User login

Discharge Medical Complexity, Change in Medical Complexity and Pediatric 30-day Readmission

Hospitalizations are disruptive, stressful, and costly for patients and families.1-5 Hospital readmissions subject families to the additional morbidity inherent to hospitalization and place patients at additional risk of hospital-acquired conditions or other harm.6-9 In pediatrics, hospital readmissions are common for specific conditions;10 with rates varying across institutions;10,11 and as many as one-third of unplanned pediatric readmissions are potentially preventable.12

Reducing pediatric readmissions requires a deeper understanding of the mechanisms through which readmissions occur. Medical complexity—specifically chronic conditions and use of medical technology—is associated with increased risk of readmission.13,14 Polypharmacy at discharge has also been associated with readmission.15,16 However, prior studies on polypharmacy and readmission risk examined the count of total medications and did not consider the nuances of scheduled versus as-needed medications, or the frequency of doses. These nuances may be critical to caregivers as discharge medical complexity can be overwhelming, even in diagnoses which are not traditionally considered complex.17 Finally, of potentially greater importance than medical complexity at discharge is a change in medical complexity during a hospitalization—for example, new diagnoses or new technologies that require additional education in hospital and management at home.

We sought to further understand the relationship between discharge medical complexity and readmission risk with regards to polypharmacy and home healthcare referrals at discharge. Specifically, we hypothesized that a change in medical complexity during an admission—ie, a new chronic diagnosis or new technology—would be a more prominent risk factor for readmission than discharge complexity alone. We examined these factors in the context of length of stay (LOS) since this is a marker of in-hospital severity of illness and a potentially modifiable function of time allowed for in-hospital teaching and discharge preparation.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective, case-control study of pediatric hospitalizations at one tertiary care children’s hospital. Children <18 years were eligible for inclusion. Normal birth hospitalizations were excluded. We randomly selected one hospitalization from each child as the index visit. We identified cases, hospitalizations at C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital between 2008 and 2012 with a subsequent unplanned 30-day readmission,18 and matched them one to one with hospitalizations at the same hospital during the same period without subsequent readmission. We matched cases to controls based on the month of admission to account for seasonality of certain illnesses. We also matched on distance and direction from the hospital to the patient’s home to account for the potential to have readmissions to other institutions. We utilized both distance and direction recognizing that a family living 30 miles in one direction would be closer to an urban area with access to more facilities, as opposed to 30 miles in another direction in a rural area without additional access. We subsequently performed medical record review to abstract relevant covariates.

Primary Predictors

Medical Complexity Models (Models 1 and 2):

We evaluated three attributes of discharge medical complexity abstracted by medical record review—discharge medications, technology assistance (ie, tracheostomy, cerebral spinal fluid ventricular shunt, enteral feeding tube, central line), and the need for home healthcare after discharge. We counted discharge medications based on the number of medications listed on the discharge summary separated into scheduled or as needed.19 We also considered the number of scheduled doses to be administered in a 24-hour period (see Appendix methods for more information on counting discharge medications). For assistance by technology, we considered the presence of tracheostomy, cerebral spinal fluid ventricular shunt, enteral feeding tube, and central lines. While we describe these technologies separately, for multivariable analyses we considered the presence of any of the four types of technology.

Change in Medical Complexity Models (Models 3 and 4)

We examined two aspects of change in medical complexity—the presence of a new complex chronic condition (CCC)20 diagnosed during the hospitalization, and a new reliance on medical technology. The presence of new CCC was determined by comparing discharge diagnoses to past medical history abstracted by medical record review. A new CCC was defined as any complex chronic condition that was captured in the discharge diagnoses but was not evident in the past medical history. By definition, all CCCs coded during birth hospitalization (eg, at discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit) were assigned to “new” CCC. We calculated a kappa statistic to determine interrater reliability in determining the designation of new CCC. A sensitivity analysis examining these birth CCCs was also performed comparing no new CCC, new CCC, and new CCC after birth hospitalization. The methods appendix provides additional information on considering new CCCs. New technology, abstracted from chart review, was defined as technology placed during hospitalization that remained in place at discharge. If a child with existing technology had additional technology placed during the hospitalization (eg, a new tracheostomy in a child with a previously placed enteral feeding tube), the encounter was considered as having new technology placed.

Covariates

We created different sets of multivariable models to account for patient/hospitalization characteristics.

Statistical Analysis

A review of 600 cases and 600 controls yields 89% power to detect statistical significance for covariates with an odds ratio of 1.25 (β = 0.22) if the candidate covariate has low to moderate correlation with other covariates (<0.3). If a candidate covariate has a moderate correlation with other covariates (0.6), we have 89% power to detect an odds ratio of 1.35 (β = 0.30).21 We calculated odds of 30-days unplanned readmission using conditional logistic regression to account for matched case-control design. All the analyses were performed using STATA 13 (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

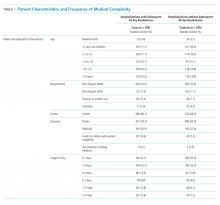

Of the 41,422 eligible index hospitalizations during the study period, 9.4% resulted in a 30-day unplanned readmission. After randomly selecting one hospitalization per child, there were 781 eligible cases. We subsequent matched all but one eligible case to a control. We randomly selected encounters for medical record review, reviewing a total of 1,212 encounters. After excluding pairs with incomplete records, we included 595 cases and 595 controls in this analysis (Figure). Patient/hospitalization characteristics are displayed in Table 1. The most frequent primary discharge diagnoses are displayed in Appendix Table 1.

Models of Medical Complexity at Discharge

Polypharmacy after discharge was common for both readmitted and nonreadmitted patients. Children who experienced unplanned readmission in 30 days were discharged with a median of four different scheduled medications (interquartile range [IQR] 2,7) which translated into a median of six (IQR 3,12) scheduled doses in a 24-hour period. In comparison, children without an unplanned readmission had a median of two different scheduled medications (IQR 1,3) with a median of three (IQR 0,7) scheduled doses in a 24-hour period. Medical technology was more common in case children (42%) than in control children (14%). Central lines and enteral tubes were the most common forms of medical technology in both cases and controls. Home health referral was common in both cases (44%) and controls (23%; Table 1).

In Model 1 (adjusting only for patient characteristics; Table 3), being discharged on two or more scheduled medications was associated with higher odds of readmission compared to being discharged without medications, with additional medications associated with even higher odds of readmission. Children with any technology had higher odds of readmission than children without medical technology. Likewise, home healthcare visits after discharge were associated with elevated odds of readmission in multivariable analyses without LOS. However, after adding LOS to the model (Model 2), home healthcare visits were no longer significantly associated with readmission.

