User login

Feasibility—and safety—of reducing the traditional 14 prenatal visits to 8 or 10

CASE Low-risk maternity patient wants fewer prenatal visits

A recently pregnant patient asks her obstetrician if she can schedule fewer prenatal visits given that she is at low risk, wants to minimize missing work, and lives an hour away from the clinic office. Her physician tells her that she needs the standard 13 to 15 visits to have a healthy pregnancy.

Obstetric care in the United States largely remains a “one-size fits all” approach despite compelling data that fewer visits for low-risk women are medically acceptable and may be more cost-effective.

Prenatal care: One size does not fit all

With nearly 4 million births annually in the United States, prenatal care is one of the most widely used preventive health care strategies.1,2 The ideal method for providing prenatal care, however, remains controversial. At the inception of early 20th century prenatal care in the United States, preventive strategies focused in part on eclampsia-related maternal morbidity and mortality, which in turn informed the content and frequency of prenatal visits.2 Despite the dramatic changes in medical practice over the last 100 years, the basic timing and quantity of prenatal care has not changed substantively.

The lack of change is not because we have not explored other models of prenatal care and sought to introduce evidence-based change. Several studies have assessed the impact of reduced prenatal care visits for low-risk women.3-7 Systematic reviews evaluated 7 randomized trials, with more than 60,000 women enrolled, of prenatal care models with a reduced number of planned antenatal visits (4 to 9 visits vs the traditional 13 to 15 visits).3,8 There were no demonstrable differences in maternal or perinatal morbidity or mortality, particularly in higher resource settings.

Despite strong safety data and the potential cost-effectiveness of a reduced schedule of prenatal visits, US prenatal care practices generally continue to have a one-size-fits-all approach. Several organizations, however, have called for a change in practice.

Endorsing a reduced number of prenatal visits for low-risk women, the US Department of Health and Human Services Expert Panel on Prenatal Care issued a report in 1989 that stated “the specific content and timing of prenatal visits, contacts, and education should vary depending on the risk status of the pregnant woman and her fetus.”9 Consistent with that recommendation, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) jointly published guidelines that recommend a system of goal-oriented antenatal visits at specific gestational ages and that support a reduced schedule of prenatal visits, compared with traditional models, for low-risk, parous women.10 The World Health Organization also published recommendations for an 8 “contact” prenatal care system to reduce perinatal mortality and improve women’s prenatal experience.11

Is obstetric dogma the reason for lack of change?

Concerns about patient satisfaction may play a role in limiting the use of a reduced prenatal care visit model. In trials that evaluated a model of reduced prenatal care visits, women were less satisfied with a reduced visit schedule and the gap between provider contacts.3,8 Anecdotally, providers have expressed concerns about perceived liability. Most compelling, perhaps, is the idea that the traditional prenatal schedule has become obstetric dogma.

Continue to: Consciously or unconsciously, clinicians may feel...

Consciously or unconsciously, clinicians may feel uncomfortable diverging from a schedule of visits that is firmly entrenched in obstetric practice. Continuing the status quo is easier than restructuring prenatal care practice. Ultimately, a paradigm shift may be required to broadly adopt a model of fewer prenatal visits for low-risk pregnancies.12 With these issues propelling the historic patterns of prenatal care, it is easy to see why we have not yet changed despite convincing reasons to do so.

In this article, we detail the reduced-visit prenatal care models developed at 3 institutions and how they incorporate use of today’s technology.

Approach #1: University of Utah Virtual Prenatal Care Program

The University of Utah Virtual Prenatal Care Program was conceived as a “baby step” toward developing a model of fewer total prenatal visits. Virtual visits were intended to reduce the number of prenatal face-to-face visits while maintaining the same total number of visits. Since large clinical trials had established the safety of reduced visits, the primary objectives were to retain patient satisfaction and to facilitate provider adoption.

Would women be satisfied with remote prenatal care? A prospective randomized controlled trial was designed in which 200 women were assigned to receive either a combination of telemedicine and 5 scheduled in-clinic prenatal visits (remote care group) or traditional in-clinic prenatal care (usual care group). Low-risk multigravida pregnant women who were between 6 0/7 and 16 0/7 weeks’ gestation were enrolled. The primary outcome was patient satisfaction.

The face-to-face visits were goal oriented, with scheduled physical examination, laboratory tests, or ultrasonography, and were conducted by the patient’s established obstetric provider (physician or nurse midwife) to maintain continuity of care. The remote care group self-collected measurements for weight, blood pressure, and fetal heart rate by handheld Doppler device prior to each telemedicine visit and entered the information into the electronic medical record. The purpose of the self-collected data was patient engagement and satisfaction, as well as increased provider comfort with the change in prenatal care schedule, rather than medical necessity.

The primary outcome of overall patient satisfaction with prenatal care was ascertained by questionnaire after delivery. The sample size calculation of 200 patients was based on noninferiority testing, and analysis was by intent-to-treat. The details of the trial are pending publication.

As expected, the remote care group had significantly fewer in-clinic prenatal care visits compared with the usual care group (7.2 vs 11.3 visits); the total number of prenatal visits was not different between groups. Overall satisfaction with prenatal care was very high in both the remote care and the usual care group (100% vs 97%).

The virtual prenatal care model for low-risk pregnancies, consisting of a novel remote monitoring strategy and a reduced number of in-clinic visits, was not associated with lower patient satisfaction compared with traditional care.

New care strategy gives patients a choice. The success of this clinical trial has led to its programmatic adoption at the University of Utah, and low-risk women currently are offered a choice between participating in the Virtual Prenatal Care Program or receiving traditional prenatal care. The University of Utah is moving on from the one-size-fits-all approach to adopt new strategies that provide personalized evidence-based prenatal care at the lowest cost, while retaining high patient satisfaction. Formal cost-effectiveness analyses are underway.

Continue to: Approach #2: Mayo Clinic OB Nest...

Approach #2: Mayo Clinic OB Nest

In 2011, the Mayo Clinic Obstetric Division partnered with 2 other Mayo Clinic divisions, the Center for Innovation and the Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, to redesign prenatal care for low-risk expectant mothers.Pregnant women and their obstetric health care teams (including obstetricians, certified nurse midwives, registered nurses, and clinical support staff) were convened to develop a novel model of prenatal care.4 The goal of this collaboration centered on:

- creating an evidence-driven prenatal care model for low-risk expectant women designed by relevant stakeholders

- focusing on meeting the on-demand needs of expectant mothers

- integrating innovative 21st century technology, and

- reducing the burden of prescheduled, low-value office visits.

Exploratory efforts to develop a novel care program. Based on feedback from the collaboration and guided by these goals, 141 expectant mothers participated in 19 different experiments, enabling the health care team to understand the impact of changing various components of prenatal care.

The experiments included integration of home monitoring (home fetal Doppler devices, drop-in fetal Doppler stations, home blood pressure monitoring devices), technology-enhanced communication with obstetric team members (video chats, tummy photos, virtual prenatal clinic appointments, proactive calls), and social media engagement (secure online prenatal care community).

Recommendations for the final components of OB Nest were based on feasibility and the potential impact on care. The recommendations included decreasing scheduled clinic appointments from 14 to 8, providing home monitoring devices to measure maternal blood pressure and fetal heart rate, establishing OB Nest virtual connected care visits with a registered nurse, and offering a secure online community of expectant mothers.

Trial assessed program’s efficacy, safety, satisfaction. A mixed-methods randomized controlled trial subsequently was conducted to evaluate the components of OB Nest.6 The trial included 300 pregnant women who were randomly assigned to standard prenatal care as recommended by ACOG or to OB Nest care.

OB Nest care consisted of 8 scheduled clinic appointments, 6 planned virtual (phone or online) connected care visits with a registered nurse dedicated to OB Nest, home monitoring of blood pressure (with a home digital sphygmomanometer) and fetal heart rate, and access to an online prenatal care community designated for OB Nest participants.

