User login

Femoral head decompression relieves SCD hip pain

FORT LAUDERDALE, FLA. – Hip joint pain and deterioration can be a painful and disabling outcome for patients with sickle cell disease, but femoral head core decompression with the addition of bone marrow aspirate concentrate decreases their pain and may help avoid or delay hip replacement, according to results of a pilot study presented at the annual meeting of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research.

Eric Fornari, MD, of the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore in Bronx, N.Y., reported on results of core decompression (CD) in 35 hips of 26 sickle cell patients; 17 underwent CD only and 18 had CD with injection of bone marrow aspirate concentrate (CD+BMAC). The average patient age was 24.3 years, with a range from 9.7-50.7 years.

“Compared to patients treated with CD alone, patients treated with CD+BMAC complained of significantly less pain and had significant improvement in their functional scores and patient-related outcomes at short-term follow-up,” Dr. Fornari said.

Among the CD+BMAC patients, pain scores declined two points on average, from 6 preoperatively to 4 postoperatively, he said. This was clinically significant, compared with the CD-only group, Dr. Fornari said.

Patients in the CD+BMAC group also reported consistently superior hip outcome and modified Harris hip scores. With either treatment, more than 90% of patients were pain-free and walked independently at their most recent follow-up, he said.

The objective of CD is to relieve pressure within the head of the femur, stimulate vascularity and target the avascular necrosis (AVN) lesion within the head that is visible on imaging. To get the bone marrow aspirate concentrate, Dr. Fornari extracts 120 cc of bone marrow from the iliac crest, then concentrates it to 12 cc. The same instrument is used to tap into the femoral head and inject the bone marrow aspirate concentrate. The study looked at clinical and radiographic outcomes of treated patients.

Average follow-up for the entire study population was 3.6 years, but that varied widely between the two groups (CD-only at almost 6 years, CD+BMAC at 1.4 years) because CD+BMAC has only been done for the last 3 years, Dr. Fornari said.

Progression to total hip arthroplasty (THA) was similar between both groups: 5 of 17 patients (29%) for CD-only vs. 4 of 18 patients (22%) for CD+BMAC (P = .711).

“When you look at progression, there were a number of hips that got CD or CD+BMAC and were better postoperatively; they went from a Ficat score of stage II to a stage I, or stage III to stage II,” he said.

X-rays were not always a reliable marker of outcome after either CD procedure, Dr. Fornari noted. “I’ve seen patients who’ve had terrible looking X-rays who have no pain, and patients who have totally normal X-rays that are completely debilitated,” he said. “We have to start asking ourselves, ‘What is the marker of success?’ because when we do this patients are feeling better.”

Multivariate analysis was used to identify factors predictive of progression to THA after the procedure, Dr. Fornari said. “Age of diagnosis, age of surgery, female gender, and lower hydroxyurea dose at surgery were predictive of advancing disease, whereas a higher dose of hydroxyurea was predictive against advancement,” he said.

The average age of patients who had no THA after either procedure was 21 years, compared with 33.9 years for those who had THA (P = .003). Average hydroxyurea dose at surgery was 24.7 mg/kg in the no-THA group vs. 12.5 mg/kg in those who had THA (P = .005).

Notably, there were no readmissions, fractures, deep vein thromboses, pulmonary embolisms or infarctions after CD, Dr. Fornari said. Transfusions were required in two CD-only and three CD+BMAC patients. Hospitalization rates for vaso-occlusive crisis were similar between groups (P = .103).

Dr. Fornari said the challenge is to identify suitable patients for these procedures. “These are complicated patients and you don’t want to put them through the process of having surgery, putting them on crutches and restricted weight bearing, if they’re not going to get better,” he said. “This procedure done minimally invasively is not the end all and be all, but we have to figure out who are the right patients for it. Patient selection is key.”

Finding those patients starts with a rigorous history and physical exam, he said. Physicians should have a “low threshold” for MRI in these patients because that will reveal findings, such as pre-collapse disease and characteristic of AVN lesions, that may appear normal on X-ray. Patient education is also important. “To think that an injection into the top of the hip is going to solve all their problems is a little naive, so you have to have an honest conversation with the patient,” he said.

Dr. Fornari reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Fornari ED et al. FSCDR 2019, Abstract JSCDH-D-19-00004.

FORT LAUDERDALE, FLA. – Hip joint pain and deterioration can be a painful and disabling outcome for patients with sickle cell disease, but femoral head core decompression with the addition of bone marrow aspirate concentrate decreases their pain and may help avoid or delay hip replacement, according to results of a pilot study presented at the annual meeting of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research.

Eric Fornari, MD, of the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore in Bronx, N.Y., reported on results of core decompression (CD) in 35 hips of 26 sickle cell patients; 17 underwent CD only and 18 had CD with injection of bone marrow aspirate concentrate (CD+BMAC). The average patient age was 24.3 years, with a range from 9.7-50.7 years.

“Compared to patients treated with CD alone, patients treated with CD+BMAC complained of significantly less pain and had significant improvement in their functional scores and patient-related outcomes at short-term follow-up,” Dr. Fornari said.

Among the CD+BMAC patients, pain scores declined two points on average, from 6 preoperatively to 4 postoperatively, he said. This was clinically significant, compared with the CD-only group, Dr. Fornari said.

Patients in the CD+BMAC group also reported consistently superior hip outcome and modified Harris hip scores. With either treatment, more than 90% of patients were pain-free and walked independently at their most recent follow-up, he said.

The objective of CD is to relieve pressure within the head of the femur, stimulate vascularity and target the avascular necrosis (AVN) lesion within the head that is visible on imaging. To get the bone marrow aspirate concentrate, Dr. Fornari extracts 120 cc of bone marrow from the iliac crest, then concentrates it to 12 cc. The same instrument is used to tap into the femoral head and inject the bone marrow aspirate concentrate. The study looked at clinical and radiographic outcomes of treated patients.

Average follow-up for the entire study population was 3.6 years, but that varied widely between the two groups (CD-only at almost 6 years, CD+BMAC at 1.4 years) because CD+BMAC has only been done for the last 3 years, Dr. Fornari said.

Progression to total hip arthroplasty (THA) was similar between both groups: 5 of 17 patients (29%) for CD-only vs. 4 of 18 patients (22%) for CD+BMAC (P = .711).

“When you look at progression, there were a number of hips that got CD or CD+BMAC and were better postoperatively; they went from a Ficat score of stage II to a stage I, or stage III to stage II,” he said.

X-rays were not always a reliable marker of outcome after either CD procedure, Dr. Fornari noted. “I’ve seen patients who’ve had terrible looking X-rays who have no pain, and patients who have totally normal X-rays that are completely debilitated,” he said. “We have to start asking ourselves, ‘What is the marker of success?’ because when we do this patients are feeling better.”

Multivariate analysis was used to identify factors predictive of progression to THA after the procedure, Dr. Fornari said. “Age of diagnosis, age of surgery, female gender, and lower hydroxyurea dose at surgery were predictive of advancing disease, whereas a higher dose of hydroxyurea was predictive against advancement,” he said.

The average age of patients who had no THA after either procedure was 21 years, compared with 33.9 years for those who had THA (P = .003). Average hydroxyurea dose at surgery was 24.7 mg/kg in the no-THA group vs. 12.5 mg/kg in those who had THA (P = .005).

Notably, there were no readmissions, fractures, deep vein thromboses, pulmonary embolisms or infarctions after CD, Dr. Fornari said. Transfusions were required in two CD-only and three CD+BMAC patients. Hospitalization rates for vaso-occlusive crisis were similar between groups (P = .103).

Dr. Fornari said the challenge is to identify suitable patients for these procedures. “These are complicated patients and you don’t want to put them through the process of having surgery, putting them on crutches and restricted weight bearing, if they’re not going to get better,” he said. “This procedure done minimally invasively is not the end all and be all, but we have to figure out who are the right patients for it. Patient selection is key.”

Finding those patients starts with a rigorous history and physical exam, he said. Physicians should have a “low threshold” for MRI in these patients because that will reveal findings, such as pre-collapse disease and characteristic of AVN lesions, that may appear normal on X-ray. Patient education is also important. “To think that an injection into the top of the hip is going to solve all their problems is a little naive, so you have to have an honest conversation with the patient,” he said.

Dr. Fornari reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Fornari ED et al. FSCDR 2019, Abstract JSCDH-D-19-00004.

FORT LAUDERDALE, FLA. – Hip joint pain and deterioration can be a painful and disabling outcome for patients with sickle cell disease, but femoral head core decompression with the addition of bone marrow aspirate concentrate decreases their pain and may help avoid or delay hip replacement, according to results of a pilot study presented at the annual meeting of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research.