Change in Medical Complexity Models

The adjudication of new CCCs had good reliability (Κ = 0.72). New CCCs occurred in 18% and new technologies occurred in 17% of cases. Comparatively, new CCCs occurred in 10% and new technologies in 7% of hospitalizations in control children (Table 1). In bivariate analyses, both aspects of change in medical complexity were associated with higher odds of readmission (Table 2). In multivariate analysis with patient characteristics (Model 3; Table 3), all aspects of change in complexity were associated with elevated odds of readmission. A new CCC was associated with higher odds of readmission (adjusted OR (AOR) 1.75, 95% CI: 1.11-2.75) as was new technology during admission (AOR 1.84, 95%CI: 1.09-3.10). Furthermore, the odds of readmission for medical complexity variables (polypharmacy and home healthcare need) remained largely unchanged when adding the change in medical complexity variables (ie, comparing Model 1 and Model 3). However, when accounting for LOS (Model 4), neither the acquisition of a new CCC nor the addition of new technology was associated with readmission. The most common form of new technology was central line followed by nonsurgically placed enteral tube (Appendix Table 2). Finally, in sensitivity analyses (results not detailed), separating new CCC acquired at birth and new CCCs in nonbirth hospitalizations, compared to hospitalizations with no new CCC, yielded similar results as the primary analyses.

DISCUSSION

We examined multiple attributes of polypharmacy—the number of scheduled medications, number of as-needed medications, and number of scheduled doses per 24 hours. Interestingly, only the scheduled medications (count of medication and number of doses) were associated with elevated readmission risk. As-needed medications have heterogeneity in the level of importance from critical (eg, seizure rescue) to discretionary (eg, antipyretics, creams). The burden of managing these types of medications may still be high (ie, parents must decide when to administer a critical medication); however, this burden does not translate into increased readmission risk in this population.

Not surprisingly, greater medical complexity—as defined by higher numbers of scheduled discharge medications and technology assistance—is associated with 30-day readmission risk. Our analyses do not allow us to determine how much of the increased risk is due to additional care burden and risks of polypharmacy versus the inherent increase in complexity and severity of illness for which polypharmacy is a marker. Tailoring discharge regimens to the realities of daily life, with the goal of “minimally disruptive medicine”22,23 (eg, integrating manageable discharge medication routines into school and work schedules), is not a common feature of pediatric discharge planning. For adult patients with complex medical conditions, tailoring medication regimens in a minimally disruptive way is known to improve outcomes.24 Similarly, adopting minimally disruptive techniques to integrate the polypharmacy inherent in discharge could potentially mitigate some of the readmission risks for children and adolescents.

Contrary to our hypothesis, new technologies and new diagnoses did not confer additional readmission risk when accounting for LOS and patient characteristics. One potential explanation is varying risks conveyed by different types of new technologies placed during hospitalization. Central lines, the most common form of new technology, is associated with higher odds of reutilization in unadjusted analyses. However, the second most common form of new technology, nonsurgically placed enteral feeding tube, was not. Further analyses of the differential effects of new technology should be further examined in larger datasets. Additionally, the lack of additional readmission risk from new technology may relate to additional teaching and support provided to families of patients undergoing unfamiliar procedures offsets the risks inherent of greater complexity. If so, it may be that the more intensive teaching and postdischarge support provided to families with new technology or a new diagnosis could be replicated through refresher teaching during hospitalizations, when a patient’s state of health is status quo for the family (ie, the child was admitted and discharged with the same technology and diagnoses). This notion is supported by prior work that demonstrated successful readmission reduction interventions for children with chronic conditions often rely on enhanced education or coaching.25,26

We elected to present models both with and without LOS as a confounder because it is a potentially modifiable attribute of hospitalization. Change in medical complexity aspects were significantly associated with readmission in multivariable models without LOS. However, with the addition of LOS, they were no longer significant. Thus, the readmission risk of new complexity is accounted for by the readmission risk inherent in a longer LOS. This finding prompts additional questions that merit further study: is it that LOS is a general marker for heightened complexity, or is it that a longer LOS can modify readmission risk through additional in-hospital care and time for enhanced education?

Our study has several strengths. We were able to discern true complexity at the time of discharge through medical record review. For example, if a child had a peripherally inserted central catheter placed during hospitalization, it cannot be ascertained through administrative data without medical record review if the technology was removed or in place at discharge. Likewise, medical record review allows for identification of medical technology which is not surgically implanted (eg, nasogastric feeding tubes). Given the “fog” families report as part of their in-hospital experience and its threats to education and postdischarge contingency planning,17 we felt it important to evaluate medical technology regardless of whether or not it was surgically placed. Additionally, the more detailed and nuanced understanding gained of polypharmacy burden can better inform both risk prediction models and interventions to improve the transition from hospital to home.

This study

CONCLUSION

Medical complexity at discharge is associated with pediatric readmission risk. Contrary to our hypothesis, the addition of new technologies and new CCC diagnoses are not associated with pediatric readmission, after accounting for patient and hospitalization factors including LOS. The dynamics of LOS as a risk factor for readmission for children with medical complexity are likely multifaceted and merit further investigation in a multi-institutional study.

Disclosures

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1K08HS204735-01A1) and a grant from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation.

1. Diaz-Caneja A, Gledhill J, Weaver T, Nadel S, Garralda E. A child’s admission to hospital: a qualitative study examining the experiences of parents. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31(9):1248-1254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-005-2728-8.

2. Lapillonne A, Regnault A, Gournay V, et al. Impact on parents of bronchiolitis hospitalization of full-term, preterm and congenital heart disease infants. BMC Pediatrics. 2012;12:171. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-12-171.

3. Leader S, Jacobson P, Marcin J, Vardis R, Sorrentino M, Murray D. A method for identifying the financial burden of hospitalized infants on families. Value Health. 2002;5(1):55-59. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1524-4733.2002.51076.x.

4. Leidy NK, Margolis MK, Marcin JP, et al. The impact of severe respiratory syncytial virus on the child, caregiver, and family during hospitalization and recovery. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):1536-1546. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-1149.

5. Rennick JE, Johnston CC, Dougherty G, Platt R, Ritchie JA. Children’s psychological responses after critical illness and exposure to invasive technology. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23(3):133-144. PubMed

6. Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):370-376. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199102073240604.

7. Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

8. Landrigan CP, Parry GJ, Bones CB, Hackbarth AD, Goldmann DA, Sharek PJ. Temporal trends in rates of patient harm resulting from medical care. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(22):2124-2134. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1004404.

9. Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(13):1198-1208. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1306801.

10. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.188351.

11. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Penaloza R, et al. Measuring hospital quality using pediatric readmission and revisit rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429-436. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3527.

12. Toomey SL, Peltz A, Loren S, et al. Potentially preventable 30-day hospital readmissions at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):pii: e20154182. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4182.

13. Bucholz EM, Gay JC, Hall M, Harris M, Berry JG. Timing and causes of common pediatric readmissions. J Pediatr. 2018;200:240-248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.04.044.

14. Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682-690. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.122.

15. Winer JC, Aragona E, Fields AI, Stockwell DC. Comparison of clinical risk factors among pediatric patients with single admission, multiple admissions (without any 7-day readmissions), and 7-day readmission. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(3):119-125. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2015-0110.

16. Brittan MS, Martin S, Anderson L, Moss A, Torok MR. An electronic health record tool designed to improve pediatric hospital discharge has low predictive utility for readmissions. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):779-782. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3043.

17. Solan LG, Beck AF, Brunswick SA, et al. The family perspective on hospital to home transitions: a qualitative study. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):e1539-e1549. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2098.

18. Auger KA, Mueller EL, Weinberg SH, et al. A validated method for identifying unplanned pediatric readmission. J Pediatr. 2016;170:105-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.11.051.