While publication of the trial results currently is pending, the OB Nest program appears to safely and effectively decrease the number of scheduled prenatal care visits for low-risk expectant mothers while improving the overall patient experience. OB Nest care now is offered as one of several options for low-risk expectant mothers at Mayo Clinic.

Additional avenues of study. Studies evaluating the impact of OB Nest in various nonacademic settings are now underway. Also under review is the potential cost savings of OB Nest as related to the productive lives of expectant mothers, while prenatal care safety is maintained.

The focus shift from a sick to a wellness perspective, stakeholder inclusion in the program design, and the integration of home monitoring tools are all major contributing factors to the success of OB Nest.

Continue to: Approach #3: Prisma Health utilizes mobile app technology...

Approach #3: Prisma Health utilizes mobile app technology

A third approach to reducing unnecessary visits for routine maternity care is to employ mobile app technology. Technology companies have developed app platforms for providers to use to educate and connect with patients; such apps reduce the number of routine obstetric office visits while maintaining patient satisfaction.

One group’s app experience. In a pilot study at a Prisma Health practice (South Carolina), 100 patients were placed on a reduced appointment schedule of 9 prenatal visits; the women self-monitored their weight gain and blood pressure using a remote monitoring system via an app called Babyscripts.7 Patient feedback was collected, with 45 of 100 patients responding.

Ninety-five percent of patients were satisfied with the mobile app, 94% reported positivity around pregnancy readiness, 90% were satisfied with their health care team, and 89% were happy with remote monitoring. Patients visited the app 3 times per week on average, and the top categories of interest were travel, exercise, genetics, and eating right.

One patient using the Babyscripts mobile health app and schedule optimization platform commented, “I am on my second pregnancy and wish this had been available for the first! The app is easy to use and I love seeing my weight on a graph. And I very much like the quality of the cuff” (personal data generated from Babyscripts).

In with the new

As clinicians strive to provide more patient-centered care, offering expectant families more than one way to receive their prenatal care is appropriate. Beyond the traditional 14-visit care model, we should offer use of novel options like mobile health apps, which improve the patient experience while decreasing the cost of care by reducing unnecessary visits.12 Note also that reducing visits for low-risk mothers opens space in the provider schedule for patients who need services more quickly.

Benefits for postpartum care. Traditionally, clinicians see the low-risk patient for a single follow-up appointment at 6 weeks postpartum. However, the World Health Organization recommends evaluating women at 3 days, 1 to 2 weeks, and 6 weeks postpartum.13 Further, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance recommends screening all women for resolution of postpartum blues at 10 to 14 days.14

ACOG also has made recommendations on optimizing postpartum care. In a committee opinion, ACOG recommends that all women have contact with their provider within the first 3 weeks postpartum.15 Recognizing that such an in-person visit may be difficult, ACOG has endorsed communication via text messaging, app-based support, and remote monitoring.15 An app such as Babyscripts would fill this need conveniently for both patient and provider.

In 2019, patients want choice. As maternity care providers, we should be open to considering novel, evidence-based options that may provide more cost-effective obstetric care.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, et al. Births: final data for 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67:1-50.

- Alexander GR, Kotelchuck M. Assessing the role and effectiveness of prenatal care: history, challenges, and directions for future research. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:306-316.

- Dowswell T, Carroli G, Duley L, et al. Alternative versus standard packages of antenatal care for low-risk pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; (7):CD000934.

- de Mooij MJM, Hodny RL, O'Neil DA, et al. OB Nest: reimagining low-risk prenatal care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93:458-466.

- Pflugeisen BM, McCarren C, Poore S, et al. Virtual visits: managing prenatal care with modern technology. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2016;41:24-30.

- Ridgeway JL, LeBlanc A, Branda M, et al. Implementation of a new prenatal care model to reduce office visits and increase connectivity and continuity of care: protocol for a mixed-methods study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:323.

- Marko KI, Krapf JM, Meltzer AC, et al. Testing the feasibility of remote patient monitoring in prenatal care using a mobile app and connected devices: a prospective observational trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5:e200.

- Carroli G, Villar J, Piaggio G, et al. WHO systematic review of randomised controlled trials of routine antenatal care. Lancet. 2001;357:1565-1570.

- Rosen MG, Merkatz IR, Hill JG. Caring for our future: a report by the expert panel on the content of prenatal care. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:782-787.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Guidelines for Perinatal Care. 8th edition. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2017.

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250796 /9789241549912-eng.pdf;jsessionid=C740C52F8AA1D7694CD9463152C193BA?sequence=1. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Woo VG, Lundeen T, Matula S, et al. Achieving higher-value obstetrical care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:240e1-250e14.

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Postnatal Care of the Mother and Newborn. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2014. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/97603/9789241506649_eng.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Postnatal care up to 8 weeks after birth. Updated February 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg37/chapter/1-Recommendations#maternal-health. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 736. Optimizing postpartum care. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2018.

CASE Low-risk maternity patient wants fewer prenatal visits

A recently pregnant patient asks her obstetrician if she can schedule fewer prenatal visits given that she is at low risk, wants to minimize missing work, and lives an hour away from the clinic office. Her physician tells her that she needs the standard 13 to 15 visits to have a healthy pregnancy.

Obstetric care in the United States largely remains a “one-size fits all” approach despite compelling data that fewer visits for low-risk women are medically acceptable and may be more cost-effective.

Prenatal care: One size does not fit all

With nearly 4 million births annually in the United States, prenatal care is one of the most widely used preventive health care strategies.1,2 The ideal method for providing prenatal care, however, remains controversial. At the inception of early 20th century prenatal care in the United States, preventive strategies focused in part on eclampsia-related maternal morbidity and mortality, which in turn informed the content and frequency of prenatal visits.2 Despite the dramatic changes in medical practice over the last 100 years, the basic timing and quantity of prenatal care has not changed substantively.

The lack of change is not because we have not explored other models of prenatal care and sought to introduce evidence-based change. Several studies have assessed the impact of reduced prenatal care visits for low-risk women.3-7 Systematic reviews evaluated 7 randomized trials, with more than 60,000 women enrolled, of prenatal care models with a reduced number of planned antenatal visits (4 to 9 visits vs the traditional 13 to 15 visits).3,8 There were no demonstrable differences in maternal or perinatal morbidity or mortality, particularly in higher resource settings.

Despite strong safety data and the potential cost-effectiveness of a reduced schedule of prenatal visits, US prenatal care practices generally continue to have a one-size-fits-all approach. Several organizations, however, have called for a change in practice.

Endorsing a reduced number of prenatal visits for low-risk women, the US Department of Health and Human Services Expert Panel on Prenatal Care issued a report in 1989 that stated “the specific content and timing of prenatal visits, contacts, and education should vary depending on the risk status of the pregnant woman and her fetus.”9 Consistent with that recommendation, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) jointly published guidelines that recommend a system of goal-oriented antenatal visits at specific gestational ages and that support a reduced schedule of prenatal visits, compared with traditional models, for low-risk, parous women.10 The World Health Organization also published recommendations for an 8 “contact” prenatal care system to reduce perinatal mortality and improve women’s prenatal experience.11

Is obstetric dogma the reason for lack of change?

Concerns about patient satisfaction may play a role in limiting the use of a reduced prenatal care visit model. In trials that evaluated a model of reduced prenatal care visits, women were less satisfied with a reduced visit schedule and the gap between provider contacts.3,8 Anecdotally, providers have expressed concerns about perceived liability. Most compelling, perhaps, is the idea that the traditional prenatal schedule has become obstetric dogma.

Continue to: Consciously or unconsciously, clinicians may feel...

