User login

October 2019 - Quick Quiz Question 2

Q2. Correct answer: C

Rationale

Vitamin B12 absorption requires intrinsic factor to bind B12 to facilitate absorption in the terminal ileum. Any interruption of terminal ileal absorptive capacity can thus lead to vitamin B12 deficiency (e.g. Crohn's disease, ileal resection). Intrinsic factor is produced by parietal cells, so any condition that leads to decreased parietal cell mass or function can lead to vitamin B12 deficiency (e.g. atrophic gastritis). In order for intrinsic factor to bind vitamin B12, B12 must first be released from binding with the R-protein, which occurs via pancreatic protease breakdown of the R-protein. Patients with chronic pancreatitis are not able to break down the R-protein as efficiently, and thus can develop vitamin B12 deficiency.

References

1. Green R. Vitamin B12 deficiency from the perspective of a practicing hematologist. Blood. 2017;129(19):2603-11.

2. Gueant GL, at al. Malabsorption of vitamin B12 in pancreatic insufficiency of the adult and of the child. Pancreas 1990 Sep;5(5):559-67.

[email protected]

Q2. Correct answer: C

Rationale

Vitamin B12 absorption requires intrinsic factor to bind B12 to facilitate absorption in the terminal ileum. Any interruption of terminal ileal absorptive capacity can thus lead to vitamin B12 deficiency (e.g. Crohn's disease, ileal resection). Intrinsic factor is produced by parietal cells, so any condition that leads to decreased parietal cell mass or function can lead to vitamin B12 deficiency (e.g. atrophic gastritis). In order for intrinsic factor to bind vitamin B12, B12 must first be released from binding with the R-protein, which occurs via pancreatic protease breakdown of the R-protein. Patients with chronic pancreatitis are not able to break down the R-protein as efficiently, and thus can develop vitamin B12 deficiency.

References

1. Green R. Vitamin B12 deficiency from the perspective of a practicing hematologist. Blood. 2017;129(19):2603-11.

2. Gueant GL, at al. Malabsorption of vitamin B12 in pancreatic insufficiency of the adult and of the child. Pancreas 1990 Sep;5(5):559-67.

[email protected]

Q2. Correct answer: C

Rationale

Vitamin B12 absorption requires intrinsic factor to bind B12 to facilitate absorption in the terminal ileum. Any interruption of terminal ileal absorptive capacity can thus lead to vitamin B12 deficiency (e.g. Crohn's disease, ileal resection). Intrinsic factor is produced by parietal cells, so any condition that leads to decreased parietal cell mass or function can lead to vitamin B12 deficiency (e.g. atrophic gastritis). In order for intrinsic factor to bind vitamin B12, B12 must first be released from binding with the R-protein, which occurs via pancreatic protease breakdown of the R-protein. Patients with chronic pancreatitis are not able to break down the R-protein as efficiently, and thus can develop vitamin B12 deficiency.

References

1. Green R. Vitamin B12 deficiency from the perspective of a practicing hematologist. Blood. 2017;129(19):2603-11.

2. Gueant GL, at al. Malabsorption of vitamin B12 in pancreatic insufficiency of the adult and of the child. Pancreas 1990 Sep;5(5):559-67.

[email protected]

A 65-year-old man with chronic pancreatitis related to long-standing alcohol use comes to see you for a second opinion. He has been abstinent from alcohol for 20 years. He reports a 1-year history of six loose, oily stools per day, but minimal abdominal pain. He was recently found to have vitamin B12 deficiency by his primary care provider.

October 2019 - Quick Question 1

Q1. Correct Answer: B

Rationale

In patients 70 years or older with a history of gastrointestinal bleeding and on chronic NSAIDs, the use of a PPI can reduce the risk of recurrent bleeding. In the setting of an acute bleeding episode, aspirin should resume within 7 days of adequate hemostasis. However, there are no advantages of enteric coated or buffered aspirin in reducing the risk of recurrent bleeding.

References

1. Kelly JP, Kaufmann DW, et al. Risk of aspirin-associated major upper-gastrointestinal bleeding with enteric-coated or buffered product. Lancet 1996;348:1413-6.

2. Laine L, Jensen D. Management of patients with ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:345-60.

Q1. Correct Answer: B

Rationale

In patients 70 years or older with a history of gastrointestinal bleeding and on chronic NSAIDs, the use of a PPI can reduce the risk of recurrent bleeding. In the setting of an acute bleeding episode, aspirin should resume within 7 days of adequate hemostasis. However, there are no advantages of enteric coated or buffered aspirin in reducing the risk of recurrent bleeding.

References

1. Kelly JP, Kaufmann DW, et al. Risk of aspirin-associated major upper-gastrointestinal bleeding with enteric-coated or buffered product. Lancet 1996;348:1413-6.

2. Laine L, Jensen D. Management of patients with ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:345-60.

Q1. Correct Answer: B

Rationale

In patients 70 years or older with a history of gastrointestinal bleeding and on chronic NSAIDs, the use of a PPI can reduce the risk of recurrent bleeding. In the setting of an acute bleeding episode, aspirin should resume within 7 days of adequate hemostasis. However, there are no advantages of enteric coated or buffered aspirin in reducing the risk of recurrent bleeding.

References

1. Kelly JP, Kaufmann DW, et al. Risk of aspirin-associated major upper-gastrointestinal bleeding with enteric-coated or buffered product. Lancet 1996;348:1413-6.

2. Laine L, Jensen D. Management of patients with ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:345-60.

A 73-year-old man with coronary artery disease requiring coronary artery bypass grafting and daily low-dose plain aspirin is hospitalized with acute anemia and melena. His aspirin is withheld and he is placed empirically on intravenous proton pump inhibitors with continuous infusion. He undergoes upper endoscopy, which reveals a single 8-mm ulcer in the duodenal bulb with a visible vessel. After successful endoscopic therapy with epinephrine injection and the use of hemoclips, he remains stable. Prior to discharge, he is recommended to resume aspirin therapy.

What is your diagnosis? - October 2019

Exercise-induced acute ischemic colitis or “runner’s colitis”