19. Auger KA, Shah SS, Davis MD, Brady PW. Counting the Ways to Count Medications: The Challenges of Defining Pediatric Polypharmacy. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(8):506-507. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3213.

20. Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatrics. 2014;14:199. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-199.

21. Hsieh FY. Sample size tables for logistic regression. Stat Med. 1989;8(7):795-802. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4780080704.

22. May C, Montori VM, Mair FS. We need minimally disruptive medicine. BMJ. 2009;339:b2803. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2803.

23. Leppin AL, Montori VM, Gionfriddo MR. Minimally disruptive medicine: a pragmatically comprehensive model for delivering care to patients with multiple chronic conditions. Healthcare (Basel). 2015;3(1):50-63. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare3010050.

24. Serrano V, Spencer-Bonilla G, Boehmer KR, Montori VM. Minimally disruptive medicine for patients with diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2017;17(11):104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-017-0935-7.

25. Auger KA, Kenyon CC, Feudtner C, Davis MM. Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2013;9(4):251-260. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2134.

26. Coller RJ, Klitzner TS, Lerner CF, et al. Complex care hospital use and postdischarge coaching: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2):pii: e20174278. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-4278.

27. Hain PD, Gay JC, Berutti TW, Whitney GM, Wang W, Saville BR. Preventability of early readmissions at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e171-e181. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0820.

28. Auger KA, Teufel RJ, 2nd, Harris JM, 2nd, et al. Children’s hospital characteristics and readmission metrics. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1720.

29. Gay JC, Agrawal R, Auger KA, et al. Rates and impact of potentially preventable readmissions at children’s hospitals. J Pediatr. 2015;166(3):613-619 e615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.10.052.

Hospitalizations are disruptive, stressful, and costly for patients and families.1-5 Hospital readmissions subject families to the additional morbidity inherent to hospitalization and place patients at additional risk of hospital-acquired conditions or other harm.6-9 In pediatrics, hospital readmissions are common for specific conditions;10 with rates varying across institutions;10,11 and as many as one-third of unplanned pediatric readmissions are potentially preventable.12

Reducing pediatric readmissions requires a deeper understanding of the mechanisms through which readmissions occur. Medical complexity—specifically chronic conditions and use of medical technology—is associated with increased risk of readmission.13,14 Polypharmacy at discharge has also been associated with readmission.15,16 However, prior studies on polypharmacy and readmission risk examined the count of total medications and did not consider the nuances of scheduled versus as-needed medications, or the frequency of doses. These nuances may be critical to caregivers as discharge medical complexity can be overwhelming, even in diagnoses which are not traditionally considered complex.17 Finally, of potentially greater importance than medical complexity at discharge is a change in medical complexity during a hospitalization—for example, new diagnoses or new technologies that require additional education in hospital and management at home.

We sought to further understand the relationship between discharge medical complexity and readmission risk with regards to polypharmacy and home healthcare referrals at discharge. Specifically, we hypothesized that a change in medical complexity during an admission—ie, a new chronic diagnosis or new technology—would be a more prominent risk factor for readmission than discharge complexity alone. We examined these factors in the context of length of stay (LOS) since this is a marker of in-hospital severity of illness and a potentially modifiable function of time allowed for in-hospital teaching and discharge preparation.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective, case-control study of pediatric hospitalizations at one tertiary care children’s hospital. Children <18 years were eligible for inclusion. Normal birth hospitalizations were excluded. We randomly selected one hospitalization from each child as the index visit. We identified cases, hospitalizations at C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital between 2008 and 2012 with a subsequent unplanned 30-day readmission,18 and matched them one to one with hospitalizations at the same hospital during the same period without subsequent readmission. We matched cases to controls based on the month of admission to account for seasonality of certain illnesses. We also matched on distance and direction from the hospital to the patient’s home to account for the potential to have readmissions to other institutions. We utilized both distance and direction recognizing that a family living 30 miles in one direction would be closer to an urban area with access to more facilities, as opposed to 30 miles in another direction in a rural area without additional access. We subsequently performed medical record review to abstract relevant covariates.

Primary Predictors

Medical Complexity Models (Models 1 and 2):

We evaluated three attributes of discharge medical complexity abstracted by medical record review—discharge medications, technology assistance (ie, tracheostomy, cerebral spinal fluid ventricular shunt, enteral feeding tube, central line), and the need for home healthcare after discharge. We counted discharge medications based on the number of medications listed on the discharge summary separated into scheduled or as needed.19 We also considered the number of scheduled doses to be administered in a 24-hour period (see Appendix methods for more information on counting discharge medications). For assistance by technology, we considered the presence of tracheostomy, cerebral spinal fluid ventricular shunt, enteral feeding tube, and central lines. While we describe these technologies separately, for multivariable analyses we considered the presence of any of the four types of technology.

Change in Medical Complexity Models (Models 3 and 4)

We examined two aspects of change in medical complexity—the presence of a new complex chronic condition (CCC)20 diagnosed during the hospitalization, and a new reliance on medical technology. The presence of new CCC was determined by comparing discharge diagnoses to past medical history abstracted by medical record review. A new CCC was defined as any complex chronic condition that was captured in the discharge diagnoses but was not evident in the past medical history. By definition, all CCCs coded during birth hospitalization (eg, at discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit) were assigned to “new” CCC. We calculated a kappa statistic to determine interrater reliability in determining the designation of new CCC. A sensitivity analysis examining these birth CCCs was also performed comparing no new CCC, new CCC, and new CCC after birth hospitalization. The methods appendix provides additional information on considering new CCCs. New technology, abstracted from chart review, was defined as technology placed during hospitalization that remained in place at discharge. If a child with existing technology had additional technology placed during the hospitalization (eg, a new tracheostomy in a child with a previously placed enteral feeding tube), the encounter was considered as having new technology placed.

Covariates

We created different sets of multivariable models to account for patient/hospitalization characteristics.

Statistical Analysis

A review of 600 cases and 600 controls yields 89% power to detect statistical significance for covariates with an odds ratio of 1.25 (β = 0.22) if the candidate covariate has low to moderate correlation with other covariates (<0.3). If a candidate covariate has a moderate correlation with other covariates (0.6), we have 89% power to detect an odds ratio of 1.35 (β = 0.30).21 We calculated odds of 30-days unplanned readmission using conditional logistic regression to account for matched case-control design. All the analyses were performed using STATA 13 (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Of the 41,422 eligible index hospitalizations during the study period, 9.4% resulted in a 30-day unplanned readmission. After randomly selecting one hospitalization per child, there were 781 eligible cases. We subsequent matched all but one eligible case to a control. We randomly selected encounters for medical record review, reviewing a total of 1,212 encounters. After excluding pairs with incomplete records, we included 595 cases and 595 controls in this analysis (Figure). Patient/hospitalization characteristics are displayed in Table 1. The most frequent primary discharge diagnoses are displayed in Appendix Table 1.

Models of Medical Complexity at Discharge

Polypharmacy after discharge was common for both readmitted and nonreadmitted patients. Children who experienced unplanned readmission in 30 days were discharged with a median of four different scheduled medications (interquartile range [IQR] 2,7) which translated into a median of six (IQR 3,12) scheduled doses in a 24-hour period. In comparison, children without an unplanned readmission had a median of two different scheduled medications (IQR 1,3) with a median of three (IQR 0,7) scheduled doses in a 24-hour period. Medical technology was more common in case children (42%) than in control children (14%). Central lines and enteral tubes were the most common forms of medical technology in both cases and controls. Home health referral was common in both cases (44%) and controls (23%; Table 1).