Eric Fornari, MD, of the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore in Bronx, N.Y., reported on results of core decompression (CD) in 35 hips of 26 sickle cell patients; 17 underwent CD only and 18 had CD with injection of bone marrow aspirate concentrate (CD+BMAC). The average patient age was 24.3 years, with a range from 9.7-50.7 years.

“Compared to patients treated with CD alone, patients treated with CD+BMAC complained of significantly less pain and had significant improvement in their functional scores and patient-related outcomes at short-term follow-up,” Dr. Fornari said.

Among the CD+BMAC patients, pain scores declined two points on average, from 6 preoperatively to 4 postoperatively, he said. This was clinically significant, compared with the CD-only group, Dr. Fornari said.

Patients in the CD+BMAC group also reported consistently superior hip outcome and modified Harris hip scores. With either treatment, more than 90% of patients were pain-free and walked independently at their most recent follow-up, he said.

The objective of CD is to relieve pressure within the head of the femur, stimulate vascularity and target the avascular necrosis (AVN) lesion within the head that is visible on imaging. To get the bone marrow aspirate concentrate, Dr. Fornari extracts 120 cc of bone marrow from the iliac crest, then concentrates it to 12 cc. The same instrument is used to tap into the femoral head and inject the bone marrow aspirate concentrate. The study looked at clinical and radiographic outcomes of treated patients.

Average follow-up for the entire study population was 3.6 years, but that varied widely between the two groups (CD-only at almost 6 years, CD+BMAC at 1.4 years) because CD+BMAC has only been done for the last 3 years, Dr. Fornari said.

Progression to total hip arthroplasty (THA) was similar between both groups: 5 of 17 patients (29%) for CD-only vs. 4 of 18 patients (22%) for CD+BMAC (P = .711).

“When you look at progression, there were a number of hips that got CD or CD+BMAC and were better postoperatively; they went from a Ficat score of stage II to a stage I, or stage III to stage II,” he said.

X-rays were not always a reliable marker of outcome after either CD procedure, Dr. Fornari noted. “I’ve seen patients who’ve had terrible looking X-rays who have no pain, and patients who have totally normal X-rays that are completely debilitated,” he said. “We have to start asking ourselves, ‘What is the marker of success?’ because when we do this patients are feeling better.”

Multivariate analysis was used to identify factors predictive of progression to THA after the procedure, Dr. Fornari said. “Age of diagnosis, age of surgery, female gender, and lower hydroxyurea dose at surgery were predictive of advancing disease, whereas a higher dose of hydroxyurea was predictive against advancement,” he said.

The average age of patients who had no THA after either procedure was 21 years, compared with 33.9 years for those who had THA (P = .003). Average hydroxyurea dose at surgery was 24.7 mg/kg in the no-THA group vs. 12.5 mg/kg in those who had THA (P = .005).

Notably, there were no readmissions, fractures, deep vein thromboses, pulmonary embolisms or infarctions after CD, Dr. Fornari said. Transfusions were required in two CD-only and three CD+BMAC patients. Hospitalization rates for vaso-occlusive crisis were similar between groups (P = .103).

Dr. Fornari said the challenge is to identify suitable patients for these procedures. “These are complicated patients and you don’t want to put them through the process of having surgery, putting them on crutches and restricted weight bearing, if they’re not going to get better,” he said. “This procedure done minimally invasively is not the end all and be all, but we have to figure out who are the right patients for it. Patient selection is key.”

Finding those patients starts with a rigorous history and physical exam, he said. Physicians should have a “low threshold” for MRI in these patients because that will reveal findings, such as pre-collapse disease and characteristic of AVN lesions, that may appear normal on X-ray. Patient education is also important. “To think that an injection into the top of the hip is going to solve all their problems is a little naive, so you have to have an honest conversation with the patient,” he said.

Dr. Fornari reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Fornari ED et al. FSCDR 2019, Abstract JSCDH-D-19-00004.

REPORTING FROM FSCDR 2019

Smoking linked to increased complication risk after Mohs surgery

, based on data from a retrospective case-control study of 1,008 adult patients.

The increased risk of complications for smokers following many types of surgery is well documented; however, “the effect of smoking in the specific setting of cutaneous tissue transfer is not well characterized in the literature describing outcomes after Mohs reconstruction,” wrote Chang Ye Wang, MD, of St. Louis University, Missouri, and colleagues.

To determine the impact of smoking on acute and long-term complications, the researchers reviewed data from 1,008 adults (396 women and 612 men) who underwent Mohs surgery between July 1, 2012, and June 30, 2016, at a single center. The study population included 128 current smokers, 385 former smokers, and 495 never smokers. The age of the patients ranged from 21 years to 90 years, with a median of 70 years. The results were published in JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery.

The overall rate of acute complications was 4.1%, and the most common complication was infection, in 19 cases; others were 10 cases of flap or graft necrosis, 10 cases of wound dehiscence, and 6 of cases of hematoma or uncontrolled bleeding; some patients experienced more than one of these complications. The risk of acute complications increased for current smokers (odds ratio 9.58) and former smokers (OR, 3.64) in a multivariate analysis. Increased risk of acute complications also was associated with a larger defect (OR, 2.25) and use of free cartilage graft (OR, 8.19).

The researchers defined acute complications as “any postsurgical infection, dehiscence, hematoma, uncontrolled bleeding, and tissue necrosis that required medical counseling or intervention,” and long-term complications as “any postsurgical functional defect or unsatisfactory cosmesis that prompted the patient to request an additional procedural intervention or the surgeon to offer it.”

The overall rate of long-term complications was 7.4%. A procedure in the center of the face was associated with a 25% increased risk of long-term complications (OR, 25.4). Other factors associated with an increased risk of long-term complications were the use of interpolation flap or flap-graft combination (OR, 3.49), larger flaps (OR, 1.42), and presence of basal cell carcinomas or other basaloid tumors (OR, 3.43). Smoking was not associated with an increased risk of long-term complications, and an older age was associated with a decreased risk of long-term complications (OR, 0.66).

The findings were limited by the retrospective study design and unblinded data collection, as well as a lack of photographs of all patients at matching time points, the researchers said. However, the results are consistent with previous studies and “may allow the surgeon to better quantify the magnitude of risk and provide helpful information for patient counseling,” they added.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Wang CY et al. JAMA Facial Plast. Surg. 2019 June 13. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2019.0243.

, based on data from a retrospective case-control study of 1,008 adult patients.

The increased risk of complications for smokers following many types of surgery is well documented; however, “the effect of smoking in the specific setting of cutaneous tissue transfer is not well characterized in the literature describing outcomes after Mohs reconstruction,” wrote Chang Ye Wang, MD, of St. Louis University, Missouri, and colleagues.

To determine the impact of smoking on acute and long-term complications, the researchers reviewed data from 1,008 adults (396 women and 612 men) who underwent Mohs surgery between July 1, 2012, and June 30, 2016, at a single center. The study population included 128 current smokers, 385 former smokers, and 495 never smokers. The age of the patients ranged from 21 years to 90 years, with a median of 70 years. The results were published in JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery.

The overall rate of acute complications was 4.1%, and the most common complication was infection, in 19 cases; others were 10 cases of flap or graft necrosis, 10 cases of wound dehiscence, and 6 of cases of hematoma or uncontrolled bleeding; some patients experienced more than one of these complications. The risk of acute complications increased for current smokers (odds ratio 9.58) and former smokers (OR, 3.64) in a multivariate analysis. Increased risk of acute complications also was associated with a larger defect (OR, 2.25) and use of free cartilage graft (OR, 8.19).

The researchers defined acute complications as “any postsurgical infection, dehiscence, hematoma, uncontrolled bleeding, and tissue necrosis that required medical counseling or intervention,” and long-term complications as “any postsurgical functional defect or unsatisfactory cosmesis that prompted the patient to request an additional procedural intervention or the surgeon to offer it.”

The overall rate of long-term complications was 7.4%. A procedure in the center of the face was associated with a 25% increased risk of long-term complications (OR, 25.4). Other factors associated with an increased risk of long-term complications were the use of interpolation flap or flap-graft combination (OR, 3.49), larger flaps (OR, 1.42), and presence of basal cell carcinomas or other basaloid tumors (OR, 3.43). Smoking was not associated with an increased risk of long-term complications, and an older age was associated with a decreased risk of long-term complications (OR, 0.66).

The findings were limited by the retrospective study design and unblinded data collection, as well as a lack of photographs of all patients at matching time points, the researchers said. However, the results are consistent with previous studies and “may allow the surgeon to better quantify the magnitude of risk and provide helpful information for patient counseling,” they added.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Wang CY et al. JAMA Facial Plast. Surg. 2019 June 13. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2019.0243.

, based on data from a retrospective case-control study of 1,008 adult patients.

The increased risk of complications for smokers following many types of surgery is well documented; however, “the effect of smoking in the specific setting of cutaneous tissue transfer is not well characterized in the literature describing outcomes after Mohs reconstruction,” wrote Chang Ye Wang, MD, of St. Louis University, Missouri, and colleagues.

