User login

Cancer deaths cost over $94 billion in lost earnings in 2015

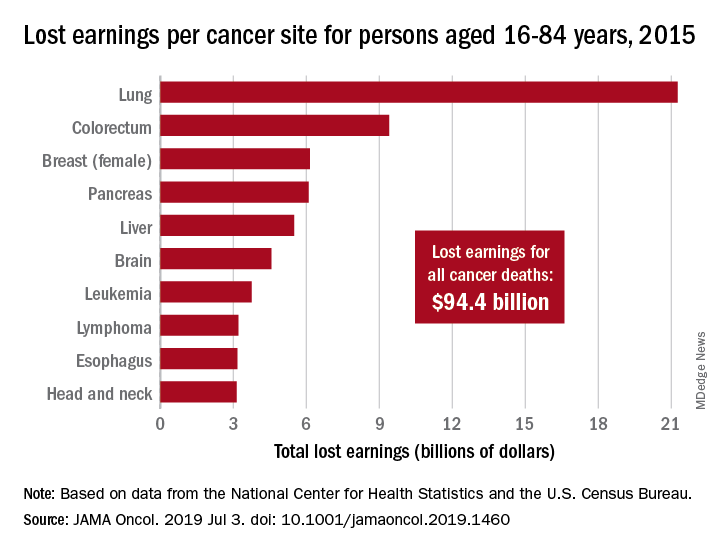

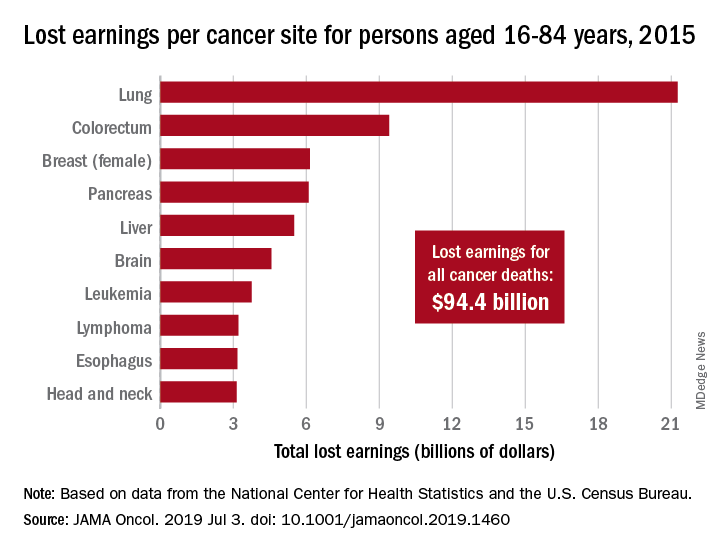

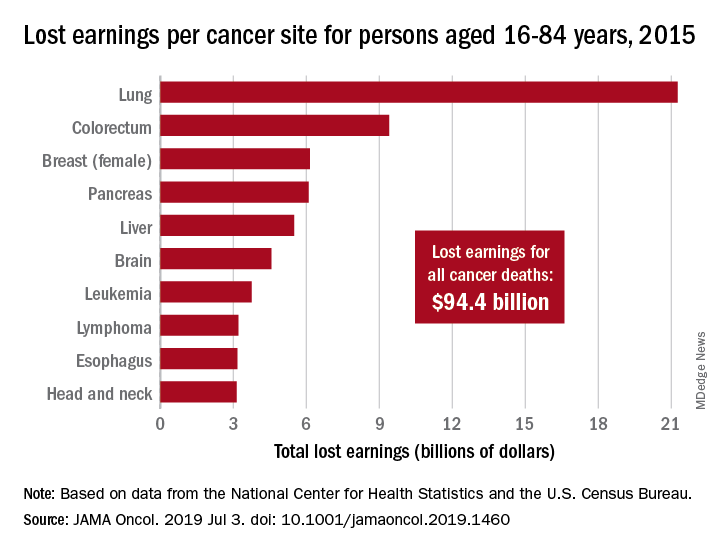

Cancer led to 492,000 deaths for Americans aged 16-84 years in 2015, and those deaths cost $94.4 billion in lost earnings that year, according to a study published in JAMA Oncology.

Cancer also took more than 8.7 million years of life from those individuals, with lung cancer being the most costly in terms of both lost earnings and years of life lost, said Farhad Islami, MD, PhD, and associates at the American Cancer Society, Atlanta.

“Person-years of life lost and lost earnings were high for many cancers associated with modifiable risk factors and effective screening and treatment, suggesting that a substantial proportion of the mortality burden is potentially avoidable,” they wrote, adding that “implementation of comprehensive cancer prevention interventions and equitable access to high-quality care across all states could reduce the burden of cancer and associated geographic and other differences in the country.”

In 2015, lung cancer took more than 2.2 million years of life and $21.3 billion in earnings from Americans aged 16-84 years. Colorectal cancer was next with 766,000 years of life lost and $9.4 billion in lost earnings, followed by female breast cancer with losses of 746,000 years of life and 6.2 billion in earnings, Dr. Islami and associated reported.

For all cancers, the cost in lost earnings per death was almost $192,000, with the highest costs coming from cancers of the brain and nervous system ($315,000) and cervix ($311,000). On that basis, lung cancer cost was lower than average at $159,000 per death, they noted.

At the state level, lost-earnings rates were lowest in Utah ($19.6 million per 100,000 persons) and highest in Kentucky ($35.3 million per 100,000). “If all states had Utah’s lost earnings rate in 2015, lost earnings in the U.S. would have been reduced by 29.3%, or $27.7 billion, and life years lost nationwide in 2015 would be reduced by 2.4 million,” Dr. Islami and his associates said in a written statement.

Data for the study were obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics (mortality) and the U.S. Census Bureau (earnings). The study was supported by the Intramural Research Department of the American Cancer Society, and all of the investigators are employees of the society.

SOURCE: Islami F et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jul 3. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1460.

Cancer led to 492,000 deaths for Americans aged 16-84 years in 2015, and those deaths cost $94.4 billion in lost earnings that year, according to a study published in JAMA Oncology.

Cancer also took more than 8.7 million years of life from those individuals, with lung cancer being the most costly in terms of both lost earnings and years of life lost, said Farhad Islami, MD, PhD, and associates at the American Cancer Society, Atlanta.

“Person-years of life lost and lost earnings were high for many cancers associated with modifiable risk factors and effective screening and treatment, suggesting that a substantial proportion of the mortality burden is potentially avoidable,” they wrote, adding that “implementation of comprehensive cancer prevention interventions and equitable access to high-quality care across all states could reduce the burden of cancer and associated geographic and other differences in the country.”

In 2015, lung cancer took more than 2.2 million years of life and $21.3 billion in earnings from Americans aged 16-84 years. Colorectal cancer was next with 766,000 years of life lost and $9.4 billion in lost earnings, followed by female breast cancer with losses of 746,000 years of life and 6.2 billion in earnings, Dr. Islami and associated reported.

For all cancers, the cost in lost earnings per death was almost $192,000, with the highest costs coming from cancers of the brain and nervous system ($315,000) and cervix ($311,000). On that basis, lung cancer cost was lower than average at $159,000 per death, they noted.

At the state level, lost-earnings rates were lowest in Utah ($19.6 million per 100,000 persons) and highest in Kentucky ($35.3 million per 100,000). “If all states had Utah’s lost earnings rate in 2015, lost earnings in the U.S. would have been reduced by 29.3%, or $27.7 billion, and life years lost nationwide in 2015 would be reduced by 2.4 million,” Dr. Islami and his associates said in a written statement.

Data for the study were obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics (mortality) and the U.S. Census Bureau (earnings). The study was supported by the Intramural Research Department of the American Cancer Society, and all of the investigators are employees of the society.

SOURCE: Islami F et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jul 3. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1460.

Cancer led to 492,000 deaths for Americans aged 16-84 years in 2015, and those deaths cost $94.4 billion in lost earnings that year, according to a study published in JAMA Oncology.

Cancer also took more than 8.7 million years of life from those individuals, with lung cancer being the most costly in terms of both lost earnings and years of life lost, said Farhad Islami, MD, PhD, and associates at the American Cancer Society, Atlanta.

“Person-years of life lost and lost earnings were high for many cancers associated with modifiable risk factors and effective screening and treatment, suggesting that a substantial proportion of the mortality burden is potentially avoidable,” they wrote, adding that “implementation of comprehensive cancer prevention interventions and equitable access to high-quality care across all states could reduce the burden of cancer and associated geographic and other differences in the country.”

In 2015, lung cancer took more than 2.2 million years of life and $21.3 billion in earnings from Americans aged 16-84 years. Colorectal cancer was next with 766,000 years of life lost and $9.4 billion in lost earnings, followed by female breast cancer with losses of 746,000 years of life and 6.2 billion in earnings, Dr. Islami and associated reported.

For all cancers, the cost in lost earnings per death was almost $192,000, with the highest costs coming from cancers of the brain and nervous system ($315,000) and cervix ($311,000). On that basis, lung cancer cost was lower than average at $159,000 per death, they noted.

At the state level, lost-earnings rates were lowest in Utah ($19.6 million per 100,000 persons) and highest in Kentucky ($35.3 million per 100,000). “If all states had Utah’s lost earnings rate in 2015, lost earnings in the U.S. would have been reduced by 29.3%, or $27.7 billion, and life years lost nationwide in 2015 would be reduced by 2.4 million,” Dr. Islami and his associates said in a written statement.

