User login

Sleepiest OSA patients have worse CV outcomes

SAN ANTONIO – Patients with obstructive sleep apnea who complain of feeling tired when they wake up, being sleepy during the day, and have a high score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale face an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, results from a population-based analysis suggest.

“OSA is a highly heterogeneous disease, with multiple clinical presentations and consequences,” the study’s first author, Diego R. Mazzotti, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies. “These patients also have diverse comorbidities, and there are arbitrary severity definitions and variable therapeutic responses. It’s difficult to lump these patients together.”

Symptom subtypes of OSA were originally described in the Icelandic Sleep Apnea Cohort, and defined as excessively sleepy, minimally symptomatic, and disturbed sleep (Eur Respir J. 2014; 44[6]:1600-7). These distinct clusters were identified based on symptom experiences and the existence of major comorbidities. “This concept is more popular today, trying to identify symptom clusters, or groups of individuals, that share similar polysomnographic data, and then compare differences in prevalence or incidence of cardiovascular disease,” said Dr. Mazzotti, a research associate at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “That’s a concept that needs to be moving forward.”

Dr. Mazzotti and colleagues set out to determine if OSA symptom subtypes are present in the Sleep Heart Health Study, a multicenter, prospective, community-based cohort of individuals aged 40 years and older designed to assess the cardiovascular (CV) consequences of OSA. They also wanted to know if there is additional evidence of the relevance of OSA symptom subtypes, particularly with respect to cardiovascular disease .

Participant-reported symptoms, such as difficulty falling and staying asleep, snoring, fatigue, drowsy driving and daytime sleepiness, and responses to the Epworth Sleepiness Scale were used to determine the patient’s subtype. Assessments including questionnaires and in-home polysomnography were conducted at baseline (between 1995 and 1998) and follow-up (between 2001 and 2003), while CV outcomes were assessed until the end of follow-up (between 2008 and 2011).

In all, 1,207 patients from the Sleep Heart Health Study met criteria for moderate to severe OSA (apnea-hypopnea index, or AHI, of 15 or greater) and were included in the final analysis. They were followed for a mean of 12 years. Based on the clustering of symptoms, the researchers identified four OSA symptom subtypes: disturbed sleep (12%), minimally symptomatic (33%), excessively sleepy (17%), and moderately sleepy (38%) – proportions that were similar to those observed in prior studies.

The disturbed sleep subtype presented with increased prevalence of “insomnialike” symptoms, such as difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, according to Dr. Mazzotti. “On the other hand, the excessively sleepy subtype presented with a very high prevalence of several symptoms related to excessive daytime sleepiness, while the moderately sleepy showed a moderately high prevalence of such symptoms, but not as much when compared to the excessively sleepy subtype,” he explained. “Finally, the minimally symptomatic subtype was found to have the lowest prevalence of all investigated symptoms, suggesting that these patients have low symptom burden. They do not complain as much, even though they have moderate-to-severe OSA.”

Next, Dr. Mazzotti and colleagues used Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate whether subtypes were associated with incident coronary heart disease (CHD), heart failure, and CV disease, including CV mortality. Similar analyses were performed comparing each symptom subtype with 2,830 individuals without OSA (AHI less than 5).

Compared with other subtypes, the excessively sleepy group had a more than threefold increased odds of prevalent heart failure, after adjustment for other CV risk factors. They also had a 1.7- to 2.3-fold increased risk for incident CV disease (P less than .001), CHD (P = .015) and heart failure (P = 0.018), after adjustment for other CV risk factors.

“Compared to individuals without OSA, the excessively sleepy subtype is the only subtype with increased risk of incident CV disease and CHD,” Dr. Mazzotti said. “It is possible that excessively sleepy OSA patients are more likely to benefit from CPAP therapy in preventing CV disease.” These results were published online earlier this year (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Feb 15. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201808-1509OC).

Dr. Mazzotti reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Mazzotti D et al. SLEEP 2019, Abstract 0586.

SAN ANTONIO – Patients with obstructive sleep apnea who complain of feeling tired when they wake up, being sleepy during the day, and have a high score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale face an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, results from a population-based analysis suggest.

“OSA is a highly heterogeneous disease, with multiple clinical presentations and consequences,” the study’s first author, Diego R. Mazzotti, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies. “These patients also have diverse comorbidities, and there are arbitrary severity definitions and variable therapeutic responses. It’s difficult to lump these patients together.”

Symptom subtypes of OSA were originally described in the Icelandic Sleep Apnea Cohort, and defined as excessively sleepy, minimally symptomatic, and disturbed sleep (Eur Respir J. 2014; 44[6]:1600-7). These distinct clusters were identified based on symptom experiences and the existence of major comorbidities. “This concept is more popular today, trying to identify symptom clusters, or groups of individuals, that share similar polysomnographic data, and then compare differences in prevalence or incidence of cardiovascular disease,” said Dr. Mazzotti, a research associate at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “That’s a concept that needs to be moving forward.”

Dr. Mazzotti and colleagues set out to determine if OSA symptom subtypes are present in the Sleep Heart Health Study, a multicenter, prospective, community-based cohort of individuals aged 40 years and older designed to assess the cardiovascular (CV) consequences of OSA. They also wanted to know if there is additional evidence of the relevance of OSA symptom subtypes, particularly with respect to cardiovascular disease .

Participant-reported symptoms, such as difficulty falling and staying asleep, snoring, fatigue, drowsy driving and daytime sleepiness, and responses to the Epworth Sleepiness Scale were used to determine the patient’s subtype. Assessments including questionnaires and in-home polysomnography were conducted at baseline (between 1995 and 1998) and follow-up (between 2001 and 2003), while CV outcomes were assessed until the end of follow-up (between 2008 and 2011).

In all, 1,207 patients from the Sleep Heart Health Study met criteria for moderate to severe OSA (apnea-hypopnea index, or AHI, of 15 or greater) and were included in the final analysis. They were followed for a mean of 12 years. Based on the clustering of symptoms, the researchers identified four OSA symptom subtypes: disturbed sleep (12%), minimally symptomatic (33%), excessively sleepy (17%), and moderately sleepy (38%) – proportions that were similar to those observed in prior studies.

The disturbed sleep subtype presented with increased prevalence of “insomnialike” symptoms, such as difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, according to Dr. Mazzotti. “On the other hand, the excessively sleepy subtype presented with a very high prevalence of several symptoms related to excessive daytime sleepiness, while the moderately sleepy showed a moderately high prevalence of such symptoms, but not as much when compared to the excessively sleepy subtype,” he explained. “Finally, the minimally symptomatic subtype was found to have the lowest prevalence of all investigated symptoms, suggesting that these patients have low symptom burden. They do not complain as much, even though they have moderate-to-severe OSA.”

Next, Dr. Mazzotti and colleagues used Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate whether subtypes were associated with incident coronary heart disease (CHD), heart failure, and CV disease, including CV mortality. Similar analyses were performed comparing each symptom subtype with 2,830 individuals without OSA (AHI less than 5).

Compared with other subtypes, the excessively sleepy group had a more than threefold increased odds of prevalent heart failure, after adjustment for other CV risk factors. They also had a 1.7- to 2.3-fold increased risk for incident CV disease (P less than .001), CHD (P = .015) and heart failure (P = 0.018), after adjustment for other CV risk factors.

“Compared to individuals without OSA, the excessively sleepy subtype is the only subtype with increased risk of incident CV disease and CHD,” Dr. Mazzotti said. “It is possible that excessively sleepy OSA patients are more likely to benefit from CPAP therapy in preventing CV disease.” These results were published online earlier this year (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Feb 15. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201808-1509OC).

Dr. Mazzotti reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Mazzotti D et al. SLEEP 2019, Abstract 0586.

SAN ANTONIO – Patients with obstructive sleep apnea who complain of feeling tired when they wake up, being sleepy during the day, and have a high score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale face an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, results from a population-based analysis suggest.

“OSA is a highly heterogeneous disease, with multiple clinical presentations and consequences,” the study’s first author, Diego R. Mazzotti, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies. “These patients also have diverse comorbidities, and there are arbitrary severity definitions and variable therapeutic responses. It’s difficult to lump these patients together.”

Symptom subtypes of OSA were originally described in the Icelandic Sleep Apnea Cohort, and defined as excessively sleepy, minimally symptomatic, and disturbed sleep (Eur Respir J. 2014; 44[6]:1600-7). These distinct clusters were identified based on symptom experiences and the existence of major comorbidities. “This concept is more popular today, trying to identify symptom clusters, or groups of individuals, that share similar polysomnographic data, and then compare differences in prevalence or incidence of cardiovascular disease,” said Dr. Mazzotti, a research associate at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “That’s a concept that needs to be moving forward.”

Dr. Mazzotti and colleagues set out to determine if OSA symptom subtypes are present in the Sleep Heart Health Study, a multicenter, prospective, community-based cohort of individuals aged 40 years and older designed to assess the cardiovascular (CV) consequences of OSA. They also wanted to know if there is additional evidence of the relevance of OSA symptom subtypes, particularly with respect to cardiovascular disease .