Consciously or unconsciously, clinicians may feel uncomfortable diverging from a schedule of visits that is firmly entrenched in obstetric practice. Continuing the status quo is easier than restructuring prenatal care practice. Ultimately, a paradigm shift may be required to broadly adopt a model of fewer prenatal visits for low-risk pregnancies.12 With these issues propelling the historic patterns of prenatal care, it is easy to see why we have not yet changed despite convincing reasons to do so.

In this article, we detail the reduced-visit prenatal care models developed at 3 institutions and how they incorporate use of today’s technology.

Approach #1: University of Utah Virtual Prenatal Care Program

The University of Utah Virtual Prenatal Care Program was conceived as a “baby step” toward developing a model of fewer total prenatal visits. Virtual visits were intended to reduce the number of prenatal face-to-face visits while maintaining the same total number of visits. Since large clinical trials had established the safety of reduced visits, the primary objectives were to retain patient satisfaction and to facilitate provider adoption.

Would women be satisfied with remote prenatal care? A prospective randomized controlled trial was designed in which 200 women were assigned to receive either a combination of telemedicine and 5 scheduled in-clinic prenatal visits (remote care group) or traditional in-clinic prenatal care (usual care group). Low-risk multigravida pregnant women who were between 6 0/7 and 16 0/7 weeks’ gestation were enrolled. The primary outcome was patient satisfaction.

The face-to-face visits were goal oriented, with scheduled physical examination, laboratory tests, or ultrasonography, and were conducted by the patient’s established obstetric provider (physician or nurse midwife) to maintain continuity of care. The remote care group self-collected measurements for weight, blood pressure, and fetal heart rate by handheld Doppler device prior to each telemedicine visit and entered the information into the electronic medical record. The purpose of the self-collected data was patient engagement and satisfaction, as well as increased provider comfort with the change in prenatal care schedule, rather than medical necessity.

The primary outcome of overall patient satisfaction with prenatal care was ascertained by questionnaire after delivery. The sample size calculation of 200 patients was based on noninferiority testing, and analysis was by intent-to-treat. The details of the trial are pending publication.

As expected, the remote care group had significantly fewer in-clinic prenatal care visits compared with the usual care group (7.2 vs 11.3 visits); the total number of prenatal visits was not different between groups. Overall satisfaction with prenatal care was very high in both the remote care and the usual care group (100% vs 97%).

The virtual prenatal care model for low-risk pregnancies, consisting of a novel remote monitoring strategy and a reduced number of in-clinic visits, was not associated with lower patient satisfaction compared with traditional care.

New care strategy gives patients a choice. The success of this clinical trial has led to its programmatic adoption at the University of Utah, and low-risk women currently are offered a choice between participating in the Virtual Prenatal Care Program or receiving traditional prenatal care. The University of Utah is moving on from the one-size-fits-all approach to adopt new strategies that provide personalized evidence-based prenatal care at the lowest cost, while retaining high patient satisfaction. Formal cost-effectiveness analyses are underway.

Continue to: Approach #2: Mayo Clinic OB Nest...

Approach #2: Mayo Clinic OB Nest

In 2011, the Mayo Clinic Obstetric Division partnered with 2 other Mayo Clinic divisions, the Center for Innovation and the Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, to redesign prenatal care for low-risk expectant mothers.Pregnant women and their obstetric health care teams (including obstetricians, certified nurse midwives, registered nurses, and clinical support staff) were convened to develop a novel model of prenatal care.4 The goal of this collaboration centered on:

- creating an evidence-driven prenatal care model for low-risk expectant women designed by relevant stakeholders

- focusing on meeting the on-demand needs of expectant mothers

- integrating innovative 21st century technology, and

- reducing the burden of prescheduled, low-value office visits.

Exploratory efforts to develop a novel care program. Based on feedback from the collaboration and guided by these goals, 141 expectant mothers participated in 19 different experiments, enabling the health care team to understand the impact of changing various components of prenatal care.

The experiments included integration of home monitoring (home fetal Doppler devices, drop-in fetal Doppler stations, home blood pressure monitoring devices), technology-enhanced communication with obstetric team members (video chats, tummy photos, virtual prenatal clinic appointments, proactive calls), and social media engagement (secure online prenatal care community).

Recommendations for the final components of OB Nest were based on feasibility and the potential impact on care. The recommendations included decreasing scheduled clinic appointments from 14 to 8, providing home monitoring devices to measure maternal blood pressure and fetal heart rate, establishing OB Nest virtual connected care visits with a registered nurse, and offering a secure online community of expectant mothers.

Trial assessed program’s efficacy, safety, satisfaction. A mixed-methods randomized controlled trial subsequently was conducted to evaluate the components of OB Nest.6 The trial included 300 pregnant women who were randomly assigned to standard prenatal care as recommended by ACOG or to OB Nest care.

OB Nest care consisted of 8 scheduled clinic appointments, 6 planned virtual (phone or online) connected care visits with a registered nurse dedicated to OB Nest, home monitoring of blood pressure (with a home digital sphygmomanometer) and fetal heart rate, and access to an online prenatal care community designated for OB Nest participants.

While publication of the trial results currently is pending, the OB Nest program appears to safely and effectively decrease the number of scheduled prenatal care visits for low-risk expectant mothers while improving the overall patient experience. OB Nest care now is offered as one of several options for low-risk expectant mothers at Mayo Clinic.

Additional avenues of study. Studies evaluating the impact of OB Nest in various nonacademic settings are now underway. Also under review is the potential cost savings of OB Nest as related to the productive lives of expectant mothers, while prenatal care safety is maintained.

The focus shift from a sick to a wellness perspective, stakeholder inclusion in the program design, and the integration of home monitoring tools are all major contributing factors to the success of OB Nest.

Continue to: Approach #3: Prisma Health utilizes mobile app technology...

Approach #3: Prisma Health utilizes mobile app technology

A third approach to reducing unnecessary visits for routine maternity care is to employ mobile app technology. Technology companies have developed app platforms for providers to use to educate and connect with patients; such apps reduce the number of routine obstetric office visits while maintaining patient satisfaction.

One group’s app experience. In a pilot study at a Prisma Health practice (South Carolina), 100 patients were placed on a reduced appointment schedule of 9 prenatal visits; the women self-monitored their weight gain and blood pressure using a remote monitoring system via an app called Babyscripts.7 Patient feedback was collected, with 45 of 100 patients responding.

Ninety-five percent of patients were satisfied with the mobile app, 94% reported positivity around pregnancy readiness, 90% were satisfied with their health care team, and 89% were happy with remote monitoring. Patients visited the app 3 times per week on average, and the top categories of interest were travel, exercise, genetics, and eating right.

One patient using the Babyscripts mobile health app and schedule optimization platform commented, “I am on my second pregnancy and wish this had been available for the first! The app is easy to use and I love seeing my weight on a graph. And I very much like the quality of the cuff” (personal data generated from Babyscripts).

In with the new

As clinicians strive to provide more patient-centered care, offering expectant families more than one way to receive their prenatal care is appropriate. Beyond the traditional 14-visit care model, we should offer use of novel options like mobile health apps, which improve the patient experience while decreasing the cost of care by reducing unnecessary visits.12 Note also that reducing visits for low-risk mothers opens space in the provider schedule for patients who need services more quickly.

Benefits for postpartum care. Traditionally, clinicians see the low-risk patient for a single follow-up appointment at 6 weeks postpartum. However, the World Health Organization recommends evaluating women at 3 days, 1 to 2 weeks, and 6 weeks postpartum.13 Further, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance recommends screening all women for resolution of postpartum blues at 10 to 14 days.14

ACOG also has made recommendations on optimizing postpartum care. In a committee opinion, ACOG recommends that all women have contact with their provider within the first 3 weeks postpartum.15 Recognizing that such an in-person visit may be difficult, ACOG has endorsed communication via text messaging, app-based support, and remote monitoring.15 An app such as Babyscripts would fill this need conveniently for both patient and provider.