Data for the study were obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics (mortality) and the U.S. Census Bureau (earnings). The study was supported by the Intramural Research Department of the American Cancer Society, and all of the investigators are employees of the society.

SOURCE: Islami F et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jul 3. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1460.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Is the vaginal or buccal route more effective when administering prostaglandins for cervical ripening at term?

Haas DM, Daggy J, Flannery KM, et al. A comparison of vaginal versus buccal misoprostol for cervical ripening in women for labor induction at term (the IMPROVE trial): a triple masked randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.04.037.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Cervical ripening is routine practice in women undergoing induction of labor who have an unfavorable cervical examination.1 This is because generating contractions against a long thick cervix is more likely to lead to failed induction and cesarean delivery. Cervical ripening can be achieved using mechanical or pharmacologic methods.

Misoprostol (a prostaglandin E1 [PGE1] analog) is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of peptic ulcer disease, but it also is widely used off-label for cervical ripening, partly due to its low cost. Misoprostol’s optimal dosing regimen and route of administration are not known. The IMPROVE trial was designed to address this knowledge gap, specifically to compare the efficacy and safety of VM versus BM in women undergoing labor induction at term.

Details of the study

The IMPROVE trial was a prospective, randomized, noninferiority, triple-masked, placebo-controlled trial of 300 women with a singleton vertex fetus requiring cervical ripening for induction of labor at term.2 Enrolled women were randomly assigned to VM or BM (same dosing regimen) and to a matching placebo administered via the opposite route.

Primary outcomes included time-to-vaginal-delivery from first dose, which was reduced in VM vs BM (20.1 vs 28.1 hours; P = .006), and urgent cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal testing, which was similarly reduced in VM (3.3% vs 9.5%; P = .33). These differences persisted after controlling for covariates. There was also a greater difference seen in multiparous versus nulliparous women.

Secondary outcomes also favored VM over BM, including more vaginal deliverieswithin 24 hours, fewer doses to achieve active labor, and a lower maximum dose of oxytocin.

Overall cesarean delivery rates were similar in the 2 groups (VM, 15.8%; BM, 22.3%; P = .15). There were no significant differences in other delivery characteristics or in maternal or fetal adverse events.

While a number of studies have evaluated the risk of cesarean delivery (CD) with the use of cervical ripening agents by different routes of administration, Handal-Orefice and colleagues studied this outcome specifically in a predominantly overweight population at a tertiary care center.1

The retrospective study included 276 women, of whom 91% had a body mass index (BMI) of 25 kg/m2 or more and 61% had a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or more at the time of delivery.

For cervical ripening, 138 women received vaginal misoprostol (25 µg) and 138 received oral misoprostol (50 µg). The frequency of CD (the primary study outcome) was significantly higher with oral compared with vaginal misoprostol use (32% vs 21%; P = .04). When the analysis was adjusted for age, BMI, parity, indication for induction, and Foley catheter use, the risk of CD remained significantly higher for the oral misoprostol group (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.01; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.07-3.76).

Other key findings:

- frequency of CD among nulliparous women: 41% in the oral misoprostol group, 28% in the vaginal misoprostol group (aOR, 2.79; 95% CI, 1.26-6.19)

- time to vaginal delivery: 41 hours for the oral misoprostol group, 31 hours for the vaginal misoprostol group (P = .01)

- uterine tachysystole: 11% in the oral misoprostol group, 20% in the vaginal misoprostol group (P = .04).

The authors noted that the strengths of the study, including the racial and ethnic diversity of the population (72% of women were of either black or Hispanic race or ethnicity), the commonly used doses of misoprostol, and the performance of inductions outside a research protocol, add to the generalizability of the results.

Reference

1. Handal-Orefice R, Friedman AM, Chouinard SM, et al. Oral or vaginal misoprostol for labor induction and cesarean delivery risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003274.

Continue to: Study strengths and limitations...

Study strengths and limitations

The IMPROVE trial had a triple-blinded study design with an intention-to-treat paradigm and good follow-up. There was also standardization of PGE1 administration criteria, which was consistent with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists standards of care. Results were similar to those of prior studies regarding rates of tachysystole, urgent cesarean delivery, and vaginal delivery.

The study has good generalizability as it included both elective and medically indicated inductions; however, patients with ruptured membranes were excluded. Although there was no difference in the overall cesarean delivery rates, the study was underpowered to look at this outcome. The authors included a patient satisfaction survey, but this is hard to interpret since study participants all received tablets orally and vaginally. The study did not address efficacy of VM versus BM administration at different doses or time intervals.

Labor induction has doubled over the past 2 decades, with almost 25% of parturients currently undergoing induction in the United States.3 This number is likely to increase given recent data suggesting that routine induction at 39 weeks may significantly decrease cesarean delivery rates.4 It is critical, therefore, that we identify the optimal technique for cervical ripening, including the ideal dosing regimen and route of administration. Results of the IMPROVE trial suggest that vaginal administration of misoprostol (25 μg initial dose, 50 μg subsequent doses) may be superior to the buccal route, with more rapid vaginal delivery, more vaginal deliveries within 24 hours, and fewer urgent cesareans for nonreassuring fetal testing (although the overall cesarean delivery rate was not significantly different).

ERROL R. NORWITZ, MD, PHD, MBA; JULIE M. STONE, MD

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 107. Induction of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(2 pt 1):386-397.

- Haas DM, Daggy J, Flannery KM, et al. A comparison of vaginal versus buccal misoprostol for cervical ripening in women for labor induction at term (the IMPROVE trial): a triple masked randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.04.037.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman M, et al. Births: final data for 2016. Nat Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67:1-55.

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal–Fetal Medicine Units Network. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

Haas DM, Daggy J, Flannery KM, et al. A comparison of vaginal versus buccal misoprostol for cervical ripening in women for labor induction at term (the IMPROVE trial): a triple masked randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.04.037.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Cervical ripening is routine practice in women undergoing induction of labor who have an unfavorable cervical examination.1 This is because generating contractions against a long thick cervix is more likely to lead to failed induction and cesarean delivery. Cervical ripening can be achieved using mechanical or pharmacologic methods.

Misoprostol (a prostaglandin E1 [PGE1] analog) is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of peptic ulcer disease, but it also is widely used off-label for cervical ripening, partly due to its low cost. Misoprostol’s optimal dosing regimen and route of administration are not known. The IMPROVE trial was designed to address this knowledge gap, specifically to compare the efficacy and safety of VM versus BM in women undergoing labor induction at term.

Details of the study

The IMPROVE trial was a prospective, randomized, noninferiority, triple-masked, placebo-controlled trial of 300 women with a singleton vertex fetus requiring cervical ripening for induction of labor at term.2 Enrolled women were randomly assigned to VM or BM (same dosing regimen) and to a matching placebo administered via the opposite route.

Primary outcomes included time-to-vaginal-delivery from first dose, which was reduced in VM vs BM (20.1 vs 28.1 hours; P = .006), and urgent cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal testing, which was similarly reduced in VM (3.3% vs 9.5%; P = .33). These differences persisted after controlling for covariates. There was also a greater difference seen in multiparous versus nulliparous women.

Secondary outcomes also favored VM over BM, including more vaginal deliverieswithin 24 hours, fewer doses to achieve active labor, and a lower maximum dose of oxytocin.

Overall cesarean delivery rates were similar in the 2 groups (VM, 15.8%; BM, 22.3%; P = .15). There were no significant differences in other delivery characteristics or in maternal or fetal adverse events.

While a number of studies have evaluated the risk of cesarean delivery (CD) with the use of cervical ripening agents by different routes of administration, Handal-Orefice and colleagues studied this outcome specifically in a predominantly overweight population at a tertiary care center.1

The retrospective study included 276 women, of whom 91% had a body mass index (BMI) of 25 kg/m2 or more and 61% had a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or more at the time of delivery.

For cervical ripening, 138 women received vaginal misoprostol (25 µg) and 138 received oral misoprostol (50 µg). The frequency of CD (the primary study outcome) was significantly higher with oral compared with vaginal misoprostol use (32% vs 21%; P = .04). When the analysis was adjusted for age, BMI, parity, indication for induction, and Foley catheter use, the risk of CD remained significantly higher for the oral misoprostol group (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.01; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.07-3.76).

Other key findings:

- frequency of CD among nulliparous women: 41% in the oral misoprostol group, 28% in the vaginal misoprostol group (aOR, 2.79; 95% CI, 1.26-6.19)

- time to vaginal delivery: 41 hours for the oral misoprostol group, 31 hours for the vaginal misoprostol group (P = .01)

- uterine tachysystole: 11% in the oral misoprostol group, 20% in the vaginal misoprostol group (P = .04).

The authors noted that the strengths of the study, including the racial and ethnic diversity of the population (72% of women were of either black or Hispanic race or ethnicity), the commonly used doses of misoprostol, and the performance of inductions outside a research protocol, add to the generalizability of the results.

Reference

1. Handal-Orefice R, Friedman AM, Chouinard SM, et al. Oral or vaginal misoprostol for labor induction and cesarean delivery risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003274.

Continue to: Study strengths and limitations...

Study strengths and limitations

The IMPROVE trial had a triple-blinded study design with an intention-to-treat paradigm and good follow-up. There was also standardization of PGE1 administration criteria, which was consistent with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists standards of care. Results were similar to those of prior studies regarding rates of tachysystole, urgent cesarean delivery, and vaginal delivery.

The study has good generalizability as it included both elective and medically indicated inductions; however, patients with ruptured membranes were excluded. Although there was no difference in the overall cesarean delivery rates, the study was underpowered to look at this outcome. The authors included a patient satisfaction survey, but this is hard to interpret since study participants all received tablets orally and vaginally. The study did not address efficacy of VM versus BM administration at different doses or time intervals.