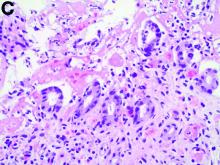

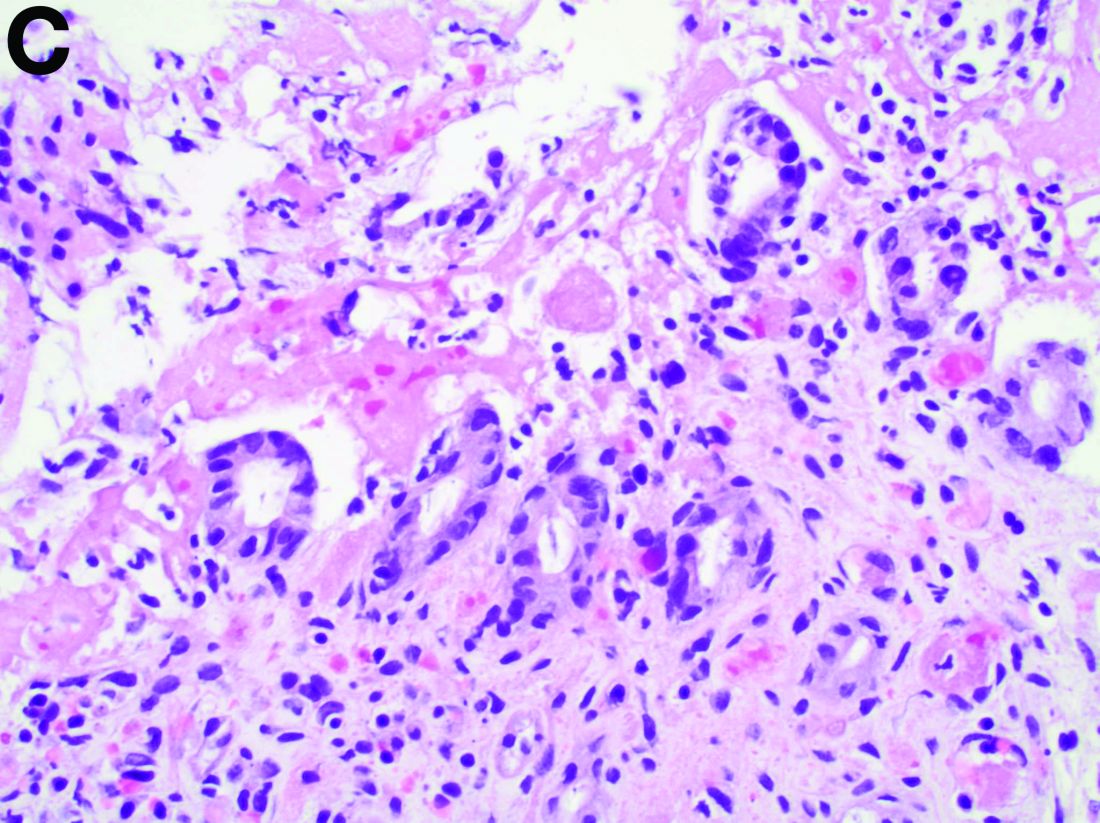

Biopsies of the abnormal mucosa noted on colonoscopy revealed mucosal necrosis with stromal hyalinization, crypt atrophy, and acute inflammation (Figure C), consistent with a diagnosis of exercise-induced acute ischemic colitis. Exercise-induced ischemic colitis, sometimes referred to colloquially as “runner’s colitis,” is a rare but well-documented complication of long distance running.1

A number of physiologic changes occur in the human body during prolonged exercise, including redirection of blood flow from the gut to exercising muscles. Although this process usually serves to better manage available oxygen and nutrients during times of stress, it can occasionally result in unfavorable outcomes as depicted herein. During exercise, the increased sympathetic tone influences rerouting blood with some studies demonstrating up to 80% reduction in splanchnic blood flow with prolonged exercise.2 In addition, the transient hypovolemia many runners experience if they do not remain adequately hydrated can impair mesenteric perfusion. The splenic flexure of the colon and the rectosigmoid junction are particularly prone to ischemic injury in these settings, given the “watershed” nature of their blood supply.

An extensive review of published cases revealed the reversible nature of this ailment, as all but one subject, who required subtotal colectomy for colonic perforation, had resolution of ischemia on repeat evaluation.3 The patient had a follow-up computed tomography angiogram 2 months after discharge that revealed unremarkable mesenteric vasculature and resolution of the previously seen colonic wall thickening and pericolonic fat stranding.

References

1. Buckman MT. Gastrointestinal bleeding in long-distance runners. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:127-8.

2. Qamar MI, Read AE. Effects of exercise on mesenteric blood flow in man. Gut.1987;28:583-7.

3. Beaumont AC, Teare JP. Subtotal colectomy following marathon running in a female patient. J R Soc Med, 1991;84:439-40.

Exercise-induced acute ischemic colitis or “runner’s colitis”

Biopsies of the abnormal mucosa noted on colonoscopy revealed mucosal necrosis with stromal hyalinization, crypt atrophy, and acute inflammation (Figure C), consistent with a diagnosis of exercise-induced acute ischemic colitis. Exercise-induced ischemic colitis, sometimes referred to colloquially as “runner’s colitis,” is a rare but well-documented complication of long distance running.1

A number of physiologic changes occur in the human body during prolonged exercise, including redirection of blood flow from the gut to exercising muscles. Although this process usually serves to better manage available oxygen and nutrients during times of stress, it can occasionally result in unfavorable outcomes as depicted herein. During exercise, the increased sympathetic tone influences rerouting blood with some studies demonstrating up to 80% reduction in splanchnic blood flow with prolonged exercise.2 In addition, the transient hypovolemia many runners experience if they do not remain adequately hydrated can impair mesenteric perfusion. The splenic flexure of the colon and the rectosigmoid junction are particularly prone to ischemic injury in these settings, given the “watershed” nature of their blood supply.

An extensive review of published cases revealed the reversible nature of this ailment, as all but one subject, who required subtotal colectomy for colonic perforation, had resolution of ischemia on repeat evaluation.3 The patient had a follow-up computed tomography angiogram 2 months after discharge that revealed unremarkable mesenteric vasculature and resolution of the previously seen colonic wall thickening and pericolonic fat stranding.

References

1. Buckman MT. Gastrointestinal bleeding in long-distance runners. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:127-8.

2. Qamar MI, Read AE. Effects of exercise on mesenteric blood flow in man. Gut.1987;28:583-7.

3. Beaumont AC, Teare JP. Subtotal colectomy following marathon running in a female patient. J R Soc Med, 1991;84:439-40.

Exercise-induced acute ischemic colitis or “runner’s colitis”

Biopsies of the abnormal mucosa noted on colonoscopy revealed mucosal necrosis with stromal hyalinization, crypt atrophy, and acute inflammation (Figure C), consistent with a diagnosis of exercise-induced acute ischemic colitis. Exercise-induced ischemic colitis, sometimes referred to colloquially as “runner’s colitis,” is a rare but well-documented complication of long distance running.1

A number of physiologic changes occur in the human body during prolonged exercise, including redirection of blood flow from the gut to exercising muscles. Although this process usually serves to better manage available oxygen and nutrients during times of stress, it can occasionally result in unfavorable outcomes as depicted herein. During exercise, the increased sympathetic tone influences rerouting blood with some studies demonstrating up to 80% reduction in splanchnic blood flow with prolonged exercise.2 In addition, the transient hypovolemia many runners experience if they do not remain adequately hydrated can impair mesenteric perfusion. The splenic flexure of the colon and the rectosigmoid junction are particularly prone to ischemic injury in these settings, given the “watershed” nature of their blood supply.

An extensive review of published cases revealed the reversible nature of this ailment, as all but one subject, who required subtotal colectomy for colonic perforation, had resolution of ischemia on repeat evaluation.3 The patient had a follow-up computed tomography angiogram 2 months after discharge that revealed unremarkable mesenteric vasculature and resolution of the previously seen colonic wall thickening and pericolonic fat stranding.

References

1. Buckman MT. Gastrointestinal bleeding in long-distance runners. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:127-8.

2. Qamar MI, Read AE. Effects of exercise on mesenteric blood flow in man. Gut.1987;28:583-7.

3. Beaumont AC, Teare JP. Subtotal colectomy following marathon running in a female patient. J R Soc Med, 1991;84:439-40.

A 28-year-old woman with a history of mild iron-deficiency anemia presented with acute onset of lower abdominal pain and bloody bowel movements. The patient reported actively training for a marathon and on the day of presentation she ran approximately 20 miles before developing acute sharp, crampy lower abdominal pain. This discomfort forced her to stop her run early and she subsequently had several loose bowel movements streaked with bright red blood that prompted evaluation.

In the emergency department, she was afebrile and hemodynamically stable with physical examination revealing slight tenderness to palpation in the left upper quadrant of her abdomen. Laboratory results were significant for mild leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 16.1 × 103/microL), anemia (hemoglobin, 10.3 g/dL), and iron deficiency (ferritin, 14 ng/mL; iron, 11 microg/dL; and iron saturation, 2%). Of note, lactate, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels were all within normal limits.

Second-generation anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy shows promise in myeloma trial

BOSTON – CT053, a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, has demonstrated efficacy and tolerability in a phase 1 trial of patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma.

CT053 produced an objective response rate of 87.5% and a complete response rate of 79.2%. All patients experienced grade 3 or higher adverse events (AEs), but none developed grade 3 or higher cytokine-release syndrome (CRS).

Siguo Hao, MD, of Xinhua Hospital, Shanghai (China) Jiaotong University, presented these results at the International Myeloma Workshop held by the International Myeloma Society.

Dr. Hao explained that CT053 consists of autologous T cells modified with a second-generation CAR that incorporates a fully human anti–B-cell maturation antigen single-chain fragment variant, a 4-1BB costimulatory domain, and a CD3-zeta–signaling domain.