In 2019, patients want choice. As maternity care providers, we should be open to considering novel, evidence-based options that may provide more cost-effective obstetric care.

CASE Low-risk maternity patient wants fewer prenatal visits

A recently pregnant patient asks her obstetrician if she can schedule fewer prenatal visits given that she is at low risk, wants to minimize missing work, and lives an hour away from the clinic office. Her physician tells her that she needs the standard 13 to 15 visits to have a healthy pregnancy.

Obstetric care in the United States largely remains a “one-size fits all” approach despite compelling data that fewer visits for low-risk women are medically acceptable and may be more cost-effective.

Prenatal care: One size does not fit all

With nearly 4 million births annually in the United States, prenatal care is one of the most widely used preventive health care strategies.1,2 The ideal method for providing prenatal care, however, remains controversial. At the inception of early 20th century prenatal care in the United States, preventive strategies focused in part on eclampsia-related maternal morbidity and mortality, which in turn informed the content and frequency of prenatal visits.2 Despite the dramatic changes in medical practice over the last 100 years, the basic timing and quantity of prenatal care has not changed substantively.

The lack of change is not because we have not explored other models of prenatal care and sought to introduce evidence-based change. Several studies have assessed the impact of reduced prenatal care visits for low-risk women.3-7 Systematic reviews evaluated 7 randomized trials, with more than 60,000 women enrolled, of prenatal care models with a reduced number of planned antenatal visits (4 to 9 visits vs the traditional 13 to 15 visits).3,8 There were no demonstrable differences in maternal or perinatal morbidity or mortality, particularly in higher resource settings.

Despite strong safety data and the potential cost-effectiveness of a reduced schedule of prenatal visits, US prenatal care practices generally continue to have a one-size-fits-all approach. Several organizations, however, have called for a change in practice.

Endorsing a reduced number of prenatal visits for low-risk women, the US Department of Health and Human Services Expert Panel on Prenatal Care issued a report in 1989 that stated “the specific content and timing of prenatal visits, contacts, and education should vary depending on the risk status of the pregnant woman and her fetus.”9 Consistent with that recommendation, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) jointly published guidelines that recommend a system of goal-oriented antenatal visits at specific gestational ages and that support a reduced schedule of prenatal visits, compared with traditional models, for low-risk, parous women.10 The World Health Organization also published recommendations for an 8 “contact” prenatal care system to reduce perinatal mortality and improve women’s prenatal experience.11

Is obstetric dogma the reason for lack of change?

Concerns about patient satisfaction may play a role in limiting the use of a reduced prenatal care visit model. In trials that evaluated a model of reduced prenatal care visits, women were less satisfied with a reduced visit schedule and the gap between provider contacts.3,8 Anecdotally, providers have expressed concerns about perceived liability. Most compelling, perhaps, is the idea that the traditional prenatal schedule has become obstetric dogma.

Continue to: Consciously or unconsciously, clinicians may feel...

Consciously or unconsciously, clinicians may feel uncomfortable diverging from a schedule of visits that is firmly entrenched in obstetric practice. Continuing the status quo is easier than restructuring prenatal care practice. Ultimately, a paradigm shift may be required to broadly adopt a model of fewer prenatal visits for low-risk pregnancies.12 With these issues propelling the historic patterns of prenatal care, it is easy to see why we have not yet changed despite convincing reasons to do so.

In this article, we detail the reduced-visit prenatal care models developed at 3 institutions and how they incorporate use of today’s technology.

Approach #1: University of Utah Virtual Prenatal Care Program

The University of Utah Virtual Prenatal Care Program was conceived as a “baby step” toward developing a model of fewer total prenatal visits. Virtual visits were intended to reduce the number of prenatal face-to-face visits while maintaining the same total number of visits. Since large clinical trials had established the safety of reduced visits, the primary objectives were to retain patient satisfaction and to facilitate provider adoption.

Would women be satisfied with remote prenatal care? A prospective randomized controlled trial was designed in which 200 women were assigned to receive either a combination of telemedicine and 5 scheduled in-clinic prenatal visits (remote care group) or traditional in-clinic prenatal care (usual care group). Low-risk multigravida pregnant women who were between 6 0/7 and 16 0/7 weeks’ gestation were enrolled. The primary outcome was patient satisfaction.

The face-to-face visits were goal oriented, with scheduled physical examination, laboratory tests, or ultrasonography, and were conducted by the patient’s established obstetric provider (physician or nurse midwife) to maintain continuity of care. The remote care group self-collected measurements for weight, blood pressure, and fetal heart rate by handheld Doppler device prior to each telemedicine visit and entered the information into the electronic medical record. The purpose of the self-collected data was patient engagement and satisfaction, as well as increased provider comfort with the change in prenatal care schedule, rather than medical necessity.

The primary outcome of overall patient satisfaction with prenatal care was ascertained by questionnaire after delivery. The sample size calculation of 200 patients was based on noninferiority testing, and analysis was by intent-to-treat. The details of the trial are pending publication.

As expected, the remote care group had significantly fewer in-clinic prenatal care visits compared with the usual care group (7.2 vs 11.3 visits); the total number of prenatal visits was not different between groups. Overall satisfaction with prenatal care was very high in both the remote care and the usual care group (100% vs 97%).

The virtual prenatal care model for low-risk pregnancies, consisting of a novel remote monitoring strategy and a reduced number of in-clinic visits, was not associated with lower patient satisfaction compared with traditional care.

New care strategy gives patients a choice. The success of this clinical trial has led to its programmatic adoption at the University of Utah, and low-risk women currently are offered a choice between participating in the Virtual Prenatal Care Program or receiving traditional prenatal care. The University of Utah is moving on from the one-size-fits-all approach to adopt new strategies that provide personalized evidence-based prenatal care at the lowest cost, while retaining high patient satisfaction. Formal cost-effectiveness analyses are underway.

Continue to: Approach #2: Mayo Clinic OB Nest...

Approach #2: Mayo Clinic OB Nest

In 2011, the Mayo Clinic Obstetric Division partnered with 2 other Mayo Clinic divisions, the Center for Innovation and the Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, to redesign prenatal care for low-risk expectant mothers.Pregnant women and their obstetric health care teams (including obstetricians, certified nurse midwives, registered nurses, and clinical support staff) were convened to develop a novel model of prenatal care.4 The goal of this collaboration centered on:

- creating an evidence-driven prenatal care model for low-risk expectant women designed by relevant stakeholders

- focusing on meeting the on-demand needs of expectant mothers

- integrating innovative 21st century technology, and

- reducing the burden of prescheduled, low-value office visits.

Exploratory efforts to develop a novel care program. Based on feedback from the collaboration and guided by these goals, 141 expectant mothers participated in 19 different experiments, enabling the health care team to understand the impact of changing various components of prenatal care.

The experiments included integration of home monitoring (home fetal Doppler devices, drop-in fetal Doppler stations, home blood pressure monitoring devices), technology-enhanced communication with obstetric team members (video chats, tummy photos, virtual prenatal clinic appointments, proactive calls), and social media engagement (secure online prenatal care community).

Recommendations for the final components of OB Nest were based on feasibility and the potential impact on care. The recommendations included decreasing scheduled clinic appointments from 14 to 8, providing home monitoring devices to measure maternal blood pressure and fetal heart rate, establishing OB Nest virtual connected care visits with a registered nurse, and offering a secure online community of expectant mothers.

Trial assessed program’s efficacy, safety, satisfaction. A mixed-methods randomized controlled trial subsequently was conducted to evaluate the components of OB Nest.6 The trial included 300 pregnant women who were randomly assigned to standard prenatal care as recommended by ACOG or to OB Nest care.

