.

May 2019 Advances in Hematology and Oncology

Click for Credit: Migraine & stroke risk; Aspirin for CV events; more

Here are 5 articles from the May issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Subclinical hypothyroidism boosts immediate risk of heart failure

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2IK0YiL

Expires January 24, 2020

2. Meta-analysis supports aspirin to reduce cardiovascular events

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2GJLgSB

Expires January 24, 2020

3. Age of migraine onset may affect stroke risk

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ZAJ5YR

Expires January 24, 2020

4. Women with RA have reduced chance of live birth after assisted reproduction treatment

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2VvKRLF

Expires January 27, 2020

5. New SLE disease activity measure beats SLEDAI-2K

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2W8SVPA

Expires January 31, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the May issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Subclinical hypothyroidism boosts immediate risk of heart failure

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2IK0YiL

Expires January 24, 2020

2. Meta-analysis supports aspirin to reduce cardiovascular events

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2GJLgSB

Expires January 24, 2020

3. Age of migraine onset may affect stroke risk

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ZAJ5YR

Expires January 24, 2020

4. Women with RA have reduced chance of live birth after assisted reproduction treatment

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2VvKRLF

Expires January 27, 2020

5. New SLE disease activity measure beats SLEDAI-2K

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2W8SVPA

Expires January 31, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the May issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Subclinical hypothyroidism boosts immediate risk of heart failure

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2IK0YiL

Expires January 24, 2020

2. Meta-analysis supports aspirin to reduce cardiovascular events

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2GJLgSB

Expires January 24, 2020

3. Age of migraine onset may affect stroke risk

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ZAJ5YR

Expires January 24, 2020

4. Women with RA have reduced chance of live birth after assisted reproduction treatment

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2VvKRLF

Expires January 27, 2020

5. New SLE disease activity measure beats SLEDAI-2K

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2W8SVPA

Expires January 31, 2020

Racing thoughts: What to consider

Have you ever had times in your life when you had a tremendous amount of energy, like too much energy, with racing thoughts? I initially ask patients this question when evaluating for bipolar disorder. Some patients insist that they have racing thoughts—thoughts occurring at a rate faster than they can be expressed through speech1—but not episodes of hyperactivity. This response suggests that some patients can have racing thoughts without a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Among the patients I treat, racing thoughts vary in severity, duration, and treatment. When untreated, a patient’s racing thoughts may range from a mild disturbance lasting a few days to a more severe disturbance occurring daily. In this article, I suggest treatments that may help ameliorate racing thoughts, and describe possible causes that include, but are not limited to, mood disorders.

Major depressive disorder

Many patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) have racing thoughts that often go unrecognized, and this symptom is associated with more severe depression.2 Those with a DSM-5 diagnosis of MDD with mixed features could experience prolonged racing thoughts during a major depressive episode.1 Untreated racing thoughts may explain why many patients with MDD do not improve with an antidepressant alone.3 These patients might benefit from augmentation with a mood stabilizer such as lithium4 or a second-generation antipsychotic.5

Other potential causes

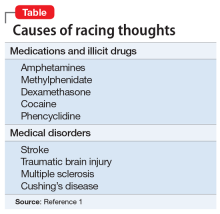

Racing thoughts are a symptom, not a diagnosis. Apprehension and anxiety could cause racing thoughts that do not require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. Patients who often worry about having panic attacks or experience severe chronic stress may have racing thoughts. Also, some patients may be taking medications or illicit drugs or have a medical disorder that could cause symptoms of mania or hypomania that include racing thoughts (Table1).

In summary, when caring for a patient who reports having racing thoughts, consider:

- whether that patient actually does have racing thoughts

- the potential causes, severity, duration, and treatment of the racing thoughts

- the possibility that for a patient with MDD, augmenting an antidepressant with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic could decrease racing thoughts, thereby helping to alleviate many cases of MDD.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:570-575.

3. Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute major depression: thirty-year meta-analytic review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(4):851-864.

4. Bauer M, Adli M, Bschor T, et al. Lithium’s emerging role in the treatment of refractory major depressive episodes: augmentation of antidepressants. Neuropsychobiology. 2010;62(1):36-42.

5. Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):980-991.