To determine the impact of smoking on acute and long-term complications, the researchers reviewed data from 1,008 adults (396 women and 612 men) who underwent Mohs surgery between July 1, 2012, and June 30, 2016, at a single center. The study population included 128 current smokers, 385 former smokers, and 495 never smokers. The age of the patients ranged from 21 years to 90 years, with a median of 70 years. The results were published in JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery.

The overall rate of acute complications was 4.1%, and the most common complication was infection, in 19 cases; others were 10 cases of flap or graft necrosis, 10 cases of wound dehiscence, and 6 of cases of hematoma or uncontrolled bleeding; some patients experienced more than one of these complications. The risk of acute complications increased for current smokers (odds ratio 9.58) and former smokers (OR, 3.64) in a multivariate analysis. Increased risk of acute complications also was associated with a larger defect (OR, 2.25) and use of free cartilage graft (OR, 8.19).

The researchers defined acute complications as “any postsurgical infection, dehiscence, hematoma, uncontrolled bleeding, and tissue necrosis that required medical counseling or intervention,” and long-term complications as “any postsurgical functional defect or unsatisfactory cosmesis that prompted the patient to request an additional procedural intervention or the surgeon to offer it.”

The overall rate of long-term complications was 7.4%. A procedure in the center of the face was associated with a 25% increased risk of long-term complications (OR, 25.4). Other factors associated with an increased risk of long-term complications were the use of interpolation flap or flap-graft combination (OR, 3.49), larger flaps (OR, 1.42), and presence of basal cell carcinomas or other basaloid tumors (OR, 3.43). Smoking was not associated with an increased risk of long-term complications, and an older age was associated with a decreased risk of long-term complications (OR, 0.66).

The findings were limited by the retrospective study design and unblinded data collection, as well as a lack of photographs of all patients at matching time points, the researchers said. However, the results are consistent with previous studies and “may allow the surgeon to better quantify the magnitude of risk and provide helpful information for patient counseling,” they added.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Wang CY et al. JAMA Facial Plast. Surg. 2019 June 13. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2019.0243.

FROM JAMA FACIAL PLASTIC SURGERY

Cyclosporine, methotrexate have lowest 6-month infection risk for AD patients

(AD) receiving systemic therapy in a real-world setting, according to a recently published population-based study.

When compared with methotrexate, there was a significant reduction in risk of serious infection at 6 months for patients with AD receiving cyclosporine. Prednisone, azathioprine, and mycophenolate carried higher risks of serious infections at 6 months than methotrexate or cyclosporine, researchers said in the study, which appeared in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Among non-biologic systemic agents, cyclosporine and methotrexate appear to have better safety profiles than mycophenolate, azathioprine, and systemic prednisone with regard to serious infections,” they concluded. “These findings may help inform clinicians in their selection of medications for patients requiring systemic therapy for atopic dermatitis,” Maria C. Schneeweiss, MD, from the departments of dermatology and medicine and Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues wrote in their study.

Using population-based claims data, the researchers evaluated rates of serious infection requiring hospitalization in 232,611 patients between January 2003 and January 2017 who received methotrexate, cyclosporine, azathioprine, prednisone or mycophenolate for treatment of AD. Patients first received the same level of corticosteroids before moving to systemic therapy or phototherapy. They also compared results with 23,908 patients in a second cohort who were new users of dupilumab (391 patients) or non-biologic systemic immunomodulators (23,517).

Overall, the rate of serious infections was 7.53 per 1,000 for patients receiving systemic non-biologic therapy at 6 months compared with 7.38 per 1,000 for patients receiving phototherapy, and 2.6 per 1,000 for patients receiving dupilumab.

When matching using propensity scores, the researchers found a significantly reduced risk at 6 months of serious infections from cyclosporine compared with methotrexate (relative risk, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.59-1.28). Compared with methotrexate, there was an increased risk of serious infection at 6 months for azathioprine (RR, 1.78; 95% CI, 0.98-3.25), prednisone (RR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.05-3.42) and mycophenolate (RR, 3.31; 95% CI, 1.94-5.64).

According to preliminary data, when compared with patients who received non-biologic systemic therapy, there was no increased risk for patients receiving dupilumab (RR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.03-3.20). Dupilumab was approved in March 2017, and “with one year of data resulting in one event among 391 patients, this analysis is limited but does not show an obvious signal for increased risk” for dupilumab, they wrote.

Dr. Schneeweiss and colleagues noted some of their analyses had wide confidence intervals, they did not account for dosing schemes or cumulative dose exposure over the study period, and the data on dupilumab showing no increase were preliminary and not conclusive.

“Our findings on systemic non-biologics are highly plausible, given the known risk of systemic immunomodulators in patients treated for other indications, the meaningful effect size, and the methodologically robust approach with a new-user active-comparator design and propensity score matching,” the researchers said.

This study was funded in part by Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. One author reported being a consultant for multiple pharmaceutical companies. The other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schneeweiss M, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.073.

(AD) receiving systemic therapy in a real-world setting, according to a recently published population-based study.

When compared with methotrexate, there was a significant reduction in risk of serious infection at 6 months for patients with AD receiving cyclosporine. Prednisone, azathioprine, and mycophenolate carried higher risks of serious infections at 6 months than methotrexate or cyclosporine, researchers said in the study, which appeared in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Among non-biologic systemic agents, cyclosporine and methotrexate appear to have better safety profiles than mycophenolate, azathioprine, and systemic prednisone with regard to serious infections,” they concluded. “These findings may help inform clinicians in their selection of medications for patients requiring systemic therapy for atopic dermatitis,” Maria C. Schneeweiss, MD, from the departments of dermatology and medicine and Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues wrote in their study.

Using population-based claims data, the researchers evaluated rates of serious infection requiring hospitalization in 232,611 patients between January 2003 and January 2017 who received methotrexate, cyclosporine, azathioprine, prednisone or mycophenolate for treatment of AD. Patients first received the same level of corticosteroids before moving to systemic therapy or phototherapy. They also compared results with 23,908 patients in a second cohort who were new users of dupilumab (391 patients) or non-biologic systemic immunomodulators (23,517).

Overall, the rate of serious infections was 7.53 per 1,000 for patients receiving systemic non-biologic therapy at 6 months compared with 7.38 per 1,000 for patients receiving phototherapy, and 2.6 per 1,000 for patients receiving dupilumab.

When matching using propensity scores, the researchers found a significantly reduced risk at 6 months of serious infections from cyclosporine compared with methotrexate (relative risk, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.59-1.28). Compared with methotrexate, there was an increased risk of serious infection at 6 months for azathioprine (RR, 1.78; 95% CI, 0.98-3.25), prednisone (RR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.05-3.42) and mycophenolate (RR, 3.31; 95% CI, 1.94-5.64).

According to preliminary data, when compared with patients who received non-biologic systemic therapy, there was no increased risk for patients receiving dupilumab (RR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.03-3.20). Dupilumab was approved in March 2017, and “with one year of data resulting in one event among 391 patients, this analysis is limited but does not show an obvious signal for increased risk” for dupilumab, they wrote.

Dr. Schneeweiss and colleagues noted some of their analyses had wide confidence intervals, they did not account for dosing schemes or cumulative dose exposure over the study period, and the data on dupilumab showing no increase were preliminary and not conclusive.

“Our findings on systemic non-biologics are highly plausible, given the known risk of systemic immunomodulators in patients treated for other indications, the meaningful effect size, and the methodologically robust approach with a new-user active-comparator design and propensity score matching,” the researchers said.

This study was funded in part by Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. One author reported being a consultant for multiple pharmaceutical companies. The other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schneeweiss M, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.073.

(AD) receiving systemic therapy in a real-world setting, according to a recently published population-based study.

When compared with methotrexate, there was a significant reduction in risk of serious infection at 6 months for patients with AD receiving cyclosporine. Prednisone, azathioprine, and mycophenolate carried higher risks of serious infections at 6 months than methotrexate or cyclosporine, researchers said in the study, which appeared in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Among non-biologic systemic agents, cyclosporine and methotrexate appear to have better safety profiles than mycophenolate, azathioprine, and systemic prednisone with regard to serious infections,” they concluded. “These findings may help inform clinicians in their selection of medications for patients requiring systemic therapy for atopic dermatitis,” Maria C. Schneeweiss, MD, from the departments of dermatology and medicine and Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues wrote in their study.

Using population-based claims data, the researchers evaluated rates of serious infection requiring hospitalization in 232,611 patients between January 2003 and January 2017 who received methotrexate, cyclosporine, azathioprine, prednisone or mycophenolate for treatment of AD. Patients first received the same level of corticosteroids before moving to systemic therapy or phototherapy. They also compared results with 23,908 patients in a second cohort who were new users of dupilumab (391 patients) or non-biologic systemic immunomodulators (23,517).