Labor induction has doubled over the past 2 decades, with almost 25% of parturients currently undergoing induction in the United States.3 This number is likely to increase given recent data suggesting that routine induction at 39 weeks may significantly decrease cesarean delivery rates.4 It is critical, therefore, that we identify the optimal technique for cervical ripening, including the ideal dosing regimen and route of administration. Results of the IMPROVE trial suggest that vaginal administration of misoprostol (25 μg initial dose, 50 μg subsequent doses) may be superior to the buccal route, with more rapid vaginal delivery, more vaginal deliveries within 24 hours, and fewer urgent cesareans for nonreassuring fetal testing (although the overall cesarean delivery rate was not significantly different).

ERROL R. NORWITZ, MD, PHD, MBA; JULIE M. STONE, MD

Haas DM, Daggy J, Flannery KM, et al. A comparison of vaginal versus buccal misoprostol for cervical ripening in women for labor induction at term (the IMPROVE trial): a triple masked randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.04.037.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Cervical ripening is routine practice in women undergoing induction of labor who have an unfavorable cervical examination.1 This is because generating contractions against a long thick cervix is more likely to lead to failed induction and cesarean delivery. Cervical ripening can be achieved using mechanical or pharmacologic methods.

Misoprostol (a prostaglandin E1 [PGE1] analog) is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of peptic ulcer disease, but it also is widely used off-label for cervical ripening, partly due to its low cost. Misoprostol’s optimal dosing regimen and route of administration are not known. The IMPROVE trial was designed to address this knowledge gap, specifically to compare the efficacy and safety of VM versus BM in women undergoing labor induction at term.

Details of the study

The IMPROVE trial was a prospective, randomized, noninferiority, triple-masked, placebo-controlled trial of 300 women with a singleton vertex fetus requiring cervical ripening for induction of labor at term.2 Enrolled women were randomly assigned to VM or BM (same dosing regimen) and to a matching placebo administered via the opposite route.

Primary outcomes included time-to-vaginal-delivery from first dose, which was reduced in VM vs BM (20.1 vs 28.1 hours; P = .006), and urgent cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal testing, which was similarly reduced in VM (3.3% vs 9.5%; P = .33). These differences persisted after controlling for covariates. There was also a greater difference seen in multiparous versus nulliparous women.

Secondary outcomes also favored VM over BM, including more vaginal deliverieswithin 24 hours, fewer doses to achieve active labor, and a lower maximum dose of oxytocin.

Overall cesarean delivery rates were similar in the 2 groups (VM, 15.8%; BM, 22.3%; P = .15). There were no significant differences in other delivery characteristics or in maternal or fetal adverse events.

While a number of studies have evaluated the risk of cesarean delivery (CD) with the use of cervical ripening agents by different routes of administration, Handal-Orefice and colleagues studied this outcome specifically in a predominantly overweight population at a tertiary care center.1

The retrospective study included 276 women, of whom 91% had a body mass index (BMI) of 25 kg/m2 or more and 61% had a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or more at the time of delivery.

For cervical ripening, 138 women received vaginal misoprostol (25 µg) and 138 received oral misoprostol (50 µg). The frequency of CD (the primary study outcome) was significantly higher with oral compared with vaginal misoprostol use (32% vs 21%; P = .04). When the analysis was adjusted for age, BMI, parity, indication for induction, and Foley catheter use, the risk of CD remained significantly higher for the oral misoprostol group (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.01; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.07-3.76).

Other key findings:

- frequency of CD among nulliparous women: 41% in the oral misoprostol group, 28% in the vaginal misoprostol group (aOR, 2.79; 95% CI, 1.26-6.19)

- time to vaginal delivery: 41 hours for the oral misoprostol group, 31 hours for the vaginal misoprostol group (P = .01)

- uterine tachysystole: 11% in the oral misoprostol group, 20% in the vaginal misoprostol group (P = .04).

The authors noted that the strengths of the study, including the racial and ethnic diversity of the population (72% of women were of either black or Hispanic race or ethnicity), the commonly used doses of misoprostol, and the performance of inductions outside a research protocol, add to the generalizability of the results.

Reference

1. Handal-Orefice R, Friedman AM, Chouinard SM, et al. Oral or vaginal misoprostol for labor induction and cesarean delivery risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003274.

Continue to: Study strengths and limitations...

Study strengths and limitations

The IMPROVE trial had a triple-blinded study design with an intention-to-treat paradigm and good follow-up. There was also standardization of PGE1 administration criteria, which was consistent with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists standards of care. Results were similar to those of prior studies regarding rates of tachysystole, urgent cesarean delivery, and vaginal delivery.

The study has good generalizability as it included both elective and medically indicated inductions; however, patients with ruptured membranes were excluded. Although there was no difference in the overall cesarean delivery rates, the study was underpowered to look at this outcome. The authors included a patient satisfaction survey, but this is hard to interpret since study participants all received tablets orally and vaginally. The study did not address efficacy of VM versus BM administration at different doses or time intervals.

Labor induction has doubled over the past 2 decades, with almost 25% of parturients currently undergoing induction in the United States.3 This number is likely to increase given recent data suggesting that routine induction at 39 weeks may significantly decrease cesarean delivery rates.4 It is critical, therefore, that we identify the optimal technique for cervical ripening, including the ideal dosing regimen and route of administration. Results of the IMPROVE trial suggest that vaginal administration of misoprostol (25 μg initial dose, 50 μg subsequent doses) may be superior to the buccal route, with more rapid vaginal delivery, more vaginal deliveries within 24 hours, and fewer urgent cesareans for nonreassuring fetal testing (although the overall cesarean delivery rate was not significantly different).

ERROL R. NORWITZ, MD, PHD, MBA; JULIE M. STONE, MD

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 107. Induction of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(2 pt 1):386-397.

- Haas DM, Daggy J, Flannery KM, et al. A comparison of vaginal versus buccal misoprostol for cervical ripening in women for labor induction at term (the IMPROVE trial): a triple masked randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.04.037.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman M, et al. Births: final data for 2016. Nat Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67:1-55.

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal–Fetal Medicine Units Network. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 107. Induction of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(2 pt 1):386-397.

- Haas DM, Daggy J, Flannery KM, et al. A comparison of vaginal versus buccal misoprostol for cervical ripening in women for labor induction at term (the IMPROVE trial): a triple masked randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.04.037.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman M, et al. Births: final data for 2016. Nat Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67:1-55.

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal–Fetal Medicine Units Network. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

Adjustment for characteristics not used by Medicare reduces hospital variations in readmission rates

Clinical question: Can differences in hospital readmission rates be explained by patient characteristics not accounted for by Medicare?

Background: In its Pay for Performance program, Medicare ties payments to readmission rates but adjusts these rates only for limited patient characteristics. Hospitals serving higher-risk patients have received greater penalties. These programs may have the unintended consequence of penalizing hospitals that provide care to higher-risk patients.

Study design: Observational study.

Setting: Medicare admissions claims from 2013 through 2014 in 2,215 hospitals.

Synopsis: Using Medicare claims for admission and linked U.S. census data, the study assessed several clinical and social characteristics not currently used for risk adjustment. A sample of 1,169,014 index admissions among 1,003,664 unique beneficiaries was analyzed. The study compared rates with and without these additional adjustments.

Additional adjustments reduced overall variation in hospital readmission by 9.6%, changed rates upward or downward by 0.4%-0.7% for the 10% of hospitals most affected by the readjustments, and they would be expected to reduce penalties by 52%, 46%, and 41% for hospitals with the largest 1%, 5%, and 10% of penalty reductions, respectively.

Bottom line: Hospitals serving higher-risk patients may be penalized because of the patients they serve rather that the quality of care they provide.

Citation: Roberts ET et al. Assessment of the effect of adjustment for patient characteristics on hospital readmission rates: Implications for Pay for Performance. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11)1498-1507.

Dr. Asuen is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: Can differences in hospital readmission rates be explained by patient characteristics not accounted for by Medicare?

Background: In its Pay for Performance program, Medicare ties payments to readmission rates but adjusts these rates only for limited patient characteristics. Hospitals serving higher-risk patients have received greater penalties. These programs may have the unintended consequence of penalizing hospitals that provide care to higher-risk patients.

Study design: Observational study.

Setting: Medicare admissions claims from 2013 through 2014 in 2,215 hospitals.

Synopsis: Using Medicare claims for admission and linked U.S. census data, the study assessed several clinical and social characteristics not currently used for risk adjustment. A sample of 1,169,014 index admissions among 1,003,664 unique beneficiaries was analyzed. The study compared rates with and without these additional adjustments.

Additional adjustments reduced overall variation in hospital readmission by 9.6%, changed rates upward or downward by 0.4%-0.7% for the 10% of hospitals most affected by the readjustments, and they would be expected to reduce penalties by 52%, 46%, and 41% for hospitals with the largest 1%, 5%, and 10% of penalty reductions, respectively.

Bottom line: Hospitals serving higher-risk patients may be penalized because of the patients they serve rather that the quality of care they provide.

Citation: Roberts ET et al. Assessment of the effect of adjustment for patient characteristics on hospital readmission rates: Implications for Pay for Performance. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11)1498-1507.

Dr. Asuen is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: Can differences in hospital readmission rates be explained by patient characteristics not accounted for by Medicare?

Background: In its Pay for Performance program, Medicare ties payments to readmission rates but adjusts these rates only for limited patient characteristics. Hospitals serving higher-risk patients have received greater penalties. These programs may have the unintended consequence of penalizing hospitals that provide care to higher-risk patients.