In preclinical studies, CT053 induced dose-dependent cytotoxic effects on multiple myeloma cell lines and completely eradicated myeloma in mice.

Dr. Hao and his colleagues conducted the phase 1 study of CT053 at three sites (NCT03716856, NCT03302403, and NCT03380039). The study enrolled 30 patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, and 24 ultimately received CT053.

In the 24 patients, the median age was 60.2 years (range, 38.5-70.0 years), and the median time since diagnosis was 3.5 years (range, 0.3-10.8 years). Nine patients had progressive disease at baseline.

The patients had received a median of 5 prior therapies (range, 2-12). All patients had received a proteasome inhibitor, 22 had received an immunomodulatory agent, 10 had undergone a transplant, and 5 had received an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody.

For this study, patients received conditioning with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide, followed by a single infusion of CT053. Most patients (n = 21) received 1.5 x 108 cells, but three received 0.5 x 108, 1 x 108, and 1.8 x 108 cells, respectively.

The median follow-up was 333 days. CAR T cells were detectable 1-7 days after infusion and peaked at 7-21 days. The cells persisted for a median of 172 days (range, 21-341 days).

A total of 21 patients responded to treatment (87.5%). There were 19 patients with a complete response or stringent complete response, 1 patient with a very good partial response, and 1 with a partial response.

Dr. Hao noted that CT053 was effective even at the lowest dose. The patient who received 0.5 x 108 cells initially achieved a very good partial response that deepened to a stringent complete response on day 502 after infusion.

Ten patients still had a stringent complete response at last follow-up, and two had a complete response. Nine patients progressed, and one patient relapsed after achieving a complete response. Three patients died, two from disease progression and one from a serious AE (neutropenic infection).

All 24 patients experienced a treatment-related AE, and all had grade 3 or higher hematologic AEs. Six patients had grade 3 or higher fever, six had grade 3 or higher infections and infestations, and one had grade 3 or higher neurotoxicity.

Three patients had grade 1 CRS, and 12 had grade 2 CRS. None of the patients had grade 3 or higher CRS.

This trial was sponsored by Xinhua Hospital/Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, and First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University in collaboration with Carsgen Therapeutics. Dr. Hao did not disclose any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hao S et al. IMW 2019, Abstract OAB-082.

BOSTON – CT053, a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, has demonstrated efficacy and tolerability in a phase 1 trial of patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma.

CT053 produced an objective response rate of 87.5% and a complete response rate of 79.2%. All patients experienced grade 3 or higher adverse events (AEs), but none developed grade 3 or higher cytokine-release syndrome (CRS).

Siguo Hao, MD, of Xinhua Hospital, Shanghai (China) Jiaotong University, presented these results at the International Myeloma Workshop held by the International Myeloma Society.

Dr. Hao explained that CT053 consists of autologous T cells modified with a second-generation CAR that incorporates a fully human anti–B-cell maturation antigen single-chain fragment variant, a 4-1BB costimulatory domain, and a CD3-zeta–signaling domain.

In preclinical studies, CT053 induced dose-dependent cytotoxic effects on multiple myeloma cell lines and completely eradicated myeloma in mice.

Dr. Hao and his colleagues conducted the phase 1 study of CT053 at three sites (NCT03716856, NCT03302403, and NCT03380039). The study enrolled 30 patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, and 24 ultimately received CT053.

In the 24 patients, the median age was 60.2 years (range, 38.5-70.0 years), and the median time since diagnosis was 3.5 years (range, 0.3-10.8 years). Nine patients had progressive disease at baseline.

The patients had received a median of 5 prior therapies (range, 2-12). All patients had received a proteasome inhibitor, 22 had received an immunomodulatory agent, 10 had undergone a transplant, and 5 had received an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody.

For this study, patients received conditioning with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide, followed by a single infusion of CT053. Most patients (n = 21) received 1.5 x 108 cells, but three received 0.5 x 108, 1 x 108, and 1.8 x 108 cells, respectively.

The median follow-up was 333 days. CAR T cells were detectable 1-7 days after infusion and peaked at 7-21 days. The cells persisted for a median of 172 days (range, 21-341 days).

A total of 21 patients responded to treatment (87.5%). There were 19 patients with a complete response or stringent complete response, 1 patient with a very good partial response, and 1 with a partial response.

Dr. Hao noted that CT053 was effective even at the lowest dose. The patient who received 0.5 x 108 cells initially achieved a very good partial response that deepened to a stringent complete response on day 502 after infusion.

Ten patients still had a stringent complete response at last follow-up, and two had a complete response. Nine patients progressed, and one patient relapsed after achieving a complete response. Three patients died, two from disease progression and one from a serious AE (neutropenic infection).

All 24 patients experienced a treatment-related AE, and all had grade 3 or higher hematologic AEs. Six patients had grade 3 or higher fever, six had grade 3 or higher infections and infestations, and one had grade 3 or higher neurotoxicity.

Three patients had grade 1 CRS, and 12 had grade 2 CRS. None of the patients had grade 3 or higher CRS.

This trial was sponsored by Xinhua Hospital/Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, and First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University in collaboration with Carsgen Therapeutics. Dr. Hao did not disclose any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hao S et al. IMW 2019, Abstract OAB-082.

BOSTON – CT053, a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, has demonstrated efficacy and tolerability in a phase 1 trial of patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma.

CT053 produced an objective response rate of 87.5% and a complete response rate of 79.2%. All patients experienced grade 3 or higher adverse events (AEs), but none developed grade 3 or higher cytokine-release syndrome (CRS).

Siguo Hao, MD, of Xinhua Hospital, Shanghai (China) Jiaotong University, presented these results at the International Myeloma Workshop held by the International Myeloma Society.

Dr. Hao explained that CT053 consists of autologous T cells modified with a second-generation CAR that incorporates a fully human anti–B-cell maturation antigen single-chain fragment variant, a 4-1BB costimulatory domain, and a CD3-zeta–signaling domain.

In preclinical studies, CT053 induced dose-dependent cytotoxic effects on multiple myeloma cell lines and completely eradicated myeloma in mice.

Dr. Hao and his colleagues conducted the phase 1 study of CT053 at three sites (NCT03716856, NCT03302403, and NCT03380039). The study enrolled 30 patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, and 24 ultimately received CT053.

In the 24 patients, the median age was 60.2 years (range, 38.5-70.0 years), and the median time since diagnosis was 3.5 years (range, 0.3-10.8 years). Nine patients had progressive disease at baseline.

The patients had received a median of 5 prior therapies (range, 2-12). All patients had received a proteasome inhibitor, 22 had received an immunomodulatory agent, 10 had undergone a transplant, and 5 had received an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody.

For this study, patients received conditioning with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide, followed by a single infusion of CT053. Most patients (n = 21) received 1.5 x 108 cells, but three received 0.5 x 108, 1 x 108, and 1.8 x 108 cells, respectively.

The median follow-up was 333 days. CAR T cells were detectable 1-7 days after infusion and peaked at 7-21 days. The cells persisted for a median of 172 days (range, 21-341 days).

A total of 21 patients responded to treatment (87.5%). There were 19 patients with a complete response or stringent complete response, 1 patient with a very good partial response, and 1 with a partial response.

Dr. Hao noted that CT053 was effective even at the lowest dose. The patient who received 0.5 x 108 cells initially achieved a very good partial response that deepened to a stringent complete response on day 502 after infusion.

Ten patients still had a stringent complete response at last follow-up, and two had a complete response. Nine patients progressed, and one patient relapsed after achieving a complete response. Three patients died, two from disease progression and one from a serious AE (neutropenic infection).

All 24 patients experienced a treatment-related AE, and all had grade 3 or higher hematologic AEs. Six patients had grade 3 or higher fever, six had grade 3 or higher infections and infestations, and one had grade 3 or higher neurotoxicity.

Three patients had grade 1 CRS, and 12 had grade 2 CRS. None of the patients had grade 3 or higher CRS.