Overall, the rate of serious infections was 7.53 per 1,000 for patients receiving systemic non-biologic therapy at 6 months compared with 7.38 per 1,000 for patients receiving phototherapy, and 2.6 per 1,000 for patients receiving dupilumab.

When matching using propensity scores, the researchers found a significantly reduced risk at 6 months of serious infections from cyclosporine compared with methotrexate (relative risk, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.59-1.28). Compared with methotrexate, there was an increased risk of serious infection at 6 months for azathioprine (RR, 1.78; 95% CI, 0.98-3.25), prednisone (RR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.05-3.42) and mycophenolate (RR, 3.31; 95% CI, 1.94-5.64).

According to preliminary data, when compared with patients who received non-biologic systemic therapy, there was no increased risk for patients receiving dupilumab (RR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.03-3.20). Dupilumab was approved in March 2017, and “with one year of data resulting in one event among 391 patients, this analysis is limited but does not show an obvious signal for increased risk” for dupilumab, they wrote.

Dr. Schneeweiss and colleagues noted some of their analyses had wide confidence intervals, they did not account for dosing schemes or cumulative dose exposure over the study period, and the data on dupilumab showing no increase were preliminary and not conclusive.

“Our findings on systemic non-biologics are highly plausible, given the known risk of systemic immunomodulators in patients treated for other indications, the meaningful effect size, and the methodologically robust approach with a new-user active-comparator design and propensity score matching,” the researchers said.

This study was funded in part by Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. One author reported being a consultant for multiple pharmaceutical companies. The other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schneeweiss M, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.073.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Surprise! High-fat dairy may protect against metabolic syndrome

SAN FRANCISCO – Here’s potential bad news for everyone who dines on skim milk and non-fat yogurt:

The findings aren’t conclusive. Still, researchers found that “among whites and African- Americans, the whole milk/high-fat dairy pattern had a protective effect on the risk of metabolic syndrome,” said epidemiologist and study lead author Dale Hardy, PhD, of Morehouse School of Medicine, in an interview. She presented the study findings at the scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Hardy launched her research as part of a project that’s examining relationships between diet, genes, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases in whites and African-Americans.

According to a 2017 study, an estimated 34% of adults in the U.S. from 2007-2012 had MetS, defined as the presence of at least 3 of these factors – elevated waist circumference, elevated triglycerides, reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high blood pressure, and elevated fasting blood glucose (Prev Chronic Dis. 2017 Mar 16;14:E24).

MetS is linked to higher rates of a variety of ills, including cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, and early death.

For the new study, Dr. Hardy and colleagues examined data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study (1987-1998) and food questionnaires (1987 and 1993). There were 9,778 white participants and 2,922 African-American participants.

Subjects with diets higher in whole milk/high-fat dairy diets were significantly less likely to develop MetS per 5-unit increase at risk ratio (RR) =.96 (0.90-1.00), for whites and RR = .81 (0.72-0.90), for African-Americans.

But whites with skim milk/low-fat dairy diets had significantly higher risks of MetS per 5-unit increase at RR = 1.11 (1.06-1.17). There was also a higher risk for African-Americans but it was not statistically significant.

There was an even bigger bump in significant risk for those with diets higher in red and processed meat per 5-unit increase at RR = 1.17 (1.12-1.23), for whites and RR=1.16 (1.08-1.25), for African-Americans.

The researchers also found evidence that whole milk/high-fat dairy diets had an even greater protective effect in whites when genetic risk was present.

What’s going on? “Maybe the fat in the [dairy] foods is holding back glucose absorption and decreasing the risk for MetS over time,” Hardy said. “This fat is different from the animal fats from meats. Fat from dairy has a shorter molecular structure chain compared to the hard animal fats. Hard animal fats are more dangerous in terms of increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.”

The dairy fat, Hardy said, could also be lowering insulin secretion.

So should everyone embrace whole milk and high-fat yogurt and cottage cheese? Hardy isn’t ready to offer this advice. “I don’t think that high-fat diary per se should be recommended as a miracle food to manage or prevent MetS,” she said. “I believe that the macronutrient composition of the meals and the day’s intake should be a more important feature of the diet. In addition, frequent exercise should be recommended to manage MetS.”

More analysis of the data is ongoing, Hardy said, and her team has found signs that diets higher in nuts and peanut butter are protective against MetS in whites.

The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The study authors had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Hardy, D. et al. 2019 ADA annual meeting Abstract 1458-P.

SAN FRANCISCO – Here’s potential bad news for everyone who dines on skim milk and non-fat yogurt:

The findings aren’t conclusive. Still, researchers found that “among whites and African- Americans, the whole milk/high-fat dairy pattern had a protective effect on the risk of metabolic syndrome,” said epidemiologist and study lead author Dale Hardy, PhD, of Morehouse School of Medicine, in an interview. She presented the study findings at the scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Hardy launched her research as part of a project that’s examining relationships between diet, genes, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases in whites and African-Americans.

According to a 2017 study, an estimated 34% of adults in the U.S. from 2007-2012 had MetS, defined as the presence of at least 3 of these factors – elevated waist circumference, elevated triglycerides, reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high blood pressure, and elevated fasting blood glucose (Prev Chronic Dis. 2017 Mar 16;14:E24).

MetS is linked to higher rates of a variety of ills, including cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, and early death.

For the new study, Dr. Hardy and colleagues examined data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study (1987-1998) and food questionnaires (1987 and 1993). There were 9,778 white participants and 2,922 African-American participants.

Subjects with diets higher in whole milk/high-fat dairy diets were significantly less likely to develop MetS per 5-unit increase at risk ratio (RR) =.96 (0.90-1.00), for whites and RR = .81 (0.72-0.90), for African-Americans.

But whites with skim milk/low-fat dairy diets had significantly higher risks of MetS per 5-unit increase at RR = 1.11 (1.06-1.17). There was also a higher risk for African-Americans but it was not statistically significant.

There was an even bigger bump in significant risk for those with diets higher in red and processed meat per 5-unit increase at RR = 1.17 (1.12-1.23), for whites and RR=1.16 (1.08-1.25), for African-Americans.

The researchers also found evidence that whole milk/high-fat dairy diets had an even greater protective effect in whites when genetic risk was present.

What’s going on? “Maybe the fat in the [dairy] foods is holding back glucose absorption and decreasing the risk for MetS over time,” Hardy said. “This fat is different from the animal fats from meats. Fat from dairy has a shorter molecular structure chain compared to the hard animal fats. Hard animal fats are more dangerous in terms of increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.”

The dairy fat, Hardy said, could also be lowering insulin secretion.

So should everyone embrace whole milk and high-fat yogurt and cottage cheese? Hardy isn’t ready to offer this advice. “I don’t think that high-fat diary per se should be recommended as a miracle food to manage or prevent MetS,” she said. “I believe that the macronutrient composition of the meals and the day’s intake should be a more important feature of the diet. In addition, frequent exercise should be recommended to manage MetS.”

More analysis of the data is ongoing, Hardy said, and her team has found signs that diets higher in nuts and peanut butter are protective against MetS in whites.

The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The study authors had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Hardy, D. et al. 2019 ADA annual meeting Abstract 1458-P.

SAN FRANCISCO – Here’s potential bad news for everyone who dines on skim milk and non-fat yogurt:

The findings aren’t conclusive. Still, researchers found that “among whites and African- Americans, the whole milk/high-fat dairy pattern had a protective effect on the risk of metabolic syndrome,” said epidemiologist and study lead author Dale Hardy, PhD, of Morehouse School of Medicine, in an interview. She presented the study findings at the scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Hardy launched her research as part of a project that’s examining relationships between diet, genes, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases in whites and African-Americans.

According to a 2017 study, an estimated 34% of adults in the U.S. from 2007-2012 had MetS, defined as the presence of at least 3 of these factors – elevated waist circumference, elevated triglycerides, reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high blood pressure, and elevated fasting blood glucose (Prev Chronic Dis. 2017 Mar 16;14:E24).

MetS is linked to higher rates of a variety of ills, including cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, and early death.

For the new study, Dr. Hardy and colleagues examined data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study (1987-1998) and food questionnaires (1987 and 1993). There were 9,778 white participants and 2,922 African-American participants.

Subjects with diets higher in whole milk/high-fat dairy diets were significantly less likely to develop MetS per 5-unit increase at risk ratio (RR) =.96 (0.90-1.00), for whites and RR = .81 (0.72-0.90), for African-Americans.

But whites with skim milk/low-fat dairy diets had significantly higher risks of MetS per 5-unit increase at RR = 1.11 (1.06-1.17). There was also a higher risk for African-Americans but it was not statistically significant.