Study design: Observational study.

Setting: Medicare admissions claims from 2013 through 2014 in 2,215 hospitals.

Synopsis: Using Medicare claims for admission and linked U.S. census data, the study assessed several clinical and social characteristics not currently used for risk adjustment. A sample of 1,169,014 index admissions among 1,003,664 unique beneficiaries was analyzed. The study compared rates with and without these additional adjustments.

Additional adjustments reduced overall variation in hospital readmission by 9.6%, changed rates upward or downward by 0.4%-0.7% for the 10% of hospitals most affected by the readjustments, and they would be expected to reduce penalties by 52%, 46%, and 41% for hospitals with the largest 1%, 5%, and 10% of penalty reductions, respectively.

Bottom line: Hospitals serving higher-risk patients may be penalized because of the patients they serve rather that the quality of care they provide.

Citation: Roberts ET et al. Assessment of the effect of adjustment for patient characteristics on hospital readmission rates: Implications for Pay for Performance. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11)1498-1507.

Dr. Asuen is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

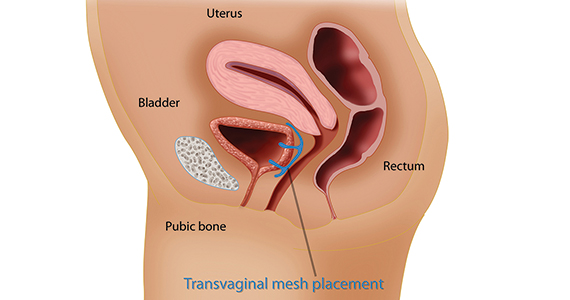

Uterus-sparing interventions to treat postpartum hemorrhage during cesarean delivery surgery

Postpartum blood loss greater than 1,000 mL occurs in approximately 7% of cesarean delivery (CD) procedures with the administration of oxytocin alone or oxytocin plus misoprostol.1 Rapid identification and control of hemorrhage is essential to avoid escalating coagulopathy and maternal instability. In cases of excess blood loss, clinicians request assistance from colleagues, endeavor to identify the cause of the bleeding, utilize additional uterotonics (methylergonovine, carboprost, misoprostol), perform uterine massage, warm the uterus, repair lacerations and replace blood products. If blood loss continues after these initial measures, obstetricians may consider uterine artery embolization (UAE) or hysterectomy. While UAE is a highly effective measure to control postpartum hemorrhage, it is not available at all obstetric hospitals. Even when available, there may be a significant time delay from the decision to consult an interventional radiologist to completion of the embolization procedure.

To avoid the permanent sterilization of a hysterectomy, or to obtain time for UAE or correction of coagulopathy, additional uterus-sparing surgical interventions should be considered. These include: 1) progressive uterine devascularization, 2) uterine compression sutures, and 3) intrauterine balloon tamponade. One caveat is that there is very little high-quality evidence from randomized trials to compare the efficacy or outcome of these uterine-sparing surgical interventions. Most of our evidence is based on limited case series and expert recommendations.

Uterine devascularization

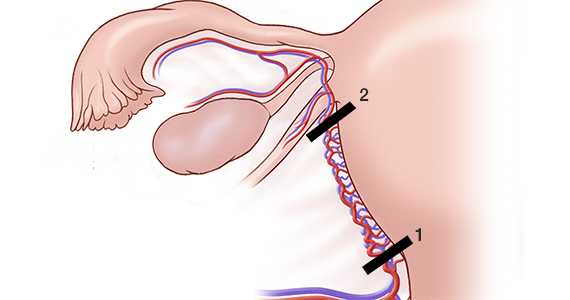

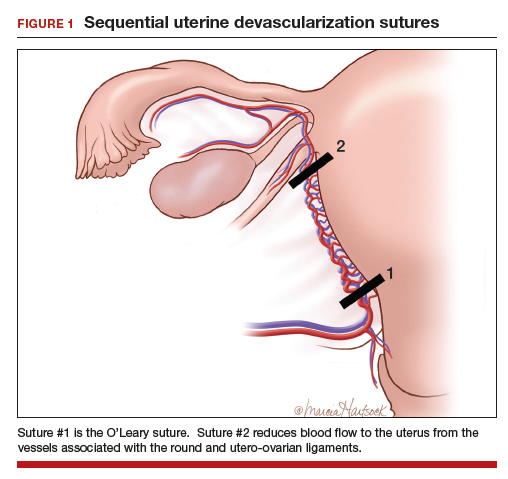

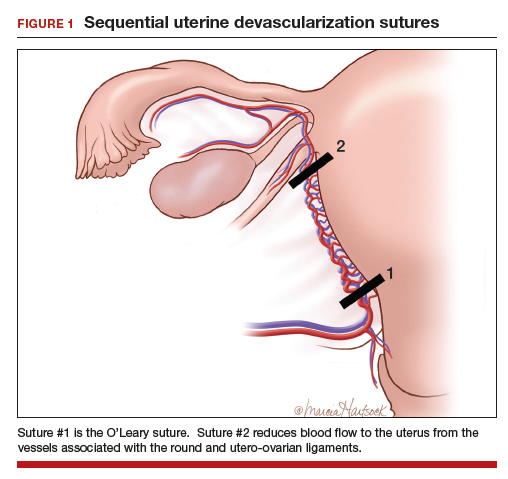

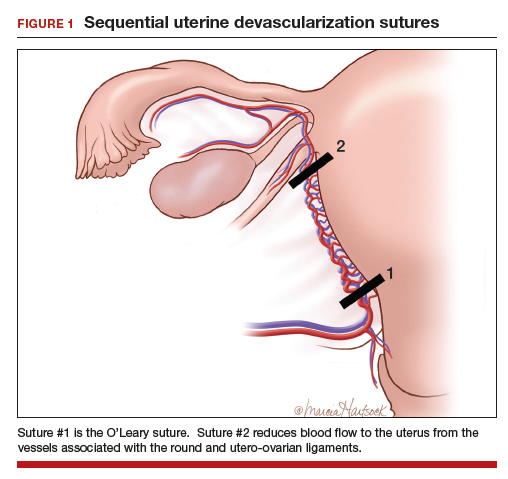

Many techniques have been described for performing progressive uterine devascularization. Most experts recommend first performing an O’Leary suture, ligating both ascending uterine arteries and accompanying veins at a point approximately 2 cm closer to the cervix than the uterine incision (FIGURE 1). An absorbable suture is passed through the myometrium, being sure to remain medial to the ascending uterine vessels. Clear visualization of the vessels posteriorly is essential, usually necessitating exteriorization of the uterus. The needle is then driven through an avascular space in the broad ligament close to the uterine vessels, and the suture is tied down. Ureteral injury can be avoided by extending the bladder flap laterally to the level of the round ligament and mobilizing the vesicouterine peritoneum inferiorly, with the suture placed directly on endopelvic fascia. If necessary, the utero-ovarian ligament can be ligated in a second step, just below the uterine-tubal junction. The progressive devascularization intervention can be limited to the first or second steps if bleeding is well controlled.

In our experience, bilateral O’Leary sutures are highly effective at controlling ongoing uterine bleeding, particularly from the lower uterine segment. In the event that they are not successful, placement does not preclude later use of UAE.

Uterine compression sutures

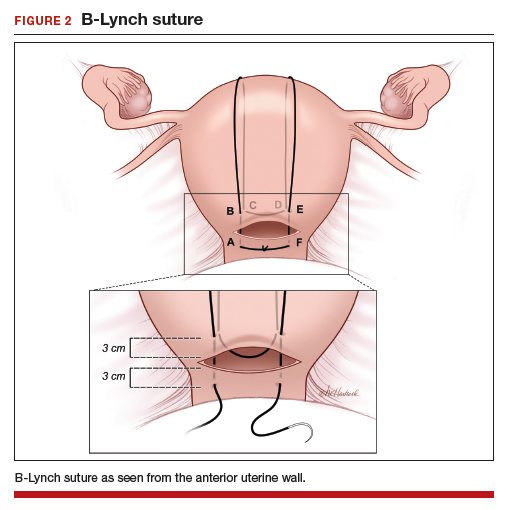

Compression sutures are most often used in the setting of refractory uterine atony. They also may be helpful for controlling focal atony or bleeding from a placental implantation site. More than a dozen different types of uterine compression sutures have been reported in the literature; the B-Lynch, Hyman, and Pereira sutures are most commonly performed.2

Continue to: The B-Lynch suture3 is performed with...

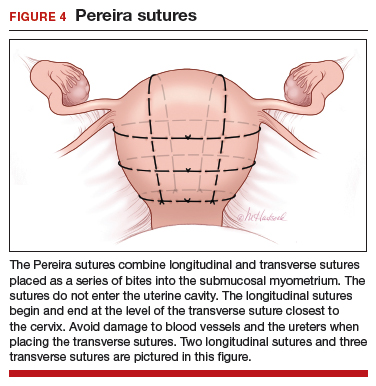

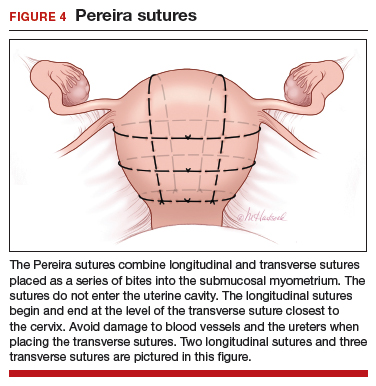

The B-Lynch suture3 is performed with a long, rapidly absorbable suture on a large needle (FIGURE 2). We use a 60-inch #1 or #2 chromic suture on a TP-1 needle in the following steps:

- Take bites on either side of the right edge of the hysterotomy incision (A and B). Place these bites approximately 3 cm from the edge of the hysterotomy incision.