Have you ever had times in your life when you had a tremendous amount of energy, like too much energy, with racing thoughts? I initially ask patients this question when evaluating for bipolar disorder. Some patients insist that they have racing thoughts—thoughts occurring at a rate faster than they can be expressed through speech1—but not episodes of hyperactivity. This response suggests that some patients can have racing thoughts without a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Among the patients I treat, racing thoughts vary in severity, duration, and treatment. When untreated, a patient’s racing thoughts may range from a mild disturbance lasting a few days to a more severe disturbance occurring daily. In this article, I suggest treatments that may help ameliorate racing thoughts, and describe possible causes that include, but are not limited to, mood disorders.

Major depressive disorder

Many patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) have racing thoughts that often go unrecognized, and this symptom is associated with more severe depression.2 Those with a DSM-5 diagnosis of MDD with mixed features could experience prolonged racing thoughts during a major depressive episode.1 Untreated racing thoughts may explain why many patients with MDD do not improve with an antidepressant alone.3 These patients might benefit from augmentation with a mood stabilizer such as lithium4 or a second-generation antipsychotic.5

Other potential causes

Racing thoughts are a symptom, not a diagnosis. Apprehension and anxiety could cause racing thoughts that do not require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. Patients who often worry about having panic attacks or experience severe chronic stress may have racing thoughts. Also, some patients may be taking medications or illicit drugs or have a medical disorder that could cause symptoms of mania or hypomania that include racing thoughts (Table1).

In summary, when caring for a patient who reports having racing thoughts, consider:

- whether that patient actually does have racing thoughts

- the potential causes, severity, duration, and treatment of the racing thoughts

- the possibility that for a patient with MDD, augmenting an antidepressant with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic could decrease racing thoughts, thereby helping to alleviate many cases of MDD.

Have you ever had times in your life when you had a tremendous amount of energy, like too much energy, with racing thoughts? I initially ask patients this question when evaluating for bipolar disorder. Some patients insist that they have racing thoughts—thoughts occurring at a rate faster than they can be expressed through speech1—but not episodes of hyperactivity. This response suggests that some patients can have racing thoughts without a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Among the patients I treat, racing thoughts vary in severity, duration, and treatment. When untreated, a patient’s racing thoughts may range from a mild disturbance lasting a few days to a more severe disturbance occurring daily. In this article, I suggest treatments that may help ameliorate racing thoughts, and describe possible causes that include, but are not limited to, mood disorders.

Major depressive disorder

Many patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) have racing thoughts that often go unrecognized, and this symptom is associated with more severe depression.2 Those with a DSM-5 diagnosis of MDD with mixed features could experience prolonged racing thoughts during a major depressive episode.1 Untreated racing thoughts may explain why many patients with MDD do not improve with an antidepressant alone.3 These patients might benefit from augmentation with a mood stabilizer such as lithium4 or a second-generation antipsychotic.5

Other potential causes

Racing thoughts are a symptom, not a diagnosis. Apprehension and anxiety could cause racing thoughts that do not require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. Patients who often worry about having panic attacks or experience severe chronic stress may have racing thoughts. Also, some patients may be taking medications or illicit drugs or have a medical disorder that could cause symptoms of mania or hypomania that include racing thoughts (Table1).

In summary, when caring for a patient who reports having racing thoughts, consider:

- whether that patient actually does have racing thoughts

- the potential causes, severity, duration, and treatment of the racing thoughts

- the possibility that for a patient with MDD, augmenting an antidepressant with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic could decrease racing thoughts, thereby helping to alleviate many cases of MDD.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:570-575.

3. Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute major depression: thirty-year meta-analytic review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(4):851-864.

4. Bauer M, Adli M, Bschor T, et al. Lithium’s emerging role in the treatment of refractory major depressive episodes: augmentation of antidepressants. Neuropsychobiology. 2010;62(1):36-42.

5. Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):980-991.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:570-575.

3. Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute major depression: thirty-year meta-analytic review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(4):851-864.

4. Bauer M, Adli M, Bschor T, et al. Lithium’s emerging role in the treatment of refractory major depressive episodes: augmentation of antidepressants. Neuropsychobiology. 2010;62(1):36-42.

5. Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):980-991.