This trial was sponsored by Xinhua Hospital/Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, and First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University in collaboration with Carsgen Therapeutics. Dr. Hao did not disclose any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hao S et al. IMW 2019, Abstract OAB-082.

REPORTING FROM IMW 2019

How does alcohol intake affect dementia risk in older adults?

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) may influence the relationship between alcohol consumption and dementia risk, a study of more than 3,000 adults suggests. In addition, , according to the study, which was published in JAMA Network Open.

“The associations of self-reported alcohol consumption with dementia risk and cognitive decline were more consistently adverse among individuals with MCI than those with normal cognition,” reported Manja Koch, PhD, a researcher in the department of nutrition at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston and colleagues. “This was particularly true for the subset of individuals [with MCI] who drank more than 14.0 servings per week, whose rate of cognitive decline and risk of dementia were the highest of any subgroup.”

Among older adults with normal cognition, the results generally were consistent with those of a recent meta-analysis that found a U-shaped relationship between drinking and dementia, the researchers said (Eur J Epidemiol. 2017 Jan;32[1]:31-42.).

“Our results did not show significant associations and clearly do not suffice to suggest a clinical benefit from even limited alcohol use,” said Dr. Koch and colleagues. “Nonetheless, our findings provide some reassurance that alcohol consumed within recommended limits was not associated with an increased risk of dementia among older adults with normal baseline cognition.”

GEMS data

To study whether alcohol consumption is associated with the risk of dementia and cognitive decline in older adults with and without MCI, the investigators analyzed data from the Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study (GEMS). GEMS was a randomized controlled trial conducted between 2000 and 2008 that found no overall association between ginkgo biloba and dementia prevention. During the trial, participants completed the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination, the Clinical Dementia Rating scale, and the cognitive portion of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale.

In the present study, the investigators analyzed data from 3,021 participants aged 72 years and older who were free of dementia at baseline and had provided information about their alcohol intake. Their median age was 78 years, and 46.2% were female. Fifty-eight percent consumed alcohol, including 45% of the participants with MCI at baseline.

During follow-up, 512 cases of dementia occurred. Among the 473 participants with MCI at baseline, the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for dementia was 1.72 for those who consumed more than 14 drinks per week, compared with light drinkers who consumed less than 1 drink per week. For participants who consumed between 7 and 14 drinks per week, the adjusted HR for dementia was 0.63 among those without MCI and 0.93 among those with MCI, relative to light drinkers who consumed less than 1 drink per week.

Among adults with normal cognition at baseline, daily low-quantity drinking was associated with lower dementia risk, compared with infrequent higher-quantity drinking (HR, 0.45).

Trial excluded adults with excessive alcohol use

Limitations of the study include a lack of data about any changes in alcohol consumption over time. In addition, the original trial excluded people with a known history of excessive alcohol use. Furthermore, it is possible that the “long preclinical phase of dementia” and other health issues affect drinking behavior, the authors said. “At present, our findings cannot be directly translated into clinical recommendations,” the authors said. Nevertheless, the results “suggest that, while caring for older adults, physicians should carefully assess the full dimensions of drinking behavior and cognition when providing guidance to patients about alcohol consumption,” they said.

The study was supported by grants from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine; the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; the Office of Dietary Supplements of the National Institute on Aging; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center; the Roena Kulynych Center for Memory and Cognition Research; and Wake Forest University School of Medicine. In addition, the researchers used plasma samples from the National Cell Repository for Alzheimer’s Disease, which receives support from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Koch had no conflicts of interest. Coauthors disclosed university and government grants and personal fees from pharmaceutical companies outside the study. One author was an employee of Genentech at the time of publication, but Genentech did not contribute to the study.

SOURCE: Koch M et al. JAMA Network Open. 2019 Sep 27. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10319.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) may influence the relationship between alcohol consumption and dementia risk, a study of more than 3,000 adults suggests. In addition, , according to the study, which was published in JAMA Network Open.

“The associations of self-reported alcohol consumption with dementia risk and cognitive decline were more consistently adverse among individuals with MCI than those with normal cognition,” reported Manja Koch, PhD, a researcher in the department of nutrition at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston and colleagues. “This was particularly true for the subset of individuals [with MCI] who drank more than 14.0 servings per week, whose rate of cognitive decline and risk of dementia were the highest of any subgroup.”

Among older adults with normal cognition, the results generally were consistent with those of a recent meta-analysis that found a U-shaped relationship between drinking and dementia, the researchers said (Eur J Epidemiol. 2017 Jan;32[1]:31-42.).

“Our results did not show significant associations and clearly do not suffice to suggest a clinical benefit from even limited alcohol use,” said Dr. Koch and colleagues. “Nonetheless, our findings provide some reassurance that alcohol consumed within recommended limits was not associated with an increased risk of dementia among older adults with normal baseline cognition.”

GEMS data

To study whether alcohol consumption is associated with the risk of dementia and cognitive decline in older adults with and without MCI, the investigators analyzed data from the Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study (GEMS). GEMS was a randomized controlled trial conducted between 2000 and 2008 that found no overall association between ginkgo biloba and dementia prevention. During the trial, participants completed the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination, the Clinical Dementia Rating scale, and the cognitive portion of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale.

In the present study, the investigators analyzed data from 3,021 participants aged 72 years and older who were free of dementia at baseline and had provided information about their alcohol intake. Their median age was 78 years, and 46.2% were female. Fifty-eight percent consumed alcohol, including 45% of the participants with MCI at baseline.

During follow-up, 512 cases of dementia occurred. Among the 473 participants with MCI at baseline, the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for dementia was 1.72 for those who consumed more than 14 drinks per week, compared with light drinkers who consumed less than 1 drink per week. For participants who consumed between 7 and 14 drinks per week, the adjusted HR for dementia was 0.63 among those without MCI and 0.93 among those with MCI, relative to light drinkers who consumed less than 1 drink per week.

Among adults with normal cognition at baseline, daily low-quantity drinking was associated with lower dementia risk, compared with infrequent higher-quantity drinking (HR, 0.45).

Trial excluded adults with excessive alcohol use

Limitations of the study include a lack of data about any changes in alcohol consumption over time. In addition, the original trial excluded people with a known history of excessive alcohol use. Furthermore, it is possible that the “long preclinical phase of dementia” and other health issues affect drinking behavior, the authors said. “At present, our findings cannot be directly translated into clinical recommendations,” the authors said. Nevertheless, the results “suggest that, while caring for older adults, physicians should carefully assess the full dimensions of drinking behavior and cognition when providing guidance to patients about alcohol consumption,” they said.

The study was supported by grants from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine; the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; the Office of Dietary Supplements of the National Institute on Aging; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center; the Roena Kulynych Center for Memory and Cognition Research; and Wake Forest University School of Medicine. In addition, the researchers used plasma samples from the National Cell Repository for Alzheimer’s Disease, which receives support from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Koch had no conflicts of interest. Coauthors disclosed university and government grants and personal fees from pharmaceutical companies outside the study. One author was an employee of Genentech at the time of publication, but Genentech did not contribute to the study.

SOURCE: Koch M et al. JAMA Network Open. 2019 Sep 27. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10319.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) may influence the relationship between alcohol consumption and dementia risk, a study of more than 3,000 adults suggests. In addition, , according to the study, which was published in JAMA Network Open.

“The associations of self-reported alcohol consumption with dementia risk and cognitive decline were more consistently adverse among individuals with MCI than those with normal cognition,” reported Manja Koch, PhD, a researcher in the department of nutrition at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston and colleagues. “This was particularly true for the subset of individuals [with MCI] who drank more than 14.0 servings per week, whose rate of cognitive decline and risk of dementia were the highest of any subgroup.”

Among older adults with normal cognition, the results generally were consistent with those of a recent meta-analysis that found a U-shaped relationship between drinking and dementia, the researchers said (Eur J Epidemiol. 2017 Jan;32[1]:31-42.).

“Our results did not show significant associations and clearly do not suffice to suggest a clinical benefit from even limited alcohol use,” said Dr. Koch and colleagues. “Nonetheless, our findings provide some reassurance that alcohol consumed within recommended limits was not associated with an increased risk of dementia among older adults with normal baseline cognition.”