Participant-reported symptoms, such as difficulty falling and staying asleep, snoring, fatigue, drowsy driving and daytime sleepiness, and responses to the Epworth Sleepiness Scale were used to determine the patient’s subtype. Assessments including questionnaires and in-home polysomnography were conducted at baseline (between 1995 and 1998) and follow-up (between 2001 and 2003), while CV outcomes were assessed until the end of follow-up (between 2008 and 2011).

In all, 1,207 patients from the Sleep Heart Health Study met criteria for moderate to severe OSA (apnea-hypopnea index, or AHI, of 15 or greater) and were included in the final analysis. They were followed for a mean of 12 years. Based on the clustering of symptoms, the researchers identified four OSA symptom subtypes: disturbed sleep (12%), minimally symptomatic (33%), excessively sleepy (17%), and moderately sleepy (38%) – proportions that were similar to those observed in prior studies.

The disturbed sleep subtype presented with increased prevalence of “insomnialike” symptoms, such as difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, according to Dr. Mazzotti. “On the other hand, the excessively sleepy subtype presented with a very high prevalence of several symptoms related to excessive daytime sleepiness, while the moderately sleepy showed a moderately high prevalence of such symptoms, but not as much when compared to the excessively sleepy subtype,” he explained. “Finally, the minimally symptomatic subtype was found to have the lowest prevalence of all investigated symptoms, suggesting that these patients have low symptom burden. They do not complain as much, even though they have moderate-to-severe OSA.”

Next, Dr. Mazzotti and colleagues used Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate whether subtypes were associated with incident coronary heart disease (CHD), heart failure, and CV disease, including CV mortality. Similar analyses were performed comparing each symptom subtype with 2,830 individuals without OSA (AHI less than 5).

Compared with other subtypes, the excessively sleepy group had a more than threefold increased odds of prevalent heart failure, after adjustment for other CV risk factors. They also had a 1.7- to 2.3-fold increased risk for incident CV disease (P less than .001), CHD (P = .015) and heart failure (P = 0.018), after adjustment for other CV risk factors.

“Compared to individuals without OSA, the excessively sleepy subtype is the only subtype with increased risk of incident CV disease and CHD,” Dr. Mazzotti said. “It is possible that excessively sleepy OSA patients are more likely to benefit from CPAP therapy in preventing CV disease.” These results were published online earlier this year (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Feb 15. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201808-1509OC).

Dr. Mazzotti reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Mazzotti D et al. SLEEP 2019, Abstract 0586.

REPORTING FROM SLEEP 2019

FDA warning letters fall on Trump’s watch

according to findings from an analysis of public records sponsored by Science magazine and published July 2.

From Jan. 20, 2017, (President Trump’s inauguration day) through May 22, 2019, FDA sent out 1,033 warning letters, compared with 1,532 warning letters sent during the 28 months ending just before the inauguration, a drop of 33%, wrote Charles Piller, an investigative journalist on the Science staff (Science. 2019 Jul 2. doi: 10.1126/science.aay5859). Also during January 2017–May 2019, “official action indicated” reports, described by Mr. Piller as a frequent precursor to warning letters, fell by 45%, from 1,879 during the final 28 months of the Obama administration to 1,040 during the first 28 months of the Trump administration. The incidence of an injunction, characterized by Mr. Piller as a ”more forceful” step than a warning letter, was 35 during the 28 months before Donald Trump became president and 26 during the 28 months after, a relative 26% decline.

More detailed numbers in the report included a 33% drop in warning letters from the FDA center that deals with tobacco products, a 37% drop in warning letters from the center that deals with food safety, and a 72% fall in letters sent from the Center for Devices & Radiological Health. However the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation & Research sent 62% more warning letters (188) during the first 28 months after Donald Trump became president, compared with the final 28 months under President Obama, when it sent 116 warning letters. A year-by-year analysis that started in 2009 showed that warning letters peaked at about 800 per year during both 2011 and 2012, and then showed a steady decline during all subsequent years, falling to a rate during the first months of 2019 that projected to an annualized rate of 385 total warning letters sent by the end of this year.

In response to publication of these findings, FDA Media Relations Director Angela Stark said “the way the data are presented in the story does not accurately reflect FDA’s overarching work to protect the public health. While one publicly visible measure of FDA action, it’s important to understand that warning letters are just one action the FDA takes to seek compliance. The FDA has several tools at its disposal to work with a company to ensure compliance, such as through regulatory meetings with companies; untitled letters; follow-up inspections; and other regulatory and compliance measures depending on the situation, and we often do much of this behind the scenes in the interest of patient safety. Our use of any one enforcement tool may fluctuate year to year based on a number of factors, including the FDA’s assessment of the violations uncovered during the course of inspections, along with additional product-monitoring efforts.”

Ms. Stark also noted that, in some FDA centers, warning letters may have decreased “because the FDA has increased its interactions with industry to resolve issues, which often achieves more timely and effective corrective action.”

She also highlighted 1,300 warning letter and monetary penalty complaints sent to retailers since September 2018 over illegal sales of e-cigarettes to minors, “tens of thousands” of warning letters sent to tobacco retailers since the start of 2017 over other tobacco-related issues, and actions against stem-cell clinics that have marketed unapproved treatments.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Piller C. Science. 2019 Jul 2. doi: 10.1126/science.aay5859)

according to findings from an analysis of public records sponsored by Science magazine and published July 2.

From Jan. 20, 2017, (President Trump’s inauguration day) through May 22, 2019, FDA sent out 1,033 warning letters, compared with 1,532 warning letters sent during the 28 months ending just before the inauguration, a drop of 33%, wrote Charles Piller, an investigative journalist on the Science staff (Science. 2019 Jul 2. doi: 10.1126/science.aay5859). Also during January 2017–May 2019, “official action indicated” reports, described by Mr. Piller as a frequent precursor to warning letters, fell by 45%, from 1,879 during the final 28 months of the Obama administration to 1,040 during the first 28 months of the Trump administration. The incidence of an injunction, characterized by Mr. Piller as a ”more forceful” step than a warning letter, was 35 during the 28 months before Donald Trump became president and 26 during the 28 months after, a relative 26% decline.

More detailed numbers in the report included a 33% drop in warning letters from the FDA center that deals with tobacco products, a 37% drop in warning letters from the center that deals with food safety, and a 72% fall in letters sent from the Center for Devices & Radiological Health. However the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation & Research sent 62% more warning letters (188) during the first 28 months after Donald Trump became president, compared with the final 28 months under President Obama, when it sent 116 warning letters. A year-by-year analysis that started in 2009 showed that warning letters peaked at about 800 per year during both 2011 and 2012, and then showed a steady decline during all subsequent years, falling to a rate during the first months of 2019 that projected to an annualized rate of 385 total warning letters sent by the end of this year.

In response to publication of these findings, FDA Media Relations Director Angela Stark said “the way the data are presented in the story does not accurately reflect FDA’s overarching work to protect the public health. While one publicly visible measure of FDA action, it’s important to understand that warning letters are just one action the FDA takes to seek compliance. The FDA has several tools at its disposal to work with a company to ensure compliance, such as through regulatory meetings with companies; untitled letters; follow-up inspections; and other regulatory and compliance measures depending on the situation, and we often do much of this behind the scenes in the interest of patient safety. Our use of any one enforcement tool may fluctuate year to year based on a number of factors, including the FDA’s assessment of the violations uncovered during the course of inspections, along with additional product-monitoring efforts.”

Ms. Stark also noted that, in some FDA centers, warning letters may have decreased “because the FDA has increased its interactions with industry to resolve issues, which often achieves more timely and effective corrective action.”

She also highlighted 1,300 warning letter and monetary penalty complaints sent to retailers since September 2018 over illegal sales of e-cigarettes to minors, “tens of thousands” of warning letters sent to tobacco retailers since the start of 2017 over other tobacco-related issues, and actions against stem-cell clinics that have marketed unapproved treatments.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Piller C. Science. 2019 Jul 2. doi: 10.1126/science.aay5859)

according to findings from an analysis of public records sponsored by Science magazine and published July 2.

From Jan. 20, 2017, (President Trump’s inauguration day) through May 22, 2019, FDA sent out 1,033 warning letters, compared with 1,532 warning letters sent during the 28 months ending just before the inauguration, a drop of 33%, wrote Charles Piller, an investigative journalist on the Science staff (Science. 2019 Jul 2. doi: 10.1126/science.aay5859). Also during January 2017–May 2019, “official action indicated” reports, described by Mr. Piller as a frequent precursor to warning letters, fell by 45%, from 1,879 during the final 28 months of the Obama administration to 1,040 during the first 28 months of the Trump administration. The incidence of an injunction, characterized by Mr. Piller as a ”more forceful” step than a warning letter, was 35 during the 28 months before Donald Trump became president and 26 during the 28 months after, a relative 26% decline.