In Model 1 (adjusting only for patient characteristics; Table 3), being discharged on two or more scheduled medications was associated with higher odds of readmission compared to being discharged without medications, with additional medications associated with even higher odds of readmission. Children with any technology had higher odds of readmission than children without medical technology. Likewise, home healthcare visits after discharge were associated with elevated odds of readmission in multivariable analyses without LOS. However, after adding LOS to the model (Model 2), home healthcare visits were no longer significantly associated with readmission.

Change in Medical Complexity Models

The adjudication of new CCCs had good reliability (Κ = 0.72). New CCCs occurred in 18% and new technologies occurred in 17% of cases. Comparatively, new CCCs occurred in 10% and new technologies in 7% of hospitalizations in control children (Table 1). In bivariate analyses, both aspects of change in medical complexity were associated with higher odds of readmission (Table 2). In multivariate analysis with patient characteristics (Model 3; Table 3), all aspects of change in complexity were associated with elevated odds of readmission. A new CCC was associated with higher odds of readmission (adjusted OR (AOR) 1.75, 95% CI: 1.11-2.75) as was new technology during admission (AOR 1.84, 95%CI: 1.09-3.10). Furthermore, the odds of readmission for medical complexity variables (polypharmacy and home healthcare need) remained largely unchanged when adding the change in medical complexity variables (ie, comparing Model 1 and Model 3). However, when accounting for LOS (Model 4), neither the acquisition of a new CCC nor the addition of new technology was associated with readmission. The most common form of new technology was central line followed by nonsurgically placed enteral tube (Appendix Table 2). Finally, in sensitivity analyses (results not detailed), separating new CCC acquired at birth and new CCCs in nonbirth hospitalizations, compared to hospitalizations with no new CCC, yielded similar results as the primary analyses.

DISCUSSION

We examined multiple attributes of polypharmacy—the number of scheduled medications, number of as-needed medications, and number of scheduled doses per 24 hours. Interestingly, only the scheduled medications (count of medication and number of doses) were associated with elevated readmission risk. As-needed medications have heterogeneity in the level of importance from critical (eg, seizure rescue) to discretionary (eg, antipyretics, creams). The burden of managing these types of medications may still be high (ie, parents must decide when to administer a critical medication); however, this burden does not translate into increased readmission risk in this population.

Not surprisingly, greater medical complexity—as defined by higher numbers of scheduled discharge medications and technology assistance—is associated with 30-day readmission risk. Our analyses do not allow us to determine how much of the increased risk is due to additional care burden and risks of polypharmacy versus the inherent increase in complexity and severity of illness for which polypharmacy is a marker. Tailoring discharge regimens to the realities of daily life, with the goal of “minimally disruptive medicine”22,23 (eg, integrating manageable discharge medication routines into school and work schedules), is not a common feature of pediatric discharge planning. For adult patients with complex medical conditions, tailoring medication regimens in a minimally disruptive way is known to improve outcomes.24 Similarly, adopting minimally disruptive techniques to integrate the polypharmacy inherent in discharge could potentially mitigate some of the readmission risks for children and adolescents.

Contrary to our hypothesis, new technologies and new diagnoses did not confer additional readmission risk when accounting for LOS and patient characteristics. One potential explanation is varying risks conveyed by different types of new technologies placed during hospitalization. Central lines, the most common form of new technology, is associated with higher odds of reutilization in unadjusted analyses. However, the second most common form of new technology, nonsurgically placed enteral feeding tube, was not. Further analyses of the differential effects of new technology should be further examined in larger datasets. Additionally, the lack of additional readmission risk from new technology may relate to additional teaching and support provided to families of patients undergoing unfamiliar procedures offsets the risks inherent of greater complexity. If so, it may be that the more intensive teaching and postdischarge support provided to families with new technology or a new diagnosis could be replicated through refresher teaching during hospitalizations, when a patient’s state of health is status quo for the family (ie, the child was admitted and discharged with the same technology and diagnoses). This notion is supported by prior work that demonstrated successful readmission reduction interventions for children with chronic conditions often rely on enhanced education or coaching.25,26

We elected to present models both with and without LOS as a confounder because it is a potentially modifiable attribute of hospitalization. Change in medical complexity aspects were significantly associated with readmission in multivariable models without LOS. However, with the addition of LOS, they were no longer significant. Thus, the readmission risk of new complexity is accounted for by the readmission risk inherent in a longer LOS. This finding prompts additional questions that merit further study: is it that LOS is a general marker for heightened complexity, or is it that a longer LOS can modify readmission risk through additional in-hospital care and time for enhanced education?

Our study has several strengths. We were able to discern true complexity at the time of discharge through medical record review. For example, if a child had a peripherally inserted central catheter placed during hospitalization, it cannot be ascertained through administrative data without medical record review if the technology was removed or in place at discharge. Likewise, medical record review allows for identification of medical technology which is not surgically implanted (eg, nasogastric feeding tubes). Given the “fog” families report as part of their in-hospital experience and its threats to education and postdischarge contingency planning,17 we felt it important to evaluate medical technology regardless of whether or not it was surgically placed. Additionally, the more detailed and nuanced understanding gained of polypharmacy burden can better inform both risk prediction models and interventions to improve the transition from hospital to home.

This study

CONCLUSION

Medical complexity at discharge is associated with pediatric readmission risk. Contrary to our hypothesis, the addition of new technologies and new CCC diagnoses are not associated with pediatric readmission, after accounting for patient and hospitalization factors including LOS. The dynamics of LOS as a risk factor for readmission for children with medical complexity are likely multifaceted and merit further investigation in a multi-institutional study.

Disclosures

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1K08HS204735-01A1) and a grant from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation.

Hospitalizations are disruptive, stressful, and costly for patients and families.1-5 Hospital readmissions subject families to the additional morbidity inherent to hospitalization and place patients at additional risk of hospital-acquired conditions or other harm.6-9 In pediatrics, hospital readmissions are common for specific conditions;10 with rates varying across institutions;10,11 and as many as one-third of unplanned pediatric readmissions are potentially preventable.12

Reducing pediatric readmissions requires a deeper understanding of the mechanisms through which readmissions occur. Medical complexity—specifically chronic conditions and use of medical technology—is associated with increased risk of readmission.13,14 Polypharmacy at discharge has also been associated with readmission.15,16 However, prior studies on polypharmacy and readmission risk examined the count of total medications and did not consider the nuances of scheduled versus as-needed medications, or the frequency of doses. These nuances may be critical to caregivers as discharge medical complexity can be overwhelming, even in diagnoses which are not traditionally considered complex.17 Finally, of potentially greater importance than medical complexity at discharge is a change in medical complexity during a hospitalization—for example, new diagnoses or new technologies that require additional education in hospital and management at home.