GEMS data

To study whether alcohol consumption is associated with the risk of dementia and cognitive decline in older adults with and without MCI, the investigators analyzed data from the Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study (GEMS). GEMS was a randomized controlled trial conducted between 2000 and 2008 that found no overall association between ginkgo biloba and dementia prevention. During the trial, participants completed the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination, the Clinical Dementia Rating scale, and the cognitive portion of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale.

In the present study, the investigators analyzed data from 3,021 participants aged 72 years and older who were free of dementia at baseline and had provided information about their alcohol intake. Their median age was 78 years, and 46.2% were female. Fifty-eight percent consumed alcohol, including 45% of the participants with MCI at baseline.

During follow-up, 512 cases of dementia occurred. Among the 473 participants with MCI at baseline, the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for dementia was 1.72 for those who consumed more than 14 drinks per week, compared with light drinkers who consumed less than 1 drink per week. For participants who consumed between 7 and 14 drinks per week, the adjusted HR for dementia was 0.63 among those without MCI and 0.93 among those with MCI, relative to light drinkers who consumed less than 1 drink per week.

Among adults with normal cognition at baseline, daily low-quantity drinking was associated with lower dementia risk, compared with infrequent higher-quantity drinking (HR, 0.45).

Trial excluded adults with excessive alcohol use

Limitations of the study include a lack of data about any changes in alcohol consumption over time. In addition, the original trial excluded people with a known history of excessive alcohol use. Furthermore, it is possible that the “long preclinical phase of dementia” and other health issues affect drinking behavior, the authors said. “At present, our findings cannot be directly translated into clinical recommendations,” the authors said. Nevertheless, the results “suggest that, while caring for older adults, physicians should carefully assess the full dimensions of drinking behavior and cognition when providing guidance to patients about alcohol consumption,” they said.

The study was supported by grants from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine; the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; the Office of Dietary Supplements of the National Institute on Aging; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center; the Roena Kulynych Center for Memory and Cognition Research; and Wake Forest University School of Medicine. In addition, the researchers used plasma samples from the National Cell Repository for Alzheimer’s Disease, which receives support from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Koch had no conflicts of interest. Coauthors disclosed university and government grants and personal fees from pharmaceutical companies outside the study. One author was an employee of Genentech at the time of publication, but Genentech did not contribute to the study.

SOURCE: Koch M et al. JAMA Network Open. 2019 Sep 27. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10319.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

CDC reports most vaping lung disease linked to THC-containing cartridges

and most products used were prepackaged, prefilled cartridges, according to new data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The majority of these products (66%) were THC-containing cartridges marketed under the brand name Dank. Dank cartridges are available at legal dispensaries and online in areas where they are legal. The Dank company posted a statement on its website warning buyers about fake cartridges and showing images of genuine cartridges. However, 89% of the cartridges were obtained on the street, from dealers, online, or from friends or social contacts, Jennifer Layden, MD, of the Illinois Department of Public Health said during a CDC telebriefing.

The illness was first recognized in Wisconsin and Illinois. Marijuana is illegal in Wisconsin; Illinois licensed recreational marijuana in 2009.

Other commonalties among cases have also emerged, Anne Schuchat, MD, deputy director of CDC, said during the call. More than two-thirds of the 805 confirmed or probable cases were male, and the median age was 23 years. The illness crosses age barriers, she said. About 62% were 18-24 years of age, and 54% under age 25. However, among the 12 deaths so far reported, the median age was 50 years. The age range was wide, from 27 to 71 years. Dr. Schuchat said data about medical comorbidities potentially linking the deaths is not yet available, although it is part of the ongoing investigation.

Other clinical commonalities included intensive use of THC-containing products and, in a small number of cases, concomitant use of benzodiazepenes, opioids, and narcotics.

Cases have now emerged in 46 states and in the U.S. Virgin Islands, although the number reported each week is dropping. However, this decrease may not represent a drop in newly occurring cases, but instead reflect delays in clinical recognition or reporting to local health departments, Dr. Schuchat said.

Regardless of the recent decline in reported cases, she said, the epidemic is serious, far reaching, and ongoing.

“I want to stress that this is a serious, life-threatening disease occurring mostly in otherwise healthy young people. These illnesses and deaths are occurring in the context of a dynamic marketplace with mix of products with mixes of ingredients, including potentially illicit substances. Users don’t know what’s in them and cannot tell from the ingredients listed on the packaging.”

Dr. Schuchat drew her data from two reports issued in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: a national case update by Peter A. Briss, MD, chair of CDC’s Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Group, and colleagues, and a regional report coauthored by Dr. Layden of cases in Illinois and Wisconsin.

In the national report, 514 patients self-reported their history of e-cigarette and vaping use. Among those, 395 (76.9%) reported using THC-containing products, and 292 (56.8%) reported using nicotine-containing products in the 30 days preceding symptom onset. Almost half (210; 40.9%) reported using both THC- and nicotine-containing products.

But there appeared to be no clear pattern of use, said Dr. Briss, who also participated in the briefing. More than a third (185; 36.0%) reported exclusive use of THC-containing products, and 82 (16.0%) reported exclusive use of nicotine-containing products.

The regional report added additional details.

Among the 86 patients who self-reported details, there were 234 unique cases of e-cigarette or THC vaping in 87 brands.

“Patients reported using numerous products and brands,” Dr. Layden noted. “Those who reported using THC products used an average of 2.1 different products and those who reported using nicotine products used about 1.3 different ones. Some patients reported using up to seven different brands, and these were used at least daily and sometimes numerous times in the day.”

According to the MMWR regional report, among the urinary THC screens obtained for 32 patients, “29 (91%) were positive for THC. One of these patients reported smoking combustible marijuana. Urinary THC levels for four patients who reported using THC-containing products exceeded 400 ng/ml, indicating intensive use of THC or THC-containing products.”

About 40% of THC users and 65% of nicotine-product users reported using the product at least five times a day; 52% said they used combustible marijuana in addition to the vapes, and 24% reported also smoking combustible tobacco.

There was a very low level of concomitant drug use. Two patients reported using LSD; one reported misusing dextroamphetamine-amphetamine (Adderall), and one reported misusing oxycodone. Two tested positive for benzodiazepines and opioids, and one each for only benzodiazepines, only opioids, only amphetamines. One patient screened positive for unidentified narcotics.

and most products used were prepackaged, prefilled cartridges, according to new data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The majority of these products (66%) were THC-containing cartridges marketed under the brand name Dank. Dank cartridges are available at legal dispensaries and online in areas where they are legal. The Dank company posted a statement on its website warning buyers about fake cartridges and showing images of genuine cartridges. However, 89% of the cartridges were obtained on the street, from dealers, online, or from friends or social contacts, Jennifer Layden, MD, of the Illinois Department of Public Health said during a CDC telebriefing.

The illness was first recognized in Wisconsin and Illinois. Marijuana is illegal in Wisconsin; Illinois licensed recreational marijuana in 2009.

Other commonalties among cases have also emerged, Anne Schuchat, MD, deputy director of CDC, said during the call. More than two-thirds of the 805 confirmed or probable cases were male, and the median age was 23 years. The illness crosses age barriers, she said. About 62% were 18-24 years of age, and 54% under age 25. However, among the 12 deaths so far reported, the median age was 50 years. The age range was wide, from 27 to 71 years. Dr. Schuchat said data about medical comorbidities potentially linking the deaths is not yet available, although it is part of the ongoing investigation.

Other clinical commonalities included intensive use of THC-containing products and, in a small number of cases, concomitant use of benzodiazepenes, opioids, and narcotics.

Cases have now emerged in 46 states and in the U.S. Virgin Islands, although the number reported each week is dropping. However, this decrease may not represent a drop in newly occurring cases, but instead reflect delays in clinical recognition or reporting to local health departments, Dr. Schuchat said.

Regardless of the recent decline in reported cases, she said, the epidemic is serious, far reaching, and ongoing.