More detailed numbers in the report included a 33% drop in warning letters from the FDA center that deals with tobacco products, a 37% drop in warning letters from the center that deals with food safety, and a 72% fall in letters sent from the Center for Devices & Radiological Health. However the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation & Research sent 62% more warning letters (188) during the first 28 months after Donald Trump became president, compared with the final 28 months under President Obama, when it sent 116 warning letters. A year-by-year analysis that started in 2009 showed that warning letters peaked at about 800 per year during both 2011 and 2012, and then showed a steady decline during all subsequent years, falling to a rate during the first months of 2019 that projected to an annualized rate of 385 total warning letters sent by the end of this year.

In response to publication of these findings, FDA Media Relations Director Angela Stark said “the way the data are presented in the story does not accurately reflect FDA’s overarching work to protect the public health. While one publicly visible measure of FDA action, it’s important to understand that warning letters are just one action the FDA takes to seek compliance. The FDA has several tools at its disposal to work with a company to ensure compliance, such as through regulatory meetings with companies; untitled letters; follow-up inspections; and other regulatory and compliance measures depending on the situation, and we often do much of this behind the scenes in the interest of patient safety. Our use of any one enforcement tool may fluctuate year to year based on a number of factors, including the FDA’s assessment of the violations uncovered during the course of inspections, along with additional product-monitoring efforts.”

Ms. Stark also noted that, in some FDA centers, warning letters may have decreased “because the FDA has increased its interactions with industry to resolve issues, which often achieves more timely and effective corrective action.”

She also highlighted 1,300 warning letter and monetary penalty complaints sent to retailers since September 2018 over illegal sales of e-cigarettes to minors, “tens of thousands” of warning letters sent to tobacco retailers since the start of 2017 over other tobacco-related issues, and actions against stem-cell clinics that have marketed unapproved treatments.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Piller C. Science. 2019 Jul 2. doi: 10.1126/science.aay5859)