There was an even bigger bump in significant risk for those with diets higher in red and processed meat per 5-unit increase at RR = 1.17 (1.12-1.23), for whites and RR=1.16 (1.08-1.25), for African-Americans.

The researchers also found evidence that whole milk/high-fat dairy diets had an even greater protective effect in whites when genetic risk was present.

What’s going on? “Maybe the fat in the [dairy] foods is holding back glucose absorption and decreasing the risk for MetS over time,” Hardy said. “This fat is different from the animal fats from meats. Fat from dairy has a shorter molecular structure chain compared to the hard animal fats. Hard animal fats are more dangerous in terms of increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.”

The dairy fat, Hardy said, could also be lowering insulin secretion.

So should everyone embrace whole milk and high-fat yogurt and cottage cheese? Hardy isn’t ready to offer this advice. “I don’t think that high-fat diary per se should be recommended as a miracle food to manage or prevent MetS,” she said. “I believe that the macronutrient composition of the meals and the day’s intake should be a more important feature of the diet. In addition, frequent exercise should be recommended to manage MetS.”

More analysis of the data is ongoing, Hardy said, and her team has found signs that diets higher in nuts and peanut butter are protective against MetS in whites.

The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The study authors had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Hardy, D. et al. 2019 ADA annual meeting Abstract 1458-P.

REPORTING FROM ADA 2019

Ketamine edges out ECT for refractory depression in small study

SAN FRANCISCO – Electroconvulsive therapy and ketamine both work well for refractory depression, but ketamine had the edge in a small, open label trial at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“Over the short term,” even a single ketamine infusion may “be as effective as ... ECT for reducing overall depression, apathy, anhedonia, and suicidal ideation,” but ECT may be more durable, said investigator Katherine Narr, PhD, an associate professor of neurology, psychiatry, and biobehavioral sciences at the school.

The study begins to address an issue that’s probably on the minds of many these days: ECT or ketamine for refractory depression? ELEKT-D (Clinicaltrials.gov NCT03113968), a large randomized, trial is underway to answer the question, but results aren’t expected for a couple of years.

In the meantime, although there was no randomization or blinding, Dr. Narr’s results are informative.

Twenty-six adults received one ketamine infusion, 0.5 mg/kg over 40 minutes, while 36 had four over about 2 weeks. Ketamine patients were allowed to stay on antidepressants. Forty-seven subjects, meanwhile, had 11 ECT treatments over 3 weeks, before which all psychiatric medications were stopped. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) was used to assess outcomes.

Suicidal ideation probability dropped from 86% to 51% in the ECT group, but from 75% to 37% after one ketamine infusion, and to 11% after four (P less than .0001). A single “ketamine infusion showed similar probability of suicidal ideation reduction as a full course of ECT,” Dr. Narr said at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting.

Improvements in overall HDRS scores were also greater after both single and serial ketamine (P less than .001).

However, HDRS scores – particularly for suicidal ideation – were beginning to creep up in the ketamine arm after just 5 weeks, but remained largely stable in the ECT group even at 3 months. In both groups, “therapeutic benefits for apathy and anhedonia last longer than for suicidal ideation,” Dr. Narr said.

At the moment, “you can’t predict who’s going to respond” better to one option or the other, “but I’m sure” biomarkers for that “are coming,” she said. Patients were 40 years old, on average, with depression first diagnosed in their early 20s. ECT subjects were equally split between the sexes, while there were more men than women in the ketamine arm, and current episodes were longer (average 6.6 years ketamine versus 3.7 years ECT). Baseline apathy scores were slightly higher in the ketamine group.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Narr didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Narr K et al., Presented at APA 2019

SAN FRANCISCO – Electroconvulsive therapy and ketamine both work well for refractory depression, but ketamine had the edge in a small, open label trial at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“Over the short term,” even a single ketamine infusion may “be as effective as ... ECT for reducing overall depression, apathy, anhedonia, and suicidal ideation,” but ECT may be more durable, said investigator Katherine Narr, PhD, an associate professor of neurology, psychiatry, and biobehavioral sciences at the school.

The study begins to address an issue that’s probably on the minds of many these days: ECT or ketamine for refractory depression? ELEKT-D (Clinicaltrials.gov NCT03113968), a large randomized, trial is underway to answer the question, but results aren’t expected for a couple of years.

In the meantime, although there was no randomization or blinding, Dr. Narr’s results are informative.

Twenty-six adults received one ketamine infusion, 0.5 mg/kg over 40 minutes, while 36 had four over about 2 weeks. Ketamine patients were allowed to stay on antidepressants. Forty-seven subjects, meanwhile, had 11 ECT treatments over 3 weeks, before which all psychiatric medications were stopped. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) was used to assess outcomes.

Suicidal ideation probability dropped from 86% to 51% in the ECT group, but from 75% to 37% after one ketamine infusion, and to 11% after four (P less than .0001). A single “ketamine infusion showed similar probability of suicidal ideation reduction as a full course of ECT,” Dr. Narr said at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting.

Improvements in overall HDRS scores were also greater after both single and serial ketamine (P less than .001).

However, HDRS scores – particularly for suicidal ideation – were beginning to creep up in the ketamine arm after just 5 weeks, but remained largely stable in the ECT group even at 3 months. In both groups, “therapeutic benefits for apathy and anhedonia last longer than for suicidal ideation,” Dr. Narr said.

At the moment, “you can’t predict who’s going to respond” better to one option or the other, “but I’m sure” biomarkers for that “are coming,” she said. Patients were 40 years old, on average, with depression first diagnosed in their early 20s. ECT subjects were equally split between the sexes, while there were more men than women in the ketamine arm, and current episodes were longer (average 6.6 years ketamine versus 3.7 years ECT). Baseline apathy scores were slightly higher in the ketamine group.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Narr didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Narr K et al., Presented at APA 2019

SAN FRANCISCO – Electroconvulsive therapy and ketamine both work well for refractory depression, but ketamine had the edge in a small, open label trial at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“Over the short term,” even a single ketamine infusion may “be as effective as ... ECT for reducing overall depression, apathy, anhedonia, and suicidal ideation,” but ECT may be more durable, said investigator Katherine Narr, PhD, an associate professor of neurology, psychiatry, and biobehavioral sciences at the school.

The study begins to address an issue that’s probably on the minds of many these days: ECT or ketamine for refractory depression? ELEKT-D (Clinicaltrials.gov NCT03113968), a large randomized, trial is underway to answer the question, but results aren’t expected for a couple of years.

In the meantime, although there was no randomization or blinding, Dr. Narr’s results are informative.

Twenty-six adults received one ketamine infusion, 0.5 mg/kg over 40 minutes, while 36 had four over about 2 weeks. Ketamine patients were allowed to stay on antidepressants. Forty-seven subjects, meanwhile, had 11 ECT treatments over 3 weeks, before which all psychiatric medications were stopped. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) was used to assess outcomes.

Suicidal ideation probability dropped from 86% to 51% in the ECT group, but from 75% to 37% after one ketamine infusion, and to 11% after four (P less than .0001). A single “ketamine infusion showed similar probability of suicidal ideation reduction as a full course of ECT,” Dr. Narr said at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting.

Improvements in overall HDRS scores were also greater after both single and serial ketamine (P less than .001).

However, HDRS scores – particularly for suicidal ideation – were beginning to creep up in the ketamine arm after just 5 weeks, but remained largely stable in the ECT group even at 3 months. In both groups, “therapeutic benefits for apathy and anhedonia last longer than for suicidal ideation,” Dr. Narr said.

At the moment, “you can’t predict who’s going to respond” better to one option or the other, “but I’m sure” biomarkers for that “are coming,” she said. Patients were 40 years old, on average, with depression first diagnosed in their early 20s. ECT subjects were equally split between the sexes, while there were more men than women in the ketamine arm, and current episodes were longer (average 6.6 years ketamine versus 3.7 years ECT). Baseline apathy scores were slightly higher in the ketamine group.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Narr didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Narr K et al., Presented at APA 2019

REPORTING FROM APA 2019

Treatment for pediatric low-grade glioma is associated with poor cognitive and socioeconomic outcomes

Children who underwent surgery alone had better neuropsychologic and socioeconomic outcomes than those who also underwent radiotherapy, but their outcomes were worse than those of unaffected siblings. These findings were published online June 24 in Cancer.

“Late effects in adulthood are evident even for children with the least malignant types of brain tumors who were treated with the least toxic therapies available at the time,” said M. Douglas Ris, PhD, professor of pediatrics and psychology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, in a press release. “As pediatric brain tumors become more survivable with continued advances in treatments, we need to improve surveillance of these populations so that survivors continue to receive the best interventions during their transition to adulthood and well beyond.”

Clinicians generally have assumed that children with low-grade CNS tumors who receive less toxic treatment will have fewer long-term effects than survivors of more malignant tumors who undergo neurotoxic therapies. Yet research has indicated that the former patients can have lasting neurobehavioral or functional morbidity.