“I want to stress that this is a serious, life-threatening disease occurring mostly in otherwise healthy young people. These illnesses and deaths are occurring in the context of a dynamic marketplace with mix of products with mixes of ingredients, including potentially illicit substances. Users don’t know what’s in them and cannot tell from the ingredients listed on the packaging.”

Dr. Schuchat drew her data from two reports issued in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: a national case update by Peter A. Briss, MD, chair of CDC’s Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Group, and colleagues, and a regional report coauthored by Dr. Layden of cases in Illinois and Wisconsin.

In the national report, 514 patients self-reported their history of e-cigarette and vaping use. Among those, 395 (76.9%) reported using THC-containing products, and 292 (56.8%) reported using nicotine-containing products in the 30 days preceding symptom onset. Almost half (210; 40.9%) reported using both THC- and nicotine-containing products.

But there appeared to be no clear pattern of use, said Dr. Briss, who also participated in the briefing. More than a third (185; 36.0%) reported exclusive use of THC-containing products, and 82 (16.0%) reported exclusive use of nicotine-containing products.

The regional report added additional details.

Among the 86 patients who self-reported details, there were 234 unique cases of e-cigarette or THC vaping in 87 brands.

“Patients reported using numerous products and brands,” Dr. Layden noted. “Those who reported using THC products used an average of 2.1 different products and those who reported using nicotine products used about 1.3 different ones. Some patients reported using up to seven different brands, and these were used at least daily and sometimes numerous times in the day.”

According to the MMWR regional report, among the urinary THC screens obtained for 32 patients, “29 (91%) were positive for THC. One of these patients reported smoking combustible marijuana. Urinary THC levels for four patients who reported using THC-containing products exceeded 400 ng/ml, indicating intensive use of THC or THC-containing products.”

About 40% of THC users and 65% of nicotine-product users reported using the product at least five times a day; 52% said they used combustible marijuana in addition to the vapes, and 24% reported also smoking combustible tobacco.

There was a very low level of concomitant drug use. Two patients reported using LSD; one reported misusing dextroamphetamine-amphetamine (Adderall), and one reported misusing oxycodone. Two tested positive for benzodiazepines and opioids, and one each for only benzodiazepines, only opioids, only amphetamines. One patient screened positive for unidentified narcotics.

and most products used were prepackaged, prefilled cartridges, according to new data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The majority of these products (66%) were THC-containing cartridges marketed under the brand name Dank. Dank cartridges are available at legal dispensaries and online in areas where they are legal. The Dank company posted a statement on its website warning buyers about fake cartridges and showing images of genuine cartridges. However, 89% of the cartridges were obtained on the street, from dealers, online, or from friends or social contacts, Jennifer Layden, MD, of the Illinois Department of Public Health said during a CDC telebriefing.

The illness was first recognized in Wisconsin and Illinois. Marijuana is illegal in Wisconsin; Illinois licensed recreational marijuana in 2009.

Other commonalties among cases have also emerged, Anne Schuchat, MD, deputy director of CDC, said during the call. More than two-thirds of the 805 confirmed or probable cases were male, and the median age was 23 years. The illness crosses age barriers, she said. About 62% were 18-24 years of age, and 54% under age 25. However, among the 12 deaths so far reported, the median age was 50 years. The age range was wide, from 27 to 71 years. Dr. Schuchat said data about medical comorbidities potentially linking the deaths is not yet available, although it is part of the ongoing investigation.

Other clinical commonalities included intensive use of THC-containing products and, in a small number of cases, concomitant use of benzodiazepenes, opioids, and narcotics.

Cases have now emerged in 46 states and in the U.S. Virgin Islands, although the number reported each week is dropping. However, this decrease may not represent a drop in newly occurring cases, but instead reflect delays in clinical recognition or reporting to local health departments, Dr. Schuchat said.

Regardless of the recent decline in reported cases, she said, the epidemic is serious, far reaching, and ongoing.

“I want to stress that this is a serious, life-threatening disease occurring mostly in otherwise healthy young people. These illnesses and deaths are occurring in the context of a dynamic marketplace with mix of products with mixes of ingredients, including potentially illicit substances. Users don’t know what’s in them and cannot tell from the ingredients listed on the packaging.”

Dr. Schuchat drew her data from two reports issued in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: a national case update by Peter A. Briss, MD, chair of CDC’s Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Group, and colleagues, and a regional report coauthored by Dr. Layden of cases in Illinois and Wisconsin.

In the national report, 514 patients self-reported their history of e-cigarette and vaping use. Among those, 395 (76.9%) reported using THC-containing products, and 292 (56.8%) reported using nicotine-containing products in the 30 days preceding symptom onset. Almost half (210; 40.9%) reported using both THC- and nicotine-containing products.

But there appeared to be no clear pattern of use, said Dr. Briss, who also participated in the briefing. More than a third (185; 36.0%) reported exclusive use of THC-containing products, and 82 (16.0%) reported exclusive use of nicotine-containing products.

The regional report added additional details.

Among the 86 patients who self-reported details, there were 234 unique cases of e-cigarette or THC vaping in 87 brands.

“Patients reported using numerous products and brands,” Dr. Layden noted. “Those who reported using THC products used an average of 2.1 different products and those who reported using nicotine products used about 1.3 different ones. Some patients reported using up to seven different brands, and these were used at least daily and sometimes numerous times in the day.”

According to the MMWR regional report, among the urinary THC screens obtained for 32 patients, “29 (91%) were positive for THC. One of these patients reported smoking combustible marijuana. Urinary THC levels for four patients who reported using THC-containing products exceeded 400 ng/ml, indicating intensive use of THC or THC-containing products.”

About 40% of THC users and 65% of nicotine-product users reported using the product at least five times a day; 52% said they used combustible marijuana in addition to the vapes, and 24% reported also smoking combustible tobacco.

There was a very low level of concomitant drug use. Two patients reported using LSD; one reported misusing dextroamphetamine-amphetamine (Adderall), and one reported misusing oxycodone. Two tested positive for benzodiazepines and opioids, and one each for only benzodiazepines, only opioids, only amphetamines. One patient screened positive for unidentified narcotics.

Private equity and independent gastroenterology practices – what do I need to know?

A few years ago, private equity (PE) firms began to focus on independent gastroenterology practices as a target for investment. The first PE investment transaction closed in March of 2016, and now an additional three such partnerships have occurred. Investment firms believe gastroenterology is ripe for investment and subsequent consolidation for the following reasons:

- Gastroenterology is a highly fragmented specialty with many small and mid-sized groups that could be rolled up into larger practice entities that create favorable scalability.

- There are multiple revenue streams through ancillary services that can be packaged into a comprehensive, high-quality gastroenterology practice that has high value for patients and that are delivered outside of a hospital environment.

- There is a growing need for gastroenterology care with increasing demand for chronic GI disease management (fatty liver disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and obesity management, for example) and increasing demand for colon cancer screening.

- Most independent gastroenterologists have natural entrepreneurial spirit.

- The current financial environment is favorable for investment and other sectors of the health care market are rapidly consolidating.

A PE transaction is not appropriate for every practice nor every physician. Further, not every physician group will be desirable for a PE firm. Nonetheless, the current business climate in the GI sector is generally favorable for accepting the PE capital model.

The following are 10 common questions dealing with a PE transaction:

1. What does a PE deal mean for the independent gastroenterologist? A PE transaction and the resulting formation of a managed services organization (MSO) will be a liquidity event for all current owners in the acquired practice. Financial benefits are typically substantial, especially when considering the funds can then be invested by the individual physician and often the money paid can be taxed as capital gains rather than ordinary income. In exchange for the pay-out, the physician group relinquishes managerial control of nonclinical decisions through a managed services agreement (MSA) with the MSO. The MSO is typically formed by the partnership between the practice and the PE firm and provides all nonclinical services to the physician group.