- Loop the suture around the fundus and reenter the uterus through the posterior uterine wall at point C, which is directly posterior to point B.

- Exit the posterior wall of the uterus through point D.

- Loop the suture over the uterine fundus.

- Anchor the suture in the lower uterine segment by taking bites on either side of the left edge of the uterine hysterotomy incision (points E and F).

- Pull the two ends of the suture tight while an assistant squeezes the uterus to aid compression.

- Place a surgical knot to secure the suture.

- Close the hysterotomy incision.

The B-Lynch suture was described with an open hysterotomy incision,3 which avoids closing off the lower uterine segment. We have successfully performed a modific tion on a closed uterus, taking care to not drive the lower uterine sutures through both the anterior and posterior walls.

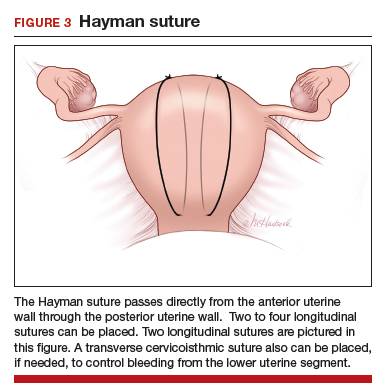

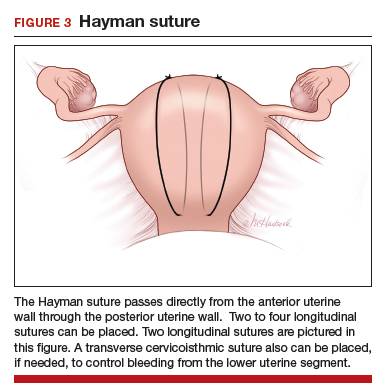

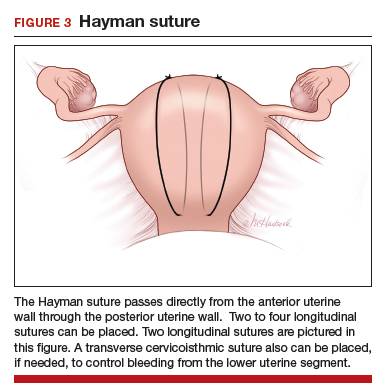

The Hayman suture4 was proposed with two important modifications: The suture is placed through-and-through the lower uterine segment with a closed hysterotomy, and the suture can be fixed to the uterine fundus to avoid slippage. This vertical compression suture (FIGURE 3) is performed by placing two to four vertical #2 chromic sutures directly through the anterior to posterior uterine wall, tying the suture on the fundus using a 3-throw technique to minimize slippage of the first knot. In the original description, Hayman also described injecting carboprost into the uterine fundus to stimulate uterine contraction and regularly inspecting the vagina to evaluate the extent of continued bleeding.4

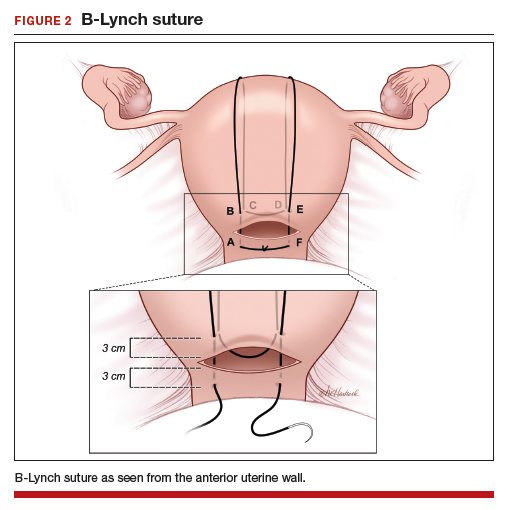

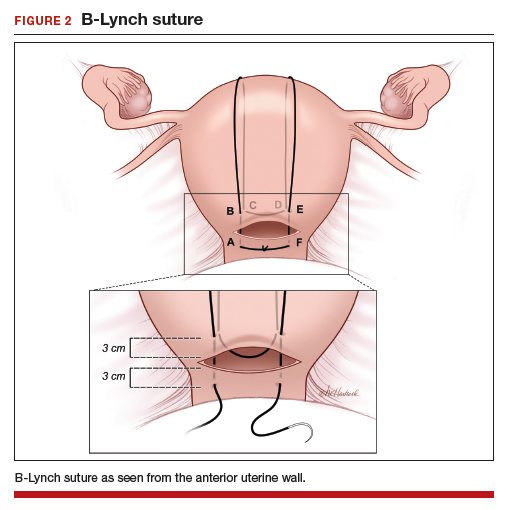

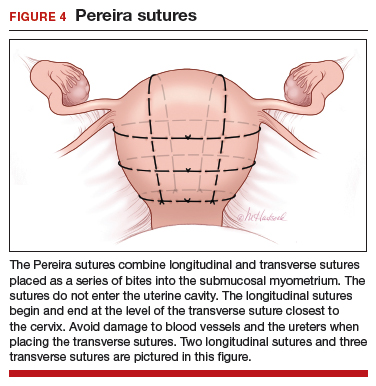

The Pereira sutures,5 also described on a closed uterus, combine vertical and horizontal sutures placed as a series of bites into the submucosal myometrium using #1 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) sutures (FIGURE 4). The sutures do not enter the uterine cavity. Two to three transverse sutures are initially placed followed by two vertical sutures. When placing the transverse sutures, it is important to cross the broad ligament in an avascular area and avoid trauma to blood vessels, ureters, gonadal vessels and fallopian tubes. The vertical sutures begin and end at the level of the transverse suture closest to the cervix.

Intrauterine balloon tamponade

Many types of balloon tamponade devices have been developed, ranging from the humble condom tied to a Foley urinary catheter to the sophisticated Bakri6,7 and Belfort-Dildy8 balloon tamponade devices. Intrauterine balloon tamponade is highly effective in controlling excess bleeding following vaginal delivery and less effective when used following a CD. In one study of 226 women with postpartum hemorrhage treated with a Bakri balloon the success rate was 89% and 66% following vaginal delivery and CD, respectively.9

Continue to: When using balloon tamponade during a CD...

When using balloon tamponade during a CD, some experts recommend partially closing the transverse hysterotomy incision by placing sutures to close edges of the hysterotomy, followed by insertion of the balloon into the uterus and the stem through the cervix into the vagina. Attachment of the stem to a collection bag should help to quickly assess the rate of blood loss. The balloon is inflated after the hysterotomy is closed. Following inflation of an intrauterine balloon, blood loss should decrease almost immediately.10 If excessive blood loss continues for more than 10 minutes, additional uterus-sparing interventions or hysterectomy may be required. Following successful balloon tamponade, the balloon may be deflated 12 to 24 hours postpartum when maternal stabilization and normal coagulation have been achieved. If bleeding resumes, the balloon may be reinflated and UAE should be considered.

Combined interventions: Uterine devascularization plus uterine compression sutures

There are no high-quality randomized trials comparing the devascularization plus compression sutures versus a single intervention alone, and case series and case reports on this topic are lacking. If uterine devascularization alone does not sufficiently control bleeding, adding a uterine compression stitch might resolve the hemorrhage. Both procedures require only suture material, which is immediately available in all operating rooms. Hence, this combination of interventions can be executed quickly.

Uterine sandwich: Intrauterine balloon tamponade plus uterine compression sutures

CD for placenta previa is associated with an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage, with bleeding from the lower uterine segment greatly contributing to total blood loss. While O’Leary sutures can stem the flow of bleeding in this area, the use of both an intrauterine balloon tamponade plus uterine compression sutures—a so-called uterine sandwich—may result in maximal reduction in blood loss.11,12

In one randomized trial, 106 women undergoing CD for a placenta previa were randomly assigned to uterine devascularization alone or double transverse compression suture at the lower uterine segment plus intrauterine Foley catheter balloon. Compared with women receiving devascularization alone, the combination of compression suture plus intrauterine balloon significantly reduced blood loss (1,350 mL vs 750 mL, respectively; P = .0001).13

Underutilization of uterine-sparing interventions

In a nationwide study of 50 consecutive Danish peripartum hysterectomy cases, an audit committee concluded that 24% of the hysterectomies could have been avoided, and an additional 30% of hysterectomies might have been avoided, if uterine-sparing surgical interventions had been utilized.14 In a recent survey of senior ObGyn residents in France, greater than 70% of respondents reported that they had not mastered uterine-sparing techniques of uterine devascularization and compression sutures, nor peripartum hysterectomy.15 Together, these studies suggest that uterine-sparing interventions are underutilized and that with more training and practice clinicians would become facile with these interventions.

The cornerstones of uterine-sparing surgical interventions are simplicity, safety, and efficacy. If a combination of pharmacologic and multiple uterine-sparing surgical interventions do not control the bleeding, the patient may need an emergency hysterectomy or, if stable, a UAE. While devascularization and compression sutures are described during CD, it is reasonable to use them after vaginal delivery if the next reasonable step would be a laparotomy. When you next face the clinical challenge of a postpartum hemorrhage, rapid recognition of excess blood loss, early identification of the cause, swift pharmacologic treatment, and timely escalation of surgical interventions will help you reduce the risk of hysterectomy and severe maternal morbidity.