Dr. Ris and colleagues invited survivors of pediatric low-grade gliomas participating in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) and a sibling comparison group to undergo a direct, comprehensive neurocognitive assessment. Of 495 eligible survivors, 257 participated. Seventy-six patients did not travel to a study site, but completed a questionnaire, and the researchers did not include data for this group in their analysis. Dr. Ris and colleagues obtained information about surgery and radiotherapy from participants’ medical records. Patients underwent standardized, age-normed neuropsychologic tests. The primary neuropsychologic outcomes were the Composite Neuropsychological Index (CNI) and estimated IQ. To evaluate socioeconomic outcomes, Dr. Ris and colleagues measured participants’ educational attainment, income, and occupational prestige.

After the researchers adjusted the data for age and sex, they found that siblings had higher mean scores than survivors treated with surgery plus radiotherapy or surgery alone on all neuropsychologic outcomes, including the CNI (siblings, 106.8; surgery only, 95.6; surgery plus radiotherapy, 88.3) and estimated IQ. Survivors who had been diagnosed at younger ages had low scores for all outcomes except for attention/processing speed.

Furthermore, surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 7.7-fold higher risk of having an occupation in the lowest sibling quartile, compared with siblings. Survivors who underwent surgery alone had a 2.8-fold higher risk than siblings of having an occupation in the lowest quartile. Surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 2.6-fold increased risk of a low occupation score, compared with survivors who underwent surgery alone.

Compared with siblings, surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 4.5-fold risk of an annual income of less than $20,000, while the risk for survivors who underwent surgery alone did not differ significantly from that for siblings. Surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 2.6-fold higher risk than surgery alone. Surgery plus radiotherapy was also associated with a significantly increased risk for an education level lower than a bachelor’s degree, compared with siblings, but surgery alone was not.

The National Cancer Institute supported the study. The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Ris MD et al. Cancer. 2019 Jun 24. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32186.

Children who underwent surgery alone had better neuropsychologic and socioeconomic outcomes than those who also underwent radiotherapy, but their outcomes were worse than those of unaffected siblings. These findings were published online June 24 in Cancer.

“Late effects in adulthood are evident even for children with the least malignant types of brain tumors who were treated with the least toxic therapies available at the time,” said M. Douglas Ris, PhD, professor of pediatrics and psychology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, in a press release. “As pediatric brain tumors become more survivable with continued advances in treatments, we need to improve surveillance of these populations so that survivors continue to receive the best interventions during their transition to adulthood and well beyond.”

Clinicians generally have assumed that children with low-grade CNS tumors who receive less toxic treatment will have fewer long-term effects than survivors of more malignant tumors who undergo neurotoxic therapies. Yet research has indicated that the former patients can have lasting neurobehavioral or functional morbidity.

Dr. Ris and colleagues invited survivors of pediatric low-grade gliomas participating in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) and a sibling comparison group to undergo a direct, comprehensive neurocognitive assessment. Of 495 eligible survivors, 257 participated. Seventy-six patients did not travel to a study site, but completed a questionnaire, and the researchers did not include data for this group in their analysis. Dr. Ris and colleagues obtained information about surgery and radiotherapy from participants’ medical records. Patients underwent standardized, age-normed neuropsychologic tests. The primary neuropsychologic outcomes were the Composite Neuropsychological Index (CNI) and estimated IQ. To evaluate socioeconomic outcomes, Dr. Ris and colleagues measured participants’ educational attainment, income, and occupational prestige.

After the researchers adjusted the data for age and sex, they found that siblings had higher mean scores than survivors treated with surgery plus radiotherapy or surgery alone on all neuropsychologic outcomes, including the CNI (siblings, 106.8; surgery only, 95.6; surgery plus radiotherapy, 88.3) and estimated IQ. Survivors who had been diagnosed at younger ages had low scores for all outcomes except for attention/processing speed.

Furthermore, surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 7.7-fold higher risk of having an occupation in the lowest sibling quartile, compared with siblings. Survivors who underwent surgery alone had a 2.8-fold higher risk than siblings of having an occupation in the lowest quartile. Surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 2.6-fold increased risk of a low occupation score, compared with survivors who underwent surgery alone.

Compared with siblings, surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 4.5-fold risk of an annual income of less than $20,000, while the risk for survivors who underwent surgery alone did not differ significantly from that for siblings. Surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 2.6-fold higher risk than surgery alone. Surgery plus radiotherapy was also associated with a significantly increased risk for an education level lower than a bachelor’s degree, compared with siblings, but surgery alone was not.

The National Cancer Institute supported the study. The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Ris MD et al. Cancer. 2019 Jun 24. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32186.

Children who underwent surgery alone had better neuropsychologic and socioeconomic outcomes than those who also underwent radiotherapy, but their outcomes were worse than those of unaffected siblings. These findings were published online June 24 in Cancer.

“Late effects in adulthood are evident even for children with the least malignant types of brain tumors who were treated with the least toxic therapies available at the time,” said M. Douglas Ris, PhD, professor of pediatrics and psychology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, in a press release. “As pediatric brain tumors become more survivable with continued advances in treatments, we need to improve surveillance of these populations so that survivors continue to receive the best interventions during their transition to adulthood and well beyond.”

Clinicians generally have assumed that children with low-grade CNS tumors who receive less toxic treatment will have fewer long-term effects than survivors of more malignant tumors who undergo neurotoxic therapies. Yet research has indicated that the former patients can have lasting neurobehavioral or functional morbidity.

Dr. Ris and colleagues invited survivors of pediatric low-grade gliomas participating in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) and a sibling comparison group to undergo a direct, comprehensive neurocognitive assessment. Of 495 eligible survivors, 257 participated. Seventy-six patients did not travel to a study site, but completed a questionnaire, and the researchers did not include data for this group in their analysis. Dr. Ris and colleagues obtained information about surgery and radiotherapy from participants’ medical records. Patients underwent standardized, age-normed neuropsychologic tests. The primary neuropsychologic outcomes were the Composite Neuropsychological Index (CNI) and estimated IQ. To evaluate socioeconomic outcomes, Dr. Ris and colleagues measured participants’ educational attainment, income, and occupational prestige.

After the researchers adjusted the data for age and sex, they found that siblings had higher mean scores than survivors treated with surgery plus radiotherapy or surgery alone on all neuropsychologic outcomes, including the CNI (siblings, 106.8; surgery only, 95.6; surgery plus radiotherapy, 88.3) and estimated IQ. Survivors who had been diagnosed at younger ages had low scores for all outcomes except for attention/processing speed.

Furthermore, surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 7.7-fold higher risk of having an occupation in the lowest sibling quartile, compared with siblings. Survivors who underwent surgery alone had a 2.8-fold higher risk than siblings of having an occupation in the lowest quartile. Surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 2.6-fold increased risk of a low occupation score, compared with survivors who underwent surgery alone.

Compared with siblings, surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 4.5-fold risk of an annual income of less than $20,000, while the risk for survivors who underwent surgery alone did not differ significantly from that for siblings. Surgery plus radiotherapy was associated with a 2.6-fold higher risk than surgery alone. Surgery plus radiotherapy was also associated with a significantly increased risk for an education level lower than a bachelor’s degree, compared with siblings, but surgery alone was not.

The National Cancer Institute supported the study. The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Ris MD et al. Cancer. 2019 Jun 24. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32186.