FROM SCIENCE

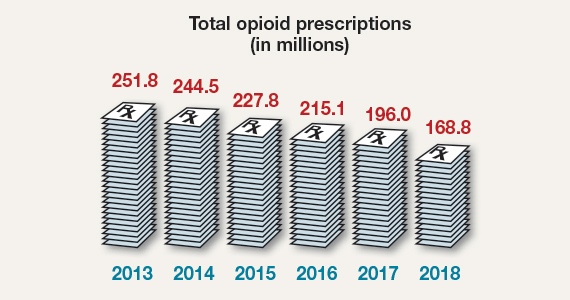

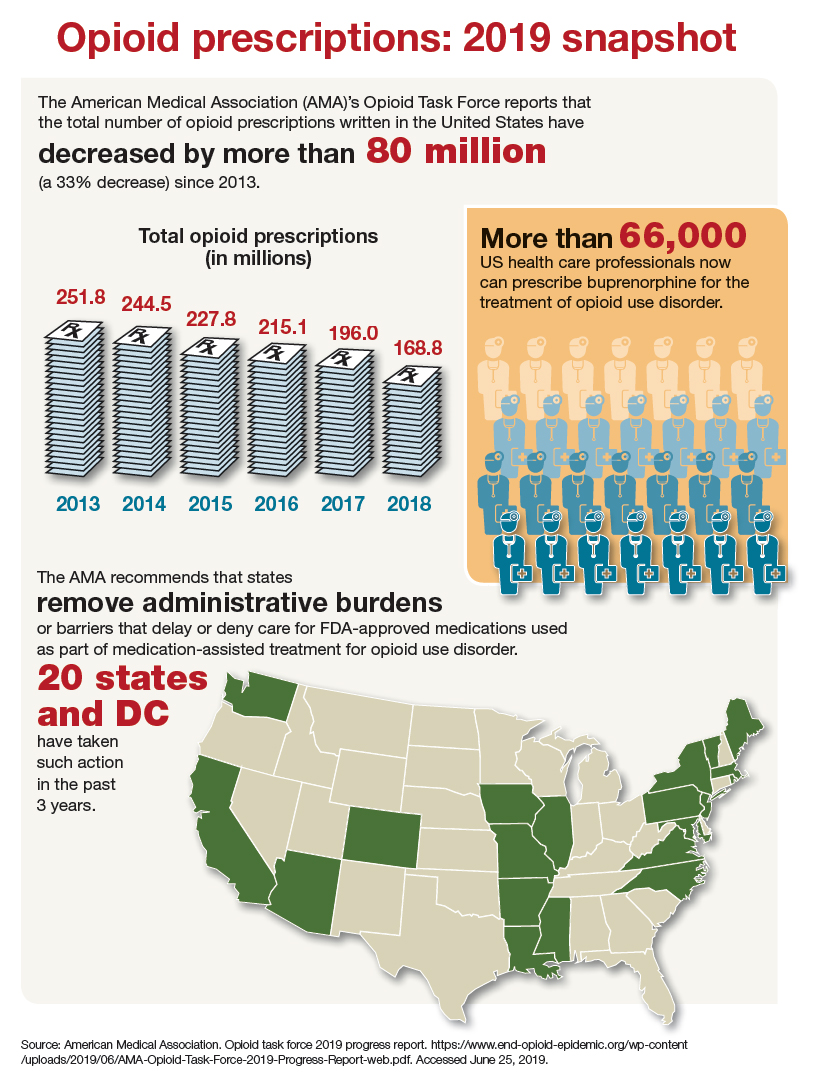

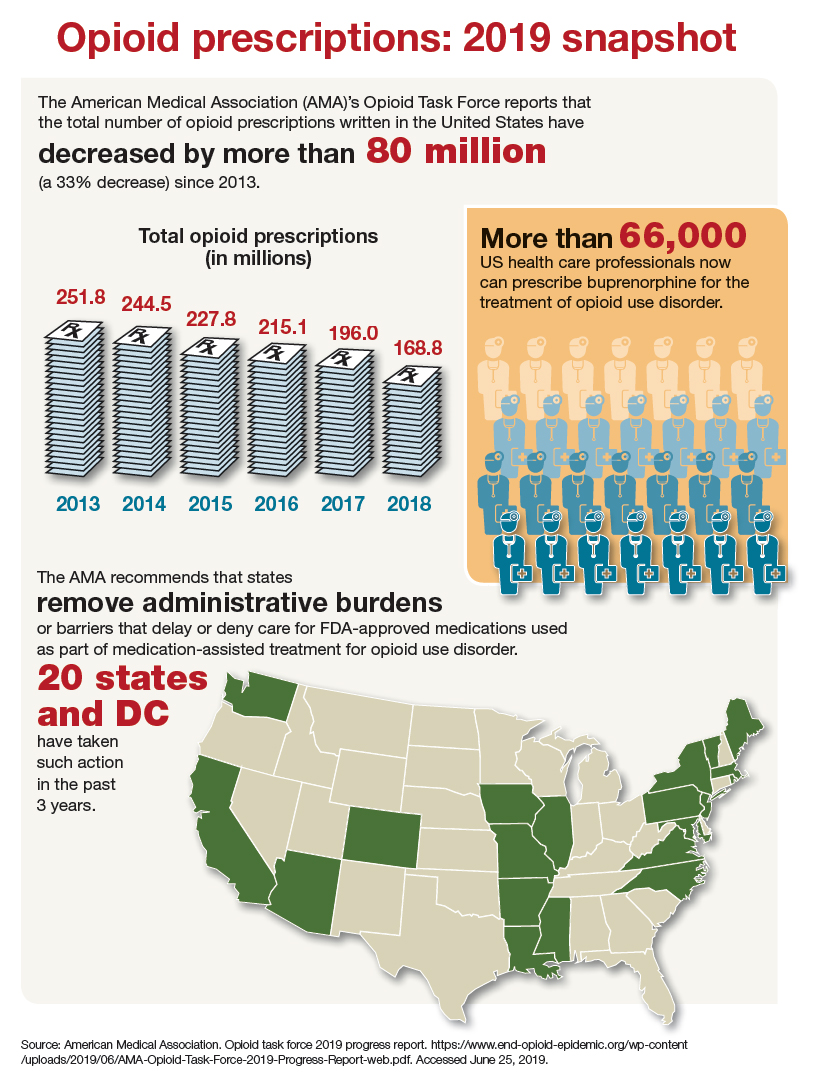

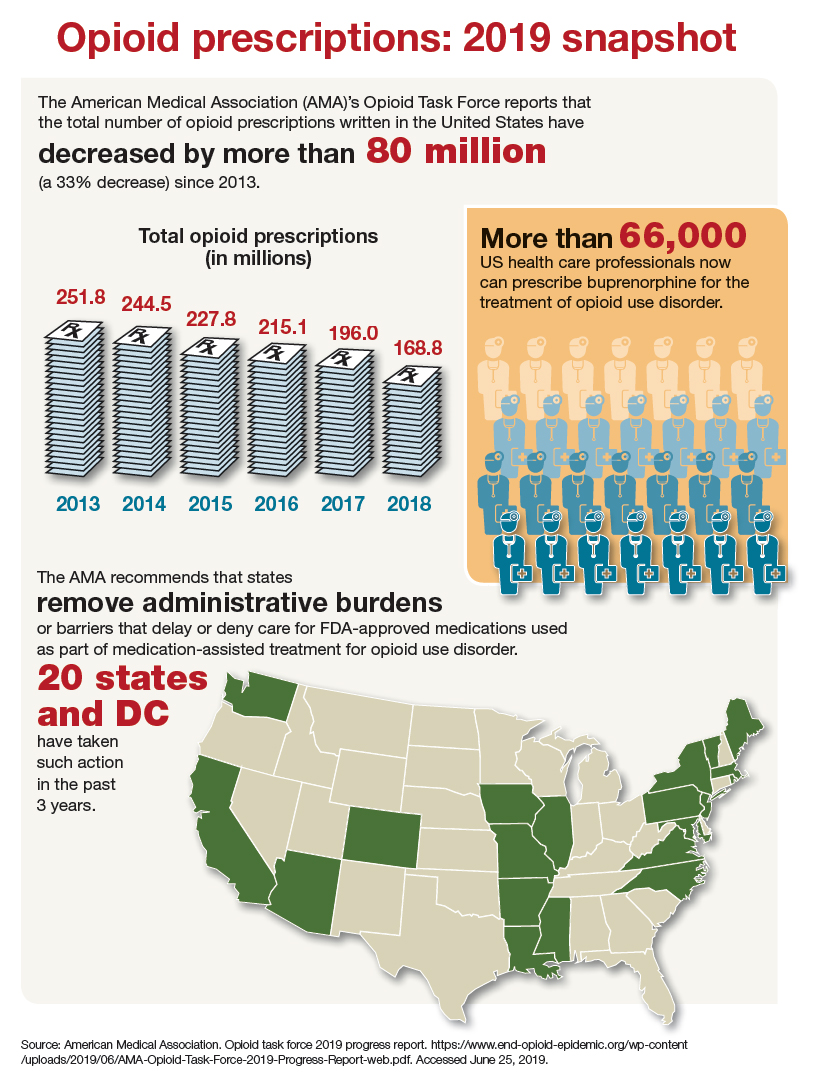

Opioid prescriptions: 2019 snapshot

Some burnout factors are within a physician’s control

SAN DIEGO – Eat a healthy lunch. Get more sleep. Move your body. How many times in the course of a week do you give patients gentle reminders to practice these most basic steps of self-care? And how many times in the course of a week do you allow these basics to go by the wayside for yourself?

Self-care is one of the elements that can defend against physician burnout, Carol Burke, MD, said at a session on physician burnout held during the annual Digestive Disease Week®. Personal self-care can make a real difference, and shouldn’t be ignored as the profession works to reel back some of the institutional changes that challenge physicians today.

In the workplace, unhealthy stress levels can contribute to burnout, disruptive behavior, decreased productivity, and disengagement. Burnout – a response to chronic stress characterized by a diminished sense of personal accomplishment and emotional exhaustion – can result in cynicism, a lack of compassion, and feelings of depersonalization, said Dr. Burke.

Contributors to physician stress have been well documented, said Dr. Burke, a professor of gastroenterology at the Cleveland Clinic. These range from personal debt and the struggle for work-life balance to an increased focus on metrics and documentation at the expense of authentic patient engagement. All of these factors are measurable by means of the validated Maslach Burnout Inventory, said Dr. Burke. A recent survey that used this measure indicated that nearly half of physician respondents report experiencing burnout.

In 2017, Dr. Burke led a survey of American College of Gastroenterology members that showed 49.3% of respondents reported feeling emotional exhaustion and/or depersonalization. Some key themes emerged from the survey, she said. Women and younger physicians were more likely to experience burnout. Having children in the middle years (11-15 years old) and spending more time on domestic duties and child care increased the risk of burnout.

And doing patient-related work at home or having a spouse or partner bring work home also upped burnout risk. Skipping breakfast and lunch during the workweek was another risk factor, which highlights the importance of basic self-care as armor against the administrative onslaught, said Dr. Burke.

Measured by volume alone, physician work can be overwhelming: 45% of physicians in the United States work more than 60 hours weekly, compared with fewer than 10% of the general workforce, said Dr. Burke.

What factors within the control of an individual practitioner can reduce the risk of debilitating burnout and improve quality of life? Physicians who do report a high quality of life, said Dr. Burke, are more likely to have a positive outlook. They also practice basic self-care like taking vacations, exercising regularly, and engaging in hobbies outside of work.

For exhausted, overworked clinicians, getting a good night’s sleep is a critical form of self-care. But erratic schedules, stress, and family demands can all sabotage plans for better sleep hygiene. Still, attending to sleep is important, said Dr. Burke. Individuals with disturbed sleep are less mindful and have less self-compassion. Sleep disturbance is also strongly correlated with perceived stress.

She also reported that the odds ratio for burnout was 14.7 for physicians who reported insomnia when compared with those without sleep disturbance, and it was 9.9 for those who reported nonrestorative sleep.

Physical activity can help sleep and also help other markers of burnout. Dr. Burke pointed to a recent study of 4,402 medical students. Participants were able to reduce burnout risk when they met the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations of achieving at least 150 minutes/week of moderate exercise or 75 minutes/week of vigorous exercise, plus at least 2 days/week of strength training (P less than .001; Acad Med. 2017;92:1006).

These physician-targeted programs can work, she said: “Faciliated interventions improve well-being, attitudes associated with patient-centered care, meaning and engagement in work, and reduce burnout.”

Practice-focused interventions to reclaim a semblance of control over one’s time are varied, and some are easier to implement than others. Virtual visits and group visits are surprisingly well received by patients, and each can be huge time-savers for physicians, said Dr. Burke. There are billing and workflow pitfalls to avoid, but group visits, in particular, can be practice changing for those who have heavy backlogs and see many patients with the same condition.

Medical scribes can improve productivity and reduce physician time spent on documentation. Also, said Dr. Burke, visits can appropriately be billed at a higher level of complexity when contemporaneous documentation is thorough. Clinicians overall feel that they can engage more fully with patients, and also feel more effective, when well-trained scribes are integrated into a practice, she said.

Female physicians have repeatedly been shown to have patient panels that are more demanding, and male and female patients alike expect more empathy and social support from their physicians, said Dr. Burke. When psychosocial complexities are interwoven with patient care, as they are more frequently for female providers, a 15-minute visit can easily run twice that – or more. Dr. Burke is among the physicians advocating for recognition of this invisible burden on female clinicians, either through adaptive scheduling or differential productivity expectations. This approach is not without controversy, she acknowledged; still, practices should acknowledge that clinic flow can be very different for male and female gastroenterologists, she said.

Dr. Burke reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Eat a healthy lunch. Get more sleep. Move your body. How many times in the course of a week do you give patients gentle reminders to practice these most basic steps of self-care? And how many times in the course of a week do you allow these basics to go by the wayside for yourself?

Self-care is one of the elements that can defend against physician burnout, Carol Burke, MD, said at a session on physician burnout held during the annual Digestive Disease Week®. Personal self-care can make a real difference, and shouldn’t be ignored as the profession works to reel back some of the institutional changes that challenge physicians today.

In the workplace, unhealthy stress levels can contribute to burnout, disruptive behavior, decreased productivity, and disengagement. Burnout – a response to chronic stress characterized by a diminished sense of personal accomplishment and emotional exhaustion – can result in cynicism, a lack of compassion, and feelings of depersonalization, said Dr. Burke.

Contributors to physician stress have been well documented, said Dr. Burke, a professor of gastroenterology at the Cleveland Clinic. These range from personal debt and the struggle for work-life balance to an increased focus on metrics and documentation at the expense of authentic patient engagement. All of these factors are measurable by means of the validated Maslach Burnout Inventory, said Dr. Burke. A recent survey that used this measure indicated that nearly half of physician respondents report experiencing burnout.

In 2017, Dr. Burke led a survey of American College of Gastroenterology members that showed 49.3% of respondents reported feeling emotional exhaustion and/or depersonalization. Some key themes emerged from the survey, she said. Women and younger physicians were more likely to experience burnout. Having children in the middle years (11-15 years old) and spending more time on domestic duties and child care increased the risk of burnout.

And doing patient-related work at home or having a spouse or partner bring work home also upped burnout risk. Skipping breakfast and lunch during the workweek was another risk factor, which highlights the importance of basic self-care as armor against the administrative onslaught, said Dr. Burke.

Measured by volume alone, physician work can be overwhelming: 45% of physicians in the United States work more than 60 hours weekly, compared with fewer than 10% of the general workforce, said Dr. Burke.

What factors within the control of an individual practitioner can reduce the risk of debilitating burnout and improve quality of life? Physicians who do report a high quality of life, said Dr. Burke, are more likely to have a positive outlook. They also practice basic self-care like taking vacations, exercising regularly, and engaging in hobbies outside of work.

For exhausted, overworked clinicians, getting a good night’s sleep is a critical form of self-care. But erratic schedules, stress, and family demands can all sabotage plans for better sleep hygiene. Still, attending to sleep is important, said Dr. Burke. Individuals with disturbed sleep are less mindful and have less self-compassion. Sleep disturbance is also strongly correlated with perceived stress.

She also reported that the odds ratio for burnout was 14.7 for physicians who reported insomnia when compared with those without sleep disturbance, and it was 9.9 for those who reported nonrestorative sleep.