- Gallos ID, Papadopoulou A, Man R, et al. Uterotonic agents for preventing postpartum haemorrhage: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2018;12:CD011689.

- Li GT, Li XF, Wu BP, et al. Three cornerstones of uterine compression sutures: simplicity, safety, and efficacy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;292:949-952.

- B-Lynch C, Coker A, Lawal AH, et al. The B-Lynch surgical technique for the control of massive postpartum hemorrhage: an alternative to hysterectomy? Five cases reported. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:372-375.

- Hayman RG, Arulkumaran S, Steer PJ. Uterine compression sutures: surgical management of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:502-506.

- Pereira A, Nunes F, Pedroso S, et al. Compressive sutures to treat postpartum bleeding secondary to uterine atony. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:569-572.

- Bakri YN. Uterine tamponade-drain for hemorrhage secondary to placenta previa-accreta. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1992;37:302-303.

- Bakri YN, Amri A, Abdul Jabbar F. Tamponade-balloon for obstetrical bleeding. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;74:139-142.

- Dildy GA, Belfort MA, Adair CD, et al; ebb Surveillance Study Team. Initial experience with a dual-balloon catheter for the management of postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:136.e1-e6.

- Revert M, Cottenet J, Raynal P, et al. Intrauterine balloon tamponade for management of severe postpartum hemorrhage in a perinatal network: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2017;124:1255-1262.

- Condous GS, Arulkumaran S, Symonds I, et al. The “tamponade test” in the management of massive postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:767-772.

- Nelson WL, O’Brien JM. The uterine sandwich for persistent uterine atony: combining the B-Lynch compression suture and an intrauterine Bakri balloon. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:e9-e10.

- Matsubara S, Kuwata T, Baba Y, et al. A novel “uterine sandwich” for haemorrhage at cesarean section for placenta praevia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;54:283-286.

- Sallam HF, Shady NW. A sandwich technique (N&H variation technique) to reduce blood loss during cesarean delivery for complete placenta previa: a randomized controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018:1-8.

- Colmorn LB, Krebs L, Langhoff-Roos J; NOSS study group. Potentially avoidable peripartum hysterectomies in Denmark: a population based clinical audit. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161302.

- Bouet PE, Madar H, Froeliger A, et al. Surgical treatment of postpartum haemorrhage: national survey of French residents in obstetrics and gynecology. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:91.

Postpartum blood loss greater than 1,000 mL occurs in approximately 7% of cesarean delivery (CD) procedures with the administration of oxytocin alone or oxytocin plus misoprostol.1 Rapid identification and control of hemorrhage is essential to avoid escalating coagulopathy and maternal instability. In cases of excess blood loss, clinicians request assistance from colleagues, endeavor to identify the cause of the bleeding, utilize additional uterotonics (methylergonovine, carboprost, misoprostol), perform uterine massage, warm the uterus, repair lacerations and replace blood products. If blood loss continues after these initial measures, obstetricians may consider uterine artery embolization (UAE) or hysterectomy. While UAE is a highly effective measure to control postpartum hemorrhage, it is not available at all obstetric hospitals. Even when available, there may be a significant time delay from the decision to consult an interventional radiologist to completion of the embolization procedure.

To avoid the permanent sterilization of a hysterectomy, or to obtain time for UAE or correction of coagulopathy, additional uterus-sparing surgical interventions should be considered. These include: 1) progressive uterine devascularization, 2) uterine compression sutures, and 3) intrauterine balloon tamponade. One caveat is that there is very little high-quality evidence from randomized trials to compare the efficacy or outcome of these uterine-sparing surgical interventions. Most of our evidence is based on limited case series and expert recommendations.

Uterine devascularization

Many techniques have been described for performing progressive uterine devascularization. Most experts recommend first performing an O’Leary suture, ligating both ascending uterine arteries and accompanying veins at a point approximately 2 cm closer to the cervix than the uterine incision (FIGURE 1). An absorbable suture is passed through the myometrium, being sure to remain medial to the ascending uterine vessels. Clear visualization of the vessels posteriorly is essential, usually necessitating exteriorization of the uterus. The needle is then driven through an avascular space in the broad ligament close to the uterine vessels, and the suture is tied down. Ureteral injury can be avoided by extending the bladder flap laterally to the level of the round ligament and mobilizing the vesicouterine peritoneum inferiorly, with the suture placed directly on endopelvic fascia. If necessary, the utero-ovarian ligament can be ligated in a second step, just below the uterine-tubal junction. The progressive devascularization intervention can be limited to the first or second steps if bleeding is well controlled.

In our experience, bilateral O’Leary sutures are highly effective at controlling ongoing uterine bleeding, particularly from the lower uterine segment. In the event that they are not successful, placement does not preclude later use of UAE.

Uterine compression sutures

Compression sutures are most often used in the setting of refractory uterine atony. They also may be helpful for controlling focal atony or bleeding from a placental implantation site. More than a dozen different types of uterine compression sutures have been reported in the literature; the B-Lynch, Hyman, and Pereira sutures are most commonly performed.2

Continue to: The B-Lynch suture3 is performed with...

The B-Lynch suture3 is performed with a long, rapidly absorbable suture on a large needle (FIGURE 2). We use a 60-inch #1 or #2 chromic suture on a TP-1 needle in the following steps:

- Take bites on either side of the right edge of the hysterotomy incision (A and B). Place these bites approximately 3 cm from the edge of the hysterotomy incision.

- Loop the suture around the fundus and reenter the uterus through the posterior uterine wall at point C, which is directly posterior to point B.

- Exit the posterior wall of the uterus through point D.

- Loop the suture over the uterine fundus.

- Anchor the suture in the lower uterine segment by taking bites on either side of the left edge of the uterine hysterotomy incision (points E and F).

- Pull the two ends of the suture tight while an assistant squeezes the uterus to aid compression.

- Place a surgical knot to secure the suture.

- Close the hysterotomy incision.

The B-Lynch suture was described with an open hysterotomy incision,3 which avoids closing off the lower uterine segment. We have successfully performed a modific tion on a closed uterus, taking care to not drive the lower uterine sutures through both the anterior and posterior walls.

The Hayman suture4 was proposed with two important modifications: The suture is placed through-and-through the lower uterine segment with a closed hysterotomy, and the suture can be fixed to the uterine fundus to avoid slippage. This vertical compression suture (FIGURE 3) is performed by placing two to four vertical #2 chromic sutures directly through the anterior to posterior uterine wall, tying the suture on the fundus using a 3-throw technique to minimize slippage of the first knot. In the original description, Hayman also described injecting carboprost into the uterine fundus to stimulate uterine contraction and regularly inspecting the vagina to evaluate the extent of continued bleeding.4

The Pereira sutures,5 also described on a closed uterus, combine vertical and horizontal sutures placed as a series of bites into the submucosal myometrium using #1 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) sutures (FIGURE 4). The sutures do not enter the uterine cavity. Two to three transverse sutures are initially placed followed by two vertical sutures. When placing the transverse sutures, it is important to cross the broad ligament in an avascular area and avoid trauma to blood vessels, ureters, gonadal vessels and fallopian tubes. The vertical sutures begin and end at the level of the transverse suture closest to the cervix.

Intrauterine balloon tamponade

Many types of balloon tamponade devices have been developed, ranging from the humble condom tied to a Foley urinary catheter to the sophisticated Bakri6,7 and Belfort-Dildy8 balloon tamponade devices. Intrauterine balloon tamponade is highly effective in controlling excess bleeding following vaginal delivery and less effective when used following a CD. In one study of 226 women with postpartum hemorrhage treated with a Bakri balloon the success rate was 89% and 66% following vaginal delivery and CD, respectively.9

Continue to: When using balloon tamponade during a CD...

When using balloon tamponade during a CD, some experts recommend partially closing the transverse hysterotomy incision by placing sutures to close edges of the hysterotomy, followed by insertion of the balloon into the uterus and the stem through the cervix into the vagina. Attachment of the stem to a collection bag should help to quickly assess the rate of blood loss. The balloon is inflated after the hysterotomy is closed. Following inflation of an intrauterine balloon, blood loss should decrease almost immediately.10 If excessive blood loss continues for more than 10 minutes, additional uterus-sparing interventions or hysterectomy may be required. Following successful balloon tamponade, the balloon may be deflated 12 to 24 hours postpartum when maternal stabilization and normal coagulation have been achieved. If bleeding resumes, the balloon may be reinflated and UAE should be considered.

Combined interventions: Uterine devascularization plus uterine compression sutures

There are no high-quality randomized trials comparing the devascularization plus compression sutures versus a single intervention alone, and case series and case reports on this topic are lacking. If uterine devascularization alone does not sufficiently control bleeding, adding a uterine compression stitch might resolve the hemorrhage. Both procedures require only suture material, which is immediately available in all operating rooms. Hence, this combination of interventions can be executed quickly.

Uterine sandwich: Intrauterine balloon tamponade plus uterine compression sutures

CD for placenta previa is associated with an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage, with bleeding from the lower uterine segment greatly contributing to total blood loss. While O’Leary sutures can stem the flow of bleeding in this area, the use of both an intrauterine balloon tamponade plus uterine compression sutures—a so-called uterine sandwich—may result in maximal reduction in blood loss.11,12

In one randomized trial, 106 women undergoing CD for a placenta previa were randomly assigned to uterine devascularization alone or double transverse compression suture at the lower uterine segment plus intrauterine Foley catheter balloon. Compared with women receiving devascularization alone, the combination of compression suture plus intrauterine balloon significantly reduced blood loss (1,350 mL vs 750 mL, respectively; P = .0001).13

Underutilization of uterine-sparing interventions

In a nationwide study of 50 consecutive Danish peripartum hysterectomy cases, an audit committee concluded that 24% of the hysterectomies could have been avoided, and an additional 30% of hysterectomies might have been avoided, if uterine-sparing surgical interventions had been utilized.14 In a recent survey of senior ObGyn residents in France, greater than 70% of respondents reported that they had not mastered uterine-sparing techniques of uterine devascularization and compression sutures, nor peripartum hysterectomy.15 Together, these studies suggest that uterine-sparing interventions are underutilized and that with more training and practice clinicians would become facile with these interventions.