We sought to further understand the relationship between discharge medical complexity and readmission risk with regards to polypharmacy and home healthcare referrals at discharge. Specifically, we hypothesized that a change in medical complexity during an admission—ie, a new chronic diagnosis or new technology—would be a more prominent risk factor for readmission than discharge complexity alone. We examined these factors in the context of length of stay (LOS) since this is a marker of in-hospital severity of illness and a potentially modifiable function of time allowed for in-hospital teaching and discharge preparation.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective, case-control study of pediatric hospitalizations at one tertiary care children’s hospital. Children <18 years were eligible for inclusion. Normal birth hospitalizations were excluded. We randomly selected one hospitalization from each child as the index visit. We identified cases, hospitalizations at C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital between 2008 and 2012 with a subsequent unplanned 30-day readmission,18 and matched them one to one with hospitalizations at the same hospital during the same period without subsequent readmission. We matched cases to controls based on the month of admission to account for seasonality of certain illnesses. We also matched on distance and direction from the hospital to the patient’s home to account for the potential to have readmissions to other institutions. We utilized both distance and direction recognizing that a family living 30 miles in one direction would be closer to an urban area with access to more facilities, as opposed to 30 miles in another direction in a rural area without additional access. We subsequently performed medical record review to abstract relevant covariates.

Primary Predictors

Medical Complexity Models (Models 1 and 2):

We evaluated three attributes of discharge medical complexity abstracted by medical record review—discharge medications, technology assistance (ie, tracheostomy, cerebral spinal fluid ventricular shunt, enteral feeding tube, central line), and the need for home healthcare after discharge. We counted discharge medications based on the number of medications listed on the discharge summary separated into scheduled or as needed.19 We also considered the number of scheduled doses to be administered in a 24-hour period (see Appendix methods for more information on counting discharge medications). For assistance by technology, we considered the presence of tracheostomy, cerebral spinal fluid ventricular shunt, enteral feeding tube, and central lines. While we describe these technologies separately, for multivariable analyses we considered the presence of any of the four types of technology.

Change in Medical Complexity Models (Models 3 and 4)

We examined two aspects of change in medical complexity—the presence of a new complex chronic condition (CCC)20 diagnosed during the hospitalization, and a new reliance on medical technology. The presence of new CCC was determined by comparing discharge diagnoses to past medical history abstracted by medical record review. A new CCC was defined as any complex chronic condition that was captured in the discharge diagnoses but was not evident in the past medical history. By definition, all CCCs coded during birth hospitalization (eg, at discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit) were assigned to “new” CCC. We calculated a kappa statistic to determine interrater reliability in determining the designation of new CCC. A sensitivity analysis examining these birth CCCs was also performed comparing no new CCC, new CCC, and new CCC after birth hospitalization. The methods appendix provides additional information on considering new CCCs. New technology, abstracted from chart review, was defined as technology placed during hospitalization that remained in place at discharge. If a child with existing technology had additional technology placed during the hospitalization (eg, a new tracheostomy in a child with a previously placed enteral feeding tube), the encounter was considered as having new technology placed.

Covariates

We created different sets of multivariable models to account for patient/hospitalization characteristics.

Statistical Analysis

A review of 600 cases and 600 controls yields 89% power to detect statistical significance for covariates with an odds ratio of 1.25 (β = 0.22) if the candidate covariate has low to moderate correlation with other covariates (<0.3). If a candidate covariate has a moderate correlation with other covariates (0.6), we have 89% power to detect an odds ratio of 1.35 (β = 0.30).21 We calculated odds of 30-days unplanned readmission using conditional logistic regression to account for matched case-control design. All the analyses were performed using STATA 13 (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Of the 41,422 eligible index hospitalizations during the study period, 9.4% resulted in a 30-day unplanned readmission. After randomly selecting one hospitalization per child, there were 781 eligible cases. We subsequent matched all but one eligible case to a control. We randomly selected encounters for medical record review, reviewing a total of 1,212 encounters. After excluding pairs with incomplete records, we included 595 cases and 595 controls in this analysis (Figure). Patient/hospitalization characteristics are displayed in Table 1. The most frequent primary discharge diagnoses are displayed in Appendix Table 1.

Models of Medical Complexity at Discharge

Polypharmacy after discharge was common for both readmitted and nonreadmitted patients. Children who experienced unplanned readmission in 30 days were discharged with a median of four different scheduled medications (interquartile range [IQR] 2,7) which translated into a median of six (IQR 3,12) scheduled doses in a 24-hour period. In comparison, children without an unplanned readmission had a median of two different scheduled medications (IQR 1,3) with a median of three (IQR 0,7) scheduled doses in a 24-hour period. Medical technology was more common in case children (42%) than in control children (14%). Central lines and enteral tubes were the most common forms of medical technology in both cases and controls. Home health referral was common in both cases (44%) and controls (23%; Table 1).

In Model 1 (adjusting only for patient characteristics; Table 3), being discharged on two or more scheduled medications was associated with higher odds of readmission compared to being discharged without medications, with additional medications associated with even higher odds of readmission. Children with any technology had higher odds of readmission than children without medical technology. Likewise, home healthcare visits after discharge were associated with elevated odds of readmission in multivariable analyses without LOS. However, after adding LOS to the model (Model 2), home healthcare visits were no longer significantly associated with readmission.

Change in Medical Complexity Models

The adjudication of new CCCs had good reliability (Κ = 0.72). New CCCs occurred in 18% and new technologies occurred in 17% of cases. Comparatively, new CCCs occurred in 10% and new technologies in 7% of hospitalizations in control children (Table 1). In bivariate analyses, both aspects of change in medical complexity were associated with higher odds of readmission (Table 2). In multivariate analysis with patient characteristics (Model 3; Table 3), all aspects of change in complexity were associated with elevated odds of readmission. A new CCC was associated with higher odds of readmission (adjusted OR (AOR) 1.75, 95% CI: 1.11-2.75) as was new technology during admission (AOR 1.84, 95%CI: 1.09-3.10). Furthermore, the odds of readmission for medical complexity variables (polypharmacy and home healthcare need) remained largely unchanged when adding the change in medical complexity variables (ie, comparing Model 1 and Model 3). However, when accounting for LOS (Model 4), neither the acquisition of a new CCC nor the addition of new technology was associated with readmission. The most common form of new technology was central line followed by nonsurgically placed enteral tube (Appendix Table 2). Finally, in sensitivity analyses (results not detailed), separating new CCC acquired at birth and new CCCs in nonbirth hospitalizations, compared to hospitalizations with no new CCC, yielded similar results as the primary analyses.

DISCUSSION

We examined multiple attributes of polypharmacy—the number of scheduled medications, number of as-needed medications, and number of scheduled doses per 24 hours. Interestingly, only the scheduled medications (count of medication and number of doses) were associated with elevated readmission risk. As-needed medications have heterogeneity in the level of importance from critical (eg, seizure rescue) to discretionary (eg, antipyretics, creams). The burden of managing these types of medications may still be high (ie, parents must decide when to administer a critical medication); however, this burden does not translate into increased readmission risk in this population.

Not surprisingly, greater medical complexity—as defined by higher numbers of scheduled discharge medications and technology assistance—is associated with 30-day readmission risk. Our analyses do not allow us to determine how much of the increased risk is due to additional care burden and risks of polypharmacy versus the inherent increase in complexity and severity of illness for which polypharmacy is a marker. Tailoring discharge regimens to the realities of daily life, with the goal of “minimally disruptive medicine”22,23 (eg, integrating manageable discharge medication routines into school and work schedules), is not a common feature of pediatric discharge planning. For adult patients with complex medical conditions, tailoring medication regimens in a minimally disruptive way is known to improve outcomes.24 Similarly, adopting minimally disruptive techniques to integrate the polypharmacy inherent in discharge could potentially mitigate some of the readmission risks for children and adolescents.