Physical activity can help sleep and also help other markers of burnout. Dr. Burke pointed to a recent study of 4,402 medical students. Participants were able to reduce burnout risk when they met the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations of achieving at least 150 minutes/week of moderate exercise or 75 minutes/week of vigorous exercise, plus at least 2 days/week of strength training (P less than .001; Acad Med. 2017;92:1006).

These physician-targeted programs can work, she said: “Faciliated interventions improve well-being, attitudes associated with patient-centered care, meaning and engagement in work, and reduce burnout.”

Practice-focused interventions to reclaim a semblance of control over one’s time are varied, and some are easier to implement than others. Virtual visits and group visits are surprisingly well received by patients, and each can be huge time-savers for physicians, said Dr. Burke. There are billing and workflow pitfalls to avoid, but group visits, in particular, can be practice changing for those who have heavy backlogs and see many patients with the same condition.

Medical scribes can improve productivity and reduce physician time spent on documentation. Also, said Dr. Burke, visits can appropriately be billed at a higher level of complexity when contemporaneous documentation is thorough. Clinicians overall feel that they can engage more fully with patients, and also feel more effective, when well-trained scribes are integrated into a practice, she said.

Female physicians have repeatedly been shown to have patient panels that are more demanding, and male and female patients alike expect more empathy and social support from their physicians, said Dr. Burke. When psychosocial complexities are interwoven with patient care, as they are more frequently for female providers, a 15-minute visit can easily run twice that – or more. Dr. Burke is among the physicians advocating for recognition of this invisible burden on female clinicians, either through adaptive scheduling or differential productivity expectations. This approach is not without controversy, she acknowledged; still, practices should acknowledge that clinic flow can be very different for male and female gastroenterologists, she said.

Dr. Burke reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Eat a healthy lunch. Get more sleep. Move your body. How many times in the course of a week do you give patients gentle reminders to practice these most basic steps of self-care? And how many times in the course of a week do you allow these basics to go by the wayside for yourself?

Self-care is one of the elements that can defend against physician burnout, Carol Burke, MD, said at a session on physician burnout held during the annual Digestive Disease Week®. Personal self-care can make a real difference, and shouldn’t be ignored as the profession works to reel back some of the institutional changes that challenge physicians today.

In the workplace, unhealthy stress levels can contribute to burnout, disruptive behavior, decreased productivity, and disengagement. Burnout – a response to chronic stress characterized by a diminished sense of personal accomplishment and emotional exhaustion – can result in cynicism, a lack of compassion, and feelings of depersonalization, said Dr. Burke.

Contributors to physician stress have been well documented, said Dr. Burke, a professor of gastroenterology at the Cleveland Clinic. These range from personal debt and the struggle for work-life balance to an increased focus on metrics and documentation at the expense of authentic patient engagement. All of these factors are measurable by means of the validated Maslach Burnout Inventory, said Dr. Burke. A recent survey that used this measure indicated that nearly half of physician respondents report experiencing burnout.

In 2017, Dr. Burke led a survey of American College of Gastroenterology members that showed 49.3% of respondents reported feeling emotional exhaustion and/or depersonalization. Some key themes emerged from the survey, she said. Women and younger physicians were more likely to experience burnout. Having children in the middle years (11-15 years old) and spending more time on domestic duties and child care increased the risk of burnout.

And doing patient-related work at home or having a spouse or partner bring work home also upped burnout risk. Skipping breakfast and lunch during the workweek was another risk factor, which highlights the importance of basic self-care as armor against the administrative onslaught, said Dr. Burke.

Measured by volume alone, physician work can be overwhelming: 45% of physicians in the United States work more than 60 hours weekly, compared with fewer than 10% of the general workforce, said Dr. Burke.

What factors within the control of an individual practitioner can reduce the risk of debilitating burnout and improve quality of life? Physicians who do report a high quality of life, said Dr. Burke, are more likely to have a positive outlook. They also practice basic self-care like taking vacations, exercising regularly, and engaging in hobbies outside of work.

For exhausted, overworked clinicians, getting a good night’s sleep is a critical form of self-care. But erratic schedules, stress, and family demands can all sabotage plans for better sleep hygiene. Still, attending to sleep is important, said Dr. Burke. Individuals with disturbed sleep are less mindful and have less self-compassion. Sleep disturbance is also strongly correlated with perceived stress.

She also reported that the odds ratio for burnout was 14.7 for physicians who reported insomnia when compared with those without sleep disturbance, and it was 9.9 for those who reported nonrestorative sleep.

Physical activity can help sleep and also help other markers of burnout. Dr. Burke pointed to a recent study of 4,402 medical students. Participants were able to reduce burnout risk when they met the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations of achieving at least 150 minutes/week of moderate exercise or 75 minutes/week of vigorous exercise, plus at least 2 days/week of strength training (P less than .001; Acad Med. 2017;92:1006).

These physician-targeted programs can work, she said: “Faciliated interventions improve well-being, attitudes associated with patient-centered care, meaning and engagement in work, and reduce burnout.”

Practice-focused interventions to reclaim a semblance of control over one’s time are varied, and some are easier to implement than others. Virtual visits and group visits are surprisingly well received by patients, and each can be huge time-savers for physicians, said Dr. Burke. There are billing and workflow pitfalls to avoid, but group visits, in particular, can be practice changing for those who have heavy backlogs and see many patients with the same condition.

Medical scribes can improve productivity and reduce physician time spent on documentation. Also, said Dr. Burke, visits can appropriately be billed at a higher level of complexity when contemporaneous documentation is thorough. Clinicians overall feel that they can engage more fully with patients, and also feel more effective, when well-trained scribes are integrated into a practice, she said.

Female physicians have repeatedly been shown to have patient panels that are more demanding, and male and female patients alike expect more empathy and social support from their physicians, said Dr. Burke. When psychosocial complexities are interwoven with patient care, as they are more frequently for female providers, a 15-minute visit can easily run twice that – or more. Dr. Burke is among the physicians advocating for recognition of this invisible burden on female clinicians, either through adaptive scheduling or differential productivity expectations. This approach is not without controversy, she acknowledged; still, practices should acknowledge that clinic flow can be very different for male and female gastroenterologists, she said.

Dr. Burke reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM DDW 2019

Functional GI disorders are common in MS

SEATTLE – according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. Managing patients’ psychiatric comorbidities could effectively reduce the burden of functional GI disorders, the researchers said.

Knowledge about the prevalence of functional GI disorders in the population of patients with MS is limited. For the most part, previous studies in this population have focused on irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). A 2013 study by Levinthal et al. (Mult Scler Int. 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/319201) investigated the prevalence of other functional GI disorders in MS, but the literature contains little information about the clinical and demographic characteristics associated with these disorders. In addition, the extent to which comorbid functional GI disorders influence health-related quality of life in MS is also unknown.

Ruth Ann Marrie, MD, PhD, professor of neurology at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, and colleagues sought to determine the prevalence of functional bowel disorders, the demographic and clinical characteristics associated with functional bowel disorders, and the effects of these disorders on health-related quality of life in a large, diverse population of persons with MS. In 2014, the investigators used the Rome III questionnaire to survey participants in the North American Research Committee on MS (NARCOMS) registry about functional bowel disorders. Participants also provided information about their sociodemographic characteristics, their disability status (using Patient-Determined Disease Steps), and any comorbid depression or anxiety, their health behaviors, and their health-related quality of life (using the RAND-12).

Dr. Marrie and colleagues used these data to determine the prevalence of IBS, functional bloating, functional constipation, functional diarrhea, and functional dyspepsia. They used multivariable logistic regression models to examine the factors associated with any functional GI disorder, and they used linear regression to analyze the association between functional GI disorders and health-related quality of life using linear regression.

Dr. Marrie and colleagues identified 6,312 eligible respondents. Approximately 77% of the population was female, and the sample’s mean age was 58.3 years. In all, 2,647 respondents (42%) had a functional GI disorder. The most common was IBS, which affected 28.2% of participants. The prevalence of all functional GI disorders increased with increasing disability. Depression and anxiety were associated with increased odds of IBS and functional dyspepsia. After adjustment for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, functional GI disorders were associated with lower physical and mental health-related quality of life.

The research was not supported by outside funding. Dr. Marrie had no disclosures, but other researchers had financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies, such as Merck, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and Teva.

SOURCE: Marrie RA et al. CMSC 2019, Abstract QOL13.

SEATTLE – according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. Managing patients’ psychiatric comorbidities could effectively reduce the burden of functional GI disorders, the researchers said.

Knowledge about the prevalence of functional GI disorders in the population of patients with MS is limited. For the most part, previous studies in this population have focused on irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). A 2013 study by Levinthal et al. (Mult Scler Int. 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/319201) investigated the prevalence of other functional GI disorders in MS, but the literature contains little information about the clinical and demographic characteristics associated with these disorders. In addition, the extent to which comorbid functional GI disorders influence health-related quality of life in MS is also unknown.