The cornerstones of uterine-sparing surgical interventions are simplicity, safety, and efficacy. If a combination of pharmacologic and multiple uterine-sparing surgical interventions do not control the bleeding, the patient may need an emergency hysterectomy or, if stable, a UAE. While devascularization and compression sutures are described during CD, it is reasonable to use them after vaginal delivery if the next reasonable step would be a laparotomy. When you next face the clinical challenge of a postpartum hemorrhage, rapid recognition of excess blood loss, early identification of the cause, swift pharmacologic treatment, and timely escalation of surgical interventions will help you reduce the risk of hysterectomy and severe maternal morbidity.

Postpartum blood loss greater than 1,000 mL occurs in approximately 7% of cesarean delivery (CD) procedures with the administration of oxytocin alone or oxytocin plus misoprostol.1 Rapid identification and control of hemorrhage is essential to avoid escalating coagulopathy and maternal instability. In cases of excess blood loss, clinicians request assistance from colleagues, endeavor to identify the cause of the bleeding, utilize additional uterotonics (methylergonovine, carboprost, misoprostol), perform uterine massage, warm the uterus, repair lacerations and replace blood products. If blood loss continues after these initial measures, obstetricians may consider uterine artery embolization (UAE) or hysterectomy. While UAE is a highly effective measure to control postpartum hemorrhage, it is not available at all obstetric hospitals. Even when available, there may be a significant time delay from the decision to consult an interventional radiologist to completion of the embolization procedure.

To avoid the permanent sterilization of a hysterectomy, or to obtain time for UAE or correction of coagulopathy, additional uterus-sparing surgical interventions should be considered. These include: 1) progressive uterine devascularization, 2) uterine compression sutures, and 3) intrauterine balloon tamponade. One caveat is that there is very little high-quality evidence from randomized trials to compare the efficacy or outcome of these uterine-sparing surgical interventions. Most of our evidence is based on limited case series and expert recommendations.

Uterine devascularization

Many techniques have been described for performing progressive uterine devascularization. Most experts recommend first performing an O’Leary suture, ligating both ascending uterine arteries and accompanying veins at a point approximately 2 cm closer to the cervix than the uterine incision (FIGURE 1). An absorbable suture is passed through the myometrium, being sure to remain medial to the ascending uterine vessels. Clear visualization of the vessels posteriorly is essential, usually necessitating exteriorization of the uterus. The needle is then driven through an avascular space in the broad ligament close to the uterine vessels, and the suture is tied down. Ureteral injury can be avoided by extending the bladder flap laterally to the level of the round ligament and mobilizing the vesicouterine peritoneum inferiorly, with the suture placed directly on endopelvic fascia. If necessary, the utero-ovarian ligament can be ligated in a second step, just below the uterine-tubal junction. The progressive devascularization intervention can be limited to the first or second steps if bleeding is well controlled.

In our experience, bilateral O’Leary sutures are highly effective at controlling ongoing uterine bleeding, particularly from the lower uterine segment. In the event that they are not successful, placement does not preclude later use of UAE.

Uterine compression sutures

Compression sutures are most often used in the setting of refractory uterine atony. They also may be helpful for controlling focal atony or bleeding from a placental implantation site. More than a dozen different types of uterine compression sutures have been reported in the literature; the B-Lynch, Hyman, and Pereira sutures are most commonly performed.2

Continue to: The B-Lynch suture3 is performed with...

The B-Lynch suture3 is performed with a long, rapidly absorbable suture on a large needle (FIGURE 2). We use a 60-inch #1 or #2 chromic suture on a TP-1 needle in the following steps:

- Take bites on either side of the right edge of the hysterotomy incision (A and B). Place these bites approximately 3 cm from the edge of the hysterotomy incision.

- Loop the suture around the fundus and reenter the uterus through the posterior uterine wall at point C, which is directly posterior to point B.

- Exit the posterior wall of the uterus through point D.

- Loop the suture over the uterine fundus.

- Anchor the suture in the lower uterine segment by taking bites on either side of the left edge of the uterine hysterotomy incision (points E and F).

- Pull the two ends of the suture tight while an assistant squeezes the uterus to aid compression.

- Place a surgical knot to secure the suture.

- Close the hysterotomy incision.

The B-Lynch suture was described with an open hysterotomy incision,3 which avoids closing off the lower uterine segment. We have successfully performed a modific tion on a closed uterus, taking care to not drive the lower uterine sutures through both the anterior and posterior walls.

The Hayman suture4 was proposed with two important modifications: The suture is placed through-and-through the lower uterine segment with a closed hysterotomy, and the suture can be fixed to the uterine fundus to avoid slippage. This vertical compression suture (FIGURE 3) is performed by placing two to four vertical #2 chromic sutures directly through the anterior to posterior uterine wall, tying the suture on the fundus using a 3-throw technique to minimize slippage of the first knot. In the original description, Hayman also described injecting carboprost into the uterine fundus to stimulate uterine contraction and regularly inspecting the vagina to evaluate the extent of continued bleeding.4

The Pereira sutures,5 also described on a closed uterus, combine vertical and horizontal sutures placed as a series of bites into the submucosal myometrium using #1 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) sutures (FIGURE 4). The sutures do not enter the uterine cavity. Two to three transverse sutures are initially placed followed by two vertical sutures. When placing the transverse sutures, it is important to cross the broad ligament in an avascular area and avoid trauma to blood vessels, ureters, gonadal vessels and fallopian tubes. The vertical sutures begin and end at the level of the transverse suture closest to the cervix.

Intrauterine balloon tamponade

Many types of balloon tamponade devices have been developed, ranging from the humble condom tied to a Foley urinary catheter to the sophisticated Bakri6,7 and Belfort-Dildy8 balloon tamponade devices. Intrauterine balloon tamponade is highly effective in controlling excess bleeding following vaginal delivery and less effective when used following a CD. In one study of 226 women with postpartum hemorrhage treated with a Bakri balloon the success rate was 89% and 66% following vaginal delivery and CD, respectively.9

Continue to: When using balloon tamponade during a CD...

When using balloon tamponade during a CD, some experts recommend partially closing the transverse hysterotomy incision by placing sutures to close edges of the hysterotomy, followed by insertion of the balloon into the uterus and the stem through the cervix into the vagina. Attachment of the stem to a collection bag should help to quickly assess the rate of blood loss. The balloon is inflated after the hysterotomy is closed. Following inflation of an intrauterine balloon, blood loss should decrease almost immediately.10 If excessive blood loss continues for more than 10 minutes, additional uterus-sparing interventions or hysterectomy may be required. Following successful balloon tamponade, the balloon may be deflated 12 to 24 hours postpartum when maternal stabilization and normal coagulation have been achieved. If bleeding resumes, the balloon may be reinflated and UAE should be considered.

Combined interventions: Uterine devascularization plus uterine compression sutures

There are no high-quality randomized trials comparing the devascularization plus compression sutures versus a single intervention alone, and case series and case reports on this topic are lacking. If uterine devascularization alone does not sufficiently control bleeding, adding a uterine compression stitch might resolve the hemorrhage. Both procedures require only suture material, which is immediately available in all operating rooms. Hence, this combination of interventions can be executed quickly.

Uterine sandwich: Intrauterine balloon tamponade plus uterine compression sutures

CD for placenta previa is associated with an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage, with bleeding from the lower uterine segment greatly contributing to total blood loss. While O’Leary sutures can stem the flow of bleeding in this area, the use of both an intrauterine balloon tamponade plus uterine compression sutures—a so-called uterine sandwich—may result in maximal reduction in blood loss.11,12

In one randomized trial, 106 women undergoing CD for a placenta previa were randomly assigned to uterine devascularization alone or double transverse compression suture at the lower uterine segment plus intrauterine Foley catheter balloon. Compared with women receiving devascularization alone, the combination of compression suture plus intrauterine balloon significantly reduced blood loss (1,350 mL vs 750 mL, respectively; P = .0001).13

Underutilization of uterine-sparing interventions

In a nationwide study of 50 consecutive Danish peripartum hysterectomy cases, an audit committee concluded that 24% of the hysterectomies could have been avoided, and an additional 30% of hysterectomies might have been avoided, if uterine-sparing surgical interventions had been utilized.14 In a recent survey of senior ObGyn residents in France, greater than 70% of respondents reported that they had not mastered uterine-sparing techniques of uterine devascularization and compression sutures, nor peripartum hysterectomy.15 Together, these studies suggest that uterine-sparing interventions are underutilized and that with more training and practice clinicians would become facile with these interventions.

The cornerstones of uterine-sparing surgical interventions are simplicity, safety, and efficacy. If a combination of pharmacologic and multiple uterine-sparing surgical interventions do not control the bleeding, the patient may need an emergency hysterectomy or, if stable, a UAE. While devascularization and compression sutures are described during CD, it is reasonable to use them after vaginal delivery if the next reasonable step would be a laparotomy. When you next face the clinical challenge of a postpartum hemorrhage, rapid recognition of excess blood loss, early identification of the cause, swift pharmacologic treatment, and timely escalation of surgical interventions will help you reduce the risk of hysterectomy and severe maternal morbidity.