Contrary to our hypothesis, new technologies and new diagnoses did not confer additional readmission risk when accounting for LOS and patient characteristics. One potential explanation is varying risks conveyed by different types of new technologies placed during hospitalization. Central lines, the most common form of new technology, is associated with higher odds of reutilization in unadjusted analyses. However, the second most common form of new technology, nonsurgically placed enteral feeding tube, was not. Further analyses of the differential effects of new technology should be further examined in larger datasets. Additionally, the lack of additional readmission risk from new technology may relate to additional teaching and support provided to families of patients undergoing unfamiliar procedures offsets the risks inherent of greater complexity. If so, it may be that the more intensive teaching and postdischarge support provided to families with new technology or a new diagnosis could be replicated through refresher teaching during hospitalizations, when a patient’s state of health is status quo for the family (ie, the child was admitted and discharged with the same technology and diagnoses). This notion is supported by prior work that demonstrated successful readmission reduction interventions for children with chronic conditions often rely on enhanced education or coaching.25,26

We elected to present models both with and without LOS as a confounder because it is a potentially modifiable attribute of hospitalization. Change in medical complexity aspects were significantly associated with readmission in multivariable models without LOS. However, with the addition of LOS, they were no longer significant. Thus, the readmission risk of new complexity is accounted for by the readmission risk inherent in a longer LOS. This finding prompts additional questions that merit further study: is it that LOS is a general marker for heightened complexity, or is it that a longer LOS can modify readmission risk through additional in-hospital care and time for enhanced education?

Our study has several strengths. We were able to discern true complexity at the time of discharge through medical record review. For example, if a child had a peripherally inserted central catheter placed during hospitalization, it cannot be ascertained through administrative data without medical record review if the technology was removed or in place at discharge. Likewise, medical record review allows for identification of medical technology which is not surgically implanted (eg, nasogastric feeding tubes). Given the “fog” families report as part of their in-hospital experience and its threats to education and postdischarge contingency planning,17 we felt it important to evaluate medical technology regardless of whether or not it was surgically placed. Additionally, the more detailed and nuanced understanding gained of polypharmacy burden can better inform both risk prediction models and interventions to improve the transition from hospital to home.

This study

CONCLUSION

Medical complexity at discharge is associated with pediatric readmission risk. Contrary to our hypothesis, the addition of new technologies and new CCC diagnoses are not associated with pediatric readmission, after accounting for patient and hospitalization factors including LOS. The dynamics of LOS as a risk factor for readmission for children with medical complexity are likely multifaceted and merit further investigation in a multi-institutional study.

Disclosures

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1K08HS204735-01A1) and a grant from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation.

1. Diaz-Caneja A, Gledhill J, Weaver T, Nadel S, Garralda E. A child’s admission to hospital: a qualitative study examining the experiences of parents. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31(9):1248-1254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-005-2728-8.

2. Lapillonne A, Regnault A, Gournay V, et al. Impact on parents of bronchiolitis hospitalization of full-term, preterm and congenital heart disease infants. BMC Pediatrics. 2012;12:171. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-12-171.

3. Leader S, Jacobson P, Marcin J, Vardis R, Sorrentino M, Murray D. A method for identifying the financial burden of hospitalized infants on families. Value Health. 2002;5(1):55-59. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1524-4733.2002.51076.x.

4. Leidy NK, Margolis MK, Marcin JP, et al. The impact of severe respiratory syncytial virus on the child, caregiver, and family during hospitalization and recovery. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):1536-1546. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-1149.

5. Rennick JE, Johnston CC, Dougherty G, Platt R, Ritchie JA. Children’s psychological responses after critical illness and exposure to invasive technology. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23(3):133-144. PubMed

6. Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):370-376. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199102073240604.

7. Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

8. Landrigan CP, Parry GJ, Bones CB, Hackbarth AD, Goldmann DA, Sharek PJ. Temporal trends in rates of patient harm resulting from medical care. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(22):2124-2134. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1004404.

9. Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(13):1198-1208. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1306801.

10. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.188351.

11. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Penaloza R, et al. Measuring hospital quality using pediatric readmission and revisit rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429-436. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3527.

12. Toomey SL, Peltz A, Loren S, et al. Potentially preventable 30-day hospital readmissions at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):pii: e20154182. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4182.

13. Bucholz EM, Gay JC, Hall M, Harris M, Berry JG. Timing and causes of common pediatric readmissions. J Pediatr. 2018;200:240-248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.04.044.

14. Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682-690. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.122.

15. Winer JC, Aragona E, Fields AI, Stockwell DC. Comparison of clinical risk factors among pediatric patients with single admission, multiple admissions (without any 7-day readmissions), and 7-day readmission. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(3):119-125. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2015-0110.

16. Brittan MS, Martin S, Anderson L, Moss A, Torok MR. An electronic health record tool designed to improve pediatric hospital discharge has low predictive utility for readmissions. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):779-782. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3043.

17. Solan LG, Beck AF, Brunswick SA, et al. The family perspective on hospital to home transitions: a qualitative study. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):e1539-e1549. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2098.

18. Auger KA, Mueller EL, Weinberg SH, et al. A validated method for identifying unplanned pediatric readmission. J Pediatr. 2016;170:105-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.11.051.

19. Auger KA, Shah SS, Davis MD, Brady PW. Counting the Ways to Count Medications: The Challenges of Defining Pediatric Polypharmacy. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(8):506-507. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3213.

20. Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatrics. 2014;14:199. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-199.

21. Hsieh FY. Sample size tables for logistic regression. Stat Med. 1989;8(7):795-802. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4780080704.

22. May C, Montori VM, Mair FS. We need minimally disruptive medicine. BMJ. 2009;339:b2803. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2803.

23. Leppin AL, Montori VM, Gionfriddo MR. Minimally disruptive medicine: a pragmatically comprehensive model for delivering care to patients with multiple chronic conditions. Healthcare (Basel). 2015;3(1):50-63. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare3010050.

24. Serrano V, Spencer-Bonilla G, Boehmer KR, Montori VM. Minimally disruptive medicine for patients with diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2017;17(11):104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-017-0935-7.

25. Auger KA, Kenyon CC, Feudtner C, Davis MM. Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2013;9(4):251-260. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2134.

26. Coller RJ, Klitzner TS, Lerner CF, et al. Complex care hospital use and postdischarge coaching: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2):pii: e20174278. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-4278.

27. Hain PD, Gay JC, Berutti TW, Whitney GM, Wang W, Saville BR. Preventability of early readmissions at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e171-e181. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0820.

28. Auger KA, Teufel RJ, 2nd, Harris JM, 2nd, et al. Children’s hospital characteristics and readmission metrics. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1720.

29. Gay JC, Agrawal R, Auger KA, et al. Rates and impact of potentially preventable readmissions at children’s hospitals. J Pediatr. 2015;166(3):613-619 e615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.10.052.