Ruth Ann Marrie, MD, PhD, professor of neurology at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, and colleagues sought to determine the prevalence of functional bowel disorders, the demographic and clinical characteristics associated with functional bowel disorders, and the effects of these disorders on health-related quality of life in a large, diverse population of persons with MS. In 2014, the investigators used the Rome III questionnaire to survey participants in the North American Research Committee on MS (NARCOMS) registry about functional bowel disorders. Participants also provided information about their sociodemographic characteristics, their disability status (using Patient-Determined Disease Steps), and any comorbid depression or anxiety, their health behaviors, and their health-related quality of life (using the RAND-12).

Dr. Marrie and colleagues used these data to determine the prevalence of IBS, functional bloating, functional constipation, functional diarrhea, and functional dyspepsia. They used multivariable logistic regression models to examine the factors associated with any functional GI disorder, and they used linear regression to analyze the association between functional GI disorders and health-related quality of life using linear regression.

Dr. Marrie and colleagues identified 6,312 eligible respondents. Approximately 77% of the population was female, and the sample’s mean age was 58.3 years. In all, 2,647 respondents (42%) had a functional GI disorder. The most common was IBS, which affected 28.2% of participants. The prevalence of all functional GI disorders increased with increasing disability. Depression and anxiety were associated with increased odds of IBS and functional dyspepsia. After adjustment for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, functional GI disorders were associated with lower physical and mental health-related quality of life.

The research was not supported by outside funding. Dr. Marrie had no disclosures, but other researchers had financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies, such as Merck, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and Teva.

SOURCE: Marrie RA et al. CMSC 2019, Abstract QOL13.

SEATTLE – according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. Managing patients’ psychiatric comorbidities could effectively reduce the burden of functional GI disorders, the researchers said.

Knowledge about the prevalence of functional GI disorders in the population of patients with MS is limited. For the most part, previous studies in this population have focused on irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). A 2013 study by Levinthal et al. (Mult Scler Int. 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/319201) investigated the prevalence of other functional GI disorders in MS, but the literature contains little information about the clinical and demographic characteristics associated with these disorders. In addition, the extent to which comorbid functional GI disorders influence health-related quality of life in MS is also unknown.

Ruth Ann Marrie, MD, PhD, professor of neurology at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, and colleagues sought to determine the prevalence of functional bowel disorders, the demographic and clinical characteristics associated with functional bowel disorders, and the effects of these disorders on health-related quality of life in a large, diverse population of persons with MS. In 2014, the investigators used the Rome III questionnaire to survey participants in the North American Research Committee on MS (NARCOMS) registry about functional bowel disorders. Participants also provided information about their sociodemographic characteristics, their disability status (using Patient-Determined Disease Steps), and any comorbid depression or anxiety, their health behaviors, and their health-related quality of life (using the RAND-12).

Dr. Marrie and colleagues used these data to determine the prevalence of IBS, functional bloating, functional constipation, functional diarrhea, and functional dyspepsia. They used multivariable logistic regression models to examine the factors associated with any functional GI disorder, and they used linear regression to analyze the association between functional GI disorders and health-related quality of life using linear regression.

Dr. Marrie and colleagues identified 6,312 eligible respondents. Approximately 77% of the population was female, and the sample’s mean age was 58.3 years. In all, 2,647 respondents (42%) had a functional GI disorder. The most common was IBS, which affected 28.2% of participants. The prevalence of all functional GI disorders increased with increasing disability. Depression and anxiety were associated with increased odds of IBS and functional dyspepsia. After adjustment for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, functional GI disorders were associated with lower physical and mental health-related quality of life.

The research was not supported by outside funding. Dr. Marrie had no disclosures, but other researchers had financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies, such as Merck, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and Teva.

SOURCE: Marrie RA et al. CMSC 2019, Abstract QOL13.

REPORTING FROM CMSC 2019

Fibroids: Patient considerations in medical and surgical management

Uterine fibroids (myomas or leiomyomas) are common and can cause considerable morbidity, including infertility, in reproductive-aged women. In this roundtable discussion, moderated by OBG

Perspectives on a pervasive problem

Joseph S. Sanfilippo, MD, MBA: First let’s discuss the scope of the problem. How prevalent are uterine fibroids, and what are their effects on quality of life?

Linda D. Bradley, MD: Fibroids are extremely prevalent. Depending on age and race, between 60% and 80% of women have them.1 About 50% of women with fibroids have no symptoms2; in symptomatic women, the symptoms may vary based on age. Fibroids are more common in women from the African diaspora, who have earlier onset of symptoms, very large or more numerous fibroids, and more symptomatic fibroids, according to some clinical studies.3 While it is a very common disease state, about half of women with fibroids may not have significant symptoms that warrant anything more than watchful waiting or some minimally invasive options.

Ted L. Anderson, MD, PhD: We probably underestimate the scope because we see people coming in with fibroids only when they have a specific problem. There probably are a lot of asymptomatic women out there that we do not know about.

Case 1: Abnormal uterine bleeding in a young woman desiring pregnancy in the near future

Dr. Sanfilippo: Abnormal uterine bleeding is a common dilemma in my practice. Consider the following case example.

A 24-year-old woman (G1P1) presents with heavy, irregular menses over 6 months’ duration. She is interested in pregnancy, not immediately but in several months. She passes clots, soaks a pad in an hour, and has dysmenorrhea and fatigue. She uses no birth control. She is very distraught, as this bleeding truly has changed her lifestyle.

What is your approach to counseling this patient?

Dr. Bradley: You described a woman whose quality of life is very poor—frequent pad changes, clotting, pain. And she wants to have a child. A patient coming to me with those symptoms does not need to wait 4 to 6 months. I would immediately do some early evaluation.

Dr. Anderson: Sometimes a patient comes to us and already has had an ultrasonography exam. That is helpful, but I am driven by the fact that this patient is interested in pregnancy. I want to look at the uterine cavity and will probably do an office hysteroscopy to see if she has fibroids that distort the uterine cavity. Are there fibroids inside the cavity? To what degree does that possibly play a role? The presence of fibroids does not necessarily mean there is distortion of the cavity, and some evidence suggests that you do not need to do anything about those fibroids.4 Fibroids actually may not be the source of bleeding. We need to keep an open mind when we do the evaluation.

Continue to: Imaging technologies and classification aids...

Imaging technologies and classification aids

Dr. Sanfilippo: Apropos to your comment, is there a role for a sonohysterography in this population?

Dr. Anderson: That is a great technique. Some clinicians prefer to use sonohysterography while others prefer hysteroscopy. I tend to use hysteroscopy, and I have the equipment in the office. Both are great techniques and they answer the same question with respect to cavity evaluation.

Dr. Bradley: We once studied about 150 patients who, on the same day, with 2 separate examiners (one being me), would first undergo saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS) and then hysteroscopy, or vice versa. The sensitivity of identifying an intracavitary lesion is quite good with both. The additional benefit with SIS is that you can look at the adnexa.

In terms of the classification by the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), sometimes when we do a hysteroscopy, we are not sure how deep a fibroid is—whether it is a type 1 or type 2 or how close it is to the serosa (see illustration, page 26). Are we seeing just the tip of the iceberg? There is a role for imaging, and it is not always an “either/or” situation. There are times, for example, that hysteroscopy will show a type 0. Other times it may not show that, and you look for other things in terms of whether a fibroid abuts the endometrium. The take-home message is that physicians should abandon endometrial biopsy alone and, in this case, not offer a D&C.

In evaluating the endometrium, as gynecologists we should be facile in both technologies. In our workplaces we need to advocate to get trained, to be certified, and to be able to offer both technologies, because sometimes you need both to obtain the right answer.

Dr. Sanfilippo: Let’s talk about the FIGO classification, because it is important to have a communication method not only between physicians but with the patient. If we determine that a fibroid is a type 0, and therefore totally intracavitary, management is different than if the fibroid is a type 1 (less than 50% into the myometrium) or type 2 (more than 50%). What is the role for a classification system such as the FIGO?

Dr. Anderson: I like the FIGO classification system. We can show the patient fibroid classification diagrammatically and she will be able to understand exactly what we are talking about. It’s helpful for patient education and for surgical planning. The approach to a type 0 fibroid is a no-brainer, but with type 1 and more specifically with type 2, where the bulk of the fibroid is intramural and only a portion of that is intracavitary, fibroid size begins to matter a lot in terms of treatment approach.

Sometimes although a fibroid is intracavitary, a laparoscopic rather than hysteroscopic approach is preferred, as long as you can dissect the fibroid away from the endometrium. FIGO classification is very helpful, but I agree with Dr. Bradley that first you need to do a thorough evaluation to make your operative plan.

Continue to: Dr. Sanfilippo...