OB Nest care consisted of 8 scheduled clinic appointments, 6 planned virtual (phone or online) connected care visits with a registered nurse dedicated to OB Nest, home monitoring of blood pressure (with a home digital sphygmomanometer) and fetal heart rate, and access to an online prenatal care community designated for OB Nest participants.

While publication of the trial results currently is pending, the OB Nest program appears to safely and effectively decrease the number of scheduled prenatal care visits for low-risk expectant mothers while improving the overall patient experience. OB Nest care now is offered as one of several options for low-risk expectant mothers at Mayo Clinic.

Additional avenues of study. Studies evaluating the impact of OB Nest in various nonacademic settings are now underway. Also under review is the potential cost savings of OB Nest as related to the productive lives of expectant mothers, while prenatal care safety is maintained.

The focus shift from a sick to a wellness perspective, stakeholder inclusion in the program design, and the integration of home monitoring tools are all major contributing factors to the success of OB Nest.

Continue to: Approach #3: Prisma Health utilizes mobile app technology...

Approach #3: Prisma Health utilizes mobile app technology

A third approach to reducing unnecessary visits for routine maternity care is to employ mobile app technology. Technology companies have developed app platforms for providers to use to educate and connect with patients; such apps reduce the number of routine obstetric office visits while maintaining patient satisfaction.

One group’s app experience. In a pilot study at a Prisma Health practice (South Carolina), 100 patients were placed on a reduced appointment schedule of 9 prenatal visits; the women self-monitored their weight gain and blood pressure using a remote monitoring system via an app called Babyscripts.7 Patient feedback was collected, with 45 of 100 patients responding.

Ninety-five percent of patients were satisfied with the mobile app, 94% reported positivity around pregnancy readiness, 90% were satisfied with their health care team, and 89% were happy with remote monitoring. Patients visited the app 3 times per week on average, and the top categories of interest were travel, exercise, genetics, and eating right.

One patient using the Babyscripts mobile health app and schedule optimization platform commented, “I am on my second pregnancy and wish this had been available for the first! The app is easy to use and I love seeing my weight on a graph. And I very much like the quality of the cuff” (personal data generated from Babyscripts).

In with the new

As clinicians strive to provide more patient-centered care, offering expectant families more than one way to receive their prenatal care is appropriate. Beyond the traditional 14-visit care model, we should offer use of novel options like mobile health apps, which improve the patient experience while decreasing the cost of care by reducing unnecessary visits.12 Note also that reducing visits for low-risk mothers opens space in the provider schedule for patients who need services more quickly.

Benefits for postpartum care. Traditionally, clinicians see the low-risk patient for a single follow-up appointment at 6 weeks postpartum. However, the World Health Organization recommends evaluating women at 3 days, 1 to 2 weeks, and 6 weeks postpartum.13 Further, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance recommends screening all women for resolution of postpartum blues at 10 to 14 days.14

ACOG also has made recommendations on optimizing postpartum care. In a committee opinion, ACOG recommends that all women have contact with their provider within the first 3 weeks postpartum.15 Recognizing that such an in-person visit may be difficult, ACOG has endorsed communication via text messaging, app-based support, and remote monitoring.15 An app such as Babyscripts would fill this need conveniently for both patient and provider.

In 2019, patients want choice. As maternity care providers, we should be open to considering novel, evidence-based options that may provide more cost-effective obstetric care.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, et al. Births: final data for 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67:1-50.

- Alexander GR, Kotelchuck M. Assessing the role and effectiveness of prenatal care: history, challenges, and directions for future research. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:306-316.

- Dowswell T, Carroli G, Duley L, et al. Alternative versus standard packages of antenatal care for low-risk pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; (7):CD000934.

- de Mooij MJM, Hodny RL, O'Neil DA, et al. OB Nest: reimagining low-risk prenatal care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93:458-466.

- Pflugeisen BM, McCarren C, Poore S, et al. Virtual visits: managing prenatal care with modern technology. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2016;41:24-30.

- Ridgeway JL, LeBlanc A, Branda M, et al. Implementation of a new prenatal care model to reduce office visits and increase connectivity and continuity of care: protocol for a mixed-methods study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:323.

- Marko KI, Krapf JM, Meltzer AC, et al. Testing the feasibility of remote patient monitoring in prenatal care using a mobile app and connected devices: a prospective observational trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5:e200.

- Carroli G, Villar J, Piaggio G, et al. WHO systematic review of randomised controlled trials of routine antenatal care. Lancet. 2001;357:1565-1570.

- Rosen MG, Merkatz IR, Hill JG. Caring for our future: a report by the expert panel on the content of prenatal care. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:782-787.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Guidelines for Perinatal Care. 8th edition. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2017.

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250796 /9789241549912-eng.pdf;jsessionid=C740C52F8AA1D7694CD9463152C193BA?sequence=1. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Woo VG, Lundeen T, Matula S, et al. Achieving higher-value obstetrical care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:240e1-250e14.

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Postnatal Care of the Mother and Newborn. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2014. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/97603/9789241506649_eng.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Postnatal care up to 8 weeks after birth. Updated February 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg37/chapter/1-Recommendations#maternal-health. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 736. Optimizing postpartum care. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2018.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, et al. Births: final data for 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67:1-50.

- Alexander GR, Kotelchuck M. Assessing the role and effectiveness of prenatal care: history, challenges, and directions for future research. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:306-316.

- Dowswell T, Carroli G, Duley L, et al. Alternative versus standard packages of antenatal care for low-risk pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; (7):CD000934.

- de Mooij MJM, Hodny RL, O'Neil DA, et al. OB Nest: reimagining low-risk prenatal care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93:458-466.

- Pflugeisen BM, McCarren C, Poore S, et al. Virtual visits: managing prenatal care with modern technology. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2016;41:24-30.

- Ridgeway JL, LeBlanc A, Branda M, et al. Implementation of a new prenatal care model to reduce office visits and increase connectivity and continuity of care: protocol for a mixed-methods study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:323.

- Marko KI, Krapf JM, Meltzer AC, et al. Testing the feasibility of remote patient monitoring in prenatal care using a mobile app and connected devices: a prospective observational trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5:e200.

- Carroli G, Villar J, Piaggio G, et al. WHO systematic review of randomised controlled trials of routine antenatal care. Lancet. 2001;357:1565-1570.

- Rosen MG, Merkatz IR, Hill JG. Caring for our future: a report by the expert panel on the content of prenatal care. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:782-787.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Guidelines for Perinatal Care. 8th edition. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2017.

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250796 /9789241549912-eng.pdf;jsessionid=C740C52F8AA1D7694CD9463152C193BA?sequence=1. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Woo VG, Lundeen T, Matula S, et al. Achieving higher-value obstetrical care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:240e1-250e14.

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Postnatal Care of the Mother and Newborn. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2014. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/97603/9789241506649_eng.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Postnatal care up to 8 weeks after birth. Updated February 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg37/chapter/1-Recommendations#maternal-health. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 736. Optimizing postpartum care. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2018.

Comment & Controversy

WHAT IS YOUR APPROACH TO THE PERSISTENT OCCIPUT POSTERIOR MALPOSITION?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD

(EDITORIAL; MARCH 2019)

A classic approach for managing fetal malposition

For those of us who trained and practiced obstetrics in the days of the 6% primary cesarean delivery (CD) rate, we never considered the management of the persistent occiput

- The cervix must be fully dilated.

- Dense regional anesthesia must be achieved.

- The vertex must have reached +1 station.

- The position must be clearly established, and this does not require anything other than the ability to palpate an ear, as it can be pointed only in one direction. If you feel ultrasonography is needed, be my guest.

- Use an obstetric lubricant to reduce resistance and minimize lacerations.

- While a trial of manual rotation is reasonable, it commonly will not succeed and requires that an operator’s hand be inserted rather than a slender and less traumatic device (forceps).