FROM CANCER

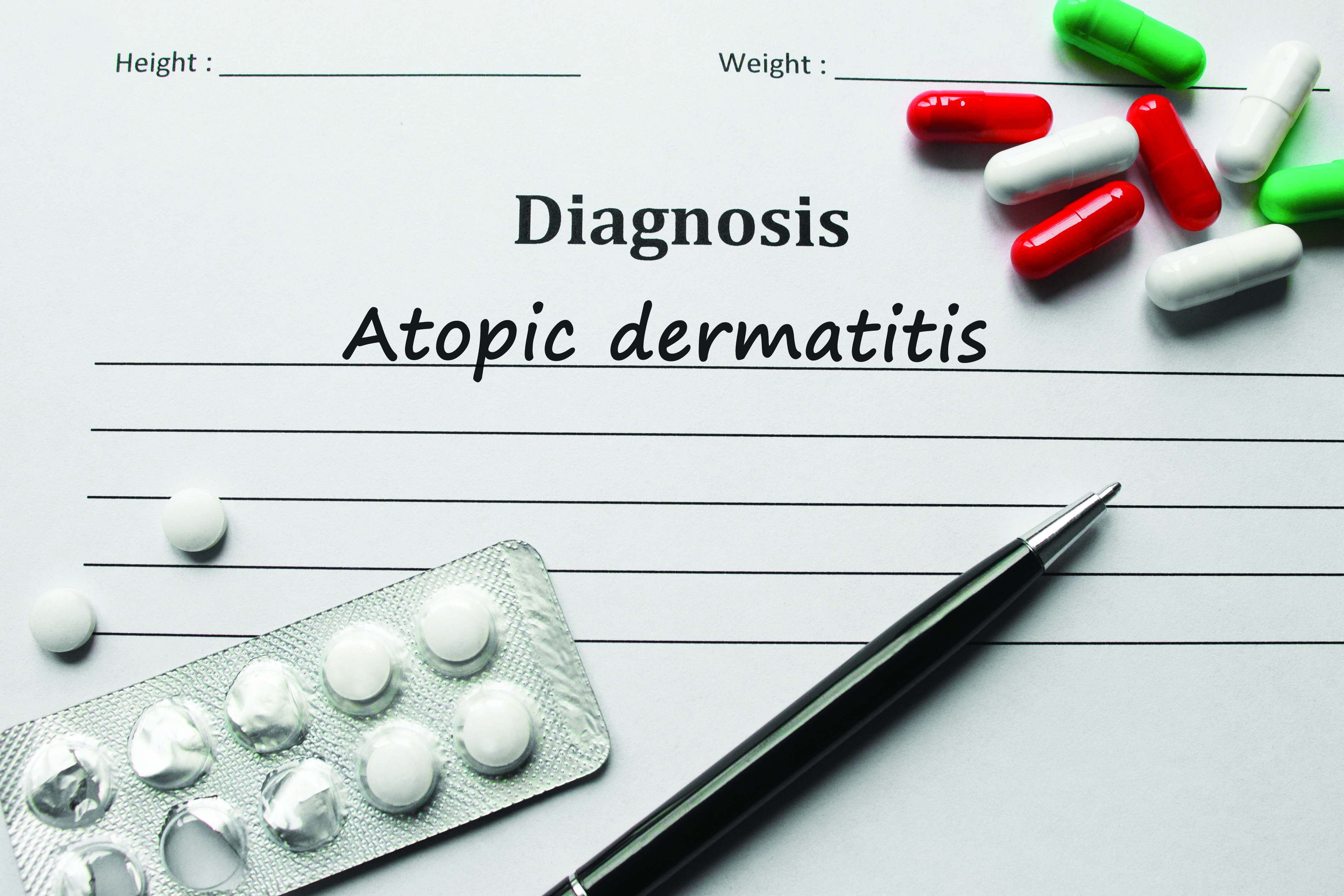

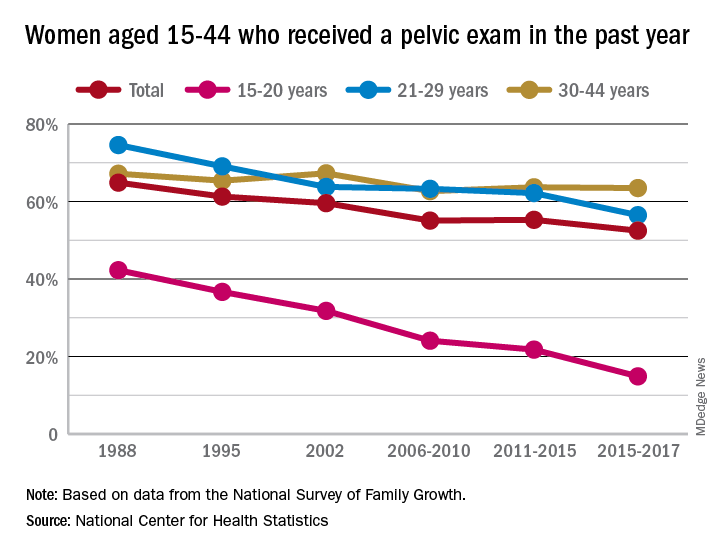

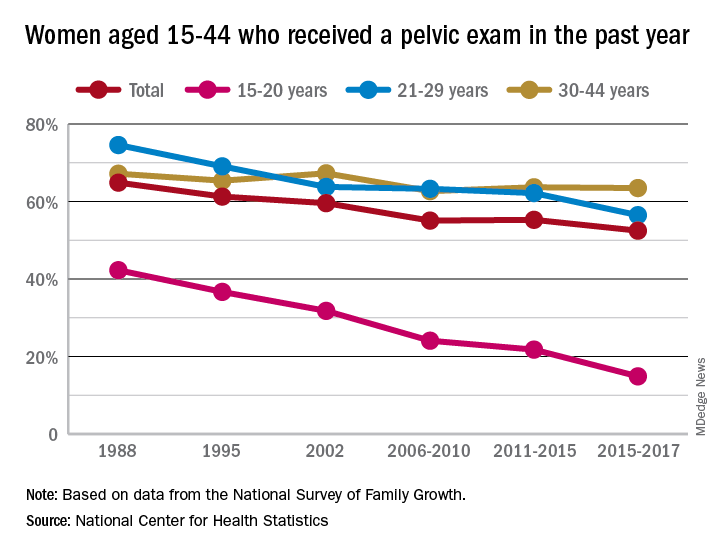

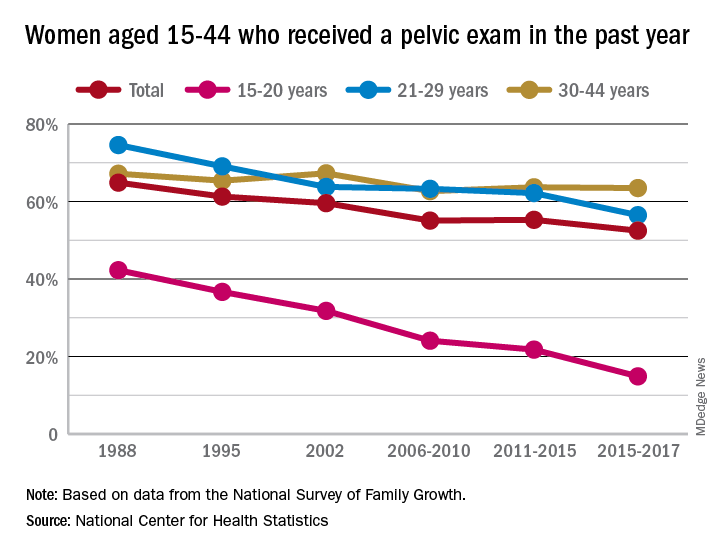

Long-term trend: Women receiving fewer pelvic exams

according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Sixty-five percent of women aged 15-44 years had received a pelvic examination in the past year when asked in 1988 as part of the National Survey of Family Growth, but the 3-year average for the 2015-2017 surveys was 53%, a significant decline, the NCHS said in a recent report.

The decrease was seen in all three of the age subgroups – 15-20 years, 21-29 years, and 30-44 years – over the length of the study period, with the trend in only the oldest women not reaching significance. The 30-44 group also was the only one of the three in which the rate ever increased at any point, the survey data show.

Data for other subgroups focused on the last 3-year period. From 2015 to 2017, non-Hispanic black women were more likely to have received a pelvic examination in the past year (60%) than were non-Hispanic white (54%) or Hispanic women (45%). An association with education level also was seen: Women with a bachelor’s degree or higher were most likely to get an exam (69%), and those with less than a high-school degree were least likely (52%), the researchers reported.

In 2018, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists altered its recommendation that annual pelvic examinations be part of the well-woman visit for those aged 21 years and over, advising instead “that pelvic examinations be performed when indicated by medical history or symptoms,” the NCHS authors explained. They also suggested that their data “could provide a benchmark for estimates of the prevalence of pelvic examinations before the 2018 ACOG-updated guidelines.”

according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Sixty-five percent of women aged 15-44 years had received a pelvic examination in the past year when asked in 1988 as part of the National Survey of Family Growth, but the 3-year average for the 2015-2017 surveys was 53%, a significant decline, the NCHS said in a recent report.

The decrease was seen in all three of the age subgroups – 15-20 years, 21-29 years, and 30-44 years – over the length of the study period, with the trend in only the oldest women not reaching significance. The 30-44 group also was the only one of the three in which the rate ever increased at any point, the survey data show.

Data for other subgroups focused on the last 3-year period. From 2015 to 2017, non-Hispanic black women were more likely to have received a pelvic examination in the past year (60%) than were non-Hispanic white (54%) or Hispanic women (45%). An association with education level also was seen: Women with a bachelor’s degree or higher were most likely to get an exam (69%), and those with less than a high-school degree were least likely (52%), the researchers reported.

In 2018, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists altered its recommendation that annual pelvic examinations be part of the well-woman visit for those aged 21 years and over, advising instead “that pelvic examinations be performed when indicated by medical history or symptoms,” the NCHS authors explained. They also suggested that their data “could provide a benchmark for estimates of the prevalence of pelvic examinations before the 2018 ACOG-updated guidelines.”

according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Sixty-five percent of women aged 15-44 years had received a pelvic examination in the past year when asked in 1988 as part of the National Survey of Family Growth, but the 3-year average for the 2015-2017 surveys was 53%, a significant decline, the NCHS said in a recent report.