2. What autonomy will be left after signing a PE deal/MSA? Autonomy after the deal closes is determined largely by terms written into the contract prior to the closing and will differ among the various PE firms. There will be conditions important to the MSO and some important to the practice that can be codified in the contract. These conditions are spelled out in an employment agreement with the continuing physician group. Both the PE group and physicians will want to ensure that practice culture is not negatively impacted through an acquisition. Physicians must feel that they retain complete autonomy when it comes to clinical decisions, and the PE group must avoid interfering in the patient-doctor relationship. The PE group wants to improve nonclinical management of the practice, without interfering with the actual care of a patient. Physicians may influence nonclinical managerial decisions, but providers must understand that all nonclinical managerial decisions ultimately will be made by the MSO and PE firm.

3. What makes a good PE partnership? The asset that a PE firm is purchasing and hoping to grow is the revenue from a medical practice that they hope to improve by increasing profitability (through enhanced efficiency), expanding ancillary services and through multiple additional acquisitions to gain scale and size. Ensuring both sides are respected and aligned in decisions helps move the organization forward. A good partnership will build and bridge three types of capital – financial, experiential, and educational. Various factors must be considered; however, most important is mutual respect and admiration between the MSO and the physicians. Managerial styles will vary, but, a shared vision of the future will lead to success.

4. What changes are ahead with a PE deal? A PE firm and the MSO that it controls will put its management team in place to optimize revenue and contain expenses. The PE firm will look to combine practices where synergies exist and growth potential is strategically beneficial. For example, one practice might bring a pathology lab, the other geographic coverage, and the third an infusion center. Larger scale will usually improve negotiating influence with payers and hospitals as well as buying power for operational necessities. The MSO will roll out best practice protocols throughout the group, both back-office as well as patient-facing services. Finally, all PE groups will transition accounting to accrual from cash based as well as work with outside auditors and consultants due to the MSO’s bank covenants.

5. What is a platform company? A variation on the PE-based MSO is the formation of a “platform company”. This structure typically comes from a more sophisticated, mature practice that already has substantial business structures and managerial team members in place. This type of company can provide services not just to the founding practice, but to others that are “added on” as the organization grows. The investment hold period by the PE firm is typically 4-6 years, and thus, adding expertise to existing processes is usually more efficient and effective than starting from the ground up. Platform companies are typically paid a higher multiple than a company or practice that is “added on” to an existing platform, especially since these owners are taking the greatest risk by being the initial investor.

6. Explain the idiom “second bite of the apple”? A portion of each owner’s proceeds from the initial sale (“first bite of the apple”) of the practice is typically converted into stock of the MSO in a tax favorable method. The PE firm will maintain the largest shareholder position in the MSO (often majority), while the physicians and management team will be minority shareholders in the MSO. The proportion of proceeds rolled into stock depends on negotiations and ranges anywhere from 20% to 50% of the proceeds. The “second bite” is when the PE firm sells the stock of the MSO to the next investor. At the time of that transaction, all shareholders have a liquidity event and often another portion of the proceeds are rolled for the “next bite of the apple”. Specific terms of the shares are defined during negotiations, specifically the vesting terms, voting rights associated, and the value of each share.

7. Why would one practice receive a higher multiple compared to another practice? Each practice will have a different intrinsic value to the MSO and PE firm. The range of multiples on the purchased earnings before interest, depreciation, taxes, and amortization (EBIDTA) will depend on the timing of the transaction in the lifecycle of the investment as well as market forces. The number, age, and productivity of a practice’s providers, the ability to add certain ancillary services (i.e., revenue sources), the quality of contracts and associated payer mix, and the location of a practice are often the critical elements which the PE firm evaluates in the determination of a group’s value. The investment strategy will not be successful if exorbitant multiples are used for every practice. Strategically, a group with multiple providers in a desirable location with limited ancillary services early in the lifecycle will likely receive a higher multiple than a smaller group.

8. What outside professional assistance is needed to consummate a PE deal? Some groups may depend on an investment banker or health care mergers and acquisitions consultant to assist in the process or even seek out a partnership. Larger, more complicated groups with various existing relationships and competing forces often require such professional assistance. However, other smaller groups being approached by the MSO/PE firm as a “bolt-on” acquisition might not require a professional banker as the terms of joining may be more uniform to create a cohesive group of providers upon closing. All transactions, however, will require experienced health care transaction attorneys to ensure compliance with the myriad regulations. Some may engage a tax law attorney or accountant to ensure terms of the transaction are favorable. The PE firm will almost certainly require a quality of earnings evaluation by an outside, third-party financial auditor. One can probably assume close to 5% of proceeds may go to various professionals assisting in the process of the deal.

9. What are the common governance structures in PE transactions for physician provider service organizations? Like most businesses, a group of individuals typically form a board of directors which work in a decision making capacity and provide advice to the management team of the MSO. The board of directors usually includes successful leaders from other industries or business which bring specific talents, connections, and experiences, as well as individuals from the PE group and management team. Often, the platform practice will have a representative physician sit on the MSO board to ensure the medical provider perspective is prominent. The board of directors typically approves acquisitions and entry into new MSAs with additional practices, sets quarterly or yearly strategic goals, approves the budget and management team compensation structure and ultimately works on an exit strategy for the PE firm. Finally, pros and cons exist to having a physician as the CEO of the MSO; regardless, the CEO must be a strong leader with a vision and solid ability to communicate, as the PE sponsor and board of directors will have certain expectations, just as the independent gastroenterologist becoming a part of a new entity will have significant insecurities and hesitancies which must be appreciated and reassured.

10. In 3-5 years, what opportunities will a gastroenterologist leaving fellowship face as far as the GI landscape? Beyond the typical hospital-based employment opportunities or academic positions, consolidation of groups from PE acquisitions will likely have led to regional and maybe even national companies competing amongst themselves for talent. Over the coming years, there may be a total of 6-8 entities consisting of 15% of all gastroenterologists. Likely, one or two of the currently backed PE companies will have a new investor (i.e., initial exit completed/“second bite”). Each group will try to provide a differing value-based proposition beyond just the location a provider will be practicing. Fellows entering a practice already owned by a PE firm (or if a sale is pending) must clearly understand the legal, financial, and governance implications of these structures. This type of business structure is much different than one would encounter when hired by a physician-owned practice. It is not yet clear how a PE exit (4-6 years after acquisition) will play out for physicians not part of the original practice.

Dr. Sonenshine is a member of Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates.

A few years ago, private equity (PE) firms began to focus on independent gastroenterology practices as a target for investment. The first PE investment transaction closed in March of 2016, and now an additional three such partnerships have occurred. Investment firms believe gastroenterology is ripe for investment and subsequent consolidation for the following reasons:

- Gastroenterology is a highly fragmented specialty with many small and mid-sized groups that could be rolled up into larger practice entities that create favorable scalability.

- There are multiple revenue streams through ancillary services that can be packaged into a comprehensive, high-quality gastroenterology practice that has high value for patients and that are delivered outside of a hospital environment.

- There is a growing need for gastroenterology care with increasing demand for chronic GI disease management (fatty liver disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and obesity management, for example) and increasing demand for colon cancer screening.

- Most independent gastroenterologists have natural entrepreneurial spirit.

- The current financial environment is favorable for investment and other sectors of the health care market are rapidly consolidating.

A PE transaction is not appropriate for every practice nor every physician. Further, not every physician group will be desirable for a PE firm. Nonetheless, the current business climate in the GI sector is generally favorable for accepting the PE capital model.

The following are 10 common questions dealing with a PE transaction:

1. What does a PE deal mean for the independent gastroenterologist? A PE transaction and the resulting formation of a managed services organization (MSO) will be a liquidity event for all current owners in the acquired practice. Financial benefits are typically substantial, especially when considering the funds can then be invested by the individual physician and often the money paid can be taxed as capital gains rather than ordinary income. In exchange for the pay-out, the physician group relinquishes managerial control of nonclinical decisions through a managed services agreement (MSA) with the MSO. The MSO is typically formed by the partnership between the practice and the PE firm and provides all nonclinical services to the physician group.