- Next, palpate the sagittal suture to determine whether the position is straight OP versus left OP or right OP. This should not be difficult unless the poor woman has gone through 2 or 3 hours of unproductive pushing, thereby creating caput.

- After proper forceps application is confirmed, gently apply upward pressure. This will make rotation easier.

- Dr. Irving’s recommendations notwithstanding, the forceps handles are not carried in a wide sweep. One should use Kielland’s forceps, which do not have a pelvic curve and were invented for this precise indication. The forceps are simply rotated.

- Try to avoid delivery as an OP, as this pulls a much larger diameter deflexed head through the pelvis and usually results in significant lacerations.

- Episiotomy is not always required if rotation has succeeded.

- Once descent to the outlet has been achieved, it is probably best to switch to a forceps with a pelvic curve to achieve easier extension.

- This should complete the delivery, but as a general rule, if more than minimal resistance is met in any of the above steps, abandon the procedure and move to CD.

- This process should result in at least a 70% success rate.

As is most likely understood by the current generation of obstetricians who appear to be satisfied with a 30% to 40% primary CD rate, the above reflects the views of a long-retired ObGyn (whose CD rate never exceeded 10%) and may be inappropriate for those who are not adequately trained in or comfortable with vaginal obstetrics.

David M. Priver, MD

San Diego, California

Continue to: HOW DO YOU FEEL ABOUT EXPECTANTLY MANAGING A WELL-DATED PREGNANCY PAST 41 WEEKS’ GESTATION?

HOW DO YOU FEEL ABOUT EXPECTANTLY MANAGING A WELL-DATED PREGNANCY PAST 41 WEEKS’ GESTATION?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD

(EDITORIAL; FEBRUARY 2019)

Membrane stripping can be problematic

The recent discussion on stripping membranes to facilitate the initiation of labor and delivery was intriguing. This practice was reviewed extensively during my training in the 1960s and abandoned when the results were disappointing or contradictory. Although the practice has been revitalized recently, I am concerned that potential risks and the absence of a recommended protocol of safeguards may allow new problems to develop.

In a metropolitan community where I provide consultative services, the only patients I see for evaluation of pregnancies beyond 40 to 41 weeks come from providers who are non-physicians. Apparently, they are concerned that they may have to turn their patients over to physician providers for interventions that they are not capable of doing. My advice to them is simply that nothing good happens after 40 to 41 weeks.

Well-grown babies may continue to grow if they are healthy, and they may incur greater risks of dystotic labor and delivery resulting in injury or the need for physician-administered surgical assistance. If, on the other hand, growth markedly diminishes or ceases, fetal harm or neonatal complications may occur through asphyxia, meconium aspiration, or trauma. In either event, physician-based assistance is strongly encouraged, as long as due diligence in determining gestational age has been done.

Promoting membrane stripping without having a protocol for ascertainment of risk factors is worrisome to me. In my opinion, large population studies that fail to demonstrate increased risks of infection may fail to demonstrate that membrane stripping may induce a degree of perinatal infection comparable to that of prolonged labor with multiple internal examinations with or without ultimate cesarean birth. Prior to considering membrane stripping as a strategy, one should recognize certain important considerations, namely:

- Patients most in need of active intervention may have the least favorable cervical findings, and as a result they are potentially at risk for the greatest discomfort.

- The frequency of group B streptococcal colonization of the vagina at term should be recognized, and a culture should be obtained immediately prior to intervention. When a culture is a positive, membrane stripping should be avoided, or at least a sober consideration of its use and appropriate antibiotic coverage should occur.

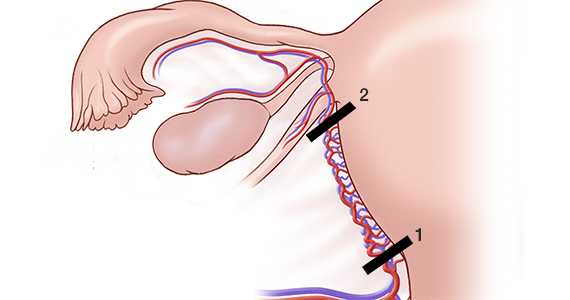

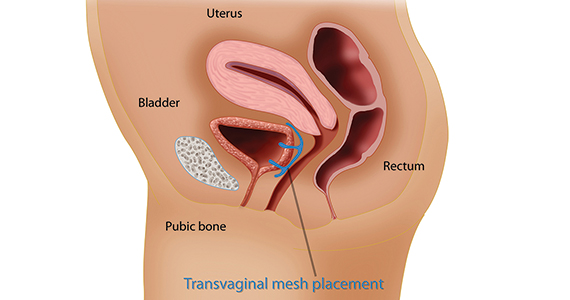

- Consider performing transvaginal ultrasonography prior to membrane stripping to exclude the possibility of a placental edge close enough to be encountered and compromised, with resultant hemorrhage in an outpatient venue ill equipped to provide adequate emergency support.

- The comparative effectiveness of other direct cervical conditioning therapies, including use of a Foley catheter or regional prostaglandin medication, has been well explored and found effective. Also, if one takes seriously the need for any intervention, admission to the hospital for overnight cervical conditioning allows for surveillance and avoids the patient experience of being sent home cramping, bleeding, brooding infection, and questioning her trust in the provider.

Continue to: I am concerned that the promotion...

I am concerned that the promotion of this potentially rather brutish practice by highly reputable advisors can result in its growing utilization by providers some of whom may be least qualified to apply proper judgment and sensitivity to its selection. In the most primitive of circumstances, it may have utility. Personally, however, I feel that medically based strategies initiated and monitored by professionals capable of dealing with any untoward departures from the expected results must be considered in the best traditions of what we do. The appeal of simplicity must not encourage the adoption of interventions that lack the proper application of thought and plan and whose only appeal is that of simplicity.

Richard P. Perkins, MD

Fort Myers, Florida; Stockton, California

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Priver for his excellent description of how to use forceps to resolve a persistent occiput posterior position. I also thank Dr. Perkins for his valuable comments and agree with him that in the United States among the options available for outpatient cervical ripening, misoprostol or a balloon are more commonly used than membrane stripping. Membrane stripping is an outpatient cervical ripening technique that is commonly used in the United Kingdom.

WHAT IS YOUR APPROACH TO THE PERSISTENT OCCIPUT POSTERIOR MALPOSITION?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD

(EDITORIAL; MARCH 2019)

A classic approach for managing fetal malposition

For those of us who trained and practiced obstetrics in the days of the 6% primary cesarean delivery (CD) rate, we never considered the management of the persistent occiput

- The cervix must be fully dilated.

- Dense regional anesthesia must be achieved.

- The vertex must have reached +1 station.

- The position must be clearly established, and this does not require anything other than the ability to palpate an ear, as it can be pointed only in one direction. If you feel ultrasonography is needed, be my guest.

- Use an obstetric lubricant to reduce resistance and minimize lacerations.

- While a trial of manual rotation is reasonable, it commonly will not succeed and requires that an operator’s hand be inserted rather than a slender and less traumatic device (forceps).

- Next, palpate the sagittal suture to determine whether the position is straight OP versus left OP or right OP. This should not be difficult unless the poor woman has gone through 2 or 3 hours of unproductive pushing, thereby creating caput.

- After proper forceps application is confirmed, gently apply upward pressure. This will make rotation easier.

- Dr. Irving’s recommendations notwithstanding, the forceps handles are not carried in a wide sweep. One should use Kielland’s forceps, which do not have a pelvic curve and were invented for this precise indication. The forceps are simply rotated.

- Try to avoid delivery as an OP, as this pulls a much larger diameter deflexed head through the pelvis and usually results in significant lacerations.

- Episiotomy is not always required if rotation has succeeded.