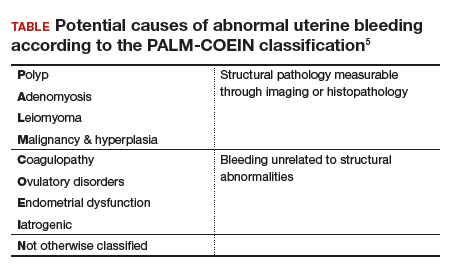

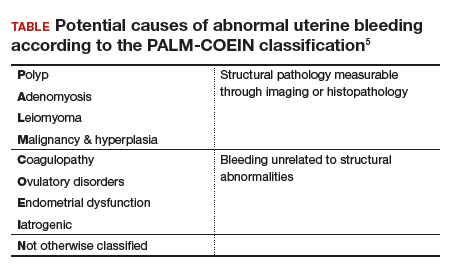

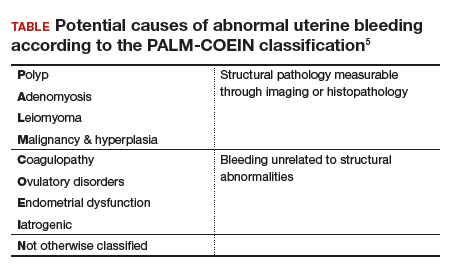

Dr. Sanfilippo: I encourage residents to go through an orderly sequence of assessment for evaluating abnormal uterine bleeding, including anatomic and endocrinologic factors. The PALM-COEIN classification system is a great mnemonic for use in evaluating abnormal uterine bleeding (TABLE).5 Is there a role for an aid such as PALM-COEIN in your practice?

Dr. Bradley: I totally agree. In 2011, Malcolm Munro and colleagues in the FIGO Working Group on Menstrual Disorders helped us to have a reporting on outcomes by knowing the size, number, and location of fibroids.5 This helps us to look for structural causes and then, to get to the answer, we often use imaging such as ultrasonography or saline infusion, sometimes magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), because other conditions can coexist—endometrial polyps, adenomyosis, and so on.

The PALM-COEIN system helps us to look at 2 things. One is that in addition to structural causes, there can be hematologic causes. While it is rare in a 24-year-old, we all have had the anecdotal patient who came in 6 months ago, had a fibroid, but had a platelet count of 6,000. Second, we have to look at the patient as a whole. My residents, myself, and our fellows look at any bleeding. Does she have a bleeding diathesis, bruising, nose bleeds; has she been anemic, does she have pica? Has she had a blood transfusion, is she on certain medications? We do not want to create a “silo” and think that the patient can have only a fibroid, because then we may miss an opportunity to treat other disease states. She can have a fibroid coexisting with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), for instance. I like to look at everything so we can offer appropriate treatment modalities.

Dr. Sanfilippo: You bring up a very important point. Coagulopathies are more common statistically at the earlier part of a woman’s reproductive age group, soon after menarche, but they also occur toward menopause. We have to be cognizant that a woman can develop a coagulopathy throughout the reproductive years.

Dr. Anderson: You have to look at other medical causes. That is where the PALM-COEIN system can help. It helps you take the blinders off. If you focus on the fibroid and treat the fibroid and the patient still has bleeding, you missed something. You have to consider the whole patient and think of all the nonclassical or nonanatomical things, for example, thyroid disease. The PALM-COEIN helps us to evaluate the patient in a methodical way—every patient every time—so you do not miss something.

The value of MRI

Dr. Sanfilippo: What is the role for MRI, and when do you use it? Is it for only when you do a procedure—laparoscopically, robotically, open—so you have a detailed map of the fibroids?

Dr. Anderson: I love MRI, especially for hysteroscopy. I will print out the MRI image and trace the fibroid because there are things I want to know: exactly how much of the fibroid is inside or outside, where this fibroid is in the uterus, and how much of a normal buffer there is between the edge of that fibroid and the serosa. How aggressive can I be, or how cautious do I need to be, during the resection? Maybe this will be a planned 2-stage resection. MRIs are wonderful for fibroid disease, not only for diagnosis but also for surgical planning and patient counseling.

Dr. Bradley: SIS is also very useful. If the patient has an intracavitary fibroid that is larger than 4.5 to 5 cm and we insert the catheter, however, sometimes you cannot distend the cavity very well. Sometimes large intramural fibroids can compress the cavity, making the procedure difficult in an office setting. You cannot see the limits to help you as a surgical option. Although SIS generally is associated with little pain, some patients may have pain, and some patients cannot tolerate the test.

Continue to: I would order an MRI for surgical planning when...

I would order an MRI for surgical planning when a hysteroscopy is equivocal and if I cannot do an SIS. Also, if a patient who had a hysteroscopic resection with incomplete removal comes to me and is still symptomatic, I want to know the depth of penetration.

Obtaining an MRI may sometimes be difficult at a particular institution, and some clinicians have to go through the hurdles of getting an ultrasound to get certified and approved. We have to be our patient’s advocate and do the peer phone calls; any other specialty would require presurgical planning, and we are no different from other surgeons in that regard.

Dr. Sanfilippo: Yes, that can be a stumbling block. In the operating room, I like to have the images right in front of me, ideally an MRI or an ultrasound scan, as I know how to proceed. Having that visual helps me understand how close the fibroid is to the lining of the uterus.

Tapping into radiologists’ expertise

Dr. Bradley: Every quarter we meet with our radiologists, who are very interested in our MRI and SIS reports. They will describe the count and say how many fibroids—that is very helpful instead of just saying she has a bunch of fibroids—but they also will tell us when there is a type 0, a type 2, a type 7 fibroid. The team looks for adenomyosis and for endometriosis that can coexist.

Dr. Anderson: One caution about reading radiology reports is that often someone will come in with a report from an outside hospital or from a small community hospital that may say, “There is a 2-cm submucosal fibroid.” Some people might be tempted to take this person right to the OR, but you need to look at the images yourself, because in a radiologist’s mind “submucosal” truly means under the mucosa, which in our liturgy would be “intramural.” So we need to make sure that we are talking the same language. You should look at the images yourself.

Dr. Sanfilippo: I totally agree. It is also not unreasonable to speak with the radiologists and educate them about the FIGO classification.

Dr. Bradley: I prefer the word “intracavitary” for fibroids. When I see a typed report without the picture, “submucosal” can mean in the cavity or abutting the endometrium.

Case 2: Woman with heavy bleeding and fibroids seeks nonsurgical treatment

Dr. Sanfilippo: A 39-year-old (G3P3) woman is referred for evaluation for heavy vaginal bleeding, soaking a pad in an hour, which has been going on for months. Her primary ObGyn obtained a pelvic sonogram and noted multiple intramural and subserosal fibroids. A sonohysterogram reveals a submucosal myoma.

The patient is not interested in a hysterectomy. She was treated with birth control pills, with no improvement. She is interested in nonsurgical options. Dr. Bradley, what medical treatments might you offer this patient?

Medical treatment options

Dr. Bradley: If oral contraceptives have not worked, a good option would be tranexamic acid. Years ago our hospital was involved with enrolling patients in the multicenter clinical trial of this drug. The classic patient enrolled had regular, predictable, heavy menstrual cycles with alkaline hematin assay of greater than 80. If the case patient described has regular and predictable heavy bleeding every month at the same time, for the same duration, I would consider the use of tranexamic acid. There are several contraindications for the drug, so those exclusion issues would need to be reviewed. Contraindications include subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cerebral edema and cerebral infarction may be caused by tranexamic acid in such patients. Other contraindications include active intravascular clotting and hypersensitivity.

Continue to: Another option is to see if a progestin-releasing intrauterine system...

Another option is to see if a progestin-releasing intrauterine system (IUS) like the levonorgestrel (LNG) IUS would fit into this patient’s uterine cavity. Like Ted, I want to look into that cavity. I am not sure what “submucosal fibroid” means. If it has not distorted the cavity, or is totally within the uterine cavity, or abuts the endometrial cavity. The LNG-IUS cannot be placed into a uterine cavity that has intracavitary fibroids or sounds to greater than 12 cm. We are not going to put an LNG-IUS in somebody, at least in general, with a globally enlarged uterine cavity. I could ask, do you do that? You do a bimanual exam, and it is 18-weeks in size. I am not sure that I would put it in, but does it meet those criteria? The package insert for the LNG-IUS specifies upper and lower limits of uterine size for placement. I would start with those 2 options (tranexamic acid and LNG-IUS), and also get some more imaging.

Dr. Anderson: I agree with Linda. The submucosal fibroid could be contributing to this patient’s bleeding, but it is not the total contribution. The other fibroids may be completely irrelevant as far as her bleeding is concerned. We may need to deal with that one surgically, which we can do without a hysterectomy, most of the time.

I am a big fan of the LNG-IUS, it has been great in my experience. There are some other treatments available as well, such as gonadotropin–releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists. I tell patients that, while GnRH does work, it is not designed to be long-term therapy. If I have, for example, a 49-year-old patient, I just need to get her to menopause. Longer-term GnRH agonists might be a good option in this case. Otherwise, we could use short-term a GnRH agonist to stop the bleeding for a while so that we can reset the clock and get her started on something like levonorgestrel, tranexamic acid, or one of the other medical therapies. That may be a 2-step combination therapy.

Dr. Sanfilippo: There is a whole category of agents available—selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs), pure progesterone receptor antagonists, ulipristal comes to mind. Clinicians need to know that options are available beyond birth control pills.

Dr. Anderson: As I tell patients, there are also “bridge” options. These are interventional procedures that are not hysterectomy, such as uterine fibroid embolization or endometrial ablation if bleeding is really the problem. We might consider a variety of different approaches. Obviously, we do not typically use fibroid embolization for submucosal fibroids, but it depends on how much of the fibroid is intracavitary and how big it is. Other options are a little more aggressive than medical therapy but they do not involve a hysterectomy.