- Gallos ID, Papadopoulou A, Man R, et al. Uterotonic agents for preventing postpartum haemorrhage: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2018;12:CD011689.

- Li GT, Li XF, Wu BP, et al. Three cornerstones of uterine compression sutures: simplicity, safety, and efficacy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;292:949-952.

- B-Lynch C, Coker A, Lawal AH, et al. The B-Lynch surgical technique for the control of massive postpartum hemorrhage: an alternative to hysterectomy? Five cases reported. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:372-375.

- Hayman RG, Arulkumaran S, Steer PJ. Uterine compression sutures: surgical management of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:502-506.

- Pereira A, Nunes F, Pedroso S, et al. Compressive sutures to treat postpartum bleeding secondary to uterine atony. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:569-572.

- Bakri YN. Uterine tamponade-drain for hemorrhage secondary to placenta previa-accreta. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1992;37:302-303.

- Bakri YN, Amri A, Abdul Jabbar F. Tamponade-balloon for obstetrical bleeding. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;74:139-142.

- Dildy GA, Belfort MA, Adair CD, et al; ebb Surveillance Study Team. Initial experience with a dual-balloon catheter for the management of postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:136.e1-e6.

- Revert M, Cottenet J, Raynal P, et al. Intrauterine balloon tamponade for management of severe postpartum hemorrhage in a perinatal network: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2017;124:1255-1262.

- Condous GS, Arulkumaran S, Symonds I, et al. The “tamponade test” in the management of massive postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:767-772.

- Nelson WL, O’Brien JM. The uterine sandwich for persistent uterine atony: combining the B-Lynch compression suture and an intrauterine Bakri balloon. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:e9-e10.

- Matsubara S, Kuwata T, Baba Y, et al. A novel “uterine sandwich” for haemorrhage at cesarean section for placenta praevia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;54:283-286.

- Sallam HF, Shady NW. A sandwich technique (N&H variation technique) to reduce blood loss during cesarean delivery for complete placenta previa: a randomized controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018:1-8.

- Colmorn LB, Krebs L, Langhoff-Roos J; NOSS study group. Potentially avoidable peripartum hysterectomies in Denmark: a population based clinical audit. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161302.

- Bouet PE, Madar H, Froeliger A, et al. Surgical treatment of postpartum haemorrhage: national survey of French residents in obstetrics and gynecology. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:91.

- Gallos ID, Papadopoulou A, Man R, et al. Uterotonic agents for preventing postpartum haemorrhage: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2018;12:CD011689.

- Li GT, Li XF, Wu BP, et al. Three cornerstones of uterine compression sutures: simplicity, safety, and efficacy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;292:949-952.

- B-Lynch C, Coker A, Lawal AH, et al. The B-Lynch surgical technique for the control of massive postpartum hemorrhage: an alternative to hysterectomy? Five cases reported. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:372-375.

- Hayman RG, Arulkumaran S, Steer PJ. Uterine compression sutures: surgical management of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:502-506.

- Pereira A, Nunes F, Pedroso S, et al. Compressive sutures to treat postpartum bleeding secondary to uterine atony. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:569-572.

- Bakri YN. Uterine tamponade-drain for hemorrhage secondary to placenta previa-accreta. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1992;37:302-303.

- Bakri YN, Amri A, Abdul Jabbar F. Tamponade-balloon for obstetrical bleeding. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;74:139-142.

- Dildy GA, Belfort MA, Adair CD, et al; ebb Surveillance Study Team. Initial experience with a dual-balloon catheter for the management of postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:136.e1-e6.

- Revert M, Cottenet J, Raynal P, et al. Intrauterine balloon tamponade for management of severe postpartum hemorrhage in a perinatal network: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2017;124:1255-1262.

- Condous GS, Arulkumaran S, Symonds I, et al. The “tamponade test” in the management of massive postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:767-772.

- Nelson WL, O’Brien JM. The uterine sandwich for persistent uterine atony: combining the B-Lynch compression suture and an intrauterine Bakri balloon. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:e9-e10.

- Matsubara S, Kuwata T, Baba Y, et al. A novel “uterine sandwich” for haemorrhage at cesarean section for placenta praevia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;54:283-286.

- Sallam HF, Shady NW. A sandwich technique (N&H variation technique) to reduce blood loss during cesarean delivery for complete placenta previa: a randomized controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018:1-8.

- Colmorn LB, Krebs L, Langhoff-Roos J; NOSS study group. Potentially avoidable peripartum hysterectomies in Denmark: a population based clinical audit. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161302.

- Bouet PE, Madar H, Froeliger A, et al. Surgical treatment of postpartum haemorrhage: national survey of French residents in obstetrics and gynecology. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:91.

Genomic study reveals five subtypes of colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer can be divided into five DNA methylation subtypes that predict molecular and clinical behavior and may offer future therapeutic targets, according to investigators.

In 216 unselected colorectal cancers, five subtypes of the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) showed “striking” associations with sex, age, and tumor location, reported lead author Lochlan Fennell, MD, of the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute in Queensland, Australia, and colleagues. CIMP level increased with age in a stepwise fashion, they noted.

Further associations with CIMP subtype and BRAF mutation status support the investigators’ recent report that sessile serrated adenomas are rare in young patients and pose little risk of malignancy. With additional research, these findings could “inform the development of patient-centric surveillance for young and older patients who present with sessile serrated adenomas,” the investigators wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“CIMP can be detected using a standardized marker panel to stratify tumors as CIMP-high, CIMP-low, or CIMP-negative.” In the present study, the investigators expanded these three existing subtypes into five subtypes, allowing for better prediction of clinical and molecular characteristics associated with disease progression.

Initial genomic testing showed that 13.4% of cases carried a BRAF V600E mutation, 34.7% were mutated at KRAS codon 12 or 13, and almost half of the patients (42.2%) had a TP53 mutation. Sorted into the three previously described subtypes, CIMP negative was most common (68.5%), followed by CIMP low (20.4%), and CIMP high (11.1%). About two-thirds (66%) of BRAF mutant cancers were CIMP high, compared with just 3% of BRAF wild-type cases (P less than .0001). KRAS mutated cases were more often CIMP-low than KRAS wild-type cancers (34.6% vs. 12.8%; P less than .001).

With use of Illumina HumanMethylation450 Bead Chip arrays and recursively partitioned mixed model clustering, five methylation clusters were identified; specifically, these were CIMP-H1 and CIMP-H2 (high methylation levels), CIMP-L1 and CIMP-L2 (intermediate methylation levels), and CIMP-negative (low methylation level). As described above, methylation level demonstrated a direct relationship with age, ranging from CIMP-negative (61.9 years) to CIMP-H1 (75.2 years). The investigators also reported unique characteristics of each new subtype. For instance, the CIMP-H1 cluster had many features in common with cases of serrated neoplasia, such as BRAF mutation positivity (73.9%; P less than .0001).

“BRAF mutations are a hallmark of the serrated neoplasia pathway, and indicate that these cancers probably arose in serrated precursor lesions,” the investigators wrote. “We previously showed that the colonoscopic incidence of sessile serrated adenomas does not differ between patients aged in their 30s and patients who are much older, whereas BRAF mutant cancers were restricted to older individuals, suggesting these BRAF mutant polyps may have limited malignant potential in young patients.”

In contrast with the CIMP-H1 cases, CIMP-H2 cancers were more often KRAS mutant (54.5% vs. 17.4%). Other findings revealed associations with subtype and location; for example, CIMP-L1 cases were located equally in the distal and proximal colon, whereas CIMP-L2 cases more often localized to the distal colon and rectum. Of note for CIMP-negative cancers, most (62.3%) occurred in the distal colon, and none had a BRAF mutation.

The five methylation subtypes also showed associations with consensus molecular subtypes (CMS) to varying degrees. The two strongest correlations were found in CIMP-H1 cancers and CIMP-H2 cancers, which were most frequently classified as CMS1 (69.6%) and CMS3 (54.5%), respectively.

Using CIBERSORT, the investigators detected a variety of associations between the five subtypes and stromal immune cell composition. For example, CIMP-H1 cases were enriched for macrophages, compared with the other subtypes, except CIMP-L2. Mast cells showed a stepwise relationship with subtype; they contributed the most to the immune microenvironment of CIMP-negative cancers and the least to cases classified as CIMP-H1. A converse trend was found with natural killer cells.

Of note, in CIMP-H1 and CIMP-H2 cancers, oncogenes were significantly more likely than tumor-suppressor genes to undergo gene body methylation, which is positively correlated with gene expression, and oncogenes in these subtypes had significantly greater gene body methylation than normal colonic mucosa.

“The five subtypes identified in this study are highly correlated with key clinical and molecular features, including patient age, tumor location, microsatellite instability, and oncogenic mitogen-activated protein kinase mutations,” they wrote. “We show that cancers with high DNA methylation show an increased preponderance for mutating genes involved in epigenetic regulation, and namely those that are implicated in the chromatin remodeling process.”

Concluding, the investigators explained the role of their research in future therapy development. “Our analyses have identified potentially druggable vulnerabilities in cancers of different methylation subtypes,” they wrote. “Inhibitors targeting synthetic lethalities, such as SWI/SNF component inhibitors for those with ARID mutations, should be evaluated because these agents may be clinically beneficial to certain patient subsets.”

The study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council, the US National Institutes of Health, Pathology Queensland, and others. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Fennell L et al. CMGH. 2019 Apr 4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2019.04.002.