- Once descent to the outlet has been achieved, it is probably best to switch to a forceps with a pelvic curve to achieve easier extension.

- This should complete the delivery, but as a general rule, if more than minimal resistance is met in any of the above steps, abandon the procedure and move to CD.

- This process should result in at least a 70% success rate.

As is most likely understood by the current generation of obstetricians who appear to be satisfied with a 30% to 40% primary CD rate, the above reflects the views of a long-retired ObGyn (whose CD rate never exceeded 10%) and may be inappropriate for those who are not adequately trained in or comfortable with vaginal obstetrics.

David M. Priver, MD

San Diego, California

Continue to: HOW DO YOU FEEL ABOUT EXPECTANTLY MANAGING A WELL-DATED PREGNANCY PAST 41 WEEKS’ GESTATION?

HOW DO YOU FEEL ABOUT EXPECTANTLY MANAGING A WELL-DATED PREGNANCY PAST 41 WEEKS’ GESTATION?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD

(EDITORIAL; FEBRUARY 2019)

Membrane stripping can be problematic

The recent discussion on stripping membranes to facilitate the initiation of labor and delivery was intriguing. This practice was reviewed extensively during my training in the 1960s and abandoned when the results were disappointing or contradictory. Although the practice has been revitalized recently, I am concerned that potential risks and the absence of a recommended protocol of safeguards may allow new problems to develop.

In a metropolitan community where I provide consultative services, the only patients I see for evaluation of pregnancies beyond 40 to 41 weeks come from providers who are non-physicians. Apparently, they are concerned that they may have to turn their patients over to physician providers for interventions that they are not capable of doing. My advice to them is simply that nothing good happens after 40 to 41 weeks.

Well-grown babies may continue to grow if they are healthy, and they may incur greater risks of dystotic labor and delivery resulting in injury or the need for physician-administered surgical assistance. If, on the other hand, growth markedly diminishes or ceases, fetal harm or neonatal complications may occur through asphyxia, meconium aspiration, or trauma. In either event, physician-based assistance is strongly encouraged, as long as due diligence in determining gestational age has been done.

Promoting membrane stripping without having a protocol for ascertainment of risk factors is worrisome to me. In my opinion, large population studies that fail to demonstrate increased risks of infection may fail to demonstrate that membrane stripping may induce a degree of perinatal infection comparable to that of prolonged labor with multiple internal examinations with or without ultimate cesarean birth. Prior to considering membrane stripping as a strategy, one should recognize certain important considerations, namely:

- Patients most in need of active intervention may have the least favorable cervical findings, and as a result they are potentially at risk for the greatest discomfort.

- The frequency of group B streptococcal colonization of the vagina at term should be recognized, and a culture should be obtained immediately prior to intervention. When a culture is a positive, membrane stripping should be avoided, or at least a sober consideration of its use and appropriate antibiotic coverage should occur.

- Consider performing transvaginal ultrasonography prior to membrane stripping to exclude the possibility of a placental edge close enough to be encountered and compromised, with resultant hemorrhage in an outpatient venue ill equipped to provide adequate emergency support.

- The comparative effectiveness of other direct cervical conditioning therapies, including use of a Foley catheter or regional prostaglandin medication, has been well explored and found effective. Also, if one takes seriously the need for any intervention, admission to the hospital for overnight cervical conditioning allows for surveillance and avoids the patient experience of being sent home cramping, bleeding, brooding infection, and questioning her trust in the provider.

Continue to: I am concerned that the promotion...

I am concerned that the promotion of this potentially rather brutish practice by highly reputable advisors can result in its growing utilization by providers some of whom may be least qualified to apply proper judgment and sensitivity to its selection. In the most primitive of circumstances, it may have utility. Personally, however, I feel that medically based strategies initiated and monitored by professionals capable of dealing with any untoward departures from the expected results must be considered in the best traditions of what we do. The appeal of simplicity must not encourage the adoption of interventions that lack the proper application of thought and plan and whose only appeal is that of simplicity.

Richard P. Perkins, MD

Fort Myers, Florida; Stockton, California

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Priver for his excellent description of how to use forceps to resolve a persistent occiput posterior position. I also thank Dr. Perkins for his valuable comments and agree with him that in the United States among the options available for outpatient cervical ripening, misoprostol or a balloon are more commonly used than membrane stripping. Membrane stripping is an outpatient cervical ripening technique that is commonly used in the United Kingdom.

WHAT IS YOUR APPROACH TO THE PERSISTENT OCCIPUT POSTERIOR MALPOSITION?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD

(EDITORIAL; MARCH 2019)

A classic approach for managing fetal malposition

For those of us who trained and practiced obstetrics in the days of the 6% primary cesarean delivery (CD) rate, we never considered the management of the persistent occiput

- The cervix must be fully dilated.

- Dense regional anesthesia must be achieved.

- The vertex must have reached +1 station.

- The position must be clearly established, and this does not require anything other than the ability to palpate an ear, as it can be pointed only in one direction. If you feel ultrasonography is needed, be my guest.

- Use an obstetric lubricant to reduce resistance and minimize lacerations.

- While a trial of manual rotation is reasonable, it commonly will not succeed and requires that an operator’s hand be inserted rather than a slender and less traumatic device (forceps).

- Next, palpate the sagittal suture to determine whether the position is straight OP versus left OP or right OP. This should not be difficult unless the poor woman has gone through 2 or 3 hours of unproductive pushing, thereby creating caput.

- After proper forceps application is confirmed, gently apply upward pressure. This will make rotation easier.

- Dr. Irving’s recommendations notwithstanding, the forceps handles are not carried in a wide sweep. One should use Kielland’s forceps, which do not have a pelvic curve and were invented for this precise indication. The forceps are simply rotated.

- Try to avoid delivery as an OP, as this pulls a much larger diameter deflexed head through the pelvis and usually results in significant lacerations.

- Episiotomy is not always required if rotation has succeeded.

- Once descent to the outlet has been achieved, it is probably best to switch to a forceps with a pelvic curve to achieve easier extension.

- This should complete the delivery, but as a general rule, if more than minimal resistance is met in any of the above steps, abandon the procedure and move to CD.

- This process should result in at least a 70% success rate.

As is most likely understood by the current generation of obstetricians who appear to be satisfied with a 30% to 40% primary CD rate, the above reflects the views of a long-retired ObGyn (whose CD rate never exceeded 10%) and may be inappropriate for those who are not adequately trained in or comfortable with vaginal obstetrics.

David M. Priver, MD

San Diego, California

Continue to: HOW DO YOU FEEL ABOUT EXPECTANTLY MANAGING A WELL-DATED PREGNANCY PAST 41 WEEKS’ GESTATION?

HOW DO YOU FEEL ABOUT EXPECTANTLY MANAGING A WELL-DATED PREGNANCY PAST 41 WEEKS’ GESTATION?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD

(EDITORIAL; FEBRUARY 2019)

Membrane stripping can be problematic

The recent discussion on stripping membranes to facilitate the initiation of labor and delivery was intriguing. This practice was reviewed extensively during my training in the 1960s and abandoned when the results were disappointing or contradictory. Although the practice has been revitalized recently, I am concerned that potential risks and the absence of a recommended protocol of safeguards may allow new problems to develop.

In a metropolitan community where I provide consultative services, the only patients I see for evaluation of pregnancies beyond 40 to 41 weeks come from providers who are non-physicians. Apparently, they are concerned that they may have to turn their patients over to physician providers for interventions that they are not capable of doing. My advice to them is simply that nothing good happens after 40 to 41 weeks.

Well-grown babies may continue to grow if they are healthy, and they may incur greater risks of dystotic labor and delivery resulting in injury or the need for physician-administered surgical assistance. If, on the other hand, growth markedly diminishes or ceases, fetal harm or neonatal complications may occur through asphyxia, meconium aspiration, or trauma. In either event, physician-based assistance is strongly encouraged, as long as due diligence in determining gestational age has been done.