Pros and cons of uterine artery embolization

Dr. Sanfilippo: If a woman desires future childbearing, is there a role for uterine artery embolization? How would you counsel her about the pros and cons?

Dr. Bradley: At the Cleveland Clinic, we generally do not offer uterine artery embolization if the patient wants a child. While it is an excellent method for treating heavy bleeding and bulk symptoms, the endometrium can be impacted. Patients can develop fistula, adhesions, or concentric narrowing, and changes in anti-Müllerian hormone levels, and there is potential for an Asherman-like syndrome and poor perfusion. I have many hysteroscopic images where the anterior wall of the uterus is nice and pink and the posterior wall is totally pale. The embolic microsphere particles can reach the endometrium—I have seen particles in the endometrium when doing a fibroid resection.

Continue to: A good early study looked at 555 women for almost a year...

A good early study looked at 555 women for almost a year.6 If women became pregnant, they had a higher rate of postpartum hemorrhage; placenta accreta, increta, and percreta; and emergent hysterectomy. It was recommended that these women deliver at a tertiary care center due to higher rates of preterm labor and malposition.

If a patient wants a baby, she should find a gynecologic surgeon who does minimally invasive laparoscopic, robotic, or open surgery, because she is more likely to have a take-home baby with a surgical approach than with embolization. In my experience, there is always going to be a patient who wants to keep her uterus at age 49 and who has every comorbidity. I might offer her the embolization just knowing what the odds of pregnancy are.

Dr. Anderson: I agree with Linda but I take a more liberal approach. Sometimes we do a myomectomy because we are trying to enhance fertility, while other times we do a myomectomy to address fibroid-related symptoms. These patients are having specific symptoms, and we want to leave the embolization option open.

If I have a patient who is 39 and becoming pregnant is not necessarily her goal, but she does not want to have a hysterectomy and if she got pregnant it would be okay, I am going to treat her a little different with respect to fibroid embolization than I would treat someone who is actively trying to have a baby. This goes back to what you were saying, let’s treat the patient, not just the fibroid.

Dr. Bradley: That is so important and sentinel. If she really does not want a hysterectomy but does not want a baby, I will ask, “Would you go through in vitro fertilization? Would you take clomiphene?” If she answers no, then I feel more comfortable, like you, with referring the patient for uterine fibroid embolization. The point is to get the patient with the right team to get the best outcomes.

Surgical approaches, intraoperative agents, and suture technique

Dr. Sanfilippo: Dr. Anderson, tell us about your surgical approaches to fibroids.

Dr. Anderson: At my institution we do have a fellowship in minimally invasive surgery, but I still do a lot of open myomectomies. I have a few guidelines to determine whether I am going to proceed laparoscopically, do a little minilaparotomy incision, or if a gigantic uterus is going to require a big incision. My mantra to my fellows has always been, “minimally invasive is the impact on the patient, not the size of the incision.”

Sometimes, prolonged anesthesia and Trendelenburg create more morbidity than a minilaparotomy. If a patient has 4 or 5 fibroids and most of them are intramural and I cannot see them but I want to be able to feel them, and to get a really good closure of the myometrium, I might choose to do a minilaparotomy. But if it is a case of a solitary fibroid, I would be more inclined to operate laparoscopically.

Continue to: Dr. Bradley...

Dr. Bradley: Our protocol is similar. We use MRI liberally. If patients have 4 or more fibroids and they are larger than 8 cm, most will have open surgery. I do not do robotic or laparoscopic procedures, so my referral source is for the larger myomas. We do not put retractors in; we can make incisions. Even if we do a huge Maylard incision, it is cosmetically wonderful. We use a loading dose of IV tranexamic acid with tranexamic acid throughout the surgery, and misoprostol intravaginally prior to surgery, to control uterine bleeding.

Dr. Sanfilippo: Dr. Anderson, is there a role for agents such as vasopressin, and what about routes of administration?

Dr. Anderson: When I do a laparoscopic or open procedure, I inject vasopressin (dilute 20 U in 100 mL of saline) into the pseudocapsule around the fibroid. I also administer rectal misoprostol (400 µg) just before the patient prep is done, which is amazing in reducing blood loss. There is also a role for a GnRH agonist, not necessarily to reduce the size of the uterus but to reduce blood flow in the pelvis and blood loss. Many different techniques are available. I do not use tourniquets, however. If bleeding does occur, I want to see it so I can fix it—not after I have sewn up the uterus and taken off a tourniquet.

Dr. Bradley: Do you use Floseal hemostatic matrix or any other agent to control bleeding?

Dr. Anderson: I do, for local hemostasis.

Dr. Bradley: Some surgeons will use barbed suture.

Dr. Anderson: I do like barbed sutures. In teaching residents to do myomectomy, it is very beneficial. But I am still a big fan of the good old figure-of-8 stitch because it is compressive and you get a good apposition of the tissue, good hemostasis, and strong closure.

Dr. Sanfilippo: We hope that this conversation will change your management of uterine fibroids. I thank Dr. Bradley and Dr. Anderson for a lively and very informative discussion.

Watch the video: Video roundtable–Fibroids: Patient considerations in medical and surgical management

- Khan AT, Shehmar M, Gupta JK. Uterine fibroids: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2014;6:95-114.

- Divakars H. Asymptomatic uterine fibroids. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;22:643-654.

- Stewart EA, Nicholson WK, Bradley L, et al. The burden of uterine fibroids for African-American women: results of a national survey. J Womens Health. 2013;22:807-816.

- Hartmann KE, Velez Edwards DR, Savitz DA, et al. Prospective cohort study of uterine fibroids and miscarriage risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:1140-1148.

- Munro MG, Critchley HOD, Fraser IS, for the FIGO Menstrual Disorders Working Group. The FIGO classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2204-2208.

- Pron G, Mocarski E, Bennett J, et al; Ontario UFE Collaborative Group. Pregnancy after uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata: the Ontario multicenter trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:67-76.

Uterine fibroids (myomas or leiomyomas) are common and can cause considerable morbidity, including infertility, in reproductive-aged women. In this roundtable discussion, moderated by OBG

Perspectives on a pervasive problem

Joseph S. Sanfilippo, MD, MBA: First let’s discuss the scope of the problem. How prevalent are uterine fibroids, and what are their effects on quality of life?

Linda D. Bradley, MD: Fibroids are extremely prevalent. Depending on age and race, between 60% and 80% of women have them.1 About 50% of women with fibroids have no symptoms2; in symptomatic women, the symptoms may vary based on age. Fibroids are more common in women from the African diaspora, who have earlier onset of symptoms, very large or more numerous fibroids, and more symptomatic fibroids, according to some clinical studies.3 While it is a very common disease state, about half of women with fibroids may not have significant symptoms that warrant anything more than watchful waiting or some minimally invasive options.

Ted L. Anderson, MD, PhD: We probably underestimate the scope because we see people coming in with fibroids only when they have a specific problem. There probably are a lot of asymptomatic women out there that we do not know about.

Case 1: Abnormal uterine bleeding in a young woman desiring pregnancy in the near future

Dr. Sanfilippo: Abnormal uterine bleeding is a common dilemma in my practice. Consider the following case example.

A 24-year-old woman (G1P1) presents with heavy, irregular menses over 6 months’ duration. She is interested in pregnancy, not immediately but in several months. She passes clots, soaks a pad in an hour, and has dysmenorrhea and fatigue. She uses no birth control. She is very distraught, as this bleeding truly has changed her lifestyle.

What is your approach to counseling this patient?

Dr. Bradley: You described a woman whose quality of life is very poor—frequent pad changes, clotting, pain. And she wants to have a child. A patient coming to me with those symptoms does not need to wait 4 to 6 months. I would immediately do some early evaluation.

Dr. Anderson: Sometimes a patient comes to us and already has had an ultrasonography exam. That is helpful, but I am driven by the fact that this patient is interested in pregnancy. I want to look at the uterine cavity and will probably do an office hysteroscopy to see if she has fibroids that distort the uterine cavity. Are there fibroids inside the cavity? To what degree does that possibly play a role? The presence of fibroids does not necessarily mean there is distortion of the cavity, and some evidence suggests that you do not need to do anything about those fibroids.4 Fibroids actually may not be the source of bleeding. We need to keep an open mind when we do the evaluation.

Continue to: Imaging technologies and classification aids...

Imaging technologies and classification aids

Dr. Sanfilippo: Apropos to your comment, is there a role for a sonohysterography in this population?

Dr. Anderson: That is a great technique. Some clinicians prefer to use sonohysterography while others prefer hysteroscopy. I tend to use hysteroscopy, and I have the equipment in the office. Both are great techniques and they answer the same question with respect to cavity evaluation.

Dr. Bradley: We once studied about 150 patients who, on the same day, with 2 separate examiners (one being me), would first undergo saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS) and then hysteroscopy, or vice versa. The sensitivity of identifying an intracavitary lesion is quite good with both. The additional benefit with SIS is that you can look at the adnexa.