2. What autonomy will be left after signing a PE deal/MSA? Autonomy after the deal closes is determined largely by terms written into the contract prior to the closing and will differ among the various PE firms. There will be conditions important to the MSO and some important to the practice that can be codified in the contract. These conditions are spelled out in an employment agreement with the continuing physician group. Both the PE group and physicians will want to ensure that practice culture is not negatively impacted through an acquisition. Physicians must feel that they retain complete autonomy when it comes to clinical decisions, and the PE group must avoid interfering in the patient-doctor relationship. The PE group wants to improve nonclinical management of the practice, without interfering with the actual care of a patient. Physicians may influence nonclinical managerial decisions, but providers must understand that all nonclinical managerial decisions ultimately will be made by the MSO and PE firm.

3. What makes a good PE partnership? The asset that a PE firm is purchasing and hoping to grow is the revenue from a medical practice that they hope to improve by increasing profitability (through enhanced efficiency), expanding ancillary services and through multiple additional acquisitions to gain scale and size. Ensuring both sides are respected and aligned in decisions helps move the organization forward. A good partnership will build and bridge three types of capital – financial, experiential, and educational. Various factors must be considered; however, most important is mutual respect and admiration between the MSO and the physicians. Managerial styles will vary, but, a shared vision of the future will lead to success.

4. What changes are ahead with a PE deal? A PE firm and the MSO that it controls will put its management team in place to optimize revenue and contain expenses. The PE firm will look to combine practices where synergies exist and growth potential is strategically beneficial. For example, one practice might bring a pathology lab, the other geographic coverage, and the third an infusion center. Larger scale will usually improve negotiating influence with payers and hospitals as well as buying power for operational necessities. The MSO will roll out best practice protocols throughout the group, both back-office as well as patient-facing services. Finally, all PE groups will transition accounting to accrual from cash based as well as work with outside auditors and consultants due to the MSO’s bank covenants.

5. What is a platform company? A variation on the PE-based MSO is the formation of a “platform company”. This structure typically comes from a more sophisticated, mature practice that already has substantial business structures and managerial team members in place. This type of company can provide services not just to the founding practice, but to others that are “added on” as the organization grows. The investment hold period by the PE firm is typically 4-6 years, and thus, adding expertise to existing processes is usually more efficient and effective than starting from the ground up. Platform companies are typically paid a higher multiple than a company or practice that is “added on” to an existing platform, especially since these owners are taking the greatest risk by being the initial investor.

6. Explain the idiom “second bite of the apple”? A portion of each owner’s proceeds from the initial sale (“first bite of the apple”) of the practice is typically converted into stock of the MSO in a tax favorable method. The PE firm will maintain the largest shareholder position in the MSO (often majority), while the physicians and management team will be minority shareholders in the MSO. The proportion of proceeds rolled into stock depends on negotiations and ranges anywhere from 20% to 50% of the proceeds. The “second bite” is when the PE firm sells the stock of the MSO to the next investor. At the time of that transaction, all shareholders have a liquidity event and often another portion of the proceeds are rolled for the “next bite of the apple”. Specific terms of the shares are defined during negotiations, specifically the vesting terms, voting rights associated, and the value of each share.

7. Why would one practice receive a higher multiple compared to another practice? Each practice will have a different intrinsic value to the MSO and PE firm. The range of multiples on the purchased earnings before interest, depreciation, taxes, and amortization (EBIDTA) will depend on the timing of the transaction in the lifecycle of the investment as well as market forces. The number, age, and productivity of a practice’s providers, the ability to add certain ancillary services (i.e., revenue sources), the quality of contracts and associated payer mix, and the location of a practice are often the critical elements which the PE firm evaluates in the determination of a group’s value. The investment strategy will not be successful if exorbitant multiples are used for every practice. Strategically, a group with multiple providers in a desirable location with limited ancillary services early in the lifecycle will likely receive a higher multiple than a smaller group.

8. What outside professional assistance is needed to consummate a PE deal? Some groups may depend on an investment banker or health care mergers and acquisitions consultant to assist in the process or even seek out a partnership. Larger, more complicated groups with various existing relationships and competing forces often require such professional assistance. However, other smaller groups being approached by the MSO/PE firm as a “bolt-on” acquisition might not require a professional banker as the terms of joining may be more uniform to create a cohesive group of providers upon closing. All transactions, however, will require experienced health care transaction attorneys to ensure compliance with the myriad regulations. Some may engage a tax law attorney or accountant to ensure terms of the transaction are favorable. The PE firm will almost certainly require a quality of earnings evaluation by an outside, third-party financial auditor. One can probably assume close to 5% of proceeds may go to various professionals assisting in the process of the deal.

9. What are the common governance structures in PE transactions for physician provider service organizations? Like most businesses, a group of individuals typically form a board of directors which work in a decision making capacity and provide advice to the management team of the MSO. The board of directors usually includes successful leaders from other industries or business which bring specific talents, connections, and experiences, as well as individuals from the PE group and management team. Often, the platform practice will have a representative physician sit on the MSO board to ensure the medical provider perspective is prominent. The board of directors typically approves acquisitions and entry into new MSAs with additional practices, sets quarterly or yearly strategic goals, approves the budget and management team compensation structure and ultimately works on an exit strategy for the PE firm. Finally, pros and cons exist to having a physician as the CEO of the MSO; regardless, the CEO must be a strong leader with a vision and solid ability to communicate, as the PE sponsor and board of directors will have certain expectations, just as the independent gastroenterologist becoming a part of a new entity will have significant insecurities and hesitancies which must be appreciated and reassured.

10. In 3-5 years, what opportunities will a gastroenterologist leaving fellowship face as far as the GI landscape? Beyond the typical hospital-based employment opportunities or academic positions, consolidation of groups from PE acquisitions will likely have led to regional and maybe even national companies competing amongst themselves for talent. Over the coming years, there may be a total of 6-8 entities consisting of 15% of all gastroenterologists. Likely, one or two of the currently backed PE companies will have a new investor (i.e., initial exit completed/“second bite”). Each group will try to provide a differing value-based proposition beyond just the location a provider will be practicing. Fellows entering a practice already owned by a PE firm (or if a sale is pending) must clearly understand the legal, financial, and governance implications of these structures. This type of business structure is much different than one would encounter when hired by a physician-owned practice. It is not yet clear how a PE exit (4-6 years after acquisition) will play out for physicians not part of the original practice.

Dr. Sonenshine is a member of Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates.

A few years ago, private equity (PE) firms began to focus on independent gastroenterology practices as a target for investment. The first PE investment transaction closed in March of 2016, and now an additional three such partnerships have occurred. Investment firms believe gastroenterology is ripe for investment and subsequent consolidation for the following reasons:

- Gastroenterology is a highly fragmented specialty with many small and mid-sized groups that could be rolled up into larger practice entities that create favorable scalability.

- There are multiple revenue streams through ancillary services that can be packaged into a comprehensive, high-quality gastroenterology practice that has high value for patients and that are delivered outside of a hospital environment.

- There is a growing need for gastroenterology care with increasing demand for chronic GI disease management (fatty liver disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and obesity management, for example) and increasing demand for colon cancer screening.

- Most independent gastroenterologists have natural entrepreneurial spirit.

- The current financial environment is favorable for investment and other sectors of the health care market are rapidly consolidating.

A PE transaction is not appropriate for every practice nor every physician. Further, not every physician group will be desirable for a PE firm. Nonetheless, the current business climate in the GI sector is generally favorable for accepting the PE capital model.

The following are 10 common questions dealing with a PE transaction:

1. What does a PE deal mean for the independent gastroenterologist? A PE transaction and the resulting formation of a managed services organization (MSO) will be a liquidity event for all current owners in the acquired practice. Financial benefits are typically substantial, especially when considering the funds can then be invested by the individual physician and often the money paid can be taxed as capital gains rather than ordinary income. In exchange for the pay-out, the physician group relinquishes managerial control of nonclinical decisions through a managed services agreement (MSA) with the MSO. The MSO is typically formed by the partnership between the practice and the PE firm and provides all nonclinical services to the physician group.