1. Diaz-Caneja A, Gledhill J, Weaver T, Nadel S, Garralda E. A child’s admission to hospital: a qualitative study examining the experiences of parents. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31(9):1248-1254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-005-2728-8.

2. Lapillonne A, Regnault A, Gournay V, et al. Impact on parents of bronchiolitis hospitalization of full-term, preterm and congenital heart disease infants. BMC Pediatrics. 2012;12:171. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-12-171.

3. Leader S, Jacobson P, Marcin J, Vardis R, Sorrentino M, Murray D. A method for identifying the financial burden of hospitalized infants on families. Value Health. 2002;5(1):55-59. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1524-4733.2002.51076.x.

4. Leidy NK, Margolis MK, Marcin JP, et al. The impact of severe respiratory syncytial virus on the child, caregiver, and family during hospitalization and recovery. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):1536-1546. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-1149.

5. Rennick JE, Johnston CC, Dougherty G, Platt R, Ritchie JA. Children’s psychological responses after critical illness and exposure to invasive technology. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23(3):133-144. PubMed

6. Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):370-376. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199102073240604.

7. Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

8. Landrigan CP, Parry GJ, Bones CB, Hackbarth AD, Goldmann DA, Sharek PJ. Temporal trends in rates of patient harm resulting from medical care. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(22):2124-2134. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1004404.

9. Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(13):1198-1208. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1306801.

10. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.188351.

11. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Penaloza R, et al. Measuring hospital quality using pediatric readmission and revisit rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429-436. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3527.

12. Toomey SL, Peltz A, Loren S, et al. Potentially preventable 30-day hospital readmissions at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):pii: e20154182. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4182.

13. Bucholz EM, Gay JC, Hall M, Harris M, Berry JG. Timing and causes of common pediatric readmissions. J Pediatr. 2018;200:240-248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.04.044.

14. Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682-690. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.122.

15. Winer JC, Aragona E, Fields AI, Stockwell DC. Comparison of clinical risk factors among pediatric patients with single admission, multiple admissions (without any 7-day readmissions), and 7-day readmission. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(3):119-125. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2015-0110.

16. Brittan MS, Martin S, Anderson L, Moss A, Torok MR. An electronic health record tool designed to improve pediatric hospital discharge has low predictive utility for readmissions. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):779-782. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3043.

17. Solan LG, Beck AF, Brunswick SA, et al. The family perspective on hospital to home transitions: a qualitative study. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):e1539-e1549. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2098.

18. Auger KA, Mueller EL, Weinberg SH, et al. A validated method for identifying unplanned pediatric readmission. J Pediatr. 2016;170:105-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.11.051.

19. Auger KA, Shah SS, Davis MD, Brady PW. Counting the Ways to Count Medications: The Challenges of Defining Pediatric Polypharmacy. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(8):506-507. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3213.

20. Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatrics. 2014;14:199. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-199.

21. Hsieh FY. Sample size tables for logistic regression. Stat Med. 1989;8(7):795-802. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4780080704.

22. May C, Montori VM, Mair FS. We need minimally disruptive medicine. BMJ. 2009;339:b2803. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2803.

23. Leppin AL, Montori VM, Gionfriddo MR. Minimally disruptive medicine: a pragmatically comprehensive model for delivering care to patients with multiple chronic conditions. Healthcare (Basel). 2015;3(1):50-63. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare3010050.

24. Serrano V, Spencer-Bonilla G, Boehmer KR, Montori VM. Minimally disruptive medicine for patients with diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2017;17(11):104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-017-0935-7.

25. Auger KA, Kenyon CC, Feudtner C, Davis MM. Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2013;9(4):251-260. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2134.

26. Coller RJ, Klitzner TS, Lerner CF, et al. Complex care hospital use and postdischarge coaching: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2):pii: e20174278. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-4278.

27. Hain PD, Gay JC, Berutti TW, Whitney GM, Wang W, Saville BR. Preventability of early readmissions at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e171-e181. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0820.

28. Auger KA, Teufel RJ, 2nd, Harris JM, 2nd, et al. Children’s hospital characteristics and readmission metrics. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1720.

29. Gay JC, Agrawal R, Auger KA, et al. Rates and impact of potentially preventable readmissions at children’s hospitals. J Pediatr. 2015;166(3):613-619 e615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.10.052.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

HHS proposes pathways for drug importation

Officials at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services have announced a new plan that they say would lay the foundation for safe importation of certain medications, with the aim of expanding drug access and lowering prescription costs for patients.

The action plan, unveiled July 31, outlines two pathways for drug importation from foreign markets. The first route would authorize states, wholesalers, or pharmacists to propose pilot demonstrations on how they would import drugs from Canada into the United States, provided these are versions of drugs already approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Similarly, a second pathway would allow manufacturers that sell in foreign countries the opportunity to import drugs that are versions of FDA-approved medications.

HHS Secretary Alex M. Azar II said the action plan is part of President Trump’s drug-pricing blueprint and is intended to combat the sky-high price tags on many prescription medications.

“President Trump has been clear: For too long American patients have been paying exorbitantly high prices for prescription drugs that are made available to other countries at lower prices,” Mr. Azar said in a statement. “[The] announcement outlines the pathways the administration intends to explore to allow safe importation of certain prescription drugs to lower prices and reduce out of pocket costs for American patients. This is the next important step in the administration’s work to end foreign freeloading and put American patients first.”

Under the first pathway, HHS would review plans submitted by states, pharmacists, or drugmakers that outline how the entities would import Health Canada–approved drugs that are in compliance with the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. The importation would occur in a manner that assures the drug’s validity and meets the cost requirements of federal rule making, according to an HHS fact sheet.

Demonstration projects would be time-limited and require regular reporting to ensure safety and cost conditions are being met.

Under the second pathway, manufacturers of FDA-approved drug products would be able to import versions of those drugs that they sell in foreign countries through a special process to be outlined by the agency. As part of the process, drugmakers would need to establish that the foreign version is the same as the U.S. version. The FDA would then allow the drug to be labeled for sale in the U.S. and imported, according to the fact sheet. HHS officials said they believe that manufacturers would use this pathway to offer U.S. patients lower-cost versions of their drugs and the medications affected could potentially include those used to treat diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disorders, and cancer.

“In recent years, multiple manufacturers have stated (either publicly or in statements to the Administration) that they wanted to offer lower cost versions but could not readily do so because they were locked into contracts with other parties in the supply chain,” HHS officials stated in the fact sheet. “This pathway would highlight an opportunity for manufacturers to use importation to offer lower-cost versions of their drugs.”

HHS plans to introduce its action plan through a formal notice of proposed rulemaking, which has not yet been finalized. Some elements of the final proposal may differ from its initial descriptions to reflect further consideration of the relevant issues, the agency noted.

Acting FDA Commissioner Ned Sharpless, MD, said the agency has a unique role to play in promoting competition that can help reduce drug prices and improve access to medicine for Americans.

“Driving down drug prices requires a comprehensive approach and we must continue to look at all innovative solutions to this challenge,” Dr. Sharpless said in a statement. “[The] proposal is the result of the hard work by the dedicated staff of the FDA, in close collaboration with HHS and the White House, to identify potential pathways we can pursue to support the safe importation of certain prescription drugs.”

Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.), chair of the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions committee, said the administration’s proposal sounds promising as long as the plan ensures the safety and efficacy of imported medications.

“This is the first administration to take concrete steps to allow importation of prescription drugs to reduce their cost and I welcome it,” Sen. Alexander said in a statement. “The key for me is whether this plan preserves the Food and Drug Administration’s gold standard for safety and effectiveness. Millions of Americans every day buy prescription drugs relying on the FDA’s guarantee of quality.”

Officials at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services have announced a new plan that they say would lay the foundation for safe importation of certain medications, with the aim of expanding drug access and lowering prescription costs for patients.

The action plan, unveiled July 31, outlines two pathways for drug importation from foreign markets. The first route would authorize states, wholesalers, or pharmacists to propose pilot demonstrations on how they would import drugs from Canada into the United States, provided these are versions of drugs already approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Similarly, a second pathway would allow manufacturers that sell in foreign countries the opportunity to import drugs that are versions of FDA-approved medications.

HHS Secretary Alex M. Azar II said the action plan is part of President Trump’s drug-pricing blueprint and is intended to combat the sky-high price tags on many prescription medications.

“President Trump has been clear: For too long American patients have been paying exorbitantly high prices for prescription drugs that are made available to other countries at lower prices,” Mr. Azar said in a statement. “[The] announcement outlines the pathways the administration intends to explore to allow safe importation of certain prescription drugs to lower prices and reduce out of pocket costs for American patients. This is the next important step in the administration’s work to end foreign freeloading and put American patients first.”

Under the first pathway, HHS would review plans submitted by states, pharmacists, or drugmakers that outline how the entities would import Health Canada–approved drugs that are in compliance with the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. The importation would occur in a manner that assures the drug’s validity and meets the cost requirements of federal rule making, according to an HHS fact sheet.

Demonstration projects would be time-limited and require regular reporting to ensure safety and cost conditions are being met.

Under the second pathway, manufacturers of FDA-approved drug products would be able to import versions of those drugs that they sell in foreign countries through a special process to be outlined by the agency. As part of the process, drugmakers would need to establish that the foreign version is the same as the U.S. version. The FDA would then allow the drug to be labeled for sale in the U.S. and imported, according to the fact sheet. HHS officials said they believe that manufacturers would use this pathway to offer U.S. patients lower-cost versions of their drugs and the medications affected could potentially include those used to treat diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disorders, and cancer.

“In recent years, multiple manufacturers have stated (either publicly or in statements to the Administration) that they wanted to offer lower cost versions but could not readily do so because they were locked into contracts with other parties in the supply chain,” HHS officials stated in the fact sheet. “This pathway would highlight an opportunity for manufacturers to use importation to offer lower-cost versions of their drugs.”

HHS plans to introduce its action plan through a formal notice of proposed rulemaking, which has not yet been finalized. Some elements of the final proposal may differ from its initial descriptions to reflect further consideration of the relevant issues, the agency noted.

Acting FDA Commissioner Ned Sharpless, MD, said the agency has a unique role to play in promoting competition that can help reduce drug prices and improve access to medicine for Americans.

“Driving down drug prices requires a comprehensive approach and we must continue to look at all innovative solutions to this challenge,” Dr. Sharpless said in a statement. “[The] proposal is the result of the hard work by the dedicated staff of the FDA, in close collaboration with HHS and the White House, to identify potential pathways we can pursue to support the safe importation of certain prescription drugs.”

Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.), chair of the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions committee, said the administration’s proposal sounds promising as long as the plan ensures the safety and efficacy of imported medications.

“This is the first administration to take concrete steps to allow importation of prescription drugs to reduce their cost and I welcome it,” Sen. Alexander said in a statement. “The key for me is whether this plan preserves the Food and Drug Administration’s gold standard for safety and effectiveness. Millions of Americans every day buy prescription drugs relying on the FDA’s guarantee of quality.”

Officials at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services have announced a new plan that they say would lay the foundation for safe importation of certain medications, with the aim of expanding drug access and lowering prescription costs for patients.

The action plan, unveiled July 31, outlines two pathways for drug importation from foreign markets. The first route would authorize states, wholesalers, or pharmacists to propose pilot demonstrations on how they would import drugs from Canada into the United States, provided these are versions of drugs already approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Similarly, a second pathway would allow manufacturers that sell in foreign countries the opportunity to import drugs that are versions of FDA-approved medications.

HHS Secretary Alex M. Azar II said the action plan is part of President Trump’s drug-pricing blueprint and is intended to combat the sky-high price tags on many prescription medications.

“President Trump has been clear: For too long American patients have been paying exorbitantly high prices for prescription drugs that are made available to other countries at lower prices,” Mr. Azar said in a statement. “[The] announcement outlines the pathways the administration intends to explore to allow safe importation of certain prescription drugs to lower prices and reduce out of pocket costs for American patients. This is the next important step in the administration’s work to end foreign freeloading and put American patients first.”

Under the first pathway, HHS would review plans submitted by states, pharmacists, or drugmakers that outline how the entities would import Health Canada–approved drugs that are in compliance with the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. The importation would occur in a manner that assures the drug’s validity and meets the cost requirements of federal rule making, according to an HHS fact sheet.

Demonstration projects would be time-limited and require regular reporting to ensure safety and cost conditions are being met.

Under the second pathway, manufacturers of FDA-approved drug products would be able to import versions of those drugs that they sell in foreign countries through a special process to be outlined by the agency. As part of the process, drugmakers would need to establish that the foreign version is the same as the U.S. version. The FDA would then allow the drug to be labeled for sale in the U.S. and imported, according to the fact sheet. HHS officials said they believe that manufacturers would use this pathway to offer U.S. patients lower-cost versions of their drugs and the medications affected could potentially include those used to treat diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disorders, and cancer.

“In recent years, multiple manufacturers have stated (either publicly or in statements to the Administration) that they wanted to offer lower cost versions but could not readily do so because they were locked into contracts with other parties in the supply chain,” HHS officials stated in the fact sheet. “This pathway would highlight an opportunity for manufacturers to use importation to offer lower-cost versions of their drugs.”

HHS plans to introduce its action plan through a formal notice of proposed rulemaking, which has not yet been finalized. Some elements of the final proposal may differ from its initial descriptions to reflect further consideration of the relevant issues, the agency noted.

Acting FDA Commissioner Ned Sharpless, MD, said the agency has a unique role to play in promoting competition that can help reduce drug prices and improve access to medicine for Americans.

“Driving down drug prices requires a comprehensive approach and we must continue to look at all innovative solutions to this challenge,” Dr. Sharpless said in a statement. “[The] proposal is the result of the hard work by the dedicated staff of the FDA, in close collaboration with HHS and the White House, to identify potential pathways we can pursue to support the safe importation of certain prescription drugs.”

Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.), chair of the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions committee, said the administration’s proposal sounds promising as long as the plan ensures the safety and efficacy of imported medications.

“This is the first administration to take concrete steps to allow importation of prescription drugs to reduce their cost and I welcome it,” Sen. Alexander said in a statement. “The key for me is whether this plan preserves the Food and Drug Administration’s gold standard for safety and effectiveness. Millions of Americans every day buy prescription drugs relying on the FDA’s guarantee of quality.”

Critics say hospital price transparency proposal ‘misses the mark’