Promoting membrane stripping without having a protocol for ascertainment of risk factors is worrisome to me. In my opinion, large population studies that fail to demonstrate increased risks of infection may fail to demonstrate that membrane stripping may induce a degree of perinatal infection comparable to that of prolonged labor with multiple internal examinations with or without ultimate cesarean birth. Prior to considering membrane stripping as a strategy, one should recognize certain important considerations, namely:

- Patients most in need of active intervention may have the least favorable cervical findings, and as a result they are potentially at risk for the greatest discomfort.

- The frequency of group B streptococcal colonization of the vagina at term should be recognized, and a culture should be obtained immediately prior to intervention. When a culture is a positive, membrane stripping should be avoided, or at least a sober consideration of its use and appropriate antibiotic coverage should occur.

- Consider performing transvaginal ultrasonography prior to membrane stripping to exclude the possibility of a placental edge close enough to be encountered and compromised, with resultant hemorrhage in an outpatient venue ill equipped to provide adequate emergency support.

- The comparative effectiveness of other direct cervical conditioning therapies, including use of a Foley catheter or regional prostaglandin medication, has been well explored and found effective. Also, if one takes seriously the need for any intervention, admission to the hospital for overnight cervical conditioning allows for surveillance and avoids the patient experience of being sent home cramping, bleeding, brooding infection, and questioning her trust in the provider.

Continue to: I am concerned that the promotion...

I am concerned that the promotion of this potentially rather brutish practice by highly reputable advisors can result in its growing utilization by providers some of whom may be least qualified to apply proper judgment and sensitivity to its selection. In the most primitive of circumstances, it may have utility. Personally, however, I feel that medically based strategies initiated and monitored by professionals capable of dealing with any untoward departures from the expected results must be considered in the best traditions of what we do. The appeal of simplicity must not encourage the adoption of interventions that lack the proper application of thought and plan and whose only appeal is that of simplicity.

Richard P. Perkins, MD

Fort Myers, Florida; Stockton, California

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Priver for his excellent description of how to use forceps to resolve a persistent occiput posterior position. I also thank Dr. Perkins for his valuable comments and agree with him that in the United States among the options available for outpatient cervical ripening, misoprostol or a balloon are more commonly used than membrane stripping. Membrane stripping is an outpatient cervical ripening technique that is commonly used in the United Kingdom.

Flying acid zombies, poster face-lifts, and feces of champions

The flying dead

Just when you thought cicada infestations couldn’t get worse – the cicadas are now zombies on an acid trip.

West Virginia University researchers recently discovered that a fungus called Massopora, which has compounds similar to those found in psychedelic mushrooms, can infect cicadas and cause seriously weird behavior.

How weird, you ask? Well, male cicadas try to mate with everything they encounter, even though the fungus has eaten away their limbs … and their genitals. Talk about a bad trip.

It gets worse. These zombie-like cicadas are flying around and exposing their healthy brethren to the fungus. So, now we have to worry about potentially billions of these buggers becoming rotting, flying, hypersexual machines.

Makes a person really want to stay inside for the whole summer, perhaps in a fortified bunker. Just in case.

Also, for the curious: One of the study’s authors concedes that if a person were “motivated enough,” they might be able to get high off the cicada fungus. Not interested in finding out exactly how many cicadas you’d have to crunch on before you start tasting colors?

Poster do-over

It’s time to get ready for a revolution – and just in time for 4th of July. No, we’re not redeclaring independence from Britain. It’s something much, much more radical, at least to the scientific community.

Get ready for … the redesign of the science poster.

Mike Morrison, a doctoral student in psychology, has proposed a new way to present information at meetings that breathes new life into the tired poster design. While fascinating insights could be held on a poster, the reality of meetings and conferences is that people often skim over the posters they see, barely registering the information.

Morrison is taking advantage of the ever-present smartphone to ramp up the classic science poster to a new level. He proposes a format where the key research finding is smack in the middle, in big, readable language. Accompanying this is a QR code you can scan, which would take you to a page with the full details of the study.

Morrison tweeted out his idea, and it spread quickly through the scientific community, gaining traction from younger scientists and students who love the idea.

We’re in the age of remakes now – in which classics are reinvented for a new audience. It’s time the science poster got a face-lift, too.

Running a marathon, one Veillonella at a time

What’s the difference between an elite athlete and a person who’s out of juice after running for 30 seconds?

Well, many things, we’re sure. A proper diet, rigorous training, not spending 12 hours a day sitting behind a computer screen. But just to add insult to injury, according to a study published in Nature Medicine, athletes even poop better than us normal people.

That may require a bit of explanation. A group of researchers from Harvard University, Boston, analyzed stool samples from elite marathon runners before and just after they participated in the 2015 Boston Marathon. They found that, following the race, the athletes had significantly higher amounts of Veillonella in their microbiota. This bacteria breaks down lactic acid, which is made during intense exercise and causes muscle fatigue and stress.

Naturally, the next step was to take that bacteria, feed it to mice, then get them running on a treadmill.

While not every mouse fed Veillonella saw increased performance, on average, mice that received the bacteria saw a 13% improvement over their non–Veillonella enhanced friends.

The researchers noted that this sort of probiotic treatment could be useful to patients with metabolic diseases, such as diabetes. Plus, there’s the obvious benefit to athletes. We look forward to hearing advertisements swearing by Veillonella-infused Wheaties, the true breakfast of champions.

Put a little boredom in your life

Is your job an endless, soul-sucking vortex of dreariness? Do you stare at the wall for hours at a time while you’re at work, wishing you had something better to do? Do you look forward to leaving early to go to the dentist? [Editor query: What does this have to do with health care? LOTME: You’ll see. We’re building dramatic tension.]

Did you answer yes to any of these questions? Way to go! You’ve taken the first step on the road to creativity. [Still waiting. We’re almost there.]

A recent study examined the effects of boredom by assigning people to either a really boring task – sorting a bowl of red and green beans by color for 30 minutes using only one hand – or a nonboring art project using paper, glue, and, of course, beans. [What’s with the beans? It’s not our fault they used beans.]

The next task was the same for both groups: Come up with some reasons for being late for work and think of ideas for a new product by a hypothetical company. The answers were graded on their uniqueness, and the bean-sorting group had more creative ideas than did the art-project group.

The point is, ladies and gentlemen, that boredom is good. Boredom is right. Boredom works. [A Gordon Gekko reference? Couldn’t you find something from this century? No.]

By now you’re probably wondering: “But how can I get one of those really boring jobs? After all, I’m a doctor. I heal the sick and care for the needy. My work is way too interesting to inspire true creativity.” Have you ever considered writing a medical humor column?

[Note to readers: We’ve pulled the staff away from their building blocks and crayons and given them a timeout. Hopefully things will be a little better by next week.]

The flying dead

Just when you thought cicada infestations couldn’t get worse – the cicadas are now zombies on an acid trip.

West Virginia University researchers recently discovered that a fungus called Massopora, which has compounds similar to those found in psychedelic mushrooms, can infect cicadas and cause seriously weird behavior.

How weird, you ask? Well, male cicadas try to mate with everything they encounter, even though the fungus has eaten away their limbs … and their genitals. Talk about a bad trip.

It gets worse. These zombie-like cicadas are flying around and exposing their healthy brethren to the fungus. So, now we have to worry about potentially billions of these buggers becoming rotting, flying, hypersexual machines.

Makes a person really want to stay inside for the whole summer, perhaps in a fortified bunker. Just in case.

Also, for the curious: One of the study’s authors concedes that if a person were “motivated enough,” they might be able to get high off the cicada fungus. Not interested in finding out exactly how many cicadas you’d have to crunch on before you start tasting colors?

Poster do-over