The decrease was seen in all three of the age subgroups – 15-20 years, 21-29 years, and 30-44 years – over the length of the study period, with the trend in only the oldest women not reaching significance. The 30-44 group also was the only one of the three in which the rate ever increased at any point, the survey data show.

Data for other subgroups focused on the last 3-year period. From 2015 to 2017, non-Hispanic black women were more likely to have received a pelvic examination in the past year (60%) than were non-Hispanic white (54%) or Hispanic women (45%). An association with education level also was seen: Women with a bachelor’s degree or higher were most likely to get an exam (69%), and those with less than a high-school degree were least likely (52%), the researchers reported.

In 2018, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists altered its recommendation that annual pelvic examinations be part of the well-woman visit for those aged 21 years and over, advising instead “that pelvic examinations be performed when indicated by medical history or symptoms,” the NCHS authors explained. They also suggested that their data “could provide a benchmark for estimates of the prevalence of pelvic examinations before the 2018 ACOG-updated guidelines.”

Siblings of bipolar disorder patients at higher cardiometabolic disease risk

The siblings of patients with bipolar disorder have a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia and higher rates of ischemic stroke than do controls, results of a longitudinal cohort study suggest.

, wrote Wen-Yen Tsao, MD, of the department of psychiatry at Taipei Veterans General Hospital in Taiwan, and associates. Previous research has identified several overlapping genes between cardiometabolic diseases and mood disorders. In addition, polymorphisms of several genes tied to obesity have been associated with bipolar disorder.

In the current study, Dr. Tsao and associates analyzed the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, which includes health care data from more than 99% of the Taiwanese population (J Affect Disord. 2019 Jun 15. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.094). Adults born before 1990 who had no psychiatric disorders, a sibling with bipolar disorder, and a metabolic disorder were enrolled as the study cohort. A control group was identified randomly. By way of ICD-9-CM codes, people with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity were identified in both cohorts. The investigators followed the metabolic status of 7,225 unaffected siblings of bipolar disorder patients and 28,900 controls from 1996 to 2011.

Dr. Tsao and associates found that the family members who had siblings with bipolar disorder had a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia (5.4% vs. 4.5%; P = .001), compared with controls. The group with siblings with bipolar disorder also were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at a younger age (34.81 vs. 37.22; P = .024), and had a higher prevalence of any stroke (1.5 vs. 1.1%; P = .007) and ischemic stroke (0.7% vs. 0.4%, P = .001), compared with controls.

A subanalysis showed that the higher risk of any stroke (odds ratio, 1.38; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.85) and ischemic stroke (OR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.60-3.70) pertained only to male siblings. That gender-specific finding might be attributed to differences in plasma triglyceride clearance between men and women, the researchers wrote.

The findings might not be generalizable to other populations, the investigators noted. In addition, they said, the prevalence of cardiometabolic disease in the groups studied might be underestimated.

“Our results may motivate additional studies to evaluate genetic factors, psychosocial factors, and other pathophysiology of bipolar disorder,” they wrote.

The study was funded by Taiwan’s Ministry of Science and Technology, and Taipei Veterans General Hospital. The researchers cited no conflicts of interest.

The siblings of patients with bipolar disorder have a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia and higher rates of ischemic stroke than do controls, results of a longitudinal cohort study suggest.

, wrote Wen-Yen Tsao, MD, of the department of psychiatry at Taipei Veterans General Hospital in Taiwan, and associates. Previous research has identified several overlapping genes between cardiometabolic diseases and mood disorders. In addition, polymorphisms of several genes tied to obesity have been associated with bipolar disorder.

In the current study, Dr. Tsao and associates analyzed the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, which includes health care data from more than 99% of the Taiwanese population (J Affect Disord. 2019 Jun 15. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.094). Adults born before 1990 who had no psychiatric disorders, a sibling with bipolar disorder, and a metabolic disorder were enrolled as the study cohort. A control group was identified randomly. By way of ICD-9-CM codes, people with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity were identified in both cohorts. The investigators followed the metabolic status of 7,225 unaffected siblings of bipolar disorder patients and 28,900 controls from 1996 to 2011.

Dr. Tsao and associates found that the family members who had siblings with bipolar disorder had a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia (5.4% vs. 4.5%; P = .001), compared with controls. The group with siblings with bipolar disorder also were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at a younger age (34.81 vs. 37.22; P = .024), and had a higher prevalence of any stroke (1.5 vs. 1.1%; P = .007) and ischemic stroke (0.7% vs. 0.4%, P = .001), compared with controls.

A subanalysis showed that the higher risk of any stroke (odds ratio, 1.38; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.85) and ischemic stroke (OR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.60-3.70) pertained only to male siblings. That gender-specific finding might be attributed to differences in plasma triglyceride clearance between men and women, the researchers wrote.

The findings might not be generalizable to other populations, the investigators noted. In addition, they said, the prevalence of cardiometabolic disease in the groups studied might be underestimated.

“Our results may motivate additional studies to evaluate genetic factors, psychosocial factors, and other pathophysiology of bipolar disorder,” they wrote.

The study was funded by Taiwan’s Ministry of Science and Technology, and Taipei Veterans General Hospital. The researchers cited no conflicts of interest.

The siblings of patients with bipolar disorder have a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia and higher rates of ischemic stroke than do controls, results of a longitudinal cohort study suggest.

, wrote Wen-Yen Tsao, MD, of the department of psychiatry at Taipei Veterans General Hospital in Taiwan, and associates. Previous research has identified several overlapping genes between cardiometabolic diseases and mood disorders. In addition, polymorphisms of several genes tied to obesity have been associated with bipolar disorder.

In the current study, Dr. Tsao and associates analyzed the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, which includes health care data from more than 99% of the Taiwanese population (J Affect Disord. 2019 Jun 15. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.094). Adults born before 1990 who had no psychiatric disorders, a sibling with bipolar disorder, and a metabolic disorder were enrolled as the study cohort. A control group was identified randomly. By way of ICD-9-CM codes, people with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity were identified in both cohorts. The investigators followed the metabolic status of 7,225 unaffected siblings of bipolar disorder patients and 28,900 controls from 1996 to 2011.

Dr. Tsao and associates found that the family members who had siblings with bipolar disorder had a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia (5.4% vs. 4.5%; P = .001), compared with controls. The group with siblings with bipolar disorder also were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at a younger age (34.81 vs. 37.22; P = .024), and had a higher prevalence of any stroke (1.5 vs. 1.1%; P = .007) and ischemic stroke (0.7% vs. 0.4%, P = .001), compared with controls.

A subanalysis showed that the higher risk of any stroke (odds ratio, 1.38; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.85) and ischemic stroke (OR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.60-3.70) pertained only to male siblings. That gender-specific finding might be attributed to differences in plasma triglyceride clearance between men and women, the researchers wrote.

The findings might not be generalizable to other populations, the investigators noted. In addition, they said, the prevalence of cardiometabolic disease in the groups studied might be underestimated.

“Our results may motivate additional studies to evaluate genetic factors, psychosocial factors, and other pathophysiology of bipolar disorder,” they wrote.

The study was funded by Taiwan’s Ministry of Science and Technology, and Taipei Veterans General Hospital. The researchers cited no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Age does not influence cladribine’s efficacy in MS

SEATTLE – In addition, age does not affect the likelihood that a patient who receives cladribine will achieve no evidence of disease activity (NEDA), according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

In the phase 3 CLARITY study, a cumulative dose of 3.5 mg/kg of cladribine over 2 years was associated with significantly reduced relapse rate and disability progression and improved MRI outcomes, compared with placebo. The drug’s efficacy persisted in patients who were switched to placebo in a 96-week extension study.

A post hoc analysis

A 2017 study by Weideman et al. suggested that disease-modifying treatment (DMT) is less effective in older patients. For this reason, Gavin Giovannoni, MBBCh, PhD, professor of neurology at Queen Mary University of London, and colleagues decided to investigate the effect of age on the efficacy of treatment with 3.5 mg/kg of cladribine. The investigators performed a post hoc analysis of the CLARITY and CLARITY extension studies of patients with relapsing-remitting MS. They categorized patients as older than 45 years or age 45 years or younger.

Patients enrolled in CLARITY were between ages 18 years and 65 years. They underwent MRI at pretrial assessment and at weeks 24, 48, and 96 or early termination. The investigators defined a qualifying relapse as one associated with changes in Kurtzke Functional Systems score and other specified clinical parameters. Qualifying relapses were confirmed by an independent evaluating physician who was blinded to treatment assignment.